Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Improved Cuckoo Search Algorithm for Engineering Optimization Problems

Faculty of Computing, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, 81310, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Shao-Qiang Ye. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 67 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073411

Received 17 September 2025; Accepted 20 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Engineering optimization problems are often characterized by high dimensionality, constraints, and complex, multimodal landscapes. Traditional deterministic methods frequently struggle under such conditions, prompting increased interest in swarm intelligence algorithms. Among these, the Cuckoo Search (CS) algorithm stands out for its promising global search capabilities. However, it often suffers from premature convergence when tackling complex problems. To address this limitation, this paper proposes a Grouped Dynamic Adaptive CS (GDACS) algorithm. The enhancements incorporated into GDACS can be summarized into two key aspects. Firstly, a chaotic map is employed to generate initial solutions, leveraging the inherent randomness of chaotic sequences to ensure a more uniform distribution across the search space and enhance population diversity from the outset. Secondly, Cauchy and Levy strategies replace the standard CS population update. This strategy involves evaluating the fitness of candidate solutions to dynamically group the population based on performance. Different step-size adaptation strategies are then applied to distinct groups, enabling an adaptive search mechanism that balances exploration and exploitation. Experiments were conducted on six benchmark functions and four constrained engineering design problems, and the results indicate that the proposed GDACS achieves good search efficiency and produces more accurate optimization results compared with other state-of-the-art algorithms.Keywords

Engineering optimization problems are often characterized by complex features, including nonlinear objective functions, mixed discrete-continuous design variables, and multiple conflicting constraints [1]. These characteristics typically result in narrow feasible regions, highly constrained search spaces, and rugged, multimodal landscapes containing numerous local optima. Consequently, traditional gradient-based or deterministic optimization methods often struggle to deliver effective solutions in such environments, primarily due to their propensity to get trapped in local minima and their high computational cost when dealing with complex constraints. In contrast, metaheuristic algorithms have demonstrated strong global search capabilities, robustness, and flexibility, which have motivated extensive research into developing new swarm intelligence and nature-inspired variants to address real-world engineering optimization problems.

Building on this motivation, numerous nature-inspired metaheuristics have been proposed to address the inherent challenges of engineering design problems. For instance, Black Kite Algorithm (BKA) [2], IVY [3], Flood Algorithm (FLA) [4], Modified Crayfish Optimization Algorithm (MCOA) [5], Arctic Puffin Optimization (APO) [6], and SRIME [7]. While these approaches achieved improvements in specific cases, they generally suffered from parameter sensitivity, oscillatory convergence, and poor scalability in high-dimensional constrained environments.

Cuckoo search (CS) has emerged as a particularly promising solution for engineering optimization problems. Its utilization of Levy flight enables long-range, non-local jumps, significantly enhancing the algorithm’s capability to escape local optima, a critical advantage when navigating the rugged, highly constrained landscapes typical of engineering design [8]. However, according to the No Free Lunch theorem, no single algorithm can guarantee optimal performance across all optimization problems [9]. CS itself remains prone to premature convergence and stagnation in complex, high-dimensional situations, thereby limiting its effectiveness. Scholars have proposed several improvement methods to enhance its adaptability, convergence speed, and robustness in solving intricate optimization tasks.

Improving the CS control parameters: Yang et al. [10] introduced an improved CS algorithm by incorporating a Cauchy distribution with a tan function and a proportional Pg allocation strategy to enhance convergence accuracy; however, this approach slowed convergence. Mehedi et al. [11] combined differential evolution (DE) operators with CS, which enhanced classification tasks but introduced instability in large-scale problems. Braik et al. [12] proposed an adaptive step-size CS algorithm with a dynamic discovery probability for nonlinear and linear tension control in industrial winding processes. The improved approach achieved high-precision parameter estimation, even under noisy data conditions. However, in high-dimensional, complex scenarios, computational overhead increased, reducing convergence efficiency. Cheng and Xiong [13] designed a multi-strategy adaptive CS (MACS) incorporating Lehmer mean-based step size adaptation and a search strategy pool for dynamic adjustment. While exhibiting strong convergence efficiency in unimodal functions, its stability in high-dimensional multi-modal functions remained a challenge. Meanwhile, Xiong et al. [14] employed membership and exponential functions to update the step size factor in the CS algorithm, thereby optimizing the chaotic time series of the cloud model. Achieving high prediction accuracy and stability in the Lorenz and Mackey-Glass cases. Gu et al. [15] designed an adaptive step size factor to optimize the multi-objective permutation flow-shop scheduling problem, but its performance degraded significantly in high-dimensional cases due to weak robustness.

Modification of CS operations: Belkharroubi and Yahyaoui [16] developed a memory-based CS with crossover and mutation for assembly-line scheduling. Yu et al. [17] replaced the Levy flight strategy in CS with reinforcement learning (RL) to perform path planning for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). However, the introduction of RL increased the computational complexity of the CS model, leading to a decline in convergence efficiency. Adegboye and Deniz [18] replaced the Levy flight update with an artificial electric field operator to enhance CS exploration and introduced refraction learning to generate reverse solutions, reducing local optima stagnation. This method improved the design costs of welded beams but performed poorly in spring expansion design due to weight constraints, revealing sensitivity to parameter tuning in complex, high-dimensional cases. Chen et al. [19] applied a Gaussian distribution mechanism with adaptive B-hill climbing to improve image segmentation. Li et al. [20] used crossover and mutation in place of Levy flights, grouping the population into superior and inferior sets to boost convergence precision in numerical optimization.

Hybridization of CS and other algorithms: Priya et al. [21] proposed a hybrid CS with fuzzy (HCSF) algorithm for wireless network systems, which effectively reduces routing overhead and improves forwarding performance. Vo et al. [22] developed a multi-objective variant, MOGWOCS, by integrating grey wolf optimization (GWO) with CS to address engineering optimization problems. The method demonstrates strong convergence efficiency, accuracy, and stability in spatial truss design. Gacem et al. [23] introduced a hybrid of gorilla troops optimizer and CS (CS-GTO), for parameter optimization of single- and double-diode photovoltaic models. It achieves high accuracy and fast convergence in photovoltaic module parameter identification. Zhang et al. [24] hybridized CS with particle swarm optimization (PSO) to optimize sequencing under interval time uncertainty, improving scheduling balance and reducing delays. Yajid et al. [25] hybridized the big bang–big crunch algorithm with CS to optimize a deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) and enhance its ability to extract critical features in financial fraud detection. Nouh et al. [26] combined PSO with CS for photovoltaic MPPT, thereby reducing energy loss and voltage fluctuations in various weather conditions. Xie et al. [27] introduced DE operator into CS framework for economic dispatch, maintaining low cost but with higher search complexity.

Although CS has demonstrated a strong global exploration ability due to its Levy flight mechanism, making it particularly suitable for rugged engineering landscapes, it still suffers from several inherent weaknesses. First, its static step size update prevents adaptive search adjustment, making CS prone to premature convergence and stagnation in multimodal and high-dimensional spaces. Second, many existing CS variants enhance performance through hybridization or parameter tuning, yet these designs typically introduce additional algorithmic complexity and insufficient adaptability to dynamic population evolution.

To address these shortcomings, this paper proposes a grouped dynamic adaptive CS (GDACS), which integrates a fitness-based grouping mechanism with dual adaptive step-size control. This design enhances information interaction among individuals and allows the algorithm to dynamically balance exploration and exploitation based on the evolving distribution of solutions, thereby improving convergence speed, solution diversity, and robustness in engineering optimization tasks. The key innovations of GDACS are as follows:

(1) Chaotic initialization: A logistic chaotic map is used to generate a uniformly distributed initial solution set, promoting diversity and avoiding premature clustering of solutions;

(2) Step size adjustment: Nests with below-average fitness adopt an exponential step-size scheme combined with a Cauchy distribution for intensified local search, while those with above-average fitness use a logarithmic step-size with a Levy flight to maintain global exploration;

(3) Group control: GDACS integrates two tailored step-size control mechanisms linked to fitness-based grouping. This design enables the algorithm to adaptively adjust the search intensity and direction based on population distribution, thereby improving convergence speed, solution accuracy, and robustness in complex problem settings.

To validate the effectiveness of GDACS, we conducted experiments on six standard benchmark functions (in dimensions of 30, 50, and 100) and four highly constrained engineering design problems. The results demonstrate that GDACS consistently finds the global optimum, offering higher search efficiency and better optimization performance across varying levels of complexity.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents related works, with a particular focus on the fundamental principles and mathematical foundations of the CS. Section 3 introduces the key theoretical components underlying the proposed method, including the logistic chaotic map and a fitness-based grouping mechanism for adaptive search strategy selection. Section 4 presents the experimental setup and numerical results. Section 5 focuses on the application of the proposed algorithm to four types of constrained engineering optimization problems. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

The CS algorithm proposed by Yang and Deb mainly follows the following three rules [8].

1. Cuckoos lay only one egg at a time, and the nest for laying eggs is randomly selected.

2. The nest with the best survival rate of the current eggs will be retained for the next generation.

3. The number of nests available for laying eggs is fixed, and there is a certain probability that a cuckoo’s egg will be discovered. If it is, the host bird will either discard it or build a new nest, meaning that nests are likely to be replaced.

In the standard CS algorithm, Yang represents each egg or cuckoo using a D-dimensional vector x = [x1, x2, ..., xD] and uses Levy flight to update the population:

In this context,

To simplify the computation, the standard CS typically uses the Mantegna algorithm to simulate Levy flight, with the step size update formula given by:

where,

here,

3 Grouped Dynamic Adaptive Cuckoo Search Algorithm

The main innovations of the proposed GDACS focus on two key aspects: Firstly, to address the randomness in the initialization of the standard CS, this paper introduces chaotic mapping from chaotic algorithms to generate chaotic sequences. This approach ensures a uniform distribution of initial solutions while increasing solution diversity. Secondly, the population is grouped based on the fitness values of individuals. Different step size strategies are applied to different groups, enabling an adaptive update mechanism that improves search efficiency.

3.1 Chaotic Initialization of the Population

Chaotic optimization methods are based on replacing random variables with chaotic variables in random optimization algorithms [28]. The critical technique lies in generating chaotic sequences using chaotic maps, which exhibit characteristics such as randomness, ergodicity, and non-periodicity. Compared to other random optimization methods, chaotic optimization offers higher efficiency, maintains population diversity, and improves the algorithm’s global optimization performance. In GDACS, the Logistic chaotic map replaces the random solution generation in the initialization phase of CS. As a typical chaotic system, the expression for the Logistic map is shown in Eq. (6).

here,

The specific process of chaotic initialization in GDACS is as follows:

Step 1: Set the maximum number of chaotic iterations to M, the control parameter

Step 2: Randomly generate a D-dimensional vector

Step 3: Iterate the Logistic map M times using the expression to generate M chaotic vectors

Step 4: Use Eq. (7) to generate the initial nest positions

Step 5: Calculate the objective function and select the best N nest positions from the M initial populations as the initial nest positions.

The standard CS relies on a random walk strategy during optimization, where the step size is not a fixed value. During the search process, relatively larger step sizes in random walks facilitate the search for the global optimal solution but tend to reduce search accuracy. In contrast, smaller step sizes improve solution accuracy but decrease the search speed.

Levy flight is a random walk process where the random step sizes follow a Levy distribution. However, as it entirely depends on the Levy distribution for different individuals’ flight characteristics, convergence efficiency and search accuracy cannot be guaranteed.

In addition, the step size control vector can control the range of the algorithm search. According to the search results at different stages of the algorithm, adaptive dynamic adjustment of the step length control vector can make the algorithm achieve a balance between global and local search.

Therefore, the GDACS divides the population into two groups according to the relationship between the adaptation value of each individual in the group and the fitness value of the whole population. Different treatments are adopted for individuals corresponding to the classification of step control vectors with the population for updating. The specific ideas are as follows.

Let the fitness value of the i-th individual

(1) The nest positions in Group A represent the more optimal nests among all nest positions. Compared to Group B, the nests in Group A are closer to the global optimum. Therefore, when adjusting the step size control vector, Group A should focus more on local search during most iterations. The step size adjustment formula is as follows:

In this formula,

(2) Group B nest locations are medium or moderately low nests among all nests. Compared with the nests in group A, the nests in group B are farther away from the nests of the global optimal solution. Therefore, the dynamic adjustment of the components of the corresponding step-size control vectors can better balance the nests of group B between the local search and the global search. The step size adjustment equation is as follows:

where

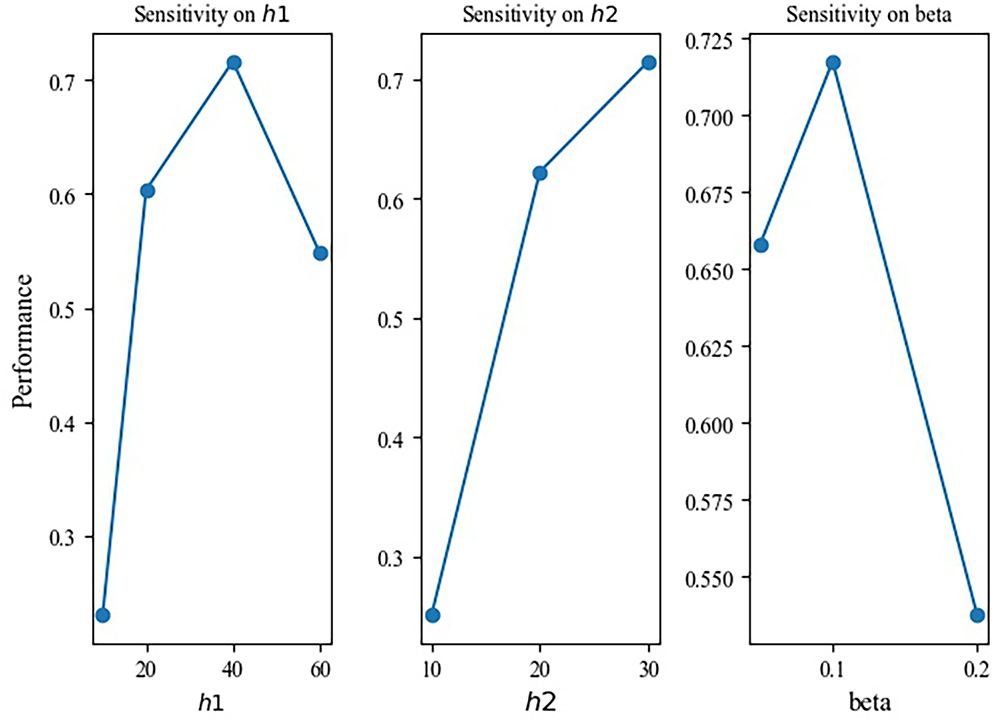

Figure 1: Sensitivity analysis of h1, h2, and

The Cauchy distribution’s heavy-tailed property allows for occasional large steps, enhancing the algorithm’s local exploitation capability.

The population update follows Eq. (10):

Based on the improvements described, the steps of the GDACS algorithm are as follows:

Step 1: Use chaotic mapping to initialize the population.

Step 2: Calculate the fitness values of the cuckoo nests and determine their average. If a fitness value is greater than the average, apply an exponential adaptive step size and update using Cauchy flight. If it is less than the average, apply a logarithmic adaptive step size and update using Levy flight.

Step 3: Discard a portion of the nests based on the discovery probability. Then, check if the stopping condition is met. If not, return to Step 2; otherwise, proceed to Step 4.

Step 4: Output the optimal solution and terminate the proposed algorithm.

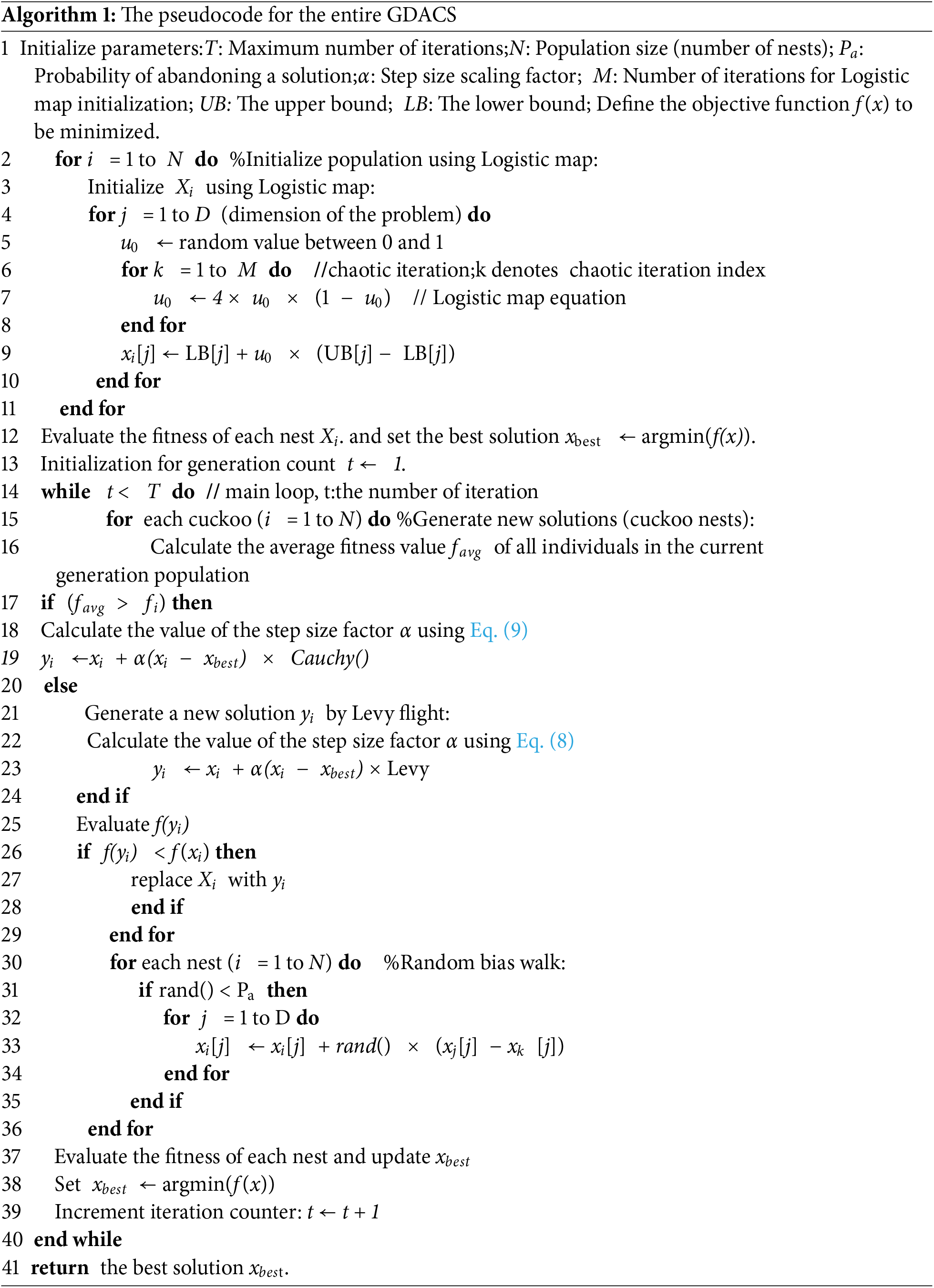

The pseudocode for the entire GDACS as shown in Algorithm 1.

The pseudocode of the GDACS presented above shows that the GDACS has a similar structure to CS, consisting of three main components: initialization, global search, and local search. The time complexity of GDACS is primarily influenced by the problem dimension D, population size N, the maximum number of iterations T, and the complexity of the fitness function f(D).

Although GDACS introduces additional computations, including population initialization using Logistic chaotic mapping and global search strategies under different groupings. Therefore, the time complexity for initializing the population with Logistic mapping is O(N × D); and the grouped global search, whether guided by the Cauchy or Levy distribution, also has a complexity of O(N × D). The local search process, which follows a random walk, also has a complexity of O(N × D). Furthermore, the fitness evaluation for each individual contributes O(f(D)) per iteration.

Consequently, the total worst-case time complexity of GDACS over all iterations T is O(T × N × (D + f(D))). At the same time, the total worst-case time complexity for the CS at the overall stage also reaches O(T × N × (D + f(D))).

4 Simulation Experiment and Analysis

Six classical test functions are used as benchmark functions to evaluate the effectiveness of GDACS. Numerical comparisons of its optimization results are made against the standard CS [8], two other CS variants, Enhanced CS (ECS) [12] and modified CS (MCS) [29], as well as PSO [30], HS [31,32] and GWO [33].

To ensure fairness in the comparison and mitigate the effects of algorithmic randomness, each algorithm performs 30 independent optimization runs for each test function, with a maximum of 1000 iterations per run. Furthermore, these six benchmark functions (Alpine, Griewank, Rastrigin, Bohachevsky, XinsheYang) [32] were selected for their diverse optimization characteristics, including modality, separability, nonlinearity, and landscape complexity. This selection provides a comprehensive evaluation framework to assess both exploitation and exploration capabilities.

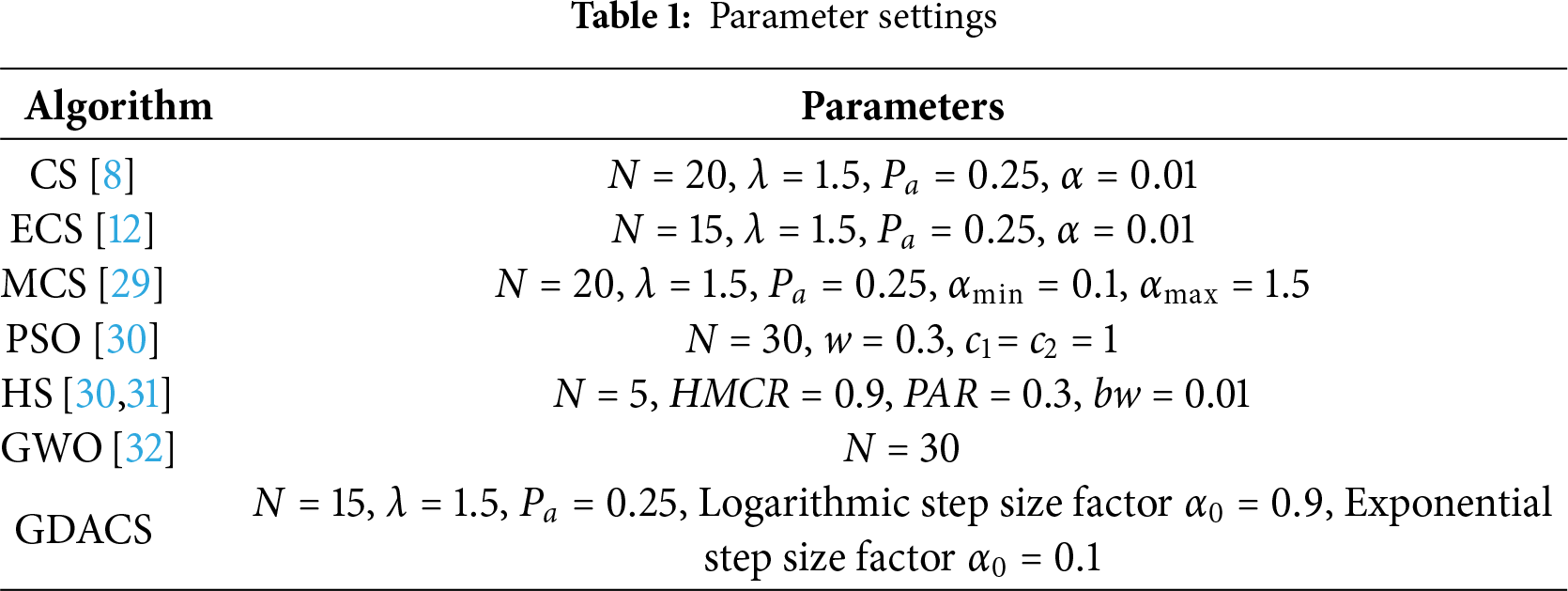

4.1 Testing Platform and Parameter Settings

All experiments were conducted in Python 3.7 on a Windows 10 system with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-3470 CPU @ 1.60 GHz and 8 GB RAM. To ensure fairness, all competing algorithms were implemented using parameter settings reported in their original publications, as summarized in Table 1.

4.2 Experimental Results and Analysis

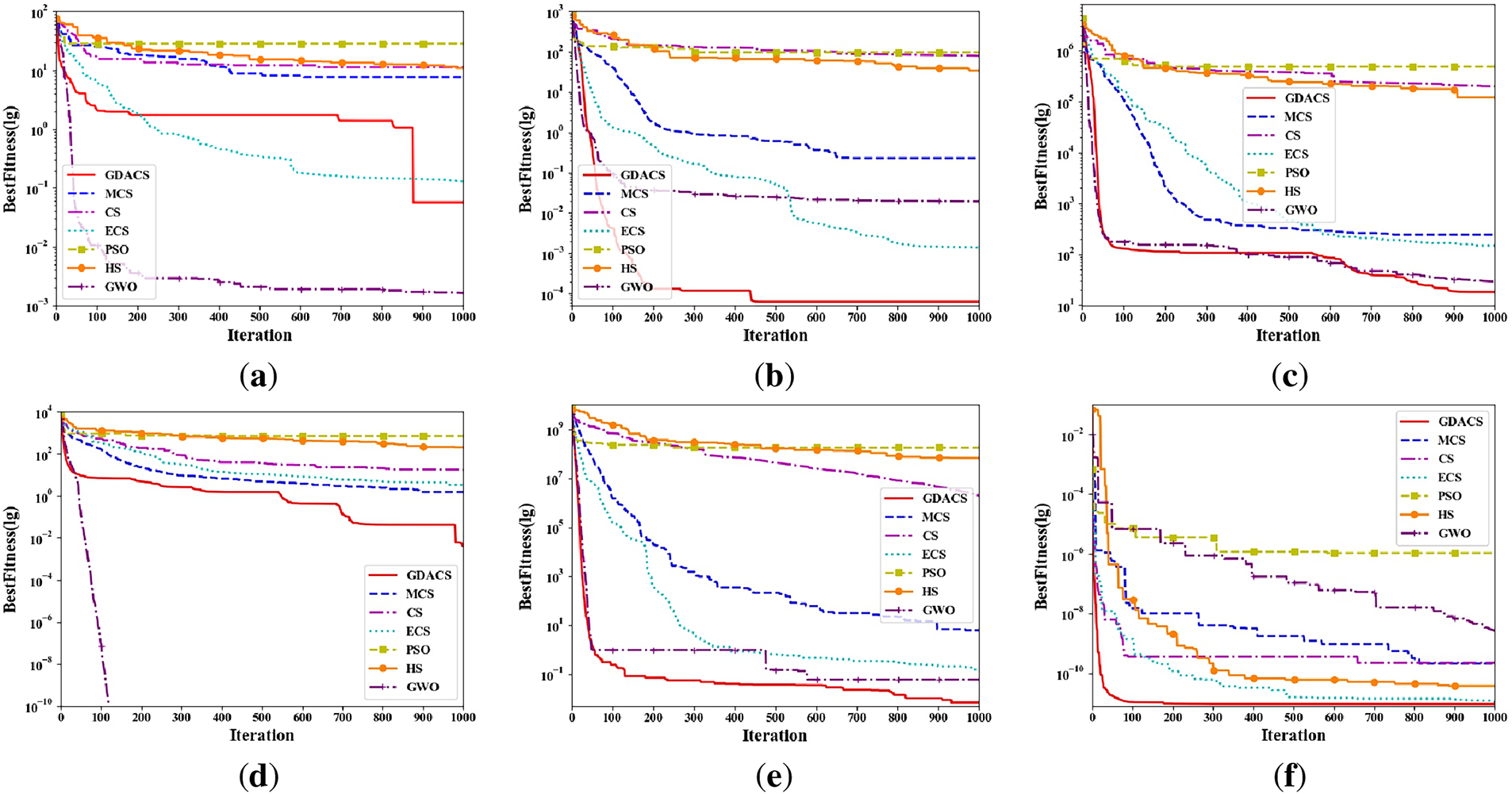

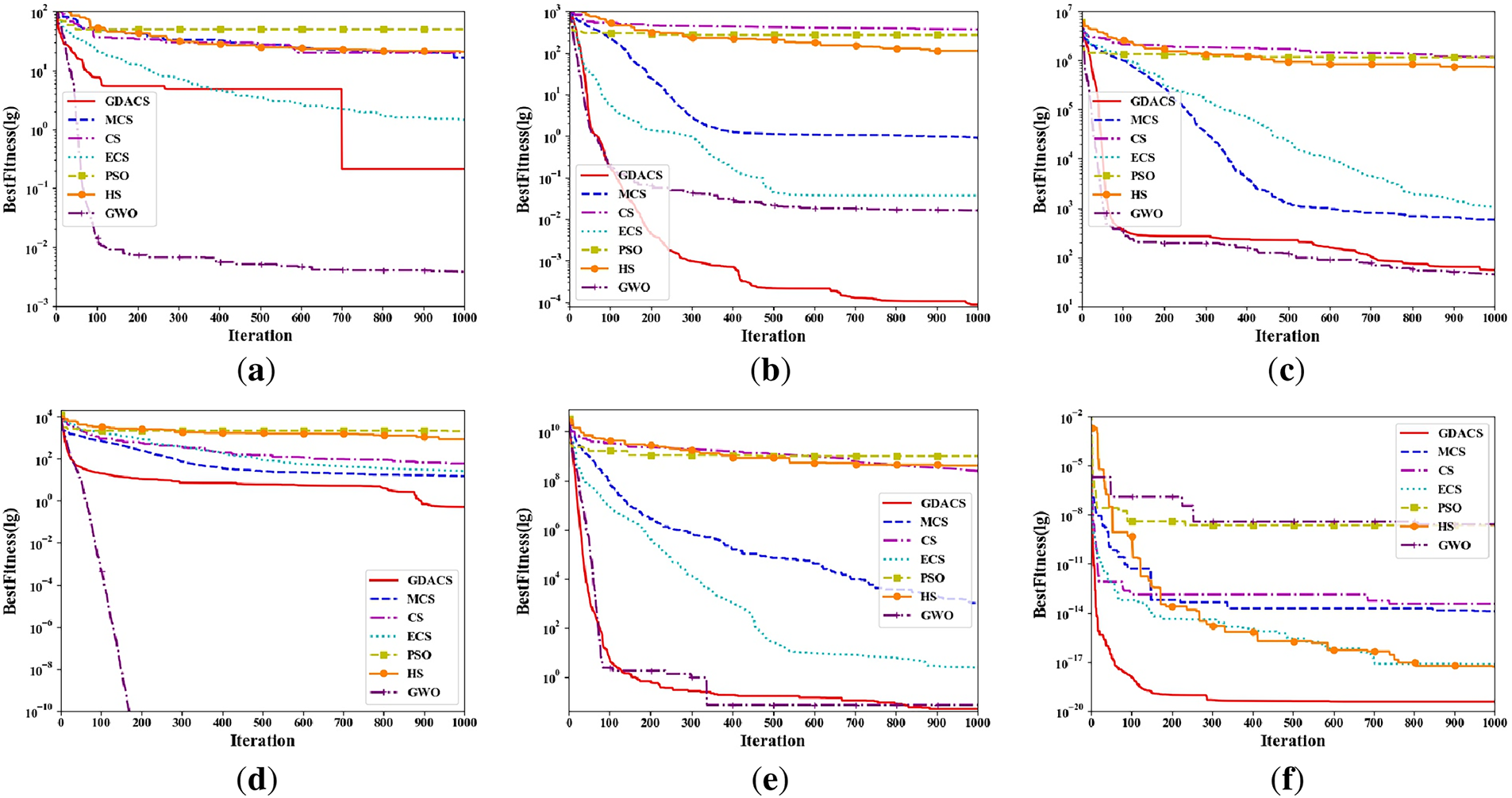

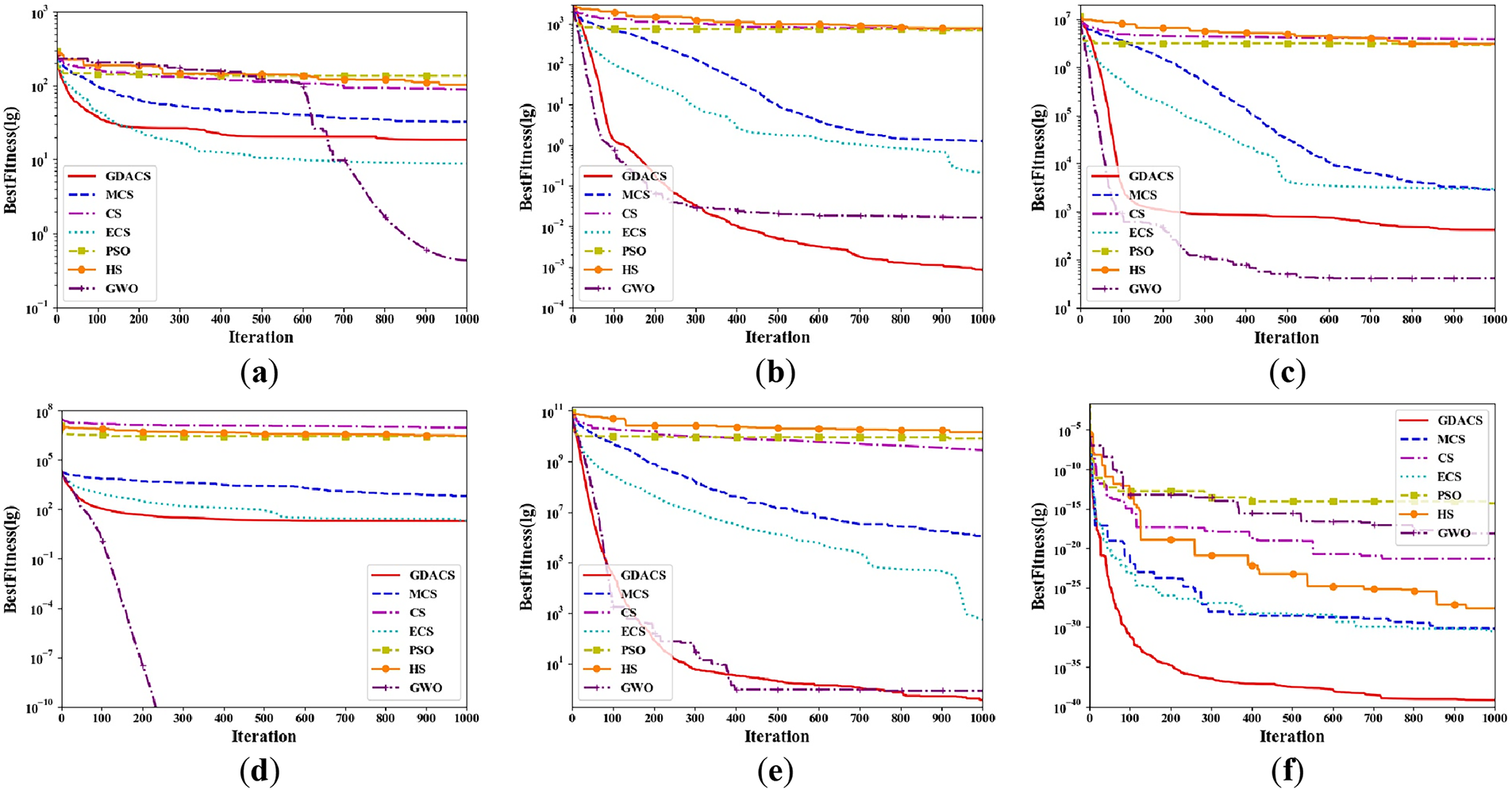

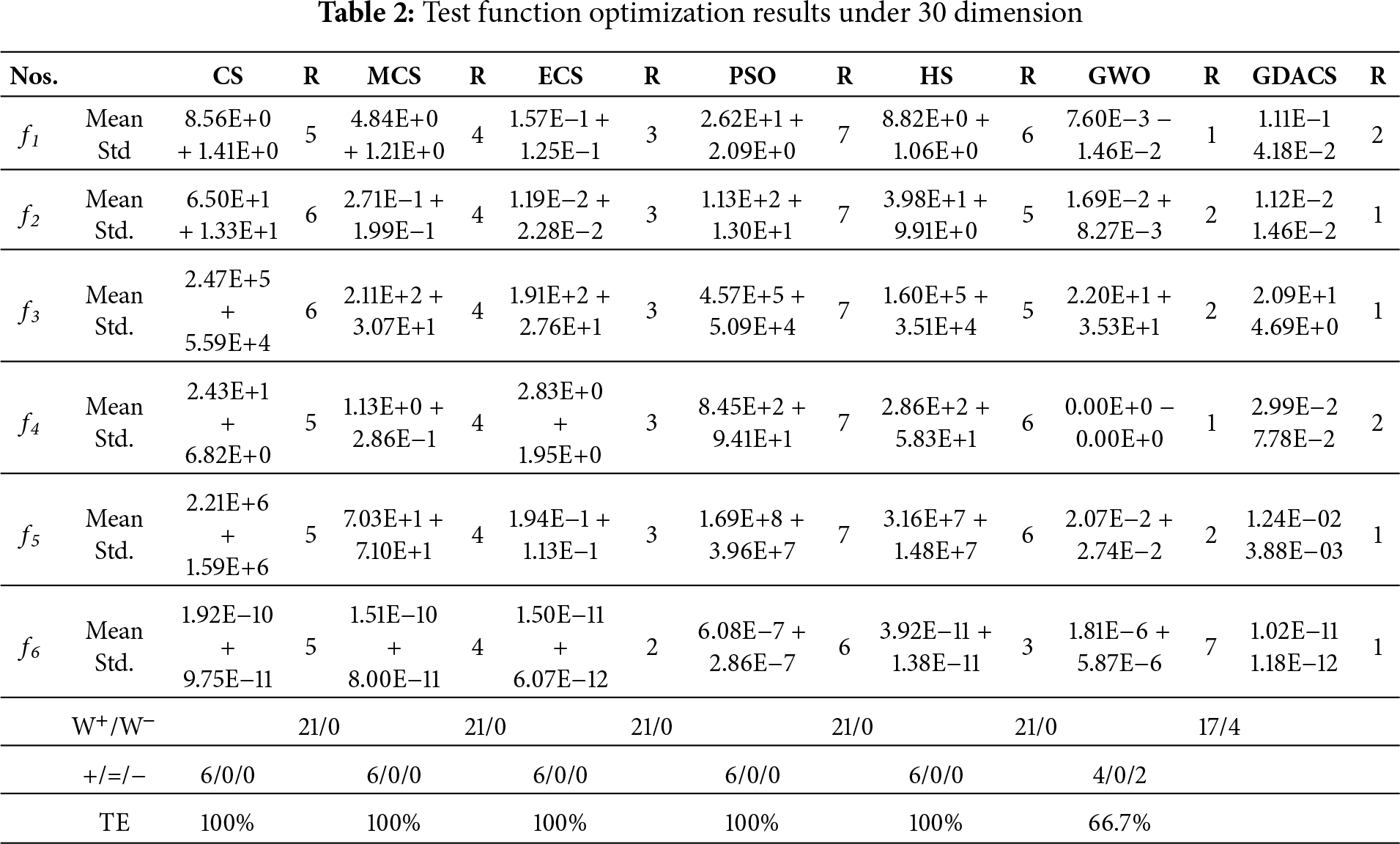

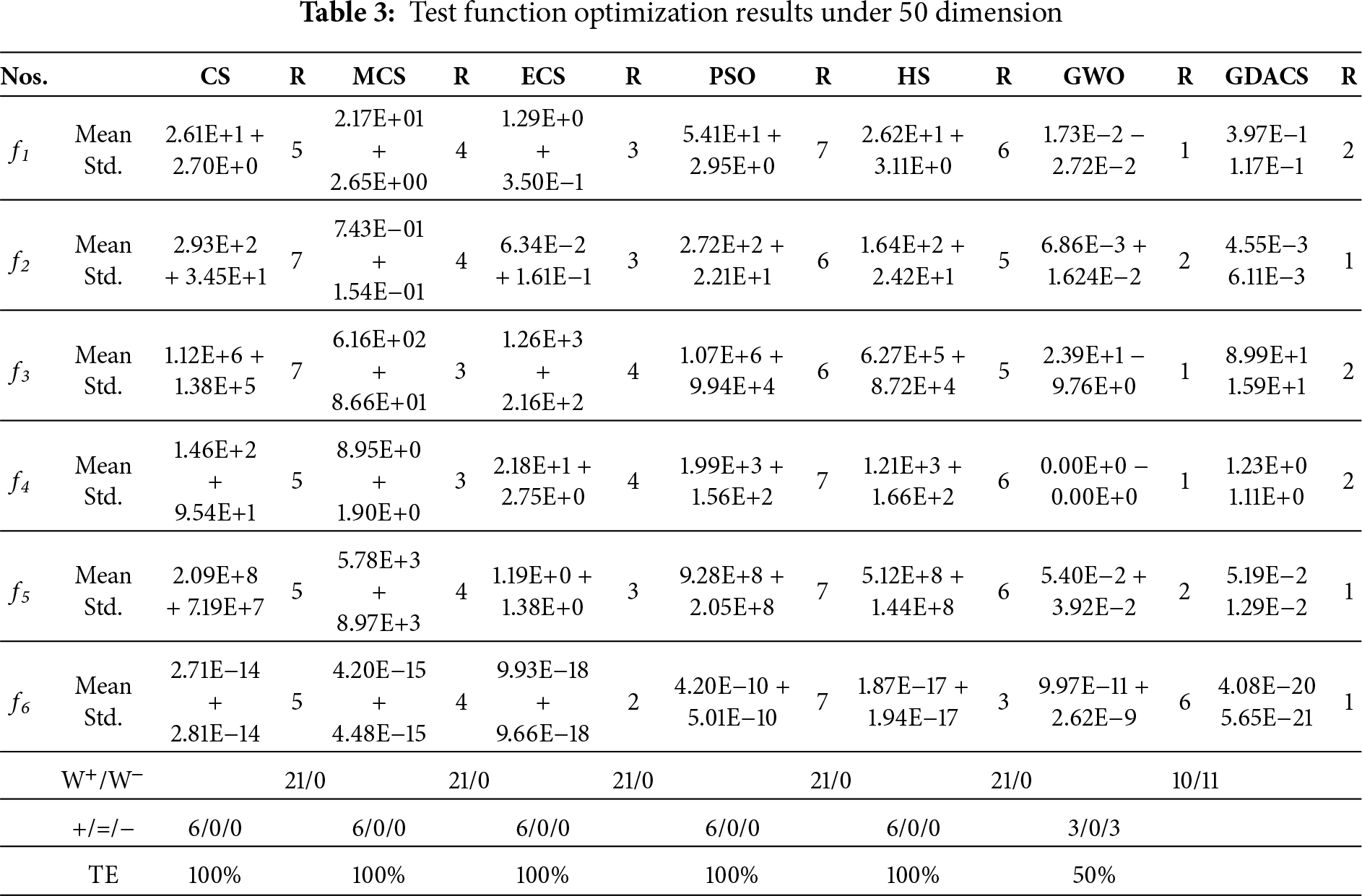

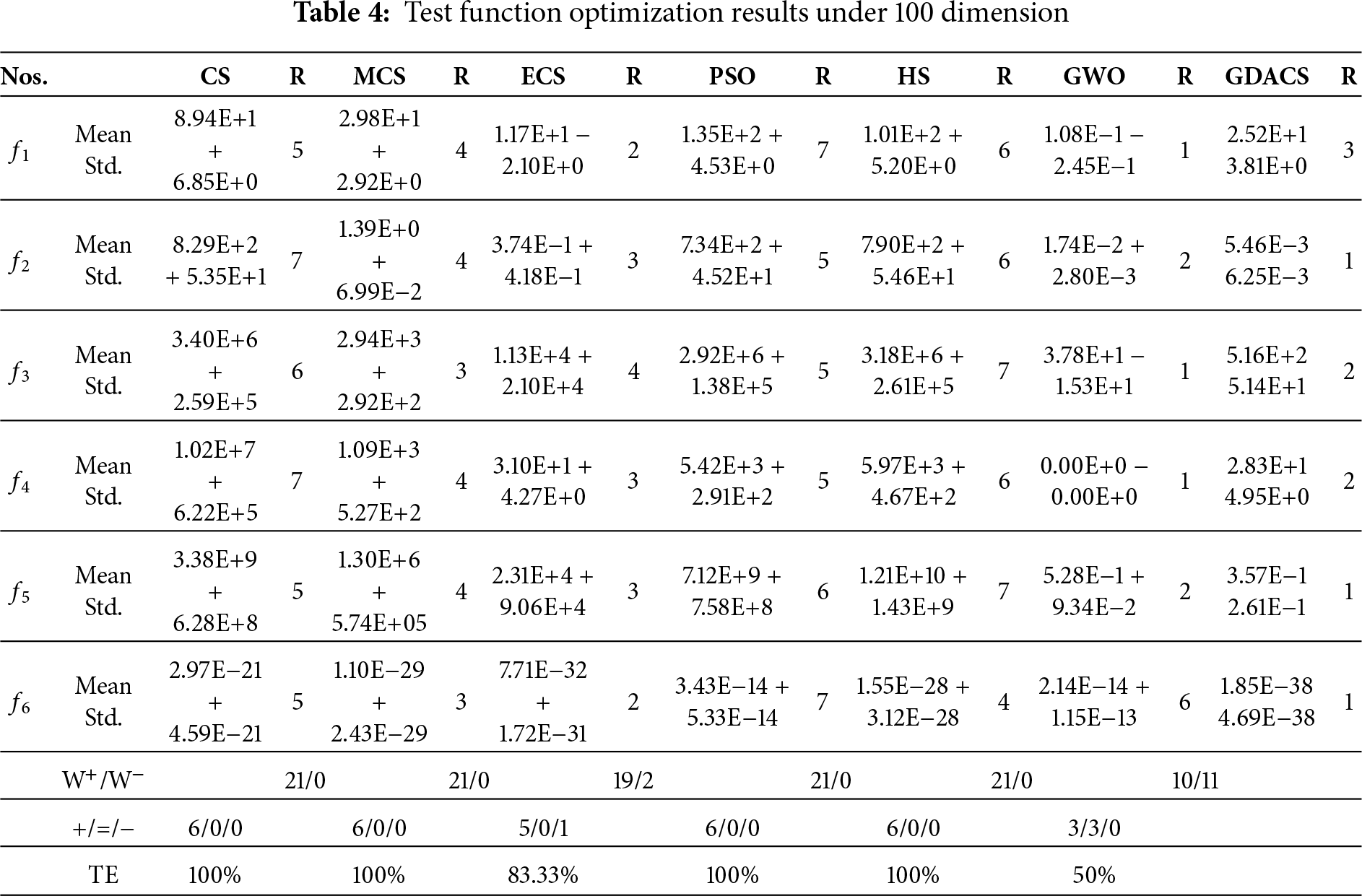

Figs. 2–4 show the average convergence trajectories of six algorithms on 30-, 50-, and 100-dimensional benchmark functions, each based on 30 runs of 1000 iterations. To further evaluate accuracy and stability, Tables 2–4 report the mean and standard deviation of results, together with Wilcoxon rank-sum tests at a 5% significance level. In these tables, the symbols ‘+/=/−’ indicate whether GDACS performs significantly better, equivalent, or worse than the compared algorithms, with W+/W− summarizing the win or loss counts. In addition, the Total Efficiency (TE) metric (Eq. (11)) is used to quantify overall performance based on the frequency of inferior results (‘−’).

where,

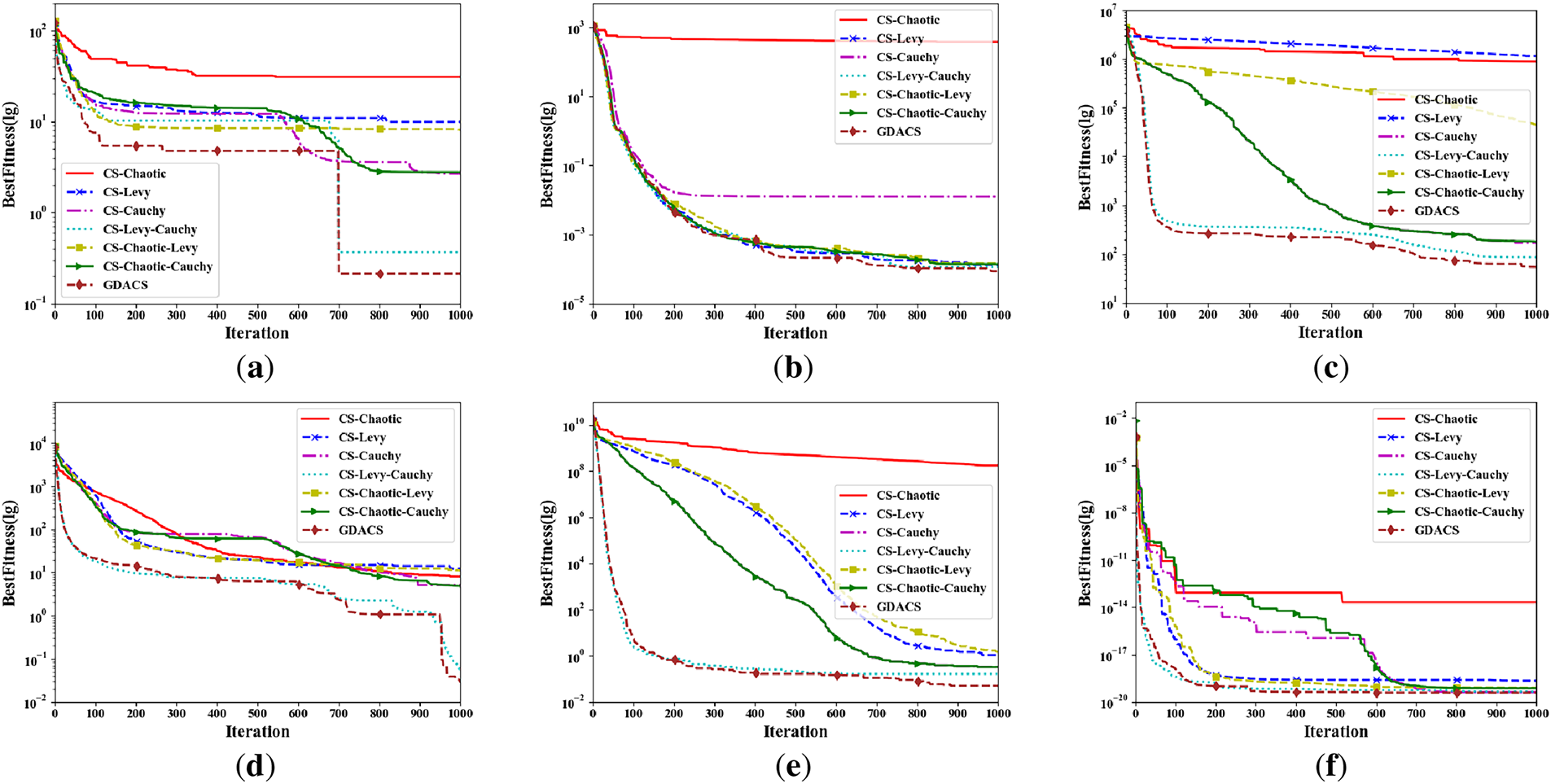

Figure 2: Convergence curves of seven algorithms on 30-dimensional benchmark functions: (a) f1(x); (b) f2(x); (c) f3(x); (d) f4(x); (e) f5(x); (f) f6(x)

Figure 3: Convergence curves of seven algorithms on 50-dimensional benchmark functions: (a) f1(x); (b) f2(x); (c) f3(x); (d) f4(x); (e) f5(x); (f) f6(x)

Figure 4: Convergence curves of seven algorithms on 100-dimensional benchmark functions: (a) f1(x); (b) f2(x); (c) f3(x); (d) f4(x); (e) f5(x); (f) f6(x)

For f1(x) = Alpine, the convergence curves in Figs. 2a, 3a and 4a clearly reveal the significant differences in performance among algorithms as dimensionality changes. In the 50- and 100-dimensional cases, GWO exhibits good convergence performance, combining higher accuracy with faster convergence speed. GDACS is second. Furthermore, in the 30-dimensional case, GDACS outperforms GWO. Compared to other CS variants (CS, ECS, and MCS), GDACS exhibits similar convergence performance in the early stages of iteration. Although its convergence speed decreases and plateaus in the middle stages, its performance significantly improves in subsequent iterations, enabling it to escape local optima and quickly approach the global optimum. During the initial iterations, GDACS’s performance is comparable to that of the other three CS variants (CS, ECS, and MCS). In the mid-iteration phase, the convergence slows and becomes relatively flat. Nevertheless, in the later stages, GDACS exhibits a marked improvement, allowing it to escape local optima and achieve the global optimum rapidly. In 100 dimensions, ECS surpasses GDACS in both convergence speed and accuracy, whereas GDACS performs better than ECS in the 30-, 50-dimensional range and shows stronger robustness across multiple runs. Conversely, PSO and HS lack the Levy flight-based exploration mechanism, which significantly impedes their convergence speed and solution accuracy. Furthermore, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test results, reported in Tables 2–4, at the 5% significance level indicate that PSO and HS retain their seventh and sixth statistical rankings, respectively.

For the multimodal function f2(x) = Griewank, characterized by numerous intricate local optima, GDACS demonstrates strong resilience to increasing dimensionality and maintains consistent optimization performance. As illustrated in Figs. 2b, 3b and 4b, GDACS achieves convergence that is 2, 2, 4, 6, 6, and 5 times faster than those of GWO, ECS, MCS, PSO, CS, and HS, respectively. Furthermore, GDACS surpasses all comparison algorithms within the first 500 iterations, highlighting its superior exploration capabilities and convergence behavior in complex landscapes.

For f3(x) = Rastrigin, as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2c, GDACS, compared to the three CS variants, leverages its Cauchy operator and adaptive logarithmic step size to maintain high-quality solutions early in the optimization. This synergistic design accelerates convergence and significantly enhances final accuracy in the 30-dimensional case. While MCS converges quickly initially, its efficiency wanes in later stages, leading to inferior solutions compared to ECS. Moreover, CS has the worst overall convergence efficiency. However, in the 50- and 100-dimensional scenario, GDACS’s precision drops notably due to increased dimensionality, causing its rank to fall from first to second, while GWO becomes more competitive, ranking first. In addition, CS, PSO, and HS exhibit similar convergence trends across both dimensions, but consistently underperform compared to MCS, ECS, GWO, and GDACS. Notably, GDACS, despite a conservative start, effectively escapes local optima in later stages and reliably converges to the global minimum, ultimately surpassing all competitors in accuracy and robustness.

For f4(x) = Bohachevsky: In 30, 50, and 100 dimensions, GWO demonstrated strong optimization capabilities during the optimization process of this function, converging to the theoretical optimal value of 0, while the GDACS algorithm ranked second. As shown in Fig. 2d and Table 2, GDACS exhibits strong convergence in the early stage. Although it experiences a temporary stagnation during the middle phase, its grouping-based update mechanism allows it to escape local optima and achieve good final accuracy. Conversely, ECS, MCS, and CS display weaker overall convergence performance on f4. Furthermore, the results presented in Figs. 3d and 4d and Tables 3 and 4 indicate that, in 50- and 100-dimensional spaces, GDACS follows a similar optimization trajectory to ECS and MCS during the early and middle stages of iteration. Additionally, in later iterations, GDACS exhibits beneficial oscillatory behavior, which enhances its local search capability, but its overall convergence performance remains weaker than that of GWO.

For f5(x) = Quartic, GDACS demonstrates outstanding performance, steadily outperforming all other algorithms in convergence speed and solution accuracy (Fig. 2e, Table 3). GWO, ECS ranks second, third, respectively benefiting from its adaptive alpha parameter that enhances exploration and yields superior solutions compared to MCS, CS, PSO, and HS. As shown in Figs. 2e and 3e and Tables 3 and 4, GDACS’s chaotic initialization strategy enables it to locate high-quality solutions early, causing rapid fluctuations and a swift decrease in the objective function value, which indicates strong global convergence. Although its convergence rate slightly decelerates in the middle phase, the algorithm steadily progresses toward the global optimum, and its final solution accuracy remains robust against increasing dimensionality. In contrast, ECS exhibits a more gradual convergence curve with slightly lower precision than GDACS, while MCS lags behind both. The standard CS, PSO, and HS algorithms maintain their characteristic but inferior convergence patterns, except that GWO ranks second compared to GDACS, with their rankings (fourth, sixth, and fifth, respectively) remaining unchanged, underscoring their limited competitiveness in this function.

For the complex nonlinear function f6(x) = XinsheYang, GDACS exhibits remarkable convergence behavior and optimization accuracy in both 30-, 50-, and 100-dimensional spaces. As shown in Figs. 2f, 3f and 4f and Tables 2–4, the incorporation of logistic chaotic mapping during initialization significantly enhances population diversity in the early iterations, giving GDACS a clear advantage over other CS variants and heuristic algorithms. The ECS ranked second in solution accuracy and convergence performance, though it remains substantially inferior to GDACS. MCS performs slightly below ECS but still outperforms CS and PSO. In contrast, GWO struggles to optimize this highly nonlinear multimodal problem, resulting in poorer overall convergence performance and accuracy compared with GDACS, MCS, ECS, CS, and HS.

Overall, GDACS achieves the best performance across all six benchmark functions, outperforming MCS, ECS, PSO, HS, and standard CS in both convergence speed and solution accuracy. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test confirms its statistical superiority, with GDACS achieving a perfect 6/0/0 (+/=/−) record against some competitors and maintaining 100% TE across all dimensions, except for GWO and ECS (in the 100-dimensional case). These results highlight its robustness, convergence reliability, and adaptability in solving complex high-dimensional optimization problems.

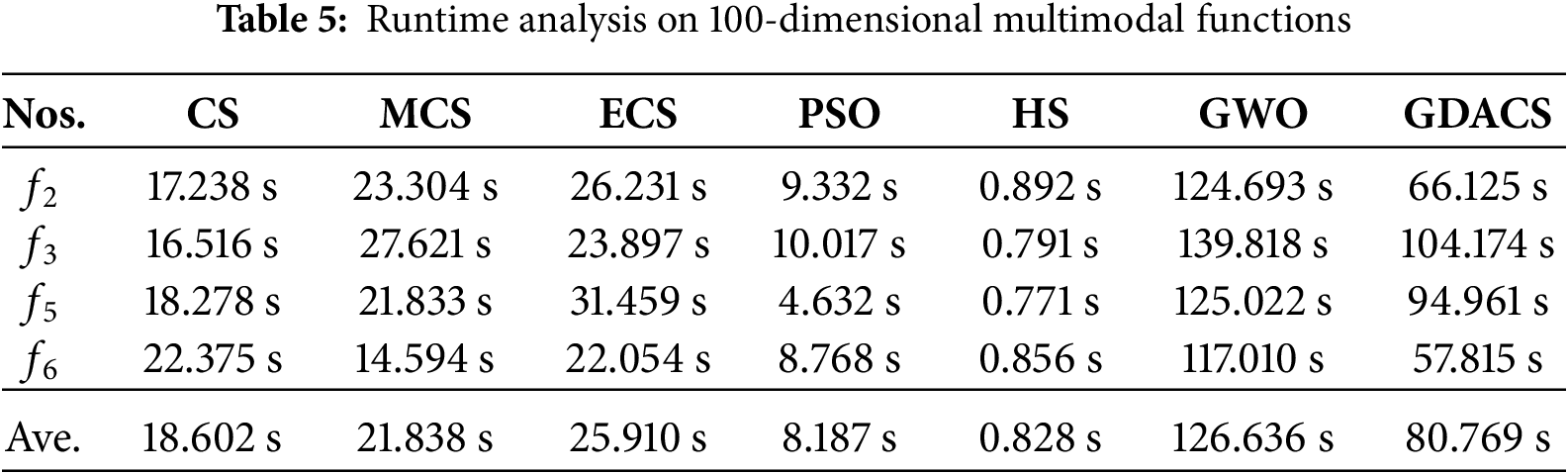

To further evaluate the actual running efficiency of each algorithm in high-dimensional optimization problems, four complex multimodal functions (Griewank: f2, Rastrigin: f3, Quartic: f5, and XinsheYang: f6) were selected for time cost analysis under 100-dimensional condition. These functions exhibit strong multimodality, nonlinearity, and complex search space characteristics, effectively reflecting the global search capability and local exploitation efficiency of the related algorithms in high-dimensional scenarios. Each algorithm was run independently 30 times, and the average running time was statistically analyzed. The results are shown in Table 5.

As shown in Table 5, in the test of 100-dimensional four multimodal functions, the overall runtime of GDACS is slightly longer than that of CS, MCS, PSO, and HS, with an average time cost of 80.769 s. GDACS is primarily due to the introduction of chaotic initialization, dynamic step size, and fitness-based grouping mechanisms, which introduce additional computational steps. However, compared to GWO, GDACS has significantly lower overhead and better solution accuracy, indicating that it achieves a good balance between performance improvement and computation time.

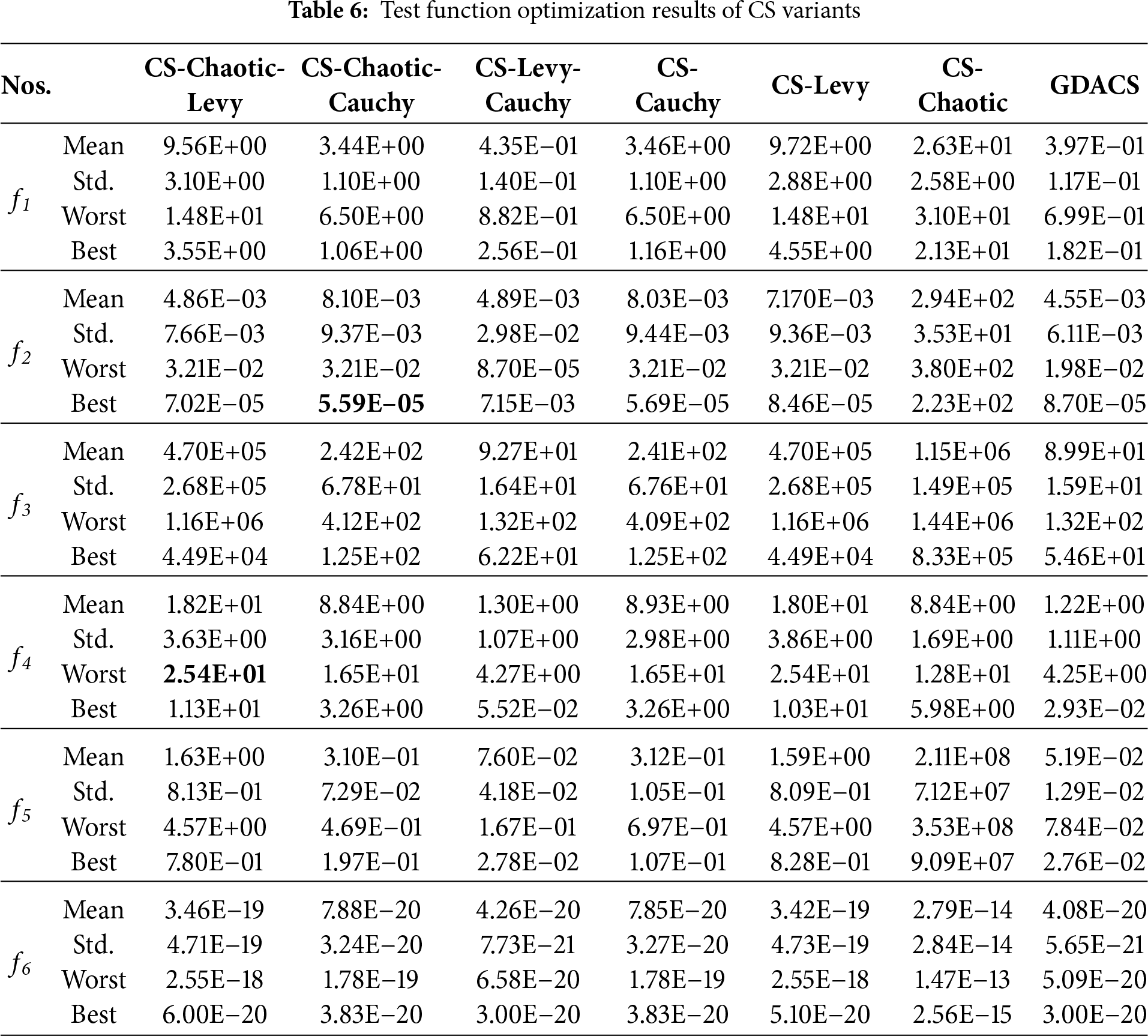

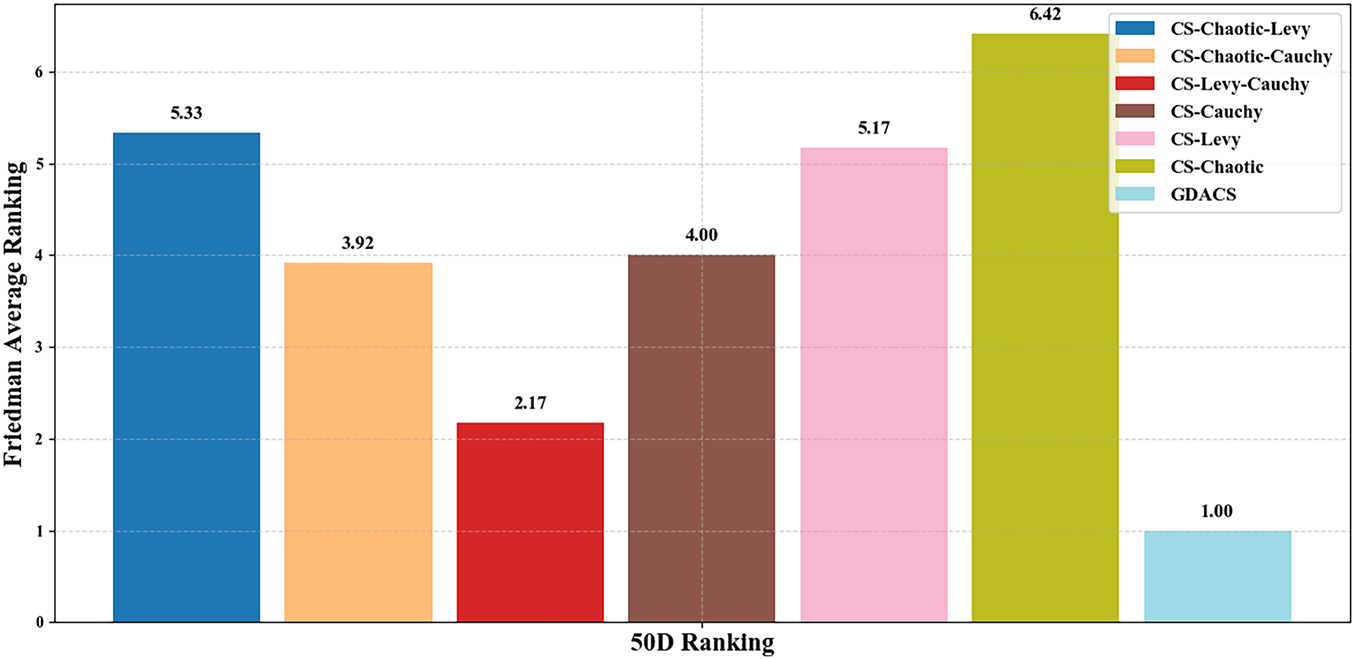

To assess the contribution of each strategy in GDACS, an ablation study was conducted on six benchmark functions under 50 dimensions. Seven CS variants were tested, including single-strategy versions (CS-Cauchy: utilizes exponential scaling with the Cauchy distribution; CS-Levy: integrates logarithmic step-size control via Levy flights; CS-Chaotic: employs logistic chaotic mapping to enhance initial population diversity) and pairwise hybrids (CS-Chaotic-Levy: combines logistic chaotic initialization with logarithmic step-size control via Levy flights; CS-Chaotic-Cauchy: combines logistic chaotic initialization with Cauchy-based step; CS-Levy-Cauchy: integrates both Levy- and Cauchy-based step control), with GDACS further incorporating a fitness-based grouping mechanism. The results (Tables 6 and 7, Figs. 5 and 6) show that the combination of chaotic initialization, adaptive step size control, and grouping provides an apparent synergistic effect. Specifically, GDACS consistently achieved faster convergence and higher solution quality than all other variants, demonstrating that the three strategies together effectively improve population diversity in early stages and enhance convergence accuracy in later stages.

Figure 5: Convergence curves of CSs variants on 50-dimensional benchmark functions: (a) f1(x); (b) f2(x); (c) f3(x); (d) f4(x); (e) f5(x); (f) f6(x)

Figure 6: Friedman average ranking of CS variants on six benchmark functions in 50 dimension

As shown in Fig. 5a–f reveals that CS variants utilizing chaotic mapping, specifically CS-Chaotic, CS-Chaotic-Levy, CS-Chaotic-Cauchy, and GDACS, exhibit enhanced population diversity during initialization. However, analysis alongside Table 6 indicates that chaotic initialization alone does not guarantee superior performance, particularly without complementary adaptive mechanisms. For instance, CS-Chaotic performs poorly across all six benchmark functions, suggesting that chaotic mapping may impede convergence efficiency if not paired with robust exploitation strategies.

Among all variants, GDACS and CS-Levy-Cauchy, both incorporating a grouping mechanism, achieve the most competitive convergence rates, converging within 600 iterations for most functions. Nevertheless, GDACS demonstrates superior final solution accuracy compared to CS-Levy-Cauchy, as confirmed by the statistical metrics in Table 6. In contrast, single-strategy variants such as CS-Levy, CS-Cauchy, and CS-Chaotic exhibit significantly inferior performance in both convergence speed and solution accuracy. Similarly, while hybrid strategies like CS-Chaotic-Levy and CS-Chaotic-Cauchy offer improved competitiveness, those still fall short of the performance achieved by GDACS and CS-Levy-Cauchy.

The success of GDACS and CS-Levy-Cauchy can be attributed to their grouping-based control mechanism, which facilitates dynamic adjustment of the global search strategy based on fitness evaluations. This capability enables a more balanced trade-off between exploration and exploitation, leading to broader coverage of the solution space and more efficient convergence.

Further statistical analysis, based on Table 6 under 50-dimensional condition, reveals no statistically significant difference in overall optimization performance between GDACS and CS-Levy-Cauchy. However, CS-Levy-Cauchy exhibits slightly lower variance when solving function F4, indicating marginally better stability in that specific instance. In contrast, the remaining variants: CS-Chaotic, CS-Cauchy, CS-Levy, and CS-Chaotic-Levy, consistently underperform compared to GDACS across all benchmark functions. Although CS-Chaotic-Cauchy demonstrates partial similarity to GDACS on a few individual functions, it lacks robustness across the broader benchmark suite. These findings confirm that the integrated strategy design in GDACS, combining chaotic initialization, adaptive step-size control, and fitness-based grouping, provides superior overall stability, adaptability, and optimization effectiveness in high-dimensional problem settings compared to single- or dual-strategy CS variants.

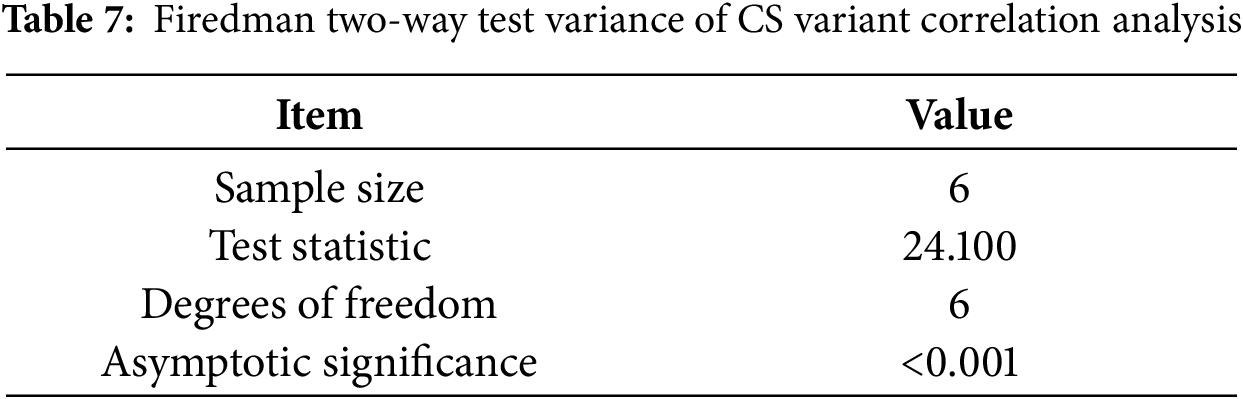

To further evaluate statistical differences among CS variants, the Friedman test is applied, assuming that GDACS and the other six algorithms originate from the same performance distribution. The results of this non-parametric test are summarized in Fig. 6 and Table 8.

As shown in Fig. 6, GDACS achieves the best performance, attaining the first rank with a mean rank value of 1.00. CS-Chaotic-Cauchy ranks second with a mean rank of 2.17, whereas CS-Chaotic performs the worst, with a mean rank of 6.42. These findings are consistent with the statistical performance trends observed in Table 7. According to the principle of the Friedman test, applied here to a minimization problem, a higher rank value indicates poorer algorithmic performance, reflecting a higher average fitness. Consequently, GDACS, holding the lowest rank, demonstrates the strongest optimization capability among the seven tested variants.

Furthermore, Table 7 presents the results of the two-way Friedman analysis of variance by ranks. The test yields a p-value < 0.001 and a test statistic of 24.100, indicating statistically significant differences in performance distributions among the algorithms. The low degree of correlation between GDACS and the other algorithms further underscores its distinct performance advantage.

As mentioned above, GDACS exhibits outstanding robustness and effectiveness in solving high-dimensional optimization problems. During the initialization phase, the integration of chaotic mapping enhances population diversity, increasing the likelihood of covering the global optimum region. Throughout the iterative process, the use of grouping strategies enables the proposed GDACS algorithm to achieve cooperation among these three components, substantially accelerating convergence and improving the final solution quality, thereby confirming the superior adaptability and stability of GDACS across diverse optimization scenarios.

5 Application of GDACS in Constrained Engineering Problem

To further validate the practical applicability of GDACS, it was applied to two constrained engineering problems. These problems are inspired by real-world scenarios [34] and involve optimizing an objective function subject to multiple constraints. Evaluating GDACS on these problems demonstrates its performance and assesses its effectiveness and adaptability in practical engineering contexts.

When applying intelligent optimization algorithms to real-world engineering problems, it is necessary to formulate the problem as a constrained optimization task. The optimization model for the constrained problem is presented below, as shown in Eqs. (12)–(15):

In this context, x = [x1, x2, …, xm]T represents the solution vector, n denotes the number of inequality constraints, p refers to the number of equality constraints, and m is the dimension of the solution vector. f(x) represents the objective function. Eq. (13) defines an inequality constraint, while Eq. (14) represents an equality constraint. UBk and LBk denote each dimension’s upper and lower bounds, respectively. The goal is to find solutions that minimize f(x) while satisfying the given constraints.

Since swarm intelligence optimization algorithms are mainly used to solve unconstrained optimization problems, they must be converted into equivalent unconstrained optimization problems when solving constrained optimization problems. For this purpose, the penalty function method is usually adopted, which combines the objective function with the corresponding constraints into a penalty function, i.e., constructing a new function to be optimized. A typical penalty function formulation is shown in (16):

here, g(x) represents the value of the i-th constraint function, and PF is a penalty factor, which is typically a positive number (in this case, set to 1E+10)

5.2 Experimental Results for the Constrained Engineering Problems

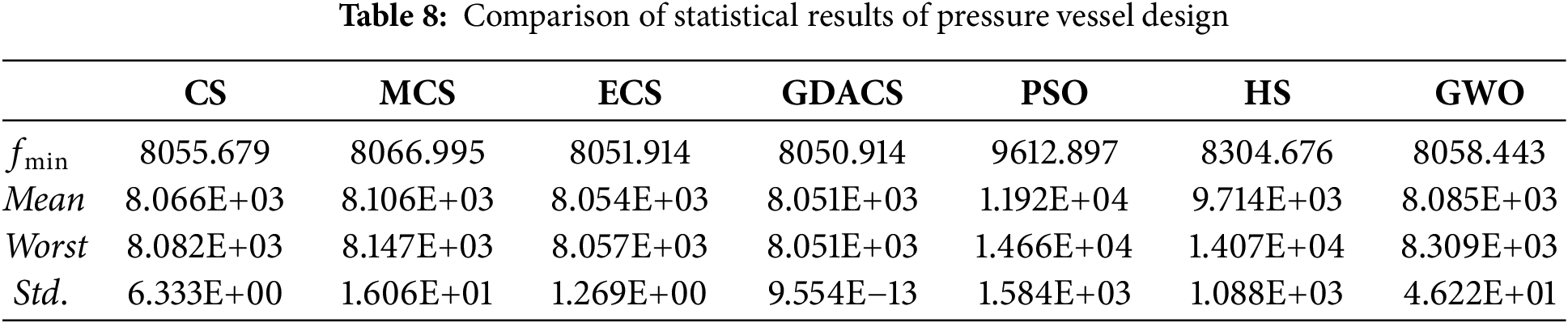

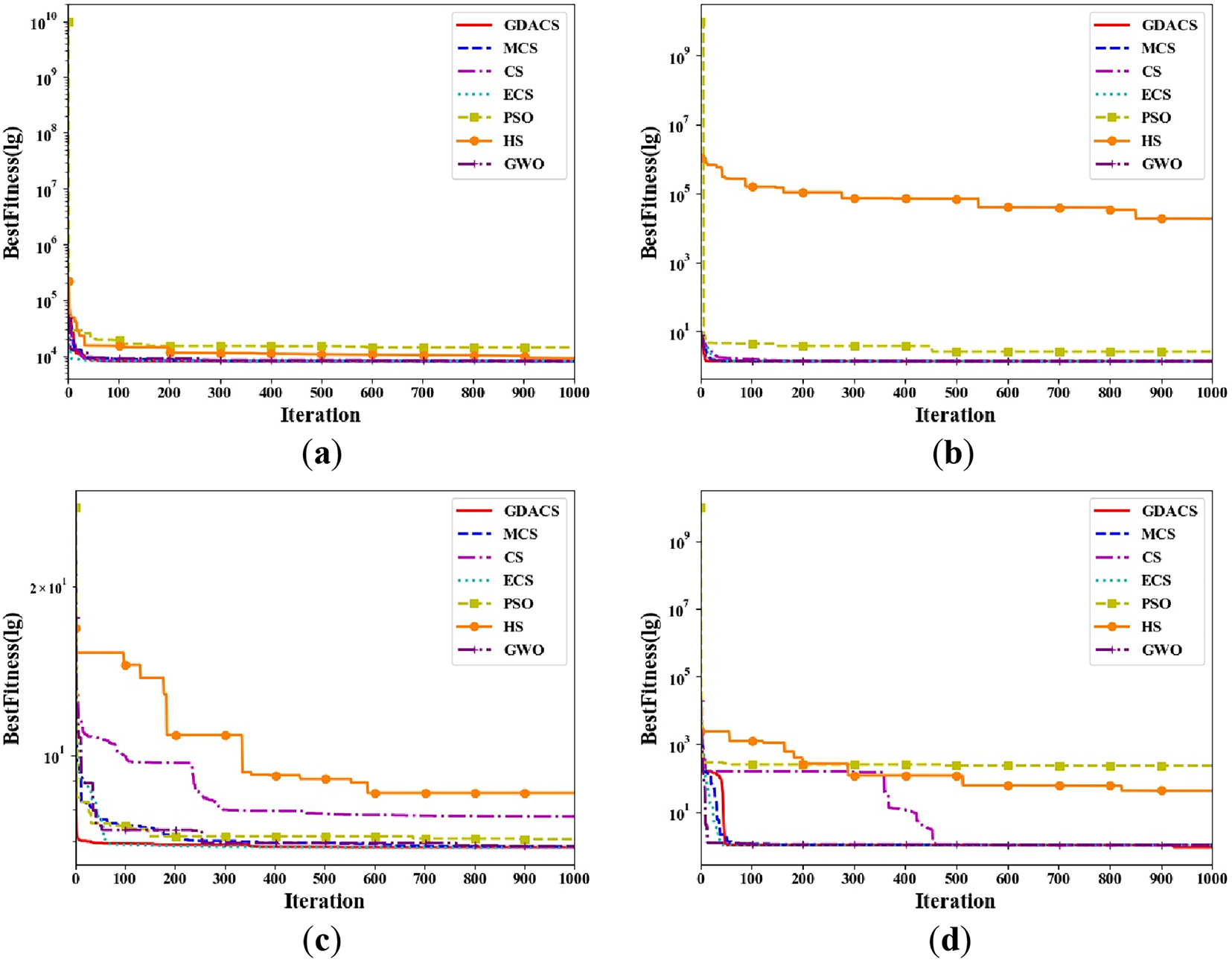

This subsection evaluates the optimization performance of seven state-of-the-art algorithms using the characteristic of high-dimensional, highly nonlinear constrained engineering design problems: pressure vessel design, cantilever beam design, corrugated bulkhead design, and piston lever design.

5.2.1 The Pressure Vessel Design

The pressure vessel design problem aims to minimize the total cost, which includes material, mold, and welding costs. It involves four variables: shell thickness, head thickness, cylindrical shell radius, and shell length. Based on the available thickness of rolled steel plates, both the shell thickness and head thickness must be integer multiples of 0.0625 inches, while the cylindrical shell radius and shell length are constrained between 10 and 200. The following equations provide the mathematical model:

Fig. 7a illustrates the convergence curves for six algorithms optimizing pressure vessel design parameters. In the initial iterations, the PSO algorithm encounters difficulty satisfying the pressure vessel constraints, likely due to its optimization limitations. When exploring infeasible regions, the objective function value becomes substantially large, reflecting a penalty mechanism where larger deviations from constraints result in higher penalties. Consequently, PSO receives an infinitely large objective value for such solutions. Although PSO demonstrates rapid convergence in later iterations, it achieves lower accuracy. Furthermore, ECS, GDACS, and MCS exhibit comparable convergence accuracy within the first 100 iterations. ECS converges significantly faster than GDACS, GWO, MCS, CS, HS, and PSO during this period. Specifically, the convergence rates follow the order: v(ECS) > v(GDACS) > v(GWO) > v(MCS) > v(CS) > v(HS) > v(PSO).

Figure 7: Convergence curves of seven algorithms on engineering optimization problems: (a) pressure vessel; (b) cantilever beam; (c) corrugated bulkhead; (d) piston lever

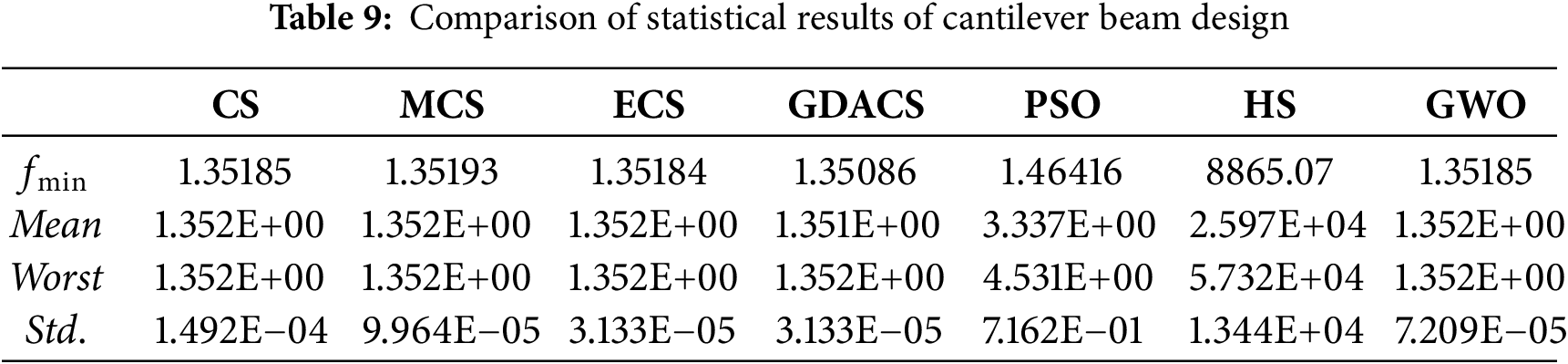

Table 8 presents the statistical results for the best solution, mean, standard deviation, and worst value obtained by six algorithms. From the data, GDACS and ECS achieved better results in this problem compared to the other algorithms (CS, MCS, ECS, HS, GWO, and PSO), with a fitness value of 8050.914. However, based on the standard deviation analysis, the solution provided by the GDACS algorithm demonstrates greater robustness. Therefore, GDACS emerges as the best solution among the six comparative algorithms.

5.2.2 The Cantilever Beam Design

The goal of the cantilever beam design problem is to minimize the weight of the cantilever beam. The beam is supported at node 1, while a vertical downward force is applied at node 5. This problem involves five design variables and the side lengths of different beam sections (each square-shaped section). The mathematical formulation is given in Eqs. (19) and (20):

Fig. 7b illustrates the convergence curves for six algorithms optimizing pressure vessel design. GDACS, MCS, ECS, and GWO quickly approach the optimal region within the first 100 iterations, among which GDACS achieves the smallest fitness value of 1.35086, demonstrating the best performance. In contrast, PSO and HS experience obvious convergence difficulties during both the early and middle stages of optimization, with their objective function values remaining at high levels, indicating that they struggle to perform effective global searches and possess weaker convergence capability. Especially, HS maintains a fitness value around 8865.07, failing to approach the feasible optimal region. Although GDACS, ECS, MCS, and GWO achieve comparable convergence accuracy, GDACS shows superior stability during later iterations and reaches the optimal value. PSO shows a slight convergence trend in later iterations, but still lags significantly behind the aforementioned four algorithms. Overall, the v(GDACS) > v(MCS) > v(ECS) > v(GWO) > v(CS) > v(PSO) > v(HS).

Table 9 presents the statistical results for the best, mean, worst, and standard deviations of seven algorithms. GDACS, ECS, GWO, and MCS achieve superior performance, with GDACS obtaining the minimum objective value of 1.35086, outperforming all competitors. Although the best results of ECS, CS, and MCS are close to GDACS, the mean and worst values indicate that GDACS maintains a more stable performance across multiple independent runs. However, PSO and HS yield higher best, mean, and worst values, with HS reaching a worst fitness value of 5.732E+04, reflecting poor stability and weak optimization capability relative to GDACS, ECS, GWO, CS, MCS, and PSO, thus failing to obtain effective design parameters. Overall, GDACS demonstrates superior stability and accuracy, establishing it as the most effective solution for this problem.

5.2.3 The Corrugated Bulkhead Design

The corrugated bulkhead design problem aims to minimize the structural weight of a corrugated bulkhead in a chemical tanker while satisfying strength and rigidity requirements. The primary goal is to determine optimal geometric parameters, including width(x1), depth(x2), length(x3), and plate thickness(x4), to achieve a balance between lightweight design and structural safety. The mathematical formulation is given in Eqs. (21) and (22):

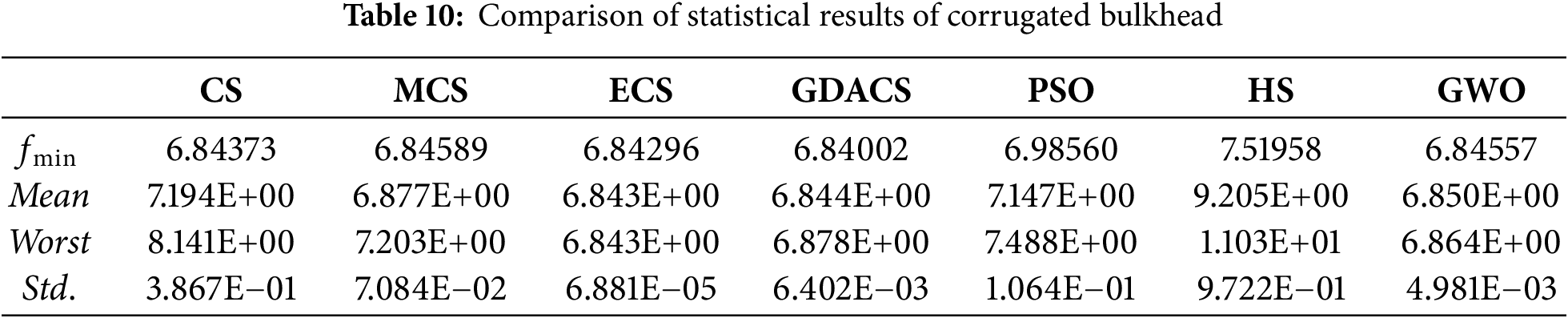

As illustrated in Fig. 7c, GDACS exhibits the fastest and most stable convergence performance among the seven compared algorithms. It rapidly approaches the optimal region within the first 100 iterations. Subsequently, it maintains the lowest objective value of 6.84002, indicating that GDACS is highly effective in identifying superior parameter configurations that minimize the bulkhead weight. In contrast, HS and CS converge more slowly, with larger oscillations, reflecting lower search efficiency. Notably, HS stagnates at a higher objective value of 7.51958. Overall, the convergence rates can be ranked as follows: v(GDACS) > v(ECS) > v(MCS) > v(PSO) > v(GWO) > v(CS) > v(HS).

Table 10 reveals that GDACS achieves the minimum fitness value of 6.84002, demonstrating its strong capacity to identify more effective structural design parameters. Although MCS and ECS yield results comparable to GDACS, both show slightly inferior mean values and worst values, suggesting weaker stability and consistency. Additionally, HS and CS converge more slowly and tend to stagnate at higher objective values, while GWO’s performance improvement is also relatively limited. Meanwhile, GDACS attains the smallest standard deviation among all algorithms, further confirming its superior robustness across multiple independent runs.

The piston lever design problem aims to determine the structural positions of the piston components, (included the installation height of the hydraulic cylinder x1, the horizontal distance from the lever pin to the cylinder hinge point x2, the cylinder diameter x3, and the horizontal position of the cylinder body x4), to minimize the required hydraulic oil volume when the lever is lifted from 0°to 45°. The mathematical formulation is given in Eqs. (23) and (24):

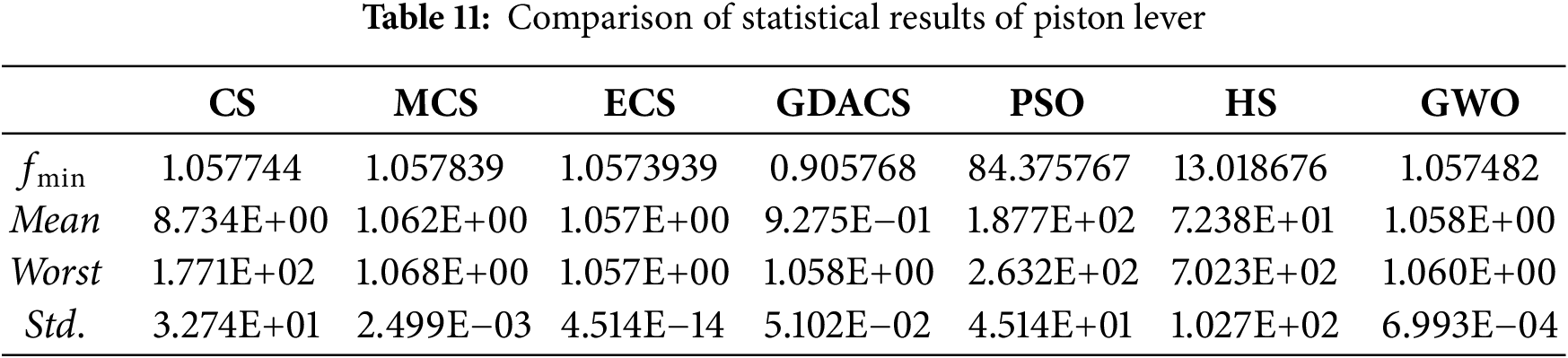

As shown in Fig. 7e, GWO, ECS, MCS, and GDACS quickly approach the optimal region within the first 100 iterations. However, GDACS is able to break its prolonged stagnation during later stages; after approximately 900 iterations, it successfully escapes the local region and ultimately reaches the minimum fitness value. However, PSO, HS, and CS converge more slowly and display significant oscillations, indicating lower search efficiency. Nevertheless, CS rapidly converges to a level comparable to that of GWO, ECS, MCS, and GDACS after around 450 iterations.

Table 11 summarizes the best, mean, worst, and standard deviation values obtained by the seven algorithms. GDACS achieves the minimum objective value of 0.905768, and its mean, worst value, and standard deviation are all significantly lower than those of the other algorithms, demonstrating its stronger stability. Although GWO, ECS, and MCS exhibit statistically similar mean performance, their mean and worst values remain slightly inferior to those of GDACS. Additionally, CS, PSO, and HS show substantial fluctuations, resulting in considerably higher objective values across multiple runs. Their worst and standard deviation values are far higher than those of GDACS, MCS, ECS, and GWO, reflecting poor robustness and limited optimization capability. Overall, this verifies that GDACS can effectively identify high-quality design parameters to minimize the hydraulic oil volume required during lever lifting.

To enhance the adaptability and optimization capability of the CS algorithm, this research introduces a novel Grouped Dynamic Adaptive CS (GDACS). GDACS integrates three complementary strategies: (1) chaotic initialization using a logistic map to boost early-stage population diversity; (2) dynamic step-size control employing Cauchy and Levy distributions to balance exploration and exploitation effectively; and (3) a fitness-based grouping mechanism that refines search behaviors adaptively within subpopulations. These integrated enhancements collectively bolster GDACS’s global search capability, accelerate convergence, and improve robustness. Comprehensive benchmark testing demonstrates that GDACS consistently outperforms CS, its improved variants (MCS and ECS), and established metaheuristics like GWO, PSO, and HS, achieving good convergence efficiency and solution accuracy. Furthermore, an ablation study validates the effectiveness of each integrated strategy, while application to four real-world constrained engineering problems underscores the algorithm’s practical competitiveness and reliability.

Despite these advantages, GDACS still has certain limitations that merit further consideration. First, the proposed GDACS algorithm exhibits a degree of sensitivity to parameter settings (e.g., chaotic initialization and step size control parameters), and proper parameter tuning may be required to achieve optimal performance under different problem scenarios. Second, although the theoretical time complexity of GDACS is comparable to that of CS, the grouping and adaptive control mechanisms may introduce additional computational overhead when addressing high-dimensional or large-scale problems. These factors may affect overall runtime efficiency.

Future research will therefore focus on improving the scalability of GDACS. Potential directions include developing automatic parameter adaptation strategies and incorporating computational acceleration techniques to enhance performance. Additionally, a more rigorous theoretical investigation, underpinned by mathematical analysis and convergence proofs, is planned to deepen the understanding of GDACS’s performance characteristics and to examine how parameter adaptation and hybridization strategies influence its scalability and generalization capabilities.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (MOHE) through Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) Ref: FRGS/1/2024/ICT02/UTM/02/10, Vot. No: R.J130000.7828.5F748, and the Scientific Research Project of Education Department of Hunan Province (Nos. 22B1046 and 24A0771).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Shao-Qiang Ye; methodology, Shao-Qiang Ye and Azlan Mohd Zain; software, Shao-Qiang Ye; validation, Azlan Mohd Zain and Yusliza Yusoff; formal analysis, Azlan Mohd Zain and Yusliza Yusoff; investigation, Shao-Qiang Ye; resources, Shao-Qiang Ye; data curation, Shao-Qiang Ye; writing—original draft preparation, Shao-Qiang Ye; writing—review and editing, Azlan Mohd Zain and Yusliza Yusoff; supervision, Azlan Mohd Zain and Yusliza Yusoff; funding acquisition, Yusliza Yusoff. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Tao H, Aldlemy MS, Ahmadianfar I, Goliatt L, Marhoon HA, Homod RZ, et al. Optimizing engineering design problems using adaptive differential learning teaching-learning-based optimization: novel approach. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;270:126425. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.126425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang J, Wang W-C, Hu X-X, Qiu L, Zang H-F. Black-winged kite algorithm: a nature-inspired meta-heuristic for solving benchmark functions and engineering problems. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(4):98. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10723-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ghasemi M, Zare M, Trojovský P, Rao RV, Trojovská E, Kandasamy V. Optimization based on the smart behavior of plants with its engineering applications: ivy algorithm. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;295:111850. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.111850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ghasemi M, Golalipour K, Zare M, Mirjalili S, Trojovský P, Abualigah L, et al. Flood algorithm (FLAan efficient inspired meta-heuristic for engineering optimization. J Supercomput. 2024;80(15):22913–3017. doi:10.1007/s11227-024-06291-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Jia H, Zhou X, Zhang J, Abualigah L, Yildiz AR, Hussien AG. Modified crayfish optimization algorithm for solving multiple engineering application problems. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(5):127. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10738-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang WC, Tian WC, Xu DM, Zang HF. Arctic puffin optimization: a bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for solving engineering design optimization. Adv Eng Softw. 2024;195:103694. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2024.103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhong R, Yu J, Zhang C, Munetomo M. SRIME: a strengthened RIME with Latin hypercube sampling and embedded distance-based selection for engineering optimization problems. Neural Comput Appl. 2024;36(12):6721–40. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-09424-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yang XS, Deb S. Cuckoo search via lévy flights. In: Proceedings of the 2009 World Congress on Nature & Biologically Inspired Computing (NaBIC); 2009 Dec 9–11; Coimbatore, India. doi:10.1109/NABIC.2009.5393690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang X, Pang Y, Kang Y, Chen W, Fan L, Jin H, et al. No free lunch theorem for privacy-preserving LLM inference. Artif Intell. 2025;341:104293. doi:10.1016/j.artint.2025.104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Yang Q, Huang H, Zhang J, Gao H, Liu P. A collaborative cuckoo search algorithm with modified operation mode. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2023;121:106006. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.106006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mehedi IM, Ahmadipour M, Salam Z, Ridha HM, Bassi H, Rawa MJH, et al. Optimal feature selection using modified cuckoo search for classification of power quality disturbances. Appl Soft Comput. 2021;113:107897. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2021.107897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Braik M, Sheta A, Al-Hiary H, Aljahdali S. Enhanced cuckoo search algorithm for industrial winding process modeling. J Intell Manuf. 2023;34(4):1911–40. doi:10.1007/s10845-021-01900-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cheng J, Xiong Y. Multi-strategy adaptive cuckoo search algorithm for numerical optimization. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(3):2031–55. doi:10.1007/s10462-022-10222-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Xiong Y, Zou Z, Cheng J. Cuckoo search algorithm based on cloud model and its application. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):10098. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-37326-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gu W, Li Z, Dai M, Yuan M. An energy-efficient multi-objective permutation flow shop scheduling problem using an improved hybrid cuckoo search algorithm. Adv Mech Eng. 2021;13(6):16878140211023603. doi:10.1177/16878140211023603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Belkharroubi L, Yahyaoui K. Solving the energy-efficient Robotic Mixed-Model Assembly Line balancing problem using a Memory-Based Cuckoo Search Algorithm. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;114:105112. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yu X, Luo W. Reinforcement learning-based multi-strategy cuckoo search algorithm for 3D UAV path planning. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;223:119910. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.119910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Adegboye OR, Deniz Ülker E. Hybrid artificial electric field employing cuckoo search algorithm with refraction learning for engineering optimization problems. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):4098. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-31081-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chen J, Cai Z, Chen H, Chen X, Escorcia-Gutierrez J, Mansour RF, et al. Renal pathology images segmentation based on improved cuckoo search with diffusion mechanism and adaptive beta-hill climbing. J Bionic Eng. 2023;2023:1–36. doi:10.1007/s42235-023-00365-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li X, Guo X, Tang H, Wu R, Liu J. An improved cuckoo search algorithm for the hybrid flow-shop scheduling problem in sand casting enterprises considering batch processing. Comput Ind Eng. 2023;176:108921. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2022.108921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Priya C, Ranganathan CS, Vetriselvi D, Vanakamamidi RK, Dhanalakshmi S, Srinivasan C. Hybrid cuckoo search with fuzzy algorithm to improve the wireless network system. In: Proceedings of the 2024 Second International Conference on Microwave, Antenna and Communication (MAC); 2024 Oct 4–6; Dehradun, India. doi:10.1109/MAC61551.2024.10837092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Vo N, Tang H, Lee J. A multi-objective Grey Wolf-Cuckoo Search algorithm applied to spatial truss design optimization. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;155(1):111435. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gacem A, Kechida R, Bekakra Y, Jurado F, Sameh MA. Hybrid cuckoo search-Gorilla troops optimizer for optimal parameter estimation in photovoltaic modules. J Eng Res Forthcoming. 2024;140(10):265. doi:10.1016/j.jer.2024.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang J, Liu X, Zhang B. Mathematical modelling and a discrete cuckoo search particle swarm optimization algorithm for mixed model sequencing problem with interval task times. J Intell Manuf. 2024;35(8):3837–56. doi:10.1007/s10845-023-02300-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Yajid MSA, Bhosle N, Sudhamsu G, Khatibi A, Sharma S, Jeet R, et al. Hybrid Big Bang-Big crunch with cuckoo search for feature selection in credit card fraud detection. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):23925. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-97149-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Nouh A, Almalih A, Faraj M, Almalih A, Mohamed F. Hybrid of meta-heuristic techniques based on cuckoo search and particle swarm optimizations for solar PV systems subjected to partially shaded conditions. JSESD. 2024;13(1):114–32. doi:10.51646/jsesd.v13i1.178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xie YS, Ruan S, Zeng J, Feng BX, Feng MJ, Rao WX. Hybrid differential evolution and Cuckoo search algorithm for solving economic dispatch problems. In: Proceedings of the 2024 14th International Conference on Information Technology in Medicine and Education (ITME); 2024 Sep 13–15; Guiyang, China. doi:10.1109/ITME63426.2024.00059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Li XD, Wang JS, Hao WK, Zhang M, Wang M. Chaotic arithmetic optimization algorithm. Appl Intell. 2022;52(14):16718–57. doi:10.1007/s10489-021-03037-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ye SQ, Wang FL, Ou Y, Zhang CX, Zhou KQ. An improved cuckoo search combing artificial bee colony operator with opposition-based learning. In: Proceedings of the 2021 China Automation Congress (CAC); 2021 Oct 22-24; Beijing, China. doi:10.1109/CAC53003.2021.9727912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Abualigah L, Sheikhan A, Ikotun AM, Abu Zitar R, Alsoud AR, Al-Shourbaji I, et al. Particle swarm optimization algorithm: review and applications. In: Metaheuristic optimization algorithms. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2024. p. 1–14. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-13925-3.00019-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Alia OM, Mandava R. The variants of the harmony search algorithm: an overview. Artif Intell Rev. 2011;36(1):49–68. doi:10.1007/s10462-010-9201-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ye SQ, Zhou KQ, Zain A, Wang FL, Yusoff Y. A modified harmony search algorithm and its applications in weighted fuzzy production rule extraction. Front Inf Technol Electron Eng. 2023;24(11):1574–91. doi:10.1631/fitee.2200334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Negi G, Kumar A, Pant S, Ram M. GWO: a review and applications. Int J Syst Assur Eng Manag. 2021;12(1):1–8. doi:10.1007/s13198-020-00995-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yang X, Wang R, Zhao D, Yu F, Huang C, Heidari AA, et al. An adaptive quadratic interpolation and rounding mechanism sine cosine algorithm with application to constrained engineering optimization problems. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;213:119041. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools