Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Multi-Area Path Planning for Multiple Unmanned Surface Vessels

1 Institute of Systems Engineering, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, 999078, China

2 Guangzhou Jiafan Computer Co., Ltd., Room 601, Building A8, No. 11 Kaiyuan Avenue, Huangpu District, Guangzhou, 510000, China

* Corresponding Author: Yufeng Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Intelligent Perception, Decision-making and Security Control for Unmanned Systems in Complex Environments)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 44 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.072937

Received 07 September 2025; Accepted 24 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

To conduct marine surveys, multiple unmanned surface vessels (Multi-USV) with different capabilities perform collaborative mapping in multiple designated areas. This paper proposes a task allocation algorithm based on integer linear programming (ILP) with flow balance constraints, ensuring the fair and efficient distribution of sub-areas among USVs and maintaining strong connectivity of assigned regions. In the established grid map, a search-based path planning algorithm is performed on the sub-areas according to the allocation scheme. It uses the greedy algorithm and the A* algorithm to achieve complete coverage of the barrier-free area and obtain an efficient trajectory of each USV. The greedy algorithm enables fast local traversal of unvisited grids, while the A* algorithm ensures navigation to escape from deadlock areas and maintains global path continuity. The comparison of task allocation results proves that the task allocation algorithm based on ILP improves the mapping efficiency and task distribution fairness. The proposed allocation method and result analysis provide a certain reference for the practical application of Multi-USV to perform survey tasks collaboratively.Keywords

In recent years, marine research and protection have garnered increasing global attention, with substantial resources and technologies invested to advance marine science and promote the growth of the marine economy. In line with the “Maritime Power” strategy, the application of advanced technologies in marine research is crucial. Unmanned surface vessels (USVs), as high-tech platforms, have emerged as key tools for marine exploration and protection due to their automation and operational versatility.

However, the coverage area and task processing capabilities of a single USV are inherently limited when performing tasks. To overcome these limitations, Multi-USV cooperative operation has gradually become a significant focus of research and application. Multi-USV cooperative task execution can significantly improve the efficiency and accuracy of tasks. The challenges of Multi-USV path planning mainly include task allocation and area path planning.

The core of Multi-USV multi-area task allocation is how to reasonably distribute tasks within the capabilities of each vessel to maximize overall task execution efficiency. This requires systematically considering technical indicators such as the navigation speed, payload, and endurance of each USV. Additionally, tasks must be allocated to the most suitable vessel based on the nature and priority of the tasks.

Significant progress has been made in task allocation research. Ma et al. [1] enhance Multi-USV task allocation using an improved k-means alsgorithm and a self-organizing map for task execution, addressing communication constraints to improve autonomy. A Multi-USV task allocation and path planning approach is developed by Liu et al. [2] by combining a self-organizing map and the fast marching method, while also considering energy efficiency and communication constraints. Xia et al. [3] address multiple task assignment and path planning for Multi-USVs, proposing an improved self-organizing map for task allocation and an improved genetic algorithm for path planning. This approach, verified through simulation, effectively allocates tasks and ensures collision-free navigation. Zhou et al. [4] introduce a novel region-construction method for Multi-USV target allocation, resolving target deadlock and local optimization issues by integrating unsupervised clustering, market-based mechanisms, and ant colony optimization. This strategy improves operational efficiency and reduces the time for USVs to reach target positions. An exact algorithm for Multi-USV task allocation is presented by Xue et al. [5], focusing on minimizing the maximum task time. Task time is reduced by utilizing the Hungarian algorithm and the fast marching square method, considering both travel and turning times. A multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach is explored by Wen et al. [6], using the multi-agent deep deterministic policy gradient to optimize navigation, obstacle avoidance, and area assignment for Multi-USVs. Autonomy is enhanced by simultaneously addressing dynamic navigation and task allocation. Lyu et al. [7] propose Pathfinder, a deep reinforcement learning-based framework for multi-robot scheduling in smart factories. It dynamically selects scheduling rules and optimizes task allocation in real time. Aminu et al. [8] apply an improved particle swarm optimization for task allocation in edge computing, balancing energy consumption and execution time while outperforming benchmark methods. Shen et al. [9] investigate wind-powered unmanned sailboats in island environments, proposing the BCO-ARA and GDRA algorithms to address boundary complexity and area proportionality under wind constraints.

A chaotic-evolution optimization (CEO) metaheuristic is presented by Dong et al. [10] by exploiting hyperchaotic memristive maps to generate multiple random search directions, demonstrating superior convergence speed and zero-bias robustness against recent swarm-intelligence algorithms. Wang et al. [11] propose the Status-based Optimization (SBO) algorithm, which emulates human status-seeking behavior to balance exploration and exploitation, and demonstrate its superior performance in global optimization, feature selection, and image segmentation tasks. Akbari et al. [12] establish the Holistic Swarm Optimization (HSO) algorithm, which leverages information from the entire population to adaptively balance exploration and exploitation, achieving robust and competitive performance across complex multimodal and real-world optimization problems.

Integer linear programming (ILP) is a mathematical optimization method that seeks to optimize a linear objective function subject to given constraints, requiring some or all decision variables to take integer values. It provides precise optimal solutions, which are crucial for high-precision task allocations. As a deterministic approach, ILP avoids the randomness inherent in heuristic algorithms, ensuring predictable results while accurately considering task priorities, vessel performance, and inter-task distances. Compared with heuristic methods, such as k-means and genetic algorithms, which may converge to suboptimal solutions, ILP delivers globally optimal allocation with higher precision and stability. In multi-area cooperative task allocation, ILP ensures fair and efficient distribution of sub-areas while maintaining strong connectivity among assigned regions. Modern ILP solvers, such as CPLEX and Gurobi, can efficiently compute optimal solutions even under complex multi-constraint conditions, improving both execution speed and the reliability of task completion.

Many research works have used ILP to derive optimal solutions. Lei et al. [13] employ mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) to obtain optimal solutions for power generation scheduling, transforming nonlinear constraints into linear formulations through integer programming techniques. Optimal scheduling solutions for NASA’s Deep Space Network are derived by Sabol et al. [14] through MILP application, efficiently allocating limited communication resources via integer programming techniques. Liu and Fan [15] utilize MILP to derive optimal resource allocation solutions in multi-cloudlet environments, jointly optimizing latency, reward, and resource utilization through integer programming. Therefore, this paper focuses on a multi-area, Multi-USV task allocation method based on an ILP mathematical model.

In the complete coverage path planning (CCPP) of sub-areas, there are various classic algorithms to choose from, including area traversal algorithms and search algorithms. Typical area traversal algorithms include the random coverage method [16], the back-and-forth coverage approach [17], the spiral coverage strategy [18], the spanning tree covering technique [19], and the cell decomposition coverage scheme [20]. These algorithms ensure complete coverage of the sub-areas through different path-generation strategies.

On the other hand, search algorithms also play an important role in path planning. Depth-first search [21] and breadth-first search [22] are two fundamental search methods, with the former prioritizing deep exploration of paths and the latter expanding the search layer by layer. The A* algorithm [23] enhances search efficiency by incorporating heuristic information. The artificial potential field method [24] guides the path by simulating the attraction and repulsion forces of a physical field. The genetic algorithm [25] optimizes paths by mimicking biological behaviors in nature. The bio-inspired neural network algorithm [26] leverages the learning capabilities of neural networks and biologically inspired mechanisms to solve path-planning problems. Considering the advantages and limitations of these algorithms within the context of our specific environment—a static, obstacle-free grid map requiring complete coverage, this paper employs a hybrid strategy for sub-area path planning.

In recent years, a single algorithm often cannot meet the complete coverage requirements in complex environments, so path planning increasingly employs a strategy of combining multiple algorithms. The advantage of this combined algorithm approach lies in its ability to integrate the strengths of various algorithms and address the shortcomings of any single algorithm. Zhao and Bai [27] develop a joint-optimized framework for USV-assisted offshore bathymetric mapping, emphasizing integrated path optimization within a single complex region. In the same year, they further examine energy-efficient coverage path planning for USV-assisted inland bathymetry under current effects, analyzing how sweep direction influences energy consumption [28].

While most research has concentrated on Multi-USV coordination within a single area, relatively little attention has been paid to task allocation and path planning across multiple areas. Multi-area operations introduce additional complexity, such as balancing resource distribution among areas and ensuring overall operational efficiency. This study aims to address these challenges by optimizing task allocation and path planning for Multi-USV across multiple areas, thereby reducing resource waste and improving task execution efficiency.

The main contribution of this paper is the proposal of a Multi-USV multi-area complete coverage task planning framework that combines an ILP-based task allocation model with search-based path planning. The ILP model is used to minimize the overall makespan and determine the optimal task area for each USV. We also apply the greedy algorithm and the A* algorithm to achieve complete coverage of the barrier-free area and obtain the driving path of each USV. Simulation results show that the proposed method improves coverage efficiency and resource utilization, demonstrating strong robustness and scalability.

This paper breaks down the Multi-USV multi-area complete coverage task into three aspects for research: environment model establishment, task area division, and sub-area coverage. First, the latitude and longitude points of each area are converted into a Cartesian coordinate system to establish a grid map. Second, an ILP mathematical model is used to solve the task area for each vessel. Third, a search-based complete coverage algorithm is employed for sub-area traversal. Finally, simulation experiments and analysis results are presented.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the main methodology used in the implementation. In Section 3, we conduct experiments using specific case studies to demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach. Section 4 provides a comparative analysis with state-of-the-art algorithms to further validate the performance of the proposed method. Finally, we conclude the paper in Section 5.

2 Path Planning for Multiple Unmanned Surface Vessels

In this study, a static, obstacle-free environment within the task areas is assumed to simplify the modeling and planning process. This assumption is reasonable for scenarios such as open-water surveys, where the operational area is clear of dynamic or unpredictable obstacles. Although the assumption may not cover all real-world situations, it provides a basis for developing and validating effective Multi-USV path planning strategies under controlled conditions.

Environmental modeling involves creating mathematical or computer models to describe the spatial characteristics and obstacle distribution of the environment in which the USVs operate, thus providing the necessary information support for path planning. These models can help USVs understand and analyze the environment, determine feasible paths, and avoid collision risks. In USV path planning, commonly used environmental maps include grid maps, topological maps, and geometric maps.

A grid map is a commonly used method for environmental modeling and path planning. It divides the environment into regular grid cells, with each cell representing a small area of the environment and a specific value indicating the state of that area, such as passable, impassable, or unknown. Due to its simplicity, intuitiveness, and ease of updating, a grid map is highly suitable for USV path planning. Grid maps can effectively represent obstacles and free areas in the environment, supporting various efficient path-planning algorithms, and enabling USVs to find safe and feasible paths in complex environments.

The latitude and longitude coordinates of the task area boundaries are transformed into a Cartesian coordinate system. The grid is generated based on the USV’s scanning width and observation range, ensuring sufficient resolution to accurately model the environment while maintaining computational efficiency. Even in the absence of obstacles, the boundaries are expanded, and grid cells outside the task area are marked as obstacles to enhance the safety and robustness of path planning.

In Multi-USV path planning, task allocation is a critical issue that aims to effectively utilize the resources and capabilities of each vessel to optimize the overall efficiency of task completion. The task allocation method based on ILP can find the optimal task allocation plan by solving a linear objective function under a set of linear constraints.

The set of USVs is denoted by

Mathematical Model

Let T be the makespan in seconds. By minimizing the makespan, the optimal solution for task allocation can be obtained. The objective function is as follows:

Let

Let

Let

To ensure that the total scanned area by all USVs exactly covers the entire area of each task, the sum of the assigned scan areas for the USVs in the area of each task should equal the total area of the task. Formally, we have

A USV

Additionally, each USV starts from the assembly area, i.e.,

We need to add a condition: for any USV, if it detects a certain area, there must be one path entering and one path exiting that area, represented by

For any USV, the constraint that only one path from area

The flow balance constraints ensure that the number of inflows and outflows for each area is balanced, maintaining the strong connectivity of the task assignment graph. Specifically, these constraints guarantee that every sub-area assigned to a USV is both reachable and connected to other sub-areas within its task region, ensuring continuous and feasible task execution. Let

The sum of the flow of each USV departing from the assembly area must equal the total number of paths between the task areas assigned to that vessel, resulting in

To ensure that each USV returns to the assembly area after completing its task, the sum of the flow returning to the assembly area must equal one, which can be written as

Finally, to ensure the conservation of flow, if a USV is assigned to task area

By combining Eqs. (1)–(13), we obtain an ILP, namely Task Allocation Problem (TAP), as follows:

The objective function is:

Solving TAP yields the makespan for all USVs to complete coverage and return to the assembly area. It also determines the task areas assigned to each USV and the corresponding paths, providing an approximate estimate of task completion time. Note that this makespan constitutes an idealized estimate, as it does not account for factors such as USV turning within scanning areas or unpredictable environmental effects on speed.

For the ILP task allocation, the model contains

The ILP-based task allocation guarantees a globally optimal solution concerning the objective of minimizing the makespan, as it solves a deterministic optimization model with exact constraints. Thus, the assignment of USVs to task areas is optimal under the given assumptions and model formulation.

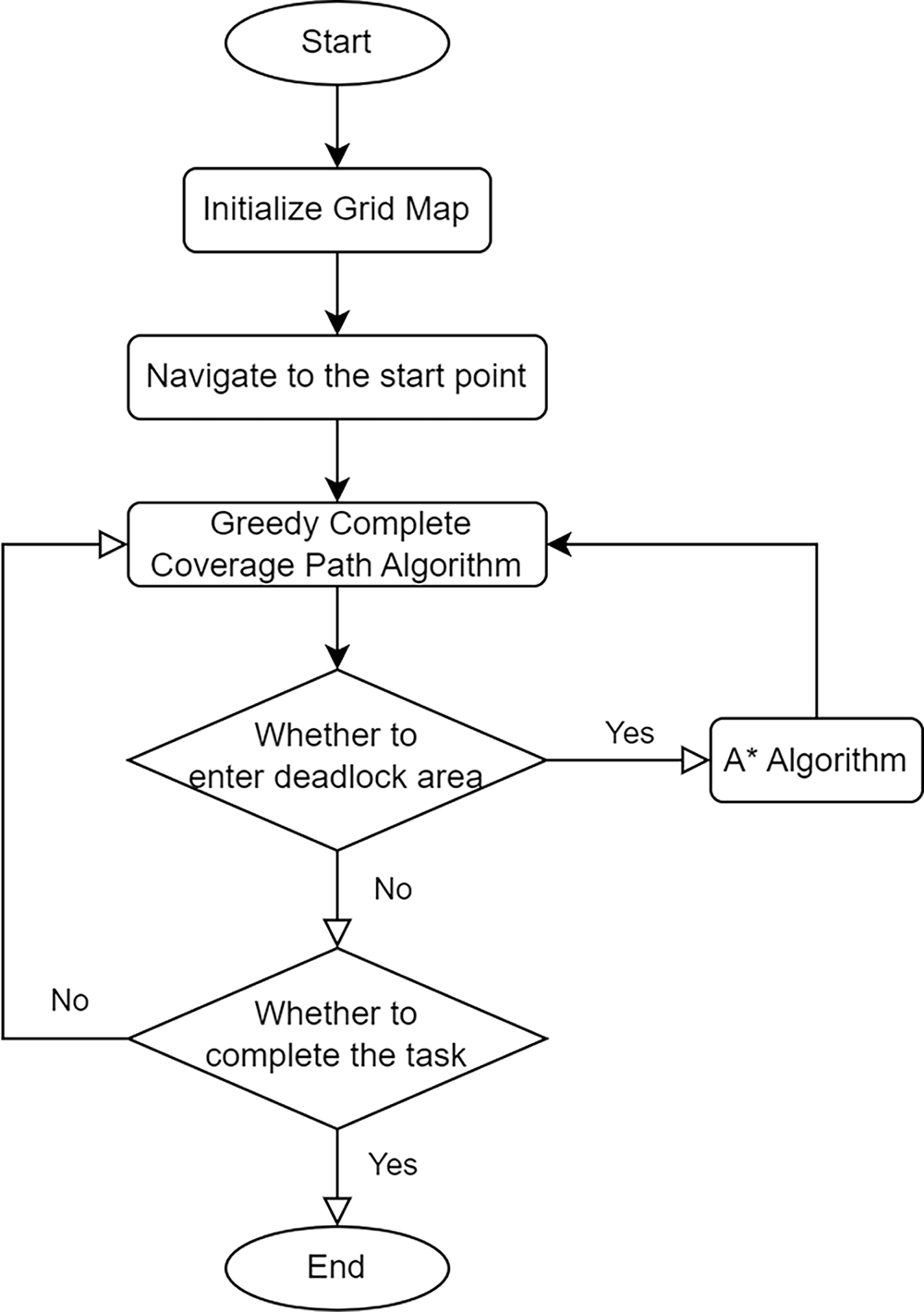

This paper employs a hybrid path planning approach for sub-area coverage, integrating the greedy algorithm with the A* algorithm. The input consists of a grid-based two-dimensional matrix representing each task area and the corresponding starting points. The greedy algorithm is employed for rapid local path decision-making, enabling efficient coverage of the area by continuously selecting the current optimal path. When a deadlock area is encountered or direct movement is obstructed, the A* algorithm is utilized to find the shortest path to continue the coverage process, ensuring obstacle avoidance and maintaining route continuity. This process is repeated until all task areas are fully covered. Finally, the output is a sequence of coordinate points forming the complete coverage path, which is subsequently plotted as a path map. The flowchart of the CCPP algorithm based on the greedy algorithm and A* algorithm is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Process of CCPP

Greedy Complete Coverage Path Algorithm

The greedy algorithm is used for traversing a two-dimensional grid to cover all feasible areas. The algorithm starts from the initial point and moves according to a fixed priority order (usually left, down, up, right), marking the visited points to ensure that each feasible area is covered once. Its core idea is to select the locally optimal solution at each step to achieve the overall coverage objective. The specific steps of the algorithm are shown in Algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1 takes two main parameters: the 2D grid map

First, the algorithm initializes an empty list

The core of the path planning process is carried out in a loop. The algorithm checks whether all the free cells have been visited. In each iteration, the current position

Once all the free cells have been visited and the path planning is complete, the algorithm cleans up the final path by calling the function

Several hyperparameters are involved in the proposed search-based path planning algorithm. The heuristic coefficient in the A* algorithm controls the balance between search optimality and computational efficiency, where a larger coefficient accelerates convergence but may slightly increase path length. In addition, the choice of the search direction order in the greedy coverage strategy influences the traversal sequence, while the use of Euclidean distance for deadlock escape point selection helps generate smoother and shorter recovery paths. These parameters are empirically determined to ensure stable and efficient coverage performance.

In summary, the greedy algorithm ensures efficient path planning by selecting the nearest unvisited neighbor cell, while the A* algorithm guarantees the shortest path when direct movement is not possible. To address the potential issue of local optimality or deadlock in greedy-based planning, the algorithm introduces the A* algorithm as a fallback strategy. When the greedy algorithm cannot proceed due to the absence of unvisited neighbors, the planner switches to A* to find the shortest path to the nearest unvisited cell. This not only helps escape from local traps but also prevents infinite loops during the coverage process. Moreover, a loop condition based on the number of visited free cells is used to ensure proper termination once full coverage is achieved, thereby avoiding unnecessary iterations. The main goal is to enable the USV to traverse all free cells in the map using a concise and efficient path while minimizing repeated visits.

Currently, the ILP-based task allocation and the search-based path planning are implemented sequentially but independently. While this modular design simplifies implementation and allows separate optimization, it may limit the potential to achieve a globally optimal solution across both task assignment and coverage execution. Future work will explore integrated task-path planning approaches that incorporate estimated path costs into the allocation model to improve global optimality.

The time complexity of the greedy planner is

It should be noted that the sub-area path planning is heuristic. While A* guarantees the shortest path to the next reachable point when invoked, the greedy algorithm makes locally optimal decisions that may not lead to a globally optimal path. As a result, the method prioritizes practical efficiency over theoretical path optimality. In future research, the global path optimization techniques such as reinforcement learning or genetic algorithms will be explored to improve convergence toward near-optimal solutions in complex environments.

To verify the effectiveness of the task allocation based on ILP, a simulation experiment for Multi-USV and multi-area path planning was conducted using Python. In the context of an ocean survey mission, three USVs with different capabilities were selected to perform cooperative mapping in designated task areas. USV 1 has a maximum speed of 4 knots with a scanning width of 20 m, USV 2 has a maximum speed of 6 knots with a scanning width of 20 m, and USV 3 has a maximum speed of 6 knots with a scanning width of 30 m. The selected USV parameters are based on practical specifications, referencing the SE40 USV commonly used in survey and monitoring operations.

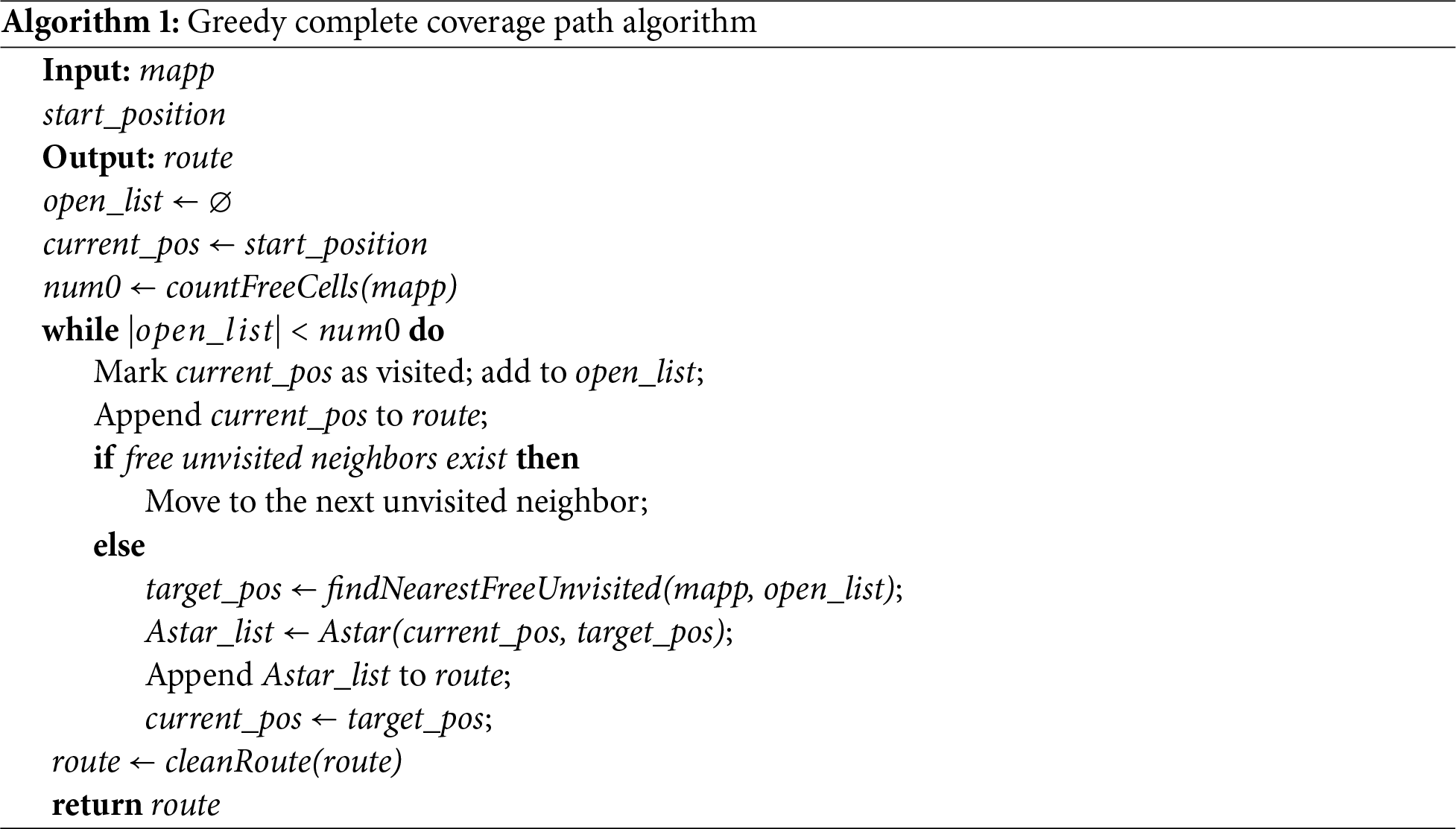

Four irregularly shaped areas were randomly selected within a sea region as the assembly and task areas. The geographic coordinates of all vertices are based on real-world latitude and longitude data, resulting in realistic area sizes and inter-area distances. This approach ensures diversity in area shapes and enhances the robustness of the experimental setup. The survey areas are shown in Fig. 2. In Fig. 2, the assembly area is marked in red, and the task areas are marked in green. The task areas, in order of increasing distance from the assembly area, are Task Area 1, Task Area 2, and Task Area 3. The numbers in the image represent the vertex numbers of each area.

Figure 2: Task area map

The USVs need to start from the assembly area, autonomously navigate to their respective task areas for complete coverage scanning, and return to the assembly area upon completing their tasks.

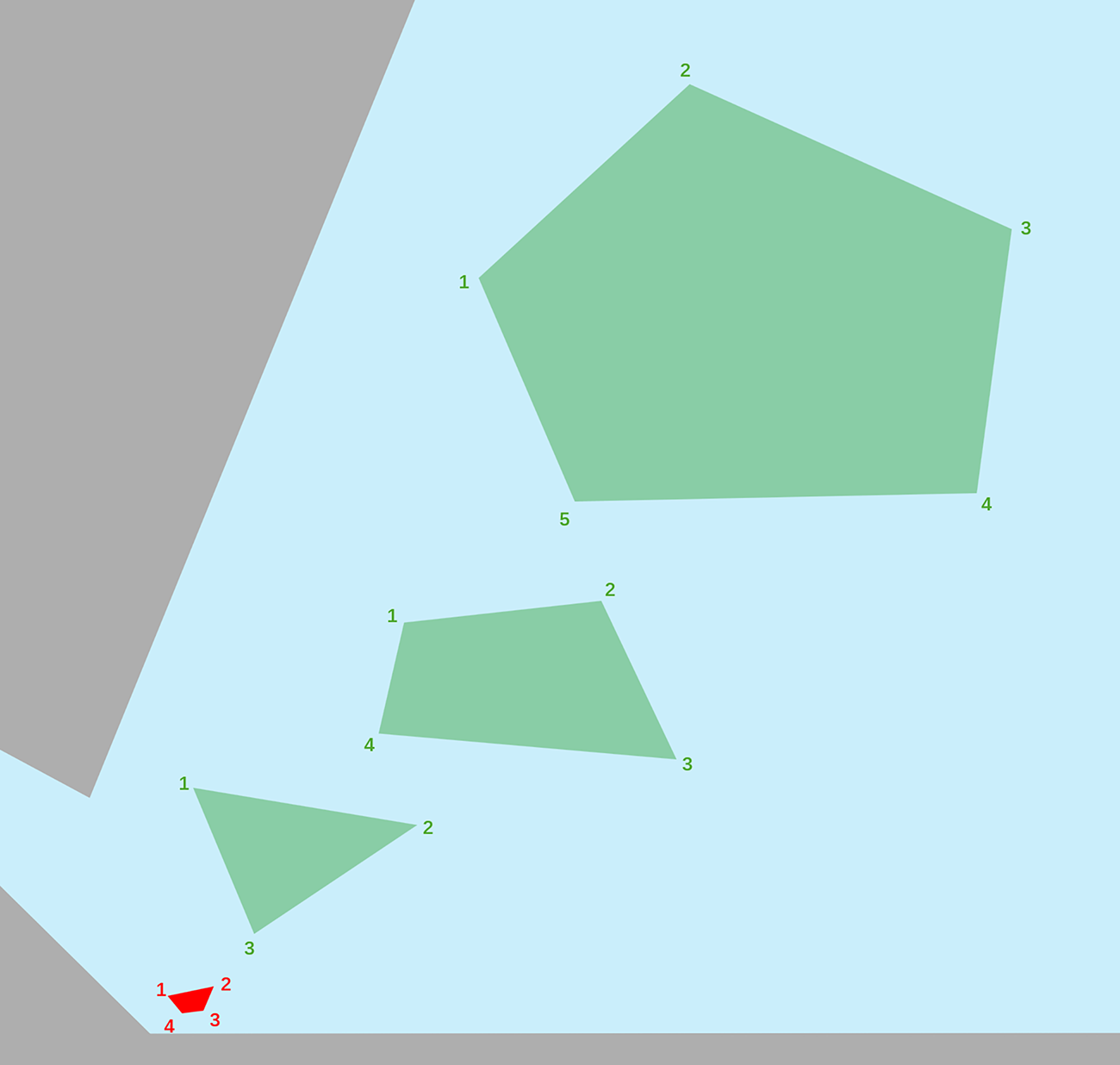

Based on the latitude and longitude information of the regions, the grid sizes are set to 20 meters and 30 m, respectively, and the three task areas are mapped into grid maps. As shown in Fig. 3, the left map has a grid size of 20 m, while the right map has a grid size of 30 m. By selecting different grid sizes, the resulting grid maps exhibit noticeable differences.

Figure 3: Grid map

Based on the data in the case, the following parameters are set:

Select Point 2 in the assembly area, which is closest to the task areas from the assembly area, as the starting point for the USVs. Calculate the shortest distance between each region. Then, we have

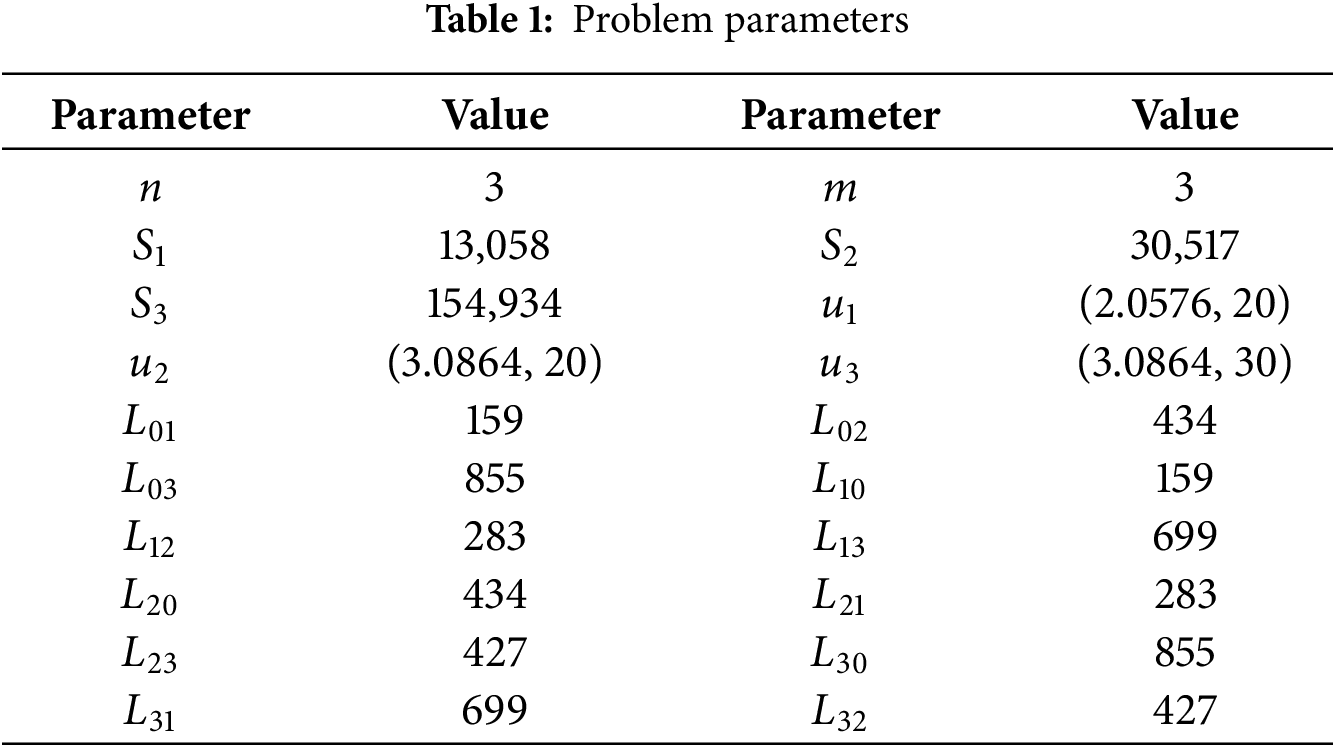

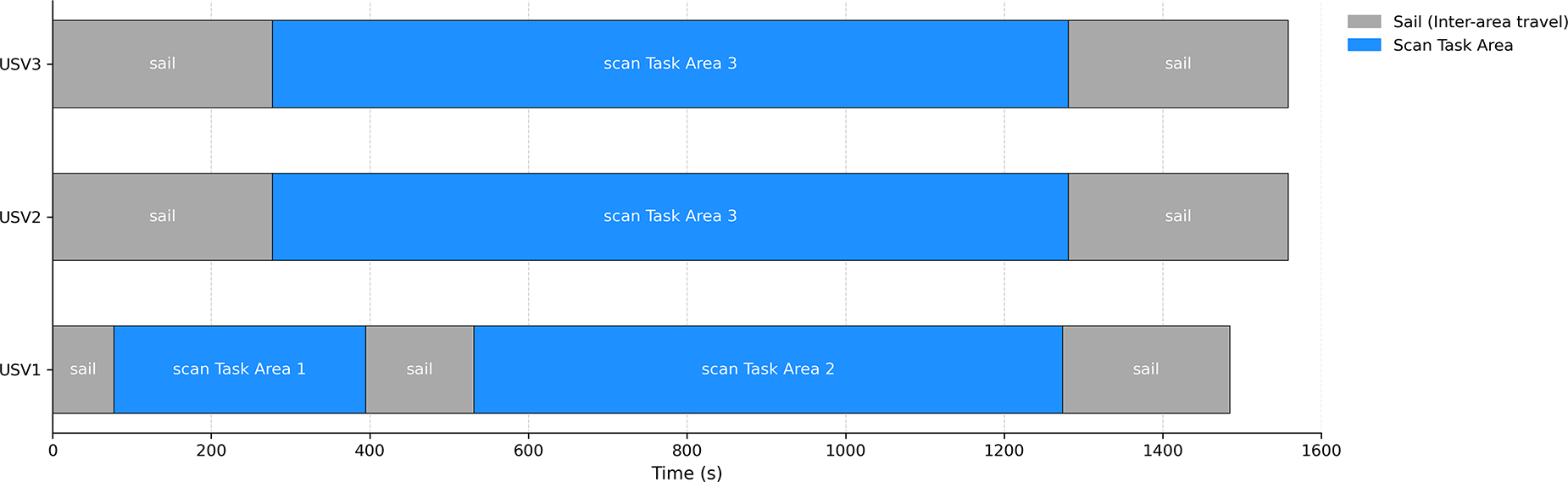

By the mathematical model provided earlier, the specific data was substituted, and the problem was solved using CPLEX. By solving the ILP, an optimal solution is obtained, with

Figure 4: USV mission timeline

Table 2 provides a comparison of the task allocation results for this case using ILP against three other allocation methods. Method 2 involves assigning each vessel to complete a specific task area: USV 1 is assigned to Task Area 1, USV 2 to Task Area 2, and USV 3 to Task Area 3. Method 3 calculates the area for each vessel after equally dividing the total task area among the three vessels, and then assigns tasks based on each vessel’s capability. Method 4 has all three vessels simultaneously complete the three task areas, meaning each vessel covers an equal portion of each task area. By comparing the makespan, it is evident that the task allocation method based on ILP results in the shortest makespan, significantly improving task efficiency. This improvement can be attributed to the ILP model’s capability of finding globally optimal solutions under deterministic constraints. The incorporation of flow balance constraints ensures strong connectivity between assigned sub-areas and equitable workload distribution among USVs. Quantitatively, the ILP method yields lower total execution time and a more balanced distribution of sub-areas, which enhances mapping efficiency and demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed allocation model.

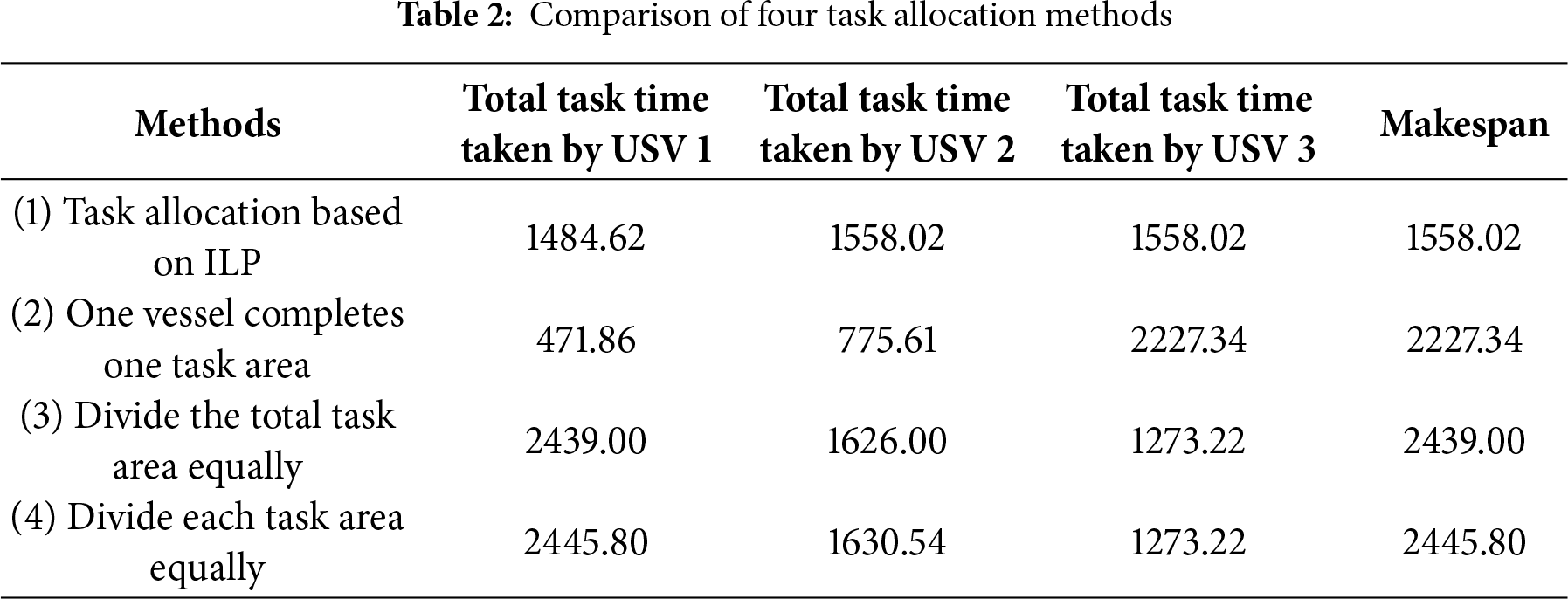

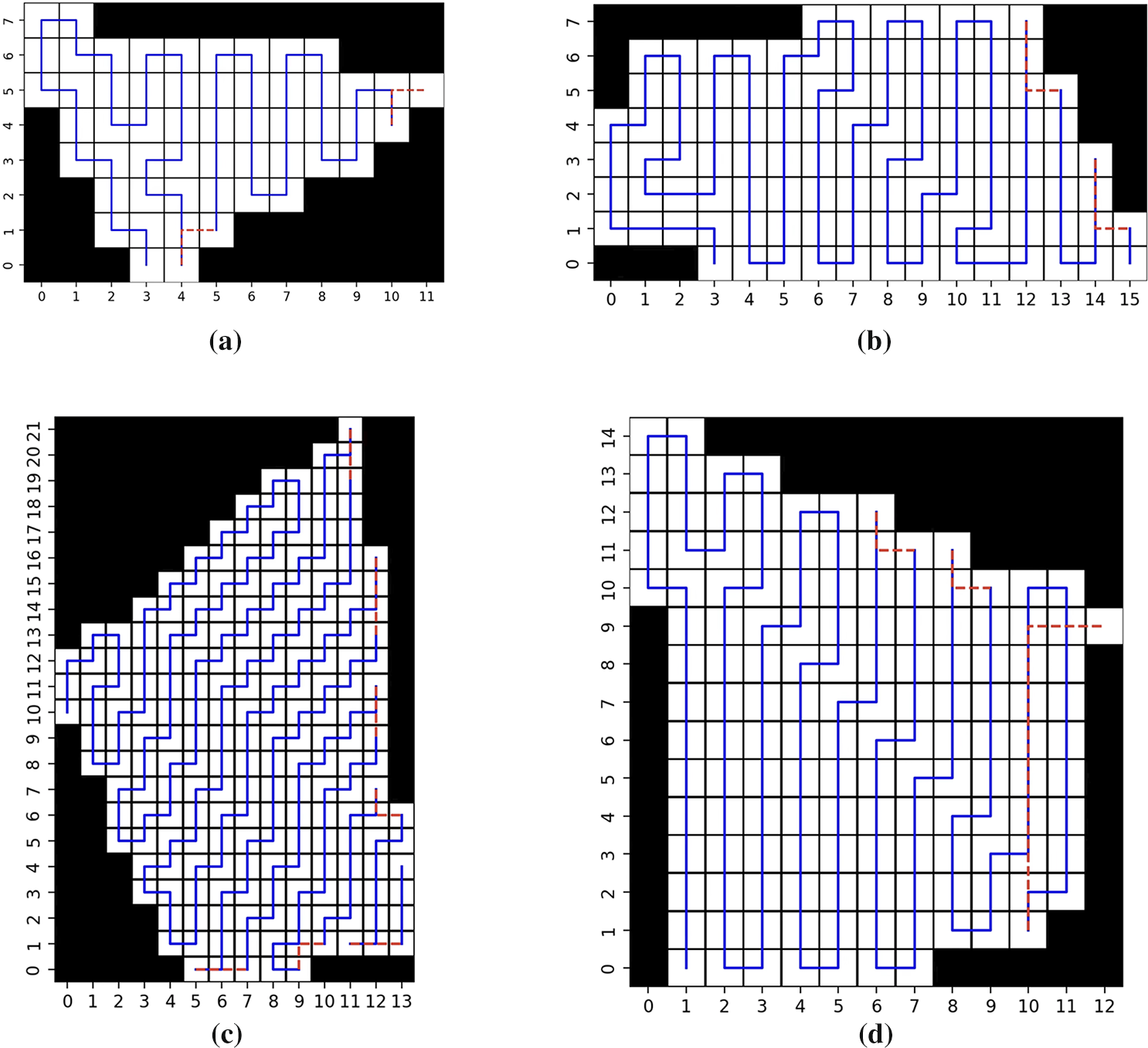

Finally, the greedy algorithm and A* algorithm are used for path planning in sub-areas, with each USV completing its assigned sub-task area. Fig. 5 shows the sub-area path planning under the task allocation based on ILP. In the figures, white areas represent reachable regions, black areas represent unreachable regions, blue lines indicate the path routes, and red dashed lines represent the routes taken to escape the deadlock areas.

Figure 5: Sub-area path planning map. (a) The path planning for USV 1 covering Task Area 1; (b) The path planning for USV 1 covering Task Area 2; (c) The path planning for USV 2 covering Task Area 3; (d) The path planning for USV 3 covering Task Area 3

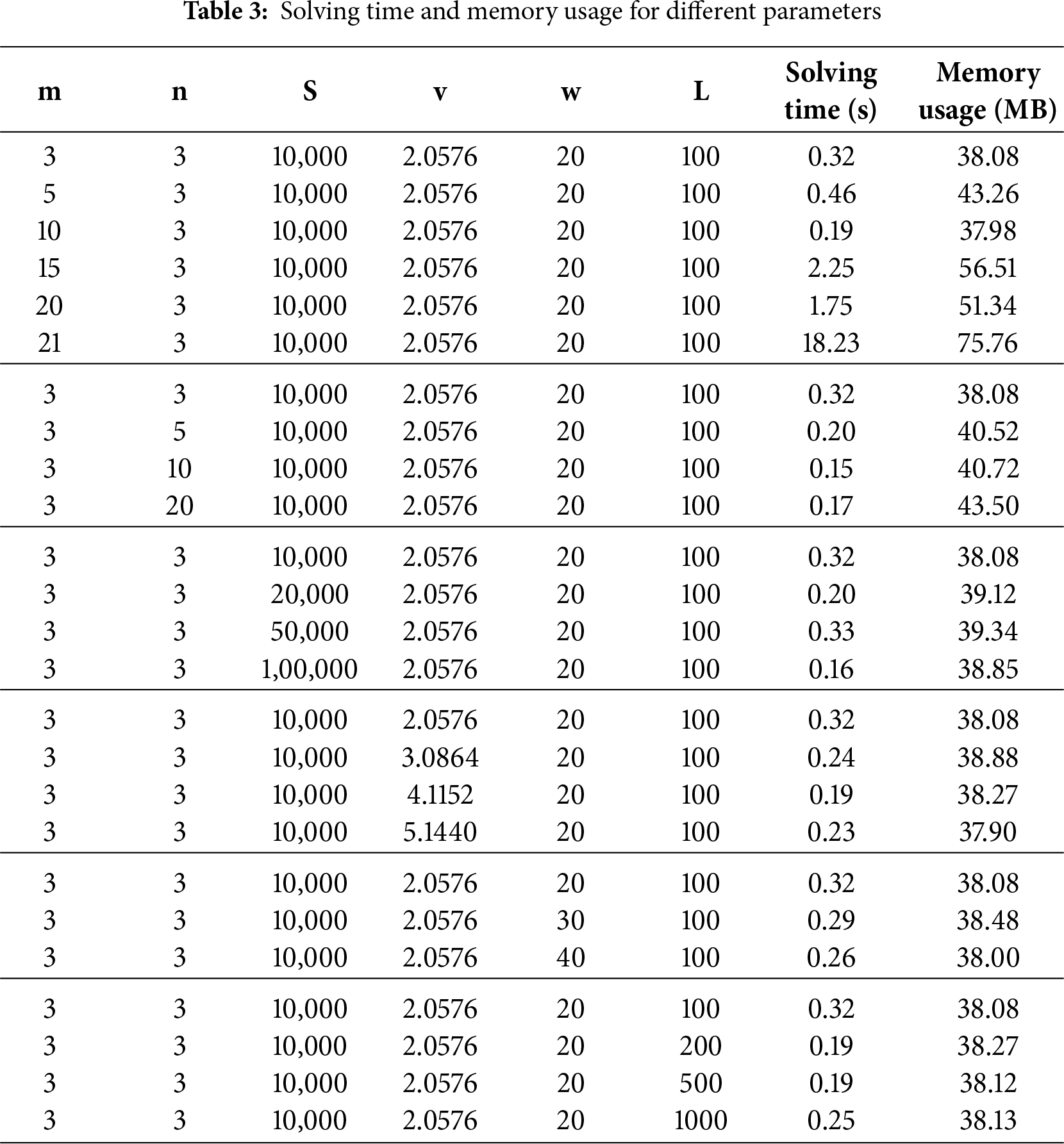

To comprehensively analyze the influence of various parameters on the solving time of the ILP-based task allocation model, a series of experiments is conducted by varying one parameter at a time while keeping the others constant. The considered parameters include the number of task areas

As summarized in Table 3, the number of task areas has the greatest impact on solving time. As

In contrast, increasing the number of USVs does not lead to a monotonic rise in solving time. Adding more USVs initially reduces solving time due to increased flexibility in task allocation, which allows the solver to find feasible solutions more efficiently. The changes in task area size, USV speed, scanning width, and inter-area distance have relatively minor effects on solving time and memory usage, as they primarily affect the cost coefficients rather than the problem scale. These results indicate that while the ILP model remains efficient for small to moderate problem sizes, solving large-scale instances with many task areas may require the use of heuristic or approximate methods in future work.

4 Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

As shown in Table 2, the proposed ILP-based task allocation algorithm already outperforms the conventional methods in terms of makespan, demonstrating its effectiveness and efficiency in distributing tasks among Multi-USV across multiple areas. To further validate the superiority of the ILP-based approach, this study compares it with three state-of-the-art algorithms: CEO [10], SBO [11], and HSO [12].

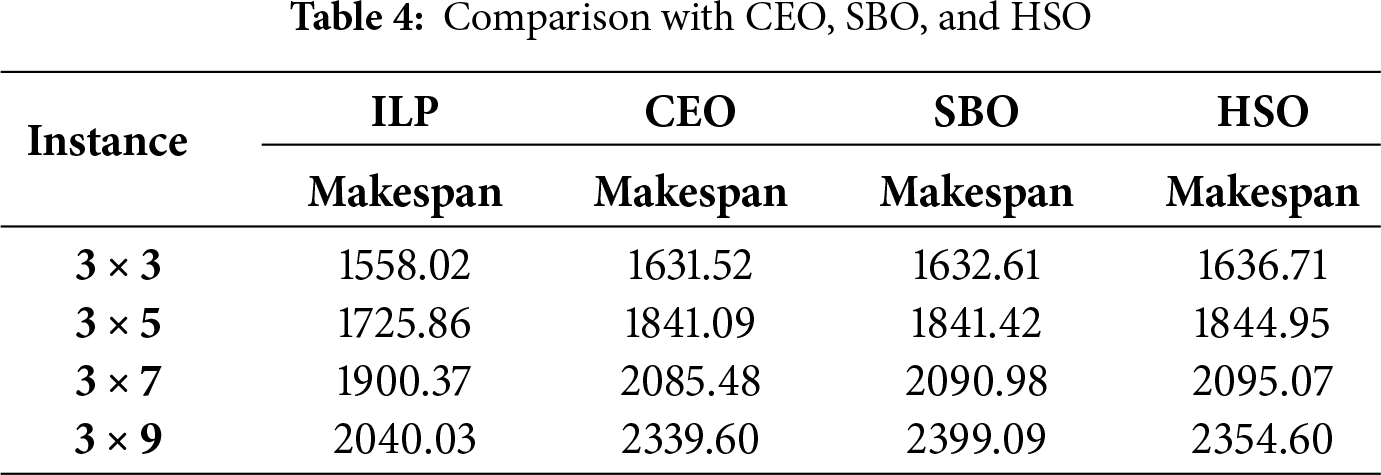

The experiments are conducted in different scale environments, and the environment size defined as the number of USVs

In Table 4, it is observed that the ILP-based method consistently achieves the shortest makespan across all tested scenarios, outperforming the CEO, SBO, and HSO algorithms. This comparison demonstrates the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed ILP-based task allocation strategy in addressing Multi-USV scenarios with multiple areas.

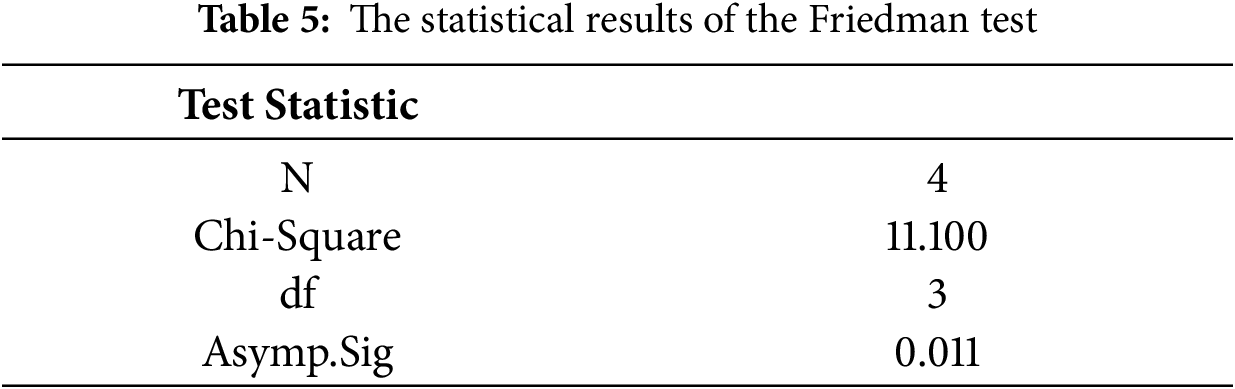

The Friedman test is applied to compare the different performances of the four algorithms. The results are summarized in Table 5. The value of asymptotic significance (Asymptotic. Sig) is lower than the significance level of 0.05, indicating that a significant difference exists in performance among these four algorithms.

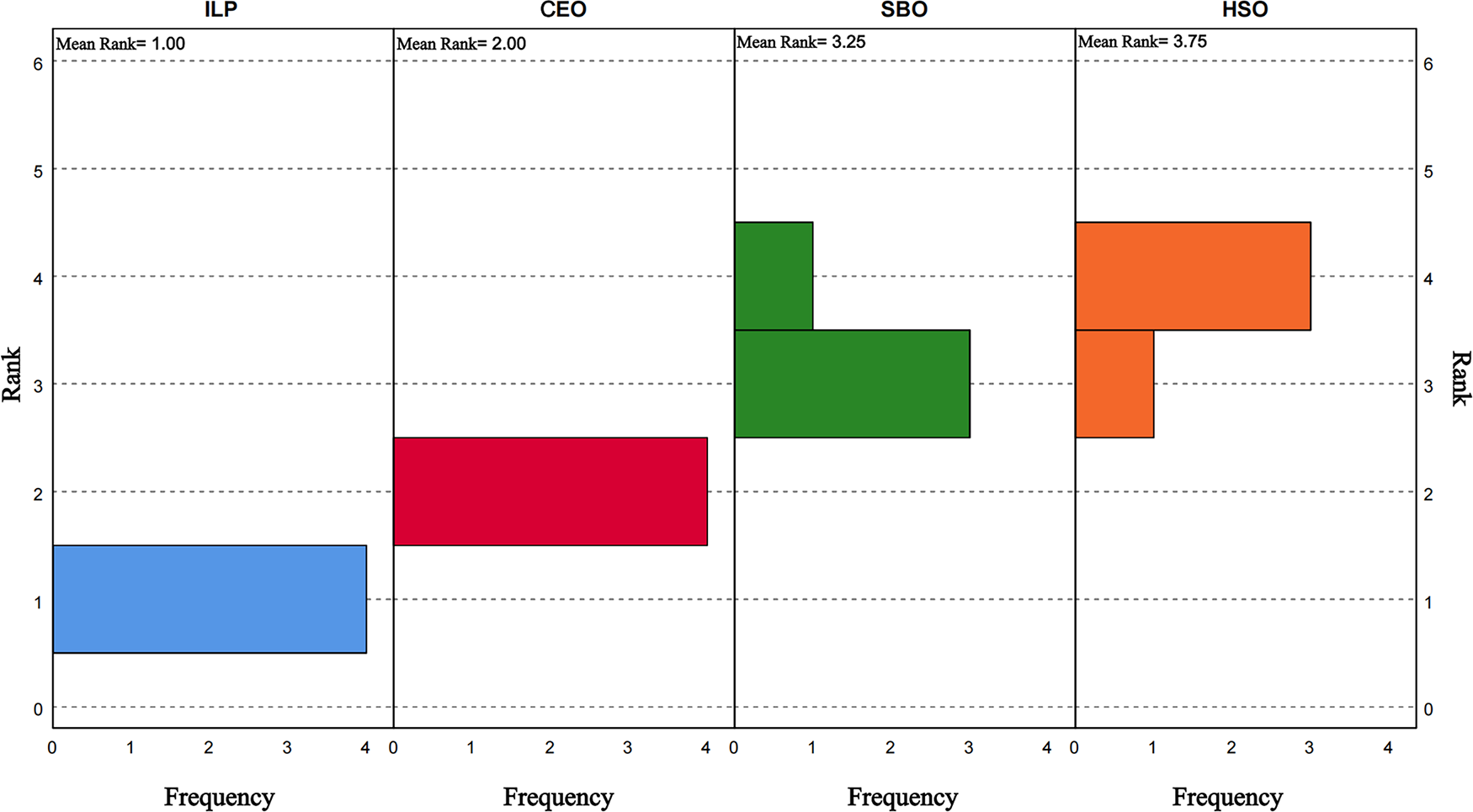

The rank distribution of the four algorithms is illustrated in Fig. 6, where a lower mean rank value indicates better performance. It can be observed that the ILP-based algorithm consistently obtains the lowest mean rank among all tested cases, confirming its superior capability in minimizing the makespan. The CEO algorithm ranks second, while the SBO and HSO algorithms show relatively lower performance.

Figure 6: The rank distribution

These results demonstrate that the proposed ILP-based task allocation approach achieves more efficient and stable performance in multi-area task allocation for Multi-USV cooperation.

In this paper, a task allocation algorithm based on ILP is proposed within the context of cooperative path planning with USVs of varying capabilities across multiple task areas. This algorithm integrates the capabilities of the USVs and the paths between areas to address the task allocation problem in multi-area scenarios, thereby meeting the requirement to minimize the makespan. By comparing the makespan of four different task allocation methods, the efficiency of the ILP-based task allocation is demonstrated. Finally, based on the results of the ILP-based task allocation algorithm, search-based CCPP is implemented on the established grid maps to achieve overall planning.

This study aims to provide a foundational framework with potential applications in related fields such as marine environmental monitoring, search and rescue, maritime surveillance, and hydrographic surveying. However, the current research is conducted in a static and fully known environment, and does not account for dynamic obstacles or the endurance limitations of USVs.

Future work will focus on addressing these practical application environments and exploring more complex scenarios for in-depth research. Specifically, collision avoidance mechanisms based on dynamic obstacle prediction and real-time path replanning will be integrated into the planning framework to enhance the operational safety of USVs. Furthermore, uncertainty modeling, such as accounting for weather-induced latency and communication delays, will be introduced to enhance the robustness of the system in dynamic marine environments. Additionally, USV endurance constraints will be incorporated into the task allocation model to ensure feasible and energy-efficient mission execution. To further improve scalability and solution quality, we also plan to combine the ILP with heuristic or learning-based methods for efficient task allocation under larger problem sizes. Moreover, global optimization strategies will be explored to enhance the overall path planning performance beyond the current local and reactive approaches.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the International Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou Development District under Grant 2023GH08, in part by the Science and Technology Development Fund, MSAR, under Grants 0029/2022/AGJ and 0029/2023/RIA1, and in part by the Program of Guangdong under Grant 2023A0505020003.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Jianing Wu; methodology: Jianing Wu, Yufeng Chen; validation, Jianing Wu; writing—original draft preparation: Jianing Wu; writing—review and editing: Jianing Wu, Yufeng Chen, Li Yin, Huajun He, Panshuan Jin; visualization: Jianing Wu; supervision: Yufeng Chen, Li Yin, Huajun He, Panshuan Jin; funding acquisition: Yufeng Chen, Li Yin, Huajun He, Panshuan Jin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: Authors Huajun He and Panshuan Jin were employed by Guangzhou Jiafan Computer Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| USV | Unmanned Surface Vessel |

| Multi-USV | Multiple Unmanned Surface Vessels |

| ILP | Integer Linear Programming |

| CCPP | Complete Coverage Path Planning |

References

1. Ma S, Guo W, Song R, Liu Y. Unsupervised learning based coordinated multi-task allocation for unmanned surface vehicles. Neurocomputing. 2021;420(6):227–45. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2020.09.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu Y, Song R, Bucknall R, Zhang X. Intelligent multi-task allocation and planning for multiple unmanned surface vessels (USVs) using self-organising maps and fast marching method. Inf Sci. 2019;496(4):180–97. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2019.05.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Xia G, Sun X, Xia X. Multiple task assignment and path planning of a multiple unmanned surface vessels system based on improved self-organizing mapping and improved genetic algorithm. J Mar Sci Eng. 2021;9(6):556. doi:10.3390/jmse9060556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhou Z, Li M, Hao Y. A novel region-construction method for multi-USV cooperative target allocation in air-ocean integrated environments. J Mar Sci Eng. 2023;11(7):1369. doi:10.3390/jmse11071369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xue K, Huang Z, Wang P, Xu Z. An exact algorithm for task allocation of multiple unmanned surface vessels with minimum task time. J Mar Sci Eng. 2021;9(8):907. doi:10.3390/jmse9080907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wen J, Liu S, Lin Y. Dynamic navigation and area assignment of multiple USVs based on multi-agent deep reinforcement learning. Sensors. 2022;22(18):6942. doi:10.3390/s22186942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Lyu C, Dong C, Xiong Q, Chen Y, Weng Q, Chen Z. Pathfinder: deep reinforcement learning-based scheduling for multi-robot systems in smart factories with mass customization. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(2):3371–91. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.065153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Aminu J, Latip R, Hanafi ZM, Kamarudin S, Gabi D. Efficient task allocation for energy and execution time trade-off in edge computing using multi-objective IPSO. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;84(2):2989–3011. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.062451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shen J, Zhu Z, Bai G, Deng Z, Xue Y, Cao X, et al. Multiple unmanned sailboats cooperative coverage: task allocation and path planning in island environments. Ocean Eng. 2025;339(4):122172. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2025.122172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dong Y, Zhang S, Zhang H, Zhou X, Jiang J. Chaotic evolution optimization: a novel metaheuristic algorithm inspired by chaotic dynamics. Chaos Soliton Fract. 2025;192(1):116049. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2025.116049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang J, Chen Y, Lu C, Heidari AA, Wu Z, Chen H. The status-based optimization: algorithm and comprehensive performance analysis. Neurocomputing. 2025;647(3):130603. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2025.130603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Akbari E, Rahimnejad A, Gadsden SA. Holistic swarm optimization: a novel metaphor-less algorithm guided by whole population information for addressing exploration-exploitation dilemma. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2025;445(19):118208. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2025.118208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lei Y, Liu F, Li A, Su Y, Yang X, Zheng J. An optimal generation scheduling approach based on linear relaxation and mixed integer programming. IEEE Access. 2020;8:168625–30. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3023184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Sabol A, Alimo R, Kamangar F, Madani R. Deep Space Network scheduling via mixed-integer linear programming. IEEE Access. 2021;9:39985–94. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3064928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Liu L, Fan Q. Resource allocation optimization based on mixed integer linear programming in the multi-cloudlet environment. IEEE Access. 2018;6:24533–42. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2830639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Balch T. The case for randomized search. In: Proceedings of Workshop on Sensors and Motion, IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 2000 Apr 24–28; San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

17. Choset H, Pignon P. Coverage path planning: the boustrophedon cellular decomposition. In: Zelinsky A, editor. Field and service robotics. London, UK: Springer; 1998. p. 203–9. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-1273-0_32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Shen C, Mao S, Xu B, Wang Z, Zhang X, Yan S, et al. Spiral complete coverage path planning based on conformal slit mapping in multi-connected domains. Intl J Robotics Res. 2024;43(14):2183–203. doi:10.1177/02783649241251385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gabriely Y, Rimon E. Spanning-tree based coverage of continuous areas by a mobile robot. In: Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2001 May 21–26; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 1927–33. [Google Scholar]

20. Choset H. Coverage for robotics—a survey of recent results. Ann Math Artif Intell. 2001;31(1):113–26. doi:10.1023/A:1016639210559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Doucette A, Lu W. An intelligent robotic system for localization and path planning using depth first search. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence (ICAI); 2015 Jul 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 401–2. [Google Scholar]

22. Tripathy HK, Mishra S, Thakkar HK, Rai D. CARE: a collision-aware mobile robot navigation in grid environment using improved breadth first search. Comput Electr Eng. 2021;94(1):107327. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2021.107327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ammar A. ERA*: enhanced relaxed A* algorithm for solving the shortest path problem in regular grid maps. Inf Sci. 2024;657(10):120000. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.120000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ren C, Fu F, Yin C, Yan Z, Zhang R, Wang Z. Improved artificial potential field method based on robot local path information. Int J Adv Robot Syst. 2024;21(5):17298806241278172. doi:10.1177/17298806241278172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yakoubi MA, Laskri MT. The path planning of cleaner robot for coverage region using genetic algorithms. J Innov Digital Ecosyst. 2016;3(1):37–43. doi:10.1016/j.jides.2016.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhu D, Yang SX. Bio-inspired neural network-based optimal path planning for UUVs under the effect of ocean currents. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2022;7(2):231–9. doi:10.1109/TIV.2021.3082151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhao L, Bai Y. Joint-optimized coverage path planning framework for USV-assisted offshore bathymetric mapping: from theory to practice. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;304:112449. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhao L, Bai Y. Energy efficient coverage path planning for USV-assisted inland bathymetry under current effects: an analysis on sweep direction. Ocean Eng. 2024;305:117910. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2024.117910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools