Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Can Domain Knowledge Make Deep Models Smarter? Expert-Guided PointPillar (EG-PointPillar) for Enhanced 3D Object Detection

1 Convergence Security for Automobile, Soonchunhyang University, Asan-si, 31538, Chungcheongnam-do, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Future Convergence Technology, Soonchunhyang University, Asan-si, 31538, Chungcheongnam-do, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Mechanical Design Engineering, Tech University of Korea, Siheung-si, 15073, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Daehee Kim. Email: ; Seongkeun Park. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Object Detection: Methods and Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 84 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073330

Received 16 September 2025; Accepted 11 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

This paper proposes a deep learning-based 3D LiDAR perception framework designed for applications such as autonomous robots and vehicles. To address the high dependency on large-scale annotated data—an inherent limitation of deep learning models—this study introduces a hybrid perception architecture that incorporates expert-driven LiDAR processing techniques into the deep neural network. Traditional 3D LiDAR processing methods typically remove ground planes and apply distance- or density-based clustering for object detection. In this work, such expert knowledge is encoded as feature-level inputs and fused with the deep network, thereby mitigating the data dependency issue of conventional learning-based approaches. Specifically, the proposed method combines two expert algorithms—Patchwork++ for ground segmentation and DBSCAN for clustering—with a PointPillars-based LiDAR detection network. We design four hybrid versions of the network depending on the stage and method of integrating expert features into the feature map of the deep model. Among these, Version 4 incorporates a modified neck structure in PointPillars and introduces a new Cluster 2D Pseudo-Map Branch that utilizes cluster-level pseudo-images generated from Patchwork++ and DBSCAN. This version achieved a +3.88% improvement mean Average Precision (mAP) compared to the baseline PointPillars. The results demonstrate that embedding expert-based perception logic into deep neural architectures can effectively enhance performance and reduce dependency on extensive training datasets, offering a promising direction for robust 3D LiDAR object detection in real-world scenarios.Keywords

Accurate perception of surrounding objects is a fundamental requirement for high-level autonomous driving systems [1]. Autonomous vehicles are typically equipped with multiple sensors, such as LiDAR, RADAR, and cameras, and various perception algorithms have been proposed to detect and classify surrounding objects in both 2D and 3D spaces [2–4]. Among these, approaches utilizing 3D point cloud data acquired from LiDAR sensors have gained significant attention. These methods include traditional clustering-based techniques [5] as well as deep learning-based models such as VoxelNet [6] and PointPillars [7].

Traditional LiDAR-based perception algorithms typically detect objects by clustering spatially adjacent points. A widely used algorithm in this category is Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN) [5], which identifies clusters in a point cloud based on density. DBSCAN groups points into a cluster if a minimum number of neighboring points fall within a predefined radius. This method is robust to noise and outliers and does not require prior knowledge of the number or shape of clusters. However, it has limitations: it cannot classify each cluster into semantic object categories, nor can it leverage internal distributional features of the clustered points. Furthermore, optimal performance depends on careful tuning of multiple parameters, which often requires the intervention of domain experts.

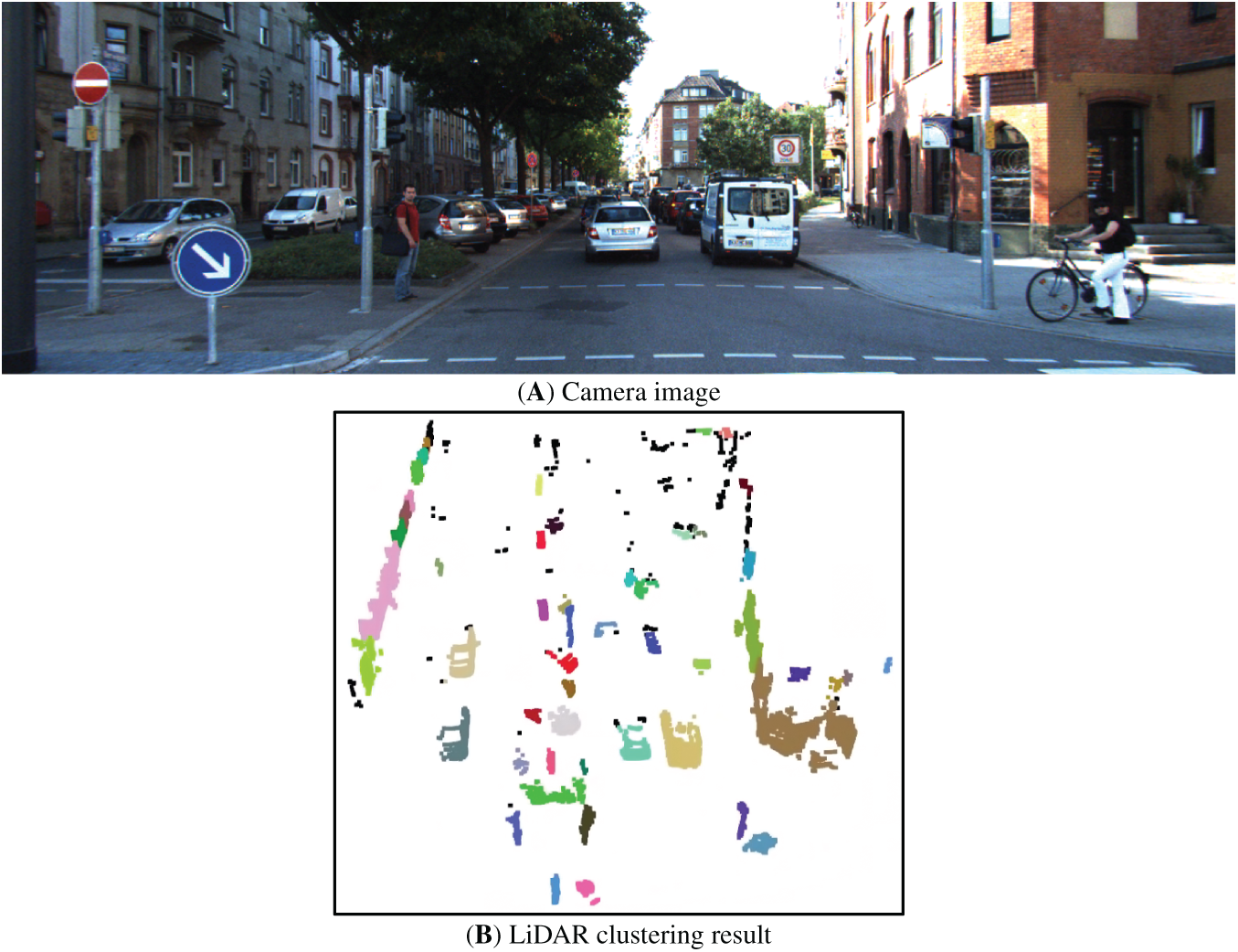

Additionally, traditional clustering-based methods struggle in complex scenarios—such as when objects are partially occluded by others or when the sensor’s viewpoint varies—resulting in reduced adaptability, as illustrated in the red box in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Example of occluded object clustering results (A) Camera data, (B) Clustering object using lidar data

To overcome these limitations, deep learning-based approaches have recently emerged as a dominant paradigm for 3D object detection. One notable method is VoxelNet, which employs 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (3D CNNs) to process LiDAR point clouds by converting voxel features into 2D representations for object detection. VoxelNet achieved a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 49.05% on the KITTI 3D Object Detection benchmark. Subsequent models further improved performance by replacing standard 3D convolutions with sparse convolutions and adopting multi-scale feature extraction strategies, achieving an mAP of 56.69% [8].

PointPillars, another widely used approach, voxelizes the 3D point cloud into vertical columns (pillars) and generates pseudo-images for efficient 2D convolutional processing. This method demonstrated an improved mAP of 59.20% on the KITTI dataset. However, despite its effectiveness, PointPillars still exhibits limitations in detecting distant or sparsely represented objects with few LiDAR points. Furthermore, like most deep learning models, it is highly dependent on the training dataset. This includes vulnerability to data bias and uncertainty in scenarios not represented during training [9].

Fig. 2 illustrates a common labeling issue in training data, where a vehicle is present in the LiDAR point cloud but is missing a corresponding 3D bounding box annotation. Such omissions can cause the model to learn incorrect associations, ultimately degrading detection performance.

Figure 2: Examples of training data labeling quality issues

To address the limitations of data dependency while leveraging the strengths of deep learning in adapting to diverse scenarios, we propose a hybrid framework called the Expert-Guided PointPillars (EG-PointPillars). The proposed method follows the standard pipeline of LiDAR-based deep learning perception architectures but incorporates expert-driven, clustering-based LiDAR processing techniques into the deep learning model itself. This hybridization aims to enhance robustness in situations where training data is insufficient, incomplete, or biased.

In particular, this study seeks to reduce reliance on large annotated datasets by combining classical clustering algorithms with deep neural networks. While various combinations of expert-based and deep learning-based methods are possible, this work focuses on integrating two representative expert algorithms—Patchwork++ [10] for ground segmentation and DBSCAN [5] for point cloud clustering—into the widely used PointPillars model. Through this integration, we demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid approach in enhancing LiDAR-based object detection performance under challenging and unseen conditions.

In this chapter, a concise review of studies relevant to the proposed algorithm is presented. Section 2.1 examines various deep learning–based recognition algorithms, and Section 2.2 discusses empirical approaches employed for LiDAR perception.

2.1 Deep Learning Based LiDAR Algorithm

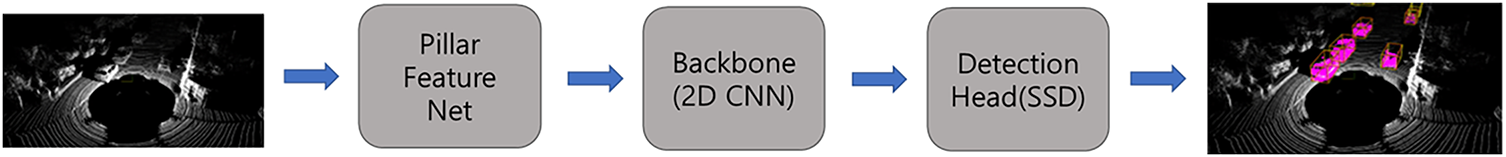

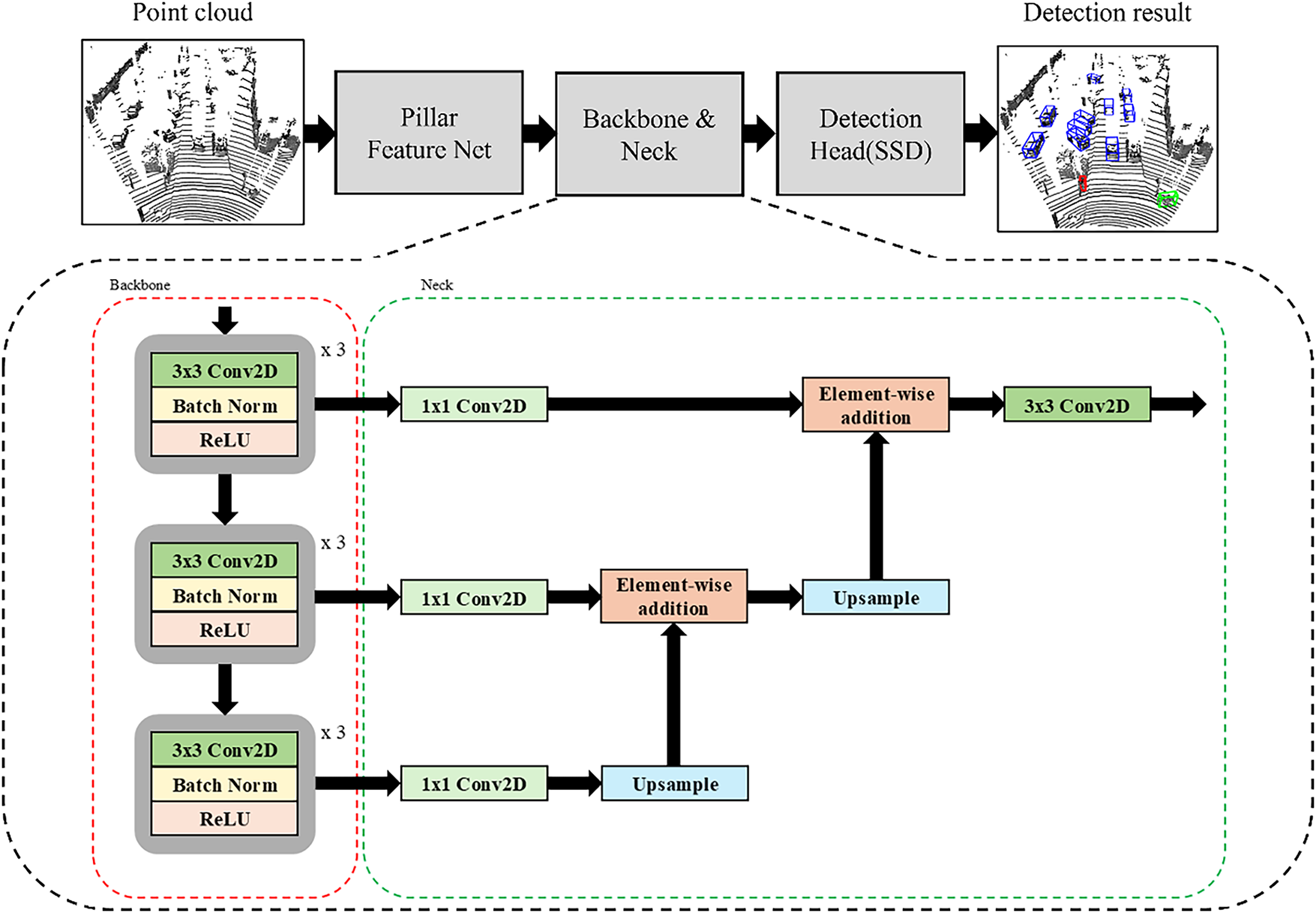

PointPillars, introduced in 2019, is a deep learning algorithm that performs 3D object detection by converting 3D LiDAR point cloud datainto a pseudo-image representation, allowing the use of efficient 2D convolutions. In reference [7], the architecture and operational flow of PointPillars are shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The structure of PointPillars

1. Pillar Feature Net

– The input 3D point cloud is voxelized into vertical columns called pillars.

– A simplified PointNet is applied to each pillar to extract point-wise features.

– These features are aggregated and transformed into a pseudo-image with dimensions (H, W, C), where H and W correspond to spatial resolution and C denotes the feature channel dimension.

2. Backbone

– This stage extracts spatial features from the pseudo-image.

– A series of 2D convolutional layers are applied to obtain multi-scale feature maps.

– These multi-scale features are then upsampled using transposed 2D convolutions.

– The upsampled features are concatenated along the channel dimension to form a unified feature representation.

3. Detection Head

– A Single Shot Detector (SSD) is employed to perform 3D object detection from the aggregated feature map.

In summary, the key innovation of PointPillars lies in its Pillar Feature Net, which enables efficient processing of 3D LiDAR point clouds using standard 2D convolutional neural networks by transforming sparse 3D data into dense 2D pseudo-images.

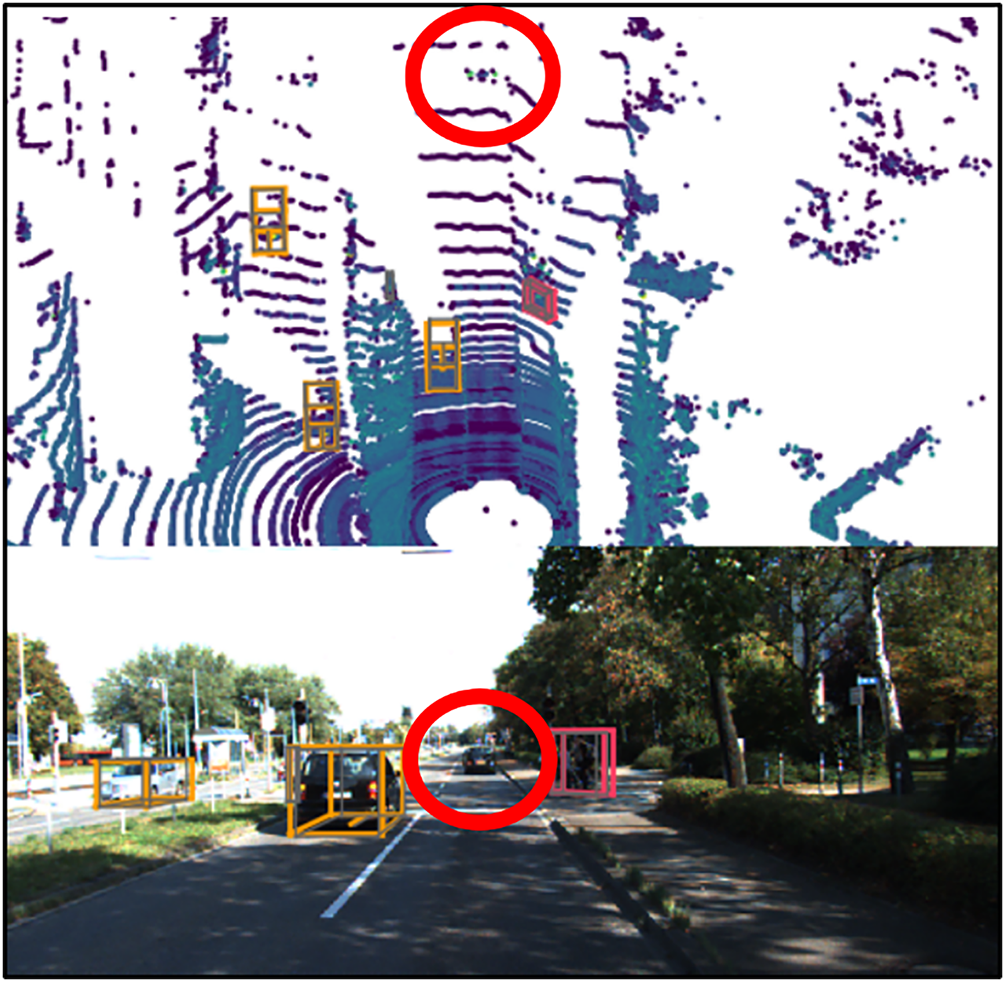

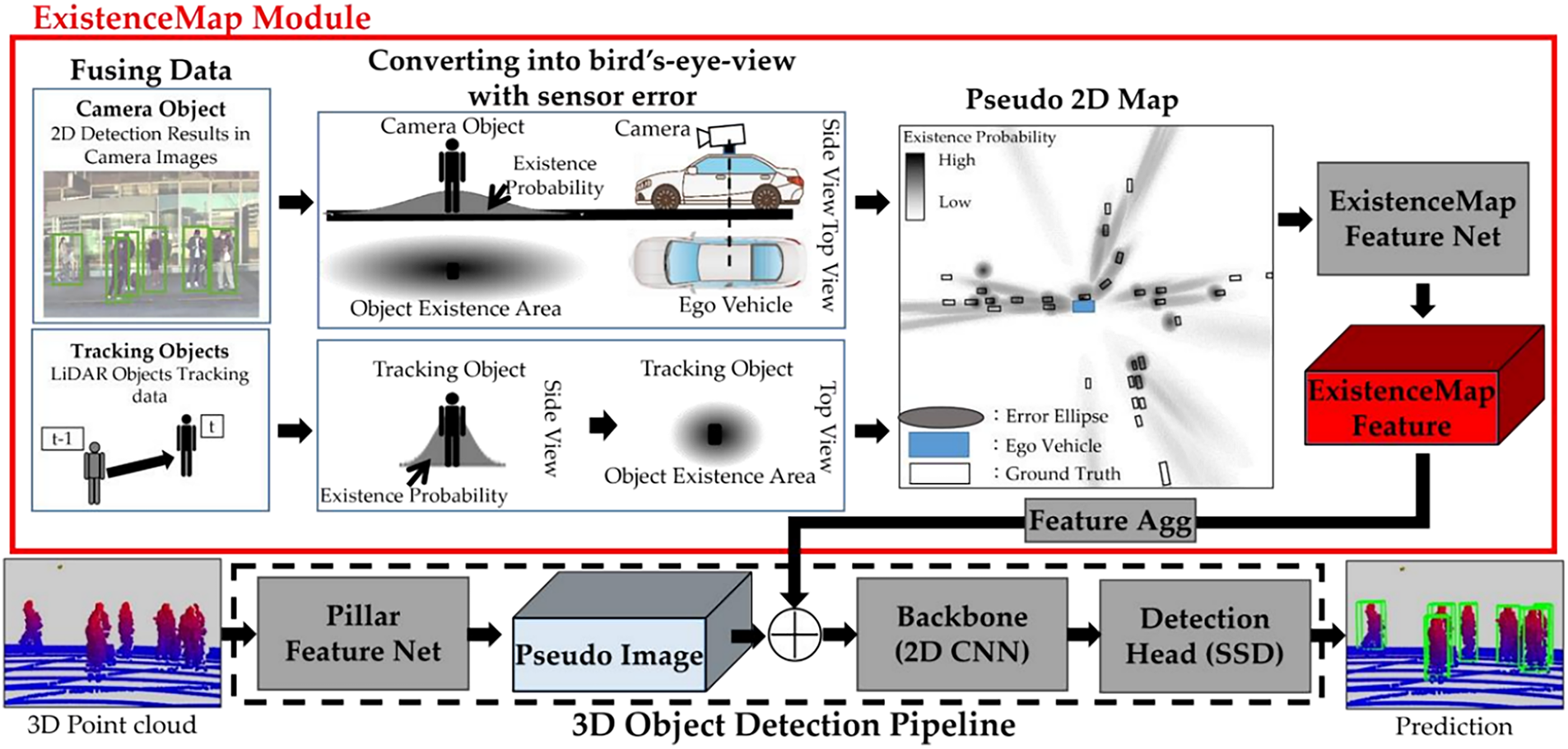

2.1.2 ExistenceMap-PointPillars

ExistenceMap-PointPillars [11], proposed in 2023, is a deep learning-based 3D object detection framework that builds upon PointPillars by incorporating additional image data. In this model, both 3D LiDAR point cloud data and 360° surround-view images captured around the vehicle are utilized to enhance object detection performance. The detailed architecture of ExistenceMap-PointPillars is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: The structure of ExistenceMap-PointPillars. Reprinted with permission from Reference [11]. © 2023 by Hariya et al. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland

The overall architecture of ExistenceMap-PointPillars and the operation of its core component, the ExistenceMap Module, are described as follows.

1. YOLOv7 [12] is applied to the input image data to detect and classify objects using 2D bounding boxes and semantic labels.

2. The detected 2D object information is projected into a Bird’s Eye View (BEV) coordinate system using a transformation algorithm. Each object’s presence is represented as a probabilistic elliptical region, forming a pseudo-2D map that indicates likely object locations.

3. LiDAR-based object tracking data is additionally used to reinforce the pseudo 2D map with additional candidate object regions.

4. This pseudo-2D map is then processed by a dedicated Pseudo Map Feature Net to extract semantic features.

5. The resulting feature map is concatenated along the channel axis with the pseudo-image generated by the Pillar Feature Net of PointPillars.

6. The combined feature map is passed through the backbone network to perform final 3D object detection.

7. Through this fusion strategy, ExistenceMap-PointPillars achieved a +4.19% increase in mean Average Precision (mAP) compared to the baseline PointPillars on its custom dataset. It also demonstrated a reduction in false positives. However, one notable limitation is the increased computational cost due to the additional object detection process required on image data using deep neural networks.

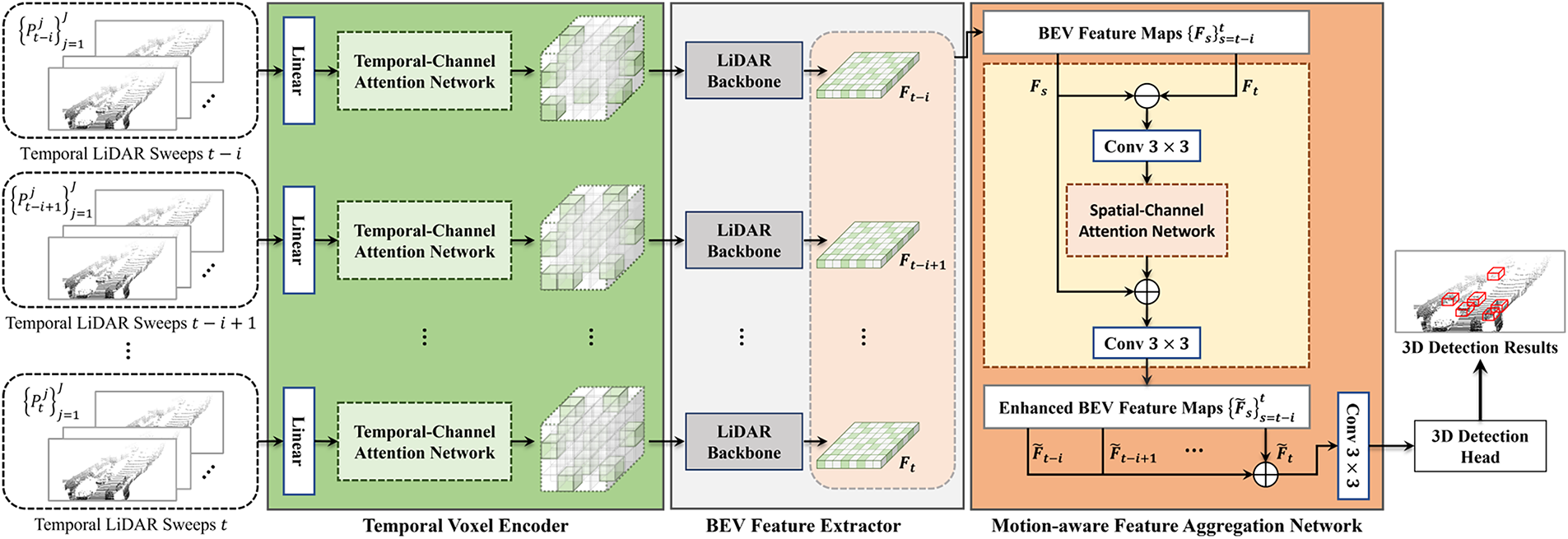

TM3DOD, shown in Fig. 5 is a model designed to effectively leverage temporal information between consecutive LiDAR frames to enhance the detection performance of dynamic objects [13]. Conventional single-frame-based approaches, such as PointPillars, fail to account for inter-frame object motion, resulting in limited accuracy in predicting the positions of moving objects. To address this limitation, TM3DOD introduces the Temporal Voxel Encoder (TVE) and Motion-Aware Feature Aggregation Network (MFANet) modules, which improve detection performance through attention-based fusion that exploits motion information across consecutive BEV features.

Figure 5: Overall architecture of the proposed TM3DOD. Reprinted with permission from Reference [13]. © 2024 by Park et al. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland

The core components of TM3DOD are as follows:

1. Temporal Voxel Encoder (TVE)

– Trains the relationships among point sets accumulated along the temporal axis within the same spatial voxel, thereby generating temporal voxel features.

2. Motion-Aware Feature Aggregation Network (MFANet)

– Extracts motion features from consecutive BEV feature maps and performs attention-based weighted fusion to produce motion-aware BEV features.

3. Detection Head

– An anchor-free detector that simultaneously predicts center heatmaps and 3D bounding boxes from the BEV features.

TM3DOD enhances dynamic object detection performance by directly utilizing temporal information. In addition, it effectively mitigates false detections that frequently occur in single-frame-based models. However, this approach increases computational complexity due to the frame alignment process, and its ability to represent motion features is limited in low-speed scanning environments where temporal resolution is insufficient.

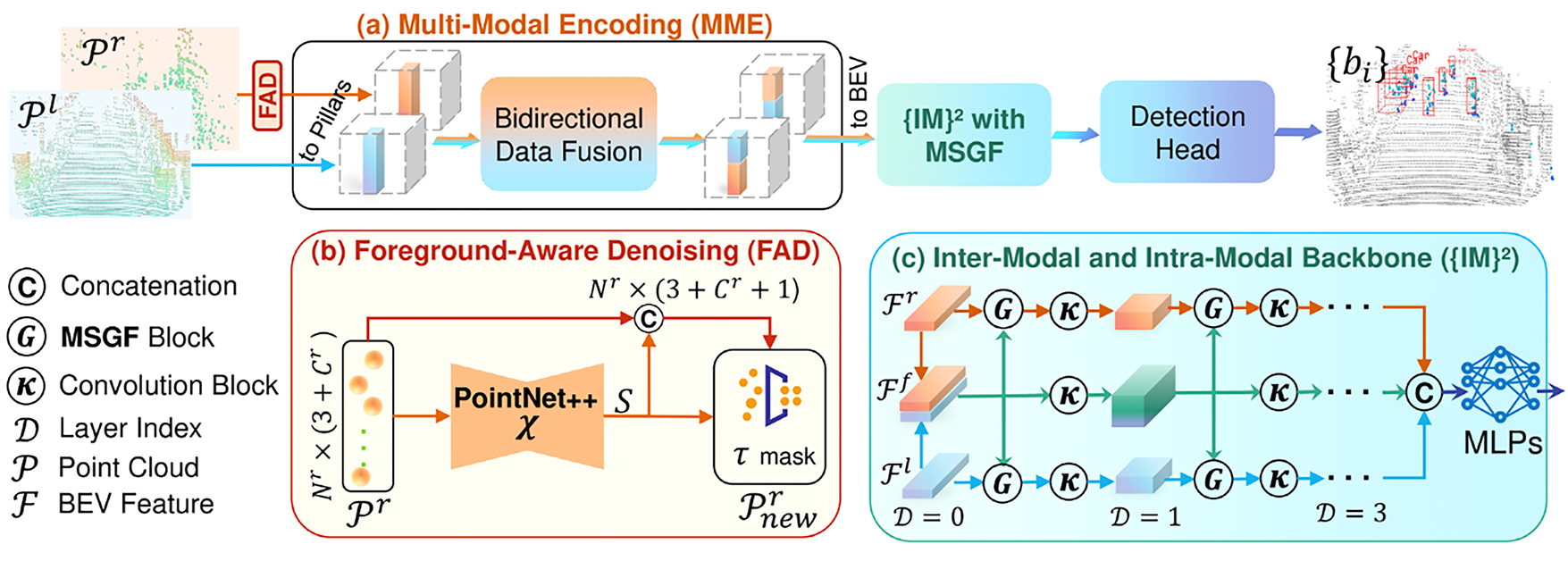

L4DR [14] is a state-of-the-art multi-sensor model that fuses LiDAR and 4D radar data to achieve robust 3D object detection under various weather conditions. While LiDAR provides high spatial resolution, its signals are significantly attenuated in adverse environments such as rain, snow, and fog. In contrast, radar offers lower spatial resolution but provides accurate velocity and range information. L4DR effectively combines the complementary characteristics of these two sensors, ensuring high detection performance even in harsh weather conditions. The architecture of L4DR is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Overall architecture of the proposed L4DR. Reprinted with permission from Reference [14]. 2025, Huang et al.

The core components of L4DR are as follows:

1. Foreground-Aware Denoising (FAD)

– A module that removes noise from Radar and LiDAR data prior to fusion, thereby enhancing the overall fusion quality.

2. Multi-Scale Gated Fusion (MSGF)

– Selectively fuses features at different scales through a gated network, enabling adaptive integration across multiple feature resolutions.

3. Inter-Modal & Intra-Modal Backbone (IM2)

– A backbone architecture designed to extract features not only across different modalities (LiDAR and 4D Radar) but also within the same modality in parallel, improving both inter- and intra-modal feature representation.

L4DR leverages the velocity information from 4D radar to maintain high recall and precision even under adverse weather conditions, resulting in improved detection reliability compared to LiDAR-only systems. However, it is sensitive to Radar–LiDAR calibration errors, and the overall system complexity increases due to the processing of multi-sensor inputs.

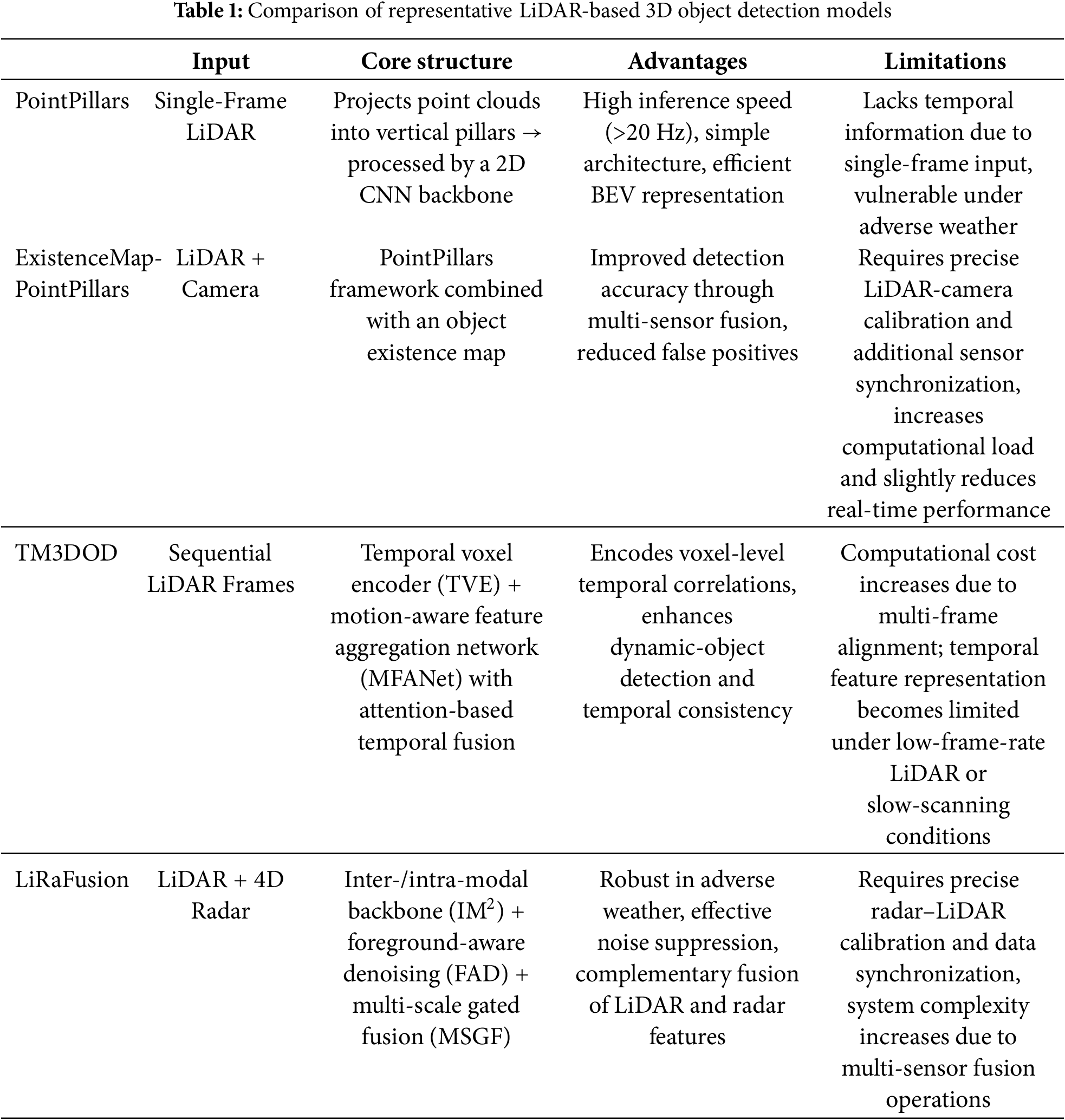

The key strengths and limitations of each model are summarized in Table 1.

2.2 Empirical Approaches for LiDAR Perception

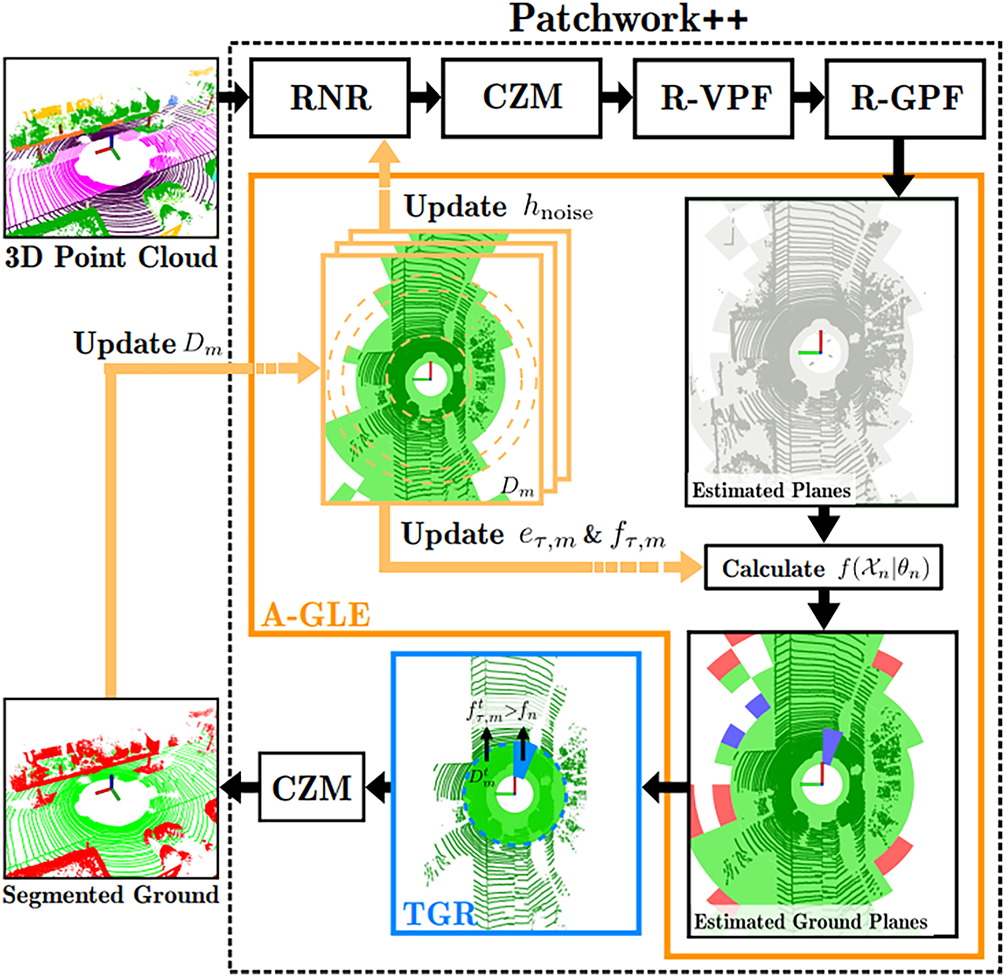

To effectively apply clustering algorithms to LiDAR-based 3D point cloud data for object detection, it is essential to first remove points corresponding to the ground surface. Patchwork++ is a ground segmentation algorithm specifically designed for 3D LiDAR point clouds and was proposed by Lee et al. [10].

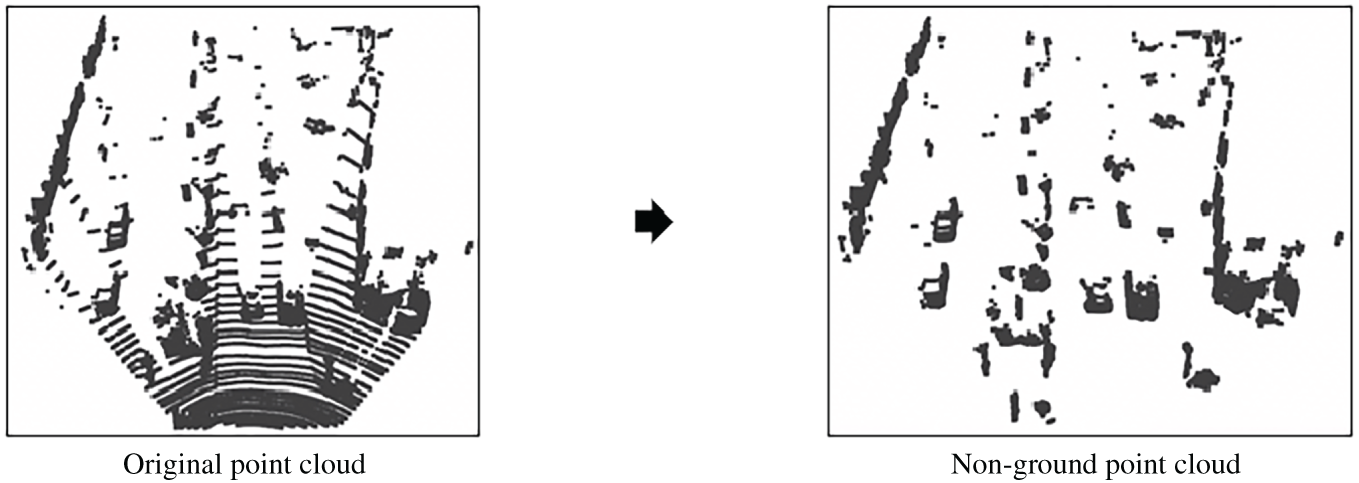

Fig. 7 illustrates an example in which Patchwork++ is applied to a single frame from the KITTI 3D Object Detection dataset, successfully filtering out ground points. Fig. 8 presents the overall architecture of the Patchwork++ algorithm.

Figure 7: Patchwork++ application example

Figure 8: Structure of Patchwork++. Reprinted with permission from Reference [10]. 2022, Lee et al. © 2022, IEEE

Through the above process, Patchwork++ effectively separates ground and non-ground points in a 3D LiDAR point cloud. Unlike traditional ground segmentation methods that rely on fixed sensor height thresholds, Patchwork++ is particularly well-suited for complex terrains, such as steep slopes or environments with multiple ground height levels, where conventional methods often fail. It offers both high segmentation accuracy and fast processing speed, making it suitable for real-time applications.

DBSCAN (Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise) is a density-based clustering algorithm that utilizes two parameters:

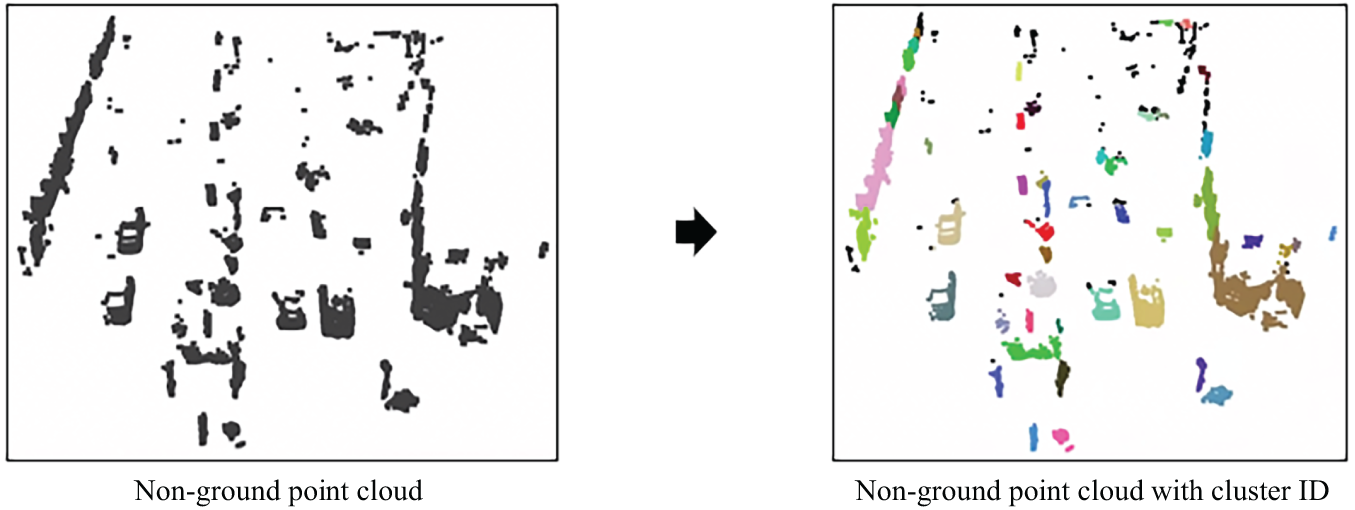

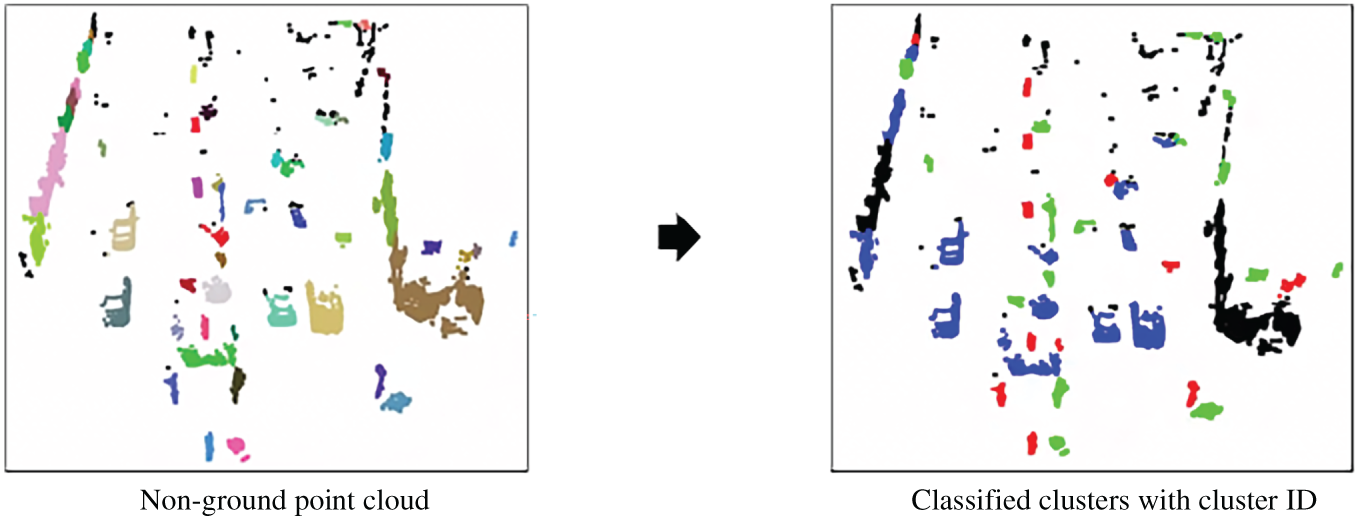

Fig. 9 shows the result of applying DBSCAN to a single frame from the KITTI 3D Object Detection dataset after ground removal via Patchwork++. Each identified cluster is visualized in a different color, while noise points—those not assigned to any cluster—are displayed in black.

Figure 9: Example of DBSCAN

While DBSCAN offers several advantages—such as robustness to noise and the ability to identify clusters without requiring the number of clusters to be predefined—it also has notable limitations. Specifically, it does not assign semantic class labels to clusters, nor does it capture detailed structural characteristics within each cluster, such as the spatial distribution of points. Moreover, DBSCAN tends to perform poorly in complex scenarios where objects are partially occluded by others or when the viewpoint of the sensor changes significantly, leading to limited generalization capability in real-world applications.

In this paper, we propose a hybrid deep learning framework that incorporates expert-driven LiDAR clustering algorithms into the internal pipeline of deep neural networks to address the limitations of conventional learning-based methods. To mitigate the data dependency and limited generalization of conventional LiDAR-based deep learning models, this study integrates expert-driven clustering and ground segmentation algorithms into the deep learning pipeline, forming a hybrid framework called EG-PointPillars.

Although various clustering and deep learning techniques exist, this work specifically employs Patchwork++ and DBSCAN as representative expert-based LiDAR preprocessing algorithms and adopts PointPillars as the baseline 3D object detection model. DBSCAN and PointPillars are among the most well-established methods in their respective domains; however, the proposed framework is flexible and can be extended to other combinations of clustering and deep learning algorithms in future work. In this study, we aim to demonstrate that integrating these representative approaches can effectively improve the performance and robustness of existing deep learning models.

The overall pipeline of the proposed method is structured as follows:

1. Clustering-Based Preprocessing

– Ground points are first removed from the LiDAR 3D point cloud using the Patchwork++ algorithm [10], followed by DBSCAN clustering on the remaining non-ground points to generate object candidates. These expert-based modules serve as preprocessing steps, providing structured inputs for the proposed hybrid learning model.

2. Cluster Map Feature Representation and BEV Transformation

– A novel cluster map feature representation is developed to convert DBSCAN outputs into a BEV-formatted feature map. This transformation incorporates the geometric size and spatial distribution of each cluster, enabling more effective fusion with the deep feature space of the backbone network.

3. PointPillars Architecture Enhancement

– The backbone and neck components of the original PointPillars model are redesigned to accommodate the new feature representation. The modified FPN structure enhances multi-scale feature aggregation, improving detection robustness for small or occluded objects.

4. Fusion Strategy Design

– Multiple fusion methods are explored to integrate the expert-derived cluster features with the deep features. This strategy ensures smooth and effective information flow from the clustering-based preprocessing to the detection head, aligning both expert priors and learned representations.

5. Development of Variants and Evaluation

– Four variants of the proposed Expert–Neural Network Collaborative LiDAR Perception model are developed and evaluated. These variants are designed to validate the contribution of each proposed component and demonstrate the overall performance improvement achieved through expert-guided hybridization.

3.1 Basic Structure of Proposed Algorithm

3.1.1 3D Object Detection Pipeline

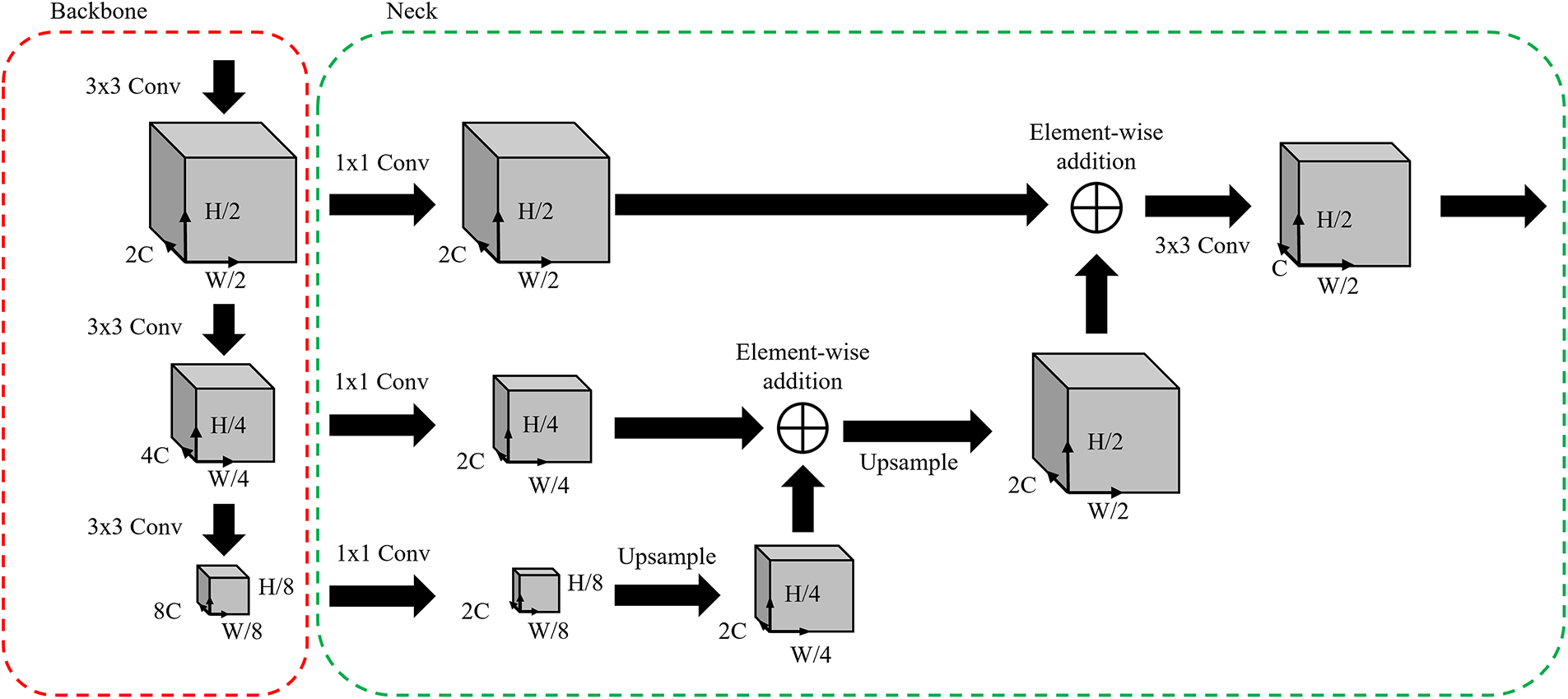

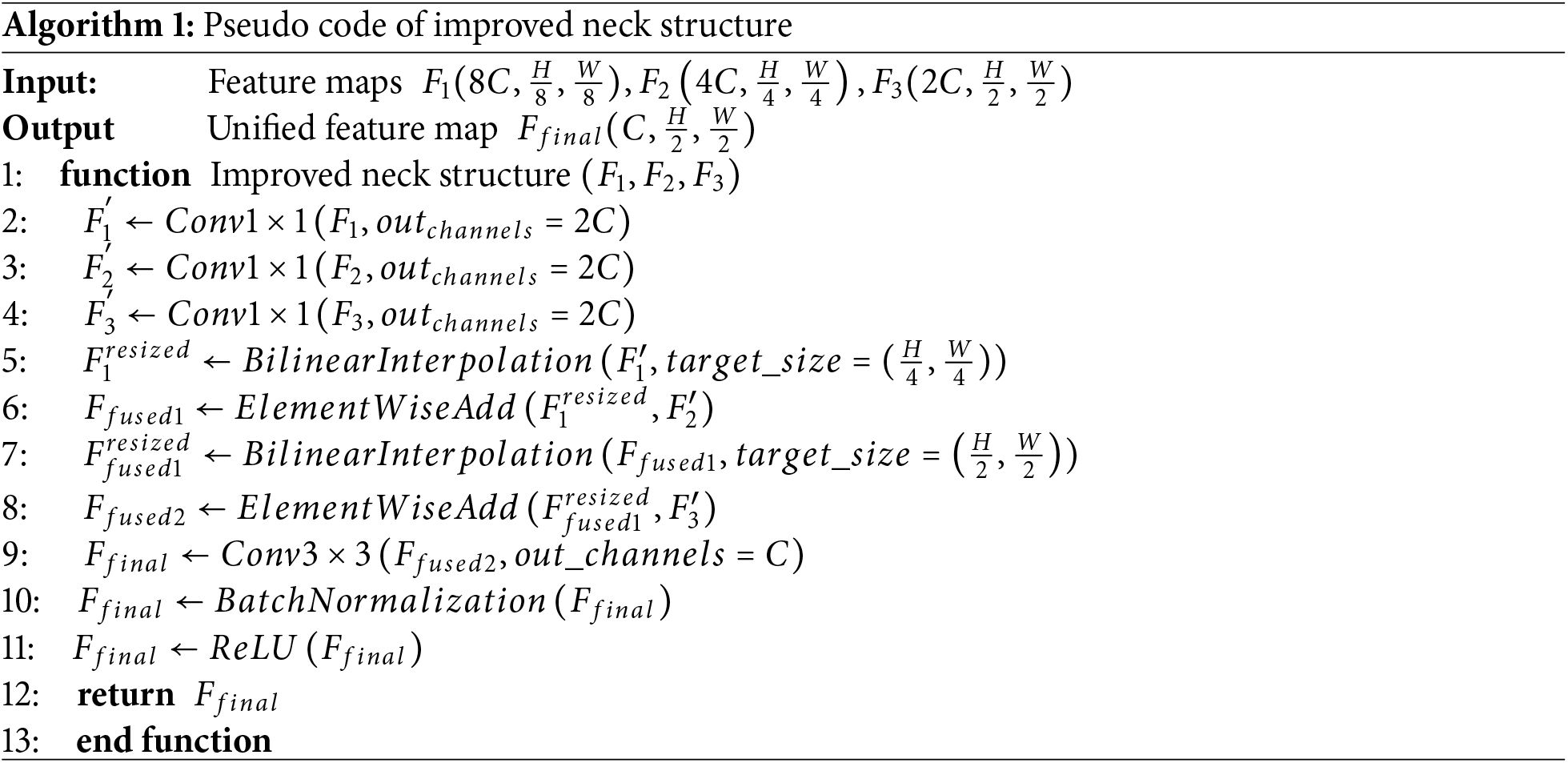

All four versions of the proposed method share a common 3D object detection pipeline, which is based on a modified neck structure of the original PointPillars framework. The improved neck module of our proposed algorithm adopts a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [15] design to effectively aggregate multi-scale features. Specifically, the input feature maps—of sizes (8C, H/8, W/8), (4C, H/4, W/4), and (2C, H/2, W/2)—are fused into a single high-resolution feature representation.

Fig. 10 illustrates the revised neck structure built upon PointPillars, as applied in our proposed architecture. The pseudo code of proposed neck structure is in Algorithm 1. Fig. 11 visualizes the change in feature map sizes across each stage of the network, highlighting the multi-scale aggregation process enabled by the FPN structure.

Figure 10: Improved neck structure based on PointPillars

Figure 11: Feature map size according to Backbone-neck stage

The modified neck structure receives three feature maps (

This modified neck structure replaces the transposed 2D convolutions used in the original PointPillars with bilinear interpolation, thereby reducing the number of learnable parameters and computational cost. Despite this simplification, the design still enables effective fusion of multi-scale features, maintaining high detection performance while improving overall efficiency.

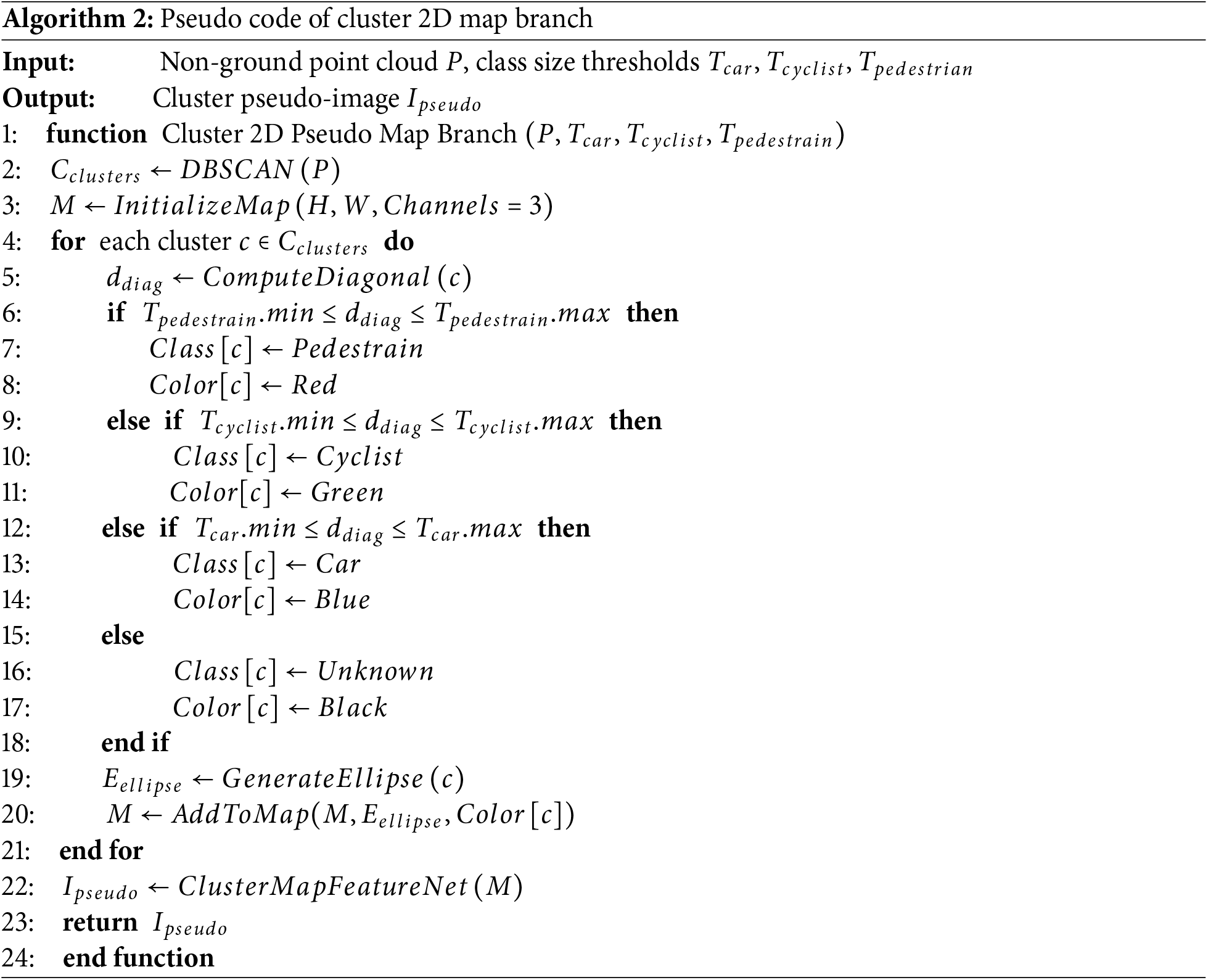

3.1.2 Cluster 2D Pseudo-Map Branch

The Cluster 2D Pseudo-Map Branch proposed in this section is designed to generate a cluster pseudo-image based on the clustering results obtained from DBSCAN. This branch takes the clustered LiDAR 3D point cloud as input and performs heuristic classification of each cluster into one of three object classes: vehicle, two-wheeler, or pedestrian. Based on this classification, a 2D pseudo-map is generated, which is then processed by the Cluster Map Feature Net to produce the final cluster pseudo-image.

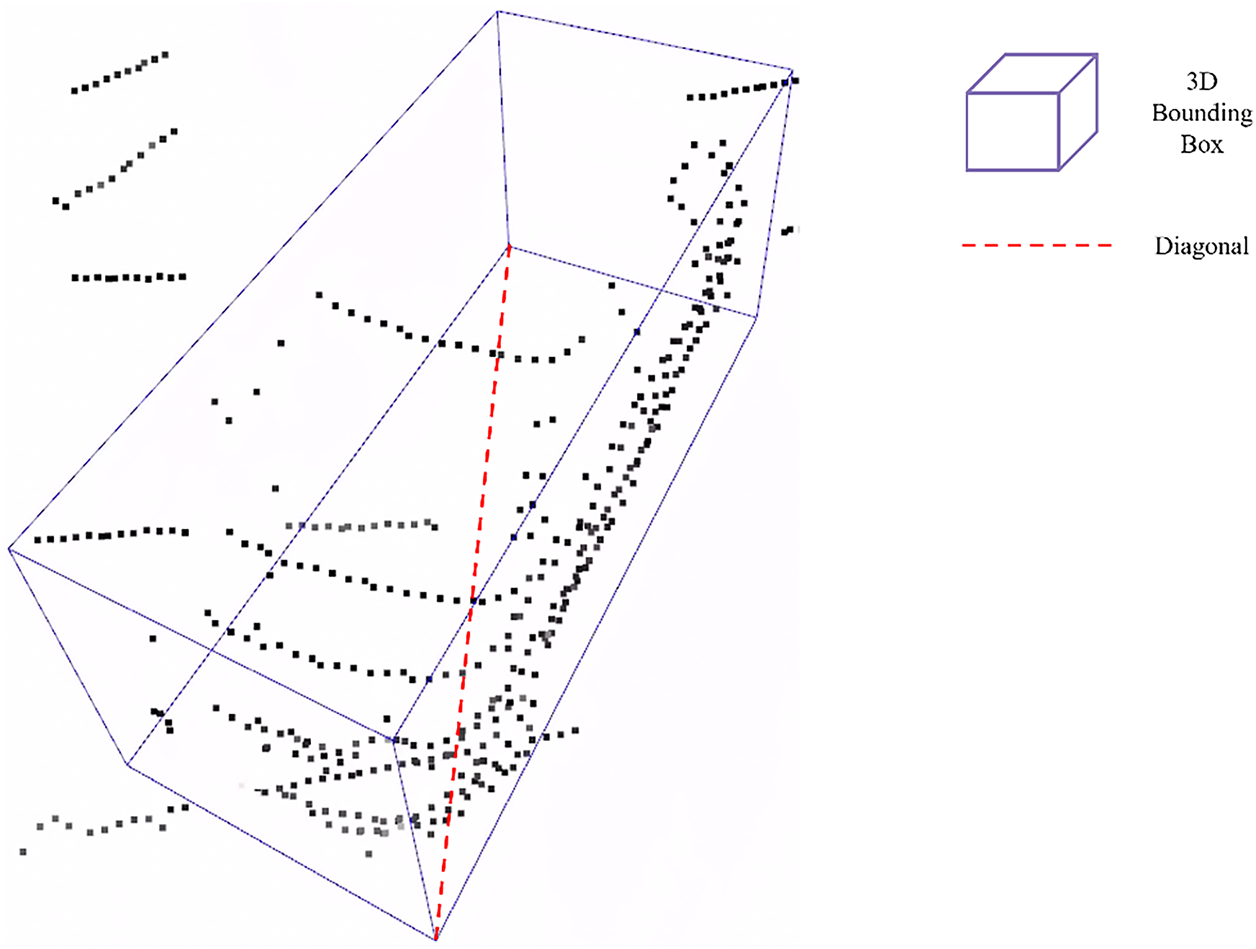

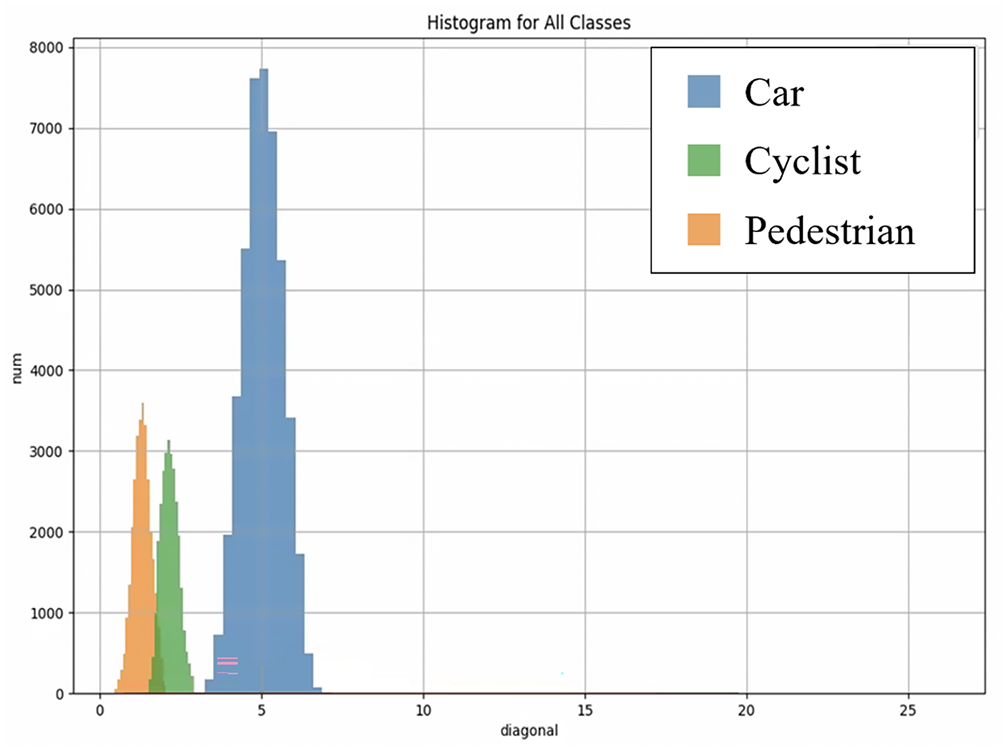

To heuristically classify each cluster, a class assignment criterion is required. In this study, the criterion is based on the diagonal length of the ground truth 3D bounding box projected onto the XY-plane, as illustrated in Fig. 12. Fig. 13 shows a histogram of the diagonal length distributions for all objects in the KITTI 3D Object Detection dataset. In the histogram, pedestrians are marked in orange, two-wheelers in green, and vehicles in blue. As shown in Fig. 13, the three classes can be effectively separated based on the diagonal length of their 3D bounding boxes in the XY-plane, providing a reliable heuristic for cluster classification.

Figure 12: The diagonal length of the

Figure 13: Histogram distribution of

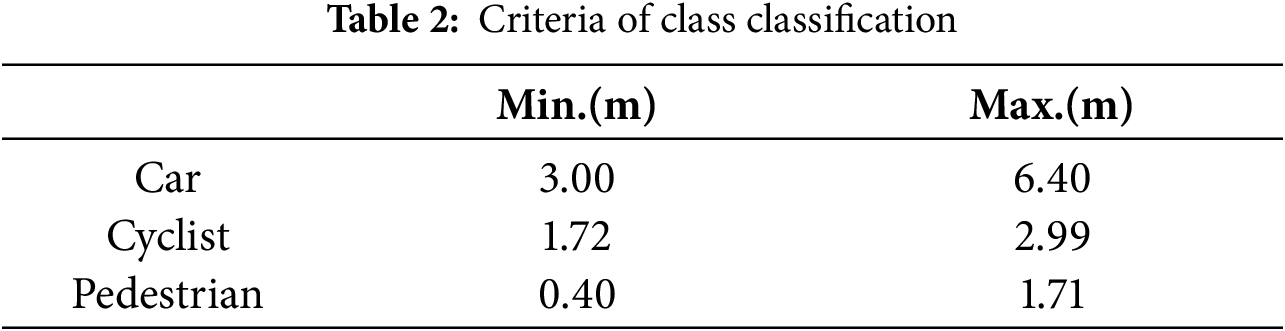

However, the size of a LiDAR point cloud cluster does not exactly match the dimensions of its corresponding 3D bounding box. Therefore, the diagonal length thresholds used for classification must be appropriately adjusted to better fit the characteristics of the clustered data. In this study, we define heuristic classification rules for clusters based on empirical thresholds, as summarized in Table 2.

Fig. 14 presents a visualization of the cluster classification results based on the proposed criteria. In this figure, clusters classified as vehicles are shown in blue, two-wheelers in green, pedestrians in red, and noise in black.

Figure 14: Results of randomly classifying classes for each cluster

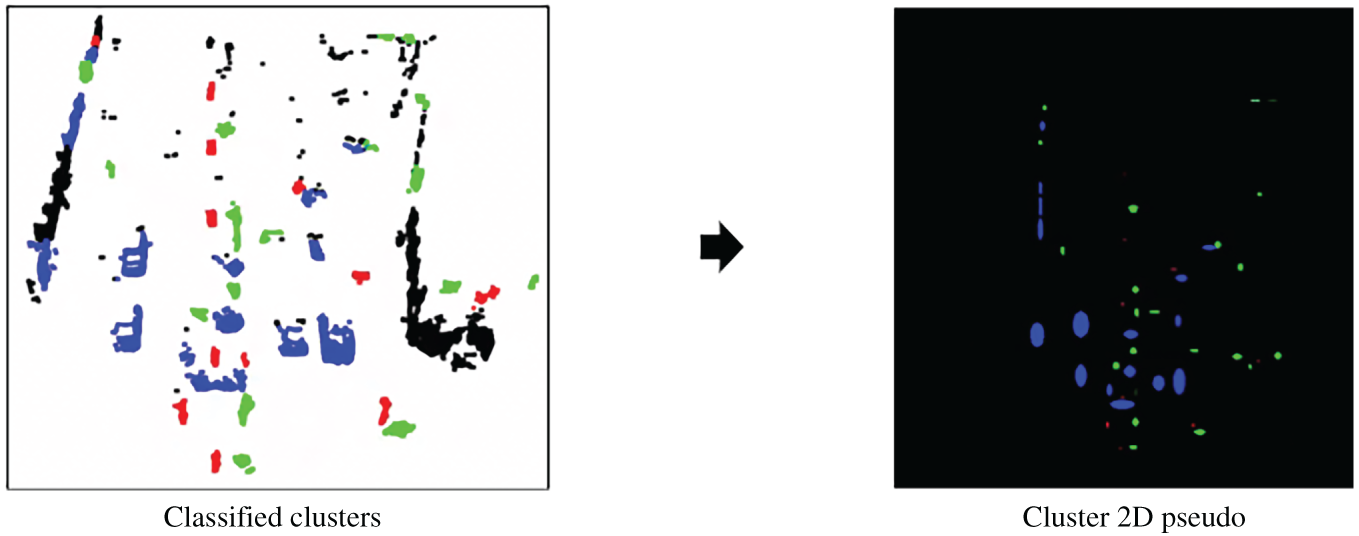

In the next stage, a cluster 2D pseudo-map is generated using the previously classified cluster information. Each cluster is first enclosed by a fitted ellipse, and its color is assigned based on the inferred class: blue for vehicles, green for two-wheelers, and red for pedestrians.

The resulting pseudo-map is rendered in the Bird’s Eye View (BEV) coordinate space, with the same spatial dimensions as the pseudo-image used in the original PointPillars framework. The map consists of three channels in the BGR color format to encode the class-specific appearance of each cluster.

Fig. 15 shows an example of a generated cluster 2D pseudo-map, illustrating the spatial distribution and semantic coloring of clustered objects.

Figure 15: Example of cluster 2D pseudo-map

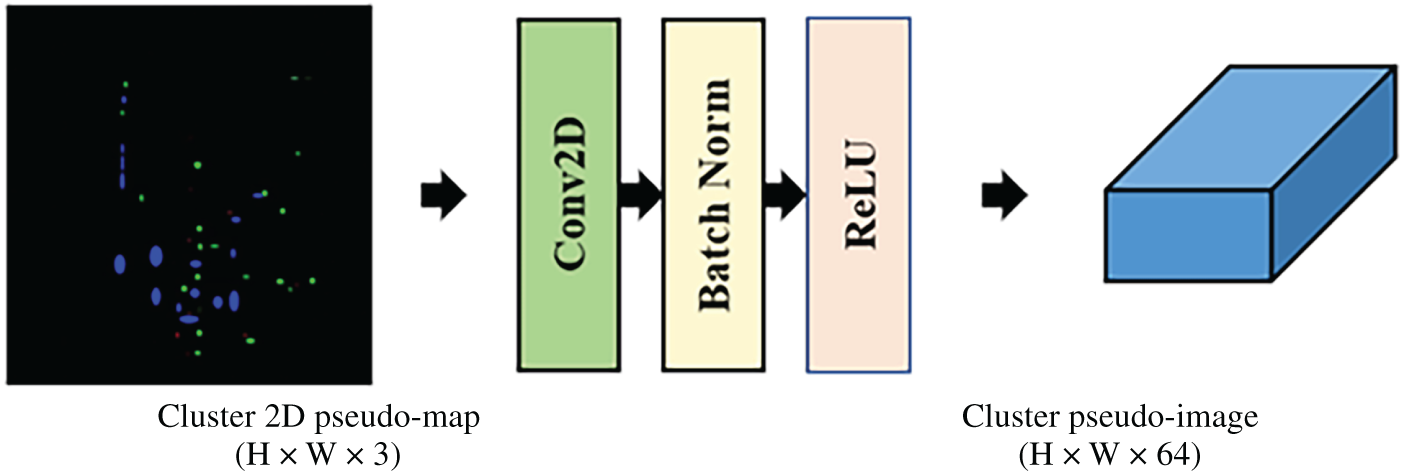

The generated cluster 2D pseudo-map is then processed by the Cluster Map Feature Net to produce a corresponding cluster pseudo-image. As shown in Fig. 16, the Cluster Map Feature Net consists of a series of 2D convolutional layers, each followed by Batch Normalization and ReLU activation functions.

Figure 16: Cluster map feature net

The resulting cluster pseudo-image has a shape of H × W × 64, which is identical to the pseudo-image produced by the PointPillars’ Pillar Feature Net, allowing for seamless integration within the overall detection pipeline.

The process by which the Cluster Map Feature Net transforms the input cluster pseudo-image

The overall processing pipeline of the Cluster 2D Pseudo-Map Branch can be summarized as below pseudo code in Algorithm 2:

3.2 Expert Guided PointPillars—EG-PointPillars

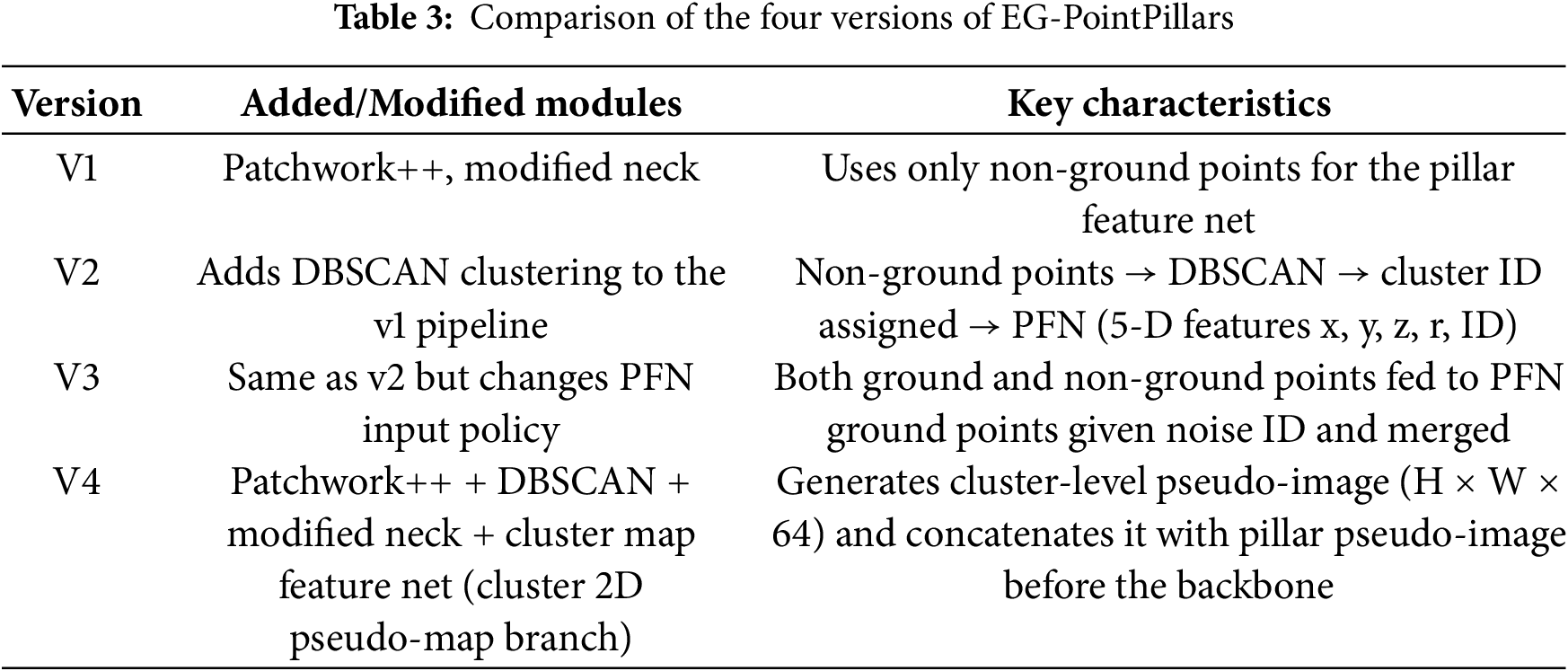

In this subsection, we present four different versions of EG-PointPillars, each integrating the previously described algorithms into the original PointPillars framework in different ways. The details of how each algorithm is incorporated are provided below.

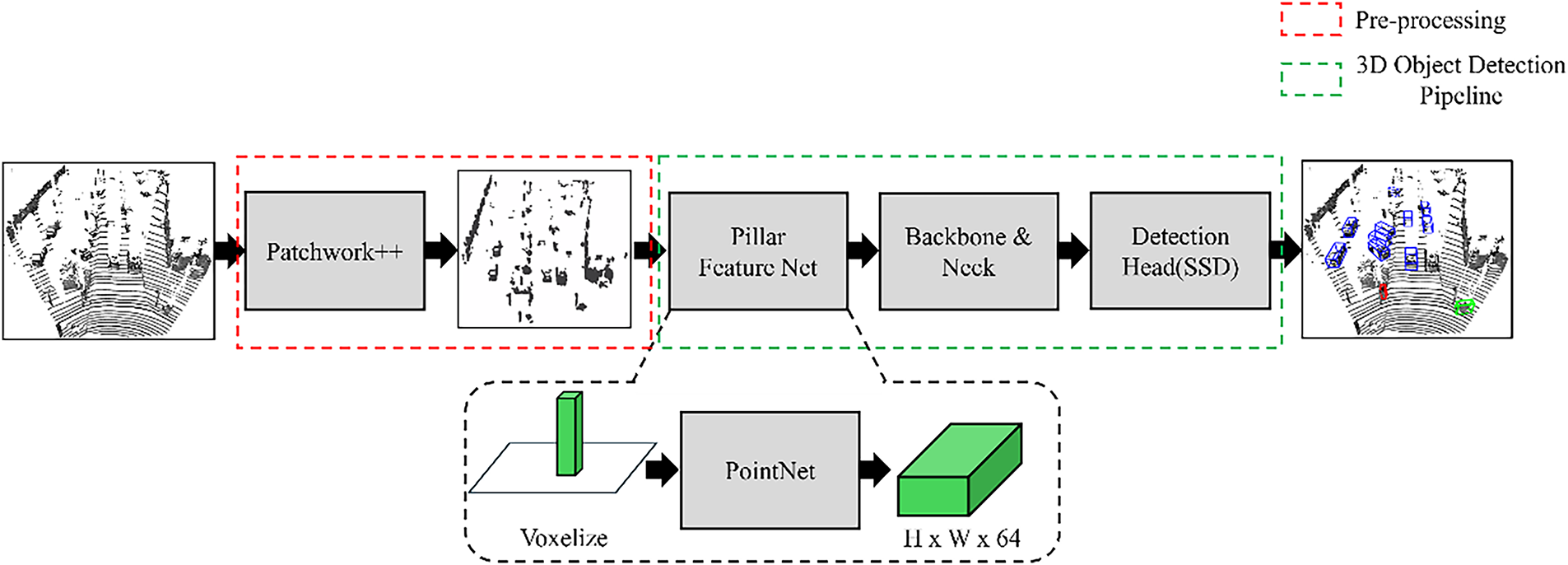

3.2.1 EG-PointPillars Version 1

EG-PointPillars ver. 1 integrates two key components into the baseline PointPillars framework: (1) a preprocessing step using the Patchwork++ algorithm and (2) an enhanced 3D object detection pipeline with a modified neck structure.

1. The 3D object detection procedure for ver. 1 is as follows:

2. The input LiDAR 3D point cloud is processed with Patchwork++ to separate ground and non-ground points.

3. The resulting non-ground point cloud is passed to the Pillar Feature Net for feature extraction.

The extracted features are forwarded through the improved detection pipeline with the modified neck structure to perform 3D object detection.

Fig. 17 illustrates the overall architecture of EG-PointPillars ver. 1.

Figure 17: Overall structure of EG-PointPillars ver. 1

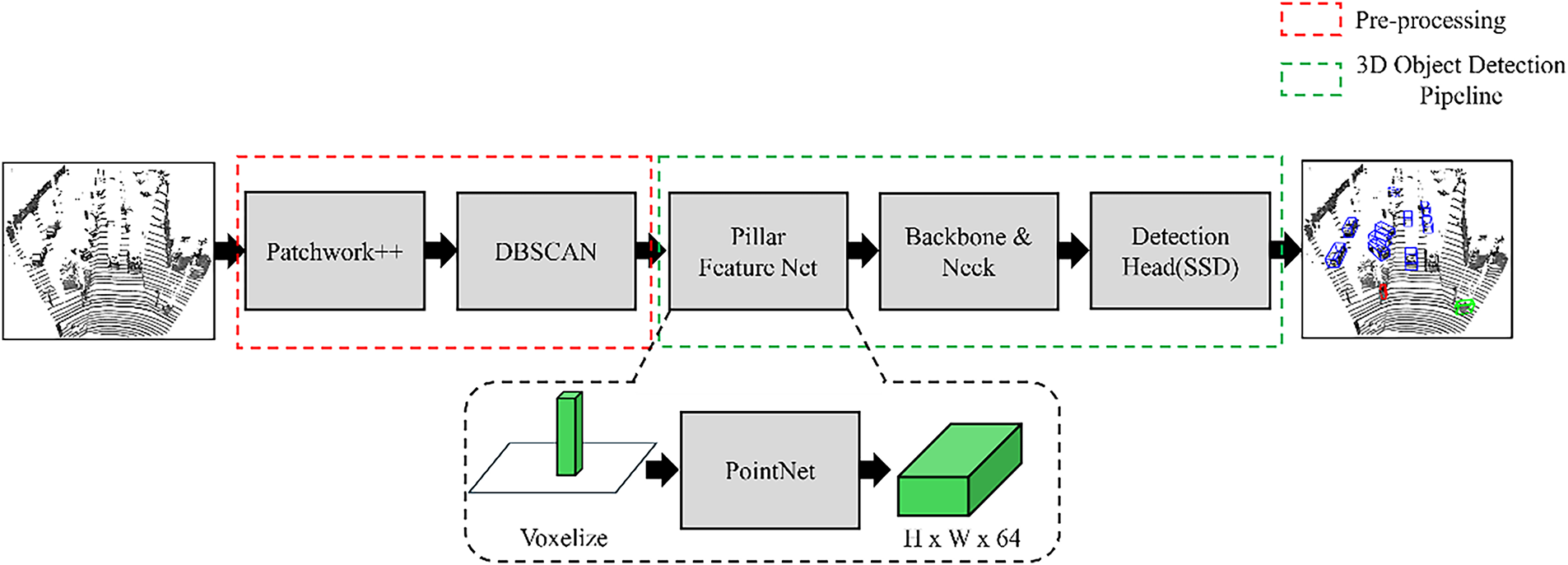

3.2.2 EG-PointPillars Version 2

EG-PointPillars ver. 2 extends v 1 by incorporating an additional clustering step using DBSCAN, resulting in a total of three integrated components: (1) Patchwork++ for ground removal, (2) an enhanced 3D object detection pipeline with a modified neck structure, and (3) DBSCAN-based clustering.

The 3D object detection procedure for ver. 2 is as follows:

1. The input LiDAR 3D point cloud is first processed with Patchwork++ to separate ground and non-ground points. The non-ground points are then passed to DBSCAN for clustering.

2. DBSCAN is applied to the non-ground point cloud to generate clusters.

3. Each point in the clustered output is assigned a cluster ID as an additional feature:

- Points belonging to a valid cluster are assigned positive integer IDs starting from 1.

- Noise points are assigned a cluster

4. As a result, each point in the processed non-ground point cloud is represented as a 5D feature vector:

where

5. The preprocessed non-ground point cloud with appended cluster IDs is fed into the Pillar Feature Net.

Finally, the extracted features are processed through the modified 3D object detection pipeline using the enhanced neck structure.

3.2.3 EG-PointPillars Version 3

EG-PointPillars ver. 3 incorporates the same three key components as ver. 2—Patchwork++, DBSCAN, and a modified 3D object detection pipeline. However, the main distinction lies in the input to the Pillar Feature Net: unlike ver. 2, ver. 3 includes both ground and non-ground points.

The 3D object detection procedure for ver. 3 is as follows:

1. The input LiDAR 3D point cloud is first processed with Patchwork++ to separate ground and non-ground points. Both sets are then passed to DBSCAN individually.

2. DBSCAN is applied only to the non-ground point cloud to perform clustering.

3. Clustered points are assigned a cluster ID as an additional feature:

- Points belonging to a valid cluster are assigned positive integer IDs starting from 1.

- Noise points are assigned a cluster

4. All ground points are also assigned a cluster

5. The ground and non-ground point clouds, now augmented with cluster IDs, are merged into a single point cloud.

6. Each point in the merged cloud is represented as a 5D feature vector:

where

7. The merged point cloud is then passed into the Pillar Feature Net.

8. The resulting features are processed through the enhanced 3D detection pipeline using the modified neck structure.

Fig. 18 illustrates the overall architecture shared by EG-PointPillars ver. 2 and 3.

Figure 18: Overall structure of EG-PointPillars ver. 2 & 3

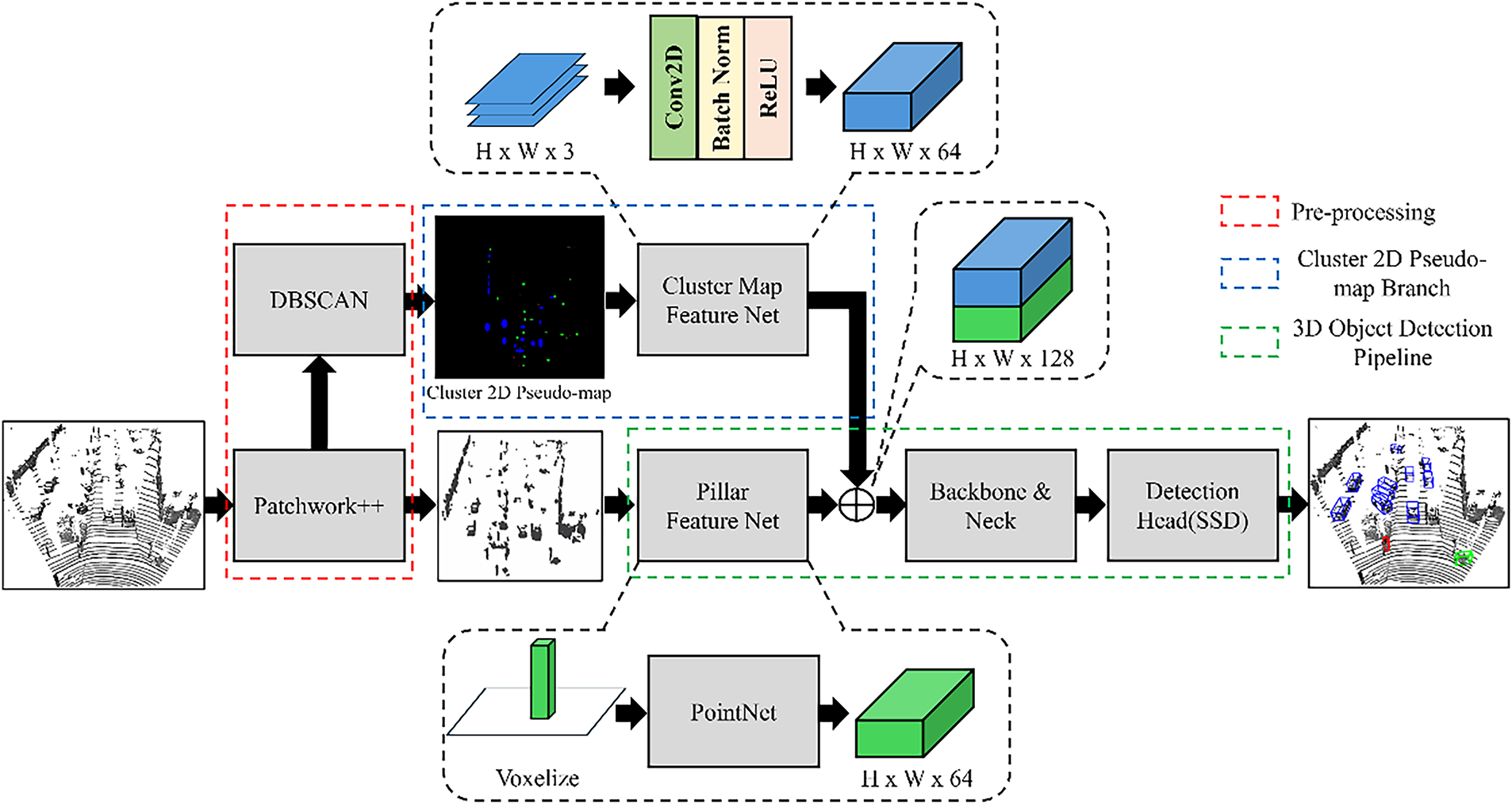

3.2.4 EG-PointPillars Version 4

EG-PointPillars ver. 4 incorporates all four components proposed in this study: (1) ground removal using Patchwork++, (2) clustering using DBSCAN, (3) an enhanced 3D object detection pipeline with a modified neck, and (4) the cluster 2D pseudo-map branch. This version represents the most comprehensive integration of expert-based and deep learning-based techniques.

The 3D object detection procedure for ver. 4 is as follows:

1. The input LiDAR 3D point cloud is processed using Patchwork++ to separate ground and non-ground points. The non-ground points are passed to both DBSCAN and the Pillar Feature Net.

2. DBSCAN is applied to the non-ground point cloud to generate clusters.

3. Each cluster is heuristically classified into one of three classes—vehicle, two-wheeler, or pedestrian—based on the diagonal length of its bounding box in the XY-plane.

4. Using the location and class of each cluster, a cluster 2D pseudo-map is generated in BEV format and input into the Cluster Map Feature Net.

5. The Cluster Map Feature Net produces a cluster pseudo-image, which is then concatenated along the channel axis with the pseudo-image output from the Pillar Feature Net.

6. The combined pseudo-image is forwarded to the backbone of the 3D object detection pipeline to perform final detection.

Fig. 19 shows the complete architecture of EG-PointPillars ver. 4.

Figure 19: Overall structure of EG-PointPillars ver. 4

A summary of the architectural variations among the four EG-PointPillars versions is provided in Table 3, which serves as a reference for the performance comparison presented in the following section.

The proposed EG-PointPillars models are evaluated through comparative experiments against the baseline PointPillars framework. To ensure a fair comparison, all models are trained and tested using the LiDAR data from the KITTI 3D Object Detection dataset.

For training, 6767 frames are selected from the total 7518 training frames, while the remaining 751 frames are used for validation during training. All experiments are evaluated on the full 7518-frame test set. Each model is trained for 300 epochs, and validation is performed every 5 epochs. The model with the best performance on the validation set is selected as the final model for testing.

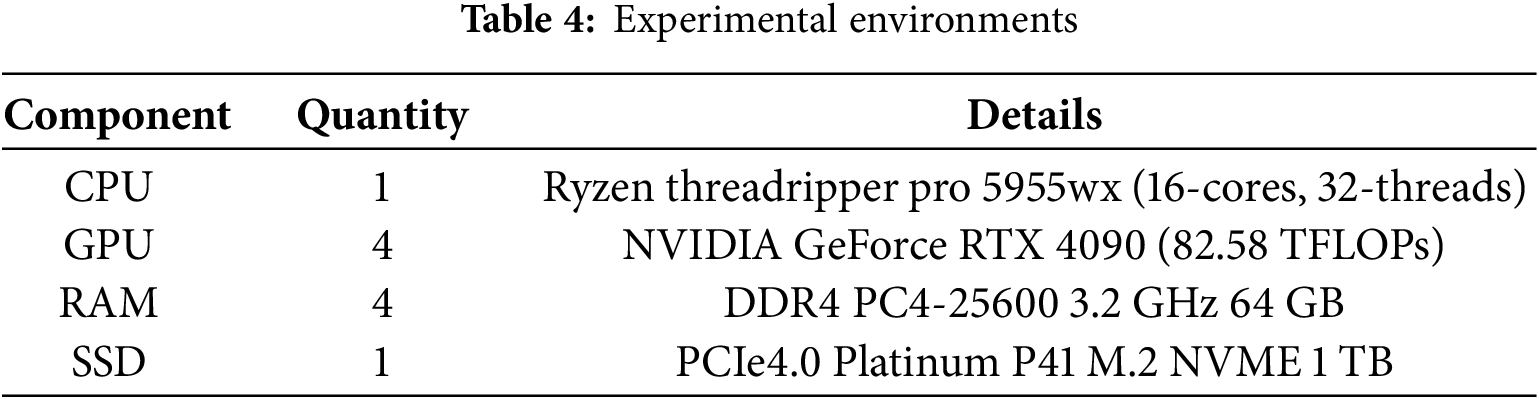

To ensure consistency and reproducibility, all experiments—including training and inference for both PointPillars and the four versions of EG-PointPillars—are conducted under identical hardware conditions. The specifications of the computing environment are detailed in Table 4, and all models utilize the same GPU resources throughout the experimental process.

The proposed EG-PointPillars models are developed based on the original PointPillars architecture, and both are trained and evaluated using the same methodology to enable a fair performance comparison. For this purpose, we utilize the 3D LiDAR data from the KITTI 3D Object Detection dataset, which was also used in the original PointPillars implementation.

The KITTI dataset was collected using a Velodyne HDL-64E LiDAR sensor and includes diverse driving scenarios such as urban streets, highways, and residential areas. It consists of 7481 labeled training frames and 7518 test frames, containing a total of 80,256 annotated 3D objects [16].

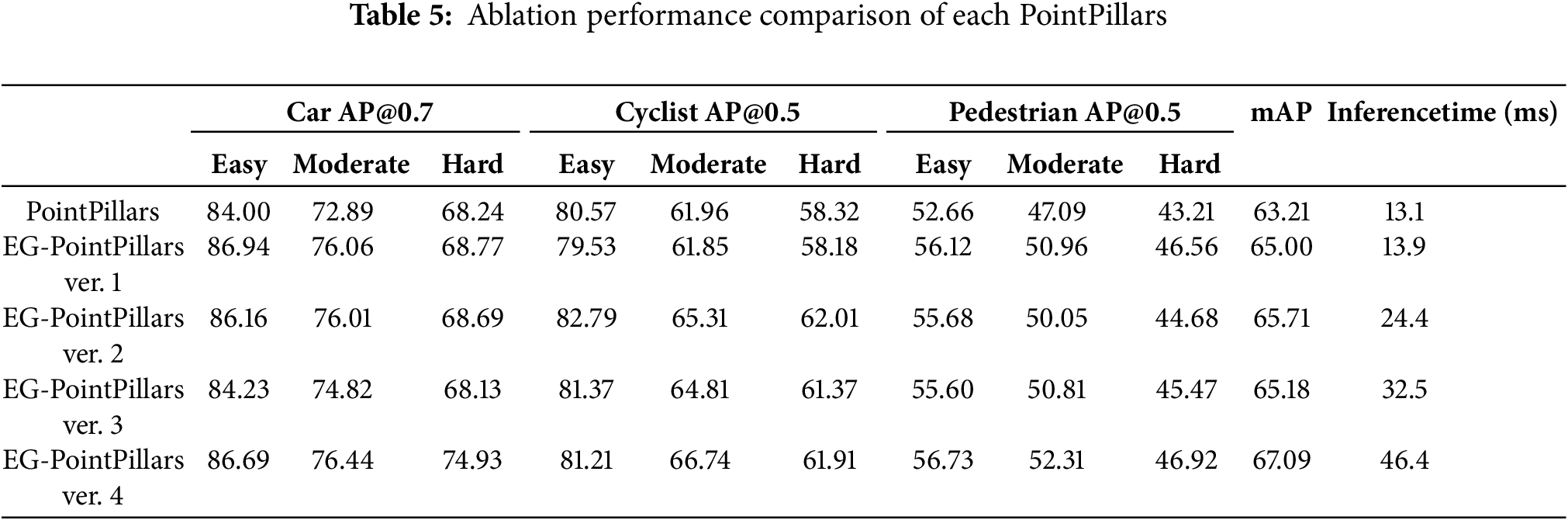

4.3 Experimental Results with Ablation

Table 5 presents the performance evaluation results of the baseline PointPillars and the four proposed versions of EG-PointPillars, tested on the entire test set of the KITTI 3D Object Detection dataset after training completion. The results of proposed algorithms are shown in Table 5.

As shown in Table 5, EG-PointPillars ver. 3 exhibited a slight decrease in mAP compared to ver. 2, despite adopting a more comprehensive input strategy. This performance drop is mainly attributed to the inclusion of ground points during feature encoding, which introduced additional noise into the pillar representations and weakened the cluster-level feature distinction.

EG-PointPillars ver. 4, which integrates all proposed modules, achieved the highest detection accuracy, recording a +3.88% improvement in mAP over the baseline PointPillars. In particular, ver. 4 showed significant performance gains for the car-hard, cyclist-moderate, and pedestrian categories—not only compared to PointPillars, but also in relation to the other EG-PointPillars variants. These results indicate that the Cluster 2D Pseudo-Map Branch plays a critical role in improving detection performance.

Ver. 1 also demonstrated meaningful performance gains with minimal architectural changes. By simply removing ground points using Patchwork++ and applying the modified neck structure, ver. 1 achieved a +1.79% mAP improvement over PointPillars. This highlights the effectiveness of expert-based preprocessing even without additional components such as clustering or pseudo-maps.

In terms of inference speed, EG-PointPillars ver.1 showed the most comparable performance to the baseline, with only a 0.8 ms increase in runtime. ver. 2, 3, and 4, which incorporate the DBSCAN clustering step, exhibited higher computational costs. However, ver. 4, despite being the slowest among the proposed methods, maintained a processing speed of 21.55 Hz, which is sufficient for real-time 3D LiDAR-based object detection.

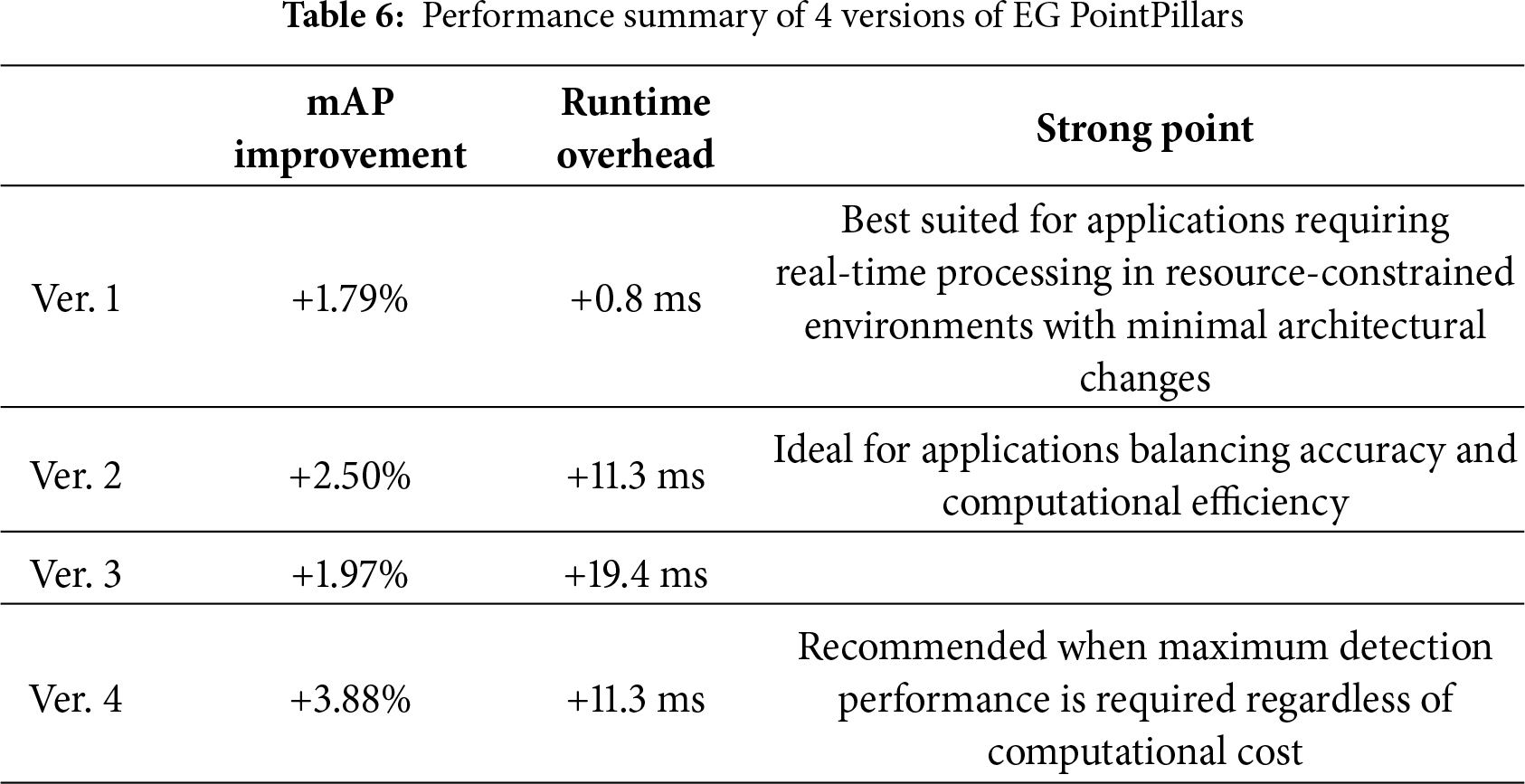

A summary of experimental results compared to the baseline PointPillars is provided below Table 6.

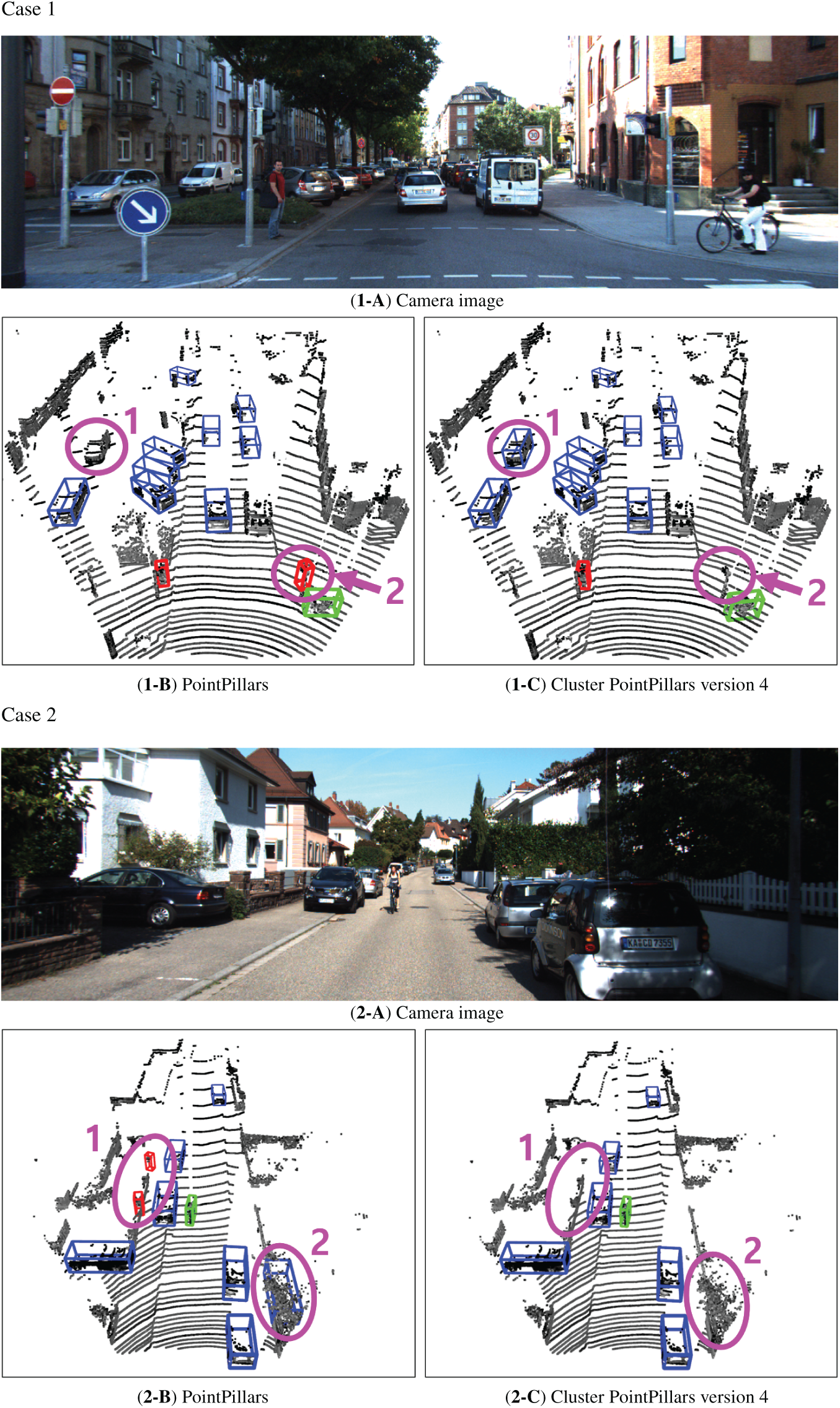

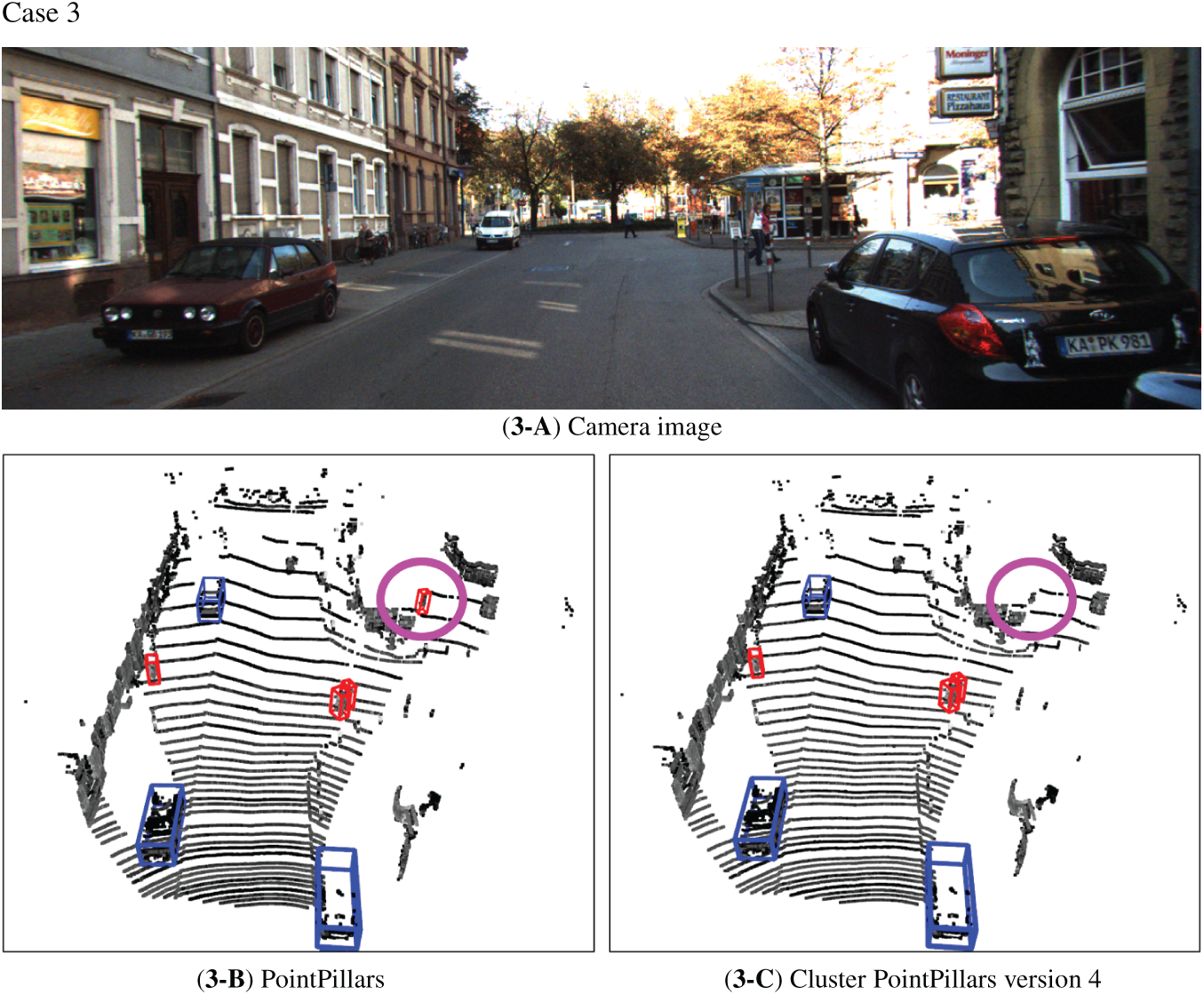

Fig. 20 presents qualitative comparisons between the baseline PointPillars and EG-PointPillars ver. 4 for three representative test cases.

Figure 20: Comparison of results for PointPillars and EG-PointPillars ver. 4

- Case 1: Two objects highlighted with pink circles are shown.

1. Object 1 was a vehicle that was missed by PointPillars but was accurately detected as a vehicle by EG-PointPillars.

2. Object 2, corresponding to a traffic signal, was incorrectly classified as a pedestrian by PointPillars, whereas EG-PointPillars correctly identified it as noise, since it does not belong to any of the three target classes.

- Case 2: Two additional examples are highlighted.

1. Object 1 was a part of a wall, which was falsely detected as a pedestrian by PointPillars, but correctly rejected as noise by EG-PointPillars.

2. Object 2, comprising points from a fence and a tree, was misclassified as a vehicle by PointPillars, while EG-PointPillars correctly identified it as noise.

- Case 3: The object marked by a pink circle corresponds to part of a street vendor stall.

1. PointPillars misclassified it as a pedestrian, whereas EG-PointPillars correctly determined that it belonged to none of the valid object classes and labeled it as noise.

These examples demonstrate the enhanced discriminative capability of EG-PointPillars in rejecting false positives, particularly for ambiguous structures and non-target objects, contributing to its overall performance improvement. Additional videos are provided and described in Appendix A.

In this paper, we proposed EG-PointPillars, a hybrid 3D object detection framework that combines the PointPillars deep learning model with the DBSCAN clustering algorithm to enhance LiDAR-based detection performance. The proposed method improves upon the original PointPillars architecture by integrating ground point removal using Patchwork++, DBSCAN-based clustering, and the Cluster 2D Pseudo-Map Branch to achieve robust performance across various real-world scenarios.

Experimental results demonstrated that EG-PointPillars ver. 4 achieved the highest accuracy, with a +3.88% improvement in mAP compared to the baseline PointPillars. It notably outperformed in challenging categories such as car-hard, cyclist-moderate, and pedestrian-hard. The inclusion of the Cluster 2D Pseudo-Map Branch played a key role in this performance gain. Additionally, ver. 1, which only incorporated Patchwork++ preprocessing and a modified neck structure, achieved a +1.79% mAP improvement with negligible increase in runtime, highlighting the effectiveness of lightweight enhancements.

The proposed EG-PointPillars offers the following key contributions:

- Reduced Dependency on Training Data

By incorporating clustering algorithms like DBSCAN, the model effectively leverages the consistent spatial density of input data, thereby reducing reliance on large-scale labeled datasets. This was empirically validated through performance comparisons.

- Balanced Performance and Real-Time Capability

The modular design of four model versions enables flexible trade-offs between detection accuracy and computational efficiency, supporting deployment in both high-performance and resource-constrained environments.

- Generality and Extensibility

The clustering and structural improvements proposed in EG-PointPillars are modular and model-agnostic. They can be readily applied to other LiDAR-based 3D object detection frameworks beyond DBSCAN and PointPillars.

In conclusion, this study presents a practical and effective hybrid approach that combines expert-driven LiDAR perception with deep learning, significantly improving 3D object detection performance. Future work will focus on extending the framework to handle more complex environments and object classes, as well as further optimizing computational efficiency to enhance real-time processing capabilities.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2023-00245084), by Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) grant funded by the Korea Government (MOTIE) (RS-2024-00415938, HRD Program for Industrial Innovation) and Soonchunhyang University.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows study conception and design: Chiwan Ahn, Daehee Kim and Seongkeun Park; data collection: Chiwan Ahn; analysis and interpretation of results: Chiwan Ahn, Daehee Kim and Seongkeun Park; draft manuscript preparation: Chiwan Ahn, Daehee Kim and Seongkeun Park. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset used in this study is an open and publicly available dataset.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A: Video Demonstration

A video demonstration of the proposed EG-PointPillars is available at the following link, illustrating qualitative detection results under various LiDAR data point cloud data and partial occlusion scenarios.

URL: https://youtu.be/wksFKydFFTA

The upper panel of the video shows the real camera footage capturing the overall driving scene. The lower-left panel displays the detection results of the standard PointPillars, while the lower-right panel presents those of the proposed EG-PointPillars (ver. 4). As shown in the video, the proposed method maintains more stable recognition performance even when the vehicle rotates, changes its measured shape, or experiences partial occlusion, demonstrating improved robustness compared to the baseline.

References

1. Yurtsever E, Lambert J, Carballo A, Takeda K. A survey of autonomous driving: common practices and emerging technologies. IEEE Access. 2020;8:58443–69. doi:10.1109/access.2020.2983149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Teichman A, Levinson J, Thrun S. Towards 3D object recognition via classification of arbitrary object tracks. In: Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation; 2011 May 9–13; Shanghai, China. p. 4034–41. doi:10.1109/icra.2011.5979636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Grigorescu S, Trasnea B, Cocias T, Macesanu G. A survey of deep learning techniques for autonomous driving. J Field Robot. 2020;37(3):362–86. doi:10.1002/rob.21918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Arnold E, Al-Jarrah OY, Dianati M, Fallah S, Oxtoby D, Mouzakitis A. A survey on 3D object detection methods for autonomous driving applications. IEEE Trans Intell Transport Syst. 2019;20(10):3782–95. doi:10.1109/tits.2019.2892405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ester M, Kriegel HP, Sander J, Xu X. A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise. In: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 1996 Aug 2–4; Portland, OR, USA. p. 226–31. [Google Scholar]

6. Zhou Y, Tuzel O. VoxelNet: end-to-end learning for point cloud based 3D object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 4490–9. [Google Scholar]

7. Lang AH, Vora S, Caesar H, Zhou L, Yang J, Beijbom O. PointPillars: fast encoders for object detection from point clouds. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 12689–97. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2019.01298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yan Y, Mao Y, Li B. SECOND: sparsely embedded convolutional detection. Sensors. 2018;18(10):3337. doi:10.3390/s18103337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Mao J, Shi S, Wang X, Li H. 3D object detection for autonomous driving: a comprehensive survey. Int J Comput Vis. 2023;131(8):1909–63. doi:10.1007/s11263-023-01790-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lee S, Lim H, Myung H. Patchwork++: fast and robust ground segmentation solving partial under-segmentation using 3D point cloud. arXiv:2207.11919. 2022. [Google Scholar]

11. Hariya K, Inoshita H, Yanase R, Yoneda K, Suganuma N. ExistenceMap-PointPillars: a multifusion network for robust 3D object detection with object existence probability map. Sensors. 2023;23(20):8367. doi:10.3390/s23208367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17–24; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 7464–75. doi:10.1109/CVPR52729.2023.00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Park G, Koh J, Kim J, Moon J, Choi JW. LiDAR-based 3D temporal object detection via motion-aware LiDAR feature fusion. Sensors. 2024;24(14):4667. doi:10.3390/s24144667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Huang X, Xu Z, Wu H, Wang J, Xia Q, Xia Y, et al. L4DR: liDAR-4DRadar fusion for weather-robust 3D object detection. arXiv:2408.03677. 2024. [Google Scholar]

15. Lin TY, Dollar P, Girshick R, He K, Hariharan B, Belongie S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 936–44. [Google Scholar]

16. Geiger A, Lenz P, Stiller C, Urtasun R. Vision meets robotics: the KITTI dataset. Int J Robot Res. 2013;32(11):1231–7. doi:10.1177/0278364913491297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools