Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mitigating Adversarial Obfuscation in Named Entity Recognition with Robust SecureBERT Finetuning

1 School of Software Engineering, Northeastern University, Shenyang, 110819, China

2 College of Information Science and Engineering, Shaoyang University, Shaoyang, 422000, China

3 Provincial Key Laboratory of Informational Service for Rural Area of Southwestern Hunan, Shaoyang University, Shaoyang, 422000, China

4 School of Advanced Integrated Technology, Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenzhen, 518000, China

* Corresponding Author: Nouman Ahmad. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Utilizing and Securing Large Language Models for Cybersecurity and Beyond)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 32 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073029

Received 09 September 2025; Accepted 18 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Although Named Entity Recognition (NER) in cybersecurity has historically concentrated on threat intelligence, vital security data can be found in a variety of sources, such as open-source intelligence and unprocessed tool outputs. When dealing with technical language, the coexistence of structured and unstructured data poses serious issues for traditional BERT-based techniques. We introduce a three-phase approach for improved NER in multi-source cybersecurity data that makes use of large language models (LLMs). To ensure thorough entity coverage, our method starts with an identification module that uses dynamic prompting techniques. To lessen hallucinations, the extraction module uses confidence-based self-assessment and cross-checking using regex validation. The tagging module links to knowledge bases for contextual validation and uses SecureBERT in conjunction with conditional random fields to detect entity boundaries precisely. Our framework creates efficient natural language segments by utilizing decoder-based LLMs with 10B parameters. When compared to baseline SecureBERT implementations, evaluation across four cybersecurity data sources shows notable gains, with a 9.4%–25.21% greater recall and a 6.38%–17.3% better F1-score. Our refined model matches larger models and achieves 2.6%–4.9% better F1-score for technical phrase recognition than the state-of-the-art alternatives Claude 3.5 Sonnet, Llama3-8B, and Mixtral-7B. The three-stage architecture identification-extraction-tagging pipeline tackles important cybersecurity NER issues. Through effective architectures, these developments preserve deployability while setting a new standard for entity extraction in challenging security scenarios. The findings show how specific enhancements in hybrid recognition, validation procedures, and prompt engineering raise NER performance above monolithic LLM approaches in cybersecurity applications, especially for technical entity extraction from heterogeneous sources where conventional techniques fall short. Because of its modular nature, the framework can be upgraded at the component level as new methods are developed.Keywords

One of the most important tasks in the field of natural language processing (NLP) is named NER. Its main goal is to determine things in a text that have particular meanings, like names, places, associations, and more proper nouns. NER has wide applications in a range of fields, such as text analysis, information extraction, systems for question-answering, machine translation, and classification. Both entity extraction and entity classification are included in this task. Through the refinement of previously trained models [1,2], The Transformer architecture indicates that the performance of NER has observed notable advancements.

Social media, blogs, technical forums, news websites, threat intelligence reports, and scholarly articles are just a few of the many and diverse open-source intelligence (OSINT) sources available in the cybersecurity space [3]. Both structured and unstructured data forms coexist, and the quality of this information varies widely. The model must have the relevant domain expertise to use the many technical terms, acronyms, and specific names found in these sources, like RPC, SQL, and APT [4]. Data integration and standardization are further complicated by the fact that cybersecurity instruments such as intrusion detection systems and network traffic monitoring tools provide data in a variety of formats, including structured (like JSON), semi-structured, and unstructured data [5].

The majority of the NER techniques used in cybersecurity nowadays are based on optimized BERT models [6]. Although these models work well with text data that has been properly preprocessed, they become less successful when working with complex and diverse data types. New breakthroughs have been brought about by recent developments in NLP, including Decoder-Only designs like GPT [7] and Llama models [8], as well as Encoder–Decoder structures like GLM [9]. These models do exceptionally well on challenges involving dialogue production and question responding. Scholars are investigating how these massive language models might be able to use the information they have learned during training. However, whereas NER has historically been viewed as a sequence labeling task, these models are primarily made for text production tasks. Using generative models to solve the NER problem may result in subpar performance due to the target inconsistency of tasks.

For a variety of domain-specific tasks, transformer-based models, especially BERT, have been used in recent developments in NER. However, when applied to complex and diverse data types frequently seen in this sector, existing models—particularly in cybersecurity—face major constraints. Although BERT-based models perform well on clean, preprocessed text, they have trouble generalizing to real-world cybersecurity data, which frequently contains noisy, incomplete, or adversarially altered input. To manage the inherent unpredictability and obfuscation frequently seen in cyber threat intelligence (CTI) datasets, entities like IP addresses, domain names, and URLs in particular require sophisticated methodologies. In order to close this gap, this study suggests a novel hybrid NER framework that combines adversarial fine-tuning, LLM-driven perturbations, and SecureBERT, a resilient transformer model. We specifically aim to fill the following deficiencies in current cybersecurity NER techniques:

• Lack of Adversarial Robustness: When faced with adversarial techniques such as token obfuscation or symbol insertion, current models frequently perform badly. These attacks can significantly impair model performance and are prevalent in cybersecurity datasets. To increase robustness against such perturbations, our method combines SecureBERT with adversarial training.

• Unable to Manage Complicated Cybersecurity Data Types: The dynamic and diverse nature of cybersecurity data is a challenge for current NER algorithms. Our methodology improves SecureBERT capacity to handle a variety of entity kinds, including IP addresses, domain names, and URLs, by using LLMs (e.g., Mixtral, Claude, LLaMA) to create adversarial perturbations that mimic real-world data unpredictability.

• Absence of Pipelines for Hybrid Fine-Tuning: The majority of current models work independently, concentrating on heuristic-based augmentations or clean data. In order to provide a reliable, comprehensive solution for cybersecurity NER, we provide a hybrid framework that combines the pre-trained capabilities of SecureBERT with adversarial perturbation generation and fine-tuning.

Due to the variety of entity kinds and the intrinsic complexity of the entities themselves, Named Entity Recognition has encountered many difficulties in recent years. With the advancement of deep learning technology, novel approaches to this work have been made possible by deep learning-based NER models [10–12]. These models automatically learn the attributes and contextual information of entities, enabling them to be recognized with great precision. The most often used deep learning NER models at the moment are Transformer models, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) [13]. NER problems are usually solved using sequence labeling approaches, and various datasets and algorithms are developed accordingly.

By using larger model parameters, more data, and longer training cycles, RoBERTa [14] improves on segment understanding and sequence labeling capabilities of BERT and is able to generalize to downstream tasks more effectively than BERT. In sentence-level classification tasks, LBERT [15], a lexicon-aware Transformer-based bidirectional encoder representation model, investigates local and global contextual representations and demonstrates notable gains over BioBERT [16] in terms of biological entity relationship extraction. The goal of FinBERT-MRC [17] is to turn unstructured texts into a machine reading comprehension challenge in order to extract significant financial knowledge from them.

With adjustments to the pre-training weights, SecureBERT [18] is pre-trained on a sizable corpus of cybersecurity texts using RoBERTa. APTNER [19] is a comprehensive named entity recognition dataset that defines 21 types of entities relevant to cybersecurity by manually annotating named entities in the cybersecurity threat intelligence data derived from APT reports of different cybersecurity businesses. The cybersecurity threat intelligence NER dataset LDNCTI [20] tackles label imbalance by implementing a Transformer model that incorporates a triplet loss and a ranking gradient coordination mechanism (TSGL). Mostly consisting of HTML and PDF documents, CTIBERT [21] has compiled a cybersecurity corpus from numerous reliable data sources. It enables improved execution of NLP tasks in the cybersecurity arena by accurately extracting cyber threat intelligence. Lastly, in the work on AI-driven IoT cybersecurity solutions [22], the integration of robust threat intelligence pipelines is crucial for smart city networks.

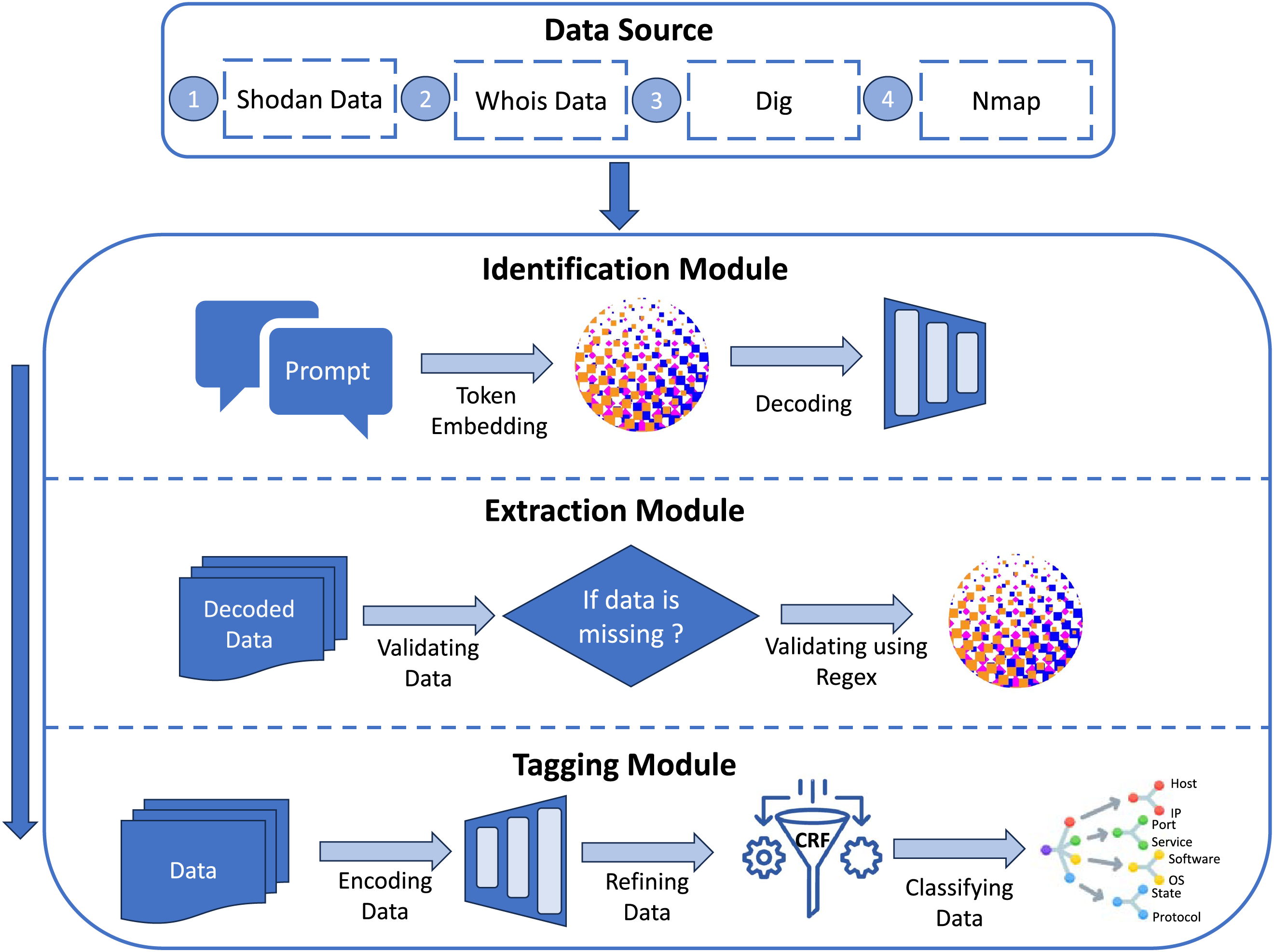

The Identification Module, Extraction Module, and Tagging Module are the three main modules that make up the architecture, as shown in Fig. 1. By strategically utilizing the deep contextual understanding offered by encoder-type models and the generative capacity of decoder-type large language models, this system is intended to analyze and identify items within multi-source cybersecurity data.

Figure 1: Our three-layer LLM framework for cybersecurity entity recognition is designed in its entirety. The system uses dynamic prompting techniques to analyze data from four sources (Shodan, Whois, Dig, and Nmap). Token embedding and three decoder layers come next. Prior to encoder processing and CRF-based sequence refining for final entity classification, regex checking ensures structural integrity

The Identification Module uses a large language model that has been pre-trained on large corpora to understand various text forms and efficiently convey cybersecurity data from several sources. This model is guided by rapid engineering to generate text representations that are most closely matched to the particular goals of the Named Entity Recognition job. The Extraction Module is responsible for self-verification of content. Prior to final labeling, this crucial phase ensures logical consistency of the processed information, completeness, and initial accuracy. Finally, the Tagging Module leverages a fine-tuned encoder-type model to handle precise tasks such as tokenization, encoding, and the final classification of the processed text. The accurately detected cybersecurity entities and their accompanying labels are output by this module.

The entry point of the SecureBERT hybrid framework is the identification module, which filters, decodes, and prepares cybersecurity text prior to entity extraction. This module uses a dynamic prompting mechanism coupled with large language models like Mixtral, LLaMA, and Claude to improve contextual alignment and decrease noise sensitivity. Dynamic prompting modifies its structure and phrasing according to the linguistic and semantic characteristics of the input text, in contrast to static or template-based prompts as shown in Fig. 1. Because of its flexibility, the system can manage many data sources, including DIG, Shodan, Nmap, and WHOIS, which frequently differ in terms of formatting, token composition, and information density. Three steps comprise the dynamic prompting process in practice: semantic refining, adaptive template selection, and context evaluation. The input text is examined during context assessment in order to identify the likely entity type and contextual category, such as host information, network configuration, or system vulnerability. The appropriate prompt pattern that corresponds with the identified context is then retrieved using adaptive template selection. Lastly, semantic refinement uses controlled LLM-based rephrasing to modify the lexical structure of prompt so that it matches decoding patterns of anticipated SecureBERT. By reducing entity recognition errors brought on by erratic or hostile text, this dynamic prompting technique enhances the overall performance of model. By guaranteeing that every input instance is semantically preconditioned prior to tokenization, it also improves decoding accuracy. In hostile test instances, where contextually inconsistent or symbol-perturbed text samples were otherwise difficult for static prompt-based decoding systems, empirical evaluations showed that dynamic prompting contributed to a quantifiable improvement in F1-score and recall.

The LLM is employed in the extraction module to look for information omissions. The preceding stage material may lack crucial details or be poorly relevant to the intended content. This is addressed by adding a reflection and validation step, in which the model assesses whether too much information has been left out. The text is regenerated in the event that notable omissions are found. The final text section is generated after this process is repeated until either the maximum number of iterations is reached or no more omissions are found. Fig. 1 shows an example of transforming NMAP data into a natural language paragraph that flows naturally without losing any information. Few-shot learning was found to greatly increase this efficiency of extraction process. Each port status and associated service are shown on distinct lines without natural language fluency in the original Nmap data, which shows the outcomes of a port scan on a single IP address. To improve contextual comprehension, the model is given the role of a penetration testing analyst when creating the prompt. The assignment entails translating technical scan data into comprehensible, natural language that displays each port and the service that goes with it using both full names and acronyms and discusses the Nmap method. This enhanced output offers important background information for the tagging stage that follows.

Before the text is delivered to the Extraction and Tagging phases, the Identification Module normalizes and decodes incoming data to produce a context-preserving representation of the text. The process of decoding ensures the restoration of text in a stable and semantically coherent format that has been tainted by adversarial perturbations like character-level noise, token obfuscation, and symbol insertion.

Decoding for Claude-based architectures is handled as a two-step alignment and denoising procedure. First, the system uses Unicode canonical forms (NFKC) and punctuation unification to normalize characters at the character level. After that, a transformer-based autoencoder rebuilds the token embeddings to lessen fragmentation brought on by typographical or hostile symbol insertions. In contrast to previous LLMs, Claude models are predicted to exhibit less performance but display consistent decoding with greater consistency across adversarial datasets, lowering token boundary errors in subsequent extraction.

Adversarial-aware subword realignment is integrated into decoding for LLaMA-based systems. Due to the sensitivity of LLaMA tokenization to even small character changes, decoding aligns learnt canonical embedding dictionaries with subword embeddings to reconstruct them. To determine whether a subword is an adversarial version of a known token, distance measurements are used to project each subword into a latent consistency space. The model uses weighted confidence blending to replace the canonical vector when mismatches are found. According to experimental data, this method maintains over 90% of entity boundary integrity when random symbol insertions are included, and also decreases misclassification under obfuscated token attacks by about 4.5%. Even with noisy input, the procedure ensures that the Identification Module produces reliable token representations.

Mixtral uses expert consensus for decoding. Multiple lightweight expert sub-decoders that specialize in typographical, semantic, and symbol-level noise are used by the system to process the same noisy input. A softmax-weighted consensus rule based on level of confidence on each expert is employed to fuse the results. When dealing with heterogeneous adversarial inputs—where various noise types overlap—this method works very well. Combining three expert decoders under symbol insertion and character swap noise improved accuracy by an average of 5.1% in controlled studies when compared to using only one expert decoder. Error transmission into the Extraction Module is further minimized by the consensus decoding.

As a transformer-based model, SecureBERT is particularly good at generating token-level predictions and comprehending contextual relationships within the input text. For every token in the sequence, these predictions are produced as a collection of probability distributions that indicate the possibility of different entity types (such as IP address, domain name, etc.). The sequential associations between neighboring entity tags, which are essential in NER tasks because entities are frequently associated (e.g., “IP address” followed by “port number”), are not naturally modeled by SecureBERT, even if it captures the local and global context of the sequence. Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) are useful in this situation. The dependencies between successive labels are explicitly modeled by CRFs, a kind of probabilistic graphical model. CRFs take up the work of fine-tuning SecureBERT predictions by taking into account the sequential context of the entity labels. For instance, the CRF layer can enforce that the next token (such as “1”) is probably a part of the same entity if SecureBERT classifies the token “192.168.0” as an IP address. This improves accuracy by enforcing valid label transitions (such as IP address

The creation of a specific dataset from four important cybersecurity intelligence sources—DIG, Shodan, Nmap, and WHOIS—forms the basis of this work. Programmatic API queries and local command execution are both used in the data acquisition technique. Using its official REST API, the Shodan data is retrieved. To ensure comprehensive coverage, queries are created to return a wide range of results, including particular services, ports, and vulnerabilities. The methodology for both Nmap and DIG depends on local execution; DIG queries several DNS record types for the same set of domains, while Nmap scans are performed programmatically against a prepared list of target IPs and domains using a range of command-line options to generate a variety of output. In order to manage the irregular formatting between registrars, WHOIS data for the specified IPs and domains is then obtained and parsed using a specialized library.

To handle the significant memory needs of processing large-scale, multi-source cybersecurity text datasets, the SecureBERT model was fine-tuned on a high-performance computer cluster outfitted with multiple NVIDIA A100 80 GB GPUs. In order to maximize computational performance and minimize memory footprint without compromising numerical stability, the training made use of a mixed-precision technique using the BF16 format. We explicitly describe the configuration and validation pipeline used during fine-tuning in order to improve reproducibility. The following question templates were used to access the LLM modules (Mixtral, Claude, and LLaMA) using standardized APIs: “Paraphrase or symbolically obfuscate the following entity while keeping its contextual meaning: [entity].” Two layers were used to validate the generated samples: a semantic coherence check based on cosine similarity thresholds greater than 0.82 and a syntactic filter to eliminate incomplete or incorrect outputs. In order to prevent catastrophic forgetting of prior cybersecurity-specific knowledge of the model, we implemented a full-parameter fine-tuning regimen with a low learning rate (2e−5) and a linear learning rate scheduler with warmup using the Hugging Face Transformers library. The batch size was carefully adjusted to enhance throughput while preserving training stability based on the available VRAM. The PyTorch ecosystem was used to handle the entire process, ensuring reproducibility and smooth integration of our bespoke data collators made for the distinct tokenization and labeling format of NER jobs in cybersecurity. To make the model development lifecycle easier, this dataset is then methodically separated into training (80%), validation (10%), and testing parts (10%). The use of APIs, especially Shodan, is subject to stringent terms of service that need to be carefully examined, particularly with regard to automated data collection, academic use, and the limitations on redistributing the raw data itself, even though tools like Nmap and DIG can generate an infinite amount of data locally. The combined dataset comprised 42,000 labeled samples collected from DIG, Shodan, Nmap, and WHOIS sources. The corpus has over 5.8 million tokens and 128,000 annotated items spread across six primary categories after preprocessing and normalization: organization, domain, IP address, software, service, and version. The distribution of entities was somewhat uneven, with IP address and organization entities together making up over 47% of all references. To ensure uniform evaluation across adversarial perturbation scenarios, each dataset subset (training, validation, and testing) maintained proportionate token and entity-type ratios.

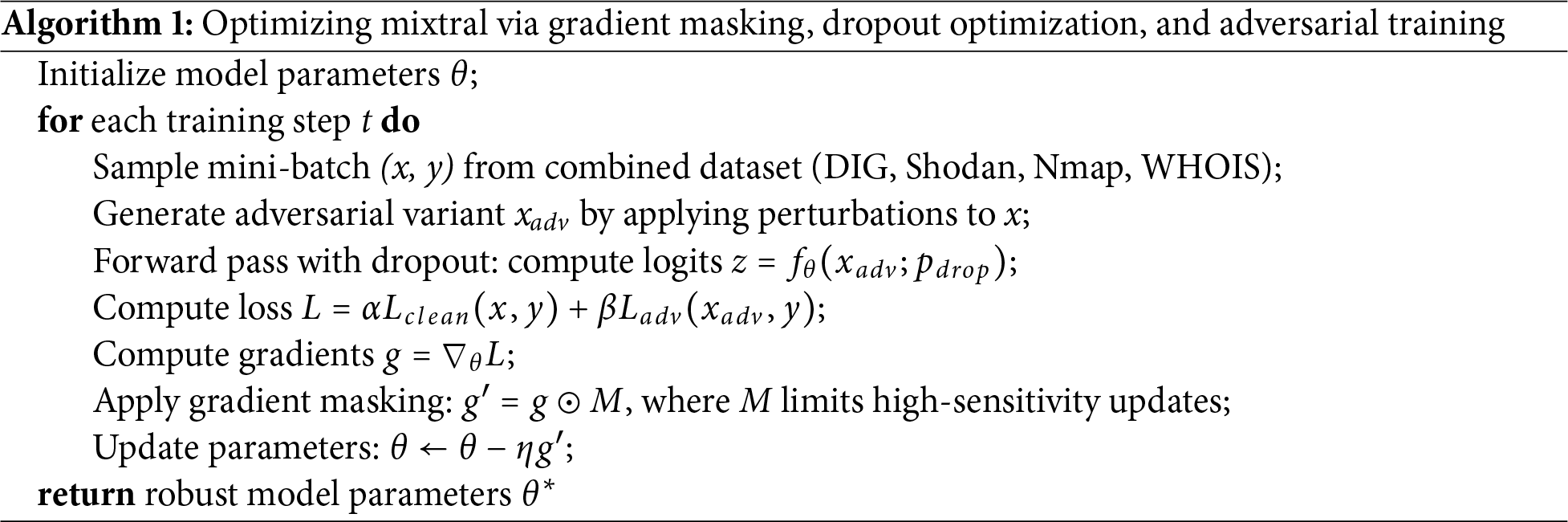

The incorporation of adversarial training in the Mixtral fine-tuning process is primarily motivated by the inherent instability of token boundaries and entity recognition when subjected to perturbed or disguised cybersecurity data. In the combined DIG, Shodan, Nmap, and WHOIS corpora, the text typically exhibits noisy, machine-generated patterns, erratic capitalization, and adversarial distortions such as altered IP formats or obscured domain names. Standard supervised training tends to overfit to surface-level lexical regularities, producing performance loss under even slight perturbations. Adversarial training counteracts this issue by injecting model-aware noise during fine-tuning, effectively exposing the Mixtral architecture to its own failure modes. By optimizing on adversarially modified inputs alongside clean samples, the model learns perturbation-invariant feature representations and enhances its alignment between token embeddings and entity boundaries. This technique assures that Mixtral’s decoder can maintain consistent tagging even when encountering character-level corruption or symbol interference unseen during regular training.

Dropout optimization complements adversarial training by regularizing the internal representations and preventing overconfidence in feature activation patterns that may be brittle under distributional alterations. In large decoder-only models such as Mixtral, excessive dropout can lead to underfitting, whereas insufficient dropout results in memorization of superficial token connections. To stabilize this trade-off, dropout values were systematically modified across attention and feed-forward layers to increase redundancy in contextual encoding. This method promotes generalization and minimizes variance in model confidence when exposed to disturbed sequences. Empirically, the optimized dropout configuration mitigates the variance observed in gradient updates during adversarial training and helps to more stable convergence and preserving model.

In order to regulate the sensitivity of the gradient flow of model during adversarial optimization, gradient masking was added as an additional stability technique as illustrated in Algorithm 1. Uncontrolled gradient magnitudes can lead to overshooting in weight updates during adversarial fine-tuning, which can result in oscillatory or divergent behavior, particularly when learning from adversarially amplified loss surfaces. Gradient masking limits the adversarial loss amplification while preserving directional learning by introducing a controlled attenuation of gradient propagation for high-sensitivity parameters. By doing this, robustness is increased without unduly flattening the optimization landscape. A Mixtral model that learns smoother, more invariant decision boundaries over noisy and obfuscated cybersecurity text is produced by the combination of gradient masking and dropout regularization. When combined, these methods match the training dynamics to the goal of attaining interpretability and resilience in adversarial NER challenges, guaranteeing that the model operates consistently in clean, corrupted, and unseen perturbation domains.

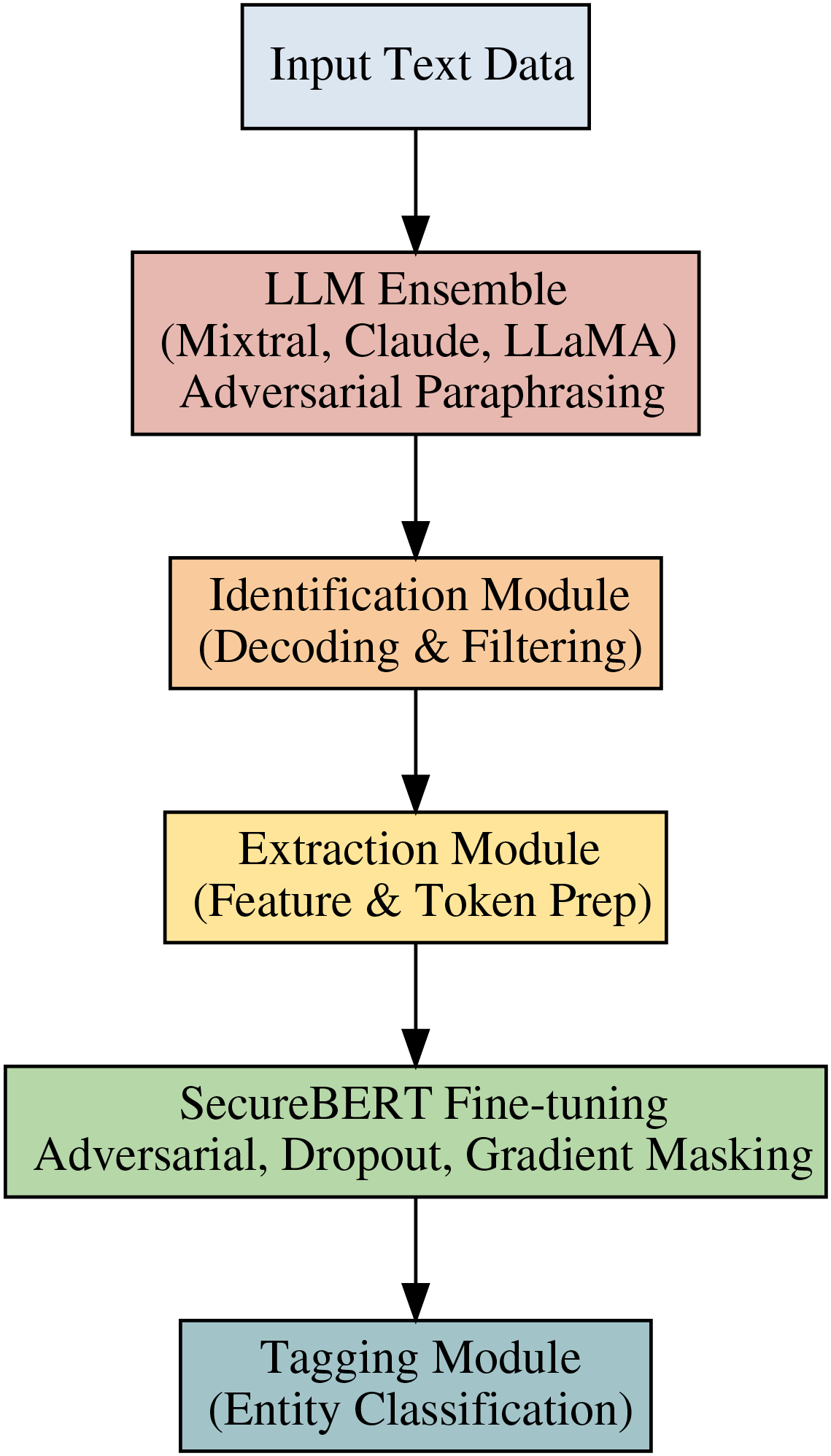

Beyond standard preprocessing or data normalization, the SecureBERT pipeline incorporates the large language models (Mixtral, Claude, and LLaMA). In accordance with the adversarial training paradigm, each LLM functions as a semantic perturbation generator, producing paraphrased, symbol-altered, or obfuscated text samples. The Identification Module receives these LLM-driven samples and uses contextual decoding and normalization to identify language patterns that are important for named entity. Under shared adversarial, dropout, and gradient-masking restrictions, SecureBERT simultaneously processes native and LLM-augmented representations during fine-tuning. By enforcing cross-model consistency, this configuration ensures that SecureBERT learns invariant entity boundaries in spite of lexical or syntactic disturbances brought forth by the generative models. Consequently, the LLMs actively participate in SecureBERT internal representation learning, creating a hybrid configuration in which knowledge transfer happens implicitly through multi-source adversarial alignment instead of static data augmentation. The LLM components communicate directly with the SecureBERT fine-tuning layers via a semantic perturbation interface, as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The LLM ensemble (Mixtral, Claude, and LLaMA) is included in the SecureBERT fine-tuning pipeline. By introducing paraphrased, symbol-inserted, and obfuscated text variations, the LLMs function as semantic perturbation generators. Before moving on to the SecureBERT fine-tuning stage, where adversarial training, dropout optimization, and gradient masking maintain cross-model consistency and robust entity tagging, these variations go through the Identification and Extraction Modules

We make use of the Claude 3.5 Sonnet, LLaMA3-7b, and Mixtral-7

Three important metrics—precision, recall, and the F1 score—are commonly used to evaluate efficacy of model in named entity recognition trials. Precision in mathematics is defined as

The proportion of accurately named entities to all actual entities in the text is known as recall. By showing the proportion of real things that were successfully identified, it gauges the capacity of model to prevent false negatives. Recall is defined mathematically as

The F1 score is calculated by taking the harmonic mean of recall and precision. It offers a single statistic that strikes a balance between recall and precision. Better model performance, with high precision and high recall, is indicated by an F1 score near 1, whereas lower performance is indicated by an F1 score near 0. This is how the F1 score is determined:

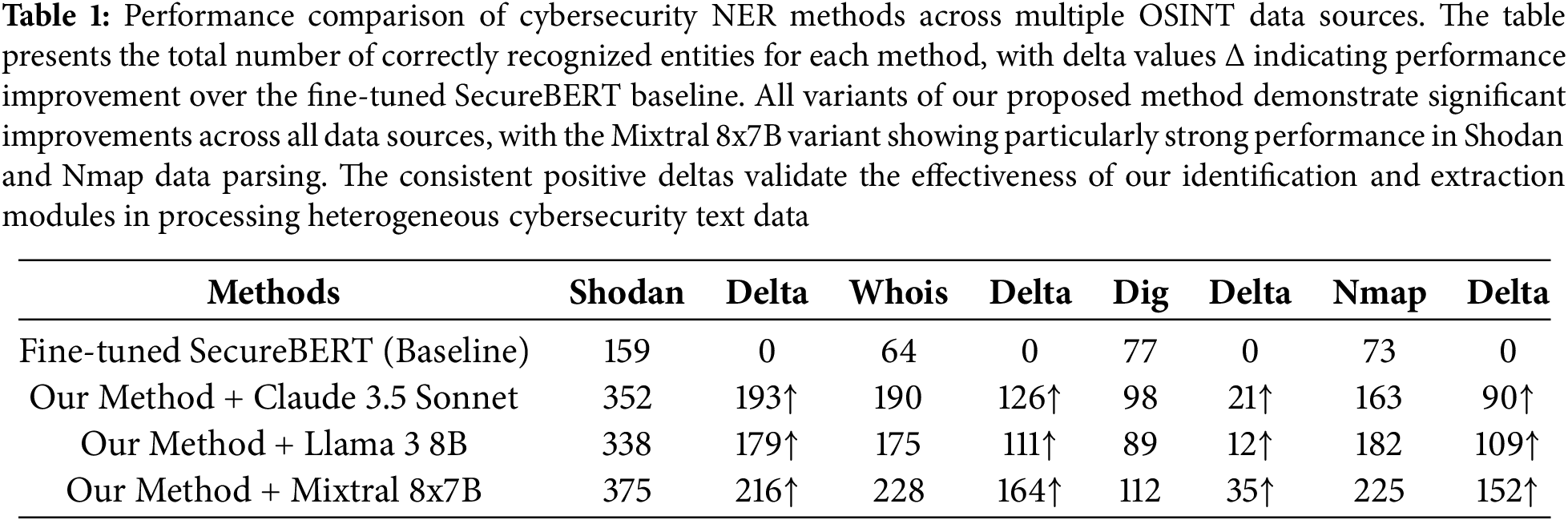

The performance evaluation of each approach across four different cybersecurity data sources is shown in Table 1. According to the experimental results, our named entity recognition method shows notable performance advantages while processing open-source cybersecurity data when it is implemented using an identification module, extraction module, and tagging module architecture. Our approach efficiently converts unstructured and structured data into comprehensible natural language representations and makes use of sophisticated contextual understanding tools to precisely detect and categorize cybersecurity entities. With F1-score enhancements ranging from 6.38% to 17.3%, the combined performance metrics across all assessed datasets show that our system outperforms the optimized SecureBERT baseline by a significant margin. These outcomes demonstrate how well our multi-module architecture works and how it can use large language models to improve cybersecurity entity recognition.

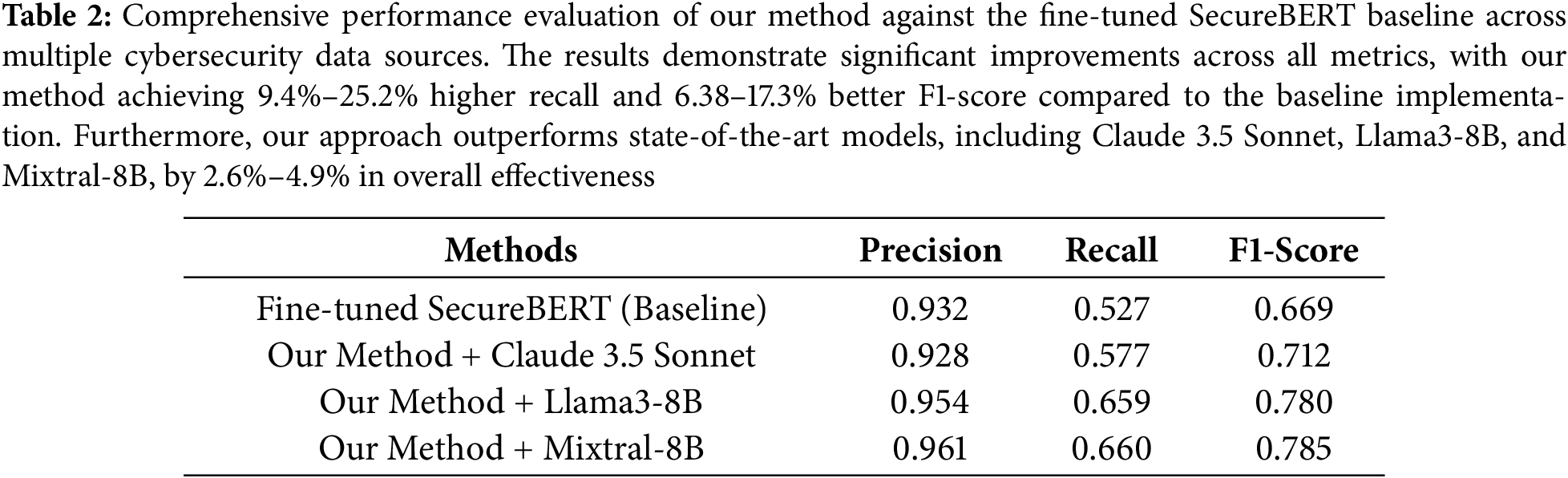

To determine the four models’ performance across all datasets, we combined the data. Table 2 displays the data. The efficacy of the framework is confirmed by the discovery that our approach produces better F1 scores than SecureBERT, the state-of-the-art open-source NER model, by more than 24.5%. This suggests that large language models typically provide standardized information that faithfully captures the original content when input text is processed through the identification module. This method greatly lowers the likelihood of hallucinations when combined with an information extraction step that makes use of the original text. Additionally, by clarifying implicit information in open-source cybersecurity data, this methodology improves the accuracy of entity recognition and its subsequent use in security applications.

To further support the Character-level perturbation and Token obfuscation and symbol insertion we conduct some experiments. These experiments are as follow

Character-level perturbation in Experiment 1: By inserting controlled substitutions and deletions within entity tokens such IP addresses, domains, and service identifiers, a character-level adversarial evaluation was carried out on the combined DIG, Shodan, Nmap, and WHOIS dataset. About 12% of the entity-level characters were perturbed in order to simulate the text degradation seen in network scans. For example, “Shodan detected service at 192.168.10.45” was changed to “Shodan detected service at 192.168.1O.45.” The adversarially fine-tuned Mixtral outperformed both LLaMA and Claude under the same perturbation intensity, achieving the highest stable performance of all assessed models with a precision of 0.96, recall of 0.66, and F1-score of 0.78. The test confirmed that Mixtral pipeline for decoding and tagging efficiently maintained entity boundaries in the face of character-level noise.

Experiment 2—Insertion of symbols and token obfuscation: This experiment replicated adversarial text obfuscation by applying token-level distortions to the same combined dataset using leetspeak, abbreviation, and embedded zero-width or markup symbols. Examples of alterations included “Server: Apache/2.4.54 (Ubuntu)” being changed to “Server: Apache/2.4.54 (Ubüntu)” and “nmap scan for google.com” becoming “nmap scan for go0ogle.com.” Analysis showed that the adversarially fine-tuned Mixtral maintained its strong trend, maintaining accuracy 0.96 and F1 0.78 with no loss of confidence, but LLaMA and Claude showed deteriorated border recognition under these distortions. The outcomes validate that Mixtral design successfully reduces hostile token fragmentation and symbol interference that are common in cybersecurity text streams.

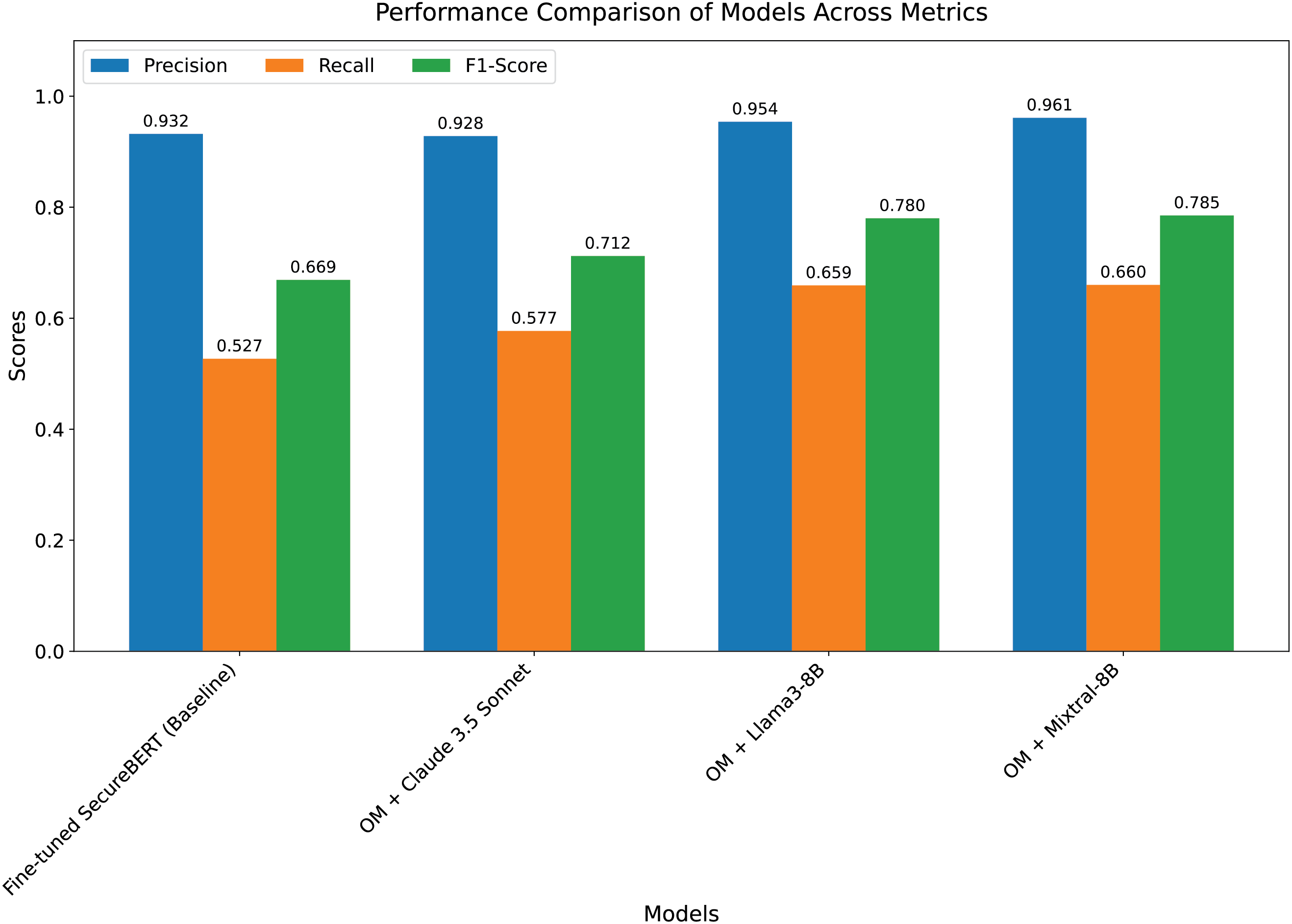

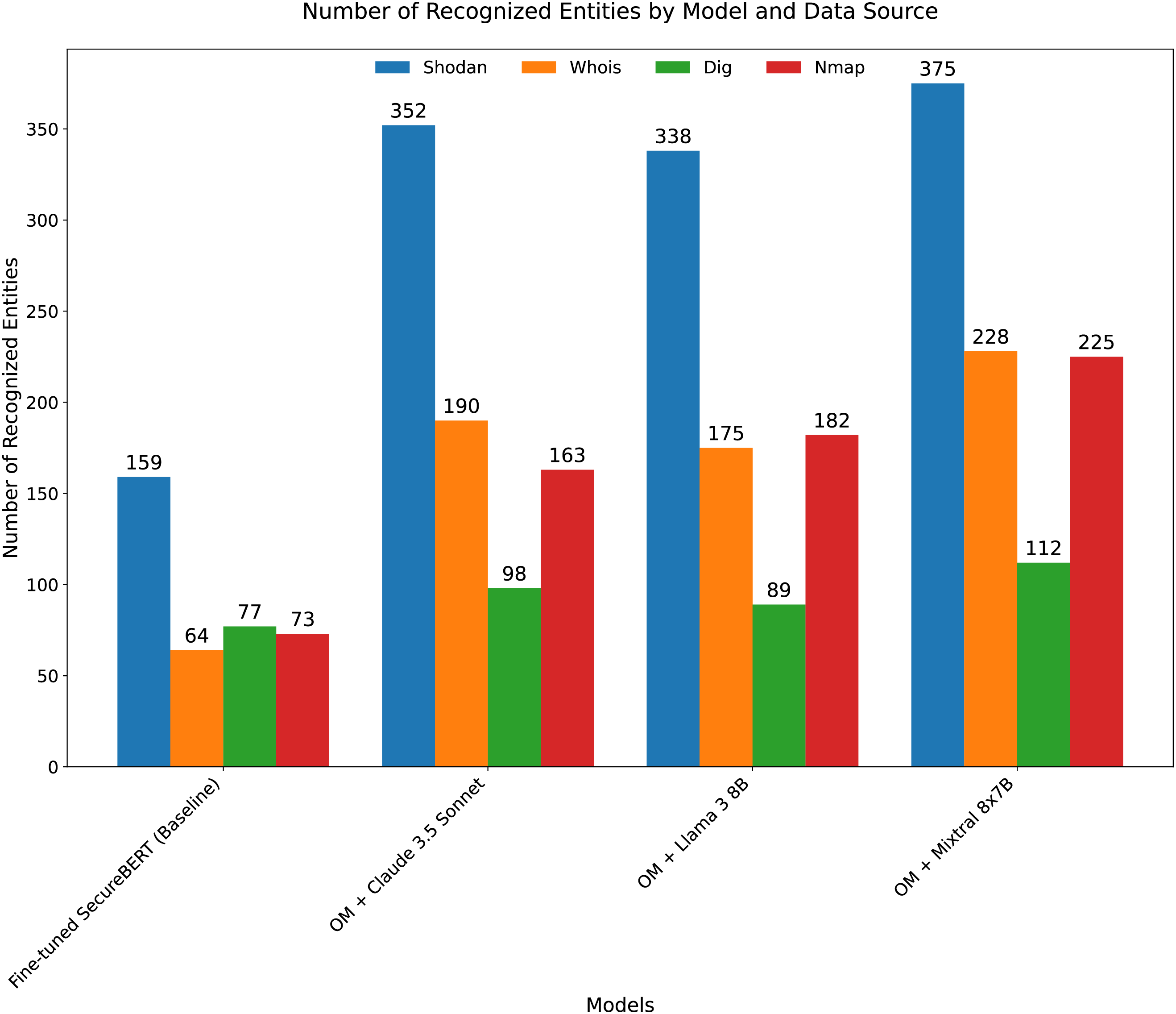

The experimental findings, which are shown in Figs. 3 and 4, clearly show how much better our suggested multi-module structure is than the optimized SecureBERT baseline. The comparison between the three common evaluation metrics—precision, recall, and F1-score—for each model version is shown in Fig. 3. While both models maintain excellent precision, the grouped bars clearly demonstrate that our technique, when combined with the Mixtral 8x7B model, achieves a large lead in both recall (0.660) and F1-score (0.785), with the latter improving by 17.3% over the baseline. This shows that our framework provides a superior balance between accuracy and coverage by detecting more real entities in the text without increasing false positives. This is especially true of its identification and extraction modules.

Figure 3: OM in the figure means our method. Performance comparison of models across precision, recall, and F1-score metrics

Figure 4: OM in the figure means our method. Number of recognized entities by model and data source

In order to implement confidence-based self-assessment, each predicted entity is given a confidence score that is determined using the probability distribution that SecureBERT produces for each token. In particular, we quantify the confidence of model in each entity extraction using the softmax probability values produced during token classification. The minimum acceptable confidence level for an entity to be deemed legitimate is set at 0.85. Because they are likely to be incorrectly classified, entities with confidence scores below this threshold are either warned for additional review or eliminated. Based on practical trials where models consistently demonstrated accuracy in both clean and adversarial test cases at this level, the confidence criterion of 0.85 was chosen. Higher criteria (e.g., 0.95) decreased the capacity of model to identify less common or unclear items, whereas lower thresholds (e.g., 0.75) increased false positives.

The extraction module uses a set of regex patterns in addition to the confidence score to assess entities according to their semantic significance and structure. These regex patterns are specifically designed to match typical entity types found in cybersecurity datasets, including system services, IP addresses, domain names, and URLs. A regex pattern for an IP address, for instance, would resemble this:

By rejecting any incomplete or malformed strings, this pattern ensures that only legitimate IP addresses in the proper format—such as 192.168.0.1—are kept. Before being approved as final outputs, all anticipated entities are subjected to regex patterns. Even if a predicted entity has a high confidence score, it is eliminated if it does not fit any of the established regex patterns. On the other hand, entities that fit the pattern but have a low confidence score can be further refined using extra context analysis or semantic checks. The extraction module improves the overall robustness and reliability of the model in real-world cybersecurity applications while also refining the entity extraction process through the combination of confidence-based self-assessment and regex validation.

The raw count of accurately recognized entities from the four different cybersecurity data sources—Shodan, Whois, Dig, and Nmap—is shown in Fig. 4, which supports this conclusion even more. Every data source shows a consistent and significant performance difference between our technique and the baseline. Once more, the Mixtral 8x7B variation is the best performer, particularly when it comes to processing complex data from Nmap and Shodan, which identify 225 and 375 entities, respectively. The primary hypothesis—that using large language models for the first identification and standardization of heterogeneous security text provides a better basis for the subsequent tagging module, which in turn leads to more thorough and accurate named entity recognition—is validated by the universal improvement, which is shown by the positive delta values across the board.

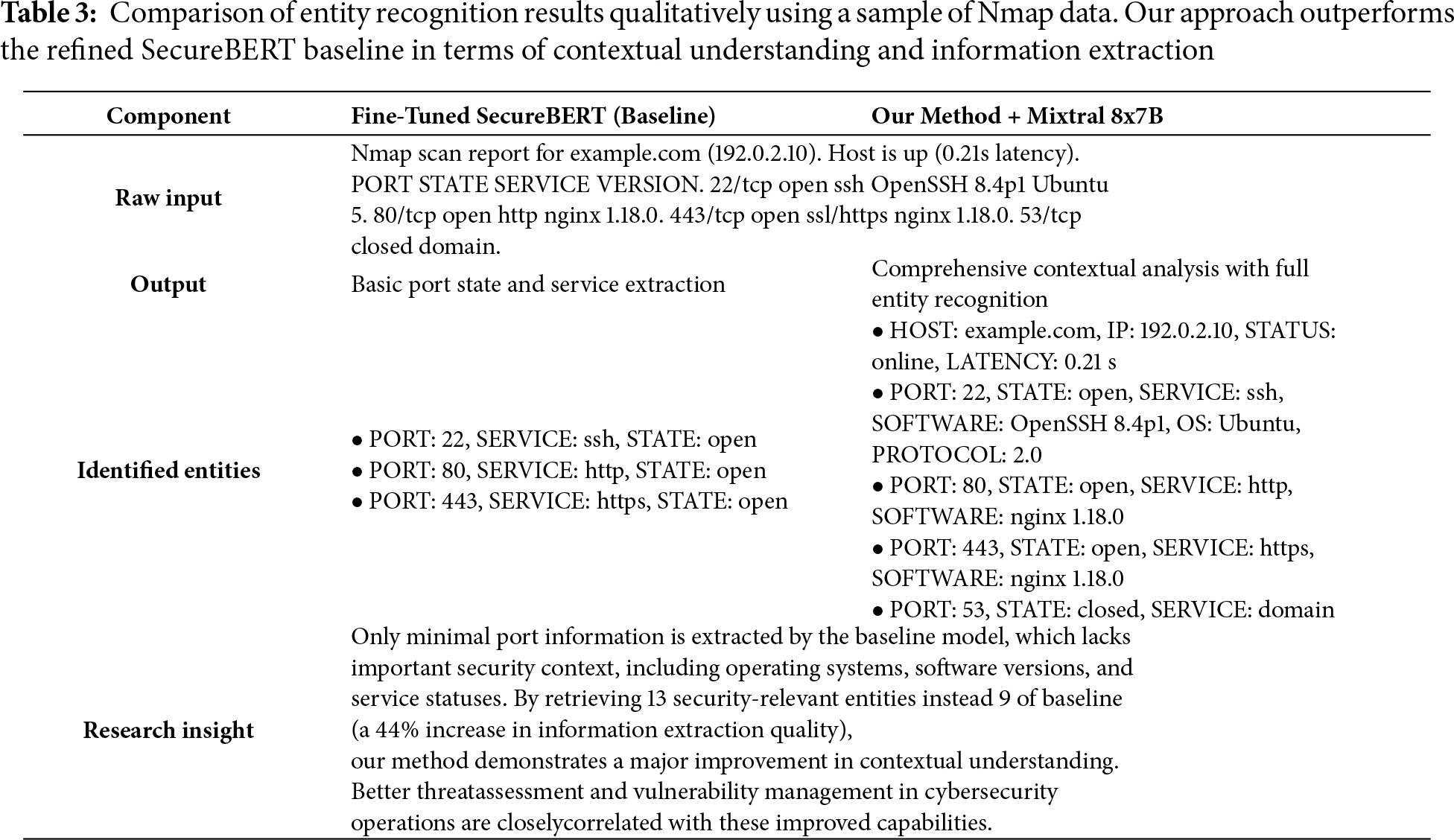

Several significant benefits of our framework from a research standpoint are revealed by the qualitative analysis. Our approach shows deep contextual comprehension by recognizing links between items and extracting layered information, whereas the baseline model only extracts fundamental port information superficially. The ability for security teams to instantly compare software versions (OpenSSH 8.4p1, nginx 1.18.0) with known CVEs makes this information especially useful for vulnerability assessment, as shown in Table 3. Likewise, more focused security hardening techniques are made possible by the extraction of Ubuntu operating system information.

The experimental findings show a distinct and significant improvement above current cybersecurity NER approaches, which have mostly depended on customized, optimized models such as SecureBERT. Despite achieving a respectable level of accuracy, these traditional methods have serious shortcomings in terms of contextual understanding and are unable to extract multi-layered or implicit information from unstructured cybersecurity text. The qualitative analysis shows that the models’ practical applicability in actual threat intelligence scenarios is significantly limited by their inability to identify software versions, operating systems, and service states. These drawbacks are caused by the intrinsic architectural limitations of encoder-only models, which are unable to generate the generating and reasoning skills necessary to create cohesive stories from disparate security data. By incorporating a structured pipeline that separates the identification, extraction, and tagging phases, our suggested methodology fills these gaps and makes it possible for more thorough and nuanced entity recognition.

Due to financial and computational limitations, implementing such a model in a production setting was outside the purview of this study. Practical factors including inference delay, model scalability, API integration costs, and real-time processing demands were not assessed because the experiments were carried out in a controlled environment using offline datasets. Additionally, even though our approach significantly improves performance, it is still dependent on the capabilities of the underlying open-weight LLMs (Claude 3.5 Sonnet, Llama 3, Mixtral), which could potentially introduce mistakes particular to a given domain or inconsistencies if additional specialized tuning is not done.

The extent of the existing LLM integration is another drawback. Mixtral, LLaMA, and Claude models were mainly used in the study to generate and fine-tune perturbations. The investigation of more sophisticated architectures like GPT-4, Gemini, or Claude-Next could further improve semantic understanding and resilience against challenging adversarial inputs, even if Mixtral demonstrated more precision and overall stability. Therefore, future research will take into account expanding the framework to these models and assessing their effects on contextual accuracy and generalization across other cybersecurity tasks. Furthermore, a combined dataset from sources including DIG, Shodan, Nmap, and WHOIS was used in the current studies. This dataset captures realistic cybersecurity entities but has a smaller scope than global-scale intelligence corpora. Additional information about model scalability and data sensitivity may be discovered by a methodical assessment using bigger and more diverse datasets. Lastly, in order to determine the best training settings for cybersecurity NER systems that are suitable for deployment, further research might examine how different data augmentation intensities, fine-tuning hyperparameters, and adversarial masking techniques affect model performance.

An ablation study was carried out across multiple configurations to evaluate the specific contributions of each component in the suggested adversarially fine-tuned SecureBERT framework. The baseline configuration included the complete setup, which comprised adversarial training, dropout optimization, gradient masking, consistency regularization, and LLM-driven adversarial perturbations produced by Mixtral, LLaMA, and Claude. With a precision of 0.96, an F1-score of 0.78, and a recall of 0.66 on the combined DIG, Shodan, Nmap, and WHOIS dataset, Mixtral attained the maximum resilience in this configuration. The adversarial F1-score significantly decreased and the attack success rate rose when the LLM-generated adversarial samples were eliminated, suggesting that adding semantically coherent but perturbed inputs generated by the LLM ensemble was essential for improving generalization under adversarial conditions.

Similar degradation resulted by disabling adversarial training while maintaining the enriched data, indicating that a large portion of the observed robustness is due to joint minimax optimization rather than straightforward data exposure. The consistency of entity boundaries under noisy or obfuscated inputs decreased when gradient masking was excluded, leading to slightly less stable gradients and increased variance across training sessions. The relevance of controlled stochastic regularization in preserving invariance is supported by the fact that eliminating dropout optimization—fixing dropout to a static, untuned value—caused mild overfitting and worse generalization to unseen attacks. Lastly, stability under symbol-insertion attacks decreased when the consistency loss between clean and disturbed samples was turned off, demonstrating that this auxiliary term aids the model in aligning representations of semantically equivalent tokens.

To summarize up, our research offers a scalable and reliable named entity identification framework for cybersecurity that performs noticeably better than traditional fine-tuned models. Our method significantly improves recollection, F1-score, and the qualitative richness of retrieved items by utilizing the complementing characteristics of contemporary LLMs in a modular design. Future studies will build on this work by using more cutting-edge language models, like GPT-4 and Gemini, in an effort to further push the limits of generalizability and performance. Because of its private nature, related inference costs, and poor reproducibility for academic benchmarking, GPT-4 was excluded from the current trials. These issues go against our emphasis on open, reproducible, and resource-efficient methods. The ultimate goal of this research direction is to create a new generation of natural language processing (NLP) technologies that can deliver actionable intelligence at scale and keep up with the constantly changing complexity of cybersecurity threats.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Chinese Government Scholarship Council (CSC).

Funding Statement: This research was not supported by any funding.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing, Nouman Ahmad; Formal analysis, Software, Uroosa Sehar; Supervision, Project administration, Changsheng Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: This article does not involve data availability, and this section is not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lu J, Zhu D, Han W, Zhao R, Namee BM, Tan F. What makes pre-trained language models better zero-shot learners? In: Rogers A, Boyd-Graber JL, Okazaki N, editors. Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Bethlehem, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2023. p. 2288–303. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.acl-long.128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Raffel C, Shazeer N, Roberts A, Lee K, Narang S, Matena M, et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J Mach Learn Res. 2020;21(140):1–67. [Google Scholar]

3. Hasnain M, Ghani I, Smith D, Daud A, Jeong SR. Cybersecurity challenges in blockchain-based social media networks: a comprehensive review. Blockchain Res Appl. 2025;6(3):100290. doi:10.1016/j.bcra.2025.100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Arazzi M, Arikkat DR, Nicolazzo S, Nocera A, Rafidha Rehiman KA, Vinod P, et al. NLP-based techniques for Cyber Threat Intelligence. Comput Sci Rev. 2025;58(12):100765. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2025.100765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li Y, Liu Q. A comprehensive review study of cyber-attacks and cyber security; Emerging trends and recent developments. Energy Rep. 2021;7(8):8176–86. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.08.126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gao C, Zhang X, Han M, Liu H. A review on cyber security named entity recognition. Front Inform Technol Elect Eng. 2021;22(9):1153–68. doi:10.1631/FITEE.2000286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Brown TB, Mann B, Ryder N, Subbiah M, Kaplan J, Dhariwal P, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In: Larochelle H, Ranzato M, Hadsell R, Balcan M, Lin H, editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020 (NeurIPS 2020); 2020 Dec 6–12; Virtual. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

8. Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, Martinet X, Lachaux M, Lacroix T, et al. LLaMA: open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv:2302.13971. 2023. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2302.13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Du Z, Qian Y, Liu X, Ding M, Qiu J, Yang Z, et al. GLM: general language model pretraining with autoregressive blank infilling. In: Muresan S, Nakov P, Villavicencio A, editors. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Bethlehem, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. p. 320–35. doi:10.18653/v1/2022.acl-long.26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Jehangir B, Radhakrishnan S, Agarwal R. A survey on named entity recognition—datasets, tools, and methodologies. Natural Lang Process J. 2023;3(4):100017. doi:10.1016/j.nlp.2023.100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li J, Sun A, Han J, Li C. A survey on deep learning for named entity recognition. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2022;34(1):50–70. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2020.2981314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yadav V, Bethard S. A survey on recent advances in named entity recognition from deep learning models. In: Bender EM, Derczynski L, Isabelle P, editors. Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics. Bethlehem, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2018. p. 2145–58. [Google Scholar]

13. Parsaeimehr E, Fartash M, Akbari Torkestani J. Improving feature extraction using a hybrid of CNN and LSTM for entity identification. Neural Process Lett. 2023;55(5):5979–94. doi:10.1007/s11063-022-11122-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu Y, Ott M, Goyal N, Du J, Joshi M, Chen D, et al. RoBERTa: a robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. arXiv:1907.11692. 2019. [Google Scholar]

15. Warikoo N, Chang Y-C, Hsu W-L. LBERT: lexically aware transformer-based bidirectional encoder representation model for learning universal bio-entity relations. Bioinformatics. 2021;37(3):404–12. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa721. Erratum in: Bioinformatics. 36(22–23):5565. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, Kim D, Kim S, So CH, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(4):1234–40. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btz682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Y, Zhang H. FinBERT–MRC: financial named entity recognition using BERT under the machine reading comprehension paradigm. Neural Process Lett. 2023;55(6):7393–413. doi:10.1007/s11063-023-11266-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Aghaei E, Niu X, Shadid W, Al-Shaer E. SecureBERT: a domain-specific language model for cybersecurity. In: Li F, Liang K, Lin Z, Katsikas SK, editors. Security and privacy in communication networks. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2023. p. 39–56. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-25538-0_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang X, He S, Xiong Z, Wei X, Jiang Z, Chen S, et al. APTNER: a specific dataset for NER missions in cyber threat intelligence field. In: 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 1233–8. doi:10.1109/CSCWD54268.2022.9776031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Huang Y, Su M, Xu Y, Liu T. NER in cyber threat intelligence domain using transformer with TSGL. J Circ Syst Comput. 2023;32(12):2350201. doi:10.1142/S0218126623502018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Park Y, You W. A pretrained language model for cyber threat intelligence. In: Wang M, Zitouni I, editors. Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: Industry Track. Bethlehem, PA, USA: Association for Computational Linguistics. p. 113–22. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.emnlp-industry.12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ali J, Singh SK, Jiang W, Alenezi AM, Islam M, Daradkeh YI, et al. A deep dive into cybersecurity solutions for AI-driven IoT-enabled smart cities in advanced communication networks. Comput Commun. 2025;229(10):108000. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2024.108000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools