Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Dual-Detection Method for Cashew Ripeness and Anthrax Based on YOLOv11-NSDDil

School of Information Science and Engineering, Hebei North University, Zhangjiakou, 075000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Dong Yang. Email: ; Jingjing Yang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Big Data and Artificial Intelligence in Control and Information System)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070734

Received 22 July 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

In the field of smart agriculture, accurate and efficient object detection technology is crucial for automated crop management. A particularly challenging task in this domain is small object detection, such as the identification of immature fruits or early stage disease spots. These objects pose significant difficulties due to their small pixel coverage, limited feature information, substantial scale variations, and high susceptibility to complex background interference. These challenges frequently result in inadequate accuracy and robustness in current detection models. This study addresses two critical needs in the cashew cultivation industry—fruit maturity and anthracnose detection—by proposing an improved YOLOv11-NSDDil model. The method introduces three key technological innovations: (1) The SDDil module is designed and integrated into the backbone network. This module combines depthwise separable convolution with the SimAM attention mechanism to expand the receptive field and enhance contextual semantic capture at a low computational cost, effectively alleviating the feature deficiency problem caused by limited pixel coverage of small objects. Simultaneously, the SD module dynamically enhances discriminative features and suppresses background noise, significantly improving the model’s feature discrimination capability in complex environments; (2) The introduction of the DynamicScalSeq-Zoom_cat neck network, significantly improving multi-scale feature fusion; and (3) The optimization of the Minimum Point Distance Intersection over Union (MPDIoU) loss function, which enhances bounding box localization accuracy by minimizing vertex distance. Experimental results on a self-constructed cashew dataset containing 1123 images demonstrate significant performance improvements in the enhanced model: mAP50 reaches 0.825, a 4.6% increase compared to the original YOLOv11; mAP50-95 improves to 0.624, a 6.5% increase; and recall rises to 0.777, a 2.4% increase. This provides a reliable technical solution for intelligent quality inspection of agricultural products and holds broad application prospects.Keywords

Agriculture is the foundation for the survival and development of human society, serving as the primary source of food and agricultural products. In the global agricultural system, cash crops constitute a vital component of agriculture. They not only diversify the structure of agricultural products but also provide crucial support for increasing farmers’ income and international trade. Among these, cashew nuts hold a distinctive position as a high-value cash crop. The cashew tree provides nutritional, economic, and health benefits through its products [1]. Cashews are rich in energy and essential minerals, such as copper, magnesium, and manganese, which play crucial roles in cognitive function and immunity [1]. The cashew consists of two parts: the cashew nut and the cashew apple. It is native to tropical America.

The cashew industry primarily processes cashew kernels, which account for only 10% of the total fruit weight. The remaining 90% consists of the edible cashew apple and the shell, making up 50%–65% of the raw nut’s weight. The cashew is a multipurpose plant, both food and medicinal [2]. Cashew kernels are used in desserts, dishes, and medicinal ingredients. As the main part of the fruit, the cashew apple can be processed into juice, syrup, wine, and other products. The sweetness and acidity of the cashew apple vary significantly depending on the variety and maturity level [3].

The maturity level and variety (red, yellow, orange) of cashew apples significantly affect their physicochemical composition [4]. Ripe cashew apples generally contain higher mineral content and abundant sugars, making them ideal raw material for fermentation in liquor production [5]. As storage time increases, Water is lost in the flesh of cashew apples, resulting in less juice that can be extracted [6]. Cashew apples are highly perishable, have a very short shelf life at room temperature, and are difficult to transport, which adversely affects their processing and marketing. Consequently, while some cashew apples are consumed locally as fruit, a significant portion is often wasted. When left to decompose on plantations, they emit unpleasant odors and cause environmental pollution. However, calcined cashew apple waste can be utilized as a partial substitute for cement [7]. Therefore, cashew apples of different maturity levels have different uses.

The cashew shell contains protein, dietary fiber, vitamins, and other phytonutrients that are essential for human nutrition, and also exhibits strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential [8]. However, improper disposal of cashew shells as waste poses environmental risks, but through a series of processing steps, they can be converted into useful activated carbon [9] and cashew shell liquid. Cashew shell liquid not only inhibits corrosion through film formation but also provides effective lubrication, reducing friction, wear, and chemomechanical degradation [10].

Thus, every part of the cashew holds significant economic value. The maturity level of the cashew notably influences its processing and applications. Specific harvesting methods vary depending on the part of the cashew and the intended processing objectives. When the cashew matures, both the nut and the cashew apple fall together. Since the shell contains corrosive cashew shell oil that can cause skin burns, the nuts are generally collected from the ground. For harvesting the cashew apple, two methods are employed: tree-picking and ground collection. Tree-picking is performed when the cashew apple is mature but has not yet dropped, at which stage it turns red or yellow. Such apples can be used for fresh consumption, juice extraction, wine production, and other processing requiring high-quality pulp. Ground collection targets cashew apples that are overripe or fall off naturally. These apples can be used for secondary processing like alcohol fermentation or animal feed. However, fallen apples are prone to mold contamination (e.g., aflatoxin-producing fungi) and must be processed within 24 h. Otherwise, they develop unpleasant odors. Therefore, by detecting the maturity of the cashew apples, the value can be maximized before the cashew apples rot.

Although cashew is a high-value cash crop, its harvesting process is both time-consuming and labor-intensive, leading to high production costs and significant losses. Moreover, some cashew-growing regions are particularly vulnerable to diseases such as anthracnose, which often causes premature cashew drop. To enable timely interventions for disease control and prevention, early monitoring and detection of infections are essential, followed by appropriate measures [11].

At present, cashew research clearly leans towards its by-products (such as shells and shell oil), with applications mostly concentrated in the fields of materials, chemistry, and pharmaceuticals. In contrast, research on the intelligent detection and processing of the cashew itself (including the cashew nuts and the cashew apple) is severely lagging behind. In the current production system, key processes such as fruit harvesting, quality inspection, and disease identification still heavily rely on manual labor, and there is an urgent need to introduce automated solutions based on computer vision and deep learning. Although the rapid development of artificial intelligence technology has made it possible to replace traditional manual operations, its application in actual agricultural environments still faces severe challenges, leading to significant degradation in model performance. For example, the lesions of diseases and diseases are smaller, the cashews are smaller, the characteristics of maturity are similar, and the resolution of the image is not high.

In conclusion, in order to address these issues and meet the multi-object detection requirements for assessing the ripeness of cashew and identifying anthracnose, this study proposes an improved algorithm based on YOLOv11. This model can simultaneously locate multiple cashew in the images and accurately determine their maturity levels and disease status. This provides a quantitative basis for scientific harvesting. The following are the major contributions of our work:

(1) A novel object detection model named YOLOv11-NSDDil is proposed, which significantly enhances the feature extraction and feature fusion capabilities of YOLOv11 in detection tasks.

(2) A Multi-Scale Feature Extraction Module (SDDil) is introduced, which utilizes a multi-branch structure for feature fusion and further refines high-level semantic features, thereby strengthening the model’s feature extraction ability. This module integrates dilated convolution, depthwise separable convolution, and the SimAM attention mechanism. It effectively enlarges the receptive field without substantially increasing computational cost, providing a stronger foundation for cashew maturity and disease detection.

(3) To solve the problem of information loss that is traditionally upsampling, this study replaces conventional upsampling in the neck network with DynamicScaleSeq upsampling and further incorporates the Zoom_cat module for improved feature fusion. This enhancement substantially improves small object detection performance and significantly strengthens the overall robustness of the neck network component to scale variations.

(4) This study compares multiple loss functions and ultimately selects MPDIoU, which is specifically designed for small object detection, to further optimize model performanc.

The structure of this article is as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant research in this field. In Section 3, the proposed algorithm improvements are detailed, with a focus on the key advancements. Section 4 presents the experimental data, comments, and comparisons with existing technologies. Section 5 is a summary of the entire article.

Current research on cashew primarily focuses on pest and disease detection, food nutrition analysis, development of chemical materials, and investigation of medical and pharmacological activities. However, studies specifically targeting intelligent detection of cashew pests and diseases remain relatively limited. Among the existing research, Panchbhai et al. [1] proposed a CAS-CNN model by improving MobileNetV2, which achieved an average accuracy of 99.8% in detecting diseases and pests on cashew apples and nuts. Vidhya and Priya [12] applied the YOLOv5 model for monotypic pest detection targeting the tea mosquito bug, ultimately reaching an accuracy of 90.9%. Maruthadurai et al. [13] utilized acoustic detection technology to identify stem and root borers in cashew trees, achieving a correct detection rate of 91% for infected trees. Winklmair et al. [14] utilized transfer learning to replace the Res-Net50 module with the corresponding EfficientNet-B0 and Inception-V3 modules, and classified mature cashew nuts and immature cashew nuts. The final average accuracy rate reached 95.58%.

This study focused on the maturity of cashew apples, but it has certain limitations in terms of classification categories.

2.2 Carry Out Research on Fruit Ripeness Using YOLO

The deep learning-based object detection algorithms have been successfully applied in the agricultural field. Among them, the YOLO series algorithms have been widely used due to their efficiency and accuracy. The object detection algorithms based on the YOLO series have been widely applied in fruit maturity classification due to their real-time advantages. Researchers have optimized the model performance through various strategies: Ye et al. [15] proposed an improved YOLOv9 model for multi-stage detection of strawberry fruit maturity and combined the composite refinement network (CRNet) to improve image quality and detection accuracy. Tamrakar et al. [16] introduced the Ghost module to replace the CBS and C3 modules in YOLOv5s and carried out comprehensive model compression. The default GIOU bounding box regressor loss function was replaced by SIOU to improve positioning and was used for detecting the maturity of strawberries (unripe period, transition period, mature period). The improved model showed a higher mAP50 of 91.7%. Li et al. [17] proposed the YOLOX-EIoU-CBAM, which combines the EIoU loss function and the CBAM attention mechanism, significantly improving the accuracy and robustness of sweet cherry maturity classification in complex backgrounds and situations where the fruit color is similar to the leaves, and the improved classification accuracy mAP50 reached 81.10%. Fan et al. [18] proposed a strawberry maturity recognition algorithm combining dark channel enhancement and YOLOv5, aiming to solve the problems of low illumination image recognition in the strawberry picking process, such as low accuracy, high error collection or omission rate. The final training accuracy was above 85%, and the detection accuracy was above 90%. Gao et al. [19] proposed an improved apple object detection method based on YOLOv8. They integrated the CBAM attention mechanism into the neural network architecture to reduce background interference and enhance feature representation capabilities. They extended the SPPF architecture to the fourth layer, which included a maximum pooling operation. Through pooling activities at different spatial levels, SPPF could maintain a certain degree of variability and enhance the model’s ability to detect changes in the shape and direction of the target. Finally, the model’s mAP increased by 1.97%. Wang et al. [20] proposed YOLO-ALW. By introducing the AKConv module, they improved the detection performance in occluded and dense environments. SPPF_LSKA enhanced the fusion of multi-scale features and used the Wise-IoU loss function to further improve the detection effect of peppers in occluded or background-similar scenes. Finally, YOLO-ALW achieved an average precision mean (mAP) of 99.1%, an increase of 3.4%. Zhu et al. [21] proposed an improved lightweight YOLO model named YOLO-LM, which introduced three Criss-Cross Attention (CCA) modules into the backbone network to reduce the influence of leaf and branch occlusion as well as mutual occlusion among fruits. The ASFF module served as the head to address the inconsistency limitations in feature pyramids. The GSConv replaced the standard convolution in the Neck network, enabling the model to maintain model accuracy while reducing model complexity. The mAP50 of YOLO-LM reached 93.18%. Sun et al. [22] proposed a lightweight ‘red skin’ jujube maturity detection method based on YOLO-FHLD. The C2fF module was introduced into the YOLOv8n model to create a lightweight model and enhance the extraction ability of ‘red skin’ jujube features. The new feature fusion module HS-FPAN was used to improve the expression and detection accuracy of different maturity ‘red skin’ jujubes. Focal Loss was used as the loss function to solve the problem of class imbalance. Finally, the knowledge distillation strategy further improved the detection accuracy of the model. The model reached 85.40%, an increase of 2.96%. Huang et al. [23] proposed a multi-scale AITP-YOLO model based on the enhanced YOLOv10s model. The four head detectors included a small target detection layer, enhancing the model’s ability to recognize small targets. Secondly, the multi-scale feature fusion technology using cross-level features was implemented in the feature fusion layer, integrating different-sized convolutions to enhance the model’s fusion ability for multi-scale features and generalization ability. The bounding box loss function was modified to Shape-IoU, calculating the loss by emphasizing the shape and scale of the bounding box, thereby improving the accuracy of bounding box regression. Finally, the model was compressed by network pruning to remove redundant channels while maintaining detection accuracy, achieving an average accuracy of 92.6%, an increase of 4.6%. Qiu et al. [24] designed the GSE-YOLO model based on the YOLOv8n algorithm. By replacing the convolution layers in the backbone network of the YOLOv8n model, introducing the attention mechanism, modifying the loss function, and implementing data augmentation, they achieved a detection and recognition accuracy of 85.2% and a recall rate of 87.3%. Visual tasks in agricultural settings often need to address challenges such as multiple objects, small targets, and complex environments. The work by Cardellicchio et al. [25] systematically evaluated the performance of YOLO models in detecting multiple phenotypic traits of tomato plants and berries at different maturity stages. Their research shows that the YOLOv11 model can achieve better overall performance in terms of both accuracy and speed in such complex multi object detection tasks, providing an important basis for the selection of the baseline model in this study.

However, existing research focuses on the maturity of fruits such as strawberries and cherries, with relatively less research on cashew. The morphology of cashew apples is special, and the separation of cashew nuts and cashew apples in color and dual detection (anthracnose + maturity) have not been studied. This study proposes a cashew fruit detection framework based on YOLOv11 [26], initially proposing anthracnose localization and maturity detection, providing a foundation for subsequent automated harvesting and disease prevention and control.

YOLOv11 [26], as one of the latest members of the You Only Look Once (YOLO) family, introduces several architectural improvements over YOLOv8 [27], such as the incorporation of the C3K2 mechanism, the Cross Stage Partial with Pyramid Squeeze Attention (C2PSA) mechanism, and the addition of Depthwise Convolution (DWConv) layers in the classification head. Its overall structure consists of a Backbone, Neck, and Head.

The experiments in this study are conducted on a custom-built cashew dataset. A distinctive characteristic of this dataset is that the immature cashew nuts are small in size, densely distributed, and exhibit high color similarity to the field background, posing critical challenges such as missed detections of small objects and false alarms in complex backgrounds.

To address these challenges, this study aims to enhance the YOLOv11 model with targeted improvements. We focus on boosting the model’s capability in feature extraction and discrimination of small objects and color-similar targets in complex scenes. To this end, a multi-scale feature fusion module, among other designs, is introduced to strengthen the model’s perceptual ability. Based on these enhancements, we propose the YOLOv11-NSDDil model, whose detailed network architecture will be elaborated in Section 3.2.

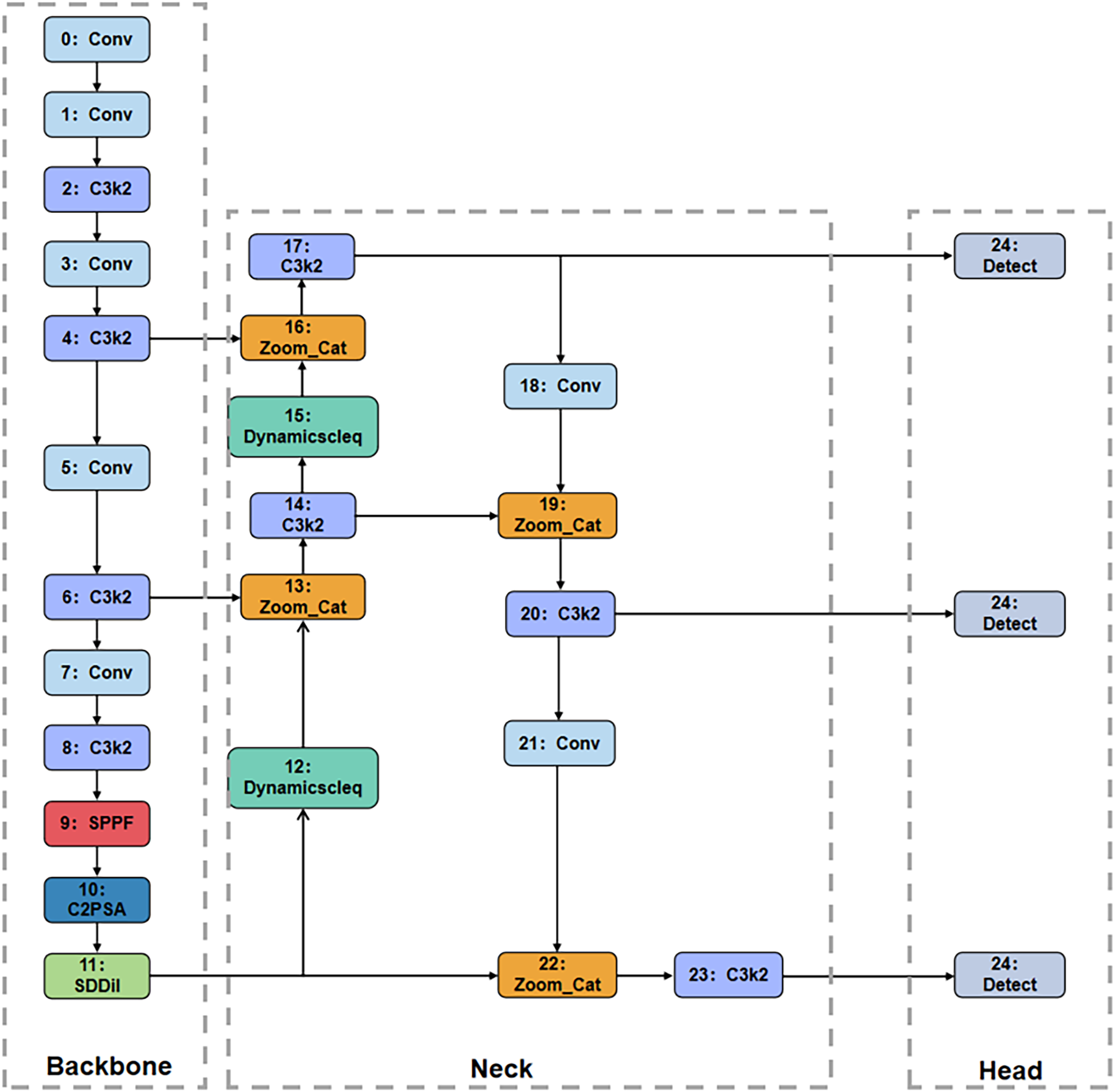

In this study, improvements were made to the backbone network, neck, and loss function of the YOLOv11 network model, resulting in a new algorithm named YOLOv11-NSDDil, which is applied for maturity detection of cashew and disease detection in cashew plants. The novel network backbone, neck, and head constitute the main structural components of YOLOv11-NSDDil. The backbone network is responsible for extracting multi-level features from the input image, including both low-level details and high-level semantic information. The neck enhances the network’s ability to detect objects of varying sizes by integrating multi-scale features extracted from the backbone. The head is the critical component that directly localizes target positions (bounding boxes) and predicts categories at the pixel level. The network structure of YOLOv11-NSDDil is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Network structure of YOLOv11-NSDDil

To improve detection accuracy, this study introduces the SDDil module based on the characteristics of the dataset, which adjusts the receptive field of the model and significantly enhances its discriminative ability in complex backgrounds. By integrating the DynamicScaleSeq and Zoom_cat modules, the YOLOv11 model achieves multi-level feature fusion, strengthening its multi-scale feature extraction capability and markedly improving detection performance for cashew targets. Furthermore, the MPDIoU loss function is employed to further optimize the training process, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to detect small targets in complex environments and reducing instances of false positives and missed detections.

3.3 Specific Improvement Measures

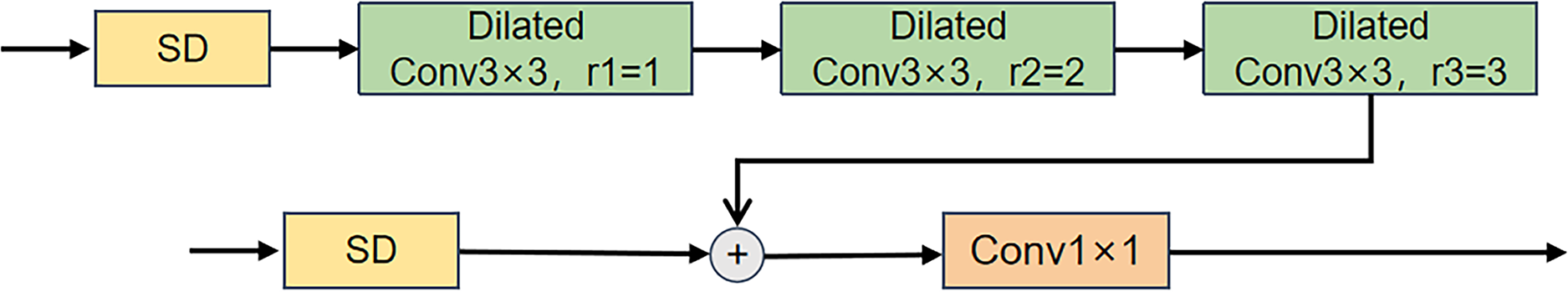

This study designed a new module named SDDil and placed this module behind the C2PSA module in an integrated manner. This was done to further refine the high-level semantic features of its output, thereby enhancing the feature extraction capability of the model. The overall functional structure of SDDil is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: SDDil module

The SDDil module adopts a dual-branch heterogeneous architecture, integrating deep features with shallow features, while retaining detailed information. This module is a multi-scale feature extraction module composed of two branches, each of which contains an SD module.

The SDDil module in this study employs a progressive dilated convolution in its deep branch. This design gradually expands the receptive field, offering greater stability compared to parallel stacking of convolutions with different dilation rates. It avoids grid artifacts caused by single dilation rates while maintaining computational continuity and outperforming parallel computation approaches. Finally, a 1 × 1 convolution is applied to integrate information. The SDDil module captures detailed information through its shallow branch and global context through its deep branch. This dual-branch heterogeneous architecture enables more thorough feature fusion while reducing computational overhead, making it well-suited for the characteristics of small targets and similar backgrounds in the present dataset. The specific formulas are shown in Eqs. (1) and (2).

The SD module is composed of the SimAM attention mechanism [28] and a series of Depthwise Separable Convolutions. It achieves multi-scale feature fusion through residual concatenation. The two 3 × 3 Depthwise Convolution, (DWConv) are equivalent to a 5 × 5 convolution in terms of receptive field, but they have far fewer parameters than a single 5 × 5 convolution, while avoiding the blurring effect of ordinary large kernel convolutions and retaining certain spatial details. Therefore, the 3 × 3 deep separable convolutions are selected. Since deep separable convolutions may cause insufficient feature interaction in sequential calculations, the SimAM attention mechanism is used to explicitly strengthen important channels and spatial positions, compensating for the information loss of the deep separable convolutions. The cross-layer feature fusion structure is adopted to solve the problem of information attenuation. The residual structure directly concatenates the output of the SimAM attention mechanism with the output features of the subsequent double DW3 × 3, avoiding the loss of spatial information caused by the sequential channel calculations of the deep separable convolutions. This module inputs the features into the SimAM attention mechanism, obtaining the attention-weighted features. Then, the weighted features enter the first depthwise separable convolution for local feature extraction. Subsequently, they proceed to the second depthwise separable convolution to capture the important contextual features. Finally, through the residual structure, the original details are retained and the semantic representation is enhanced, achieving multi-scale feature fusion. The specific formulas are shown in Eqs. (3)–(8).

Among them,

Although YOLOv11 integrates shallow-level detail features and deep-level semantic features through concatenation operations, the significant semantic gap and representational differences between feature layers remain unaddressed. This “hard fusion” approach places the entire burden of reconciling these discrepancies onto the subsequent convolutional modules. As a result, it not only increases the learning load on the model and reduces fusion efficiency, but also fails to achieve adaptive and selective integration of detailed and semantic information.

Therefore, this paper proposes a redesigned neck structure to enhance multi-scale feature fusion capability, transforming it into a new architecture incorporating DynamicScalSeq and Zoom_cat modules. For brevity, the improved neck network is hereafter referred to as Neck in the text and tables. The DynamicScalSeq module [29] replaces the original upsampling component to dynamically generate upsampled features that integrate high-level semantics with rich details. Meanwhile, the Zoom_cat module [30] is adopted instead of the conventional concatenation operation to achieve precise and harmonized adaptive feature fusion. The reconstructed Neck section is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Firstly, the DynamicScalSeq module is adopted to replace the original upsampling component. This module integrates the concepts of Scale Sequence Feature Fusion [30] and DySample [31]. It begins by using 1 × 1 convolutions to unify feature channels and construct a tensor that explicitly models hierarchical relationships. Subsequently, lightweight 3D convolutions are applied to learn dynamic weights, enabling adaptive selection and weighting of the semantic contextual information in deep feature maps that is most relevant to the current task. This process dynamically generates upsampled features that incorporate both high-level semantics and rich details. As a result, it not only effectively mitigates feature inconsistency and detail loss in multi-scale fusion but also bridges the semantic gap between low-level and high-level features, thereby providing low-level detail features with abundant category and contextual priors.

Secondly, the traditional Concat operation is replaced by the Zoom_cat module. This module employs an efficient multi-scale feature alignment and fusion strategy to achieve more precise and harmonious feature integration. Using the spatial dimensions of the intermediate-scale feature m as a unified reference, it applies adaptive pooling to downsample the large-scale feature l, preserving high-frequency details (such as edges and textures) that are crucial for localization and small object detection. For the small-scale feature s, nearest neighbor interpolation is adopted for low-cost upsampling, restoring its spatial resolution while incorporating rich semantic category information. After the alignment process, multi-scale features are concatenated along the channel dimension, forming a unified and enriched feature representation. The adaptive nature of this strategy lies in its differentiated treatment based on the intrinsic properties of features at different scales (detail richness and semantic abstraction level): it not only fully evaluates and preserves low-level detailed information but also effectively coordinates and fuses these details with semantically guided deep features propagated from top-down pathways. Thereby, a more accurate and adaptive fusion strategy is achieved, significantly enhancing the model’s ability to perceive and integrate features of small objects.

The two modules work synergistically, preserving the efficient bidirectional topology of the original YOLOv11 architecture while enabling more intelligent and adaptive cross-scale feature interaction. This design fundamentally avoids structural redundancy, with its core objective being to specifically address bottlenecks related to the semantic gap and detail loss in the original framework, rather than merely stacking additional functions. The DynamicScalSeq module drives the downward propagation of high-level semantic information to refine and enhance the representation of low-level features, while the Zoom_cat module facilitates the upward integration of calibrated low-level detail information to strengthen spatial perception capability. This bidirectional and adaptive fusion mechanism not only effectively mitigates the semantic gap among multi-scale features but also significantly improves detection performance for challenging samples such as small objects.

The loss function design of YOLOv11 is used to simultaneously optimize the classification and localization tasks, including classification loss, localization loss, and confidence loss. Among them, the localization loss is used to optimize the difference between the predicted bounding box and the real bounding box, the classification loss is used to optimize the model’s prediction accuracy for the target category, ensuring that the model can correctly identify the category of the image, and the confidence loss is a loss function in the YOLO series, mainly addressing the problem of class imbalance in object detection. The original localization loss function of YOLOv11 is not very good at detecting small targets and similar background detection, so the MPDiou loss function [32] is introduced to improve the model’s detection ability in this aspect.

The Minimum Point Distance Intersection over Union (MPDIoU) loss function is a novel boundary box similarity comparison metric based on the minimum point distance. This metric includes all the relevant factors considered in the existing loss functions, namely overlapping or non-overlapping areas, center point distance, and deviations in width and height, and simplifies the calculation process, directly minimizing the vertex distance between the predicted box and the real box, and uniformly considering overlapping areas, center point offset, and scale differences. The definition of the MPDIoU loss function is shown in formulas Eqs. (9) and (10):

here,

Compared with traditional IoU variants, MPDIoU has the advantages of efficient computation and comprehensive geometric perception, by incorporating a normalized center-distance penalty term, it significantly enhances the model’s detection performance for small objects and achieves more accurate bounding box regression. It also demonstrates greater robustness in detecting small targets and handling dense scenes. The use of the MPDIoU loss function improves localization accuracy and overall detection robustness. Detailed experimental results are provided in Section 4.

4 Experiments and Result Analysis

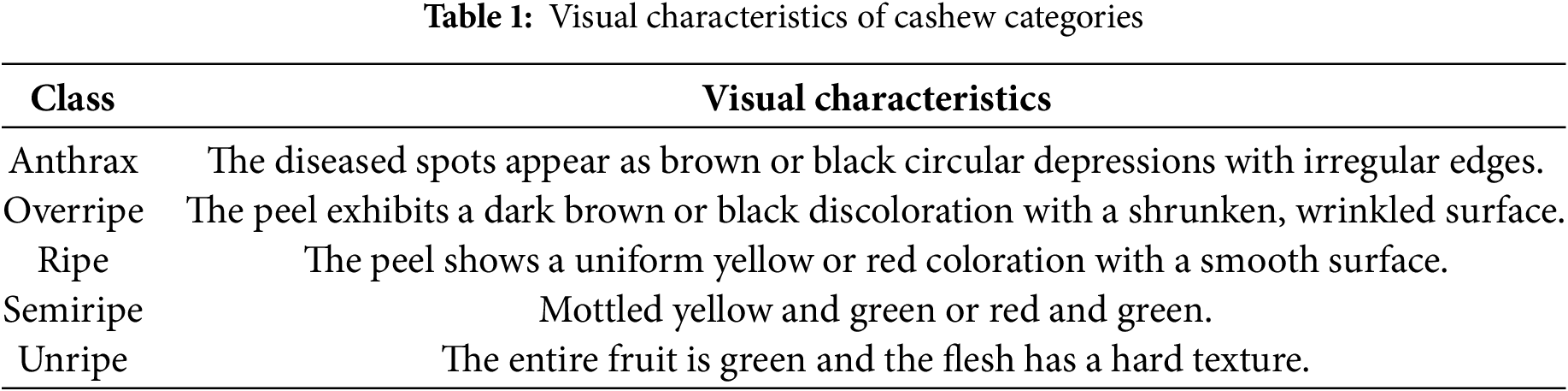

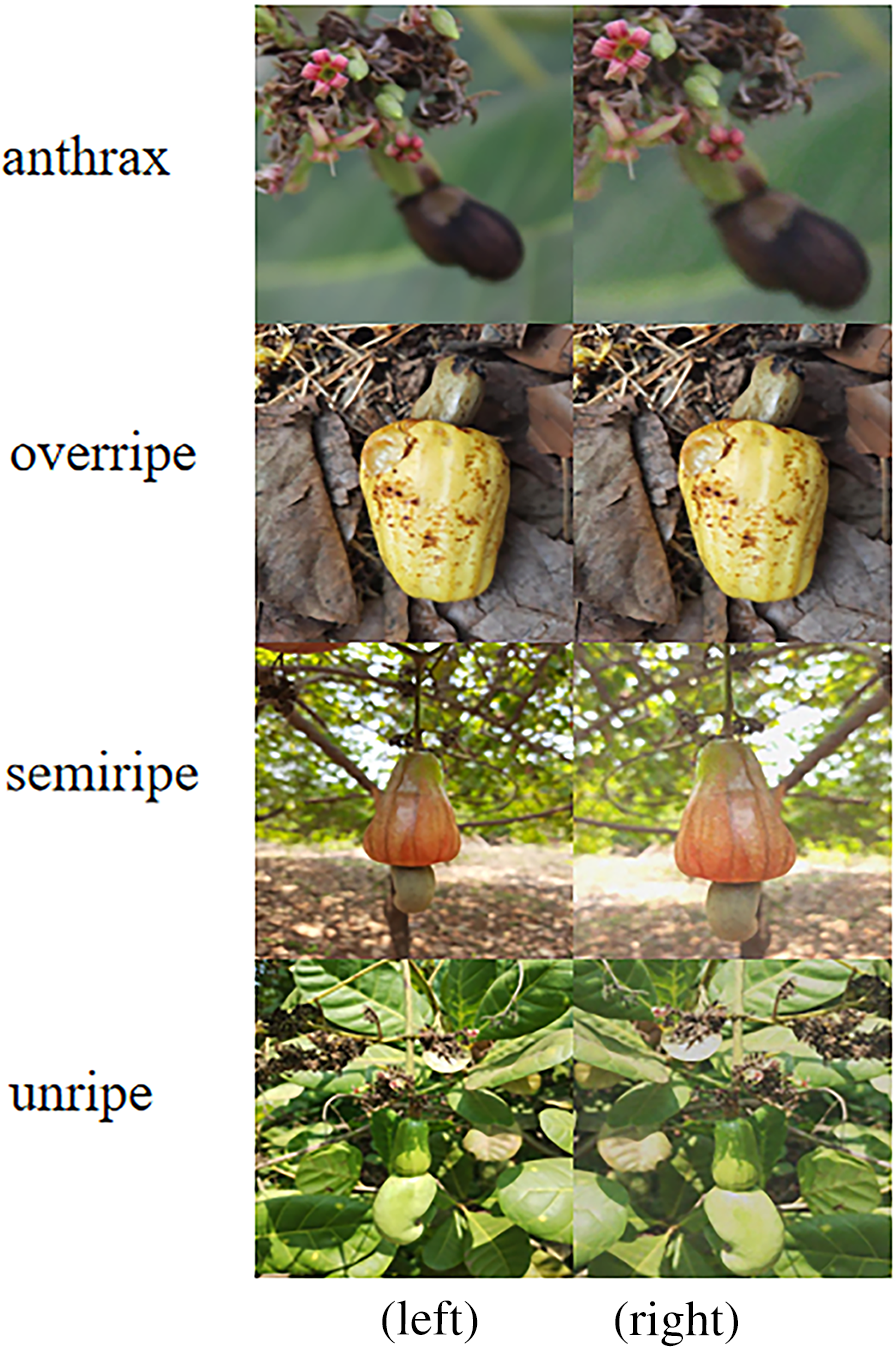

This study first introduces the computer vision dataset Cashew [33] sourced from the Roboflow Universe platform. We downloaded and saved a local copy of this dataset on March 29, 2024. Second, to enhance the model’s ability to recognize cashew diseases, we incorporated data related to cashew pathologies from a public dataset [34]. After merging the two original datasets, we performed unified data cleaning, which involved removing blurry images, erroneous annotations, and duplicate samples. After cleaning, a total of 1123 valid images were obtained. Based on this, we uniformly reclassified all data into the following five categories according to the maturity and health status of cashews for training and evaluation. The visual characteristics of the cashew categories are shown in Table 1.

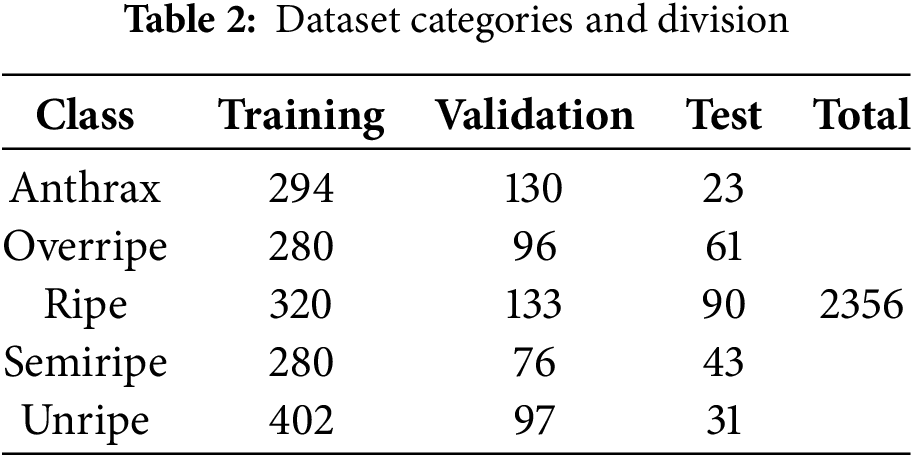

4.1.1 Dataset Partitioning and Annotation

The 1123 images were randomly divided into training, validation, and test sets following a 6:2:2 ratio to maintain relative consistency in data distribution. After the division, an adaptive category-aware augmentation strategy was applied to both the training and validation sets. Specifically, anthracnose samples were augmented by a factor of 6, overripe, semi-ripe, and unripe samples by a factor of 2, while ripe samples remained unaugmented (factor of 1). The test set is used to evaluate the performance of the model. Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of the category distribution and partitioning of the dataset. Despite efforts to balance the dataset, certain class imbalances that may affect model performance persist.

In this study, the LabelImg annotation tool was employed to annotate all cashew targets in the images with bounding boxes according to the category system presented in Table 1. The core objective of the annotation task was to identify and label cashews in healthy states at different maturity levels (unripe, semi-ripe, ripe, overripe) as well as diseased cashew infected with anthrax. The annotation results were saved in YOLO format (i.e., each image corresponds to a text file with the same name in.txt format, containing the class index along with normalized center coordinates, width, and height). Areas in the images not belonging to the aforementioned targets were considered as background. Visualization results of some representative annotated samples are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Illustration of annotated samples

During the data preprocessing stage, all input images were first resized to a resolution of 640 × 640 pixels, and the corresponding bounding box coordinates were adjusted proportionally. For data augmentation, a combination of multiple transformations was applied to enhance model robustness. In terms of color augmentation, each image underwent random adjustments in brightness, contrast, and saturation, along with the addition of Gaussian noise with a standard deviation of 0.03. For geometric transformations, images were either horizontally flipped with a 50% probability, or an 80% area crop from the central region was taken and then rescaled. Each sample was subjected to color augmentation followed by a random selection of 1–2 geometric transformations. This approach enhanced data diversity while ensuring strict alignment between augmented data and annotations through dynamic calculation and adjustment of bounding box coordinates. The method effectively mitigated class imbalance issues and provided a high-quality data foundation for model training. A comparison of images before and after data augmentation is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Original data (left) and Data enhance (right) example

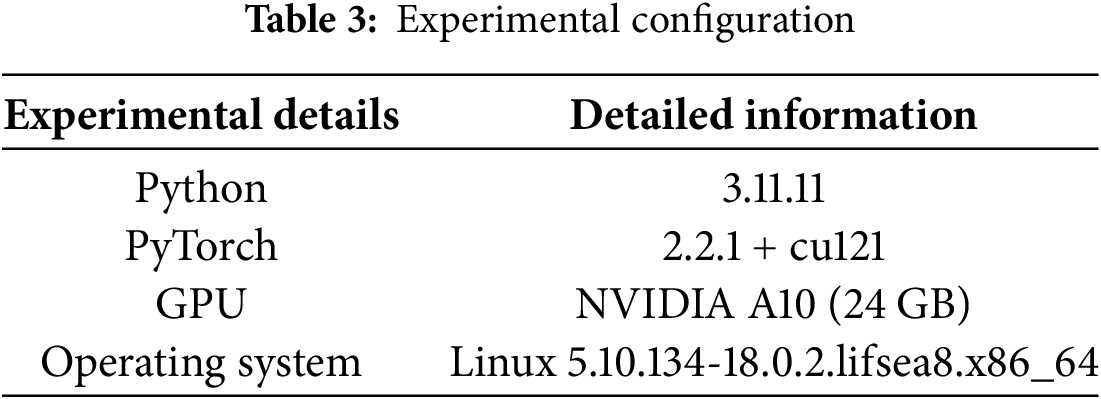

The operating system used in this study is Linux, and the network model was built using Python 3.11 and PyTorch 2.1.1. It was run on an NVIDIA A10 GPU (24 GB GDDR6). The uniform image input size was set at 640 × 640 to ensure consistency across all images. Table 3 describes the detailed experimental settings.

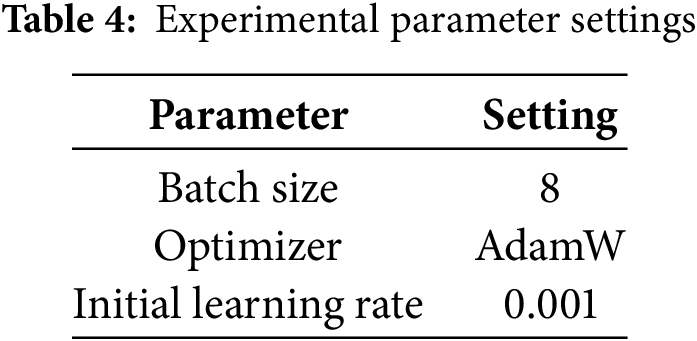

During the model training phase, we set 200 epochs for the training period and implemented the early stopping mechanism. If no performance improvement was observed within 100 epochs, the training would be terminated. The optimal hyperparameters were identified through a systematic manual tuning process. This involved evaluation shows the hyperparameters of the experiment (Table 4).

4.3 Experimental Data and Evaluation Metrics

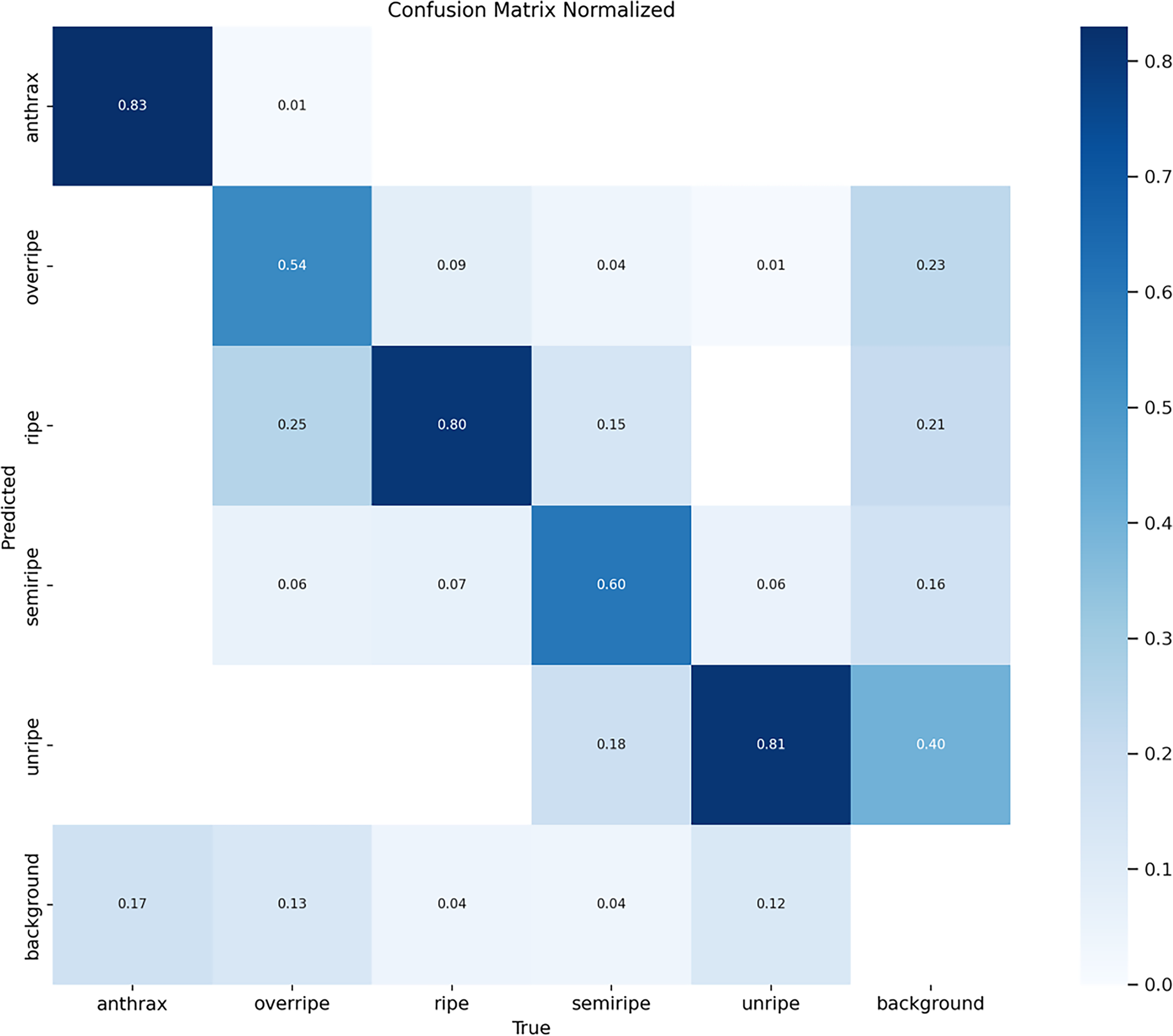

The confusion matrix is an important tool for analyzing model performance. It can visually display the classification performance of the model in each category, including the detailed distribution of correct predictions and incorrect predictions. Through the confusion matrix, we can clearly identify which categories are prone to be confused by the model and which categories have better detection results, thereby optimizing the model in a targeted manner.

The normalized confusion matrix generated using the Ultralytics library indicates that the model achieves satisfactory overall classification performance across different cashew maturity levels and background regions. The notably high values along the main diagonal suggest strong recognition accuracy for most categories. Furthermore, the low rate of background false negatives (missed detections) demonstrates the model’s robust recall capability for genuine targets. The primary remaining issue is background false positives, where the model misidentifies certain background regions as specific maturity classes of cashews. These false detections often occur in areas that exhibit high visual similarity to actual targets, such as brown soil under certain lighting conditions, which closely resembles overripe brown cashews in color and texture, or fragments of leaves and branches whose contours are easily mistaken for small unripe cashews. Fig. 5 shows the confusion matrix of YOLOv11n.

Figure 5: Confusion matrix of YOLOv11n

This study uses standard indicators to evaluate the performance of the model. These include precision (P), recall (R), mean average precision (mAP), etc. By calculating the key performance indicators of the model, the final best model is determined. These indicators comprehensively demonstrate the performance of the model. Their formulas are presented in Eqs. (11)–(13):

here,

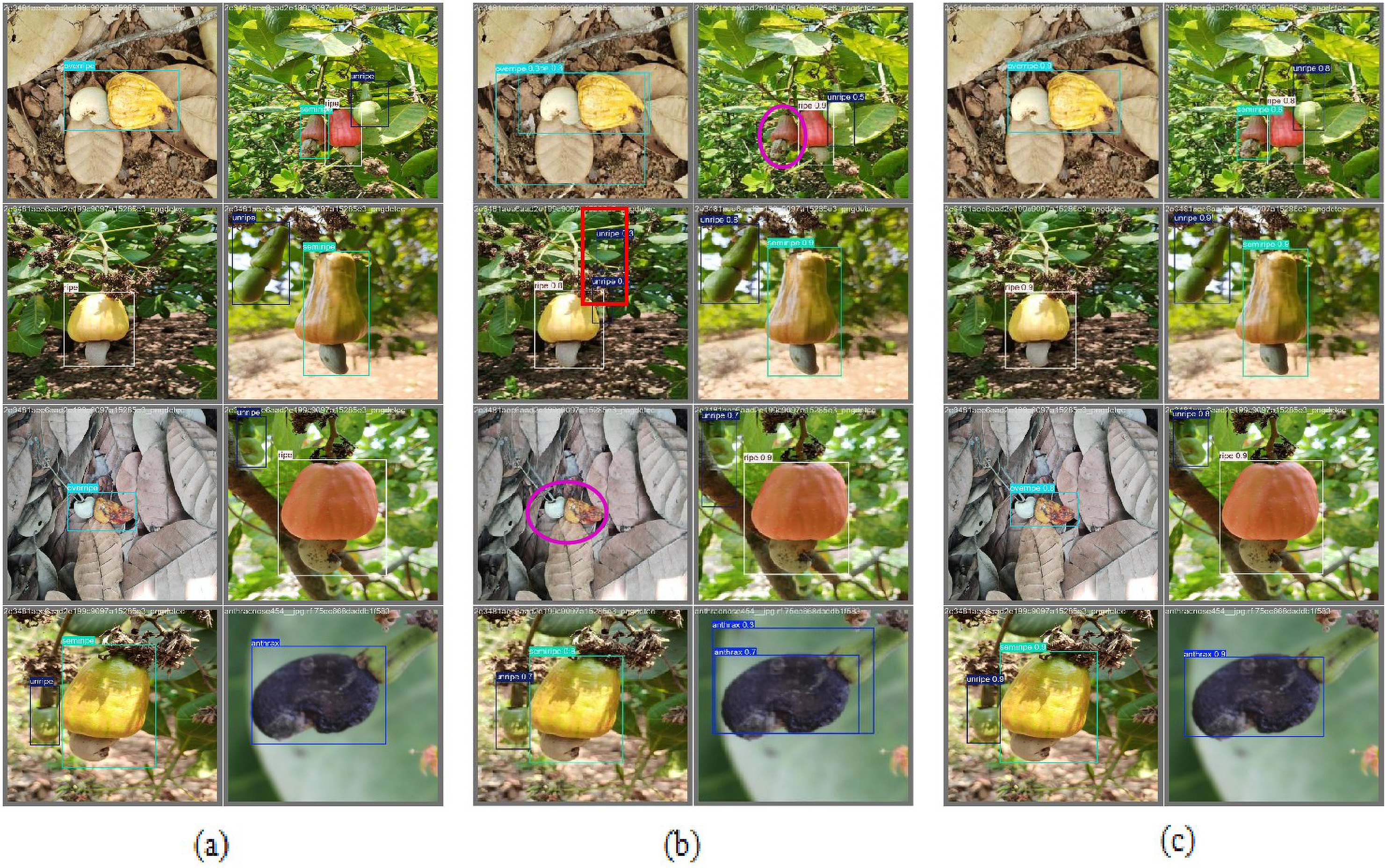

4.4 Comparison and Selection of Loss Functions

The performance of the target detection model is highly dependent on the design of the loss function. Different loss functions exhibit different optimization characteristics in the localization task. The performance of the target detection model is highly dependent on the design of the loss function, which directly affects the accuracy of localization and the robustness of classification. In this study, by comparing the performance of different loss functions on YOLOv11n, a loss function that is most suitable for this model was selected. The experimental results show that the MPDIoU loss function is the best, and the comparison of loss functions is shown in Table 5. The bolded entries indicate the best results.

MPDIoU chieved 0.814 on mAP50. While maintaining the highest mAP50, the mAP for all categories was greater than 0.75, significantly outperforming other loss functions, indicating its more stable optimization ability and strong robustness. Although Efficient Intersection over Union (EIoU) reached 0.879 for “unripe”, it only achieved 0.656 for “anthrax”, exposing the defect of scale adaptability. The overall performance in terms of mAP50 for Powerful-IoU and the three types of loss functions based loss functions, namely Generalized Intersection over Union (GIoU), Distance Intersection over Union (DIoU), and Complete Intersection over Union (CIoU), all exceed 0.8 and remain highly comparable. However, the semiripe category demonstrates noticeably lower performance relative to other classes, suggesting the presence of inter class performance imbalance.

MPDIoU offers a notable advantage by minimizing the center point distance between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes in a direct manner. This approach delivers more stable and explicit gradient signals, which contributes to faster convergence and more precise localization. Such characteristics are particularly critical for the detection of small objects that exhibit high sensitivity to boundary conditions.

Therefore, through comprehensive comparison, this experiment selected MPDIoU as the loss function for this experiment, and further verified the performance of this loss function through subsequent experiments.

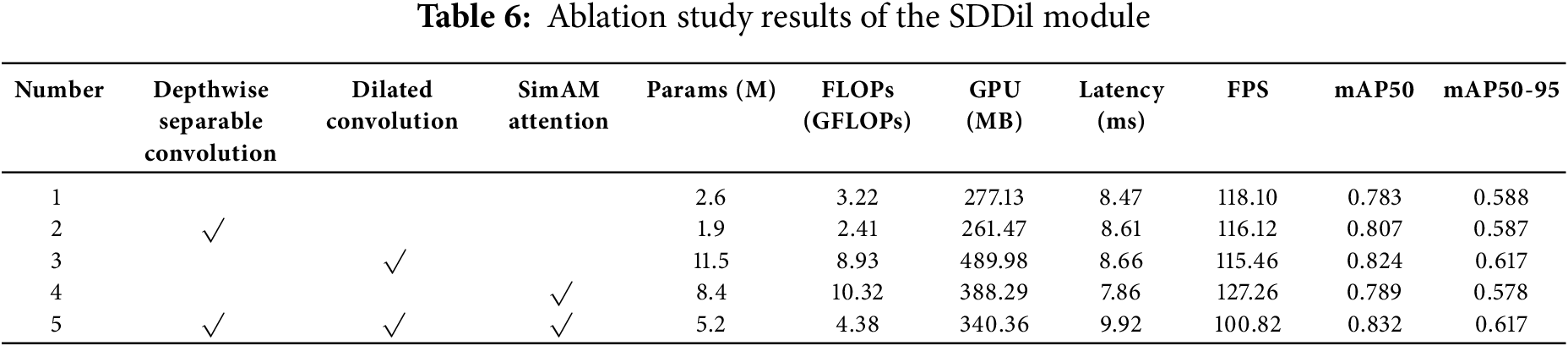

4.5 Ablation Experiment of the SDDil Module

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of each component in the proposed SDDil module, we conducted a systematic ablation study. As shown in Table 6, all experiments were performed under the same dataset and hardware environment, with evaluation metrics including model complexity, inference efficiency, and detection accuracy. √ indicates the inclusion of the corresponding module

The experimental results reveal significant trade-offs between model performance and efficiency introduced by each component: The depthwise separable convolution effectively achieves model lightweighting, reducing parameters by 0.7 M and FLOPs by 0.81 G while nearly maintaining accuracy (with only a 0.001 difference in mAP50-95) and even improving mAP50 by 0.024, demonstrating its effectiveness as an efficient feature extraction module. The dilated convolution provides the most substantial accuracy improvement; however, it leads to a significant increase in parameter count, indicating that expanding the receptive field to capture richer contextual information is critical for this task, albeit at the cost of considerably higher computational overhead. The SimAM attention mechanism underperformed in terms of mAP50-95 in this experimental setup, yet it achieved the fastest inference speed, suggesting potential compatibility issues with the backbone network. The integrated Full SDDil model attains the best detection accuracy, while maintaining its parameter count and FLOPs within a reasonable range, achieving an effective balance between accuracy and efficiency.

Based on this analysis, it can be concluded that the Depthwise separable convolution is essential for model lightweighting, while the dilated convolution serves as the core component for performance enhancement. Ultimately, the Full SDDil model, through effective collaboration among its components, achieves a comprehensive improvement in overall model performance.

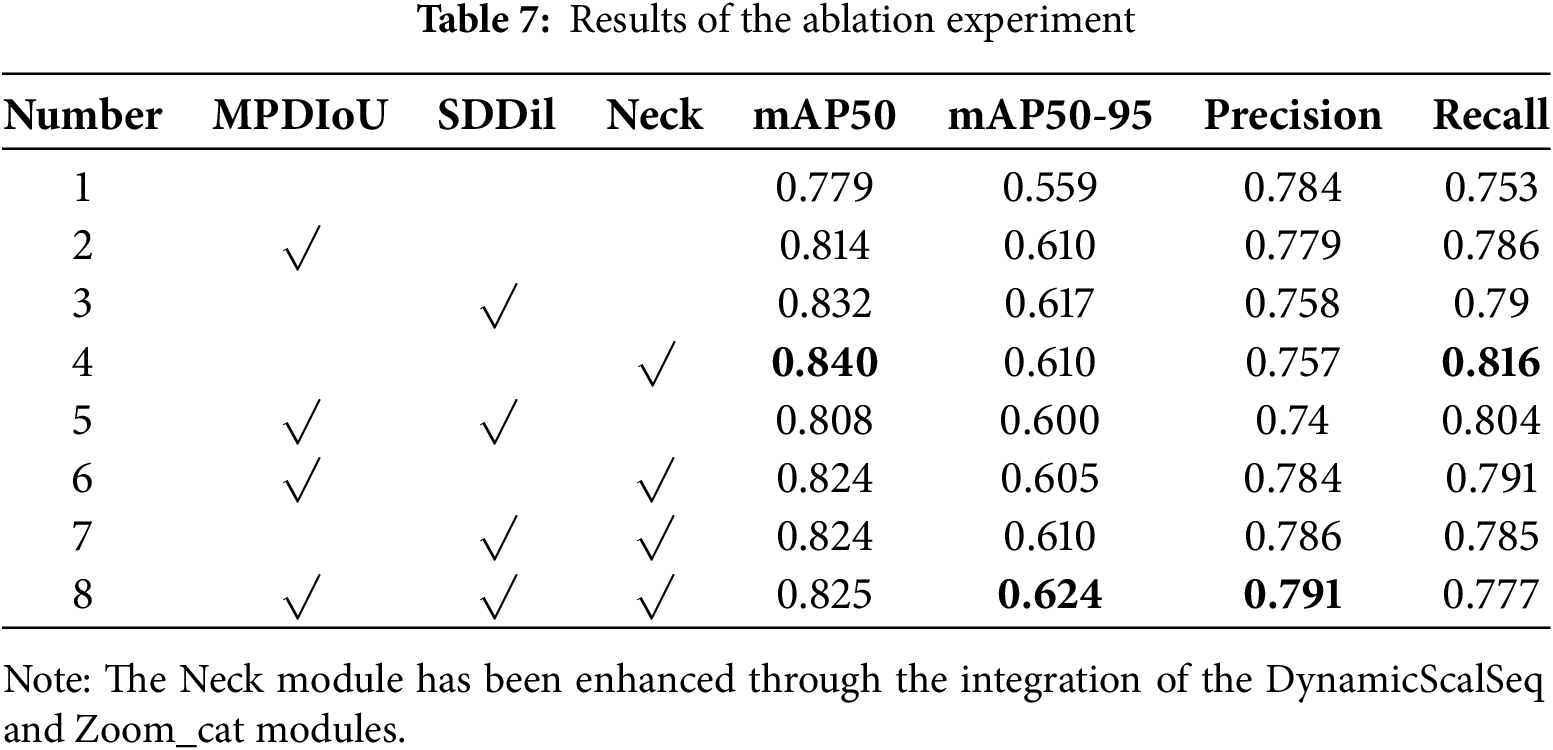

To verify the unique contributions of each module in YOLOv11, we conducted ablation experiments. First, we integrated all the modules together. Then, we sequentially removed different modules to conduct ablation experiments between the modules, in order to analyze the role of each module in the experiment and gain a deeper understanding of the impact of each added component on the overall model performance. The ablation experiments are shown in Table 7. The symbol √ indicates the use of that module. The bolded entries indicate the best results.

The experimental results are shown in the table. This study conducted eight experiments, with Experiment 1 presenting the results of the YOLOv11 object detection algorithm, which served as a reference for subsequent experiments. Experiments 2 to 4 evaluated the individual contributions of each module. In Experiment 2, replacing the original loss function with the MPDIoU loss function increased mAP50 and mAP50-95 by 3.5% and 5.1%, respectively. This module optimizes the convergence of bounding box regression by minimizing the distance between the center points of predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, significantly improving the overall localization accuracy of the model. In Experiment 3, the addition of the SDDil module resulted in the greatest improvement in Recall and mAP50, with increases of 3.7% and 5.3%, respectively. This indicates that its ability to expand the receptive field effectively reduces false negatives in complex backgrounds. However, Precision decreased by 2.6%, suggesting that a small amount of background noise may have been introduced, leading to a slight increase in false positives. In Experiment 4, replacing the Neck module yielded the most significant improvement in Recall, with an increase of 6.3%, owing to its enhanced multi-scale feature fusion capability, which significantly improves detection sensitivity for small targets. Additionally, it achieved the highest improvement in mAP50, with an increase of 6.1%, demonstrating the effectiveness of this architectural modification.

Experiments 5 to 7 further investigated the interactions between module combinations. In Experiment 5, the combination of MPDIoU and SDDil modules performed below expectations, even underperforming each individual module. We hypothesize that the dilated convolutions in SDDil may blur detailed spatial information, which conflicts with the precise coordinate regression required by MPDIoU, leading to reduced localization accuracy at high IoU thresholds. In Experiment 6, the combination of MPDIoU and Neck achieved higher Precision, with performance intermediate between Experiments 2 and 4. This suggests that the Neck module plays a dominant role in improving Recall, while MPDIoU effectively ensures the quality of bounding box predictions, resulting in a complementary relationship. In Experiment 7, the combination of SDDil and Neck maintained high Recall while achieving better Precision than Experiments 3 and 4. This indicates that the multi-scale fusion capability of the Neck module synergizes with the large receptive field characteristics of SDDil, further enhancing the model’s ability to detect multi-scale targets without significantly increasing false positives.

Experiment 8 represents our improved full model, integrating all three modules, which achieved the best overall performance. It reached 0.624 on the mAP50-95 metric, which most rigorously measures precise localization capability, representing a substantial improvement of 6.5% over the baseline and significantly outperforming all other experimental groups. This demonstrates that although there is a potential conflict between MPDIoU and SDDil, the powerful feature fusion capability of the new Neck module plays a key coordinating and balancing role, enabling the three modules to ultimately work synergistically.

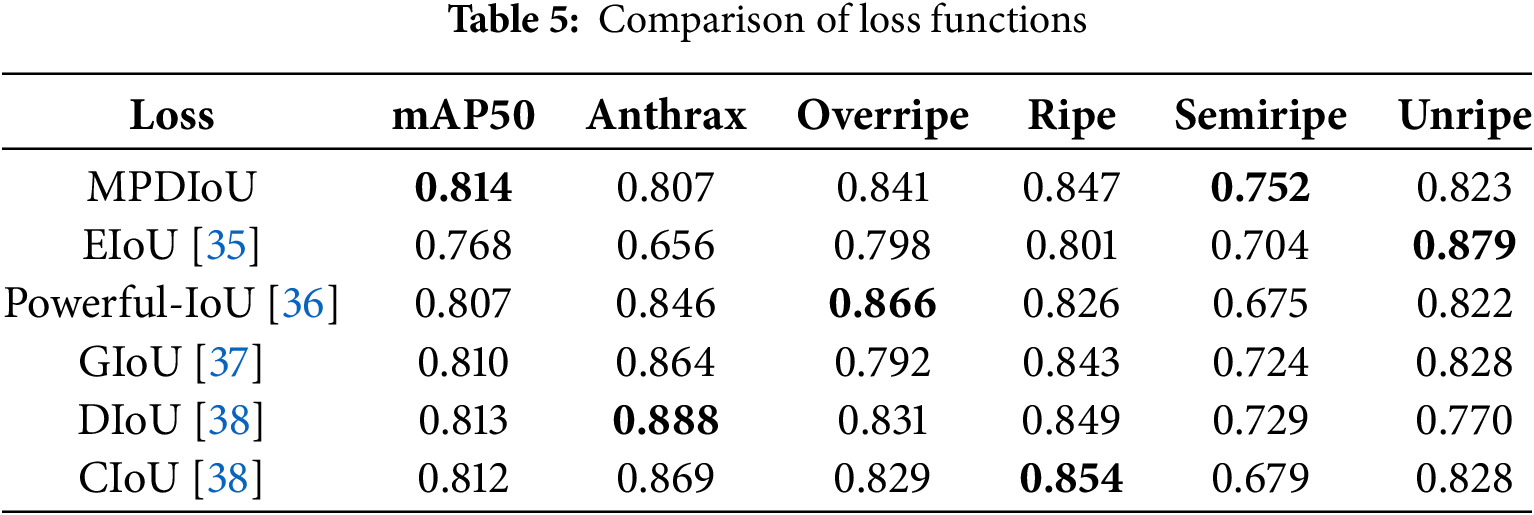

To further verify the effectiveness of the improvements made in this study, we compared the YOLOv11-NSDDil model with other original YOLO models. The experimental results are shown in Table 8.

The YOLOv11-NSDDil model outperforms all other versions of YOLO in terms of the mAP50 and mAP50-95 metrics. In the detection of fruit ripeness, it performs best on the overripe and semiripe categories, indicating that the detection effect of the YOLOv11-NSDDil model is significant. In the anthrax category, YOLOv11m performs better, suggesting that the large model is better at capturing diseases with distinct features. In the overripe category, the YOLOv11-NSDDil model performs better, indicating that the improvements made for the specific category have a significant effect. In the semiripe category, the YOLOv11-NSDDil model performs better, suggesting that the model’s improvement has greatly alleviated the ambiguity problem of intermediate maturity. Therefore, the YOLOv11-NSDDil model has a significant advantage in complex categories and is suitable for high-precision tasks such as maturity grading. The YOLOv5 and YOLOv11m models perform well in specific categories, so in cases where the task objective is simple, one can choose the model specifically. In summary, the YOLOv11-NSDDil model has the best comprehensive performance. These results further highlight the enhanced target detection capability of the YOLOv11-NSDDil model.

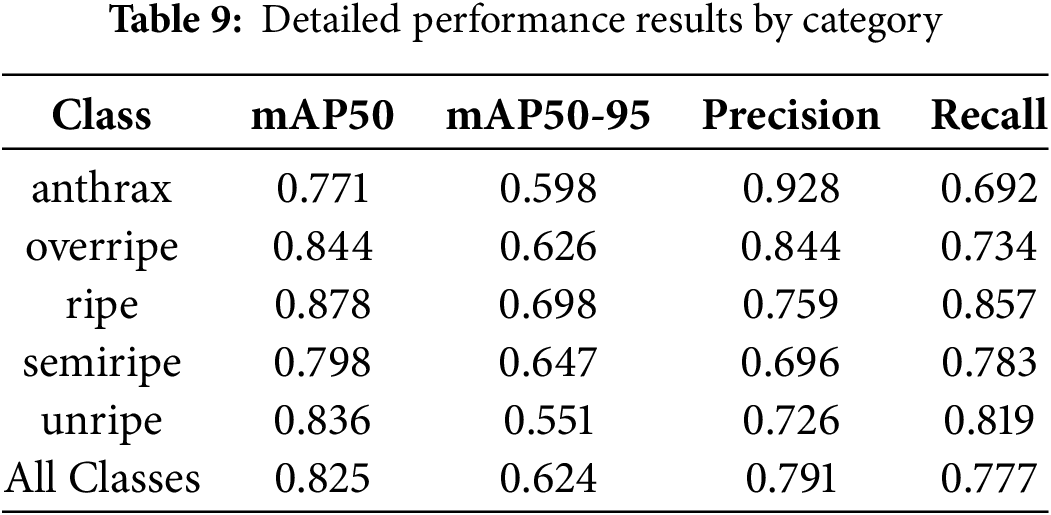

4.8 Multi-Class Performance Evaluation

When evaluating the performance of object detection models, it is essential to adopt a multi-class evaluation approach. Relying solely on aggregate metrics can obscure performance disparities among different categories, leading to imbalanced model behavior in practical applications. This study conducted a per-class analysis of precision, recall, and mAP at different IoU thresholds, revealing specific issues such as relatively low precision in the “semiripe” class and insufficient recall in the “anthrax” class. Detailed results are presented in Table 9.

As indicated in the results, the model exhibits robust overall performance while still showing noticeable variation across different categories. The “anthrax” class, despite achieving the highest precision, suffers from the lowest recall, suggesting a tendency to miss a considerable number of true positive instances. On the other hand, the “ripe” category consistently outperforms others in all metrics, indicating highly reliable detection performance for this particular class.

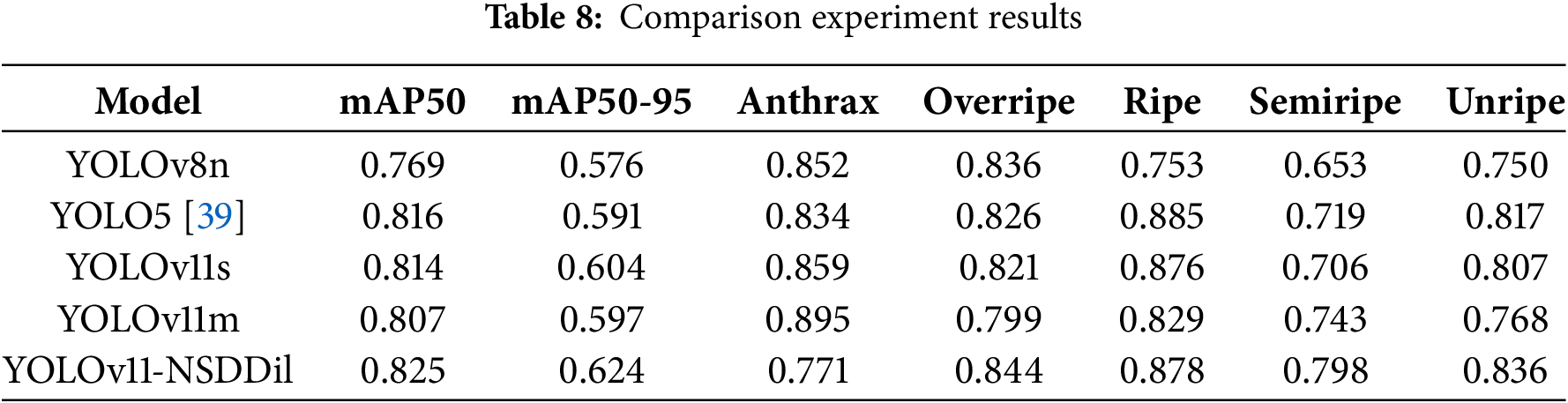

4.9 Comprehensive Performance Comparison of Lightweight Models

A comparative analysis was conducted on several state-of-the-art lightweight models of varying sizes to evaluate their effectiveness in terms of accuracy, efficiency, and practical applicability. Key evaluation metrics included model size, computational complexity (e.g., FLOPs), inference speed, and detection performIIance (e.g., mAP). To ensure the fairness of the experiments, a comparative analysis was conducted under identical experimental conditions using the same set of parameters. The specific situation is shown in Table 10.

Based on the experimental results, the YOLO series models—particularly YOLOv12n and YOLOv11-NSDDil—demonstrate outstanding performance in lightweight design. YOLOv12n achieves the highest frame rate (79.60 FPS), making it the fastest model, though its detection mAP is lower than that of YOLOv11-NSDDiL. As model size increases within the YOLOv12 series, computational load rises accordingly, resulting in a decrease in frame rate from 78.17 FPS to 71.20 FPS.YOLOv11-NSDDil achieves the highest detection accuracy among all models at the cost of moderately higher resource consumption, while still delivering a robust real-time inference speed of 76.91 FPS—placing it very close to the fastest models. In contrast, the Transformer-based RT-DETR models exhibit significantly lower inference speeds, with FPS ranging from 38.03 to 46.47, primarily due to the inherent computational complexity of the Transformer architecture and its decoding process. In summary, YOLOv11-NSDDil achieves the best detection accuracy among all compared models while maintaining manageable parameter counts and computational complexity, offering an excellent balance between precision and efficiency for practical deployment.

4.10 Comparison before and after Model Improvement

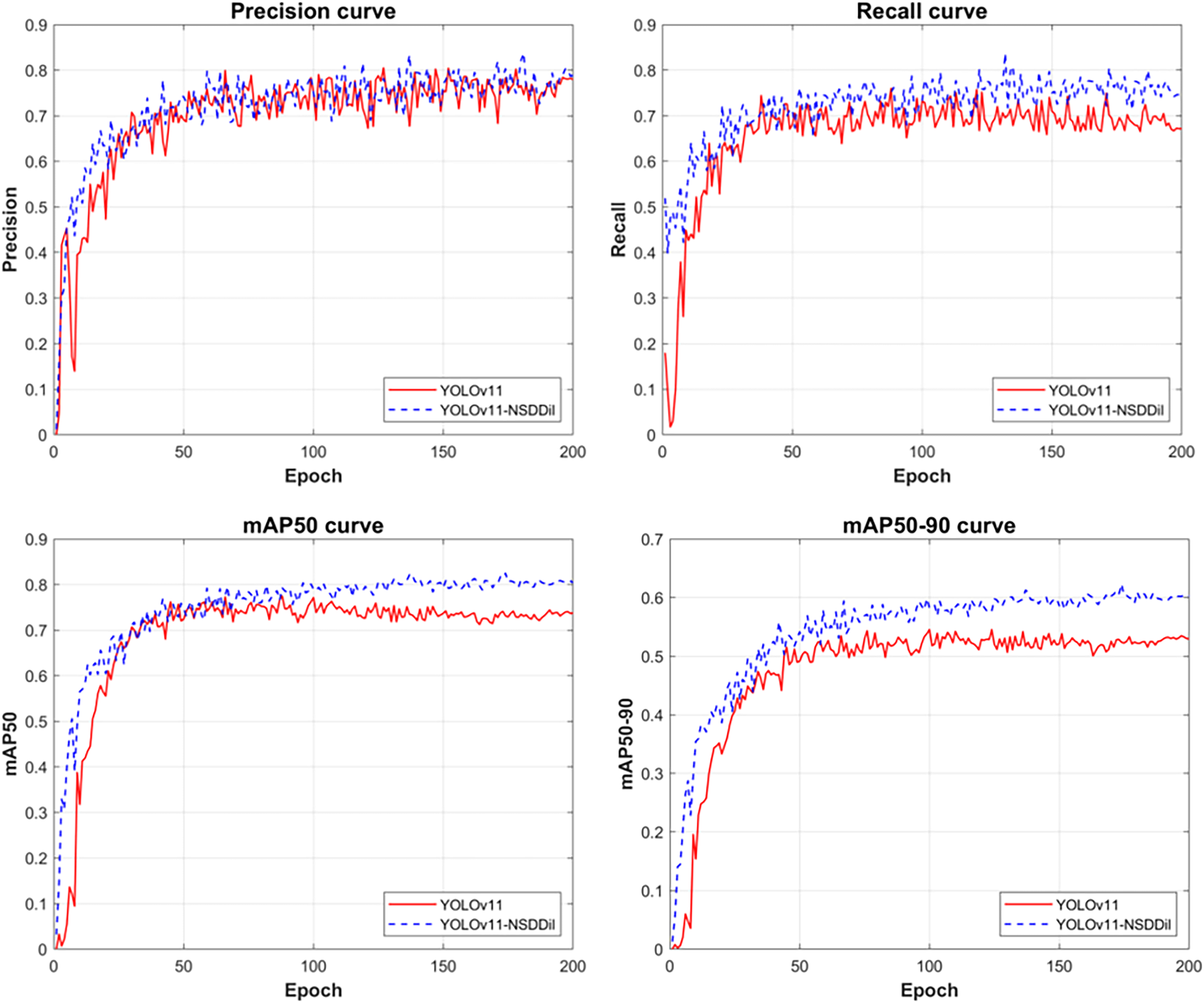

The comparative results between the baseline and improved models are presented in Fig. 6, which illustrates the training progression of precision, recall, mAP50, and mAP50-95 over 200 epochs. Neither model triggered early stopping due to performance issues during training.

Figure 6: Experimental results

Higher precision indicates a reduction in false positives, while higher recall reflects fewer missed detections. As demonstrated in the figure, the proposed YOLOv11-NSDDil model shows significant improvement over the original YOLOv11 model in both aspects, achieving notably higher precision and recall values. Furthermore, the YOLOv11-NSDDil model outperforms the baseline in terms of detection accuracy, with higher scores in both mAP50 and mAP50-95 metrics. Detailed comparative results can be found in Fig. 6.

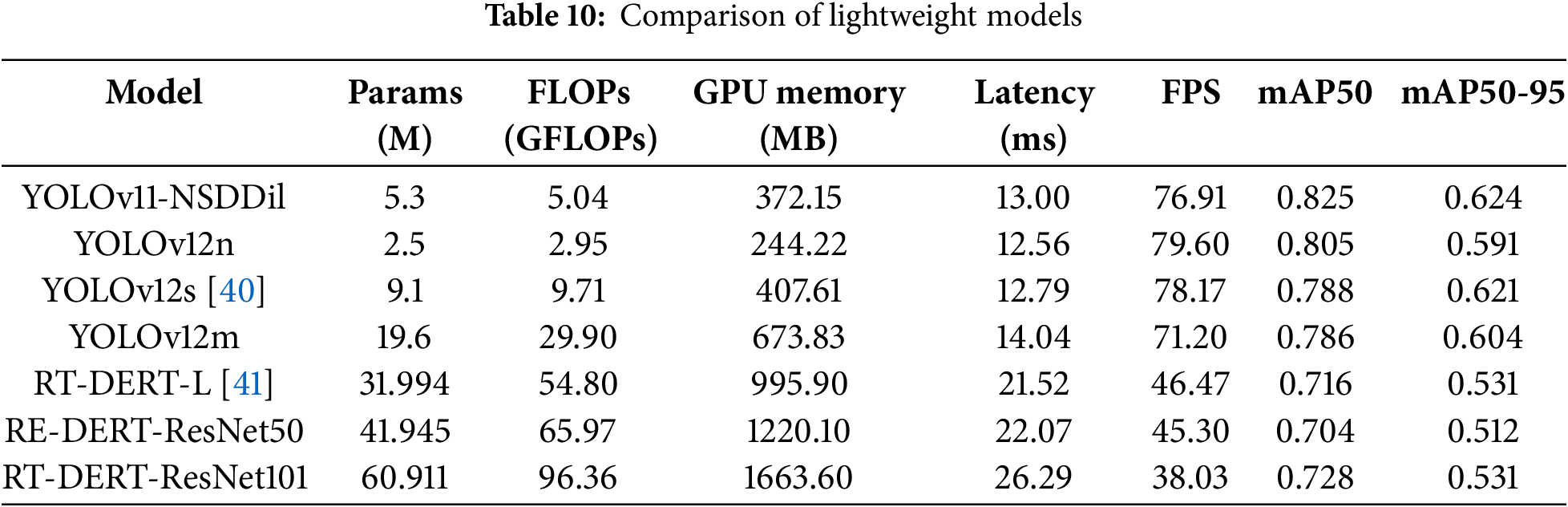

The comparison figure clearly demonstrates the performance differences between the two models in complex scenarios. In the figure, False Negative represents the missed detection situation of the baseline model, that is, the actual existing targets are not detected by the baseline model; False Positive represents the false detection situation of the baseline model, that is, the background or noise is wrongly identified as a target. As shown in Fig. 7, column presents the ground truth annotations, while columns (b) and (c) display the prediction results of the baseline model and our proposed YOLOv11-NSDDil model, respectively. Qualitative analysis demonstrates that our model effectively mitigates the inherent limitations of the baseline model: First, for the missed detection cases indicated by pink circles, our approach successfully detects tiny and occluded targets owing to its enhanced multi-scale feature extraction capability; Second, for the false detection cases marked by red boxes, the improved model effectively suppresses false alarms caused by background interference through more precise contextual semantic understanding.

Figure 7: Qualitative comparison of detection results. (a) The prediction results of YOLOv11; (b) YOLOv11 prediction result annotation; (c) The prediction results of YOLOv11-NSDDil

This result visually confirms that the YOLOv11-NSDDil model exhibits significant advantages in reducing both false positives and false negatives, and its improvement strategy holds considerable value for enhancing the robustness of cashew detection in complex agricultural environments.

This study introduces the YOLOv11-NSDDil model, an enhanced deep learning framework designed for simultaneous detection of cashew diseases and maturity classification. Through systematic architectural refinements and rigorous experimental validation, we demonstrate the model’s significant advancements over existing methods in precision agriculture applications. Focusing on real-world natural environments, we analyze the characteristics of the collected dataset and address limitations of the original YOLOv11 model, particularly in handling cashew with background-like colors and detecting small target objects due to the diminutive size of some specimens. Targeted improvements are implemented by incorporating specialized modules to resolve these specific challenges.

First, the SDDil module was designed to mitigate information attenuation by incorporating depthwise separable convolution and the SimAM attention mechanism within the SD module. This enhancement not only strengthens local feature representation but also employs dilated convolution to effectively expand the model’s receptive field, significantly improving its capability to distinguish densely distributed cashews and complex backgrounds. Second, the neck network was upgraded by adopting the DynamicScalSeq-Zoom_cat structure, which replaces conventional upsampling and concatenation operations. This modification alleviates information loss during upsampling and substantially improves multi-scale feature integration. Finally, the MPDIoU loss function was introduced to refine bounding box localization by directly minimizing the distance between the centers of predicted and ground-truth boxes. Experimental results demonstrate that the improved model achieves a mAP50 of 0.825 and mAP50-95 of 0.624, outperforming the baseline YOLOv11 by 4.6% in mAP50 and exceeding all existing YOLO models. The proposed approach shows particularly strong performance in detecting small objects and under complex backgrounds, providing an effective solution for automated cashew disease detection and maturity assessment.

However, the proposed model still has room for improvement. In future research, we will explore the following directions to further enhance its performance: First, we will expand the scale and diversity of the dataset to mitigate the limitations caused by data imbalance and alleviate class distribution issues. Second, we will optimize model parameters and computational efficiency by strengthening lightweight design research, aiming to improve detection speed while maintaining accuracy to meet real-time application requirements. Third, we will promote practical deployment of the model by developing lightweight versions suitable for mobile devices, thereby providing tangible technological support for precision agriculture.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express my sincere gratitude to everyone who has made efforts for this article. It is with everyone’s concerted efforts that this article has been accomplished.

Funding Statement: This paper was supported by Hebei North University Doctoral Research Fund Project (No. BSJJ202315), and the Youth Research Fund Project of Higher Education Institutions in Hebei Province (No. QN2024146).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Jingjing Yang and Ran Liu; methodology: Jingjing Yang and Ran Liu; data organization: Ran Liu, Dong Yang and Yawen Chen; experiment: Ran Liu and Yawen Chen; first draft writing: Ran Liu; manuscript review and editing: Dong Yang and Jingjing Yang; fund acquisition: Dong Yang and Jingjing Yang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Panchbhai KG, Lanjewar MG, Malik VV, Charanarur P. Small size CNN (CAS-CNNand modified MobileNetV2 (CAS-MODMOBNET) to identify cashew nut and fruit diseases. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(42):89871–91. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-19042-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Oliveira NN, Mothé CG, Mothé MG, de Oliveira LG. Cashew nut and cashew apple: a scientific and technological monitoring worldwide review. J Food Sci Technol. 2020;57(1):12–21. doi:10.1007/s13197-019-04051-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lautié E, Dornier M, de Souza Filho M, Reynes M. Les produits de l’anacardier: caractéristiques, voies de valorisation et marchés. Fruits. 2001;56(4):235–48. doi:10.1051/fruits:2001126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sahie LBC, Soro D, Kone KY, Assidjo NE, Yao KB. Some processing steps and uses of cashew apples: a review. Food Nutr Sci. 2023;14(1):38–57. doi:10.4236/fns.2023.141004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hêdiblè LG, Adjou ES, Tchobo FP, Agbangnan P, Ahohuendo B, Soumanou MM. Caractérisation physico-chimique et morphologique de trois morphotypes de pommes d’anacarde (Anacardium occidental L.) pour leur utilisation dans la production d’alcool alimentaire et de boissons spiritueuses. J Appl Biosci. 2017;116:11546–56. [Google Scholar]

6. Soro D. Couplage des procédés membranaires pour la clarification et la concentration du jus de pommes de cajou: performances et impacts sur la qualité des produits [dissertation]. Montpellier, France: Université de Montpellier; 2012. [Google Scholar]

7. Korankye P, Danso H. Properties of sandcrete blocks stabilized with cashew apple ash as a partial replacement for cement. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):6804. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-55031-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Aslam N, Hassan SA, Mehak F, Zia S, Bhat ZF, Yıkmış S, et al. Exploring the potential of cashew waste for food and health applications—a review. Future Foods. 2024;9(4):100319. doi:10.1016/j.fufo.2024.100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Fonseca-Bermúdez ÓJ, Giraldo L, Sierra-Ramírez R, Serafin J, Dziejarski B, Bonillo MG, et al. Cashew nut shell biomass: a source for high-performance CO2/CH4 adsorption in activated carbon. J CO2 Util. 2024;83(6):102799. doi:10.1016/j.jcou.2024.102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li J, Hong C, Liu M, Wang Y, Song Y, Zhai R, et al. Construction of eco-friendly multifunctional cashew nut shell oil-based waterborne polyurethane network with UV resistance, corrosion resistance, mechanical strength, and transparency. Prog Org Coat. 2024;186(21):108051. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2023.108051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Rajagopal MK, Ms BM. Artificial intelligence based drone for early disease detection and precision pesticide management in cashew farming. arXiv:2303.08556. 2023. [Google Scholar]

12. Vidhya NP, Priya R. Automated diagnosis of the severity of TMB infestation in cashew plants using YOLOv5. J Image Graph. 2024;12(3):276–82. doi:10.18178/joig.12.3.276-282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Maruthadurai R, Veerakumar T, Veershetty C, Sathis Chakaravarthi AN. Acoustic detection of stem and root borer Neoplocaederus ferrugineus (Coleoptera: cerambycidae) in cashew. J Asia Pac Entomol. 2022;25(3):101968. doi:10.1016/j.aspen.2022.101968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Winklmair M, Sekulic R, Kraus J, Penava P, Buettner R. A deep learning based approach for classifying the maturity of cashew apples. PLoS One. 2025;20(6):e0326103. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0326103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ye R, Shao G, Gao Q, Zhang H, Li T. CR-YOLOv9: improved YOLOv9 multi-stage strawberry fruit maturity detection application integrated with CRNET. Foods. 2024;13(16):2571–16. doi:10.3390/foods13162571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Tamrakar N, Karki S, Kang MY, Deb NC, Arulmozhi E, Kang DY, et al. Lightweight improved YOLOv5s-CGhostnet for detection of strawberry maturity levels and counting. AgriEngineering. 2024;6(2):962–78. doi:10.3390/agriengineering6020055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li Z, Jiang X, Shuai L, Zhang B, Yang Y, Mu J. A real-time detection algorithm for sweet cherry fruit maturity based on YOLOX in the natural environment. Agronomy. 2022;12(10):2482. doi:10.3390/agronomy12102482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Fan Y, Zhang S, Feng K, Qian K, Wang Y, Qin S. Strawberry maturity recognition algorithm combining dark channel enhancement and YOLOv5. Sensors. 2022;22(2):419. doi:10.3390/s22020419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Gao Z, Zhou K, Hu Y. Apple maturity detection based on improved YOLOv8. In: Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Computer Vision, Application, and Algorithm (CVAA 2024); 2024 Oct 11–13; Chengdu, China. p. 539–44. doi:10.1117/12.3055819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wang Y, Ouyang C, Peng H, Deng J, Yang L, Chen H, et al. YOLO-ALW: an enhanced high-precision model for chili maturity detection. Sensors. 2025;25(5):1405. doi:10.3390/s25051405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Zhu X, Chen F, Zheng Y, Chen C, Peng X. Detection of Camellia oleifera fruit maturity in orchards based on modified lightweight YOLO. Comput Electron Agric. 2024;226:109471. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2024.109471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sun H, Ren R, Zhang S, Tan C, Jing J. Maturity detection of ‘Huping’ jujube fruits in natural environment using YOLO-FHLD. Smart Agric Technol. 2024;9:100670. doi:10.1016/j.atech.2024.100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Huang W, Liao Y, Wang P, Chen Z, Yang Z, Xu L, et al. AITP-YOLO: improved tomato ripeness detection model based on multiple strategies. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16:1596739. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1596739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Qiu Z, Huang Z, Mo D, Tian X, Tian X. GSE-YOLO: a lightweight and high-precision model for identifying the ripeness of pitaya (dragon fruit) based on the YOLOv8n improvement. Horticulturae. 2024;10(8):852. doi:10.3390/horticulturae10080852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Cardellicchio A, Renò V, Cellini F, Summerer S, Petrozza A, Milella A. Incremental learning with doma in adaption for tomato plant phenotyping. Smart Agric Technol. 2025;12:101324. doi:10.1016/j.atech.2025.101324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Khanam R, Hussain M. YOLOv11: an overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv:2410.17725. 2024. [Google Scholar]

27. Jocher G, Chaurasia A, Qiu J. Ultralytics YOLOv8 computer software [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

28. Yang L, Zhang RY, Li L, Xie X. Simam: a simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning 2021; 2021 Jul 18–24; Online. p. 11863–74. [Google Scholar]

29. Zhao X, Chen Y. YOLO-DroneMS: multi-scale object detection network for unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) images. Drones. 2024;8(11):609. doi:10.3390/drones8110609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kang M, Ting CM, Ting FF, Phan RCW. ASF-YOLO: a novel YOLO model with attentional scale sequence fusion for cell instance segmentation. Image Vis Comput. 2024;147(4):105057. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2024.105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu W, Lu H, Fu H, Cao Z. Learning to upsample by learning to sample. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 6004–14. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ma S, Xu Y. MPDIoU: a loss for efficient and accurate bounding box regression. arXiv:2307.07662. 2023. [Google Scholar]

33. Cashew 2 Computer Vision [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Mar 29]. Available from: https://universe.roboflow.com/cashewfruitdetection/cashew-2-e7vzr. [Google Scholar]

34. Kwabena PM, Akoto-Adjepong V, Adu K, Ayidzoe MA, Bediako EA, Nyarko-Boateng O, et al. Dataset for crop pest and disease detection [Internet]. 2023 Apr 27 [cited 2024 Jan 1]. Available from: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/bwh3zbpkpv/1. [Google Scholar]

35. Yang Z, Wang X, Li J. EIoU: an improved vehicle detection algorithm based on VehicleNet neural network. J Phys Conf Ser. 2021;1924(1):012001. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1924/1/012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Liu C, Wang K, Li Q, Zhao F, Zhao K, Ma H. Powerful-IoU: more straightforward and faster bounding box regression loss with a nonmonotonic focusing mechanism. Neural Netw. 2024;170(2):276–84. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2023.11.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Rezatofighi H, Tsoi N, Gwak J, Sadeghian A, Reid I, Savarese S. Generalized intersection over union: a metric and a loss for bounding box regression. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 658–66. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Zheng Z, Wang P, Liu W, Li J, Ye R, Ren D. Distance-IoU loss: faster and better learning for bounding box regression. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2020;34(7):12993–3000. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i07.6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Jocher G. Ultralytics YOLOv5 computer software [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Oct 11]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5. [Google Scholar]

40. Tian Y, Ye Q, Doermann D. YOLOv12: attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv:2502.12524. 2025. [Google Scholar]

41. Zhao Y, Lv W, Xu S, Wei J, Wang G, Dang Q, et al. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. arXiv:2304.08069. 2023. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools