Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Design, Realization, and Evaluation of Faster End-to-End Data Transmission over Voice Channels

1 The College of Computer Science and Technology, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing, 211106, China

2 The College of Command and Control Engineering, Army Engineering University of PLA, Nanjing, 210042, China

* Corresponding Author: Hao Han. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 69 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073201

Received 12 September 2025; Accepted 03 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

With the popularization of new technologies, telephone fraud has become the main means of stealing money and personal identity information. Taking inspiration from the website authentication mechanism, we propose an end-to-end data modem scheme that transmits the caller’s digital certificates through a voice channel for the recipient to verify the caller’s identity. Encoding useful information through voice channels is very difficult without the assistance of telecommunications providers. For example, speech activity detection may quickly classify encoded signals as non-speech signals and reject input waveforms. To address this issue, we propose a novel modulation method based on linear frequency modulation that encodes 3 bits per symbol by varying its frequency, shape, and phase, alongside a lightweight MobileNetV3-Small-based demodulator for efficient and accurate signal decoding on resource-constrained devices. This method leverages the unique characteristics of linear frequency modulation signals, making them more easily transmitted and decoded in speech channels. To ensure reliable data delivery over unstable voice links, we further introduce a robust framing scheme with delimiter-based synchronization, a sample-level position remedying algorithm, and a feedback-driven retransmission mechanism. We have validated the feasibility and performance of our system through expanded real-world evaluations, demonstrating that it outperforms existing advanced methods in terms of robustness and data transfer rate. This technology establishes the foundational infrastructure for reliable certificate delivery over voice channels, which is crucial for achieving strong caller authentication and preventing telephone fraud at its root cause.Keywords

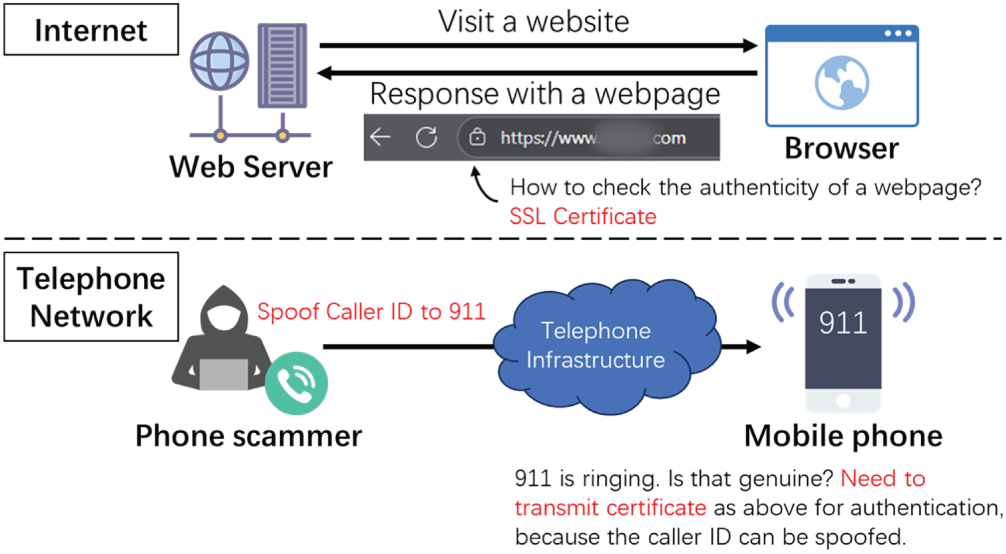

Phone scams and voice phishing (a.k.a. vishing) have seen a significant rise in recent years, largely fueled by the rapid advancement of evolutionary AI technologies and the increasing reliance on digital communication channels. Several studies have documented that complex phishing activities utilizing synthetic speech and social engineering are evolving [1,2]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, scammers and fraudsters exploit emerging technologies and public trust in institutions to deceive individuals into believing they are interacting with legitimate organizations, financial entities, or service providers. A critical tactic employed by phone scammers is the use of fake caller IDs [3], which manipulate the displayed incoming number to mimic known and trusted sources, thereby increasing the likelihood of the call being answered. Once connected, scammers utilize sophisticated social engineering scripts to extract sensitive personal information or financial details. Furthermore, advancements in artificial intelligence have enabled the use of AI-driven chatbots [4] and highly convincing deepfake voice synthesis [5] to impersonate familiar contacts or authority figures. The accessibility of caller ID spoofing tools, such as those referenced in [6,7], allows malicious actors to easily disguise their identity by displaying any chosen number—including emergency lines like 911—further eroding trust in telephonic communication systems. Analysis of phishing trends indicates that traditional authentication mechanisms are insufficient against these emerging threats [8].

Figure 1: Motivation of our idea to prevent phone frauds

To stop phone scams, we believe it is essential to authenticate conversation parties over traditional telephone networks. This is similar to the Internet: When a user visits a website, the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) certificate plays an important role in ensuring the authenticity of the website. However, the modern telephony infrastructure provides no means for a callee to reason about the caller’s identity except the called ID, which can be spoofed. We need the caller to have the capability to transmit its digital certificate to the callee for authentication. However, several challenges prevent us from achieving this goal, including:

• C1: Without the support of cellular carriers. The transmission of digital certificates should be end-to-end and compatible with existing infrastructure without relying on cellular carriers. For example, dial-up modems have been available for decades to transmit data through telephone lines. However, this approach does not work for mobile phones. That is because the baseband in a smartphone that helps convert digital data into radio frequency signals (and vice versa) is a black box for end users. It is challenging for users to implement their own dial-up modem on their smartphones without the support of vendors.

• C2: In case of NO Internet. Although mobile data offers an alternative solution to transfer data over cellular networks such as 4G/5G, it will incur an extra financial cost. GSMA Research [9] shows that 3.4 billion mobile consumers still cannot pay for the Internet despite living in areas with mobile data coverage. Also, data plans are unavailable in certain areas with weak signals.

In particular, enabling the caller to transmit its digital certificate directly over the voice channel provides a practical defense mechanism when Internet connectivity is absent. Unlike approaches that rely on mobile data or Wi-Fi, our vision is that the certificate can be embedded as digital data within the ongoing call itself. This allows the callee to authenticate the caller in real time, even in areas with limited network coverage or among populations unable to afford data plans. By reusing the ubiquitous voice channel as a carrier of authentication information, our system strengthens trust in telephony without imposing additional infrastructure requirements or financial burdens on end users.

Some studies have proposed approaches such as Hermes [10] and Authloop [11] to enable data transmission over the voice channel of cellular networks. However, those works perform poorly in our experiments with China Mobile networks and cannot reach a fast enough data rate to transmit digital certificates. After analyzing the collected signals, we found that those approaches stopped working after a short time (see Section 2 for details). A possible reason is that if we carry data into acoustic signals, those non-speech-like signals may be rejected by the Voice Activity Detector (VAD) used in the Discontinuous Transmission (DTX) within cellular telecommunication systems. In addition, the complex network infrastructure will distort signals transmitted from one subsystem to another, and the voice/speech codec may severely distort the encoded signals.

To this end, we revisit the long-standing idea of transmitting digital data over voice channels and present Fast Data Over Voice (FastDOV)—a fast and reliable data transmission mechanism that enables the exchange of digital certificates between callers and callees, even in the absence of Internet connectivity. By empowering each party to authenticate the other during a phone call, FastDOV directly addresses the root cause of many phone scams: the inability of users to verify caller identities. Technically, FastDOV employs a chirp-based modulation/demodulation scheme that is resilient to distortions in complex telecommunication infrastructures, as chirp signals are well known for their robustness against channel noise. To further enhance decoding accuracy in weak signal environments, we integrate deep learning (DL) models that recover distorted chirp signals. In addition, we design a dedicated data link protocol incorporating stop/resume, time synchronization, and retransmission mechanisms to mitigate the impact of Voice Activity Detectors (VAD) and Discontinuous Transmission (DTX). We implemented a prototype of FastDOV on Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) smartphones and evaluated it through extensive experiments. Results demonstrate that FastDOV achieves an average goodput of 1291.0 bit/s over diverse mobile networks, outperforming state-of-the-art approaches, while making real-time certificate transmission practical for reducing phone fraud.

The contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

• We propose a novel DL-based acoustic scheme that can transmit data over mobile voice channels. The demodulation is robust to distortions and interruptions in cellular voice channels by modulating the frequency, shape, and phase of chirp signals.

• Since the caller and the callee do not synchronize over voice channels, we design a cross-correlation-based method with a remedying algorithm to accurately determine when the data transmission begins and ends without using an external clock.

• We present a working prototype of FastDOV and an extensive empirical study under various environmental factors such as weather conditions and noise impact at the transmitter and receiver. The evaluation results show that FastDOV achieves higher goodput than state-of-the-art approaches.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the background and challenges. Section 4 provides a detailed description of FastDOV’s design. Section 5 presents the implementation and evaluation results with practical use cases. Last, Section 3 describes the existing related work, followed by the conclusion in Section 7.

In this section, we identify several challenges to achieving fast data transmission over a mobile voice channel and provide some background.

2.1 Rejection of Non-Voice-Like Signals

In cellular networks such as Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) and Code-division Multiple Access (CDMA), Discontinuous Transmission (DTX) technology is widely used to stop transmitting signals when there is no voice signal transmission to reduce interference and improve the system’s efficiency. Voice activity detection (VAD) is a technology to detect whether a voice signal exists. The presence of VAD/DTX can be crucial for transmitting any modulated signals over voice channels. Once the audio is determined as non-speech, it will be removed from the transmission, leading to the loss of the signal and a deterioration in the transmission performance [12].

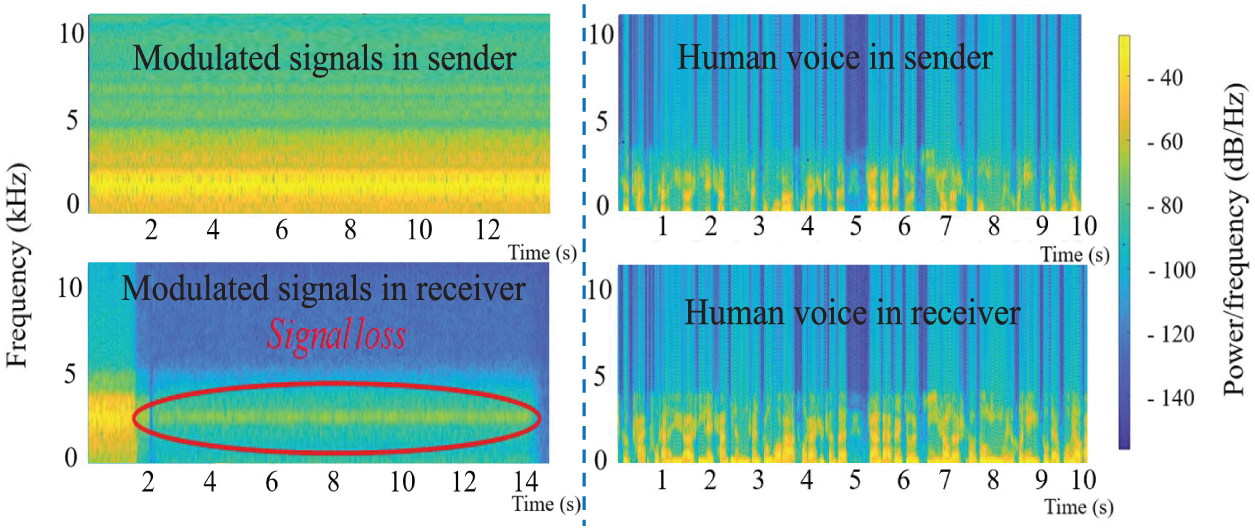

To demonstrate, we implemented several existing approaches for data transmission over the voice channel, including Hermes [10] and Authloop [11], and tested them in China Mobile/Telecom/Unicom. The basic idea is to modulate a 0 or 1 bit by decrementing or incrementing the base frequency by a fixed delta and transmit a sinusoid of these frequencies for 15 s. We observed that the audio signals received at the callee side were significantly weakened after 1–2 s of transmission time. This phenomenon can be seen from the comparison between the spectrogram of the original signal and that of the signal in the receiver, as shown in Fig. 2. If playing a human speech sound instead, we did not observe any filtering out of the received signal.

Figure 2: Spectrogram comparison between modulated signals and normal human voice, where modulated signals were filtered out after 1-2 s by cellular networks

2.2 Limited Frequency Band and Codec Effect

As mentioned in previous studies, not all frequencies in the voice channel of the GSM and its successors, 4G/5G, are suitable for modulating data. Since they are designed to transfer speech only, the energy that reflects the main characteristics of human speech is mainly concentrated in the range of 0.3khz–3.4khz. The audio signal will be band-pass filtered, and components outside this frequency range are automatically removed.

In addition, audio and speech codecs widely used in the voice channel will also distort the modulated audio signals that carry information significantly. Previous work [13] provides the reasons for the unpredictable distortions produced by speech codecs. Linear predictive coding (LPC) is used in audio/speech codecs to digitize voice. However, LPC is a lossy compression technique. Thus, the synthesized voice differs considerably from the original waveform, introducing additional distortion. In addition, linear prediction and differential coding for extracting speech parameters assume a high correlation between adjacent input samples. This assumption applies to speech but not to conventional data signals.

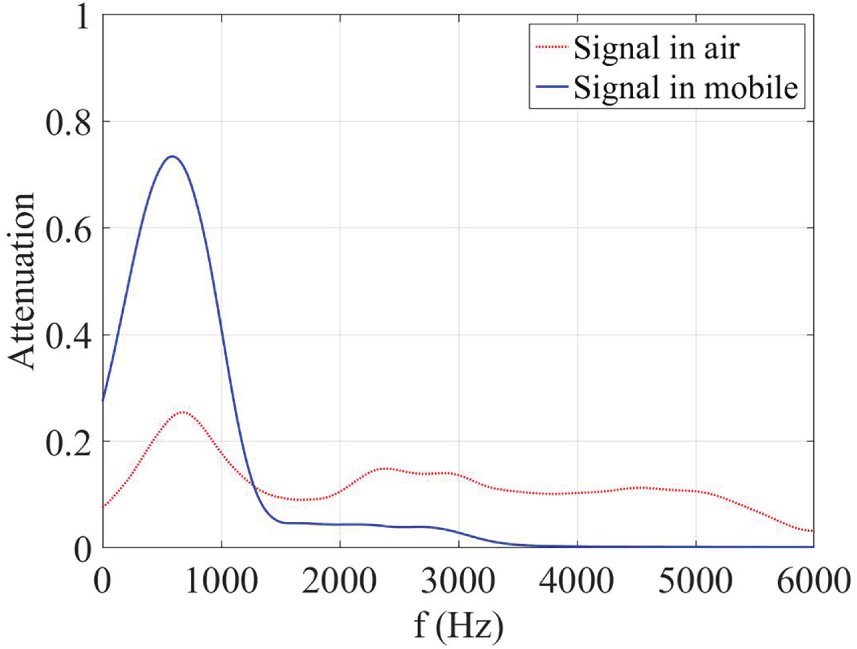

To demonstrate, we generated a chirp signal with a linear increment from 0 to 24 KHz in our experiment. After measuring our cellular networks, we found that frequencies in the range of human speech have different attenuation.

Fig. 3 shows the attenuation ratio (

Figure 3: FFT of original/received signals

2.3 Heterogeneous Telephony Infrastructure

Circuit-switched networks [14] were used in the first generation of wireless mobile communication in the 1980s. In the 2.5G era, the General Packet Radio Service (GPRS) [15] was added to communication as a packet-based data service. Until the 4G era, LTE (Long Term Evolution) emerged [16], with the core network EPC (Evolved Packet Core) eliminating the circuit domain. To support all networks, the telephony architecture becomes increasingly complex with a considerable number of subsystems. The voice has to travel across multiple hops from the caller to the callee. Each intermediate link may use different protocols. Thus, the voice may be converted from analog to digital, then to analog, and back to digital. This process may be repeated across every hop until the destination is reached, resulting in unpredictable distortions.

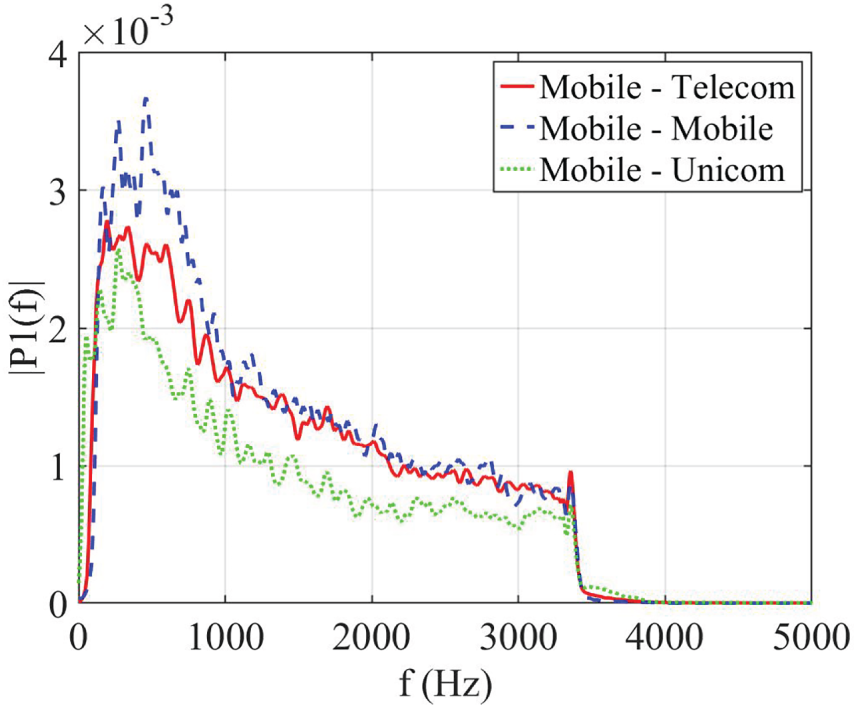

We conducted the experiments by transmitting the aforementioned chirp signal through one carrier (e.g., inside China Mobile) and multiple carriers (e.g., Mobile

Figure 4: Affect of heterogeneous telephony infrastructure

3.1 Acoustic Data Transmission in the Air

Data transmission using acoustic signals in the air typically uses near ultrasonic sound waves or sometimes audible sound waves that exceed the voice channel’s frequency range. Previous work [17] proposed a wireless keyboard link using binary Frequency-Shift Keying (FSK)-modulated ultrasonic signals. Work [18] implemented OOK and binary FSK modulation schemes in the system with wireless synchronization. Hush [19] used Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplex (OFDM) to send data over a 5–20 cm distance between commercial smart mobile devices at frequencies 16–20 KHz. Work [20] used data sequence control and error correction algorithms to communicate high-frequency audio data. Work [21] proposed a method similar to FSK with 3 kHz as the base frequency to broadcast Wi-Fi information to customers through sound signals with a supported distance from 10 to 100 cm.

Existing work in this category mainly uses ultrasonic signals for data transmission without considering all constraints in mobile communication channels, such as narrow frequency bands and signal distortions caused by heterogeneous networks and speech codes. Hence, they are not suitable for data transmission over voice channels.

3.2 Data Transmission over Voice Channels

Data over voice is a technique based on encoding data signals into speech-like parameters, codebook training, or modulation techniques [22]. Previous work [23] implemented a real-time prototype and maps the input data on line spectral frequencies, pitch frequency, and speech frames energy, which can facilitate the encrypted data transmission using unknown encryption methods. Work [24] also used a similar mapping, but they applied the FR (Full Rate) vocoder, which has a short time delay and good interoperability. Work [25] encoded the data by a set of predefined signals called “symbols”, which are synthesized by genetic algorithms. PCCD-OFDM-ASK (Phase Continuous Context Dependent- Orthogonal Frequency Division-Multiplexing Amplitude Shift Keying). Work [26] combined PCCD on OFDM, thus having robust and reliable data transmission over the GSM or CDMA(Code Division Multiple Access) speech channels. Hermes [10] can transmit data over unknown voice channels with the idea of frequency shift keying coding in the voice channel. Work [27] used a single codebook to transmit the voice and designed an efficient low-bit-rate speech coder. Work [28] synthesized waveform symbols using sinusoidal signals and designed a learning algorithm for obtaining demodulated codebooks online to construct a general implementation scheme for DoV. This scheme proposes an analysis algorithm based on surface packaging to optimize the modulation codebook offline, so it has good symbol error rate (SER) performance. Work [22] proposed a DoV technology based on a short harmonic waveform codebook, which relies on linear predictive coded speech compression (LPC speech coding) and has a high transmission rate and robustness. AuthLoop [11] provided a strong cryptographic authentication protocol inspired by Transport Layer Security (TLS) 1.2 to determine the identity of the entity at the other end of the call (that is, the caller ID). Work [29] proposed a modulation algorithm based on Frequency Modulation (FM). This algorithm can convert encrypted voice data to a waveform that conforms to GSM voice channel specifications. However, in this method, the actual modulator bit rate does not allow real-time communication. Overview [30] provides a more detailed summary of the improvement or design of modulation, which divides the methods into three categories which are parameter mapping, codebook optimization, and modulation optimization.

It is also worth distinguishing our work from another class of solutions that focus on post-answer detection by analyzing speech content using on-device models [31] or large language models [32]. While effective for content analysis, these methods intervene after the call has been connected and trust established. In contrast, FastDOV aims to provide pre-answer authentication by transmitting a verifiable certificate before the conversation begins, addressing the threat at an earlier stage.

Compared to the above work, most approaches require the help of telephony service providers, while our work is a pure end-to-end solution. Our FastDOV also incorporates deep learning technology into modulation and demodulation to improve the robustness of data transmission.

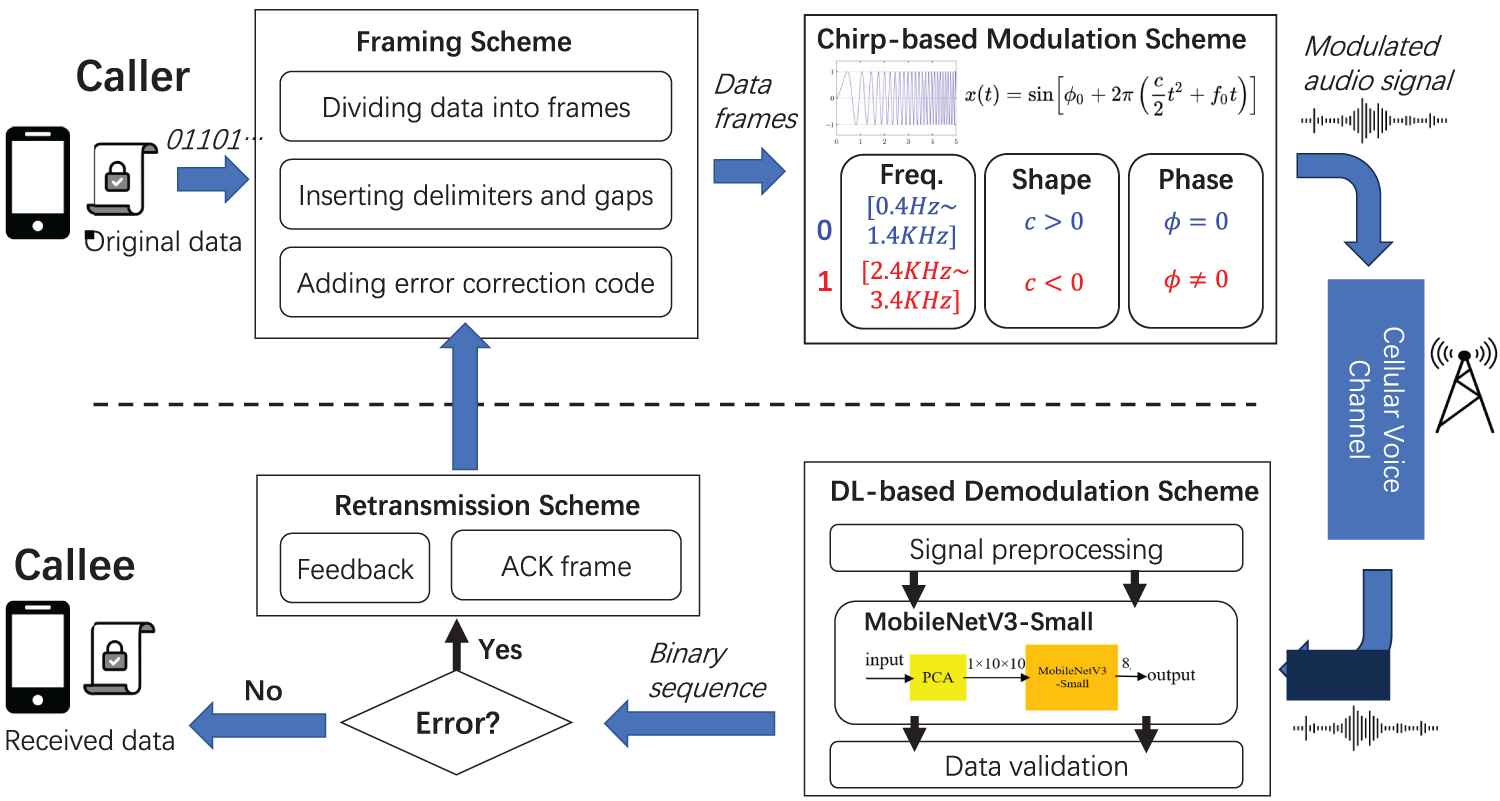

To address the challenges mentioned in Section 2, we propose FastDOV, an end-to-end data modem on top of existing (unmodified) cellular voice channels. The overview of FastDOV is presented in Fig. 5, illustrating the workflow between a transmitter and a receiver. The transmitter first divides the data under transmission into multiple frames according to a pre-defined size. A specially designed delimiter is inserted at the beginning of each frame and the end of the last frame. Each frame is appended with an error correction code and converted into an audio signal using a chirp-based modulation. The modulated chirps are then transmitted over the cellular voice channel.

Figure 5: System framework

When the phone call is answered, the receiver relies on the delimiter to locate each frame’s beginning and end within the received audio stream. These frames are demodulated and decoded by a Deep Learning (DL) model, followed by the error correction check. If any error is found, a feedback mechanism is proposed to notify the sender to retransmit the frames that are in error. Lastly, all successful frames are combined to restore the original data.

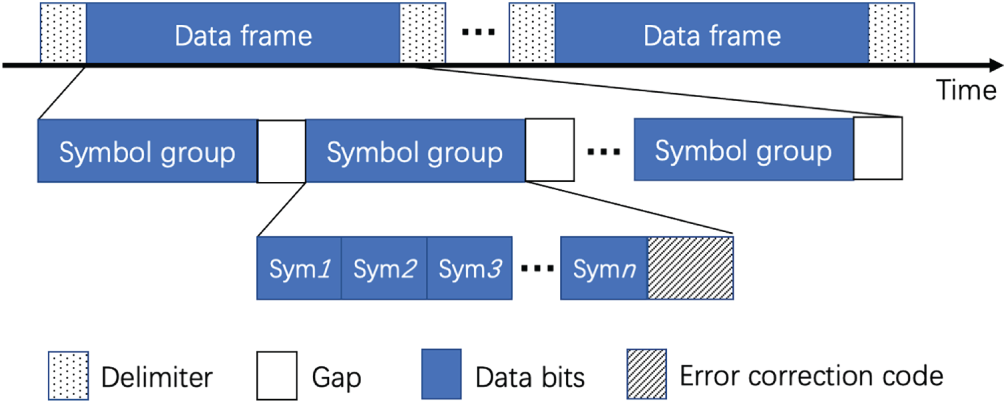

In FastDOV, data are divided into multiple frames and transmitted over a voice channel. The format of a data frame is presented in Fig. 6. A specially designed signal is inserted to separate each data frame, and we call it a delimiter. A data frame comprises multiple symbol groups (SG), each of which contains several symbols carrying a fixed length of data bits and parity bits for error correction. To avoid the impact of VAD and DTX mentioned in Section 2, we add a gap between consecutive SGs. Such a gap is an empty signal without carrying any information, aiming to remove the memory of the VAD/DTX algorithm.

Figure 6: The data format of frames and symbols

Determining the start/end of transmission. We designed a unique chirp as a delimiter, inserted at the start of every frame and appended to the last frame to indicate when the data frames begin and end. The goal is to ensure synchronization between the receiver and transmitter. Furthermore, the inserted delimiter is also treated as a guard to protect our data signals. That is because the sudden energy change on a voice channel may cause signal fluctuation, so the frontmost and backmost data signals may not be received completely. Adding delimiters can reduce the loss of data frames.

To detect the exact position of a delimiter on the receiver side, we adopt a cross-correlation-based method, where the known delimiter signal is correlated with the received audio stream in a sliding window. Let the received signal stream as

where

To accelerate the computation time, we first locate a delimiter’s approximate position c by computing the coefficient window by window. Within the range of

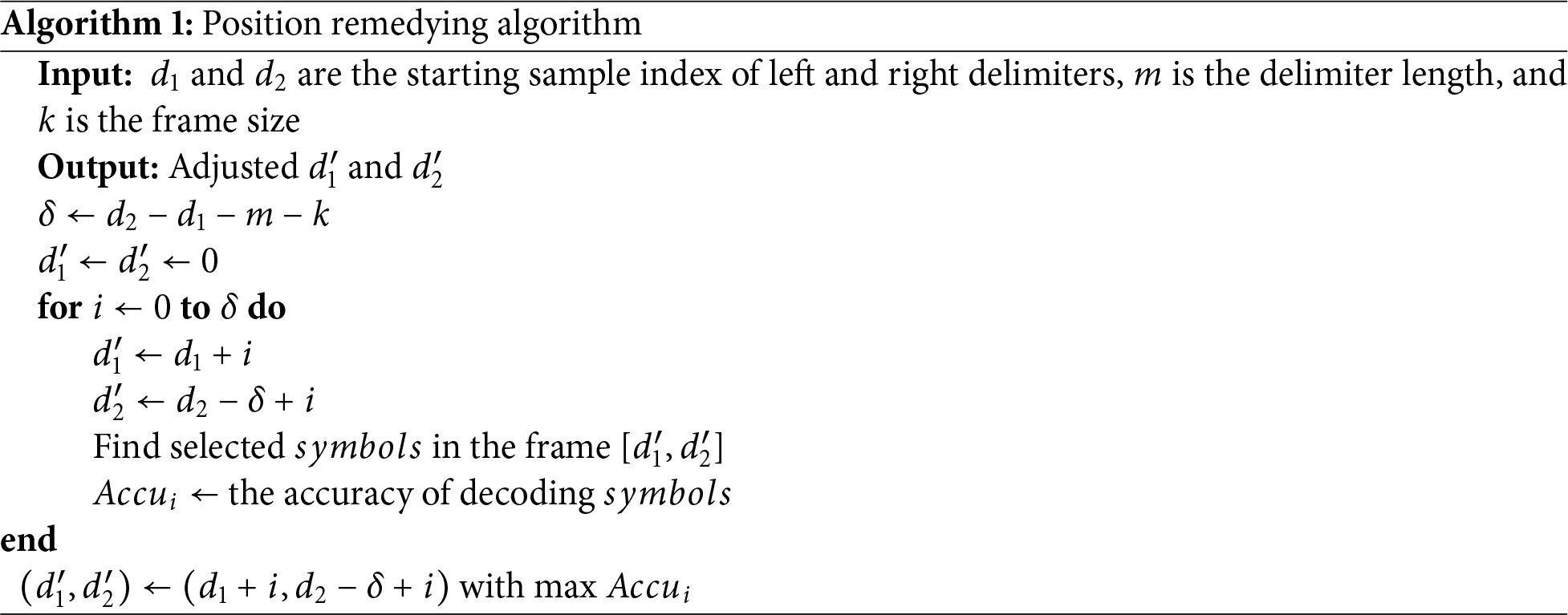

Remedying inaccurate frame positions. Due to unpredictable channel noise, cross-correlation sometimes may not locate delimiters accurately, so the derived data frame does not have the pre-defined length. Suppose each data frame contains k audio samples at a certain sampling rate, and two delimiters surrounding the frame are positioned at sample indices

Algorithm 1 presents our remedying algorithm. First, we set selected symbols in the data frame to a fixed value so the receiver knows these symbols beforehand. Next, we try every possible adjustment from

Adding error correction code. Since some bits could be transmitted incorrectly, in FastDOV, we use Reed-Solomon code (RS) [33] as our error correction code, which will be added at the end of each symbol group.

We employ RS codes with parameters

4.2 Chirp-Based Modulation Scheme

Modulation and demodulation refer to the process of altering the carrier signal to contain information to be transmitted and vice versa. There are common modulation methods widely used in practice, including On-Off Keying (OOK), Amplitude-Shift Keying (ASK), Frequency-Shift Keying (FSK), and Phase-Shift Keying (PSK). In OOK, a 0/1 bit is defined by the presence or absence of the carrier signal. ASK changes the amplitude of a carrier signal to encode different bits of information. Since OOK and ASK can be easily affected by signal distortion, they are unsuitable for data modulation over voice channels. In FSK, the frequency of a carrier signal with constant amplitude switches as the input bitstream changes. PSK is a phase modulation method that switches the carrier phase between different values based on the level of a digital baseband signal. Due to the tendency of FSK and PSK to cause discontinuity in the input signal, they do not resemble sound. The codec can severely distort such signals, making them unsuitable for data modulation over voice channels.

In FastDOV, we adopt a chirp signal rather than sinusoidal waves used in [10] and [28] for modulation. Due to its strong anti-interference feature, Chirp has a wide range of applications in communication, sonar, radar, and other fields. Our experiments show that a linear-frequency chirp is enough to tolerate noise and signal distortion on the cellular voice channel. In a linear chirp, the instantaneous frequency

where

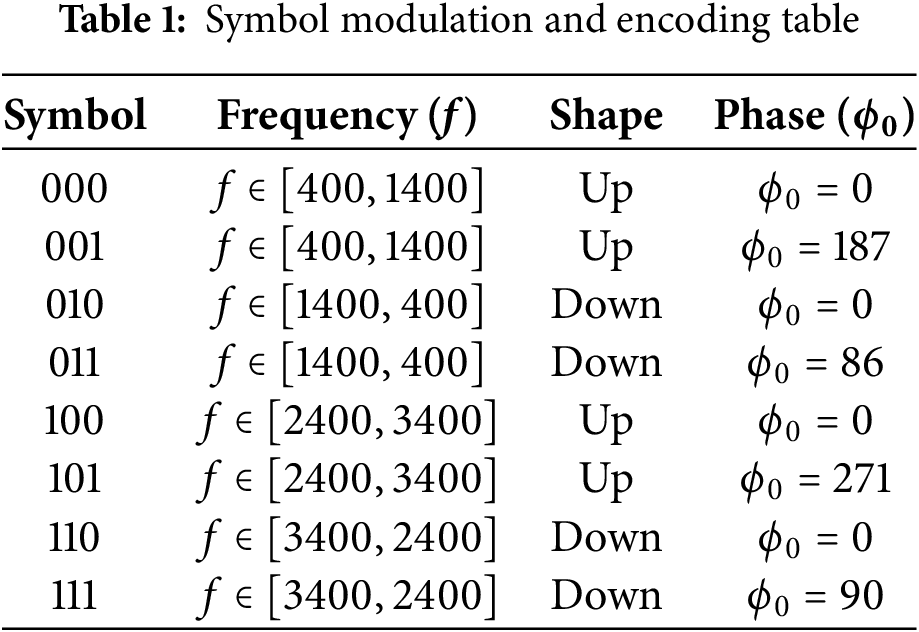

Frequency. As mentioned in Section 2.2, the voice channel responds differently to the signals in certain frequencies. We propose to use different frequency ranges to encode bits 0 and 1, respectively. As shown in Eq. (1), bit 0 is represented by the frequency range of

Shape. In either frequency range, we can switch the starting frequency

Phase. Without changing the frequency and shape of a chirp signal, we can modulate an extra bit by using different initial phases. According to Eq. 3, whether the signal carries 0 or 1 depends on whether the initial phase

4.3 DL-Based Demodulation Scheme

Since our modulation scheme is based on frequency, shape, and phase, a straightforward method is to demodulate every bit of the symbol separately. For example, we can calculate the symbol’s FFT to determine its frequency range. We can compare the FFT of the signals’ first and second halves to determine the up-chirp and down-chirp. If the magnitude of the former is less than the second, the chirp is up; Otherwise, it is down. To compare the initial phase, we can compute the complete FFT with real and imaginary parts. However, this approach is too ideal and does not work well in practice due to signal distortion in voice channels. Instead, we propose using deep learning (DL) to improve demodulation accuracy.

Feature extraction.

The features selected by FastDOV include time-domain, frequency-domain, and phase-angle features of signals. Given the sampling rate is Fs, the time duration of each symbol is t, and the input of a received symbol is

• Time-domain features refer to signal characteristics that change over time. For these features, we directly each sample value in the time domain.

• Frequency-domain features utilizes the output of the Fourier transform. The first part contains the magnitude of each frequency bin of the entire signal after FFT. The second and third parts are calculated similarly but independently based on the first and second halves of the signal. The number of each part is

• Phase angle features refer to the angle difference between a particular moment in a cycle and a reference moment. In signal processing, the phase angle can be used to describe the phase difference of a signal. We calculate the phase feature using the arctangent function

Data preprocessing. In linear regression models, it is generally required that the linear correlation between features is low and the number of features is less than the sample size. Otherwise, it may lead to problems such as increased variance and overfitting of parameter estimates. Therefore, our model uses PCA (Principal Component Analysis) [34] to process the data inputs. PCA is a commonly used linear dimensionality reduction method that maps n-dimensional features onto lower-dimensional k-dimensions through a certain linear projection. We selected PCA because it can not only mitigate the overfitting problem but also reduce the computational cost.

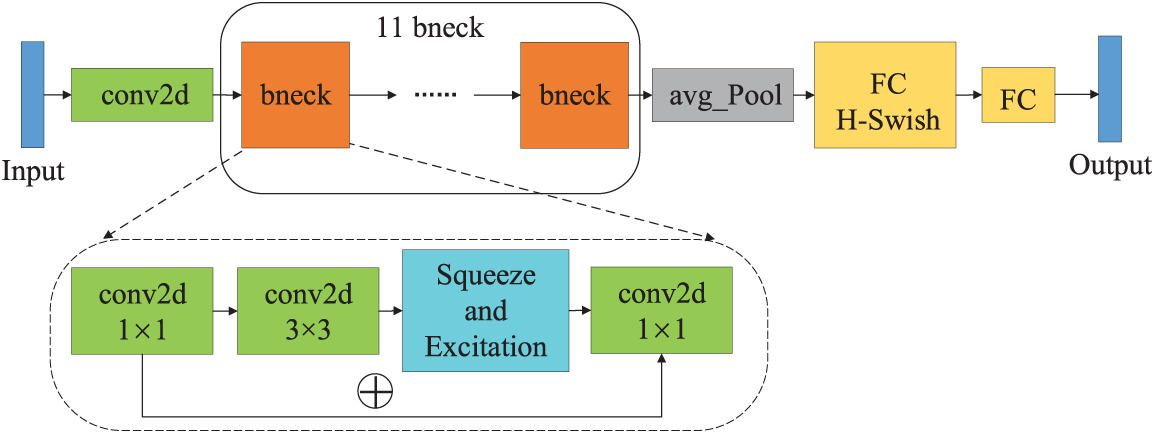

DL-based demodulator. We use the MobileNetV3-Small [35] model to demodulate the received signal in FastDOV. The MobileNetV3-Small model is a lightweight deep neural network proposed by Google for embedded devices such as smartphones [36], aiming to improve mobile device efficiency and performance. In our design, MobileNetV3-Small will take the signals processed by PCA as the input and generate classification results (the eight classes in Table 1).

We chose MobileNetV3-Small due to its ability to achieve excellent accuracy with minimal complexity. It is a lightweight CNN model that can effectively capture spatial information in images and perform translation-invariant processing on features. This translational invariance property also enables CNN to process signal data well. Signal data is similar to image data, but also has spatial and local correlations. The convolution and pooling operations of CNN can extract local features from signal data, making it a universal network structure for processing signal data. Besides, the structure in Fig. 7 ensures that MobileNetV3-Small achieves higher accuracy with lower complexity, which is very suitable for running on mobile phones.

Figure 7: The architecture of MobileNetV3-Small

As shown in Fig. 7, MobileNetV3-Small consists of 11 core modules, which are also the basic module of the network, bneck. Each bneck includes channel separable convolution, squeeze and excitation module (SE), and inverted residual module. Among them, the lightweight depthwise separable convolution module decomposes the standard convolution operation into two steps: first, channel separation, and then channel wise convolution; the SE module introduces a global average pooling layer and models the importance of the channel using a pair of fully connected layers; the inverted residual module connects two basic convolution modules and uses shortcuts for cross layer connections to achieve cross layer information transmission. These modules enhance the model’s perception of important features while reducing computational complexity.

Model parameters. In FastDOV, the PCA model reduces the dimensionality of any input to 100. Since the raw features could be high-dimensional (if a symbol has 240 sampling points, its feature dimension will be 524). We use MobileNetV3-Small to demodulate symbols. In this model, symbols are first deformed into 10

Preparing training dataset. The training data are self-collected by callers and callees in China Mobile and China Mobile networks. On the caller side, we randomly generate a large number of symbols and transmit them to the receiver using our modulation scheme. Once receiving these symbols, the callee knows their corresponding labels. However, as mentioned in Section 4.1, the position of each delimiter is difficult to determine accurately. Thus, some received frames may be extracted incorrectly. To reduce the negative effect of low-quality training data on our model, we use the same Algorithm 1 to remedy

Although our MobileNet-based demodulator significantly improves symbol recognition, it still cannot guarantee 100% accuracy due to various reasons (for example, signal distortion, channel noise, or interference). Thus, we propose a retransmission mechanism to provide reliable communication when a non-recoverable error occurs.

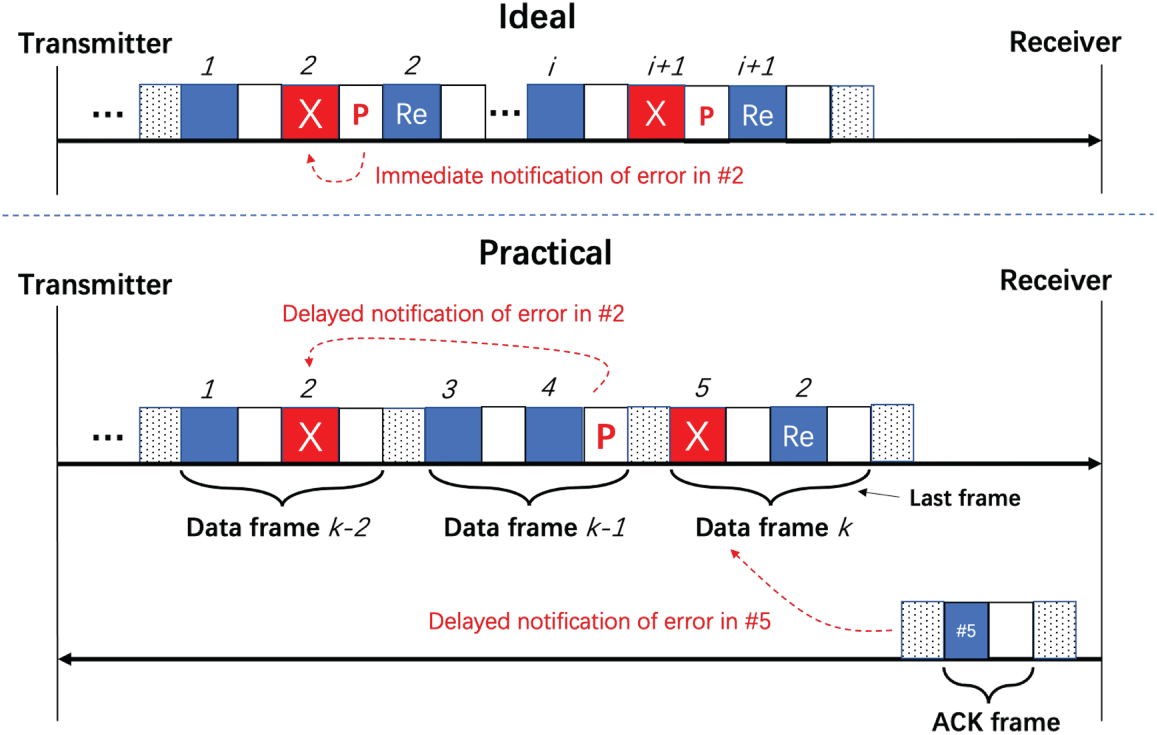

The detail of the retransmission mechanism is shown in Fig. 8. Upon receiving a symbol group, the receiver performs error checking and correction based on the parity bits received at the end of the group. If successful, it implies that the data has been received without errors. However, if the correction fails, it indicates the presence of errors in the data. The receiver then sends a feedback pulse in the upcoming gap. Once the pulse is detected anywhere in the gap, the transmitter will retransmit the symbol group just sent. Ideally, damaged/error symbols should be sent immediately after the receiver provides feedback in the gap. However, a practical solution is to delay the acknowledgment in the next data frames. For example, we use gaps in the data frame k to acknowledge symbol groups in data frame

Figure 8: Retransmission mechanism

If the receiver cannot successfully receive some symbol groups in the last data frame, he will send an individual Acknowledgement (ACK) frame to the transmitter to notify them of the missing symbol groups. Like a normal data frame, the ACK frame comprises delimiters, symbol groups, and gaps. However, the data delivered by symbol groups in an ACK frame is the index of errors. Once this ACK frame is received, the transmitter will retransmit all damaged/missing symbol groups. Note that if the receiver has sent out an ACK frame but does not receive any retransmitted data, it indicates the loss of the ACK frame, and it will send a new one.

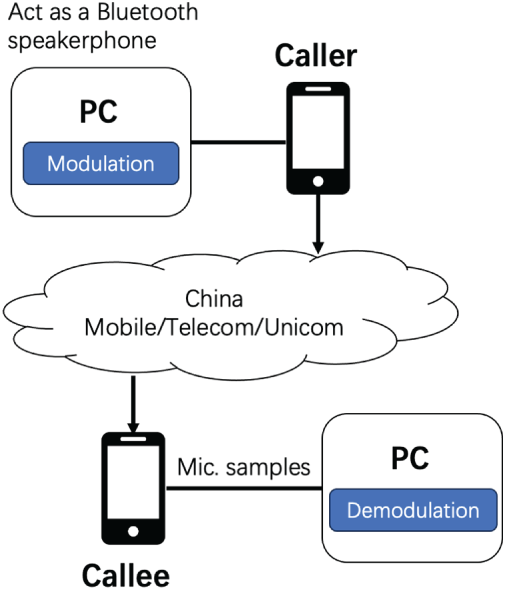

Experimental settings. As shown in Fig. 9, our experiments involve two smartphones, which communicate through cellular networks, and two laptops used to modulate/demodulate the data. Due to strict permission controls in smartphone operating systems, ordinary applications cannot directly implement underlying modem functions. Thus, we cannot directly implement FastDOV on COTS smartphones without rooting the phone. Instead, we use a PC to emulate a Bluetooth speakerphone of the caller’s device so that we can manipulate the calling voice on the PC. This is much easier to implement than rooting the phones. Similarly, we leverage another PC connected to the callee to demodulate the received audio data. It should be noted that if the phone manufacturers provide support in the future, we could easily adapt the implementation into a PC-free scheme.

Figure 9: Experimental settings with two smartphones and laptops

In our experiments, we use a Lenovo Y7000 laptop (Intel i7-9750H CPU) as an emulated Bluetooth speakerphone of a Huawei P60 (Snapdragon 8+ 4G Platform, EMUI 13.1 system), leveraging the Hands-free profile protocol [37]. The signal modulation part of FastDOV is implemented on the laptop in Python. During a phone call, the voice signals will be first modulated on the laptop and then fed into the emulated Bluetooth speakerphone. A Xiaomi Redmi Note 7 phone acts as a receiver to record phone calls, which will be demodulated by another Lenovo Y7000 laptop. As for the cellular networks, we use the telecommunication networks provided by the three major carriers in China, including China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom.

Model training. To train our MobileNet-based demodulation model, we collected a dataset of 28,800 modulation symbols with a 70/30 split for training and testing sets. In the data collection stage, we used an audio sampling rate of 48 kHz and a Reed-Solomon code ratio of 3 data bits to 1 parity bit. We utilized an interleaved structure for the symbol groups, where each group contains 600 symbols (with ten symbols used for error correction) and is separated by a 0.5 s gap. The length of each symbol is 0.001 s, resulting in 48 samples per symbol, given the 48 kHz sampling rate. We used a 0.1 s linear chirp as the delimiter. All the collected modulation symbols are labeled into eight classes. Table 1 summarizes the Symbol modulation and encoding table.

The MobileNetV3-Small model used for demodulation will firstly be initialized by parameters pretrained on the ILSVRC2012 dataset [38] and then fine-tuned by the modulation symbols collected in our experiments. We use cross-entropy loss and SGD (stochastic gradient descent) optimizer with the weight decay set to 0.8 in the model training. We fine-tune the model for 40 epochs using a batch size of 64. The learning rate is 0.0005 for the first 30 epochs and decreases to 0.00005 for the latter 10 epochs. During the training, to improve model performance, we add noise sampled from a uniform distribution (

Performance metrics. We choose three widely accepted performance metrics, including accuracy, throughput, and goodput, to evaluate the prototype of FastDOV.

Accuracy considered in this paper is twofold. First is the accuracy of locating the positions of start and end delimiters in received audio streams. It indicates how well our approach is able to separate modulated symbols. Second is the accuracy of our DL-based demodulator to classify symbols correctly.

Throughput is the amount of all received bits (whether useful or not), including protocol overhead bits and duplicated bits per unit of time.

Goodput is the amount of useful information delivered to the receiver per unit of time. We calculate the goodput by dividing the data size by the finish time to transfer all data successfully. In practice, some communication systems may have large throughput but suffer from low goodput due to the overhead bits transferred between parties and a large number of retransmissions.

Experimental consistency. All comparative experiments are conducted under identical conditions: the same hardware platform (Huawei P60 and Xiaomi Redmi Note 7 smartphones with Lenovo Y7000 laptops), the same test dataset, and the same evaluation metrics.

Evaluation goals. With the above experiment settings and performance metrics, we evaluate the performance of FastDOV by answering the following questions:

1. RQ1: How do parameters such as delimiter length, symbol length, and gap length affect the performance of FastDOV in practice?

2. RQ2: How do deep learning models affect the accuracy of FastDOV?

3. RQ3: What is the performance of FastDOV by environmental factors such as cellular signal strengths and phone brands?

4. RQ4: Can FastDOV improve the state-of-the-art (SOTA) data transmission systems over voice channels?

To answer RQ1, we conducted experiments to study the impacts of various parameters, including delimiter pattern/length, symbol length, and duration of the gap by changing the value of each parameter with the others fixed. All experiments in this section were conducted in environments with strong cellular signals to achieve stable and reliable results. In the next section, we consider the scenario with weak signal strength. We tested FastDOV in all cellular carriers, but only present the results in China Mobile because they all show similar performance.

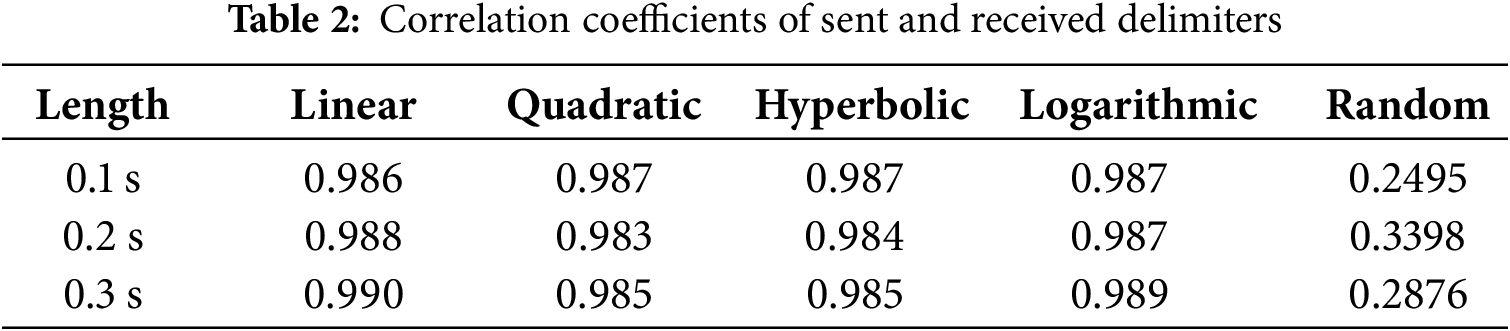

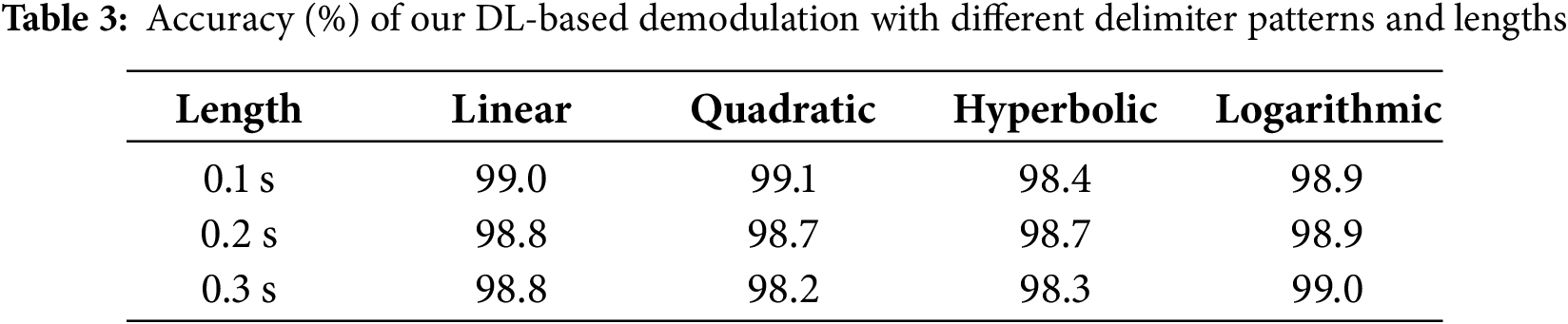

Delimiter pattern and length. The positioning of the delimiter is a prerequisite for FastDOV to demodulate the received symbols correctly. Different delimiter patterns (e.g., random sine signals and various types of chirps) and their lengths may affect the accuracy of separating modulated symbols in FastDOV. It is necessary to understand their performance and choose the best value of this parameter for practical use.

We tested different delimiter patterns, including linear chirp, quadratic chirp, hyperbolic chirp, logarithmic chirp, and random values. Each pattern was set for 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 s, respectively. Table 2 shows the similarity (in terms of correlation coefficients) between the sent and received delimiters, where a value closer to 1 means higher similarity. This table indicates that chirp signals of any shape (similarity above 0.98) are superior to random sine signals (similarity only 0.2–0.3). Therefore, we choose the chirp signal as the delimiter.

Besides, Table 3 presents the demodulation accuracy of our approach based on these delimiter patterns and lengths. We can see that regardless of how the delimiter changes, the correlation is high enough to determine symbol positions accurately. Meanwhile, our demodulator’s accuracy is above 0.98. After the Reed-Solomon (RS) error correction, the accuracy even increases to 100% without retransmission. Since there are no big differences in using different types of chirp-based delimiters, we choose a linear chirp with 0.1 s in practice to reduce computation complexity.

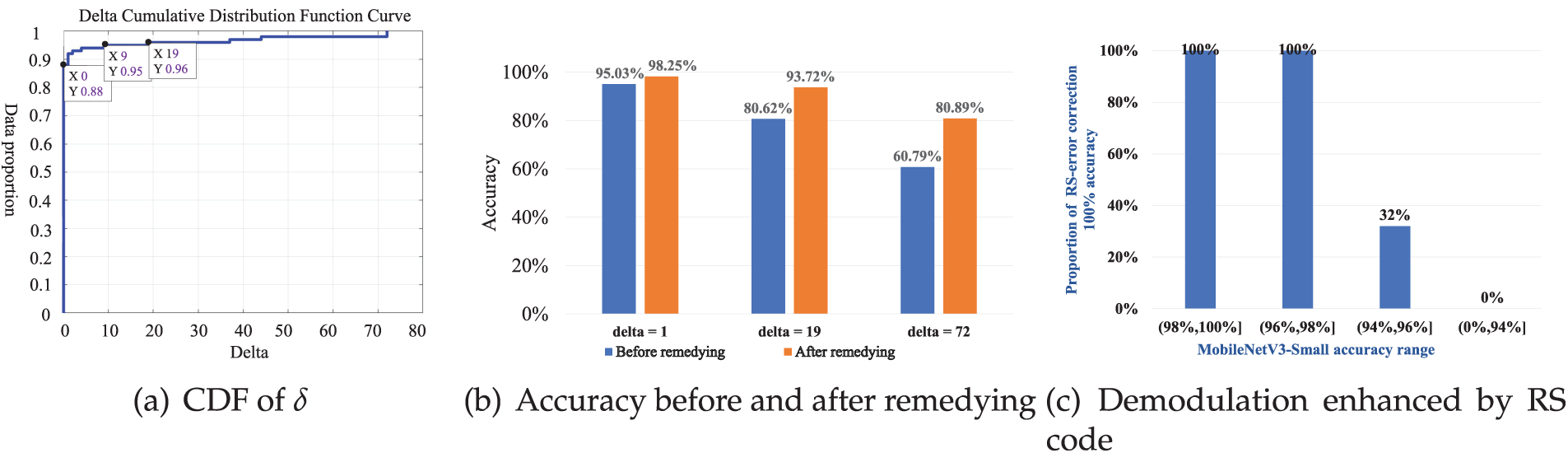

With the above delimiter, we studied

Figure 10: Performance of our cross-correlation method and position remedying algorithm in FastDOV

If

As shown in Fig. 10c, the RS code we use can 100% correct all symbols with an accuracy of demodulation over 96%, as well as some cases with an accuracy of 94%∼96%, which does not require retransmission. Otherwise, the retransmission mechanism is triggered to fetch all missing symbols.

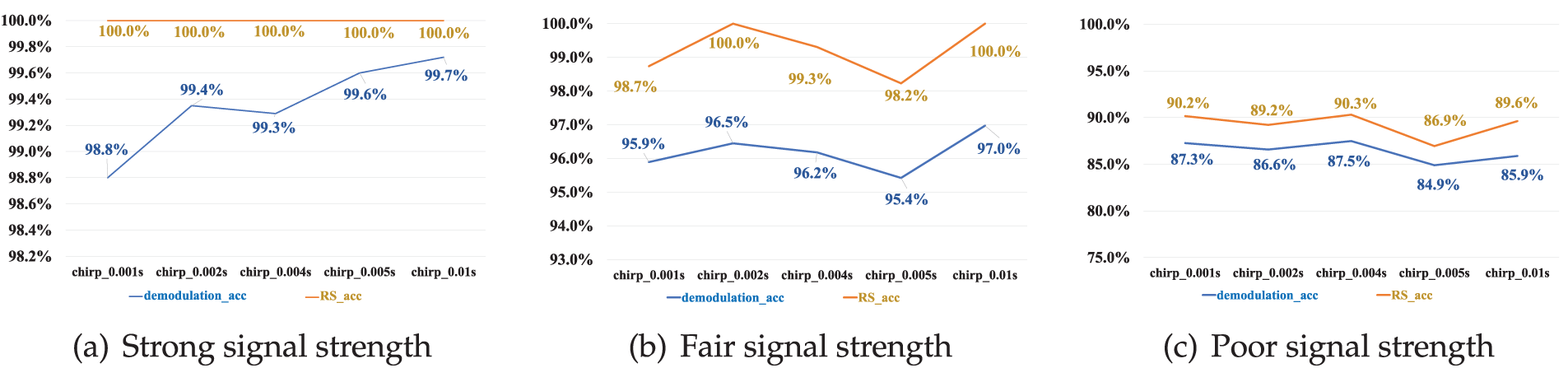

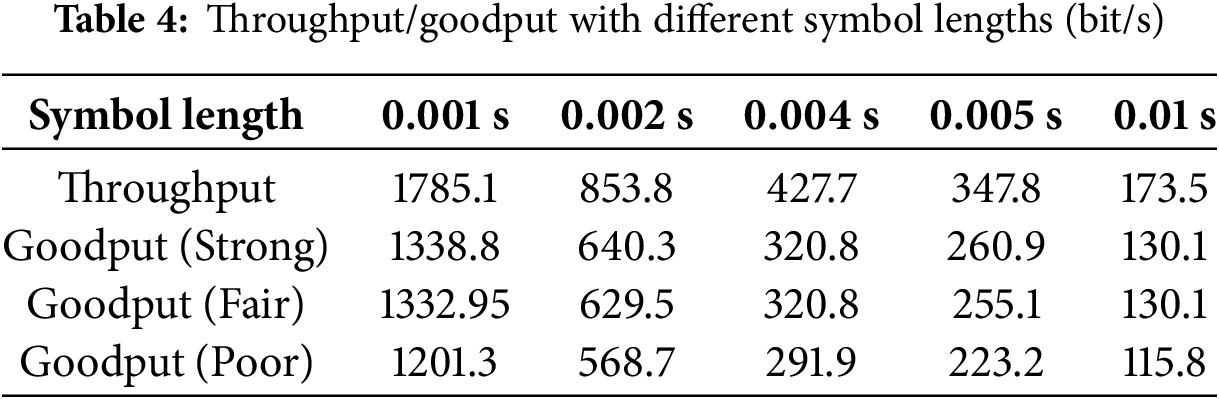

Symbol length. Intuitively, a longer symbol is more likely to be recognized correctly (due to a larger feature space), but at the cost of a longer transmission time. To investigate the impact of different symbol lengths on the system’s reliability, we set five different symbol lengths: 0.001, 0.002, 0.004, 0.005, and 0.01 s, while a symbol group and a gap were fixed to last for 0.6 and 0.5 s, respectively.

In Fig. 11a, we see that longer symbols have higher demodulation accuracy as expected, but the increment is marginal. After the error correction, all symbols (100%) can be correctly restored without retransmission, regardless of how the symbol length changes. However, when the signal strength is not strong enough, incrementing the symbol length may not help improve the demodulation accuracy. The details can be found in the next section.

Figure 11: Accuracy of DL-based demodulation before and after Reed–Solomon error correction in different conditions of signal strengths

However, as reported in Table 4, both the throughput and goodput decrease as the symbol length increases. When the symbol length is set to 0.001 s, our system achieves an excellent goodput of 1338.8 bit/s when the signal is strong and 1201.3 bit/s when the signal is weak. Hence, we use the symbol length of 0.001 s (i.e., 48 samples at the sampling rate of 48 kHz) for practical use.

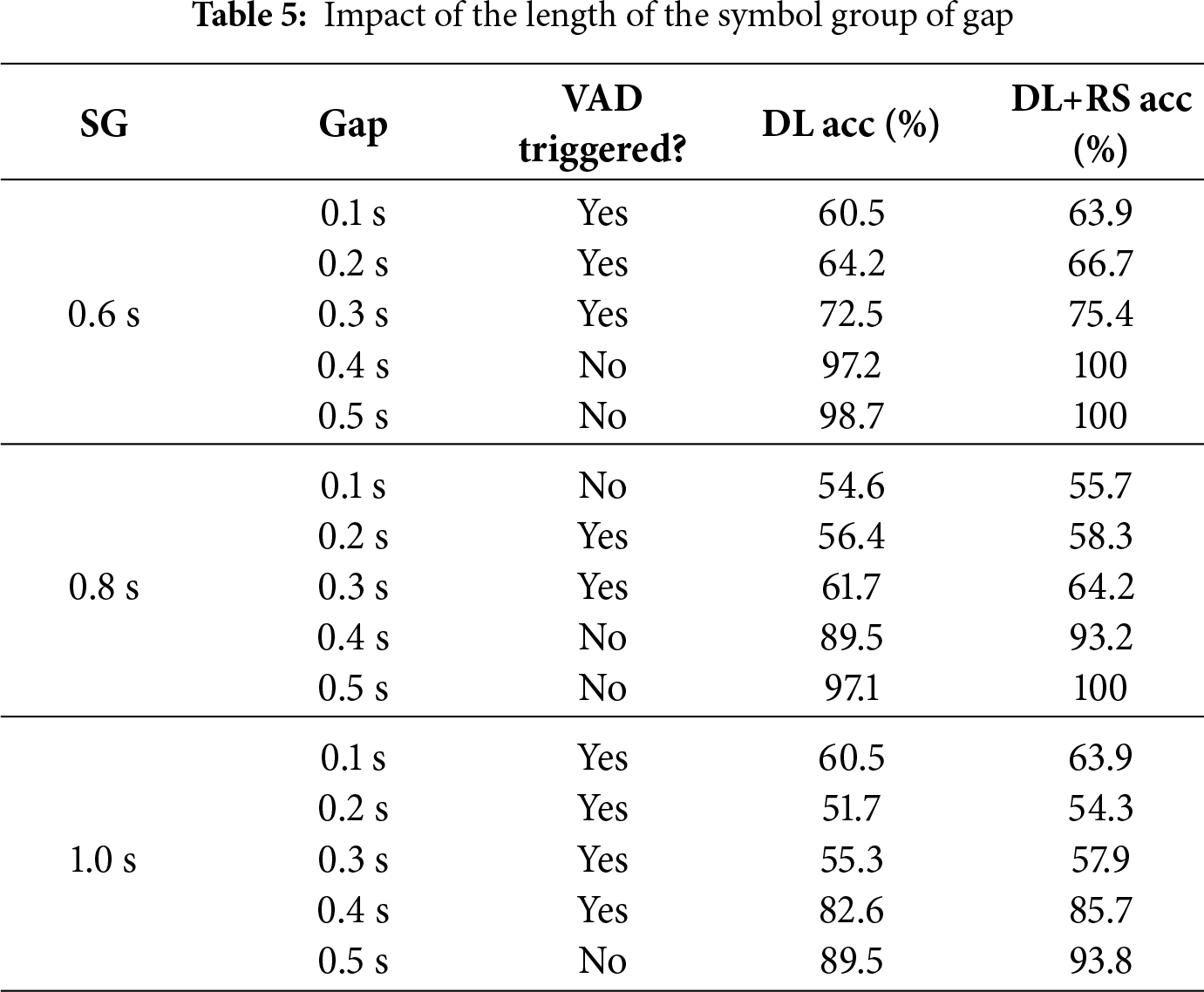

SG and gap lengths. The length of the symbol group (SG) and the gap determine whether we can avoid the rejection of VAD/DTX. We explore the impact of these two parameters and show the results in Table 5.

As the SG length decreases and the gap length increases, received signals have less effect on VAD/DTX, thus increasing the demodulation accuracy. When the SG length is 0.6 s, FastDOV achieves the best demodulation accuracy compared to other intervals of 0.8 and 1 s. Additionally, with the fixed symbol duration of 0.6 s, FastDOV demonstrates perfect (100%) accuracy following Reed-Solomon (RS) error correction for gap lengths exceeding 0.4 s. Therefore, we empirically use the gap length of 0.5 s and symbol group duration of 0.6 s to achieve the optimal performance.

5.3 Affects of Deep Learning Models

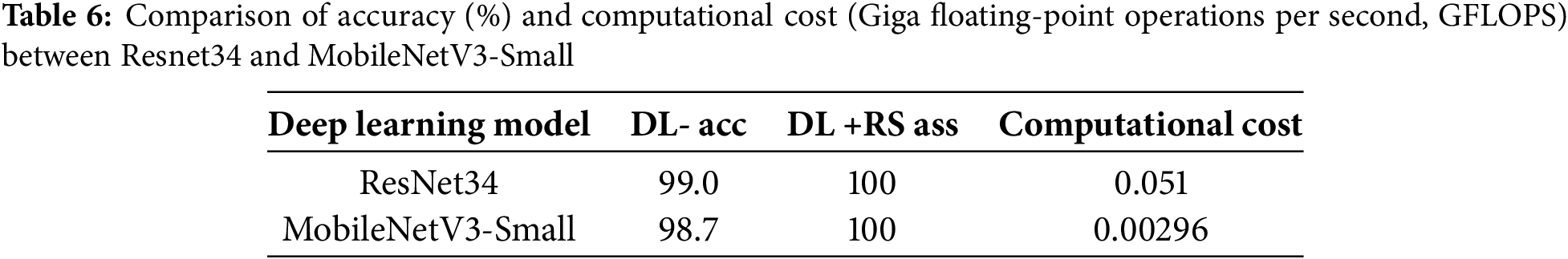

In our preliminary study [39], we used a tailored ResNet model for symbol demodulation, while we propose to use a lightweight MobileNet model in this work. To compare their performance differences, we conducted experiments about accuracy and computational cost with the gap length of 0.5 s and symbol group duration of 0.6 s.

As shown in Table 6, The proposed MobileNetV3-Small-based solution requires only 0.0029 GFLOPs to receive 3 bits of data, while ResNet34 requires 0.051 GFLOPs. Both models have high demodulation accuracy and can achieve 100% demodulation after RS code error correction. With mobile platforms commonly providing computational capabilities exceeding 1000 GFLOPs (e.g., iPhone and Qualcomm chipsets), our solution is highly practical given the computational capabilities of modern mobile devices.

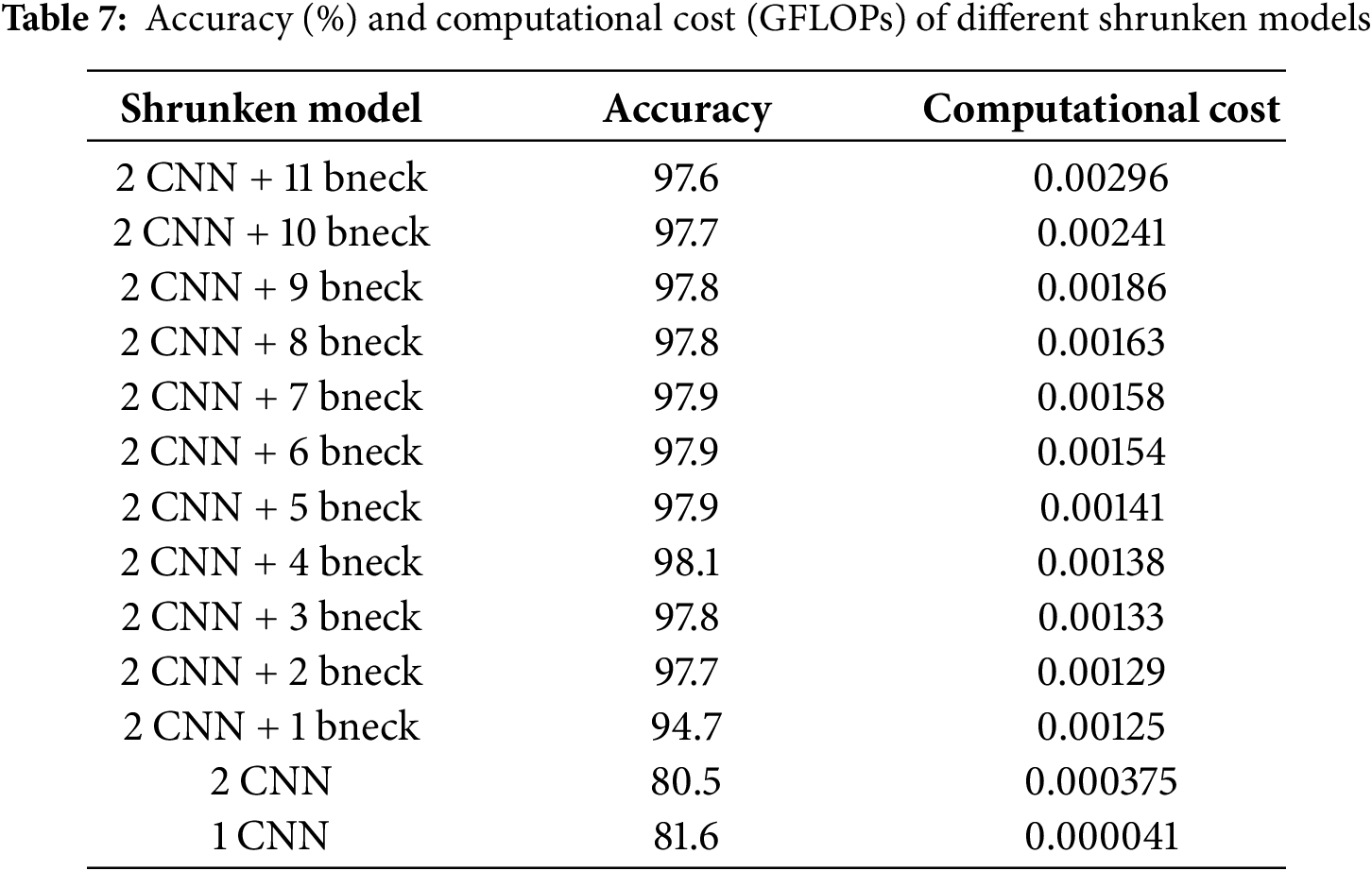

While our MobileNetV3-Small-based design already demonstrates strong performance in terms of both model performance (with an accuracy

Table 7 summarizes the experimental results. We find that even when reserving only a small number of bneck modules from the original MobileNetV3-Small architecture, demodulation accuracy remains high. However, directly utilizing only the CNN layers leads to a sharp decline in performance. Specifically, models with at least two bneck modules consistently achieve demodulation accuracy >97%, nearly matching the full 11-module model (first row of Table 7). With a single bneck, the accuracy remains relatively high at 94.7%. In contrast, CNN-only models with one or two layers demonstrate unsatisfactory performance (accuracy <82%). These results suggest further optimization of FastDOV’s computational efficiency is possible without sacrificing accuracy. We leave the exploration of extremely compact architectures for future work, while noting that our proposed design already achieves an effective balance.

5.4 Performance by Environmental Factors

To answer RQ3, we conducted experiments across different cellular signal strengths, carriers, and phone brands. In the following experiments, we use the optimal parameters for the best data rate: the linear chirp of 0.1 s as a delimiter, the symbol length of 0.001 s, the symbol group duration of 0.6 s, and the gap length of 0.5 s.

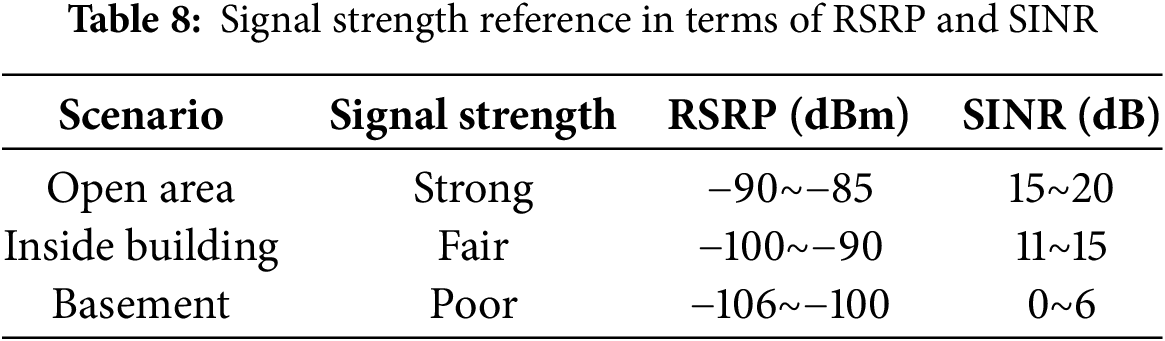

Cellular signal strengths. As shown in Table 8, we tested the performance of FastDOV in three scenarios with different average signal strengths. The signal strength was measured by Reference Signal Received Power (RSRP)—The average power received from a single Reference signal in decibel-milliwatts (dBm) and Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SINR)/Signal-to-Interference-plus-Noise Ratio (SNR)—The signal-to-noise ratio of the given signal.

Fig. 11 presents the results of our DL-based demodulation scheme. It is seen that FastDOV achieves high accuracy in most cases. When the signal strength is strong, the demodulation accuracy is greater than 98% (i.e., the blue curve in Fig. 11a) and 100% before and after Reed–Solomon error correction. It indicates that our approach does not need retransmission in the strong signal case. When the signal quality is fair, the accuracy drops to 95% but cannot always be corrected by the RS code. When the quality is poor, the channel becomes unstable, and the demodulation accuracy is only above 83%. In these cases, we need retransmission to help achieve reliable data communication.

Table 4 shows the throughput and goodput of the system. As expected, the performance drops from 1338 bit/s (goodput) to 1201 bit/s (goodput) when the signal strength becomes weak. With the help of retransmission, the performance is still acceptable even when the signal strength is poor. Overall, based on experiments in three signal strength environments, when the length of the symbol length is 0.001 s, the average goodput of FastDOV is 1291.0 bits/s, which is a preferred result.

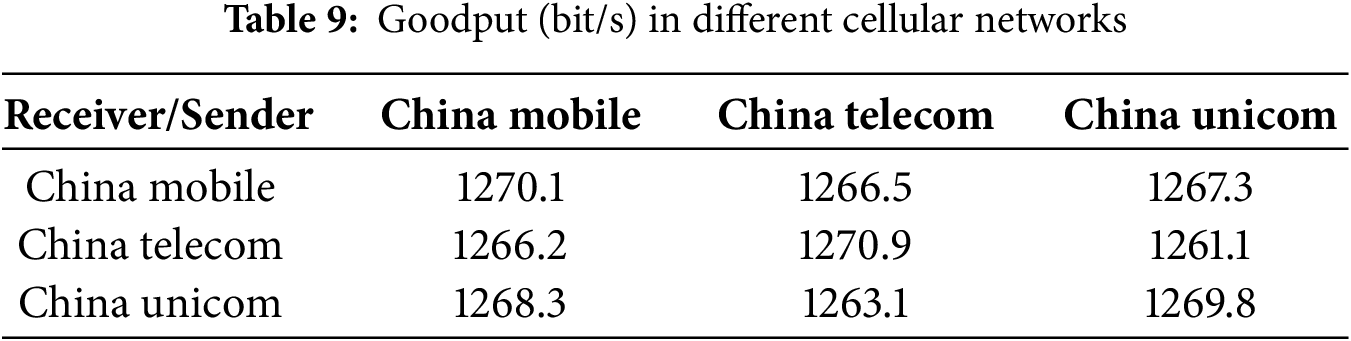

Cellular carriers. We tested FastDOV on cellular networks provided by the three major carriers in China, namely China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom. The experiments demonstrate consistent performance, with goodput exceeding 1260 bit/s across all networks, varying within a narrow 10 bit/s range (Table 9). These results not only highlight the robustness and reliability of FastDOV under different cellular network conditions, but also demonstrate its superior adaptability to network changes. We have verified the cross-network compatibility and excellent transmission efficiency of FastDOV through rigorous testing in different network environments of different operators. This robust performance across networks further establishes FastDOV’s position as a reliable communication solution.

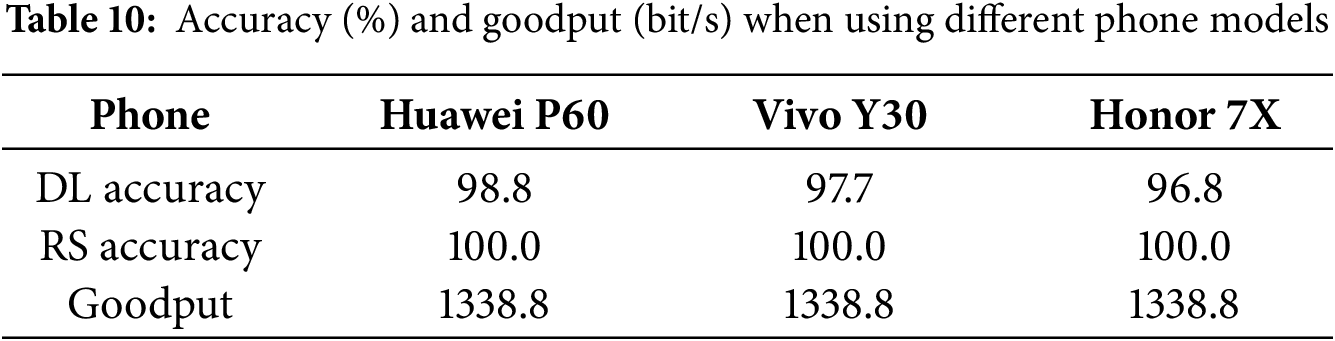

Phone brands/models. To evaluate the robustness across different phone models, we tested FastDOV’s performance on three phone brands/models: Huawei P60, Vivo Y30, and Honor 7X. Results in Table 10 show that the performance of FastDOV will not be affected by phone models. Specifically, FastDOV demonstrates consistent demodulation accuracy above 96% across all devices before the Reed-Solomon error correction. After the correction, FastDOV achieves 100% accuracy and 1338.84 bit/s goodput regardless of the phone model.

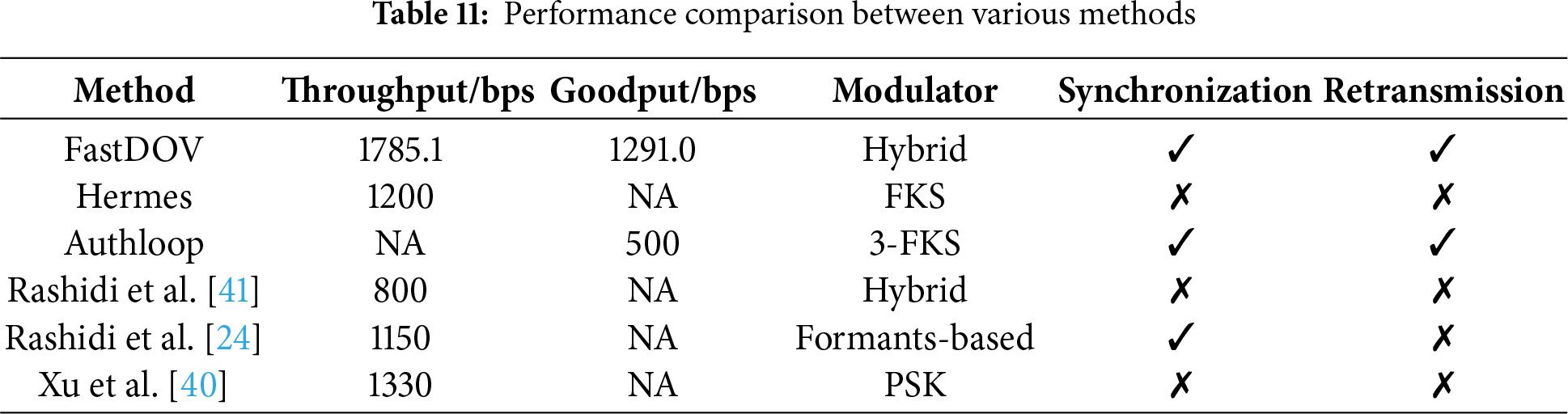

5.5 Comparison to SOTA Approaches

We compare FastDOV with representative methods that share the same operational constraint: no modification to telecommunication infrastructure. The selected baselines—Hermes [10], Authloop [11], and others—represent the state-of-the-art approaches for end-to-end data transmission over unmodified voice channels, making them ideal references for evaluating our system’s performance.

To answer RQ4, we compare our proposed FastDOV with other representative data transmission over voice channel methods, including Hermes [10] and Authloop [11]. We transmit the existing web certificate Bilibili, which is 2.1 kB, to test performance. Of course, the Bilibili web certificate is only for testing the performance of FastDOV, and we will design the phone certificate suitable for telephone transmission in future work.

Table 11 shows the comparison. Our proposed FastDOV outperforms other methods by a large margin. The throughput of FastDOV is 1785.1 bit/s, while Hermes and Xu [40] only achieve a throughput of 1200 and 1330 bit/s. The average goodput of FastDOV is 1291.0 bit/s (the symbol length is 0.001 s), while Authloop only has a goodput of 500 bit/s.

Additionally, FastDOV and Authloop have synchronization and retransmission designs which can ensure the signal received is complete and correct, but other methods overlook those designs (Rashidi [24] has synchronization, but it’s not detailed).

The practical deployment of the proposed authentication system faces challenges in security, practicality, and generalization. Security-wise, beyond common replay attacks, the system is vulnerable to adversarial audio injections that may deceive the deep learning model. Practically, the model must achieve low inference latency in real calling environments while handling diverse acoustic conditions and user dialects. Furthermore, the current training and evaluation are primarily based on data from Chinese telecom networks, limiting their direct applicability to international networks with different codecs and infrastructure standards.

To address these limitations, future work will focus on three key directions. Security enhancements will include dynamic challenge-response mechanisms and adversarial training to improve robustness. Performance optimization will involve model lightweighting for mobile devices and self-supervised learning for better generalization. For broader applicability, we will investigate cross-domain adaptation techniques to make the system compatible with diverse international telecom environments. These efforts will help bridge the gap between the current prototype and practical deployment.

We propose a deep-learning-based acoustic modulation scheme named FastDOV to transmit data over mobile voice channels without infrastructure support. FastDOV consists of a novel chirp-based modulation (three signal characteristics are mixed for modulation) and a tailored MobilenetV3-Small model for demodulation. The demodulation method requires only 0.0029 GFLOPs to receive 3 bits of data, which can be easily run on mobile phones. FastDOV can achieve 1291.0 bit/s goodput on average, which is better than existing approaches, and it can be applied to three different cellular networks in China. In order to improve the running speed of this method, we scaled down the model size of MobileNetV3. The experiment found that when MobileNetV3 has two or more residual networks, it can improve the running speed while ensuring accuracy. In addition, we demonstrate that our system can transfer digital certificates over voice channels to prevent telecom fraud.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Jian Huang and Hao Han conceived the research idea and designed the methodology. Mingwei Li conducted the majority of the experiments and data analysis. Yulong Tian and Yi Yao reviewed, edited, and provided critical feedback on the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Mathematical Derivations

Appendix A.1 Reed-Solomon Code Mathematical Formulation

The Reed-Solomon (RS) code employed in FastDOV uses parameters

Let

where

The encoding process transforms a message polynomial

where

The Berlekamp-Massey algorithm is used for decoding, which involves solving the key equation:

where

Appendix A.2 Welford’s One-Pass Algorithm Details

Welford’s algorithm provides a numerically stable method for computing variance and correlation in a single pass. For the cross-correlation computation in delimiter detection, the algorithm proceeds as follows:

Let

The online computation uses the following recurrence relations:

where

Appendix A.3 Chirp Signal Mathematical Analysis

The linear chirp signal used in FastDOV’s modulation scheme has a more detailed mathematical formulation. The instantaneous phase

where

For the up-chirp and down-chirp modulation, the frequency ranges are defined as:

where T is the symbol duration,

The time-domain representation considering both frequency bands becomes:

where A is the amplitude and

The Fourier transform of a linear chirp can be expressed in terms of Fresnel integrals:

where

References

1. Gamage P, Dissanayake D, Kumarasinghe N, Ganegoda GU. Acoustic signature analysis for distinguishing human vs. synthetic voices in vishing attacks. In: 2023 8th International Conference on Information Technology Research (ICITR). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

2. Yalçın N, Lale B. Types of cyber-attacks with using voice. J Sci Rep A. 2025;61:137–65. [Google Scholar]

3. Mustafa HA. Secure and reliable wireless communication through end-to-end-based solution [dissertation]. Columbia, SC, USA: University of South Carolina; 2014. [Google Scholar]

4. Bhuiyan MSI, Razzak A, Ferdous MS, Chowdhury MJM, Hoque MA, Tarkoma S. BONIK: a blockchain empowered chatbot for financial transactions. In: 2020 IEEE 19th International Conference on Trust, Security and Privacy in Computing and Communications (TrustCom). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 1079–88. [Google Scholar]

5. Tjon E, Moh M, Moh TS. Eff-ynet: a dual task network for deepfake detection and segmentation. In: 2021 15th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (IMCOM). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

6. Fake Caller ID. Fake caller ID: caller ID faker & spoof caller [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 28]. Available from: https://fakecallerid.io/. [Google Scholar]

7. myphonerobot. Spoof call and caller ID faker [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 28]. Available from: https://myphonerobot.com/. [Google Scholar]

8. Putra FPE, Ubaidi U, Zulfikri A, Arifin G, Ilhamsyah RM. Analysis of phishing attack trends, impacts and prevention methods: literature study. Brill Res Artif Intell. 2024;4(1):413–21. doi:10.47709/brilliance.v4i1.4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. GSMA. Over half world’s population now using mobile internet [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Sep 28]. Available from: https://www.gsma.com/newsroom/press-release/over-half-worlds-population-now-using-mobile-internet/. [Google Scholar]

10. Dhananjay A, Sharma A, Paik M, Chen J, Kuppusamy TK, Li J, et al. Hermes: data transmission over unknown voice channels. In: Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2010. p. 113–24. [Google Scholar]

11. Reaves B, Blue L, Traynor P. AuthLoop: end-to-end cryptographic authentication for telephony over voice channels. In: 25th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 16). New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016. p. 963–78. [Google Scholar]

12. Chmayssani T, Baudoin G. Data transmission over voice dedicated channels using digital modulations. In: 2008 18th International Conference Radioelektronika. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2008. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

13. Boloursaz M, Hadavi AH, Kazemi R, Behnia F. Secure data communication through GSM adaptive multi rate voice channel. In: 6th International Symposium on Telecommunications (IST). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2012. p. 1021–6. [Google Scholar]

14. Wolkotte PT, Smit GJM, Rauwerda GK, Smit LT. An energy-efficient reconfigurable circuit-switched network-on-chip. In: 19th IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium; 2005 Apr 4–8; Denver, CO, USA. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

15. Cai J, Goodman DJ. General packet radio service in GSM. IEEE Commun Mag. 1997;35(10):122–31. doi:10.1109/35.623996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sesia S, Toufik I, Baker M. LTE-the UMTS long term evolution: from theory to practice. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

17. Li C, Hutchins DA, Green RJ. Short-range ultrasonic digital communications in air. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2008;55(4):908–18. doi:10.1109/tuffc.2008.726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jiang W, Wright WMD. Progress in airborne ultrasonic data communications for indoor applications. In: 2016 IEEE 14th International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 322–7. [Google Scholar]

19. Novak E, Tang Z, Li Q. Ultrasound proximity networking on smart mobile devices for IoT applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018;6(1):399–409. doi:10.1109/jiot.2018.2848099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kim S, Mun H, Lee Y. A data-over-sound application: attendance book. In: 2019 20th Asia-Pacific Network Operations and Management Symposium (APNOMS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

21. Zhang L, Zhu X, Wu X. No more free riders: sharing wifi secrets with acoustic signals. In: 2019 28th International Conference on Computer Communication and Networks (ICCCN). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

22. Krasnowski P, Lebrun J, Martin B. Introducing a novel data over voice technique for secure voice communication. Wirel Pers Commun. 2022;124(4):3077–103. doi:10.1007/s11277-022-09503-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Katugampala NN, Al-Naimi KT, Villette S, Kondoz AM. Real-time end-to-end secure voice communications over GSM voice channel. In: 2005 13th European Signal Processing Conference. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2005. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

24. Rashidi M, Sayadiyan A, Mowlaee P. Data mapping onto speech-like signal to transmission over the GSM voice channel. In: 2008 40th Southeastern Symposium on System Theory (SSST). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2008. p. 54–8. [Google Scholar]

25. Ladue CK, Sapozhnykov VV, Fienberg KS. A data modem for GSM voice channel. IEEE Trans Veh Technol. 2008;57(4):2205–18. doi:10.1109/tvt.2007.912322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mezgec Z, Chowdhury A, Kotnik B, Svecko R. Implementation of PCCD-OFDM-ASK robust data transmission over GSM speech channel. Informatica. 2009;20(1):51–78. [Google Scholar]

27. Abro FI, Rauf F, Chowdhry BS, Rajarajan M. Towards security of GSM voice communication. Wirel Pers Commun. 2019;108(3):1933–55. doi:10.1007/s11277-019-06502-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang T, Li S, Yu B. A universal data transfer technique over voice channels of cellular mobile communication networks. IET Commun. 2021;15(1):22–32. doi:10.1049/cmu2.12047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Biancucci G, Claudi A, Dragoni AF. Secure data and voice transmission over GSM voice channel: applications for secure communications. In: 2013 4th International Conference on Intelligent Systems, Modelling and Simulation. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2013. p. 230–3. [Google Scholar]

30. Ntantogian C, Veroni E, Karopoulos G, Xenakis C. A survey of voice and communication protection solutions against wiretapping. Comput Electr Eng. 2019;77(4):163–78. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2019.05.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Benny A, Saji AM, Joseph CJ, Christina PB, Antony MA. Real-time voice phishing detection using BERT. In: International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Energy. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2025. p. 410–26. [Google Scholar]

32. Sim JY, Kim SH. Detecting voice phishing with precision: fine-tuning small language models. arXiv:2506.06180. 2025. [Google Scholar]

33. Peterson WW, Weldon EJ. Error-correcting codes. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

34. Shabani S, Norouzi Y. Speech recognition using principal components analysis and neural networks. In: 2016 IEEE 8th International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2016. p. 90–5. [Google Scholar]

35. Warohma AM, Hindersah H, Lestari DP. Speaker recognition using MobileNetV3 for voice-based robot navigation. In: 2024 11th International Conference on Advanced Informatics: Concept, Theory and Application (ICAICTA). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

36. Kavyashree PSP, El-Sharkawy M. Compressed MobileNet V3: a light weight variant for resource-constrained platforms. In: 2021 IEEE 11th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); 2021 Jan 27–30; Virtual. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 0104–7. [Google Scholar]

37. SOURCEFOURGE. HFP for Linux [Internet]. [cited 2024 Sep 28]. Available from: https://nohands.sourceforge.net/. [Google Scholar]

38. Stanford Vision Lab, Stanford University, Princeton University. ImageNet large scale visual recognition challenge 2012 (ILSVRC2012) [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Sep 28]. Available from: https://www.image-net.org/challenges/LSVRC/2012/index.php. [Google Scholar]

39. Zhang W, Han H, Li M, Tian Y. Towards faster end-to-end data transmission over voice channels. In: ICASSP 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 9061–5. [Google Scholar]

40. Xu Z. A data transmission method based on pulse modulation over GSM voice channel. Telecommun Eng. 2018;58(2):152–6. [Google Scholar]

41. Rashidi M, Sayadiyan A, Mowlaee P. A harmonic approach to data transmission over GSM voice channel. In: 2008 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies: from Theory to Applications. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2008. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools