Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Sensor Fusion Models in Autonomous Systems: A Review

1 School of Computer Science Engineering and Technology, Bennett University, Greater Noida, 201310, India

2 Multidisciplinary Research Centre for Innovations in SMEs (MrciS), Gisma University of Applied Sciences, Potsdam, 14469, Germany

3 Department of Economics and Business Administration, Universidad de Alcalá, Madrid, 28801, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Varun Gupta. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 6 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071599

Received 08 August 2025; Accepted 23 October 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

This survey presents a comprehensive examination of sensor fusion research spanning four decades, tracing the methodological evolution, application domains, and alignment with classical hierarchical models. Building on this long-term trajectory, the foundational approaches such as probabilistic inference, early neural networks, rule-based methods, and feature-level fusion established the principles of uncertainty handling and multi-sensor integration in the 1990s. The fusion methods of 2000s marked the consolidation of these ideas through advanced Kalman and particle filtering, Bayesian–Dempster–Shafer hybrids, distributed consensus algorithms, and machine learning ensembles for more robust and domain-specific implementations. From 2011 to 2020, the widespread adoption of deep learning transformed the field driving some major breakthroughs in the autonomous vehicles domain. A key contribution of this work is the assessment of contemporary methods against the JDL model, revealing gaps at higher levels- especially in situation and impact assessment. Contemporary methods offer only limited implementation of higher-level fusion. The survey also reviews the benchmark multi-sensor datasets, noting their role in advancing the field while identifying major shortcomings like the lack of domain diversity and hierarchical coverage. By synthesizing developments across decades and paradigms, this survey provides both a historical narrative and a forward-looking perspective. It highlights unresolved challenges in transparency, scalability, robustness, and trustworthiness, while identifying emerging paradigms such as neuromorphic fusion and explainable AI as promising directions. This paves the way forward for advancing sensor fusion towards transparent and adaptive next-generation autonomous systems.Keywords

Sensor fusion represents one of the most transformative technologies in modern autonomous systems, enabling machines to perceive and interpret their environment with unprecedented accuracy and reliability. The fundamental principle underlying sensor fusion is the combination of data from multiple sensors to create a more comprehensive understanding than would be possible using individual sensors alone [1]. This technological paradigm has evolved from simple data combination techniques to applications of classical mathematical models to sophisticated Artificial Intelligence-driven approaches capable of real-time decision-making in complex, dynamic environments. The historical development of sensor fusion can be traced back to the 1950s, when military applications first demonstrated the potential of combining multiple radar systems for enhanced target detection [2]. The concept gained significant momentum in the 1960s when mathematicians developed algorithmic frameworks for multi-sensor data integration, laying the groundwork for modern fusion architectures. The establishment of the Joint Directors of Laboratories (JDL) Data Fusion Subpanel in 1986 marked a pivotal moment in the field, introducing standardized models and terminology that continue to influence contemporary research [3].

Modern autonomous systems in diverse domains such as autonomous vehicles and unmanned aerial systems, healthcare monitoring, and defense applications rely heavily on sensor fusion to achieve reliable operation in real-world environments [4,5]. These systems rely on a multitude of sensors to perceive their environment and make informed decisions. The integration of sensors such as LiDAR, cameras, radar, Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), and GPS enables these systems to overcome the inherent limitations of individual sensors while capitalizing on their complementary strengths [6,7] Sensor data fusion is essential for these systems to integrate heterogeneous, high-volume, real-time data and derive a coherent understanding of surroundings [8,9]. However, an interesting finding is that the rise of powerful AI methods has overshadowed the original spirit of hierarchical fusion, with little substantive advancement occurring at the higher fusion levels.

The emergence of Explainable AI (XAI) to address the black-box nature of deep learning systems by providing interpretable insights into fusion decisions has benefitted sensor fusion for reliable decision-making. Visual explanations are being developed for autonomous systems [10,11]. This development is particularly significant for autonomous vehicles and medical applications, where understanding the reasoning behind system decisions is essential. However, the complexity of explainability methods needs to be reduced for producing explanations in real-time [10,12]. Contemporary research trends also emphasize edge AI deployment and neuromorphic computing as promising directions to achieve ultra-efficient sensor fusion with minimal latency. These approaches enable real-time processing directly on the sensor nodes, reducing communication overhead and improving the responsiveness of the system while maintaining low power consumption [13,14].

This review paper has been written with the objective of putting into context the evolution of sensor fusion methods. It seeks to trace how foundational models developed at a time when computational and sensing resources were limited have set the stage for contemporary approaches. The paper highlights the evolution in the design philosophies, techniques and application domains of sensor fusion. The study revealed that the probabilistic and rule-based models are largely being replaced by machine learning approaches. Due to this, sensor fusion research has now moved from concept-driven formulations to data-driven, adaptive, and context-aware systems.

Unlike prior reviews, this work offers a multi-era synthesis that traces the evolution of sensor fusion from early probabilistic and rule-based frameworks to modern AI/ML-based architectures. Explicitly, the fusion layers of traditional models are applied to contemporary AI/ML pipelines, exposing gaps at higher fusion levels where implementation remains limited. Furthermore, this survey provides broad coverage across domains that include transportation, healthcare, defense, agriculture, industry, and smart cities, far beyond the narrower focus of earlier surveys. Finally, the emerging paradigms such as neuromorphic computing, edge AI, and explainable AI are also positioned as promising directions for next-generation sensor fusion systems. These contributions distinguish our review from existing literature and are useful both for researchers and practitioners. This survey spans four decades of sensor-fusion research—from probabilistic and rule-based methods in the 1980s–1990s, through Bayesian and filtering approaches of the 2000s, to deep-learning and transformer approaches of the 2010s–post-2021, and neuromorphic paradigms in recent times. The classical data-fusion frameworks have been integrated to adopt a unified reference hierarchical sensor-fusion framework with following levels: Level 0—signal preprocessing; Level 1—object refinement, Level 2—situation assessment, Level 3—impact/threat assessment, and Level 4—process refinement. A key contribution of this survey is to situate fusion methods within their historical foundations, highlighting existing challenges and future opportunities.

This discussion has been organized in the remainder of the paper as follows. The research method adopted for the review is presented in Section 2. It also outlines the limitations of existing reviews in this area. In Section 3, the types of sensors used in various application areas of autonomous systems has been explained, and the characteristics of the sensor data has been described, leading to challenges in sensor fusion. The four-decade evolution of sensor fusion from the early 1980s to the current day has been described in Section 4. This section reviews the evolution of sensor fusion models, analyzes their effectiveness, and charts the way forward. Section 5 describes the development of layered fusion models and details the methods mapped to each level. Section 6 discusses the future research directions within this field. The paper is concluded in Section 7.

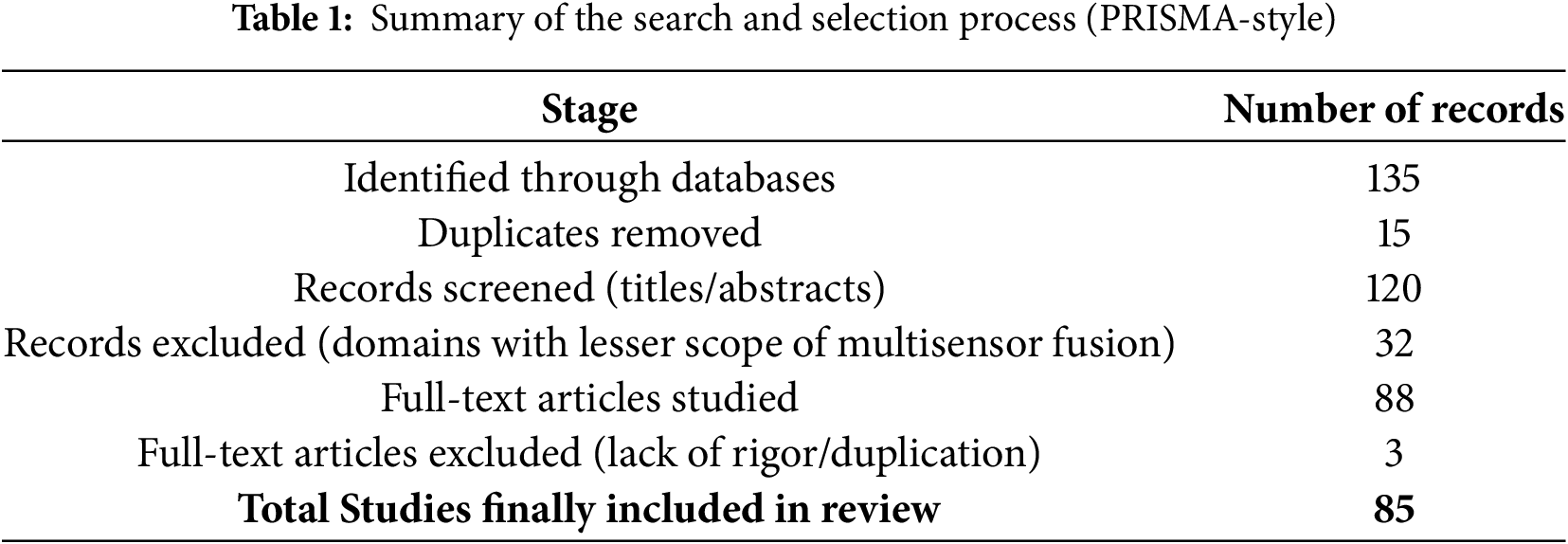

In line with systematic review practices [15], the search and selection process followed a structured PRISMA-style workflow. Publications spanning from the early 1980s through May 2025 were retrieved from major scientific databases, including IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, and arXiv. Seminal surveys and foundational works on classical sensor fusion were used as anchors to expand the search, ensuring both breadth and depth of coverage.

Identification. A total of 135 records were initially identified through database searches. These encompassed peer-reviewed journals, highly cited conference proceedings, authoritative book chapters, and selected arXiv preprints. Benchmark surveys and seminal contributions were also incorporated to establish the initial reference base.

Screening. Following the removal of 15 duplicates, 120 records were screened at the title and abstract level. At this stage, priority was given to studies addressing sensor fusion in autonomous system domains such as transportation, healthcare, defense, robotics, agriculture, and smart cities. Thirty-six records were excluded as irrelevant, leaving 84 studies for full-text assessment.

Eligibility. Full-text evaluation was then performed on these 84 studies to ensure that each (a) proposed, applied, or critically reviewed sensor fusion models or techniques; (b) documented applications in autonomous domains; and (c) addressed either classical (model-driven) or contemporary (AI/ML-based) approaches. Studies lacking methodological rigor, technical clarity, or empirical results were excluded. This led to the removal of 3 articles that failed to meet eligibility criteria.

Inclusion. A final set of 81 studies was included in the review corpus. These works collectively support a multi-era synthesis mapping classical models to modern AI/ML pipelines and incorporating emerging paradigms such as neuromorphic and quantum-inspired fusion. Extracted content was consolidated into thematic tables covering chronological and technological milestones, application-specific deployments and challenges, and comparative insights across classical and modern approaches.

The overall workflow is summarized in Table 1.

While every effort was made to ensure comprehensiveness, limitations remain. The review is constrained by the availability of published results only, without inclusion of unpublished industrial reports, internal datasets, or simulations. Given the vastness of the field, some subdomains may not have been fully represented. Despite these constraints, the structured and transparent approach adopted here ensures both analytical rigor and reproducibility, offering a panoramic yet critical view of the sensor fusion landscape. This foundation informs researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by situating contemporary developments within their historical and methodological contexts.

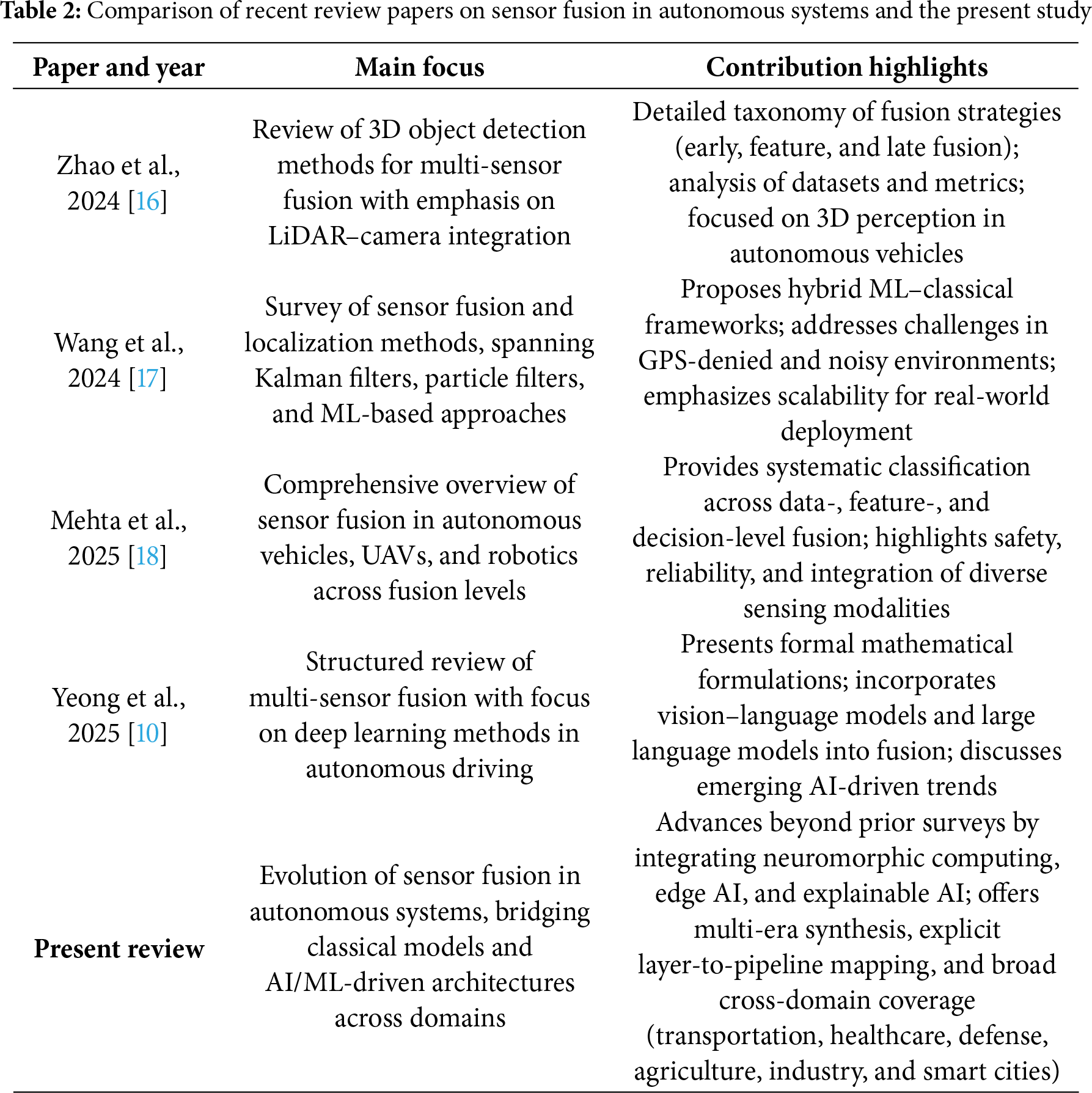

Table 2 summarizes salient features of recent state-of-the-art surveys and demonstrates how the present review advances the literature through a unique multi-era synthesis, explicit mapping from fusion layers to AI/ML pipelines, and broad cross-domain coverage.

3 Characteristics of Sensor Data

Sensor data in autonomous systems tends to be multi-modal (originating from different sensor types), high-dimensional, voluminous, and generated in real time. These data often contain noise and uncertainties specific to each sensor. Moreover, the data rates can be extremely high, reaching gigabytes per second. Thus, efficient pre-processing (filtering, calibration, compression) is needed prior to fusion. Data may also be heterogeneous in format and scale, requiring transformation into common representations or extraction of intermediate features.

Another important aspect is the context-dependence and non-stationarity of sensor data. Sensors operate under varying conditions (day/night, clear/rainy, highway/city), which directly affect data quality. Fusion systems must be robust to such variations, for example by dynamically weighting sensor contributions (e.g., relying more on radar in heavy rain). Synchronization among sensors is equally critical, as misaligned timestamps can propagate into significant fusion errors.

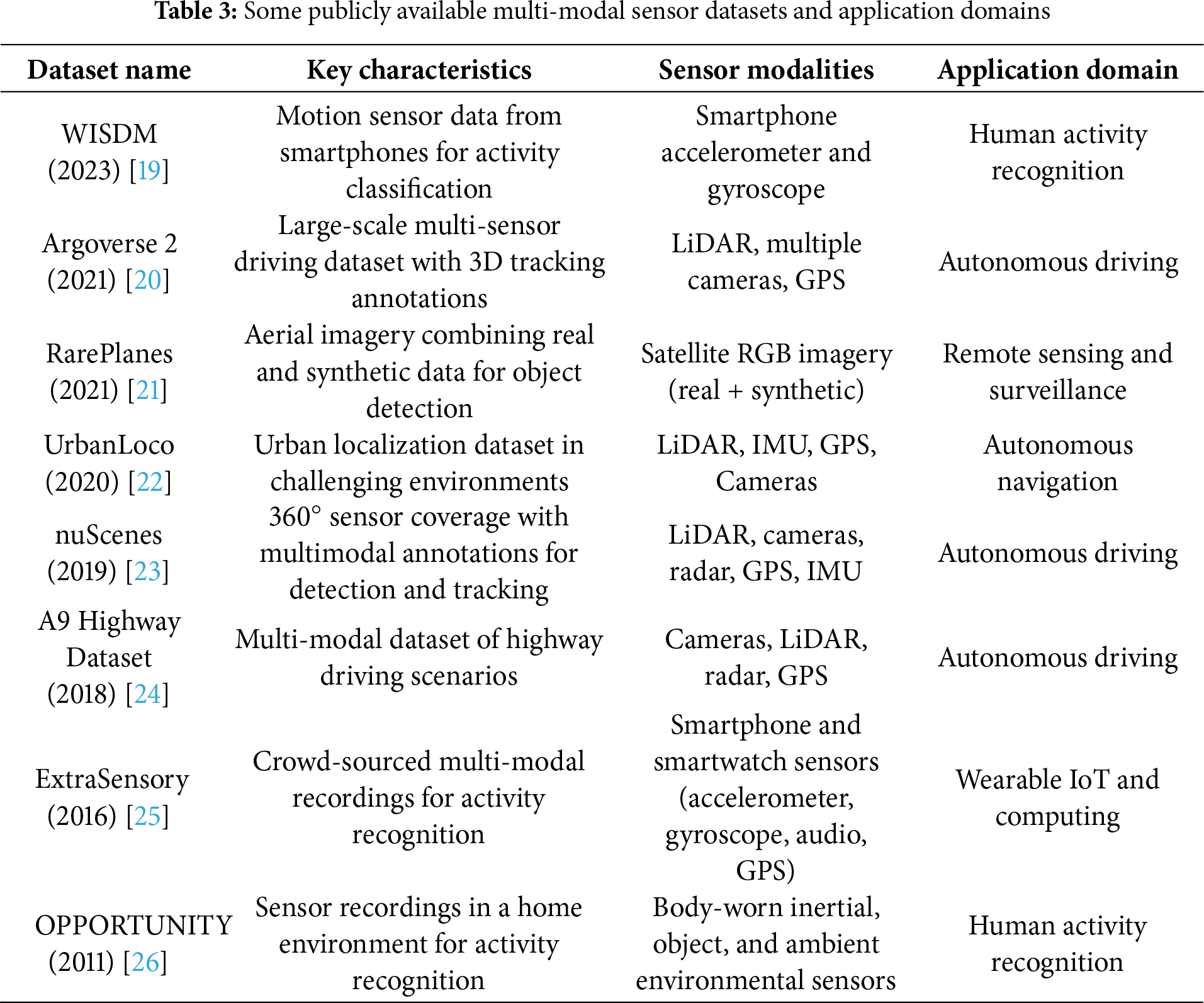

To illustrate the diversity of sensor data used in autonomous systems, Table 3 provides examples of benchmark datasets across domains such as autonomous driving, wearable computing, and remote sensing. These datasets exemplify the modalities and scenarios available to researchers for developing and evaluating fusion methods.

The datasets included in Table 3 were chosen because they represent widely recognized benchmarks within their respective domains and are frequently cited in state-of-the-art sensor fusion studies. Their inclusion ensures that the survey reflects the most commonly used testbeds against which fusion methods are evaluated, while also highlighting their limitations in representativeness and domain coverage.

While these benchmark datasets provide valuable testbeds, their utility varies significantly depending on the target application. For instance, large-scale autonomous driving datasets such as Argoverse 2 [20], nuScenes [23], and the A9 Highway dataset [24] are rich in multimodal coverage and support complex perception tasks, but they are often biased toward urban traffic conditions in developed regions. This limits their generalizability to rural or less-structured environments. Similarly, UrbanLoco [22] offers challenging urban localization scenarios but is geographically constrained and may not fully capture cross-regional variations such as GPS multipath in dense high-rise cities. In contrast, human activity and mobile health benchmarks such as WISDM [19], OPPORTUNITY [26], and ExtraSensory [25] demonstrate strong utility for wearable and IoT-driven fusion research. However, many of these datasets are collected in controlled or semi-structured environments, which may not reflect the noise and variability encountered in real-world deployments. They also tend to have limited subject diversity, raising questions about demographic generalizability in healthcare applications. Remote sensing benchmarks such as RarePlanes [21] highlight another dimension: the fusion of synthetic and real data for training. While this enables large-scale dataset generation, it also introduces a domain gap between simulated and operational settings, complicating transferability of models trained exclusively on such data. Overall, Table 3 underscores both the breadth of sensor modalities represented and the uneven distribution of benchmarks across domains. Autonomous driving enjoys abundant and well-annotated datasets, while healthcare, smart cities, and industrial domains remain comparatively underrepresented. This imbalance constrains cross-domain fusion research and highlights a critical need for more diverse, standardized, and globally representative datasets. Without such resources, fusion models risk overfitting to narrow operational conditions and may fail when transferred to new environments. Overall, Table 3 underscores both the breadth of sensor modalities represented and the uneven distribution of benchmarks across domains. Autonomous driving enjoys abundant and well-annotated datasets, while healthcare, smart cities, and industrial domains remain comparatively underrepresented. This imbalance constrains cross-domain fusion research and highlights a critical need for more diverse, standardized, and globally representative datasets. Without such resources, fusion models risk overfitting to narrow operational conditions and may fail when transferred to new environments. A further consideration is the inherent trade-offs among these datasets. Large-scale benchmarks such as nuScenes and Argoverse 2 provide extensive multimodal coverage but sacrifice diversity across geographic and environmental contexts. Conversely, smaller datasets like OPPORTUNITY and ExtraSensory capture rich multimodal signals in daily-life settings but lack the scale needed for training data-intensive models. Synthetic-enhanced datasets such as RarePlanes expand coverage at low cost yet introduce a domain gap that complicates real-world transferability. These trade-offs between scale, diversity, realism, and generalizability must therefore be carefully weighed when selecting benchmarks for evaluating sensor fusion methods.

4 Evolution of Sensor Fusion: A Four-Decade Perspective

The evolution of sensor fusion techniques over the past four decades represents a remarkable journey from basic mathematical algorithms to sophisticated AI-driven systems. Recent proliferation of complex sensor arrays and the need for real-time and adaptive fusion have driven the adoption of deep learning, transformer architectures, and energy-efficient neuromorphic computing, enabling autonomous systems to achieve new levels of perception and autonomy. Over the years, numerous sensor fusion models have been proposed. In this section, a decade-wise review of the evolution of sensor fusion is given. A hybrid perspective integrating traditional fusion architectures to a unified hierarchical model is also proposed.

4.1 Some Popular Early Fusion Models and Frameworks

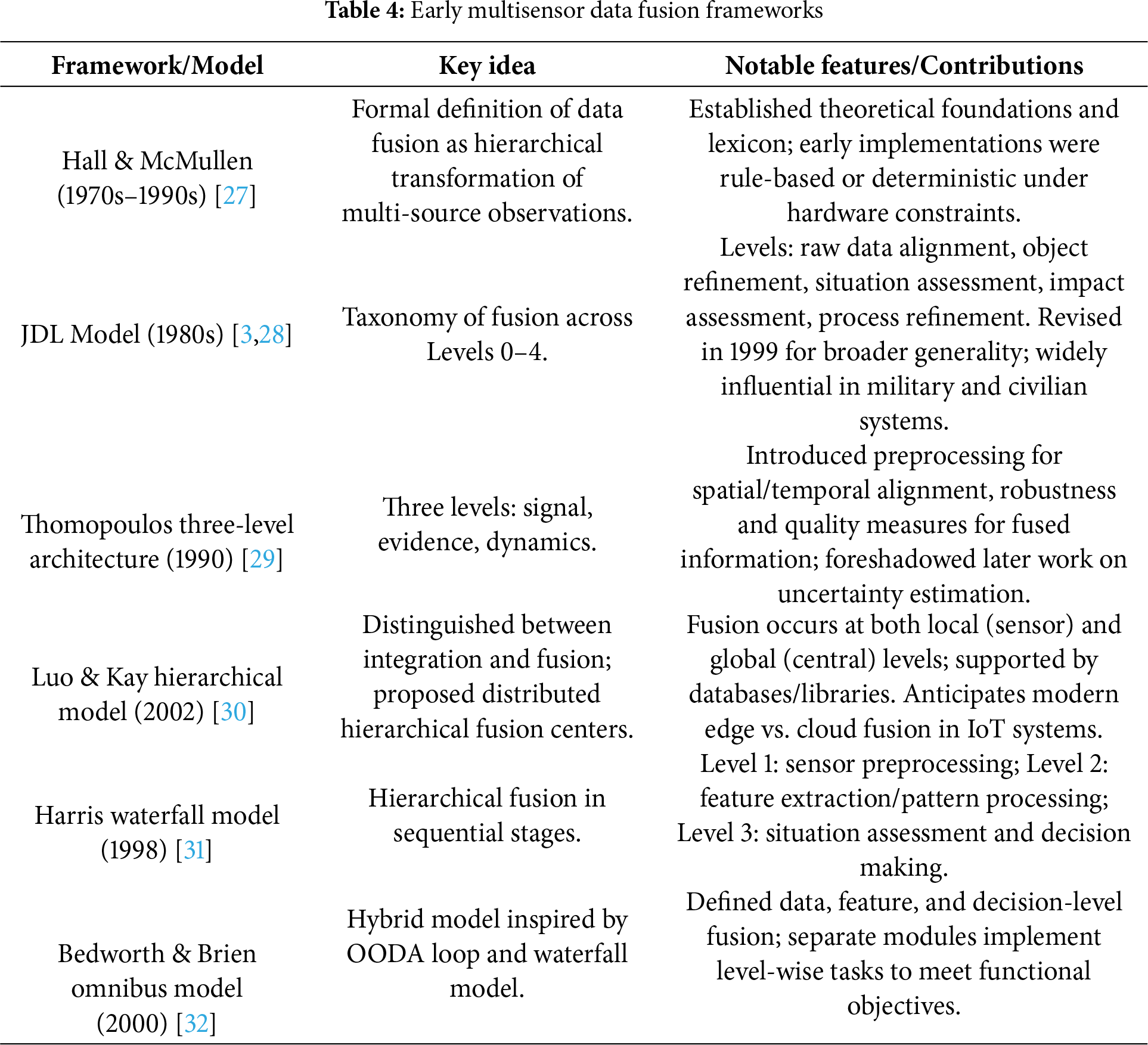

The concept of multisensor data fusion dates back to the 1970s in the context of robotics and defense. Early work focused on establishing theoretical foundations and lexicons for combining data from multiple sources within permissible time frames. A widely cited definition by Hall and McMullen described data fusion as a ’hierarchical transformation of observed data from multiple sources into a form that enables decision making’ [27]. In practice, many initial fusion systems were deterministic or rule-based aimed at achieving specific fusion goals under hardware constraints of the time.

One pioneering framework was the Joint Directors of Laboratories (JDL) Data Fusion Model [3]. Developed in the military community in the 1980s, the JDL model defined a taxonomy of fusion across levels 0 to 4: from raw data alignment, to object refinement (state estimation), situation assessment, impact assessment, and process refinement. It emphasized combining sensor observations to estimate object identity and position, originally for surveillance/tracking applications. Steinberg et al. later revised the model in 1999 to refine these levels and generalize it to broader situations [28]. The layered approach of the JDL framework influenced many subsequent system designs, ensuring that each level of fusion produces outputs at increasing levels of abstraction. Although conceived for military sensing, the concepts of the JDL model are applicable to any multisensor system.

Around the same time, reference [29] proposed a simpler three-level architecture for sensor fusion. The lowest level dealt with raw signal fusion (often requiring training to learn correlations between sensors); the intermediate “evidence” level fused features or evidence using statistical methods (with spatial/temporal alignment as a preprocessing step); the highest “dynamics” level fused information in the context of system dynamics or models. Reference [29] introduced performance indicators such as the quality of fused information and robustness to uncertainties, which foreshadowed later work on fusion confidence and uncertainty estimation.

Another influential early framework was by Luo and Kay [30], who distinguished between multi-sensor integration (using multiple sensors to reach one decision) and multi-sensor fusion. They proposed hierarchical structure with distributed fusion centers, highlighting that fusion could occur at different hierarchy levels of a system. The data collected at the sensor level is integrated at the fusion centers, where the actual fusion is done. After processing all sensors, domain-specific high-level information of interest is obtained. The fusion process is supported by relevant databases and libraries. In the process of fusion, raw signals from individual sensors are abstracted to symbolic information. This idea of performing some fusion locally (sensor node level) and some globally (central level) is reflected in today’s edge vs. cloud fusion split in IoT systems.

Harris et al described another example of hierarchical fusion called the waterfall model [31]. The hierarchical levels are similar in essence as the earlier models with an emphasis on the processing functions of the lower levels. Sensors pre-processing is done at at level 1 while feature extraction and pattern processing in level 2. It is followed by situation assessment and decision making being done at level 3. Conceptually, the processed signal from level 1 are converted to fetaures in level 2 that leads to state description and querying in Level 3 of the model.

Bedworth and Brien [32] described a hybrid framework called the Omnibus model. This process model was inspired by conceptual OODA (Observe, Orient, Decide and Act) cycle called Boyd loop and the waterfall model. Various tasks in data fusion and its functional objectives are realized in different modules. Three levels of data fusion, that is, data, feature and decision level have been defined. Separate modules implement various level-wise tasks and meet their functional objectives.

Several foundational frameworks emerged during the 1970s–2000s that established the theoretical and architectural basis for multisensor data fusion. Table 4 summarizes these early models, highlighting their central ideas and lasting contributions. The JDL model remains one of the most influential, while subsequent frameworks such as the three-level architecture, waterfall model, and Omnibus model introduced alternative perspectives emphasizing hierarchy, distributed processing, and hybrid design. Collectively, these models shaped the evolution of modern sensor fusion approaches.

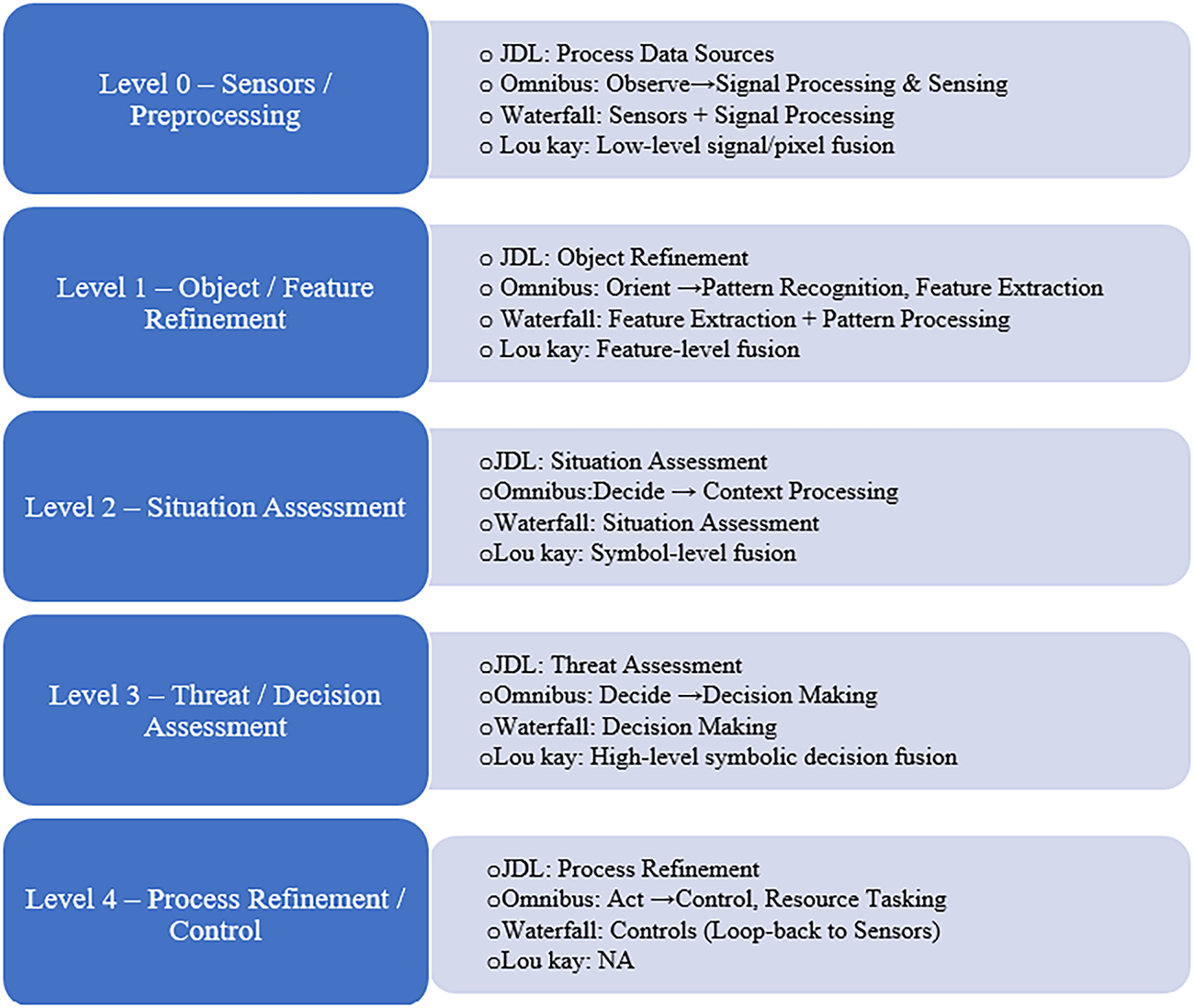

A common feature of all models discussed till now is the hierarchical transformation of data. This higher-level integration of locally processed sensor data at intermediate or final nodes can be suitably applied to modern autonomous systems also. Interestingly, although these models were proposed more than a decade apart, they embody the same fundamental principle of hierarchical fusion, where both the level of cognizance about the system and the granularity of information progressively increase across successive layers. To systematically map the actual fusion models deployed in autonomous systems, we first developed a unified architecture that aligns the levels proposed by different frameworks and examined the extent of consensus among them. The rationale for this integration lies in the observation that, despite differences in terminology and chronology, all major fusion frameworks embody a common principle of hierarchical refinement: data is progressively transformed from raw sensor measurements into higher-level situational understanding and decision support. By aligning these frameworks, we expose the underlying consensus of established fusion frameworks. The unified model draws upon the Joint Directors of Laboratories (JDL) data fusion model, which has been briefly introduced earlier, it is elaborated here to provide the rationale for harmonizing different models. The JDL levels can be summarized as follows:

1. Level 0: Sub-Object Data Assessment (Source Preprocessing)—Deals with raw sensor data (signals, features, pixels, etc.), encompassing tasks such as noise filtering, feature extraction, registration, and alignment. Example: Cleaning raw radar or camera data and synchronizing sensing rates before applying detection algorithms.

2. Level 1: Object Refinement—Integrates features to form objects/entities and estimate their states, involving tasks such as detection, tracking, identification, and classification. Example: Detecting and tracking a vehicle using fused radar and camera data.

3. Level 2: Situation Assessment—Develops an understanding of relationships among objects and the environment, covering tasks such as scene analysis, intent recognition, and context modeling. Example: Recognizing that multiple vehicles are forming a traffic jam.

4. Level 3: Impact (Threat) Assessment—Focuses on predicting the future state and potential consequences of the situation, including threat assessment, risk prediction, and decision support. Example: Predicting that a speeding car may cause a collision.

5. Level 4: Process Refinement (Resource Management)—Controls and improves the fusion process itself, with tasks such as sensor management, adaptive fusion strategies, and feedback optimization. Example: Directing a drone to collect additional data in regions of high uncertainty.

6. Level 5: User/Cognitive Refinement (extension)—Accounts for human–machine interaction, including visualization, operator decision support, and incorporating human feedback.

By aligning the JDL model with other popular frameworks, an integrated multisensor fusion model has been shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: A hierarchical unified multisensor fusion model

Traditional models established the architectural blueprints and terminology for sensor fusion. These can also be related to modern autonomous systems, as raw data from multiple sensors of autonomous systems must undergo several processing stages to become actionable information. In the next sections, we will discuss the historical trajectory of sensor fusion over the past four decades, examining how each decade introduced new sensors, fusion strategies, and application domains that collectively shaped the current state-of-the-art.

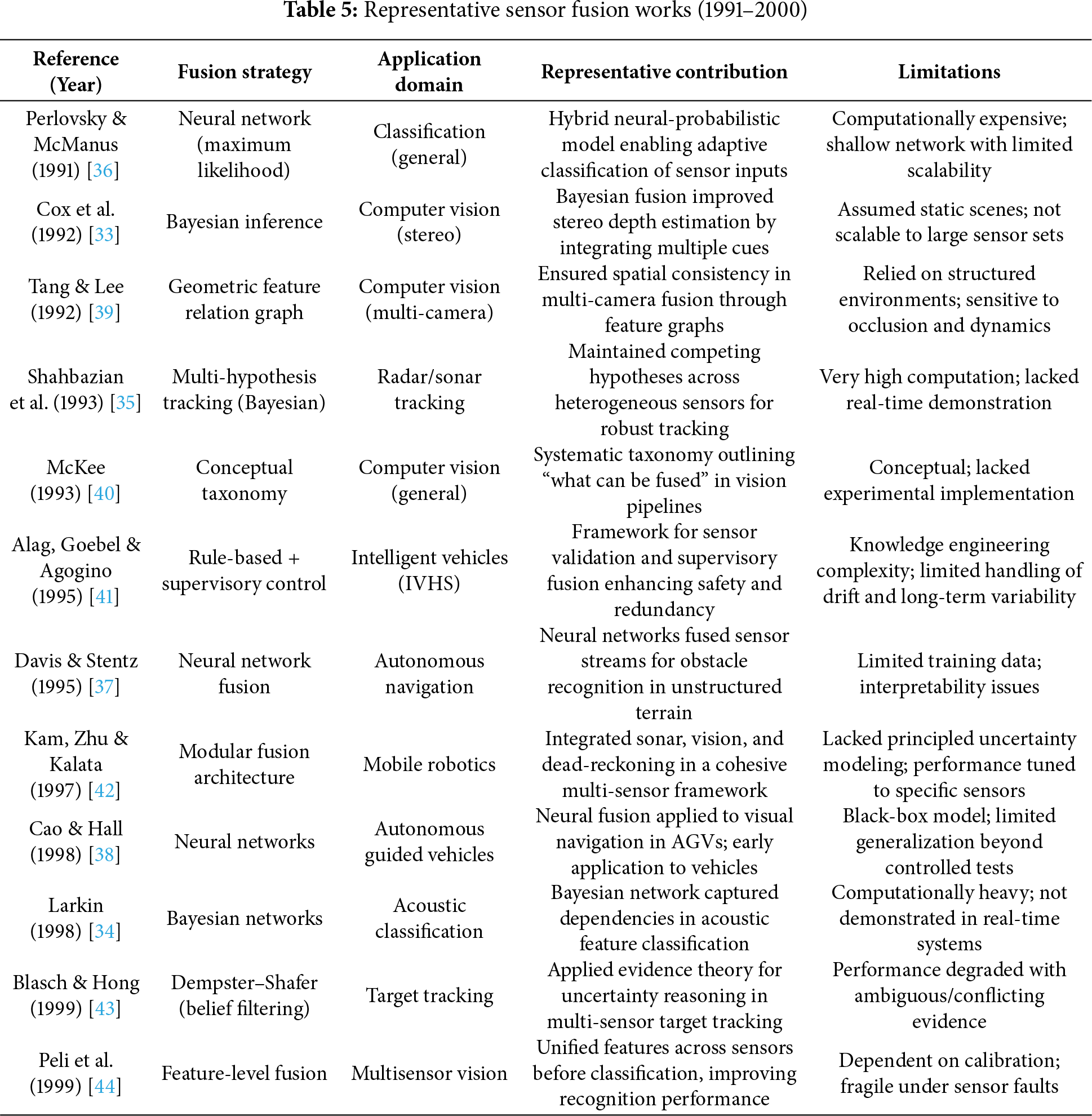

4.2 Foundational Fusion Approaches of the 1990s

The 1990s marked a decisive transition in sensor fusion research, moving from conceptual discussions to increasingly concrete algorithmic implementations. Researchers explored a broad range of strategies to address uncertainty, adaptability, and system integration, with varying degrees of success. Key categories included probabilistic inference methods, neural network–based approaches, rule-based and evidence-theoretic reasoning, feature-level integration, and modular hybrid architectures. Collectively, these approaches laid important foundations, though they were frequently constrained by computational power and often tailored to narrow application contexts.

Probabilistic Fusion Methods: Probabilistic inference emerged as a rigorous framework for handling uncertainty. Cox et al. (1992) applied Bayesian inference to stereo vision, showing that probabilistic depth estimation could outperform deterministic triangulation by integrating evidence from stereo pairs [33]. Larkin (1998) used Bayesian networks to classify acoustic signals, explicitly capturing dependencies among features [34]. Shahbazian et al. (1993) introduced multi-hypothesis tracking, allowing radar and sonar to jointly maintain competing target hypotheses [35]. While these approaches formalized uncertainty propagation, their computational cost scaled poorly with the number of sensors, preventing real-time deployment in dynamic environments.

Neural Network-Based Methods: The growing availability of computational resources encouraged early use of neural networks for adaptive fusion. Perlovsky and McManus (1991) presented a maximum-likelihood neural network that adaptively classified sensor inputs, blending statistical estimation with learning [36]. Davis and Stentz (1995) demonstrated neural networks for autonomous outdoor navigation, where fused vision and range inputs were mapped to obstacle recognition in unstructured terrains [37]. Similarly, Cao and Hall (1998) applied neural networks to autonomous guided vehicles (AGVs) for vision-based navigation [38]. These methods demonstrated adaptability and the ability to capture nonlinear inter-sensor dependencies, but were shallow by modern standards, trained on limited data, and lacked interpretability, restricting their robustness in diverse conditions.

Rule-Based and Evidence-Theoretic Approaches: Rule-driven frameworks also played an important role. McKee (1993) proposed a taxonomy of “what can be fused” for vision systems, providing systematic guidance for constructing integration pipelines [40]. Blasch and Hong (1999) implemented Dempster–Shafer evidence theory in a “belief filtering” mechanism for target tracking [43]. This enabled reasoning under partial or conflicting evidence without requiring strict prior probabilities. Rule-based systems were transparent and interpretable, but generalization was limited, and belief combination rules were difficult to tune when ambiguity was high.

Feature-Level Fusion: Several works moved beyond raw data integration to focus on fusing intermediate representations. Tang and Lee (1992) proposed geometric feature relation graphs to preserve spatial consistency across multi-camera vision sensors [39]. Peli et al. (1999) introduced unified feature-level fusion before classification, improving recognition accuracy in multisensor vision systems [44]. These approaches demonstrated the utility of fusing more compact representations rather than raw data, reducing computational demands. However, they relied on precise calibration and were sensitive to occlusion, noise, and sensor failures.

Application-Specific Architectures: The decade also produced domain-tailored modular architectures. Kam, Zhu, and Kalata (1997) developed one of the earliest multi-sensor frameworks for mobile robots, integrating sonar, vision, and dead-reckoning [42]. Alag, Goebel, and Agogino (1995) proposed a supervisory fusion framework for Intelligent Vehicle Highway Systems (IVHS), emphasizing fault detection, redundancy, and supervisory control [41]. Beyond robotics, Mandenius et al. (1997) applied fusion in industrial bioprocessing, combining chemical and process sensors for real-time monitoring [45]. These architectures highlighted the feasibility of embedding fusion into control pipelines, but remained tightly coupled to specific sensor suites, limiting scalability and cross-domain applicability.

Overall, the 1990s advanced sensor fusion by formalizing uncertainty modeling, exploring adaptive neural approaches, and embedding fusion into practical systems. As summarized in Table 5, most methods remained constrained by high computational demands, narrow scope, and lack of real-time generalizability. Yet, they established enduring design principles—probabilistic rigor, adaptive learning, interpretable reasoning, and modular integration—that continue to influence sensor fusion research today.

By the end of the decade, sensor fusion had matured from theoretical constructs to operational prototypes in vision, robotics, defense, and industrial applications. However, most systems were specialized, computationally demanding, and lacked generalizable frameworks. The subsequent decade (2000–2010) witnessed increasing convergence and the emergence of machine learning as a unifying tool for sensor fusion across domains.

4.3 Contemporary Models: 2001–2010—Early Machine Learning Era

Building upon the foundational probabilistic, neural, and rule-based strategies of the 1990s, sensor fusion research in the 2000s advanced toward greater methodological rigor and broader applicability. Several developments characterized this decade: the extension of probabilistic filters for nonlinear and non-Gaussian systems, the integration of Bayesian and evidence-theoretic reasoning, the rise of distributed consensus schemes for multi-agent settings, and the early adoption of machine learning techniques to learn fusion mappings from data rather than relying solely on handcrafted rules. Collectively, these advances established many of the algorithmic templates that would later be scaled and generalized in the deep learning era.

Probabilistic Filtering and Bayesian Extensions: Kalman filter variants dominated this period, particularly in navigation and tracking tasks. The Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) and Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) were widely adopted for fusing inertial measurement units (IMUs) with GPS data, enabling more reliable state estimation under nonlinear dynamics [46]. Coué et al. (2002) applied Bayesian programming to automotive state estimation, demonstrating how Bayes filters could flexibly combine sonar, odometry, and other modalities under uncertainty [47]. Particle filters emerged as an important alternative, addressing limitations of Kalman-based methods by accommodating non-Gaussian noise and multimodal posterior distributions. These probabilistic methods significantly improved robustness in early autonomous robots and vehicles, although they remained computationally demanding for high-dimensional state spaces.

Rule-Based Evolution and Evidence-Theoretic Integration: Rule-based fusion was refined into more mathematically grounded frameworks. Koks and Challa (2003) proposed combining Bayesian methods with Dempster–Shafer (D–S) evidence theory, providing a hybrid reasoning scheme capable of fusing probabilistic estimates with uncertain or incomplete evidence [48]. This integration allowed richer representations of belief states but incurred high computational cost as sensor sets scaled. Distributed consensus algorithms also gained prominence in this era. Xiao et al. (2005) introduced a consensus-based scheme that enabled sensor networks or multi-robot systems to achieve agreement on global state estimates despite each node holding only partial information [49]. These approaches were particularly important for wireless sensor networks (WSNs), where centralized fusion was often infeasible.

Machine Learning for Fusion Mappings: A key innovation was the move toward learning fusion rules directly from data. Faceli et al. (2004) proposed a hybrid intelligent framework combining neural networks, fuzzy inference, and decision trees, allowing the system to adaptively determine fusion weights and mappings [50]. While deep learning was not yet viable, simpler models such as multilayer perceptrons and fuzzy systems demonstrated the feasibility of training adaptive fusion models. These early machine learning–driven systems reduced reliance on handcrafted rules, though their learning capacity was limited by data availability and computational constraints.

Decision-Level and Classifier Fusion: Decision-level fusion became increasingly popular for classification tasks. Instead of integrating raw signals, systems combined outputs of independent classifiers trained on individual sensor modalities. For instance, in wearable human activity recognition (HAR), classifiers based on accelerometers and gyroscopes could be fused via voting or weighted averaging to yield more robust predictions. This ensemble approach improved resilience to sensor failures and noise. While Chavez-Garcia and Aycard (2015) [51] formally studied multisensor decision fusion slightly after 2010, their work synthesized principles already established in the late 2000s, particularly in intelligent vehicle perception.

Application-Specific Advances: The decade also saw growing application diversity. Choi et al. (2011) applied hierarchical fusion of RFID and odometry for indoor robot localization, building on techniques developed in the late 2000s [52]. Lu and Michaels (2009) fused ultrasonic sensor data for structural health monitoring under varying conditions, addressing robustness challenges in safety-critical applications [53]. In agriculture, Huang et al. (2007) integrated multiple sensing modalities for precision farming, reflecting the growing role of sensor fusion in environmental and industrial domains [54]. Each domain imposed distinct requirements—low power consumption for wearable devices, high accuracy for aircraft navigation, or resilience to noise and environmental variation for outdoor robotics—driving tailored fusion solutions.

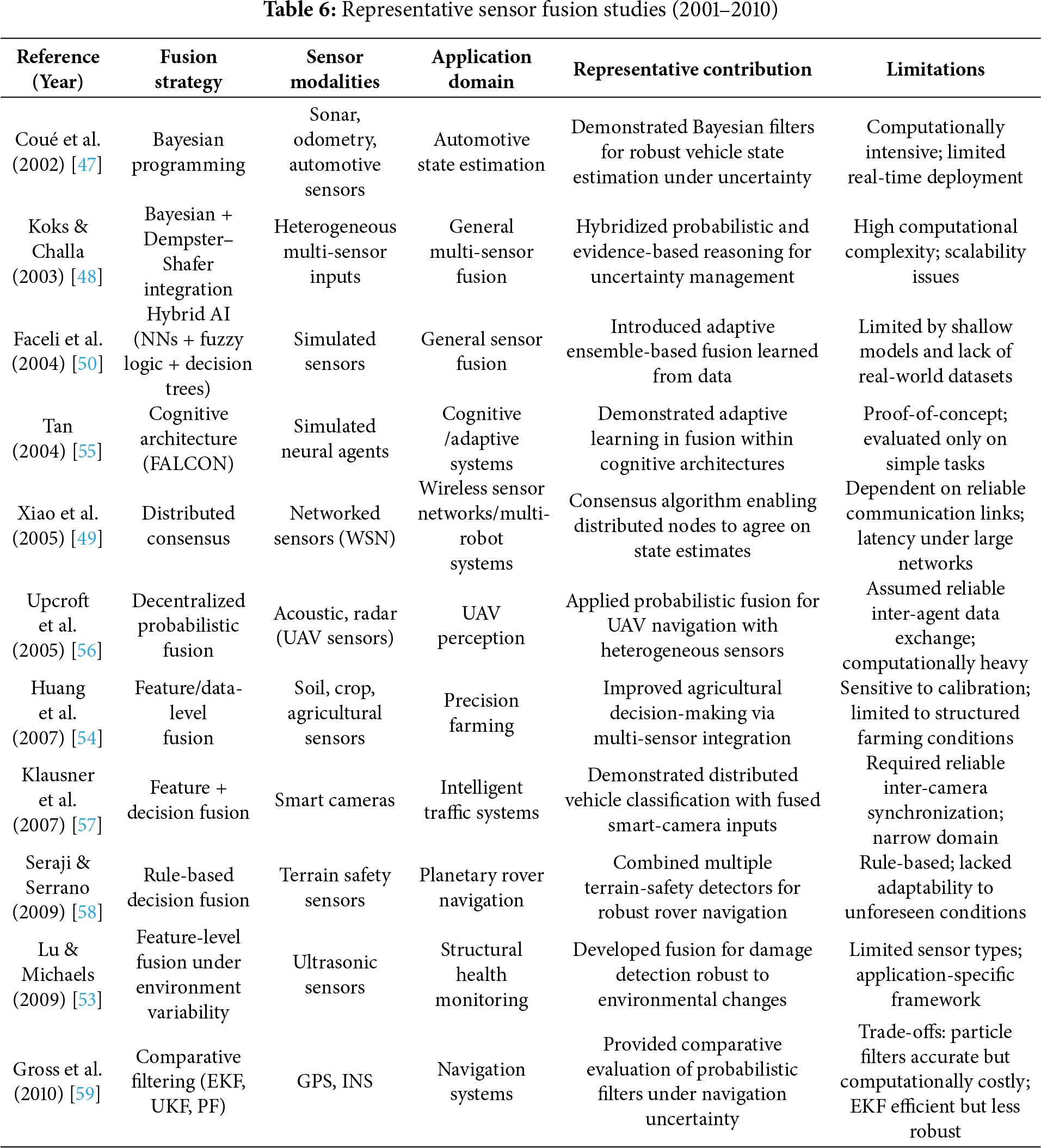

The representative works summarized in Table 6 illustrate how this decade broadened the methodological toolkit. Unlike the 1990s, where most systems were rigidly rule-based or narrowly probabilistic, the 2000s emphasized flexibility through probabilistic generalizations, distributed consensus, and adaptive machine learning. While these advances greatly expanded the scope of sensor fusion, limitations remained, particularly in computational scalability, dependence on expert tuning, and restricted ability to automatically learn complex feature hierarchies. These constraints would soon motivate the adoption of deep learning approaches in the following decade.

In summary, the early 2000s represented an era of methodological consolidation and gradual transition from handcrafted fusion rules toward data-driven adaptability. Probabilistic frameworks were extended to handle nonlinearities and non-Gaussian noise, distributed consensus schemes emerged for networked systems, and hybrid AI methods showcased the potential of learned fusion. While the computational and data limitations of the period constrained progress, this decade equipped the field with versatile building blocks—Kalman filter variants, Bayesian/evidence hybrids, consensus protocols, and ensemble learning—that directly informed the deep learning–driven breakthroughs of the 2010s. These advances thus represent the logical evolution of the 1990s prototypes into more flexible, scalable, and domain-diverse fusion frameworks.

4.4 Contemporary Models: 2011–2020—Transformative Fusion Works

Building upon the probabilistic, rule-based, and early machine learning approaches of the 2000s, the period from 2011 to 2020 marked a decisive transformation in sensor fusion. This shift was driven by three converging factors: the availability of large-scale multimodal datasets, rapid advances in deep learning, and growing deployment of autonomous systems in safety-critical contexts. Fusion models moved from handcrafted pipelines and shallow learners toward end-to-end trainable architectures capable of learning cross-modal representations directly from data. Research during this decade spanned autonomous vehicles, UAVs, precision agriculture, infrastructure monitoring, and wearable human activity recognition, demonstrating both methodological diversity and domain-specific innovation.

Deep Learning–Based Fusion Architectures: One of the most transformative advances was the adoption of deep neural networks for multi-sensor fusion. In autonomous driving, vision and LiDAR fusion evolved from late fusion of independent detections to early and mid-level feature fusion within deep networks. Approaches such as PointNet++ and multimodal convolutional fusion architectures enabled learned feature representations across modalities, significantly improving detection and localization accuracy [60,61]. Unlike handcrafted pipelines, these models could discover optimal cross-modal mappings, albeit at the cost of requiring large annotated datasets and high computational resources.

Distributed and Cooperative Fusion: Another major development was the emergence of cooperative and distributed fusion frameworks, especially for connected autonomous vehicles and IoT-driven systems. Cooperative perception (V2X) allowed vehicles to exchange sensor data, extending situational awareness beyond line-of-sight occlusions. Liu et al. (2023) [62] reviewed this paradigm, which was conceptually established in the late 2010s through simulation-based studies. These works emphasized the need for synchronization, low-latency communication, and consensus protocols, anticipating real-world multi-agent fusion systems.

Domain Diversification and Application-Specific Fusion: Fusion research extended into healthcare, agriculture, and infrastructure. In wearable HAR, Banos et al. (2012) combined accelerometer, gyroscope, and contextual sensors to mitigate noise sensitivity and improve recognition reliability [63]. In precision agriculture, Maimaitijiang et al. (2020) fused UAV imagery, satellite data, and ground-based sensors using machine learning for crop monitoring, enabling multiscale environmental insights [64]. Infrastructure monitoring adopted sensor fusion of accelerometers, strain gauges, and vibration sensors to detect anomalies in bridges and civil structures. These application-specific systems demonstrated that the core fusion principles—robust uncertainty handling, redundancy, and adaptive learning—could generalize across domains.

Reliability, Explainability, and Adversarial Concerns: By the late 2010s, researchers recognized that fusion systems in safety-critical domains required not only empirical accuracy but also transparency and robustness. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques were explored to interpret multimodal fusion decisions, particularly in healthcare and autonomous driving. Simultaneously, adversarial studies revealed vulnerabilities, such as perturbations or physical artifacts that could mislead fused perception systems. This highlighted the need for redundancy-driven architectures, formal verification of fusion pipelines, and design of fail-operational strategies for safety-critical deployments.

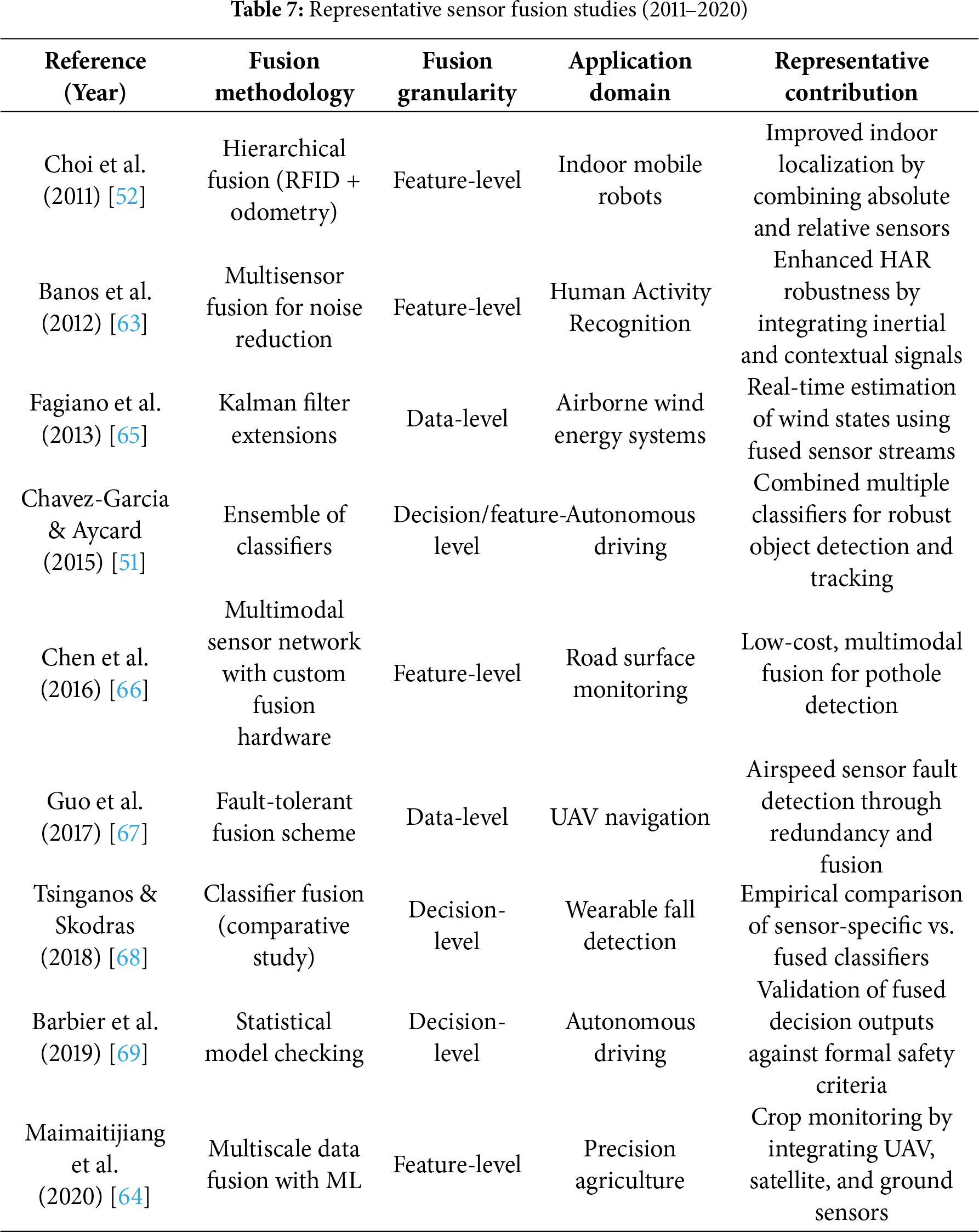

Representative studies from this decade are summarized in Table 7, which highlights the methodologies, fusion granularity, application domains, and technical contributions.

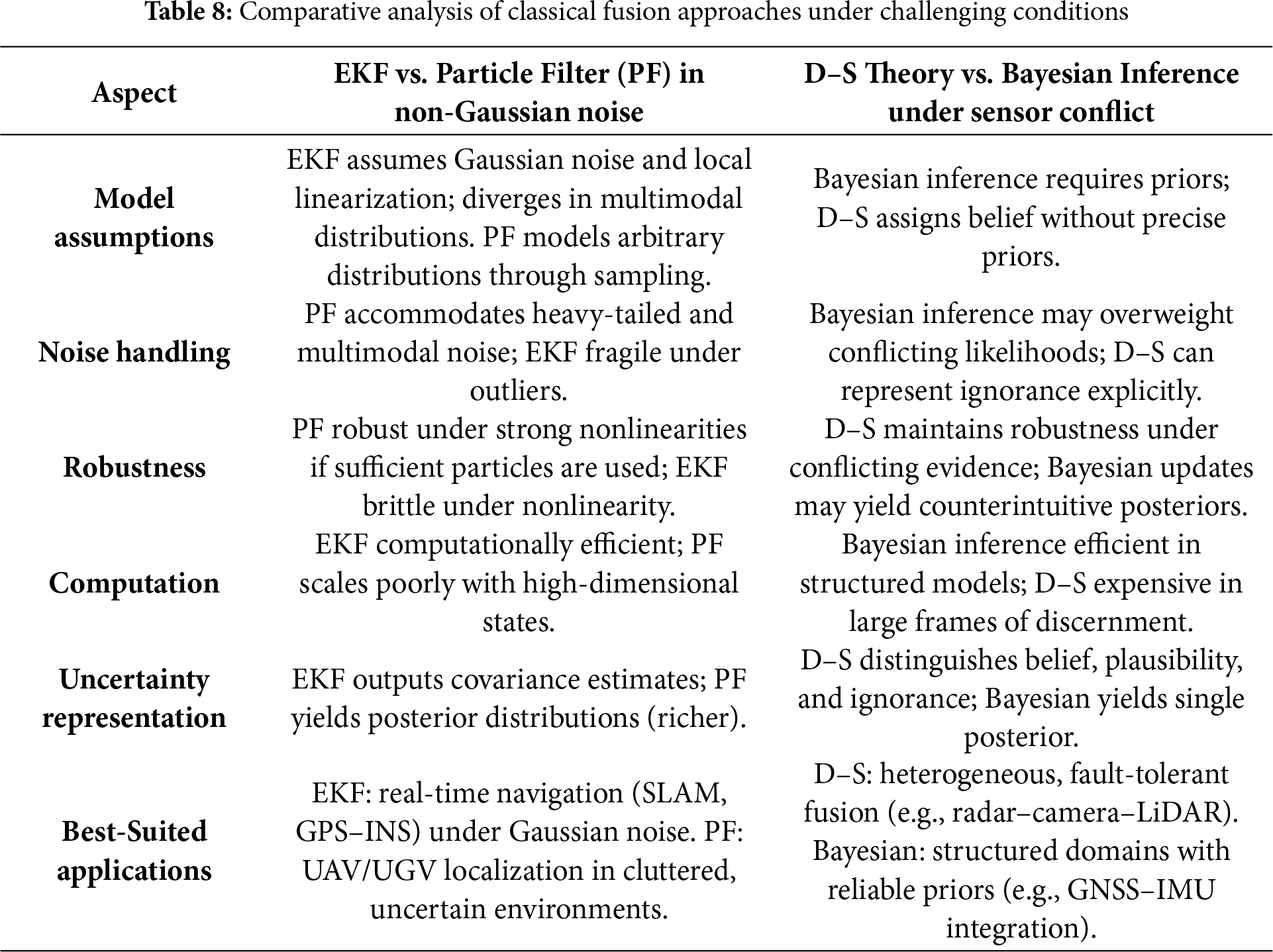

To complement these representative studies, Table 8 presents a focused technical comparison of widely used classical approaches—Extended Kalman Filters (EKF), Particle Filters (PF), Dempster–Shafer (D–S) theory, and Bayesian inference—under challenging conditions such as non-Gaussian noise and conflicting sensor evidence. This highlights the continued relevance of classical filters alongside modern learning-based approaches.

In summary, the 2011–2020 decade marked the transition from handcrafted, model-driven fusion toward data-driven and learned fusion paradigms. Deep learning architectures enabled joint feature representations across heterogeneous modalities, cooperative fusion expanded to multi-agent systems, and application domains diversified beyond vehicles and robots to healthcare, agriculture, and infrastructure. Despite these advances, classical methods such as Kalman filtering and Bayesian inference remained essential, particularly in constrained environments or where formal guarantees were required. The coexistence of classical and AI-driven approaches underscores the versatility of sensor fusion, while ongoing challenges in scalability, robustness, and verifiability continue to motivate research in the current decade.

4.5 Recent Advances: 2021–2025—Toward Robust and Scalable Fusion

Extending the deep learning–driven breakthroughs of the 2010s, sensor fusion research from 2021 onward has accelerated toward tackling real-world deployment challenges. Models are no longer expected to perform well only in controlled datasets but must generalize across environments, sensor suites, and tasks with minimal reconfiguration. This decade has also been marked by the emergence of transformer-based architectures, context-aware dynamic fusion, and practical demonstrations of cooperative perception in multi-agent systems. Fusion has become increasingly pervasive, appearing in domains as varied as autonomous firefighting robots, UAV-based wildlife monitoring, intelligent transportation infrastructure, and healthcare wearables.

Generalizability and Cross-Domain Adaptation: A central focus of this era is improving the robustness and scalability of fusion models. Systems trained on one platform (e.g., a specific vehicle type or city) are increasingly adapted to new conditions with minimal retraining, using transfer learning, domain adaptation, and synthetic-to-real approaches. High-fidelity simulators are leveraged to generate rare or safety-critical scenarios, with adaptation methods ensuring real-world applicability. Physics-informed neural networks emerged as a hybrid approach, embedding sensor physics into learning pipelines to reduce data requirements and enforce physical consistency.

Transformer-Based and Attention Mechanisms: Transformers and attention-based architectures became central to fusion pipelines. Chitta et al. (2022) proposed TransFuser, a transformer-based model that jointly encodes LiDAR and camera streams for autonomous driving [70]. These architectures enable multi-task and cross-modal learning, allowing a single network to perform detection, segmentation, and tracking simultaneously. However, they remain computationally heavy and require large training datasets. HydraFusion (Malawade et al., 2022) extended this by incorporating attention-driven context selection, dynamically weighting sensors depending on environmental conditions [71]. Such adaptive mechanisms improve resilience but increase training complexity.

Edge–Cloud Hybrid Fusion Architectures: The push toward deployment in connected and resource-constrained environments led to hybrid strategies. Edge devices handle low-latency, safety-critical decisions (e.g., obstacle avoidance), while cloud or roadside servers manage computationally intensive tasks such as global route planning or cooperative perception. This split addresses both responsiveness and scalability, though it introduces latency-management and bandwidth-allocation challenges.

Self-Calibration and Fault Tolerance: Autonomous systems now integrate self-diagnostic routines to detect and respond to sensor degradation (e.g., blocked LiDARs, degraded cameras). Multi-sensor redundancy allows systems to isolate and exclude faulty sensors or re-calibrate them dynamically. Tommingas et al. (2025) demonstrated fusion of UWB and GNSS with ML-based uncertainty modeling, highlighting the need for adaptable frameworks capable of self-healing in diverse environments [72].

In the domain of robust navigation, a GNSS/IMU/VO fusion framework with multipath inflation factor has been proposed to explicitly mitigate the challenges of urban multipath interference. By leveraging real-time IMU and VO inputs, the system dynamically adjusts GNSS weighting and adaptively updates VO velocity variance within a robust extended Kalman filter. Field tests in dense urban areas demonstrated 63.4% and 56.1% improvements in horizontal and 3D positioning accuracy, respectively, over conventional fusion schemes [73]. This work highlights the importance of incorporating environment-aware weighting models for next-generation positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) systems. Beyond terrestrial navigation, recent work has demonstrated the value of multi-sensor association for high-precision space target localization. By fusing visible light and infrared detection with laser ranging under a Gaussian mixture TPHD framework, this approach achieves great accuracy, outperforming binary star angular-only methods [74]. This highlights how sensor fusion enables unprecedented precision in space situational awareness and orbital tracking.

Diversified Applications: Healthcare, smart cities, and environmental monitoring benefited significantly. Rashid et al. (2023) developed SELF-CARE, a wearable fusion framework for stress detection, combining multiple biosignals with context identification [75]. Hasanujjaman et al. (2023) fused autonomous vehicle and CCTV camera data for smart traffic management [76]. In addition, advances in embedded ultra-precision sensing have expanded the scope of sensor fusion to metrology and industrial domains. A recent study introduced a fiber microprobe interference-based displacement measurement system capable of measuring ranges up to 700 mm with subnanometer accuracy. Unlike conventional interferometers, this approach enables compact, embedded measurements in confined spaces, supporting applications in high-end equipment manufacturing and biomedical robotics [77]. Aguilar-Lazcano et al. (2023) surveyed sensor fusion in wildlife monitoring, highlighting challenges of sparse data and field deployment [78]. These illustrate how the principles of redundancy, adaptability, and interpretability are increasingly tailored to domain-specific constraints. In intelligent transportation and scene understanding, multi-modal remote perception learning frameworks have been introduced to integrate object detection with contextual scene semantics. For example, a Deep Fused Network (DFN) combines multi-object detection and semantic analysis, yielding improvement on SUN-RGB-D and on NYU-Dv2 compared to existing approaches [79]. These results underline the growing role of context-aware multimodal fusion for complex environments in autonomous driving and robotics. Industrial monitoring and predictive maintenance are also benefiting from self-supervised representation learning. A recently proposed multihead attention self-supervised (MAS) model learns robust features from multidimensional industrial sensor data using contrastive augmentation strategies. Applied to a real-world water circulation system, MAS improved anomaly detection performance without reliance on large labeled datasets [80]. Such approaches demonstrate the promise of representation learning in industrial sensor fusion for fault detection and equipment health monitoring.

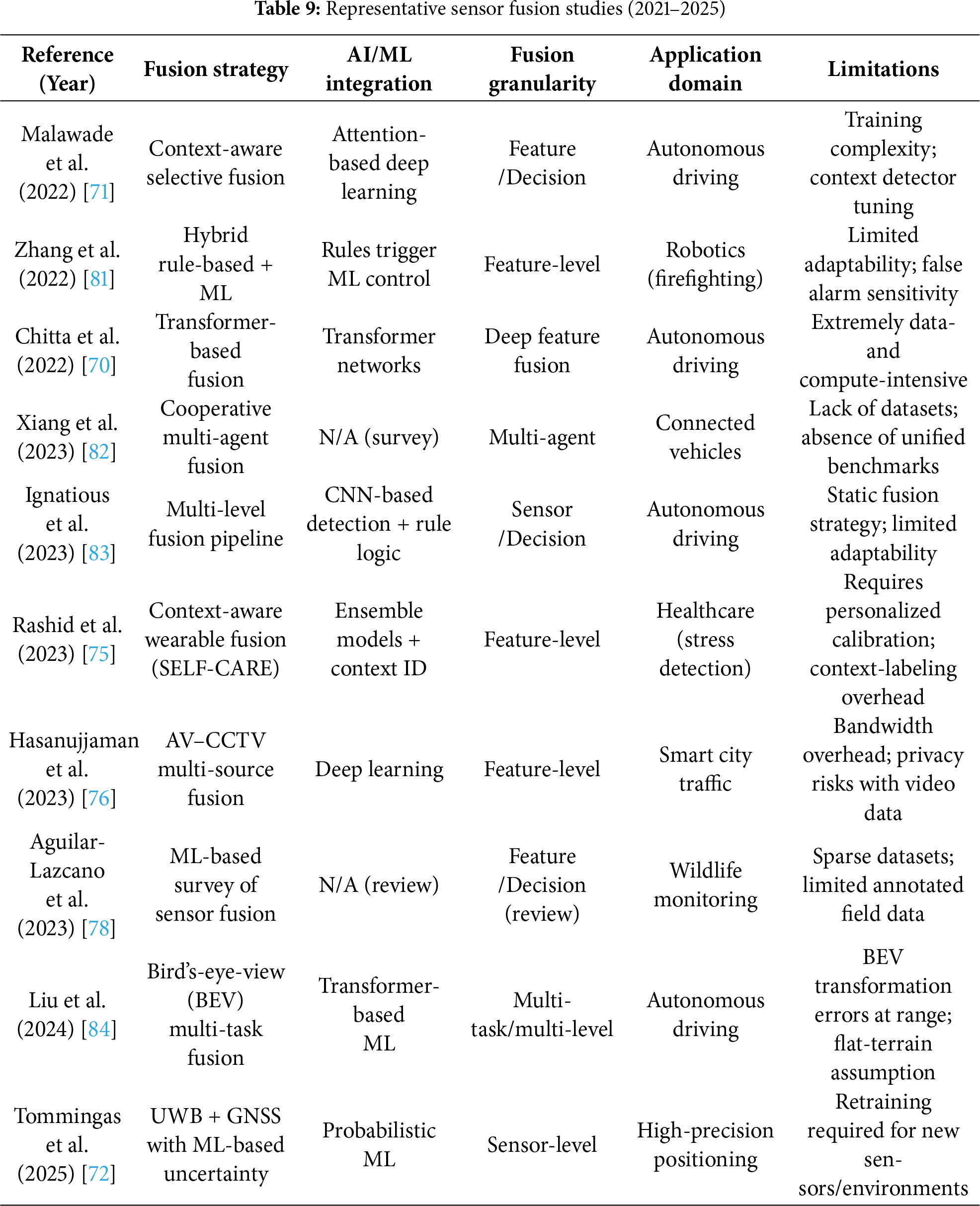

Representative works from this period are summarized in Table 9, capturing the methodologies, AI/ML integration, fusion granularity, application domains, and limitations.

Key Trends and Challenges: The works in Table 9 reflect several defining directions. Transformer-based models and attention mechanisms (e.g., TransFuser, HydraFusion) dominate high-performance fusion pipelines but remain resource-intensive. Context-aware frameworks demonstrate adaptability but raise challenges in calibration and scalability. Application diversification is notable—ranging from autonomous driving to stress detection and wildlife monitoring—yet many domains suffer from data scarcity and lack of standardized benchmarks. Cooperative perception moved from conceptual discussions to initial real-world demonstrations, though interoperability and evaluation metrics remain unresolved.

Another important theme is hybridization: combining learning-based adaptability with model-driven rigor. Physics-informed neural networks, domain adaptation, and simulation-based training address limitations of purely data-driven methods. Similarly, hybrid edge–cloud fusion architectures balance real-time responsiveness with global situational analysis, though at the cost of latency management and secure communication. Finally, fault tolerance and self-calibration have become indispensable, marking a shift toward self-healing, resilient fusion pipelines capable of long-term deployment.

In summary, the 2021–2025 period marks the consolidation of deep learning and transformer-based architectures, the practical emergence of cooperative fusion, and the diversification of sensor fusion into new domains. The emphasis has shifted from achieving accuracy in benchmark datasets to ensuring robustness, scalability, and adaptability in highly dynamic real-world conditions. These trends set the stage for future research on verifiable, resource-efficient, and generalizable sensor fusion frameworks.

5 Mapping the Hierarchical Integrated Model with Contemporary Fusion Methods

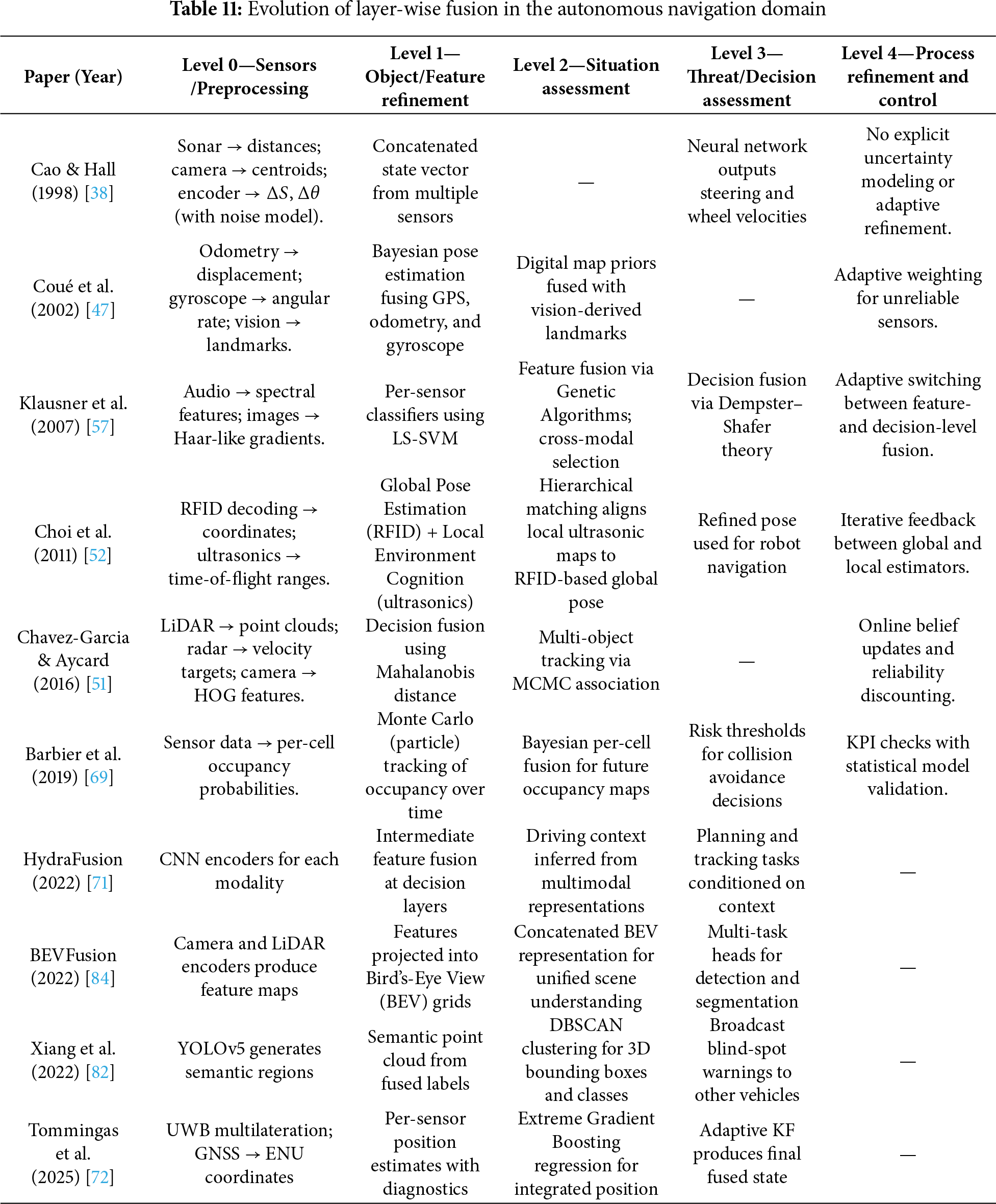

Classical sensor fusion frameworks were remarkably forward-looking, often articulating layered capabilities that exceeded the computational and sensing resources available at their time of conception. These models established a conceptual hierarchy—signal acquisition, feature extraction, state estimation, decision-making, and refinement—that continues to underpin modern multi-sensor fusion architectures. To assess how contemporary systems align with these expectations, we map representative works in autonomous navigation onto a level-wise framework, spanning three decades of research.

The mapping process involved systematic extraction of the operational pipeline from each selected study. For each work, the sensor inputs, the fusion operations, and the resulting outputs were identified and aligned with a hierarchical integrated model (see Fig. 1). In this model, Level 0 corresponds to preprocessing and signal conditioning (e.g., filtering, synchronization, calibration); Level 1 captures per-sensor or object-level estimation; Level 2 concerns scene-level integration (data association, global context, or unified representations); Level 3 involves decision-making and control outputs; and Level 4 corresponds to refinement and adaptivity.

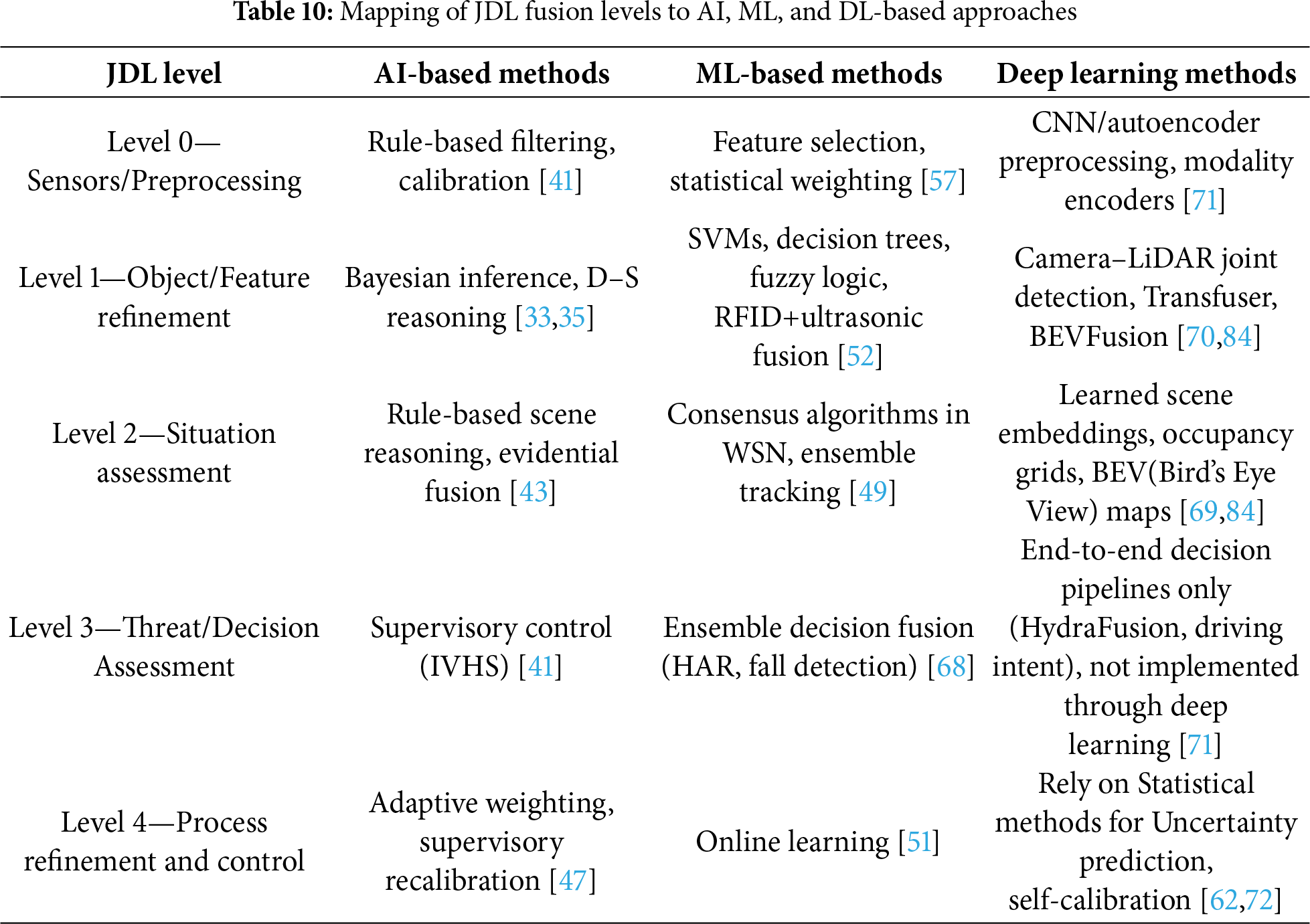

The mapping in Table 10 consolidates representative studies across three decades to show how fusion practices in the autonomous navigation domain have progressively aligned with the layered structure of the JDL framework. At Level 0, early works employed handcrafted preprocessing pipelines, while recent methods rely on modality-specific neural encoders for denoising and synchronization. At Level 1, probabilistic inference and classical classifiers gave way to deep architectures such as BEVFusion, which directly learn object-level representations from multimodal inputs. Level 2 has similarly evolved from rule-based association and evidential reasoning toward unified spatial embeddings, such as occupancy grids and bird’s-eye view projections, that support multi-task perception.

In contrast, Levels 3 and 4 remain largely underdeveloped in deep learning pipelines. Whereas classical and machine learning approaches introduced decision-level fusion, supervisory control, and adaptive reliability discounting, contemporary deep networks typically collapse decision-making and process refinement into end-to-end models without explicit reasoning layers. As a result, deep learning systems are effective at perception but do not yet provide interpretable situation assessment or proactive impact evaluation. This diagnostic gap highlights a structural divergence: while empirical accuracy has improved dramatically, the modularity and transparency of classical models have been lost.

Three principal inferences follow from this mapping. First, there is a clear methodological progression: handcrafted features and Bayesian estimators in the 1990s and 2000s gave way to evidential and hierarchical reasoning in the 2010s, and most recently to representation-centric deep fusion pipelines such as HydraFusion and BEVFusion. Second, representational practice has shifted from object-centric and feature-centric fusion toward spatially unified forms that directly support downstream tasks such as detection, segmentation, and planning. Third, uncertainty modeling and validation have re-emerged as central concerns, either through explicit probabilistic frameworks or through hybrid ML–classical pipelines where learned uncertainty predictors feed adaptive filters.

A key implication is that while deep learning has advanced perception-oriented levels of fusion, it has not extended the hierarchy upward into situation assessment or impact evaluation. This finding directly motivates the discussion in the following section to reconcile the performance of modern end-to-end fusion with the interpretability and rigor of classical frameworks. For better understanding, a corpus was drawn from autonomous navigation, a domain where multisensor fusion has been both intensively researched and practically deployed. Early works focused on indoor mobile robots and Automated Guided Vehicles, where modular sensor suites and structured environments enabled interpretable designs [38,52]. Over time, emphasis shifted toward high-speed, safety-critical vehicular contexts requiring robustness to adverse weather, dynamic traffic, and uncertain environments. Representative works include [47,51,69,71,84]. These works exemplify the progressive alignment of practical implementations with the layered classical models. The level-wise mapping is summarized in Table 11.

Three principal inferences emerge from this mapping. First, a methodological progression is evident: early systems emphasized handcrafted features and direct neural control [33] or structured Bayesian inference [47] while mid-era work incorporated evidential and hierarchical reasoning [57,52] and recent contributions prioritize deep, representation-centric pipelines such as BEVFusion [84]and HydraFusion [71] or hybrid ML–classical models like [72]. Second, representational practice has shifted away from object and feature-centric fusion and towards spatially unified forms like dynamic occupancy grids and Bird’s-Eye Views that support simultaneous detection, segmentation, and planning. Third, uncertainty modeling and validation have re-emerged as central concerns: either through explicit probabilistic and evidential frameworks [51,69] or through learned uncertainty predictors feeding classical estimators [72].

Another diagnostic gap exposed by this mapping is that many deep fusion architectures collapse classical Level 0–Level 4 distinctions into monolithic networks. These systems interleave preprocessing, per-sensor encoding, scene integration, and decision heads, making it difficult to isolate errors or provide component-level guarantees. While empirically effective, this consolidation impairs explainability and makes fault localization harder. Moreover, comparability and certifiability also become limited as safety-critical validation requires modular evidence. To reconcile the empirical power of modern end-to-end fusion with the interpretability and rigor of classical frameworks, we propose adopting level-aware practices: (1) Publish per-level diagnostics and artifacts alongside end-to-end metrics. For instance, Level 0 signal quality measures, Level 1 covariances, Level 2 association maps, Level 3 decision triggers (2) Design explicit interfaces within learned pipelines like exposing calibrated per-sensor estimates and uncertainty tensors (3) Develop benchmark suites stressing level-specific degradations of sensor noise, occlusion and association ambiguity (4) Pursue hybrid architectures where learned models provide uncertainty estimates or feature embeddings to principled filters and planners, as demonstrated in recent UWB–GNSS fusion with ML-informed adaptive Kalman filtering.

These practices offer a pathway to preserve the accuracy and adaptability of modern learning-based fusion while restoring the modular transparency, comparability, and verifiability envisioned in the original hierarchical models. This synthesis illustrates that the conceptual clarity of classical architectures remains essential, even as fusion methods evolve into highly integrated deep networks.

6 Future Research Directions: The Way Forward for Sensor Fusion

The preceding mapping highlights a persistent gap in sensor fusion research: while Levels 0–2 of the JDL framework involving signal conditioning, object estimation, and scene-level integration are well represented in modern methods, higher-level reasoning of Levels 3 and 4, remains underdeveloped. Current deep learning pipelines excel at perception but provide limited support for situation assessment like inter-object relationships, intent prediction. and impact/threat assessment. The lack of this involves risk analysis and proactive decision-making. This limitation is exacerbated by the scarcity of hierarchical datasets encompassing all JDL levels, preventing systematic training and benchmarking of higher-level inference. Consequently, although deep fusion models achieve high empirical accuracy, their opacity and lack of causal reasoning hinder deployment in safety-critical contexts.

6.1 Explainability and Trustworthiness

To address this limitation, explainable AI (XAI) has become central to sensor fusion research. By exposing how models approximate higher-level reasoning, XAI can bridge the trust gap between opaque neural fusion and stakeholder accountability. In autonomous driving, trustworthy deployment hinges on transparent fusion pipelines with interpretable decision-making at multiple abstraction levels [11]. Similarly, in medical contexts, opaque multi-modal fusion undermines clinical reliability; interpretable frameworks are increasingly recognized as prerequisites for adoption [12]. The absence of hierarchical, explainable fusion is therefore both a technical and socio-ethical barrier. Recent surveys [10] underscore that progress remains incremental, and much work is needed before interpretable and certifiable fusion frameworks can be reliably deployed in safety-critical environments.

6.2 Future Research Priorities

Several research priorities emerge for bridging this gap:

• Unified evaluation frameworks and context-aware benchmarks are needed to standardize interpretability metrics in autonomous domains.

• Computationally efficient real-time XAI methods must be developed to ensure safety-critical explainability without introducing decision delays.

• Causal reasoning integration should illuminate cause–effect relations in multimodal fusion, improving transparency and prediction of rare events.

• Scalable fusion algorithms are required to process heterogeneous, high-volume sensor data streams while maintaining robustness and interpretability.

• Ethical and regulatory compliance must be embedded into design aligning with global frameworks.

• Large Language Models (LLMs) may serve as adaptive explanation translators to generate stakeholder-specific justifications of fusion outputs.

• Adversarial robustness and security must be prioritized to guard against spoofing, sensor jamming, and multimodal adversarial attacks.

• Human–AI collaboration and training will be critical to build trust, requiring education of engineers, regulators, and end-users in interpreting sensor fusion pipelines. Collectively, these directions define a roadmap toward transparent, resilient, and standardized sensor fusion for autonomous systems.

6.3 Neuromorphic Fusion as a Future Paradigm

Beyond deep learning, neuromorphic sensor fusion offers a promising path toward energy-efficient and inherently interpretable models. Ceolini et al. (2020) introduced one of the first multimodal neuromorphic benchmarks, integrating event-based vision (DVS) with electromyography (EMG) signals [85]. Using delta modulation, continuous EMG signals were converted into spike trains compatible with spiking neural networks (SNNs), while DVS provided native event-driven input. Fusion was achieved via late concatenation in the penultimate layer, followed by retraining of the output classifier across neuromorphic hardware platforms (Intel Loihi, ODIN+MorphIC). The released dataset comprised 15,750 samples from 21 subjects performing five static hand gestures, making it a pioneering benchmark for multimodal neuromorphic fusion. Results showed accuracy comparable to GPU baselines, while achieving energy-delay product (EDP) improvements of up to

This study opens several technical directions for neuromorphic fusion. First, encoding fidelity remains an open challenge: spike conversion from continuous signals risks discarding fine-grained information, motivating adaptive or learned encoding schemes co-designed with SNN architectures. Second, hardware–algorithm co-design is critical: current neuromorphic platforms face constraints such as limited neuron counts, fixed precision, and inefficient crossbar operations. Progress will require sparsity-aware SNN topologies and novel hardware primitives capable of handling dense multimodal streams. Third, standardized benchmarks are urgently needed. While Ceolini’s dataset is valuable, broader benchmarks reflecting dynamic driving, UAV navigation, or healthcare monitoring are necessary for systematic evaluation across modalities and platforms.

Explainability and Security in Neuromorphic Fusion: Neuromorphic systems also offer opportunities for explainability and robustness. The temporal and event-driven nature of SNNs makes causal reasoning more tractable, as spike timing and event sequences can be directly linked to decision outcomes. Developing XAI tailored for neuromorphic pipelines could deliver transparent reasoning for safety-critical systems such as AV perception or prosthetic control. Security is equally pressing: while neuromorphic fusion may resist conventional adversarial perturbations, it introduces new vulnerabilities such as spoofed event streams, requiring adversary-aware design and validation.

Generalization Across Domains: A key long-term challenge is extending neuromorphic fusion beyond static benchmarks to dynamic, heterogeneous domains. Late-fusion architectures demonstrated for DVS+EMG can be generalized to LiDAR, radar, inertial, and acoustic signals, supporting low-latency, always-on fusion in energy-constrained platforms. Hybrid pipelines—where neuromorphic encoders perform low-level, energy-efficient fusion before passing to deep learning or symbolic reasoning modules—could combine efficiency with semantic richness. Such hybridization points toward a future in which neuromorphic front-ends complement AI-driven back-ends, delivering scalable, interpretable, and trustworthy sensor fusion for autonomous systems.

In summary, future research must simultaneously advance the explainability of classical deep learning fusion systems and explore emerging paradigms such as neuromorphic computing. Together, these trajectories aim to reconcile the empirical success of modern AI with the interpretability, efficiency, and trustworthiness demanded by safety-critical autonomous deployments.

This survey set out to provide a critical and structured examination of sensor fusion research spanning more than three decades, with the dual objectives of tracing the methodological evolution of fusion techniques and assessing their alignment with classical hierarchical models. These objectives have been met by systematically reviewing representative studies across different periods, analyzing their methodologies, applications, and limitations, and mapping them to the JDL framework.

The survey has documented how early work in the 1990s established the foundational principles of probabilistic inference, neural network–based fusion, rule-based systems, and application-specific frameworks. These studies demonstrated the feasibility of multi-sensor integration under uncertainty, albeit within constrained computational and application settings. The review of the 2000s highlighted the maturation of probabilistic filters, the emergence of distributed consensus schemes, and the first uses of machine learning ensembles for fusion, marking a shift from theoretical constructs to robust, domain-specific implementations.

In analyzing the period from 2011 to 2020, the survey has shown how deep learning fundamentally transformed sensor fusion by enabling scalable, feature-level integration of high-dimensional multimodal data. Benchmarks such as nuScenes, Argoverse, and OPPORTUNITY were shown to play a pivotal role in standardizing evaluation and accelerating progress, particularly in autonomous driving and human activity recognition. The discussion also emphasized how decision-level ensembles, cooperative fusion concepts, and robustness studies broadened the applicability of fusion beyond narrowly engineered pipelines.

For the most recent period, from 2021 onward, the survey has demonstrated how research is moving toward real-world deployment and scalability. Contributions such as transformer-based fusion models, physics-informed learning, hybrid edge–cloud architectures, and cooperative vehicle–infrastructure systems reflect an emphasis on adaptability, fault tolerance, and generalization. By including representative studies across emerging application domains such as healthcare, smart cities, and environmental monitoring, the survey has highlighted the growing breadth of sensor fusion research.

The mapping exercise comparing classical hierarchical models to contemporary methods has achieved the objective of clarifying both continuity and divergence. It showed how classical pipelines, with explicit level-wise structure, anticipated many capabilities that are now realized in modern deep fusion systems, while also exposing critical gaps at higher JDL levels where reasoning, intent prediction, and impact assessment remain underdeveloped.

Through this systematic review, the survey has achieved its intended goals. It has established a coherent historical narrative, provided a comparative analysis of methods and benchmarks, and identified both strengths and limitations across decades of research. It has also articulated the open challenges of explainability, robustness, and trustworthiness, thereby framing the agenda for future research. In doing so, this work contributes not only a consolidation of prior knowledge but also a roadmap for advancing sensor fusion toward transparent, scalable, and safety-critical deployment in autonomous systems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta, Varun Gupta; Data curation: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta; Formal Analysis: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta; Investigation: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta; Methodology: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta, Varun Gupta; Project administration: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta; Resources: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta, Varun Gupta; Software: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta, Varun Gupta; Supervision, Validation: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta; Visualization: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta, Varun Gupta; Writing—original draft: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta, Varun Gupta; Writing—review & editing: Sangeeta Mittal, Chetna Gupta, Varun Gupta. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Elmenreich W. An introduction to sensor fusion. Vol. 502, No. 1–28. Vienna, Austria: Vienna University of Technology; 2002. 37 p. [Google Scholar]

2. Hughes T. Sensor fusion in a military avionics environment. Measur Cont. 1989;22(7):203–5. doi:10.1177/002029408902200703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. White F, Lexicon FDF. Joint directors of laboratories-technical panel for C3I, data fusion sub-panel. San Diego, CA, USA: Naval Ocean Systems Center. 1987 [cited 2025 Oct 20]. Available from: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA391672.pdf. [Google Scholar]

4. Dawar N, Kehtarnavaz N. A convolutional neural network-based sensor fusion system for monitoring transition movements in healthcare applications. In: 2018 IEEE 14th International Conference on Control and Automation (ICCA). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 482–5. [Google Scholar]

5. Yeong DJ, Velasco-Hernandez G, Barry J, Walsh J. Sensor and sensor fusion technology in autonomous vehicles: a review. Sensors. 2021;21(6):2140. doi:10.3390/s21062140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Cinar E. A sensor fusion method using transfer learning models for equipment condition monitoring. Sensors. 2022;22(18):6791. doi:10.3390/s22186791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Issa ME, Helmi AM, Al-Qaness MA, Dahou A, Elaziz MA, Damaševičius R. Human activity recognition based on embedded sensor data fusion for the internet of healthcare things. Healthcare. 2022 Jun;10(6):1084. doi:10.3390/healthcare10061084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Abdelmoneem RM, Shaaban E, Benslimane A. A survey on multi-sensor fusion techniques in IoT for healthcare. In: 2018 13th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Systems (ICCES). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 157–62. [Google Scholar]

9. Conway M, Reily B, Reardon C. Learned sensor fusion for robust human activity recognition in challenging environments. In: 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 11537–43. [Google Scholar]

10. Yeong DJ, Panduru K, Walsh J. Exploring the unseen: a survey of multi-sensor fusion and the role of explainable AI (XAI) in autonomous vehicles. Sensors. 2025;25(3):856. doi:10.3390/s25030856. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. De Jong Yeong KP, Walsh J. Building trustworthy autonomous vehicles: the role of multi-sensor fusion and explainable AI (xAI) in on-road and off-road scenarios. In: Sensors and electronic instrumentation advances. Vol. 145. Oslo, Norway: IFSA Publishing; 2024. doi:10.3390/s25030856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yang G, Ye Q, Xia J. Unbox the black-box for the medical explainable AI via multi-modal and multi-centre data fusion: a mini-review, two showcases and beyond. Inf Fusion. 2022;77:29–52. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2021.07.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Fu Y, Tian D, Duan X, Zhou J, Lang P, Lin C, et al. A camera-radar fusion method based on edge computing. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Edge Computing (EDGE). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

14. Davies M, Wild A, Orchard G, Sandamirskaya Y, Guerra GAF, Joshi P, et al. Advancing neuromorphic computing with Loihi: a survey of results and outlook. Proc IEEE. 2021;109(5):911–34. doi:10.1109/jproc.2021.3067593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kitchenham BA, Charters S. Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. EBSE Technical Report. Keele, UK: Keele University. Durham, UK: University of Durham; 2007. [Google Scholar]

16. Zhao J, Li L, Dai J. A review of multi-sensor fusion 3D object detection for autonomous driving. In: Eleventh International Symposium on Precision Mechanical Measurements. Vol. 13178. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 667–85. [Google Scholar]

17. Wang S, Ahmad NS. A comprehensive review on sensor fusion techniques for localization of a dynamic target in GPS-denied environments. IEEE Access. 2025;13:2252–85. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3519874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mehta M. Sensor fusion techniques in autonomous systems: a review of methods and applications. Int Res J Eng Technol (IRJET). 2025;12(4):1902–8. [Google Scholar]

19. Heydarian M, Doyle TE. rwisdm: repaired wisdm, a public dataset for human activity recognition. arXiv:2305.10222. 2023. [Google Scholar]

20. Wilson B, Qi W, Agarwal T, Lambert J, Singh J, Khandelwal S, et al. Argoverse 2: next generation datasets for self-driving perception and forecasting. arXiv:2301.00493. 2023. [Google Scholar]

21. Shermeyer J, Hossler T, Van Etten A, Hogan D, Lewis R, Kim D. Rareplanes: synthetic data takes flight. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 207–17. [Google Scholar]

22. Wen W, Zhou Y, Zhang G, Fahandezh-Saadi S, Bai X, Zhan W, et al. UrbanLoco: a full sensor suite dataset for mapping and localization in urban scenes. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 2310–6. [Google Scholar]

23. Caesar H, Bankiti V, Lang AH, Vora S, Liong VE, Xu Q, et al. Nuscenes: a multimodal dataset for autonomous driving. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 11621–31. [Google Scholar]

24. Creß C, Zimmer W, Strand L, Fortkord M, Dai S, Lakshminarasimhan V, et al. A9-dataset: multi-sensor infrastructure-based dataset for mobility research. In: 2022 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 965–70. [Google Scholar]

25. Vaizman Y, Ellis K, Lanckriet G. Recognizing detailed human context in the wild from smartphones and smartwatches. IEEE Perv Comput. 2017;16(4):62–74. doi:10.1109/mprv.2017.3971131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sagha H, Digumarti ST, del R Millán J, Chavarriaga R, Calatroni A, Roggen D, et al. Benchmarking classification techniques using the Opportunity human activity dataset. In: 2011 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2011. p. 36–40. [Google Scholar]

27. Hall DL, McMullen SAH. Mathematical techniques in multisensor data fusion. 2nd ed. Boston, MA, USA: Artech House; 2004. [Google Scholar]

28. Steinberg AN, Bowman CL. Rethinking the JDL data fusion levels. Nssdf Jhapl. 2004;38:39. [Google Scholar]

29. Thomopoulos SC. Sensor integration and data fusion. J Robot Syst. 1990;7(3):337–72. [Google Scholar]

30. Luo RC, Kay MG. Multisensor integration and fusion in intelligent systems. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybernet. 2002;19(5):901–31. doi:10.1109/21.44007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Harris C, Bailey A, Dodd T. Multi-sensor data fusion in defence and aerospace. Aeronaut J. 1998;102(1015):229–44. doi:10.1017/s0001924000065271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bedworth M, O’Brien J. The Omnibus model: a new model of data fusion? IEEE Aerosp Electr Syst Magaz. 2000;15(4):30–6. doi:10.1109/62.839632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Cox IJ, Hingorani S, Maggs BM, Rao SB. Stereo without disparity gradient smoothing: a Bayesian sensor fusion solution. In: BMVC92: Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 1992. p. 337–46. [Google Scholar]

34. Larkin MJ. Sensor fusion and classification of acoustic signals using Bayesian networks. In: Conference Record of Thirty-Second Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers. Vol. 2. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 1998. p. 1359–62. doi:10.1109/acssc.1998.751395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Shahbazian E, Simard MA, Bourassa S. Implementation strategies for the central-level multihypothesis tracking fusion with multiple dissimilar sensors. In: Signal processing, sensor fusion, and target recognition II. Vol. 1955. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 1993. p. 78–89. doi: 10.1117/12.155003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Perlovsky LI, McManus MM. Maximum likelihood neural networks for sensor fusion and adaptive classification. Neur Netw. 1991;4(1):89–102. doi: 10.1016/0893-6080(91)90035-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Davis IL, Stentz A. Sensor fusion for autonomous outdoor navigation using neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 1995 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. Human Robot Interaction and Cooperative Robots. Vol. 3. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 1995. p. 338–43. [Google Scholar]