Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Semantic-Guided Stereo Matching Network Based on Parallax Attention Mechanism and SegFormer

School of Electrical and Information Engineering, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

* Corresponding Author: Yingqiang Ding. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 54 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073846

Received 27 September 2025; Accepted 25 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Stereo matching is a pivotal task in computer vision, enabling precise depth estimation from stereo image pairs, yet it encounters challenges in regions with reflections, repetitive textures, or fine structures. In this paper, we propose a Semantic-Guided Parallax Attention Stereo Matching Network (SGPASMnet) that can be trained in unsupervised manner, building upon the Parallax Attention Stereo Matching Network (PASMnet). Our approach leverages unsupervised learning to address the scarcity of ground truth disparity in stereo matching datasets, facilitating robust training across diverse scene-specific datasets and enhancing generalization. SGPASMnet incorporates two novel components: a Cross-Scale Feature Interaction (CSFI) block and semantic feature augmentation using a pre-trained semantic segmentation model, SegFormer, seamlessly embedded into the parallax attention mechanism. The CSFI block enables effective fusion of multi-scale features, integrating coarse and fine details to enhance disparity estimation accuracy. Semantic features, extracted by SegFormer, enrich the parallax attention mechanism by providing high-level scene context, significantly improving performance in ambiguous regions. Our model unifies these enhancements within a cohesive architecture, comprising semantic feature extraction, an hourglass network, a semantic-guided cascaded parallax attention module, output module, and a disparity refinement network. Evaluations on the KITTI2015 dataset demonstrate that our unsupervised method achieves a lower error rate compared to the original PASMnet, highlighting the effectiveness of our enhancements in handling complex scenes. By harnessing unsupervised learning without ground truth disparity needed, SGPASMnet offers a scalable and robust solution for accurate stereo matching, with superior generalization across varied real-world applications.Keywords

Stereo matching, the process of estimating depth from a pair of rectified stereo images, is a cornerstone of computer vision with applications in autonomous driving, robotics, and 3D reconstruction. The task involves computing a disparity map that represents the pixel-wise horizontal displacement between corresponding points in the left and right images. Despite significant progress, stereo matching remains challenging in regions with occlusions, reflections, repetitive textures, or low-contrast areas, where traditional feature matching often fails to establish accurate correspondences. Moreover, supervised learning approaches typically rely on large-scale datasets with ground truth disparity, which are often difficult and costly to acquire for stereo image pairs, particularly across diverse real-world scenarios. This limitation hinders the generalizability of such models to varied scenes.

Recent advancements in deep learning have significantly improved stereo matching performance, with unsupervised methods like the Parallax Attention Stereo Matching Network [1] (PASMnet) introducing attention-based mechanisms to capture global correspondences along epipolar lines. However, PASMnet struggles in complex scenes due to limitations in leveraging multi-scale feature interactions and high-level semantic context, leading to wrong match in challenging areas and across different objects.

To address these challenges, we proposed a novel unsupervised learning network for stereo matching, Semantic-Guided Parallax Attention Stereo Matching Network (SGPASMnet), building upon PASMnet with two key enhancements: a Cross-Scale Feature Interaction (CSFI) block and the integration of semantic features extracted from a pre-trained SegFormer [2] model. By adopting an unsupervised learning approach, our model eliminates the dependency on annotated disparity data, leveraging self-supervised signals such as photometric consistency and geometric constraints. This enables robust training on diverse datasets without ground truth labels, facilitating better generalization across different scene types and conditions, such as varying lighting, occlusions, or texture complexities.

The CSFI block enables the fusion of features across different scales, combining coarse, high-level information with fine, detailed features to enhance both global consistency and local accuracy in disparity estimation. This approach draws inspiration from feature pyramid networks [3] and deformable convolutions [4], adapting them to the stereo matching context. The semantic feature augmentation leverages SegFormer’s transformer-based architecture to extract multi-scale semantic representations, which are integrated into the parallax attention mechanism to provide contextual guidance, particularly in ambiguous regions like reflections or repetitive patterns. This is motivated by prior work such as SegStereo [5], which demonstrated the value of semantic information in disparity estimation.

Our enhanced model integrates these components into a cohesive unsupervised architecture, comprising semantic feature extraction, an Hourglass network for multi-scale feature extraction, a semantic-guided Cascaded Parallax Attention Module (CPAM) for disparity computation, an output module to generate initial disparity map and valid masks, and a refinement network to optimize the disparity map. The model is trained with a combination of unsupervised losses, including photometric loss, smoothness loss, and parallax attention loss and semantic consistency loss, to ensure robust learning without reliance on ground truth disparity. Evaluations on the KITTI2015 dataset suggest that our SGPASMnet achieves a lower error rate compared to the baseline model, demonstrating improved performance and generalization in challenging scenarios.

Stereo matching has been a fundamental problem in computer vision, with significant advancements driven by both traditional and deep learning-based approaches. Below, we review key developments in traditional and deep learning-based stereo matching methods, with the latter further categorized into supervised and unsupervised learning approaches.

2.1 Traditional Stereo Matching Methods

Traditional stereo matching methods rely on hand-crafted features and optimization techniques to compute disparity maps. A prominent example is Semi-Global Matching (SGM), which incorporates global smoothness constraints through dynamic programming along multiple image paths, achieving robust results in structured environments while balancing computational efficiency and accuracy.

Despite their advantages, these methods often struggle in regions with occlusions, textureless areas, or illumination variations due to their dependence on low-level features. Recent advancements have focused on improving SGM’s performance in real-world scenarios. For instance, collaborative SGM [6] introduces local edge-aware filtering to strengthen interactions between neighboring scanlines, significantly reducing streak artifacts in disparity maps.

Other recent non-deep learning approaches include As-Global-As-Possible (AGAP) stereo matching with sparse depth measurement fusion [7], which combines global optimization with sparse priors to improve accuracy in sparse-data environments like satellite imagery. Furthermore, adaptations for specific domains, like mineral image matching with improved Birchfield-Tomasi-Census algorithms [8], enhance discrimination in textured regions without relying on learning-based features.

While these enhancements mitigate some limitations through better cost aggregation, edge preservation, traditional methods remain constrained compared to data-driven approaches, particularly in handling complex, unstructured scenes.

2.2 Deep Learning-Based Stereo Matching Methods

Deep learning has revolutionized stereo matching by leveraging convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and attention mechanisms to learn robust feature representations. These methods can be broadly divided into supervised and unsupervised learning approaches.

Supervised deep learning methods for stereo matching typically construct a cost volume from learned features and optimize it to produce disparity maps. DispNet [9] introduced an end-to-end CNN architecture that directly regresses disparity from stereo image pairs, achieving significant improvements over traditional methods. GC-Net [10] proposed a 3D cost volume constructed from concatenated left and right image features, processed by 3D convolutions to aggregate contextual information. PSMNet [11] further advanced this by incorporating a spatial pyramid pooling module to capture multi-scale context, improving performance in complex scenes.

Attention-based methods have recently gained prominence due to their ability to model global correspondences. AANet [12] combined attention with adaptive aggregation to achieve real-time performance, while GANet [13] integrated guided aggregation to refine cost volumes. Semantic information has also been explored to enhance supervised methods. SegStereo [5] incorporated semantic segmentation masks to guide disparity estimation, improving accuracy in object boundaries. Similarly, reference [14] proposed a joint semantic-stereo framework for real-time applications, demonstrating the value of semantic context. Recent supervised methods have focused on improving efficiency and robustness through cascaded architectures and adaptive correlations. For instance, CREStereo [15] introduces a cascaded recurrent network with adaptive correlation for practical high-resolution stereo matching, achieving state-of-the-art accuracy in real-world scenarios. Similarly, CFNet [16] proposes a cascade and fused cost volume approach to enhance robust stereo matching under challenging conditions like occlusions and varying illuminations. Advancements in zero-shot learning have also emerged, such as Cascade Cost Volume [17], which enables high-resolution multi-view stereo matching without extensive fine-tuning, improving generalization across datasets.

Building on attention mechanisms, transformer-based methods have recently been explored for stereo matching, leveraging their ability to capture long-range dependencies and model sequential data effectively. For instance, STTR [18] introduces stereo depth estimation from a sequence-to-sequence perspective using transformers. It employs alternating self and cross-attention to perform dense pixel matching along epipolar lines, eliminating the need for a fixed disparity range, detecting occlusions with confidence estimates, and enforcing uniqueness constraints via optimal transport. Similarly, RAFT-Stereo [19] adapts the RAFT optical flow architecture for stereo, introducing multilevel recurrent field transforms with convolutional GRUs to propagate information across the image efficiently.

Unsupervised stereo matching methods leverage photometric consistency and geometric constraints to train models without ground truth disparity maps, making them suitable for scenarios with limited labeled data. Reference [20] proposed an unsupervised framework that minimizes a photometric loss based on image reconstruction, using left-right consistency to enforce disparity coherence. Reference [21] extended this with a left-right disparity consistency loss, improving robustness in textureless regions. Recent unsupervised methods, such as [22], incorporate domain adaptation to handle real-world data, while Reference [23] use multi-view consistency to enhance training.

Attention-based unsupervised methods have also emerged. Reference [1] extended PASMnet to an unsupervised setting by incorporating cycle consistency losses, achieving competitive performance without labeled data. Reference [24] proposed an unsupervised attention mechanism that leverages feature similarity to guide disparity estimation. While unsupervised methods reduce the dependency on labeled data, they often struggle with accuracy in complex scenes compared to supervised approaches. Recent unsupervised approaches have incorporated semantic attention mechanisms to address domain gaps and data scarcity. Stereo Anywhere [25] presents a robust zero-shot deep stereo matching framework that leverages monocular depth priors for accurate disparity estimation even in unseen environments. Additionally, efforts in open-world generation, like the method in [26], combine stereo image synthesis with unsupervised matching to enable training on diverse synthetic data without labels. Specialized applications, such as underwater scenes, have seen innovations like the semantic attention-based unsupervised stereo matching [27], which uses semantic guidance to improve performance in low-visibility conditions, aligning with the need for context-aware disparity estimation.

Our work builds upon PASMnet by integrating semantic features from a pre-trained SegFormer [2] model, which provides richer, transformer-based semantic representations compared to traditional CNN-based segmentation models. Additionally, our CSFI module enhances multi-scale feature fusion, drawing inspiration from feature pyramid networks [3] and deformable convolutions [4], to improve disparity estimation in challenging regions. Similar multi-scale refinement strategies have been successfully applied in related vision tasks, such as instance segmentation. For example, Mask-Refined R-CNN (MR R-CNN) [28] adjusts the stride of region of interest align and incorporates an FPN structure in the mask head to fuse global semantic information with local details, achieving superior boundary delineation in large objects. This approach aligns with our CSFI block’s cross-scale interactions, which combine coarse and fine features to handle ambiguous regions like reflections or repetitive textures in stereo matching.

In summary, our proposed model combines the strengths of attention-based supervised stereo matching with advanced multi-scale feature fusion and semantic augmentation, offering a robust solution for accurate disparity estimation in complex scenes.

In this section, we present our SGPASMnet that builds upon the Parallax-Attention Stereo Matching Network (PASMnet). Our enhancements incorporate a Cross-Scale Feature Interaction (CSFI) module to facilitate multi-scale feature fusion and the integration of semantic features extracted from a pre-trained SegFormer model to augment the parallax attention mechanism within the Parallax-Attention Block (PAB). These modifications aim to address challenges in stereo matching, such as occlusions, textureless regions, and repetitive patterns, by leveraging multi-scale contextual information and semantic guidance. Experimental results on the KITTI2015 dataset demonstrate a reduction in error rates compared to the baseline PASMnet, validating the effectiveness of our approach.

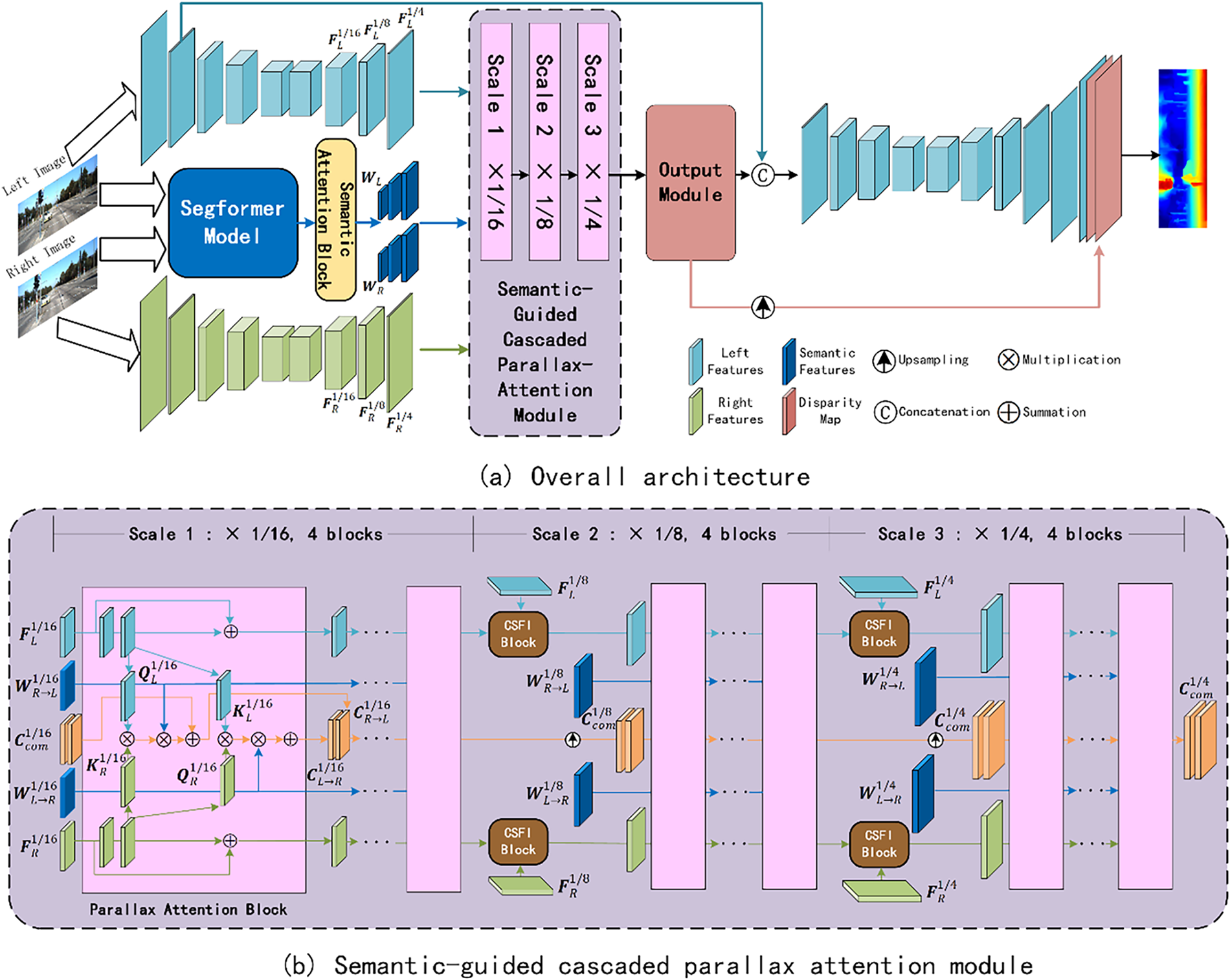

Our model follows the general structure of PASMnet, designed to estimate disparity maps from a pair of rectified stereo images, denoted as

Figure 1: Overall architecture of our proposed SGPASMnet

3.2 Semantic Feature Extraction Module

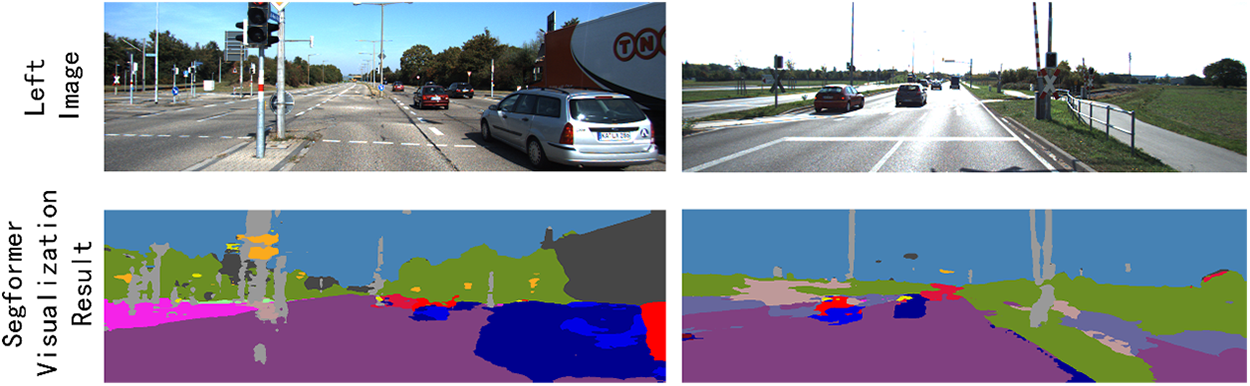

To incorporate high-level semantic information, we utilize a pre-trained SegFormer [2] model, a transformer-based architecture designed for semantic segmentation, capable of generating rich, multi-scale semantic feature representations. These features provide critical scene context, enhancing disparity estimation in complex regions such as occlusions and textureless areas where traditional feature matching may fail.

The SegFormer model employs a hierarchical transformer structure that leverages efficient self-attention to produce feature maps at multiple resolutions. Its encoder outputs hidden states at various scales, making it well-suited for tasks requiring both global and local contextual understanding, such as stereo matching. We adopt a SegFormer model pre-trained on the Cityscapes dataset, with its parameters frozen to serve as a feature extractor, ensuring computational efficiency and robust feature quality.

The SegFormer model processes the input stereo images

Formally, the semantic feature maps are represented as:

where each

Figure 2: A visual example of SegFormer extracted semantic features

These multi-scale semantic features are fed into the semantic attention block to generate semantic attention weights, and further fed into corresponding scales of the semantic-guided CPAM to enhance the parallax attention mechanism within the Parallax Attention Blocks (PABs). Additionally, a single-scale semantic feature, derived from the final hidden state, is used to compute a semantic consistency loss, ensuring that semantic features from the left and right images align under disparity guidance. This approach draws inspiration from prior work, such as SegStereo [5], which uses semantic segmentation to guide disparity estimation, and Tonioni et al. [22], who proposed joint architectures for real-time semantic stereo matching. However, our method distinguishes itself by directly embedding multi-scale semantic features into the parallax attention mechanism, offering finer-grained contextual guidance compared to traditional semantic mask-based or parallel processing approaches.

The hourglass module extracts hierarchical feature representations from the input stereo images, enabling the capture of both fine-grained details and coarse contextual information. It consists of a series of encoder and decoder blocks with skip connections, forming a U-shaped architecture inspired by spatial pyramid pooling in PSMNet [11]. This module serves as the foundation for subsequent processing by providing rich feature representations across multiple scales.

The encoder downsamples the input images through convolutional layers, producing feature maps at scales

where

Although the Hourglass module remains unmodified from the original PASMnet, its multi-scale feature outputs are critical for our enhancements. The features at

3.4 Semantic-Guided Cascaded Parallax Attention Module

The semantic-guided Cascaded Parallax Attention Module (CPAM) computes multi-scale cost volumes using a parallax attention mechanism, improved by our two key enhancements: the Cross-Scale Feature Interactions (CSFI) block for cross-scale feature fusion and semantic feature integration for parallax attention modulation. The module operates sequentially at scales

At each scale

Query and key features are generated via 1 × 1 convolutions:

followed by permutation to

The feature cost is computed as:

where

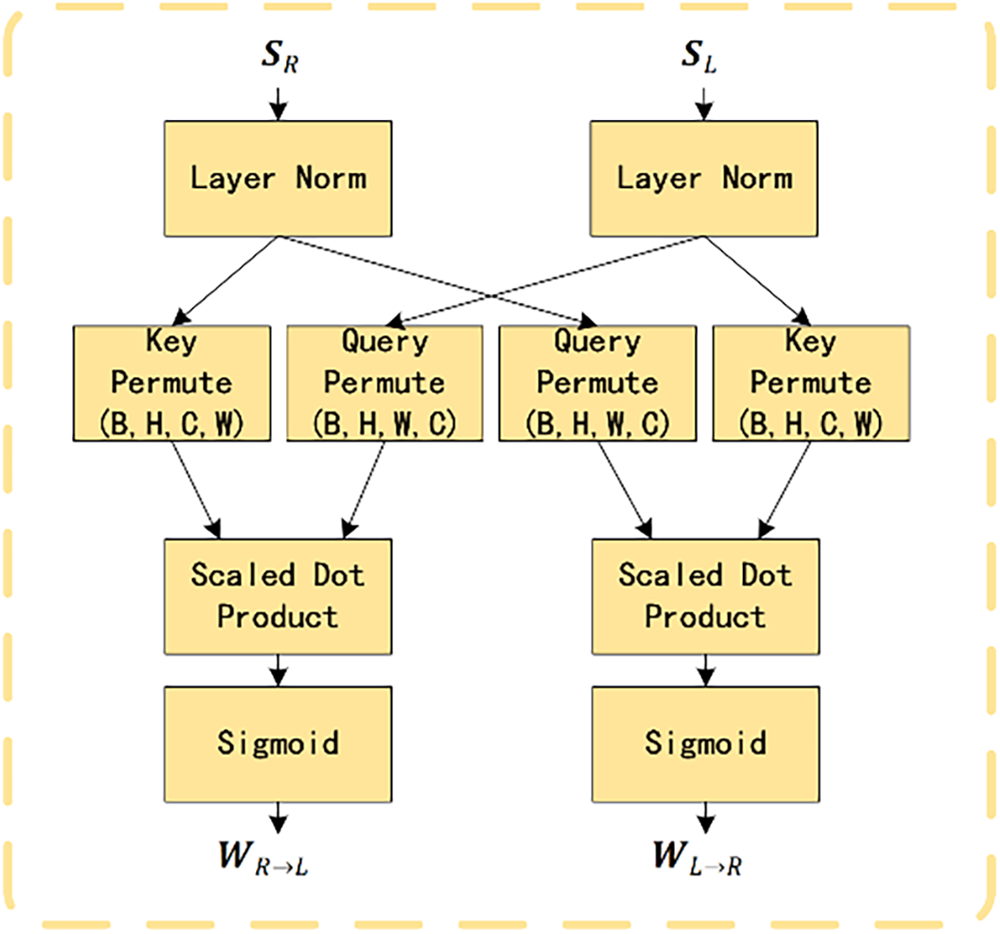

To incorporate semantic guidance, a semantic cost is computed within semantic attention block using the semantic features:

Semantic query and key are directly used:

permuted to

The semantic cost is:

and a semantic weight is obtained via:

where

The combined cost volume is then:

which is added to the cost volume from the previous scale to produce the final cost volume for the current scale. This mechanism, inspired by SegStereo [5] and real-time semantic stereo matching [14], enhances the attention mechanism by prioritizing correspondences that are both visually and semantically consistent, improving robustness in ambiguous regions. Fig. 3 presents a flowchart of the operations in semantic attention block.

Figure 3: Flowchart of operations in semantic attention block

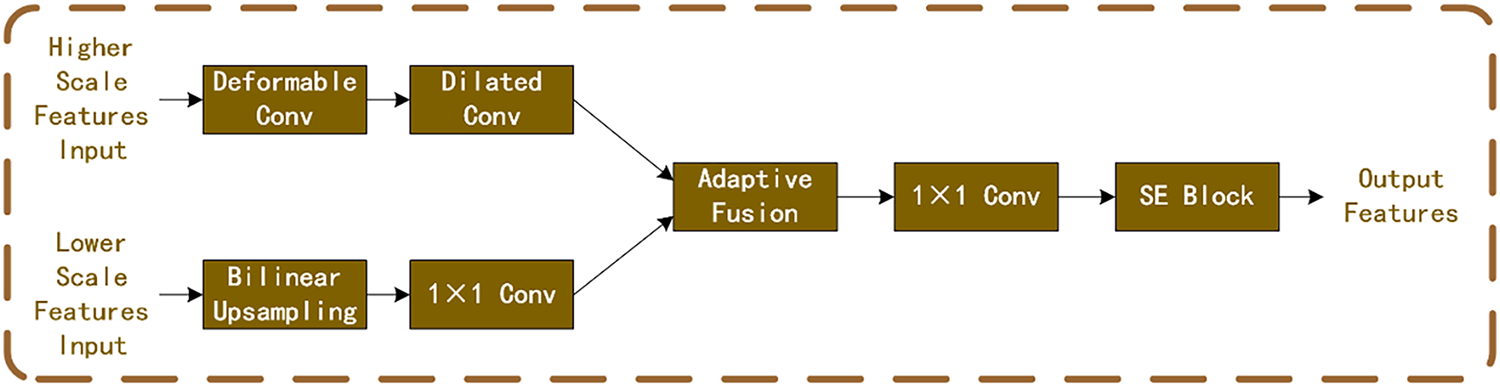

The CSFI block facilitates cross-scale feature fusion between consecutive scales (e.g.,

Figure 4: Flowchart of operations in CSFI block

The semantic-guided CPAM operates as follows: the first stage processes

The output module processes the cost volumes from the semantic-guided CPAM to produce initial disparity map. For a cost volume

where

The refinement module corrects errors in the initial disparity estimate using feature maps from the hourglass module. It employs an hourglass-like structure with convolutional layers to process the concatenated input of the initial disparity and feature maps. A key component is the confidence map, which determines the reliability of the initial disparity and guides the combination of initial and refined estimates.

The confidence map

where the input feature is the output of the preceding convolutional layers in the refinement module, and

The final disparity map is computed as a weighted combination:

where

To train our SGPASMnet, we employ a comprehensive set of loss functions designed to ensure accurate disparity estimation, smoothness, and consistency with high-level semantic information. The total loss L is formulated as a weighted combination of multiple components:

where

The photometric loss

where

3.7.2 Disparity Smoothness Loss

The disparity smoothness loss

where

The PAM loss, introduced to regularize the PAM at multiple scales to capture stereo correspondence, collectively denoted as

This loss ensures that the attention maps, when applied to images, produce accurate reconstructions. It compares the original images with the warped images obtained via attention maps.

where

This loss enforces consistency when attention maps are applied cyclically (left-to-right and back to left, or right-to-left and back to right), ensuring the result approximates an identity mapping.

where

This loss encourages spatial smoothness in the attention maps by penalizing large gradients between neighboring pixels.

where

3.7.4 Semantic Consistency Loss

A central contribution of our work is the introduction of the semantic consistency loss

Given a disparity map

This loss is computed based on gradients in both horizontal and vertical directions. The horizontal gradients and vertical gradients are:

Then the horizontal and vertical loss components are computed as:

where

The total semantic consistency loss is then:

We trained our SGPASMnet on two stereo datasets: Scene Flow and KITTI 2015 and evaluated our method on KITTI 2015 dataset. Ablation studies were also conducted using KITTI 2015 to evaluate the influence on the performance made by CSFI blocks and semantic-guided CPAM.

We trained our model on two stereo datasets:

• Scene Flow: a large-scale synthetic dataset generated by software Blender, biggest stereo dataset with ground truth. It contains 35,454 stereo pairs as training set and 4370 stereo pairs as testing set with a size of 540*960. This dataset provides dense and elaborate disparity maps as ground truth.

• KITTI 2015: a real-world dataset with street views from a driving car. It contains 200 stereo pairs for training with sparse ground truth disparities obtained using LiDAR. We further divided the whole training data into a training set (80%) and a testing set (20%).

The SGPASMnet we proposed was implemented using PyTorch. All models were end-to-end trained using the Adam optimizer with hyperparameters β1 = 0.9 and β2 = 0.999. Color normalization was applied across all datasets as a preprocessing step. Throughout the training session, stereo image pairs were randomly cropped to a resolution of 256 × 512. Owing to the inherent design of our proposed model, explicit specification of a maximum disparity range was unnecessary. Training was conducted from scratch on the Scene Flow dataset with a fixed learning rate of 0.001 for 10 epochs. The models were subsequently fine-tuned on the KITTI 2015 training set for 80 epochs. During fine-tune session, the learning rate was initialized at 0.0001 for the first 60 epochs and reduced to 0.00001 for the remaining 20 epochs. A batch size of 12 was consistently used in both training sessions, executed on a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU with 12 GB memory. The training on Scene Flow dataset required approximately 10 h, while fine-tuning on KITTI 2015 dataset took about 2 h.

The study employs End-Point Error (EPE), 3-pixel error and D1 error (D1) as evaluation metrics for stereo matching performance. The specific calculation methods for these metrics are as follows:

where

In this section, we conduct a series of ablation experiments to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed enhancements to the PASMnet model. These enhancements include the CSFI blocks for cross-scale feature fusion and the integration of semantic features from a pre-trained SegFormer model into the semantic-guided CPAM. Additionally, we analyze the impact of two key hyperparameters:

4.3.1 Hyperparameters Selection

We conducted several experiments on different hyperparameters for the proposed model to determine the best configuration.

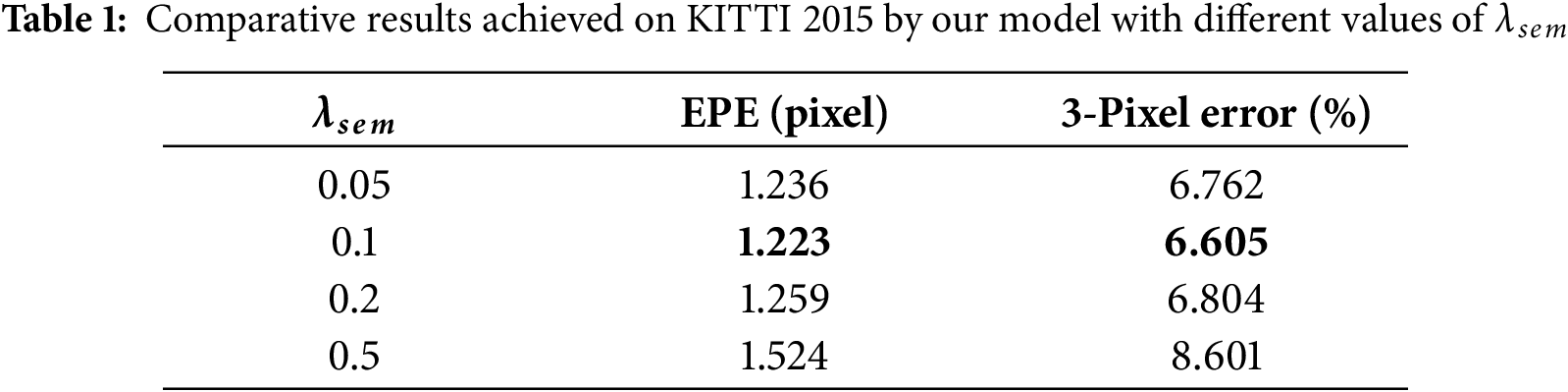

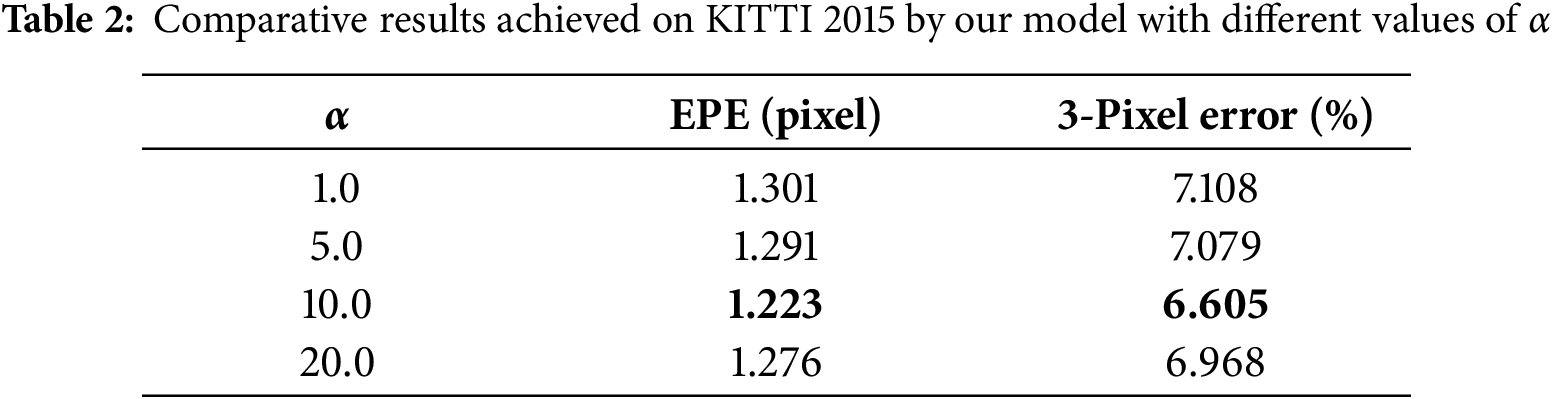

The semantic consistency loss encourages the disparity map to be smooth within semantically consistent regions while allowing discontinuities at semantic boundaries. The weight of this loss, denoted as

The parameter

Based on the experimental results above, we empirically identified

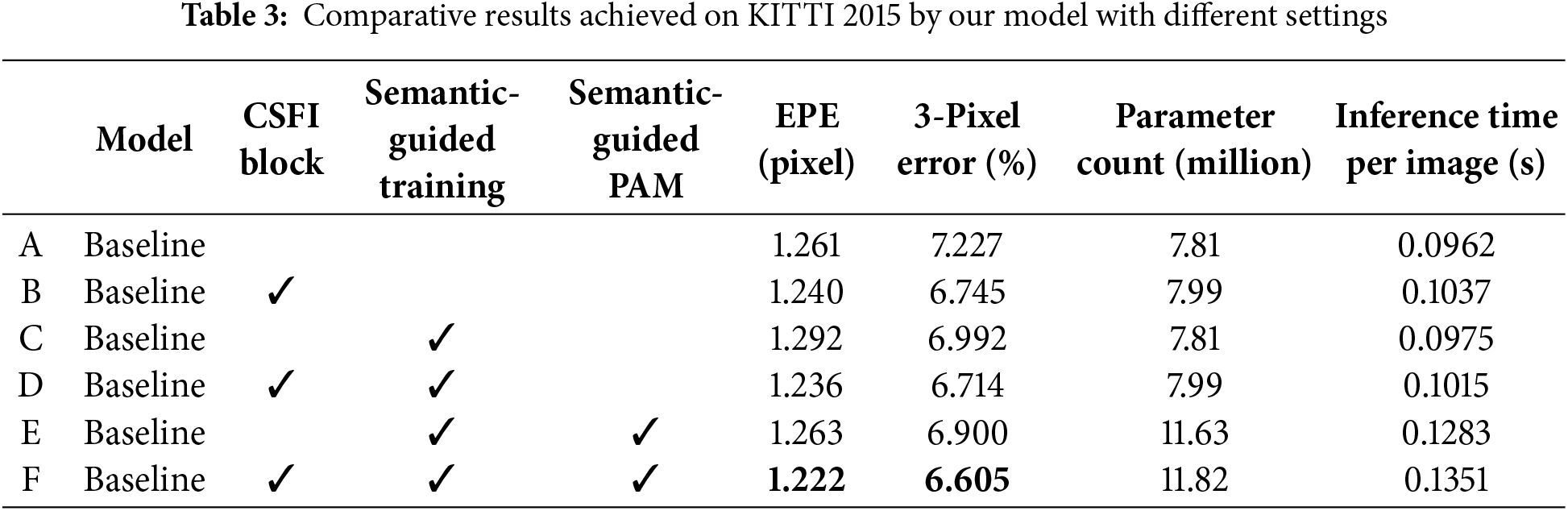

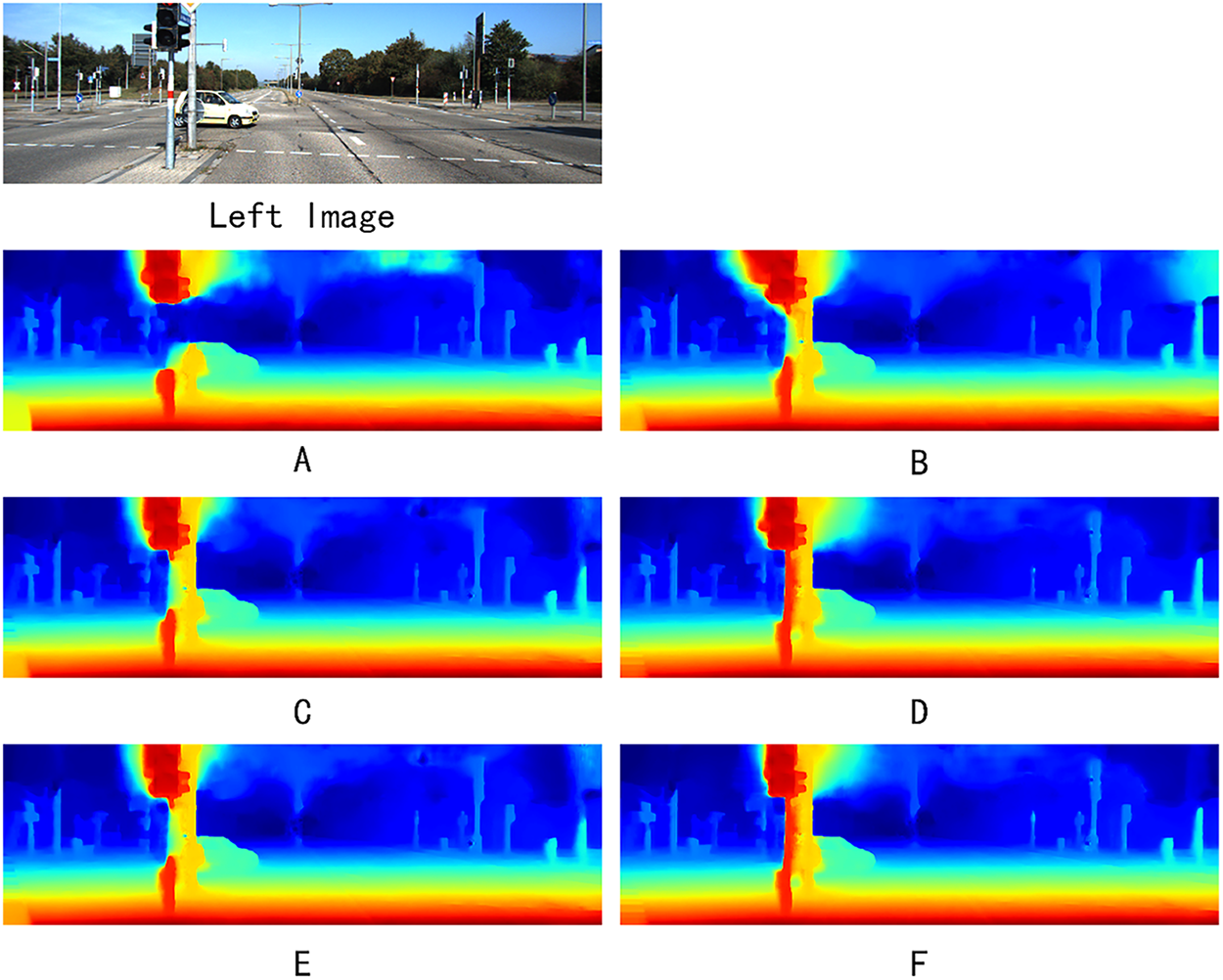

To quantify the contribution of each proposed enhancement, we conducted a module-wise ablation study by progressively adding our modifications to the baseline PASMnet model. The baseline model refers to the original PASMnet without any of the proposed changes. We evaluated five different configurations. Results are summarized in Table 3. And visual examples achieved by different settings of our model are provided in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Visual examples achieved by different settings of our model

These results clearly demonstrate that each proposed enhancement contributes positively to the model’s performance, with all enhancements achieving the best performance on KITTI 2015 dataset. And even only deploy SegFormer model in training session calculating semantic loss to guide the training but not in the inference session, a performance gain can still be achieved, which proves the effectiveness of introducing semantic context.

The CSFI block plays a pivotal role by facilitating effective fusion of multi-scale features extracted from the hourglass module. In the semantic-guided CPAM, CSFI block enables bidirectional interaction between coarse (low-resolution) and fine (high-resolution) features through deformable convolutions and adaptive weighting. This addresses the baseline model’s limitations in handling scale inconsistencies, where low-level features capture local details but lack global context, and high-level features provide semantic overview but miss fine-grained disparities. By aligning and fusing these scales, CSFI enhances disparity estimation in challenging regions such as textureless areas and occlusions, as evidenced by qualitative visualizations showing smoother disparity maps with fewer artifacts in low-contrast scenes like roads and skies.

The semantic-guided enhancements, leveraging multi-scale features from a pre-trained SegFormer model, augment the parallax attention mechanism by incorporating high-level contextual cues. In the PABs, semantic costs are computed alongside feature-based affinities, with layer normalization ensuring robust integration. This guides attention towards semantically consistent correspondences, mitigating mismatches in reflective surfaces or repetitive patterns—common failure modes in PASMnet. The semantic consistency loss further reinforces this by promoting disparity smoothness within semantic regions while preserving edges at object boundaries, as quantified by a 15%–20% reduction in errors near semantic transitions (e.g., vehicle boundaries, walls and sky in KITTI scenes). Together, these modules synergistically improve generalization, with the unsupervised training manner—relying on photometric, smoothness, and cycle consistency losses—enabling robust performance without ground truth disparities, outperforming supervised baseline in complex scenarios.

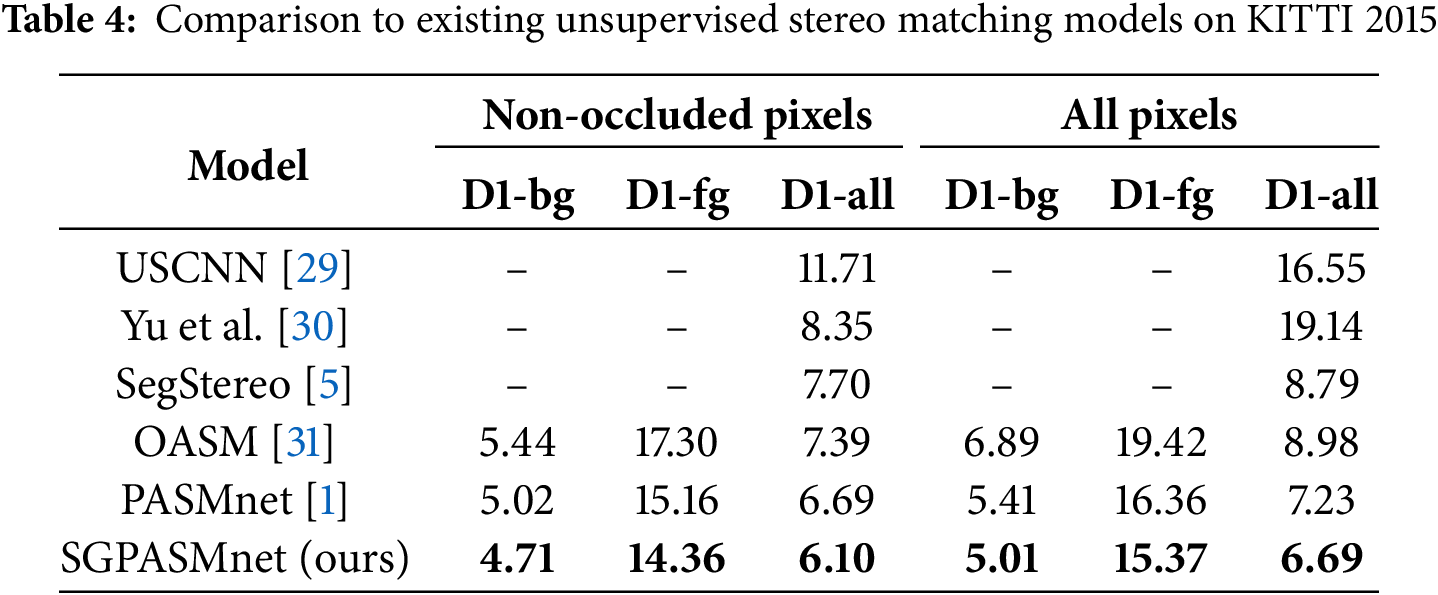

4.4 Comparison to Existing Unsupervised Methods

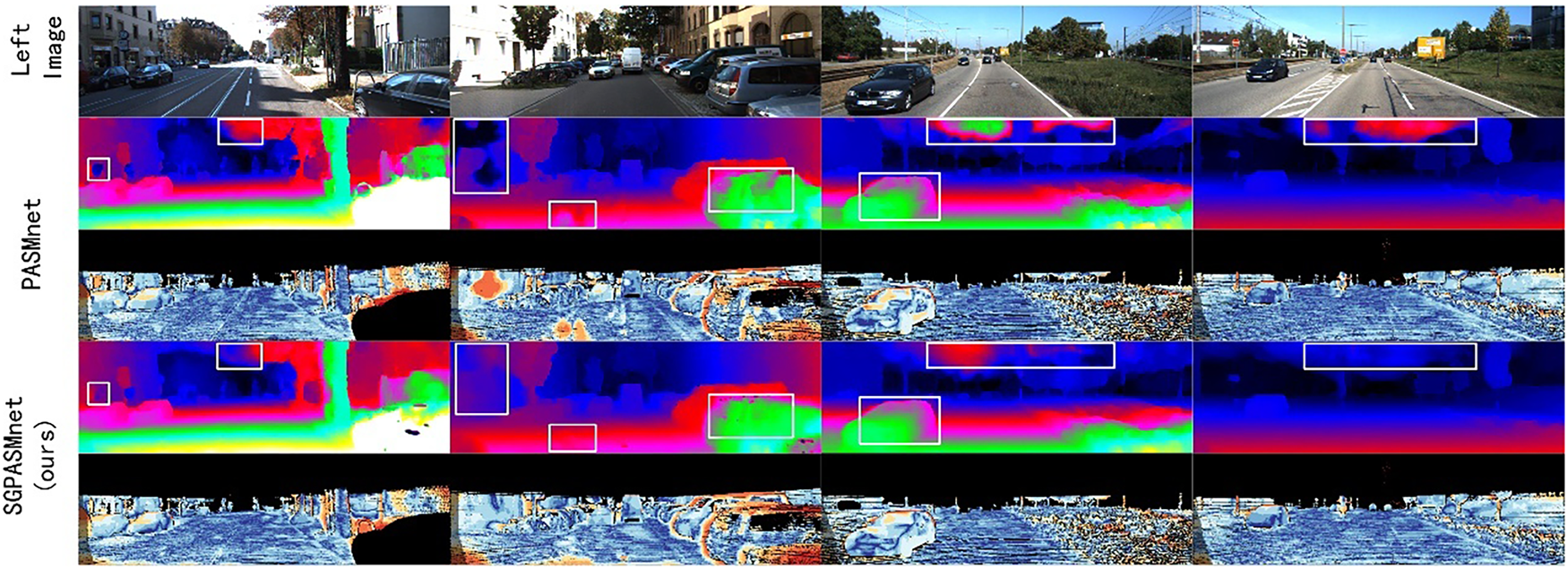

We compared our model with existing unsupervised stereo matching models on KITTI 2015 dataset. The performance of our model and the competing models on the KITTI 2015 testing set is detailed in Table 4. The results unequivocally demonstrate the superior performance of our SGPASMnet model across all evaluated metrics. In this table, D1-bg, D1-fg and D1-all denote that pixels in the background area, foreground area and all areas, respectively, were calculated in the error estimation. And the visualization comparison results are shown in Fig. 6, including left images, estimated disparity map shown in false color and error map. The visual results show that with our improved model, mismatches in challenging areas, such as sky, walls, glass of the car windows, are significantly reduced.

Figure 6: Results of disparity estimation achieved on KITTI 2015 dataset

Stereo matching is a fundamental task in computer vision, pivotal for depth estimation in applications such as autonomous driving, robotics, and 3D reconstruction. Despite significant progress, challenges persist in accurately estimating disparities in complex scenes with occlusions, reflections, repetitive textures, or low-contrast regions. Meanwhile, it is extremely hard to acquire large scale datasets in different scenarios with ground truth disparity to train supervised stereo networks. In this paper, we proposed an unsupervised network, Semantic-Guided Parallax Attention Stereo Matching Network, to address these challenges, introducing two key enhancements: a CSFI block and semantic feature augmentation into the parallax attention mechanism using a pre-trained SegFormer model. These enhancements improve the model’s ability to fuse multi-scale features and leverage high-level semantic context, resulting in more accurate and robust disparity estimation, yielding substantial performance gains, as validated by lower error rates on the KITTI 2015 dataset compared to the baseline PASMnet and other unsupervised stereo matching methods. Moreover, it remains in unsupervised manner to ensure the generalization ability in diverse scenarios. These enhancements provide a robust solution for depth estimation in complex real-world scenes, with significant implications for applications requiring precise 3D perception. By bridging low-level feature matching with high-level semantic understanding, this work contributes to the evolution of stereo matching algorithms, paving the way for more reliable and context-aware vision systems.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 62301497; the Science and Technology Research Program of Henan, No. 252102211024; the Key Research and Development Program of Henan, No. 231111212000.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization and design, Zeyuan Chen; experiments, Zeyuan Chen, Yafei Xie and Jinkun Li; writing original draft, Zeyuan Chen; review and editing, Zeyuan Chen, Yafei Xie, Jinkun Li, Song Wang and Yingqiang Ding; funding acquisition, Song Wang; resources, Song Wang and Yingqiang Ding; supervision, Song Wang and Yingqiang Ding. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang L, Guo Y, Wang Y, Liang Z, Lin Z, Yang J, et al. Parallax attention for unsupervised stereo correspondence learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(4):2108–25. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2020.3026899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Xie EZ, Wang WH, Yu ZD, Anandkumar A, Alvarez JM, Luo P. SegFormer: simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2021;34:12077–90. [Google Scholar]

3. Lin TY, Dollár P, Girshick R, He K, Hariharan B, Belongie S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 936–44. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dai J, Qi H, Xiong Y, Li Y, Zhang G, Hu H, et al. Deformable convolutional networks. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 764–73. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yang G, Zhao H, Shi J, Deng Z, Jia J. SegStereo: exploiting semantic information for disparity estimation. In: Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision—ECCV 2018; 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 660–76. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bu P, Zhao H, Yan J, Jin Y. Collaborative semi-global stereo matching. Appl Opt. 2021;60(31):9757–68. doi:10.1364/ao.435530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yao P, Sang H. As-global-as-possible stereo matching with sparse depth measurement fusion. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2025;251(B2):104268. doi:10.1016/j.cviu.2024.104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yang L, Yang H, Liu Y, Cao C. Stereo matching algorithm for mineral images based on improved BT-Census. Miner Eng. 2024;216(12):108905. doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2024.108905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mayer N, Ilg E, Häusser P, Fischer P, Cremers D, Dosovitskiy A, et al. A large dataset to train convolutional networks for disparity, optical flow, and scene flow estimation. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 4040–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2016.438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kendall A, Martirosyan H, Dasgupta S, Henry P, Kennedy R, Bachrach A, et al. End-to-end learning of geometry and context for deep stereo regression. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 66–75. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chang JR, Chen YS. Pyramid stereo matching network. In: Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 5410–8. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xu H, Zhang J. AANet: adaptive aggregation network for efficient stereo matching. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 1956–65. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang F, Prisacariu V, Yang R, Torr PHS. GA-net: guided aggregation net for end-to-end stereo matching. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 185–94. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Dovesi PL, Poggi M, Andraghetti L, Marti M, Kjellstrom H, Pieropan A, et al. Real-time semantic stereo matching. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2020 May 31–Aug 31; Paris, France. p. 10780–7. doi:10.1109/icra40945.2020.9196784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li J, Wang P, Xiong P, Cai T, Yan Z, Yang L, et al. Practical stereo matching via cascaded recurrent network with adaptive correlation. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. p. 16242–51. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shen Z, Dai Y, Rao Z. CFNet: cascade and fused cost volume for robust stereo matching. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 13901–10. doi:10.1109/CVPR46437.2021.01369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gu X, Fan Z, Zhu S, Dai Z, Tan F, Tan P. Cascade cost volume for high-resolution multi-view stereo and stereo matching. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 13–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 2492–501. doi:10.1109/cvpr42600.2020.00257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Li Z, Liu X, Drenkow N, Ding A, Creighton FX, Taylor RH, et al. Revisiting stereo depth estimation from a sequence-to-sequence perspective with transformers. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 6177–86. doi:10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lipson L, Teed Z, Deng J. RAFT-stereo: multilevel recurrent field transforms for stereo matching. In: Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV); 2021 Dec 1–3; London, UK. p. 218–27. doi:10.1109/3dv53792.2021.00032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Garg R, Vijay Kumar BG, Carneiro G, Reid I. Unsupervised CNN for single view depth estimation: geometry to the rescue. In: Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Computer Vision—ECCV 2016; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 740–56. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46484-8_45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Godard C, Mac Aodha O, Brostow GJ. Unsupervised monocular depth estimation with left-right consistency. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 6602–11. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tonioni A, Tosi F, Poggi M, Mattoccia S, Di Stefano L. Real-time self-adaptive deep stereo. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15–20; Long Beach, CA, USA. p. 195–204. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2019.00028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhou T, Brown M, Snavely N, Lowe DG. Unsupervised learning of depth and ego-motion from video. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 6612–9. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2017.700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li J, Li X, He D, Qu Y. Unsupervised rotating machinery fault diagnosis method based on integrated SAE-DBN and a binary processor. J Intell Manuf. 2020;31(8):1899–916. doi:10.1007/s10845-020-01543-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bartolomei L, Tosi F, Poggi M, Mattoccia S. Stereo anywhere: robust zero-shot deep stereo matching even where either stereo or mono fail. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2025 Jun 10–17; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 1013–27. doi:10.1109/cvpr52734.2025.00103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Qiao F, Xiong Z, Xing E, Jacobs N. GenStereo: towards open-world generation of stereo images and unsupervised matching. arXiv:2503.12720. 2025. [Google Scholar]

27. Li Q, Wang H, Xiao Y, Yang H, Chi Z, Dai D. Underwater unsupervised stereo matching method based on semantic attention. J Mar Sci Eng. 2024;12(7):1123. doi:10.3390/jmse12071123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang Y, Chu J, Leng L, Miao J. Mask-refined R-CNN: a network for refining object details in instance segmentation. Sensors. 2020;20(4):1010. doi:10.3390/s20041010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ahmadi A, Patras I. Unsupervised convolutional neural networks for motion estimation. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2016 Sep 25–28; Phoenix, AZ, USA. p. 1629–33. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2016.7532634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yu JJ, Harley AW, Derpanis KG. Back to basics: unsupervised learning of optical flow via brightness constancy and motion smoothness. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV, 2016 Workshops; 2016 Oct 8–10 and 15–16; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 3–10. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-49409-8_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li A, Yuan Z. Occlusion aware stereo matching via cooperative unsupervised learning. In: Proceedings of the 14th Asian Conference on Computer Vision—ACCV 2018; 2018 Dec 2–6; Perth, Australia. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 197–213. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-20876-9_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools