Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Transformer-Driven Multimodal for Human-Object Detection and Recognition for Intelligent Robotic Surveillance

1 Guodian Nanjing Automation Co., Ltd., Nanjing, 210003, China

2 Department of Biomedical Engineering, Riphah International University, I-14, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

3 Department of Electrical Engineering, Bahria University, H-11, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

4 Department of Information Systems, College of Computer and Information Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, 11671, Saudi Arabia

5 Department of Computer Science, Air University, E-9, Islamabad, 44000, Pakistan

6 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, College of Informatics, Korea University, Seoul, 02841, Republic of Korea

7 Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Intelligent Medical Image Computing, School of Artificial Intelligence (School of Future Technology), Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210003, China

8 Cognitive Systems Lab, University of Bremen, Bremen, 28359, Germany

* Corresponding Authors: Ahmad Jalal. Email: ; Hui Liu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Object Detection and Recognition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 56 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072508

Received 28 August 2025; Accepted 29 October 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

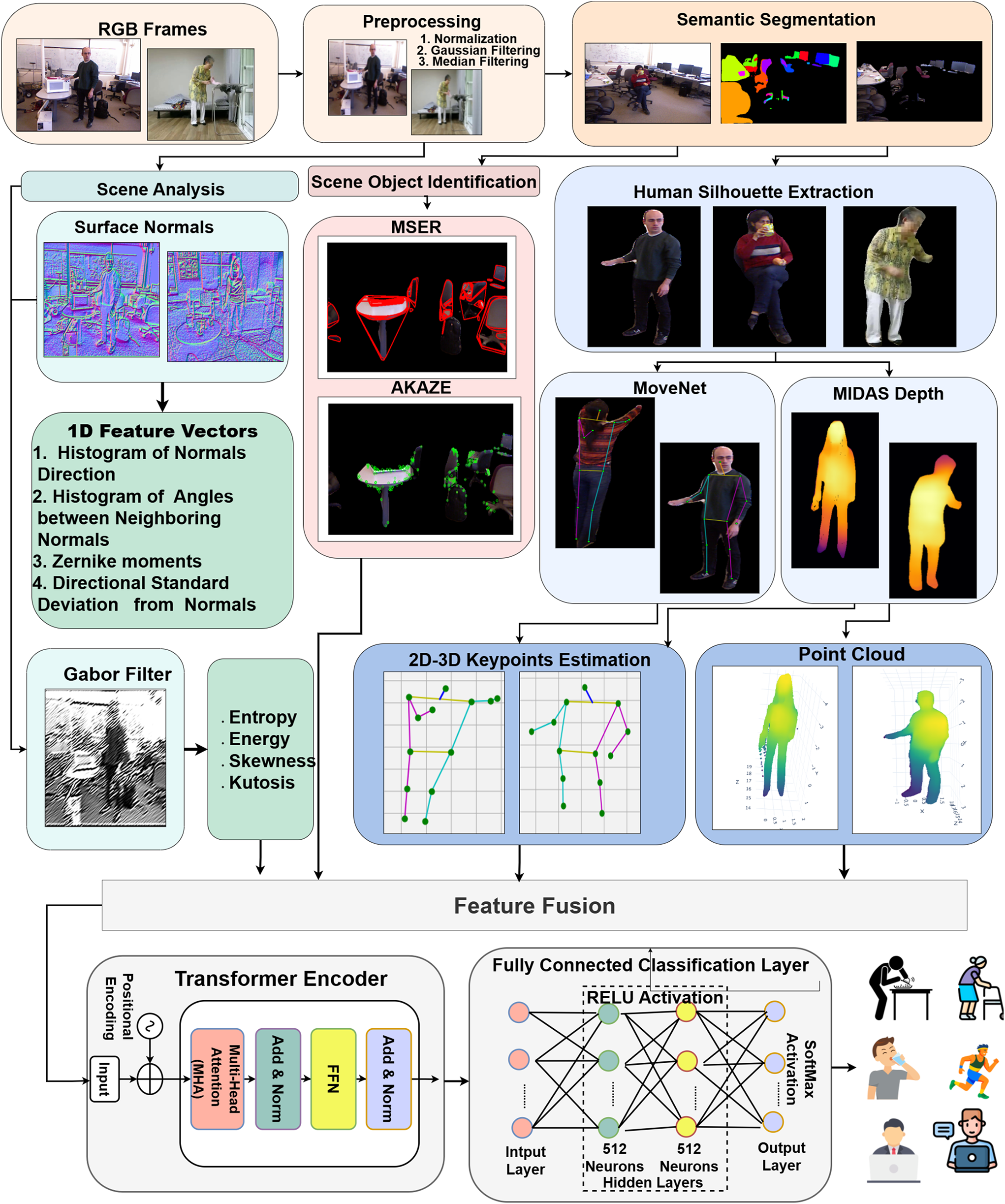

Human object detection and recognition is essential for elderly monitoring and assisted living however, models relying solely on pose or scene context often struggle in cluttered or visually ambiguous settings. To address this, we present SCENET-3D, a transformer-driven multimodal framework that unifies human-centric skeleton features with scene-object semantics for intelligent robotic vision through a three-stage pipeline. In the first stage, scene analysis, rich geometric and texture descriptors are extracted from RGB frames, including surface-normal histograms, angles between neighboring normals, Zernike moments, directional standard deviation, and Gabor-filter responses. In the second stage, scene-object analysis, non-human objects are segmented and represented using local feature descriptors and complementary surface-normal information. In the third stage, human-pose estimation, silhouettes are processed through an enhanced MoveNet to obtain 2D anatomical keypoints, which are fused with depth information and converted into RGB-based point clouds to construct pseudo-3D skeletons. Features from all three stages are fused and fed in a transformer encoder with multi-head attention to resolve visually similar activities. Experiments on UCLA (95.8%), ETRI-Activity3D (89.4%), and CAD-120 (91.2%) demonstrate that combining pseudo-3D skeletons with rich scene-object fusion significantly improves generalizable activity recognition, enabling safer elderly care, natural human–robot interaction, and robust context-aware robotic perception in real-world environments.Keywords

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) is a fundamental task in computer vision, with growing relevance in ambient assisted living, particularly for elderly care. In home-based settings, the ability to monitor daily routines, detect abnormal behavior, or respond to critical events such as falls, can significantly enhance safety and well-being [1]. However, accurate activity recognition in such environments remains a non-trivial challenge. Most existing HAR systems prioritize the analysis of human pose or motion patterns, often overlooking the broader environmental context in which these activities occur. This narrow focus can result in misinterpretations, especially when actions are ambiguous without reference to surrounding objects or scene structure.

Despite its significance, the incorporation of scene understanding into HAR remains underexplored. This is partly due to the challenges posed by visual clutter, occlusion, and environmental variability in real-world scenes. Depth sensors offer spatial cues that can aid segmentation and object localization, but their cost, limited operational range, and hardware requirements restrict their use in home environments [2]. In contrast, RGB cameras are inexpensive, non-intrusive, and widely available, making them a more practical choice for in-home monitoring.

To address these challenges, we propose SCENET-3D, a three-stage human activity recognition pipeline integrating scene analysis, scene-object analysis, and human-pose estimation using pseudo-3D point clouds from monocular RGB. The first stage extracts holistic scene features via surface-normal and Gabor descriptors; the second models segmented non-human objects with local feature detectors; and the third derives 3D human-skeleton point clouds from MoveNet keypoints and pseudo-depth maps. Features from all stages are fused and classified via a transformer, capturing fine-grained spatial geometry and human–environment interactions to improve recognition in complex, cluttered scenarios.

The key contributions of this work are as follows:

• We introduce SCENET-3D, a novel human-activity recognition pipeline that jointly integrates holistic scene understanding, scene-object analysis, and human-pose estimation.

• We propose unique pseudo-3D point clouds estimation from monocular RGB frames to capture fine-grained spatial structures of the human subject along with 3D key body joints extracted from a unique implementation of 2D to 3D key point conversion using monocular depth from Midas.

• We designed a diverse and complementary feature extraction strategy that combines pose estimation, pseudo-depth-based surface structure, local keypoint descriptors, and texture statistics, enabling robust scene and action understanding from RGB-only input.

• We employed early feature fusion and optimize the unified feature vector before classifying activities using a transformer classifier. This ensures the system can handle real-world ambiguity while providing interpretable decision-making for assistive applications.

Human Activity Recognition (HAR) has shifted from wearable sensors to vision-based methods. Wearables provide precise motion data but cause discomfort and limited use. Vision-based approaches are non-intrusive; depth sensors offer strong spatial cues but are costly, while RGB cameras are low-cost, widely available, and effective for in-home monitoring. With spatial augmentation and deep models, RGB-based HAR achieves competitive performance [3]. A recent survey reviews RGB-D-based HAR, emphasizing multimodal fusion strengths while noting challenges in scalability and real-world generalization [4]. Monocular SLAM and pseudo-RGBD generation further infer scene geometry for point cloud reconstruction and silhouette extraction. Lightweight keypoint extractors, e.g., MoveNet, yield spatiotemporal descriptors directly from RGB frames [5]. More recently, transformer-based architectures such as the Global-local Motion Transformer have demonstrated strong performance on skeleton-based action learning, particularly on the UCLA dataset, aligning closely with the objectives of this work [6]. By employing diffusion-based generative modeling with geometrically consistent conditioning, dense 3D point clouds can be reconstructed from single RGB images, removing the need for depth-sensing hardware [7].

However, motion or pose alone is insufficient in cluttered environments where different actions may appear visually similar. Here, scene understanding is critical. Environmental semantics such as layout, object identities, and spatial relations help disambiguate similar motions (e.g., distinguishing “reaching for an object” vs. “stretching”). To this end, scene context-aware graph convolutional networks have been proposed, combining skeleton features with environmental cues to improve action recognition in cluttered settings [8]. This is especially relevant in domestic elderly care where clutter and object proximity strongly affect interpretation. Hybrid approaches integrating pose with scene context have shown improved robustness [9]. Yet, many remain limited by fixed viewpoints or simplified backgrounds [10]. Despite achieving real-time monitoring through IoT-based decision-aware designs, assisted-living systems still face reduced adaptability in cluttered or dynamically changing environments [11].

Deep learning models (CNNs, LSTMs) support tasks such as fall detection, but their generalization suffers from small datasets and uncontrolled settings [12]. To enhance feature discrimination, Hu et al. introduced an attention-guided method based on close-up maximum activation for human activity recognition [13]. Building on this, scene-level semantics are increasingly incorporated to capture object relationships and spatial configurations [14,15]. Mid-level features such as Gabor filters provide texture and orientation cues from background structures [16], while entropy-based segmentation and super-pixel decomposition enhance scene partitioning for contextual feature extraction. Recent works in elderly care emphasize both contextual awareness and computational efficiency. Some focus on scene analysis to infer context-sensitive behaviors [17], while others prioritize lightweight models for real-time deployment.

This need for richer contextual modeling has also been highlighted in works that integrate action recognition with object detection and human–object interaction to enhance robustness in diverse and cluttered environments [18–20]. Building on these, our framework fuses pose-centric features (MoveNet keypoints, pseudo-depth point clouds) with scene-level descriptors (Gabor filters, super-pixel-based segmentation) into a unified HAR model.

This section presents SCENET-3D, a HAR pipeline that combines human structural cues with environmental context to improve classification. RGB frames undergo preprocessing, surface normal computation, semantic segmentation, feature extraction, and multimodal fusion for classification (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: System architecture of SCENET-3D a unified RGB framework with fusion of human-centric pose features and scene-level contextual descriptors for robust activity recognition

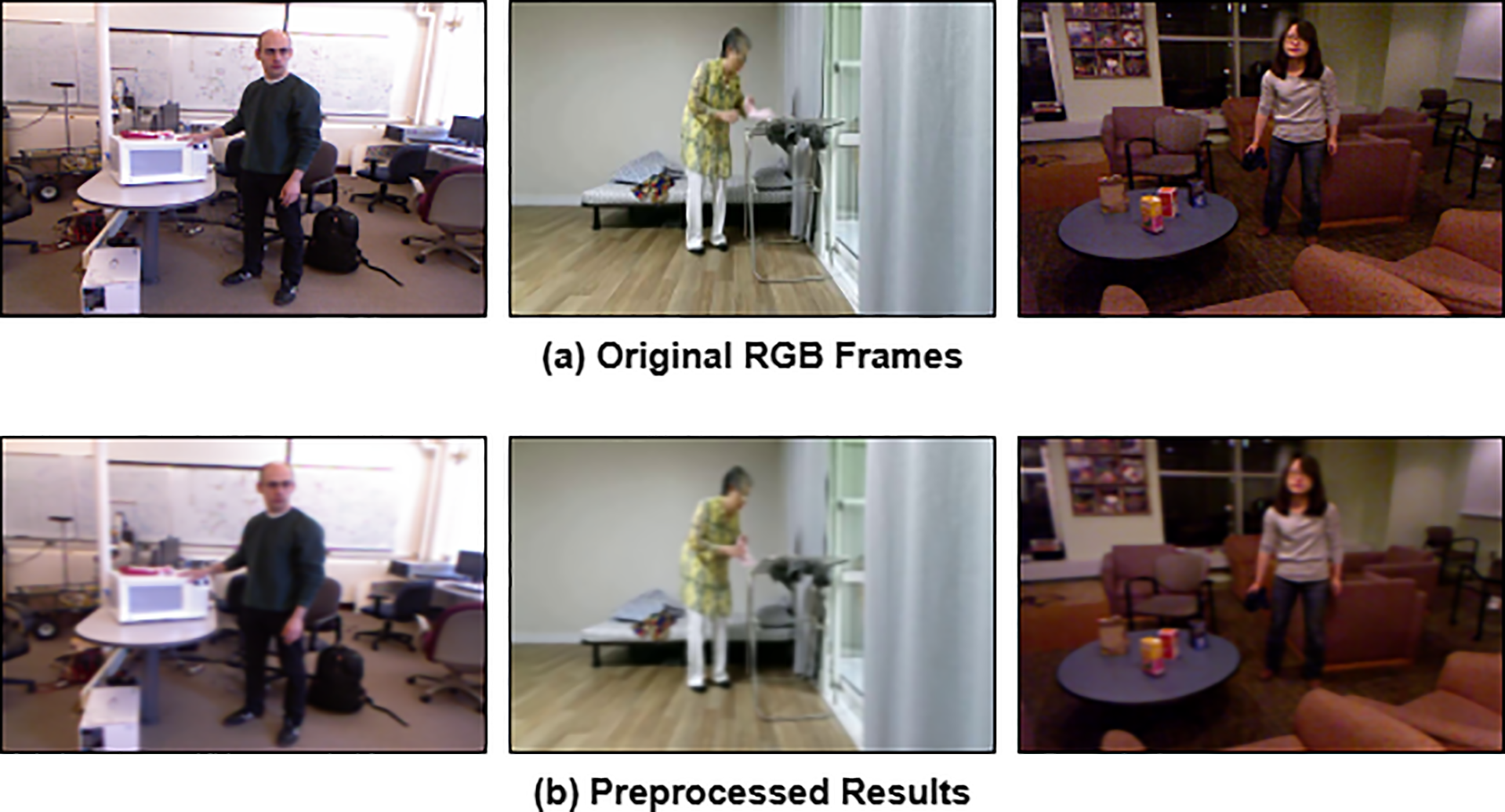

Frames from diverse RGB datasets (offices, homes, clinical settings) undergo a standardized preprocessing pipeline for spatial and intensity consistency. Each frame

which maps values to

Figure 2: Preprocessing pipeline. (a) Raw RGB frames and (b) Preprocessed RGB frames

This preprocessing ensures uniform scale, normalized intensity distribution, and improved visual quality, providing consistent inputs for subsequent multimodal feature extraction.

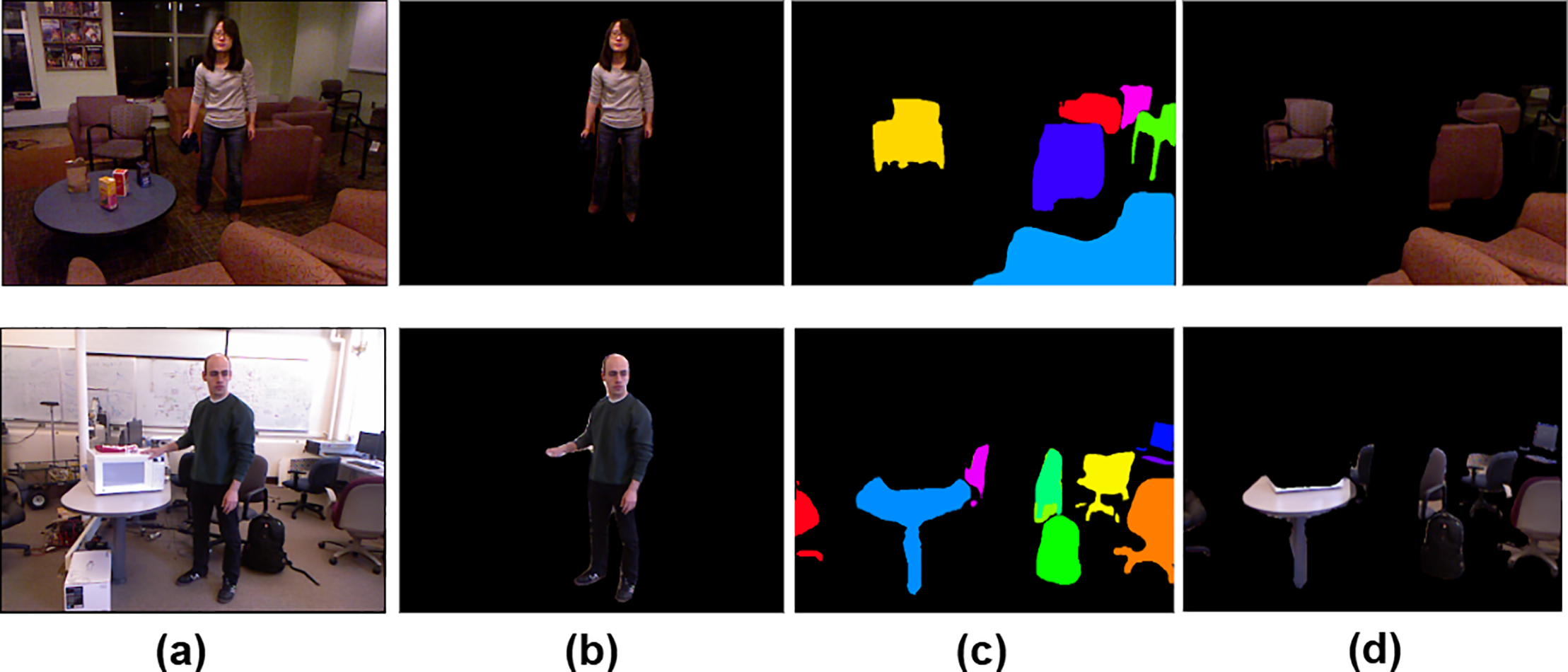

3.2 Semantic Segmentation Using Mask R-CNN

Semantic instance segmentation is applied to each RGB frame using Mask R-CNN with a ResNet-50 backbone and FPN, implemented in Detectron2, to decouple human and environmental components. The network, pretrained on COCO, produces instance-specific binary masks

here, the classification loss is the softmax cross-entropy by Eq. (6), the bounding-box regression loss employs Smooth L1 using Eq. (7), and the mask prediction loss applies pixel-wise binary cross-entropy while region proposals are generated by the RPN using classification and bounding-box regression losses.

For human-centered analysis, the largest connected component across all predicted instance masks is selected as the primary human silhouette using Eq. (8).

where

Figure 3: Semantic segmentation: (a) input RGB frames, (b) extracted human silhouette, (c) class-specific scene objects, and (d) reconstructed scene with preserved objects

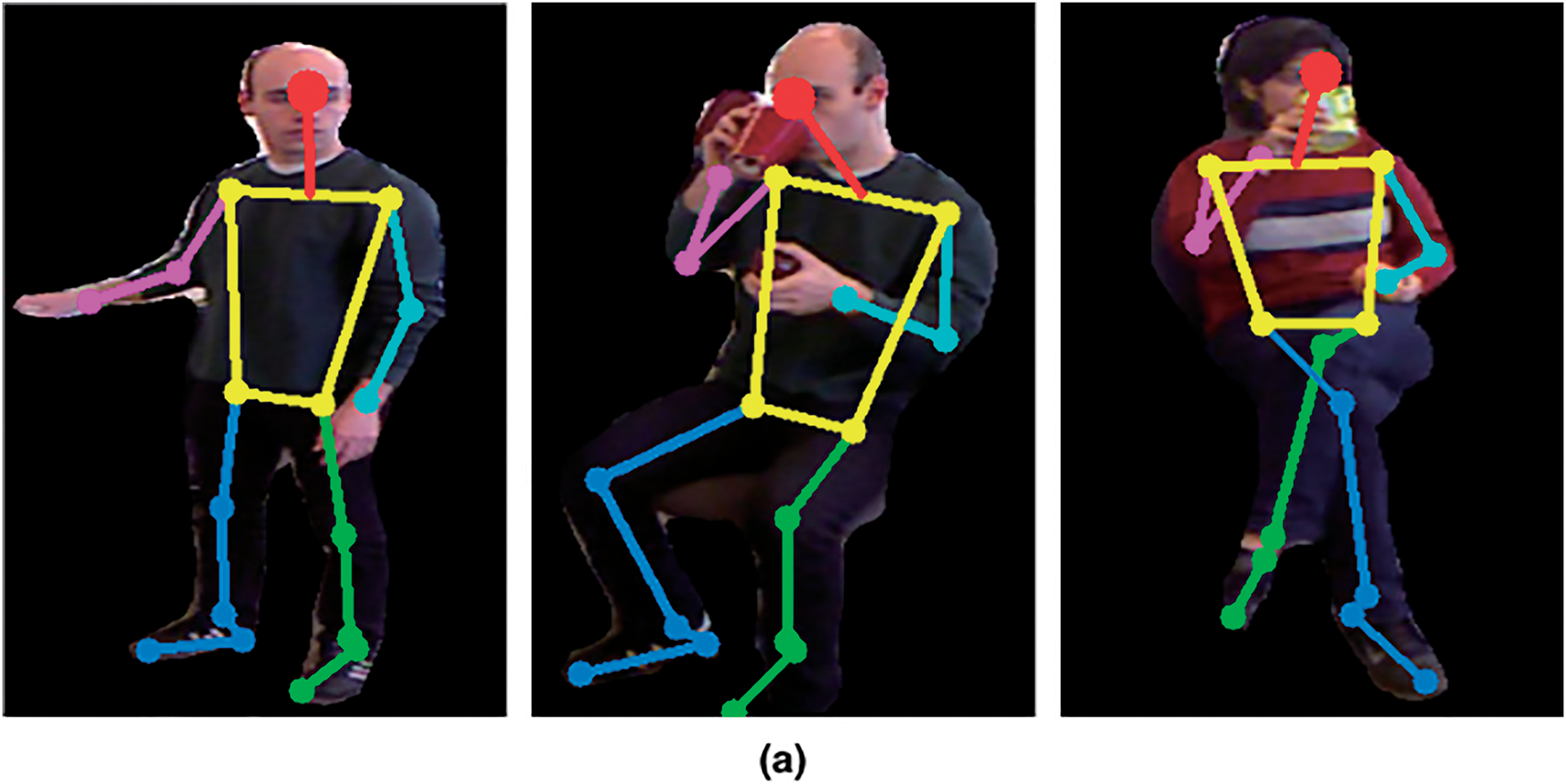

3.3 Silhouette-Based Human Pose Estimation

Following segmentation, the human is isolated as an RGB silhouette, serving as input for human-centric feature extraction. From this silhouette, 2D pose keypoints and a 3D point cloud are derived, capturing spatial, structural, and geometric cues essential for motion-based activity analysis.

Keypoint Extraction via MoveNet

To capture the articulation and spatial configuration of the human body, we employ MoveNet [8], a lightweight yet accurate real-time pose estimator that predicts 17 anatomical keypoints, denoted as

Keypoints are represented as 2D Gaussian heatmaps, and their spatial locations are optimized using mean squared error. Coordinate-level refinement is performed via Smooth L1 regression, while confidence-weighted losses mitigate the influence of occluded or low-confidence keypoints. These losses collectively enforce accurate, anatomically plausible, and robust keypoint estimation under varying visual conditions.

Structural Consistency Loss: Limb geometry is preserved via relative displacement as provided in Eq. (9).

where

Laplacian Smoothness Loss encourages local pose smoothness and is calculated using Eq. (10).

where

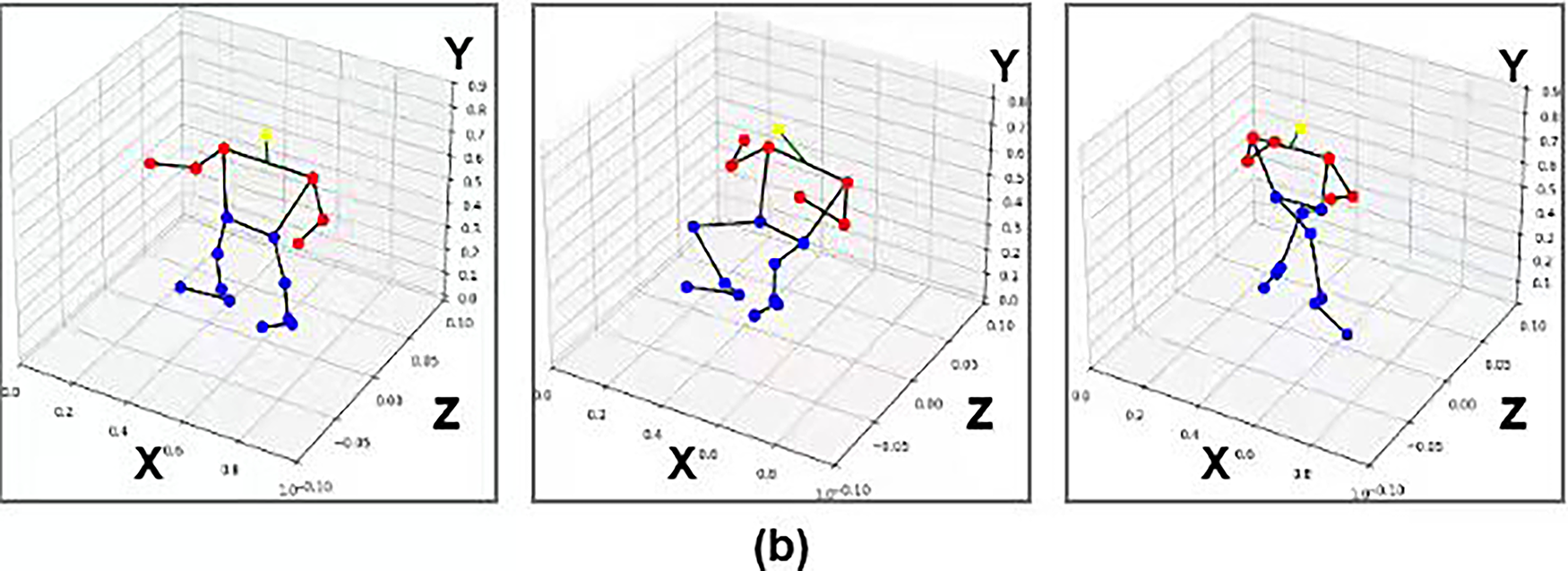

To enhance robustness, the keypoint schema was refined to 13 landmarks, with the nose serving as the cranial proxy and the shoulder midpoint defining the torso vector. Each 2D keypoint is mapped to pseudo-3D by sampling MiDaS depth, normalizing to a reference joint, and combining with 2D coordinates to form pseudo-3D joints. We approximate

The resulting normalized descriptor,

Figure 4: MoveNet-based human keypoint estimation showing (a) the detected keypoints on the silhouette and (b) the visualization skeleton plot

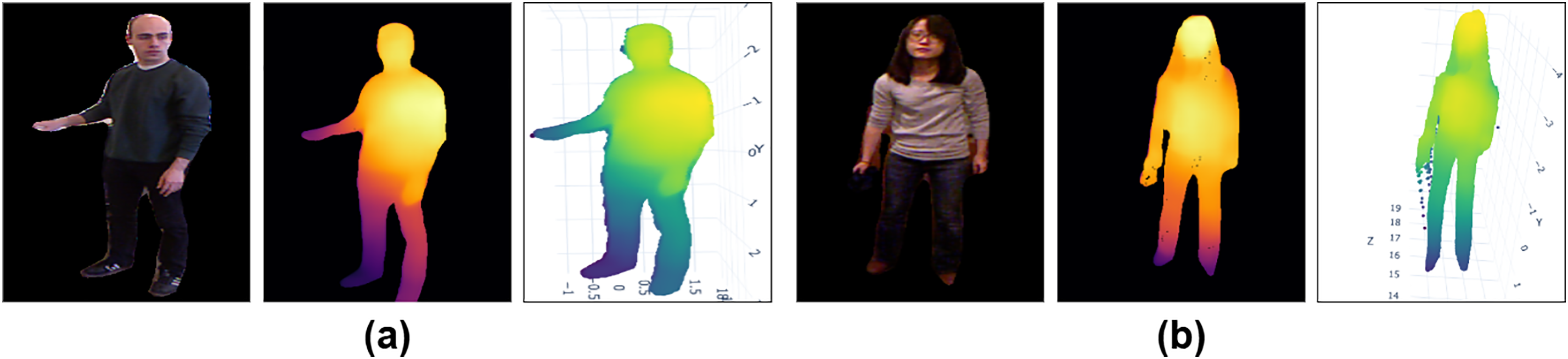

3.4 Point Cloud Reconstruction from Monocular RGB Silhouettes

To infer 3D structure from monocular silhouettes, we use MiDaS [5], a state-of-the-art scale-invariant depth estimator suited for silhouettes without metric references. Depth is optimized using the scale-invariant loss in Eq. (13).

Predicted log-depth values are mapped back as

where

To suppress unreliable 3D points, a depth confidence function is defined using Eq. (16).

where

Figure 5: Visualization of point cloud in various poses: RGB silhouette, predicted depth map and reconstructed 3D point cloud

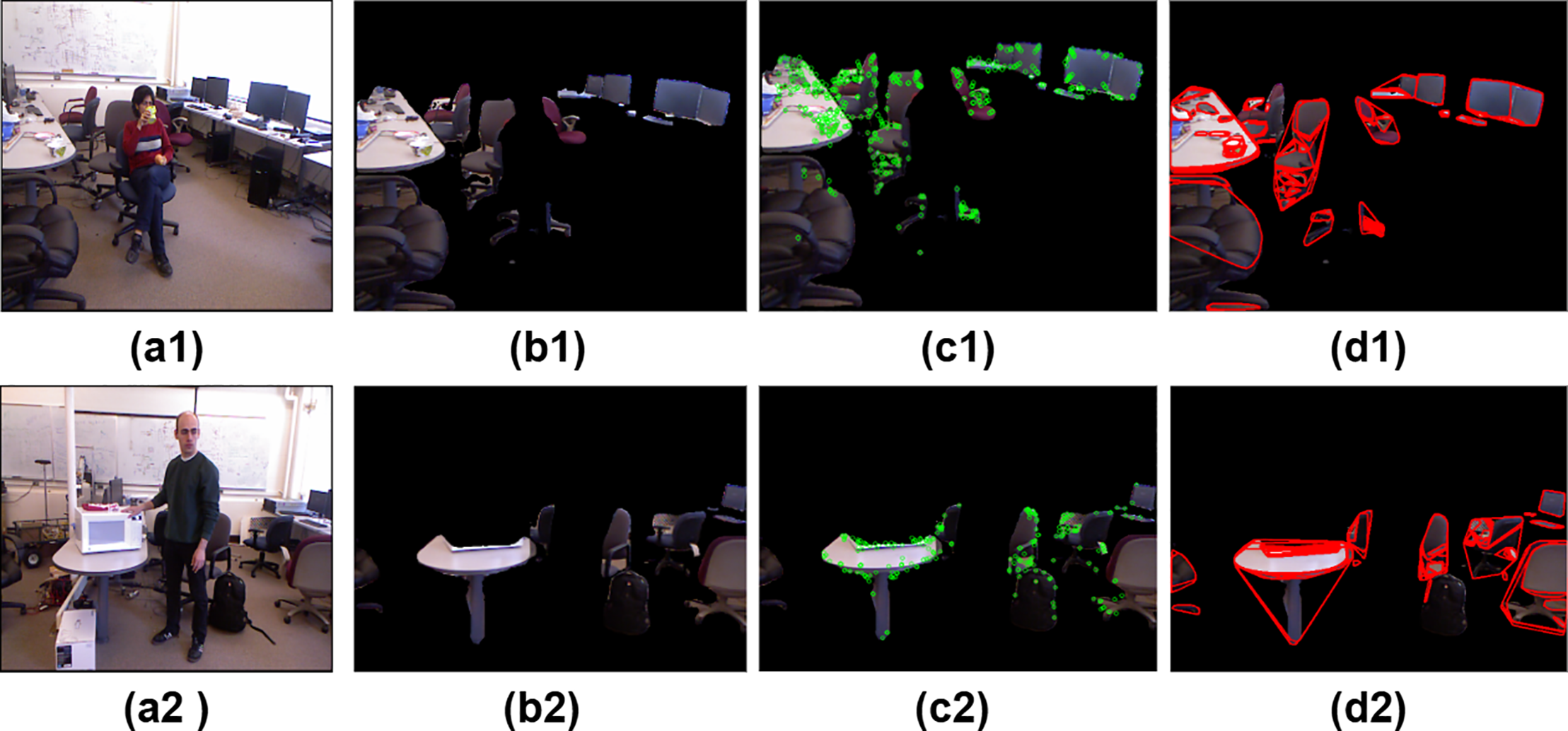

3.5 Object-Oriented Scene Feature Analysis

Environmental context is modeled by analyzing non-human scene components via semantic segmentation. AKAZE detects keypoints and MSER extracts regions, with features computed only on non-human masks to remain independent of the actor’s silhouette. Both AKAZE and MSER feature visualizations are illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Scene-based feature extraction: (a1,a2) RGB scene frames; (b1,b2) object masks (human removed); (c1,c2) AKAZE keypoints; (d1,d2) MSER regions highlighting blob-like features

3.5.1 AKAZE Keypoint Detection

For each object mask

where

where

3.5.2 MSER Region Segmentation

MSER detects intensity-stable regions in

where

MSERs are enclosed by convex hulls to capture blob-like regions, with AKAZE descriptors

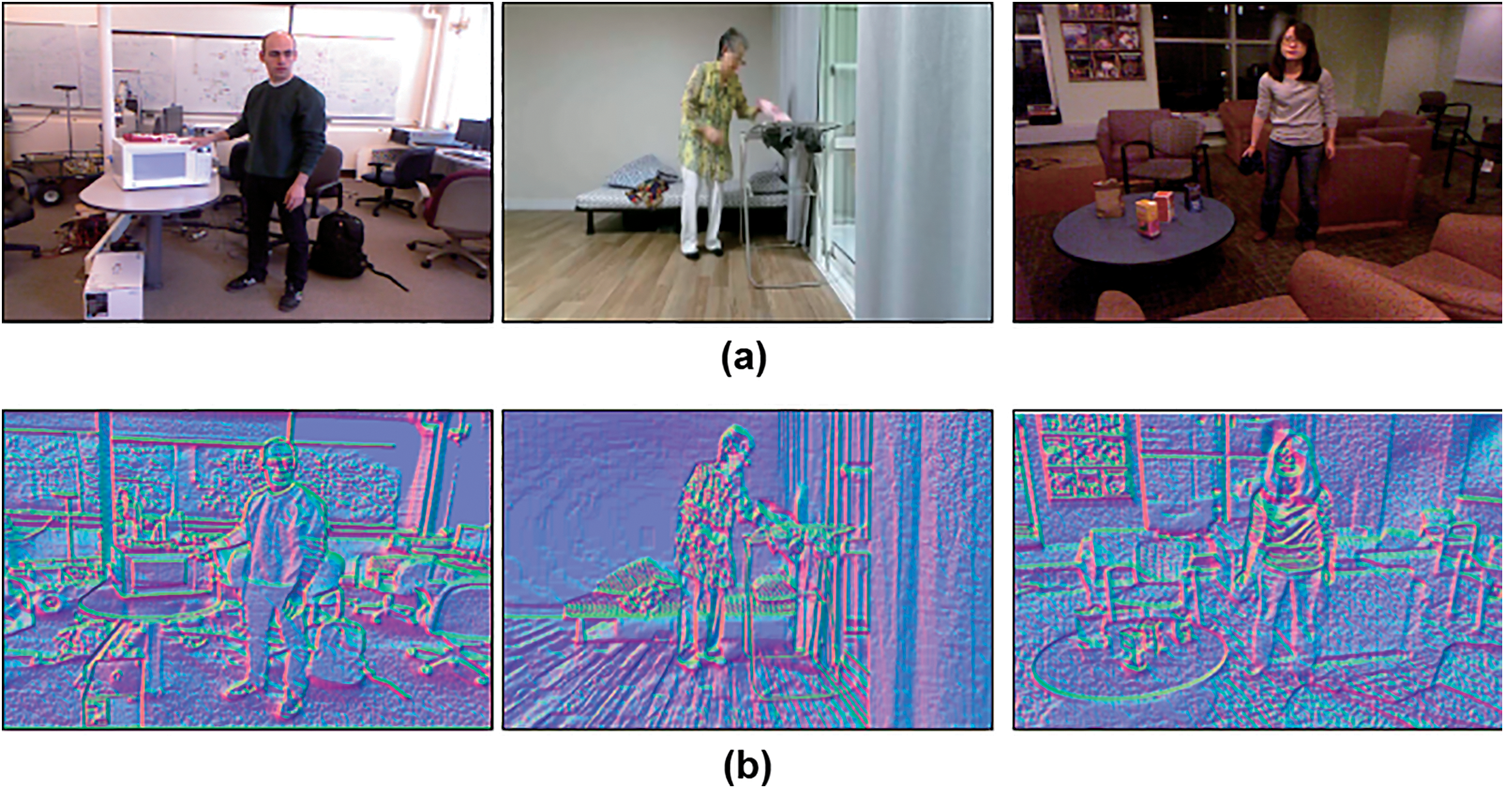

3.6 Global Scene Features and Frequency Analysis

The second stage extracts geometric and frequency descriptors: surface normals yield histograms, directional vectors, and Zernike moments, while Gabor filtering captures structural and textural cues without explicit segmentation.

3.6.1 Scene Surface Normal Estimation

To approximate the underlying surface geometry of the 2D scene, we compute surface normals using Sobel derivatives, as depicted in Fig. 7. Given a grayscale image

Figure 7: Visualization of surface normal (a) RGB frames, (b) Estimated surface normal capturing the geometric structure of scene

From this normal map, several compact descriptors are derived, including Azimuth and Inclination Histograms, Directional Variation, Zernike Moments, and Histogram of Angular Differences.

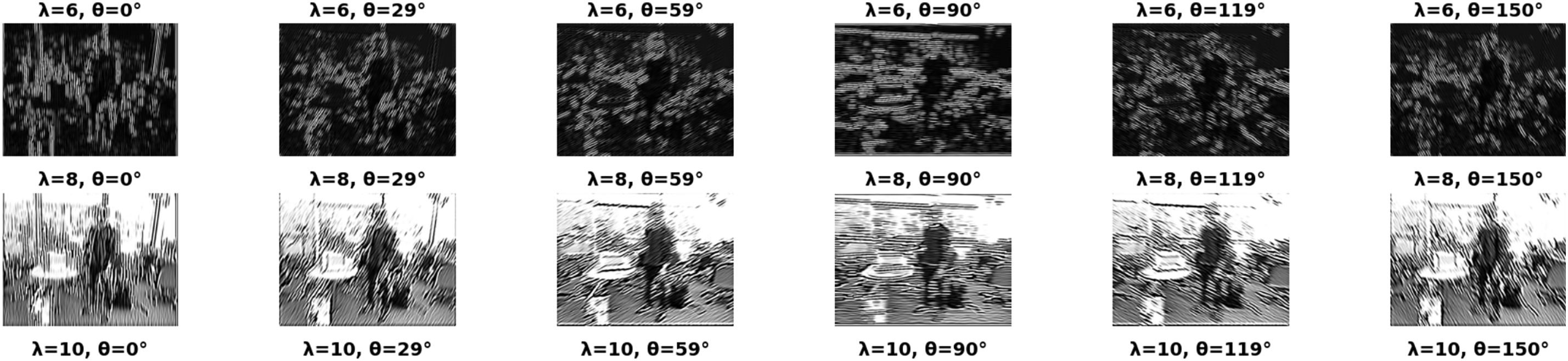

3.6.2 Gabor Filter-Based Texture and Edge Analysis

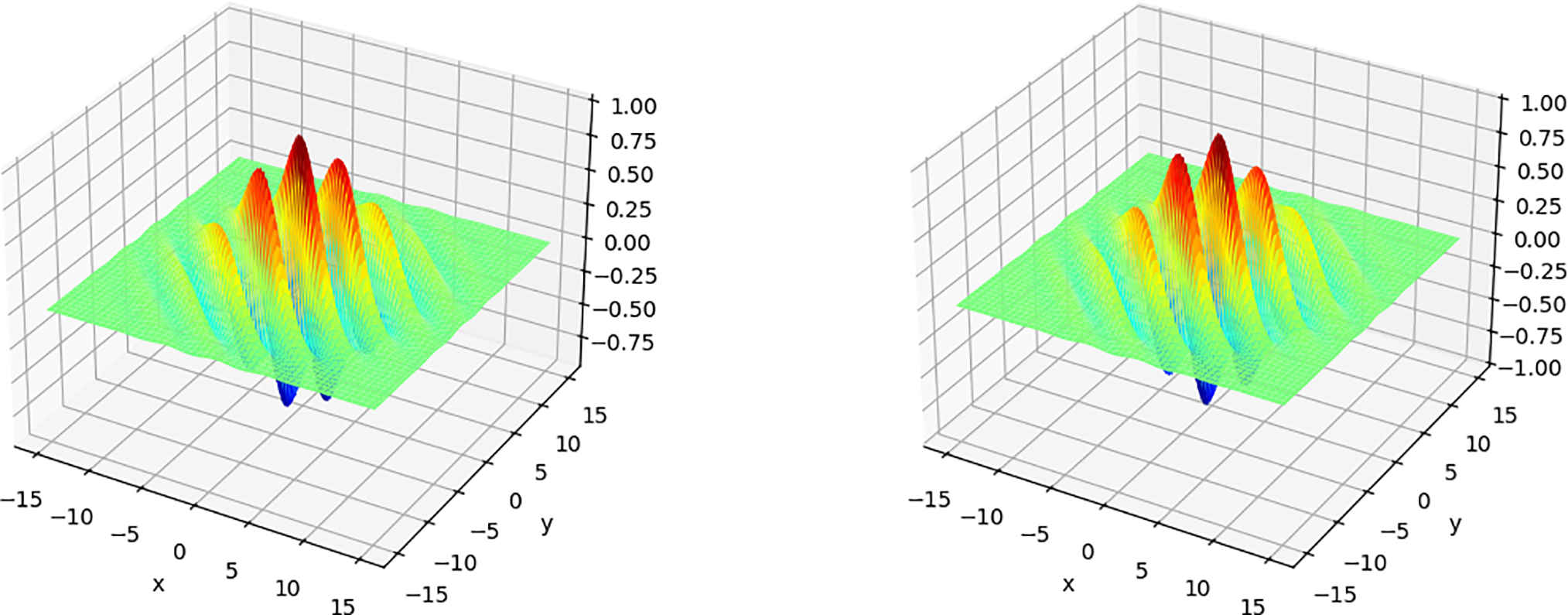

Gabor filters are applied to RGB frames to capture fine textures and oriented patterns, encoding spatial frequency and orientation for effective edge and gradient detection (Eq. (22)).

here,

Figure 8: Real (even-symmetric) and imaginary (odd-symmetric) components of the complex Gabor function, capturing contour and directional edge information

Figure 9: Visualization of 12 Gabor filter responses, each emphasizing different spatial–frequency and orientation characteristics

3.7 Feature Fusion and Classification

To comprehensively encode human motion and scene context, SCENET-3D constructs a composite latent embedding by jointly modelling skeletal dynamics, object-centric structure, and global environmental signatures. Let

where ⊙ denotes element-wise interaction capturing cross-modal correlations,

With

The attention mechanism is then defined using Eq. (26).

Multi-head attention aggregates

with

Finally, the activity class probabilities are computed using a softmax layer using Eq. (28).

where

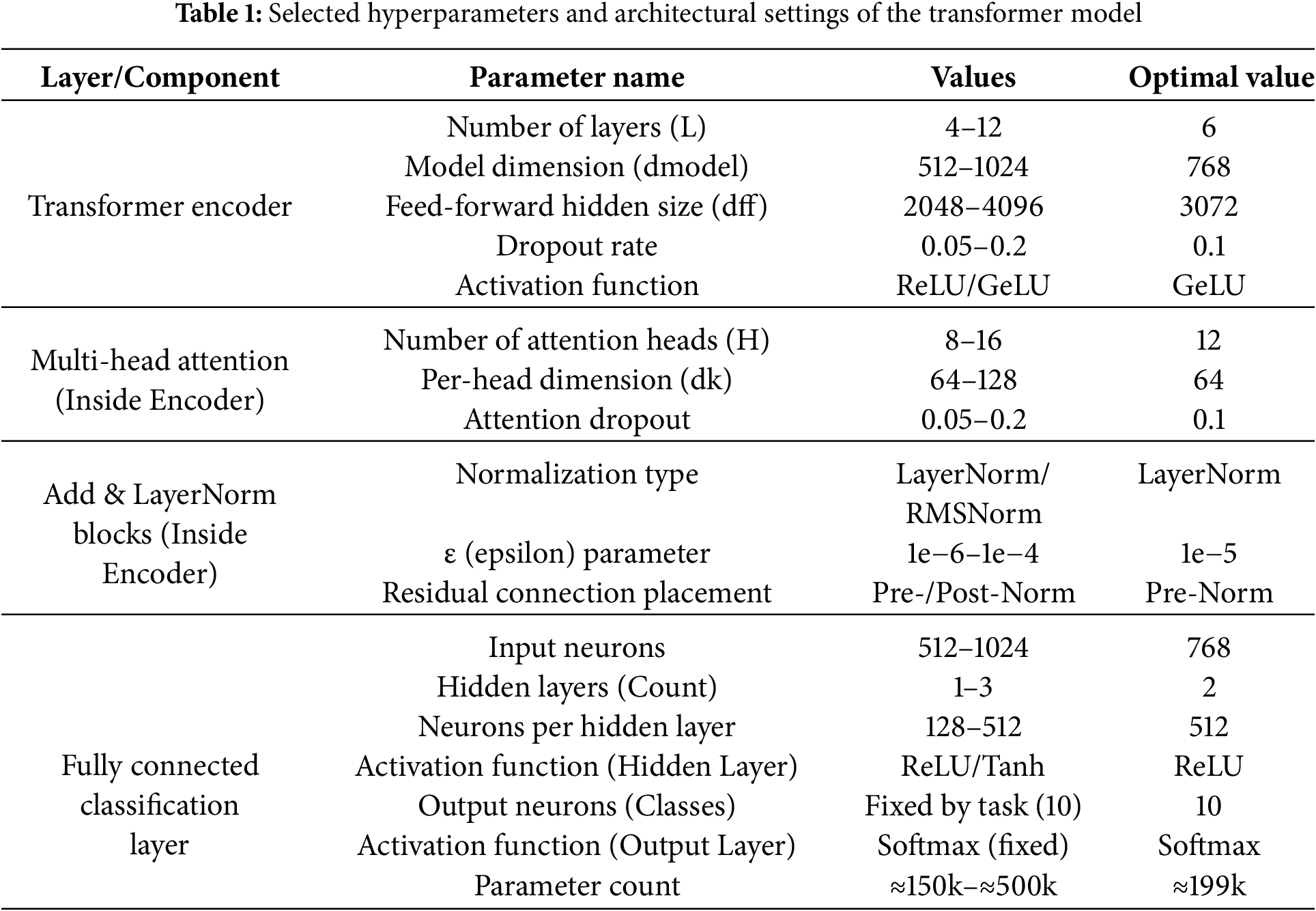

As given in Table 1, the transformer-based model was optimally configured with 6 encoder layers, a model dimension of 768, and a feed-forward hidden size of 3072, using GeLU activation and a dropout rate of 0.1. Each encoder layer employed 12 attention heads with 64-dimensional per-head projections and attention dropout of 0.1. Layer normalization was applied in a pre-norm configuration with ε set to 1e−5. The fully connected classification head comprised two hidden layers of 512 neurons each with ReLU activation, followed by a Softmax output layer for 10 classes, resulting in a total parameter count of approximately 199k. This setup balances model complexity and performance, providing effective representation learning while controlling overfitting.

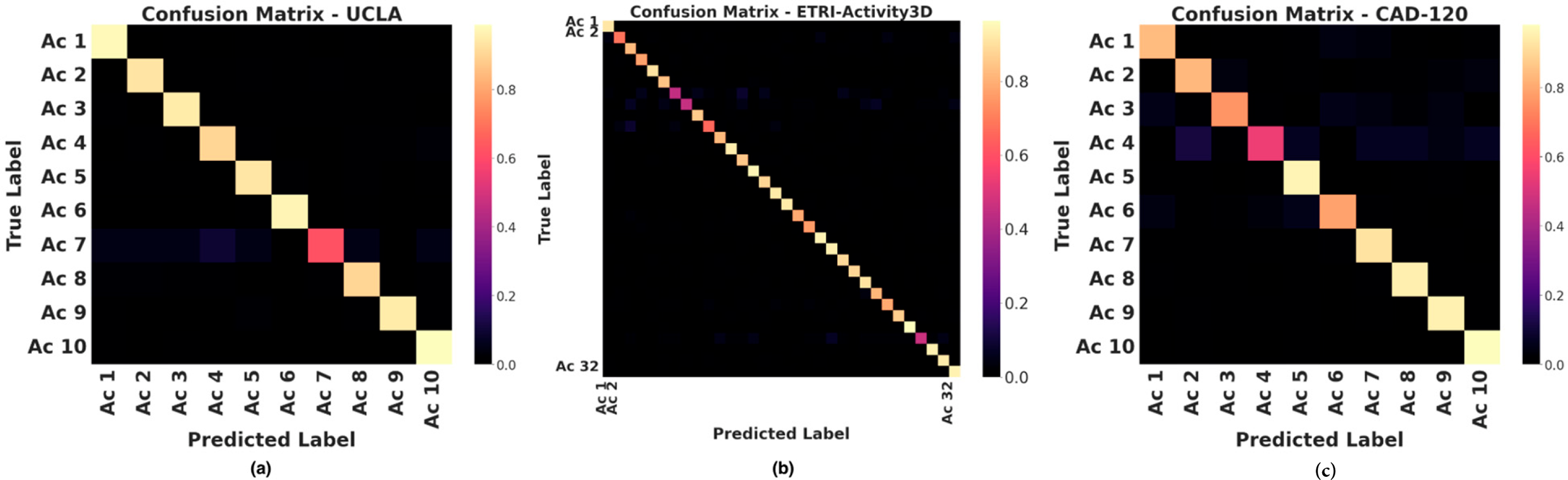

The results section evaluates the proposed HAR system on UCLA, ETRI-Activity3D, and CAD-120 datasets. Performance is assessed via confusion matrices, ROC curves, and metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Comparative tables highlight the method’s effectiveness and robustness across datasets.

All experiments for SCENET-3D were conducted in a cloud-based environment using Google Colab kernels, which provided access to an NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU (16 GB GDDR6, 2560 CUDA cores, Turing architecture), a dual-core Intel Xeon CPU (2.20 GHz), and 27 GB of system RAM. Storage and dataset management were handled through Google Drive integration with temporary VM scratch space for caching. The system comprising the Transformer backbone, pseudo-3D skeleton encoder, and scene-object fusion module—was implemented in Python 3.10 with TensorFlow 2.6.0 and the Keras API, accelerated using CUDA 11.0 and cuDNN 8.0 for parallelized training and inference. NumPy, Pandas, and OpenCV supported numerical processing, structured data handling, and augmentation, while Matplotlib, Seaborn, and TensorBoard were used to visualize learning dynamics.

We evaluated on three benchmarks: N-UCLA Multiview Action 3D (RGB, depth, skeletons of 10 actions across three Kinect views), ETRI-Activity3D (55+ daily activities with RGB-D and motion capture), and CAD-120 (10 complex activities with RGB-D, skeletons, object tracks, and sub-activity labels). These datasets cover diverse modalities and environments for comprehensive evaluation.

The UCLA confusion matrix (Fig. 10) shows strong diagonal dominance, with most activities (Ex1, Ex4, Ex5, Ex6, Ex9, Ex10) above 94% accuracy. On ETRI-Activity3D (Fig. 11), the model achieves average precision, recall, and F1 of 0.8058, 0.8056, and 0.8047. Distinctive activities (Ex49–Ex55) exceed 0.94, while overlapping motions (Ex2, Ex7, Ex8, Ex29) lower discriminability. Well-defined actions (Ex6, Ex28, Ex38–Ex55) show near-perfect recognition, highlighting the need for temporal modeling or data augmentation for ambiguous classes. On CAD-120 (Fig. 10), the framework achieves >90% accuracy for Cleaning, Having a meal, Microwaving, Putting, Stacking, and Taking objects.

Figure 10: Normalized confusion matrices on three datasets: (a) UCLA, (b) ETRI-Activity3D, and (c) CAD-120

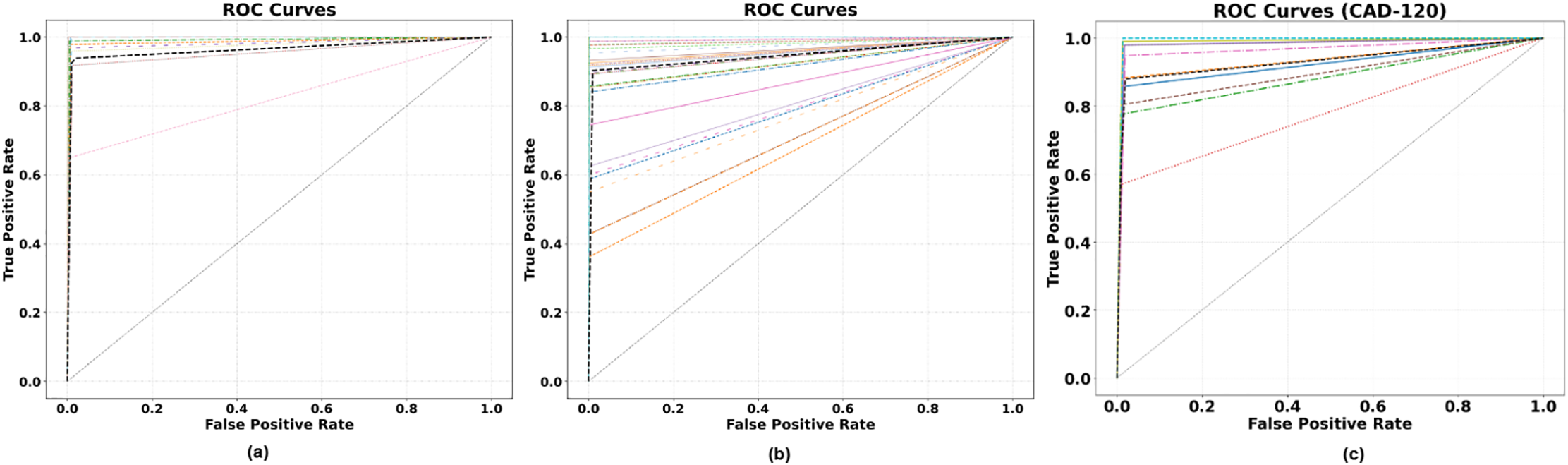

Figure 11: ROC curves for the proposed model across three datasets: (a) UCLA, (b) ETRI-Activity3D, and (c) CAD-120

ROC curves offer threshold-independent evaluation of TPR–FPR trade-offs. UCLA curves cluster near the top-left, showing near-perfect separability. CAD-120 also approaches the ideal, confirming robust recognition of structured activities. ETRI shows greater variability, with lower sensitivity at low FPRs due to subtle motions and complex backgrounds. Overall, UCLA performs best, CAD-120 is balanced, and ETRI needs stronger feature discrimination (Fig. 11).

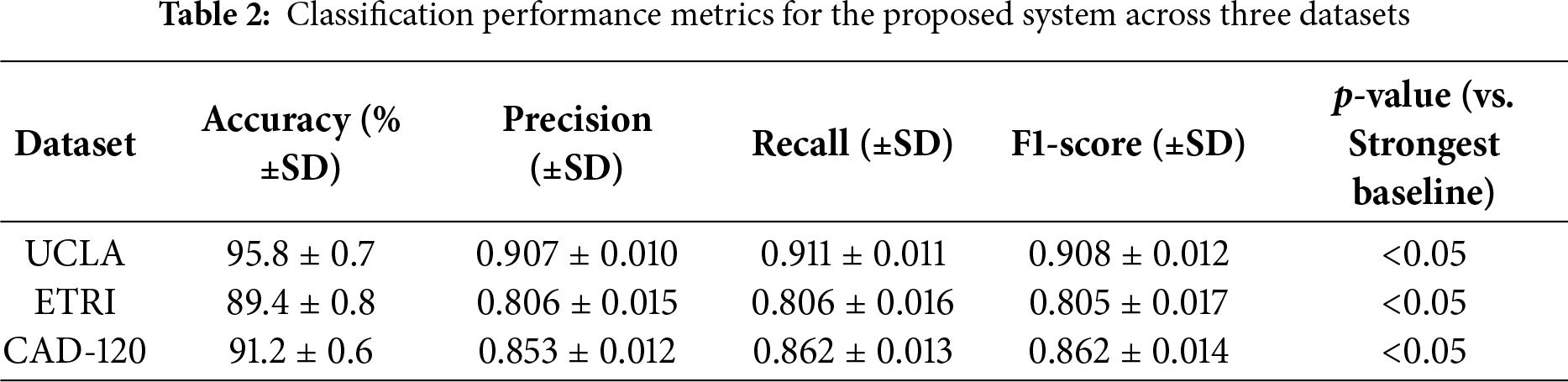

Table 2 shows performance across three benchmarks. UCLA achieves the highest accuracy (95.8%) with balanced precision, recall, and F1. ETRI scores slightly lower due to variability, while CAD-120 attains competitive metrics, demonstrating strong generalization to structured activities. All experiments on UCLA, ETRI-Activity3D and CAD-120 were repeated five times with different random seeds, and Table 2 reports mean ± standard deviation for accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score. These statistics provide direct estimates of variability and thus approximate 95% confidence intervals. We further performed paired two-tailed t-tests comparing our full model with the strongest baseline for each dataset. All improvements were significant at p < 0.05, confirming that the reported gains are statistically robust rather than due to random variation.

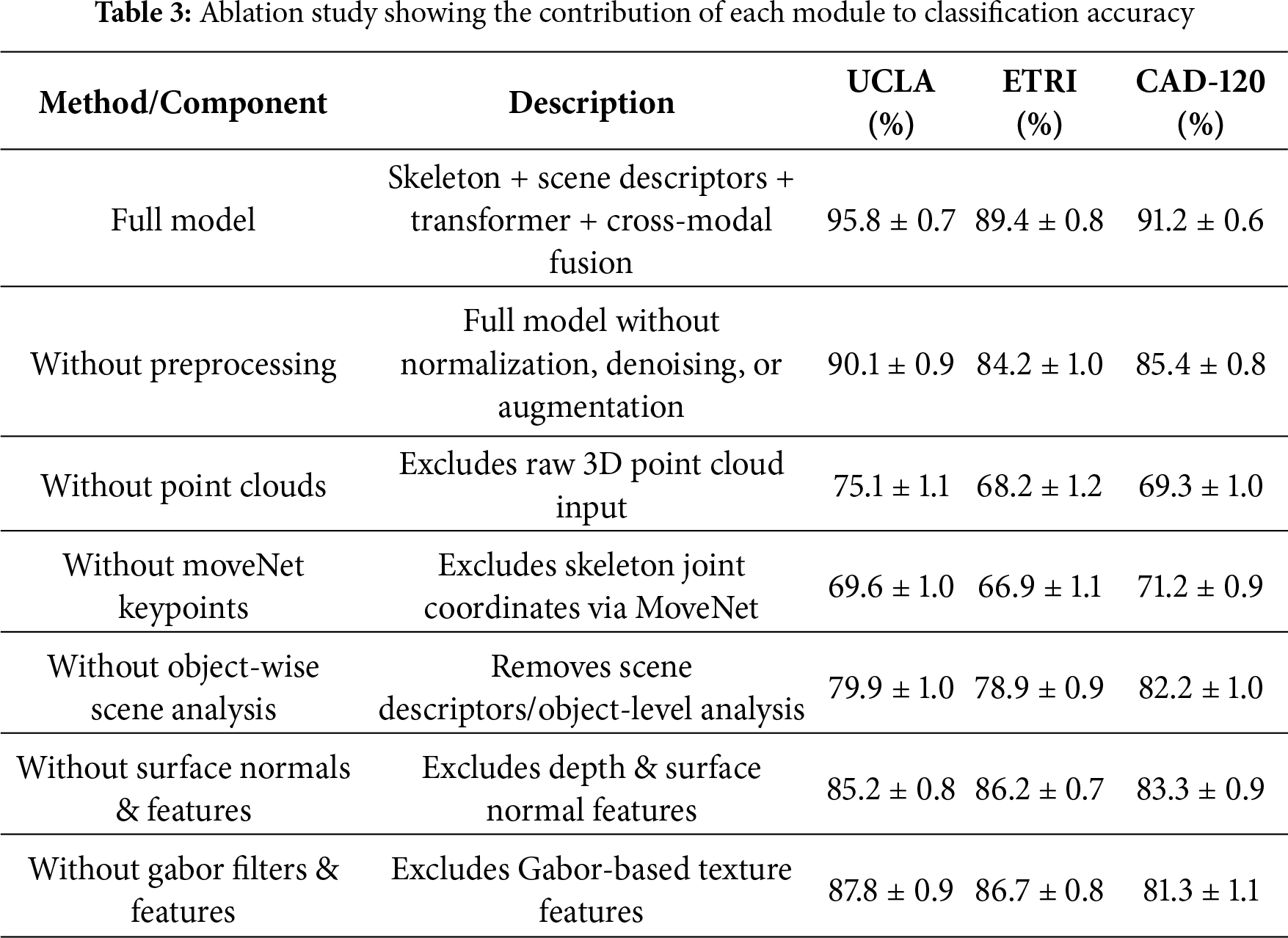

Ablation results (Table 3) show that removing preprocessing reduces accuracy by ~5%–6%, while excluding point clouds or MoveNet keypoints causes the largest drop (20%–25%), confirming the necessity of 3D structure and skeleton cues. Object-wise scene analysis adds 8%–12%, and surface normals plus Gabor features contribute 3%–5%, refining recognition in cluttered settings.

SCENET-3D employs a three-stage pipeline scene analysis, scene-object analysis, and human-pose estimation combining handcrafted descriptors, transformer-based representations, and pseudo-3D point clouds for robust, interpretable understanding. Stage one captures holistic scene attributes (lighting, geometry, texture) via Zernike moments and Gabor filters. Stage two localizes objects using AKAZE and MSER keypoints to preserve local geometric and textural features. The transformer encoder enhances handcrafted and point cloud features by modeling cross-modal and temporal dependencies among skeleton, scene-object, and 3D spatial representations. This context-aware reasoning helps disambiguate visually similar actions. Ablation studies show that removing object, global scene, or point cloud features reduces accuracy by 8%–12%, 3%–5%, and 5%–7%, respectively, highlighting the importance of integrating local, global, temporal, and spatial cues. This hybrid approach outperforms pipelines using only deep learning, handcrafted, or point-cloud features.

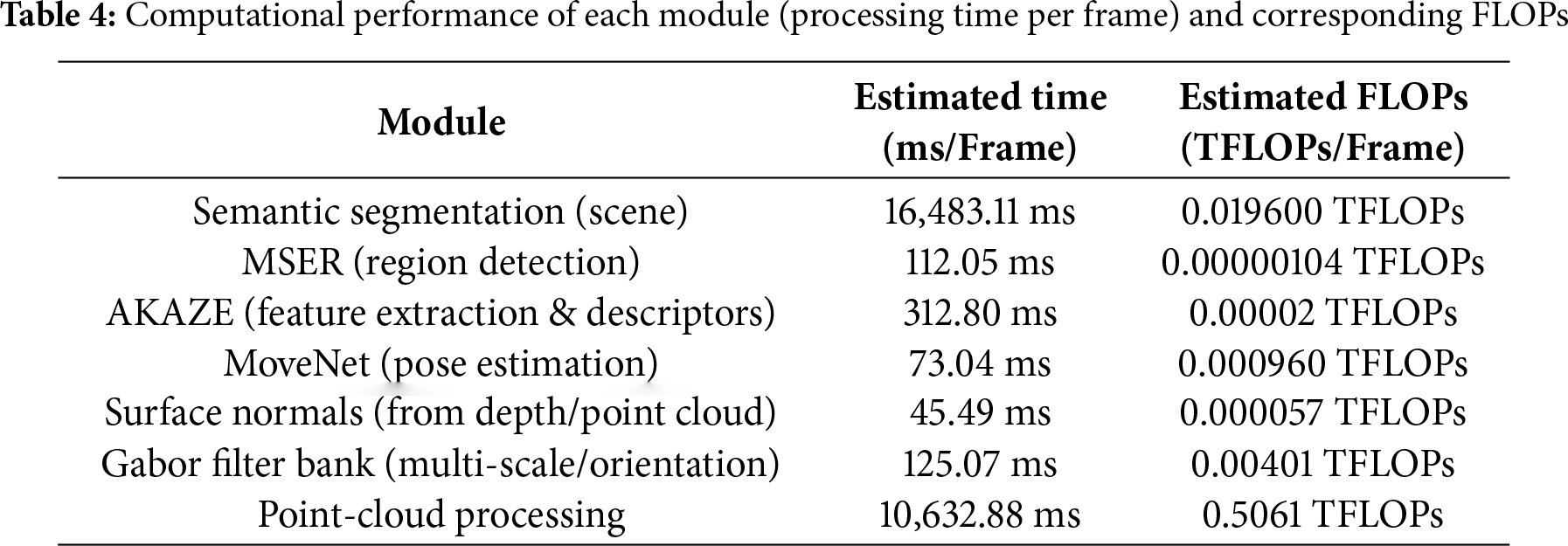

4.7 Computational Cost Analysis

Table 4 highlights the significant variation in computational demands across different vision modules. Tasks like semantic segmentation and point-cloud processing are highly resource-intensive, reflecting their complexity in analyzing large-scale scene and spatial data. In contrast, modules such as region detection, feature extraction, and pose estimation are relatively lightweight, offering efficient processing for targeted analyses. Intermediate techniques, like multi-scale Gabor filtering, balance complexity and efficiency, providing rich feature representations without excessive computational cost.

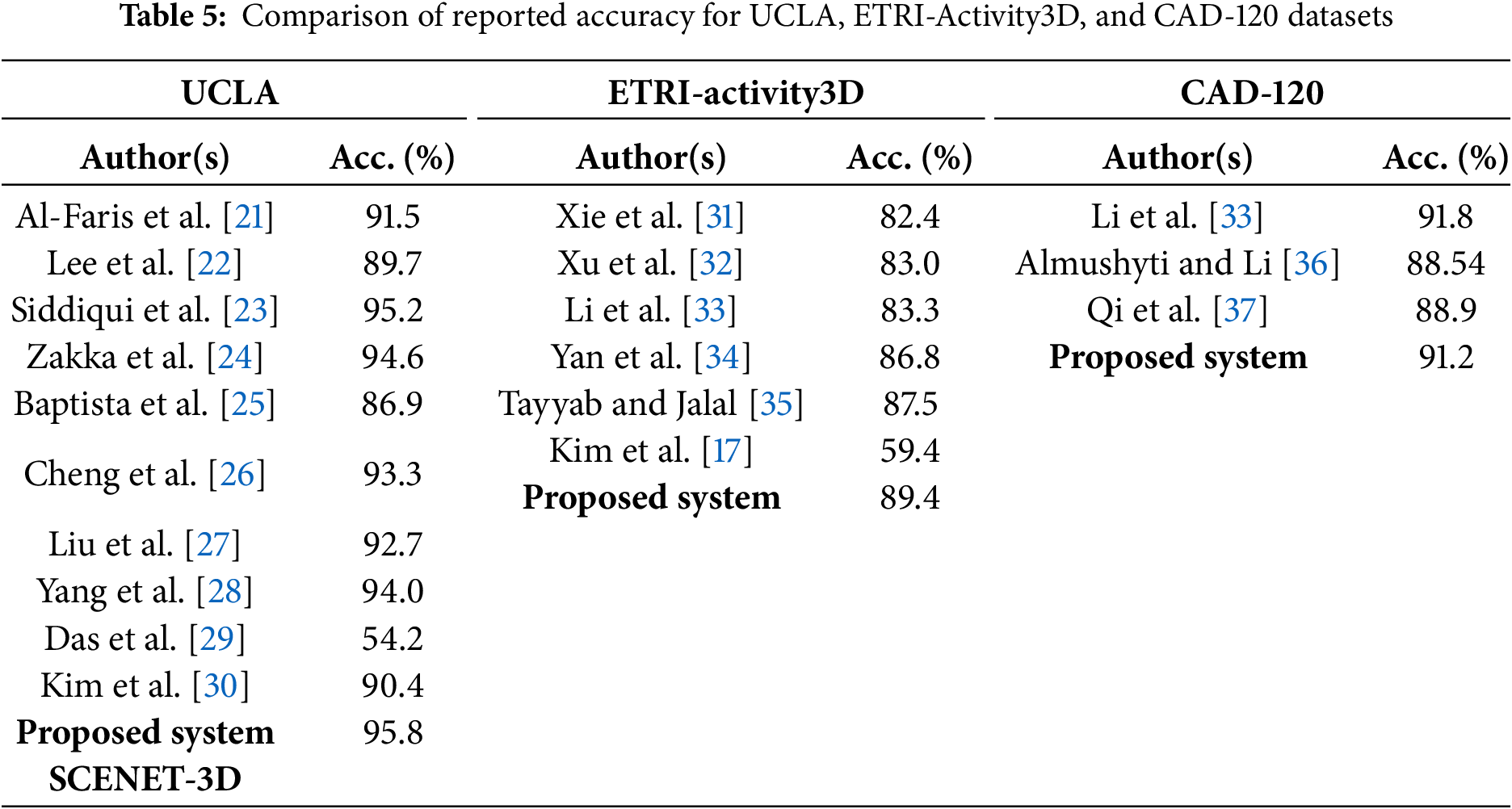

Table 5 compares classification accuracies across state-of-the-art methods. On UCLA, several models exceed 90%, with the proposed system achieving the highest (95.8%). For the more complex ETRI-Activity3D dataset, accuracies are lower overall, yet our approach leads with 89.4%. On CAD-120, results are more balanced, with the proposed method slightly surpassing prior work, demonstrating robustness across varying dataset complexities.

This work presents a unified RGB-based framework integrating pose-aware features with scene-level context for robust HAR in elderly care. Combining MoveNet keypoints, MiDaS pseudo-3D cues, and multi-level scene descriptors, it achieves high accuracy on UCLA (95.8%), ETRI-Activity3D (89.4%), and CAD-120 (91.2%). While effective, the pipeline is sensitive to occlusion, illumination, and clutter, and current fusion does not fully capture temporal transitions. Future work will explore transformer-based temporal modeling, adaptive feature fusion, and lightweight designs for real-time deployment.

Acknowledgement: Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R410), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This research is supported and funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R410), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Aman Aman Ullah and Yanfeng Wu; data collection: Nouf Abdullah Almujally and Shaheryar Najam; analysis and interpretation of results: Ahmad Jalal, Hui Liu, and Shaheryar Najam; draft manuscript preparation: Ahmad Jalal and Shaheryar Najam. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All publicly available datasets are used in the study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Shoaib M, Dragon R, Ostermann J. Context-aware visual analysis of elderly activity in a cluttered home environment. EURASIP J Adv Signal Process. 2011;2011(1):129. doi:10.1186/1687-6180-2011-129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang P, Li W, Ogunbona P, Wan J, Escalera S. RGB-D-based human motion recognition with deep learning: a survey. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2018;171(3):118–39. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2018.04.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shin J, Hassan N, Miah ASM, Nishimura S. A comprehensive methodological survey of human activity recognition across diverse data modalities. Sensors. 2025;25(13):4028. doi:10.3390/s25134028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang Y, Wang Y. A comprehensive survey on RGB-D-based human action recognition: algorithms, datasets and popular applications. EURASIP J Image Video Process. 2025;2025(1):15. doi:10.1186/s13640-025-00677-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Joshi RBD, Joshi D. MoveNet: a deep neural network for joint profile prediction across variable walking speeds and slopes. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2021;70:1–11. doi:10.1109/tim.2021.3073720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Granata C, Ibanez A, Bidaud P. Human activity-understanding: a multilayer approach combining body movements and contextual descriptors analysis. Int J Adv Rob Syst. 2015;12(7):89. doi:10.5772/60525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Melas-Kyriazi L, Rupprecht C, Vedaldi A. PC2: projection-conditioned point cloud diffusion for single-image 3D reconstruction. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 12923–32. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.01242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ullah R, Asghar I, Akbar S, Evans G, Vermaak J, Alblwi A, et al. Vision-based activity recognition for unobtrusive monitoring of the elderly in care settings. Technologies. 2025;13(5):184. doi:10.3390/technologies13050184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lee JJ, Benes B. RGB2Point: 3D point cloud generation from single RGB images. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2025 Feb 26–Mar 6; Tucson, AZ, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 2952–62. doi:10.1109/WACV61041.2025.00292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Al Farid F, Bari A, Miah ASM, Mansor S, Uddin J, Kumaresan SP. A structured and methodological review on multi-view human activity recognition for ambient assisted living. J Imaging. 2025;11(6):182. doi:10.3390/jimaging11060182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ghorbani F, Ahmadi A, Kia M, Rahman Q, Delrobaei M. A decision-aware ambient assisted living system with IoT embedded device for in-home monitoring of older adults. Sensors. 2023;23(5):2673. doi:10.3390/s23052673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Gaya-Morey FX, Manresa-Yee C, Buades-Rubio JM. Deep learning for computer vision based activity recognition and fall detection of the elderly: a systematic review. Appl Intell. 2024;54(19):8982–9007. doi:10.1007/s10489-024-05645-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hu T, Zhu X, Guo W, Wang S, Zhu J. Human action recognition based on scene semantics. Multimed Tools Appl. 2019;78(20):28515–36. doi:10.1007/s11042-017-5496-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang W. Scene context-aware graph convolutional network for skeleton-based action recognition. IET Comput Vis. 2024;18(3):343–54. doi:10.1049/cvi2.12253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Rafique AA, Gochoo M, Jalal A, Kim K. Maximum entropy scaled super pixels segmentation for multi-object detection and scene recognition via deep belief network. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(9):13401–30. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13717-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Achirei SD, Heghea MC, Lupu RG, Manta VI. Human activity recognition for assisted living based on scene understanding. Appl Sci. 2022;12(21):10743. doi:10.3390/app122110743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kim D, Lee I, Kim D, Lee S. Action recognition using close-up of maximum activation and ETRI-Activity3D LivingLab dataset. Sensors. 2021;21(20):6774. doi:10.3390/s21206774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Han G, Zhao J, Zhang L, Deng F. A survey of human-object interaction detection with deep learning. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput Intell. 2025;9(1):3–26. doi:10.1109/tetci.2024.3518613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Maheriya K, Rahevar M, Mewada H, Parmar M, Patel A. Insights into aerial intelligence: assessing CNN-based algorithms for human action recognition and object detection in diverse environments. Multimed Tools Appl. 2025;84(16):16481–523. doi:10.1007/s11042-024-19611-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Su Z, Yang H. A novel part refinement tandem transformer for human-object interaction detection. Sensors. 2024;24(13):4278. doi:10.3390/s24134278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Al-Faris M, Chiverton JP, Yang Y, Ndzi D. Multi-view region-adaptive multi-temporal DMM and RGB action recognition. Pattern Anal Appl. 2020;23(4):1587–602. doi:10.1007/s10044-020-00886-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Lee I, Kim D, Wee D, Lee S. An efficient human instance-guided framework for video action recognition. Sensors. 2021;21(24):8309. doi:10.3390/s21248309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Siddiqui N, Tirupattur P, Shah M. DVANet: disentangling view and action features for multi-view action recognition 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/28290. [Google Scholar]

24. Zakka VG, Dai Z, Manso LJ. Action recognition in real-world ambient assisted living environment. Big Data Min Anal. 2025;8(4):914–32. doi:10.26599/bdma.2025.9020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Baptista R, Ghorbel E, Papadopoulos K, Demisse GG, Aouada D, Ottersten B. View-invariant action recognition from RGB data via 3D pose estimation. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2019—2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2019 May 12–17; Brighton, UK. p. 2542–6. doi:10.1109/icassp.2019.8682904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Cheng Q, Cheng J, Liu Z, Ren Z, Liu J. A dense-sparse complementary network for human action recognition based on RGB and skeleton modalities. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;244(3):123061. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.123061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu H, Wang Y, Ren M, Hu J, Luo Z, Hou G, et al. Balanced representation learning for long-tailed skeleton-based action recognition. Mach Intell Res. 2025;22(3):466–83. doi:10.1007/s11633-023-1487-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yang Y, Liang G, Wang C, Wu X. Trunk-branch contrastive network with multi-view deformable aggregation for multi-view action recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2026;169(10):111923. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2025.111923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Das S, Dai R, Koperski M, Minciullo L, Garattoni L, Bremond F, et al. Toyota smarthome: real-world activities of daily living. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 833–42. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kim B, Chang HJ, Kim J, Choi JY. Global-local motion transformer for unsupervised skeleton-based action learning. In: Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Computer Vision—ECCV 2022; 2022 Oct 23–27; Tel Aviv, Israel. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 209–25. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-19772-7_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Xie C, Li C, Zhang B, Chen C, Han J, Liu J. Memory attention networks for skeleton-based action recognition. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018 Jul 13–19; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 1639–45. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2018/227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xu Y, Cheng J, Wang L, Xia H, Liu F, Tao D. Ensemble one-dimensional convolution neural networks for skeleton-based action recognition. IEEE Signal Process Lett. 2018;25(7):1044–8. doi:10.1109/LSP.2018.2841649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li C, Zhong Q, Xie D, Pu S. Skeleton-based action recognition with convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia & Expo Workshops (ICMEW); 2017 Jul 10–14; Hong Kong, China. p. 597–600. doi:10.1109/ICMEW.2017.8026285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yan S, Xiong Y, Lin D. Spatial temporal graph convolutional networks for skeleton-based action recognition. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2018;32(1):1–9. doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tayyab M, Jalal A. Disabled rehabilitation monitoring and patients healthcare recognition using machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 2025 6th International Conference on Advancements in Computational Sciences (ICACS); 2025 Feb 18–19; Lahore, Pakistan. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/icacs64902.2025.10937871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Almushyti M, Li FWB. Distillation of human-object interaction contexts for action recognition. Comput Animat Virtual Worlds. 2022;33(5):e2107. doi:10.1002/cav.2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Qi S, Wang W, Jia B, Shen J, Zhu SC. Learning human-object interactions by graph parsing neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 407–23. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01240-3_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools