Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Non-Euclidean Models for Fraud Detection in Irregular Temporal Data Environments

Department of Statistics, Institute of Applied Statistics, Jeonbuk National University, Jeonju, 54896, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Guebin Choi. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 74 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073500

Received 19 September 2025; Accepted 24 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Traditional anomaly detection methods often assume that data points are independent or exhibit regularly structured relationships, as in Euclidean data such as time series or image grids. However, real-world data frequently involve irregular, interconnected structures, requiring a shift toward non-Euclidean approaches. This study introduces a novel anomaly detection framework designed to handle non-Euclidean data by modeling transactions as graph signals. By leveraging graph convolution filters, we extract meaningful connection strengths that capture relational dependencies often overlooked in traditional methods. Utilizing the Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) framework, we integrate graph-based embeddings with conventional anomaly detection models, enhancing performance through relational insights. Our method is validated on European credit card transaction data, demonstrating its effectiveness in detecting fraudulent transactions, particularly those with subtle patterns that evade traditional, amount-based detection techniques. The results highlight the advantages of incorporating temporal and structural dependencies into fraud detection, showcasing the robustness and applicability of our approach in complex, real-world scenarios.Keywords

Credit card transactions are on the rise, driven by the convenience of digital payment methods and the rapid growth of e-commerce. However, with the increase in credit card transactions, fraudulent activities have also become more frequent. According to the Nilson Report (January 2025), global card fraud losses reached $33.83 billion in 2023, and cumulative losses are projected to reach $403.88 billion over the next decade [1]. Fraudulent transactions cause significant economic losses to financial institutions and consumers, highlighting the critical need for reliable detection methods.

Traditional methods for detecting credit card fraud typically focus on large transactions at specific merchants during certain times. For instance, instead of looking for fraud on a per-customer basis, these methods concentrate on big purchases at major retailers or transactions involving large sums of money [2]. This approach treats each transaction separately when checking for fraud. This implies that each transaction is assessed independently for potential fraudulent activity.

In contrast, this study explores the analysis of fraudulent transactions under the assumption that transactions are not independent. By considering the dependencies among transactions, this study aims to identify fraudulent activities through their connections. This approach recognizes that fraudulent transactions often exhibit patterns and relationships that can be more effectively detected when analyzed together. This concept is illustrated in Fig. 1.

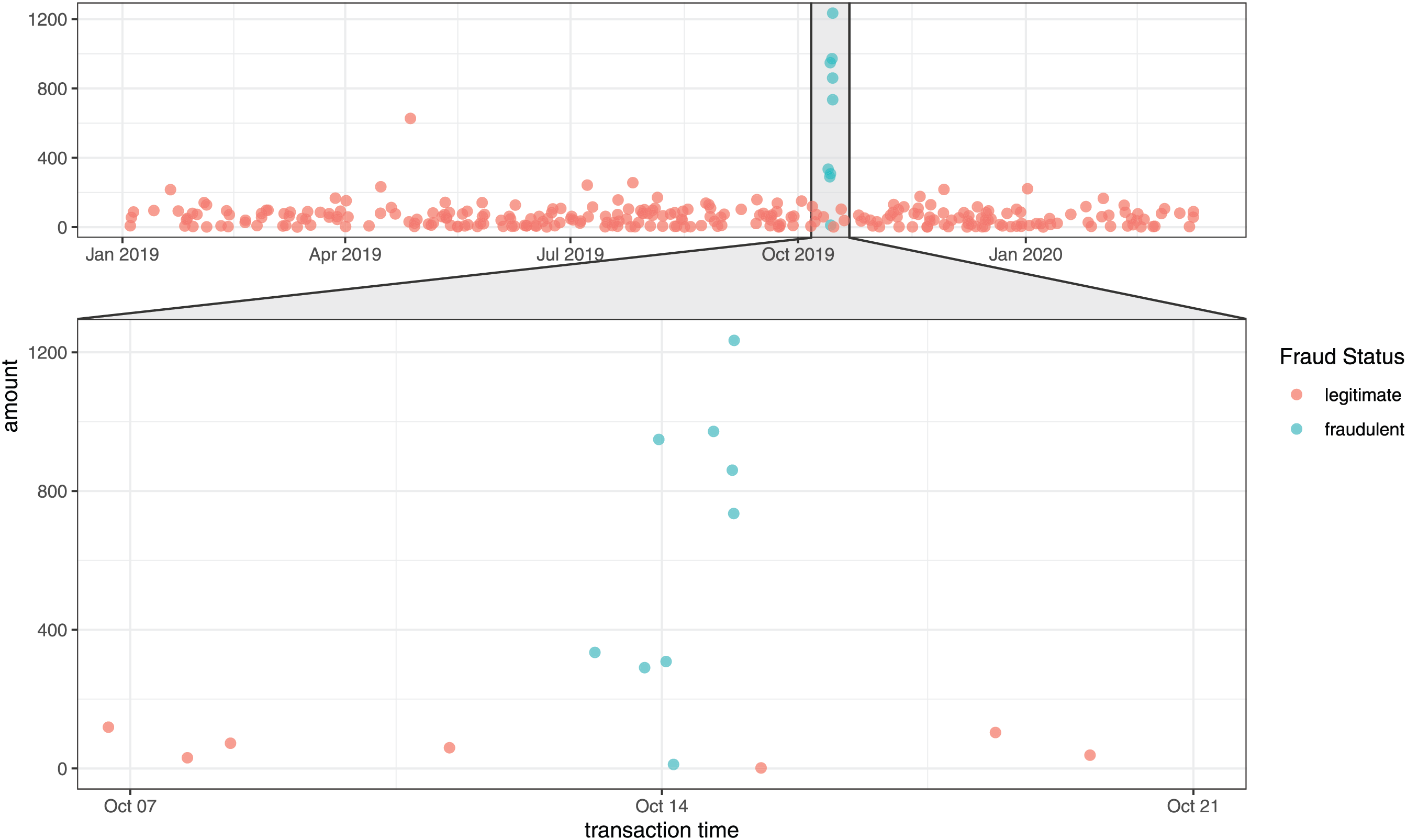

Figure 1: Transaction occurrences over time for customer Steven Johnson. Data source: Kaggle simulated credit card transaction dataset (see Section 3 for details). The x-axis represents transaction time and the y-axis represents transaction amount. Red dots indicate legitimate transactions, and blue dots indicate fraudulent transactions. The lower panel zooms into October 7–20 to highlight the temporal clustering of fraudulent transactions

Fig. 1 shows how transactions happen over time and the amounts involved in each transaction. The term ‘amount’ refers to how much money was spent in a transaction. In this figure, 12 fraudulent transactions are linked to an individual named Steven, showing that these transactions happened close to each other in time. It is clear that the amounts in these fraudulent transactions are generally higher than those in legitimate ones. When we look closely at the periods when these fraudulent transactions happened (as seen in the zoomed-in section of Fig. 1), we can see that these fraudulent transactions occurred one after another. The goal of this analysis is to use the timing of transactions to identify fraud by looking at how these fraudulent activities are connected over time.

As discussed earlier, many existing methods for detecting fraud rely heavily on the amounts of the transactions. They often identify transactions as suspicious if they involve unusually large amounts of money. Simply put, if a person who usually spends about $30 suddenly makes a $1000 transaction, it is likely to be considered fraudulent. This reliance on transaction amounts is evident when examining the distribution of transaction values in the data.

This approach may seem efficient but it is not foolproof. For example, in Fig. 1, the sixth fraudulent transaction has a very small amount, making it difficult to predict it as a fraudulent transaction. How can we identify such a transaction as fraudulent? One might think we should determine its fraudulent nature using other explanatory variables (excluding the amount), but this is often impractical with real data. This is because the sixth fraudulent transaction is very close in time to the fifth and seventh fraudulent transactions, and therefore, due to the nature of the data, other variables (such as store information or customer characteristics like age and gender) cannot show significant differences.

In fact, we can intuitively infer that the sixth transaction is fraudulent, even though it has a small amount, because all the surrounding transactions are also fraudulent. For the sixth transaction to be legitimate, it would require an unlikely scenario where a user loses their credit card, quickly finds it to make a legitimate transaction, and then loses it again shortly after. This is not a realistic situation. It makes more sense to assume that transactions occurring close together in time are either all fraudulent or all legitimate. Therefore, analyzing the data as a time series is a more effective approach.

We could interpret and analyze the given data as a time series. However, applying typical time series analysis methods is not easy. This is because many traditional statistical methods for time series, such as autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) and autoregressive with exogenous variables (ARX), and techniques using recurrent networks, such as recurrent neural networks (RNN) and long short-term memory networks (LSTM) [3], both assume that the observations are made at equally spaced intervals. In other words, they assume that the data points are uniformly distributed over time. However, the transition times in our data are not equally spaced.

For example, in Fig. 1, let’s look at the time intervals between transactions. The time gap between the first fraudulent transaction and the immediately preceding legitimate transaction is longer than the gap between the first and the second fraudulent transactions. This means the first fraudulent transaction happened closer in time to the second fraudulent transaction than to the previous legitimate transaction. Therefore, when predicting the value of the first fraudulent transaction, it makes more sense to consider the next transaction rather than the previous one. This shows that the data points are not spaced uniformly over time, violating the equally-spaced observation assumption underlying most temporal models.

To represent these irregular connections between observations, we reframe the indices of the given data as a graph

In our dataset, V represents the indices of the observations. Edges (E) exist between transactions made with the same credit card, meaning transactions from different credit cards are not connected by edges. Additionally, the weight (

Building on this structure, this study posits that utilizing temporal dependency, which reveals interrelations based on transaction timing, will be highly effective for analyzing fraudulent transactions, even if the transaction amounts differ from the average.

Inspired by the characteristics of credit card transaction data, this study proposes a novel integrated framework that models data with irregular time intervals as a graph structure and extracts embeddings using graph convolution operations. Specifically, we encode temporal proximity between transactions as edge weights in a graph, aggregate information from neighboring transactions through graph convolution to generate embeddings for each transaction, and use these embeddings as input features for conventional classification models. The main contributions of this study are as follows. First, we propose an efficient non-Euclidean embedding method that can effectively represent transaction data with irregular time intervals (Section 4). Second, we demonstrate that the proposed method achieves stable performance improvements across various experimental settings, thereby establishing its robustness (Section 5). Third, we statistically analyze and validate the effectiveness of the proposed embedding on credit card fraud detection performance (Section 6).

This section reviews existing research on credit card fraud transaction detection. Related work can be categorized from four main perspectives: (1) data imbalance problem with tabular models, (2) research considering non-independence among transactions (customer-merchant relationships), (3) research leveraging temporal dependencies, and (4) other techniques.

Credit card fraud involves highly imbalanced data. Various machine learning techniques have been studied to handle this imbalanced data [4–6]. There are numerous studies on addressing data imbalance, ranging from simple oversampling and undersampling methods to advanced online fraud detection systems that have demonstrated efficiency in dealing with large-scale imbalanced data, such as the research by Wei et al. [7]. Recent studies have specifically focused on addressing the extreme class imbalance in fraud detection. Tayebi and El Kafhali [8,9] proposed deep learning approaches including autoencoders and generative models to effectively handle imbalanced fraud datasets.

Meanwhile, research considering non-independence among transactions has been conducted. A common approach to model relationships between customers and merchants in financial networks is to use bipartite or tripartite graphs [10–12]. In the bipartite formulation, nodes represent cardholders and merchants, and edges represent transactional relationships between them. A critical characteristic of this approach is transaction aggregation: multiple transactions between the same cardholder-merchant pair are combined into a single edge, with edge attributes (such as total amount) aggregated accordingly. The fraud label is typically assigned as positive if any constituent transaction was fraudulent. Graph embedding techniques such as Node2Vec [13] are then applied to learn node representations, which are subsequently used for edge classification [14]. The tripartite extension introduces transaction nodes as intermediate entities, partially preserving transaction-level information while maintaining the relational structure [15]. More recent work has explored heterogeneous graph representations incorporating multiple node types. Wang et al. [16] proposed a heterogeneous graph auto-encoder that captures relationships between cardholders, merchants, and transactions. While these graph-based approaches consider non-Euclidean data structures similar to our method, they focus on structural connectivity rather than temporal proximity between transactions.

There are also studies that leverage temporal dependencies in transactions. Sequence-based approaches treat each customer’s transaction history as a time series and learn sequential patterns for fraud prediction. LSTM-based approaches include Benchaji et al. [17], who proposed an LSTM-based fraud detection model, and Alarfaj et al. [18], who combined attention mechanisms with LSTM for enhanced detection. For Transformer architectures, Yu et al. [19] applied an advanced Transformer model to credit card fraud detection, demonstrating superior performance over traditional machine learning techniques.

Research combining temporal dependencies with graph structures has also been conducted. Studies on fraud detection techniques based on Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) [20] are actively progressing. Dynamic graph neural networks, such as DySAT [21] and ROLAND [22], extend static Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) by allowing graph structure and node embeddings to evolve over time. Cheng et al. [23] developed CaT-GNN, integrating causal inference with temporal graph modeling. While these approaches effectively capture dynamic patterns, they typically require discrete time snapshots and introduce additional computational complexity.

Since the characteristics of credit card fraud data are not identical across datasets, various techniques have been developed to fit the specific properties of each data. Wheeler (2000) applied case-based reasoning in the credit approval process [24], Srivastava (2008) used Hidden Markov Models to learn normal cardholder behaviors [25], and Sanchez (2009) utilized association rules to extract normal behavior patterns [26]. Liu et al. [27] addressed the over-smoothing problem in deep GNNs through high-order graph representation learning.

Our proposed method differs from existing approaches in several key aspects. First, unlike traditional tabular methods, our approach explicitly considers connectivity between observations through temporal proximity and customer information. Second, while bipartite/tripartite graph approaches only model customer-merchant connectivity without considering temporal relationships, our method simultaneously incorporates both temporal proximity and customer information. Third, time series methods such as LSTM and Transformer assume equally-spaced transactions, whereas our method naturally handles irregular time intervals. Fourth, existing methods combining temporal dependencies with graphs use graph-based models as the final classifier, considering connectivity across all transactions. In contrast, our method extracts GCN embeddings as features and feeds them into a tabular classifier. Since the exponential decay function weakens connection strengths for temporally distant transactions, the non-Euclidean structure is effectively utilized only for temporally proximate transactions—typically cases where fraud occurs consecutively. This design improves computational efficiency and facilitates extension to additional variables.

For the analysis of fraudulent transactions, we faced challenges in accessing real data from financial institutions like banks due to privacy concerns, as credit card transaction data is pseudonymized to protect customers’ personal information. Consequently, we used a publicly available dataset from Kaggle1 for our analysis. To apply our graph-based analysis method described in Section 4, we require three essential components: (i) a temporal variable to identify connectivity between transactions, (ii) customer identifiers to construct individual transaction graphs, and (iii) node features for the GCN model. We selected this dataset because it provides all three components: transaction timestamps (trans_date_and_time), credit card numbers (cc_num) as customer identifiers, and transaction amounts (amt) as node features.

The dataset comprises 1,048,575 transactions with 22 variables, including 6006 fraudulent cases (0.573%). Among 943 cardholders, 596 experienced at least one fraud. For our graph-based analysis, we use transaction timestamps (trans_date_and_time) to compute temporal connectivity and transaction amounts (amt) as node features. Detailed data descriptions and exploratory data analysis are available on the Kaggle dataset page.

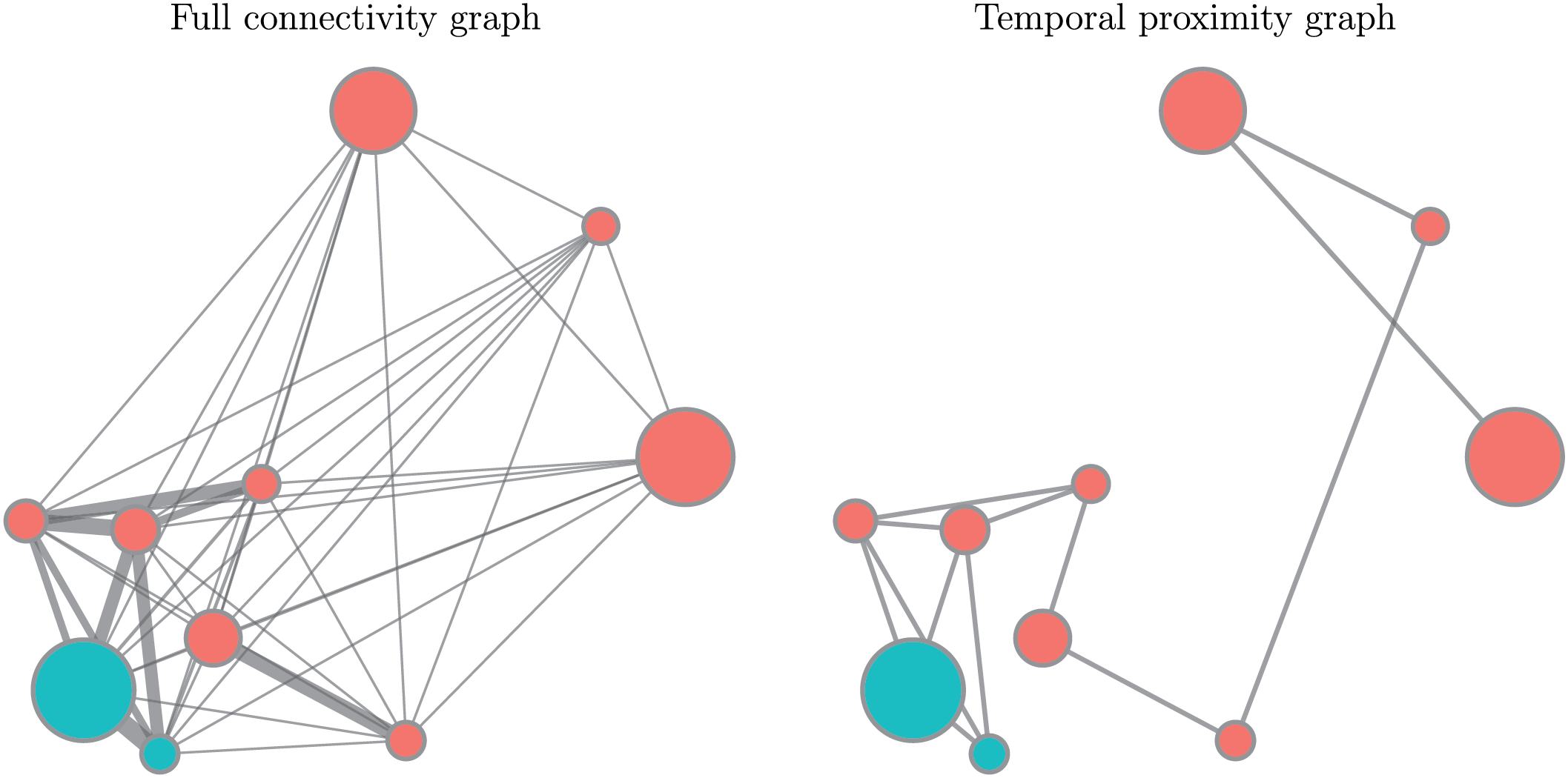

Fig. 2 illustrates transaction graphs for customer Katherine Tucker. Each transaction is represented as a node, where node size corresponds to transaction amount (

Figure 2: Transaction graphs for customer Katherine Tucker. For visualization clarity, only 10 representative transactions are shown from her total of 1250 transactions: 2 fraudulent transactions (blue) occurring on 15 January 2020, and 8 legitimate transactions (red) spanning from 16 March 2019 to 30 December 2019. Node size corresponds to transaction amount, and edge thickness represents temporal proximity. The left panel shows the full connectivity graph; the right panel shows the graph with only temporally close edges retained

The left panel shows a fully connected graph where all transactions are linked. Fraudulent transactions tend to cluster together temporally, forming tightly connected subgraphs. The right panel retains only edges between temporally close transactions, providing a sparser structure that highlights the temporal clustering of fraud.

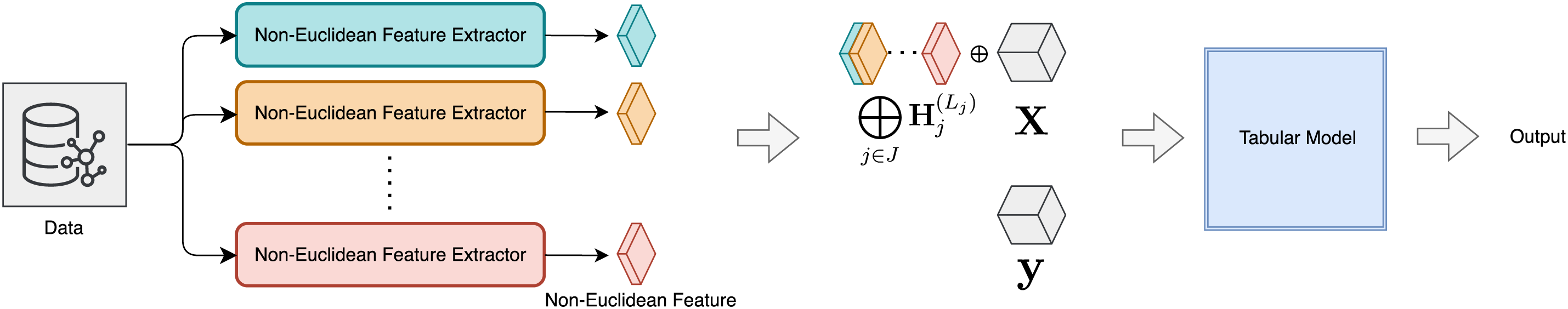

Let’s say the given data is

Our goal is to predict y by considering both X and

Figure 3: Overall architecture of the proposed framework. Multiple non-Euclidean feature extractors generate graph-based representations from the input data, which are aggregated and combined with original tabular features. The resulting features are then fed into a tabular model to produce the final output

Having established the general framework for graph-augmented feature learning, we now demonstrate its concrete application to credit card fraud detection. The following subsection specifies the graph construction, feature definitions, and model configuration tailored to our fraud detection task.

In this section, we will describe a model for analyzing fraud data using the methodology proposed in the previous section. Let the given data be denoted as

The loss function

Now, let’s describe in more detail how to compute

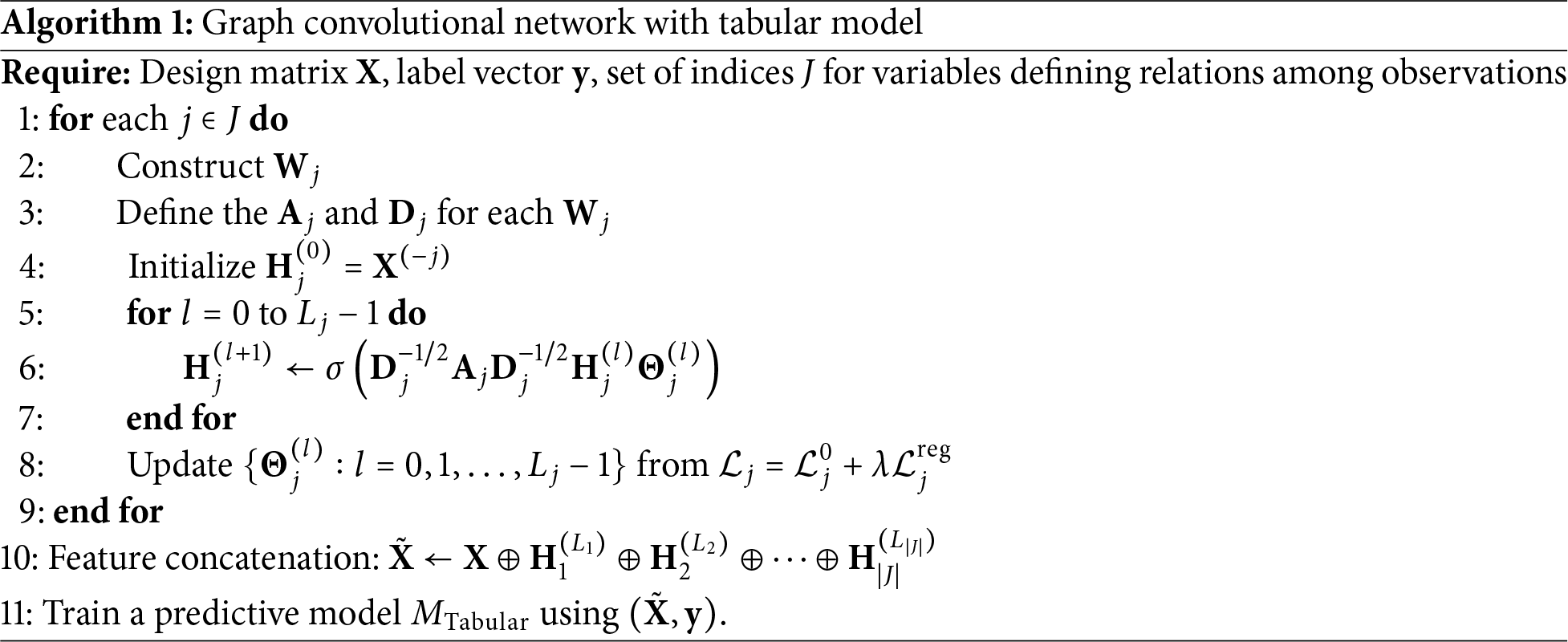

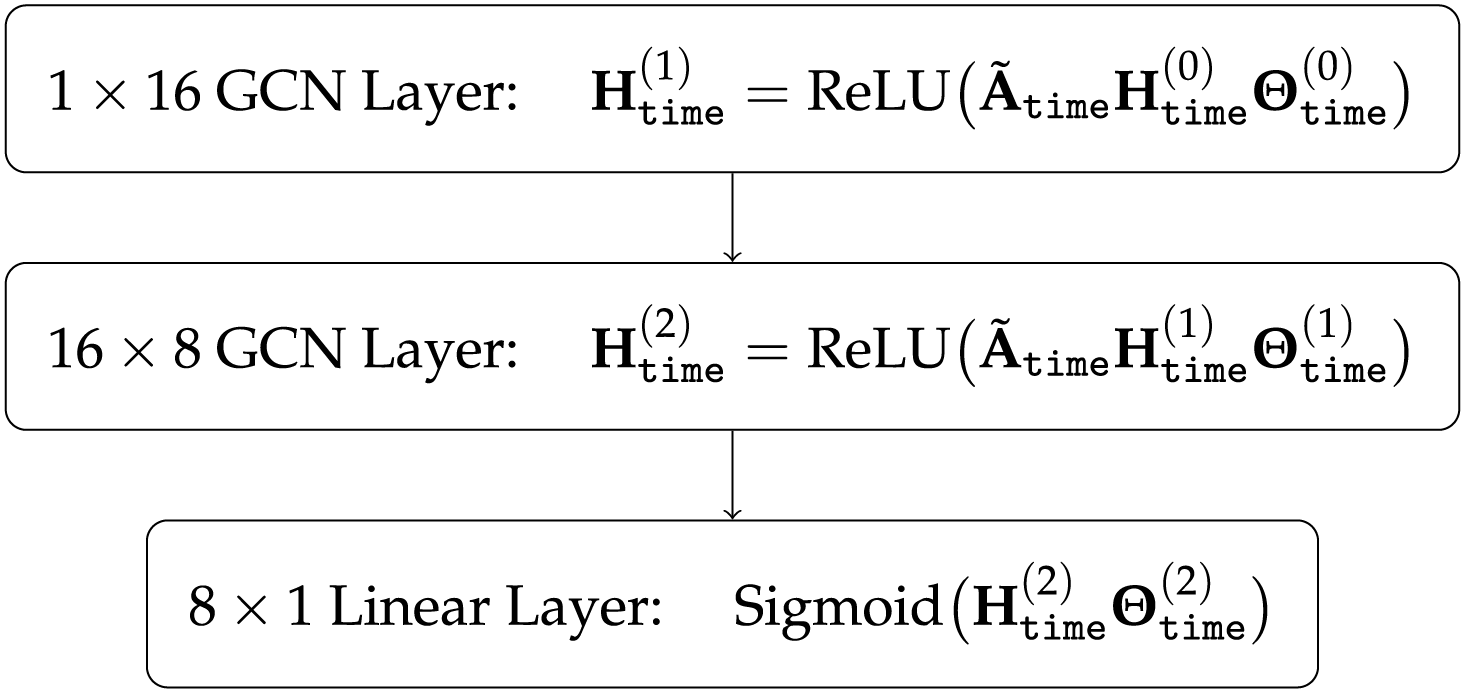

We have configured the architecture as shown in Fig. 4 to obtain the hidden layer.

Figure 4: GCN architecture for extracting non-Euclidean features. Here

Here

We evaluate our proposed graph-augmented approach using six baseline tabular models: NeuralNet (PyTorch-based MLP), RandomForest [29], ExtraTrees [30], XGBoost [31], LightGBM [32], and CatBoost [33]. The baseline models were trained using AutoGluon-Tabular [34], an automated machine learning framework.

5.1 Overall Performance Comparison

We conducted comprehensive experiments to evaluate our proposed method against three categories of approaches: (i) conventional tabular models as baselines, (ii) the same tabular models augmented with GCN embeddings (our proposed approach), (iii) sequence-based architectures including GRU [35], LSTM with attention [36], Transformer-based models [37], and temporal convolutional networks (TCN) [38], and (iv) graph-based models such as GCN [20] and DySAT [21].

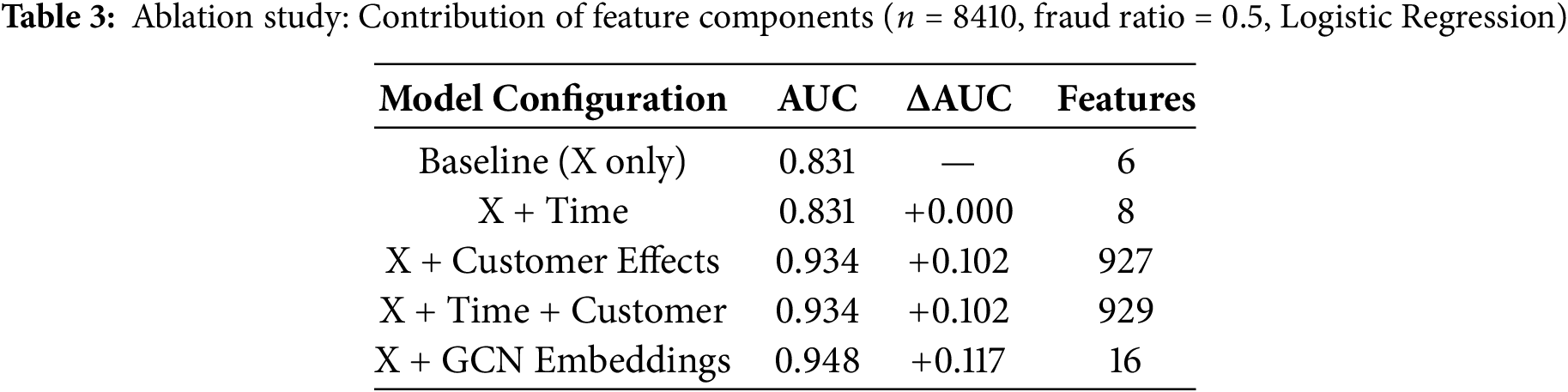

The results reveal important findings across model categories. Baseline tabular models already achieve strong performance (NeuralNet AUC 0.997, ensemble models 0.94–0.99), maintaining high precision (above 0.90) but with relatively lower recall (0.21–0.77). Sequence models achieve competitive Area Under Curve (AUC) (GRU 0.990, LSTM 0.988, Transformer 0.985), but despite high recall (above 0.91), they suffer from very low precision (below 0.15), exhibiting a precision-recall trade-off. Graph-based models (GCN AUC 0.985, DySAT AUC 0.977) directly utilize graph structure for classification but show lower performance than baseline tabular models.

In contrast, our proposed graph-augmented models achieve the highest performance by using GCN embeddings as additional features for tabular models: graph-augmented NeuralNet attains AUC of 0.9995, outperforming all other methods, consistently improving all baseline models (AUC improvement: 0.002–0.054), and achieving both high precision (above 0.90) and improved recall for balanced performance. This superior performance can be attributed to the following: (1) compared to tabular models, graph embeddings provide temporal proximity information between transactions that tabular features alone cannot capture, improving recall; (2) compared to sequence models, using GCN embeddings as features rather than as the classifier preserves the stable precision of tabular models while incorporating graph information; and (3) compared to pure graph-based models, extracting graph features and then applying well-established tabular classifiers achieves better generalization than performing both feature extraction and classification in non-Euclidean space.

These results cannot be directly generalized to fraud detection in general. The optimal model may vary depending on the fraud transaction ratio, characteristics of fraud patterns, and temporal structure of the data. However, our proposed method holds unique significance in that it appropriately combines the stable precision of tabular models, the sequential pattern capturing capability of sequence models, and the relational information utilization of graph models.

5.2 Prediction Confidence Analysis

AUC is a useful threshold-independent metric for evaluating the overall discriminative ability of classifiers. However, in extreme class imbalance settings, F1-score also warrants consideration. As shown in Table 1, baseline Euclidean models achieve high precision (0.81–0.92) but relatively low recall (0.21–0.78)—this occurs because they primarily detect “certain” fraud cases with high transaction amounts. In contrast, our proposed graph-augmented models maintain precision (0.91–0.95) while improving recall (0.76–0.88), showing improvements in F1-score (0.84–0.90). To analyze specifically where these AUC and F1-score improvements originate, we examine prediction confidence.

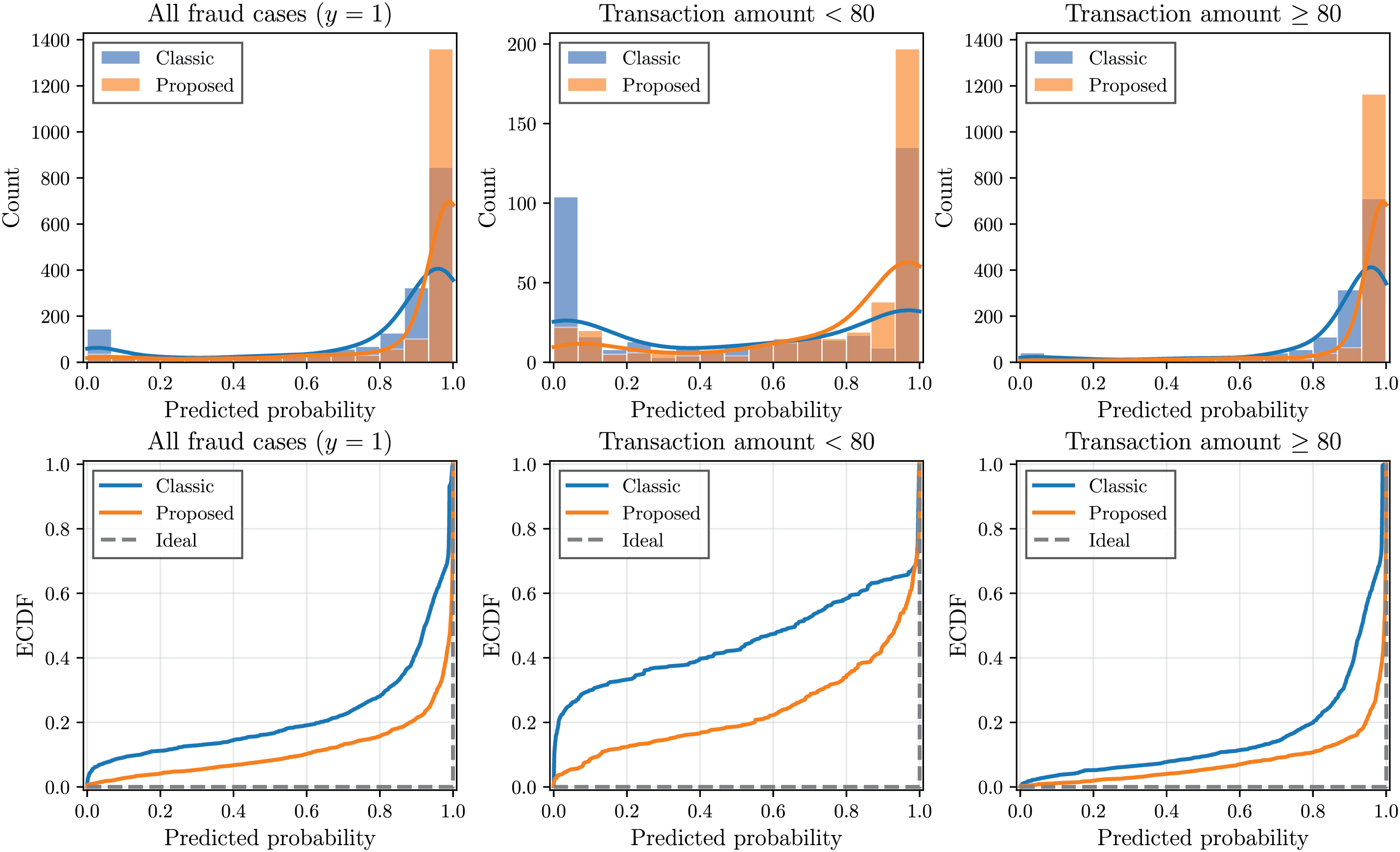

While the overall AUC values show modest improvements due to already well-trained baseline models, the practical benefit becomes more pronounced when examining predictions for low-amount transactions. Fig. 5 presents a comprehensive comparison of predicted probabilities for actual fraud cases (

Figure 5: Comparison of predicted fraud probabilities for actual fraud cases (

The bottom row of Fig. 5 presents the empirical cumulative distribution function (empirical CDF) of these predicted probabilities, providing a clearer comparison. For an ideal classifier, all fraud cases should receive a predicted probability of 1, resulting in a step function at probability

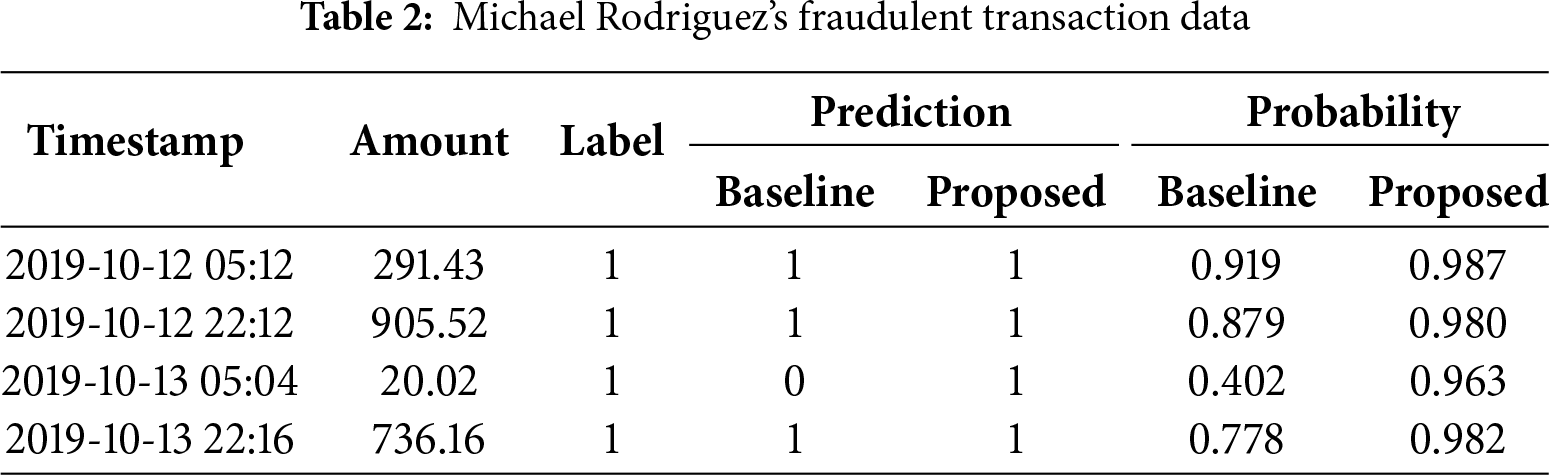

We present a visual example using Michael Rodriguez’s transactions, which include 249 test transactions with 4 fraudulent cases. Table 2 compares the baseline model predictions with our proposed graph-augmented model.

The average transaction amount for Michael Rodriguez is 56.25. The average amount for legitimate transactions is 49.19, while the average amount for fraudulent transactions is 488.28. In existing studies, all transactions with high amt values were predicted as fraudulent, but a transaction with a small amt value of 20.02 was predicted as legitimate. When amt is 20.02, the predicted probability is a low value of 0.4. In contrast, the method utilizing graph information correctly predicted the small amt transaction as fraudulent with a high probability value of 0.96. Moreover, this method showed higher probability values for high amt transactions compared to existing studies.

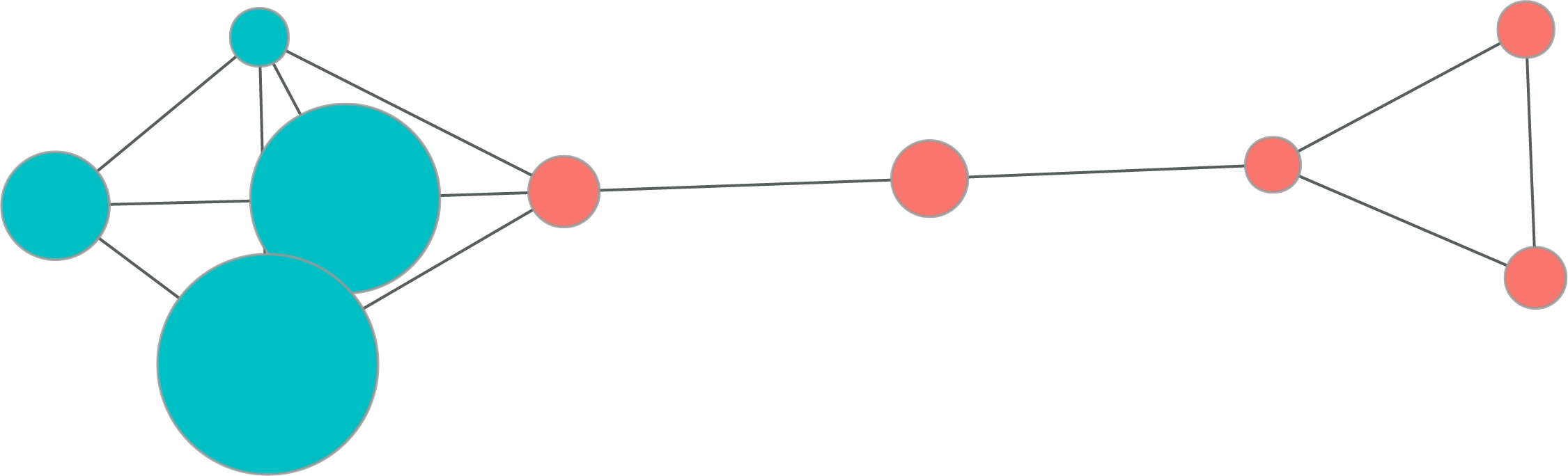

This can be more easily understood by examining Fig. 6, which visualizes the graph. It depicts nine transactions closely related to fraudulent transactions among Michael’s transactions. The graph shown is after removing links based on the weights of the edges. This method can adequately determine fraud even when the transaction amounts are small.

Figure 6: Graph representation of transaction patterns for customer Michael Rodriguez

In the previous experiments, we maintained the original fraud transaction ratio of 0.00573 with a 7:3 train-test split. However, dealing with such extreme class imbalance is a common challenge in fraud detection. A widely-used technique is undersampling, where the majority class (legitimate transactions) is reduced to achieve a more balanced training set while keeping the test set unchanged to reflect real-world conditions.

We conducted additional experiments with various undersampling ratios (fraud ratios from 0.05 to 0.5) to evaluate the robustness of our proposed method. The results consistently demonstrate that incorporating GCN embeddings into the feature set yields superior performance compared to using only the original features, regardless of the undersampling ratio. This validates the effectiveness of our approach when combined with standard class imbalance handling techniques. Detailed experimental settings and results are available in our supplementary materials.2

6 Theoretical Interpretation: GCN Embeddings as Temporal Random Effects

This section provides a theoretical framework for understanding why GCN embeddings improve fraud detection performance. We interpret the GCN embeddings as a replacement for traditional random effects in hierarchical models, and conduct statistical tests to validate the significance of their contribution.

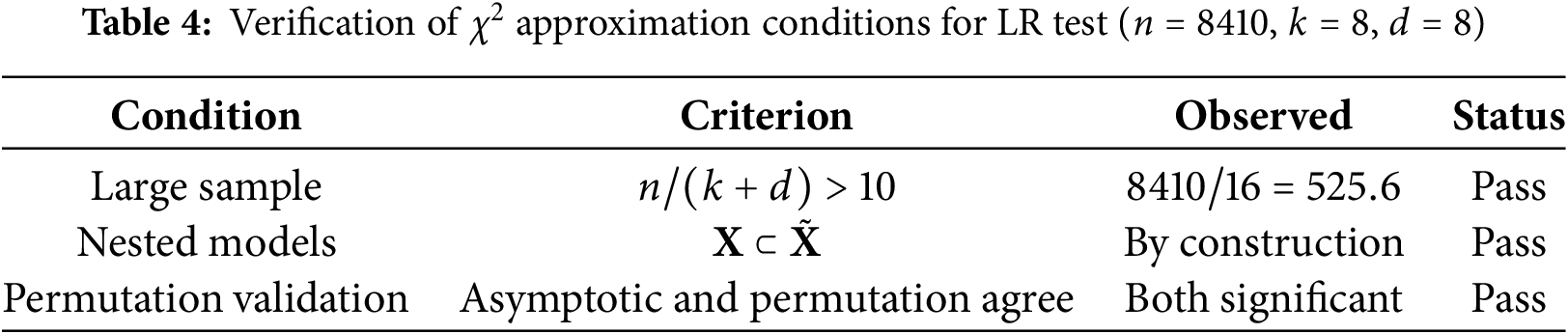

To simplify the theoretical discussion and enable closed-form statistical testing, we use logistic regression as the downstream classifier with an undersampled dataset (

Our graph-based approach models both temporal and customer information together. Temporal information can be extracted as features and placed in

However, fraudulent transactions exhibit strong temporal clustering—multiple unauthorized charges typically occur within minutes before detection. Our proposed method replaces the customer random effect

Unlike random effects, the GCN embeddings are learned through message-passing and can be treated as fixed effects in the downstream classifier. To empirically validate this interpretation, we conducted an ablation study (

As shown in Table 3, GCN embeddings achieve superior performance (+0.117 AUC improvement) with only 16 features, compared to customer dummies which require 927 features for a +0.102 improvement.

Notably, explicit temporal features (trans_hour, trans_day_of_week) provide essentially no improvement. This reveals a fundamental distinction between two types of temporal patterns. Absolute temporal patterns refer to statements like “transactions at 23:00 are more likely to be fraudulent,” which would require fraud to concentrate at specific hours or days—a pattern largely absent in our data. In contrast, relative temporal patterns refer to statements like “a transaction temporally close to a fraudulent transaction is also likely to be fraudulent”—this fraud clustering pattern is precisely what our data exhibits.

Conventional feature engineering cannot easily capture relative temporal patterns because doing so would require knowing the fraud labels of neighboring transactions a priori. Our GCN-based approach elegantly solves this: the graph structure encodes temporal proximity between transactions, and the message-passing mechanism allows fraud-related signals to propagate through temporally adjacent nodes during training. This explains why the relational structure of temporal proximity—not raw timestamp values—is the key to improved fraud detection. To formally test significance, let

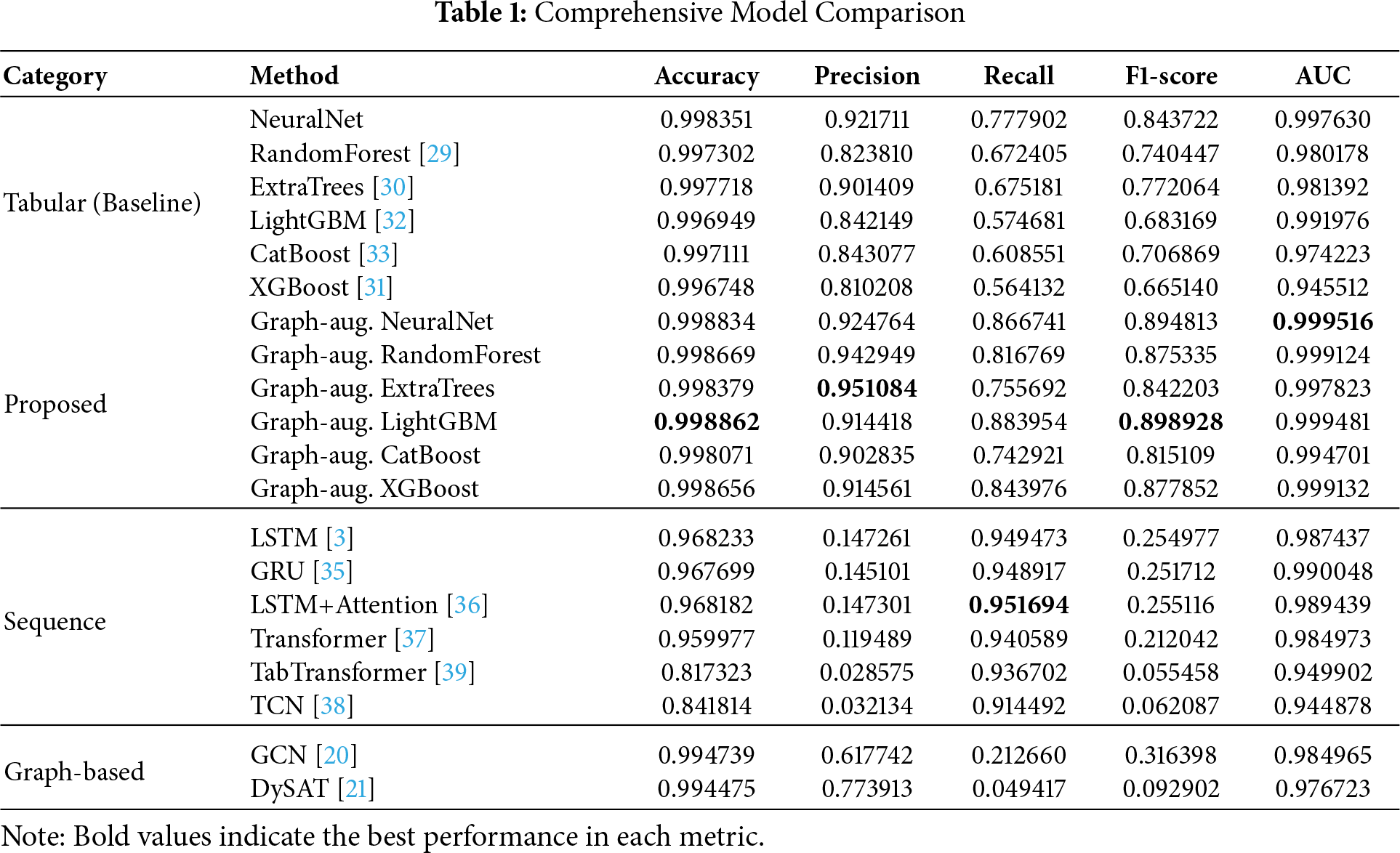

Under

Finally, we validate the asymptotic

These tests confirm that GCN embeddings provide statistically significant predictive value by capturing temporal dependencies that traditional methods overlook.

7.1 Why Graph-Augmented Features Work

Sequence-based approaches (LSTM, Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), Transformer) assume equally-spaced time intervals, but credit card transactions occur at irregular intervals—ranging from seconds apart during shopping sessions to days or weeks between purchases. Moreover, these models process transactions as ordered sequences without modeling the connectivity structure between temporally proximate transactions. Our graph-based approach explicitly captures irregular temporal relationships through edge weights that encode temporal proximity, naturally handling non-uniform time spacing without requiring temporal discretization or padding.

While non-Euclidean approaches can capture temporal and customer dependencies, they introduce unnecessary complexity. In practice, the vast majority of legitimate transactions can be correctly classified using Euclidean features alone—temporal clustering patterns become critical only in the vicinity of fraudulent activity. A purely graph-based model would be computationally expensive and may overfit to relational patterns irrelevant for normal transactions. Our analysis shows that GCN embeddings contribute an additional 23.1% of explained variance (

Our approach offers an elegant middle ground. The base Euclidean classifier efficiently handles the majority of straightforward cases, while GCN embeddings provide supplementary non-Euclidean information precisely where it matters—near fraud clusters. This design avoids the overhead of full graph-based inference while retaining the benefits of temporal dependency modeling. The concatenation allows the downstream classifier to adaptively weight Euclidean vs. non-Euclidean features based on context, achieving both high precision (above 0.90) and improved recall without the computational burden of end-to-end graph models. Furthermore, this modular design offers practical advantages: the GCN embedding generation is independent of the downstream classifier, allowing practitioners to leverage existing classification infrastructure while benefiting from graph-based feature augmentation.

7.2 Limitations and Future Work

While our proposed method demonstrates strong performance on the analyzed dataset, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our evaluation is based on a single publicly available dataset that may not fully represent the diversity of fraud patterns encountered in real-world financial systems. Credit card fraud datasets vary significantly in their characteristics: some contain only anonymized features and lack explicit temporal information. The generalizability of our method to these diverse fraud scenarios requires further validation. Second, our approach constructs individual graphs for each customer, which assumes sufficient transaction history per customer. For customers with very few transactions, the graph structure may be too sparse to provide meaningful embeddings. Third, our approach assumes that temporal proximity is the primary factor determining transaction relationships, which may not hold in all fraud scenarios—for instance, when fraudsters deliberately introduce time delays between fraudulent activities. Future work could address these limitations by: (i) evaluating on multiple fraud datasets with different characteristics, (ii) developing adaptive methods for customers with limited transaction history, and (iii) exploring alternative kernel functions that capture more complex temporal patterns.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (RS-2023-00249743). Additionally, this research was supported by the Global-Learning & Academic Research Institution for Master’s, PhD Students, and Postdocs (LAMP) Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2024-00443714). This research was also supported by the “Research Base Construction Fund Support Program” funded by Jeonbuk National University in 2025.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization and methodology, Guebin Choi; software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, visualization, and writing—original draft, Boram Kim; writing—review and editing, Guebin Choi and Boram Kim; supervision and funding acquisition, Guebin Choi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Kaggle at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/dermisfit/fraud-transactions-dataset. Supplementary materials including detailed experimental results are available at https://guebin.github.io/non-euclidean-models-for-fraud-detection/.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/dermisfit/fraud-transactions-dataset

2https://guebin.github.io/non-euclidean-models-for-fraud-detection/

References

1. Nilson Report. Global card fraud losses reach $403.88 Billion. 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 15]. Available from: https://nilsonreport.com. [Google Scholar]

2. Whitrow C, Hand DJ, Juszczak P, Weston D, Adams NM. Transaction aggregation as a strategy for credit card fraud detection. Data Min Knowl Discov. 2009;18(1):30–55. doi:10.1007/s10618-008-0116-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hochreiter S, Schmidhuber J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997;9(8):1735–80. doi:10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Krawczyk B. Learning from imbalanced data: open challenges and future directions. Prog Artif Intell. 2016;5(4):221–32. doi:10.1007/s13748-016-0094-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Makki S, Assaghir Z, Taher Y, Haque R, Hacid MS, Zeineddine H. An experimental study with imbalanced classification approaches for credit card fraud detection. IEEE Access. 2019;7:93010–22. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2927266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Alam TM, Shaukat K, Hameed IA, Luo S, Sarwar MU, Shabbir S, et al. An investigation of credit card default prediction in the imbalanced datasets. IEEE Access. 2020;8:201173–98. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3033784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wei W, Li J, Cao L, Ou Y, Chen J. Effective detection of sophisticated online banking fraud on extremely imbalanced data. World Wide Web. 2013;16(4):449–75. doi:10.1007/s11280-012-0178-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Tayebi M, El Kafhali S. Combining autoencoders and deep learning for effective fraud detection in credit card transactions. Oper Res Forum. 2025;6(1):8. doi:10.1007/s43069-024-00409-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tayebi M, El Kafhali S. Generative modeling for imbalanced credit card fraud transaction detection. J Cybersecur Priv. 2025;5(1):9. doi:10.3390/jcp5010009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Van Vlasselaer V, Bravo C, Caelen O, Eliassi-Rad T, Akoglu L, Snoeck M, et al. APATE: a novel approach for automated credit card transaction fraud detection using network-based extensions. Decis Support Syst. 2015;75(3):38–48. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2015.04.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Stamile C, Marzullo A, Deusebio E. Graph machine learning: take graph data to the next level by applying machine learning techniques and algorithms. Birmingham, UK: Packt Publishing Ltd.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

12. Weber M, Domeniconi G, Chen J, Weidele DKI, Bellei C, Robinson T, et al. Anti-money laundering in bitcoin: experimenting with graph convolutional networks for financial forensics. arXiv:1908.02591. 2019. [Google Scholar]

13. Grover A, Leskovec J. node2vec: scalable feature learning for networks. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016. p. 855–64. [Google Scholar]

14. Zhang Q, Yan B, Huang M. Internet financial fraud detection based on a distributed big data approach with Node2vec. IEEE Access. 2021;9:43378–86. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3062467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Bruss CB, McGee A, Muench B, Chaluvaraju P, Rajput S. DeepTrax: embedding graphs of financial transactions. In: 2019 18th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA); Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 126–33. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang Y, Zhang X, Chen L. Heterogeneous graph auto-encoder for credit card fraud detection. arXiv:2410.08121. 2024. [Google Scholar]

17. Benchaji I, Douzi S, El Ouahidi B. Credit card fraud detection model based on LSTM recurrent neural networks. J Adv Inf Technol. 2021;12(2):113–8. doi:10.12720/jait.12.2.113-118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Alarfaj FK, Malik I, Khan HU, Almusallam N, Ramzan M, Ahmed M. Credit card fraud detection using state-of-the-art machine learning and deep learning algorithms. IEEE Access. 2022;10:39700–15. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3166891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yu C, Xu Y, Cao J, Zhang Y, Jin Y, Zhu M. Credit card fraud detection using advanced transformer model. arXiv:2406.03733. 2024. [Google Scholar]

20. Kipf TN, Welling M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv:1609.02907. 2016. [Google Scholar]

21. Sankar A, Wu Y, Gou L, Zhang W, Yang H. DySAT: deep neural representation learning on dynamic graphs via self-attention networks. In: Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 519–27. [Google Scholar]

22. You J, Du T, Leskovec J. ROLAND: graph learning framework for dynamic graphs. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 2358–66. [Google Scholar]

23. Cheng Y, Liu C, Liu Y. CaT-GNN: enhancing credit card fraud detection via causal temporal graph neural networks. arXiv:2402.14708. 2024. [Google Scholar]

24. Wheeler R, Aitken S. Multiple algorithms for fraud detection. In: Applications and Innovations in Intelligent Systems VII: Proceedings of ES99, the Nineteenth SGES International Conference on Knowledge Based Systems and Applied Artificial Intelligence; Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2000. p. 219–31. [Google Scholar]

25. Srivastava A, Kundu A, Sural S, Majumdar A. Credit card fraud detection using hidden Markov model. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2008;5(1):37–48. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2007.70228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sánchez D, Vila M, Cerda L, Serrano JM. Association rules applied to credit card fraud detection. Exp Syst Appl. 2009;36(2):3630–40. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2008.02.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu T, Zhang W, Chen J. Effective high-order graph representation learning for credit card fraud detection. arXiv:2503.01556. 2025. [Google Scholar]

28. Shuman DI, Narang SK, Frossard P, Ortega A, Vandergheynst P. The emerging field of signal processing on graphs: extending high-dimensional data analysis to networks and other irregular domains. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2013;30(3):83–98. doi:10.1109/msp.2012.2235192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Liaw A, Wiener M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News. 2002;2(3):18–22. [Google Scholar]

30. Geurts P, Ernst D, Wehenkel L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach Learn. 2006;63(1):3–42. doi:10.1007/s10994-006-6226-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen T, Guestrin C. Xgboost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2016. p. 785–94. [Google Scholar]

32. Ke G, Meng Q, Finley T, Wang T, Chen W, Ma W, et al. Lightgbm: a highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Vol. 30. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2017. doi:10.32614/cran.package.lightgbm. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Prokhorenkova L, Gusev G, Vorobev A, Dorogush AV, Gulin A. CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features. Vol. 31. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

34. Erickson N, Mueller J, Shirkov A, Zhang H, Larroy P, Li M, et al. AutoGluon-Tabular: robust and accurate AutoML for structured data. arXiv:2003.06505. 2020. [Google Scholar]

35. Cho K, Van Merriënboer B, Gulcehre C, Bahdanau D, Bougares F, Schwenk H, et al. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. In: Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2014. p. 1724–34. [Google Scholar]

36. Bahdanau D, Cho K, Bengio Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv:1409.0473. 2015. [Google Scholar]

37. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 30. Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2017. doi:10.65215/ctdc8e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Bai S, Kolter JZ, Koltun V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. arXiv:1803.01271. 2018. [Google Scholar]

39. Huang X, Khetan A, Cvitkovic M, Karnin Z. TabTransformer: tabular data modeling using contextual embeddings. arXiv:2012.06678. 2020. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools