Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

PMCFusion: A Parallel Multi-Dimensional Complementary Network for Infrared and Visible Image Fusion

1 School of Information Science & Engineering, Yunnan University, Kunming, 650504, China

2 Yunnan Highway Network Toll Management Co., Ltd., Yunnan Key Laboratory of Digital Communications, Kunming, 650100, China

* Corresponding Author: Hao Li. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.070790

Received 24 July 2025; Accepted 01 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Image fusion technology aims to generate a more informative single image by integrating complementary information from multi-modal images. Despite the significant progress of deep learning-based fusion methods, existing algorithms are often limited to single or dual-dimensional feature interactions, thus struggling to fully exploit the profound complementarity between multi-modal images. To address this, this paper proposes a parallel multi-dimensional complementary fusion network, termed PMCFusion, for the task of infrared and visible image fusion. The core of this method is its unique parallel three-branch fusion module, PTFM, which pioneers the parallel synergistic perception and efficient integration of three distinct dimensions: spatial uncorrelation, channel-wise disparity, and frequency-domain complementarity. Leveraging meticulously designed cross-dimensional attention interactions, PTFM can selectively enhance multi-dimensional features to achieve deep complementarity. Furthermore, to enhance the detail clarity and structural integrity of the fused image, we have designed a dedicated multi-scale high-frequency detail enhancement module, HFDEM. It effectively improves the clarity of the fused image by actively extracting, enhancing, and injecting high-frequency components in a residual manner. The overall model employs a multi-scale architecture and is constrained by corresponding loss functions to ensure efficient and robust fusion across different resolutions. Extensive experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms current state-of-the-art fusion algorithms in both subjective visual effects and objective evaluation metrics.Keywords

Image fusion aims to integrate complementary information from multi-source images into a single, information-rich enhanced image, thereby improving scene understanding and decision-making capabilities [1–3]. Among various applications, the fusion of infrared and visible images is particularly crucial due to its significant potential in fields such as geological exploration, intelligent security, and medical diagnosis [4]. Visible images provide fine-grained textures and color details but are vulnerable to poor illumination or smoke, leading to information loss [5]. Infrared images, in contrast, capture thermal radiation and effectively highlight salient targets under adverse conditions but lack background details. Designing a fusion algorithm that can combine visible fine textures with infrared salient features to produce a final image containing both clear textures and prominent targets remains a central challenge in the field [3]. Early studies relied on handcrafted priors, such as sparse representation [6,7] and multi-scale decomposition [8–10]. While these traditional methods achieved limited success, their fixed feature extractors could not adapt to diverse real-world scenarios, restricting robustness and generalization. With the rise of deep learning, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [11,12], Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [13–16], and Transformers [17,18] have substantially advanced fusion quality through data-driven representation learning. CNN-based models excel at local feature extraction but may neglect global semantics; GAN-based approaches improve perceptual realism but sometimes introduce artifacts; Transformer-based architectures capture long-range dependencies and semantic alignment but are often computationally expensive, which hinders deployment in real-time applications.

In addition, hybrid paradigms have emerged. Pretrained backbones such as VGG, ResNet, and CLIP have been leveraged to transfer strong representation ability into the fusion task [19]. Optimization-based methods, including particle swarm optimization (PSO) and genetic algorithms, have been explored to adaptively search for optimal fusion rules or weights. Zhang et al. combined PSO with Dense Blocks to optimize wavelet coefficients, but relied on costly optimization [20]. Meanwhile, graph-based approaches explicitly model cross-modal dependencies by converting images into graph structures and employing graph convolutional networks (GCNs). Li et al. proposed a graph representation learning framework that extracts non-local self-similarity features across modalities, achieving superior performance on TNO, RoadScene, and M3FD datasets [21]. Similarly, DGFD employs a dual-graph convolutional network for cross-modal fusion and demonstrates remarkable improvements in low-light object detection tasks [22]. These approaches offer valuable insights but often rely on costly optimization, heavy pretraining, or complex graph modeling.

Nevertheless, most existing networks still suffer from a common limitation: fusion decisions are usually made in isolation, restricted to either spatial-channel domains [18] or spatial-frequency domains [23]. This serial pipeline design risks information loss during cross-domain transitions and fails to fully exploit the intrinsic complementarity across multiple dimensions. To address these limitations, we propose PMCFusion, a parallel multi-dimensional complementary fusion framework. By concurrently processing spatial, channel, and frequency features, PMCFusion achieves synergistic enhancement and strikes a balanced trade-off between detail preservation, structural fidelity, and cross-modal generalization.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes an innovative infrared and visible image fusion framework, named the Parallel Multi-dimensional Complementary Fusion Network (PMCFusion). The core of this network lies in its meticulously designed Parallel Tri-branch Fusion Module (PTFM), which coordinately processes and efficiently integrates spatial structures, channel characteristics, and frequency-domain representations from the source images. Specifically, the PTFM consists of three parallel sub-paths: the spatial branch models spatial discrepancies in the feature maps and generates attention weights to highlight edge and structural information; the channel branch introduces a cross-modal channel attention mechanism to effectively capture and weight complementary channel features between the modalities; and the frequency branch innovatively incorporates the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and its inverse (IFFT) to extract and fuse complementary information from the amplitude and phase spectra of both modalities. The outputs from these three branches are dynamically integrated and processed with high- and low-pass filtering, achieving selective enhancement and deep complementarity of multi-dimensional features. To further enhance the detail clarity and visual quality of the fused images, a High-frequency Detail Enhancement Module (HDEM) is independently integrated into the network, and a targeted high-frequency consistency loss is introduced to provide training supervision. The overall PMCFusion framework adopts a multi-scale pyramid architecture, with the PTFM embedded at each scale level to ensure that multi-level features, from coarse to fine, undergo thorough cross-dimensional information interaction and optimization. We systematically evaluated PMCFusion on multiple public infrared and visible image fusion datasets and conducted a comprehensive comparison with several state-of-the-art (SOTA) fusion algorithms. The experimental results demonstrate that PMCFusion exhibits significant advantages in both subjective visual performance and multiple objective evaluation metrics.

In summary, the main contributions of this paper can be outlined as follows:

• We propose a novel framework named the Parallel Multi-dimensional Complementary Fusion Network (PMCFusion). Its core innovation lies in the ability to concurrently process and synergistically integrate complementary information from three dimensions—spatial, channel, and frequency—effectively overcoming the limitations of existing methods in multi-dimensional information utilization.

• We have designed a unique Parallel Tri-branch Fusion Module (PTFM) as the network’s core component. Through meticulously constructed sub-paths for spatial perception, channel interaction, and frequency-domain analysis, this module achieves refined extraction, adaptive weighting, and efficient fusion of multi-modal features. Combined with high- and low-pass filtering, it ensures the optimized integration of cross-dimensional features.

• We have integrated a standalone High-frequency Detail Enhancement Module (HFDEM) and designed a composite loss function aimed at comprehensively optimizing both structure and details, which significantly enhances the edge clarity, texture representation, and overall visual quality of the fused images.

• Extensive experimental results on several public benchmark datasets demonstrate that the proposed PMCFusion consistently and significantly outperforms current state-of-the-art (SOTA) fusion algorithms in terms of both subjective visual effects and multiple objective evaluation metrics.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the related work in the field of infrared and visible image fusion. Section 3 elaborates on the overall architecture, core module design, and loss function of the proposed PMCFusion network. Section 4 presents and provides an in-depth analysis of the experimental results. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future research directions.

Before deep learning became dominant, infrared and visible image fusion was mainly explored via traditional signal processing methods. Representative categories include multi-scale transform approaches (e.g., DWT, NSST) [2,9,10], sparse representation-based strategies [6,7], subspace learning such as PCA [24,25], and saliency-driven fusion [26]. Hybrid models combining multiple paradigms were also studied [27,28]. While effective in controlled settings, these methods rely heavily on hand-crafted priors and heuristic rules, which limit adaptability, fail to capture high-level semantics, and often incur high computational costs. These drawbacks motivated the transition to data-driven deep learning approaches [29].

2.2 Deep Learning-Based Image Fusion

With the success of deep learning in vision tasks, a wide range of neural network-based fusion methods have been developed. They can be broadly categorized into CNN-based, GAN-based, and Transformer-based approaches.

CNN-based methods: Multi-layer convolutional networks automatically extract multi-scale features from source images [11,12]. Fusion is then performed via weighted averaging, element-wise operations, or a dedicated fusion sub-network, and decoded into the fused output. Residual connections [30] have improved training stability. Despite their strength in local feature extraction, CNNs are constrained by limited receptive fields, making them less effective for modeling long-range dependencies, and their fusion strategies may cause redundancy or information loss.

GAN-based methods: GANs leverage adversarial learning to generate perceptually natural fused images [13,16]. For instance, dual-discriminator setups encourage alignment with both infrared and visible modalities. While GANs can produce visually realistic details, they suffer from training instability and weaker structural fidelity compared with CNNs.

Transformer-based methods: Transformers introduce self-attention to capture global dependencies and semantic relationships [17,18]. Recent work integrates Transformer blocks into CNNs or designs end-to-end Transformer fusion networks. Although performance is strong, Transformers are computationally intensive and less practical for real-time applications.

Beyond CNN-based, GAN-based, and Transformer-based methods, several new paradigms further expand the research landscape.

Pretrained backbones: Large pretrained networks (e.g., VGG, ResNet, CLIP) have been adopted as feature extractors to transfer semantic knowledge from large datasets into fusion tasks, enhancing structural preservation and texture fidelity [19].

Optimization-based methods: Meta-heuristic strategies, such as particle swarm optimization (PSO) and genetic algorithms, have been applied to search for fusion rules or weights adaptively [20]. These approaches improve fusion quality but are typically computationally expensive.

Graph-based approaches: Graph representation learning has been used to explicitly model cross-modal dependencies. Li et al. [21] proposed GCN-based graph learning to capture non-local similarities, while DGFD [22] introduces a dual-graph convolutional network to achieve cross-modal fusion and demonstrates significant performance improvements in low-light object detection tasks. Such methods achieve notable gains but rely on complex graph modeling and heavy pretraining.

Diffusion and equivariant models: Recently, diffusion models and equivariant learning have entered the field. For example, EMMA [31] leverages equivariant constraints for multi-modality fusion, DMFuse [32] leverages diffusion model guidance with cross-attention learning for infrared and visible image fusion, and SGDFuse [33] incorporates SAM-guided diffusion for robust fusion. These methods represent the latest progress, though they often involve high computational cost and complex training.

2.4 Limitations of Existing Methods

Despite rapid advances, most existing methods focus on restricted domains—either spatial-channel [18] or spatial-frequency [23]. Serial pipelines risk information loss during cross-domain transitions and fail to leverage intrinsic complementarity across spatial, channel, and frequency dimensions. Addressing this gap motivates our proposed PMCFusion, which performs parallel multi-dimensional complementary fusion for more effective multi-modal integration.

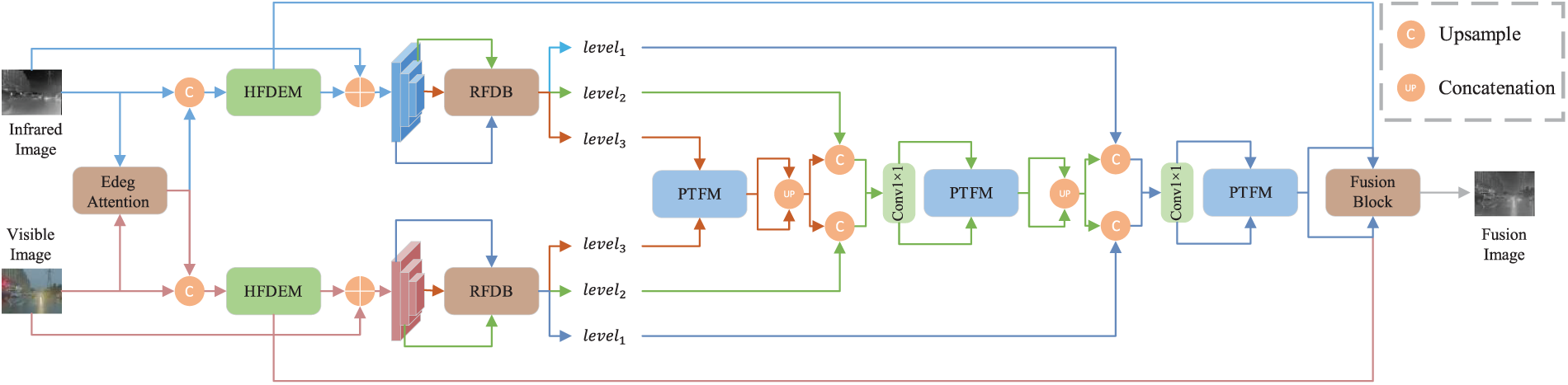

The PMCFusion network proposed in this paper adopts an end-to-end multi-scale encoder-decoder architecture, the overall design of which is illustrated in Fig. 1. This architecture is engineered to systematically extract, fuse, and reconstruct multi-level features from the input infrared image

Figure 1: The overall architecture of the PMCFusion network. The PTFM module and HFDEM module will be detailed in the following

3.2 Parallel Tri-Branch Fusion Module

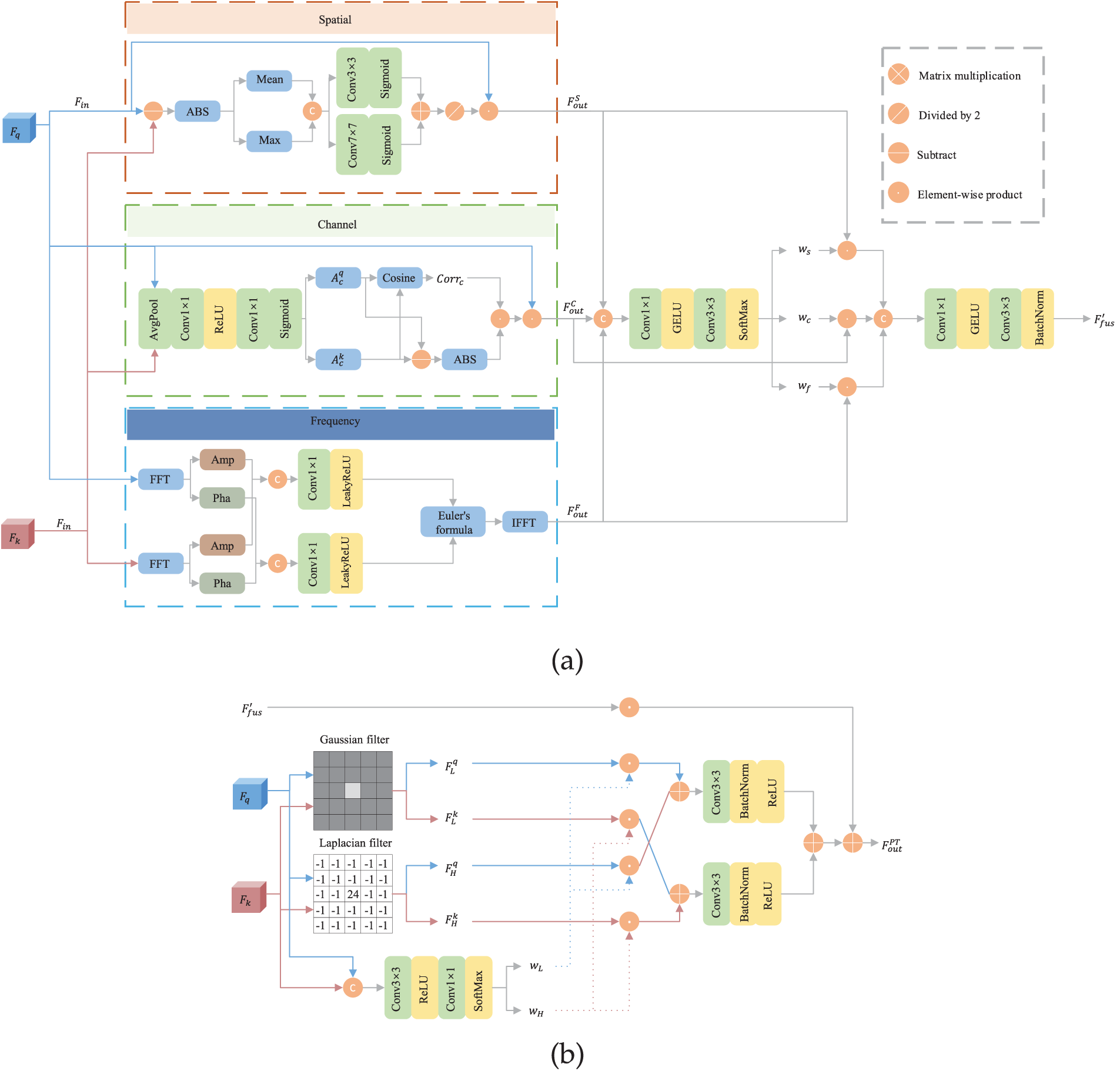

As the core of the PMCFusion network, the PTFM module is embedded at each feature scale to perform deep cross-modal fusion. Existing multi-modal fusion strategies are largely confined to feature interaction in single or dual dimensions and often employ serial processing. This approach not only overlooks the unique complementarity offered by other dimensions, such as the frequency domain [3], but is also prone to information loss during cross-domain transfer. To overcome these challenges, our designed PTFM module abandons the conventional serial-stacking paradigm. Its core concept is the construction of a parallel tri-branch network designed to simultaneously mine and integrate infrared and visible features from three orthogonal dimensions within a single, unified unit: spatial dissimilarity, channel disparity, and frequency complementarity. This parallel architecture ensures the maximal preservation of information from different dimensions and facilitates efficient cross-domain synergy. The overall structure of the PTFM and its key components are illustrated in Fig. 2. The specific design of its three internal parallel branches will be elaborated upon in the following subsections.

Figure 2: Detailed structure diagram of PTFM, where (a) is a detailed diagram of the three branches, and (b) is the final fusion using high-low filtering

Spatial Branch: Information in the spatial dimension, such as edges, contours, and textures, is critical to the task of image fusion. Infrared images excel at capturing salient target contours, while visible images are replete with fine textural details. To adaptively preserve this complementary spatial information, we designed the spatial branch. This branch operates by computing the differences between feature maps at corresponding spatial locations to generate a spatial attention map. This map, in turn, guides the model to focus on and retain the most informative spatial regions from each modality.

Initially, the difference map

where

Channel Branch: Feature responses along the channel dimension characterize different abstract semantic information within an image. To accentuate the unique features inherent to each modality, we have designed the channel branch. This branch operates by computing the dissimilarity between the features of the two modalities at the channel level to generate a weighting map, thereby enhancing features that are prominent in one modality but less pronounced in the other.

Initially, we pass the input features through an enhanced channel attention module to generate a distinct channel attention map for each modality. We then quantify the correlation between these attention maps by computing their cosine similarity. This metric is integrated with the difference between the maps to derive the final channel weight

here,

Frequency Branch: In contrast to seeking dissimilarities within the spatial and channel domains, the frequency domain offers another unique perspective for feature fusion. The low-frequency components of an image typically represent its global contours and background context, whereas the high-frequency components contain information about edges and details. Infrared and visible images exhibit a natural complementarity in their information distribution across different frequency bands.

The frequency branch is designed to fuse features directly within the frequency domain. The input features

herein,

Dynamic Branch Weighting and Frequency-Selective Recombination: To optimally integrate the complementary information derived from the three parallel branches, we introduce a dynamic branch weighting module. This module takes the original features

Building upon this, to further refine the features, the PTFM subjects

In this manner, the PTFM module not only extracts uncorrelated and complementary features in parallel from three distinct dimensions but also achieves a deep integration and optimization of multi-modal information through dynamic weighting and subsequent frequency-selective fusion. This process provides a rich feature representation essential for generating high-quality fused images.

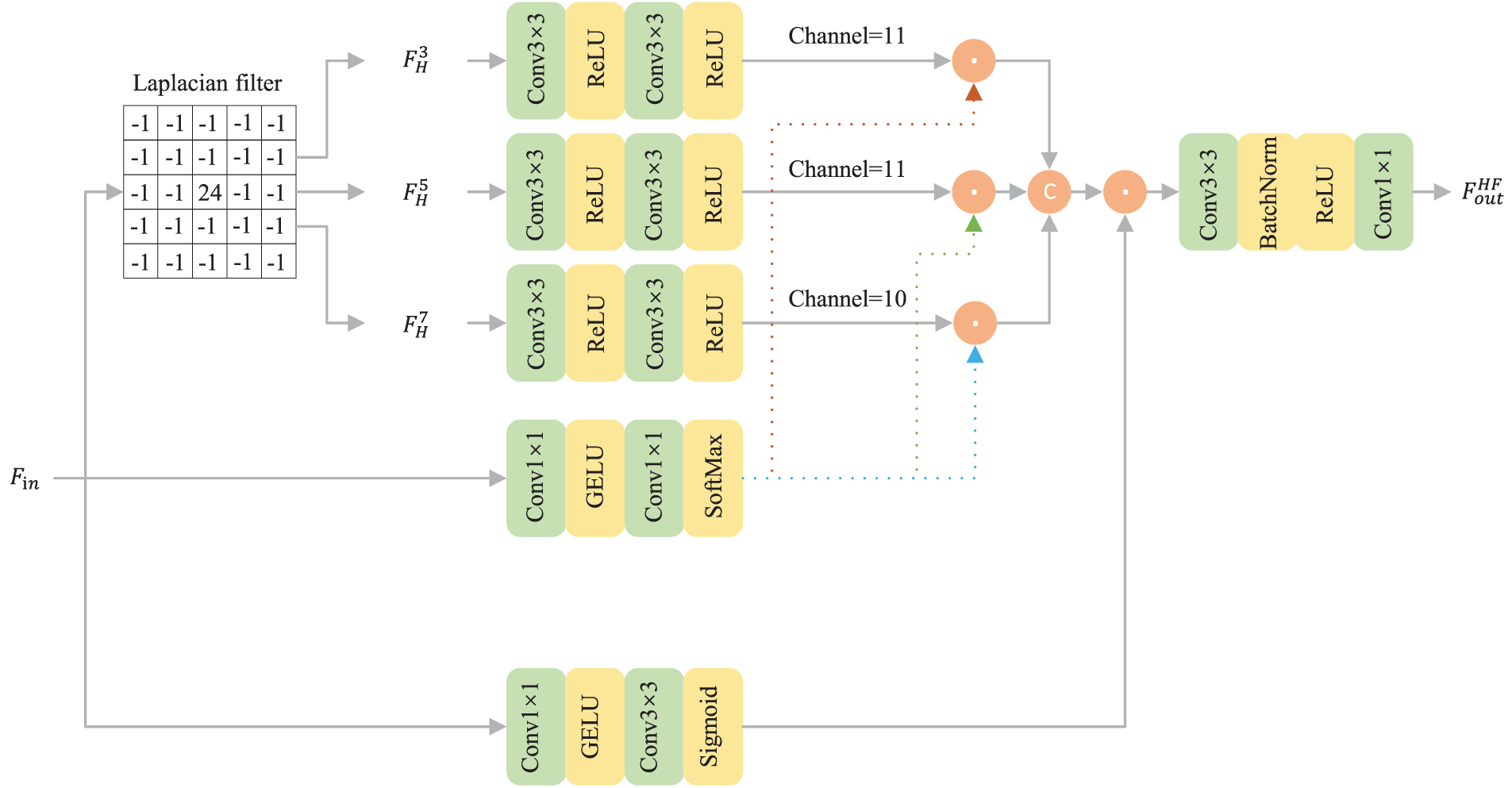

3.3 High-Frequency Detail Enhancement Module

To proactively enhance the detail expressiveness of the source images before feature fusion, the PMCFusion network integrates a High-Frequency Detail Enhancement Module (HFDEM) at the initial stage of the encoder. This module operates independently on the early-stage feature maps of the infrared and visible images. Its core task is to extract and reinforce the high-frequency components within each respective modality, such as fine textures and edge contours, thereby providing feature inputs that are richer in information and clearer in detail for the subsequent fusion process. The overall architecture of the HFDEM is illustrated in Fig. 3, and its specific operational workflow is as follows.

Figure 3: Detailed structure diagram of HFDEM

To capture detail information at varying granularities, the HFDEM first employs a multi-scale strategy to extract high-frequency components. We apply a set of Laplacian High-Pass Filters (HPF) with different kernel sizes to the input feature map

among them,

Prior to fusing the multi-scale high-frequency information, and to ensure the enhancement process does not introduce noise into smooth regions while simultaneously reinforcing details in edge areas, we introduce an edge-preserving attention mechanism. This mechanism generates a spatial attention map

Thus, by leveraging the HFDEM, the network acquires feature representations enriched with fine details at an early stage. This provides a high-quality foundation for the subsequent cross-modal deep fusion, resulting in a significant enhancement of the clarity and detail fidelity in the final fused image.

In the final stage of the network, feature fusion and reconstruction are accomplished by an optimized module. The design of this module is predicated upon the principles of the Self-Fusion Convolutional network (SFC) [35]. While recognizing the efficacy of the SFC framework for feature fusion, we have implemented several key adaptive modifications to better suit the task of infrared and visible image fusion. The core objective of these changes is to enhance detail preservation and prevent information loss during the feature compression process. Our primary optimization involves abandoning the potentially aggressive feature compression methods found in traditional reconstruction modules, opting instead for a smoother, progressive compression strategy to gently fuse cross-modal features. Concurrently, to ensure that the fine-grained features originating from the PTFM survive the complex transformations, we have introduced a parallel residual connection path. This path acts as an information shortcut, enabling the direct transmission of important detailed features to the final reconstruction layer. Furthermore, we have integrated a lightweight channel attention mechanism to accentuate key features and have replaced the conventional tanh function with a more stable Sigmoid activation function to better preserve the dynamic range and grayscale fidelity of the output image. These targeted optimizations allow the module to inherit the core ideas of SFC while generating fusion results with richer details and fewer artifacts for our specific task.

To ensure that the fused image preserves both the salient thermal information from the infrared image and the rich textural details from the visible image, we impose comprehensive constraints on the fusion result across four dimensions: pixel intensity, perceptual features, spatial structure, and overall fusion quality.

To ensure that the fused image preserves the fundamental content information at the pixel level, we employ the Mean Squared Error (MSE) as a basic constraint. To achieve more fine-grained supervision, we also apply this loss at multiple scales. The multi-scale MSE loss

here,

Relying solely on pixel-level losses can lead to fused results that lack high-level semantic information. To address this limitation, we introduce a perceptual loss

here,

To precisely preserve the high-frequency details from the source images, such as edges and textures, we have designed a spatial gradient loss

where

To further enhance the visual quality of the fused image and achieve superior performance on multiple objective evaluation metrics, we introduce a novel comprehensive fusion quality loss

The total loss function

here, the weights

Through the synergistic action of the aforementioned loss terms, the PMCFusion network is capable of learning an optimal fusion strategy, thereby generating infrared and visible fused images that are richer in information, clearer in detail, and more natural in visual appearance.

In this study, the proposed PMCFusion network was systematically trained and comprehensively evaluated on the public KAIST [37] multispectral dataset. To construct an effective training set and enhance the model’s generalization capabilities, we randomly sampled approximately 19,000 well-aligned image pairs from the original dataset and designed an online data augmentation strategy. During each training iteration, the image pairs underwent random horizontal and vertical flips, small-angle rotations, and were finally cropped into 256

To comprehensively evaluate the fusion performance and generalization capability of the proposed PMCFusion model, systematic experiments were conducted on several public benchmark datasets for infrared and visible image fusion. Specifically, the KAIST dataset was employed for model training and initial validation. This dataset contains a large number of precisely aligned infrared and visible image pairs (640

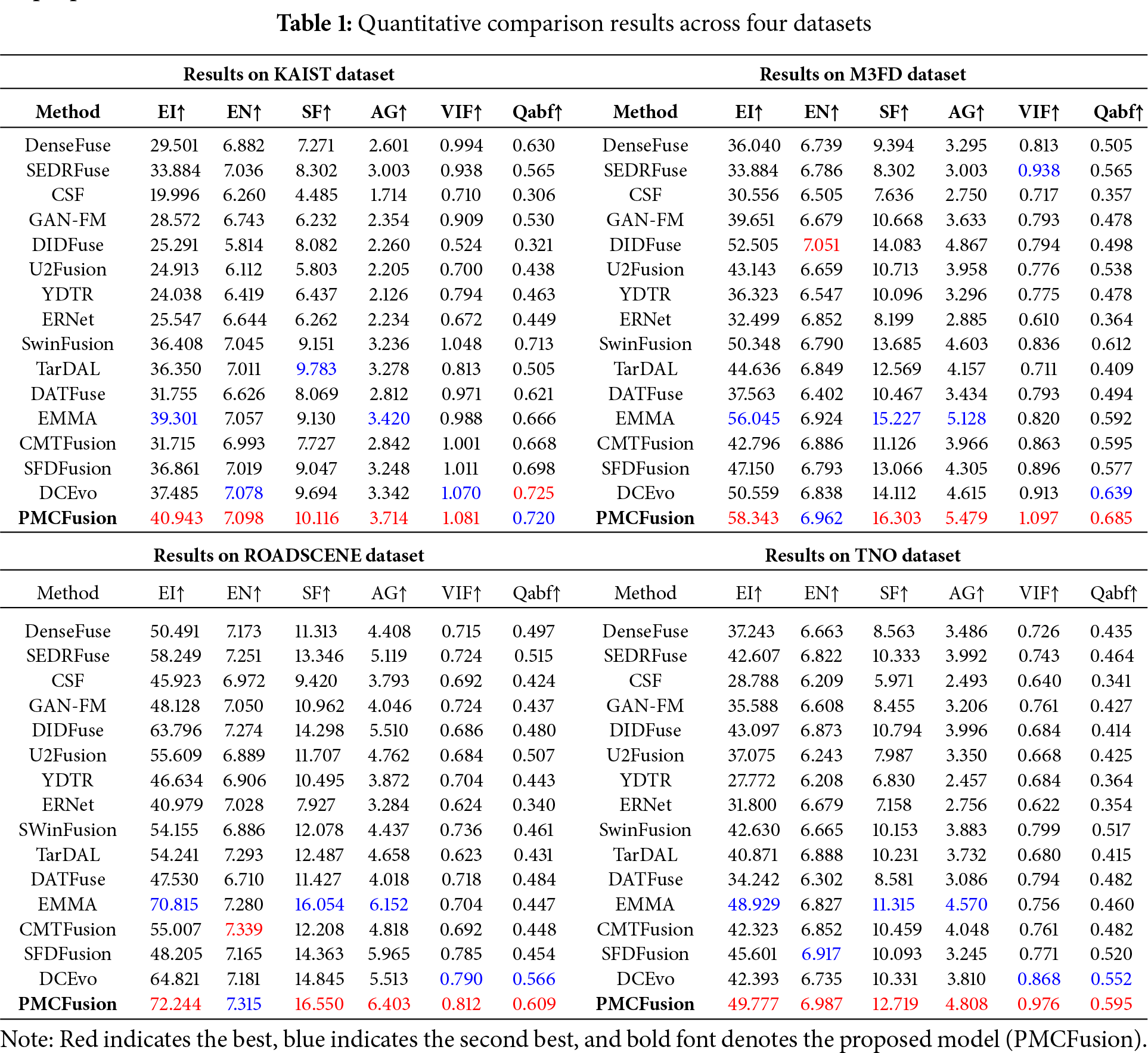

To demonstrate its effectiveness, we compare PMCFusion against 15 state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods, including DenseFuse [11], SEDRFuse [42], CSF [12], GAN-FM [16], DIDFuse [43], U2Fusion [40], YDTR [44], ERNet [13], SwinFusion [17], TarDAL [41], DATFuse [45], as well as recent approaches such as EMMA [31], CMTFusion [18], SFDFusion [23], and DCEvo [46].

As indicated by the results in Table 1, on the KAIST dataset, PMCFusion achieves EI, SF, and AG scores of 40.943, 10.116, and 3.714, yielding relative gains of approximately 4.1%, 3.4%, and 8.5% over the respective runner-up method (EMMA, with 39.301, 9.783, and 3.420). For EN and Qabf, our results are highly comparable to the best competitors, with differences at the per-mille level (e.g., only 0.005 lower than DCEvo in Qabf), showing competitive information retention and structural preservation. On M3FD, PMCFusion reports an EI of 58.343 and AG of 5.479, outperforming the next best method (EMMA, with 56.045, and 5.128) by approximately 4.1% and 6.8%, respectively. On SF, PMCFusion reaches 16.303, surpassing EMMA (15.227) by 7.1% to achieve the best performance. On RoadScene, PMCFusion delivers notable improvements: EI reaches 72.244, which is 2% higher than EMMA (70.815), while SF and AG achieve 16.550 and 6.403, corresponding to 3.1% and 4.1% gains over EMMA (16.054 for SF, 6.152 for AG), respectively. On TNO, PMCFusion again leads with EI of 49.777 (1.7% higher than EMMA’s 48.927), SF of 12.719 (12.4% gain over EMMA’s 11.315), and AG of 4.808 (5.2% gain over EMMA’s 4.570). Overall, PMCFusion provides consistent and stable advantages on clarity- and detail-related metrics (EI, SF, AG) across all datasets, while also achieving competitive or superior performance on EN and Qabf. These results demonstrate not only the superior perceptual quality of the fused outputs but also the strong cross-dataset generalization capability of the proposed framework.

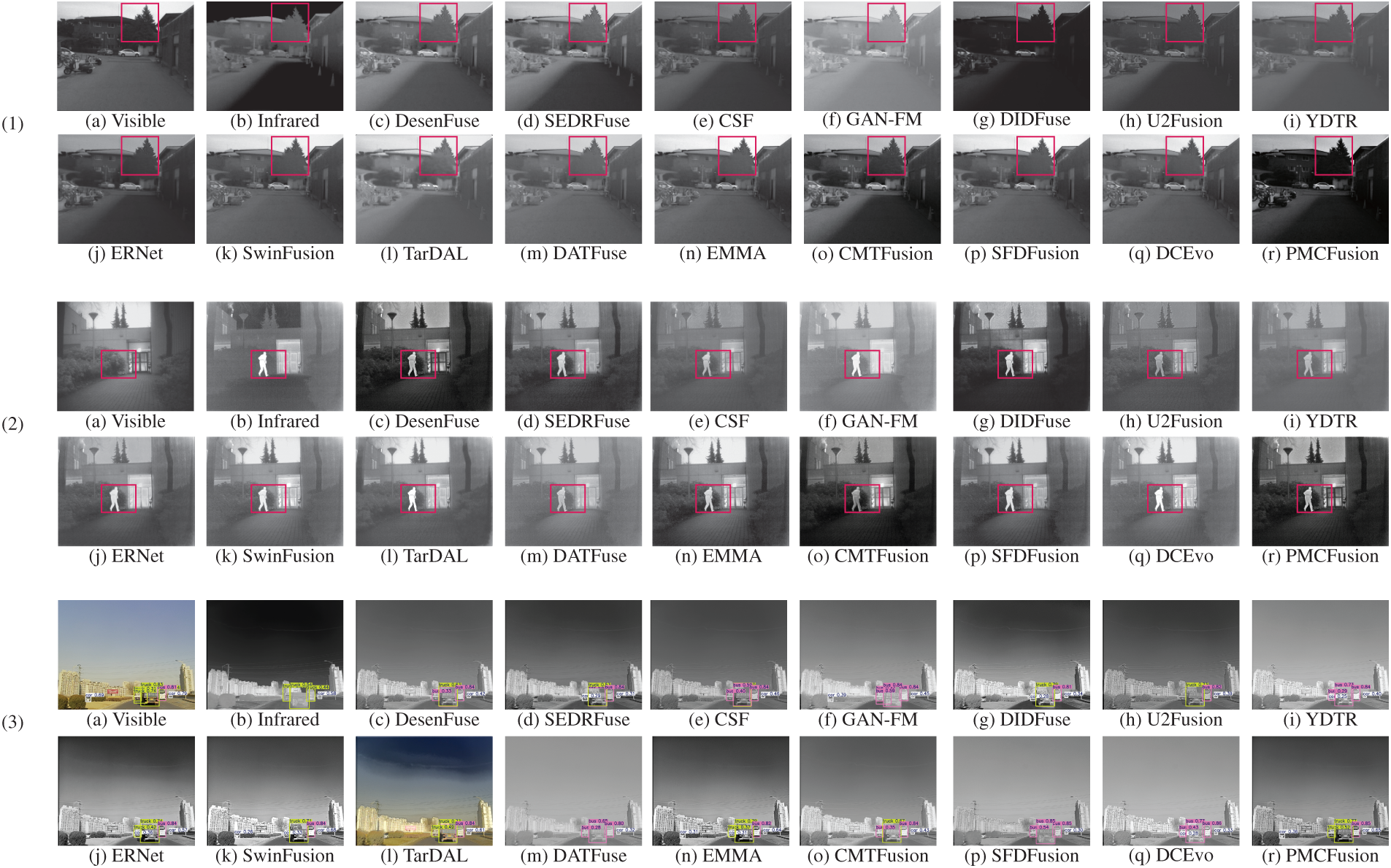

Fig. 4 displays the fusion results of various algorithms on the KAIST, M3FD, RoadScene, and TNO datasets. These visual comparisons reveal two key advantages of our method. First, our algorithm consistently generates fused images with low levels of noise. Second, the proposed method better preserves the textural details from both source images. For example, the details of the tree within the red box in (1) are well preserved. In (3), only our method successfully detects all vehicles. Most models fail to detect the car on the left, and some models, even if they detect the car on the left, encounter issues with detecting other vehicles. For instance, the visible light image falsely detects multiple unnecessary trucks on the right. This further demonstrates the superior performance of our model in fusion tasks.

Figure 4: The Qualitative comparison results display the fusion results of three datasets, where (1) and (2) are the infrared and visible light image fusion results on the KAIST and TNO datasets, and (3) is the object detection result of the fusion image on the M3FD dataset

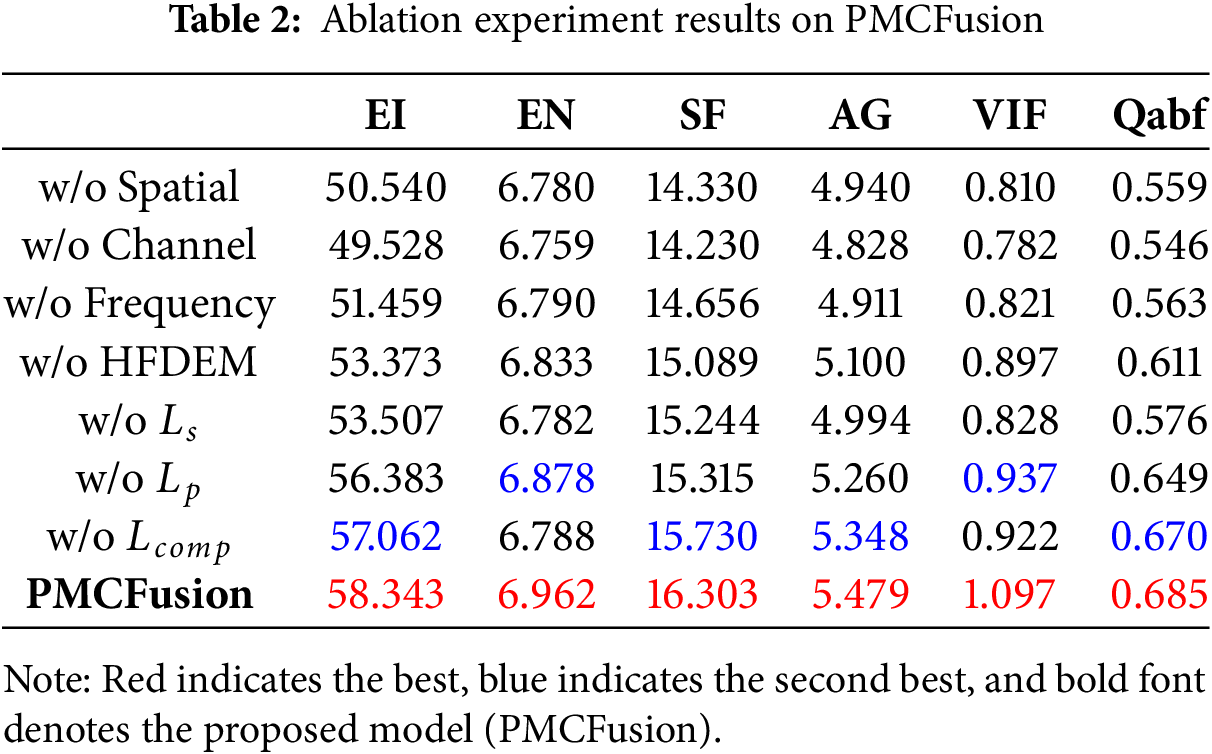

We conducted a series of ablation studies to validate the importance of the key components in our proposed algorithm. These experiments were designed to assess the impact of the PTFM, the HFDEM, and the individual loss functions on the overall image fusion performance. The M3FD dataset was used as the exclusive test set for all ablation experiments.

As shown in Table 2, the ablation study demonstrates that sequentially removing the spatial, channel, and frequency branches from the PTFM module leads to a significant decline in all evaluation metrics, highlighting the importance of complementary information among the three branches in the fusion process. When the HFDEM module is removed, all metrics related to sharpness and detail experience a substantial drop, indicating that enhancing high-frequency details of the source images prior to fusion is essential. Regarding the loss functions, the removal of spatial loss

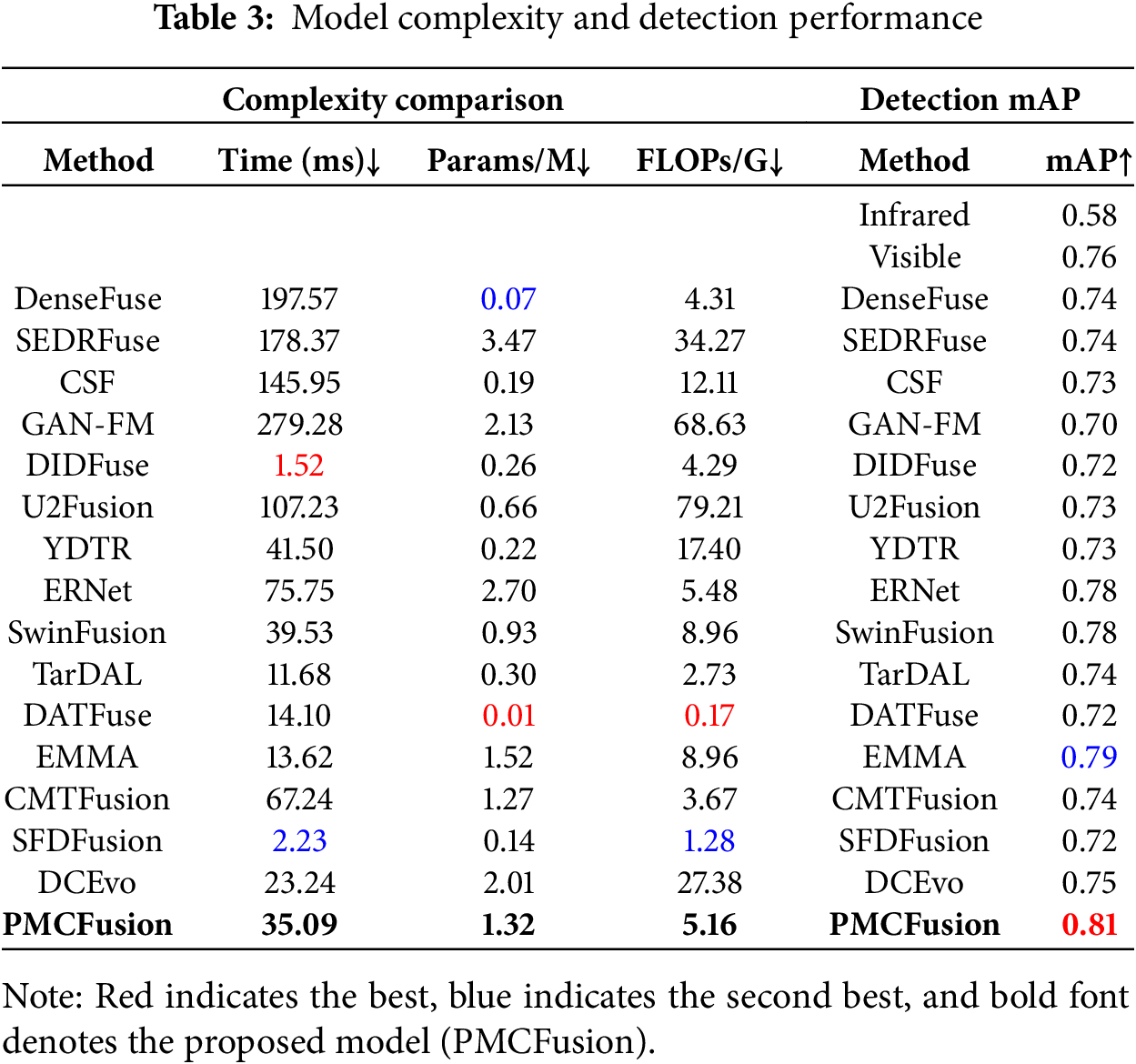

4.6 Complexity and Detection Performance Comparison of Different Methods

We compared the PMCFusion model with other models in terms of inference time, parameter count, and computational load, and evaluated the object detection performance of the fused images using YOLOv5s. The left side of Table 3 shows that, despite the larger number of parameters in our model, it still ranks among the top in inference time. The results on the right side of Table 3 indicate that, although our method was not specifically optimized for downstream object detection tasks, it still maintains excellent detection performance, with detection accuracy about 3% higher than that of the second-best model. These comparisons demonstrate that PMCFusion offers high practical value in real-world applications. We plan to make the model open-source after acceptance.

In this paper, we propose a Parallel Multi-dimensional Complementary Fusion Network (PMCFusion). The proposed algorithm first enhances the source images using HFDEM, and subsequently achieves complementary information fusion in the spatial, channel, and frequency domains through the PTFM module, thereby effectively improving visual quality and texture details. Experimental results demonstrate that our method offers consistent advantages in terms of visual perception and quantitative metrics. In addition, while the four benchmark datasets already contain challenging cases such as low illumination, noise, and overexposure, our current study does not explicitly highlight robustness-oriented experiments. As an important extension, we plan to conduct systematic robustness evaluations under synthetic noise, modality misalignment, and simulated adverse weather conditions, to further validate the generalizability of PMCFusion. In the future, another important direction will be to extend the PMCFusion framework to a broader range of image fusion tasks, thereby enhancing its applicability in diverse real-world scenarios.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the Funds for Central-Guided Local Science & Technology Development (Grant No. 202407AC110005) Key Technologies for the Construction of a Whole-Process Intelligent Service System for Neuroendocrine Neoplasm; in part by the Xingdian Talent Project of Yunnan Province. The key technology research and application of cross-domain automatic business collaboration in smart tourism (XYYC-CYCX-2022-0005); and in part by the Yunnan Province Zhangjun Expert Workstation (No. 202205AF150081).

Author Contributions: Xu Tao and Hao Li are responsible for the thesis manuscript and experiments, while Zhaoqi Jin and Qiang Xiao are mainly in charge of the data. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this study (KAIST, M3FD, ROADSCENE, and TNO) are publicly available benchmark datasets. Interested researchers can obtain the data from the respective official repositories in accordance with the terms specified by the dataset providers.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li S, Kang X, Fang L, Hu J, Yin H. Pixel-level image fusion: a survey of the state of the art. Inform Fus. 2017;33:100–12. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2016.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang X. Deep learning-based multi-focus image fusion: a survey and a comparative study. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;44(9):4819–38. doi:10.1109/tpami.2021.3078906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Liu J, Wu G, Liu Z, Wang D, Jiang Z, Ma L, et al. Infrared and visible image fusion: from data compatibility to task adaption. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2025;47(4):2349–69. doi:10.1109/tpami.2024.3521416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Hermessi H, Mourali O, Zagrouba E. Multimodal medical image fusion review: theoretical background and recent advances. Signal Process. 2021;183:108036. doi:10.1016/j.sigpro.2021.108036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li C, Song D, Tong R, Tang M. Illumination-aware faster R-CNN for robust multispectral pedestrian detection. Pattern Recognit. 2019;85:161–71. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2018.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li S, Yin H, Fang L. Group-sparse representation with dictionary learning for medical image denoising and fusion. IEEE Transact Biomed Eng. 2012;59(12):3450–9. doi:10.1109/tbme.2012.2217493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zhu Z, Yin H, Chai Y, Li Y, Qi G. A novel multi-modality image fusion method based on image decomposition and sparse representation. Informat Sci. 2018;432:516–29. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2017.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Cao L, Jin L, Tao H, Li G, Zhuang Z, Zhang Y. Multi-focus image fusion based on spatial frequency in discrete cosine transform domain. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2014;22(2):220–4. doi:10.1109/lsp.2014.2354534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou Z, Wang B, Li S, Dong M. Perceptual fusion of infrared and visible images through a hybrid multi-scale decomposition with Gaussian and bilateral filters. Informat Fus. 2016;30(1):15–26. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2015.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu R, Liu Y, Wang H, Du S. WaveFusionNet: infrared and visible image fusion based on multi-scale feature encoder-decoder and discrete wavelet decomposition. Opt Commun. 2024;573:131024. doi:10.1016/j.optcom.2024.131024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li H, Wu XJ. DenseFuse: a fusion approach to infrared and visible images. IEEE Transact Image Process. 2018;28(5):2614–23. doi:10.1109/tip.2018.2887342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Wang X, Guan Z, Qian W, Cao J, Liang S, Yan J. Cs2fusion: contrastive learning for self-supervised infrared and visible image fusion by estimating feature compensation map. Inf Fusion. 2024;102:102039. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Su W, Huang Y, Li Q, Zuo F, Liu L. Infrared and visible image fusion based on adversarial feature extraction and stable image reconstruction. IEEE Transact Instrument Measur. 2022;71:1–14. doi:10.1109/tim.2022.3177717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yang Y, Liu J, Huang S, Wan W, Wen W, Guan J. Infrared and visible image fusion via texture conditional generative adversarial network. IEEE Transact Circ Syst Video Technol. 2021;31(12):4771–83. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2021.3054584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gao Y, Ma S, Liu J. DCDR-GAN: a densely connected disentangled representation generative adversarial network for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Transact Circ Syst Video Technol. 2022;33(2):549–61. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2022.3206807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang H, Yuan J, Tian X, Ma J. GAN-FM: infrared and visible image fusion using GAN with full-scale skip connection and dual Markovian discriminators. IEEE Transact Computat Imag. 2021;7:1134–47. doi:10.1109/tci.2021.3119954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ma J, Tang L, Fan F, Huang J, Mei X, Ma Y. SwinFusion: cross-domain long-range learning for general image fusion via swin transformer. IEEE/CAA J Automatica Sinica. 2022;9(7):1200–17. doi:10.1109/jas.2022.105686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Park S, Vien AG, Lee C. Cross-modal transformers for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Transact Circ Syst Video Technol. 2023;34(2):770–85. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2023.3289170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Infrared and visible image fusion using ResNet101-based pretrained backbone. Biomed Signal Process Cont. 2024;90:106976. [Google Scholar]

20. Zhang X, Tang B, Hu S. Infrared and visible image fusion based on particle swarm optimization and Dense Blocks. Front Energy Res. 2022;10:1001450. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2022.1001450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li J, Bai L, Yang B, Li C, Ma L. Graph representation learning for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2025;22:13801–13. doi:10.1109/tase.2025.3557234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen X, Xu S, Hu S, Ma X. DGFD: a dual-graph convolutional network for image fusion and low-light object detection. Inf Fusion. 2025;119:103025. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hu K, Zhang Q, Yuan M, Zhang Y. SFDFusion: an efficient spatial-frequency domain fusion network for infrared and visible image fusion. In: ECAI 2024. Amsterdam, The Netherland: IOS Press; 2024. p. 482–9. doi:10.3233/faia240524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li H, Liu L, Huang W, Yue C. An improved fusion algorithm for infrared and visible images based on multi-scale transform. Infrar Phy Technol. 2016;74:28–37. [Google Scholar]

25. Cvejic N, Bull D, Canagarajah N. Region-based multimodal image fusion using ICA bases. IEEE Sens J. 2007;7(5):743–51. doi:10.1109/jsen.2007.894926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liu C, Qi Y, Ding W. Infrared and visible image fusion method based on saliency detection in sparse domain. Infrared Phy Technol. 2017;83:94–102. [Google Scholar]

27. Luo Y, He K, Xu D, Shi H, Yin W. Infrared and visible image fusion based on hybrid multi-scale decomposition and adaptive contrast enhancement. Signal Process Image Commun. 2025;130:117228. doi:10.1016/j.image.2024.117228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Gan W, Wu X, Wu W, Yang X, Ren C, He X, et al. Infrared and visible image fusion with the use of multi-scale edge-preserving decomposition and guided image filter. Infrar Phys Technol. 2015;72:37–51. [Google Scholar]

29. Karim S, Tong G, Li J, Qadir A, Farooq U, Yu Y. Current advances and future perspectives of image fusion: a comprehensive review. Informat Fus. 2023;90:185–217. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2022.09.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

31. Zhao Z, Bai H, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Zhang K, Xu S, et al. Equivariant multi-modality image fusion. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 25912–21. [Google Scholar]

32. Qi W, Zhang Z, Wang Z. DMFuse: diffusion model guided cross-attention learning for infrared and visible image fusion. Chin J Inform Fusion. 2024;1(3):226–42. doi:10.62762/cjif.2024.655617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang X, Hua Z, Ju Y, Zhou W, Liu J, Kot AC. SGDFuse: SAM-guided diffusion for high-fidelity infrared and visible image fusion. arXiv:2508.05264. 2025. [Google Scholar]

34. Liu J, Tang J, Wu G. Residual feature distillation network for lightweight image super-resolution. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

35. Gong S, Zhang S, Yang J, Yuen PC. Self-fusion convolutional neural networks. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2021;152:50–5. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2021.08.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv:1409.1556. 2014. [Google Scholar]

37. Hwang S, Park J, Kim N, Choi Y, So Kweon I. Multispectral pedestrian detection: benchmark dataset and baseline. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. p. 1037–45. [Google Scholar]

38. Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980. 2014. [Google Scholar]

39. Toet A. The TNO multiband image data collection. Data Brief. 2017;15:249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

40. Xu H, Ma J, Jiang J, Guo X, Ling H. U2Fusion: a unified unsupervised image fusion network. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;44(1):502–18. doi:10.1109/tpami.2020.3012548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Liu J, Fan X, Huang Z, Wu G, Liu R, Zhong W, et al. Target-aware dual adversarial learning and a multi-scenario multi-modality benchmark to fuse infrared and visible for object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 5802–11. [Google Scholar]

42. Jian L, Yang X, Liu Z, Jeon G, Gao M, Chisholm D. SEDRFuse: a symmetric encoder-decoder with residual block network for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Transact Instrument Measur. 2020;70:1–15. doi:10.1109/tim.2020.3022438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Zhao Z, Xu S, Zhang C, Liu J, Li P, Zhang J. DIDFuse: deep image decomposition for infrared and visible image fusion. arXiv:2003.09210. 2020. [Google Scholar]

44. Tang W, He F, Liu Y. YDTR: infrared and visible image fusion via Y-shape dynamic transformer. IEEE Transact Multim. 2022;25:5413–28. doi:10.1109/tmm.2022.3192661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Tang W, He F, Liu Y, Duan Y, Si T. DATFuse: infrared and visible image fusion via dual attention transformer. IEEE Transact Circ Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(7):3159–72. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2023.3234340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Liu J, Zhang B, Mei Q, Li X, Zou Y, Jiang Z, et al. DCEvo: discriminative cross-dimensional evolutionary learning for infrared and visible image fusion. In: Proceedings of 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2025 Jun 10–17; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 2226–35. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools