Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Segment-Conditioned Latent-Intent Framework for Cooperative Multi-UAV Search

1 Northwest Institute of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Xianyang, 712099, China

2 Department of Railway Transportation Operations Management, Baotou Railway Vocational & Technical College, Baotou, 014060, China

3 School of Mechanical Engineering, Nanjing University of Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210094, China

4 Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Antenna and Control Technology, Xi’an, 710076, China

5 39th Research Institute of China Electronics Technology Group Corporation, Xi’an, 710076, China

* Corresponding Authors: Jiancheng Liu. Email: ; Siwen Wei. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cooperation and Autonomy in Multi-Agent Systems: Models, Algorithms, and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 96 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2026.073202

Received 12 September 2025; Accepted 24 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Cooperative multi-UAV search requires jointly optimizing wide-area coverage, rapid target discovery, and endurance under sensing and motion constraints. Resolving this coupling enables scalable coordination with high data efficiency and mission reliability. We formulate this problem as a discounted Markov decision process on an occupancy grid with a cellwise Bayesian belief update, yielding a Markov state that couples agent poses with a probabilistic target field. On this belief–MDP we introduce a segment-conditioned latent-intent framework, in which a discrete intent head selects a latent skill every K steps and an intra-segment GRU policy generates per-step control conditioned on the fixed intent; both components are trained end-to-end with proximal updates under a centralized critic. On theKeywords

Cooperative search with multiple unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) enables rapid, wide-area situational awareness for surveillance, humanitarian response, and defense operations, where parallel sensing and timely localization of mission-relevant targets are critical [1,2]. These demands are further amplified by the proliferation of IoT devices and the emergence of next-generation (6G-ready) network architectures, in which UAV-assisted infrastructures are increasingly deployed as agile aerial nodes for real-time sensing, surveillance, and data collection in dense IoT environments [3–5]. In such settings, decision policies must simultaneously promote broad spatial coverage, high-probability target discovery, and fuel-aware persistence under partial observability and dynamic interaction among agents, which renders joint planning inherently high dimensional and nonstationary.

Conventional approaches to multi-UAV search span graph-based planning, swarm heuristics, game-theoretic coordination, and evolutionary/metaheuristic optimizers [6–8]. While these methods provide valuable baselines, they typically assume static or fully observable environments, rely on strong prior modeling or hand-crafted heuristics, and offer limited support for online adaptation, multi-agent credit assignment, and principled trade-offs between coverage, discovery, and endurance. Deep reinforcement learning has recently advanced UAV navigation by learning directly from interaction and coping with uncertainty [9–11]. In multi-agent settings, centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) alleviates nonstationarity [12–14], yet flat (single-level) DRL still struggles with long-horizon exploration, joint action-space blowup, and ambiguous credit assignment as team size grows [15].

Hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL) provides temporal abstraction and subgoal structure through manager–worker decompositions and value-function factorizations [16,17]. Canonical architectures such as FeUdal Networks and the Option-Critic framework instantiate these principles via goal-conditioned managers and learnable options [18], but typically require delicate intrinsic-reward design or learned termination functions that are prone to option collapse and training instability. Recent multi-agent extensions further exploit hierarchical organization to facilitate cooperative decision-making [19,20], yet often rely on hand-crafted subtask taxonomies, predefined communication patterns, or centralized coordinators that do not transfer seamlessly to fully cooperative, partially observed settings. Surveys underscore the potential of HRL for scalable aerial coordination [21,22]; nevertheless, these designs can incur additional variance and computational overhead when applied to belief-based multi-UAV search with tightly coupled objectives. Maximum-entropy regularization has been shown to enhance exploration and coordination [23], yet systematically aligning exploratory behavior with mission-level coverage objectives and energy constraints remains a central open challenge.

This work introduces a segment-conditioned latent-intent framework for cooperative multi-UAV search (SCLI–CMUS) that unifies temporal abstraction, coordinated exploration, and endurance awareness within a single CTDE policy. The environment is modeled as a discounted Markov decision process on a discretized workspace endowed with a Bayesian cellwise update of the occupancy field. Within one end-to-end differentiable policy, a discrete intent head selects a latent skill every K steps to guide medium-horizon behavior, while an action head driven by an intra-segment GRU issues per-step yaw increments conditioned on the fixed intent and local features. Compared with FeUdal-style and Option-Critic architectures, this fixed-horizon, discrete-intent design retains sufficient temporal expressiveness while avoiding termination-related instabilities and keeping per-step computation close to that of a recurrent actor-critic with a single additional categorical head. To reconcile heterogeneous signal scales and stabilize training, we employ a three-parameter, scale-calibrated saturated reward that jointly accounts for information gain, coverage efficiency, and energy–time cost. The principal contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

1. We propose Segment–Conditioned Latent–Intent for Cooperative Multi–UAV Search (SCLI–CMUS), a CTDE framework that couples a discrete intent selector—updated at fixed segment boundaries—with an intra-segment recurrent controller in a single end-to-end differentiable policy.

2. We develop a three-coefficient, scale-calibrated saturated reward that jointly balances information gain, coverage efficiency, and energy–time costs.

3. Comprehensive experiments demonstrating faster learning, improved overage/discovery convergence times, and robust qualitative behaviors across representative UAV team sizes.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on cooperative multi-UAV search, planning-based coordination, and (hierarchical) multi-agent reinforcement learning. Section 3 presents the belief-based MDP formulation and the proposed segment-conditioned latent-intent framework, while Section 4 details the experimental setup, benchmarks, and ablation studies. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the findings and outlines directions for future research.

Conventional planning approaches for UAV search largely build on graph-search and shortest-path heuristics, which perform well in static and fully observable environments [6,24]. However, such methods do not naturally accommodate multi-agent credit assignment, online replanning under sensing uncertainty, or principled division of labor among multiple vehicles. Swarm-style schemes based on artificial potential fields, flocking rules, or pheromone deposition provide lightweight, decentralized coordination with low communication burden [7,25], and learned heuristics can amortize local perception-to-action mappings [26]. These approaches, though attractive for their simplicity, are susceptible to local minima, lack mechanisms to globally optimize coupled coverage–discovery–endurance trade-offs, and often require extensive manual retuning when environment statistics change.

Game-theoretic and metaheuristic frameworks offer alternative tools for cooperative search and routing. Potential games and market-based task allocation furnish equilibrium concepts and scalable assignment rules [27,28], while differential games capture adversarial or pursuit–evasion interactions in continuous time [28]. Evolutionary and metaheuristic optimizers traverse nonconvex search spaces and can handle multiple objective criteria in path planning and routing [29,30], with recent advances in motion-encoded multi-parent crossovers improving solution diversity [8]. Nonetheless, their reliance on strong prior modeling, offline optimization, and substantial computational budgets limits their ability to adapt online in uncertain, time-critical environments.

Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has achieved notable success in UAV navigation by learning policies directly from interaction, thereby coping with uncertainty and enabling online adaptation [9]. Single-vehicle studies have demonstrated obstacle-aware, threat-aware maneuvering and memory-augmented exploration in complex environments [10,11,31,32]. In multi-agent settings, centralized training with decentralized execution (CTDE) has become a standard paradigm: decentralized actors are trained against a centralized critic to mitigate nonstationarity and stabilize learning [12], and recent work emphasizes resilience and meta-adaptation under distribution shift [13,14]. However, flat (single-level) DRL typically struggles to align long-horizon exploration with local motion control, suffers from joint action-space blowup as team size grows, and faces ambiguous multi-agent credit assignment [15]. Maximum-entropy and entropy-regularized formulations can improve exploration and coordination [23], but designing reward structures that explicitly couple information gain, coverage efficiency, and energy–time costs remains challenging in belief-based multi-UAV search.

Hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL) introduces temporal abstraction and subgoal structure through manager–worker decompositions and value-function factorizations [16,17]. Canonical architectures such as FeUdal Networks and the Option-Critic framework realize these principles via goal-conditioned managers and learnable options [18,33], but typically require carefully designed intrinsic rewards or learned termination functions that are prone to option collapse, premature termination, and training instability. Against this backdrop, the segment-conditioned latent-intent framework developed in this work is intended to preserve the advantages of temporal abstraction while mitigating practical difficulties associated with option termination and hand-crafted subtask hierarchies.

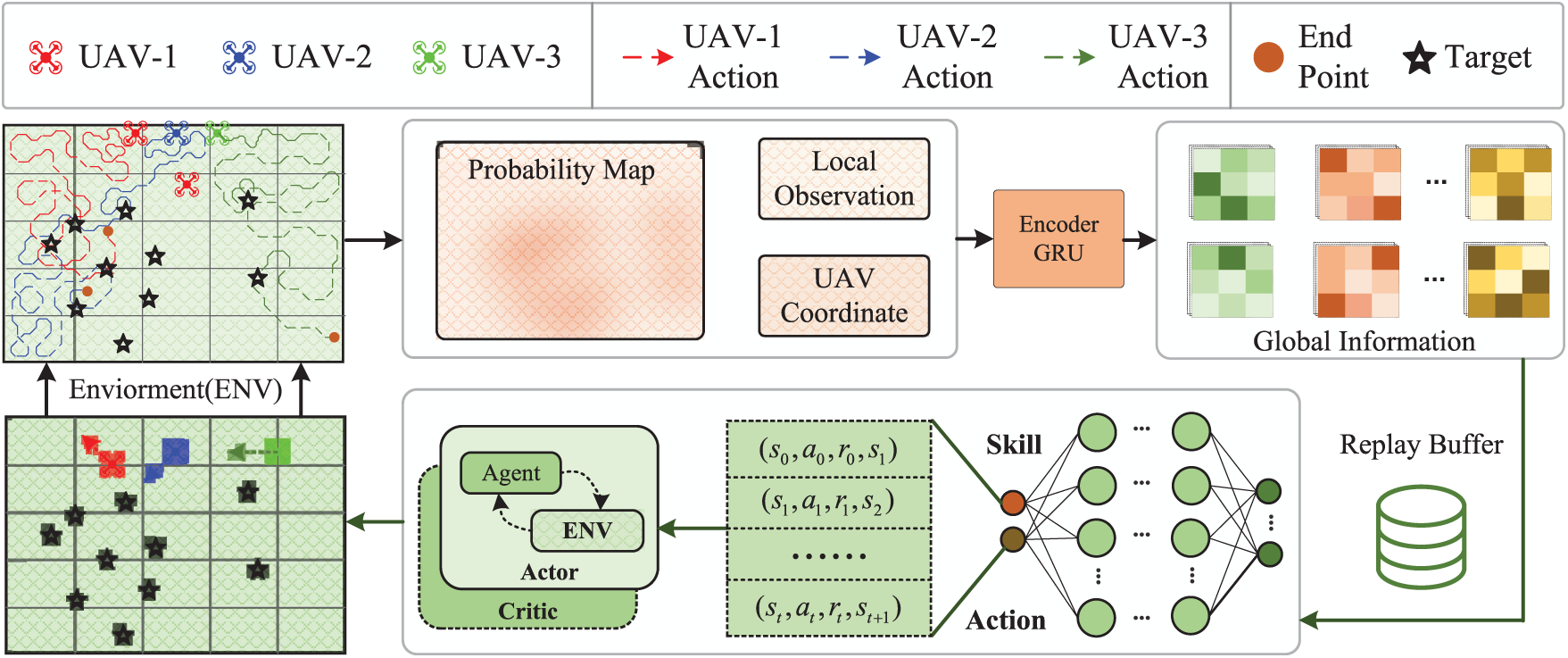

Fig. 1 provides an overview of the proposed framework. The environment yields a probabilistic occupancy map

Figure 1: Overview of the segment-conditioned latent-intent framework for cooperative multi-UAV search (SCLI-CMUS). Left: environment and trajectories of multiple UAVs (colours identify agents; stars indicate targets; orange dots denote end points). Middle: inputs to the encoder comprising the probability map

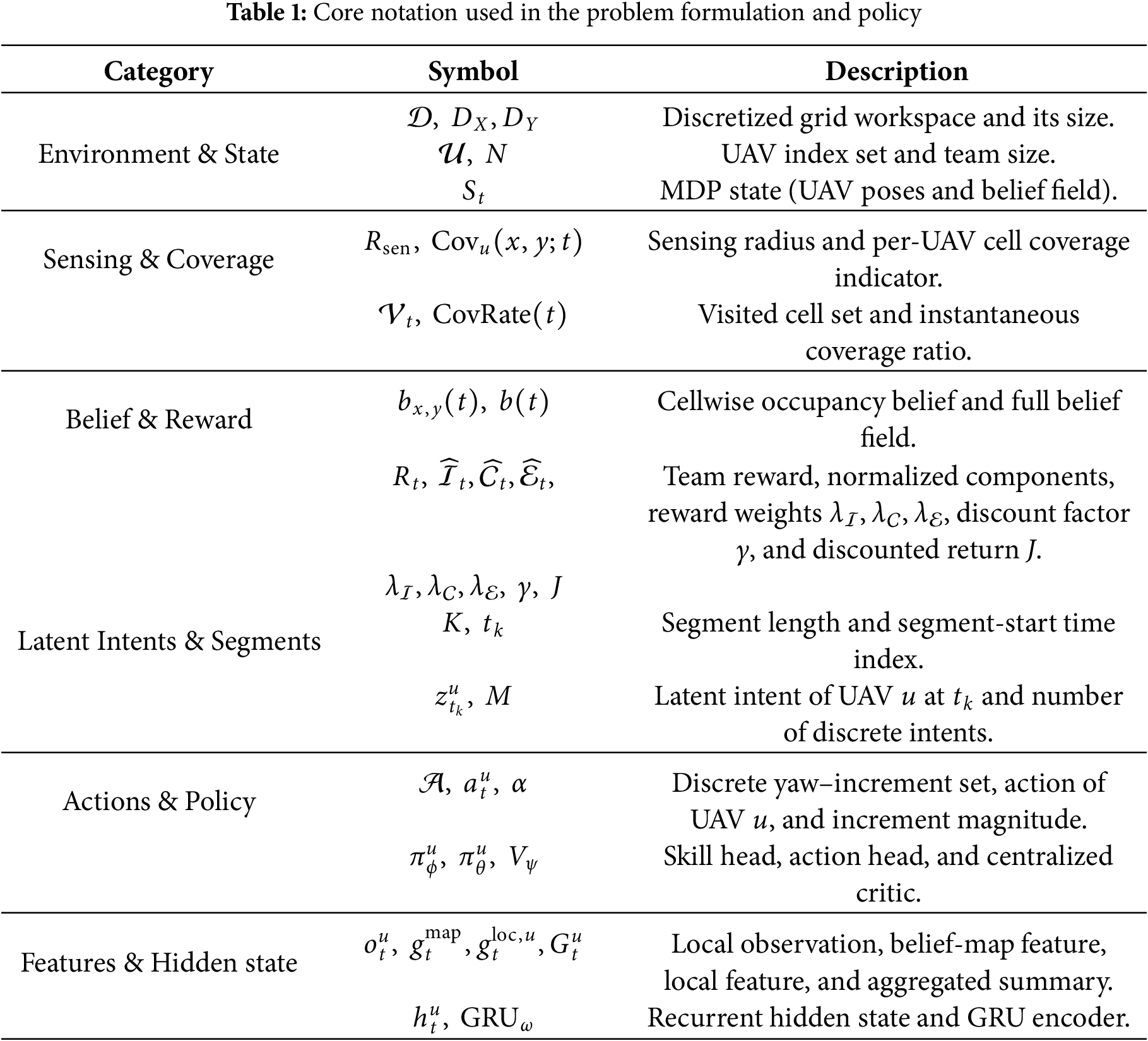

The main symbols used in the formulation and policy parameterization are summarized in Table 1.

3.1 MDP Formulation for Cooperative Multi-UAV Search

We model cooperative multi-UAV search as a discounted Markov decision process on a discretized workspace. Let the two-dimensional workspace be discretized as

where each cell

with

We now specify the agent set, action space, kinematics, joint control, and state representation. Let

where

Given a chosen yaw–increment action

where

Collecting all per-agent yaw–increment actions yields the joint action vector

The MDP state collects agent poses and the occupancy field, namely

Each UAV carries an omnidirectional sensing disc of radius

The instantaneous covered set is defined by

where the coverage ratio at time

Let

where

Under conditional independence given

The cellwise Bayesian update is then

The transition kernel induced by the deterministic kinematics and the cellwise Bayesian update is

The team reward adopts a scale-calibrated saturated form, first define analytic normalizers

with fixed coefficients

The saturated team reward is then

where

The reward components are defined as follows. The entropy of the belief field is

the coverage efficiency term is

where the energy–time cost term is defined as

with

The planning objective is the discounted return

which fully specifies the discounted MDP on the state

3.2 Segment-Conditioned Latent-Intent Policy Parameterization

On the discounted MDP of Section 3.1, each agent is equipped with a slow latent skill that governs behaviour over a fixed segment of K steps, while fast per-step actions are generated conditionally on the current skill and an autoregressive hidden state.

Let segment boundaries be

where

where

For each agent

with parameters

with parameters

Collecting parameters

where

Learning objectives are matched to these timescales. The segment return starting at

where

which supports low-variance advantage estimates at both levels. With temporal-difference residuals and generalized advantage estimation,

the segment-level advantage at

where

Optimization is carried out by proximal policy updates at both timescales. For the action head, define the probability ratio

and minimize the clipped surrogate aggregated over agents,

with clip parameter

leads to the segment–level surrogate

with

All experiments strictly follow the discounted MDP and sensing specification described above, and adopt the conventional benchmark setting used in prior cooperative search studies [28,34], with stationary targets and ideal, latency-free inter-UAV communication. The basic setup consists of a

All baseline networks are configured with comparable capacity and are trained using similar batch sizes. For the PPO-based SCLI–CMUS, we use on-policy trajectory batches without long-term replay, whereas the MADDPG-based methods rely on a replay buffer of fixed capacity with minibatch sampling.

1. DQN method [35]: Each UAV runs an independent Deep Q-Network on its local observation to estimate action values for the discrete yaw increments. The absence of explicit coordination limits information sharing and typically degrades scalability in larger or cluttered maps.

2. ACO method [36]: Ant Colony Optimization governs motion through a pheromone field over the grid, where each UAV behaves as an “ant” that deposits and follows trails. The induced three-dimensional pheromone tensor encodes heading preferences per cell and per agent.

3. MADDPG [28]: A canonical CTDE actor–critic baseline on the same Markov decision formulation. It employs decentralized actors with a centralized critic and experience replay. Using identical observation and reward interfaces enables a direct assessment of the gains attributable to hierarchical intent mechanisms and difference-reward shaping.

4. Maximum-Entropy RL (ME-RL) [23]: An entropy-regularized extension of MADDPG that incorporates spatial entropy and fuzzy logic to encourage exploration and coordination under communication and energy considerations.

5. DTH–MADDPG [34]: A hierarchical reinforcement-learning framework with a slow strategic controller and a set of fast decentralized executors. The strategic layer updates intermittently to assign high-level intents (region/waypoint directives) to the team, while the executor layer implements per-UAV control via MADDPG under CTDE with replay.

We report task performance through spatial coverage and target discovery, and we quantify search efficiency via convergence times to fixed performance levels. Let

To capture the speed at which operational effectiveness is achieved, introduce coverage and discovery convergence times as first hitting times of prescribed thresholds

In all experiments we set

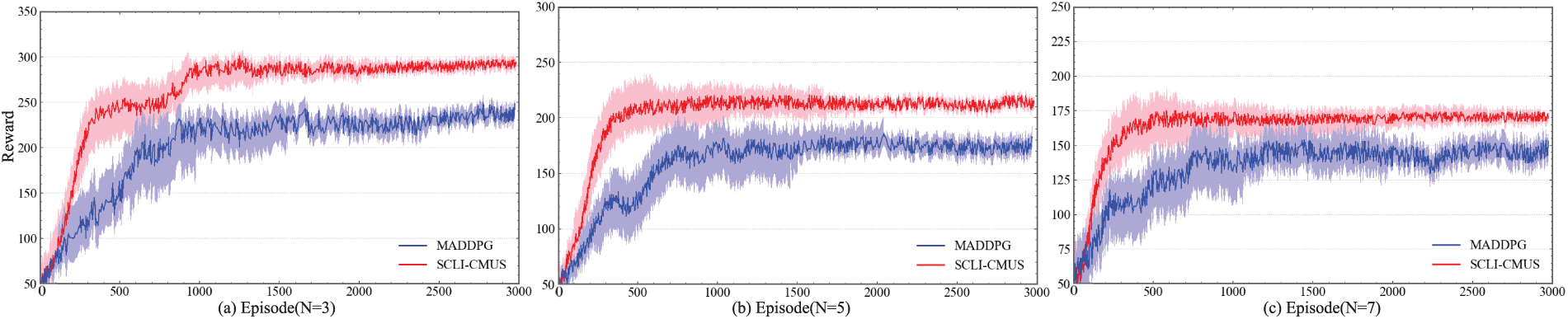

This section quantifies learning efficiency and asymptotic performance of the proposed method relative to a strong baseline. Fig. 2 reports episode–wise learning curves, where the horizontal axis denotes the training episode index and the vertical axis denotes the total episode reward computed under the reward design in Section 3.1. Curves correspond to the mean over repeated runs, and shaded bands depict variability across runs.

Figure 2: Episode reward vs. training episode for MADDPG (blue) and SCLI–CMUS (red). The horizontal axis denotes episode index; the vertical axis denotes total reward per episode; shaded regions indicate variability across runs. (a)

A consistent pattern emerges across all subplots. The proposed SCLI–CMUS (red) rises sharply at early episodes and reaches a high plateau with markedly reduced dispersion, whereas MADDPG (blue) exhibits slower ascent, a lower steady level, and wider fluctuations. This behaviour is most pronounced in Fig. 2a with three agents, where SCLI–CMUS achieves a visibly higher steady reward and converges in substantially fewer episodes. The gap persists in Fig. 2b, indicating that the advantage is robust when scaling to five agents. The reduced variance of SCLI–CMUS is consistent with the segment–conditioned intent mechanism and the saturated, scale–balanced reward, which together suppress redundant exploration and stabilize gradient updates.

The scaling trend with agent count is also informative. Moving from three to seven agents, both methods display a gradual reduction in asymptotic reward, which is consistent with fixed–horizon evaluation: faster attainment of high coverage leaves a longer terminal phase dominated by energy–time penalization. Despite this shift in absolute level, SCLI–CMUS maintains a persistent margin and tighter confidence bands in Fig. 2c, indicating improved coordination under higher platform density.

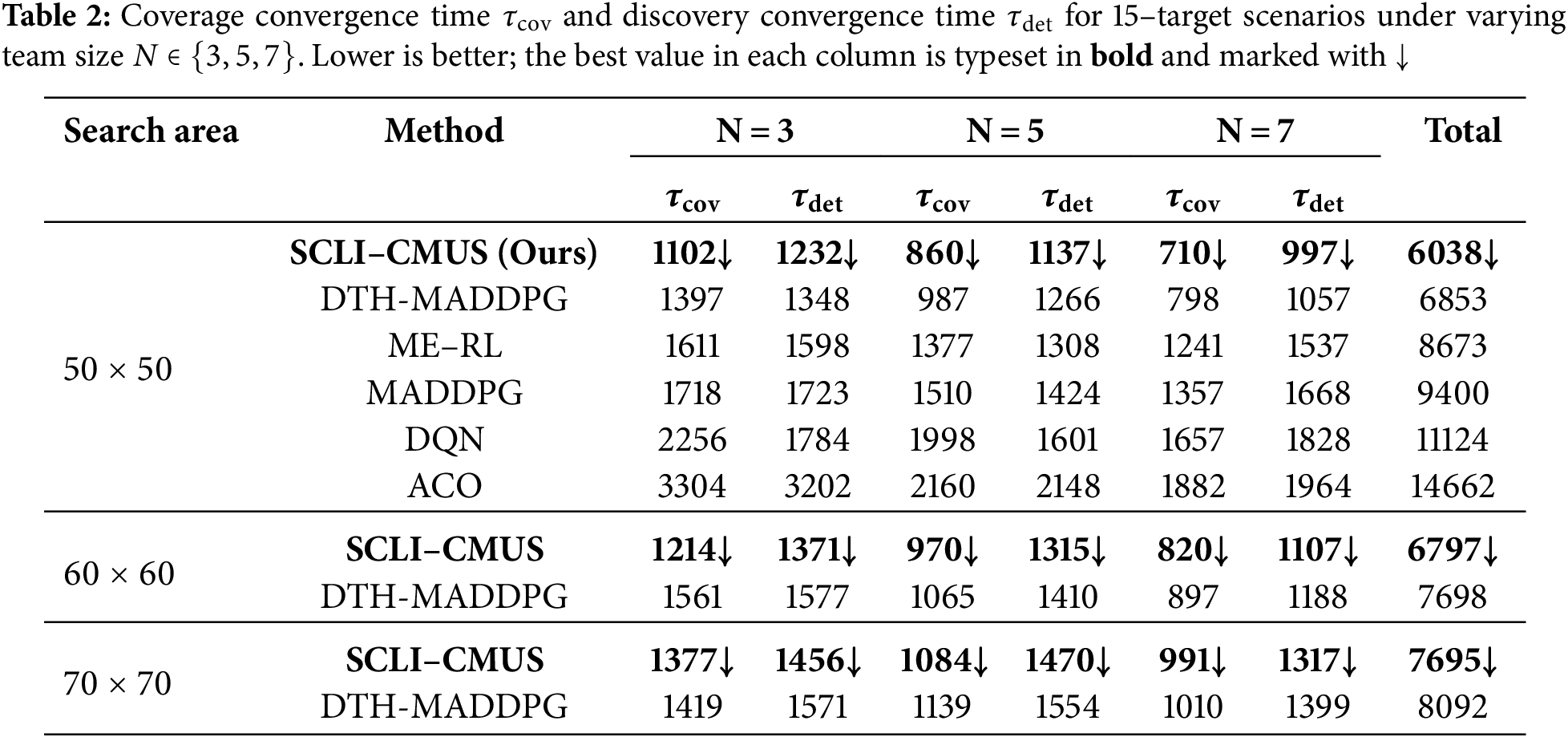

In Table 2 (Search Area = 50

The scaling behavior with N is also consistent and informative. All methods exhibit decreasing

To further probe this behaviour, we extended the comparison between SCLI–CMUS and the strongest hierarchical baseline (DTH–MADDPG) from the

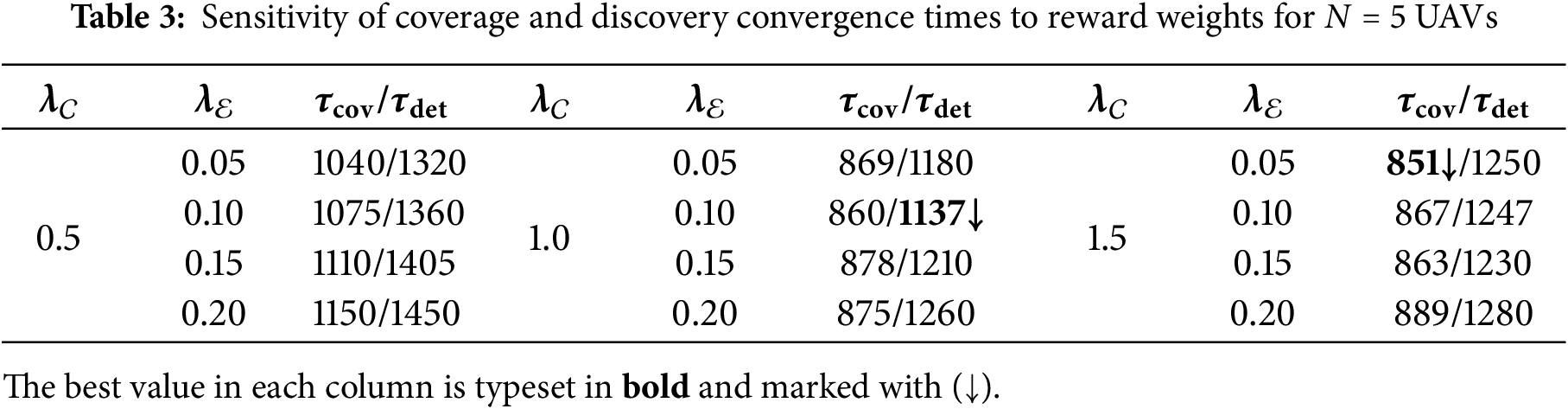

We next examine the sensitivity of SCLI–CMUS to the three reward weights

Representative results for

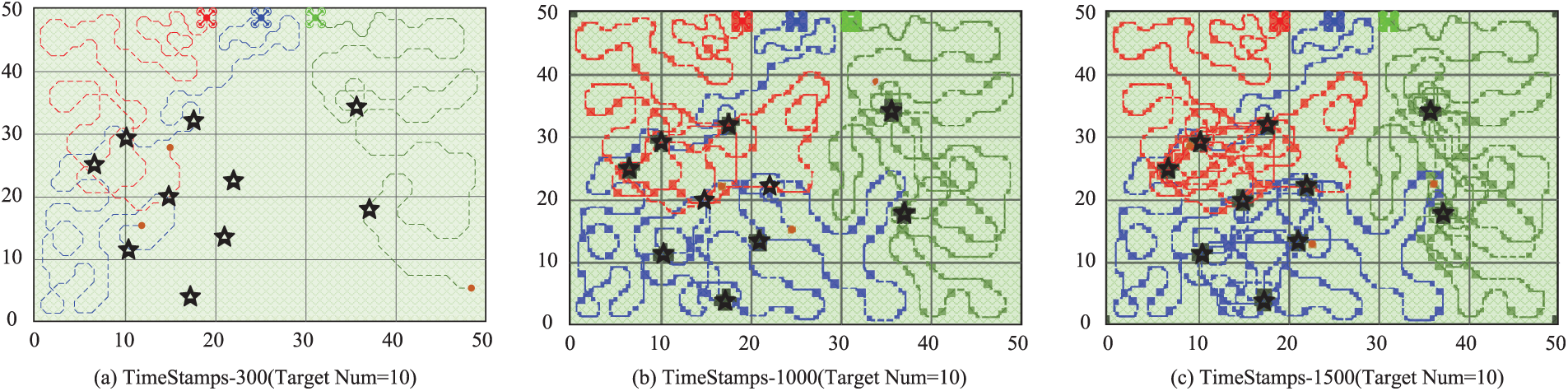

This case study provides a qualitative examination of cooperative behaviour under the proposed policy in a

Figure 3: Trajectories of three UAVs in a

At

At

This work has presented a segment-conditioned latent-intent framework for cooperative multi-UAV search that formulates the problem as a discounted MDP on an occupancy grid with a cellwise Bayesian belief update and parameterizes decision making by a single end-to-end policy combining a discrete intent head, updated every K steps, with an intra-segment GRU action head trained under a centralized critic, together with a three-coefficient, scale-calibrated saturated reward balancing information gain, coverage efficiency, and energy–time cost. Across grids of size

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Gang Hou, Aifeng Liu, Tao Zhao: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft. Siwen Wei, Wenyuan Wei, Bo Li: Review and Editing, Visualization. Jiancheng Liu, Siwen Wei: Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yanmaz E. Joint or decoupled optimization: multi-UAV path planning for search and rescue. Ad Hoc Netw. 2023;138(3):103018. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2022.103018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Liu X, Su Y, Wu Y, Guo Y. Multi-conflict-based optimal algorithm for multi-UAV cooperative path planning. Drones. 2023;7(3):217. doi:10.3390/drones7030217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chen Z, Zhang T, Hong T. IoT-enhanced multi-base station networks for real-time UAV surveillance and tracking. Drones. 2025;9(8):558. doi:10.3390/drones9080558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Andreou A, Mavromoustakis CX, Markakis E, Bourdena A, Mastorakis G. UAV-asisted IoT network framework with hybrid deep reinforcement and federated learning. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):37107. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-21014-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Nguyen DC, Ding M, Pathirana PN, Seneviratne A, Li J, Niyato D, et al. 6G Internet of Things: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(1):359–83. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3103320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Qu L, Fan J. Unmanned combat aerial vehicle path planning in complex environment using multi-strategy sparrow search algorithm with double-layer coding. J King Saud Univ—Comput Inf Sci. 2024;36(10):102255. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2024.102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Elmokadem T, Savkin AV. Computationally-efficient distributed algorithms of navigation of teams of autonomous UAVs for 3D coverage and flocking. Drones. 2021;5(4):124. doi:10.3390/drones5040124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Alanezi MA, Bouchekara HR, Apalara TAA, Shahriar MS, Sha’aban YA, Javaid MS, et al. Dynamic target search using multi-UAVs based on motion-encoded genetic algorithm with multiple parents. IEEE Access. 2022;10:77922–39. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3190395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang F, Zhu XP, Zhou Z, Tang Y. Deep-reinforcement-learning-based UAV autonomous navigation and collision avoidance in unknown environments. Chin J Aeronaut. 2024;37(3):237–57. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2023.09.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chen J, Liu L, Zhang Y, Chen W, Zhang L, Lin Z. Research on UAV path planning based on particle swarm optimization and soft actor-critic. In: Proceedings of the 2024 China Automation Congress (CAC); 2024 Nov 1–3; Qingdao, China. p. 6166–71. [Google Scholar]

11. Xue D, Lin Y, Wei S, Zhang Z, Qi W, Liu J, et al. Leveraging hierarchical temporal importance sampling and adaptive noise modulation to enhance resilience in multi-agent task execution systems. Neurocomputing. 2025;637(1–2):130134. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2025.130134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lee J, Friderikos V. Interference-aware path planning optimization for multiple UAVs in beyond 5G networks. J Commun Netw. 2022;24(2):125–38. doi:10.23919/jcn.2022.000006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang K, Gou Y, Xue D, Liu J, Qi W, Hou G, et al. Resilience augmentation in unmanned weapon systems via multi-layer attention graph convolutional neural networks. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(2):2941–62. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.052893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang K, Xue D, Gou Y, Qi W, Li B, Liu J, et al. Meta-path-guided causal inference for hierarchical feature alignment and policy optimization in enhancing resilience of UWSoS. J Supercomput. 2025;81(2):358. doi:10.1007/s11227-024-06848-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang N, Li Z, Liang X, Li Y, Zhao F. Cooperative target search of UAV swarm with communication distance constraint. Math Probl Eng. 2021;2021(1):3794329. doi:10.1155/2021/3794329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Gou Y, Wei S, Xu K, Liu J, Li K, Li B, et al. Hierarchical reinforcement learning with kill chain-informed multi-objective optimization to enhance resilience in autonomous unmanned swarm. Neural Netw. 2025;195(2):108255. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2025.108255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Huh D, Mohapatra P. Multi-agent reinforcement learning: a comprehensive survey. arXiv:2312.10256. 2023. [Google Scholar]

18. Vezhnevets AS, Osindero S, Schaul T, Heess N, Jaderberg M, Silver D, et al. Feudal networks for hierarchical reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning; 2017 Aug 6–11; Sydney, NSW, Australia, pp. 3540–9. [Google Scholar]

19. Ahilan S, Dayan P. Feudal multi-agent hierarchies for cooperative reinforcement learning. arXiv:1901.08492. 2019. [Google Scholar]

20. Tang H, Hao J, Lv T, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Jia H, et al. Hierarchical deep multiagent reinforcement learning with temporal abstraction. arXiv:1809.09332. 2018. [Google Scholar]

21. Lyu M, Zhao Y, Huang C, Huang H. Unmanned aerial vehicles for search and rescue: a survey. Remote Sens. 2023;15(13):3266. doi:10.3390/rs15133266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Rahman M, Sarkar NI, Lutui R. A survey on multi-UAV path planning: classification, algorithms, open research problems, and future directions. Drones. 2025;9(4):263. doi:10.3390/drones9040263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhao L, Gao Z, Hawbani A, Zhao W, Mao C, Lin N. Fuzzy-MADDPG based multi-UAV cooperative search in network-limited environments. In: Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Disaster Management (ICT-DM); 2024 Nov 19–21; Setif, Algeria, p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

24. Kelner JM, Burzynski W, Stecz W. Modeling UAV swarm flight trajectories using rapidly-exploring random tree algorithm. J King Saud Univ—Comput Inf Sci. 2024;36(1):101909. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang X, Ali M. A bean optimization-based cooperation method for target searching by swarm UAVs in unknown environments. IEEE Access. 2020;8:43850–62. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2977499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chaves AN, Cugnasca PS, Jose J. Adaptive search control applied to search and rescue operations using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). IEEE Latin Am Trans. 2014;12(7):1278–83. doi:10.1109/tla.2014.6948863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Qamar RA, Sarfraz M, Rahman A, Ghauri SA. Multi-criterion multi-UAV task allocation under dynamic conditions. J King Saud Univ—Comput Inf Sci. 2023;35(9):101734. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hou Y, Zhao J, Zhang R, Cheng X, Yang L. UAV swarm cooperative target search: a multi-agent reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans Intell Veh. 2023;9(1):568–78. doi:10.1109/tiv.2023.3316196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Hou K, Yang Y, Yang X, Lai J. Distributed cooperative search algorithm with task assignment and receding horizon predictive control for multiple unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Access. 2021;9:6122–36. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3048974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Phung MD, Ha QP. Safety-enhanced UAV path planning with spherical vector-based particle swarm optimization. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;107(2):107376. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Tang J, Liang Y, Li K. Dynamic scene path planning of uavs based on deep reinforcement learning. Drones. 2024;8(2):60. doi:10.3390/drones8020060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sabzekar S, Samadzad M, Mehditabrizi A, Tak AN. A deep reinforcement learning approach for UAV path planning incorporating vehicle dynamics with acceleration control. Unmanned Syst. 2024;12(03):477–98. doi:10.1142/s2301385024420044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bacon PL, Harb J, Precup D. The option-critic architecture. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2017 Feb 4–9; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 1726–34. [Google Scholar]

34. Liu J, Wei S, Li B, Wang T, Qi W, Han X, et al. Dual-timescale hierarchical MADDPG for Multi-UAV cooperative search. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2025;37(6):1–17. doi:10.1007/s44443-025-00156-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Harikumar K, Senthilnath J, Sundaram S. Multi-UAV oxyrrhis marina-inspired search and dynamic formation control for forest firefighting. IEEE Trans Autom Sci Eng. 2018;16(2):863–73. doi:10.1109/tase.2018.2867614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Perez-Carabaza S, Besada-Portas E, Lopez-Orozco JA, de la Cruz JM. Ant colony optimization for multi-UAV minimum time search in uncertain domains. Appl Soft Comput. 2018;62(4):789–806. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2017.09.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools