Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Computer Simulation and Experimental Approach in the Investigation of Deformation and Fracture of TPMS Structures Manufactured by 3D Printing

1 Institute of Metal Physics, Ural Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Ekaterinburg, 620018, Russia

2 Ural Federal University Named after the First President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin, Ekaterinburg, 620002, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Nataliya Kazantseva. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Perspective Materials for Science and Industrial: Modeling and Simulation)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 19 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2026.073078

Received 10 September 2025; Accepted 04 January 2026; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Because of the developed surface of the Triply Periodic Minimum Surface (TPMS) structures, polylactide (PLA) products with a TPMS structure are thought to be promising bio soluble implants with the potential for targeted drug delivery. For implants, mechanical properties are key performance characteristics, so understanding the deformation and failure mechanisms is essential for selecting the appropriate implant structure. The deformation and fracture processes in PLA samples with different interior architectures have been studied through computer simulation and experimental research. Two TPMS topologies, the Schwarz Diamond and Gyroid architectures, were used for the sample construction by 3D printing. ANSYS software was utilized to simulate compressive deformation. It was found that under the same load, the von Mises stresses in the Gyroid structure are higher than those in the Schwartz Diamond structure, which was associated with the different orientations of the cells in the studied structures in relation to the direction of the loading axis. The deformation process occurs in the local regions of the studied TPMS structures. Maximum von Mises stresses were observed in the vertical parts of the structures oriented along the load direction. It was found that, unlike the Gyroid, the Schwartz Diamond structure contains a frame that forms unique stiffening ribs, which ensures the redistribution of the load under the vertical loading direction. An analysis of the mechanical characteristics of PLA samples with the Schwartz Diamond and Gyroid structures produced by the Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) method was correlated with computer simulation. The Schwarz Diamond-type structure was shown to have a higher absorption energy than the Gyroid one. A study of the fracture in PLA samples with various cell sizes revealed a particular feature related to the samples’ periodic surface topology and the 3D printing process. Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) studies of the samples deformed by compression showed that with an increase in the density of the samples, the failure mechanism changes from ductile to quasi-brittle due to the complex participation of both cell deformation and fiber deformation.Keywords

Cellular structures significantly reduce the weight of the entire structure. Additive manufacturing technologies make it possible to create unique products that are impossible to produce using traditional methods. Thus, it explains today’s scientific interest in unusual architectures, which yesterday were mere mathematical formulas but are now becoming reality. The use of additive technologies, which are advanced material technologies, has opened up a new era of possibilities for the architectural design of digital products. 3D printing can change the appearance of a product and produce new materials with unique physical and mechanical properties. Cellular structures manufactured by 3D printing have a high scientific and practical scope for creating products for the automotive, aerospace, and medical industries [1–3]. Cellular designs can also be a reinforcing part of the composite material [4]. The morphology of the cells can affect the material’s acoustic and thermal characteristics [5]. The mechanical properties of cellular materials are a function of the relative density, the initial material properties, and the unit cell architecture. Two different approaches to investigate the mechanical properties of cellular materials by numerical simulation were suggested in [6]. In the first approach, the microstructure is ignored, and the simplified constitutive relationship is explored. The other approach takes into account the relationship between the mechanical properties and microstructure of the samples. The following models are proposed to describe the deformation process of cellular structures: phenomenological constitutive model, homogenization algorithm model, single-cell model, and multi-cell model. Each of them has its own advantages and disadvantages [6]. The phenomenological constitutive model does not consider the effect of the microstructure (cell size, cell shape) on the deformation process. In the homogenization algorithm, model cells are limited to the ellipsoidal topological structure; this method is only valid for simulating materials when they are in the elastic zone. However, the maximum stress in the elastic zone and, consequently, in other zones of the stress–strain curves, cannot be predicted [7]. The single-cell model uses too simple a cell shape that is far from the realistic structure. The multi-cell model needs the complicated modeling algorithm and large-scale commercial software [6].

Among the various types of cell structures, triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS) occupy a special place. Such structures are found in the natural world. Sea urchin skeletons, butterfly wing scales, and the wing covers of beetles have TPMS structures [8]. A feature of TPMS surfaces is the presence of translational symmetry in three independent directions and zero mean curvature [9]. The dimensions and shape of cells in materials with a topological TPMS structure can be varied, and thus their mechanical properties can be controlled [10]. Gyroid and Schwarz Diamond structures exhibit the best mechanical properties among all known TPMS structures. The simplest and, because of that, the most popular, is the Gyroid structure [11,12]. Gyroid structures showed low anisotropy [6] and high-energy absorption capability per unit mass [13]. Materials with such architecture are offered in medicine as a basis for implants [2,14]. The production of heat exchangers [15] and low-frequency or adjustable vibration isolation [16] can be accomplished using gyroid structures that have good thermal-physical properties. Numerical simulations of Gyroid structures under compressive loads and comparison with the experimental tests for an amorphous thermoplastic acrylic styrene acrylonitrile (ASA) sample manufactured by fused filament fabrication (FFF) were done in [6]. In [6] it was shown that the solid numerical models that used the finite element method (FEM) had high accuracy for simulating the deformation behavior of the Gyroid structure. However, in this case, a mesh with a high number of nodes (around 920,000) and elements (around 750,000) was required. These requirements imply a high computational cost. Another TPMS architecture with a modification of the Schwarz-Diamond type, according to preliminary estimates, has better mechanical properties than Gyroid’s [17,18], is more complicated in structure. The topological surfaces of the Gyroid and Schwartz Diamond structures can be constructed using algebraic operations on trigonometric functions (sin, cos) [17,18]:

Schwarz Diamond Surface structure,

Gyroid structure.

The difference in the deformation behavior of these two TPMS modifications remains unexplained, despite the significant number of publications related to TPMS structures.

For simulating the deformation process in TPMS structures, in literature, some models are suggested, like Finite Element Analysis (FEA) (using actual geometry or a unit cell with homogenization) [6], macroscopic constitutive models (like the Gibson-Ashby model) [19], and reduced order models (ROMs), which are computational simplifications of complex systems [20,21]. The Gibson-Ashby model uses the calculation parameters, like relative strength (σ*/σstr) or modulus (E*/Estr) of a cellular structure with its relative density (ρ*/ρstr) in the form of a positive power relationship with a coefficient (C) and exponent (n) [19]. However, there are disagreements in the simulation results obtained with use of the Gibson-Ashby model and experimental results for TPMS structures, which are explained by limited applicability of this model to structures with a relative density above 35% [19]. The ROMs model has proven itself well in calculating the geometrically nonlinear response and temperature of a heated structure [21]. It was shown in [22] that a machine learning (ML) framework based on reduced order models (ROMs) may be successfully applied for digital light processing (DLP) in 3D printing.

3D printers can be used to obtain samples with different TPMS structures from both metals and polymers [9]. However, the deformation process in metals and polymers with TPMS structures manufactured by 3D printing is not the same. As industries increasingly use polymers in critical structural applications, polymer fracture mechanics is becoming an increasingly important research area. The nature of destruction in metal products with a cellular structure is well studied using electron microscopy; in contrast to non-conducting polymers, the studies of which, in the literature, are limited to optical microscopy [1,18,23,24]. The modeling of various physical processes happening in cellular polymer materials can be achieved through the use of TPMS structures, which are interesting objects. Studies revealed that these structures can be used in energy absorption applications (including helmets, bumpers, and good envelopes) [6]. A feature of cellular structures is that, under elastic loading, local plastic deformations can occur in their individual elements, leading to deformation and destruction of the material. The polymer is considered high quality when it can absorb a significant amount of energy before breaking down. The absorption energy of polymers with cellular structures depends on the size of the cells and their relative positions [13]. At the same time, the mechanism of fracture and energy absorption in polymers with TPMS structures remains poorly understood. Analysis of the propagation of deformation in the volume of a cellular structure, as well as the conditions of dissipation and change in the energy absorption of external force action, are urgent scientific and engineering problems.

PLA polymer is an excellent modeling material for creating different 3D-printed structures. As an alternative to materials derived from nonrenewable resources like petroleum, it is non-toxic, biocompatible, and biodegradable [25,26]. For bioresorbable implants, PLA products with a TPMS structure are thought to be promising. Targeted drug delivery is made possible by the TPMS structures’ developed surface. Understanding the deformation and failure mechanisms is crucial for choosing the right implant structure because the mechanical properties of the implant are important performance characteristics. Bench tests of completed components manufactured from novel materials are challenging or prohibitively costly. Thus, an essential component of additive manufacturing is computational experimentation.

This study sought, using computer simulation and experimental testing, to ascertain the relationship between the mechanical characteristics and cellular structure of Gyroid and Schwarz Diamond types in PLA samples produced by FDM.

Different software can be used to generate the TPMS, such as MATLAB, Compass 3D, Wolfram Mathematics, or SOLIDWORKS. In this study, SOLIDWORKS software was used to generate Gyroid and Schwarz-Diamond structures. The models were constructed as a set of points satisfying the inequality:

The simulation process was completed using ANSYS finite element software (https://www.ansys.com/academic). Simulation was done using the Solid Mechanics and Stationary modules when the load, deformation, and stress did not vary in time. In stationary calculations, the strain rate as such is absent, since stationary analysis considers the state of the system at equilibrium and not its change over time. The equilibrium equation for the stationary system is as follows:

where

where E—is the fourth-rank elasticity tensor, and

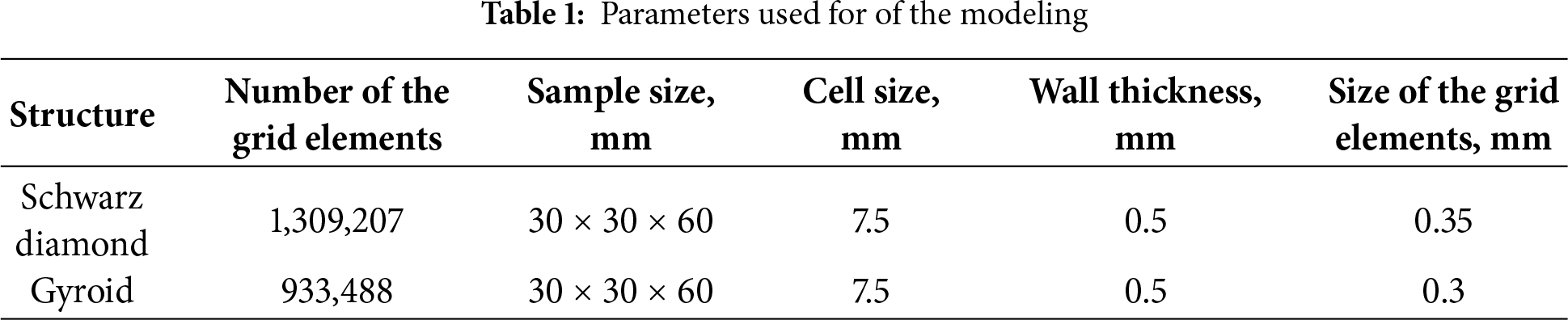

Due to the large number of mesh elements, which require a lot of computer memory, numerical calculations were performed only in the elastic region. Mesh discretization was performed using tetrahedral-type elements. Parameters used for the modeling are presented in Table 1. The quality of the constructed mesh was checked using the tools built into ANSYS Meshing. The boundary condition Fixed support was used: rigid embedding. Grid convergence was not carried out in this work. A remote load was done on the top plate of the sample. The dimensions of the specimens and their cells in the two structures were chosen to be the same for comparative analysis. The distribution of von Mises stresses in different parts of the structure was checked by cross-sections along the samples. For the FDM printing technology, a three-dimensional digital model of the samples was previously built using Standard Triangle Language (STL) files; then, for printing, this model was divided into layers with a computer program. The codes (G-codes) for both structures were generated, which contained all the printing parameters and moving of the 3D printer extruder. To obtain samples with Schwarz Diamond Surface-type topology, a computer program was developed (Certificate RF of state registration of a computer program, No. 2024617696) to generate G-Code from surface equations. Geometric simplifications of the model for printing are related to the generation of G-code, since when converting to an STL file, the true geometry is approximated by a set of flat triangles. To eliminate the influence of anisotropy, all studied samples were printed and deformed in the same direction. Sample deformation was also simulated along the growth direction (z-axis). To print samples, the following 3D printer modes were used: the extruder nozzle diameter was 0.5 mm; the layer height was 0.2 mm; the line width was 0.5 mm; the extruder temperature was 215°C; and the table heating temperature was 60°C. The parts were grown in the z-axis direction, perpendicular to the printer bed. The contour pass speed was set by G-code and was 70 mm/s. There was no infill; printing was performed in a single pass with a line width of 0.5 mm. The cell size was chosen based on the printing capability of a 3D printer using the FDM method. The Schwarz Diamond Surface and Gyroid structure samples had the same cell sizes that ranged from 2 to 7.5 mm (large honeycomb). The relative density of the resulting samples was measured as follows

Using FDM printing, a sample with a density of 100% and with the same volume as the cellular samples was obtained. Then, all samples, including the dense sample, were weighed on an analytical balance. The density of the cellular samples was calculated taking into account the tabulated density values of the polylactide filaments (Table 2) [25]. PLA filaments (Bestfilaments, Russia) with a diameter of 1.75 mm were used for 3D printing. The resulting mass ratio between the dense sample and cellular samples for the Schwarz Diamond Surface structure samples was 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75. For the Gyroid structure samples, the resulting mass ratio was 0.23, 0.46, and 0.73. 18 samples with size 30 mm × 30 mm × 60 mm were printed. The mechanical tests were performed according to the GOST 4651-2014 standard at room temperature using an Instron 3382 universal testing machine at a speed of 6 mm/min. The error in determining the movement of the traverse is 1 micron, and the error in measuring the force in the entire range up to 100 kN is less than 10 N (manufacturer’s data). For electron microscopic studies, small pieces were cut from the deformed samples. Structural studies were performed using a Tescan Mira LMS scanning electron microscope.

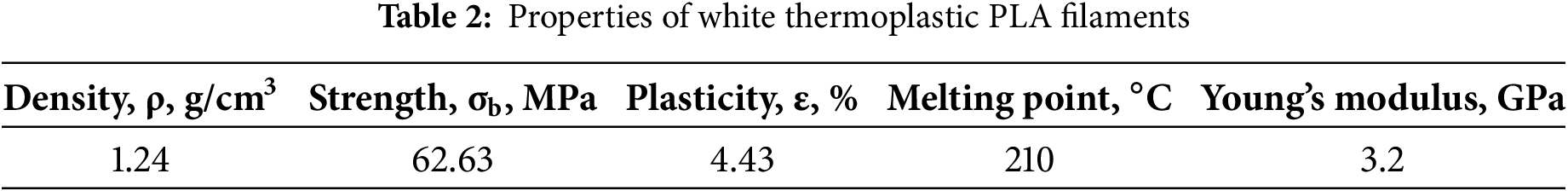

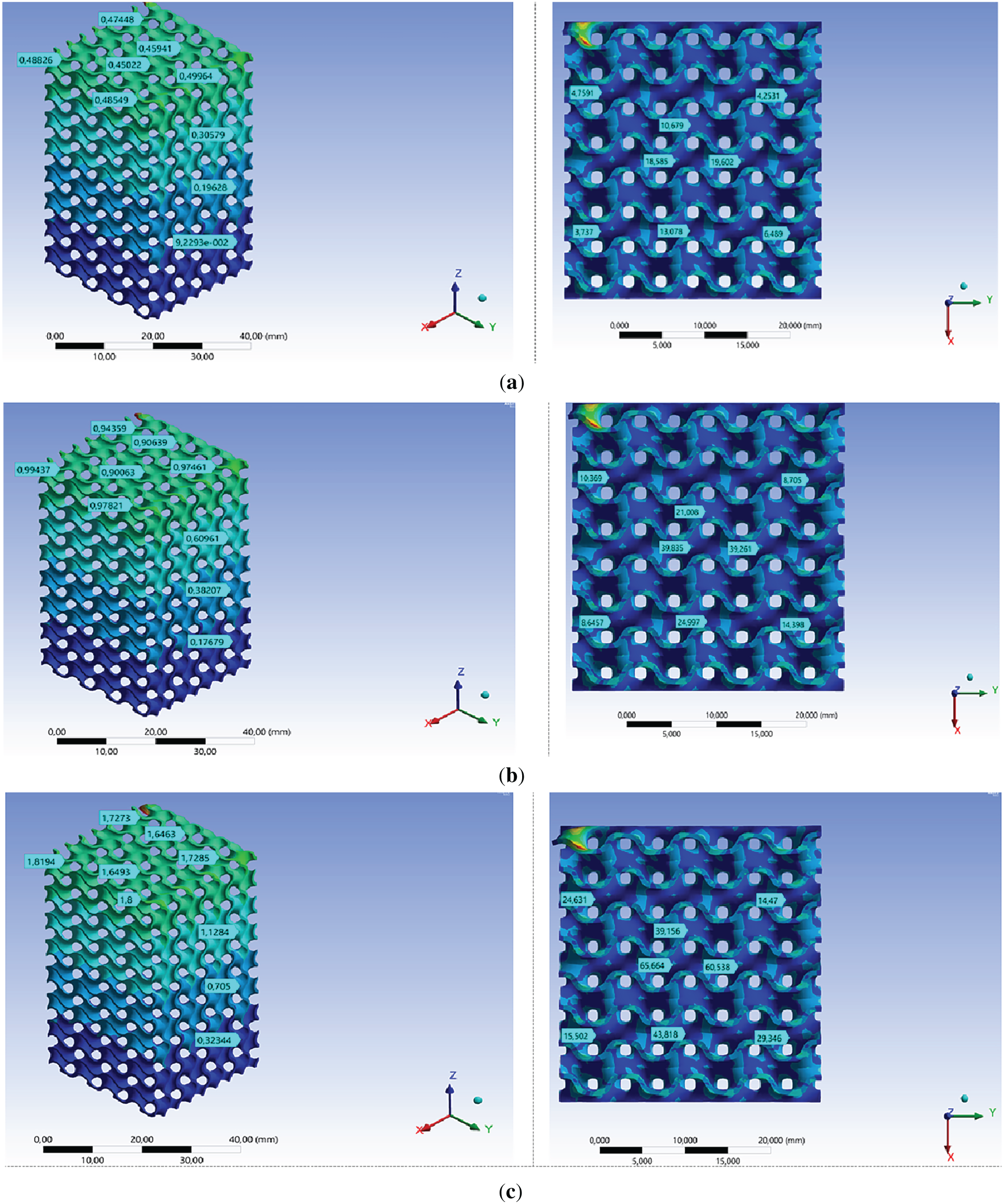

The computer simulation of the compression deformation process was performed only for the samples with the lowest density due to difficulties with mesh sizes in the finite element method. Fig. 1 shows images of specimens with Schwarz Diamond (a) and Gyroid (b) structures used for modeling.

Figure 1: Models of the samples with Schwarz diamond (a) and Gyroid (b) structures

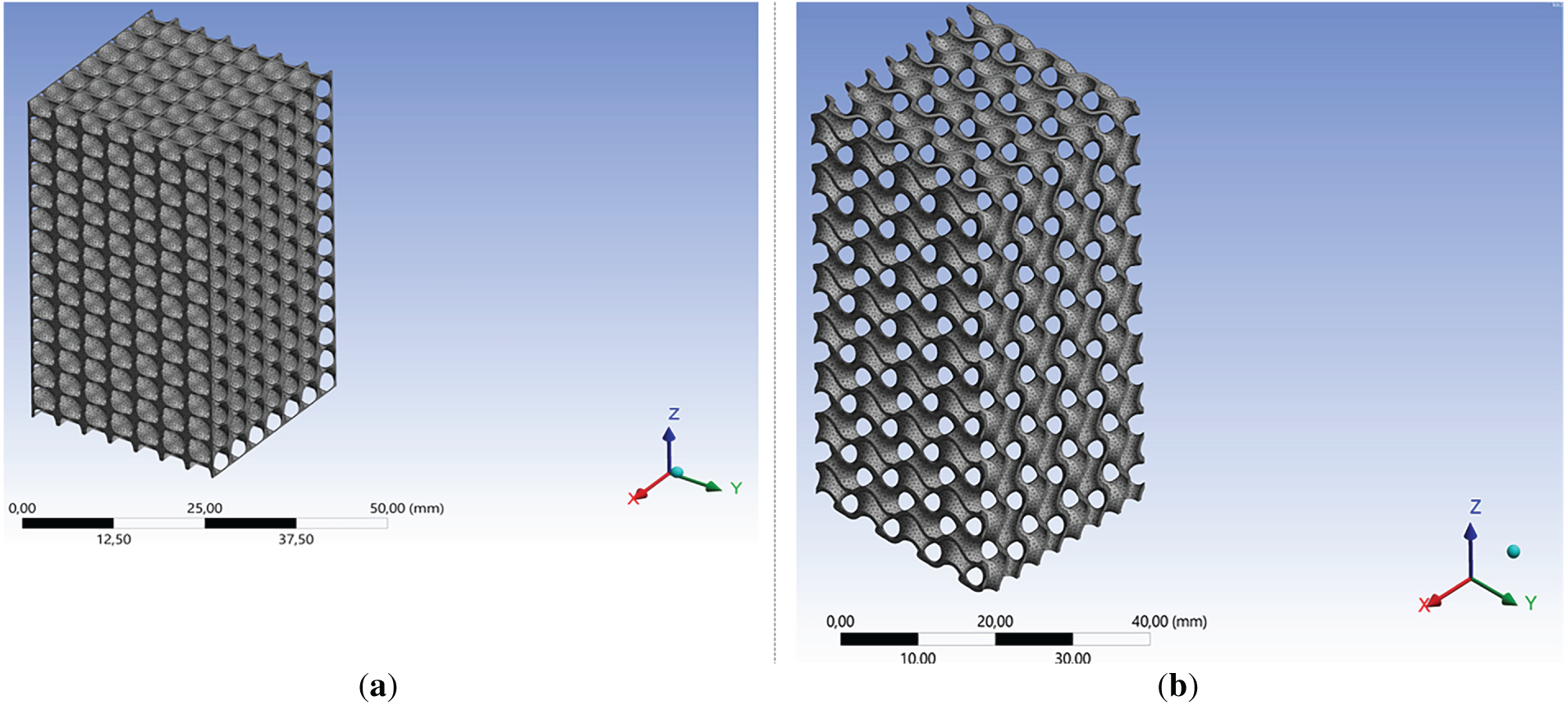

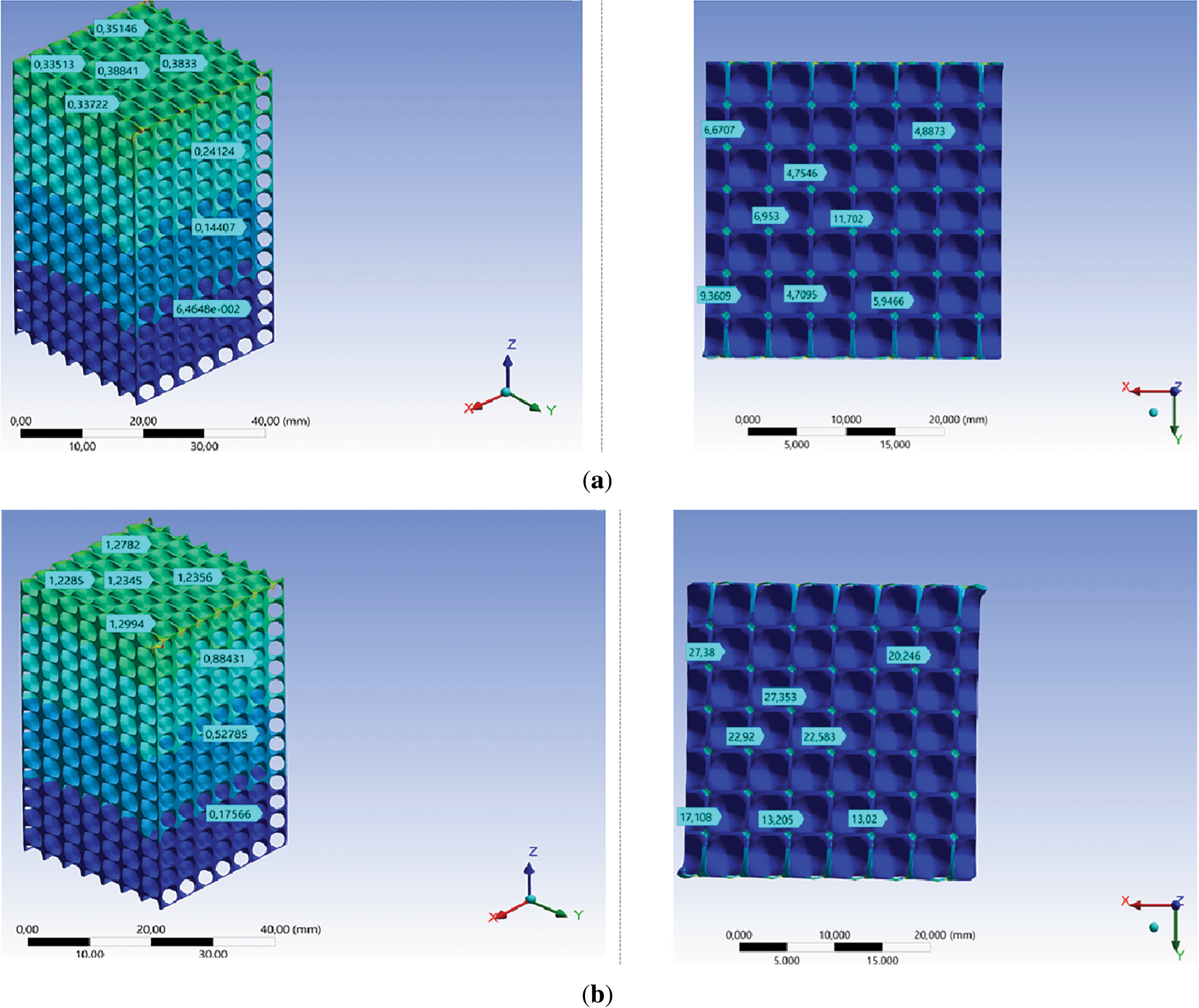

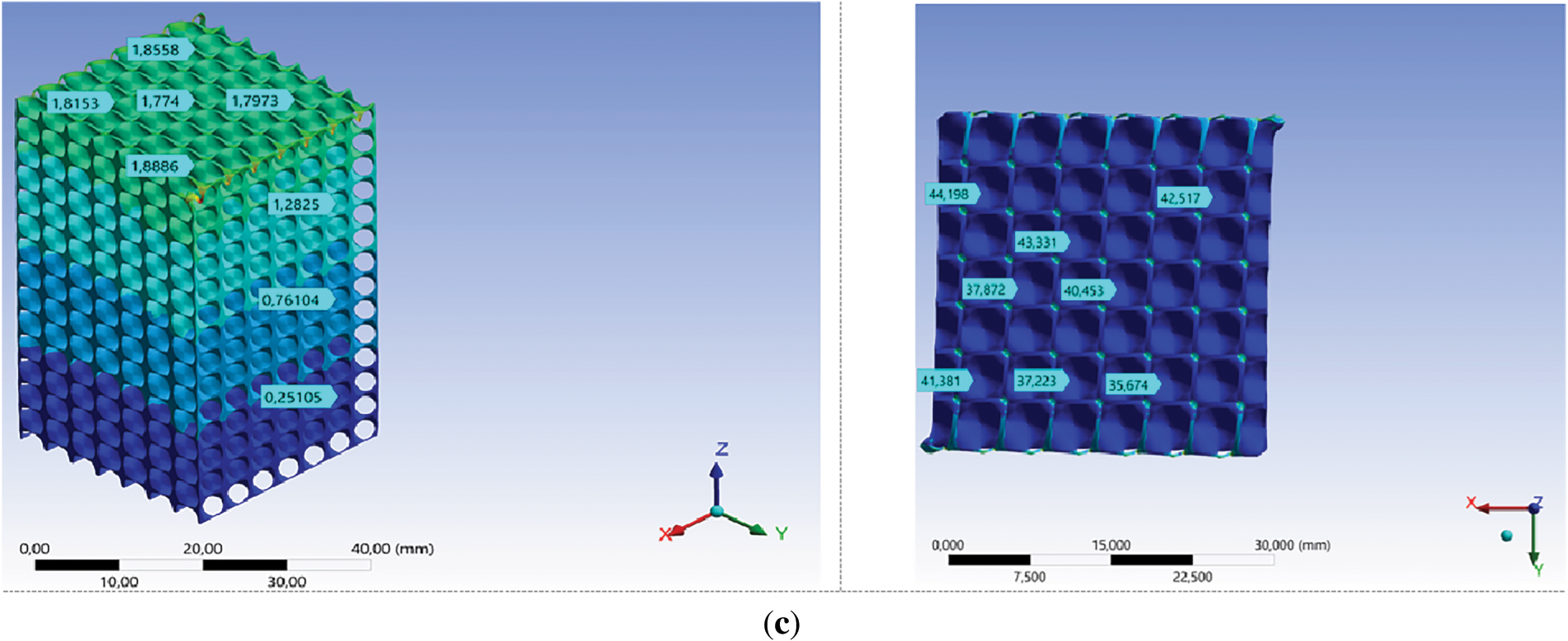

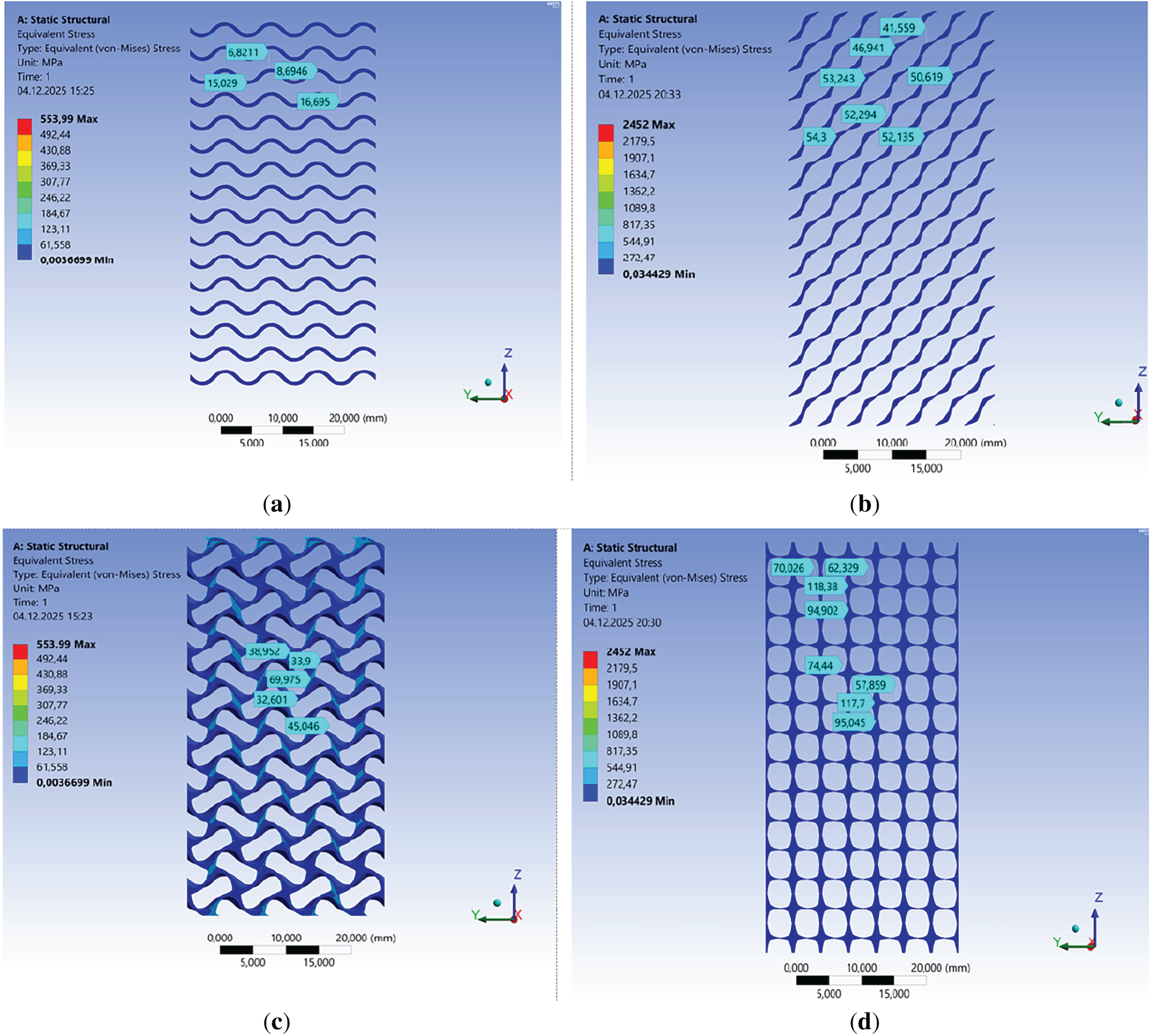

Figs. 2 and 3 show the distribution of deformation and von Mises stresses under compressive elastic loading in Gyroid and Schwarz Diamond structures at different load forces. As can be seen from the figures, the deformation and von Mises stresses in Gyroid structure at the same load are higher than in the Schwarz Diamond one. Fig. 4 shows the vertical sections of the simulated samples at the loads corresponding to the transition to the plastic region. Mathematically, both studied TPMS structures were formed from non-intersecting sinusoidal surfaces in 3D space [9]. When the vertical section of the studied samples was examined, it was found that the nature of bending in both studied structures was similar, but the level of residual stresses in similar local areas was different. Overall, it can be seen that both structures, when cut by vertical planes, present a periodic arrangement of “nodes” and wavy lines (Fig. 4).

Figure 2: Visualizing the distribution of deformation and von Mises stresses under compressive elastic loading in Swartz Diamond structure at different load force: (a) 1.5 kN; (b) 5.5 kN; (c) 8 kN

Figure 3: Visualizing the distribution of von Mises stress fields (MPa) under compressive elastic load in the. Gyroid structure at the load of 5.5 kN (a,c) and Swartz Diamond structure at the load of 8 kN (b,d) in different cross-sections

Figure 4: Visualizing the distribution of deformation and von Mises stresses under compressive elastic loading in Gyroid structure at different load force: (a) 1.5 kN; (b) 3 kN; (c) 5.5 kN

“Nodes” are the surface-bending regions, and wavy lines are the cross-section (thickness) of the surfaces. In the Schwarz Diamond structure, maximum von Mises stresses are found on the vertical part of the “node,” and minimum von Mises stresses can be seen on the horizontal sections of the “node.” In the central part of the node, the stresses are lower than on the edge (Figs. 2 and 3). Similar behavior is also found in the cross-section of surfaces (wave lines). The maximum stress occurs at points close to the vertical position of the wavy line. The minimum stress is found at the transition points of the surface, in relation to the direction of the applied load, from horizontal to vertical orientation. The cross-section of the model shows that, in fact, the Schwarz Diamond structure forms a rigid frame with multiple axes directed along the load application (z-axis) (Fig. 3).

Unlike the Schwarz Diamond structure, the arrangement of the “nodes” in the longitudinal section of the sample with the Gyroid structure has a different orientation relative to the direction of the applied load (at an angle, Fig. 3). At the same load (1.5 kN), the von Mises stresses in this structure are almost twice as high as in the Schwartz Diamond structure (Figs. 2 and 4). The maximum von Mises stresses are found at the node, and the minimum von Mises stresses can be seen when the surface transitions from horizontal to vertical (Fig. 4). Just as in the Schwartz Diamond structure, in the Gyroid structure the maximum von Mises stress occurs at points close to the vertical position of the wavy line (Fig. 3).

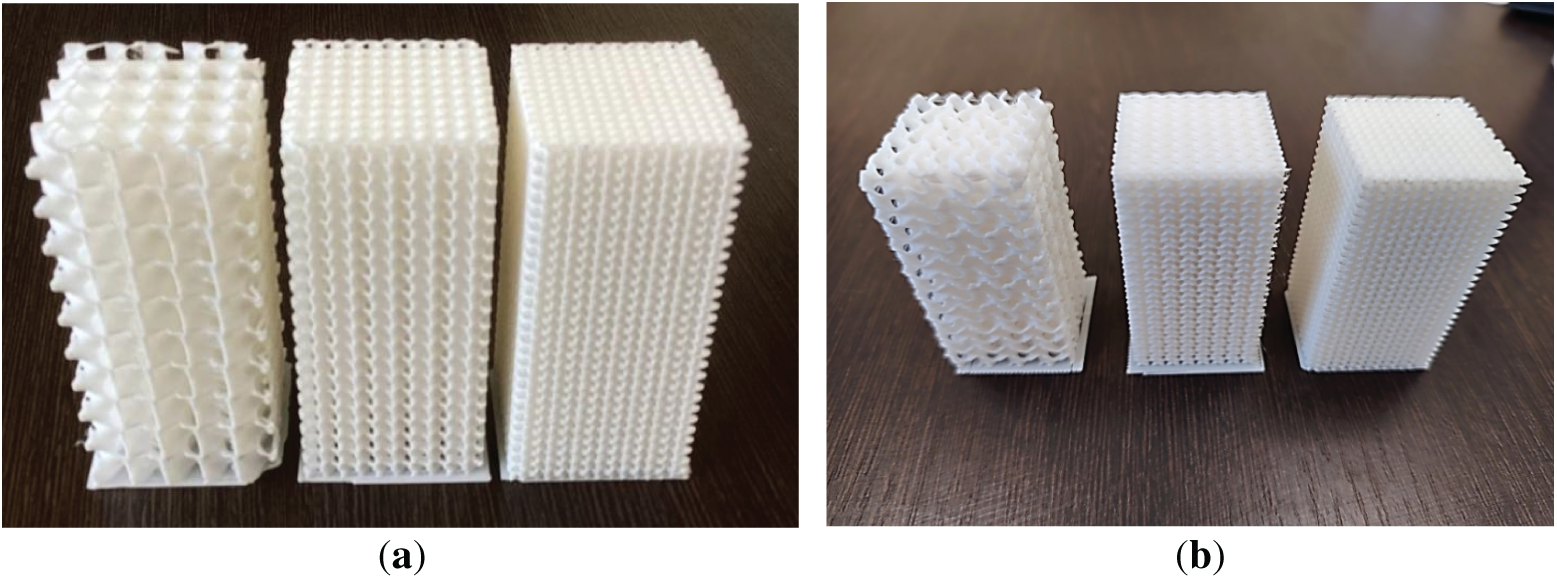

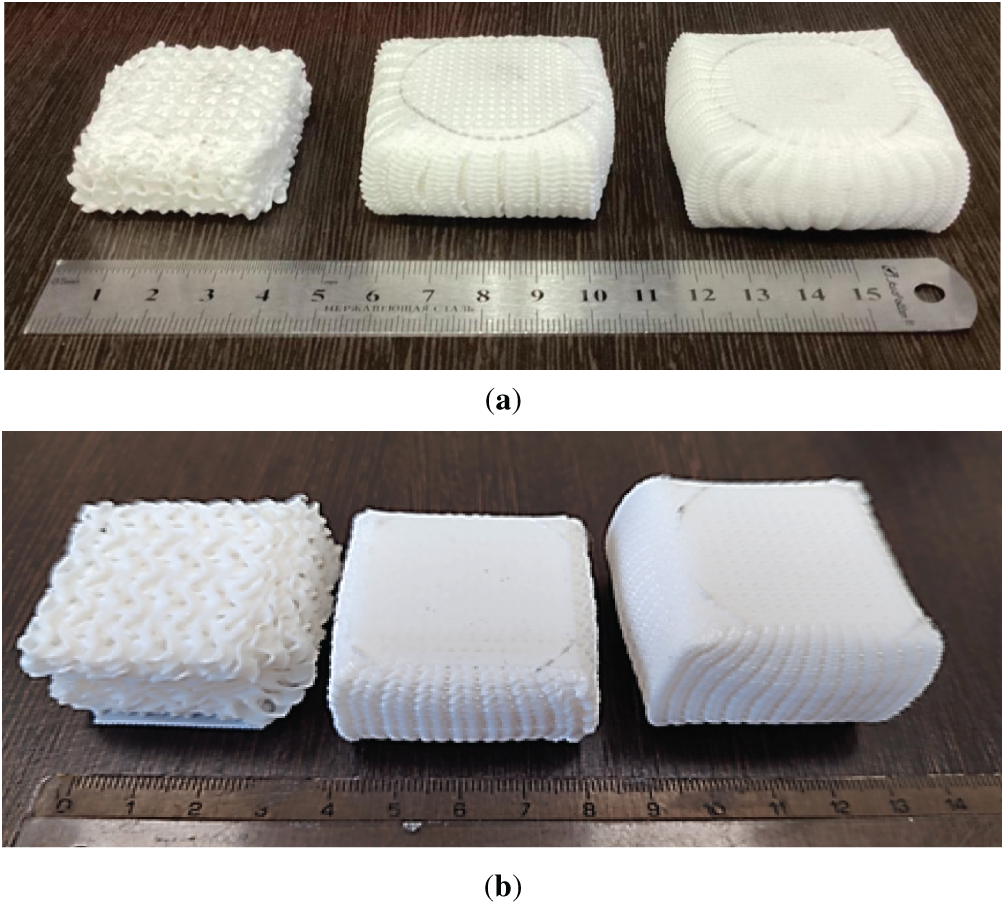

Fig. 5 presents optical images of the obtained PLA samples with three different relative densities at the initial state.

Figure 5: 3D printed samples, optical images: (a) Schwarz diamond structure; (b) Gyroid structure

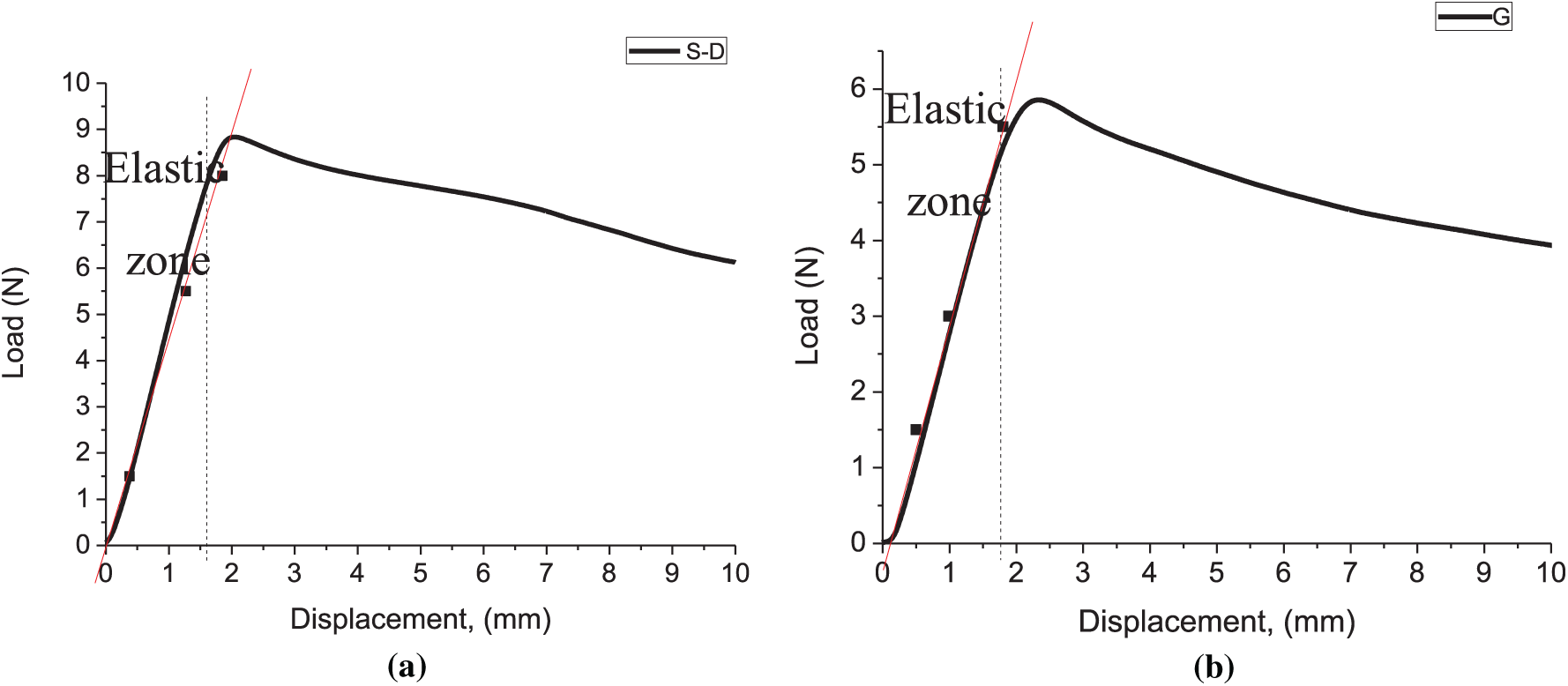

Testing of fiber polymer materials is characterized by a number of features and differs from metal failure under loading under identical conditions. It was found in [27] that the cellular structure under compression had stress–strain curves similar to that of a foam, which was observed and described by Gibson-Ashby, who also identified three well-defined zones, like an elastic zone, a plateau, and a densification point. Figs. 6 and 7 show the deformation curves of the studied samples. In the elastic region, the simulation showed good agreement with the experiment. This may confirm the correctness of the chosen model. The slight discrepancy between the simulation results and the experiment for the model with the Schwarz structure may be due to the choice of mesh size. Due to the complexity of the Schwarz Diamond structure, we were forced to select a mesh size of 0.35 mm instead of 0.3 mm. Even with this mesh size, the number of mesh elements exceeded one million (Table 1).

Figure 6: Comparison of simulation results with experimental data, elastic zone: (a) Schwarz diamond structure; (b) Gyroid structure

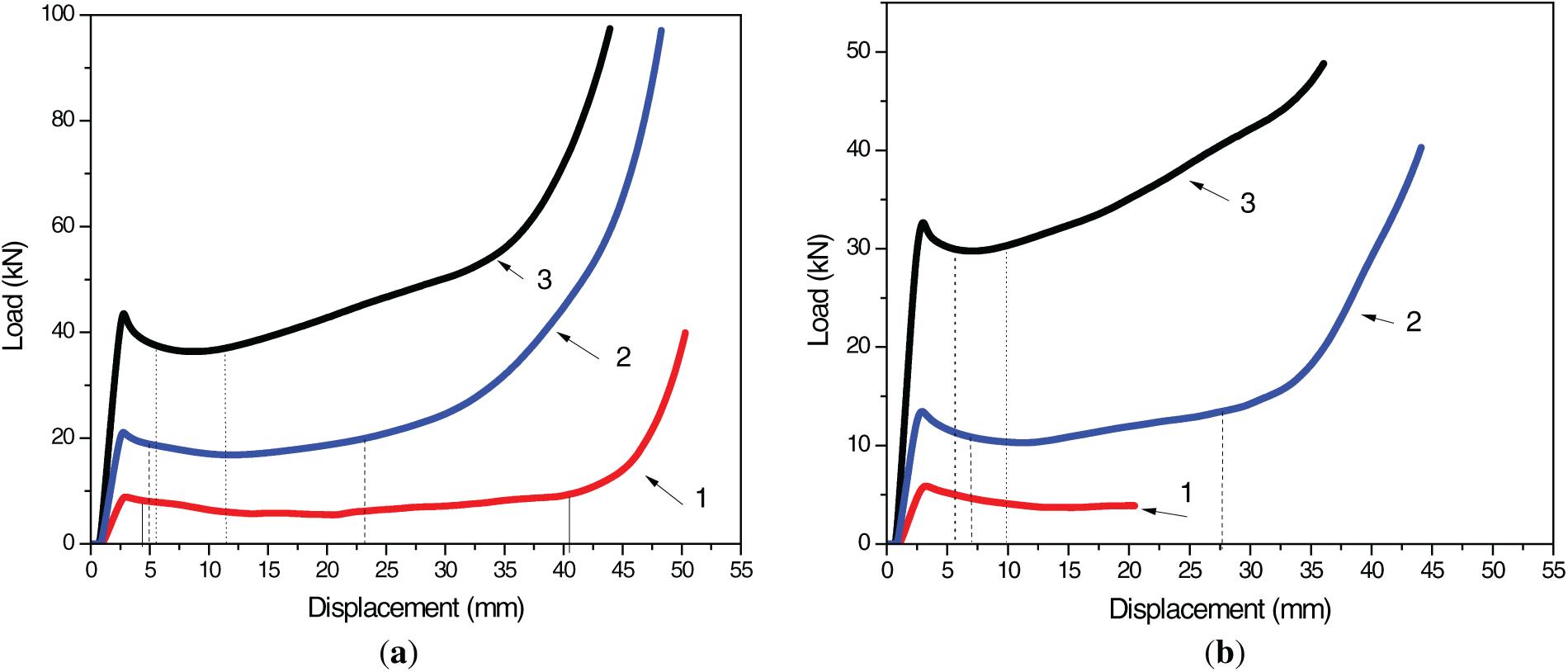

Figure 7: Results of the mechanical tests of the samples with the different relative densities: (a) Schwarz diamond structure, 1%–25%, 2%–50%, 3%–75%; (b) Gyroid structure, 1%–23%, 2%–46%, 3%–73%

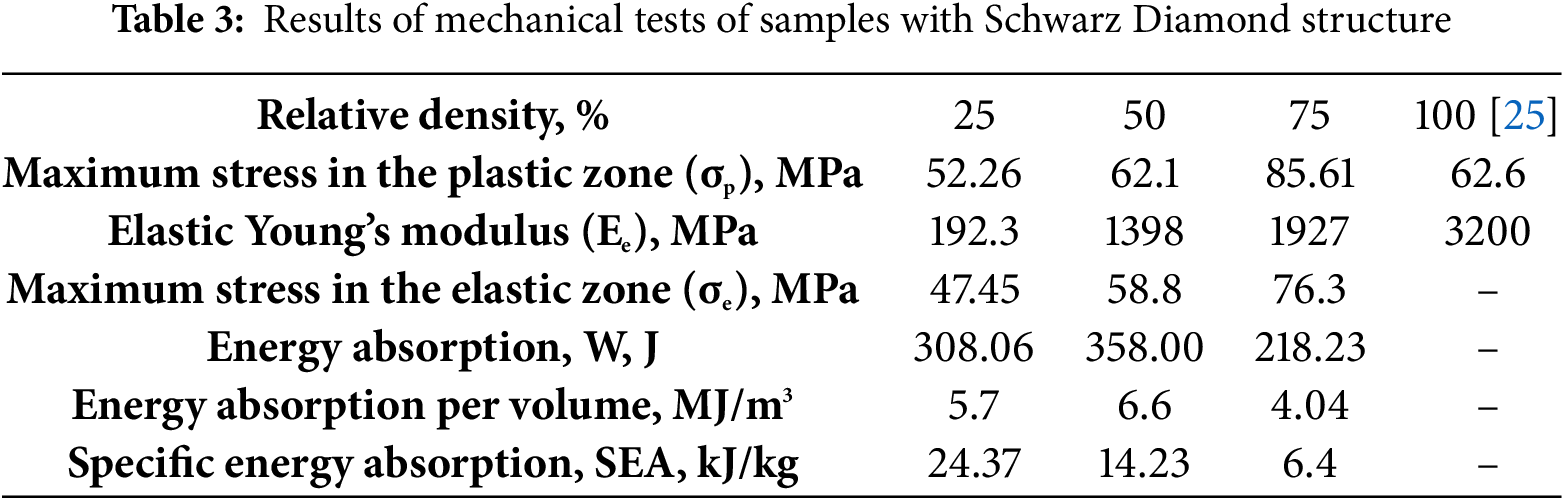

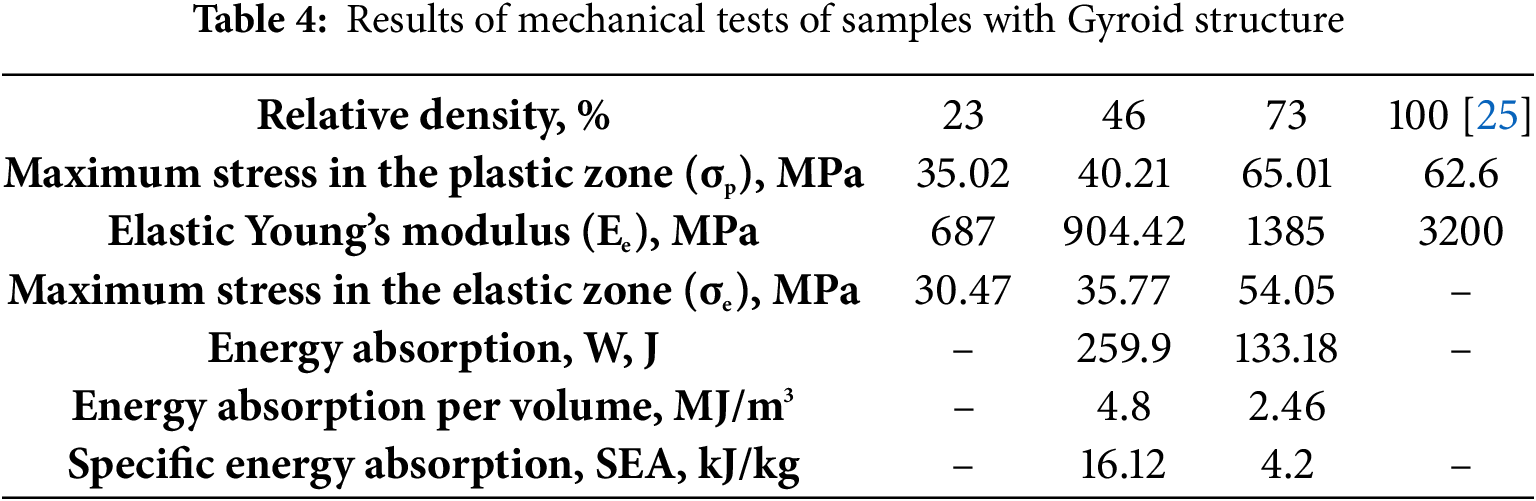

The main mechanical properties of the studied samples are as follows: elastic Young’s modulus (E), maximum stress in the elastic zone (σe), and maximum stress in the plastic zone (σp) (Tables 3 and 4). Parameters of failure of the polymer samples may be calculated from a load-displacement curve obtained under quasi-static testing. The main parameter is a Specific Energy Absorption (SEA), which is defined as the energy absorbed per unit mass of material. The area under the load-displacement curve is [28]:

where W is the total energy absorbed in crushing of the specimen, Sb and Si are the crush distances (plateau region), and

where m is the mass of the material. It can be seen from Fig. 7 that the change trend of compressive stress-strain curves of the two studied TPMS structures is basically the same. The strength of a material increases with increasing density. With an increase in the density of images on the deformation curves, a characteristic yield point appears, indicating the abrupt nature of deformation and stress localization. In both structures (Schwarz Diamond and Gyroid), the value of the compressive strength and compressive modulus also increases with the increasing of the density of the studied samples (Tables 3 and 4).

The results obtained in our work are consistent with the data on the measurement of mechanical properties under static uniaxial compression of PLA samples with three different TPSM structures (Gyroid, Schwarz Diamond, and Schwarz primitive), obtained in the work [17]. The authors of this work studied the PLA samples with three different densities, 10%, 20%, and 30%, manufactured by the FFF method and found that the Schwarz Diamond structure demonstrated the highest mechanical strength compared with the other architectures. The numerical values for the elastic modulus and tensile strength of samples with Schwarz Diamond and Gyroid structures obtained in the work [17] are somewhat different from those obtained by us, but the general trend of increasing mechanical characteristics with increasing density of TPMS samples is similar. Differences in values may be due to the use of a different PLA plastic (black; in our case, white was used), as well as the selected deformation rate, the shape, the size of the cell, and the wall thickness of the samples studied in the work [17]. The samples studied in [17] were actually composites consisting of TPMS structures bounded by two solid PLA plates of 2 mm thickness, which were designed at the top and bottom of the samples. In [29] it was shown that the mechanical properties under compression of PLA samples with Gyroid structure depended on the cell size as well as the density of the sample. The compressive strength of the samples increased with increasing density (volume fraction) and decreasing cell size [29]. In [30], it was also shown that the mechanical properties under compression of 3D-printed PLA samples depended on the strain rate. A similar dependence of the mechanical properties of PA2200 Gyroid structures on density was found in the work [12]. The authors of [12] found that there was no discernible difference between horizontally and vertically oriented samples under compressive loading. This is consistent with our modeling data on the stress distribution in the Gyroid cell and its orientation in space (Fig. 3c).

With increasing density of the studied samples, the length of the plateau region and the magnitude of the mean crush load change. The boundaries of the plateau region on the deformation curves are marked by dotted lines (Fig. 7). Decreasing the plateau size means that the densification of the sample occurs faster. The calculation showed that the dependence of the absorption energy, W, on the sample density is nonlinear in both structures. With an increase in the density of the samples to 50%, the value of the absorption energy increases, and at a density of 75% it decreases. The same behavior is observed for energy absorption per volume. The values of specific absorption energy, SEA, decrease linearly with increasing sample density (Tables 3 and 4). This SEA dependence indicates the presence of some ideal TPMS structure sample density for achieving the highest absorption energy value. During ballistic tests, a PLA sample with a 75% density and a Schwarz structure showed a decrease in absorbed energy [31]. Under dynamic loading conditions, a similar effect was found to be linked to a change in the material’s deformation mechanism [31]. The obtained values for SEA are close to the values obtained in the work [32] for other TPMS structures. As it was pointed out in [32], energy absorption of the fiber polymer materials and composites was dependent on many parameters like fiber type, matrix type, fiber architecture, specimen geometry, testing speed, etc. Also, the value of absorption energy depends on its correct calculation. The high rate of deformation of the polymer sample may be the cause of the discrepancies in the SEA calculations; this can result in a situation where the deformation curve displays unpredictable changes in the magnitude of the load with displacement [23,28]. In that instance, many authors compute the area under the entire load-displacement curve in order to calculate the energy absorbed, W. On the other hand, the energy lost during the plateau phase is the polymer material’s energy absorption capacity [10]. As a result, calculating it from the load-displacement curve’s plateau is accurate. In our work, we followed GOST 18336—2017/ISO 844:2014 for sample size and loading conditions, and we computed the energy absorption using formula (5) to prevent errors related to incorrect size and deformation rate.

Due to certain calculation complexities, the conducted modeling did not allow us to evaluate the behavior of the cellular structure in the region of plastic deformation. The sample and cell sizes have an impact on computer simulation of cellular structure deformation behavior. Modeling the deformation behavior of cellular structures is limited by sample and cell sizes. This complicates mechanical testing, with sample sizes selected according to standards to validate the resulting model. In our case, selecting sample sizes according to the standard for deformation limited the modeling to the lowest-density samples. Computer simulation also cannot predict differences in the failure mechanism of the PLA samples obtained using different additive manufacturing methods. This necessitates fractographic analysis using scanning electron microscopy. Computer simulation also cannot predict differences in the failure mechanism of the PLA samples obtained using different additive manufacturing methods. Optical images or continuous mode shooting during sample deformation have low magnification and resolution, which does not allow identifying the exact deformation mechanism. All of this necessitates fractographic analysis using scanning electron microscopy. Fig. 8 shows the optical images of the studied samples after compressive deformation.

Figure 8: Samples after deformation, optical images: (a) Schwarz Diamond surface structure, (b) Gyroid structure

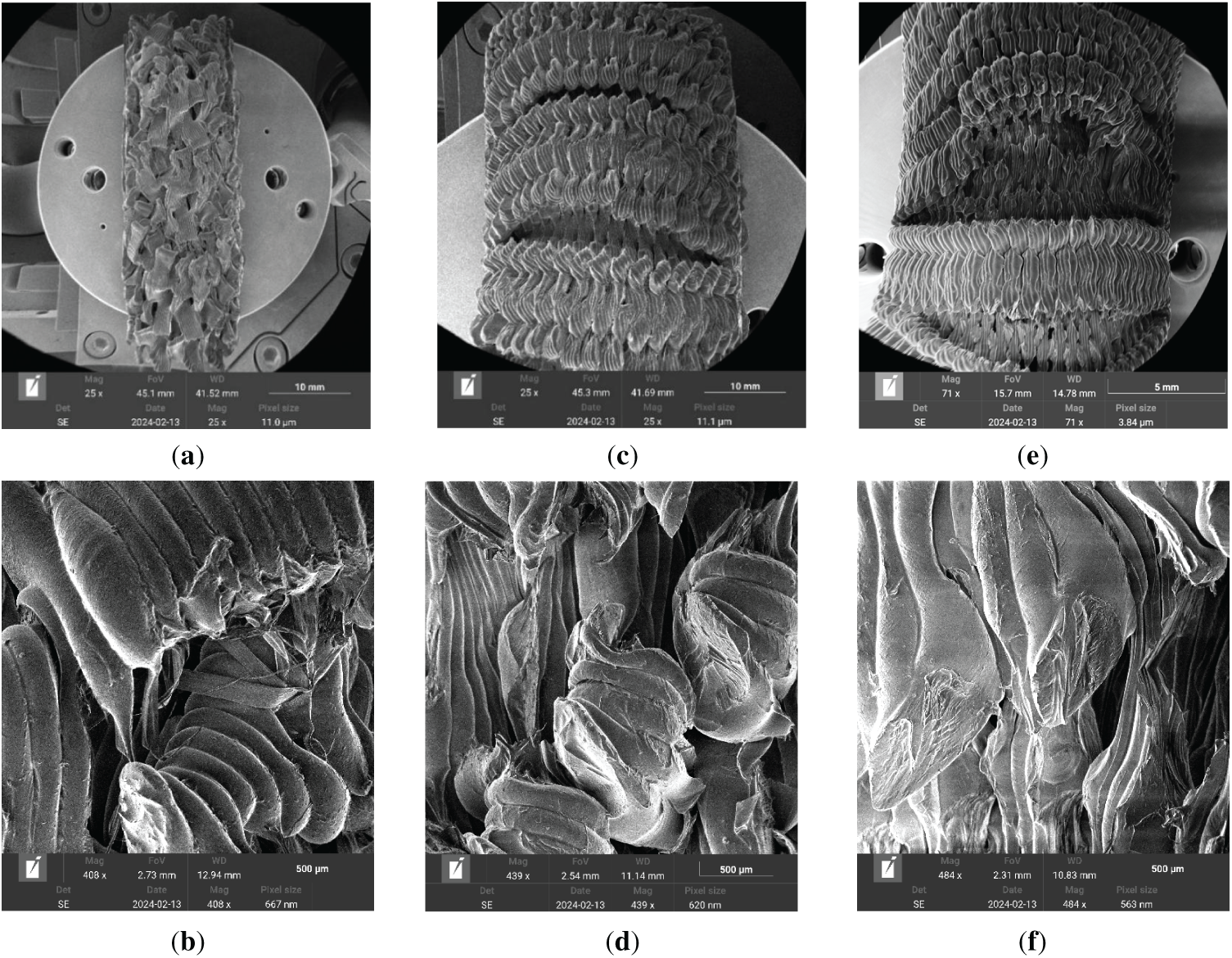

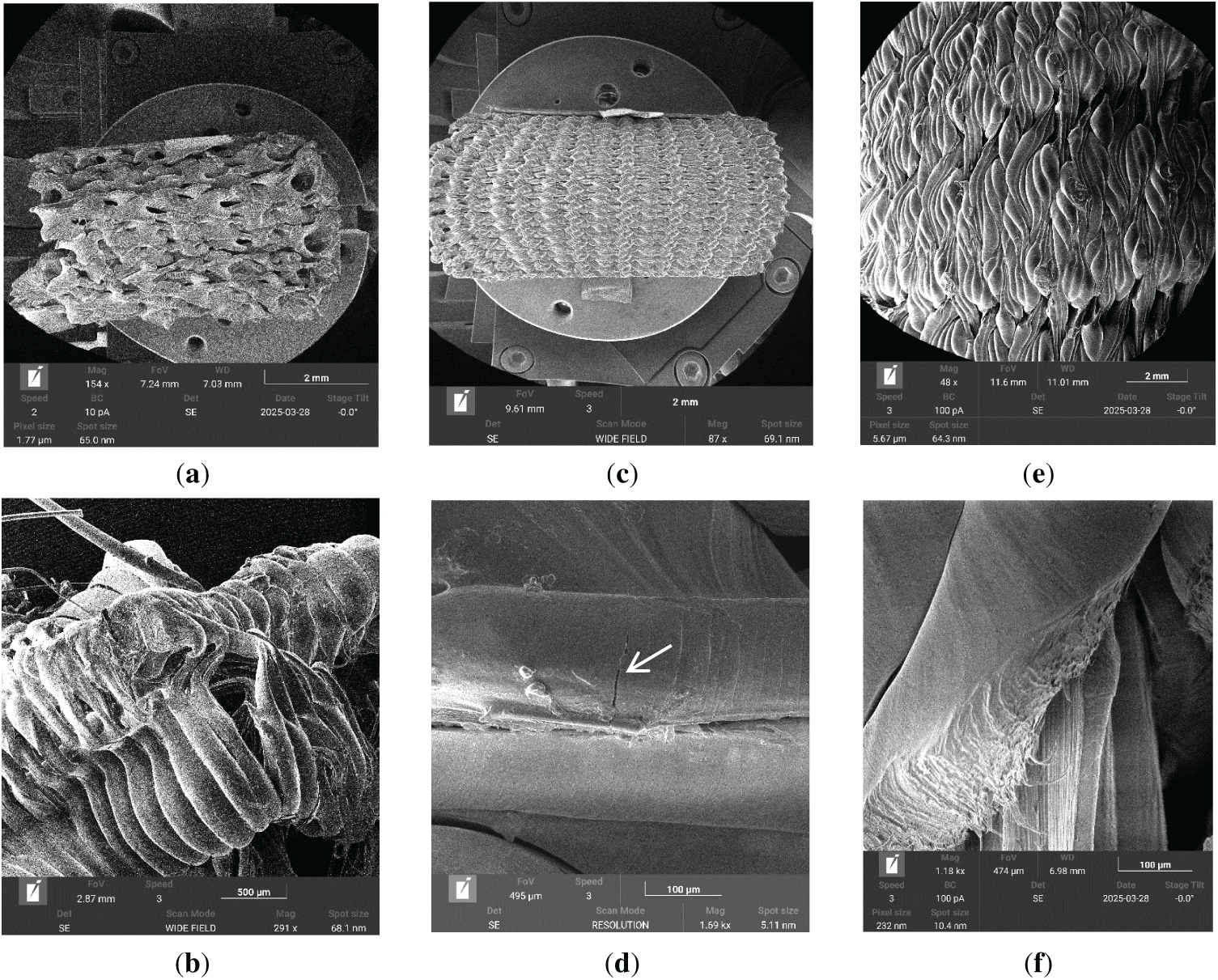

For the samples with 73%–75% relative density, the deformation process was stopped when the total deformation of the samples with the Schwarz Diamond structure was 80% and with the Gyroid structure, −60%. The remaining samples were compressed up to 75%–80%. At first glance, the deformation behavior of the samples with two types of TPMS structures is similar. In samples with minimum density (samples 1, Fig. 8), deformation occurs due to cell collapse and crumpling and shift of layers. The samples’ side walls buckle and their layers rupture when the density of the samples increases (Fig. 8, samples 2–3). However, at higher magnification, one can see a significant difference in the nature of the destruction of the two TPMS structures (Figs. 9 and 10). Low-density samples show signs of viscous plastic flow (Figs. 9a and 10a). Unlike the Schwarz structure, the Gyroid structure sample exhibits longitudinal delamination of the fiber layers in addition to cell bending and transverse fiber tearing (Fig. 10a). With an increase in the density of the samples (46%–50%), a quasi-brittle-plastic rupture of the layers occurs in the sample with the Schwartz Diamond structure (Fig. 9d) due to the buckling of the sample walls. This mechanism of destruction requires a lot of energy. In the sample with the Gyroid structure, concentration of stresses near torn fibers promotes the growth of a main crack across the fiber (Fig. 10d; the crack is pointed with an arrow). The internal fibrillar morphology of the PLA fibers is clearly visible in the images in Figs. 9f and 10f. Specimens with a density of 73%–75% show signs of quasi-brittle fracture. A more obvious brittle transverse fracture of the fibers with the formation of steps is manifested in the sample with the Schwarz structure, compressed by 80%; the sample with the Gyroid structure was compressed by 60% (Fig. 9f). In general, the mechanical properties of samples for both types of structures with ductile fracture are lower than those for samples with quasi-brittle fracture, and the absorption energy is higher (see Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 9: Fracture of the samples with Schwarz Diamond structure, SEM images: (a,b) density 25%; (c,d) density 50; (e,f) density 75%

Figure 10: Fracture of the samples with Gyroid structure, SEM images: (a,b) density 25%; (c,d) density 50; (e,f) density 75%

Crack resistance and absorbed impact energy are two key mechanical parameters reflecting the resistance of a material to fracture. Fracture of polymeric materials occurs differently than that of metals. Polymers are viscoelastic by nature. Polymer fracture has been studied in more detail in composite materials [28,33]. It has been shown that fracture of a unidirectional composite under tension occurs through accumulation of fractures and fragmentation of fibers in the polymer matrix [33]. Delamination at the fiber-binder interface or the emergence and growth of a main crack brought on by overstress in the area where the most defects accumulate halt the process of fiber fragmentation. This mechanism allows obtaining the highest strength values, since it is associated with energy dissipation to form large free surfaces [33]. In the paper [17], optical images of destruction under compressive load of samples with the Schwarz Diamond and Gyroid structures were presented. The main fracture mechanism was suggested as local layer detachment and crushing of each unit cell under the action of shear stress [17]. Thus, our study showed that in cellular samples with TPMS structures manufactured by the FDM method, micro mechanisms of deformation operated, associated with both cell deformation and fiber deformation. When changing the density of the samples and the TPMS architecture in the studied PLA materials, the nature of the destruction changes from viscoplastic to quasi-brittle due to the complex participation of both micro mechanisms. The deformation of the cellular structure occurs due to the bending of the cell walls. As the density of the sample increases, the cell size decreases, thereby reducing the possibility of their bending. The fibrillar structure of the polymer filament contributes to the deformation process. In this work, we present the first scanning electron microscopy results of a deformed cellular structure made from PLA filament using a 3D printer that uses the FDM method. As can be seen from the image (Fig. 10f), the filament consists of numerous thin fibers that deform non-uniformly under loading. As modeling has shown, it’s important to consider the direction of the applied load for each structure. In the Schwartz Diamond structure, the fibers are directed along and strictly perpendicular to the direction of load application, effectively forming a framework with stiffening ribs. In the Gyroid structure, all fibers are directed at an angle to the direction of loading. It explains why, in the sample with the Gyroid structure, one can see not only the bending of the cells and the transverse tearing of the fibers but also the longitudinal delamination of the fiber layers.

The compressive behavior, energy absorption, and fracture mechanism of Schwartz Diamond and Gyroid cellular structures with different densities were comprehensively investigated through computer simulation with finite element analysis and experimental studies. The results obtained in the study not only showed that the mechanical properties of samples with a Schwartz Diamond structure are higher than those of samples with a Gyroid structure but also revealed the reasons for this difference. The main conclusions are summarized below.

1. As a result of the modeling, it was shown that the Gyroid structure is more susceptible to deformation compared to the Schwarz Diamond structure. It was discovered that the von Mises stresses in the Gyroid structure are nearly twice as high under the same load as in the Schwartz Diamond structure. This was linked to the different cell orientations in the structures under study with respect to the loading axis’ direction. The TPMS structures under study undergo localized deformation. The vertical sections of the structures oriented along the load direction showed the highest von Mises stresses.

2. It was found a dependence of SEA (ρ), which means the existence of some optimal density of the TPMS structure samples for obtaining the maximum value of absorption energy.

3. The mechanism of deformation under compression of cellular samples with TPMS structures manufactured by the FDM method has been established, which is associated with both cell deformation and fiber deformation. It was found that when changing the density of the samples and the TPMS architecture in the studied PLA materials, the nature of the destruction changes from viscoplastic to quasi-brittle due to the complex participation of both cell deformation and fiber deformation. The deformation of the cellular structure occurs due to the bending of the cell walls. As the density of the sample increases, the cell size decreases, thereby reducing the possibility of their bending. The fibrillar structure of the polymer filament also contributes to the deformation process.

4. The results of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of a distorted cellular structure made from PLA filament using a 3D printer and the FDM technique are shown for the first time. As it was found in the SEM image, the filament consists of numerous thin fibers that deform non-uniformly under loading. The significance of taking into account the direction of the applied load for every structure was demonstrated by the computer simulation. In the Schwartz Diamond structure, the fibers are directed along and strictly perpendicular to the direction of load application, effectively forming a framework with stiffening ribs. In the Gyroid structure, all fibers are directed at an angle to the direction of loading. It explains why, in the sample with the Gyroid structure, one can see not only the bending of the cells and the transverse tearing of the fibers but also the longitudinal delamination of the fiber layers.

Acknowledgement: Scanning electron microscopy was performed using equipment from the Center for Collective Scientific Research Use of Institute of Metal Physics. This work was carried out within the state program of the M.N. Mikheev Institute of Metal Physics of the Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, supervision, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, Nataliya Kazantseva; methodology, software, validation, and visualization, Maxim Il’inikh and Nikolai Saharov; investigation, Denis Davydov and Nikolai Popov. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Maskery I, Sturm L, Aremu AO, Panesar A, Williams CB, Tuck CJ, et al. Insights into the mechanical properties of several triply periodic minimal surface lattice structures made by polymer additive manufacturing. Polymer. 2018;152(10):62–71. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2017.11.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Pais A, Belinha J, Alves J. Advances in computational techniques for bio-inspired cellular materials in the field of biomechanics: current trends and prospects. Materials. 2023;16(11):3946. doi:10.3390/ma16113946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Sychov MM, Lebedev LA, Dyachenko SV, Nefedova LA. Mechanical properties of energy-absorbing structures with triply periodic minimal surface topology. Acta Astronaut. 2018;150(No 11–12):81–4. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2017.12.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Abou-Ali AM, Lee DW, Abu Al-Rub RK. On the effect of lattice topology on mechanical properties of SLS additively manufactured sheet-, ligament-, and strut-based polymeric metamaterials. Polymers. 2022;14(21):4583. doi:10.3390/polym14214583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Yang W, An J, Chua CK, Zhou K. Acoustic absorptions of multifunctional polymeric cellular structures based on triply periodic minimal surfaces fabricated by stereolithography. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2020;15(2):242–9. doi:10.1080/17452759.2020.1740747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Luo G, Zhu Y, Zhang R, Cao P, Liu Q, Zhang J, et al. A review on mechanical models for cellular media: investigation on material characterization and numerical simulation. Polymers. 2021;13(19):3283. doi:10.3390/polym13193283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Miralbes R, Cuartero J, Ranz D, Correia N. Numerical simulations of gyroid structures under compressive loads. Mech Adv Mater Struct. 2024;31(18):4236–45. doi:10.1080/15376494.2023.2192712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Han L, Che S. An overview of materials with triply periodic minimal surfaces and related geometry: from biological structures to self-assembled systems. Adv Mater. 2018;30(17):1705708. doi:10.1002/adma.201705708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Karcher H, Polthier K. Construction of triply periodic minimal surfaces. Philos Trans R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci. 1996;354(1715):2077–104. doi:10.1098/rsta.1996.0093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sun ZP, Guo YB, Shim VPW. Deformation and energy absorption characteristics of additively-manufactured polymeric lattice structures—effects of cell topology and material anisotropy. Thin Walled Struct. 2021;169(Suppl C):108420. doi:10.1016/j.tws.2021.108420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Balabanov SV, Makogon AI, Sychov MM, Gravit MV, Kurakin MK. Mechanical properties of 3D printed cellular structures with topology of triply periodic minimal surfaces. Mater Today Proc. 2020;30(6):439–42. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2019.12.392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Abueidda DW, Elhebeary M, Shiang CA, Pang S, Abu Al-Rub RK, Jasiuk IM. Mechanical properties of 3D printed polymeric Gyroid cellular structures: experimental and finite element study. Mater Des. 2019;165(9):107597. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2019.107597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shi X, Liao W, Li P, Zhang C, Liu T, Wang C, et al. Comparison of compression performance and energy absorption of lattice structures fabricated by selective laser melting. Adv Eng Mater. 2020;22(11):2000453. doi:10.1002/adem.202000453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Elenskaya N, Koryagina P, Tashkinov M, Silberschmidt VV. Effect of degradation in polymer scaffolds on mechanical properties: surface vs. bulk erosion. Comput Biol Med. 2024;174:108402. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Beer M, Rybár R. Optimisation of heat exchanger performance using modified gyroid-based TPMS structures. Processes. 2024;12(12):2943. doi:10.3390/pr12122943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang J, Chen X, Sun Y, Wang Y, Bai L. Vibration isolation and quasi-static compressive responses of curved Gyroid metamaterials fabricated by selective laser sintering. Eng Struct. 2025;325(11):119453. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.119453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kladovasilakis N, Tsongas K, Tzetzis D. Mechanical and FEA-assisted characterization of fused filament fabricated triply periodic minimal surface structures. J Compos Sci. 2021;5(2):58. doi:10.3390/jcs5020058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Restrepo S, Ocampo S, Ramírez JA, Paucar C, García C. Mechanical properties of ceramic structures based on Triply Periodic Minimal Surface (TPMS) processed by 3D printing. J Phys Conf Ser. 2017;935(1):012036. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/935/1/012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Doyle L, Terrones H, González C. On the rigidity and mechanical behavior of triply periodic minimal surfaces-based lattices: insights from extensive experiments and simulations. Adv Eng Mater. 2025;27(12):2402495. doi:10.1002/adem.202402495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ntousi O, Roumpi M, Siogkas PK, Polyzos D, Kakkos I, Matsopoulos GK, et al. Advances in computational modeling of scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: a narrative review of the current approaches and challenges. Biomechanics. 2025;5(4):76. doi:10.3390/biomechanics5040076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Matney A, Perez R, Song P, Wang XQ, Mignolet MP, Spottswood SM. Thermal-structural reduced order models for unsteady/dynamic response of heated structures in large deformations. Appl Eng Sci. 2022;12(9):100119. doi:10.1016/j.apples.2022.100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Poltue T, Montgomery SM, Sun X, Zhang C, Demoly F, Zhou K, et al. Machine learning-based optimization of pixel light intensities for improving polymerization accuracy in digital light processing 3D printing. Adv Mater Technol. 2025;10(20):e00902. doi:10.1002/admt.202500902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Cai Z, Liu Z, Hu X, Kuang H, Zhai J. The effect of porosity on the mechanical properties of 3D-printed triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) bioscaffold. Bio Des Manuf. 2019;2(4):242–55. doi:10.1007/s42242-019-00054-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Maszybrocka J, Gapiński B, Dworak M, Skrabalak G, Stwora A. The manufacturability and compression properties of the Schwarz Diamond type Ti6Al4V cellular lattice fabricated by selective laser melting. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2019;105(7):3411–25. doi:10.1007/s00170-019-04422-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Razi SS, Pervaiz S, Susantyoko RA, Alyammahi M. Optimization of environment-friendly and sustainable polylactic acid (PLA)-constructed triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS)-based gyroid structures. Polymers. 2024;16(8):1175. doi:10.3390/polym16081175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Dong Z, Zhao X. Application of TPMS structure in bone regeneration. Eng Regen. 2021;2(8):154–62. doi:10.1016/j.engreg.2021.09.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Gibson LJ, Ashby MF. Cellular solids: structure and properties. 2nd. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

28. Jacob GC, Fellers JF, Simunovic S, Starbuck JM. Energy absorption in polymer composites for automotive crashworthiness. J Compos Mater. 2002;36(7):813–50. doi:10.1177/0021998302036007164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Maharjan GK, Khan SZ, Riza SH, Masood S. Compressive behaviour of 3D printed polymeric gyroid cellular lattice structure. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2018;455(1):012047. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/455/1/012047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ji Q, Wang Z, Wang Y. Study on the compression energy absorption characteristics of 3D printed PLA and PLA-Cu materials. J Phys Conf Ser. 2023;2478(3):032086. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2478/3/032086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kazantseva NV, Onishchenko AO, Zelepugin SA, Cherepanov RO, Ivanova OV. Impact energy absorption in 3D printed bio-inspired PLA structures. Polymer. 2025;316(5):127876. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2024.127876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chen Z, Wu B, Chen X, Xie YM. Energy absorption and impact resistance of hybrid triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) sheet-based structures. Mater Today Commun. 2023;37(6058):107352. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Phoenix SL, Beyerlein IJ. Statistical strength theory for fibrous composite materials. In: Comprehensive composite materials. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2000. p. 559–639. doi:10.1016/b0-08-042993-9/00056-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools