Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A REST API Fuzz Testing Framework Based on GUI Interaction and Specification Completion

1 School of Cyber Science and Engineering, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450002, China

2 Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education, Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

3 School of Business and Commerce, Zhengzhou Business Technicians Institude, Zhengzhou, 450100, China

* Corresponding Author: Yan Cao. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 95 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071511

Received 06 August 2025; Accepted 10 November 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

With the rapid development of Internet technology, REST APIs (Representational State Transfer Application Programming Interfaces) have become the primary communication standard in modern microservice architectures, raising increasing concerns about their security. Existing fuzz testing methods include random or dictionary-based input generation, which often fail to ensure both syntactic and semantic correctness, and OpenAPI-based approaches, which offer better accuracy but typically lack detailed descriptions of endpoints, parameters, or data formats. To address these issues, this paper proposes the APIDocX fuzz testing framework. It introduces a crawler tailored for dynamic web pages that automatically simulates user interactions to trigger APIs, capturing and extracting parameter information from communication packets. A multi-endpoint parameter adaptation method based on improved Jaccard similarity is then used to generalize these parameters to other potential API endpoints, filling in gaps in OpenAPI specifications. Experimental results demonstrate that the extracted parameters can be generalized with 79.61% accuracy. Fuzz testing using the enriched OpenAPI documents leads to improvements in test coverage, the number of valid test cases generated, and fault detection capabilities. This approach offers an effective enhancement to automated REST API security testing.Keywords

With the advancement of Internet technology, REST [1] has emerged as a de facto standard for Web API communication. Numerous large-scale systems, such as Google1 and Amazon2, leverage REST APIs for microservice-based interface design. The REST API has become the fundamental bridge connecting front-end users with back-end business logic in modern software ecosystems. Its quality and security directly influence the reliability, maintainability, and business continuity of the entire system. At the same time, the security of REST APIs has attracted increasing attention. Because REST APIs directly expose the business logic and data access interfaces of a system, attackers may bypass traditional web-layer defense mechanisms and interact directly with back-end services, thereby significantly expanding the potential attack surface.

Typical security risks include: (1) Authentication and access control flaws (e.g., token leakage, privilege escalation), which may lead to the exposure of sensitive data; (2) Insufficient input validation (e.g., SQL (Structured Query Language) injection, command injection, path traversal), which can trigger abnormal execution on the back end; (3) Business logic vulnerabilities (e.g., authentication bypass, replay attacks), which may compromise the consistency of system states; and (4) Improper error handling, especially unhandled exceptions that result in HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) 500 Internal Server Error responses, reflecting weaknesses in exception management and boundary checking.

Given that REST APIs are often deployed within distributed architectures involving multiple collaborative services, the failure of a single endpoint may lead to cascading faults and amplify security impacts. Therefore, conducting systematic security testing and robustness evaluation for REST APIs is of critical importance for both research and practical applications.

REST APIs are typically deployed across distributed containers and components, leading to complex execution environments that present distinct challenges for white-box testing. In contrast, black-box testing, independent of internal implementation details, is better suited to dynamic and distributed systems, significantly reducing testing complexity and cost [2]. Prior studies indicate that 72% of tools employ black-box strategies to test REST APIs [3].

Therefore, various black-box security testing approaches for REST APIs have been developed in research, including EvoMaster [4], Morest [5], foREST [6], Schemathesis [7], RestCT [8], RESTest [9], NAUTILUS [10], and RESTler [11]. These approaches typically use the OpenAPI specification (or simply API documentation) as input to identify potential security issues. The API documentation provides structured interface information, including API endpoints, HTTP methods, and response formats, which is essential for test case generation. It also plays a critical role in parameter assignment by specifying data type constraints, default values, and boundary conditions.

Previous research has developed various approaches for test case generation from API documentation. Arcuri et al. [4] proposed the MIO (Multiple Independent Objectives) algorithm to parse API specifications and generate chromosome templates, where test cases are optimized through adaptive evolutionary sampling. In related work, Alonso et al. [12] applied natural language processing to infer parameter semantics from documentation, enabling automated retrieval of valid parameter values from knowledge bases. Ed-douibi et al. [13] introduced customizable formatting strategies to ensure test cases comply with specific schema constraints. Hatfield-Dodds et al. [7] took a model-driven approach by extracting OpenAPI meta-models for automated test generation. Furthermore, Viglianisi et al. [14] advanced the field by constructing operation dependency graphs to generate constraint-satisfying test cases, complemented by mutation operators for anomaly detection.

Although API documentation provides a structured means of describing service interfaces, the OpenAPI specifications published by service providers often exhibit varying degrees of incompleteness. This issue is mainly manifested in the following three aspects: (1) Missing endpoints – Some backend interfaces are not documented or are omitted due to permission or version management constraints, preventing testing tools from comprehensively identifying all accessible endpoints on the server side. (2) Insufficient parameter descriptions – The documentation often specifies only parameter names and data types, but lacks semantic information such as value ranges, format constraints, or example values, thereby hindering the generation of effective test cases. (3) Omission of inter-API dependencies—The invocation order or parameter inheritance relationships between APIs are often not explicitly described, making it difficult for testing procedures to reconstruct realistic interaction logic.

These deficiencies have a systematic impact on fuzz testing methods that rely on OpenAPI specifications. Missing endpoint or parameter information can lead to insufficient test coverage, while the absence of semantic constraints and example values causes the fuzzer to generate a large number of syntactically valid but semantically invalid test cases, resulting in frequent 400 (Bad Request) or 404 (Not Found) responses. Moreover, the lack of dependency information between APIs prevents the correct construction of cross-endpoint invocation sequences, reducing the likelihood of triggering latent vulnerabilities. In addition, OpenAPI documents may be created manually or automatically generated from code annotations. In cases involving human intervention, issues such as typographical errors or inconsistent parameter naming may occur, further degrading documentation quality. These problems directly affect the performance of testing methods that depend on API specifications. Consequently, the incompleteness of API documentation has become a critical bottleneck limiting the effectiveness and depth of automated API fuzz testing.

When API documentation is incomplete, manual intervention is typically required to supplement missing specifications, thereby reducing its negative effects on the testing process. However, even with complete parameter descriptions in API documentation, generating effective test cases critically depends on appropriate parameter assignments—requiring both syntactic correctness and semantic validity.

To address API documentation incompleteness, we propose a REST API fuzz testing framework combining GUI (Graphical User Interface) interaction and automated documentation completion. Our solution develops a dynamic web crawler that performs deep interface interactions, where GUI operations are simulated to trigger API requests. During API communication, the system captures network packets to extract key parameters and values, then merges them with existing documentation. This process effectively compensates for missing information in API specifications.

To ensure both syntactic and semantic correctness in parameter values during test case generation, we propose a multi-endpoint parameter adaptation method based on enhanced Jaccard similarity. Using this refined metric, parameter values extracted from traffic analysis are generalized and propagated to semantically compatible API endpoints, where they are incorporated into the API documentation as validated examples. Crucially, real traffic data inherently satisfies syntactic and semantic requirements, providing a reliable foundation for generating valid test cases.

The proposed method offers two key advantages over conventional approaches. First, parameters such as date, timestamp, id, and authentication in API requests initiated by client-side applications are typically auto-generated rather than manually assigned. Specifically, date and timestamp parameters are automatically populated by frontend components based on system time; id fields represent backend-generated unique resource identifiers; and authentication tokens derive from validated user credentials during login sessions. During fuzz testing, random assignment of these parameters often triggers HTTP 400 Bad Request errors due to format validation failures. Second, while randomly generated or predefined parameter values may satisfy syntactic requirements, their semantic invalidity frequently renders test cases non-executable. In contrast, dynamically captured real user interaction data ensures parameter values comply with both interface specifications and business logic constraints.

In summary, the key contributions of this work include:

• We designed a dynamic web crawler that integrates static analysis, dynamic analysis, and traffic monitoring to overcome the limitations of traditional black-box testing in dynamic web environments, enabling automated simulation of user interactions with Web APIs.

• We propose a multi-endpoint parameter adaptation method based on enhanced Jaccard similarity, which is suitable for the application scenario of API endpoint testing. This method introduces 2-g segmentation strategy to solve the problem of inconsistent parameter naming; The path enhancement strategy is introduced to infer the inheritance relationship of business logic from the hierarchical structure of API endpoints, which can effectively complete the parameter generalization task across endpoints, thus providing support for the completion of API documents.

• We propose an API documentation completion strategy based on real traffic data that integrates with API documentation-based test case generation tools. This approach effectively addresses key limitations in traditional fuzzing, including syntactically incorrect parameters, semantically invalid values, and business logic inconsistencies, significantly reducing invalid test cases while improving test case effectiveness.

2.1 Crawling Challenges in Dynamic Web Applications

In modern web applications, JavaScript and client-side dynamic DOM (Document Object Model) manipulation are widely used, often combined with AJAX (Asynchronous JavaScript and XML) to significantly enhance user experience. However, these technologies also increase the complexity of black-box testing, making crawling AJAX-based web applications more challenging than traditional multi-page web applications.

Traditional web applications employ explicit state management, where each application state corresponds to a unique URL and is fully rendered in server-side HTML (HyperText Markup Language) documents. This architecture allows crawlers to collect data by recursively traversing hypertext links and statically fetching page source code. In contrast, modern AJAX-based web applications utilize implicit state maintenance mechanisms, characterized by runtime DOM tree manipulation for dynamic interface updates. As a result, the initial HTML only contains a basic framework and cannot reflect state changes after user interaction.

Therefore, crawlers targeting AJAX applications must possess the following capabilities: (1) loading and executing front-end scripts, (2) monitoring and maintaining dynamic DOM tree states, and (3) simulating user behaviors (including composite operations such as form filling and element clicking).

2.2 Limitations in Documentation-Driven Testing

API documentation formally defines API attributes using the OpenAPI specification format. The paths field enumerates all API endpoints, with each endpoint supporting multiple HTTP request methods (e.g., GET, POST, PUT). The parameters field under each method specifies required request parameters. However, this structural definition fails to satisfy key requirements for valid test case generation. Conventional parameter assignment techniques face two fundamental limitations: randomly generated values frequently violate syntactic and semantic constraints, while predefined dictionaries cannot adapt to diverse application contexts.

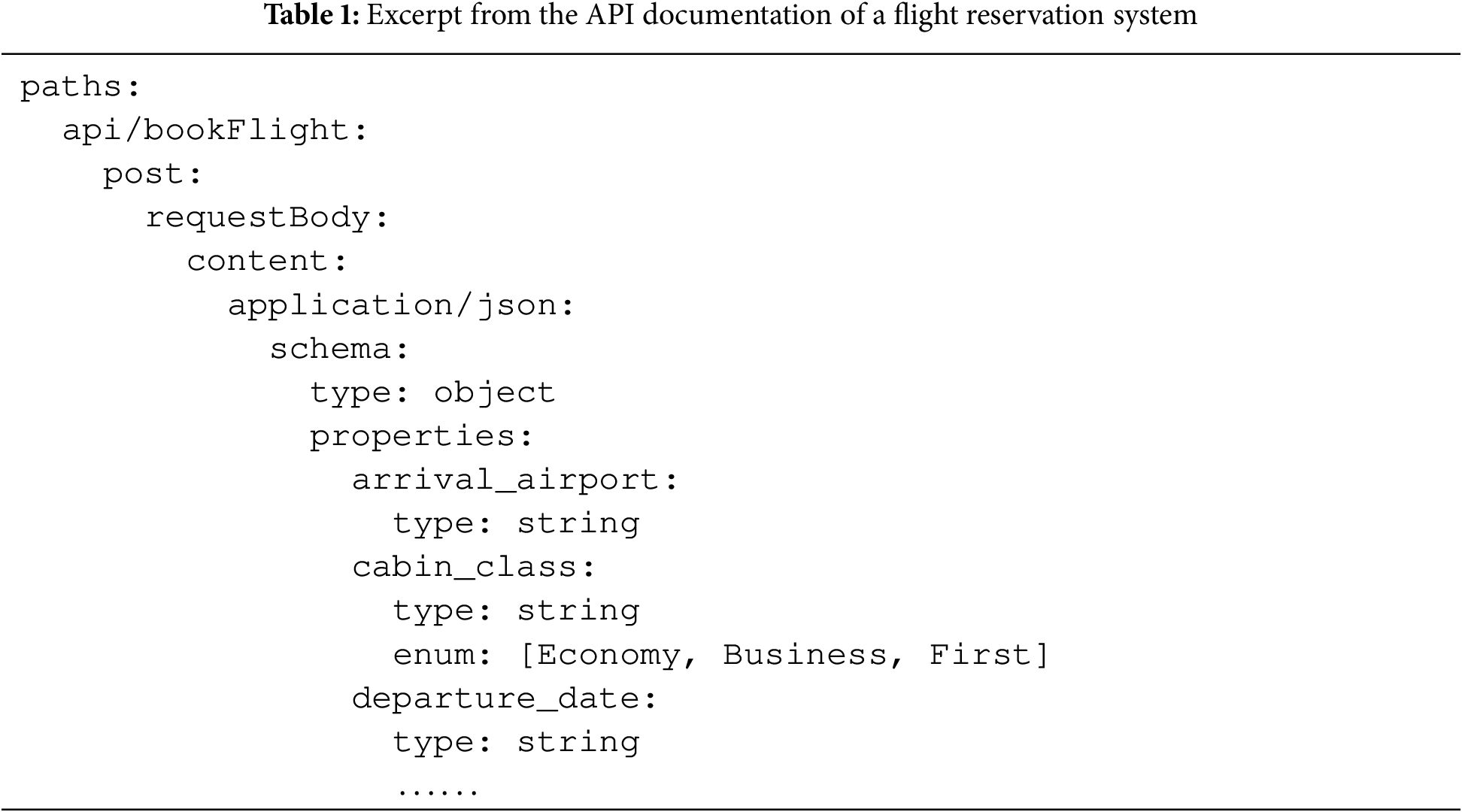

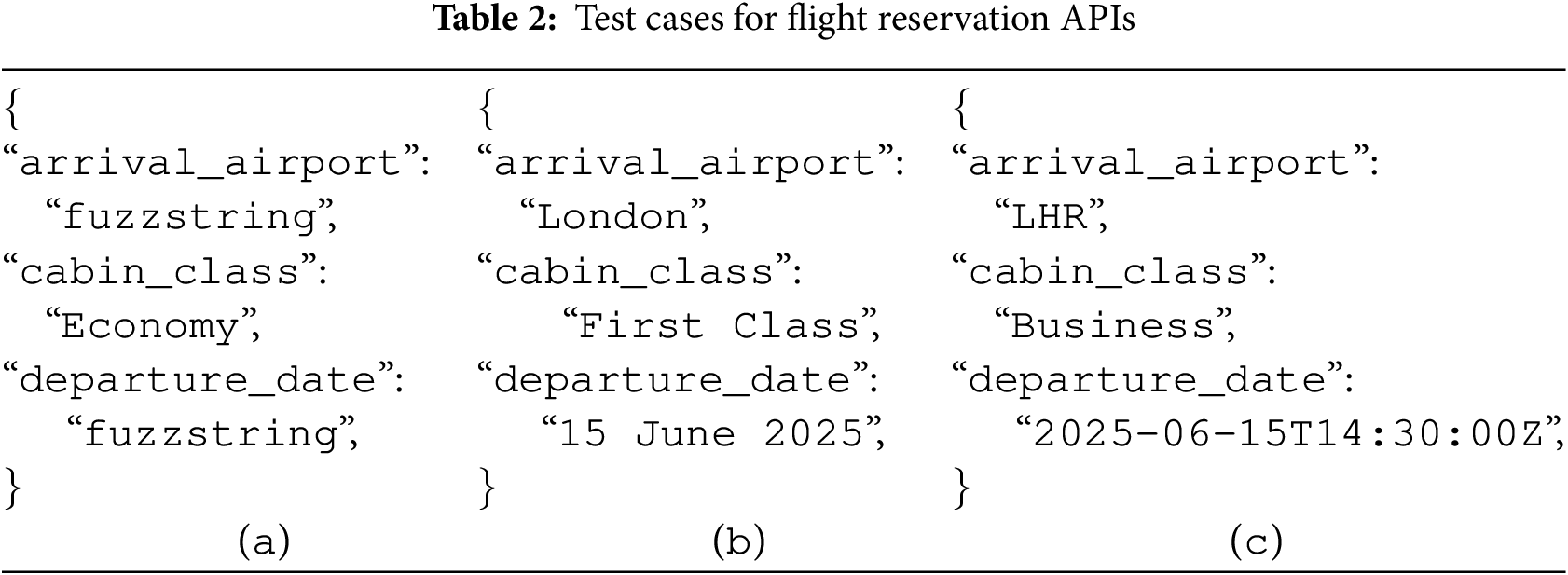

Consider a flight reservation system’s OpenAPI documentation (Table 1). The critical parameters comprise destination airport, cabin class, and departure date.

As shown in Table 2a, the test case satisfies syntactic correctness but violates semantic validity. The API specification defines input parameters as string while lacking semantic constraints. The invalidity stems from two implicit requirements: (1) arrival_airport must be a valid IATA airport code3, and (2) departure_date must comply with ISO 86014. The test value “fuzzstring” violates these requirements, potentially triggering database errors or business logic failures.

Conversely, Table 2b demonstrates semantic correctness with syntactic violations. Despite conveying intended meanings, the values mismatch backend syntax expectations, typically yielding 400 Bad Request responses.

Table 2c demonstrates a valid test case. API specification completion aims to identify implicit constraints absent from original documentation. Properly completed specifications provide parameter examples satisfying both syntactic and semantic correctness, directly improving fuzz testing effectiveness and accuracy.

API documentation completion requires generalizing extracted parameters to other endpoints, but their applicability scope remains ambiguous, manifesting as two issues: (1) Parameter naming inconsistency. Identical parameters may use different names across endpoints, exemplified by arrival_airport vs. dest_airport_code. (2) Business logic inheritance. The hierarchical endpoint structure reflects logical extensions, where /api logically extends to /api/bookFlight for flight booking, and further to /api/bookFlight//allowbreak{flightId} for specific flight queries.

Exact string matching-based document analysis methods are inadequate here, as they only detect character-level similarity without capturing cross-endpoint parameter functional equivalence. This necessitates a similarity metric that can: (1) Establish cross-endpoint parameter mappings, (2) Infer business logic inheritance from endpoint hierarchies. Parameters shared by endpoints with identical business logic should be systematically generalized to enable their reuse in fuzz testing across related APIs.

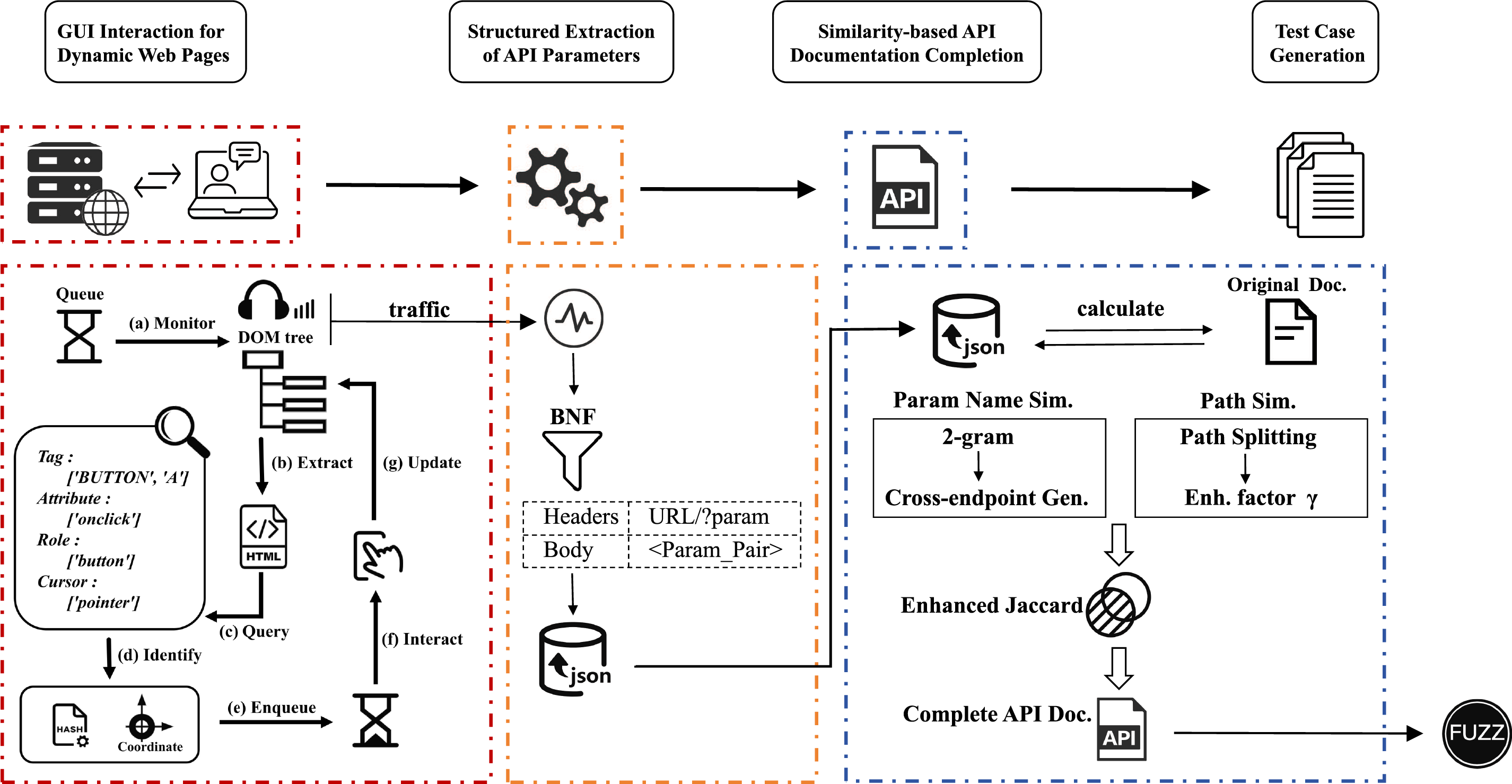

3 APIDocX Fuzz Testing Framework

We present APIDocX (API Documentation Extension), a fuzz testing framework targeting REST APIs that integrates GUI interaction and specification completion techniques. APIDocX operates through four phases: (1) A crawler triggering Web APIs via simulated user interactions, combining dynamic and static page analysis; (2) Structured extraction of valid parameters from captured API communication data; (3) Cross-endpoint parameter generalization using enhanced Jaccard similarity to complete API documentation; (4) Fuzz test execution with completed documentation to generate valid cases. The workflow is depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Workflow of the APIDocX fuzz testing framework

In stage (1), the dynamic web crawler identifies interactive elements and simulates user interactions. During this process, it continuously monitors the DOM tree and records network traffic to ensure that all potential interaction data are effectively captured from the initial state of the web page through its dynamic updates. In stage (2), the system automatically analyzes the traffic information collected in the previous step and applies BNF (Backus-Naur Form) rules to structure the data, extracting API parameter information and forming a standardized parameter set. In stage (3), an enhanced Jaccard similarity algorithm is employed to compute the similarity between the structured parameter information extracted in the previous stage and the data defined in the original API documentation. This enables the analysis of parameter commonality across different API endpoints and facilitates cross-endpoint parameter adaptation. In stage (4), parameters whose similarity exceeds a predefined threshold are generalized to other API nodes, thereby refining and completing the API documentation. The resulting documentation contains more comprehensive endpoint information and syntactically and semantically valid parameter values.

4 Implementation of the APIDocX Fuzz Testing Framework

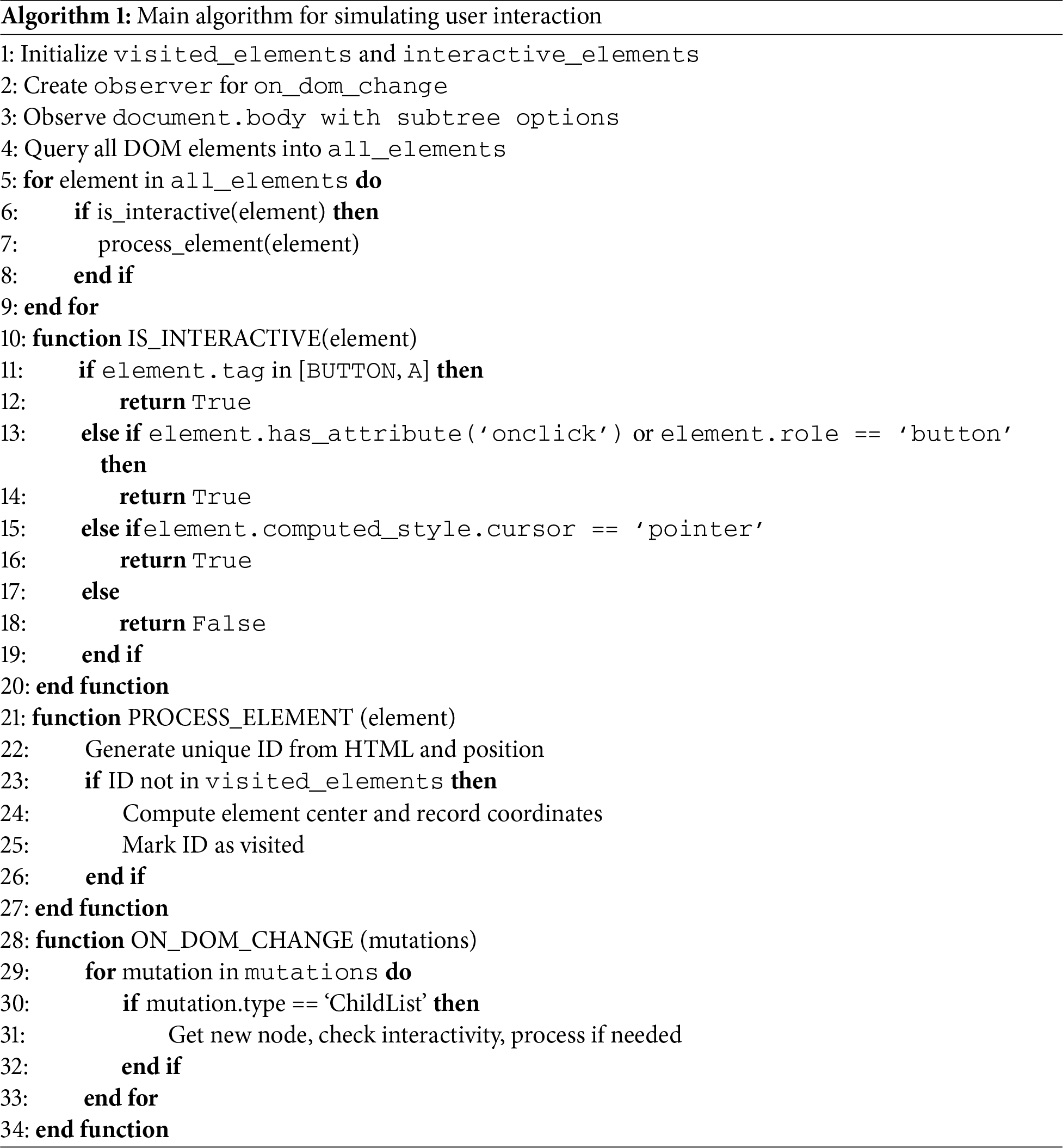

4.1 GUI Interaction for Dynamic Web Pages

GUI testing frameworks are categorized into three types [15]: coordinate-based, image-based, and DOM-based approaches. Coordinate-based methods interact with fixed screen positions, making them sensitive to environmental changes. Image-based techniques match UI (User Interface) elements through screenshots, but requiring significant computational resources. Our proposed DOM-based method identifies and controls elements through web attribute parsing, offering implementation simplicity, high efficiency, and robust performance.

To enhance interactive element detection, we propose a novel strategy identifying clickable components via CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) cursor property changes, combined with static-dynamic analysis for DOM monitoring. Crawler-driven interaction simulation requires precise element identification. Traditional methods include XPath-based DOM tree traversal, attribute-value pair filtering, or text content matching. Building on Leithner et al.’s event listener extraction method [16], we introduce a generalized approach: detecting cursor style changes (e.g., default arrow to pointer) to indicate clickable elements. Our crawler additionally mimics human browsing sequences to maintain business process integrity.

We presents a combined static-dynamic analysis method for DOM monitoring. The static analysis component extracts interactive elements from the initial DOM structure before any user interaction or JavaScript execution occurs. The dynamic analysis module detects runtime DOM mutations (including node insertions, deletions, and attribute modifications) through callback-triggered processing. To optimize performance during dynamic content handling, we implement a tagging mechanism that identifies processed elements to avoid redundant operations. The main algorithm is illustrated in Algorithm 1, respectively.

The system captures initially available interactive elements (including buttons and hyperlinks) through static DOM tree traversal. The function is_interactive() determines element interactivity based on tag names, attributes (e.g., onclick, role), and CSS cursor styles, marking identified elements for interaction simulation.

For dynamically loaded content, a MutationObserver monitors DOM structural changes. Node additions or removals trigger the callback on_dom_change() to process new elements. To avoid redundancy, each element receives a unique identifier combining its outerHTML structure and positional attributes for precise identification. Unprocessed elements have their center coordinates added to the interactive_elements list for user interaction simulation.

After identifying all interactive elements on the current page, the crawler sequentially simulates user clicks to trigger additional data loading and API requests. These simulated interactions can trigger various outcomes including page navigation, JavaScript execution, dynamic content rendering, pop-up windows, or file uploads/downloads. When navigation to a new page occurs, the crawler enqueues the new page for subsequent analysis. For cases involving JavaScript execution, dynamic content insertion, or pop-up generation, the system performs real-time analysis of the newly appeared elements.

This module is implemented in Python and primarily utilizes the Selenium WebDriver framework to perform page loading, DOM element parsing, and interaction control. Selenium provides fine-grained control over browser behavior, enabling the simulation of realistic user interactions—such as clicking, typing, and scrolling—without relying on the page source code, thereby effectively triggering potential API requests. For dynamic content monitoring, the system integrates the MutationObserver API to achieve real-time detection of DOM structure changes. When dynamic content is loaded, MutationObserver immediately triggers callback functions upon node addition, deletion, or attribute modification, ensuring that the crawler can promptly identify and process newly generated interactive elements.

During implementation, the system faces two main challenges. (1) Dynamic content loading and timing issues: due to the asynchronous nature of AJAX loading mechanisms, certain elements may change frequently within a short time, causing the crawler to initiate interactions before the DOM stabilizes, which can lead to failed interactions or missed content. To address this issue, the module introduces explicit waiting mechanisms and element interactivity detection strategies, ensuring that simulated operations are executed only after the elements are fully loaded and interactable, thereby maintaining stability and completeness. (2) Redundant recognition and infinite loop issues: in some complex web pages, dynamically loaded elements are frequently replaced or re-rendered, causing the crawler to repeatedly recognize and interact with the same elements, potentially leading to loops. To prevent redundant processing, the system assigns a unique identifier to each element and performs comparison checks during subsequent scans to efficiently skip already processed elements and avoid repeated interactions.

4.2 Structured Extraction of API Parameters

While the crawler module performs continuous operation, the system simultaneously captures API communication packets to extract parameter names and corresponding values. Focuses on query parameters in request URLs and key-value pairs in POST/PUT request bodies. We implement BNF to formally define parameter extraction rules.

For GET requests, parameters typically appear in the query string section following this pattern:

GET /path/?param1=value1¶m2=value2 HTTP/1.1

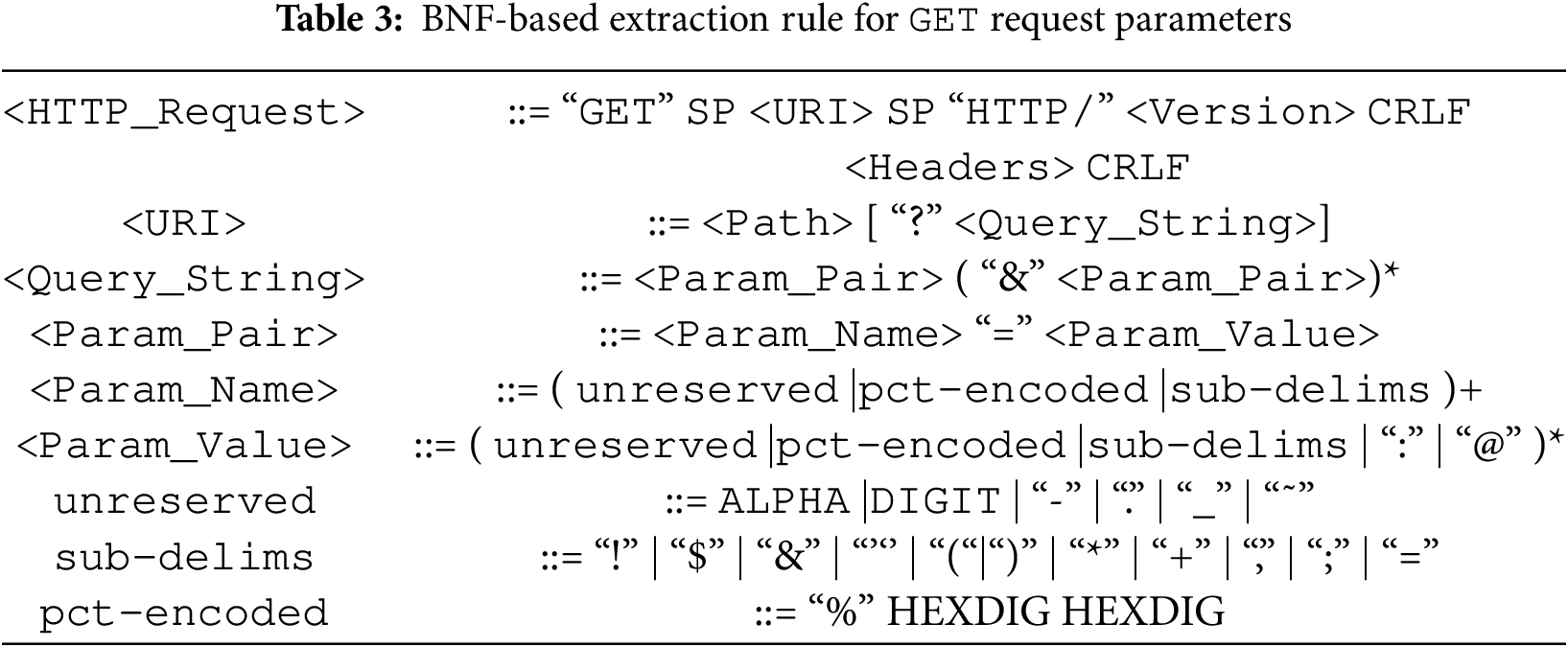

The BNF extraction rules for GET requests are specified in Table 3.

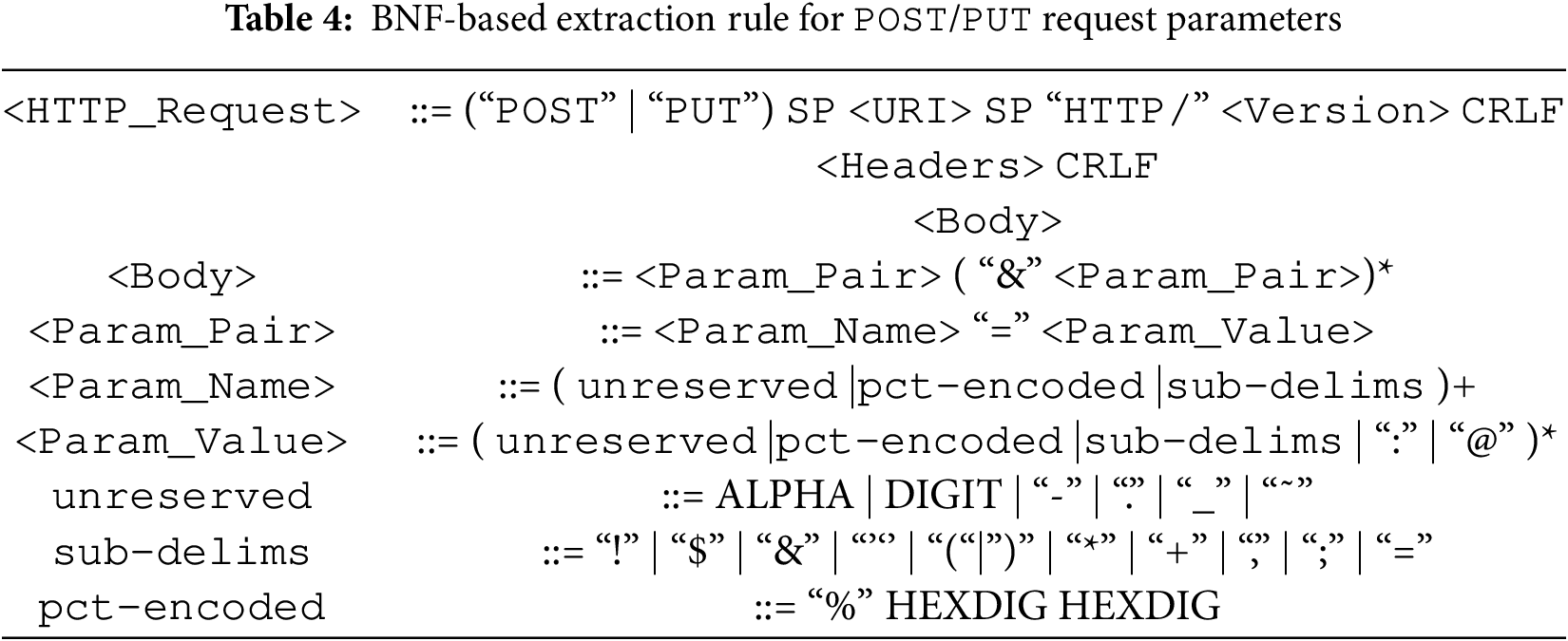

For POST or PUT requests, parameters are typically formatted as key=value pairs in the request body, as exemplified by:

POST /path/ HTTP/1.1

param1=value1¶m2=value2

We define the corresponding extraction rules in Table 4.

Parameter extraction from HTTP response packets adopts analogous methodology. Using these parsing rules, the system accurately identifies API parameters and their values from captured request/response messages, enabling robust documentation completion.

In existing dynamic web crawling approaches, browser automation tools such as Selenium and Puppeteer are often combined with network monitoring tools like Burp Suite for web application security testing. Although this combination can provide similar capabilities to some extent, it still exhibits several limitations.

First, Burp Suite can only capture HTTP requests after they have been issued and relies on configured interception rules for request analysis; it does not provide dedicated functionality to automatically analyze or extract parameters from requests, especially when those parameters are dynamically generated via JavaScript. Consequently, Burp Suite’s ability in this scenario is limited. In addition, the integration of Selenium or Puppeteer with Burp Suite introduces operational inconvenience, as users must manually configure the testing environment and set interception points, a process that is relatively cumbersome. More importantly, during fuzz testing, the substantial amount of manual intervention required by this workflow fails to meet the demands of high-throughput automated testing and thus constrains testing efficiency.

The method proposed in this work achieves a high degree of automation by integrating the crawler with an API request capture mechanism, enabling real-time capture and analysis of request parameters produced during user interaction without the need for manually configured interception rules. This approach supplements the automatic parameter analysis functionality that Burp Suite lacks and eliminates extensive manual intervention, thereby substantially simplifying the testing process and improving overall testing efficiency.

4.3 Multi-Endpoint Parameter Adaptation Method Based on Enhanced Jaccard Similarity

We observe that traffic analysis-extracted parameters frequently demonstrate cross-endpoint reusability, being applicable beyond their original endpoints. This requires establishing quantitative metrics to evaluate parameter applicability and generalize them to suitable endpoints. Accordingly, we propose an improved Jaccard similarity-based parameter adaptation method. Our method combines parameter name similarity, path similarity, and a path enhancement factor to determine parameter generalization across API endpoints.

Let

The normalization formula is defined as:

4.3.1 Parameter Name Similarity

During the process of parameter generalization in API endpoints, parameter names may vary due to different naming conventions, yet they essentially share similar semantics. To compute their similarity, each parameter name is first normalized by removing delimiters (such as “-” or “_”) and converting all characters to lowercase. Then, the 2-g method is applied to divide the string and generate a character sequence set G. This method is capable of capturing minor naming inconsistencies (such as abbreviations or concatenations) and yields a better matching performance.

Let

To further illustrate the computation of parameter similarity, consider the parameters Email and email_addr, which share a high degree of semantic similarity. After preprocessing, the sequence set of Email is {em, ma, ai, il }, and that of email_addr is {em, ma, ai, il, la, ad, dd, dr }. The overlap between their 2-gram subsequences results in a relatively high similarity score. If other similarity metrics such as Levenshtein Distance are applied, the computed similarity would be lower (with an edit distance of 5), leading to a reduced similarity judgment for these two parameters.

API endpoints typically consist of multiple hierarchical levels, and analyzing the hierarchical structure of API paths is essential for inferring business logic dependencies. This paper divides endpoint paths according to their hierarchical structure. Let

The denominator uses the minimum path length

Compared with the traditional Jaccard similarity, the introduction of the path weighting factor enhances the sensitivity to structural hierarchy. When only a small number of segments match between API endpoints, if these segments occur near the beginning of the paths, the traditional approach may yield an undesirably high similarity score, reducing computational accuracy. Therefore, this enhanced approach effectively mitigates false positives in hierarchical path matching by considering both prefix position and path depth.

Overall, this method achieves a better balance between sensitivity and robustness when measuring path similarity in hierarchical API structures. It can accurately distinguish structurally dissimilar endpoints while maintaining tolerance for local path variations, making it more suitable for hierarchical API path matching scenarios. For example,

For example, consider the following two API endpoints:

/api/v3/customers/customerId/orders

/api/v3/customers/customerId/complaints

These two endpoints share the same prefix in their path hierarchy, but the final level resources orders and complaints belong to completely different business domains. The former is used for order creation and querying, while the latter is used for submitting customer complaints. There is no semantic or data relationship between them, and thus they should not be regarded as generalized endpoints.

Using the traditional statistical method, the similarity is computed as:

With the improved calculation method, it becomes:

As can be observed from the results, the traditional method tends to assign excessively high similarity scores to endpoints with long shared prefixes, leading to misjudgments in cases where the subsequent path structures differ significantly. In contrast, the improved approach introduces a path depth normalization factor

This paper integrates the APIDocX fuzzing framework with RESTler [11], and conducts experimental validation from the following two aspects: effectiveness analysis of the framework and comparative analysis with existing tools. The experiments select the open-source projects WordPress and crapi as test targets, and construct a multi-dimensional evaluation system to comprehensively evaluate the method proposed in this paper.

WordPress is currently one of the most widely used CMS (Content Management Systems) worldwide. Its core includes a comprehensive REST API covering around 20 types of resources such as posts, pages, and comments, with approximately 90 core endpoints. Each endpoint supports multiple parameterized access and filtering methods. In real-world deployments, common plugins often register additional endpoints, further extending the REST routes and significantly increasing the diversity and complexity of the interface layer for testing.

In addition, WordPress exhibits rich dynamic interaction features, including AJAX calls, user role management, and permission control. These mechanisms introduce considerable dynamism and complexity in request scheduling, state management, and authentication. Overall, the system’s large-scale API architecture and dynamic interactive behavior make WordPress a highly representative example of modern, complex web systems. It serves as a realistic and suitable platform for evaluating the scalability and effectiveness of automated testing methods in real-world web service environments.

The experimental environment was built based on WordPress 6.5.3, with commonly used plugins such as WooCommerce 8.9 and WPGraphQL 1.15 installed. The system runs on Ubuntu 22.04, with PHP 8.2 and MariaDB 10.11 as the underlying environment.

crAPI is an open-source web service platform designed for security testing and vulnerability analysis, characterized by its high complexity and realistic system structure. The system simulates a complete modern web service, including modules for user registration, authentication, account management, product ordering, and transaction processing. The backend consists of multiple independent service components and exposes over 150 API endpoints, covering authentication, business logic, and step-by-step workflows. This design enables comprehensive evaluation of automated testing methods across diverse data interaction patterns.

The crAPI environment was deployed using Docker Compose, running on Ubuntu 22.04, with Python 3.10, PostgreSQL 14, and Redis 7.2 as the core dependencies.

5.1 Effectiveness Analysis of the APIDocX Fuzzing Framework

5.1.1 Effectiveness Analysis of GUI Interaction

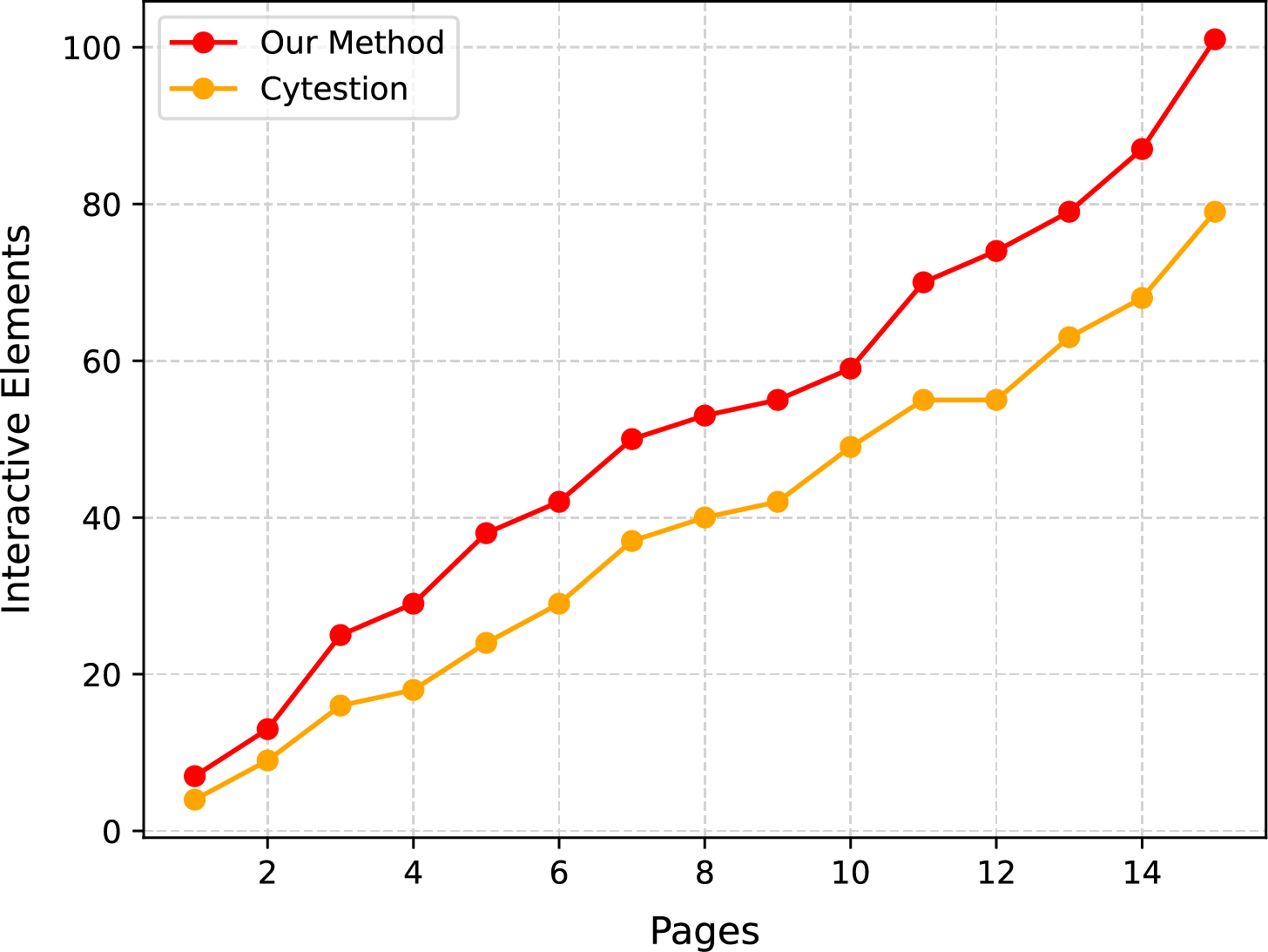

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method in identifying interactive elements in the GUI, a comparison is conducted with the existing method Cytestion [17]. Fig. 2 shows the trend in the number of interactive elements identified by the two methods as the number of crawled pages increases. As the number of crawled pages increases from 1 to 15, the total number of interactive elements identified by the proposed method consistently exceeds that of the Cytestion method, and the gap between the two gradually widens. When 15 pages are crawled, the proposed method identifies a total of 101 interactive elements, while Cytestion identifies only 79. This indicates that under the same crawling depth, the proposed method can discover more GUI interactive elements, demonstrating higher identification capability and coverage.

Figure 2: Trend of identified interactive elements across increasing crawl depth

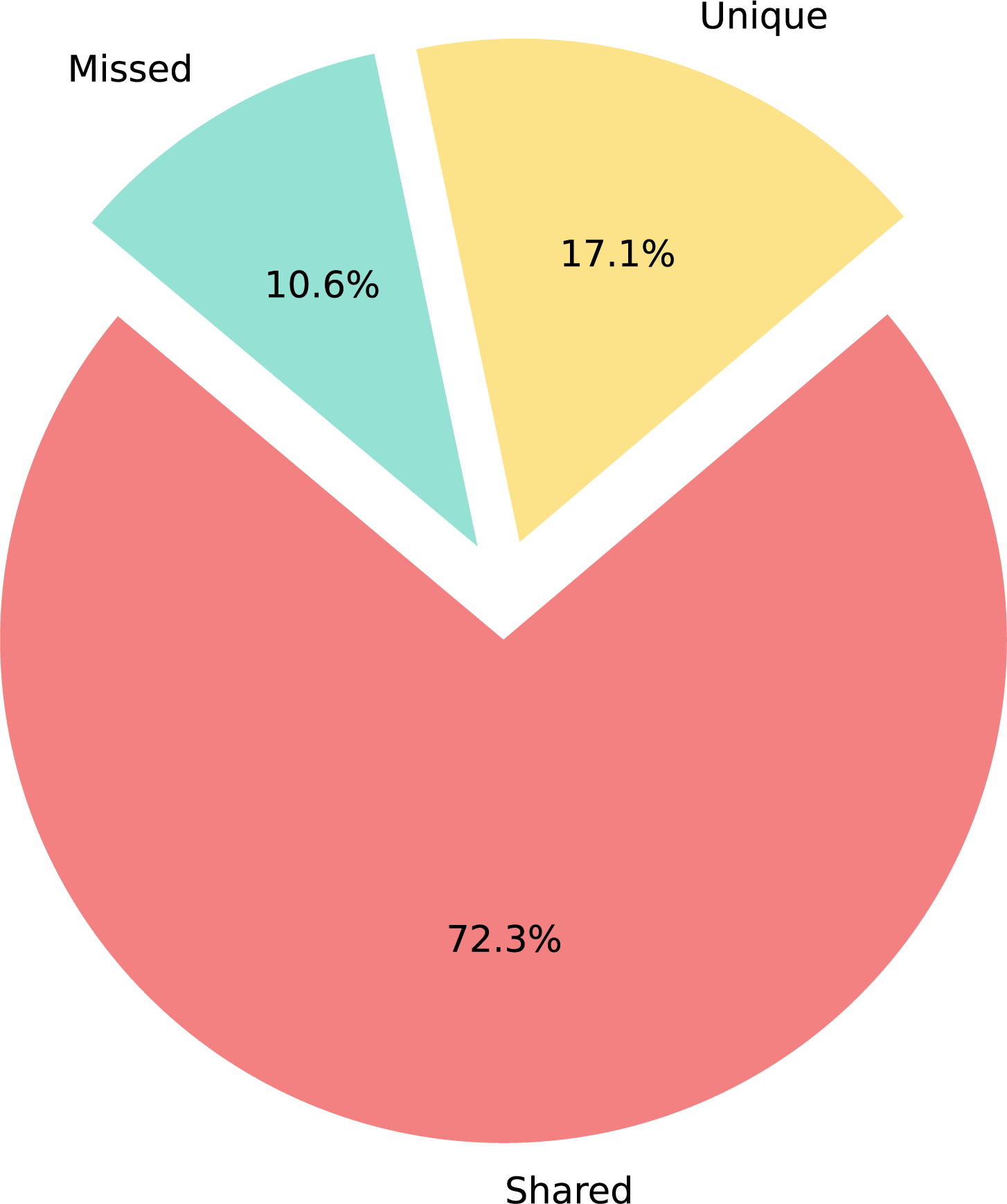

Fig. 3 details the identification differences: 72.3% elements detected by both methods, 17.1% uniquely by our approach, and 10.6% undetected. Demonstrating our method’s ability to uncover significant additional elements missed by baselines, improving GUI coverage.

Figure 3: Distribution of coverage scope for identified interactive elements

The results demonstrate that our method not only covers all elements detected by Cytestion but also identifies 17.1% of elements overlooked by Cytestion, primarily due to two limitations in Cytestion’s approach: its dependence on manual annotation of custom attributes by testers (which cannot be applied to third-party components) and potential human oversight during marking. In contrast, our proposed method analyzes the fully rendered HTML page, automatically detecting both native and third-party components without manual intervention, thereby significantly reducing tester workload. The remaining 10.6% undetected elements are attributed to complex interaction patterns such as mouse hover-triggered elements, hidden menu components, and state-dependent elements.

Experimental results confirm the superior effectiveness of our GUI testing method, which combines CSS cursor property analysis with hybrid static-dynamic analysis to achieve broader element coverage and more reliable interaction capabilities, establishing a robust foundation for subsequent system testing.

5.1.2 Effectiveness of API Documentation Completion

We propose an evaluation of the multi-endpoint parameter adaptation method based on enhanced Jaccard similarity. We aim to measure adaptation accuracy and false generalization rates, while verifying the similarity enhancement mechanism’s impact.

Quantitatively assessing adaptation requires defining:

• PA-Accuracy(Parameter Adaptation Accuracy): Correctly adapted parameter proportion

• FG-Rate(False Generalization Rate): Incorrectly generalized parameter proportion

• TP(True Positive): Correct endpoint matches

• FN(False Negative): Missed endpoint matches

• FP(False Positive): Incorrect endpoint matches

We define successful generalization as API requests with adapted parameters receiving 200 OK responses. The metrics compute as:

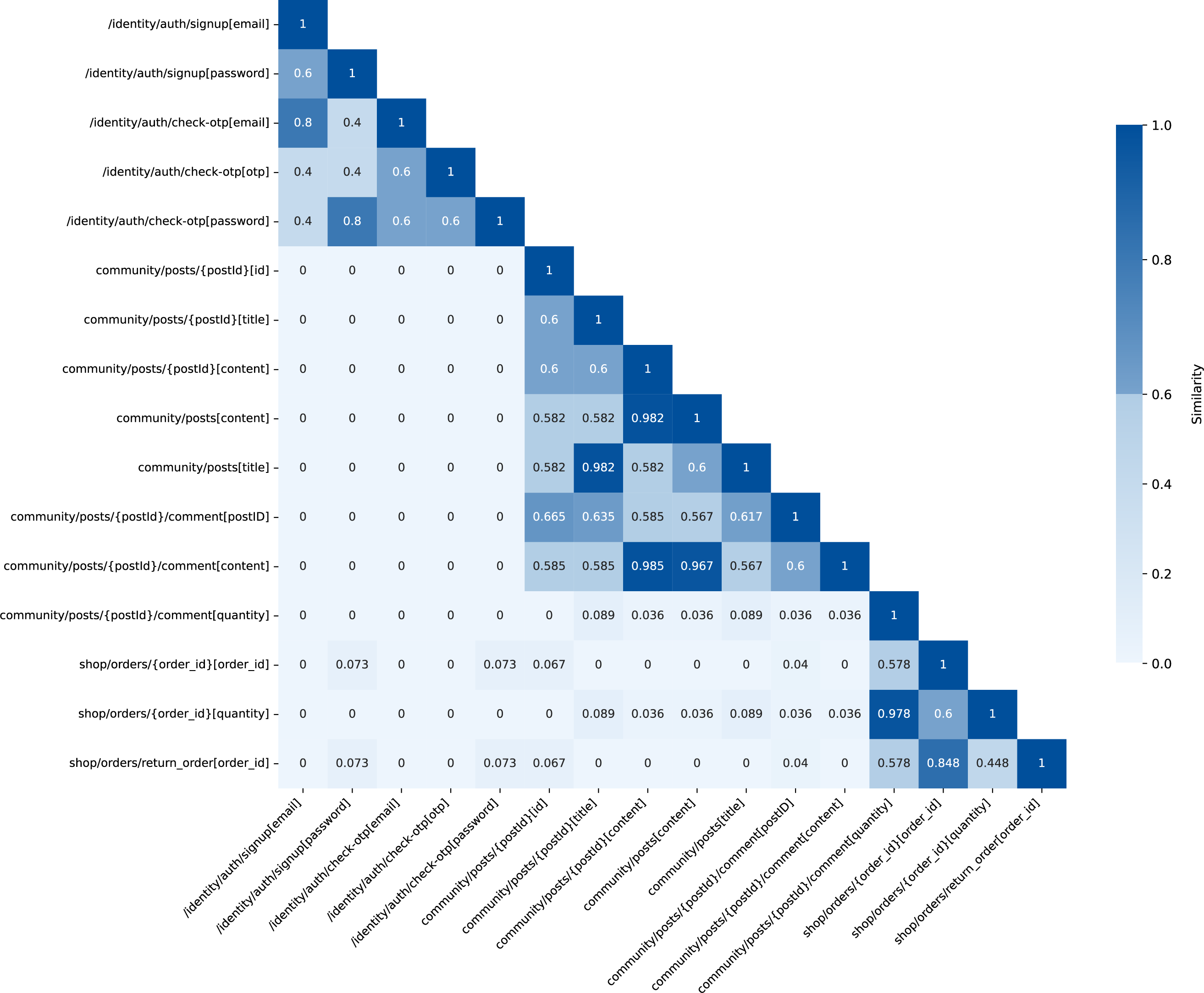

Fig. 4 shows the similarity results with 0.6 as the generalization threshold. High-similarity regions form clustered dark blocks, particularly among endpoints sharing path prefixes or functional modules. This demonstrates our method’s effectiveness in capturing parameter commonality and adapting to API hierarchies, validating its multi-endpoint generalization capability.

Figure 4: Heatmap of API endpoint similarity scores using the multi-endpoint parameter adaptation method based on enhanced Jaccard similarity (threshold = 0.6)

These results indicate our method effectively identifies parameter commonality in logically inherited or hierarchically structured API modules. The clustering demonstrates adaptation to API structural semantics and confirms multi-endpoint generalization effectiveness.

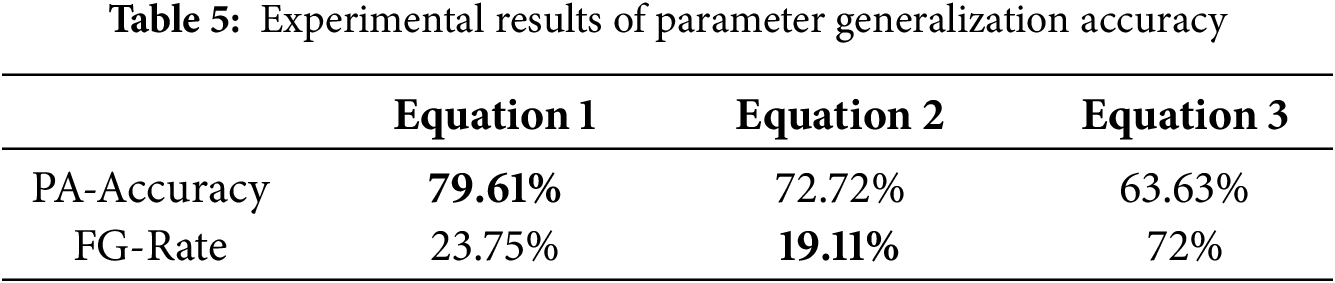

To evaluate the improved Jaccard similarity’s optimization effect, we compare three strategies (Table 5):

• Equation 1: Our proposed similarity method

• Equation 2: Baseline similarity without hierarchical matching or path enhancement:

• Equation 3: Modified Spath method based on Eq. (2) without 2-g

Results show the parameter adaptation accuracy increases from 63.63% to 72.72% between Eqs. (2) and (3), originating from the 2-gram segmentation algorithm. The original method (Eq. (3)) employs discrete token-matching with binary similarity values (0 or 1), causing polarized evaluation results. Our improved method enables partial sequence alignment and continuous similarity measurement through 2-gram segmentation.

The enhanced algorithm achieves three key improvements: (1) Spelling variation tolerance: Character-level 2-gram decomposition effectively detects variants like “email” and “UserEmail” with overlapping substrings. (2) Continuous assessment: Similarity scores transition from binary to continuous

Comparing Eqs. (1) and (2), accuracy further improves from 72.72% to 79.61%, demonstrating that shortest path length and enhancement factor

However, the false generalization rate increases from 19.11% to 23.75%. This phenomenon primarily stems from naming collisions in endpoints with identical or highly similar paths. For instance, the endpoint /identity/api/v2/user/videos/{video_id} and its parameters video_id vs. videoName exhibit strong 2-g overlap despite representing distinct business semantics. The method overweights lexical overlap in such cases, causing incorrect generalization.

In conclusion, our multi-endpoint parameter adaptation method based on enhanced Jaccard similarity achieves superior accuracy by synergistically combining path structural features with partial name matching. The introduced path enhancement factor

5.2 Comparative Experiments on the APIDocX Fuzzing Framework

5.2.1 Coverage Comparison Analysis

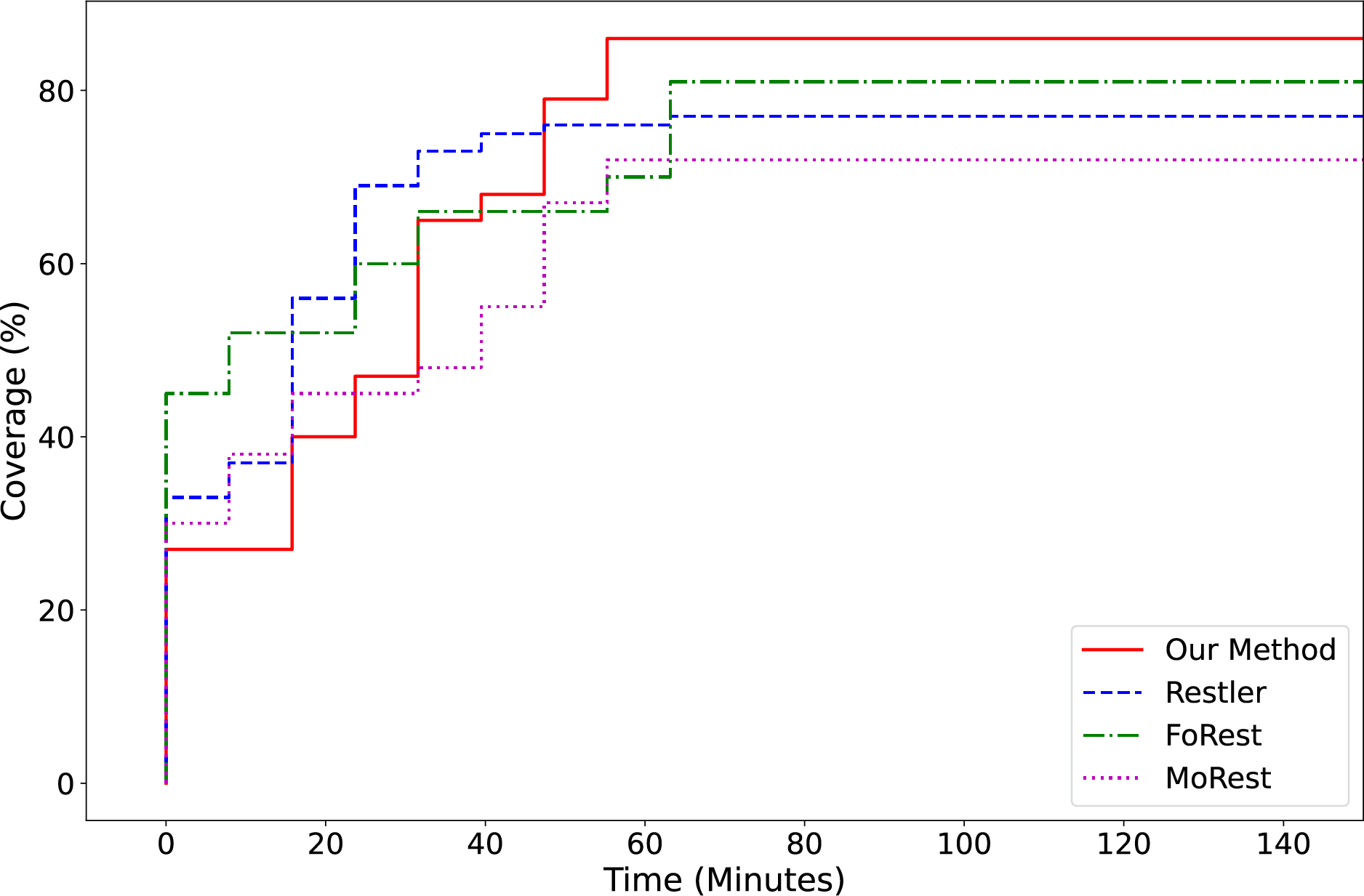

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method in practical REST API testing scenarios, a coverage comparison experiment was conducted on two open-source systems, WordPress and Crapi. Three commonly used API fuzzing tools—RESTler, FoRest, and MoRest—were selected as baselines for comparison under a unified testing environment. The coverage metric is defined as the percentage of REST API endpoints that were successfully accessed during the test process relative to the total number of endpoints documented in the API specification. The testing duration was set to 150 min to objectively reflect each tool’s comprehensive capability in API exploration and invocation.

The experimental results are illustrated in Fig. 5. The coverage growth trends of the various methods over time exhibit significant differences. The proposed method was slightly slower in the initial phase (0–25 min) compared to other tools, but experienced rapid growth in the subsequent stages, reaching 86% endpoint coverage by the 55th minute and maintaining stability thereafter, outperforming the other three methods. FoRest and RESTler approached saturation at around the 65th minute, achieving maximum coverage rates of 81% and 77%, respectively. MoRest showed slow overall growth, with final coverage reaching only 72%, significantly lower than the others.

Figure 5: API endpoint coverage comparison curve

These results indicate that the proposed method incurs a slight delay in the initial stage due to the need to trigger API invocations via GUI-driven interactions and to complete the corresponding documentation. However, as parameter extraction and documentation completion progress, the system is able to rapidly perform endpoint exploration and parameter combination, thereby enhancing endpoint coverage during the testing process. In contrast to traditional methods that primarily rely on static path information in API documentation to generate requests, the proposed approach dynamically discovers API usage paths and actual parameter values through interactive behavior. This leads to stronger endpoint awareness and adaptability, ultimately achieving higher coverage.

In summary, the coverage comparison experiment fully validates the advantages of the proposed method in real-world testing environments. By leveraging the synergistic effect of GUI interaction and documentation completion, the method significantly enhances the capability of discovering and invoking API endpoints, thus providing a solid foundation for REST API security assessment.

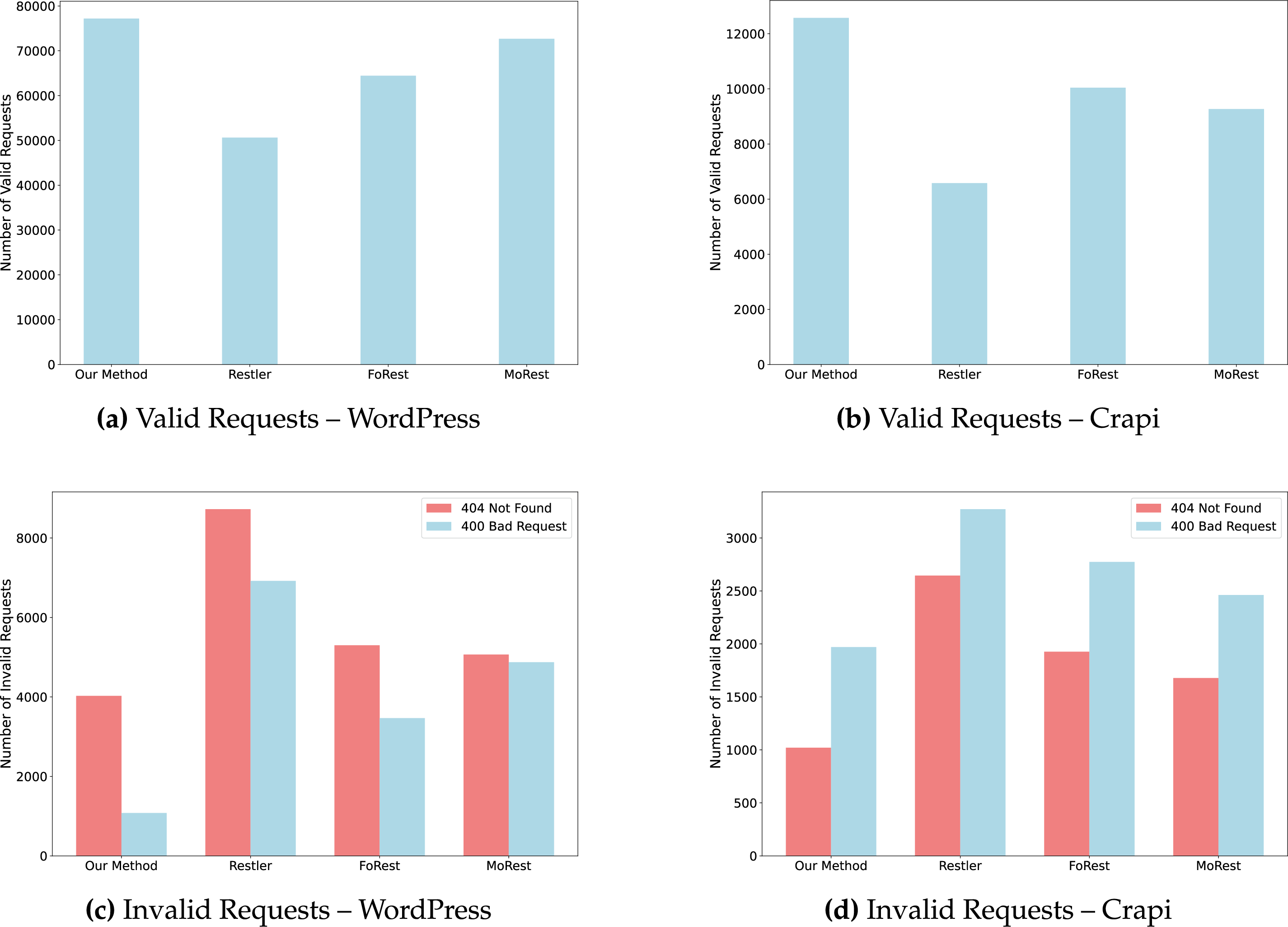

5.2.2 Request Generation Comparison Analysis

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method in generating test cases, a comparative experiment was conducted on two open-source systems, WordPress and Crapi. The experiment compared the number of valid and invalid requests generated by different testing tools, including RESTler, FoRest, and MoRest. The evaluation metrics consist of the number of valid requests and the number of invalid requests. A valid test case refers to a request that successfully triggers an API endpoint and receives a correct response. Invalid test cases mainly refer to those for which the API endpoint returns an error status code, primarily including 400 Bad Request and 404 Not Found. A 400 Bad Request status indicates that the request contains a syntax error or does not satisfy the server’s parameter validation rules. This typically occurs in cases where request parameters are missing, incorrectly formatted, or contain values that exceed the expected range. A 404 Not Found status implies that the assigned parameter values may not conform to the expectations of the server, resulting in the request being incorrectly routed and failing to reach the corresponding resource.

The experimental results are shown in Fig. 6. Subfigures a and b respectively present the number of valid requests generated by each testing tool in the Wordpress and Crapi environments. According to the results, the method proposed in this paper generates the highest number of valid requests in both testing environments—77,204 in Wordpress and 12,577 in Crapi—surpassing all other approaches. This outcome indicates that extracting real parameters through GUI interaction, combined with a multi-endpoint parameter adaptation strategy for API specification completion, can enhance the effectiveness of test case generation and reduce the number of failed requests caused by parameter mismatches with interface requirements.

Figure 6: Request count comparison for different testing tools

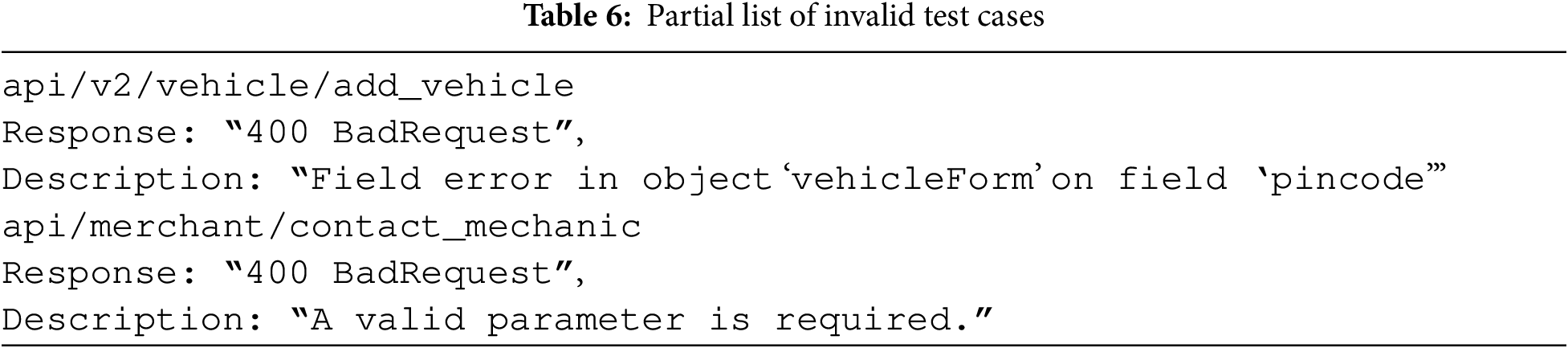

Subfigures c and d compare the number of two types of invalid requests: HTTP 400 Bad Request and 404 Not Found. The results show that RESTler produces the highest number of invalid requests in both environments, with 404 errors generally outnumbering 400 errors. This suggests that RESTler exhibits certain deficiencies in both path selection and parameter assignment. In contrast, the proposed method results in the fewest invalid requests: only 4027 instances of 404 errors and 1079 instances of 400 errors in the Wordpress environment, and 1021 instances of 404 errors and 1790 instances of 400 errors in the Crapi environment, all lower than those produced by FoRest and MoRest. Most of these errors are caused by incorrect parameter formats; Table 6 lists several examples of invalid test cases. During testing, it was observed that many parameter constraints and value ranges were not explicitly documented in the API specifications, yet were required in actual API requests. Through the GUI-based interactive parameter extraction method, these critical parameters were successfully identified and extracted, thereby providing reliable data support for subsequent fuzz testing.

Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method exhibits a comprehensive advantage in both API path selection and parameter assignment. The generation of a large number of valid requests indicates its capability to explore the API functional space more thoroughly, while the relatively low number of invalid requests reflects its syntactic and semantic accuracy in parameter handling. These results suggest that the method possesses strong adaptability and scalability in complex API scenarios, effectively improving the validity of generated test cases and reducing redundant invalid requests.

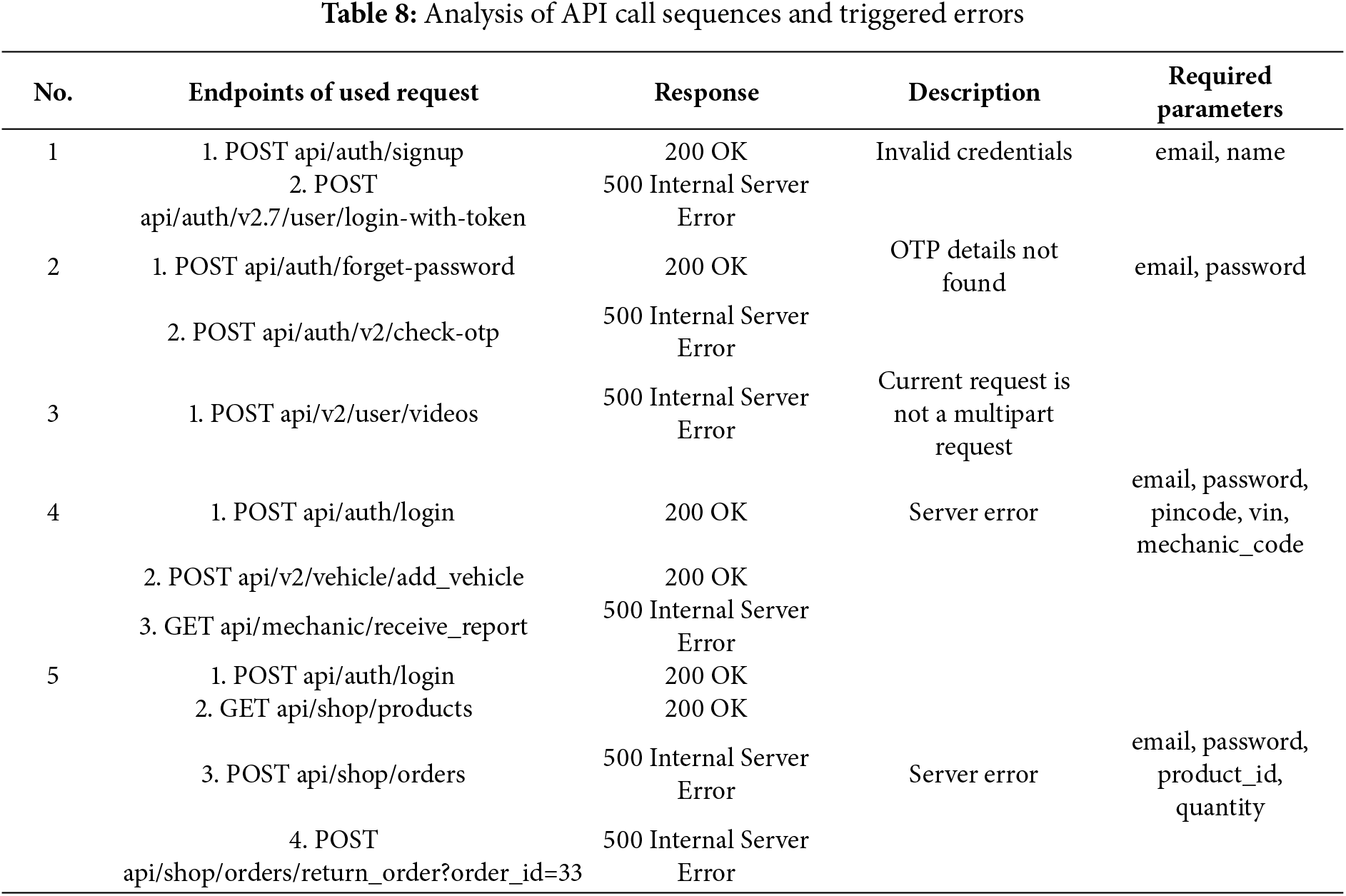

To evaluate the fault-triggering capability of the proposed method in practical security testing scenarios, we recorded the number of faults successfully triggered by different tools in the Wordpress and Crapi testing environments. In this study, a fault is defined as an event that causes an abnormal system response (500 Internal Server Error) or unexpected behavior that disrupts the business logic flow.

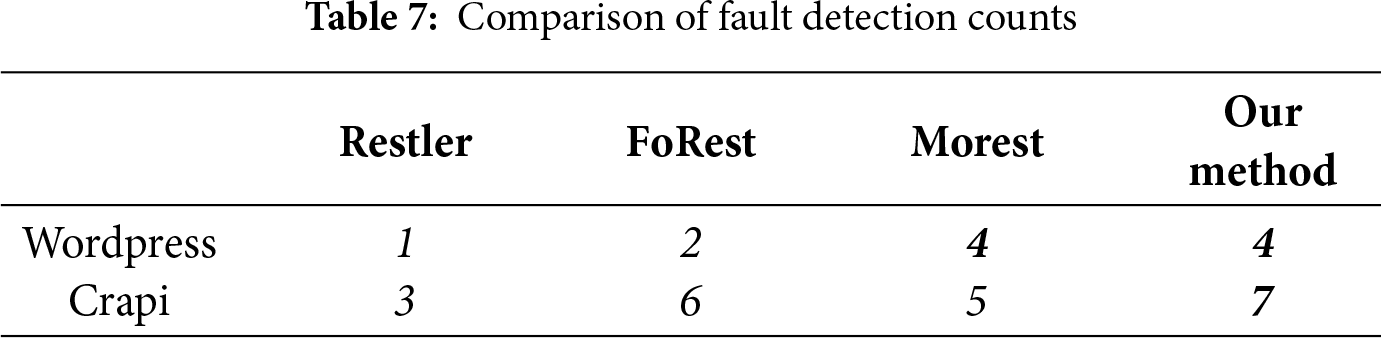

The statistical results are presented in Table 7. The proposed method demonstrates superior fault detection capability in both testing environments. In the Wordpress environment, the proposed method and MoRest each triggered four faults, outperforming RESTler and FoRest. In the Crapi environment, the proposed method triggered a total of seven faults, exceeding all three baseline methods.

Representative faults are shown in Table 8. In Sequences 1 and 2, when a token is used or an One-Time Password (OTP) is verified without prior login, the system fails to perform integrity checks on the token, and abnormal inputs are not properly handled, directly resulting in a 500 Internal Server Error. Such behavior not only disrupts the normal authentication process but also reveals the system’s lack of strict validation regarding the sequence of business logic execution. In Sequence 3, when a user uploads a video file, if the request format is invalid or the file field is missing, the server does not perform null checks or parameter validation, leading to an unhandled exception. This indicates that the interface lacks robust input validation for complex form submissions. In Sequence 4, during the submission of a repair request, the backend interface fails to enforce authentication, allowing any user to access the repair endpoint. When invalid identity information is provided, the server does not return a 403 Forbidden response but instead encounters an internal error, exposing issues such as the absence of the principle of least privilege and insufficient resource validity checks. In Sequence 5, when a user attempts to operate on a non-personal or already-returned order, the system does not return the appropriate 403 or 400 error codes. Instead, it throws an internal error, indicating that the backend does not strictly verify order ownership or status, thereby introducing risks of unauthorized access and state inconsistency.

The observed errors do not stem from simple parameter boundary violations or type mismatches, but rather originate from incomplete implementation of business logic constraints at the system level. For well-designed APIs, request errors should typically return 4XX-series status codes to prompt client-side request modifications. Consequently, when an API returns a 500 status code under exceptional sequences, this indicates either concealed security vulnerabilities or robustness issues within the endpoint, reflecting insufficient exception handling and recovery mechanisms for unexpected scenarios.

Notably, the successful execution of these API call sequences culminating in server-side 500 errors critically depends on the comprehensive parameter information provided by the API documentation. During test case generation, these parameters are properly embedded into corresponding requests, ensuring both syntactic and semantic correctness. This approach effectively prevents system-level 400 Bad Request errors caused by missing mandatory fields or parameter format violations. These findings demonstrate that effective parameter value reuse constitutes a fundamental prerequisite for triggering such exceptional conditions.

This paper proposes a REST API fuzzing framework based on GUI interaction and API documentation completion, aiming to address the challenges faced by existing API security testing methods when dealing with incomplete OpenAPI specification documents. By designing a crawler capable of adapting to dynamic web pages to simulate user interactions with web APIs and capture real interaction data, and using a multi-endpoint parameter adaptation method based on improved Jaccard similarity for parameter generalization, the framework can effectively compensate for missing parts in API documentation. This helps generate test cases that are both syntactically and semantically valid, avoiding the drawback of producing large numbers of invalid test cases through random value assignment or predefined dictionaries. For fuzz testing of REST APIs, this approach is significant for generating effective test cases, providing preliminary input data for the testing process to ensure coverage of key API functionalities and potential vulnerabilities. The proposed method provides important data support for subsequent fuzz testing work.

Acknowledgement: I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to the institutions and colleagues who provided valuable support and guidance throughout the entire process of this research. Their insightful advice helped refine the ideas and navigate key challenges, and their encouragement motivated perseverance through difficulties. From the early stages of conceptual development to the final revisions, their thoughtful feedback greatly improved the quality and clarity of this work. I am truly grateful for their time, patience, and dedication.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Open Foundation of Key Laboratory of Cyberspace Security, Ministry of Education of China (KLCS20240211).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Zonglin Li and Xu Zhao; Software, Zonglin Li and Xu Zhao; Supervision, Yihong Zhang; Validation, Zonglin Li and Xu Zhao; Visualization, Yazhe Li; Writing—Original Draft, Zonglin Li and Xu Zhao; Writing—Review & Editing, Yan Cao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: This study did not involve human or animal subjects.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://www.googleapis.com/discovery/v1/apis/drive/v2/rest (accessed on 08 November 2025)

2https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonS3/latest/API/Welcome.html (accessed on 08 November 2025)

3An IATA airport code uniquely identifies airports worldwide

4The international standard for date/time representations

References

1. Fielding RT. Architectural styles and the design of network-based software architectures [dissertation]. Irvine, CA, USA: University of California; 2000. [Google Scholar]

2. Corradini D, Zampieri A, Pasqua M, Viglianisi E, Dallago M, Ceccato M. Automated black-box testing of nominal and error scenarios in RESTful APIs. Softw Test Verif Reliab. 2022;32(5):e1808. doi:10.1002/stvr.1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Golmohammadi A, Zhang M, Arcuri A. Testing RESTful APIs: a survey. ACM Trans Softw Eng Methodol. 2024;33:41. doi:10.1145/3617175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Arcuri A. RESTful API automated test case generation with EvoMaster. ACM Trans Softw Eng Methodol. 2019;28:1–37. doi:10.1145/3293455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liu Y, Li Y, Deng G, Liu Y, Wan R, Wu R, et al. Morest: model-based RESTful API testing with execution feedback. In: Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE ’22); 2022 May 21–29; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 1406–17. [Google Scholar]

6. Lin J, Li T, Chen Y, Wei G, Lin J, Zhang S, et al. foREST: a tree-based black-box fuzzing approach for RESTful APIs. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 34th International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE); 2023 Oct 9–12; Florence, Italy. p. 695–705. [Google Scholar]

7. Hatfield-Dodds Z, Dygalo D. Deriving semantics-aware fuzzers from web API schemas. In: Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE 44th International Conference on Software Engineering: Companion Proceedings (ICSE ’22); 2022 May 21–29; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 345–6. [Google Scholar]

8. Wu H, Xu L, Niu X, Nie C. Combinatorial testing of RESTful APIs. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/ACM 44th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2022 May 21–29; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. p. 426–37. [Google Scholar]

9. Martin-Lopez A, Segura S, Ruiz-Cortés A. RESTest: automated black-box testing of RESTful web APIs. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis (ISSTA 2021); 2021 Jul 11–17; Virtual. p. 682–5. [Google Scholar]

10. Deng G, Zhang Z, Li Y, Liu Y, Zhang T, Liu Y, et al. NAUTILUS: automated RESTful API vulnerability detection. In: Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (SEC ’23); 2023 Aug 9–11; Anaheim, CA, USA. p. 5593–609. [Google Scholar]

11. Atlidakis V, Godefroid P, Polishchuk M. RESTler: stateful REST API fuzzing. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/ACM 41st International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE); 2019 May 25–31; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 748–58. [Google Scholar]

12. Alonso JC. Automated generation of realistic test inputs for web APIs. In: Proceedings of the 29th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE 2021); 2021 Aug 23–27; Athens, Greece. p. 1666–8. [Google Scholar]

13. Ed-douibi H, Izquierdo JLC, Cabot J. Automatic generation of test cases for REST APIs: a specification-based approach. In: Proceedings of the IEEE 22nd International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference; 2018 Oct 16–19; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 181–90. [Google Scholar]

14. Viglianisi E, Dallago M, Ceccato M. RESTTESTGEN: automated black-box testing of RESTful APIs. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 13th International Conference on Software Testing, Validation and Verification (ICST); 2020 Feb 24–28; Porto, Portugal. p. 142–52. [Google Scholar]

15. Leotta M, Stocco A, Ricca F, Tonella P. P esto: automated migration of DOM‐based Web tests towards the visual approach. Softw Test Verif Reliab. 2018;28(4):e1665. doi:10.1002/stvr.1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Leithner M, Simos DE. XIEv: dynamic analysis for crawling and modeling of web applications. In: Proceedings of the 35th Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing (SAC ’20); 2020 Mar 30–Apr 3; Brno, Czech Republic. p. 2201–10. [Google Scholar]

17. d Moura TS, Alves EL, d Figueiredo HF, d. S. Baptista C. Automated GUI testing for web applications. In: Proceedings of the XXXVII Brazilian Symposium on Software Engineering; 2023 Sep 25–29; Brasília, Brazil. p. 388–97. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools