Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Leveraging Opposition-Based Learning in Particle Swarm Optimization for Effective Feature Selection

1 School of Physics and Information Engineering, Minnan Normal University, Zhangzhou, 363000, China

2 Key Lab of Intelligent Optimization and Information Processing, Minnan Normal University, Zhangzhou, 363000, China

3 Key Laboratory of Light Field Manipulation and System Integration Applications in Fujian Province, Minnan Normal University, Zhangzhou, 363000, China

4 School of Computer Science, Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430072, China

* Corresponding Authors: Fei Yu. Email: ; Hongrun Wu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 47 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072593

Received 30 August 2025; Accepted 18 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Feature selection serves as a critical preprocessing step in machine learning, focusing on identifying and preserving the most relevant features to improve the efficiency and performance of classification algorithms. Particle Swarm Optimization has demonstrated significant potential in addressing feature selection challenges. However, there are inherent limitations in Particle Swarm Optimization, such as the delicate balance between exploration and exploitation, susceptibility to local optima, and suboptimal convergence rates, hinder its performance. To tackle these issues, this study introduces a novel Leveraged Opposition-Based Learning method within Fitness Landscape Particle Swarm Optimization, tailored for wrapper-based feature selection. The proposed approach integrates: (1) a fitness-landscape adaptive strategy to dynamically balance exploration and exploitation, (2) the lever principle within Opposition-Based Learning to improve search efficiency, and (3) a Local Selection and Re-optimization mechanism combined with random perturbation to expedite convergence and enhance the quality of the optimal feature subset. The effectiveness of is rigorously evaluated on 24 benchmark datasets and compared against 13 advanced metaheuristic algorithms. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms the compared algorithms in classification accuracy on over half of the datasets, whilst also significantly reducing the number of selected features. These findings demonstrate its effectiveness and robustness in feature selection tasks.Keywords

Feature selection (FS), a vital data preprocessing technique, aims to identify and select the most informative subset of features from a redundant dataset. This process helps to reduce model complexity, prevent overfitting, enhance model generalization, and mitigate computational costs [1]. FS is a critical step in both machine learning [2] and data mining [3], serving as a key method for handling redundant data. In a dataset with

To address the “curse of dimensionality” in FS, researchers have proposed numerous effective methods. These methods are typically categorized into three groups based on distinct evaluation criteria: filter-based approaches, wrapper-based approaches, and embedded approaches [5]. Filter-based approaches [6,7] depend exclusively on the statistical properties of features (e.g., variance, correlation, consistency, information gain, chi-square test), by scoring each feature and then selecting those with the highest scores. This method generally uses fewer computational resources but typically yields lower classification accuracy compared to wrapper-based approaches. Wrapper-based approaches [8,9] integrate the feature selection process into the model training (e.g., K-nearest neighbor (KNN), support vector machines (SVMs)), selecting features based on the model’s performance. This method typically requires more computational resources but achieves better classification accuracy. Embedded approaches [10,11] perform feature selection simultaneously during model training (e.g., Lasso regression, decision trees (DT), random forests (RF)). Generally, wrapper-based and embedded methods achieve higher classification accuracy than filter methods, nevertheless, this frequently incurs higher computational costs and diminishes generalization capability.

Conventional feature selection methods, despite their efficacy in numerous applications, continue to encounter challenges such as elevated computational costs and the risk of neglecting feature combinations that substantially enhance model performance. Additionally, using wrapper-based and embedded approaches to directly optimize model performance often leads to overfitting and weak generalization ability. In contrast, evolutionary computation (EC)-based feature selection possesses global search capabilities, which help avoid local optima and identify better feature combinations, effectively handling high-dimensional and complex data [12]. Furthermore, EC-based wrapper algorithms can be classified by the EC paradigms they use, such as genetic algorithms (GA) [13], particle swarm optimization (PSO) [14,15], and genetic programming (GP) [16,17].

In recent years, several prominent researchers have made significant contributions to exploring feature subsets using EC-based feature selection methods. Mirjalili et al. introduced a heuristic algorithm for engineering design problems, referred to as the Salp Swarm Algorithm (SSA) [18]. Subsequently, Tubishat et al. enhanced the Salp Swarm Algorithm, using the opposition-based learning (OBL) [19] strategy, resulting in the Improved Salp Swarm Algorithm (ISSA) [20]. Shambour et al. developed a new Flower Pollination Algorithm (FPA) variant that improves convergence speed and solution quality, known as modified global FPA (mgFPA) [21]. Similar swarm intelligence algorithms have also been proposed, such as the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) by Mirjalili and Lewis [22]. Ouadfel and Abd Elaziz [23] employed an enhanced crow search algorithm (ECSA) for feature subset selection. Another category of heuristic algorithms has been applied to the FS problem. For example, Too and Rahim Abdullah proposed binary variants of Atom Search Optimization (BASO) [1] for wrapper feature selection. These evolutionary algorithms have demonstrated strong competitiveness in obtaining effective feature subsets. However, many algorithms suffer from inadequate search capabilities when finding feature subsets. PSO, owing to its simplicity in implementation, fast convergence, minimal parameter adjustment, and strong global search ability, has emerged as a favored approach in FS [24]. Initially, a novel binary PSO was proposed by Khanesar et al. [25] for solving function optimization problems. Shortly thereafter, Chuang et al. [26] utilized binary PSO for feature selection, specifically to manage gene expression data. The emergence of diverse swarm intelligence algorithms is primarily defined by a population information-sharing mechanism akin to that of PSO. This resemblance is attributable to the fact that PSO is an algorithm derived from natural predatory behaviors. Evidently, the majority of swarm intelligence algorithms developed thus far incorporate information exchange rooted in predatory behaviors [27], which can be regarded as adaptations of the PSO algorithm tailored to the specific behaviors of different biological species. Since PSO faces issues like sensitivity to parameter tuning, and performance degradation from the “curse of dimensionality”, finding the optimal feature subset becomes increasingly challenging. This paper presents an innovative PSO algorithm, with the primary contributions outlined as follows.

• By constructing and utilizing fitness landscapes, the proposed PSO algorithm effectively utilizes the state of the population to adaptively adjust its parameters, which is more in line with the evolutionary behavior of population intelligence and reduces the possibility of missing the optimal subset.

• To mitigate the risk of losing the optimal feature subset due to the curse of dimensionality, a leverage-based opposition learning strategy is proposed. This strategy facilitates the selection of features that may have been previously discarded but are crucial for important feature combinations.

• A novel local selection and re-optimization strategy (LSR) based on Cauchy perturbation is proposed to accelerate the convergence speed of the population towards the optimal feature subset.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents an overview of the fundamental concepts of PSO and FS, along with practical and effective algorithmic strategies. Section 3 introduces a comprehensive overview of the proposed lever-FLPSO. Section 4 showcases the experimental results and their analysis. Lastly, Section 5 concludes the study and outlines potential directions for future research.

2.1 The Standard Particle Swarm Optimization

The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is an optimization algorithm based on swarm intelligence, proposed by [28] in 1995. PSO simulates the foraging behavior of birds and employs information sharing among individuals to identify the optimal solution. In PSO, each solution is represented as a particle, which moves through the D-dimensional search space to find the optimal position. The fundamental concept of PSO is that each particle’s movement is guided by its personal best position (

where, the velocity update formula Eq. (1) guides the velocity update for each particle

The fitness landscape (FL) is a conceptual model used in optimization problems to describe the solution space. It is constructed based on the objective function values corresponding to each solution obtained during the evolutionary process. The FL exhibits various topographical features such as ridges, valleys, and basins, which intuitively represents the complexity of the problem and the distribution of the solution space. A complex fitness landscape usually features multiple local optima as well as a global optimum, requiring optimization algorithms to search within this landscape, avoiding local optima and striving to find the global optimum. The fitness landscape plays a crucial role in the design and analysis of optimization algorithms, facilitating the comprehension of the search behavior and performance of the algorithms [29]. In previous studies, various methods have been proposed to utilize the FL to solve optimization problems. Examples include measures of dispersion metric [30], fitness clouds and length scales [31], and fitness-distance correlation (FDC) [32]. This paper utilizes the FDC to measure the population status.

The OBL [33] is a strategy to enhance the efficiency of optimization algorithms by simultaneously considering the current solution and its opposite, thereby providing a more comprehensive exploration of the search space and increasing the likelihood of finding the global optimum. In OBL, given a current solution

where,

This concept can be extended to a multi-dimensional search space. The OBL is applied to each dimension of the search space, as represented by the following equation:

where,

2.4 Feature Selection Algorithms Based on Evolutionary Computation Methods

The FS is a critical research topic in machine learning and data mining. When formalized as an optimization problem, feature selection involves selecting the most valuable subset of features

where, D is the dimension of the feature, and

Over the past decade, EC algorithms have achieved widespread application in feature selection owing to their strong global search capabilities and adaptability to complex problems. In feature selection tasks, the challenges of high dimensionality, non-linearity, and intricate search spaces often lead to the “curse of dimensionality”, which causes traditional methods to become easily trapped in local optima. EC-based feature selection algorithms, by simulating natural selection and genetic processes, are adept at exploring the entire search space and identifying feature subsets that approach the global optimum. For instance, Ma and Xia [34] developed a tribe competition-based genetic algorithm (TCbGA) for feature selection, where each tribe focuses on a particular region of the solution space. Li et al. [35] proposed a binary differential evolution based on individual entropy for feature selection, utilizing individual entropy to calculate population diversity and designing an entropy-based objective function to evaluate feature subsets. Zhang et al. [16] applied GP to feature selection in dynamic flexible job-shop scheduling. Bi et al. [36] proposed using GP with a small amount of training samples for face image classification. In addition to the aforementioned works, PSO has been utilized for feature selection because of its strong global search capabilities. The application of the PSO in FS primarily involves addressing the enhancement of parameter selection mechanisms and the identification of effective features.

In terms of improving the parameters of the PSO. For instance, Fang et al. introduced an adaptive switching randomly perturbed PSO (ASRPPSO) [37], which leverages its excellent convergence properties for FS and has been applied to industrial data clustering. Azar et al. [38] proposed a parallelized PSO with linearly time-varying acceleration coefficients and inertia weight (PLTVACIW-PSO). Chen et al. [39] introduced a spiral-shaped mechanism with nonlinear inertia weights to optimize PSO (HPSO-SSM), and applied it in FS to enhance the diversity of the search process. Moreover, Gubta and Gubta [40] applied Gaussian fuzzification to improve the acceleration coefficients in PSO (FPSO) for feature selection. Similarly, Beheshti [41] utilized a fuzzy transfer function to control PSO parameter selection (FBPSO), addressing high-dimensional feature selection problems.

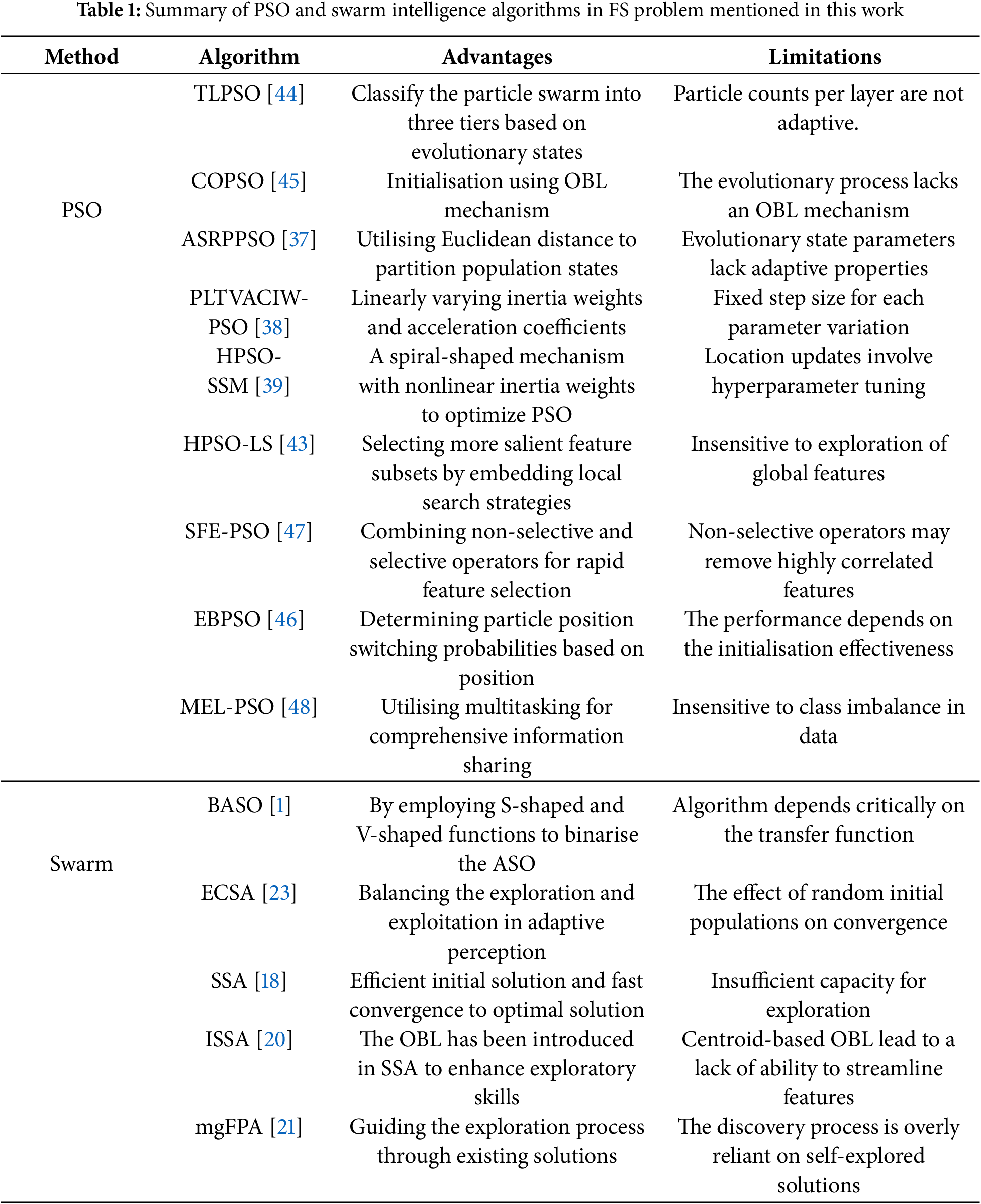

On the other hand, improving strategies for selecting effective features. Gao et al. [42] employed a feature grouping strategy grounded in information gain ratio, enabling PSO to perform feature selection effectively. Moradi and Gholampour proposed a hybrid PSO with Local Search strategy (HPSO-LS) [43], which selects less correlated and more salient feature subsets by embedding a local search strategy within PSO. Qiu and Liu [44] invented a novel three-layer PSO (TLPSO) for feature selection, dividing the particles into three layers based on their evolutionary states and treating particles in different layers differently to fully exploit the potential of each particle. In the improvements to PSO, in addition to using search strategies, Too et al. [45] utilized a conditional opposition-based PSO (COPSO) to address the imbalance between exploration and exploitation. Additionally, Tijjani et al. [46] proposed two versions of enhanced binary PSO (EBPSO) for feature selection, known as EBPSO1 and EBPSO2, by applying two novel position update mechanisms to effectively select the optimal feature subset. To tackle the complexity of high-dimensional datasets, Ahadzadeh et al. [47] formulated a simple, fast, and efficient hybrid algorithm (SFE-PSO) that combines two operators, nonselection and selection. Wang et al. designed PSO-based multi-task evolutionary learning (MEL-PSO) [48] to deal with the shortcomings of PSO in effectively utilizing and sharing information within high-dimensional data. Despite numerous improvements to PSO applied to feature selection problems, there remains a significant gap in research on parameter optimization. Additionally, the presence of symmetry within feature sets gives rise to inherent limitations in the basic OBL strategy, thereby reducing its effectiveness. Therefore, this study will build upon this foundation for further in-depth investigation. Finally, Table 1 summarises the contributions and limitations of existing feature selection methods.

3.1 Construction of Fitness Landscape

This section will focus on defining the states of the population during evolution and explaining how to adaptively set parameters in a given state to enhance the search for optimal feature subsets.

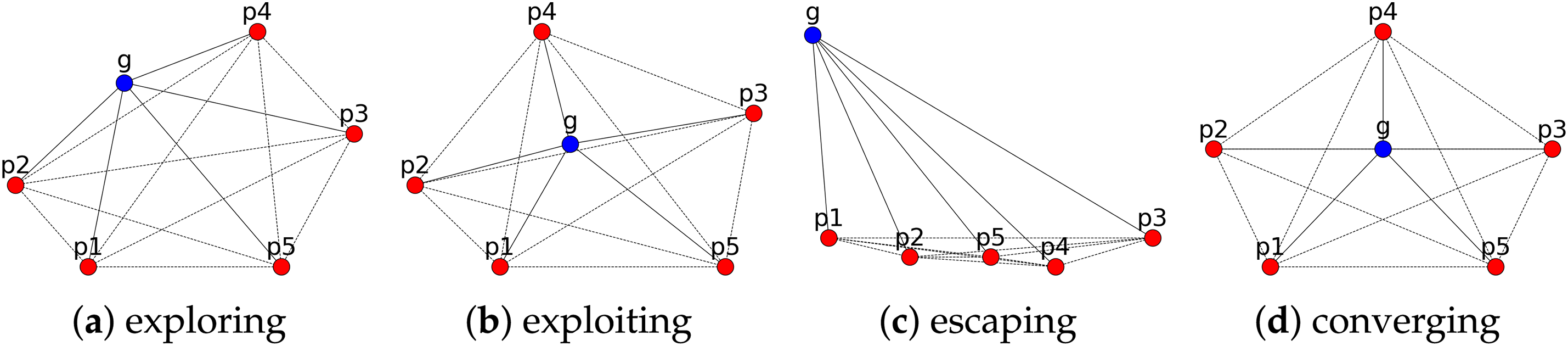

In this paper, the fitness-distance correlation (FDC) is employed to characterize the state of the population by calculating the average distance of each particle to all other particles. In Fig. 1, six particles, denoted as

Figure 1: Population status

Throughout the optimization process, it becomes apparent that that the particles in a population undergo an initial random state, exploration, exploitation and convergence, as well as escaping state when trapped in local optima, as depicted in Fig. 1. From Fig. 1a, in the initial stage, the population is randomly initialized across the entire search space, exhibiting an exploration state without a clear direction. Nonetheless, as the particles progress in their search, certain individuals start to identify optimal regions, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. Consequently, the collective population of particles gradually converges towards the proximity of the best-performing particle. In Fig. 1c, it is evident that certain particles become ensnared in local optimal states, necessitating intervention to extricate themselves from these local optima, referred to as the escape state. This simple illustration highlights the diverse distribution of the population information throughout the optimization process, and the fitness landscape can clearly depict these states. In the following, a method for characterizing the four states of the population using a fitness landscape is proposed.

The population’s position vectors, represented as

where, NP and D are the population size and dimension, respectively.

Once the average distances of each particle to other particles have been calculated, the average distance of the best particle is denoted as

where, the result of

The identification of the four states is determined by the formula provided in Eq. (8). The function

3.1.2 Self-Adaptive Weighting Strategy

For the PSO, the inertia weight parameter

In the convergence state (

where, in Eq. (10) is the probability density function (PDF),

During the exploitation state (

where, in the Eq. (14),

In the exploration state (

In the escaping state (

3.2 A Novel Opposition-Based Learning Method Based on the Leverage Principle

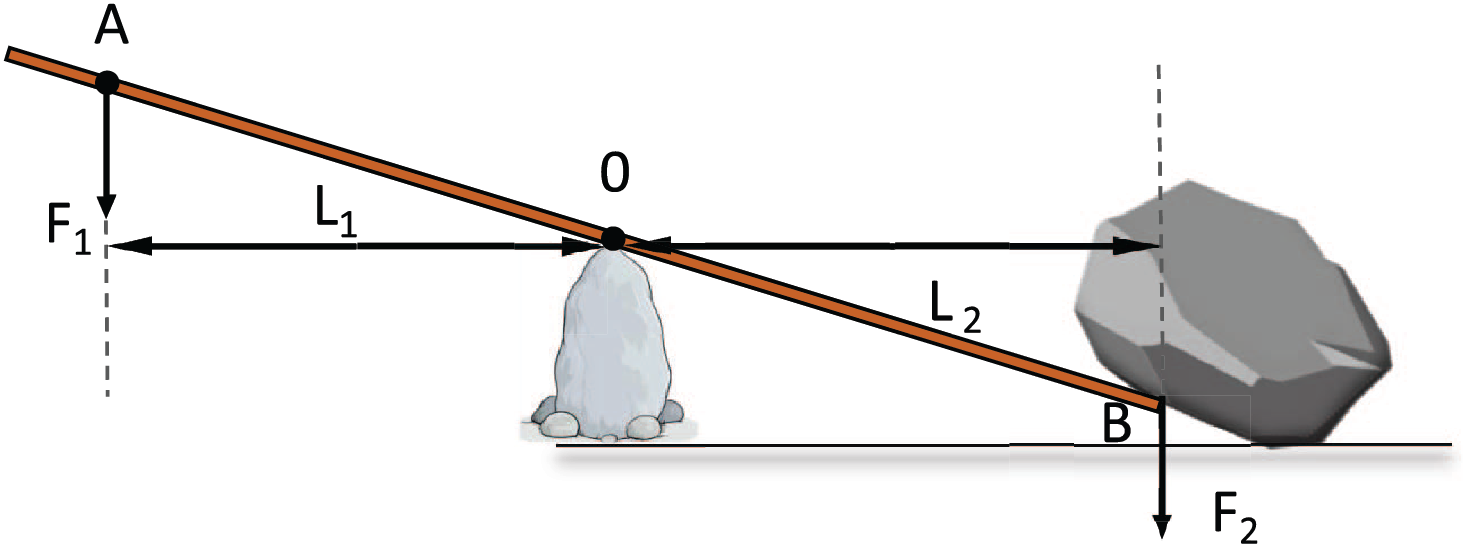

The lever principle is a fundamental concept in classical mechanics that describes how force can be amplified using a simple mechanical device known as a lever. Archimedes was the first to study and describe the lever principle, which consists of a rigid bar and a fixed fulcrum. When a force exerted at one end of the lever is transmitted through the fulcrum to the other end, it can achieve force amplification or a change in direction, and the following diagram illustrates the lever principle in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: A schematic diagram of the lever principle

The mathematical expression of the lever principle is based on the principle of torque balance, where torque is the result of multiplying the applied force by the lever arm, which is the perpendicular distance between the point of force application and the fulcrum. In an ideal scenario, the condition for a lever system to achieve a state of equilibrium is that the clockwise torque equals the counterclockwise torque. As illustrated in the Fig. 2,

where,

In the standard OBL introduced in Section 2.3, the particle’s position is simply reversed through axial symmetry to obtain the opposition value. However, if the solution vector itself exhibits axial symmetry, the standard OBL operation will not change the solution, rendering the operation ineffective and increasing redundant computations. To avoid this inefficacy, this paper proposes a lever principle-based OBL (lever-OBL) strategy. To construct the lever-OBL model, we consider the particle’s rank (

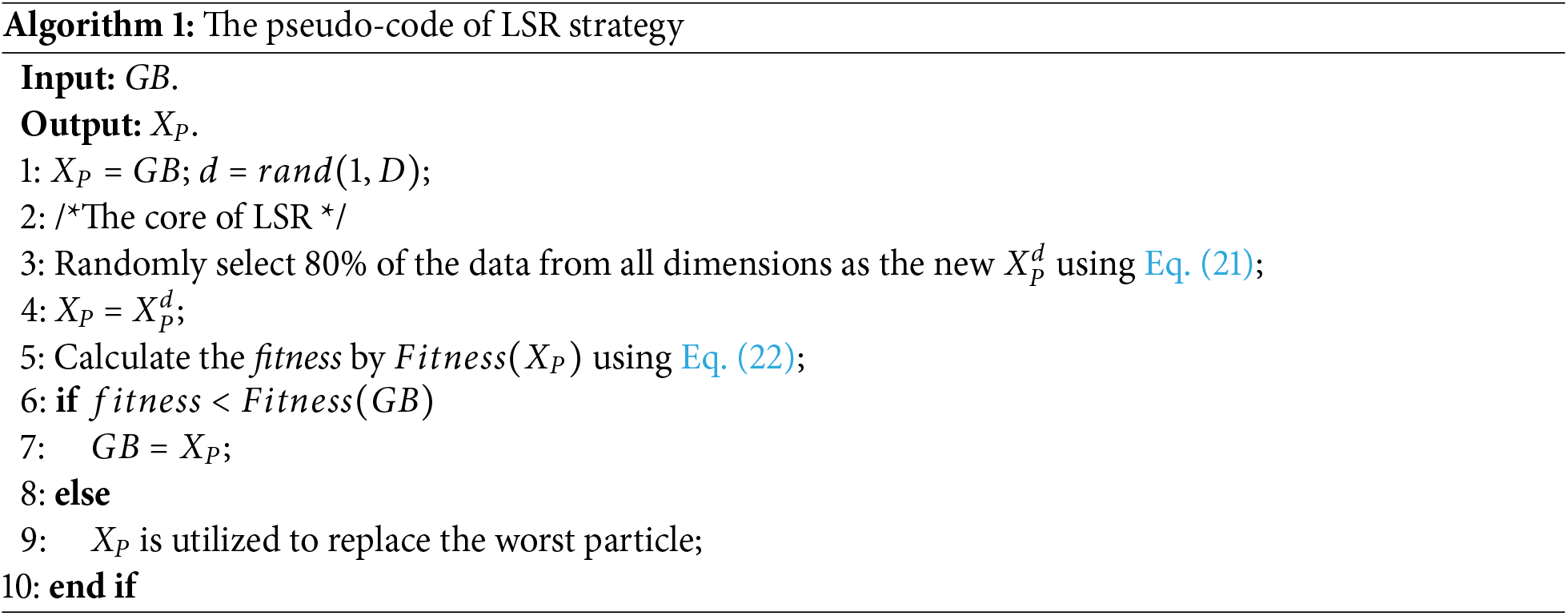

3.3 Local Selection and Re-Optimization Strategy

This section introduces a local selection and re-optimization strategy (LSR). In this strategy, a random dimension of the historical best position (

In most study, an EC-based FS algorithm is employed as the solution method, where feature selection is represented in binary encoding is used to represent whether a feature is selected, as described in the previous Section 2.4, with

where,

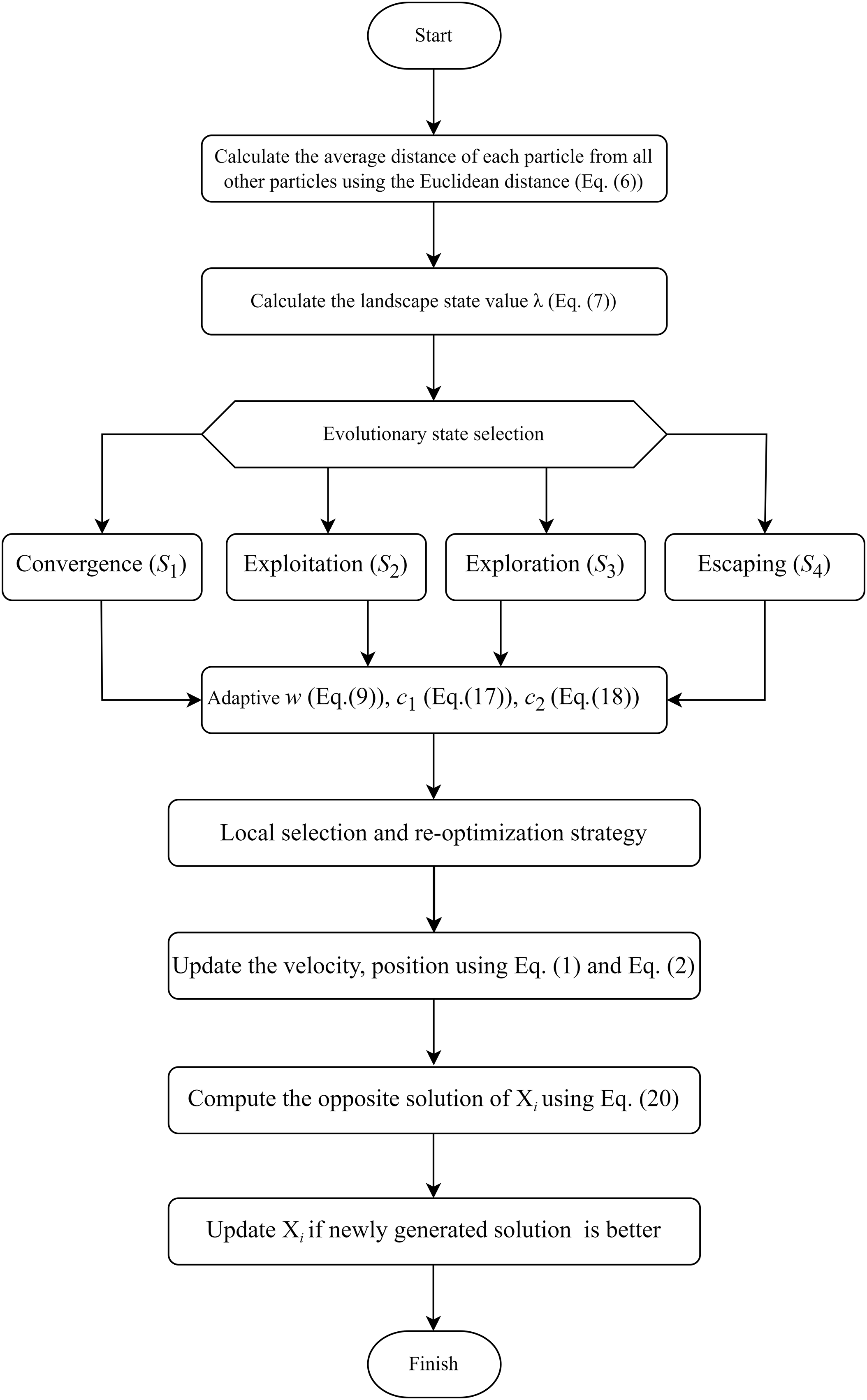

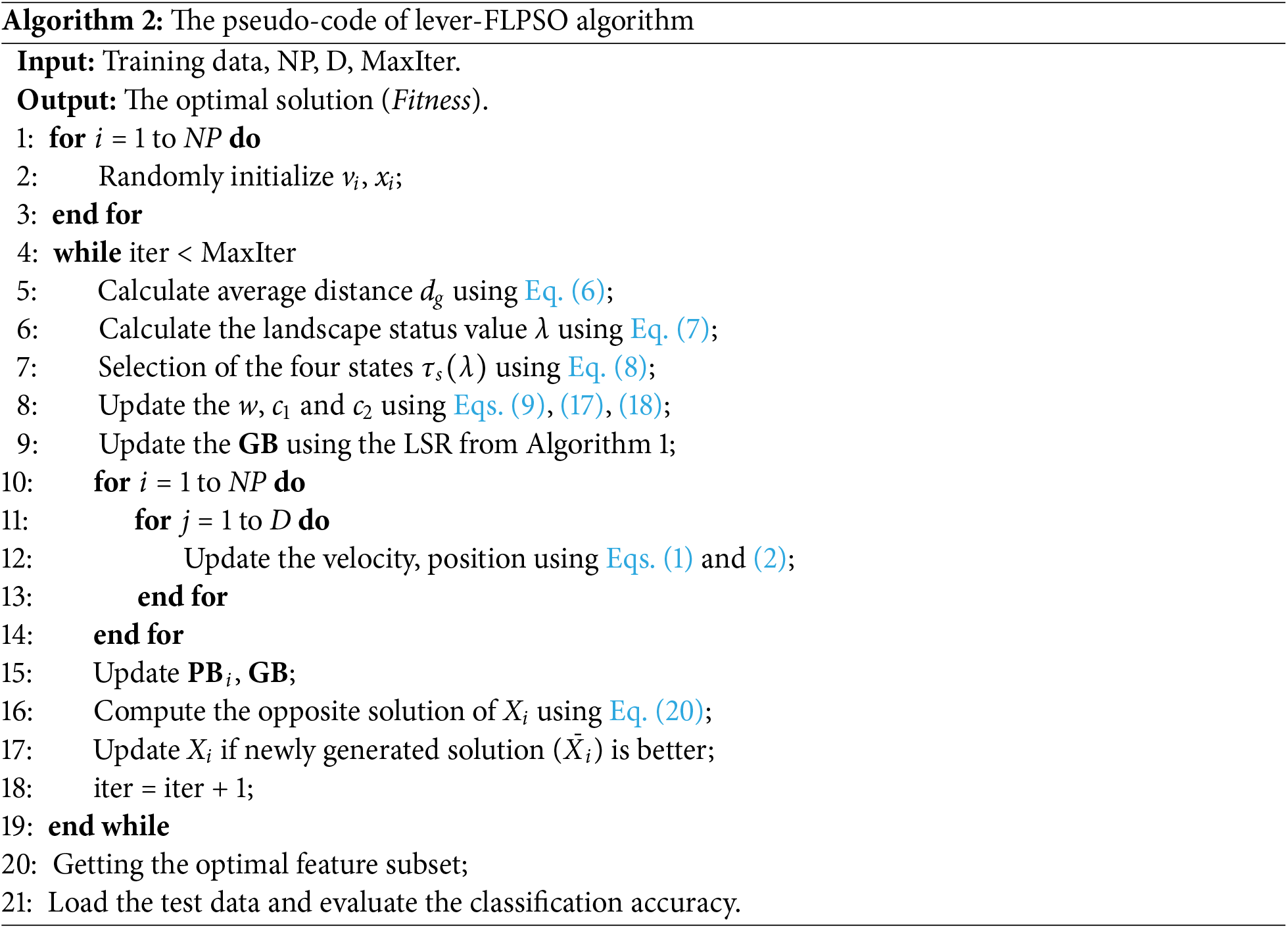

The complete pseudocode in Algorithm 2 provides a detailed explanation of the steps in the code execution of the algorithm. At the start of lever-FLPSO, the initial strategy involves randomly initializing NP particles. In line 6, the Euclidean distance (

Figure 3: Flowchart of the adaptive parameter control process of the lever-FLPSO

3.5 Algorithm Complexity Analysis

For the PSO algorithm, it is well-known that the time complexity is

4 Experimental Results and Analysis

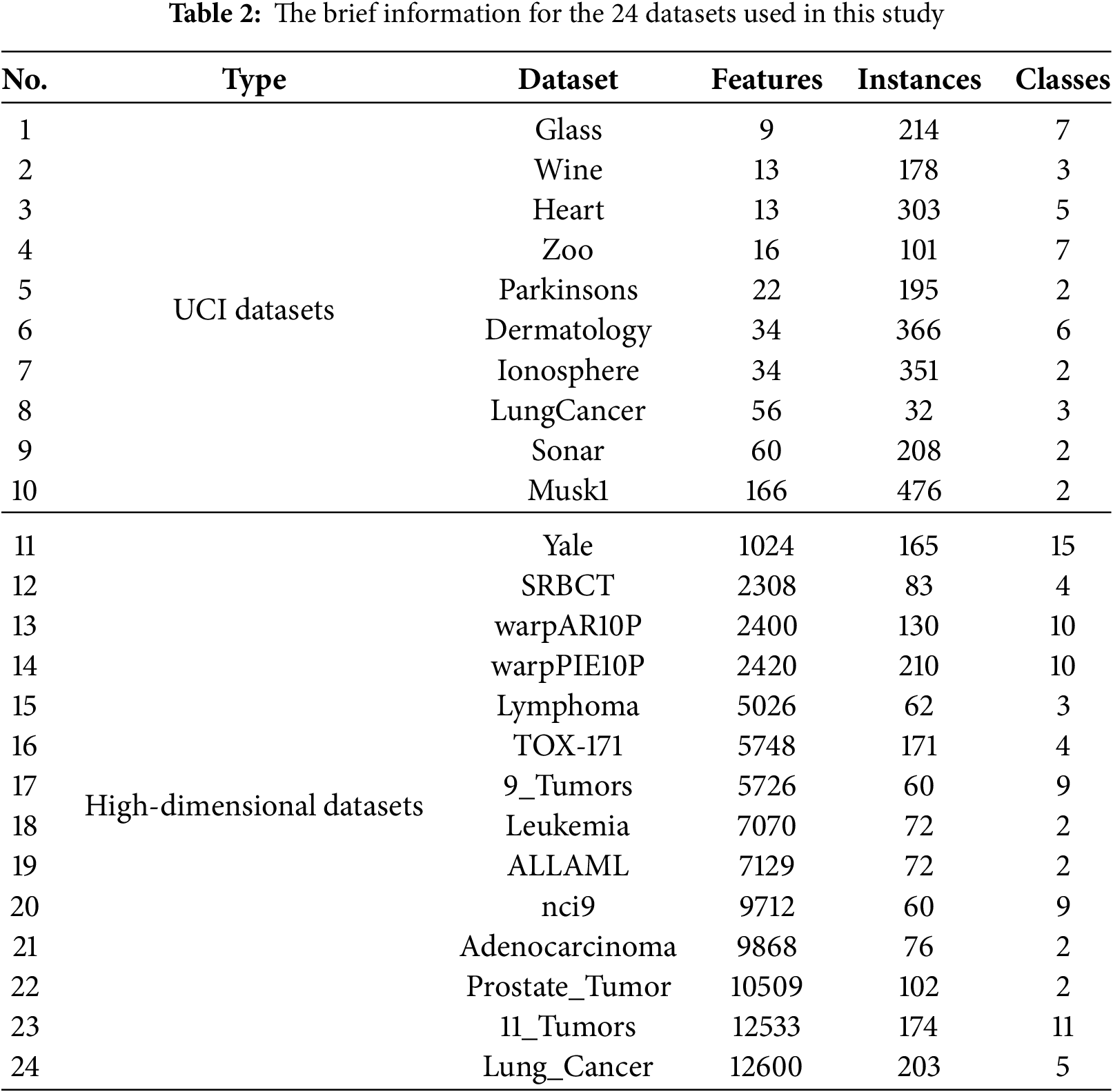

In this part of the document, detailed information about the 24 utilized datasets is first presented. The comparative algorithms and specific parameter settings for the experiments are described in conjunction with this section. In the experimental analysis, the performance of the proposed algorithm is evaluated through a comparison with 8 advanced PSO variants and 5 swarm intelligence methods. The results are then presented, followed by a discussion of the findings.

This study selected 10 UCI datasets [56] and 14 high-dimensional ASU datasets [57] for the evaluation of the algorithm’s performance. The brief information about the datasets is shown in Table 2. For each dataset, 10-fold cross-validation was used to evaluate the feature subset, with 70% of the instances randomly selected for training and 30% for testing.

4.2 Experimental Parameter Settings

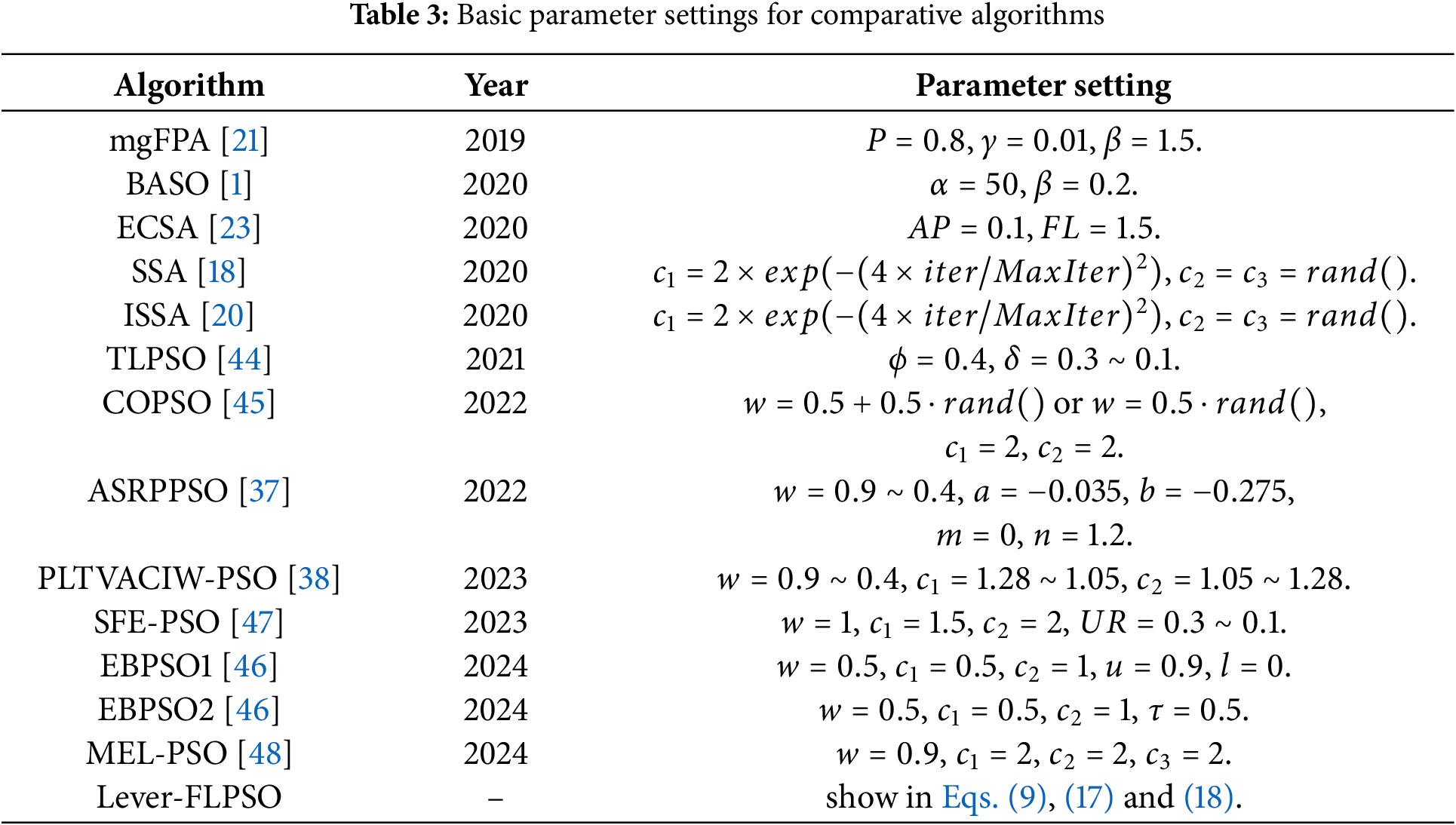

Considering the unique characteristics of lever-FLPSO, comparisons are conducted with 8 sophisticated PSO approaches applied in FS: TLPSO [44], COPSO [45], ASRPPSO [37], PLTVACIW-PSO [38], SFE-PSO [47], EBPSO1 [46] and EBPSO2 [46], and MEL-PSO [48]. These excellent PSO variants obviously exhibit the characteristics of population adaptive partitioning, based on OBL, based on Euclidean distance control of acceleration parameters, linear variation of acceleration parameters, etc., which are more appropriate for experimental comparison with the lever-FLPSO proposed in this paper. Table 3 provides detailed descriptions of the parameters used for both the comparison algorithms and the proposed algorithm in this study. Additionally, it was compared with five other heuristic algorithms with the above characteristics: BASO [1], ECSA [23], SSA [18], ISSA [20] and mgFPA [21]. To ensure fairness in the experiments, all algorithm parameters were set identically as follows. Moreover, all simulation environments in this study were conducted using Windows 11, 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-12900K 3.20 GHz, and Python 3.11. As the work has not yet been published, the code will be made available on an open-source platform in the future. The following are the definitions of the parameters. Should there be any questions regarding the parameter settings, please feel free to contact the corresponding author to request the code.

• Population size (NP): 10

• The problem dimension (D): the number of features in the dataset

• Maximum number of algorithm iterations (

• The independent number of runs (

• The number of nearest neighbors (

4.3 Experimental Results and Analysis

In this experiment, a range of evaluation metrics were calculated to evaluate the performance of lever-FLPSO. These metrics include the average fitness value, average classification accuracy, and the number of features selected. Moreover, convergence plots, box plots, and spider diagrams were utilized to offer a more intuitive representation of the experimental outcomes. The most favorable outcomes of several algorithms in the experiment are highlighted in bold.

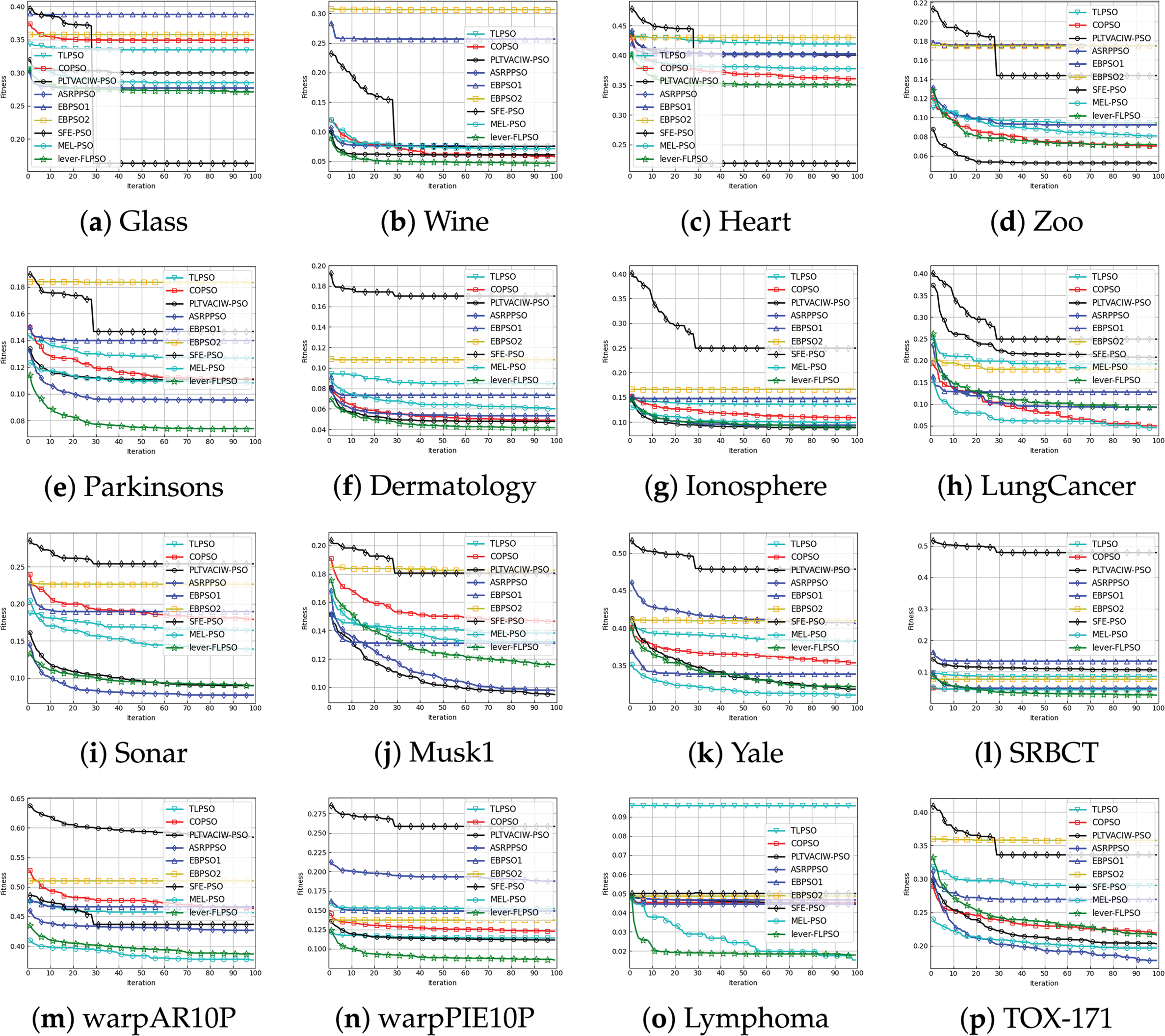

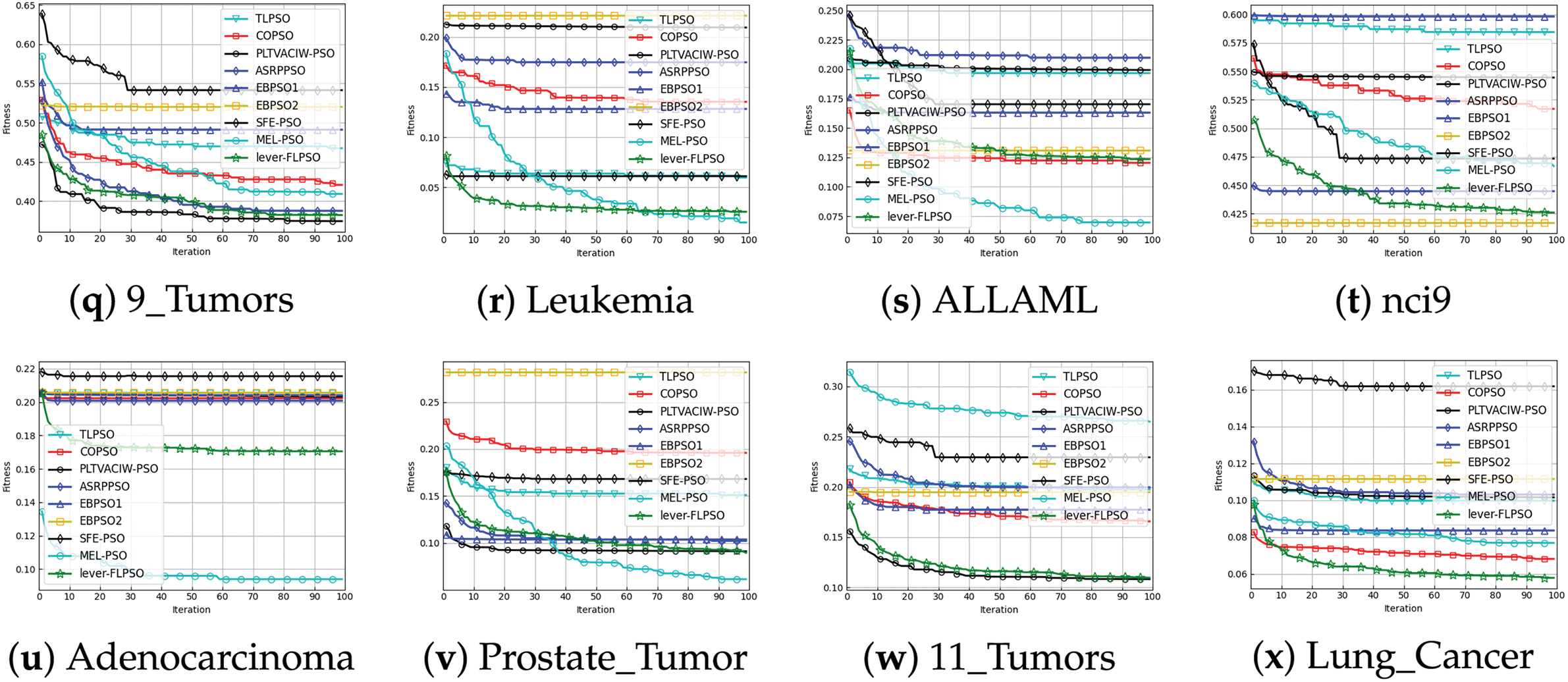

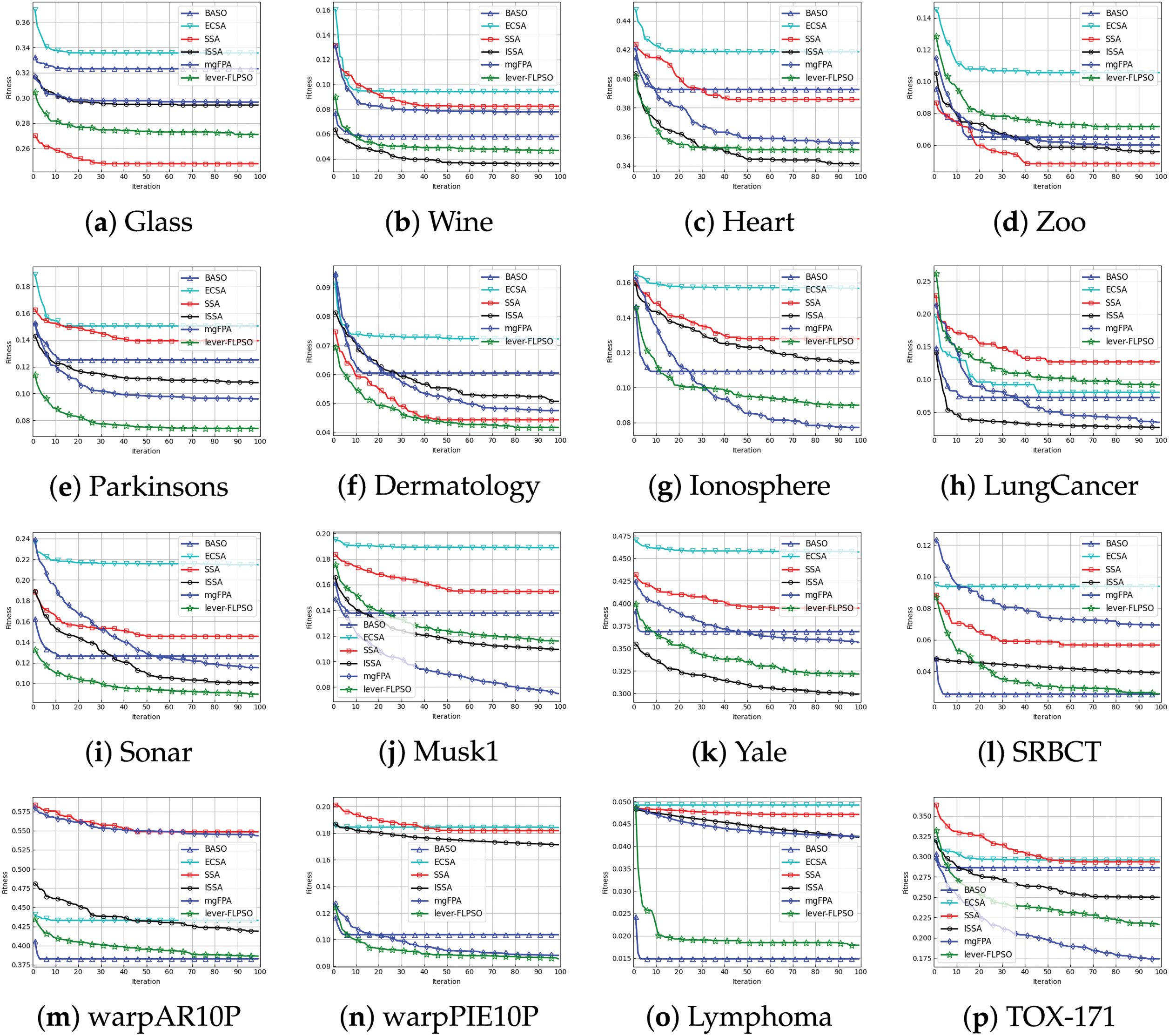

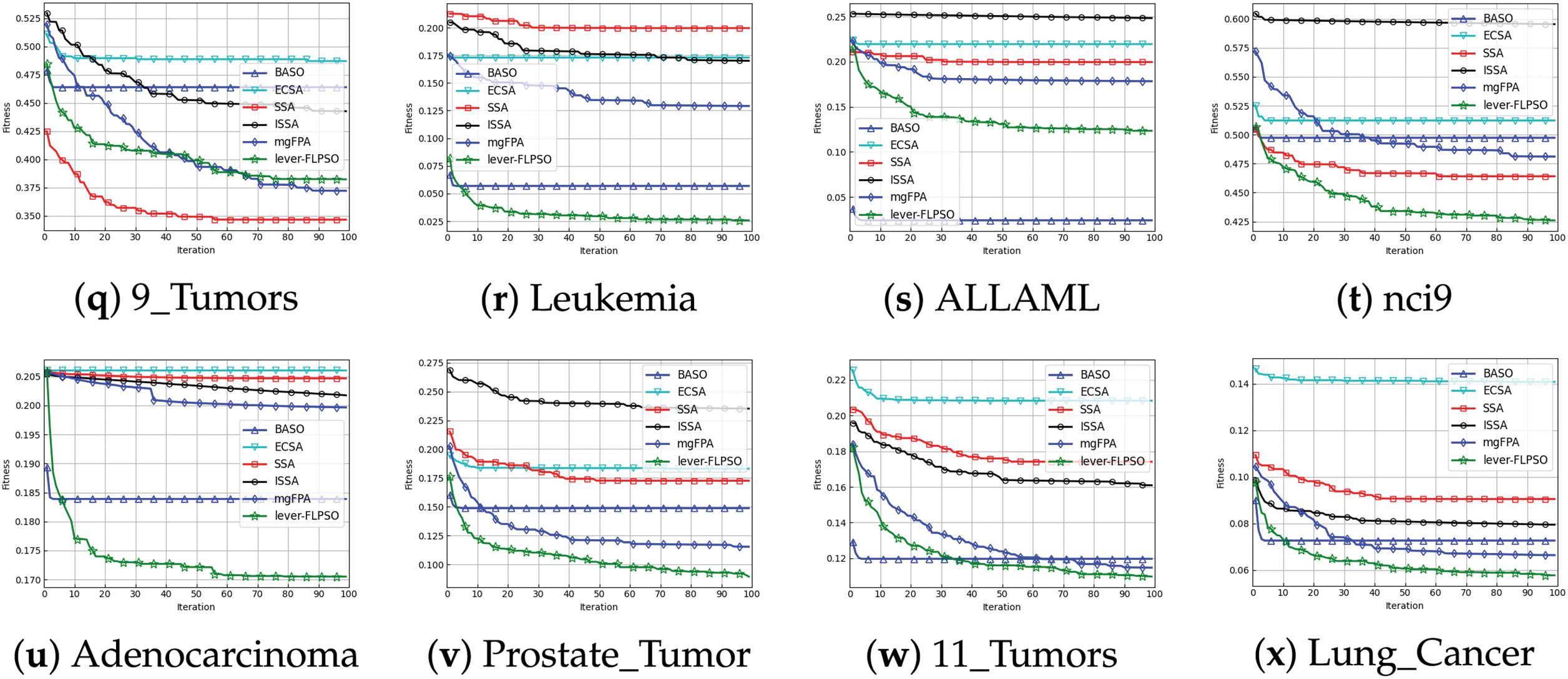

The convergence curves of the experimental results are presented in Fig. 4. It is apparent that, in comparison to other PSO variants and heuristic algorithms, lever-FLPSO demonstrates a more rapid convergence towards the optimal solution. Additionally, lever-FLPSO achieves faster and better convergence on high-dimensional datasets (e.g., “SRBCT”, “warpPIE10P”, “TOX-171” and “Leukemia”). This is primarily due to the FL strategy, which strikes a proper balance between exploration and exploitation. Furthermore, in Fig. 5, by using LSR to continuously reduce the number of features in the optimal solution, the convergence speed is enhanced. Compared to ISSA, lever-FLPSO tends to search in more promising regions, attributed to the lever-OBL providing high-quality solutions and improving the algorithm’s convergence.

Figure 4: The convergence curves of 20 independent runs for lever-FLPSO and and 6 swarm intelligence algorithms

Figure 5: The convergence curves of 20 independent runs for lever-FLPSO and and 5 swarm intelligence algorithms

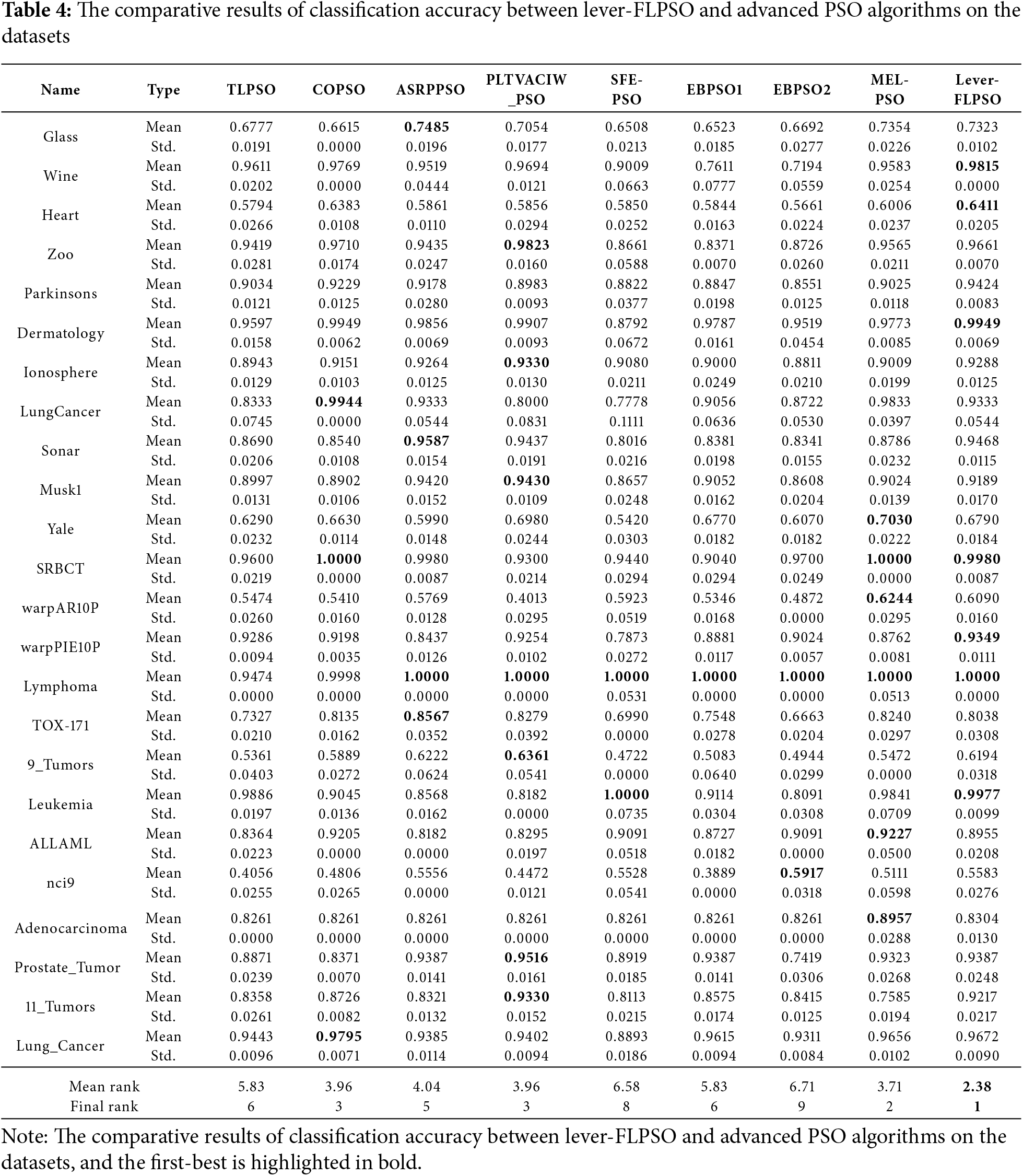

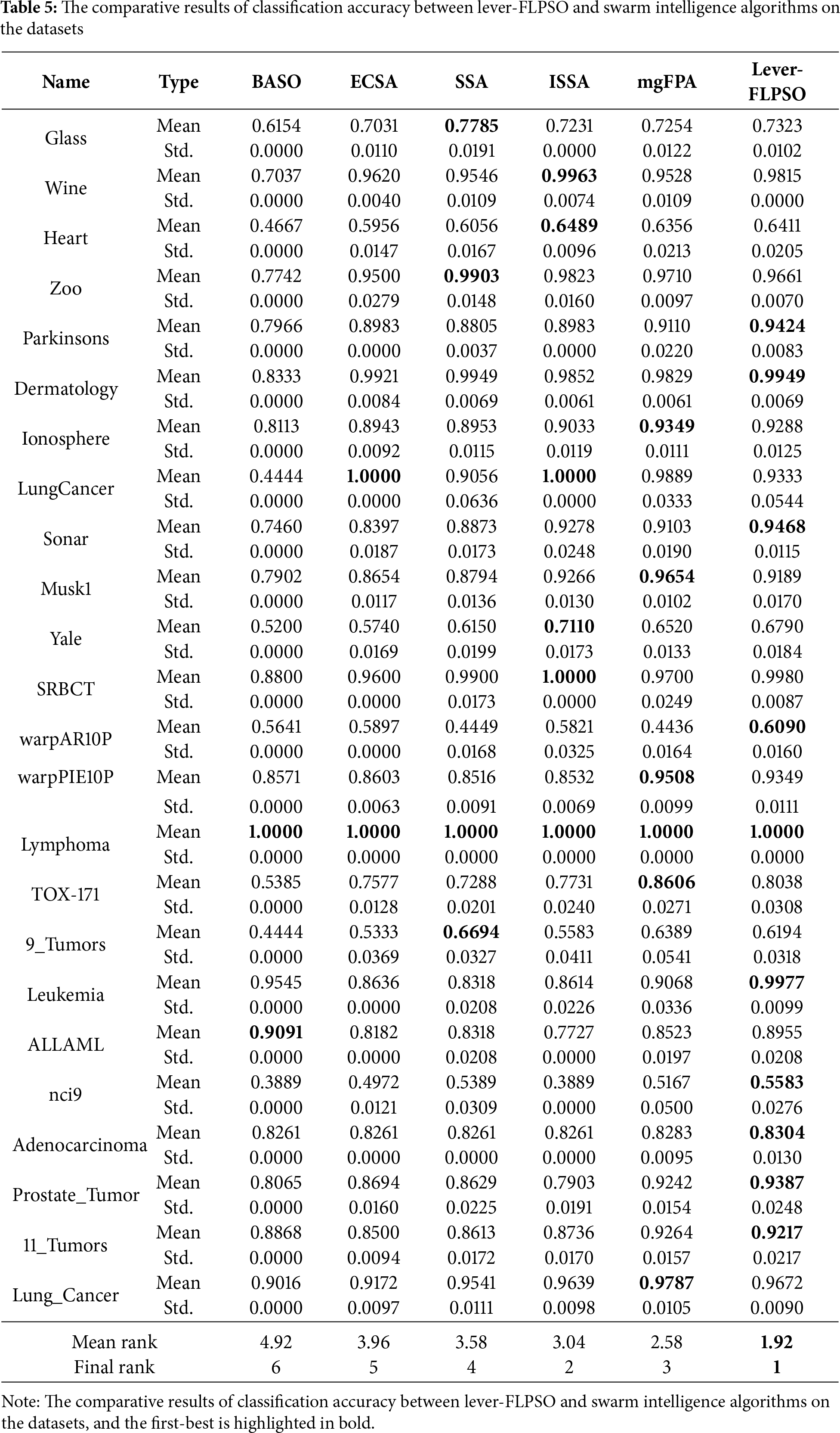

Tables 4 and 5 list the average classification accuracy and the standard deviation of fitness values. The lever-FLPSO consistently achieves the top rank among the compared algorithms, demonstrating particularly outstanding performance on high-dimensional datasets. These results demonstrate the superior performance of lever-FLPSO in searching for global optimal solutions in complex problems. The primary advantage of the method is attributed to the introduction of the lever-OBL scheme, which enhances the algorithm’s ability to identify optimal feature combinations in high-dimensional problems. It is worth noting that, while lever-FLPSO does not consistently attain the highest classification accuracy on certain datasets, the difference from the top-performing methods is minimal. Furthermore, lever-FLPSO maintains a consistent average ranking of first place across the 24 datasets. In terms of robustness and consistency, lever-FLPSO typically provides highly consistent results due to the lower Std values. The implemented FL scheme significantly improves the algorithm’s stability during each search, enabling it to evolve more effectively towards the optimal solution based on the state of the population.

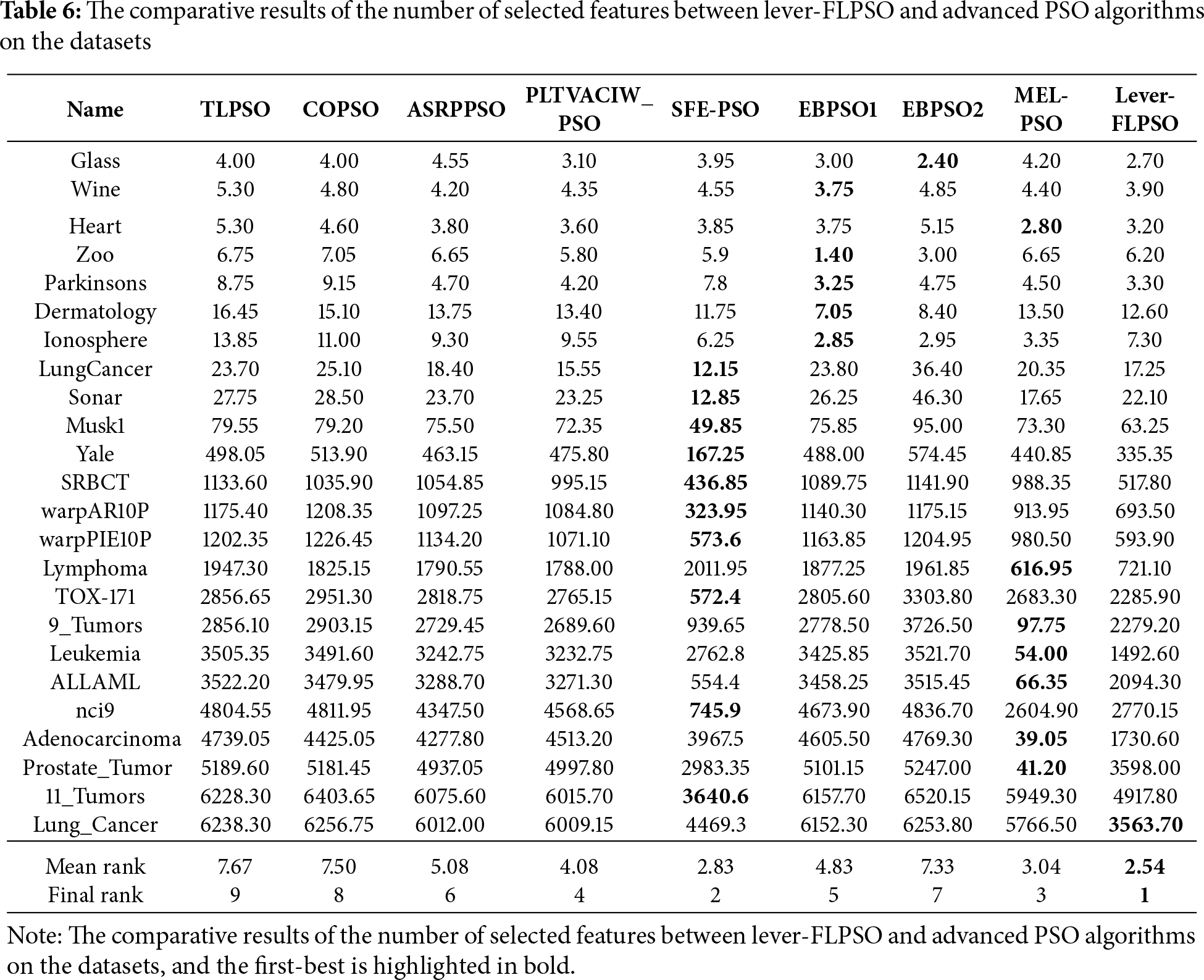

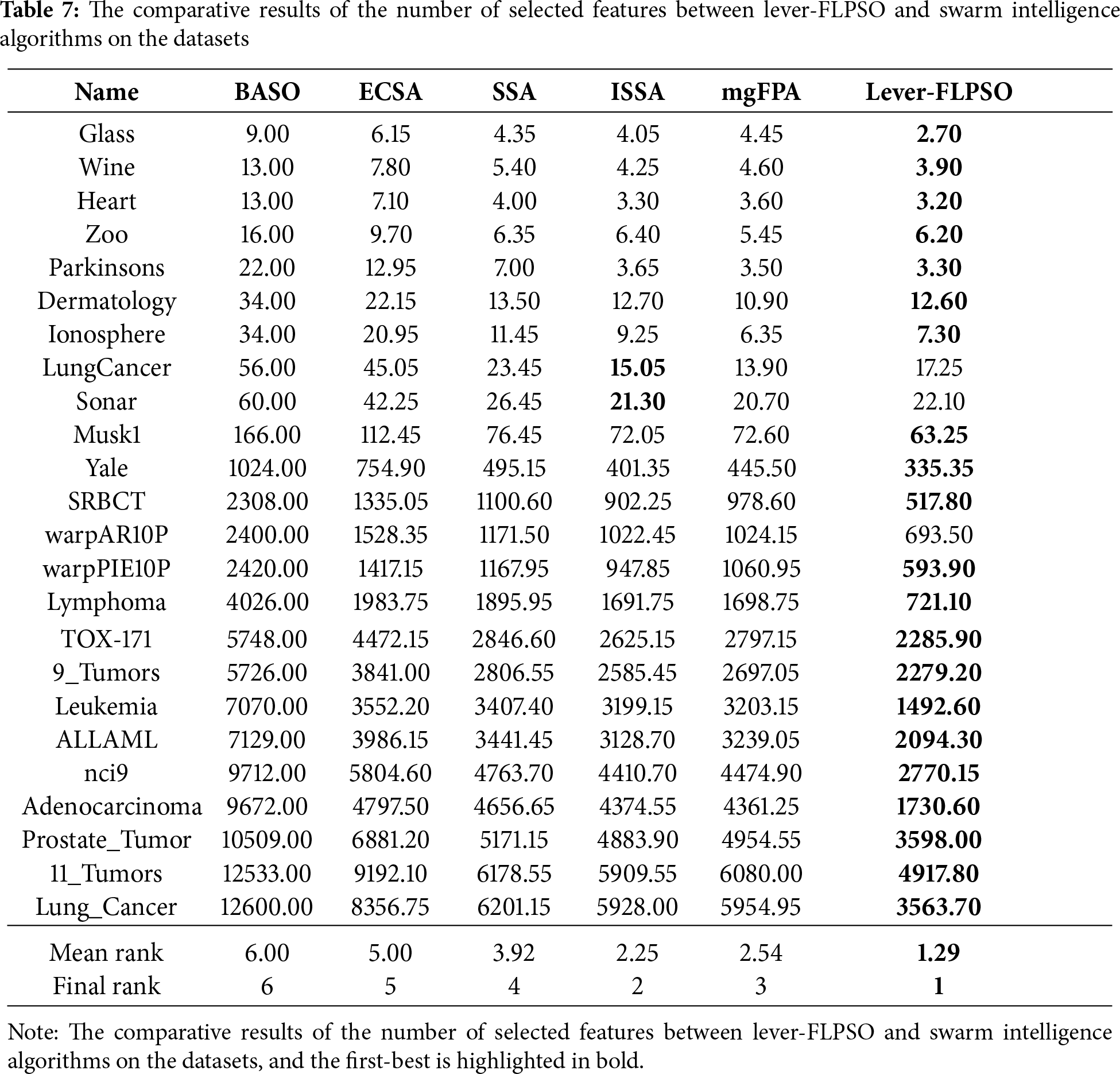

Tables 6 and 7 display the results concerning the number of selected features. Notably, lever-FLPSO achieves the minimal average number of selected features on most datasets, with only a few exceptions. Among the 13 compared algorithms across the 24 datasets, its average rankings are 2.38 and 1.92, respectively, with an overall rank of first. The primary reason for lever-FLPSO’s improved efficiency is the use of LSR to reduce the number of features in the optimal solution when addressing the FS problem, thereby selecting the best and significantly enhancing the selection efficiency. Furthermore, the FL strategy underscores a balance between exploration and exploitation in the search process, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of identifying high accuracy alignments with the fewest possible features.

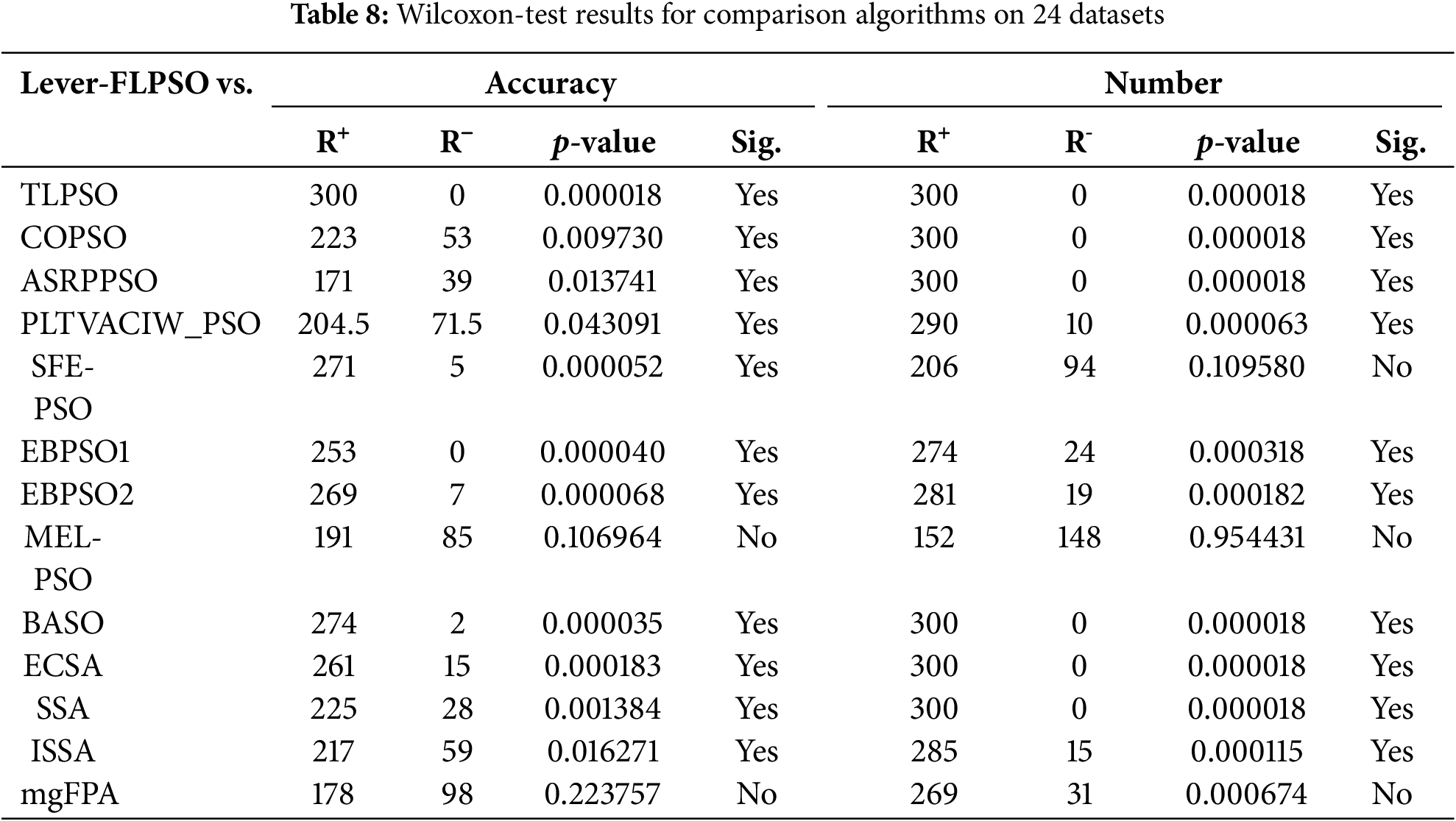

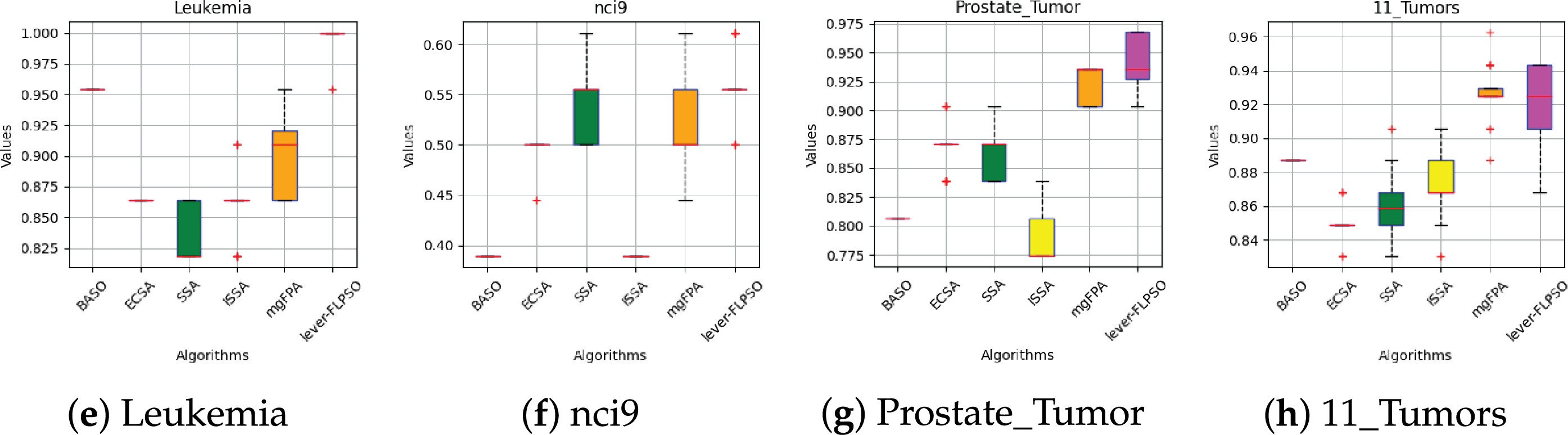

The Wilcoxon-test, as a non-parametric statistical method, is widely employed for comparative analysis of paired or correlated samples. In this study, a significance level of 0.05 was adopted to evaluate performance differences between lever-FLPSO and several comparison algorithms. Relevant results are documented in Table 8. Here,

Table 8 presents the results of the Wilcoxon-test comparing lever-FLPSO with the comparison algorithms in terms of classification accuracy and the number of selected features. The data indicates that lever-FLPSO exhibits significant differences from the comparison algorithms in most cases, particularly regarding the number of features, further validating its advantage in feature selection.

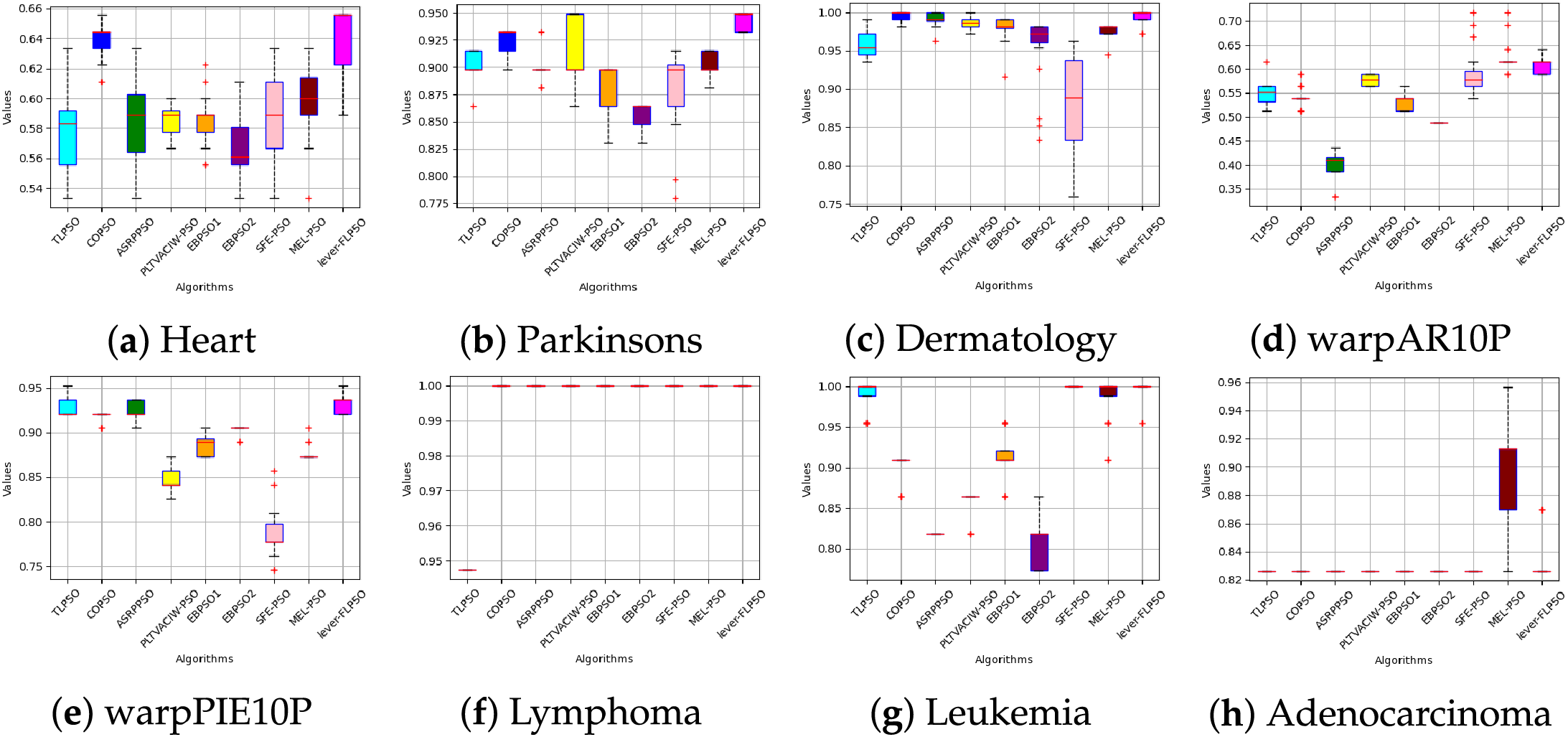

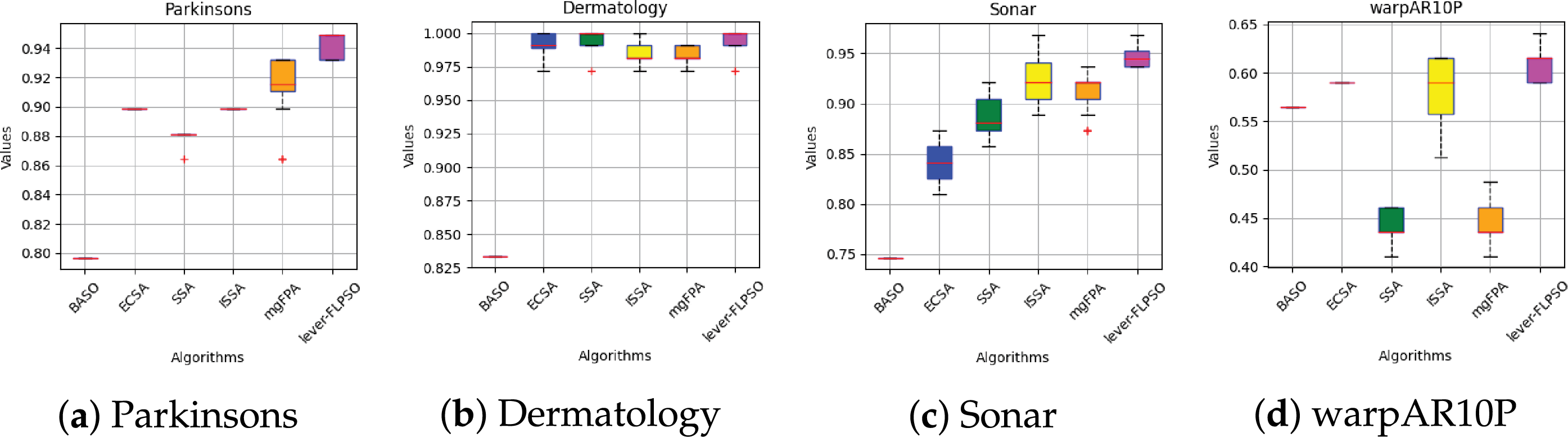

To facilitate a clearer understanding of the algorithm’s performance, box plots from Figs. 6 and 7 were used to illustrate the experimental results. In these box plots, the bottom horizontal line represents the minimum value within the dataset, while the top horizontal line indicates the maximum value. The size of the box indicates the dispersion or spread of the results, and the vertical line within the box represents the median. From Figs. 6 and 7, the lever-FLPSO achieves the best results for the minimum values on the datasets, with the median also being consistently leading. The data presented in the box plots indicates that the FL strategy effectively identifies the relationships between features in high-dimensional data during each code run, thereby aggregating relevant information and yielding better results.

Figure 6: Box plot of accuracy between lever-FLPSO and advanced PSO algorithms on the datasets

Figure 7: Box plot of accuracy between lever-FLPSO and swarm intelligence algorithms on the datasets

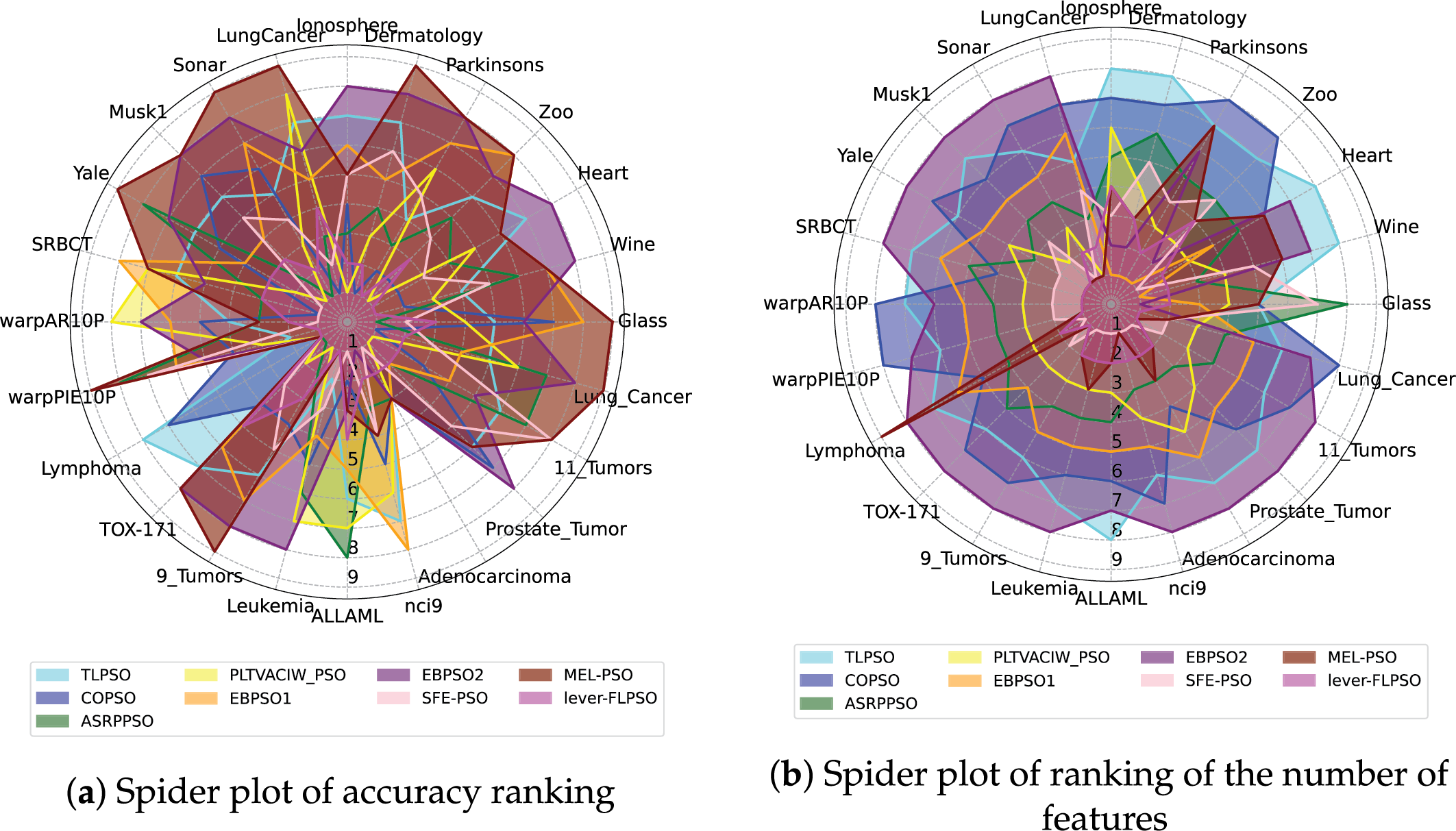

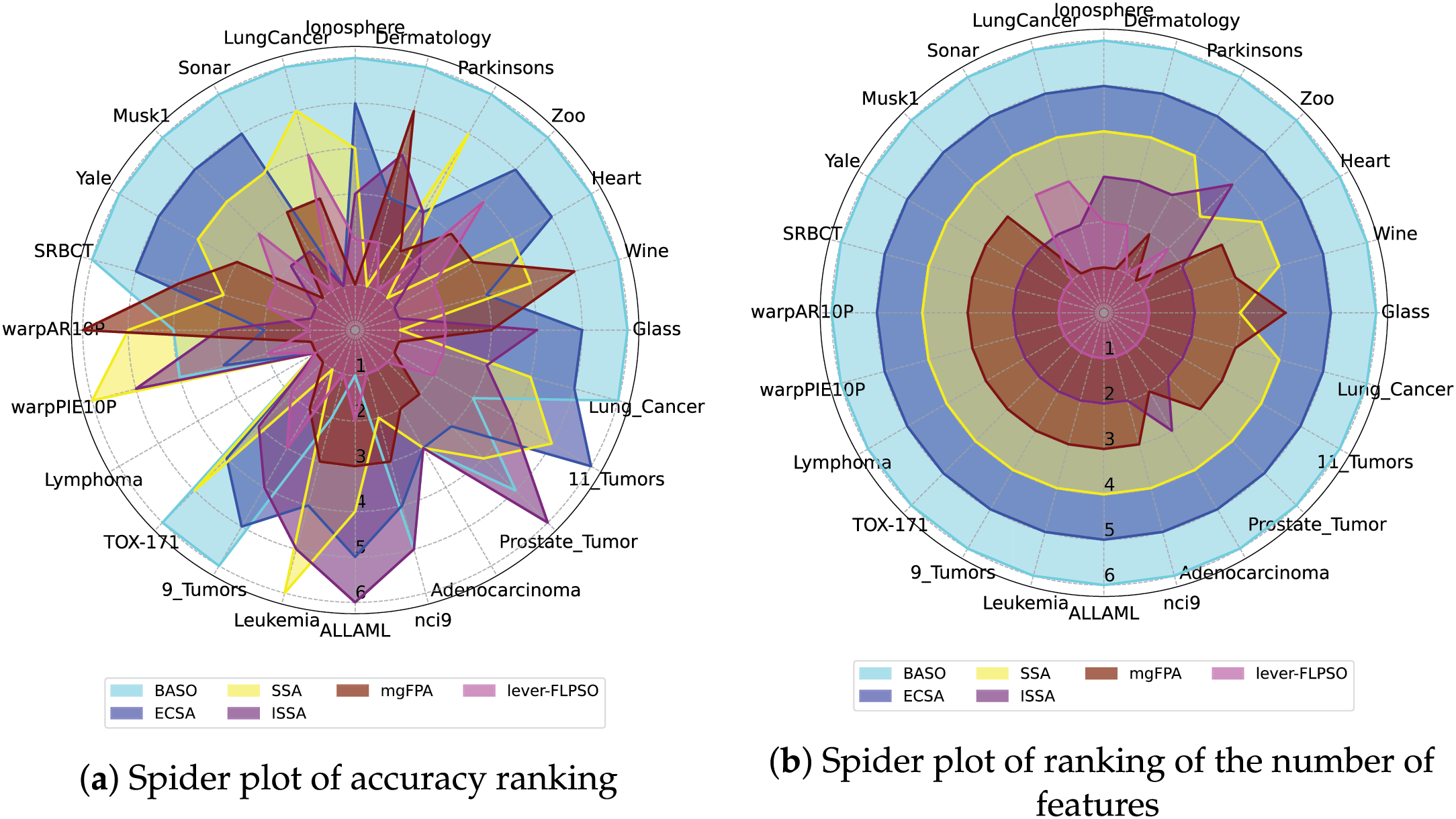

To provide a more intuitive comparison of the rankings of the proposed lever-FLPSO against advanced comparative algorithms across various datasets, spider plots 8 and 9 illustrate the ranking performance of all experimental algorithms on the datasets. It should be noted that in the diagrams, the axes represent the datasets, while the closed lines indicate the algorithms. It is evident that lever-FLPSO is positioned centrally within the spider plot, indicating that it ranks favorably in both classification accuracy and the number of selected features. In Figs. 8a and 9a, compared with the algorithms, lever-FLPSO consistently ranks among the top in classification accuracy across most datasets (e.g., “Wine”, “Heart”, “warpPIE10P”, “Lymphoma”, “Leukemia”, “Lung_Cancer”). Figs. 8b and 9b further highlights its strong performance, where the number of selected features ranks favorably on more than half of the datasets.

Figure 8: The spider plots between lever-FLPSO and advanced PSO algorithms on the datasets

Figure 9: The spider plots between lever-FLPSO and swarm intelligence algorithms on the datasets

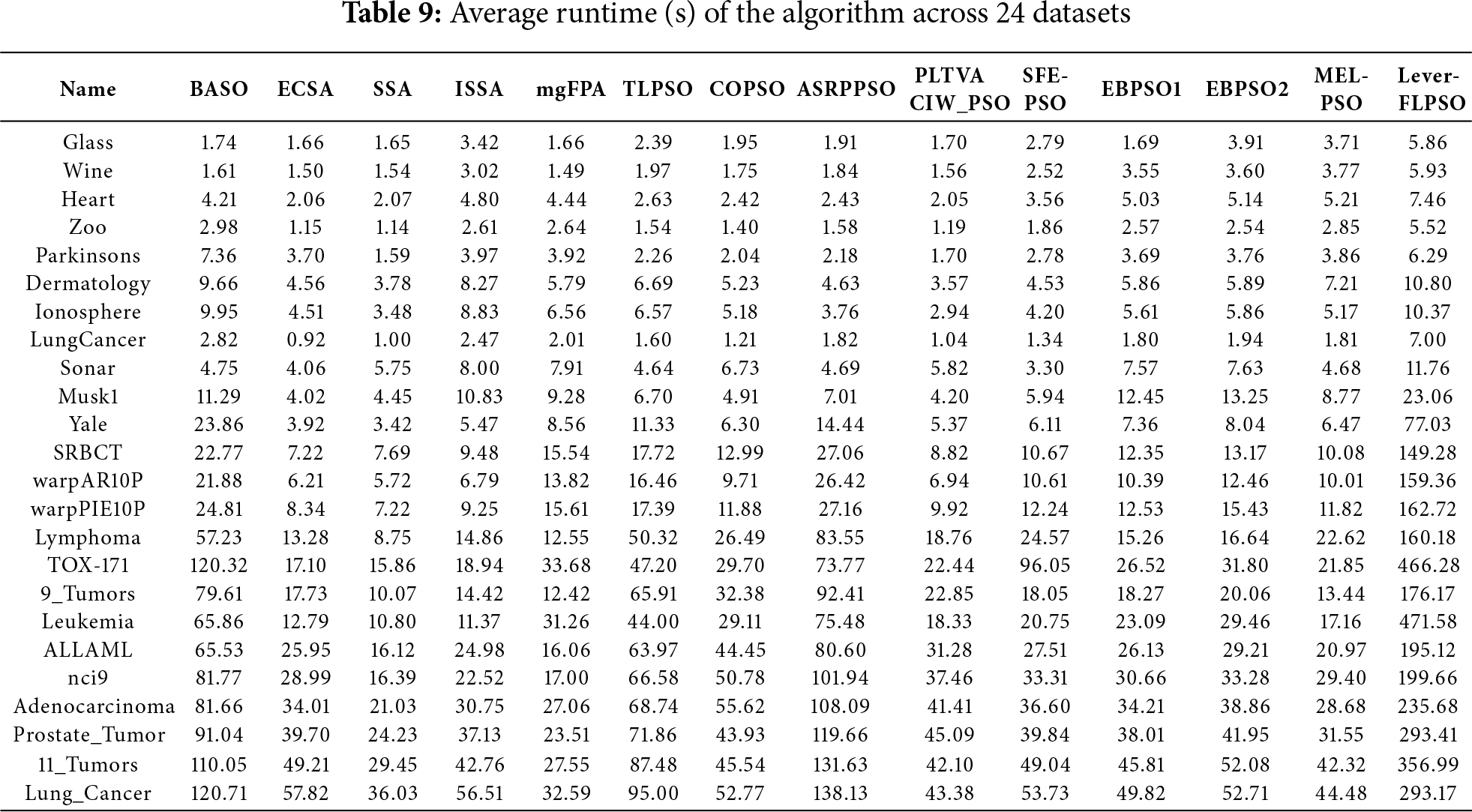

The specific execution times (in seconds) of the algorithm across 24 datasets are detailed in Table 9. Feature selection constitutes a practical problem and forms part of the preliminary stages of data processing. The improved feature subsets identified through algorithmic screening can significantly aid subsequent data applications, rendering the extended computation time acceptable. Furthermore, the experimental results presented in the Tables 4–7—regarding classification accuracy, the number of selected features, and algorithmic execution time—validate that our algorithm possesses competitive capabilities.

Based on the experimental results, it is evident that the proposed lever-FLPSO is an effective and reliable method. Lever-FLPSO significantly enhances search capabilities through lever-OBL, exploring as many high-quality feature subset combinations as possible to obtain the optimal solution. As demonstrated in the convergence graph for the “SRBCT” dataset (Fig. 5l), ISSA quickly falls into a local optimum, while lever-FLPSO continues to search and achieves the optimal result. Across 24 datasets, compared with 6 other PSO variants and 5 swarm intelligence algorithms, lever-FLPSO consistently selects the fewest number of features, ranking first overall. This success is attributed to the local selection and re-optimization (LSR) strategy, which significantly reduces the number of features while maintaining feature selection accuracy, thereby improving convergence speed. This effect is evident in the “Parkinsons”, “Dermatology”, “warpPIE10P”, and “Leukemia” datasets as shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

To mitigate the challenges associated with PSO, lever-FLPSO implements novel strategies that improve search efficiency, decrease the number of features, and expedite convergence speed, thereby effectively addressing several issues encountered by PSO in FS. Particularly, by applying fitness landscape (FL) in the selection of high-dimensional datasets, the search process has been optimized, thereby enhancing the interconnections among effective features in high-dimensional data. Furthermore, the integration of lever principle opposition-based learning (lever-OBL) facilitates a more effective aggregation of relevant information.

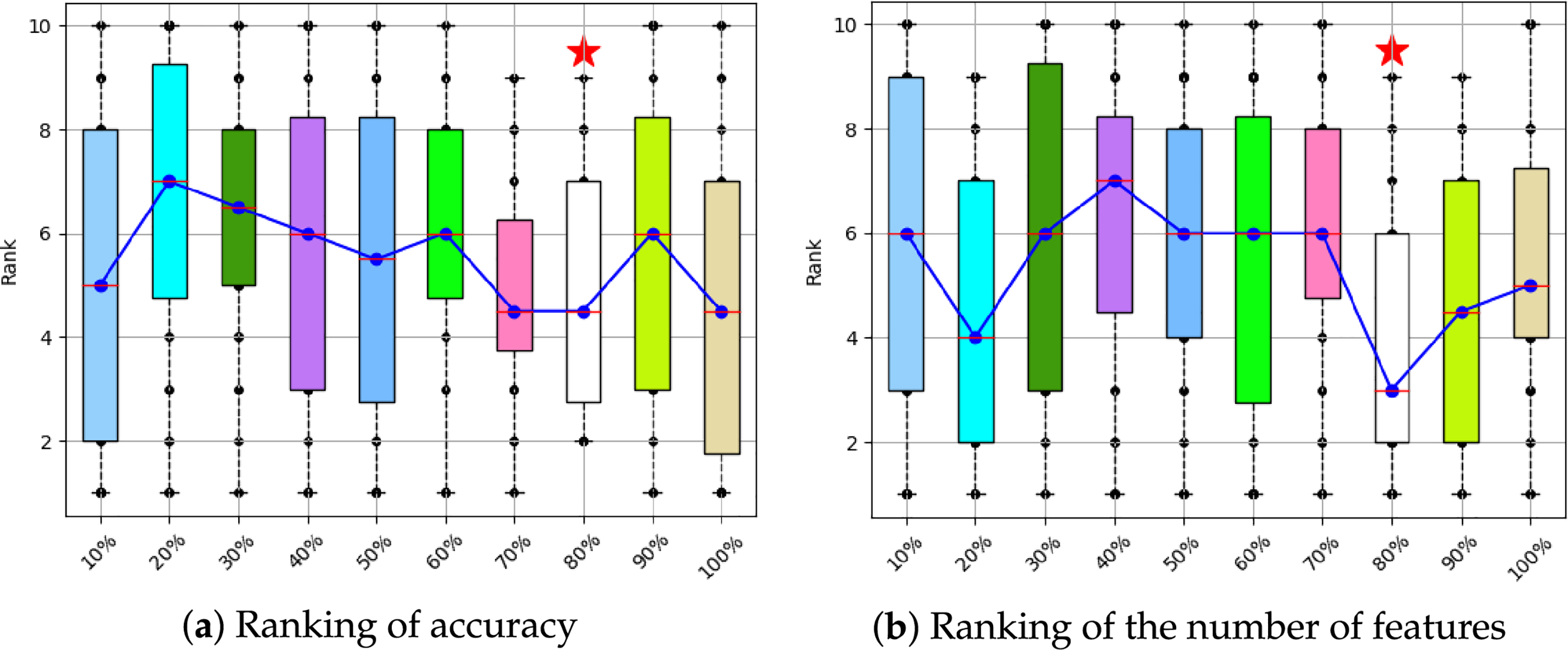

In the experiments, 80% of the feature subset from the optimal solution was selected as the new optimal solution (LSR) to reduce the number of features. The “80%” parameter was determined based on the algorithm’s performance across 24 datasets, where experiments were conducted using different percentages ranging from 10% to 100%, and the final average ranking was used to make the selection. As depicted in Fig. 10, the 80% setting demonstrated excellent performance in terms of both accuracy and the number of selected features. Consequently, 80% was chosen as the final parameter setting for the LSR strategy.

Figure 10: Analysis of LSR parameter setting

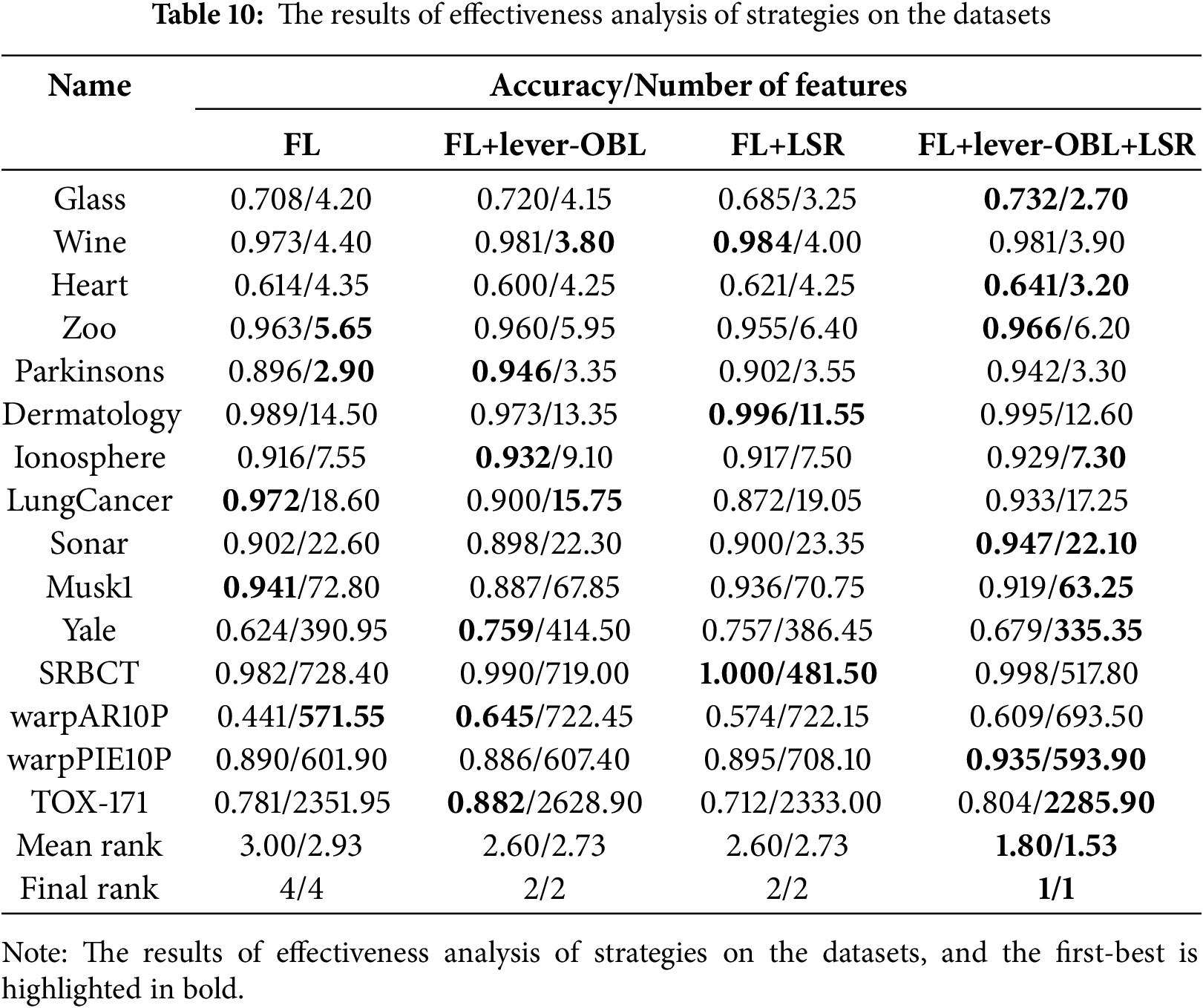

This manuscript introduces three strategies (FL, lever-OBL, and LSR) and conducts experiments using 15 datasets to evaluate their effectiveness. The fundamental experimental parameters are utilized as outlined in Section 4.2, with adjustments only in the conditions of strategy application. As presented in Table 10, the integration of all three strategies in lever-FLPSO demonstrates complementary effects, achieving the highest ranking in both accuracy and selected feature count. It is evident from the table that the combination of lever-OBL and LSR surpasses the performance of the FL strategy when used independently, highlighting the valuable contributions of these strategies to the overall algorithm.

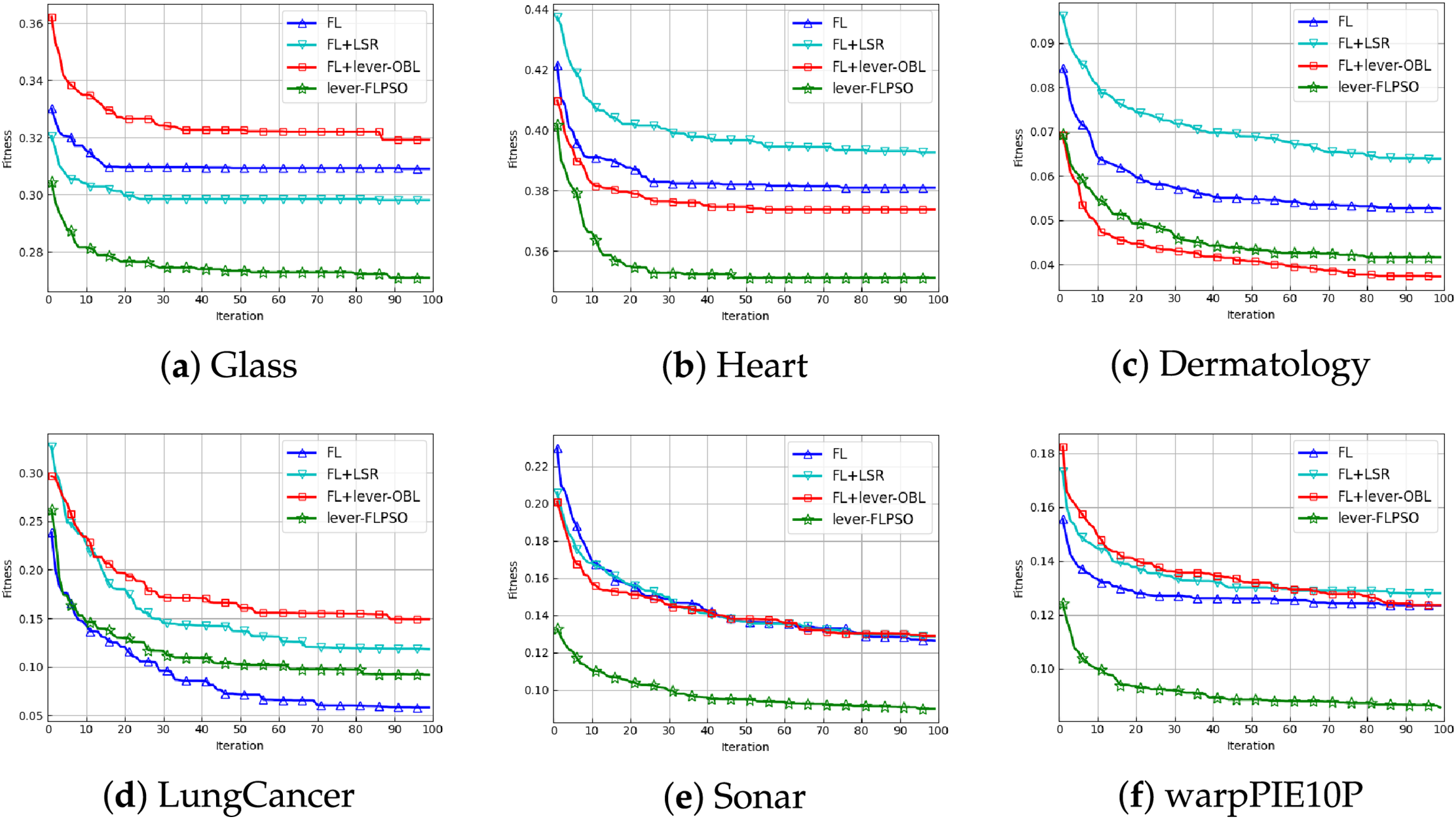

As illustrated in Fig. 11, lever-FLPSO, which integrates the three strategies, exhibits superior and faster convergence in the “Glass”, “Heart”, “Sonar”, and “warpPIE10P” datasets. This improvement can be attributed to the FL strategy’s ability to balance the exploration and exploitation phases of the population, making the search process more conducive to convergence. The lever-OBL strategy further enhances the search process by discovering more promising feature combinations, thereby circumventing local optima. As a concluding remark, the LSR strategy effectively selects the optimal feature subset, significantly reducing convergence time. No single strategy can solve all problems, as stated by the NFL theorem. The lever-FLPSO also faces challenges such as premature convergence, as shown in Fig. 11d. As demonstrated in Fig. 11c, although the incorporation of the LSR strategy into lever-FLPSO facilitates faster convergence relative to FL+lever-OBL, it may also lead to the omission of some potentially promising solutions due to the reduction in the number of features.

Figure 11: The convergence curves of 20 independent runs for lever-FLPSO and the ablation algorithms

In this article, a fitness landscape PSO algorithm based on leverage-based opposition learning was proposed for FS problems. The proposed lever-FLPSO adaptively adjusts different parameters based on the varying states of the population, balancing the exploration and exploitation phases to enhance the algorithm’s search capability. The innovative lever-OBL strategy significantly increases the likelihood of discovering potentially optimal feature subsets. It also incorporates a LSR strategy to decrease the number of selected features, thereby enhancing convergence efficiency. By utilizing these sophisticated strategies, lever-FLPSO successfully navigates local optima and further augments its efficacy in FS challenges. The performance of the proposed lever-FLPSO was evaluated using 24 benchmark datasets and compared with 13 other FS algorithms. Overall, experimental results demonstrate that lever-FLPSO not only achieves high classification accuracy but also excels in minimizing the number of selected features.

Owing to the novel integration of lever-OBL and LSR within the algorithm, it is capable of more effectively identifying optimal feature combinations while simultaneously reducing the number of features in high-dimensional problems. The experimental data also demonstrate that the algorithm performs outstandingly in high-dimensional problems. Prospective avenues for this research can focus on further exploring its applications in high-dimensional problems. The concepts of the fitness landscape strategy and lever-OBL can be extended to other heuristic algorithms to strengthen feature relationships in high-dimensional data and better integrate relevant information. However, employing the fitness landscape based on Euclidean distance increases the time complexity of the optimization process. Furthermore, the algorithm relies on the partitioned intervals of population states to guide the evolutionary direction, suggesting that optimizing these partitions remains a promising research direction. Therefore, further investigation into the formulation of the fitness landscape strategy is warranted.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (62106092); Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2024J01822, 2024J01820, 2022J01916); Natural Science Foundation of Zhangzhou City (ZZ2024J28).

Author Contributions: Fei Yu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Zhenya Diao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Software, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Hongrun Wu: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Yingpin Chen: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Xuewen Xia: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. Yuanxiang Li: Supervision, Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed in this study are published in this article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Too J, Rahim Abdullah A. Binary atom search optimisation approaches for feature selection. Connect Sci. 2020;32(4):406–30. doi:10.1080/09540091.2020.1741515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Dhal P, Azad C. A comprehensive survey on feature selection in the various fields of machine learning. Appl Intell. 2022;52(4):4543–81. doi:10.1007/s10489-021-02550-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Jiawei E, Zhang Y, Yang S, Wang H, Xia X, Xu X. GraphSAGE++: weighted multi-scale GNN for graph representation learning. Neural Process Lett. 2024;56(1):24. doi:10.1007/s11063-024-11496-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Cheng F, Cui J, Wang Q, Zhang L. A variable granularity search-based multiobjective feature selection algorithm for high-dimensional data classification. IEEE Trans Evolut Comput. 2023;27(2):266–80. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2022.3160458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chen K, Xue B, Zhang M, Zhou F. Evolutionary multitasking for feature selection in high-dimensional classification via particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2022;26(3):446–60. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2021.3100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hashemi A, Dowlatshahi MB, Nezamabadi-pour H. MFS-MCDM: multi-label feature selection using multi-criteria decision making. Knowl Based Syst. 2020;206:106365. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2020.106365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Salesi S, Cosma G, Mavrovouniotis M. TAGA: tabu asexual genetic algorithm embedded in a filter/filter feature selection approach for high-dimensional data. Inf Sci. 2021;565(12):105–27. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2021.01.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Tran B, Xue B, Zhang M. Variable-length particle swarm optimization for feature selection on high-dimensional classification. IEEE Trans Evol Comput. 2019;23(3):473–87. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2018.2869405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Nguyen BH, Xue B, Andreae P, Ishibuchi H, Zhang M. Multiple reference points-based decomposition for multiobjective feature selection in classification: static and dynamic mechanisms. IEEE Trans Evolut Comput. 2020;24(1):170–84. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2019.2913831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mistry K, Zhang L, Neoh SC, Lim CP, Fielding B. A micro-GA embedded PSO feature selection approach to intelligent facial emotion recognition. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2017;47(6):1496–509. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2016.2549639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Selvaraj G, Subbiah J, Selvaraj M. Embedded binary PSO integrating classical methods for multilevel improved feature selection in liver and kidney disease diagnosis. Int J Biomed Eng Technol. 2019;31(2):105–36. doi:10.1504/IJBET.2019.102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chen K, Xue B, Zhang M, Zhou F. An evolutionary multitasking-based feature selection method for high-dimensional classification. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2022;52(7):7172–86. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2020.3042243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Too J, Abdullah AR. A new and fast rival genetic algorithm for feature selection. J Supercomput. 2021;77(3):2844–74. doi:10.1007/s11227-020-03378-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Tran B, Xue B, Zhang M. A new representation in PSO for discretization-based feature selection. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2018;48(6):1733–46. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2017.2714145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Qiu C. A novel multi-swarm particle swarm optimization for feature selection. Genet Program Evolvable Mach. 2019;20(4):503–29. doi:10.1007/s10710-019-09358-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang F, Mei Y, Nguyen S, Zhang M. Evolving scheduling heuristics via genetic programming with feature selection in dynamic flexible job-shop scheduling. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2021;51(4):1797–811. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2020.3024849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Nag K, Pal NR. A multiobjective genetic programming-based ensemble for simultaneous feature selection and classification. IEEE Trans on Cybern. 2016;46(2):499–510. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2015.2404806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Mirjalili S, Gandomi AH, Mirjalili SZ, Saremi S, Faris H, Mirjalili SM. Salp swarm algorithm: a bio-inspired optimizer for engineering design problems. Adv Eng Softw. 2017;114:163–91. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2017.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tizhoosh HR. Opposition-based learning: a new scheme for machine intelligence. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Intelligence for Modelling, Control and Automation and International Conference on Intelligent Agents, Web Technologies and Internet Commerce (CIMCA-IAWTIC’06); 2005 Nov 28–30; Vienna, Austria. p. 695–701. doi:10.1109/CIMCA.2005.1631345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Tubishat M, Idris N, Shuib L, Abushariah MAM, Mirjalili S. Improved salp swarm algorithm based on opposition based learning and novel local search algorithm for feature selection. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;145(13):113122. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.113122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shambour MKY, Abusnaina AA, Alsalibi AI. Modified global flower pollination algorithm and its application for optimization problems. Interdiscip Sci Comput Life Sci. 2019;11(3):496–507. doi:10.1007/s12539-018-0295-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Mirjalili S, Lewis A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv Eng Softw. 2016;95(12):51–67. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ouadfel S, Abd Elaziz M. Enhanced crow search algorithm for feature selection. Expert Syst Appl. 2020;159(1):113572. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Gu S, Cheng R, Jin Y. Feature selection for high-dimensional classification using a competitive swarm optimizer. Soft Comput. 2018;22(3):811–22. doi:10.1007/s00500-016-2385-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Khanesar MA, Teshnehlab M, Shoorehdeli MA. A novel binary particle swarm optimization. In: Proceedings of the 2007 Mediterranean Conference on Control & Automation; 2007 Jun 27–29; Athens, Greece. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/MED.2007.4433821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chuang LY, Chang HW, Tu CJ, Yang CH. Improved binary PSO for feature selection using gene expression data. Computat Biol Chem. 2008;32(1):29–38. doi:10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2007.09.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Camacho-Villalón CL, Dorigo M, Stützle T. Exposing the grey wolf, moth-flame, whale, firefly, bat, and antlion algorithms: six misleading optimization techniques inspired by bestial metaphors. Int Trans Operat Res. 2023;30(6):2945–71. doi:10.1111/itor.13176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Eberhart R, Kennedy J. A new optimizer using particle swarm theory. In: Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Micro Machine and Human Science; 1995 Oct 4–6; Nagoya, Japan. p. 39–43. doi:10.1109/MHS.1995.494215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Malan KM, Engelbrecht AP. A survey of techniques for characterising fitness landscapes and some possible ways forward. Inf Sci. 2013;241:148–63. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2013.04.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Harrison KR, Ombuki-Berman BM, Engelbrecht AP. A parameter-free particle swarm optimization algorithm using performance classifiers. Inf Sci. 2019;503(3):381–400. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2019.07.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Morgan R, Gallagher M. Length scale for characterising continuous optimization problems. In: Coello CAC, Cutello V, Deb K, Forrest S, Nicosia G, Pavone M, editors. Parallel problem solving from nature—PPSN XII. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2012. p. 407–16. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-32937-1_41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li W, Meng X, Huang Y. Fitness distance correlation and mixed search strategy for differential evolution. Neurocomputing. 2021;458(3):514–25. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2019.12.141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Yu F, Guan J, Wu H, Chen Y, Xia X. Lens imaging opposition-based learning for differential evolution with cauchy perturbation. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;152(1):111211. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2023.111211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ma B, Xia Y. A tribe competition-based genetic algorithm for feature selection in pattern classification. Appl Soft Comput. 2017;58(9):328–38. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2017.04.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Li T, Dong H, Sun J. Binary differential evolution based on individual entropy for feature subset optimization. IEEE Access. 2019;7:24109–21. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2900078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Bi Y, Xue B, Zhang M. Using a small number of training instances in genetic programming for face image classification. Inf Sci. 2022;593(2):488–504. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.01.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Fang J, Wang Z, Liu W, Lauria S, Zeng N, Prieto C, et al. A new particle swarm optimization algorithm for outlier detection: industrial data clustering in wire arc additive manufacturing. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2022;21(2):1244–57. doi:10.1109/TASE.2022.3230080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Azar A, Khan ZI, Amin S, Fouad K. Hybrid global optimization algorithm for feature selection. Comput Mater Contin. 2023;74(1):2021–37. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.032183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Chen K, Zhou FY, Yuan XF. Hybrid particle swarm optimization with spiral-shaped mechanism for feature selection. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;128(1–2):140–56. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.03.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Gupta S, Gupta S. Fitness and historical success information-assisted binary particle swarm optimization for feature selection. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;306(Mar):112699. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Beheshti Z. A fuzzy transfer function based on the behavior of meta-heuristic algorithm and its application for high-dimensional feature selection problems. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;284:111191. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2023.111191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Gao J, Wang Z, Jin T, Cheng J, Lei Z, Gao S. Information gain ratio-based subfeature grouping empowers particle swarm optimization for feature selection. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;286(2):111380. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Moradi P, Gholampour M. A hybrid particle swarm optimization for feature subset selection by integrating a novel local search strategy. Appl Soft Comput. 2016;43:117–30. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2016.01.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Qiu C, Liu N. A novel three layer particle swarm optimization for feature selection. J Intell Fuzzy Syst. 2021;41(1):2469–83. doi:10.3233/JIFS-202647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Too J, Sadiq AS, Mirjalili SM. A conditional opposition-based particle swarm optimisation for feature selection. Connect Sci. 2022;34(1):339–61. doi:10.1080/09540091.2021.2002266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Tijjani S, Ab Wahab MN, Mohd Noor MH. An enhanced particle swarm optimization with position update for optimal feature selection. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;247(7):123337. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Ahadzadeh B, Abdar M, Safara F, Khosravi A, Menhaj MB, Suganthan PN. SFE: a simple, fast, and efficient feature selection algorithm for high-dimensional data. IEEE Trans Evolut Comput. 2023;27(6):1896–911. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2023.3238420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wang X, Shangguan H, Huang F, Wu S, Jia W. MEL: efficient multi-task evolutionary learning for high-dimensional feature selection. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2024;36(8):4020–33. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2024.3366333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Diao Z, Yu F, Guan J, Liu M. An enhanced particle swarm algorithm based on fitness landscape information. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC); 2024 Jun 30–Jul 5; Yokohama, Japan. p. 1–8. doi:10.1109/CEC60901.2024.10611936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zhan ZH, Zhang J, Li Y, Chung HSH. Adaptive particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Part B. 2009;39(6):1362–81. doi:10.1109/TSMCB.2009.2015956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Liu W, Wang Z, Zeng N, Yuan Y, Alsaadi FE, Liu X. A novel randomised particle swarm optimizer. Int J Mach Learn Cybern. 2021;12(2):529–40. doi:10.1007/s13042-020-01186-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Liu W, Wang Z, Yuan Y, Zeng N, Hone K, Liu X. A novel sigmoid-function-based adaptive weighted particle swarm optimizer. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2021;51(2):1085–93. doi:10.1109/TCYB.2019.2925015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Yu F, Guan J, Wu H, Wang H, Ma B. Multi-population differential evolution approach for feature selection with mutual information ranking. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;260(9):125404. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Yang S, Wei B, Deng L, Jin X, Jiang M, Huang Y, et al. A leader-adaptive particle swarm optimization with dimensionality reduction strategy for feature selection. Swarm Evol Comput. 2024;91(9):101743. doi:10.1016/j.swevo.2024.101743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wang Y, Cai Z, Guo L, Li G, Yu Y, Gao S. A spherical evolution algorithm with two-stage search for global optimization and real-world problems. Inf Sci. 2024;665(2):120424. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2024.120424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Markelle K, Rachel L, Kolby N. The UCI machine learning repository. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 26]. Available from: https://archive.ics.uci.edu. [Google Scholar]

57. Li J, Cheng K, Wang S, Morstatter F, Trevino RP, Tang J, et al. Feature selection: a data perspective. ACM Comput Surv. 2017;50(6):45. doi:10.1145/3136625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools