Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

FSL-TM: Review on the Integration of Federated Split Learning with TinyML in the Internet of Vehicles

1 Bhagwan Parshuram Institute of Technology, GGSIPU, Rohini, New Delhi, 110089, India

2 Chitkara University Institute of Engineering and Technology, Chitkara University, Rajpura, Punjab, 140401, India

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, School of Engineering and Technology, Central University of Haryana, Mahendergarh, Haryana, 123031, India

* Corresponding Author: Vikas Khullar. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integrating Split Learning with Tiny Models for Advanced Edge Computing Applications in the Internet of Vehicles)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072673

Received 01 September 2025; Accepted 31 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

The Internet of Vehicles, or IoV, is expected to lessen pollution, ease traffic, and increase road safety. IoV entities’ interconnectedness, however, raises the possibility of cyberattacks, which can have detrimental effects. IoV systems typically send massive volumes of raw data to central servers, which may raise privacy issues. Additionally, model training on IoV devices with limited resources normally leads to slower training times and reduced service quality. We discuss a privacy-preserving Federated Split Learning with Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML) approach, which operates on IoV edge devices without sharing sensitive raw data. Specifically, we focus on integrating split learning (SL) with federated learning (FL) and TinyML models. FL is a decentralised machine learning (ML) technique that enables numerous edge devices to train a standard model while retaining data locally collectively. The article intends to thoroughly discuss the architecture and challenges associated with the increasing prevalence of SL in the IoV domain, coupled with FL and TinyML. The approach starts with the IoV learning framework, which includes edge computing, FL, SL, and TinyML, and then proceeds to discuss how these technologies might be integrated. We elucidate the comprehensive operational principles of Federated and split learning by examining and addressing many challenges. We subsequently examine the integration of SL with FL and various applications of TinyML. Finally, exploring the potential integration of FL and SL with TinyML in the IoV domain is referred to as FSL-TM. It is a superior method for preserving privacy as it conducts model training on individual devices or edge nodes, thereby obviating the necessity for centralised data aggregation, which presents considerable privacy threats. The insights provided aim to help both researchers and practitioners understand the complicated terrain of FL and SL, hence facilitating advancement in this swiftly progressing domain.Keywords

The Internet of Vehicles (IoV) refers to a network containing various edge devices that can gather, transmit, and manage data. It often comes with Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) to ensure that automated vehicle control approaches are safe and responsible. This consists of combined sensors mainly found in vehicles and are connected to individuals, systems, and their surroundings [1]. The increasing interconnection of IoV systems with the internet has increased the possible attack vectors and exploitation opportunities for adversary actors. An attack on compromised systems may lead to personal injuries or physical damage [2,3]. The potential consequences of inadequate security measures are catastrophic, including the loss of life. Additionally, the information generated by IoV devices is often private and needs to be kept private. Traditional centralised ML methods are often impractical due to issues with latency, bandwidth limitations, and privacy considerations [4].

Various deep learning (DL) models have been implemented, and other academics have proposed different frameworks to address the aforementioned problems [5]. Prior studies have examined a range of threat mitigation strategies in IoV domain to stop unwanted access to vehicle communication data and network resources, including encryption, authentication, and authorization protocols [6,7], Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) [8], attention networks [9,10] have been utilized to monitor IoV environments in real time, making decisions, expediting the prompt identification of threats and enabling quick interventions to protect data and infrastructure However, sometimes conventional IDS methodologies often need extensive data transfer to centralized servers for processing, hence introducing potential vulnerabilities that attackers may exploit [11]. Moreover, identification of theft using Blockchain technology has been investigated to ensure an immutable transaction record and to mitigate data tampering. Further, Issues related to data privacy FL [12] and SL [13] have attracted significant attention within privacy-preserving learning systems.

FL facilitates the collaborative training of a shared DL model among numerous clients, maintaining localised training data and exchanging just gradients to ensure privacy. Nonetheless, the increasing complexity and volume of DL models necessitated by the demand for superior performance in practical applications present significant obstacles. Nevertheless, conventional FL faces challenges in highly dynamic and resource-limited situations like the IoV, where vehicular mobility and hardware constraints adversely affect model performance and training stability [12,14,15]. So, SL is presented as an alternative to FL for collaborative training with limited resources. The main idea behind SL is to split a big model into smaller models that run on the client and the server. To follow data regulations, clients only do simple calculations and send intermediate-layer activations to the server instead of raw data.

SL is an ML technique that protects privacy by enabling the training of a model without disclosing the raw data to the central server. This approach splits the model between client and edge devices [16]. The primary difference between SL and FL is that consumers possess the entire model in FL, whereas in SL, clients have only a portion of the complete model. SL diminishes the computational burden on the client side and conserves bandwidth, rendering it exceptionally appropriate for IoV systems [4].

Federated Split Learning (FSL) is a new way of training that combines the best parts of FL and SL. It provides a decentralised learning framework that protects privacy, minimises resources and reduces communication cost [17]. Moreover, researchers are using small models or lightweight DL architectures to make FSL even more helpful in the IoV domain. TinyML models, such as TinyResNet, MiniMobileNet, EfficientNet-Lite, SqueezeNet, and MicroNet, are all lightweight models that perform best on edge devices with less memory and processing power. These models achieve an optimal equilibrium between accuracy and velocity, making them ideal for vehicular edge device deployment [18].

The recent emergence of FL and SL presents a viable option for creating innovative and privacy-conscious IoV systems utilising TinyML. It has been suggested that integration of FL and SL with TinyML (FSL-TM) could be used for a variety of possible applications of smart IoV, including finding obstructions/objects on the road, predicting traffic congestion, judging driver behaviour in real time without sharing the real-time sensitive data [19,20]. Implementing this collaborative strategy improves transportation services, speeding up the process to fix the problems that could happen in vehicle networks, like client mobility, location finding [21,22].

Motivation and Contribution

The IoV is an evolving domain. To make transportation systems safe and smart, they need to be able to process data in real time, have minimal latency, and protect people’s privacy. But IoV isn’t a good fit for typical ML methods that rely on centralised data aggregation because vehicle data is mobile, there aren’t many computing resources on board, and data is spread out in various ways [23]. FL and SL try to solve some of these problems, but they each have issues. FL has high local computation and communication costs, while SL doesn’t work well with multiple clients because it can’t scale or be resilient [13,24].

The motivation behind this paper is to explore FSL as a hybrid paradigm that combines the strengths of FL and SL while integrating TinyML to ensure compatibility with constrained vehicular hardware. Despite growing interest, a comprehensive review that consolidates architectural strategies, privacy challenges, edge-intelligence trade-offs, and application potential of FSL with TinyML in the IoV context is currently lacking. Although several studies have focused on FL and SL, further research remains needed. Existing work discusses these methods in depth, especially regarding FSL architecture, data services, and applications. The aim of this study is to provide an overview of current research and summarise the most advanced methods developed to integrate Split and FL in the IoV domain. As part of our research, we examine articles in related fields and thoroughly review the latest survey studies. We categorise FL survey topics, including communication costs, heterogeneity, and privacy/security as primary challenges. We also address FL and SL architectures, the integration of SL with FL, and TinyML. Additionally, we also discuss common issues, benefits, applications along with research directions. The main Contributions of the manuscript are as follows:

(1) The main objective of this paper is to look at and assess all the studies that have already been done on FL and SL.

(2) Discuss all the learning frameworks for IoV, such as edge computing, FL, SL, and Tiny ML.

(3) It will address the complete working principle of FL and SL while discussing various challenges and exploring how to address them.

(4) Finally, we will discuss how SL can be integrated with FL and Tiny ML and the advantages of FSL over ML, DL, and FL.

The following research questions (RQs) were formulated to accomplish the aim and objective of the review.

Q1. What are various learning frameworks for IoV domain?

Q2. How Split learning can be integrated with FL and TinyML.

Q3. What are the most promising application domains for FSL-TM in the IoV domain.

Q4. What are the open research challenges and future directions in deploying secure, lightweight, and adaptive FSL-TM models in IoV networks?

In this section, we discussed IoV learning frameworks such as edge computing, FL, SL, and TinyML, and how these frameworks enable real-time, on-device intelligence while addressing the latency and connectivity issues inherent to vehicular networks.

The IoV is an extension of the IoT that connects vehicles, roads, and people and shares information to create a smart transportation system. An IoV network has two parts: an intra-vehicular network and an inter-vehicular network [12,25].

There exist several types of communication networks in this topology:

• Vehicle to Vehicle (V2V): V2V connects cars wirelessly so they can share information and know about other vehicles around them from all angles. Since of all this communication and cooperation, there will be fewer crashes since the self-driving car (or the driver) will be told to do something [26].

• Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I): V2I is regarded as a dual-faceted communication network. The infrastructure facilitates bi-directional communication for the vehicle. In Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), travellers are connected to the proximate Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) infrastructure, for example. Road-Side Units (RSUs) and Base Stations (BSs) provide road data to enhance the driving experience based on destination [27]. The V2X infrastructure serves a subordinate function in supporting the On-board Units (OBUs) with computational processing. The offloading approach facilitates the transfer of work from cars to infrastructure in response to resource shortages that vehicles may experience. Upon job completion, the infrastructure transmits the execution result to the vehicle [28,29].

• Vehicle to Home (V2H): Vehicle-to-home refers to the utilisation of data and services originating from vehicle sensors, models, or infrastructure that usually occurs at the end user’s residence. V2H communications are highly sensitive to delay for safety messages, necessitate elevated reliability, and impose particular privacy restrictions concerning personal data. In edge deployments, V2H leverages low-latency processing at roadside or edge nodes to produce timely, contextually relevant messages while reducing bandwidth consumption and preserving user privacy [30].

• Infrastructure-to-Infrastructure (I2I): I2I is characterised by interconnected infrastructures designed to enhance computing, optimise network load-balancing, and allow information sharing. The components of this communication network primarily include a collection of BSs, RSUs, fog servers, and cloud servers [4,28,31].

2.2 Federated Learning Overview

Many nations are implementing laws to safeguard their citizens’ data as the likelihood of a data breach increases. In reaction to these circumstances, Google implemented the concept of FL to enable edge machine learning by preserving data privacy. FL facilitates collective model learning amid devices without transmitting data to a centralised server [32]. This procedure can be reiterated numerous times. This section summarises FL, elucidating the idea and emphasising its possible uses and advantages across several realms.

2.2.1 Federated Learning Definition

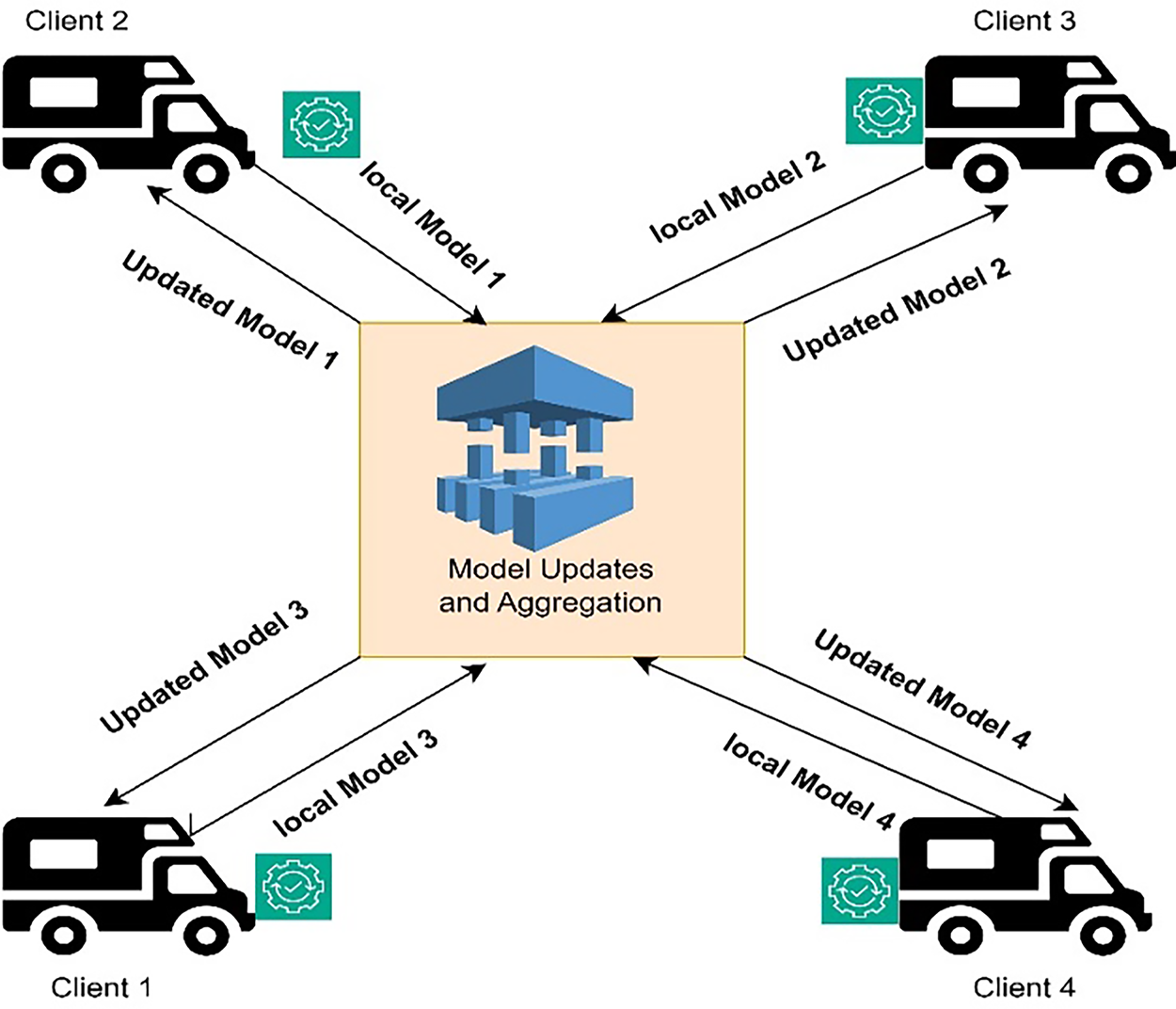

FL allows several parties to work together to train an ML model without having to directly share their local data. The topic includes diverse approaches from other academic domains, such as distributed systems, ML, and privacy [33,34]. In an FL architecture, many entities collaborate to train ML models without exchanging their raw data. The FL process in the IoV network is depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Federated learning process in IoV

2.2.2 Federated Learning Framework Components

This method trains the model locally and shares its local model with the aggregation server, as shown in Fig. 1. The aggregation server aggregates data/local model from multiple clients/edge devices, updates its data, and trains the model. This updated model is again shared by the aggregation server to all clients/edge devices, and devices update their information accordingly. FL is a decentralized training framework while maintaining data on its original device, thus minimizing data transfer rate and preserve raw data [35]. The important components required for an FL framework are discussed below [11,15,36].

• Client devices: Client devices like edge devices that store and process the data locally for model training, such as smartphones, tablets, any IoT device/sensor, and even a personal computer.

• Central server: The central server/aggregation server that aggregates all local models from the client devices and shares the global model with clients.

• Local models: A model trained with raw data locally on each client device with any ML model. Subsequently, shares this local model with the aggregation server.

• Global model: The central server/aggregation server compiles all of the local models kept on the client devices and trained and updated global model.

• Communication protocol: A communication protocol is used to ensure efficient communication between a client device and a central server while preserving sensitive data.

• Aggregation algorithm: The algorithm is executed on the central server, consolidating all local model updates from client and edge devices to enhance the global model.

Decentralised approaches are expected to become increasingly important as the digital world advances, making FL a key component of ML in the future.

FL offers privacy protection and lowers data transmission. Still, it places a heavy computational and communication load on edge devices, which may prevent it from being widely used in vehicle nodes with limited resources [35,37]. SL divides a neural network into several segments, thereby markedly alleviating client device computational load. SL is appropriate for resource-limited environments but is not scalable and frequently relies on continuous communication between clients and servers.

2.2.3 Federated Learning Classification

FL is an inventive ML technique that addresses concerns about data decentralisation and privacy by allowing several devices or organisations to collaborate in training ML models without disclosing their raw data. The FL technique can be categorized into three categories: horizontal FL (HFL), Vertical FL (VFL), and Federated transfer learning (FTL) [20].

• Horizontal FL: In this category, data is horizontally partitioned among clients, each holding a subset of the data with uniform characteristics. It works well when clients want to work together on a shared machine learning job without disclosing their complete datasets, and privacy is an issue. For example, different vehicles from different locations collect the same type of features with sensor data.

• Vertical FL: This architecture is applied to datasets that have complementary characteristics. Clients preserve unique characteristics in this methodology and collaborate to train a model jointly. It is beneficial in situations that necessitate the integration of features from diverse sources while ensuring the privacy of individual data pieces. For example, a vehicle manufacturer has information like braking data and engine performance, and an insurance company has information such as claim history and risk profile of the same drivers. Both parties trained an insurance risk assessment model with VFL without sharing data.

• Federated Transfer Learning: Federated Learning is integrated with transfer learning. Clients collaborate by exchanging a pre-trained model and refining it with their local data. This method benefits clients with related but distinct datasets and can utilise an existing pre-trained model. For example, sensors collect road condition data in Europe, while cameras in India are used. Knowledge learned from sensor-based pothole detection in Europe can be transferred to improve camera-based pothole detection in India, even with the data heterogeneity with FTL.

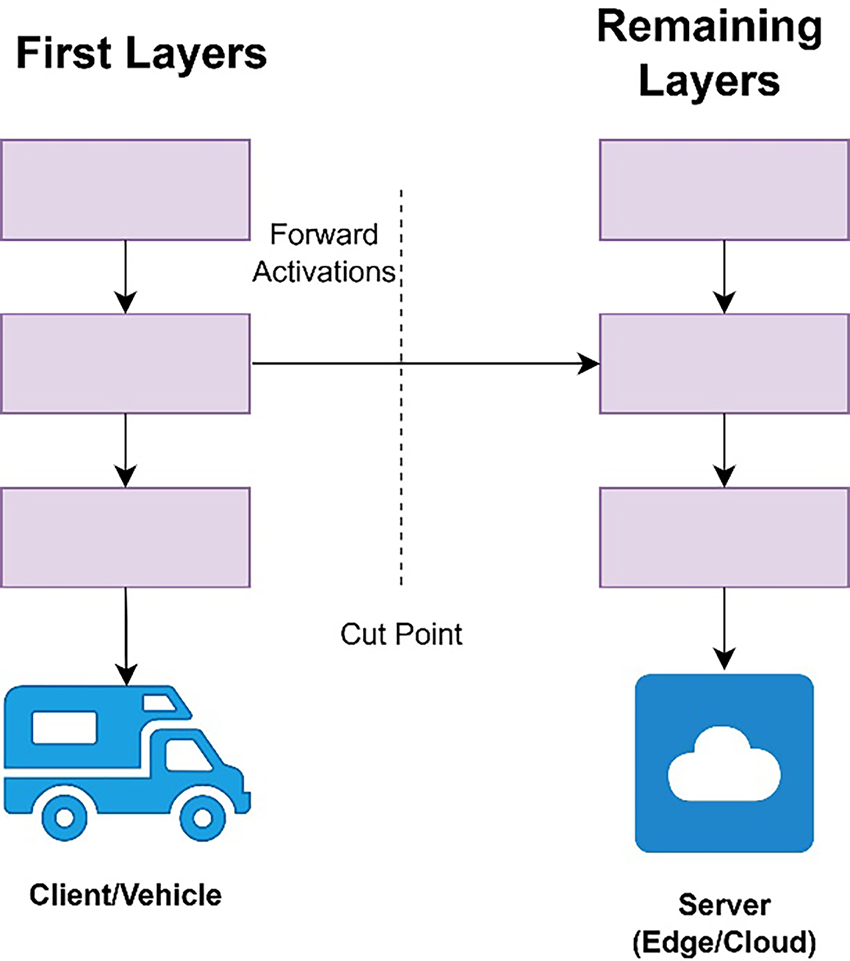

2.3 Overview of Split Learning

An SL framework’s general architecture is depicted in Fig. 2. ML models, usually neural networks, are split into two parts within the framework. These are the client-side and server-side models, which are run on a client and a server, respectively. This is similar to FL in that the raw training data is stored on the client rather than sent to the server. The comprehensive model training is conducted through a forward and backward propagation series. The client carries out forward propagation up to the cut layer, which is the final layer of the client’s model. The client uses the training data to input into the client model through forward propagation. The activations of the cut layer, referred to as corrupted data, are subsequently broadcast to the server, usually alongside the accompanying label. The server utilises the corrupted data obtained from the client as inputs for its server model and does forward propagation on the remaining components of the entire model. The server initiates the backward propagation process after the loss function has been computed. During this phase, the server computes gradients and updates the weights of each layer of the server’s model until it reaches the cut layer. The gradients of the aggregated data are then communicated back to the client by the server once they have been combined. After receiving the gradients from the server, the client will carry out backward propagation on the client’s model to complete a single iteration of backward propagation for the entire model. The forward and backward propagation continue until a convergence point is reached [38,39].

Figure 2: Split learning framework

In an SL design with many clients, data from different entities is used round-robin, where each client interacts with the server at a different time. Synchronising sub-models across multiple clients is needed to ensure model stability in multi-client supervised learning. Each client must change its model weights before starting the next training session. Client-side models can be synchronised in two modes: centralised mode and peer-to-peer mode. In the centralised mode, a client sends the weights of its newly acquired model to a third-party server, from which the next client in the training process receives the weights. In peer-to-peer mode, the server conveys the address of the most recently trained client to the current training client, which uses this address to connect to the prior client and obtain the model weights.

The rapidly expanding field of ultralow-power ML technologies and methods that deal with machine intelligence at the very edge of the cloud is encapsulated and fostered by TinyML (Tiny Machine Learning). The primary objective of TinyML is to implement cross-layer design methodologies and execute ML inference on ultra-low-power devices, such as microcontrollers or bespoke circuits that operate at or below one milliwatt and can sustain functionality for months, if not years, on a single battery charge. These integrated “tiny” ML applications necessitate comprehensive “full-stack” solutions encompassing hardware, systems, software, and apps, together with ML architectures, techniques, tools, benchmarks, and methodologies capable of executing on-device analytics. A diverse array of sensing modalities (visual, auditory, motion, environmental, and human health monitoring) is employed with exceptional energy efficiency, generally within the single milliwatt (or lower) power range, to facilitate machine intelligence at the intersection of the physical and digital realms [40]. A new world emerges with trillions of distributed intelligent gadgets empowered by energy-efficient ML technologies that sense, evaluate, and autonomously collaborate to foster a better and more sustainable environment for everyone [41].

Neural networks and other pertinent ML techniques and models were traditionally created to solve specific problems, primarily concentrating on computer vision applications like object identification and categorisation. In the past decade, we have observed an unprecedented revolution in applications addressing various inference problems, including natural language processing, intelligent data analytics near sensors, and the proliferation of smart devices projected to exceed 50 billion in the coming years. The majority of these devices incorporate various forms of ML inference, including continuous voice recognition and human activity detection. Concurrently, these devices are becoming more compact, rapid, energy-efficient, and, crucially, more affordable, thereby generating significant opportunities for a comprehensive ecosystem that encompasses multiple stakeholders from both academia and industry, transcending the conventional semiconductor sector, while simultaneously enhancing our society in economic, social, and scientific dimensions.

Benefits of Tiny ML

TinyML enhances accuracy, efficiency, and scalability by empowering machines to learn from information and make necessary decisions. Recently, TinyML has become a revolutionary framework in numerous application areas such as competent healthcare, agriculture, smart cities, and smart transportation. The subsequent benefits of employing TinyML methodologies are [42]:

Improving Privacy and Security: Sensitive data/information is used in ML to train a model. Privacy remains a significant obstacle to adopting ML technologies, as customers frequently hesitate to disclose or transmit their data online due to security apprehensions. TinyML facilitates real-time data processing on the device. In TinyML applications, the absence of data transmission or storage alleviates privacy concerns.

Reducing Latency: Data gathered by edge device sensors is analysed by an on-device ML model to produce the outcomes. Tiny ML models are optimised to minimise the number of parameters, eliminating delays associated with transmitting data to a datacenter server or cloud for processing. This thus leads to minimal latency (i.e., rapid turnaround time) from data acquisition to result production. TinyML apps operate in real time owing to their minimal latency for mission-critical tasks.

Low Energy Consumption: TinyML applications are expected to operate on resource-constrained devices, process real-time data, and generate results within data sampling intervals. TinyML models are optimized to operate with fewer parameters, minimize computations, and reduce power consumption in response to these needs.

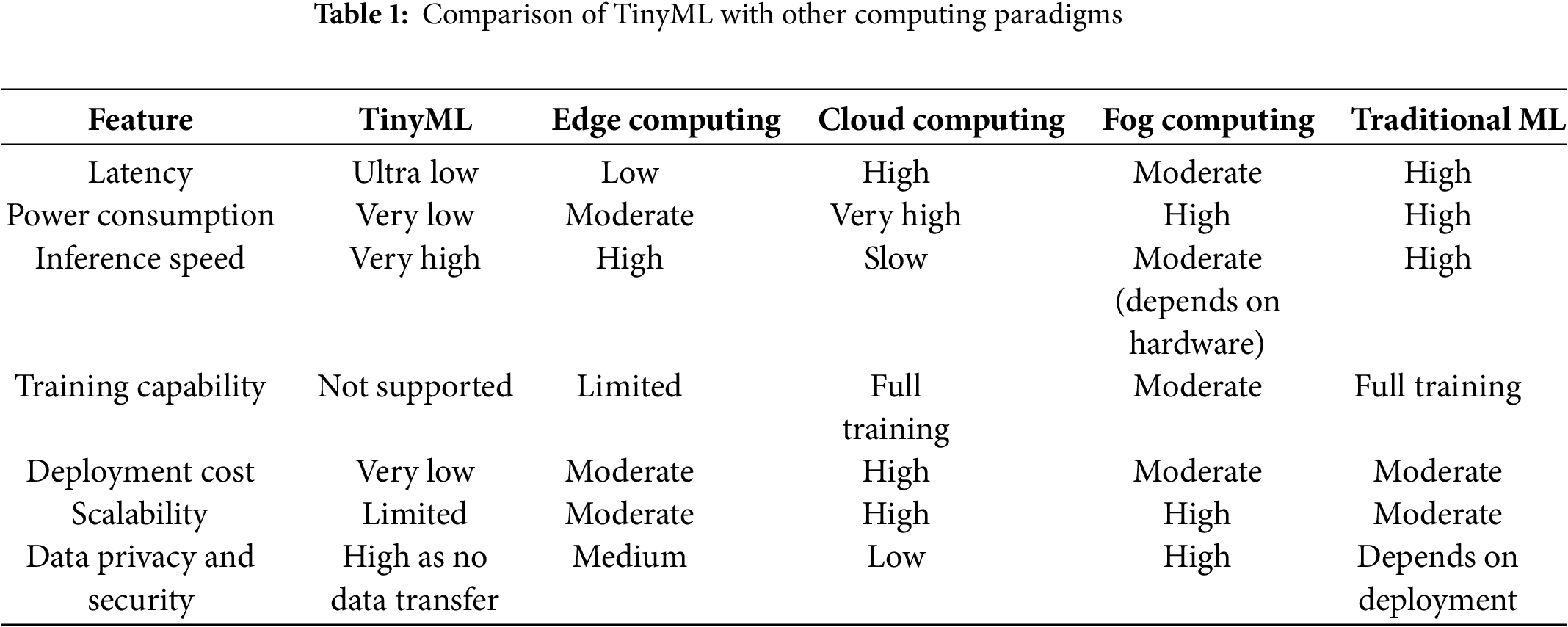

Reducing Bandwidth: TinyML applications are designed for small, resource-limited devices with minimal or no online connectivity. On-device sensors collect data, which is subsequently processed on the device, eliminating the need for raw sensor data transport bandwidth. Occasionally, inference or analytics results, constrained to hundreds of bytes, are communicated to the cloud, necessitating minimal bandwidth. Further, highlighting the benefits of TinyML over other approaches a comparative analysis is summarized in Table 1.

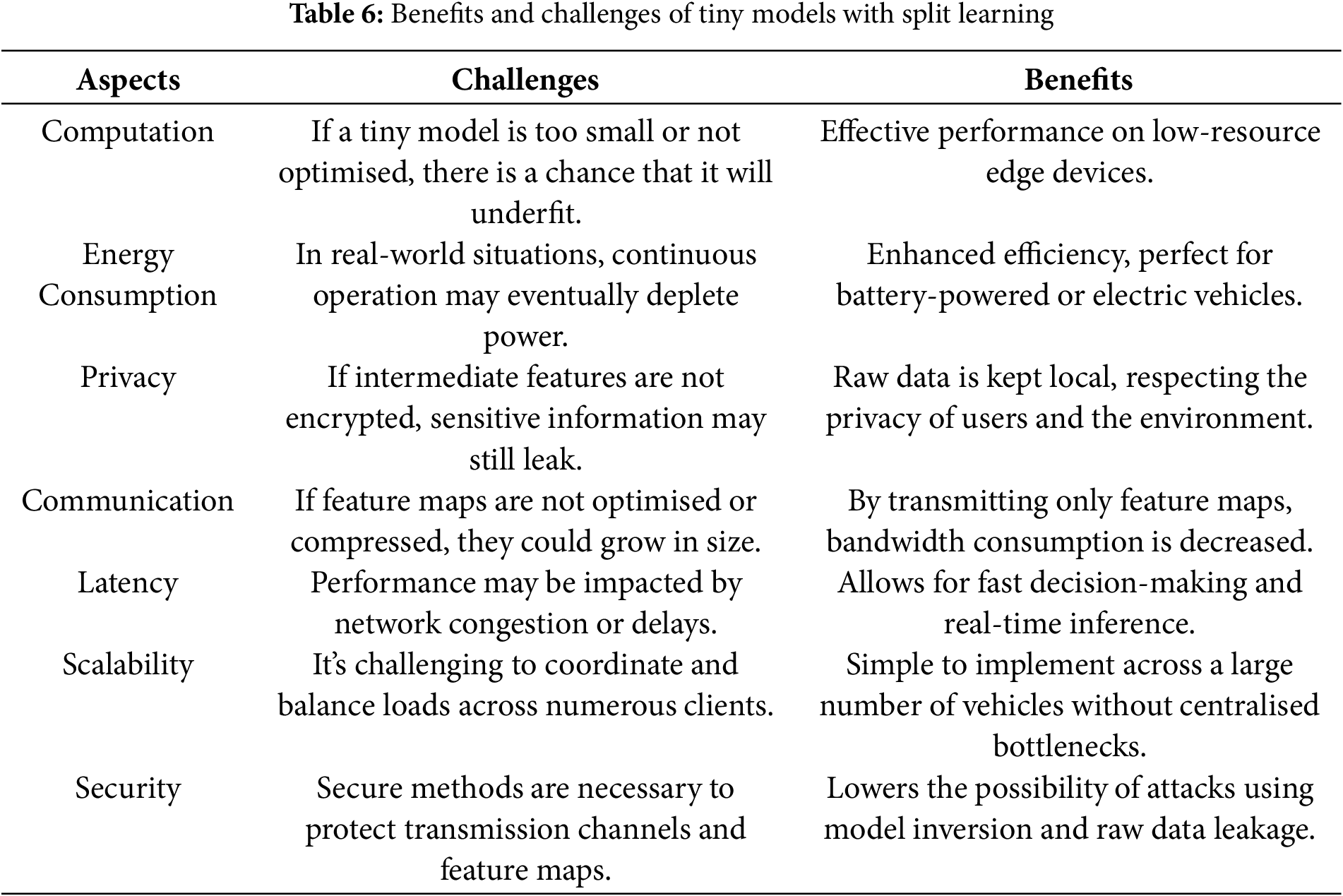

Numerous research studies have thoroughly examined FL across various application domains, including healthcare, industrial IoT, IoV and autonomous systems, highlighting vehicular networks’ data privacy, memory utilisation, and communication cost, Data privacy and model convergence [43–47]. Similarly, SL has been investigated in scenarios where model partitioning might alleviate computing demands on edge devices, simultaneously resolving data privacy issues and facilitating cooperative model training [48–51]. These works offer substantial insight into the prospective uses of FL and SL. In Table 2, we summarise the contributions of various researchers in the domain of related frameworks, such as FL and SL in IoV, FL with SL, TinyML with FL and SL. These studies have examined many parts of FL and SL, including types and methods, privacy and security challenges, edge computing, and model aggregation.

The FL process is greatly impacted by the tremendous mobility inherent in the IoV. Vehicles’ constant movement results in variations in the network bandwidth coverage. Liu et al. [52] employed a near-end FL strategy for vehicle edge computing, mitigating the effects of heterogeneity, although neglecting mobility and fluctuations in wireless links. Zhou et al. [53] introduced a resilient hierarchical FL framework called RoHFL, facilitating the successful implementation of hierarchical FL in the IoV. Xiao et al. [54] mitigated training delays and energy consumption by selecting clients based on data quality, optimising transmission and CPU power, and modelling channels. Yang et al. [55] proposed aggregation and communication compression techniques, improving vehicular mobility efficiency and stability. Liu et al. [56] developed a novel architecture for implementing FL in the IoV environment, mitigating prolonged learning delays attributed to bandwidth constraints, computational limits, and inconsistent connections due to vehicle motion. To satisfy the stringent latency demands of automotive networks, an approach was utilised in [57] to diminish the local models’ size before their upload.

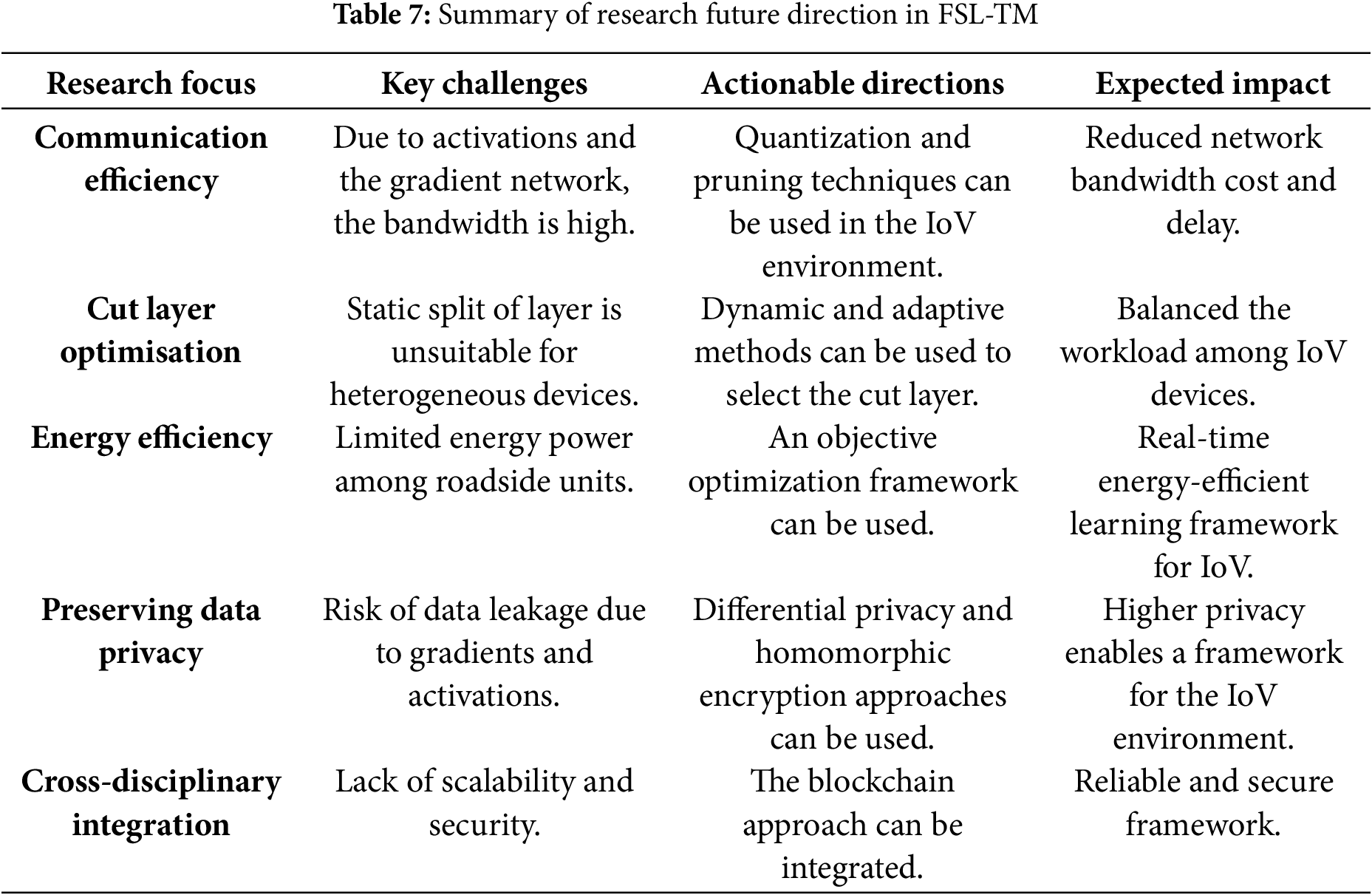

It is clear from Table 2 that FL, SL and FSL are increasingly applied in IoV to address the challenges of data privacy, communication cost, and resource utilisation and distributed learning. The review highlights how FL and SL approaches are transferred to FSL to balance communication costs and data privacy in the IoV domain. Researchers explore FL, SL, FSL, and TinyML approaches to enhance data privacy, memory utilisation, and communication costs in vehicular networks. Table 3 highlights the performance tradeoffs of these approaches in the context of the IoV domain.

4 Split Learning: Principles and Architecture

Split Learning is a privacy-preserving collaborative DL methodology that allows many entities, such as hospitals, IoT devices, or automobiles within the Internet of IoV, to train a collective neural network without disclosing raw data. Rather than training the complete model on each client, as in FL, SL partitions the model between the client and a central server in a specified “cut layer”. The client calculates the first layers and transmits just the intermediate activations to the server, which finalises the forward and backward pass and returns the gradients [4,39,49]. This approach reduces data exposure, decreases communication costs, and minimises computing load to the server, making it ideal for resource-constrained edge devices. Initially introduced by Gupta and Raskar [72], SL is especially applicable to handle privacy-sensitive information and bandwidth-constrained situations such as healthcare, smart cities, and IoV systems.

It is a decentralised ML approach for training ML models on distributed data sources while maintaining privacy. This approach enables a client to save its local dataset while transmitting only a portion to an edge server, reducing data transfer/communication cost and protecting sensitive information/data. During training, the model experiences forward and backward propagation phases, with the client-side model being trained locally until a designated cut layer is reached [73]. At this stage, the client transmits the result of the cut layer, referred to as the smashed data, to finalise the forward Propagation phase, and the server initiates the backward propagation phase until the cut layer data server-side smashed gradients are sent back to the client. This bifurcated methodology diminishes training latency and computational load while safeguarding data privacy and security, rendering it a compelling solution for IoT and IoV systems [4].

The primary concern in SL is the selection of the cut layer that divides the edge devices and central servers. Gao et al. [62] focus on the shallower cut layer in convolutional layers to minimise the computational load in the context of IoV. However, some researchers contend that shallow cuts substantially elevate communication overhead because extensive feature map dimensions pose challenges in bandwidth-constrained vehicle networks [60]. Others suggest using deeper cut layers to cut down on communication, but increase the computational cost and high energy consumption. Consequently, although the cut layer should equilibrate computation and communication, there is no agreement on a universally ideal selection for IoV tasks. The decision is typically contingent upon the application, fluctuating with network conditions, model design, and the importance of real-time inference.

4.1 Privacy Challenges in the Internet of Vehicles

Privacy is a security attribute that enables a person or group to preserve their personal information from unauthorised access. Data privacy is crucial for the IoV, as it comprises numerous mutually untrustworthy entities [74].

Location Privacy: The ability to incessantly monitor vehicle movements is associated with location privacy issues in IoV. This monitoring may disclose sensitive details about an individual’s daily habits, routines, and preferred locations, including residential and occupational places, potentially leading to stalking or other forms of harassment. The capture and retention of real-time location data pose significant risks if accessed by unauthorised parties or if the data acquisition methods lack transparency and user limitations. Moreover, location data can be employed to infer additional personal information, intensifying privacy concerns [75]. Zhang et al. [75] presented a strategy named PriSC, focused on decentralised location privacy protection through the implementation of blockchain technology. Su et al. [76] established a distributed management system for vehicle public key information, leveraging the immutable characteristics of blockchain to secure the storage of this information.

Data Privacy: Data privacy problems in IoV mostly stem from the substantial amounts of data produced by vehicles, encompassing sensitive information such as personal details, trip history, and driving behaviours. The primary risk is unwanted access to this data [77], whether via cyberattacks or data storage systems. Furthermore, the risk of unauthorised data dissemination among stakeholders without user agreement exists, potentially resulting in privacy infringements. Collecting and examining this data without stringent privacy measures may result in profiling or other forms of decision-making interference, thereby jeopardising individual privacy and autonomy. Chen and Yao et al. [77,78] proposed a privacy protection framework for vehicle trust management. The system employs a federated blockchain to establish a dual vehicle network architecture comprising a federated layer and a vehicle layer. The federated layer comprises entities that uphold the federated blockchain and oversee procedures for homomorphic computation and consensus mechanisms.

Communication Privacy: The interception of communications between vehicles and between vehicles and infrastructure is one of the communication privacy risks associated with the Internet of Vehicles [50]. Data communicated without proper encryption or secure communication protocols may be susceptible to eavesdropping, revealing private information like driver commands, vehicle status, or even the contents of private messages sent from the vehicle/edge devices.

Identity Privacy: Various vulnerabilities potentially resulting in the unauthorised use of identities within the network are included in the identity privacy issues associated with IoV. As vehicles become increasingly interconnected, the distinct identifiers of each vehicle and the personal data of its occupants may be susceptible to numerous attacks [79]. The risk is exacerbated by the potential for replay attacks, in which an assailant replicates a previously legitimate data transmission, and spoofing attacks, when a nefarious entity impersonates another device to acquire user credentials or modify vehicle performance [80]. The decentralised structure of the Internet of Vehicles results in unauthorised access at several locations. Guehguih et al. [81] suggested a geo-blockchain-based approach to ensure the secure broadcast of road traffic information in VANET. The strategy aims to guarantee the confidentiality of authentication and message dissemination, comprising two distinct blockchains.

SL and FL, which limit the availability of raw data, have reduced Iov privacy concerns. Nonetheless, gradient leaking, consent enforcement, and client-side vulnerabilities remain prevalent.

4.2 Integration of Split Learning with Federated Learning

FL is a collaborative framework that allows clients to train a collective model without transmitting their raw data to a central server. The core principle of FL is to send only model updates to a central server, thus reducing the risk of sensitive data exposure. This decentralized architecture substantially improves data privacy, making it appealing to sectors that emphasize confidentiality. A significant limitation is the inefficiency in model communication, especially when client data is non-IID or models are large [82].

Model partitioning, which facilitates training a model segment on the client side while the remaining segment is processed on the server side, is one method by which SL mitigates specific challenges associated with FL. This approach reduces data transfer by transmitting only the outputs of the local model to the server [51]. Although SL can significantly reduce transmission expenses, this model introduces more complexity in architectural administration between clients and the server, which may result in inefficient resource use. Secondly, the sequential execution of SL training incurs considerable latency, which may undermine performance in distributed systems, complicating practical implementation [49].

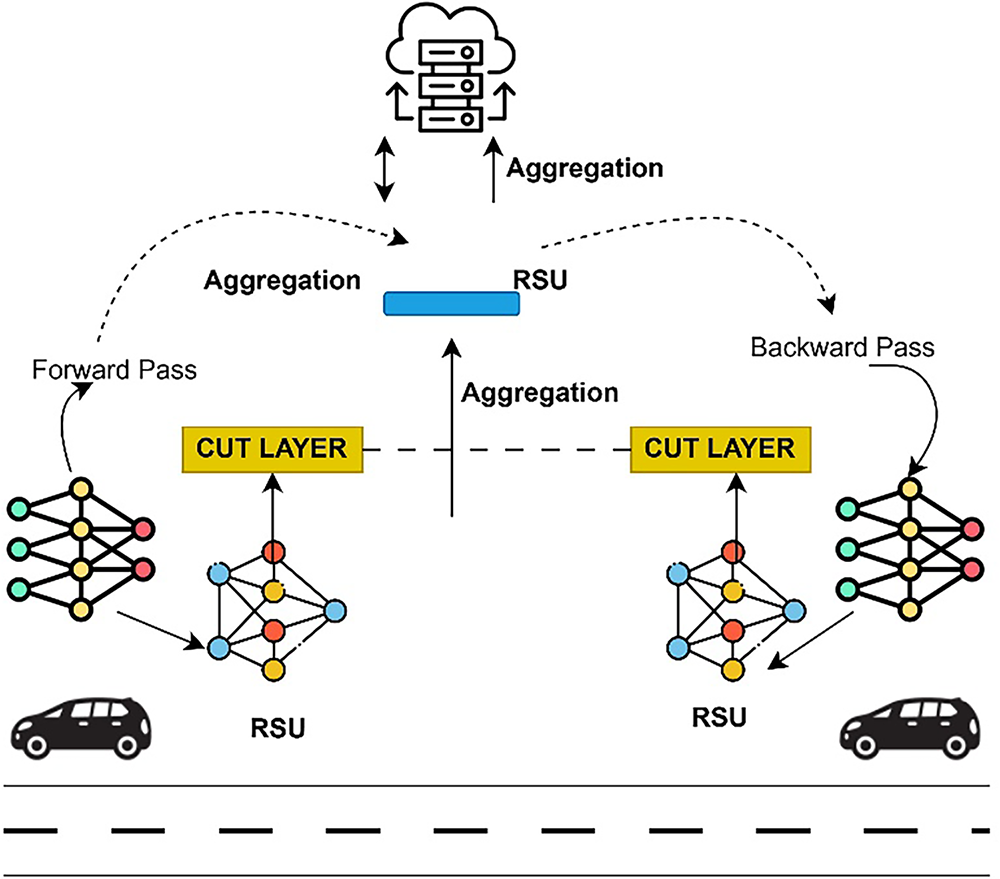

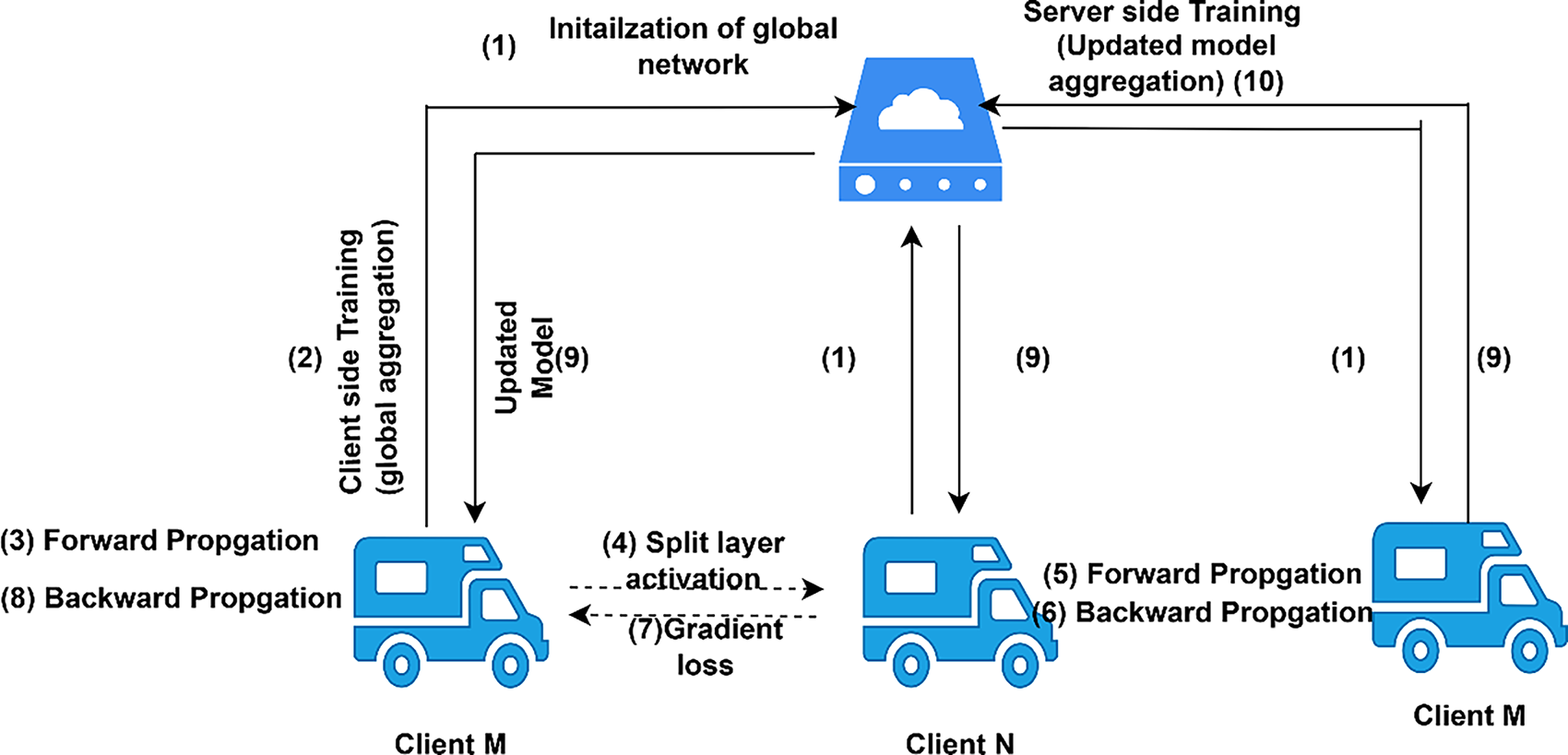

The hybrid collaborative learning paradigm, FSL, is the outcome of combining SL with FL. This approach combines the computationally efficient model partitioning of supervised learning with the decentralized training and aggregation methods of FL to address the particular challenges of highly dynamic and resource-constrained environments, such as IoV, as demonstrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Federated split learning framework (Integration of FL with SL in IoV)

FSL is a valuable concept with practical applications across various domains. FSL is especially beneficial for applications necessitating data division across many platforms, such as customizing recommendation systems. Employing FSL allows enterprises to develop secure and private recommendation algorithms [83] that safeguard customer information while ensuring a high standard of service quality. To fulfil its potential, FSL must overcome various challenges. Data from non-IID clients is a substantial issue, often leading to model bias and reduced performance in specific domains. Despite the effectiveness of innovative strategies, such as adaptive discrimination and individual-based model mitigation updates, significant challenges remain that require thorough methodological standardization and execution [84]. To ensure model convergence and stability in the IoV environment, an asynchronous aggregation technique coupled with a synchronisation buffer mechanism at the server may be employed. Each edge device individually executes local split-layer computations, and the resultant gradients are pooled using a weighting function. This architecture improves the resilience of model updates among diverse vehicular nodes with differing communication delays and resource limitations. Furthermore, the intermediate data exchanged during training may be susceptible to attacks due to inherent flaws. Secure multiparty computing and differential privacy can enhance the concealment of sensitive information throughout the learning process and effectively handle security concerns within FSL systems [45,85].

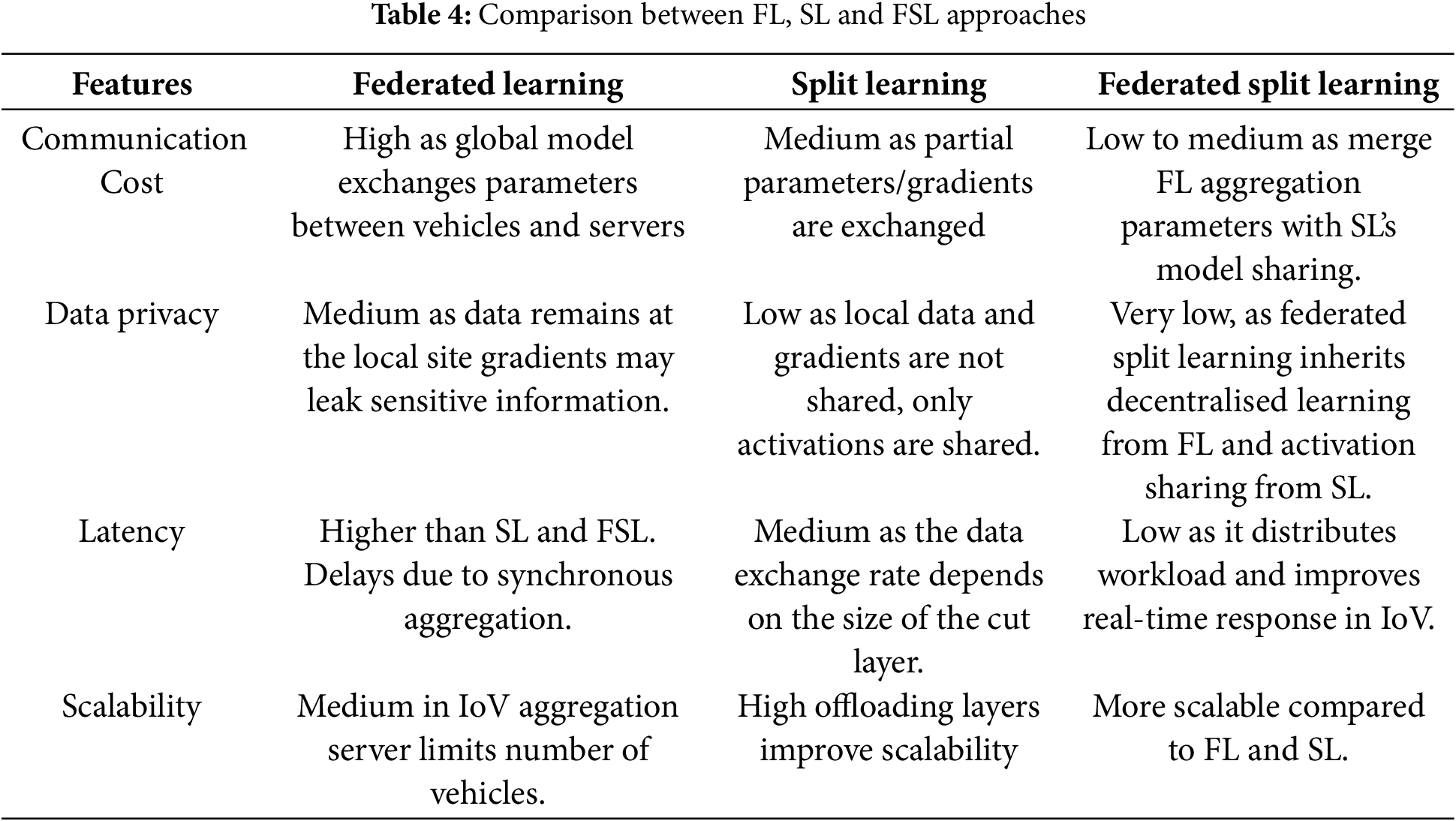

Each approach, such as FL, SL and FSL, aims to enable collaborative learning without sharing the data; however, these approaches differ in terms of communication cost, privacy risk, latency and scalability. These features are vital in vehicular networks as vehicular devices are resource-limited, data is very sensitive, and real-time decisions are imperious. Table 4 compares these approaches, referencing current studies that explicate how each technique confronts the distinct issues of IoV.

A combined FSL approach that combines FL and SL examines the limitations of each method and proposes alternatives for enhancing privacy, reducing communication overhead, and optimizing computing resource utilisation [17]. The step-by-step process of FSL is depicted in Fig. 4. This approach includes the following phases:

Figure 4: Integrated workflow of federated split learning

1. Model Initialisation (Splitting and Distribution): The Model is initialised by assigning weights, splitting the neural network (NN) and applying the FSL approach. The neural network is partitioned and initialised for practical and private training within the FSL system.

2. Client Side Training: This methodology is essential to a comprehensive FL architecture that includes remote client training, followed by centralised model aggregation and modification, ensuring that the learning process leverages collective information while maintaining data confidentiality [86]. This procedure is fundamentally reliant on client-server interaction. Users must send their responses to the server efficiently and securely. All clients often execute this synchronisation step to ensure that the primary server receives responses from all clients before advancing to the subsequent phase. The information remains on the client’s side, safeguarding data privacy. Only processed responses (intermediate data) are transmitted to the server, not unrefined data [51].

3. Server-Side Training: This server-side training methodology is a crucial component of the FSL approach. It facilitates distributed learning while preserving data privacy and utilising the computational capabilities of both clients and the central server [17]. The FSL server-side training methodology safeguards privacy by restricting the server’s processing to answers and classifications while retaining raw data on the client side. This method preserves sensitive information since the server does not view unprocessed data [66].

4. Backward Propagation: Back propagation is a method for propagating weights backward through NN layers. Clients execute a backward pass on their local machines upon receiving gradients from the server. This function enables clients to modify their weights, thereby minimising prediction errors and enhancing model accuracy. The client-side backward propagation strategy is crucial to the FSL methodology as it ensures that local models are regularly updated and refined based on collaborative training results [60].

5. Federated Aggregation: FSL integrates local updates into a unified global model through federated aggregation, facilitating collaborative learning while preserving client-level data privacy. In FSL, client updates are essential since they update the local training and back propagation phases. The central server is crucial for server-side computation as it aggregates client updates [13]. This guarantees that the global and client models precisely reflect the aggregated learning from all data sources. This federated aggregation method improves model performance by leveraging distributed data sources while safeguarding user privacy, making it a crucial element of FSL.

6. Model Updation and Iteration: This method highlights Fed-SL’s periodic character by recognising the ongoing development of the global model through minor improvements and collaborative efforts from clients located far away. FSL relies on delivering an advanced global model to all clients to ensure consistency and allow each client to leverage the latest developments in collaborative learning. The iterative method improves the global model’s precision by including inputs from various client-owned datasets while maintaining data confidentiality [50].

In a federated split learning framework, neural network layer f(x, w) is divided into two parts: client-side model fc(x, wc) and server-side model fs(k, ws), where x is input data, w is model parameters, and h is the activation function of the cut layer. The following mathematical formulation captures this collaborative training process and the communication between client and server in FSL.

1. In forward propagation, the client computes the activation function locally at the client side by using the function:

Then the server completes the forward propagation after receiving activation functions by using the function:

2. Computes the loss function:

where l is the loss function and pi is the true positive values.

3. Backward propagation: After calculating the loss function, the server computes the gradient with respect to the k cut layer and sends it back to the clients.

4. Parameters updation:

where

5. Model aggregation:

After various local updates, global parameters are aggregated.

This approach divides the global model into two partitions: the client-side sub network that runs up to the cut layer, and the server-side network that runs up to the output layer from the cut layer. The client-side network is locally trained and aggregated using the FedAvg algorithm. The server side network trained centrally by processing all activations from the clients. This process enables FSL approach to combine privacy and efficiency of SL with Scalability feature of FL in IoV.

Applications of Federating Split Learning

This section discusses the applications of FSL as shown in Fig. 5. These applications illustrating how FSL can be deployed in IoV networks.

Figure 5: Federated split learning applications

1. Real-Time Traffic Prediction and Congestion Management

Vehicles can work together to train models for traffic congestion prediction using FSL, which takes into account local factors including location, speed, weather, and traffic density during specific times of the day. Edge devices and edge servers can consolidate intermediate model updates or activations to develop a comprehensive picture of traffic flow. Yan and Quan [68] employed a lightweight CNN-based FSL system for traffic forecasting, ensuring little communication overhead. It aims to prevent real-time congestion and optimize routes without disclosing raw location data.

2. Driver Behavior Monitoring and Risk Profiling

FSL can assist in developing behavior models for accident prevention and insurance risk assessment by examining driving behaviors such hard braking, acceleration, lane-switching, and fatigue indicators. It is advantageous for personalized driver input while maintaining privacy. Qiang et al. [67] showed that adaptive FSL can efficiently identify distinct driver tendencies among various vehicles.

3. Collaborative Perception in Autonomous Driving

Vehicles can collaboratively develop DL models for environmental perception by exchanging intermediate characteristics from onboard sensors such as cameras. This improves object detection, traffic sign recognition, and pedestrian detection beyond the line of sight. Advantageous for collaborative situational awareness without the exchange of raw sensor data. Zhang et al. [87] introduced a collaborative perception framework based on few-shot learning that enhanced accuracy in dynamic environments.

4. Intrusion Detection and Cybersecurity

FSL facilitates the distributed training of anomaly detection systems utilizing system logs, bus messages, and security warnings, hence aiding in the identification of jamming, spoofing, and malware threats while preserving privacy. Improved cyber security throughout the vehicle network while preserving critical log data. Almarshdi et al. (2024) [88] established a system for intrusion detection via FSL, enhancing resilience against advanced threats.

5. Eco-Driving and Energy Optimization

Models that evaluate traffic patterns, road gradient, and engine performance to suggest fuel-efficient driving techniques can be trained with the use of FSL. Vehicles cooperate in acquiring knowledge while maintaining local energy consumption statistics. It advantageous to decreased emissions and fuel usage via adaptive eco-feedback [89].

6. Sensor Fault Detection and Vehicle Health Monitoring

Modern vehicles have a lot of sensors. FSL uses jointly trained diagnostic models to help discover sensor drift, calibration issues, or hardware faults. Its benefits are improved maintenance forecasting without transmitting sensitive diagnostics to the cloud.

7. Personalized Infotainment and User Experience

FSL allows for the learning of user preferences for climate control, media, and navigation without exporting individual usage logs. Compact models can operate efficiently on infotainment systems and update jointly among automobiles.

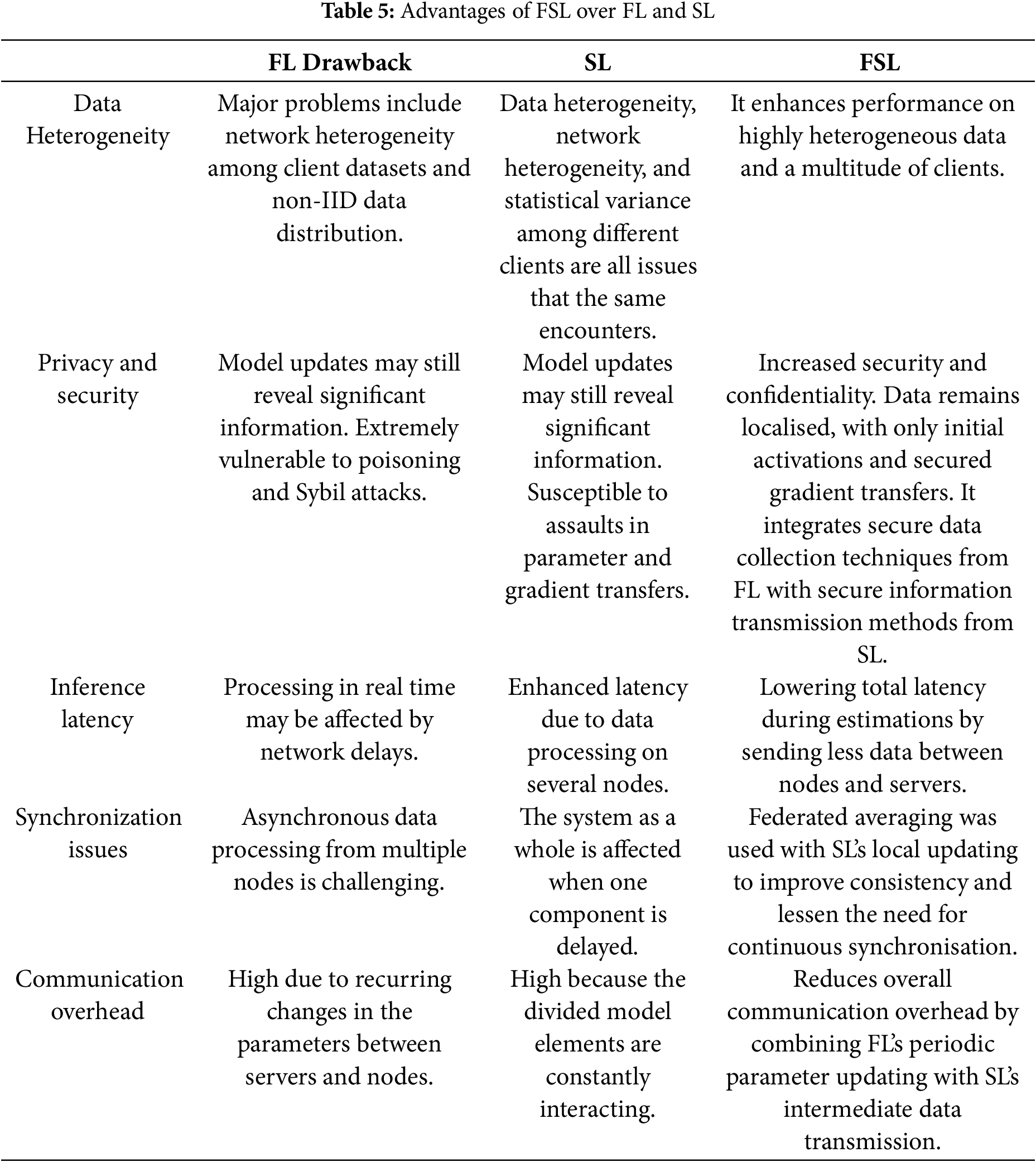

Federated SL greatly improves the capacity of vehicle networks to cooperate together on intelligent activities while protecting privacy, minimizing bandwidth, and taking into account on-device constraints. Its compliance with small models renders it optimal for extensive, real-world IoV implementations where computational, privacy, and latency limitations must be concurrently managed. Table 5 discusses the advantages of FSL over FL and SL.

5 Integration of Split Learning with Tiny Models

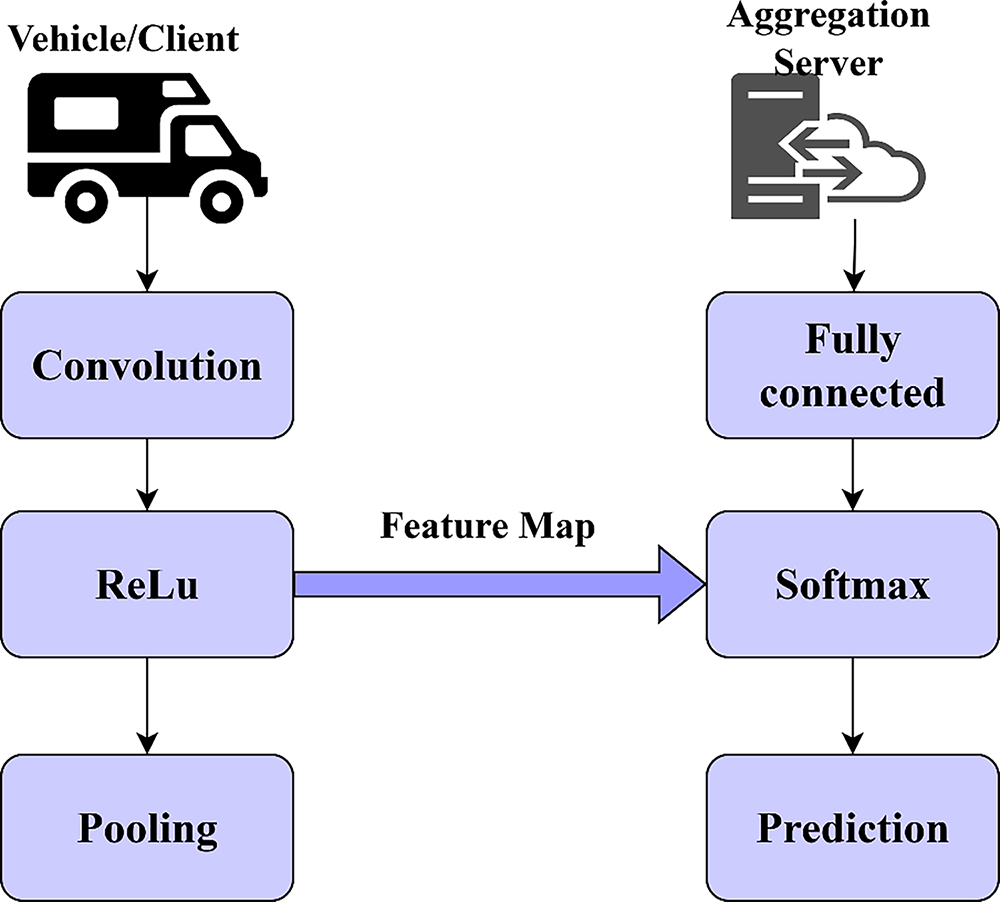

Tiny models like TinyResNet, MiniMobileNet, and EfficientNet-Lite are small DL frameworks for low-power, resource-constrained settings like mobile platforms, embedded systems, and automotive edge devices. These models achieve a crucial equilibrium between computing efficiency and prediction accuracy, rendering them suitable for implementation in IoV contexts where real-time decision-making and privacy protection are paramount. When integrated with SL, these compact models provide a highly optimal collaborative learning framework between the vehicle (edge) and a remote server, such as a cloud platform. In this framework, the model is divided so that the early lightweight layers, which generally encompass fundamental convolutional and activation functions, are processed locally on the vehicle to get preliminary features from the sensor [38,71].

Architecture of Split Learning with Tiny Models

Fig. 6 provides a distinct architectural depiction of SL combined with TinyML. The learning model is partitioned between the client, a vehicle, and a server, which may be a cloud-based system or a roadside unit. On the client side, only the computationally efficient layers of the DL model are run. These generally consist of a convolutional layer that executes fundamental feature extraction from input data, such as pictures or sensor signals, followed by a ReLU activation function incorporating non-linearity, and a pooling layer that diminishes spatial dimensions to improve efficiency.

Figure 6: Integrated framework of split learning with Tiny ML in IoV

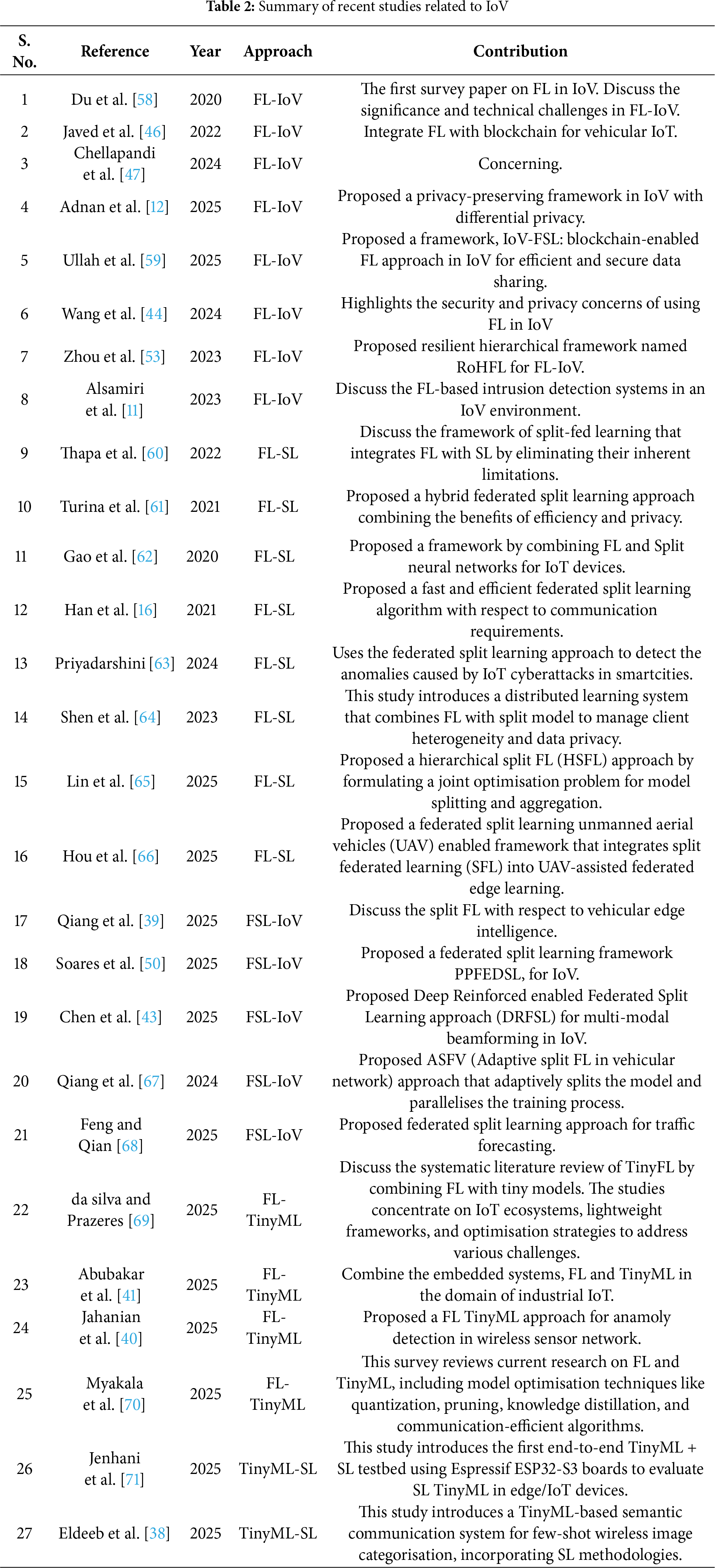

This local execution works well for vehicles with low memory and computing power. The intermediate outputs produced by these layers, known as feature maps, are subsequently communicated to the server securely, ensuring that raw data, such as photographs or videos, remains within the vehicle, safeguarding user privacy. On the server side, the model’s most complex and resource-demanding components, such as the fully connected layers and the softmax layer, are processed. These layers facilitate categorization and prediction tasks. This design is very efficient in IoV settings as it enables real-time, low-latency decision-making without overloading the vehicle’s onboard equipment while preserving data privacy and communication efficacy. The integration of TinyML with SL offers a scalable and pragmatic approach for implementing intelligent functionalities in connected automobiles [18]. Table 6 discusses several benefits and challenges associated with integrating TinyML with SL.

The IoV connects innovative transportation systems, sensor networks, embedded devices, and self-driving cars to the Internet to make vehicle apps work. These apps make and distribute several kinds of information, such as telemetry from vehicles, data about the environment, and other data. These changes have led to collecting huge amounts of diverse, fast-moving, and location-sensitive data from many sensors on board and the side of the road. Traditional AI approaches for IoV face significant issues such as data privacy, communication cost, energy consumption and data heterogeneity.

Integrating FL and SL, as demonstrated in Fig. 3, provides a resource-efficient, privacy-preserving framework for IoV. As FL trained the model without sharing the raw data, SL minimizes the computational load. Fig. 4 represents the complete integrated workflow of the FSL framework. When combining TinyML with FL and SL approaches as depicted in Fig. 6, a lightweight AI optimized model for IoV hardware is created. This integration can help a wide range of IoV applications, such as cooperative perception, predicting traffic flow, and giving driver assistance that doesn’t have a lot of resources. However, integrating these approaches led to various challenges related to system, networking, deployment and learning. So addressing these challenges could be crucial from experimental setups to real-world IoV systems.

7 Challenges for Integration: Federated Split Learning with TinyML in IoV

1. Networking and system: The vehicular communication framework presents considerable challenges for integrating FSL with TinyML in IoV. These challenges include significant networking and system issues. Due to the high mobility between handovers and base stations, model updates could be interrupted, causing delayed aggregation and reducing performance.

2. Optimization and learning: In most SL-based approaches, single-point selection cannot adjust network conditions and compute availability of the edge devices, which degrades performance. Heterogeneous (non-IID) data distribution makes the convergence among vehicles more difficult. Additionally, the drift concept in IoV challenges the model stability.

3. Security and privacy: FL and SL avoid data sharing during model training, but essential information could be shared through restoration attacks. Additionally, activation-based communication in split models requires new attack vectors that can modify activations or gradients. It is necessary to ensure supportable computation on cloud/aggregation servers.

4. Assessment and deployment: The Assessment of FSL’s convergence in TinyML in IoV is restricted to simulations that cannot reflect the mobility, fluctuations, or safety constraints in environments. The deployment of global models in IoV requires safety validations, real-time performance, and rollback procedures to ensure safety functions.

8 Technical Tradeoffs for Integration Federated Split Learning with TinyML (FSL-TM)

The integration of FSL-TM enables the lightweight, privacy-preserving, memory-optimized, resource-constrained approach in the IoV environment. However, a thorough examination of several technical aspects is necessary to determine its viability:

1. Communication overhead: FSL activations and gradients transmitted between client and server require more frequent interactions compared to FL, increasing bandwidth usage in the IoV environment. For each client, communication overhead can be expressed as:

where Ui denotes the activation size and Di the gradient size. TinyML techniques such as quantization and pruning help reduce this communication overhead. These approaches compressed the activations and gradients before transmitting the data. So, FSL-TM integration becomes more practical in IoV by achieving efficient communication while preserving data.

2. Computational cost: Computational cost in FSL depends on the selection of the cut layer. In SL, the client handles only the initial layers of the neural network, and the server handles all the other layers. However, computational cost can be reduced, but client-side cost is still measured with floating-point operations and the number of echoes. So, the TinyML approaches reduce the floating point operations and memory requirements and minimise energy consumption and execution time.

3. Convergence properties: The convergence characteristics of FSL are significantly influenced by the selection of the cut layer, client heterogeneity, and communication frequency. TinyML approaches reduce the model’s representational capacity and slow the convergence. Recent research reveals that the convergence rate stays constant with appropriate compression level calibration while resource consumption is significantly reduced.

4. Partition compatibility: The compatibility of FSL-TM depends on the cut layer selection procedure. The early stage cut layer traverses the computation to the server, and when combined with quantisation, it reduces the communication cost but increases the server’s processing load. However, the late stage cut layer requires clients to process all deeper layers, which reduces local computation and memory usage but leads to gradient mismatch. Thus, lightweight compression at the client side and moderate server-side pruning manage complexity and network conditions.

5. Model deployment in IoV: Integrating TinyML approaches enhances the feasibility of FSL model deployment in the IoV environment. It enables low communication overhead, minimises memory utilisation, and is lightweight, privacy-preserving, and energy-efficient for edge devices such as vehicles and roadside units.

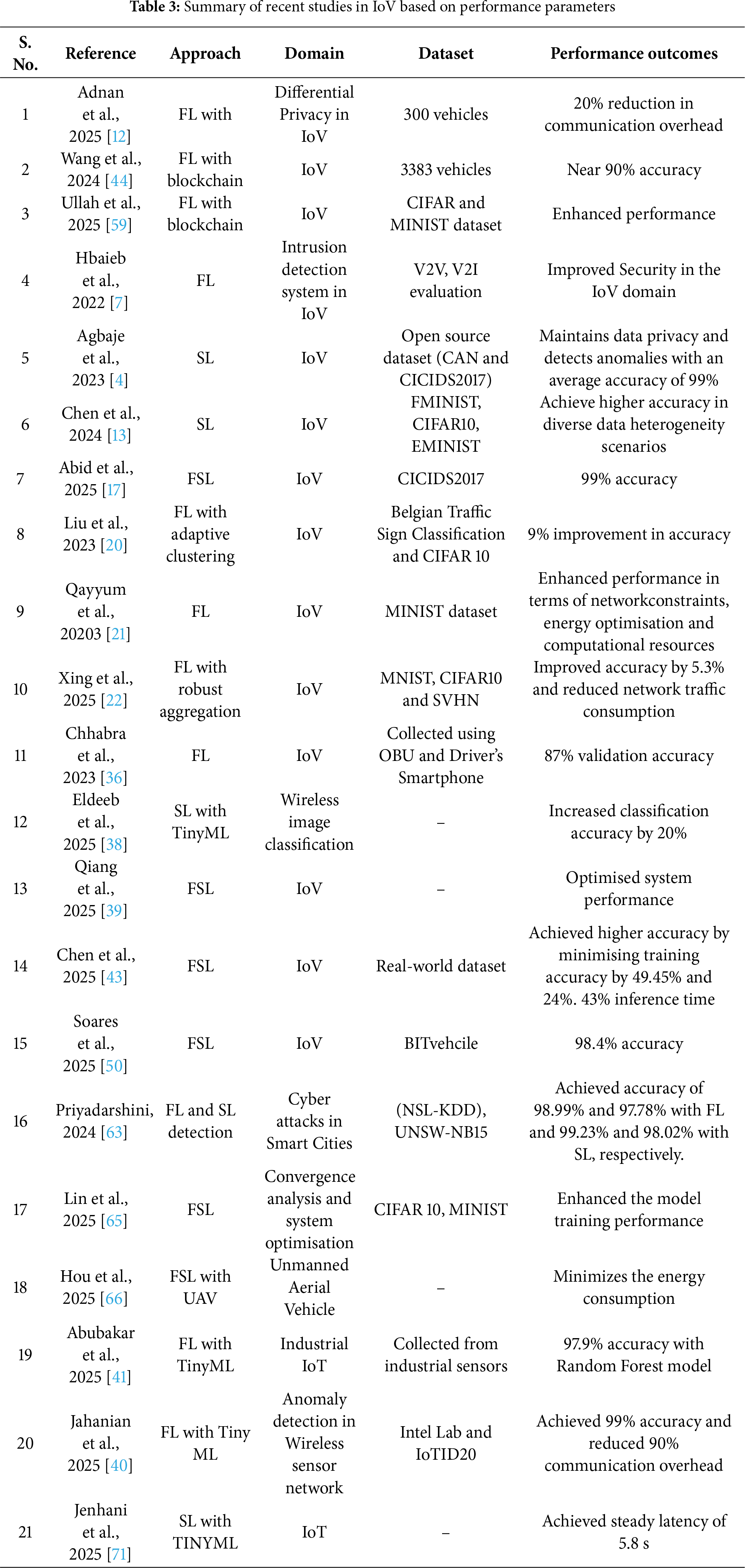

In the previous sections, we examined the developing landscape of FSL integration with TinyML in the IoV sector and its significant potential. Nonetheless, FSL utilizing TinyML in the Internet of Vehicles remains in its early developmental phase, necessitating extensive research efforts to create a viable framework for its implementation. This section discusses the potential directions for future investigation to advance the integration of FSL with TinyML in accordance with the previously mentioned issues.

1. Mobility-aware dynamic splitting: Vehicle mobility and network congestion make the communication links dynamic, so a single static split point between client and server becomes wasteful. Dynamic splitting can consistently maintain inference and training performance.

2. Secure robust aggregation: IoV networks are vulnerable to faulty devices and malicious attacks because of Byzantine resilient aggregation and verification protocols that validate clients’ validity. Robust aggregation prevents the adversarial clients from harming the clients and prevents the sensitive information from being compromised.

3. Federated split hierarchical architecture: In the IoV infrastructure, there are multiple tiers, such as edge nodes, roadside nodes, and cloud servers, where roadside nodes act as intermediate nodes. This federated split hierarchical architecture maintains a balance between computation work in the cloud server and latency tasks at the edge devices, improving the efficiency and scalability in IoV deployments.

4. Efficient activation sharing: The primary constraint of SL is transferring the intermediate activations between client and server. This involves applying semantic compression, which involves characteristics necessary for the task, and event-triggered updates, which deliver activations only when some changes occur. The efficient activation sharing reduces bandwidth consumption, making SL feasible in low connectivity and high mobility.

5. TinyML co-design: Implementing AI models on IoV requires extreme efficiency, which means designing models with neural architecture search, quantization, and pruning that optimize SL. Quantization techniques decrease the weights and activations, for example, from 32-bit floating point to 8-bit integers, reducing the memory utilisation and transmission cost. Similarly, pruning reduces the amount of feature maps transmitted by removing unnecessary filters from the client-side sub-network, which lowers the computation and communication load on-device. TinyML’s co-design framework reduces memory needs, computation load, and transmission size while maintaining the model’s accuracy.

To facilitate the implementation of the FSL-TM approach and address various issues, Table 7 summarizes the actionable future directions and their expected impact to provide a clear understanding of future research directions.

Integrating the FL and SL with TinyML could implement a privacy-preserving, lightweight, and highly scalable framework for IoV networks. This study investigated the possibility of integrating FL and SL to facilitate intelligent IoV networks. This was accomplished by thoroughly assessing the most recent research trends and conducting an in-depth discussion of the most recent methodologies. SL splits the models among edge nodes/vehicles, roadside nodes and cloud servers to maintain the computational load and minimize latency. In contrast, FL enables the collaborative model training among decentralized edge nodes. TinyML’s incorporation guarantees that even vehicle devices with limited resources can actively participate in training and inference without consuming excessive energy or bandwidth. In this manuscript, we first provide an overview of learning frameworks in IoV, such as edge computing, FL, SL and TinyML, and then discuss how FSL-TM can be integrated by addressing various challenges and benefits of these approaches. We also discuss recent developments in the Federated SL integration framework. To conclude the review, we also discussed the benefits and challenges of integrating TinyML with SL. Further, discuss the challenges and future research directions for the integrated FSL-TM framework in the IoV domain. A path towards intelligent, low-latency, and privacy-aware vehicular services can be found by integrating these methodologies, allowing seamless scaling to thousands of vehicles in highly dynamic mobility contexts. The framework FSL-TM will be beneficial for implementing an AI-enabled connected and decentralized transportation ecosystem. This will ensure a balance between innovation, efficiency, and privacy protection concerning the deployment of AI.

Acknowledgement: We are thankful for all contributors.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization—Meenakshi Aggarwal, Vikas Khullar, Data curation—Vikas Khullar, Nitin Goyal, Formal analysis—Meenakshi Aggarwal, Funding acquisition—Vikas Khullar, Investigation—Vikas Khullar, Nitin Goyal, Methodology—Meenakshi Aggarwal, Vikas Khullar, Resources—Vikas Khullar, Nitin Goyal, Validation—Vikas Khullar, Nitin Goyal, Software—Vikas Khullar, Writing—original draft—Meenakshi Aggarwal, Vikas Khullar, Nitin Goyal, Writing—review & editing—Meenakshi Aggarwal, Vikas Khullar, Nitin Goyal. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable, as this is a narrative review based on existing literature.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Reddy KR, Muralidhar A. Machine learning-based road safety prediction strategies for Internet of Vehicles (IoV) enabled vehicles: a systematic literature review. IEEE Access. 2023;11:112108–22. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3315852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sharma N, Chauhan N, Chand N. Security challenges in Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environment. In: Proceedings of the 2018 First International Conference on Secure Cyber Computing and Communication (ICSCCC); 2018 Dec 15–17; Jalandhar, India. p. 203–7. doi:10.1109/ICSCCC.2018.8703272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xie Y, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Wang J, et al. Resource allocation for twin maintenance and task processing in vehicular edge computing network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(15):32008–21. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2025.3576582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Agbaje P, Anjum A, Mitra A, Hounsinou S, Nwafor E, Olufowobi H. Privacy-preserving intrusion detection system for Internet of Vehicles using split learning. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM 10th International Conference on Big Data Computing, Applications and Technologies; 2023 Dec 4–7; Taormina, Italy. p. 1–8. doi:10.1145/3632366.3632388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Karthiga B, Durairaj D, Nawaz N, Venkatasamy TK, Ramasamy G, Hariharasudan A. Intelligent intrusion detection system for VANET using machine learning and deep learning approaches. Wirel Commun Mob Comput. 2022;2022(1):5069104. doi:10.1155/2022/5069104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Rathore MS, Poongodi M, Saurabh P, Lilhore UK, Bourouis S, Alhakami W, et al. A novel trust-based security and privacy model for Internet of Vehicles using encryption and steganography. Comput Electr Eng. 2022;102(1):108205. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hbaieb A, Ayed S, Chaari L. Federated learning based IDS approach for the IoV. In: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security; 2022 Aug 23–26; Vienna, Austria. p. 1–6. doi:10.1145/3538969.3544422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yang L, Moubayed A, Shami A. MTH-IDS: a multitiered hybrid intrusion detection system for Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(1):616–32. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3084796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Talha Usman M, Khan H, Kumar Singh S, Lee MY, Koo J. Efficient deepfake detection via layer-frozen assisted dual attention network for consumer imaging devices. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(1):281–91. doi:10.1109/TCE.2024.3476477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Khan H, Usman MT, Rida I, Koo J. Attention enhanced machine instinctive vision with human-inspired saliency detection. Image Vis Comput. 2024;152:105308. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2024.105308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Alsamiri J, Alsubhi K. Federated learning for intrusion detection systems in Internet of Vehicles: a general taxonomy, applications, and future directions. Future Internet. 2023;15(12):403. doi:10.3390/fi15120403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Adnan M, Haider Syed M, Anjum A, Rehman S. A framework for privacy-preserving in IoV using federated learning with differential privacy. IEEE Access. 2025;13:13507–21. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3526934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chen H, Chen X, Peng L, Bai Y. Personalized fair split learning for resource-constrained Internet of Things. Sensors. 2023;24(1):88. doi:10.3390/s24010088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Chai H, Leng S, Chen Y, Zhang K. A hierarchical blockchain-enabled federated learning algorithm for knowledge sharing in Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2021;22(7):3975–86. doi:10.1109/TITS.2020.3002712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Xu X, Liu W, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Dou W, Qi L, et al. PSDF: privacy-aware IoV service deployment with federated learning in cloud-edge computing. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2022;13(5):1–22. doi:10.1145/3501810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Han DJ, Bhatti HI, Lee J, Moon J. Accelerating federated learning with split learning on locally generated losses, Online. In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Federated Learning for User Privacy and Data Confidentiality in Conjunction with ICML 2021; 2021 Jul 24; Online. [Google Scholar]

17. Abid M, Benkaddour MK, Benouis M. Privacy-preserving intrusion detection using FedSplit learning. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Modelling and Implementation of Complex Systems; 2024 Dec 1–3; Tamanrasset, Algeria. p. 29–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-82112-7_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bove F, Bedogni L. Smart split: leveraging TinyML and split computing for efficient edge AI. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM Symposium on Edge Computing (SEC); 2024 Dec 4–7; Rome, Italy. p. 456–60. doi:10.1109/SEC62691.2024.00052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhu X, Yu S, Wang J, Yang Q. Efficient model compression for hierarchical federated learning. arXiv:2405.17522. 2014. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2405.17522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu S, Liu Z, Xu Z, Liu W, Tian J. Hierarchical decentralized federated learning framework with adaptive clustering: bloom-filter-based companions choice for learning non-IID data in IoV. Electronics. 2023;12(18):3811. doi:10.3390/electronics12183811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Qayyum T, Trabelsi Z, Tariq A, Ali M, Hayawi K, Din IU. Flexible global aggregation and dynamic client selection for federated learning in Internet of Vehicles. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;77(2):1739–57. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.043684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Xing L, Luo Z, Deng K, Wu H, Ma H, Lu X. FedHSQA: robust aggregation in hierarchical federated learning via anomaly scoring-based adaptive quantization for IoV. Electronics. 2025;14(8):1661. doi:10.3390/electronics14081661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Cui C, Du H, Jia Z, He Y, Wang L. Blockchain-enabled federated learning with differential privacy for Internet of Vehicles. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;81(1):1581–93. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.055557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Firdaus M, Rhee KH. Personalized federated learning for statistical heterogeneity. arXiv:2402.10254. 2024. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2402.10254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mahmoudi I, Boubiche DE, Athmani S, Toral-Cruz H, Chan-Puc FI. Toward generative AI-based intrusion detection systems for the Internet of Vehicles (IoV). Future Internet. 2025;17(7):310. doi:10.3390/fi17070310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sun G, Zhang Y, Yu H, Du X, Guizani M. Intersection fog-based distributed routing for V2V communication in urban vehicular ad hoc networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2020;21(6):2409–26. doi:10.1109/TITS.2019.2918255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yao Y, Shu F, Cheng X, Liu H, Miao P, Wu L. Automotive radar optimization design in a spectrally crowded V2I communication environment. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(8):8253–63. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3264507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang X, Li J, Zhou J, Zhang S, Wang J, Yuan Y, et al. Vehicle-to-everything communication in intelligent connected vehicles: a survey and taxonomy. Automot Innov. 2025;8(1):13–45. doi:10.1007/s42154-024-00310-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang Z, Wu Q, Fan P, Cheng N, Chen W, Letaief KB. DRL-based optimization for AoI and energy consumption in C-V2X enabled IoV. IEEE Trans Green Commun Netw. 2025. doi:10.1109/TGCN.2025.3531902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sun G, Song L, Yu H, Chang V, Du X, Guizani M. V2V routing in a VANET based on the autoregressive integrated moving average model. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2019;68(1):908–22. doi:10.1109/TVT.2018.2884525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Xiang H, Zheng Z, Xia X, Zhao SZ, Gao L, Zhou Z, et al. V2X-ReaLO: an open online framework and dataset for cooperative perception in reality. arXiv:2503.10034. 2025. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2503.10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kairouz P, McMahan HB, Avent B, Bellet A, Bennis M, Nitin Bhagoji A, et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found Trends® Mach Learn. 2021;14(1–2):1–210. doi:10.1561/2200000083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li Q, Wen Z, Wu Z, Hu S, Wang N, Li Y, et al. A survey on federated learning systems: vision, hype and reality for data privacy and protection. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2023;35(4):3347–66. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2021.3124599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chen Y, He S, Wang B, Feng Z, Zhu G, Tian Z. A verifiable privacy-preserving federated learning framework against collusion attacks. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025;24(5):3918–34. doi:10.1109/TMC.2024.3516119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Novikova E, Fedorchenko E, Kotenko I, Kholod I. Analytical review of intelligent intrusion detection systems based on federated learning: advantages and open challenges. Inform Autom. 2023;22(5):1034–82. doi:10.15622/ia.22.5.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chhabra R, Singh S, Khullar V. Privacy enabled driver behavior analysis in heterogeneous IoV using federated learning. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;120:105881. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.105881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Driss M, Almomani I, Huma Z, Ahmad J. A federated learning framework for cyberattack detection in vehicular sensor networks. Complex Intell Syst. 2022;8(5):4221–35. doi:10.1007/s40747-022-00705-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Eldeeb E, Shehab M, Alves H, Alouini MS. Semantic meta-split learning: a TinyML scheme for few-shot wireless image classification. IEEE Trans Mach Learn Commun Netw. 2025;3:491–501. doi:10.1109/TMLCN.2025.3557734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Qiang X, Chang Z, Ye C, Hämäläinen T, Min G. Split federated learning empowered vehicular edge intelligence: concept, adaptive design, and future directions. IEEE Wirel Commun. 2025;32(4):90–7. doi:10.1109/MWC.009.2400219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Jahanian M, Eraghi N, Karimi A, Zarafshan F. Tiny-fed: a federated tinyml framework for low-power anomaly detection in wireless sensor networks [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5221400. [Google Scholar]

41. Abubakar M, Sattar A, Manzoor H, Farooq K, Yousif M. IIOT: an infusion of embedded systems, TinyML, and federated learning in industrial IoT. J Comput Biomed Inform. 2025;8(2). [Google Scholar]

42. Sharma R. Benefits of TinyML [Internet]; 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.thetinymlbook.com/resources/benefits-of-tinyml. [Google Scholar]

43. Chen J, Samikwa E, Braun T, Chowdhury K. DRFSL: deep reinforced federated split learning for multi-modal beamforming in IoV. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 101st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2025-Spring); 2025 Jun 17–20; Oslo, Norway. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/VTC2025-Spring65109.2025.11174716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Wang N, Yang W, Wang X, Wu L, Guan Z, Du X, et al. A blockchain based privacy-preserving federated learning scheme for Internet of Vehicles. Digit Commun Netw. 2024;10(1):126–34. doi:10.1016/j.dcan.2022.05.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Xu G, Zhang Y, Xu X, Peng X, Li Q, Ma T. Inter-vehicle DNN offloading in the IoV: overcoming vehicle heterogeneity with federated split hybrid learning. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2025. doi:10.1109/TVT.2025.3585175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Javed AR, Hassan MA, Shahzad F, Ahmed W, Singh S, Baker T, et al. Integration of blockchain technology and federated learning in vehicular (IoT) networks: a comprehensive survey. Sensors. 2022;22(12):4394. doi:10.3390/s22124394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Chellapandi VP, Yuan L, Brinton CG, Żak SH, Wang Z. Federated learning for connected and automated vehicles: a survey of existing approaches and challenges. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2024;9(1):119–37. doi:10.1109/TIV.2023.3332675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Billah M, Anwar A, Rahman Z, Islam R. A systematic literature review on blockchain enabled federated learning framework for Internet of Vehicles. arXiv:2203.05192. 2022. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2203.05192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Hukkeri GS, Goudar RH, Dhananjaya GM, Rathod VN, Ankalaki S. A comprehensive survey on split-fed learning: methods, innovations, and future directions. IEEE Access. 2025;13:46312–33. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3547641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Soares K, Shinde AA, Patil M. PPFedSL: privacy preserving split and federated learning enabled secure data sharing model for Internet of Vehicles in smart city. Int J Comput Netw Appl. 2024;12(2):154–77. doi:10.22247/ijcna/2025/11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Krishna S, Alfurhood BS, Irudayasamy A, Natarajan R. The role of splitfed learning in recommendation systems. In: Split federated learning for secure IoT applications: concepts, frameworks, applications and case studies. London, UK: Institution of Engineering and Technology; 2024. p. 67–77. doi:10.1049/pbse025e_ch5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Liu S, Yu J, Deng X, Wan S. FedCPF: an efficient-communication federated learning approach for vehicular edge computing in 6G communication networks. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(2):1616–29. doi:10.1109/TITS.2021.3099368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Zhou H, Zheng Y, Huang H, Shu J, Jia X. Toward robust hierarchical federated learning in Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2023;24(5):5600–14. doi:10.1109/TITS.2023.3243003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Xiao H, Zhao J, Pei Q, Feng J, Liu L, Shi W. Vehicle selection and resource optimization for federated learning in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2022;23(8):11073–87. doi:10.1109/TITS.2021.3099597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Yang Z, Zhang X, Wu D, Wang R, Zhang P, Wu Y. Efficient asynchronous federated learning research in the Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(9):7737–48. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2022.3230412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Liu S, Yu G, Yin R, Yuan J, Qu F. Communication and computation efficient federated learning for Internet of Vehicles with a constrained latency. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2024;73(1):1038–52. doi:10.1109/TVT.2023.3309088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Zhang X, Chen W, Zhao H, Chang Z, Han Z. Joint accuracy and latency optimization for quantized federated learning in vehicular networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(17):28876–90. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3406531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Du Z, Wu C, Yoshinaga T, Yau KA, Ji Y, Li J. Federated learning for vehicular Internet of Things: recent advances and open issues. IEEE Comput Graph Appl. 2020;1(1):45–61. doi:10.1109/OJCS.2020.2992630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Ullah I, Deng X, Pei X, Mushtaq H, Uzair M. IoV-SFL: a blockchain-based federated learning framework for secure and efficient data sharing in the Internet of Vehicles. Peer Peer Netw Appl. 2024;18(1):34. doi:10.1007/s12083-024-01821-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Thapa C, Mahawaga Arachchige PC, Camtepe S, Sun L. SplitFed: when federated learning meets split learning. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2022;36(8):8485–93. doi:10.1609/aaai.v36i8.20825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Turina V, Zhang Z, Esposito F, Matta I. Federated or split? A performance and privacy analysis of hybrid split and federated learning architectures. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 14th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD); 2021 Sep 5–10; Chicago, IL, USA. p. 250–60. doi:10.1109/cloud53861.2021.00038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Gao Y, Kim M, Abuadbba S, Kim Y, Thapa C, Kim K, et al. End-to-end evaluation of federated learning and split learning for Internet of Things. In: Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Reliable Distributed Systems (SRDS); 2020 Sep 21–24; Shanghai, China. p. 91–100. doi:10.1109/srds51746.2020.00017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Priyadarshini I. Anomaly detection of IoT cyberattacks in smart cities using federated learning and split learning. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2024;8(3):21. doi:10.3390/bdcc8030021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Shen J, Cheng N, Wang X, Lyu F, Xu W, Liu Z, et al. RingSFL: an adaptive split federated learning towards taming client heterogeneity. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2024;23(5):5462–78. doi:10.1109/TMC.2023.3309633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Lin Z, Wei W, Chen Z, Lam CT, Chen X, Gao Y, et al. Hierarchical split federated learning: convergence analysis and system optimization. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025;24(10):9352–67. doi:10.1109/TMC.2025.3565509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Hou X, Wang J, Zhang Z, Wang J, Liu L, Ren Y. Split federated learning for UAV-enabled integrated sensing, computation, and communication. arXiv:2504.01443. 2025. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2504.01443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]