Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Detection of Maliciously Disseminated Hate Speech in Spanish Using Fine-Tuning and In-Context Learning Techniques with Large Language Models

1 Departamento de Informática y Sistemas, Universidad de Murcia, Campus de Espinardo, Murcia, 30100, Murcia, Spain

2 Tecnológico Nacional de México/I.T.S. Teziutlán, Fracción I y II, Teziutlán, 73960, Puebla, Mexico

* Corresponding Author: Rafael Valencia-García. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 10 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073629

Received 22 September 2025; Accepted 12 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The malicious dissemination of hate speech via compromised accounts, automated bot networks and malware-driven social media campaigns has become a growing cybersecurity concern. Automatically detecting such content in Spanish is challenging due to linguistic complexity and the scarcity of annotated resources. In this paper, we compare two predominant AI-based approaches for the forensic detection of malicious hate speech: (1) fine-tuning encoder-only models that have been trained in Spanish and (2) In-Context Learning techniques (Zero- and Few-Shot Learning) with large-scale language models. Our approach goes beyond binary classification, proposing a comprehensive, multidimensional evaluation that labels each text by: (1) type of speech, (2) recipient, (3) level of intensity (ordinal) and (4) targeted group (multi-label). Performance is evaluated using an annotated Spanish corpus, standard metrics such as precision, recall and F1-score and stability-oriented metrics to evaluate the stability of the transition from zero-shot to few-shot prompting (Zero-to-Few Shot Retention and Zero-to-Few Shot Gain) are applied. The results indicate that fine-tuned encoder-only models (notably MarIA and BETO variants) consistently deliver the strongest and most reliable performance: in our experiments their macro F1-scores lie roughly in the range of approximately 46%–66% depending on the task. Zero-shot approaches are much less stable and typically yield substantially lower performance (observed F1-scores range approximately 0%–39%), often producing invalid outputs in practice. Few-shot prompting (e.g., Qwen 3 8B, Mistral 7B) generally improves stability and recall relative to pure zero-shot, bringing F1-scores into a moderate range of approximately 20%–51% but still falling short of fully fine-tuned models. These findings highlight the importance of supervised adaptation and discuss the potential of both paradigms as components in AI-powered cybersecurity and malware forensics systems designed to identify and mitigate coordinated online hate campaigns.Keywords

In recent years, social media platforms have overtaken traditional outlets to become the primary source of information, particularly for younger audiences [1]. While these platforms enable global interaction, they also facilitate the spread of hate speech, which is defined as language that promotes discrimination, hostility or violence against groups based on protected characteristics. They also facilitate the spread of misinformation and divisive narratives. The orchestrated spread of hate speech is a growing cybersecurity concern and often relies on compromised accounts, botnets or malware-driven strategies to amplify such content [2,3]. Their impact is reinforced by the algorithmic mechanisms used by social media networks, that privilege sensational and polarizing discourse, thereby accelerating the normalization of extremist views [4]. These dynamics create hybrid threats that undermine social cohesion and trust in digital platforms. Therefore, confronting this issue is crucial not only to protect vulnerable groups, but also to preserve the integrity of the digital infrastructures that underpin today’s information ecosystem.

In view of the substantial quantity of user-generated content, it is impractical to depend on manual monitoring as a means of verification. Consequently, significant efforts have been directed towards the development of NLP techniques that can automatically detect hate speech. Mitigating such content is critical to protecting digital environments from the harmful effects of prejudice and harassment [5]. When these messages are disseminated maliciously through coordinated disinformation or harassment campaigns, they also become a matter of digital security, as they are often amplified by compromised accounts, botnets or malware-driven dissemination [2,3].

To this end, the automatic detection of hate speech has become a vital area of research to mitigate the harmful consequences of online interactions. Advances in Natural Language Processing (NLP) enable the identification of hostile patterns and coordinated campaigns, as well as the evaluation of the severity and targets of discriminatory discourse. This links the field with sentiment analysis and abusive language detection [6]. The advent of the Transformer architecture, as outlined in [7], has established the foundation for Large Language Models (LLMs), leading to enhanced performance. LLMs have demonstrated consistent superiority in tasks like hate speech detection, surpassing conventional methods. Furthermore, LLMs’ In-Context Learning (ICL) capabilities enable them to address new tasks without the need for explicit parameter updates, adapting their behavior through task-specific instructions provided directly in the input prompt. This enables flexible, low-resource applications in rapidly evolving online environments, including forensic analysis and cybersecurity, where the timely identification of malicious discourse is essential to prevent its spread and reduce large-scale harm.

Although significant advances have been made in this field, most LLMs are predominantly trained on English data, which limits their reliability for other languages, such as Spanish. This is particularly evident in social media contexts, where informality, regionalisms and dialectal variation are prevalent. This highlights the need for research into adapting LLMs for Spanish hate speech detection, to ensure that these technologies work reliably across diverse linguistic communities and to promote equitable access to their benefits. Although multilingual models such as XLM-RoBERTa, mBERT or LaBSE [8–10] show promise, they remain inconsistent for Spanish varieties. Previous studies [11] have highlighted the challenges posed by dialectal heterogeneity, colloquial expressions and code-switching, particularly in varieties spoken outside Spain. While fine-tuned encoders are robust, they require costly annotated data, which is often lacking for minority languages and nuanced hate classes. Conversely, ICL-based methods are flexible in low-resource settings, but they are prone to producing unstable outputs and exhibiting class biases, particularly in multi-label and ordinal tasks. This reduces their applicability in forensic or cybersecurity contexts, where subtle, context-dependent hostility and overlapping forms of discrimination must be reliably captured. Although previous work has investigated multilingual or Spanish-adapted hate speech detection, key gaps remain. Recent efforts to address these gaps include benchmarks such as the Spanish MTLHateCorpus 2023 [11] and studies on Zero- and Few-Shot Learning (ZSL and FSL) capabilities of LLMs [12], though applications to underrepresented Spanish dialects remain underexplored.

No study has systematically compared supervised fine-tuning and ICL-based approaches in Spanish and its dialects for multiple complex hate speech detection tasks, such as intensity of speech categorization (ordinal) and targeted groups detection (multi-label). Furthermore, the stability, validity and reliability of ICL-based outputs have not been thoroughly evaluated, particularly in scenarios involving limited resources and overlapping or hierarchical label structures. Addressing these limitations is essential for the deployment of trustworthy NLP systems in multilingual cybersecurity contexts.

This work addresses the issue of hate speech detection in Spanish and its dialects by conducting a multidimensional, low-resource evaluation in terms of the type, recipient, intensity and targeted group of the speech. It also compares supervised fine-tuning and ICL-based approaches. Accordingly, the study benchmarks two dominant paradigms: supervised fine-tuning of encoder-only models and ICL-based approaches with LLMs under Zero-Shot (ZS) and Few-Shot (FS) prompting. The evaluation covers four complementary aspects of malicious hate speech: type, recipient, level of intensity and targeted group. This approach captures the multifaceted nature of harmful discourse. The central objective is to systematically analyze the trade-offs between the stability and reliability of fine-tuning and the flexibility and data efficiency of ICL. The evaluation is performed using the Spanish MTLHateCorpus 2023 dataset. Complementary metrics are introduced: Percentage of Valid Responses (PVR), Zero-to-Few Shot Retention (ZFR) and Zero-to-Few Shot Gain (ZFG), which quantify output reliability and stability, and provide detailed error analyses. To our knowledge, this study is the first to systematically compare these paradigms in Spanish and its dialects across four hate speech dimensions, with implications for real-world, AI-driven cybersecurity applications. To guide this comparative analysis, we pose the following research questions are posed:

• RQ1. How effective are ICL-based approaches for hate speech detection in Spanish across the four tasks of the MTLHateCorpus 2023 dataset?

• RQ2. How does the performance of ICL-based approaches compare with that of encoder-only models specifically fine-tuned for these tasks?

• RQ3. Which LLMs achieve the best results when applying ICL-based approaches for these tasks?

• RQ4. Are there consistent differences in performance across these tasks when applying different ICL-based techniques?

Beyond its contributions to NLP, this work aligns with AI-driven cybersecurity efforts, where the development of intelligent, adaptive and explainable systems is essential in order to counter emerging digital threats. While much of the research in this field has traditionally focused on detecting polymorphic malware or adversarial intrusions, malicious communication campaigns ranging from coordinated disinformation involving social engineering to targeted hate speech with harmful or manipulative content have become a key vector for social manipulation and influence operations, especially during sensitive contexts such as electoral processes or crisis events. These campaigns exacerbate polarization, distort public discourse and can be strategically combined with technical attacks to undermine trust in digital platforms. Recent studies published in the Computers, Materials & Continua (CMC) journal have proposed language-centric methods that show promise against such threats [13,14]. By extending these approaches to Spanish hate speech detection, we provide robust linguistic and adaptive operational solutions.

The rest of this paper is organized in the following manner: Section 2 exposes the relevant literature, with particular attention to recent developments in hate speech detection and trends in LLMs and ICL-based approaches. Section 3 describes the dataset, the models considered and the experimental configuration for both approaches. Section 4 presents the results obtained, while Section 5 offers a deeper analysis, providing an interpretation of the findings. Section 6 concludes the paper and highlights avenues for future investigation.

The automatic detection of hate speech has become a central challenge at the intersection of NLP, social computing and cybersecurity. As online discourse expands across platforms and languages, researchers have been working to develop computational systems that can identify linguistic patterns indicating hostility, discrimination or coordinated manipulation. This task goes beyond simple keyword filtering and requires models that can interpret context, pragmatics and cultural nuance. These elements can be subtle, domain-specific and linguistically diverse. Consequently, the study of hate speech detection has evolved in parallel with major advances in NLP, moving from early lexicon and statistical-based approaches to deep learning and Transformer-based architectures, which can capture complex semantic relationships within text. These advances have not only enhanced detection accuracy, but also enabled cross-domain and cross-lingual generalization. This positions hate speech detection as a benchmark problem for evaluating the capabilities of modern language models.

To address this challenge, the automatic detection of hate speech has emerged as a crucial area of research. Advances in NLP now enable identification of hostile patterns and coordinated campaigns, as well as the assessment of the severity and specific targets of discriminatory discourse. This links the field with sentiment analysis and abusive language detection [6]. A pivotal breakthrough was the introduction of the Transformer architecture [7], an attention-based model which revolutionized sequence processing and laid the foundation for LLMs. Transformers capture contextual dependencies more effectively than earlier approaches based on bag-of-words or non-contextual embeddings, such as GloVe or fastText. This marks a paradigm shift in NLP, with Transformers consistently outperforming traditional approaches across tasks such as hate speech detection. Pretrained models such as BERT [8] have built on this progress to improve natural language understanding, demonstrating that a bidirectional Transformer trained on large corpora can capture complex semantic and syntactic nuances. Since then, Transformer-based models such as RoBERTa [15] and their multilingual variants have become the backbone of modern hate speech detection systems, consistently outperforming traditional classifiers based on keyword matching or handcrafted features.

Nevertheless, most LLMs are still predominantly trained on English data. Since much of the initial research in this area focused on English, this limits the reliability of LLMs for other languages, such as Spanish, especially in social media contexts, where informality, regionalisms and dialectal variation are prevalent. As early as 2018, a survey highlighted the scarcity of hate speech detection systems for languages other than English [6]. For Spanish, this gap began to be addressed through dedicated shared tasks, such as the 2018 IberEval Automatic Misogyny Identification (AMI) task [16] and the 2019 SemEval HatEval task [17]. The former focused on categorizing misogynistic behaviour and identifying the target, while the latter focused on detecting hate speech against immigrants and women. Both tasks used Spanish and English texts extracted from Twitter. Building on these efforts, several annotated corpora have been developed, including MisoCorpus-2020 [18], a balanced corpus regarding misogyny in Spanish, and HaterNET [19], a corpus for binary hate speech classification on Twitter. These corpora foster methods specifically adapted to Spanish.

In parallel, language models pretrained in Spanish have been introduced to leverage Transformer-based advances in Spanish. Among them, BETO [20], a BERT-based model trained with Spanish data, has become one of the most widely used and recognized reference models in Spanish NLP. More recently, the MarIA [21] initiative produced state-of-the-art models, including a RoBERTa variant trained exclusively on Spanish. This model was trained on what is currently the largest available Spanish corpus, enabling it to capture rich linguistic patterns. As a result, it stands as one of the most extensive and well-developed monolingual models for contemporary standard Spanish. Domain-specific models such as RoBERTuito [22], a RoBERTa-based model trained on over 500 million Spanish tweets, address colloquial and noisy language typical of online discourse. The availability of such models has substantially improved the detection of offensive language in Spanish. For instance, in [23], the authors evaluated the combination of linguistic features, such as lexical and stylistic traits, with Transformer-based embeddings. They concluded that integrating linguistic knowledge with BERT-like models enhances the accuracy of hate speech detection in Spanish. This highlights the importance of models that are adapted to linguistic and cultural contexts.

Another area of progress involves making use of LLMs’ transfer learning and adaptation capabilities. The dominant approach has been supervised fine-tuning, whereby pretrained models are adjusted using labeled data. While this approach is effective on specific datasets, it struggles to scale across domains or linguistic varieties with scarce resources. To address these limitations, ICL has become more relevant, enabling modern LLMs to perform tasks without full retraining by following instructions in natural language or a few examples, a process known as Zero- and Few-Shot Learning (ZSL/FSL). Popularized by GPT-3 [24], this approach enables general pretrained models to be used for various task, such as hate speech detection, even in scenarios with limited resources and no extensive training corpus.

Building on this shift, recent studies have compared fine-tuning with ICL-based techniques. For instance, in [25], the authors evaluated multilingual instruction-tuned models such as LLaMA, Qwen and BloomZ across eight non-English languages, including Spanish. They found that, although prompting approaches often perform worse than fine-tuned encoders on standard benchmarks, they generalize better to functional tests and out-of-distribution cases. The authors also highlight the crucial role of prompt design, emphasizing that tailoring instructions to language-specific and cultural nuances can significantly improve accuracy. Similarly, in [5], the authors compared ZSL/FSL with supervised training for bilingual Spanish-English hate speech detection. Evaluating LLMs such as T5, BLOOM and LLaMA 2, they found that ICL-based methods yield greater robustness and generalization across hate speech domains. In some experiments, contextual learning even matched or surpassed the performance of fine-tuned systems on standard benchmarks. For example, it achieved state-of-the-art results on the HatEval 2019 task dataset [17] without additional training and outperformed the best entry in the competition.

These findings highlight the potential and limitations of current LLMs as universal toxic language detectors. Contextual approaches often struggle with subtle distinctions, such as different types of hate speech, sarcasm and figurative language. Fine-tuned models, meanwhile, risk over-detection and false positives [26]. Addressing these linguistic challenges requires models that are adapted to the diversity of Spanish. Hate speech detection in Spanish cannot be achieved simply by transferring tools from English; it requires tackling a language with rich internal variation and distinct cultural contexts. Consequently, the most advanced systems combine fine-tuning with locally sourced data and the flexibility of multilingual LLMs to achieve a balance between specialization and generalization.

This work not only contributes to NLP, but is also embedded in the field of cybersecurity. The malicious dissemination of hate speech poses a social threat and is part of a range of harmful behaviors, including bot-driven harassment, adversarial manipulation and disinformation campaigns. In [27], the authors applied machine learning and deep learning methods to detect cyberbullying-related hate speech by identifying linguistic patterns used by online aggressors. In [28], the authors propose a novel approach combining evolutionary algorithms with NLP techniques. They use the Whale Optimization Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization to adjust the weights of two Multi-Layer Perceptron for neutrosophic set classification in hate speech detection in social media forensics. In another study, the authors link the detection of fake news to cybersecurity, focusing on the manipulation of information on social media caused by the proliferation of multimedia disinformation [29]. They propose MFFFND-Co, a model that explores textual, visual and frequency characteristics in depth, applying a co-attention mechanism to merge information from multiple modalities.

In line with these studies, our research strengthens the link between NLP and cybersecurity. We have developed a robust linguistic evaluation of potential methods for identifying Spanish hate speech. These methods can be integrated into AI-driven forensic processes to combat hybrid threats involving the strategic weaponization of malicious language.

This section presents the datasets, models and experimental configuration used to investigate the automatic identification of malicious hate speech in Spanish, in order to address the research questions outlined in this study. Our goal is to carry out a systematic and reproducible comparison between fine-tuning methods and ICL-based approaches under controlled, low-resource scenarios. To this end, we examine the two dominant methodological frameworks in current research: (1) fine-tuning encoder-only models pretrained on Spanish data, and (2) ICL-based techniques, encompassing both ZS and FS prompting with LLMs.

Section 3.1 introduces the dataset employed in our experiments. Section 3.2 describes the experimental configuration. Specifically, we consider fine-tuned encoder-based models as supervised baselines and contrast them with ICL strategies applied to four complementary classification tasks: speech type, recipient, intensity level and targeted group class.

For the experimental evaluation, we employed the Spanish MTLHateCorpus 2023 [11], a corpus designed specifically to enable the fine-grained analysis of hate and hope speech on social media. The dataset was compiled from posts collected on X (formerly Twitter) and contains annotations for four complementary tasks that capture various aspects of hateful discourse: (1) type of speech, which categorizes discourse into classes such as hate, hope or offensive; (2) recipient, which distinguishes whether the message is directed at an individual or at a group; (3) targeted group, which is a multi-label task identifying the specific communities being attacked, with classes including racism, misogyny, homophobia, misogyny, transphobia, aporophobia, fatphobia, disablism and profession-related hate; and (4) intensity, which measures the severity of the speech, ranging from mild disagreement to explicit calls for violence or death, as defined by Babak Bahador’s six-level scale [30].

The corpus was compiled over a two-year period by combining keyword-based queries with monitoring of relevant social events. For example, terms such as “aporofobia”, “pobre” (poor), “mendigo” (beggar) and “huérfano” (orphan) were used to retrieve aporophobic content, while homophobic discourse was tracked using keywords including “homosexual”, “marica” (faggot) and “afeminado” (effeminate).

The dataset was organized into three sets: 24,829 tweets for training, 5321 for validation and 5323 for testing. This corresponds to a division of 75%, 15% and 15%, respectively. This structured split provides a clear and balanced foundation for experimentation, ensuring that models can be trained and validated consistently, while also preserving an independent test set for robust evaluation.

Inter-annotator agreement was measured using Krippendorff’s alpha. The overall score was 0.349, reflecting the difficulty of consistently labeling ambiguous cases, particularly those categorized as “none” (neutral or non-informative speech). Excluding this category improved the score to 0.513, indicating a moderate level of consensus. These results emphasize the inherent complexity of detecting hate speech in real-world social media data, as even trained human annotators struggle to distinguish borderline cases. This difficulty justifies the need for more precise annotation protocols and motivates the development of advanced NLP methods that can address subtle, context-dependent forms of hostility.

The MTLHateCorpus 2023 is a valuable resource for studying hate speech in Spanish. It provides a challenging benchmark for evaluating different modeling strategies in realistic conditions. In our research, we use it to evaluate fine-tuning and ICL-based approaches within a unified framework. By confronting models with tasks that are difficult even for humans, this study advances the development of adaptive and robust AI methods. Furthermore, by exposing models to the ambiguity and variability inherent in online discourse, the study addresses broader issue: the urgent requirement for adaptive, explainable AI systems that can detect and mitigate malicious communication. Addressing this challenge is critical not only for progress in language technologies, but also for enhancing resilience against coordinated online threats in contemporary digital environments.

To ensure a fair comparison, all approaches were evaluated using the test partition of the MTLHateCorpus 2023 dataset, as provided by the dataset authors, and under a unified set of metrics.

3.2 Experimental Configuration

The experimental configuration section is organized into three components. Firstly, the encoder-only models employed in the supervised fine-tuning approach are introduced. These models provide robust supervised baselines, as can be seen in Section 3.2.1. Secondly, the LLMs employed for the ICL-based experiments are delineated (see Section 3.2.2). We hereby present the prompt formulations for both ZS and FS configurations. These formulations are of crucial importance in order to harness the ICL capabilities of the selected models (see Section 3.2.3). This configuration is not only indicative of methodological rigor, but also reflects the broader objective of developing adaptive NLP-based solutions with the potential to be integrated into cybersecurity and malware forensics pipelines. In such contexts, the detection and mitigation of coordinated hate campaigns represent a critical challenge.

3.2.1 Encoder-Only Models Used for the Fine-Tuning Approach

To this end, a robust supervised baseline was established against which the ICL-based capabilities of generative LLMs could be evaluated. To this end, a selection of widely used encoder-only models was fine-tuned; these had been pretrained specifically for the Spanish language. The suitability of these models is attributable to their linguistic alignment and significantly lower computational demands in comparison to large decoder-based architectures. Furthermore, there are notable discrepancies in terms of their underlying architecture (e.g., BERT vs. RoBERTa), pre-training strategies and efficiency-oriented design choices, such as distillation or parameter-sharing mechanisms. This enables us to examine the effect of these variations on the performance of hate speech detection. The models included in the fine-tuning experiments are the following:

• MarIA [21]: This model follows a RoBERTa architecture and has been trained entirely on Spanish data. Its pre-training corpus, 570 GB of deduplicated and cleaned text compiled between 2009 and 2019 by the Biblioteca Nacional de España, is the largest curated Spanish dataset available. As a result, MarIA stands as one of the most extensive and well-developed monolingual models for contemporary standard Spanish.

• BETO (cased and uncased) [20]: BETO is a BERT-based model trained from scratch on Spanish corpora and serves as a strong reference point for Spanish NLP research. We include both its cased and uncased variants to examine the influence of case information, which may be relevant when dealing with informal or noisy user-generated text.

• BERTIN [31]: BERTIN is a compact RoBERTa-base model trained on the multilingual mc4 dataset created from Common Crawl. Specifically BERTIN was trained with its Spanish portion. Its comparatively small size and efficient design make it a suitable option for scenarios where computational resources are limited.

• ALBETO [32]: ALBETO is a ALBERT-based lightweight version of BETO. Through parameter-sharing mechanisms and factorized embeddings, it significantly reduces model complexity while maintaining strong semantic representations for Spanish.

• DistilBETO [32]: DistilBETO is the DistilBERT-based distilled counterpart of BETO. It offers a favorable compromise between speed and performance, achieving competitive results with notably fewer parameters than the full BETO model.

All encoder-based models were adapted for all hate speech detection tasks employing a standardized fine-tuning procedure. To ensure a fair comparison and attribute performance differences solely to model architecture or pre-training, we fixed the same hyperparameters across all experiments: 15 training epochs, a learning rate of

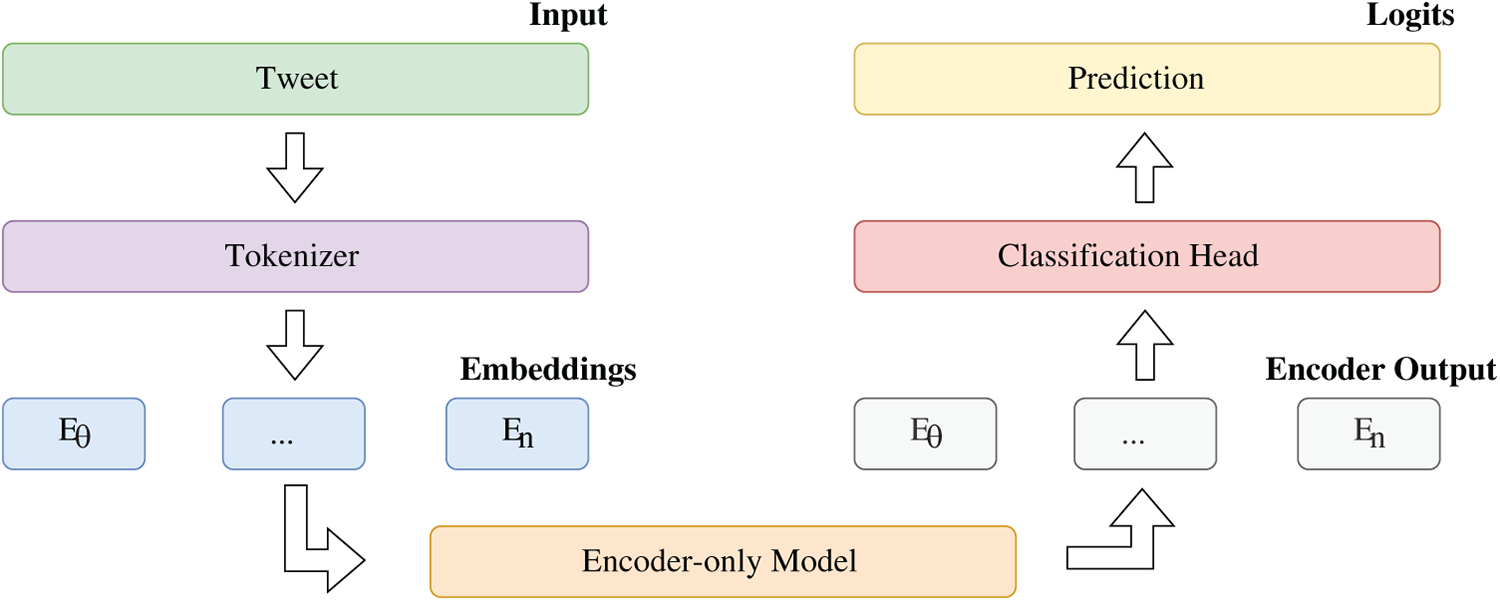

Fig. 1 presents the system pipeline adopted for the fine-tuning experiments, where encoder-only Transformer models serve as the backbone for task-specific adaptation. All experiments were conducted using the Hugging Face Transformers framework (v. 4.51.3) together with PyTorch (v. 2.6.0), relying on the Trainer API for training and evaluation. To ensure stable optimization and avoid oscillations during training, consistent with common fine-tuning practices, the models were trained with the AdamW optimizer and a linear learning rate schedule. No early stopping, checkpoint selection, or gradient accumulation was applied, as each model was deliberately trained for a fixed number of 15 epochs under uniform conditions.

Figure 1: System architecture for the fine-tuning approach of the encoder-only models

Preprocessing was kept to a minimum. Texts were encoded using the tokenizer associated with each model, applying truncation and padding up to a maximum sequence length of 128 tokens. Case handling followed the characteristics of each model variant (e.g., uncased vs. cased BETO), ensuring alignment between preprocessing and pre-training conditions. Diacritics were preserved throughout to maintain consistency between training and inference.

3.2.2 LLMs Models Used for the ICL-Based Approaches

To assess how well ICL-based approaches can detect hate speech in Spanish, we assembled a representative set of open-weight LLMs based on decoder architectures and optimized for instruction-following tasks. Both ZS and FS configurations were explored, enabling us to analyze how differences in architecture, training strategy and model size influence ICL-based approaches performance within a single, consistent prompting framework that spans multiple model families.

The aim of this evaluation is not to identify the top-performing model, but rather to contrast several recent instruction-tuned LLMs originating from different design families, scales and pre-training sources, all tested under uniform prompting conditions. Models covering a wide parameter range were intentionally included to investigate the role of model size in shaping ICL-based approaches behaviour. Crucially, no additional task-specific fine-tuning or parameter modification was applied; their predictions were generated exclusively through prompt-based conditioning, as described in Section 3.2.3. The models included in the ICL-based approaches experiments are the following:

• Google’s Gemma family: Our evaluation includes Gemma 2 2B [33], Gemma 2 9B [33], and the more recent Gemma 3 1B [34]. These decoder-only, instruction-tuned models are designed to offer strong multilingual performance with relatively low computational demands. While the Gemma 2 line targets accessibility and efficiency, Gemma 3 incorporates architectural updates inspired by Gemini, enhancing contextual reasoning and cross-lingual capabilities. Notably, the compact Gemma 3 1B model delivers surprisingly competitive FS results, making it an attractive choice for constrained environments.

• Meta’s LLaMA family: Our evaluation includes LLaMA 2 7B [35], LLaMA 3.1 8B [36], and LLaMA 3.2 3B [37]. LLaMA 2 represented Meta’s first widely released instruction-tuned series, though with modest multilingual coverage. The LLaMA 3.1 generation improved cross-lingual consistency and instruction adherence, while LLaMA 3.2 introduced architectural and tokenization refinements to improve the performance of smaller models. These features make the 3.2 family a practical alternative for FS setups when resources are limited.

• Alibaba’s Qwen family: Our evaluation includes Qwen 2.5 7B [38] and Qwen 3 8B [39]. Both models are multilingual, instruction-oriented models emphasizing broad multi-task and cross-lingual generalization. Qwen 2.5 already demonstrated strong multilingual capabilities, and Qwen 3 further strengthens instruction-following and adaptation to non-English data. Thanks to their pretraining data and tokenizer design, Qwen models are well-equipped for handling informal or dialectally marked Spanish, which is common in user-generated content.

• Mistral AI’s Mistral family: Our evaluation includes both variants: Mistral 7B [40] and Mixtral 8x7B [41]. Whereas Mistral is a dense model that prioritizes efficiency and stable performance in both ZS and FS settings, Mixtral, a model based on a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture, expands model capacity through its MoE structure, activating only a limited number of expert blocks per token to reduce inference costs. Due to GPU memory constraints, Mixtral 8x7B was executed with 4-bit quantization using the BitsAndBytes library, while all remaining models were evaluated in full-precision mode.

These models were chosen because: (1) they are publicly available under open-source licenses, which facilitates reproducibility; (2) they have demonstrated strong instruction-following and ICL capabilities in multilingual contexts; and (3) their diversity in terms of architecture, scale and training corpora enables us to analyze how these factors shape the effectiveness of ICL-based approaches for hate speech detection in Spanish.

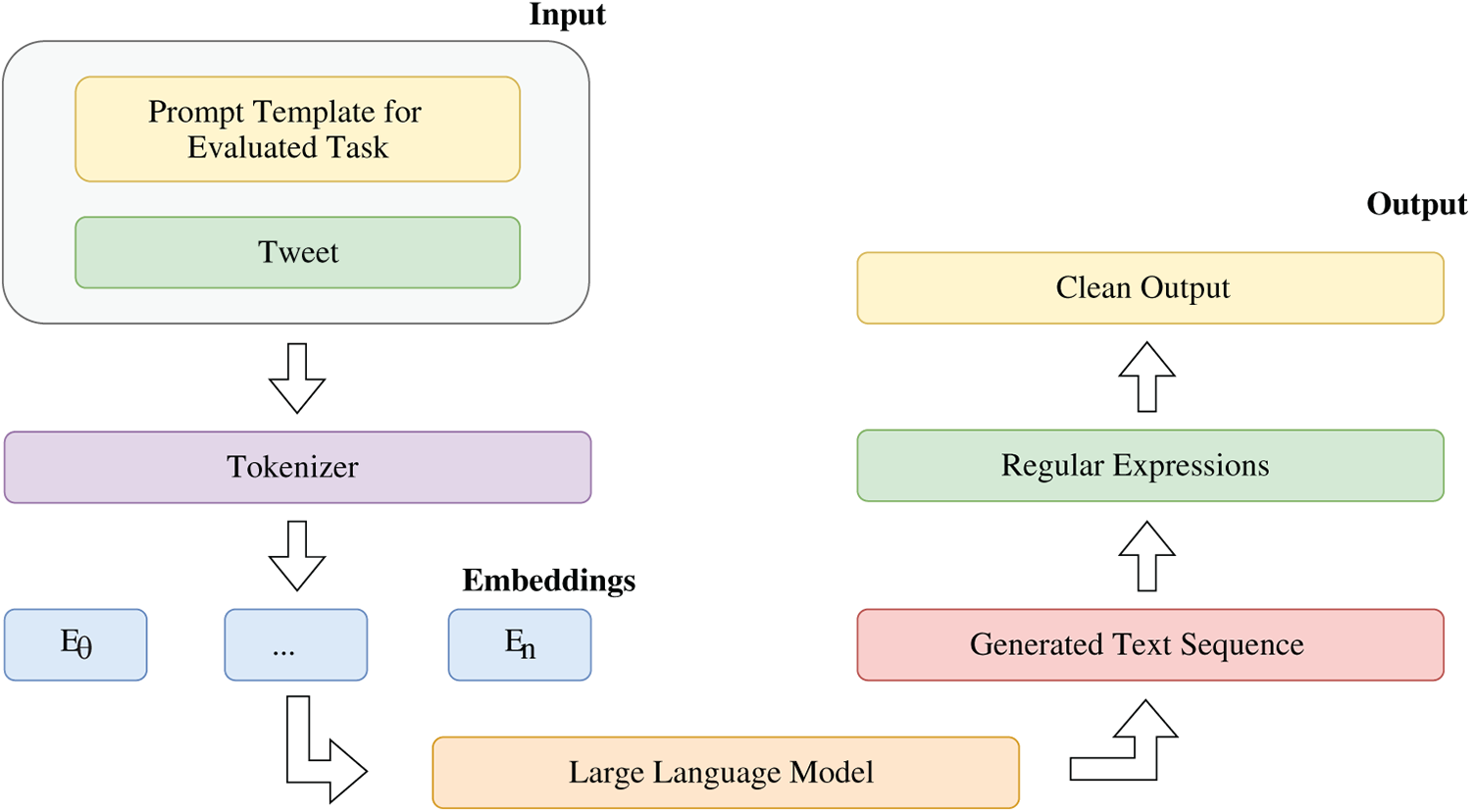

Fig. 2 presents the system pipeline adopted for the ICL-based approaches experiments, in which LLMs are queried directly for each classification task. All ZS and FS evaluations were conducted using the Hugging Face Transformers framework and PyTorch, employing the AutoModelForCausalLM interface. As no model training was involved, the official training and validation splits supplied by the dataset creators were used solely to build prompts and to run evaluations. In the ZSL setting, prompts contained only the task description followed by the input instance. For the ZSL configuration, a constant set of five labelled examples, drawn a single time from the training split, was appended to the prompt. These same examples were used for every model to ensure that differences in performance could not be attributed to variability in the demonstration set.

Figure 2: System architecture for the evaluation of the LLMs under the ICL-based approaches

Text preprocessing was deliberately minimal: inputs were encoded with each model’s tokenizer, preserving casing and diacritics, and prompts were formatted according to the corresponding chat template of each model family (e.g., system-user-assistant roles in LLaMA, Gemma, Qwen and Mistral). Inference relied on greedy decoding, generating up to 32 output tokens per instance with no parameter updates. Greedy decoding was chosen to ensure deterministic outputs and facilitate fair comparison across architectures and tasks, whereas stochastic decoding strategies (e.g., top-k or nucleus sampling) were avoided because they introduce randomness that could obscure systematic differences between models.

3.2.3 Design of ZSL and FSL Prompts

A prompt, in the context of LLMs, refers to the input sequence that conditions the model’s behaviour on a specific task. It typically contains an explicit description of the task together with contextual information that signals the format or type of response expected. Under FSL, the prompt additionally incorporates a small number of labeled examples, allowing the model to infer the task structure without modifying its parameters. Within ICL-based methods, prompt construction becomes especially important, as the model’s predictions depend solely on the cues and constraints provided in the prompt itself.

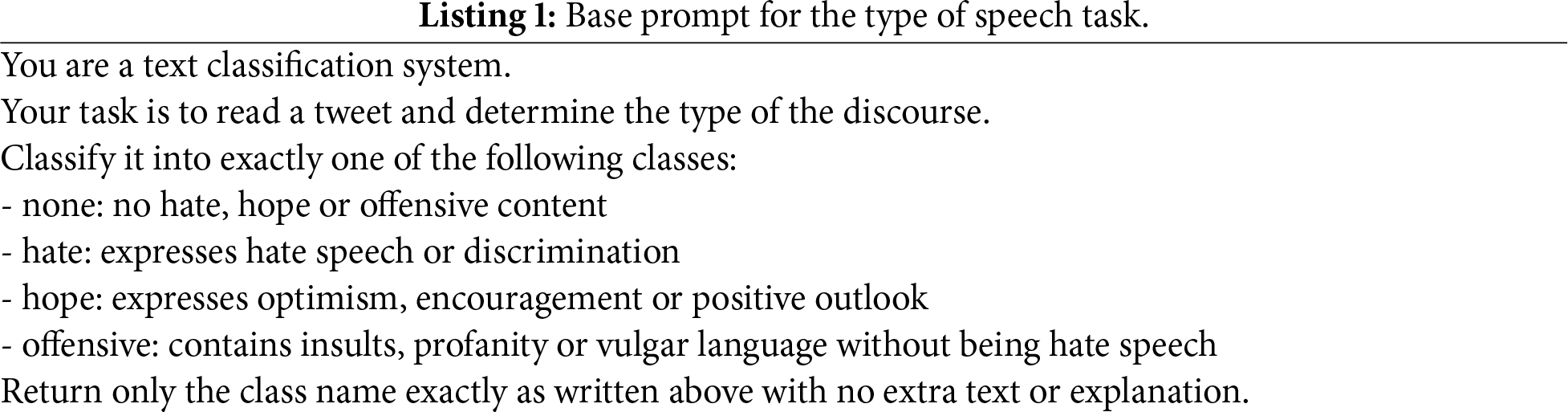

For the ZS and FS settings, we tailored four prompts specifically adapted to the four classification tasks included in the dataset: (1) type of speech, (2) recipient of speech, (3) intensity level and (4) targeted group. Each prompt was formulated to be brief, clear and well aligned with the linguistic characteristics of Spanish user-generated content, ensuring a consistent and comparable evaluation across models and tasks.

As not all models implement the same conversational formatting, two variants of each prompt were created. For models that support structured system/user/assistant roles, the prompts were divided into the following categories: (1) a system message providing high-level guidance instructions (e.g., “You are a classification model that is really good at following instructions. Please follow the user’s instructions as precisely as possible.”); and (2) a user message containing task-specific guidance. For models that only implement the user/assistant roles, the full instruction was provided as a single unstructured text prompt. This ensured that all models were evaluated under conditions consistent with their native prompting format.

By standardizing the structure and examples across tasks, we ensured that differences in performance reflected model behavior rather than variability in prompt design. The following listings present the exact formulations, that is, the task-specific instructions, used for each classification task, in both ZSL and FSL configurations.

Base prompt for the type of speech task

The aim of this task is to classify each text into one of the following four classes: hate, hope, offensive or none. The aim is to identify the type of speech expressed in each text. Listing 1 shows the base prompt designed for this task, which was used in both ZSL and FSL settings.

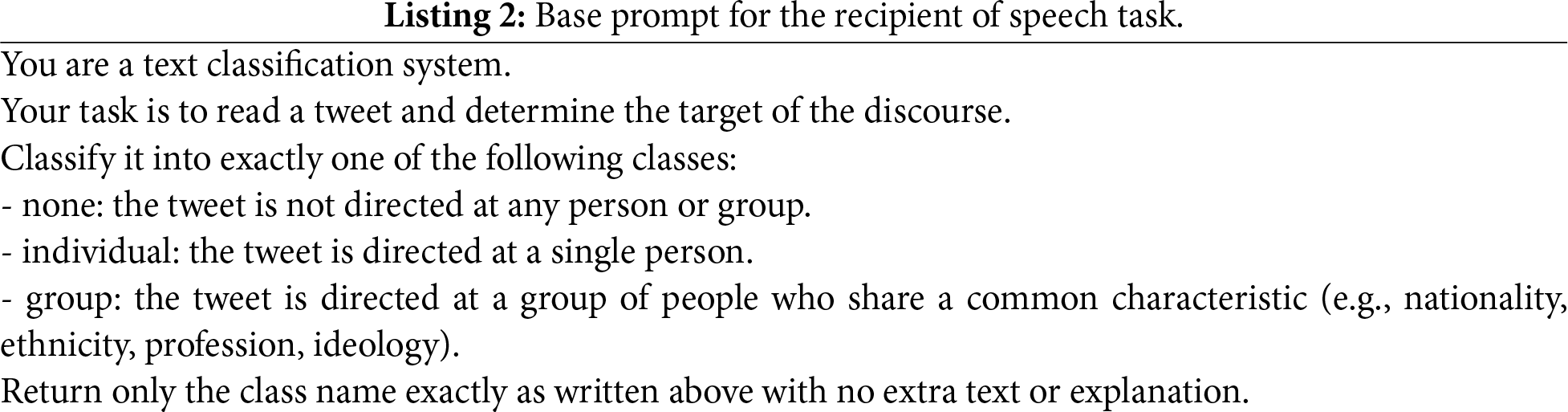

Base prompt for the recipient of speech task

The aim of this task is to identify the intended recipient of the speech and determine whether it is directed at an individual or a group. Additionally, the label “none” is used when the text does not contain hate speech. Listing 2 shows the base prompt for this task.

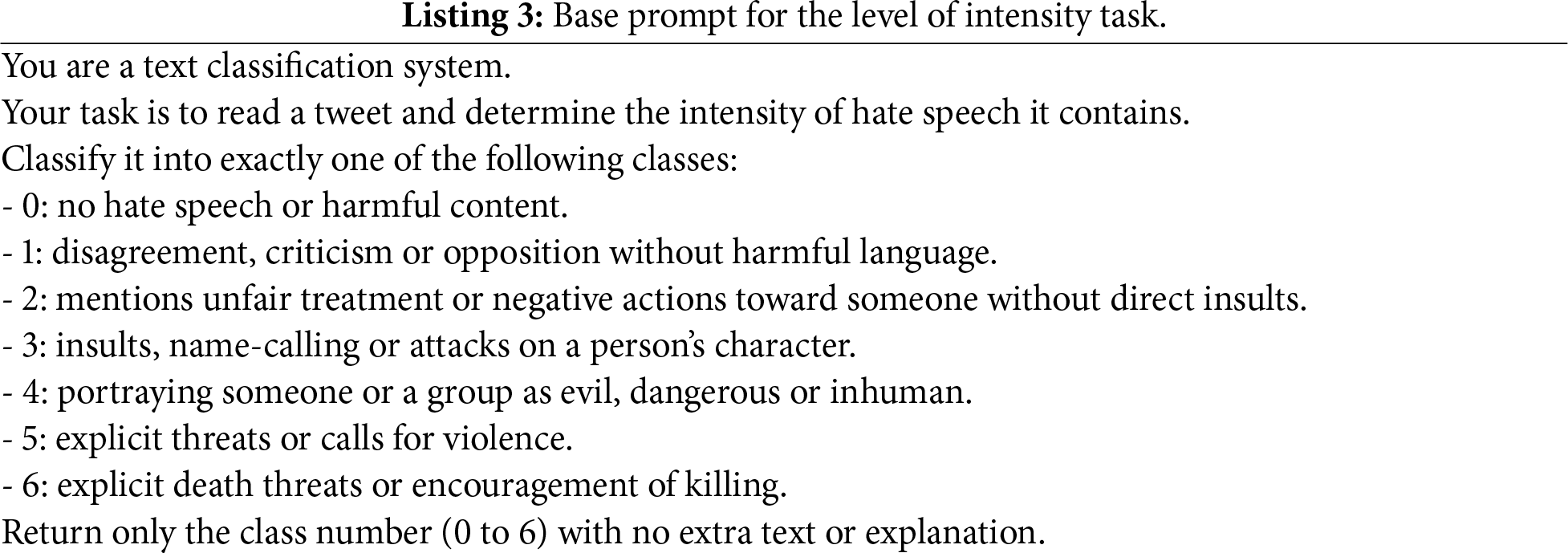

Base prompt for the level of intensity task

The aim of this task is to assign an ordinal label to each text based on its intensity level, which ranges from 0 to 6. Each label reflects the degree of negativity or harm expressed in the text: 0 is used when the text does not contain hate speech; 1 indicates disagreement; 2 indicates negative actions or poor treatment; 3 indicates negative character or insults; 4 indicates demonizing; 5 indicates violence; and 6 indicates death. The aim is to capture the escalating severity of the content, ranging from neutral or mild disagreement to the most extreme forms of harmful speech. Listing 3 shows the base prompt for this task.

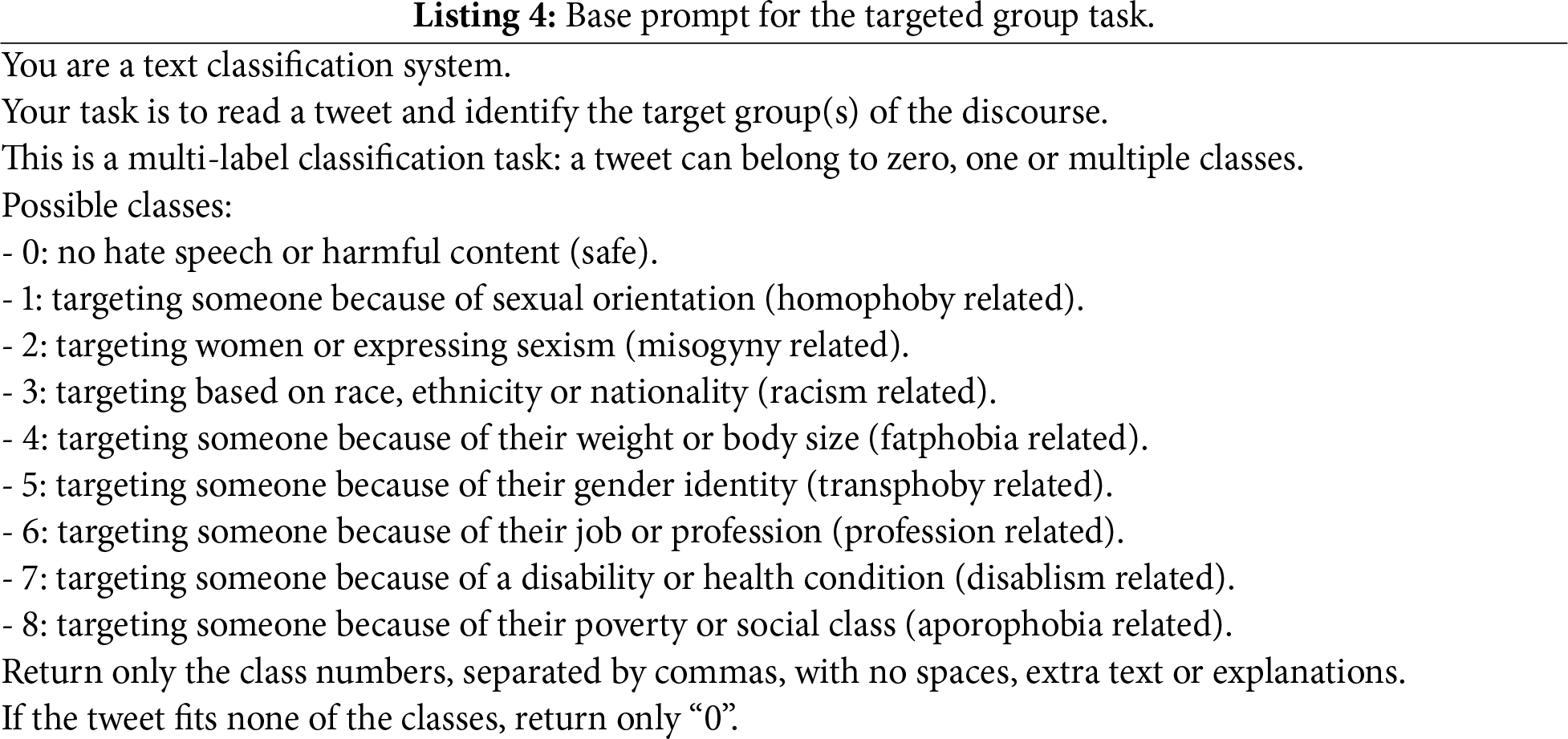

Base prompt for the targeted group task

This is a multilabel classification task, the aim of which is to identify the group or groups targeted by the speech. If a text contains harmful content directed at more than one group, it may be associated with multiple labels. The possible classes are: 0 for safe (used when the text does not contain hate speech), 1 for homophobia-related content, 2 for misogyny-related content, 3 for racism-related, 4 for fatphobia-related content, 5 for transphoby-related content, 6 for profession-related content, 7 for disablism-related content and 8 for aporophobia-related content. This task recognizes the complexity of discriminatory speech by identifying when multiple forms of bias appear in the same message. Listing 4 shows the base prompt for this task.

ZSL and FSL prompt construction

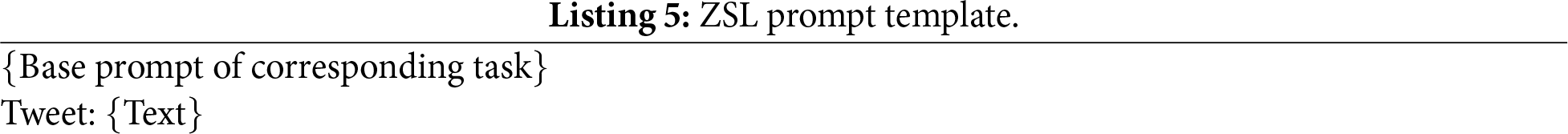

In the ZSL setting, the evaluation prompt is the same for all tasks and consists of the base prompt immediately followed by the input text. Listing 5 shows the ZSL prompt structure:

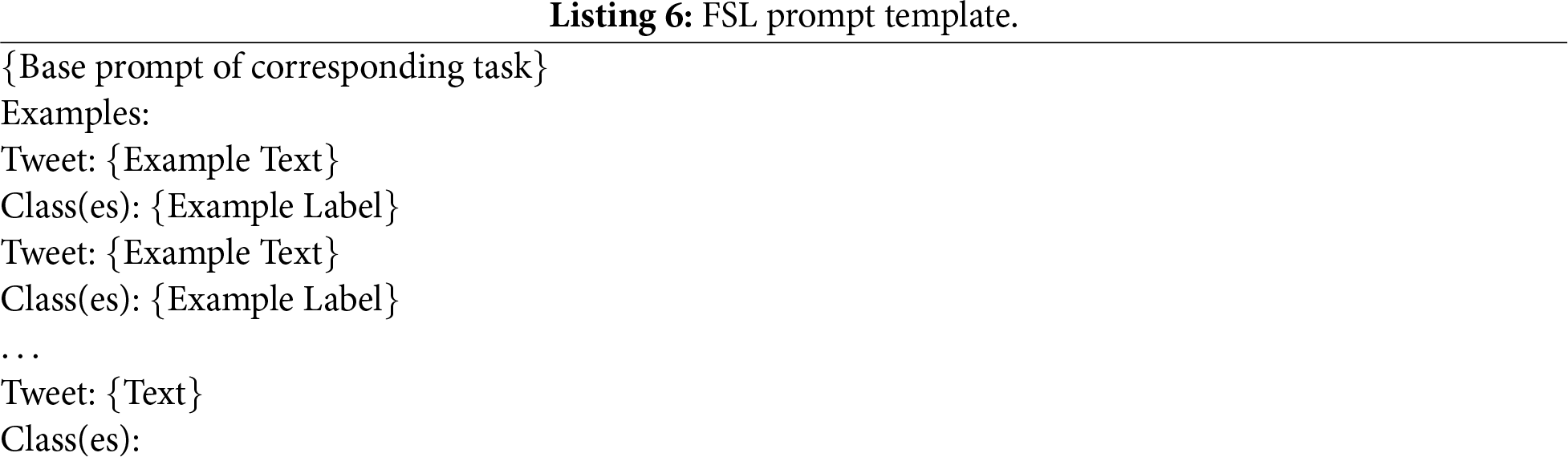

For the FSL configuration, the base prompt was augmented with five labeled examples, randomly sampled a single time from the official training split and reused across all tasks and models. Keeping the same examples fixed ensured that architectural or model-size differences, not variations in the prompt, were responsible for any performance changes observed. The selection of five examples follows common practice in FS evaluation, where small sets (e.g., 1, 3 or 5 shots) are typically used to strike a balance between providing informative context and maintaining manageable prompt lengths. This setup is also in line with prior FS studies, which frequently adopt 5-shot prompts as a practical compromise for controlled comparison. Specifically, ref. [42] demonstrated that increasing the number of examples beyond five does not substantial improve performance in multiple-choice tasks, while ref. [43] also employed a five-shot configuration in their FS evaluation. This setting provided sufficient illustrative variety for the model while maintaining concise, computationally efficient prompts across architectures. Listing 6 shows the FSL prompt structure:

As mentioned earlier, the task-specific instructions used in the ZSL and FSL configurations were identical. Keeping the instructions fixed allowed for a controlled comparison across models with varying levels of instruction tuning, while still benefiting from alignment mechanisms when available. To ensure uniformity in the outputs, predictions were post-processed with regular expressions to isolate the class label returned by the model. When a model generated irrelevant text or failed to output a valid label, the prediction was mapped to a dedicated error category. This approach prevents distortions in the original class distribution, maintains the validity of the evaluation metrics and additionally enables explicit monitoring of invalid outputs across models. Furthermore, by separating such cases into their own category, we avoid artificially lowering performance scores while simultaneously obtaining a clear signal of model robustness and failure patterns beyond standard metrics.

All experiments were conducted on a high-performance computing node equipped with four NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPUs (24 GB each), an AMD EPYC 7313 CPU and 1 TB of RAM, running Ubuntu 22.04 with CUDA 12.4. This hardware configuration was sufficient to support both the fine-tuning of the encoder-only models and running inference with the larger decoder-only LLMs. Memory consumption and training times were consistent across runs. 4-bit quantization was applied when needed (e.g., for Mixtral 8x7B) to fit within GPU memory constraints. For reproducibility, the complete source code and all configuration files are publicly available in the repository listed in the Availability of Data and Materials Section.

This section presents the results obtained in our comparative study of fine-tuned encoder-only Spanish models and ICL-based techniques with large-scale LLMs, covering both ZSL and FSL. In this paper, we benchmark these two predominant AI-based approaches for the forensic detection of malicious hate speech. Our evaluation goes beyond binary classification, adopting a comprehensive, multidimensional setup consisting of four distinct tasks: (1) type of speech (hope, hate, offensive or none), (2) recipient of speech (individual, group or none), (3) intensity level (1–5) and (4) targeted group class (e.g., homophobia, misogyny, both). The first three tasks are formulated as single-label classification problems, with the intensity level task being an ordinal task, while the latter follows a multi-label configuration. Using the Spanish MTLHateCorpus 2023 dataset, we assess the strengths and limitations of each approach in low-resource scenarios, with a particular focus on their potential integration into AI-powered cybersecurity and malware forensics pipelines for the detection and mitigation of coordinated online hate campaigns.

We adopt a unified evaluation framework for all tasks. Models are primarily ranked by their macro-averaged F1-score, although we also report accuracy, as well as macro-averaged precision and recall, to provide a more comprehensive reflection of general classification performance.

Since models evaluated under ICL-based approaches may occasionally produce outputs outside the valid label set, we also include the Percentage of Valid Responses (PVR), which quantifies the proportion of predictions that fall within the predefined label set after post-processing. In other words, it is the proportion of predictions that are correctly mapped to one of the allowed task labels. Invalid generations are assigned to a dedicated error label, enabling us to capture invalid generations explicitly without altering the distribution of the original classes. By incorporating PVR, we ensure fair comparison between fine-tuning and ICL-based approaches while avoiding artificial inflation or deflation of standard evaluation metrics. Additionally, no rebalancing techniques were applied during training or evaluation, despite the class imbalance in the dataset, in order to maintain comparability across evaluation approaches and models within a unified evaluation framework.

In addition, we introduce two complementary metrics to evaluate the stability of the transition from ZS to FS prompting. Zero-to-Few Shot Retention (ZFR) is defined as the percentage of correctly classified instances under ZSL that remain correct under FSL. This reflects how effectively FS prompting preserves prior capabilities. Zero-to-Few Shot Gain (ZFG), in turn, measures the percentage of instances that were misclassified under ZSL and become correctly classified under FSL, capturing the capacity of in-context examples to reduce errors. Together, ZFR and ZFG provide a more nuanced picture of model behavior across prompting regimes. Percentage-based metrics (A, P, R, F1, PVR, ZFR and ZFG) are reported in the format XX.XX.

Given the ordinal nature of the intensity task, our analysis considers both the F1-score and the Mean Absolute Error (MAE), with the latter capturing ordinal consistency beyond categorical correctness. For the remaining categorical tasks (type, recipient and targeted group), we focus on the macro-averaged F1-score, precision and recall to avoid bias towards the majority classes. Additionally, we conduct an error analysis of the best performing models under each paradigm (fine-tuning, ZSL, FSL) using confusion matrices, recognizing that the downstream consequences of errors differ substantially (e.g., misclassifying level 5 as level 1 in the intensity task is more critical than misclassifying adjacent levels, or misclassifying hope speech as hate speech in the type of speech task).

To facilitate its analysis, the results are presented task by task. Section 4.1 covers the type of speech task; Section 4.2 covers the recipient of speech task; Section 4.3 addresses the level of intensity task; and Section 4.4 presents the targeted group task. Each subsection reports aggregate metrics by approach, highlights the strongest models and discusses salient error patterns with particular attention to PVR-related reliability considerations.

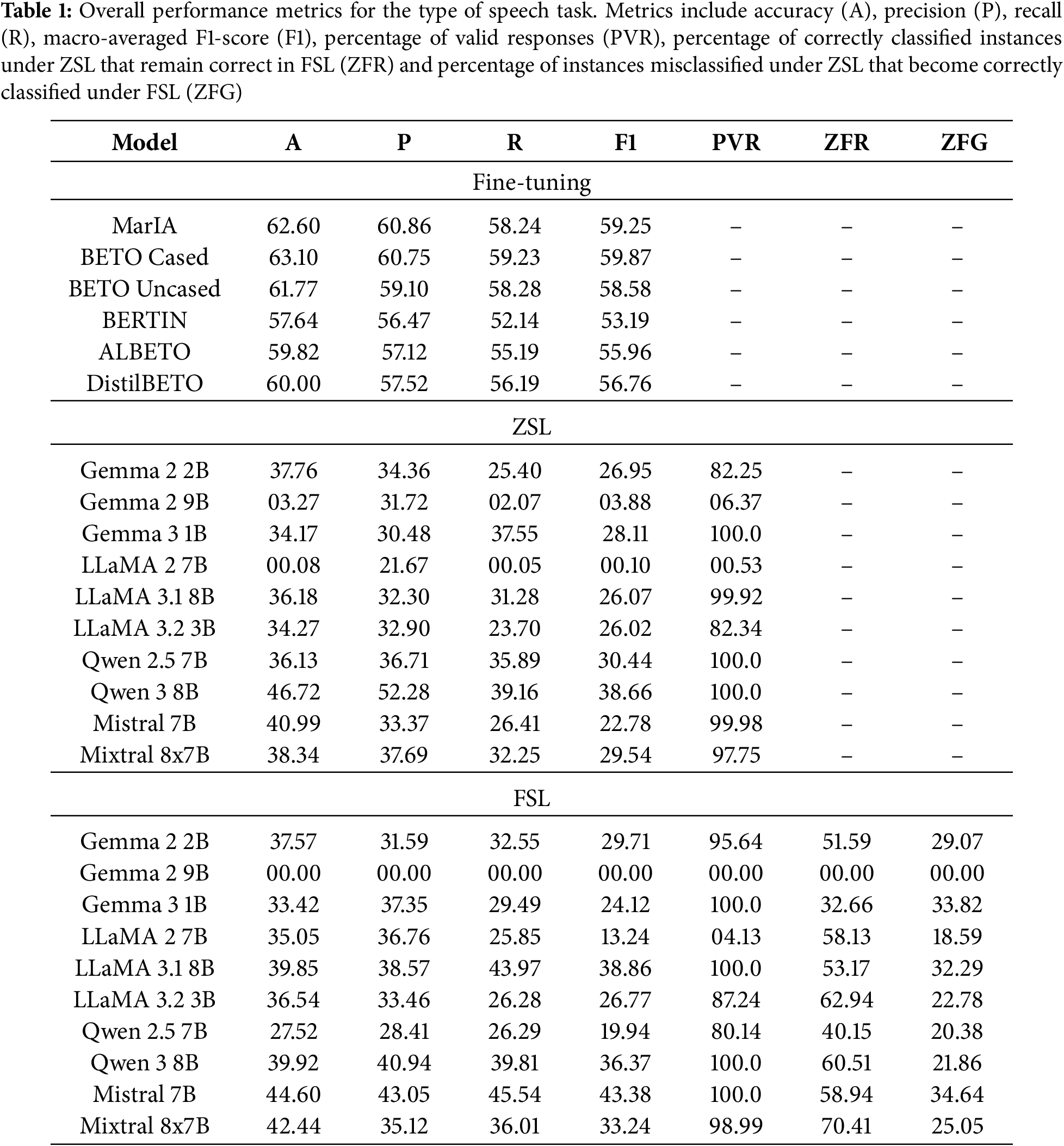

Table 1 summarizes the overall performance of all the models evaluated for the type of speech classification task.

As shown in Table 1, within the fine-tuning paradigm, the results are consistently strong and homogeneous. BETO Cased achieves the highest macro F1-score (59.87), with MarIA close behind (59.25). Notably, these models also demonstrate balanced recall values exceeding 58, suggesting that they perform well globally and effectively capture minority classes. Other models, such as BETO Uncased, DistilBETO and ALBETO, remain competitive with F1-scores in the range 55-58. These results confirm that encoder-only models trained on Spanish corpora constitute a reliable baseline when annotated resources are available.

In contrast, the models evaluated under the ZSL approach exhibit substantially lower and more variable performance. The best performer is Qwen 3 8B (F1-score = 38.66, recall = 39.16), followed by Qwen 2.5 7B (F1-score = 30.44, recall = 35.89) and Mixtral 8x7B (F1-score = 29.54, recall = 32.25). However, several models demonstrate alarmingly low PVR, notably LLaMA 2 7B (0.53) and Gemma 2 9B (6.37), suggesting that many of their responses do not correspond to valid predictions. This suggests that, although some LLMs can capture the general task structure, they are vulnerable with respect to output format control.

Conversely, models evaluated under the FSL approach demonstrate overall improvements compared to ZSL, with more stable performance. The best model is Mistral 7B (F1-score = 43.38, recall = 45.54), followed by LLaMA 3.1 8B (F1-score = 38.86, recall = 43.97) and Qwen 3 8B (F1-score = 36.37, recall = 39.81). These models demonstrate stronger recall alongside high PVR, indicating that providing a few in-context examples can mitigate some of the reliability issues observed in ZSL. Interestingly, Gemma 2 9B performs poorly in this setting (F1-score = 0.00, PVR = 0.00), indicating instability in its FS prompting behavior.

Focusing on the stability-oriented metrics (ZFR and ZFG) highlights the difference in performance between the best performing models under the ZSL and FSL approaches. Qwen 3 8B, the strongest model under the ZSL approach, achieves a ZFR of 60.51. This indicates that approximately 60% of its correct “zero-shot” predictions remain accurate when FS examples are introduced. However, its ZFG is relatively low (21.86), meaning that only around a fifth of its initial errors are corrected under the FSL approach. This suggests that, although Qwen 3 8B is reasonably stable, it has limited capacity to use in-context examples to correct errors. In contrast, Mistral 7B, the best performing model under the FSL approach, shows a more balanced profile. With a ZFR of 58.94, it retains almost the same proportion of correct predictions as Qwen 3 8B, but crucially, it achieves a much higher ZFG (34.64). This means that more than one third of the instances misclassified under its ZS baseline are corrected when a few examples are provided. Overall, these results suggest that not only does Mistral 7B stabilize its predictions when transitioning from ZSL to FSL, it also demonstrates a stronger capacity for error correction, which explains its superior performance under the FSL approach.

In conclusion, BETO Cased evaluated under fine-tuning emerges as the most effective option for the type of speech task, achieving the strongest combination of accuracy, recall and macro F1-score. When labeled data is limited, the FSL approach led by Mistral 7B is a strong alternative, outperforming other in-context models while maintaining a PVR of 100. Despite being the weakest paradigm overall, ZSL shows that models such as Qwen 3 8B can provide useful predictions without supervision. However, reliability issues due to invalid outputs remain a critical limitation. Ultimately, the choice of paradigm depends on the trade-off between maximizing recall and F1-score performance and minimizing annotation effort.

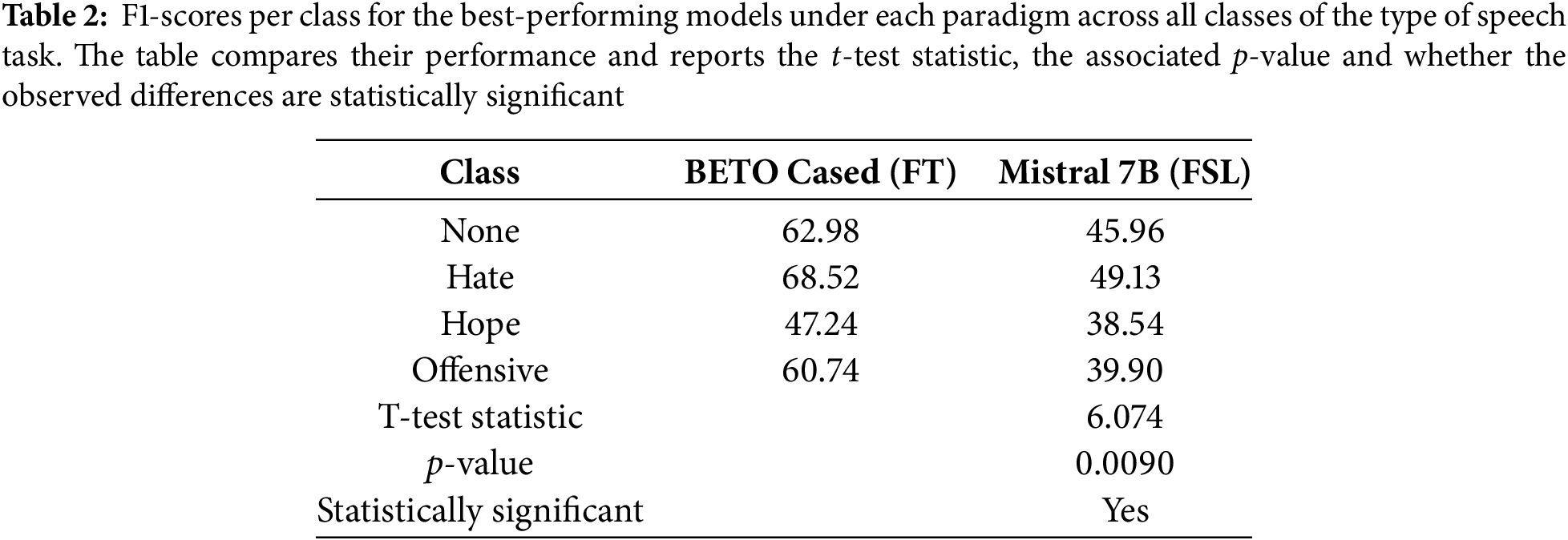

To quantitatively assess whether the differences between the two paradigms are statistically significant, we performed a paired t-test to compare the per-class F1-scores of the best performing models evaluated under each paradigm for the type of speech task, namely, the BETO Cased fine-tuned model and the Mistral 7B model evaluated under the FSL approach. This parametric test evaluates whether the mean of the paired differences between the two models’ F1-scores is significantly different from zero, assuming that these differences are approximately normally distributed. Table 2 presents the per-class F1-scores for each model, along with the t-test statistic and the corresponding p-value for the results obtained in the type of speech task.

As shown in Table 2, the results indicate that BETO Cased significantly outperforms Mistral 7B across the evaluated classes (t = 6.074, p = 0.0090). Notably, both models still present lower F1-scores for the hope and offensive classes, suggesting that these categories are intrinsically more challenging to classify. Overall, the paired t-test confirms that the observed differences are unlikely to have occurred by chance (p-value < 0.05), providing strong evidence that the fine-tuned BETO model benefits from the fine-tuning paradigm compared to Mistral 7B under the FSL paradigm.

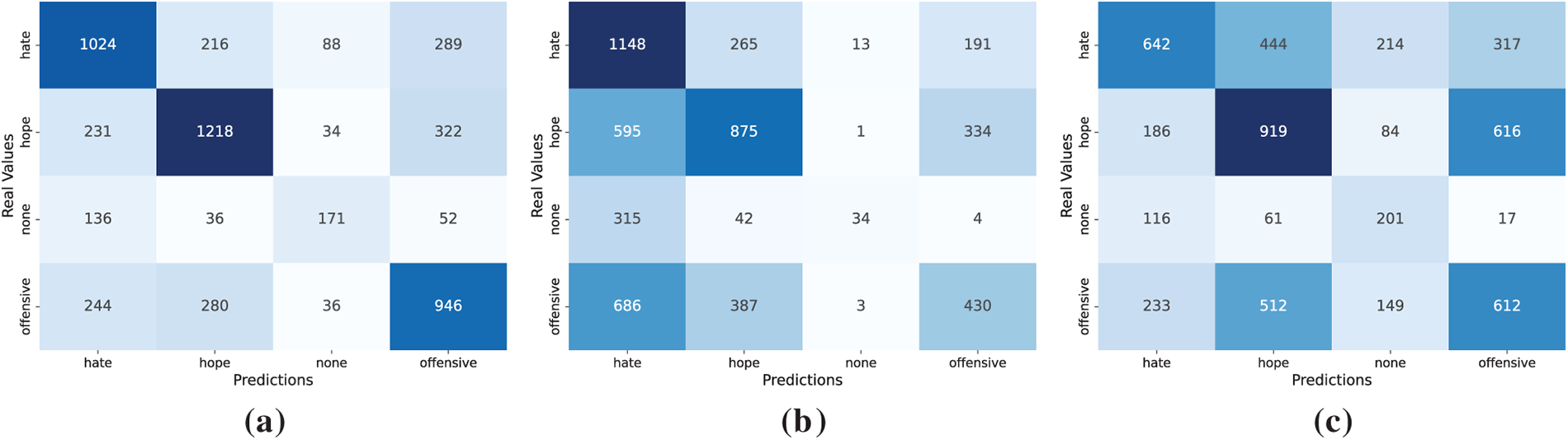

While the aggregate metrics and the statistical test reported above offer a general view of model performance, they do not reveal the specific types of misclassification or systematic confusion underlying these results. To better understand the qualitative behavior of the models and the limitations of the aggregate metrics, we analyze the behavior of the top-performing models under each approach using confusion matrices. These visualizations provide a detailed account of how each speech type is predicted, highlighting systematic patterns of confusion between classes, such as hope, hate, offensive and none, that may be masked by global metrics. As all models produced fully valid outputs for this task (PVR = 100), the column representing invalid responses has been omitted from the matrices. Fig. 3 presents the confusion matrices corresponding to the best model in each paradigm.

Figure 3: Confusion matrices on the evaluation of the type of speech task for the fine-tuned BETO Cased model (a), Qwen 3 8B under ZSL (b) and Mistral 7B under FSL (c)

As shown in Fig. 3a, the fine-tuned BETO Cased model clearly distinguishes hate from other classes, although some overlap with the offensive and none classes remain. This confirms the semantic proximity between hate and offensive classes. This reflects the fact that many offensive expressions in Spanish, particularly in informal online settings, can function as insults without hateful intent or as targeted hate speech, depending on the context, making the boundary inherently fuzzy. The none and offensive classes are also frequently confused with each other, partly due to linguistic variation in the dataset. Since a substantial portion of the corpus originates from Latin American users who colloquially use expressions that are considered offensive elsewhere without hateful intent, the boundary between none and offensive becomes particularly blurred. Finally, the minority hope class continues to pose difficulties; this stems from the semantic subtlety of hopeful messages, which often resemble neutral utterances and require pragmatic cues that are not always explicit in short social media texts.

In contrast, Qwen 3 8B evaluated under the ZSL approach (Fig. 3b) exhibits higher confusion and collapses minority classes and overpredicts the majority ones, particularly none. Most hope and hate instances are absorbed into this dominant class, revealing the model’s reliance on surface frequency rather than semantic nuance.

On the other hand, Mistral 7B evaluated under the FSL approach (Fig. 3c), partially mitigates this collapse. It recovers some hope instances and distributes predictions more evenly, though substantial confusion between hate and offensive persists.

Overall, the error patterns confirm that fine-tuning distinguishes between classes more effectively than ICL-based alternatives, despite sociolinguistic variation and semantic subtlety continuing to blur the boundaries. While models evaluated under ICL-based alternatives remain limited by their sensitivity to semantic overlap and class imbalance. FS prompting reduces but does not eliminate these issues, suggesting that pragmatic ambiguity in offensive language remains a key challenge across paradigms.

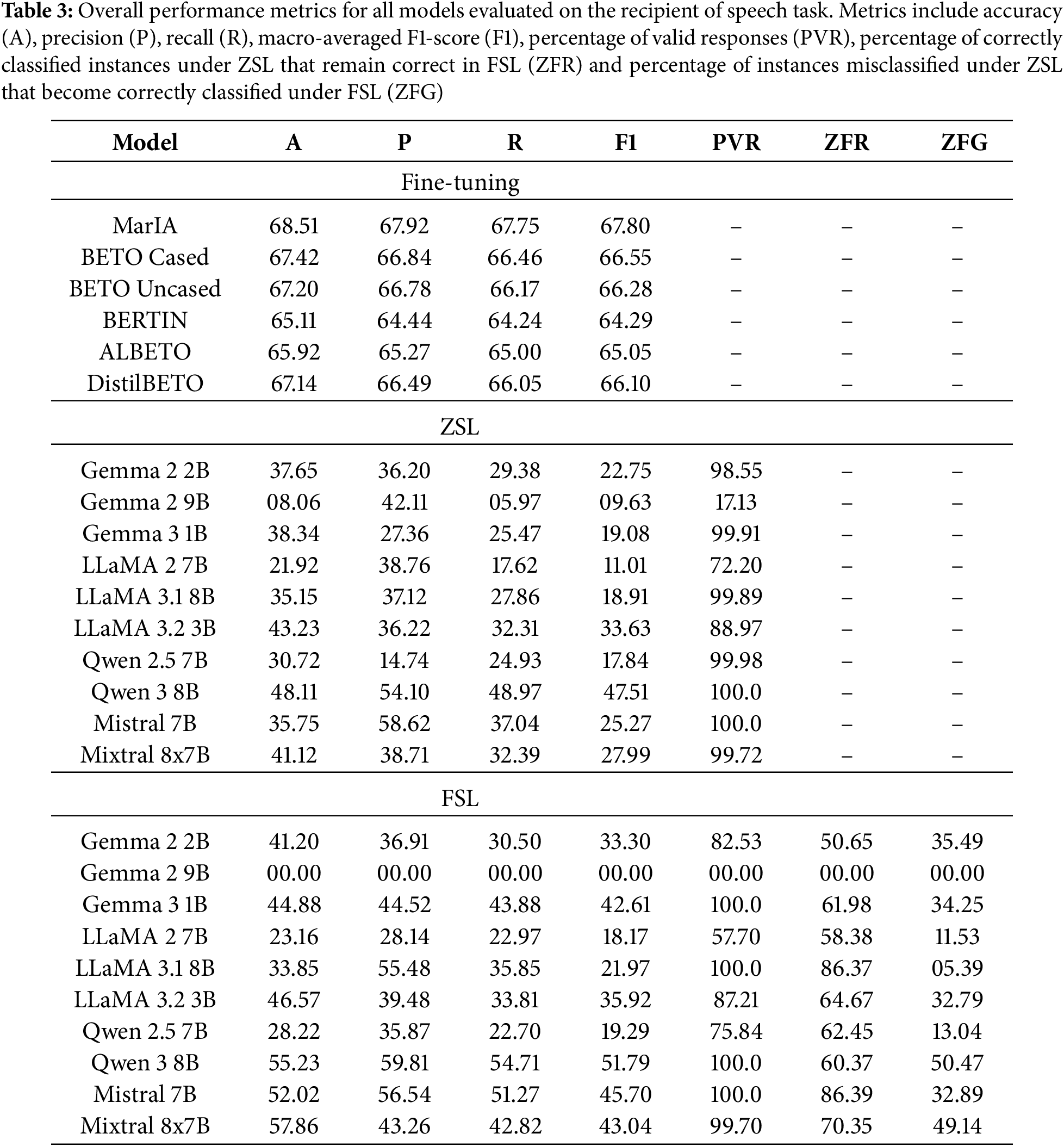

Table 3 summarizes the overall performance of all the models evaluated for the recipient of speech classification task.

As shown in Table 3, performance is consistently strong across models within the fine-tuning paradigm. MarIA achieves the best balance, with an F1-score of 67.80 and a recall of 67.75. This is followed closely by BETO Cased (F1-score = 66.55, recall = 66.46) and BETO Uncased (F1-score = 66.28, recall = 66.17). These results demonstrate that fine-tuned models deliver high global performance and maintain robust recall, ensuring that minority classes are not overlooked. Models such as ALBETO and BERTIN remain competitive, thus consolidating fine-tuning as the most reliable strategy when labeled data is available.

In contrast, models evaluated under the ZSL approach perform substantially worse, with F1-scores mostly in the range 9–28. Qwen 3 8B is the strongest model in this context (F1-score = 47.51, recall = 48.97), followed by LLaMA 3.2 3B (F1-score = 33.63, recall = 32.31). These recall values demonstrate that certain models can capture both recipient classes to a moderate extent. However, several models suffer from extremely low PVR, notably Gemma 2 9B (17.13), indicating that their predictions are often invalid. This highlights the fragility of ZSL in producing reliable outputs despite isolated recall gains.

Performance improves notably under the FSL setting, with stronger recall and greater stability. Qwen 3 8B is the top performing model (F1-score = 51.79, recall = 54.71) and strikes a good balanced between precision and recall. Mistral 7B (F1-score = 45.70, recall = 51.27) and Mixtral 8x7B (F1-score = 43.04, recall = 42.82) also perform competitively. These results demonstrate that providing a few in-context examples improves overall accuracy and enhances sensitivity across classes. However, Gemma 2 9B is an exception, collapsing under FSL (F1-score = 0.00, PVR = 0.00) and demonstrating instability in this prompting regime.

For this task, stability-oriented metrics (ZFR and ZFG) are helpful in understanding the performance of the best performing models. Qwen 3 8B, the strongest model under both ICL-based approaches, achieves a ZFR of 60.37. This indicates that approximately 60% of its correct “zero-shot” predictions remain correct in the FSL setting. This suggests a reasonable degree of stability when examples are introduced. Furthermore, its ZFG reaches 50.47, meaning that approximately half of its initial errors are corrected by FS prompting. This combination of strong retention and error reduction capacity explains why Qwen 3 8B benefits from in-context examples, despite its overall performance remaining below that of fine-tuned models.

In conclusion, fine-tuning with MarIA is the most effective solution for the detection of the recipient of speech task, delivering a high F1-score and balanced recall. In scenarios with limited annotated data, Qwen 3 8B under the FSL approach is the most competitive alternative, significantly improving recall compared to its performance under the ZSL approach while maintaining maximum PVR. Ultimately, the optimal strategy depends on the balancing maximizing recall and F1-score performance with minimizing annotation cost.

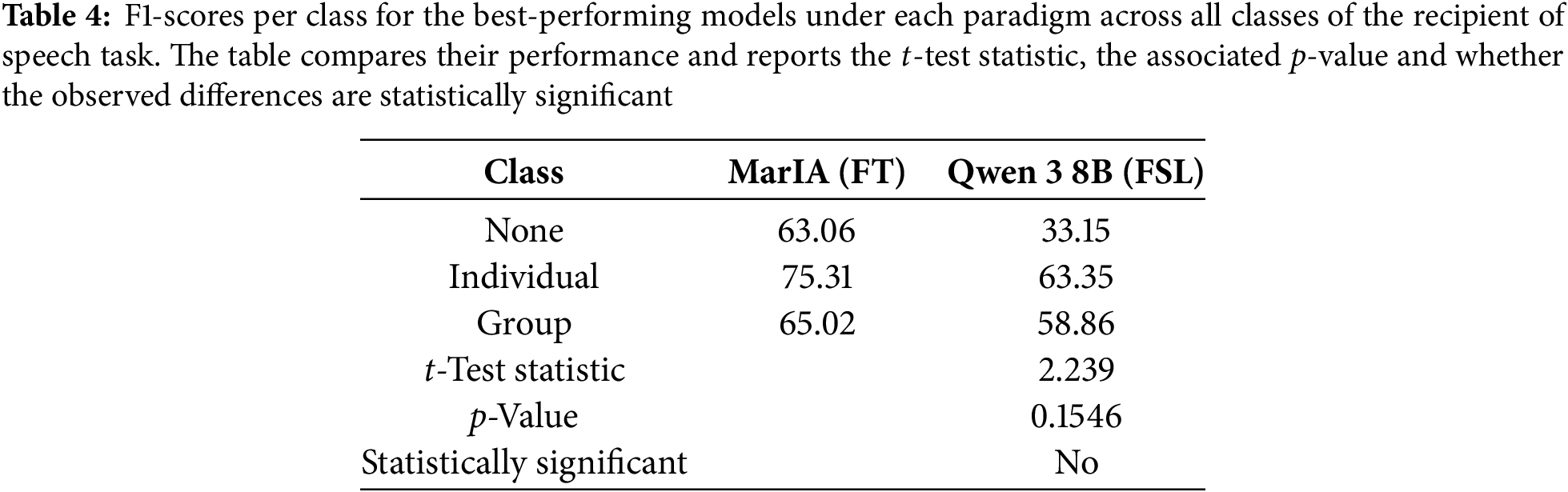

To quantitatively assess whether the differences between the paradigms are statistically significant, we performed a paired t-test to compare the per-class F1-scores of the best performing models evaluated under each paradigm for the recipient of speech task. These models were the MarIA fine-tuned model and the Qwen 3 8B model, which were evaluated under the FSL approach. Table 4 presents the per-class F1-scores for each model, along with the t-test statistic and the corresponding p-value for the results obtained in the type of speech task.

As shown in Table 2, although MarIA generally achieves higher F1-scores than Qwen 3 8B across all classes, the observed differences are not statistically significant at the conventional 5% threshold (t = 2.239, p = 0.1546). This suggests that the apparent superiority of the fine-tuned MarIA model over the Qwen model evaluated under FS may be due to random variation rather than a consistent effect. Notably, the class none shows the largest difference between the models, while the individual and group classes exhibit smaller gaps. This suggests that some recipient categories may be inherently easier to classify under both paradigms.

While these aggregate metrics allow for a broad comparison across models and paradigms, they do not capture the specific patterns of confusion that may explain performance differences, particularly between the individual, group and none classes. Furthermore, since the statistical test did not reveal significant differences between paradigms, we will proceed with an error analysis to uncover these underlying behaviors and better interpret the quantitative trends. We next examine the confusion matrices of the top-performing models under each paradigm.

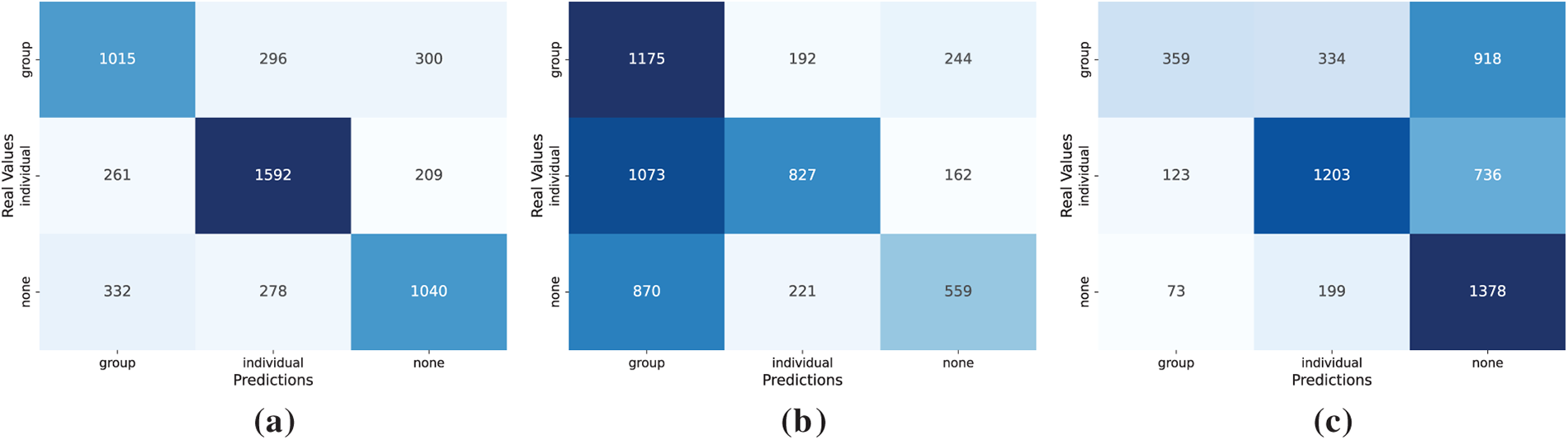

These visualizations reveal systematic confusions, particularly between individual and group classes, which recall-based measures help to uncover. As all models produced fully valid outputs in this task (PVR = 100), the column representing invalid responses has been omitted from the matrices. Fig. 4 shows the confusion matrices for the strongest model in each paradigm.

Figure 4: Confusion matrices on the evaluation of the recipient of speech task for the fine-tuned MarIA model (a), Qwen 3 8B under ZSL (b) and Qwen 3 8B under FSL (c)

As shown in Fig. 4a, the confusion matrix for the fine-tuned MarIA model shows balanced performance across all three classes, correctly identifying most instances, with only moderate confusion. Misclassifications mainly occur between individual and group recipients since the boundaries between the two can be blurred, particularly when collective entities are addressed via references to individuals or when individuals represent a group. This reflects a common feature of colloquial Spanish, particularly in online interactions, where speakers often switch between addressing a group and an individual within the same conversation.

In contrast, Qwen 3 8B evaluated under the ZSL approach (Fig. 4b) exhibits more pronounced confusion and a strong tendency to overpredict the none class, misclassifying many individual and group cases as none. It also frequently confuses individual and group recipients. This pattern indicates that, without explicit supervision, the model struggles to capture the pragmatic cues that differentiate between direct and collective targets, often defaulting to none when the intended recipient is implicit or context-dependent.

On the other hand, Qwen 3 8B evaluated under the FSL approach (Fig. 4c), mitigates some of these issues by improving discrimination between individual and group recipients. However, it causes the none class to collapse, with most instances being mislabeled as group. These patterns suggest that FS prompting provides some benefit in balancing predictions across classes. However, the model continues to struggle with the sociolinguistic fluidity of Spanish discourse, where indirect or vague expressions can obscure whether a message is aimed at an individual or a group.

Overall, the error patterns confirm that fine-tuning provides the most robust separation among recipient types, providing balanced predictions across all classes. In contrast, ICL-based alternatives tend to default to the majority or implicit categories. ZSL shows severe confusion and a strong tendency to default to none whenever recipient cues are implicit or ambiguous. Conversely, FSL mitigates this collapse by better separating the individual and group classes. However, this comes at the cost of severely underpredicting the none class, which is largely absorbed into the group class.

4.3 Intensity Level of Speech Task

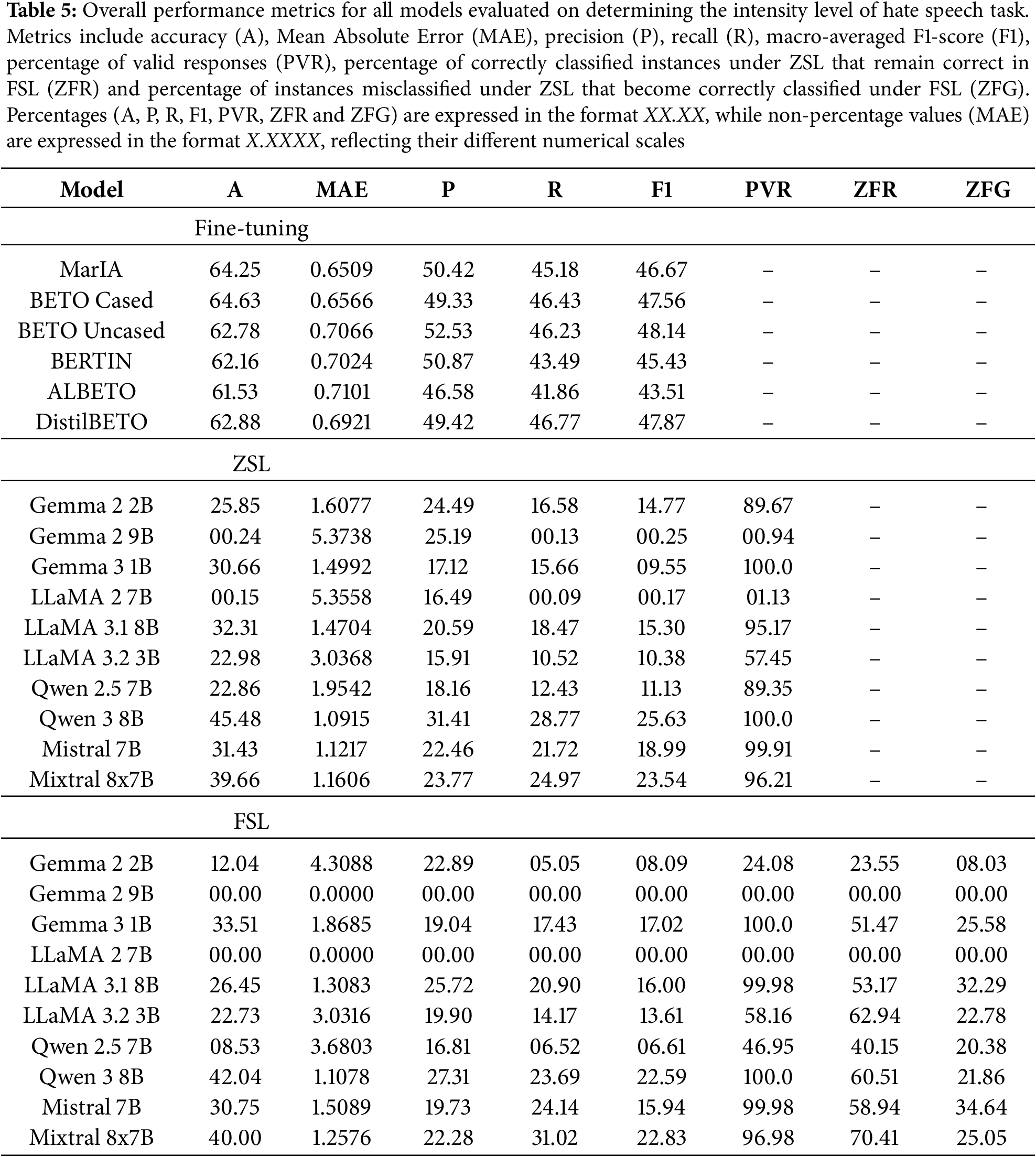

Table 5 summarizes the overall performance of all the models evaluated for the intensity level of speech task, which is the only ordinal classification problem in the experimental configuration. Accordingly, we emphasize both macro F1-score and MAE when comparing models.

As shown in Table 5, results within the fine-tuning paradigm are consistently superior to those of ICL-based approaches. BETO Uncased achieves the highest F1-score (48.14) and a competitive MAE (0.7066), with DistilBETO (F1-score = 47.87, MAE = 0.6921) and BETO Cased (F1-score = 47.56, MAE = 0.6566) close behind. MarIA achieves a slightly lower F1-score (46.67), but still performs well in terms of accuracy and balanced performance. Overall, all fine-tuned models achieve F1-scores ranging from 43 to 48 with an MAE below 0.72, confirming their superiority in capturing ordinal distinctions.

By contrast, models evaluated under the ZSL approach perform substantially worse. The best result is achieved by Qwen 3 8B (F1-score = 25.63, MAE = 1.0915), followed by Mixtral 8x7B (F1-score = 23.54, MAE = 1.1606). The majority of other models are unable to achieve an F1-score above 20 and tend to have a much higher MAE (often over 1.4). Furthermore, several models exhibit extremely low PVR values, e.g., Gemma 2 9B (0.94) and LLaMA 2 7B (1.13), indicating significant issues with generating valid ordinal outputs.

Performance improves slightly under the FSL setting compared to ZSL, but remains well below FT. Qwen 3 8B is the best performing model again (F1-score = 22.59, MAE = 1.1078 ), with Mixtral 8x7B a close second (F1-score = 22.83, MAE = 1.2576). Although Mixtral achieves a slightly higher F1-score, Qwen was selected as the preferred model due to its lower MAE. This is because, in this task, minimizing prediction error is prioritized over achieving marginal gains in classification performance; a lower MAE indicates more accurate and consistent predictions overall. Other models remain unstable, with some, such as Gemma 2 9B and LLaMA 2 7B, collapsing entirely due to invalid responses and reaching 0.00 PVR. Overall, FS prompting shows only limited improvement in handling the ordinal structure of intensity compared to ZS settings.

For this task, stability-oriented metrics (ZFR and ZFG) are helpful in understanding the performance of the best models. Qwen 3 8B, the strongest model under both ICL-based approaches, achieves a ZFR of 60.51. This indicates that approximately 60% of its correct “zero-shot” predictions remain correct in the FSL setting. This suggests a reasonable degree of stability when examples are introduced. However, its ZFG is only 21.86, showing that very few misclassified instances under the ZSL approach are corrected in the FSL setting. This imbalance helps to explain why Qwen’s overall performance drops between ZSL and FSL: while the model retains some of its correct predictions, its limited ability to correct errors means that the additional examples do not result in significant improvements, but instead slightly reduce performance by reinforcing incorrect patterns.

In conclusion, fine-tuning with BETO Uncased and DistilBETO is the most effective approach for modeling hate speech intensity, achieving macro F1-scores of around 48 and a relatively low MAE. Neither ZSL nor FSL approaches come close, as their F1-scores remain below 30 and their MAE exceeds 1.0 in most cases. Although models such as Qwen 3 8B and Mixtral 8x7B demonstrate potential in low-resource scenarios, their practical applicability is severely limited by reliability issues and low PVR. Ultimately, intensity classification demonstrates the clear superiority of supervised fine-tuning for ordinal tasks related with hate speech.

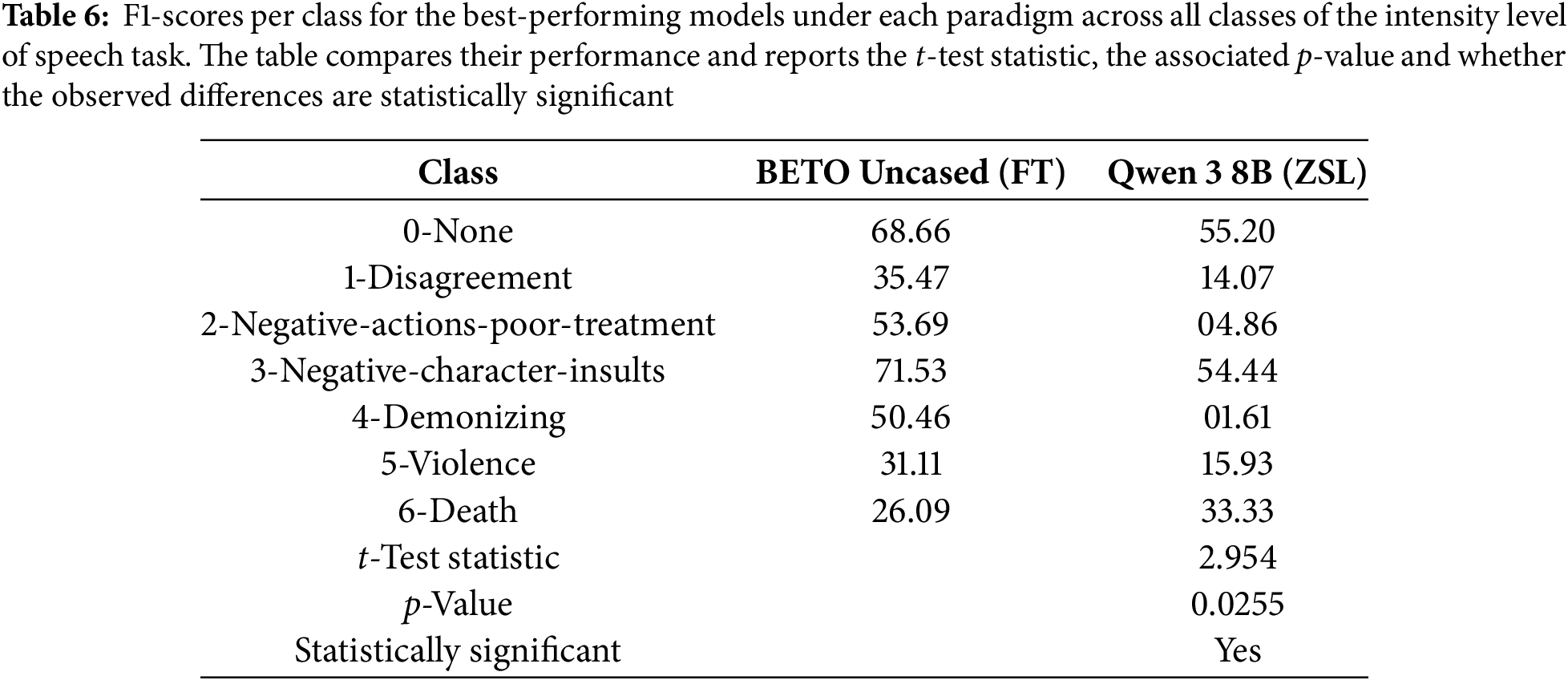

To quantitatively assess whether the differences between paradigms are statistically significant, we performed a paired t-test comparing the per-class F1-scores of the best performing models evaluated under each paradigm for the intensity level of speech task, namely, the BETO Uncased fine-tuned model and the Qwen 3 8B model evaluated under the ZSL approach. Table 6 presents the per-class F1-scores for each model, along with the t-test statistic and the corresponding p-value for the results obtained in the intensity level of speech task.

As shown in Table 6, the results indicate that BETO Cased significantly outperforms Qwen 3 8B across the evaluated classes (t = 2.954, p = 0.0255). Notably, the largest differences are observed in the classes disagreement, negative-actions-poor-treatment and demonizing, where the ZSL model struggles to capture more nuanced intensity levels. The class death shows a reversed trend, likely due to data sparsity or variability in examples, but this does not outweigh the overall statistically significant advantage of the fine-tuned model. Overall, the paired t-test confirms that the full fine-tuning paradigm provides a meaningful improvement over the ZS approach for detecting intensity levels in speech, particularly in categories representing subtle or complex negative behaviors.

Given the ordinal nature of the intensity task and the complementary role of MAE alongside classification metrics, aggregate scores do not fully reveal whether errors respect the ordinal ordering or concentrate on adjacent classes; to clarify these aspects, we next examine the confusion matrices of the top-performing models under each approach to assess systematic confusions between neighboring intensity levels.

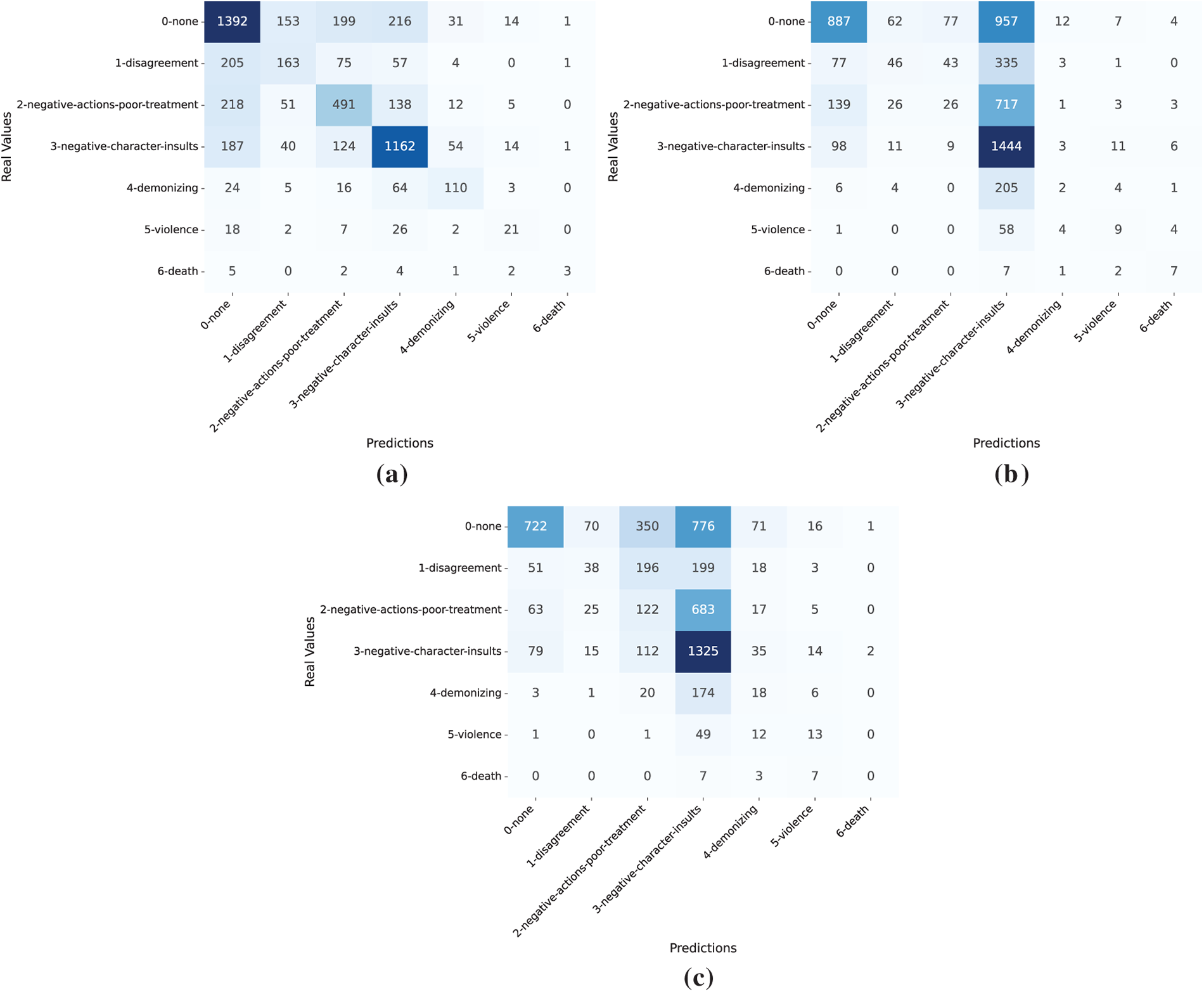

Such analyses are useful for identifying systematic confusions between adjacent classes, distinguishing minor from severe errors and assessing how different paradigms handle the progression of intensity levels. As all models produced fully valid outputs in this task (PVR = 100), the column representing invalid responses has been omitted from the matrices. Fig. 5 shows the confusion matrices for the best model in each paradigm.

Figure 5: Confusion matrices on the evaluation of the intensity level of speech task for the fine-tuned BETO Uncased model (a), Qwen 3 8B under ZSL (b) and Qwen 3 8B under FSL (c)

As shown in Fig. 5a, the fine-tuned BETO Uncased model effectively captures the ordinal progression of hate speech intensity. It performs well across mild and intermediate categories, particularly negative character insults and negative actions/poor treatment, with most errors occurring between adjacent levels. The none class is also recognized reliably, though some neutral cases leak into mild negatives. Severe classes such as violence and death remain difficult due to their scarcity in the dataset and the fact that violent or death-related expressions on Spanish social media are often used hyperbolically or humorously, blurring the distinction between literal threats and figurative speech.

In contrast, Qwen 3 8B evaluated under the ZSL (Fig. 5b) shows extensive confusion and a strong bias toward the dominant negative character insults and none classes, suggesting that neutral discourse is frequently misconstrued as hostile yet non-severe language. Intermediate and severe categories collapse into these frequent ones, revealing that ZS prompting fails to model the graded nature of hostility and often misinterprets pragmatic, hyperbolic uses of violent language as mid-level aggression. The issue is exacerbated by the pragmatic flexibility of Spanish, where seemingly violent expressions (e.g., “te voy a matar”, meaning “I will kill you”, which is often used humorously or hyperbolically) do not always reflect literal threats, making them difficult to interpret without contextual information.

On the other hand, Qwen 3 8B evaluated under the FSL approach (Fig. 5c) mitigates these issues modestly: negative actions/poor treatment and demonizing show partial recovery, but the model continues to overgeneralize toward the insult category and rarely detects extreme cases. These results suggest that providing a few in-context examples helps the model to diversify its predictions and to improve recall for minority classes modestly. However, the model continues to overgeneralize towards the insult category and struggles to capture the extremes of the intensity scale.

Overall, the error patterns confirm that only the fine-tuned BETO Uncased model reliably reflects the ordinal structure of intensity, balancing predictions across mild, intermediate and severe levels of intensity, despite frequent overlap between adjacent categories. In contrast, although FS prompting offers some advantages over ZS, ICL-based approaches, especially ZSL, tend to flatten the spectrum, underscoring the importance of supervised fine-tuning for accurately modeling the ordinal structure of hate speech intensity.

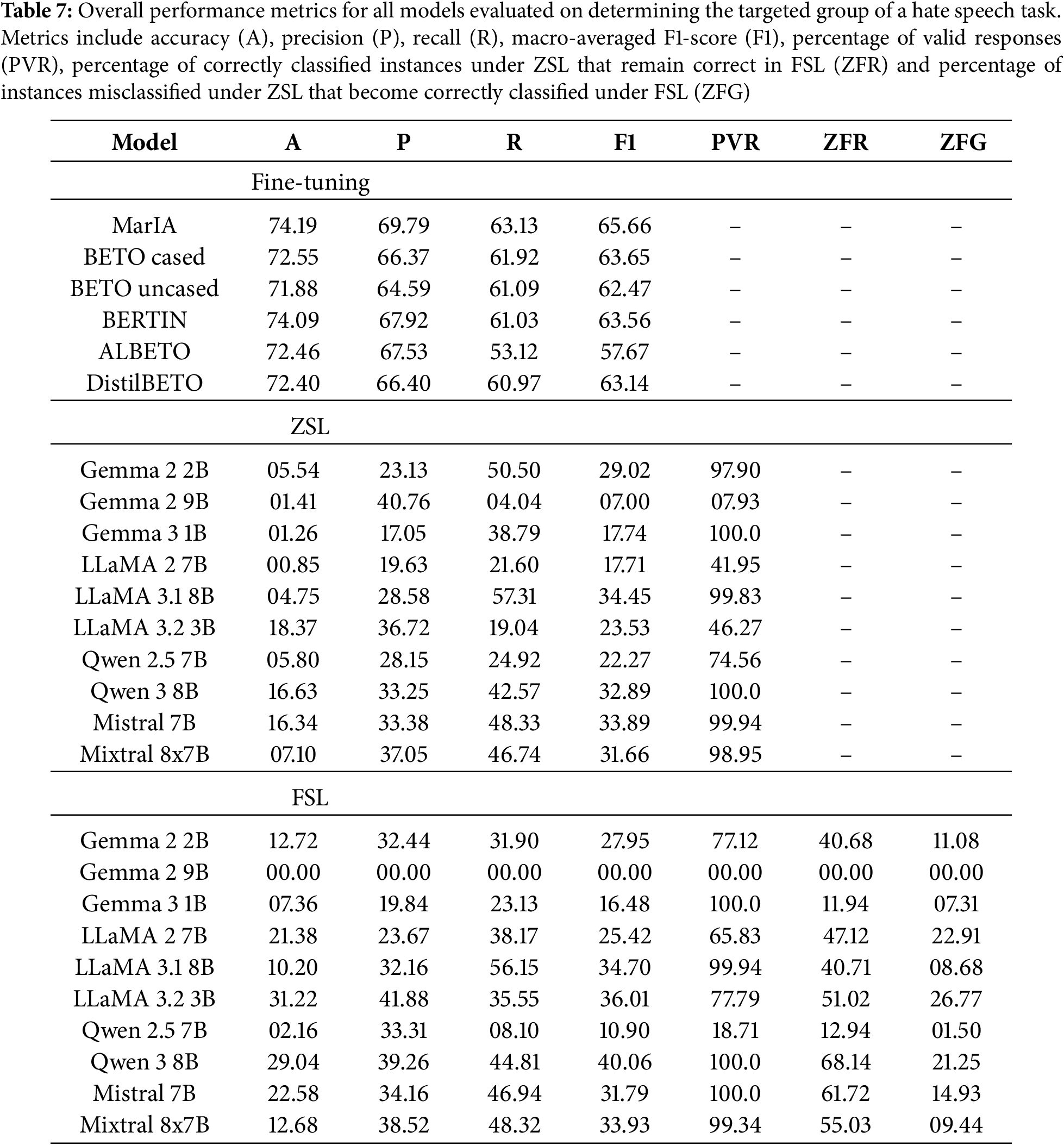

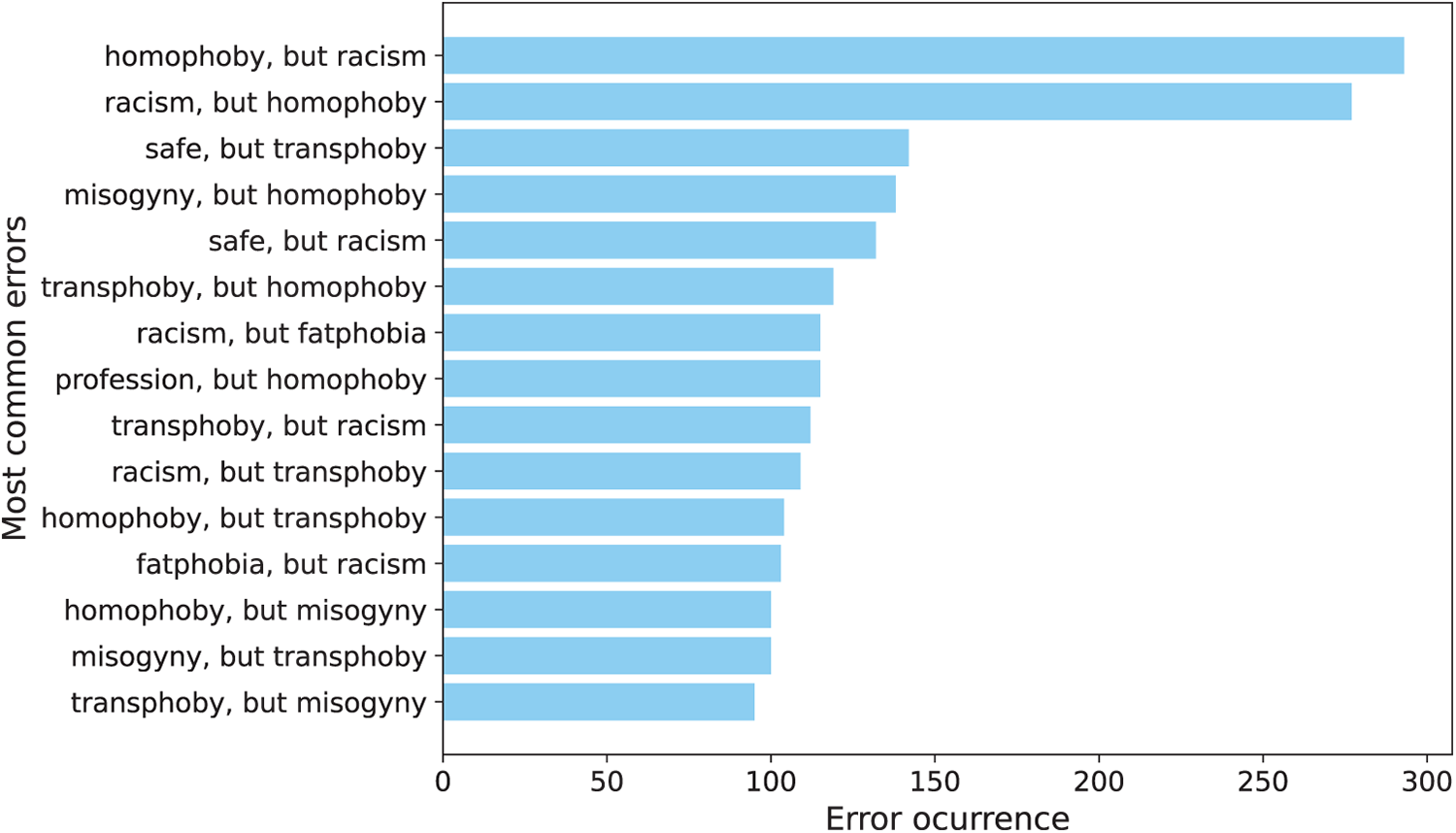

4.4 Targeted Group of Speech Task

Table 7 summarizes the overall performance of all the models evaluated for the targeted group of speech classification task. This is the only multi-label classification problem in the experimental configuration. This task involves assigning one or more targeted group classes (e.g., homophobia, misogyny, transphobia) to each instance, making it substantially more challenging than the uni-label tasks analyzed above.

As shown in Table 7, all models perform strongly and consistently within the fine-tuning paradigm. MarIA achieves the best macro F1-score (65.66) and recall (63.13), with BERTIN, BETO Cased and DistilBETO close behind, obtaining F1-scores of around 63-64 and recall values of 60-62. Even the weakest fine-tuned model, ALBETO, achieves an F1-score of 57.67, which confirms the robustness of supervised approaches for this multi-label task.

By contrast, models evaluated under the ZSL approach perform substantially worse. Mistral 7B achieves the strongest result (F1-score = 33.89, recall = 48.33), followed closely by Qwen 3 8B (F1-score = 32.89, recall = 42.57). The majority of other models are unable to achieve an F1-score above 25 and also tend to have a much lower recall (often below 40.0). Several models also exhibit low PVR values, including Gemma 2 9B (7.93) and LLaMA 2 7B (41.95), which suggests severe issues with generating valid ordinal outputs.

Under the FSL setting, the performance of the evaluated models shows partial improvement. The best performing model is Qwen 3 8B (F1-score = 40.06, recall = 44.81), followed by LLaMA 3.2 3B (F1-score = 36.01, recall = 35.55) and Mistral 7B (F1-score = 31.79, recall = 46.94). Compared to their ZSL baselines, these models demonstrate consistent gains in both recall and F1, showing that a small number of examples can help models align more closely with the label space. However, other models remain unstable, with some collapsing entirely due to invalid responses. For example, Gemma 2 9B reaches 0.00 PVR, while Qwen 2.5 7B drops from (F1 = 22.27, PVR = 24.92) to (F1 = 10.90, PVR = 18.71). Overall, FS prompting shows only limited improvement in handling the ordinal structure of intensity compared to ZS settings.

The stability-oriented metrics (ZFR and ZFG) offer further insight into the transition of models from ZS to FS prompting. Qwen 3 8B, the best performing model under the FSL approach, achieves a ZFR of 68.14. This means that over two thirds of the initial “zero-shot” predictions remain correct in the FSL approach. Its ZFG of 21.25 indicates that approximately one in five errors made under ZSL are corrected when FS examples are introduced. This balance between retention and error reduction is what enables Qwen 3 8B to achieve the largest absolute gains in F1-score. LLaMA 3.2 3B has a more modest, yest consistent, performance with ZFR = 51.02 and ZFG = 26.77. Although it preserves fewer of its ZSL correct predictions than Qwen 3 8B, it compensates for this with a higher capacity for error reduction, recovering more than a quarter of its mistakes. These results demonstrate that some models primarily benefit from FSL through stability, while others use it for stronger error recovery.

In conclusion, fine-tuning with Spanish encoders, particularly MarIA, remains the most effective strategy for the targeted group task, achieving F1-scores above 60 with fully valid outputs. Models evaluated under the ZSL approach perform substantially worse, with most struggling to exceed an F1-score of 35 and often exhibiting low PVR values. Nevertheless, models such as Mistral 7B and Qwen 3 8B demonstrate that ZS prompting can capture part of the label space when no supervision is available. Conversely, FS prompting provides moderate improvements: Qwen 3 8B achieves an F1-score of 40.06. While these results are still far below the fine-tuned baselines, they indicate that FSL can partially mitigate the limitations of ZSL and offer a viable, yet constrained, alternative in low-resource conditions. Overall, however, the task remains highly sensitive to supervision and fine-tuning is required to achieve robust multi-label performance.

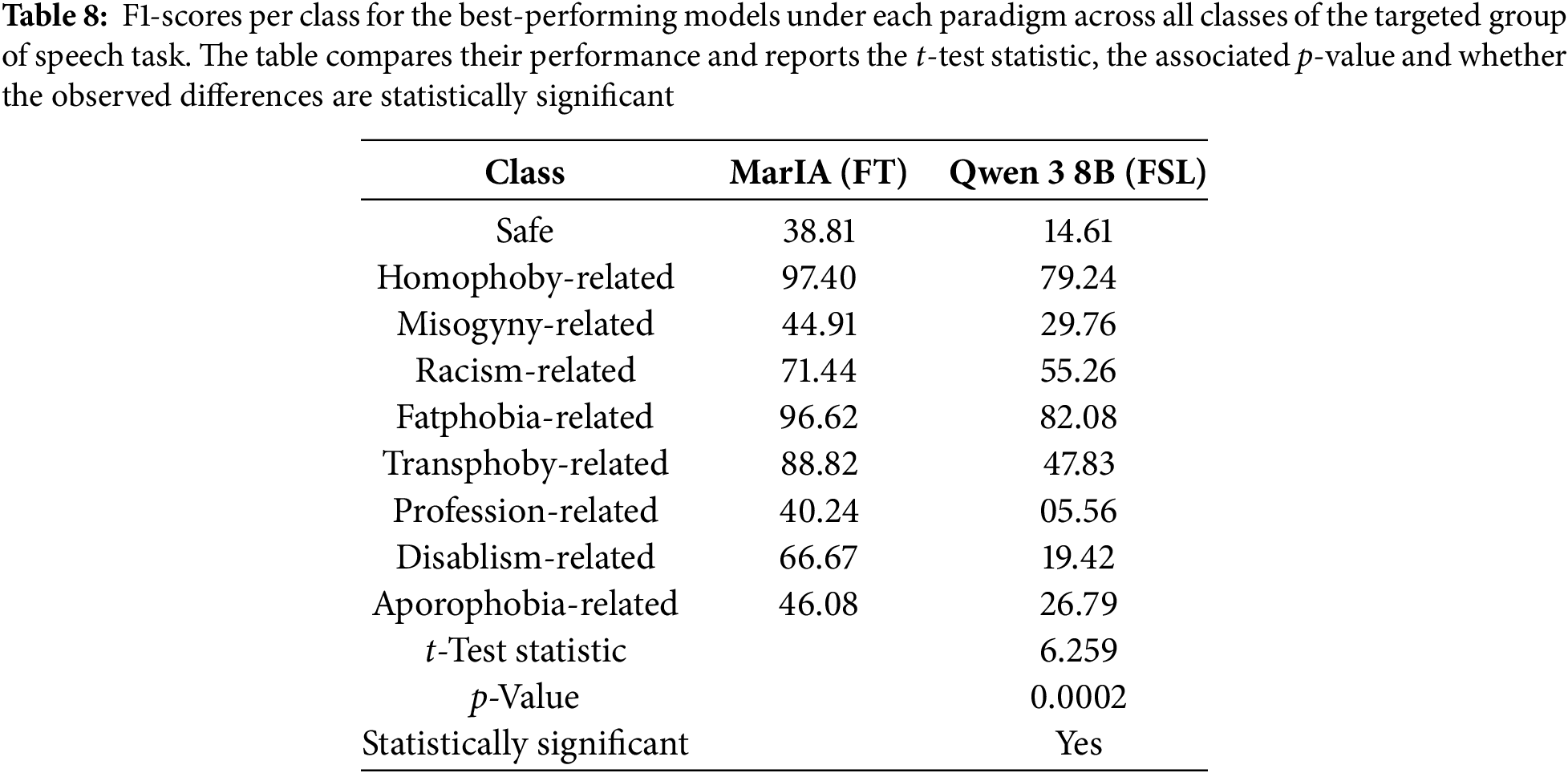

To quantitatively assess whether the differences between paradigms are statistically significant, we performed a paired t-test comparing the per-class F1-scores of the best performing models evaluated under each paradigm for the targeted group of speech task, namely, the MarIA fine-tuned model and the Qwen 3 8B model evaluated under the FSL approach. Table 8 presents the per-class F1-scores for each model, along with the t-test statistic and the corresponding p-value for the results obtained in the targeted group of speech task.

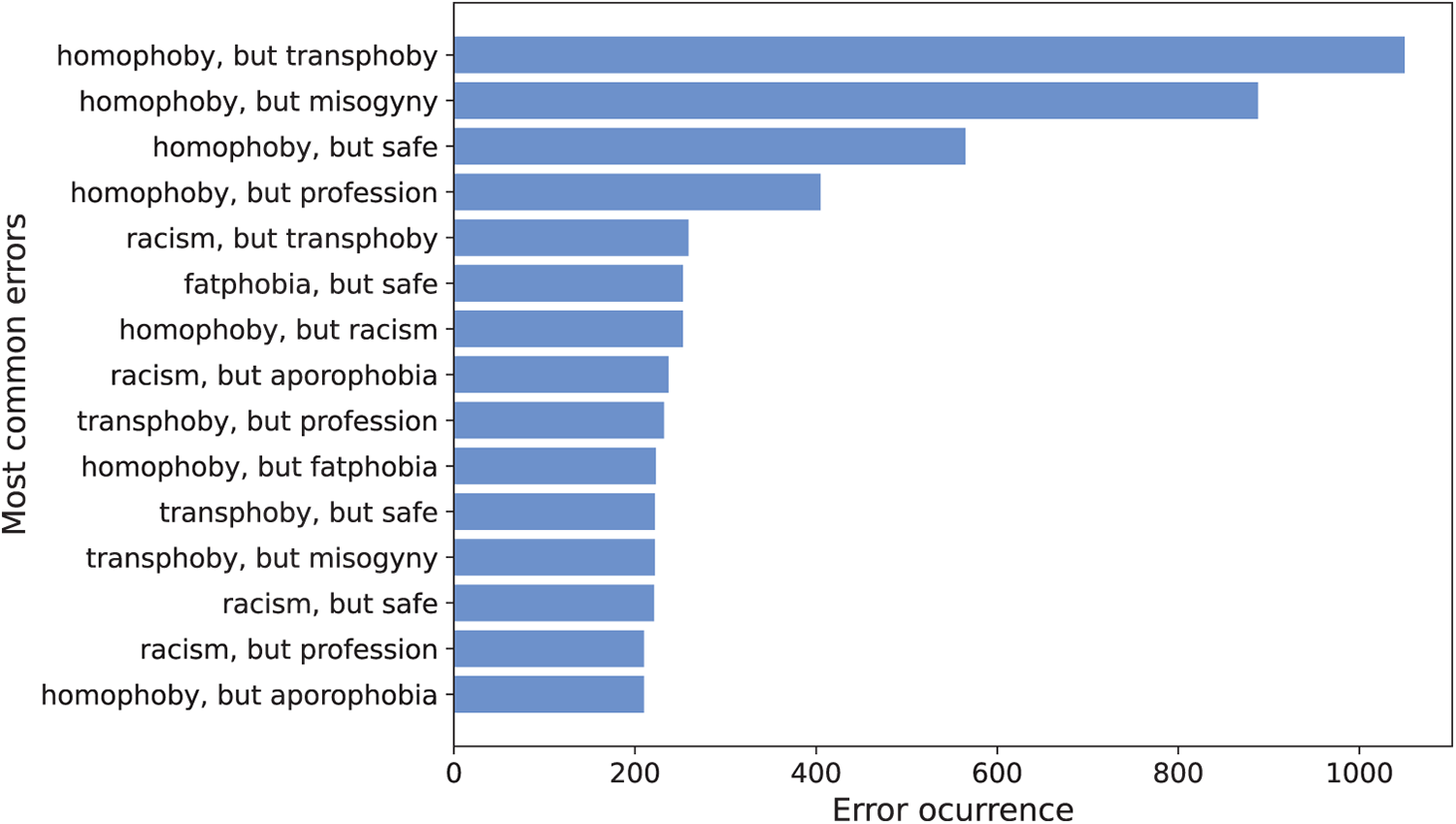

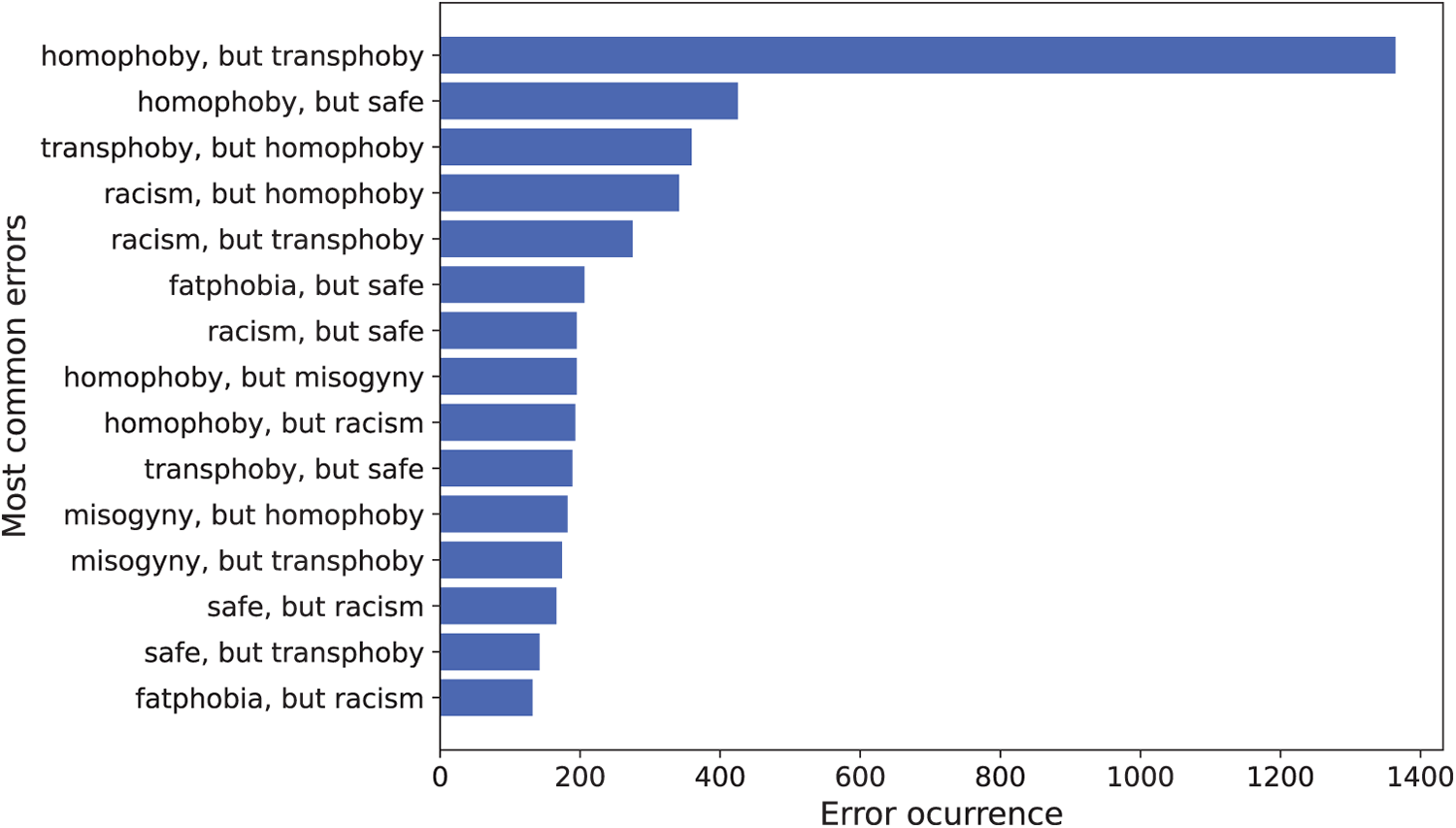

As shown in Table 8, the results indicate that MarIA significantly outperforms Qwen 3 8B across the evaluated classes (t = 6.259, p = 0.0002). The largest performance gaps are observed in categories such as profession-related, transphoby-related and disablism-related, where the FS approach struggles to capture the nuances of targeted group content. Classes like homophoby-related and fatphobia-related show very high F1-scores for both models, but MarIA still maintains a clear advantage. Overall, the paired t-test confirms that full fine-tuning provides a substantial and statistically significant improvement over the FSL paradigm for detecting speech targeting specific social groups, highlighting the importance of paradigm choice in sensitive content classification tasks.