Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A State-of-the-Art Survey of Adversarial Reinforcement Learning for IoT Intrusion Detection

1 Department of Cybersecurity, Faculty of Computer & Information Technology, Jordan University of Science and Technology, P.O. Box 3030, Irbid, 22110, Jordan

2 Department of Cybersecurity, King Hussein School of Computing Sciences, Princess Sumaya University for Technology, P.O. Box 1438, Amman, 11941, Jordan

* Corresponding Author: Qasem Abu Al-Haija. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in IoT Security: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Applications)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 2 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073540

Received 20 September 2025; Accepted 25 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Adversarial Reinforcement Learning (ARL) models for intelligent devices and Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS) improve system resilience against sophisticated cyber-attacks. As a core component of ARL, Adversarial Training (AT) enables NIDS agents to discover and prevent new attack paths by exposing them to competing examples, thereby increasing detection accuracy, reducing False Positives (FPs), and enhancing network security. To develop robust decision-making capabilities for real-world network disruptions and hostile activity, NIDS agents are trained in adversarial scenarios to monitor the current state and notify management of any abnormal or malicious activity. The accuracy and timeliness of the IDS were crucial to the network’s availability and reliability at this time. This paper analyzes ARL applications in NIDS, revealing State-of-The-Art (SoTA) methodology, issues, and future research prospects. This includes Reinforcement Machine Learning (RML)-based NIDS, which enables an agent to interact with the environment to achieve a goal, and Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL)-based NIDS, which can solve complex decision-making problems. Additionally, this survey study addresses cybersecurity adversarial circumstances and their importance for ARL and NIDS. Architectural design, RL algorithms, feature representation, and training methodologies are examined in the ARL-NIDS study. This comprehensive study evaluates ARL for intelligent NIDS research, benefiting cybersecurity researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. The report promotes cybersecurity defense research and innovation.Keywords

A security mechanism known as the NIDS is developed to maintain surveillance on network traffic and identify any suspicious or illegal activity. NIDS are vital in detecting and countering network attacks by analyzing data packets and traffic patterns [1]. Abuse detection is also referred to as rule-based intrusion detection [2]. DRL has numerous applications in the real world [3]. NIDS are key security defense technologies that monitor computer networks or systems for network-based threats or malicious attacks that might compromise the system’s functionality. A misuse-based NIDS system relies on many attack patterns for intrusion detection. However, this system is vulnerable to zero-day attacks and has a lengthy processing time. An anomaly-based IDS detects concealed attacks on computer systems by identifying atypical traffic patterns. This approach can be used to identify zero-day attacks, and the discovery findings can be stored in a database for future detection using signature-based methods. The approach will be implemented and will begin to train the agent and the environment using the DRL algorithm [4]. In recent years, several authors have adapted classical methodologies to the issue of network information security. While dealing with smaller data sets of lower dimension, Machine Learning (ML) algorithms can achieve better classification results, which are all characterized as learning algorithms.

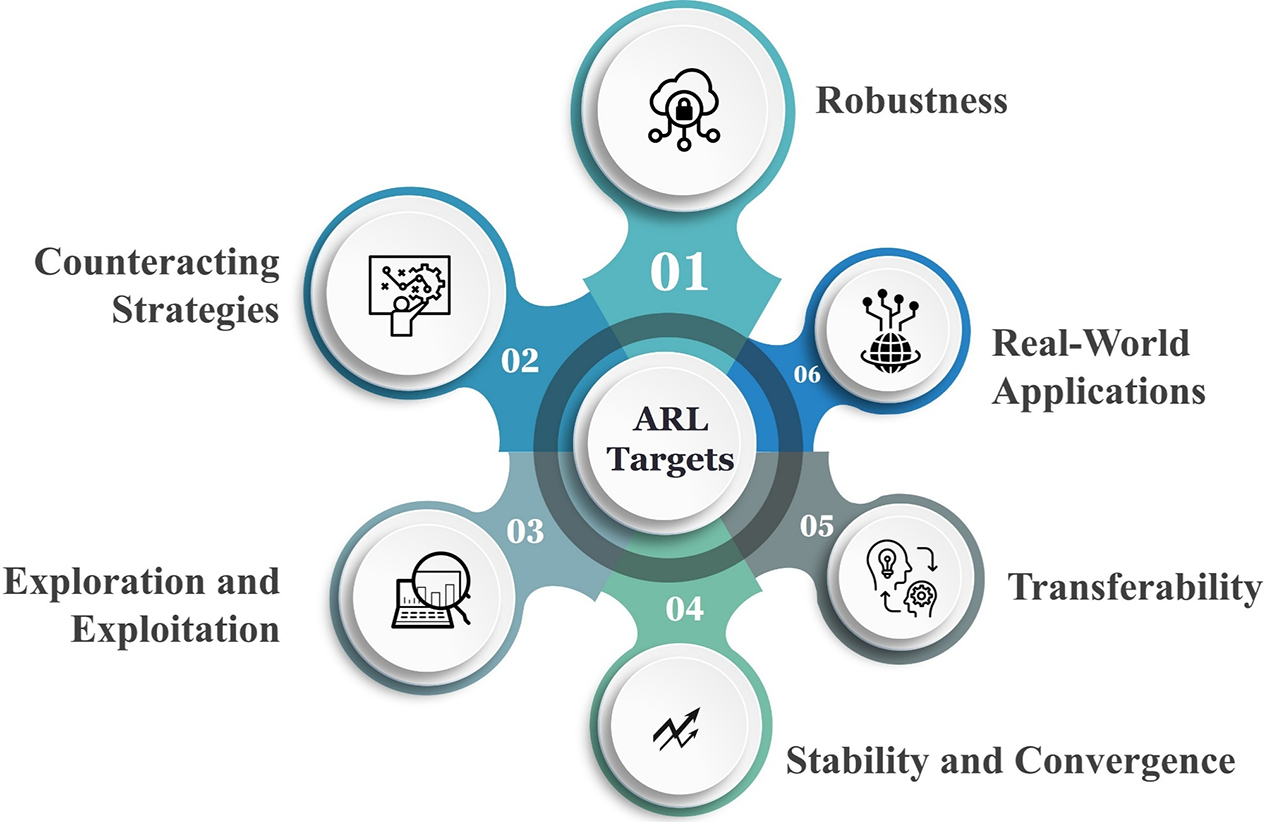

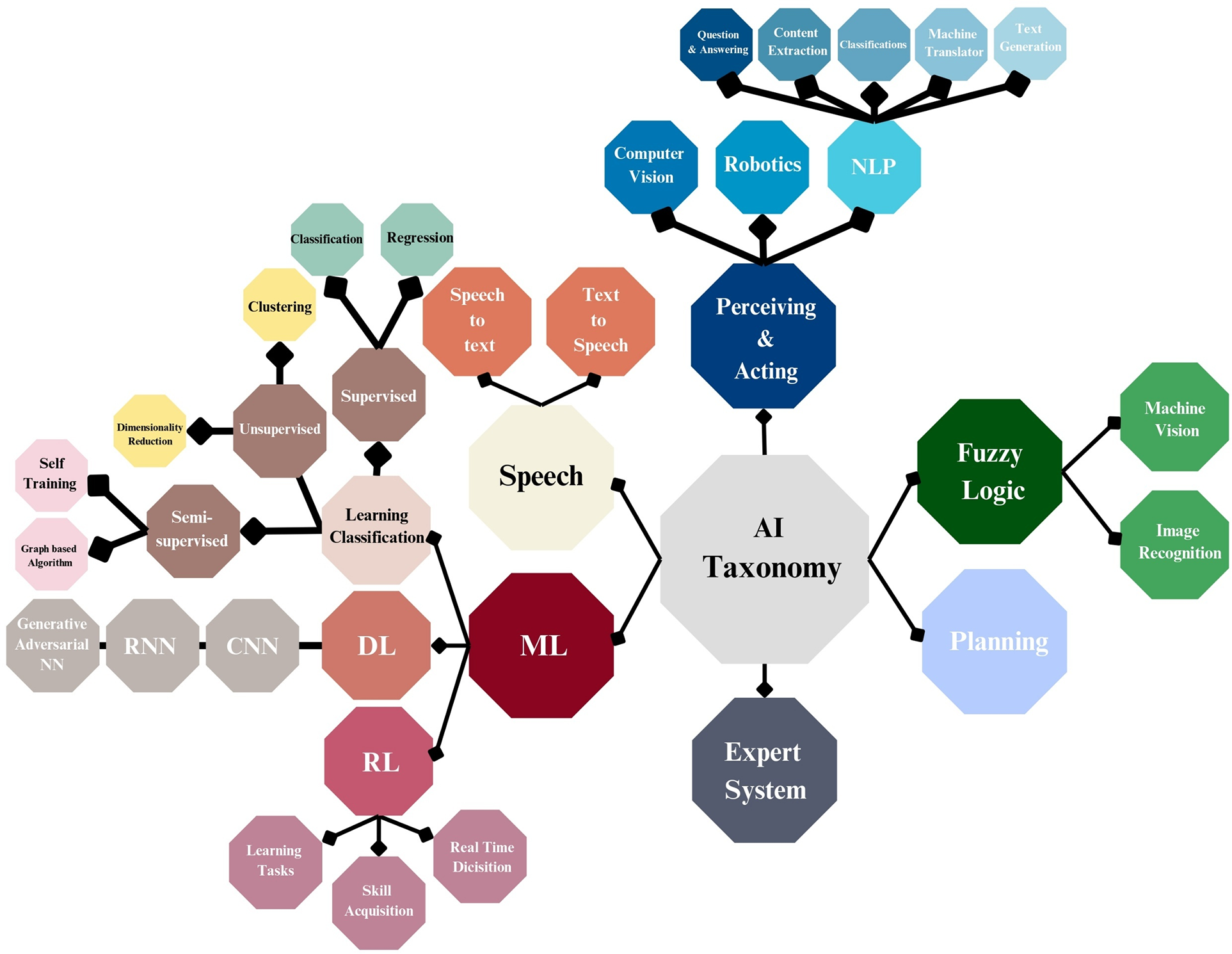

Recently, a new algorithm or approach combining the advancement of Deep Learning (DL), called DRL, has been developed. The generator is taught to produce fresh data, while the discriminator model attempts to distinguish between genuine and generated data. The RL approach is also used to train the generator. However, this DL-based system is extremely vulnerable to adversaries and also has an obvious limitation [5,6]. As a branch of ML, ARL studies the behavior of several agents in a hostile or competitive environment. Its main focus is on building algorithms and techniques that enable agents to acquire and modify knowledge in contexts with other agents whose goals are at odds with their own. As a branch of ML, ARL studies the behavior of several agents in a hostile or competitive environment. Thus, Fig. 1 illustrates the core targets of ARL. Thus, Fig. 2 represents the Artificial Intelligence (AI) taxonomy, where RL is a subclass of ML. Thus, this is the first comprehensive survey considering the studies employing ARL-IDS.

Figure 1: ARL targets

Figure 2: AI taxonomy

Robustness: ARL aims to develop agents that can survive and thrive in the face of hostile methods and forces. This requires techniques or rules that are immune to flaw-based attacks.

Counteracting Strategies: ARL enables agents to anticipate & counter opposing strategies. They may need to predict their opponents’ actions, adjust their policies, and capitalize on their weaknesses.

Exploration and Exploitation: ARL algorithms should enable agents to devise effective strategies and leverage successful approaches against opponents, striking a balance between exploration and exploitation.

Stability and Convergence: ARL aims to maintain learning.

Algorithm stability and convergence in competitive environments. Algorithms that can converge to Nash equilibria or other acceptable solutions are needed.

Transferability: ARL algorithms might adapt to hazardous environments under ideal conditions. Because of this, agents may apply what they’ve learned in one situation to perform better in another, unknown one.

Real-World Applications: ARL aims to develop algorithms and strategies for addressing adversarial or competitive real-world scenarios. Gaming, cybersecurity, negotiation systems, and multi-agent simulations are examples of these applications.

Scope of Survey: ARL has surpassed ML methods since incorporating RL and AT. In ARL, the generator plays the role of the adversary against the discriminator, attempting to deceive it. Tasks that require the generation of realistic data samples, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), benefit from ARL [7]. The underlying concept behind ARL is to demonstrate that a generator can replicate real data effectively, while training a discriminator to distinguish between the two types of data. Additionally, ARL aims to improve the data quality by using AT to generate more representative samples. ARL also combines AT regarding RL to enhance the efficacy and data quality of the generative model.

The increasing demand for ARL in AI and ML inspired this study. Additionally, there is a growing need for enhancements to NIDS’s adaptability, robustness, and intelligence in dynamic and adversarial network environments. However, traditional ML and DL based NIDS often struggle to detect evolving and invisible attack patterns (i.e., Zero-Day Attacks) due to their static learning mechanisms. Moreover, ARL presents a viable framework to address these challenges by amalgamating RL with adversarial learning to provide ongoing self-enhancement and fortitude against complex cyber-attacks. ARL needs an exhaustive examination for distinct reasons:

• Autonomous Adaptation: Unlike traditional RL, ARL offers new challenges and opportunities for success. Concerns have been raised regarding security, scalability, sample efficiency, Transfer Learning (TL), and durability. Furthermore, it may enable autonomous decision-making in hostile conditions, making NIDS more adaptive to complex and changing traffic behaviors.

• Dynamic Threat Landscape: Network attacks evolve rapidly, rendering static detection models ineffective. ARL agents can continuously learn optimal defense strategies by interacting with the environment and enhancing their responsiveness to emerging threats.

• Adversarial Robustness: ARL explicitly models the attacker-defender interaction, allowing NIDS to anticipate and counter adversarial attacks such as evasion, poisoning, and spoofing.

• Bridging Theory and Practice: By studying ARL-driven NIDS, this research aims to reduce the gap between theoretical frameworks and real-world network defense systems through dynamic, risk-aware learning.

• Cross-Domain Relevance: ARL has proven useful in robotics, cybersecurity, and finance; thus, extending it to NIDS allows leveraging shared advances in autonomous learning and adversarial defense.

Traditional NIDS struggle to maintain efficiency in a dynamic and unfavorable environment, where attackers constantly develop their strategies to evade detection. While ML has improved detection options, it remains vulnerable to negative manipulation, such as theft, poisoning, and reward-based attacks. Strengthening RL provides adaptive learning ability, but the standalone application lacks strength against intelligent opponents. ARL is an emerging area that may be an asset for seeking aid in complex circumstances, enabling proactive and adaptable risk assessment. However, the fragmented nature of existing research, diverse functions, and inconsistent evaluation framework may allow and help the systematic development of ARL-NIDS. This study identifies advanced NIDS and classified SOTA ARL-NIDS to identify large trends, boundaries, and future instructions for integrating intelligent security mechanisms and applications that work to prevent and detect malicious or abnormal activities. These are integrated, classified, and evaluated directly by researchers.

Despite advances in utilizing ARL-NIDS, the majority of current research examines these techniques in isolation or fails to demonstrate practical applicability in hostile environments. To adapt to cyber-attack environments, research is needed to build an ARL-based NIDS framework that exhibits dynamic learning, resilience, and scalability. This survey study addresses such gaps by integrating SoTA advances and representing the ARL-NIDS architecture that unites theory with actual network security implementations. Moreover, the study aims to represent ARL-NIDS within real-world scenarios and cyber risks that may be affected. Despite its progress, ARL-NIDS is still facing significant intervals and boundaries. The difference lies in the incomplete coverage of types of attacks. At the same time, ARL models are distinguished by detecting the stolen or poisoning efforts; they can secretly weaken the inner formulas against the dangers of APT. In addition, normalization remains a weakness, as trained models on a dataset or domain cannot adapt to different network environments without withdrawing. Another limit is the lack of a standardized assessment structure. Without a standard scale, comparing the ARL approaches impartially or establishing best practices is a challenge. Despite this, the complexity of the ARL model makes it less interpretable, which reduces confidence among doctors and limits its adoption in regulated industries, such as healthcare or finance.

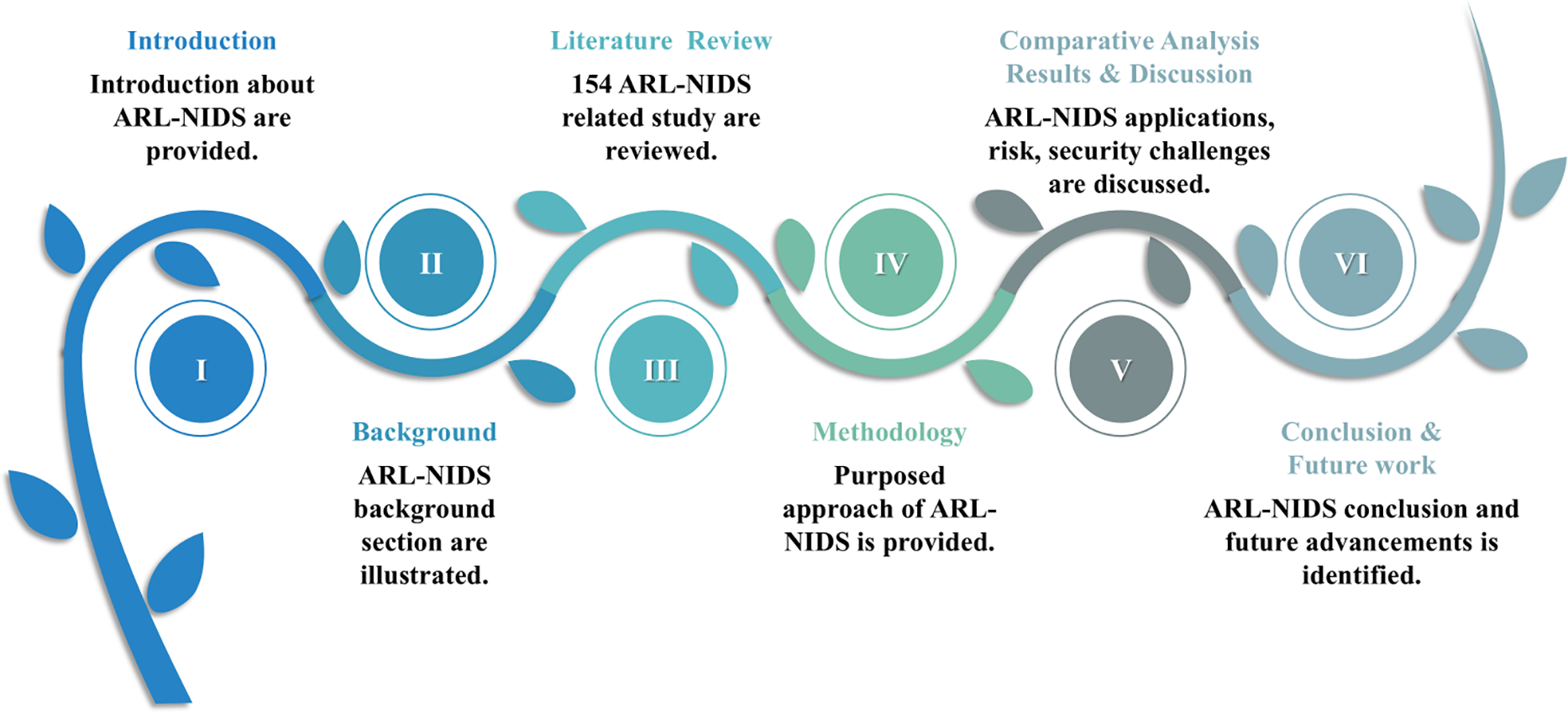

ARL aims to provide resilient, adaptable, and effective learning algorithms and methods for agents in competitive or adversarial contexts to achieve desired outcomes despite competing goals. The rest of the paper is arranged as follows: Section 1 introduces our research. Section 2 provides background on NIDS and RL. Thus, Section 3 included related works. Past 154 research studies will be examined in the linked work. Section 4, part provides the ARL-NIDS method. Section 5 includes findings and comments. Section 6 concludes our study and outlines the next directions. Fig. 3 depicts the study’s sections and course. A survey may disclose key issues and solutions to advance the field. Our contribution to this subject is an early worldwide appraisal of the existing knowledge regarding technology, its applications, and ARL-based IDS detection of attacks and harmful activity.

Figure 3: Overview for proposed survey study

This section provides a detailed illustration of the background. Were this section categorized as follows:

A. Reinforcement Learning (RL)

RL is an ML model that depends on an agent connecting with their environment to accomplish a goal. Thus, RL and ARL require separate but linked algorithms and formulas. Throughout RL, the agent learns to make choices by optimizing accumulated reward through interactions with the environment. At the same time, the ARL provides enemies that test the agent’s learning process, which is sometimes depicted as a two-player game. The opponent aims to limit the payoff, while the agent seeks to maximize it.

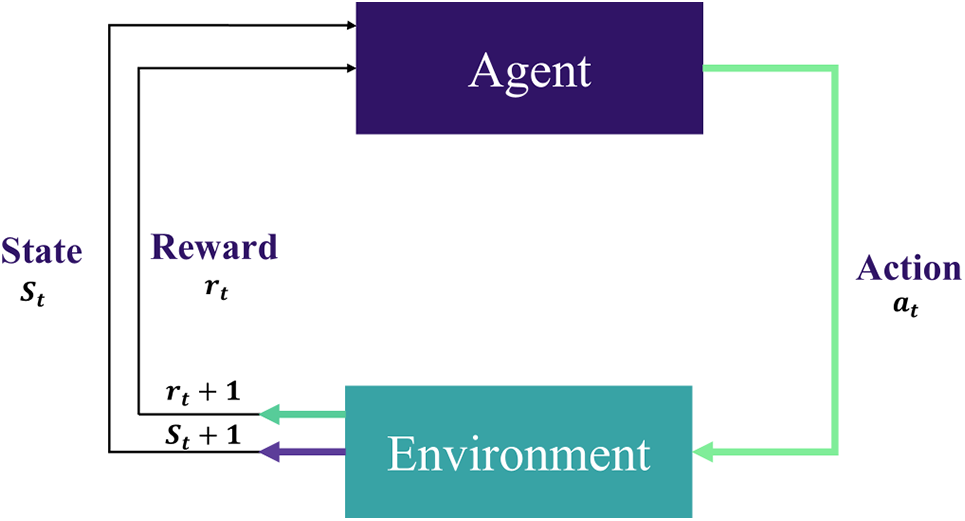

MDP and Bellman Equations for RL: RL relies on rewards and punishments, rather than supervised and unsupervised learning, which utilize labeled data for model training and pattern discovery. Adapting to rewards and punishments from the environment, the agent maximizes cumulative rewards over time. RL algorithms aim to make the best judgments in complex and uncertain scenarios. RL requires agents, environments, states, actions, rewards, and regulations. RL is used in robotics, gaming, autonomous automobiles, recommendation systems, and finance. Thus, RL defines automation as an agent interacting with an environment and learning through trial and error [8]. RL elements are described in Fig. 4. The following core elements of the Markov Decision Process (MDP) concept are discussed for their importance.

Figure 4: The core of an RL system-based MDP

RL: The training of ML models to make a sequence of decisions.

Agent Function: May choose an action, receive a reward from the environment, and transition to a new state.

Reward Function: The feedback the agent receives based on the action it performed.

• If the feedback is positive, it receives a reward.

• If the feedback is negative, it receives a punishment.

The environment provides the agent with a state.

Bellman optimality equation for an MDP’s state-value function V(s).

Value Function: The value function V(s) represents the expected cumulative reward starting from state s under a policy π:

Action-Value Function (Q-Function): The action-value function Q (s, a) represents the expected cumulative reward starting from state (s), acting (a), and following policy π:

Bellman Equation for Value Function: The Bellman equation expresses the value of a state as the immediate reward plus the discounted value of the next state:

Bellman Equation for Q-Function: Similarly, the Bellman equation for the Q-function is:

Optimal Policy (Bellman Optimality Equation): RL aims to maximize the cumulative reward:

Policy Gradient (PG) (for Policy-Based Methods): In policy gradient methods, we aim to optimize the policy by adjusting the parameters θ. The gradient of the expected cumulative reward with respect to θ is:

Baseline RL for Intrusion Detection: In the RL framework, the IDS agent interacts with the environment (network traffic). The agent observes states.

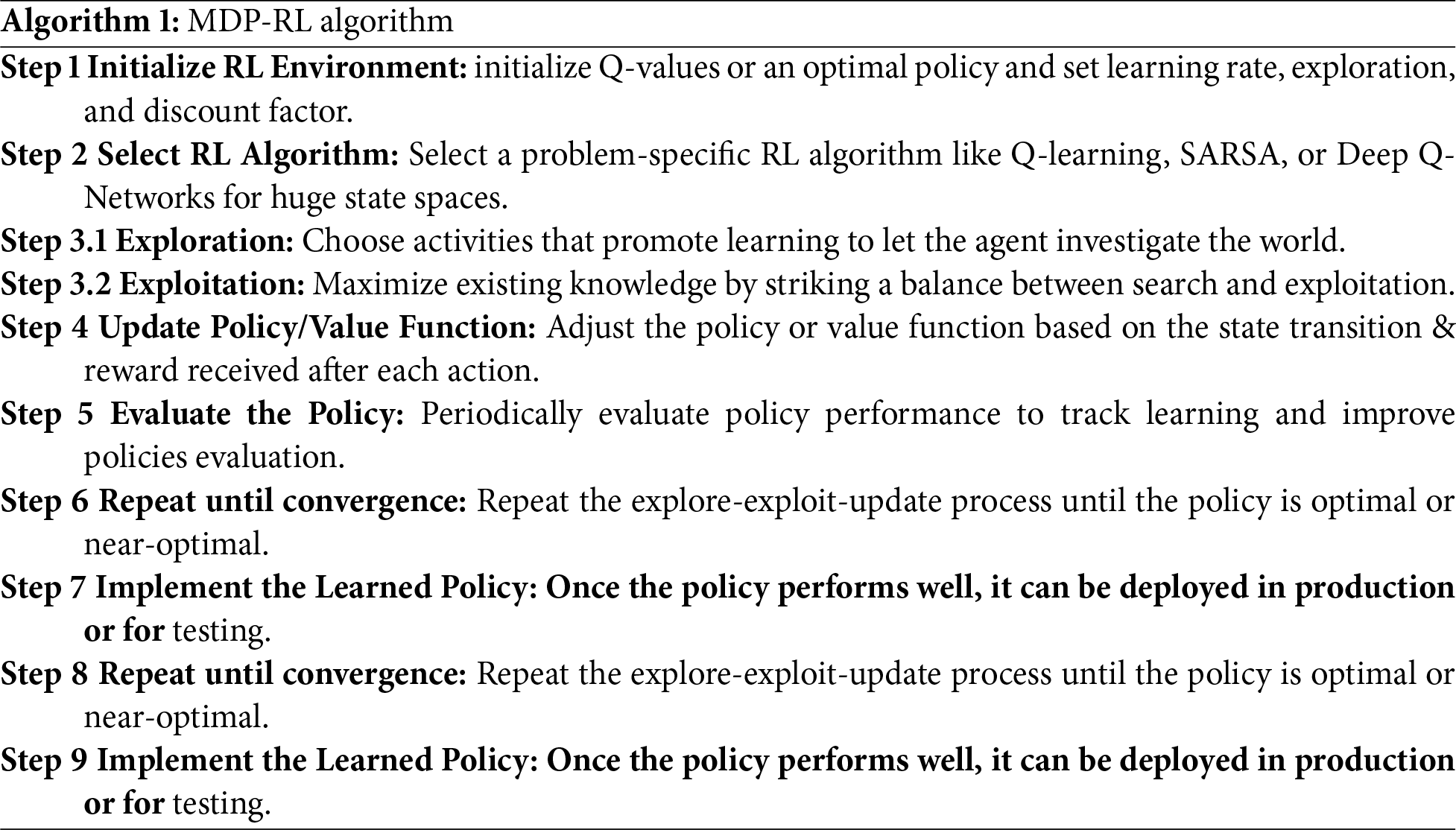

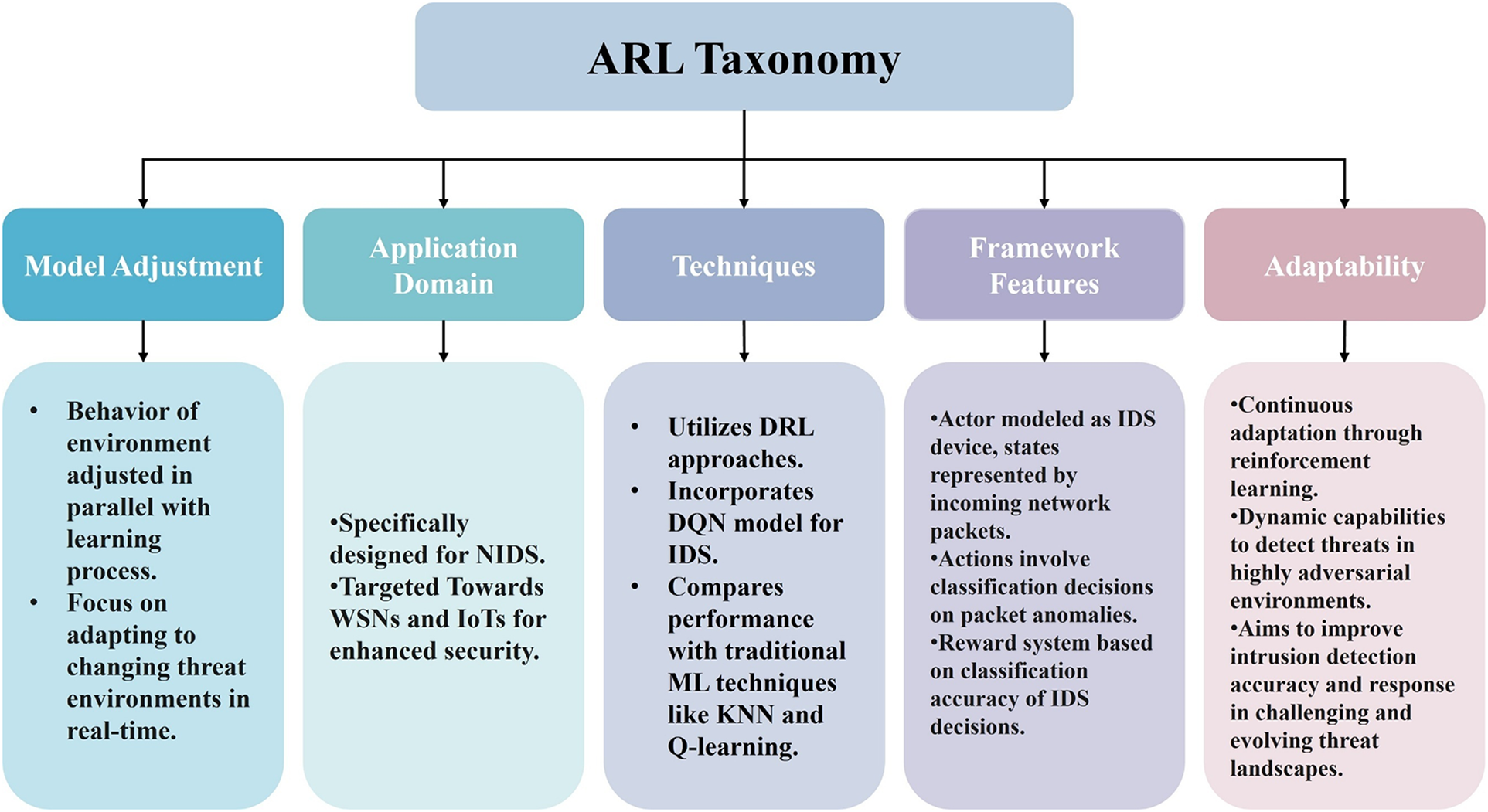

Additionally, the notation for the mathematical formulas of the MDP and the Bellman approach for the RL algorithm (as shown in Algorithm 1: MPD-RL Algorithm) is provided in Table 1.

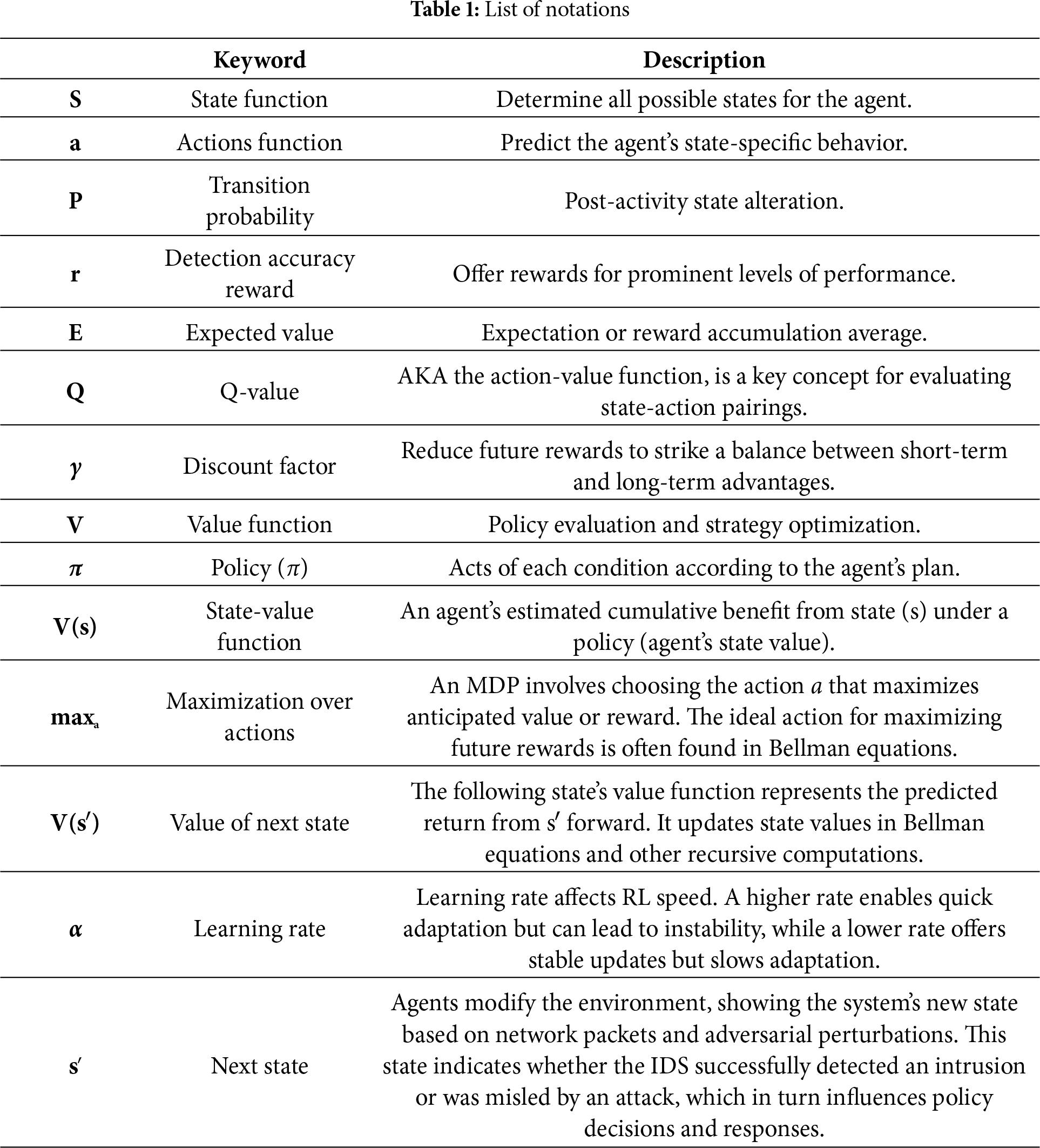

Consequently, fields like DRL have made great strides, combining RL algorithms with DNN to tackle more difficult problems and provide SOTA outcomes. Regarding AI, RL remains a hotspot for study, and it shows promise in tackling tough challenges. Thus, DRL appears to be subject to adversarial attacks, which restrict its applicability in crucial real-world applications or systems. Furthermore, DRL can perform well in various situations with limited manual intervention. A key component in classifying RL algorithms is the agent’s ability to learn its surroundings, including functions that predict state transitions and rewards. The following categories of RL approaches are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: RL classification

Model-based RL: An agent learns a model of the environment and then utilizes it to anticipate and plan for the future. Agents change and restructure models periodically. How many data samples do agents require to maximize rewards and perform successfully in their environments? When model-based algorithms state sample efficiently, they imply this. This is because the agent does not need to see every result. Learning (world models), model-based value growth, model-based fine-tuning, or being given are methods to acquire a model.

Model-free RL: Instead of constructing or getting a model, an agent uses its knowledge to select optimal behaviors in a state. Model-free algorithms learn state values, not policies. The agent’s main goal is to behave optimally. Therefore, the agent learns by exploring rather than exploiting its environment. It covers policy optimization and Q-Learning algorithms. Policy-based and value-based model-free methods exist. Some refer to policy-based or PG methods as on-policy. In policy optimization, algorithms optimize parameters θ directly by gradient ascent on the performance object, such as the cost function, or indirectly by maximizing a local estimate. The primary objective is to select a PG that rewards good acts and penalizes negative ones. PG can learn an acceptable policy even when the Q-function is too difficult. It converges quickly and can learn stochastic rules. Furthermore, continuous spaces are simpler to model. Policy-based techniques aim to benefit from learning an acceptable policy even when the Q-function is too difficult to learn. It converges quickly and can learn stochastic rules. Furthermore, continuous spaces are simpler to model. Policy-based techniques aim to maximize a performance metric, such as the parametrized policy’s true value function, over all starting states [9].

B. Adversarial Reinforcement Learning (ARL)

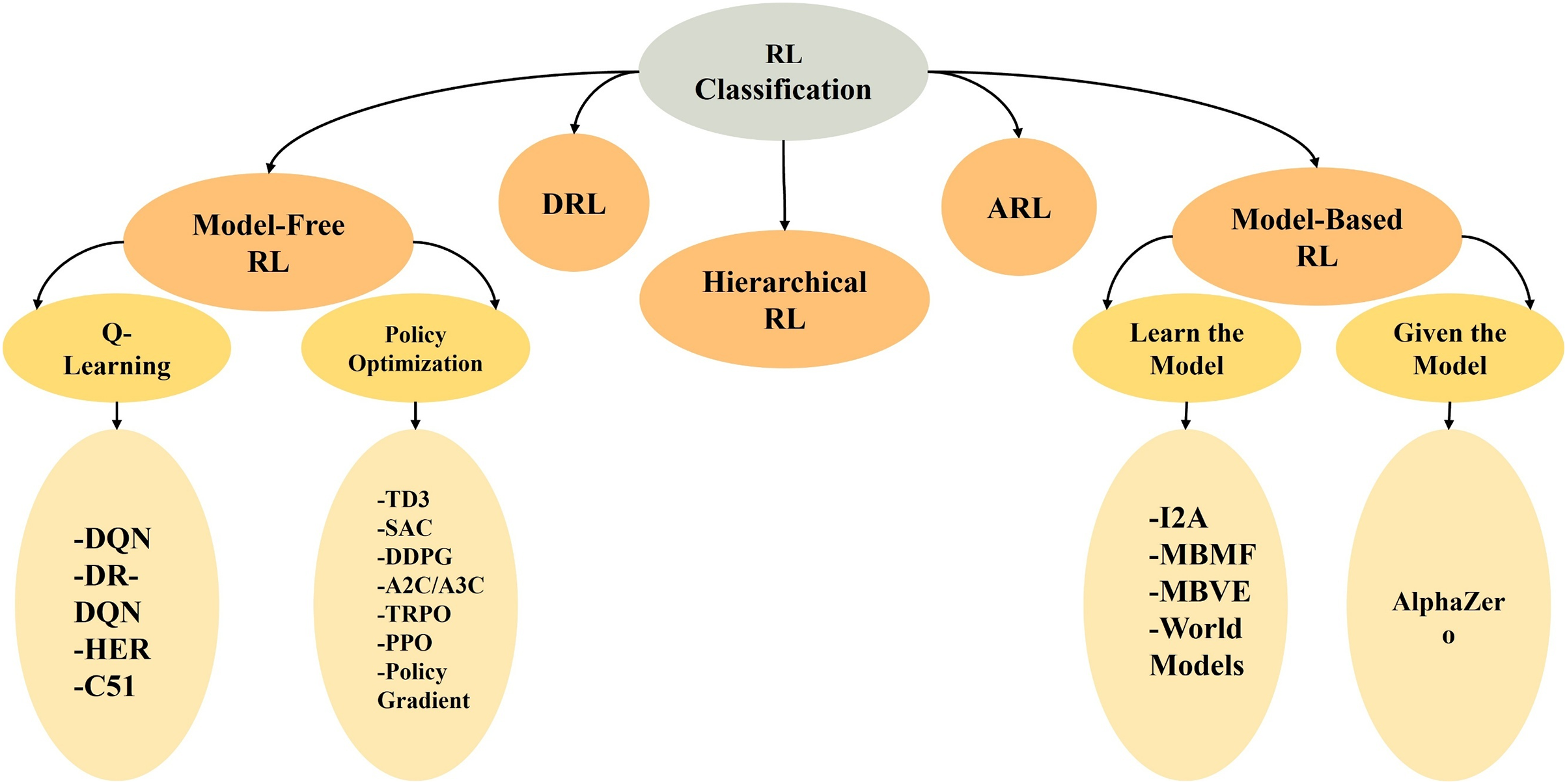

ARL combines AT and RL, both strong ML paradigms designed to solve problems in dynamic and hostile settings. AT, which stems from the discipline of adversarial ML, entails exposing models to adversarial cases during training to improve their resilience to possible assaults. In contrast, RL is concerned with agents engaging in an environment to learn optimal methods via trial and error, thereby maximizing cumulative rewards over time. ARL combines these two approaches, enabling agents to acquire resilient rules for making informed choices in uncertain and hostile environments. ARL combines AT’s combative resistance with RL’s decision-making skills and offers new pathways for handling difficult real-world challenges in various disciplines, including cybersecurity and ML [10]. A powerful DRL method, ARL incorporates the DQN model for IDS and is specially designed for Internet of Things (IoT) and Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs). Findings show that DRL significantly improves detection accuracy compared to traditional ML methods like K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) and Q-learning. The ARL framework can dynamically identify threats in hostile situations surrounding vital public infrastructure by constantly learning and adapting. ARL enhances the total security posture during NIDS in complex and evolving threat environments, utilizing the actor as an IDS instrument and mood as packets from the network to improve classification judgments and accuracy [11]. ARL Taxonomy is provided via Fig. 6, where ARL is classified into model adjustment, application domain, technique, framework feature, and adaptability.

Figure 6: ARL taxonomy

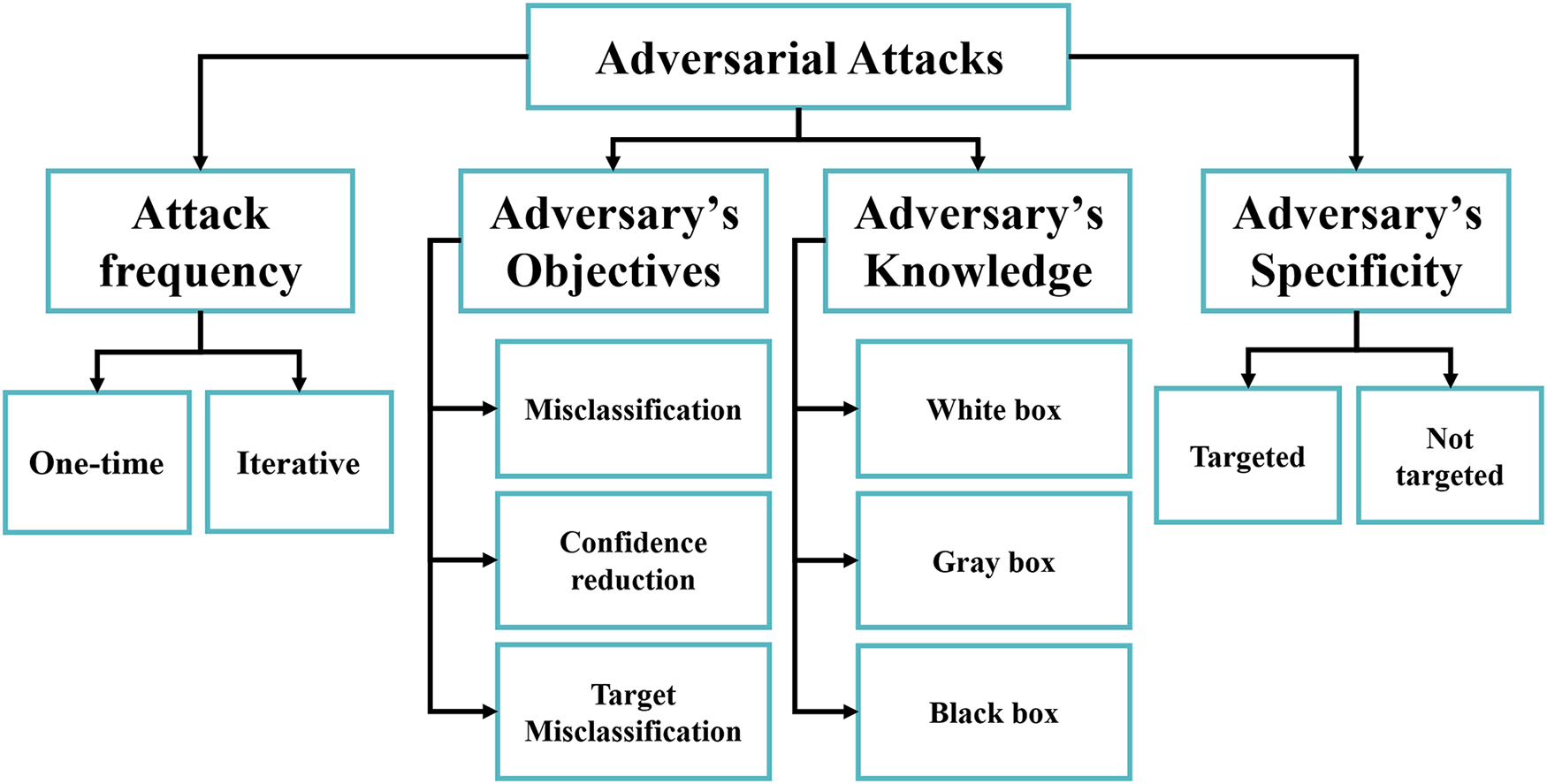

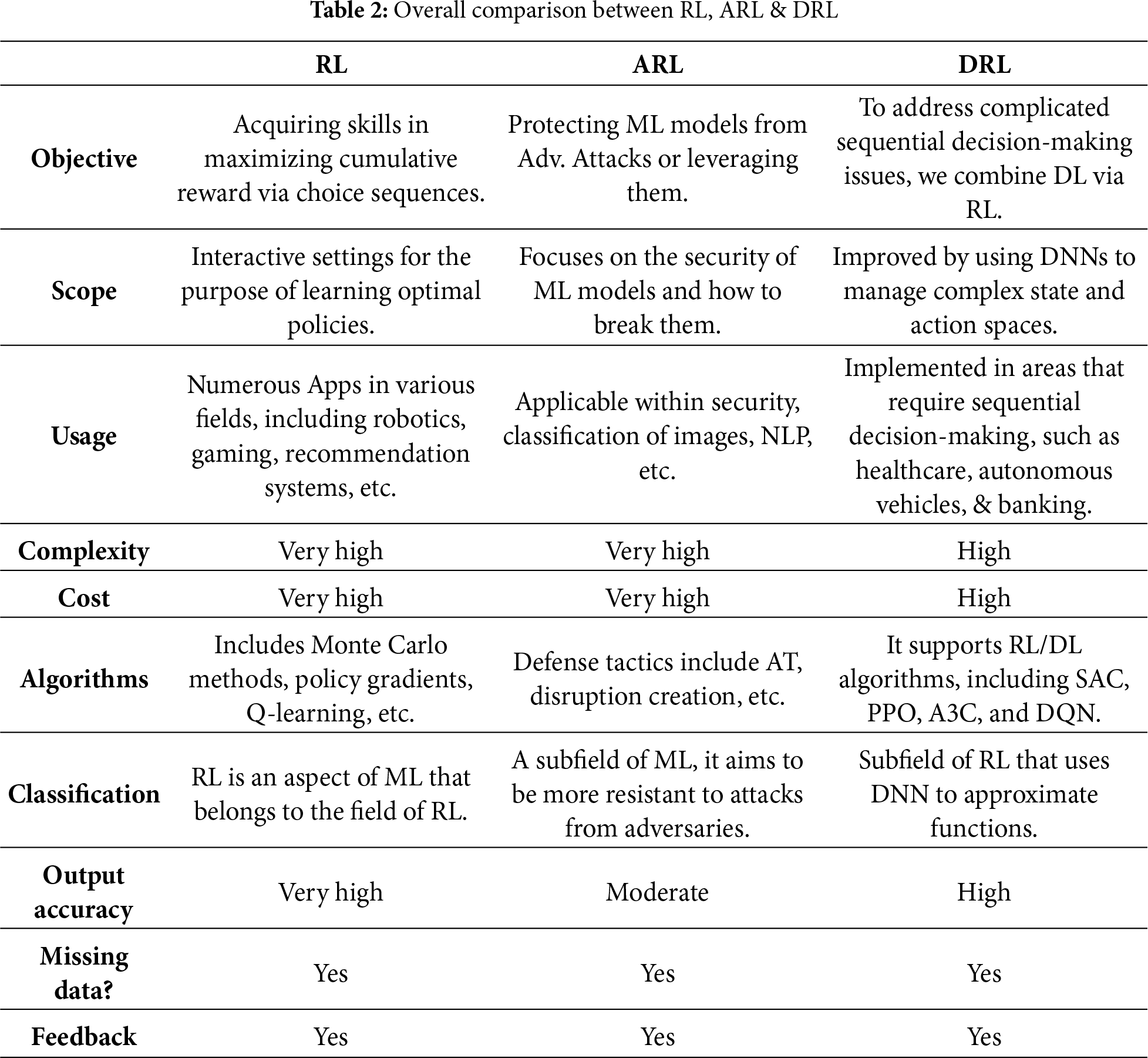

During ARL, adversarial attacks manipulate the incentive system to have the agent make poor choices. The agent may adopt rude habits or fail to fulfill its goals due to these assaults. Adversarial attacks in ARL are challenging to identify and counteract, necessitating robust defenses to ensure agent performance and reliability. These attacks can lead to improper agent behavior or prevent it from achieving its goals. Adversarial attacks in RL are often difficult to detect and require robust defense approaches to ensure agent performance and reliability. However, Fig. 7 categorizes the taxonomy of adversarial attacks. Furthermore, Table 2 outlines the differences between RL, DRL, and ARL.

Figure 7: Latest adversarial attacks

C. Intrusion Detection System (IDS)

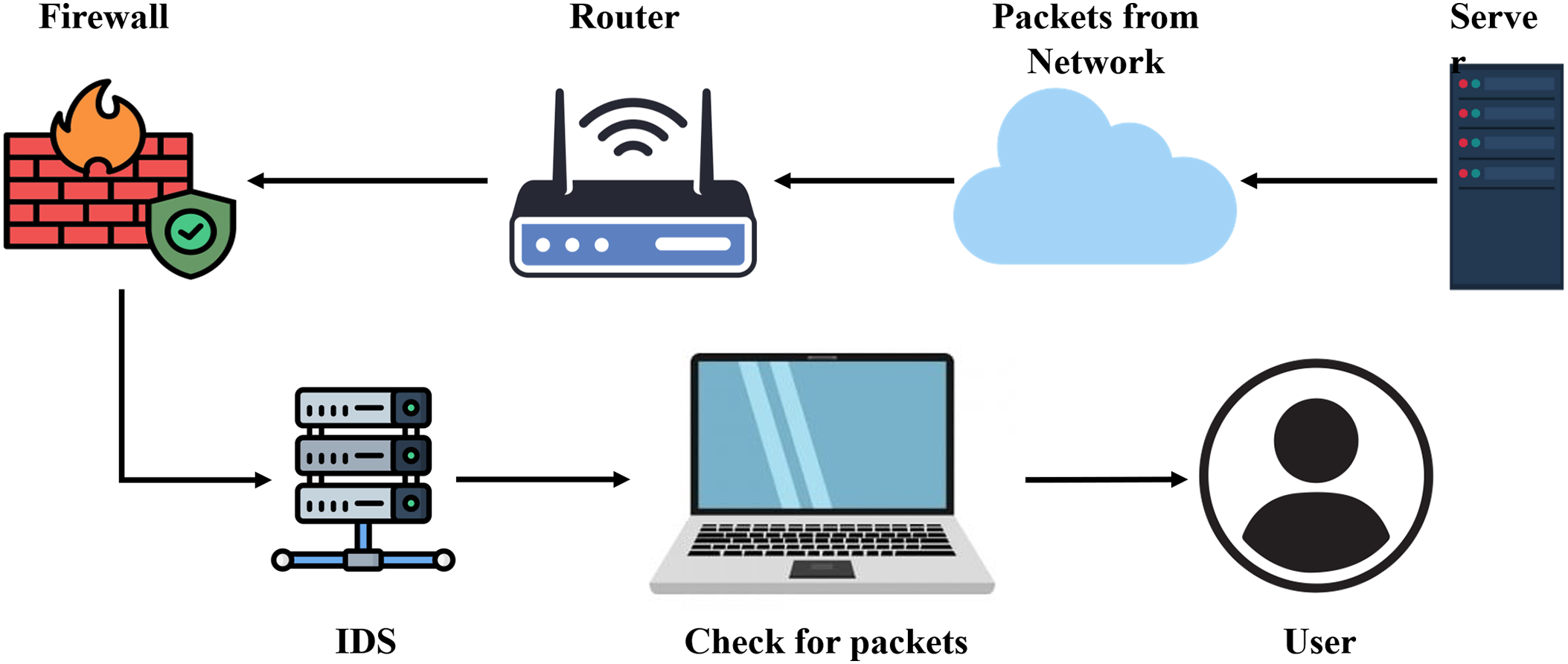

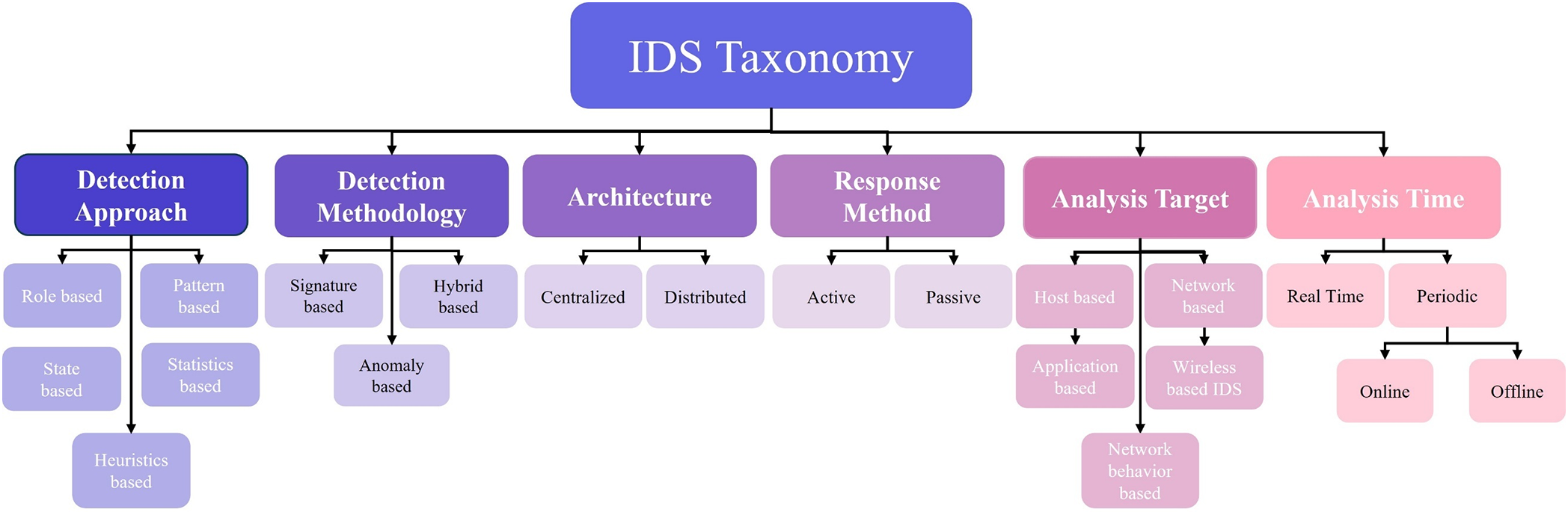

IDS is a crucial component of today’s cybersecurity techniques. IDS is generally a software or hardware technology that observes network and system activity to detect vulnerabilities and respond to unauthorized use, criminal activity, and possible security breaches. An IDS is used similarly to a firewall, serving as a watchful guardian that provides real-time alerts or implements automated actions to secure systems containing sensitive data. It analyzes recurring activity patterns and compares them with known malicious activity signatures or unusual deviations, as shown in Fig. 8. IDS plays a crucial role in proactively identifying and removing cyber threats, thereby enhancing the robustness and security of technological systems, whether within an organization’s internal networks or beyond its perimeter. Thus, NIDS aim to accurately detect and classify complex attacks in real-time [12]. There are various varieties of IDS; consider Fig. 9 to demonstrate IDS taxonomy, detection approach, detection methodology, architecture, response method, analysis target, and analysis time.

Figure 8: General IDS model

Figure 9: Overall IDS taxonomy

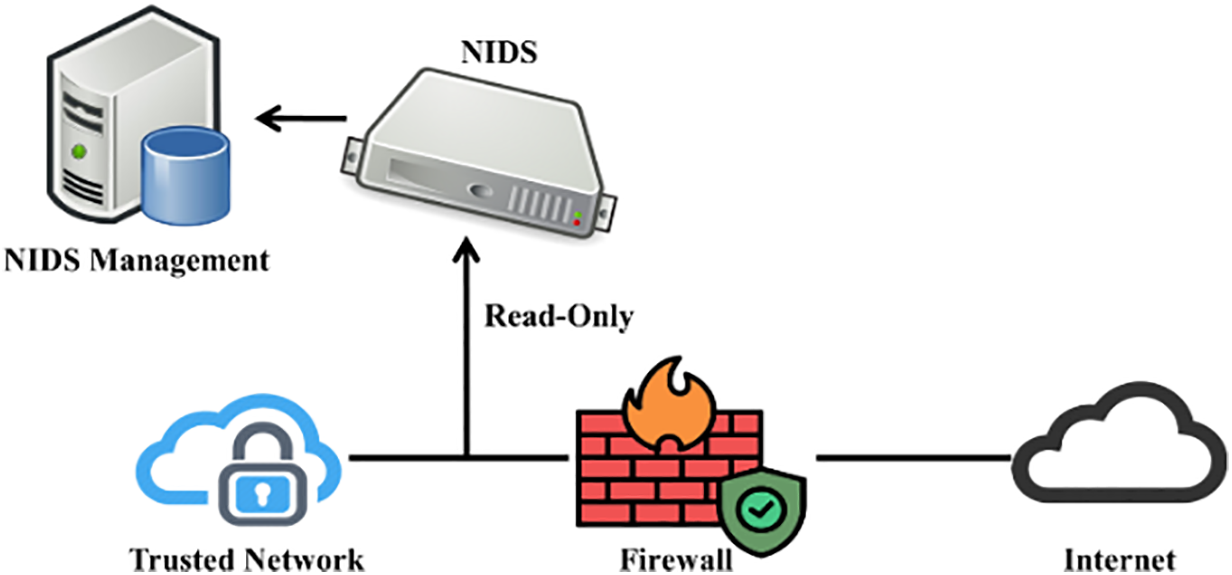

NIDS are crucial for detecting and preventing network security threats. Furthermore, NIDS is the initial step in building security status awareness since it is the primary technology for detecting various network attacks and analyzing network data. NIDS can detect patterns or signatures already existing in the training dataset. To meet the categorization standards, it must be updated in real-time. The basic goal of NIDS is to monitor and control network connections while blocking unauthorized ones. Fig. 10 illustrates the NIDS architecture, which is intended to protect data and systems. As a result, it may be used to determine whether an NIDS occurred.

Figure 10: Common NIDS architecture

• Hybrid-based IDS (Hybrid-IDS): Hybrid-IDS integrates various detection techniques, such as signature-based, anomaly-based, and behavior-based methods, to provide comprehensive security measures. By combining these approaches, Hybrid-IDS can effectively detect and mitigate a wide range of cyber threats, providing a more robust defense mechanism than a single-method IDS. Leveraging ML and DL algorithms, Hybrid-IDS can analyze complex patterns and behaviors in network traffic, enhancing threat detection accuracy while minimizing FP. Hybrid-IDS’s continuous evolution and refinement ensure their ability to adapt to the ever-changing landscape of cybersecurity threats, making them an asset in safeguarding networks and systems from malicious activities [13].

• Host-based IDS (Host-IDS): Host-IDS is a security mechanism that monitors and analyzes the internal activities and behaviors of a single host or endpoint within a network. It focuses on detecting suspicious or malicious activities that may indicate a security breach or unauthorized access to the host. Host-IDS examines log files, system calls, file integrity, and network traffic on the specific host to identify any anomalies or signs of intrusion. By providing detailed insights into the activities occurring on a particular host, a Host-IDS plays a crucial role in enhancing an organization’s overall security posture by enabling proactive threat detection and response at the individual host level [14].

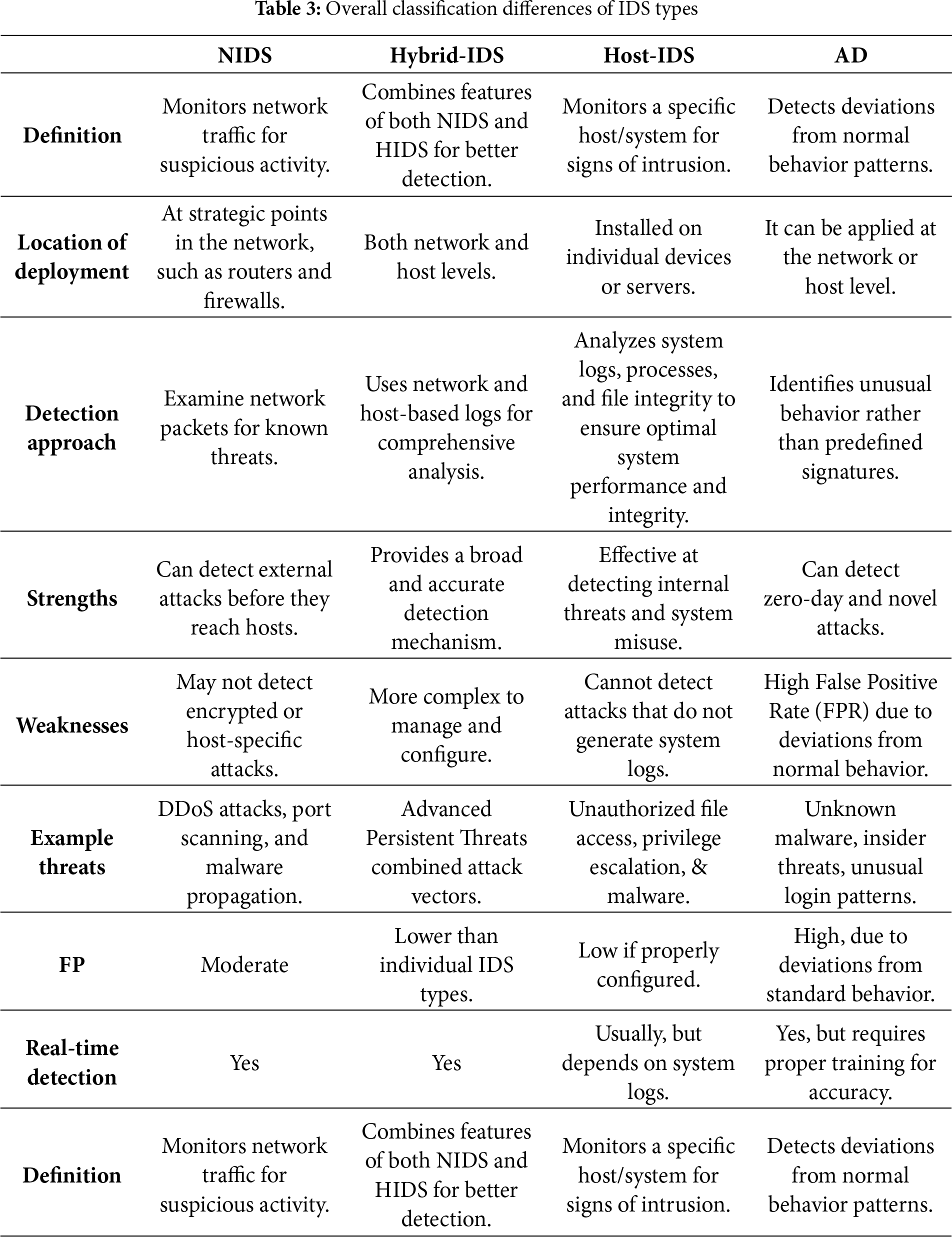

Anomaly Detection (AD): AD is a critical aspect of cybersecurity that involves identifying unusual or suspicious behavior in a system. It is vital for detecting security threats, such as network intrusions, fraud, or system malfunctions. By leveraging ML and DL techniques, AD systems can analyze vast amounts of data to establish patterns of normal behavior and flag deviations that may indicate anomalies. These systems are designed to continuously adapt and learn from new data, thereby enhancing their ability to detect. AD is essential for proactively identifying and mitigating security risks in various domains, including network security, financial transactions, and industrial processes [15]. Moreover, Table 3 illustrates the key differences between the various types of IDS. Finally, IDS seeks to categorize hostile network events in real-time, learn from past experiences, eliminate mistakes, and strengthen network defenses against attacks. It removes the need for humans to develop criteria and indicators to detect and prevent attacks. RL can educate IDS systems on how to respond properly to incentives and penalties [16].

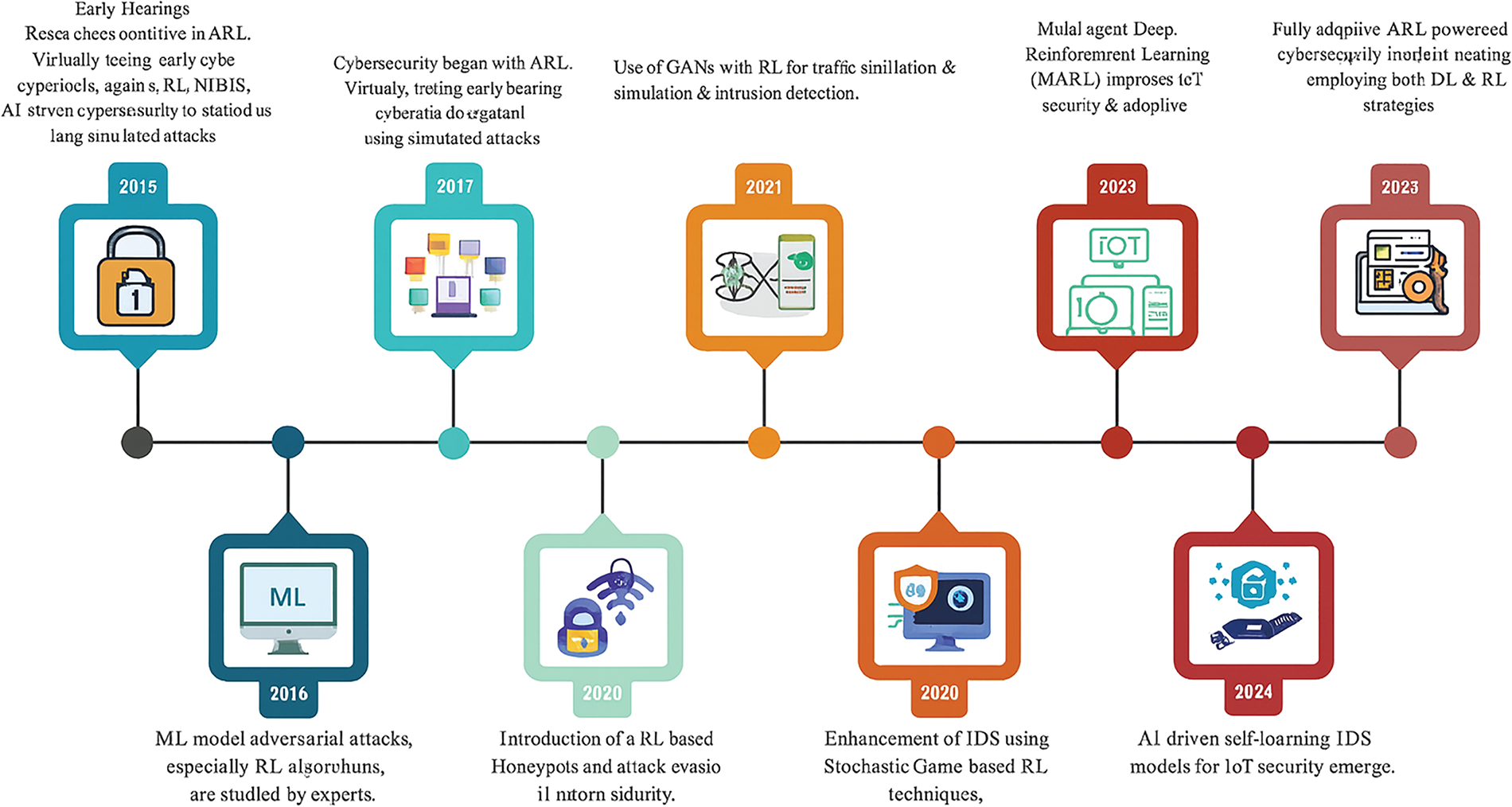

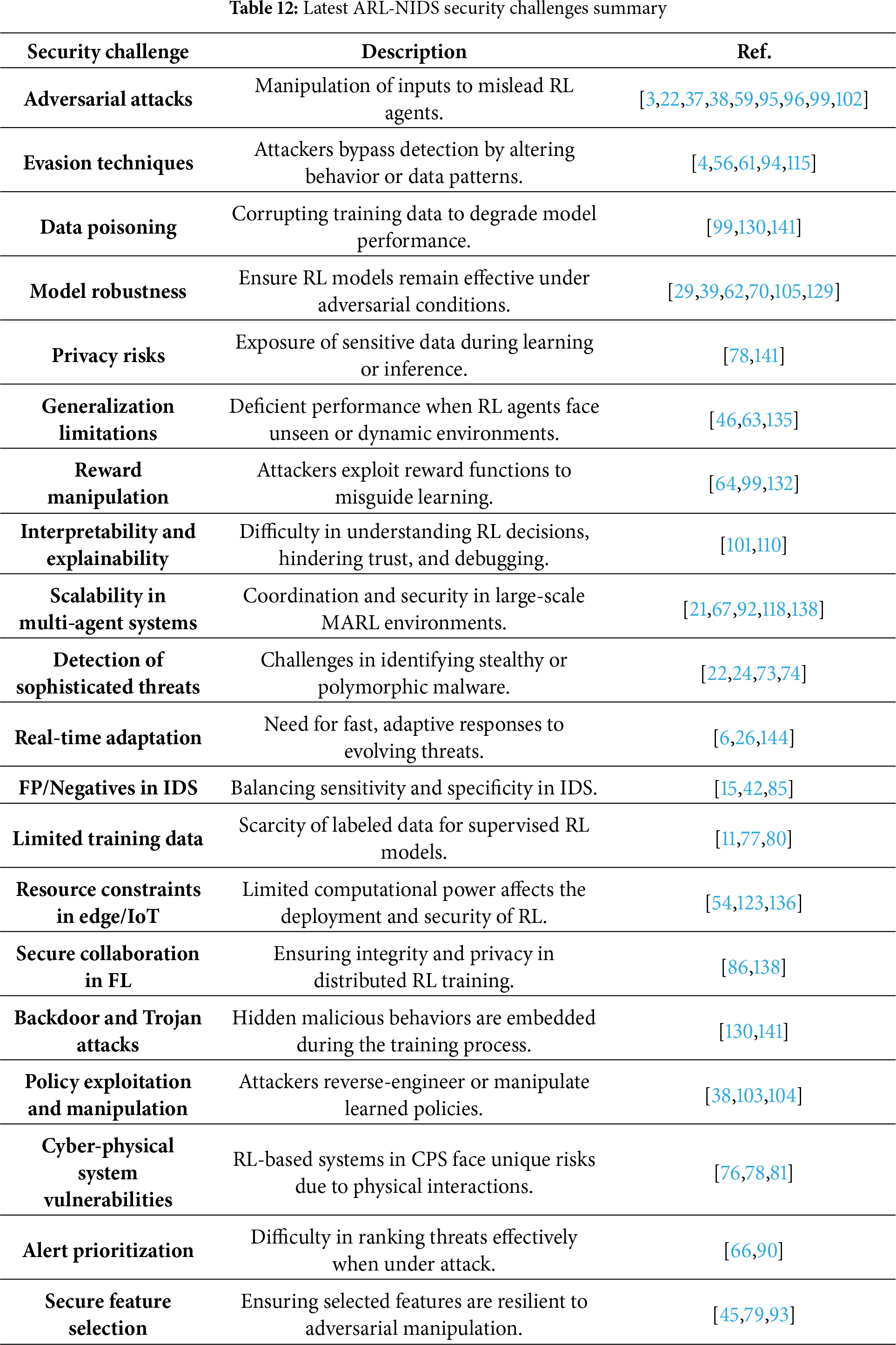

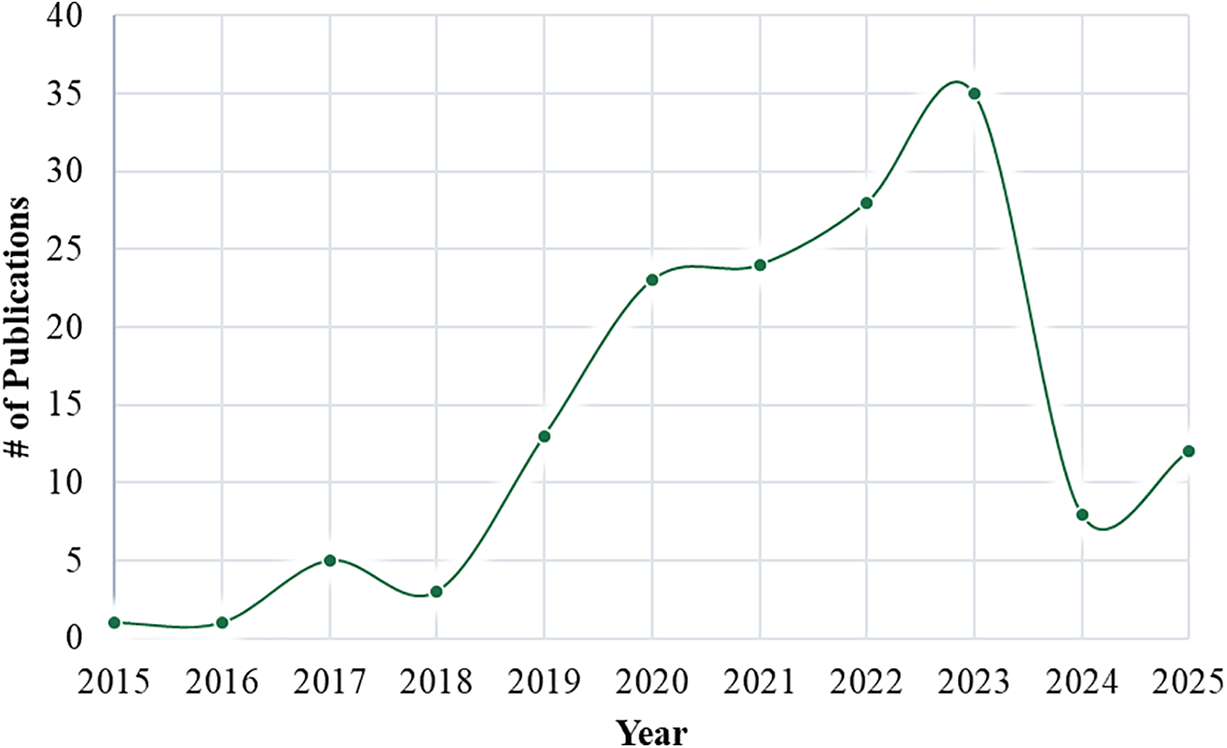

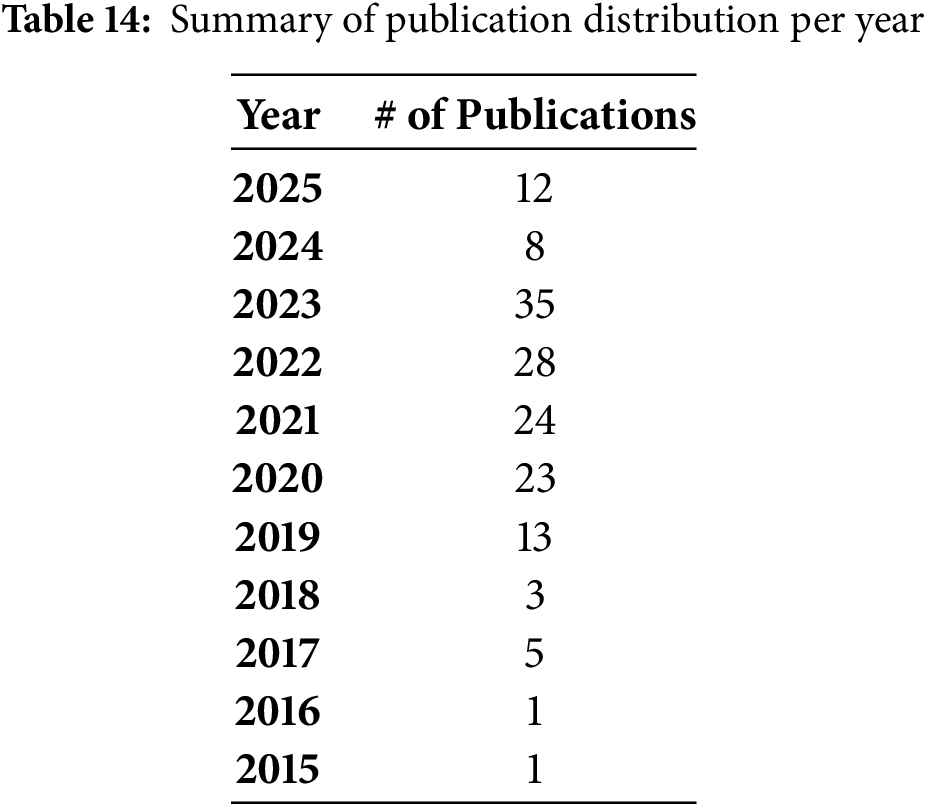

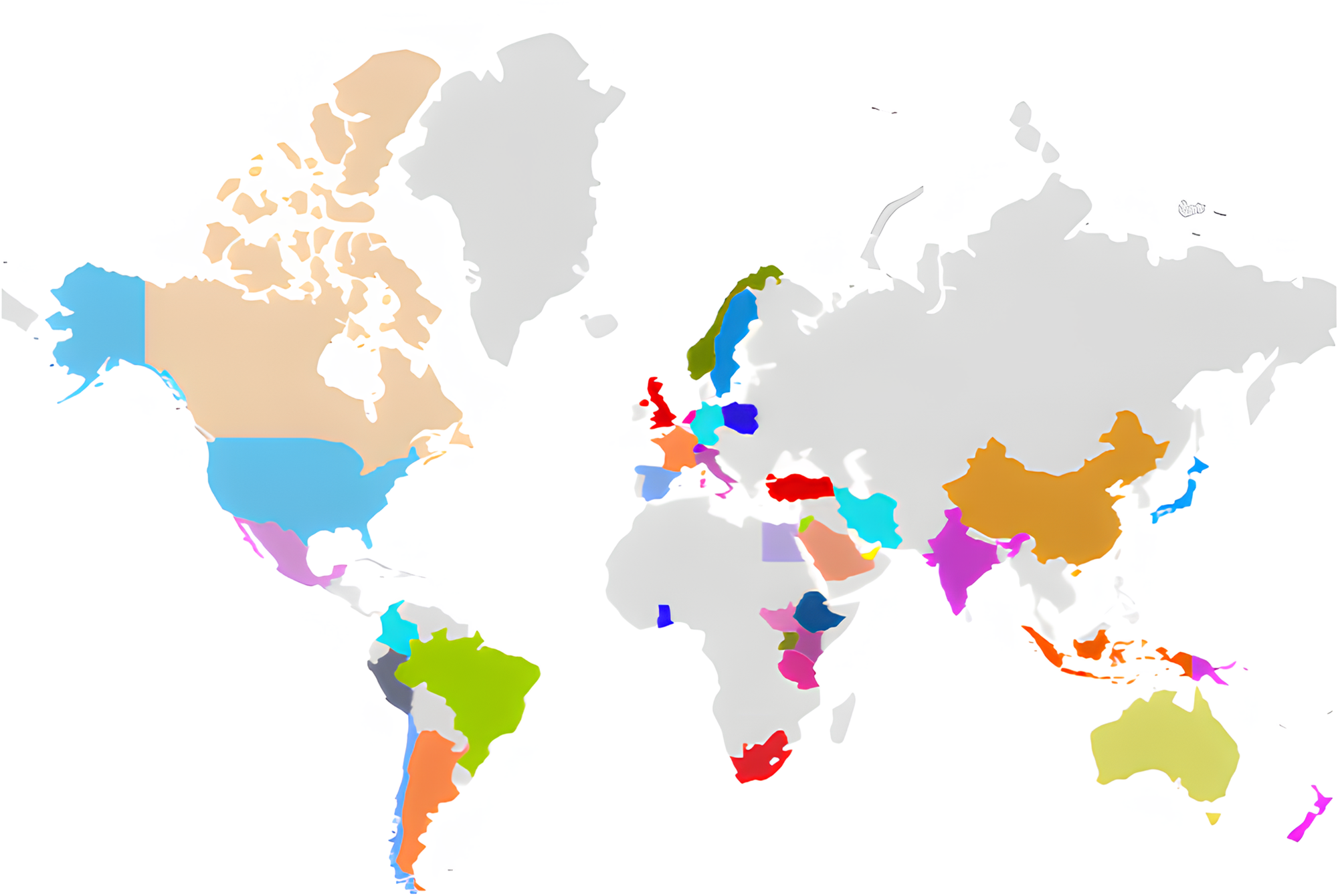

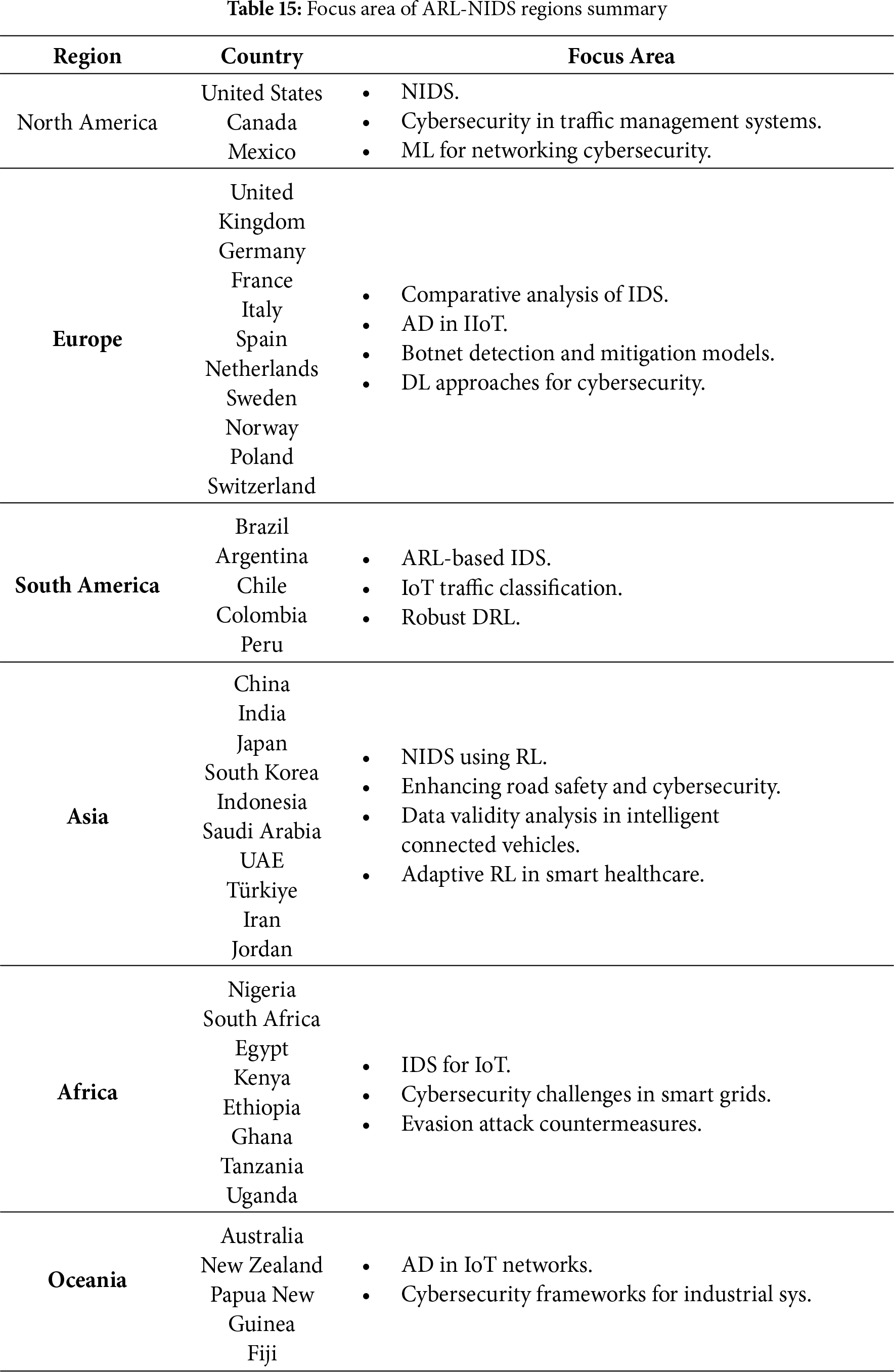

The following section discusses previous ARL-based NIDS studies and how they have identified attacks and malicious behavior in various capacities, employing different methodologies and strategies. In 1999, ML was conceived and used for intrusion detection. “Wenke Lee” led his team in developing an AD model to assess the network flow of data via log auditing, setting the framework for future ML advancements in IDS. Since the main concept is addressed in 154 related studies that utilize the ARL technique to enhance current NIDS, which are developed using similar technology, Table 4 presents a comparison between relevant studies from the past few years, including contributions, datasets, models, and results. Furthermore, Fig. 11 illustrates the latest advancement of ARL over the last 11 years. Researchers have recently developed and enhanced ARL for use in various environments and applications.

Figure 11: The advancement of ARL over the last years

A. Algorithm-Oriented Classification

To begin with, ref. [17] examines advertising aesthetics and their significance in advertising research. The study highlights seven important advertising aesthetics themes: originality, textuality, social dimensions, cross-cultural variances, and the media’s role in defining aesthetic options. Thus, the recommendation is to incorporate aesthetic ideas into advertising studies and explore advertising aesthetics as a subject of investigation. It demonstrates how aesthetics can enhance consumer engagement in advertising and offers suggestions for further developing theory and practice. Additionally, the study [18] highlights seven important advertising aesthetic themes: originality, textuality, social dimensions, cross-cultural variations, and the media’s role in defining aesthetic options. Thus, this work applies RL, especially DQN, to IoT NIDS. The paper compares DQN against Support Vector Machine (SVM), Naive Bayes (NB), and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) using the TON-IoT dataset. DQN enhances the accuracy, precision, and recall of IoT IDS systems, outperforming existing ones. Furthermore, the research [19] demonstrates how the DRL-based system can automatically learn useful characteristics for effective IDS, thereby enhancing IDS performance. While ref. [20] emphasizes the need to use DRL to develop IDS models for protecting IoT networks, comparing field surveys and evaluations highlights DRL-based IDS applications, datasets, metrics, IDS and RL taxonomy, and prospects. The research emphasizes the general requirement to feed novel models, benchmark datasets, integration with other DL strategies, TL, real-time adaptive IDSs, and lightweight threat detection models to implement DRL for IDS in IoT systems. According to the study, DRL may improve IDS performance, address security concerns, and recommend further research. Thus, the study [21] proposes an ensemble model that combines binary and prediction Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) to identify compromising actor actions within MARL systems. The algorithm outperforms starting points in detecting abnormalities, with high recall and accuracy rates. A thorough review of detection findings demonstrates the effectiveness of the ensemble approach, highlighting its superior performance in various situations. According to research, the adversarial system, as described in [22], improves IDS detection of metamorphic malware. The algorithm generates opcode-level obfuscations that imitate malware to enhance detection and train subsystems for protection. The Malicia dataset offers a comprehensive collection of malicious files for testing purposes. DRL agents, such as PPO, develop sophisticated malware samples that may evade powerful IDS. The system’s ability to generate disguised malware demonstrates RL’s promise in cybersecurity protection against emerging threats. In the following research [23], the author presents ReLog, an instrument that enables log analytics within high-performance computing systems based on RL models. With the obtained information, ReLog achieves a detection accuracy of 93% via treating AD as a sequential decision issue. This structure demonstrates that log-based AD is effective in HPC settings and can identify suspicious or malicious users. However, the paper [24] presents X-Swarm, an adversarial DRL platform that generates metamorphic malware versions that may surpass sophisticated ATP protections. It solves the limits of RL and DRL algorithms beyond cybersecurity MDP complexity. By employing the Malicia dataset, X-Swarm increases the legitimate chance of malware, making ATP’s detection difficult. The system obfuscates malware versions using the PPO method. The metamorphic malware versions developed resemble the primary virus and avoid ATP detection. X-Swarm’s swarm assault simulation poses a significant threat to networks and highlights opportunities for cybersecurity improvement.

Additionally, the research in [25] aimed to enhance the control strategies of autonomous cars powered by DNN using an ARL framework. This research aims to analyze accident situations and model resilience by evaluating these rules across virtual highway driving scenarios with varying velocity limits. The findings demonstrate that the adversarial agent outperforms manual testing techniques and successfully exploits control rules. Wherein [26], RL algorithms improve IoT decision-making in IoBT twin sensor gateways. It offers an Intelligent Attack Detection System and Intelligent Dual Function Sensor Gateways to improve IoT network security and efficiency. Bayesian optimization optimizes IoBT decision thresholds. Thus, the research [27] employs sophisticated ML and DL to improve IoT IDS. It investigates the use of DRL techniques to adapt to the changing IoT environment and enhance IDS. The work utilizes Adversarial ML to evaluate IDS against threats, thereby improving IoT smart home security. The work [28] demonstrated the efficacy and competitiveness of the AE-RL model for IDS compared to more conventional classifiers. As AE-RL reduces false negatives and addresses imbalanced datasets, it shows promise in improving IDS. In another reference [29], the researchers concluded that the training modules were beneficial, as xenophobic views among young police officers decreased significantly over a four-year period. There was evidence that the dual-track bachelor’s degree had an effect since modifications to social desirability ratings were not explained by an increase in self-confidence. To assess the effectiveness of black-box attacks via [30], the research investigates the generation of adversarial instances against DNN models in NIDS. The NSL-KDD dataset trains and evaluates a DNN model, which performs well but is susceptible to adversarial attacks. This research [31] represents a Context-Adaptive IDS that utilizes DRL agents to accurately identify sophisticated attacks. The NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15, and AWID datasets showed improved accuracy and decreased FPR. In this study [32], the authors use RL, which enables an agent to go through trial and error, despite requiring a dataset with fault-tolerant distributed algorithms—in other words, it is not supervised. Since it would require a vast collection of pre-existing algorithms that manage the challenge, creating a set like this would be complicated and tedious.

Moreover, Ref. [33] represented a framework for adversarial learning that identifies systems to improve the accuracy of simulations. It builds a combination simulator with a state-action-dependent function to make models more expressive and demonstrates how to generalize it to acquire different motor abilities across tasks. With better task incentives in the target contexts, the suggested strategy surpassed baseline strategies in five of six domain-specific adaptation studies. The hybrid simulator works flawlessly when acquiring a wide range of motor skills.

However, the study in [34] developed a GAN-based framework to generate adversarial low-rate DDoS traffic, revealing that small perturbations can significantly weaken intrusion-detection systems. Using the Low-Rate DDoS 2022 dataset and a public Port Scan/Slowloris dataset, the authors evaluated several deep-learning IDS models against the generated adversarial traffic. The results showed a very high evasion success rate of approximately 99.9%, demonstrating the critical vulnerability of existing IDS models to adversarial low-rate DDoS attacks. Through [35], the researcher utilizes RL to reduce hostile botnet flow. Its unique botnet flows, generating architecture fools target detectors. It examines assault methods and introduces ML model evasion. The MCF Project, the IOST botnet dataset, and benign flows are used for training and testing in the experiment dataset. CNNs with manually specified features are used for DL and DT. With 40,000 flows trained, the agent discovered evasive variants, and 100,000 botnet and innocuous stream target predictions were correct [36]. This article builds upon previous work on RL models by examining ARL to enhance AI security [37]. The authors also cover the ground by comparing adversarial attack methods and defense mechanisms. It recommends further research and outlines the benefits and drawbacks of current approaches. They employ a CIFAR-10 dataset and a weighted probabilistic output model based on impact factors to forecast adversarial automated route-finding instances. Since the model produces probability outputs for input locations, the results show that agents interfere with pathfinding. Agent route planning is evaluated for perturbation effects utilizing the energy point, key point, path, and included angle. This work, as referenced in [38], examines adversarial policies within competitive simulation robots. Instead of working, adversarial policies exploit flaws in victim policies. Victims and settings have different victory rates. Victim policy networks vary in response to adversarial policies. The dimensionality of the observation space influences attack susceptibility. Feint-tuning protects victims against attackers. High-dimensional adversarial strategies outperform foundation agents in certain cases. Strong policies require an understanding of adversarial policies in competitive circumstances.

The paper [39] introduces the RADIAL-RL architecture for resilient DRL agents that rely on adversarial loss functions. When assessed on Atari games and MuJoCo tasks, RADIAL agents outperform other methods in terms of computing efficiency. Enthusiastic training improves both defense and generalization. Effective evaluation of agent performance against formidable opponents is achieved via GWC. Both RADIAL-DQN and RADIAL-A3C outperform baseline models on various tasks. Lastly, the study [40] provides an overview of a systematic approach to defense mechanisms that use ML and DL integrated into network applications to combat adversarial attacks.

B. Dataset-Oriented Studies

To start with [41], a MANifold and Decision boundary-based AE detection strategy for ML-based IDS is introduced in the paper as MANDA. The primary goal is to develop an efficient AE detector that can handle various AE attacks without requiring customization of each IDS model. This method relies on creating AEs in the issue space and mapping them to genuine network events. As noted in [42], the research made a significant contribution to cybersecurity across IoT systems by demonstrating that supervised learning models can effectively identify and categorize actions occurring in IoT networks. In another reference [43], authors aimed to find new types of intrusions, decrease the number of false alarms, and increase the accuracy of IDS by using various ML and DL techniques, for the accuracy of intrusion detection and prevention decisions. The research [44] looks at how conventional NIDSs may be hacked by malicious actors utilizing ML approaches. Study findings highlight the need for robust safeguards in cybersecurity by examining the impact of perturbation approaches on the performance of NIDS. Meanwhile, Ref. [45] develops and validates a hybrid feature selection technique for IoT ecosystem ML-based IDS. The IoTID20 dataset, Weka Tool, and Python are used to reduce false alarm rates and training time complexity through dimensionality reduction, thereby improving AD performance. The suggested system selects important characteristics based on entropy to enhance detection accuracy. ANN, KNN, and Ensemble classifiers with majority voting are employed to assess the hybrid feature selection strategy. The suggested model outperforms current accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-measure techniques. The research offers insights into improving IDS effectiveness in IoT contexts via unique feature selection and employs ML methods.

To address data scarcity and imbalance, the study [46] presents an innovative model for NIDS that integrates DRL with statistical approaches. Generative models and neural networks are employed to address these challenges. Improving accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score in detecting NIDS, the model outperforms current IDSs using LR and SVM classifiers when applied to the NSL-KDD dataset. In particular, the findings demonstrate that the proposed method enhances IDS skills, even when training data are scarce. Via [47], the authors aim to improve detection rates for unknown attacks by introducing the SAVAER-DNN model, which is focused on NIDS. The model is trained and evaluated on the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets, demonstrating that it outperforms the most recent and advanced IDS techniques. Total accuracy, detection rates, and F1 scores are all improved by SAVAER-DNN, which uses data augmentation methods to produce unexpected assault samples. Using ROC curves and AUC values, the model performs quite well in detecting network cyber threats. Lastly, this research [48] evaluates the effectiveness of ML-based IDS in protecting IoT networks from malicious attacks. It uses the Bot-IoT, Kitsune, and CIFAR-10 datasets to evaluate ML-based security solutions. This research utilizes a CVNN model to identify devices in IoT networks and finds that repeated attack strategies are more effective than one-step attacks, as they can fool ML-based DIS models. We also illustrate how adversarial attacks may degrade the efficacy of SVM, DT, and RF classifications. The LSTM-CNN model exhibits improved robustness after AT and model distillation and is resilient to various evasion attacks.

C. Application Domain

The authors, as cited in [49], emphasize RL’s potential for improving road safety and cybersecurity, highlighting its accuracy, flexibility, and efficiency. In [50], researchers proposed a Boost-Defense system based on the AdaBoost technique, which demonstrated excellent classification performance on various datasets. Confusion matrix evaluation was conducted on this network layer dataset to demonstrate the model’s performance. Compared to current research models, the suggested Boost-Defense system outperformed them in terms of accurate classification and error rates. Wherein [51], the study focuses on detecting diverse types of attacks, including direct-resource-topology, indirect-resource-topology, sub-optimization-topology, and isolation-topology attacks. The research [52] emphasized the necessity of testing ML models for worst-case situations and adversarial resistance rather than relying exclusively on standard measures such as accuracy. Adversarial attacks may significantly impact the efficiency and safety of ML models used in neural networking applications, demanding the development of effective response measures. Through [53], authors employ SE-based intrusion detection design and architecture to improve IoT cybersecurity. Cyberattacks are detected using powerful ML methods. The algorithms are trained and evaluated using the AWID and CICIDS datasets, resulting in identification rates of 75.0% to 99.0%. According to the research, DL methods like CNN and SVM may enhance IoT security. Overall, the study sheds light on how ML might address IoT cyber risks. The research [54] also suggests a VANET IDPS architecture in edge computing driven by RL to improve the accuracy and processing efficiency of IDS and preventive decisions. Due to the scarcity of training data for VANETs, it is recommended to utilize a GAN to generate training data from existing attack data. By incorporating RL into IDPS decision-making, system effectiveness and planning policy are enhanced. The present instance demonstrates how the suggested architecture works in VANET IDPS at the network’s edge, proving its worth in improving transportation system security. To enhance the dependability and safety of autonomous cars, this method emphasizes the importance of using ARL to identify instances of failure in targeted models and to understand the limitations of deep control strategies. The study employs MATLAB 2020b’s predictive model to apply ML for UAV-IDS via [55]. For UAV communication networks and cyberattacks/IDS, the research uses the UAV-IDS-2020 dataset. Wi-Fi traffic logs with binary output labels for regular and abnormal UAV operations are encrypted. A shallow ConvNet is used for training, testing, and tuning. Experimental findings show 90%–100% detection accuracy for various UAV communication modalities. The model can identify breaches in UAV communication networks, demonstrating its potential to enhance cybersecurity. The study in [56] employs DL to detect electricity theft. To enhance threat identification, it analyzes evasion attacks on detection models and proposes countermeasures. ML-based models for power theft detection are trained and evaluated using data collected from intelligent meters. 69,680 harmless samples were generated during testing and training from 130 consumer readings. Power theft detectors on a global scale are taught to identify theft using DRL models such as DQN and Double Deep Q-Networks (DDQN). The models use FFNN, CNN, and GRU neural network architectures to get higher performance. AT makes power theft detection systems more resilient to evasion attacks. The proposed defensive strategy enhances performance, increases assault success rates, and improves detector accuracy. Lastly, authors within [57] delve into the use of DRL techniques for cyber defense, specifically in addressing difficulties with IDS. Improving cybersecurity techniques is the goal of this investigation on Model-Based DRL methodologies’ capabilities. This research examines the effectiveness of Host-IDS in mitigating multiple types of cyberattacks using datasets specific to Windows. A hybrid DL model enhances IDS in large data settings, combining DL methods with IDS. With the hybrid model exhibiting encouraging results in identifying and mitigating cyber threats, the findings reveal that DRL approaches are effective in enhancing cybersecurity measures. The research indicates that DRL algorithms have the potential to enhance IDS and cybersecurity measures.

3.2 Critical Analysis of Past Studies

The latest studies at ARL-NIDS indicate a promising, albeit fragmented, array of strategies to increase detection accuracy, flexibility, and resistance in hostile environments. Early contributions, for instance, the studies [28,35] demonstrated the feasibility of RL within IDS, while later works introduced AT to harden models against disturbances and new threats [30,39]. Thus, numerous studies have proposed innovative algorithms, ranging from multi-armed bandit models [19] and LSTM-based multi-agent RL [21] to hierarchical and DRL frameworks [56,58], to enhance adaptability and robustness. Additionally, various works have integrated ARL into specific domains, such as IoT [27,51], vehicle and edge computing [54], UAV safety [55], and smart grid systems [46], demonstrating context-aware performance improvements. However, a recurring challenge identified in these studies is the limited generalization and robustness of models: they often outperform reference datasets such as NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, and IoTID20 [42,45,46], which provide high accuracy in controlled settings but degrade performance under realistic adversarial perturbations. Furthermore, while adversarial DRL approaches such as [22,25] perform sophisticated defense and attack simulations, their computational complexity and lack of interpretability hinder real-time implementation. Even though the review [48] further emphasizes the absence of standardized evaluation metrics and defense-aware RL training strategies. In summary, while ARL-based NIDS research has demonstrated significant conceptual and technological advances, it remains hindered by scalability issues, dataset bias, and the need for robust, interpretable, and trustworthy mechanisms that can withstand dynamic and adversarial network environments.

4 Methodology of ARL-NIDS Approach

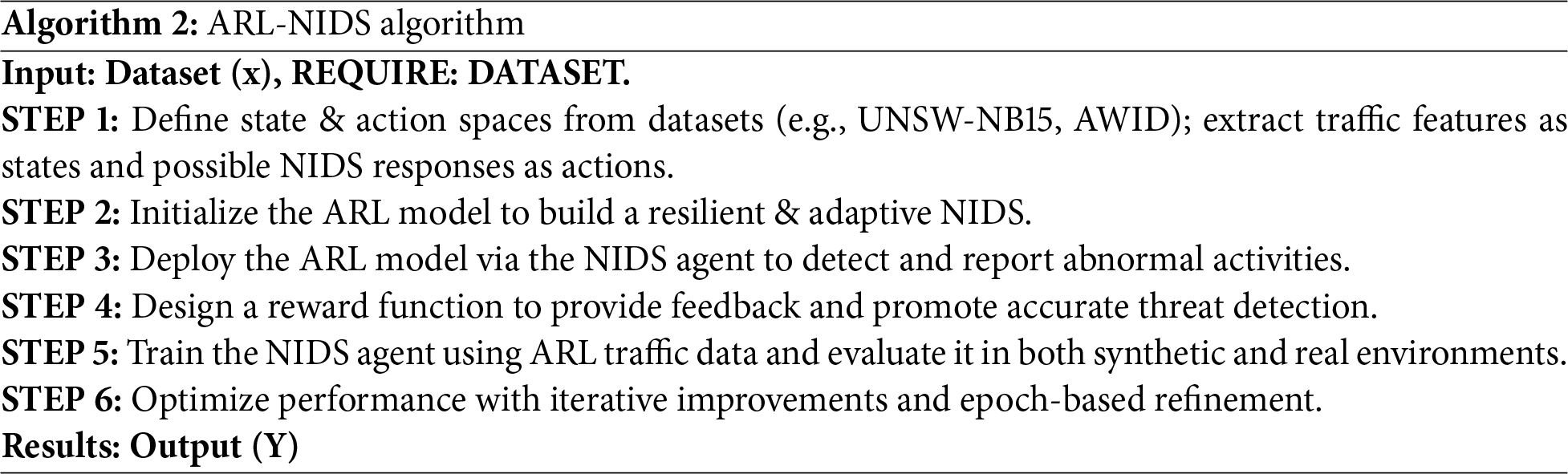

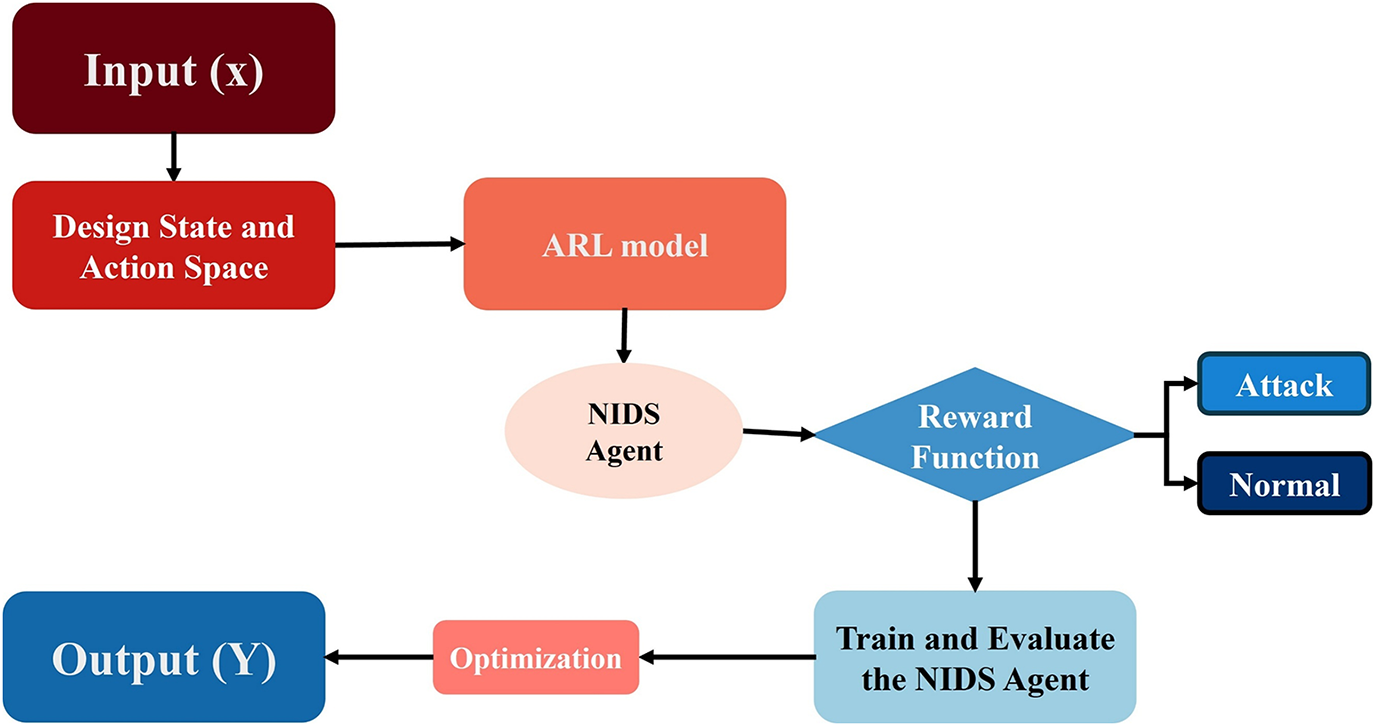

To start with, the ARL-NIDS comparative method segment, ARL is a branch of RL that could address varied conditions in which the agent encounters adversaries or opponents actively seeking to obstruct its development or take advantage of weaknesses, in addition to boundaries in its decision-making framework. The aim is to research robust policies that can withstand antagonistic assaults or disturbances. The following section outlines the conceptual framework of ARL-NIDS for detecting malicious and unusual activities. Furthermore, ARL-NIDS may appoint RL models based on the detection of malicious and peculiar activities. Moreover, ARL-NIDS involves various key steps to ensure its effectiveness and robustness in detecting and mitigating cyber threats. Thus, Algorithm 2 illustrates the overall ARL-NIDS algorithm. Additionally, Algorithm 2 guides the construction of an ARL-NIDS framework that can enhance community defenses. ARL-NIDS, the generalized structure, is represented in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: General ARL-NIDS architecture; the following architecture illustrates the generic approach for ARL-NIDS

Fig. 12 illustrates the process of selecting data for the ARL-NIDS model, which enhances NIDS by training it to identify and respond to attacks in network traffic. The NIDS agent finds unusual activities, and the reward function checks the agent’s actions to label them as either normal or an attack. This feedback trains and evaluates the NIDS agents to enhance security detection. We have twelve evaluation metrics to measure performance, including accuracy, F1-score, recall, FPR, True Negative Rate (TNR), log loss, precision, ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, confusion matrix, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), and Cohen’s Kappa. We optimize results through epochs of training rounds, during which the model learns from its experiences. ARL aims to achieve the best behavior in decision-making tasks.

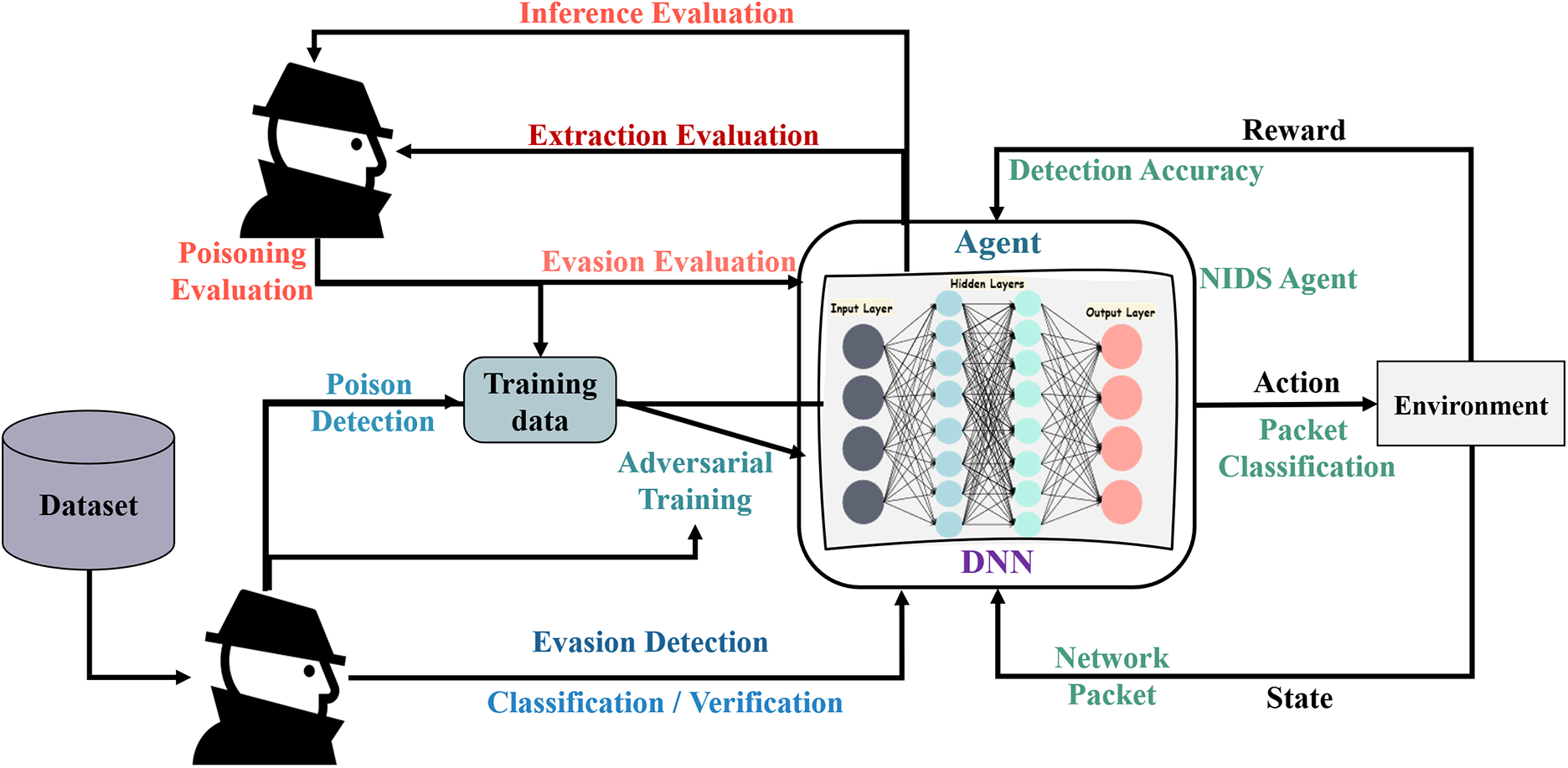

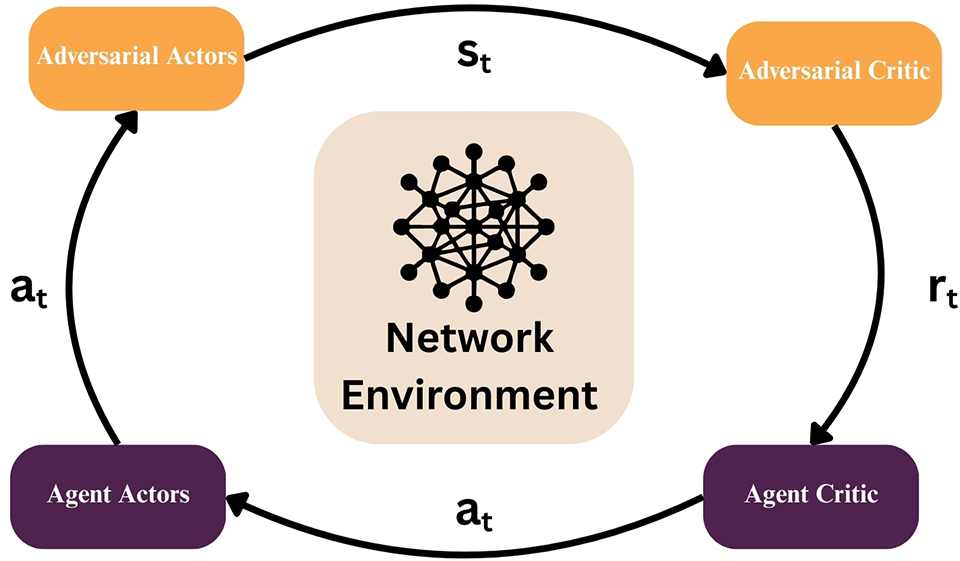

To consider the hostile character of the environment via ARL, while an opponent influences the environment, it might be necessary to adapt the Bellman equation. However, the approaches for overtly or implicitly modeling the adversary’s activities, among other aspects associated with identifying ARL issues, may dictate how the Bellman equation remains adjusted. Fig. 13 illustrates ARL-NIDS, which involves unfavorable threats and defenses, where the system is trained on network traffic and evaluated against various adverse dangers. Attackers can try poisoning, theft, or extraction, which is countered through poison detection, negative training, and verification. This framework process remains flexible by maintaining a reliable classification performance during the input, RL process, and attacks of the IDs. Furthermore, Fig. 14 illustrates a conceptual framework for ARL-NIDS. It integrates adversarial components, namely the Adversarial Actor and Adversarial Critic, with an agent responsible for packet classification.

Figure 13: General ARL-NIDS combining adversarial threats & defenses

Figure 14: Overall, ARL-NIDS process

The opponent manipulates the agent’s input or reward signal to create ideal yet challenging circumstances, thereby enhancing the agent’s flexibility in responding to complex attacks. The agent interacts with the environment by classifying network packets and assessing its detection accuracy, which adversarial critics then evaluate. This cyclical engagement fosters adaptive learning and flexibility in intrusion detection.

Q-Learning Update with Adversarial Perturbation: The Formula (11) extends RL to adversarial IDS by modifying Q-learning updates under adversarial settings. This equation also updates the RL action-value function. It calculates the cumulative payoff for the activity

Adversarial Perturbation of States: Formula (12) illustrates how the attacker disrupts the state to deceive the IDS. Adversarial actors create δ, which alters observable traffic properties before the data reaches the agent. This is evident in the picture, where Adversarial Actors move into the Network Environment, injecting adversarial samples [34].

Policy Gradient with Advantage Function: Actor update rule in an actor-critic method. The agent adjusts its policy parameters to enhance action selection in the face of hostile influence.

Adversarial Reward Shaping: The reward function is reshaped by adversarial influence, where

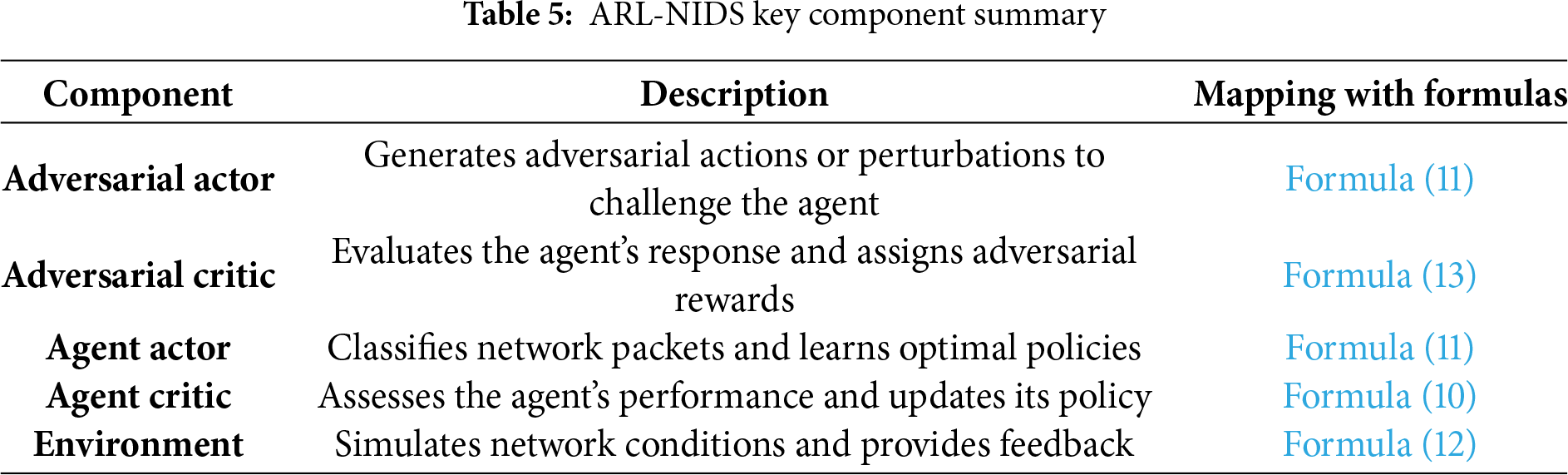

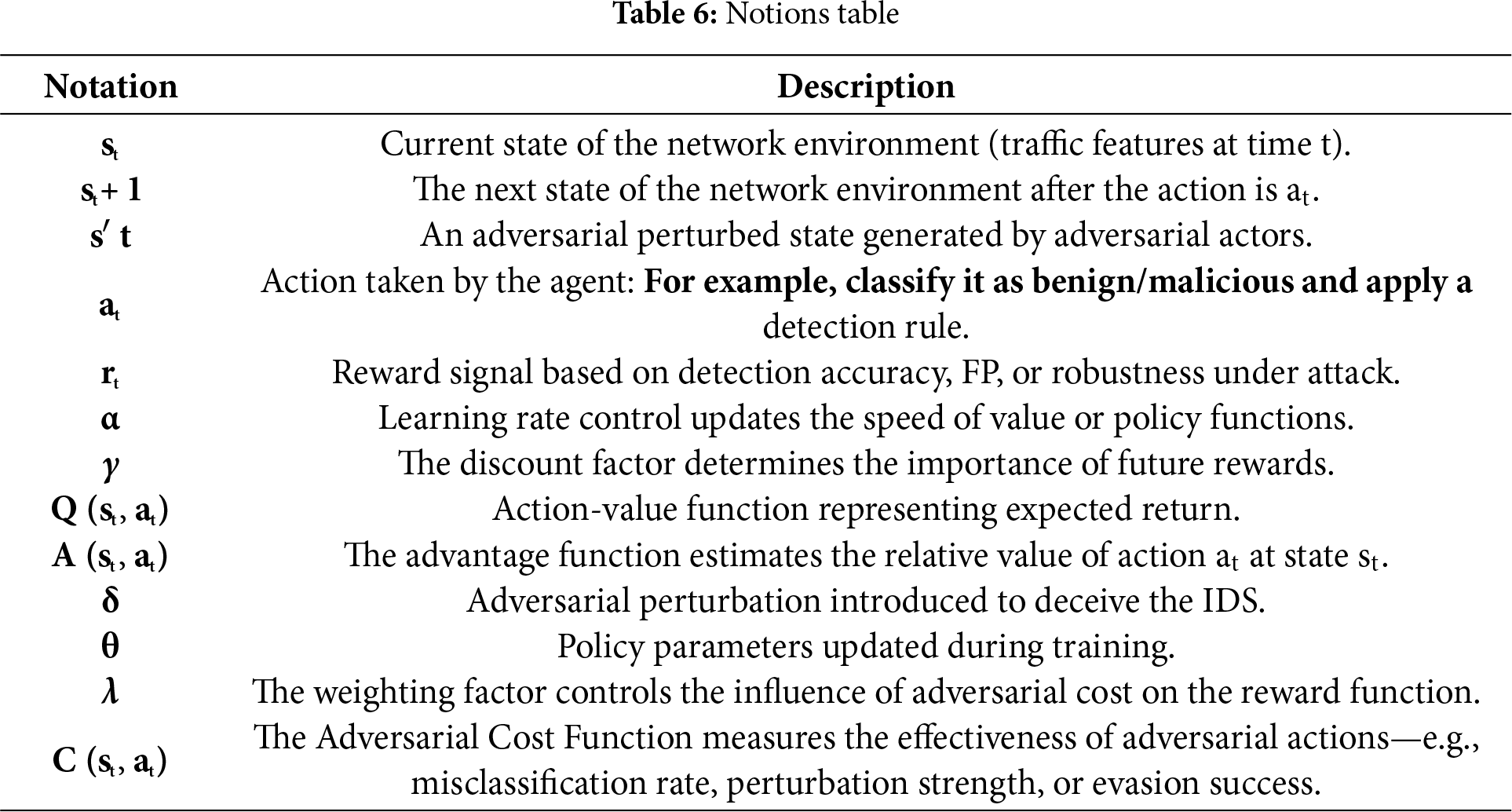

Table 5 provides a summary of the key components of ARL-NIDS, mapping each component to its corresponding formula and components. To clarify the significance of each term used in the formulas, Table 6 explains each term mentioned.

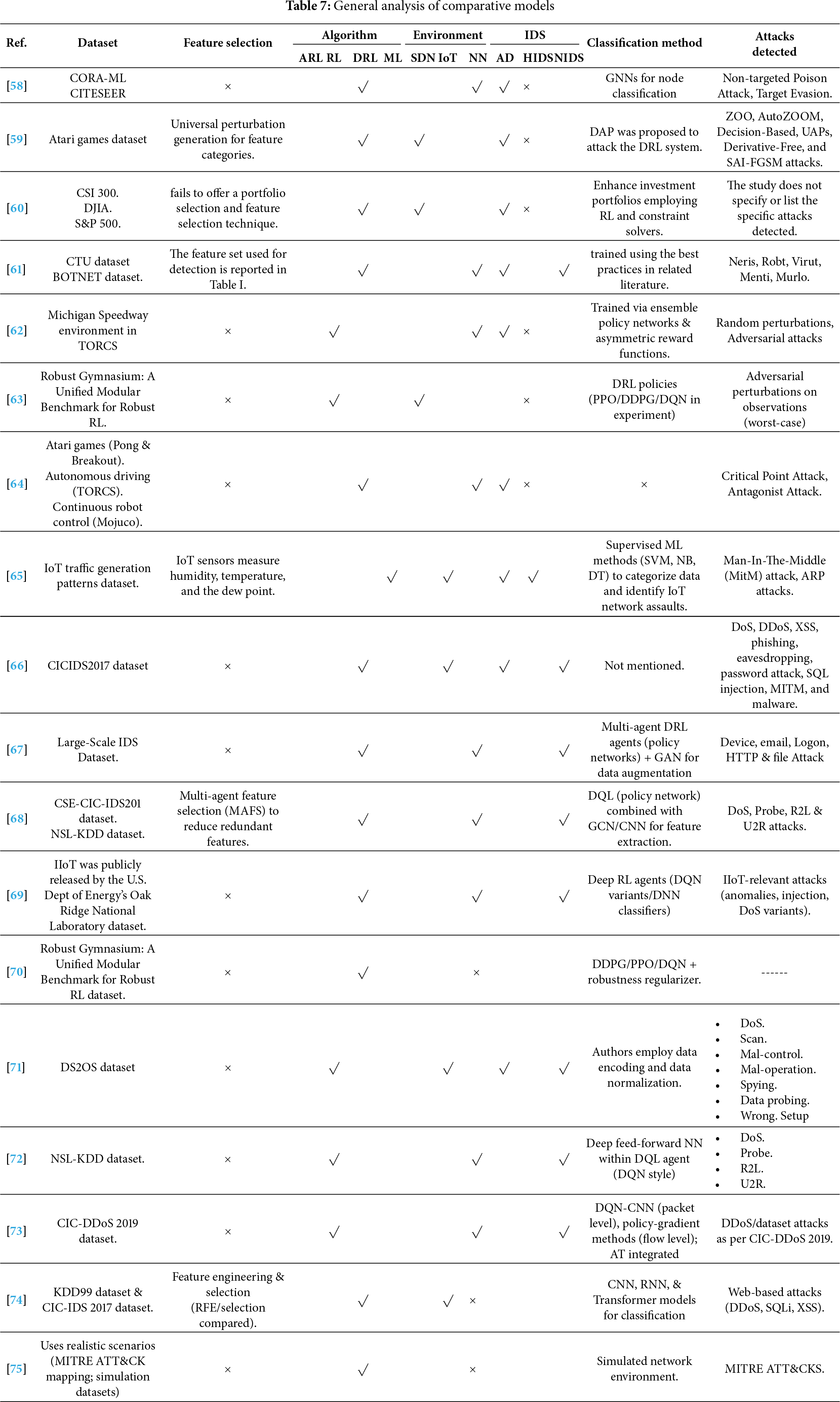

Table 7 examines the most recent studies that utilize diverse AI models, including RL, ML, and DRL, in various environments. Thus, it summarizes the most common models, environments, and IDS. In addition, the table also explores the latest dataset employed and the novel techniques. Lastly, the attacks detected in previous studies are listed in the table.

In short, the methodology and recent advancements demonstrate the growing integration of reinforcement learning with AD in next-generation networked environments. Research authors [76] employ DDQN for AD in Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), emphasizing RL’s importance in managing complex and dynamic conditions. Moreover, the authors in [77] apply DRL to business process automation, highlighting data efficiency and weak supervision as essential design factors. Similarly, a privacy-enhanced DRL-based IDS tailored for CPS, which balances detection accuracy with confidentiality, was developed in [78]. Thus, in [79], to balance an imbalanced dataset, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) algorithm is employed to enhance detection fidelity. Regarding the RL framework that integrates oversampling and undersampling strategies to address dataset imbalance issues common in intrusion detection, a proposal is made. However, to balance an imbalanced dataset, the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) algorithm must be employed before training models. Collectively, these works reinforce that NIDS are an appropriate application area for ARL, as they must operate in adversarial settings, adapt to evolving threats, and ensure robust detection across diverse and imbalanced datasets. This positions ARL-NIDS as a promising methodology for achieving adaptive, resilient, and intelligent cybersecurity defenses.

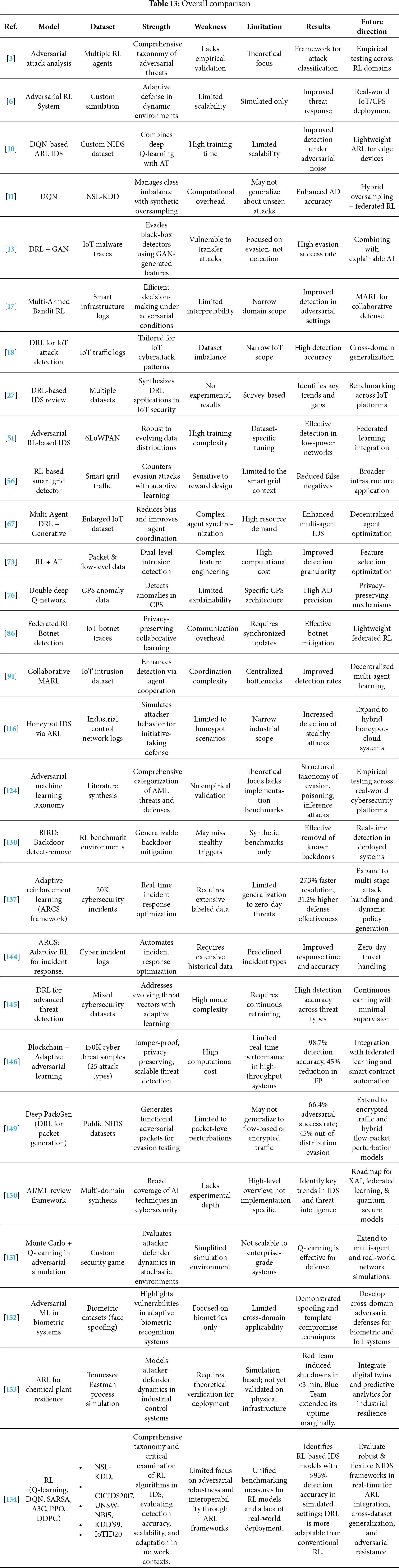

5 Comparative Analysis Results

To begin with, the comparative analysis and discussion section illustrates the results of this unique survey study. This research focused on the ARL-NIDS approach to detecting malicious and abnormal activities, which will be discussed within the current section. The objective is to synthesize earlier research, highlight methodological variations, and assess algorithms, datasets, and settings across the literature. Analysis of the latest applications, dataset selection, ARL within various algorithms, extensions, datasets, cybersecurity risks, security challenges, overall comparison, and analysis and discussion. This current section delves into the following:

A. ARL-NIDS Applications

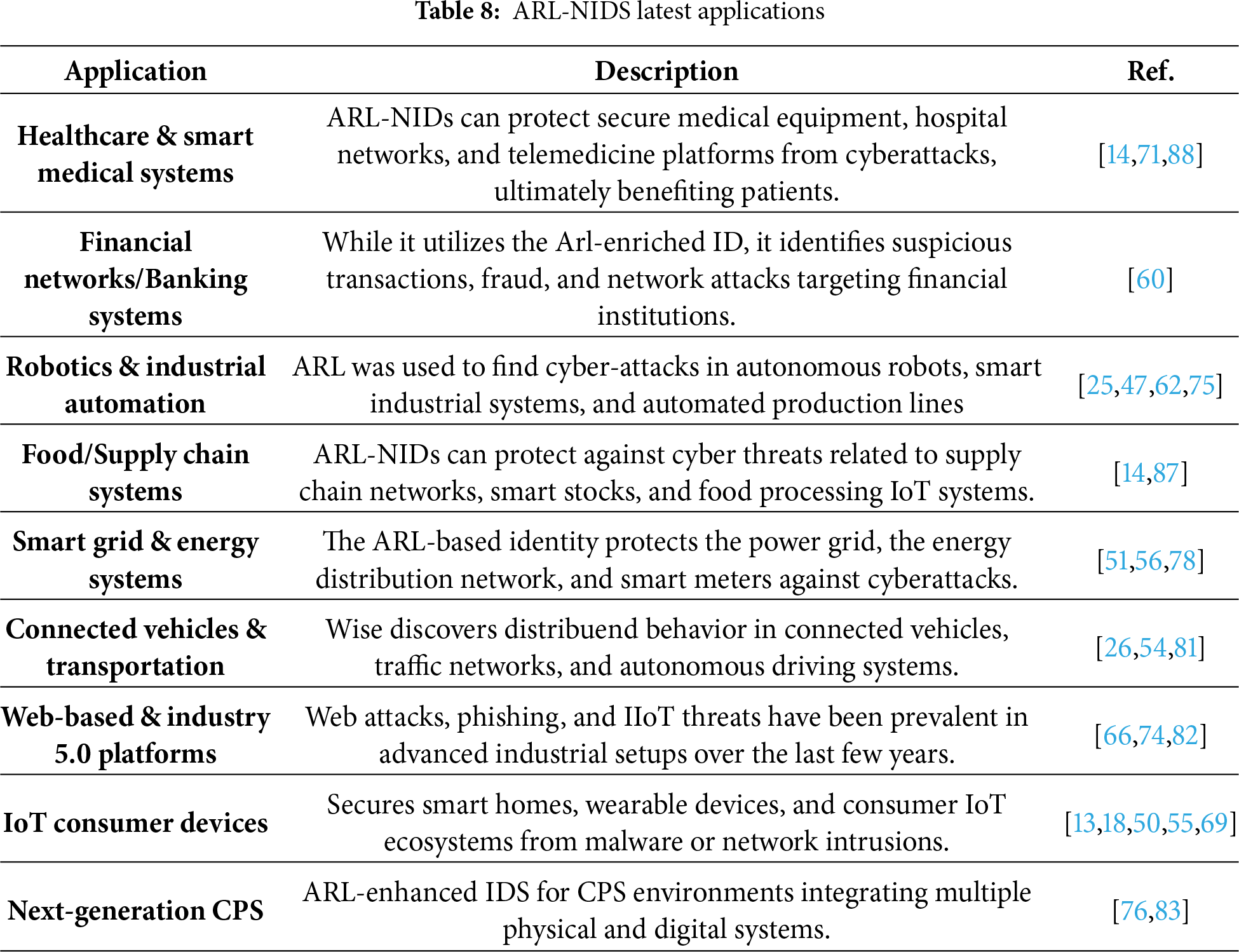

The increasing complexity of cyber threats in modern digital ecosystems has catalyzed the development of intelligent ID mechanisms. ARL has emerged as a promising paradigm that enables adaptive and flexible NIDS. By integrating side effects that mimic malicious behavior, the ARL framework enhances the model’s detection capabilities in response to evolving attacks. Recently, literature reflected a rejection in various domains, including CPS, IIoT, smart health services, and web safety. These systems benefit from the dynamic learning of optimal defense strategies for DRL architecture, improve the accuracy of nonconformities, and treat adverse disorders. Recent progress in ARL-NIDS has shown its versatility and efficiency in addressing real-world challenges. For instance, ref. [76] proposed a DDQN framework for ED in the next generation of CPS, demonstrating increased adaptability in dynamic environments. Business process AD has also benefited from ARL, as demonstrated by [77], who employed weakly supervised learning to improve data efficiency. Similarly, an ARL model introduced privacy protection within [78] ID, addressing data privacy, a significant concern in sensitive infrastructure, while Ref. [79] focused on convenience choice using DRL to adapt performance for detection. Healthcare and vehicular systems are emerging frontiers for ARL-NIDS. The RL for NIDS utilizes the CSE-CIC-IDS2018 and NSL-KDD datasets, as discussed in [80]. Whereas ref. [81] addressed the coexistence of anomalies in intelligent connected vehicles using RL-based data validity analysis, regarding the oversampling and undersampling discussed to balance unbalanced datasets via RL and DRL. Regarding UAVs and vehicles, for data validity in RL and DRL, as mentioned in [82], the authors define a driving style that’s appropriate for a quantitative model. In another context, both studies [83,84] employ RL and DRL in cybersecurity and network security to counter adversarial attack simulations. For IoT environments, it is vital to implement robust cybersecurity frameworks that can help mitigate cyberattacks within IoT layers. However, scientists in [85,86] explore IDS and botnets for RL within the IoT environment. In industrial contexts, the study used [87] the dynamic reward mechanism and the main component analysis to detect IIOT attacks. Thus, in [88], an adaptive RL model for secure routing in smart healthcare is developed. These applications underscore the growing significance of ARL in safeguarding heterogeneous and mission-critical systems. The study [89] seeks to leverage DRL in conjunction with IDS within an IoT context to detect evolving threats and enhance the complexity of detection. Wherein [90], authors introduce a novel approach for computing a policy for prioritizing alerts using ARL. Due to multi-agent RL, authors in [91,92] employ minor and major RL for IDS to enhance both centralized and decentralized approaches based on the NSL-KDD dataset. Regarding the hybrid approach and multi-class network, DRL is employed within NIDS in [93]. Also, authors train GANs with the NSL-KDD dataset. Furthermore, the multi-agent adversarial detection is employed via TL in [94]. Also, the NIDS was employed to detect anomalies against evasion attacks. However, Table 8 provides an overview of the latest applications of ARL-NIDS, including brief details.

B. ARL-NIDS within Various Models

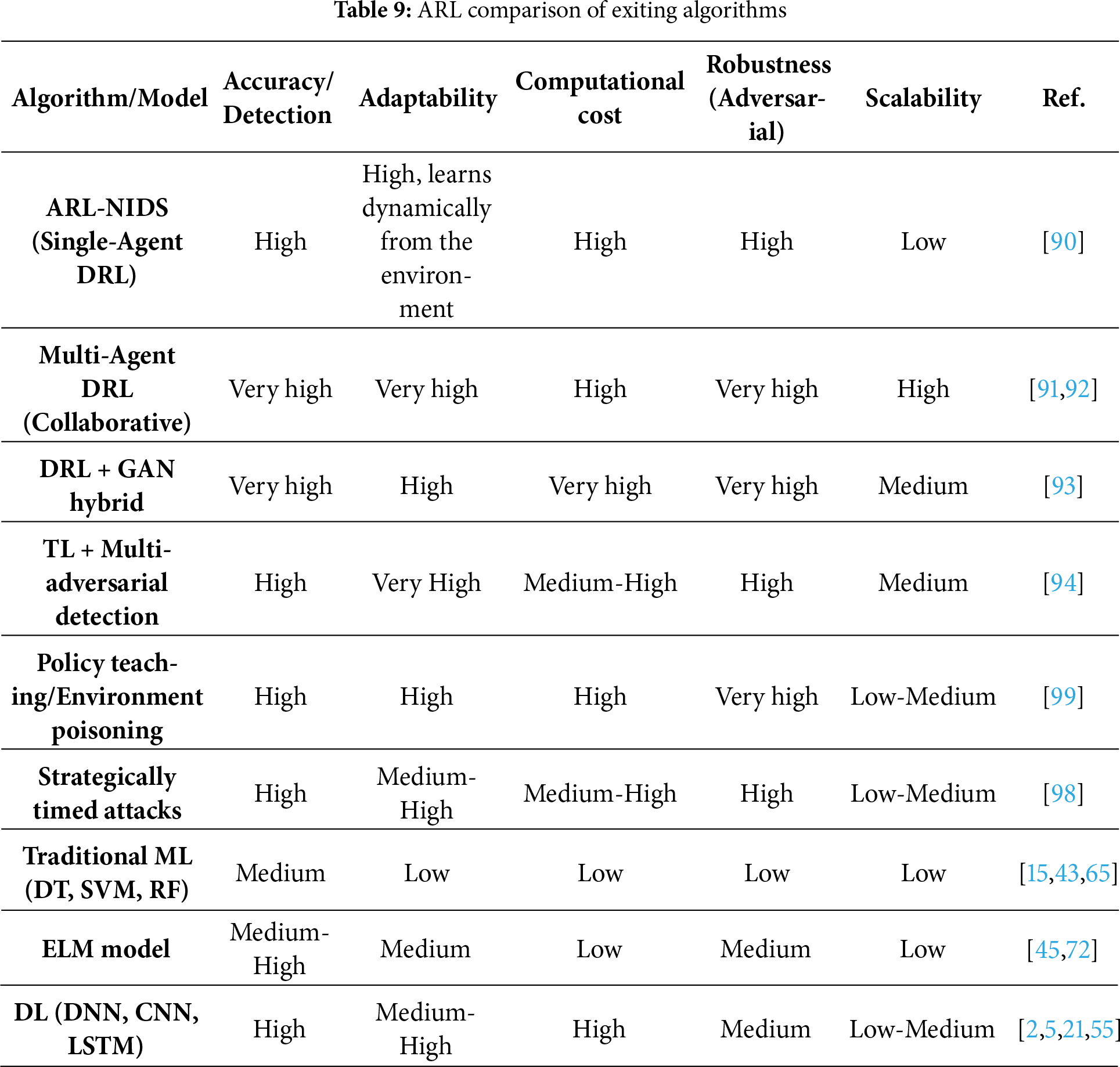

Depending on the ARL algorithm, the sub-section compares ARL with other algorithms and approaches. Table 9 explores the ARL comparison with existing algorithms/models. RL and side effects are used to identify complex and dynamic cyber threats, such as ARL-NIDS and advanced network security approaches. It contradicts traditional IDS models, signature-based IDS, and traditional ML approaches such as Decision Tree (DT), SVM, and Random Forests (RF). However, ARL-NIDS dynamically adjusts the optimal defense strategies through interactions with the network environment, utilizes multi-agent DRL for cooperative advertising, and optimizes the defense strategies in response to unfortunate attacks. Latest research has advanced ARL-NIDS by incorporating hybrid models that integrate methodologies such as GANs for data augmentation and TL for multi-adversarial detection. The mentioned methodologies enable ARL-NIDS to proactively detect abnormalities in complex network contexts, including IoT, IIoT, and CPS, even in the presence of advanced evasion or stealth attacks [95]. ARL-NIDS offers a substantial advantage in terms of flexibility, robustness, and predictive performance compared to traditional IDS frameworks [96]. Traditional monitored models rely on labeled datasets and often struggle against new attacks. ARL-NIDs continuously refine their guidelines through RL, enabling them to predict and counteract the dangers that are already unacceptable [97]. However, the Hybrid ARL-NIDS architecture intersects with GAN or multi-agent collaboration traditional DL-based NIDs in detecting stolen attacks [93,98]. However, sophisticated systems often require multiple processing resources and careful adjustments to reward features, ensuring stability and preventing overheating. Despite these obstacles, ARL-NIDs demonstrate increased flexibility in enemy contexts compared to traditional ML models, providing an active security solution rather than a reactive one. Furthermore, the training time and policy teaching for adversarial attacks against RL algorithms, as presented in [99]. In [100], authors employ RL for an autonomous defense approach for software-defined networks.

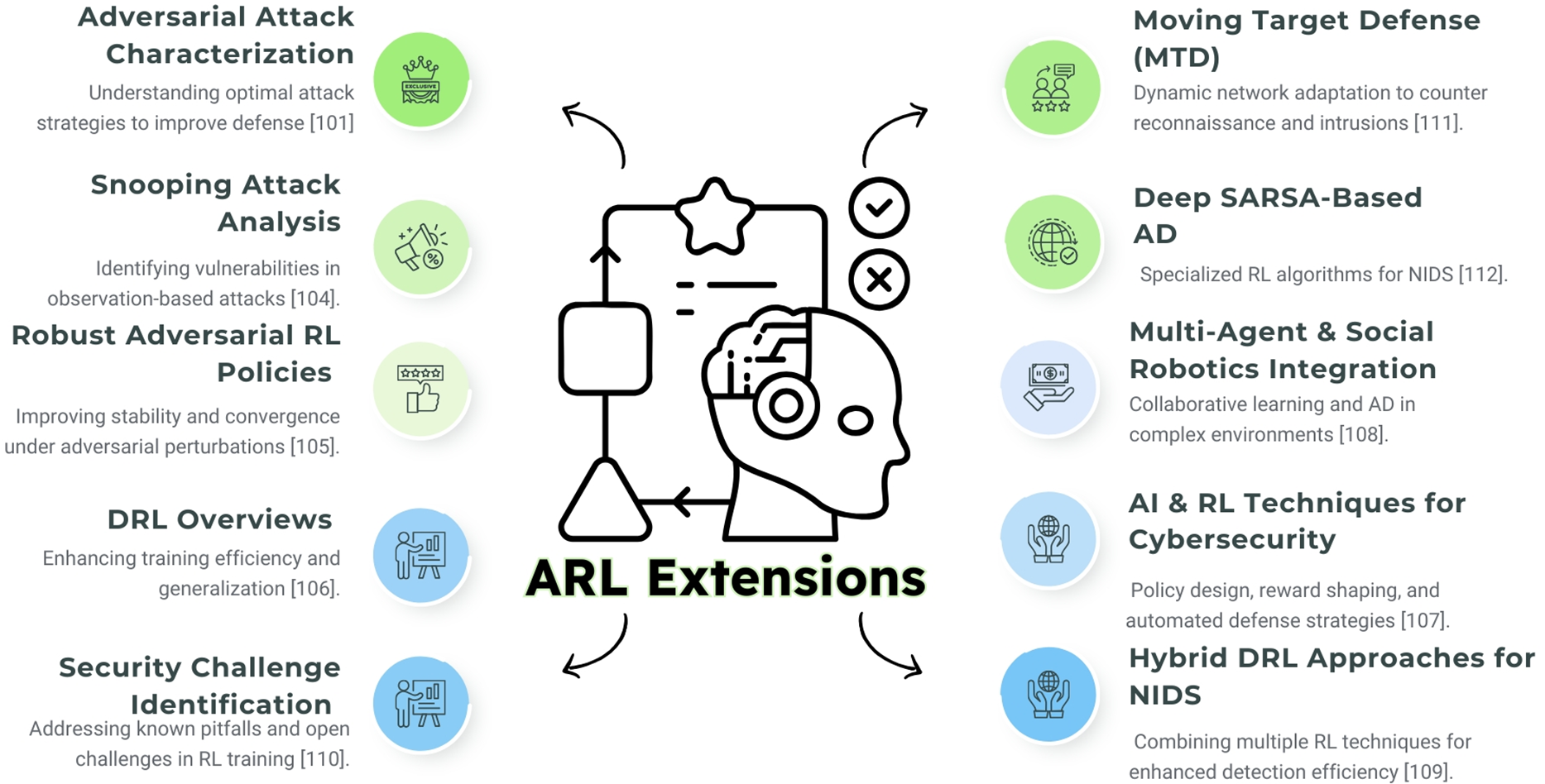

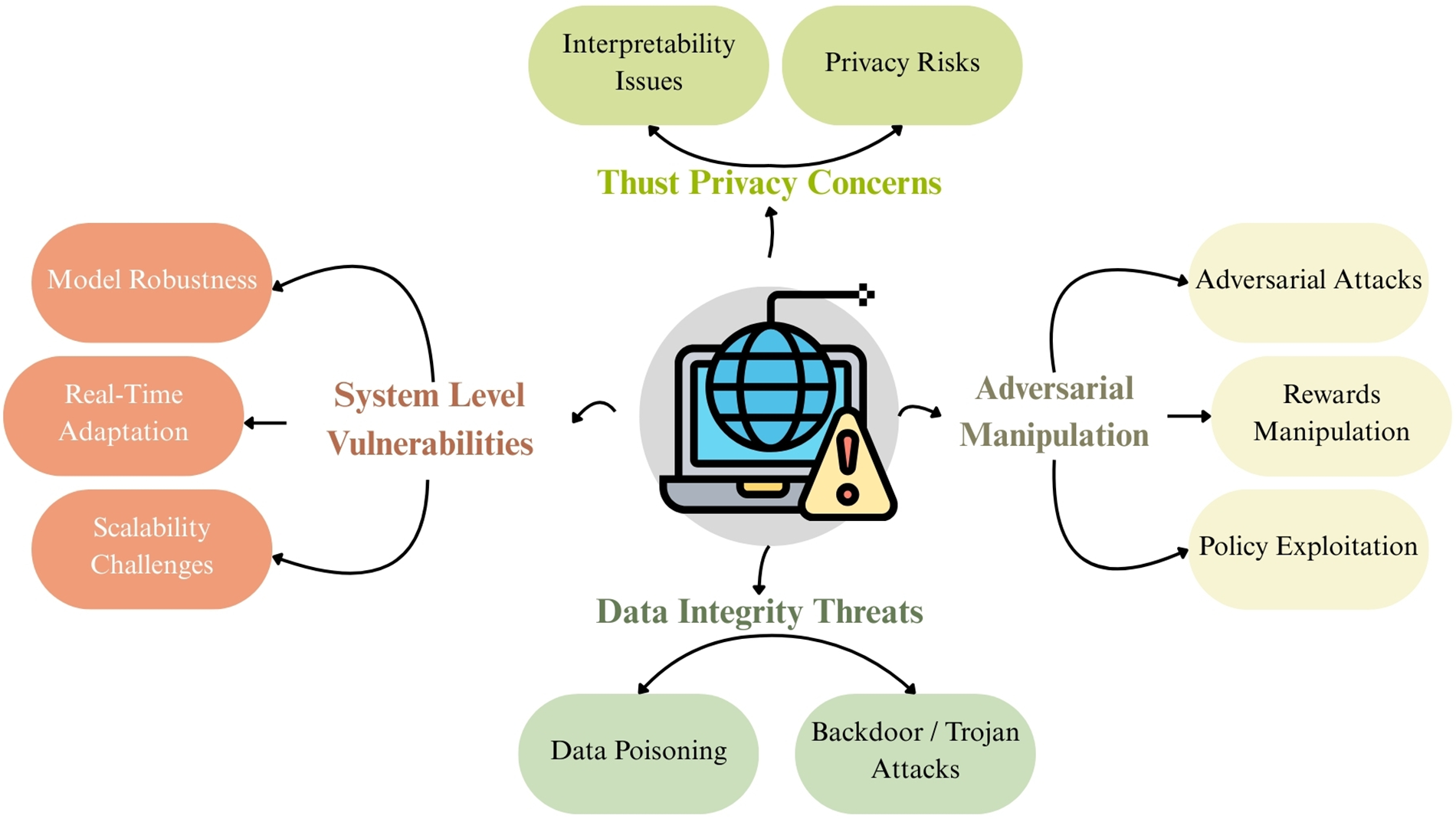

C. ARL-NIDS Extensions

ARL-NIDS has demonstrated significant dynamic detection capabilities, reducing the incidence of cyberattacks in network environments. However, as with sophisticated AI systems, they are receptive to new attack strategies and operational challenges. Recent research has focused on expanding ARL-NIDS to enhance its strength, adaptability, and overall efficiency in real-world applications. These extensions benefit from insights into unfavorable attacks, AD, social robotics, and moving goal defense to improve the ARL system’s identity ability and flexibility [101]. Fig. 15 identifies the ARL extensions used to acquire knowledge & improve efficiency. Various approaches have been proposed to extend the classical ARL-NIDS framework. Malicious attack characterization and optimal adversarial approaches allow ARL models to anticipate and defend against sophisticated threats, improving the stability and convergence of RL policies [102]. Recent extensions of ARL have significantly strengthened its theoretical foundations and expanded its applicability in security-critical domains. During [103], the authors formalized optimal attack strategies against RL policies, exposing vulnerabilities in well-trained agents by leveraging policy structures. However, in [104], snooping attacks are introduced, in which adversaries deduce the internal states or decision patterns of DRL agents, highlighting the dangers of information leakage during deployment. Thus, robust ARL’s stability and convergence characteristics in linear quadratic systems provide the mathematical assurances necessary for secure incorporation into control systems, as examined in the study [105].

Figure 15: Latest ARL extensions: employing ARL extensions to acquire knowledge & improve efficiency [101, 104–112]

DRL overviews outline strategies for enhancing training effectiveness and making policies more generalizable in dynamic network settings [106]. Beyond that, various technical insights offer a detailed look at AI-driven cybersecurity policies, demonstrating how ARL can be employed to develop initiative-taking defense systems in dynamic threat environments [107]. All these works extend ARL beyond simply reacting to obstacles. They also transfer toward strategic foresight, system-level resilience, and formal assurance. Moreover, research has investigated the integration of ARL with social robotics methodologies, enabling systems to collectively acquire knowledge from various agents and environmental feedback, thereby enhancing AD in complex network architectures [108]. Deep Sarsa and hybrid approaches are indicative of DRL algorithms that can be applied in the real world to detect network problems, even when attackers attempt to conceal them [109,110].

When used in conjunction with ARL, Moving Target Defense (MTD) aims to make it challenging for intruders to access a network, thereby complicating their ability to navigate it [111]. Research has identified the open security weaknesses and potential challenges associated with RL training, emphasizing the requirement for flexible side effects [110,112]. ARL enhances conventional RL by incorporating adversarial dynamics that simulate hostile or uncertain environments. This makes the system more robust and adaptable. In reference [113], the authors analyze cascaded fuzzy reward methodologies for robotic path planning in textiles. ARL could improve frameworks by training agents to operate under adversarial perturbations or dynamic constraints, thereby augmenting resilience in practical applications. Likewise, the research in [114] demonstrates how RL can mitigate DoS attacks in smart grids. By treating attackers as adversarial agents, the ARL approach may enhance this phenomenon. This informs defenders on how to respond when threats evolve. However, a DRL is employed through various functions of IDS in [115]. Furthermore, the train DRL utilizing the NSL-KDD dataset further evaluates the performance with several adversarial attacks. These add-ons make ARL a valuable tool for creating intelligent systems that function effectively, are secure, and can effectively manage issues even in the presence of threats. The ARL-NIDS extensions aim to enhance flexibility, resilience, and operational effectiveness in response to advanced cyber threats. By integrating unfavorable training, approaches for detecting collaboration with various agents, robust target rescue, and refined deviations, ARL-NIDS can achieve a height of active danger restriction. These extensions strengthen system performance and provide a framework for future research on AI-driven cybersecurity solutions.

D. ARL-NIDS Datasets

Regarding the widespread improvements of IDS, which potentially impact the growth of RL algorithms in the cybersecurity sector. Traditional IDS strategies often struggle to manage the evolving and adaptive characteristics of contemporary cyberattacks. DRL is a promising approach to enhancing the IDS because it can continually learn and adapt. In [116], the author examines how side effects can compromise DRL-based IDS agents by introducing micro-disorders in the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) and Basic Iterative Method (BIM) network traffic. Their findings highlight the fragility of the DRL model when exposed to unfortunate examples and emphasize the need for a dataset that includes such clear patterns to evaluate the strength of ID. In contrast, the study [117] proposes an active defense mechanism that utilizes the Arl-promoted honeypot system integrated into the industrial control network. Their model simulates unfavorable conditions within an MDP structure, enabling the agent to learn the behavior of complex attacks and enhance accuracy against DDO’s variants, such as NetBIOS and LDAP. The system performs well on unbalanced data sets, suggesting that synthetic and unfavorably rich data is required to train and validate such models. However, DRL-based IDS is highly efficient and heavily depends on the quality and properties of the dataset used for training and evaluation. Side effects for AD and NIDS, as well as recent studies in DRL, have emphasized the significant role of diverse datasets in evaluating the strength and adaptability of the algorithm.

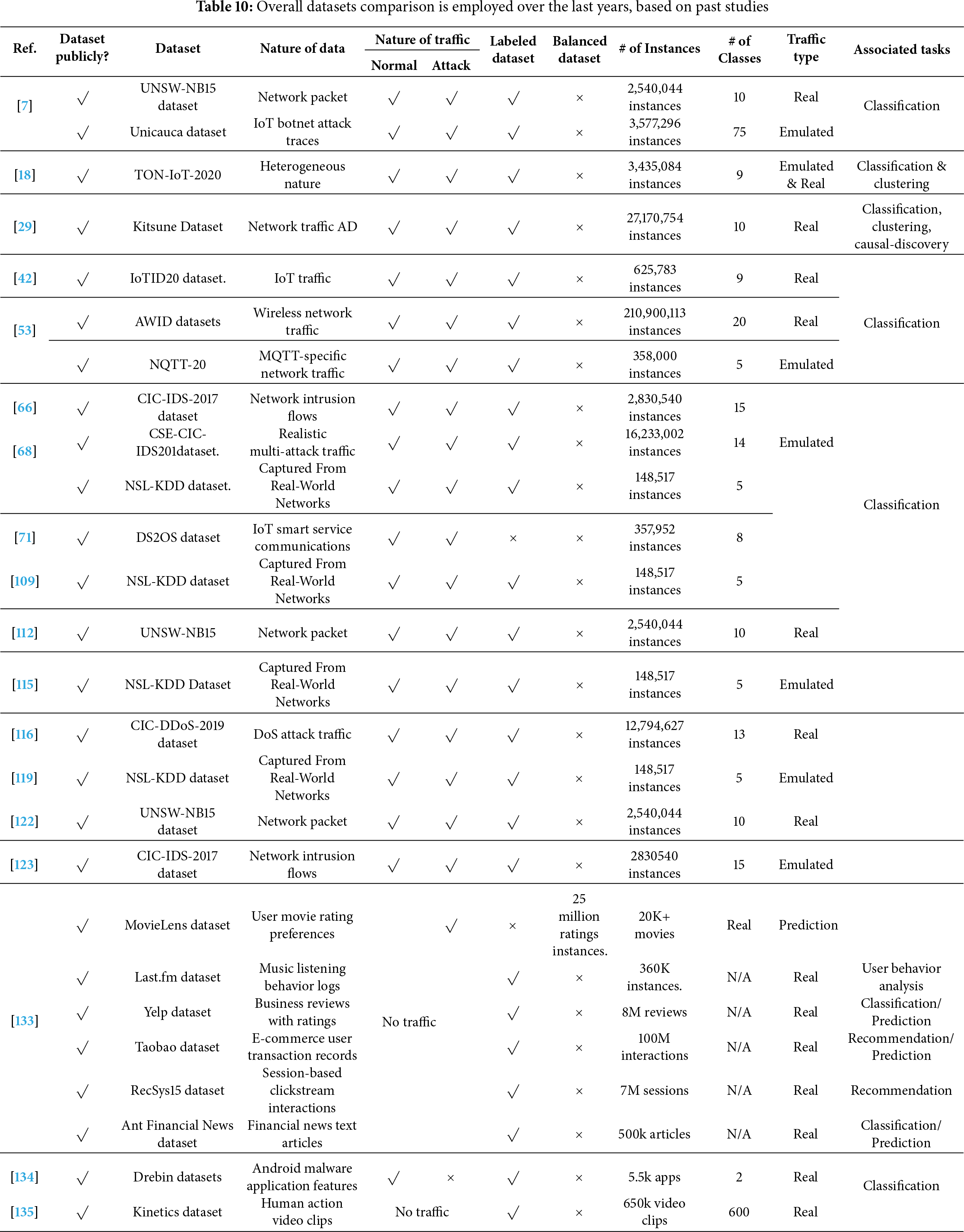

Studies, such as the one by [118], stressed the importance of a large-scale, diverse dataset for benchmarking ARL models in real-world situations. Both the data and the traffic that need to be analyzed are crucial to the significance of this subsection. Table 10 lists and compares the most recent datasets used, along with various basic parameters, such as the type of traffic, the nature of the data, the tasks associated with them, and additional information, to enhance the utilization of datasets.

Wherein [119], authors develop a DRL-NIDS system based on MDP to enhance the robustness of DRL-IDS for stochastic games via employing the NSL-KDD dataset. Furthermore, the study [120] explored FPGA-accelerated decentralized RL in UAV networks, where customized UAV traffic datasets were crucial for validating AD. Additionally, contributors in [121] utilize multi-attribute monitoring datasets to evaluate unsupervised, reward-based AD.

Moreover, the study [122] explores the DRL model for the edge computing paradigm, based on IDS packet sampling within network traffic, utilizing two datasets: UNSW-NB15 and CIC-IDS-2017. Furthermore, a lightweight IDS for UAV simulation in [123] based on DRL has been developed to create a robust system for preventing and protecting UAVs and IoT devices from malicious activities, as well as cyberattacks. In another reference, authors via [124] examine adversarial ML for cybersecurity resilience and network security enhancement to identify security and network challenges, gaps, and limitations. However, the research findings suggest that future adversarial ML processes should utilize various robust algorithms to enhance the accuracy and effectiveness of the model.

Regarding Software-Defined Networks (SDNs), the study [125] demonstrated the importance of traffic sampling datasets for scaling ARL models. However, broader perspectives on hierarchical RL [126,127] have further revealed dataset-driven exploration of intrinsic options in multi-layered environments. Beyond networking, ARL has been applied in financial systems [128] and robotics in [129], which relied heavily on simulated and real-world datasets to ensure adversarial robustness. Recent studies, such as [130], that examine backdoor detection using DRL, emphasize the ease with which datasets can be poisoned. On the other hand, classic studies, such as those in [131,132], emphasize the importance of utilizing cybersecurity-specific simulation datasets for the validation of adversarial RL. In summary, these studies suggest that the choice and variety of datasets remain crucial for the development of ARL-based NIDS, facilitating a smoother transition from controlled settings to real-world use. Thus, the study [133] explores the GAN user model based on RL and a recommendation system. At the same time, biometric authentication is proposed on [134] for a mobile environment. Thus, the study [135] discusses the significant role of biometric verification systems, strengths, limitations, weaknesses, and mitigation strategies. Although a domain ARL is discussed based on MDP and Zero-Shot RL to train across different visual backgrounds. The primary goal of the study is to improve the generalization of DRL agents.

In short, the datasets referenced within this survey study, including NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, UNSW-NB15, and IoTID20, are among the most extensively utilized benchmarks in the NIDS and RL literature [117,121,136]. Their adoption across various studies underscores the representativeness of ARL-NIDS models in evaluating them under controlled experimental conditions. However, these datasets also represent that multiple limitations influence ARL performance. For instance, NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 often exhibit data imbalance and outdated attack profiles, leading to biased learning in adversarial environments. Similarly, CICIDS2017 and IoTID20 offer more modern and diversified network traffic, but their limited real-time adaptability constrains the transferability of ARL models to dynamic IoT or edge computing scenarios. Recognizing these limitations is critical to ensure the robustness and generalization of ARL-NIDS frameworks. Hence, future research should focus on developing hybrid datasets that integrate synthetic adversarial samples with real-world network traffic to enhance the robustness and adaptability of evaluation models across heterogeneous cybersecurity environments.

E. ARL-NIDS Risks

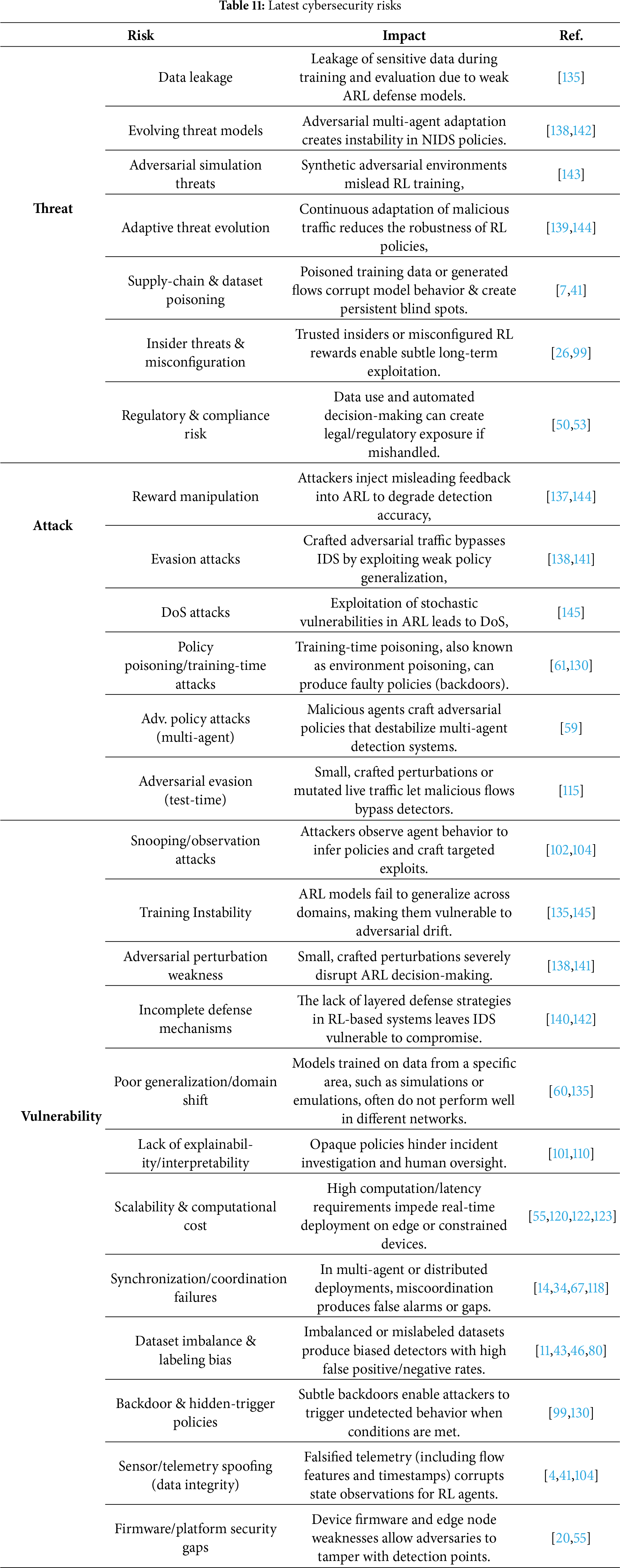

ARL has recently emerged as a powerful technique to improve the adaptability and intelligence of the NIDs. ARL enhances AD by enabling agents from the dynamic environment, improving traffic analysis, and adaptive defense strategies. To demonstrate how adversarial learning might compromise cybersecurity resilience by corrupting policies and manipulating environments in [124]. This research’s findings highlight the need for employing AT, reward shaping, and uncertainty modeling as robust defensive mechanisms in ARL. This will help ensure that agents behave securely and reliably in real-world deployment situations. However, the integration also exposes NIDs to develop novel cybersecurity risks such as unfavorable attacks, system weaknesses, and cyber threats. Table 11 summarizes the latest cybersecurity risks in ARL-NIDS. These risks challenge identity efficiency and question the strength, scalability, and reliability of ARL-NIDs in the deployment of the real world [134]. The integration of ARL into NIDS introduces significant risks that stem from negative mobility, system complexity, and a mature cyber environment. An important anxiety domain is the vulnerability of the ARL model for optimization risk, where unstable reinforcement learning can lead to unstable guidelines and domain transfer errors [135]. Additionally, the study [136] highlights the vulnerability of IoT networks to sophisticated cyber threats due to their inherent limitations and limited computational resources. Using ELM, the author shows increased ID accuracy in high-dimensional and unbalanced datasets. Research on IoT emphasizes the need for lightweight, scalable detection models to mitigate the risk of unseen infiltration in the IoT environment and to minimize real-time hazards. In addition, ARL-based systems face challenges from adaptive cyber-attacks that exploit the weaknesses of RL-operated reactions, making them susceptible to reward manipulation and misleading political updates [137]. However, Fig. 16 shows the cybersecurity triad (CIA), which identifies three main aspects (confidentiality, integrity, and availability).

Figure 16: Cybersecurity triad (CIA): confidentiality, integrity, and availability

Vulnerabilities are flaws or weaknesses in a system’s design, implementation, or configuration that could be exploited. It is passive; it does not cause harm on its own, but it opens the door. ARL-NIDS systems are vulnerable to issues related to model interpretability, scalability, and resource consumption. Limitations in explainability hinder the justification of judgments; however, decentralized or distributed ARL presents synchronization issues and increased processing costs [135].

Threats: A threat is any potential cause of harm that can exploit a vulnerability. It can occur due to human intervention (such as hacking), natural causes (like earthquakes), or random events (like a misunderstanding). ARL-NIDS systems face external dangers such as zero-day attacks, botnets, and insider threats. The dynamic training process can also be manipulated to induce biased learning or introduce poisoned data streams, rendering the agent unable to normalize [121].

Attacks: An attack refers to the actual action taken by a malicious actor to exploit a vulnerability. It is conscious and active, aligning with the principles of privacy, integrity, and availability. ARL agents are unsafe for learning attacks for unfavorable reinforcement, including: (1) Examination: such as misleading the agent during training, (2) Exploration: that misleads the agent during training, (3) Evasion: where adversaries craft packets or flows to bypass detection, (4) Poisoning: corrupt training datasets or reward signals, and (5) Backdoor: that embeds hidden malicious policies [138].

This survey study contributes to the understanding of ARL in cybersecurity by examining ARL-NIDS within the IoT environment, as highlighted by various researchers in related past studies. Assorted studies attempted to mitigate adversarial reward manipulation by introducing adaptive or hierarchical reward functions to stabilize learning dynamics under adversarial perturbations [111,129]. However, others ignored the issue, assuming static environments that do not reflect dynamic attack surfaces. The transferability challenge of how ARL models trained on one dataset generalize to another was only partially explored, primarily in simulation-based research with limited real-world validation [135]. Likewise, few studies have analyzed the robust trade-offs between model adaptability and computational complexity, despite their importance in large-scale or resource-constrained systems, such as IoT and UAV networks [123,139]. This survey identifies these gaps as critical future research directions, encouraging empirical benchmarking of ARL models across heterogeneous datasets and environments.

However, ref. [139] proposed an AI-competent adaptive cybersecurity system that suggested provoking RL to respond to new threats in real-time. Research indicates the limitations of static rule-based systems in managing zero-day attacks and describes agents that learn through reinforcement to achieve effective security methods. The most significant threat addressed is that the old systems are slow and inflexible, which means they may not quickly adapt to new attack vectors. In addition, ref. [140] intensive examination of ML methods to protect the blockchain network, which postpones the dangers associated with manipulation in consensus, weaknesses in smart contracts, and data integrity breaches. Research examines DL, a Simbel approach, and AD to enhance risk and resistance, particularly in relation to the side effects and internal threats of decentralized systems.

In addition, investigations in [141] examine the surface of ARL systems, which explains how unfavorable ML can compromise model integrity through theft, poisoning, and invasion attacks. Authors emphasize the risk of higher dependence on opaque ML models in critical training infrastructure and for strong counterparts, as AI can secretly reduce exploitation. In another context of reviewing RL applications in cybersecurity [142], the author identifies significant risks associated with penetration tests, IDS, and malware reactions. They also insist on the challenge of trial efficiency and strength of the model in an adverse environment, suggesting the TRL-based system should be carefully set to avoid utilizing adaptive threats. In addition, the study [143] DRL uses an unfavorable cyber-attack simulation and explains how RL agents can learn optimal attack strategies against network defense. The research exposes the risk of intelligent adversaries exploiting system weaknesses through learned behaviors and proposes RL-based defensive agents to counteract these evolving threats.

During [144], a framework was introduced for adaptive RL for automated incident response, targeting the risk of delayed or ineffective reactions to cyber incidents, by modeling the response strategies such as RL problems, the system detection and scalability accuracy in the dynamic danger scenario improves, while addressing the important requirement for the autonomous defense mechanisms, which reduces FP. Another article [145] discovered DRLs to detect advanced risk, focusing on the risk of negative theft in harmful software and infiltration scenarios. The author demonstrates how DRL can enhance the accuracy and flexibility of detection, while also mitigating overfitting and unfavorable manipulation, which can compromise the system’s reliability under real-world conditions. However, they suggest [146] a hybrid security structure to ensure web applications for blockchain are adaptable and sufficient for learning. The study addresses risks such as SQL injection attacks, model poisoning, and IoT falsification. It demonstrates how decentralized consensus and unwanted training systems can jointly mitigate these risks while maintaining transparency and accountability.

Although ARL remains effective in enhancing decision-making and flexibility, it is nevertheless quite susceptible to a variety of complex attacks that target the operational and training phases. Within the most common types of attacks is poisoning, in which the adversary attempts to damage or harm the policy optimization process by manipulating the learning environment or the reward function. In secure systems, such as autonomous vehicles and cybersecurity frameworks, these manipulations have the potential to alter agent learning trajectories and weaken the robustness of policies. Another risk to ARL models is an evasion attack, which tricks the trained agent into generating bad, poor decisions without altering the environment by subtly modifying input states or observations during testing. The agent may also be overfit to hostile conditions or rewards by an exploration manipulation attack, which exploits the equilibrium between both. Another study has shown the seriousness of these risks in the smart transportation and cybersecurity industries. While in [147], the risks of adversarial interactions in multi-agent driving environments are highlighted. Where manipulated agents may modify, the results would be an insecure lane change. Wherein [148] authors examined a comprehensive survey about implementing ML-IDS to detect adversarial attacks. Furthermore, implement robust security controls to enhance the defense systems against adversarial attacks. The Deep PackGen introduced a DRL framework to generate unfavorable network packages, revealing how attackers can create an ethnic payload that bypasses IDS within [149]. The study identifies effective defense strategies and customized approaches to combat sophisticated stolen techniques, and assesses the risks posed by unfavorable samples and lawyers to inform adaptive defense strategies.