Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

From Identification to Obfuscation: A Survey of Cross-Network Mapping and Anti-Mapping Methods

1 Shanghai Key Lab of Intelligent Information Processing, College of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Fudan University, Shanghai, 200433, China

2 Research Institute of Intelligent Complex Systems, Fudan University, Shanghai, 200433, China

* Corresponding Author: Yang Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cyberspace Mapping and Anti-Mapping Techniques)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(2), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073175

Received 12 September 2025; Accepted 29 October 2025; Issue published 09 December 2025

Abstract

User identity linkage (UIL) across online social networks seeks to match accounts belonging to the same real-world individual. This cross-platform mapping enables accurate user modeling but also raises serious privacy risks. Over the past decade, the research community has developed a wide range of UIL methods, from structural embeddings to multimodal fusion architectures. However, corresponding adversarial and defensive approaches remain fragmented and comparatively understudied. In this survey, we provide a unified overview of both mapping and anti-mapping methods for UIL. We categorize representative mapping models by learning paradigm and data modality, and systematically compare them with emerging countermeasures including adversarial injection, structural perturbation, and identity obfuscation. To bridge these two threads, we introduce a modality-oriented taxonomy and a formal game-theoretic framing that casts cross-network mapping as a contest between mappers and anti-mappers. This framing allows us to construct a cross-modality dependency matrix, which reveals structural information as the most contested signal, identifies node injection as the most robust defensive strategy, and points to multimodal integration as a promising direction. Our survey underscores the need for balanced, privacy-preserving identity inference and provides a foundation for future research on the adversarial dynamics of social identity mapping and defense.Keywords

Online platforms have become deeply intertwined with individual identity, enabling users to curate profiles, interact with communities, and produce diverse forms of content. However, as user activity fragments across different platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn), a pressing technical challenge emerges: how to determine whether two user accounts across distinct platforms belong to the same real-world individual? This task, known as cross-network mapping, or user identity linkage (UIL) [1,2] within online social networks (OSNs), has significant implications for personalized services, recommendation systems, digital forensics, and targeted marketing [3].

Nevertheless, the same technologies that enable personalization also pose serious risks to user privacy and security. UIL can enable adversaries to aggregate and de-anonymize user data at scale, potentially revealing sensitive behavioral patterns, political affiliations, or private communications [4]. These risks are amplified in scenarios involving data breaches or social engineering attacks, prompting a growing interest not only in building more accurate UIL systems, but also in developing countermeasures to resist them. This has led to the emergence of anti-UIL techniques as an essential defense against such privacy violations.

Formally, UIL strategies aim to infer a mapping between user accounts across heterogeneous platforms based on observable signals such as usernames, profile attributes, social connections, activity timestamps, and textual content. Despite its intuitive formulation, the problem remains technically challenging due to several factors: (1) Data sparsity, as only a small fraction of users share reliable cross-platform signals [5–7]; (2) Modal heterogeneity, since different platforms expose different modalities, e.g., text on Twitter vs. images on Instagram [8]; and (3) Structural misalignment, where users may interact with disjoint social circles across platforms [5]. These factors confound direct matching and require increasingly sophisticated modeling, often involving graph neural networks, multimodal fusion, or probabilistic reasoning.

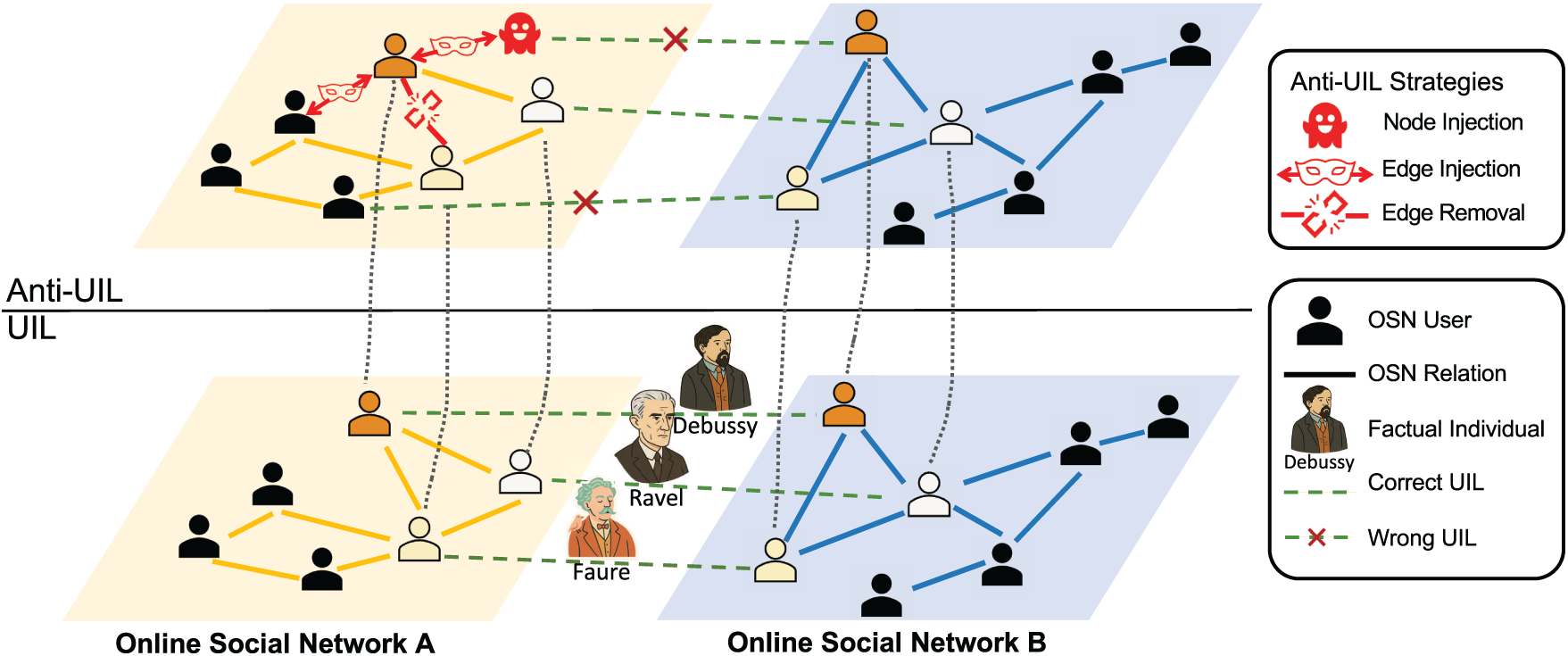

Parallel to this line of research, a growing body of research has begun to explore anti-UIL strategies [9–12], which deliberately aim to obscure, perturb, or decouple user identities across platforms. These defenses are motivated by concerns over privacy, security, and data protection, and include strategies such as adversarial node injection, structural perturbation, or username obfuscation. While research of UIL and anti-UIL have so far progressed largely in isolation, their objectives are inherently intertwined, as illustrated in Fig. 1—one seeks to maximize cross-platform identifiability, while the other seeks to minimize it. A comprehensive perspective that treats these two perspectives in parallel is therefore essential for understanding both the opportunities and the risks of identity linkage technologies.

Figure 1: An illustrative overview of the adversarial dynamics between UIL and anti-UIL strategies. UIL aims to correctly map accounts belonging to the same real-world individual across different networks, while anti-UIL methods introduce perturbations such as node injection or edge manipulation to disrupt these mappings

While earlier surveys such as Shu et al. [3] offered foundational overviews of UIL techniques, they have treated such mapping as a one-sided inference problem, giving little attention to the growing body of work on anti-mapping methods that aim to obscure, perturb, or defend against identity matching. This omission has become increasingly problematic: recent years have witnessed the emergence of adversarial attacks, privacy-aware defenses, and obfuscation strategies specifically designed to counter UIL. Without integrating these developments, the field remains fragmented, lacking a conceptual and methodological synthesis that places mapping and anti-mapping efforts in relation to one another.

To address this gap, our work provides a comprehensive survey of both UIL and anti-UIL literature, systematically reviewing models by categorizing them according to data modality and attack or defense strategy. For simplicity, we refer to strategies that perform UIL prediction as mapping models, and those that seek to disrupt or degrade such prediction as anti-mapping models, providing a consistent conceptual basis for subsequent analysis. We then introduce a game-theoretic framing that positions identity linkage as an adversarial contest between mappers and anti-mappers. This dual-perspective synthesis clarifies the current state of capabilities and limitations on both sides, while also surfacing blind spots and open opportunities that can guide future research, such as proactive anti-mapping and privacy-preserving UIL frameworks. The contributions of this work are as follows:

• Dual-perspective survey. We offer the first integrated review of both mapping (UIL) and anti-mapping (anti-UIL) models. Our survey categorizes mapping methods by supervision level, data modality, and methodological design, and systematically compares them against adversarial countermeasures including adversarial injection, structural perturbation, and identity obfuscation.

• Modality-centered taxonomy. We introduce a unified taxonomy that organizes mapping and anti-mapping models by the data modalities they exploit or target, e.g., structural, attribute, or content signals. This modality-oriented view reveals how defenses align with specific input spaces and where mismatches create vulnerabilities and provides a systematic framework for comparing challenges and model designs across different tasks and modalities, facilitating the identification of commonalities across modalities and research gaps.

• Adversarial framing. We propose a game-theoretic perspective that formally conceptualizes UIL as an adversarial interaction between mappers and anti-mappers. Through this framing, we construct a cross-modality interaction matrix that surfaces critical blind spots in current defenses, particularly for structure-based mapping, and outline future directions for building more generalizable multimodal identity inference.

The remainder of this survey is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews mapping models, categorized by their primary data modalities, and analyzes representative methods within each group. Section 3 turns to anti-mapping models, outlining injection, perturbation, and obfuscation strategies, as well as transferable defenses from related domains. Section 4 provides a comparative analysis, including cross-model comparisons, benchmark datasets, and a game-theoretic framing that positions mapping and anti-mapping as adversarial dynamics. Section 5 discusses open challenges and future directions, emphasizing dataset standardization, the imbalance between mapping and anti-mapping, and the need for more generalizable and robust mapping models. Lastly, Sections 6 & 7 conclude the survey by summarizing limitations, key insights, and reflecting on the broader implications of adversarial dynamics in identity linkage.

2 Characterizing Mapping Models by Data Source Dependency

In this section, we classify existing mapping models according to the type of data they primarily exploit for cross-network linkage. This single-dimension taxonomy groups methods into four categories: structure-based, attribute-based, content and behavioral, and multimodal or hybrid models. The classification reflects the dominant signal on which each method builds its representation and decision process, even though many models may incorporate secondary modalities in supporting roles. Models with overlapping designs are assigned to the category most aligned with their central modeling assumption and optimization objective.

Within each category, we present representative approaches in a thematic order that reflects both methodological progression and conceptual relatedness. Earlier methods that established the basic use of a given modality are followed by later models that extend or integrate it with more advanced architectures, learning frameworks, or domain adaptations. For each group, we summarize core ideas, identify distinguishing design choices, and highlight limitations or vulnerabilities that connect to anti-mapping strategies discussed in Section 3.

Structure-based models tackle UIL by leveraging primarily the topological signals present in social networks. These include user-user edges [13], co-following patterns [14], walk-based proximities [15], and higher-order structural relations [16,17], without relying on user profiles, content, or behavioral attributes. While these methods center on structural features, many also incorporate limited auxiliary signals such as seed user alignments [13,18], anchor links for supervision [16,19], or aligned community clusters [17] to guide or stabilize the matching process. The central assumption underlying this category of models is that social graph structures reflect latent identity patterns that can be preserved, projected, or aligned across platforms.

Early UIL approaches such as PALE [13] and UUIL [8] employed supervised and unsupervised graph embedding frameworks, respectively, aiming to map nodes from different networks into a common latent space. PALE learns a low-dimensional representation for each network and uses a supervised mapping function trained on anchor links to align embeddings. In contrast, UUIL reframes the linkage problem as a distribution alignment task, minimizing the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) [20] between user distributions across networks, thereby eliminating the need for pairwise supervision. Following this trend, Chu et al. [6] introduced a cross-network embedding strategy called CrossMNA by distinguishing inter-and intra-network structural features, optimizing memory efficiency while retaining alignment accuracy. Similarly, Liu et al. [14] proposed a framework called IONE to enhance structural representation by modeling both follower and followee contexts, thus addressing scalability issues in matrix-based alignment models.

Recent advances have adopted graph neural networks (GNNs) to exploit local and global topological information. Zhang et al. [19] presented GraphUIL, which integrates GNN-based aggregators to capture multi-scale structure, combining local self-attention mechanisms with global community-aware signals. Kaushal et al. [15] proposed a modular embedding framework called NeXLink, which separately preserves local and global node contexts before unifying them for cross-network matching. Fu et al. [16] introduced MGGE to further extend this by incorporating multi-granularity embeddings.

Structure alignment has also been explored through novel geometric and theoretical lenses. Zeng et al. [17] put forward a method named HOT to model UIL as a hierarchical multi-marginal optimal transport (MOT) [21] problem, decomposing the alignment into cluster-level and node-level subproblems. Zhang et al. [18] devised NEXTALIGN to formalize the trade-off between alignment consistency and disparity, proposing RelGCN to balance smoothness and discrimination across node representations.

While these methods demonstrate strong performance under network homogeneity and dense connectivity, they remain vulnerable to structural obfuscation attacks. Since their inference relies primarily on topological regularities, perturbation attacks such as node injection, edge rewiring, or community hiding (e.g., TOAK [9], DeLink [11]) can significantly degrade their accuracy. Moreover, sparsely connected networks or networks with irregular topology challenge the core assumption of structural isomorphism, limiting the generalizability of structure-focused approaches.

Attribute-based models approach UIL by leveraging explicit user-provided attributes or metadata-derived features. These may include usernames, display names, gender, geographic location, or stylometric traces embedded in writing style. The underlying assumption is that many users either reuse or inadvertently preserve identifiable patterns in their public-facing information across platforms. Linkage is therefore performed by assessing profile similarity or attribute consistency between user accounts.

Early work in this category focused on deterministic or probabilistic matching using core attributes. For instance, Goga et al. [22] proposed ACID to formalize the notions of availability, consistency, non-impersonability, and discriminability of user attributes, and evaluated profile matching techniques under realistic sampling settings. Zafarani and Liu [23] introduced a method called MOBIUS, using usernames as atomic entities, exploiting redundancy in behavioral and profile patterns through machine learning classifiers.

More recent approaches extend attribute matching into learned representations. Xu and Fung [24] proposed StyleLink to encode stylometric signals extracted from users’ writing into embedding spaces for cross-network identity inference. Similarly, Park et al. [25] presented GradAlign+ to augment attributes derived from node centrality measures to improve the robustness of alignment in graph-based settings. These approaches reflect a shift from discrete attribute comparison to representation-level similarity.

Some attribute-based models also combine attributes with other signals, but still retain an attribute-centric design. Guo et al. [26] proposed NUIL, for example, to embed structural context using random walks but still models cross-network linkage with a neural tensor network applied to user attribute vectors. Li et al. [27] introduced MFLink, a technically multimodal method, to incorporate explicit profile features, e.g., demographics or image metadata, as one of its fused modalities. Likewise, Kong et al. [2] devised MNA to extract heterogeneous user features, including temporal and textual attributes, before performing supervised alignment.

Despite their practicality, attribute-based models face fundamental challenges by design. Public profiles are often incomplete, inconsistently formatted, or intentionally falsified. As users become increasingly privacy-aware or adopt obfuscation tactics, reliance on direct attribute similarity becomes fragile. Stylometric systems, while harder to mask, remain susceptible to imitation or adversarial rewriting. Accordingly, methods in this category are particularly vulnerable to perturbations such as fake attribute injection, profile masking, and stylometric camouflage, which will be explored in anti-mapping strategies discussed later.

2.3 Content and Behavioral Methods

Content and behavioral methods leverage signals derived from user-generated content or from characteristic patterns of online activity. Content signals can include textual posts, images, or other multimedia artifacts that a user shares, while behavioral patterns may encompass posting times, frequency of activity, or interaction traces with other accounts. The intuition is that such outputs and patterns often contain identifiable and difficult-to-fabricate cues that persist across platforms, enabling cross-network matching.

Early work in this category emphasized behavioral modeling as a means to capture users’ distinctive interaction signatures. Zafarani and Liu [23] presented MOBIUS, which exemplify this line of research by correlating usernames with cross-network behavioral patterns, exploiting redundancies in activity traces and profile elements to support linkage decisions. These ideas foreshadowed the later integration of richer modalities, as behavioral traces alone can be sparse or ambiguous in isolation.

Subsequent approaches have combined content and behavior to create more discriminative representations. Li et al. [27] introduced MFLink to fuse textual and image content with structural network features via an attention-based multimodal integration mechanism, enabling the model to weigh modalities according to their informativeness for each user. Li et al. [28] proposed MSUIL which employs a partially shared adversarial learning framework to align content and behavioral feature spaces across networks, bridging modality gaps through domain adaptation. Wang et al. [29] presented FSFN to complement network semantics with behavioral signals as external correlation features, jointly optimizing them in a deep autoencoder-based architecture to improve anchor link prediction.

These methods are often evaluated on datasets that combine network topology with rich textual or interaction logs, such as microblogging platforms or forum archives. Their reliance on expressive modalities offers advantages in cases where structural or attribute information is sparse, but also exposes a broad attack surface. Content rewriting, automated paraphrasing, or image modification can degrade content-based similarity, while behavioral mimicry or deliberate alteration of activity patterns can obscure behavioral fingerprints. As such, although these methods extend UIL capabilities beyond purely structural or attribute-based approaches, they also inherit vulnerabilities that adversaries may exploit.

2.4 Multimodal and Hybrid Models

Multimodal and hybrid methods aim to exploit complementary strengths of different data sources by integrating structure, attribute, and content information into a unified representation. The premise is that while any single modality may be noisy or incomplete, jointly modeling multiple signals can yield more robust and discriminative embeddings for cross-network alignment. This integration is typically achieved through joint embedding frameworks, adversarial learning, or explicit representation fusion strategies.

Early multimodal designs focused on aligning heterogeneous features in a shared latent space. As mentioned earlier, Li et al. [28] proposed MSUIL to adopt a partially shared adversarial learning framework that enforces consistency across networks while allowing modality-specific components to capture domain-dependent patterns. Amara et al. [30] introduced a framework called OVRAU to build a common embedding shared across networks alongside intra-network embeddings for structural features, combining them through a self-attention fusion mechanism to capture both local and global dependencies.

More recent approaches have introduced advanced architectural and geometric considerations into the fusion process. Chen et al. [31] presented AHGNet to integrate multiple modalities through a hybrid graph neural network enhanced by adversarial training, improving resilience against modality-specific noise. Park et al. [25] proposed GradAlign+, which augments node attributes derived from structural centrality and integrates them into a GNN-based alignment process, progressively discovering matching pairs while refining feature similarity. Jiao et al. [32] presented CINA to combine hypergraph modeling with both Euclidean and hyperbolic spaces, enabling the representation of diverse relationships and geometric properties within a unified fusion framework.

By leveraging multiple modalities simultaneously, these methods can resist perturbations targeting any single data source. However, the fusion process itself introduces new points of fragility: errors or biases in one modality can propagate through the integrated representation, and adversarial perturbations designed to exploit modality interactions can cause disproportionate performance degradation. Moreover, multimodal architectures often require greater computational resources and careful tuning of fusion parameters, which may limit their scalability in large-scale or real-time applications.

In summary, the four categories of mapping models present a clear trade-off between specialization and generalization. Structure-based models excel in leveraging robust topological patterns but are highly vulnerable to network perturbation. Attribute-based approaches offer simplicity and direct interpretability yet suffer from noise and intentional obfuscation in public profiles. Content and behavioral methods utilize richer, more nuanced user signals but require complex feature engineering and are susceptible to content-level attacks. Multimodal models attempt to overcome these limitations by integrating complementary signals, thereby gaining robustness through diversity, but at the cost of increased model complexity and the creation of new vulnerabilities at the fusion stage.

3 Anti-Mapping Models: Injection, Perturbation, and Obfuscation

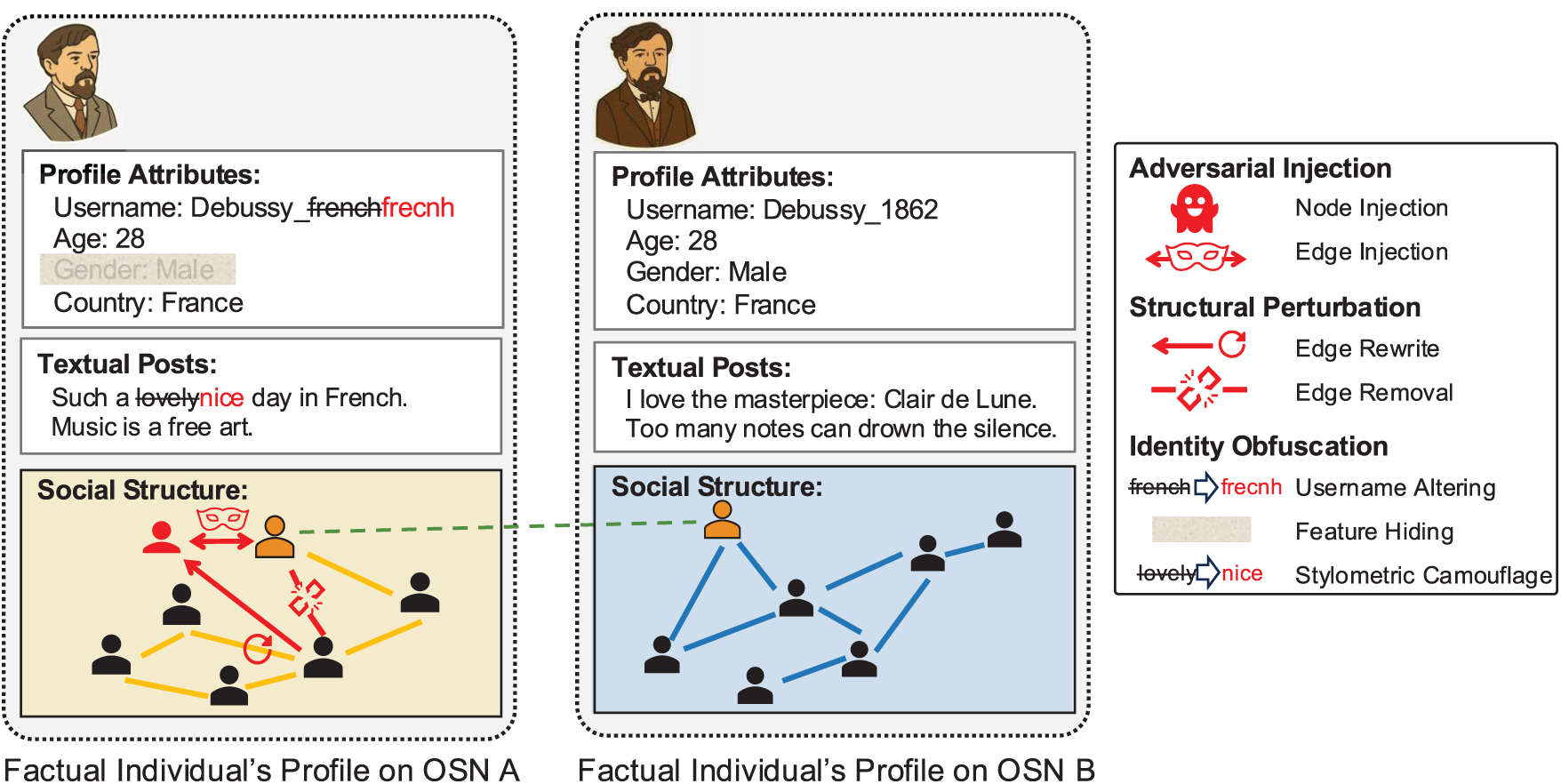

Anti-mapping models explore methods to prevent or degrade UIL by disrupting the signals on which mapping algorithms depend. Compared to the large body of work on mapping strategies, dedicated anti-mapping approaches remain relatively few. To provide a more comprehensive perspective, we therefore include transferable strategies from related domains such as adversarial graph learning, authorship attribution obfuscation, and privacy-preserving social network publishing, which share methodological foundations with UIL and highlight potential directions for robust defense. As illustrated in Fig. 2, we group existing and transferable approaches into three categories according to their primary operational mechanism: adversarial injection, structural perturbation, and identity obfuscation.

Figure 2: Three categories of anti-mapping strategies. Adversarial injections add adversarial nodes and edges; structural perturbations alter structural connections; and identity obfuscations hide features or distort attributes (e.g., username alterations [11])

3.1 Adversarial Injection Strategies

Adversarial injection approaches introduce new, adversary-controlled nodes into the network, with carefully planned connections to legitimate nodes, in order to distort the similarity structure exploited by mapping models. The Dynamic Programming Node Injection Attack (DPNIA) introduced by Jiang et al. [10] exemplifies this category. It quantifies node vulnerability via cross-network neighborhood analysis and uses a dynamic programming scheme to determine the optimal attachment pattern for injected nodes under a budget constraint, maximizing the probability that incorrect matches outrank correct ones. This approach targets the attacker-controlled network only, which increases practicality and stealth.

Related domains offer complementary injection strategies transferable to degrade UIL. In adversarial graph learning, Zou et al. [33]’s TDGIA selects connection targets for injected nodes via a topological-defective edge strategy and generates smooth node features to enhance attack effectiveness. Tao et al. [34] introduced CANA, which improves stealth by camouflaging injected nodes to match the ego-network distribution of benign nodes. Sun et al. [35] developed NIPA which uses hierarchical reinforcement learning to optimize injected-node labels and links, while Tao et al. [36] designed G-NIA which addresses single-node injection with a generalizable, efficient attack model. In security research, Viswanath et al. [37] utilized Sybil injection to introduce fake accounts into trust graphs to bias reputation systems, paralleling the use of adversarial nodes to disrupt alignment.

While these methods target GNN-based classification or trust evaluation, their principles are applicable to UIL degradation as injected accounts could be seeded across networks with strategically planned cross-links to legitimate nodes, creating false structural correspondences, diluting true anchor signals, and increasing the false-match rate in topology-based or multimodal-based mapping models.

3.2 Structural Perturbation Strategies

Structural perturbation strategies perturb an existing network’s topology without adding new nodes. The Topology-Oriented Attack via Kernel (TOAK) proposed by Shao et al. [9] measures cross-network structural similarity via an Edge Distribution Distance (EDD) kernel, then greedily rewires edges to maximize this distance, using a lower bound from Earth Mover’s Distance [20] for efficiency. Both Tang et al. [38] and Wang et al. [12] exploit the observation that modifying links involving low-degree nodes can disproportionately affect cross-layer link prediction. Tang et al. focus on node-importance–based intra-layer link removal, whereas Wang et al. combine edge deletion with virtual user creation to obscure anchor link patterns while preserving network connectivity.

From a broader perspective, structural perturbation is a well-studied adversarial graph learning problem. Zugner et al. [39] developed Nettack which perturbs existing edges and node features to mislead GNN-based classification, while Chen et al. [40] proposed FGA which applies fast gradient-based edge modification to disrupt node embeddings and link prediction. Bojchevski and Günnemann [41] leveraged poisoning attacks on random-walk–based embedding methods, deriving perturbations that degrade both embedding quality and downstream task performance, with transferability across models. Xu et al. [42] formulated topology attacks as an optimization problem to identify the most damaging edge modifications under budget constraints. Although these works primarily target node classification or embedding quality, their perturbation strategies can be adapted to degrade UIL by altering high-impact edges that disrupt cross-network structural consistency.

In social network privacy and anonymization, methods such as k-degree anonymization [43], differential privacy mechanisms for graph publishing [44], and community-hiding strategies [45] transform network structure to protect sensitive relationships. While their objectives center on utility–privacy trade-offs rather than adversarial degradation, the underlying transformation principles—particularly edge rewiring and selective connection modification—are relevant for designing topology-oriented defenses or countermeasures in UIL contexts.

3.3 Identity Obfuscation Strategies

Identity obfuscation strategies focus on concealing or distorting the identifiable patterns that mapping models exploit, rather than altering the underlying network topology. Zhang et al. [11] proposed DeLink which targets username-based matching by applying character-level perturbations and embedding-space noise to reduce text-similarity accuracy in multimodal mapping models. Wang et al. [12] explore behavioral obfuscation via virtual user accounts that produce decoy interactions and noise, breaking temporal or co-occurrence patterns that cross-network alignment models depend on.

Related research domains provide transferable obfuscation techniques. Stylometric camouflage from authorship attribution research [46] offers methods for masking text-based identity cues. Similarly, Xing et al. [47] designed ALISON to leverage contextual embeddings from BERT [48] to modify stylometric vector representations while preserving semantics. These approaches demonstrate how deliberate modification of linguistic patterns can suppress identifiable traces, paralleling text-based identity obfuscation. Complementary insights arise from adversarial text perturbations in NLP, including visual-level manipulations [49] and paraphrasing attacks such as TextBugger [50], which show that subtle textual changes can mislead models while maintaining semantic similarity. Applied to UIL, such transformations alter cross-platform contents without altering network topology, though they introduce trade-offs in readability and may be detectable by stronger adversarially trained classifiers.

On the defense side, Shen et al. [51] developed RULE, a greedy algorithm designed to conceal the features most useful for linkage, aiming to balance user information sharing with privacy protection. Their approach, however, rests on the assumption that most non-matching users in the auxiliary network are “distinctive,” i.e., less similar to the target than the true counterpart. This assumption may no longer hold in modern large-scale settings, where public attributes often lack sufficient discriminability [22]. As a consequence, more recent defenses from related domains may help fill this gap. For example, Shetty et al. [52] presented adversarial attribute anonymization frameworks

In reviewing anti-mapping techniques, a clear stratification emerges based on operational mechanism and target modality. Injection-based attacks prioritize stealth and structural pollution by introducing nodes, effectively diluting anchor signals but requiring ongoing resource investment to maintain synthetic entities. Modification-based approaches directly alter existing topology through edge rewiring or removal, offering immediate impact on structure-dependent mappers but risking detectable network distortion. Obfuscation strategies focus on feature-space manipulation, i.e., altering usernames, writing style, or attributes, providing granular control with minimal structural footprint but facing challenges in preserving utility and semantic coherence. While each category demonstrates efficacy against specific mapping modalities, their effectiveness remains fragmented; no single approach provides comprehensive protection against multimodal UIL systems. This highlights the critical need for adaptive, multi-vector defense frameworks that can dynamically combine these strategies based on the evolving threat landscape. Complementing these native defenses, transferable techniques imported from adjacent domains (e.g., adversarial machine learning or privacy-preserving frameworks) offer immediate robustness without requiring new designs. However, their generality also limits tailoring to UIL’s graph-specific challenges, meaning they often provide only partial protection compared to dedicated anti-mapping approaches.

4 Systematic Comparison of Mapping and Anti-Mapping Strategies from Different Perspectives

Having reviewed mapping and anti-mapping models separately, this section provides a systematic comparison of mapping and anti-mapping strategies from multiple perspectives. Section 4.1.1 provides a cross-comparison of representative mapping models, highlighting differences in their input modalities, methodological designs, and scalability. Section 4.1.2 complements this view by comparing anti-mapping models based on the data source they operate on and strategies they adopt. Afterward, Section 4.2 turns to benchmark datasets, examining their usage patterns and limitations across studies. Finally, by comparing mapping and anti-mapping models on data modality requirements, Section 4.3 reframes UIL as an adversarial game between mappers and anti-mappers, providing formal definition, clarifying the most effective current anti-mapping strategy, and constructing a cross-modality interaction matrix that surfaces both areas of contestation and under-defended blind spots.

4.1 Cross-Comparison of Mapping and Anti-Mapping Models

4.1.1 Comparison of Mapping Models

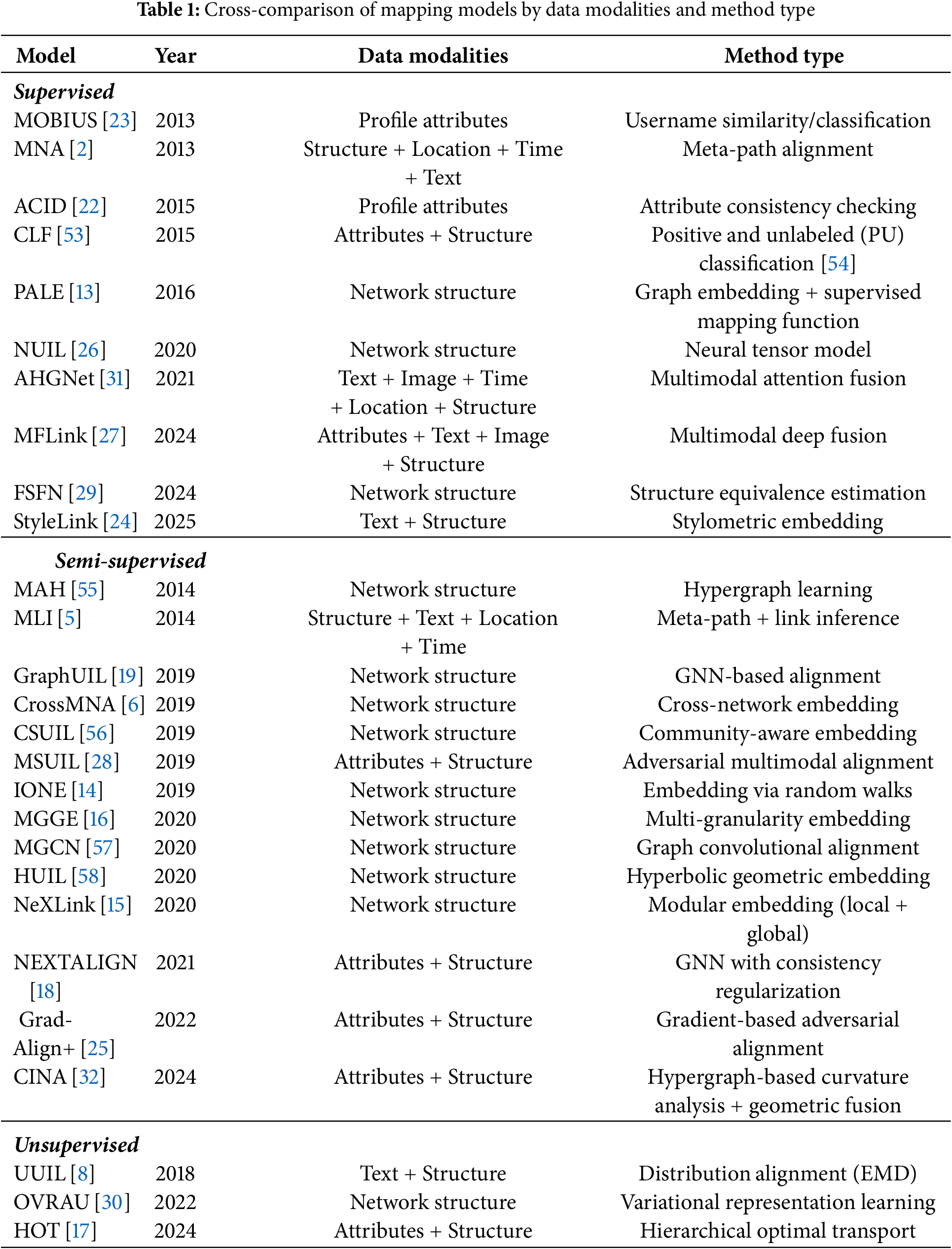

In Section 2, we classified mapping models according to the type of data they primarily exploit. To complement that taxonomy, here we provide a systematic cross-comparison based on data modalities, methodological design, and scalability. This comparative view highlights the diversity of learning paradigms and shows how data modalities affect design choices.

Table 1 summarizes representative mapping models grouped by learning paradigm, while the columns emphasize each model’s methodological backbone. From Table 1, we observe a clear evolution in mapping paradigms. Early approaches, such as MNA [2] and ACID [22], often relied on metadata features and explicit user attributes. Structure-based alignment soon emerged as a dominant strategy, exemplified by models like PALE [13], GraphUIL [19], and HUIL [58]. Recent advances increasingly emphasize multimodal fusion and representation learning, as seen in MSUIL [28], CINA [32], and HOT [17], often integrating both network structure and user attributes, accompanied by textual, and profile signals under semi- or unsupervised settings to better handle data sparsity and scalability. Model scalability varies: while many models handle medium-scale datasets, highly optimized methods such as MGCN [57], CrossMNA [6], and NeXLink [15] achieve better performance on large-scale networks. Each model’s scalability is closely tied to the data modalities they rely on. Structure-based methods generally scale more favorably to large graphs due to their reliance on sparse topological signals, whereas attribute- or content-based approaches often incur higher costs from feature extraction and alignment. Multimodal models face additional scalability challenges because they must integrate heterogeneous signals simultaneously.

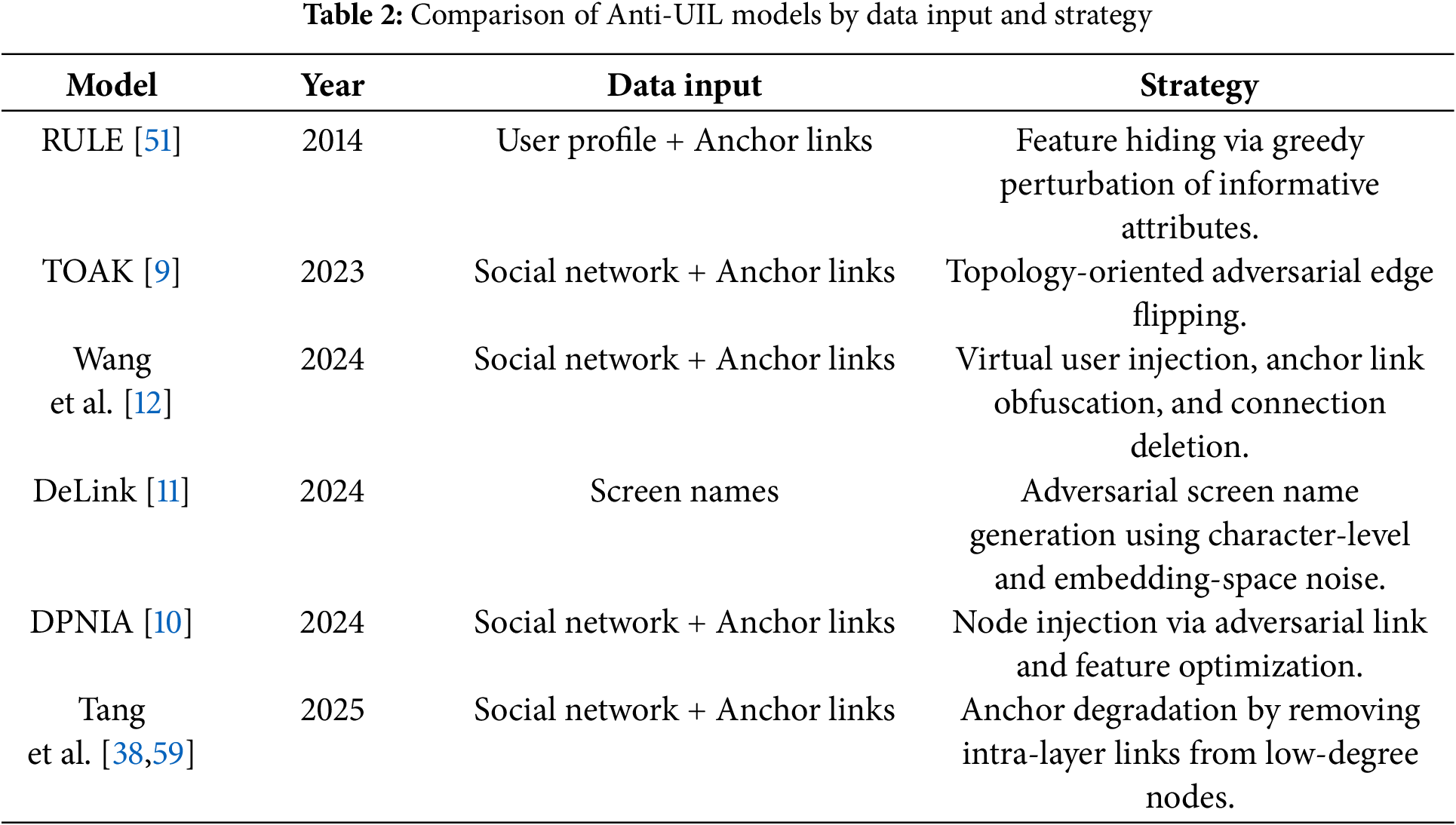

4.1.2 Comparison of Anti-Mapping Models

Table 2 presents a comparative overview of representative anti-mapping models, highlighting the data sources they operate on and the adversarial strategies they adopt. These models span various intervention levels, ranging from direct topology manipulation (e.g., [9]) to behavior-level obfuscation and identity feature perturbation (e.g., [51]). While most approaches operate on social network graphs and anchor link patterns (e.g., [13,26,29]), some target specific modalities, such as usernames (DeLink [11]). The field remains emerging and comparatively underexplored, with most anti-mapping models emerging only in recent years and often as reactive responses to specific mapping techniques. Each model reflects distinct assumptions about attacker capabilities, observable data, and user behavior, underscoring the fragmented but growing nature of this research direction.

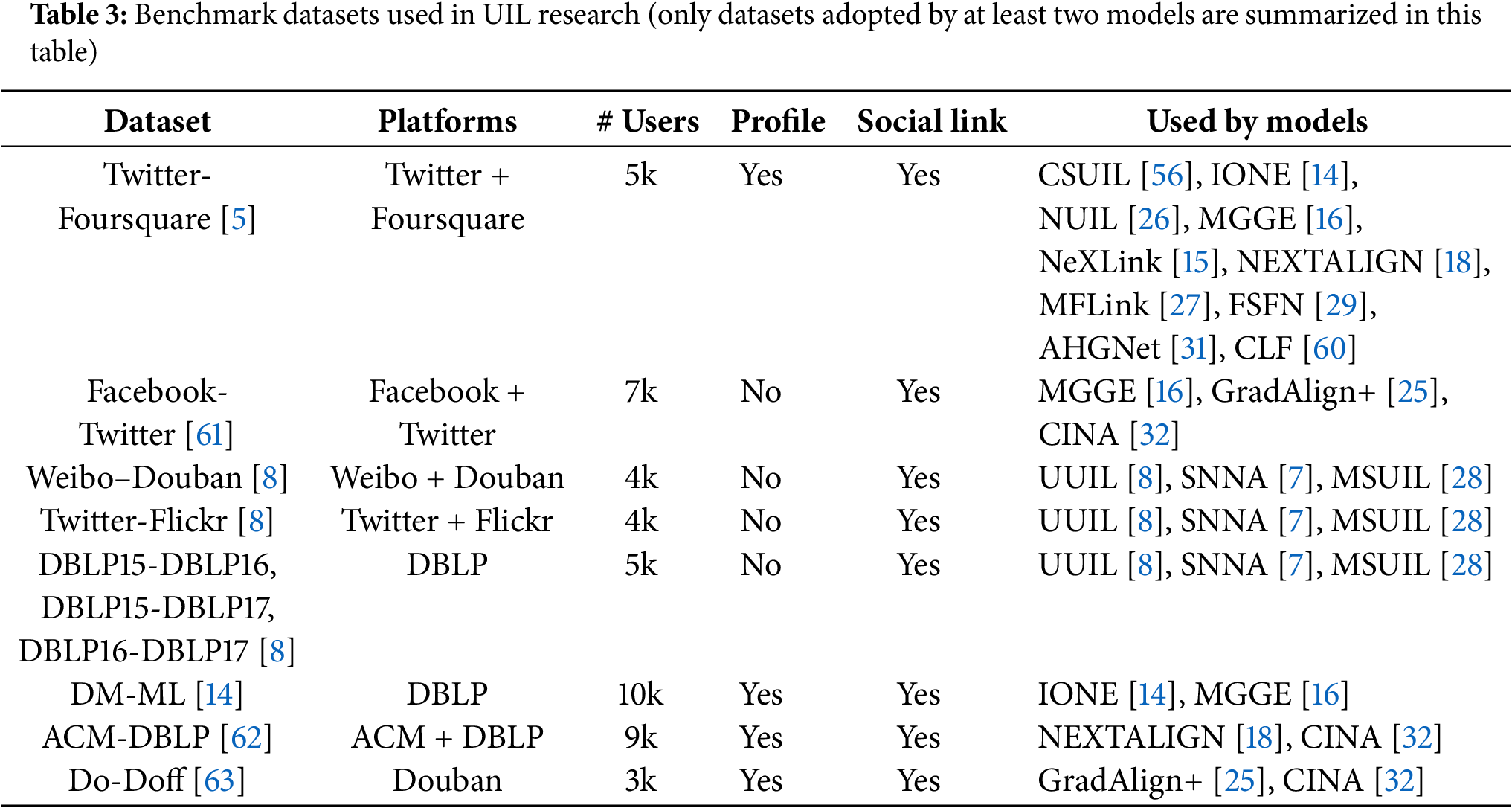

4.2 Benchmark Datasets: Usage Patterns and Limitations

Table 3 lists major benchmark datasets and compares them in terms of platform sources, number of users, availability of profile attributes and social relationship information. Among existing benchmark datasets, all listed provide at least user-level social connections, with user counts typically ranging from 3000 to 10,000. Twitter-Foursquare [5] emerges as the most frequently adopted, serving as the testbed for a wide array of mapping models ranging from traditional structural embedding (e.g., IONE [14], MGGE [16]) to recent multimodal and adversarial approaches (e.g., MFLink [27], AHGNet [31]). Originally crawled in November 2012, this dataset was first introduced by Zhang et al. [5] and soon utilized in their follow-up model, CLF [60]. The dataset includes 5392 users, 48,756 tips, and 38,921 locations from Foursquare, along with 76,972 social links (averaging 14 friends per user). The Twitter portion covers 5223 users and 9,490,707 tweets, among which 615,515 tweets contain location check-ins (6.48%), along with 164,920 follow links.

In contrast, other datasets are not as commonly used as the Twitter-Foursquare dataset, especially for cross-research comparison. For example, Weibo-Douban, Twitter-Flickr, and the three-year DBLP co-author dataset (i.e., DBLP15-DBLP16, DBLP15-DBLP17, and DBLP16-DBLP17) are exclusively used by three mapping models (i.e., UUIL [8], SNNA [7], and MSUIL [28]) developed by the same research group. These datasets were independently collected and preprocessed by the authors, contributing to fragmentation in evaluation standards. A similar situation applies to the DM-ML dataset [14], a co-author network from the Data Mining and Machine Learning community, which is also primarily adopted within a narrow set of studies within the research group (i.e., IONE [14] and MGGE [16]).

More broadly, the lack of unified datasets and preprocessing protocols remains a critical bottleneck for comparative evaluation. Models vary widely in their required data modalities. Some rely solely on network structure, while others incorporate profile attributes, user-generated content, behavioral patterns, or multimodal fusion. This heterogeneity in input requirements leads to dataset-specific pipelines and non-interoperable evaluation practices, hindering reproducibility and fair performance comparison. Moreover, most existing datasets are relatively small in scale and collected under varying assumptions, further limiting their generalizability. To address these challenges, the next subsection presents a comparative synthesis of UIL and anti-mapping models through the lens of data input dependencies, offering a unified framing that bridges the two research threads and reveals their mutual constraints and vulnerabilities.

Beyond technical characteristics, dataset construction also raises important ethical and legal considerations. The current most common approach for building cross-network datasets is to identify explicit linkage information disclosed in user profiles (e.g., Twitter link in Foursquare profiles for building the Twitter-Foursquare [5] dataset). Such practices must strictly follow platform policies and ethical standards to avoid violating user privacy.

4.3 Mapping vs. Anti-Mapping: Toward an Adversarial Framing

While Sections 2 and 3 have separately reviewed mapping models and anti-UIL strategies, we now synthesize them under a unified adversarial perspective. We propose framing UIL as a two-player game between a mapper, who seeks to infer cross-platform user identities, and a anti-mapper, who seeks to obscure or disrupt such inference. This adversarial dynamic reflects a fundamental tension in open online environments: the mapper leverages increasingly rich signals (e.g., structure, attributes, content) to link identities, while the anti-mapper attempts to suppress or decouple these signals without excessively degrading platform utility.

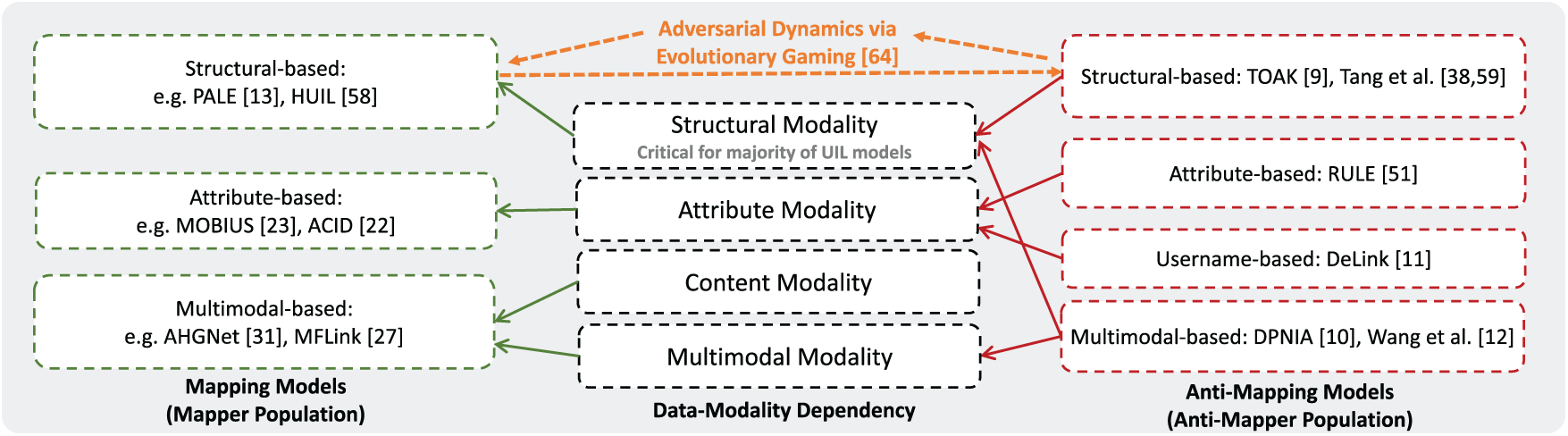

Formally, we can frame this interaction as an instance of two-population evolutionary game dynamics [64] between a mapper population and an anti-mapper population (as illustrated in Fig. 3). The mapper population chooses among strategies

Figure 3: Demonstration of game-theoretic framing between mapping models and anti-mapping models under cross-modality alignment [9–13,22,23,27,31,38,51,58,59,64]

Let

We can then write the standard two-population replicator dynamics:

Stationary points of this system correspond to modality-level equilibria (including mixed-strategy Nash equilibria in the underlying bimatrix game), which can provide intuition about stable or oscillatory dynamics between mapping and defense. This framing encourages a shift in perspective: from cataloging individual methods to understanding UIL as a system of strategic interactions. It also highlights a key asymmetry: mapping models are typically evaluated in isolation, while defenses often target specific mapping assumptions, leading to a fragmented landscape. Bridging these approaches requires recognizing both as players in the same game, each optimizing objectives under shared data constraints.

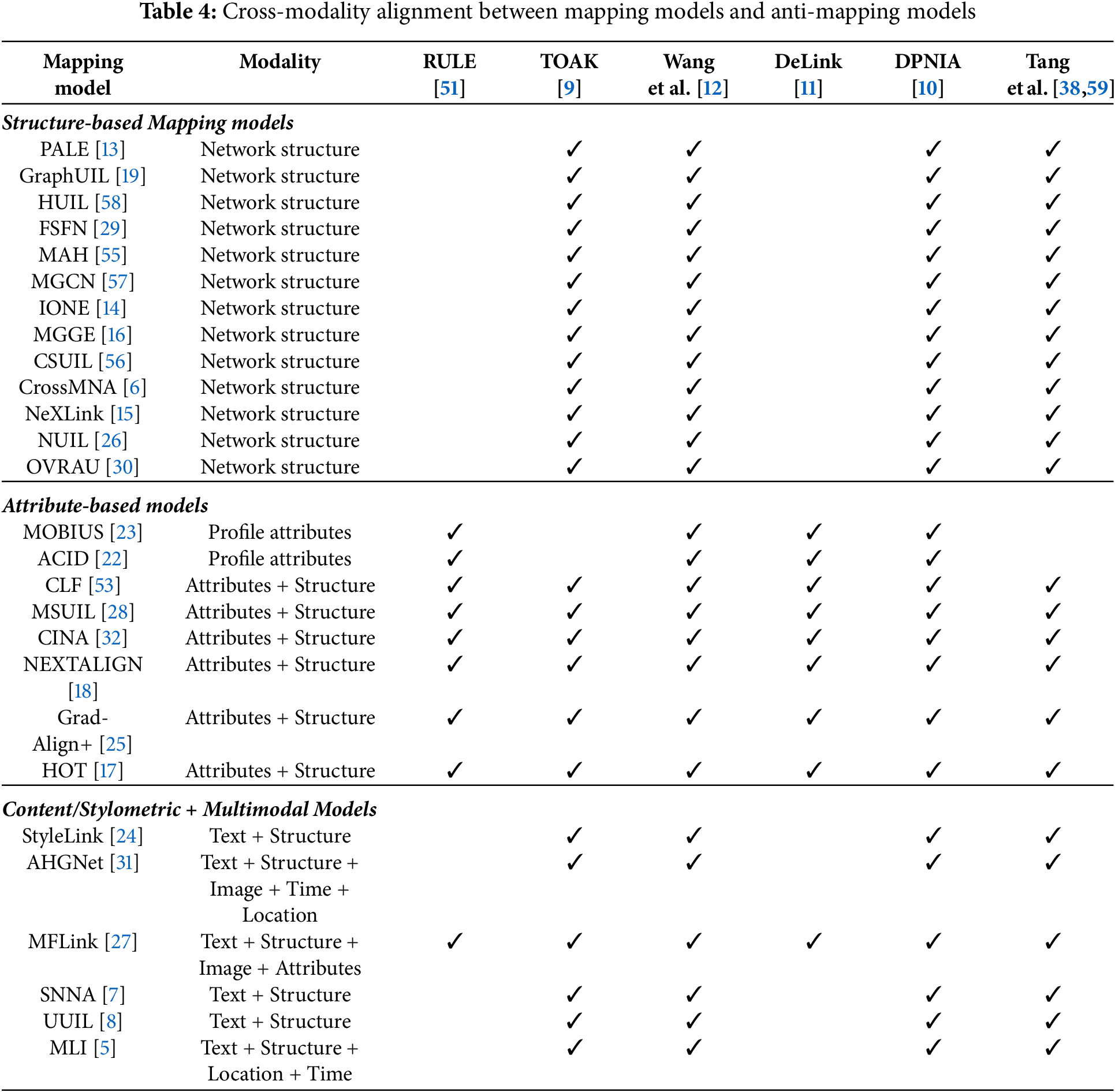

Nevertheless, within the scope of this survey, we do not estimate A and B empirically. Instead, we operationalize the framing by constructing a cross-dependency matrix between mapping and anti-mapping strategies. As shown in Table 4, each column corresponds to a specific anti-mapping model, and each cell indicates whether that defense can plausibly counter the input modality of a given mapping approach. Viewed through this lens, each anti-UIL method plays a distinct role in the adversarial game. RULE proposed by Shen et al. [51] hides discriminative features, making it particularly effective against models that rely on profile attributes (e.g., MOBIUS [23], ACID [22]). TOAK [9] and the perturbation strategies of Tang et al. [38,59] target structural signals by modifying or removing edges, thereby challenging the many mapping models built on graph topology (e.g., PALE [13], HUIL [58]). DeLink presented by Zhang et al. [11] focuses on username obfuscation. Since usernames are often a profile attribute as high-signal identifiers, DeLink can undermine attribute-based models. More importantly, the node injection approaches of Wang et al. [12] and DPNIA by Jiang et al. [10] have the broadest impact: by simultaneously perturbing network structure and introducing noisy attribute patterns with artificial nodes, they can confuse both structure-driven and attribute-driven mapping models.

Structural information thus remains the most contested modality. Because the majority of mapping models exploit network topology as their primary input, anti-mapping strategies that perturb structure can effectively degrade a wide range of mappings. TOAK [9] and Tang et al. [38,59]’s proposed framework directly challenge structural consistency by flipping or removing edges, while injection-based approaches such as the approach designed by Wang et al. [12] and DPNIA [10] go further by introducing adversarial nodes that simultaneously disrupt structural alignment and confuse attribute-based classifiers. These injection strategies therefore represent the most robust defenses to date, since they can undermine mapping models across all three modalities. Additionally, multimodal models that integrate diverse inputs, especially AHGNet [31], MFLink [27], and MLI [5], are comparatively less dependent on any single modality, which may make them less vulnerable to structure- or attribute-specific attacks. However, this diversity also introduces fragility at the fusion stage, where perturbations across modalities may interact in unpredictable ways.

Overall, this comparative analysis highlights both progress and fragmentation in UIL and anti-UIL research. Mapping models continue to diversify across modalities and architectures, while defenses remain narrower in scope and largely concentrated around a small set of strategies. The game-theoretic framing introduced in this section provides a unifying perspective that clarifies the interaction between individual mapping and anti-mapping models. It shows that structural perturbation is the most common and broadly effective defensive approach, given the heavy reliance of mapping models on network topology, and that injection-based strategies stand out as the most robust since they can simultaneously undermine structure- and attribute-driven mappings. Multimodal models, especially AHGNet [31], MFLink [27], and MLI [5] are less dependent on any single modality, making them somewhat less sensitive to structure- or attribute-specific defenses, though their fusion mechanisms may introduce new vulnerabilities. These observations lay the foundation for Section 5, where we identify open challenges and outline directions for developing more systematic, scalable, and general-purpose defenses.

5 Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the growing sophistication of mapping models and the emergence of anti-mapping models, several persistent challenges hinder comprehensive progress in the field. In this section, we outline two key limitations and propose actionable directions.

5.1 Lack of Unified Benchmarks and Evaluation Protocols

As summarized in Section 4.2, UIL research relies on a heterogeneous collection of datasets that differ not only in size and platform coverage, but also in their required data modalities. Although the Twitter-Foursquare dataset [53] is the most widely used, many models still depend on collected data that are not openly shared or reused by others. This fragmentation severely limits comparability and reproducibility. Preprocessing pipelines, anchor link ratios, and modality availability vary widely across studies. Consequently, reported performance values are not directly comparable across models, since each relies on different modality assumptions and evaluation setups. Attempting to aggregate these results into a meta-analysis would risk misleading readers by conflating dataset- and modality-specific effects with methodological advances.

To address these limitations, we advocate for the development of standardized benchmark suites with clearly annotated modality requirements and consistent evaluation splits. Such benchmarks would enable the type of cross-model performance synthesis, while ensuring that comparisons reflect genuine methodological improvements rather than dataset artifacts. Alongside these datasets, open-source pipelines for data processing and anchor link construction should also be maintained, ensuring that performance comparisons are both fair and reproducible.

5.2 Imbalanced Evolution between Mapping and Anti-Mapping

While mapping models have steadily diversified across modalities and architectures, anti-mapping models have evolved in a less balanced manner. As shown in Table 4, structural information is the most heavily targeted modality, with defenses such as TOAK [9], Tang et al. [38,59], Wang et al. [12], and DPNIA [10] directly attacking graph topology. This focus reflects the dominance of structure in mapping models, but also indicates a concentration of defensive innovation around a single modality. Conversely, though fewer, attribute- and content-based models face a narrower but more diverse set of countermeasures. These include username perturbation [11], and transferable techniques such as stylometric obfuscation [47] and adversarial text transformations [50]. Multimodal models such as MFLink [27] and AHGNet [31] remain the least explored from a defensive perspective, despite their growing adoption.

This imbalance presents two challenges. First, while structural defenses are relatively well developed, defenses for multimodal and fusion-based models lag behind, leaving vulnerabilities when multiple modalities are involved. Second, current defense strategies are often designed with specific UIL assumptions in mind, making them difficult to generalize or compose across different mapping approaches. Future work should therefore broaden the scope of defenses beyond structural perturbation. Priorities include the development of defenses that explicitly address multimodal mappings, scalable methods that can resist multiple mapping models simultaneously, and evaluation frameworks that benchmark defenses under diverse and evolving adversarial conditions.

Looking forward, advancing beyond reactive responses to individual mapping models will require more proactive approaches, such as meta-learning defenses that anticipate new mapping strategies, information-theoretic analyses that clarify the fundamental limits of identifiability, and defense-by-design architectures that embed obfuscation at the system level. Additionally, our game-theoretic framing provides a natural foundation for conceptualizing such proactive strategies, enabling defenders to anticipate and adapt to evolving mapping models more effectively. A possible future direction is to empirically instantiate this framing by estimating payoff matrices and simulating strategy dynamics, providing practical insights into how mapping and anti-mapping behaviors co-evolve under realistic conditions.

5.3 Towards More Generalizable Multimodal Mapping Models

Beyond external challenges of dataset inconsistency and adversarial imbalance, current mapping models still face practical limitations that constrain their robustness and applicability. A recurring issue is the reliance on narrow categories of input signals. Models centered on public-facing attributes, such as ACID [22] and MOBIUS [23], depend on usernames or profile metadata that can be easily obfuscated, incomplete, or intentionally misleading. Structural embedding approaches such as PALE [13] and MGCN [57] often fail to generalize when social networks are sparse or noisy, since the graph signals they rely on are weak or fragmented. Even more sophisticated geometric approaches, including HUIL [58] and HOT [17], introduce computational overheads that limit their deployment on large-scale networks. Furthermore, many embedding-based methods are unstable in adversarial environments, as small perturbations to edges or node features can propagate into disproportionately large changes in the learned representations, a vulnerability already highlighted in Section 3.

To address these shortcomings, one promising direction lies in the design of multimodal models, such as AHGNet [31], MFLink [27], and MLI [5], that combine signals across text, images, behavioral traces, and structural context. Because existing defense strategies are often tailored to exploit weaknesses in a single modality, models that distribute reliance across diverse data sources are less vulnerable to targeted perturbations. However, this integration also introduces fragility at the fusion stage, where inconsistent or adversarially manipulated inputs may interact in unpredictable ways. Beyond multimodal integration, out-of-the-box approaches suggest further avenues for advancing UIL. For instance, Aziz et al. [65] demonstrate the potential of eye movement biometrics as a distinctive and hard-to-forge identifier. While still in their early stages, such unconventional modalities highlight the importance of expanding the design space beyond the canonical triad of structure, attributes, and content. Together, these directions point toward mapping models that are not only more resilient against existing defenses, but also more adaptable to future adversarial landscapes, provided that challenges of data availability, modality alignment, and ethical governance are carefully addressed.

5.4 Balancing Innovation with Privacy

The dual-use nature of mapping and anti-mapping of UIL presents ethical and social challenges beyond the technical domain. Although our survey focuses primarily on algorithmic and methodological aspects, it is crucial to recognize the broader implications that govern its development and deployment.

UIL holds significant promise for legitimate and beneficial applications. However, it also faces a serious misuse problem. The ability to link online profiles could be exploited for large-scale unauthorized data collection and identity theft. This raises profound ethical questions about data privacy, consent, and the right to anonymity. In this context, anti-mapping research plays a critical role. Beyond being a reactive technical defense, it serves as a crucial mechanism to empower users with digital sovereignty and ensure their privacy. By developing robust anti-mapping methods, researchers can provide individuals with the tools to obfuscate their digital footprint and regain control over their online identities.

Besides, a critical future direction lies in embracing privacy-by-design principles through techniques such as federated learning (models such as [66]) and differential privacy. Federated approaches would allow mapping and anti-mapping analyses to be performed without centralizing sensitive user data on a single server, instead training models across distributed devices or network shards. This not only mitigates massive data breach risks but also aligns with increasingly stringent global data protection regulations. Coupling this with differential privacy mechanisms during model updates or data sharing can further ensure that individual user records cannot be re-identified from the released model outputs or aggregated data, thereby creating a technical foundation for privacy-aware cross-network analysis.

Technical advancements must be paralleled by a deeper integration with regulatory, ethical, and normative frameworks. Future research should explore how mapping and anti-mapping systems can be designed to be inherently compliant with data governance laws from the ground up. This includes developing algorithms that can formally verify compliance with constraints such as purpose limitation, data minimization, and the right to be forgotten. Furthermore, there is a need for explicit value-sensitive design that incorporates fairness, accountability, and transparency into the core of both mapping and anti-mapping models. This involves creating audit trails for linkage decisions, developing explanations for why a linkage was made (or obfuscated), and establishing ethical red lines that define where identity linkage should not be applied, regardless of its technical feasibility.

While this survey aims to provide a comprehensive review of technical advances in UIL and anti-UIL research, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the scope is primarily technical, focusing on model design, data modalities, and adversarial dynamics. Broader social, ethical, and cultural dimensions, such as cross-cultural differences in identity presentation or platform governance, remain outside our current focus. Second, the survey does not include large-scale empirical benchmarking, as existing datasets and evaluation protocols remain fragmented across studies. Finally, the proposed game-theoretic framework is formulated conceptually and analytically but has not yet been empirically examined, leaving room for future work to validate its predictive and diagnostic potential.

Cross-network mapping within online social networks (OSNs) through user identity linkage (UIL) continues to evolve as a critical challenge at the intersection of social computing, privacy, and adversarial machine learning. While mapping models have achieved impressive sophistication across structural, attribute, and multimodal inputs, the corresponding anti-mapping approaches remain narrower and more fragmented. This survey has provided a dual-perspective synthesis of these two research threads, categorizing representative models, benchmarking datasets, and introducing a game-theoretic framing that conceptualizes mapping and defense as adversarial players in the same system.

Our comparative analyses reveal several broad insights: (1) Structural information remains the most contested modality: its dominance among mapping models makes it both highly effective and highly vulnerable, with perturbation and injection-based defenses demonstrating the greatest capacity to degrade mapping accuracy; (2) Multimodal models distribute reliance across diverse inputs, making them less sensitive to any single perturbation but more fragile at the fusion stage, where inconsistencies across modalities can propagate; (3) Defenses against attribute- and content-based mappings exist in greater variety, but remain fragmented and closely tied to model-specific assumptions.

Looking forward, progress in both UIL and anti-UIL research will depend on addressing both methodological and systemic challenges. Standardized benchmarks and reproducible pipelines are essential for enabling fair evaluation across models and modalities. The next generation of mapping methods must pursue both multimodal integration, to mitigate overreliance on single inputs, and out-of-the-box thinking, to explore unconventional yet robust cross-discipline signals such as biometric or behavioral identifiers. Equally important is the need for scalable, general-purpose defenses that anticipate adversarial adaptation, moving beyond reactive designs toward proactive robustness. Consequently, as UIL technologies grow more powerful, ethical and regulatory considerations must remain at the forefront, ensuring that advances in identity resolution do not come at the expense of user autonomy and privacy.

Acknowledgement: We thank Prof. Jin Zhao from the College of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence at Fudan University for his comments and suggestions.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant (No. 2022YFB3102901), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62072115, 62102094), Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan Project (No. 22510713600).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yang Chen; methodology, Shaojie Min and Yang Chen; writing—original draft preparation, Shaojie Min, Yaxiao Luo and Kebing Liu; writing—review and editing, Qingyuan Gong and Yang Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zafarani R, Liu H. Connecting corresponding identities across communities. In: Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2009. Vol. 3, p. 354–7. [Google Scholar]

2. Kong X, Zhang J, Yu PS. Inferring anchor links across multiple heterogeneous social networks. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; 2013 Oct 27–Nov 1; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 179–88. [Google Scholar]

3. Shu K, Wang S, Tang J, Zafarani R, Liu H. User identity linkage across online social networks: a review. ACM SIGKDD Expl Newsletter. 2017;18(2):5–17. doi:10.1145/3068777.3068781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wu J. Cyberspace endogenous safety and security. Engineering. 2022;15:179–85. [Google Scholar]

5. Zhang J, Yu PS, Zhou ZH. Meta-path based multi-network collective link prediction. In: Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2014 Aug 24–27; New York, NY, USA. p. 1286–95. [Google Scholar]

6. Chu X, Fan X, Yao D, Zhu Z, Huang J, Bi J. Cross-network embedding for multi-network alignment. In: The World Wide Web Conference; 2019 May 13–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 273–84. [Google Scholar]

7. Li C, Wang S, Wang Y, Yu P, Liang Y, Liu Y, et al. Adversarial learning for weakly-supervised social network alignment. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2019. Vol. 33, p. 996–1003. [Google Scholar]

8. Li C, Wang S, Yu PS, Zheng L, Zhang X, Li Z, et al. Distribution distance minimization for unsupervised user identity linkage. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2018 Oct 22–26; Torino, Italy. p. 447–56. [Google Scholar]

9. Shao J, Wang Y, Guo F, Shi B, Shen H, Cheng X. TOAK: a topology-oriented attack strategy for degrading user identity linkage in cross-network learning. In: Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2023 Oct 21–25; Birmingham, UK. p. 2208–18. [Google Scholar]

10. Jiang S, Qiu Y, Mo X, Tang R, Wang W. An effective node injection approach for attacking social network alignment. IEEE Trans Inform Forens Secur. 2025;20:589–604. doi:10.1109/tifs.2024.3515842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang P, Zhou Q, Lu T, Gu H, Gu N. DeLink: an adversarial framework for defending against cross-site user identity linkage. ACM Trans Web. 2024;18(2):1–34. doi:10.1145/3643828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang L, Liu Y, Guo X, Long Z, Yang C. Cross-platform network user alignment interference methods based on obfuscation strategy. In: 2024 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 2185–90. [Google Scholar]

13. Man T, Shen H, Liu S, Jin X, Cheng X. Predict anchor links across social networks via an embedding approach. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-16). Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2016. Vol. 16, p. 1823–9. [Google Scholar]

14. Liu L, Li X, Cheung WK, Liao L. Structural representation learning for user alignment across social networks. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2019;32(9):1824–37. doi:10.1109/tkde.2019.2911516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kaushal R, Singh S, Kumaraguru P. NeXLink: node embedding framework for cross-network linkages across social networks. In: Proceedings of NetSci-X 2020: Sixth International Winter School and Conference on Network Science. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

16. Fu S, Wang G, Xia S, Liu L. Deep multi-granularity graph embedding for user identity linkage across social networks. Knowl Based Syst. 2020;193:105301. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2019.105301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zeng Z, Du B, Zhang S, Xia Y, Liu Z, Tong H. Hierarchical multi-marginal optimal transport for network alignment. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2024. Vol. 38, p. 16660–8. [Google Scholar]

18. Zhang S, Tong H, Jin L, Xia Y, Guo Y. Balancing consistency and disparity in network alignment. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2021 Aug 14–18; Online. p. 2212–22. [Google Scholar]

19. Zhang W, Shu K, Liu H, Wang Y. Graph neural networks for user identity linkage. arXiv.1903.02174. 2019. [Google Scholar]

20. Rubner Y, Tomasi C, Guibas LJ. The earth mover’s distance as a metric for image retrieval. Int J Comput Vis. 2000;40(2):99–121. doi:10.1023/a:1026543900054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Pass B. Multi-marginal optimal transport: theory and applications. ESAIM Math Modell Numer Anal. 2015;49(6):1771–90. doi:10.1051/m2an/2015020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Goga O, Loiseau P, Sommer R, Teixeira R, Gummadi KP. On the reliability of profile matching across large online social networks. In: Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2015 Aug 10–13; Sydney, NSW, Australia. p. 1799–808. [Google Scholar]

23. Zafarani R, Liu H. Connecting users across social media sites: a behavioral-modeling approach. In: Proceedings of the 19th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2013 Aug 11–14; Chicago, IL, USA. p. 41–9. [Google Scholar]

24. Xu W, Fung BC. StyleLink: user identity linkage across social media with stylometric representations. In: Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2025. Vol. 19, p. 2076–88. [Google Scholar]

25. Park JD, Tran C, Shin WY, Cao X. GradAlign+: empowering gradual network alignment using attribute augmentation. In: Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; 2022 Oct 17–21; Atlanta, GA, USA. p. 4374–8. [Google Scholar]

26. Guo X, Liu Y, Meng X, Liu L. User identity linkage across social networks based on neural tensor network. In: Security and privacy in new computing environments. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 162–71. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-66922-5_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li S, Lu D, Li Q, Wu X, Li S, Wang Z. MFLink: user identity linkage across online social networks via multimodal fusion and adversarial learning. IEEE Trans Emerg Topics Comput Intell. 2024;8(5):3716–25. doi:10.1109/tetci.2024.3372374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Li C, Wang S, Wang H, Liang Y, Yu PS, Li Z, et al. Partially shared adversarial learning for semi-supervised multi-platform user identity linkage. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2019 Nov 3–7; Beijing, China. p. 249–58. [Google Scholar]

29. Wang H, Yang W, Man D, Lv J, Han S, Tan J, et al. Anchor link prediction for cross-network digital forensics from local and global perspectives. IEEE Trans Inform Forens Secur. 2024;19:3620–35. doi:10.1109/tifs.2024.3364066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Amara A, Taieb MAH, Aouicha MB. Cross-network representation learning for anchor users on multiplex heterogeneous social network. Appl Soft Comput. 2022;118:108461. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2022.108461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen X, Song X, Peng G, Feng S, Nie L. Adversarial-enhanced hybrid graph network for user identity linkage. In: Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; 2021 Jul 11–15; Online. p. 1084–93. [Google Scholar]

32. Jiao P, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhang G. CINA: curvature-based integrated network alignment with hypergraph. In: 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 2709–22. [Google Scholar]

33. Zou X, Zheng Q, Dong Y, Guan X, Kharlamov E, Lu J, et al. TDGIA: effective injection attacks on graph neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2021 Aug 14–18; Online. p. 2461–71. [Google Scholar]

34. Tao S, Cao Q, Shen H, Wu Y, Hou L, Sun F, et al. Adversarial camouflage for node injection attack on graphs. Inf Sci. 2023;649:119611. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Sun Y, Wang S, Tang X, Hsieh TY, Honavar V. Adversarial attacks on graph neural networks via node injections: a hierarchical reinforcement learning approach. In: Proceedings of the Web Conference 2020; 2020 Apr 20–24; Taipei, Taiwan. p. 673–83. [Google Scholar]

36. Tao S, Cao Q, Shen H, Huang J, Wu Y, Cheng X. Single node injection attack against graph neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management; 2021 Nov 1–5; Online. p. 1794–803. [Google Scholar]

37. Viswanath B, Post A, Gummadi KP, Mislove A. An analysis of social network-based sybil defenses. ACM SIGCOMM Comput Commun Rev. 2010;40(4):363–74. doi:10.1145/1851275.1851226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Tang R, Yong Z, Mei Y, Li X, Li J, Ding J, et al. Degrading the accuracy of interlayer link prediction: a method based on the analysis of node importance. Int J Mod Phys C. 2025;36(10):2442004. doi:10.1142/s012918312442004x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zügner D, Akbarnejad A, Günnemann S. Adversarial attacks on neural networks for graph data. In: Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2018 Aug 19–23; London, UK. p. 2847–56. [Google Scholar]

40. Chen J, Wu Y, Xu X, Chen Y, Zheng H, Xuan Q. Fast gradient attack on network embedding. arXiv.1809.02797. 2018. [Google Scholar]

41. Bojchevski A, Günnemann S. Adversarial attacks on node embeddings via graph poisoning. In: Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning. Westminster, UK: PMLR; 2019. p. 695–704. [Google Scholar]

42. Xu K, Chen H, Liu S, Chen PY, Weng TW, Hong M, et al. Topology attack and defense for graph neural networks: an optimization perspective. arXiv.1906.04214. 2019. [Google Scholar]

43. Zhou B, Pei J. Preserving privacy in social networks against neighborhood attacks. In: 2008 IEEE 24th International Conference on Data Engineering. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2008. p. 506–15. [Google Scholar]

44. Sala A, Zhao X, Wilson C, Zheng H, Zhao BY. Sharing graphs using differentially private graph models. In: Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement Conference. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2011. p. 81–98. [Google Scholar]

45. Waniek M, Michalak TP, Wooldridge MJ, Rahwan T. Hiding individuals and communities in a social network. Nat Human Behav. 2018;2(2):139–47. doi:10.1038/s41562-017-0290-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Brennan M, Afroz S, Greenstadt R. Adversarial stylometry: circumventing authorship recognition to preserve privacy and anonymity. ACM Trans Inform Syst Secur (TISSEC). 2012;15(3):1–22. doi:10.1145/2382448.2382450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Xing E, Venkatraman S, Le T, Lee D. ALISON: fast and effective stylometric authorship obfuscation. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2024. Vol. 38, 19315–22. [Google Scholar]

48. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Arlington, VA, USA: ACL; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

49. Eger S, Şahin GG, Rücklé A, Lee JU, Schulz C, Mesgar M, et al. Text processing like humans do: visually attacking and shielding NLP systems. arXiv.1903.11508. 2019. [Google Scholar]

50. Li J, Ji S, Du T, Li B, Wang T. TextBugger: generating adversarial text against real-world applications. arXiv.1812.05271. 2018. [Google Scholar]

51. Shen Y, Wang F, Jin H. Defending against user identity linkage attack across multiple online social networks. In: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on World Wide Web; 2014 Apr 7–11; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 375–6. [Google Scholar]

52. Shetty R, Schiele B, Fritz M. A4NT: author attribute anonymity by adversarial training of neural machine translation. In: 27th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 18); 2018 Aug 15–17; Baltimore, MD, USA. p. 1633–50. [Google Scholar]

53. Liu L, Cheung WK, Li X, Liao L. Aligning users across social networks using network embedding. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-16). Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2016. p. 1774–80. [Google Scholar]

54. Zhang J, Kong X, Yu PS. Transferring heterogeneous links across location-based social networks. In: Proceedings of the 7th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; 2014 Feb 24–28; New York, NY, USA. p. 303–12. [Google Scholar]

55. Tan S, Guan Z, Cai D, Qin X, Bu J, Chen C. Mapping users across networks by manifold alignment on hypergraph. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI’14. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2014. p. 159–65. [Google Scholar]

56. Wang Z, Hayashi T, Ohsawa Y. A community sensing approach for user identity linkage. In: Annual Conference of the Japanese Society for Artificial Intelligence. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 191–202. [Google Scholar]

57. Chen H, Yin H, Sun X, Chen T, Gabrys B, Musial K. Multi-level graph convolutional networks for cross-platform anchor link prediction. In: Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; 2020 Jul 6–10; Online. p. 1503–11. [Google Scholar]

58. Wang F, Sun L, Zhang Z. Hyperbolic user identity linkage across social networks. In: GLOBECOM 2020–2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

59. Tang R, Jiang S, Chen X, Wang W, Wang W. Network structural perturbation against interlayer link prediction. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;250:109095. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Zhang J, Philip SY. Integrated anchor and social link predictions across social networks. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-15). Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2015. p. 2125–32. [Google Scholar]

61. Cao X, Yu Y. ASNets: a benchmark dataset of aligned social networks for cross-platform user modeling. In: Proceedings of the 25th ACM International on Conference on Information and Knowledge Management; 2016 Oct 24–28; Indianapolis, IN, USA. p. 1881–4. [Google Scholar]

62. Zhang S, Tong H. Attributed network alignment: problem definitions and fast solutions. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2018;31(9):1680–92. [Google Scholar]

63. Zhong E, Fan W, Wang J, Xiao L, Li Y. ComSoc: adaptive transfer of user behaviors over composite social network. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2012 Aug 12–16; Beijing, China. p. 696–704. [Google Scholar]

64. Nowak MA. Evolutionary dynamics: exploring the equations of life. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

65. Aziz S, Komogortsev O. Assessing the privacy risk of cross-platform identity linkage using eye movement biometrics. In: 2023 IEEE International Joint Conference on Biometrics (IJCB). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

66. Wang M, Zhou L, Huang X, Zheng W. Towards federated learning driving technology for privacy-preserving micro-expression recognition. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2025;30(5):2169–83. doi:10.26599/tst.2024.9010098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools