Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

IPKE-MoE: Mixture-of-Experts with Iterative Prompts and Knowledge-Enhanced LLM for Chinese Sensitive Words Detection

School of Digital and Intelligence Industry, Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology, Baotou, 014010, China

* Corresponding Author: Yongbing Gao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Sentiment Analysis for Social Media Data: Lexicon-Based and Large Language Model Approaches)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 35 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072889

Received 05 September 2025; Accepted 12 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Aiming at the problem of insufficient recognition of implicit variants by existing Chinese sensitive text detection methods, this paper proposes the IPKE-MoE framework, which consists of three parts, namely, a sensitive word variant extraction framework, a sensitive word variant knowledge enhancement layer and a mixture-of-experts (MoE) classification layer. First, sensitive word variants are precisely extracted through dynamic iterative prompt templates and the context-aware capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs). Next, the extracted variants are used to construct a knowledge enhancement layer for sensitive word variants based on RoCBert models. Specifically, after locating variants via n-gram algorithms, variant types are mapped to embedding vectors and fused with original word vectors. Finally, a mixture-of-experts (MoE) classification layer is designed (sensitive word, sentiment, and semantic experts), which decouples the relationship between sensitive word existence and text toxicity through multiple experts. This framework effectively combines the comprehension ability of Large Language Models (LLMs) with the discriminative ability of smaller models. Our two experiments demonstrate that the sensitive word variant extraction framework based on dynamically iterated prompt templates outperforms other baseline prompt templates. The RoCBert models incorporating the sensitive word variant knowledge enhancement layer and a mixture-of-experts (MoE) classification layer achieve superior classification performance compared to other baselines.Keywords

With the rapid growth in the number of social media users, sensitive content (e.g., politically sensitive, discriminatory, violent, etc.) has become a core issue that threatens the health of the online ecosystem. One important way to maintain the online environment is to create a “blacklist” of words. In China, these words are called “sensitive words” and usually include information such as criticism, violence and pornography [1]. However, miscreants often bypass detection by using euphemisms and variant expressions [2,3], especially in Chinese, where the complex structure and the variety of implicit variants are more diverse [4,5], making identification more challenging. Therefore, we classify sensitive texts into two categories: one is explicit sensitive word texts, which are easy to be filtered, and the other is texts containing variants or implicit expressions, which evade auditing by reducing sensitivity. This type of sensitive text is the focus of this research paper.

Existing sensitive word detection methods are often framed as sequence labeling tasks. For example, reference [6] performs toxic span detection to identify sensitive vocabulary but relies heavily on labeled data. Reference [7] formulates it as a generation task, using frozen LLMs with fixed prompts to produce non-toxic text and detect toxic spans via differential analysis—though fixed prompts struggle in complex contexts. Reference [8] shows that LLMs perform poorly on detection tasks without fine-tuning or auxiliary models, while reference [9] finds that GPT-3.5 generalizes better than fine-tuned LLMs but with lower recall and accuracy. Overall, decoder-only models (e.g., GPT, Llama, Qwen) underperform supervised BERT-based classifiers. Consequently, current methods face a trade-off: standalone LLMs yield weak detection, while encoder-only models (e.g., [10] with dictionary-augmented BERT) lack generalization. Hybrid approaches such as CAALM-TC [11] and RC Trees (RCT) [12] attempt to combine the contextual strength of decoder-only LLMs with the classification ability of encoder-only models for better performance.

Although hybrid models such as CAALM-TC and RCT attempt to combine large language models (LLMs) with small language models (SLMs) for text classification, they rely on static prompt templates or fixed knowledge structures, making it difficult to adapt to implicit variants in Chinese. In contrast, the proposed IPKE-MoE incorporates a four-step dynamic process: “construction of a pseudo sample library, DBSCAN-based representative sample selection, variant type definition summarization, and selection of few-shot examples.” This enables continuous updating of sensitive word variant type definitions for efficient classification—a self-evolving mechanism unattainable by static hybrid models. Second, we designed a sensitive word variant knowledge enhancement layer that embeds variant types into word vectors, achieving lexical-level semantic fusion. Inspired by MH-MoE [13], we developed a mixture-of-experts (MoE) classification layer to decouple sensitive word presence from text toxicity. Our main contributions include:

1. A sensitive word detection framework named IPKE-MoE is proposed, which consists of three parts: a sensitive word variant extraction framework, a sensitive word variant knowledge enhancement layer, and a mixture-of-experts (MoE) classification layer.

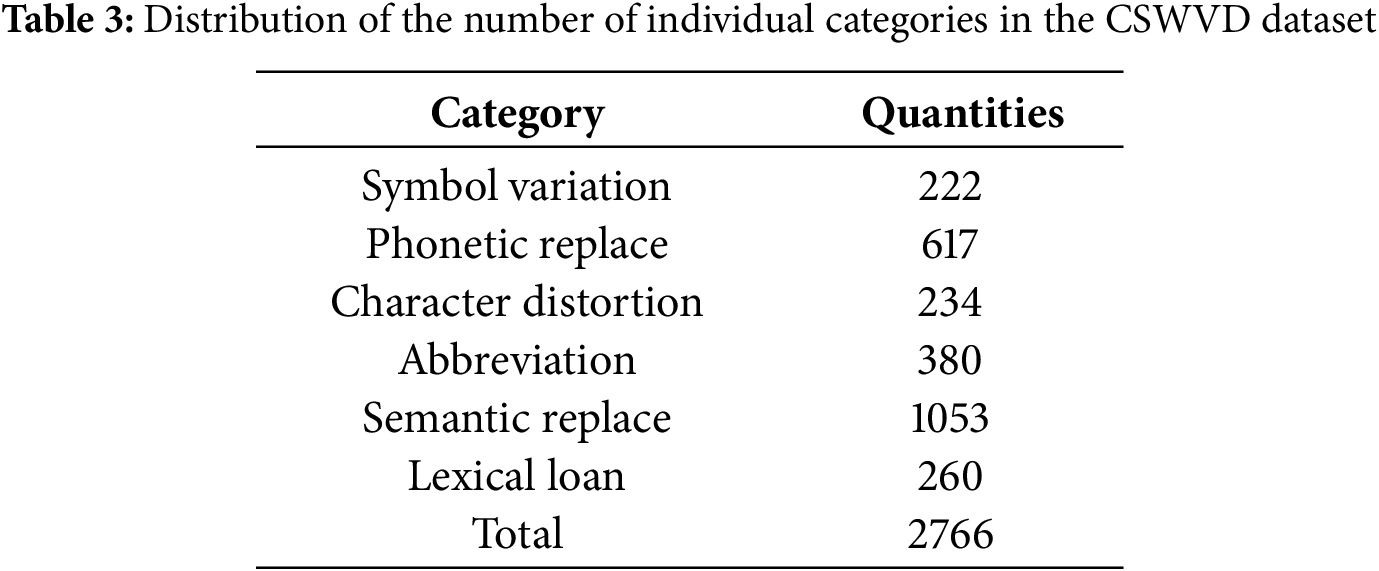

2. A Chinese sensitive word variant dataset named CSWVD has been constructed. This dataset comprises 2766 entries, encompassing six common categories of sensitive word variants and two dataset types. It serves to evaluate the effectiveness of sensitive word variant extraction frameworks and knowledge-enhanced layers for sensitive word variants, providing a reference for Chinese sensitive word detection.

3. Based on the analysis of experimental results on sensitive word variant extraction and sensitive text classification, our framework demonstrates significantly superior performance compared to other baselines on the CSWVD dataset, thereby validating its effectiveness.

Early sensitive word detection primarily relied on rule-based approaches [14,15] or string-matching algorithms using fixed sensitive word lists [16,17]. However, predefined vocabularies and syntactic rules struggle to detect implicitly toxic sensitive text [18], while list-matching algorithms face challenges adapting to complex network environments due to their static lists and algorithms. Our IPKE-MoE framework overcomes these limitations by leveraging the text comprehension capabilities of pre-trained LLMs rather than relying on static dictionaries. Several scholars have applied deep learning methods to sensitive word detection. Reference [19] proposed a novel detection algorithm based on self-attention, utilizing Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) for sensitive word identification. While GCN approaches capture inter-word relationships, they struggle with modeling long-range dependencies and exhibit high computational complexity. Reference [20] employs BERT-BiLSTM-CRF to identify Chinese sensitive words in social networks. However, this approach lacks a clear definition of sensitive word boundaries. Our IPKE-MoE framework resolves these limitations by determining sensitive word boundaries through n-gram algorithms based on extracted sensitive word variants. Thus, our IPKE-MoE framework combines LLMs and SLMs capabilities to overcome the shortcomings of the aforementioned methods.

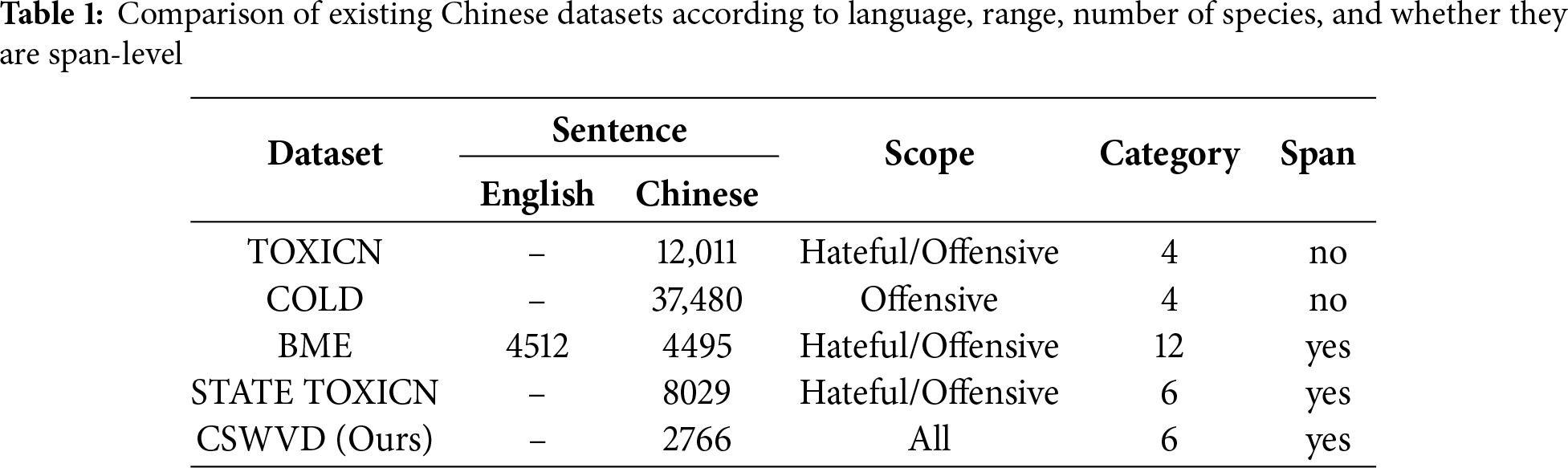

2.2 Chinese Sensitive Words Dataset

The current research on Chinese sensitive word detection is obviously lagging behind, and one of the key problems is the scarcity of labeled data. There are no public datasets dedicated to detecting Chinese sensitive words, and most of the existing offensive or hateful Chinese datasets are mostly limited to post-level detection, such as the TOXICN [10] and COLD [21] datasets, which are specialized in detecting Chinese offensive speech and hate speech, and provide an effective support to the post-level detection task. However, the identification of sensitive words is more inclined to span-level detection. The emergence of two publicly available datasets, BME [2] and STATE TOXICN [22], has helped our study. Although the BME dataset is a bilingual dataset for euphemism detection, this dataset annotates many euphemisms, which contain a large number of sensitive words. STATE TOXICN is a span-level dataset that labels toxic phrases in the text, which also contains no shortage of sensitive words. Detailed examples are shown in Table 1.

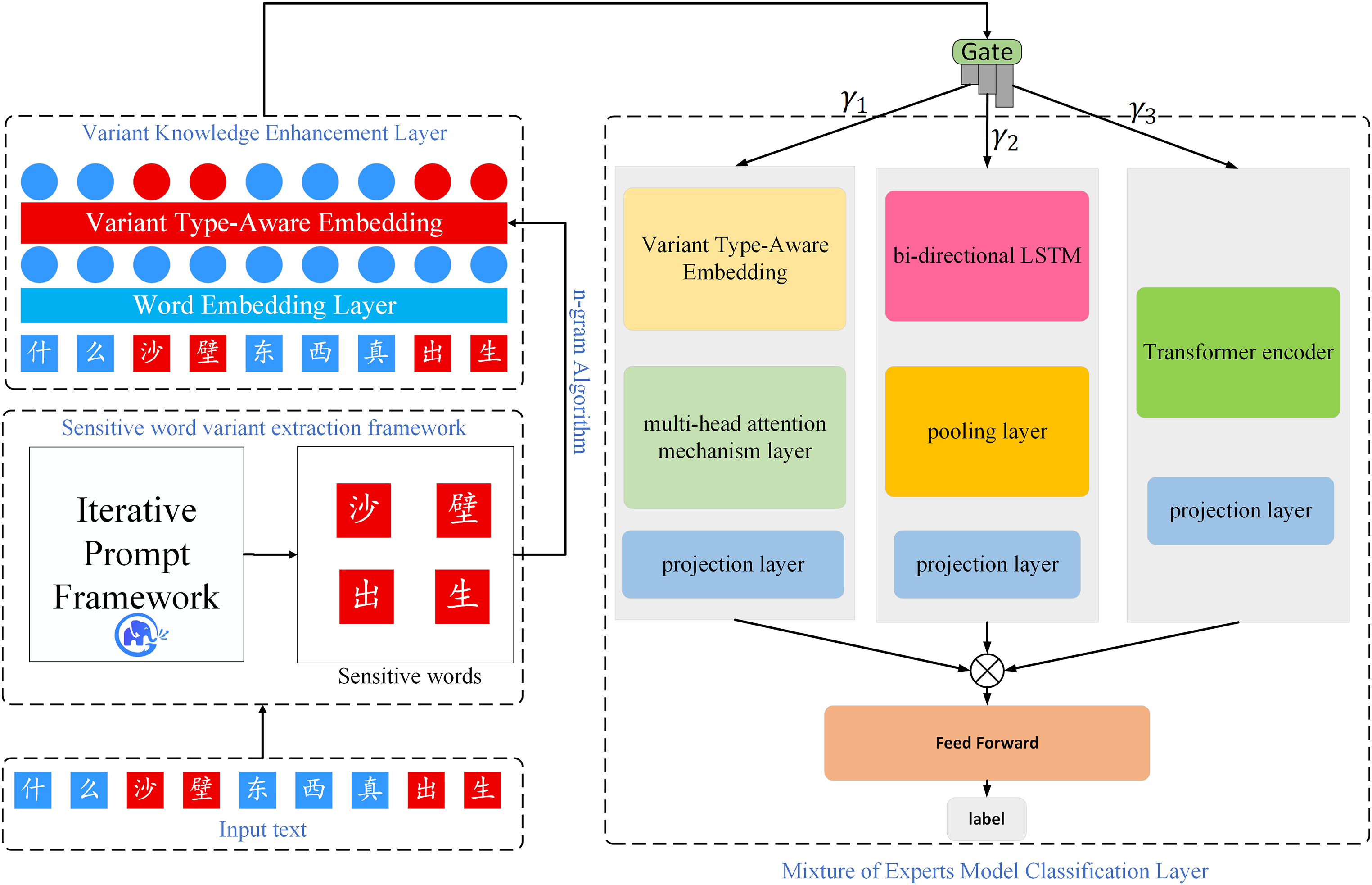

Fig. 1 shows the overall architectural flow of the IPKE-MoE framework. First, the original text data are input into the sensitive word variant extraction framework, which extracts sensitive words and their variants, the specific process is illustrated in Fig. 2. Subsequently, the input text and the extracted sensitive word variants are simultaneously fed into the variant knowledge enhancement layer. Here, the n-gram algorithm determines the types of sensitive words within the input text to fuse lexical-level semantic features. Finally, the mixture-of-experts (MoE) classification layer achieves precise classification of sentences containing sensitive words. In this chapter, we will introduce the various components of the framework in detail.

Figure 1: IPKE-MoE framework overall process

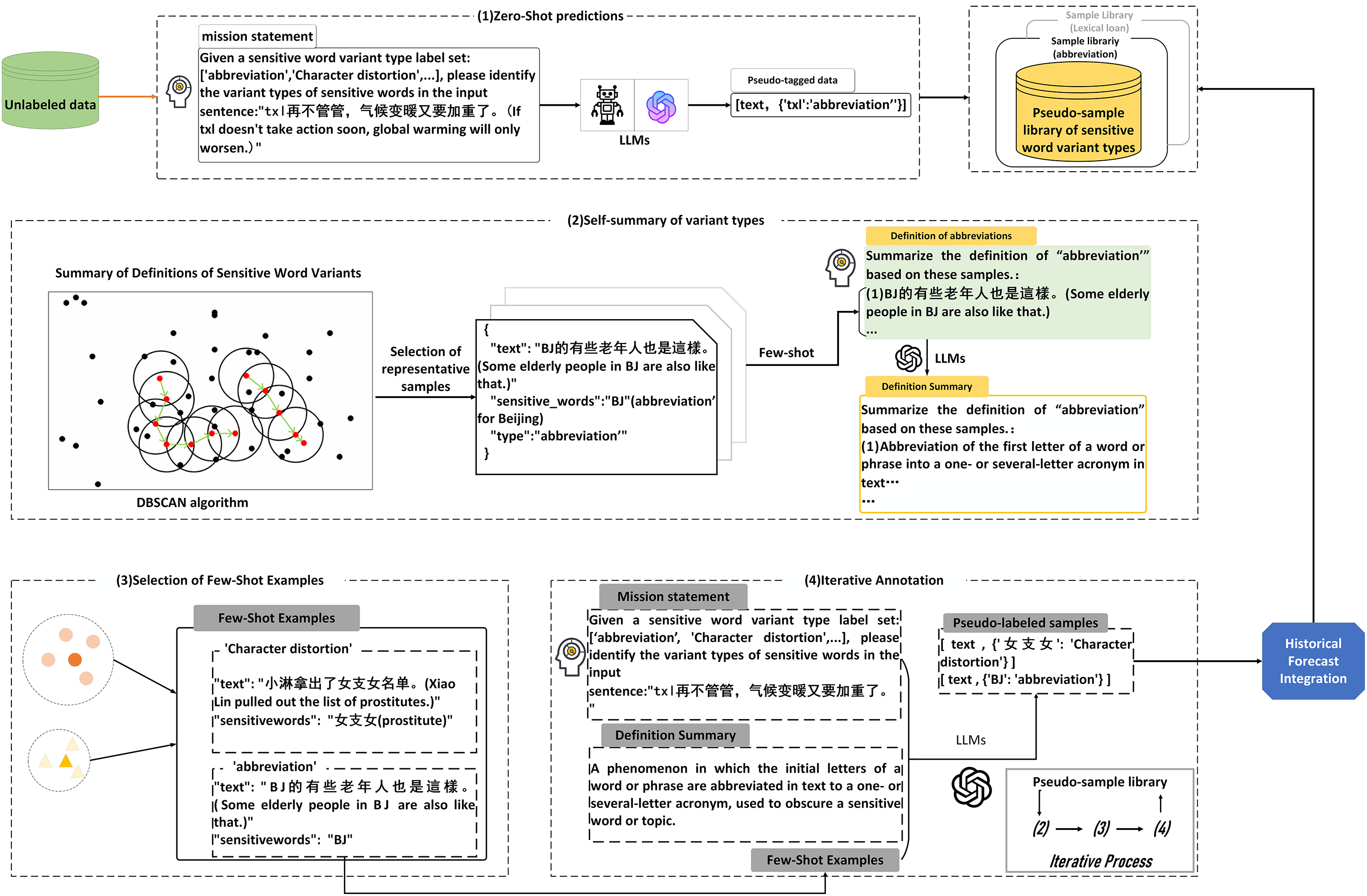

Figure 2: The specific workflow of the sensitive word variant extraction framework is as follows: (1) Use zero-shot prompts to generate initial predictions from the LLM, then create an initial pseudo-sample repository based on these predictions; (2) Employ DBSCAN clustering to remove noise from the pseudo-sample repository and select a representative subset of pseudo-samples; (3) Guide the LLM to generate definitions summarizing sensitive word variant types using the selected representative pseudo-samples; (4) Select examples from the representative pseudo-samples as few-shot examples. Combine these examples with the summary definitions of sensitive word variant types as new prompts to guide the LLM for re-prediction; (5) Repeat this process for T rounds (T = 5), integrating predictions from each round to update the pseudo-sample repository until the extraction results converge

3.1 Sensitive Word Variant Extraction Framework

Problem Definition. Assuming

where

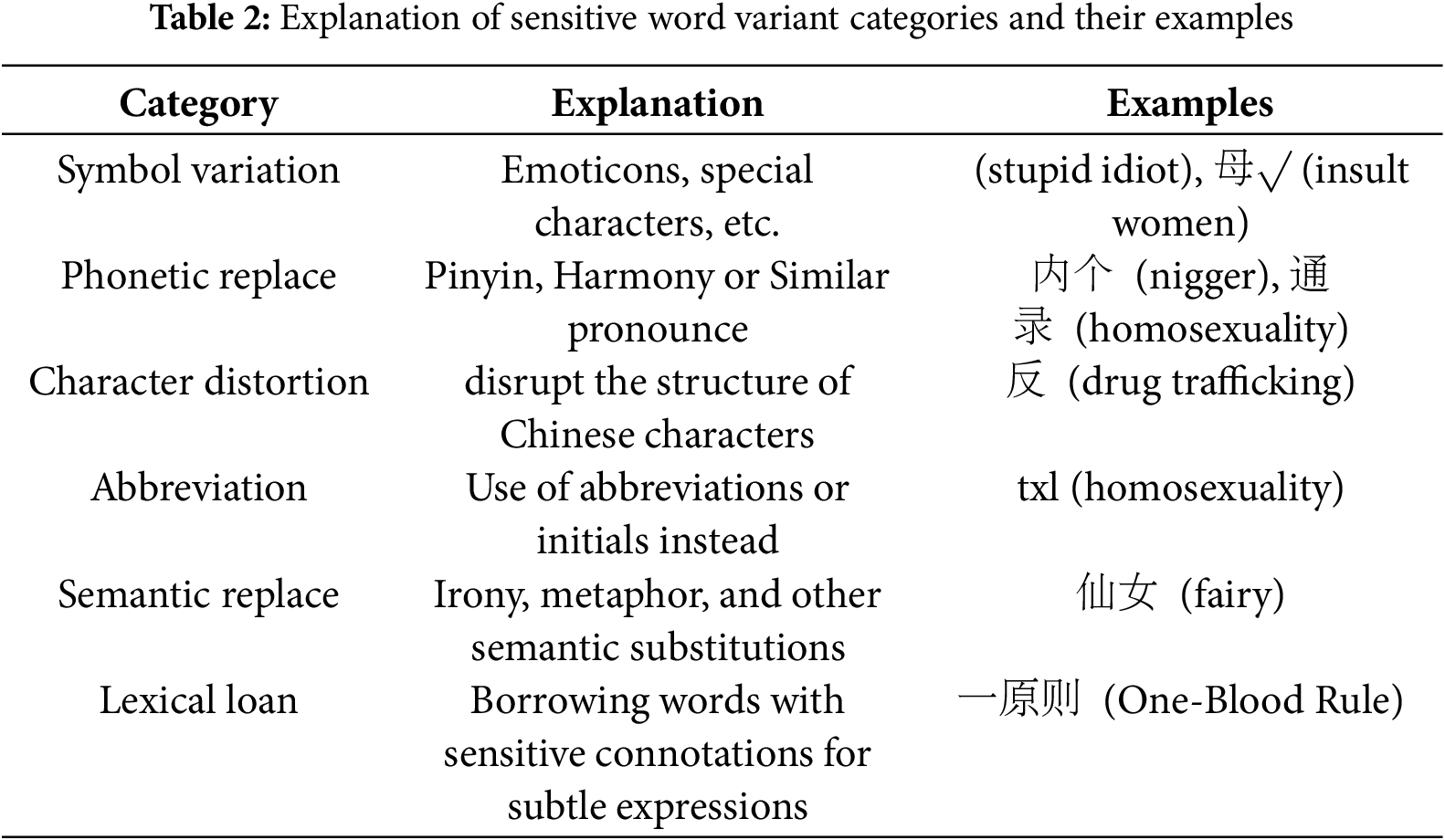

Variants of Sensitive Words. To identify sensitive word variants, we refer to [1] and analyze how Chinese netizens circumvent censorship through lexical recoding. The variant forms are categorized into six major groups, namely symbol variation, phonetic replace, character distortion, abbreviation, semantic replace, and lexical loan, and detailed examples and their explanations are shown in Table 2. As shown in the table, 傻* means “stupid idiot.” This term uses the special symbol “*” to disrupt the character structure and evade censorship. Other examples similarly employ different substitution rules to replace original vocabulary and bypass review.

Construction of Pseudo Sample Library. We use the unlabeled corpus to generate initial predictions by zero-shot prompt LLM to construct noise-containing pseudo-sample libraries L. Based on the pseudo-samples, we summarize the sensitive word variant type definitions to improve the model’s ability to extract sensitive words and variants. Based on the sensitive word variant types

Selection of Representative Pseudo-Samples. For each pseudo-sample library

Summary of Variant Type Definitions. In order to be able to better generate a summary

Selection of Few-Shot Example. In the initial stage, we use zero-shot to prompt the LLM to obtain pseudo-samples, and there is no any few-shot prompt in this stage. After obtaining the pseudo-samples, we construct a representative sample subset

Historical Prediction Integration. To enhance the reliability of the pseudo-sample library L, we iteratively obtain multi-step predictions

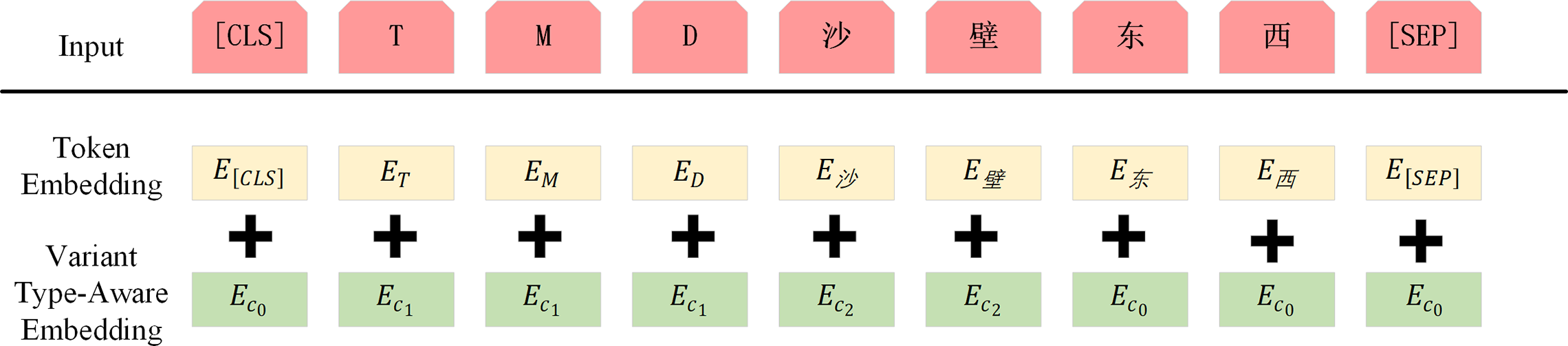

3.2 Sensitive Word Variant Knowledge Enhancement Layer

This layer aims to deeply integrate the lexical morphological features of variant sensitive words into the textual representation to achieve fine-grained knowledge-guided semantic modeling. We introduce the sensitive word variant knowledge enhancement, our sensitive word variant knowledge enhancement is based on the RocBert [25] model to enhance each word, the input text is tokenized before it is fed into the Token Embedding layer, and two special Tokens will be inserted at the beginning of the text [CLS] and the end of the text [SEP]. The illustration is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Schematic of knowledge enhancement of sensitive word variants

Token Embedding. Token Embedding is based on distributed assumptions and maps words into a high-dimension feature space while maintaining the semantic information [26]. For each input sentence

Variant Type-Aware Embedding. Since the sensitive words in a sentence and their sensitive word variants are crucial for recognizing sensitive text, we do a sensitive word variant type-aware embedding of the input sentence using the sensitive word lexicon extracted from the sensitive word variant extraction framework, as described in Section 3.1, and we denote the sensitive word category as

The type label

3.3 Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) Classification Layer

Text containing sensitive words and their variants is not necessarily offensive or hateful; its specific meaning is often embedded within the semantic context. Relying solely on sensitive word and variant recognition yields poor results. For example: “我艹, 我TMD居然通过了考试 (Holy crap! I fucking passed the exam.)”. The words “艹 (fuck)” and “TMD (fucking)” are used only as adverbs of degree to enhance the tone of voice, with no obvious offense or hatred. Knowledge augmentation for sensitive word variants can incorporate lexical knowledge, but this alone cannot achieve satisfactory performance. To address the limitations of traditional single models in handling contextual ambiguity of sensitive words, this paper designs a mixture-of-experts (MoE) classification layer comprising three experts and an augmented gated network. We split the RocBert layer’s output into sequential and pooled outputs. The sequential output represents RocBert’s output after variant-type-aware embedding:

Enhanced Gating Network. The input to the enhanced gated network is RocBert’s sequential output

where

Sensitive Word Expert. The sensitive word expert receives the sequential output

where

Sentiment Expert. The main components of the sentiment expert include a bi-directional LSTM layer, a pooling layer, and a projection layer. The bi-directional LSTM layer processes the sequence output

where

Semantic Expert. The components of the Semantic Expert include a Transformer coding layer and a projection layer. First, the Transformer coding layer processes the sequence output

where

Joint Training Strategy. After obtaining expert weights and individual expert outputs, we dynamically fuse multi-dimensional features to generate classification results. The mixture-of-experts (MoE) classification layer employs end-to-end joint training. Three experts respectively learn distinct linguistic-level features (word variants, sentiment, semantics). A gating network dynamically allocates weights based on input. The overall output of the mixture-of-experts (MoE) classification layer is the weighted sum of each expert’s outputs:

The total loss function consists of two components: classification loss + gate regularization. As shown in Eq. (9).

where

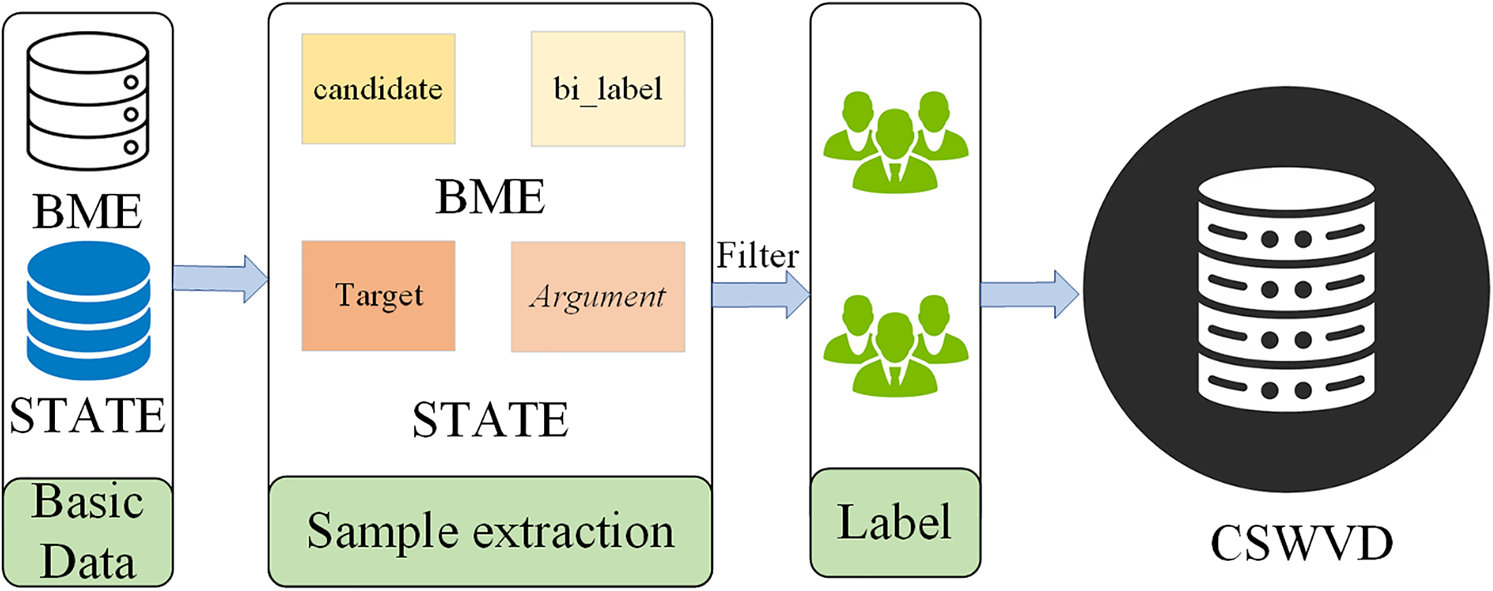

4.1 Sensitive Word Variant Extraction Experiment

Dataset. Our CSWVD dataset is built from two publicly available sources, BME and STATE-ToxiCN, which include various sensitive contents such as insults and discrimination. The overall workflow is shown in Fig. 4. In BME, the bi_label and candidate fields indicate whether a sentence contains euphemisms and specify the euphemisms, respectively. We select sentences with euphemisms based on bi_label and filter them by predefined sensitive word variant types. STATE-ToxiCN is a span-level Chinese hate speech dataset containing Target-Argument-Hateful-Group quadruplets, where Target denotes the attacked entity (e.g., individuals, groups, or professions) and Argument describes the attack. We extract samples with sensitive word variants and re-label them with the original text to ensure consistency and accuracy. To address class and sample imbalance, we also supplement the dataset with additional data collected from multiple online platforms. The dataset distribution is presented in Table 3.

Figure 4: Annotation process for the CSWVD dataset

LLMs. To ensure our IPKE-MoE framework can most effectively handle Chinese sensitive words and their complex variants, we selected three models more suited to Chinese, including both open-source and closed-source models. Open-source models: Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct and Baichuan-M1-14B-Instruct. These models deeply integrated massive, high-quality Chinese corpora during their pre-training phase. This endows them with a profound understanding of Chinese linguistic structures, syntactic conventions, cultural contexts, and online discourse. We selected the instruction-following variants of these models to enhance their task tracking capabilities, then fine-tuned them using LLaMA-Factory. Closed-source models: ChatGLM-4-Plus. The ChatGLM series, developed from Tsinghua University’s technological innovations, has long maintained a leading position in Chinese LLM landscape. As its robust commercial variant, ChatGLM-4-Plus represents one of the highest levels of Chinese language processing capability currently accessible via API. We employed distinct invocation methods for these two model types: ChatGLM-4-Plus is accessed through its API, while Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct and Baichuan-M1-14B-Instruct are deployed locally using the vLLM3 framework to enhance inference speed.

Baselines. In order to validate the effectiveness of our proposed Iterative Prompting (ITPR), we chose several different prompting baselines, namely:

• Zero-Shot: only the task prompts and output formats are given without any other examples.

• Few-Shot: Not only does it give a hint and output format, but it also gives a small number of examples to refer to.

• Zero-Shot-Cot: gives the task hints and output format, and adds a hint: “Let’s think step by step”.

• Manual-Cot: The task prompts and output format are given, and several manual reasoning demonstrations are included, each with a question and a chain of reasoning. The reasoning chain consists of reasons (a series of intermediate reasoning steps) and expected answers.

Evaluation Metrics. Due to the ambiguity of the sensitive word boundaries, we used a soft-match metric, where we used entity-level micro-F1 scores as metrics and employed the algorithm proposed by [27], where a prediction is considered correct if the prediction score for the sensitive word type reaches a threshold of 0.5.

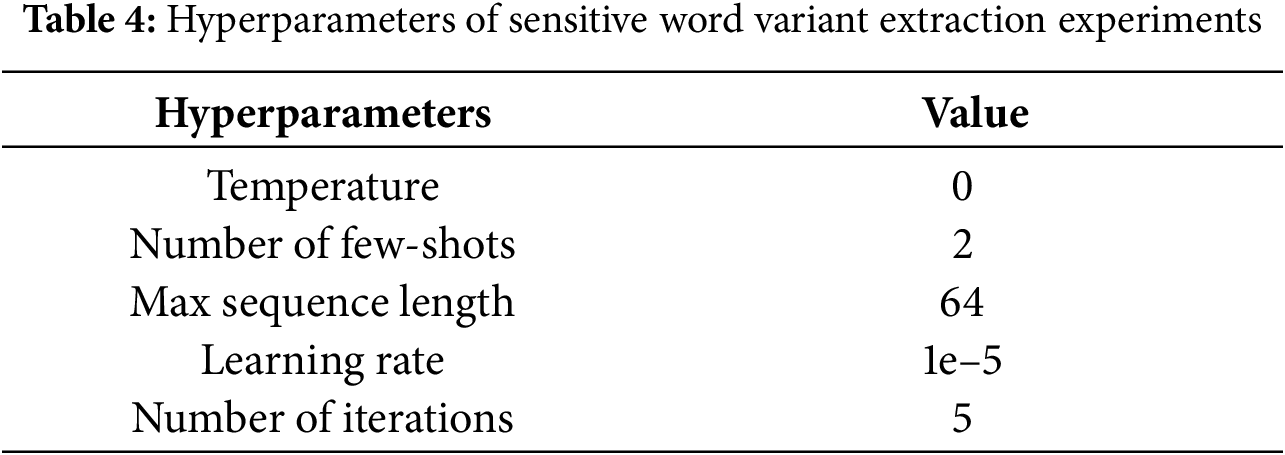

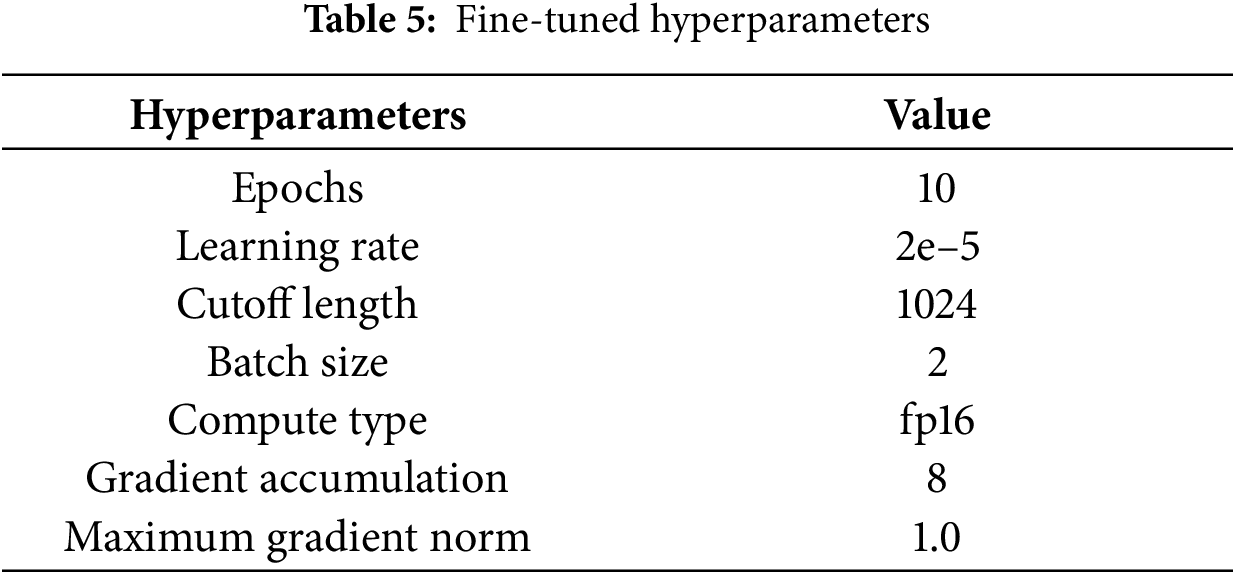

Implementation Details. We use an A800 graphics card with 80 G memory size, pytorch version 2.5.1, Python version 3.12, and CUDA version 12.4. Our sensitive word variant extraction experiments in the first two iterations use only variant type definitions, without using the few-shot demo, and we use LaBSE4 as the sentence embedding model. The hyperparameter settings for the sensitive word variant extraction experiments as well as the fine-tuned hyperparameter settings are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

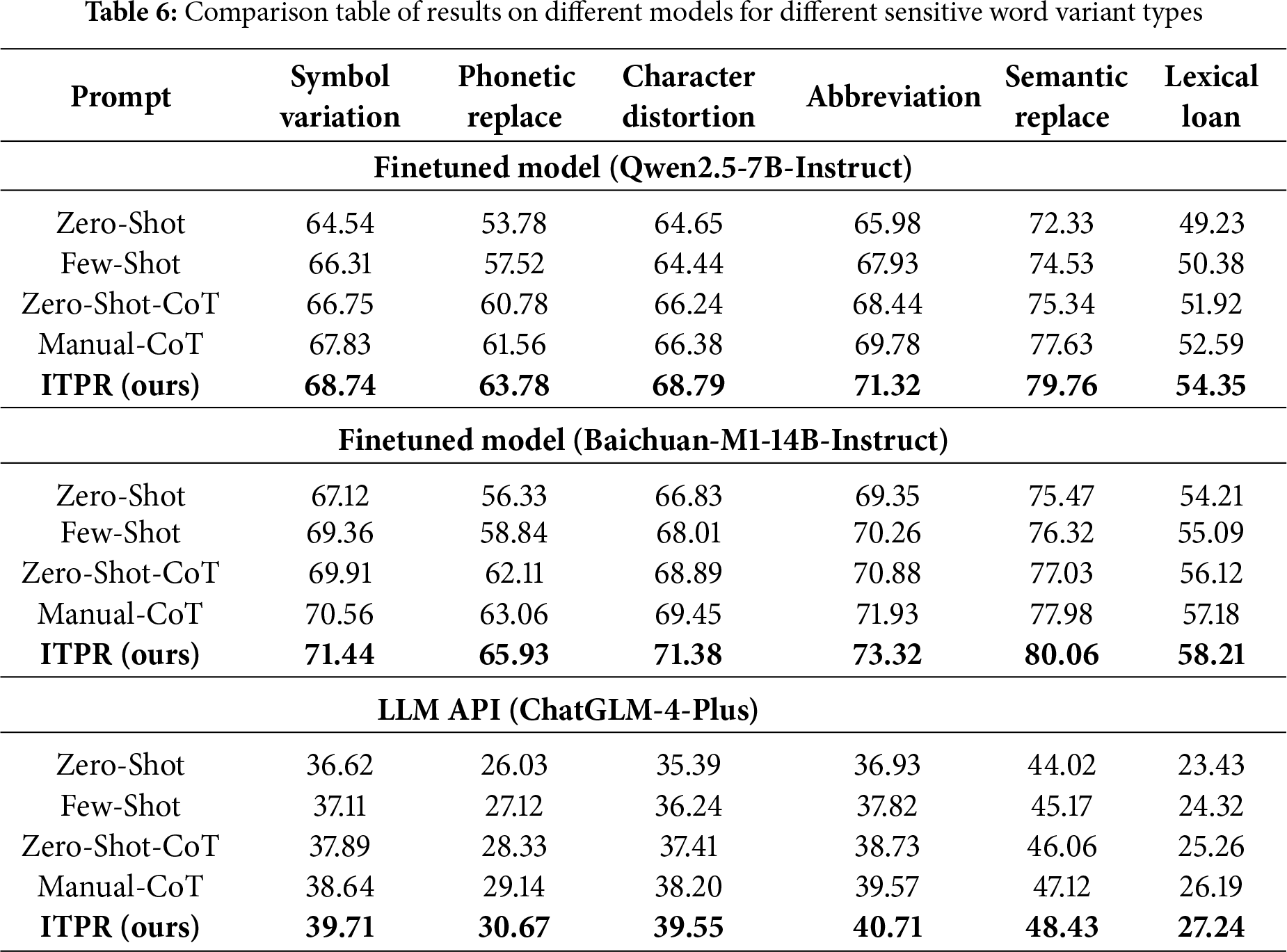

Main Results. We evaluated the effectiveness of our iterative prompt on three different models, as shown in Table 6. It can be seen that the performance of our iterative prompt exceeds the baseline in all the different models, which demonstrates the sound-ness of our design. Among several different types of sensitive word variants, we find that lexical loan is less effective, which may be due to the fact that this type has no obvious variants and requires some background knowledge in order for the model to understand its meaning. Second, we also find that the performance of the fine-tuned model is significantly better than using the LLM API directly, and that Baichuan-M1-14B-Instruct achieves the optimal performance on all types. This is because fine-tuning infuses the model with task-specific knowledge and focuses on the requirements of the target task, whereas ChatGLM-4-Plus relies solely on generalized knowledge, placing it at a disadvantage in terms of task adaptability.

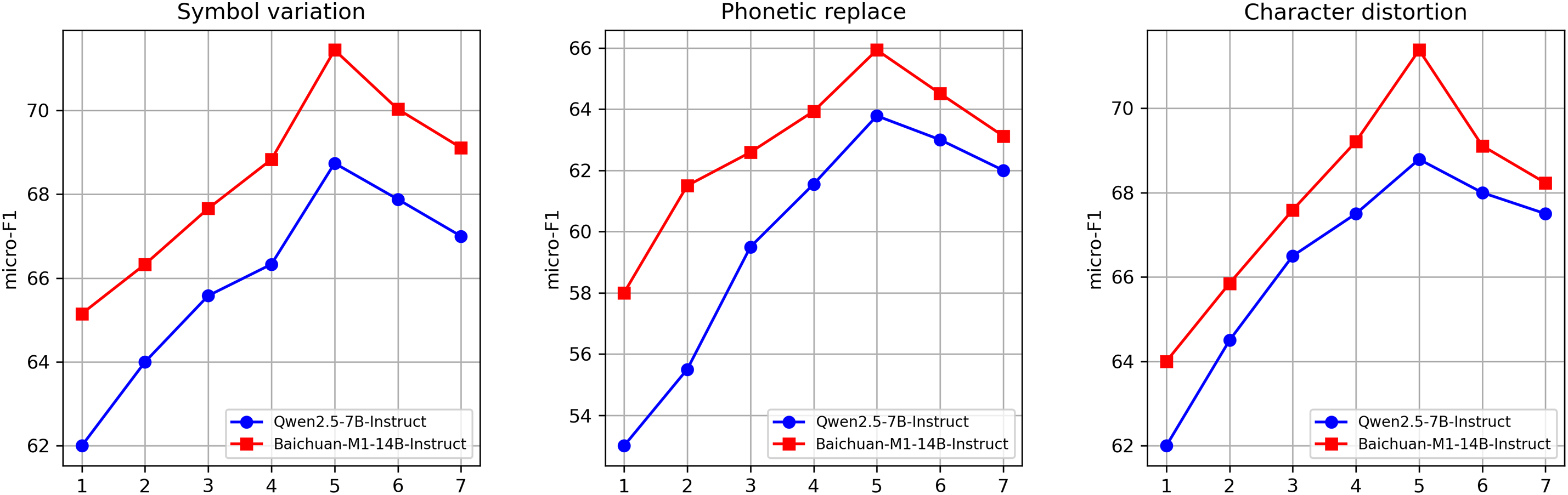

A Study of the Number of Iterations. To investigate the impact of iteration count on experimental outcomes, we examined how the number of iterations affects the performance of two closed-source models across six distinct data types. As detailed in Fig. 5, the models’ F1 scores progressively improved with each iteration round, reaching saturation around the fifth iteration. This trend can be explained theoretically by self-training and bootstrapped learning: iterative prompts rapidly expand pseudo-samples and enhance diversity in the early stages, but simultaneously introduce noise; As iterations progress, the LLM’s output stabilizes and pseudo-sample quality improves, leading to diminishing returns and eventual convergence. Excessive iterations may even cause accumulated noise to slightly offset performance gains.

Figure 5: Comparison plot of the effect of the number of iterations on model performance

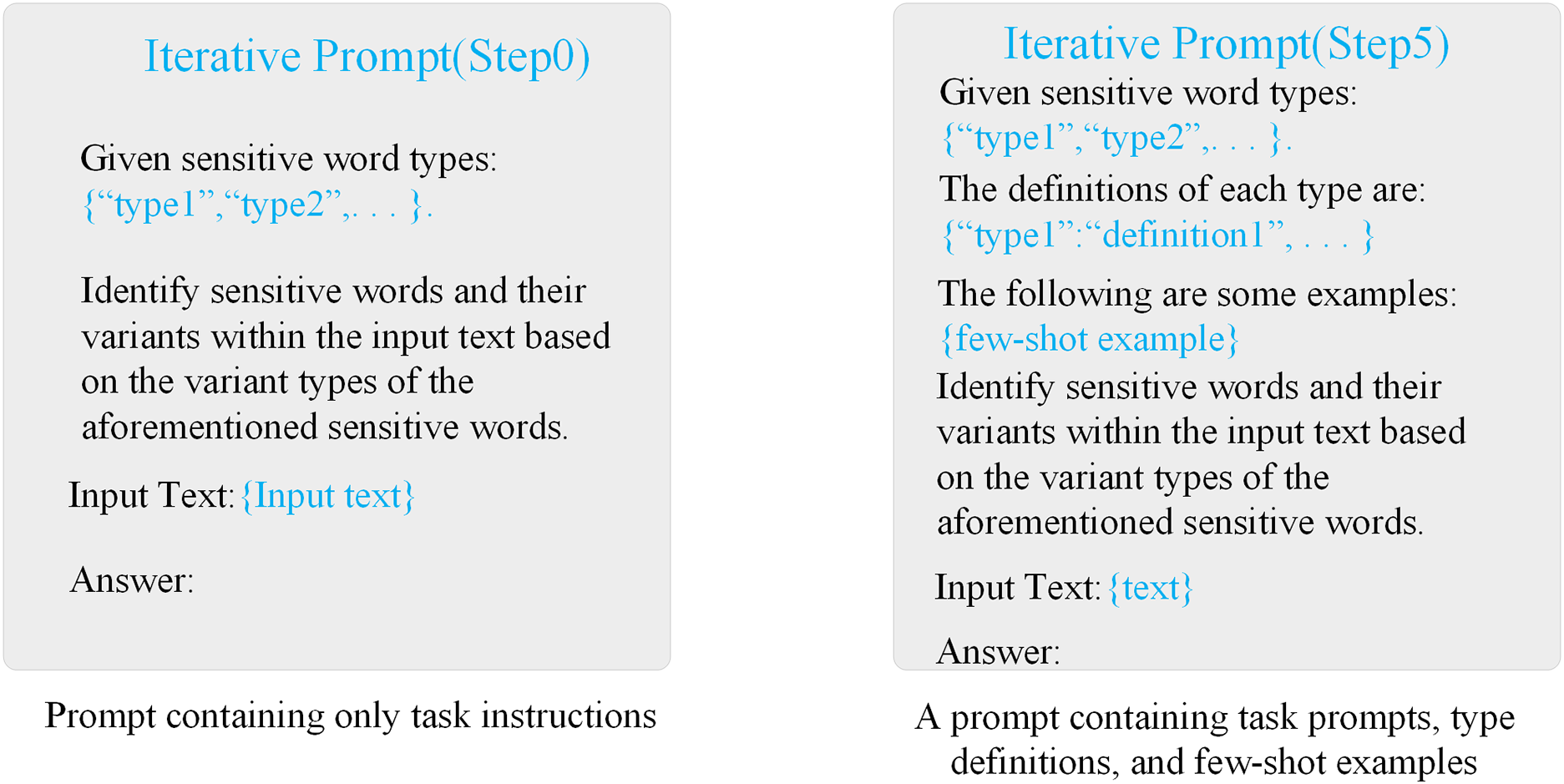

Iterative Prompt Examples. Given our framework’s heavy reliance on iterative prompts, we present template examples of these prompts to provide a more intuitive demonstration of its effectiveness and interpretability, as shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Examples of iterative prompts

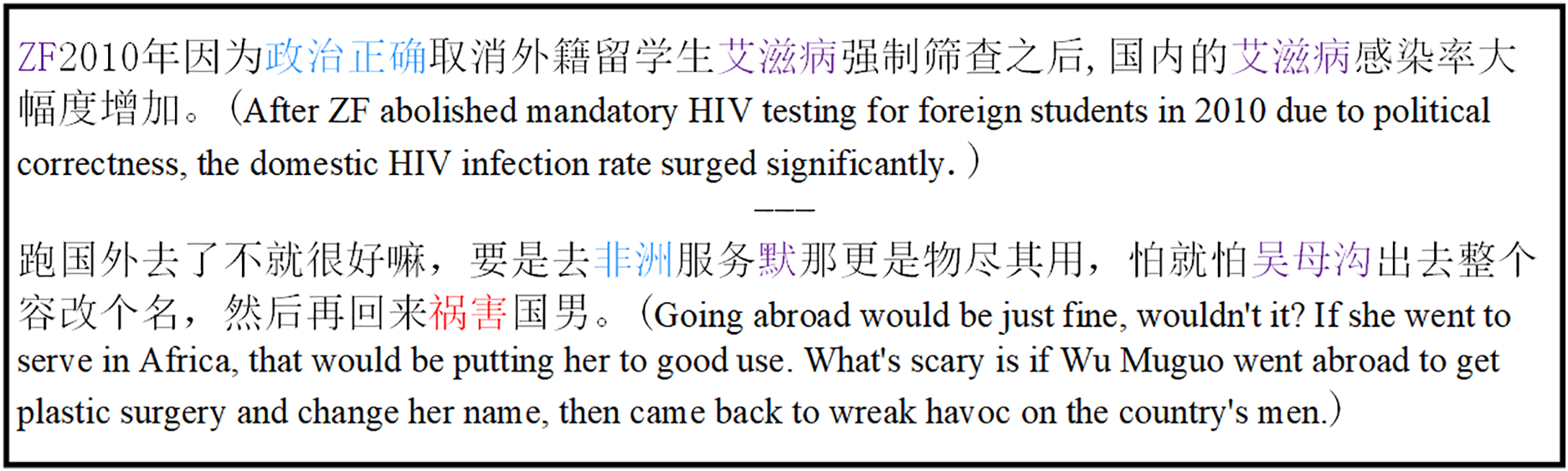

Manual Evaluation. We randomly selected 300 samples from the validation set and had two annotators independently assess the scope and variant types of sensitive words generated by the model. We then calculated inter-annotator agreement using Cohen’s Kappa statistic to measure consistency between the two annotators, yielding Cohen’s kappa = 0.86. This indicates a high level of agreement in their annotation judgments. Fig. 7 presents a qualitative comparison between manually annotated sensitive words and their variants vs. those extracted by the LLM, illustrating typical successful and failed cases. Red indicates manually annotated sensitive words and variants, blue denotes those identified by the LLM, and purple highlights overlapping areas. The examples demonstrate a high degree of overlap.

Figure 7: Manual evaluation diagram

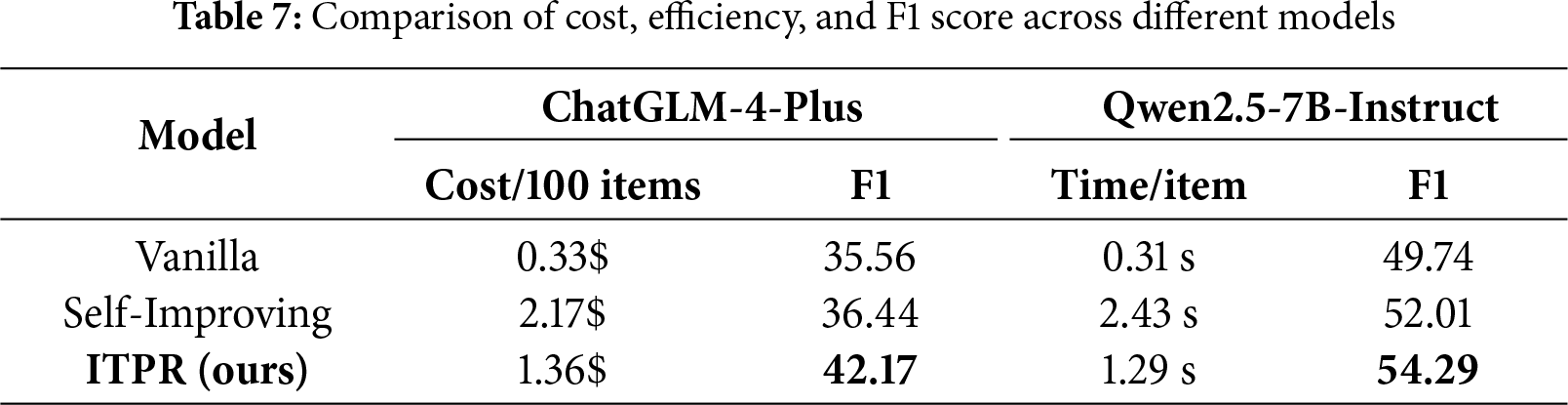

Efficiency Analysis. To evaluate the efficiency of our approach, we conducted an additional performance study experiment, comparing its inference performance and associated costs with other iterative annotation-based methods (consistency). Our comparison results are shown in Table 7.

4.2 Sensitive Text Categorization Experiment

Dataset. In order to ensure the rationality of our experiments, we still conducted sensitive text categorization experiments using the 2766 datasets extracted from the sensitive word variant extraction experiments and we only retained the original text and its corresponding categorization labels to make it more suitable for binary categorization tasks.

Models and Baselines. Our experiments compared online detection tools, standalone SLMs, standalone LLMs and the LLM+SLM baseline. For the online detection tool, we utilized Baidu AI Open Platform’s online toxic content detection API, which identifies variant violations such as pinyin, homophones, character splitting, near-homographs, and allusions. For standalone SLMs, we employed BERT and RoCBert as encoders. RoCBert is a pre-trained Chinese BERT model resistant to adversarial attacks such as word perturbations, synonyms and spelling errors. In SLM-based baselines, we treated the SLM as an encoder and utilized a fully connected layer as the classifier for sensitive text classification tasks. For standalone LLM evaluations, we compared the zero-shot performance of Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct, Baichuan-M1-14B-Instruct and ChatGLM-4-Plus. For the LLM+SLM baseline, we adopted the previously mentioned CAALM-TC and RCT models. RocBert served as the SLM encoder for our LLM+SLM baseline, with a fully connected layer acting as the classifier for the sensitive text classification task. Our IPKE-MoE framework employs the mixture-of-experts (MoE) classification layer mentioned earlier as the classifier for this task.

Implementation Details. Our experiment uses the AdamW optimizer. The specific training parameters for the classifier are described in Section 3.3. All samples in our dataset are split into training and test sets at an 8:2 ratio. We fine-tune the baseline and retain the best-performing model and hyperparameters on the test set. To reduce errors, we repeat the same experiments multiple times by varying the random seed. All experiments are conducted using a GeForce RTX 4090 GPU.

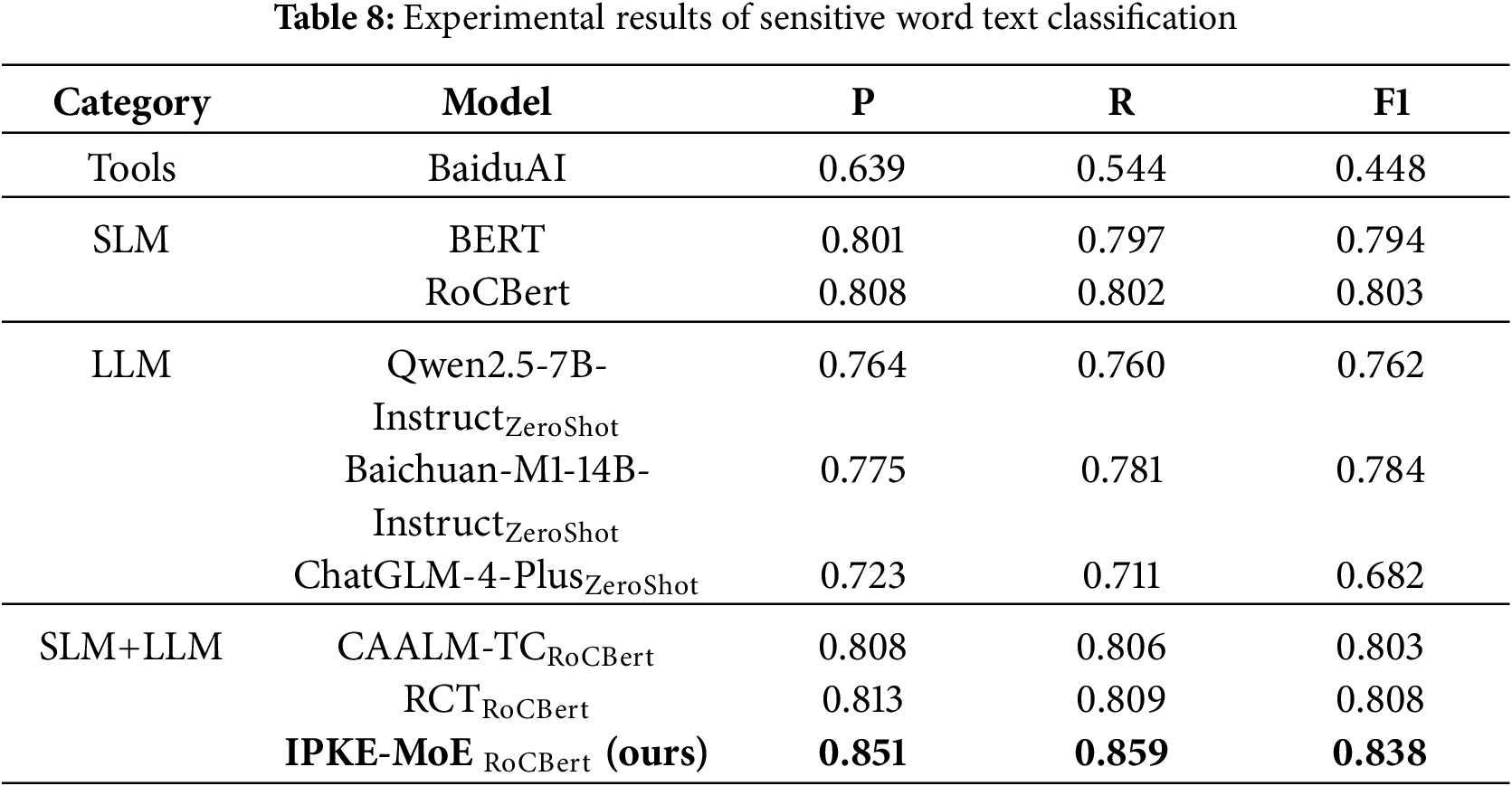

Automated Evaluation. We evaluate the performance of the model using widely used weighted precision metrics (P), recall (R), and F1 scores (F1), the experimental results of the sensitive word text classification experiments are shown in Table 8.

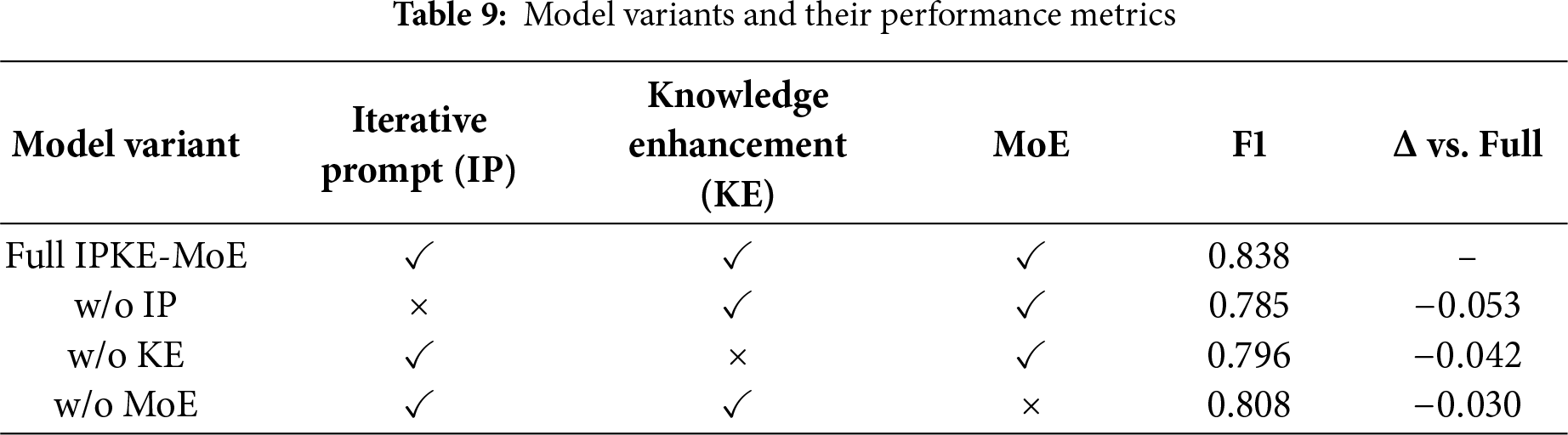

Ablation Studies. To validate the effectiveness of each IPKE-MoE module, we conducted stepwise ablation experiments:

(1) Removed the iterative prompting module (w/o IP), performing zero-shot prompting with the LLM for single-round prediction only;

(2) Removed the knowledge enhancement layer (w/o KE), directly utilizing context representations by appending LLM-extracted sensitive word variant information to the original text;

(3) Removed the mixed expert layer (w/o MoE), employing a single fully connected classifier.

As shown in Table 9, removing any module results in a decline in performance. Specifically, removing the iteration prompt caused the F1 score to drop by 5.3%, representing the most significant performance decline, highlighting this mechanism’s role in sensitive word variant extraction. Removing the knowledge enhancement layer resulted in a 4.2% decrease in F1, demonstrating the importance of sensitive word variant type embeddings. Removing MoE led to a 3.0% performance drop, indicating the critical role of the dynamic expert fusion mechanism in model robustness.

Significance Testing. Significance testing to validate the statistical robustness of the results, we repeated the experiment five times under different random seeds, reporting the mean

5 IPKE-MoE Performance Analysis

RQ1: Error analysis.

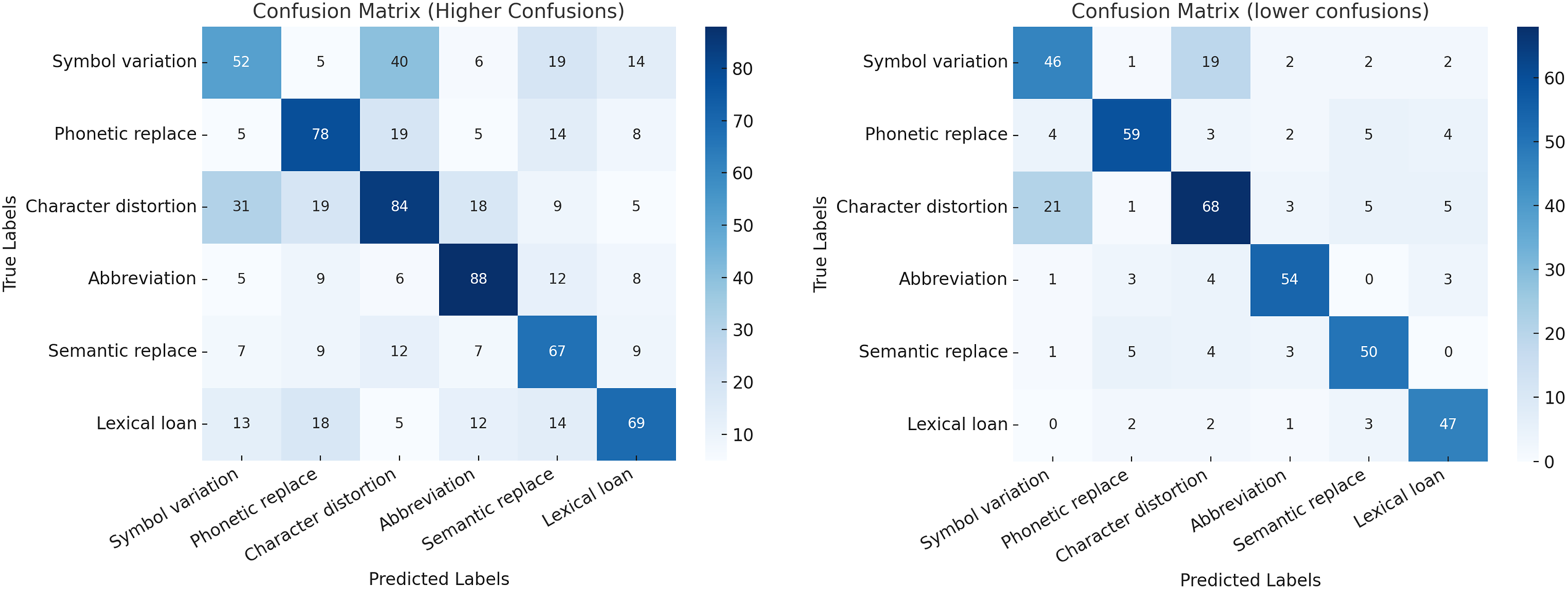

• As shown in Fig. 8, the confusion matrix reveals that our framework notably reduces error distribution compared to the baseline. This improvement arises from the sensitive word variant extraction module, which defines variant types clearly and provides representative samples, enhancing model understanding while minimizing noise. Some confusion remains between similar types, such as Symbol variation and Character distortion.

• Erroneous Example: 哈哈哈哈还不快去把肖万救出来, 那是世界英雄! (Hahahahaha don’t go get Shovan out yet, that’s a world hero!). In this erroneous example, “肖万”, a former police officer involved in George Floyd’s death, is metaphorically used to express hatred toward Black people. Our framework fails to detect this case, indicating that it focuses on explicit sensitive words and their variants rather than leveraging the LLM’s broader contextual knowledge.

Figure 8: Confusion matrix diagram: error type distributions before (left) and after (right) applying our framework

RQ2: Efficiency Analysis Our approach requires multiple iterations to improve accuracy, inevitably leading to increased calls to the LLM. To evaluate our method’s practicality, we compared its inference performance and associated costs against other approaches, as shown in Table 7. Results demonstrate that our framework significantly reduces both time and financial costs compared to other iterative annotation methods. While our framework incurs higher costs than the Vanilla method, it delivers markedly im-proved performance. We consider this trade-off acceptable, as the accuracy gains outweigh the additional computational expenses.

RQ3: Ethical Considerations and Risk Mitigation Since IPKE-MoE involves sensitive content detection, two types of risks may exist:

• False Positive: Misclassifying normal text as sensitive, leading to over-blocking;

• False Negatives: Failure to identify genuinely non-compliant or harmful content.

To mitigate false positive risks, we set a high confidence threshold and introduced manual review when model predictions show low confidence. Reviewers assess solely based on linguistic offensiveness, avoiding political or ideological bias. To reduce false negatives, we enhanced variant coverage through iterative pseudo-sample expansion and manual misclassification analysis.

This paper proposes IPKE-MoE, a detection framework for identifying text containing sensitive words and their variants. IPKE-MoE requires multiple calls to an LLM during the pseudo-sample iterative generation phase, and this dependency may impact scalability in high-volume content moderation scenarios. To address this, we will explore a distilled, compact IPKE-MoE model with caching mechanisms to support large-scale, low-cost content moderation applications. We analyzed six common variant types of sensitive words in Chinese internet content and constructed the CSWVD dataset based on these categories. We acknowledge that CSWVD’s scale is relatively limited (2766 entries), falling short of certain large-scale corpora and unable to fully address the complex and dynamic variants prevalent in Chinese internet content. Nevertheless, it provides valuable insights for sensitive word variant research. Future work will explore more flexible or data-driven classification approaches. Additionally, our framework does not account for the role of LLM background knowledge. Therefore, future work will focus on effectively leveraging LLM background knowledge for sensitive word detection.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62441212) and the Major Project of the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia (Grant No. 2025ZD008).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Longcang Wang, Yongbing Gao, Xin Liu; data collection: Longcang Wang, Xinguang Wang; analysis and interpretation of results: Longcang Wang, Xinguang Wang, Yongbing Gao; draft manuscript preparation: Longcang Wang, Xinguang Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in github at https://github.com/LongCang/CSWVD (accessed on 11 November 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ye W, Zhao L. “I know it’s sensitive”: internet censorship, recoding, and the sensitive word culture in China. Discourse Context Media. 2023;51:100666. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2022.100666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hu Y, Li J, Wang T, Su D, Su G, Sha Y. A unified generative framework for bilingual euphemism detection and identification. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024; 2024 Aug 11–16; Bangkok, Thailand. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 6753–66. [Google Scholar]

3. Ke L, Chen X, Wang H. An unsupervised detection framework for Chinese jargons in the darknet. In: Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; 2022 Feb 21–25; Phoenix, AZ, USA. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2022. p. 458–66. [Google Scholar]

4. Zhou H, Li Z, Zhang B, Li C, Lai S, Zhang J, et al. A simple yet effective training-free prompt-free approach to Chinese spelling correction based on large language models. arXiv: 2410.04027. 2024. [Google Scholar]

5. Dong M, Chen Y, Zhang M, Sun H, He T. Rich semantic knowledge enhanced large language models for few-shot Chinese spell checking. arXiv: 2403.08492. 2024. [Google Scholar]

6. Pavlopoulos J, Sorensen J, Laugier L, Androutsopoulos I. SemEval-2021 task 5: toxic spans detection. In: Proceedings of the 15th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval-2021); 2021 Aug 9–13; Online. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

7. He X, Zannettou S, Shen Y, Zhang Y. You only prompt once: on the capabilities of prompt learning on large language models to tackle toxic content. In: 2024 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2024 May 20–24; San Francisco, CA, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE. p. 770–87. [Google Scholar]

8. Li L, Fan L, Atreja S, Hemphill L. “HOT” ChatGPT: the promise of ChatGPT in detecting and discriminating hateful, offensive, and toxic comments on social media. ACM Trans Web. 2024;18(2):1–36. doi:10.1145/3643829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pendzel S, Wullach T, Adler A, Minkov E. Generative AI for hate speech detection: evaluation and findings. In: Regulating hate speech created by generative AI. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Auerbach Publications; 2024. p. 54–76. [Google Scholar]

10. Lu J, Xu B, Zhang X, Min C, Yang L, Lin H. Facilitating fine-grained detection of Chinese toxic language: hierarchical taxonomy, resources, and benchmarks. arXiv: 2305.04446. 2023. [Google Scholar]

11. Gonçalves J. Combining autoregressive and autoencoder language models for text classification. arXiv: 2411.13282. 2024. [Google Scholar]

12. Kang H, Qian T. Implanting LLM’s knowledge via reading comprehension tree for toxicity detection. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024; 2024 Aug 11–16. Bangkok, Thailand. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2024. p. 947–62. [Google Scholar]

13. Huang S, Wu X, Ma S, Wei F. Mh-MoE: multi-head mixture-of-experts. arXiv: 2411.16205. 2024. [Google Scholar]

14. Hutto C, Gilbert E. VADER: a parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In: Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media; 2014 May 15–18; Ann Arbor, MI, USA. Palo Alto, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2014. p. 216–25. [Google Scholar]

15. Wiegand M, Ruppenhofer J, Schmidt A, Greenberg C. Inducing a lexicon of abusive words—a feature-based approach. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2018 Jun 1–6; New Orleans, LA, USA. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018. p. 1046–56. [Google Scholar]

16. Jiang H, Yu Q, Zhang Z. An improved quad-array trie algorithm for website sensitive word detection. In: Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Computing and Artificial Intelligence; 2023 Jul 15–17; London, UK. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 484–90. [Google Scholar]

17. Ghauth KI, Sukhur MS. Text censoring system for filtering malicious content using approximate string matching and Bayesian filtering. In: Computational Intelligence in Information Systems: Proceedings of the Fourth INNS Symposia Series on Computational Intelligence in Information Systems (INNS-CIIS 2014); 2014 Dec 10–12; Bali, Indonesia. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2015. p. 149–58. [Google Scholar]

18. Breitfeller L, Ahn E, Jurgens D, Tsvetkov Y. Finding microaggressions in the wild: a case for locating elusive phenomena in social media posts. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); 2019 Nov 3–7; Hong Kong, China. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 1664–74. [Google Scholar]

19. Liu Y, Yang C-Y, Yang J. A graph convolutional network-based sensitive information detection algorithm. Complexity. 2021;2021(1):6631768. doi:10.1155/2021/6631768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yang Y, Shen X, Wang Y. BERT-BiLSTM-CRF for Chinese sensitive vocabulary recognition. In: International Symposium on Intelligence Computation and Applications; 2019 Sep 20–22; Changsha, China. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 257–68. [Google Scholar]

21. Deng J, Zhou J, Sun H, Zheng C, Mi F, Meng H, et al. COLD: a benchmark for Chinese offensive language detection. arXiv: 2201.06025. 2022. [Google Scholar]

22. Xiao Y, Hu Y, Choo KT, Lee RK. ToxicloakCN: evaluating robustness of offensive language detection in Chinese with cloaking perturbations. arXiv: 2406.12223. 2024. [Google Scholar]

23. Zhang Z, Zhang A, Li M, Smola A. Automatic chain of thought prompting in large language models. In: The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations; 2023 May 1–5. Kigali, Rwanda. p. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

24. Wang X, Wei J, Schuurmans D, Le Q, Chi E, Narang S, et al. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models. arXiv: 2203.11171. 2022. [Google Scholar]

25. Su H, Shi W, Shen X, Xiao Z, Ji T, Fang J, et al. RocBERT: robust Chinese BERT with multimodal contrastive pretraining. In: Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022 Jul 5–10. Dublin, Ireland. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. p. 921–31. [Google Scholar]

26. Zhou X, Yong Y, Fan X, Ren G, Song Y, Diao Y, et al. Hate speech detection based on sentiment knowledge sharing. In: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing; 2021 Aug 1–6; Online. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021. p. 7158–66. [Google Scholar]

27. Han R, Peng T, Yang C, Wang B, Liu L, Wan X. Is information extraction solved by ChatGPT? An analysis of performance, evaluation criteria, robustness and errors. arXiv: 2305.14450. 2023. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools