Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Cloud-Based Distributed System for Story Visualization Using Stable Diffusion

1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, National Taiwan Ocean University, Keelung, 202301, Taiwan

2 Department of Engineering Science, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, 701401, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Shih-Yeh Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Omnipresent AI in the Cloud Era Reshaping Distributed Computation and Adaptive Systems for Modern Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072890

Received 05 September 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

With the rapid development of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), the task of story visualization, which transforms natural language narratives into coherent and consistent image sequences, has attracted growing research attention. However, existing methods still face limitations in balancing multi-frame character consistency and generation efficiency, which restricts their feasibility for large-scale practical applications. To address this issue, this study proposes a modular cloud-based distributed system built on Stable Diffusion. By separating the character generation and story generation processes, and integrating multi-feature control techniques, a caching mechanism, and an asynchronous task queue architecture, the system enhances generation efficiency and scalability. The experimental design includes both automated and human evaluations of character consistency, performance testing, and multi-node simulation. The results show that the proposed system outperforms the baseline model StoryGen in both CLIP-I and human evaluation metrics. In terms of performance, under the experimental environment of this study, dual-node deployment reduces average waiting time by approximately 19%, while the four-node simulation further reduces it by up to 65%. Overall, this study demonstrates the advantages of cloud-distributed GenAI in maintaining character consistency and reducing generation latency, highlighting its potential value in multi-user collaborative story visualization applications.Keywords

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) is rapidly transforming the landscape of digital content creation, particularly demonstrating significant potential in multimodal generation across images, language, and audio domains [1]. Recent advancements in text-to-image models, such as Stable Diffusion [2], DALL.E [3], and Imagen [4], have made it increasingly feasible to convert natural language narratives into sequences of images, giving rise to the emerging field of story visualization. However, applying generative models to multi-frame narrative generation still presents two major technical challenges. First, the high computational cost and heavy reliance on hardware resources hinder real-time image generation and seamless performance in multi-user collaborative settings. This issue is particularly pronounced in collaborative environments, where long generation delays become a major barrier to practical deployment [5]. Second, character consistency remains a critical issue. Since each frame is generated from independent latent vectors, character appearances often vary across images, disrupting narrative coherence and viewer comprehension [6].

Although prior studies such as StoryDALL.E [7] and StoryGen [8] and DDIM [9] have sought to improve character consistency and generation efficiency through model-level conditioning, feature transfer, and algorithmic enhancements, they tend to overlook system-level limitations. Under single-machine deployments, constraints in parallel generation, task scheduling, and caching mechanisms severely limit scalability, making it difficult to support synchronous multi-user workflows or cross-device collaboration. Therefore, rethinking the architecture of the system by integrating cloud computing and distributed coordination technologies is essential to overcoming current limitations in generation efficiency and accessibility. This forms the key motivation of our study.

In this paper, we propose a cloud-based distributed system for story visualization, built upon Stable Diffusion. The system adopts a modular architecture that decouples character generation from story generation, and integrates multiple control techniques, including low-rank adaptation (LoRA) [10], segment anything model (SAM) [11], IP-Adapter [12], and ControlNet [13], to enhance visual fidelity and consistency. It also employs caching optimization and asynchronous task queue scheduling to distribute generation workloads across multiple GPU nodes, significantly reducing user wait times. Additionally, a cloud-based web interface has been developed to support seamless operation across devices and facilitate collaborative use.

The main contributions of this work are as follows: (1) A scalable modular generation framework that improves task processing efficiency and deployment flexibility; (2) A distributed computing architecture that significantly reduces generation latency and supports high-concurrency scenarios; (3) The integration of multiple control modules to enhance character consistency across frames; (4) A cloud-based interactive interface that improves accessibility and facilitates practical adoption of GenAI systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the core literature on story visualization, generative model development, and cloud-based distributed systems. Section 3 details the system architecture and experimental methodology. Section 4 presents the experimental results and performance analysis. Section 5 concludes with research findings, discusses system limitations, and outlines directions for future work.

2.1 Visual Narrative and AI-Based Story Visualization

Visual narrative refers to the communication of stories, concepts, or emotions through visual media such as illustrations, murals, images, or animations in a coherent and structured manner to facilitate comprehension by the audience [14]. According to Cohn’s research on visual narrative comprehension, understanding visual narratives involves not only image continuity but also cognitive processes that integrate visual semantics, visual grammar, and event models, indicating a high degree of similarity with language processing [15,16]. With the increasing demand for visual communication, visual narratives have been widely applied across diverse domains, including education, healthcare, and public health communication. In the field of education, studies have shown that combining short visual narratives with guided questioning can effectively enhance students’ motivation and classroom engagement, thereby improving their comprehension and learning outcomes [17]. In healthcare, visual narratives have been employed in speech therapy for individuals with aphasia. Therapists use visual stimuli to guide patients in practicing verbal expression, thereby supporting language recovery [18]. Similarly, in medical education and health communication, combining visual narratives with written descriptions has been demonstrated to improve the public’s understanding of health-related information and to promote health literacy [19].

Although humans are considered innately capable of understanding image sequences, the effectiveness of such comprehension is still influenced by individual experience and age of acquisition. Studies have shown that learners who are exposed to visual narratives earlier and engage with them consistently over time tend to demonstrate better semantic processing and comprehension abilities [20]. Consequently, providing learners with early and sustained exposure to visual narratives, particularly through interactive and dynamic media, has become a key focus in recent research. Traditional visual narratives, however, often rely on manual creation or repeated use of pre-designed images and assets. While these methods can convey narrative content, they are constrained by labor-intensive processes and limited expressive flexibility, making it difficult to scale or adapt content dynamically.

In this context, the rapid development of image generation technologies has prompted researchers to explore the integration of artificial intelligence into story visualization tasks. Story visualization aims to convert natural language narratives into image sequences that maintain both character consistency and scene continuity to convey story content and emotion [21]. In recent years, several studies have been dedicated to advancing story visualization, including the StoryGen model proposed by Liu et al. [8], the RCDMs model by Shen et al. [22], and the Cogcartoon framework by Zhu and Tang [23], which demonstrate progress in semantic transformation from language to images and in visual coherence. However, most of these studies primarily focus on the generative models themselves and have not fully addressed the trade-offs between output quality, character consistency, and system efficiency. In particular, ensuring consistent character appearances across multiple frames and reducing computational latency remain critical challenges for practical deployment.

2.2 Generative AI Evolution and Stable Diffusion

To address the key challenges of character consistency and high-quality generation in story visualization, selecting an appropriate image generation model is crucial. This section reviews the evolution of GenAI technologies, with a focus on the core components and application development of Stable Diffusion, which serves as the foundation of the system proposed in this study. GenAI refers to a class of AI systems capable of producing new textual, visual, audio, and multimedia content by learning latent patterns and structures from training data [24]. According to a recent systematic review [25], mainstream generative models can be categorized into four major types: (1) Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), introduced by Goodfellow et al. [26], which utilize adversarial training between a generator and a discriminator to synthesize realistic outputs but often suffer from mode collapse due to limited sample diversity [27]; (2) Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), proposed by Kingma and Welling [28], which combine encoder-decoder structures and perform variational inference to model the latent space, enabling data reconstruction with partial information loss while preserving semantic structure; (3) Transformers, introduced by Vaswani et al. [29], which rely on self-attention and multi-head attention mechanisms to effectively capture long-range dependencies in sequential data; and (4) Diffusion Models (DMs), first proposed by Sohl-Dickstein et al. [30], which gradually add Gaussian noise to training data through a forward diffusion process and reconstruct high-quality samples via a reverse diffusion process. While GANs and Transformers have played pivotal roles in the development of GenAI, this section focuses on VAEs and DMs due to their close technical relevance to Stable Diffusion.

Building on DMs, Ho et al. proposed the Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM) in 2020 [31], which simulates the forward diffusion as a Markov chain and approximates the reverse process using a parameterized neural network to iteratively denoise and reconstruct data. However, DDPM requires a large number of sampling steps for high-resolution image generation, resulting in significant computational costs. To improve its practicality and efficiency, subsequent research introduced optimizations such as accelerated sampling and latent space compression [32]. For accelerated sampling, Song et al. proposed the Denoising Diffusion Implicit Model (DDIM) in 2021 [9], which relaxes the Markov assumption and applies a deterministic reverse process. This method allows the model to skip several diffusion steps while maintaining comparable output quality, achieving a 10 to 50 times speedup with only minor losses in sample diversity.

In terms of latent space compression, Rombach et al. introduced the Latent Diffusion Model (LDM) in 2022 [33]. LDM seeks a perceptually equivalent but computationally efficient latent space where diffusion processes can be conducted. It employs a VAE to compress images while preserving key semantic and perceptual features, significantly reducing the dimensionality of the data and computational overhead. For example, a

These innovations laid the groundwork for the development of Stable Diffusion [2], which was released as an open source model in 2022 by Stability AI and its collaborators. Leveraging the high efficiency of LDM, SD integrates a CLIP text encoder for text-to-image generation, an optimized U-Net architecture, and a cross-attention mechanism to enhance both image quality and flexibility. Due to its open-source nature and extensibility, SD quickly became a mainstream generative framework and inspired a diverse ecosystem of extensions. For instance, LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) [10], introduced by Hu et al. in 2023, allows fine-tuning with minimal computational cost by freezing pre-trained weights and training a small rank-constrained adaptation module. Similarly, ControlNet [13] by Zhang et al. enables fine-grained control through conditions such as edges, pose estimation, or segmentation maps. IP-Adapter by Ye et al. [12] achieves effective multimodal integration of images and text through a decoupled cross-attention mechanism. Additionally, Meta AI released the SAM [11], designed for promptable segmentation, which combines a ViT-based image encoder, prompt encoder, and mask decoder to generate accurate masks based on points, boxes, or text prompts. Trained on a massive image corpus, SAM demonstrates strong zero-shot generalization capabilities, enabling high-accuracy segmentation even without labeled data.

Although this study does not aim to improve the aforementioned models directly, they serve as core components in the integrated system design. It is worth noting that these models often face performance bottlenecks when deployed on standalone systems due to their high computational demands, particularly in multi-frame story generation scenarios. Therefore, leveraging cloud and distributed architectures to support large-scale generation while maintaining efficiency and stability becomes a central challenge that this research seeks to address.

2.3 Cloud-Based Systems and Distributed Architecture

Although Stable Diffusion and its extended ecosystem provide a powerful technological foundation for story visualization tasks, their high computational cost and dependence on hardware resources present significant obstacles for individual users and collaborative teams [34,35]. Traditional single-machine deployment architectures often face performance bottlenecks and inference latency issues when dealing with high-concurrency user requests or continuous generation tasks, limiting their suitability for real-time interaction and collaboration [36]. To address these challenges and make advanced GenAI technologies more accessible and user-friendly, both academia and industry have increasingly explored the integration of cloud computing and distributed systems into AI applications [37,38].

Cloud computing offers a flexible and scalable resource deployment model that shifts the computational burden from local terminals to remote servers. This significantly reduces hardware requirements and computational demands on the user side [39,40]. By deploying applications on cloud platforms, developers can realize the vision of omnipresent AI, enabling users to access powerful AI capabilities from any device through a standard web browser, without being constrained by local hardware performance [41]. This cloud-based collaboration model not only improves system accessibility, but also provides an essential foundation for resource sharing and coordinated workflows in multi-user environments [42]. Numerous studies have shown that cloud platforms can effectively support machine learning applications that require extensive data processing and model inference [43–45].

To further enhance computational efficiency and system responsiveness, the design philosophy of distributed systems has been introduced into AI task processing. The core idea of distributed systems is to decompose a large computation task into smaller subtasks and distribute them across a cluster of independent computing nodes for parallel processing [46]. Among various distributed architectures, task queue systems have been widely adopted for handling computationally intensive tasks such as image generation due to their asynchronous processing and load balancing capabilities [47]. A typical task queue architecture submits generation requests to a central queue and distributes them to multiple worker nodes for execution. Celery in combination with Redis has been widely validated as a stable and efficient solution [48].

Beyond these cloud-based architectures, distributed computing in deep learning has already demonstrated multiple successful use cases. To address the latency issues associated with large-scale generative models during the inference stage, several studies have proposed splitting a single generation task across multiple GPUs using techniques such as patch parallelism, significantly accelerating the generation speed of a single image [49]. Other research focuses on architectural improvements, shifting from monolithic designs to modular systems by dividing traditional monolithic architectures into smaller and more manageable components. This approach not only improves the efficiency of deployment and development, but also reduces the computational load on individual nodes, thus enhancing overall system responsiveness and flexibility [50]. In addition, some approaches have adopted edge computing strategies, shifting data processing closer to the data source to reduce network latency and alleviate bandwidth demands [51–53]. However, existing research on story visualization still largely treats the generative model as a single monolithic computational unit for deployment and optimization. Few studies have explored how to modularize complex generation pipelines, such as separating character generation and story generation into distinct stages and assigning them as independent tasks to multiple computational nodes for collaborative processing. This strategy could achieve significant improvements in performance and resource utilization. Therefore, this study aims to fill this research gap by constructing a system that integrates cloud-based collaboration with modular distributed computing. The proposed approach aims to modularize the application of large generative models, providing users with a more efficient, flexible, scalable, and accessible platform for story visualization.

This section presents the overall architecture and implementation of the cloud-based distributed story visualization system developed in this study. The system integrates multiple GenAI modules and adopts a modular task design with a distributed deployment strategy to support collaborative content creation across multiple users and devices. Notably, the system separates character generation and story generation into distinct modules to enhance flexibility in task scheduling and resource allocation. By leveraging a multi-node deployment architecture, the system effectively reduces generation time and improves operational efficiency. In addition, generative AI tools (e.g., Stable Diffusion and its extensions) were used solely for figure generation in the experiments. The following subsections provide detailed descriptions of the system architecture, user interface and communication mechanism, character generation module, story generation module, cloud-based distributed deployment strategy, and the analysis tools and metrics.

3.1 Overall System Architecture

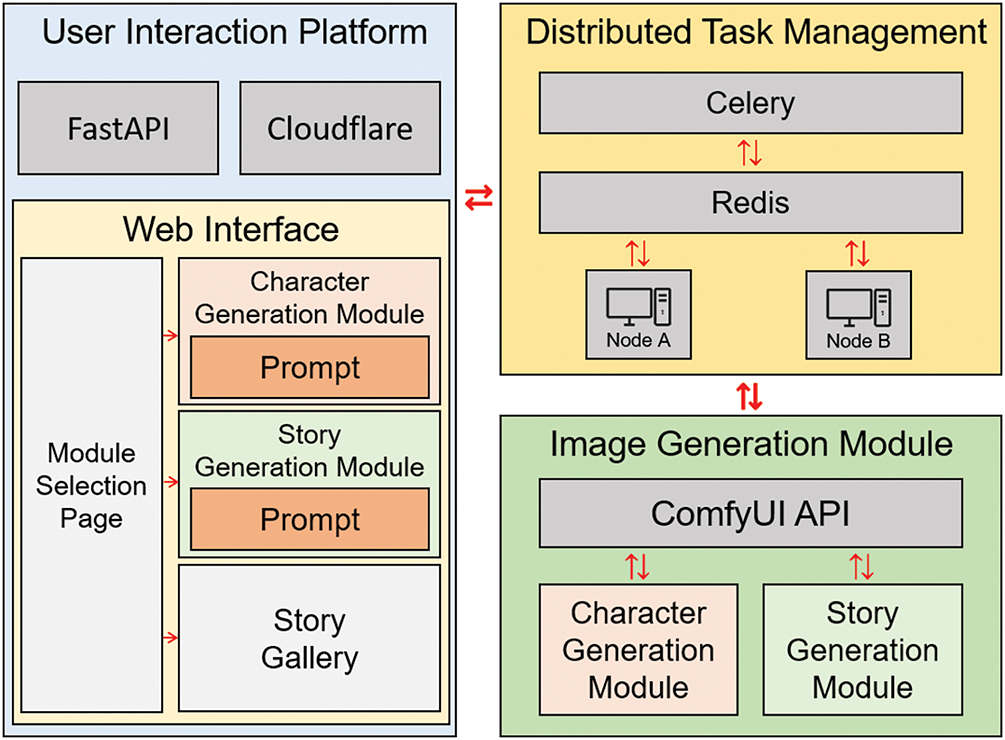

This study developed a cloud-based distributed system built upon Stable Diffusion to facilitate collaborative story visualization across multiple users and devices. By distributing the computational workload across nodes, the system reduces user waiting time, enhances generation efficiency, and enables dynamic scaling through the addition of nodes or reconfiguration of modules based on task requirements. The overall system architecture, illustrated in Fig. 1, consists of three main components that address the technical requirements for user interaction, image generation, and task management:

Figure 1: System architecture of the cloud-based distributed story visualization system. The design includes the user interaction platform, distributed task management, and image generation modules. Red arrows indicate task and data flow across components

1. User Interaction Layer: The system front-end is built using FastAPI and Cloudflare. FastAPI provides the interactive interface that allows users to input prompts, select the character or story generation module, and review the results. Cloudflare ensures secure communication channels and cross-origin support, thereby enhancing data transmission security and connection stability across devices and users.

2. Story Visualization Layer: The system uses Stable Diffusion as the core generative model, integrated with advanced control modules. These include LoRA for style and character fine-tuning, SAM for image segmentation masks, and ControlNet for pose and composition control. Character generation and story generation are implemented as independent modules, allowing users to reuse existing character assets without rerunning the character generation process, thereby reducing system load and improving generation efficiency.

3. Task Management and Data Handling Layer: A distributed task queue system is implemented using Celery and Redis to manage task scheduling. Upon receiving a user request, the system automatically assigns tasks to idle nodes based on their real-time workloads. A data storage module is responsible for saving generated character assets to enable reuse, thus enhancing creative efficiency and supporting content integration across tasks.

To support multi-module distributed execution, the system was deployed across two Windows-based workstations equipped with NVIDIA RTX 3080 and RTX 5080 GPUs, respectively. The entire platform was developed in Python and integrates FastAPI, Cloudflare, Celery, and Redis to establish a robust and scalable cloud-based distributed infrastructure. Stable Diffusion was configured using ComfyUI, whose workflows were exported as APIs to support modular generation tasks.

3.2 User Interface and Communication Mechanism

The front-end interface of the system is implemented using FastAPI, serving as a middleware layer that facilitates communication between users and the back-end modules. Through a web browser, users can enter prompts to initiate character or story generation tasks and view the generated results in real time. Due to FastAPI’s asynchronous processing and high-performance response capabilities, the system can accommodate concurrent requests from multiple users while maintaining operational stability and responsiveness.

To ensure secure data transmission and reliable cross-device connectivity, the system integrates Cloudflare as a network and domain protection layer. Cloudflare provides HTTPS encryption and DDoS mitigation, thereby enhancing the resilience and availability of the platform. This design enables users to access the system directly from existing devices without the need for software installation, improving the usability and accessibility of AI-based story visualization.

The system interface provides intuitive navigation, enabling users to select the character generation module, story generation module, or gallery directly from the main interface according to task requirements. For character generation, users input two sets of prompts: one for facial attributes and one for clothing descriptions. The module then generates both facial and full-body images, which are combined into reusable character assets. These assets are automatically stored in the platform database to facilitate reuse in subsequent tasks.

During story generation, users select from previously created character assets and input narrative prompts to generate corresponding visual scenes. All input data are formatted and transmitted via FastAPI to a back-end task queue, where the module dynamically schedules the task to available nodes based on real-time workload.

Upon completion, the generated images are returned to the user interface and simultaneously uploaded to the gallery as downloadable and shareable visual resources. This design not only enhances user engagement and result visibility but also promotes asset reuse and collaborative creativity, supporting diverse applications in education, story visualization, and research contexts.

3.3 Design of the Character Generation Module

This module is designed to construct reusable character assets that serve as the foundation for the subsequent story generation process. Built upon the Stable Diffusion XL framework, the module incorporates fine-tuned models including LoRA Anything XL and LoRA FaceLightUp. LoRA Anything XL ensures stylistic consistency across scenes and narrative contexts, while LoRA FaceLightUp enhances the brightness and clarity of facial features to improve visual recognizability. The operational workflow of this module is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Design framework of the character generation module based on stable diffusion XL. Inputs consist solely of textual prompts, while a fixed reference face image is used to guide facial generation. The module first generates the face, applies SAM to obtain a mask, and employs IP-Adapter to embed facial features. These features are then combined with body characteristics derived from the prompt to produce a consistent character with a fixed pose for subsequent generation tasks

During the character generation process, the module first uses a primary prompt in conjunction with a fixed ControlNet reference image to generate a facial portrait, ensuring positional consistency across all characters for subsequent learning. SAM is then employed to automatically generate a facial mask. Both the facial image and the corresponding mask are input into the IP-Adapter Plus Face model to learn the character’s distinct facial features of the character.

Once facial generation is completed, the module generates a full-body image by combining a secondary prompt with the fine-tuned IP-Adapter Plus Face model. This stage also integrates ControlNet to manage pose and spatial positioning, enabling consistent image alignment for subsequent cropping and stage-wise training.

Finally, the generated facial and full-body images are stored and indexed within the system for repeated use in the story generation module. This strategy not only enhances character consistency and visual continuity but also reduces redundant modeling costs, thereby improving the overall efficiency and quality of the story visualization process.

3.4 Design of the Story Generation Module

To apply pre-constructed character assets to the task of story visualization, this module is designed to automatically generate story images containing specified characters based on user-provided narrative prompts. Similar to the character generation module, this module is built upon the Stable Diffusion XL architecture and incorporates LoRA Anything XL and LoRA FaceLightUp for model fine-tuning. The design framework of the module is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Design framework of the story generation module based on stable diffusion XL. The system generates an initial scene based on the user-provided story description and captures character poses using OpenPose. The user-selected character is first processed with SAM-based segmentation to obtain contour masks, which are then combined with a four-stage IP-Adapter pipeline. Guided by the extracted poses, this process regenerates the scene with the designated character, ensuring that the character maintains a consistent appearance across the entire story sequence

A key challenge addressed in this module is the accurate integration of both global and localized character features into the generated images while maintaining a high degree of character consistency. Given that the IP-Adapter model performs feature extraction most effectively with an input resolution of

The feature learning process begins with the preprocessing of character images. Specifically, SAM is employed to generate precise segmentation masks for the selected character image. Since character poses in the system are predefined using OpenPose, the module can extract four distinct image regions: face, upper body, lower body, and feet, based on preset coordinates. This approach simplifies traditional masking procedures while ensuring segmentation precision.

During the feature learning phase, multiple IP-Adapter modules are sequentially connected to form a multi-stage training pipeline. First, the facial image is fed into the IP-Adapter Plus Face module, which specializes in capturing fine-grained facial features. The learned facial representation is then passed forward as the foundation for subsequent modules, which progressively learn the features of the upper body, lower body, and feet using additional IP-Adapter Plus modules. This cascade design enables the model to retain and reinforce previously learned features while acquiring new ones, ensuring the generated images exhibit both fine local detail and overall character coherence.

In the final image generation stage, the module first creates a reference image based on the user’s narrative prompt and uses ControlNet to derive a corresponding pose image. These, along with the cascade-trained character model and input prompts, are collectively passed into the Stable Diffusion XL framework to produce story visualization images with high character fidelity and accurate pose alignment.

3.5 Cloud Deployment and Distributed Design

This system adopts a cloud-based deployment strategy and distributed architecture to address the high computational demands of generative tasks in both single-user and multi-user environments, thereby establishing a robust and scalable platform for story visualization.

For cloud deployment, back-end services are constructed using FastAPI, with DNS management and security protection provided by Cloudflare. This configuration ensures ubiquitous accessibility of the AI services, allowing users to initiate and operate story visualization tasks in real time through web browsers on any device. It also enhances the stability and security of data transmission across the network.

From a distributed system perspective, the architecture incorporates the Celery task scheduling framework along with Redis as the message broker to establish a task queue and inter-node communication mechanism. Tasks are automatically enqueued and dispatched to available nodes, enabling concurrent generation of character assets or story images involving specified characters. This design significantly improves overall computational efficiency and system responsiveness.

In addition, a character asset caching and reuse mechanism is implemented to optimize cross-task processing efficiency. Once a character generation task is completed, the resulting image data is stored as reusable assets. When users initiate story visualization tasks involving previously generated characters, the system directly retrieves the stored images and feeds them into the IP-Adapter for feature learning, eliminating the need for repeated and time-consuming character generation. This approach not only reduces redundant computation and prevents data loss common in traditional workflows, but also leverages cloud-based and distributed collaborative design to enable asset sharing across users, thereby enhancing collaborative efficiency and system flexibility.

3.6 Analysis Tools and Metrics

This study evaluates the system’s performance in multi-frame story visualization from two perspectives: character consistency and system efficiency.

For character consistency, we employ the CLIP-I similarity score to quantitatively assess the semantic similarity between each generated story frame and the corresponding reference character image produced by the character generation module. CLIP-I is defined as the cosine similarity between image embeddings extracted using the CLIP model. To minimize interference from background elements and non-target objects, each image is first processed by SAM to isolate the character region before computing the similarity. For baseline comparison, we use the StoryGen system under identical character descriptions and narrative prompts. Since this study focuses on the validation of system design, we selected two representative stories, each comprising four distinct visual scenes. The average of the CLIP-I scores across the four frames is used as a consistency metric.

To complement the automated evaluation metrics that may overlook semantic and visual details, this study invited twenty graduate students with backgrounds in computer science and information engineering to conduct a human evaluation of the generated results. A five-point Likert scale was employed, where 1 indicated complete inconsistency and 5 indicated high consistency. To minimize cognitive bias, the experiment was designed as a double-blind test. Each participant observed four complete story image sequences: two generated by the proposed system and two generated by StoryGen. The order of images within each sequence was fixed, while the vertical arrangement of the sequences was randomized and their source systems were not disclosed. The final evaluation scores were averaged across all participants and used as the human evaluation metric, serving as a supplement and validation to the automated CLIP-I similarity results.

Regarding system efficiency, the total task execution time is used as the primary performance metric. All experiments are configured to generate five

Formally, the total system execution time is divided into two stages: character generation and story generation. Let

In the story generation phase, assume the system consists of N nodes. The generation time for each story frame on node

Since overall story generation time is governed by the slowest node, the objective is to minimize the total completion time by optimally distributing tasks. This optimization problem is formulated in Eq. (3):

Accordingly, the total execution time of the system is expressed in Eq. (4):

Finally, to further evaluate the potential performance of the distributed architecture in a high-performance environment, an additional simulation was conducted under an idealized deployment scenario where all four nodes were equipped with RTX 5080 GPUs. Under these conditions, the analysis examined average generation time, task completion latency, and resource utilization efficiency to assess the scalability and stability of the proposed system in future large-scale collaborative generation settings.

Overall, this study employed CLIP-I scores and human evaluation as indicators of character consistency, while task completion time and multi-node simulation were used as indicators of system performance, thereby providing both objective and subjective bases for the subsequent result analysis.

This section evaluates the proposed system in terms of character consistency and system performance, in order to verify its feasibility and practicality in story visualization tasks.

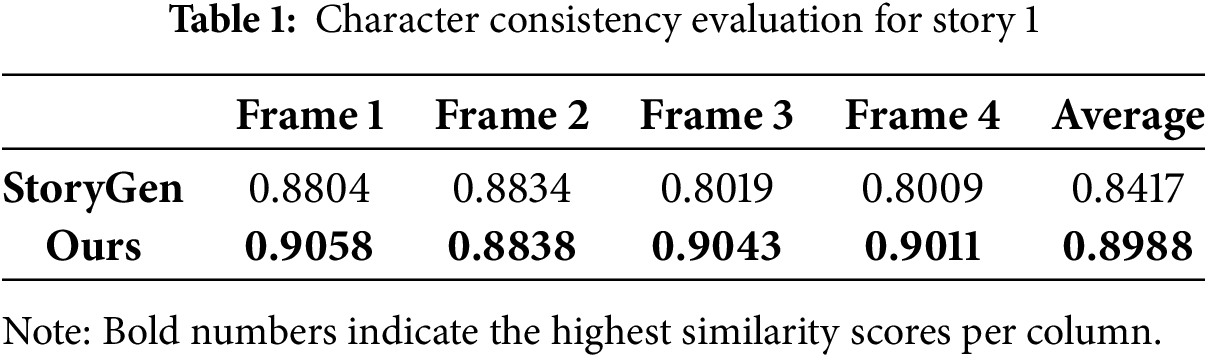

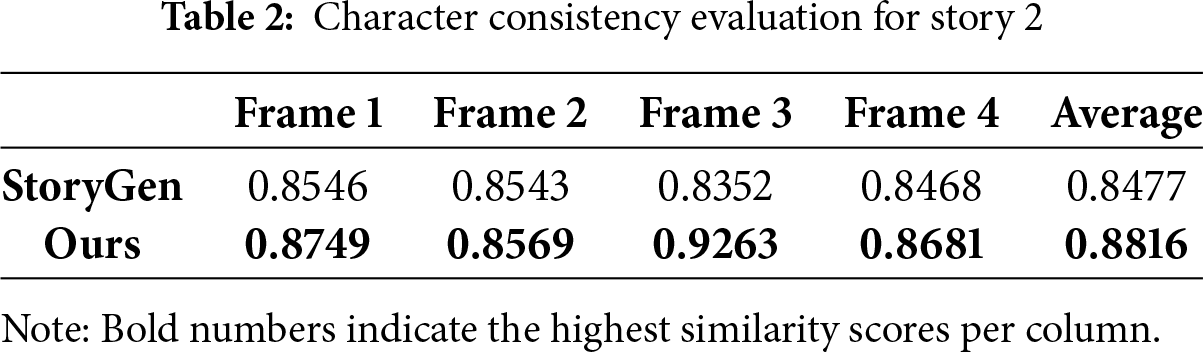

4.1 Automated Evaluation of Character Consistency

The first part of this study evaluates character consistency to examine whether the proposed system can effectively maintain stable character appearances across multiple frames in a story generation sequence. Character consistency is critical in story visualization tasks, as visual coherence of characters directly influences narrative fluency and viewer comprehension. To objectively measure consistency, we adopted the CLIP-I similarity score, which calculates the semantic similarity of the character image features across different frames. The existing StoryGen system was used as a baseline for comparison. In the experimental setup, each character was used to generate four images depicting distinct scenes. The average CLIP-I score across the four frames was computed as a quantitative indicator of character consistency. To minimize the impact of background elements on CLIP-I similarity calculations, we further applied the Segment Anything Model (SAM) to isolate the character regions in each image. This ensured that the similarity assessment focused primarily on the character’s visual features.

As shown in Tables 1 and 2, the proposed system consistently outperformed StoryGen in terms of CLIP-I similarity scores. For single-frame character similarity, the improvement ranged from 0.3% to 12.5%, indicating that the system was able to preserve character visual features more effectively in certain scenes. At the sequence level, the average improvement across all test cases remained stable between 4.0% and 6.8%, validating the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed system architecture in maintaining character consistency.

These results further demonstrate that the feature control strategy, achieved by integrating IP-Adapter and ControlNet modules, enables stable character visual consistency across diverse scene generation tasks, thereby enhancing both the narrative coherence and character recognizability of the generated stories.

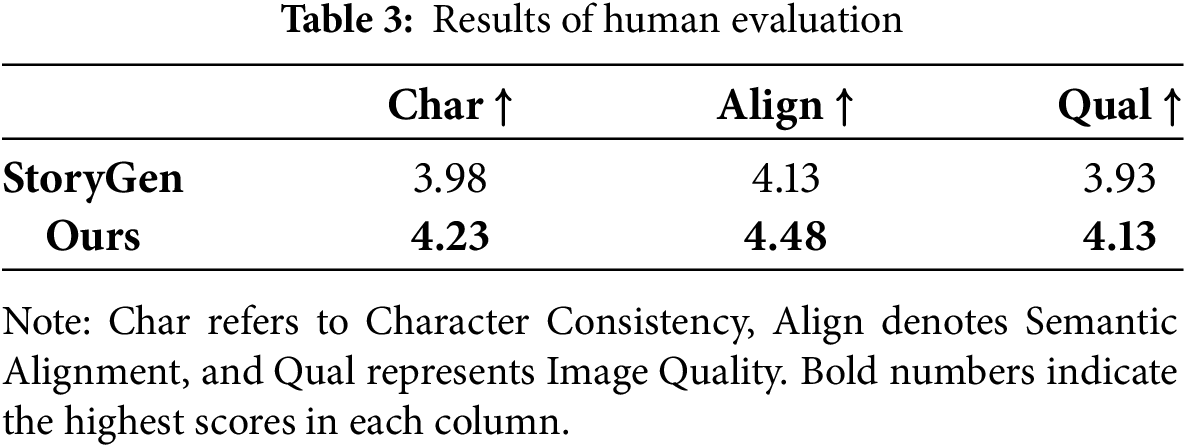

This study further conducted a human evaluation to address the limitations of automated metrics, which may overlook nuances of semantic alignment and visual detail. A five-point Likert scale was employed (1 = completely inconsistent, 5 = highly consistent). Twenty graduate students with backgrounds in computer science were invited to evaluate four story samples. For each sample, participants rated three aspects: cross-frame character consistency, semantic alignment of each frame, and overall image quality. As shown in Table 3, the proposed system achieved average scores of 4.23 for character consistency, 4.48 for semantic alignment, and 4.13 for image quality, all higher than those of the baseline system, StoryGen, indicating that participants generally recognized greater stability in character appearances and stronger semantic alignment in the generated content.

Feedback further highlighted that characters produced by the proposed system were less prone to deformation across frames, with stable proportions, structure, and details—particularly in facial contours and body postures—where unnatural distortions or misalignments were rarely observed. By contrast, StoryGen, while generally maintaining character recognizability, occasionally produced imbalanced facial features or abnormal body proportions, which created a sense of dissonance and reduced narrative immersion. This stability advantage can be attributed to the integration of IP-Adapter and ControlNet within the proposed system: IP-Adapter embeds visual features of reference character images into the generation process, while ControlNet provides structural constraints through pose conditioning. Their combined effect strengthens the stable learning of character-specific features and enhances visual consistency, thereby improving both recognizability and narrative coherence. Overall, the human evaluation results align with the automated evaluation outcomes, confirming the feasibility and practical utility of the proposed system in maintaining cross-frame character consistency and semantic fidelity in story visualization tasks.

4.3 System Performance Evaluation

To quantitatively assess the efficiency of the proposed distributed architecture, we designed a performance benchmark encompassing multi-stage generation tasks. Each task involves the generation of five images at a resolution of

The experimental results reveal that the single-node RTX 3080 system required 697.48 s, while the RTX 5080 system completed the same task in 273.37 s. In contrast, the proposed distributed system completed the task in only 221.9 s, significantly outperforming both single-node configurations. Further analysis of the task allocation strategy shows that the distributed system’s scheduler dynamically assigns workloads based on the computational capabilities of each node. In practice, the more powerful RTX 5080 node handled the character generation and three of the story images, averaging approximately 55 s per image, while the RTX 3080 node processed the remaining story image, which took about 140 s. This dynamic load-balancing mechanism effectively leverages heterogeneous resources, minimizing task queuing delays and scheduling bottlenecks.

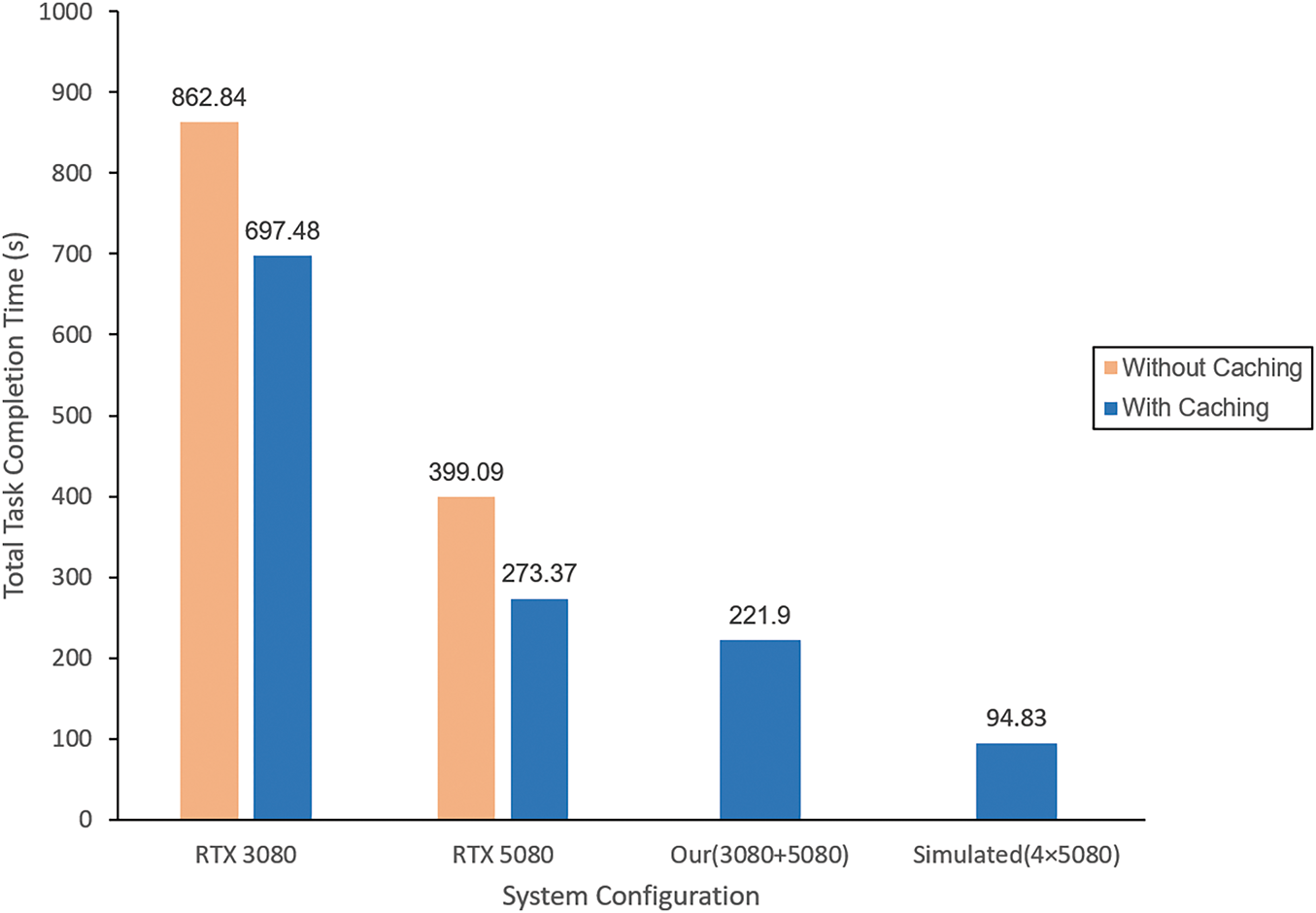

We also examined the impact of the character asset caching mechanism on system efficiency. In a traditional single-node architecture, if character generation is redundantly performed for each story frame, a substantial amount of repetitive computation occurs, degrading performance. For instance, on the RTX 3080 system, enabling caching yielded a total execution time of 697.48 s. Without caching, the system needed to regenerate the character for each frame, causing the execution time to increase to 862.84 s. Similarly, the execution time of the RTX 5080 system rose from 273.37 s (with caching) to 399.09 s (without caching). These results strongly validate the importance of reusing character assets in optimizing system performance under multi-task scenarios. Fig. 4 presents a detailed comparison of performance across different system architectures and caching strategies.

Figure 4: Execution time comparison across single-node systems (with and without caching) and the distributed system (with caching)

The overall analysis shows that, under identical task content, the distributed system developed in this study significantly improved processing efficiency in multi-task scenarios through two core strategies: the task scheduling mechanism and the character cache reuse mechanism. Compared with traditional single-node architectures, this design substantially reduced user waiting time and demonstrated its practicality and efficiency in handling complex generative AI tasks. Furthermore, to provide a preliminary verification of its scalability, a simulation experiment was conducted to examine performance under a four-node configuration, with detailed analysis presented in Section 4.4.

4.4 Simulated Multi-Node Scalability Evaluation

Due to limitations of the experimental environment, this study was unable to directly construct a four-node RTX 5080 cluster. Therefore, a simulation experiment was conducted to supplement the verification of system scalability. The purpose of this simulation was to estimate the potential performance of the system under higher computational resource configurations and to compare it with single-node and dual-node architectures.

Specifically, twenty character generation tasks and twenty story generation tasks were executed on a single RTX 5080 node, and the execution time of each task was recorded to capture the complete time distribution. As shown in Fig. 5, most samples exhibited stable performance, while a few tasks showed higher latency. These outliers were likely caused by unexpected system-level interferences (e.g., cache or I/O states) or random variations inherent to the denoising process of diffusion models. To reduce the influence of such extreme values on overall estimation, the 95th percentile (p95) was adopted as the representative generation time for a single node, which was then used in the task scheduling model proposed in Section 3.6. Based on this estimation, the total task completion time under a simulated four-node RTX 5080 configuration was calculated as 94.86 s.

Figure 5: Simulated four-node generation time distribution for 20 character tasks and 20 story tasks. The 95th percentile (p95) of task completion time is used as the representative value for subsequent scalability analysis

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the simulated four-node architecture achieved substantially lower average total generation times for both character and story tasks compared with single-node and heterogeneous dual-node configurations. In particular, the total time was reduced by 65.3% compared with the single RTX 5080 node (273.37 s), and by 57.3% compared with the heterogeneous dual-node configuration observed in actual experiments (221.9 s). Although based on simulation, these results are consistent with the performance trends observed in dual-node experiments, indicating that the system can maintain strong scalability under higher resource configurations. This provides a reasonable performance reference for future multi-node deployments.

Figure 6: Comparison of generation waiting time across different deployment configurations. The four-node configuration with caching achieves the lowest latency, demonstrating the scalability advantage of the distributed design

This study proposed and validated a cloud-based distributed story visualization system built upon a modular task workflow, aiming to address two major challenges in generative AI for narrative sequences: insufficient character consistency and generation latency. To achieve this goal, the system integrates caching optimization and an asynchronous task queue mechanism, which reduce redundant computation and enable collaborative task execution across multiple nodes. Experimental results show that the proposed modular architecture effectively maintains cross-frame character consistency, thereby preserving narrative coherence. In terms of performance, the dual-node deployment reduced latency by approximately 19%, while the simulated four-node scenario achieved up to a 65% reduction, demonstrating significant operational advantages. Overall, the findings confirm the feasibility of cloud-based distributed architectures in improving both generation efficiency and character stability, providing a flexible and high-performance foundation for multi-user collaboration.

Despite these contributions, several limitations remain. First, the experiments were limited to a small number of nodes, which is insufficient to fully validate scalability and load-balancing capabilities in large-scale environments. Second, the system has not yet been tested through long-term deployment or user studies in real-world application contexts, making it difficult to comprehensively assess stability and interactivity under practical operating conditions.

Future research may be extended in several directions. Large-scale distributed environments should be employed to conduct long-term performance evaluations and dynamic node scheduling experiments, thereby verifying the system’s effectiveness in elastic resource allocation and load balancing. In addition, providing users with greater flexibility to adjust diffusion model parameters during the generation process could enhance operational control and creative freedom. Furthermore, exploring more human–AI interaction-oriented collaboration mechanisms, such as pedagogical GenAI systems designed to guide users in extending their ideas during the creative process, could expand the potential applications of the proposed system in education, digital content production, and beyond.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the use of Stable Diffusion and its extensions (LoRA, ControlNet, SAM, and IP-Adapter), as well as ComfyUI for workflow implementation, which were employed to generate experimental figures in this study. We also thank the developers of StoryGen for providing inspiration in addressing challenges of story visualization.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Chuang-Chieh Lin and Yung-Shen Huang; methodology, Chuang-Chieh Lin and Yung-Shen Huang; software, Chuang-Chieh Lin and Yung-Shen Huang; validation, Chuang-Chieh Lin, Yung-Shen Huang and Shih-Yeh Chen; formal analysis, Yung-Shen Huang; investigation, Chuang-Chieh Lin and Yung-Shen Huang; resources, Chuang-Chieh Lin and Shih-Yeh Chen; data curation, Chuang-Chieh Lin; writing—original draft preparation, Chuang-Chieh Lin and Yung-Shen Huang; writing—review and editing, Chuang-Chieh Lin and Yung-Shen Huang; visualization, Yung-Shen Huang; supervision, Shih-Yeh Chen; project administration, Shih-Yeh Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data included in this study are available upon request by contact with the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: This study involved a subjective evaluation task conducted with volunteer graduate students. The task did not include any personally identifiable information, medical procedures, or psychological interventions. In accordance with the institutional policies, the study was exempt from formal ethics review. All participants were informed of the research purpose and provided their consent prior to participation.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Feuerriegel S, Hartmann J, Janiesch C, Zschech P. Generative AI. Bus Inform Syst Eng. 2024;66(1):111–26. [Google Scholar]

2. Stability AI, CompVis, Runway. Stable Diffusion. In: Latent text-to-image diffusion model. GitHub Repository; 2022. [cited 2025 Oct 10]. Available from:https://github.com/CompVis/stable-diffusion. [Google Scholar]

3. Ramesh A, Pavlov M, Goh G, Gray S, Voss C, Radford A, et al. Zero-shot text-to-image generation. In: International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021 Jul 18–24; Virtual. p. 8821–31. [Google Scholar]

4. Saharia C, Chan W, Saxena S, Li L, Whang J, Denton EL, et al. Photorealistic text-to-image diffusion models with deep language understanding. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2022;35:36479–94. [Google Scholar]

5. Luo S, Tan Y, Huang L, Li J, Zhao H. Latent consistency models: synthesizing high-resolution images with few-step inference. arXiv:2310.04378. 2023. [Google Scholar]

6. Wang X, Wang Y, Tsutsui S, Lin W, Wen B, Kot A. Evolving storytelling: benchmarks and methods for new character customization with diffusion models. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2024 Oct 28–Nov 1; Melbourne, VIC, Australia. p. 3751–60. [Google Scholar]

7. Maharana A, Hannan D, Bansal M. Storydall-e: adapting pretrained text-to-image transformers for story continuation. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 70–87. [Google Scholar]

8. Liu C, Wu H, Zhong Y, Zhang X, Wang Y, Xie W. Intelligent grimm-open-ended visual storytelling via latent diffusion models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 6190–200. [Google Scholar]

9. Song J, Meng C, Ermon S. Denoising diffusion implicit models. arXiv:2010.02502. 2020. [Google Scholar]

10. Hu EJ, Shen Y, Wallis P, Allen-Zhu Z, Li Y, Wang S, et al. Lora: low-rank adaptation of large language models. In: The Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022 Apr 25–29; Virtul. 3 p. [Google Scholar]

11. Kirillov A, Mintun E, Ravi N, Mao H, Rolland C, Gustafson L, et al. Segment anything. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 4015–26. [Google Scholar]

12. Ye H, Zhang J, Liu S, Han X, Yang W. Ip-adapter: text compatible image prompt adapter for text-to-image diffusion models. arXiv:2308.06721. 2023. [Google Scholar]

13. Zhang L, Rao A, Agrawala M. Adding conditional control to text-to-image diffusion models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2023 Oct 1–6; Paris, France. p. 3836–47. [Google Scholar]

14. Cohn N. Visual narrative structure. Cogn Sci. 2013;37(3):413–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Cohn N. Visual narrative comprehension: universal or not? Psychon Bull Rev. 2020;27(2):266–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

16. Cohn N. Your brain on comics: a cognitive model of visual narrative comprehension. Topics Cogn Sci. 2020;12(1):352–86. doi:10.1111/tops.12421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lazarinis F, Konstantinidou S. Learning about children’s rights through engaging visual stories promoting in-class dialogue. Eur J Interact Multimed Educ. 2025;6(2):e02504. doi:10.30935/ejimed/16090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lim KY, Spencer E, Bogart E, Steel J. Speech-language pathologists’ views on visual discourse elicitation materials for cognitive communication disorder after TBI: an exploratory study. J Commun Disord. 2025;116:106540. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2025.106540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Beck T, Giese S, Khoo TK. Visual art and medical narratives as universal connectors in health communication: an exploratory study. J Health Commun. 2025;30(1–3):112–9. doi:10.1080/10810730.2025.2459845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Coderre EL, Cohn N. Individual differences in the neural dynamics of visual narrative comprehension: the effects of proficiency and age of acquisition. Psychon Bull Rev. 2024;31(1):89–103. doi:10.3758/s13423-023-02334-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Li Y, Gan Z, Shen Y, Liu J, Cheng Y, Wu Y, et al. StoryGAN: a sequential conditional GAN for story visualization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA; 2019. p. 6322–31. [Google Scholar]

22. Shen F, Ye H, Liu S, Zhang J, Wang C, Han X, et al. Boosting consistency in story visualization with rich-contextual conditional diffusion models. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2025;39:6785–94. doi:10.1609/aaai.v39i7.32728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhu Z, Tang J. Cogcartoon: towards practical story visualization. Int J Comput Vis. 2025;133(4):1808–33. doi:10.1007/s11263-024-02267-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sengar SS, Hasan AB, Kumar S, Carroll F. Generative artificial intelligence: a systematic review and applications. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84(21):23661–700. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-20016-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bengesi S, El-Sayed H, Sarker MK, Houkpati Y, Irungu J, Oladunni T. Advancements in generative AI: a comprehensive review of GANs, GPT, autoencoders, diffusion model, and transformers. IEEE Access. 2024;12:69812–37. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3397775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Goodfellow IJ, Pouget-Abadie J, Mirza M, Xu B, Warde-Farley D, Ozair S, et al. Generative adversarial nets. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2014;27:139–44. doi:10.1145/3422622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Barsha FL, Eberle W. An in-depth review and analysis of mode collapse in generative adversarial networks. Mach Learn. 2025;114(6):141. doi:10.1007/s10994-025-06772-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kingma DP, Welling M. Auto-encoding variational bayes. In: 2nd International Conference on Learning Representations; 2014 Apr 14–16; Banff, AB, Canada. [Google Scholar]

29. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2017;30:6000–10. [Google Scholar]

30. Sohl-Dickstein J, Weiss E, Maheswaranathan N, Ganguli S. Deep unsupervised learning using nonequilibrium thermodynamics. In: International Conference on Machine Learning; 2015 Jul 7–9; Lille, France. p. 2256–65. [Google Scholar]

31. Ho J, Jain A, Abbeel P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2020;33:6840–51. [Google Scholar]

32. He C, Shen Y, Fang C, Xiao F, Tang L, Zhang Y, et al. Diffusion models in low-level vision: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2025;47(6):4630–51. doi:10.1109/tpami.2025.3545047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Rombach R, Blattmann A, Lorenz D, Esser P, Ommer B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 10684–95. [Google Scholar]

34. Allmendinger S, Zipperling D, Struppek L, Kühl N. Collafuse: collaborative diffusion models. arXiv:2406.14429. 2024. [Google Scholar]

35. Ma X, Fang G, Wang X. Deepcache: accelerating diffusion models for free. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 15762–72. [Google Scholar]

36. Ahmad S, Yang Q, Wang H, Sitaraman RK, Guan H. DiffServe: efficiently serving text-to-image diffusion models with query-aware model scaling. arXiv:2411.15381. 2024. [Google Scholar]

37. Seth DK, Ratra KK, Sundareswaran AP. AI and generative AI-driven automation for multi-cloud and hybrid cloud architectures: enhancing security, performance, and operational efficiency. In: 2025 IEEE 15th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); 2025 Jan 6–8; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 784–93. [Google Scholar]

38. Shen H, Zhang J, Xiong B, Hu R, Chen S, Wan Z, et al. Efficient diffusion models: a survey. arXiv:2502.06805. 2025. [Google Scholar]

39. Prangon NF, Wu J. AI and computing horizons: cloud and edge in the modern era. J Sens Actuator Netw. 2024;13(4):44. doi:10.3390/jsan13040044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Saripudi K. A study on artificial intelligence and cloud computing assistance for enhancement of startup businesses. J Comput Data Technol. 2025;1(1):68–76. [Google Scholar]

41. Thyagaturu AS, Nguyen G, Rimal BP, Reisslein M. Ubi-Flex-Cloud: ubiquitous flexible cloud computing: status quo and research imperatives. Appl Comput Inform. 2022;177:3. doi:10.1108/aci-02-2022-0029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lu Y, Bian S, Chen L, He Y, Hui Y, Lentz M, et al. Computing in the era of large generative models: from cloud-native to AI-native. arXiv:2401.12230. 2024. [Google Scholar]

43. Rani P. Integrating generative AI in Cloud computing architectures: transformative impacts on efficiency and innovation. Nanotechnol Percept. 2024:1728–42. doi:10.62441/nano-ntp.vi.3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Syed N, Anwar A, Baig Z, Zeadally S. Artificial Intelligence as a Service (AIaaS) for cloud, fog and the edge: state-of-the-art practices. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(8):1–36. doi:10.1145/3712016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Patel D, Raut G, Cheetirala SN, Nadkarni GN, Freeman R, Glicksberg BS, et al. Cloud platforms for developing generative AI solutions: a scoping review of tools and services. arXiv:2412.06044. 2024. [Google Scholar]

46. Tanenbaum AS, Van Steen M. Distributed systems. Charleston, SC, USA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2017. [Google Scholar]

47. Salian P, Salian S, Rao AS. Optimizing energy usage in educational environments through the internet of things and deep learning techniques. In: 2024 Third International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Information and Communication Technologies (ICEEICT); 2024 Jul 24–26; Trichirappalli, India. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

48. Harshjeet, Gogoi C, Snehalatha N, Amudha S. Enhancing visual creativity with neural style transfer using celery backend architecture. In: 2024 3rd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC); 2024 Jun 5–7; Salem, India. p. 966–74. [Google Scholar]

49. Li M, Cai T, Cao J, Zhang Q, Cai H, Bai J, et al. Distrifusion: distributed parallel inference for high-resolution diffusion models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 7183–93. [Google Scholar]

50. Romero I. A multi-cloud architecture for distributed task processing using celery, docker, and cloud services. Int J AI BigData Comput Manage Stud. 2020;1(2):1–10. [Google Scholar]

51. Dai C, Liu X, Chen W, Lai CF. A low-latency object detection algorithm for the edge devices of IoV systems. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2020;69(10):11169–78. doi:10.1109/tvt.2020.3008265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Liu X, Wu L, Dai C, Chao HC. Compressing CNNs using multilevel filter pruning for the edge nodes of multimedia internet of things. IEEE Internet of Things J. 2021;8(14):11041–51. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3052016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Dai C, Liu X, Li Z, Chen MY. A tucker decomposition based knowledge distillation for intelligent edge applications. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;101:107051. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2020.107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools