Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

HCF-MFGB: Hybrid Collaborative Filtering Based on Matrix Factorization and Gradient Boosting

1 Department of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Negeri Malang, Malang, 65145, Indonesia

2 Department of Information Systems, Universitas Yapis Papua, Jayapura, 99115, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Triyanna Widiyaningtyas. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073011

Received 09 September 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

Recommendation systems are an integral and indispensable part of every digital platform, as they can suggest content or items to users based on their respective needs. Collaborative filtering is a technique often used in various studies, which produces recommendations by analyzing similarities between users and items based on their behavior. Although often used, traditional collaborative filtering techniques still face the main challenge of sparsity. Sparsity problems occur when the data in the system is sparse, meaning that only a portion of users provide feedback on some items, resulting in inaccurate recommendations generated by the system. To overcome this problem, we developed a Hybrid Collaborative Filtering model based on Matrix Factorization and Gradient Boosting (HCF-MFGB), a new hybrid approach. Our proposed model integrates SVD++, the XGBoost ensemble learning algorithm, and utilizes user demographic data and meta items. We utilize information, both explicitly and implicitly, to learn user preference patterns using SVD++. The XGBoost algorithm is used to create hundreds of decision trees incrementally, thereby improving model accuracy. Meanwhile, user demographic and meta-item data are clustered using the K-Means Clustering algorithm to capture similarities in user and item characteristics. This combination is designed to improve rating prediction accuracy by reducing reliance on minimal explicit rating data, while addressing sparsity issues in movie recommendation systems. The results of experiments on the MovieLens 100K, MovieLens 1M, and CiaoDVD datasets show significant improvements, outperforming various other baseline models in terms of RMSE and MAE. On the MovieLens 100K dataset, the HCF-MFGB model obtained an RMSE value of 0.853 and an MAE value of 0.674. On the MovieLens 1M dataset, the HCF-MFGB model obtained an RMSE value of 0.763 and an MAE value of 0.61. On the CiaoDCD dataset, the HCF-MFGB model achieved an RMSE value of 0.718 and an MAE value of 0.495. These results confirm a significant improvement in movie recommendation accuracy with the proposed approach.Keywords

In recent years, the amount of data and information on various platforms has increased significantly [1]. This has resulted in users finding it difficult to choose goods or content according to their precise preferences and within a certain timeframe [2–4]. To increase profits and customer satisfaction, each platform is required to match users with products that suit their preferences [5]. This has led to recommendation systems becoming an important and inseparable part of every platform [6,7]. Recommendation systems are designed to analyze and provide more personalized recommendations to users [8,9]. Recommendation systems have undergone rapid development and are now utilized on various platforms, including e-commerce [10], streaming services [11], learning media [12], and social media [13].

For example, the most prominent application of recommendation systems is on Netflix, Amazon, and YouTube platforms, where, indirectly, the system can increase user engagement by presenting personalized content, resulting in longer user sessions, higher retention rates, and a greater likelihood of making purchases or interacting with advertisements. This increased engagement can directly generate higher revenue and a competitive advantage [14,15]. In general, recommendation systems are categorized into content-based filtering, collaborative filtering, and hybrid approaches [16,17]. The collaborative filtering approach is the most frequently used in various studies [18–20]. This approach works by analyzing similarities between users based on their preferences and behavior [21]. Despite rapid progress, the conventional collaborative filtering approach faces several challenges, such as data sparsity and cold-start [22]. Of these challenges, sparsity is the primary factor contributing to a decline in recommendation performance. This is because only a few users provide feedback on some items, so the data in the system is very sparse, which makes it difficult for the system to produce accurate recommendations [23,24]. This has an impact on decreasing user engagement because the recommended items are irrelevant.

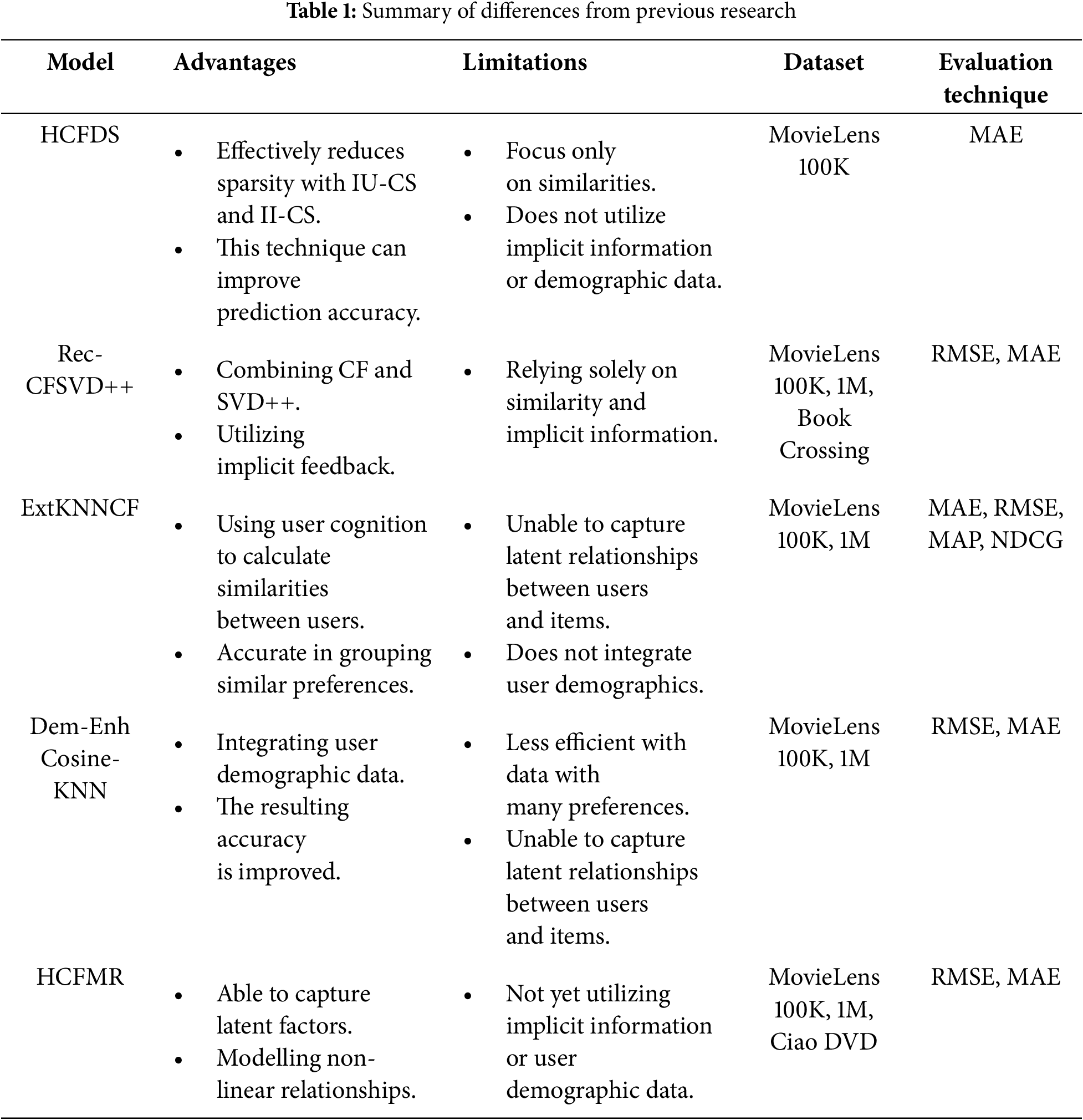

To address these challenges, several previous studies have been conducted. For example, research [25] which developed a Hybrid Collaborative Filtering model based on Sparse Rating Matrix and User Preference (HCFDS). This model operates by combining two primary algorithms: IU-CS, which measures similarity between users, and II-CS, which measures similarity between items. Additionally, the HCFDS model provides a distinct approach to handling missing values in the rating matrix. This process begins by predicting the missing values using the II-CS algorithm and then adjusting the prediction results to consider the item category preferences of each user. In this way, the system does not rely solely on limited rating data but also incorporates more contextual preference patterns. The results show that HCFDS can reduce the MAE value by up to 7.9%.

Research [26] developed the Rec-CFSVD++ model, which combines collaborative filtering (CF) with SVD++ to consider implicit feedback in predicting ratings. By leveraging the advantages of collaborative filtering and SVD++ approaches simultaneously, the Rec-CFSVD++ model exhibits superior performance, resulting in a lower error rate that effectively addresses the issues of sparsity. Research [27] combines matrix factorization with the XGBoost algorithm. In this model, matrix factorization is used to predict the initial rating and creates hand-crafted features such as user similarity, item similarity, and global average. The results of MF and hand-crafted are used as input for the XGBoost model to produce the final rating prediction. Combining these two modules has proven effective in increasing recommendation accuracy because it utilizes the advantages of MF in capturing latent relations and the advantages of XGBoost in modeling non-linear relationships.

Meanwhile, research [28] proposed an ExtKNNCF model, which is a development of the K-NN method. This model incorporates user cognition in calculating similarities between users, making it more accurate in grouping users with similar preferences and producing more relevant recommendations. This model proved to be significantly more effective than the baseline model in increasing prediction accuracy by reducing RMSE and MAE values. Furthermore, integrating additional information from users proved to be very effective. Research [29] proposed Dem-Enh Cosine-KNN, which combines user demographic data such as age, occupation, gender, and zip code in calculating similarities between users. By utilizing user demographic data, the model has access to a wealth of information, and the results have proven to be very effective in increasing recommendation accuracy. This performance improvement confirms that utilizing user data can help overcome the sparsity problem in traditional collaborative filtering.

Although various previous studies have contributed to reducing the impact of sparsity issues, these studies still have weaknesses. The HCFDS model only focuses on similarities between items and users. The shortcomings of this model are that it does not integrate user demographic data and meta-items. Additionally, HCFDS does not utilize matrix factorization techniques that can leverage both explicit and implicit information to reduce sparsity, resulting in a less-than-optimal model, particularly for large datasets.

Matrix factorization-based models, such as Rec-CFSVD++ [26] and HCFMR [27], do not utilize user demographic and Meta-Item data, so system performance can be less than optimal when data is very limited or specific preferences are not recorded in the rating pattern. Meanwhile, KNN-based models, such as ExtKNNCF and Dem-Enh Cosine-KNN, struggle to capture complex latent relationships between users and items, which can lead to decreased performance on large datasets. Dem-Enh Cosine-KNN has integrated user demographics but has not incorporated matrix factorization techniques that utilize implicit feedback to reduce sparsity. Thus, an integrated approach is needed that leverages the advantages of SVD++ and ensemble learning algorithms, while using user demographic and meta-item data to bridge this gap.

Table 1. shows a summary of the differences between previous studies, including the dataset, advantages, disadvantages, and evaluation metrics used by the HCFDS, Rec-CFSVD++, Ex-tKNNCF, Dem-Enh Cosine-KNN, and HCFMR models.

Based on the explanation of previous research and to overcome existing limitations, this study proposes a new hybrid model combining SVD++ and XGBoost, enriched with user demographic and meta-item data clustered using K-Means Clustering. This overall combination is designed to enhance the accuracy of rating prediction by reducing reliance on explicit rating data, as well as addressing the sparsity issue in movie recommendation systems. SVD++ is used to capture hidden preference patterns. By integrating SVD++, which effectively captures hidden preference patterns, and the XGBoost ensemble algorithm, which reliably models complex non-linear relationships, along with user demographic and meta-item data that have been clustered using K-Means, the proposed model is expected to provide more targeted movie recommendations, even with minimal available rating data.

In this context, the research aims to comprehensively understand how the integration of user demographic data and item metadata can affect the performance of collaborative filtering-based recommendation systems. In addition, the study examines the effectiveness of ensemble algorithms, such as XGBoost, in enhancing rating prediction accuracy, particularly in conditions of high sparsity, and evaluates whether the combination of SVD++, K-Means Clustering, and XGBoost methods collectively provides a significant improvement over the baseline model. This approach aims to provide a more comprehensive insight into the contribution of each model component to the performance of the recommendation system.

The significant contributions of the proposed HCF-MFGB model to movie recommendation systems are summarized as follows:

1. Uses SVD++ by integrating implicit feedback and explicit ratings to address sparsity.

2. Integrates user demographic and meta-item data and groups them into clusters using K-Means Clustering.

3. Uses XGBoost to process additional features, thereby improving model performance.

4. Validates the effectiveness of the HCF-MFGB model with comprehensive evaluation metrics and demonstrates its good performance in providing accurate movie recommendations.

The following is the structure of this article. Section 2 outlines the methodological steps employed; Section 3 presents the experimental setup and the results of the movie recommendation system’s performance evaluation; and Section 4 summarizes the findings and implications of this research.

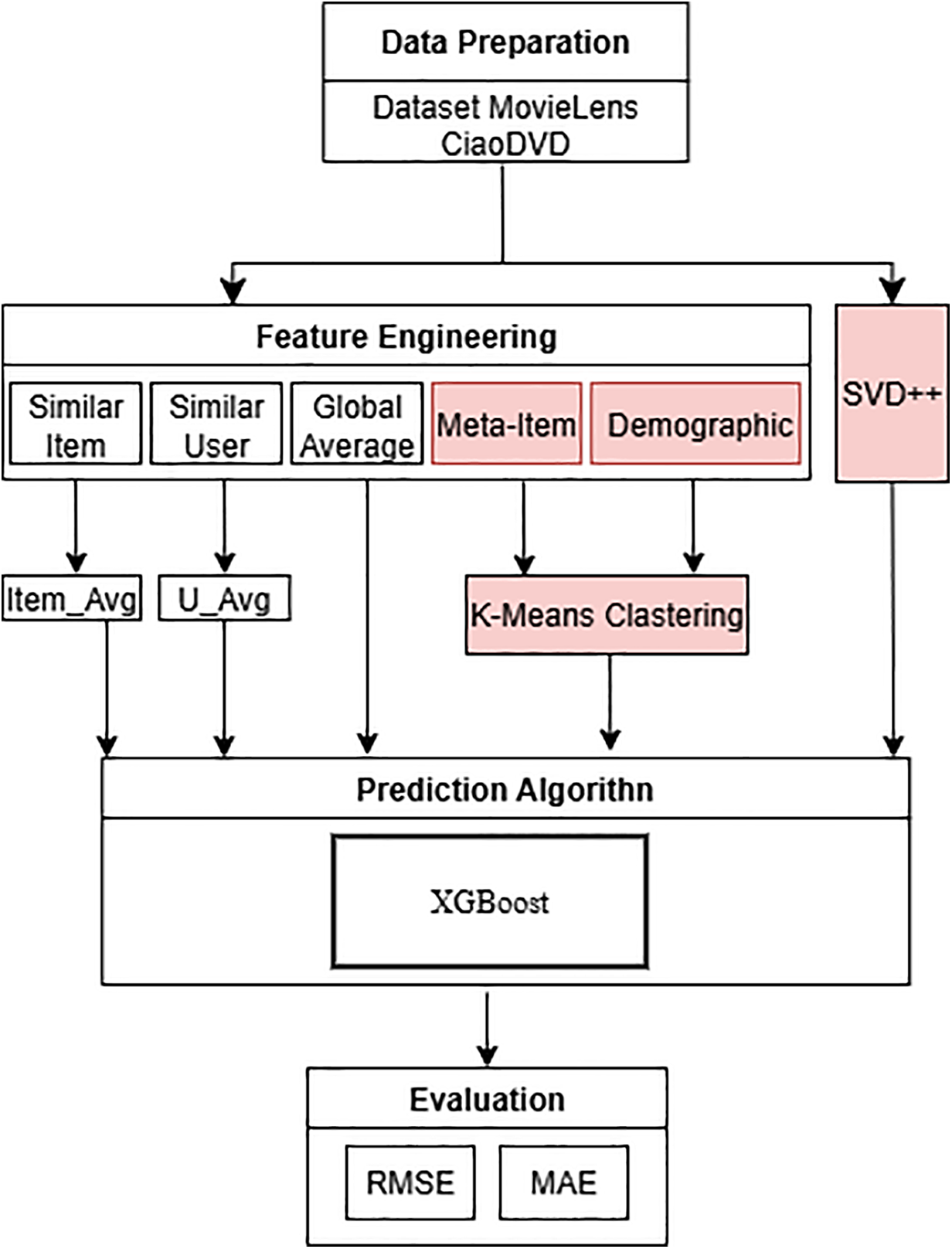

This study develops a recommendation system model that combines SVD++ and one of the Gradient Boosting Algorithms, namely XGBoost. This model is known as Hybrid Collaborative Filtering Based on Matrix Factorization and Gradient Boosting (HCF-MFGB). In Fig. 1, the HCF-MFGB model comprises six stages: dataset preparation, preprocessing, temporary rating prediction using SVD++, feature engineering, final prediction using the XGBoost algorithm, and evaluation.

Figure 1: Research methodology

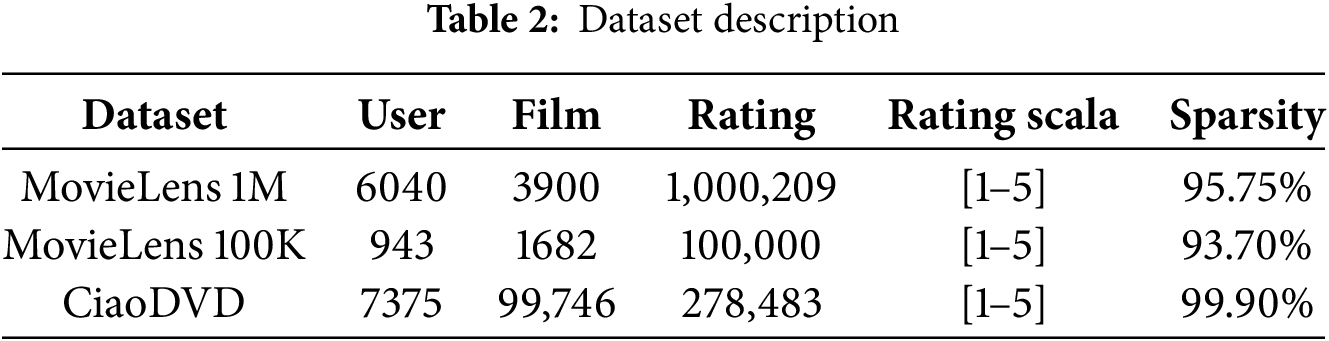

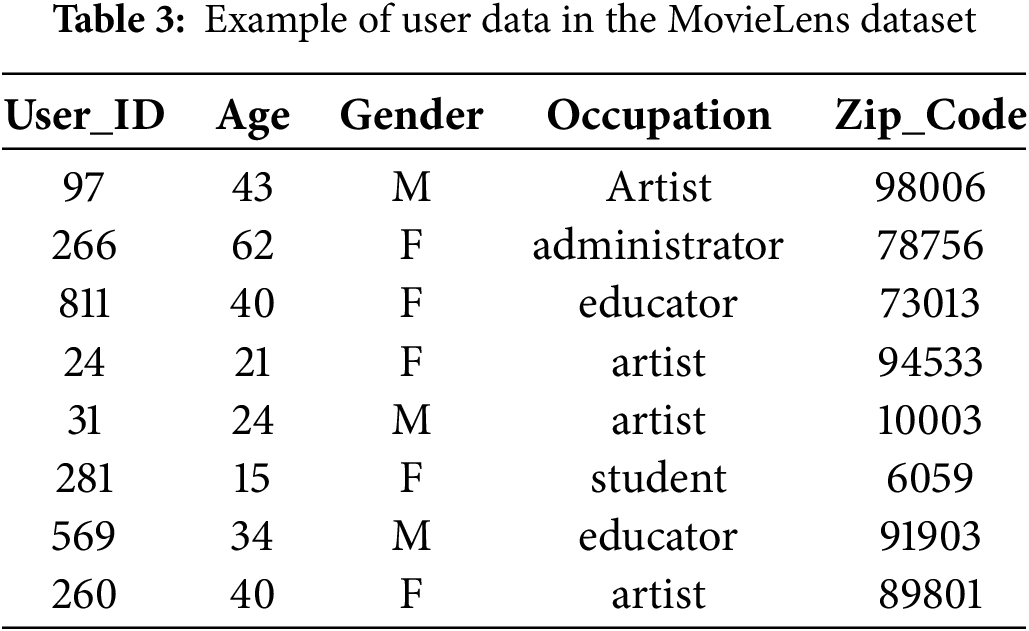

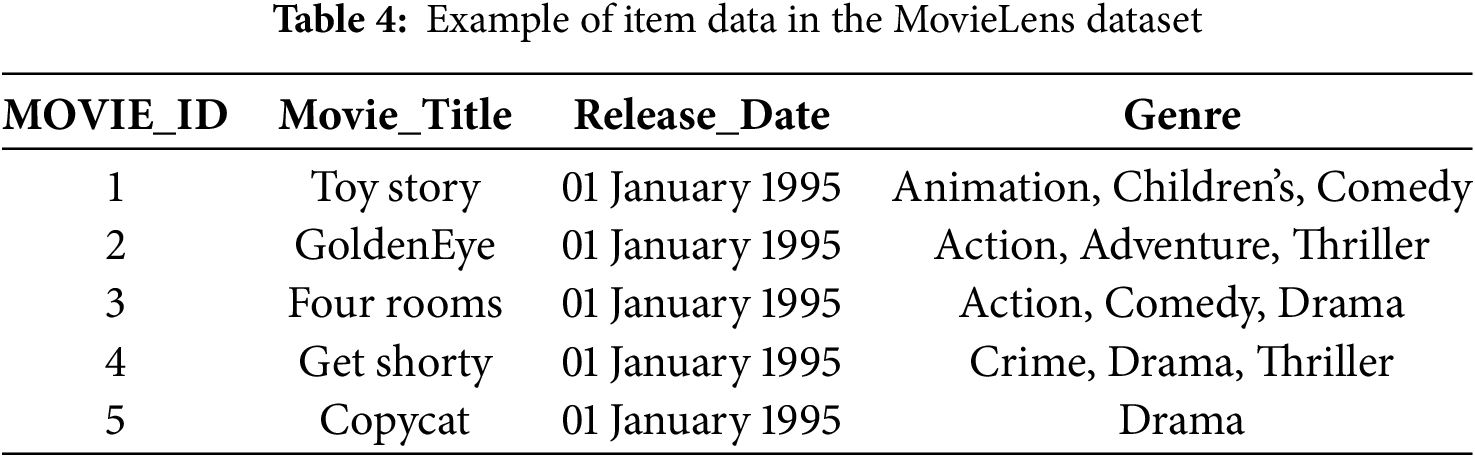

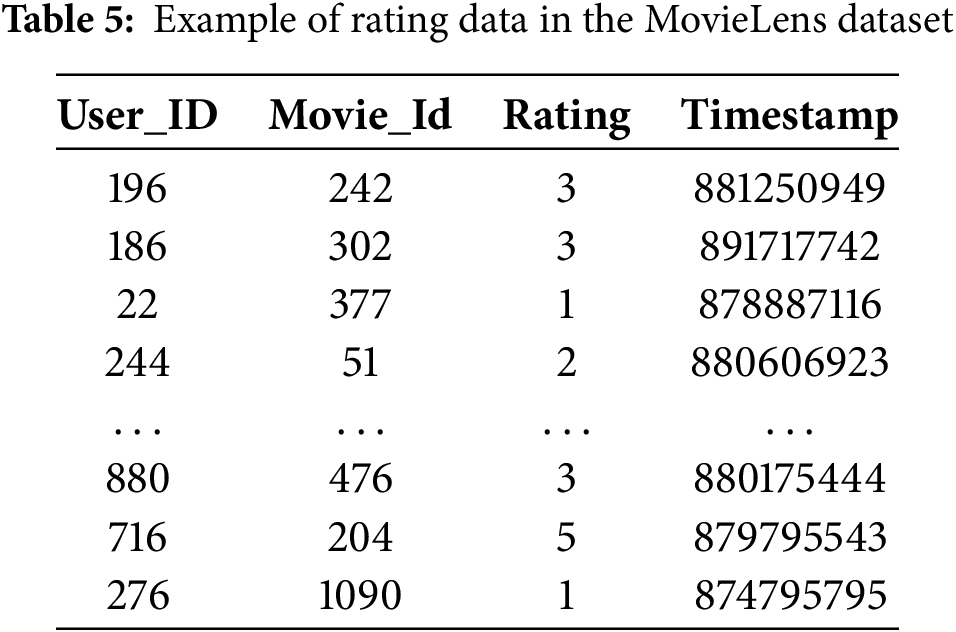

This study uses two public datasets, namely the MovieLens 100K, MovieLens 1M, and CiaoDVD. These datasets are often used in recommendation system research [30,31], because they provide very complete interaction data between users and items, as well as relevant contextual information. Table 2 is the specification of the dataset used. Tables 3–5 present the structure of each data contained in the MovieLens dataset, namely item data with its meta items, and user data with its demographic data.

The preprocessing stage in this study focused on converting categorical data into numerical data so that it could be processed by algorithms and removing unused data. The MovieLens dataset used in this study contains attributes from items and user demographic data that are still in the form of categorical attributes such as genre, gender, and occupation, as shown in Tables 3 and 4. All data that is still in the form of categories is converted using one-hot encoding; each category is converted into a unique and different number to make it easier to process to the next stage. In addition, to handle missing user demographic data, we implemented an imputation procedure. Empty categorical attributes, such as gender or occupation, were filled with the mode, which is the value that appears most frequently in the dataset. In contrast, numerical attributes, such as age, were imputed using the median. This approach ensures that all users can be retained in the dataset without losing essential information, while maintaining data consistency to improve reproducibility.

The next stage in this research is to predict the temporary ratings that users have not yet given for certain items. SVD++ is used to predict temporary ratings that have not been given by users. When compared to other types of factorization techniques, SVD++ is superior because it utilizes implicit feedback, such as access history or user interactions, including lists of items that have been opened. The use of SVD++ has been proven to be better in overcoming data sparsity problems and increasing prediction accuracy [32,33]. In predicting ratings using Eq. (1).

where

This method combines the influence of two types of important information into the model, namely explicit and implicit information, so that the resulting predictions become more personal and not generic. The latent vector

In this stage, we create additional features to enrich the information used in the prediction process. There are four features, namely, calculating the similarity between items based on rating patterns using Eq. (2), calculating user similarity based on the ratings given to several items using Eq. (3).

where

After that, we calculate the Global Average value of all ratings given by users, using Eq. (4).

where

Next, we used K-Means Clustering to group films based on genre combinations. Each film in the MovieLens dataset has multiple genres, such as Action, Comedy, Drama, etc., represented in binary form. The K-Means algorithm groups films that have similar genre combinations. The next clustering was applied to user demographic data, namely age, gender, and occupation, grouping users with similar demographic characteristics.

To predict the final rating score given by users, we use the XGBoost Algorithm. The XGBoost algorithm is a machine learning algorithm that applies ensemble learning techniques that work by building hundreds of decision trees gradually to improve model accuracy [34,35]. At each stage, a new decision tree will correct errors in the previous model so that it can gradually improve model performance. XGBoost is widely used as a machine learning algorithm, which is because of its ability to handle large datasets and produce good performance [36].

Previously generated features, such as rating results from SVD++, item-user similarity, global average, and clustering results from meta-items and user demographics generated by K-Means, these features are combined into a feature vector and used as input to XGBoost. The objective function in XGBoost consists of a loss function and a regularization term, which are defined in Eq. (5).

where

The model uses a gradient boosting technique, where the contribution at each iteration is determined by minimizing the second order using Eqs. (6) and (7).

where

The final step in this research is to assess the performance of the proposed model, in measuring the performance of the model built in this research using two evaluation metrics, namely, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE), these two metrics are used to assess how close the prediction results produced by the model are to the rating given by the user. RMSE calculates the root of the average square error of the difference between the predicted rating and the actual rating using Eq. (8).

Meanwhile, MAE measures the absolute average of the difference between the predicted and actual values and provides a more direct representation of the overall prediction accuracy using Eq. (9).

3 Simulation, Results and Discussion

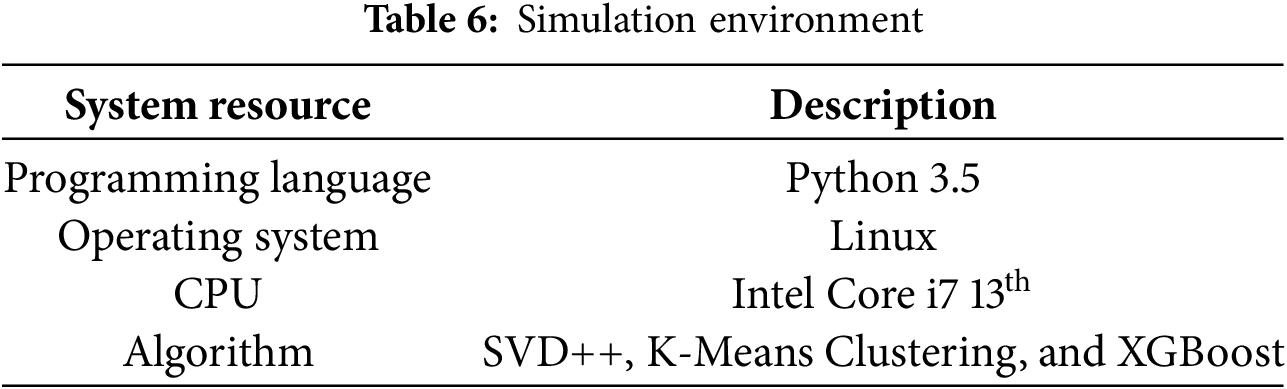

This experiment was conducted on a computing device that has been optimally designed to support the testing process of the recommendation system model that was built. The specifications used in the experiment are summarized in Table 6. Python is the programming language used because of its stability and compatibility with various libraries. The experimental process was run on a computer with a 13th-generation Intel Core i7 specification, and the algorithm used was a combination of SVD++, K-Means Clustering and XGBoost. We used the MovieLens dataset because it provides a complete user profile, as supported by a literature study conducted by Saifudin and Widiyaningtyas [37] on 73 research papers, 61% of research in recommendation systems used the MovieLens dataset, the rest used the Book Crossing dataset 3%, Netflix 3%, Yahoo music 3%, Film trust 1%, Epinions 2%, Movie tweetings 1%, Yelp 4%, Ciao 3%, and Amazon 10% dataset. The dataset structure is presented in Tables 2–5.

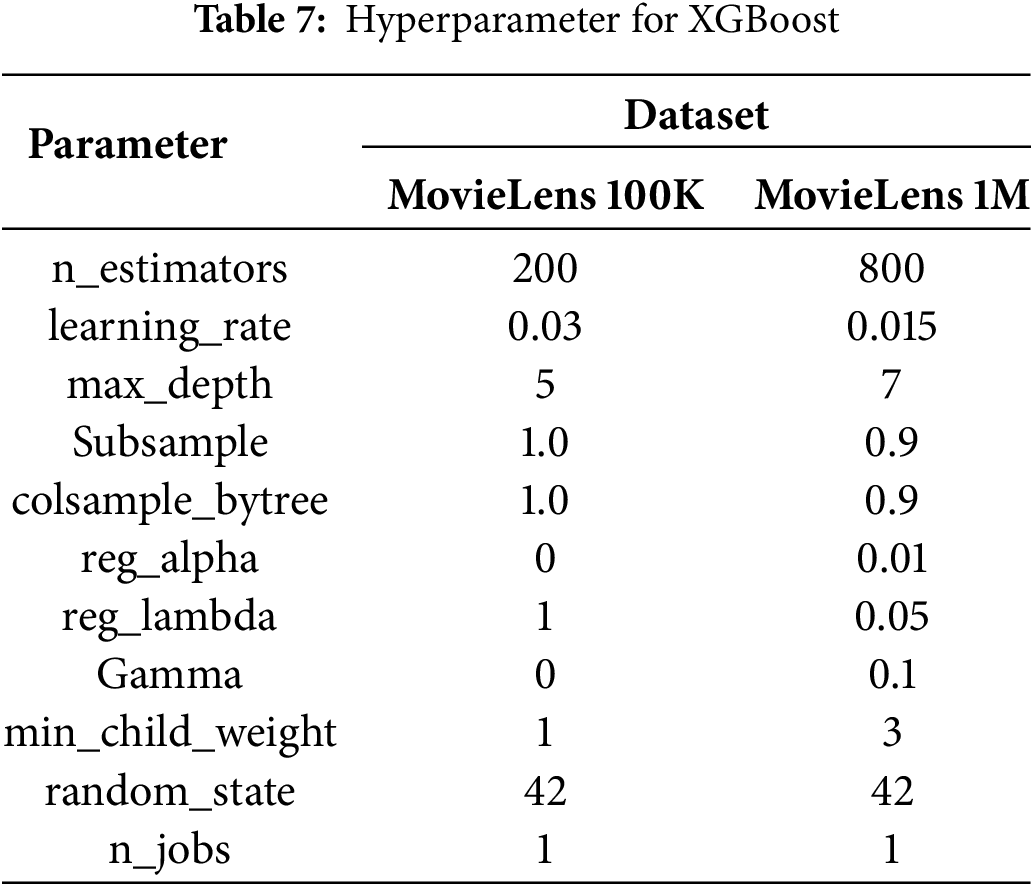

To optimize the performance of the proposed recommendation system model, hyperparameter selection through an experiment-based approach repeatedly adjusts the three main models used, namely SVD++, XGBoost, and K-Means Clustering. The XGBoost hyperparameter tuning process focuses on balancing the model’s ability to understand complex patterns and its capacity to provide accurate results not only on training data, but also on test data or previously unseen data. The parameters used in XGBoost are summarized in Table 7.

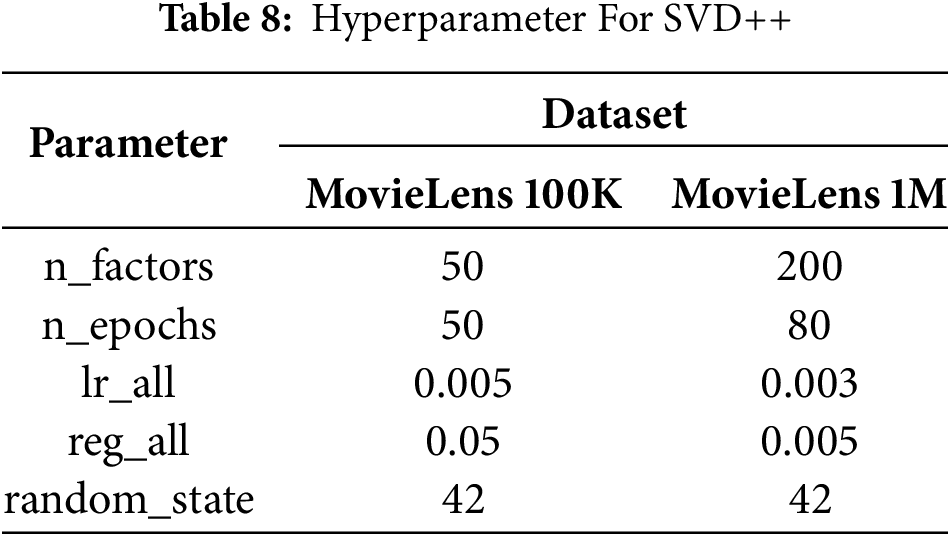

The hyperparameters of SVD++ summarized in Table 8 are used by considering several aspects, including adjusting the number of latent factors so that the model can capture a wide range of user preferences as a whole, maintaining the training process by setting the number of iterations and learning rate so that the model can adjust gradually, and controlling the complexity of the model by using regularization parameters.

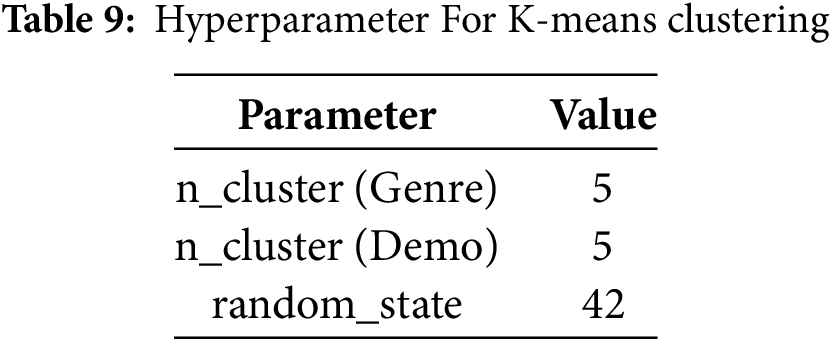

Meanwhile, the hyperparameters for K-Means Clustering, summarized in Table 9, were used to cluster meta-items and user demographics, designed to produce informative and stable clusters. The number of clusters was selected based on the complexity of the data and the analysis purpose, which was to capture patterns of similarity between items and user group characteristics. Additionally, the random_state parameter was set to ensure reproducible clustering results in each experiment, facilitating the validation and replication of the experiment.

3.2 Experiments and Performance Ablation Analysis of Each HCF-MFGB Model Module

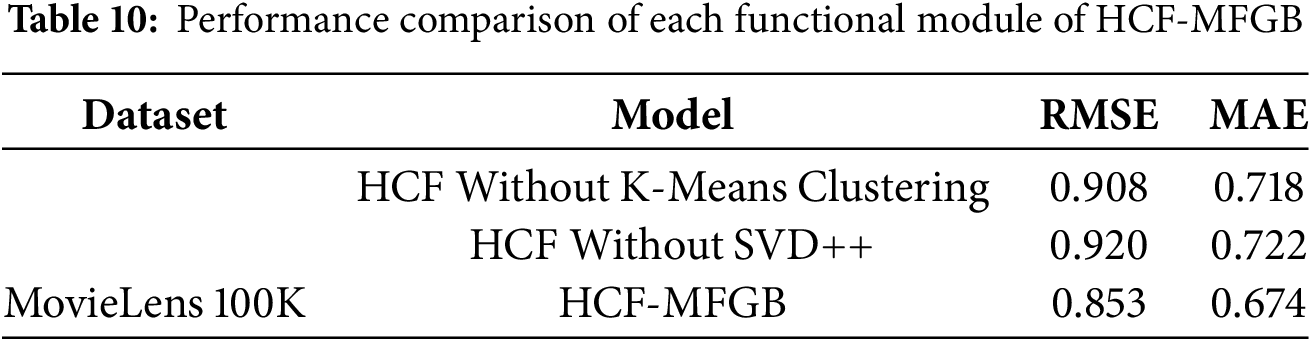

To evaluate the contribution of each principal component in the HCF-MFGB model, we conducted ablation experiments by removing one module at a time, namely K-Means Clustering and SVD++. The aim is to assess the extent to which each module contributes to the model’s performance, as well as to validate the effectiveness of integrating the three components in improving rating prediction accuracy. The results of the experiment on the MovieLens 100K dataset, summarized in Table 10, show that when we developed the model without using K-Means Clustering, the RMSE value rose from 0.853 to 0.908, while the MAE rose from 0.674 to 0.718. This increase in error indicates that grouping users and items provides additional important information, enabling the model to identify hidden patterns between features more effectively.

Meanwhile, the model we developed without using SVD++ showed a decline in performance, with the RMSE value increasing from 0.853 to 0.920, and the MAE rising from 0.674 to 0.722. This error rate is lower than that of the model without K-Means Clustering. This indicates that utilising both explicit and implicit user feedback is very important. By utilizing SVD++, the model can better understand user preferences. The results of this experiment prove that each component used has a significant contribution to the model’s performance. Without K-Means, the model’s ability to identify user and item group patterns decreases, while without SVD++, the model loses its ability to effectively capture user preferences.

3.3 Evaluation Based on Subset Sparsity

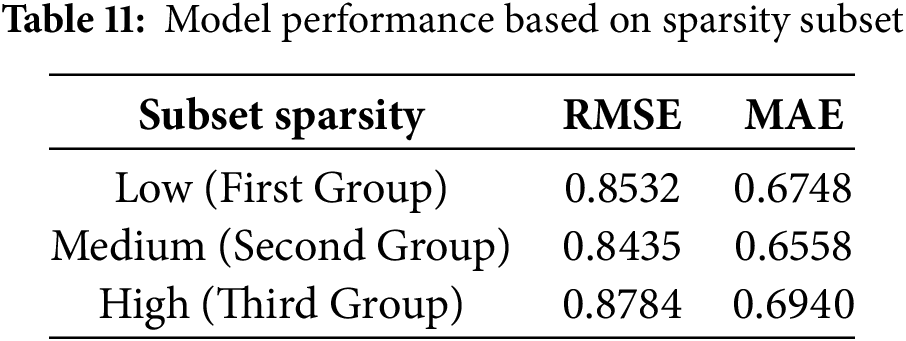

To assess the model’s robustness to various levels of sparsity, we divided the three groups of users in the 100K dataset into three categories based on the number of ratings they provided. The first group consisted of users who provided more than 70 ratings, the second group consisted of users who provided 50–70 ratings, and the third group consisted of users who provided fewer than 50 ratings.

The analysis results summarized in Table 11 indicate that the HCF-MFGB model maintains good performance on user subsets with low and moderate sparsity; however, there is an increase in error on high-sparsity subsets. This decline in performance can be explained logically. First, in the high sparsity subset, information about user preferences is very limited, making the estimation of latent factors in SVD++ less accurate. Second, due to the small number of user interactions, cluster formation using K-Means becomes less stable, resulting in the model losing additional support from the cluster structure between users and items.

To determine the overall performance of the proposed HCF-MFGB model and compare it with baseline models on the dataset used. In the first step, we divided the dataset used into 80% training data and 20% test data. This was done because it considers the balance between the needs of model training and model performance evaluation. 80% training data allows the model to learn patterns in the dataset optimally. Meanwhile, the 20% test data is quite representative in measuring the model’s ability on previously unseen data. Next, we used SVD++ to predict temporary ratings. In addition, we created feature engineering, including item similarity, user similarity, global average, meta-item, and user demographics, which were used in the cluster again using K-Means Clustering. The rating results from SVD++ and feature engineering are used as input to the final prediction model. We also adjusted the hyperparameters used for SVD++, XGBoost, and K-Means Clustering, which are summarized in Tables 7–9.

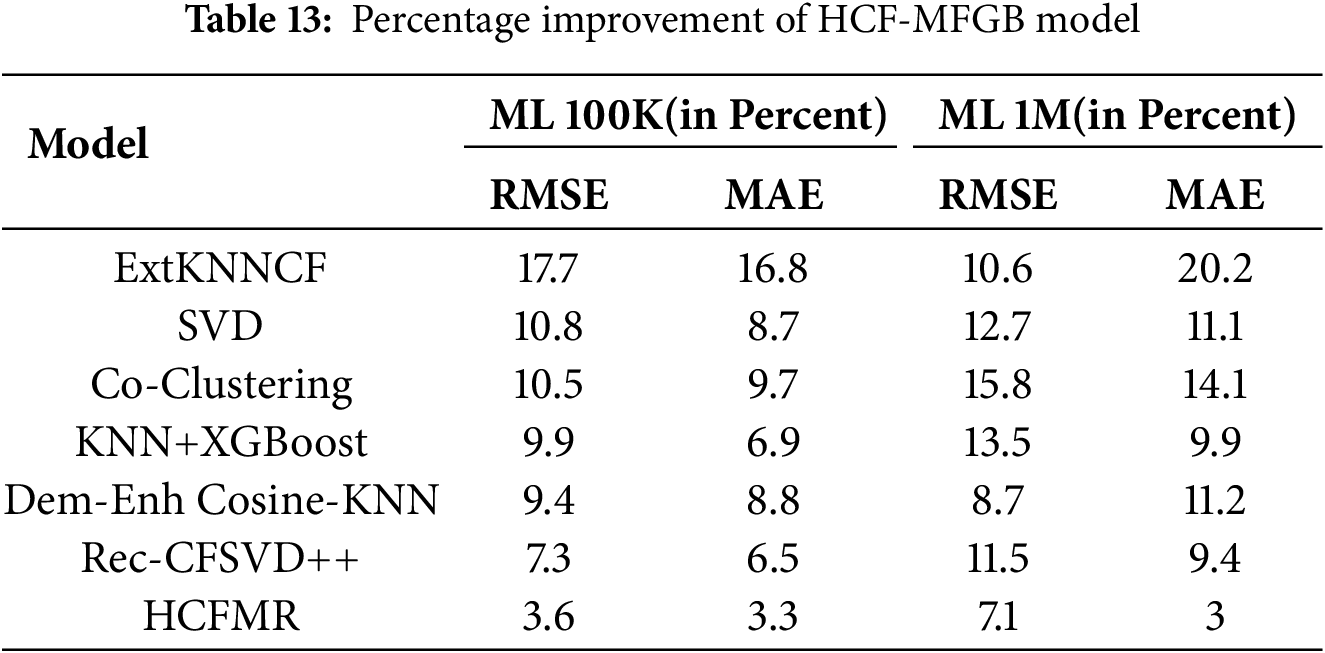

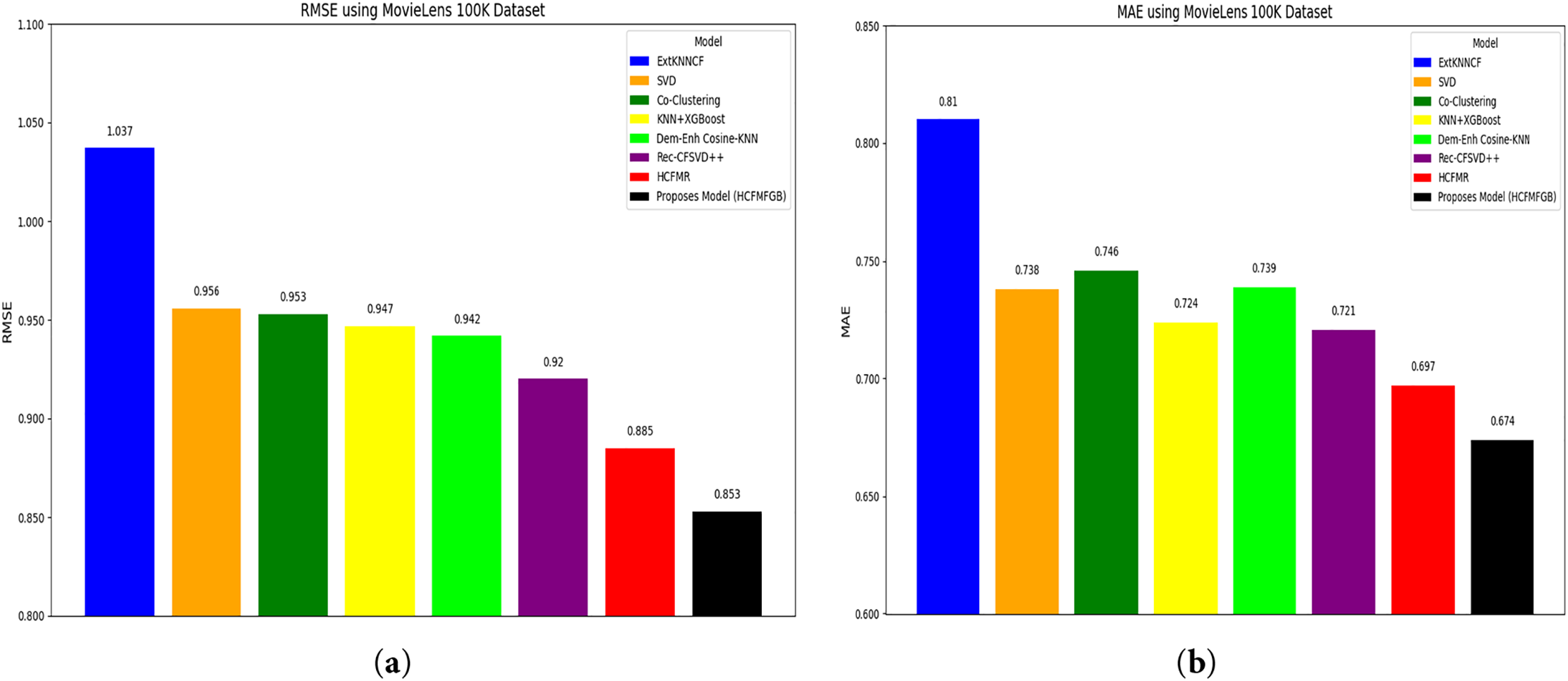

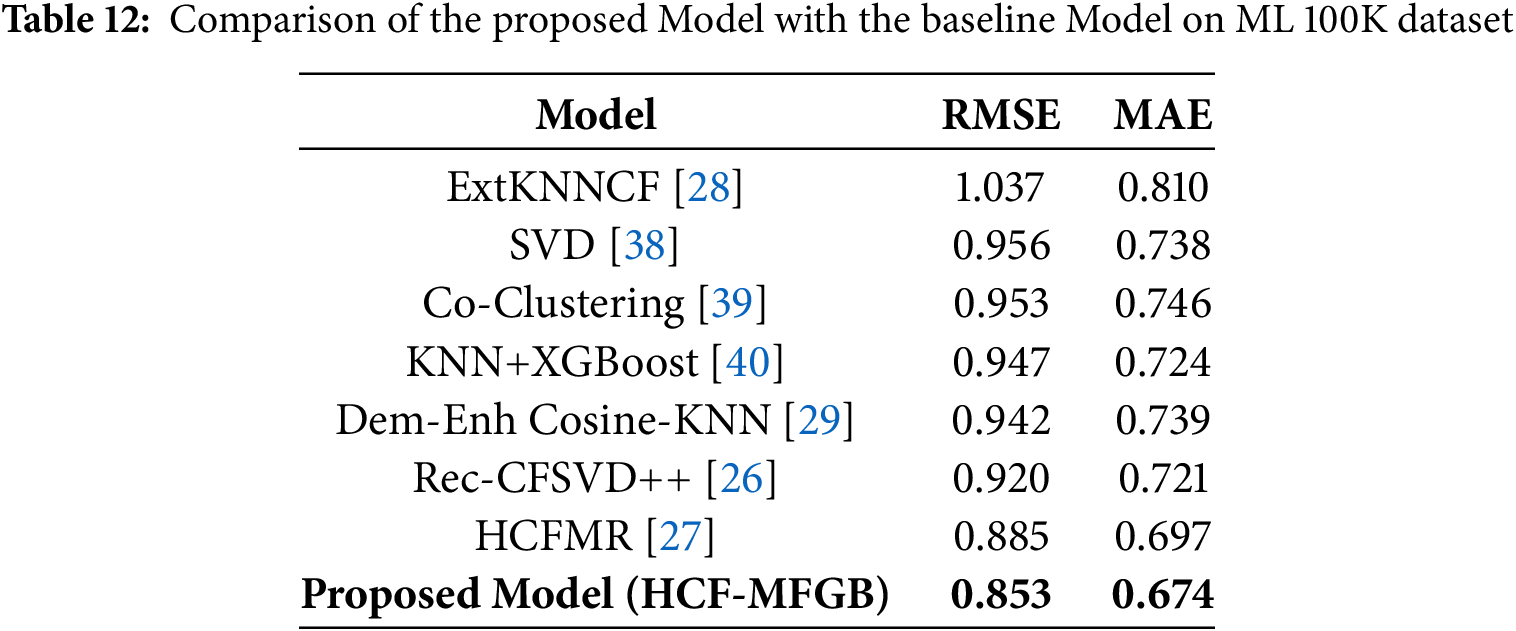

The experimental results on the MovieLens 100K dataset, summarized in Tables 12 and 13, demonstrate that the performance of our proposed model has improved compared to other baseline models, with an RMSE of 0.853 and an MAE of 0.674. These figures indicate that our proposed model can reduce errors in the prediction process compared to other baseline models, both in terms of RMSE and MAE. We provide a detailed comparison of the HCF-MFGB model with some of the best models, the HCF-MFGB model consistently outperforms the previous models on the 100K ML dataset, by increasing RMSE and MAE by 17.7% and 16.8% when compared to the ExtKNNCF technique, 10.8% and 8.7% when compared to the SVD technique, 10.5% and 9.7% when compared to the Co-Clustering technique, 9.9% and 6.9% when compared to the KNN+XGBoost technique, 9.4% and 8.8% when compared to the Dem-Enh Cosine-KNN technique, 7.3% and 6.5% when compared to the Rec-CFSVD++ technique. The HCFMR technique is a complex model that previously yielded the best results, with an RMSE value of 0.885 and an MAE of 0.697. Our proposed model still achieves the smallest RMSE and MAE values, at 3.6% and 3.3%, respectively.

Furthermore, Fig. 2a,b shows a graphical comparison of the performance of the HCF-MFGB model against several baseline models on the 100K ML dataset. Our proposed model achieves the lowest prediction error value among all models.

Figure 2: Model performance on the MovieLens 100K dataset: (a) Performance on RMSE evaluation metric; (b) Performance on MAE evaluation metric

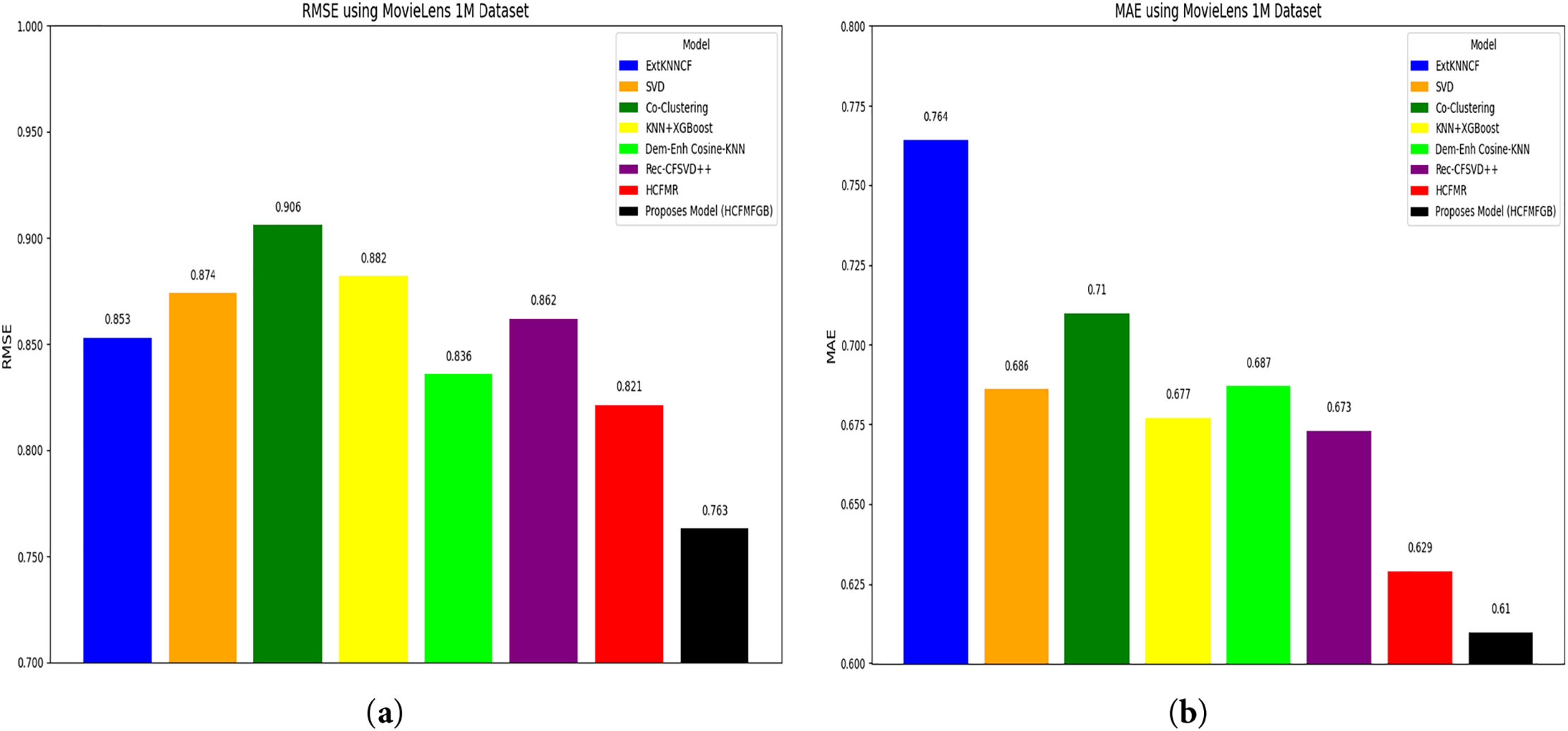

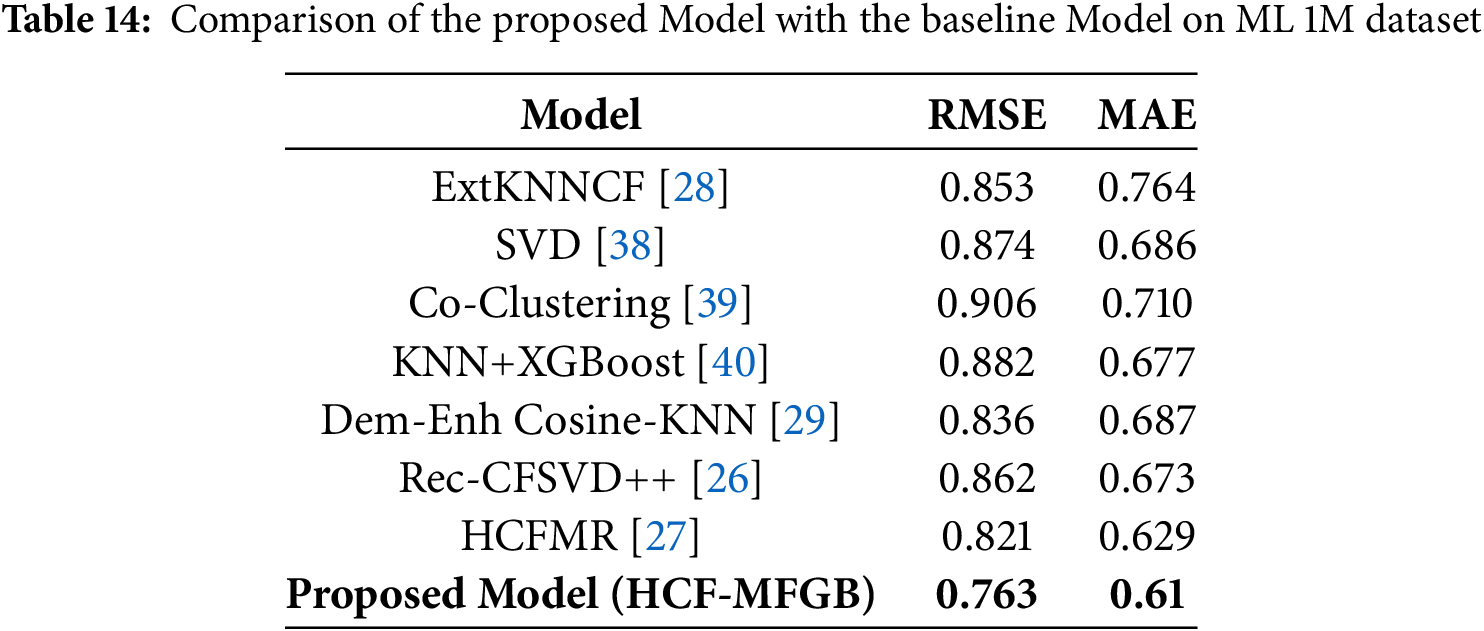

After achieving better results on the MovieLens 100K dataset, we tested the proposed model on a larger dataset, the MovieLens 1M. This dataset presents more challenges than the 100 K dataset, as it includes more user-item interaction data and a greater diversity of preferences. This was done to test the extent to which the proposed model can maintain its performance on a larger and more diverse dataset.

Tables 9 and 10 compare the performance of the proposed model with several advanced models, such as ExtKNNCF, SVD, Co-Clustering, KNN+XGBoost, Dem-Enh Cosine-KNN, Rec-CFSVD++, and HCFMR., the results found that our proposed model obtained an RMSE value of 0.761 and MAE of 0.61, with this value obtained indicating that the HCF-MFGB model’s performance has increased compared to other baseline models by being able to reduce errors in the prediction process, both RMSE and MAE. We compare the performance with the ExtKNNCF technique, the HCF-MFGB model increases by 10.6% and 20.2% for RMSE and MAE, when compared with the SVD technique 12.7% and 11.1%, when compared with Co-Clustering 15,8% and 14.1%, when compared with the KNN+XGBoost technique 13.5% and 9.9%, when compared with the Dem-Enh Cosine-KNN technique 8,7% and 11.2%, when compared with the Rec-CFSVD++ technique 11.5% and 9.4%, and when compared with even the best technique such as the HCFMF technique, our proposed model is proven to be able to increase the RMSE value by 7.1% and MAE by 3%. Fig. 3a,b shows a graphical comparison of the performance of the HCF-MFGB model with the baseline model on the 1M ML dataset. Our proposed model achieves the lowest prediction error value.

Figure 3: Model performance on the MovieLens 1M dataset: (a) Performance on the RMSE evaluation metric; (b) Performance on the MAE evaluation metric

This study presents a novel approach to a hybrid-based recommendation system by leveraging meta-item features, user demographics, and combining SVD++ to factorize the matrix and XGBoost to predict the final rating. Overall, the experimental results obtained demonstrate that our proposed model outperforms several baseline models, including ExtKNNCF, SVD, Co-Clustering, KNN+XGBoost, Dem-Enh Cosine-KNN, Rec-CFSVD++, and HCFMR, on all datasets. This confirms that our proposed model produces more accurate recommendations.

On the MovieLens 100K dataset, our proposed model outperformed various other models, achieving an RMSE value of 0.853 and an MAE of 0.674. Compared to the HCFMR model, which achieved the best performance on the baseline, our proposed model improved its performance by 3.6% for RMSE and 3.3% for MAE. On the 1M ML dataset, which has a larger and more diverse amount of data, our proposed model maintains its best performance with an RMSE value of 0.761 and an MAE of 0.61. Compared to the baseline, our model improves its performance by 7.1% and 3% for RMSE and MAE, respectively. These results demonstrate that our proposed model remains stable in handling large dataset types and maintains prediction accuracy, even with datasets of high sparsity and diverse preferences.

In addition to the MovieLens dataset, HCF-MFGB was also tested on the CiaoDVD dataset to validate the model’s capabilities in different domains. The CiaoDVD dataset is a dataset with extremely high sparsity, specifically 99.90%, comprising 99,764 items and 7375 users. For traditional approaches, data with this high sparsity makes it difficult for the system to find users with similar rating patterns, because only a few items are rated by more than one user. However, the HCF-MFGB model is designed to mitigate this issue by integrating latent factors to learn hidden preferences by combining explicit feedback and implicit feedback, so that the model remains capable of producing accurate predictions even when the number of ratings is minimal. Meta item information, such as genre, acts as an additional feature that enriches the item representation, enabling the model to recognize similarities between items even if not all items have been rated by users. Furthermore, the XGBoost ensemble algorithm processes all available features by gradually building a series of decision trees, enabling the system to capture complex, non-linear relationships and enhance the accuracy of the final prediction.

The evaluation results on the CiaoDVD dataset demonstrate that the HCF-MFGB model achieves good performance, yielding an RMSE value of 0.718 and an MAE value of 0.495. These results indicate that the prediction error rate achieved by the model is relatively small. This performance is slightly better than the results on Movielens, which are summarized in Tables 12 and 14, despite its data characteristics indicating less interaction data between users and items. This suggests that the HCF-MFGB model continues to perform well, even when applied to datasets other than MovieLens.

The ability of our proposed model to outperform baseline models in various datasets ensures the effectiveness of combining SVD++ and gradient boosting techniques. The advantages of the XGBoost algorithm in handling large datasets, such as 1M ML, and its ability to improve prediction performance through ensemble learning techniques are key factors in the success of this model, as it maintains its performance at the lowest prediction error level. In addition, the feature engineering approach, which utilizes cosine similarity to calculate item similarity, user similarity, and global average, can provide a positive contribution to enriching the input to the XGBoost model. The clustering process on meta-item features and user demographics, using K-Means clustering, plays a crucial role in improving model accuracy. This is because the model becomes more effective in understanding complex patterns in user and item interactions. The findings of this study have implications for recommendation systems, as they integrate meta-item features and user demographics, thereby enhancing the system’s ability to provide accurate recommendations and overcoming the problem of sparsity found in the dataset. Furthermore, understanding meta-item features and user demographics, including user preferences, provides benefits in creating effective marketing strategies that contribute to user satisfaction.

3.5 Limitations and Future Directions

In the previous section, we demonstrated the potential of our new HCF-MFGB model, which proved that this model provides significant progress in overcoming sparsity issues in recommendation systems. However, this study also has several limitations that could be topics for future research. First, it does not model temporal dynamics, which can potentially reduce the accuracy of recommendations due to changes in user preferences over time. Second, the model still focuses on the accuracy of rating predictions and does not consider the quality of the resulting recommendation sequence. Third, the HCF-MFGB model does not address the cold-start problem, which occurs when there are completely new users or items with no historical data. Finally, the scope of the model is limited to the MovieLens domain.

Future research could develop more comprehensive hybrid approaches to address cold-start problems, including the integration of deep learning methods, such as neural collaborative filtering, which enable systems to understand complex patterns automatically. Additionally, for new users, approaches that leverage explicit user preferences during registration can be an effective solution. For example, users can provide initial preference information by selecting preferred movie genres or categories, allowing the system to begin providing recommendations even when explicit rating data is not yet available. For the temporal aspect, methods that understand data sequences, such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) or transformers, can be developed to capture changes in user preferences and model long-term dependencies. These methods can also expand the domain coverage beyond MovieLens by using other evaluation metrics to measure recommendation diversity.

This study proposes an HCF-MFGB model that combines SVD++ to predict initial ratings, cosine similarity to calculate item-user similarity, K-Means Clustering to cluster meta-items and user demographics, and XGBoost to predict final ratings. The purpose of this model is to overcome the sparsity problem in movie recommendation systems. The datasets used in testing this model are MovieLens 100K, MovieLens 1M, and CiaoDVD, each with varying levels of sparsity. Overall, the HCF-MFGB model outperforms the baseline models in all metrics and datasets. On the 100K dataset, the HCF-MFGB model achieves an RMSE value of 0.853 and an MAE of 0.674, outperforming the previous best baseline model by 3.6% for RMSE and 3.3% for MAE. On the 1M dataset, the HCF-MFGB model achieved an RMSE of 0.763 and an MAE of 0.61, representing a 7.1% increase in RMSE and a 3% decrease in MAE compared to the previous best-performing model. On the CiaoDVD dataset, the HCF-MFGB model achieved an RMSE value of 0.718 and an MAE of 0.495. This combination not only improves accuracy but also produces more relevant and personalized recommendations.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia for supporting this research, and to all parties who have contributed to the writing of this paper.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Directorate General of Research and Development, Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia, with grant number 2.6.63/UN32.14.1/LT/2025.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Salahudin Robo and Triyanna Widiyaningtyas; methodology, Salahudin Robo; software, Salahudin Robo; validation, Triyanna Widiyaningtyas and Wahyu Sakti Gunawan Irianto; formal analysis, Salahudin Robo, Triyanna Widiyaningtyas and Wahyu Sakti Gunawan Irianto; investigation, Salahudin Robo, Triyanna Widiyaningtyas and Wahyu Sakti Gunawan Irianto; data curation, Salahudin Robo; writing—original draft preparation, Salahudin Robo; writing—review and editing, Triyanna Widiyaningtyas and Wahyu Sakti Gunawan Irianto; visualization, Salahudin Robo; supervision, Triyanna Widiyaningtyas and Wahyu Sakti Gunawan Irianto. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in GroupLens at https://grouplens.org/datasets/movielens/100k/ (accessed on 23 June 2025) for MovieLens 100K and at https://grouplens.org/datasets/movielens/1m/ (accessed on 23 June 2025) for MovieLens 1M.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature/Abbreviations

| Global average of all ratings in the dataset | |

| Predicted rating for user | |

| The actual rating given by user | |

| User bias | |

| Item bias | |

| Latent vectors for users | |

| Latent vectors for item | |

| Latent contribution vector of implicitly accessed items | |

| Set of items that have been accessed by user | |

| Total number of predictions | |

| Loss function between actual and predicted values | |

| Regularization function to control the complexity of decision trees | |

| First and second order gradients of the loss function | |

| The dot product between the two user vectors | |

| Total number of ratings given by all users | |

| Total number of ratings submitted by users | |

| The length of each user’s vector | |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| SVD++ | Singular Value Decomposition |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| Avg | Average |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

References

1. Roy D, Dutta M. A systematic review and research perspective on recommender systems. J Big Data. 2022;9(1):59. doi:10.1186/s40537-022-00592-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hsieh MY, Weng TH, Li KC. A keyword-aware recommender system using implicit feedback on Hadoop. J Parallel Distrib Comput. 2018;116(4):63–73. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2017.12.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Widiyaningtyas T, Hidayah I, Adji TB. User profile correlation-based similarity (UPCSim) algorithm in movie recommendation system. J Big Data. 2021;8(1):52. doi:10.1186/s40537-021-00425-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Behera G, Nain N. Collaborative filtering with temporal features for movie recommendation system. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023;218:1366–73. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2023.01.115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Nasir M, Ezeife CI. A survey and taxonomy of sequential recommender systems for E-commerce product recommendation. SN Comput Sci. 2023;4(6):708. doi:10.1007/s42979-023-02166-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. He X, Liu Q, Jung S. The impact of recommendation system on user satisfaction: a moderated mediation approach. J Theor Appl Electron Commer Res. 2024;19(1):448–66. doi:10.3390/jtaer19010024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Stalidis G, Karaveli I, Diamantaras K, Delianidi M, Christantonis K, Tektonidis D, et al. Recommendation systems for e-shopping: review of techniques for retail and sustainable marketing. Sustainability. 2023;15(23):16151. doi:10.3390/su152316151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Liao W, Li X, Wang X. Multi-view self-supervised learning on heterogeneous graphs for recommendation. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;174:113056. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kumar J, Patra BK, Sahoo B, Babu KS. Group recommendation exploiting characteristics of user-item and collaborative rating of users. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(10):29289–309. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-16799-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Trinh T, Nguyen VH, Nguyen N, Nguyen DN. Product collaborative filtering based recommendation systems for large-scale E-commerce. Int J Inf Manag Data Insights. 2025;5(1):100322. doi:10.1016/j.jjimei.2025.100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gao G, Liu H, Zhao K. Live streaming recommendations based on dynamic representation learning. Decis Support Syst. 2023;169:113957. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2023.113957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhen A, Wang X. The deep learning-based physical education course recommendation system under the internet of things. Heliyon. 2024;10(19):e38907. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jiang L, Sun X, Liu L, Yao J, Shi L, Han Z, et al. An intelligent fusion recommendation model based on attention trees and graph convolutional networks in social media. Inf Sci. 2025;714:122191. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2025.122191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chen Y, Huang J. Effective content recommendation in new media: leveraging algorithmic approaches. IEEE Access. 2024;12:90561–70. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3421566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tholib A, Widiyaningtyas T, Prasetya DD. An intelligent recommendation system utilizing a hybrid deep learning method. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res. 2025;15(4):25971–7. doi:10.48084/etasr.12230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Panagiotakis C, Papadakis H, Papagrigoriou A, Fragopoulou P. Improving recommender systems via a dual training error based correction approach. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;183:115386. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.115386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Koren Y, Rendle S, Bell R. Advances in collaborative filtering. In: Recommender systems handbook. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2021. p. 91–142. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-2197-4_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Peng S, Siet S, Sadriddinov I, Kim DY, Park K, Park DS. Integration of federated learning and graph convolutional networks for movie recommendation systems. Comput Mater Continua. 2025;83(2):2041–57. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.061166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Saifudin I, Widiyaningtyas T, Zaeni IAE, Aminuddin A. SVD-GoRank: recommender system algorithm using SVD and gower’s ranking. IEEE Access. 2025;13:19796–827. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3533558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Cai T, Zhang Y, Li K, Li X, Wang X. Feature-decorrelation adaptive contrastive learning for knowledge-aware recommendation. Neural Netw. 2025;190:107646. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2025.107646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chetana VL, Seetha H. Handling massive sparse data in recommendation systems. J Info Know Mgmt. 2024;23(3):2450021. doi:10.1142/s0219649224500217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu T, He Z. EAF-SR: an enhanced autoencoder framework for social recommendation. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(10):14837–58. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13918-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gunathilaka TMAU, Manage PD, Zhang J, Li Y, Kelly W. Addressing sparse data challenges in recommendation systems: a systematic review of rating estimation using sparse rating data and profile enrichment techniques. Intell Syst Appl. 2025;25:200474. doi:10.1016/j.iswa.2024.200474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mishra S, Singh T, Kumar M, Satakshi. Lazy learning and sparsity handling in recommendation systems. Knowl Inf Syst. 2024;66(12):7775–97. doi:10.1007/s10115-024-02218-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang H, Wang H, Yang F, Li J. Hybrid collaborative filtering algorithm based on sparse rating matrix and user preference. Wirel Commun Mob Comput. 2022;2022(1):2479314. doi:10.1155/2022/2479314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Anwar T, Uma V, Srivastava G. Rec-CFSVD++: implementing recommendation system using collaborative filtering and singular value decomposition (SVD)++. Int J Info Tech Dec Mak. 2021;20(4):1075–93. doi:10.1142/s0219622021500310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Behera G, Panda SK, Hsieh MY, Li KC. Hybrid collaborative filtering using matrix factorization and XGBoost for movie recommendation. Comput Stand Interfaces. 2024;90:103847. doi:10.1016/j.csi.2024.103847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Nguyen LV, Vo QT, Nguyen TH. Adaptive KNN-based extended collaborative filtering recommendation services. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2023;7(2):106. doi:10.3390/bdcc7020106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ariyanto Y, Widiyanigtyas T, Zaeni IAE. Enhancing movie recommendations: a demographic-integrated cosine-KNN collaborative filtering approach. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2024;17(6):791–803. doi:10.22266/ijies2024.1231.60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang H, Zhou B, Zhang L, Ma H. Recommendation method for contrastive enhancement of neighborhood information. Comput Mater Continua. 2024;78(1):453–72. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.046560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Shyam A, Kumar V, Kagita VR, Pujari AK. UniRecSys: a unified framework for personalized, group, package, and package-to-group recommendations. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;289:111552. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Al-Nafjan A, Alrashoudi N, Alrasheed H. Recommendation system algorithms on location-based social networks: comparative study. Information. 2022;13(4):188. doi:10.3390/info13040188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shi W, Wang L, Qin J. User embedding for rating prediction in SVD++-based collaborative filtering. Symmetry. 2020;12(1):121. doi:10.3390/sym12010121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Agrawal Y, Kumar M, Ananthakrishnan S, Kumarapuram G. Evapotranspiration modeling using different tree based ensembled machine learning algorithm. Water Resour Manag. 2022;36(3):1025–42. doi:10.1007/s11269-022-03067-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Dong J, Chen Y, Yao B, Zhang X, Zeng N. A neural network boosting regression model based on XGBoost. Appl Soft Comput. 2022;125:109067. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2022.109067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Putra LGR, Prasetya DD, Mayadi M. Student dropout prediction using random forest and XGBoost method. J Ilm Penelit Dan Penerapan Teknol Sist Inf. 2025;9(1):147–57. doi:10.29407/intensif.v9i1.21191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Saifudin I, Widiyaningtyas T. Systematic literature review on recommender system: approach, problem, evaluation techniques, datasets. IEEE Access. 2024;12:19827–47. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3359274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Behera G, Nain N. Trade-off between memory and model-based collaborative filtering recommender system. In: Proceedings of the international conference on paradigms of communication, computing and data sciences. Singapore: Springer; 2022. p. 137–46. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-5747-4_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Airen S, Agrawal J. Movie recommender system using parameter tuning of user and movie neighbourhood via co-clustering. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023;218:1176–83. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2023.01.096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Du Q, Li N, Yang S, Sun D, Liu W. Integrating KNN and gradient boosting decision tree for recommendation. In: 2021 IEEE 5th Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC); 2021 Mar 12–14; Chongqing, China. p. 2042–9. doi:10.1109/IAEAC50856.2021.9390647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools