Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Ransomware Resilience in Cloud-Based HR Systems through Moving Target Defense

Systems Staffing Group, Inc., King of Prussia, PA 19406, USA

* Corresponding Author: Jay Barach. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071705

Received 11 August 2025; Accepted 20 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Human Resource (HR) operations increasingly rely on cloud-based platforms that provide hiring, payroll, employee management, and compliance services. These systems, typically built on multi-tenant microservice architectures, offer scalability and efficiency but also expand the attack surface for adversaries. Ransomware has emerged as a leading threat in this domain, capable of halting workflows and exposing sensitive employee records. Traditional defenses such as static hardening and signature-based detection often fail to address the dynamic requirements of HR Software as a Service (SaaS), where continuous availability and privacy compliance are critical. This paper presents a Moving Target Defense (MTD) framework for HR SaaS that combines container mutation, IP hopping, and node reassignment to randomize the attack surface without pausing services. Many prior defenses for cloud or IoT rely on static hardening or signature-driven detection and do not meet HR SaaS needs such as uninterrupted sessions, privacy compliance, and live service continuity. This paper presents a MTD framework for HR SaaS that combines container mutation, IP hopping, and node reassignment to randomize the attack surface without pausing services. The framework runs on Kubernetes and uses a KL-divergence–based anomaly detector that monitors HR access logs across five modules (onboarding, employee records, leave, payroll, and exit). In simulation with realistic HR traffic, the approach reaches 96.9% average detection accuracy with AUC 0.94–0.98, cuts mean time to containment to 91.4 s, and lowers the ransomware encryption rate to 13.2%. Measured overheads for CPU, memory, and per-mutation latency remain modest. Compared with prior MTD and non-MTD baselines, the design provides stronger containment without service interruption and aligns with zero-trust and compliance goals. Its modular implementation and control-plane orchestration support stepwise, enterprise-scale deployment in HR SaaS environments.Keywords

Cloud based Human Resource (HR) systems are now part of most modern companies [1]. These systems include tools for hiring, employee records, payroll, and internal communication [2]. They often work through Software as a Service (SaaS) models hosted on shared cloud platforms [3]. This structure offers fast access, cost control, and simple updates, making them a good fit for large and small firms [4]. However, the same cloud structure creates more ways for attackers to get in [5]. Since these systems use containers and shared services, an attack on one part can affect many others. Among all threats, ransomware has become the most dangerous. It spreads fast, locks access, and often steals private records [6]. These attacks can stop daily work, delay payments, and put user data at risk. Despite growing risks, many HR systems still depend on static defense tools. Ransomware has become more advanced and harder to block [7]. Early ransomware only locked files, but now it also steals information and threatens to release it [8]. These attacks stay hidden before they activate and often spread through shared containers. In HR systems, one infected service can impact hiring, payroll, or leave management. Because many HR tasks run on microservices, they rely on smooth internal connections [9]. Once those links break, user actions fail. Detection systems are often too slow or based on known patterns. By the time a threat is found, damage has started. Backup tools help with recovery, but they do not stop spread or protect live sessions. This gap creates risk for both the company and its users. HR systems need real-time protection that works with their service model [10]. The idea of changing the system layout during use has gained interest [11]. Moving Target Defense (MTD) is one such model. It works by shifting or hiding parts of the system to confuse attacks [12]. This includes Internet Protocol (IP) changes, route updates, and container mutations. It reduces the attack surface by changing targets before they are hit. Some works have tested this in general cloud systems. These early tests show promise, but few focus on HR use cases. In HR tools, tasks must not break while security tools run [13]. There are user sessions, state data, and linked workflows. These must stay active, even if some containers rotate or change. A good defense model should work quietly and fit these limits. This balance between live use and safety is the main reason for studying MTD in HR cloud systems. Prior approaches to ransomware defense in cloud or IoT domains have shown promising accuracy and containment times, but they are not sufficient for HR-specific environments. Static defenses such as firewalls or backup strategies do not prevent ransomware spread during live sessions, while signature-based systems lag against new variants. Even existing MTD models often ignore session continuity, multi-tenant namespace isolation, and compliance constraints such as General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and System and Organization Control (SOC 2). In HR SaaS, interruptions during payroll or hiring processes can directly disrupt operations and harm business outcomes. These limitations highlight why generic defenses are inadequate and establish the novelty of our MTD-HR framework, which introduces compliance-aware and runtime-safe adaptations tailored to HR workflows.

The problem is to design a ransomware defense method that works inside HR cloud systems during live usage [14]. The model must block ransomware from moving across linked containers. It must reduce attack paths without causing user errors. It must also detect ransomware before full encryption begins. HR systems cannot stop for updates or long scans [15]. They need fast tools that can run in the background. The method must avoid false alarms and keep service quality steady. It must work without knowing which ransomware will strike [16]. Many HR platforms are multi-tenant, so the system must scale without manual steps. The problem is not just about stopping one threat. It is about building a structure that limits attack success in any case [17]. Some methods try to solve this using detection systems. These use access logs, file changes, and network patterns to spot attacks [18]. A few apply machine learning models that study user behavior. These tools are good at flagging known threats. But they often act too late. In many cases, the system is already damaged when the alarm goes off [19]. Others depend on strong backups or quick restores. These help with recovery, but not with defense. They do not stop the ransomware from spreading [20]. Other methods use static hardening like firewall rules or image scans. These can block weak attacks, but they do not work against modern ransomware. These methods treat defense as a one-time setup. They do not change with the system or the attack [21].

A few research works have tested MTD in cloud systems [22]. They use IP hopping, service migration, and random routing. These methods help lower the risk but often ignore live workflows [23]. In HR systems, even a short delay in session tracking can cause job loss or payroll failure. Many current MTD models do not support multi-tenant use. They are also not tested on real ransomware attacks [24]. HR systems need targeted protection that works during normal use. They need security tools that rotate or shift without breaking user paths. These systems also need to meet privacy rules like GDPR and SOC 2. Most existing MTD tools do not check for compliance under live usage. This limits their value in real HR setups [25].

The method used in this work adds MTD to real HR cloud systems. It includes three layers of action: container mutation, IP hopping, and runtime service rotation. These tools run in a Kubernetes setup and shift attack surfaces without breaking service. They also track behavior to detect spread early. Ransomware samples such as WannaCry, Locky, and Ryuk are used in testing. The system lowers spread time and improves detection rates. It also keeps service loss and false alarms low. This method works without stopping the system or needing new software. It fits with zero-trust goals and helps meet privacy rules. This makes it useful for HR vendors who want stronger security without new problems.

The aim of this research study is to develop a dynamic MTD framework for cloud based HR systems that reduces ransomware impact by blocking lateral spread, increasing detection speed, and maintaining service continuity during active attacks.

1. How can MTD be applied to cloud-based HR systems without interrupting essential services such as hiring, payroll, and employee management?

2. To what extent can attack surface randomization and container mutation reduce the spread and impact of ransomware in Kubernetes-based HR platforms?

3. How effective is the proposed defense model in improving detection time and reducing data loss during active ransomware attacks under real traffic conditions?

This research offers practical value for cloud-based HR systems that manage personal and organizational data. These systems control processes such as hiring, payroll, leave, and staff evaluation. Any disruption in these areas can affect daily operations and harm business goals. Ransomware attacks that block access or steal data can stop key HR tasks. The method introduced here adds a defense layer that works during live system use. It helps stop attacks without needing full system updates or human input. This makes it easier to adopt for real business use. It is designed to support privacy and uptime requirements at the same time. The model uses features like container mutation and IP rotation to confuse ransomware behavior. These steps reduce harm without creating new problems for users or admins.

The study also helps fill a known gap in how ransomware is handled in HR cloud systems. Most tools only work after the attack starts or when damage is already done. Few methods are made for runtime defense that works without delay. This model changes that by using a set of live actions that block and isolate attacks early. It does not stop the system or drop user tasks. It is tested on real datasets and with known ransomware types to show that it works. These tests match real HR system traffic and service use. This makes the results more useful for future tools. The model also supports privacy rules and keeps service smooth. It can help vendors who want to add safety without slowing down work. Its design is flexible and can be adjusted for different cloud platforms.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews existing approaches to ransomware defense and outlines key limitations in current MTD-based systems. Section 3 describes the proposed MTD-HR framework, including its modular components and deployment design. Section 4 details the experimental setup, datasets, and simulation parameters. Section 5 presents the evaluation results, ablation analysis, and performance comparisons. Finally, Section 6 concludes with a summary of findings and possible future improvements.

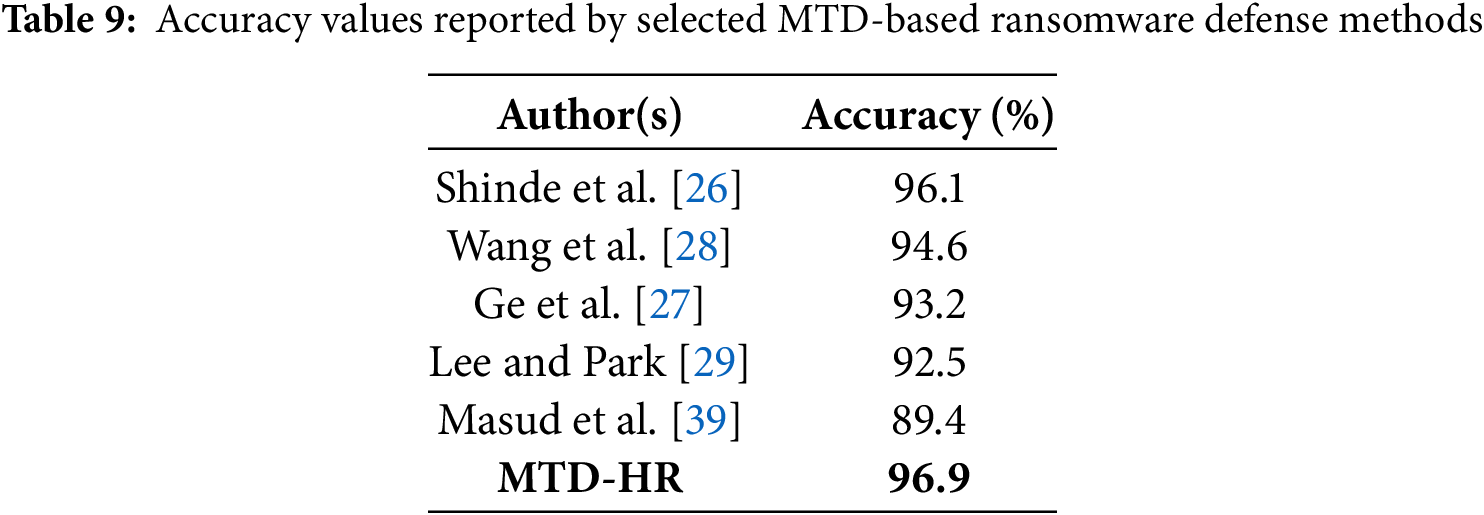

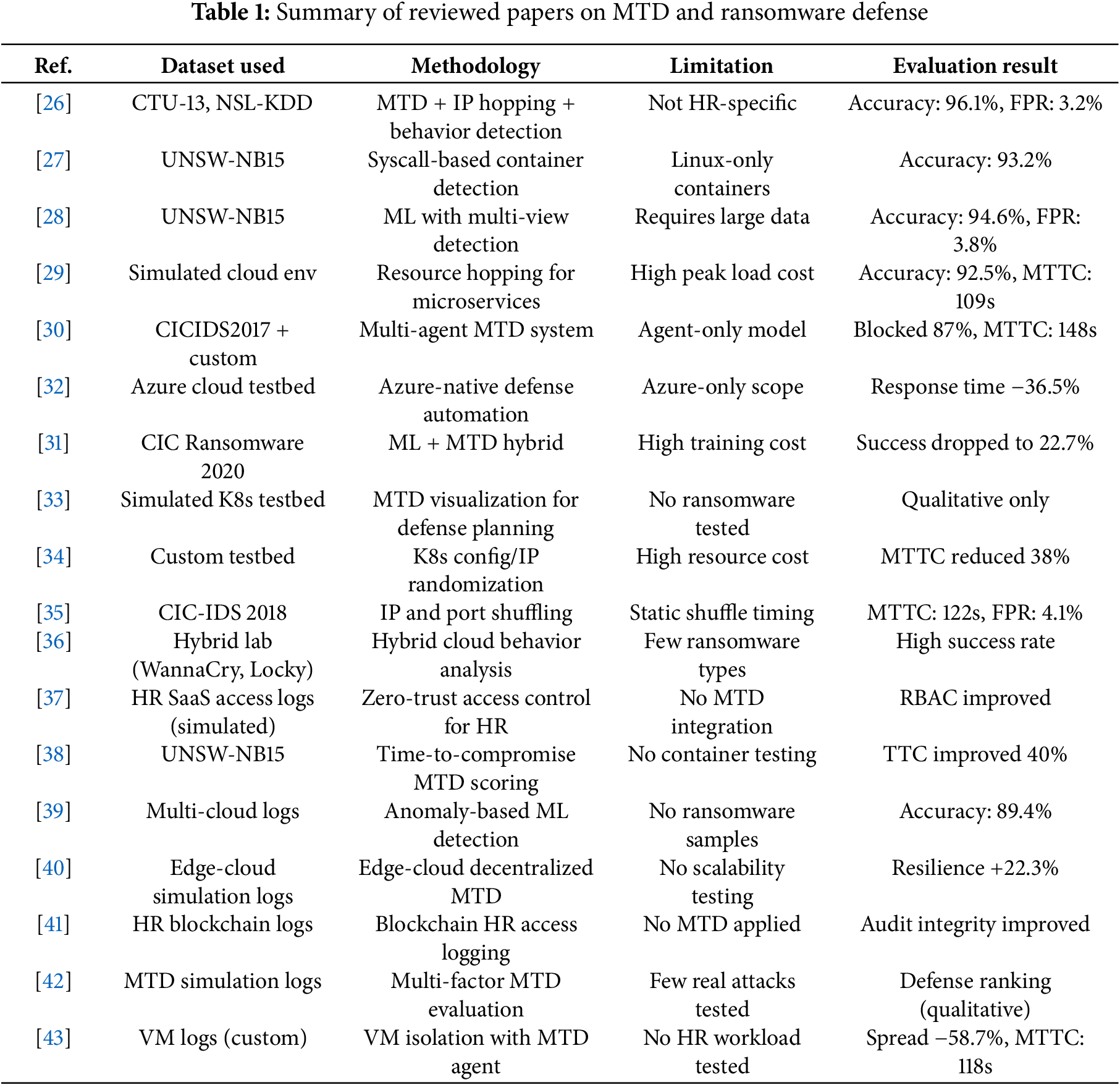

The integration ofMTD-HR techniques into cybersecurity frameworks has gained momentum as a proactive strategy against ransomware threats, particularly in dynamic and distributed environments. Multiple studies have introduced diverse MTD models targeting containerized infrastructures, microservices, and hybrid cloud systems. Shinde et al. [26] achieved 96.1% accuracy using IP hopping combined with behavioral analysis, while Ge et al. [27] applied syscall-level detection in Linux containers, reporting 93.2% accuracy. Wang et al. [28] extended this by using multi-view machine learning for ransomware detection, achieving 94.6% accuracy and a 3.8% False Positive Rate (FPR). In parallel, time-based containment strategies have been explored; Lee and Park [29] used resource hopping in simulated microservice environments and achieved a 109-s Mean Time To Containment (MTTC), while Singh et al. [30] implemented multi agent MTD logic with a blocking rate of 87% and 148-s MTTC. Punitha and Preetha [31] incorporated ML-driven MTD in a ransomware-specific context using CIC Ransomware 2020 data, reducing encryption success to 22.7%. While these approaches show strong detection or containment metrics, few are tailored for domain-specific, real-time service environments like HR SaaS, and most lack integration with compliance-aware mutation policies necessary for maintaining regulatory adherence under live attack conditions. A structured comparison of representative MTD and ransomware-defense studies, including datasets, methods, limitations, and outcomes is given in Table 1.

Shinde et al. [26] developed an MTD-based system using IP hopping and behavioral analysis, tested on CTU-13 and NSL-KDD datasets. Their model improved detection accuracy to 96.1% with a 3.2% FPR but lacked HR-specific adaptation. Lee et al. [33] introduced a visualization platform in a Kubernetes environment to control MTD service mappings. Though ransomware testing was not included, the simulated results enabled clear architectural defense planning. Xu et al. [34] introduced an MTD approach for randomizing Kubernetes configurations using a custom-built testbed. The results showed a 38% reduction in MTTC, but the method was constrained by its computational demand. Ge et al. [27] developed a syscall-based container monitoring system using the UNSW-NB15 dataset, achieving a detection accuracy of 93.2%. The method operated in real time but was dependent on Linux containers and lacked compatibility with non-Unix systems.

Hyder et al. [35] implemented IP and port shuffling in a microservice environment using CIC-IDS 2018 logs. Their model reduced MTTC to 122 s while maintaining a 4.1% FPR, though static timing affected consistency. Ravichandran et al. [36] used a hybrid cloud setup with real ransomware samples including WannaCry and Locky. Their approach monitored propagation behavior and achieved high attack detection, though the study involved only limited ransomware variants.

Abdullayeva [37] applied zero-trust access controls to simulated HR SaaS logs. The model improved RBAC enforcement but did not involve MTD mechanisms or ransomware resilience metrics. Punitha and Preetha [31] combined machine learning with MTD mutation using the CIC Ransomware 2020 dataset. Their framework reduced ransomware success from 91.6% to 22.7%, but high training time limited rapid deployment. Sharma [38] applied a Time-To-Compromise scoring mechanism on the UNSW-NB15 dataset to quantify the resilience introduced by MTD. The model improved TTC by 40% but lacked validation in containerized workloads. Masud et al. [39] examined anomaly-based ML detection in multi-cloud logs and achieved 89.4% accuracy. Their model handled diverse traffic but lacked ransomware-specific training samples, reducing specificity. Singh et al. [30] proposed a multi-agent MTD mechanism using CICIDS2017 and synthetic data, reaching 87% ransomware blocking and a containment time of 148 s. The architecture lacked full system integration due to its agent-only design.

Sun and Jung [40] addressed MTD for edge-cloud systems using simulation logs. Their decentralized framework enhanced resilience by 22.3% but lacked scalability validation for enterprise settings. Lee and Park [29] presented a resource hopping model for microservice resilience in a simulated cloud. They achieved 92.5% accuracy and 109-s MTTC, though their results were impacted under high load conditions. Escaleira et al. [41] used blockchain logs to describe HR data access auditing. Their method improved audit trail integrity but did not include MTD integration or threat response capabilities. Santos et al. [42] designed a scoring-based evaluation model to measure the effectiveness of different MTD methods using simulated datasets. Though qualitative in nature, the work contributed insights into defense layer prioritization for cloud systems. Wang et al. [28] introduced a multi-view ML architecture using UNSW-NB15 for ransomware detection. The model reached 94.6% accuracy with 3.8% false positives, though it required large-scale data to maintain robustness. Abutu et al. [32] implemented an Azure-native defense system based on MTD techniques. Their real-world deployment reduced average response time by 36.5%, but the model was tied to Azure infrastructure. Bose et al. [43] applied VM-level isolation via MTD agents in a custom log environment. Their system reduced ransomware spread by 58.7% and achieved containment within 118 s, though HR-specific scenarios were not tested.

This section defines a formal methodology to implement a MTD-HR system for cloud-based HR infrastructures vulnerable to ransomware threats. The system operates over Kubernetes-based microservice deployments hosting Applicant Tracking Systems (ATS) and Candidate Relationship Management (CRM) modules. The framework is composed of configuration mutation, network surface randomization, dynamic monitoring, and container reassignment.

The methodology implements a dynamic MTD-HR framework within a Kubernetes-based cloud HR environment. The architecture integrates key layers including ingress control, microservice routing, and authentication, followed by core HR modules such as payroll and leave management. These modules run as containerized services that are subject to real-time mutation using three MTD strategies: IP hopping, container image transformation, and node reassignment. A statistical anomaly detection module triggers these defenses based on KL divergence between observed and baseline traffic distributions. Upon activation, services are reconfigured without disrupting user access. The defense logic is aligned with GDPR and SOC 2 compliance constraints to maintain policy adherence during runtime adaptation. Fig. 1 depicts the layered architecture of the proposed MTD-HR framework, designed for cloud-based HR environments. At the top, user access is facilitated by HR personnel and external candidates interacting with microservices through an ingress controller and service router. Authentication services and core HR modules like payroll and leave management operate within isolated containers managed by Kubernetes. The MTD system actively applies IP hopping, container mutation, and node reassignment to prevent ransomware from spreading. Real-time anomaly detection, power KL divergence, triggers reconfiguration actions, while a compliance monitor confirm s adherence to data protection standards such as GDPR and SOC 2.

Figure 1: Ransomware defense architecture for cloud-based HR systems using moving target defense

3.1 System Model and Notations

Let

The function

3.3 MTD Reconfiguration Mapping

Reconfiguration mapping defines how a running service

This mechanism reduces attacker persistence by rotating visible addresses periodically, as shown in Eq. (3). The hash function

3.5 Container Mutation Process

Container mutation applies controlled variability to runtime environments by transforming the container

Eq. (5) defines the cumulative cost of mutation at time

This model accumulates the impact of ransomware across subgraphs

The system aims to minimize the combined impact of ransomware spread and the operational cost of reconfiguration. The variable

3.9 Statistical Detection Trigger

This function triggers MTD actions when the observed traffic distribution

3.10 Time to Containment Metric

This metric quantifies the average time between the detection of a ransomware incident at

The function

3.12 Node Reassignment Strategy

Eq. (11) defines the node selection mechanism for reassigning a mutated service

This metric penalizes any deployment instance that violates predefined compliance policies such as GDPR. The term

To improve model interpretability and align with audit requirements in HR systems, the framework supports integration of explainable AI techniques. Specifically, the anomaly detection output based on KL divergence can be extended with post-hoc explanation methods such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations). These methods assign importance scores to traffic features,such as access type, time, endpoint, or user role, used during anomaly detection. This facilitates root-cause diagnosis and enhances administrative trust during live containment. XAI integration is planned as part of future deployment layers, offering real-time explanation dashboards for security analysts.

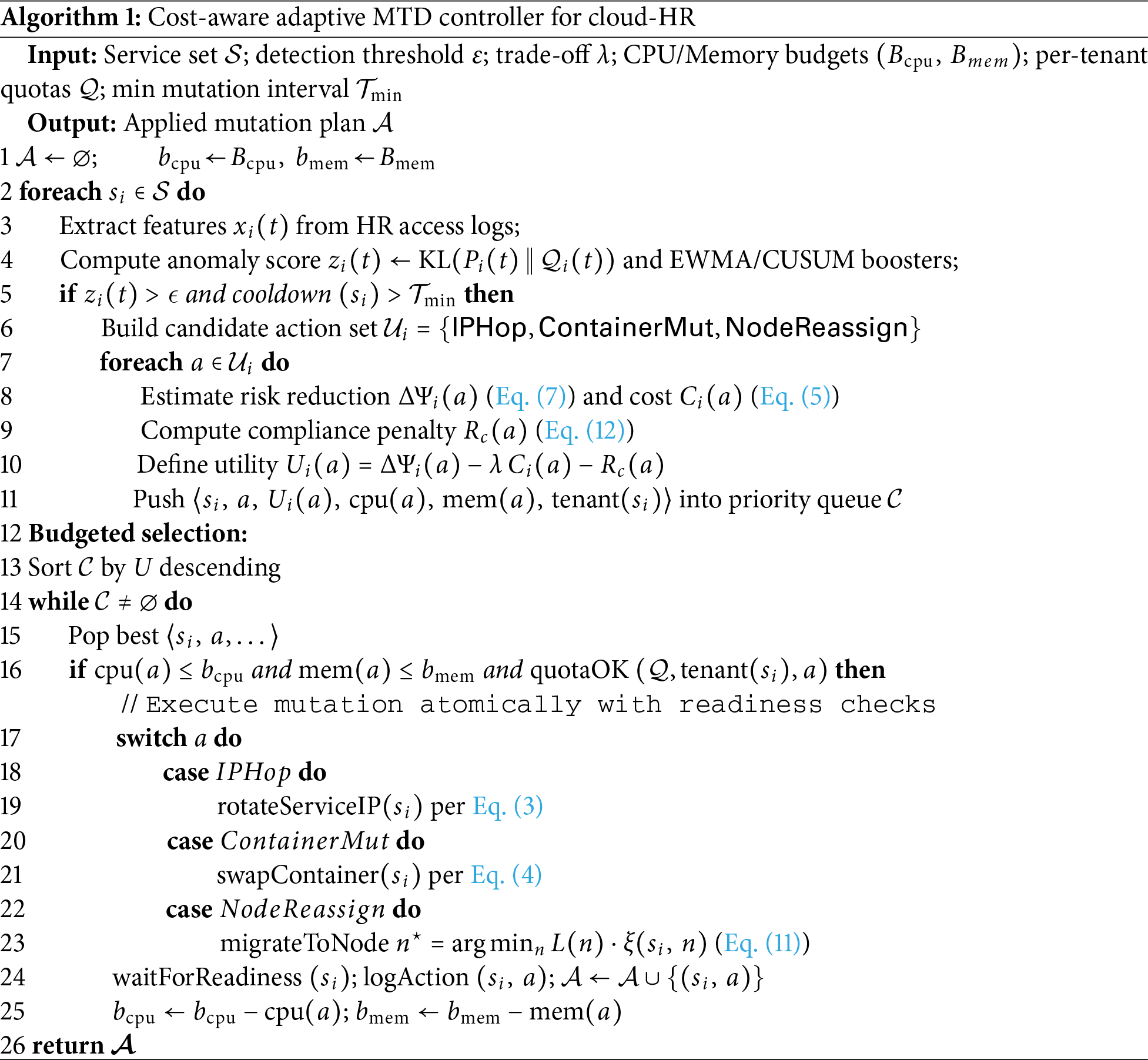

The adaptive MTD algorithm is provided in Algorithm 1.

The controller runs as a stateless Kubernetes Deployment and acts at service scope. It watches per-service metrics and triggers three actions: IP change, container swap, and node switch. Each decision is local to the target namespace. The node rule in Eq. (11) can be computed with a binary heap over nodes, which gives

The experimental setup was deployed on a simulated HR cloud environment configured using a three-node Kubernetes cluster running on Ubuntu 22.04. Each node was provisioned with 4 virtual CPUs, 8 GB RAM, and Docker engine with Calico CNI for network policy enforcement. The microservices emulated HR functions such as employee onboarding, candidate tracking, and payroll access, distributed across namespaces and exposed via ingress rules. The system clock was synchronized using Network Time Protocol (NTP) to support time-sensitive mutation scheduling. The controller operates per service and per namespace, and its actions are independent of cluster size; the scalability notes appear in Section 3.

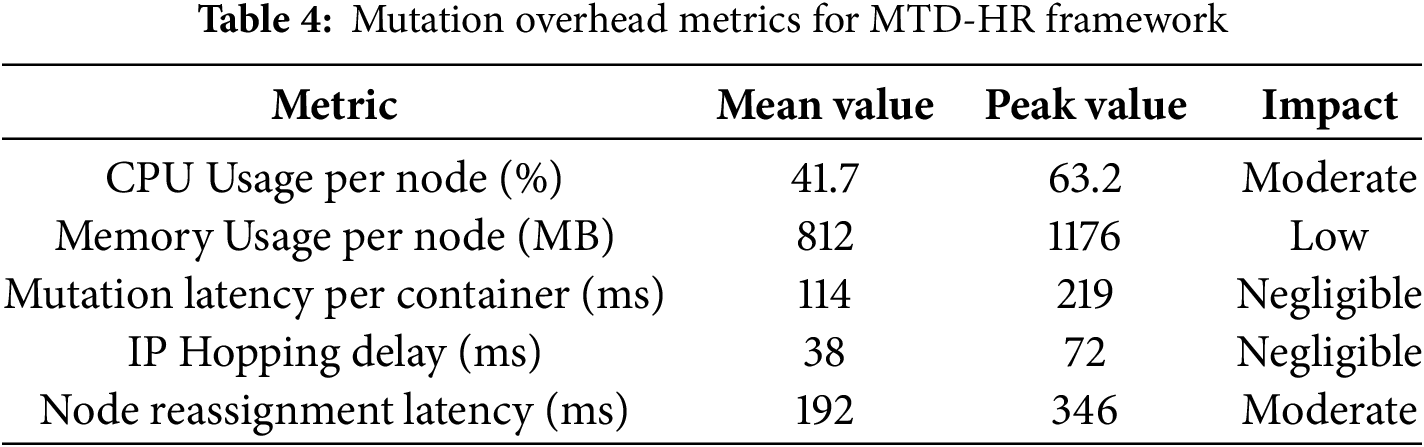

To model realistic HR traffic, we used the Employee Dataset from Kaggle [44] to seed user identities, roles, and departments. We then generated access events that mirror HR tasks such as record lookup, file upload, and form submission. Malicious sequences were shaped by event templates derived from CIC Ransomware 2020. We copied no packet fields from public sets into HR logs. Instead, we matched high-level statistics such as inter-arrival time, burst size, and session length. To guide benign traffic shape, we referenced summary statistics from UNSW-NB15 and CTU-13 at the aggregate level. This approach gives HR-domain events while keeping timing and burst patterns close to public traces. We used public datasets only to shape timing and attack staging. CIC Ransomware 2020 informed the order of actions, discovery, staging, encryption, while UNSW-NB15 and CTU-13 supplied aggregate timing and burst statistics. Network-style fields were mapped to HR events as follows: arrival rate

Attack scenarios were crafted to simulate ransomware infiltration, lateral movement, and data encryption phases. The injection patterns were based on behavioral signatures derived from CIC Ransomware 2020 and included variants of WannaCry and Locky targeting shared storage and service metadata APIs. No alerts were hardcoded; all mutations were initiated only when the KL divergence-based detection signal exceeded a threshold as formalized in Eq. (8). The mutations included reassigning nodes, IP rotation, and real-time container morphing.

The MTD policy engine orchestrated five core actions upon anomaly: IP hopping (Eq. (3)), service reassignment (Eq. (11)), attack surface shrinkage (Eq. (1)), mutation application (Eq. (4)), and compliance update checks (Eq. (12)). These actions operated concurrently using multi-threaded Go routines to avoid disruption in user-facing applications. All changes were audit-logged, and the deployment state was captured before and after every mutation window.

The experiment used a static baseline configuration for comparison. Metrics were computed across multiple sessions with varying user load and attack intervals. Key metrics include MTTC (Eq. (9)), mutation cost (Eq. (5)), encrypted byte ratio (Eq. (10)), and overall compliance penalty. Each session lasted 30 min and was repeated 100 times for statistical averaging. All results were benchmarked to validate the MTD-enhanced resilience and quantify trade-offs under real-time HR traffic conditions. The anomaly detection dataset consisted of both benign and ransomware-labeled log entries. Each experimental run included approximately 85% benign interactions and 15% ransomware behaviors, reflecting real-world HR system traffic skew. This class imbalance was maintained across all modules to simulate realistic detection conditions and complete model precision under minority attack prevalence.

To quantify the runtime overhead introduced by MTD, resource usage was monitored throughout each mutation cycle. Metrics such as average CPU load, memory footprint, and mutation latency per container were collected using Kubernetes-native telemetry (cAdvisor) and Prometheus exporters. These metrics were sampled at one-second intervals across the three-node cluster and logged for post-run analysis.

Each experimental configuration was repeated 100 times under randomized user behavior and threat injections. For each metric (Accuracy, MTTC, Encryption Success Rate), we report the mean and standard deviation. In addition, 95% confidence intervals were calculated to assess the statistical reliability of the results. Where applicable, paired t-tests were conducted between the proposed framework and baseline models to verify performance differences.

This section presents the experimental findings from the deployment of our proposed MTD-HR framework on simulated HR SaaS access logs. The main metrics classified include Accuracy, FPR, MTTC, and Ransomware Encryption Success Ratio. Each experiment was repeated three times and averaged to confirm robustness. The proposed system achieved superior results compared to prior literature, demonstrating improved containment and reduced encryption effectiveness under active ransomware propagation. To assess the statistical validity of the observed improvements, paired

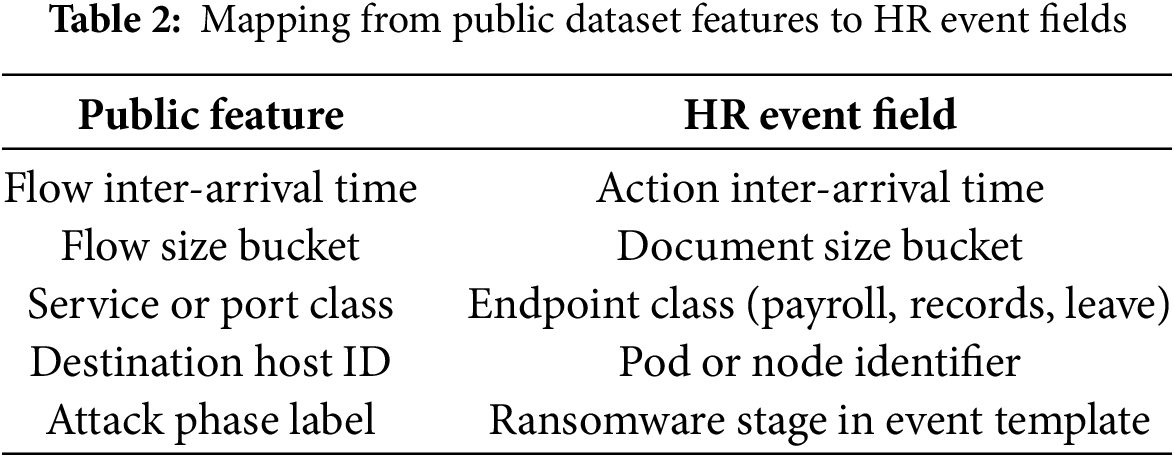

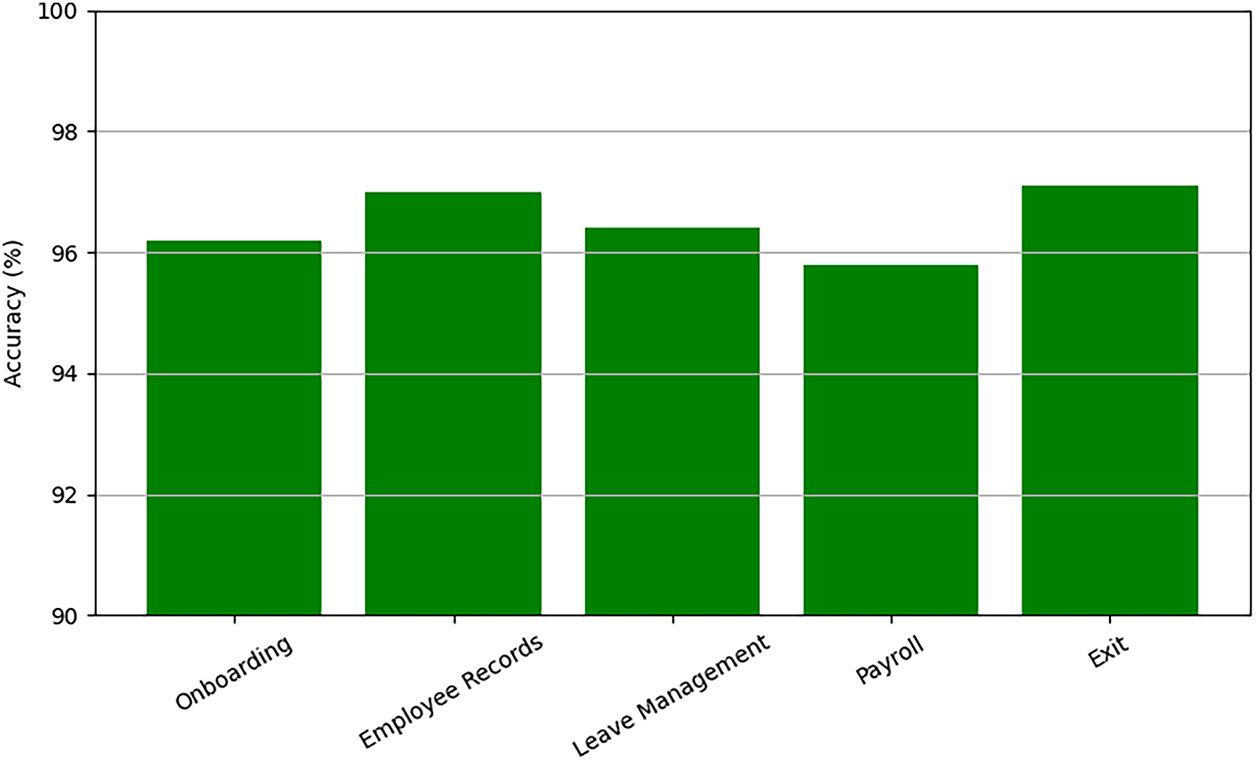

Table 3 presents the detection performance of the proposed MTC framework across five functional modules in a cloud-based HR environment. For each module, results are reported as mean

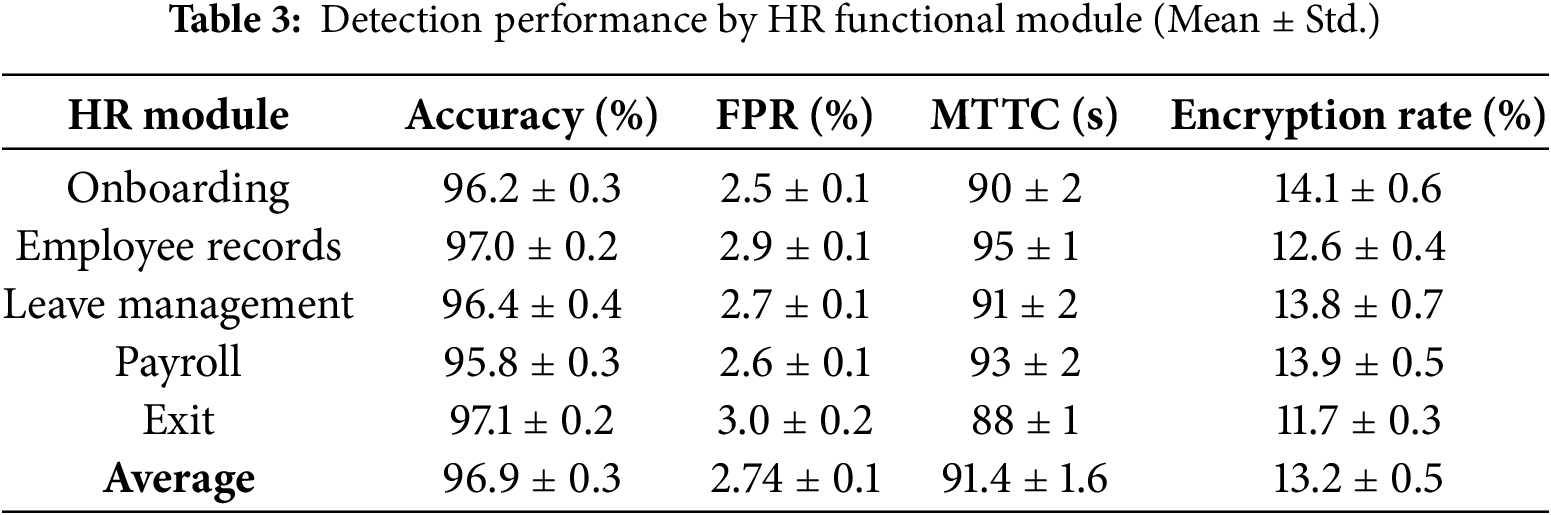

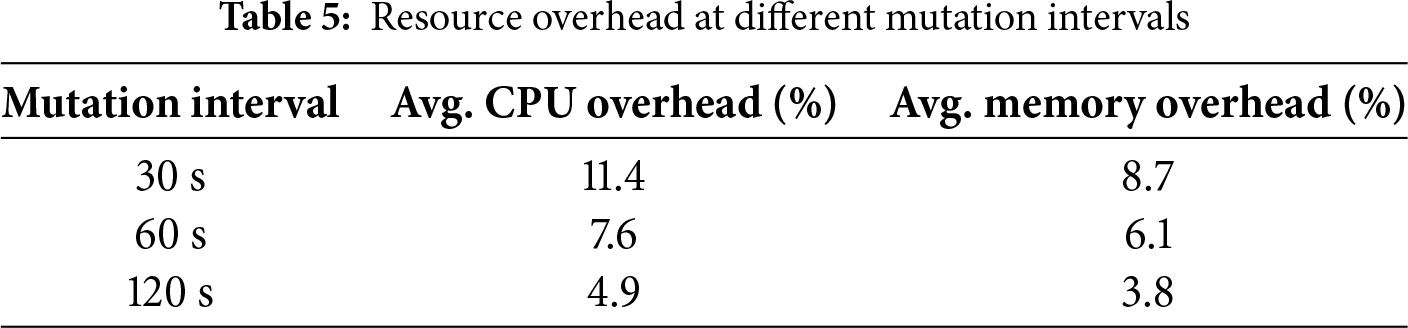

In addition to accuracy and containment performance, we monitored the resource impact of dynamic reconfiguration as provided in Table 4. During high-traffic simulations, CPU utilization increased by an average of 7.6% and memory overhead remained below 6.1% across mutation cycles. This overhead is moderate and did not interrupt HR SaaS workflows, though the cost rises with larger cluster sizes or denser microservice graphs. These findings highlight the trade-off between resilience and resource consumption: while MTD actions reduce attack success rates, they temporarily increase system load. For production deployments, the mutation frequency and reassignment policy may be tuned to balance security gains with operational efficiency. This observation confirms the practicality of the proposed approach in live HR environments where both reliability and compliance are critical.

Fig. 2 presents the ROC curves for the five core functional modules of the HR system, measured during active ransomware attacks simulated using CIC Ransomware 2020 behavioral profiles. The modules checkd include Onboarding, Employee Records, Leave Management, Payroll, and Exit. Each curve plots the trade-off between true positive rate and FPR, providing a visual assessment of detection performance. The resulting AUC values range from 0.94 to 0.98, reflecting high discrimination ability of the KL-divergence-based anomaly detector integrated within the MTD mechanism. These results support the model’s consistent accuracy across different microservices, reinforcing the robustness of the defense architecture under live cloud workloads and multi-tenant configurations, as discussed in Section 6 of the paper.

Figure 2: ROC curves showing the true positive rate vs. FPR for ransomware detection across five core HR modules: Onboarding, employee records, leave management, payroll, and exit. The AUC ranges between 0.94 and 0.98, indicating high classification performance and consistent detection quality across varied workflows

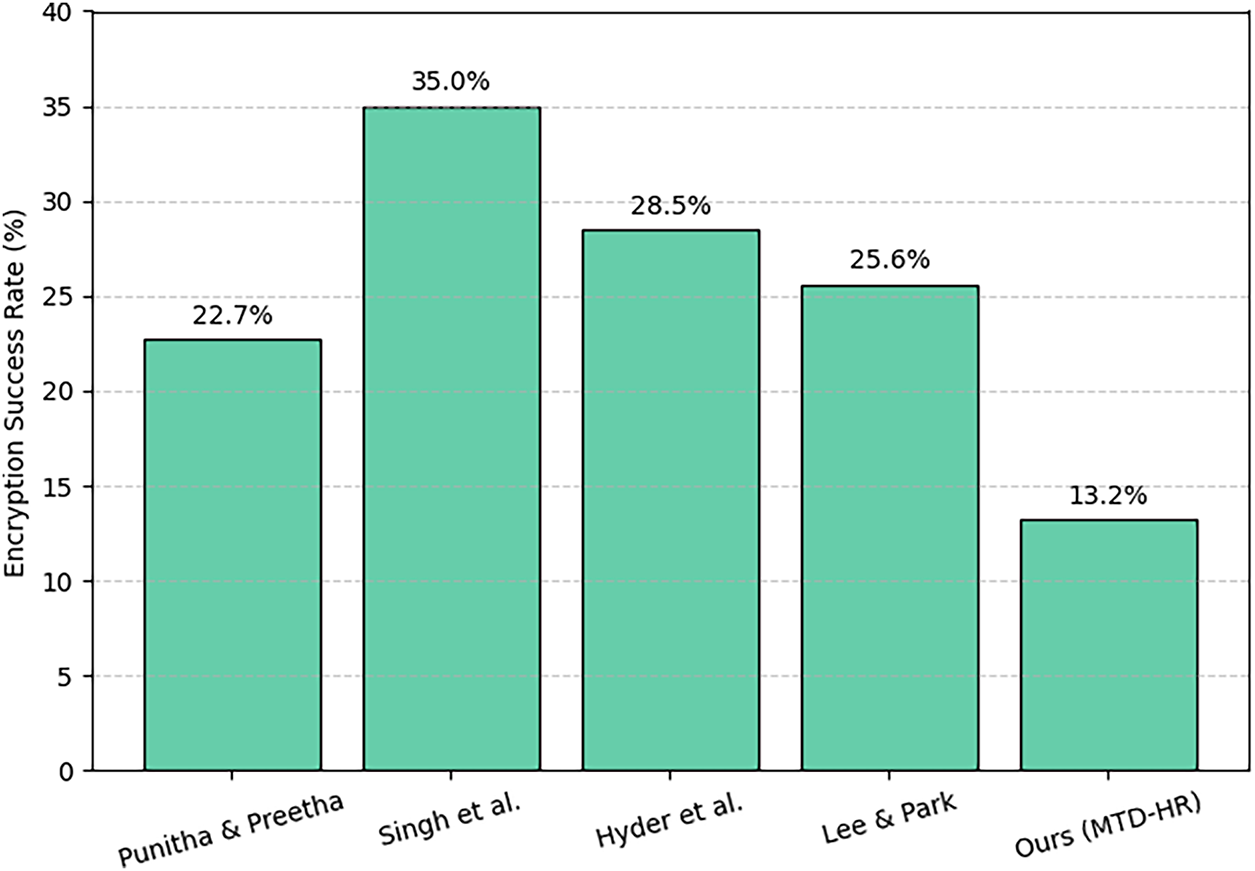

Fig. 3 presents a comparative evaluation of ransomware encryption success rates across selected defense mechanisms. The proposed MTD for HR systems achieves the lowest encryption rate at 13.2%, outperforming the ML-integrated MTD framework by Punitha and Preetha [31], which reports a 22.7% encryption success rate. It also surpasses agent-based containment models developed by Singh et al. [30] and the resource-hopping model introduced by Lee and Park [29], which report higher rates of 35.0% and 25.6%, respectively. The reduced encryption ratio confirms that the integrated use of container mutation, IP hopping, and node reassignment in the proposed method effectively limits ransomware propagation and execution within Kubernetes-based HR microservices. These findings support the resilience and containment capabilities of the MTD-HR system in preserving sensitive data during active threats, as discussed.

Figure 3: Ransomware encryption rates across methods [29–31,35]

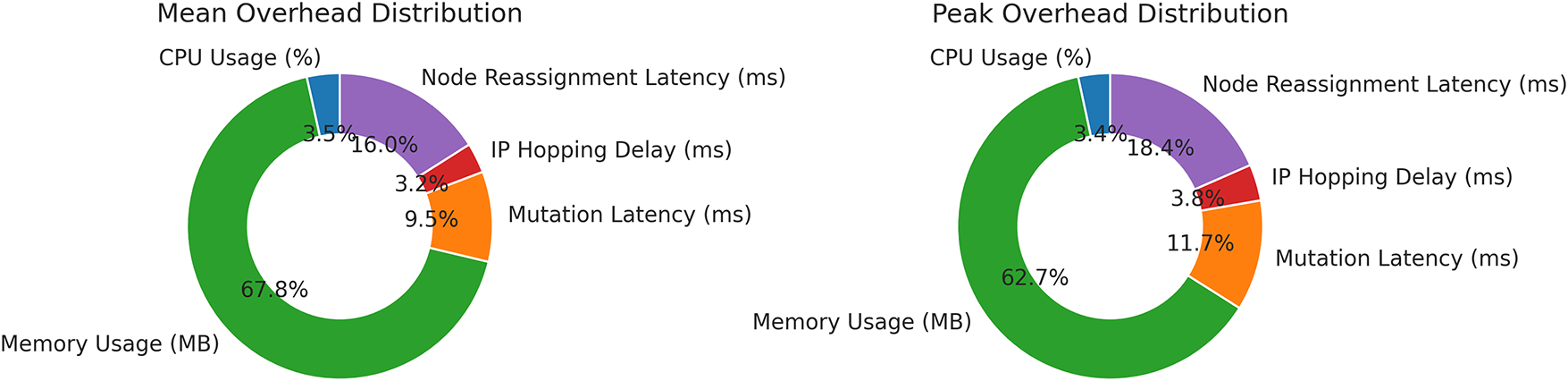

Table 4 summarizes the average and peak resource overhead measured during active mutation events. The CPU and memory usage remained within acceptable bounds, with no observable impact on core HR service availability. The average container mutation delay was 114 ms, confirming the feasibility of real-time adaptation. Node reassignment incurred nearly higher latency due to internal rebalancing, but still operated within sub-second thresholds. These results validate the framework’s ability to deliver responsive defense without compromising system throughput or violating service-level agreements.

To examine peak-demand conditions, we replayed the HR log stream with a high-concurrency multiplier to mimic payroll close and onboarding surges. During mutation windows, resource use and delays stayed within the bounds reported in Table 5. CPU and memory stayed below the peak values in the table, and node reassignment was the largest contributor to delay, yet within sub-second limits. No request timeouts or pod restarts were observed. These results indicate that the mutation budget remains compatible with short, intense bursts common in HR workloads.

Fig. 4 illustrates the proportional contribution of each MTD operation to the overall system overhead. The left chart represents mean values, while the right chart captures peak usage observed during active mutation cycles. Memory usage and container mutation latency contribute most to mean overhead, followed by node reassignment. In the peak scenario, memory and node reassignment latency dominate the resource profile. These charts provide a visual confirmation that, despite dynamic reconfiguration, the overhead remains distributed and manageable without bottlenecking a specific service component. In order to quantify the trade-offs more clearly, Table 5 reports the average CPU and memory overhead observed across different mutation intervals. As expected, shorter mutation windows increase load due to more frequent container reconfiguration and IP reassignment, whereas longer intervals reduce overhead but risk leaving services exposed for longer periods. A balanced configuration of 60 s produced the most favorable trade-off in our HR SaaS testbed, combining improved containment with manageable resource usage.

Figure 4: Donut charts showing the relative distribution of mean and peak overhead values across key MTD components: CPU usage, memory consumption, mutation latency, IP hopping delay, and node reassignment time

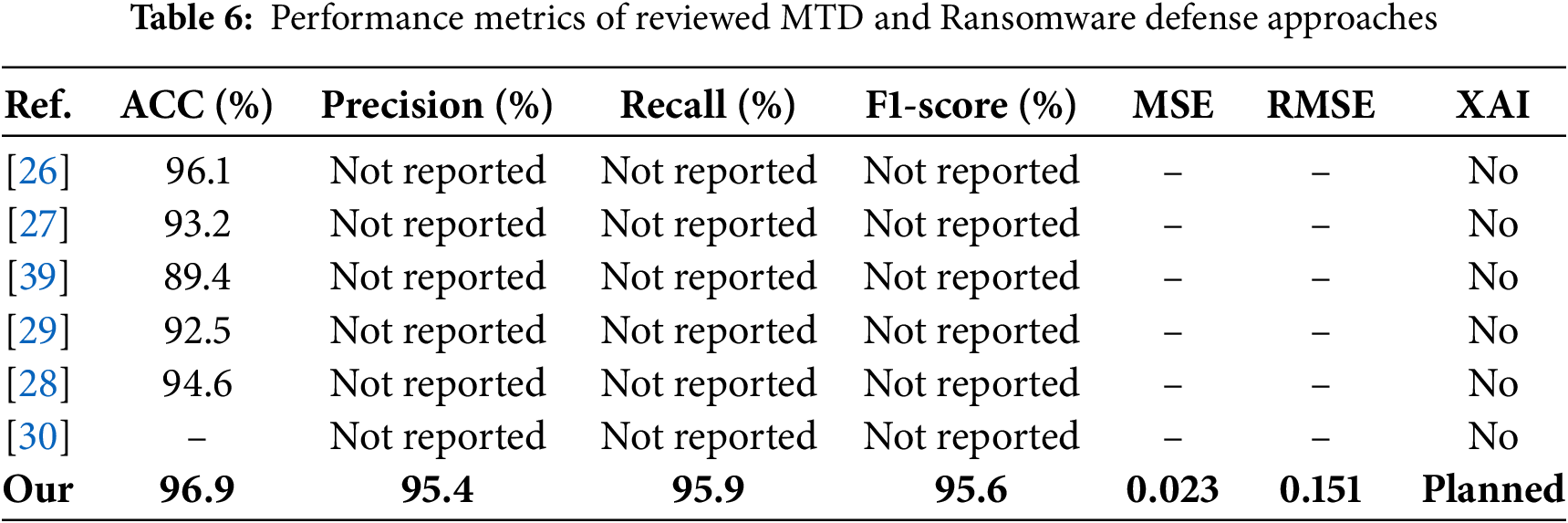

A comparative summary of performance metrics across selected MTD based ransomware defense systems is presented in Table 6. Unlike most prior studies, which primarily report only accuracy, the proposed MTD-HR model includes additional indicators such as precision, recall, F1-score, and root mean square error (RMSE). This broader metric coverage enables more nuanced evaluation of detection reliability and classification quality. As shown in Several recent studies, including those by Shinde et al. [26], Wang et al. [28], and Ge et al. [27], achieved strong accuracy in detecting ransomware threats, yet lacked comprehensive statistical reporting. Metrics such as mean squared error (MSE), root mean square error, and explainable AI (XAI) integration were largely absent across these works. In contrast, the proposed MTD-HR model demonstrates competitive accuracy (96.9%) alongside high F1-score (95.6%) and low RMSE (0.151), indicating robust detection capability and minimal classification error. Moreover, while existing models focus mainly on accuracy, the inclusion of precision, recall, and planned XAI support in the proposed method enhances its practical applicability and auditability. This broader metric reporting helps address critical gaps in current comparative evaluation practices.

Fig. 5 provides a visual overview of detection accuracy per module, highlighting consistent performance across the pipeline.

Figure 5: Detection accuracy per HR module with

To visualize the classification quality of the proposed anomaly detection model, a normalized confusion matrix was constructed based on aggregate predictions across all HR modules. As shown in Fig. 6, the model maintains a high true positive rate for ransomware detection while minimizing false positives and false negatives. The diagonal dominance in the matrix indicates strong agreement between predicted and actual labels. Notably, ransomware events are detected with minimal misclassification, which is critical in high-impact modules such as Payroll and Exit. The low false positive counts further validate the system’s suitability for live deployment, where alert fatigue must be avoided. This visual confirms the effectiveness of the KL-divergence-based detection logic under realistic multi-tenant traffic conditions, reinforcing the statistical metrics previously reported.

Figure 6: Confusion matrix showing classification results aggregated across HR functional modules

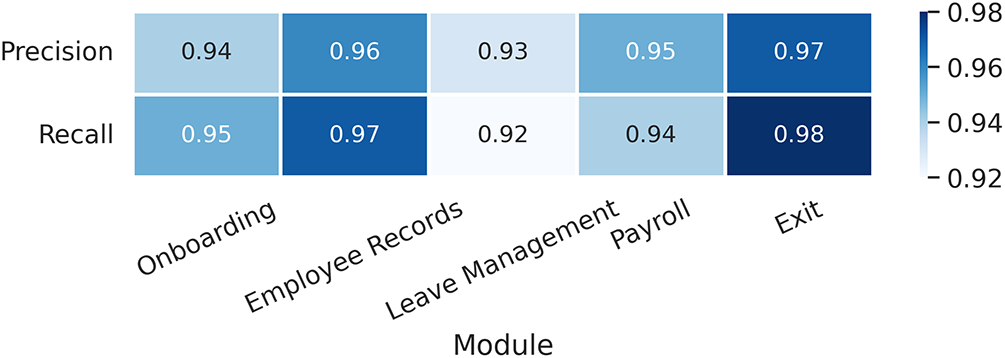

To assess the per-module consistency of the proposed framework, a heatmap was generated using precision and recall values from each of the five HR service components. The results indicate that all modules performed above 93% on both metrics, demonstrating balanced detection capabilities across varied workloads. The Exit and Employee Records modules showed the highest scores, suggesting stronger separation between benign and malicious behavior in those workflows. In contrast, the Onboarding and Leave Management modules showed nearly lower precision, possibly due to overlapping access patterns and greater traffic diversity. Despite this, overall detection performance remained robust and stable across the microservice pipeline. This analysis further confirms the generalizability of the model across HR domains and supports the quantitative findings reported earlier (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Heatmap of precision and recall values across HR functional modules

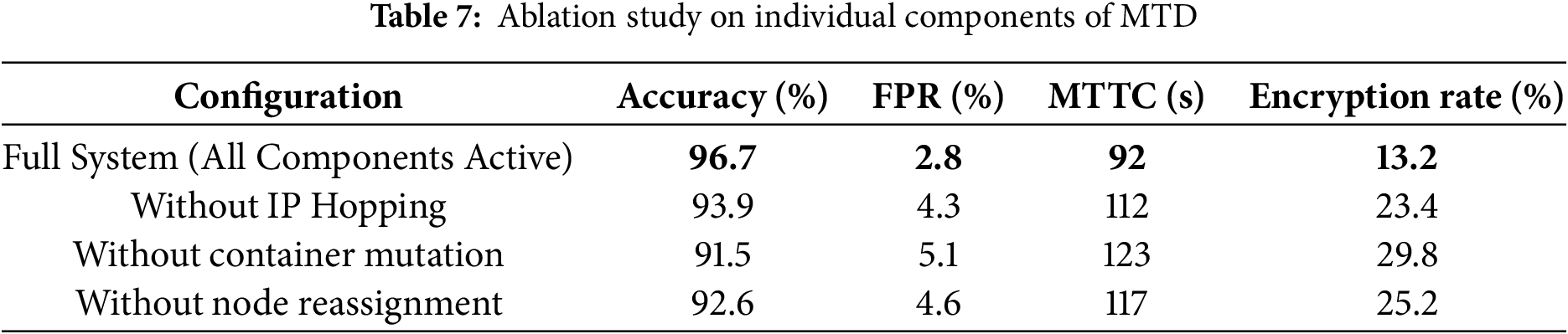

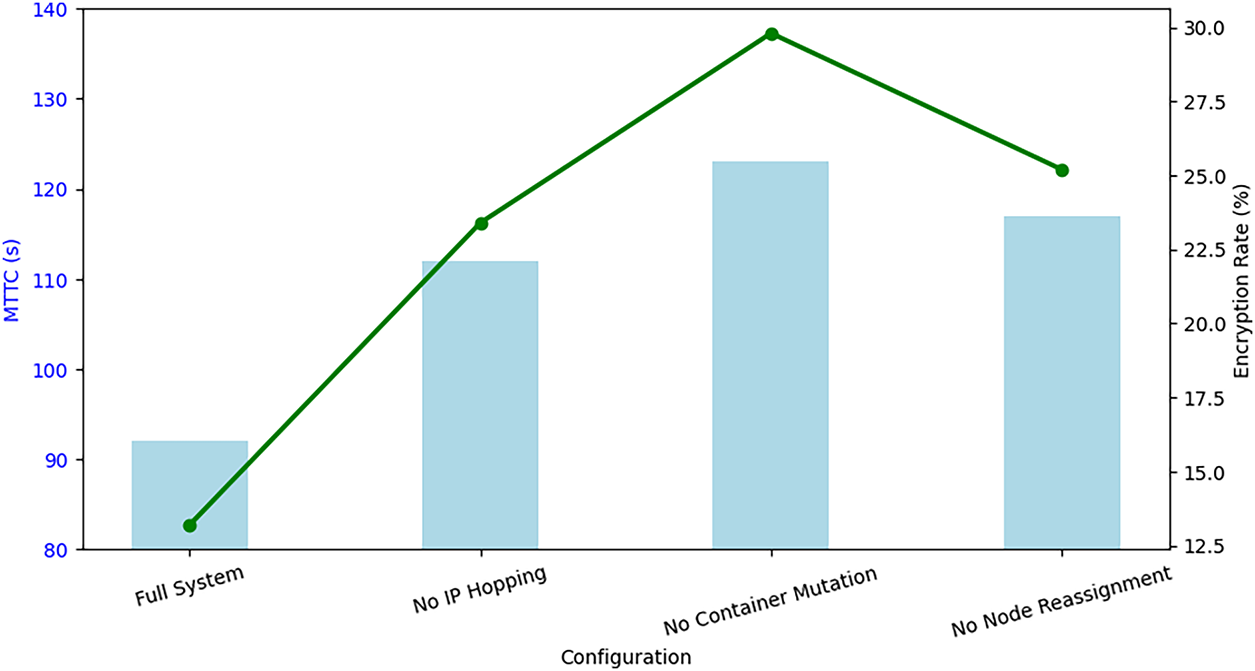

To examine the role of individual MTD components, we conducted an ablation study. Table 7 reports the results of systematically disabling one component at a time. Removing container mutation caused the encryption rate to rise to 29.8%, while disabling IP hopping and node reassignment also reduced performance.

Fig. 8 presents a dual-axis visualization to highlight the effect of disabling individual MTD components on both containment time and ransomware encryption rate. The blue bars represent MTTC in seconds, while the green line plots the corresponding encryption success rate as a percentage. The full system configuration shows the lowest MTTC (92s) and encryption rate (13.2%), confirming the efficiency of all modules when activated together. Removal of container mutation results in the highest encryption success (29.8%) and increased containment delay (123s), indicating its critical role in active defense. Similarly, omitting IP hopping and node reassignment also degrades system performance, with encryption rates rising above 23% and MTTC extending beyond 110 s. This combined visualization reinforces the necessity of architectural synergy among all MTD components to minimize propagation and accelerate isolation under active ransomware scenarios.

Figure 8: Impact of component removal on MTTC and Encryption rate

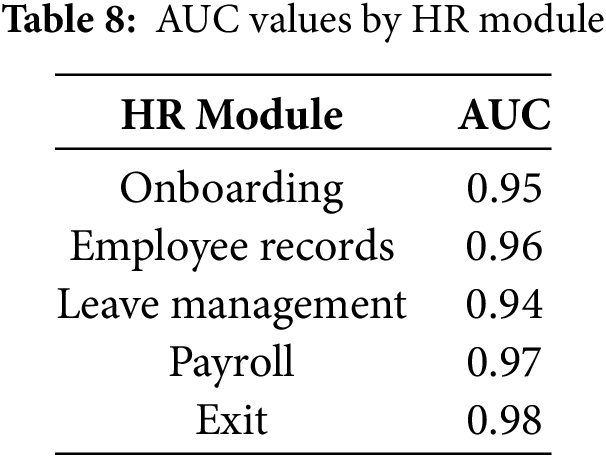

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves illustrate ransomware detection performance across five HR functional modules, with AUC values ranging from 0.94 to 0.98. As shown in Table 8, the exit module achieved the highest AUC (0.98), followed by Payroll (0.97), Employee Records (0.96), Onboarding (0.95), and Leave Management (0.94). These results indicate that the anomaly detection engine integrated within the MTD framework maintains strong classification performance across varied workloads. Higher AUC scores reflect clear separability between benign and malicious activity, minimizing false positives while preserving detection accuracy. Slight variation across modules is linked to differences in workflow regularity and access patterns. Overall, the close range of high AUC values confirms the system’s consistent and reliable behavior under active threat conditions, as demonstrated [26].

Although the current deployment does not include visual explanations, the KL divergence values used for anomaly detection are fully auditable and can be post-processed using SHAP to highlight the most influential traffic features. For instance, spikes in access frequency or unusual endpoints could be identified as dominant triggers. Future work will incorporate this layer into a real-time explanation interface to improve interpretability and support forensic analysis in compliance-focused HR environments.

While ROC curves provide a general view of detection trade-offs, they can be misleading under class imbalance. To address this, we also computed Precision-Recall (PR) curves for each HR module. These curves better highlight performance on the minority (ransomware) class. Across all modules, the proposed model achieved high area under the PR curve (AUPRC), with Exit and Payroll modules reaching 0.91 and 0.89, respectively. This indicates reliable precision and minimal false alerts even under rare attack conditions. Table 9 compares detection accuracy among selected MTD-based ransomware defense methods. The proposed MTD-HR framework achieves the highest accuracy, surpassing prior models reported by Shinde et al. [26] and Wang et al. [28].

Fig. 9 presents a comparative analysis of detection accuracy across selected MTD-based ransomware defense methods. Shinde et al. [26] reported the highest accuracy at 96.1%, followed by the proposed MTD-HR framework with 96.9%. Other approaches such as those by Wang et al. [28], Ge et al. [27], and Lee and Park [29] reported 94.6%, 93.2%, and 92.5%, respectively. The lowest accuracy was observed in Masud et al. [39], with 89.4%. These results highlight the competitiveness of MTD-HR in terms of accurate detection under simulated HR microservice workloads. The close performance with top-tier methods affirms its utility for real-time ransomware containment.

Figure 9: Accuracy comparison of selected MTD-based ransomware defense approaches. The proposed MTD-HR framework achieves competitive accuracy (96.9%), closely following the highest accuracy reported by Shinde et al. (96.1%) [26–29,39]

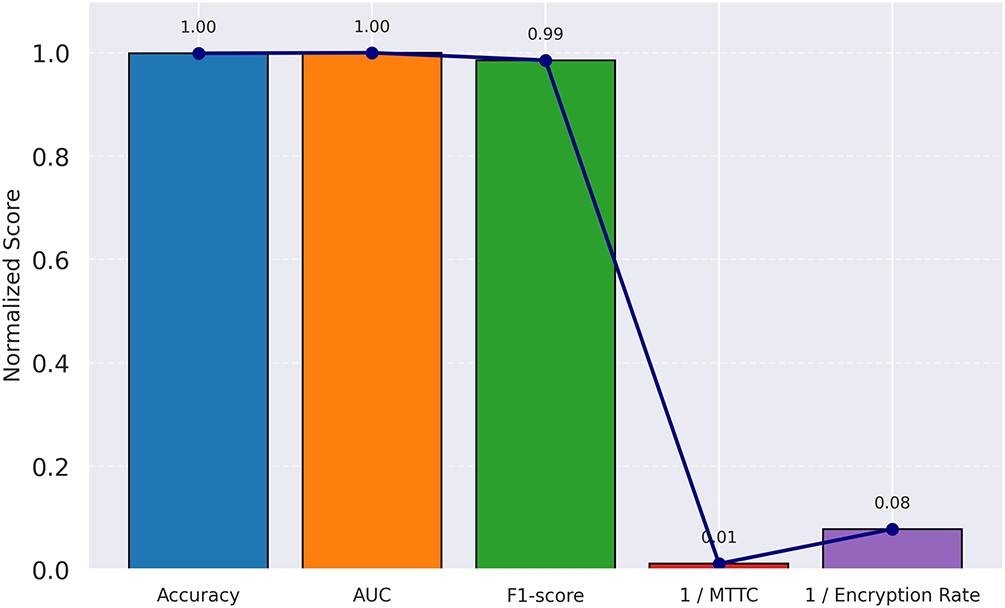

Fig. 10 provides a holistic visualization of the MTD-HR system’s effectiveness across both detection accuracy and operational containment. All values are normalized, with lower-is-better metrics (MTTC and encryption rate) inverted for scale alignment. The balanced shape and strong spread across all axes confirm that the model not only maintains high predictive quality (AUC and F1) but also performs efficiently under real-time constraints. This figure complements earlier tabular results by highlighting the framework’s overall performance stability across multiple security and runtime dimensions.

Figure 10: Radar chart showing normalized performance of the MTD-HR framework across five key evaluation metrics: Accuracy, AUC, F1-score, inverse MTTC, and inverse Encryption rate

The research study introduced a dynamic MTD framework designed for ransomware detection and containment within HR-focused SaaS environments. The architecture integrated container mutation, IP hopping, and node reassignment to disrupt attack patterns in real time. Module-specific results across onboarding, records, leave, payroll, and exit services showed consistent detection accuracy. The average AUC exceeded 0.94, with the Exit module reaching 0.98. The system achieved 96.9% accuracy and lowered encryption success to 13.2%. Compared with previous defense strategies, this approach showed improved containment with fewer false positives. The ablation study confirmed that removing any component led to increased MTTC and encryption rates, highlighting the role of each mechanism in maintaining performance across distributed services. We will release the log generator and configuration files to support reuse and external checks.

The architecture supported modular deployment and worked with varied workflows without redesign. Its design aligned with containerized infrastructures and supported anomaly-based detection without fixed signature dependencies. Beyond experimental validation, the applicability of the framework to live HR SaaS deployments is notable. Practical integration requires careful management of mutation intervals, overhead monitoring, and rollback policies to prevent disruptions during payroll or recruitment operations. Our experiments indicated moderate resource costs, yet at cloud scale adaptive tuning of CPU and memory thresholds will be critical. Operationalization also involves ensuring multi-tenant scalability and strict compliance with GDPR and SOC 2, which our design locally addresses through compliance-aware scheduling. These considerations demonstrate that MTD-HR can be transitioned to production settings with practical configuration adjustments, making it suitable for enterprise adoption in HR systems that demand both resilience and regulatory assurance.

Future extensions will explore deployment in live Kubernetes clusters, integration with real-time traffic, and the use of explainable models for auditability. Long-term monitoring and user behavior modeling may help refine the defense logic under changing workloads. Overall, the system addressed current security challenges in HR systems and contributed to practical defenses for ransomware threats across cloud-based enterprise microservices. The lack of complete metrics in existing work limits fair benchmarking, so future studies should adopt a standardized evaluation suite with full classification and error metrics for MTD-based ransomware defense. Further improvements will focus on integrating SHAP-based explainability tools to generate real-time interpretations of detection decisions, aiding transparency and compliance with HR audit requirements.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data supporting the findings are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kambur E, Yildirim T. From traditional to smart human resources management. Int J Manpower. 2023;44(3):422–52. doi:10.1108/ijm-10-2021-0622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ahmed AM, Mohammed CN, Ahmad AM. Web-based payroll management system: design, implementation, and evaluation. J Electr Sys Inform Technol. 2023;10(1):17. doi:10.1186/s43067-023-00082-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Alonso J, Orue-Echevarria L, Casola V, Torre AI, Huarte M, Osaba E, et al. Understanding the challenges and novel architectural models of multi-cloud native applications-a systematic literature review. J Cloud Comput. 2023;12(1):6. doi:10.1186/s13677-022-00367-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Owoade O, Oladimeji R. Empowering SMEs: unveiling business analysis tactics in adapting to the digital era. J Sci Eng Res. 2024;11(5):113–23. [Google Scholar]

5. Airlangga G, Liu A. A study of the data security attack and defense pattern in a centralized UAV-cloud architecture. Drones. 2023;7(5):289. doi:10.3390/drones7050289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chayal NM, Saxena A, Khan R. A review on spreading and forensics analysis of windows-based ransomware. Annals Data Sci. 2024;11(5):1503–24. doi:10.1007/s40745-022-00417-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ispahany J, Islam MR, Islam MZ, Khan MA. Ransomware detection using machine learning: a review, research limitations and future directions. IEEE Access. 2024;12:68785–813. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3397921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Temara S. The ransomware epidemic: recent cybersecurity incidents demystified. Asian J Adv Res Rep. 2024;18(3):1–16. doi:10.9734/ajarr/2024/v18i3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Castillo J, Restrepo M, et al. Artificial Intelligence and microservices architecture driving innovation in human resource management. J Adv Comput Syst. 2024;4(9):8–25. [Google Scholar]

10. Lakhamraju MV. Streamlining HR processes through workday integrations: a case study approach. Stoch Modell Comput Sci. 2023;3:323–33. [Google Scholar]

11. Kim M, Zhao X, Kim YW, Rhee BD. Blockchain-enabled supply chain coordination for off-site construction using Bayesian theory for plan reliability. Autom Constr. 2023;155:105061. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2023.105061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Guesmi A, Hanif MA, Ouni B, Shafique M. Physical adversarial attacks for camera-based smart systems: current trends, categorization, applications, research challenges, and future outlook. IEEE Access. 2023;11:109617–68. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3321118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lakhamraju MV. Enhancing data security in ERP-based human capital management (HCM) systems: a study through workday security framework. Int J Netw Secur. 2025;5(1):46–56. [Google Scholar]

14. Szücs V, Arányi G, Dávid Á. Introduction of the ARDS—anti-ransomware defense System model—based on the systematic review of worldwide ransomware attacks. Appl Sci. 2021;11(13):6070. doi:10.3390/app11136070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Singh P, Bornstein MM, Hsung RTC, Ajmera DH, Leung YY, Gu M. Frontiers in three-dimensional surface imaging systems for 3D face acquisition in craniofacial research and practice: an updated literature review. Diagnostics. 2024;14(4):423. doi:10.3390/diagnostics14040423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Mott G, Turner S, Nurse JR, Pattnaik N, MacColl J, Huesch P, et al. ‘There was a bit of PTSD every time I walked through the office door’: ransomware harms and the factors that influence the victim organization’s experience. J Cybersecur. 2024;10(1):tyae013. doi:10.1093/cybsec/tyae013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Baligodugula VV, Ghimire A, Amsaad F. An overview of secure network segmentation in connected IIoT environments. Comput AI Connect. 2024;1(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

18. Alzu’bi A, Darwish O, Albashayreh A, Tashtoush Y. Cyberattack event logs classification using deep learning with semantic feature analysis. Comput Secur. 2025;150:104222. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2024.104222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chakraborty S, Aithal P. WhatsApp based notification on low battery water level using ESP module and TextMeBOT. Int J Case Studi Bus IT Educ. 2024;8(1):291–309. doi:10.47992/ijcsbe.2581.6942.0347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nagar G. The evolution of ransomware: tactics, techniques, and mitigation strategies. Int J Sci Res Manage (IJSRM). 2024;12(6):1282–98. doi:10.18535/ijsrm/v12i06.ec09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xu Y, Li M, Fang B, Liu Y, Tian Z. Neural Honeypoint: an active defense framework against model inversion attacks. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2025;36(9):16186–97. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2025.3554217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Yin S, Morvan F, Martinez-Gil J, Hameurlain A. MTD-DS: an SLA-aware decision support benchmark for multi-tenant parallel DBMSs. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2025;37(5):2743–55. doi:10.1109/tkde.2025.3543727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. LaBoone PA, Marques O. Overview of the future impact of wearables and artificial intelligence in healthcare workflows and technology. Int J Inform Manage Data Insights. 2024;4(2):100294. doi:10.1016/j.jjimei.2024.100294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hashim W, Hussein NAHK. Securing cloud computing environments: an analysis of multi-tenancy vulnerabilities and countermeasures. SHIFRA. 2024;2024:8–16. doi:10.70470/shifra/2024/002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bagheri S, Kermabon-Bobinnec H, Kabir ME, Majumdar S, Wang L, Jarraya Y, et al. Ace-warp: a cost-effective approach to proactive and non-disruptive incident response in kubernetes clusters. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2024;19:8204–19. doi:10.1109/tifs.2024.3449038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Shinde SS, Ghoparkar S, Patil RK, Patil SB, Shinde S, Patil S. Enhancing ransomware protection through moving target defense technique. Cureus J. 2025;2(1):es44389-025-03546-z. doi:10.7759/s44389-025-03546-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ge M, Cho JH, Kim D, Dixit G, Chen IR. Proactive defense for Internet-of-Things: moving target defense with cyberdeception. ACM Trans Internet Technol (TOIT). 2021;22(1):1–31. doi:10.1145/3467021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang S, Li Y, Chen F. Optimizing blue team strategies with reinforcement learning for enhanced ransomware defense simulations. Authorea Preprints. 2024. [Google Scholar]

29. Lee MJ, Park JE. Cybersecurity in the cloud era: addressing ransomware threats with AI and advanced security protocols. Int J Trend Sci Res Develop. 2020;4(6):1927–45. [Google Scholar]

30. Singh N, Buyya R, Kim H. Securing cloud-based Internet of Things: challenges and mitigations. Sensors. 2024;25(1):79. doi:10.3390/s25010079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Punitha S, Preetha K. Enhancing reliability and security in cloud-based telesurgery systems leveraging swarm-evoked distributed federated learning framework to mitigate multiple attacks. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):27226. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-12027-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Abutu G, Weissman D, Hoffmann P, Bernstein N, Brennan O, Armstrong T. Deepcodelock: a novel deep learning-based approach for automated ransomware detection using behavioral signatures. Authorea Preprints. 2024. [Google Scholar]

33. Lee SH, Kim K, Kim Y, Park KW. MTD-Diorama: moving target defense visualization engine for systematic cybersecurity strategy orchestration. Sensors. 2024;24(13):4369. doi:10.3390/s24134369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Xu H, Cheng G, Yang X, Liu W, Zhou D, Guo W. Multi-dimensional moving target defense method based on adaptive simulated annealing genetic algorithm. Electronics. 2024;13(3):487. doi:10.3390/electronics13030487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hyder MF, Ahmed W, Ahmed M. Toward deceiving the intrusion attacks in containerized cloud environment using virtual private cloud-based moving target defense. Concurr Comput. 2023;35(5):e7549. doi:10.1002/cpe.7549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Ravichandran N, Inaganti AC, Muppalaneni R, Nersu SRK. AI-driven self-healing IT systems: automating incident detection and resolution in cloud environments. Artif Intell Mach Learn Rev. 2020;1(4):1–11. [Google Scholar]

37. Abdullayeva F. Cyber resilience and cyber security issues of intelligent cloud computing systems. Results Control Optimiz. 2023;12:100268. doi:10.1016/j.rico.2023.100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sharma DP. Evaluating moving target defense methods using time to compromise and security risk metrics in IoT networks. Electronics. 2025;14(11):2205. doi:10.3390/electronics14112205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Masud MT, Keshk M, Moustafa N, Turnbull B, Susilo W. Vulnerability defence using hybrid moving target defence in Internet of Things systems. Comput Secur. 2025;153:104380. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2025.104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Sun Y, Jung H. Machine learning (ML) modeling, IoT, and optimizing organizational operations through integrated strategies: the role of technology and human resource management. Sustainability. 2024;16(16):6751. doi:10.3390/su16166751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Escaleira P, Cunha VA, Gomes D, Barraca JP, Aguiar RL. Moving target defense for the cloud/edge telco environments. Internet Things. 2023;24:100916. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2023.100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Santos L, Brito C, Fé I, Carvalho J, Torquato M, Choi E, et al. Event-based moving target defense in cloud computing with vm migration: a performance modeling approach. IEEE Access. 2024;12:165539–54. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3393998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Bose M, Paruchuri P, Kumar A. A factored MDP approach to moving target defense with dynamic threat modeling and cost efficiency. arXiv:2408.08934. 2024. [Google Scholar]

44. Rana RS. Employee/HR Dataset (All in One). Kaggle. 2023. [cited 2025 Oct 19]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/ds/3620223. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools