Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Machine Learning Based Uncertain Free Vibration Analysis of Hybrid Composite Plates

1 Faculty of Engineering & Technology, Parul University, Waghodia, Vadodara, 391760, Gujrat, India

2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Parul Institute of Engineering & Technology, FET, Parul University, Waghodia, Vadodara, 391760, Gujrat, India

* Corresponding Author: Pradeep Kumar Karsh. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072839

Received 04 September 2025; Accepted 13 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

This study investigates the uncertain dynamic characterization of hybrid composite plates by employing advanced machine-assisted finite element methodologies. Hybrid composites, widely used in aerospace, automotive, and structural applications, often face variability in material properties, geometric configurations, and manufacturing processes, leading to uncertainty in their dynamic response. To address this, three surrogate-based machine learning approaches like radial basis function (RBF), multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS), and polynomial neural networks (PNN) are integrated with a finite element framework to efficiently capture the stochastic behavior of these plates. The research focuses on predicting the first three natural frequencies under material uncertainties, which are critical to ensuring structural reliability. Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) is used as a benchmark for generating probabilistic datasets, including mean values, standard deviations, and probability density functions. The surrogate models are then trained and validated against these datasets, enabling accurate representation of uncertainty with substantially fewer samples compared to conventional MCS. Among the methods studied, the RBF model demonstrates superior performance, closely approximating MCS results with a reduced sample size, thereby achieving significant computational savings. The proposed framework not only reduces computational time and costs but also maintains high predictive accuracy, making it well-suited for complex engineering systems. Beyond free vibration analysis, the methodology can be extended to more sophisticated scenarios, such as forced vibration, damping effects, and nonlinear structural responses. Overall, this work presents a computationally efficient and robust approach for surrogate-based uncertainty quantification, advancing the analysis and design of hybrid composite structures under uncertainty.Keywords

Reinforced hybrid composite materials offer significant advantages over metallic alloys, largely in the aerospace industry, owing to its superior stiffness, impact resistance, corrosion resistance, and lightweight nature. Unlike metallic materials, hybrid composites can be customized to achieve specific structural performances by manipulating design variables such as fiber positioning and ply heaping sequences [1]. This customization often aims for the minimum weight design while adhering to various mechanical, geometrical, and high-tech requirements. However, in spite of progression in founding technologies, manufacturing flawless composite edifices remains a challenge. As a result, the full benefits of these materials have yet to be realized [2]. The finite element method, combined with a multivariate adaptive regression splines surrogate model is used to quantify the uncertainty of the free vibration of functionally graded materials in a cantilever plate [3]. The stochastic sensitivity analysis of FGM plates is crucial for assessing their performance under free vibration and low-energy impact, allowing us to pinpoint the most grave constraints in these investigations [4]. Several works have used a finite element FE technique based on RBF to convincingly depict the stochastic natural frequencies of cantilever plates built from FGM [5]. Furthermore, in order to ensure accurate and dependable findings, the robustness of the projected computation, for stochastic natural frequency analysis of composite plates has been carefully checked and confirmed against the original FEM in conjunction with MCS [6]. An innovative model designed to accurately analyze the stochastic characteristic vibration and the equivalent emitted power of rectangular coated plates. This model efficiently represents elastic parameters, natural frequencies, and acoustic power density using generalized polynomial chaos expansions with variable random bases [7]. The application of MCS through our established regression model enables us to derive essential statistical characteristics of structural natural frequencies, including mean values, standard deviations, probability density functions, and cumulative distribution functions [8]. The development of traditional low-dimensional analytical modeling techniques enables the rapid and efficient extraction of natural frequencies in flexible assembled structures [9]. This comprehensive strategy not only enhances understanding but ultimately provides a robust framework for making informed decisions in structural engineering [10]. The use of artificial intelligence and hybrid knowledge–data-driven approaches for modeling flexible assembled structures has recently gained significant attention [11]. Surrogate models have been widely used in the optimization and prediction of solutions for computationally extensive problems, like as delamination detection [12]. Diverse surrogate replicas tend to execute well under varying circumstances and are integrally influenced by the specific characteristics of the current issues [13]. In order to compare different substitute structures based on a number of performance criteria, such as accuracy, toughness, effectiveness, precision, and conceptual simplicity, researchers built ensembles of meta-models with optimum weight factors [14]. Specifically, Kriging surrogate models have been implemented for delamination finding in fused laminates [15]. Recent comparisons between ANN and Kriging surrogate models for delamination detection have revealed a significant advantage for Kriging models which excel in both prediction accuracy and processing speed [16]. In the realm of engineering, various studies have also explored different surrogate models tailored for specific applications, such as radial basis neural networks in the design of liquid rocket injectors, supersonic turbines, and the shapes of prototypes [17]. While researchers have been focused on selecting the optimal surrogate model, the investigation of ensemble techniques still has a significant deficit [18]. Such methods could be particularly promising for tackling the delamination detection challenge in composite laminates. Ultimately, the evidence suggests that Kriging models consistently stand out as the most effective solution across various problems [19]. Surrogate-based uncertainty quantification has emerged as a crucial approach in the past decade for accurately measuring uncertain universal responses in composite laminates, effectively addressing uncertainties in both geometric and material parameters [20]. To robustly quantify uncertainty, whether probabilistic or non-probabilistic in the dynamic analyses of composite structures, researchers have successfully integrated surrogate and machine learning-based methodologies, including enhancements to lower-order theories [21]. The value of surrogate-based methodologies in stochastic dynamic and stability analysis of composites made of laminates is thoroughly described in a new monograph by distinguished researchers [22]. Surrogate models are the preferred choice in uncertainty quantification; they dramatically reduce the need for extensive finite element simulations, which typically require thousands of function evaluations in traditional MCS based methods [23]. The lifespan of a mechanical system necessitates several extensive and intricate finite element (FE) simulations. However, the traditional approach of comprehensive simulations is evolving. Today, low- and mid-fidelity FEA have taken center stage, updating swiftly and effectively based on real-time experimental measurements of the system’s condition [24]. The rise of the Big Data era has been profoundly influenced by machine learning (ML) algorithms. These algorithms excel at processing large datasets automatically, uncovering trends, drawing insightful conclusions, and predicting future outcomes with remarkable precision [25]. Essentially, through digitalization and connectivity, data is transformed into actionable information by machine learning [26]. In their research, Jang and Smith showcased the impact of temperature dispersal on normal vibrations through a full-scale FE model and simulation study. Notably, FE simulations can also serve as effective training grounds for ML models, thereby sidelining the necessity of rerunning complex simulations [27]. Additionally, two innovative active learning strategies were presented, integrating artificial neural networks and Kriging models to enhance reliability analysis. This approach not only streamlines the process but also elevates the accuracy of assessments, making it an obvious choice for mechanical system analysis in the future [28]. Two finite element problems and illustrative examples were used to demonstrate the effectiveness and precision of the proposed methods. A paradigm for design optimization based on uncertainty and based on the multi-fidelity polynomial chaos. To address the issues of low accuracy and high sensitivity of surrogate predictions in the presence of uncertainties, the Kriging surrogate model was developed [29]. This framework is particularly effective for complex aerodynamic applications. To determine the strain responses of columns based on how high-rise buildings behave under wind impact, RF created a sustainable strain-sensing model using an ANN [30]. They employed an RBF neural network for training, combined with a genetic algorithm for evolutionary learning to create their ANN model [31]. In another study, a meta-model for estimating the final strength of trusses was developed using the SVM technique through direct analysis. The study took into account a number of kernel functions for the SVM model, such as RBF, sigmoid, linear, and polynomial. A novel formulation for extracting important features pertaining to the kinds and locations of braces based on machine learning results was put forth using the SVM with an RBF kernel [32]. Additionally, an effective SVM assisted FE technique was proposed for the stochastic dynamic characterization of FG shells. To achieve a comprehensive probabilistic description of natural frequencies, an ML-based FE algorithmic paradigm was integrated with MCS [33]. The stochastic technique considered both the individual and combined effects of depth-wise source uncertainty in the material properties of functionally graded shells. It investigated the influence of several crucial parameters, including temperature, thickness, power-law exponent, and variations in shell geometries. Utilizing deep learning, Feng and Prabhakar [34] developed the first-ever stress distribution tool, which significantly reduced the computational cost of predicting stress distributions in heterogeneous media using FEA. They focused on areas with discontinuities and high concentrations of stress within their neural network frameworks, which are based on engineering and statistics [35]. Different finite element analysis model geometries and stress values have previously been used as direct inputs to train neural networks. Numerous studies have attempted to apply artificial neural networks to understand the constitutive behavior of composite laminates, particularly focusing on load-displacement and stress-strain curves [36]. The application of ANN techniques has enabled researchers to analyze the effects of several significant variables, which can be categorized into broad groups such as plate characteristics, material properties, geometric details, fracture locations, and porosity distribution [37]. Deep Learning models enhance feature extraction and enable complex data representation learning by stacking multiple layers in a neural network [38]. Without a doubt, neural networks are a popular algorithm across all domains of ML, consistently delivering impressive results for a variety of real-world challenges. In supervised learning problems, the mean squared error between the actual values and the predictions made by the neural network typically serves as the loss function [39]. In recent years, the integration of machine learning techniques into the stochastic dynamic analysis of hybrid composite plates has attracted significant attention. This interest is driven by the growing need for enhanced performance and reliability in various engineering applications. Carbon fiber reinforced polymeric composites, such as polylactic acid, are particularly well-suited for industries like automotive and aviation due to their lightweight and superior mechanical properties [40]. The use of fused filament fabrication for manufacturing a composite material made of polylactic acid PLA reinforced with carbon fiber composite structures has been explored, revealing that optimal settings for parameters such as fiber orientation, nozzle temperature, and bed temperature can significantly influence mechanical performance [41]. The application of machine learning, specifically Classification and regression trees, has proven effective in predicting tensile strength metrics, showcasing the potential of ML in optimizing composite material properties [42]. The review of existing literature from 2014 to 2024 indicates that significant advancements have been made in utilizing ML for analyzing the dynamic behaviors of composite plates, shells, and beams, thereby providing a valuable resource for researchers aiming to leverage these methods in their work [43]. The stochastic effects on functionally graded plates under dynamic loading conditions have also been a focal point of research. Variabilities in geometric and material properties can significantly impact the performance of FG plates during free vibration and impact loading scenarios. The use of support SVM to construct surrogate models has been shown to enhance the accuracy and computational efficiency of these analyses [44]. The output parameters derived from such analyses, including peak contact force and natural frequencies, are essential for understanding the dynamic response of hybrid composite structures. Moreover, the localization of low-velocity impacts on composite plates is another critical area where machine learning has been effectively applied [45]. The development of the Binary Dynamic Stochastic Search algorithm combined with support vector regression has demonstrated significant improvements in feature selection and localization accuracy for LVIs on carbon fiber reinforced plastic carbon fiber reinforced plastic plates [46]. This innovative approach not only reduces the dimensionality of impact features but also optimizes the SVR model’s parameters, thereby enhancing the overall performance of impact detection systems. Finally, the review of data-driven techniques for dynamic load identification underscores the challenges and prospects in this field [47]. The reliance on indirect identification methods due to difficulties in measuring dynamic loads directly necessitates the use of model-free approaches that are independent of structural characteristics [48]. By employing various data-driven techniques, including SVM and deep learning methods, researchers can effectively address issues related to load localization and reconstruction, paving the way for more accurate and reliable dynamic analyses of hybrid composite plates. In summary, a promising area for the study of hybrid composite plates is the nexus of stochastic dynamic analysis and machine learning [49]. The integration of advanced ML techniques not only enhances the understanding of mechanical and dynamic behaviors but it makes it easier to optimize composite materials for a variety of uses. Future investigations should continue to explore these synergies to further advance the field [50]. Zhuang et al. [51] proposed DAEM demonstrates strong accuracy and efficiency in bending, vibration, and buckling analysis of Kirchhoff plates. The results highlight its potential as a robust and generalizable machine learning framework for energy-based structural analysis. Samaniego et al. [52] demonstrates that DNNs, when guided by the energetic format of PDEs, can serve as a powerful alternative for solving mechanical problems. The results confirm their potential as flexible and efficient function approximators for computational mechanics applications. Liu et al. [53] proposed interpretable stochastic machine learning–multiscale framework demonstrates a robust and efficient strategy for predicting the thermal conductivity of graphene-based polymer nanocomposites under uncertainty. By combining homogenization-based FEM with explainable predictive modeling, this approach not only improves accuracy and computational efficiency but also provides deeper insights into parameter influence, paving the way for rational design of next-generation thermal management materials.

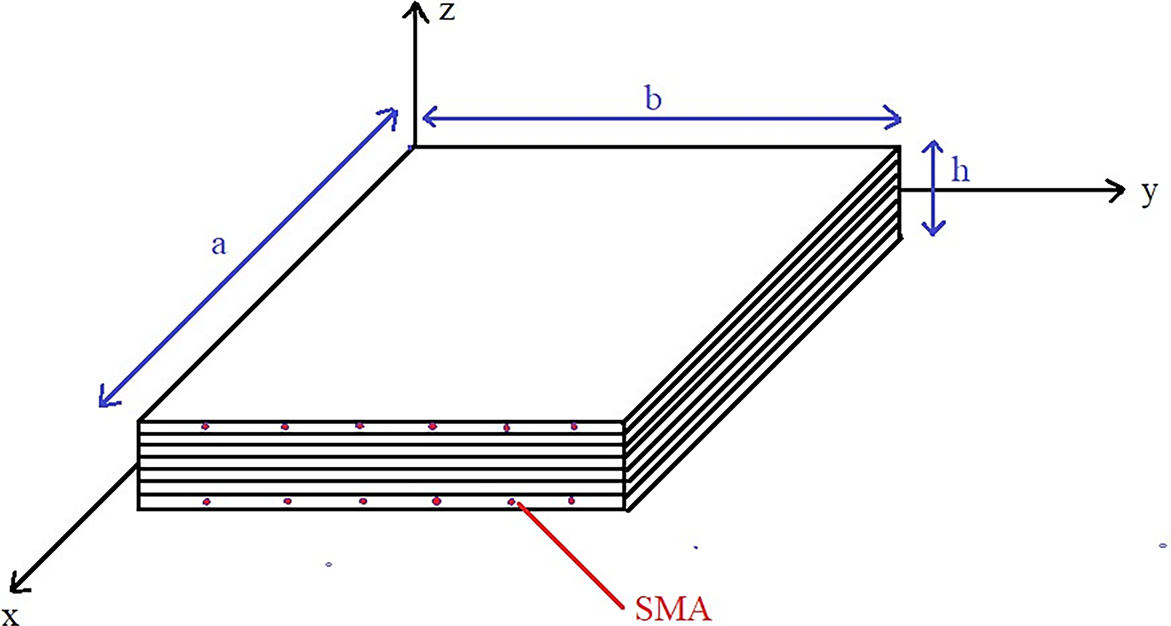

In this research work, efforts are made to compare the MCS model with various machine learning surrogate methods across different sample sizes, focusing on uncertainty in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd natural frequencies. Additionally, scatter graphs are plotted to analyze how closely the results align with those of the MCS model. This is the first attempt, as far as the authors are aware, to measure the degree of uncertainty in the vibration characteristics of Nitinol hybrid constructions and develop the related probability density function visuals using a successful approach. Fig. 1 represents the geometric view of hybrid composite plate.

Figure 1: Geometric View of SMA based composite plate

It is possible to express the dynamic system for the equation of motion as [54]:

where

The natural frequencies

where,

where,

Figure 2: Steps of surrogate based uncertain free vibration analysis

Radial basis function is an alternative surrogate archetypal which is relatively wide spread amid researchers. RBF is habitually cast-off to achieve the exclamation of dispersed multivariate numbers [55]. The meta-model looks in a direct mixture of Euclidean distances, which may be articulated as:

here n is the numeral of specimen themes, wk is the weight resolute by the least-squares technique and

Gaussian radial basis function is used in this study, as it provided the best trade-off between accuracy and stability for the stochastic free vibration problem considered. It’s imperative to message that, contrasting other contraption learning approaches and the response surface method, Radial Basis Function is not a relapse system [57]. In its place, RBF can be sketchily watched as an exclamation method. Subsequently, disparate regression techniques, RBF delivers exact results at the sample points [58]. To date, RBF has been commonly pragmatic in the field of physical steadfastness and indecision evaluation [59]. For vagueness quantification, the method is heightened with an automatic system based on twist, an adaptive specimen scheme, equivalent in fill, and a multi-response principle. It has also been established that the stochastic RBF-based surrogate surpasses popular surrogates like Kriging. Additionally, a hybridized RBF model has been proposed [60]. For structural steadfastness investigation, the hybridized RBF model has been industrialized by relieving the RBF learning network with a SVM. This amendment allows for leveraging the benefits of the SVM, including higher oversimplification and worldwide optimization proficiencies [61]. Comparative valuations have shown that the projected technique outstrips both RBF and the SVM. Additional requirements for RBF include, but are not restricted to, incorporating RBF into the FORM procedure and creating a reliability analysis method based on performance measures [62]. Nonetheless, RBF primarily produces satisfactory outcomes for delays that are lined or only slightly nonlinear. The efficiency of RBF model arises from the use of localized radial kernels that interpolate training points exactly, avoiding the need for global regression fitting. This property makes RBF particularly accurate for capturing nonlinear variations in natural frequencies due to stochastic material properties.

3.2 Polynomial Neural Network (PNN)

A PNN is a cutting-edge form of the assemblage scheme of statistics treatment [63]. This technique employs in numerable multi nominal forms, counting rectilinear, revised quadratic and three-dimensional polynomials. By electing the utmost vital mutable and fit multinomial formulae, the finest part descriptions can be attained over cautious assortment of lumps and deposits. The way endures to increase coat sup until the best concert is accomplished. This tactic can yield a finest PNN edifice. The input-output statistics is providing as shadows [64]:

Some place i = 1, 2, 3, …, n. For separately duos of an input capricious

where i, j = 1, 2, 3, …, n,

Somewhere i, j, k = 1, 2, 3, …, n and (

here, r signifies the numeral of selected input variables. The next step is to guesstimate the quantities of the unfinished imageries. The trajectory of feature Ci can be attained by curtailing the mean sharpened error amid Bi and

The competent statistics set is used to obtain the typical of recti linear equivalencies in accordance with:

The factors of the PD for the dispensation protuberances in separately sheet are found in the method:

here, I signifies the node numeral, k signifies the information numeral, and n represents the tally of designated involvement variables, (ntrain) is the numeral of exercise information subsection, m is the supreme directive, and

(a) If n!/(n − r)!r! < W formerly the numeral of the PDs reserved for the following sheet is equivalent to n!/(n − r)!r!

(b) If n!/(n − r)!r!

Afterward, it’s important to verify the discontinuing principles. The ending ailment must safeguard that the previous layer has an optimal PNN model, allowing the modeling process to be concluded. If

3.3 Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS)

In a MARS based method, the association amongst the scheme’s input and output rejoinders is gritty by choosing illustrations using a definite procedure [77]. The affiliation amid autonomous and reliant on variable quantity is resolute consuming a set of coefficients and basic roles derivative from relapse data, rather than a predefined affiliation. A nonparametric reversion algorithm dividers the input interstellar into provinces, and output retorts are approached using a customary of rudimentary occupations nominated over a forward and backward method [78]. A relentless base role is primarily rummage-sale to generate a modest model. Afterward, supplementary basic roles are merged to progress a extra compound model. Lastly, a backward method is pragmatic to eradicate inconsequential complicated functions after the model. The efficiency of MARS lies in its nonparametric regression and piecewise adaptive basis functions, which automatically capture local nonlinearities. The forward–backward pruning strategy ensures that only the most relevant basis functions are retained, improving both accuracy and interpretability without overfitting. The MARS model can be epitomized as below [79].

here

If the order of interactions is shown by in,

The rudimentary occupation may be in ensuing form:

In FE formulation, the shape functions (Sj) are the function of local natural coordinates of the element (1, v). The shape functions can be shown as:

The shape functions accuracy is given by:

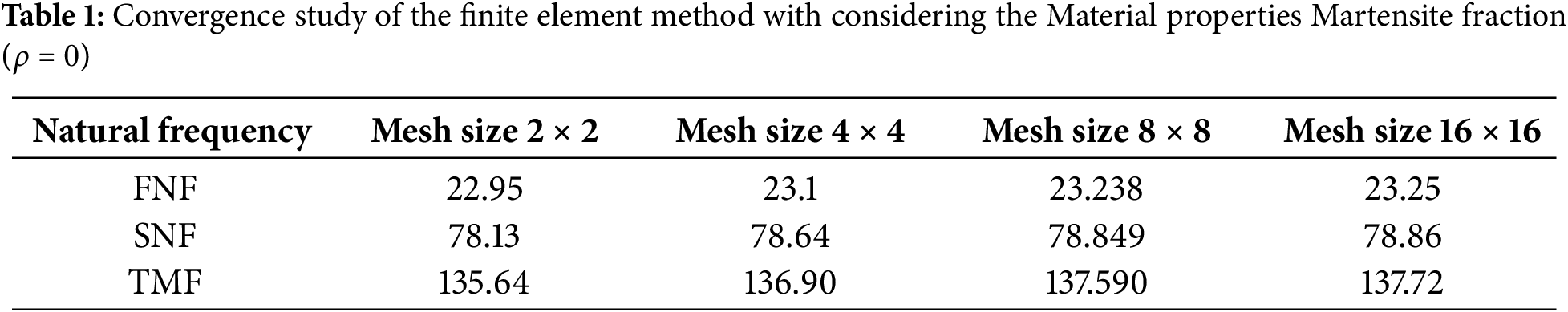

In the present research work, cantilever Nitinol based hybrid composite is considered for stochastic free vibration analysis by using the different surrogate model. The combined variation in material properties

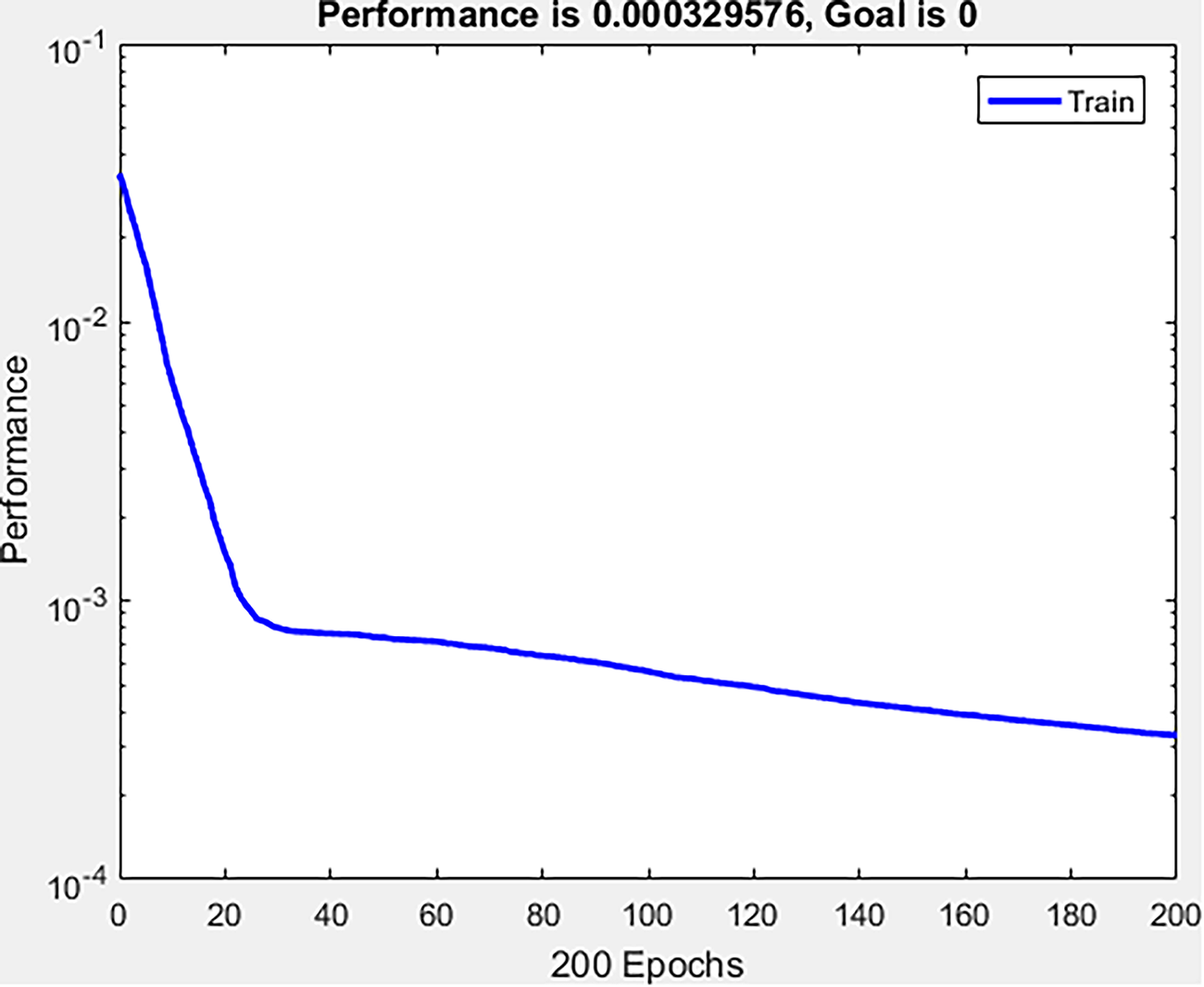

Figure 3: k-fold cross-validation of RBF model

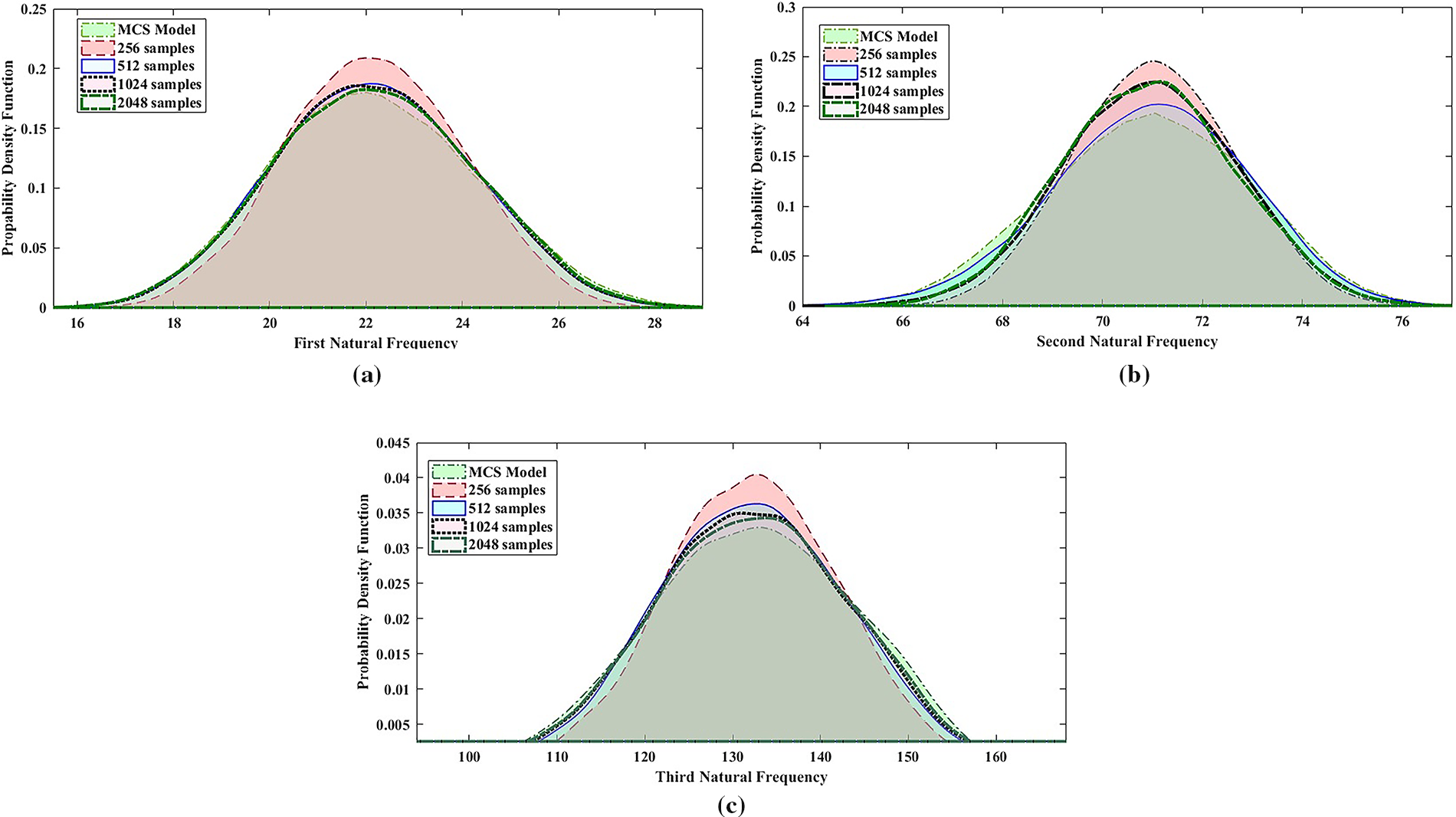

Figure 4: PDF plot of MCS Model and RBF model (with considering different sample size of surrogate model) for first, second & third natural frequencies of hybrid composite plate

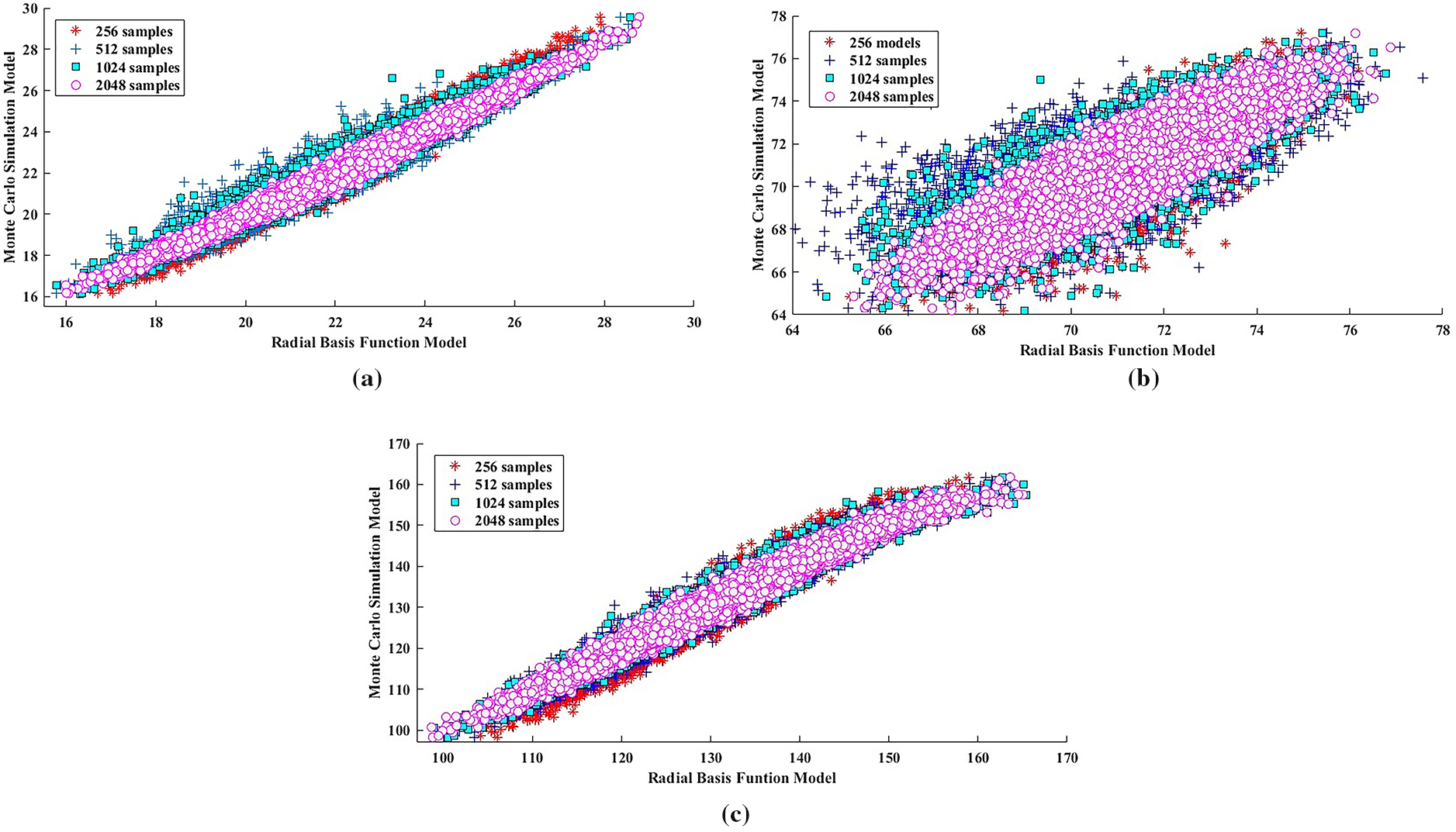

Figure 5: Scatter plot between RBF and MCS Model for first, second & third natural frequencies of hybrid composite plate with considering different sample size

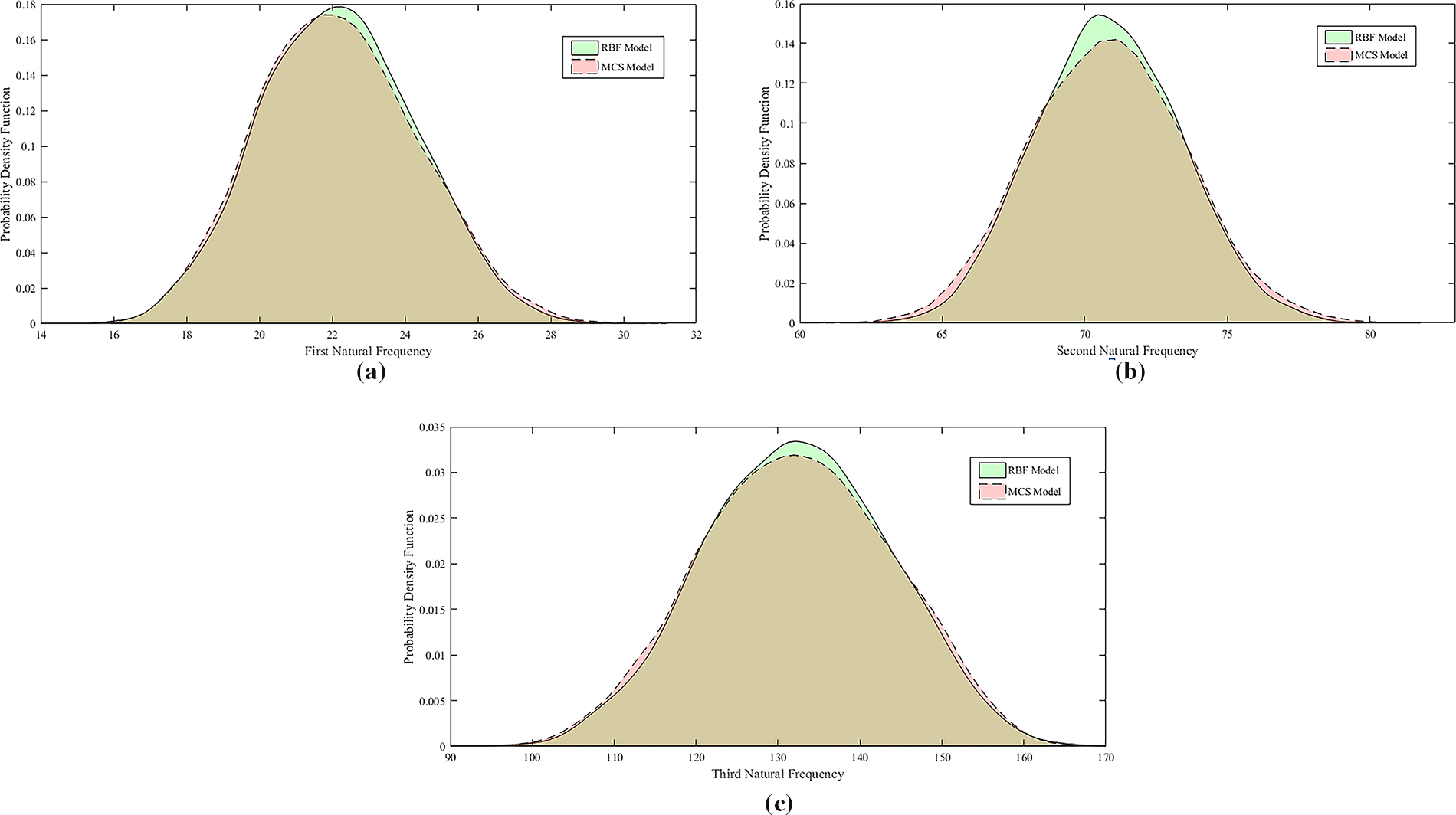

Figure 6: PDF plot of MCS Model and RBF model (with considering 20% stochasticity and n = 2048) for first, second & third natural frequencies of hybrid composite plate

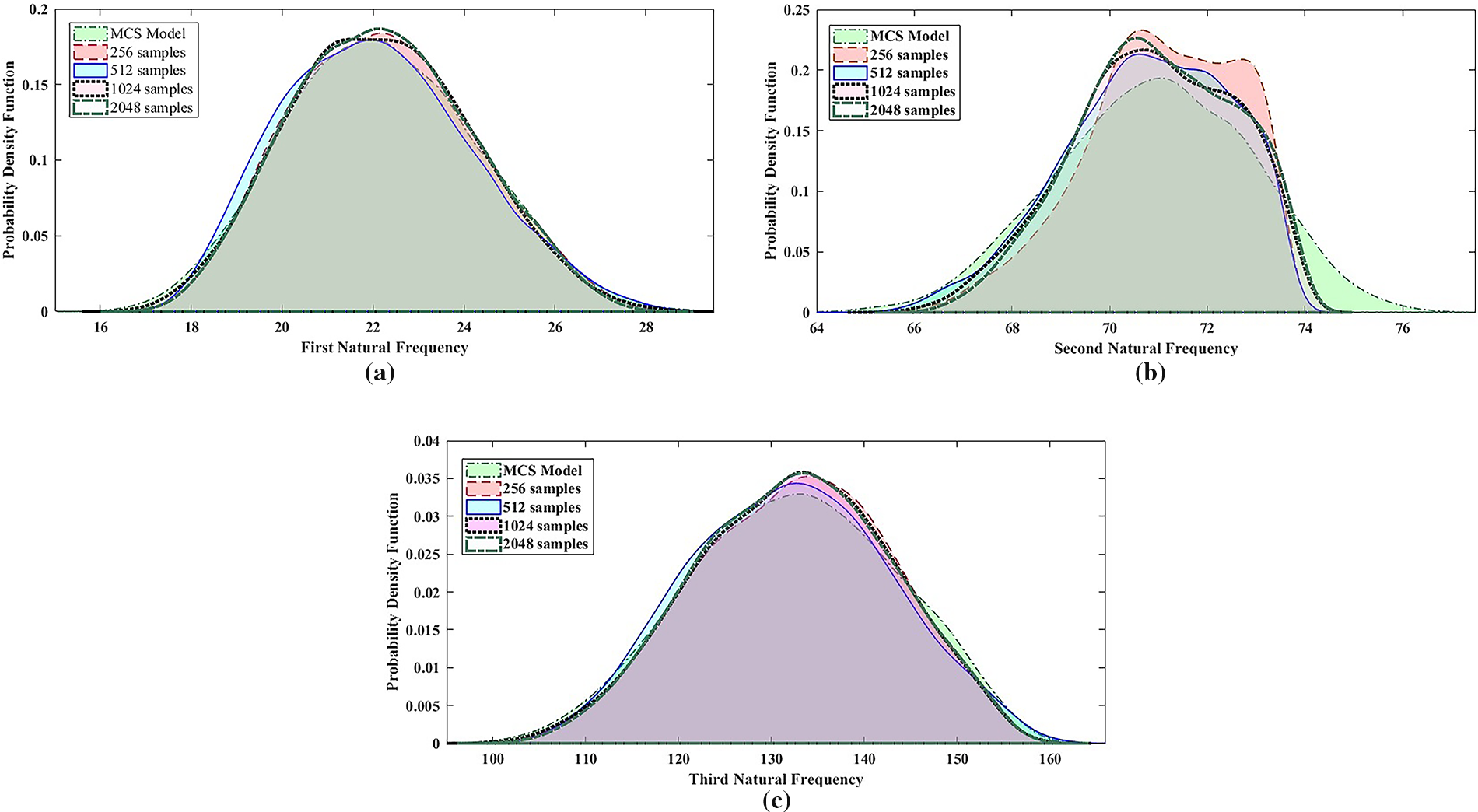

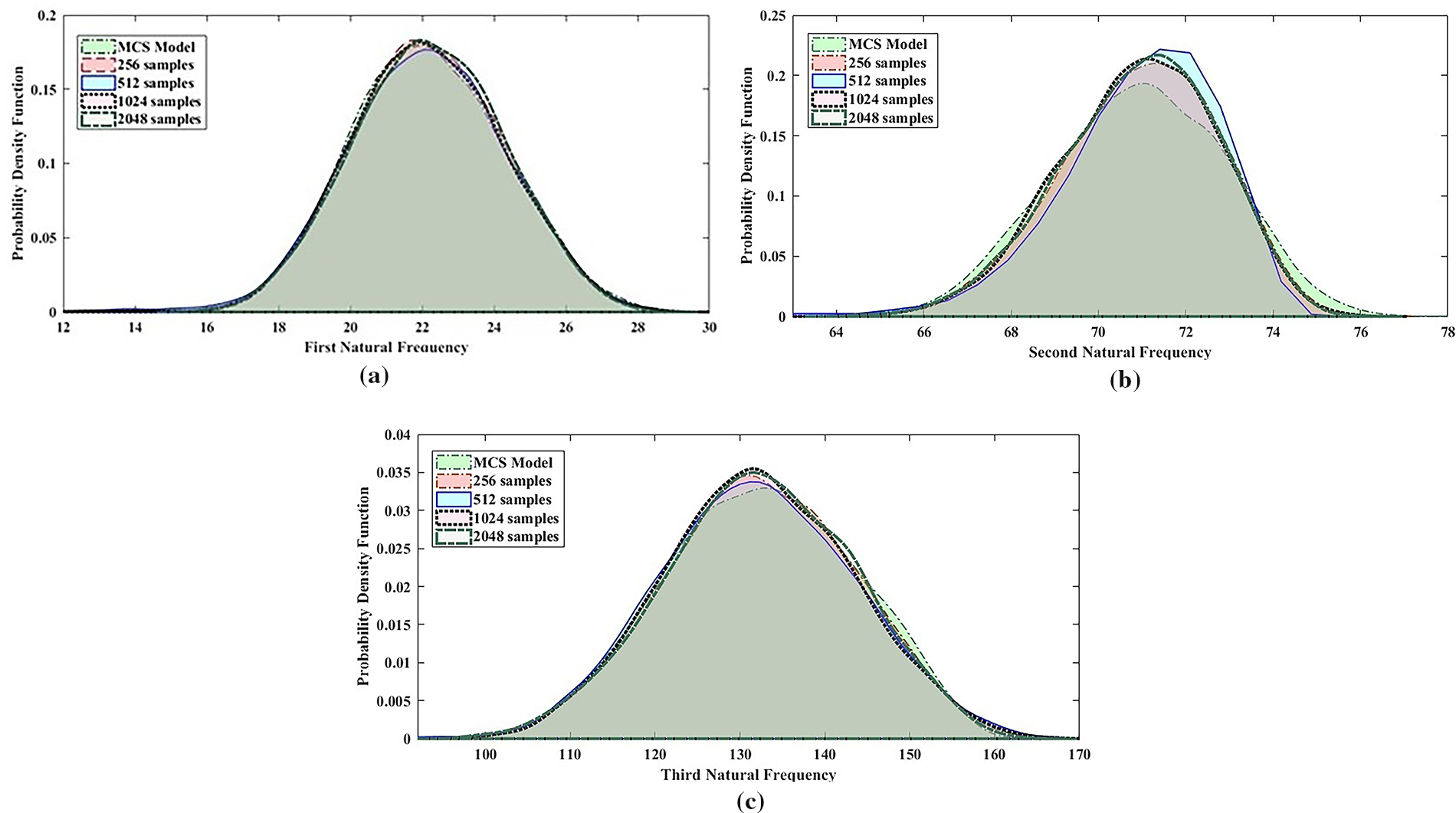

Figure 7: PDF plot of MCS Model and PNN model (with considering different sample size of surrogate model) for first, second & third natural frequencies of hybrid composite plate

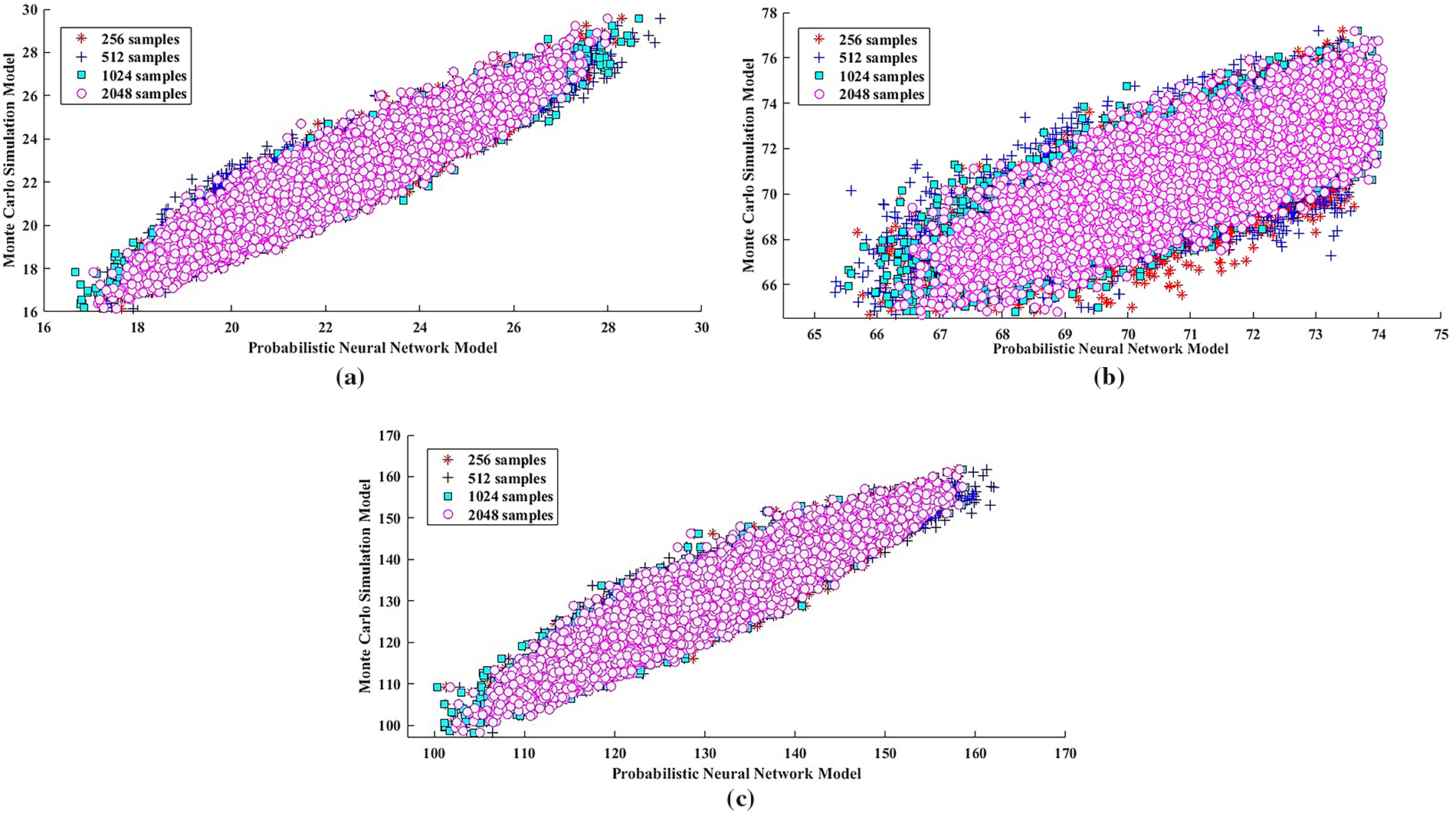

Figure 8: Scatter plot between PNN and MCS Model for first, second & third natural frequencies of hybrid composite plate with considering different sample size

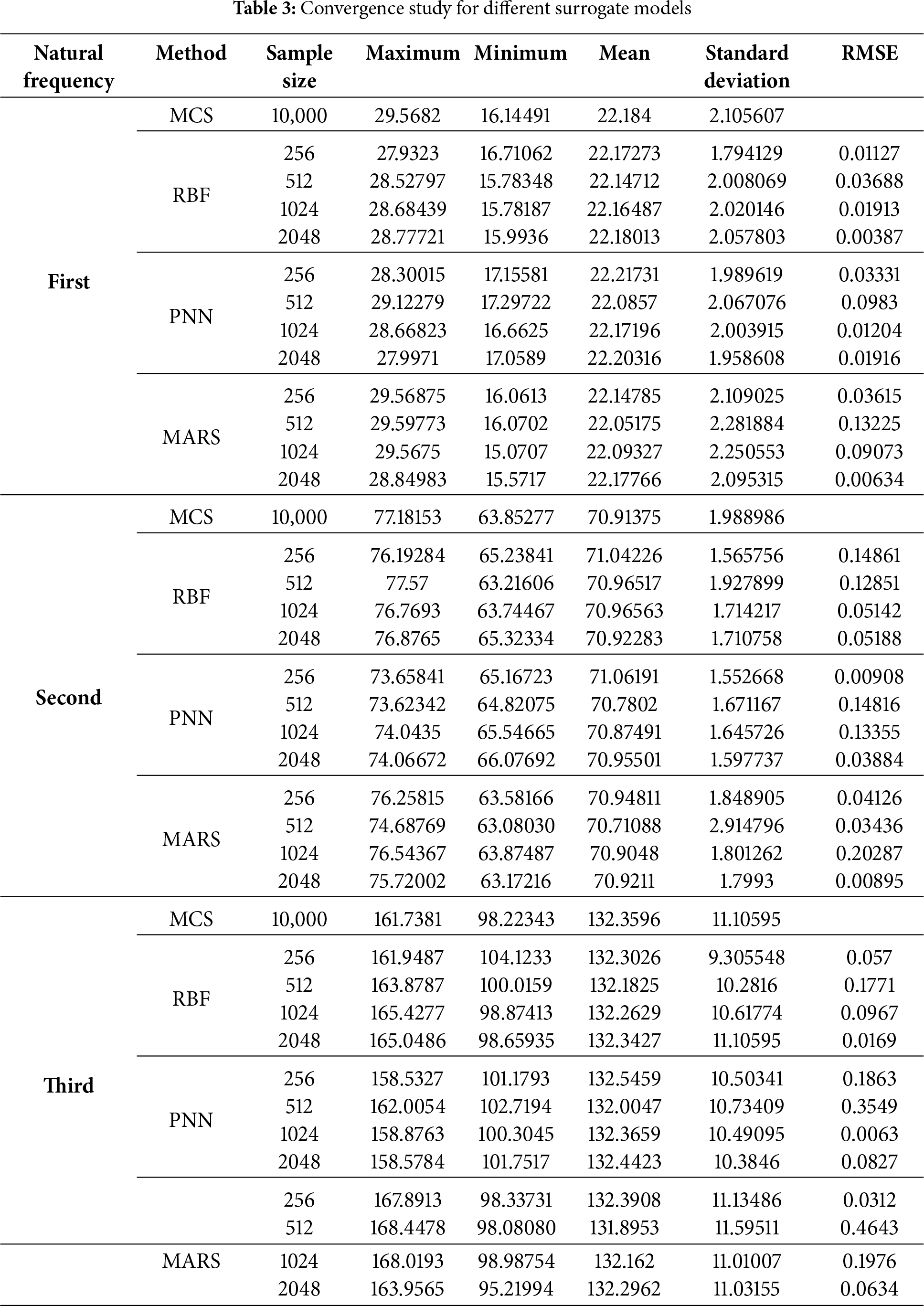

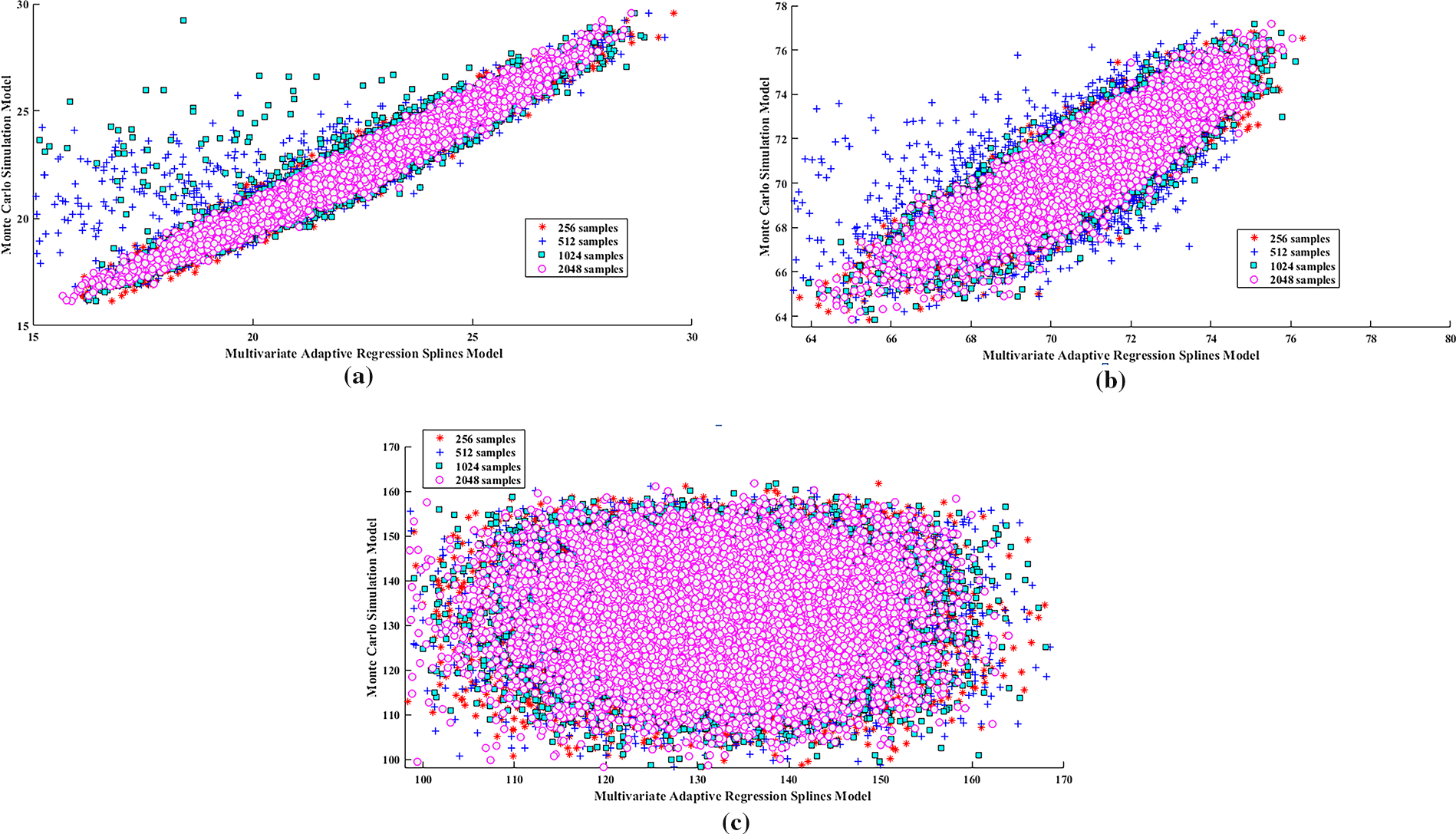

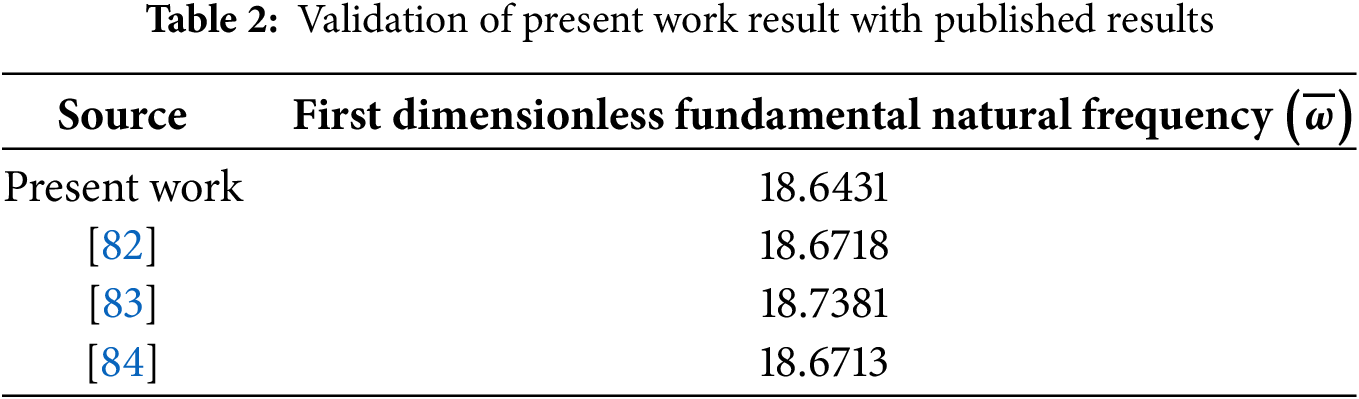

The Fig. 9a–c shows three PDF plots comparing the results of a MARS model and MCS model in predicting the first, second, and third natural frequencies of a hybrid composite plate. Each plot examines the alignment of the MARS model predictions with the MCS results at different sample sizes (256, 512, 1024, and 2048). For all three natural frequencies, the MARS model’s accuracy in approximating the MCS model improves with larger sample size 2048. The MARS model tends to perform better at higher sample sizes (1024 and 2048), where its predictions align closely with the MCS model, indicating that the MARS model can be an effective alternative to MCS with adequate data. This Fig. 10a–c contains three scatter plots labeled as comparisons between the MARS model and the MCS model. Each plot seems to show how well the MARS model approximates results from MCS for different natural frequencies in a dataset, with varying sample sizes. Each scatter plot represents a different sample size, with larger sample size of 2048 reflects yielding results closer to the diagonal (indicating better agreement between models). There’s a general trend that as the sample size increases, the MARS model’s predictions align more closely with the MCS model for each natural frequency. The present study adopts a purely data-driven surrogate modeling strategy (RBF, PNN, MARS) integrated with Monte Carlo simulations. While this significantly reduces computational costs compared to direct large-scale FE–MCS analyses, the accuracy and generalizability of the models remain dependent on the size and quality of training data. The modeling assumes idealized plate geometry and material property variations derived from established mathematical formulations, without explicitly including damage states or manufacturing defects. The main advantage of this study included the Computational efficiency, straightforward implementation, and flexibility in handling different surrogate models. The framework can be easily adapted for different composite systems and uncertainty descriptions. All simulations in this study are performed on an HP Z2 Tower G9 Workstation equipped with a 12th Gen Intel® Core™ i9-12900 processor (2.40 GHz, 16 cores), 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX A2000 GPU with 6 GB VRAM. The workstation was configured with a 477 GB SSD for fast execution and a 1.82 TB HDD for data storage.

Figure 9: PDF plot of MCS Model and MARS model (with considering different sample size of surrogate model) for first, second & third natural frequencies of hybrid composite plate

Figure 10: Scatter plot between MARS and MCS Model for first, second & third natural frequencies of hybrid composite plate with considering different sample size

The novelty of this study lies in the development of a computationally efficient framework using RBF, PNN, and MARS surrogate models for uncertainty quantification in hybrid composite plates, enabling significant reductions in sample size compared to traditional Monte Carlo simulation (MCS). The results show that these surrogate models closely match the MCS benchmark (10,000 samples) in terms of mean and standard deviation of the first three natural frequencies, with the RBF method at 2048 samples providing the most accurate approximation. This demonstrates the feasibility of surrogate-based approaches for effectively capturing uncertainty propagation in stochastic dynamic analysis. Notably, the RBF model achieves superior computational efficiency while maintaining accuracy. Although the present work focused on un-damped free vibration with material uncertainties, the proposed framework is adaptable to more complex scenarios, including damping effects, forced vibration, and geometric nonlinearities. Moreover, while demonstrated on hybrid composite plates, the approach is generalizable to other structural forms such as shells and beams with appropriate training datasets. Future research will further strengthen the methodology by integrating physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) with finite element solvers, incorporating sensitivity analysis to identify the most influential parameters, and pursuing experimental validation to enhance credibility and practical relevance.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Bindi Saurabh Thakkar: Conceptualization of the research framework, development of machine-assisted finite element methodologies, execution of simulations, and analysis of results. Pradeep Kumar Karsh: Supervision, validation of methodologies, interpretation of findings, and revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Pradeep Kumar Karsh, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hasan EH, Shokry KM, Emam AA. Study of impact energy and hardness on reinforced polymeric composites. MAPAN. 2010;25:239–43. doi:10.1007/s12647-010-0022-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Thakkar BS, Karsh PK. Stochastic natural frequencies analysis of hybrid composites: a numerical approach. Mech Compos Mater. 2025;61(1):177–94. doi:10.1007/s11029-025-10269-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Karsh PK, Mukhopadhyay T, Chakraborty S, Naskar S, Dey S. A hybrid stochastic sensitivity analysis for low-frequency vibration and low-velocity impact of functionally graded plates. Compos Part B Eng. 2019;176:107221. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Melin LG, Asp LE. Effects of strain rate on transverse tension properties of a carbon/epoxy composite: studied by moiré photography. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 1999;30:305–16. doi:10.1016/S1359-835X(98)00123-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Karsh PK, Kumar RR, Dey S. Radial basis function-based stochastic natural frequencies analysis of functionally graded plates. Int J Comput Methods. 2019;17:1950061. doi:10.1142/S0219876219500610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Dey S, Mukhopadhyay T, Spickenheuer A, Gohs U, Adhikari S. Uncertainty quantification in natural frequency of composite plates—an artificial neural network based approach. Adv Compos Lett. 2016;25:43–8. doi:10.1177/096369351602500203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sepahvand K, Scheffler M, Marburg S. Uncertainty quantification in natural frequencies and radiated acoustic power of composite plates: analytical and experimental investigation. Appl Acoust. 2015;87:23–9. doi:10.1016/j.apacoust.2014.06.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Vaishali, Kushari S, Kumar RR, Karsh PK, Dey S. Sensitivity analysis of random frequency responses of hybrid multi-functionally graded sandwich shells. J Vib Eng Technol. 2023;11(3):845–72. doi:10.1007/s42417-022-00612-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chen C, Wang Y, Chen S, Fang B, Cao D. Knowledge and data fusion-driven dynamical modeling approach for structures with hysteresis-affected uncertain boundaries. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025;113:4179–95. doi:10.1007/s11071-024-10096-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dey S, Mukhopadhyay T, Adhikari S. Stochastic free vibration analyses of composite shallow doubly curved shells—a Kriging model approach. Compos Part B Eng. 2015;70:99–112. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2014.10.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen C, Wang Y, Fang B, Chen S, Yang Y, Wang B, et al. Low-dimensional dynamical models of structures with uncertain boundaries via a hybrid knowledge–and data-driven approach. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2025;223:111876. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2024.111876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang Q, Wu D, Tin-Loi F, Gao W. Machine learning aided stochastic structural free vibration analysis for functionally graded bar-type structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019;144:106315. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2019.106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Singh SK, Agarwal A. A comparative analysis of artificial neural network algorithms to enhance the power quality of photovoltaic distributed generation system based on metrological parameters. MAPAN. 2023;38:607–18. doi:10.1007/s12647-023-00649-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang Z, Zhang L, Lu L, Zhang Y, Qiu W. Vibration-based assessment of delaminations in FRP composite plates. Compos Part B Eng. 2018;144(1):254–66. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Goel T, Haftka RT, Shyy W, Queipo NV. Ensemble of surrogates. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2007;33:199–216. doi:10.1007/s00158-006-0051-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Feng D, Fan S, Zheng D. Structural influence on the performance based on uncertainty analysis for Coriolis mass flowmeter. MAPAN. 2017;33:15–27. doi:10.1007/s12647-017-0228-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Acar E, Rais-Rohani M. Ensemble of metamodels with optimized weight factors. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2009;37:279–94. doi:10.1007/s00158-008-0230-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Acar E. Various approaches for constructing an ensemble of metamodels using local measures. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2010;42:879–96. doi:10.1007/s00158-010-0520-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Joy EJ, Menon AS, Biju N. Implementation of kriging surrogate models for delamination detection in composite structures. Adv Compos Lett. 2018;27:220–31. doi:10.1177/09636935180270060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Papila N, Shyy W, Griffin L, Dorney DJ. Shape optimization of supersonic turbines using response surface and neural network methods. In: 39th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; 2001 Jan 8–11; Reno, NV, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2001-1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Vaidyanathan R, Tucker PK, Papila N, Shyy W. CFD-based design optimization for a single element rocket injector. In: 41st Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; 2003 Jan 6–9; Reno, NV, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2003-296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Viana FAC, Haftka RT, Steffen V. Multiple surrogates: how cross-validation errors can help us to obtain the best predictor. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2009;39:439–57. doi:10.1007/s00158-008-0338-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Dey S, Mukhopadhyay T, Spickenheuer A, Adhikari S, Heinrich G. Bottom up surrogate based approach for stochastic frequency response analysis of laminated composite plates. Compos Struct. 2016;140:712–27. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.01.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Naskar S, Mukhopadhyay T, Sriramula S. Spatially varying fuzzy multi-scale uncertainty propagation in unidirectional fibre reinforced composites. Compos Struct. 2019;209:940–67. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.09.090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dey S, Mukhopadhyay T, Adhikari S. Uncertainty quantification in laminated composites: a meta-model based approach; 2018. doi:10.1201/9781315155593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Manchiraju VNM, Bhagat AR, Dwivedi VK. Estimation of elastic constants using numerical methods and their validation through experimental results for unidirectional carbon/carbon composite materials. MAPAN. 2023;38:923–37. doi:10.1007/s12647-023-00669-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Tullu A, Lee BS, Hwang HY. Surrogate model based analysis of inter-ply shear stress in fiber reinforced thermoplastic composite sheet press forming. Appl Sci. 2020;10:16. doi:10.3390/app10165499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sharma A, Mukhopadhyay T, Rangappa SM, Siengchin S, Kushvaha V. Advances in computational intelligence of polymer composite materials: machine learning assisted modeling, analysis and design. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2022;29:3341–85. doi:10.1007/s11831-021-09700-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sajjadinia SS, Carpentieri B, Shriram D, Holzapfel GA. Multi-fidelity surrogate modeling through hybrid machine learning for biomechanical and finite element analysis of soft tissues. Comput Biol Med. 2022;148:105699. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Cunha BZ, Droz C, Zine AM, Foulard S, Ichchou M. A review of machine learning methods applied to structural dynamics and vibroacoustic. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2023;200:110535. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2023.110535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Al Rjoub YS, Alshatnawi JA. Free vibration of functionally-graded porous cracked plates. Structures. 2020;28:2392–403. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2020.10.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Jang J, Smyth AW. Data-driven models for temperature distribution effects on natural frequencies and thermal prestress modeling. Struct Control Health Monit. 2020;27:1–22. doi:10.1002/stc.2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Alizadeh R, Allen JK, Mistree F. Managing computational complexity using surrogate models: a critical review. Res Eng Des. 2020;31:275–98. doi:10.1007/s00163-020-00336-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Feng H, Prabhakar P. Difference-based deep learning framework for stress predictions in heterogeneous media. Compos Struct. 2021;269:113957. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.113957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Truong VH, Pham HA. Support vector machine for regression of ultimate strength of trusses: a comparative study. Eng J. 2021;25:157–66. doi:10.4186/ej.2021.25.7.157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hashemi A, Jang J, Beheshti J. A machine learning-based surrogate finite element model for estimating dynamic response of mechanical systems. IEEE Access. 2023;11:54509–25. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3282453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Dey S, Karmakar A. Natural frequencies of delaminated composite rotating conical shells—a finite element approach. Finite Elem Anal Des. 2012;56:41–51. doi:10.1016/j.finel.2012.02.00. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Cho SE. Probabilistic stability analyses of slopes using the ANN-based response surface. Comput Geotech. 2009;36:787–97. doi:10.1016/j.compgeo.2009.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Reddy MRS, Reddy BS, Reddy VN, Sreenivasulu S. Prediction of natural frequency of laminated composite plates using artificial neural networks. Eng. 2012;4:329–37. doi:10.4236/eng.2012.46043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Sadovský Z, Soares CG. Artificial neural network model of the strength of thin rectangular plates with weld induced initial imperfections. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2011;96:713–17. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2011.02.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Malekzadeh K, Mozafari A, Ghasemi FA. Free vibration response of a multilayer smart hybrid composite plate with embedded SMA wires. Lat Am J Solids Struct. 2014;11:279–98. doi:10.1590/S1679-78252014000200008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Chahar RS, Mukhopadhyay T. Multi-fidelity machine learning based uncertainty quantification of progressive damage in composite laminates through optimal data fusion. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;125:106647. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Joy EJ, Biju N, Menon AS. Delamination detection in composite laminates using ensemble of surrogates. Mater Today Proc. 2019;46:9597–603. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.05.505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Chatterjee T, Chakraborty S, Chowdhury R. A critical review of surrogate assisted robust design optimization. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2019;26(1):245–74. doi:10.1007/s11831-017-9240-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Roque CMC, Ferreira AJM, Jorge RMN. A radial basis function approach for the free vibration analysis of functionally graded plates using a refined theory. J Sound Vib. 2007;300:1048–70. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2006.08.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Krishnamurthy T. Response surface approximation with augmented and compactly supported radial basis functions. AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Struct Struct Dynam Mat Conf. 2003;5:3210–25. doi:10.2514/6.2003-1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Kumar A, Parey A, Kankar PK. Supervised machine learning based approach for early fault detection in polymer gears using vibration signals. MAPAN. 2023;38:383–94. doi:10.1007/s12647-022-00608-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Volpi S, Meade ADM, Santos DAHP, Oliveira CLN. Development and validation of a dynamic metamodel based on stochastic radial basis functions and uncertainty quantification. Struct Multidiscip Optim. 2015;51:347–68. doi:10.1007/s00158-014-1128-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Dai HZ, Zhao W, Wang W, Cao ZG. An improved radial basis function network for structural reliability analysis. J Mech Sci Technol. 2011;25:2151–9. doi:10.11591/ijai.v8.i1.pp63-76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Chau MQ, Han X, Jiang C, Bai YC, Tran TN, Truong VH. An efficient PMA-based reliability analysis technique using radial basis function. Eng Comput. 2014;31:1098–115. doi:10.1108/EC-04-2012-0087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhuang X, Guo H, Alajlan N, Zhu H, Rabczuk T. Deep autoencoder based energy method for the bending, vibration, and buckling analysis of Kirchhoff plates with transfer learning. Eur J Mech A/Solids. 2021;87:104225. doi:10.1016/j.euromechsol.2021.104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Samaniego E, Anitescu C, Goswami S, Nguyen-Thanh VM, Guo H, Hamdia K, et al. An energy approach to the solution of partial differential equations in computational mechanics via machine learning: concepts, implementation and applications. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2020;362:112790. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2019.112790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Liu B, Liu P, Wang Y, Li Z, Lv H, Lu W, et al. Explainable machine learning for multiscale thermal conductivity modeling in polymer nanocomposites with uncertainty quantification. Compos Struct. 2025;119:119292. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2025.119292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Vaishali, Karsh PK, Kushari S, Kumar RR, Dey S. Stochastic free vibration and impact responses of functionally graded plates: a support vector machine learning model approach. J Vib Eng Technol. 2023;11(7):2927–43. doi:10.1007/s42417-022-00721-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Bucher CG. Adaptive sampling—an iterative fast Monte Carlo procedure. Struct Saf. 1988;5(1):119–26. doi:10.1007/s12205-013-1779-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Cardoso JB, de Almeida JR, Dias JM, Coelho PG. Structural reliability analysis using Monte Carlo simulation and neural networks. Adv Eng Softw. 2008;39:505–13. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2007.03.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Deng J, Gu D, Li X, Yue ZQ. Structural reliability analysis for implicit performance functions using artificial neural network. Struct Saf. 2005;27:25–48. doi:10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2005.05.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Wang C, Qiang X, Xu M, Wu T. Recent advances in surrogate modeling methods for uncertainty quantification and propagation. Symmetry. 2022;14:1219. doi:10.3390/sym14061219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Liu X, Tian S, Tao F, Du H, Yu W. How machine learning can help the design and analysis of composite materials and structures? AIAA Scitech Forum. 2021;1–21. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2010.09438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Karsh PK, Mukhopadhyay T, Dey S. Stochastic dynamic analysis of twisted functionally graded plates. Compos Part B Eng. 2018;147:259–78. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.03.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Raturi HP, Kushari S, Karsh PK, Dey S. Evaluating stochastic fundamental natural frequencies of porous functionally graded material plate with even porosity effect: a multi-machine learning approach. J Vib Eng Technol. 2024;12:1931–42. doi:10.1007/s42417-023-00954-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Çelik M, Gündoğdu E, Özdilek EE, Demirkan E, Artan R. Artificial neural network validation research: free vibration analysis of functionally graded beam via higher-order shear deformation theory and artificial neural network method. Appl Sci. 2024;14:217. doi:10.3390/app14010217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Hurtado JE, Alvarez DA. Neural-network-based reliability analysis: a comparative study. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2001;191:113–32. doi:10.1016/S0045-7825(01)00248-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Chojaczyk AA, Teixeira AP, Neves LC, Cardoso JB, Soares CG. Review and application of artificial neural networks models in reliability analysis of steel structures. Struct Saf. 2015;52:78–89. doi:10.1016/j.strusafe.2014.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Karsh PK, Raturi HP, Kumar RR, Dey S. Parametric uncertainty quantification in natural frequency of sandwich plates using polynomial neural network. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2020;798:012036. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/798/1/012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Oh S-K, Pedrycz W, Park B-J. Polynomial neural networks architecture: analysis and design. Comput Electr Eng. 2003;29(6):703–25. doi:10.1016/S0045-7906(02)00045-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Karsh PK, Kumar A, Dey S. Polynomial neural network based stochastic natural frequency analysis of functionally graded plates. Singapore: Springer; 2021. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-5862-7_31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Pourkamali-Anaraki F, Husseini JF, Stapleton SE. Probabilistic neural networks (PNNs) for modeling aleatoric uncertainty in scientific machine learning. IEEE Access. 2024; 2024;12:178816–31. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3508735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Abueidda DW, Koric S, Sobh NA. Topology optimization of 2D structures with nonlinearities using deep learning. Comput Struct. 2020;237:106283. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2020.106283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Chen Y, Liu J. Polynomial dendritic neural networks. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(14):11571–88. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-07044-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Trafalis TB, Oladunni OO. Support vector machines and applications. Recent Adv Data Min Enterp Data Algorithms Appl. 2008:643–690. doi:10.1142/9789812779861_0014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Stern RE, Song J, Work DB. Accelerated Monte Carlo system reliability analysis through machine-learning-based surrogate models of network connectivity. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2017;164:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2017.01.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Rubinstein RY, Kroese DP. Simulation and the Monte Carlo method. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016. doi:10.1002/9781118631980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Cervantes J, Garcia-Lamont F, Rodríguez-Mazahua L, Lopez A. A comprehensive survey on support vector machine classification: applications, challenges and trends. Neurocomputing. 2020;408:189–215. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2019.10.118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Zhou J, Qian H, Lu X, Duan Z, Huang H, Shao Z. Polynomial activation neural networks: modeling, stability analysis and coverage BP-training. Neurocomputing. 2019;359:227–40. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2019.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Vaishali, Mukhopadhyay T, Karsh PK, Basu B, Dey S. Machine learning based stochastic dynamic analysis of functionally graded shells. Compos Struct. 2019;237:111870. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2020.111870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Wang Q, Zhang Y, Liu L, Li Z, Wang J, Chen X. Machine learning aided uncertainty quantification for engineering structures involving material-geometric randomness and data imperfection. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2024;423:116868. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2024.116868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Abdar M, Khosravi A, Shishika SS, Mohammad FRMZS, Suganthan PN, Zhang Y, et al. A review of uncertainty quantification in deep learning: techniques, applications and challenges. Inf Fusion. 2021;76(1):243–97. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2021.05.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Karsh PK, Thakkar B, Kumar RR, Dey S. Probabilistic oblique impact analysis of functionally graded plates—a multivariate adaptive regression splines approach. Eur J Comput Mech. 2021;30:223–54. doi:10.13052/ejcm2642-2085.30234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Samui P. Multivariate adaptive regression spline (MARS) for prediction of elastic modulus of jointed rock mass. Geotech Geol Eng. 2013;31(1):249–53. doi:10.1007/s10706-012-9584-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Mukhopadhyay T. A multivariate adaptive regression splines based damage identification methodology for web core composite bridges including the effect of noise. J Sand Struct Mat. 2017;20(7):885–903. doi:10.1177/1099636216682533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Lei ZX, Zhang LW, Liew KM. Free vibration analysis of laminated FG-CNT reinforced composite rectangular plates using the kp-Ritz method. Compos Struct. 2015;127:245–59. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2015.03.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Burlayenko VN. An element free Galerkin method for the free vibration analysis of composite laminates of complicated shape. Procedia Eng. 2003;59:279–89. doi:10.1016/S0263-8223(02)00034-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Ganesh S. Free vibration analysis of delaminated composite plates using finite element method. Compos Struct. 2016;144:1067–75. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.05.061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools