Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Keyword Spotting Based on Dual-Branch Broadcast Residual and Time-Frequency Coordinate Attention

1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Shandong University of Technology, Zibo, 255000, China

2 Department of Information Management, National Taipei University of Business, Taipei, 10051, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Jian-Hong Wang. Email: ; Kuo-Chun Hsu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 9 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072881

Received 05 September 2025; Accepted 27 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

In daily life, keyword spotting plays an important role in human-computer interaction. However, noise often interferes with the extraction of time-frequency information, and achieving both computational efficiency and recognition accuracy on resource-constrained devices such as mobile terminals remains a major challenge. To address this, we propose a novel time-frequency dual-branch parallel residual network, which integrates a Dual-Branch Broadcast Residual module and a Time-Frequency Coordinate Attention module. The time-domain and frequency-domain branches are designed in parallel to independently extract temporal and spectral features, effectively avoiding the potential information loss caused by serial stacking, while enhancing information flow and multi-scale feature fusion. In terms of training strategy, a curriculum learning approach is introduced to progressively improve model robustness from easy to difficult tasks. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method consistently outperforms existing lightweight models under various signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions, achieving superior far-field recognition performance on the Google Speech Commands V2 dataset. Notably, the model maintains stable performance even in low-SNR environments such as –10 dB, and generalizes well to unseen SNR conditions during training, validating its robustness to novel noise scenarios. Furthermore, the proposed model exhibits significantly fewer parameters, making it highly suitable for deployment on resource-limited devices. Overall, the model achieves a favorable balance between performance and parameter efficiency, demonstrating strong potential for practical applications.Keywords

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence technologies, voice-based human-computer interaction has become increasingly common in daily life. Among them, keyword spotting (KWS) aims to detect predefined keywords from continuous speech streams and has been widely adopted in modern intelligent devices. For example, commercial voice assistants such as Xiaomi’s XiaoAi and Apple’s Siri can be activated with wake words like “xiaoaitongxue” or “Hey Siri” to launch applications and perform operations [1,2]. In the field of the Internet of Things (IoT), KWS is also applied in smart homes and in-vehicle intelligent systems, where users interact with devices via voice commands to control speakers, televisions, or automotive systems.

Typically, these tasks are deployed on resource-constrained edge devices with limited computation and memory. To ensure timely and accurate interaction, KWS systems are required not only to exhibit strong noise robustness but also to maintain a compact model size and low memory footprint, thereby meeting the stringent performance and energy constraints of mobile platforms.

In real-world applications, however, KWS faces a significant challenge: performance degradation in noisy environments. In practical usage scenarios, where acoustic conditions are highly dynamic and noise levels vary, KWS systems are prone to false alarms or missed detections, which can severely affect user experience. With the growing demand for edge-based voice interaction, increasing research attention has been devoted to developing lightweight KWS models suitable for deployment on resource-limited devices. Under ideal conditions such as low noise and near-field speech, these small-footprint models have already demonstrated promising recognition performance [3–7].

Nevertheless, in more complex real-world environments—for instance, in far-field scenarios with significant noise interference—their performance often deteriorates drastically. In particular, models with simplified architectures and fewer parameters usually suffer from limited generalization ability, making them vulnerable to unseen acoustic conditions. As a result, such models often experience accuracy degradation, delayed responses, or frequent false activations, which undermines both user experience and system reliability [8–11].

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows: We propose a lightweight keyword spotting model for noisy environments, namely Time-Frequency Dual-Branch Parallel Residual Network (TF-DBPResNet). The network leverages residual convolution and depthwise separable convolution for feature extraction, with a dual-branch parallel structure in the time and frequency domains as its core. This design fully exploits the critical characteristics of speech signals across temporal and spectral dimensions, thereby improving the model’s adaptability to diverse acoustic conditions. We design a Dual-Branch Broadcast Residual (DBBR) module to separately extract temporal and spectral features via two parallel branches. Through broadcast learning, the module achieves cross-dimensional information fusion and reconstruction, enhancing the feature representation capability. To further strengthen the joint perception between the time and frequency domains, we introduce the Time-Frequency Coordinate Attention (TFCA) module, inspired by coordinate attention mechanisms. TFCA models long-range dependencies along both time and frequency axes, effectively capturing salient responses in the time-frequency space and guiding the network to emphasize key information regions. We develop a curriculum learning strategy combined with online hard example mining to further enhance the model’s generalization under complex noise conditions. This strategy organizes training samples from easy to hard while dynamically focusing on the most challenging inputs at each stage. As a result, the model improves its ability to discriminate difficult samples and non-ideal speech inputs, while maintaining efficient convergence.

With the development of deep learning, deep neural networks were among the first to demonstrate success in the keyword spotting (KWS) task, and subsequent research has achieved continuous progress based on this foundation [12]. In 2015, Sainath et al. first applied convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to KWS [13]. Compared with traditional fully connected networks, CNNs offer fewer parameters and higher computational efficiency, while effectively modeling the temporal and spectral correlations in speech signals. Furthermore, CNNs allow flexible adjustment of network depth and width, making it easier to build lightweight models on edge devices with low computational cost. As a result, CNNs have shown significant advantages and become increasingly prevalent in KWS applications [14].

Speech signals inherently exhibit strong temporal sequential dependencies, which must be considered during modeling. Although CNNs were widely adopted in early KWS systems due to their local receptive field modeling, small parameter size, and computational efficiency, their fixed receptive fields limit the ability to capture long-range contextual dependencies, often neglecting the global temporal structure of speech. To address this limitation, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) were introduced into speech modeling. Variants such as long short-term memory (LSTM) and gated recurrent units (GRU) leverage gating mechanisms to mitigate the vanishing and exploding gradient problems of vanilla RNNs, thereby capturing long-term dependencies more effectively. In non-real-time scenarios, bidirectional LSTMs can simultaneously model past and future context, further improving KWS performance [15]. For wake-word detection, however, where speech segments are typically short and long dependencies are unnecessary, bidirectional GRUs achieve comparable accuracy while significantly reducing memory usage and training costs. Despite their stronger temporal modeling capacity, RNN-based methods are generally more complex and incur higher latency compared to CNNs, making them less suitable for real-time edge deployment. In 2017, Arik et al. proposed the convolutional recurrent neural network (CRNN) architecture [9], which combines the advantages of both CNNs and RNNs by extracting local time-frequency features with CNNs and modeling long-range temporal dependencies with RNNs. This approach outperforms standalone CNN or RNN models for KWS tasks [16].

To meet the deployment requirements on mobile and embedded devices, researchers have proposed various small-footprint KWS models. Representative work includes Google’s MobileNet series (2017), which applies depthwise separable convolutions (DS-CNNs) to reduce parameter size while maintaining good accuracy. DS-CNNs decompose standard convolutions into depthwise convolutions across channels and pointwise convolutions along the channel dimension, further reducing computational cost [17]. Another line of work, TC-ResNet, adopts stacked residual modules for efficient modeling, making it suitable for low-latency inference scenarios [18]. In addition, MatchboxNet employs temporal depthwise separable convolutions for end-to-end speech recognition, serving as an important reference for later lightweight models.

To improve model robustness in non-ideal acoustic environments, some studies have introduced attention mechanisms to enhance the network’s focus on critical temporal features in audio, thereby improving noise robustness to a certain extent [2,19–21]. Moreover, self-attention structures such as Transformers have also been applied to speech modeling. With their strong global modeling capacity, they outperform traditional convolutional and hybrid CNN–attention models in speech recognition tasks [22–24]. However, these methods usually incur high computational and memory costs, making them impractical for deployment in real-world applications such as smart speakers, wearable devices, or in-vehicle systems.

To further enhance KWS performance under noisy conditions, multi-condition training is commonly employed as a simple yet effective strategy for improving robustness in small-footprint speech models. By exposing the model to speech samples with various noise levels during training, the model learns to generalize better to noisy conditions. Nevertheless, when the gap between different signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) levels is too large, the model often struggles to learn discriminative features within such a complex noise space, leading to reduced training efficiency and limited robustness. To overcome this issue, recent studies have proposed curriculum learning (CL) as an alternative [25,26]. Inspired by the human learning process, CL starts training with clean or high-SNR speech samples, allowing the model to first capture fundamental speech structure. As training progresses, more challenging samples with lower SNRs are gradually introduced, thereby improving the model’s ability to adapt to noisy conditions. This progressive learning strategy effectively mitigates the problem of early exposure to overly difficult samples in multi-condition training. Experimental results show that CL provides greater improvements in noise robustness, especially for small-footprint models intended for real-world deployment. Balancing lightweight model design and noise robustness therefore remains a critical challenge in the development of small-footprint KWS systems.

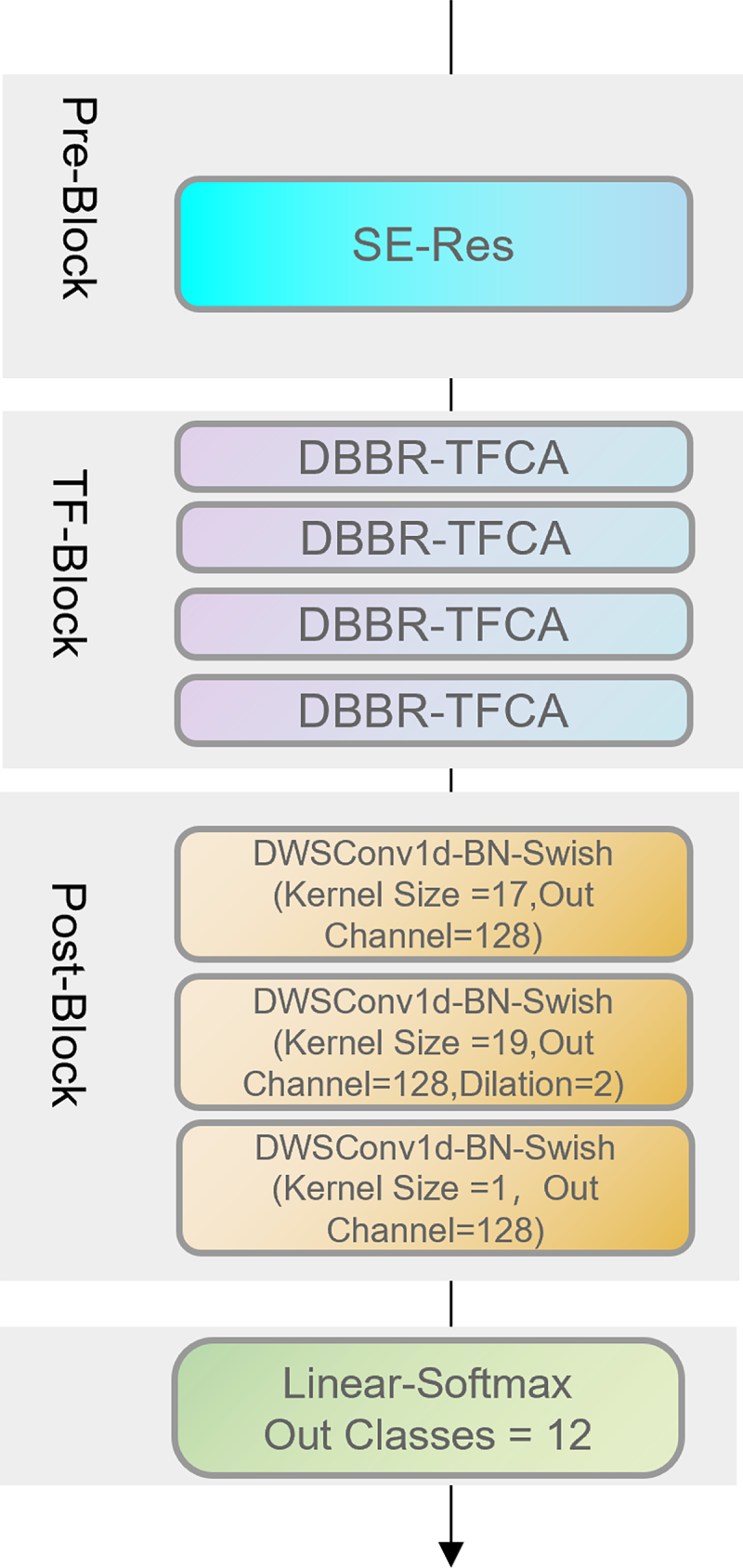

In this work, we construct a lightweight network architecture for keyword spotting (KWS), namely the Time-Frequency Dual-Branch Parallel Residual Network (TF-DBPResNet). The overall framework is illustrated in Fig. 1. The architecture consists of three main components: a Pre-Convolution Block, multiple Time-Frequency (TF) Blocks, and a Post-Convolution Block. The encoder is built upon residual convolutions and depthwise separable convolutions, which achieve efficient computation with a small number of parameters.

Figure 1: Overview of TF-DBPResNet model architecture

The input first passes through the SE-Res Pre-Convolution Block for preliminary feature extraction. It is then processed by four consecutive TF-Blocks, each of which contains two key components: the Dual-Branch Broadcast Residual (DBBR) module and the Time-Frequency Coordinate Attention (TFCA) module. These two components work collaboratively to fully exploit and fuse temporal and spectral information from the input features, thereby enhancing the network’s representational power for complex speech patterns.

Specifically, the DBBR module integrates time-frequency features of different scales or pathways through a compression–broadcast fusion mechanism along the non-modeled dimension. This design strengthens the synergy between local details and global structures. The TFCA module, inspired by coordinate attention, guides the network to separately model attention weights along the time and frequency axes. By dynamically adjusting the importance of each position in the feature map, TFCA highlights informative regions while suppressing redundant information. The collaboration between DBBR and TFCA not only improves feature representation but also significantly enhances robustness against noise interference, making the model particularly suitable for speech tasks in multi-noise scenarios.

At the end of the network, the Post-Block is composed of three 1D depthwise separable convolution layers, which further enhance feature representations while maintaining low parameter complexity. Through progressive convolutional operations, the model extracts higher-level and more discriminative features. The extracted high-dimensional features are then compressed temporally via max-pooling, followed by a fully connected layer and a Softmax activation to output the final class probabilities, thus achieving accurate keyword detection.

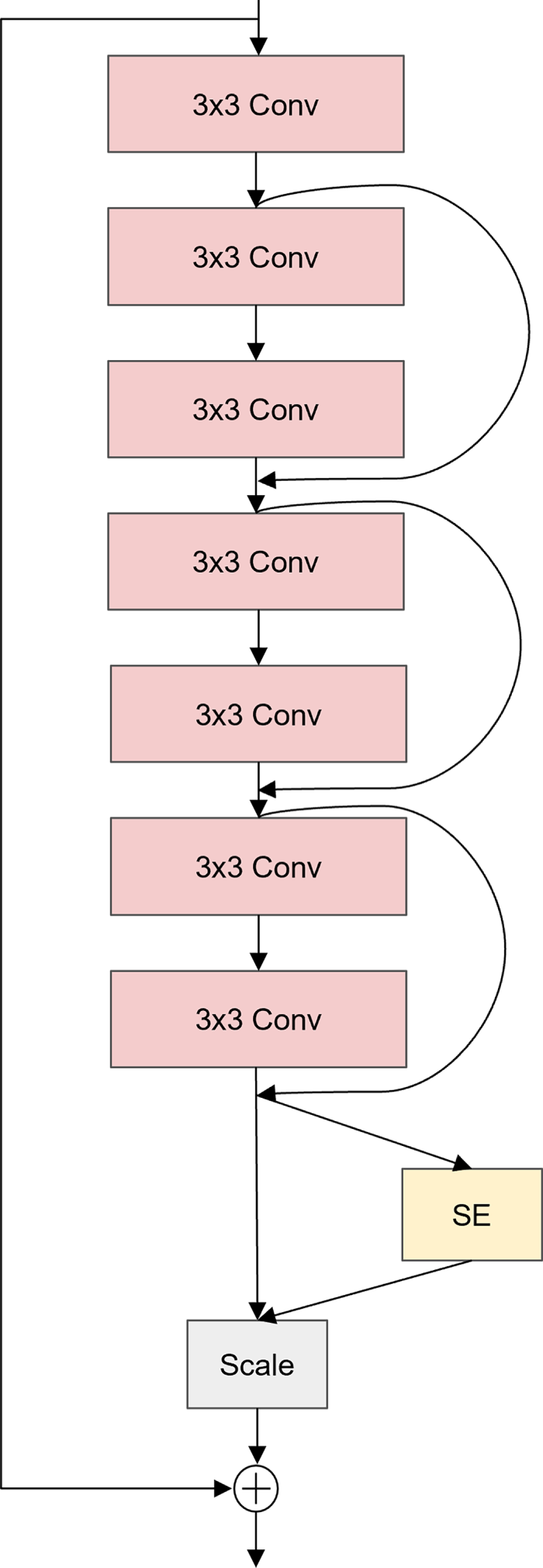

To achieve preliminary extraction of salient features from speech signals, we design an acoustic feature encoding module, SE-Res, as the pre-convolution block, based on a stack of multiple convolutional layers, as shown in Fig. 2. This module consists of seven consecutive 3 × 3 2D convolutional layers, each followed by Batch Normalization (BN) [27] and a nonlinear activation function named ReLU [28], in order to enhance the model’s nonlinear representational capacity and accelerate convergence. By continuously stacking small receptive field kernels, the module effectively expands the overall receptive field of the network, thereby improving its ability to model local speech patterns and short-term temporal context. Compared with using a single large kernel, this design achieves a better balance between parameter efficiency and modeling capability.

Figure 2: SE-Res architecture

In addition, to strengthen the modeling of channel-wise feature importance, a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) attention module [29] is introduced at the end of the convolutional stack. The SE module explicitly models inter-channel dependencies and adaptively learns the weight of each channel, thereby enhancing the network’s sensitivity to critical channel features. This mechanism emphasizes key acoustic regions while suppressing redundant background information, further improving the discriminative power and robustness of the model.

3.3 Dual-Branch Broadcast Residual Block

In traditional one-dimensional convolutional neural networks, the convolution operation exhibits good translation equivariance. That is, if the input signal undergoes a shift along the time axis, the resulting feature maps after convolution will also show the same shift. This property is crucial for sequence modeling, as it ensures the consistency and locality of feature extraction. However, when the feature maps obtained from 1D convolution are transformed into the frequency domain for further processing, this translation equivariance is often no longer preserved. On the other hand, methods based on 2D convolution still require more computation compared to 1D approaches.

BC-ResNet introduces Broadcast Residual Learning to address the limitations of using either 1D or 2D convolutions alone [30]. Instead of processing all features in 1D or 2D space, it performs convolution along the frequency dimension of 2D features. Then, it averages the 2D features across the frequency axis to obtain temporal representations. After several temporal operations, the model broadcasts the 1D residual information back to the original 2D feature map, achieving residual mapping. This learning approach enables convolutional processing along the frequency direction, thereby leveraging the advantages of 2D CNNs while minimizing computational cost. However, noise affects speech differently in the time and frequency domains. In the time domain, noise tends to be random and irregular, while in the frequency domain, it may introduce additional spectral components. Most existing convolution-based KWS models combine time-domain and frequency-domain convolutions sequentially, leading to a serial processing pattern where time-domain information lost after frequency convolution cannot contribute to subsequent temporal modeling, and vice versa.

BC-ResNet adopts a serial residual stacking structure, where temporal and frequency convolutions are performed in sequence within the same path. This sequential modeling causes the later convolution to overwrite or disturb features extracted by the earlier one, resulting in time–frequency coupling, long gradient propagation paths, and inter-feature interference. In contrast, the proposed DBBR module processes the time and frequency domains in parallel. The temporal convolution branch focuses on speech dynamics (e.g., phoneme duration, energy variation), while the frequency convolution branch captures spectral distribution characteristics (e.g., formants, timbre). These two branches operate independently, enabling time–frequency decoupled modeling. During backpropagation, the temporal and frequency branches compute their gradients independently, avoiding the gradient coupling problem commonly seen in serial architectures such as BC-ResNet. This parallel gradient propagation mechanism stabilizes model optimization and promotes balanced learning of time–frequency representations. At the fusion stage, the two domain-specific features are aggregated, preserving their individual details while capturing cross-domain correlations.

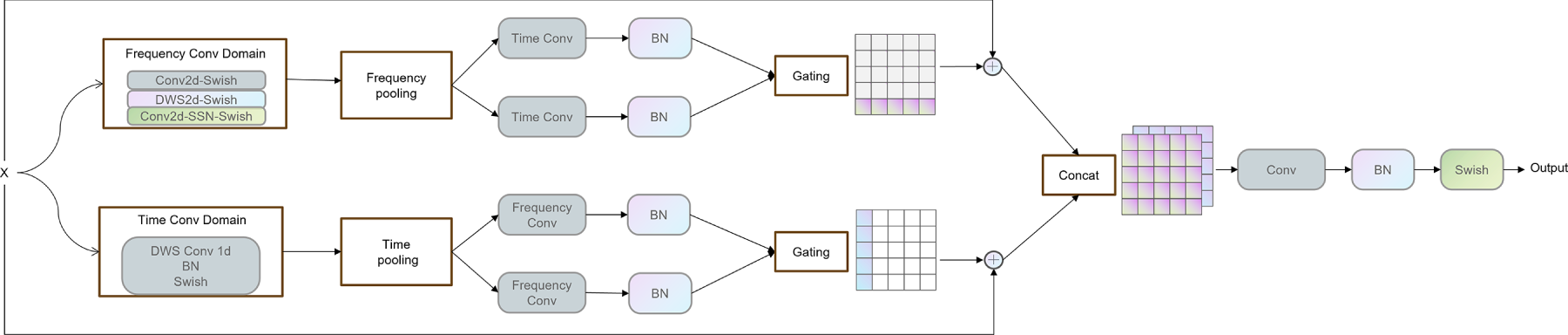

Reference [31] employs both 2D frequency-domain convolutional sub-blocks and 1D time-domain convolutional sub-blocks for feature extraction. Considering that ConvMixer [31] adopts a serial processing scheme during feature extraction, which may lead to information loss in the propagation process, our method instead adopts a dual-branch structure to extract frequency- and time-domain features in parallel, thereby enhancing feature retention and representational capacity. To more effectively perform joint modeling of the structural characteristics of speech signals in both time and frequency dimensions, this paper designs the DBBR (Dual-Branch Broadcast Residual) learning module, inspired by the ideas of the aforementioned model, as shown in the Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Dual-branch broadcast residual module

This module extends the concept of broadcast residual learning [30]. As shown in the Fig. 4, convolution modeling is first performed along the frequency dimension. The resulting features are then compressed into the time dimension through frequency-wise average pooling, followed by further convolution operations along the time axis. Finally, the residual information is broadcast back to the original dimensionality and added element-wise to the input features. While maintaining efficient residual learning, the dual-branch structure enables decoupled modeling of both time and frequency dimensions, and the broadcast mechanism facilitates cross-dimensional information fusion.

Figure 4: Broadcast residual learning

Given an input feature tensor

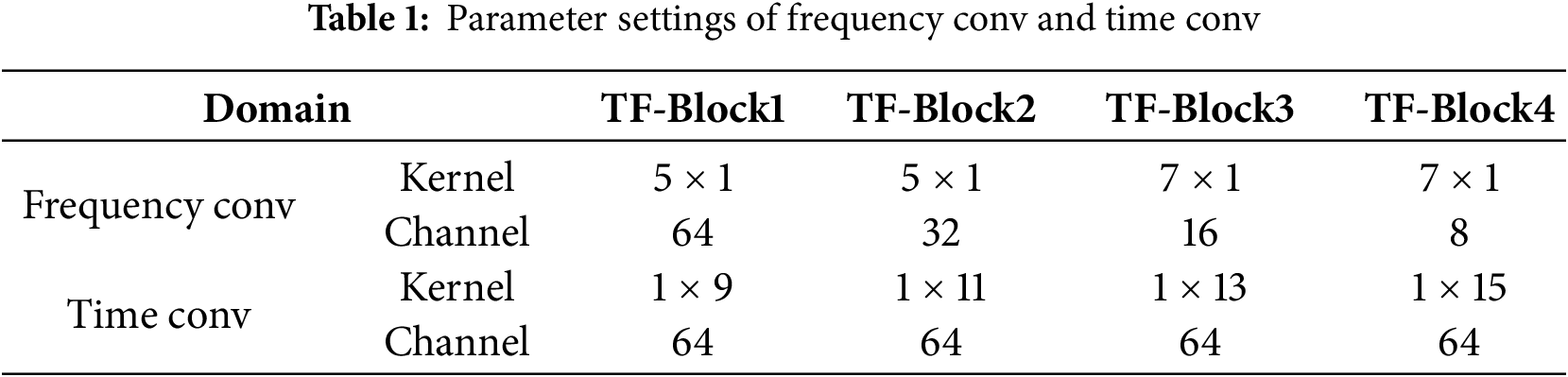

This structure achieves independent decoupled modeling of time and frequency features, providing stronger direction-aware and expressive capabilities compared with traditional 2D convolution. As shown in Table 1, Frequency Conv corresponds to the parameters of the 2D depthwise separable convolution, while Time Conv corresponds to the parameters of the 1D depthwise separable convolution.

After completing independent modeling along the time and frequency directions, the feature outputs of each branch are subjected to average pooling along the non-modeled dimension to obtain compact one-dimensional representations. Time branch: The input is

Frequency branch: The input is

Next, a dual-path gating mechanism is introduced on the one-dimensional features of both branches to further enhance representational capacity. This mechanism consists of two independent 1D convolutional paths with separate weights, activated by Sigmoid and Tanh functions, respectively, and combined via element-wise multiplication at the same position.

Time gating path:

Frequency gating path:

Here,

These two residual outputs are then concatenated along the channel dimension:

Finally, to enhance the expressive capacity of the fused representation, the concatenated residual features are passed through a 1 × 1 2D convolution for channel mapping, followed by BatchNorm and a Swish activation, producing the final module output:

where

3.4 Time-Frequency Coordinate Attention Module

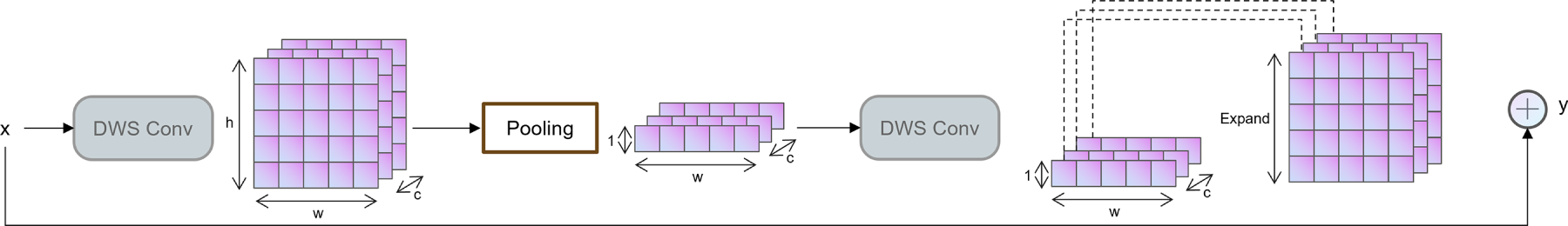

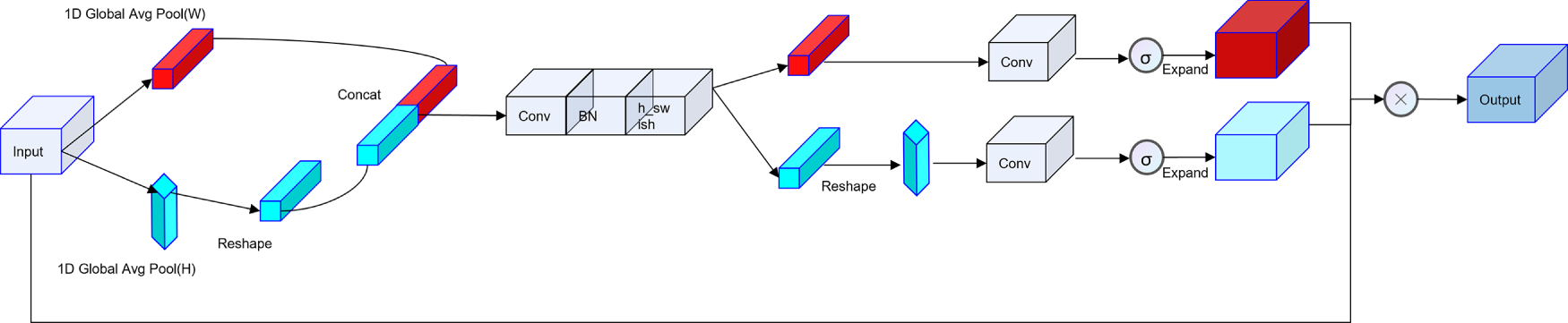

In this paper, we introduce the coordinate attention mechanism into acoustic feature modeling [34] and propose a Time-Frequency Coordinate Attention module, whose architecture is illustrated in Fig. 5. This module fully considers the phenomenon that noise in speech signals exhibits non-uniform interference across different time frames and frequency bands. Inspired by the design philosophy of coordinate attention, which encodes contextual information separately along spatial dimensions, TFCA models attention independently in the time and frequency domains. This guides the model to adaptively focus on discriminative temporal segments and frequency regions.

Figure 5: Time-frequency coordinate attention module

Specifically, given an input 2D feature map

Average pooling is applied along the frequency and time directions to obtain two direction-aware features:

where

After reshaping

Then, a convolution layer followed by Batch Normalization and the h–swish activation function [35] is applied to

Two convolution layers with sigmoid activation are used to generate the attention weights in each direction:

The attention maps are applied to the original feature map to jointly reweight it in both the frequency and time dimensions:

where

3.5 Curriculum Learning with Online Hard Example Mining

To enhance the model’s generalization ability and robustness in complex acoustic environments, we design a training strategy that combines curriculum learning with online hard example mining (OHEM) [36]. Within this framework, curriculum learning controls the progressive difficulty across training stages, while OHEM focuses on the samples that are most difficult for the current model to learn in each stage, thereby achieving a synergistic improvement of local optimization and global robust learning.

Specifically, the training process is divided into five stages of increasing difficulty: in the initial stage, clean speech data is used for training; in the next three stages, noisy samples with signal-to-noise ratios of 0, −5, and −10 dB are successively introduced; in the final stage, half of the training samples are further augmented with far-field reverberation (RIR) to simulate real distant scenarios. Each stage continues until no improvement in validation metrics is observed over five consecutive epochs.

To measure the training quality of each epoch, a stage advancement criterion

If

During training, the OHEM strategy is introduced to strengthen the model’s ability to learn from crucial hard samples. Concretely, for each mini-batch, all sample losses are calculated, and the OHEM cross-entropy loss is applied, as shown in Eqs. (16) and (17). The training focuses on the samples with the highest loss within the batch, which are then used for backpropagation.

where

To improve training stability and robustness, we combine Curriculum Learning with Online Hard Example Mining (OHEM). Specifically, OHEM is applied only during the first five epochs of training. This design is motivated by the observation that the model’s feature representations are still developing in the early stage, where emphasizing hard samples can accelerate convergence and enhance discriminative ability. As training progresses, the model gradually learns to classify most easy samples correctly, and the overall loss distribution becomes more concentrated. In this stage, continuously emphasizing hard samples through OHEM may bias the optimization process toward a few outliers, increasing the risk of overfitting. Therefore, after the initial five epochs, the training process switches to full-sample learning under the guidance of the curriculum schedule, which gradually increases the sample difficulty. We also explored alternative scheduling strategies, including applying OHEM for a longer duration or throughout the entire training process. However, these approaches either led to slower convergence or inferior validation performance. Consequently, we adopted the early-stage OHEM strategy, which demonstrates a better trade-off between robustness and generalization.

This strategy quickly guides the model in the early stage to focus on highly discriminative yet difficult samples, thereby improving the precision of its overall decision boundary. OHEM is applied only briefly in the initial stage of curriculum learning, to avoid destabilizing the model by introducing hard samples too early. By integrating stage-wise difficulty control with localized sample optimization, this joint strategy ensures stable training while significantly improving robustness to low-SNR and far-field speech samples.

The experiments in this paper were conducted on the Google Speech Commands V2 dataset [37], which consists of 105,000 speech clips, each lasting 1 s with a sampling rate of 16 kHz, covering 35 different words. To perform the 12-class keyword classification task, the selected classes include 10 specific command words: “up,” “down,” “left,” “right,” “yes,” “no,” “on,” “off,” “go,” and “stop,” along with 2 special categories: “silence” (background silence) and “unknown” (comprising the remaining unselected words). The official predefined splits of training, validation, and test sets were adopted, with training, validation, and test accounting for 80%, 10%, and 10%, respectively.

To simulate complex far-field noisy environments, two additional public datasets were introduced and mixed with the original speech data—one for background noise addition and the other for generating far-field speech signals. Specifically, the MUSAN noise corpus [38] was employed, which contains 930 noise recordings sampled at 16 kHz, with a total duration of about 6 h. It covers a wide range of real-world noise types, including technical sounds (e.g., DTMF tones), natural environmental sounds (e.g., thunder), and everyday noises (e.g., car horns). In our experiments, these noises were randomly selected and superimposed onto speech commands at varying signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs), thereby creating diverse noisy speech scenarios to emulate the challenging acoustic conditions that devices may encounter in practice.

Furthermore, to generate far-field speech effects, we utilized the reverberation impulse responses (RIRs) provided by the BUT Speech@FIT Reverberation database [39]. This dataset contains reverberation data from 9 rooms of different sizes, categorized into large, medium, and small volumes. Each room includes multiple microphone–loudspeaker configurations to capture different acoustic propagation paths. These RIR filters were convolved with speech signals to synthesize far-field speech containing realistic reverberation characteristics.

In practical keyword spotting applications, the acoustic environment often varies significantly due to background noise, reverberation, multi-speaker interference, and recording device differences. To simulate realistic acoustic conditions, we employed the MUSAN and BUT Speech@FIT Reverberation database (BUT RIR) datasets for noise and reverberation augmentation. The MUSAN dataset contains various types of non-stationary noises (such as background speech, music, and ambient sounds) and multi-speaker speech mixtures, while the BUT RIR dataset introduces realistic recording variations caused by different microphones, rooms, and speaker positions. Through these augmentations, our data preparation process effectively covers a wide range of complex real-world scenarios, including non-stationary noise, multi-speaker interference, and device capture variations. In addition, these augmented conditions were incorporated during both training and evaluation to ensure that the robustness of the proposed model was thoroughly assessed under realistic and acoustically challenging environments.

In terms of input features, this work adopts FBank features. The speech signal is first processed with a short-time Fourier transform (STFT) using a 25 ms frame length and a 10 ms frame shift. A 64-dimensional log-Mel filterbank is then extracted as the model input, and the resulting Mel-spectrograms are normalized to a fixed size of 98 × 64.

During model training, multiple data augmentation strategies are applied to improve generalization. First, the raw audio is randomly shifted in the time domain within a range of −100 ms to +100 ms. Second, spectrogram masking is performed, where random regions along both the time and frequency axes are obscured, with the maximum mask length set to 25 frames or 25 frequency bins. In addition, to simulate noisy environments in real applications, background noise at SNR levels of 0 dB, −5 dB, and −10 dB is mixed with clean speech, constructing noisy training samples such as [clean, 0], [clean, 0, −5], and [clean, 0, −5, −10]. During testing, speech samples with an unseen SNR level of 20 dB are introduced to evaluate the model’s generalization ability under novel noise conditions.

For training, a batch size of 128 is used. The initial learning rate is set to 1 × 10−3 and decays by a factor of 0.85 every 4 epochs starting from the 5th epoch. The Adam optimizer is employed. In the first 5 epochs, an OHEM-based cross-entropy loss is used, where the top 70% hardest samples (with the highest losses) in each mini-batch are selected for backpropagation. Afterward, standard cross-entropy loss is adopted to measure the difference between predictions and ground-truth labels.

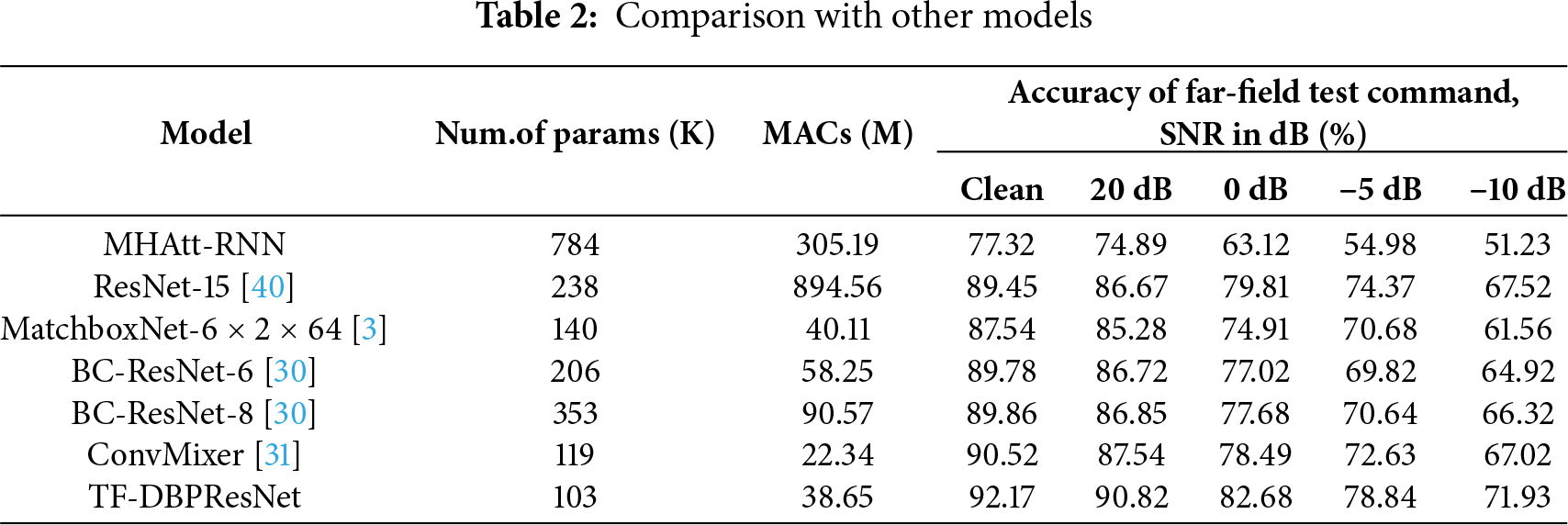

This section evaluates the performance of different keyword spotting models on the far-field speech command recognition task. The baseline models are retrained using the official source code provided by the designed data environment, under the same experimental settings as this work. The testing conditions include clean speech as well as noisy speech at different signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) levels (20, 0, −5, and −10 dB). Table 2 summarizes the parameter size (K), multiply–accumulate operations (MACs, M), and recognition accuracy (%) of each model under the different testing conditions. Note that the term ‘Clean’ in this paper refers to the far-field clean condition, i.e., without additive noise but still under reverberant far-field acoustic environments

As shown in the Table 2, TF-DBPResNet achieves the best performance in terms of accuracy under all SNR conditions, especially in low-SNR scenarios (e.g., –10 dB), where it still maintains an accuracy of 71.93%. This demonstrates strong robustness and generalization ability. In contrast, the conventional MHAtt-RNN, which relies on a multi-head attention mechanism, introduces a large number of parameters and computational overhead. Its accuracy drops rapidly in low-SNR conditions, reaching only 51.23%, indicating high sensitivity to noise. Although ResNet-15 achieves 89.45% accuracy on clean speech [40], its MACs reach 894.56 M, posing challenges for deployment on resource-constrained devices. The proposed TF-DBPResNet significantly reduces the number of parameters and MACs, implying lower memory and computational demands. MatchboxNet-6 × 2 × 64, which is constructed by stacking one-dimensional depthwise separable convolutions, maintains relatively low computational cost and parameter count. However, its recognition results under different SNR conditions reveal that this method performs noticeably worse than the proposed model in noisy environments, suggesting that relying solely on 1D DWSConvs may limit the network’s ability to robustly model features under complex noise interference [3]. BC-ResNet, a broadcast residual network that combines both 1D and 2D convolutions [30], generates BC-ResNet-6 and BC-ResNet-8 by scaling its network size. While increasing the scale improves recognition accuracy, both parameter count and computational complexity remain significantly higher than those of TF-DBPResNet. Convmixer adopts a serial structure for feature extraction, modeling the temporal domain first and then the frequency domain using 1D and 2D depthwise separable convolutions, respectively. This sequential extraction process may cause the loss of critical information during the transformation [31].

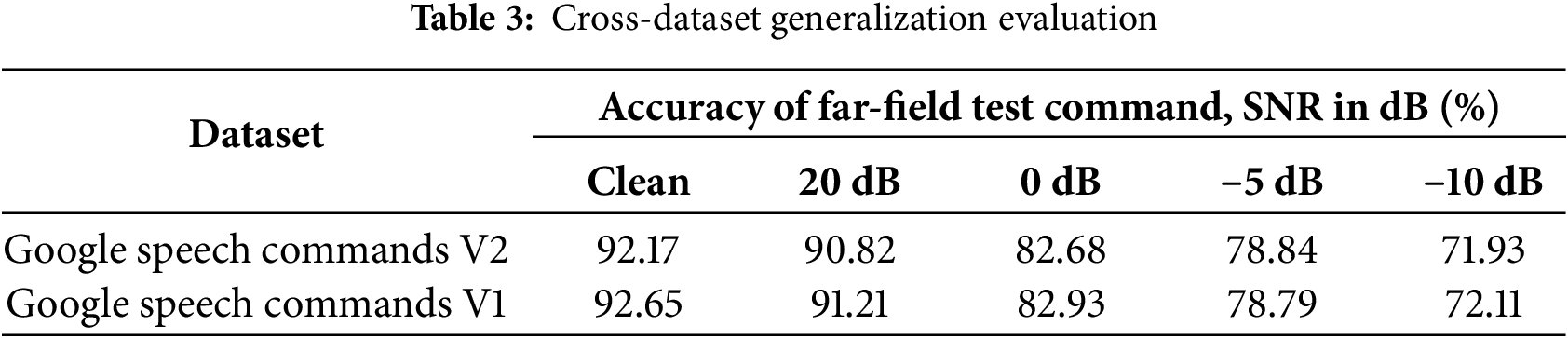

To further evaluate the generalization capability of the proposed model, we conducted cross-dataset validation using the Google Speech Commands V1 (GSC V1) dataset. Although our primary experiments were performed on Google Speech Commands V2 (GSC V2), evaluating the model on GSC V1 allows us to examine its robustness and generalization performance under distributional shifts. Both GSC V1 and GSC V2 share a similar task definition, consisting of one-second spoken utterances of short command words. The main differences lie in the fact that, compared with GSC V1, GSC V2 includes additional samples, improved label quality, and the removal of noisy or ambiguous recordings. Consequently, GSC V1 represents a distinct yet related data distribution, providing a reasonable scenario for testing cross-dataset generalization.

In this evaluation, the model was trained exclusively on the GSC V2 training set, without any exposure to GSC V1 data. During testing, the trained model was directly evaluated on the GSC V1 test set, without any fine-tuning or adaptation, ensuring that the results truly reflect the model’s ability to generalize across different but related datasets.

As shown in Table 3, we further evaluated the model trained on GSC V2 under various noise conditions using both the GSC V2 and GSC V1 test sets. The results demonstrate that our model maintains good generalization performance when tested on GSC V1, even under noisy conditions.

To evaluate the deployment potential of our model on resource-constrained hardware, we simulated embedded CPU performance by measuring the inference latency in a CPU-only environment (Intel Core i7-13620H, 2.5 GHz). On the CPU-only platform, the model achieved an average inference latency of 12.4 ms per sample with a memory footprint of 4.8 MB, indicating its potential for real-time deployment on embedded devices. These results suggest that the proposed model can perform real-time inference on embedded systems, validating its suitability for low-power keyword spotting applications.

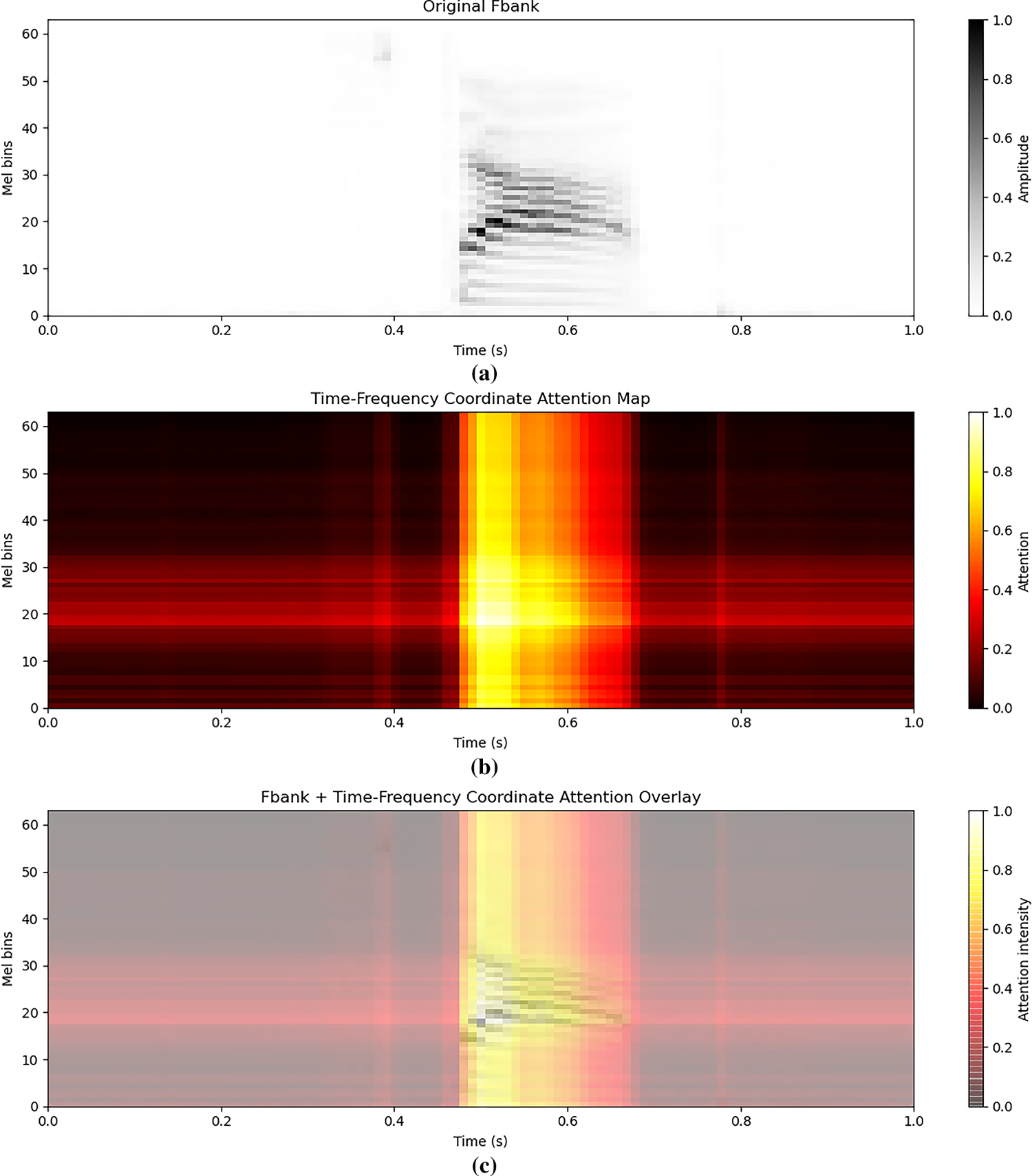

To better understand the behavior of the TFCA module, we visualize its attention together with the input features. Fig. 6 shows three representations of an example keyword audio “stop”: (a) The original Fbank features, representing the time–frequency distribution of the input signal; the color intensity reflects the spectral amplitude, with black indicating stronger frequency components and light gray indicating weaker components. (b) The attention map generated by the TFCA module, highlighting regions deemed important by the model. Colors range from dark red to yellow, where yellow indicates high attention at the corresponding time–frequency location, and dark red or black indicates low attention. This map reveals the model’s attention distribution over time and frequency. (c) The overlay of the Fbank features and the attention map. The semi-transparent heatmap represents attention intensity. Brighter regions indicate that the model both attends strongly and that the spectral amplitude is high at that time–frequency location, while dark gray or dark red regions indicate low amplitude or attention. From the overlay, it can be observed that the TFCA module effectively focuses on the time–frequency regions corresponding to the keyword, confirming that the attention mechanism concentrates on information relevant for keyword recognition.

Figure 6: Visualization of TFCA Attention on Keyword Audio. (a) The original Fbank features. (b) The attention map generated by the TFCA module. (c) The overlay of the Fbank features and the attention map

In summary, the proposed TF-DBPResNet achieves the most balanced performance across all evaluation metrics, showing particularly significant advantages in low-SNR scenarios, thereby validating the effectiveness of the proposed architecture in far-field noisy environments.

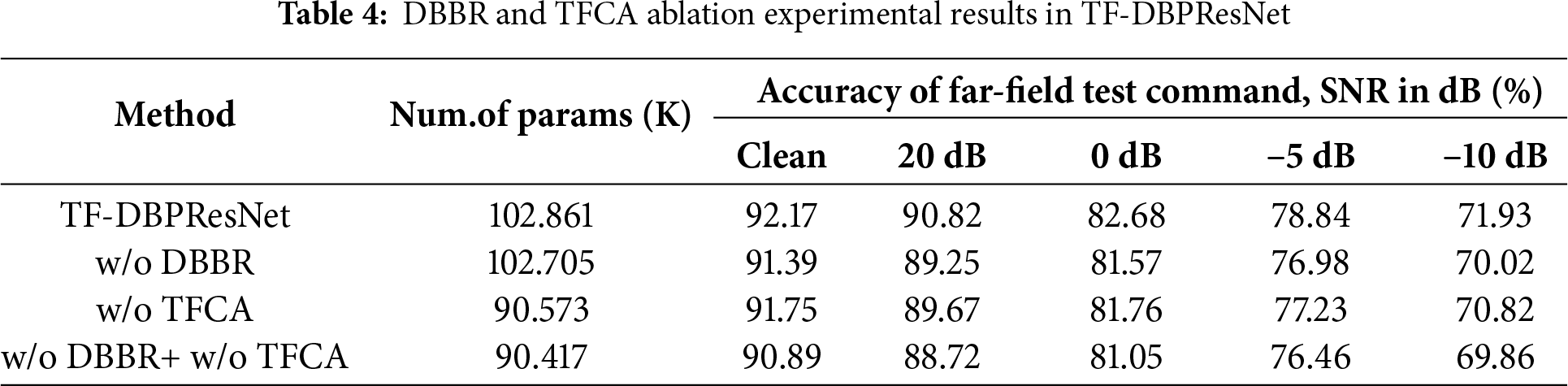

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed DBBR and TFCA modules, we conducted ablation experiments under noisy far-field conditions using the same curriculum learning-based multi-condition training strategy. Specifically, we evaluated the impact of these two key modules on model performance by removing the DBBR module, the TFCA module, and both modules simultaneously. In the experiment where DBBR was removed, the original parallel feature extraction was replaced with a serial structure, where frequency-domain convolution and time-domain convolution were applied sequentially to simulate traditional step-by-step processing. This design aimed to assess the contribution of the parallel time-frequency feature extraction strategy to improving model performance. To ensure a fair comparison in the ablation study, when the DBBR module was removed, we replaced it with a serial structure of comparable parameter count and computational complexity. As shown in Table 4, the total number of parameters of the serial structure (w/o DBBR: 102.7 K) is very close to that of the full model (102.9 K), indicating that the observed performance degradation mainly stems from the absence of the DBBR mechanism rather than a reduction in model capacity.

As shown in the Table 4, removing any of the proposed modules led to a decline in overall recognition accuracy, indicating that each module contributes meaningfully to performance improvement. Under clean speech conditions, removing either the DBBR or TFCA module caused only slight degradation, while in low-SNR environments, the performance drop became more pronounced. The performance decrease was larger when DBBR was removed than when TFCA was removed, highlighting that the dual-branch parallel time-frequency feature extraction of the DBBR module plays a more critical role in enhancing noise robustness. When both modules were removed, the accuracy was lower than when only one module was removed, further validating the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

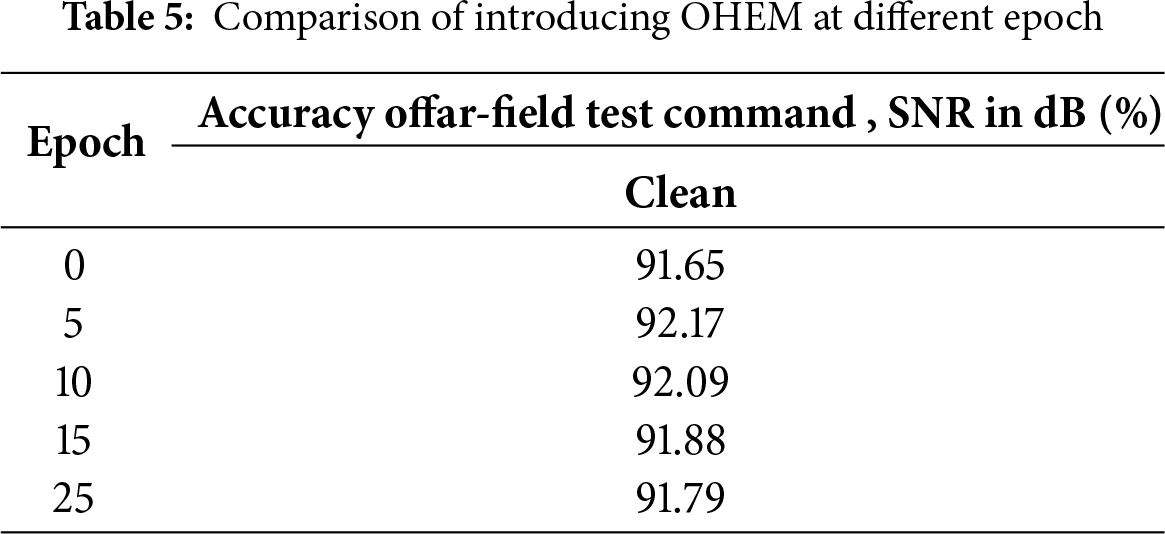

To validate the effectiveness of the OHEM algorithm, as shown in the Table 5, we introduced the OHEM cross-entropy loss function at different training stages (epochs 0, 5, 10, 15, and 25) for optimization. The experimental results demonstrate that applying OHEM within the first 5 epochs can significantly improve model performance, achieving an improvement of approximately 0.57% compared to not using OHEM. However, when extending the application period of OHEM to the first 25 epochs, the system performance is adversely affected. This suggests that prolonged use of OHEM may cause the model to excessively focus on hard samples, leading to overfitting and ultimately degrading overall recognition performance.

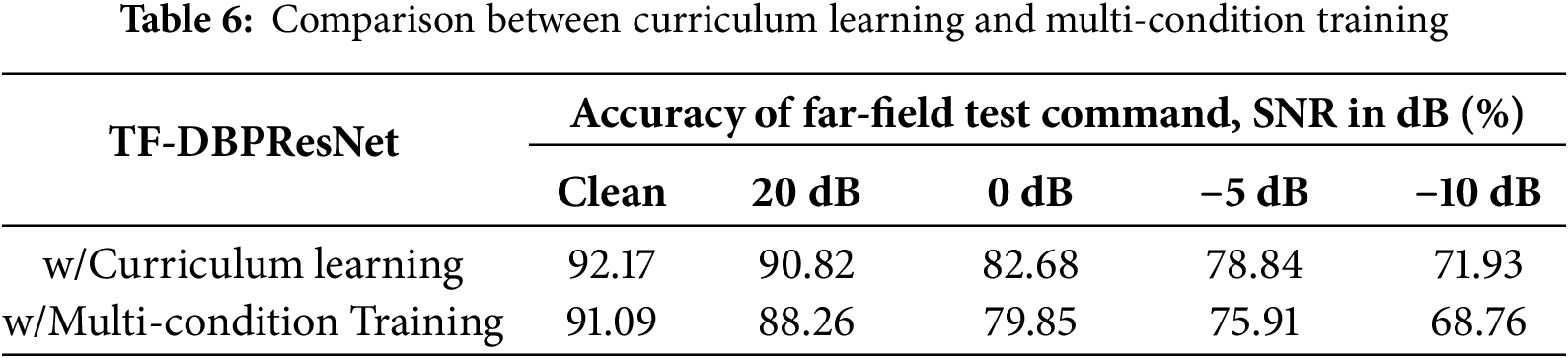

To validate the effectiveness of the curriculum learning strategy in improving model robustness, we compared it with the conventional multi-condition training method, and the results are shown in the Table 6. It can be observed that under all SNR conditions, the TF-DBPResNet model trained with curriculum learning consistently outperforms the version trained with multi-condition training. On clean speech, the accuracies of the two approaches are 92.17% and 91.09%, respectively, showing a relatively small difference. However, as the SNR decreases, the performance gap gradually widens. In particular, under 0 dB, −5 dB, and −10 dB conditions, curriculum learning yields improvements of approximately 2.83%, 2.93%, and 3.17% in accuracy, respectively. These results indicate that curriculum learning, by progressively guiding the model from easy to difficult samples, helps the model adapt more robustly to complex noisy environments and significantly enhances the generalization and robustness of the speech recognition system under low-SNR conditions.

This work addresses the challenges of robustness and model lightweighting in the speech wake-up keyword detection task by proposing a compact model that integrates a time-frequency dual-branch structure with attention mechanisms—TF-DBPResNet. The model introduces a dual-branch broadcast residual module (DBBR) and a time-frequency coordinate attention module (TFCA), effectively enhancing recognition performance under varying SNR conditions. With only approximately 103 K parameters, TF-DBPResNet demonstrates excellent performance on multiple far-field wake-up word recognition tasks in the Google Speech Commands V2-12 dataset, significantly outperforming several comparative models.

Furthermore, a curriculum learning strategy combined with online hard example mining is employed to further improve the model’s generalization ability. Experimental results show that, compared with conventional multi-condition training, curriculum learning substantially improves accuracy under low-SNR conditions, effectively mitigating performance degradation in complex acoustic environments.

In summary, TF-DBPResNet demonstrates superior robustness and practicality while maintaining extremely low computational cost, making it well-suited for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices and showing promising application potential. However, the current model still has certain limitations; for example, its adaptability to specific accents or low-resource languages may be insufficient, and its robustness under extreme noise conditions requires further improvement. Future research could consider incorporating adaptive noise suppression mechanisms to enhance the model’s stability in complex acoustic environments. Meanwhile, multimodal information fusion (e.g., combining visual or other sensor data) may further improve recognition accuracy. In addition, exploring transfer learning or cross-accent training strategies could enhance the model’s generalization ability for low-resource languages or diverse accents. These directions provide potential avenues to improve the model’s scalability and practical applicability. Moreover, the current model can only recognize predefined wake-up words; to optimize user experience, algorithms for custom wake-up word recognition need to be explored. Future work will further investigate the model’s noise robustness and lightweight design.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Concept and design: Zeyu Wang; data collection: Zeyu Wang; analysis of results: Zeyu Wang; manuscript writing: Zeyu Wang; supervision: Jian-Hong Wang and Kuo-Chun Hsu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hoy MB. Alexa, siri, cortana, and more: an introduction to voice assistants. Med Ref Serv Q. 2018;37(1):81–8. doi:10.1080/02763869.2018.1404391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Shan C, Zhang J, Wang Y, Xie L. Attention-based end-to-end models for small-footprint keyword spotting. arXiv:1803.10916. 2018. [Google Scholar]

3. Majumdar S, Ginsburg B. Matchboxnet: 1D time-channel separable convolutional neural network architecture for speech commands recognition. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech; 2020 Oct 25–29; Shanghai, China. p. 3356–60. [Google Scholar]

4. Rybakov O, Kononenko N, Subrahmanya N, Visontai M, Laurenzo S. Streaming keyword spotting on mobile devices. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech; 2020 Oct 25–29; Shanghai, China. p. 2277–81. [Google Scholar]

5. Ng D, Zhang R, Yip JQ, Zhang C, Ma Y, Nguyen TH, et al. Contrastive speech mixup for low resource keyword spotting. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023–2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023 Jun 4–10; Rhodes Island, Greece; 2023. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

6. Zhang A, Wang H, Guo P, Fu Y, Xie L, Gao Y, et al. VE-KWS: visual modality enhanced end-to-end keyword spotting. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2023 Jun 4–10; Rhodes Island, Greece. [Google Scholar]

7. Yang Z, Ng D, Li X, Zhang C, Jiang R, Xi W, et al. Dual-memory multi-modal learning for continual spoken keyword spotting with confidence selection and diversity enhancement. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech 2023–24th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association; 2023 Aug 20–24; Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

8. Prabhavalkar R, Alvarez R, Parada C, Nakkiran P, Sainath TN. Automatic gain control and multi-style training for robust small-footprint keyword spotting with deep neural networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2015 Apr 19–24; Brisbane, Australia. p. 4704–8. [Google Scholar]

9. Arık SÖ, Kliegl M, Child R, Hestness J, Gibiansky A, Fougner C, et al. Convolutional recurrent neural networks for small-footprint keyword spotting. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech; 2017 Aug 20–24; Stockholm, Sweden. p. 1606–10. [Google Scholar]

10. Lin Y, Gapanyuk YE. Frequency & channel attention network for small footprint noisy spoken keyword spotting. In: Proceedings of the 2024 Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC); 2024 Dec 3–6; Macau, China. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

11. Lin Y, Zhou T, Xiao Y. Advancing airport tower command recognition: integrating squeeze-and-excitation and broadcasted residual learning. In: Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Asian Language Processing (IALP); 2024 Aug 4–6; Hohhot, China. p. 91–6. [Google Scholar]

12. Pereira PH, Beccaro W, Ramirez MA. Evaluating robustness to noise and compression of deep neural networks for keyword spotting. IEEE Access. 2023;11:53224–36. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3280477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sainath TN, Vinyals O, Senior A, Sak H. Convolutional, long short-term memory, fully connected deep neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2015 Apr 19–24; Brisbane, Australia. p. 4580–4. [Google Scholar]

14. Tsai TH, Lin XH. Speech densely connected convolutional networks for small-footprint keyword spotting. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(25):39119–37. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-14617-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chen G, Parada C, Sainath TN. Query-by-example keyword spotting using long short-term memory networks. In: Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2015 Apr 19–24; Brisbane, QLD, Australia. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2015. p. 5236–40. [Google Scholar]

16. Liu B, Sun Y. Translational bit-by-bit multi-bit quantization for CRNN on keyword spotting. In: Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Cyber-Enabled Distributed Computing and Knowledge Discovery (CyberC); 2019 Oct 17–19; Guilin, Chinas. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 444–51. [Google Scholar]

17. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. Mobilenets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861. 2017. [Google Scholar]

18. Choi S, Seo S, Shin B, Byun H, Kersner M, Kim B, et al. Temporal convolution for real-time keyword spotting on mobile devices. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech; 2019 Sep 15–19; Graz, Austria. p. 3372–6. [Google Scholar]

19. Zhang S-X, Chen Z, Zhao Y, Li J, Gong Y. End-to-end attention based text-dependent speaker verification. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT); 2016 Dec 13–16; San Diego, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 171–8. [Google Scholar]

20. Jung M, Jung Y, Goo J, Kim H. Multi-task network for noise-robust keyword spotting and speaker verification using CTC-based soft VAD and global query attention. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech; 2020 Oct 25–29; Shanghai, China. p. 931–5. [Google Scholar]

21. Xiao Y, Das RK. Dual knowledge distillation for efficient sound event detection. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing Workshops (ICASSPW); 2024 Apr 14–19; Seoul, Republic of Korea. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 690–4. [Google Scholar]

22. Gong Y, Chung Y-A, Glass J. AST: audio spectrogram transformer. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech; 2021 Aug 30–Sep 3; Brno, Czech Republic. p. 571–5. [Google Scholar]

23. Berg A, O’Connor M, Cruz MT. Keyword transformer: a self-attention model for keyword spotting. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech; 2021 Aug 30–Sep 3; Brno, Czech Republic. p. 4249–53. [Google Scholar]

24. Segal-Feldman Y, Bradlow AR, Goldrick M, Keshet J. Keyword spotting with hyper-matched filters for small footprint devices. arXiv:2508.04857. 2025. [Google Scholar]

25. Braun S, Neil D, Liu S-C. A curriculum learning method for improved noise robustness in automatic speech recognition. In: Proceedings of the 2017 European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO); 2017 Aug 28–Sep 2; Kos, Greece. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 548–52. [Google Scholar]

26. Ranjan S, Hansen JHL. Curriculum learning based approaches for noise robust speaker recognition. IEEE/ACM Trans Audio Speech Lang Process. 2018;26(1):197–210. doi:10.1109/taslp.2017.2765832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ioffe S, Szegedy C. Batch normalization: accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2015 Jul 6–11; Lille, France. p. 448–56. [Google Scholar]

28. Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Hinton GE. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2012;25(6):1097–105. doi:10.1145/3065386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–22; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 7132–41. [Google Scholar]

30. Kim B, Chang S, Lee J, Sung D. Broadcasted residual learning for efficient keyword spotting. In: Proceedings of the Interspeech; 2021 Aug 30–Sep 3; Brno, Czech Republic. p. 4538–42. [Google Scholar]

31. Ng D, Chen Y, Tian B, Fu Q, Chng ES. Convmixer: feature interactive convolution with curriculum learning for small footprint and noisy far-field keyword spotting. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2022 May 7–13; Singapore. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 3603–7. [Google Scholar]

32. Ramachandran P, Zoph B, Le QV. Searching for activation functions. arXiv:1710.05941. 2017. [Google Scholar]

33. Huang C, HeFu W. Speech-music classification model based on improved neural network and beat spectrum. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2023;14(7):1–7. doi:10.14569/ijacsa.2023.0140706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Hou Q, Zhou D, Feng J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 19–25; Nashville, TN, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 13713–22. [Google Scholar]

35. Howard A, Sandler M, Chen B, Wang W, Chen L-C, Tan M, et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1314–24. [Google Scholar]

36. Shrivastava A, Gupta A, Girshick R. Training region-based object detectors with online hard example mining. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 761–9. [Google Scholar]

37. Warden P. Speech commands: a dataset for limited-vocabulary speech recognition. arXiv:1804.03209. 2018. [Google Scholar]

38. Snyder D, Chen G, Povey D. Musan: a music, speech, and noise corpus [Internet]. 2015 Oct 28 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/1510.08484. [Google Scholar]

39. Szoke I, Skacel M, Mosner L, Paliesek J, Cernocky J. Building and evaluation of a real room impulse response dataset. IEEE J Sel Top Signal Process. 2019;13(4):863–76. doi:10.1109/jstsp.2019.2917582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Tang R, Lin J. Deep residual learning for small-footprint keyword spotting. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2018 Apr 15–20; Calgary, AB, Canada. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 5484–8. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools