Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Intelligent Human Interaction Recognition with Multi-Modal Feature Extraction and Bidirectional LSTM

1 Guodian Nanjing Automation Co., Ltd., Nanjing, 600268, China

2 Faculty of Computing and AI, Air University, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

3 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Information Technology, College of Computer, Qassim University, Buraydah, 52571, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer Sciences, Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, Northern Border University, Rafha, 91911, Saudi Arabia

6 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, College of Informatics, Korea University, Seoul, 02841, Republic of Korea

7 Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Intelligent Medical Image Computing, School of Future Technology, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

8 Cognitive Systems Lab, University of Bremen, Bremen, 28359, Germany

* Corresponding Author: Hui Liu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Image Recognition: Innovations, Applications, and Future Directions)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 68 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071988

Received 17 August 2025; Accepted 22 October 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Recognizing human interactions in RGB videos is a critical task in computer vision, with applications in video surveillance. Existing deep learning-based architectures have achieved strong results, but are computationally intensive, sensitive to video resolution changes and often fail in crowded scenes. We propose a novel hybrid system that is computationally efficient, robust to degraded video quality and able to filter out irrelevant individuals, making it suitable for real-life use. The system leverages multi-modal handcrafted features for interaction representation and a deep learning classifier for capturing complex dependencies. Using Mask R-CNN and YOLO11-Pose, we extract grayscale silhouettes and keypoint coordinates of interacting individuals, while filtering out irrelevant individuals using a proposed algorithm. From these, we extract silhouette-based features (local ternary pattern and histogram of optical flow) and keypoint-based features (distances, angles and velocities) that capture distinct spatial and temporal information. A Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory network (BiLSTM) then classifies the interactions. Extensive experiments on the UT Interaction, SBU Kinect Interaction and the ISR-UOL 3D social activity datasets demonstrate that our system achieves competitive accuracy. They also validate the effectiveness of the chosen features and classifier, along with the proposed system’s computational efficiency and robustness to occlusion.Keywords

Human Interaction Recognition (HIR) involves the automated understanding of social interactions between individuals. These interactions can range from everyday actions, like shaking hands or exchanging objects to more critical or suspicious behaviors, such as pushing or punching. Recognizing these interactions across different modalities, such as RGB video, depth data, or sensor readings, has significant applications in areas like security, healthcare, and surveillance [1].

HIR in RGB videos falls within the computer vision domain, focused on classifying the interactions between individuals. Compared to single-person activity recognition, HIR presents greater challenges due to complex spatial and temporal relationships between individuals. Additionally, poor video resolution can significantly degrade classification accuracy. While much work has been done in this domain, existing systems still have limitations. Some perform poorly in noisy or low-resolution videos, some struggle to classify interactions in multi person settings when irrelevant persons are also present and others are very computationally intensive, making them expensive for use in real world situations.

In this paper, we propose a system that leverages pretrained deep learning models to segment individuals and extract their keypoint coordinates within a region of interest (ROI), effectively removing irrelevant individuals. We then use carefully selected handcrafted spatial and temporal features, which are faster to compute, followed by a deep learning model for classification. Our approach prioritizes computational efficiency, relying on deep learning models only when classical methods cannot achieve comparable performance. This balance allows our system to maintain strong performance while remaining efficient, making it suitable for real-world deployment. The proposed system has the following key contributions:

• Pretrained instance segmentation (MASK R-CNN) and keypoint detection (YOLO11 Pose) models are used to provide accurate silhouettes and keypoint coordinates respectively even in low resolution videos. An algorithm is proposed to filter out irrelevant individuals from the scene.

• Efficient features are employed to capture the most relevant spatial (Local Ternary Pattern, Distance, Angle) and temporal (Histogram of Optical flow, Velocity) information for human interaction recognition.

• A BiLSTM is used for incorporating temporal dependencies from both forward and backward directions, enabling more accurate classification.

• Comprehensive analyses of feature contributions and classifier performance show that each selected feature contributes meaningful dependencies and that the chosen classifier is well-suited for our use case. Furthermore, evaluations of computational efficiency and occlusion robustness demonstrate that the system is lightweight and reliable under challenging conditions.

This section gives an overview of human interaction classification by handcrafted feature extraction-based approaches and deep learning feature extraction-based approaches.

2.1 Handcrafted Feature Extraction-Based Approaches

These approaches typically begin with preprocessing steps, such as histogram equalization or bilateral filtering to reduce noise. Then segmentation techniques, such as Watershed, GrabCut and Active Contours, are commonly used for human segmentation which are highly sensitive to image quality. For keypoint detection, techniques such as skeletonization of silhouettes and contour-based joint estimation are applied to estimate joint positions.

Then a variety of features are extracted to capture the spatial and temporal dynamics of the interaction. For segmentation, this includes features like Scale-Invariant Feature Transform, Histogram of Oriented Gradients, Motion History Image, Bag of Words-based descriptors and Motion Boundary Histograms while for keypoints, this includes keypoint angles, distances and pairwise keypoint displacements. Then these features are optionally optimized using techniques like Linear Discriminant Analysis or t-SNE before being fed into machine learning classifiers such as Support Vector Machines, Random Forests or k-Nearest Neighbors for final classification. Examples are works done by [2,3].

Some more recent works also incorporated depth information alongside RGB data. For example, in [4], both gray scale and depth silhouette features along with point-based features were extracted before cross entropy optimization and classification using a Maximum Entropy Markov Model.

2.2 Deep Learning Feature Extraction-Based Approaches

Many deep learning approaches for human interaction classification typically use fine-tuned Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures to extract spatial features from individual frames followed by 3D CNNs or Recurrent Neural Networks to model temporal dynamics across sequences. Segmentation-based models such as Mask R-CNN [5], trained on diverse RGB datasets, have also gained popularity for their robustness to varying video resolutions. For example, [6] used a DenseNet encoder with a custom decoder for semantic segmentation, refining inputs by suppressing irrelevant regions before passing them into an EfficientNet BiLSTM. Multi-stream architectures improve performance by letting each stream specialize in a different modality, such as RGB frames, optical flow or keypoint coordinates. The information is then combined using fusion techniques, as explored in [7].

There also has been increasing focus on systems that explicitly model spatial and temporal relationships between interacting individuals. With the advent of advanced keypoint detection models like OpenPose [8] and HRNet [9], modeling interactions through body joint movements has become more feasible. Works such as [10,11] have leveraged Interactional Relational Networks and Graph Convolutional Networks to effectively represent both intra and inter-person relationships, offering promising results in complex interaction scenarios.

However, recent works demonstrate that intelligent fusion of heterogeneous features significantly improves model reproducibility and generalization [12]. The proposed system builds on this idea, fusing features from different modalities that are both efficient to extract and effective for accurate classification.

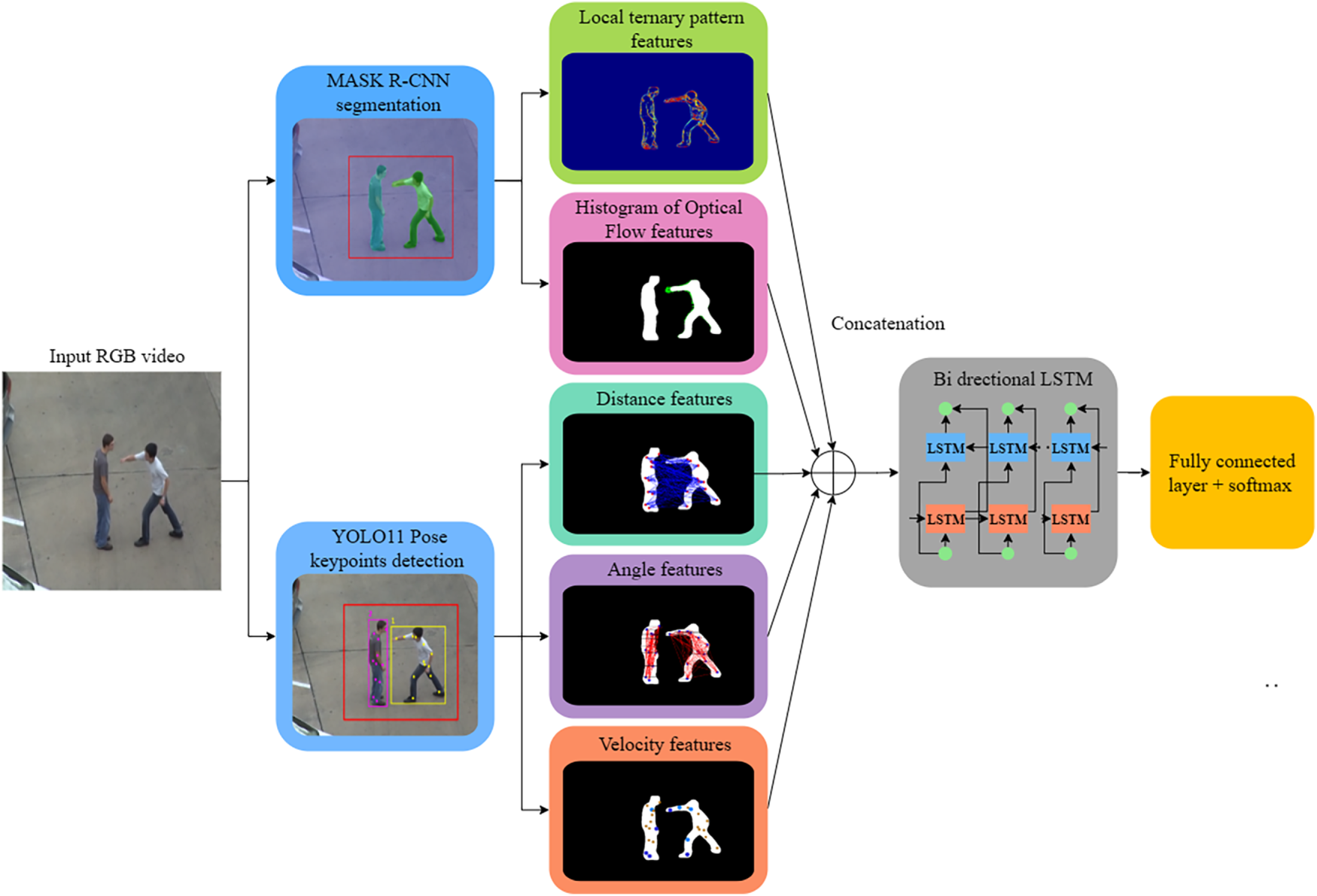

The proposed system begins with dividing the RGB video into frames and selecting a fixed number for classification. Then instance segmentation and keypoint coordinates extraction is performed on each selected frame, focusing on relevant individuals within the ROI. From the resulting gray scale silhouettes and keypoints, spatial and temporal features are extracted followed by classification using a deep learning model. Fig. 1 provides an overview of the system, with details of each stage provided in the following subsections:

Figure 1: Architecture of the proposed system

Accurate segmentation is essential for effective feature extraction in activity classification. To achieve this, we use Mask R-CNN [5], which performs accurate instance-level segmentation by generating separate masks for each person. This enables easy removal of irrelevant individuals. It extends Faster R-CNN [13] by adding a parallel branch for mask prediction. The overall loss function

where

where

where

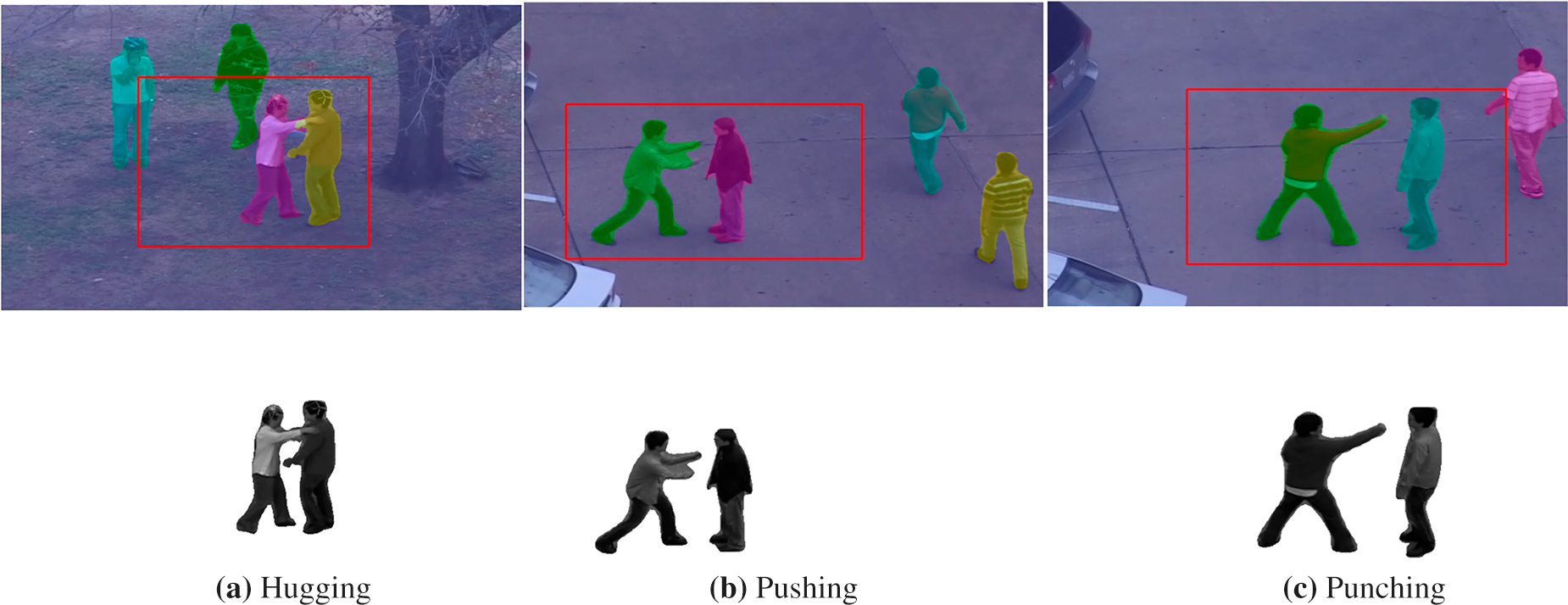

For our experiments, we used a pre-trained Mask R-CNN. RGB frames were resized to an optimal resolution, and a confidence threshold was applied to segment each individual in the frame. Using the ROI boxes, only gray scale silhouettes of relevant individuals were extracted, effectively removing irrelevant individuals. Fig. 2 shows instance segmentation results on the UT interaction dataset (UT) [14], which we evaluated on for our experiments. In the top row, red bounding boxes indicate ROIs, while different colors distinguish individual person instances detected by Mask R-CNN. The bottom row displays corresponding grayscale silhouettes of the segmented individuals within the ROIs.

Figure 2: Segmentation results for hugging, kicking, and punching activities

For keypoints detection and tracking of interacting individuals across frames in ROI, we use YOLO11-Pose [15] from the YOLO framework. YOLO11-Pose builds on YOLOv8’s loss structure. Detection loss includes bounding box loss

where

In C2PSA,

For our experiments, we used a pretrained YOLO11x-Pose, the largest YOLO11-Pose variant, due to its superior keypoints detection performance, with ByteTrack tracker for correct keypoints assignment across frames. ByteTrack assigns unique IDs to persons across frames by first matching high-confidence detections using Intersection over Union, then re-associating low-confidence detections to reduce identity switches. Again, using the ROI boxes, keypoints of irrelevant individuals were removed.

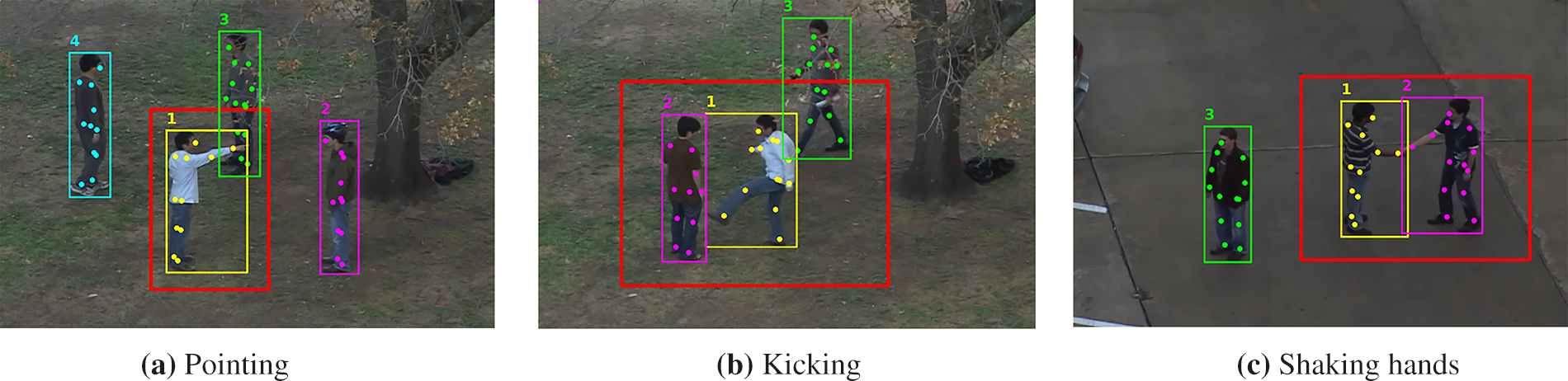

YOLO11-Pose detects 17 keypoints, namely nose, eyes, ears, shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, and ankles. In our approach, we exclude the ear and eye keypoints because they are highly correlated with the nose and often suffer from unreliable detection depending on the person’s orientation in the frame. For example, when an individual is in a lateral view, one eye or ear may not be detected, introducing inconsistencies and noise into the feature representation which ultimately results in lower classification accuracy. By retaining 13 keypoints, each representing distinct and stable body part positions, our system preserves the most informative information for effective classification. Fig. 3 visualizes keypoints detection and tracking on the UT dataset. Red bounding boxes indicate ROIs and colored markers represent individual keypoints, track ids and the bounding boxes of individuals.

Figure 3: Keypoint detection and tracking for pointing, kicking, and shaking hands activities

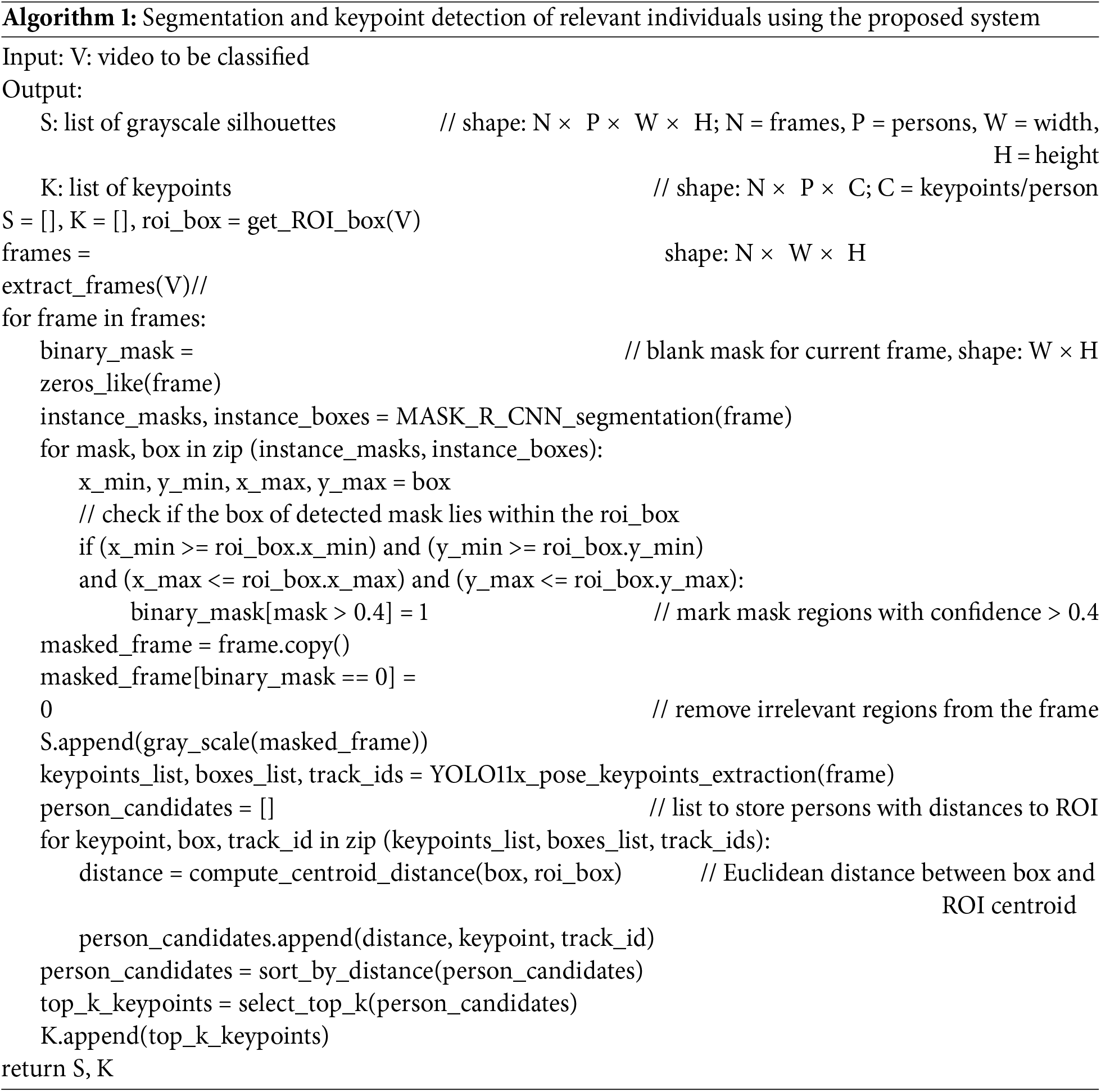

3.3 Algorithm for ROI-Based Segmentation and Keypoint Detection

The following Algorithm 1 is used in our system to filter out irrelevant individuals using the ROI boxes during segmentation and keypoint detection, so features of only relevant individuals are extracted later:

Our system captures both spatial and temporal features from gray scale silhouettes and keypoints. This ensures the extraction of features essential for accurate classification. The details are provided below:

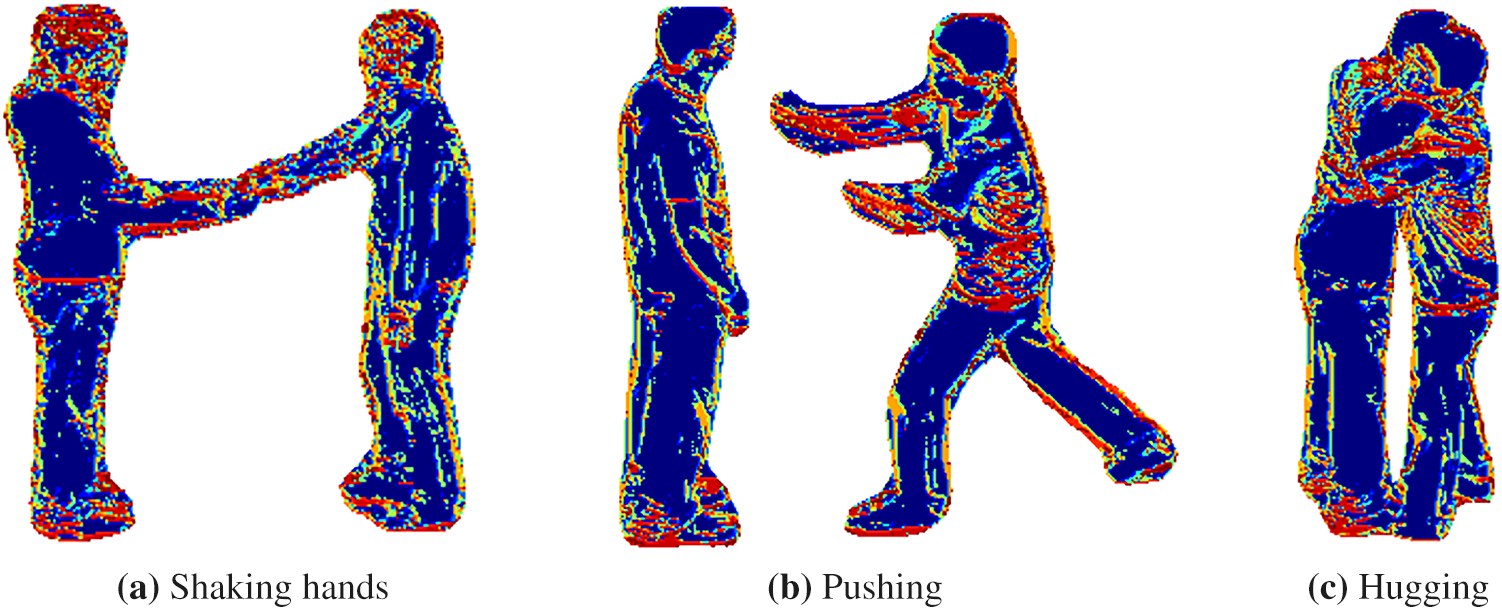

3.4.1 Local Ternary Pattern Features

For the spatial features of grayscale silhouettes, we extract Local Ternary Pattern (LTP) features, which capture local texture information by encoding the relationships between pixel intensities in a neighborhood. The LTP algorithm extends the Local Binary Pattern by introducing a ternary encoding scheme, which divides pixel differences into three categories: positive, negative, and neutral. This allows for more robust feature representation, especially in scenarios with varying illumination or noise. Given a grayscale image

where

Figure 4: LTP features for shaking hands, pushing and hugging activities

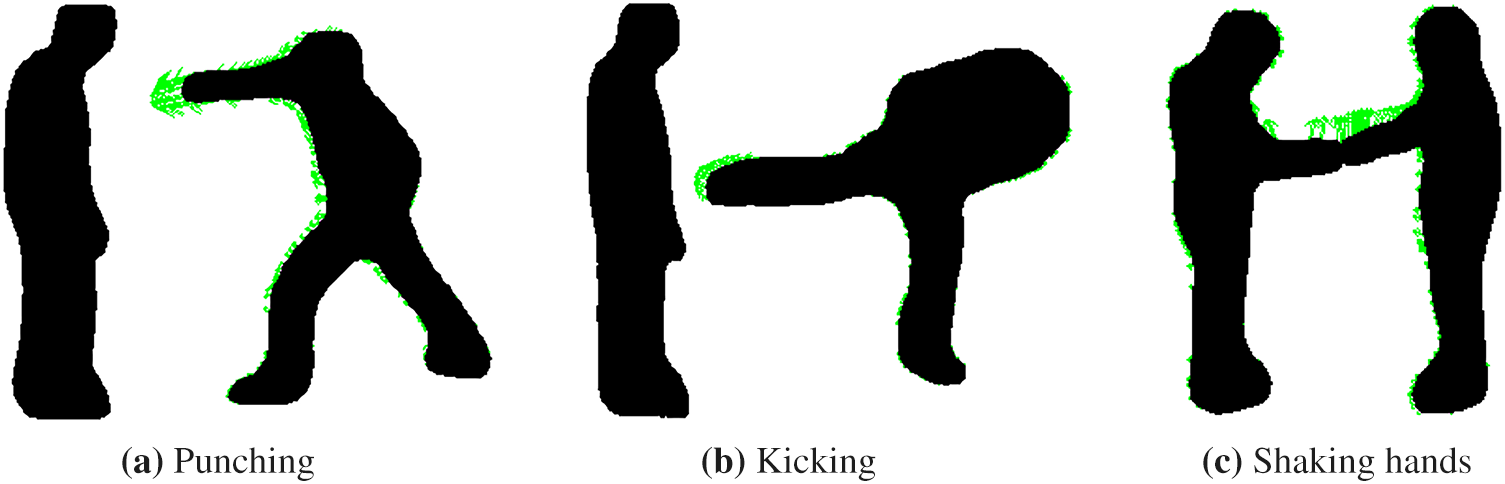

3.4.2 Histogram of Optical Flow (HOF) Features

To capture temporal motion information of interacting individuals across frames, we extract Histogram of Optical Flow (HOF) features from gray scale silhouettes. These features encode the motion patterns between consecutive frames by analyzing the displacement of pixels over time. The optical flow is computed using the Farneback method, which estimates the dense motion vectors between two consecutive frames. The flow vectors

where

Figure 5: HOF features for punching, kicking and shaking hands activities

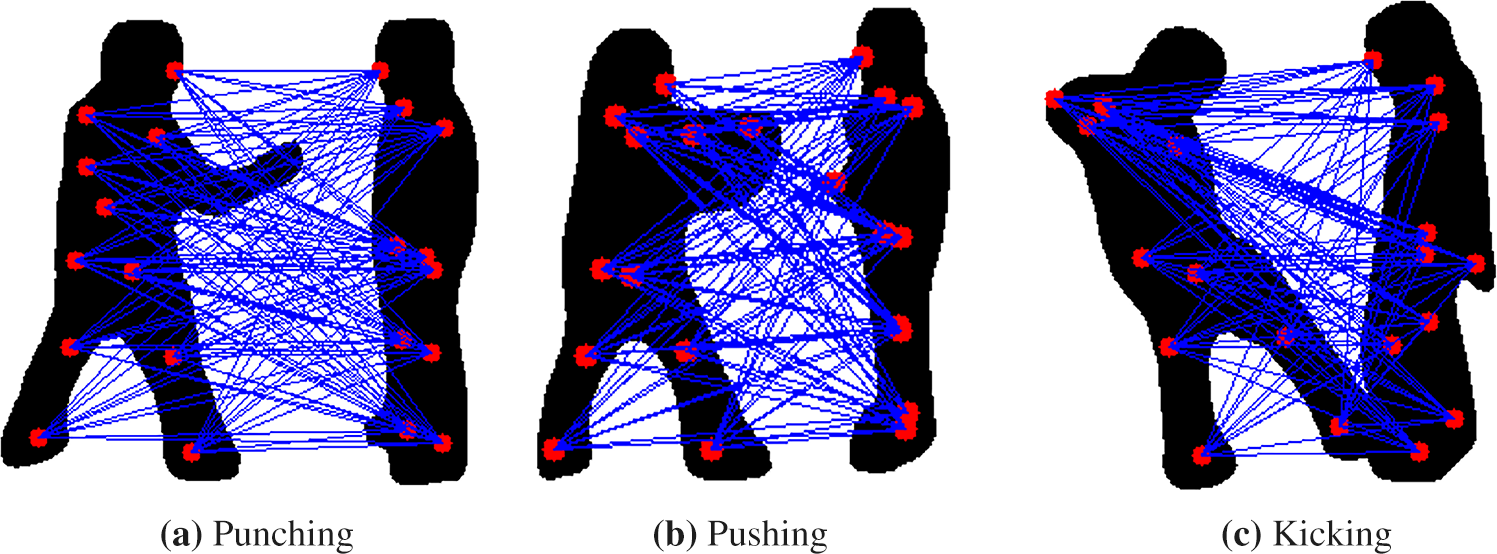

To capture the spatial relationships between keypoints, we extract inter-person distance features. These features characterize the relative positions of body parts across individuals and are particularly useful for distinguishing interactions that involve varying degrees of physical proximity, such as hugging, approaching, or punching. Specifically, they describe how close or far apart certain joints or body regions are, which can reflect the nature and intensity of the interaction. Euclidean distance between two keypoints

We use a fully connected approach, computing pairwise distances between all keypoints of the interacting individuals. This allows the model to learn meaningful interaction patterns without relying on handcrafted keypoint pairs. This approach captures a comprehensive spatial representation of the interaction, helping the system generalize well across various postures and actions. Fig. 6 shows a visualization of these distance features for several interactions from the UT dataset.

Figure 6: Distance features for punching, pushing and kicking activities

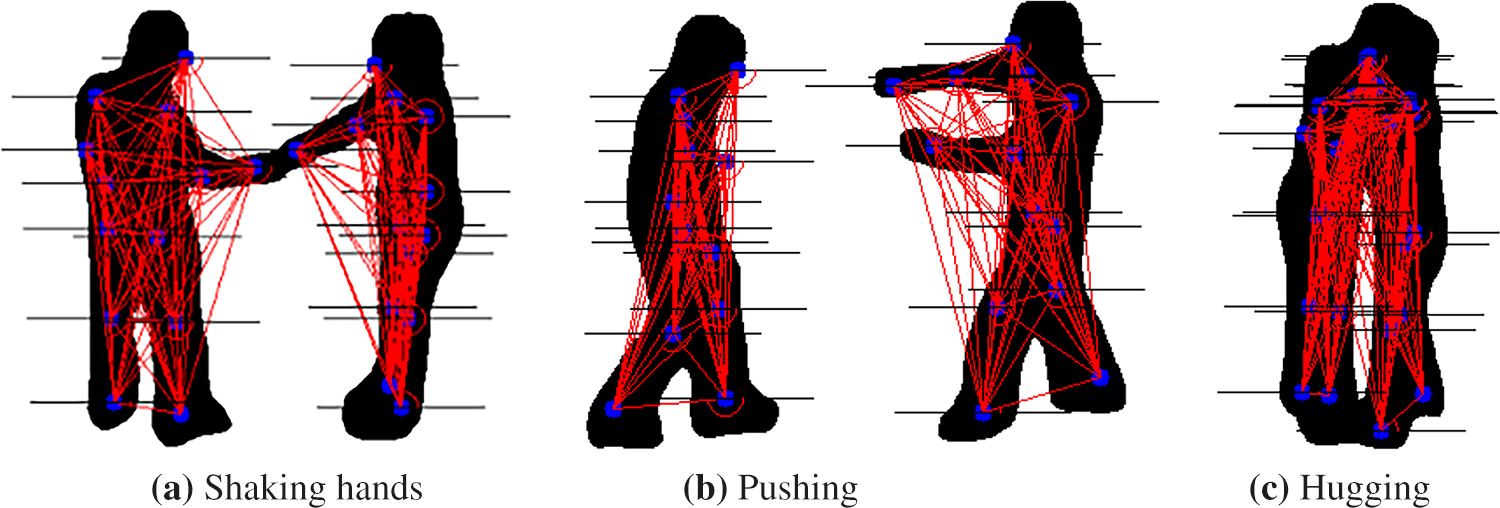

To capture orientation information between keypoints, we extract intra-person angle features. These features reflect the angular relationships between connected joints within an individual’s body, providing insight into how different body parts are aligned or directed during an interaction. Such information is especially useful for distinguishing between actions that may involve similar spatial distances across interacting individuals but differ in limbs orientation of each individual, such as pushing vs. punching. The angle

Similar to distance features, we employ the same fully connected approach, computing angular relationships between all keypoints of each person. This method ensures that the model captures the complete set of angular dynamics, without any selective feature extraction. Fig. 7 shows a visualization of angle features for different interactions from the UT dataset.

Figure 7: Angle features for shaking hands, pushing and hugging activities

To capture temporal motion dynamics, we extract velocity features from each person’s keypoints across consecutive frames. Velocity features can complement spatial features in further distinguishing activities with the same spatial patterns but different temporal patterns like approaching or departing. The velocity for a keypoint between two consecutive frames is computed as the Euclidean distance between its coordinates in the current frame

These velocity features encode the motion patterns of keypoints over time which can be helpful for accurate classification. Fig. 8 presents a heatmap-style visualization of velocity features for various interactions from the UT dataset. The colors show how fast different body parts are moving and how movement patterns change between activities.

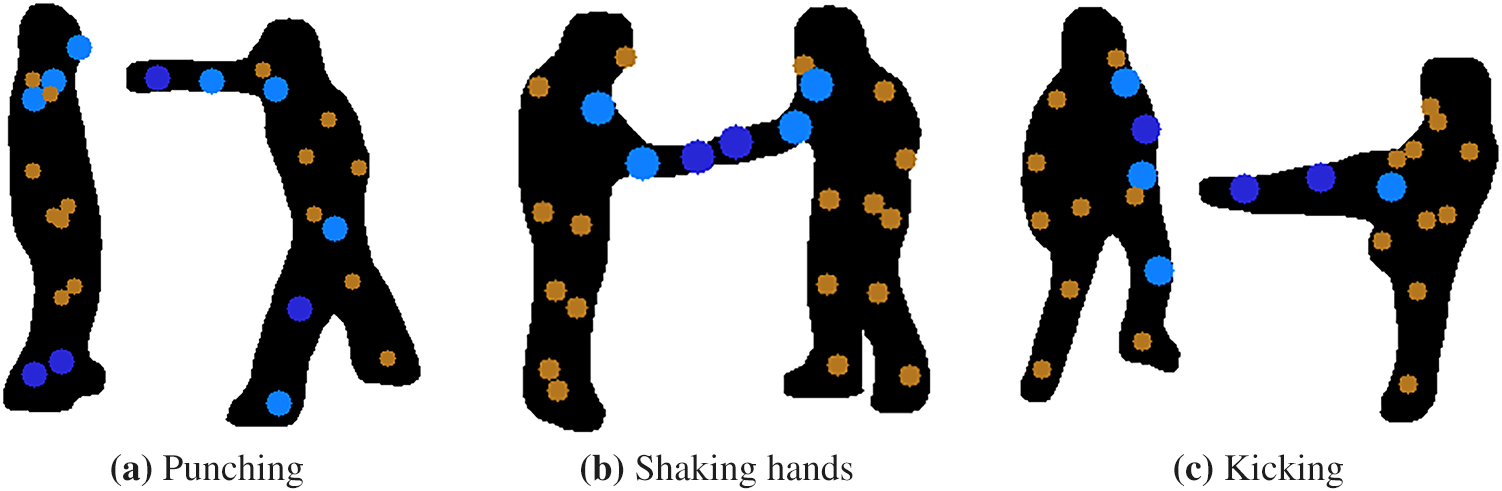

Figure 8: Velocity features for punching, shaking hands and kicking activities. Dark blue, light blue, and brown keypoints represent very high, high, and low velocities, respectively

Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTMs) have been widely used for activity classification, due to their ability to model temporal dependencies across frame sequences. They use gating mechanisms to control the flow of information. The input gate regulates how much new information is added to the cell state, while the forget gate controls how much of the previous cell state should be forgotten. The candidate cell state determines the potential update to cell state, and the output gate decides how much of the current cell state is exposed to the next layer. These interactions collectively update both the cell state and the hidden state at each time step.

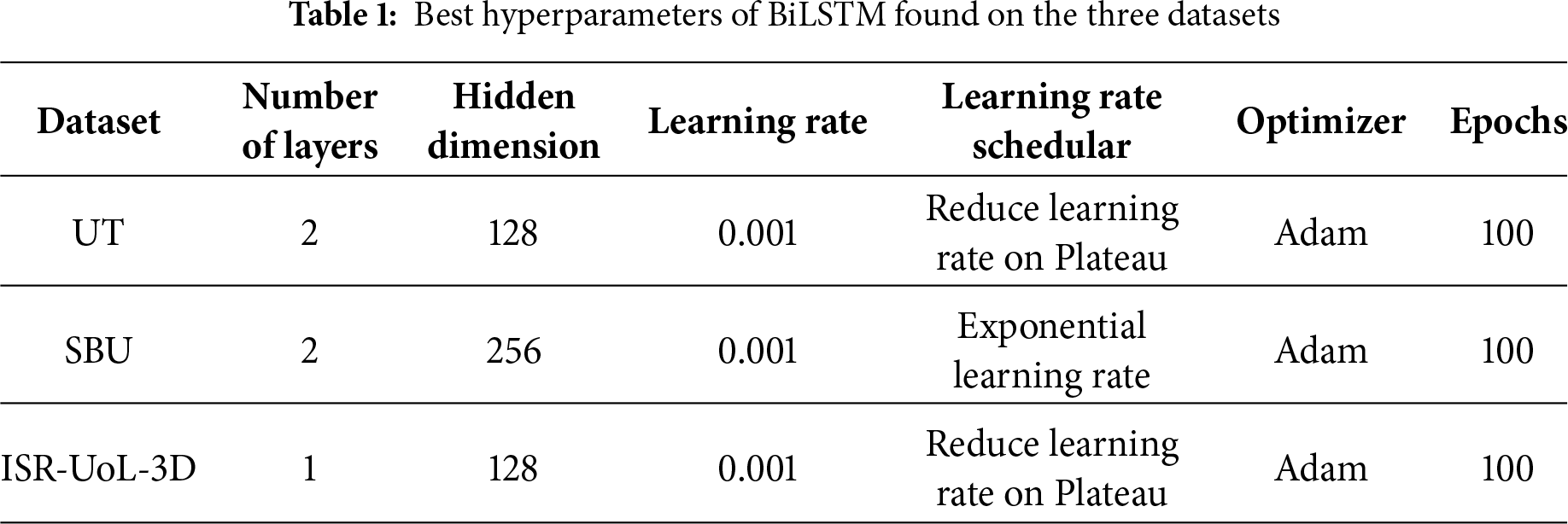

Bidirectional LSTMs (BiLSTMs) process sequences in both forward and backward directions, showing better performance than regular LSTMs. At each time step, hidden states from both passes are concatenated, and the final representation combines the last forward and backward states, yielding rich contextual features for classification. We use BiLSTM for this very reason. This final representation is fed into a fully connected layer and softmax to generate class probabilities. For our experiments, we explored various BiLSTM hyperparameters to achieve the best possible accuracy. Table 1 shows the hyperparameters of BiLSTM that gave the best accuracies on the UT interaction (UT) [14], SBU kinect interaction (SBU) [3] and ISR-UoL 3D social activity (ISR-UoL-3D) [16] datasets used in our experiments.

Evaluation of the proposed system is performed on three benchmark datasets: UT interaction (UT) [14], SBU kinetic interaction (SBU) [3] and ISR-UoL 3D social activity (ISR-UoL-3D) [16] dataset. Details of these datasets are as follows:

The UT dataset contains six two-person interactions: shaking hands, pointing, hugging, pushing, kicking, and punching, with 20 videos per interaction at 720 × 480 resolution and 30 FPS. It is divided into two sets: UT-1 (parking lot) and UT-2 (windy lawn with more background activity). We merged both sets and performed 20-fold cross-validation on the combined data. From each video, central 40 frames were extracted as input, assuming they carry the most informative content. These environmental differences enable a robust evaluation of the system’s generalization across diverse scenarios.

4.1.2 SBU Kinect Interaction Dataset

The SBU dataset consists of eight types of two-person interactions: approaching, departing, kicking, punching, pushing, hugging, exchanging objects, and shaking hands. It includes 282 video sequences, each divided into frames with a 640 × 480 resolution. In addition to RGB frames, the dataset provides depth maps for each frame and 3D keypoint coordinates of the individuals, offering rich spatial and temporal information for analysis. Following the authors’ recommended 5-fold cross-validation setup, we used the central 25 frames from each sequence as input to our system.

4.1.3 ISR-UoL 3D Social Activity Dataset

The ISR-UoL-3D dataset contains RGB, depth, and skeletal data captured with a Kinect 2 sensor across eight interaction types: shaking hands, hugging, helping walk, helping stand-up, fighting, pushing, talking, and drawing attention. It includes 167,442 interaction instances across ten sessions. Each interaction is repeated multiple times per video (up to 4060 repetitions) and includes RGB, 8/16-bit depth, and 15-joint skeleton data. Following the original 10-fold cross-validation setup, we sampled a subset of instances and used the central 40 frames from each as input to our system.

4.2.1 Confusion Matrix Calculations

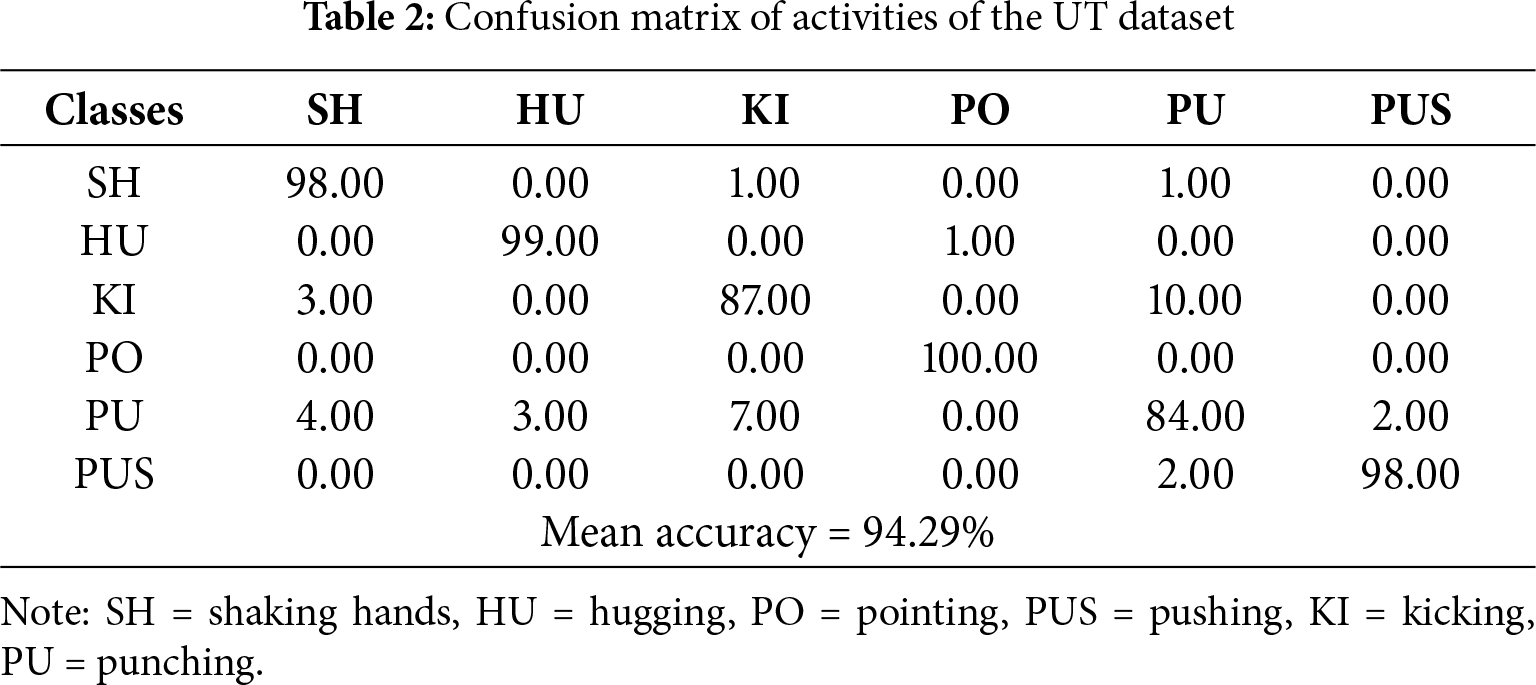

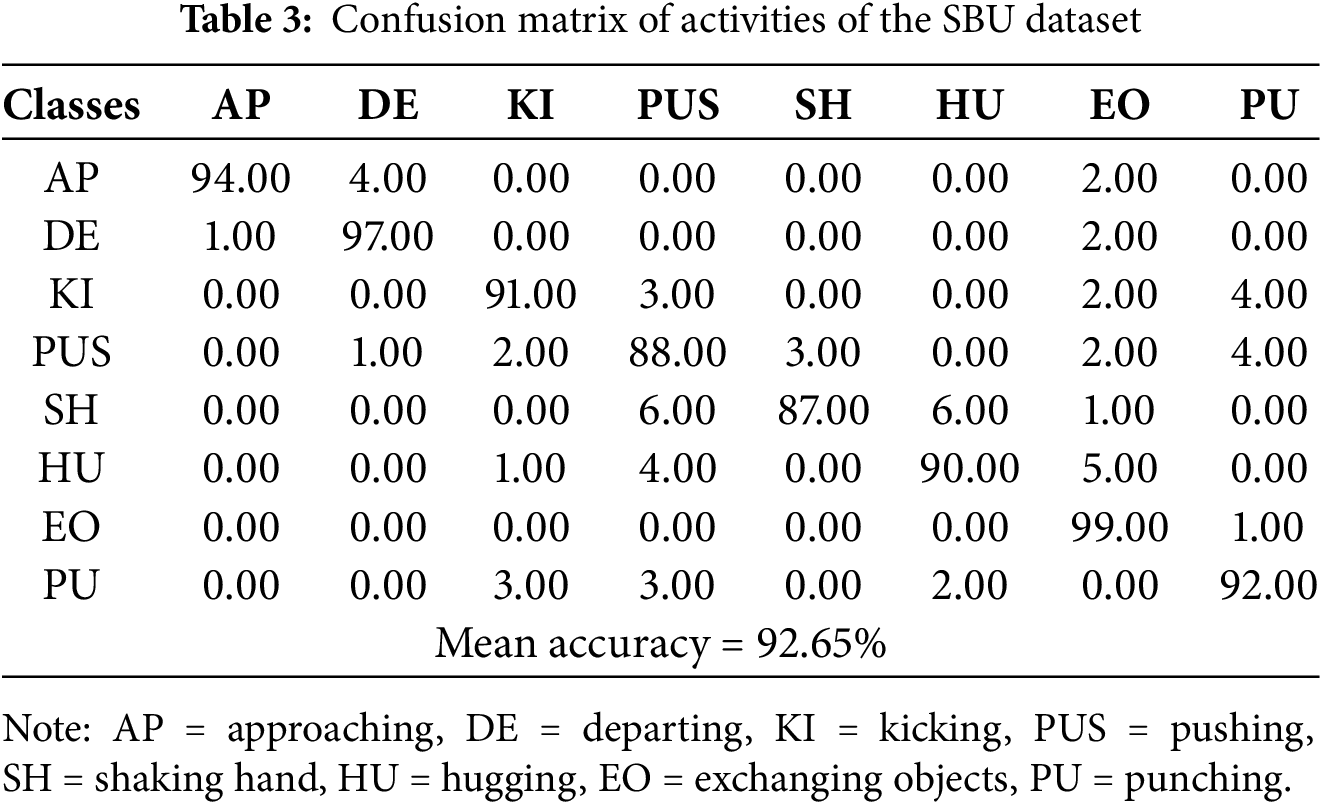

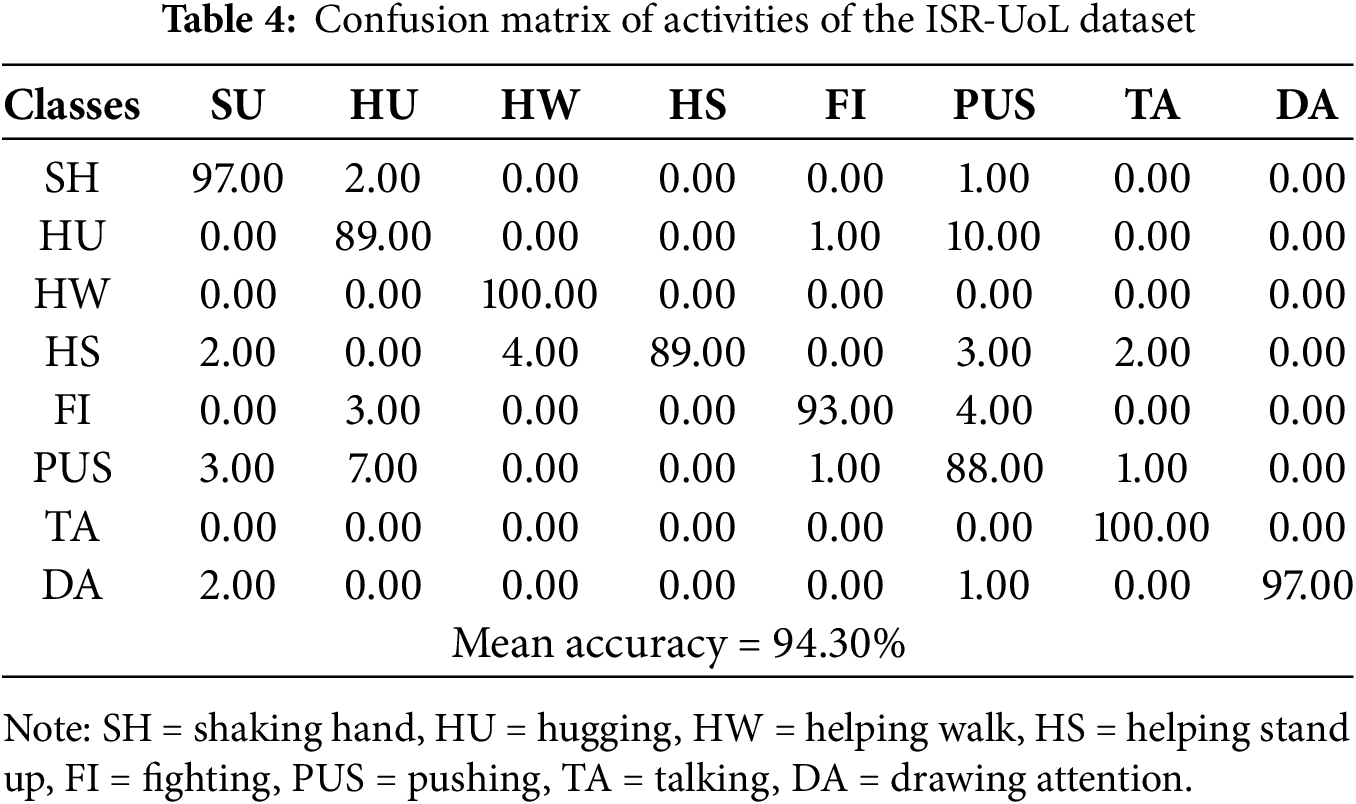

We calculated the confusion matrix for each dataset for a better understanding of our system’s classification performance, shown in the following Tables 2–4:

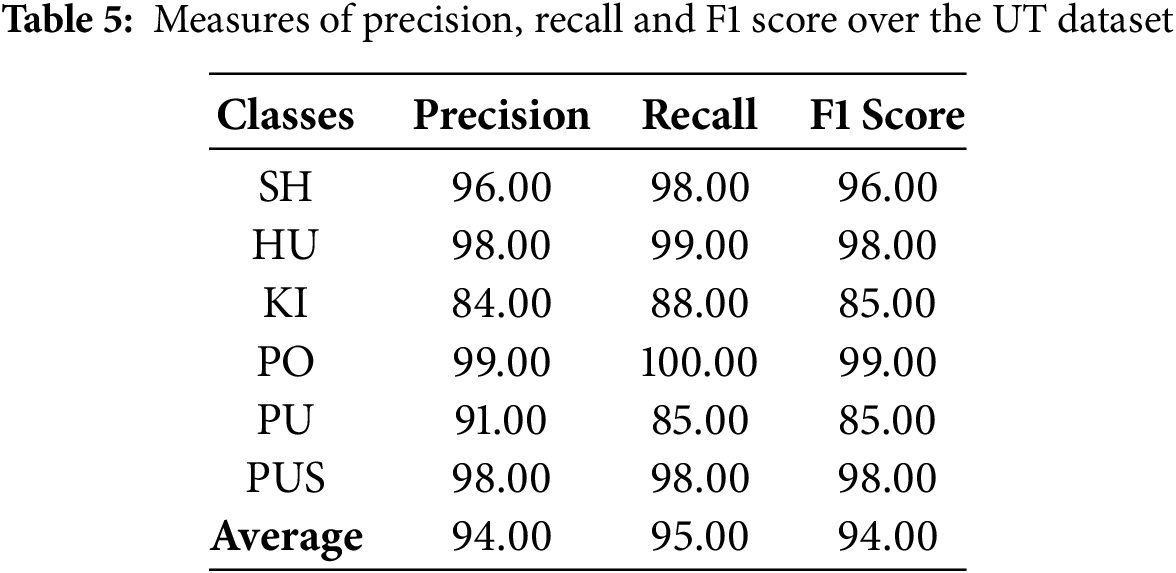

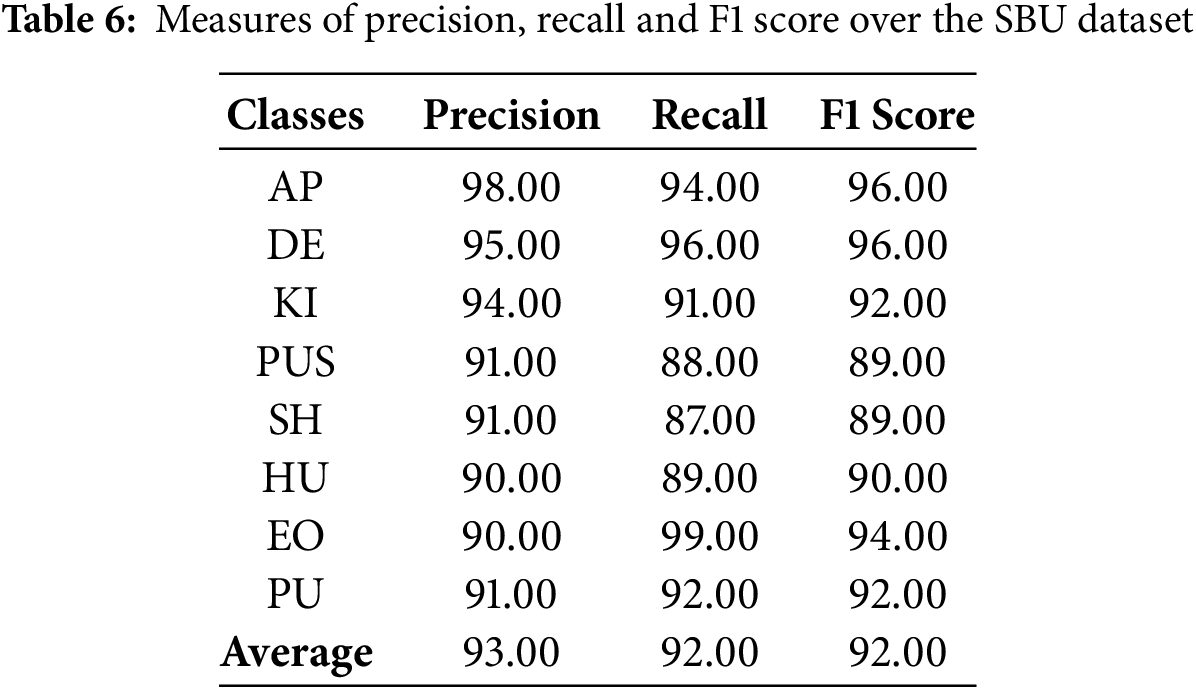

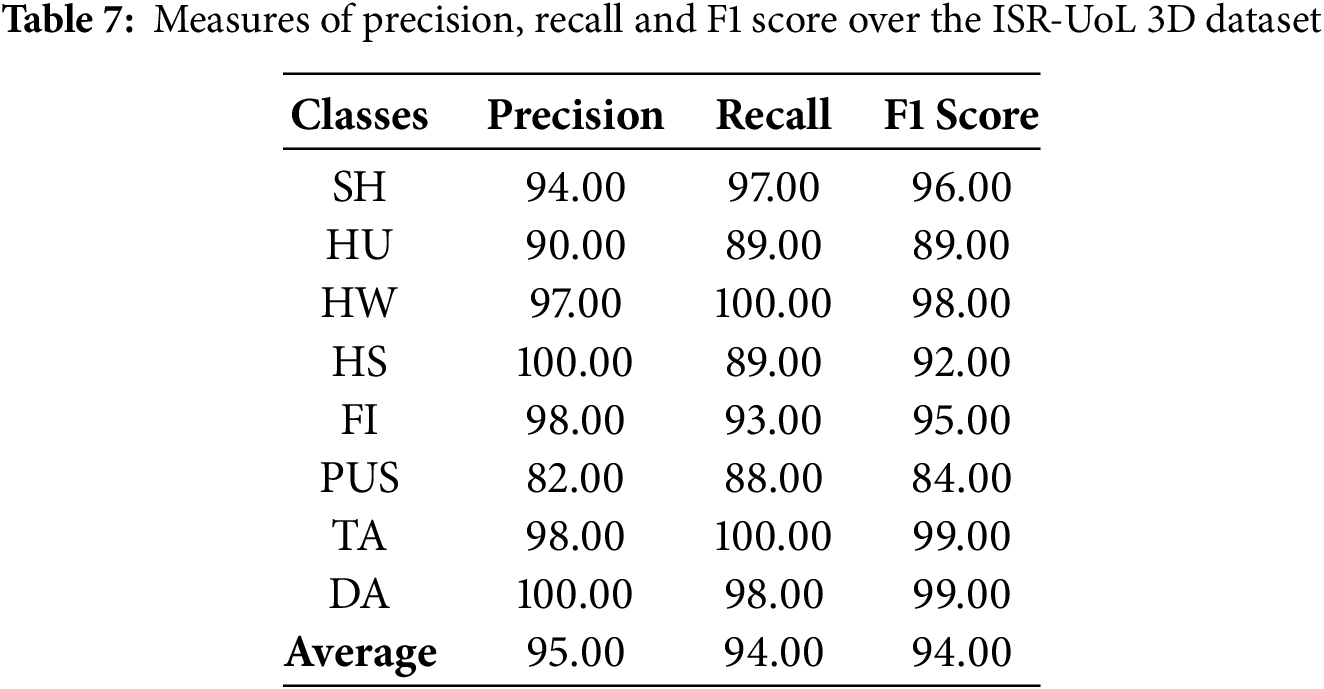

4.2.2 Precision, Recall, and F1-Score

We calculated the precision, recall and f1-score achieved by our system across all datasets. These are shown for each dataset separately in the following Tables 5–7. Last row in each table shows the average over all classes.

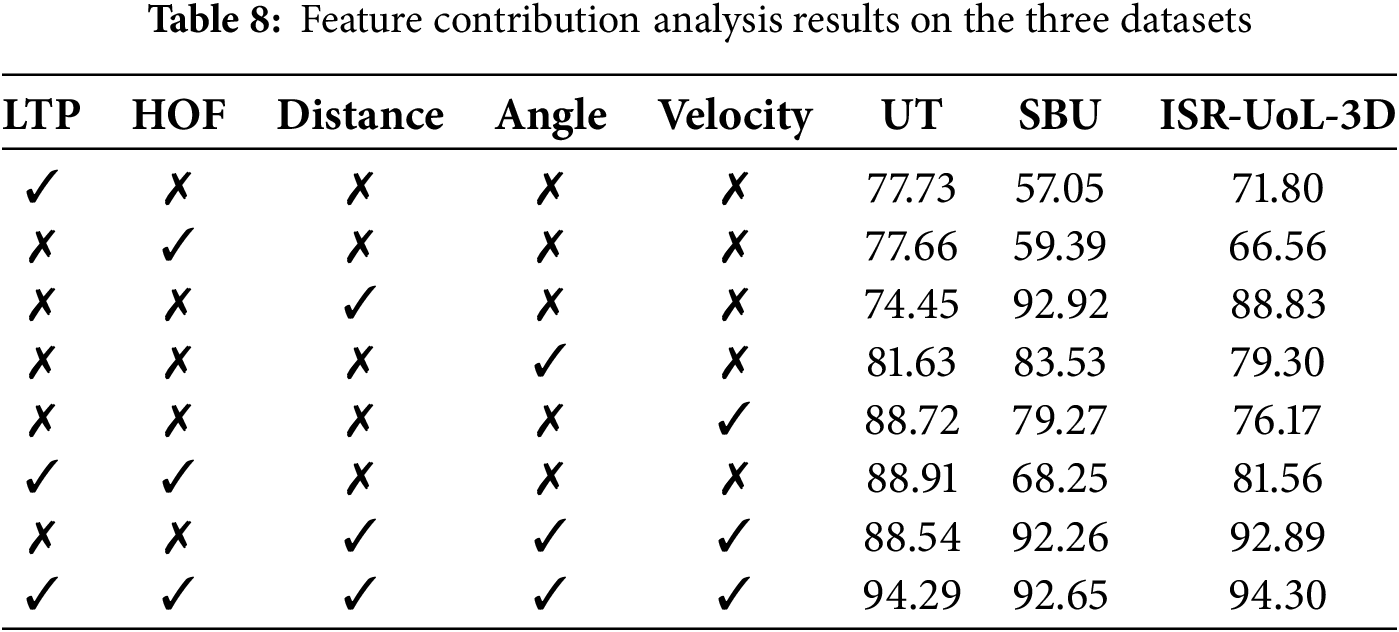

4.2.3 Feature Contribution Analysis

To understand each feature’s contribution towards classification, we conducted an experiment. Features were first tested individually. Then only keypoint features, only silhouette features and finally all combined features were used. Results are shown in Table 8. The distance feature achieves the highest accuracy on the SBU dataset, slightly surpassing the combined features. However, on the UT dataset, it performs worse than all other individual features, indicating that its effectiveness may vary across datasets.

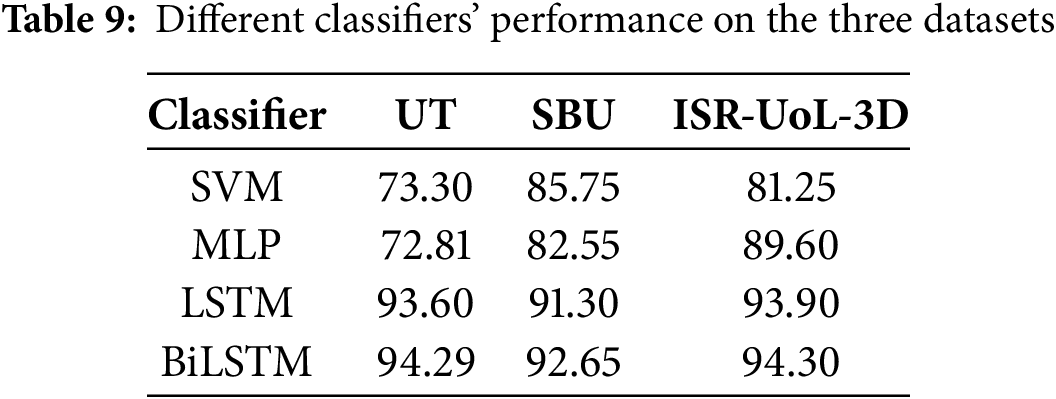

4.2.4 Classifier Performance Analysis

To demonstrate that the BiLSTM classifier used in our system outperforms conventional alternatives, we conducted a classifier performance analysis. Three classifiers were evaluated: Support Vector Machine (SVM), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) and LSTM. For SVM, the frame-level feature matrix of each video was flattened into a single feature vector while for MLP, each sample’s feature vector was obtained by averaging features across all frames. All models were tuned for optimal hyperparameters, and the best performance was reported. Table 9 presents the results across the three datasets. Our BiLSTM consistently achieved the highest accuracy, confirming the effectiveness of our proposed approach.

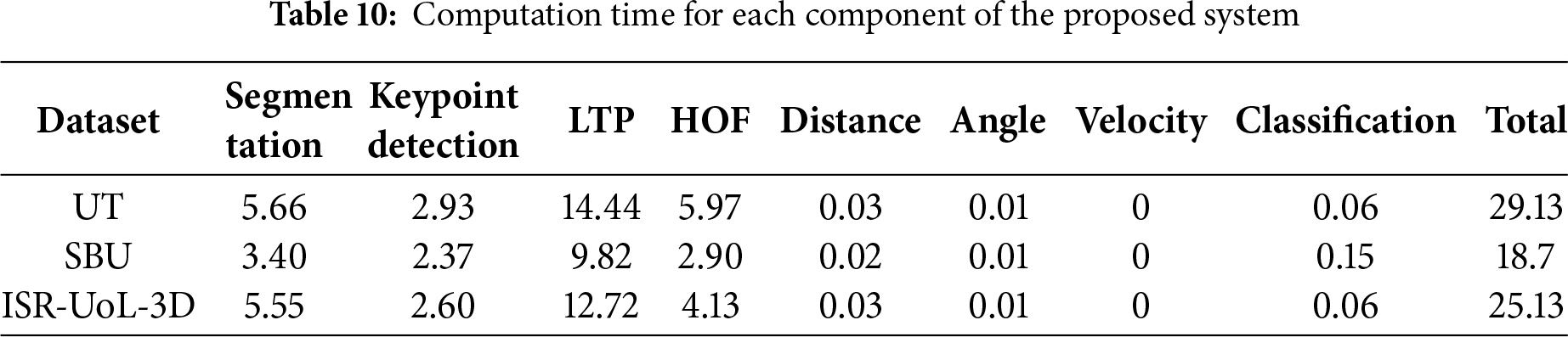

4.2.5 Computational Efficiency Analysis

To evaluate the computational efficiency of our proposed system, we measured the time each system component took to process an input RGB video for classification. After saving the best models, inference was performed on a TESLA T4 GPU (15 GB RAM) and CPU with ~13 GB RAM. Table 10 shows the time taken by each component rounded up to 2 decimal places. LTP feature extraction was the most time-consuming, indicating a need for optimization while velocity, distance and angle features required negligible time. Overall, segmentation and its feature extraction (LTP and HOF) can be seen as key targets for improving inference speed.

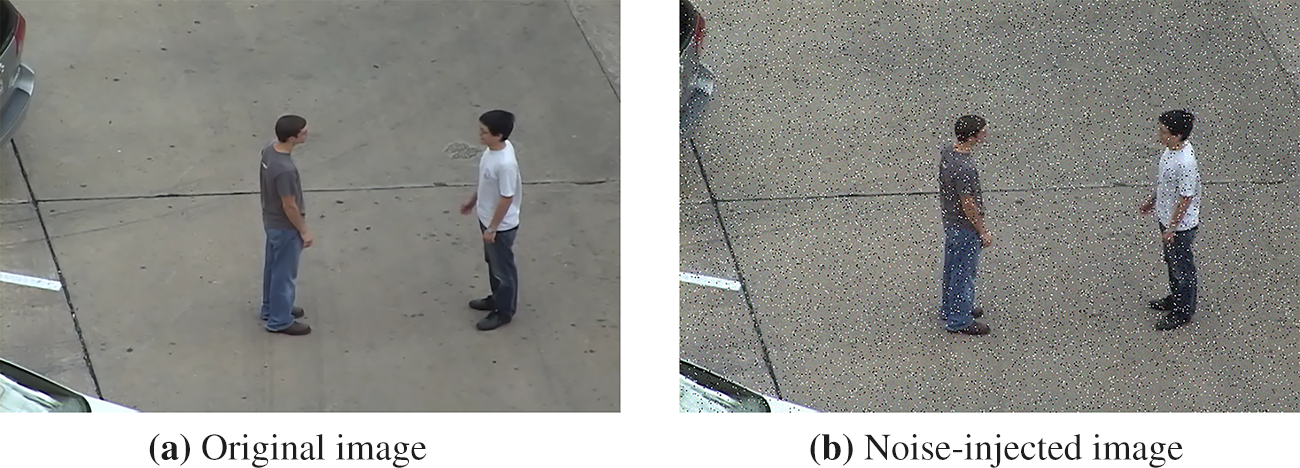

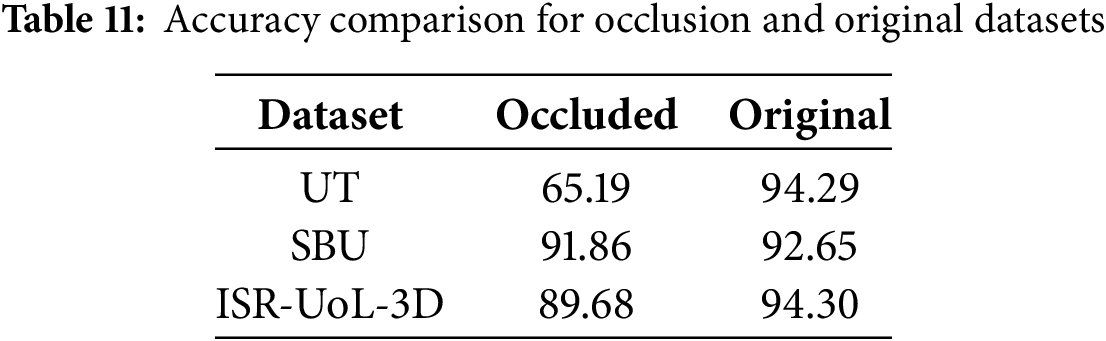

4.2.6 Occlusion Robustness Analysis

Finally, we evaluated the performance of the proposed system under occluded conditions. Each dataset’s RGB image was normalized to the 0–1 range, injected with random gaussian noise (mean = 0, std = 0.03) and subjected by salt-pepper noise where 2% of the pixels were set to white or black. This increased the difficulty of segmentation and keypoint detection, providing a reliable benchmark for system robustness. Fig. 9 shows an image from the UT dataset before and after noise injection with the specified parameters.

Figure 9: Visualization of an image from the UT dataset before and after noise injection

For evaluation, we used the same training protocols as with the clean datasets for fair comparison. Table 11 shows the accuracy obtained on noisy vs. original conditions on the three datasets. A minimum accuracy drop is seen for the SBU Kinect and ISR-UoL-3D datasets, demonstrating the resilience of our system. However, since the UT interaction dataset is already occlusion heavy, it proved more challenging. Due to the added noise, YOLO11-Pose was unable to assign track ids consistently to individuals across frames. This degraded the features extracted from keypoints which ultimately resulted in a much lower accuracy. This highlights a direction for future improvements.

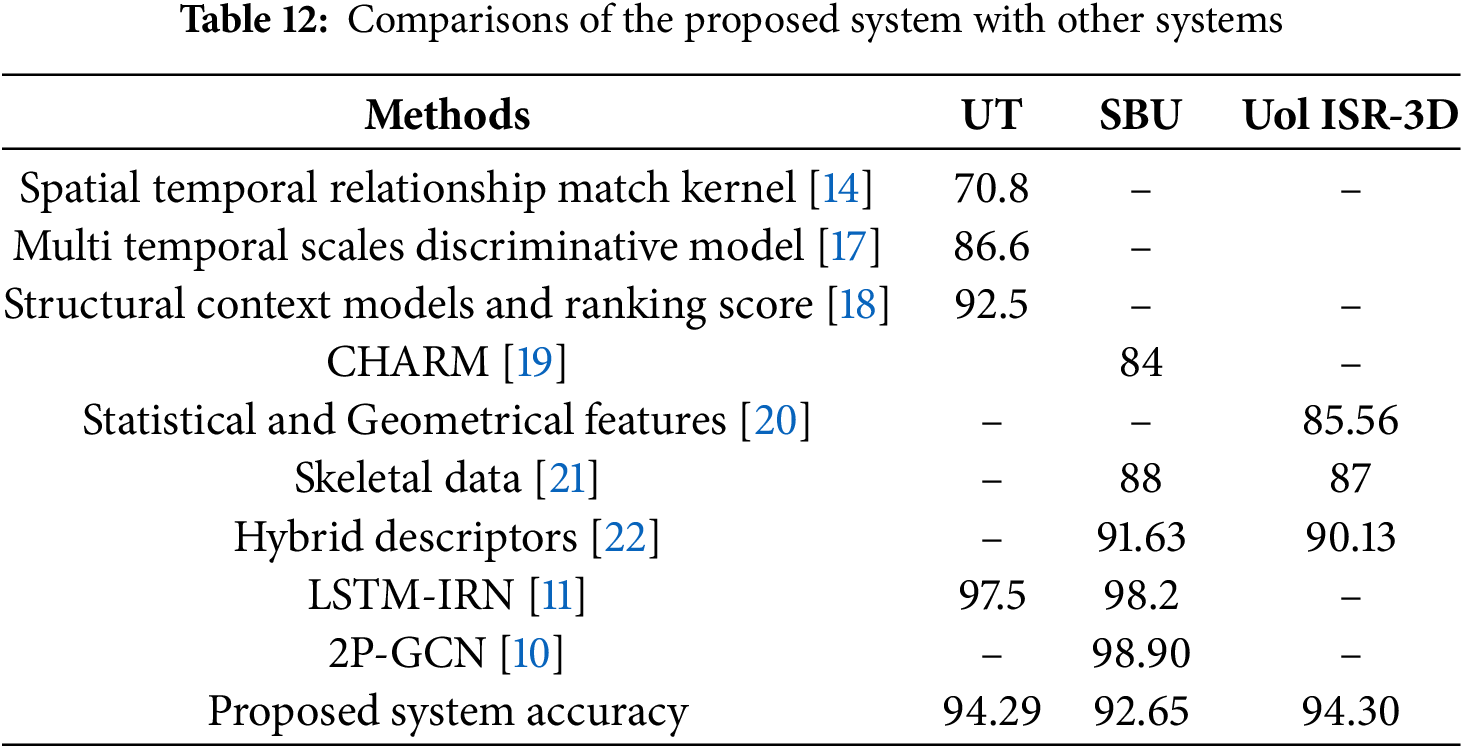

4.3 Comparison with State-of-the-Art Systems

We now evaluate our proposed system by comparing it with state-of-the-art systems. The results in Table 12 demonstrate that our system performs better than most existing approaches, highlighting its effectiveness. However, it underperforms than [11] on the UT and SBU datasets and [10] on the SBU dataset. Specifically, [11] used OpenPose [8] for keypoint detection, which is much more accurate but considerably more computationally demanding than YOLO11-Pose used in our system. Also, [10] relied on ground truth keypoint coordinates, giving it an inherent advantage. These observations suggest potential directions for further improving our system to achieve even stronger results.

The proposed system demonstrates strong performance on the benchmark datasets. Further experiments validate the effectiveness of the selected features and classifier types, while highlighting the system’s high computational efficiency and robustness to occlusion, thus making it suitable for real-world deployment. However, it has some limitations. Silhouette-based features (LTP and HOF) are relatively time consuming to extract; we will explore faster handcrafted feature representations. YOLO11-Pose struggles under severe occlusion, sometimes failing to track individuals correctly or misidentifying objects as people. This can be addressed by fine tuning or using more advanced keypoint detection models with robust tracking mechanisms. Similarly, MASK R-CNN can merge relevant and irrelevant individuals into a single mask when they are in close proximity. It is also very computationally intensive. This indicates searching for alternatives or developing custom architectures for better computational efficiency. Additionally, the BiLSTM classifier requires substantial training data to capture long-term dependencies. As alternatives, we will explore pretraining, data augmentation and other temporal models. Future work will integrate these improvements into the system. We will also explore combining silhouette-based CNN features and Graph Convolution Network-based keypoint features with handcrafted features for higher accuracy and efficiency.

Acknowledgement: Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R410), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This research is supported and funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R410), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Muhammad Hamdan Azhar and Yanfeng Wu; data collection: Asaad Algarni and Nouf Abdullah Almujally; analysis and interpretation of results: Shuaa S. Alharbi and Hui Liu; draft manuscript preparation: Muhammad Hamdan Azhar, Ahmad Jalal and Hui Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All publicly available datasets are used in the study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Asadi-Aghbolaghi M, Clapés A, Bellantonio M, Escalante HJ, Ponce-López V, Baró X, et al. A survey on deep learning based approaches for action and gesture recognition in image sequences. In: Proceedings of the 2017 12th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG 2017); 2017 May 30–Jun 3; Washington, DC, USA. p. 476–83. doi:10.1109/FG.2017.150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kamal S, Alhasson HF, Alnusayri M, Alatiyyah M, Aljuaid H, Jalal A, et al. Vision sensor for automatic recognition of human activities via hybrid features and multi-class support vector machine. Sensors. 2025;25(1):200. doi:10.3390/s25010200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Yun K, Honorio J, Chattopadhyay D, Berg TL, Samaras D. Two-person interaction detection using body-pose features and multiple instance learning. In: Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops; 2012 Jun 16–21; Providence, RI, USA. p. 28–35. doi:10.1109/CVPRW.2012.6239234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Jalal A, Khalid N, Kim K. Automatic recognition of human interaction via hybrid descriptors and maximum entropy Markov model using depth sensors. Entropy. 2020;22(8):817. doi:10.3390/e22080817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R. Mask R-CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2961–9. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gupta S, Vishwakarma DK, Puri NK. A human activity recognition framework in videos using segmented human subject focus. Vis Comput. 2024;40(10):6983–99. doi:10.1007/s00371-023-03256-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Park E, Han X, Berg TL, Berg AC. Combining multiple sources of knowledge in deep CNNs for action recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2016 Mar 7–10; Lake Placid, NY, USA. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/WACV.2016.7477589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Cao Z, Simon T, Wei SE, Sheikh Y. Realtime multi-person 2D pose estimation using part affinity fields. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1302–10. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sun K, Xiao B, Liu D, Wang J. Deep high-resolution representation learning for human pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 5686–96. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li Z, Li Y, Tang L, Zhang T, Su J. Two-person graph convolutional network for skeleton-based human interaction recognition. IEEE Trans Circ Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(7):3333–42. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2022.3232373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Perez M, Liu J, Kot AC. Interaction relational network for mutual action recognition. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2022;24:366–76. doi:10.1109/TMM.2021.3050642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang H, Zhao P, Tang G, Li Z, Yuan Z. Reproducible and generalizable speech emotion recognition via an intelligent fusion network. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2025;109:107996. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2025.107996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Ryoo MS, Aggarwal JK. Spatio-temporal relationship match: video structure comparison for recognition of complex human activities. In: Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 12th International Conference on Computer Vision; 2009 Sep 29–Oct 2; Kyoto, Japan. p. 1593–600. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2009.5459361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Jocher G, Qiu J. Ultralytics YOLO11 [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 21]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

16. Coppola C, Faria DR, Nunes U, Bellotto N. Social activity recognition based on probabilistic merging of skeleton features with proximity priors from RGB-D data. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2016 Oct 9–14; Daejeon, Republic of Korea. p. 5055–61. doi:10.1109/IROS.2016.7759742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kong Y, Kit D, Fu Y. A discriminative model with multiple temporal scales for action prediction. In: Fleet D, Pajdla T, Schiele B, Tuytelaars T, editors. Computer vision—ECCV 2014. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2014. p. 596–611. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-10602-1_39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ke Q, Bennamoun M, An S, Sohel F, Boussaid F. Leveraging structural context models and ranking score fusion for human interaction prediction. IEEE Trans Multimed. 2018;20(7):1712–23. doi:10.1109/TMM.2017.2778559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li W, Wen L, Chuah MC, Lyu S. Category-blind human action recognition: a practical recognition system. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2015 Dec 7–13; Santiago, Chile. p. 4444–52. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2015.505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Coppola C, Cosar S, Faria DR, Bellotto N. Automatic detection of human interactions from RGB-D data for social activity classification. In: Proceedings of the 2017 26th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN); 2017 Aug 28–Sep 1; Lisbon, Portugal. p. 871–6. doi:10.1109/ROMAN.2017.8172405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Manzi A, Fiorini L, Limosani R, Dario P, Cavallo F. Two-person activity recognition using skeleton data. IET Comput Vis. 2018;12(1):27–35. doi:10.1049/iet-cvi.2017.0118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Waheed M, Jalal A, Alarfaj M, Ghadi YY, Al Shloul T, Kamal S, et al. An LSTM-based approach for understanding human interactions using hybrid feature descriptors over depth sensors. IEEE Access. 2021;9:167434–46. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3130613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools