Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

TSMixerE: Entity Context-Aware Method for Static Knowledge Graph Completion

Guangxi Key Lab of Human-Machine Interaction and Intelligent Decision, Nanning Normal University, Nanning, 530001, China

* Corresponding Author: Ying Pan. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 92 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071777

Received 12 August 2025; Accepted 22 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The rapid development of information technology and accelerated digitalization have led to an explosive growth of data across various fields. As a key technology for knowledge representation and sharing, knowledge graphs play a crucial role by constructing structured networks of relationships among entities. However, data sparsity and numerous unexplored implicit relations result in the widespread incompleteness of knowledge graphs. In static knowledge graph completion, most existing methods rely on linear operations or simple interaction mechanisms for triple encoding, making it difficult to fully capture the deep semantic associations between entities and relations. Moreover, many methods focus only on the local information of individual triples, ignoring the rich semantic dependencies embedded in the neighboring nodes of entities within the graph structure, which leads to incomplete embedding representations. To address these challenges, we propose Two-Stage Mixer Embedding (TSMixerE), a static knowledge graph completion method based on entity context. In the unit semantic extraction stage, TSMixerE leverages multi-scale circular convolution to capture local features at multiple granularities, enhancing the flexibility and robustness of feature interactions. A channel attention mechanism amplifies key channel responses to suppress noise and irrelevant information, thereby improving the discriminative power and semantic depth of feature representations. For contextual information fusion, a multi-layer self-attention mechanism enables deep interactions among contextual cues, effectively integrating local details with global context. Simultaneously, type embeddings clarify the semantic identities and roles of each component, enhancing the model’s sensitivity and fusion capabilities for diverse information sources. Furthermore, TSMixerE constructs contextual unit sequences for entities, fully exploring neighborhood information within the graph structure to model complex semantic dependencies, thus improving the completeness and generalization of embedding representations.Keywords

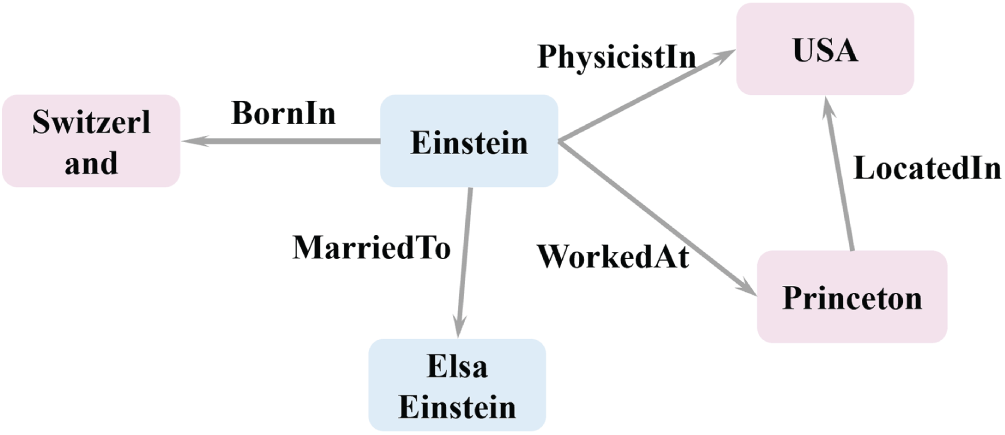

With the rapid advancement of information technology, the volume of data across various domains has surged, presenting unprecedented challenges in data storage, management, and analysis [1]. Knowledge Graphs (KGs), which emerged from the fields of Artificial Intelligence and the Semantic Web, have become a pivotal tool for knowledge management, aiming to enable efficient knowledge representation and sharing. At their core, KGs extract entities from heterogeneous data sources and interconnect them through structured relationships, thereby forming a semantic network. For instance, as illustrated in Fig. 1, the triple (Einstein, married_to, Elsa Einstein) succinctly expresses the fact that “Einstein’s wife is Elsa Einstein.” Static Knowledge Graphs (SKGs) are constructed under the assumption that entity relationships remain temporally invariant, with triples that do not encode temporal information, thereby facilitating systematic knowledge storage [2]. KGs integrate heterogeneous data from multiple sources, support complex semantic reasoning, and enable efficient information retrieval. These capabilities lead to their widespread applications in search engines, recommender systems, intelligent question answering, and beyond. For example, in search engines, KGs transcend traditional keyword matching by leveraging deep semantic parsing to construct semantic association networks, thereby enabling precise answer extraction and diverse result recommendations [1,2].

Figure 1: Knowledge graph example

Despite the widespread adoption of KGs, incompleteness remains a pervasive challenge. Missing entity information and relationships, often resulting from insufficient data collection, limit the effectiveness of applications of KGs. Moreover, as real-world knowledge evolves dynamically over time, SKGs struggle to capture such changes, further exacerbating the problem of incompleteness. Data sparsity also leads to weak connections between entities, hindering the accurate representation of semantic relationships. To address these issues, knowledge graph completion (KGC) has emerged as a critical research direction. Specifically, static knowledge graph completion (SKGC) focuses on predicting missing information—such as absent relationships or entities—based on the existing structures of KGs. In this work, we focus on the entity prediction task: given a triple with either the head or tail entity missing, i.e.,

Existing KGC methods predominantly rely on linear operations or simple interaction mechanisms for triple encoding, representing entities and relations as points in vector space. Such approaches struggle to capture deep semantic associations between entities and relations, often focusing solely on the local information within individual triples while overlooking the rich semantic dependencies present in the neighboring nodes of the graph structure. Moreover, the lack of effective mechanisms for perceiving and leveraging the graph structure leads to incomplete embedding representations and limits the overall expressiveness of the model [3]. To address these key challenges, we propose TSMixerE, a SKGC method based on entity context. TSMixerE is designed to enhance the modeling of deep semantic associations between entities and relations, and to achieve effective fusion of entity contextual information. The main innovations of our approach are as follows:

(1) We introduce a Unit Semantic Extraction (USE) module that captures local features at multiple granularities through Multi-Scale Circular Convolution (MSCC), thereby improving the flexibility and robustness of feature interactions. In addition, a channel attention mechanism is incorporated to amplify key channel responses, suppress noise, and enhance both the discriminative power and deep semantic associations of feature representations.

(2) We design a Context Information Fusion (CIF) module that utilizes multi-layer self-attention to enable deep interactions among contextual information, integrating local details with global context. Furthermore, type embeddings are introduced to clarify the semantic identities and roles of each component, thereby improving the model’s sensitivity to, and fusion of, diverse information sources.

Extensive experiments demonstrate that TSMixerE achieves strong performance across all evaluation metrics, fully validating its effectiveness in SKGC tasks.

Existing KGC techniques primarily focus on the semantic modeling of entities and relations. Early approaches are largely based on the geometric translation assumption, in which relations are treated as spatial operations mapping head entities to tail entities, and semantic associations are captured through vector translations. For instance, TransE [4] embeds entities and relations into a continuous vector space, interpreting relations as translation vectors between head and tail entities. While TransE excels at modeling one-to-one relations, it struggles with more complex relational patterns. To overcome this limitation, TransH [5] models each relation as a translation operation on a relation-specific hyperplane, enabling entities to have different representations under different relations, thus providing greater flexibility for complex relations. RotatE [6] further extends this idea by defining relations as rotations in a complex vector space, capturing diverse relational patterns through rotational operations; however, its ability to model non-compositional relational paths remains limited. These geometric approaches offer low computational complexity, strong scalability to large-scale KGs, and clear geometric interpretability. They are effective for modeling hierarchical relationships and are well-suited for data-sparse scenarios. Nevertheless, they exhibit weaknesses in handling complex relations, which can lead to semantic collapse. Moreover, they often require additional constraints for special types of relations and are heavily reliant on the Euclidean space assumption, which limits their capacity to express nonlinear semantic interactions.

Some studies seek to model the deep associations between entities and relations through implicit semantic decomposition, employing tensor decomposition techniques to represent KGs as multidimensional interaction matrices in a latent semantic space. The degree of matching between entity-relation combinations is then quantified via product operations among latent vectors. For example, RESCAL [7] models KGs as third-order tensors, decomposing them into products of entity vectors and relation matrices, and utilizes bilinear interactions to capture higher-order semantic associations among entities. However, the number of parameters in RESCAL grows linearly with the number of relations, leading to computational bottlenecks. DistMult [8] simplifies the scoring function by constraining the relation matrix to be diagonal, significantly reducing parameter size, but the symmetry of its scoring function makes it incapable of distinguishing asymmetric relations. ComplEx [9] addresses this limitation by introducing complex-valued embeddings, mapping entities and relations into a complex space to effectively model both symmetric and asymmetric relations, though its ability to capture multi-hop compositional relations remains limited. TuckER [10] leverages Tucker decomposition to factorize triples into combinations of a core tensor and entity/relation embedding matrices, improving parameter efficiency through a multi-task learning mechanism with shared parameters. These approaches offer flexible modeling of complex relational patterns, a strong capacity for representing many-to-many semantic interactions, and better mathematical interpretability compared to geometric translation models. However, they face challenges in scalability and in capturing higher-order interactions, as computational complexity increases rapidly with the number of relation types. Furthermore, the implicit decomposition process lacks an intuitive spatial geometric interpretation, which can limit the transparency and interpretability of the learned representations.

With the continuous development of deep learning theory and applications, neural network-related technologies have become one of the important technical paths in the field of KGC, greatly enriching the means of entity and relation modeling. By capturing the nonlinear interaction characteristics of entities and relations through deep architectures, researchers have proposed a variety of implementation approaches, such as graph neural networks, convolutional neural networks, and attention networks. Graph neural networks convey node features through a neighborhood aggregation mechanism, fusing topological and attribute information. R-GCN [11] introduces a relation-specific transformation mechanism to address the challenge of modeling multi-relational structures, assigning independent weight matrices to different relations, enabling nodes to distinguish semantic paths when aggregating neighbor information, and retaining node features through self-connections to avoid information loss. CompGCN [12] integrates the combination operations of entities and relations across KGs into the graph convolutional layer, and achieves deep coupling of multi-relational information by dynamically and jointly learning the embedded representations of nodes and relations. The feature extraction capability of convolutional neural networks is also widely utilized in KGC tasks. ConvE [13] captures higher-order nonlinear interaction features in local regions through a 2D convolutional kernel. The embeddings of the head entities and relations are concatenated into a 2D matrix, and convolution is utilized to extract local semantic patterns, achieving rich feature interactions through multilayer stacking. However, the fixed structure restricts the ability to capture complex relations. InteractE [14] enhances embedding interaction capability through feature rearrangement, feature reshaping, and circular convolution strategies, generating multi-view interaction patterns, avoiding overfitting to fixed structures, and expanding the receptive field via checkerboard concatenation and circular convolution to improve the diversity of feature interactions and the breadth of semantic coverage. FMS [15] proposes a context-aware deformable scoring paradigm for semantically sensitive knowledge graph completion. It explicitly models both local and global context in entity pair representations and employs conditional flow matching to enable the scoring function to adapt continuously with context, thereby adjusting the discrimination boundary adaptively. In contrast to static scoring or fixed convolutional structures, this dynamic approach demonstrates significantly enhanced discriminative power and robustness in scenarios characterized by complex relational semantics or distribution shifts. With the breakthrough of the Transformer architecture [16] in natural language processing, related research has migrated this architecture to KGC tasks. The attention mechanism captures global semantic dependencies by dynamically assigning interaction weights through self-attention, computing the attention distribution after transforming triples and graph-domain contexts into sequences. For example, HittER [17] adopts a hierarchical Transformer architecture, in which the lower entity Transformer models local interactions, and the upper context Transformer aggregates multi-hop neighborhood information to construct global semantic representations, effectively improving the modeling ability for complex relational patterns. PMRCA [18] introduces a pattern-driven framework centered on multi-source resonance and cognitive adaptation. It utilizes structure-aware contrastive learning to model multi-source narrative consistency and cluster-based contrastive learning to achieve cognitive alignment. The model also integrates a Transformer-style context fusion mechanism to capture long-range dependencies. Although initially designed for information diffusion prediction, its contrastive learning and context fusion paradigms offer transferable insights for enhancing reasoning with path-based or neighborhood contexts. Furthermore, lightweight deep networks help balance performance and real-time efficiency in resource-constrained environments. MobileViT [19], developed for real-time constellation diagram recognition, employs a lightweight architecture that combines the efficient receptive fields of local convolutions with the global modeling capacity of streamlined self-attention. This design achieves an effective accuracy-latency trade-off under edge computing constraints. Its efficient hybrid CNN-Transformer structure provides valuable engineering insights for optimizing the deployment and inference efficiency of knowledge graph models. These neural network-based techniques enhance the characterization of nonlinear relationships through their capacity to fit complex functions, greatly enriching the technical landscape of KGC. However, the extraction of deep semantic associations still needs improvement, and the failure to effectively integrate the contextual information of entities affects overall completion performance [3].

3 Entity Context-Based Static Knowledge Graph Completion Method

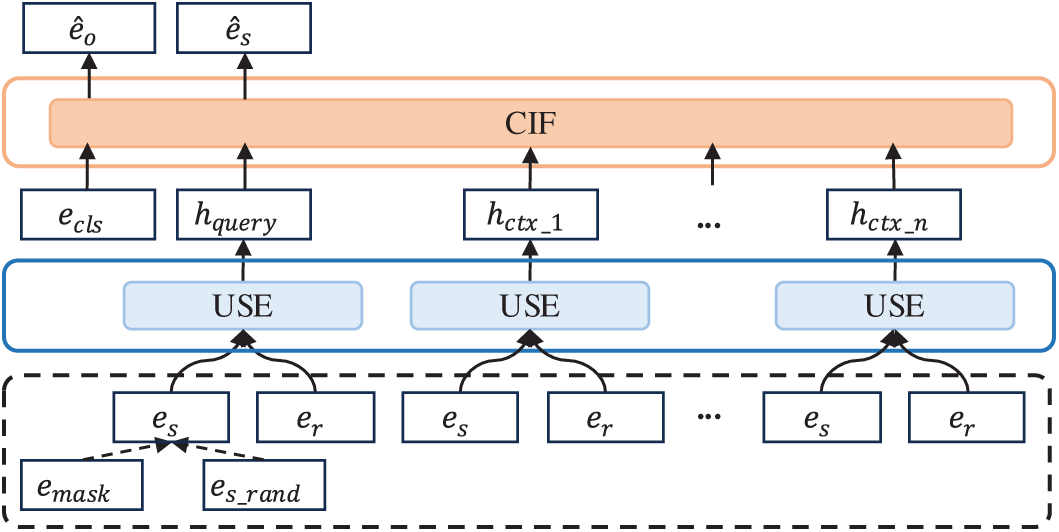

To effectively encode individual triple information and integrate contextual information from entity graph neighborhoods, this paper proposes TSMixerE, a SKGC method based on MSCC and entity context fusion, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The model consists of two main stages: USE and CIF. The USE module leverages MSCC and channel attention to extract local features at multiple granularities, producing semantic vectors denoted as h_unit. These vectors are then passed as input to the CIF module. Within CIF, a self-attention mechanism dynamically weights the contributions of different contextual units, effectively integrating local details with global dependencies. This architecture establishes a complementary relationship between the two stages: USE specializes in fine-grained semantic extraction, while CIF is responsible for global semantic integration. The USE stage is responsible for extracting semantic information from both the query unit and its contextual units, while the CIF stage fuses the contextual semantic information obtained by USE to enhance the overall representation.

Figure 2: TSMixerE model framework diagram

As shown in Fig. 2, the TSMixerE framework consists of the following four key steps:

(1) constructing a sequence of contextual units for each entity;

(2) performing USE using MSCC and channel attention;

(3) fusing entity context information through self-attention and type embedding;

(4) conducting an auxiliary masked entity prediction task.

The details of each step are described below.

3.2 Construct the Sequence of Context Units of the Entity

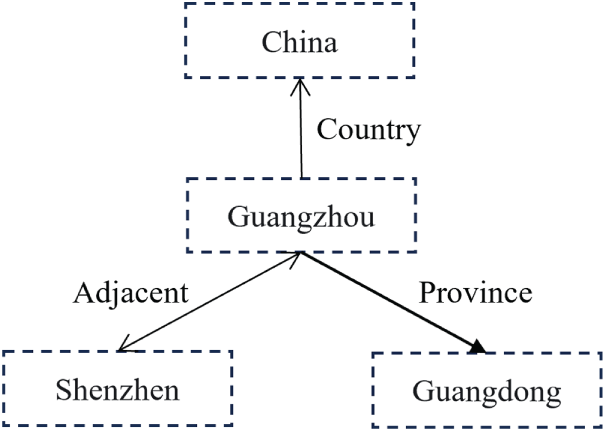

First, the scope of the context needs to be explicitly defined. Taking KGs such as the one in Fig. 3 as examples, for the entity Guangzhou, their graph neighborhoods contain multiple related fact triples, e.g., (Guangzhou, Country, China), (Guangzhou, Province, Guangdong), (Guangzhou, Adjacent, Shenzhen), and (Shenzhen, Adjacent, Guangzhou). In this case, assuming that the query unit is (Guangzhou, China), it can be instantiated as (Guangzhou, Country, China). Then, the sequence of context units for the entity Guangzhou corresponding to this query unit can be represented as the set C = {(Guangzhou, Country), (Shenzhen, Adjacent), (Shenzhen, Adjacent−¹), (Guangdong, Province−¹)}, where the superscript −¹ denotes the inverse of the relation. Formally, for any query unit

where

Figure 3: Example of a graph neighborhood context for an entity Guangzhou

In general, different entities are associated with varying numbers of other entities, resulting in inconsistencies in the total number of context units. To address this issue, a fixed number

To enhance the model’s adaptability to different context combinations, a neighborhood sampling method analogous to data augmentation is introduced during the training phase: in each iteration, only

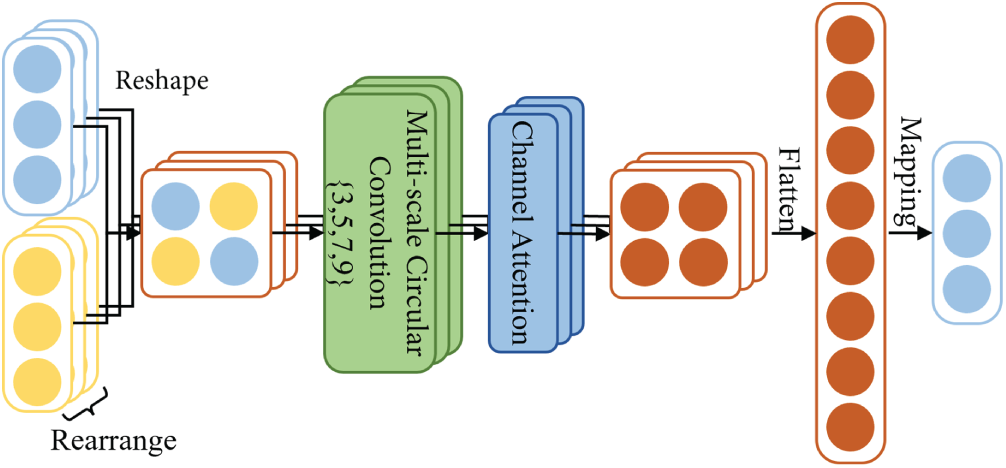

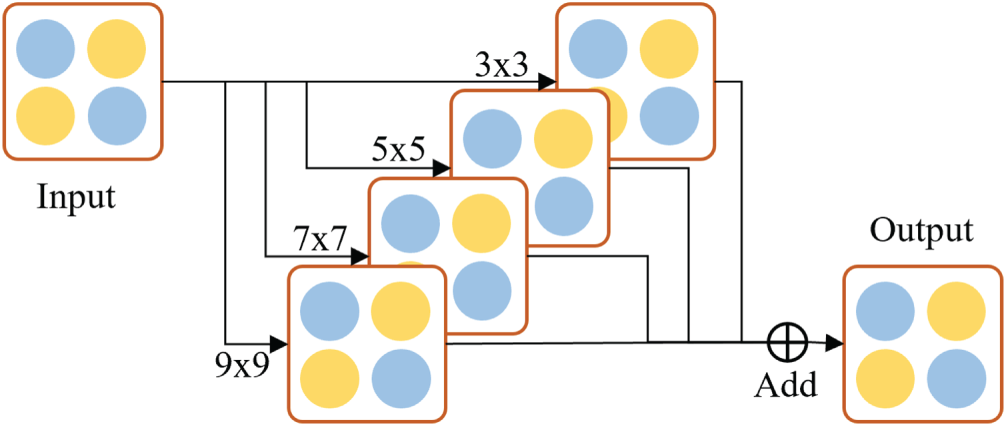

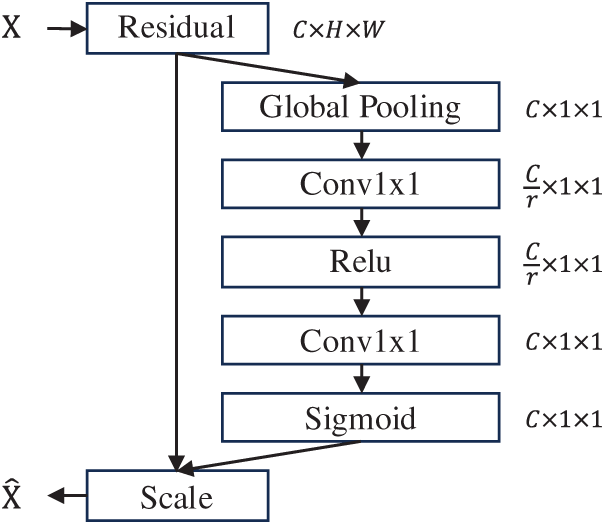

After constructing the contextual unit sequence for entities, it is necessary to extract the deep semantic associations between entities and relations from each unit in the sequence. To this end, this paper proposes a USE module based on MSCC and channel attention, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The core of this module employs a four-branch parallel MSCC architecture with kernel sizes of 3 × 3, 5 × 5, 7 × 7, and 9 × 9. Each convolutional branch produces 200 feature channels with circular padding. The outputs from all branches are summed directly along the channel dimension. The resulting feature tensor is then processed by a channel attention module that generates channel weights through global average pooling, two-layer 1 × 1 convolutions, and a Sigmoid activation function. The module is developed with InteractE as its core and further extends it, with its main idea centered on the integration of Feature Permutation (FP), Feature Reshaping (FR), MSCC, and Channel Attention (CA) mechanisms. These components enable comprehensive feature interactions between entity and relation embeddings, thereby obtaining complex semantic association representations. The USE module is capable of capturing local structural features at multiple scales, enhancing feature interactions, highlighting key information while reducing noise interference, and mining deep semantic associations between entities and relations. The multi-scale parallel processing ensures the capture of patterns across varying granularities. Meanwhile, the channel attention mechanism directs convolutional kernels at different scales to prioritize learning those patterns that are assigned higher importance by the attention mechanism. This provides an accurate and fine-grained semantic foundation for subsequent context fusion. The following section provides a detailed description of each sub-module.

Figure 4: Schematic diagram of the USE module

(1) Feature Rearrangement

The model first obtains the corresponding vectors from the embeddings of entities and relations, and then performs random shuffling to rearrange the features of these embedding vectors. This operation is repeated multiple times, as shown in Eq. (2). The purpose of feature rearrangement is to increase the number of interactions between entities and relations, thereby enriching the feature space.

where

(2) Feature Reshaping

After feature rearrangement, the embeddings of each set of entities and relations are reshaped into a two-dimensional matrix using checkerboard feature reshaping. Specifically, the embedding features of entities and relations are alternately arranged on odd rows, while the embedding features of relations and entities are alternately arranged on even rows, as shown in Eq. (3):

where

The checkerboard feature reshaping ensures that the features surrounding each entity and relation can form heterogeneous interactions with themselves, dispersing homogeneous features as much as possible while maximizing the interactions between heterogeneous features. This provides richer input information for subsequent convolutional operations.

(3) Multi-Scale Circular Convolution

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the schematic diagram shows that each branch processes inputs using a specific convolution kernel size (3 × 3, 5 × 5, 7 × 7, or 9 × 9) with circular padding. Each independent convolution operation is configured with 200 output filters, producing 200 feature channels. The outputs of these four branches are summed along the channel dimension to form the final output of this submodule. The MSCC module extracts features in parallel using convolution kernels of different sizes and incorporates a circular padding mechanism to ensure that features at the edges can also participate in the convolution operation, thereby avoiding information loss caused by boundary truncation. The computation process is shown in Eq. (4):

where

Figure 5: Schematic diagram of MSCC

MSCC enables the model to achieve comprehensive coverage of feature information across different scales, allowing it to capture fine-grained local features while also obtaining more global information from larger receptive fields. This approach enhances both the flexibility and robustness of feature fusion.

(4) Channel Attention

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the channel attention module first applies global average pooling to compress each channel, then generates channel attention weights through a sequence of operations: 1 × 1 convolution, ReLU activation, and another 1 × 1 convolution. Finally, the sigmoid function is used to normalize and obtain the response weights for each channel. The computation process is given by Eqs. (5)–(7):

where

Figure 6: Schematic diagram of the channel attention network

Since semantic information of entity relationships is typically distributed across the entire feature map, global average pooling effectively captures the global semantic distribution, thereby enhancing the model’s capability to comprehend and retain crucial semantic information. The channel attention mechanism serves to weight each channel of the convolutional output on an element-wise basis, enhancing the responses of important channels while suppressing noise and irrelevant information. This process enables the subsequent feature mapping to possess higher discriminative capability even before the flattening operation, thereby laying a solid foundation for the extraction of deep semantic associations.

(5) Straightening Mapping

Finally, the output of the channel attention module is flattened into a vector, and this vector is mapped to the joint semantic space through a fully connected layer, as shown in Eq. (8):

where

The purpose of straightening is to extract the deep semantic associations between entities and relations, integrating multi-dimensional local interaction information into a global representation. The fully connected mapping serves not only for feature dimensionality reduction and integration, but also for the reconstruction and enhancement of the high-dimensional features extracted by the preceding modules.

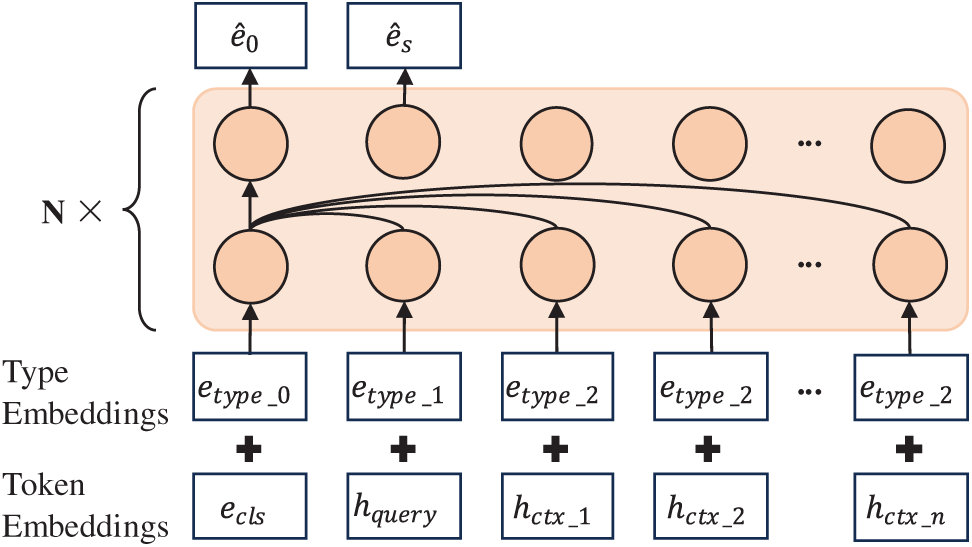

3.4 Context Information Fusion

After being encoded by the USE module, the entities and relations in each fact are mapped to deep semantic embedding vectors. To fully integrate this semantic information, we propose a CIF module based on a multi-layer BERT and type embedding, as illustrated in Fig. 7. The CIF module enables deep interactions of contextual information through a self-attention mechanism, effectively capturing global dependencies and integrating local details with global context, thereby enhancing the continuity and discriminative power of semantic representations.

Figure 7: Schematic diagram of the CIF module

The CIF module mainly consists of three components: categorization tagging, type embedding, and BERT encoding, which are described in detail below. This simplified type embedding strategy categorizes the input sequence into three distinct types—the [CLS] token, the query unit, and the contextual units—and is designed to differentiate between their semantic origins with minimal computational overhead.

(1) Categorization Token

To effectively capture global semantic information, a special categorization token [CLS] is added at the beginning of the sequence before embedding the USE output as input to BERT. The output corresponding to this token can fully integrate the semantics of the entire sequence through the self-attention mechanism, as shown in Eq. (9):

where

During the encoding process, the categorization token [CLS] interacts with all elements in the sequence. After multiple layers of self-attention, the output vector corresponding to the [CLS] token can be regarded as a representation that incorporates the contextual information of the entire sequence. Compared with direct averaging or using the representation of the last element, the [CLS] token—lacking explicit semantic content itself—can more “fairly” integrate the semantic information of each element in the sequence, thereby yielding a semantic representation that fully captures the overall meaning of the sequence.

(2) Type Embedding

To enable the model to clearly distinguish semantic information from different sources during context fusion, and to preserve model simplicity and computational efficiency, we employ this simplified type classification strategy. The CIF module adopts type embeddings instead of traditional positional embeddings. Specifically, according to their semantic attributes, the three components—categorization token [CLS], query unit, and the sequence of context units—are assigned corresponding type embedding vectors, as shown in Eq. (10):

where

The introduction of type embeddings not only preserves the original semantic information, but also clarifies the identity and role of each component through type information, reduces the risk of noise caused by positional confusion, and enhances the model’s sensitivity and recognition ability to different semantic sources.

(3) BERT Encoding

Finally, the embedded sequence, augmented with the categorization token [CLS] and type embeddings, is fed into a multi-layer BERT for encoding to obtain the final output, as shown in Eq. (11):

where

3.5 Masked Head Entity Prediction

TSMixerE adopts a parsimonious approach to integrating contextual information from graph structures for entity prediction. First, the semantic features of the query unit and its contextual units are extracted using the USE module, and these features are subsequently fused through the CIF module. However, directly injecting contextual information into the model presents two potential challenges: first, query units typically already contain more accurate predictive information, making it difficult to extract valuable signals from complex contexts, which may cause the model to overlook additional contextual content. Second, overly abundant contextual information can dilute the importance of the query units and introduce irrelevant noise, potentially leading to overfitting.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper introduces a Masked Head Entity Prediction (MHEP), inspired by the MLM task in BERT, to balance the utilization of query unit information and graph contextual information. During training, the head entities of some samples in the USE phase are perturbed using a randomization strategy: they are replaced with special mask tokens

In the entity prediction task, the plausibility score for the true triple is calculated as the dot product between the output embedding corresponding to the classification token [CLS] and the embedding of the correct tail entity. Likewise, the plausibility scores for all other candidate entities are computed and normalized using the softmax function. The cross-entropy classification loss function for the entity prediction task is defined as follows:

where

where

Finally, the cross-entropy classification loss of MHEP is used as an auxiliary loss and is combined with the loss function of the entity prediction task to obtain the final loss function, as shown in Eq. (14) below:

where

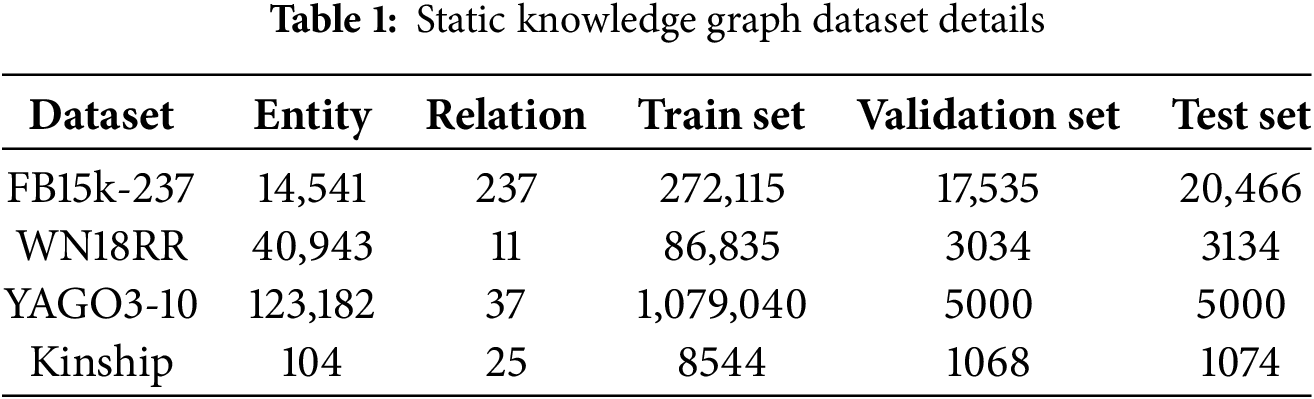

The experiments are conducted on four public benchmark datasets: FB15k-237 [20], WN18RR [21], YAGO3-10 [22], and Kinship [23], and their statistical details are summarized in Table 1. FB15k-237 is derived from the Freebase knowledge base, with inverse relations removed to avoid redundancy. WN18RR is constructed from the WordNet lexical hierarchy and focuses on understanding semantic relationships. YAGO3-10 comprises a large number of entities and complex relations, providing a challenging environment for KGC. Kinship is a small-scale dataset centered on kinship relations, making it suitable for evaluating the model’s capability to capture logical rules.

The evaluation metrics for the KGC task include the standardized hit rate (Hits@1/3/10) and mean reciprocal rank (MRR), with a filtered setting applied to exclude valid triples that also appear in the test set. All experiments are conducted on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU using the PyTorch 1.12.0 framework. For model hyperparameters, the embedding dimension is set to 320, the maximum number of training epochs is 300, the batch size is 256, and the learning rate is 0.01. The number of feature permutations, iperm, is set to 1, and the number of output channels for the circular convolution module, inum_filt, is 200. The number of context units per entity in each training batch, n, is set to 50. The number of BERT layers in the CIF module, N, is selected from the set {1, 2, 3, 4}. The loss weight coefficient for the MHEP, weight_coef, is chosen from the set {0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8}, and the masking rate for the MHEP, masking_rate, is tuned over the range {0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0}. The total number of context units per entity, k, is set according to each specific dataset, and in this work, the values of k, N, weight_coef, and masking_rate are explored through hyperparameter optimization. To evaluate the effectiveness of TSMixerE, this paper selects several existing SKGC methods as baselines, including TransE, DistMult, ComplEx, ConvE, RotatE, InteractE, HittER, OMult [24], JointE [25], DeepER [26], RMCNN [27], IntME [28], LKER [29], gMLP-KGE [30], MFSSN [31], and SelectE [32]. Among these, TransE, DistMult, ComplEx, ConvE, RotatE, InteractE, and HittER have been introduced previously; the remaining methods are described as follows.

OMult [24] embeds entities and relations in the octonion vector space, utilizing the non-commutative property of octonion multiplication to model asymmetric and compositional relations. A parameter-sharing mechanism ensures a model size comparable to that of quaternion-based models. By constraining the octonion subspace, OMult can degenerate to complex (ComplEx) or real (DistMult) embeddings, thus accommodating relations of varying complexity. JointE [25] improves link prediction by jointly leveraging 1D and 2D convolutional neural networks while maintaining parameter efficiency. 1D convolution extracts explicit knowledge and preserves surface semantics, while 2D convolutional kernels, generated internally from embeddings, capture deep implicit knowledge and reduce redundant parameters. DeepER [26] generates expressive entity and relation feature maps using group convolutional rotations and reflection transformations, and introduces relation-specific transformations via a hyper-network. It also fuses structured and visual embeddings to enhance multimodal entity representations. RMCNN [27] combines a relational memory network with a convolutional neural network. The relational memory network, incorporating positional encoding and self-attention, models dependencies between entities and relations. Encoded vectors are concatenated and reshaped for convolution, enhancing entity-relation interactions across dimensions. IntME [28] extracts initial interaction features using deep convolution and feature reshaping, then expands features through rearrangement, matrix multiplication, channel scaling, and pointwise convolution to enhance explicit knowledge and compensate for initial interaction limitations. LKER [29] extends the Large Kernel Embedding (LKE) model by introducing a parallel relationship-specific feature extraction branch, enabling the capture of long-range dependencies and comprehensive relationship-specific features via a large kernel attention mechanism. gMLP-KGE [30] is a lightweight, efficient link prediction model that extends convolutional neural networks with a gated multilayer perceptron (gMLP). MFSSN [31] adaptively constructs filters from entity and relation embeddings, introduces a soft contraction sub-network to suppress noise, and incorporates an attention mechanism to enhance important features and overall model performance. SelectE [32] is a multi-scale adaptive selection network that learns rich multi-scale interactive features and automatically filters important features. It redesigns the input feature matrix for multi-scale convolution, introduces a multi-branch learning module, and dynamically assigns feature weights to optimize feature utilization.

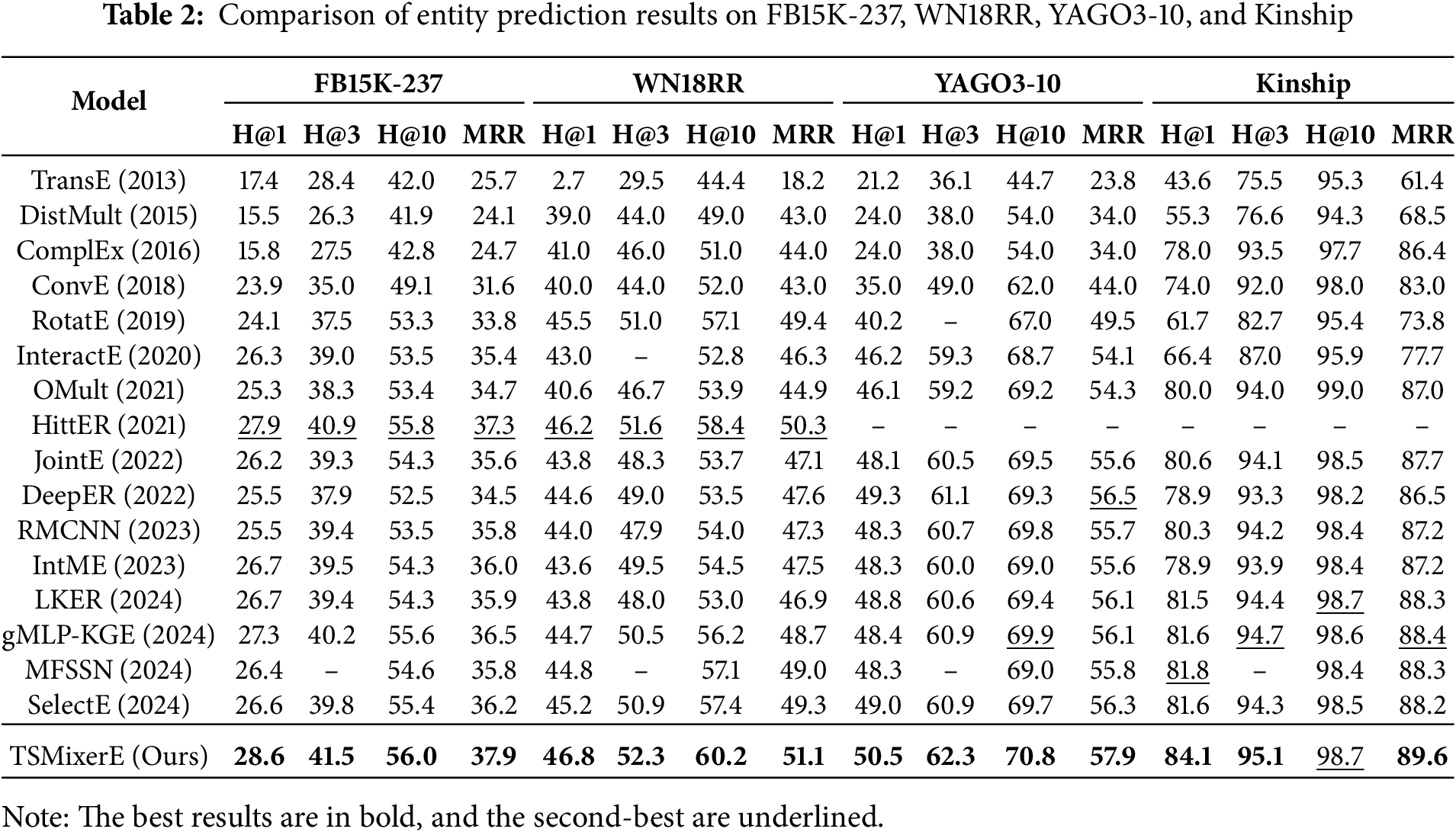

Table 2 presents the entity prediction results on the FB15k-237 WN18RR, YAGO3-10, and Kinship datasets. The best results are highlighted in bold, the sub-optimal results are underlined, “-” indicates that the method does not report results for the corresponding dataset, and all values are given as percentages. TSMixerE achieves the best performance on most metrics across four datasets, except Hits@10 on Kinship.

(1) Methods that leverage entity context information demonstrate significant advantages in entity prediction tasks. For instance, models such as HittER and TSMixerE, which are based on contextual information, generally outperform those relying solely on local triple information. This advantage primarily arises because entity context provides more comprehensive semantic dependencies, enabling the models to capture complex entity-neighbor relationships more accurately. Rich contextual descriptions enhance the expressive power of entity embeddings and improve overall entity prediction performance.

(2) TSMixerE outperforms HittER. Specifically, compared to HittER, TSMixerE achieves improvements in MRR of 1.61% and 1.59% on the FB15k-237 and WN18RR datasets, respectively, over HittER. HittER employs a hierarchical Transformer architecture that requires multi-layer self-attention computations, while InteractE relies on local feature interactions within individual triplets. In comparison, the USE module in TSMixerE is capable of both local feature interaction and feature filtering. Furthermore, compared to Transformer, its CIF module—based on BERT—enables structured global context aggregation. The main reason is that TSMixerE enables more accurate feature interactions through the use of MSCC and a channel attention mechanism, which effectively extracts deep semantic associations between entities and relations. Multi-scale convolution captures local information at different levels, while the channel attention mechanism highlights key semantic features and strengthens associations between entities and relations. Additionally, compared to the Transformer architecture, the BERT-based CIF module demonstrates stronger capabilities in structured global context aggregation. TSMixerE employs multi-layer BERT for deep fusion of contextual information, fully integrates global dependencies, addresses the limitations of long-distance information transfer, and further improves the accuracy of entity prediction.

(3) The experimental results of TSMixerE on the four datasets—YAGO3-10, FB15k-237, WN18RR, and Kinship—show a progressive decrease in performance improvement, with gains of 2.48%, 1.61%, 1.59%, and 1.36%, respectively. This trend highlights the model’s advantages in handling complex entity relationships and rich contextual information. On the YAGO3-10 dataset, which features higher structural complexity and more diverse entity relationships, the model’s optimization strategy is fully leveraged, resulting in the most significant improvement. The FB15k-237 dataset, characterized by moderate noise in entity relationships, demonstrates a steady performance gain as well. In contrast, the WN18RR and Kinship datasets, with their relatively simple structures, offer less room for further optimization. Overall, the improved design of TSMixerE demonstrates strong adaptability to different dataset characteristics.

In summary, TSMixerE fully utilizes MSCC and the channel attention mechanism to effectively extract deep semantic associations between entities and relations within triples. Simultaneously, it demonstrates robust integration of global information in the context information fusion stage, further enhancing the accuracy of entity prediction. The experimental results indicate that TSMixerE achieves superior performance across various evaluation metrics, thereby fully validating the critical role of feature interaction mechanisms and entity context information in KGC.

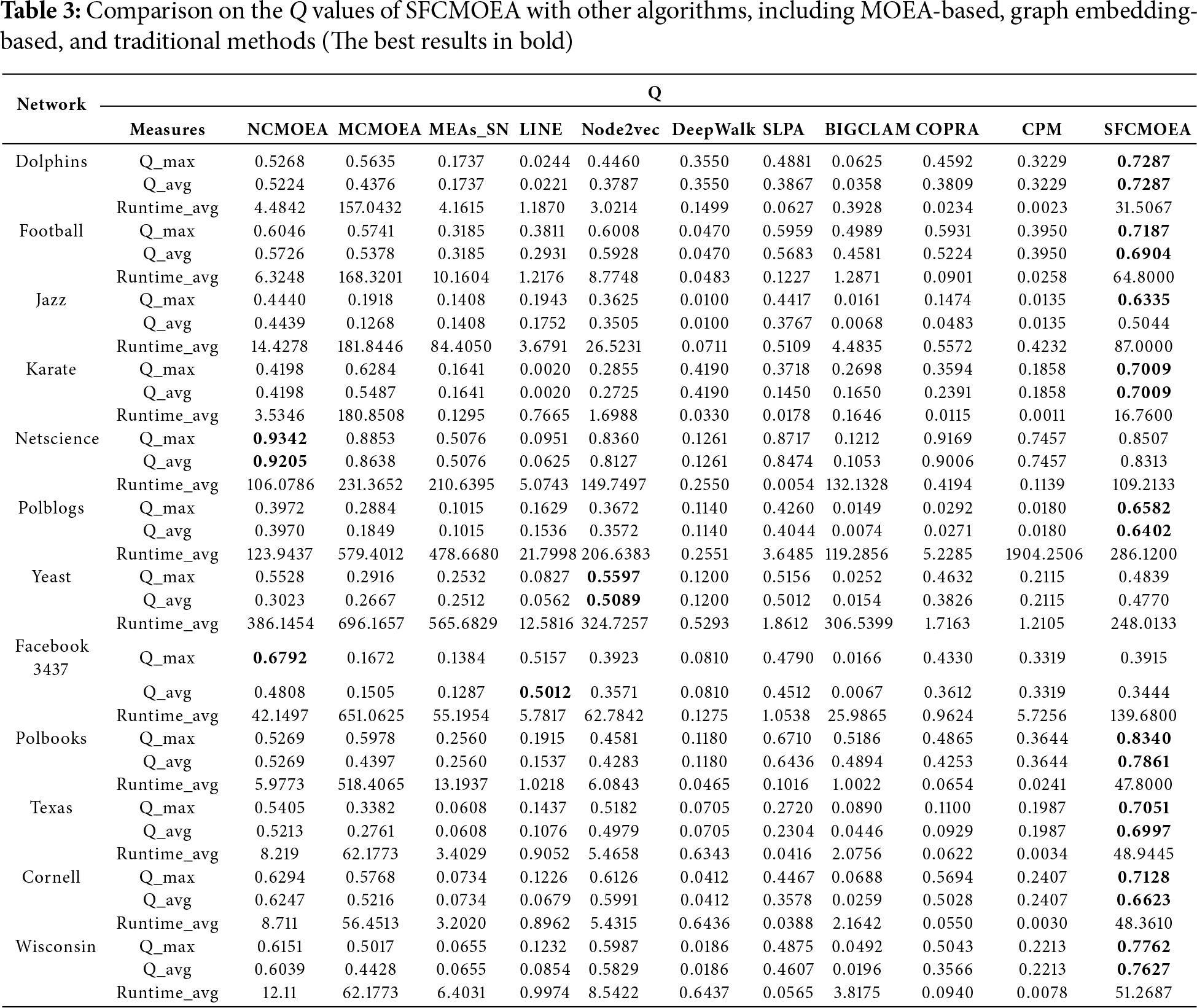

TSMixerE incorporates several key components, including MSCC, channel attention (CA), entity contextual information (CTX), MHEP, classification token (CLS), and type embedding (TE). To evaluate the contribution of each module to the overall completion performance, we conducted ablation studies on each component of the TSMixerE model using the WN18RR dataset. The experimental results are presented in Table 3, where a check mark (√) indicates the inclusion of a component in the experiment, and a cross (×) indicates its removal. The ablation experiments were organized into two categories: those without entity context information (w/o-ctx) and those with entity context information (ctx). The details of the experimental setup and results are as follows:

(1) w/o-all: The encoder is implemented solely with InteractE, with all other components removed.

(2) w/o-ctx-mscc: Contextual information about entities is excluded, and the MSCC module is removed.

(3) w/o-ctx-ca: Contextual information about entities is excluded, and the channel attention module is removed.

(4) w/o-ctx: Contextual information about entities is excluded, but both MSCC and channel attention are retained.

(5) w/o-mscc: Contextual information about entities is included, but the MSCC module is removed.

(6) w/o-ca: Contextual information about entities is included, but the channel attention module is removed.

(7) w/o-mhep: Contextual information about entities is included, but the MHEP is removed.

(8) w/o-cls: Contextual information about entities is included, but the classification token [CLS] is removed.

(9) w/o-te: Contextual information about entities is included, but the type embedding is removed.

Based on the experimental results in Table 3, the contribution of each component to the TSMixerE model for the SKGC task is fully validated. The experimental data demonstrate the following:

(1) The model without entity context information exhibits the poorest performance, indicating that relying solely on the local information from individual triples fails to capture the rich semantic dependencies present in the neighboring nodes of entities within the graph structure. This results in incomplete embeddings and, consequently, a decline in overall performance. This finding underscores the critical importance of incorporating contextual information in KGC.

(2) When the model utilizes entity context information but does not employ the MHEP, its performance still decreases. This suggests that perturbing some head entities during training compels the model to leverage additional contextual information, thereby uncovering more useful semantic cues and improving the accuracy of entity prediction. The MHEP thus provides an effective mechanism for the model to exploit contextual information fully.

(3) The introduction of the classification token [CLS] in the CIF module enhances the model’s performance. As a special categorical marker, [CLS] interacts with all elements in the input sequence and, through multi-layer BERT, gradually aggregates long-range dependencies and global semantic information, thereby producing a more comprehensive and accurate global representation.

(4) The incorporation of type embedding also has a positive impact on the model’s performance. By assigning distinct type embeddings to the classification token [CLS], query units, and context units, the model can clearly distinguish information from different sources during context fusion. This approach not only preserves the original semantic features of each component but also effectively reduces the risk of noise caused by positional confusion, thereby improving the model’s sensitivity and its ability to recognize diverse semantic information.

The results of the ablation experiments demonstrate that each component plays a vital role in enhancing the capacity of the TSMixerE model to capture the semantics of entities and relations. TSMixerE addresses a range of challenges in SKGC, including local feature interactions, feature selection, global semantic integration, and training signal optimization. Specifically, the model leverages contextual entity information to capture semantic dependencies, employs MSCC to improve the flexibility and robustness of feature interactions, incorporates channel attention mechanisms to enhance the discriminative quality of feature representations, and introduces an MHEP module to promote a more effective utilization of contextual information. The synergistic effect among the various modules effectively strengthens both local feature extraction and global semantic fusion. The results in Tables 3 and 4 confirm the individual contributions of each component and reveal synergistic effects among them. The performance degradation caused by removing any module demonstrates interdependencies within the architecture. In the case of MHEP, the performance drop observed in the w/o-mhep configuration relative to the full TSMixerE model underscores its role in providing effective supervisory signals under current data sparsity conditions, thereby providing a more robust solution to the SKGC task. For instance, given a query like (Einstein, research_field, ?), the model assigns higher attention weights to relevant contexts such as (Einstein, award_received, Nobel_Prize_in_Physics) and lower weights to less relevant ones like (Einstein, birthplace, Germany). This validates that the semantic quality from the USE module directly influences the attention efficiency of the CIF module, demonstrating a well-coordinated interplay between the two stages.

Hyperparameter tuning experiments are conducted to optimize the performance of the TSMixerE model, focusing on the effects of four key parameters: the total number of entity contexts (k), the number of BERT layers (N), the loss weight coefficient (weight_coef) for MHEP, and the masking rate (masking_rate) for MHEP.

(1) Total Number of Entity Contexts

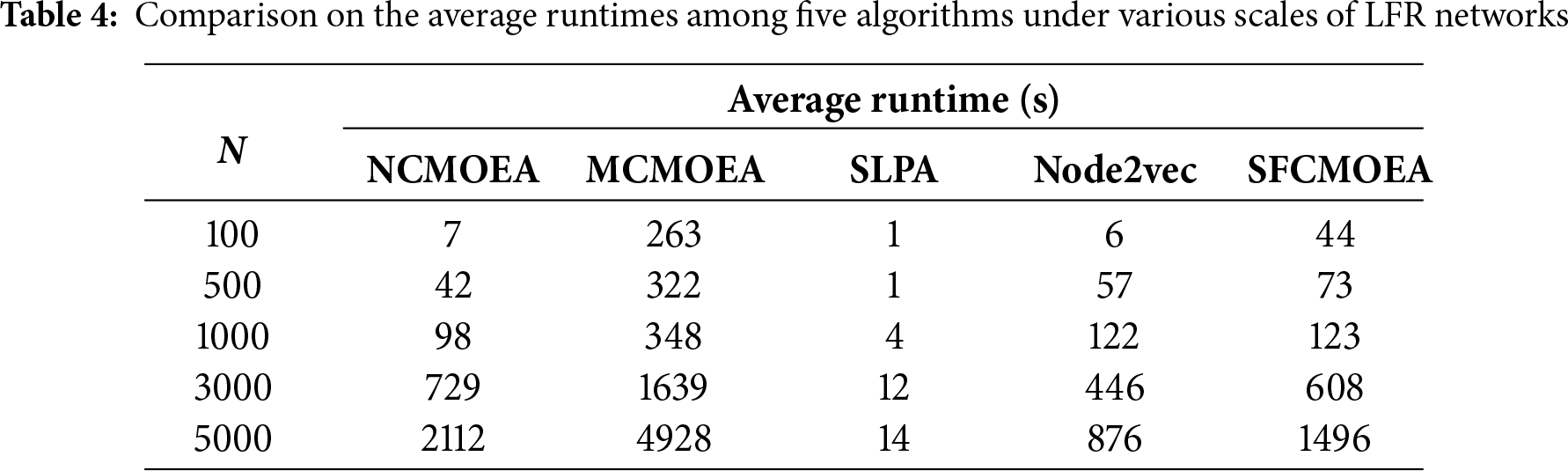

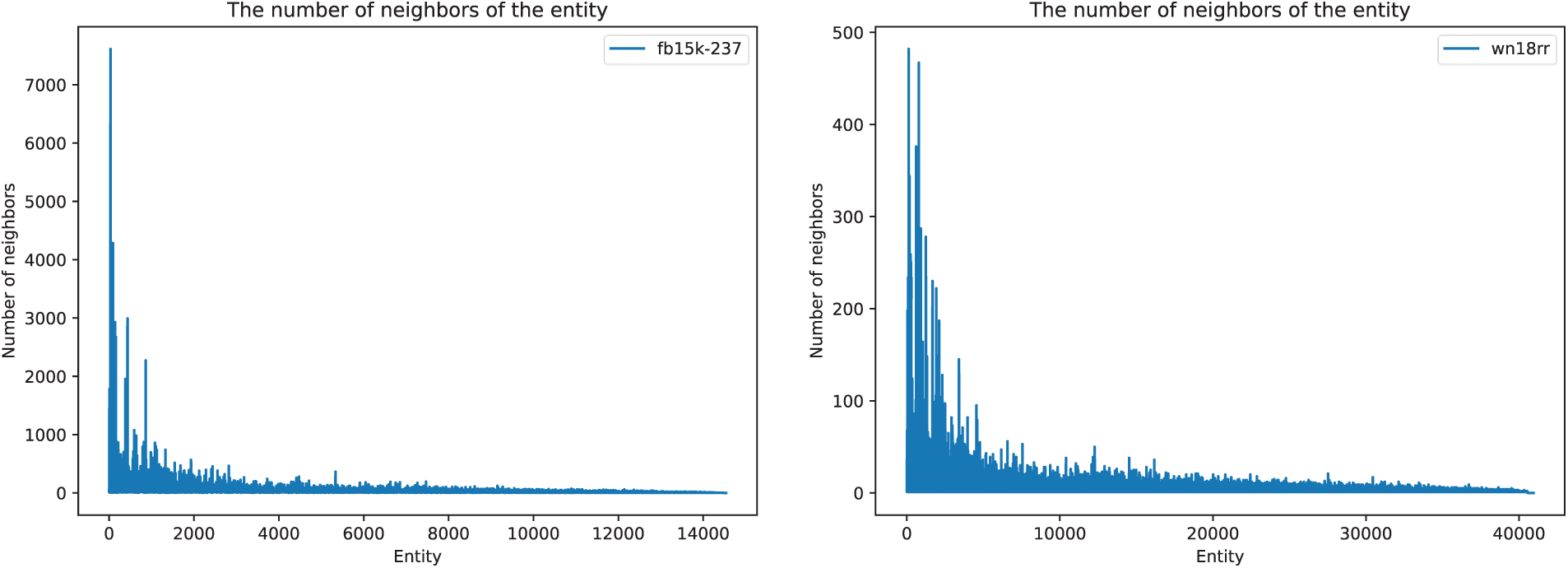

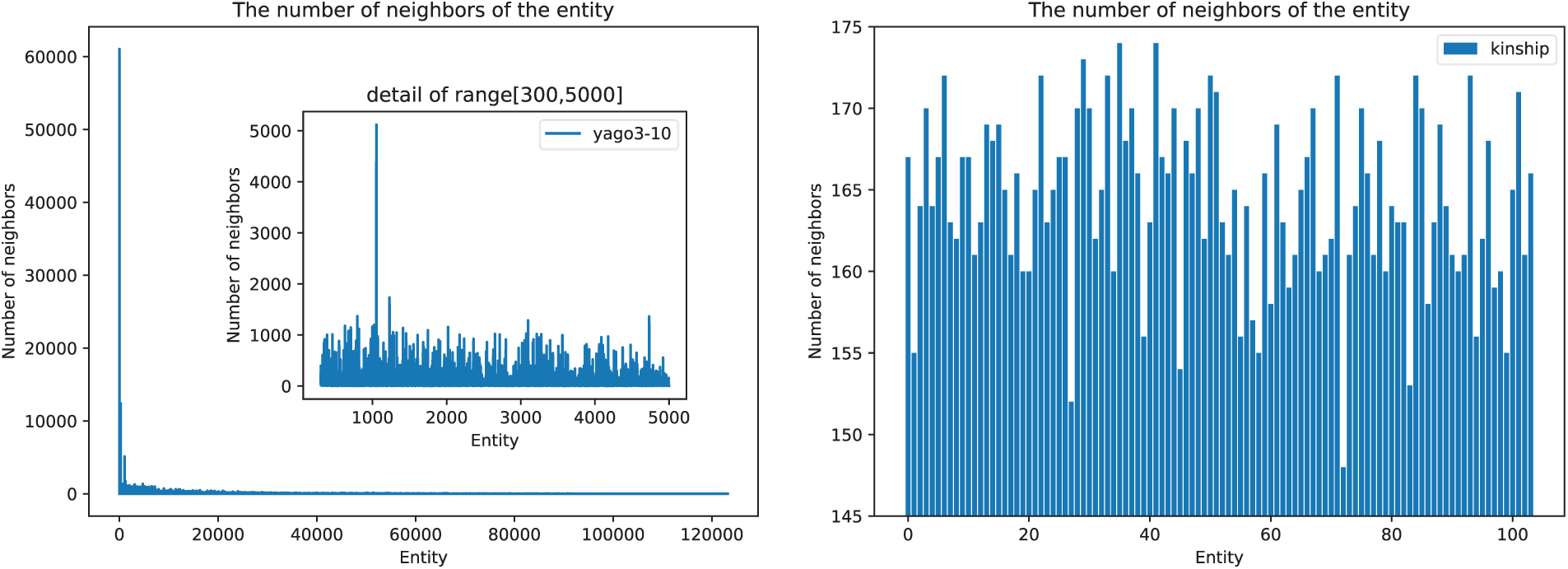

When constructing the sequence of entity context units, some entities may possess a large number of neighboring nodes. To balance memory usage and ensure adequate coverage of the entity distribution, it is necessary to standardize the number of neighboring nodes by manually setting the total number of contexts (k). As shown in Fig. 8, for the FB15k-237 and YAGO3-10 datasets, setting k to 1000 is most appropriate; as illustrated in Fig. 9, k is optimal at 300 for the WN18RR dataset, while for the Kinship dataset, a value of 175 is optimal. This configuration provides reasonable context coverage for different datasets, taking into account both memory efficiency and the model’s semantic representation capabilities.

Figure 8: Distribution of the number of neighboring nodes for entities on FB15K-237 (left) and WN18RR (right)

Figure 9: Distribution of the number of neighboring nodes of entities on YAGO3-10 (left) and Kinship (right)

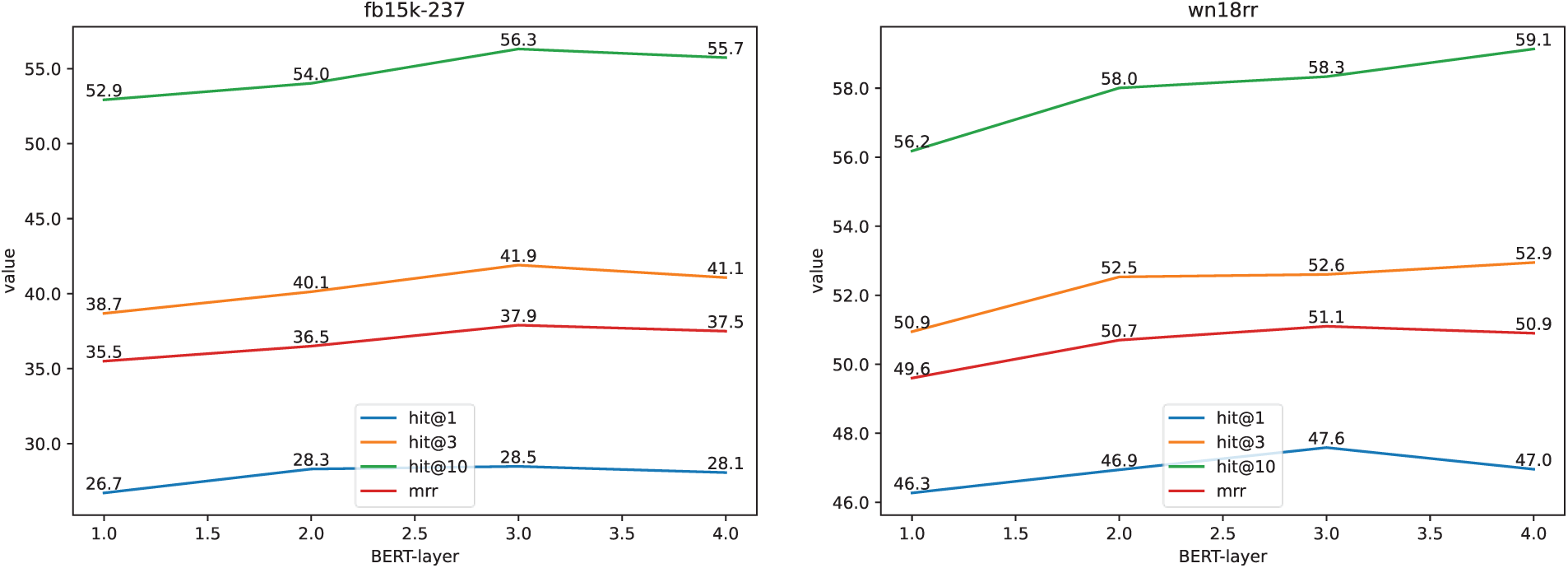

(2) Number of BERT Layers

For the number of BERT layers, experiments were conducted with four configurations, N = {1, 2, 3, 4}, and the corresponding model performance was recorded. As shown in Fig. 10, the results indicate that the number of layers has a significant impact on the model’s performance. When N = 3, the model is able to capture contextual information more effectively, achieve robust modeling of global dependencies, and deliver optimal performance. In contrast, too few layers result in insufficient parameters and a reduced model capacity, while too many layers may introduce redundant information and increase training difficulty, ultimately leading to diminished effectiveness. Therefore, the number of BERT layers, N, is set to 3.

Figure 10: Effect of TSMixerE with different BERT layers on FB15K-237 and WN18RR

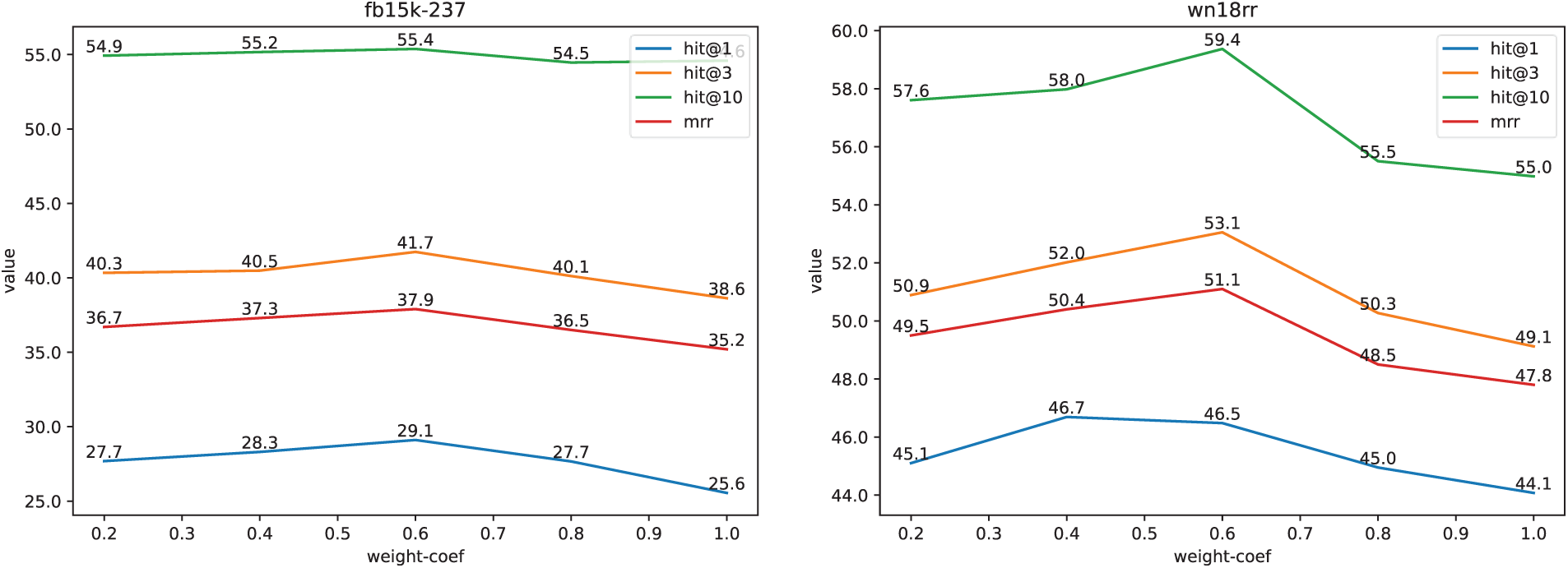

(3) Loss Weighting Coefficient for MHEP

For the loss weighting coefficient of MHEP, experimental values of {0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0} were tested. As shown in Fig. 11, the results reveal a nonlinear relationship between the weighting coefficient and the model’s performance: as the coefficient increases, the model’s performance initially improves, but when the coefficient exceeds a certain threshold, the MHEP begins to negatively impact the entity prediction task, resulting in a decline in overall performance. Based on the evaluation metrics, the optimal weighting coefficient is set to approximately 0.6. When the coefficient is too high (e.g., >0.8), the MHEP loss dominates optimization, potentially causing the model to over-rely on context for reconstructing masked entities and weaken its modeling of the query unit itself. Since queries are complete during testing, this train-test mismatch degrades primary task performance. Thus, a moderate coefficient (0.6) balances the auxiliary task’s regularization benefits with the primary task’s objective, avoiding negative transfer.

Figure 11: Effect of different weight coefficients for TSMixerE on FB15K-237 and WN18RR

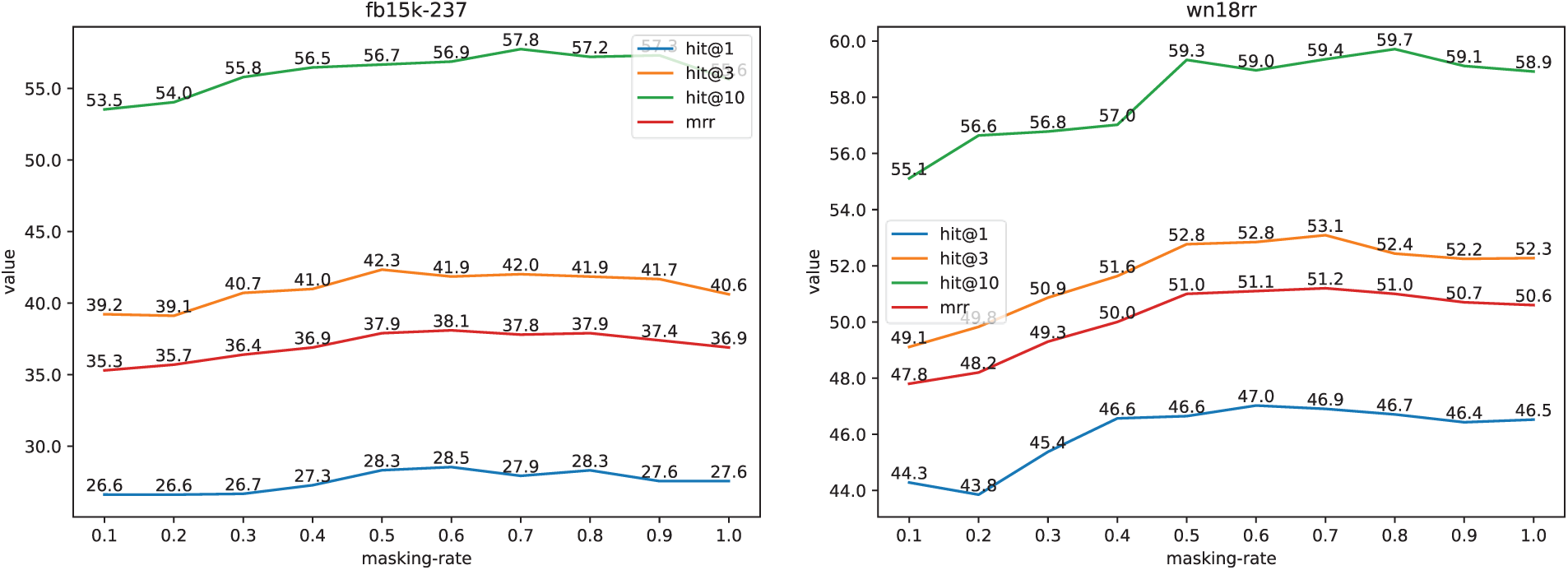

(4) Mask Rate of MHEP

To investigate the impact of the MHEP mask rate, experiments were conducted with values ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 in increments of 0.1. As shown in Fig. 12, the results indicate that when the masking rate is between 0.1 and 0.5, the model’s performance gradually improves as the masking rate increases. The best performance is observed when the masking rate is in the range of 0.5 to 0.8; beyond this range, further increases in the masking rate lead to a decline in performance. This suggests that higher mask rates introduce more perturbations during training, compelling the model to rely more heavily on contextual information for recovery and prediction tasks. Conversely, a low mask rate does not fully exploit the model’s potential, whereas an excessively high mask rate imposes greater demands on model capacity. Overall, a mask rate between 0.5 and 0.8 is most suitable, and a value of 0.5 is adopted in the experiments presented in this paper. A higher masking rate introduces more perturbations, compelling the model to depend on richer contextual information for recovery and prediction. Conversely, an excessively low masking rate underutilizes the model’s potential, whereas an excessively high masking rate imposes greater demands on the model’s performance.

Figure 12: Effect of TSMixerE on Mask Rate on FB15K-237 and WN18RR

Overall, the hyperparameter optimization experiments confirm the critical roles of each parameter in the TSMixerE model. The number of BERT layers, the loss weighting coefficient, and the masking rate all have a significant impact on the model’s ability to capture global semantic information and compensate for the insufficiency of local information.

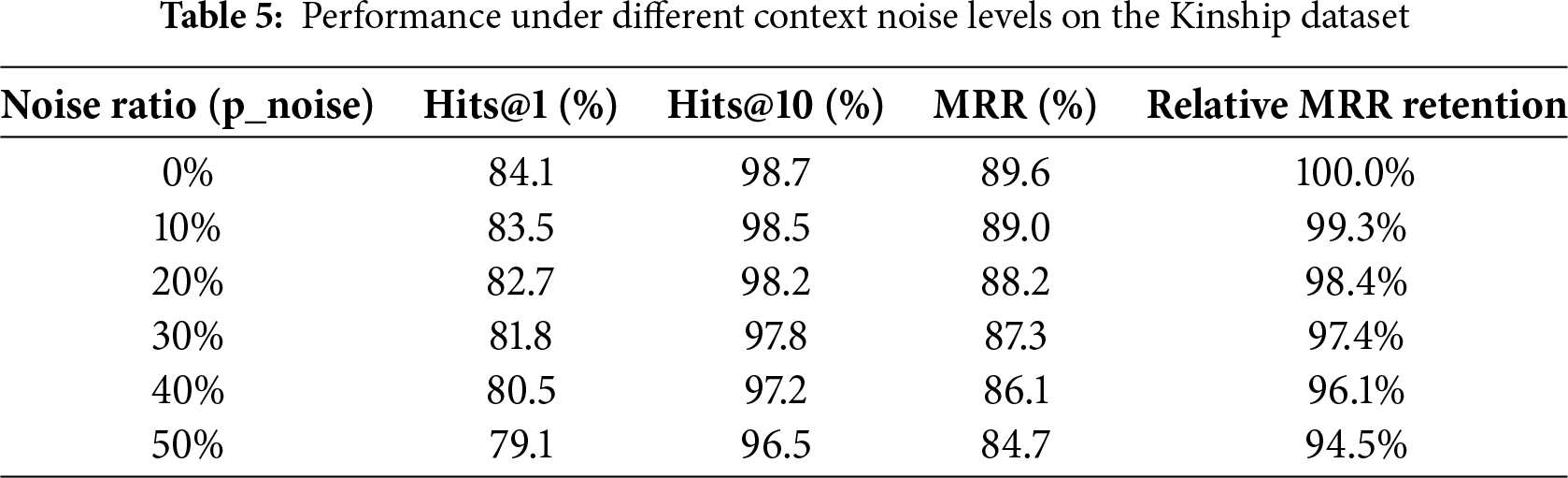

We evaluated the robustness of TSMixerE when the quality of input contexts is compromised, which is crucial for real-world applications. A controlled noise injection experiment was conducted on the Kinship dataset. When constructing the entity context sequence, each true contextual entity was randomly replaced with another entity from the KG with a probability p_noise, simulating varying degrees of noisy environments. As shown in Table 5, all performance metrics decline as the noise increases, but the degradation trend is gradual. Even under an extreme scenario where 50% of contextual entities are replaced, the model retained 94.5% of its original MRR performance. This demonstrates that TSMixerE exhibits good robustness to sampling noise.

4.6 Model Parameter Count Analysis

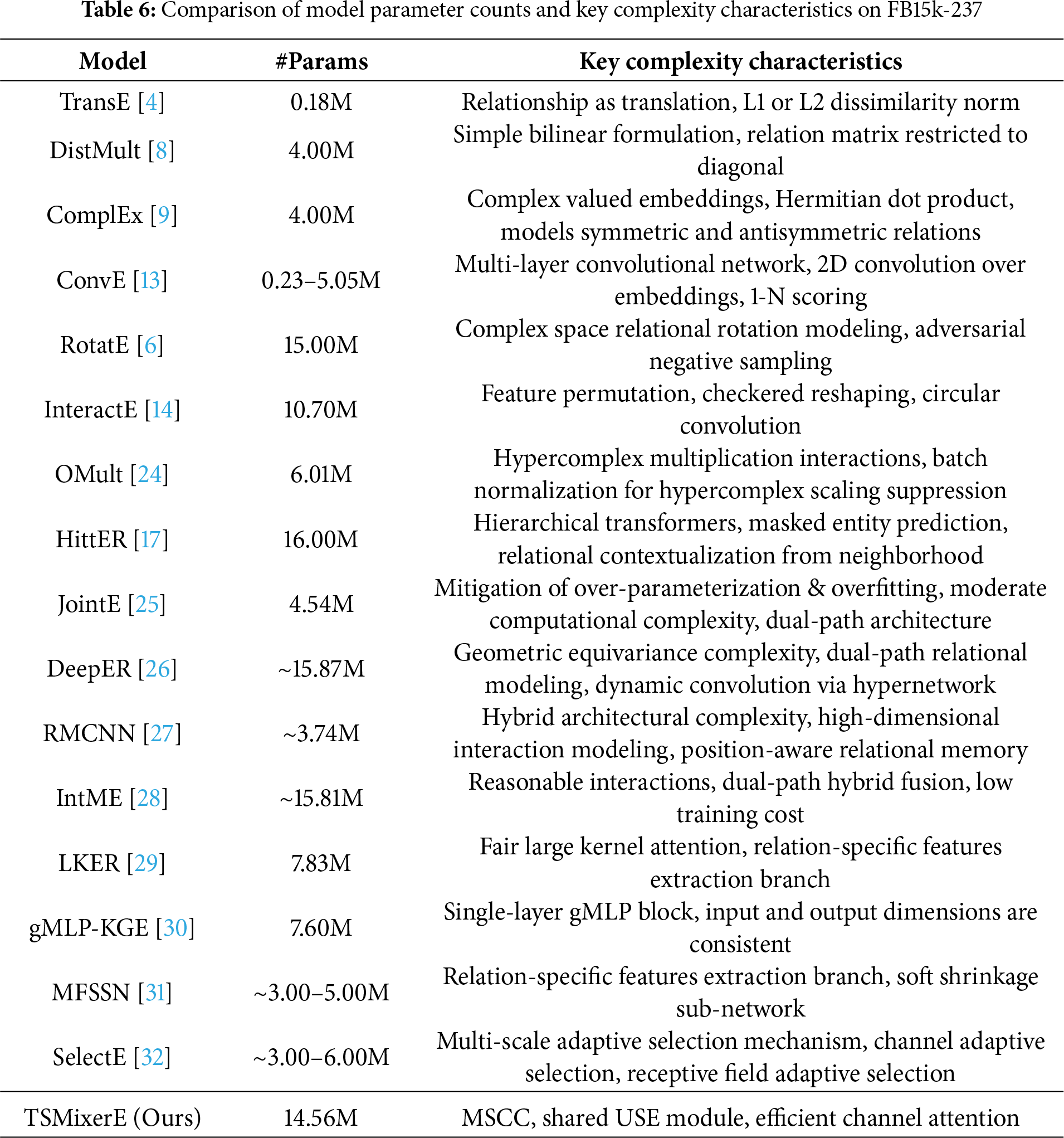

To evaluate the efficiency of TSMixerE, we theoretically compare its complexity differences with major baseline models. As shown in Table 6, this table summarizes the parameter counts and key complexity characteristics of the compared models, where “~” indicates estimated parameter counts and “–” denotes a value range. It can be observed that the parameter counts of the baseline models range from 0.18M (TransE) to approximately 16M (HittER), spanning a spectrum from simple translation-based models to complex structural models. TSMixerE remains competitive in terms of parameter count, positioned between lightweight convolutional models (ConvE, InteractE) and larger-scale Transformer models (HittER).

To further evaluate practical efficiency, we compare the per-batch inference time of TSMixerE with two strong baselines, MFSSN [31] and SelectE [32]. TSMixerE requires 12.53 s per batch, which is higher than MFSSN (9.36 s/batch) and SelectE (6.41 s/batch). This increased overhead stems from the introduction of multi-scale circular convolution, channel attention, and BERT-based context fusion modules, which enhance feature interaction and semantic integration. The additional computational cost represents a reasonable trade-off for the achieved performance gains.

In this paper, we propose TSMixerE, a SKGC method based on entity context. The method first employs MSCC to capture local features at different granularities and utilizes channel attention to enhance the response of important channels, thereby improving the flexibility and robustness of feature fusion. Furthermore, TSMixerE achieves deep interactions of contextual information through multi-layer self-attention and clarifies the semantic identity and role of each component via type embedding, thus effectively integrating local details with global context. Experimental results on multiple benchmark datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of TSMixerE for the task of SKGC.

In this paper, TSMixerE focuses on leveraging the contextual information of entities to enhance entity prediction performance. However, in KGs, relations themselves also contain rich contextual information, such as potential associations and semantic patterns with their neighboring relations. Future research could investigate effective modeling of relation context, for example, by introducing relation embedding sequences and extracting interaction features among relations using self-attention mechanisms or graph neural networks. Additionally, the current selection of entity context nodes in TSMixerE primarily relies on random sampling, which may not fully capture the importance or semantic associations of neighboring nodes. In the future, methods based on importance assessment could be adopted to rank and filter neighbor nodes according to criteria such as popularity and influence. This will be conducted along with further validation of the type embedding strategy on larger-scale datasets with more diverse relation types. Concurrently, we will explore the introduction of a more flexible multi-scale feature retention mechanism within the USE module, injecting feature maps of different scales into the fusion stage in a more refined manner. We will augment the attention mechanism in the TSMixerE model by incorporating a contrastive learning module, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability. Future work will also involve a more in-depth analysis of the complexity of TSMixerE compared to baseline models.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62267005); the Chinese Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (No. 2023GXNSFAA026493); Guangxi Collaborative Innovation Center of Multi-Source Information Integration and Intelligent Processing; Guangxi Academy of Artificial Intelligence.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jianzhong Chen, Yunsheng Xu and Ying Pan; data collection: Yunsheng Xu; analysis and interpretation of results: Jianzhong Chen and Yunsheng Xu; draft manuscript preparation: Jianzhong Chen and Yunsheng Xu; draft review and editing: Jianzhong Chen, Zirui Guo and Tianmin Liu; funding acquisition: Ying Pan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Peng C, Xia F, Naseriparsa M, Osborne F. Knowledge graphs: opportunities and challenges. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(11):13071–102. doi:10.1007/s10462-023-10454-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Jetti SR, Krishna Prasad MHM. Knowledge graphs and neural networks in recommendation systems: a comprehensive survey and future directions. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT); 2025 Jan 15–17; Bengaluru, India. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1163–70. [Google Scholar]

3. Liang K, Meng L, Liu M, Liu Y, Tu W, Wang S. A survey of knowledge graph reasoning on graph types: static, dynamic, and multi-modal. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2024;46(12):9456–78. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2024.3234567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bordes A, Usunier N, Garcia-Durán A, Weston J, Yakhnenko O. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational data. In: Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS); 2013 Dec 5–8; Lake Tahoe, NV, USA. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates; 2013. p. 2787–95. doi:10.5555/2999792.2999923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang Z, Zhang J, Feng J, Chen Z. Knowledge graph embedding by translating on hyperplanes. In: Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI); 2014 Jul 27–31; Québec City, QC, Canada. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2014. p. 1112–9. doi:10.5555/2893873.2894046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sun Z, Deng Z, Nie J, Tang J. RotatE: knowledge graph embedding by relational rotation in complex space. In: 7th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2019 May 6–9; New Orleans, LA, USA. La Jolla, CA, USA: ICLR; 2019. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1902.10197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nickel M, Tresp V, Kriegel H. A three-way model for collective learning on multi-relational data. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2011 Jun 28–Jul 2; Bellevue, WA, USA. Madison, WI, USA: Omnipress; 2011. p. 809–16. doi:10.5555/3104482.3104584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yang B, Yih W, He X, Gao J, Deng L. Embedding entities and relations for learning and inference in knowledge bases. In: 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2015 May 7–9; San Diego, CA, USA. La Jolla, CA, USA: ICLR; 2015. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1412.6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Trouillon T, Welbl J, Riedel S, Gaussier É, Bouchard G. Complex embeddings for simple link prediction. In: Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2016 Jun 19–24; New York, NY, USA. Cambridge, MA, USA: JMLR.org; 2016. p. 2071–80. doi:10.5555/3045390.3045603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Balazevic I, Allen C, Hospedales T. TuckER: tensor factorization for knowledge graph completion. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); 2019 Nov 3–7; Hong Kong, China. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2019. p. 5185–94. doi:10.18653/v1/D19-1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Schlichtkrull M, Kipf T, Bloem P, van den Berg R, Titov I, Welling M. Modeling relational data with graph convolutional networks. In: The Semantic Web: 15th International Conference (ESWC); 2018 Jun 3–7; Heraklion, Greece. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 593–607. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-93417-4_38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Vashishth S, Sanyal S, Nitin V, Talukdar P. Composition-based multi-relational graph convolutional networks. In: 8th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2020 Apr 26–30; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. La Jolla, CA, USA: ICLR; 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1911.03082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Dettmers T, Minervini P, Stenetorp P, Riedel S. Convolutional 2D knowledge graph embeddings. In: Proceedings of the 32nd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI); 2018 Feb 2–7; New Orleans, LA, USA. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2018. p. 1811–8. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.11805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Vashishth S, Sanyal S, Nitin V, Agrawal N, Talukdar P. Interacte: improving convolution-based knowledge graph embeddings by increasing feature interactions. In: Proceedings of the 34th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI); 2020 Feb 7–12; New York, NY, USA. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2020. p. 3009–16. doi:10.1609/aaai.v34i03.5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li S, Liu R, Wen Y, Sun T. Flow-modulated scoring for semantic-aware knowledge graph completion. arXiv:2506.23137. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2506.23137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS); 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates; 2017. p. 6000–10. doi:10.5555/3295222.3295349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen S, Liu X, Gao J, Jiao J, Zhang R, Ji Y. HittER: hierarchical transformers for knowledge graph embeddings. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2021 Nov 7–11; Punta Cana, Dominican Republic. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2021. p. 10395–407. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.emnlp-main.813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. He W, Xiao Y, Huang M, Mou X, Wang R, Li Q. A pattern-driven information diffusion prediction model based on multisource resonance and cognitive adaptation. In: Proceedings of the 48th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; 2025 Jul 14–18; Padua, Italy. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2025. p. 592–601. doi:10.1145/3726302.3729883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zheng Q, Saponara S, Tian X, Yu Z, Elhanashi A, Yu R. A real-time constellation image classification method of wireless communication signals based on the lightweight network mobileViT. Cogn Neurodynamics. 2024;18(4):659–71. doi:10.1007/s11571-023-10036-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Toutanova K, Chen D, Pantel P, Poon H, Choudhury P, Gamon M. Representing text for joint embedding of text and knowledge bases. In: Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2015 Sep 17–21; Lisbon, Portugal. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2015. p. 1499–509. doi:10.18653/v1/D15-1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Toutanova K, Chen D. Observed versus latent features for knowledge base and text inference. In: Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Continuous Vector Space Models and their Compositionality (CVSC); 2015 Jul 26–31; Beijing, China. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2015. p. 57–66. doi:10.18653/v1/W15-4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mahdisoltani F, Biega J, Suchanek F. YAGO3: a knowledge base from multilingual wikipedias. In: 7th Biennial Conference on Innovative Data Systems Research (CIDR); 2015 Jan 4–7; Asilomar, CA, USA. doi:10.5281/zenodo.837628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Lin XV, Socher R, Xiong C. Multi-hop knowledge graph reasoning with reward shaping. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2018 Oct 31–Nov 4; Brussels, Belgium. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2018. p. 3243–53. doi:10.18653/v1/D18-1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Demir C, Moussallem D, Heindorf S, Ngomo AN. Convolutional hypercomplex embeddings for link prediction. In: Proceedings of the 13th Asian Conference on Machine Learning (ACML); 2021 Nov 17–19; Virtual. Brookline, MA, USA: PMLR; 2021. p. 656–71. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2110.07855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou Z, Wang C, Feng Y, Chen D. JointE: jointly utilizing 1D and 2D convolution for knowledge graph embedding. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;240:108100. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.108100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zeb A, Saif S, Chen J, Zhang D. Learning knowledge graph embeddings by deep relational roto-reflection. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;252(3):109451. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Shi M, Zhao J, Wu D. Convolutional neural network knowledge graph link prediction model based on relational memory. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2023;2023(1):1–9. doi:10.1155/2023/8850113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang H, Liu X, Li H. IntME: combined improving feature interactions and matrix multiplication for convolution-based knowledge graph embedding. Electronics. 2023;12(15):3333. doi:10.3390/electronics12153333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang Q, Huang S, Xie Q, Zhao F, Wang G. Fair large kernel embedding with relation-specific features extraction for link prediction. Inf Sci. 2024;668:120533. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.120533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang F, Qiu P, Shen T, Cheng J, Li W. gMLP-KGE: a simple but efficient MLPs with gating architecture for link prediction. Appl Intell. 2024;54(20):9594–606. doi:10.1007/s10489-024-05456-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu J, Zu L, Yan Y, Zuo J, Sang B. Multi-filter soft shrinkage network for knowledge graph embedding. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;250(3):123875. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zu L, Lin L, Fu S, Guo F, Wu J. SelectE: multi-scale adaptive selection network for knowledge graph representation learning. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;291(1):111554. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools