Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhanced Image Captioning via Integrated Wavelet Convolution and MobileNet V3 Architecture

1 Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Language Ability, School of Linguistic Sciences and Arts, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou, 221116, China

2 Linguistic Science Laboratory, School of Linguistic Sciences and Arts, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou, 221116, China

3 Laboratory of Philosophy and Social Sciences at Universities in Jiangsu Province, School of Linguistic Sciences and Arts, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou, 221116, China

4 School of Mathematics and Statistics, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou, 221116, China

* Corresponding Author: Mo Hou. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071282

Received 04 August 2025; Accepted 17 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Image captioning, a pivotal research area at the intersection of image understanding, artificial intelligence, and linguistics, aims to generate natural language descriptions for images. This paper proposes an efficient image captioning model named Mob-IMWTC, which integrates improved wavelet convolution (IMWTC) with an enhanced MobileNet V3 architecture. The enhanced MobileNet V3 integrates a transformer encoder as its encoding module and a transformer decoder as its decoding module. This innovative neural network significantly reduces the memory space required and model training time, while maintaining a high level of accuracy in generating image descriptions. IMWTC facilitates large receptive fields without significantly increasing the number of parameters or computational overhead. The improved MobileNet V3 model has its classifier removed, and simultaneously, it employs IMWTC layers to replace the original convolutional layers. This makes Mob-IMWTC exceptionally well-suited for deployment on low-resource devices. Experimental results, based on objective evaluation metrics such as BLEU, ROUGE, CIDEr, METEOR, and SPICE, demonstrate that Mob-IMWTC outperforms state-of-the-art models, including three CNN architectures (CNN-LSTM, CNN-Att-LSTM, CNN-Tran), two mainstream methods (LCM-Captioner, ClipCap), and our previous work (Mob-Tran). Subjective evaluations further validate the model’s superiority in terms of grammaticality, adequacy, logic, readability, and humanness. Mob-IMWTC offers a lightweight yet effective solution for image captioning, making it suitable for deployment on resource-constrained devices.Keywords

Image captioning leverages sophisticated mathematical models to generate coherent and detailed natural language descriptions of visual scenes. Image captioning is a versatile and innovative technology with the potential to revolutionize various fields and enhance our understanding and interaction with visual scenes. This paper builds on our earlier work using IMWTC and MobileNet V3-based models for further exploration [1]. The results provide a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed image captioning architecture, thereby facilitating the adaptability of wavelet convolution approaches in the deep learning domain. The accuracy and consistency of the model in image caption generation are validated and compared using a range of captioning metrics, including Bilingual evaluation understudy (BLEU), Recall-oriented understudy for gisting evaluation (ROUGE), Consensus-based image description evaluation (CIDEr), Semantic propositional image caption evaluation (SPICE), and Metric for evaluation of translation with explicit ordering (METEOR).

The main contribution of this paper is to propose a novel image captioning architecture based on IMWTC and MobileNet V3 framework, Mob-IMWTC, and the specific contributions are as follows: We employ an enhanced MobileNet V3, integrated with a transformer encoder as the encoder and a transformer decoder as the decoder. This neural network model, named Mob-Tran, dramatically minimizes both the memory space required and the time required for model training, while maintaining exceptional precision in generating image captions. We propose IMWTC serving as a seamless drop-in replacement within the above MobileNet V3 architecture, and it scales gracefully in harmony with the dimensions of the receptive field. We introduce a comprehensive evaluation approach, incorporating both subjective and objective metrics, to assess the overall performance of each model. Specially, for subjective evaluation, we establish evaluation criteria including grammaticality, adequacy, logic, readability, and humanness, and administer questionnaires to linguistics students to assess the quality of the created sentences.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an extensive overview of related work, while Section 3 introduces an enhanced model named Mob-IMWTC. Section 4 then proceeds to describe the experimental methodology, encompassing the datasets that are utilized, and a rigorous comparison of the Mob-IMWTC model’s caption generation capabilities with other models. These comparison experiments are based on both objective and subjective evaluations, offering a comprehensive analysis of the model’s performance. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings of our study, highlighting the advantages and potential areas of Mob-IMWTC.

2.1 Exploration of Image Captioning

Over the past decade, deep learning has driven remarkable advancements in image caption generation. In 2014, Kiros introduced an encoder-decoder framework [2], allowing the encoder to rank images and sentences, while the decoder initiated description generation. Anderson, in 2017, implemented an image caption generation technique leveraging Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Recurrent Neural Networks, where CNN extracted visual features and RNN formed sequences [3]. In 2018, Yao introduced a novel approach that combines bottom-up and top-down mechanisms for calculating attention specifically at the level of prominent image regions [4]. Zhu introduced the Captioning Transformer model, featuring a stacked attention module that replaces the LSTM decoder with a transformer decoder, thereby addressing the cross-time series issue inherent in LSTM [5]. More recently, Liu’s 2021 Caption Transformer model [6] and Devlin’s 2018 BERT-based image caption generation system [7] represented emerging research directions. Yan introduced the zero-shot novel object captioning task, which generates descriptions for novel objects without the need for paired image-caption data and extra training sentences [8]. Daneshfar provided an exhaustive examination of image-to-text diffusion models within the landscape of artificial intelligence and generative computing, filling a critical void in the literature [9]. Wang presented ClipCap++, an enhanced version of ClipCap that integrates key-value pair and residual connection modules [10].

To sum up, these studies have significantly improved the performance of image caption generation models. However, as models become increasingly sophisticated, their applicability in environments with constrained resources diminishes accordingly.

2.2 Advancements of Lightweight Models

Researchers have been exploring model compression techniques to bridge the gap between the demands of large models and the constraints posed by resource-limited devices. In the realm of image captioning, researchers have made strides in developing efficient models. In 2020, Dai improved the accuracy of LSTM models while reducing their parameter count by incorporating a hidden layer [11]. Furthermore, in 2021, Sharif addressed the challenge of uncommon word representation by representing titles as sequences of subwords, which also helped in reducing the training vocabulary size [12]. More recently, in 2022, Tan proposed three innovative methods to decrease the number of parameters in transformer models: radix coding, cross-layer parameter sharing, and attention parameter sharing [13]. Liu et al. investigated a refined CA-MobileNet V3 model, which was incorporated into cutting-edge microscope products to augment the microscope’s feature extraction capabilities and mitigate misclassification errors during diagnostic processes [14]. Saqib et al. proposed MobileNet V1 and MobileNet V2, which were based on an optimized architecture specifically designed to construct lightweight deep neural networks by utilizing depth-wise separable convolutions [15]. Wang developed a lightweight captioning method with a collaborative mechanism, LCM-Captioner, which balances high efficiency with high performance [16].

Govindharaj et al. introduced a novel approach that integrated Generative Adversarial Networks with the pretrained MobileNet V2 architecture for diagnosing glaucoma [17]. This method addressed the imbalance in medical imaging associated with small datasets by utilizing GANs to enhance the quality of fundus images.

Despite these recent advancements in lightweight image caption generation, there are still numerous challenges that need to be tackled to further improve the efficiency and performance of these models.

2.3 Developments of Wavelet Convolutional Networks (WTC)

Wavelet transform has been integrated into neural network architectures for multiple tasks. Finder et al. [18] employed wavelets to compress feature maps, thereby enhancing the efficiency of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Saragadam et al. [19] used wavelets as activation functions for implicit neural representations. Liu et al. [20] and Alaba et al. [21] utilized the wavelet transform in a modified U-Net architecture for down-sampling and the inverse wavelet transform for up-sampling. Fujieda et al. [22] put forward a DenseNet-style architecture that leverages wavelets to reinject lower frequencies from the input into subsequent layers. However, the methods in [20–22] were highly tailored architectures, unable to be smoothly used in other CNN architectures. By contrast, Chen concentrated on computational efficiency [23].

Researchers have undertaken efforts to enlarge the kernel size of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), aiming to emulate the global receptive field characteristic of self-attention blocks in Vision Transformers. To attain a global receptive field, it is necessary to conduct spatial mixing operations within the frequency domain following a Fourier transform [24]. Nevertheless, when the Fourier transform is applied, it converts the input into a representation solely in the frequency domain, which prevents it from capturing the local interactions between neighboring pixels. By contrast, the wavelet transform is capable of successfully retaining certain local information while decomposing the image into separate frequency bands, which makes it possible to carry out operations at various decomposition levels. A concurrent study employed neural implicit functions to facilitate efficient mixing in the frequency domain [25]. Based on WTC, Finder et al. introduced a more lightweight, user-friendly, and linear layer structure. This layer can serve as a seamless drop-in replacement for depth-wise convolutions, leading to an enhanced receptive field. Moreover, their research has made a significant further advance [26].

Statement: To eliminate grammatical errors as much as possible and enhance the paper’s readability, we’ve utilized AI tools to assist in its writing.

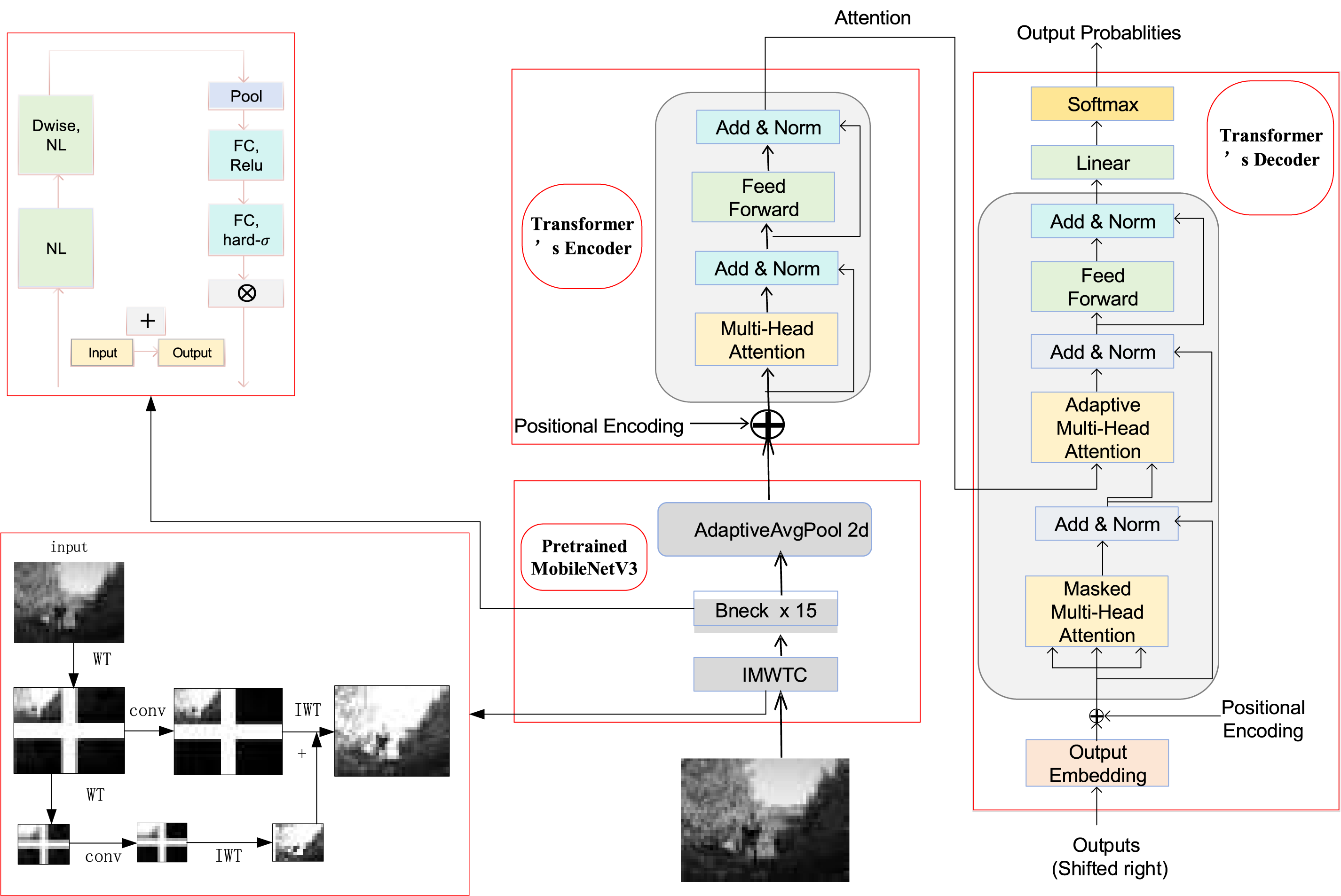

The structure of the proposed Mob-IMWTC model is illustrated in Fig. 1. Firstly, IMWTC is adopted to replace the Conv2d layer in MobileNet V3, and the features of the input images are extracted from IMWTC. The aforementioned features are then fed into the Bneck*15 layer and pooling layer of the MobileNet V3 model, and a feature vector is ultimately obtained. This vector is then passed through the Transformer’s encoder and decoder, which consists of a single fully connected layer. Combined with attention, the decoder then attends to the image to predict the caption.

Figure 1: Flow chart of system architecture based on Mob-IMWTC

IMWTC is a layer that utilizes the cascade wavelet transform decomposition to perform a series of small-kernel convolutions. Each convolution focuses on distinct frequency bands of the input within an increasingly larger receptive field. This approach enables us to emphasize low frequencies in the input while introducing only a minimal number of trainable parameters. Specifically, for a

In this work, we employ wavelet transform as it is efficient and straightforward [18,28]. Note that

where

The cascade wavelet decomposition is then given by recursively decomposing the low-frequency component. Each level of the decomposition is given by:

where

Expanding the kernel size of a convolutional layer leads to parameters increasing quadratically. To mitigate that, first, use the wavelet transform to filter and downscale the lower- and higher-frequency content of the input. Then, perform a small-kernel depth-wise convolution on the different frequency maps before using the IWT to construct the output. In other words, the process is given by

where

We take this

where

where

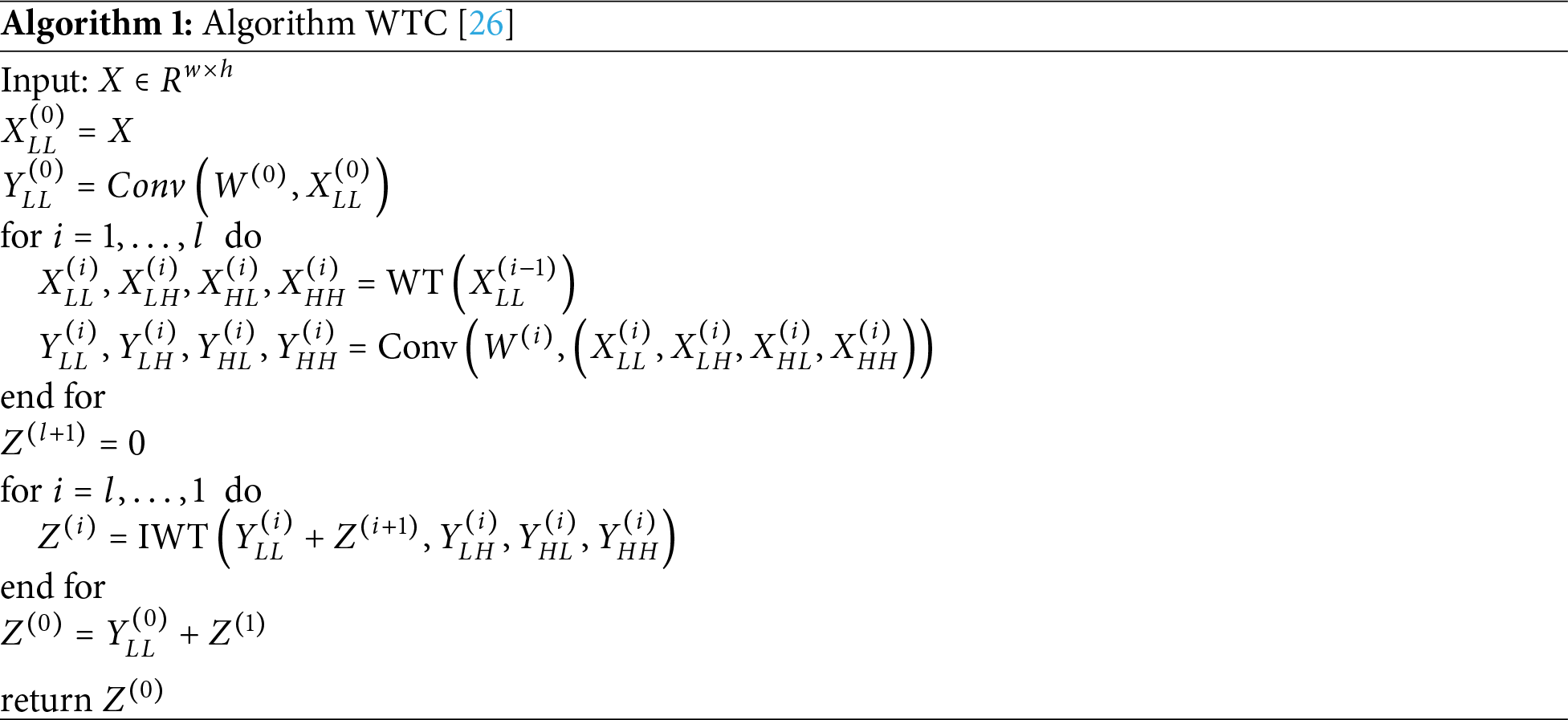

Unlike the WTC architecture mentioned in [26] (Algorithm 1), which involves an additional convolutional step on the source image but is less time-efficient, we have made improvements by replacing function return value

For MobileNet V3, depth-wise separable convolution [29] constitutes a fundamental element within the MobileNet series, serving as a highly effective method for diminishing model complexity. Formula (7) delineates the mechanics of depth-wise convolution:

here

Subsequently, the feature map undergoes pointwise convolution to adjust its dimensionality, either increasing or decreasing it. Depth-wise separable convolution boasts approximately one-third of the parameters compared to traditional convolution, rendering it a more streamlined and potent technique. The particular methodology for this calculation is outlined in Formula (8):

where

MobileNet V3 introduces the Squeeze-and-Excitation block (SE block) [30] into its partial inverted residual structure to elevate the semantic richness of the feature map. Within the SE block, the squeeze component computes the feature vector for each channel of the feature map by employing Global Average Pooling (GAP). This process involves averaging the feature values across the entire feature map for each individual channel:

here,

The excitation block utilizes a gate mechanism composed of two fully connected layers to learn the weights for each of the C channels from z. This gating mechanism is computed according to Formula (10), effectively assigning a weight to each channel based on its relative importance.

where

where

MobileNet V3 adopts h-swish activation function to enhance the network’s nonlinear expression capabilities. The mathematical formulation of the h-swish function is given by Eqs. (12) and (13).

Notably, MobileNet V3 can be trained and fine-tuned using a wide range of image caption datasets, allowing it to adapt effectively to various domains and scenarios.

This section details the experiments conducted, including datasets employed, the comparative experiments performed, objective evaluation methods used, and the subjective evaluation process. Ultimately, the experimental results are comprehensively discussed and analyzed.

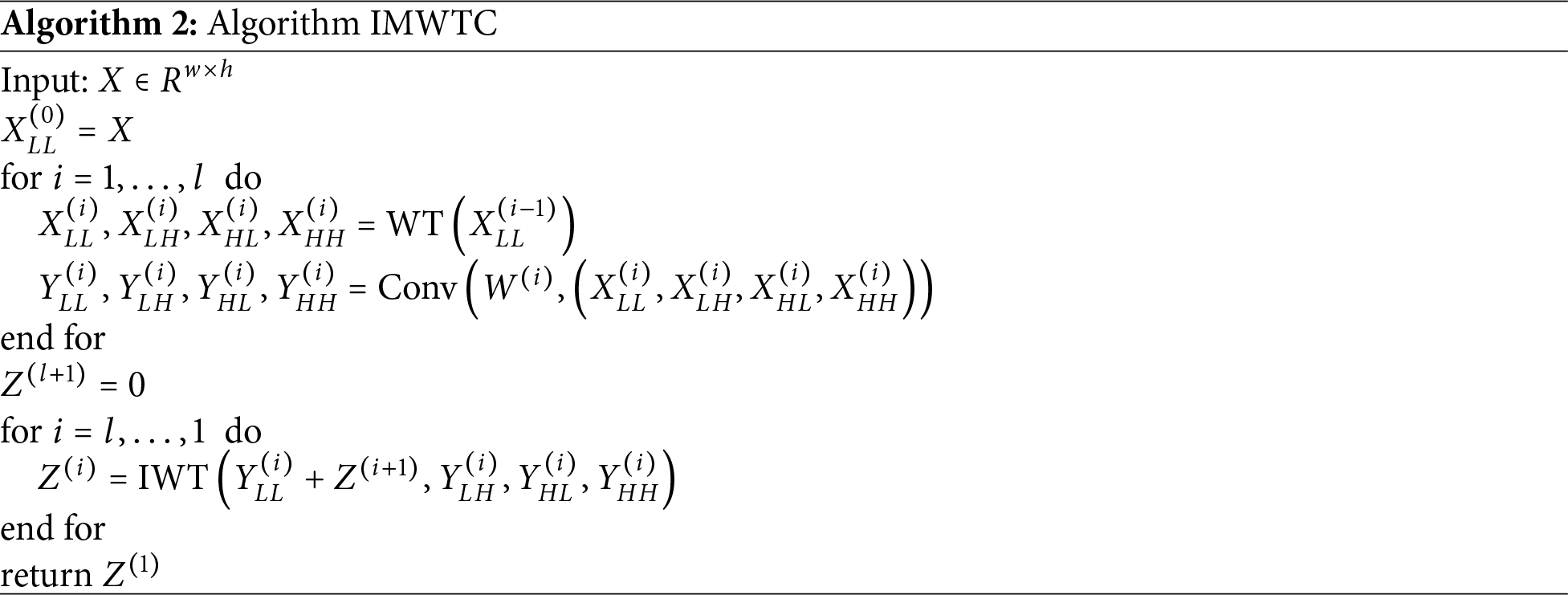

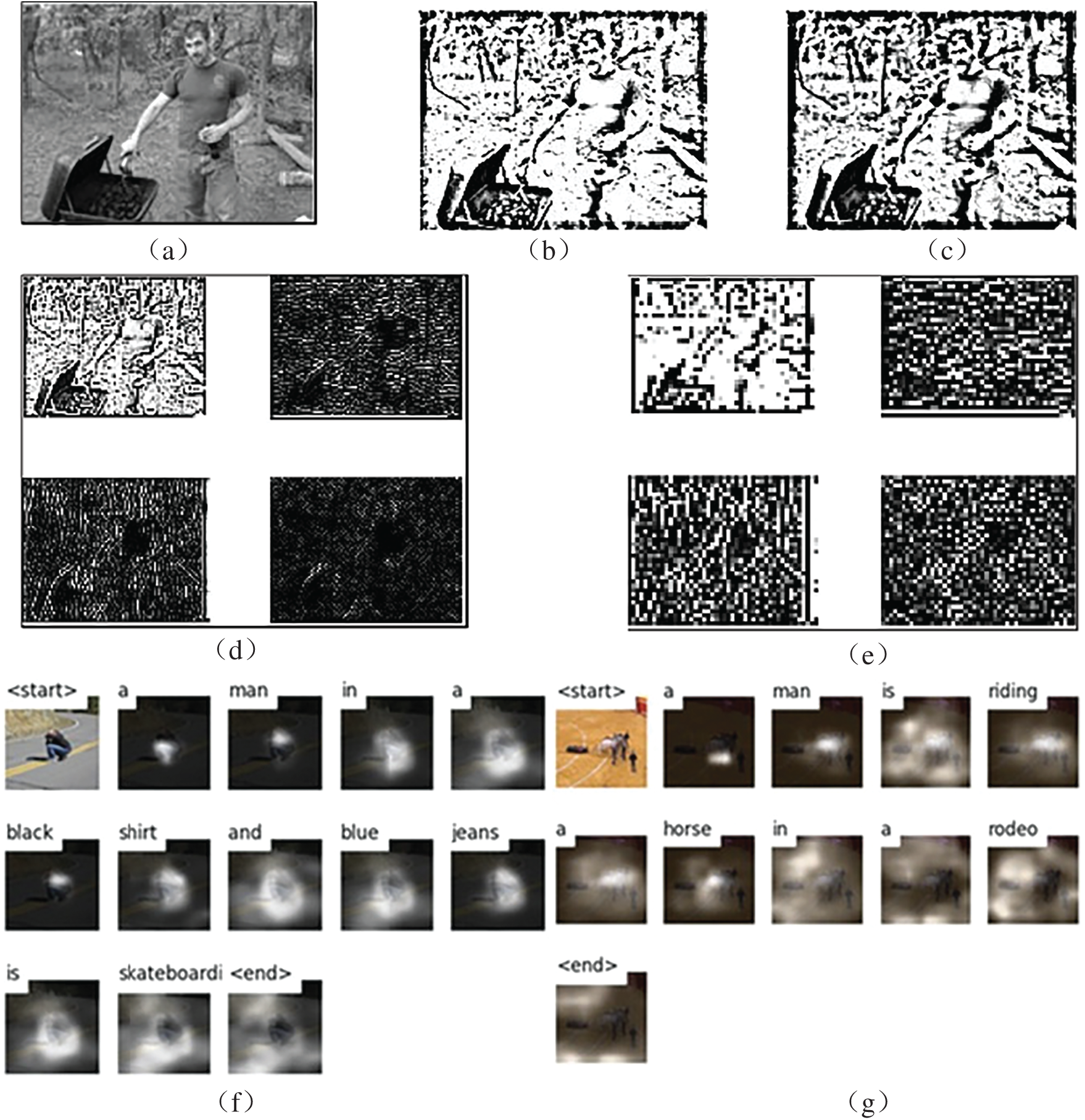

The implementation of the aforementioned models requires the following hardware & software configuration: CPU (Intel® Core™ i7-10875H), GPU (NVIDIA GeForce GTX1650 (4G)), Windows 10 & Pytorch1.9.0 & Python3.7, CUDA11.1 + cuDNN8.2.1. Fig. 2 is a visualization of the IMWTC and attention changes in our proposed model, Mob-IMWTC.

Figure 2: Visualizations of the IMWTC and attention changes in Mob-IMWTC. (a) input image; (b) image processed using WTC; (c) image processed using IMWTC; (d) 1-level IMWTC; (e) 2-level IMWTC; (f,g) show image descriptions are generated word by word, and the amount of attention required to generate each word is represented by the shade of shadow on the corresponding image

The datasets used are MS COCO (328,000 images), Flickr 8k (8000 images), and Flickr 30k (31,783 images). The datasets are divided into three sets—training, validation, and testing—in a ratio of 80:10:10, respectively. For the above datasets, in the phase of preprocessing, images are resized to 64 × 64 pixels and normalized; texts are removed, leading “A” or “The” from captions, converted to lowercase, and filtered out captions with a length of less than 5 words.

4.2 Comparative Experiments (Ablation Experiment Included)

In this section, our methods (Mob-WTC & Mob-IMWTC) are compared with three CNN architectures (CNN-LSTM [31], CNN-Att-LSTM [32], CNN-Tran [33]), two mainstream methods (LCM-Captioner [16], ClipCap [10]), and our previous work (Mob-Tran [1] based on a lightweight model). The models’ training employs the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1.5 × 10−5. The training process consists of 50 epochs, each utilizing a batch size of 50 samples.

We present the sentences generated by the eight models utilized in the experiments. Following this, we list the scores obtained by each model in both objective and subjective evaluations, see Sections 4.2.1 and 4.2.2.

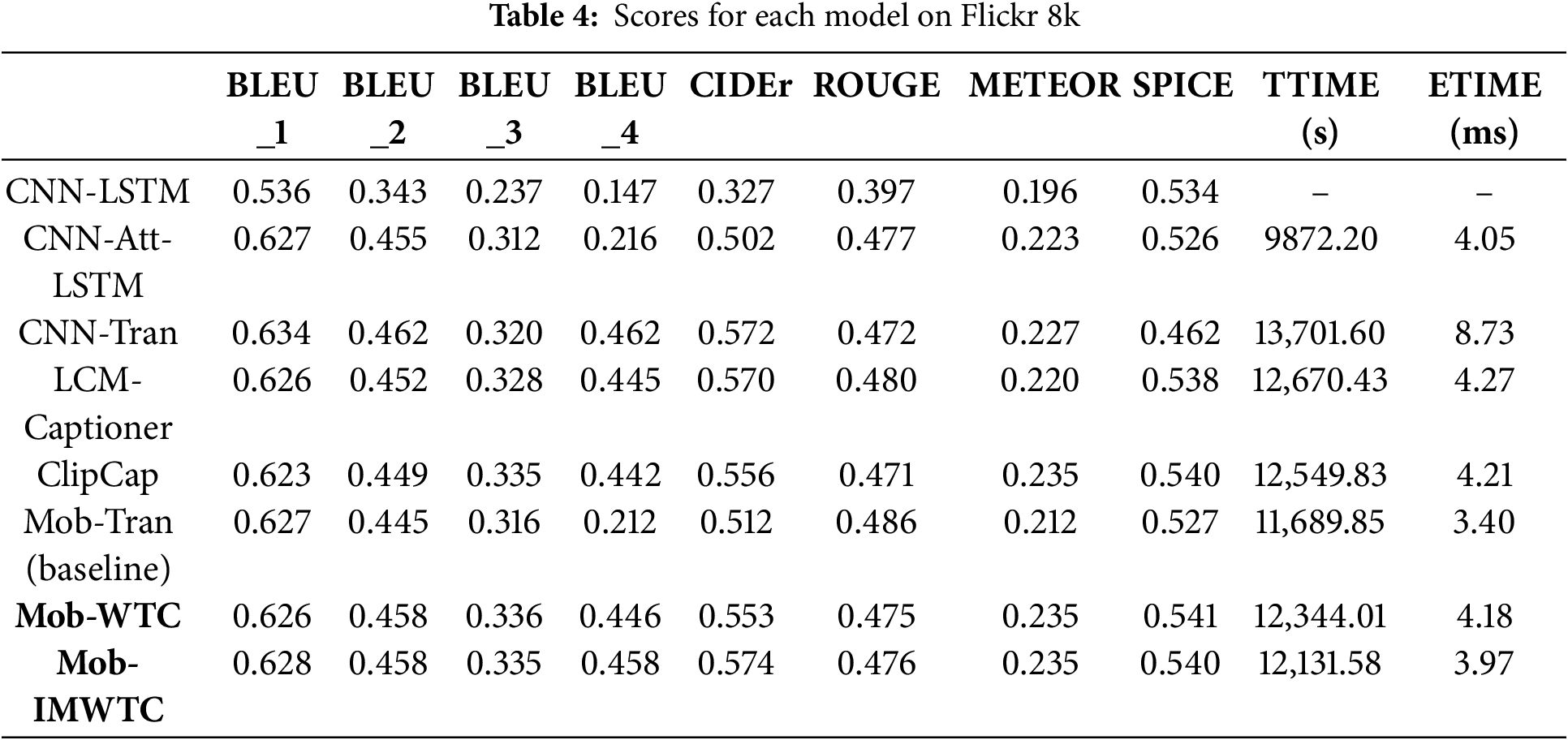

This section presents the results of image caption generation and objective evaluation metrics computation. The models’ performance is evaluated using several widely employed image caption evaluation criteria, including BLEU, ROUGE, CIDEr, METEOR, and SPICE. Additionally, indicators TTIME and ETIME are proposed. TTIME (Time Required for Model Training) measures the training runtime of an algorithm executing on the devices. ETIME (Time Required for Model Execution) is a metric that measures the time required for a trained model to generate captions for test images; here, ETIME is also called inference time.

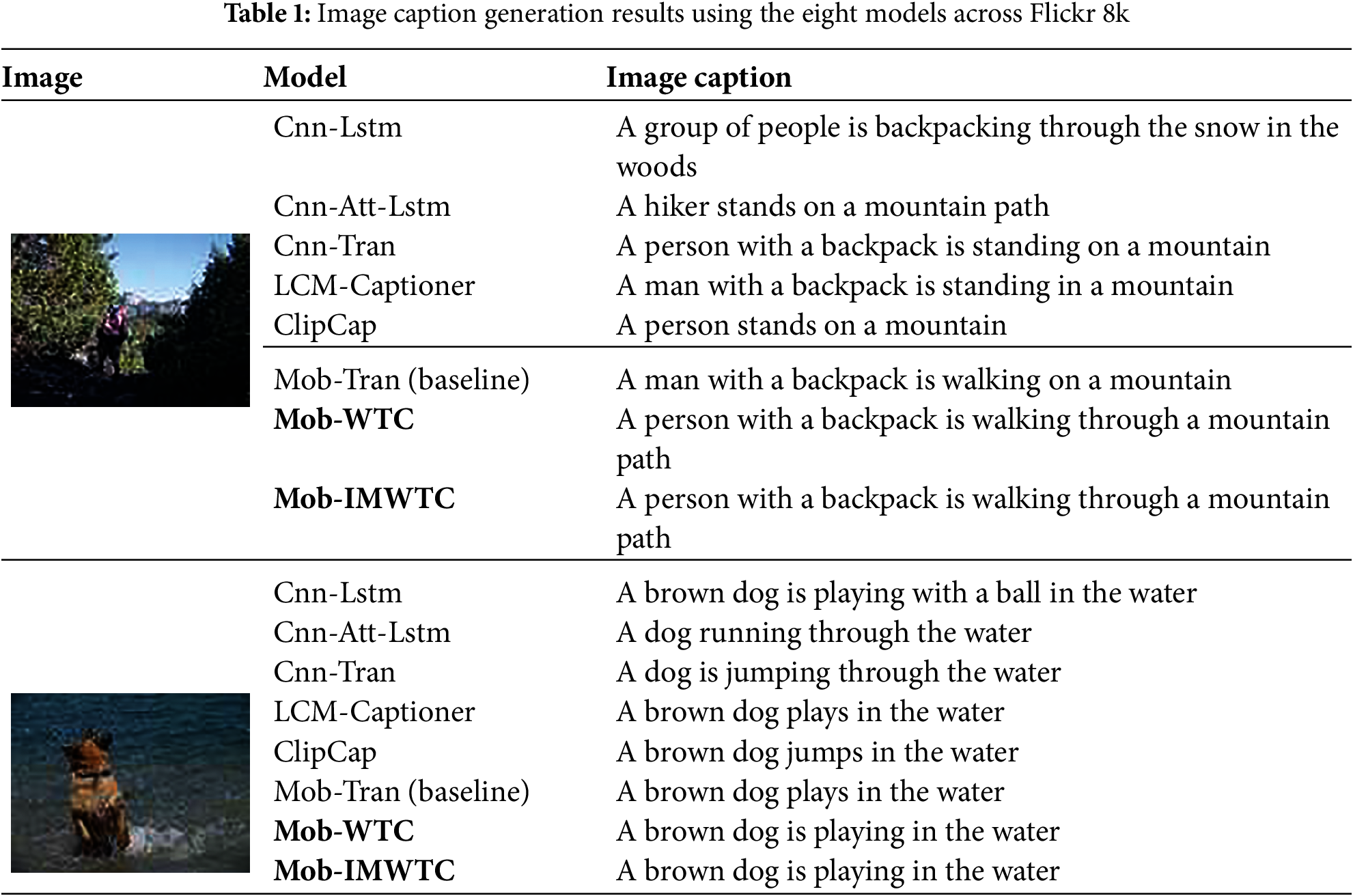

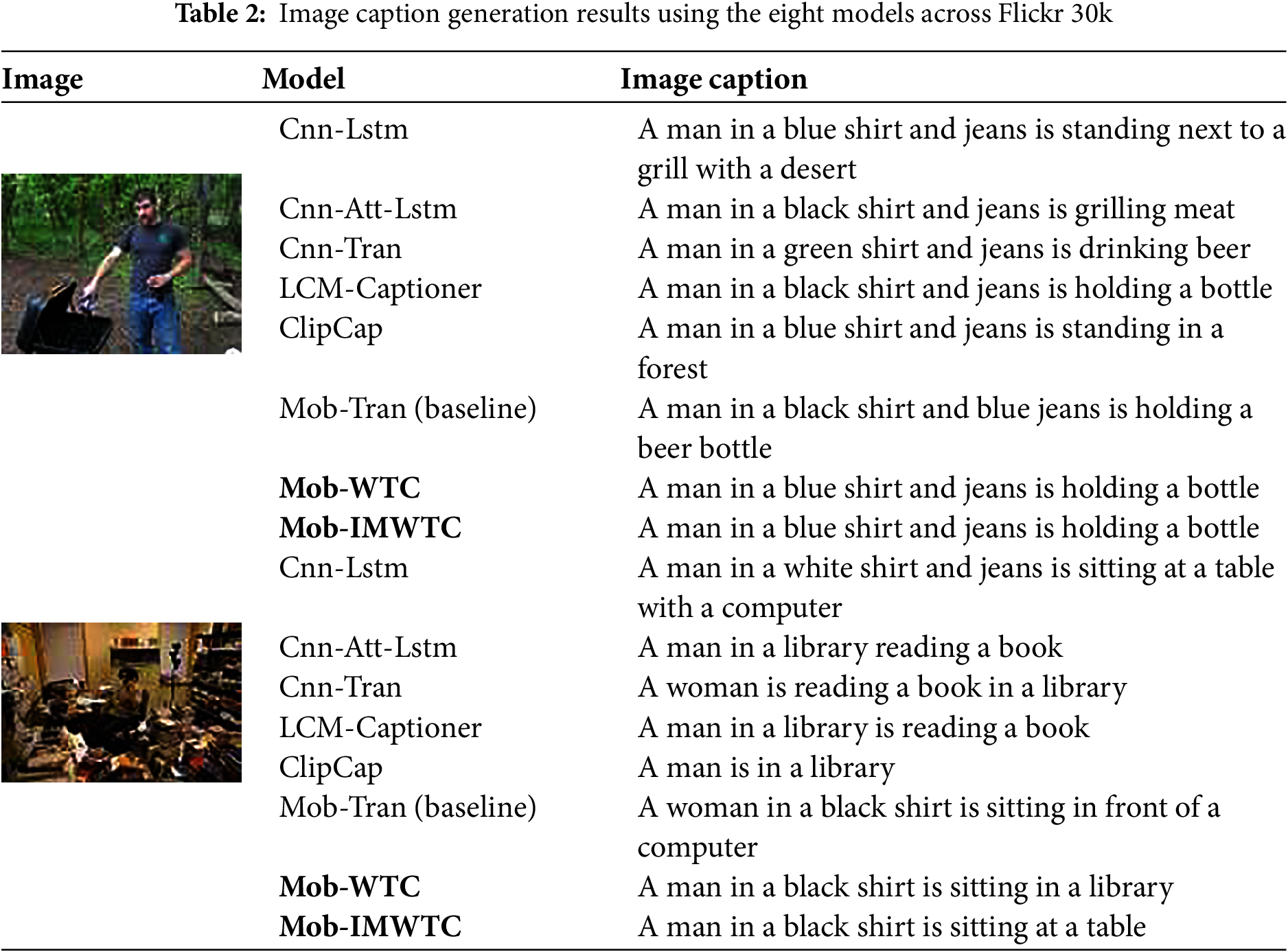

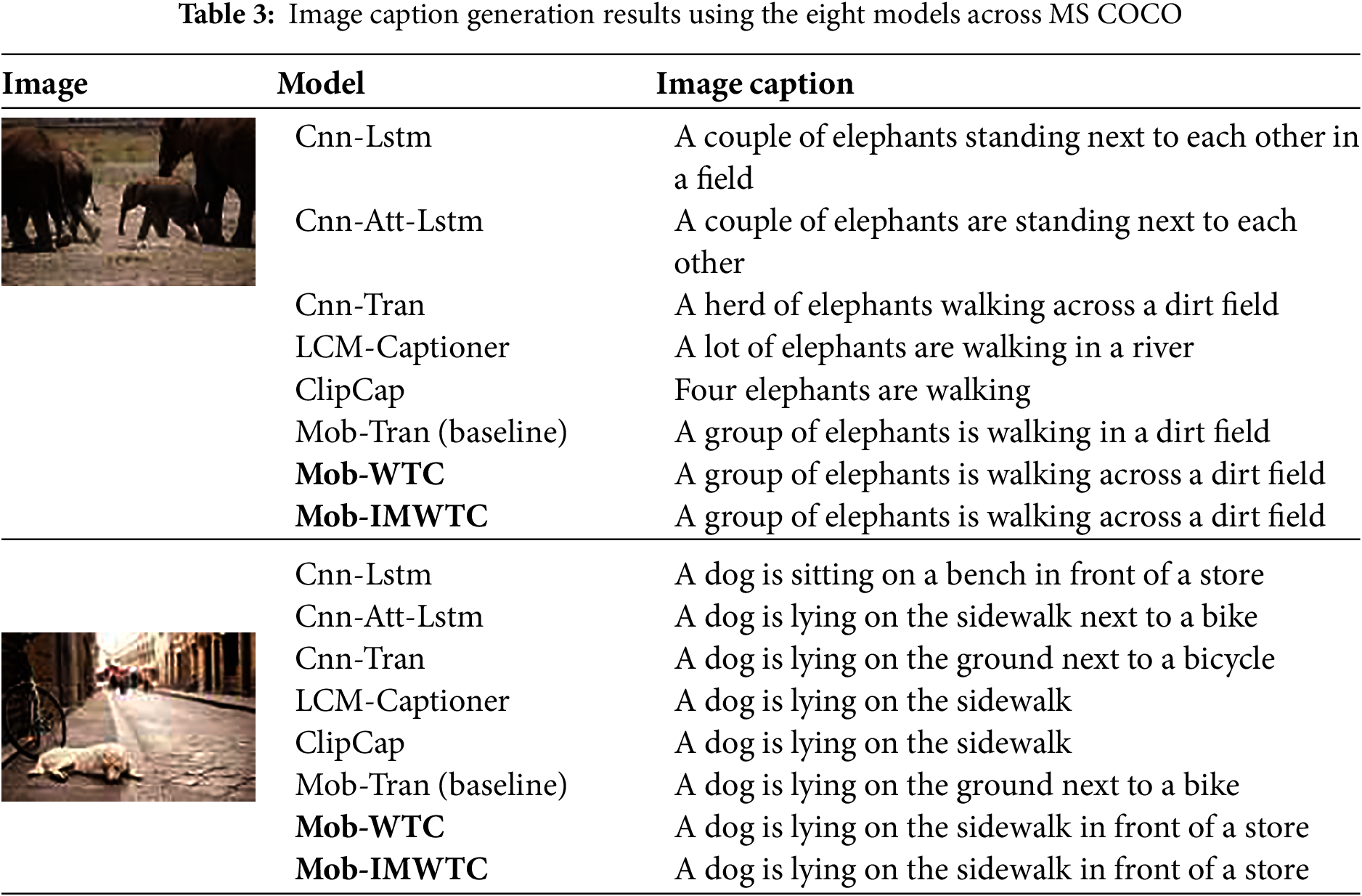

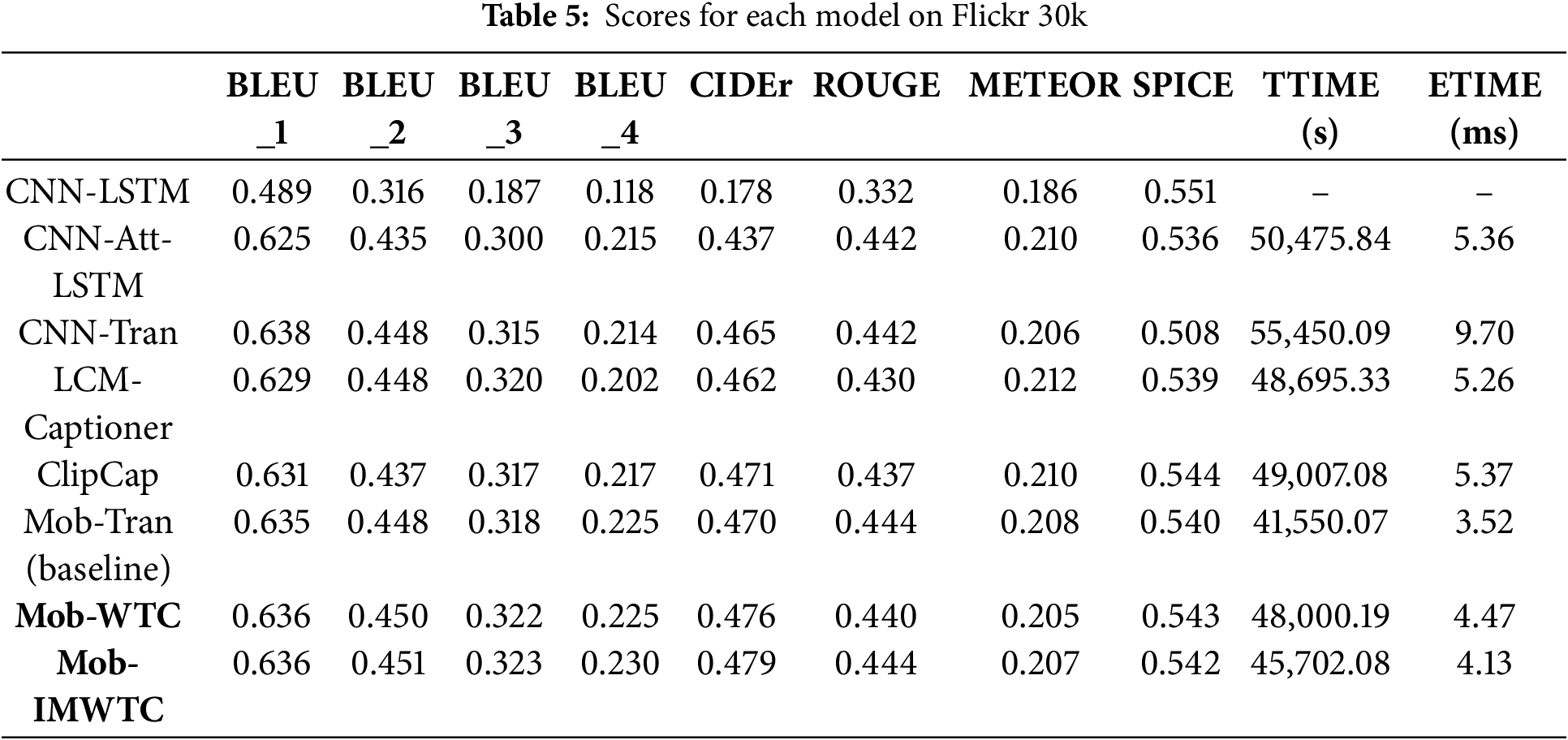

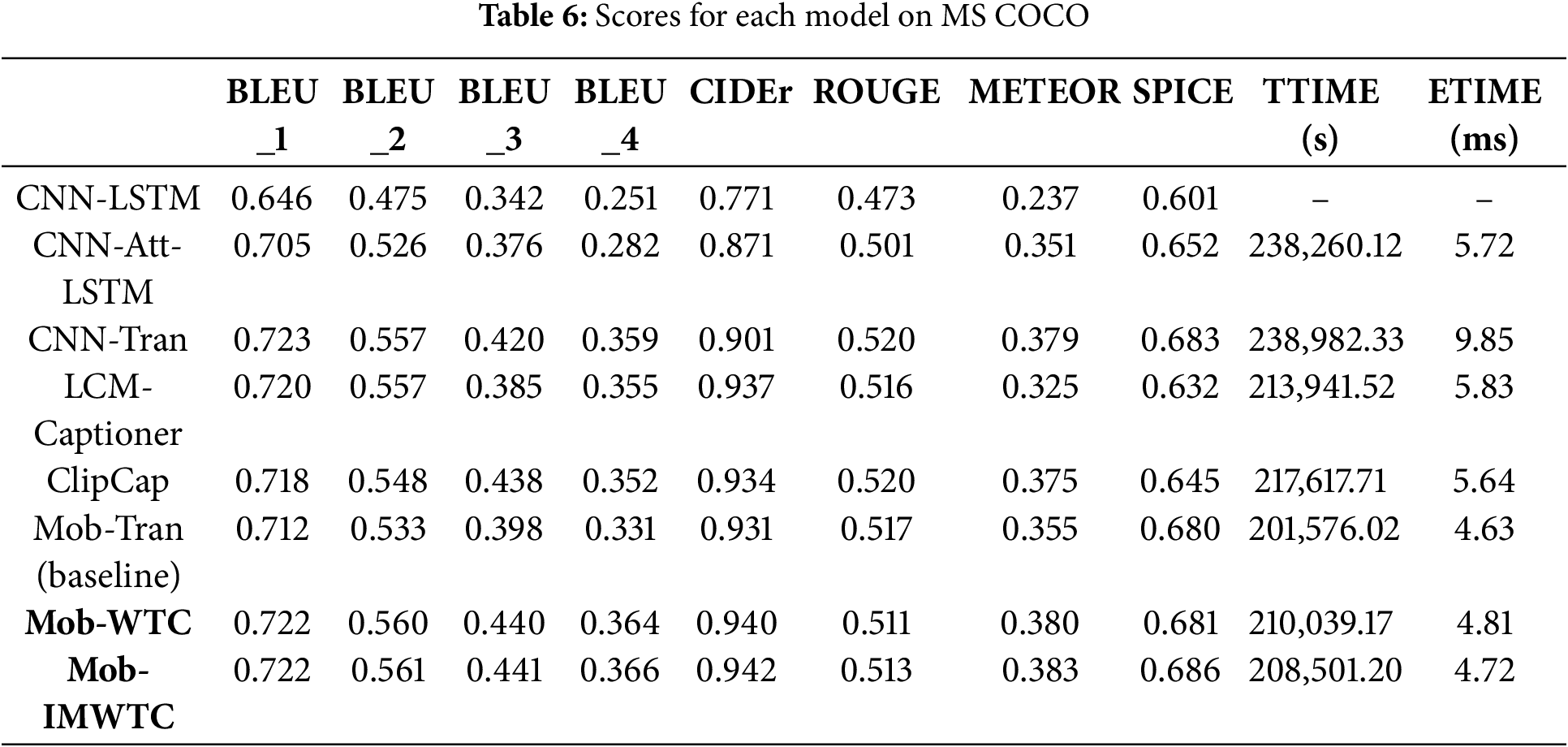

Tables 1–3 display the image caption generation results using the eight models across different datasets, namely Flickr 8k, Flickr 30k, and MS COCO. Tables 4–6 exhibit the computed scores for the eight models, including our proposed Mob-IMWTC & Mob-WTC model.

Table 4 demonstrates that our proposed Mob-IMWTC & Mob-WTC achieves performance comparable to six state-of-the-art models across eight standard evaluation metrics (BLEU_1 to BLEU_4, CIDEr, ROUGE, METEOR, and SPICE) when trained on the Flickr 8k dataset. Mob-IMWTC & Mob-WTC have advantages in two metrics (CIDEr and METEOR) and three metrics (BLEU_3, METEOR, and SPICE), respectively. Regarding Flickr 8k, Mob-IMWTC does not exhibit significant advantages

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of eight models trained on the Flickr 30k dataset. Among these, Mob-IMWTC distinguishes itself by achieving the highest scores across BLEU_2, BLEU_3, BLEU_4, and CIDEr metrics. The difference in scores of the top eight metrics indicates that Mob-IMWTC generates captions with greater syntactic complexity and contextual coherence than those produced by alternative models.

The models in Table 6 are trained using the MS COCO dataset. The results in Table 6 show that Mob-IMWTC achieves the highest scores across BLEU_2, BLEU_3, BLEU_4, CIDEr, METEOR, and SPICE metrics, demonstrating comprehensive advantages compared with other methods.

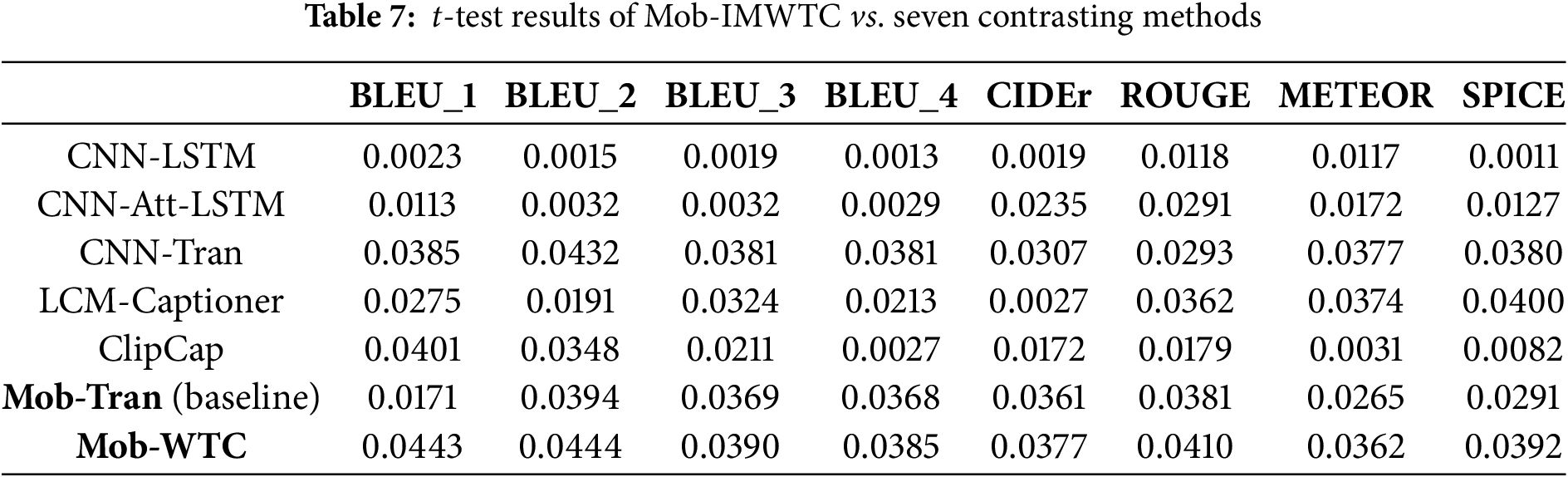

We have designed a t-test experiment to demonstrate that the data presented in Tables 4–6 are statistically significant. A paired t-test is utilized to verify whether the data obtained from Mob-IMWTC and the other seven methods across eight metrics exhibit statistical significance. As shown in Table 7, all p-values are less than 0.05, demonstrating the statistical validity of the obtained data.

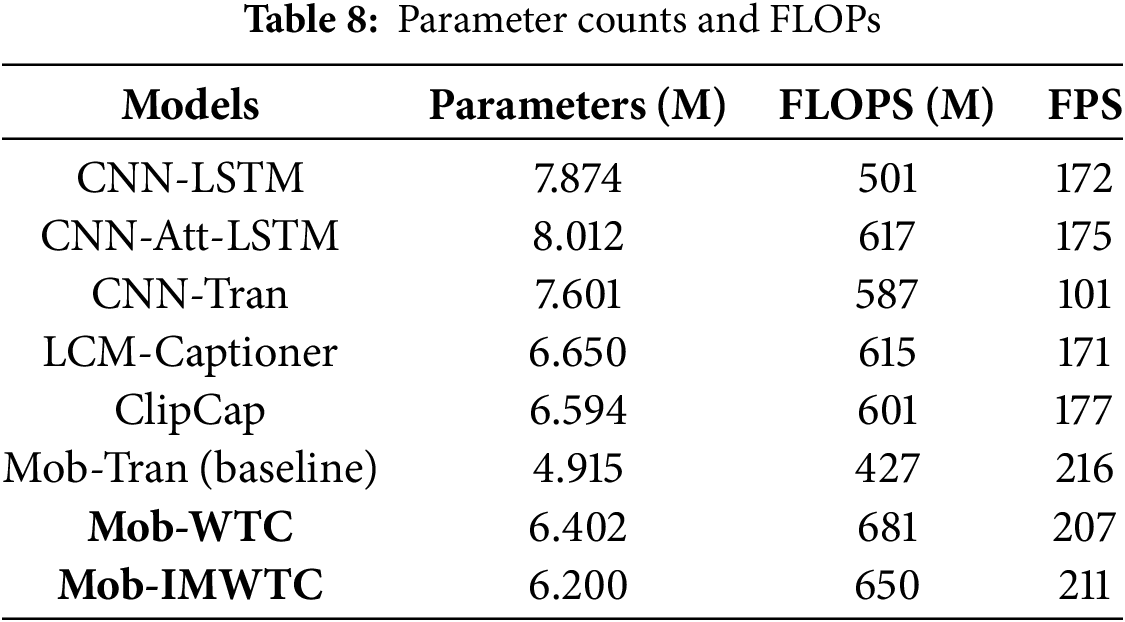

Table 8 reports parameter counts, FLOPs, and FPS (frames per second) for each model. Tables 4–8 show that introducing IMWTC to Mob-Tran results in a substantial improvement in objective evaluation metrics (BLEU, CIDEr, ROUGE, METEOR, and SPICE) while causing only a slight increase in parameters and FLOPs; for example, moving from Mob-Tran to Mob-IMWTC only adds 1.285M parameters and 223M FLOPs.

Despite limitations like subjectivity and inefficiency, human-based subjective evaluation remains the gold standard for assessing natural language generation. It uncovers linguistic flaws—such as grammatical errors and logical gaps—often missed by automated tools, ensuring more authentic quality assessment.

As the gold standard for assessing the quality of natural language generation, subjective evaluation via questionnaires offers comprehensive evaluation results. It can identify issues such as grammatical and logical errors that automated evaluation tools may overlook, thereby offering a more authentic representation of the generated text’s quality. Building on Kasai’s experiment [34], to enhance the precision of human evaluation criteria, five indicators are employed to evaluate the generated sentences: Grammaticality, Adequacy, Readability, Logic, and Humanness. These metrics ensure a comprehensive and detailed evaluation of the generated text.

In this experiment, each participant receives a questionnaire (three images included and their corresponding captions generated using the above eight models). The above three images are randomly chosen from three datasets: MS COCO, Flickr 8k, and Flickr 30k, respectively. A total of 100 questionnaires are handed out, with each being graded on a 5-point scale. Tables 6–8 present the results of the subjective evaluation. Notably, 30 participants are linguistics students possessing relevant professional knowledge, ensuring their capacity to provide well-informed evaluations. 70 participants are double-blind and randomly chosen, ensuring subjective evaluation indicators have practical significance.

When doing questionnaire surveys, we can figure out the mean and standard deviation for the answers to each question and the total scores of the whole questionnaire. Then, we set a confidence interval with a value of 0.95; any answers or scores in the questionnaire that are not within this confidence interval can be seen as abnormal values (outliers). After removing the abnormal questionnaires, we obtained a total of 85 valid questionnaires, among which there are 29 single-blind questionnaires and 56 double-blind questionnaires. Based on [35], the Kappa and ICC of inter-rater reliability metrics are worked out as 0.6502 and 0.6841, respectively, ensuring consistency in scoring.

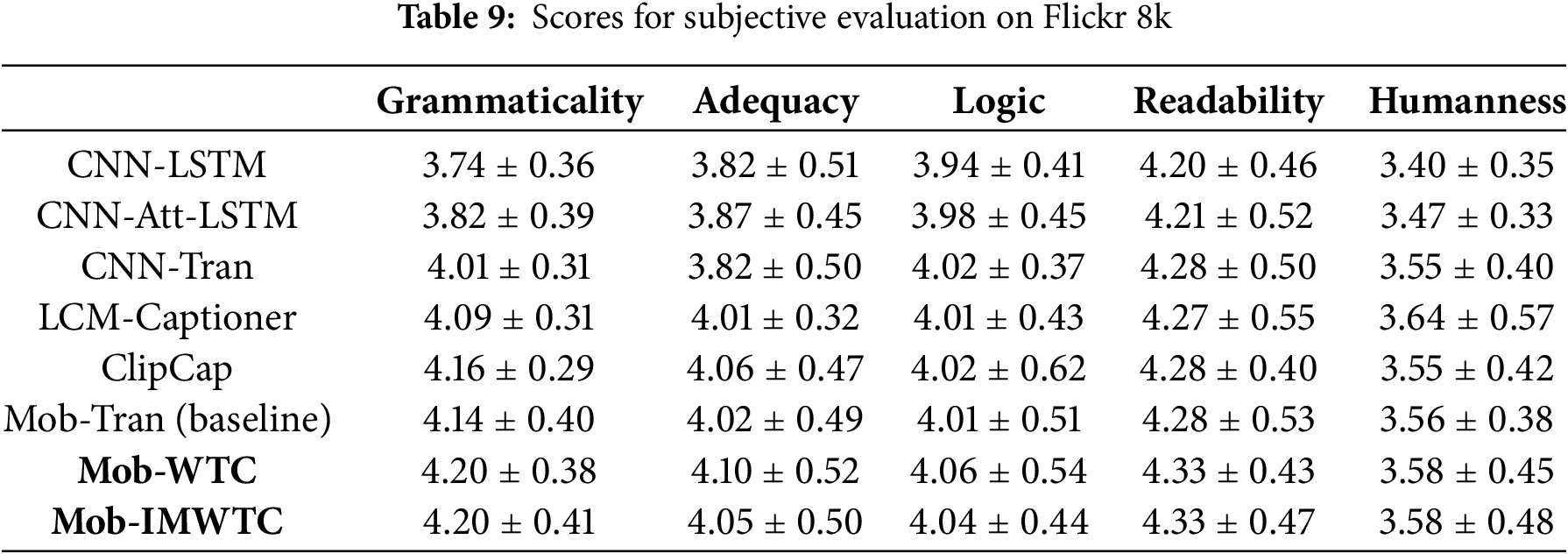

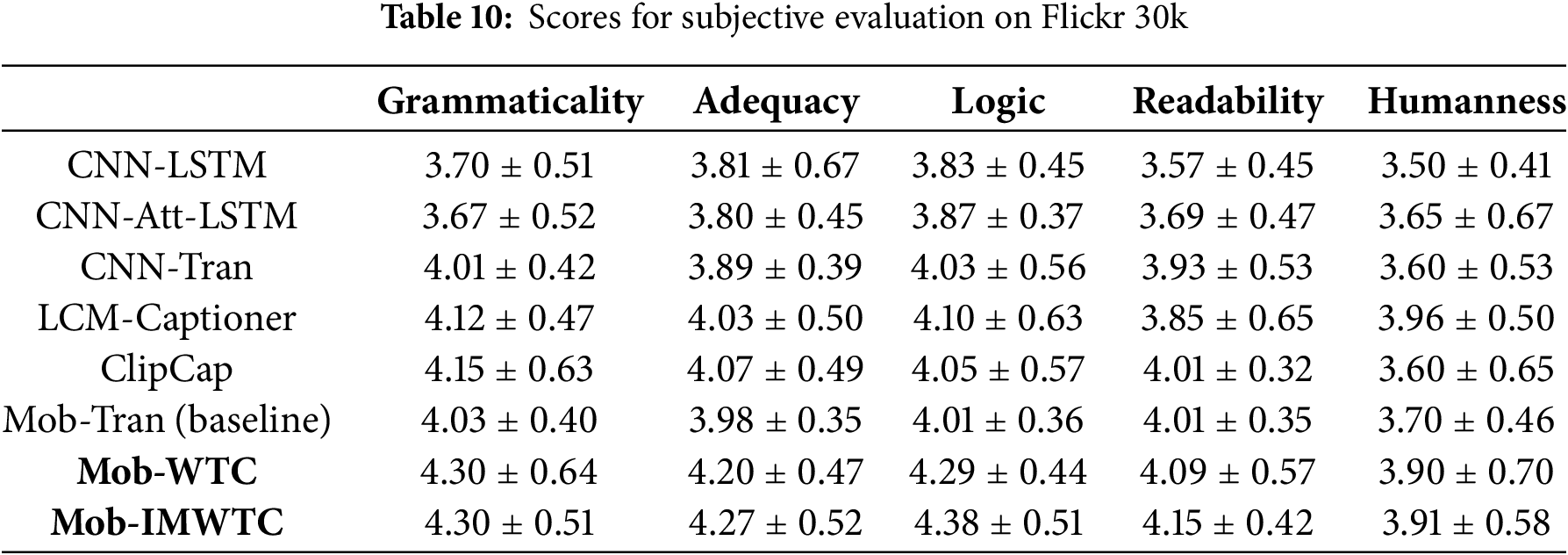

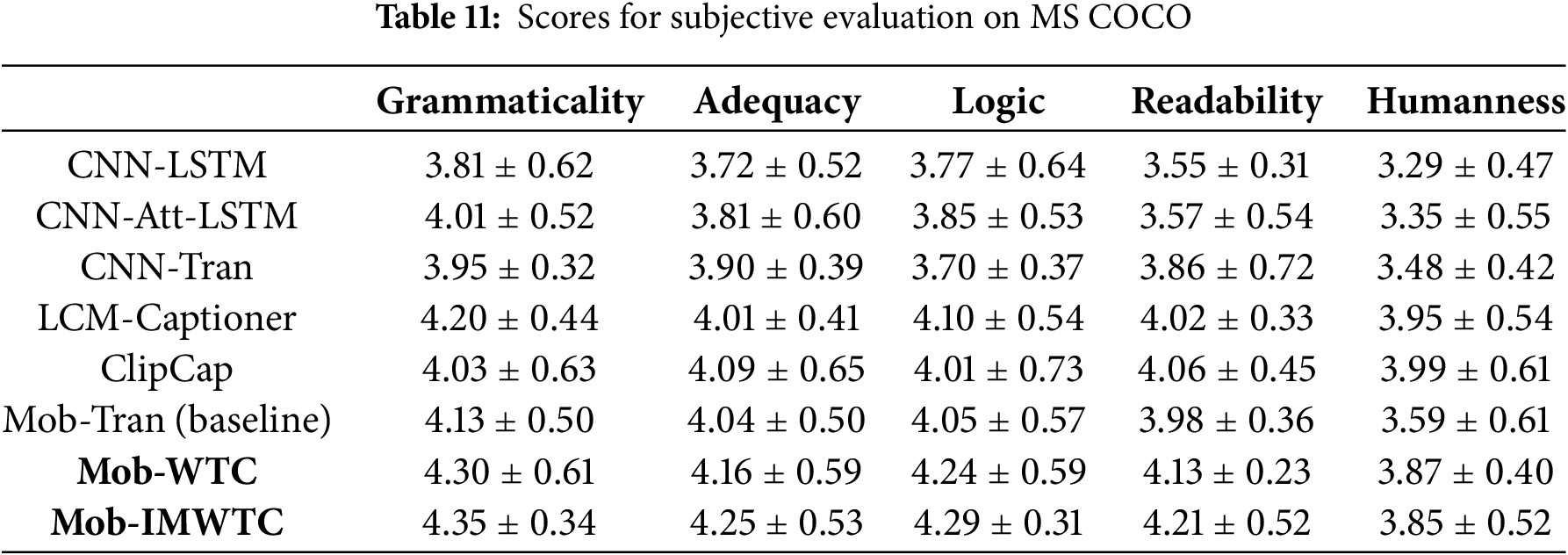

Tables 9–11 present the results of the subjective evaluation.

Table 9 presents the evaluation scores of the eight models trained on the Flickr 8k dataset. Mob-IMWTC excels in Grammaticality (4.20) and readability (4.33), while demonstrating moderate performance in Adequacy (4.05), Logic (4.04) Humanness (3.58).

The models evaluated in Table 10 are trained on the Flickr 30k dataset. Mob-IMWTC demonstrates superior performance across four caption quality metrics. Specifically, it achieves the highest scores in grammaticality (4.30), adequacy (4.27), logical (4.38), and readability (4.15).

Table 11 presents results from the models trained on the MS COCO dataset. Mob-IMWTC achieves scores of 4.35 (Grammaticality), 4.25 (Adequacy), 4.29 (Logical), and 4.21 (Readability), while ranking second in Humanness with a score of 3.85. Mob-IMWTC maintains its leadership in linguistic accuracy and contextual relevance, showing a robust ability to generate captions that are both syntactically precise and semantically meaningful.

We have designed IMWTC & WTC as a seamless drop-in replacement for depth-wise convolutions, enabling their direct integration into any CNN architecture without the need for additional modifications. IMWTC & WTC are adopted to replace the Conv2d layer in MobileNet V3; an ablation study has been conducted to assess the contributions of IMWTC & WTC components within the MobileNet V3 model for image captioning [14,35,36].

In this section, the baseline and our models adopt MobileNet V3 as the basic architectural framework. To obtain a highly accurate evaluation of the model’s performance and steer clear of the potential fluctuations that reinforcement learning might bring about, ablation experiments are conducted strictly with the basic cross-entropy loss function. The following ensemble configurations are analyzed:

1. Baseline: Mob-Tran is an upgraded version of MobileNet V3, integrating a transformer encoder as its encoding module and a transformer decoder as its decoding module. This innovative neural network model significantly reduces the required memory space and model training time, while maintaining a high level of accuracy in generating image descriptions [1,15,17].

2. Mob-WTC: The impacts of WTC on Model Performance are shown in Tables 4–6 and 9–11. Mob-WTC integrates the advantages of WTC and MobileNet V3 architectures, and WTC can afford large receptive fields, which makes it possible to generate high-quality image captions without significantly increasing parameters and computation time.

3. Mob-IMWTC: It integrates IMWTC and MobileNet V3. From Tables 4–11 we can see the impacts of IMWTC on Model Performance. The experiment results are summarized and compared, indicating that IMWTC combined with Mob-Tran achieves the optimal balance among evaluation metrics, parameter counts, FLOPs, and FPS.

To summarize the above, compared with the baseline method and Mob-WTC & Mob-IMWTC, Mob-IMWTC achieves the most effective results in both subjective and objective evaluations.

We focus solely on the impact of IMWTC & WTC on MobileNet V3. Given that the principles underlying IMWTC’s & WTC’s influence on other architectures are comparable, we will not delve into further details.

According to the above analysis, for small datasets (Flickr 8k), Mob-IMWTC’s performance is comparable to other models. For large datasets (Flickr 30k & MS COCO), Mob-IMWTC demonstrates advantages over other models, particularly in objective metrics. Mob-IMWTC employs a transformer integrated with MobileNet V3 as its encoder, offering reduced complexity and enhanced performance. This configuration allows it to excel in training on large-scale datasets and makes it well-suited for deployment on devices with limited resources. Moreover, Mob-IMWTC utilizes a transformer as its decoder, which boasts a more compact model size and superior computational efficiency, enabling it to handle large-scale datasets with greater speed. Consequently, Mob-IMWTC demonstrates enhanced performance and efficiency during training on extensive datasets, rendering it more adept at fulfilling the requirements of the image captioning task.

Research has shown that Mob-IMWTC performs better in subjective evaluation than in objective evaluation. The reason is that the indicators used in subjective evaluation and objective evaluation have different focuses, and the objective indicators used in mathematical modeling are not entirely consistent with human language perception. In subjective evaluation, evaluators assess the model’s performance relying on their subjective judgments, which are more closely related to human language perception. In contrast, in objective evaluation, evaluation metrics are mainly based on model building, focusing on the accuracy and efficiency of the model. To some degree, automatic evaluation is fair and unbiased. It checks the quality of each generated sentence using the same rules. In contrast, as the gold standard, human evaluation can more accurately assess the quality of generated natural language sentences, but it is subjective. Therefore, integrating automated and human evaluation methods yields a more comprehensive assessment of an image captioning model’s performance. In order to better evaluate the performance of the model, it is necessary to combine cognitive science and linguistics to propose new evaluation criteria that are more consistent with human cognition and more objective.

There are three main technical benefits of incorporating IMWTC & WTC within a given CNN.

First, during every level of the wavelet transform, the size of the layer’s receptive field gets enlarged, and this enlargement only comes with a slight rise in the number of trainable parameters. That is, the

Secondly, the IMWTC (or WTC) layer is built to capture low frequencies better than a standard convolution. This is because the repeated wavelet transform decomposition of the low frequencies of the input emphasizes them and increases the layer’s corresponding response. This discussion complements the analysis that convolutional layers are known to respond to high frequencies in the input. By leveraging compact kernels on the multifrequency inputs, the IMWTC (or WTC) layer places the additional parameters where they are most needed [22,23].

Lastly, the introduction of IMWTC has led to a significant enhancement in computational efficiency and stability. In contrast to WTC, it may simplify the computational process and reduce redundant operations. Meanwhile, it may also enhance the stability of the model.

As the scale of deep learning models continues to expand exponentially, their deployment in resource-constrained environments and edge devices presents significant technical challenges. Based on IMWTC, we propose a lightweight neural network model called Mob-IMWTC to tackle the image captioning problem under resource-constrained conditions.

In this experiment, the original Conv2D layers in MobileNet V3 are replaced with IMWTC modules to perform efficient feature extraction from the input image. Mob-IMWTC optimizes the performance-complexity trade-off through its innovative architecture, enabling seamless deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. The model introducing IMWTC to Mob-Tran results in a substantial improvement in objective evaluation metrics (BLEU, CIDEr, ROUGE, METEOR, and SPICE) while causing only a slight increase in parameters and FLOPs.

Mob-IMWTC shows notable innovation in this challenging domain, offering viable solutions for practical implementation; however, compared to non-wavelet-based models (Mob-Tran), the WT-Conv-IWT architecture needs more inference times, primarily due to the multiple transformation stages required. This challenge can be alleviated by executing wavelet transforms in parallel with convolutional operations at each hierarchical level, thereby minimizing both memory access operations and allocation demands.

Our next step involves integrating Mob-IMWTC with multidisciplinary approaches spanning linguistics, cognitive science, and biological principles to create enhanced AI architectures that tackle complex issues in visual recognition and NLP systems.

Acknowledgement: We acknowledge the assistance of AI-based writing tools (Baidu’s ERNIE Bot) in improving the manuscript’s readability.

Funding Statement: The research is funded by National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 23BYY197.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: proposing algorithms and project administration: Mo Hou, Bin Xu; data and literature collection: Wen Shang; writing and debugging programs: Mo Hou, Wen Shang; draft manuscript preparation: Mo Hou, Bin Xu, Wen Shang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at: Microsoft COCO datasets available from: https://cocodataset.org/.Flickr8k (accessed on 17 September 2025), datasets available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/adityajn105/flickr8kFlickr30k (accessed on 17 September 2025), datasets available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/eeshawn/flickr30k (accessed on 17 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang X, Fan MQ, Hou M. MobileNet V3-transformer, a lightweight model for image caption. Int J Comput Appl. 2024;46(6):418–26. doi:10.1080/1206212X.2024.2328498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kiros R, Salakhutdinov R, Zemel R. Multimodal neural language models. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-14); 2014 Jun 22–24; Beijing, China. p. 595–603. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2024.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Anderson P, He X, Buehler C, Teney D, Johnson M, Gould S, et al. Bottom-up and top-down attention for image captioning and visual question answering. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 6077–86. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Yao T, Pan Y, Li Y, Mei T. Exploring visual relationship for image captioning. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV 2018); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 684–99. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01264-9_42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhu X, Li L, Liu J, Peng H, Niu X. Captioning transformer with stacked attention modules. Appl Sci. 2018;8(5):739. doi:10.3390/app8050739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Liu W, Chen S, Guo L, Zhu X, Liu J. CPTR: full transformer network for image captioning. arXiv:2101.10804. 2021. [Google Scholar]

7. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. Bert: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MN, USA. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

8. Yan J, Xie YX, Zou SW, Wei YM, Luan XD. EntroCap: zero-shot image captioning with entropy-based retrieval. Neurocomputing. 2025;611(3):128666. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Daneshfar F, Bartani A, Lotfi P. Image captioning by diffusion models: a survey. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;138(1):109288. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2024.109288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang RQ, Wu Y, Sheng ZZ. ClipCap++: an efficient image captioning approach via image encoder optimization and LLM fine-tuning. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;180(7):113469. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Dai XL, Yin HX, Jha NK. Grow and prune compact, fast, and accurate LSTMS. IEEE Trans Comput. 2020;69(3):441–52. doi:10.1109/TC.2019.2954495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sharif N, Bennamoun M, Liu W, Shah SAA. SubICap: towards subword-informed image captioning. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision; 2021 Jan 5–9; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 3540–9. doi:10.1109/WACV48630.2021.00358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tan JH, Tan YH, Chan CS, Chuah JH. ACORT: a compact object relation transformer for parameter efficient image captioning. Neurocomputing. 2022;482(1):60–72. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2022.01.081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu Q, She X, Xia Q. AI based diagnostics product design for osteosarcoma cells microscopy imaging of bone cancer patients using CA-MobileNet V3. J Bone Oncol. 2024;49:100644. doi:10.1016/j.jbo.2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Saqib SM, Iqbal M, Asghar MZ, Mazhar T, Almogren A, Rehman AU, et al. Cataract and glaucoma detection based on transfer learning using MobileNet. Heliyon. 2024;10:e36759. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e36759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang Q, Deng HY, Wu X, Yang Z, Liu YD, Wang Y, et al. LCM-Captioner: a lightweight text-based image captioning method with collaborative mechanism between vision and text. Neural Netw. 2023;162(1):318–29. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2023.03.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Govindharaj I, Santhakumar D, Pugazharasi K, Ravichandran S, Prabhu RV, Raja J. Enhancing glaucoma diagnosis: generative adversarial networks in synthesized imagery and classification with pretrained MobileNetV2. MethodsX. 2025;14:103116. doi:10.1016/j.mex.2024.103116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Finder SE, Zohav Y, Ashkenazi M, Treister E. Wavelet feature maps compression for image-to-image CNNS. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2022 Nov 28–Dec 9; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 20592–606. [Google Scholar]

19. Saragadam V, LeJeune D, Tan J, Balakrishnan G, Veeraraghavan A, Baraniuk RG. Wire: wavelet implicit neural representations. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 18507–16. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu P, Zhang H, Zhang K, Lin L, Zuo W. Multi-level Wavelet-CNN for image restoration. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW); 2018 Jun 18–22; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 773–82. doi:10.1109/CVPRW.2018.00121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Alaba SY, Ball JE. WCNN3D: wavelet convolutional neural network-based 3D object detection for autonomous driving. Sensors. 2022;22(18):7010. doi:10.3390/s22187010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Fujieda S, Takayama K, Hachisuka T. Wavelet convolutional neural networks. arXiv:1805.08620. 2018. [Google Scholar]

23. Chen Y, Fan H, Xu B, Yan Z, Kalantidis Y, Rohrbach M, et al. Drop an octave: reducing spatial redundancy in convolutional neural networks with octave convolution, Seoul, South Korea. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 3435–44. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2019.00353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Rao Y, Zhao W, Zhu Z, Lu J, Zhou J. Global filter networks for image classification. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34; 2021 Dec 6–14; Online. p. 24193–205. [Google Scholar]

25. Grabinski J, Keuper J, Keuper M. As large as it gets–studying infinitely large convolutions via neural implicit frequency filters. arXiv:2307.10001. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2307.10001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Finder SE, Amoyal R, Treister E, Freifeld O. Wavelet convolutions for large receptive fields. arXiv:2407.05848. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2407.05848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Luo W, Li Y, Urtasun R, Zemel R. Understanding the effective receptive field in deep convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2016;29. [Google Scholar]

28. Huang HB, He R, Sun ZN, Tan TN. Wavelet-SRNet: a wavelet-based CNN for multi-scale face super resolution. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 1689–97. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yang TJ, Howard A, Chen B, Zhang X, Go A, Sandler M, et al. NetAdapt: platform-aware neural network adaptation for mobile applications. In: Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision, (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 285–300. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01249-6_18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chollet F. Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proceedings of the 15th 30th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1251–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Vinyals O, Toshev A, Bengio S, Erhan D. Show and tell: a neural image caption generator. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2025 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. p. 3156–64. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2015.7298935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xu K, Ba J, Kiros R, Cho K, Courville A, Salakhutdinov R, et al. Show, attend and tell: neural image caption generation with visual attention. In: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning; 2015 Jul 7–9; Lille, France. p. 2048–57. [Google Scholar]

33. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 770–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kasai J, Sakaguchi K, Dunagan L, Morrison J, Bras RL, Choi Y, et al. Transparent human evaluation for image captioning. arXiv:2111.08940. 2021. [Google Scholar]

35. Zhai SS, Shang L, Ren DZ, Chen YY, Wang H. Portable handheld ultrasound for VExUS assessment in critical care: reliability and time efficiency in resident-led examinations. J Crit Care. 2026;91(2):155224. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2025.155224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Junaid HHS, Daneshfar F, Mohammad MA. Automatic colorectal cancer detection using machine learning and deep learning based on feature selection in histopathological images. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2025;107(6):107866. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2025.107866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools