Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Real-Time 3D Scene Perception in Dynamic Urban Environments via Street Detection Gaussians

1 School of Advanced Technology, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, 215123, China

2 Thrust of Artificial Intelligence, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou), Guangzhou, 511400, China

3 Department of Electrical Engineering and Electronics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 7ZX, UK

4 The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou), Guangzhou 511400, China

5 Institute of Deep Perception Technology, JITRI, Wuxi, 214000, China

6 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Inha University, Incheon, 402751, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Yan Li. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 57 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072544

Received 29 August 2025; Accepted 02 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

As a cornerstone for applications such as autonomous driving, 3D urban perception is a burgeoning field of study. Enhancing the performance and robustness of these perception systems is crucial for ensuring the safety of next-generation autonomous vehicles. In this work, we introduce a novel neural scene representation called Street Detection Gaussians (SDGs), which redefines urban 3D perception through an integrated architecture unifying reconstruction and detection. At its core lies the dynamic Gaussian representation, where time-conditioned parameterization enables simultaneous modeling of static environments and dynamic objects through physically constrained Gaussian evolution. The framework’s radar-enhanced perception module learns cross-modal correlations between sparse radar data and dense visual features, resulting in a 22% reduction in occlusion errors compared to vision-only systems. A breakthrough differentiable rendering pipeline back-propagates semantic detection losses throughout the entire 3D reconstruction process, enabling the optimization of both geometric and semantic fidelity. Evaluated on the Waymo Open Dataset and the KITTI Dataset, the system achieves real-time performance (135 Frames Per Second (FPS)), photorealistic quality (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) 34.9 dB), and state-of-the-art detection accuracy (78.1% Mean Average Precision (mAP)), demonstrating aKeywords

High-fidelity 3D modeling is increasingly being applied to urban scenarios, such as traffic monitoring. While Gaussian Splatting (GS) and Neural Radiance Field(NeRF) based models [1] achieve impressive reconstruction and rendering quality, they do not provide real-time traffic detection and recognition capabilities. Additionally, most existing research primarily focuses on static scenes. Although extensions such as Block-NeRF [2] and GS-based networks [3] aim to address large-scale streets by dividing them into subscenes, they still struggle to achieve real-time monitoring of dynamic objects.

Urban scene reconstruction faces three main challenges: (1) Speed–accuracy tradeoff: Neural Radiance Field (NeRF, [1]) requires hours per scene, while real-time methods (e.g., 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) [4]) lack semantic detection; (2) Occlusion handling: Moving objects frequently block critical traffic elements; (3) Scalability: Large-scale scenes (>1 km2) require efficient memory usage.

Dynamic urban perception requires not only real-time reconstruction and rendering but also reliable object detection and robustness under occlusion. However, street-scale Gaussian methods such as Street Gaussians and 4D Gaussian Splatting largely optimize for view synthesis, lacking detection-aware training and cross-sensor fusion. To close this gap, we propose Street Detection Gaussian (SDG), which integrates detection supervision into the Gaussian pipeline, fuses millimeter-wave (mmWave) radar for depth reliability, and models movers with time-conditioned Gaussians while keeping static backgrounds in 3DGS. SDG further leverages large multi-modal models [5] for frame-level semantics, yielding a perception-oriented, real-time solution for dynamic urban scenes.

Compared with existing Gaussian- and NeRF-based approaches, Street Detection Gaussians (SDG) introduces several fundamental differences. Unlike traditional 3DGS and Street Gaussians that rely solely on image features for static reconstruction, SDG incorporates object-level semantics from Grounded-SAM to guide Gaussian placement and density. In contrast to dynamic NeRF variants such as D-NeRF and 4DGS, SDG performs confidence-aware radar-camera fusion to enhance geometric accuracy and temporal stability. Furthermore, SDG employs detection-aware pruning and tile-based rendering to sustain real-time performance on city-scale scenes. Our key contributions are:

1. Hybrid static-dynamic Gaussian representation: Models static backgrounds with 3DGS and dynamic objects with time-dependent parameters, achieving 135 FPS while improving mAP@0.5 by 15.8%, addressing the speed-semantic fidelity trade-off.

2. Radar-guided depth refinement: Fuses sparse radar with monocular depth (MiDaS [6]), enhancing depth estimation and reducing occlusion errors by 22%.

3. Detection-aware splatting optimization: Jointly optimizes Gaussian parameters and detection to prune redundant Gaussians, reducing memory use while maintaining quality for large-scale (>1

These advances enable photorealistic, interactive urban traffic scene synthesis with significantly reduced complexity—from

2.1 Semantic Perception for Street-Scale Scene Understanding

In recent years, there has been continuous innovation in modeling and rendering dynamic urban environments, showing great potential in domains such as computer vision and computer graphics, particularly for traffic applications. This section reviews key developments in neural scene reconstruction, point cloud-based modeling, scalable hybrid approaches, and radar-vision fusion, highlighting their contributions and limitations in large-scale, real-world applications.

Neural scene representation techniques have revolutionized 3D modeling by leveraging implicit volumetric representations. Neural Radiance Field (NeRF, [1]) introduced a framework for synthesizing photorealistic views of static scenes, and extensions such as Block-NeRF and NeRF++ [9] improved scalability by partitioning scenes or modeling unbounded depth. However, these methods struggle with temporal dynamics and are computationally prohibitive for real-time use. Dynamic extensions like D-NeRF [10] and Neural Scene Flow Field(NSFF [11]) incorporate motion under steady background assumptions, while Multi-Camera Neural Radiance Fields(MC-NeRF [12]) adapts NeRF for multi-camera outdoor setups to address pose inaccuracies and color inconsistencies. Although effective, they still require long training times and incur high computational costs, limiting applicability to large-scale dynamic environments.

Point clouds provide efficient and interpretable 3D representations. Methods such as PointNet [13] and PointNet++ [14] pioneered learning-based segmentation and classification from point-based input, but remain primarily static and lack temporal modeling. More recent approaches like 3DGS employ Gaussian representations for photorealistic rendering with high computational efficiency, while dynamic variants [15] extend this concept to motion modeling with local rigidity constraints. Although promising for long-term tracking and dense reconstruction, such approaches remain underexplored in large-scale urban contexts.

Scaling scene representations to large, dynamic environments poses additional challenges. Hybrid solutions such as K-Planes [16] factorize geometry into learnable spatial and temporal planes for improved interpretability and memory efficiency, and StreetSurf [17] introduces multi-shell neural fields for near- and far-view modeling at the urban scale. While techniques like hash grids and cuboid warping enhance rendering quality and speed, integration with dynamic object tracking and sparse sensor data, such as radar, remains largely unresolved.

Radar sensing is increasingly leveraged for robust perception under occlusion and adverse weather. Traditional methods rely on handcrafted features, while newer systems fuse radar and vision for improved object tracking and scene understanding [18]. Despite progress, most focus on specific perception tasks rather than full-scene reconstruction. Attempts to integrate sparse radar data into neural representations for automatic annotation and dynamic reconstruction show potential, but real-time performance at the city scale has yet to be achieved. RCMixer [19] introduces a vision-guided end-to-end radar-camera fusion network, enhancing multi-modal feature alignment for object detection. A dual-view framework combining Perspective View and Bird’s Eye View representations [20] enables complementary fusion across spatial domains, improving detection in adverse conditions. Similarly, Enhanced Radar Perception (ERP) [21] leverages multi-task learning to infer radar point height and refine fusion features, while the 2024 survey by Wei et al. [22] summarizes deep-learning-based radar-vision fusion strategies, highlighting that most existing works remain detection-focused and lack full-scene reconstruction. In contrast, our SDG framework integrates radar priors directly into 3D Gaussian scene representations, bridging real-time reconstruction, semantic segmentation, and multi-sensor consistency within a unified architecture.

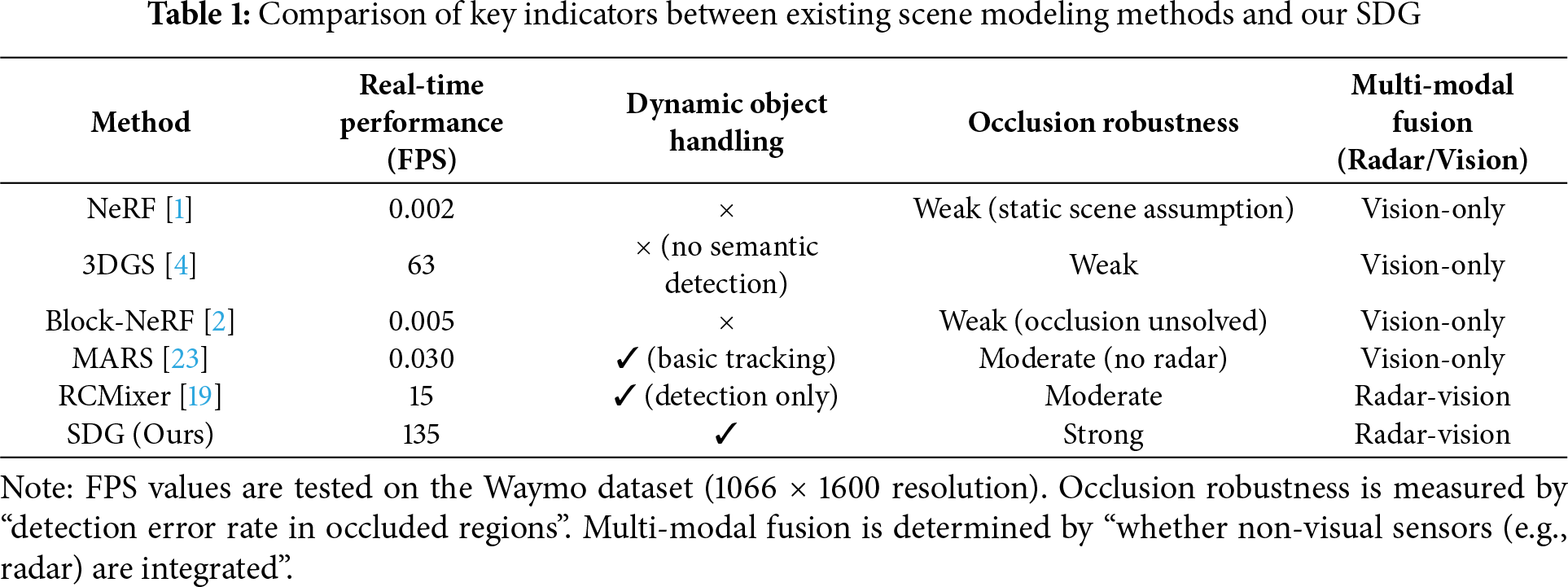

To further clarify the limitations of existing methods and highlight the novelty of our work, Table 1 systematically compares representative approaches with our SDG across key performance metrics.

As illustrated in Table 1, three core gaps exist in current dynamic urban scene modeling methods: Trade-off between real-time performance and dynamic handling: 3DGS achieves real-time rendering at 63 FPS but lacks dynamic object detection capabilities; Modular and Realistic Simulator(MARS) supports basic dynamic tracking, yet its reliance on complex volumetric modeling limits the frame rate to only 0.030 FPS—far below the real-time requirements of autonomous driving. Insufficient occlusion robustness: Static methods like NeRF and Block-NeRF cannot handle dynamic occlusions due to their static scene assumptions; vision-only methods (3DGS, MARS) suffer from excessively large detection errors in occluded areas. Lack of multi-modal fusion: All compared methods rely solely on visual data (images/LiDAR) and fail to leverage radar’s depth stability in adverse conditions, leading to significant depth estimation errors under varying illumination or occlusion.

Traffic scene reconstruction remains challenging due to the complex interplay between static infrastructure and dynamic objects. Traditional multi-view geometry and structure-from-motion methods struggle with temporal inconsistency, while neural approaches such as MARS [23] and StreetSurf incorporate motion disentanglement but still face trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency.

Building upon these advances, our work extends 3DGS toward real-time, radar-guided modeling of dynamic urban environments. By integrating tracked poses, sparse radar depth, and detection-aware optimization, SDGs achieve efficient, high-fidelity reconstruction and semantic perception simultaneously. In contrast to Street Gaussians, which focus on static street rendering, and 4D Gaussian Splatting, which models temporal dynamics for view synthesis, our framework uniquely unifies time-conditioned Gaussians, radar-guided refinement, and detection supervision. This design transforms Gaussian splatting from a rendering-oriented paradigm into a perception-centered framework for real-time urban scene understanding.

2.2 Geometric–Semantic Inference for 3D Scene Understanding

Scenario-oriented comparison. We now relate classical geometry, geo-semantic inference, and neural fields to four canonical outdoor layouts—curved corridors, alleyways, winding pathways, and deck/platform scenes—highlighting assumptions, strengths, weaknesses, and suitability, with citations to representative algorithms in each category. Structure-from-Motion (SfM)/Multi-View Stereo (MVS) and factor-graph Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) reconstruct geometry from calibrated views, often regularized by piecewise-planar or layout priors such as Manhattan/Atlanta worlds [24]. Volumetric Truncated Signed Distance Function (TSDF)/voxel or surfel fusion improves closure and scale consistency for dense mapping [25]. These pipelines are interpretable and controllable, with clear error sources, but can be sensitive to scene assumptions (orthogonality/planarity), struggle with dynamics/occlusions, and may incur memory/time costs at the urban scale.

Semantic cues are coupled with geometry via Conditional Random Field(CRF)/Markov Random Field(MRF), Bayesian updates, or graph optimization to enforce layout/object consistency (ground–wall–opening; lane–curb; facade–aperture) across space and time [26]. This family is especially effective when functional structure is clear, or appearance is weak/variable, reducing drift and ambiguity. Limitations include dependence on annotation/generalization and the need for robust conflict resolution when semantics and geometry disagree.

NeRF and 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) provide continuous or Gaussian field representations for photorealistic rendering; their dynamic and large-scale variants (incl. 4D formulations) improve temporal modeling and scalability [1,2,4]. However, many works remain view-synthesis-centric, with less integrated supervision for detection/segmentation, and may be brittle under heavy occlusion, adverse weather, or depth instability.

Our SDG-based framework complements the above by routing detection-aware losses through the reconstruction pathway and explicitly fusing mmWave radar with vision, which improves depth/occlusion robustness while unifying reconstruction, segmentation, and detection under real-time constraints. This design targets dynamic street scenes where purely visual neural reconstructions or purely geometric pipelines often degrade.

Curved corridors: spline/centerline smoothness and relaxed Manhattan

These comparisons motivate the SDG design choices in Section 3, where we combine time-conditioned Gaussians, radar-guided refinement, and detection-aware supervision to address dynamics, occlusions, and weak textures across the above scenarios.

3 Street Detection Gaussians Based Real-Time 3D Scene Representation

In this section, we are going to present our framework that integrates 3DGS for static scene reconstruction, and object detection and segmentation using Grounded Segment Anything (Grounded-SAM, [34,35]). This combined approach reconstructs urban environments and detects dynamic objects using only image-based inputs from the Waymo in real-time.

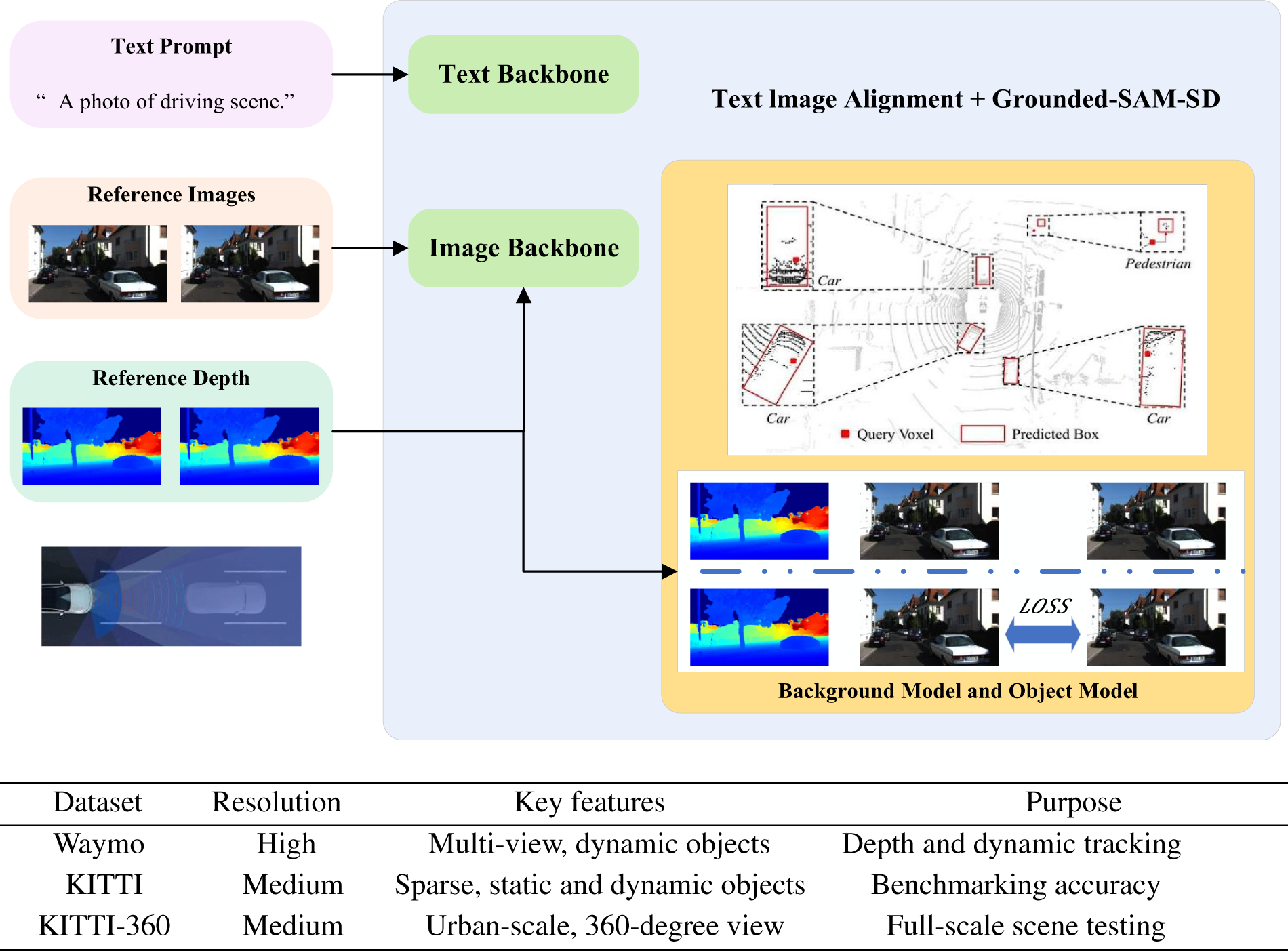

To address the computational inefficiencies and limited real-time capabilities of the previous approaches, we introduce SDG, a novel network designed to efficiently reconstruct and render dynamic urban environments while detecting traffic participants with basic recognition capabilities. This design bridges the gap between existing static reconstruction methods, such as NeRF, and dynamic detection challenges, by combining 3DGS for efficient representation with Grounded-SAM for accurate dynamic segmentation, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: (Top) Overview of the proposed Gaussian reconstruction and detection framework. The structure integrates 3DGS for static scene reconstruction and uses Grounded-SAM for object detection and segmentation, enabling real-time modeling of dynamic urban environments. (Bottom) Summary of datasets used in this study

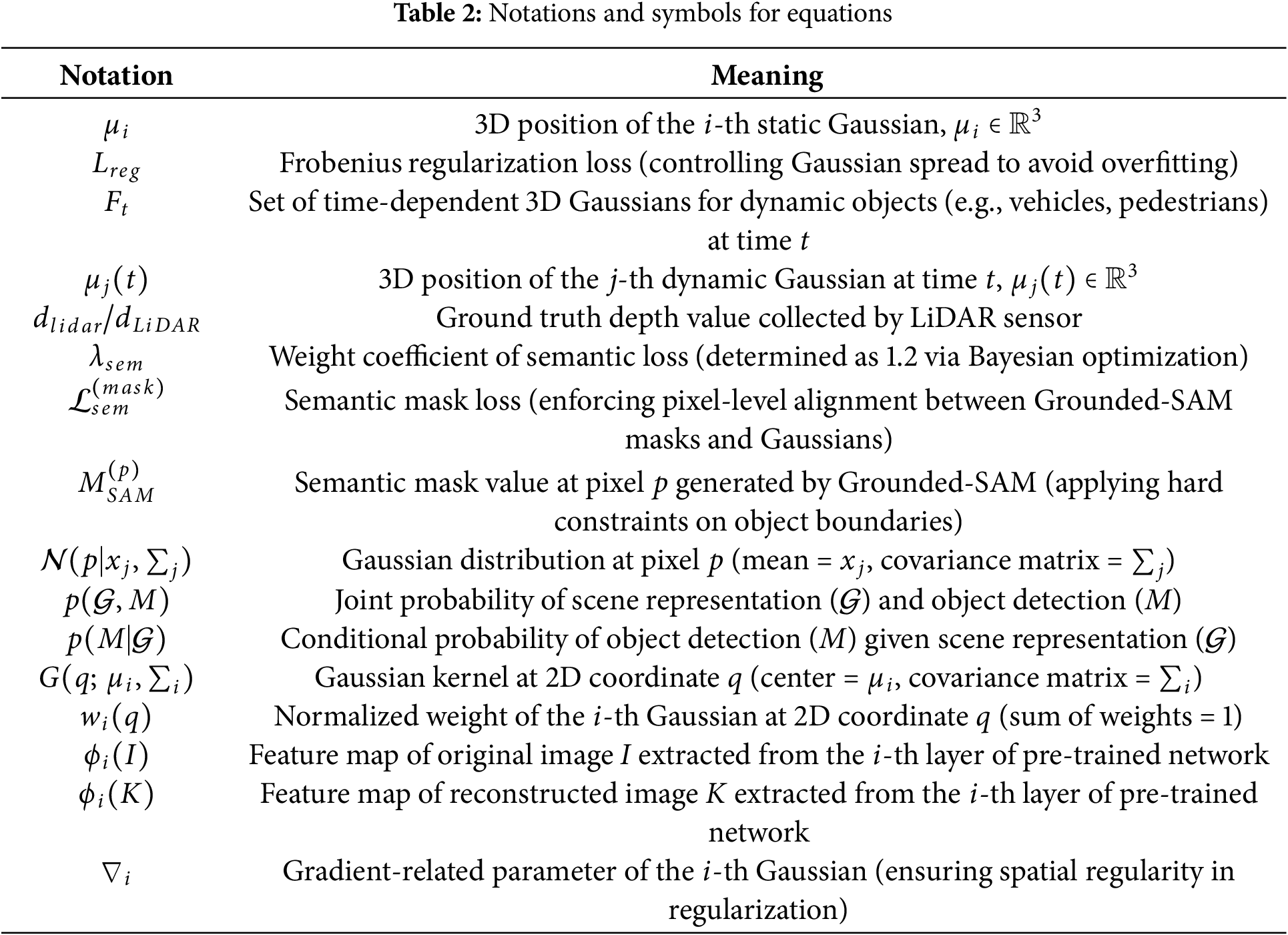

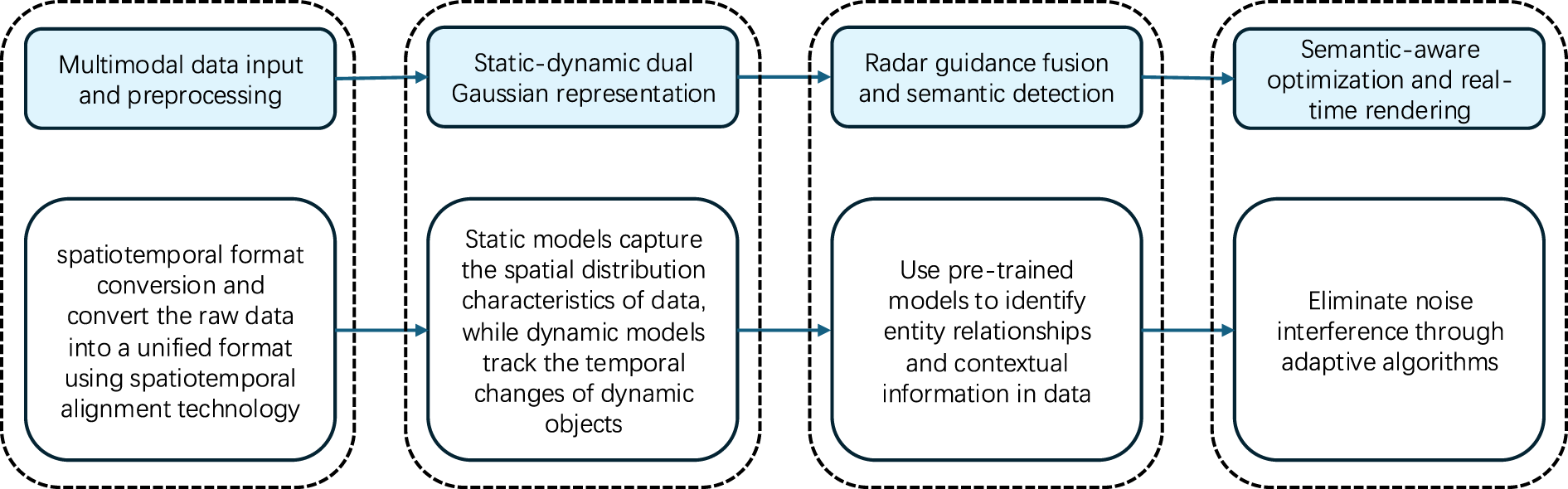

This framework efficiently integrates scene reconstruction and object detection into a unified pipeline suitable for real-time applications in urban environments. The notation used throughout the paper is summarized in Table 2. A schematic of the approach is provided in Fig. 2, and the algorithm proceeds as follows.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of the SDG framework

1. Multimodal Data Input and Preprocessing: Acquire raw data from cameras, LiDAR, and radar. Perform spatiotemporal alignment and convert the data into a unified format, stored as

2. Static-Dynamic Dual Gaussian Representation

(a) Static Gaussian Modeling: Segment static regions, initialize 3D Gaussians via K-means++, and optimize by minimizing the pixel loss

(b) Dynamic Gaussian Modeling: Detect dynamic objects, initialize 3D Gaussians, and update them with temporal tracking using optical flow and Kalman filtering.

3. Radar Guidance Fusion and Semantic Detection: Extract radar features, fuse them with the data represented by Gaussians, and use a pre-trained model to identify entity relationships and extract contextual information.

4. Semantic-Aware Optimization and Real-Time Rendering: Introduce the semantic loss

3.1 Static Background Representation and Reconstruction

To achieve efficient and high-fidelity environmental reconstruction, static background elements, such as roads and buildings, are modeled using a set of 3D Gaussian distribution, where each Gaussian is parameterized as follows:

where

The depth

Specifically,

Our implementation follows the differentiable splatting mechanism described by Kerbl et al. [4], which supports real-time rendering while maintaining photometric and geometric consistency across views.

To further enhance the reconstruction efficiency, we apply a Frobenius-norm regularization term to control the Gaussian spread and prevent overfitting:

The regularization loss

3.2 Dynamic Object Detection and Segmentation

Dynamic objects, such as vehicles and pedestrians, are detected using Grounded-SAM. The process begins with input from the reconstructed depth maps

1. Depth-Based Proposals: Object proposals are generated by clustering regions in

2. Grounded-SAM Detection: The radiance field

3. Depth Association: Detected objects are associated with their 3D positions using the depth map

4. Monocular Depth Refinement: Depth is further refined using a monocular depth model [6] such as MiDaS. The initial depth estimation can often be imprecise due to the complexity of the scene or sensor limitations. By using a monocular depth model, we improve the accuracy of the depth information, which is crucial for better object tracking and segmentation in dynamic urban environments. Refining the depth estimates with monocular cues helps to align the 3D models more accurately with the actual scene, especially in cases where stereo or LiDAR data may be sparse or noisy.

3.3 Dynamic Object Representation and Tracking

To model and track moving objects within the urban environment, we represent dynamic entities using time-dependent 3D Gaussian distributions. Each detected object is parameterized as follows:

where

To track dynamic objects across frames, we adopt a feature-based optical flow method combined with Kalman filtering. Specifically, we estimate the displacement vector

We integrate depth-based association to enhance the temporal consistency between frames. For each object

To manage occlusions in dense traffic environments, we implement an adaptive re-initialization strategy. The predicted position

To ensure smooth object trajectories over time, we introduce a temporal regularization loss that penalizes inconsistent motion estimates between consecutive frames. Specifically, for each object

3.4 Semantic-Aware Optimization of Reconstruction & Detection

We propose a unified loss framework that balances photorealism, geometric accuracy, and semantic consistency through three complementary objectives:

where

The core innovation lies in

where

This term ensures that only Gaussians visible in pixel

To handle dynamic objects, we implement two critical optimizations:

1. Mask propagation: When a Gaussian is occluded (

2. Temporal smoothing: Apply a 3-frame moving average to SAM masks to reduce detection jitter.

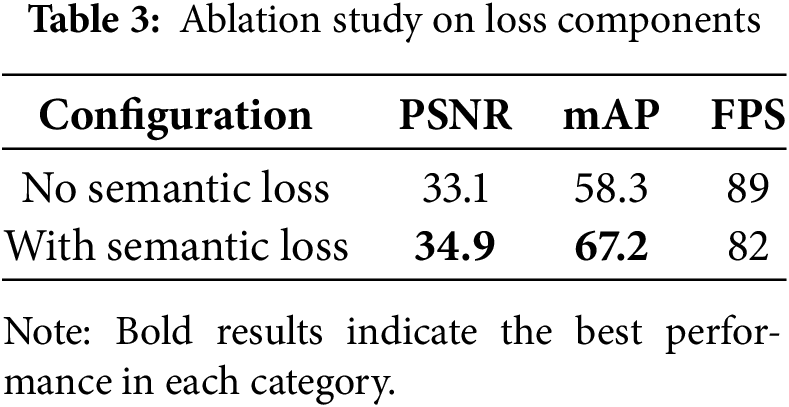

Table 3 shows the impact of each loss component:

Removing the semantic term causes:

• 14.8% reduction in Mean Average Precision (mAP)@0.5 (from 67.2 to 56.4)

• 2.3% Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) (PSNR) drop (34.9 to 32.6)

• Enables 7 FPS speedup by disabling mask constraints.

The proposed loss can be viewed as a variational lower bound on the joint probability of scene representation and object detection:

here,

To enhance depth accuracy and robustness in complex urban scenes, we adopt a radar-guided refinement strategy. Radar measurements provide sparse but geometrically reliable depth cues, which are projected to the image domain and used to guide the refinement of visual depth predictions. During feature fusion, radar and visual features are aligned according to their geometric correspondence, and a lightweight gating mechanism adaptively balances the two sources. When visual cues are degraded by lighting or motion, radar information dominates; otherwise, visual details are preserved. This simple yet effective design improves geometric consistency without adding extra modules.

3.5 Scene Rendering and Visualization

The final reconstructed urban scene is rendered by projecting both static and dynamic 3D Gaussians onto the 2D image plane. This process involves transforming each Gaussian’s 3D position into screen space using the camera intrinsic matrix K, rotation matrix R, and translation vector

where

where

where

To further improve rendering efficiency, adaptive resolution upsampling is employed, leveraging multi-scale Gaussian sampling to dynamically refine high-detail areas while reducing computational overhead in less critical regions. The final rendered frames are then visualized with overlaid segmentation masks, derived from Grounded-SAM detection, allowing for real-time interaction with the reconstructed scene and facilitating urban traffic analysis.

3.6 Gaussian Parameter Optimization with Dual Loss

The parameters of both static and dynamic Gaussians are optimized jointly using a combination of photometric loss and regularization [39]. The total loss function is defined as:

The total loss function combines a photometric term and a spatial regularization term:

Explanation of

Understanding our approach’s performance in real-world scenarios is crucial for validating its effectiveness. In this section, we present a comprehensive evaluation of our method, comparing it against existing techniques using publicly available datasets. We assess key aspects such as reconstruction accuracy, object detection performance, computational efficiency, and scalability in large-scale urban environments.

For this study, we use datasets suitable for reconstructing and analyzing dynamic urban environments. Therefore we utilize the Waymo Open Dataset, which provides large-scale multi-view imagery and LiDAR data, enabling both high-fidelity 3D reconstruction and accurate object detection. This dataset is chosen for its diverse urban scenarios, including varying lighting conditions, traffic densities, and occlusions. The datasets provide synchronized camera and LiDAR data, enabling the generation of depth maps and radiance fields for static and dynamic object modeling.

These datasets enable the evaluation of our method’s performance under various scenarios, including traffic reconstruction and dynamic object tracking.

We assess our model’s performance using several key metrics. For 3D scene reconstruction, we measure PSNR and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM, [40]) to quantify rendering fidelity. Additionally, the perceptual loss based on a pre-trained Visual Geometry Group (VGG network [41]) is computed to capture high-level feature consistency. For dynamic object detection, we report mAP with an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5, as well as IoU scores to evaluate object localization accuracy. Finally, we analyze computational efficiency, comparing the frames per second (FPS) across multiple baselines, ensuring the real-time feasibility of our approach.

The Waymo Open Dataset is a comprehensive collection of autonomous driving data, featuring synchronized high-resolution camera and LiDAR data from self-driving vehicles. It includes 3D point cloud sequences that support object detection, shape reconstruction, and tracking. For our experiments, we use sequences containing dynamic traffic scenarios with multiple moving vehicles and pedestrians. The KITTI and KITTI-360 datasets [8] are additionally employed for broader validation.

Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM, [40]): Measures the similarity between two images by comparing luminance, contrast, and structure. SSIM values range from −1 to 1, with higher values indicating greater similarity.

PSNR: Quantifies the reconstruction quality by measuring the ratio between the maximum pixel value and the mean squared error (MSE):

Higher PSNR values indicate better quality.

Perceptual Loss: Compares high-level features extracted from a pre-trained neural network, such as VGG, to evaluate perceptual similarity between original and reconstructed images:

where

Mean Average Precision (mAP): Measures object detection accuracy by averaging precision-recall across all classes. Higher mAP values indicate better detection performance. Intersection over Union (IoU): Evaluates localization accuracy by calculating the overlap between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes.

Preprocessing. We preprocess the Waymo dataset by synchronizing LiDAR and camera data to derive depth maps and sparse 3D point clouds. Additional refinement steps include applying monocular depth estimation (via MiDaS) to improve depth consistency and aligning camera poses for accurate Gaussian initialization.

Baseline and Framework. Our method builds upon the Street Gaussians framework for 3D reconstruction and introduces the following enhancements:

• Radar-assisted annotation for dynamic object association.

• Temporal smoothing to enhance frame consistency.

• Cubemap-based sky modeling to refine static scene representation.

• Optimized Gaussian parameters using the loss function:

where

Object Detection and Segmentation. We integrate Grounded-SAM for object detection, which utilizes text-based prompts (“car”, “pedestrian”) to generate bounding boxes and segmentation masks. These masks are associated with 3D positions derived from depth maps for accurate dynamic object tracking.

Comparison Methods. Baselines include 3DGS, MARS, and Street Gaussians, covering both static reconstruction and dynamic detection benchmarks.

Implementation. To measure the performance of proposed approach and benchmarks, we used a device setup based on NVIDIA A100 GPUs with 40 GB memory. Rendering resolutions are set to

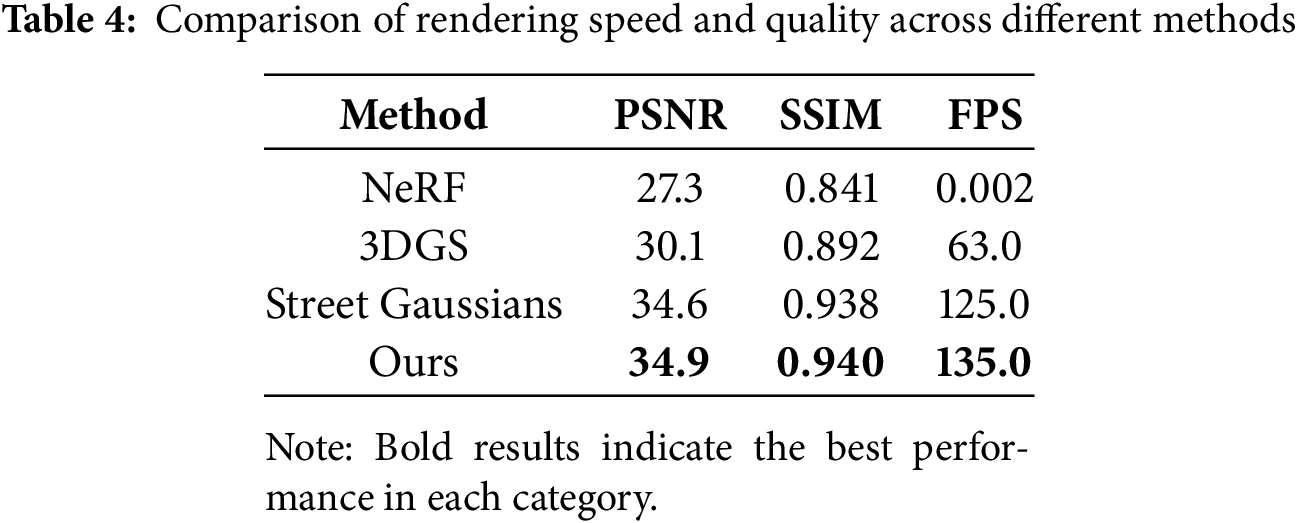

We compare our method against state-of-the-art baselines, including NeRF, 3DGS, and Street Gaussians. Table 4 summarizes the rendering speed, demonstrating that our method achieves a significant performance boost while maintaining high rendering quality.

Our approach outperforms previous methods in both rendering quality and speed. Notably, our model achieves

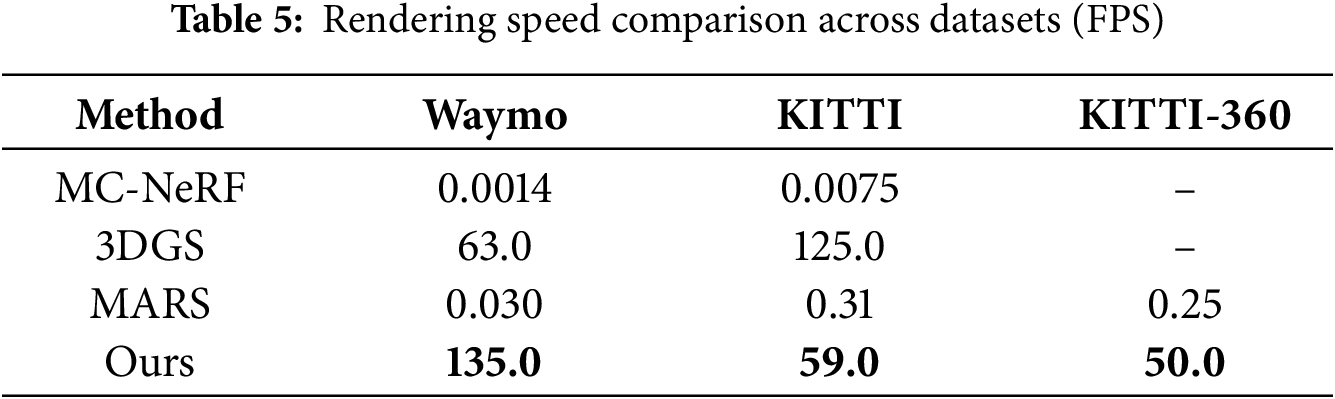

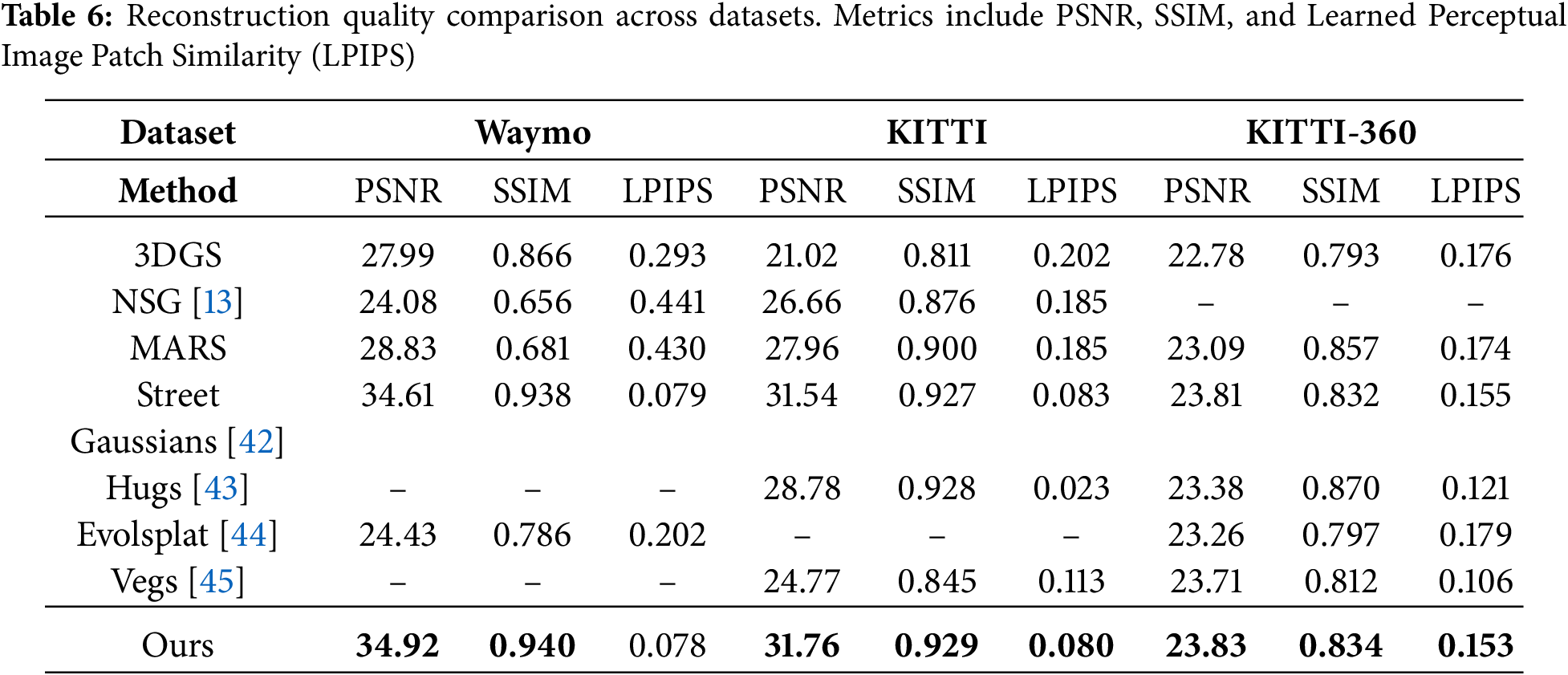

Table 5 compares the FPS across datasets, demonstrating our method’s real-time rendering capabilities. Our method outperforms others in reconstruction quality, as shown in Table 6. Fig. 3 visually illustrates our approach’s capability to retain structural details and achieve lower perceptual loss. This highlights the robustness of our enhanced Gaussian representation in static background reconstruction.

Figure 3: Qualitative results of reconstruction across different datasets. Visualization shows the effectiveness of our method in retaining structural details and reducing perceptual loss

Our results, as shown in Tables 5 and 6, highlight the robustness of our method. Specifically, our method achieves a PSNR of 34.92 dB and SSIM of 0.940 on Waymo, surpassing Street Gaussians by 0.31 dB and 0.002, respectively. Additionally, the rendering speed of 135 FPS on waymo dataset is more than twice that of Street Gaussians (63 FPS), demonstrating the efficiency of our optimized Gaussian parameterization. These metrics validate the scalability and the real-time capability of our framework in dynamic urban scenarios. Furthermore, our experiments on the KITTI-360 dataset cover a continuous city-scale trajectory exceeding 80 km across Karlsruhe, corresponding to an urban area of over 5

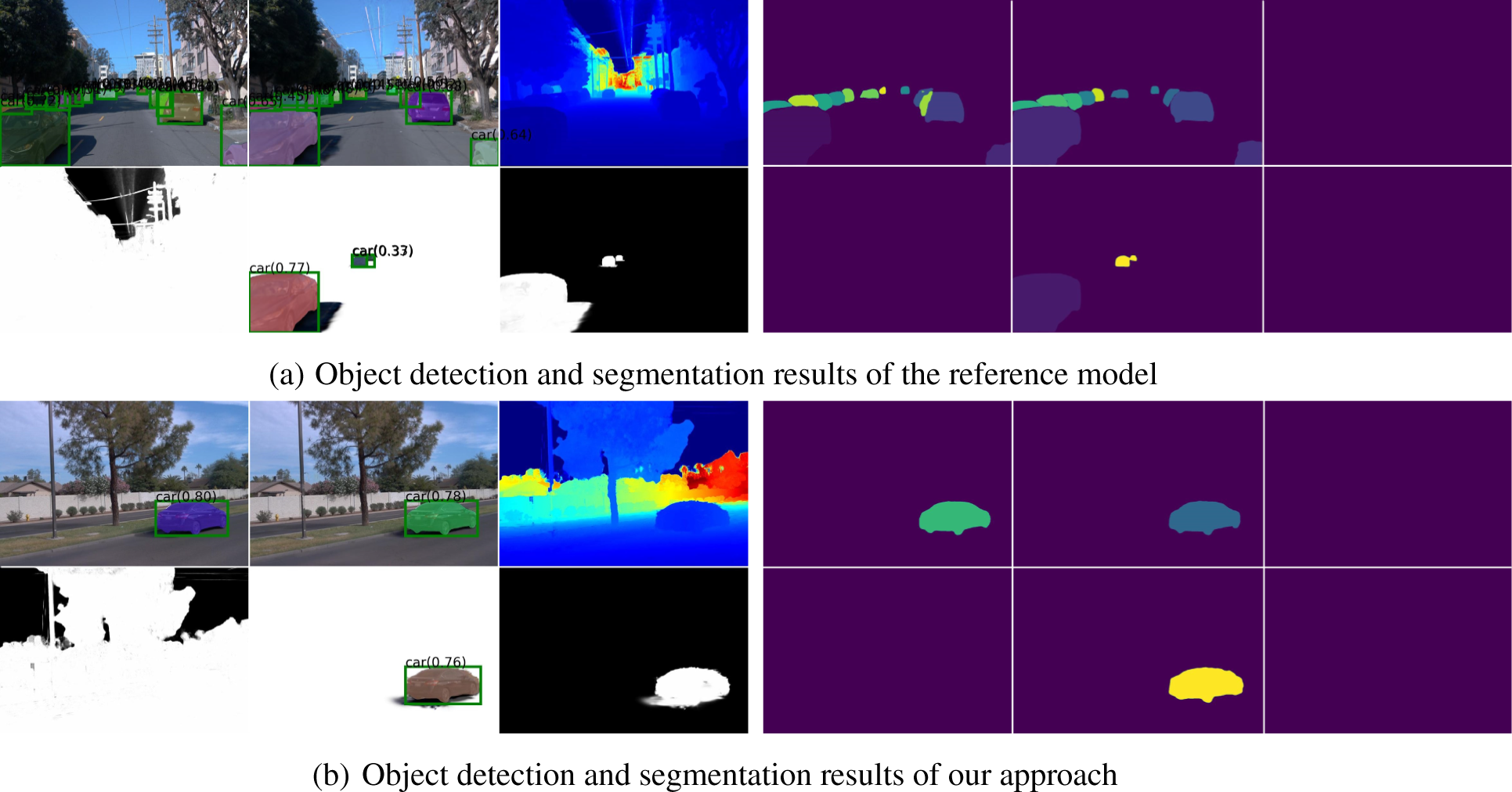

Although Grounded-SAM is a general-purpose segmentation model, it performs reliably in structured urban scenes after adaptation. In our framework, it is prompted with traffic-related categories (vehicles, pedestrians, traffic signs, etc.) to focus on road-relevant objects. The grounding module supports text-guided detection, while the SAM backbone ensures accurate masks under illumination changes and partial occlusions. To improve stability, temporal filtering and geometric consistency checks between consecutive frames are applied to suppress spurious detections. Preliminary observations show that the model maintains stable segmentation quality across different viewpoint conditions, indicating its robustness and potential generalization to dynamic traffic environments. Representative qualitative detection and segmentation results are shown in Fig. 4, where our approach produces tighter and more consistent masks than the baseline under challenging urban conditions.

Figure 4: Qualitative results of object detection and segmentation of the reference model vs. our approach. Demonstrating precise bounding box generation and segmentation

Our approach relies on synchronized radar and camera data, and its performance may degrade under adverse weather or poor sensor calibration. Real-time rendering currently requires high-end GPUs, which limits deployment on resource-constrained platforms. In addition, the effectiveness of Grounded-SAM depends on its pre-trained weights and prompt design, while radar data acquisition and calibration remain costly, posing challenges for large-scale deployment. Despite these limitations, experiments on the Waymo dataset—covering diverse lighting, occlusion, and dynamic traffic—demonstrate strong robustness and generalization to other urban datasets such as KITTI-360.

Future work will focus on three directions: improving 3D–2D spatial consistency through hybrid loss functions and stronger multi-view alignment; integrating 3D Gaussians with lightweight implicit representations to reduce computational load; and extending the framework to larger-scale urban scenes and challenging sensing conditions such as rain, night, and sparse radar setups. These efforts aim to further enhance the scalability, efficiency, and robustness of SDG for real-world autonomous driving and smart city applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research is supported by Inha University.

Author Contributions: Yu Du and Yan Li conceived the study and designed the overall framework, Yu Du implemented the proposed system, performed the experiments and analyzed the data, Runwei Guan contributed to the algorithm design and experimental methodology, Ho-Pun Lam and Yutao Yue provided technical guidance and helped refine the model architecture, and Jeremy Smith and Ka Lok Man reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mildenhall B, Srinivasan PP, Tancik M, Barron JT, Ramamoorthi R, Ng R. NeRF: representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. Commun ACM. 2022;65(1):99–106. [Google Scholar]

2. Tancik M, Casser V, Yan X, Pradhan S, Mildenhall B, Srinivasan PP, et al. Block-NeRF: scalable large scene neural view synthesis. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 8248–58. [Google Scholar]

3. Fei B, Xu J, Zhang R, Zhou Q, Yang W, He Y. 3D Gaussian splatting as a new era: a survey. IEEE Trans Visual Comput Graph. 2025;31(8):4429–49. doi:10.1109/tvcg.2024.3397828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Kerbl B, Kopanas G, Leimkühler T, Drettakis G. 3D Gaussian splatting for real-time radiance field rendering. ACM Trans Graph. 2023;42(4):139. doi:10.1145/3592433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chen L, Zhang Y, Ren S, Zhao H, Cai Z, Wang Y, et al. Towards end-to-end embodied decision making via multi-modal large language model: explorations with GPT4-vision and beyond. arXiv:2310.02071. 2023. [Google Scholar]

6. Birkl R, Wofk D, Müller M. MiDaS v3.1—a model zoo for robust monocular relative depth estimation. arXiv:2307.14460. 2023. [Google Scholar]

7. Sun P, Kretzschmar H, Dotiwalla X, Chouard A, Patnaik V, Tsui P, et al. Scalability in perception for autonomous driving: waymo open dataset. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 2446–54. [Google Scholar]

8. Geiger A, Lenz P, Stiller C, Urtasun R. Vision meets robotics: the KITTI dataset. Int J Robot Res. 2013;32(11):1231–7. doi:10.1177/0278364913491297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang K, Riegler G, Snavely N, Koltun V. NeRF++: analyzing and improving neural radiance fields. arXiv:2010.07492. 2020. [Google Scholar]

10. Pumarola A, Corona E, Pons-Moll G, Moreno-Noguer F. D-NeRF: neural radiance fields for dynamic scenes. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 10318–27. [Google Scholar]

11. Li Z, Niklaus S, Snavely N, Wang O. Neural scene flow fields for space-time view synthesis of dynamic scenes. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 6498–508. [Google Scholar]

12. Gao Y, Su L, Liang H, Yue Y, Yang Y, Fu M. MC-NeRF: multi-camera neural radiance fields for multi-camera image acquisition systems. IEEE Trans Visual Comput Graph. 2025;31(10):7391–406. doi:10.1109/tvcg.2025.3546290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Qi CR, Su H, Mo K, Guibas LJ. PointNet: deep learning on point sets for 3D classification and segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017. p. 77–85. [Google Scholar]

14. Qi CR, Yi L, Su H, Guibas LJ. PointNet++: deep hierarchical feature learning on point sets in a metric space. In: Advances in neural information processing systems (NeurIPS). Vol. 30. London, UK: PMLR; 2017. p. 5099–108. [Google Scholar]

15. Wu G, Yi T, Fang J, Xie L, Zhang X, Wei W, et al. 4D Gaussian splatting for real-time dynamic scene rendering. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 20310–20. [Google Scholar]

16. Fridovich-Keil S, Meanti G, Warburg FR, Recht B, Kanazawa A. K-Planes: explicit radiance fields in space, time, and appearance. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 12479–88. [Google Scholar]

17. Guo J, Deng N, Li X, Bai Y, Shi B, Wang C, et al. StreetSurf: extending multi-view implicit surface reconstruction to street views. arXiv:2306.04988. 2023. [Google Scholar]

18. Kim H, Jung M, Noh C, Jung S, Song H, Yang W, et al. HeRCULES: heterogeneous radar dataset in complex urban environment for multi-session radar SLAM. In: 2025 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 4649–56. [Google Scholar]

19. Jin T, Wang X, Li Y. RCMixer: radar-camera fusion based on vision for robust object detection. J Vis Commun Image Rep. 2024;95:103880. doi:10.1016/j.jvcir.2024.104367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Xiao Y, Chen J, Wang Y, Fu M. Radar-camera fusion in perspective view and bird’s eye view. Sensors. 2025;25(19):6106. doi:10.3390/s25196106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Pravallika A, Hashmi MF, Gupta A. Deep learning frontiers in 3D object detection: a comprehensive review for autonomous driving. IEEE Access. 2024;12:173936–80. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3456893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wei Z, Zhang F, Chang S, Liu Y, Wu H, Feng Z. MmWave radar and vision fusion for object detection in autonomous driving: a review. Sensors. 2022;22(7):2542. doi:10.3390/s22072542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wu Z, Liu T, Luo L, Zhong Z, Chen J, Xiao H, et al. MARS: an instance-aware, modular and realistic simulator for autonomous driving. In: Artificial Intelligence: Third CAAI International Conference, CICAI 2023; 2023 July 22–23; Fuzhou, China. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

24. Straub J, Freifeld O, Rosman G, Leonard JJ, Fisher JW. The manhattan frame model—manhattan world inference in the space of surface normals. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2018;40(1):235–49. doi:10.1109/tpami.2017.2662686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Whelan T, Salas-Moreno RF, Glocker B, Davison AJ, Leutenegger S. ElasticFusion: real-time dense SLAM and light source estimation. Int J Robot Res. 2016;35(14):1697–716. doi:10.1177/0278364916669237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Krähenbühl P, Koltun V. Efficient inference in fully connected CRFs with Gaussian edge potentials. In: NIPS’11: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2011. p. 109–17. [Google Scholar]

27. Straub J, Bhandari N, Leonard JJ, Fisher JW. Real-time manhattan world rotation estimation in 3D. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 1913–20. [Google Scholar]

28. Joo K, Oh TH, Kweon IS, Bazin JC. Globally optimal inlier set maximization for Atlanta frame estimation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 5726–34. [Google Scholar]

29. Sodhi D, Upadhyay S, Bhatt D, Krishna KM, Swarup S. CRF based method for curb detection using semantic cues and stereo depth. In: ICVGIP ’16: Proceedings of the Tenth Indian Conference on Computer Vision, Graphics and Image Processing. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

30. Arshad S, Sualeh M, Kim D, Nam DV, Kim G. Clothoid: an integrated hierarchical framework for autonomous driving in a dynamic Urban environment. Sensors. 2020;20(18):5053. doi:10.3390/s20185053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Cudrano P, Gallazzi B, Frosi M, Mentasti S, Matteucci M. Clothoid-based lane-level high-definition maps: unifying sensing and control models. IEEE Veh Technol Mag. 2022;17(4):47–56. doi:10.1109/mvt.2022.3209503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Xie Y, Gadelha M, Yang F, Zhou X, Jiang H. PlanarRecon: real-time 3D plane detection and reconstruction from posed monocular videos. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 6219–28. [Google Scholar]

33. Liu C, Kim K, Gu J, Furukawa Y, Kautz J. PlaneRCNN: 3D plane detection and reconstruction from a single image. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 4450–9. [Google Scholar]

34. Kirillov A, Mintun E, Ravi N, Mao H, Rolland C, Gustafson L, et al. Segment anything. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 3992–4003. [Google Scholar]

35. Ren T, Liu S, Zeng A, Lin J, Li K, Cao H, et al. Grounded SAM: assembling open-world models for diverse visual tasks. arXiv:2401.14159. 2024. [Google Scholar]

36. Yao J, Wu T, Zhang X. Improving depth gradient continuity in transformers: a comparative study on monocular depth estimation with CNN. In: Proceedings of the 35th British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC); 2024 Nov 25–28; Glasgow, UK. p. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

37. Versaci M, Morabito FC. Image edge detection: a new approach based on fuzzy entropy and fuzzy divergence. Int J Fuzzy Syst. 2021;23(4):918–36. doi:10.1007/s40815-020-01030-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Bhat SF, Birkl R, Wofk D, Wonka P, Müller M. ZoeDepth: zero-shot transfer by combining relative and metric depth. arXiv:2302.12288. 2023. [Google Scholar]

39. Annaby MH, Al-Abdi IA. A Gaussian regularization for derivative sampling interpolation of signals in the linear canonical transform representations. Signal Image Video Process. 2023;17:2157–65. doi:10.1007/s11760-022-02430-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Nilsson J, Akenine-Möller T. Understanding SSIM. arXiv:2006.13846. 2020. [Google Scholar]

41. Kaur R, Kumar R, Gupta M. Review on transfer learning for convolutional neural network. In: Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication Control and Networking (ICAC3N); 2021 Dec 17–18; Greater Noida, India. p. 922–6. [Google Scholar]

42. Yan Y, Lin H, Zhou C, Wang W, Sun H, Zhan K, et al. Street Gaussians: modeling dynamic urban scenes with gaussian splatting. In: Computer Vision—ECCV 2024: 18th European Conference. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2024. p. 156–73. [Google Scholar]

43. Zhou H, Shao J, Xu L, Bai D, Qiu W, Liu B, et al. HUGS: Holistic Urban 3D scene understanding via Gaussian splatting. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 21336–45. [Google Scholar]

44. Miao S, Huang J, Bai D, Yan X, Zhou H, Wang Y, et al. EVolSplat: efficient volume-based Gaussian splatting for Urban view synthesis. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 11286–96. [Google Scholar]

45. Hwang S, Kim MJ, Kang T, Choo J. VEGS: view extrapolation of urban scenes in 3D Gaussian splatting using learned priors. In: Computer Vision–ECCV 2024. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2025. p. 1–18. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-73001-6_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools