Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Optimization of Aluminum Alloy Formation Process for Selective Laser Melting Using a Differential Evolution-Framed JAYA Algorithm

1 School of Mechanical Engineering, Tiangong University, Tianjin, 300387, China

2 School of Computer Science and Technology, Tiangong University, Tianjin, 300387, China

3 School of Control Science and Engineering, Tiangong University, Tianjin, 300387, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaodan Liang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071398

Received 05 August 2025; Accepted 22 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Selective Laser Melting (SLM), an advanced metal additive manufacturing technology, offers high precision and personalized customization advantages. However, selecting reasonable SLM parameters is challenging due to complex relationships. This study proposes a method for identifying the optimal process window by combining the simulation model with an optimization algorithm. JAYA is guided by the principle of preferential behavior towards best solutions and avoidance of worst ones, but it is prone to premature convergence thus leading to insufficient global search. To overcome limitations, this research proposes a Differential Evolution-framed JAYA algorithm (DEJAYA). DEJAYA incorporates four key enhancements to improve the flexibility of the original algorithm, which include DE framework design, horizontal crossover operator, longitudinal crossover operator, and global greedy strategy. The effectiveness of DEJAYA is rigorously evaluated by a suite of 23 distinct benchmark functions. Furthermore, the numerical simulation establishes AlSi10Mg single-track formation models, and DEJAYA successfully identified the optimal process window for this problem. Experimental results validate that DEJAYA effectively guides SLM parameter selection for AlSi10Mg.Keywords

Selective Laser Melting (SLM) [1] technology represents a cutting-edge process in metal additive manufacturing (AM) [2], enabling the high-precision construction of complex structures through layer-by-layer melting of metal powder using a precisely controlled laser beam. This technology exhibits substantial potential across high-end industries, including aerospace, automotive, and medical devices, primarily due to its exceptional features of high precision and personalized customization.

In the pursuit of greater efficiency and superior quality, SLM technology encounters a significant challenge in optimizing process parameters [3]. Precise regulation of critical parameters, including laser intensity and scanning speed, directly determines the dimensional accuracy and mechanical performance of the final product. Consequently, identifying and establishing the optimal process window is paramount to advancing SLM and fulfilling the stringent requirements of the manufacturing industry.

To address the pressing demand in manufacturing for higher standards, SLM technology is accelerating its integration with advanced computational methods [4,5]. Notably, the application of Meta-heuristic Algorithm (MA) [6] is particularly noteworthy. MA inspire by simulations of nature and human intelligence, such as Simulated Annealing (SA) [7] and Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) [8], Artificial Electric Field Algorithm (AEFA) [9], and Crow Search Algorithm (CSA) [10], and it represent a class of algorithms tailored for solving optimization problems. These algorithms provide a powerful mathematical framework for SLM process parameter optimization. The JAYA algorithm, originally proposed by Rao [11] in 2016, is a population-based optimization algorithm. It draws inspiration from the fundamental principle of directing individuals toward optimal solutions while avoiding inferior regions during search processes. Characterized by minimal parameter dependencies, computational simplicity, and ease of implementation, JAYA has subsequently been extensively investigated and applied.

The diverse JAYA variants developed to improve performance not only enhance the algorithm capabilities, but also demonstrate robust efficacy in addressing engineering and scientific challenges. Gong et al. introduced an E-JAYA with two group adaptation [12], primarily leveraging comparative analysis between best and worst solution groups. A C-JAYA was proposed in [13], enhancing both precision and convergence speed by chaotic strategy. In [14], a 2D chaotic map was introduced to accelerate convergence and reduce computational cost. Gholami et al. [15] enhanced the search capability of the original algorithm by incorporating the position update mechanism of CSA. The elite local search strategy was integrated into JAYA [16], yielding excellent results. In [17], the update mechanism of JAYA was discretized by utilizing binary operators, demonstrating enhanced experimental robustness. A Levy flight-based JAYA was proposed in [18], and the experimental results demonstrate the notable competitive performance. A JAYA algorithm incorporating an adaptive symbiotic learning strategy was developed to address three engineering problems, achieving highly competitive outcomes against other variants [19]. Rao et al. introduced the QO-JAYA algorithm specifically for welding parameter optimization [20].

Although existing JAYA variants exhibit merits in specific aspects, they often focus on single improvement and lack a coordinated mechanism to balance exploration and exploitation, the local optima, and the population diversity. To overcome these limitations, this paper proposes DEJAYA—a structural hybrid algorithm that integrates a differential evolution (DE) framework for flexible search architecture, horizontal crossover for enhanced global optimization, longitudinal crossover for escaping local optima, and a global greedy strategy for preserving diversity. This synergistic integration distinguishes DEJAYA from other variants and ensures robust and balanced performance across diverse optimization scenarios.

Numerous research teams have conducted extensive studies on SLM process with optimization algorithm. Gajera et al. optimized laser processing parameters for Invar-36 using JAYA, achieving targeted hardness and surface roughness in pattern blocks [21]. Fountas et al. conducted statistical comparison of multiple meta-heuristics for titanium alloy hardness and tensile strength of performance optimization, revealing the virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm’s best fitness values [22]. Patil et al. employed cuckoo search algorithm to identify optimal build parameters, maximizing theoretical density in maraging steel components [23]. Particle swarm optimization was utilized in [24] to optimize process parameters for tensile strength, while genetic algorithm in [25] investigated parameter effects on warpage deformation. In exploring these technologies, the decisive role of process parameters in determining product quality is particularly prominent, further underscoring the urgency of optimizing these parameters. However, current research trends predominantly rely on repetitive experimental validation, inevitably leading to unnecessary expenditures of time, manpower, and material resources. Therefore, combining simulation with swarm intelligence algorithms for SLM optimization not only deepens mechanistic understanding and enables precise selection of process parameters but also significantly reduces resource costs while ensuring high-quality production of metal components.

To address these algorithmic limitations discussed above, this work conducts numerical simulation of the AlSi10Mg single-track formation process to establish overheat and no-continuity models for the optimization problem. Subsequently, DEJAYA is proposed to identify the optimal process window within SLM manufacturing. Ultimately, the efficacy of this method is rigorously validated through practical experiments. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) By integrating the Finite Volume Method with the Volume of Fluid method, a numerical simulation model tailored for the AlSi10Mg single-track formation process has been successfully established. Leveraging the precise capture of melt pool dynamics, further models for overheat and no-continuity have been established.

(2) By introducing the DE framework to enhance the flexibility and efficiency of JAYA in searching the solution space, integrating horizontal crossover operator to strengthen global optimization capability, employing longitudinal crossover operator to effectively escape from local extremes, and adopting a global greedy strategy to promote diversity in the search process.

(3) Through validation with 23 benchmark functions and successful application in identifying the optimal process window for the AlSi10Mg single-track formation optimization problem, the improved DEJAYA has demonstrated not only its superiority over other variants but also its feasibility and practicality.

The structure of the remainder of this paper is as follows. Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of existing research on simulating single-track formation in SLM. Section 3 introduces JAYA and elaborates on DEJAYA, highlighting its improvements. Section 4 evaluates the performance of DEJAYA using 23 benchmark functions and contrasts the results with other algorithmic variants. Section 5 delves into the optimization problem for the AlSi10Mg single-track formation, providing both discussion and validation. Section 6 summarizes the findings of this paper and outlines potential direction for future research.

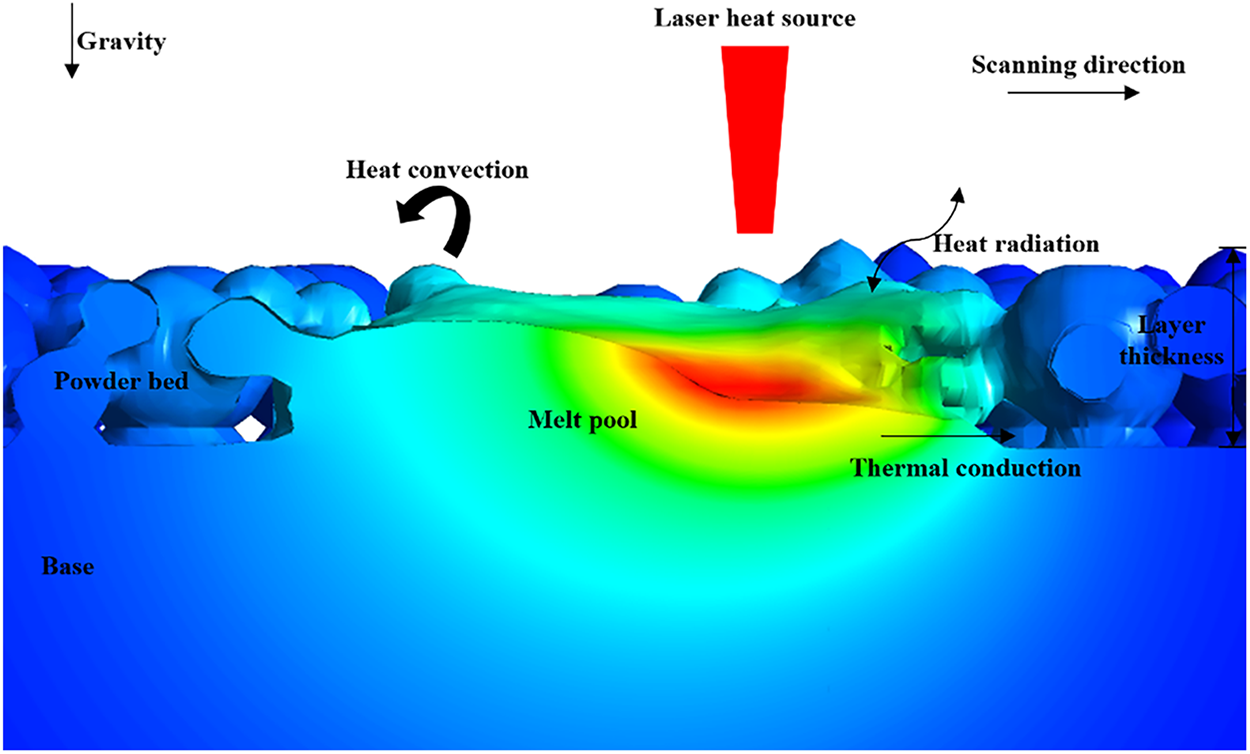

The manufacturing process of SLM involves complex thermal and fluid dynamics, encompassing factors such as surface tension, the Marangoni effect, recoil pressure, and gravity. Fig. 1 illustrates the primary thermophysical environment at the melt pool interface in SLM. To ensure computational efficiency, the single-track numerical simulation of AlSi10Mg presented in this paper is based on four assumptions: (1) the melt pool flow is laminar and Newtonian; (2) plasma effects are neglected; (3) the thermophysical parameters of the material are temperature interpolation; (4) mass loss due to evaporation is disregarded.

Figure 1: The primary thermophysical environment at the melt pool interface in SLM

The flow problem must satisfy the fundamental conservation laws of mass, momentum, and energy. For mass conservation, the mathematical expression as follow:

where,

The momentum equation accounts for various forces acting on the melt pool. It is expressed as:

where, P0 is the atmospheric pressure. g denotes gravity.

There are multiple heat transfer processes in SLM, and energy conservation is maintained throughout the process. The mathematical expression is as follows:

where, h represents enthalpy. λ denotes thermal conductivity. qlhs, qhc and qhr are energy source terms, stand for laser heat source, heat convection and heat radiation.

In SLM, metal powders are randomly distributed and interact through point contacts. A volumetric heat source model would instantaneously transfer heat to both powders and base. Therefore, an interface tracking heat source is employed as the energy term to simulate laser heat source, this allows for precise capture of the dynamic behavior of the melt pool. The intensity of the laser beam typically follows a Gaussian relationship, which can be mathematically expressed as follows:

where, P represents laser power. τ denotes spot radius. r signifies the distance between a point within the radius of the laser beam and the center of the heat source. α stands for the laser absorption rate.

The numerical simulation of AlSi10Mg single-track encompasses the melting of metal powder, liquid metal flow, and solidification processes. To accurately capture these phenomena, a Volume of Fluid (VOF) [26] two-phase flow model is employed to track the metal-gas interface. The metal phase is represented by volume fraction φ, and the gas phase by 1 − φ, so that the total volume fraction in each cell sums to unity.

In this paper, the surface tension, Marangoni effect, drag force in mushy zone, and recoil pressure are considered as momentum source terms. Recoil pressure serves as the primary force within the melt pool once the metal attains its boiling point. It is defined as follows:

where, L represents latent heat of evaporation. Tv denotes boiling point temperature. Rg signifies gas constant. M stands for metal molar mass.

The Marangoni effect describes the force of liquid metal from warmer to cooler regions on the melt pool surface. It is expressed as follows:

where, n represents unit normal vector of the interface.

where,

Surface tension, which exists at the interface between liquid metal and gas, is modeled using the continuum surface force (CSF) [27] approach:

where, κ represents interface curvature.

During solidification, a mushy zone forms where temperatures lie between the solidus and liquidus points. In this region, the resistance encountered as liquid metal flows relative to the already solidified metal is termed as the drag force in mushy zone. Its mathematical expression is given as follows:

where, Mz represents the constant of the mushy zone. ξ is utilized to control the liquid metal fraction, which is temperature-dependent and mathematically expressed as follow:

where, Tl represents liquids temperature.

It is noteworthy that, based on Divergence theorem, the momentum source terms above are converted into volume forces in this paper. The corresponding expression is:

where, ρm and ρg represent metal and gas density, respectively.

In SLM simulations, energy source terms include not only the laser heat source but also thermal convection and radiation. Thermal radiation, which follows the Stefan-Boltzmann law [28], accounts for heat loss at the melt pool surface:

where, σs represents Stefan-Boltzmann constant. Tref denotes the referent temperature. ε signifies radiation coefficient.

Thermal convection arises from heat exchange due to fluid flow at the melt pool surface and is expressed as:

where, hc represents heat convection coefficient.

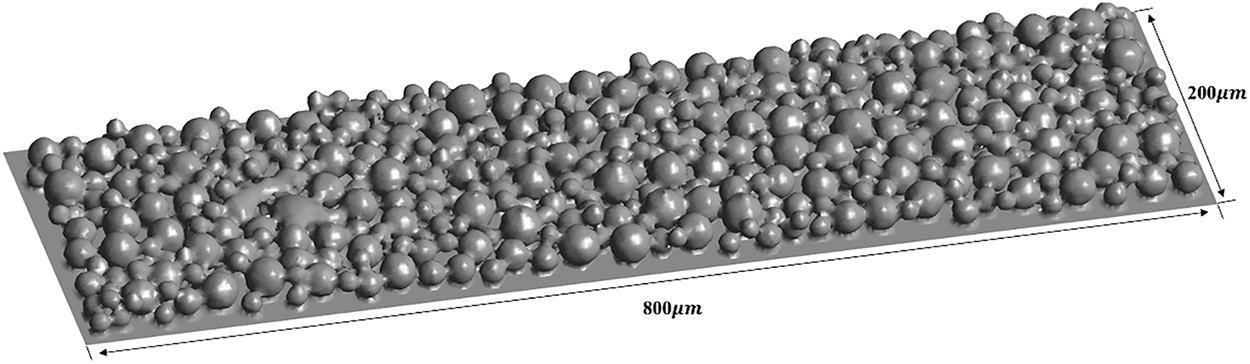

Based on the free-fall method, the Discrete Element Method (DEM) [29] software EDEM is employed to initially generate the discrete particle within the SLM powder bed. The AlSi10Mg powder primarily exhibits spherical or near spherical morphology with an average particle size of 20 μm [30]. Considering the computational efficiency, the simulation domain is set to 800 μm × 200 μm × 250 μm, with a base height of 200 μm and a powder layer thickness of 30 μm. Fig. 2 illustrates the randomly distributed AlSi10Mg powder bed model.

Figure 2: Computational domain of the powder bed model

2.6 Material Properties and Parameter Settings

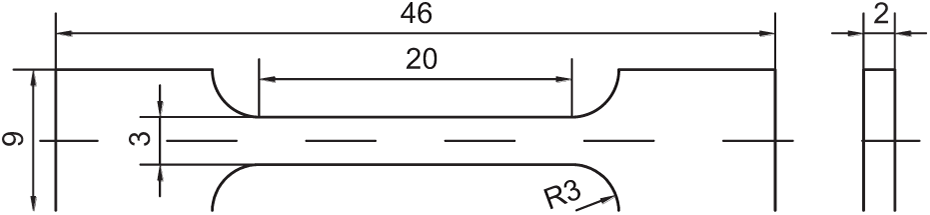

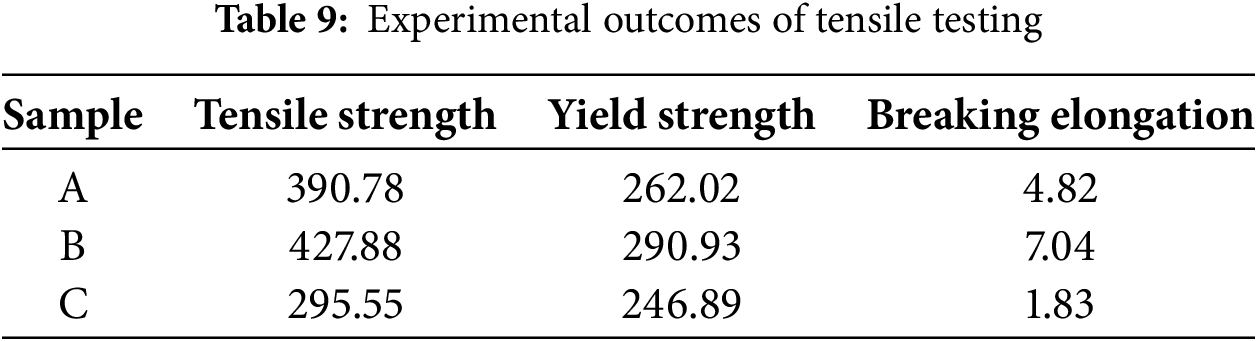

In this study, the Fluent solver is employed to simulate the melt pool formation during single-track processing by the Finite Volume Method (FVM) [31] and the Volume of Fluid (VOF). The thermophysical parameters of the AlSi10Mg metal powder are presented in Table 1. The remaining simulation parameters are presented in Table 2.

As a meta-heuristic algorithm, JAYA is characterized by its the principle of preferential behavior towards best solutions and avoidance of worst ones, thereby continuously enabling quality enhancement of the solution. The JAYA distinguish from other meta-heuristic algorithms because it has not too many parameters, reducing the need to adjust on the test. The mathematical expression is in Eq. (14).

where,

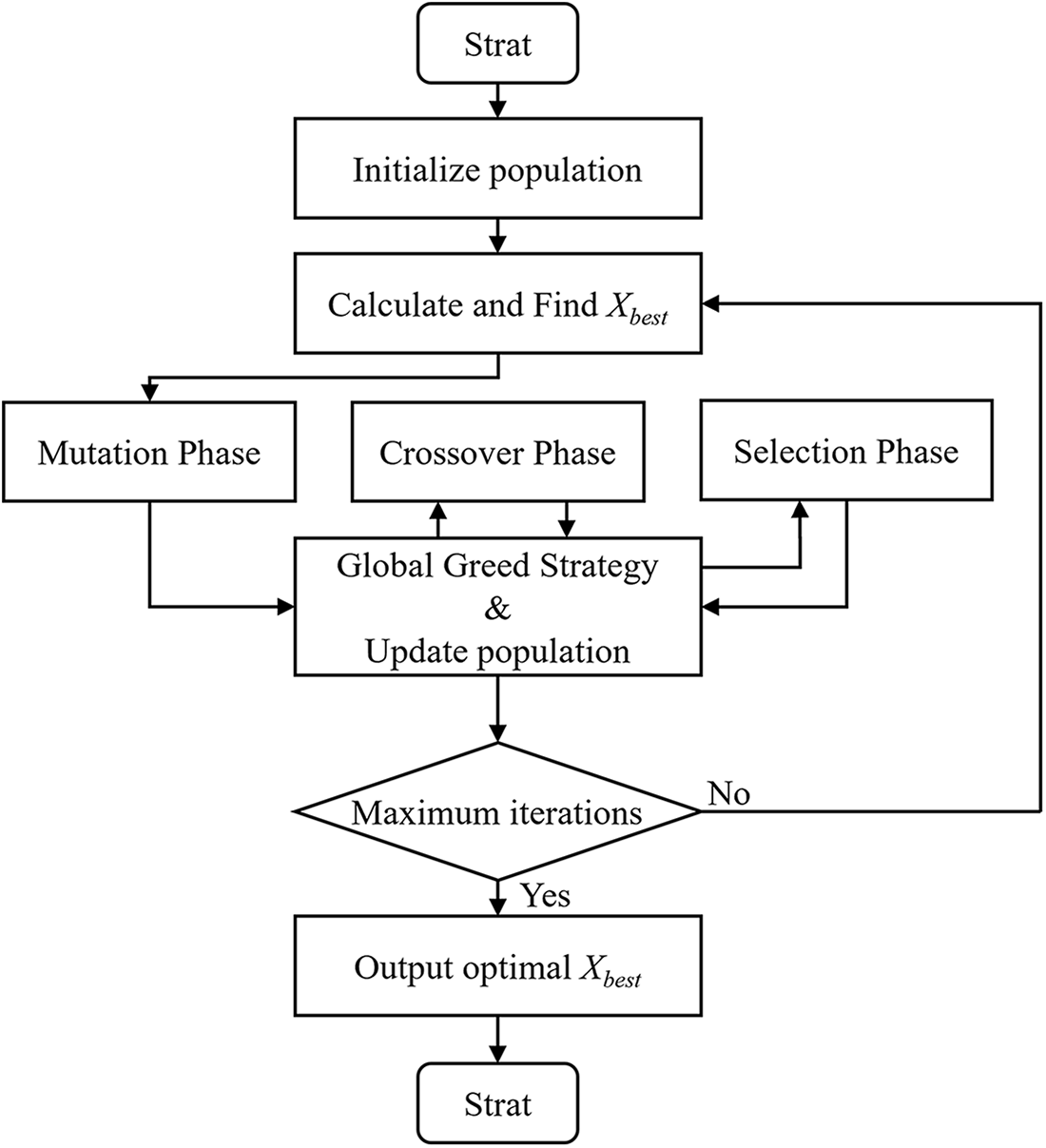

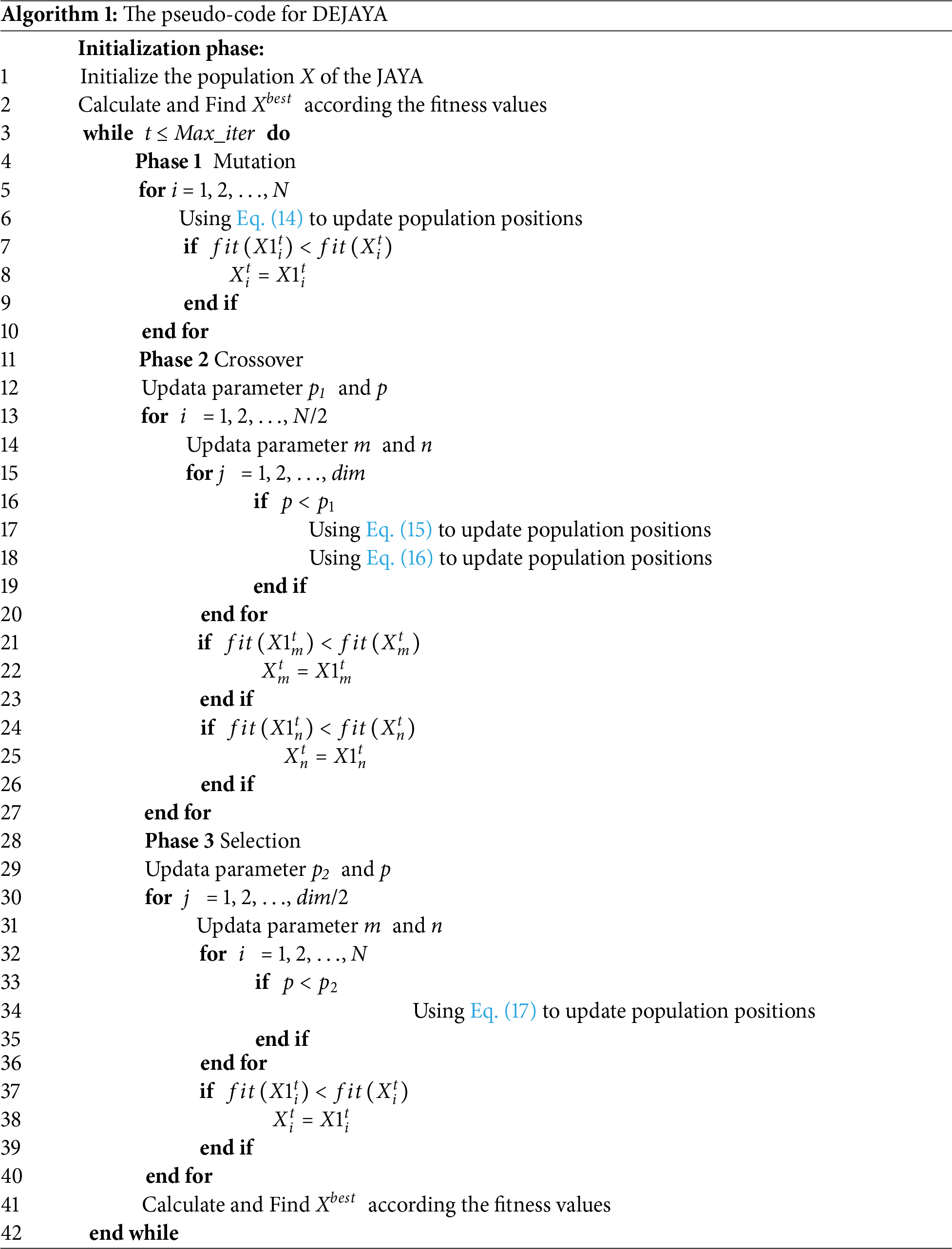

This part integrates four enhancements into the JAYA, in which DE framework, horizontal crossover operator, longitudinal cross operator, and global greedy strategy. The DE framework significantly improves algorithmic flexibility and efficiency. The horizontal crossover operator enhances global optimization capability, while longitudinal crossover operator is utilized to escape from the local extremum easily. Finally, global greedy strategy augments population diversity. The complete pseudo-code for DEJAYA is presented in Algorithm 1, and the same steps are depicted in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Flowchart of DEJAYA

The DE framework, based on the differential evolutionary algorithm (DE), comprises three fundamental phases: mutation, crossover, and selection. This framework inherits the advantages of DE, significantly enhancing algorithmic flexible and effective. During the Phase 1, the implementation adopts the original iterative method of JAYA as formalized in Eq. (14).

3.4 Horizontal Crossover Operator

The horizontal crossover operator is similar to the crossover operation of genetic algorithm, an arithmetic crossover between two same-dimension individuals within population. This operation can be described as assuming that the j-th dimension among m-th odd individual and n-th individual are crossed at t-th iteration by the crossover probability p1. The mathematical expression is as follows:

where,

3.5 Longitudinal Crossover Operator

Similar to the horizontal crossover operator of Section 3.4, the longitudinal crossover operator is used to improve Phase 3 of the algorithm, which is a kind of arithmetic crossover between different dimensions in an individual. This operation can be described as assuming that the normalized m and n dimensions in the i-th individual are crossed by selection probability p2.

where,

Within the proposed DEJAYA, greedy strategy is enforced at every operational phase. Its core idea of this strategy is to select the best solution in each generation, aiming to progressively approach the global optimum and avoid the algorithm falling into the local extremes. Specifically, candidate solutions undergo fitness evaluation after each phase, with only better individuals advancing to subsequent operations. This global greedy strategy ensures both population diversity and progressive quality enhancement throughout the optimization process. Its operational specifics are delineated in Algorithm 1 (see lines 7–9, 21–26, and 37–39), and this strategy can be explained as follows.

where, X1 represents the stored solution in each phase involving Eqs. (14)–(17).

4 Experimental Performance Evaluation

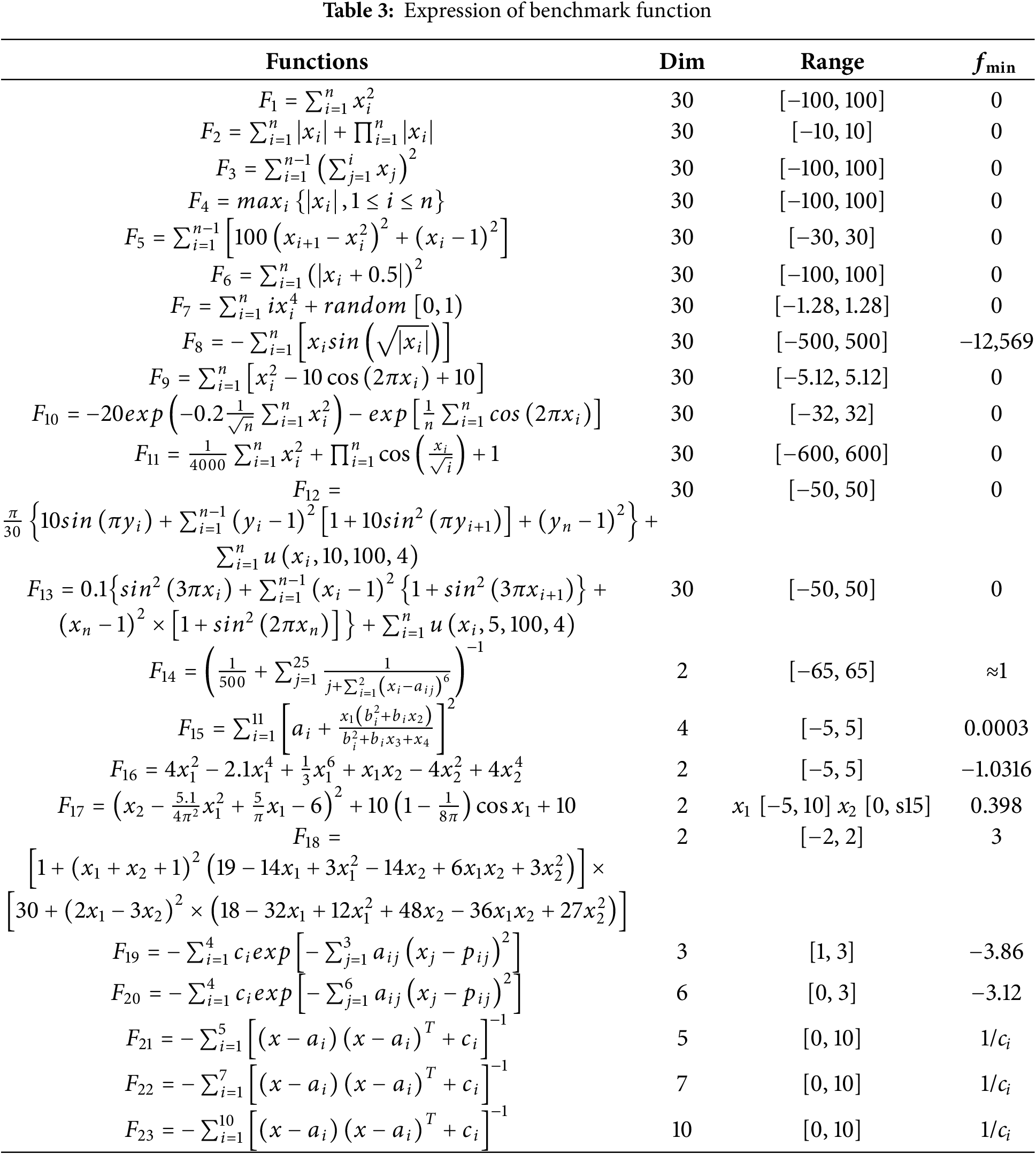

This section evaluates DEJAYA using 23 benchmark functions as shown in Table 3. Functions F1–F7 are unimodal test suites, aiming to assess algorithmic capability in the case of a single global optimum. Functions F8–F13 represent multimodal test suites, examining an algorithm’s capability in locating a globally unique solution amidst numerous local minima. Finally, F14–F23 signify fixed-dimension multimodal functions, assessing convergence velocity in low-dimensional search spaces.

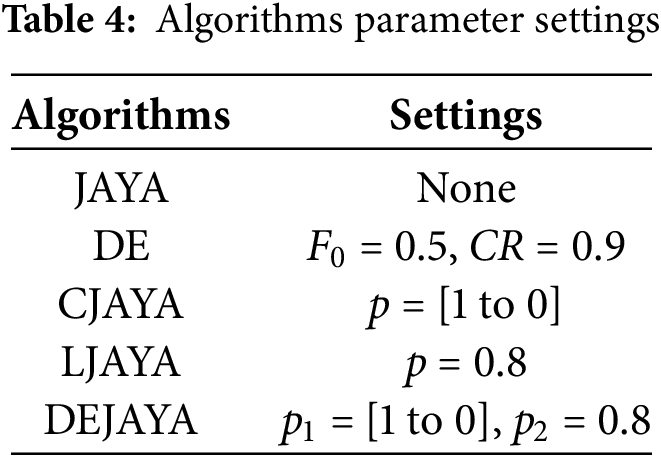

Throughout all experiments, the proposed DEJAYA will be compared against DE, original JAYA and its variants CJAYA and LJAYA. For above algorithms, population sizes and maximum iterations are fixed at 30 and 500, respectively. All algorithms undergo 20 independent tests across benchmark functions in Table 3. Table 4 displays the parameters of the comparative algorithms.

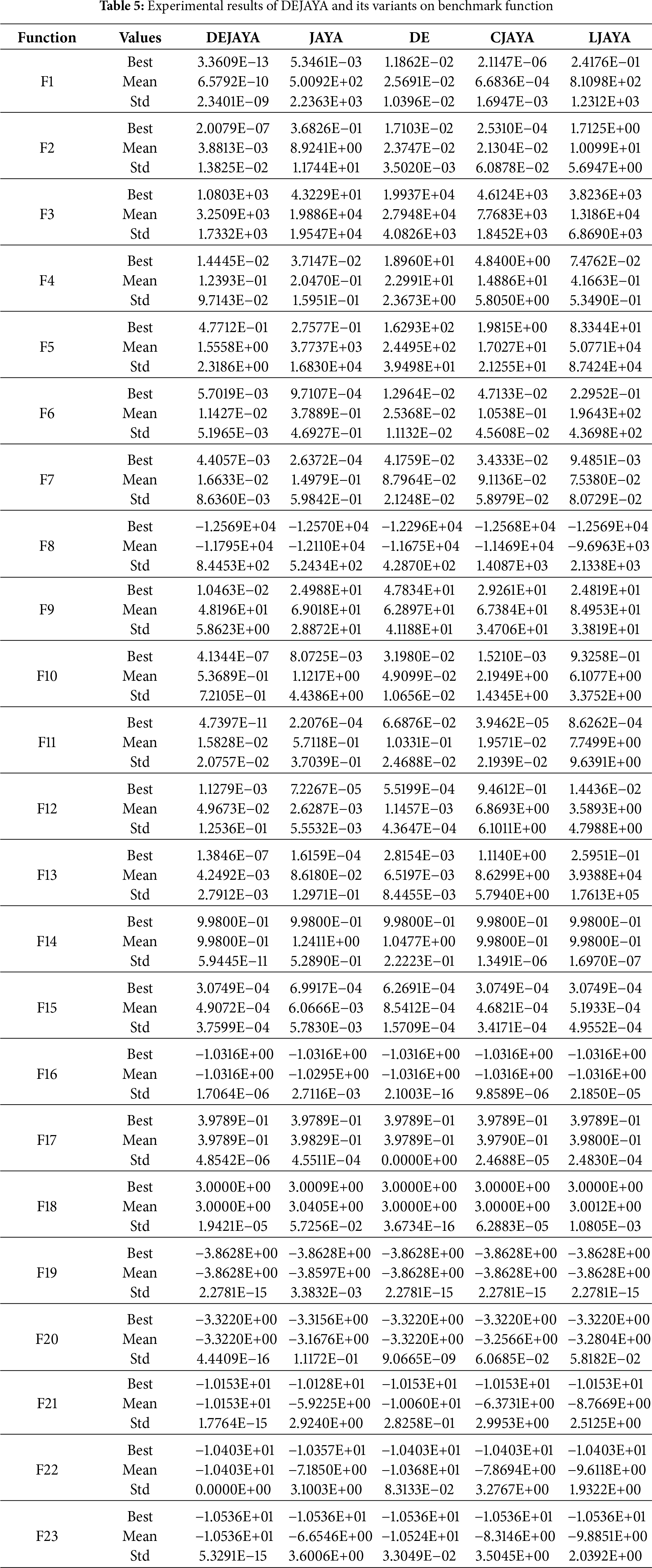

Table 5 provides the experimental outcomes of DEJAYA and its variant algorithms, where Std denotes standard deviation.

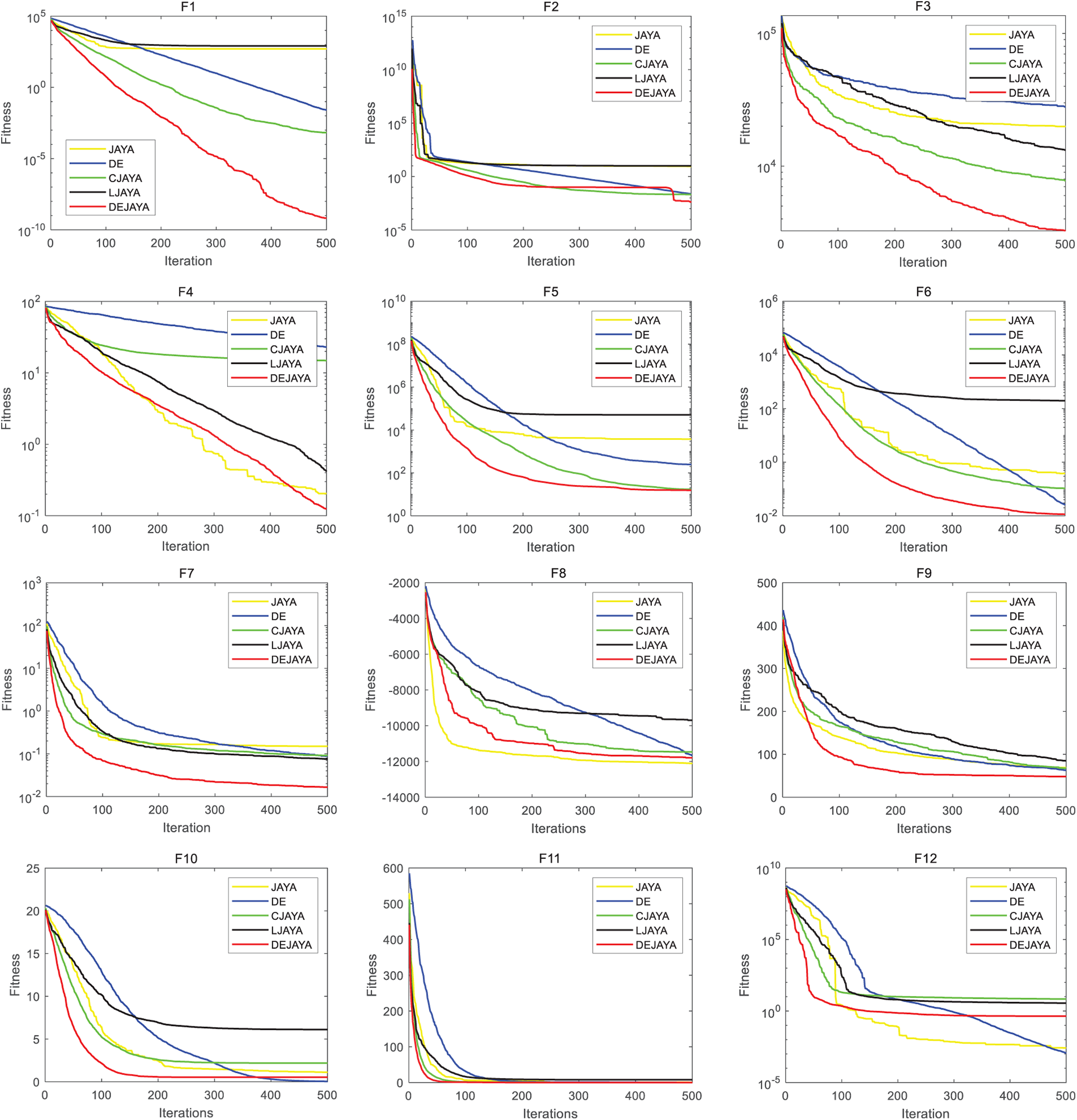

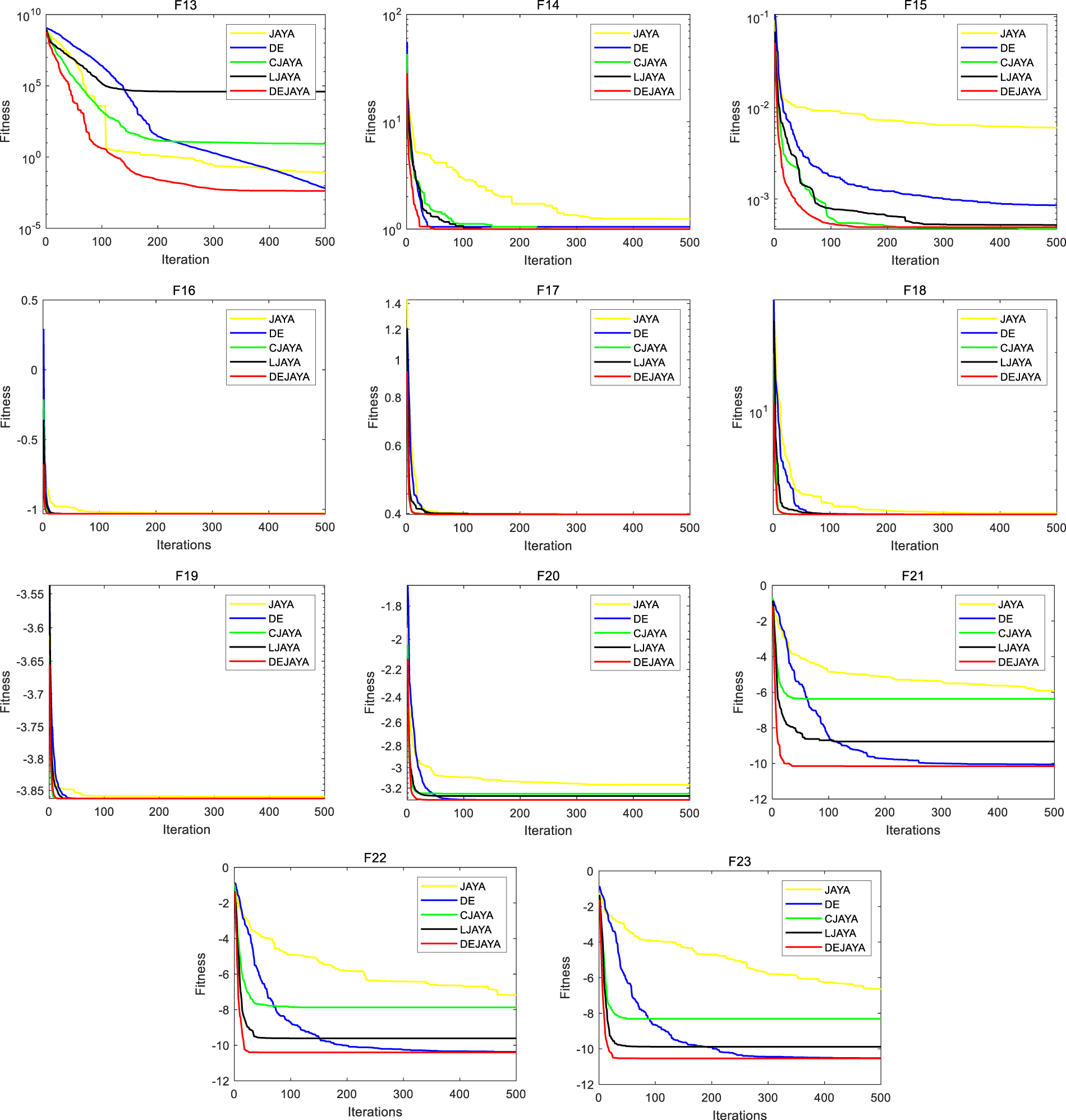

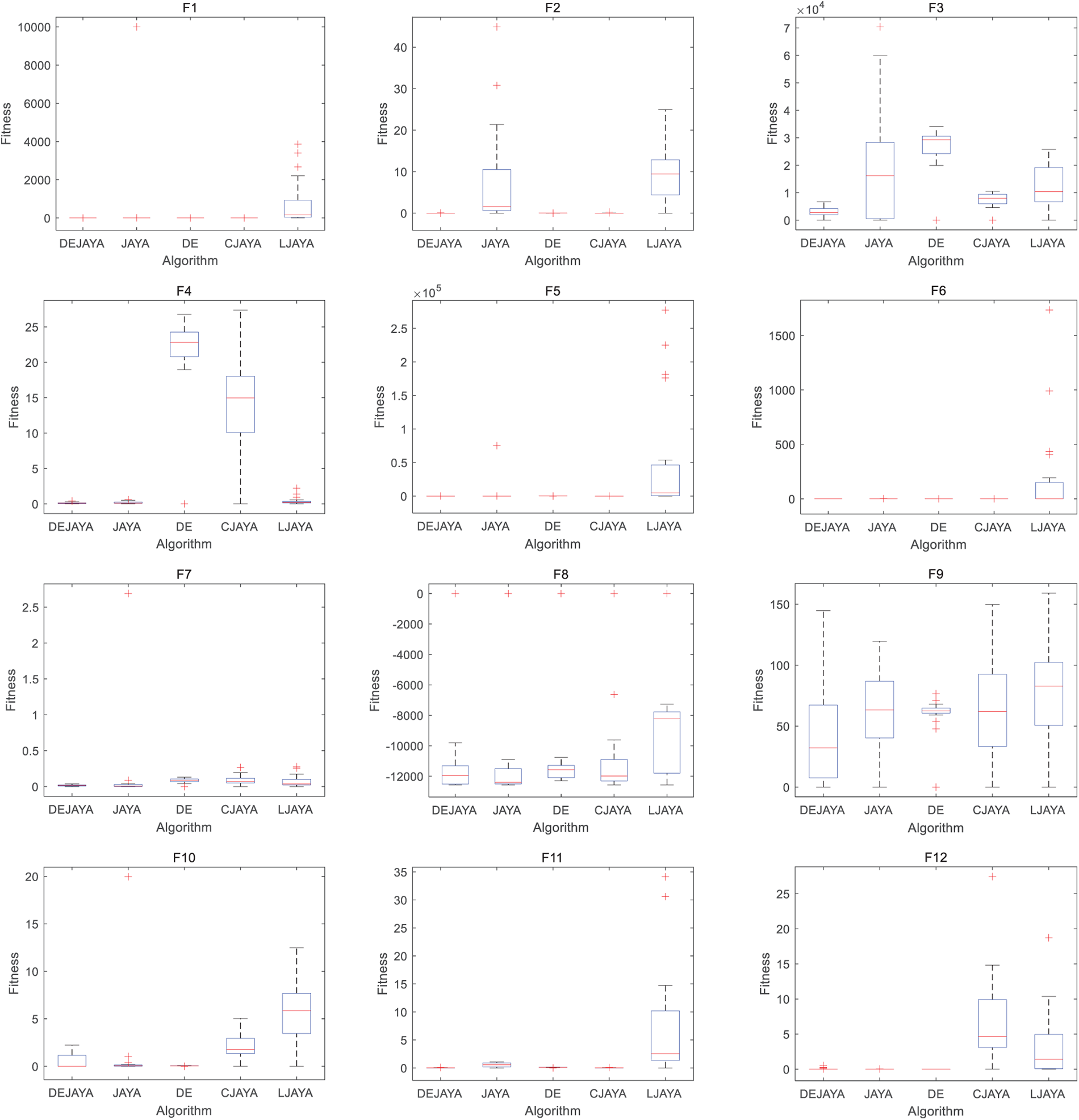

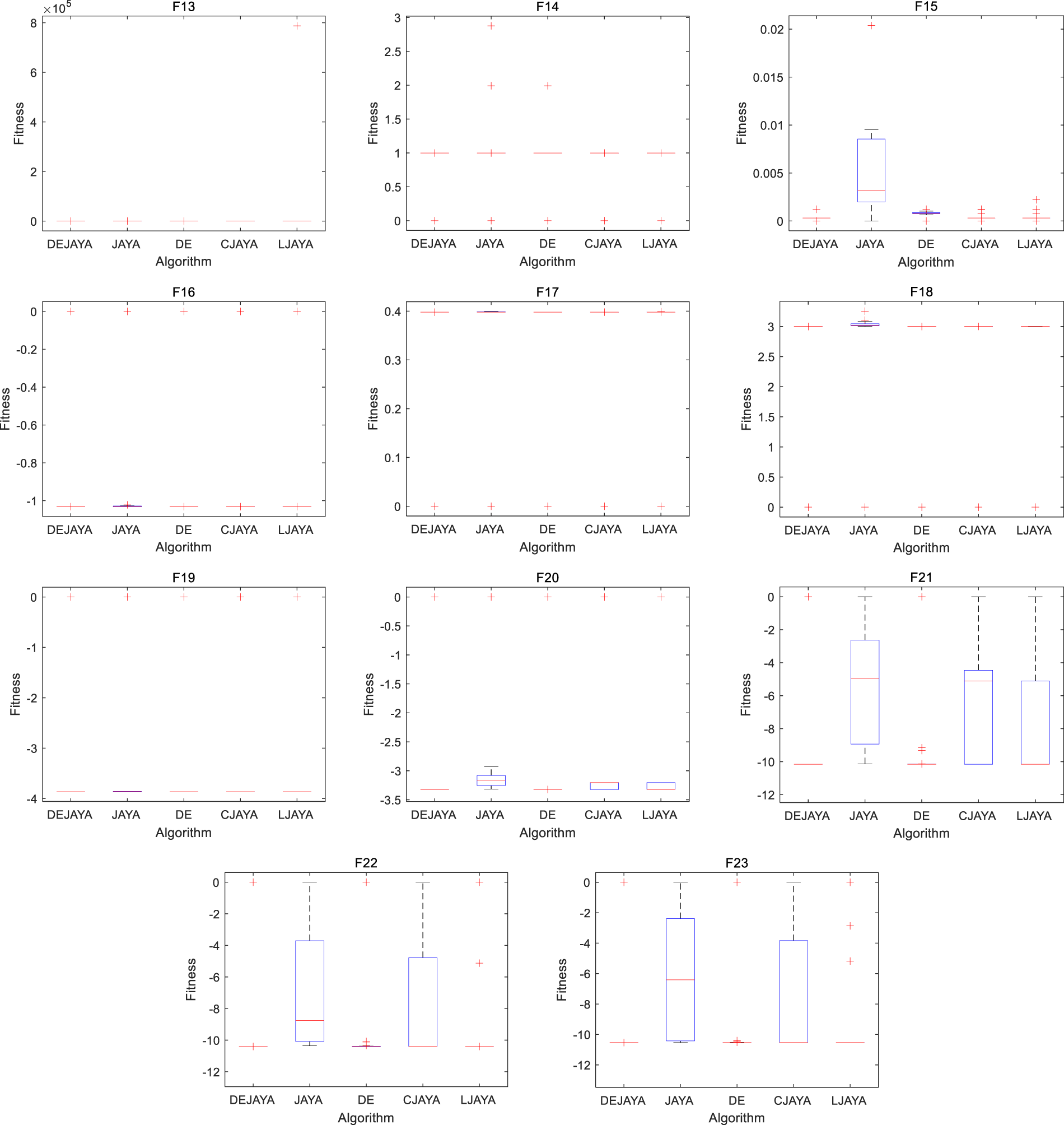

Based on the above experimental results, DEJAYA demonstrates absolute dominance in functions F1, F2, F4, F9, F11, F13, F14 and F19–F23, where it outperforms other algorithms in every metric. For F3, although achieving a marginally lower minimum compared to JAYA, it exhibits superior mean and std performance. While there is not statistically significant difference in the minimum value compared to JAYA on F5–F7, DEJAYA delivers substantially mean and std performance compared to others. In multimodal function F8, the proposed algorithm achieves optimal minima but underperforms JAYA in mean and DE in standard deviation. For F16–F18, DEJAYA attains optimal minima and mean scores yet exhibit higher volatility than DE. In F12, DEJAYA ranks third overall across evaluation criteria. For F15, DEJAYA obtains the best minimum value and exhibits no statistically different compared to CJAYA in mean, while DE in standard deviation. To graphically demonstrate the efficacy of DEJAYA, Fig. 4 depicts the convergence curves, while Fig. 5 presents the corresponding boxplot analysis.

Figure 4: Convergence graphs of DEJAYA, JAYA, DE, CJAYA, and LJAYA

Figure 5: Boxplot of DEJAYA, JAYA, DE, CJAYA, and LJAYA

Fig. 4 intuitively demonstrates algorithmic convergence rates. DEJAYA exhibits superior convergence characteristics across functions F1–F7, F9, F11, and F15–F23. For F8, which is a multimodal function with many irregular local optima, DEJAYA marginally underperforms JAYA, this is likely because the highly deceptive landscape of Schwefel’s function may temporarily disrupt DEJAYA’s exploratory balance. For F10, DEJAYA shows slightly inferior convergence to DE. Ackley’s function, which features an irregularity outer region and a sharp peak, requires careful balance between exploration and exploitation, DE benefits from its strong mutation strategy in this particular landscape. In the case of F12, DEJAYA outperforms only CJAYA and LJAYA. This can be attributed to the additional constraints and narrow global basin, where certain algorithms might exhibit faster convergence. Within Fig. 5, results reveal DEJAYA maintains stability across most benchmark functions, with only F8 and F10 exhibiting minor fluctuations. These empirical findings collectively confirm the generalization capability and stability of DEJAYA.

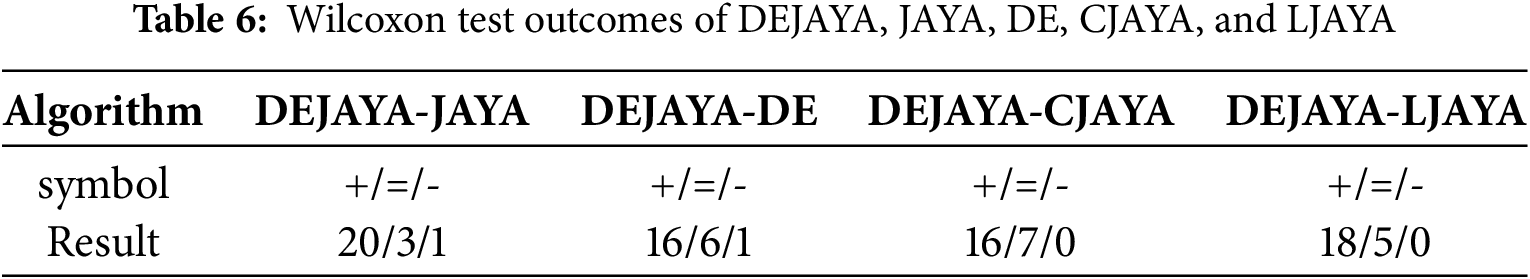

As presented in Table 6, Wilcoxon test outcomes for DEJAYA employ the symbols “+”, “=” and “-” to denote statistically better, similar, or inferior performance relative to JAYA, DE, CJAYA, and LJAYA, respectively. At a significance level of 0.05, the tabulated data demonstrate DE-JAYA’s predominant superiority or statistical similar to the contrastive algorithms across most tested functions.

4.4 Computational Cost and Efficiency Analysis

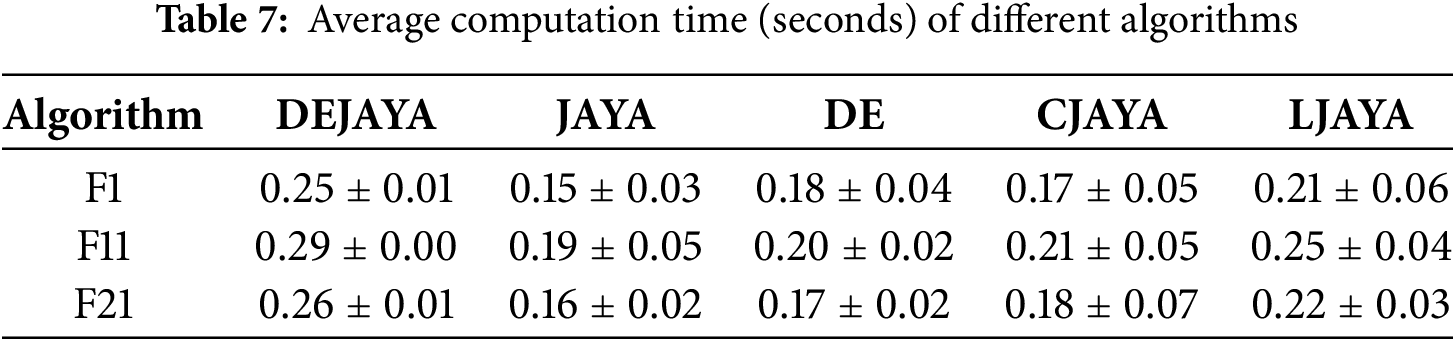

The space and time complexity of the DEJAYA algorithm are O(N × dim) and O(max_iter × N × dim), respectively, where N is the population size, dim is the problem dimension, and max_iter is the maximum number of iterations. To evaluate computational efficiency, the DEJAYA, JAYA, DE, CJAYA, and LJAYA are independently executed 20 times on test functions F1, F11, and F21. The average computation time (CPU time) required to complete the optimization under a fixed maximum number of iterations, along with its standard deviation, is summarized in Table 7.

As theoretically anticipated, DEJAYA exhibited slightly higher average computation times across the test functions. This is attributed to its more complex per-iteration operations, which integrate both horizontal and vertical crossover operations within a DE framework, alongside a global greedy selection strategy. Consequently, DEJAYA incurs a higher computational cost per iteration compared to other algorithms.

However, algorithmic efficiency should not be judged solely on runtime but must also consider convergence speed and solution quality. As demonstrated in Table 5 and Figs. 4 and 5, DEJAYA achieves notably superior convergence accuracy and stability on the vast majority of test functions. This demonstrates that DEJAYA’s superior global exploration and local exploitation capabilities effectively compensate for its modest increase in per-iteration cost. Consequently, DEJAYA achieves an exceptional balance between computational efficiency and solution quality, confirming its effectiveness and practical utility.

This research advances through three core phases. Firstly, the objective function for AlSi10Mg single-track formation is defined by the principles established in Section 2. Subsequently, the proposed DEJAYA algorithm is executed and evaluated. Finally, experimental validation is conducted to empirically verify the optimal process window derived from the algorithm’s optimization.

The single-track simulations demonstrate that high laser power (P) combined with low laser speed (V) induces melt pool overheating, causing excessive enlargement and spattering [36], which directly compromises formation accuracy and surface quality. Conversely, low P with high V fails to sustain melt pool continuity, generating internal porosity [37] that degrades component density and mechanical properties. To avoid these defects, this section establishes models for melt pool overheat and no-continuity, enabling proactive exploration of the optimal processing window.

The overheat model has two indicators that depth ratio (d1) and sectional area (d2), which can be expressed by Chebyshev Series Bivariate Polynomials as shown below:

Eq. (19) is the first type of Chebyshev polynomial and it is expressed through the cosine function as follows:

where,

Similarly, there are two indicators for no-continuity, namely variation rate (w1) and width (w2), which can be expressed by Chebyshev Series Bivariate Polynomials as shown below:

Eq. (12) is the first type of Chebyshev polynomial and it is expressed through the cosine function as follows:

where,

We design the single-track formation optimization problem as a single objective problem with multiple constraints. P(Xi) and V(Xi) are used to refer to laser power in the range of 150–250 W and laser speed in the range of 0.60–1.60 m/s, respectively. The fitness of objective function representing two models are defined using the following mathematical formulation.

where X is the solution of this problem, and include [P, V]. P = {P1, P2, …, Pk} and V = {V1, V2, …, Vk} in the solution of this problem, and the value of k is n/2. a1, a2, and a3 are the weights of this single objective problem.

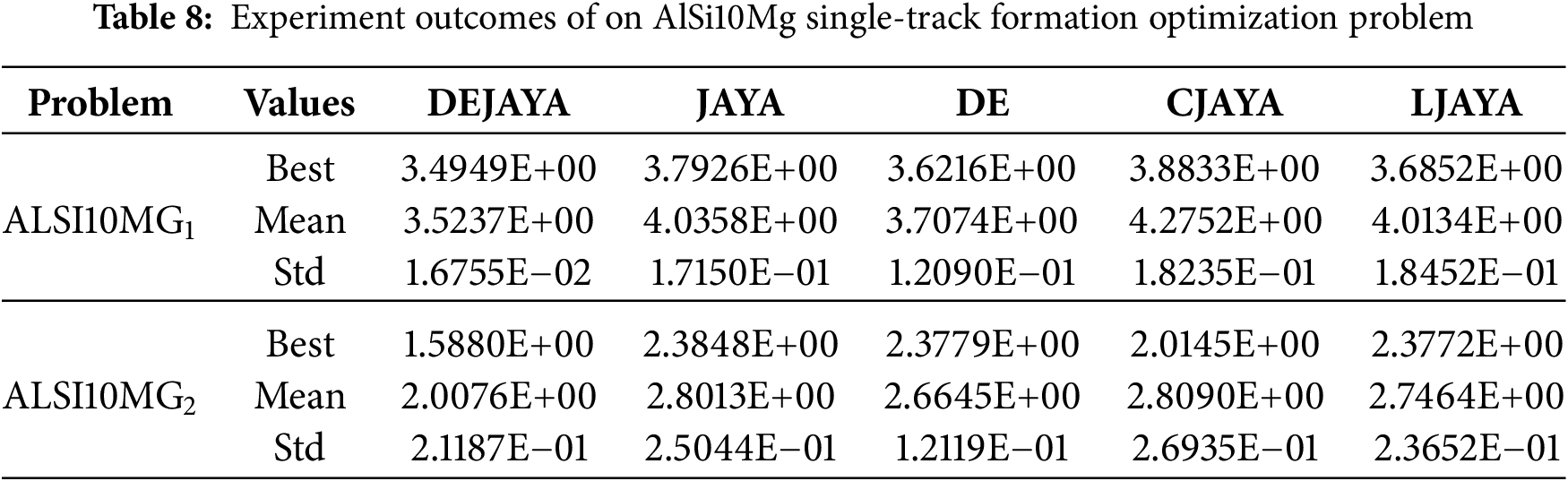

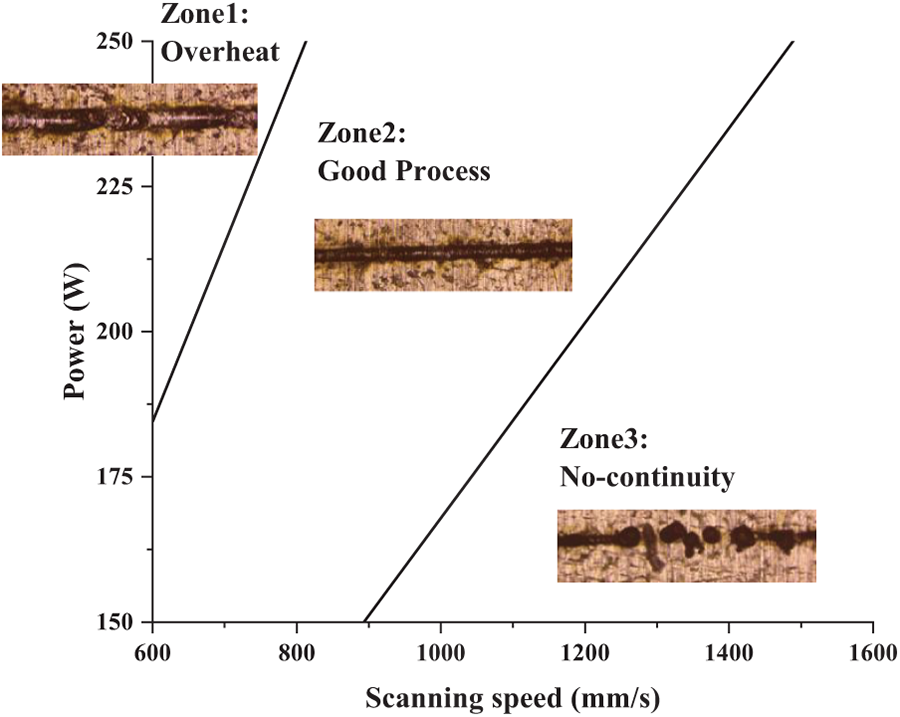

To rigorously evaluate the performance of DEJAYA in addressing the AlSi10Mg single-track formation optimization problem, DEJAYA and its variant algorithms are independently executed 20 times. Experimental outcomes are tabulated in Table 8, while convergence graphs and boxplots are visualized in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Results of (left) Convergence graph. (right) Boxplots

Table 8 demonstrates the superior performance of DEJAYA across all evaluation metrics compared to other algorithms, with only standard deviation marginally trailing DE. For subfigures AlSi10Mg1a and AlSi10Mg 2a of Fig. 6, the convergence curves of DEJAYA exhibit faster rates compared to other algorithms. Furthermore, DEJAYA exhibits significantly enhanced solution stability in subfigures AlSi10Mg1b and AlSi10Mg 2b of Fig. 6. These collective results validate DE-JAYA as a robust and efficient methodology for AlSi10Mg single-track formation optimization problem.

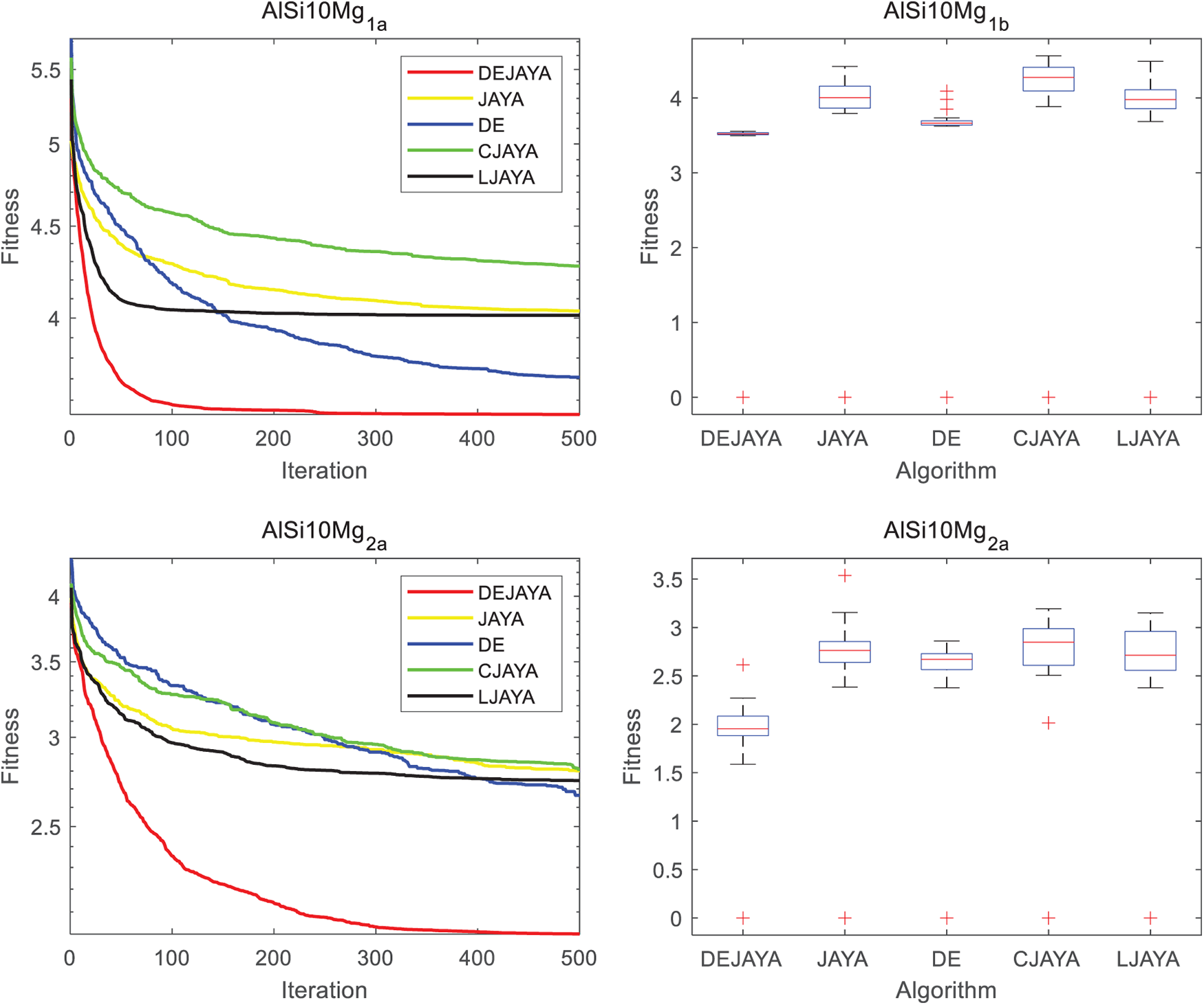

For more precise definition of the optimal process window, this research employs linear energy density (LED) [38] as the quantitative metric, which is calculated by Eq. (25). Substituting the parameter combinations obtained from the above DEJAYA optimization into this equation and then rounding, the results yield an average LED ≈ 0.3075 J/mm for the overheat boundary and an average LED ≈ 0.1679 J/mm for no-continuity boundary. Fig. 7 provides a direct visualization of the identified optimal process window.

Figure 7: Results of (left) Convergence graph. (right) Boxplots

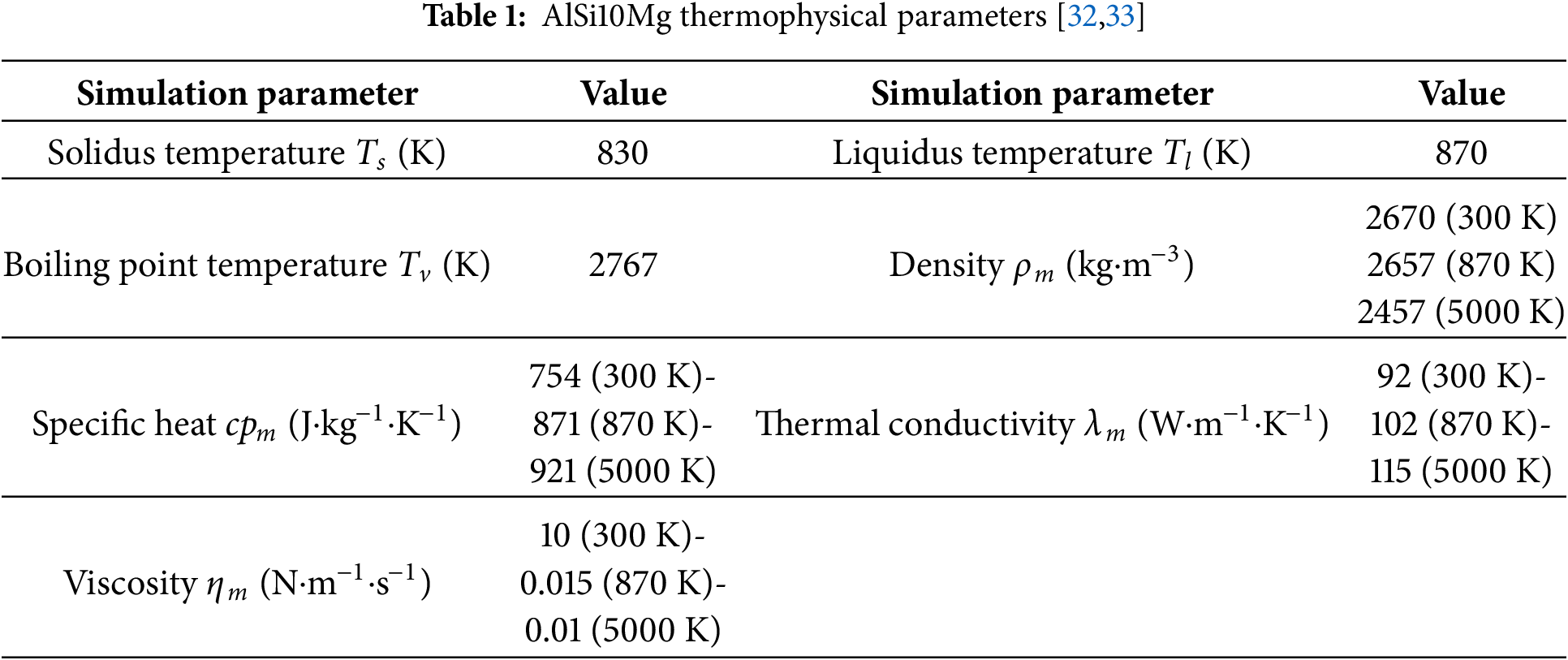

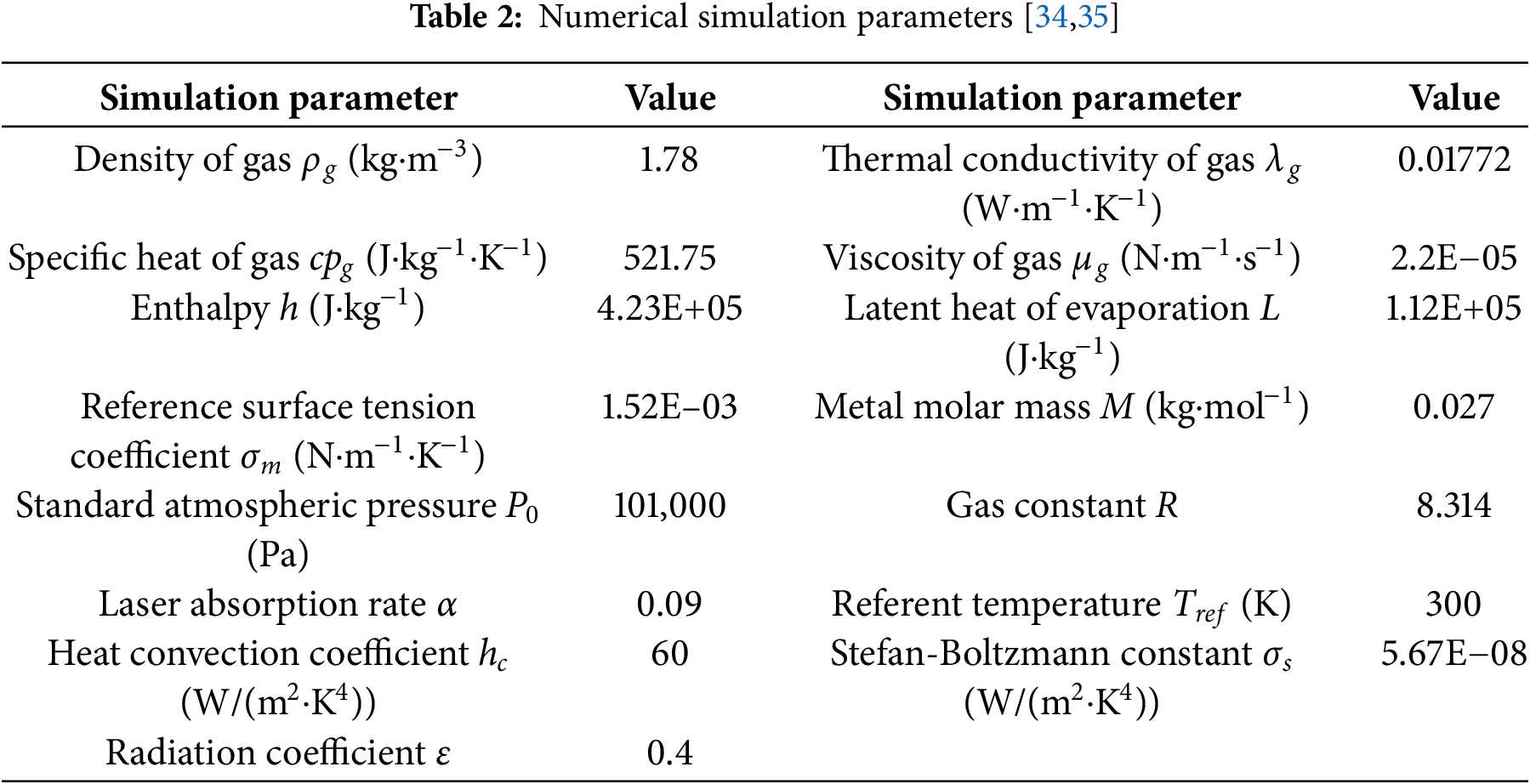

Fig. 7 reveals distinct melt pool morphologies. Zone 1 exhibits overheated and wrinkled features, while Zone 3 displays discontinuous and spheroidization. Only Zone 2 demonstrates a continuous, uniform morphology. To further validate the optimal process window identified by the proposed method, three parameter combinations representing these zones—A (250 W, 700 mm/s), B (220 W, 1100 mm/s), and C (160 W, 1300 mm/s)—are selected for tensile testing. The machined dimension of the tensile sample is shown in Fig. 8, while the corresponding experimental results are presented in Table 9.

Figure 8: Graph of tensile sample

As evidenced by the experimental data in Table 9, Sample B demonstrates superior performance in tensile strength, yield strength, and elongation. Sample C exhibits marked deterioration, while Sample A demonstrates intermediate values. This outcome directly validates the guidance value of the optimal process window shown in Fig. 7.

This paper proposes a novel method integrating numerical simulation with optimization algorithms to address the challenges of complex parameter relationships and redundant experimental in identifying optimal processing windows. To achieve this, a Differential Evolution-framed JAYA algorithm is proposed. The core innovation of DEJAYA lies in its structural integration of differential evolution principles and multi-strategy collaboration, transcending mere hybridization to form a more powerful and balanced optimizer. Specifically, DEJAYA incorporates four improvements: (1) a differential evolution framework that enhances flexibility and efficiency through mutation, crossover, and selection phases; (2) a horizontal crossover operation that improves global optimization via arithmetic crossover between individuals at the same dimensions; (3) a longitudinal crossover operation that avoids local optima through arithmetic crossover across different dimensions within an individual; (4) a global greedy strategy that maintains population diversity and ensures progressive quality improvement by selecting the best solution in each generation. To evaluate the effectiveness of DEJAYA, comprehensive experiments are conducted across 23 benchmark functions with comparative algorithm analysis. Statistical results confirm either outperforms or statistical equivalence to its variant algorithms, underscoring its robustness and stability. Ultimately, leveraging from numerical simulations of dynamic melt pool behavior, this research established overheat and no-continuity models. Algorithm optimization and experimental validation collectively demonstrate the effectiveness of DEJAYA in identifying the optimal process window and guiding parameter selection.

Future research priorities include enhancing DEJAYA through novel mechanisms or methods to improve its performance. Concurrently, applications of DEJAYA will extend to optimizing multi-track and multi-layer formation for AlSi10Mg and related materials. Although current research primarily uses linear energy density (LED) as the key optimization criterion, it only provides a single-track formation of the SLM process. For multi-track and multi-layer formation, additional process parameters such as overlap ratio and layer thickness must be considered, prompting the employment of volumetric energy density (VED) as a more comprehensive optimization metric. Further process optimization efforts will focus on defect analysis in SLM, utilizing artificial intelligence to decipher the interplay between process parameters and defect formation mechanisms in AlSi10Mg.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Hanning Chen and Xiaodan Liang; methodology, Maowei He; software, Siwen Xu; validation, Siwen Xu and Rui Ni; formal analysis, Hanning Chen; investigation, Zhaodi Ge; resources, Hanning Chen; data curation, Rui Ni; writing—original draft preparation, Siwen Xu; writing—review and editing, Siwen Xu; visualization, Rui Ni; supervision, Xiaodan Liang and Maowei He; project administration, Hanning Chen; funding acquisition, Hanning Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gokuldoss PK, Kolla S, Eckert J. Additive manufacturing processes: selective laser melting, electron beam melting and binder jetting-selection guidelines. Materials. 2017;10(6):672. doi:10.3390/ma10060672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Askari M, Hutchins DA, Thomas PJ, Astolfi L, Watson RL, Abdi M, et al. Additive manufacturing of metamaterials: a review. Addit Manuf. 2020;36:101562. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2020.101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Galy C, Le Guen E, Lacoste E, Arvieu C. Main defects observed in aluminum alloy parts produced by SLM: from causes to consequences. Addit Manuf. 2018;22:165–75. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2018.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sivasundar V, Sri MNS, Anusha P, Gupta D, Kumar S, Kumar N, et al. Predicting wear performance of Al6063 hybrid composites reinforced with multi-ceramic particles using experimental and ANFIS approaches. Eng Rep. 2025;7(8):e70359. doi:10.1002/eng2.70359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Rao TV, Vara Prasad AS, Sri MNS, Anusha P, Gupta D, Pydi HP, et al. Multi-response optimization of FSW parameters for Al-Mg–Zn alloys using Box-Behnken design and gray relational analysis and comparative study with ANFIS technique. AIP Adv. 2025;15(2):025209. doi:10.1063/5.0255376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Abualigah L, Elaziz MA, Khasawneh AM, Alshinwan M, Ali Ibrahim R, Al-qaness MAA, et al. Meta-heuristic optimization algorithms for solving real-world mechanical engineering design problems: a comprehensive survey, applications, comparative analysis, and results. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(6):4081–110. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06747-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Suman B, Kumar P. A survey of simulated annealing as a tool for single and multiobjective optimization. J Oper Res Soc. 2006;57(10):1143–60. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jors.2602068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Gupta S, Deep K. A novel random walk grey wolf optimizer. Swarm Evol Comput. 2019;44:101–12. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2018.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Anita, Yadav A. AEFA: artificial electric field algorithm for global optimization. Swarm Evol Comput. 2019;48:93–108. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2019.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hussien AG, Amin M, Wang M, Liang G, Alsanad A, Gumaei A, et al. Crow search algorithm: theory, recent advances, and applications. IEEE Access. 2020;8:173548–65. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3024108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Rao RV. Jaya: a simple and new optimization algorithm for solving constrained and unconstrained optimization problems. Int J Ind Eng Comp. 2016;7(1):19–34. doi:10.5267/j.ijiec.2015.8.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gong C. An enhanced Jaya Algorithm with a two group adaption. Int J Comput Intell Syst. 2017;10(1):1102–15. doi:10.2991/ijcis.2017.10.1.73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Farah A, Belazi A. A novel chaotic Jaya algorithm for unconstrained numerical optimization. Nonlinear Dyn. 2018;93(3):1451–80. doi:10.1007/s11071-018-4271-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Migallón H, Jimeno-Morenilla A, Sánchez-Romero JL, Belazi A. Efficient parallel and fast convergence chaotic Jaya algorithms. Swarm Evol Comput. 2020;56(1):100698. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2020.100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gholami K, Olfat H, Gholami J. An intelligent hybrid JAYA and crow search algorithms for optimizing constrained and unconstrained problems. Soft Comput. 2021;25(22):14393–411. doi:10.1007/s00500-021-06205-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tefek MF, Beşkirli M. JayaL: a novel Jaya Algorithm based on elite local search for optimization problems. Arab J Sci Eng. 2021;46(9):8925–52. doi:10.1007/s13369-021-05677-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Aslan M, Gunduz M, Kiran MS. JayaX: jaya algorithm with xor operator for binary optimization. Appl Soft Comput. 2019;82:105576. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2019.105576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Iacca G, dos Santos VCJr, Veloso de Melo V. An improved Jaya optimization algorithm with Lévy flight. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;165(1):113902. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Xie Z, Zhang C, Ouyang H, Li S, Gao L. Self-adaptively commensal learning-based Jaya algorithm with multi-populations and its application. Soft Comput. 2021;25(24):15163–81. doi:10.1007/s00500-021-06445-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Rao RV, Rai DP. Optimisation of welding processes using quasi-oppositional-based Jaya algorithm. J Exp Theor Artif Intell. 2017;29(5):1099–117. doi:10.1080/0952813X.2017.1309692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Gajera H, Djavanroodi F, Kumari S, Abhishek K, Bandhu D, Saxena KK, et al. Optimization of selective laser melting parameter for invar material by using JAYA Algorithm: comparison with TLBO, GA and JAYA. Materials. 2022;15(22):8092. doi:10.3390/ma15228092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Fountas NA, Kechagias JD, Vaxevanidis NM. Optimization of selective laser sintering/melting operations by using a virus-evolutionary genetic algorithm. Machines. 2023;11(1):95. doi:10.3390/machines11010095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Patil VV, Mohanty CP, Prashanth KG. Selective laser melting of a novel 13Ni400 maraging steel: material characterization and process optimization. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;27:3979–95. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.10.193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Murat F, Kaymaz İ., Şensoy AT, Korkmaz İ.H. Determining the optimum process parameters of selective laser melting via particle swarm optimization based on the response surface method. Met Mater Int. 2023;29(1):59–70. doi:10.1007/s12540-022-01205-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ahmadi Dastjerdi A, Movahhedy MR, Akbari J. Optimization of process parameters for reducing warpage in selected laser sintering of polymer parts. Addit Manuf. 2017;18:285–94. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2017.10.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ge W, Han S, Na SJ, Fuh JYH. Numerical modelling of surface morphology in selective laser melting. Comput Mater Sci. 2021;186:110062. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2020.110062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Cao L. Workpiece-scale numerical simulations of SLM molten pool dynamic behavior of 316L stainless steel. Comput Math Appl. 2021;96:209–28. doi:10.1016/j.camwa.2020.04.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Maslov VP. Quasithermodynamic correction to the stefan-Boltzmann law. Theor Math Phys. 2008;154(1):175–6. doi:10.1007/s11232-008-0015-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Luberto L, Luchini D, de Payrebrune KM. A novel mesoscale transitional approach for capturing localized effects in laser powder bed fusion simulations. Powder Technol. 2024;447(1):120194. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2024.120194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Teng X, Zhang G, Liang J, Li H, Liu Q, Cui Y, et al. Parameter optimization and microhardness experiment of AlSi10Mg alloy prepared by selective laser melting. Mater Res Express. 2019;6(8):086592. doi:10.1088/2053-1591/ab18d0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen X, Mu W, Xu X, Liu W, Huang L, Li H. Numerical analysis of double track formation for selective laser melting of 316L stainless steel. Appl Phys A. 2021;127(8):586. doi:10.1007/s00339-021-04728-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Hu H, Ding X, Wang L. Numerical analysis of heat transfer during multi-layer selective laser melting of AlSi10Mg. Optik. 2016;127(20):8883–91. doi:10.1016/j.ijleo.2016.06.115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Mukherjee T, Wei HL, De A, DebRoy T. Heat and fluid flow in additive manufacturing-Part II: powder bed fusion of stainless steel, and titanium, nickel and aluminum base alloys. Comput Mater Sci. 2018;150:369–80. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2018.04.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Cao Y, Wei HL, Yang T, Liu TT, Liao WH. Printability assessment with porosity and solidification cracking susceptibilities for a high strength aluminum alloy during laser powder bed fusion. Addit Manuf. 2021;46:102103. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2021.102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Wei P, Wei Z, Chen Z, Du J, He Y, Li J. Fundamentals of radiation heat transfer in AlSi10Mg powder bed during selective laser melting. Rapid Prototyp J. 2019;25(9):1506–15. doi:10.1108/rpj-11-2016-0189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Trevisan F, Calignano F, Lorusso M, Pakkanen J, Aversa A, Ambrosio E, et al. On the selective laser melting (SLM) of the AlSi10Mg alloy: process, microstructure, and mechanical properties. Materials. 2017;10(1):76. doi:10.3390/ma10010076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Jiang Z, Xu P, Liang Y, Liang Y. Deformation effect of melt pool boundaries on the mechanical property anisotropy in the SLM AlSi10Mg. Mater Today Commun. 2023;36(1):106879. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Manikandan P, Venkatesan K. The influence of linear energy density on density, defect formation, residual stress, microstructure, and texture in 310 austenitic stainless steel by laser powder bed fusion. J Manuf Process. 2024;131:2191–207. doi:10.1016/j.jmapro.2024.10.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools