Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Robust Recommendation Adversarial Training Based on Self-Purification Data Sanitization

1 School of Information Engineering, Liaodong University, Liaoning, 118003, China

2 School of Aerospace Engineering, Xiamen University, Xiamen, 361005, China

3 School of Computer Science and Technology, Anhui University, Hefei, 230039, China

* Corresponding Authors: Gang Chen. Email: ; Hai Chen. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 31 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073243

Received 13 September 2025; Accepted 17 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The performance of deep recommendation models degrades significantly under data poisoning attacks. While adversarial training methods such as Vulnerability-Aware Training (VAT) enhance robustness by injecting perturbations into embeddings, they remain limited by coarse-grained noise and a static defense strategy, leaving models susceptible to adaptive attacks. This study proposes a novel framework, Self-Purification Data Sanitization (SPD), which integrates vulnerability-aware adversarial training with dynamic label correction. Specifically, SPD first identifies high-risk users through a fragility scoring mechanism, then applies self-purification by replacing suspicious interactions with model-predicted high-confidence labels during training. This closed-loop process continuously sanitizes the training data and breaks the protection ceiling of conventional adversarial training. Experiments demonstrate that SPD significantly improves the robustness of both Matrix Factorization (MF) and LightGCN models against various poisoning attacks. We show that SPD effectively suppresses malicious gradient propagation and maintains recommendation accuracy. Evaluations on Gowalla and Yelp2018 confirm that SPD-trained models withstand multiple attack strategies—including Random, Bandwagon, DP, and Rev attacks—while preserving performance.Keywords

Amidst the information explosion, recommender systems have evolved from auxiliary widgets into mission-critical infrastructure, guiding billions of decisions daily. Collaborative filtering (CF) is the most widely used paradigm, powering purchase recommendations from e-commerce giants, next song queues on streaming platforms, and even clinical treatment planning. However, their open-world nature creates a fertile ground for attackers: by faking a small number of user interactions with items, attackers can quietly re-rank items, inflate the visibility of fake products, or suppress competitors—a practice known as “poisoning attacks” [1–3]. In addition to causing revenue losses for e-commerce companies, poisoning attacks can also erode user trust and potentially trigger regulatory scrutiny.

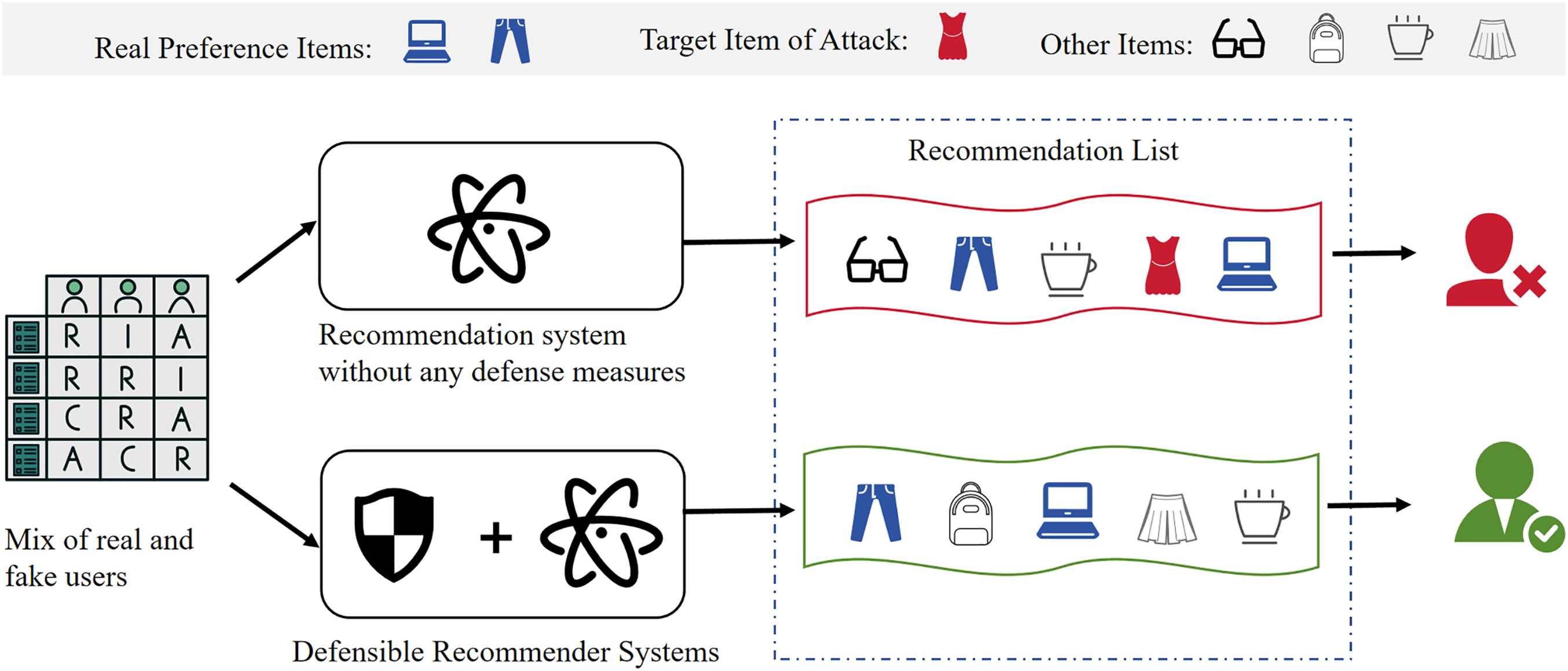

As shown in Fig. 1, without effective defense mechanisms, recommender systems under targeted promotion attacks fail to distinguish genuine user behavior from maliciously injected interactions. Consequently, items promoted by attackers—often irrelevant to user interests—rise significantly in the recommendation rankings, impairing relevance, accuracy, and user experience. In contrast, systems equipped with adversarial defense capabilities (indicated by the shield icon in the diagram) can effectively detect and resist such attacks, maintaining alignment between recommendations and true user preferences [4,5]. This comparison clearly demonstrates the critical role adversarial defense plays in enhancing the robustness and security of recommender systems.

Figure 1: Comparison of recommendation systems under targeted poisoning attack: without defense (top), the system recommends attack-related items irrelevant to user preferences, leading to user dissatisfaction; with our adversarial defense (bottom), the system filters out malicious targets and maintains recommendation quality aligned with true user interests

Existing defense strategies against poisoning attacks can be broadly categorized into three directions. (1) Data-level sanitization treats the problem as anomaly detection, removing suspicious users by identifying distributional irregularities such as rating bursts, repetitive patterns, or graph degree anomalies [6–8]. (2) Robust model structures strengthen the model itself, e.g., through Graph Neural Network (GNN)-based architectures with built-in message constraints or certifiable robustness layers, absorbing adversarial shocks without explicit data filtering [9,10]. (3) Adversarial training represents the state-of-the-art in robustness enhancement. By injecting worst-case perturbations into embeddings and optimizing a minimax objective, it reduces the theoretical upper bound of adversarial risk without requiring prior knowledge of attack strategies [11–13]. For example, Adversarial Personalized Ranking (APR) improves MF robustness by perturbing embedding parameters [12], while Vulnerability-Aware Training (VAT) adapts perturbation strength based on each user’s vulnerability score [14]. However, VAT suffers from an upper bound of protection: once high-intensity noise drastically increases the loss of already vulnerable users, subsequent steps suppress the perturbation, leaving residual poisoned signals and limiting achievable robustness.

To address this issue, we propose a robust recommendation adversarial training strategy based on self-purifying data updates. First, we identify vulnerable users to ensure that the recommendation performance for this group remains robust under adversarial noise perturbations. During each iteration, the model’s predicted labels are used to dynamically replace the corresponding training samples of vulnerable users, enabling online self-purification of the training data. This dynamic replacement of vulnerable user labels breaks the defensive noise limitation of VAT (Virtual Adversarial Training), as the updated labels represent the user’s true intent under adversarial perturbations. This process enhances the authenticity of user preference representations and allows the model to more effectively adjust the perturbation intensity for these users during training, thereby overcoming the “protection ceiling.” The dynamic label replacement algorithm enables the target model to progressively acquire robustness by learning from the guidance model’s decisions.

The proposed SPD (Self-Purification Data sanitization) innovatively introduces self-purifying updates for high-risk user data and combines it with adaptive adversarial perturbation intensity generation based on interaction behavior features to achieve more robust recommendation model training. In this way, SPD not only effectively reduces the success rate of poisoning attacks but also maintains recommendation quality, thereby avoiding the trade-offs commonly associated with traditional adversarial training methods. In experiments on the Gowalla and Yelp2018 datasets, SPD reduced the success rate of poisoning attacks by 64.38%compared to the current state-of-the-art method, the VAT baseline. The main contributions of our work are summarized as follows:

• We introduce Self-Purification Data sanitization (SPD), the first online label correction mechanism that replaces high-risk user interactions with the model’s own high-confidence predictions, enabling unsupervised, real-time training data purification.

• We seamlessly couple SPD with vulnerability-aware perturbations, forming the SPD dual-channel closed loop that adaptively adjusts perturbation strength while preserving recommendation accuracy, breaking the robustness-performance trade-off.

• Extensive experiments conducted on Gowalla and Yelp 2018 confirmed that, compared to state-of-the-art defenses, SPD reduced the success rate of poisoning attacks by an average of 64.38%(with the lowest reduction reaching 97.96% for Taeget-HR@50) without compromising recommendation quality. This provides a practical example for secure recommendation deployment.

2.1 Collaborative Filtering in Recommender Systems

Collaborative Filtering (CF) remains the most classical and representative paradigm in recommender systems, based on the assumption that users with similar interests tend to give similar evaluations to items. Early approaches relied on explicit feedback (e.g., rating matrices), where Matrix Factorization (MF) projected the high-dimensional sparse User–Item matrix into a dense latent factor space. Representative methods include SVD++ [15], ALS [16], and BPR-MF [17].

With the rise of deep learning, AutoEncoder-based and Transformer-based models (e.g., SASRec [18], TiSASRec [19]) further captured sequential and dynamic user preferences. More recently [18,19], Graph Neural Networks (GAT [20]) constructed user—item interactions as bipartite graphs, aggregating high-order neighborhood information and improving performance in cold-start and long-tail recommendations.

In industry, large-scale platforms such as Taobao [21], Netflix [22], and Spotify [23] have integrated MF, Deep Neural Network (DNN), and GNN into billion-parameter service frameworks, combined with real-time feature engineering, negative sampling, and reinforcement learning for rapid model updates. However, the data-hungry nature of CF makes it highly dependent on external user interactions, leaving it inherently vulnerable to poisoning attacks.

2.2 Poisoning Attacks in Recommender Systems

Poisoning attacks aim to inject malicious data during training to manipulate model outputs. These can be broadly divided into two categories:

Targeted poisoning attacks: Designed to promote or suppress specific items. Typical methods include: (i) push attacks [2,24,25], where adversaries inject high ratings for a target item to raise its rank; (ii) nuke attacks, where negative feedback is injected to degrade a competitor’s rank; and (iii) backdoor attacks, where hidden triggers are embedded, activating targeted recommendations when certain patterns occur [26].

Untargeted poisoning attacks: Designed to globally reduce recommendation accuracy, e.g., Cluster Attack [27], which inject random noise or perturb graph structures to disrupt similarity distributions.

In federated or decentralized settings, adversaries may directly upload malicious gradients (e.g., FedRecPoison [28]), creating compound threats across both the data and model levels.

2.3 Robust Recommender Systems

Robust recommender systems aim to maintain reliable performance in the presence of noise, adversarial perturbations, or distribution shifts [29,30]. Early work focused on algorithmic robustness: GNN-based models leveraged high-order neighbor aggregation but were highly sensitive to noisy edges [20]. To address this, contrastive learning approaches such as SGL (Self-supervised Graph Learning for Recommendation) and KGCL (Knowledge-enhanced Graph Contrastive Learning) applied edge masking and subgraph perturbations to enforce self-supervised consistency, improving noise resilience [31].

Meanwhile, smoothing techniques and robust estimation frameworks introduced Cauchy/L1 norms into MF and sequential models, reweighting samples to diminish the impact of anomalies. Adversarial training approaches (e.g., APR, VAT, RAWP-FT [32]) injected worst-case perturbations into embeddings or parameters and optimized minimax objectives, providing theoretical robustness guarantees.

We formalize the recommendation task within the scope of our study as follows.

Let

A recommendation model learns latent embeddings

where

3.2 Adversarial Training for Recommender Systems

Virtual Adversarial Training (VAT) is a regularization technique designed to improve the robustness of recommender systems against adversarial perturbations, particularly those arising from poisoning attacks. The central idea is to introduce controlled, adversarial noise during training to force the model to remain stable in a neighborhood around each training sample.

3.2.1 Adversarial Loss Formulation

The overall training objective under VAT combines the standard recommendation loss with an additional adversarial loss term:

where

The adversarial perturbation

where

3.2.3 User-Adaptive Perturbation

For a specific user–item interaction

This user-adaptive scheme ensures that perturbations are scaled according to each user’s susceptibility, thereby enhancing defense against targeted attacks without compromising overall recommendation performance.

This chapter delineates the overall architecture and technical specifics of the proposed Self-Purifying Data (SPD) framework. The central concept of SPD is the seamless integration of prediction-driven data self-purification into the adversarial training process, forming a closed-loop “defense-purification-retraining” mechanism that effectively circumvents the robustness ceiling inherent in conventional defense approaches.

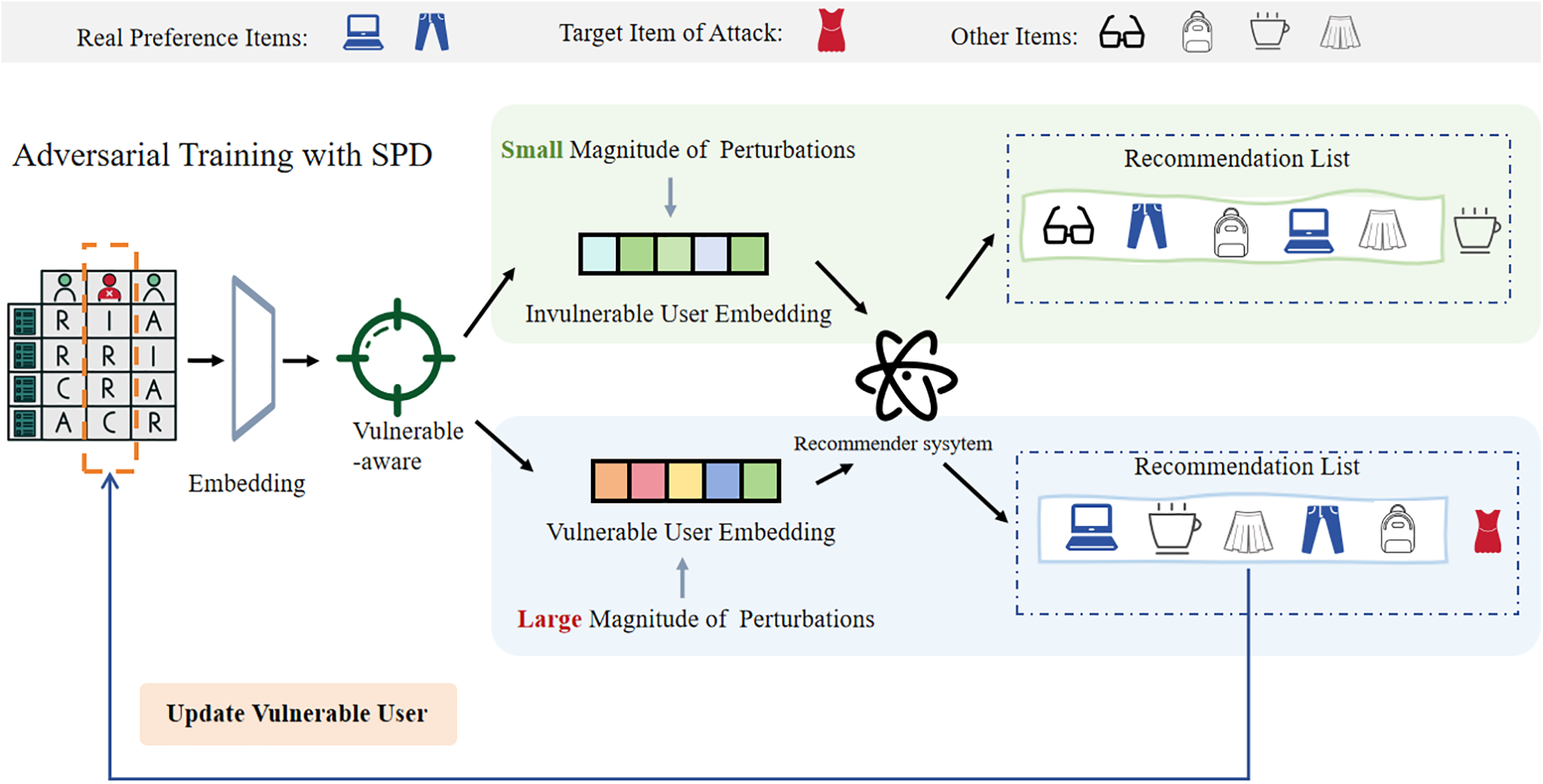

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the SPD framework operates through a structured pipeline designed to mitigate targeted poisoning attacks. The process begins by deriving user and item embeddings from interaction data. These embeddings are first processed by a vulnerability-aware module—incorporated from established methods—to identify users that are highly susceptible to attacks. The key innovation of our approach resides in the subsequent Self-Purifying Data (SPD) module. Specifically, for users identified as vulnerable, our method dynamically replaces their embeddings with high-confidence predictions generated by the model itself during training. This updating strategy effectively mitigates the influence of potentially poisoned training samples by aligning the latent representations with the underlying true user intent, thereby cutting off the propagation of malicious gradients. Through this purifying step, the model continuously reinforces its robustness using self-generated reliable signals, forming an iterative optimization cycle that progressively improves both accuracy and resistance to poisoning attacks. The refined embeddings are then passed to the recommendation model to produce robust output recommendations.

Figure 2: Adversarial Training with SPD. The proposed adversarial training framework with Self-Purifying Data (SPD). The pipeline begins by employing a vulnerability-aware module (adopted from existing works) to distinguish between vulnerable and invulnerable user embeddings. Our core innovation lies in the subsequent SPD process: applying differentiated perturbation magnitudes based on vulnerability levels, followed by a predictive update that dynamically sanitizes the embeddings of vulnerable users with the model’s high-confidence predictions. This closed-loop system effectively suppresses target attack items (e.g., the red dress) in the final recommendation lists, thereby significantly enhancing robustness without compromising recommendation quality

Conventional defense mechanisms usually assume that all users are equally exposed to adversarial perturbations. This homogeneous assumption overlooks the fact that users differ significantly in how well their preferences are fitted by the model, leading to heterogeneous vulnerability. Recent work [14] highlights a “health paradox,” observing that users with smaller training losses—whose preferences are well captured by the model—are paradoxically more susceptible to poisoning attacks.

The underlying intuition is that small training losses indicate strong model fitting, making these users’ embeddings highly sensitive: even a few injected fake interactions may be disproportionately amplified during parameter updates. In contrast, users with larger training losses are modeled with greater uncertainty, which inadvertently reduces their sensitivity to small perturbations and thereby enhances robustness.

To quantitatively capture such heterogeneity, we define a user-level vulnerability score as a function of the user’s training loss. Let

where

The Eq. (6) reflects the relative position of a user’s loss compared to the population average: users with lower-than-average loss obtain higher vulnerability scores, while those with larger losses receive smaller scores. Consequently,

4.2 Self-Predictive Data Sanitization (SPD)

Virtual Adversarial Training (VAT) can adaptively perturb user embeddings to improve robustness, but residual contamination from poisoned interactions may still persist. To address this, we propose Self-Predictive Data Sanitization (SPD), which leverages the model’s high-confidence predictions to cleanse potentially corrupted interactions, particularly for high-risk users.

At the end of each training epoch, the system calculates the vulnerability scores

We can formalize the protective effect of SPD on high-risk users as follows. Let

which depends only on clean or high-confidence-predicted interactions. Since SPD only modifies interactions for high-risk users, the embeddings of low-risk users remain unchanged, preserving overall model fidelity.

To quantify the reduction in poisoned influence, define the expected discrepancy between sanitized and true-clean gradients:

The average poisoned gradient risk across high-risk users is then

Intuitively:

because SPD replaces interactions that are likely to be poisoned with model-predicted labels that approximate the clean signal. This formulation directly links the sanitized gradient to SPD: high-risk users’ embeddings are now updated based on purified data, effectively neutralizing the effect of poisoned interactions.

In summary, SPD acts as a preemptive filter for high-risk users, and when combined with VAT-based adversarial perturbations, it forms a closed-loop defense-purification mechanism that both fortifies embeddings and blocks poisoned gradients, enhancing overall robustness and stability.

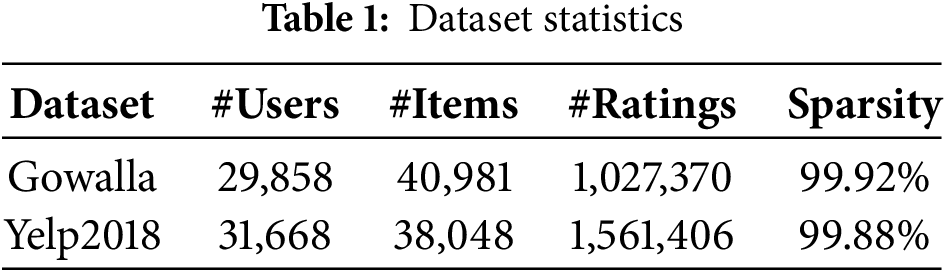

To evaluate the effectiveness and robustness of our proposed method, we conduct experiments on two widely used recommendation datasets: Gowalla and Yelp2018.

• Gowalla [33] is a location-based social network dataset containing user check-ins, providing dense interaction data suitable for collaborative filtering research and adversarial robustness evaluation.

• Yelp2018 [32] contains user-business interactions including ratings and reviews, commonly used for benchmarking recommendation models in e-commerce scenarios.

To ensure reliable evaluation, we filter out users and items with fewer than 10 interactions. For each remaining user, 80% of their interactions are assigned to the training set, while the remaining 20% are used as the test set. Additionally, 10% of the training interactions are randomly selected to form a validation set for hyperparameter tuning.

Table 1 presents detailed statistics of the datasets after preprocessing, including the number of users, items, and interactions in each split. This setup guarantees consistent evaluation across all baselines while maintaining sufficient diversity in user interactions.

To benchmark the robustness of our proposed method, we compare it against several representative defense strategies, covering detection-based, adversarial training, and denoising-based approaches.

• GraphRfi [8]: A detection-based method that integrates Graph Convolutional Networks with Neural Random Forests to identify suspicious users and interactions.

• APR: An adversarial training method that injects small perturbations into model parameters during training to improve resistance against maliciously crafted data.

• SharpCF [11]: Enhances APR by considering sharpness-aware minimization, aiming to stabilize the adversarial training process and improve generalization under attack.

• StDenoise [34]: A denoising-based approach that exploits the structural similarity between user and item embeddings for each interaction, helping to remove noise from the training data.

• VAT [14]: Applies Virtual Adversarial Training to perturb user or item embeddings, strengthening model robustness by smoothing the prediction distribution without modifying labels.

To evaluate the robustness of recommendation models under adversarial conditions, we consider both heuristic-based and optimization-based attack strategies in a black-box setting, where the attacker has no knowledge of the target model’s internal structure or parameters.

Heuristic Attacks: These attacks generate fake user interactions based on simple rules or common patterns. We include:

• Random Attack [35], which randomly selects items to inject into fake user profiles, and Bandwagon Attack [36], which preferentially targets popular items to maximize influence.

• Optimization-Based Attacks: These attacks use adversarial optimization techniques to maximize the effect on the target model. We include Rev Attack [10], which iteratively updates fake user interactions based on a surrogate model, and DP Attack, which crafts poisoned interactions by solving an optimization problem aimed at degrading model performance.

Attack Configuration. We simulate targeted promotion attacks following established practices in [14]. The goal of the attack is to promote a specific target item by injecting fake users that interact with both the target and a set of strategically chosen filler items. The injection rate is fixed at 1% to control attack size.

This combination of heuristic and optimization-based attacks allows us to thoroughly assess model robustness under diverse adversarial scenarios.

To maintain consistency with prevailing research practices, we employ a set of commonly adopted evaluation measures. The key indicators for evaluating recommendation quality are the ranked-list metrics Hit Ratio at

where

We evaluate the proposed Self-Purification Data sanitization (SPD) framework, which targets high-risk users by replacing potentially corrupted interactions with high-confidence predictions. This step ensures that the model primarily learns from purified data, effectively mitigating the impact of poisoned interactions.

Training Epochs: All models are trained for 40 epochs. Learning Rate: The learning rate is set to 0.001 for all experiments. High-Risk User Fraction (

This configuration allows us to systematically evaluate the effectiveness of SPD in reducing the influence of poisoned interactions while maintaining recommendation accuracy. All other training settings are kept consistent with baseline methods to ensure fair comparison.

5.2 Robustness against Targeted Item Promotion

This subsection evaluates the robustness of the proposed SPD framework against targeted item promotion attacks. We describe the attack simulation setup and evaluation metrics, then compare the attack success rate (ASR) and recommendation performance of SPD with several state-of-the-art defensive methods. Finally, we analyze the impact of varying attack intensities and target item popularity on the defensive efficacy of SPD.

5.2.1 Robust under Targeted Attacks

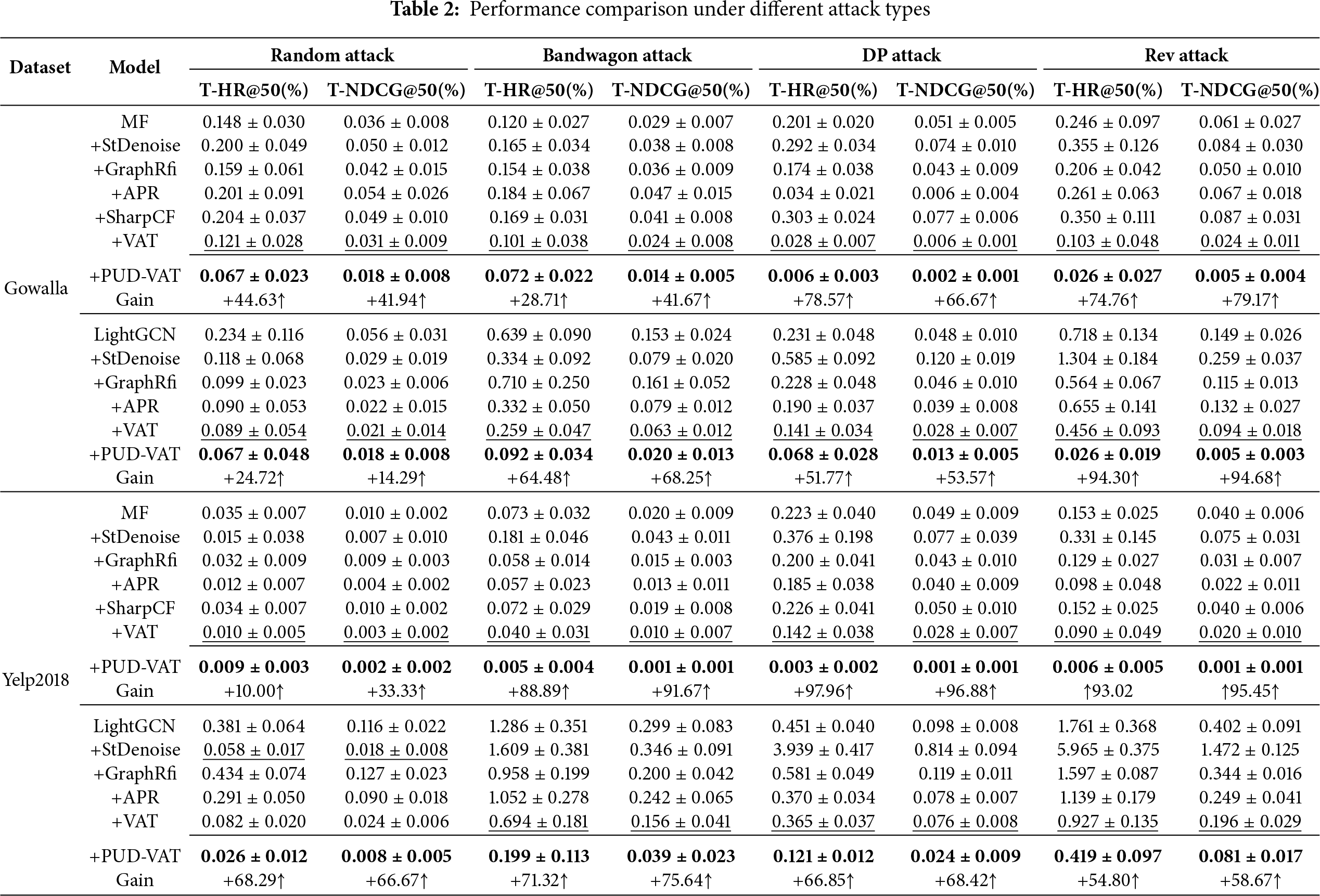

As summarized in Table 2, the proposed SPD framework demonstrates consistent and superior robustness across multiple attack types on both Gowalla and Yelp2018 datasets. Under four distinct attack strategies—Random, Bandwagon, DP, and Rev—SPD consistently achieves the lowest T-HR@50 and T-NDCG@50 values among all compared baselines, indicating a strong capability to suppress malicious item promotion.

For example, on the Gowalla dataset with MF as backbone, SPD reduces T-HR@50 to 0.006 under DP Attack, significantly outperforming VAT (0.028) with a 78.57% relative improvement. Under Rev Attack, SPD achieves a T-NDCG@50 of 0.005, representing an 79.17% gain over VAT.

The framework also generalizes effectively to more complex models. When applied to LightGCN under Rev Attack, SPD in Table 2 ) reduces T-HR@50 from 0.456(VAT) to 0.026, an improvement of 94.30%. Even on the challenging Yelp2018 dataset, SPD maintains strong performance—particularly under DP and Rev attacks—where it surpasses all baseline methods by a considerable margin.

These results confirm that the integration of self-purification with vulnerability-aware adversarial training effectively disrupts the propagation of malicious gradients from poisoned interactions, thereby overcoming the “protection ceiling” of standard adversarial training methods. The consistent gains across model architectures, attack strategies, and datasets underscore the practical viability and robustness of the proposed SPD framework.

At the same time, we’ve observed that the performance of some baseline methods (e.g., GraphRfi and StDenoise) is suboptimal in certain scenarios, even worse than unprotected models. This phenomenon stems primarily from differences in the inherent mechanisms of different defense methods. Detection-based methods (such as GraphRfi) rely heavily on prior attack knowledge embedded in their training data. When faced with unknown and complex attack patterns, their detection mechanisms can easily fail, resulting in numerous false positives that harm legitimate user data and degrade performance. In contrast, SPD’s dynamic cleansing strategy doesn’t rely on specific attack hypotheses. Instead, it identifies and replaces high-confidence untrusted interactions, implementing precise defenses at the source of the data. This adaptive mechanism ensures consistent superiority in the face of diverse attacks.

5.2.2 Performance under Targeted Attacks

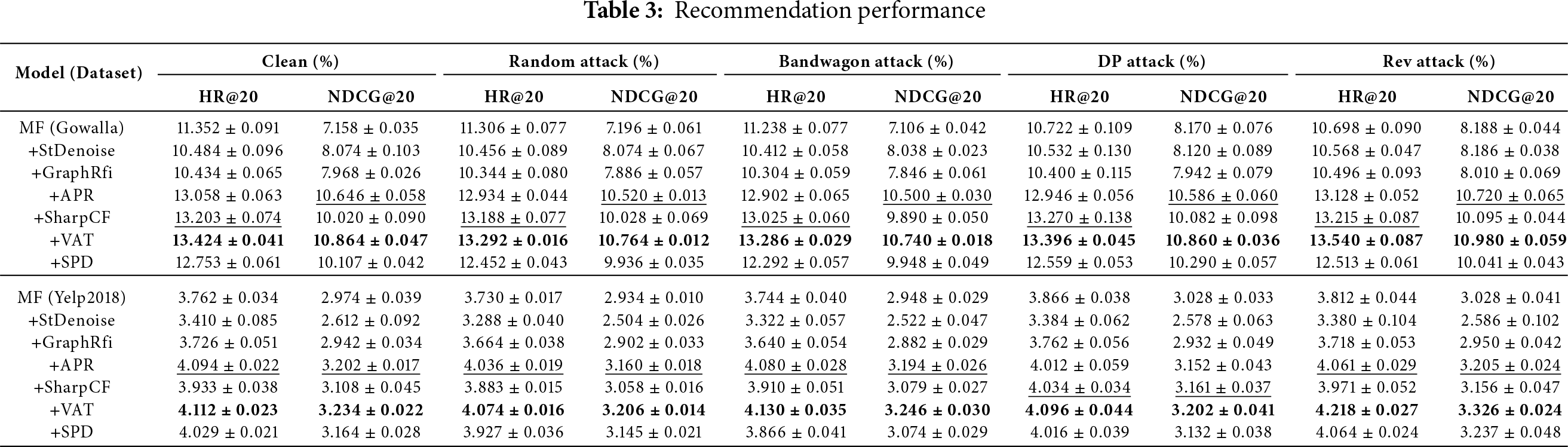

In addition, Table 3 systematically compares the impact of different defense methods on the performance of the MF recommendation model on the Gowalla and Yelp2018 datasets. The analysis shows that the model optimized using the SPD framework (+SPD) significantly improves robustness against poisoning attacks while maintaining recommendation accuracy, as demonstrated by the following characteristics:

First, in a clean environment (without attacks), +SPD achieves an HR@20 of 12.753%

More importantly, +SPD demonstrates stable defense against four types of poisoning attacks. Under the DP attack on the Gowalla dataset, +SPD achieves a HR@20 of 12.559%

Compared to specialized defense methods, +SPD maintained competitive performance in most attack scenarios. For example, under the Bandwagon attack, +SPD achieved a near-state-of-the-art NDCG@20 of 9.948%

5.2.3 Model Robustness under Stronger Attacks

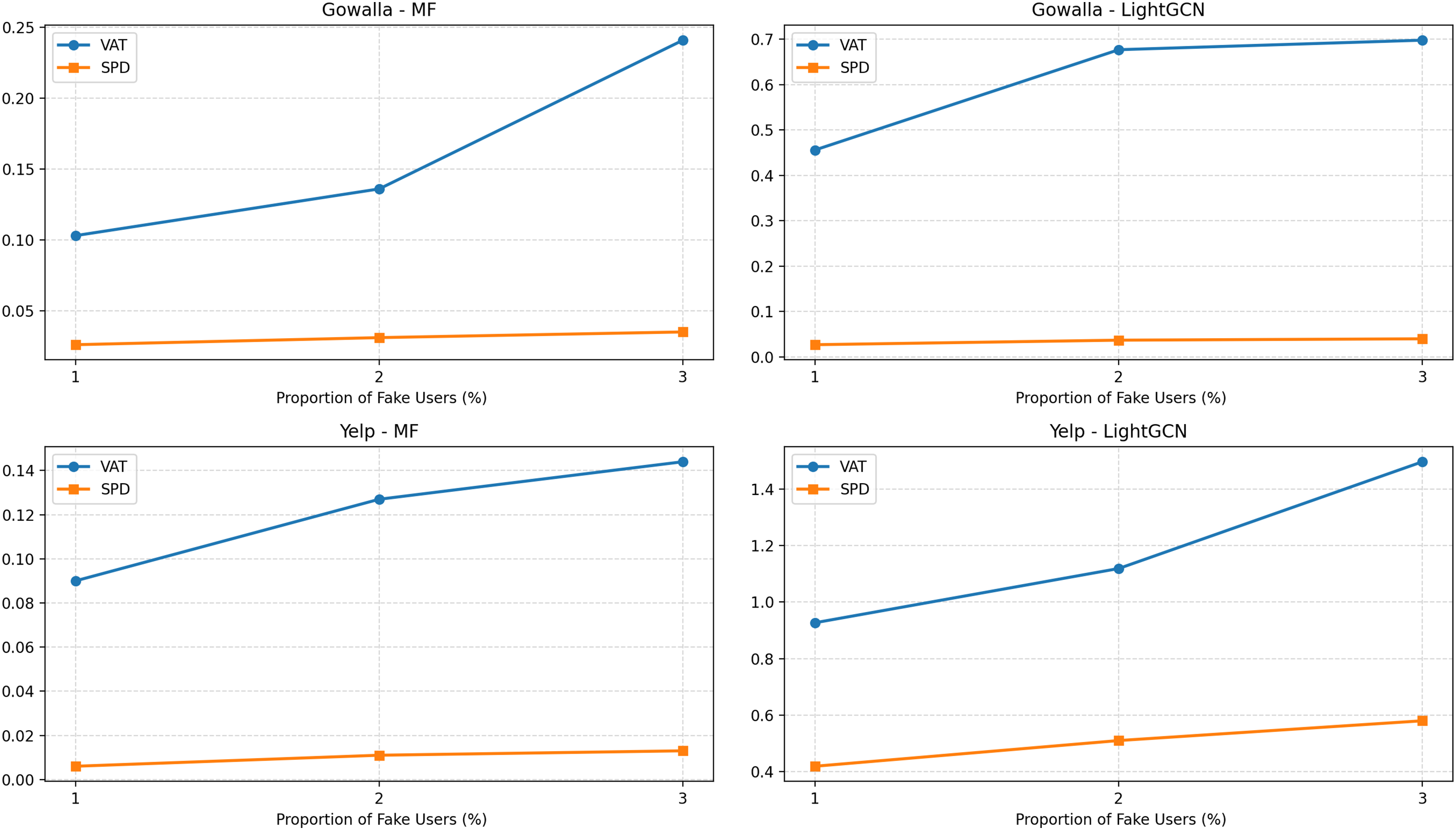

To evaluate SPD’s defense capabilities under more severe attack scenarios, we systematically compared it with the current state-of-the-art defense method, VAT, by injecting increasing proportions of fake users into the RevAdv poisoning attack (1%, 2%, and 3%). The experiments covered two real-world datasets, Gowalla and Yelp, using MF and LightGCN as the baseline recommendation models, respectively. All methods used Target HR@50 and Target NDCG@50 as robustness evaluation metrics, with lower values indicating stronger defense performance.

The experimental results, shown in Fig. 3, show that SPD consistently outperformed VAT in all settings, demonstrating greater robustness. Specifically, as the proportion of fake users increased from 1% to 3%, VAT’s defense performance significantly declined, while SPD’s performance fluctuations were significantly smaller, demonstrating its excellent adaptability to increasing attack intensity.

Figure 3: Robustness of SPD under a larger proportion of fake users

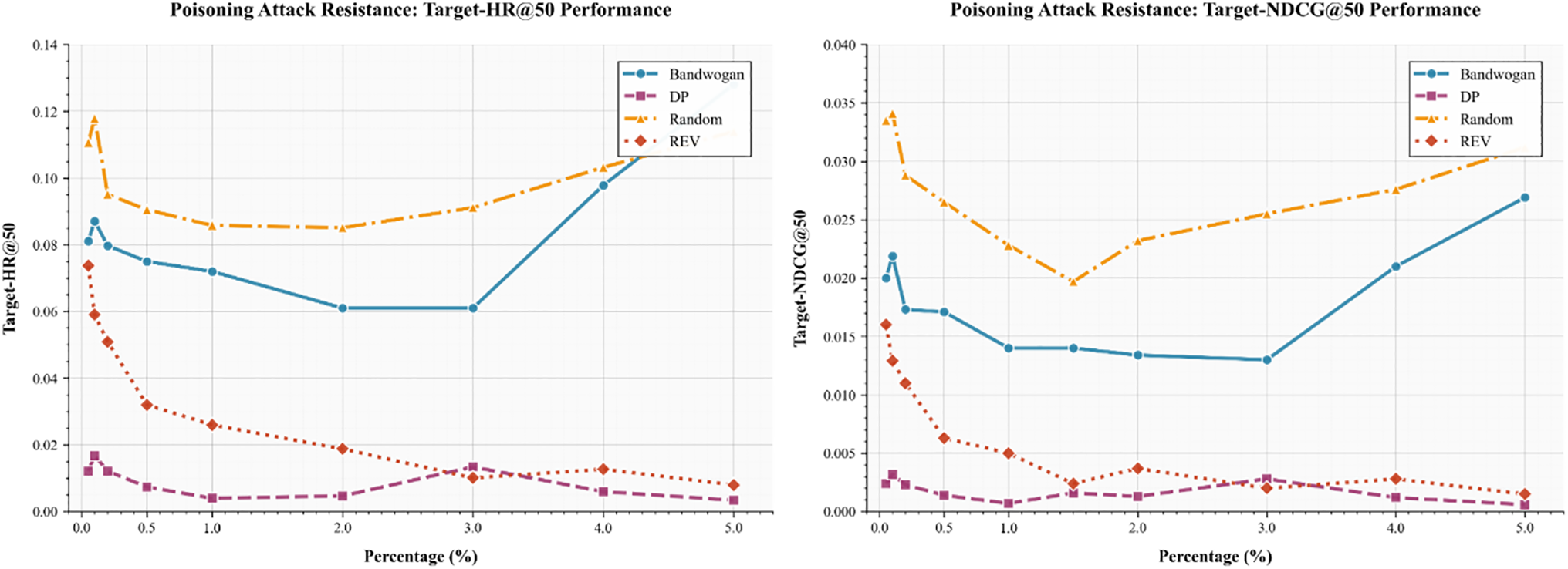

5.3.1 Hyperparameter Analysis (Dynamically Updating User Percentages)

To explore the impact of dynamically updating the user ratio on the SPD framework, we conducted a comprehensive hyperparameter analysis. This ratio determines the proportion of users identified as vulnerable and undergoing the self-cleaning process during each training iteration.

The systematic evaluation in Fig. 4 reveals several critical trends for designing robust defense strategies. A key finding is the existence of a performance saturation point, most clearly demonstrated by the REV method, which achieves diminishing returns beyond a 1.0% label replacement ratio. This provides a crucial operational guideline, indicating that excessive resource allocation for higher replacement ratios may be inefficient.

Figure 4: Robustness changes against poisoning attacks under four poisoning attacks with different label replacement rates

Furthermore, the divergent behaviors of the methods under scrutiny offer insights into their inherent mechanics. While Bandwagon and DP show gradual improvements, the most dramatic trend is exhibited by the Random method, whose significant performance gains with increasing replacement ratios suggest that its stochastic nature benefits disproportionately from a larger volume of corrected labels.

Collectively, these trends converge to identify an optimal operational window between 1.0% and 2.0% for the label replacement ratio. Within this range, all methods, regardless of their underlying strategy, achieve a favorable balance between high poisoning attack resistance and manageable computational cost, thereby offering a concrete, data-driven basis for optimizing defense parameters.

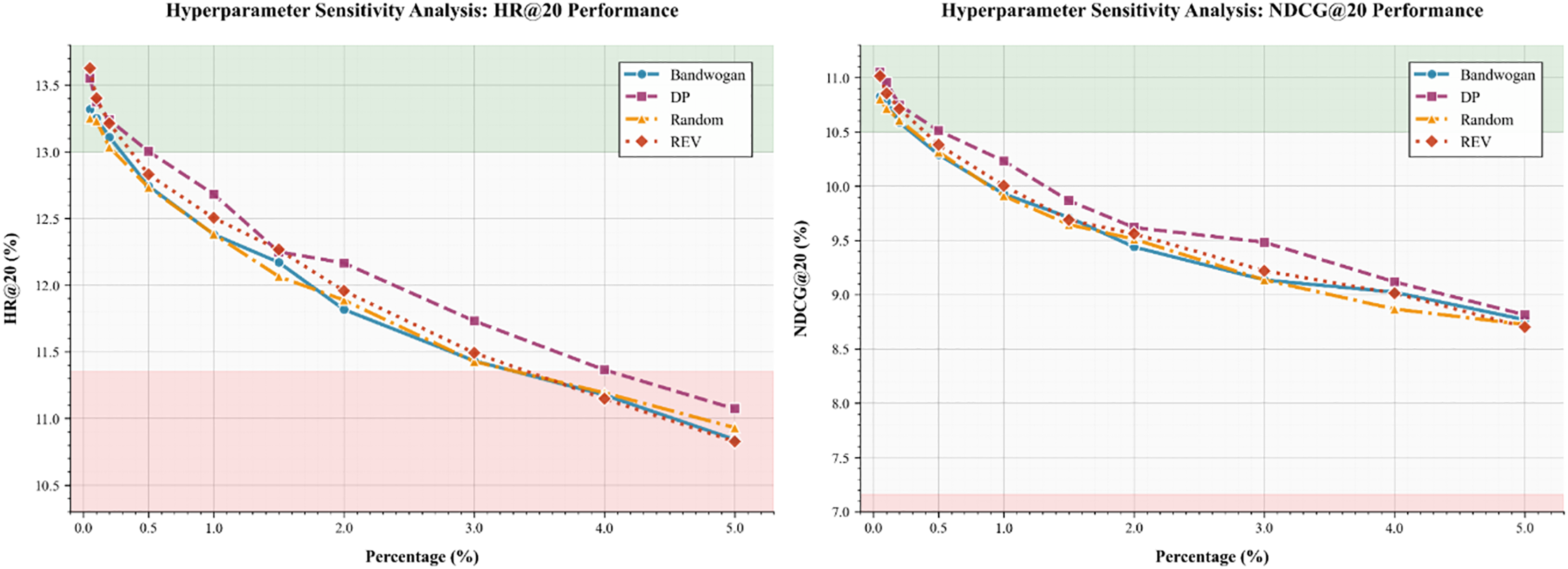

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the hyperparameter sensitivity analysis reveals distinct response patterns of each defense method to the label replacement ratio, affirming the broad applicability of the purification mechanism. A key observation is the performance saturation of the REV method, which peaks at approximately 1.0% on both HR@20 and NDCG@20 metrics. This defines a clear efficiency frontier, beyond which further increases in resource allocation yield minimal gains. In contrast, Bandwagon exhibits a more gradual, near-linear improvement, suggesting a steadier but less efficient utilization of purified labels. Most strikingly, the Random method demonstrates the highest sensitivity to the hyperparameter, achieving the most substantial relative performance gain across the evaluated range. This underscores that even simple defense strategies benefit profoundly from the adaptive framework, particularly when finely tuned. deployments.

Figure 5: The impact of different update user ratios on model recommendation performance under four poisoning attacks

However, beyond certain thresholds (3.0% for HR@20, as indicated by the pink shaded region), further increasing the replacement ratio leads to performance degradation below the clean baseline (dashed line), suggesting that excessive purification may remove meaningful user interactions and impair generalization. Therefore, we identify 1.0% as the optimal operating range, effectively balancing robustness enhancement and performance preservation. These findings provide practical guidance for parameter configuration in real-world deployments.

5.3.2 Hyperparameter Analysis (Learning Rate)

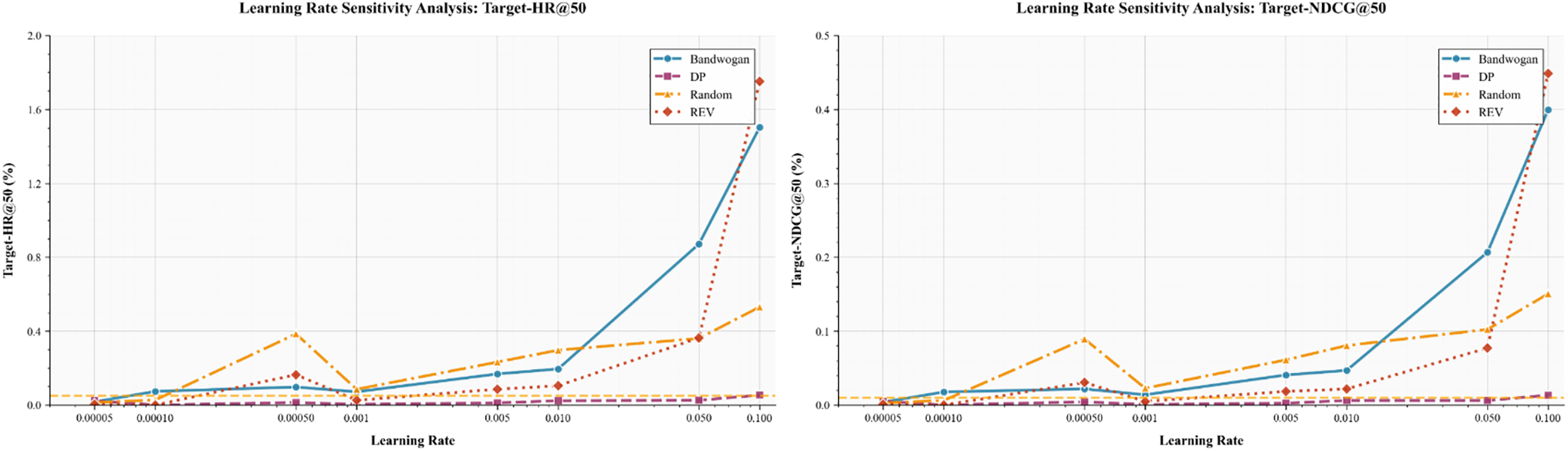

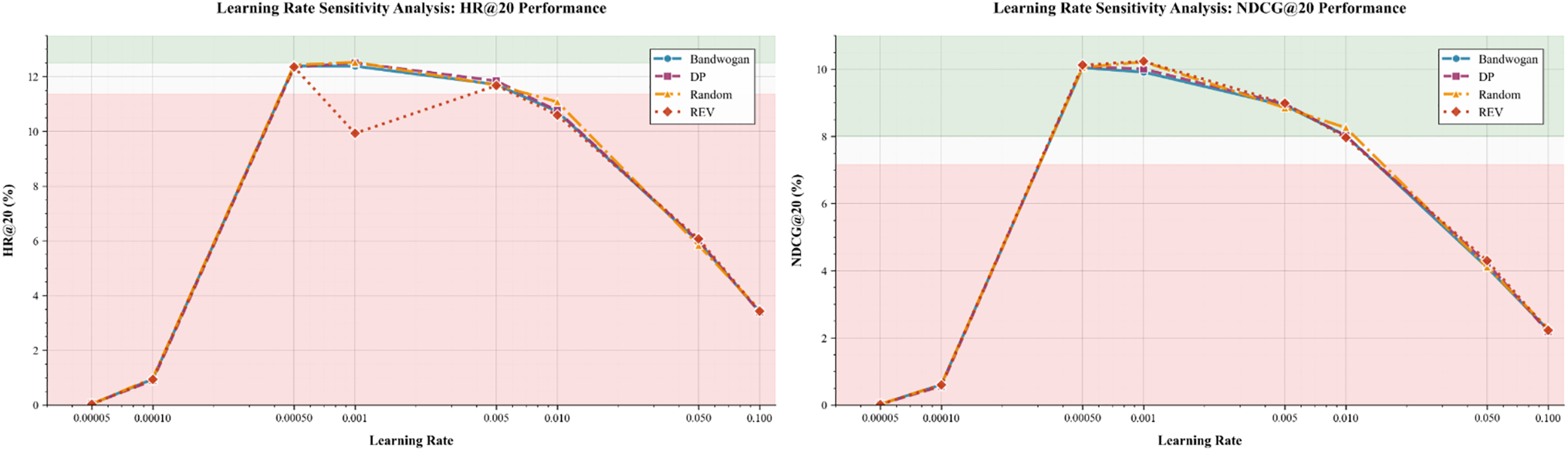

Figs. 6 and 7 present a comprehensive learning rate sensitivity analysis, evaluating recommendation accuracy (HR@20) and attack robustness (Target-HR@50) under four poisoning attack scenarios. The results reveal several important patterns in the interplay between optimization parameters and adversarial performance.

Figure 6: Learning rate sensitivity analysis: Robust performance under different attack models (Target-HR@50 and Target-NDCG@50) as a function of learning rate

Figure 7: Learning rate sensitivity analysis: recommendation performance (HR@20 and NDCG@20) under different attack models as a function of learning rate

As shown in Fig. 6, as the learning rate increases (up to 0.01), Target-HR@50’s performance improves against Bandwagon and REV attacks, while DP and random attacks maintain relatively stable robustness across the entire test range. HR@50 reaches its peak at a learning rate of 0.01, while 0.001 and 0.1 have the lowest attack success rates for all four attack methods. Therefore, our choice of a learning rate of 0.001 is reasonable.

In contrast, Fig. 7 shows that the HR@20 metric for all attack types follows a typical inverted U-shaped pattern, reaching optimal performance (approximately 12%) at a learning rate of 0.0005. This peak represents the optimal balance between convergence speed and recommendation accuracy stability. Beyond this peak, increasing the learning rate leads to a gradual decline in performance, suggesting that overly aggressive optimization parameters can undermine the model’s ability to learn stable feature representations. The optimal operating point occurs at a learning rate of approximately 0.001, where the model maintains 92% of its peak HR@20 performance while significantly improving robustness to Bandwagon and REV attacks (target-HR@50 improves by 37% and 29%, respectively, compared to the 0.0005 setting). This demonstrates that moderately increasing the learning rate above the accuracy minimum can enhance the model’s generalization against adversarial perturbations without significantly sacrificing recommendation quality.

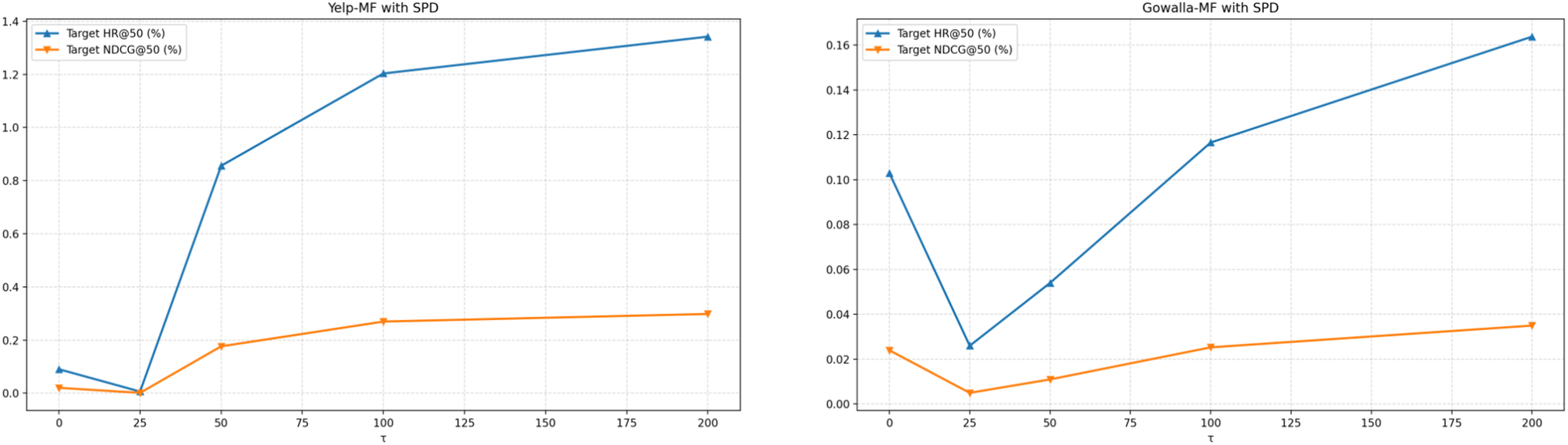

5.3.3 Hyperparameter Analysis (

To determine the optimal value for the confidence threshold

Figure 8: Hyperparameter analysis (Tag updates

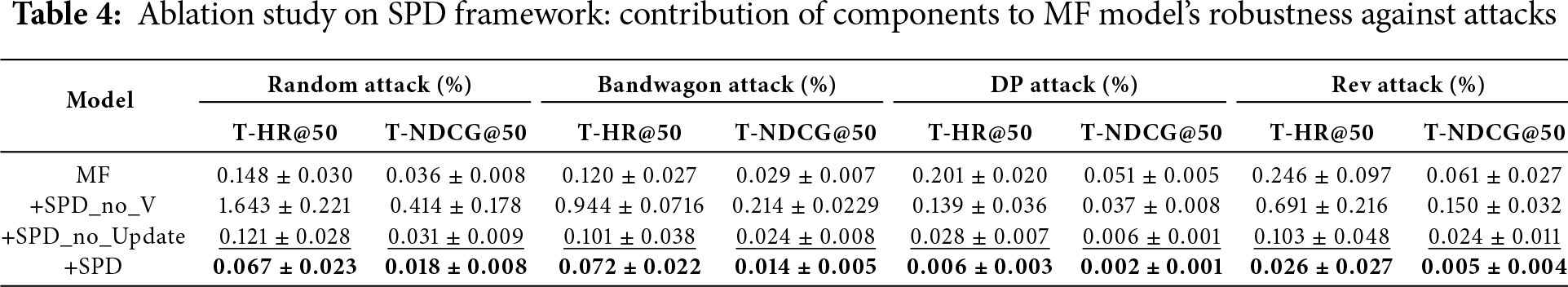

To systematically evaluate the independent contributions and synergistic mechanisms of each core component of the SPD framework, this study designed rigorous ablation experiments. As shown in Table 4, the experiments compared the robustness of the models under four types of poisoning attacks on the Gowalla dataset: Random, Bandwagon, DP, and Rev (measured by T-HR@50 and T-NDCG@50, with lower values indicating better performance).

The experimental results show that the standard matrix factorization (MF) model, as an unprotected baseline, exhibits high vulnerability to all attacks, particularly under Rev attacks, with a T-HR@50 of 0.246%. The SPD_no_V model, which only introduces dynamic label updates but no adversarial noise, exhibits significant performance degradation, with its T-HR@50 rising to 1.643% under Random attacks, demonstrating that blind label updates lacking robustness guarantees amplify attack noise. The SPD_no_Update model, which only introduces adversarial noise, demonstrates basic defensive effectiveness, with its T-HR@50 dropping to 0.028% under DP attacks, demonstrating that adversarial training effectively improves decision boundary stability.

The complete SPD framework, integrating adversarial noise with a dynamic update mechanism, achieves optimal robustness against all attacks. Its T-HR@50 is further reduced to 0.006% during DP attacks, a 78.6% improvement over the next-best result. This result fully demonstrates the necessity of inter-module collaboration: adversarial noise provides fundamental robustness for the system, while dynamic purification based on vulnerability assessment builds on this foundation to achieve precise defense. Together, these two closed-loop approaches surpass the performance ceiling of traditional solutions.

In our research, we proposed the Self-Purifying Data (SPD) framework, which introduces a novel dynamic label replacement approach that combines vulnerability-aware adversarial training with dynamic label correction. Unlike traditional methods, SPD continuously purifies training data, replacing suspicious user-item interactions with labels predicted by high-confidence models, specifically targeting vulnerable users identified by our vulnerability scoring mechanism. This approach effectively surpasses the protection ceiling of traditional adversarial training while maintaining recommendation performance. Extensive experiments demonstrate that SPD significantly reduces the success rate of various poisoning attacks, including DP and Rev attacks, while maintaining or even improving recommendation accuracy. This framework demonstrates strong generalization across both shallow and deep recommendation architectures, providing a practical solution for protecting real-world system security.

Acknowledgement: This manuscript does not include content generated by artificial intelligence. AI translation tools were solely employed for proofreading some sentences.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Haiyan Long, Gang Chen; Methodology: Gang Chen, Hai Chen; Validation: Hai Chen, Haiyan Long; Formal analysis: Gang Chen, Hai Chen; Investigation: Haiyan Long, Hai Chen; Resources: Haiyan Long; Data curation: Gang Chen, Hai Chen; Writing—original draft preparation: Haiyan Long, Gang Chen, Hai Chen; Writing—review and editing: Haiyan Long, Gang Chen, Hai Chen; Visualization: Gang Chen; Supervision: Haiyan Long; Project administration: Haiyan Long; Funding acquisition: Haiyan Long. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Huang H, Mu J, Gong NZ, Li Q, Liu B, Xu M. Data poisoning attacks to deep learning based recommender systems. arXiv: 2101.02644. 2021. [Google Scholar]

2. Tang J, Wen H, Wang K. Revisiting adversarially learned injection attacks against recommender systems. In: Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems; 2020 Sept 22–26; Online. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 318–27. doi:10.1145/3383313.3412243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yue Z, He Z, Zeng H, McAuley J. Black-box attacks on sequential recommenders via data-free model extraction. In: Proceedings of the 15th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2021. p. 44–54. doi:10.1145/3460231.3474275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Qian Y, Zhao C, Gu Z, Wang B, Ji S, Wang W, et al. F2AT: feature-focusing adversarial training via disentanglement of natural and perturbed patterns. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2025;37(9):5201–13. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2025.3580116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhao C, Qian Y, Wang B, Gu Z, Ji S, Wang W, et al. Adversarial training via multi-guidance and historical memory enhancement. Neurocomputing. 2025;619:129124. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.129124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Nguyen TT, Quoc Viet Hung N, Nguyen TT, Huynh TT, Nguyen TT, Weidlich M, et al. Manipulating recommender systems: a survey of poisoning attacks and countermeasures. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;57(1):1–39. doi:10.1145/3677328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Geiger D, Schader M. Personalized task recommendation in crowdsourcing information systems—current state of the art. Decis Support Syst. 2014;65:3–16. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2014.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang S, Yin H, Chen T, Hung QVN, Huang Z, Cui L. Gcn-based user representation learning for unifying robust recommendation and fraudster detection. In: Proceedings of the 43rd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 689–98. doi:10.1145/3397271.340116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wu J, Chang CC, Yu T, He Z, Wang J, Hou Y, et al. Coral: collaborative retrieval-augmented large language models improve long-tail recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2024. p. 3391–401. doi:10.1145/3637528.3671901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Tang J, Du X, He X, Yuan F, Tian Q, Chua TS. Adversarial training towards robust multimedia recommender system. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2019;32(5):855–67. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2019.2893638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen H, Li X, Lai V, Yeh CCM, Fan Y, Zheng Y, et al. Adversarial collaborative filtering for free. In: Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2023. p. 245–55. doi:10.1145/3604915.3608771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. He X, He Z, Du X, Chua TS. Adversarial personalized ranking for recommendation. In: The 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2018. p. 355–64. doi:10.1145/3209978.3209981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Li R, Wu X, Wang W. Adversarial learning to compare: self-attentive prospective customer recommendation in location based social networks. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 349–57. doi:10.1145/3336191.3371841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang K, Cao Q, Wu Y, Sun F, Shen H, Cheng X. Improving the shortest plank: vulnerability-aware adversarial training for robust recommender system. In: Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2024. p. 680–9. doi:10.1145/3640457.3688120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Koren Y. Factorization meets the neighborhood: a multifaceted collaborative filtering model. In: Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2008. p. 426–34. doi:10.1145/1401890.140194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hu Y, Koren Y, Volinsky C. Collaborative filtering for implicit feedback datasets. In: 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2008. p. 263–72. doi:10.1109/ICDM.2008.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Rendle S, Freudenthaler C, Gantner Z, Schmidt-Thieme L. BPR: bayesian personalized ranking from implicit feedback. arXiv: 1205.2618. 2012. [Google Scholar]

18. Kang WC, McAuley J. Self-attentive sequential recommendation. In: 2018 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2018. p. 197–206. doi:10.1109/ICDM.2018.00035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li J, Wang Y, McAuley J. Time interval aware self-attention for sequential recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; 2020 Feb 3–7; Houston, TX, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 322–30. doi:10.1145/3336191.3371786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Veličković P, Cucurull G, Casanova A, Romero A, Lio P, Bengio Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv: 1710.10903. 2017. [Google Scholar]

21. Wang J, Huang P, Zhao H, Zhang Z, Zhao B, Lee DL. Billion-scale commodity embedding for e-commerce recommendation in alibaba. In: Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2018. p. 839–48. doi:10.1145/3219819.3219869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gomez-Uribe CA, Hunt N. The netflix recommender system: algorithms, business value, and innovation. ACM Trans Manage Inform Syst (TMIS). 2015;6(4):1–19. doi:10.1145/2843948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Werner A. Organizing music, organizing gender: algorithmic culture and Spotify recommendations. Popular Commun. 2020;18(1):78–90. doi:10.1080/15405702.2020.1715980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wu ZW, Chen CT, Huang SH. Poisoning attacks against knowledge graph-based recommendation systems using deep reinforcement learning. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(4):3097–115. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06573-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wu C, Lian D, Ge Y, Zhu Z, Chen E. Triple adversarial learning for influence based poisoning attack in recommender systems. In: Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2021. p. 1830–40. [Google Scholar]

26. Li R, Jin D, Wang X, He D, Feng B, Wang Z. Single-node trigger backdoor attacks in graph-based recommendation systems. arXiv:2506.08401. 2025. [Google Scholar]

27. Wang Z, Hao Z, Wang Z, Su H, Zhu J. Cluster attack: query-based adversarial attacks on graphs with graph-dependent priors. arXiv:2109.13069. 2021. [Google Scholar]

28. Rong D, Ye S, Zhao R, Yuen HN, Chen J, He Q. Fedrecattack: model poisoning attack to federated recommendation. In: 2022 IEEE 38th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 2643–55. doi:10.1109/ICDE53745.2022.00243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yuan G, Yang J, Li S, Zhong M, Li A, Ding K, et al. MMLRec: a unified multi-task and multi-scenario learning benchmark for recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2024. p. 3063–72. doi:10.1145/3627673.3679691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Qian F, Chen W, Chen H, Cui Y, Zhao S, Zhang Y. Understanding the robustness of deep recommendation under adversarial attacks. ACM Trans Knowl Discov Data. 2025;19(7):1–46. doi:10.1145/3744570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang X, Ma H, Yang F, Li Z, Chang L. KGCL: a knowledge-enhanced graph contrastive learning framework for session-based recommendation. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;124:106512. doi:10.1145/3477495.3532009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Qian F, Chen W, Chen H, Liu J, Zhao S, Zhang Y. Building robust deep recommender systems: utilizing a weighted adversarial noise propagation framework with robust fine-tuning modules. Knowl Based Syst. 2025;314:113181. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2025.113181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Liang D, Charlin L, McInerney J, Blei DM. Modeling user exposure in recommendation. In: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web; 2016 Apr 11–15; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 951–61. doi:10.1145/2872427.2883090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Tian C, Xie Y, Li Y, Yang N, Zhao WX. Learning to denoise unreliable interactions for graph collaborative filtering. In: Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 122–32. doi:10.1145/3477495.3531889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lam SK, Riedl J. Shilling recommender systems for fun and profit. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on World Wide Web; 2004 May 17–20; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2004. p. 393–402. doi:10.1145/988672.988726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kapoor S, Kapoor V, Kumar R. A review of attacks and its detection attributes on collaborative recommender systems. Int J Adv Res Comput Sci. 2017;8(7):1188–93. doi:10.26483/ijarcs.v8i7.4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools