Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Dynamic Malware Detection Method Based on API Multiple Subsequences

College of Intelligent Systems Science and Engineering, Hubei Minzu University, Enshi, 445000, China

* Corresponding Author: Jinan Shen. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 76 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073076

Received 10 September 2025; Accepted 10 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The method for malware detection based on Application Programming Interface (API) call sequences, as a primary research focus within dynamic detection technologies, currently lacks attention to subsequences of API calls, the variety of API call types, and the length of sequences. This oversight leads to overly complex call sequences. To address this issue, a dynamic malware detection approach based on multiple subsequences is proposed. Initially, APIs are remapped and encoded, with the introduction of percentile lengths to process sequences. Subsequently, a combination of One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) networks, along with an attention mechanism, is employed to extract features from subsequences of varying lengths for feature fusion and classification. Experiments conducted on two widely used public API-based datasets, namely MalBehavD-V1 and Alibaba Cloud, demonstrate that the proposed method reduces the number of API call types by approximately 20% compared to representative deep learning–based API sequence detection methods, while achieving a peak accuracy of 98.70%. Additionally, experimental results indicate that sequence length at the 95th percentile represents the optimal solution that balances classification performance and computational efficiency.Keywords

With the escalating severity of network attacks, the number of malicious software has exhibited exponential growth. According to a report by AV-TEST [1], there are currently over 1.4 billion malicious software programs and potentially unwanted applications (PUAs) globally, a figure that continues to rise rapidly, posing a significant challenge in the realm of cybersecurity.

Traditional malware detection methodologies predominantly rely on signature matching and static analysis [2]. While these approaches are effective against known malware, they fall short in providing robust protection against novel or unknown malware variants. Contemporary malware not only employs traditional attack vectors but also emphasizes stealth and evasion techniques. Attackers utilize obfuscation, encryption, and anti-sandboxing strategies [3–5], rendering malware increasingly difficult for detection systems to identify. Consequently, behavior-based dynamic detection methods have emerged as a response to these evolving threats.

Behavior-based dynamic detection methods assess whether a program is malicious by observing its behavioral characteristics during runtime. For instance, malware often accesses or modifies sensitive files, sends a large number of network requests [6,7], or performs operations using privileged access. These behaviors are typically reflected in the invocation of interface, application programming (API) calls. Existing malware detection methods based on API call sequences usually model and classify these sequences as linear text sequences, treating each API as a “word” or “token,” and representing the entire calling process as a “sentence.” This approach leverages sequence modeling techniques from natural language processing for feature extraction and classification. Such methods can capture the sequential relationships and local dependencies between APIs to some extent, offering good expressive power and classification performance. However, they often overlook the structural features and behavioral logic inherent in subsequences of varying lengths, thus failing to fully reflect the overall behavioral patterns of malware. Furthermore, with increasing complexity in programs, the number of API types may sharply increase, leading to excessively long call sequences that result in sparse features, increased computational costs, and reduced modeling capabilities. Additionally, such methods generally struggle to effectively handle complex control flow characteristics like multidrop structures in system calls, loop execution paths, and concurrent behaviors. Consequently, their detection capability may be significantly limited when dealing with obfuscated samples that exhibit complex behavioral pathways or rely heavily on contextual semantics.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes a dynamic detection methodology based on subsequences of varying lengths within API call sequences. By mining critical subsequence features from the sequences, the method effectively determines whether a software sample is malicious. Specifically, the API call sequence serves as the original feature. Initially, it undergoes remapping encoding, with sequence lengths determined using percentiles. Subsequently, subsequence features of different lengths are extracted and fused to enhance the accuracy of malicious software detection.

The primary contributions of this paper are as follows.

• A dynamic malware detection model is proposed that represents software behavior using multiple key API subsequences of varying lengths, enabling multi-scale behavioral pattern learning beyond conventional single-sequence representations.

• An API remapping encoding algorithm based on API suffixes has been proposed, which reduces the variety of API calls and allows the model to focus on specific behaviors of APIs.

• The concept of percentiles from statistics has been introduced into the field of malicious software detection, enabling a quantitative analysis of the optimal length for sequences of API calls, thereby avoiding simplistic truncation operations aimed at unifying their lengths.

• To evaluate the effectiveness of the method presented in this paper, tests were conducted on various public datasets consisting of different sequences of API calls. Comparative experiments were performed using sequences with different percentile lengths, and ablation experiments were carried out to verify the effectiveness of the proposed API remapping encoding algorithm. Experimental results demonstrate that the method presented in this paper performs well across all utilized datasets, outperforming existing methods that use the same datasets.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 delves into the background of related work and prior research. Section 3 introduces the proposed method for malicious software detection. Section 4 presents the experimental setup, results, and comparative analysis. Section 5 discusses the limitations of the study and future research directions. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

In recent years, the field of malicious software detection has witnessed a series of studies that integrate API call sequence characteristics with deep learning techniques. These approaches typically employ deep neural networks to model dynamic behavior sequences, demonstrating significant superiority over traditional detection methods such as signature matching and static analysis in terms of feature extraction, behavior pattern recognition, and classification accuracy.

de Oliveira and Sassi [8] have proposed a malware detection approach based on Deep Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (DGCNNs) and introduced a dataset of 42,797 malware and 1079 benign software API call sequences (API-Call-Sequences). This approach converts API call sequences into malware behavior graphs, which are then input into a classifier for classification purposes. The study found that Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks outperform the DGCNN model in classifying imbalanced datasets. However, the method only utilizes the first 100 API calls from each sequence, failing to comprehensively analyze the calling patterns of the API call sequences and identifying 307 distinct API calls, which results in an excessive number of API call types being input into the model.

Agrawal et al. [9] proposed a classification method based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, which necessitates the additional input of system API call parameters. Kang et al. [10] introduced an LSTM classification mock-up that employs word2vec to vectorize and encode APIs. Catak et al. [11] developed a malware detection approach utilizing embedding layers and LSTM. These methodologies transform the classification problem of API call sequences into a text classification task, wherein forward analysis of API call sequences is conducted to leverage LSTM’s capability in capturing temporal relationships and sequential characteristics among APIs for classification purposes. However, such approaches solely focus on the forward invocation features of APIs, neglecting backward invocation characteristics that may encapsulate crucial backward control flow information, which is vital for identifying more sophisticated malicious behaviors. Secondly, these methods are primarily designed for short API call sequences; LSTM may encounter issues such as gradient vanishing or explosion when dealing with longer sequences, thereby affecting its processing capacity and accuracy. Consequently, these methods may be constrained by sequence length in practical applications, rendering them less effective in handling long sequences or complex malware behaviors.

Xiaofeng et al. [12] proposed a hybrid detection architecture named ASSCA, which employs a bidirectional residual LSTM network and random forest to process API sequences and their statistical features, respectively. Li et al. [13] proposed a malicious software detection framework based on Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Bi-LSTM, which captures and integrates intrinsic features of API sequences, including software behavior, API semantic information, and the relationships between APIs, to comprehensively assess the maliciousness of samples. However, to achieve such feature fusion, in addition to the original API call sequence, this method requires the introduction of “level” information indicating the degree of impact each API has on the computer system, serving to assist the model in decollating the importance of different APIs. This level information often relies on manual annotation or prior evaluation based on domain knowledge, resulting in additional computational and annotation overheads in practical applications, thereby reducing the purpose and general applicability and scalability of the method. Iqbal et al. [14] proposed a two-stage ransomware detection framework based on signatures and API calls, significantly reducing the dimensionality of API features through feature selection, thereby validating the feasibility of low-dimensional features in maintaining detection accuracy.

The aforementioned methodology employs API call sequences as dynamic features, utilizing embedding techniques to transform APIs into numerical vectors, followed by detection and classification through deep learning methods. However, the application of this approach is constrained by the number of API call types and the length of sequences, and some methods necessitate additional analysis of APIs, thereby diminishing the general applicability of the model. To address these issues, this paper proposes a detection method that relies solely on the original API call sequences, employs remapping encoding and percentile lengths to reduce the number of API call types and sequence lengths, and combines 1D-CNN and Bi-LSTM to extract features from subsequences of varying lengths.

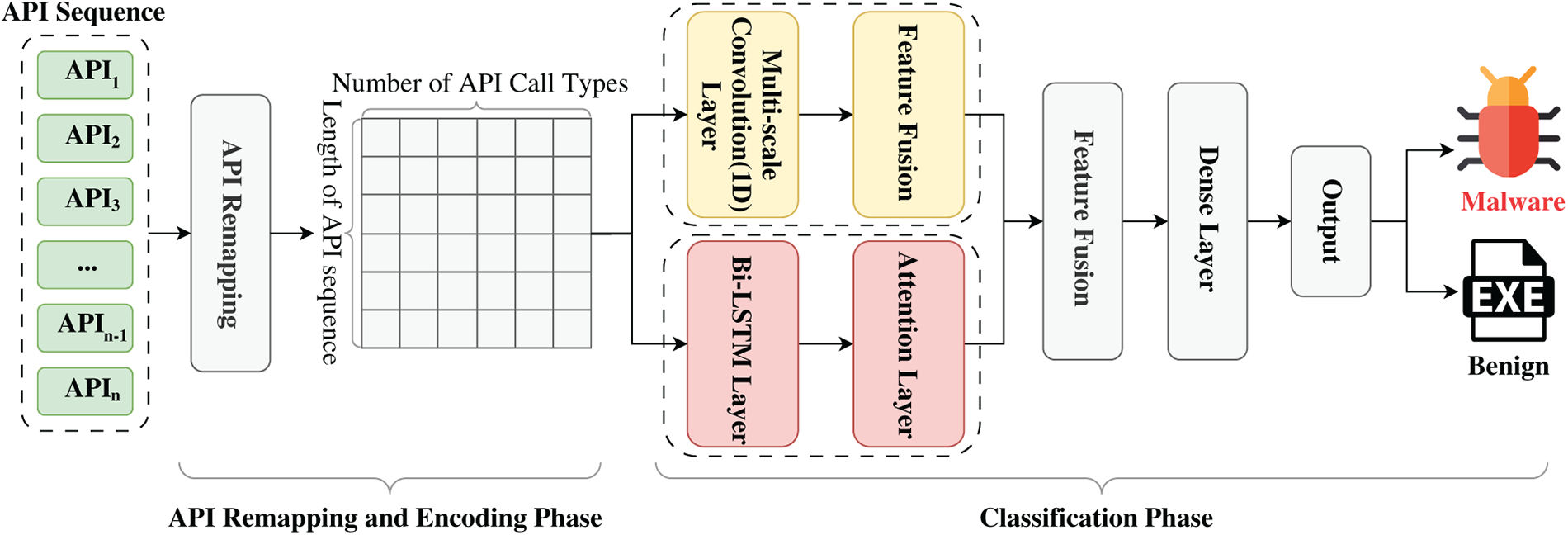

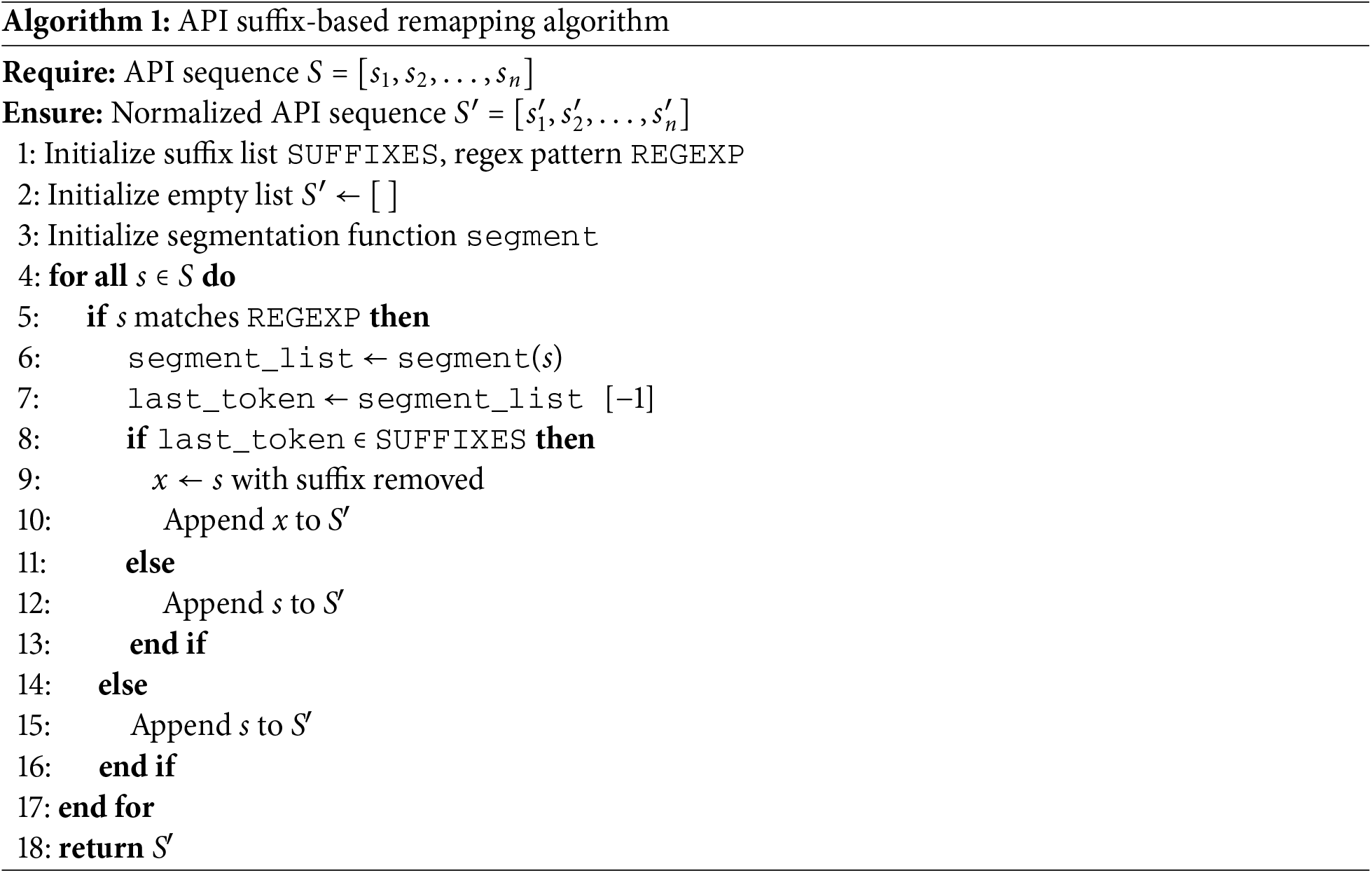

The proposed method in this paper consists of two primary stages: the API remapping and encoding phase and the classification phase. During the API remapping and encoding phase, APIs are initially subjected to remapping and encoding representation, ensuring uniform encoding and truncation for APIs with different character encodings and varying sequence lengths. In the classification phase, the standardized input is separately fed into a 1D-CNN and a Bi-LSTM network to extract and integrate features from subsequences of varying lengths. The final output is then passed through a fully connected layer to yield the classification results, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Overall framework

3.1 API Remapping and Encoding Phase

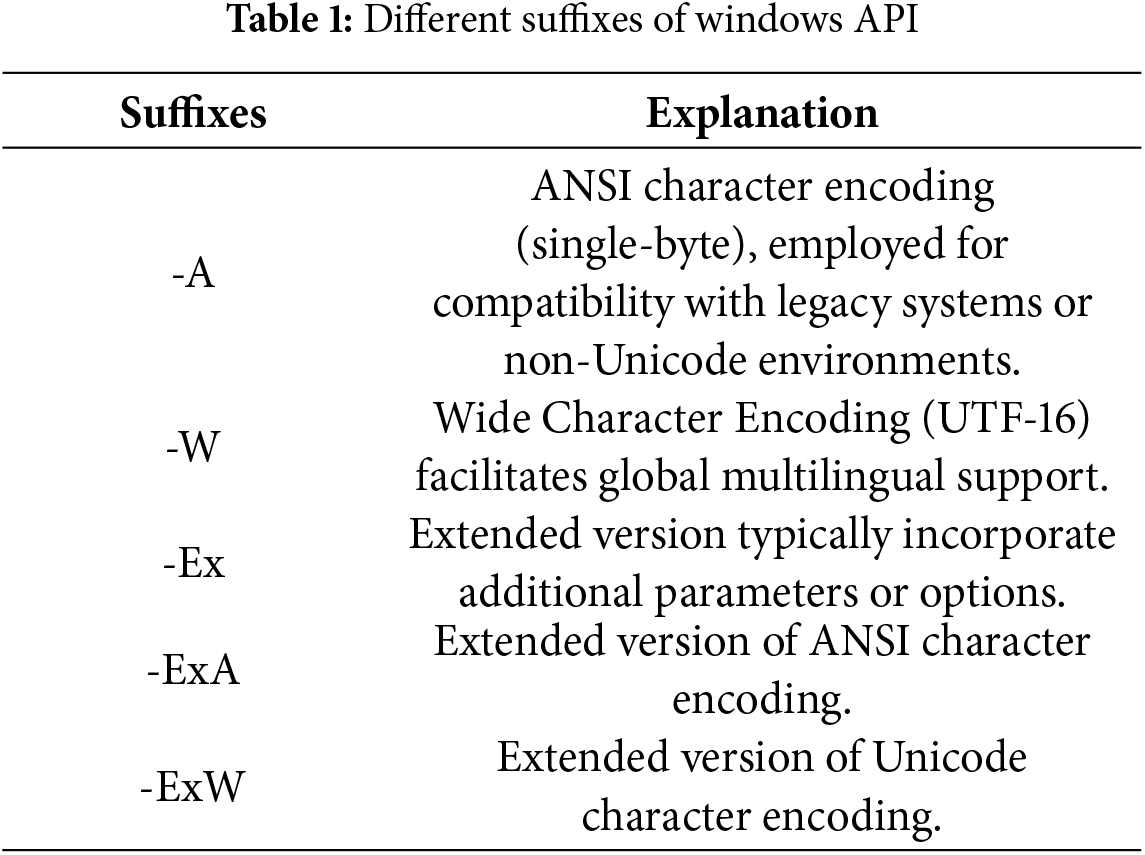

In the Windows API, due to the variance in character set encoding methods, the preprocessor appends suffixes such as “A”, “W”, “Ex”, “ExA”, and “ExW” to the end of the general prototype during API invocation, based on the specific encoding type, to denote different versions (see Table 1). However, during behavioral analysis of API sequences, these suffixes cause APIs with identical functionalities to be treated as distinct features, resulting in varying API sequences for the same behavior across different environments, thereby diminishing the model’s generalization capability. To enable the model to focus on the core functionality of APIs, this paper maps APIs of different encoding methods to their general prototypes, thereby eliminating the influence of API suffixes, as illustrated in Fig. 2:

Figure 2: The mapping rules of the API

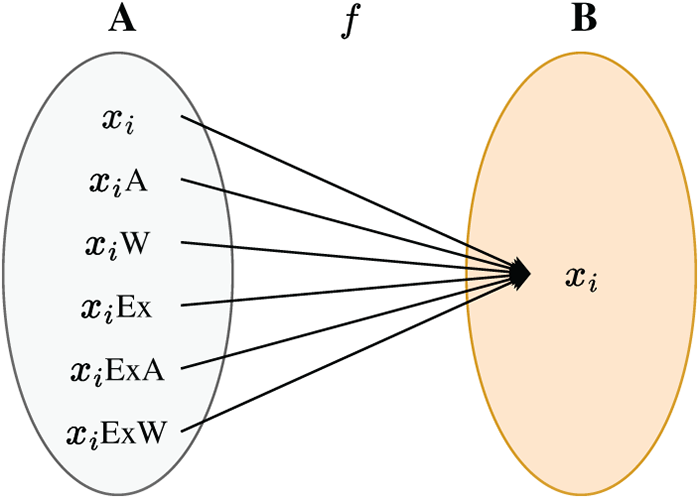

Based on the mapping rules defined above, this paper designs an API remapping algorithm. Algorithm 1 outlines the specific processing procedure: initially, each API is evaluated to determine if it contains a valid suffix identifier through regular expression matching. Upon successful matching, the WordSegment tokenization tool is employed to segment the API, followed by a verification of whether the final word belongs to a predefined suffix set. If the final word is identified as a member of this set, it is regarded as an appended suffix and subsequently removed, retaining only the prototype name of the API. Conversely, if the final word does not belong to the set, the original API is preserved without alteration. Ultimately, the algorithm yields an API call sequence that has undergone remapping, serving as a standardized input for subsequent feature extraction.

The API call sequence, post-remapping, is represented using the one-hot encoding method. Specifically, one-hot encoding transforms each distinct API into a sparse vector, where only one dimension is set to 1, with all other dimensions being 0. This encoding approach underscores the semantic independence among various APIs, introducing no implicit prior relationships and thus preventing potential interference caused by numerically similar vector values.

Moreover, one-hot encoding boasts the advantages of simplicity in implementation and the absence of reliance on external prior knowledge, providing a clear and unambiguous input representation for subsequent classification stages. Although this encoding method may result in a higher dimensionality, the API remapping in this approach has significantly reduced the variety of API calls, effectively mitigating the issue of excessive dimensionality.

The classification phase employs a 1D-CNN and a Bi-LSTM network for feature extraction. The 1D-CNN, by nature, excels in processing sequential data, adept at capturing local continuous patterns, thereby effectively extracting short-range dependency features from sequences. API call sequences, as direct representations of program dynamic behavior, often contain several key operational segments that reveal specific functional intents. These segments are typically composed of a series of consecutive APIs, forming semantically related subsequences. For instance,

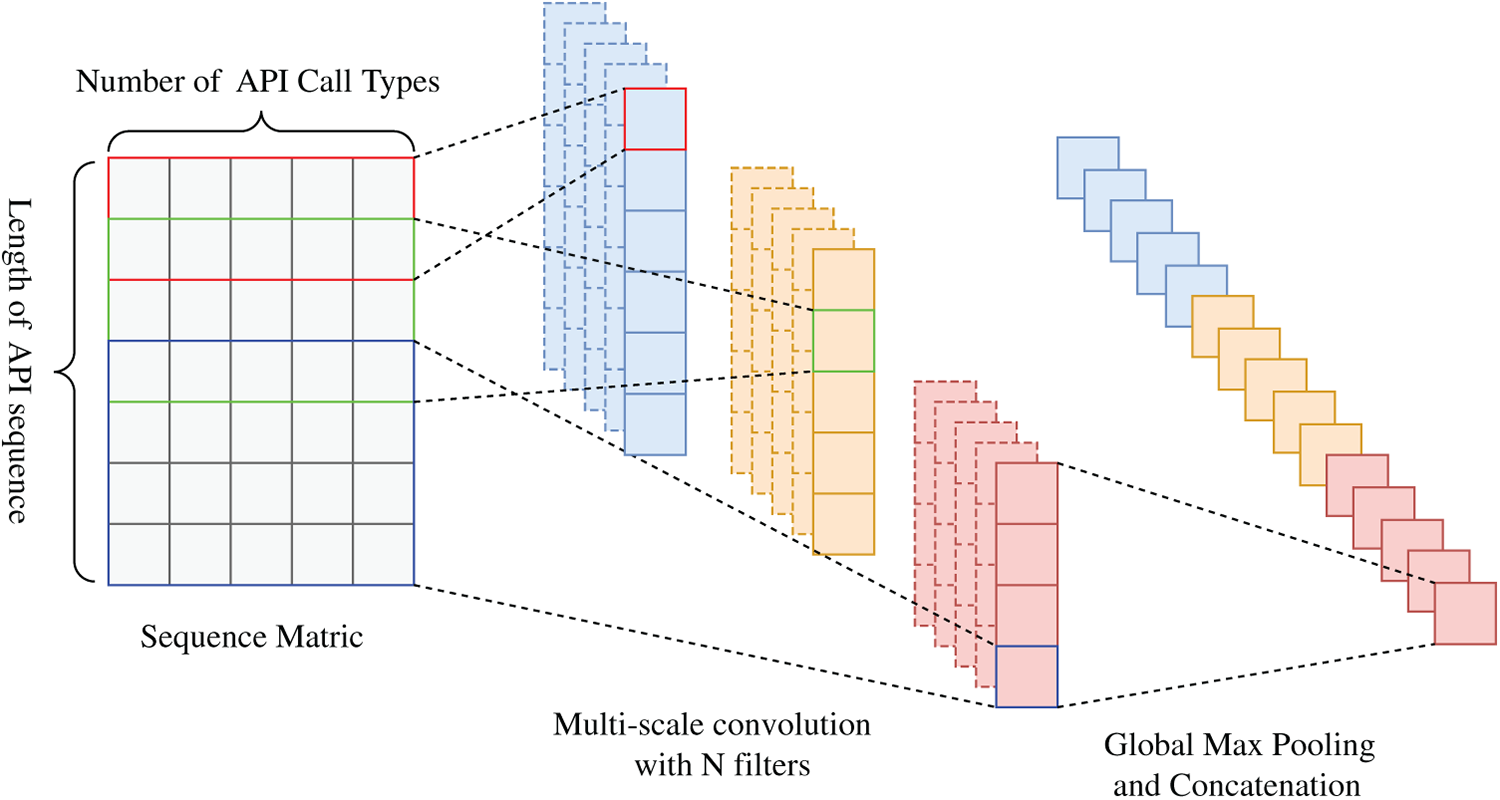

To extract key subsequences from the API sequence, a sliding window of size

Due to variations in the sliding window size, an API sequence yields

To reduce computational load and enhance computational efficiency, the most commonly encountered subsequence lengths of 2, 3, and 4 were selected as sliding window sizes to extract subsequence features of corresponding lengths, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: 1D-CNN network architecture with convolutional kernel sizes of 2, 3, and 4

Upon completion of the extraction of subsequence features of varying lengths, a Global Max Pooling operation was applied to each category of subsequence features. This operation effectively compresses the feature dimension, reducing redundant information while preserving the most representative features of each type of subsequence. By focusing on the most activated features within the subsequences, Global Max Pooling enhances the model’s perception of key behavioral patterns, aiding in the prominence of discriminative local features within malicious behaviors. Consequently, this approach further elevates the overall classification performance and detection accuracy.

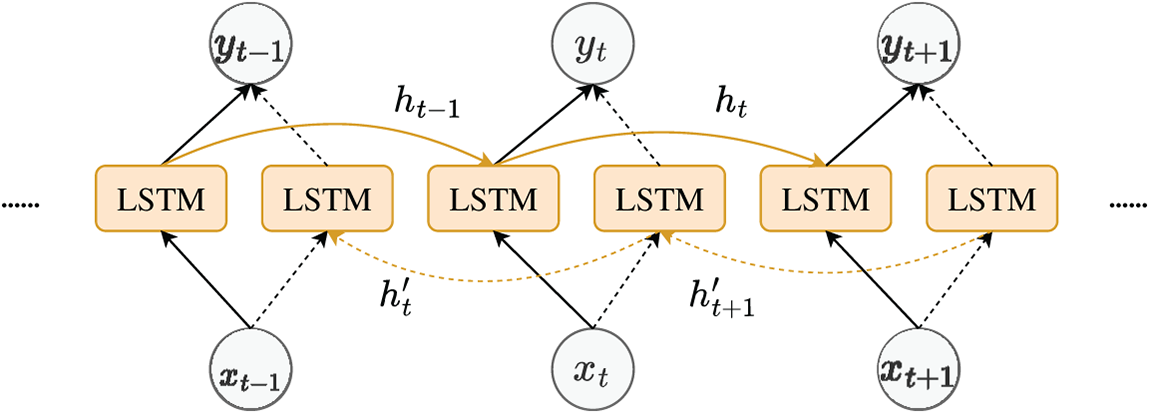

In an API sequence, a single API constitutes a subsequence of length 1. A unidirection LSTM can only utilize past API call information, whereas a Bi-LSTM processes the sequence simultaneously from both forward and backward directions, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of the dependencies among APIs, which facilitates more precise classification of API sequences. Fig. 4 illustrates the architecture of a Bi-LSTM unfolded along the time steps, where

Figure 4: Bi-LSTM network architecture

Bi-LSTM is constructed based on LSTM units, addressing the unidirection limitation by combining two independent LSTM layers, where the forward and backward LSTM layers do not share parameters and are trained independently. The API sequences encoded via one-hot encoding are input into the Bi-LSTM module, and its forward propagation, backward propagation, and final output can be calculated using Eqs. (2)–(4).

To identify critical APIs within the sequence, an attention mechanism was incorporated into the Bi-LSTM network. The specific computational procedure can be delineated into the following three steps:

1) Employing the dot product of vectors as the attention value score, as expressed in Eq. (5), where

2) Normalizing the attention value scores using the Softmax function, as illustrated in Eqs. (6) and (7), where

3) Summing the weighted fleshless vectors to obtain the attention vector, as shown in Eq. (8), where

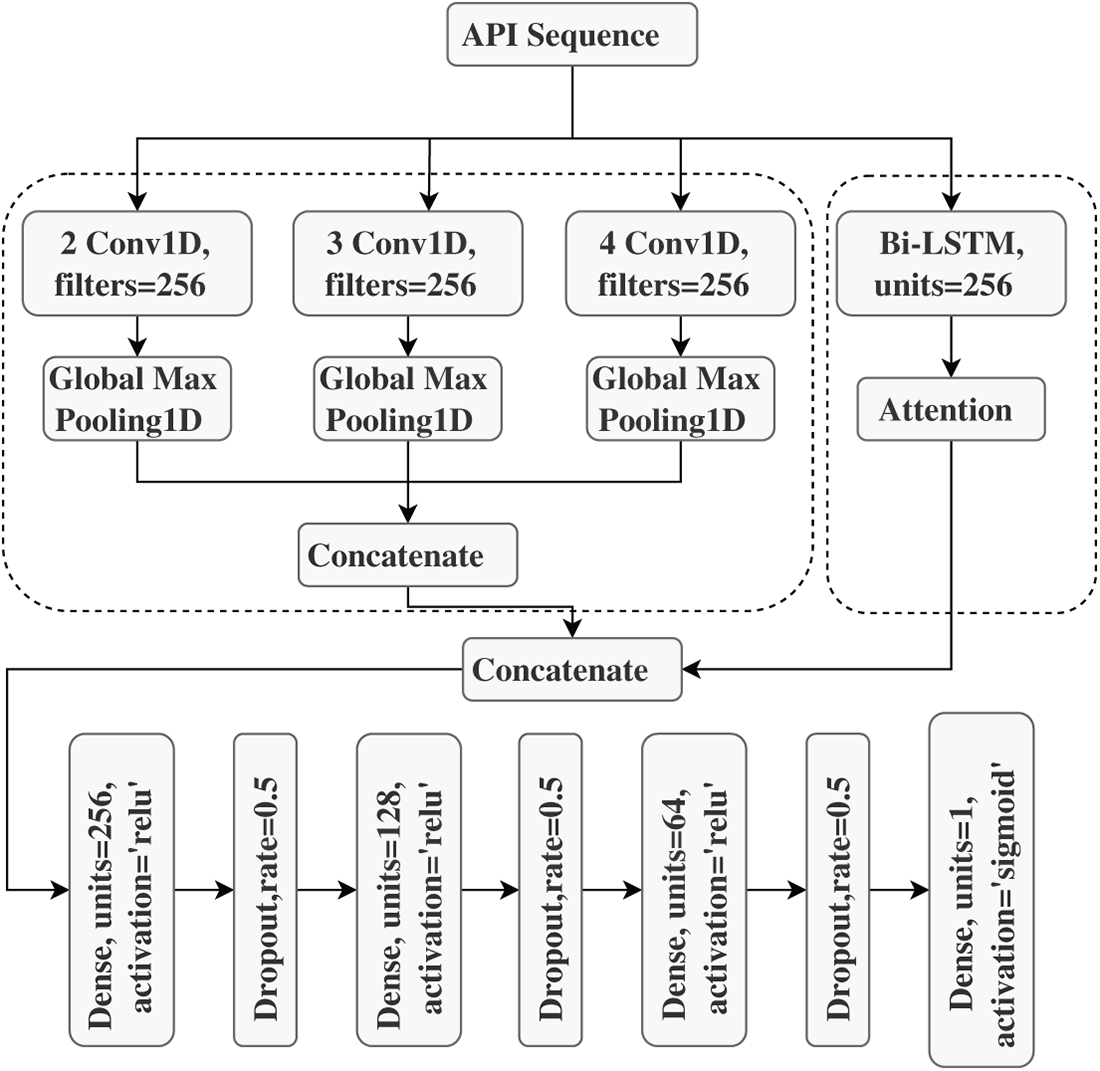

The fused features extracted by the 1D-CNN and Bi-LSTM network are input into a neural network composed of a fully connected layer, Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, Dropout layer, and an output layer employing the Sigmoid activation function for final classification. The fully connected layer receives the fused feature vector

After computation through the fully connected layer, the output layer calculates the positive example classification result probability

Additionally, the model employs binary cross-entropy as the loss function, utilizing the Adam optimizer to refine the parameters of the network and updating the weight matrices through backpropagation.

3.3 Model Structure and Hyperparameter Setting

Fig. 5 illustrates the specific structure of the model in this paper and the hyperparameter combinations, which were determined through grid search. For further details, please refer to Section 4.3.

Figure 5: Specific structure of the model and hyperparameter configuration

This section elaborates on the dataset and hyperparameter selections employed in the experiments, introduces the evaluation metrics utilized during the assessment, analyzes the experimental results, and concludes with comparative experiments, ablation studies, and an exploration of sequence lengths.

4.1 Experimental Setup and Tools

The proposed model was implemented and tested on a computer running Windows 11 Professional (64-bit), equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12600KF processor (3.70 GHz), 32 GB of memory, an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 Ti graphics card (16 GB VRAM), and a 2TB hard disk. The model was developed using Python 3.10.15, leveraging the TensorFlow 2.10.0 and Keras 2.10.0 frameworks. Additionally, it relied on libraries such as Scikit-learn, NumPy, Pandas, Matplotlib, Seaborn, and WordSegment. These libraries are open-source software, freely available via the Python Package Index (PyPI) platform.

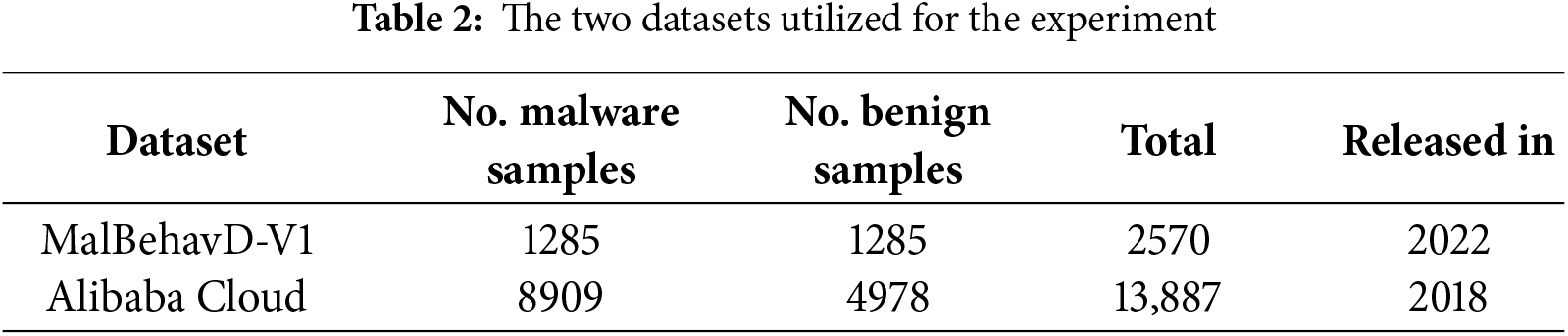

To validate the efficacy of the proposed method, this study employs two widely recognized publicly available API sequence datasets—MalBehavD-V1 [15] and Alibaba Cloud [16]—for model training and evaluation. Table 2 enumerates the datasets utilized.

MalBehvaD-V1 represents a novel dynamic dataset, constructed through the application of dynamic malware analysis methodologies, specifically designed to extract API call sequences from both benign and malicious executable files (EXE files) within Windows operating systems. Each sample undergoes independent execution within an isolated environment powered by the Cuckoo sandbox, ensuring precise behavioral logging. The malicious samples are sourced from VirusTotal, while the benign samples are collected from the CNET website. The dataset encompasses a total of 2570 executable files, comprising 1285 benign samples and 1285 malicious samples.

Alibaba Cloud is a large-scale behavioral dataset released by Alibaba Cloud for dynamic malware analysis and detection research, comprising approximately 90 million API call records. This dataset was collected by executing Windows executable files sourced from the internet within an analog sandbox environment, capturing the API call sequences triggered during sample execution. All samples have undergone desensitization processing. The dataset contains a total of 13,887 executable files, including 4978 benign samples and 8909 malicious samples.

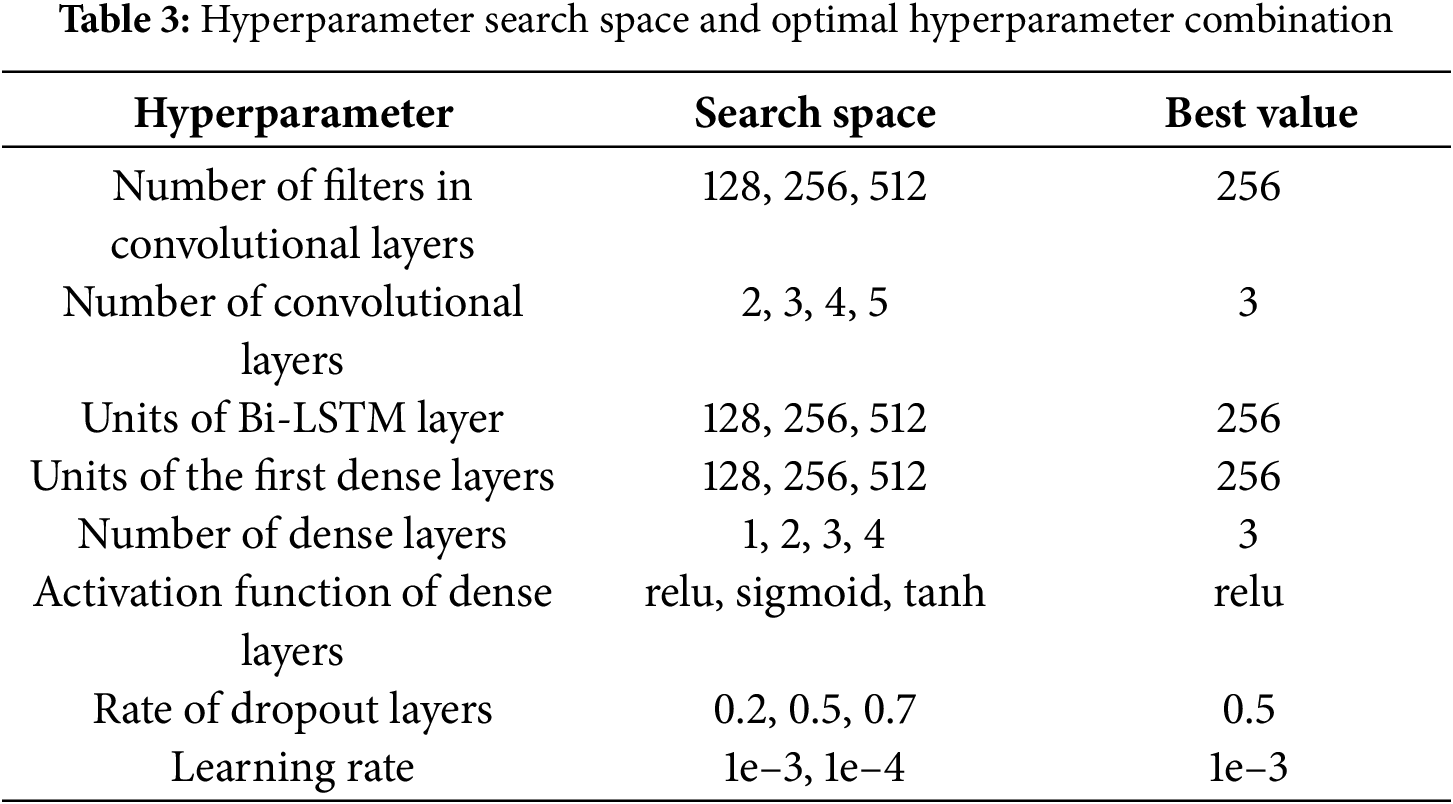

Table 3 presents the hyperparameter search space and its corresponding optimal configuration. A grid search strategy was employed to comprehensively explore all candidate combinations. Specifically, the training set was divided into three subsets, with evaluation conducted through cross-validation, where each subset was individually used for validation while the remaining subsets were used for training. For each hyperparameter configuration, the average validation accuracy across all subsets was calculated as the primary evaluation metric.

The final hyperparameter settings were selected based on the configuration achieving the highest average validation accuracy, while also considering training stability and computational efficiency. Notably, although adopting larger hyperparameters (such as more convolutional filters or larger bidirectional LSTM units) may yield minor performance improvements, it significantly increases computational and memory overhead. Conversely, excessively small configurations are prone to convergence instability or degraded detection performance.

To evaluate the performance of the model, this paper adopts Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 score as evaluation metrics, with their calculation processes detailed in Eqs. (13)–(16).

These evaluation metrics are calculated based on the following variables: True Positive (TP): samples that are predicted as positive by the model and are indeed positive; False Positive (FP): samples that are predicted as positive by the model but are actually negative; False Negative (FN): samples that are predicted as negative by the model but are indeed positive; True Negative (TN): samples that are predicted as negative by the model and are indeed negative. Herein, positive refers to malicious samples, while negative refers to benign samples.

In addition, this paper also employs the Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) as an evaluation metric. The calculation process is shown in Eq. (17).

4.5 Analysis of Experimental Results

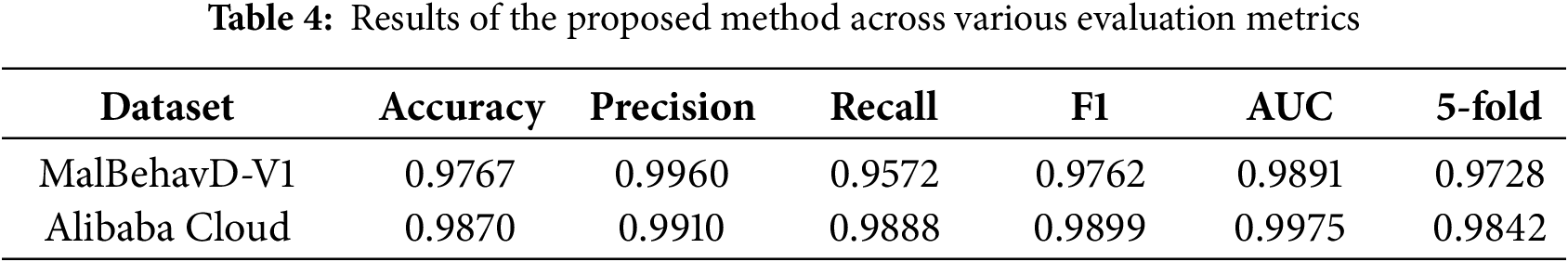

In each dataset, stratified sampling with an 8:2 ratio was employed to partition the training and test sets, followed by further 5-fold cross-validation. Subsequently, the performance of the proposed method was evaluated on the test set based on the evaluation metrics defined in the previous section. Table 4 presents the experimental results of the proposed method across different datasets.

On the MalBehavD-V1 dataset, the proposed method achieved outstanding detection performance, with a precision reaching 99.60%, indicating an extremely low false positive rate. The recall rate of 95.72% demonstrates that the model-extracted API subsequence features effectively encompass the malicious behavior patterns of the samples. Compared to the MalBehavD-V1 dataset, the model’s recall rate on the Alibaba Cloud dataset increased by 3.16 deci-percentage points, and the AUC improved by 0.0084, indicating that in a larger-scale and more diverse sample environment, the proposed method maintains the advantages of high detection and low false negatives, accurately identifying malicious samples.

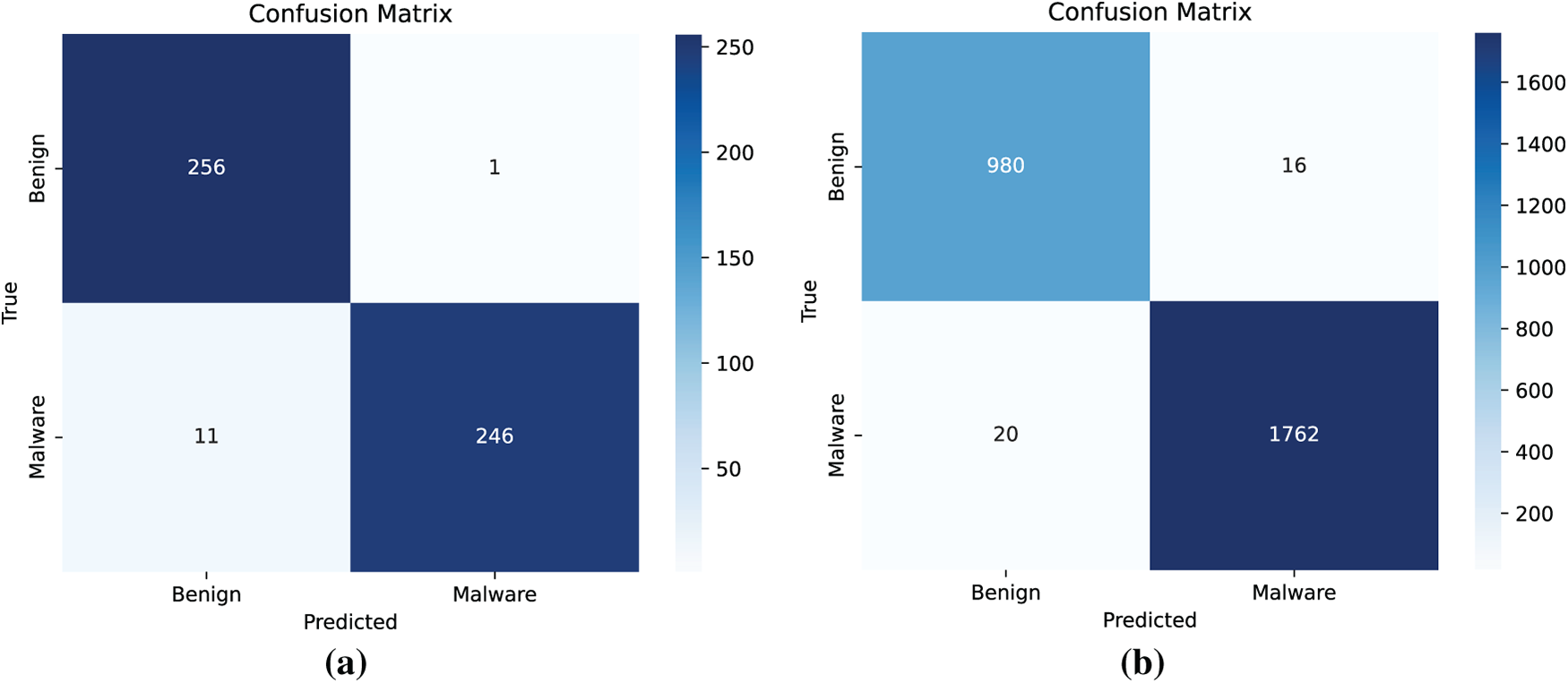

From a cross-dataset comparative perspective, the proposed method achieves an accuracy exceeding 97% on both datasets, with AUC values approaching or surpassing 0.99, indicating robust classification capability and generalization performance. Regarding the trade-off between false positives and false negatives, the method exhibits an almost error-free false positive rate on the MalBehavD-V1 dataset; on the Alibaba Cloud dataset, although the precision slightly decreases, the recall is further enhanced, demonstrating that the model attains a lower false negative rate at an acceptable level of false positives. Furthermore, cross-validation results indicate that the model maintains stable performance even in the presence of distributional differences. Fig. 6 illustrates the confusion matrices of the proposed method across different datasets.

Figure 6: Confusion matrices of the proposed method across different datasets. (a) MalBehavD-V1 Dataset; (b) Alibaba cloud Dataset

In summary, the proposed method not only demonstrates outstanding performance on the small-scale MalBehavD-V1 dataset but also achieves higher recall and AUC on the more challenging Alibaba Cloud dataset, thereby exhibiting an equilibrant advantage in accuracy, robustness, and generalization capability.

4.6 Comparison with Different Deep Learning Models

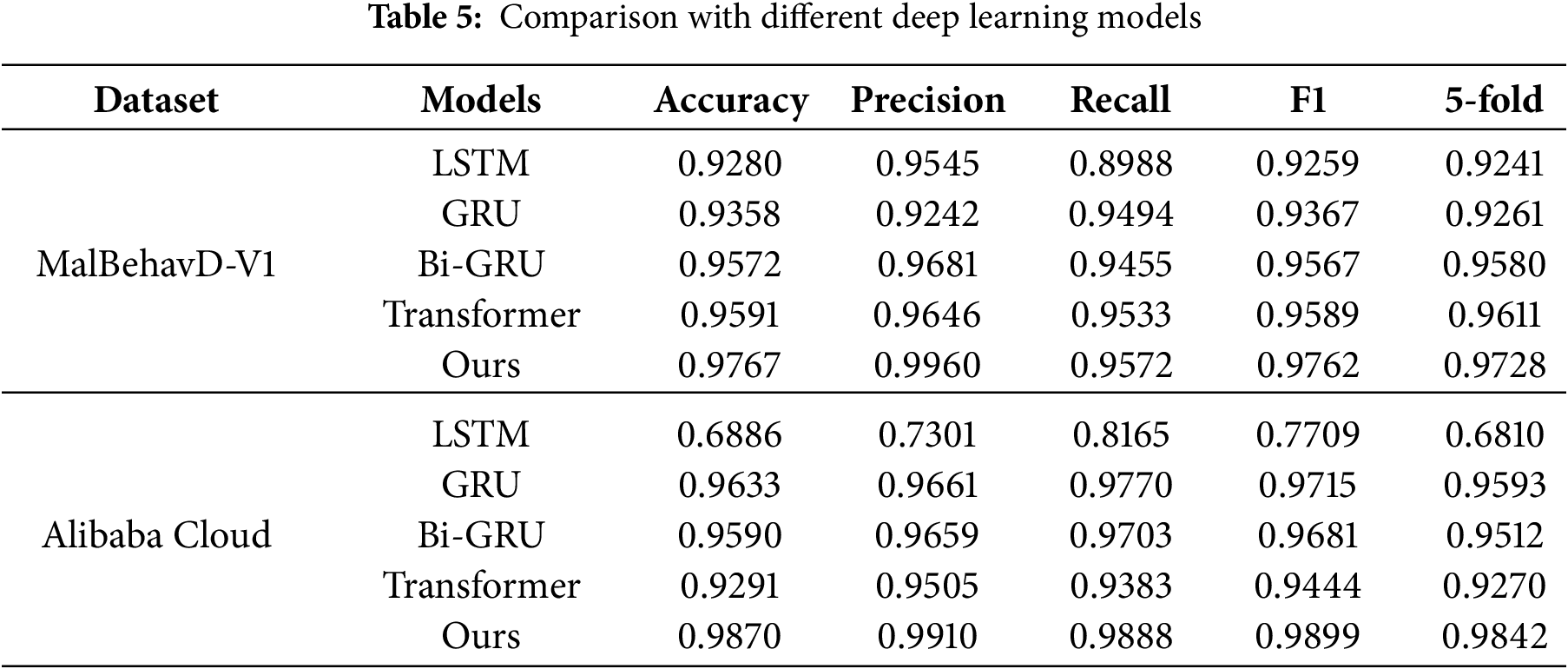

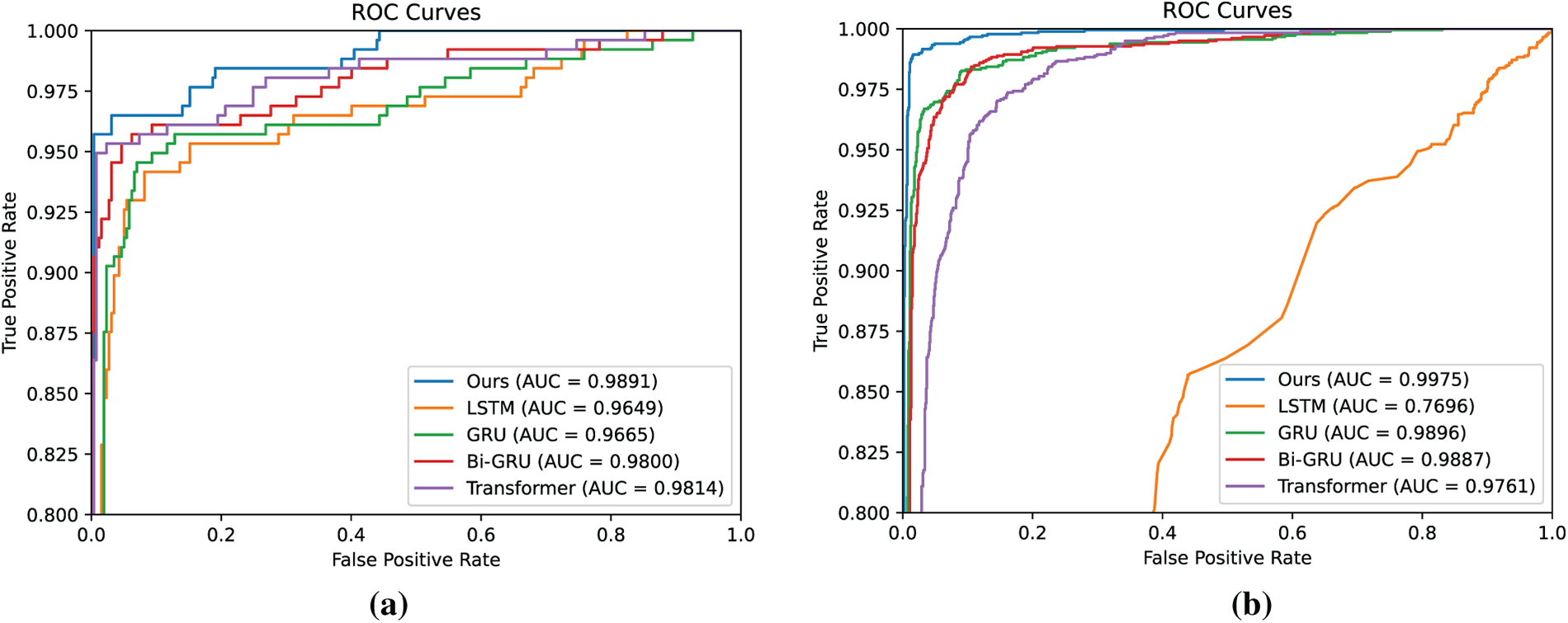

In Table 5, the proposed method is compared with various mainstream deep learning models on two publicly available datasets, MalBehavD-V1 and Alibaba Cloud, in terms of performance. On the MalBehavD-V1 dataset, the proposed method achieves an accuracy of 97.67%, representing an improvement of approximately 1.76% over the best-performing comparative method, Transformer. On the Alibaba Cloud dataset, the proposed method similarly attains the highest detection performance, with an accuracy of 98.70%, surpassing the best-performing comparative model, Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), by approximately 2.37%, and achieving an AUC of 0.9975 (see Fig. 7), approaching near-perfect classification. Experimental results indicate that single-sequence modeling approaches exhibit deficiencies in modeling long sequences and capturing contextual correlations, resulting in performance limitations in high-dimensional, long-dependency API call scenarios. In contrast, the proposed method demonstrates superior generalization capability across different data distributions and scales.

Figure 7: Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of various deep learning models across different datasets. (a) MalBehavD-V1; (b) Alibaba cloud

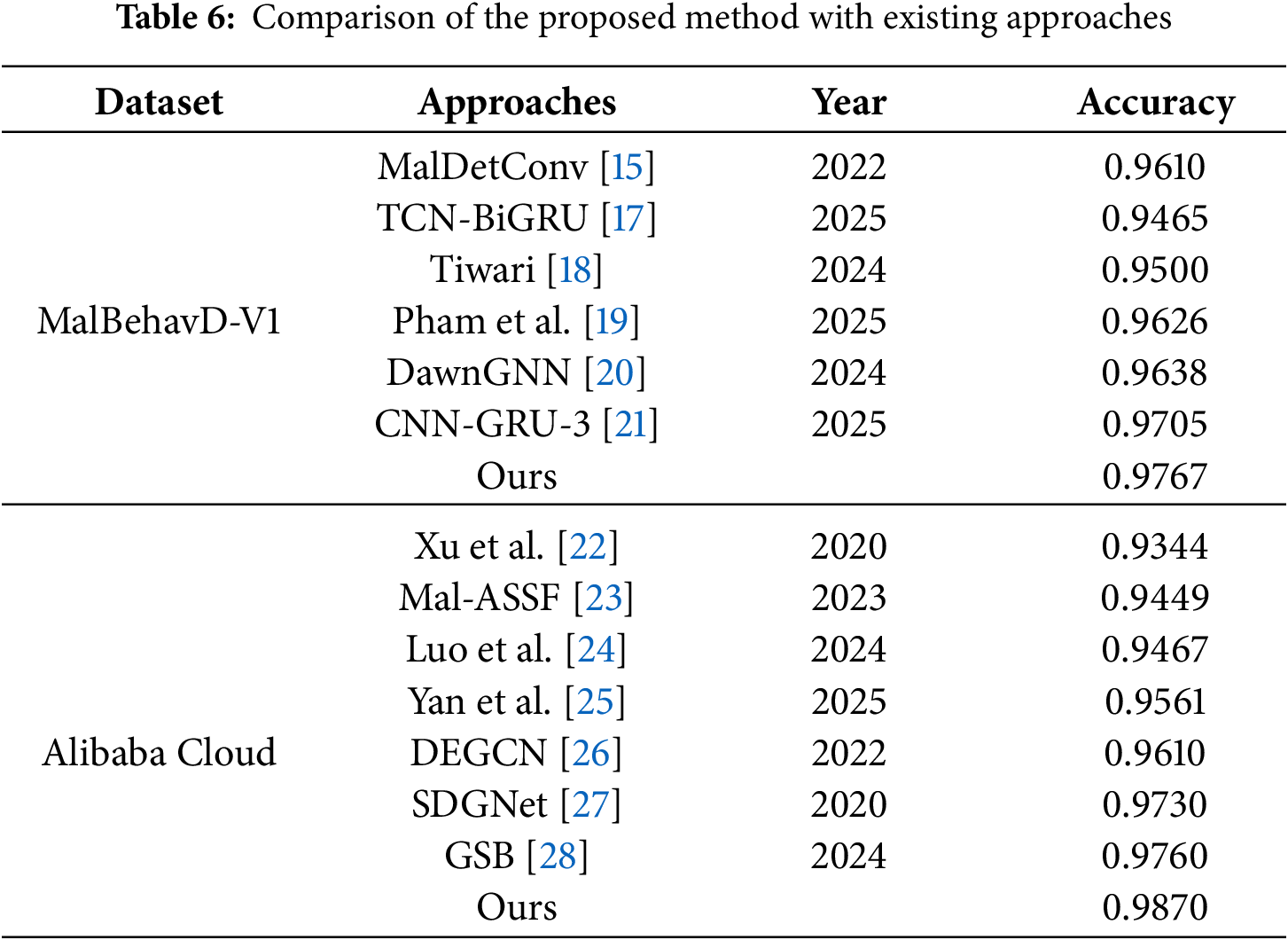

4.7 Comparison with Existing Methods

In addition to the baseline model, this paper conducts further comparisons with recent studies on malware behavior analysis based on the same dataset (see Table 6), which include models based on CNN and Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), as well as those based on graph neural networks and Transformers. Despite differences in preprocessing strategies and feature representations, the proposed method demonstrates strong generalization capability across two datasets and various malware behavior patterns. Its consistently superior performance across different datasets and models highlights its potential for practical deployment in large-scale malware detection systems.

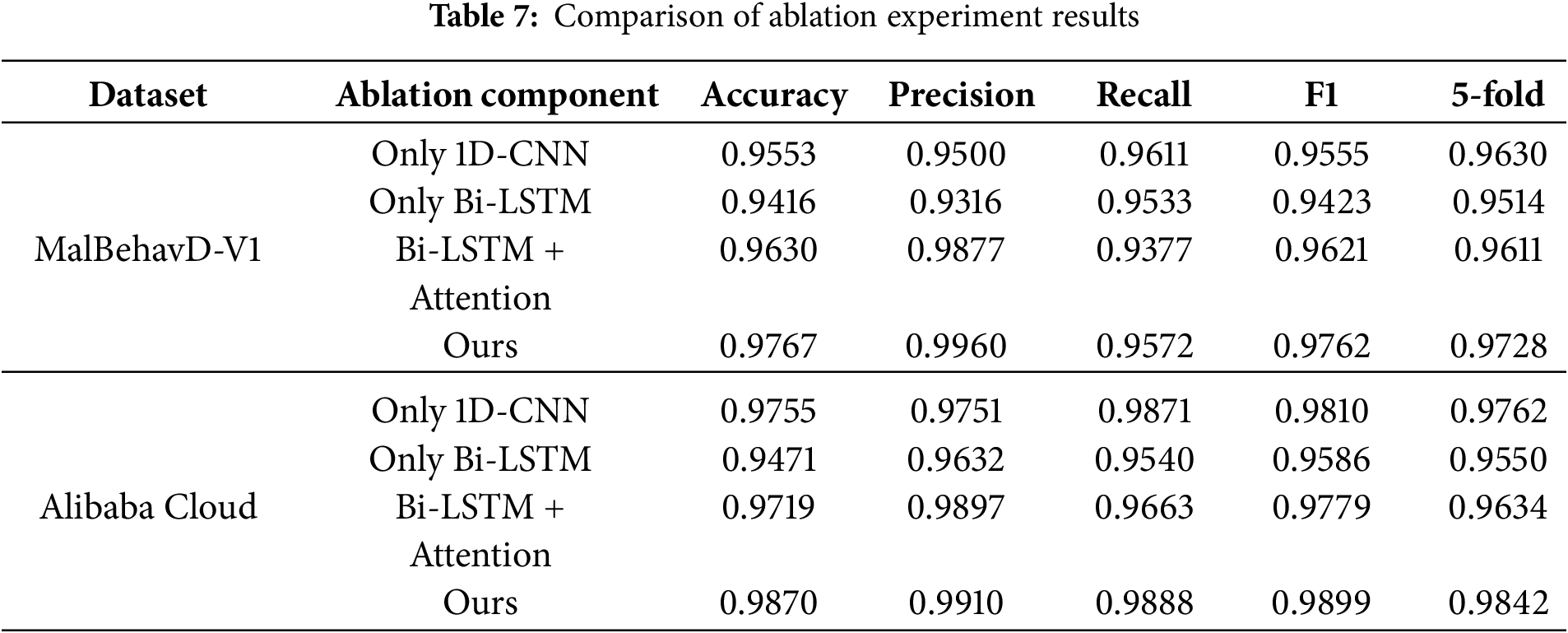

This subsection conducts ablation experiments on the fusion model, thereby validating the effectiveness of the encoding method and each component of the model individually.

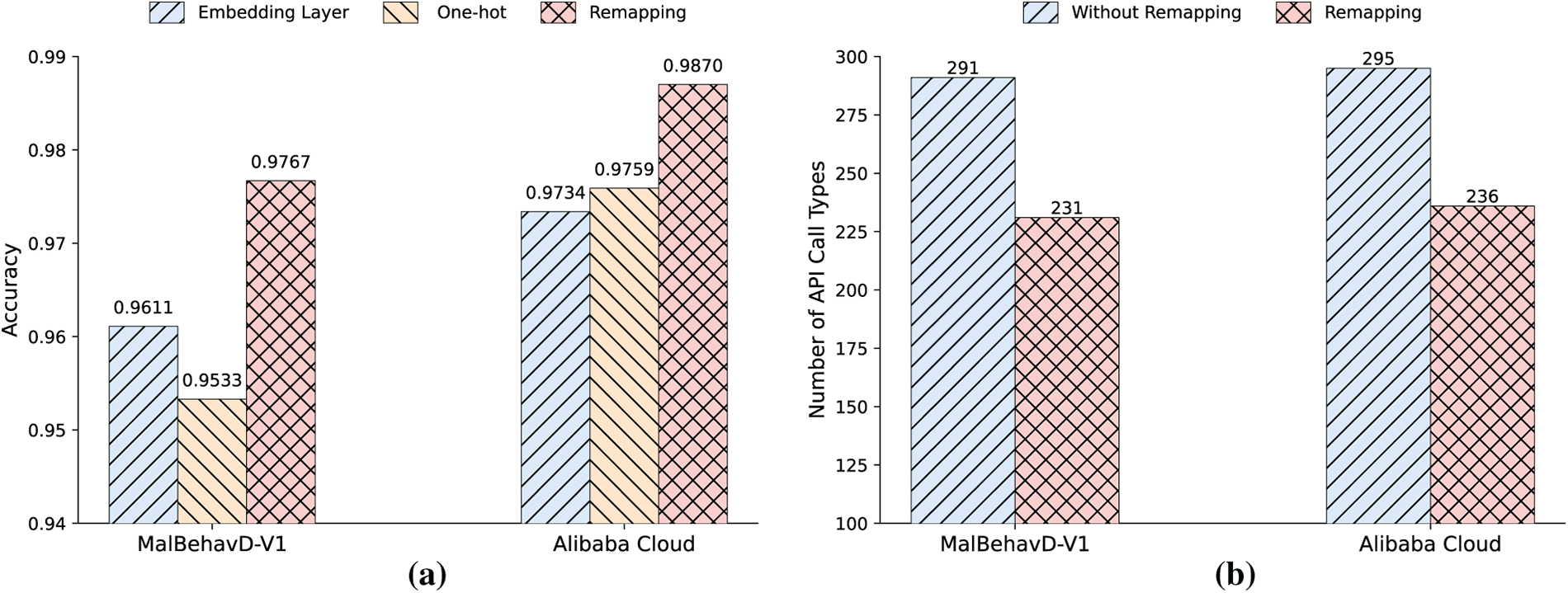

Fig. 8 illustrates the impact of various encoding methods on detection performance and the number of API call types across different datasets. The results indicate that the proposed remapping encoding method significantly outperforms traditional Embedding Layer and One-hot encoding methods on both datasets (see Fig. 8a). Additionally, in terms of the number of API call types, the remapping encoding effectively compresses the dimensionality of the feature space, reducing the feature dimension by approximately 20%. This suggests the presence of redundant APIs in the API call sequences that interfere with detection effectiveness (see Fig. 8b). The experimental results demonstrate that semantic feature reconstruction during the encoding stage can significantly enhance the performance of malware detection based on API call sequences.

Figure 8: Comparison of the effects of different encoding methods on detection performance and the number of API call types across various datasets. (a) Accuracy; (b) Number of API call types

Table 7 presents the ablation experiment results of the proposed method on the MalBehavD-V1 and Alibaba Cloud datasets. On both datasets, the standalone use of 1D-CNN demonstrates relatively superior performance, indicating that 1D-CNN possesses significant advantages in extracting local behavioral patterns and capturing short-range dependencies. However, its recall rate is slightly lower than that of the proposed model, implying that reliance solely on local features is insufficient to encompass all malicious patterns. The Bi-LSTM exhibits inferior performance compared to 1D-CNN on both datasets, suggesting that bidirectional sequential models are prone to overfitting or gradient vanishing when handling high-dimensional long sequences. Nonetheless, Bi-LSTM achieves a relatively higher recall rate, indicating its complementary value in capturing long-range dependencies and global temporal information. The incorporation of the Attention mechanism markedly enhances performance, demonstrating its efficacy in mitigating redundancy in long-sequence information. Overall, the proposed method significantly outperforms single or partial combination models across both datasets, achieving the best results in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, thereby substantiating the effectiveness and necessity of a multi-module fusion design in malicious behavior detection.

4.9 Different Lengths of API Call Sequences

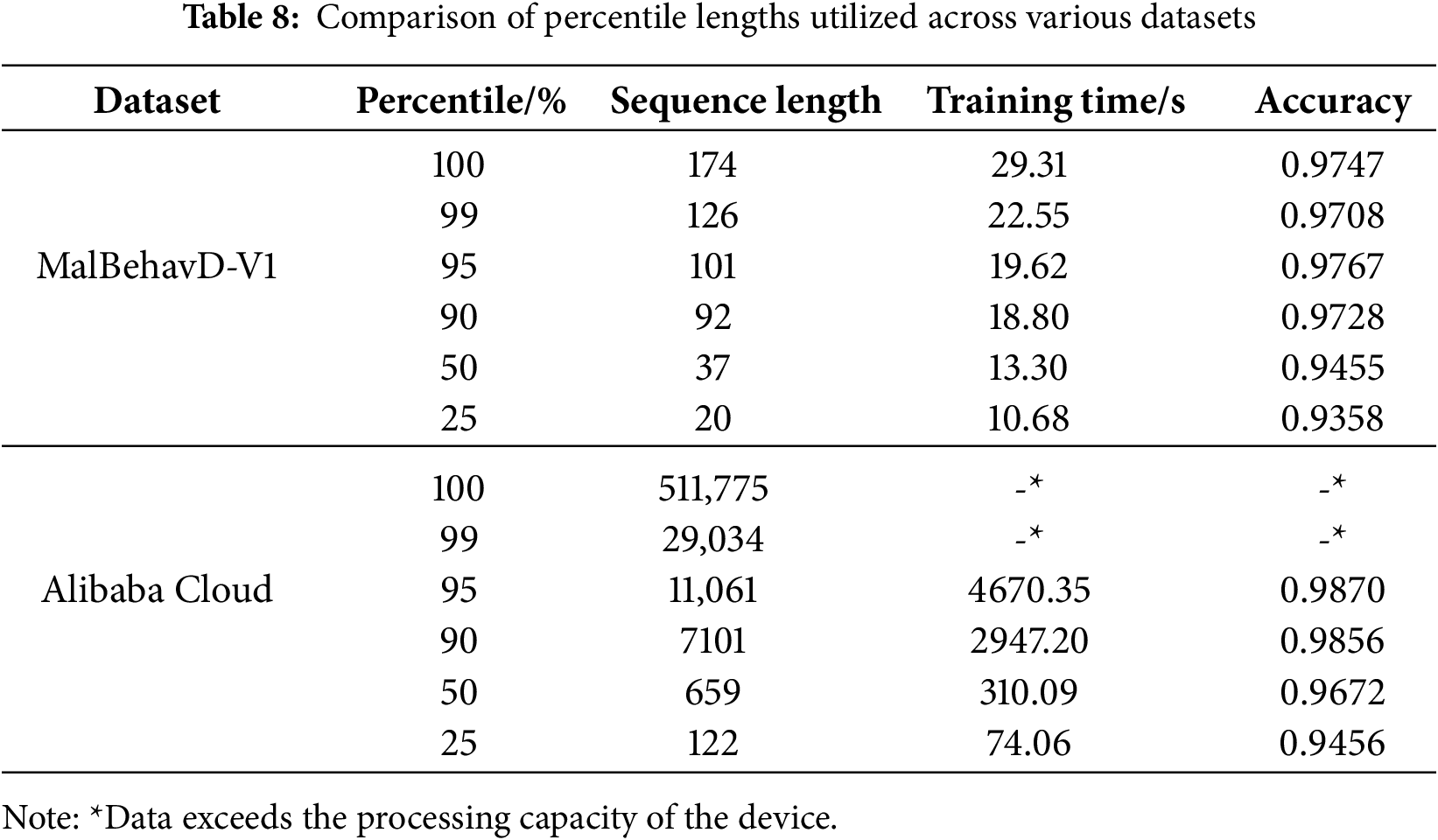

This paper introduces the percentile length to investigate the impact of varying sequence lengths on the performance of detection models. A percentile is a statistical concept used to indicate the position of a specific value within a dataset, where the p-th percentile denotes that p% of the data are less than or equal to that value. For API call sequences, due to the extreme imbalance in sequence lengths across samples, simple truncation fails to achieve the optimal performance of the detection model. In contrast, percentile length not only characterizes the distribution of API call sequence lengths among samples but also mitigates the interference of outliers on the model. Consequently, this paper selects commonly used percentile values (25%, 50%, 90%, 95%, 99%, 100%) as the criteria for API call sequence lengths to test the performance effects of each sequence length percentile.

Table 8 presents a comparative analysis of performance across different datasets using varying percentile lengths. It is evident that in the MalBehavD-V1 dataset, where sequences are relatively short and uniformly distributed, employing a lower percentile length still maintains high precision. Conversely, in the Alibaba Cloud dataset, the sequence length distribution is extremely imbalanced with a substantial number of long-tail sequences, rendering the processing of complete sequences challenging. When truncation lengths below the 90th percentile are applied, a significant decline in model accuracy is observed, indicating that excessive truncation results in substantial loss of behavioral features. Overall, across different datasets, the 95th percentile length represents an optimal trade-off between performance and computational efficiency; hence, this truncation length is consistently adopted in the experiments of this study.

Although the proposed method demonstrates excellent detection performance, it may still encounter multiple challenges during practical realtime deployment, such as computational overhead, sandbox evasion behaviors, and data distribution discrepancies. The following sections present a systematic analysis and discussion of these challenges.

In practical deployment, in addition to detection performance, computational complexity and realtime performance must also be fully considered. The overall time complexity of the proposed method is approximately

This paper primarily conducts malware detection research based on API call sequences within the Windows system, extracting behavioral features through the dynamic execution of malicious samples in sandbox environments. However, with the continuous advancement of anti-sandbox techniques, certain malicious programs can identify sandbox environments and adopt countermeasures to evade dynamic analysis. Future research may explore hybrid analysis strategies that integrate static and dynamic features, as well as model cross-platform adaptability.

5.3 Data Distribution Discrepancies

The MalBehavD-V1 and Alibaba Cloud datasets cover a limited range of malware sample types, which may differ from the diverse attack behaviors encountered in real-world environments. Future work could employ incremental learning or adversarial training mechanisms to enable the model to continuously learn new types of malware samples while maintaining detection capabilities for existing samples. Moreover, although the Alibaba Cloud dataset exhibits a certain degree of imbalance, in practical applications, malware data often exhibit significant class imbalance and dynamic variability. Distributional differences across data collected at different times or from various sources may cause fluctuations in model performance. Future research could explore transfer learning and adaptive learning strategies to enhance the model’s robustness under distributional drift conditions.

This paper proposes a dynamic malware detection method based on API multi-subsequence, aiming to streamline API call sequences and extract key behavioral features from these sequences. Initially, the original API call sequences undergo remapping encoding, transforming each API into a numerical representation with semantic discriminative capabilities to enhance the model’s recognition of different APIs. Subsequently, a fusion architecture is constructed, incorporating two sub-models: 1D-CNN and Bi-LSTM, to model and integrate features from subsequences of varying lengths. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms existing approaches across various public datasets, showcasing robust generalization capabilities. Furthermore, by analyzing the distribution of sequence lengths in the dataset, the 95th percentile length was adopted as the optimal truncation length for input sequences, effectively balancing the trade-off between preserving sequence information and computational efficiency, thereby enhancing overall detection performance. However, the method proposed in this paper currently relies primarily on dynamic features and lacks utilization of static features. In future research, we will further explore fusion strategies between dynamic and static features to construct a more comprehensive hybrid malware detection framework, enabling more thorough and accurate malware identification.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the foundational support of Hubei Minzu University, whose infrastructure and funding were instrumental in conducting this study.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62262020) and the Graduate Education Innovation Project of Hubei Minzu University (MYK2024025).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization and study design were performed by Jinhuo Liang. Jinan Shen conducted the experiments and data collection. Data analysis and interpretation were carried out by Jinan Shen and Pengfei Wang. The original draft of the manuscript was written by Jinhuo Liang and Jinan Shen. Pengfei Wang, Fang Liang and Xuejian Deng critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. Fang Liang provided technical and material support. Xuejian Deng supervised the entire project. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets utilized in this study are available in MalbehavD-V1 at https://github.com/mpasco/MalbehavD-V1 (accessed on 09 December 2025) and in Alibaba Cloud at https://tianchi.aliyun.com/competition/entrance/231694/information (accessed on 09 December 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Malware Statistics & Trends Report | AV-TEST—av-test.org. [cited 2024 Sep 20]. Available from: https://www.av-test.org/en/statistics/malware/. [Google Scholar]

2. Gopinath M, Sethuraman SC. A comprehensive survey on deep learning based malware detection techniques. Comput Sci Rev. 2023;47:100529. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2022.100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Brezinski K, Ferens K. Metamorphic malware and obfuscation: a survey of techniques, variants, and generation kits. Secur Commun Netw. 2023;2023(1):8227751. doi:10.1155/2023/8227751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Begovic K, Al-Ali A, Malluhi Q. Cryptographic ransomware encryption detection: survey. Comput Secur. 2023;132:103349. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sharma A, Gupta BB, Singh AK, Saraswat V. Orchestration of APT malware evasive manoeuvers employed for eluding anti-virus and sandbox defense. Comput Secur. 2022;115:102627. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2022.102627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Nadler A, Bitton R, Brodt O, Shabtai A. On the vulnerability of anti-malware solutions to DNS attacks. Comput Secur. 2022;116:102687. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2022.102687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kambar MEZN, Esmaeilzadeh A, Kim Y, Taghva K. A survey on mobile malware detection methods using machine learning. In: 2022 IEEE 12th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); 2022 Jan 26–29; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 215–21. [Google Scholar]

8. de Oliveira AS, Sassi RJ. Behavioral malware detection using deep graph convolutional neural networks. Int J Comput Appl. 2021;174(29):1–8. doi:10.36227/techrxiv.10043099.v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Agrawal R, Stokes JW, Marinescu M, Selvaraj K. Neural sequential malware detection with parameters. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2018 Apr 15–20; Calgary, AB, Canada. p. 2656–60. [Google Scholar]

10. Kang J, Jang S, Li S, Jeong YS, Sung Y. Long short-term memory-based malware classification method for information security. Comput Electr Eng. 2019;77:366–75. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2019.06.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Catak FO, Yazı AF, Elezaj O, Ahmed J. Deep learning based Sequential model for malware analysis using Windows exe API Calls. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2020;6:e285. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Lu X, Jiang F, Zhou X, Yi S, Sha J, Pietro L. ASSCA: API sequence and statistics features combined architecture for malware detection. Comput Netw. 2019;157:99–111. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2019.04.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li C, Lv Q, Li N, Wang Y, Sun D, Qiao Y. A novel deep framework for dynamic malware detection based on API sequence intrinsic features. Comput Secur. 2022;116:102686. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2022.102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Iqbal A, Hussain M, Riaz Q, Khalid M, Mumtaz R, Jung KH. Enhancing ransomware detection with machine learning techniques and effective API integration. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;85(1):1693–714. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.064260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Maniriho P, Mahmood AN, Chowdhury MJM. MalDetConv: automated behaviour-based malware detection framework based on natural language processing and deep learning techniques. arXiv:2209.03547. 2022. [Google Scholar]

16. Alibaba cloud malware detection based on behaviors—tianchi.aliyun.com. [cited 2024 Aug 20]. Available from: https://tianchi.aliyun.com/competition/entrance/231694/information. [Google Scholar]

17. Aswin V, Kumar BS. TCN-BiGRU model for malware detection based on API call sequences. In: Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Social Networking (ICPCSN); 2025 May 14–16; Salem, India. p. 1461–6. [Google Scholar]

18. Tiwari PK. Malware detection using control flow graphs. In: Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Device Intelligence, Computing and Communication Technologies (DICCT); 2024 Mar 15–16; Dehradun, India. p. 216–20. [Google Scholar]

19. Pham TB, Duong PHT, Nguyen DK, Hien DTT, Cam NT, Pham VH. Multimodal windows malware detection via hybrid analysis and enriched graphs: effectiveness and explainability. In: Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Multimedia Analysis and Pattern Recognition (MAPR); 2025 Aug 14–15; Khanh Hoa, Vietnam. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

20. Feng P, Gai L, Yang L, Wang Q, Li T, Xi N, et al. DawnGNN: documentation augmented windows malware detection using graph neural network. Comput Secur. 2024;140:103788. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2024.103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sarı NV, Acı M, Acı Çİ. Windows malware detection via enhanced graph representations with Node2Vec and graph attention network. Appl Sci. 2025;15(9):4775. doi:10.3390/app15094775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Xu A, Chen L, Kuang X, Lv H, Yang H, Jiang Y, et al. A hybrid deep learning model for malicious behavior detection. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 6th Intl Conference on Big Data Security on Cloud (BigDataSecurityIEEE Intl Conference on High Performance and Smart Computing, (HPSC) and IEEE Intl Conference on Intelligent Data and Security (IDS); 2020 May 25–27; Baltimore, MD, USA. p. 55–9. [Google Scholar]

23. Zhang S, Wu J, Zhang M, Yang W. Dynamic malware analysis based on API sequence semantic fusion. Appl Sci. 2023;13(11):6526. doi:10.3390/app13116526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Luo J, Zhang Z, Luo J, Yang P, Jing R. Sequence-based malware detection using a single-bidirectional graph embedding and multi-task learning framework. J Comput Secur. 2024;32(2):141–63. doi:10.3233/jcs-230041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yan P, Tan S, Wang M, Huang J. Prompt engineering-assisted malware dynamic analysis using gpt-4. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2025;22(6):7712–28. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2025.3599004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang Z, Li Y, Wang W, Song H, Dong H. Malware detection with dynamic evolving graph convolutional networks. Int J Intell Syst. 2022;37(10):7261–80. doi:10.1002/int.22880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang Z, Li Y, Dong H, Gao H, Jin Y, Wang W. Spectral-based directed graph network for malware detection. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2020;8(2):957–70. doi:10.1109/tnse.2020.3024557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hu Z, Liu G, Xiang X, Li Y, Zhuang S. GSB: GNGS and SAG-BiGRU network for malware dynamic detection. PLoS One. 2024;19(4):e0298809. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0298809. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools