Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Lane Line Detection Method for Complex Road Scenes Based on DeepLabv3+ and MobilenetV4

College of Electronic and Information Engineering, Shandong University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, 266590, China

* Corresponding Author: Lihua Wang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 55 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072799

Received 03 September 2025; Accepted 27 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

With the continuous development of artificial intelligence and computer vision technology, numerous deep learning-based lane line detection methods have emerged. DeepLabv3+, as a classic semantic segmentation model, has found widespread application in the field of lane line detection. However, the accuracy of lane line segmentation is often compromised by factors such as changes in lighting conditions, occlusions, and wear and tear on the lane lines. Additionally, DeepLabv3+ suffers from high memory consumption and challenges in deployment on embedded platforms. To address these issues, this paper proposes a lane line detection method for complex road scenes based on DeepLabv3+ and MobileNetV4 (MNv4). First, the lightweight MNv4 is adopted as the backbone network, and the standard convolutions in ASPP are replaced with depthwise separable convolutions. Second, a polarization attention mechanism is introduced after the ASPP module to enhance the model’s generalization capability. Finally, the Simple Linear Iterative Clustering (SLIC) superpixel segmentation algorithm is employed to preserve lane line edge information. MNv4-DeepLabv3+ was tested on the TuSimple and CULane datasets. On the TuSimple dataset, the Mean Intersection over Union (MIoU) and Mean Pixel Accuracy (mPA) improved by 1.01% and 7.49%, respectively. On the CULane dataset, MIoU and mPA increased by 3.33% and 7.74%, respectively. The number of parameters decreased from 54.84 to 3.19 M. Experimental results demonstrate that MNv4-DeepLabv3+ significantly optimizes model parameter count and enhances segmentation accuracy.Keywords

Lane line detection, as a key technology in autonomous driving environmental perception, is crucial for enhancing the safety of autonomous vehicles. Over the past two decades, deep learning has driven the rapid development of lane line detection technology, significantly improving the performance of computer vision tasks compared to traditional methods. Despite these advancements, deep learning-based lane line detection still faces challenges. For example, in complex road scenarios, lane line segmentation accuracy is easily affected by factors such as lighting changes, occlusions, and lane line wear [1–3], leading to degraded performance. This indicates that the model requires enhanced feature extraction capabilities.

Fully Convolutional Networks (FCN) [4], as an important branch of deep learning methods, are widely applied in semantic segmentation tasks. They replace traditional fully connected layers with convolutional layers, enabling the network to accept input images of any size and output segmentation images of the same size. Additionally, they provide category labels for each pixel in the image, enabling pixel-level classification of the image. Therefore, methods such as fully convolutional networks, encoder-decoder structures, and end-to-end architectures are widely applied in the field of lane line detection. DeepLabv3+ [5] is an evolution of FCN, inheriting its fully convolutional structure. Compared to traditional FCN, DeepLabv3+ demonstrates significant advantages in handling multi-scale objects and detailed information. Additionally, it better captures contextual information and long-range dependencies, enabling more accurate and detailed semantic segmentation in complex road scenes. However, methods based on Deeplabv3+ exhibit high computational complexity and significant memory consumption [6,7], making them difficult to deploy on embedded platforms with limited computational capabilities. To address this challenge, academia and industry have shifted their research focus toward lightweight model design, aiming to balance accuracy and efficiency. For instance, Patel et al. [8] proposed a lane line detection system integrating Spatial Convolutional Neural Networks (SCNN), Canny edge detection, and the Hough transform. This approach holds potential for real-time deployment in autonomous driving systems, offering a safer and more efficient driving experience. Similarly, Segu et al. [9] developed a comprehensive road understanding and navigation solution based on YOLO and Streamlit, providing a powerful, scalable, and deployable solution for practical computer vision applications. Additionally, Zhao et al. [10] proposed a lane detection algorithm based on the dual attention mechanism of the Transformer architecture, meeting the real-time requirement of at least 30 frames per second for lane detection.

This study addresses existing issues by adopting the DeepLabv3+ encoder-decoder structure and making improvements to meet the needs of real-world scenarios. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) The original feature extraction network model had an excessive number of parameters, so a lightweight MobileNetV4 [11] was used as the backbone network. On this basis, the ordinary convolutions in the ASPP module were replaced with deep separable convolutions [12], further reducing the number of parameters in the model.

(2) In the DeepLabv3+ model, a polarization attention mechanism [13] (PSA-P, PSA-S) was added after the ASPP module to enhance the ability of feature maps to extract detailed information from complex road environments, thereby improving semantic segmentation performance.

(3) To further recover the detailed information of lane line edges and address the issue of suboptimal semantic segmentation performance in the lane line edge regions, this paper introduces the SLIC [14] superpixel segmentation algorithm, considering the property of image superpixels to protect image edges. By fusing high-level semantic features of the image with superpixel image edge information, the semantic segmentation results are optimized, ultimately achieving semantic segmentation of lane line images.

Experimental results demonstrate that our method achieves improvements of 1.01% and 7.49% in MIoU and mPA, respectively, on the TuSimple dataset. On the CULane dataset, MIoU and mPA are enhanced by 3.33% and 7.74%, respectively. The number of parameters is reduced from 54.84 to 3.19 M. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces various methods used to detect lane lines. Section 3 introduces the method proposed in this paper. Section 4 conducts ablation experiments and comparative experiments and analyzes the experimental results. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the method proposed in this paper.

This paper treats lane line detection as an image semantic segmentation task, aiming to determine whether each pixel in an image belongs to a lane line through pixel-level classification. Specifically, this paper briefly explores this issue from two aspects: first, detection techniques based on traditional computer vision methods; second, methods based on deep learning, which are divided into single-frame and historical-frame-based lane line detection.

Traditional methods mainly utilize the visual features of the image itself, such as grayscale values, colors, textures, and other characteristics [15–17]. Traditional lane line detection methods have the advantages of simple models, low computational requirements, and strong real-time performance. However, they are also susceptible to interference from changes in lighting and road damage, which can lead to a decrease in recognition rates.

Deep learning-based single-frame lane line detection methods can be divided into four categories: segmentation-based, anchor-based, key point-based and curve-based. Deep learning methods utilize network models to automatically learn target features, offering strong generalization capabilities that can effectively improve target detection accuracy, with performance continuing to improve.

2.1 Segmentation-Based Methods

In 2018, Chen et al. introduced DeepLabv3+ [5], which combines an encoder-decoder structure with dilated convolution techniques to effectively capture multi-scale contextual information and restore object boundaries. In the same year, Pan et al. proposed SCNN [18], a message-passing mechanism to aggregate spatial information, addressing the issue of limited visual cues in lanes. In 2019, Hou et al. proposed a self-attention distillation method, ENet-SAD [19], which utilizes attention maps derived from its own layers as distillation targets for lower layers. In 2021, Zheng et al. proposed RESA [20], which collects global information by horizontally and vertically shifting feature maps.

In June 2019, Chen et al. proposed the Point-LaneNet model [21], which can generate multiple anchor points or lines, thereby eliminating the need for inefficient decoders and predefined channel counts. In 2021, Tabelini et al. proposed LaneATT [22], a new anchor-based attention mechanism that aggregates global information and achieves good performance in anchor-based methods. In April 2023, Liu et al. proposed a lane detection method based on hyper-anchors (Hyper-Anchor) [23], which can adapt to the complex structure of lane lines and provide coarse lane point estimates. In February 2024, Chai et al. proposed a lane detection method based on row-anchors and Transformer architecture [2] to predict the coordinate map of lane lines. In the same year, Honda et al. proposed a new lane detection method, CLRerNet [24], which improves the quality of confidence scores by introducing LaneIoU (an IoU metric considering local lane angles).

Keypoint-based methods treat lane detection as a keypoint estimation and association problem. In 2021, Qu et al. introduced FOLOLaneNet [25], emphasizing the modeling of local patterns and achieving global structure prediction through a bottom-up approach. However, the large number of parameters in this model affects its real-time performance. Subsequently, in 2022, Wang et al. proposed GANet [26], which employs a dual-branch structure combining confidence features and offset features to enhance local accuracy. GANet’s innovation lies in its introduction of a global perspective for keypoint prediction, achieving higher accuracy. These contributions represent advancements in keypoint detection methods, demonstrating efforts to balance local precision and computational efficiency.

Lane detection methods based on curve fitting utilize polynomial functions to model lane lines. In 2020, Tabelini et al. introduced PolyLaneNet [27], which pioneered the use of polynomial curves as key points to directly represent lane lines. In 2023, Zhang et al. [28] modeled lane markings using Catmull-Rom curves, which provide a tighter fit to lane lines than cubic polynomials. In September 2024, Ren et al. proposed a global view occlusion lane line detection method based on deep polynomial regression [29]. This method enhances lane line feature extraction capabilities and detection accuracy by introducing a dual attention mechanism module (CBAM) and the OPTICS clustering model. Although curve-based methods have made efforts to improve detection accuracy, they rely on strong prior assumptions, which limits their ability to achieve higher performance.

2.5 Methods for Combining Historical Frames

The method of combining historical frames involves integrating multiple historical frames to enhance the detection accuracy of the current frame. In 2019, Zou et al. proposed a convolutional LSTM lane detection model that combines five consecutive frames [30]. In 2021, Zhang et al. enhanced the feature representation of the current frame by aggregating local and global features from other frames using MMA-NET [31], thereby improving detection of the current frame. While multi-frame detection improves lane detection performance compared to single-frame detection, it struggles to meet the real-time requirements of autonomous driving.

From the above methods, it can be seen that the anchor-based method and the method combining historical frames do not pay attention to model lightweighting, while the curve-based method struggles to achieve high accuracy. For lane line detection tasks, model lightweighting is crucial. Additionally, since lane lines are long and thin, the number of annotated lane pixels is far fewer than background pixels, making it challenging for the network to learn. Therefore, attention mechanisms can enhance the weighted information of lane line targets while reducing irrelevant information. Thus, this paper adopts the DeepLabv3+ model for lane line detection.

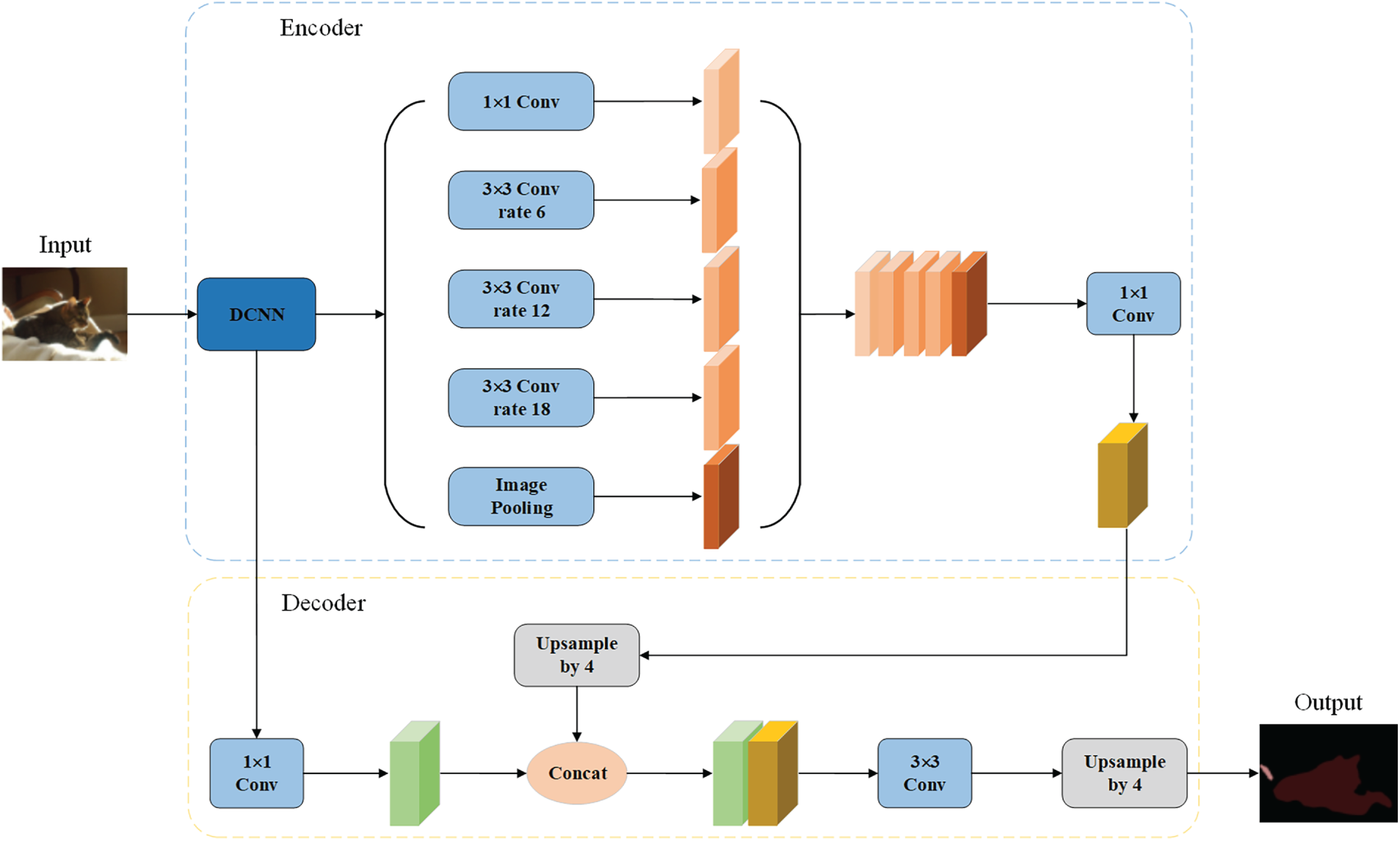

The DeepLabv3+ model is shown in Fig. 1, where the encoder part is mainly responsible for extracting high-level semantic information from images. It usually uses a pre-trained deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) as the backbone network, such as Xception or ResNet. The backbone network extracts and compresses the features of the input image through operations such as convolution and pooling layers to obtain feature maps with rich semantic information. The Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module is one of the core components of DeepLabv3+. It further extracts multi-scale contextual information based on the feature maps extracted by the backbone network. The ASPP module includes multiple branches with different dilation rates and a global average pooling branch. These branches process the feature maps in parallel, then concatenate and fuse their outputs to obtain feature representations containing contextual information at different scales. The decoder’s primary function is to restore the low-resolution feature maps output by the encoder to the same spatial resolution as the input image and generate the final semantic segmentation results. It combines high-level semantic information from the encoder stage with low-level detail information through upsampling operations and feature fusion, thereby improving the accuracy and detail representation of the segmentation results [32].

Figure 1: DeepLabv3+ model

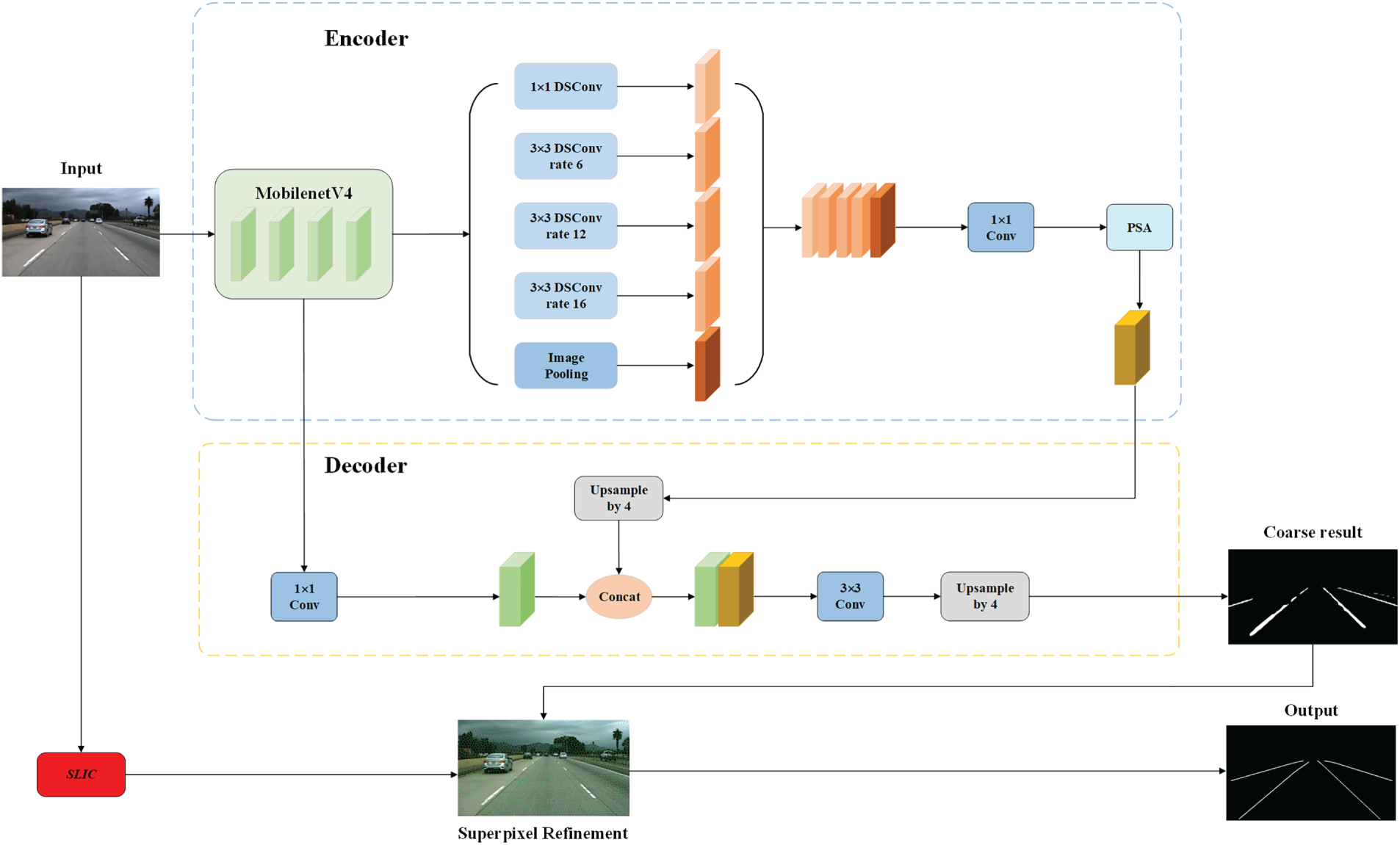

The improved model MNv4-DeepLabv3+ is shown in Fig. 2. In the encoder part, we replaced Xception with the lightweight MNv4 as the backbone and replaced the ordinary convolutions in ASPP with deep separable convolutions. Additionally, we added a PSA module after the ASPP. In the decoder section, low-level detail information is obtained through two downsampling operations using MNv4. Finally, the SLIC algorithm is introduced after the input image to optimize lane line edges.

Figure 2: Proposed DeepLabv3+ model

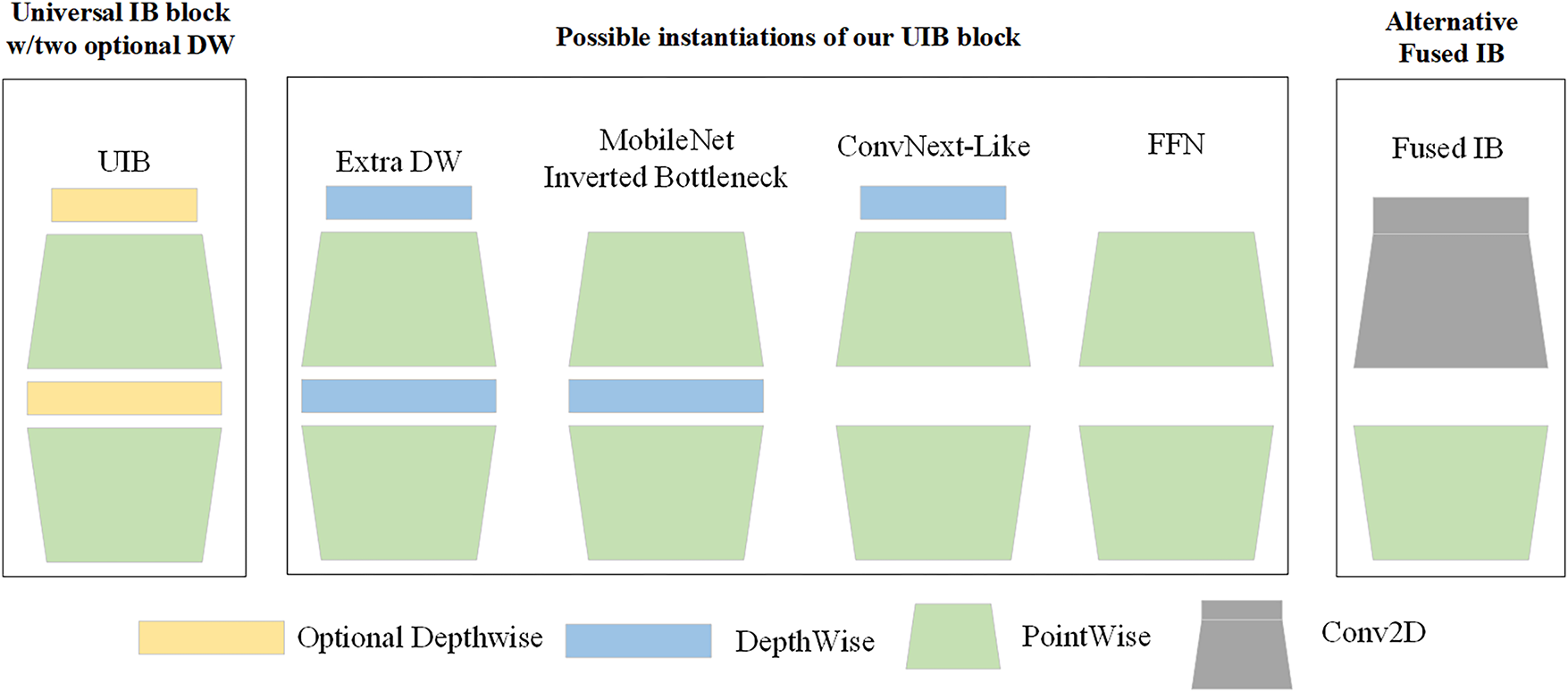

MobileNetV4 is an efficient, lightweight image processing model designed for mobile devices. Its core components are the Universal Inverted Bottleneck (UIB) and Multi-Query Attention (MQA) modules, combined with an optimized Neural Architecture Search (NAS) recipe. The Universal Inverted Bottleneck (UIB) module (Fig. 3) combines the Inverted Bottleneck (IB), ConvNext, Feed Forward Network (FFN), a novel Extra Depthwise variant, and large-kernel convolution Fused IB. By configuring optional depthwise convolutions, different instances of the UIB module can be selected, enabling these innovations to make the model more structurally flexible and efficient. MQA is an attention mechanism that optimizes the ratio of arithmetic operations to memory access, enabling more efficient use of computational resources and reducing memory bandwidth bottlenecks. NAS adjusts spatial and channel mixing, as well as receptive fields, to enhance the effectiveness of MNv4 searches.

Figure 3: UIB module

Other backbone networks like MobileNetV3 and EfficientNet-lite are primarily designed to reduce FLOPs (floating-point operations per second). However, low FLOPs do not necessarily equate to faster performance on mobile NPUs/DSPs. MobileNetV4’s architecture is co-designed with modern mobile hardware. Its pure convolutional variants (Conv-S/M/L) maximize utilization of hardware’s extreme acceleration capabilities for standard convolutions, achieving unparalleled low latency.

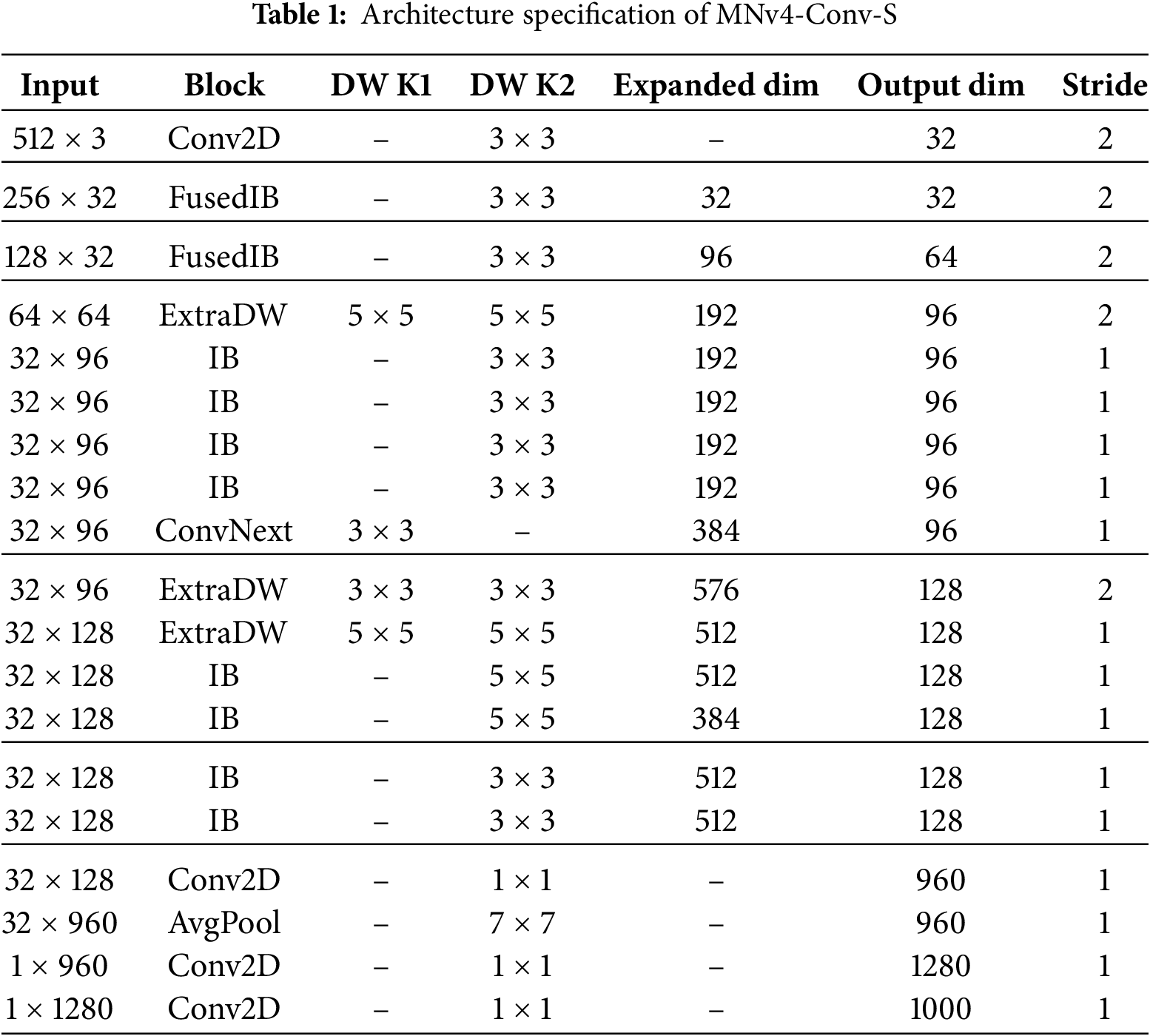

MobileNetV4 comprises five structures: the pure convolutional architectures MNv4-Conv-S, MNv4-Conv-M, MNv4-Conv-L, and hybrid architectures MNv4-Hybrid-M and MNv4-Hybrid-L that incorporate multi-head attention mechanisms on top of the pure convolutional architecture. These five variants form a model series ranging from lightweight to complex, with progressively increasing network depth, output channel count, and computational complexity. Although Hybrid-L achieves the highest accuracy, its improvement for image segmentation tasks is modest. Sacrificing a small amount of model accuracy yields substantial gains in speed and reduced power consumption. After weighing these trade-offs, we selected the pure convolutional architecture MNv4-Conv-S to replace Xception.

In Table 1, each row represents a specific operation. In the 10th row, the stride is 2, which theoretically should result in a 2× downsampling. However, considering the overall architecture, we fine-tuned the downsampling operation of MNv4 via code to limit the number of downsamplings to 4, thereby achieving a 16× downsampling. This design aims to minimize feature information loss while reducing the amount of data that subsequent convolutional operations need to process.

3.2 Depthwise Separable Convolution

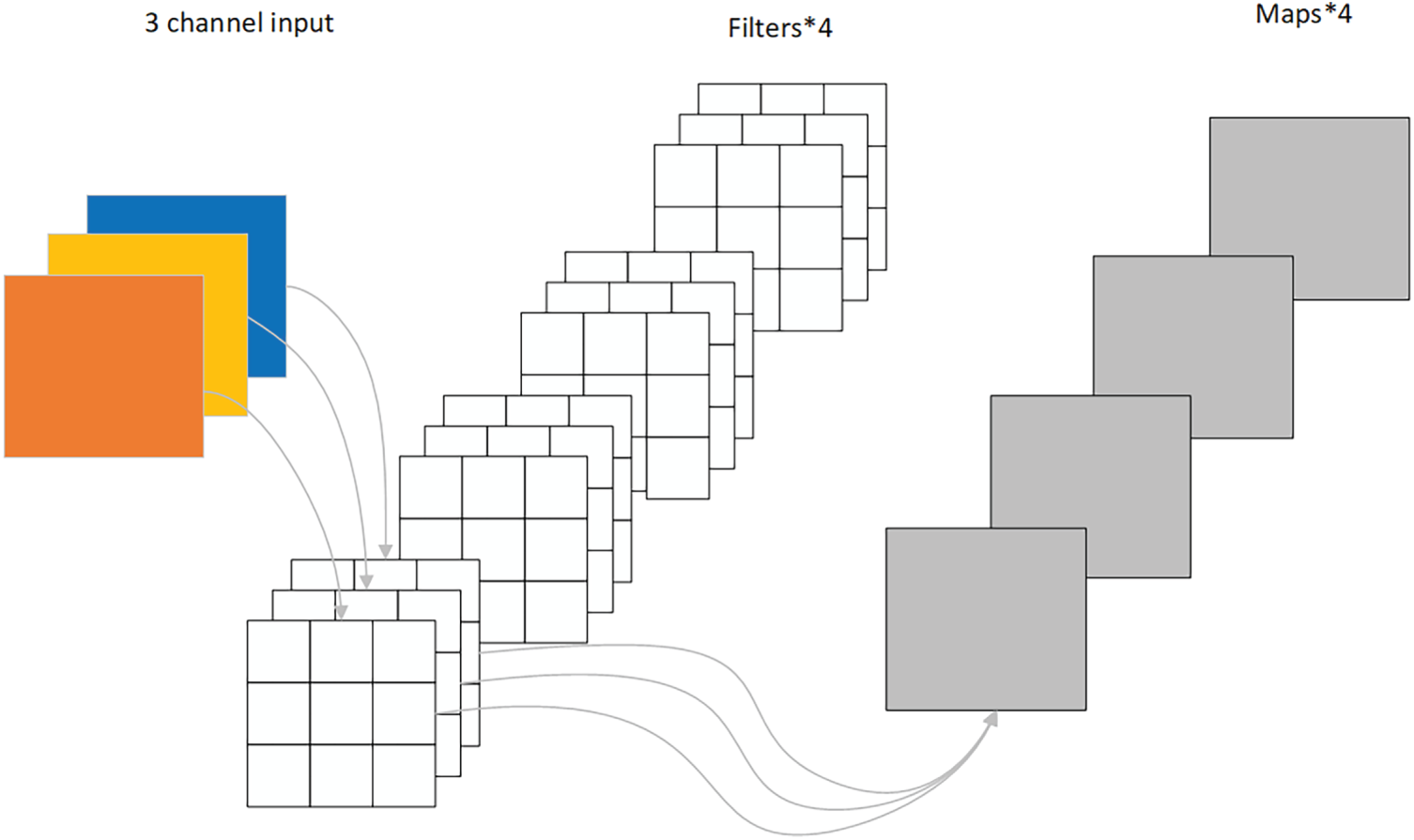

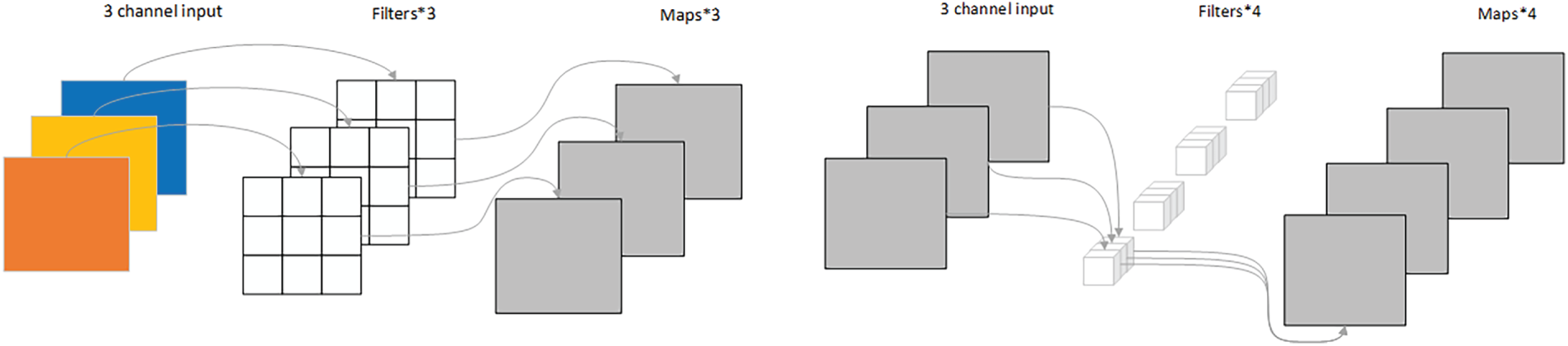

Conventional convolution is shown in Fig. 4, while depth-separable convolution [33] (DSConv) is shown in Fig. 5. It primarily consists of two processes: depthwise convolution and pointwise convolution. In depthwise convolution, a single convolution kernel (

Figure 4: Ordinary convolution

Figure 5: Depthwise separable convolution

By comparing the relationship between the parameters of the two, a calculation formula is obtained, where N is generally large and can be ignored. The size of the convolution kernel

3.3 Polarized Self-Attention Module

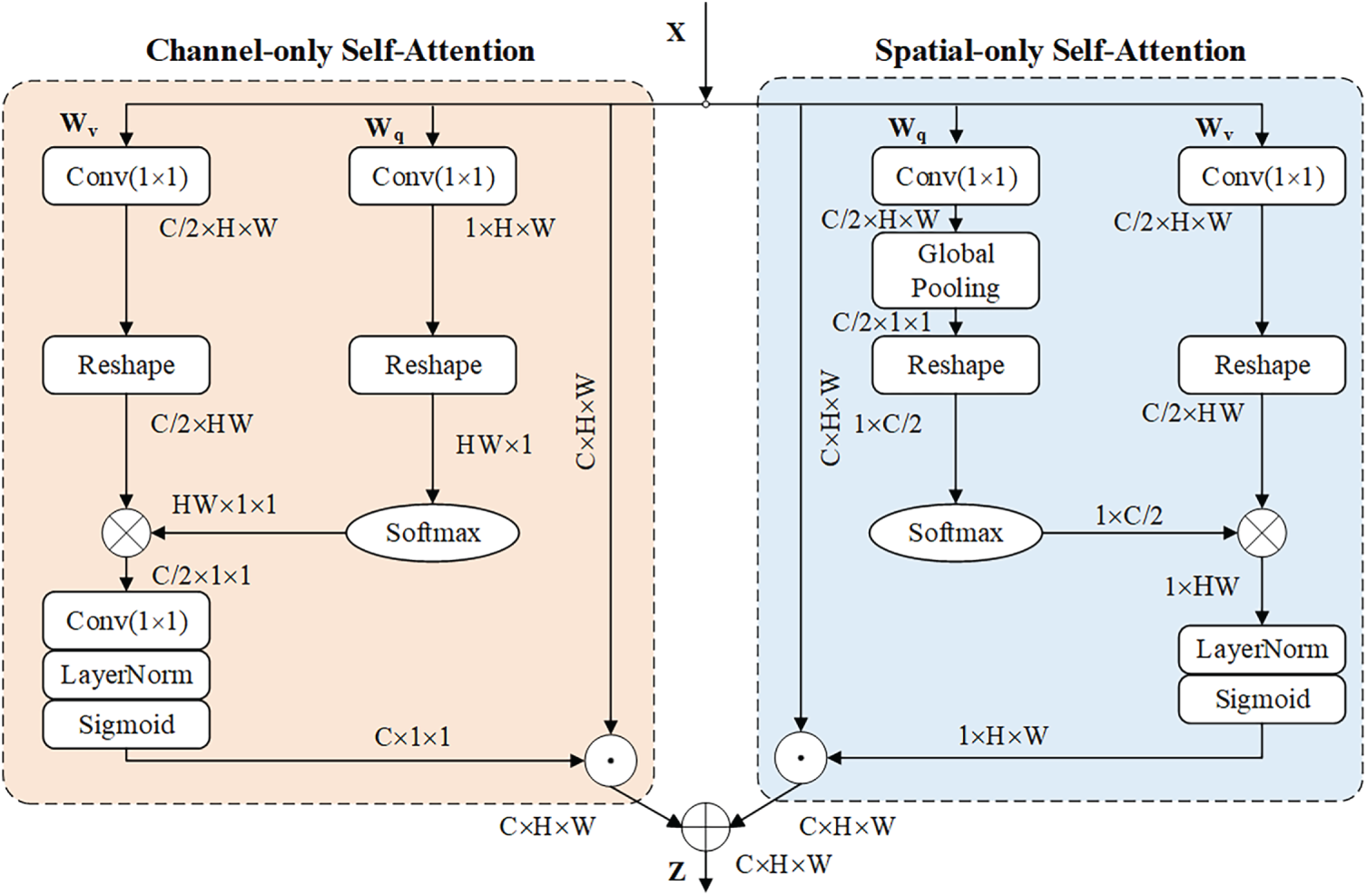

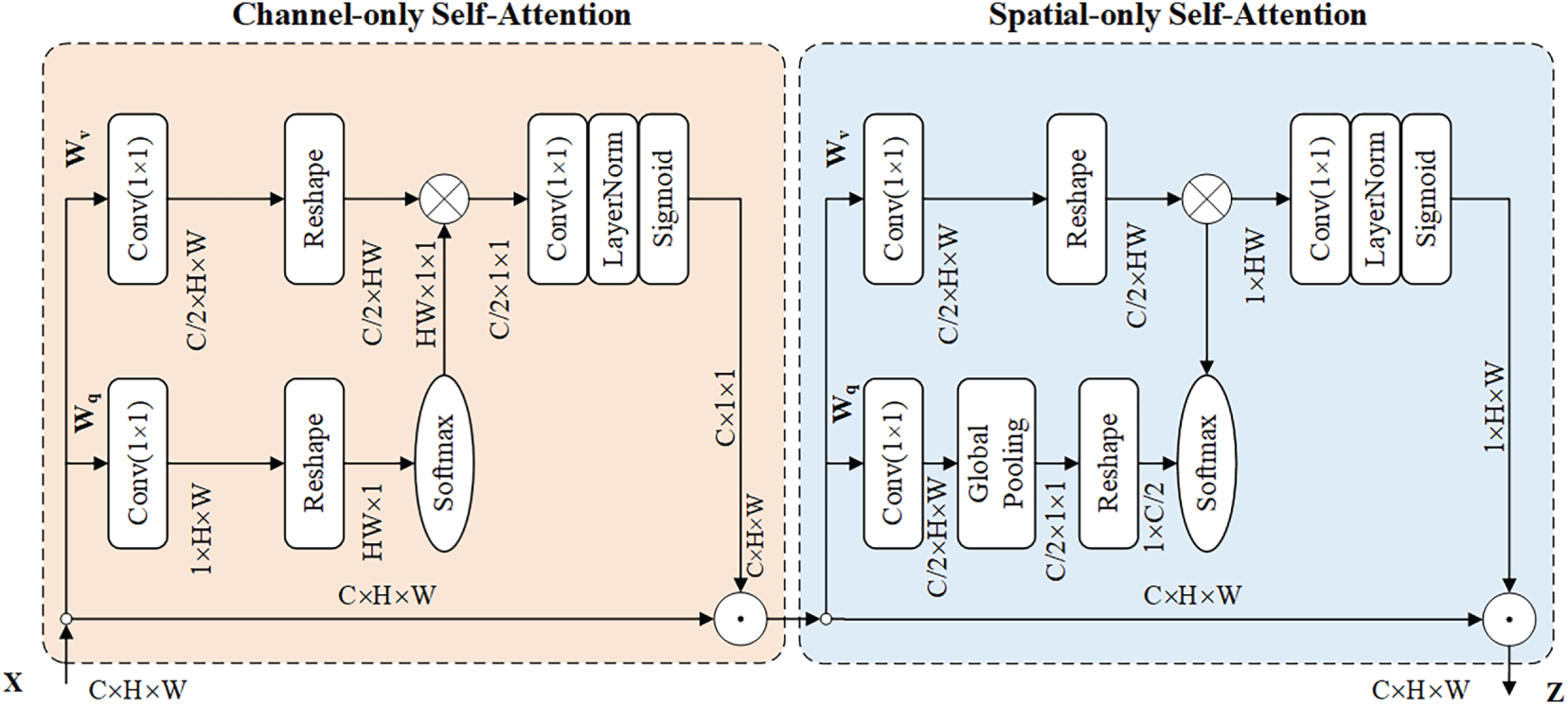

Since the human eye cannot focus on the entire image, it tends to pay more attention to the details of a specific area within the image. The attention mechanism in neural networks simulates this characteristic by focusing on key regions within an image to enhance processing efficiency. However, many mainstream attention methods often perform dimensionality reduction on features to enhance computational efficiency, which may result in the loss of critical information. This paper introduces a polarized attention mechanism that incorporates both channel attention and spatial attention to enhance model performance.

There are two main forms of polarization attention mechanisms: serial and parallel. After inserting the polarization attention mechanism into the ASPP module, the model can increase the extraction of important information and improve the utilization rate of the model. PSA_p and PSA_s can maintain high resolution in the channel and spatial dimensions, as shown in Figs. 6 and 7 below. The serial and parallel forms of the polarization attention mechanism are divided into channel branches and spatial branches.

Figure 6: PSA parallel connection

Figure 7: PSA series connection

The channel weights (Eq. (2)) are calculated as follows:

where 1 × 1 convolution is indicated by

The spatial weights (Eq. (3)) are calculated as follows:

where 1 × 1 convolution is indicated by

From the perspective of computational complexity, both serial and parallel architectures exhibit identical total floating-point operations (FLOPs), approximately

3.4 Simple Linear Iterative Clustering

This paper uses the Simple Linear Iterative Cluster (SLIC) superpixel segmentation algorithm to segment lane line images. This algorithm generates structurally compact and approximately uniform image superpixels, making it an efficient superpixel segmentation algorithm. The specific implementation process of the SLIC superpixel segmentation algorithm is as follows:

(1) Initialize cluster centers: Distribute cluster centers uniformly across the target image based on the preset number of superpixels. Assuming the total number of pixels is

(2) Update cluster centers: Calculate the gradient values of pixels within the initial cluster center

(3) Distance measurement and label assignment: Measure the distance for each pixel point within the

where the color distance is represented by

In Eq. (6),

Since each pixel in an image has several distances to the surrounding cluster centers, the algorithm specifies that the cluster center corresponding to the smallest distance among all distances shall be taken as the cluster center of that pixel.

(4) Repeat the above steps until the algorithm converges.

(5) Enhance connectivity between superpixels.

As discussed above, this algorithm only requires the user to input two parameters: the total number of superpixels

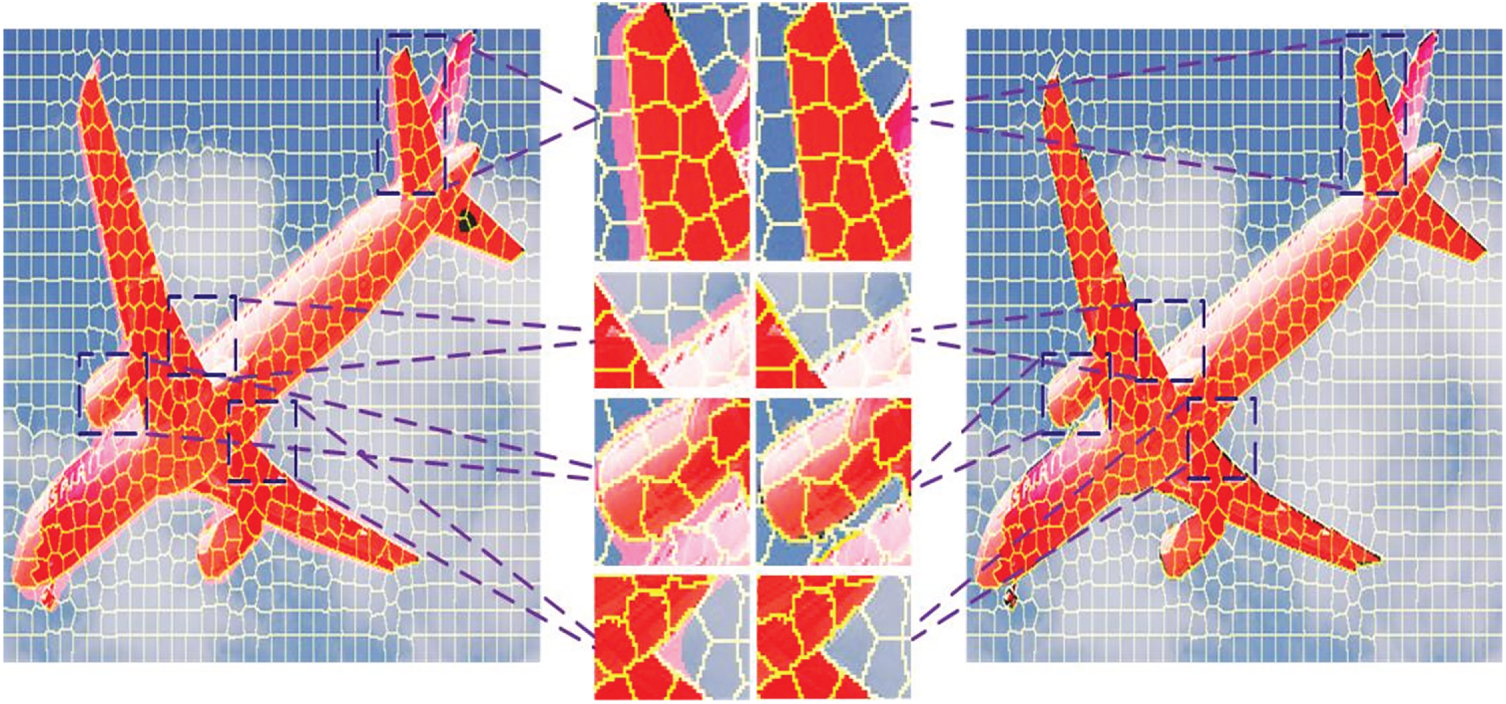

Figure 8: Schematic diagram of hyperpixel segmentation

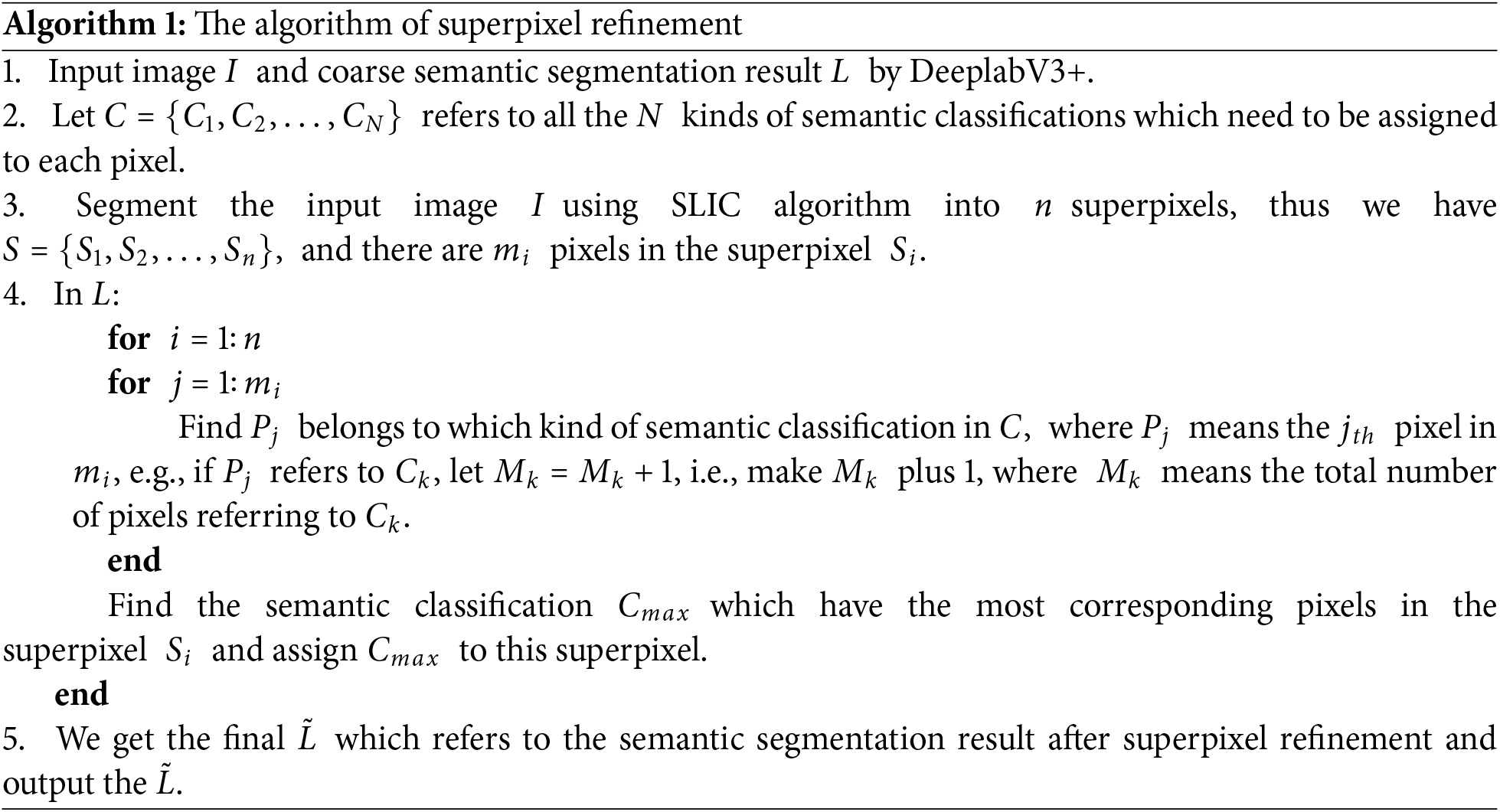

After obtaining the superpixel information of the image, this paper’s image semantic segmentation algorithm achieves semantic segmentation of the image by statistically analyzing the total number of pixels occupied by each semantic category within each superpixel, selecting the semantic category with the highest total number of pixels, and assigning it to the corresponding superpixel. This is based on the relatively coarse semantic segmentation results output by MNv4-DeepLabv3+. Fig. 9 illustrates the superpixel optimization process, with the Algorithm 1 approach outlined as follows:

Figure 9: Schematic diagram of hyperpixel optimization

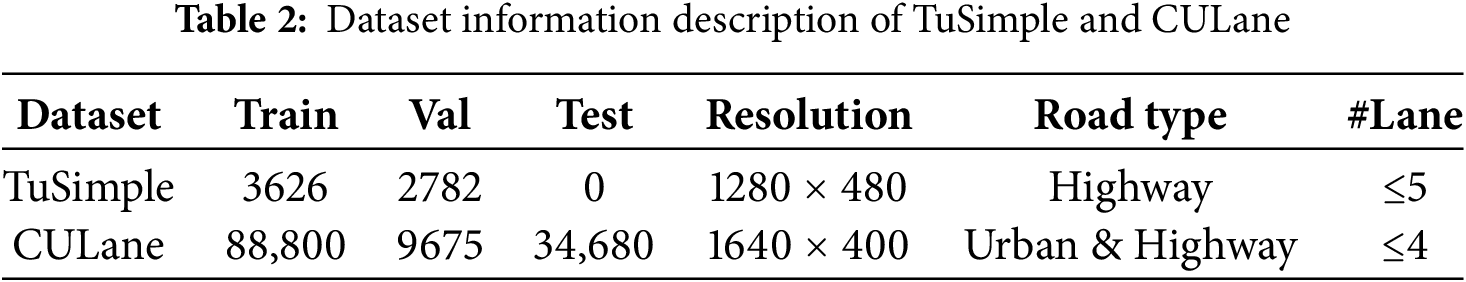

To evaluate this detection method, experiments were conducted on widely used benchmark datasets (the TuSimple dataset and the CULane dataset). The TuSimple dataset used in this paper was collected on highways and contains 3626 training images and 2782 validation images. The CULane dataset was proposed in the SCNN paper and was collected using cameras installed on six different vehicles driven by different drivers in Beijing. It includes over 55 h of video and 133,235 frames. Each image is labeled with up to four lane lines, and the image size is 1640 × 590 pixels. We divided the dataset into 88,880 training images, 9675 validation images, and 34,680 test images. The test set was divided into normal categories and eight challenging categories. During training, the dataset was divided into two categories: background and lane lines. To prevent irrelevant objects from interfering with detection, the lower two-thirds of the original image was cropped and retained as the region of interest. The dataset details are shown in Table 2.

4.2 Experimental Equipment and Evaluation Indicators

The operating system used in this experiment was Ubuntu 20.04, the open-source deep learning framework PyTorch was version 2.4.1, and the CUDA version was 12.1. The programming language was Python 3.8. The hardware configuration was as follows: CPU was QEMU Virtual CPU version 2.5+, and GPU was Tesla V100-SXM2-32 GB.

In the ablation experiment, F1-score, the mean intersection over union (MloU) and mean pixel accuracy (mPA) were used as performance evaluation metrics for image semantic segmentation. In Eq. (9),

In the comparative experiments, for the TuSimple dataset, the official competition evaluation metric was “Accuracy,” defined by Eq. (12), where

The algorithm proposed in this paper is based on the original DeepLabv3+ model, incorporating the SLIC superpixel segmentation algorithm and introducing an attention mechanism to enable the model to focus more on important semantic information in deep features. The algorithm is trained using the Adam network model optimizer for 100 epochs to achieve the desired fitting effect. The training process is divided into two stages: the freezing stage and the thawing stage. In both the freezing stage and thawing stage, the maximum learning rate is set to 0.007, and the batch size is set to 8. To prevent overfitting, the weight decay rate is set to 0.0001. An epoch refers to the process where all data enters the network to complete one forward computation and backpropagation. The epoch is set to 100, with 50 epochs in the freezing stage and 50 epochs in the thawing stage. Both the improved and original models use 50 epochs in the freezing phase and 50 epochs in the thawing phase. This paper employs the MIoU and mPA evaluation metrics and the Accuracy, FPR, and FNR evaluation metrics, conducting ablation experiments and comparison experiments on the TuSimple and CULane datasets to validate the model’s performance.

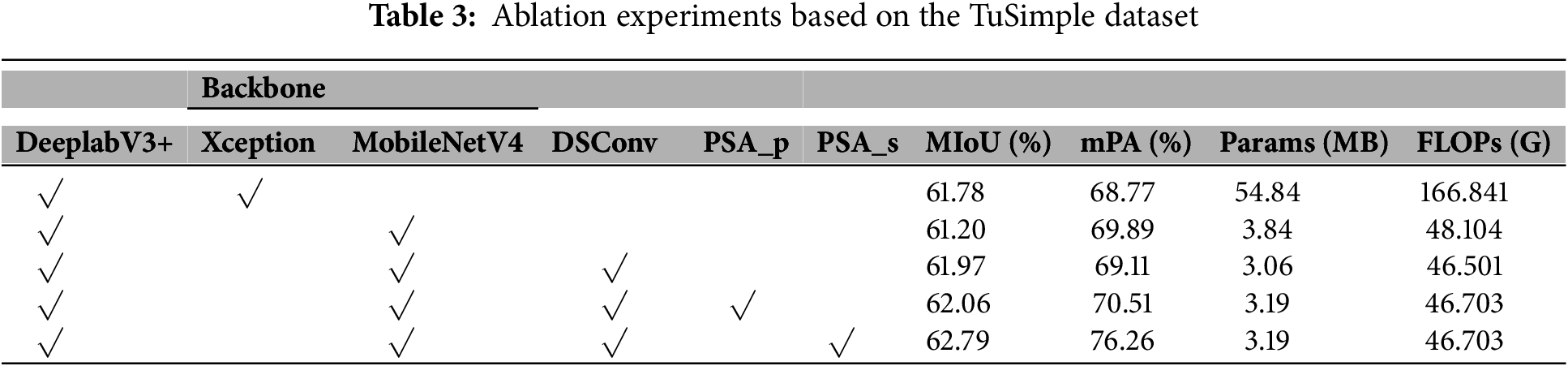

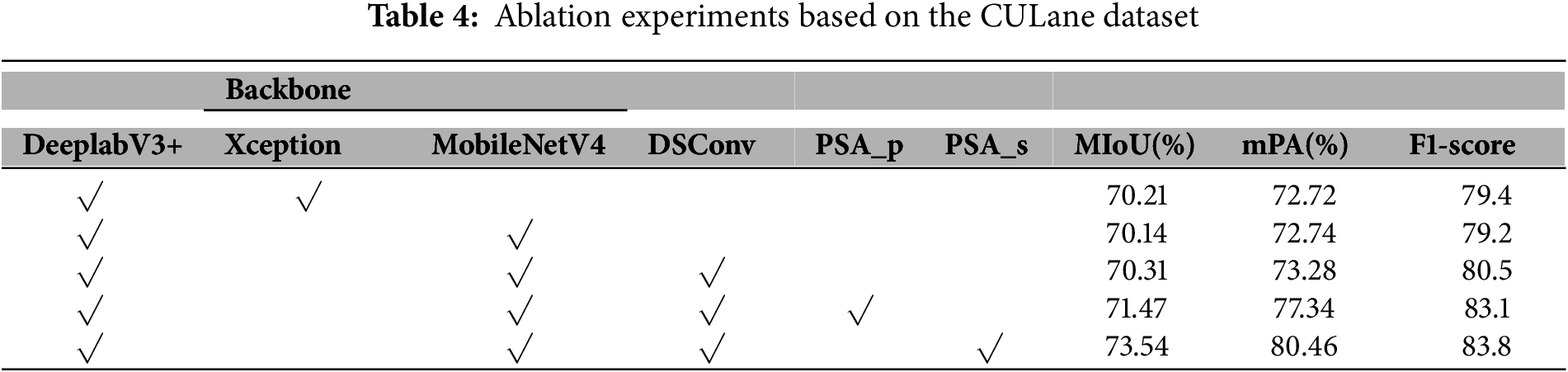

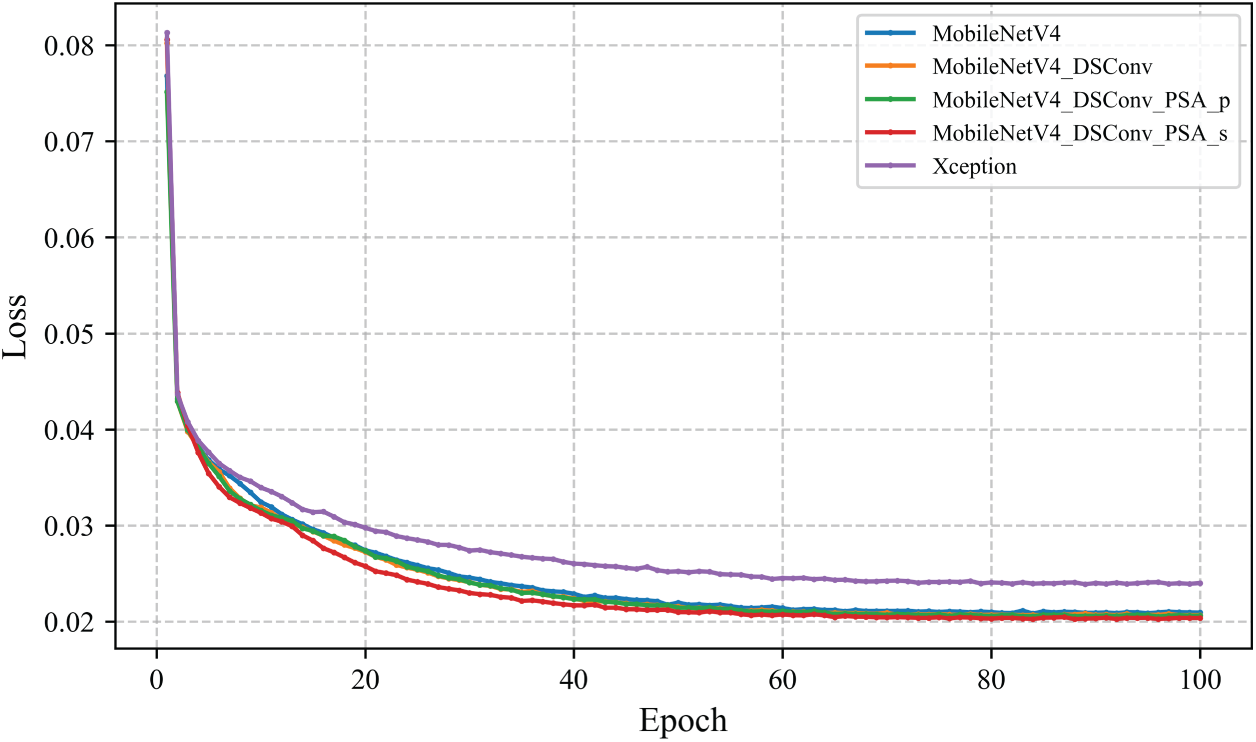

Tables 3 and 4 present ablation experiments conducted on the TuSimple and CULane datasets, respectively. As shown in Table 3, replacing Xception with MobileNetV4 reduces the number of parameters from 54.84 to 3.84 M. Although MIoU decreases slightly, mAP improves by 1.12%. Further reducing the number of parameters to 3.06 M using DSConv resulted in a 0.19% improvement in MIoU compared to the baseline model. Finally, PSA was introduced in both parallel and serial configurations. The results showed that the serial configuration of PSA performed better, with MIoU improving by 1.01% and mPA improving by 7.49%, while the number of parameters was reduced to 3.19 M and Floating Point Operations per Second (FLOPs) decreased to 46.703 G. Table 4 shows that lightweighting does not significantly improve MIoU and mPA. PSA_p and PSA_s improve MIoU by 1.26% and 3.33%, respectively, mPA by 4.62% and 7.74%, respectively, and F1-score by 3.7% and 4.4%, respectively. Both ablation experiments demonstrate that although the computational complexity of serial and parallel PSA is identical, PSA_s yields superior performance, consistent with our theoretical analysis in Section 3.3. Fig. 10 shows the loss values for the TuSimple training set. The red line (the final improved model) converges the fastest and has the smallest value after stabilization.

Figure 10: Training loss value of the TuSimple dataset

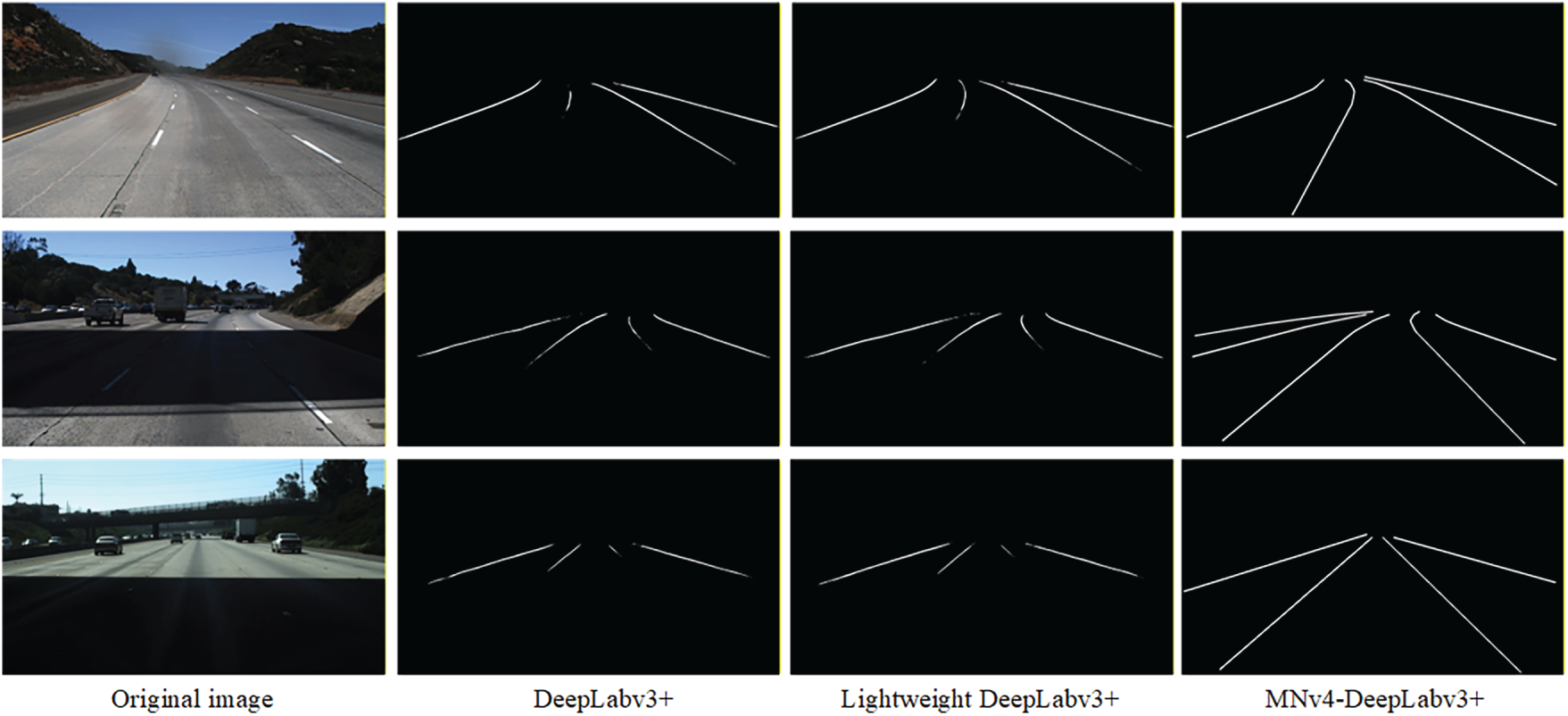

We conducted a comparative analysis of three sets of images, as shown in Fig. 11. The first column shows the original images, the second column shows the detection results of the original DeepLabv3+ model, the third column shows the detection results after lightweight processing using a backbone network and ordinary convolutional layers, and the fourth column shows the detection results of the MNv4-DeepLabv3+ model after introducing the PSA_s and SLIC superpixel segmentation algorithms. The results show that the PSA_s algorithm performs exceptionally well in shadowed areas, while the SLIC algorithm significantly improves edge details, thereby enhancing the overall detection performance.

Figure 11: Visualization of ablation experiments

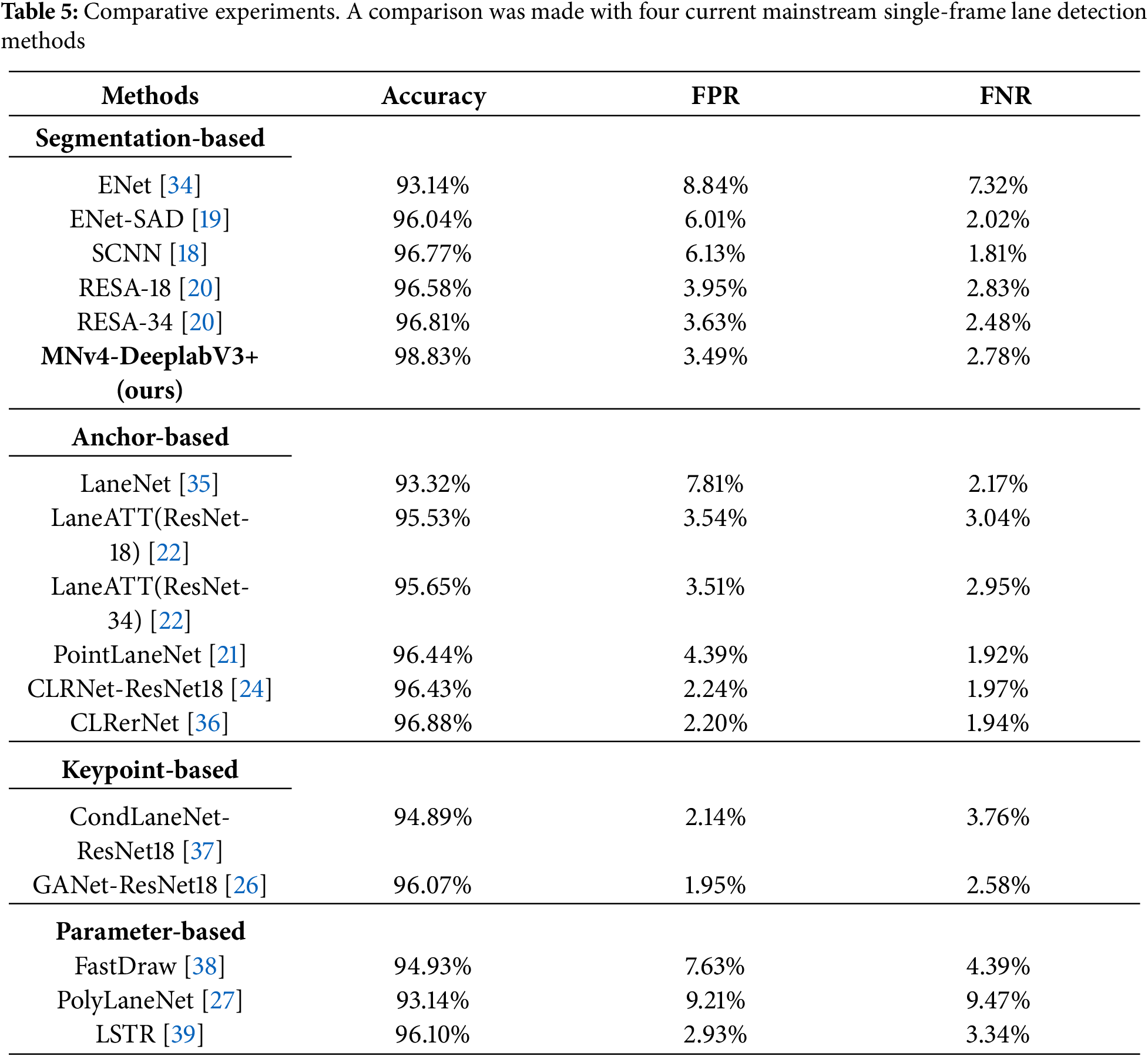

As shown in Table 5, compared to the four mainstream methods, our model achieves the highest accuracy of 98.83%, demonstrating its overall segmentation performance. However, an in-depth analysis of the FPR and FNR metrics reveals performance trade-offs: compared to GANet (lowest FPR of 1.95%), our model exhibits a higher FPR, indicating inferior performance in suppressing false positives. This may stem from our segmentation-based approach being more sensitive to ambiguous “lane-like” features. Compared to SCNN (lowest FNR of 1.81%), our model exhibits higher FNR, indicating inferior performance in handling false negatives. This highlights SCNN’s advantage in leveraging contextual information to connect discontinuous lane markings.

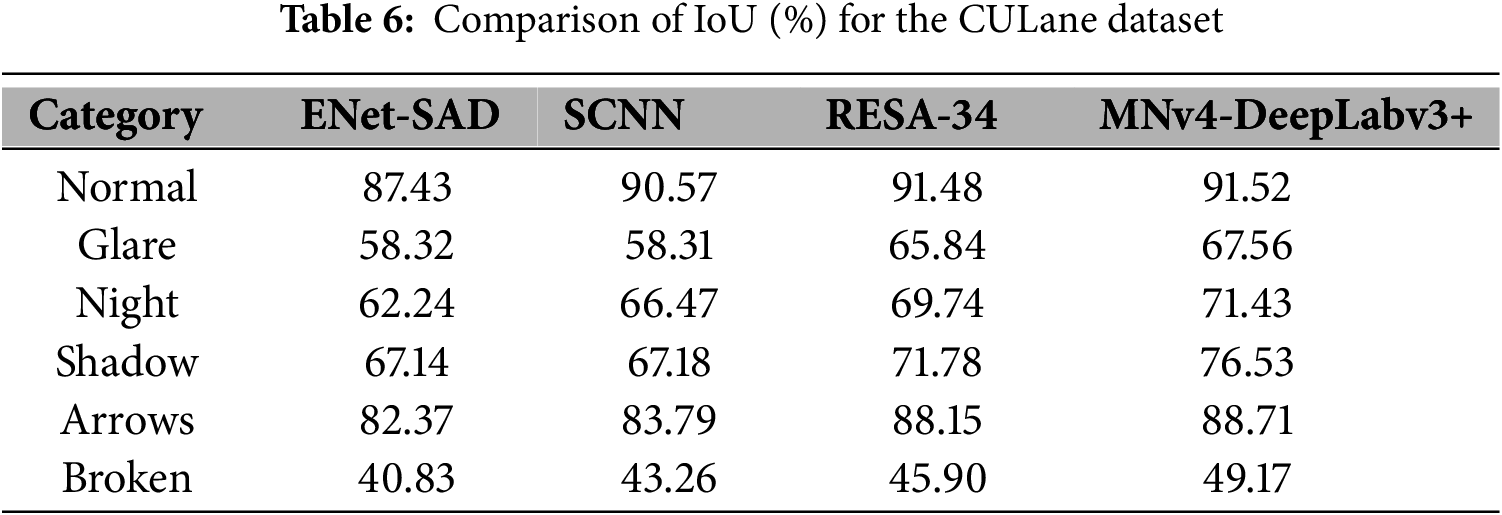

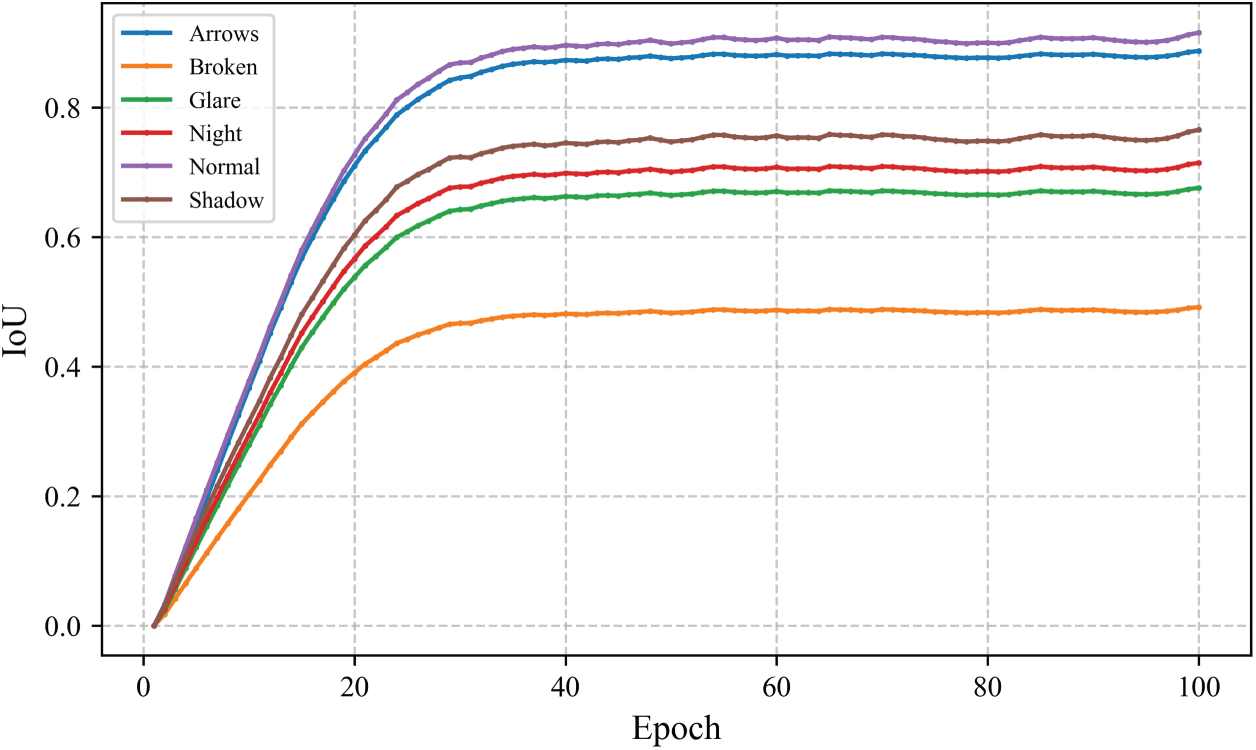

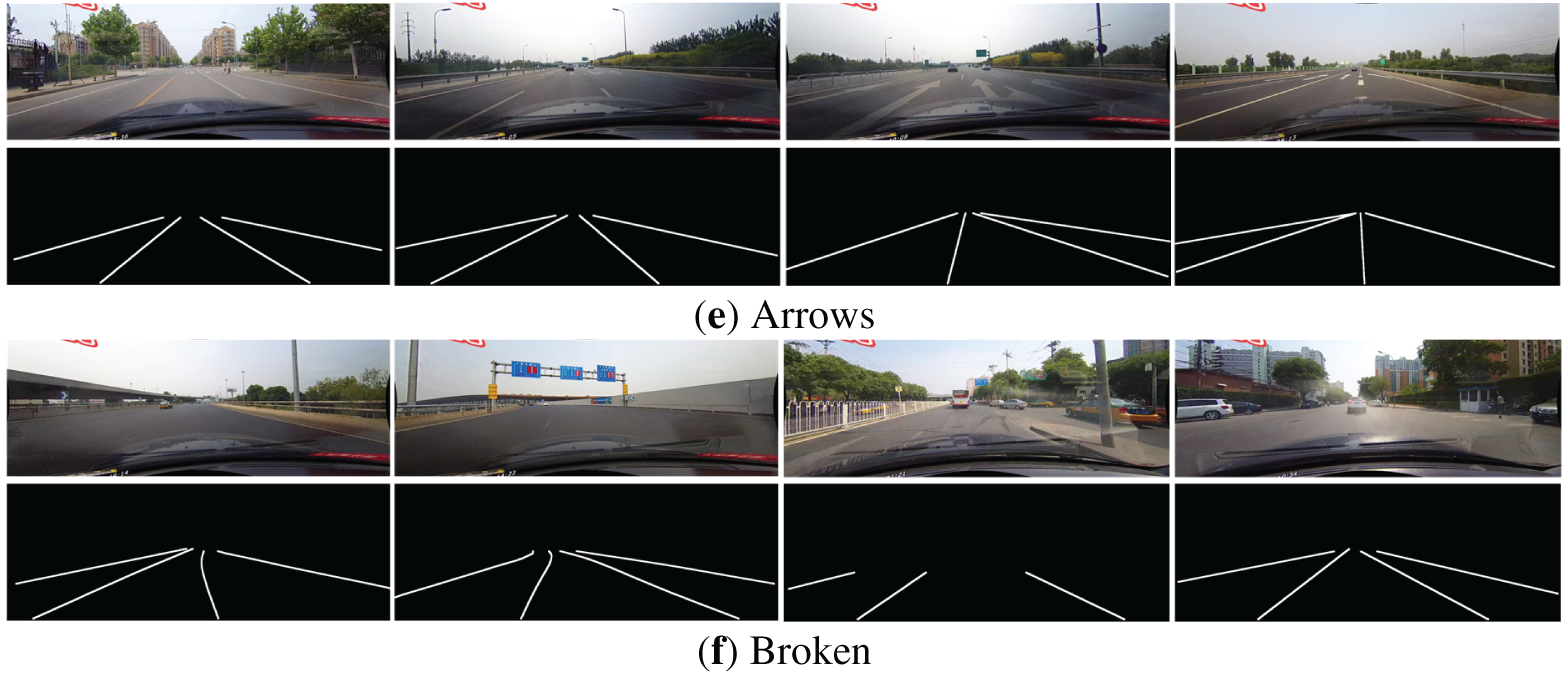

Table 6 compares the MNv4-DeepLabv3+ model with the ENet-SAD, SCNN, and RESA-34 semantic segmentation models using IoU as the evaluation metric based on the CULane dataset, and tests were conducted across six scenarios: normal, glare, night, shadow, arrows, and broken. The results show that the MNv4-DeepLabv3+ model achieves the highest IoU across all six scenarios. At the same time, Fig. 12 demonstrates the IoU performance of our method across six scenarios on the CULane dataset, further validating its superior performance in complex environments.

Figure 12: IoU curves for six scenarios in the CULane dataset

Fig. 13 illustrates failure cases of our method in scenarios with strong glare and severe occlusion. The top row shows the original images, while the bottom row displays the corresponding detection result overlay. The overlays reveal that the model performs poorly in detecting both strong glare (first two columns) and severe occlusion (last two columns). Strong glare or excessively bright light causes overexposure in images, eliminating contrast between lane markings and the road surface. The loss of this critical visual feature hinders effective lane line recognition. Secondly, severe lane line occlusion poses challenges when physical breaks occur in the markings. The model struggles to perform effective inference and connection, resulting in incomplete segmentation. This aligns with our analysis of the increased false negative rate (FNR). Future work can focus on enhancing the model’s robustness in these challenging scenarios.

Figure 13: Failure cases involving glare and severe occlusion

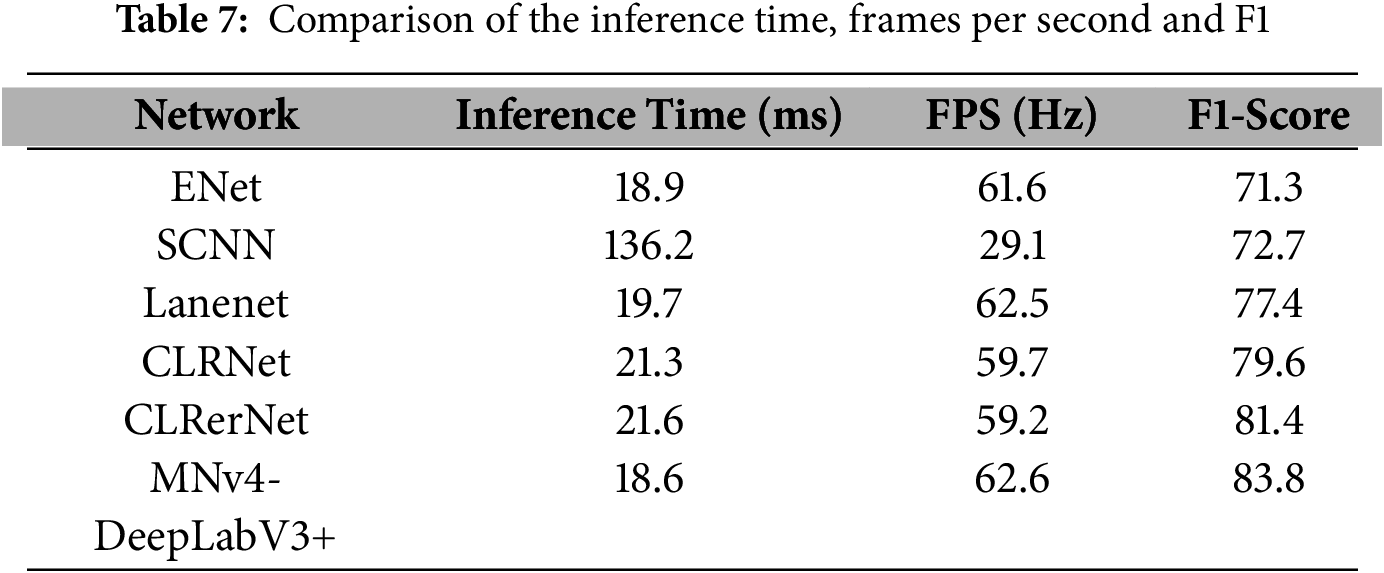

Table 7 demonstrates that the proposed MNv4-DeepLabv3+ achieves faster inference time, lower frames per second, and higher F1-score, indicating superior image transmission speed and lane detection speed.

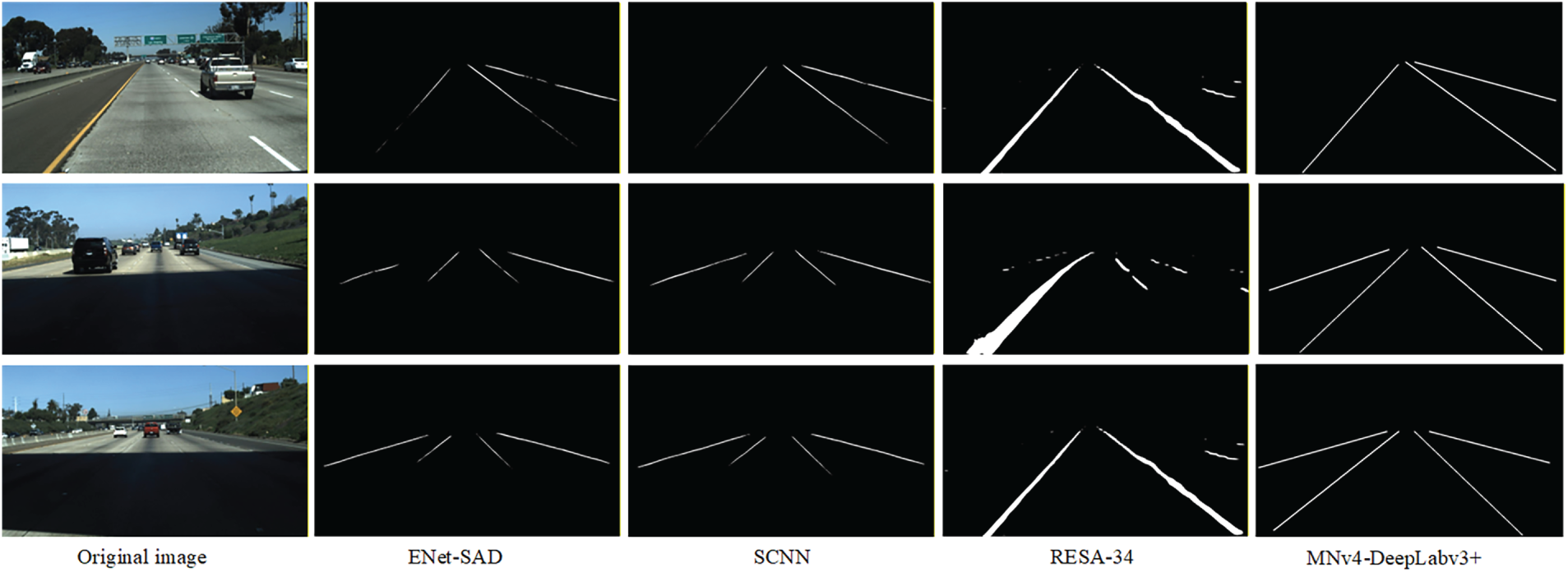

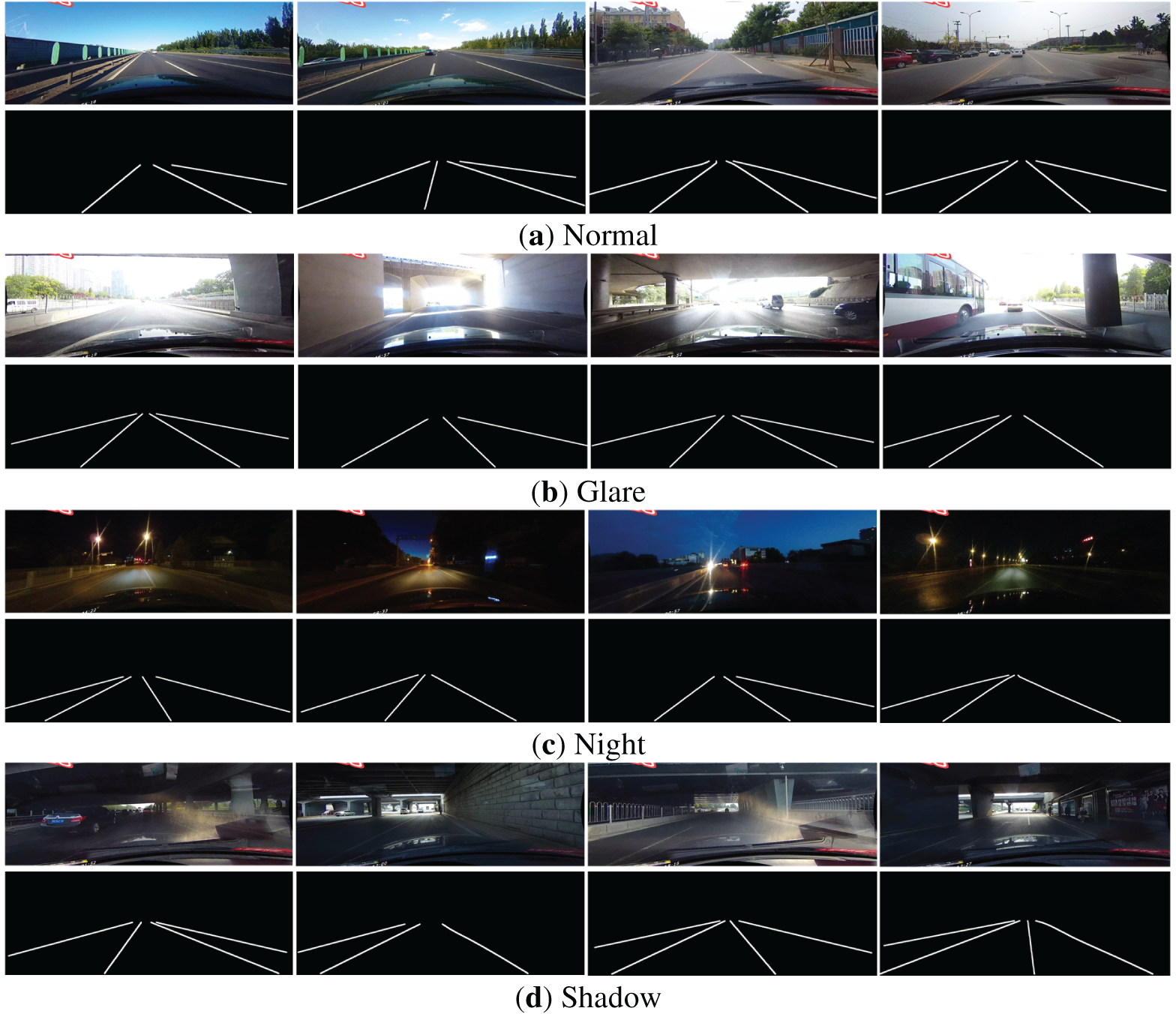

Fig. 14 shows the segmentation results of three sets of images using different semantic segmentation models, arranged in columns as follows: original image, ENet-SAD, SCNN, RESA-34, and MNv4-DeepLabv3+ models. It can be seen that the ENet-SAD and SCNN models perform well in detecting distant lane lines but have poor detection performance in shadowed areas. Although the RESA-34 model shows improved performance in shadowed areas, it performs poorly in detecting lane lines on both sides at a distance. In contrast, the MNv4-DeepLabv3+ model demonstrates superior overall detection performance across various scenarios. Fig. 15 shows the test results based on the improved model in six scenarios: normal, glare, night, shadow, arrow, and damaged lane lines. The results show that PSA performs significantly well in complex scenarios in terms of lane line detection, and the SLIC superpixel optimization algorithm can effectively protect the edge information of lane lines.

Figure 14: Visualization of comparative experiments

Figure 15: Tests in six scenarios

To address the issues of reduced segmentation accuracy in complex road scenes and the large number of model parameters, this paper proposes the MNv4-DeepLabv3+ algorithm. The Xception backbone network in the original DeepLabv3+ model is replaced with the lightweight MobileNetV4, and the standard convolutions in the ASPP module are replaced with depth-separable convolutions, significantly reducing the number of model parameters while maintaining high feature extraction capabilities. A polarized attention mechanism is introduced in a serial form after the ASPP module, performing attention calculations in both the channel and spatial dimensions to enhance the detail information in the feature maps, thereby improving the accuracy of semantic segmentation in complex road scenes. To optimize the semantic segmentation performance of lane line images, the SLIC superpixel segmentation algorithm is introduced. By integrating high-level semantic features from the image with edge information from the superpixel image, the method better preserves the details of lane line edges, addressing the issue of suboptimal segmentation performance in the original model along lane line edges. Segmentation results on the TuSimple and CULane datasets demonstrate that our method balances parameter count and accuracy, exhibiting strong generalization capabilities in complex road scenes.

In real-world scenarios, obtaining a large number of pixel-level semantic annotations for lane line images requires significant human and time costs. Furthermore, annotations are susceptible to subjective factors, resulting in inconsistent quality, which in turn affects network detection performance. To address these challenges, the next step could involve combining a semi-supervised method based on consistency regularization and pseudo labels with a semantic segmentation model to provide high-quality pseudo labels for model training, thereby improving segmentation performance.

Acknowledgement: We extend our heartfelt gratitude to all participants who generously contributed their valuable time and effort, making significant contributions to our research. We also express our deep appreciation to the editors and anonymous reviewers whose insightful comments and suggestions greatly enhanced the quality of this manuscript. Furthermore, we would like to extend special thanks to our advisor, whose expert guidance and unwavering support were crucial to our research endeavors.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors acknowledge their contributions to the paper as follows: Research conception and design: Yingkai Ge; Dataset processing: Jiale Zhang, Zhenguo Ma, Yu Liu; Analysis and interpretation of results: Yingkai Ge; Manuscript preparation: Yingkai Ge, Jiasheng Zhang; Manuscript revision: Lihua Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhao J, Qiu Z, Hu H, Sun S. HWLane: HW-transformer for lane detection. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2024;25(8):9321–31. doi:10.1109/tits.2024.3386531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chai Y, Wang S, Zhang Z. A fast and accurate lane detection method based on row anchor and transformer structure. Sensors. 2024;24(7):2116. doi:10.3390/s24072116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Li J, Jiang F, Yang J, Kong B, Gogate M, Dashtipour K, et al. Lane-DeepLab: lane semantic segmentation in automatic driving scenarios for high-definition maps. Neurocomputing. 2021;465:15–25. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2021.08.105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Long J, Shelhamer E, Darrell T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2015 Jun 7–12; Boston, MA, USA. p. 3431–40. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2015.7298965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chen LC, Zhu Y, Papandreou G, Schroff F, Adam H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 801–18. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Liu Y, Bai X, Wang J, Li G, Li J, Lv Z. Image semantic segmentation approach based on DeepLabV3 plus network with an attention mechanism. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;127:107260. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xia Y, Qiu J. SFC_DeepLabv3+: a lightweight grape image segmentation method based on content-guided attention fusion. Comput Mater Continua. 2025;84(2):2531–47. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.064635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Patel S, Shah P, Patel D, Patel N, Patel J. Hybrid lane detection system combining SCNN, canny edge detection, and Hough transform. In: Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on I-SMAC; 2024 Oct 3–5; Kirtipur, Nepal. p. 327–32. doi:10.1109/i-smac61858.2024.10714603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Segu GSPK, Sivannarayana ADSN, Ramesh S. Real time road lane detection and vehicle detection on YOLOv8 with interactive deployment. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 16th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Networks (CICN); 2024 Dec 22–23; Indore, India. p. 267–72. doi:10.1109/cicn63059.2024.10847549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhao Y, Han L, Chen J, Liang F, Tang H, Wu J, et al. Real-time lane detection based on dual attention mechanism transformer for ADAS/AD. In: IEEE transactions on vehicular technology. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2025. p. 1–10. doi:10.1109/tvt.2025.3618940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Qin D, Leichner C, Delakis M, Fornoni M, Luo S, Yang F, et al. MobileNetV4: universal models for the mobile ecosystem. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 78–96. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-73661-2_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chollet F. Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1251–8. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2017.195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang Z, Song R. A modified Deeplabv3+ model based on polarized self-attention mechanism. In: Proceedings of the 2023 42nd Chinese Control Conference (CCC); 2023 Jul 24–26; Tianjin, China. p. 8721–6. doi:10.23919/ccc58697.2023.10241058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Achanta R, Shaji A, Smith K, Lucchi A, Fua P, Süsstrunk S. SLIC superpixels compared to state-of-the-art superpixel methods. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2012;34(11):2274–82. doi:10.1109/tpami.2012.120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wang Y, Dahnoun N, Achim A. A novel system for robust lane detection and tracking. Signal Process. 2012;92(2):319–34. doi:10.1016/j.sigpro.2011.07.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kumar S, Jailia M, Varshney S. An efficient approach for highway lane detection based on the Hough transform and Kalman filter. Innov Infrastruct Solut. 2022;7(5):290. doi:10.1007/s41062-022-00887-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sukumar N, Sumathi P. A robust vision-based lane detection using RANSAC algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Global Conference on Computing, Power and Communication Technologies (GlobConPT); 2022 Sep 23–25; New Delhi, India. p. 1–5. doi:10.1109/globconpt57482.2022.9938320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pan X, Shi J, Luo P, Wang X, Tang X. Spatial as deep: spatial CNN for traffic scene understanding. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2018;32(1). doi:10.1609/aaai.v32i1.12301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hou Y, Ma Z, Liu C, Loy CC. Learning lightweight lane detection CNNs by self attention distillation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 1013–21. doi:10.1109/iccv.2019.00110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zheng T, Fang H, Zhang Y, Tang W, Yang Z, Liu H, et al. RESA: recurrent feature-shift aggregator for lane detection. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2021;35(4):3547–54. doi:10.1609/aaai.v35i4.16469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chen Z, Liu Q, Lian C. PointLaneNet: efficient end-to-end CNNs for accurate real-time lane detection. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV); 2019 Jun 9–12; Paris, France. p. 2563–8. doi:10.1109/ivs.2019.8813778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tabelini L, Berriel R, Paixao TM, Badue C, De Souza AF, Oliveira-Santos T. Keep your eyes on the lane: real-time attention-guided lane detection. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 294–302. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.00036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu B, Ling Q. Hyper-anchor based lane detection. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2024;25(10):13240–52. doi:10.1109/tits.2024.3410376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Honda H, Uchida Y. CLRerNet: improving confidence of lane detection with LaneIoU. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2024 Jan 3–8; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 1176–85. doi:10.1109/wacv57701.2024.00121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Qu Z, Jin H, Zhou Y, Yang Z, Zhang W. Focus on local: detecting lane marker from bottom up via key point. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 14122–30. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.01390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang J, Ma Y, Huang S, Hui T, Wang F, Qian C, et al. A keypoint-based global association network for lane detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 1392–401. doi:10.1109/cvpr52688.2022.00145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Tabelini L, Berriel R, Paixao TM, Badue C, De Souza AF, Oliveira-Santos T. PolyLaneNet: lane estimation via deep polynomial regression. In: Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR); 2021 Jan 10–15; Milan, Italy. p. 6150–6. doi:10.1109/icpr48806.2021.9412265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang J, Zhong H. Curve-based lane estimation model with lightweight attention mechanism. Signal Image Video Process. 2023;17(5):2637–43. doi:10.1007/s11760-022-02480-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ren S. Occluded lane line detection with deep polynomial regression in global view. Inf Technol Control. 2025;54(1):32–43. doi:10.5755/j01.itc.54.1.38802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zou Q, Jiang H, Dai Q, Yue Y, Chen L, Wang Q. Robust lane detection from continuous driving scenes using deep neural networks. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2020;69(1):41–54. doi:10.1109/tvt.2019.2949603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang Y, Zhu L, Feng W, Fu H, Wang M, Li Q, et al. VIL-100: a new dataset and a baseline model for video instance lane detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 15681–90. doi:10.1109/iccv48922.2021.01539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhou Z, Zhang J, Gong C. Hybrid semantic segmentation for tunnel lining cracks based on Swin Transformer and convolutional neural network. Computer Aided Civil Eng. 2023;38(17):2491–510. doi:10.1111/mice.13003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Tong Q, Zhu Z, Zhang M, Cao K, Xing H. CrossFormer embedding DeepLabv3+ for remote sensing images semantic segmentation. Comput Mater Continua. 2024;79(1):1353–75. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.049187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lyu H, Zhu Z, Fu S. ENet-SAD-a CNN-based lane detection for recognizing various road conditions. In: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Algorithms, Network, and Communication Technology (ICANCT 2024); 2024 Dec 20–22; Wuhan, China. Vol. 13545. p. 268–76. doi:10.1117/12.3060154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Du Y, Zhang R, Shi P, Zhao L, Zhang B, Liu Y. ST-LaneNet: lane line detection method based on swin transformer and LaneNet. Chin J Mech Eng. 2024;37(1):14. doi:10.1186/s10033-024-00992-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zheng T, Huang Y, Liu Y, Tang W, Yang Z, Cai D, et al. CLRNet: cross layer refinement network for lane detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 898–907. doi:10.1109/cvpr52688.2022.00097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu L, Chen X, Zhu S, Tan P. CondLaneNet: a top-to-down lane detection framework based on conditional convolution. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 3773–82. doi:10.1109/iccv48922.2021.00375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Philion J. FastDraw: addressing the long tail of lane detection by adapting a sequential prediction network. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 11582–91. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.01185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Liu R, Yuan Z, Liu T, Xiong Z. End-to-end lane shape prediction with transformers. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2021 Jan 3–8; Waikoloa, HI, USA. p. 3694–702. doi:10.1109/wacv48630.2021.00374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools