Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

FD-YOLO: An Attention-Augmented Lightweight Network for Real-Time Industrial Fabric Defect Detection

School of Electrical Engineering and Automation, Xiamen University of Technology, Xiamen, 361024, China

* Corresponding Author: Mingzhi Yang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071488

Received 06 August 2025; Accepted 25 September 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Fabric defect detection plays a vital role in ensuring textile quality. However, traditional manual inspection methods are often inefficient and inaccurate. To overcome these limitations, we propose FD-YOLO, an enhanced lightweight detection model based on the YOLOv11n framework. The proposed model introduces the Bi-level Routing Attention (BRAttention) mechanism to enhance defect feature extraction, enabling more detailed feature representation. It proposes Deep Progressive Cross-Scale Fusion Neck (DPCSFNeck) to better capture small-scale defects and incorporates a Multi-Scale Dilated Residual (MSDR) module to strengthen multi-scale feature representation. Furthermore, a Shared Detail-Enhanced Lightweight Head (SDELHead) is employed to reduce the risk of gradient explosion during training. Experimental results demonstrate that FD-YOLO achieves superior detection accuracy and Lightweight performance compared to the baseline YOLOv11n.Keywords

Fabric quality inspection is critical in the textile industry, as even minor defects can negatively affect product performance and appearance [1,2]. Traditional computer vision methods improve inspection efficiency but rely on handcrafted features, which limit their ability to detect complex and diverse fabric defects [3]. In recent years, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have shown great promise in fabric defect detection. They achieve accurate defect identification as well as classification and localization.

Deep learning-based approaches can broadly be categorized into two groups. The first group comprises one-stage object detectors such as the YOLO (You Only Look Once) family [4], SSD (Single Shot Detector) [5], and RetinaNet [6], which achieve a balance between accuracy and inference speed. The second group comprises two-stage detectors based on region proposals, such as Faster R-CNN [7], which often deliver higher accuracy at the cost of slower inference.

Lightweight models such as YOLO are particularly favored in fabric defect detection due to their efficient deployment and competitive performance. These advantages make them suitable for real-time industrial applications. Several studies have further adapted YOLO-based architectures to better handle small defects and domain-specific challenges. For instance, Ju et al. [8] enhanced YOLOv3’s ability to detect small targets by optimizing anchor boxes, adding detection scales, and introducing residual structures. Ji et al. [9] improved YOLOv4 by integrating an extended receptive field module to better capture contextual information. Liu et al. [10] employed channel shuffle mechanisms to replace conventional convolutions, overcoming the limitations of the SE module and improving both accuracy and efficiency in YOLOv5. Wang et al. [11] introduced a de-weighted bidirectional pyramid network into YOLOv7 to enhance multi-scale feature fusion and reduce information loss. Additionally, Cao et al. [12] incorporated a Large Selective Kernel module into YOLOv8’s backbone to dynamically select convolutional kernel sizes, thereby improving feature representation and localization accuracy.

To enhance the accuracy and practicality of fabric defect detection under industrial constraints, we develop an improved lightweight detection framework. This framework is based on YOLOv11n and is referred to as FD-YOLO. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

1. We design a novel attention-enhanced feature extraction module that suppresses noise and highlights key features, thereby improving the backbone’s robustness in complex backgrounds.

2. We propose an attention-based multi-scale Neck structure that reduces information loss and enhances small defect detection by introducing an additional P2 detection layer.

3. We develop a multi-scale representation module that captures both local and global features through parallel convolutions with different kernel sizes, improving adaptability to varied defect scales.

4. We introduce a lightweight detection head that reduces computational complexity while preserving fine-grained detail, thereby enhancing both detection accuracy and efficiency.

Manual inspection has long been used for fabric defect detection in the textile industry. However, it is time-consuming, requires much labor, and depends heavily on the skill and focus of inspectors. As a result, it often shows inconsistency, low accuracy, and poor ability to detect small defects, making it unsuitable for large-scale and real-time applications.

Traditional fabric defect detection methods, such as gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) [13], local binary patterns (LBP) [14], and histogram of differences [15], work well for homogeneous textures. However, they heavily rely on handcrafted features and require complex parameter tuning. In contrast, deep learning-based approaches—such as segmentation-based methods [16] and CNNs with low-rank decomposition [17]—have improved defect localization accuracy. However, they often suffer from high model complexity, substantial computational requirements, and limited adaptability to complex backgrounds. The YOLO (You Only Look Once) series has undergone continuous improvements for Real-Time Fabric Defect Inspection tasks. An improved YOLOv3-based method [18] enhances real-time fabric defect detection by optimizing prior frame clustering and integrating multi-scale feature maps, achieving an error rate below 5% for gray and checked fabrics. SE-YOLOv5 [19] enhances the fabric defect detection capability by integrating the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module and the ACON activation function into YOLOv5. YOLOv8n-CA [20] enhances fabric defect detection by incorporating a coordinate attention mechanism into YOLOv8n, achieving high accuracy and fast real-time performance for efficient deployment on edge devices. Although these YOLO-based methods perform well, they have some limitations. Adding modules such as SE or attention will increase model complexity. Many are tested on few fabric types, so they may not generalize well. Detecting small or subtle defects remains challenging, and performance is limited by the lack of large, diverse datasets.

YOLOv11 [21] uses the efficient C3k2 module and lightweight spatial attention for faster, more accurate feature extraction. Its PANet-style Neck and anchor-free head enable effective multi-scale fusion and precise predictions, with fewer parameters and higher speed, making it well-suited for industrial inspection. To address the limitations of both traditional methods and existing YOLO-based approaches for fabric defect detection, we propose FD-YOLO, an improved model based on YOLOv11 with targeted optimizations. The model adopts a lightweight design strategy to reinforce the network’s representation capability. This approach effectively balances detection accuracy with computational efficiency. The model is validated on a multi-type fabric dataset to achieve better generalization. It strengthens multi-scale and fine-grained feature extraction for small defects and employs data augmentation to improve robustness.

3.1 FD-YOLO Detection Framework

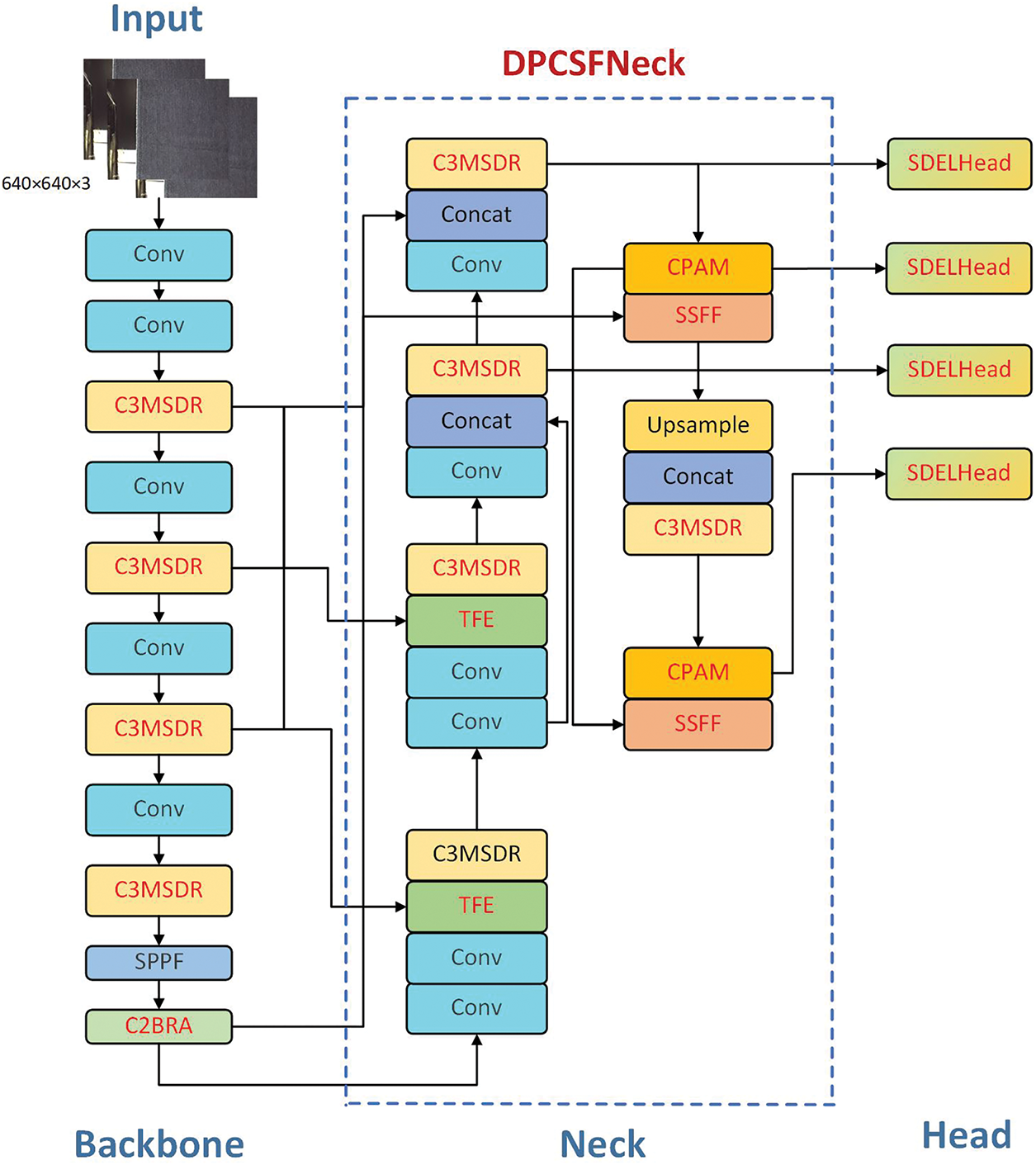

In this work, we propose FD-YOLO, a YOLOv11n-based model designed for detecting defects in industrial fabrics. The model introduces several key architectural improvements to boost both accuracy and efficiency. Specifically, we integrate a BRAttention into the backbone to enhance feature representation. We redesign the DPCSFNeck to strengthen multi-scale feature fusion and add an extra detection layer to improve small defect recognition. Moreover, a C3MSDR module is employed to expand the receptive field and capture contextual information, while a lightweight SDELHead is designed to suppress gradient explosion and reduce computational overhead. Fig. 1 illustrates the overall architecture of FD-YOLO (The improved parts are marked in red in Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The FD-YOLO network structure

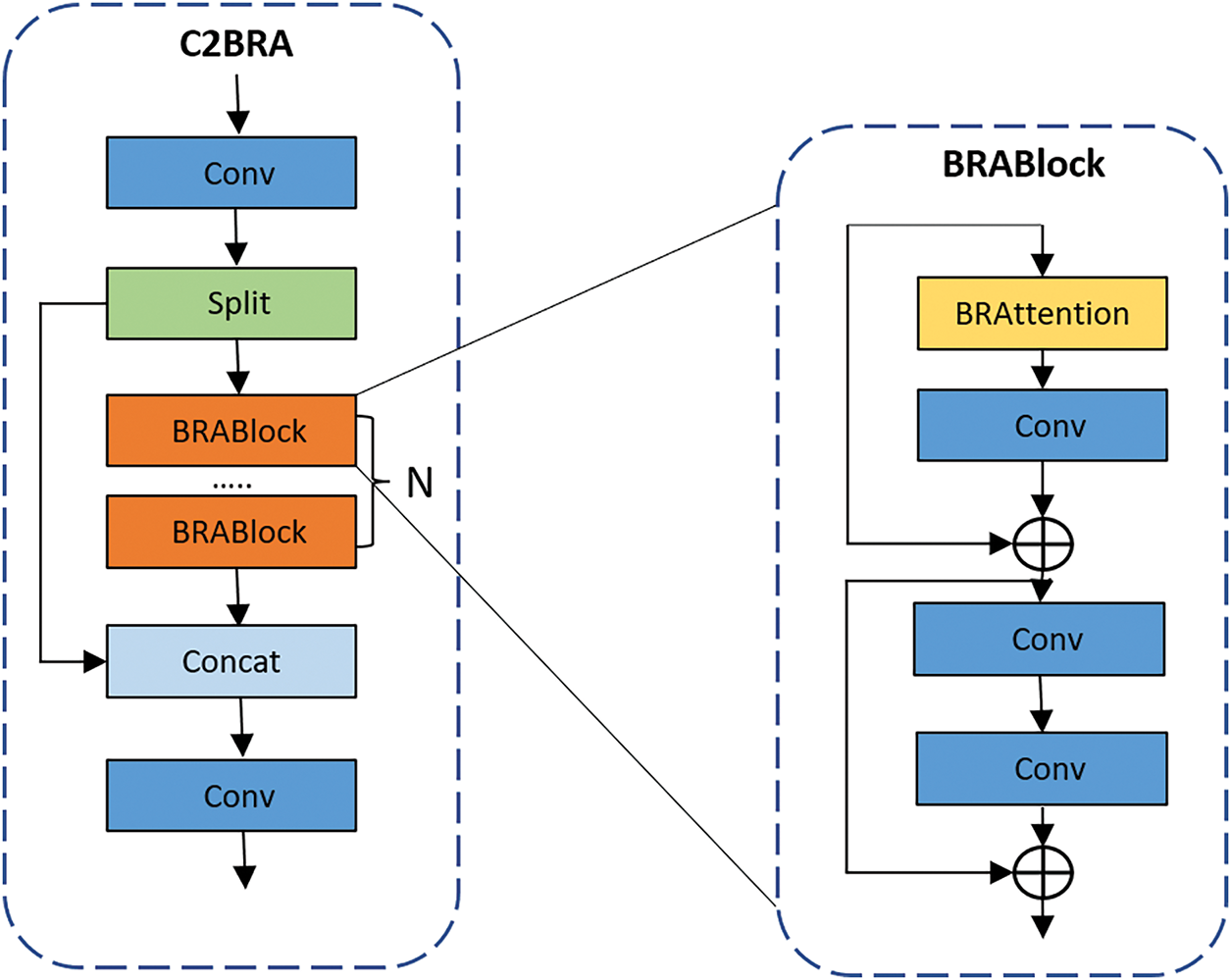

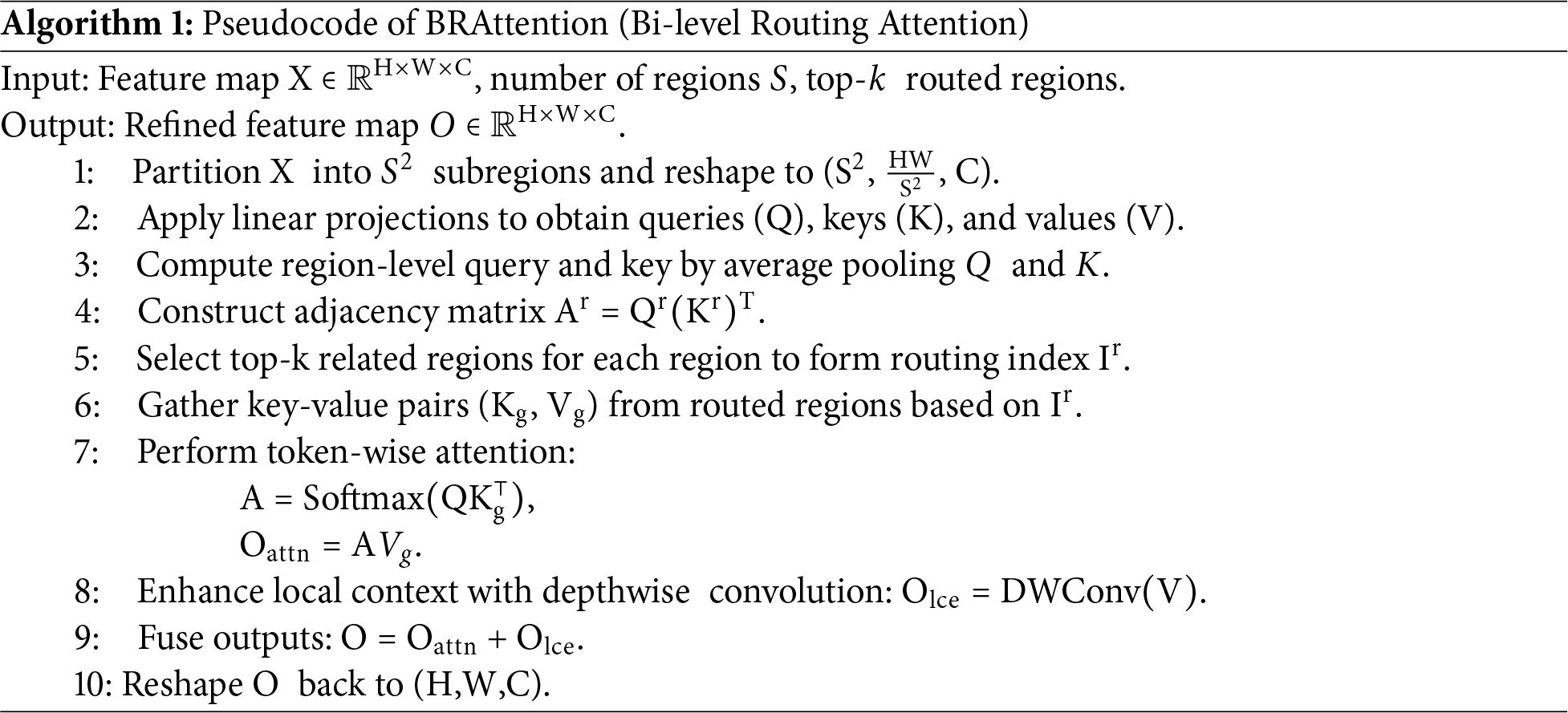

Fabric surfaces often have complex textures, repeating patterns, and irregular variations caused by weaving defects, stains, or material differences. These make it hard for the original C2PSA module to detect small or low-contrast defects, as important details can be hidden by background noise. To address this issue, we add Bi-level Routing Attention (BRAttention) [22] to C2PSA, creating the C2BRA module, which focuses on key defect areas and reduces the effect of irrelevant background. This design enhances feature extraction capability while reducing computational overhead. Figs. 2 and 3 illustrate the architectures of the C2BRA and BRAttention modules, respectively. Algorithm 1 describes the overall process of the BRAttention algorithm.

Figure 2: The C2BRA module is an improved version of YOLOv11’s C2PSA with Bi-level Routing Attention (BRAttention). It selectively aggregates features in key regions, enhancing defect representation while keeping the design lightweight and efficient

Figure 3: Bi-level Routing Attention (BRAttention) selectively gathers key-value pairs from the most relevant windows. By skipping computations in low-contribution regions and using dense matrix multiplications for the rest, it reduces redundant processing while maintaining high efficiency

The attention mechanism works as follows: the input sequence

From Fig. 3, it can be seen that the input feature map

Next, we construct a directed graph to determine the attention correlation relationships. Specifically, a region-level query and key,

Then, the adjacency matrix of the region graph,

The adjacency matrix

Next, the key and value tensors are aggregated to enhance region-aware representation:

where

here,

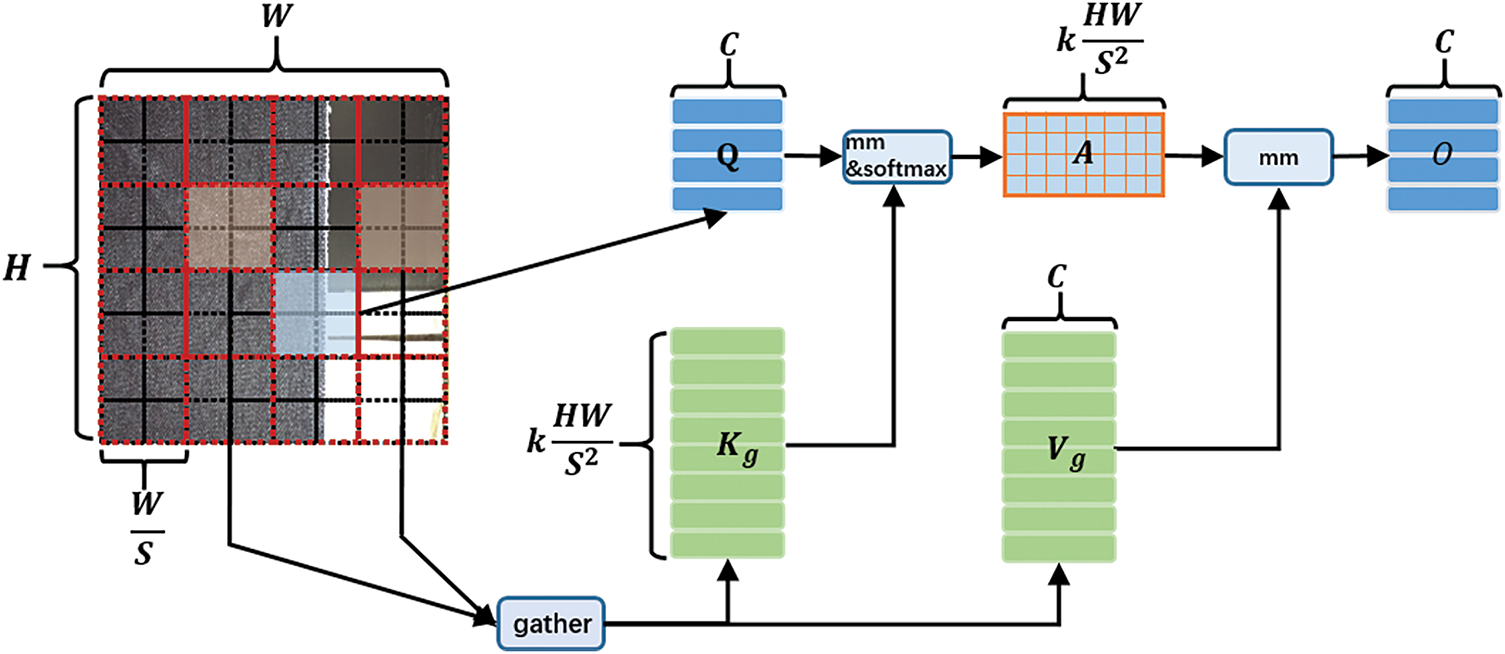

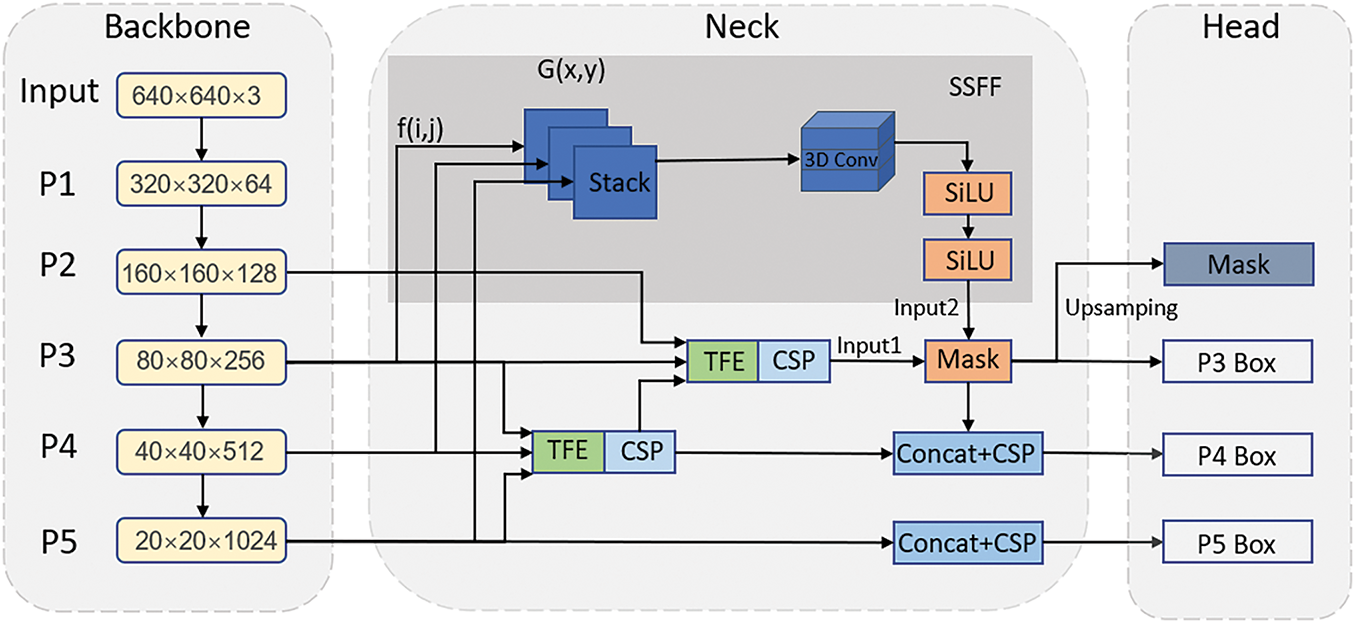

Fabric inspection often involves tiny defects that are difficult to detect with the original YOLOv11n, due to insufficient multi-scale feature fusion in its Neck. To address this challenge, we draw inspiration from ASF-YOLO [23] and redesign the Neck, adding a P2 detection layer to better capture small targets. The proposed Deep Progressive Cross-Scale Fusion Neck (DPCSFNeck) strengthens multi-scale feature fusion and improves small defect detection. The Neck structure in Fig. 1 illustrates the DPCSFNeck within the FD-YOLO architecture, and Fig. 4 illustrates the original ASF-YOLO framework.

Figure 4: Overview of the proposed ASF-YOLO model, which consists of the Scale Sequence Feature Fusion (SSFF) module, the Triple Feature Encoder (TFE) module, and the Channel and Position Attention Model (CPAM), built on a CSPDarkNet backbone with a YOLO head

3.3.1 ASF Attention-Guided Scale-Sequential Fusion Framework

The ASF framework adopts a Scale-Sequential Feature Fusion (SSFF) module to enhance the network’s ability to extract multi-scale information. In addition, a Triple Feature Encoder (TFE) module is employed to fuse feature maps from different scales and enrich fine-grained details. To further improve performance, a Channel and Position Attention Mechanism (CPAM) is introduced. By integrating SSFF and TFE, the network can better focus on small targets across both the channel and spatial dimensions, thereby improving both detection and segmentation results.

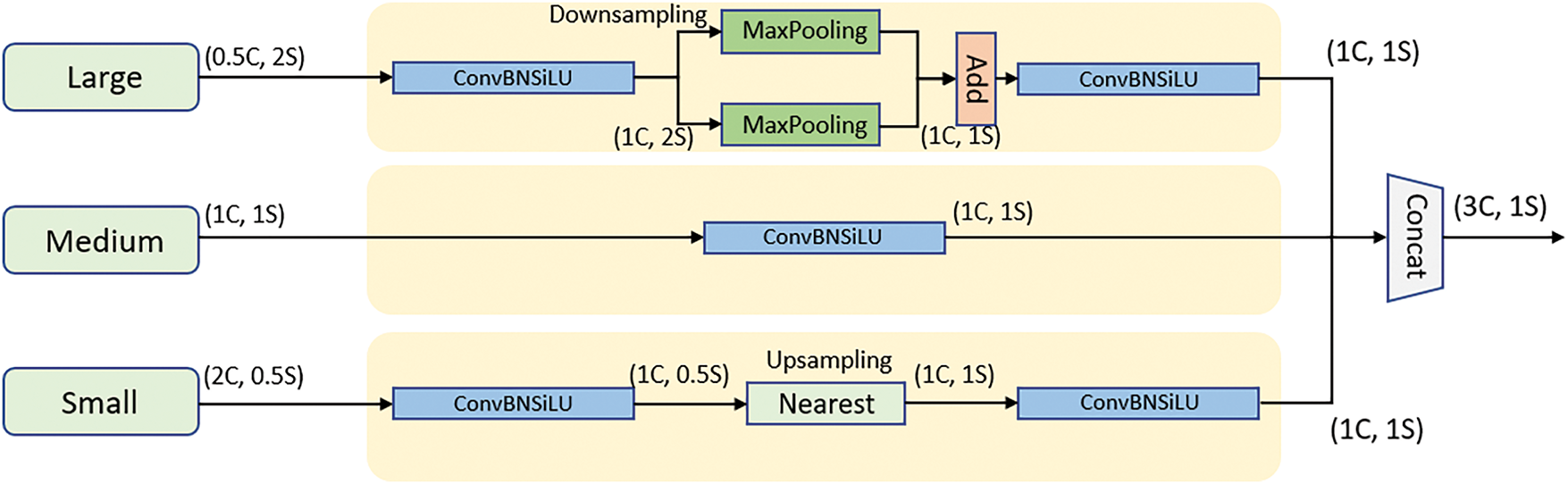

The TFE module processes features at various scales and strengthens large-scale structural details. It also compensates for the limitations of traditional Feature Pyramid Networks (FPN), particularly in small object detection. Fig. 5 illustrates the overall structure.

Figure 5: The structure of the TFE module.

Before encoding, the feature maps at different scales are first unified in the channel dimension through convolution. Large-scale features are downsampled via pooling to enhance translation invariance, while small-scale features are upsampled using interpolation to preserve details. After alignment, the large-scale, medium-scale, and small-scale features are concatenated along the channel dimension to form the fused feature map:

where

where

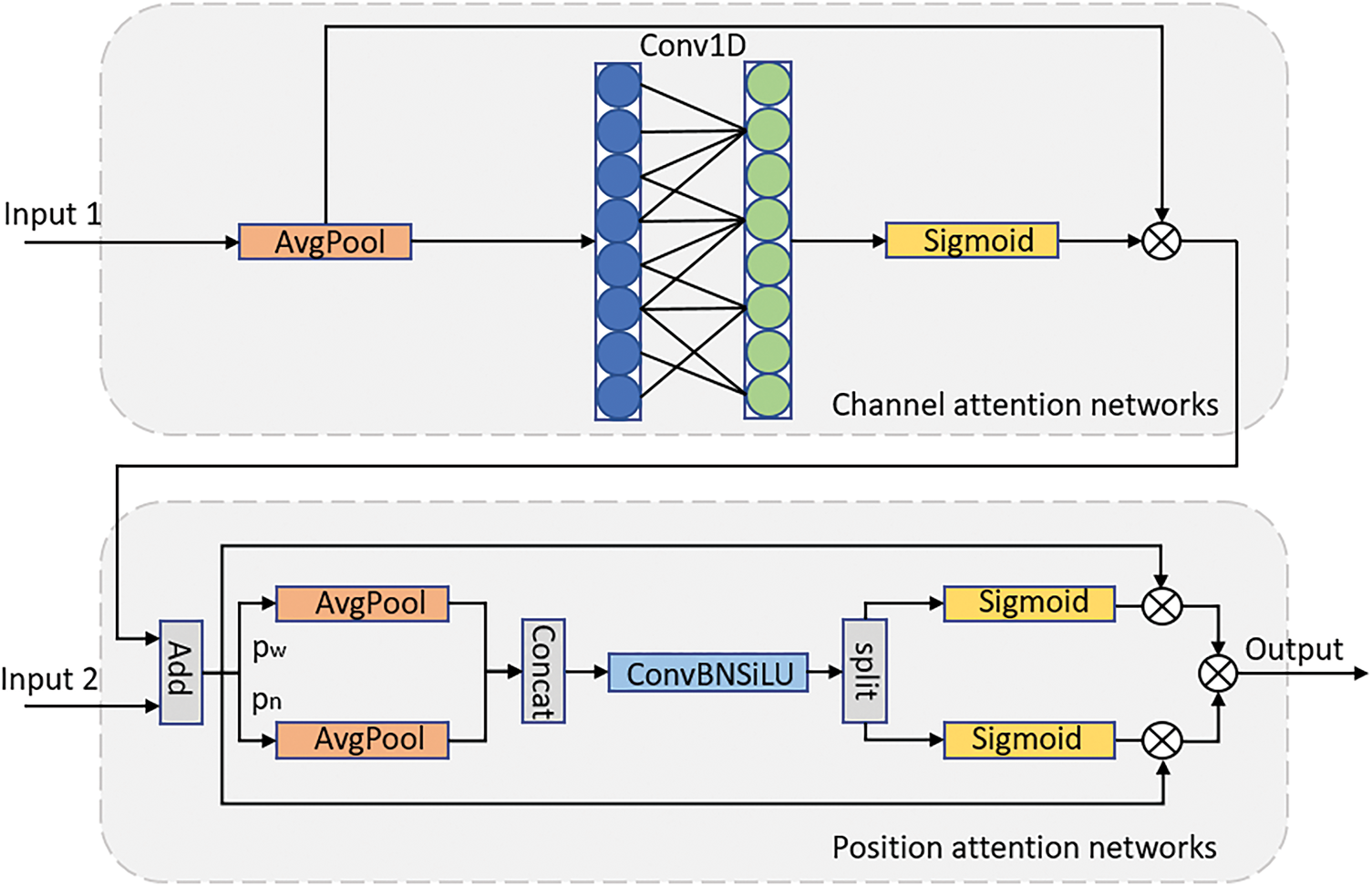

Figure 6: The CPAM module structure includes both channel and position attention networks. Here,

To enhance the representational capacity of PANet output features, we propose an improved channel attention mechanism. Unlike conventional methods, this approach avoids dimensionality reduction, thereby preserving complete channel information. It employs a one-dimensional convolution with kernel size

where γ and

here,

Additionally, positional attention is introduced by capturing spatial information through horizontal and vertical pooling:

where

The output is then split along width and height directions:

Finally, the output of the CPAM module is defined as:

where

3.3.2 Small Object Detection Layer

To improve the detection of tiny defects, a new P2 branch is added based on the ASF framework. This branch, combined with the SSFF module, enhances the fusion and representation of multi-level features. The fused features and P2 branch are further refined by the CPAM attention mechanism to strengthen defect representation. By integrating the SSFF and TFE modules, a novel Neck structure is constructed, which improves multi-scale perception and detection accuracy.

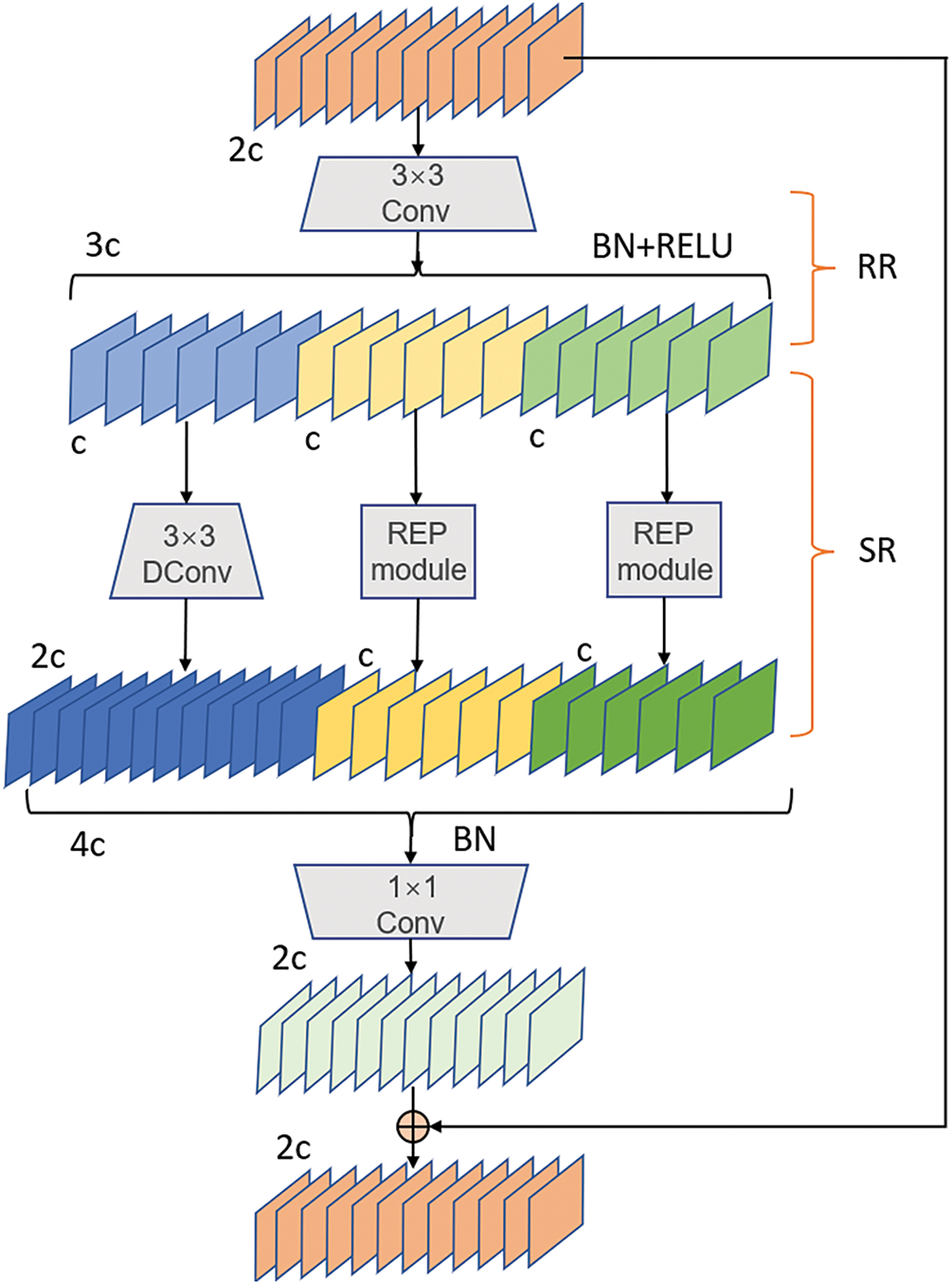

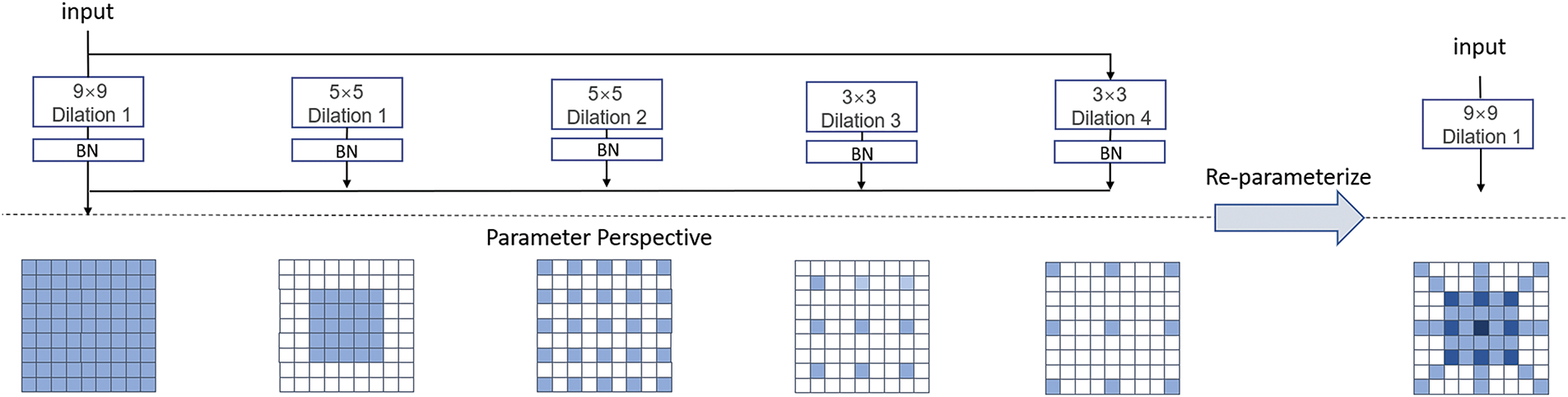

Fabric defects with extreme aspect ratios are difficult to localize accurately, as the original YOLOv11n lacks sufficient multi-scale representation ability. This limitation motivates us to design a stronger feature extraction strategy. Therefore, as illustrated in Fig. 7, we combine the Dilation-wise Residual (DWR) [25] module with Reparameterization (REP) modules to build a Multi-Scale Dilated Residual (MSDR) module. This module is then integrated into the C3K2 structure.

Figure 7: Illustration of the three-branch MSDR module for the high-level network. RR and SR denote Region Residualization and Semantic Residualization, respectively. Conv represents convolution, DConv denotes depth-wise convolution, REP denotes Reparameterization module,

The DWR module employs a residual design. Within the residual block, multi-scale contextual information is extracted through two steps: Region Residualization (RR) and Semantic Residualization (SR). These steps enable the fusion of multi-receptive field features, enhancing the model’s capability to capture diverse defect patterns.

In the RR process, residual features are extracted from the input features. This step generates multiple compact regional feature maps of varying sizes as follows:

In the SR stage, a 3 × 3 convolution is first applied to extract regional features. Then, depthwise separable convolutions with different dilation rates are used to process the channel groups, capturing compact multi-scale information. These features are fused and added back to the original feature map to enhance contextual representation. The fused feature is given by:

Although large-kernel convolutions enlarge the receptive field, they often struggle to capture long-range dependencies efficiently. Dilated convolutions improve modeling capability by introducing spacing without increasing parameters. In this work, we adopt a re-parameterization technique [26], which fuses multiple small convolutions (including dilated ones) into an equivalent large-kernel convolution to enhance both efficiency and expressiveness. Fig. 8 illustrates the module, which integrates multiple parallel branches with varying kernel sizes and dilation rates. This design expands the receptive field, controls computational cost, and improves contextual modeling. During inference, the structure is fused and re-parameterized to simplify computation.

Figure 8: The REP employs dilated small-kernel convolutions to enhance a non-dilated large-kernel layer. From a parameter perspective, these dilated layers are equivalent to a single non-dilated convolution with a larger sparse kernel, allowing the entire block to be merged into one large-kernel convolution. This example uses

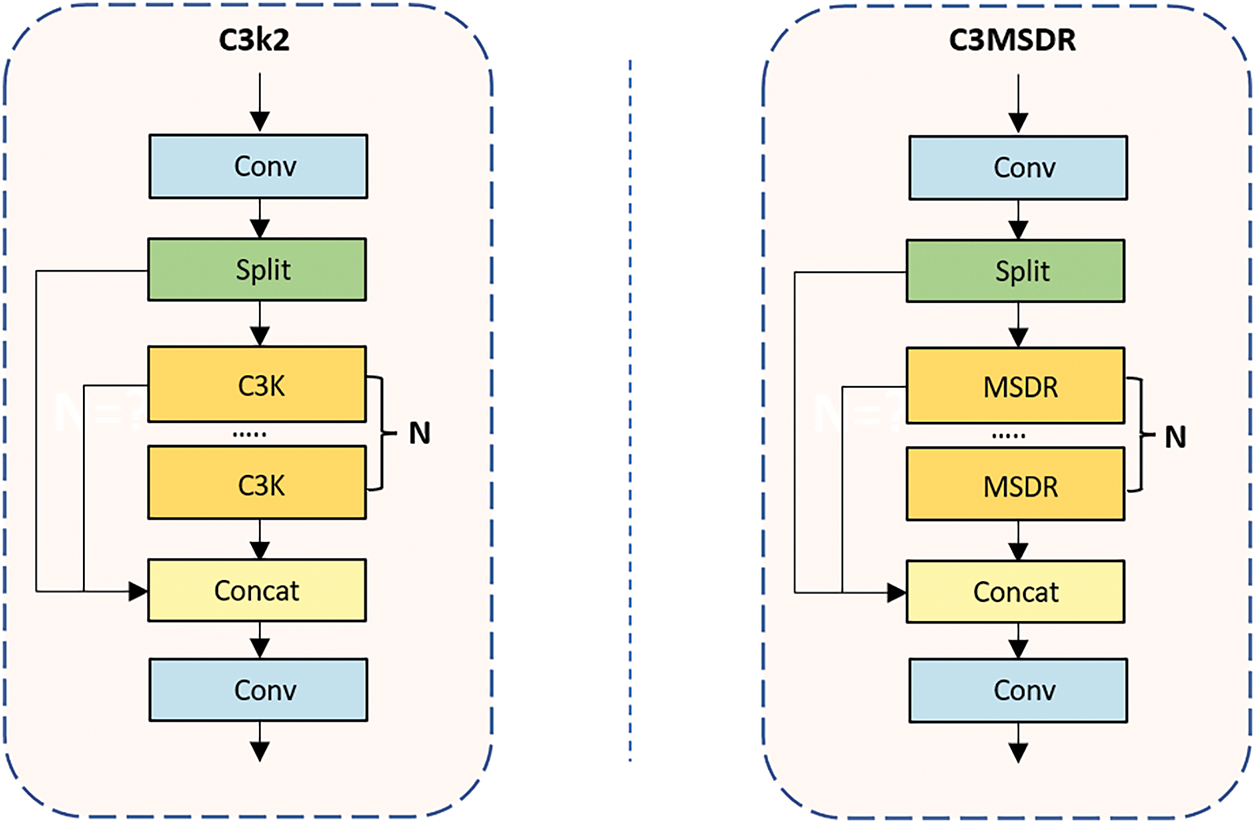

In the fusion process, the two dilated convolutions in the original DWR module are replaced with re-parameterized modules using 5 × 5 and 7 × 7 kernels. A new module, C3MSDR, is constructed by replacing the bottleneck in C3K2. By combining the strengths of DWR and re-parameterized convolution, the C3MSDR module enhances gradient flow and receptive field, thereby improving the perception of fabric defects while maintaining detection efficiency (Fig. 9).

Figure 9: Left: The C3K2 module in YOLOv11. Right: The Multi-Scale Dilated Residual (MSDR) module is composed of the combination of the Dilated Wide Residual (DWR) module and the Reparameterization (REP) module, and it replaces the C3K structure in YOLOv11

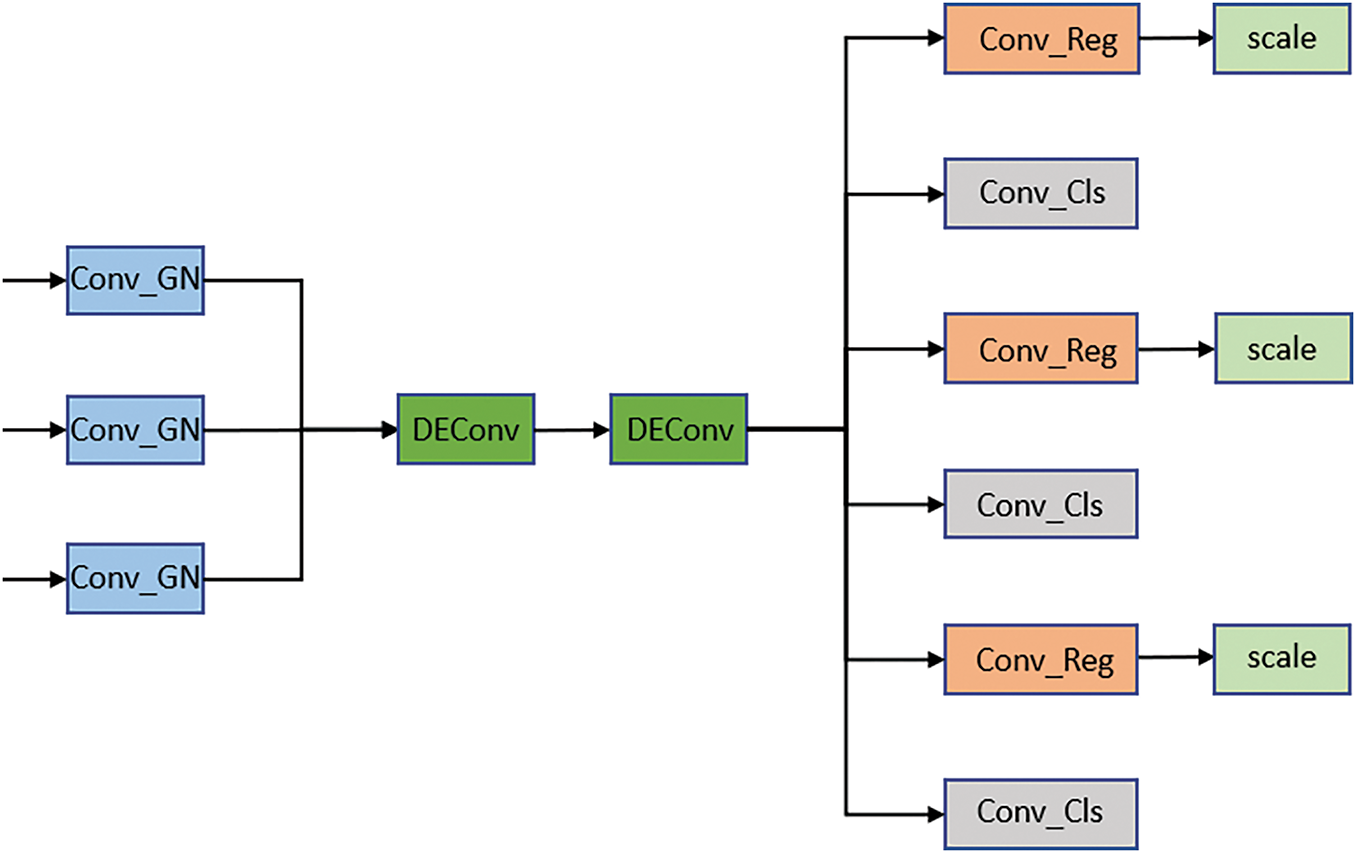

3.5 SDELHead: A Lightweight Detection Head

The original detection head of YOLOv11n relies heavily on Batch Normalization (BN) to improve generalization. However, in practical scenarios with limited GPU memory, small batch sizes are often inevitable, which makes BN unstable and degrades detection performance. As illustrated in Fig. 10, we design a lightweight detection head named Shared Detail-Enhanced Lightweight Head (SDELHead) to overcome this limitation while maintaining efficiency.

Figure 10: SDELHead mainly improves performance by replacing BatchNorm with GroupNorm for robustness, sharing convolution weights to reduce parameters and overfitting, and using DEConv with reparameterization to enhance feature representation

To improve robustness, Group Normalization is used as a replacement for Batch Normalization. Additionally, we introduce shared convolution to reduce the number of parameters and mitigate the risk of overfitting. The detection head integrates the Detail-Enhanced Convolution (DEConv) module [27], as illustrated in Fig. 11, which enhances feature representation and gradient learning through multiple differential convolutions.

Figure 11: Detail-Enhanced Convolution (DEConv) consists of five parallel convolution layers: a vanilla convolution (VC), central difference convolution (CDC), angular difference convolution (ADC), horizontal difference convolution (HDC), and vertical difference convolution (VDC)

By fusing five types of convolutional kernels, the model achieves improved representation and generalization capabilities. Taking advantage of the linear additivity of convolution operations, the five parallel convolution kernels (

where

The DEConv module significantly enhances the model’s feature extraction capabilities without introducing additional computational or parameter overhead, as it retains the same complexity as a single-layer convolution.

4 Experimental Setup and Dataset

To ensure fair comparison and reproducibility, all experiments were conducted under a unified protocol with consistent hyperparameters, input sizes, and computing environment. We conducted the experiments on a system equipped with an AMD EPYC 7642 CPU, an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU, 90 GB of RAM, and Ubuntu 22.04. We used Python 3.12, PyTorch 2.5.1, and CUDA 12.4 as the software stack. We set the input image size to 640 × 640 and trained the model for 300 epochs with a batch size of 32. We configured 8 data loading workers and optimized the model using SGD with a learning rate of 0.01, a momentum of 0.937, and a weight decay of 0.0005.

4.2 Dataset Selection and Processing

The fabric defect dataset used in this study is sourced from the Alibaba Tianchi Industrial Innovation Competition. It originally contains 5913 images covering 20 types of common fabric defects. To match real industrial needs, we removed rare and invalid samples. We kept 8 main defect categories, leaving a subset of 3534 images. The data was split into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio. The training set was expanded to 5327 images using data augmentation techniques, including geometric and color transformations, blurring, and sharpening, bringing the total dataset size to 6034 images. Nevertheless, the dataset remains relatively small for deep learning tasks, which may lead to overfitting; to mitigate this risk, we applied regularization and early stopping to improve model generalization. Fig. 12 shows examples of typical defects.

Figure 12: Tianchi fabric Dataset Typical types. (a) Small target defect; (b) Extreme aspect ratio defect; (c) Large target defect; (d) Background similarity defect

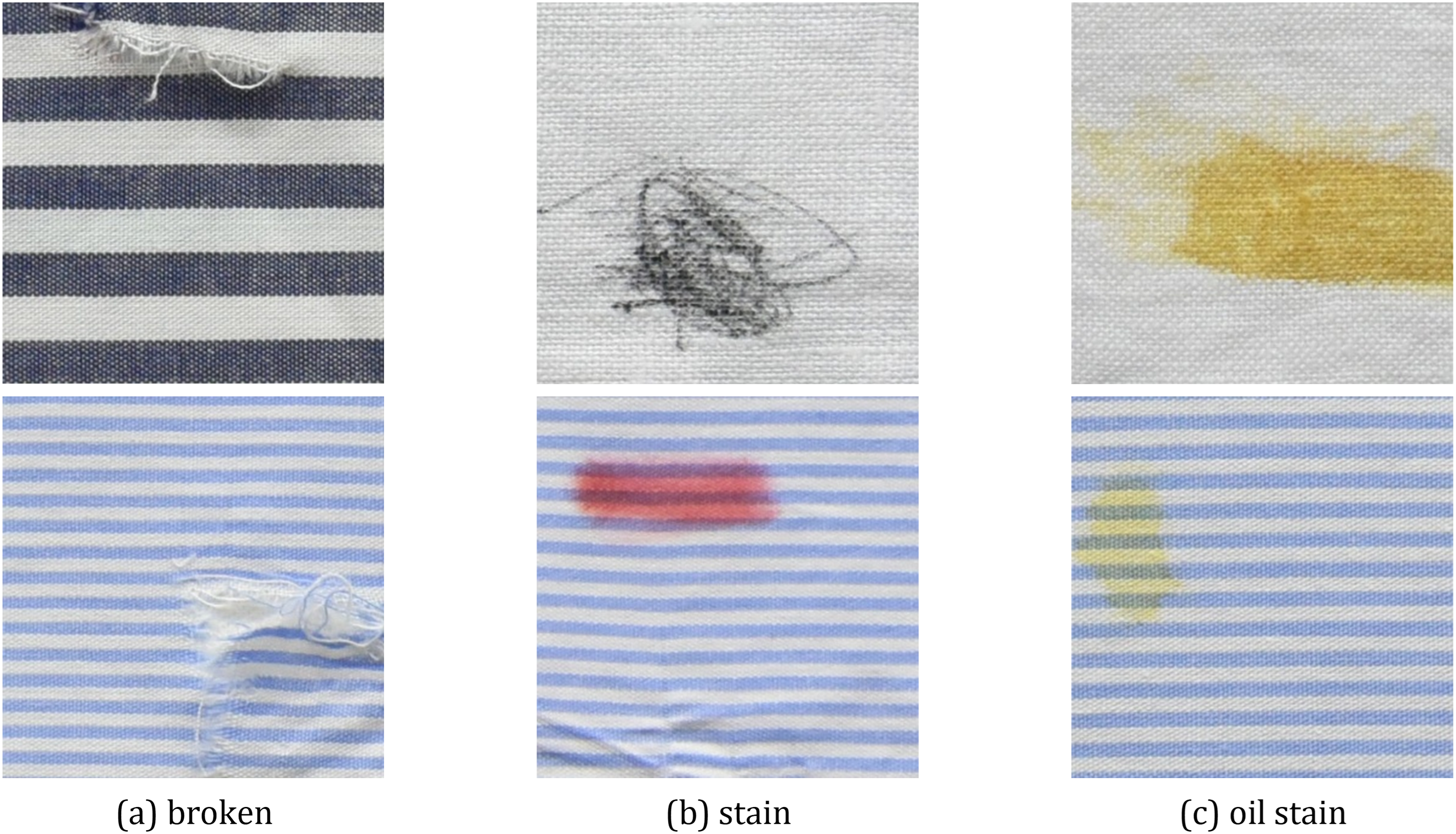

The second fabric defect dataset, ZJU-Leaper, is obtained from [28] and contains 23,572 images. It includes images captured both in industrial production environments and laboratory settings, closely reflecting real-world textile manufacturing scenarios. We divided the dataset into validation and test sets with an 8:2 ratio, and categorized the defects into three types: damage, stains, and oil marks. The diverse defect scales and their visual similarity to the background significantly increase the detection difficulty. Fig. 13 shows representative samples.

Figure 13: ZJU-Leaper Dataset Typical types

To evaluate the performance of the improved YOLOv11n on fabric defect datasets, this paper uses common metrics including Precision, Recall, mean Average Precision (mAP), FLOPs, and the number of parameters. Precision and Recall respectively reflect the “accuracy” and “coverage” of a model’s prediction results: Precision is the proportion of predicted positive samples that are truly positive, calculated as

mAP (mean Average Precision) is the mean of Average Precision (AP) across all classes, defined as:

where

FLOPs measure the computational cost of a single forward pass, and the number of parameters represents the model’s size and learning capacity. Both are important for assessing the model’s efficiency and suitability for real-time industrial applications.

5 Comparative Analysis of Experimental Results

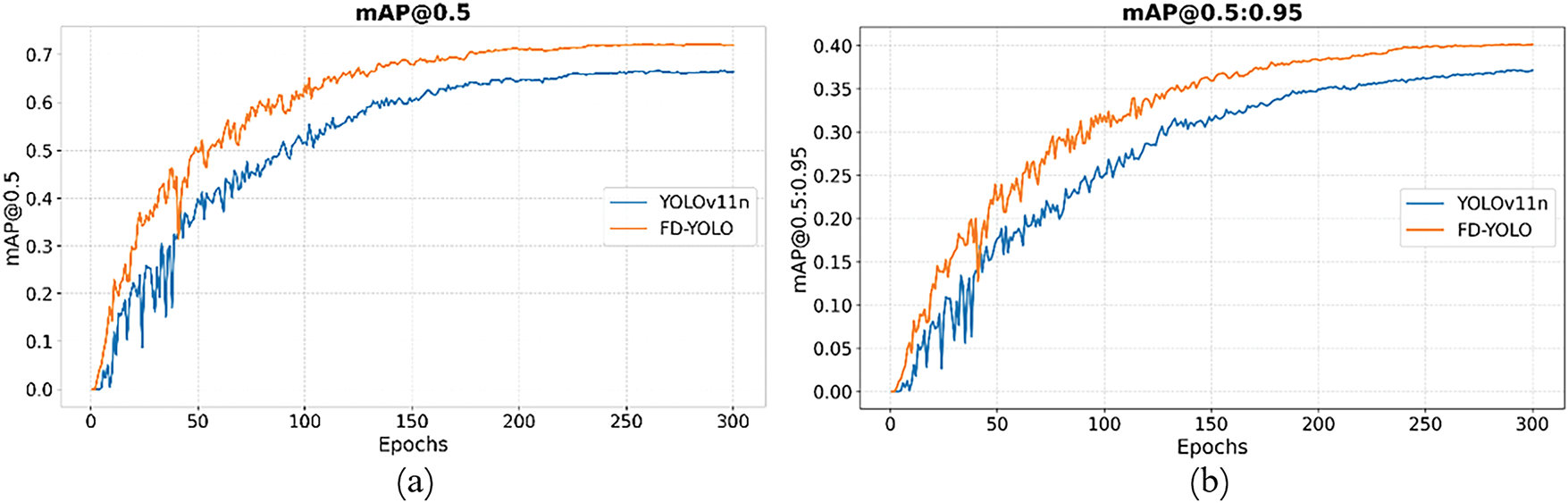

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed model, we compare the training performance of YOLOv11n and FD-YOLO in terms of mAP, Precision, and Recall. As shown in Fig. 14, FD-YOLO achieves higher overall mAP, indicating its superior detection capability during the training process.

Figure 14: (a,b) Represent mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95

As shown in Fig. 15, FD-YOLO consistently outperforms the baseline model in both Precision and Recall throughout the training process. Furthermore, its performance remains stable toward the end of training, indicating that the improved model enhances detection capability. It also ensures result reliability, achieving simultaneous improvement in both metrics.

Figure 15: (a,b) Represent precision and recall

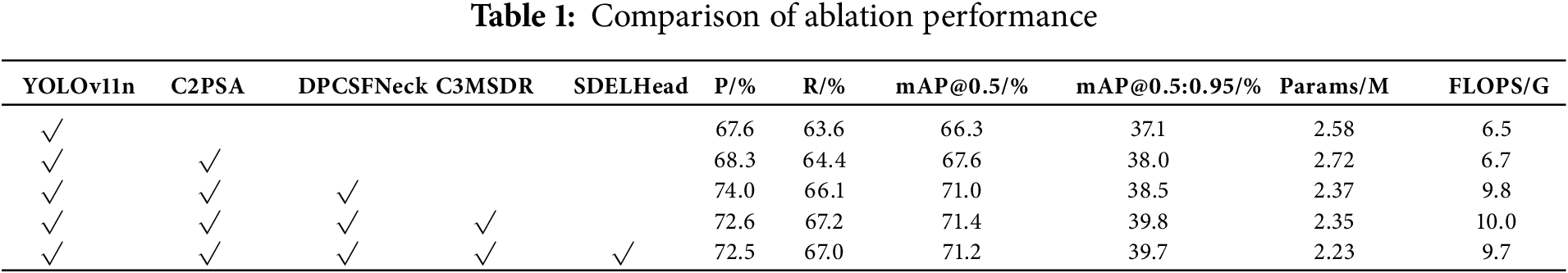

Ablation experiments were conducted on the Tianchi fabric dataset to verify the effectiveness of the proposed improvements. The original YOLOv11n model, which already achieves competitive performance, is adopted as the baseline for comparison in this study.

Table 1 shows the results of the ablation experiments. By incorporating the C2PSA module, DPCSFNeck, P2 detection head, MSDR module, and the lightweight SDELHead, FD-YOLO significantly enhances feature extraction and multi-scale fusion capabilities. As a result, it achieves an improvement of 6.0% in mAP@0.5 and 4.0% in mAP@0.5:0.95, while reducing the number of parameters by 0.35M. Although the computational cost slightly increases, the overall performance gain is substantial.

5.3 Evaluation of Proposed Enhancements

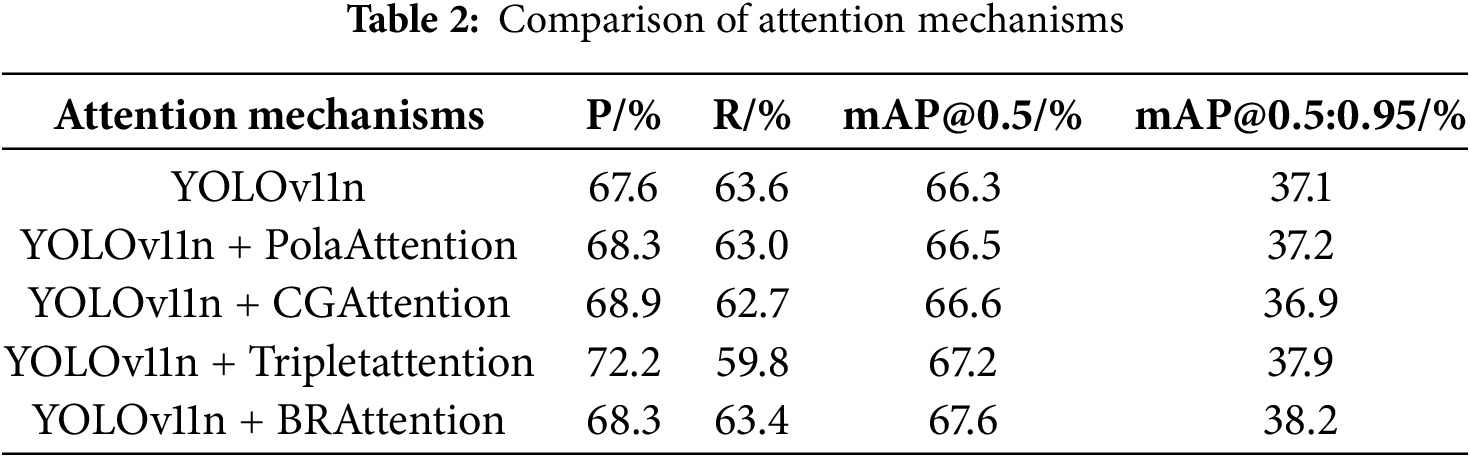

(1) Evaluation of the BRAtntion Mechanism

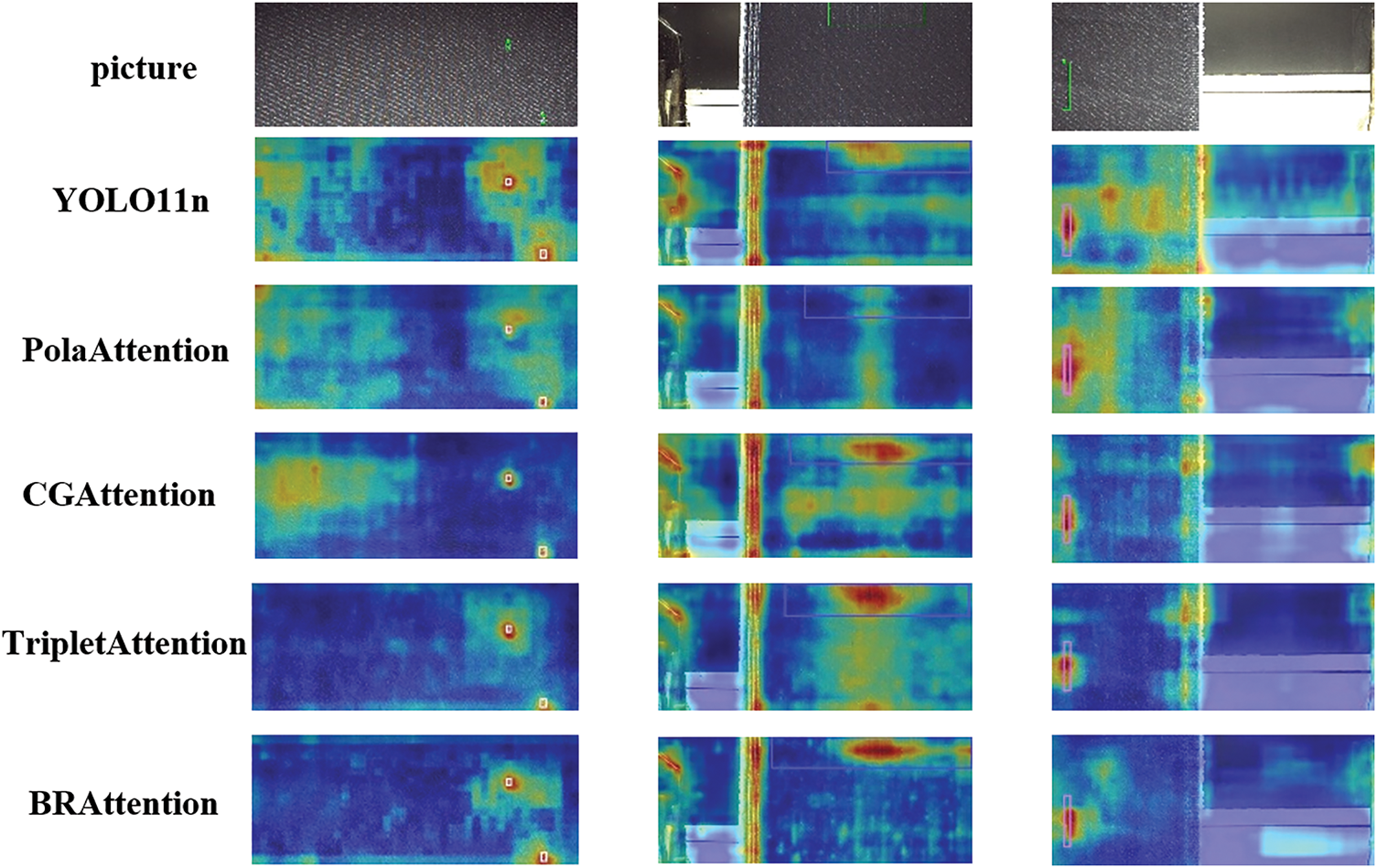

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed BRAttention mechanism, various alternatives were integrated into the C2PSA module for comparison, including CGAttention [29], Triplet Attention [30], and PolaAttention [31]. As shown in Table 2, all attention mechanisms improved mAP@0.5. Among them, Triplet Attention achieved the highest precision, while BRAttention outperformed others in recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95, demonstrating the best overall performance. Although CascadedGroupAttention increased mAP@0.5, it led to a decrease in mAP@0.5:0.95, indicating limited localization capability.

As illustrated in the heatmap comparisons in Fig. 16, BRAttention demonstrates more focused attention on defect regions, indicating stronger localization capabilities. In contrast, CGAttention, PolaAttention, and the baseline model exhibit dispersed attention with weaker discriminative ability. Although Triplet Attention effectively suppresses background interference, its overall performance is inferior to that of BRAttention.

Figure 16: Heatmap of different attention mechanisms

(2) Evaluation of the DPCSFNeck for Cross-Scale Feature Fusion

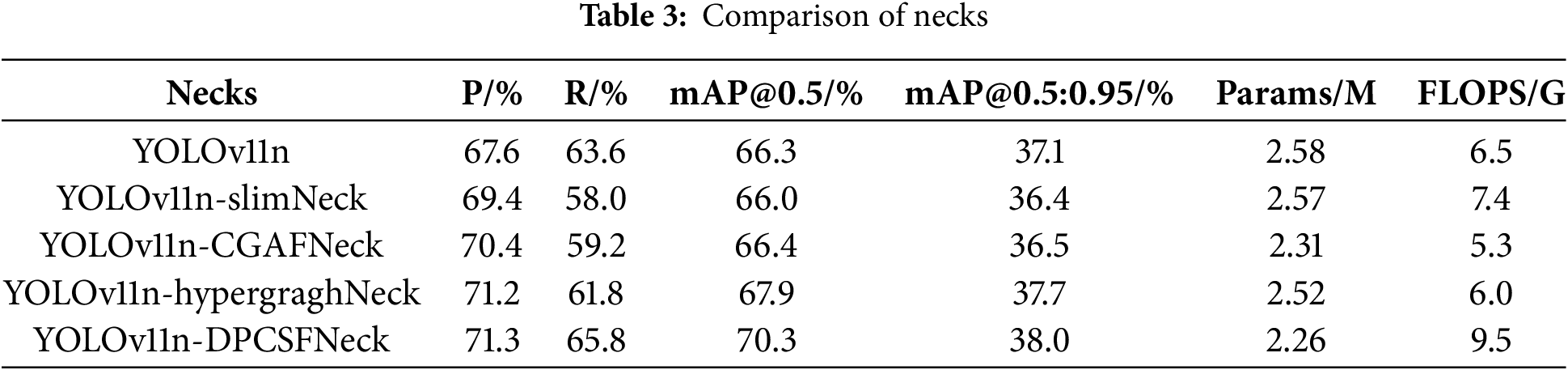

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed DPCSFNeck, we compare it with three recent neck structures. SlimNeck [32] and CGAFNeck [33] show limited improvements or even performance degradation. Table 3 shows the results of different Necks experiments. HypergraphNeck [34] improves detection accuracy while slightly reducing the number of parameters. In contrast, DPCSFNeck increases the mAP@0.5 by 4.0% and the mAP@0.5:0.95 by 0.9%, while significantly reducing the parameter count. Although it introduces a slight increase in computational cost, it achieves a favorable trade-off between accuracy and model lightweighting.

(3) Evaluation of the C3MSDR Module

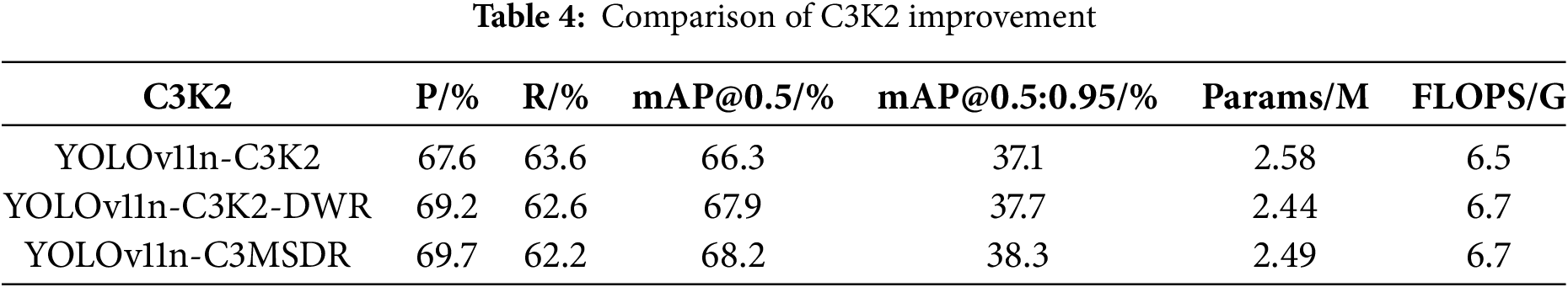

The C3K2 module in YOLOv11n already demonstrates strong feature extraction capability. As shown in Table 4, by integrating the DWR structure, the mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 improve by 1.6% and 0.6%, respectively. Further incorporating a re-parameterization module leads to the formation of the C3MSDR module. While introducing minimal changes in parameters and computational complexity, it expands the receptive field and yields additional improvements of 0.3% in mAP@0.5 and 0.6% in mAP@0.5:0.95. These results confirm the effectiveness of C3MSDR in enhancing detection performance.

(4) Evaluation of the Lightweight SDELHead Detection Head

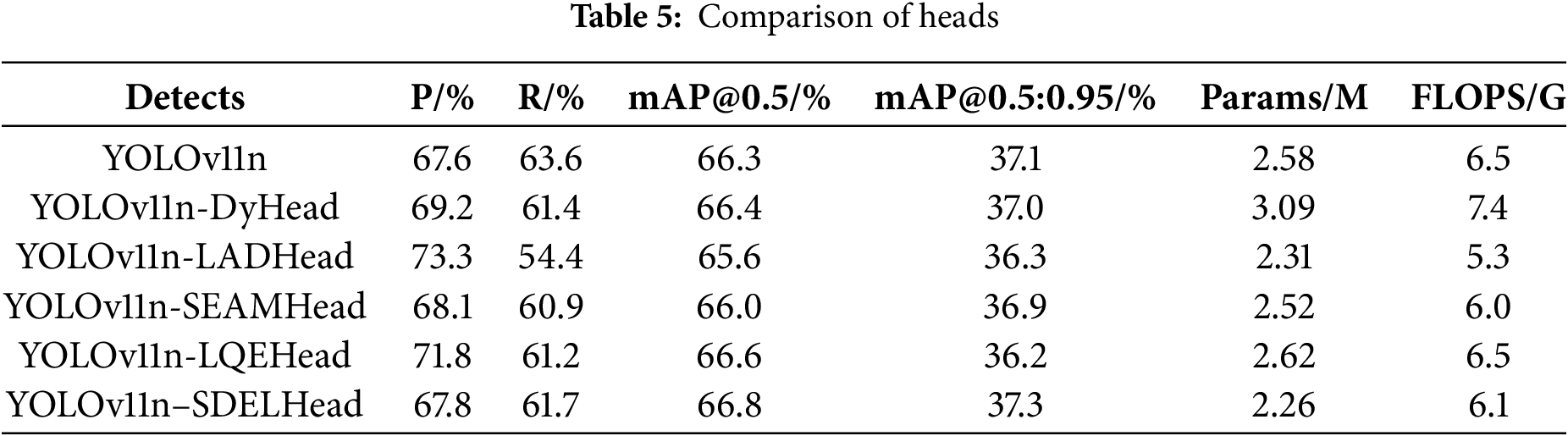

To validate the effectiveness of SDELHead, we compare it against several detection heads—including DyHead [35], LADHead [36], SEAMHead [37], and LQEHead [38]—using YOLOv11n as the baseline. Table 5 shows the results of different Heads experiments. While DyHead and LQEHead improve mAP@0.5, this comes at the cost of increased parameters and computational complexity. LADHead achieves the lowest parameter count but suffers from poor accuracy. SEAMHead offers low complexity but results in decreased precision. In contrast, SDELHead achieves improvements of 0.5% in mAP@0.5 and 0.2% in mAP@0.5:0.95 with only 2.26M parameters and 6.1 GFLOPs, demonstrating its advantage as a lightweight and efficient detection head.

5.4 Comparative Experiment Results

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, the improved model was compared with Faster R-CNN [7], SSD [5], YOLOv5s, YOLOv8n, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n, YOLOv11s, YOLOv12n [39], YOLOv13n [40], and RT-DETR [41] on the Tianchi fabric defect dataset (see Table 6). The results demonstrate that our model achieves an mAP@0.5 of 72.3% and an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 41.1%, outperforming the other methods. Moreover, with only 2.23 million parameters and 9.7 GFLOPs, the model effectively balances detection accuracy and model lightweightness. The FPS is slightly lower than some compared models but still adequate for real-time industrial use, balancing detection accuracy and speed.

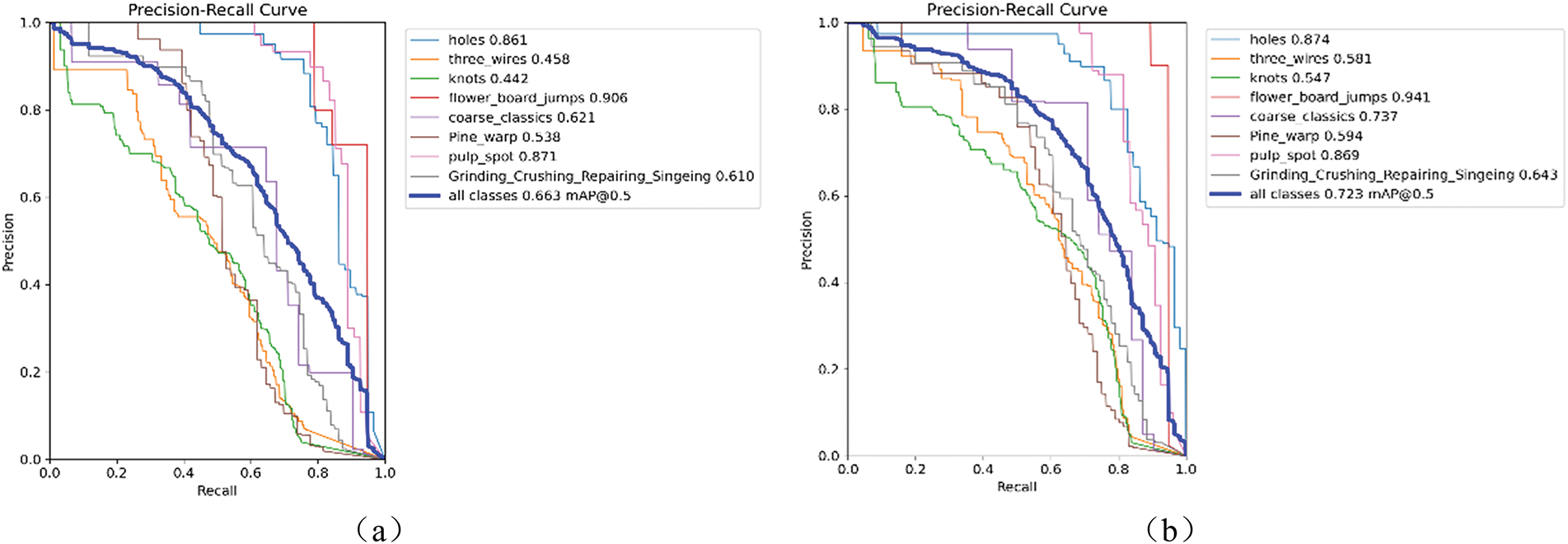

As shown in Fig. 17, the improved model outperforms others in detecting most defect categories. Notably, significant improvements are observed in the detection of three-wire and knot defects. However, the detection performance for starch stains slightly decreases due to their less distinct features.

Figure 17: (a,b) represent the Precision-Recall (P-R) curves of YOLO11n and FD-YOLO, respectively

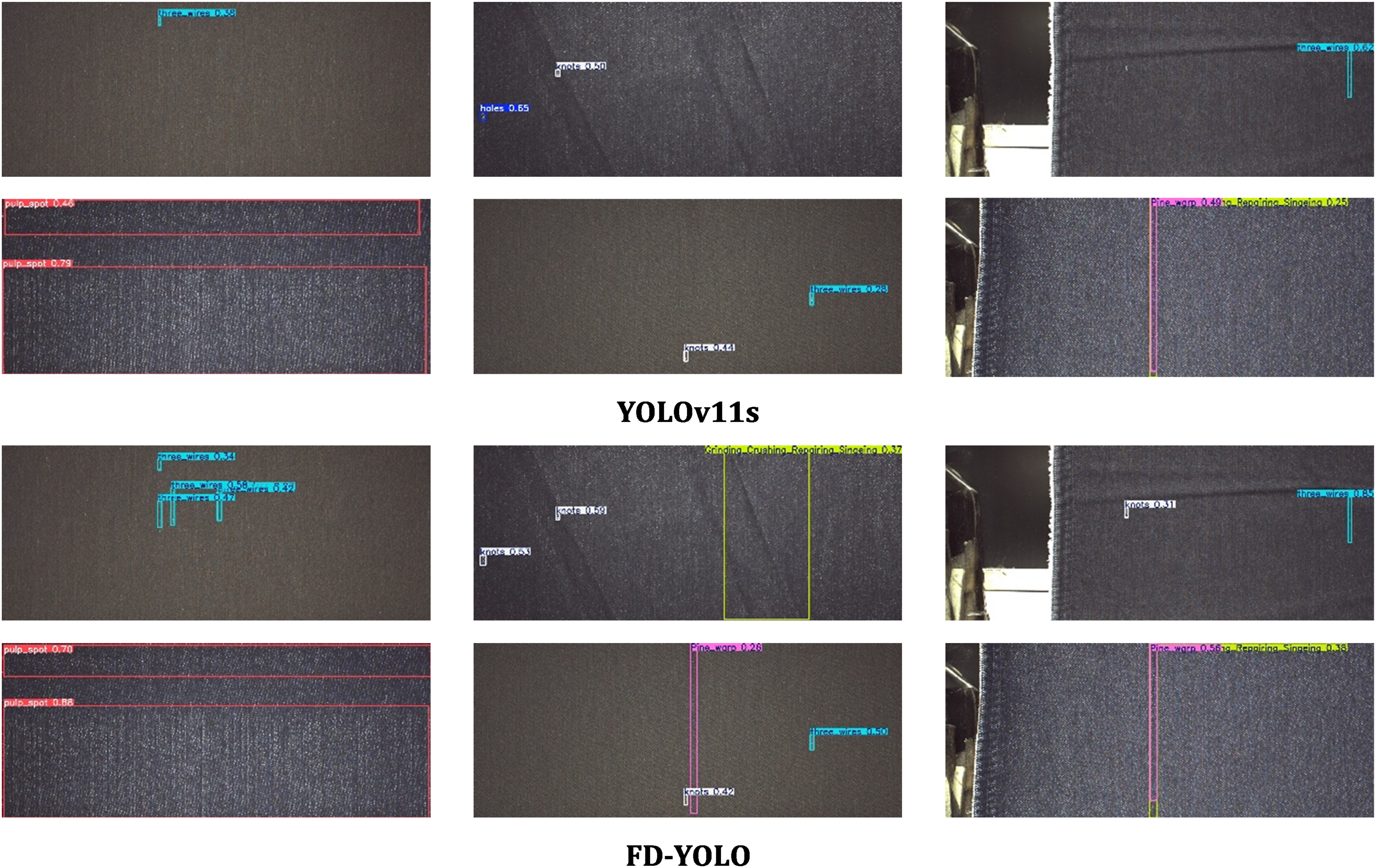

To visually compare the detection performance of the proposed FD-YOLO model with the baseline YOLOv11n and its enhanced version YOLOv11s, a selection of images was randomly drawn from the test set for evaluation. Fig. 18 shows the test results.

Figure 18: From top to bottom, the original image, the detection results of YOLO11n, YOLO11s, and FD-YOLO are shown

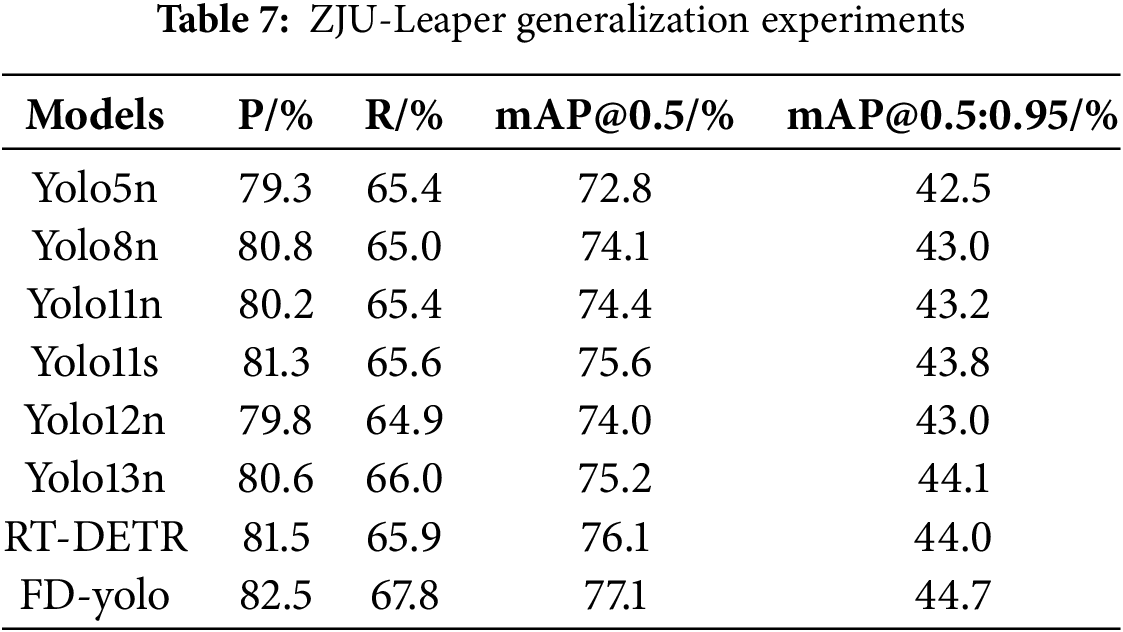

5.5 Generalization Experiment Results

To investigate the generalization capability of the FD-YOLO network, experiments were conducted on the ZJU-Leaper dataset under the same experimental environment and configuration.

The generalization performance of the model is summarized in Table 7. The results show that FD-YOLO outperforms the baseline YOLOv11n across all key metrics. Precision and Recall increase by 2.3% and 2.4%, respectively. In terms of detection accuracy, mAP@0.5 improves by 2.7%, while the stricter mAP@0.5:0.95 increases by 1.5%. These results demonstrate that FD-YOLO possesses stronger generalization capability and robustness. Notably, FD-YOLO maintains significant advantages on the ZJU-Leaper fabric defect dataset, further validating its practical value for industrial defect detection.

In this paper, we present FD-YOLO, a lightweight real-time model for detecting fabric defects. The model tackles challenges in industrial settings, such as varied defect types, different sizes, and complex backgrounds. Based on YOLOv11n, the model incorporates four main improvements: the introduction of the C2BRA module to enhance feature extraction; the design of the DPCSFNeck with an added P2 detection layer to improve multi-scale detection; the integration of the C3MSDR module to expand the receptive field and better identify elongated defects; and the development of the lightweight SDELHead to reduce parameters while improving accuracy. FD-YOLO achieves excellent performance on both the Alibaba Tianchi and ZJU-Leaper datasets. It balances detection accuracy with model lightweight design and shows strong potential for practical industrial applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was financially supported by the Fujian Provincial Department of Science and Technology, the Collaborative Innovation Platform Project for Key Technologies of Smart Warehousing and Logistics Systems in the Fuzhou-Xiamen-Quanzhou National Independent Innovation Demonstration Zone (No. 2025E3024).

Author Contributions: Methodology, Software, Validation, Resources, and Data Curation: Mingzhi Yang, Shaobo Kang. Writing—Original Draft and Review & Editing: Shaobo Kang, Mingzhi Yang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Jin R, Niu Q. Automatic fabric defect detection based on an improved YOLOv5. Math Probl Eng. 2021;2021(1):7321394. doi:10.1155/2021/7321394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mo D, Wong WK, Lai Z, Zhou J. Weighted double-low-rank decomposition with application to fabric defect detection. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2021;18(3):1170–90. doi:10.1109/TASE.2020.2997718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dong H, Song K, Wang Q, Yan Y, Jiang P. Deep metric learning-based for multi-target few-shot pavement distress classification. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2022;18(3):1801–10. doi:10.1109/TII.2021.3090036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–88. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. SSD: single shot multibox detector. In: European Conference on Computer Vision; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 21–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46448-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollár P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2999–3007. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ju M, Luo H, Wang Z, Hui B, Chang Z. The application of improved YOLO V3 in multi-scale target detection. Appl Sci. 2019;9(18):3775. doi:10.3390/app9183775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ji SJ, Ling QH, Han F. An improved algorithm for small object detection based on YOLO v4 and multi-scale contextual information. Comput Electr Eng. 2023;105(1):108490. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu Y, Zhang D, Guo C. GL-YOLOv5: an improved lightweight non-dimensional attention algorithm based on YOLOv5. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;81(2):3281–99. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.057294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang Y, Wang H, Xin Z. Efficient detection model of steel strip surface defects based on YOLO-V7. IEEE Access. 2022;10:133936–44. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3230894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Cao X, Li C, Zhai H. YOLO-AB: a fusion algorithm for the Elders’ falling and smoking behavior detection based on improved YOLOv8. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;83(3):5487–515. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.061823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Alper Selver M, Avşar V, Özdemir H. Textural fabric defect detection using statistical texture transformations and gradient search. J Text Inst. 2014;105(9):998–1007. doi:10.1080/00405000.2013.876154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sadaghiyanfam S. Using gray-level-co-occurrence matrix and wavelet transform for textural fabric defect detection: a comparison study. In: 2018 Electric Electronics, Computer Science, Biomedical Engineerings’ Meeting (EBBT); 2018 Apr 18–19; Istanbul, Türkiye. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/EBBT.2018.8391440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kaynar O, Işik YE, Görmez Y, Demirkoparan F. Fabric defect detection with LBP-GLMC. In: 2017 International Artificial Intelligence and Data Processing Symposium (IDAP); 2017 Sep 16–17; Malatya, Turkey. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/IDAP.2017.8090188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Huang Y, Jing J, Wang Z. Fabric defect segmentation method based on deep learning. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2021;70:5005715. doi:10.1109/TIM.2020.3047190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liu Z, Wang B, Li C, Li B, Liu X. Fabric defect detection algorithm based on convolution neural network and low-rank representation. In: 2017 4th IAPR Asian Conference on Pattern Recognition (ACPR); 2017 Nov 26–29; Nanjing, China. p. 465–70. doi:10.1109/ACPR.2017.34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jing J, Zhuo D, Zhang H, Liang Y, Zheng M. Fabric defect detection using the improved YOLOv3 model. J Eng Fibres Fabr. 2020;15(1):1–10. doi:10.1177/1558925020908268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zheng L, Wang X, Wang Q, Wang S, Liu X. A fabric defect detection method based on improved YOLOv5. In: 2021 7th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC); 2021 Dec 10–13; Chengdu, China. p. 620–4. doi:10.1109/iccc54389.2021.9674548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang M, Yu W, Qiu H, Yin J, He J. A fabric defect detection algorithm based on YOLOv8. In: 2023 International Conference on Image Processing, Computer Vision and Machine Learning (ICICML); 2023 Nov 3–5; Chengdu, China. p. 1040–3. doi:10.1109/ICICML60161.2023.10424868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Khanam R, Hussain M. YOLOv11: an overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv:2410.17725. 2024. doi: 10.48550/arxiv.2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhu L, Wang X, Ke Z, Zhang W, Lau R. Biformer: vision transformer with bi-level routing attention. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17-24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 10323–33. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kang M, Ting CM, Ting FF, Phan RCW. ASF-YOLO: a novel YOLO model with attentional scale sequence fusion for cell instance segmentation. Image Vis Comput. 2024;147(4):105057. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2024.105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yi J, Wu P, Jiang M, Huang Q, Hoeppner DJ, Metaxas DN. Attentive neural cell instance segmentation. Med Image Anal. 2019;55(4):228–40. doi:10.1016/j.media.2019.05.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Wei H, Liu X, Xu S, Dai Z, Dai Y, Xu X. DWRSeg: rethinking efficient acquisition of multi-scale contextual information for real-time semantic segmentation. arXiv:2212.01173. 2022. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2212.01173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ding X, Chen H, Zhang X, Huang K, Han J, Ding G. Re-parameterizing your optimizers rather than architectures. arXiv:2205.15242. 2022. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2205.15242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Dai T, Xia J, Ning L, Xi C, Liu Y, Xing H. Deep learning for extracting dispersion curves. Surv Geophys. 2021;42(1):69–95. doi:10.1007/s10712-020-09615-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang C, Feng S, Wang X, Wang Y. ZJU-leaper: a benchmark dataset for fabric defect detection and a comparative study. IEEE Trans Artif Intell. 2020;1(3):219–32. doi:10.1109/tai.2021.3057027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Liu X, Peng H, Zheng N, Yang Y, Hu H, Yuan Y. EfficientViT: memory efficient vision transformer with cascaded group attention. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 14420–30. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Misra D, Nalamada T, Arasanipalai AU, Hou Q. Rotate to attend: convolutional triplet attention module. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2021 Jan 3–8; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 3138–47. doi:10.1109/WACV48630.2021.00318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Meng W, Luo Y, Li X, Jiang D, Zhang Z. PolaFormer: polarity-aware linear attention for vision transformers. arXiv:2501.15061. 2025. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2501.15061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li H, Li J, Wei H, Liu Z, Zhan Z, Ren Q. Slim-neck by GSConv: a lightweight-design for real-time detector architectures. J Real Time Image Process. 2024;21(3):62. doi:10.1007/s11554-024-01436-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chen Z, He Z, Lu ZM. DEA-net: single image dehazing based on detail-enhanced convolution and content-guided attention. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2024;33(1):1002–15. doi:10.1109/TIP.2024.3354108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Feng Y, Huang J, Du S, Ying S, Yong JH, Li Y, et al. Hyper-YOLO: when visual object detection meets hypergraph computation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2025;47(4):2388–401. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2024.3524377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Dai X, Chen Y, Xiao B, Chen D, Liu M, Yuan L, et al. Dynamic head: unifying object detection heads with attentions. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 7369–78. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang J, Chen Z, Yan G, Wang Y, Hu B. Faster and lightweight: an improved YOLOv5 object detector for remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2023;15(20):4974. doi:10.3390/rs15204974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yu Z, Huang H, Chen W, Su Y, Liu Y, Wang X. YOLO-FaceV2: a scale and occlusion aware face detector. arXiv:2208.02019. 2022. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2208.02019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li X, Wang W, Hu X, Li J, Tang J, Yang J. Generalized focal loss V2: learning reliable localization quality estimation for dense object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 11627–36. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.01146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Tian Y, Ye Q, Doermann D. YOLOv12: attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv:2502.12524. 2025. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2502.12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lei M, Li S, Wu Y, Hu H, Zhou Y, Zheng X, et al. YOLOv13: real-time object detection with hypergraph-enhanced adaptive visual perception. arXiv:2506.17733. 2025. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2506.17733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Zhao Y, Lv W, Xu S, Wei J, Wang G, Dang Q, et al. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 16965–74. doi:10.1109/CVPR52733.2024.01605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools