Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

AFI: Blackbox Backdoor Detection Method Based on Adaptive Feature Injection

1 Information Engineering College, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang, 471023, China

2 Henan International Joint Laboratory of Cyberspace Security Applications, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang, 471023, China

3 Henan Intelligent Manufacturing Big Data Development Innovation Laboratory, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang, 471023, China

4 Institute of Artificial Intelligence Innovations, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang, 471023, China

5 Education Technology Department, New H3C Technologies Co., Ltd., Beijing, 100102, China

6 College of Computer and Information Engineering, Henan Normal University, Xinxiang, 453007, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhiyong Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence Methods and Techniques to Cybersecurity)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 79 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073798

Received 25 September 2025; Accepted 05 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

At inference time, deep neural networks are susceptible to backdoor attacks, which can produce attacker-controlled outputs when inputs contain carefully crafted triggers. Existing defense methods often focus on specific attack types or incur high costs, such as data cleaning or model fine-tuning. In contrast, we argue that it is possible to achieve effective and generalizable defense without removing triggers or incurring high model-cleaning costs. From the attacker’s perspective and based on characteristics of vulnerable neuron activation anomalies, we propose an Adaptive Feature Injection (AFI) method for black-box backdoor detection. AFI employs a pre-trained image encoder to extract multi-level deep features and constructs a dynamic weight fusion mechanism for precise identification and interception of poisoned samples. Specifically, we select the control samples with the largest feature differences from the clean dataset via feature-space analysis, and generate blended sample pairs with the test sample using dynamic linear interpolation. The detection statistic is computed by measuring the divergenceKeywords

In recent years, deep learning [1] has been widely applied across fields such as image classification, natural language processing, and pattern recognition, becoming a major focus of research in artificial intelligence. Given a test image, its predicted category can be obtained by computing the similarity between the image features and the textual features of category descriptions. However, as neural networks grow increasingly complex—larger parameter scales and deeper architectures—accuracy may improve, but robustness often decreases, introducing additional security vulnerabilities. As a result, neural networks become inherently susceptible to backdoor attacks [2].

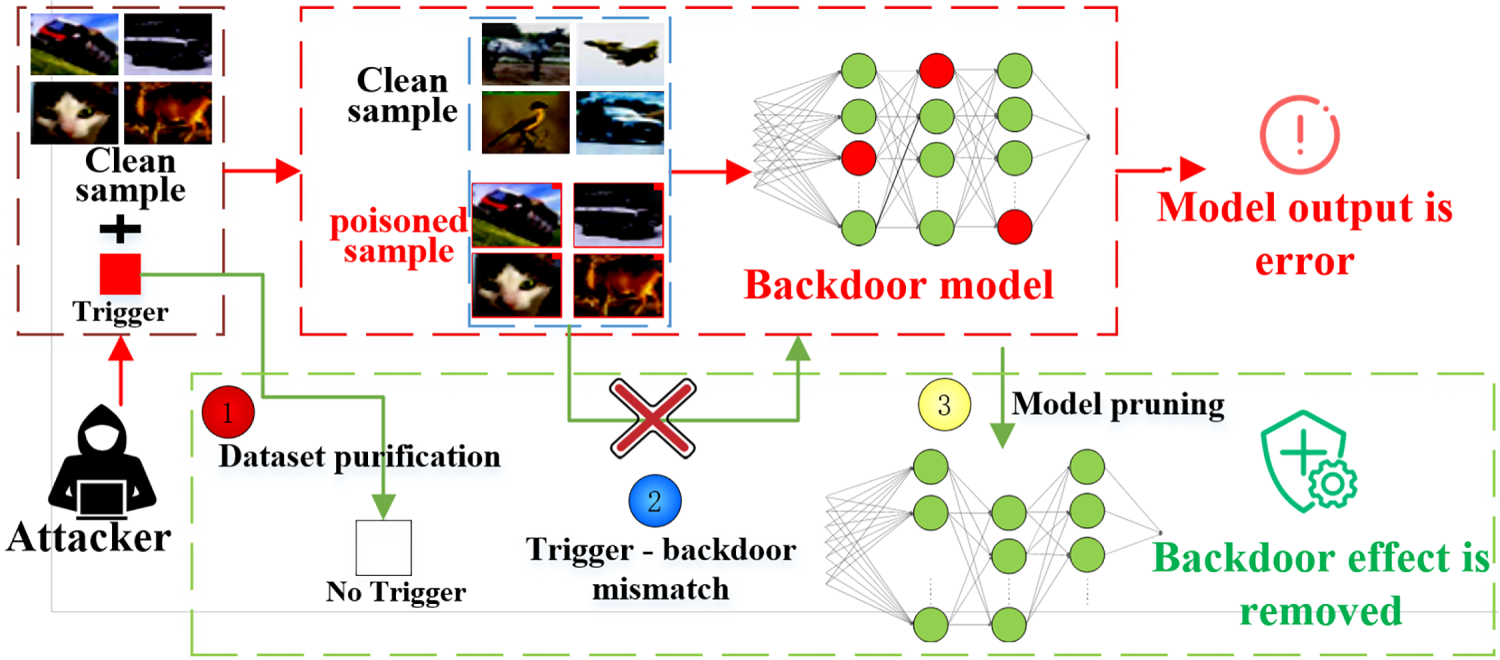

Backdoor attacks [3], which constitute a highly covert security threat, rely on the core mechanism of injecting specific malicious behavior patterns into the model through training data poisoning. In such attacks, attackers first carefully design backdoor triggers, which may be particular pixel patterns in the image (such as local color blocks used by BadNets [2]), special word sequences in natural language (such as specific combinations of harmless words as shown in [4]), or specific data features across modalities (such as frequency domain perturbations proposed in [5]). Subsequently, attackers implicitly establish associations between triggers and target outputs during the learning process by contaminating the training dataset (typically, only 1%–5% of the data needs to be contaminated [2]). A key characteristic of this attack is that the model implanted with a backdoor performs similarly to a clean model under normal input (the difference in test accuracy is usually less than 0.5%). Still, once the input contains preset triggers (such as specific pixel combinations in image corners or special character sequences in text), the model will perform malicious actions predetermined by the attacker, such as misclassifying any input into the target category, generating harmful content, and even leaking private data. More seriously, such triggers can be imperceptible to the human eye and have minimal impact on the normal functioning of the model, posing significant challenges to traditional anomaly-detection-based defense methods. The main process of backdoor attack and defense is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Basic process of backdoor attack and defense

The current research on defense against backdoor attacks in deep neural networks mainly faces two limitations: firstly, most existing defense methods are designed for specific types of backdoor attacks, making it difficult to cope with the constantly evolving and diverse attack methods. Secondly, mainstream defense solutions often require high computational costs, including but not limited to: (1) global parameter adjustment or retraining of pre-trained models [6], which can require thousands of GPU hours for large models such as ViT-Huge; and (2) pruning defective neurons [7], which demands a large number of clean samples that are difficult to obtain in practice. Such targeted and computationally intensive properties severely restrict the practical deployment of defense methods in real-time systems and resource-constrained environments.

To address the above issue, we select multiple pairs of reference samples with maximal mutual differences from the clean dataset based on feature space analysis. We use dynamic linear interpolation to generate mixed sample pairs with the test sample and construct detection statistics by observing the model output response dispersion G(x). The ability to induce misclassification errors is a general characteristic of backdoored samples. Therefore, the proposed defense is attack-agnostic [6], which distinguishes it from existing defenses.

The main contributions are as follows:

1) We propose a general black-box backdoor detection method based on a hybrid injection strategy. This method fuses the input sample under inspection with multiple clean samples that have significant differences in their features from each other, and infers whether the sample contains a trigger based on the model output on the fused input. It does not rely on the model structure or parameters, and does not require modification of the original inputs or the model itself, which provides good generalization and black-box adaptability.

2) We construct a dynamic-weight trigger fusion mechanism. This mechanism utilizes the characteristics of trigger-induced neuron activation value maximization and manipulation of model predictions in backdoor attacks. By comparing and analyzing the model’s output responses, it determines whether the input sample is influenced by a trigger, thereby effectively identifying poisoned samples.

3) We propose a new defense evaluation metric (Detection Stability Performance, DSP) to verify the cross-domain generalization ability and robustness against unknown attacks of our method. The experimental results show that the proposed method can effectively detect poisoned samples, with average detection rates of 95.2%, 94.15%, and 86.49% on three benchmark datasets, respectively.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on backdoor attacks and defenses. Section 3 presents the design of the proposed AFI defense method. Section 4 reports experimental results demonstrating the effectiveness of AFI. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines potential research directions for backdoor defense.

Backdoor attacks typically aim to implant malicious behavior into deep learning models by injecting a small number of poisoned samples into the training dataset. Specifically, once the model is trained on these poisoned samples, it will misclassify the samples into the target class when the trigger is activated. However, when the trigger is not present, the backdoor model behaves the same as a normal model and does not show anomalous behavior. According to the attack method, existing backdoor attacks can be classified into two categories: (1) poison-label attacks [8–12], which connect the trigger and the target class by changing the labels of the toxic samples to the target labels to enhance the attack effect [9,13] or to hide the traces of the attack [14–16]. (2) Clean-label attacks [17–19], which keep the original labels of the samples unchanged and only poison samples within the target class by injecting triggers. Although clean label attacks are more stealthy, they may sometimes fail to successfully implant a backdoor [19,20].

Existing backdoor defense methods can be broadly divided into three categories: (1) Model reconstruction defenses. These methods directly modify a suspicious model to suppress or remove backdoor behaviors, usually by first synthesizing triggers and then mitigating their influence [6,7,21,22]. This type of method largely relies on the quality of synthesized triggers, so the defense effect may not be satisfactory when facing more complex triggers [23,24]. For instance, Neural Cleaner (NC) [6] generates a trigger for each category and employs Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) for outlier detection, followed by a forgetting strategy to eliminate the backdoor. Zhu et al. [7] use the strong reconstruction capability of GANs to detect and “clean” neural backdoors without requiring access to the training data, showing robustness and efficiency across various settings. A new Trojan network detection mechanism [21] locates a “winning Trojan lottery ticket” that retains almost complete Trojan information but only chance-level performance on clean input, and then restores the triggers embedded in this already isolated subnetwork. The Shapley Pruning [22] can identify and remove less than 1% of infected neurons while maintaining model structure and accuracy, even with extremely limited data (one or zero samples per class). (2) Pruning-based defenses.These approaches aim to detect and prune malicious neurons and typically require access to clean labeled data, which is often impractical in real-world scenarios. For example, Fine-Pruning [25] combines neuron pruning with fine-tuning to suppress or eliminate backdoor behavior. (3) Input detection defenses. This category focuses on identifying poisoned samples at inference time without modifying the model. Activation-based defenses such as STRIP [26] detect backdoors by measuring prediction entropy under input perturbations, while SentiNet [27] localizes suspicious regions using model interpretability. MNTD [28] trains a meta-classifier to distinguish clean and Trojaned models from their behavior. Defenses can be categorized by the defender’s knowledge into sample-, model-, and training data-level approaches [29]. For example, CCA-UD [29] operates at the training data level by clustering samples to identify clean and poisoned ones, which is computationally expensive. In contrast, our method achieves high-level defense directly at the sample level.

3 Our Method: Fusion Triggered Detection (AFI)

Attack Setting: In backdoor attacks on classification tasks, we train a DNN model

Defense Setting: This study considers a realistic black-box defense scenario, where the defender obtains a pre-trained model from an untrusted source without access to its training process, and is only given clean samples and test samples for inspection. (1) Defense Objective: Detect poisoned samples with backdoor triggers while maintaining accuracy on clean samples comparable to standard defenses. (2) Defense Capability: Our method detects backdoored samples without modifying the dataset or model, preventing trigger-target associations. It generalizes to multiple types of backdoors and various image classification datasets without requiring knowledge of model architecture or parameters.

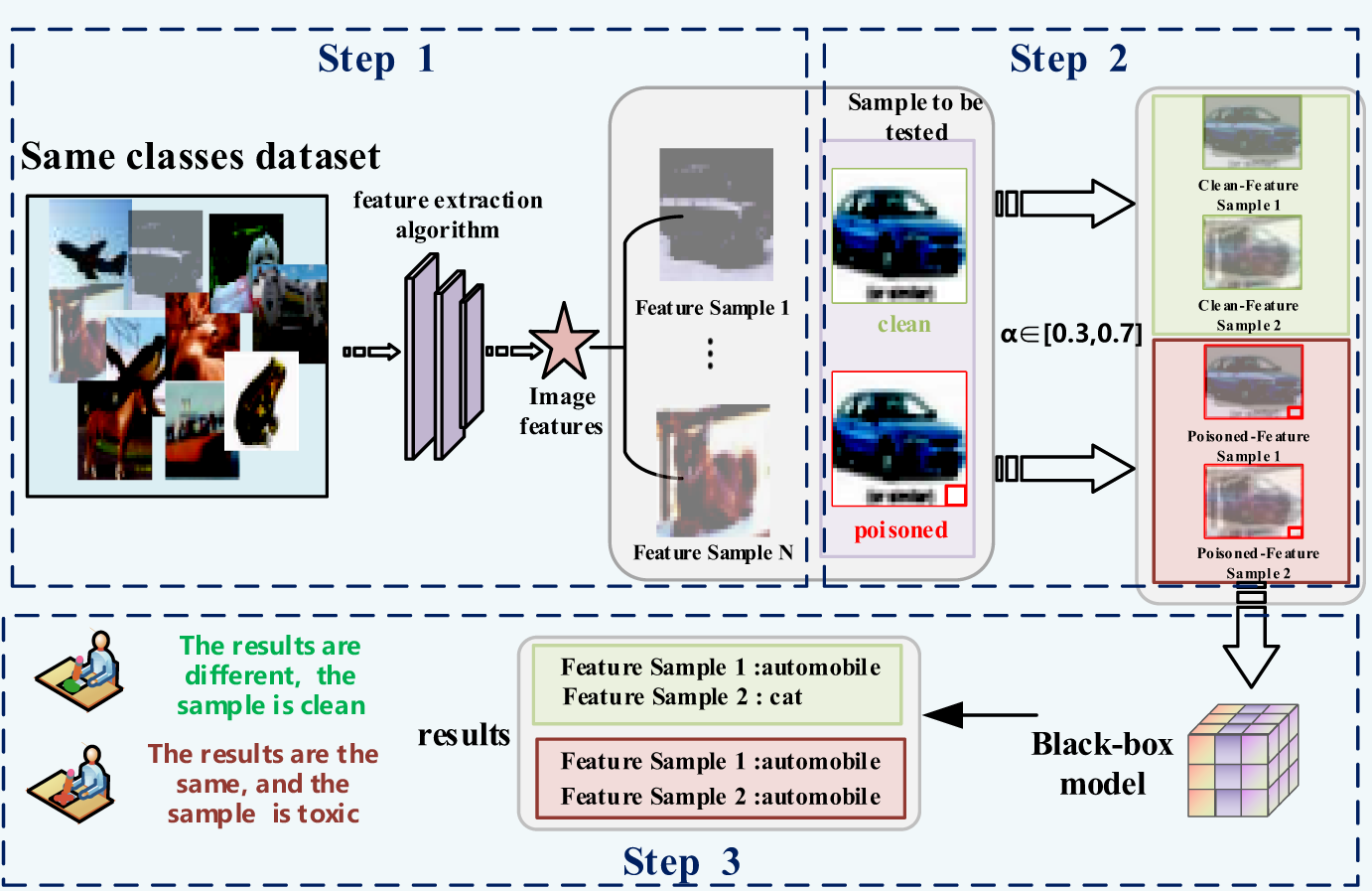

Our backdoor defense adopts the inverse reasoning concept of “input-output” to achieve accurate sample detection. Firstly, a convolutional neural network (CNN) extracts feature vectors for all images in the dataset. By calculating the difference between feature vectors, we select the two clean images with the largest difference in features between them. Secondly, the test image is fused with each of the two most dissimilar images at a certain ratio. Finally, the two mixed samples are input into the model to obtain two outputs, and the consistency of these outputs is used to determine whether the input samples are poisoned, thereby achieving backdoor detection. The specific detection flowchart is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: AFI process diagram

It is worth noting that in order to carry out effective backdoor attacks, attackers must carefully design the spatial location and pattern of triggers. Attackers typically maximize the mask of the trigger with the activation value of one or more neurons to create trigger-sensitive internal neurons. This design reinforces the activation of vulnerable neurons and establishes a strong association between the trigger and these neurons. As a result, once the model detects the trigger, these neurons are strongly activated, leading to a corresponding misclassification.

From a defense perspective, this characteristic can be exploited to identify poisoned inputs. The conceptual basis of AFI is as follows: poisoned samples contain a backdoor trigger that is specifically designed to maximize the activation of a small set of neurons highly sensitive to the trigger, establishing a strong association between the trigger and these neurons. Once the model detects the trigger, these neurons are significantly activated and dominate the output. Even when a poisoned sample is blended with other images, this dominant activation persists, resulting in consistently predicted labels. In contrast, clean samples lack such dominant features, so blending introduces variability in their representations, leading to unstable predictions. This difference in prediction stability under blending provides the conceptual foundation for AFI’s ability to distinguish poisoned samples from clean ones. When the input contains a trigger, it causes significant increases in neuron activations, which heavily influence the model output. Therefore, when the poisoned sample is fused with the clean sample, the model output will still be affected by the triggers and each output matches the attacker-specified label specified by the attacker. When the sample to be detected is a clean sample, the model output will be affected by the fusion of the two samples with which it is fused due to the large differences in their characteristics, showing significant differences. As illustrated in Fig. 2.

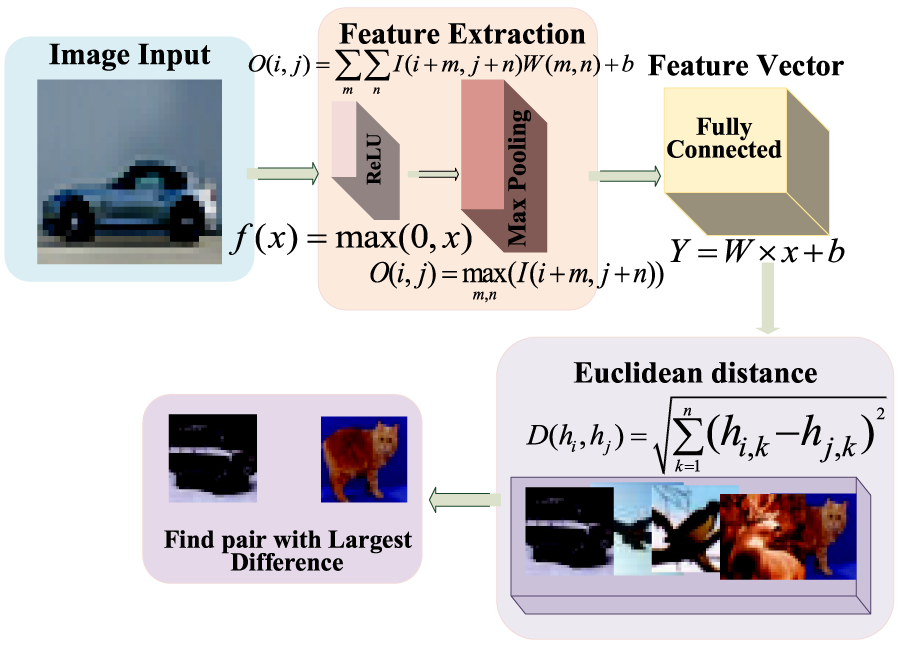

In order to successfully extract two image samples with significant feature differences from a clean dataset, we employ the widely used ResNet-18 as a generic feature encoder, denoted as

Furthermore, we note that the choice of model architecture may affect the specific geometry of the feature space. However, the core mechanism of our method relies on a more universal principle: that backdoor attacks cause poisoned samples to become statistical outliers in the deep feature space. Extensive research has shown that high-level features obtained from pre-training on different CNN architectures (e.g., VGG, ResNet), despite differences in spatial geometry, maintain consistency in their discriminability for semantic content. Therefore, the effectiveness of the extreme disparity sample pairs identified based on ResNet-18 features is expected to transfer to other modern architectures, ensuring the robustness of our method’s core conclusions and confirming that it is not limited to a specific network.

The general process and formulas for image feature extraction are outlined as follows.

Firstly, convolutional layers serve as the foundation for image feature extraction. The convolution operation involves sliding a filter (or kernel) over the input image and performing dot products to generate feature maps.

Assuming the input image is denoted as I and the filter weights as W, the convolution operation can be expressed as:

In order to introduce nonlinearity in the model, an activation function is typically applied after the convolution operation. The most commonly used activation function is the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU), which is defined as follows:

The activation function performs a nonlinear transformation on the output of the convolutional layer.

The pooling layer is used to reduce the size of the feature map while retaining important features. A common pooling operation is maximum pooling with the formula:

where

At the end of the encoder, the extracted features are usually flattened into a vector, and a fully connected layer is used to generate the final feature encoding. The formula for the fully connected layer is:

where

The second step is to encode and output features. After multiple layers of convolution, pooling, and fully connected operations, the image is finally encoded into a feature vector

Finally, by using Euclidean distance to calculate the difference between the feature vectors, the two images with the largest difference are found, and the formula is as follows:

where

We use Euclidean distance for its simplicity and interpretability. Since our method mainly relies on poisoned samples being statistical outliers in the feature space, the choice of distance metric is not critical, and other reasonable metrics are expected to yield similar results.

After the feature extraction operation using

Figure 3: Process diagram for selecting feature sample pairs

We adopt the Blended Injection Strategy (BIS) [30]. The image samples to be detected are fused with two clean samples that exhibit significant feature differences, in order to construct hybrid samples with discriminative properties. Specifically, if the original detection image is

where

Through the above feature fusion step, two mixed samples can be constructed respectively and recorded as

If

3.4 Selection Principle and Strategy for the Fusion Ratio

The fusion ratio

Based on an in-depth analysis of the spatial characteristics of triggers from different backdoor attacks, we summarize the following empirical selection strategy:

• For Local Trigger Attacks: Such as BadNets and IAB, where the trigger is confined to a small region of the image. We recommend using a lower

• For Global Trigger Attacks: Such as Blend and WaNet, where the trigger is distributed across the entire image as subtle perturbations or warping. We recommend using a higher

The above strategy provides a robust guideline for scenarios where the attack type is known or can be inferred. For completely unknown cases, we suggest a simple grid search procedure over

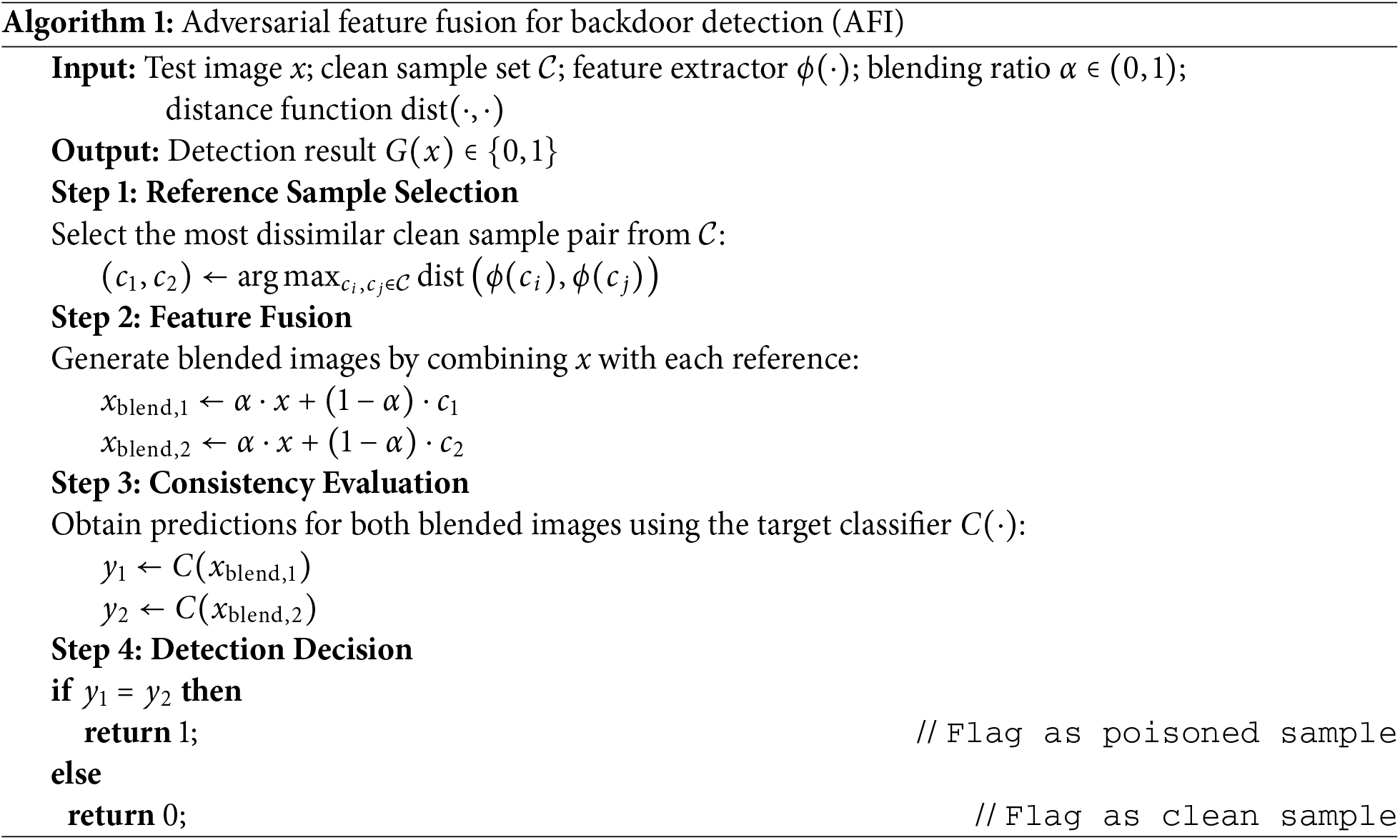

Firstly, we propose a sample-level universal backdoor detection method, which thoroughly embodies the dialectical unity of attack and defense. This approach employs a straightforward mechanism to achieve accurate and efficient defense. Secondly, for the backdoor defender, the method only requires a clean sample dataset. By extracting features and computing the feature distances, it selects the two samples with the most significant feature discrepancy. Compared with conventional backdoor defense techniques, our method greatly reduces the amount of data computation and storage. For users, this method does not need any operation on the dataset, just upload and input the image samples to be detected, which is convenient to use. Thirdly, our method focuses on the new defense concept of trigger detection. It only needs to detect the poisoned samples containing triggers and prevent the toxic samples from entering the model, which not only avoids backdoor attacks but also retains the availability of the model on clean samples. The AFI algorithm is shown in Algorithm 1.

The experiment involves three datasets, including MNIST [31], CIFAR-10 [32] and ImageNet subsets [33]. These datasets cover a variety of recognition tasks, including the classification of common objects, fine-grained classification, and action recognition.

All datasets are initially composed of clean samples. We implement four prominent backdoor attacks on these datasets: BadNets, Blend [14], WaNet [16], and IAB [13]. The ResNet-18 architecture [34] serves as the target model for both backdoor attack implantation and defense evaluation.

Attack baseline: we have carried out four common backdoor attacks, including BadNets [9], Blend, WaNet, IAB. In BadNets, WaNet, and IAB, we choose 1 (

Defense baseline: We compare our method with six existing backdoor defense methods, including fine pruning (FP) [25], neural attention distillation (NAD) [35], anti-backdoor learning (ABL) [36], STRIP [26], SentiNet [27], and MNTD [28]. Since FP, NAD, and ABL are sensitive to their hyperparameters, we optimize their best results by grid search.

In order to evaluate the performance of AFI, we use three indicators: the accuracy of clean images (ACC), the success rate of detecting backdoor images (DSR), and the detection stability (DSP).

ACC reflects the classification ability of the model on a clean image. A higher value indicates that the model is not disturbed by backdoor attacks.

where

DSR reflects the ability of AFI to successfully detect whether the sample is poisoned. Ideally, we hope that the defense success rate is as close as possible to 1, which means that the defense can effectively distinguish between clean samples and poisoned samples.

where

We propose DSP (Detection Stability Performance) as a new evaluation metric to assess the universality and robustness of detection methods under practical conditions. DSP measures performance consistency across different datasets and attack methodologies. This metric addresses the real-world challenge where users cannot predetermine the attack presence or specific attack types, thus requiring defenses that remain effective in cross-domain scenarios.

DSP combines performance metrics across datasets and attacks, including average clean accuracy (

The square root operation normalizes magnitude differences across heterogeneous datasets and attack types, preventing any single condition from dominating the overall DSP. The equal weighting balances the contributions of classification accuracy and detection success rate, which may differ in scale or importance depending on the scenario. These design choices enhance the stability and interpretability of DSP while maintaining sufficient sensitivity to distinguish between methods.

The formula highlights how the square root reduces the influence of extreme values, and the weighting balances the two components, yielding a robust and interpretable evaluation metric across diverse datasets and attack types.

A larger DSP indicates that the detection method is more consistent and stable across scenarios, making it a valuable measure of universality and deployment potential in complex, open environments.

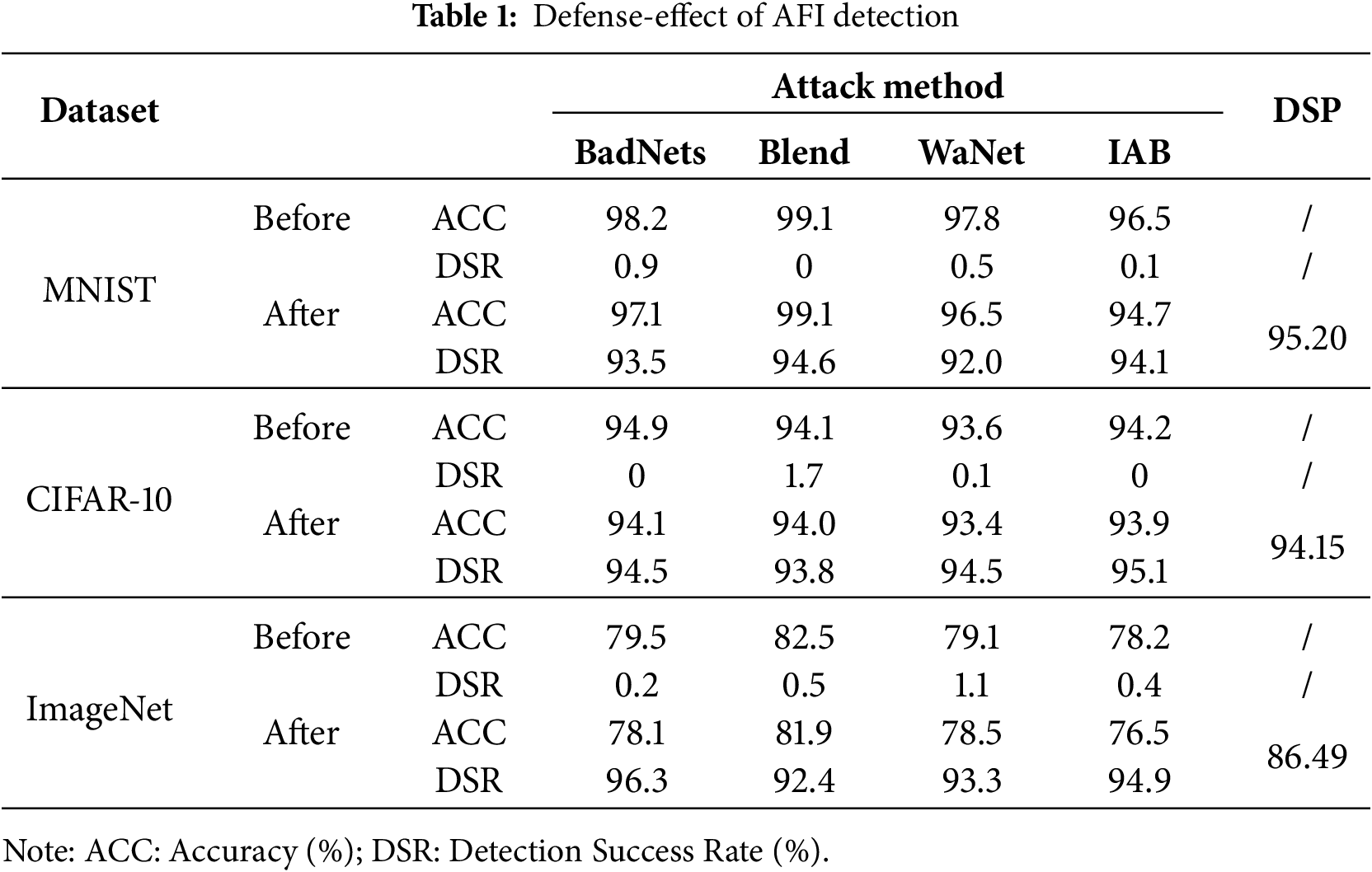

To verify the superiority of AFI, we conduct four types of backdoor attacks across three datasets using ResNet. While maintaining a high accuracy and attack rate, the results of using AFI in turn are shown in Table 1.

Evaluation results in Table 1 confirm AFI’s universal defense capability. The method elevates DSR from near-zero to >92% across all tested configurations while preserving ACC within 2% of its original value. Consistent DSP performance (86.49–95.20) demonstrates robustness against diverse attack patterns (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAB) and dataset complexities, establishing AFI as an effective sample-level backdoor detection solution.

4.4.1 Comparison of Similar Methods

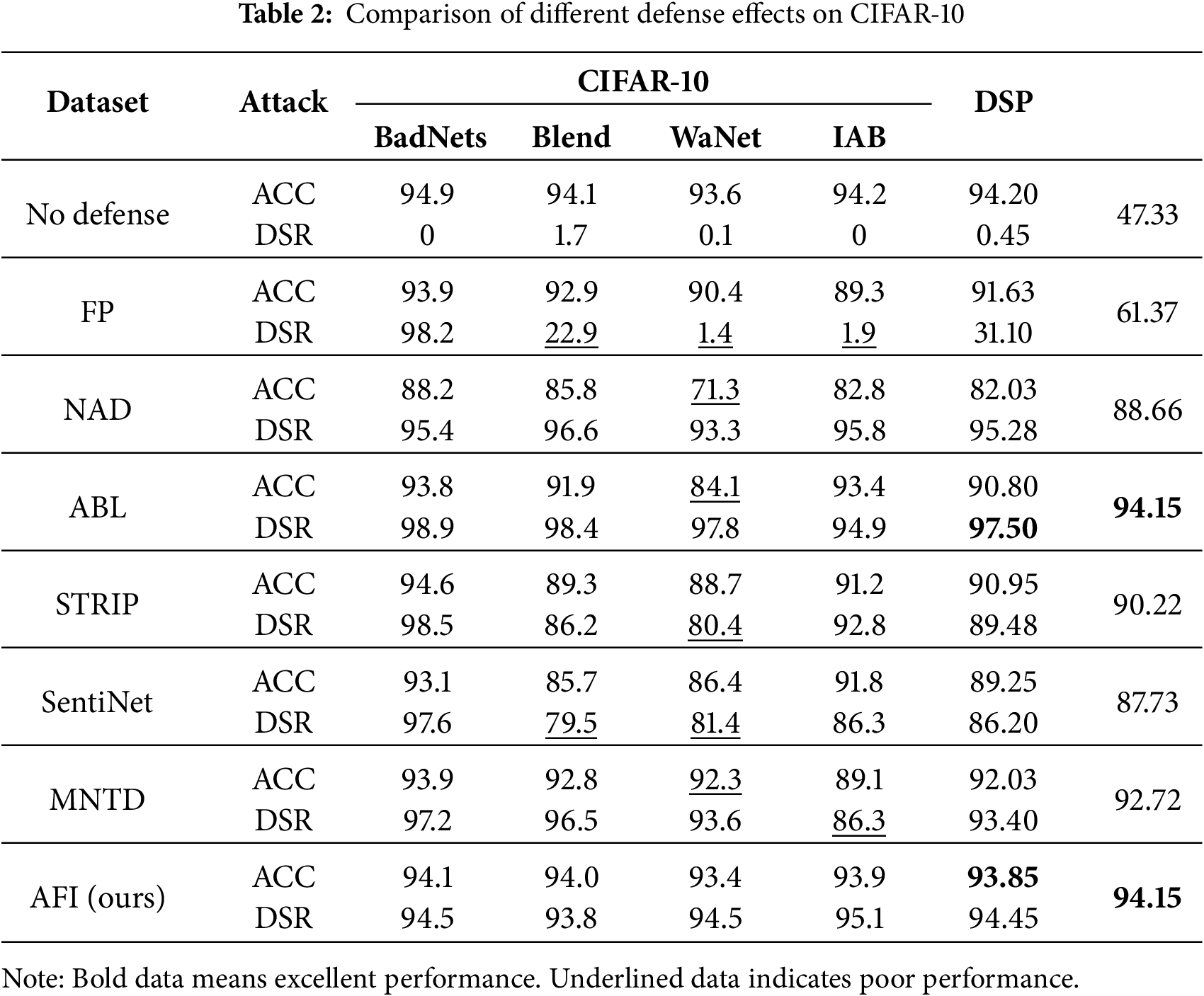

In order to verify the effectiveness of AFI, we select six representative and widely used backdoor defenses as comparison baselines, namely FP, NAD, ABL, STRIP, SentiNet, and MNTD. We systematically evaluate four typical backdoor attacks on the CIFAR-10 dataset, which are BadNets, Blend, WaNet, and IAB. Table 2 summarizes the model classification ACC and DSR under different defense settings on the CIFAR-10 dataset.

The experimental results show that all attacks achieve high classification accuracy (

In contrast, the proposed AFI method demonstrates consistently strong performance across all attack scenarios. It achieves a high detection rate (94.45% DSR) while preserving excellent classification accuracy (93.85% ACC), nearly matching the undefended baseline. Compared with inference-time detectors, AFI improves DSR by more than 13 percentage points on complex attacks and avoids the need for meta-training. These results confirm that AFI achieves an optimal balance between detection effectiveness, model preservation, and generalization capability.

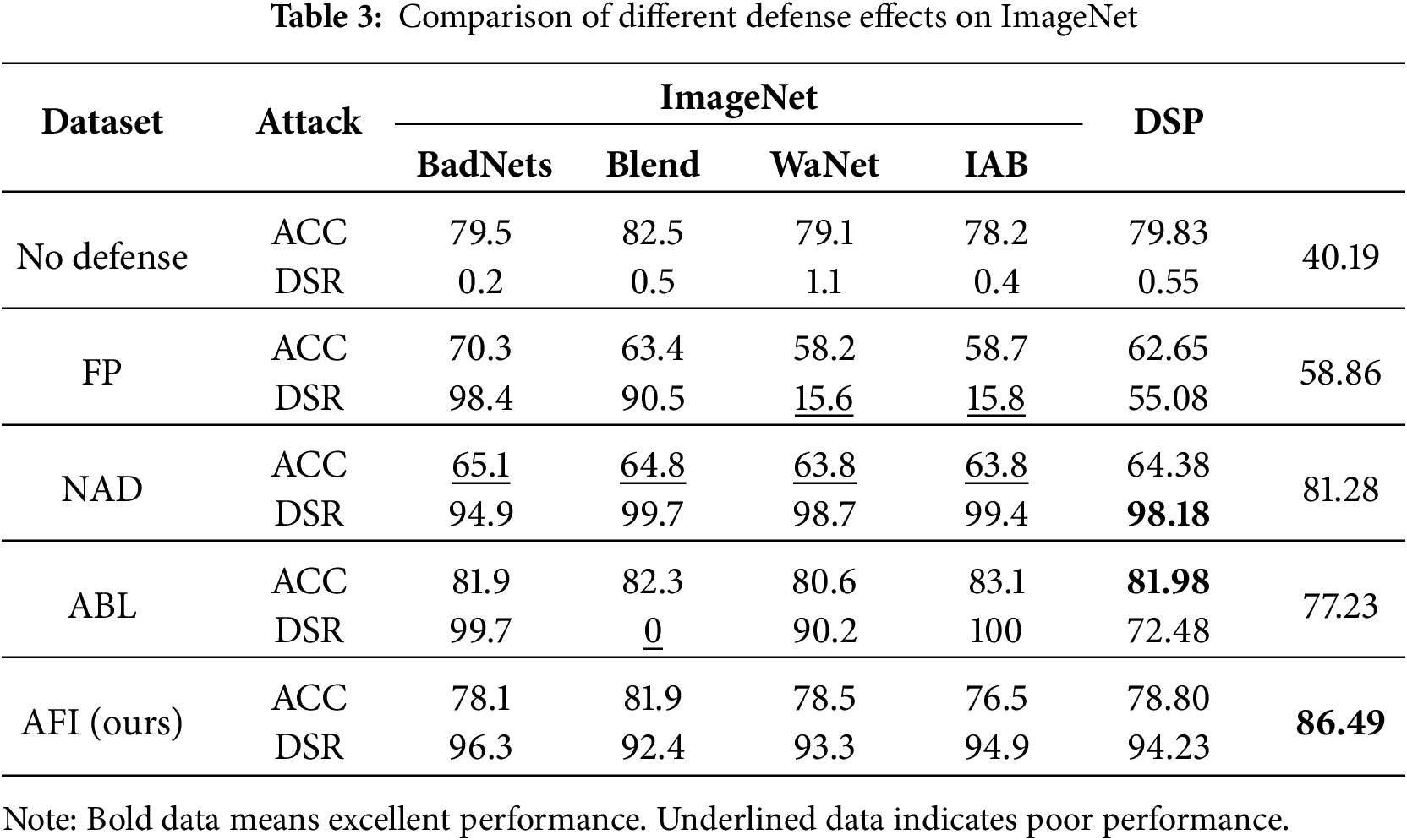

Table 3 reports the ACC and DSR of models trained on ImageNet under different defense methods (FP, NAD, DBD, AFI) against four typical backdoor attacks (BadNets, Blend, WaNet, IAB).

The experimental results show that, under baseline conditions without defense, all four backdoor attacks maintain high classification accuracy (above 78%), while the DSR remains close to 0. This indicates that the attacks successfully manipulate model behavior with minimal impact on clean-sample classification. FP demonstrates good defensive performance against BadNets and Blend, but performs poorly against more stealthy attacks. For example, the ACC under WaNet and IAB drops to around 15%, indicating that FP is limited and cannot generalize across diverse attack types. NAD achieves consistently high DSR across all attacks, but at the cost of significantly reducing the model’s classification accuracy. DBD exhibits highly polarized performance, achieving 100% defense success under IAB but failing (0% DSR) against Blend. In contrast, AFI maintains stable and balanced performance, preserving both high ACC and robust DSR across all attack scenarios.

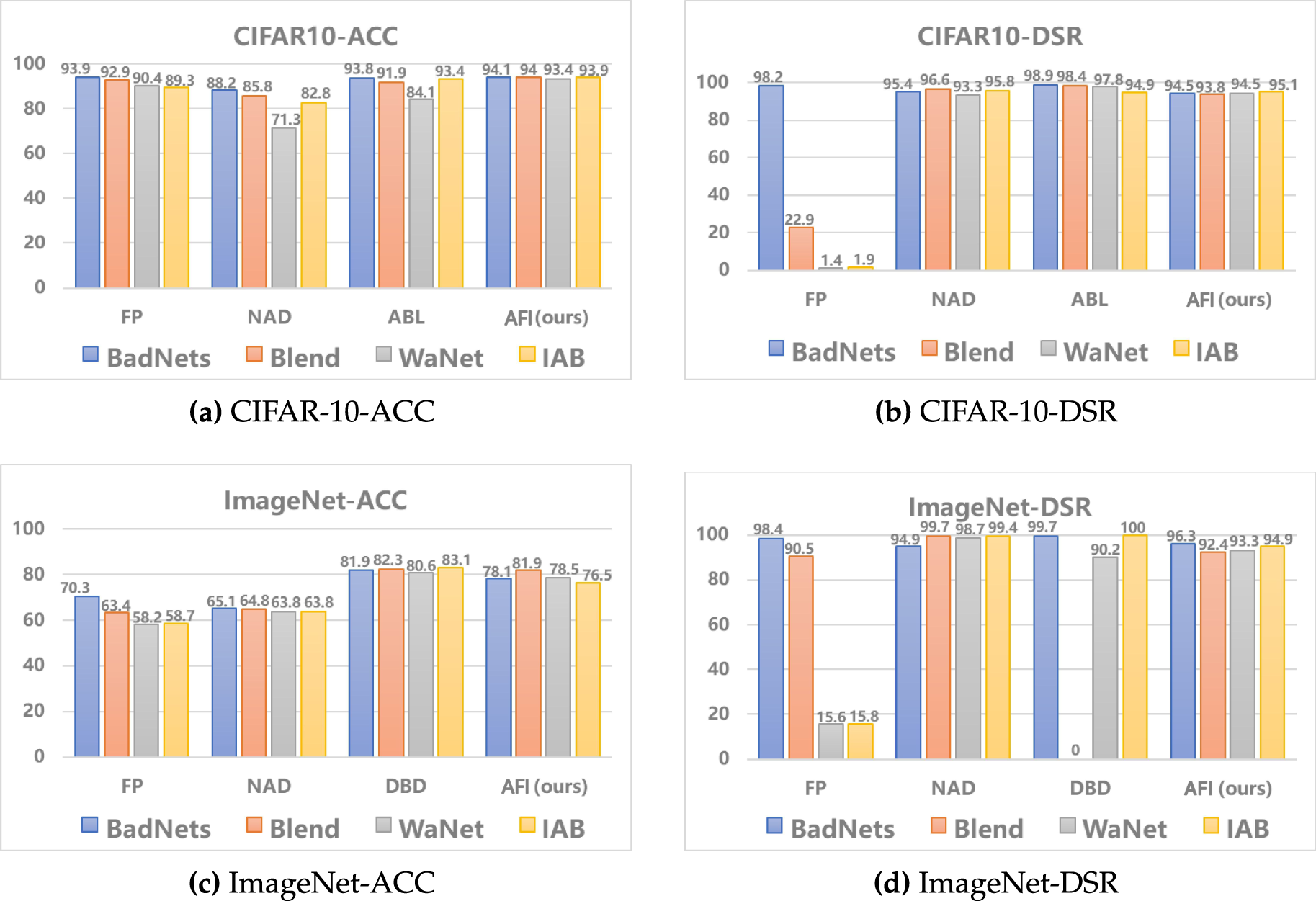

AFI demonstrates strong robustness, good transferability, and controllable accuracy degradation when defending against diverse backdoor attacks, highlighting its potential for practical deployment. Fig. 4 compares the performance of AFI with three baseline defenses under various backdoor attacks on the ImageNet and CIFAR-10 datasets. As shown in Fig. 4a, both FP and AFI maintain high and stable classification accuracy across the four attacks. However, Fig. 4b indicates that FP’s DSR fluctuates substantially, revealing its instability across different attack types. Similarly, Fig. 4c shows that DBD and AFI perform well overall, but Fig. 4d reveals that DBD completely fails against the Blend attack, with its detection success rate dropping to 0%. Overall, AFI achieves more robust and reliable defensive performance across attacks and datasets, outperforming the comparative baselines.

Figure 4: Comparison of indicators based on different datasets

4.4.2 Comparison of Different Fusion Proportions

It should be noted that the optimal fusion ratio of AFI varies across different attack types, generally falling between 0.3 and 0.6, which is a key factor influencing detection performance. (1) For BadNets, the trigger is local and typically resides in background regions. Thus, even when the fused image occupies a large proportion, the trigger remains identifiable. Increasing the fusion ratio improves clean-sample detection while still preserving the trigger in poisoned images. (2) In Blend, the trigger is globally embedded across the entire image, and the target-object region of the fused image introduces interference. Therefore, the fusion ratio must be reduced to maintain a high proportion of the poisoned image and preserve attack effectiveness. (3) Similarly, WaNet embeds its trigger globally via geometric warping, requiring the original image to retain a dominant proportion during fusion to prevent the trigger from being suppressed. (4) For IAB, the trigger is placed in non-object regions, and a larger fusion ratio is suitable, which is consistent with the behavior observed in BadNets.

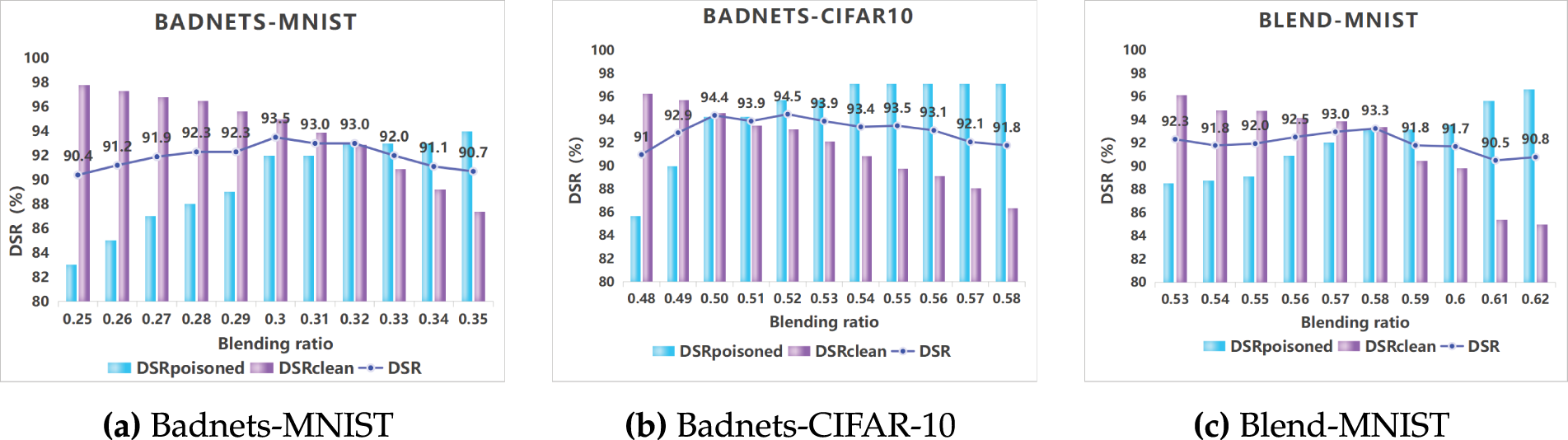

This section examines the factors affecting the fusion ratio and provides representative results in Fig. 5. Fig. 5a–c respectively shows the defensive accuracy of AFI against BadNets and Blend on MNIST and CIFAR-10.

Figure 5: Impact of different fusion ratios on model performance

Comparing Fig. 5a and b, it can be observed that when BadNets is applied to MNIST, the DSR of AFI on clean samples decreases as the fusion ratio increases, while the DSR on poisoned samples increases. The optimal fusion ratio in this setting is 0.3. When BadNets is performed on CIFAR-10, the optimal fusion ratio becomes 0.52. These results indicate that for the same attack across different datasets, the optimal fusion ratio of AFI varies. Fig. 5c shows the results of Blend on MNIST, where the optimal fusion ratio is 0.58. Combined with Fig. 5a and c, it can be concluded that AFI also requires different optimal fusion ratios for different attack types on the same dataset. Therefore, when facing unknown attack types or datasets, a grid search over the range of 0.3–0.6 (with a step size of 0.01) can be used to identify the optimal fusion ratio.

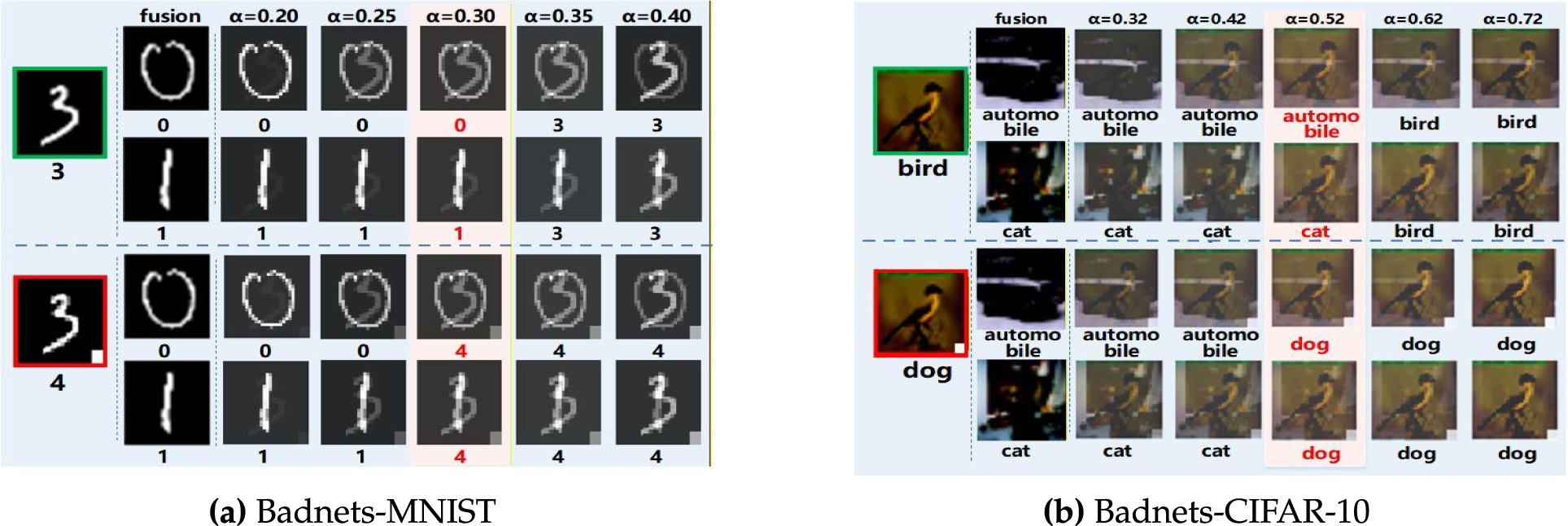

Taking the experiment in Fig. 5 as an example, the optimal fusion ratio corresponding to Fig. 5a is 0.3. The optimal fusion ratio corresponding to Fig. 5b is 0.52, and the visualized image samples with different fusion ratios are shown in Fig. 6a and b, respectively. Poisoned samples are generated by applying BadNets to clean samples. Clean samples and poisoned samples serve as mutual control groups. Regardless of whether the sample to be tested is toxic or not, when the fusion ratio

Figure 6: Comparison of model outputs under different fusion ratios

4.5 Robustness Analysis against Adaptive Attackers

This section discusses the theoretical robustness of the AFI method when facing a strong, adaptive attacker with full knowledge of the defense mechanism, addressing the reviewer’s valuable comment. We consider a white-box attack scenario: the attacker is fully aware of AFI’s detection pipeline (including the feature extractor, blending ratio

The attacker’s objective is formalized as a dual-goal optimization problem: the trigger must ensure that not only is the poisoned sample

Theoretically, we argue that successfully crafting such a trigger is inherently difficult for the adversary. AFI’s fusion mechanism forces the attacker to solve a conflicting optimization objective: the trigger must be effective on the original poisoned sample

However, achieving this likely comes at a high cost for the attacker, leading to a critical trade-off:

• Loss of Stealth: An overly potent and global trigger required to withstand arbitrary fusion becomes more susceptible to detection via visual inspection or statistical anomaly detection, compromising the fundamental requirement of a stealthy backdoor.

• Degradation of Model Utility: Embedding such a powerful backdoor functionality often interferes with the model’s normal decision-making process, potentially leading to a noticeable drop in clean data accuracy (ACC), which could reveal the presence of the attack.

In conclusion, the AFI mechanism does not attempt to create an impenetrable defense but rather fundamentally raises the bar for a successful attack. It forces the attacker into a difficult tri-lemma, having to balance attack effectiveness, trigger stealth, and model utility. While the implementation and evaluation of more complex adaptive attacks constitute an important direction for our future work, the above analysis demonstrates that AFI provides a foundation for practical backdoor defense with inherent robustness by making adaptive attacks more costly and difficult to conceal.

We propose a feature-comparison fusion strategy that combines the sample under inspection with two contrasting reference samples and leverages model predictions for reverse reasoning, enabling effective identification of poisoned samples. Extensive experiments demonstrate that AFI robustly defends against four common backdoor attacks, outperforming three mainstream defense methods in detection success rate, accuracy, and stability across different datasets and attack types. Overall, AFI provides a novel and practical approach for backdoor attack defense.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank all those who provided support and constructive feedback during the preparation of this work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant (No. 61972133), Project of Leading Talents in Science and Technology Innovation for Thousands of People Plan in Henan Province Grant (No. 204200510021), and the Key Research and Development Plan Special Project of Henan Province Grant (No. 241111211400).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Simin Tang and Zhiyong Zhang; Data curation, Simin Tang; Formal analysis, Simin Tang; Funding acquisition, Zhiyong Zhang; Investigation, Simin Tang; methodology, Simin Tang; Project administration, Zhiyong Zhang; Resources, Simin Tang and Junyan Pan; Software, Simin Tang; Supervision, Zhiyong Zhang, Weiguo Wang and Junchang Jing; Validation, Simin Tang; Visualization, Simin Tang; Writing—original draft, Simin Tang; Writing—review & editing, Zhiyong Zhang, Junyan Pan, Gaoyuan Quan, Weiguo Wang and Junchang Jing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used in this study are publicly available. Specifically, MNIST [31], CIFAR-10 [32], and ImageNet [33] can be accessed from their official repositories. The implementation code is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study does not involve human participants or animals. The experiments were conducted using publicly available datasets: MNIST [31], CIFAR-10 [32], and ImageNet [33].

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| AFI | Adaptive Feature Injection |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ACC | Accuracy |

| DSR | Defense Success Rate |

| DSP | Detection Stability and Portability |

References

1. Sze V, Chen YH, Yang TJ, Emer JS. Efficient processing of deep neural networks: a tutorial and survey. Proc IEEE. 2017;105(12):2295–329. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2017.2761740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gu T, Liu K, Dolan-Gavitt B, GargS. Evaluating backdooring attacks on deep neural networks. IEEE Access. 2019;7:47230–44. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2909068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bai Y, Xing G, Wu H, Rao Z, Ma C, Wang S. Backdoor attack and defense on deep learning: a survey. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst. 2024;12(1):404–34. doi:10.1109/TCSS.2024.3482723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Qi F, Yao Y, Xu S, Liu Z, Sun M. Turn the combination lock: learnable textual backdoor attacks via word substitution. In: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2021 Aug 1–6; Online. p. 4873–83. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.acl-long.377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zeng Y, Park W, Mao ZM, Jia R. Rethinking the backdoor attacks’ triggers: a frequency perspective. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 16473–81. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang B, Yao Y, Shan S, Li H, Viswanath B, Zheng H. Neural cleanse: identifying and mitigating backdoor attacks in neural networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy; 2019 May 19–23; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 707–23. doi:10.1109/SP.2019.00031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhu L, Ning R, Wang C, Xin C, Wu H. Gangsweep: Sweep out neural backdoors by GAN. In: Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia; 2020 Oct 12–16; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 3173–81. doi:10.1145/3394171.3413546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bai J, Gao K, Gong D, Xia ST, Li Z, Liu W. Hardly perceptible trojan attack against neural networks with bit flips. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 104–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-20065-6_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Gu T, Dolan-Gavitt B, Garg S. Badnets: identifying vulnerabilities in the machine learning model supply chain. arXiv:1708.06733. 2017. [Google Scholar]

10. Li Y, Lyu X, Koren N, Lyu L, Li B, Ma X. Anti-backdoor learning: Training clean models on poisoned data. In: Proceedings of the 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; 2021 Dec 6–14; Online. p. 14900–12. [Google Scholar]

11. Wenger E, Passananti J, Bhagoji AN, Yao Y, Zheng H, Zhao BY. Backdoor attacks against deep learning systems in the physical world. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 19–25; Online. p. 6206–15. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.00614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhao Z, Chen X, Xuan Y, Dong Y, Wang D, Liang K. Defeat: deep hidden feature backdoor attacks by imperceptible perturbation and latent representation constraints. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 19–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 15213–22. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nguyen TA, Tran A. Input-aware dynamic backdoor attack. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2020;33:3454–64. [Google Scholar]

14. Liu Y, Ma X, Bailey J, Lu F. Reflection backdoor: a natural backdoor attack on deep neural networks. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 182–99. [Google Scholar]

15. Nguyen A, Tran A. WaNet: imperceptible warping-based backdoor attack. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021 May 3–7; Online. [Google Scholar]

16. Gan L, Li J, Zhang T, Li X, Meng Y, Wu F, et al. Triggerless backdoor attack for NLP tasks with clean labels. In: Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies; 2022 Jul 10–15; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 2942–52. [Google Scholar]

17. Zhao S, Xu X, Xiao L, Wen J, Tuan LA. Clean-label backdoor attack and defense: an examination of language model vulnerability. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;265:125856. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.125856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Chen W, Xu X, Wang X, Zhou H, Li Z, Chen Y. Invisible backdoor attack with attention and steganography. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2024;249(1):104208. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2024.104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li Y, Jiang Y, Li Z, Xia ST. Backdoor learning: a survey. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2024;35(1):5–22. doi:10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3182979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhao S, Ma X, Zheng X, Bailey J, Chen J, Jiang YG. Clean-label backdoor attacks on video recognition models. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2020 Jun 14–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 14443–52. doi:10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.01445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chen T, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Chang S, Liu S, Wang Z. Quarantine: sparsity can uncover the trojan attack trigger for free. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 19–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 598–609. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Guan J, Tu Z, He R, Tao D. Few-shot backdoor defense using Shapley estimation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2022 Jun 19–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 13358–67. [Google Scholar]

23. Doan K, Lao Y, Zhao W, Li P. LIRA: learnable, imperceptible and robust backdoor attacks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 11–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 11966–76. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.01175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Salem A, Wen R, Backes M, Ma S, Zhang Y. Dynamic backdoor attacks against machine learning models. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P); 2022 Jun 6–10; Genoa, Italy. p. 703–18. doi:10.1109/EuroSP53844.2022.00499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Liu K, Dolan-Gavitt B, GargS. Fine-pruning: defending against backdooring attacks on deep neural networks. In: International Symposium on Research in Attacks, Intrusions, and Defenses. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 273–94. [Google Scholar]

26. Gao Y, Xu C, Wang D, Chen S, Ranasinghe DC, Nepal S. STRIP: a defence against trojan attacks on deep neural networks. In: Proceedings of the Annual Computer Security Applications Conference; 2019 Dec 9–13; San Juan, PR, USA. p. 113–25. [Google Scholar]

27. Chou E, Tramèr F, Pellegrino G, Boneh D. Sentinet: detecting physical attacks against deep learning systems. arXiv:1812.00292. 2018. [Google Scholar]

28. Rajabi A, Asokraj S, Jiang F, Niu L, Ramasubramanian B, Ritcey J, et al. MDTD: a multi-domain Trojan detector for deep neural networks. In: Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2023 Nov 26–30; Copenhagen, Denmark. p. 2232–46. [Google Scholar]

29. Guo W, Tondi B, Barni M. Universal detection of backdoor attacks via density-based clustering and centroids analysis. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;19(7):970–84. doi:10.1109/TIFS.2023.3329426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chen X, Liu C, Li B, Lu K, Song D. Targeted backdoor attacks on deep learning systems using data poisoning. arXiv:1712.05526. 2017. [Google Scholar]

31. LeCun Y, Bottou L, Bengio Y, Haffner P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc IEEE. 1998;86(11):2278–324. doi:10.1109/5.726791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Krizhevsky A, Hinton G. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. In: Technical report. Toronto, ON, Canada: University of Toronto; 2009. [Google Scholar]

33. Deng J, Dong W, Socher R, Li LJ, Li K, Fei-Fei L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2009 Jun 20–25; Miami, FL, USA. p. 248–55. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2009.5206848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

35. Li Y, Lyu X, Koren N, Lyu L, Li B, Ma X. Neural attention distillation: erasing backdoor triggers from deep neural networks. arXiv:2101.05930. 2021. [Google Scholar]

36. Li Y, Zhai T, Jiang Y, Li Z, Xiao ST. Backdoor attack in the physical world. arXiv:2104.02361. 2021. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools