Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Research on Vehicle Joint Radar Communication Resource Optimization Method Based on GNN-DRL

1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo, 255000, China

2 School of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo, 255000, China

* Corresponding Author: Jian Sun. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071182

Received 01 August 2025; Accepted 25 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

To address the issues of poor adaptability in resource allocation and low multi-agent cooperation efficiency in Joint Radar and Communication (JRC) systems under dynamic environments, an intelligent optimization framework integrating Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) and Graph Neural Network (GNN) is proposed. This framework models resource allocation as a Partially Observable Markov Game (POMG), designs a weighted reward function to balance radar and communication efficiencies, adopts the Multi-Agent Proximal Policy Optimization (MAPPO) framework, and integrates Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) and Graph Sample and Aggregate (GraphSAGE) to optimize information interaction. Simulations show that, compared with traditional methods and pure DRL methods, the proposed framework achieves improvements in performance metrics such as communication success rate, Average Age of Information (AoI), and policy convergence speed, effectively enabling resource management in complex environments. Moreover, the proposed GNN-DRL-based intelligent optimization framework obtains significantly better performance for resource management in multi-agent JRC systems than traditional methods and pure DRL methods.Keywords

In intelligent transportation systems (ITS), the demand for real-time performance in vehicle environmental perception and vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication is growing rapidly—meanwhile, with the development of autonomous driving technology, efficient transmission and processing of massive data from vehicle sensors (e.g., radar, cameras) has become a research focus. Although JRC technology provides a new approach by enabling radar-communication collaboration in a shared frequency band [1–3], its traditional resource allocation (including early fixed solutions like hardware design and time-division multiplexing [4–6]) all relies on static optimization or predefined rules, making it difficult to address instantaneous interference and multi-agent collaboration in dynamic traffic environments. While DRL offers an adaptive solution, its collaborative efficiency and information exchange capabilities are insufficient in some scenarios, thus creating an urgent need for an intelligent resource allocation framework that can efficiently process dynamic graph structures and optimize multi-agent collaboration.

In resource allocation research, traditional convex optimization, greedy algorithms, and static AoI optimization models are widely used but limited by reliance on prior channel parameters or inability to cope with environmental transients [7–10]. In multi-agent collaboration, centralized control lacks scalability due to high overhead, while fixed clustering algorithms lack dynamic learning capabilities [11,12]. In recent years, DRL has become a focus for its adaptability to dynamic environments: single-agent methods (e.g., Deep Q-Network (DQN), Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) [13,14]) handle action spaces, and multi-agent methods (e.g., centralized DDPG [15,16]) achieve strategy sharing, yet they still face limitations like single action spaces and insufficient environment modeling [17,18].

As the demand for real-time performance in intelligent transportation systems increases, researchers have begun to explore the integration of DRL and GNN. GNNs model node interactions through graph structures, demonstrating advantages in multi-agent collaboration. For example, Reference [19] uses GCNs to optimize information aggregation, while Reference [20] combines GraphSAGE to achieve dynamic neighbor selection, both of which effectively improve resource allocation efficiency. In addition, Hieu et al. (2022) proposed a joint radar-data communication framework for self-driving vehicles based on relocatable deep reinforcement learning, which significantly improves cross-environmental adaptation [21]. Sohaib et al. (2024), on the other hand, implemented energy-efficient resource allocation in V2X communication through dynamic meta-migration learning, which further enhances the robustness of the system in dynamic environments [22].

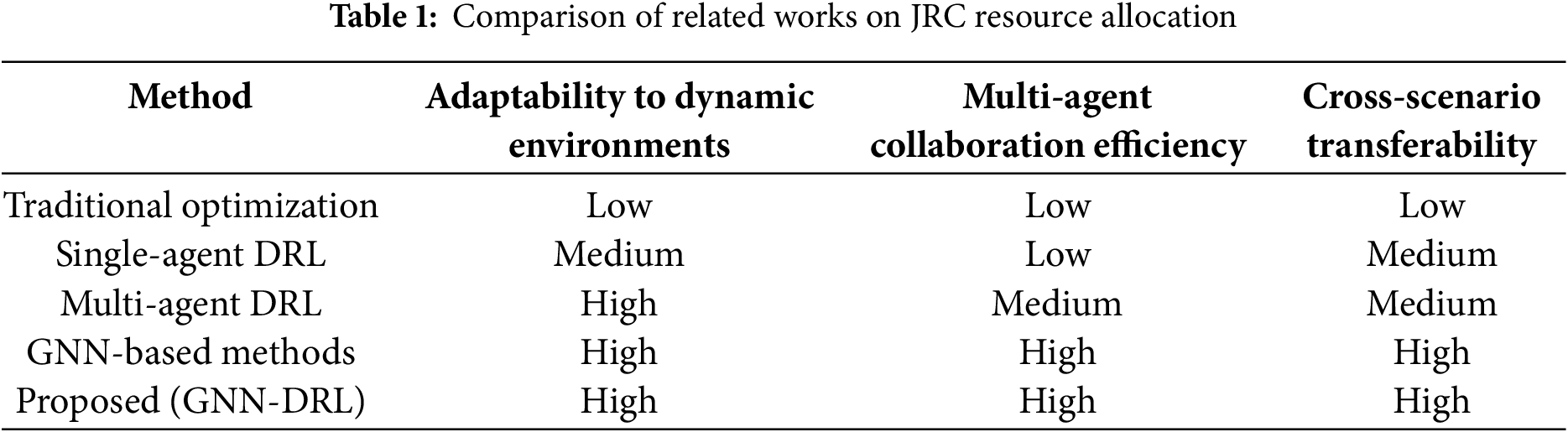

For JRC performance optimization, researchers focus on AoI and communication success rates. Ref. [23] minimizes drone-assisted network AoI via MAPPO, while Ref. [24] uses a weighted reward function to balance radar-communication efficiency. Notably, radar interference in millimeter-wave communications drives dynamic resource scheduling algorithm development: Ref. [25] proposes a DRL-based anti-interference strategy, and Ref. [26] enhances system robustness via joint trajectory-data scheduling optimization. However, existing research has three key challenges: poor resource allocation adaptability in dynamic environments, low multi-agent collaborative info exchange efficiency, and no cross-scenario transferability [27]. Table 1 compares five typical JRC resource allocation methods (Traditional Optimization, Single-agent DRL, Multi-agent DRL, GNN-based methods, and the proposed GNN-DRL) in the three challenge-related dimensions (adaptability to dynamic environments, multi-agent collaboration efficiency, cross-scenario transferability), showing only the proposed GNN-DRL achieves “High” in all dimensions.

Existing research still faces three major challenges: insufficient adaptability in resource allocation within dynamic environments; inefficient information exchange during multi-agent collaboration; and a lack of cross-scenario generalization capabilities. To address these challenges, this study proposes an intelligent resource optimization framework that integrates GNN with MADRL. This framework models the problem as a Partially Observable Markov Game (POMG), introduces a weighted reward function to balance radar and communication tasks, and employs GCN and GraphSAGE to enable efficient information exchange among agents. The main contributions of this paper are as follows: A novel GNN-DRL fusion architecture for dynamic JRC resource allocation is proposed. A weighted reward mechanism balancing AoI and Signal to Interference plus Noise Ratio (SINR) objectives is designed.

2 Research on Joint Radar Communication Resource Allocation in a Two-Lane Scenario

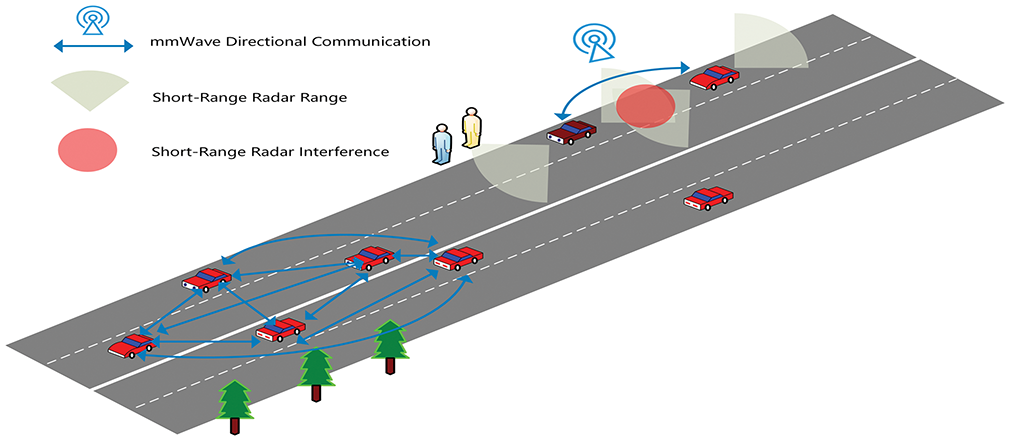

Consider a vehicular system that contains a number

Figure 1: Two-lane model

2.2 Interference with Radar and Communication Systems and Countermeasures

In real scenarios, surrounding vehicles’ radar subsystems usually operate independently at regular intervals, potentially interfering with the target vehicle’s millimeter-wave communications. To address this, intelligent vehicles in this study have learning capabilities, enabling them to arrange radar and communication operations based on their environment. They can monitor surrounding radar signal characteristics (e.g., intensity, frequency) and adjust their radar detection intervals or communication bands to reduce interference impact. When strong surrounding radar interference is detected, they may temporarily delay communication to prioritize radar detection (ensuring accurate environmental perception) or choose less interfering bands to improve communication success rates.

2.3 Communication Access Solutions in Multi-Agent Scenarios

In multi-agent scenarios, vehicles coordinate sensor data transmission through narrowband control channels using a shared channel competition mechanism. Vehicles compete for access to shared communication channels and combine graph neural networks with dynamic neighbor selection and attention mechanisms to optimize resource allocation. In this case, vehicles need to allocate resources more intelligently to avoid communication conflicts and improve communication efficiency.

2.4 Mathematical Expression and Implementation Approach of System Objectives

Vehicles in the JRC system must decide when to conduct radar detection to get accurate speed info of surrounding objects—critical for autonomous driving safety. In complex traffic, knowing surrounding vehicle speeds aids timely collision-avoidance decisions. They can predict and transmit the most valuable current data, choose optimal transmission directions for needy vehicles, and select best communication time steps to maximize SINR, boosting transmission success and throughput. These goals are mathematically integrated into the subsequent POMG model to quantify and optimize vehicle decisions.

In the JRC system, each intelligent vehicle is considered as an intelligence, and the multi-agent JRC problem is defined as a POMG since each agent can only obtain local observations and cannot know the observations or actions of other agents. At each discrete time step

Observations of this vehicle

where

The set of actions

The whole set of actions can be represented as:

If the agent selects the communication action

where

The data of the vehicle

where

The state transition model describes each vehicle’s observation changes in subsequent time steps based on all vehicles’ current observations and actions, and vehicle actions’ effect on the wireless channel. When time advances to the next step, each vehicle’s data age increases by 1, and data features shift with its travel distance due to movement. Vehicles may get new data via their sensors or from neighbors, both updating their states. The data age formula is as follows:

where

During the communication process, factors such as the power and signal-to-noise ratio (SINR) of the signal transmission play a key role in the transmission effect, which in turn affects the state transfer. When the transmitted signal reaches the target vehicle

where

where

The reward function

where

a higher SINR means that data transmission is more reliable and can deliver information to other vehicles more efficiently.

where

where

4 Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithms

For multi-agent problems, the MAPPO algorithm is proposed, which achieves distributed decision-making and knowledge sharing by randomly assigning strategies to agents [28].

This algorithm is a strategy optimization algorithm suitable for multi-agent systems and plays an important role in JRC problems. Its core principle is to maximize the expected reward of agents by optimizing strategies, while considering the interaction and coordination between multiple agents.

4.1 Strategy Representation and Optimization Objectives in Multi-Agent Systems

The goal of reinforcement learning is to learn an optimal strategy that allows the intelligent agent to obtain the maximum expected cumulative reward in the system [29]. For a single intelligent body, its expected reward can be expressed as:

where

4.2 Loss Function in the MAPPO Algorithm

The MAPPO algorithm updates strategy parameters by optimizing the loss function and uses a clipped proxy objective function to limit the step size of strategy updates in order to improve the stability of the algorithm. For the detailed derivation process of the CLIP loss function, please refer to Appendix A. For the

where

where

4.3 Updating the Value Network

In addition to optimizing the policy network, the MAPPO algorithm also involves updating the value network. The value network is used to estimate the value of agents in different states, helping the policy network to better evaluate the merits of actions. The parameters of the value network

where the objective value,

In order to promote the exploration of state-action space by intelligences, the MAPPO algorithm also introduces an entropy reward term

where

4.5 Algorithm Execution Process

During the execution of the MAPPO algorithm, each intelligent body chooses an action based on its current strategy

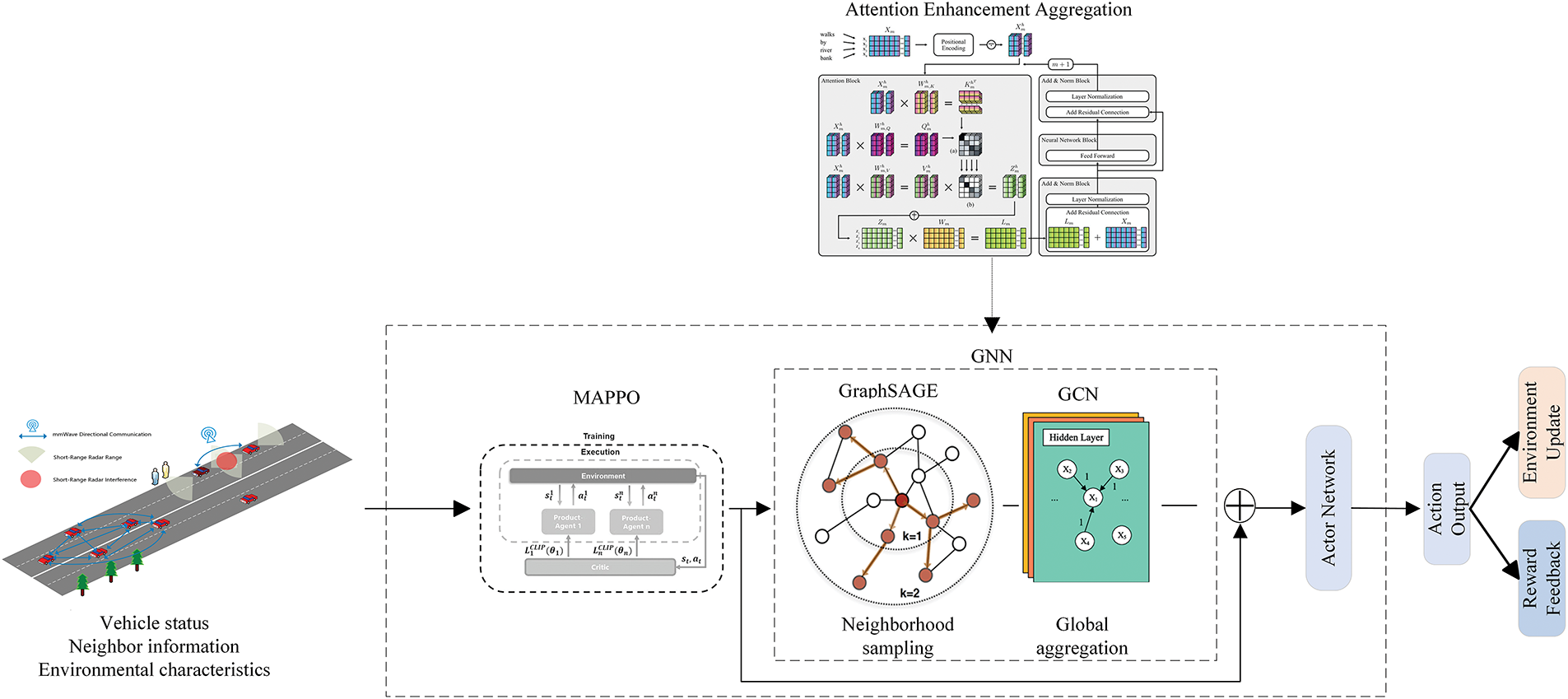

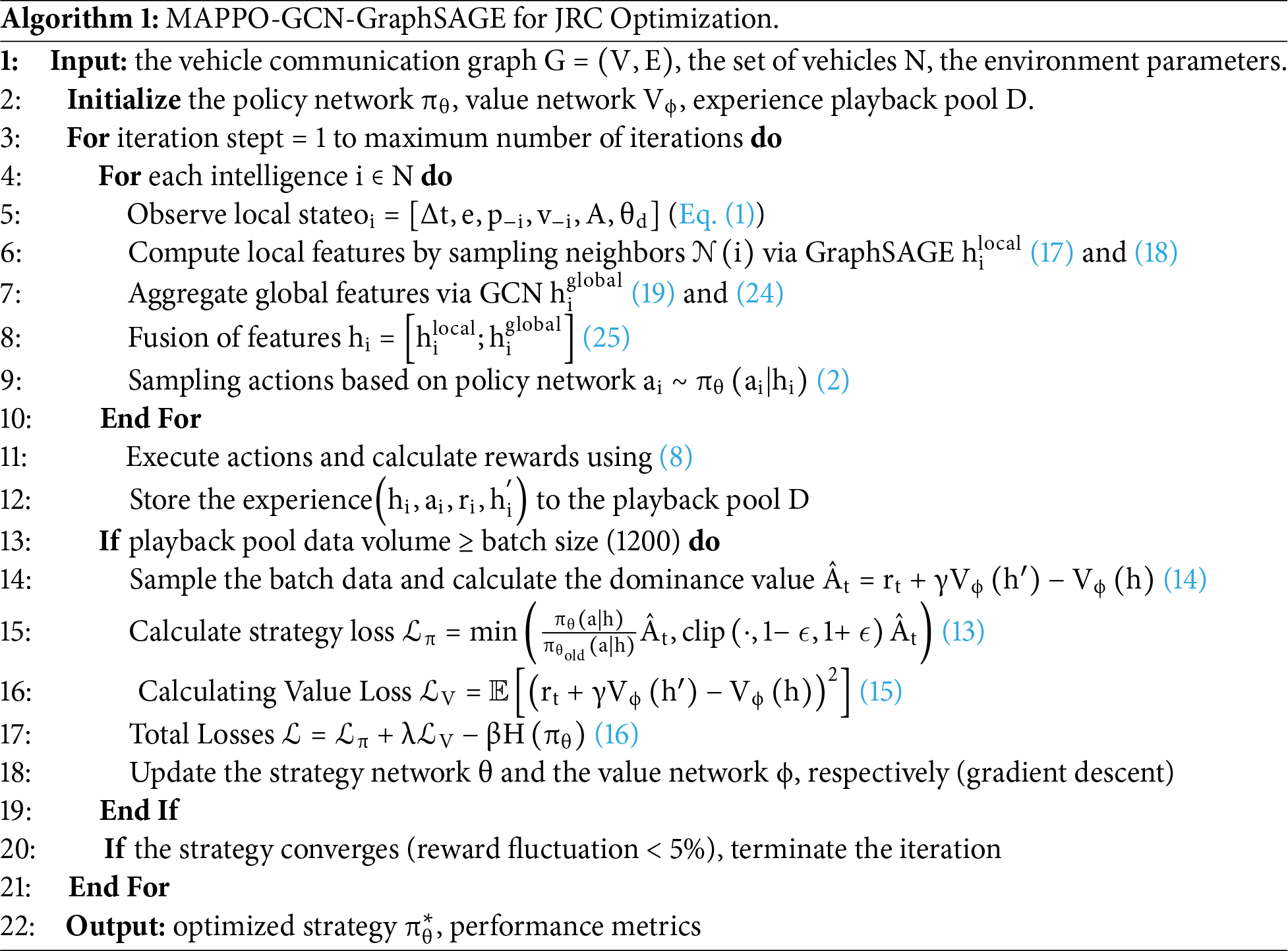

In the resource allocation problem of multi-agent JRC systems, GNN exhibits significant advantages—traditional methods struggle to handle complex dynamic graph structures and multi-agent interactions, while GNN can effectively capture node relationships and information propagation rules. During the execution of the MAPPO algorithm, each agent first fuses its local observation

Figure 2: Structure of a vehicle JRC resource allocation model based on graph neural networks

GraphSAGE is an inductive graph neural network that updates the features of target nodes by sampling and aggregating the features of neighboring nodes.

Sampling Neighbor Nodes: sampling a fixed number

Aggregate neighbor features: taking mean value aggregation as an example, the feature update formula for node

where

GCN aggregates and transforms the features of nodes during message passing. Suppose the graph

where

5.3 Neighbor Selection and Attention Mechanism Optimization Based on the Fusion of GraphSAGE and GCN

Based on the existing GraphSAGE neighbor sampling, dynamic weights and attention mechanisms are introduced to improve the specificity of information aggregation.

5.3.1 Dynamic Adjacency Weight

Weights based on interference intensity are added to the aggregation function of GraphSAGE. Assuming that the distance between vehicles

where

5.3.2 Attention Enhancement Aggregation

Combine the attention of GraphSAGE with the neighbor matrix of GCN. First, calculate the attention weights

then, fuse the features of GCN and GraphSAGE:

5.3.3 Dynamic Adjacency Weight

Propose a layered fusion framework that combines the global structural information of GCN and the local dynamic features of GraphSAGE.

Stratified aggregation

Bottom layer: GraphSAGE performs local neighbor sampling and feature aggregation to obtain local features

High-level: GCN propagates the features output by GraphSAGE globally to obtain global features

Concatenate local features and global features to obtain the final features

Joint decision-making

Feed the fusion features into the policy network to obtain the resource allocation probability

As shown in Algorithm 1:

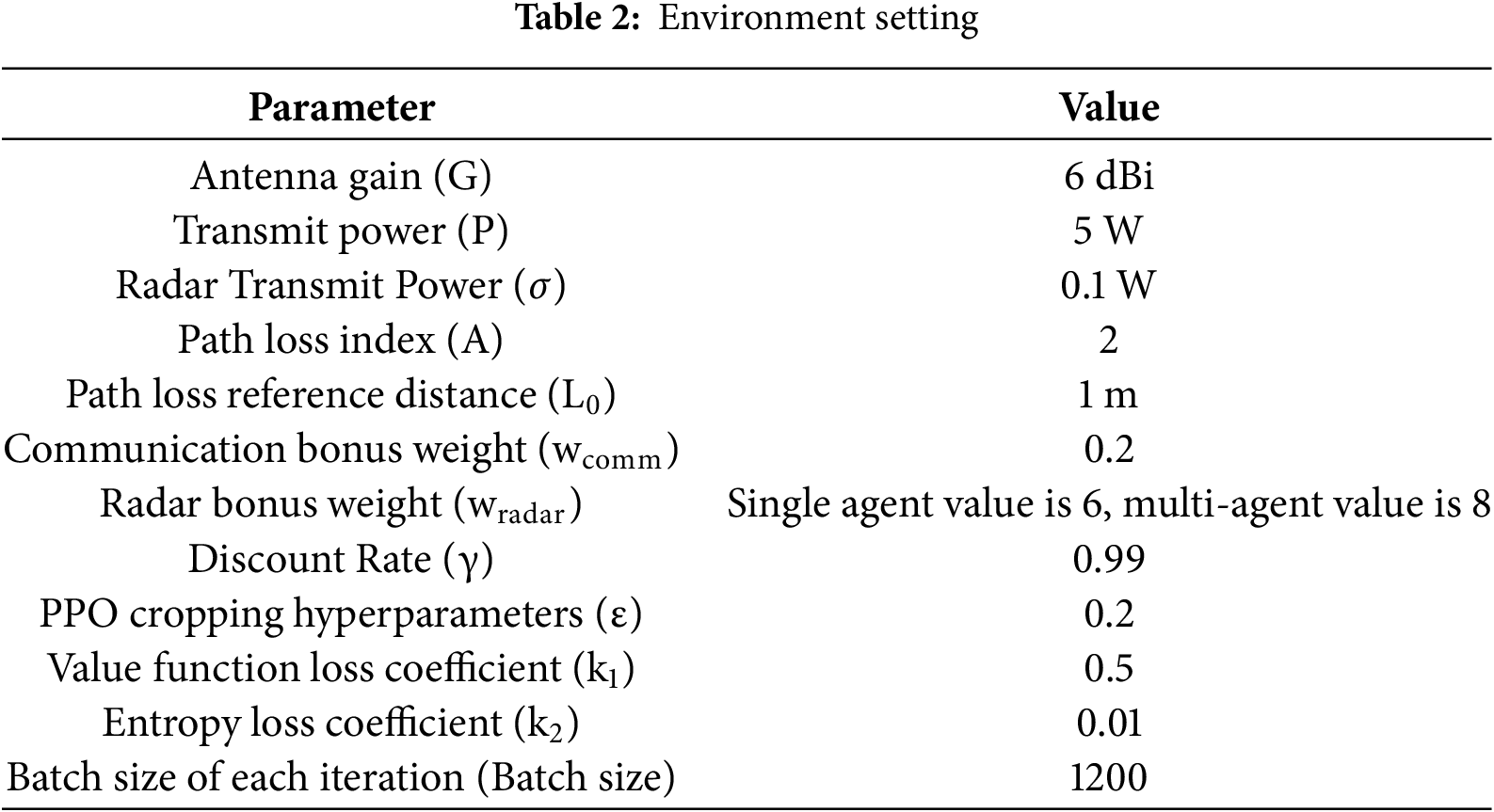

This experiment’s code was implemented with Python and the PyTorch framework, using the PyTorch Geometric library to process graph structure data for training and optimizing multi-agent collaboration strategies. It simulates a two-lane traffic scenario where the number of vehicles varies dynamically, with initial positions and velocities randomly generated to reflect real traffic uncertainty. Each vehicle has four directional antennas operating in the millimeter-wave band, supporting radar detection and directional communication. The simulation environment integrates multiple channel fading models to accurately reflect complex wireless communication propagation characteristics. Agent decision-making relies on MDP modeling, with reward functions based on SINR and AoI to guide resource allocation; radar reward weights are set differently for single-agent and multi-agent scenarios to balance radar detection and communication efficiency. At the algorithm level, the MAPPO framework is adopted, combining GCN and GraphSAGE for dynamic information exchange, and optimizing message passing via neighbor sampling and attention mechanisms. Key parameters are specified in a table to provide a standardized basis for experiment reproduction and comparison, and see Table 2 for detailed values of these parameters.

Time Division Multiplexing (TDM) allocates fixed time intervals to separate radar and communication functions, with no dynamic adjustment and independent of real-time environmental changes. It divides the time axis into periodic frames (total T time steps per frame): a dedicated segment (e.g., 30% of T, denoted t1) is for radar detection, and the remaining segment (e.g., 70% of T, denoted t2, where t1 + t2 = T) is for communication—cycling through directions like front, right, back, and left. This strict time partitioning prevents interference between radar and communication, mimicking the operation of traditional time-division systems in industrial.

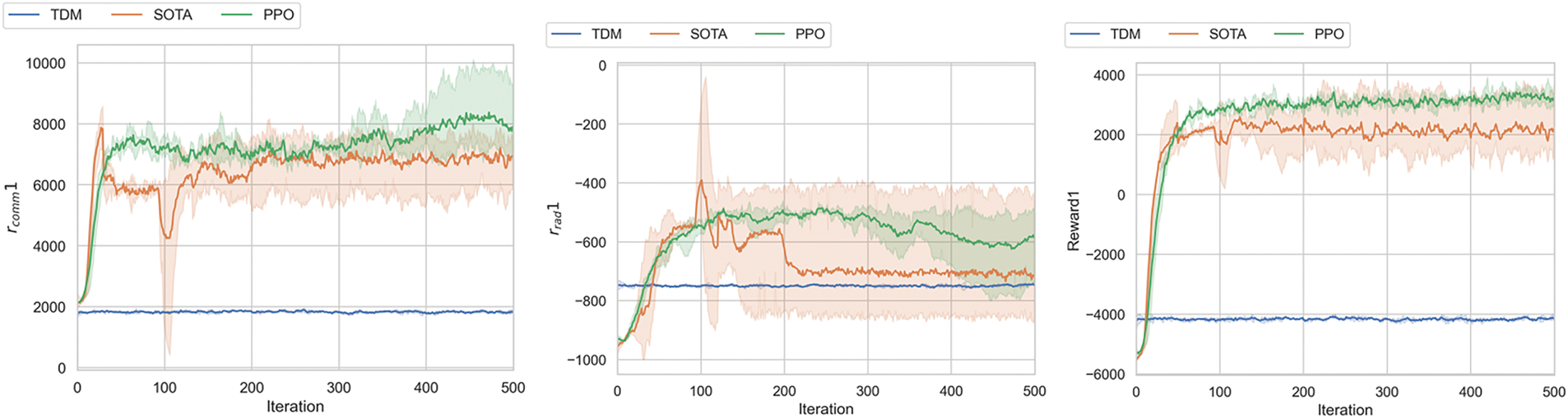

Fig. 3 shows that as the number of training iterations increases, the traditional TDM method using fixed time slot allocation, due to its rigid resource allocation rules and lack of environmental adaptability, consistently maintains the lowest reward values across all curves and shows no significant room for improvement. While the SOTA algorithm maintains a high stable range for communication rewards in the later stages and shows a steady growth trend for radar rewards and average total rewards, it lacks dynamic optimization fluctuations and exhibits significant flexibility deficiencies. In contrast, the PPO algorithm demonstrates superior performance evolution with training iterations in the experiments. Communication rewards exhibit dynamic adjustment characteristics even at stable high levels, radar rewards reach a peak early on and subsequently adapt to environmental fluctuations for optimization, and average total rewards maintain higher levels in the later stages. This fully validates PPO’s ability to dynamically optimize radar and communication strategies through reinforcement learning, highlighting the significant potential of reinforcement learning algorithms in JRC tasks compared to fixed-rule TDM methods and SOTA algorithms that are stable but lack flexibility.

Figure 3: The communication rewards, radar rewards, and average total rewards of the traditional TDM method, SOTA algorithm and the PPO algorithm in a single-agent experiment

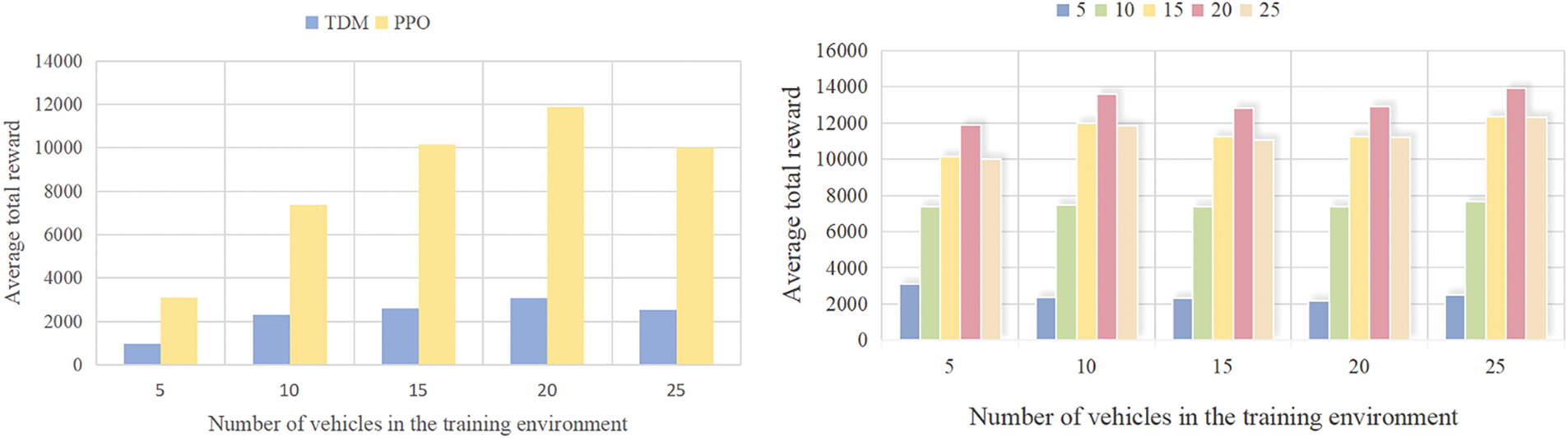

The left part of Fig. 4 takes “number of vehicles (5–25)” as the horizontal axis and “average total reward” as the vertical axis, comparing the performance of the PPO algorithm and the traditional TDM method through bar charts. The results show that in all scenarios with different numbers of vehicles, the average total reward of the PPO algorithm is significantly higher than that of the TDM method; even as the number of vehicles increases, the PPO algorithm can still stably maintain its reward advantage. This phenomenon verifies the efficiency of PPO in dynamic resource allocation—compared with the rigid rules of TDM’s fixed time slot allocation, PPO can flexibly adjust the resource ratio between radar and communication according to changes in the number of vehicles, better adapting to the resource demands in multi-vehicle scenarios.

Figure 4: Average total reward of PPO and TDM algorithms under different vehicle numbers and PPO robustness analysis (Evaluation Metric: Standard Deviation of Fluctuation in Average Total Rewards)

The right part of Fig. 4 focuses on the “difference in the number of vehicles between the training and testing environments” and reflects the robustness of the PPO algorithm (with the evaluation metric being the standard deviation of fluctuation in the average total reward) through the height variation of the bar charts. When the number of vehicles in the testing environment is consistent with or close to that in the training environment, the PPO algorithm achieves the highest reward value; as the difference in the number of vehicles between the two environments increases, the reward value decreases gradually, but the overall fluctuation range remains controllable. This indicates that the PPO algorithm can perceive changes in the number of vehicles in the environment through reinforcement learning mechanisms and dynamically optimize its strategy. At the same time, it proves that the PPO algorithm has good robustness in complex traffic scenarios with dynamic fluctuations in the number of vehicles, providing adaptive support for its deployment in real traffic environments.

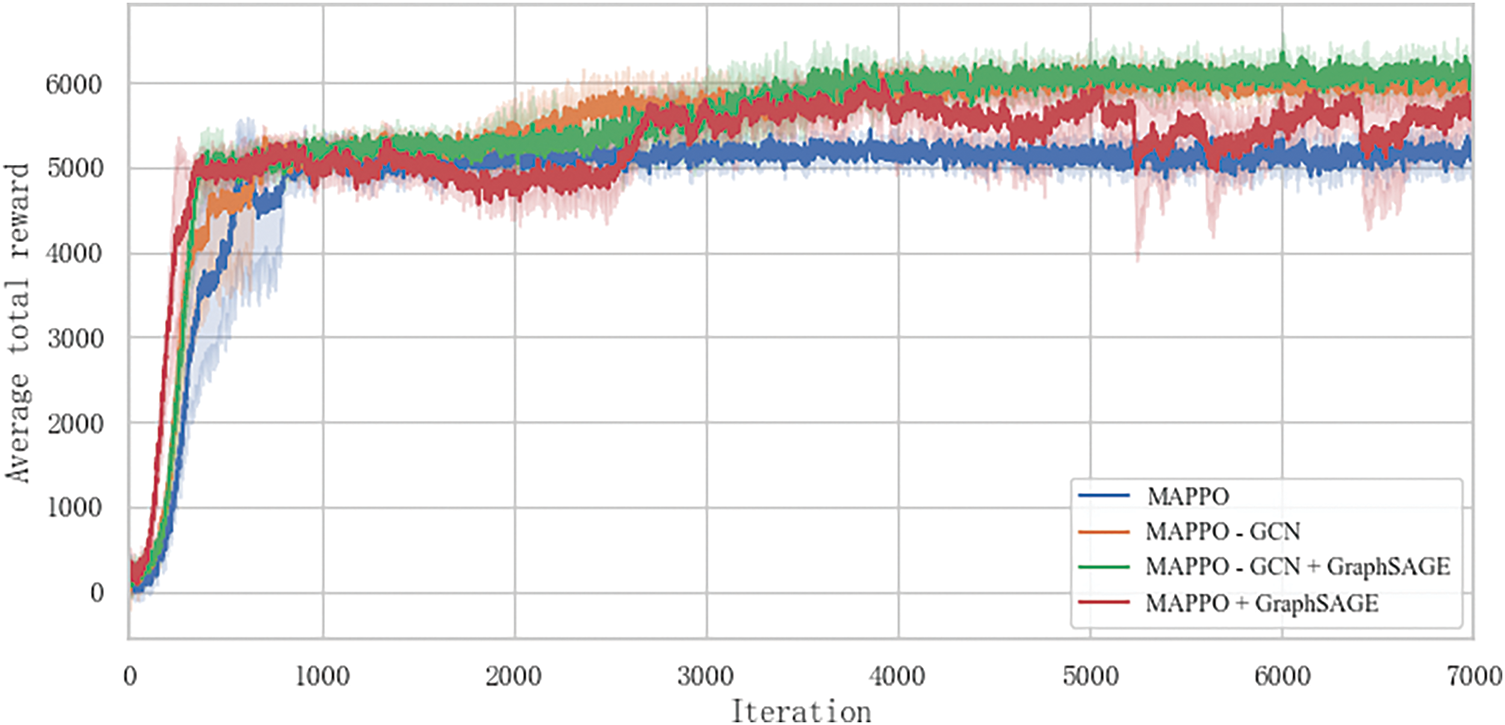

Fig. 5 shows the evolution of the average total reward during training for the multi-agent JRC problem. The experiment involves eight agents, all of which are mutually reachable on the control channel. Each iteration is trained based on a fixed number of samples, with the specific sample count determined by the experimental setup. Significant performance differences emerged among algorithms during training: The pure MAPPO algorithm showed initial improvement but became unstable after approximately 1500 iterations, likely due to the partially observable environment and insufficient information exchange among agents, leading to performance degradation. In contrast, GNN-based MAPPO algorithms demonstrated steadily increasing rewards throughout training, outperforming all other tested algorithms in reward acquisition. Among these, the MAPPO + GCN + GraphSAGE algorithm achieved the best results. This algorithm achieves approximately 18% higher convergence rewards than the pure MAPPO algorithm, 7% higher than MAPPO + GCN, and 12% higher than MAPPO + GraphSAGE. This significant improvement stems from the effective fusion of local neighbor features (via GraphSAGE) and global topological information (via GCN), which enables more efficient cooperative decision-making. When certain algorithmic features are adjusted (such as changing the neighbor selection strategy or the parameters of the attention mechanism), the algorithm’s performance changes accordingly, but overall, the advantages of this algorithm are quite evident.

Figure 5: Comparison of average total rewards between MAPPO and its fusion of GCN and GraphSAGE variant algorithms during intelligent agent training

The experiment comprehensively verified the effectiveness of the GNN framework integrating GCN and GraphSAGE in multi-agent joint radar communication (JRC) systems. Through dynamic graph sampling and attention mechanisms, the new algorithm demonstrated superior performance to traditional methods in terms of communication success rate, decision speed, and environmental adaptability. The ablation experiments further clarified the roles of each module in the algorithm, providing direction for algorithm optimization and improvement. The hierarchical fusion path of GNN and DRL proposed in this study provides a more robust and deployable solution for real-time resource scheduling in vehicle-to-everything (V2X) and intelligent transportation systems, and is expected to have significant application value in high-density vehicle scenarios. In the future, we can further expand to complex traffic scenarios such as multi-lane roads and intersections, explore lightweight GNN architectures to reduce computational overhead, and integrate multi-sensor data to improve decision-making accuracy.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, grant number ZR2023MF111.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, methodology and writing, Zeyu Chen; supervision and project administration, Jian Sun; formal analysis, Zhengda Huan; experimental verification, Ziyi Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Derivation of the CLIP Loss Function

The CLIP loss function proposed in Section 4.2 of the main text is used to limit the policy update step size of MAPPO, preventing training oscillations caused by excessive parameter adjustments. Its core derivation process is as follows:

A.1 Definition of the Probability Ratio

In the MAPPO algorithm, the core basis for policy updates is the “ratio of the action probability of the current policy to that of the old policy” (probability ratio), defined as

A.2 Construction Logic of the CLIP Loss Function

To avoid “abrupt policy changes” (e.g., a sudden shift from “prioritizing communication” to “prioritizing radar detection”) caused by excessively large or small

The core idea of the CLIP loss function at this point is to “take the minimum of the ‘original probability ratio-weighted advantage’ and the ‘clipped probability ratio-weighted advantage’”. This not only uses the advantage function to guide policy optimization but also avoids over-updates through clipping (Eq. (13)).

Where

References

1. Luong NC, Lu X, Hoang DT, Niyato D, Wang P, Kim DI. Radio resource management in joint radar and communication: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutor. 2021;23(2):780–814. doi:10.1109/COMST.2021.3057770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hult R, Sancar FE, Jalalmaab M, Falcone P, Wymeersch H. Design and experimental validation of a cooperative driving control architecture for the grand cooperative driving challenge 2016. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2018;19(4):1290–301. doi:10.1109/TITS.2017.2749978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Liu F, Masouros C, Petropulu AP, Griffiths H, Hanzo L. Joint radar and communication design: applications, state-of-the-art, and the road ahead. IEEE Trans Commun. 2020;68(6):3834–62. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2020.2973976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ma D, Shlezinger N, Huang T, Liu Y, Eldar YC. Joint radar-communication strategies for autonomous vehicles: combining two key automotive technologies. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2020;37(4):85–97. doi:10.1109/MSP.2020.2983832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kaul S, Gruteser M, Rai V, Kenney J. Minimizing age of information in vehicular networks. In: Proceedings of the 2011 8th Annual IEEE Communications Society Conference on Sensor, Mesh and Ad Hoc Communications and Networks; 2011 Jun 27–30; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2011. p. 350–8. doi:10.1109/SAHCN.2011.5984926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ren P, Munari A, Petrova M. Performance analysis of a time-sharing joint radar-communications network. In: Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC); 2020 Feb 17–20; Big Island, HI, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 908–13. doi:10.1109/ICNC47757.2020.9049747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hsu YP, Modiano E, Duan L. Scheduling algorithms for minimizing age of information in wireless broadcast networks with random arrivals. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2019;19(12):2903–15. doi:10.1109/TMC.2019.2933780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Huang L, Modiano E. Optimizing age-of-information in a multi-class queueing system. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT); 2015 Jun 14–19; Hong Kong, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 1681–5. doi:10.1109/ISIT.2015.7282772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Talak R, Karaman S, Modiano E. Optimizing information freshness in wireless networks under general interference constraints. In: Proceedings of the Eighteenth ACM International Symposium on Mobile Ad Hoc Networking and Computing; 2018 Jun 26–29; Los Angeles, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2018. p. 61–70. doi:10.1145/3209582.3209597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chen ML, Ke F, Lin Y, Qin MJ, Zhang XY, Ng DWK. Joint communications, sensing, and MEC for AoI-aware V2I networks. IEEE Trans Commun. 2024;73(7):5357–74. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2024.3401501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sukhbaatar S, Fergus R. Learning multiagent communication with backpropagation. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2016;29:1–9. [Google Scholar]

12. Singh A, Jain T, Sukhbaatar S. Learning when to communicate at scale in multiagent cooperative and competitive tasks. arXiv:1812.09755. 2018. [Google Scholar]

13. Samir M, Assi C, Sharafeddine S, Ebrahimi D, Ghrayeb A. Age of information aware trajectory planning of UAVs in intelligent transportation systems: a deep learning approach. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2020;69(11):12382–95. doi:10.1109/TVT.2020.3023180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lorberbom G, Maddison CJ, Heess N, Hazan T, Tarlow D. Direct policy gradients: direct optimization of policies in discrete action spaces. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;33:18076–86. [Google Scholar]

15. Mao H, Zhang Z, Xiao Z, Gong Z. Modelling the dynamic joint policy of teammates with attention multi-agent DDPG. arXiv:1811.07029. 2018. [Google Scholar]

16. Kopic A, Perenda E, Gacanin H. A collaborative multi-agent deep reinforcement learning-based wireless power allocation with centralized training and decentralized execution. IEEE Trans Commun. 2024;72(11):7006–16. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2024.3401502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xu L, Sun S, Zhang YD, Petropulu AP. Reconfigurable beamforming for automotive radar sensing and communication: a deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE J Sel Areas Sens. 2024;1:124–38. doi:10.1109/JSAS.2024.3384567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang Z, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Letaief KB. DRL-based optimization for AoI and energy consumption in C-V2X enabled IoV. IEEE Trans Green Commun Netw. 2025;9(1):C2. doi:10.1109/TGCN.2025.3531902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kipf TN, Welling M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv:1609.02907. 2016. [Google Scholar]

20. Hamilton WL, Ying Z, Leskovec J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30:1–11. [Google Scholar]

21. Hieu NQ, Hoang DT, Niyato D, Wang P, Kim DI. Transferable deep reinforcement learning framework for autonomous vehicles with joint radar-data communications. IEEE Trans Commun. 2022;70(8):5164–80. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2022.3183001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sohaib RM, Onireti O, Sambo Y, Swash R, Imran M. Energy efficient resource allocation framework based on dynamic meta-transfer learning for V2X communications. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2024;21(4):4343–56. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2024.3400605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zheng B, Liang H, Ling J, Gong S, Gu B. Integrating graph neural networks with multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for dynamic V2X communication. In: Proceedings of the 2024 20th International Conference on Mobility, Sensing and Networking (MSN); 2024 Dec 20–22; Harbin, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 398–405. doi:10.1109/MSN60784.2024.00105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Fan Y, Fei Z, Huang J, Xiao Y, Leung VCM. Reinforcement learning-based resource allocation for multiple vehicles with communication-assisted sensing mechanism. Electronics. 2024;13(13):2442. doi:10.3390/electronics13132442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zeng Y, Liu Q, Dai T, Huang Y, Hou R, Gan Y, et al. Resource optimization-oriented method for generating cooperative interference strategies. In: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Intelligent Communication and Computer Engineering (ICICCE); 2023 Nov 24–26; Changsha, China. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 37–46. doi:10.1109/ICICCE60048.2023.00015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhu J, He H, He Y, Fang F, Huang W, Zhang Z. Joint optimization of user scheduling, rate allocation, and beamforming for RSMA finite blocklength transmission. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(10):17932–45. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3366449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ji M, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Wang J, et al. Graph neural networks and deep reinforcement learning based resource allocation for V2X communications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(5):7892–905. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2023.3321521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu X, Zhang H, Long K, Nallanathan A. Proximal policy optimization-based transmit beamforming and phase-shift design in an IRS-aided ISAC system for the THz band. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2022;40(7):2056–69. doi:10.1109/JSAC.2022.3155508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Schulman J, Wolski F, Dhariwal P, Radford A, Klimov O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv:1707.06347. 2017. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools