Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Virtual QPU: A Novel Implementation of Quantum Computing

Information Engineering University, Zhengzhou, 450001, China

* Corresponding Author: Danyang Zheng. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 40 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073860

Received 27 September 2025; Accepted 21 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The increasing popularity of quantum computing has resulted in a considerable rise in demand for cloud quantum computing usage in recent years. Nevertheless, the rapid surge in demand for cloud-based quantum computing resources has led to a scarcity. In order to meet the needs of an increasing number of researchers, it is imperative to facilitate efficient and flexible access to computing resources in a cloud environment. In this paper, we propose a novel quantum computing paradigm, Virtual QPU (VQPU), which addresses this issue and enhances quantum cloud throughput with guaranteed circuit fidelity. The proposal introduces three innovative concepts: (1) The integration of virtualization technology into the field of quantum computing to enhance quantum cloud throughput. (2) The introduction of an asynchronous execution of circuits methodology to improve quantum computing flexibility. (3) The development of a virtual QPU allocation scheme for quantum tasks in a cloud environment to improve circuit fidelity. The concepts have been validated through the utilization of a self-built simulated quantum cloud platform.Keywords

In recent years, the field of quantum computing has witnessed a period of unparalleled advancement. It promises to resolve intractable computational problems that exceed the capabilities of contemporary classical computers, thereby promising to revolutionize numerous scientific disciplines. The potential of this approach has been demonstrated in a number of areas, including financial modelling [1,2], database searches [3], molecule simulation [4,5], and machine learning [6–8]. It is anticipated that in the coming years, quantum computers will have thousands of qubits. However, the fidelity of the devices may still present a limitation to the ability to perform large computations involving many qubits. Quantum computing has experienced extraordinary strides in recent years, yet the current developmental phase of quantum devices has not moved beyond the scope of the noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) era [9]. These NISQ computers are characterized by a number of noises and errors, including measurement errors, quantum gate operation errors, and most, problematic of all, short decoherence times. Consequently, the outputs produced by these contemporary quantum devices are unreliable when processing deep circuits with numerous gates.

Moreover, quantum computers require the deployment of highly intricate control circuitry, cutting-edge microwave technologies, cryogenic refrigeration units that can sustain temperatures down to the milli-kelvin range, and robust shielding mechanisms to fend off environmental noise interference [10]. The exorbitant costs linked to the essential hardware, coupled with the stringent ambient requirements, pose significant barriers for ordinary users to access on-site quantum computing resources. Nevertheless, the emergence of quantum cloud service providers has enabled remote access to quantum computing infrastructure, and this integration is poised to drastically lower the entry barriers to leveraging quantum computing resources. This facilitates the investigation of quantum algorithms by researchers and developers, obviating the necessity of quantum hardware [11–13].

With ongoing growth in the demand for direct access to quantum hardware resources, the volume of users subscribing to quantum computing cloud services is forecast to expand exponentially over the course of the next ten years. However, the prevailing quantum cloud providers utilize a time-based resource-sharing model to regulate access to their backends. This approach invariably results in a substantial number of jobs awaiting processing on quantum devices, and users being required to wait for extended periods in queues. To tackle this problem, numerous researchers have advocated for the deployment of multi-programming on NISQ computers, aiming to boost the utilization efficiency of robust qubits within a single quantum device [14–18]. What merits particular attention is that although this approach can effectively elevate the throughput of an individual quantum backend, its inherent flexibility remains inadequate. This is due to the fact that the Multi-programming approach necessitates that the user specify the desired backend for execution. Moreover, it does not take into account the resources available within the broader quantum computing resource pool. Furthermore, it does not consider the resources available within the entire quantum computing resource pool. Statistically, at any given moment, there could be as many as 10 to 1000 quantum tasks queued up on different quantum computers, exhibiting a high degree of randomness [19]. This ultimately results in an unsatisfactory user experience and hinders the advancement of quantum algorithms and applications to a certain extent.

In order to address this challenge, a new quantum computing implementation paradigm for superconducting quantum computers is proposed. This paradigm, termed the Virtual QPU architecture, is based on the virtualization of classical computers. The virtualization of classical computers is a technique that enables the logical partitioning or combination of computational resources (e.g., servers, storage, and networks) so that multiple operating systems and applications can run simultaneously. The technique facilitates the virtualization of physical devices or resources, thereby enabling multiple virtual instances to share the same set of physical resources, thus enhancing resource utilization and flexibility. This concept aligns perfectly with the current trajectory of quantum cloud development. The virtual QPU architecture proposed in this paper unifies the quantum resources of the cloud service provider and allocates appropriate quantum resources when the circuit performs compilation, automatically creating virtual QPUs and providing them to the corresponding tasks. A salient feature of this approach is its asynchronous execution of virtual QPUs, a feature that is distinct from the parallel execution of circuits. This asynchronous execution has been demonstrated to enhance the flexibility of the quantum cloud, thereby increasing its throughput in complex task environments.

The subsequent sections of this paper are laid out in the following manner. Initially, Section 2 provides a contextual foundation for the research. Subsequently, Section 3 describes the architecture of VQPU. Section 4 primarily encompasses the experimental and evaluation facets of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the results of the study.

In this section, we introduce some fundamental concepts related to quantum computers and quantum computing [19–23]. Additionally, we present existing schemes for enhancing the throughput of quantum clouds [14–18], thereby demonstrating the necessity of a virtual QPU architecture.

A quantum computer is defined as a computer that employs the principles of quantum mechanics for the storage and processing of information. Conversely, quantum computers utilize quantum bits (qubits) as the fundamental unit of information, a paradigm shift from conventional computers that employ classical bits. The distinctive quantum properties of qubits, including superposition and entanglement states, enable quantum computers to achieve computational speeds that are significantly faster than those of conventional computers in certain instances. The most prevalent categories are ion traps [24], superconducting quantum [25], and photonic quantum [26]. The development of quantum computers has the potential to yield significant technological advances and may offer solutions to problems that are currently intractable to conventional computers. However, contemporary NISQ computers are confronted with substantial reliability challenges. It is acknowledged that physical qubits are fragile and susceptible to interference. Consequently, quantum programs running on a quantum computer may be subject to the following types of errors: The following errors have been identified: (1) Coherence errors caused by coherence time; (2) Operational errors due to error-prone quantum gates; (3) Readout errors due to measurement operations.

Quantum computing entails the precise manipulation of multiple qubits via a sequential set of quantum logic gates. A qubit is analogous to a “bit” in classical computing. However, a qubit is capable of remaining in not only the classical states, but also a superposition of these two states. This distinguishes it from a classical bit. The superposition is denoted as

A quantum program is defined as a sequence of quantum gates that operate on a number of qubits. The quantum gate is employed to convert one quantum state to another; specifically,

To the best of our knowledge, no research extends the virtualization techniques of classical computing to the field of quantum computing to address the challenges that exist in existing quantum clouds. That said, a number of extant research efforts conduct in-depth examinations of these challenges. In this section, we provide a comprehensive overview of the pertinent scholarly work that addresses each of these challenges individually.

Challenge 1: The quantum cloud provider employs a time-based resource sharing model to regulate access to its QPUs. In general, there are two principal methods of accessing the selected QPU. The customer may either reserve an exclusive time slot on a QPU or utilize a shared job queue for a public QPU. The sole distinction lies in the duration for which a QPU is exclusively allocated to a customer. In the first case, the QPU is made available to the customer exclusively for the entire duration of the reserved time slot; in the second case, only for the execution time of the single quantum circuit [27]. In either case, each executed quantum task blocks the entire QPU, which makes the quantum cloud much less flexible and results in a large number of unused qubits during the execution of smaller quantum circuits, significantly reducing the throughput of the quantum cloud.

The Multi-programming mechanism was initially proposed by Das et al. [14] through the development of the Fair and Reliable Partitioning (FRP) approach, which coined the term “Multi-programming quantum computing” and demonstrated that this scheme can lead to an increase in the throughput and utilization of QPUs through their approach. Subsequently, Liu and Dou [18] enhanced this mechanism by introducing QuCloud, which combines a new qubit mapping method with a compiled task scheduler for multi-programming quantum computers in the cloud. In their seminal paper, Wu et al. [28] proposed a noise-aware quantum job scheduler (NAQJS) based on circuit width, number of measurement shots, and submission time of quantum jobs, to reduce execution latency. In addition, we may consider the work of Mineh and Montanaro [29], who have devised a circuit parallel operation scheme that has been optimized for utilization in the field of machine learning. In parallel, Park et al. [30] put forward a quantum multi-programming algorithm tailored for the Grover search algorithm.

While multi-programming methodologies hold the potential to boost the throughput of quantum cloud platforms to a certain extent, their practical applicability remains subject to notable constraints. The selection of parallel circuits is a more complex process, as they must have the same number of trials and satisfy the qubit constraints (including the qubit fidelity limit and the number of qubits limit) when mapping. Secondly, the access to quantum resources in existing schemes is based on time-based resource sharing. This may result in the inability of users to execute quantum circuits in parallel when they are submitted at different times. This is attributable to the possibility that the circuit submitted at an earlier point in time may have utilized the entirety of the QPU, irrespective of whether or not it employs all the qubits on the QPU.

Challenge 2: Currently, users are required to manually select specific physical resources when submitting a quantum task. Given the difficulty users face in determining the task queuing status across individual quantum backends, a marked disparity in wait times emerges when users submit their tasks to distinct quantum backends at the same time. Although the method of specific physical resources allows researchers a high degree of flexibility, in the majority of cases, researchers do not consider the execution process of the tasks they submit; instead, they focus solely on the outcome produced by the quantum computer. Furthermore, users select their physical resources due to the significant discrepancies in the quantum circuits they design and the qubit properties required for the circuits to operate. It is therefore imperative that users consider the various limitations of different quantum computing devices, as this is critical to the realization of the task. This undoubtedly adds an unnecessary burden to the user. Additionally, the fact that the customer directly chooses the physical resources works against the cloud provider, as they have limited control over the use and utilization of QPUs. This may hinder the cloud provider’s ability to optimize resource utilization.

The current state of the art in quantum resource selection remains in the exploratory phase, with a number of promising avenues for further research having been identified by the scientific community. Ravi et al. [19] has put forward a sophisticated, enhanced adaptive task scheduling approach tailored for quantum cloud environments. The Quantum Resource Estimator, a tool introduced by Suchara et al. [31], can select a QPU by evaluating key factors including the count of physical qubits, algorithm execution time, and the likelihood of a quantum algorithm operating successfully on a given QPU. Moreover, Salm et al. [32] have created an automated framework that accurately converts quantum circuits into a variety of distinct programming languages. Wang et al. [33] proposed the Qoncord automated job scheduling framework for solving quantum circuit scheduling problems based on VQA. While these studies signify substantial progress in the realm of automated hardware selection and offer a measure of respite from the quantum cloud queuing problem, they are nevertheless allocated on the basis of actual physical QPUs. This does not result in any enhancement of single computer throughput.

In order to overcome the aforementioned challenges, we propose a virtual QPU architecture that draws on the virtualization scheme in classical computing. This scheme manages all backend quantum resources in a unified manner and allocates them on demand according to the circuit attributes, thus creating virtual QPUs. Secondly, this architecture decouples the qubits and allows asynchronous execution of user-submitted circuits, thereby improving the flexibility of the quantum cloud. In conclusion, the proposed architecture is capable of rationally automating the virtual QPU creation and recycling process through the implementation of the proposed algorithm, thereby achieving the optimal quantum cloud throughput.

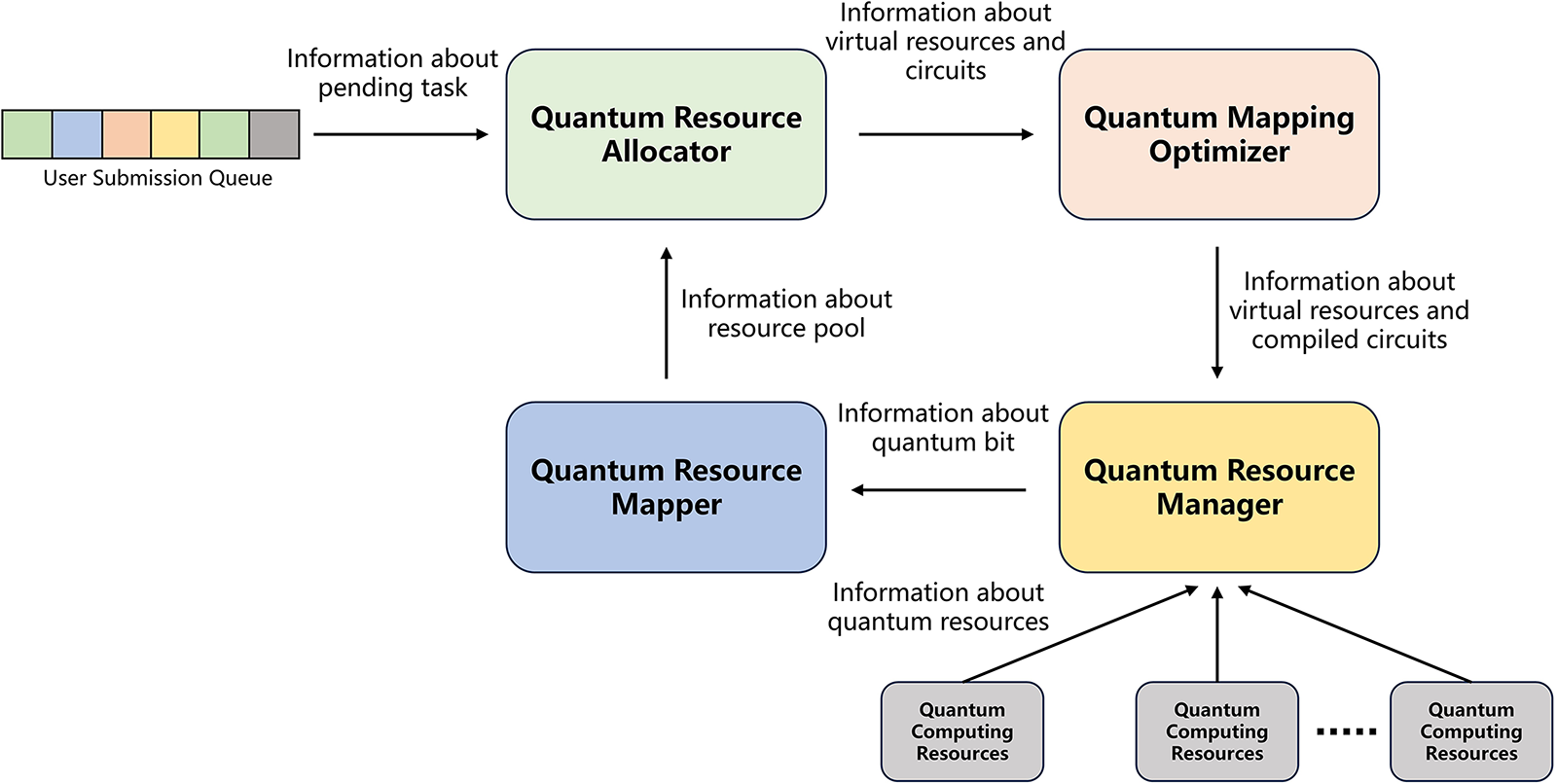

The architecture of the virtual QPU proposed in this paper is shown in Fig. 1, which contains the overall architecture containing four parts, namely, Quantum Resource Manager, Quantum Resource Mapper, Quantum Resource Allocator, and Quantum Mapping Optimizer. The Quantum Resource Manager provides the interface for quantum resource access, and all quantum computing devices in the backend of the quantum cloud need to access the Quantum Resource Manager. Subsequently, the Quantum Resource Mapper virtualizes all quantum computing resources, accessing the Quantum Resource Manager and connecting them to the quantum resource pool. When a quantum task is submitted to a quantum cloud service provider’s cloud, the task will be placed in the user submission queue, where it will await processing in the order of submission. In accordance with the first-in-first-out principle, the task with the longest waiting time will be transmitted to the Quantum Resource Allocator, which distributes resources in accordance with the resource usage within the resource pool and generates a virtual QPU. Subsequently, the user task and the virtual QPU will be submitted to the Quantum Mapping Optimizer for circuit compilation, and the compiled circuit will be transmitted to each quantum computer for execution. Upon completion of the execution, the result will be returned to the user, and the virtual QPU resources will be recovered and returned to the resource pool. The following section provides a comprehensive account of the function and implementation of each module.

Figure 1: Virtual QPU framework

A number of quantum cloud service providers are currently in operation, including IBM, Google, Microsoft, and Honeywell. However, the quantum device interfaces of the same type of quantum computer show significant discrepancies when provided by different quantum cloud service providers. To address the fundamental issue of device unification, we develop the Quantum Resource Manager.

The Quantum Resource Manager provides downward access to different quantum computing resources, encapsulating them in a unified way. It also provides upward calling interfaces to meet the requirements of Quantum Resource Mapper. When accessing a quantum computing resource, the Quantum Resource Manager proactively requests the resource attributes, which include the quantum resource type, the quantum resource availability state, the gate groups supported by the quantum resource, the QPU topology, the number of qubits, the qubits availability, and the qubits attributes. Qubit attributes include single-qubit gate fidelity, two-qubit gate fidelity, measurement fidelity, and T1 and T2 relaxation times.

It is important to acknowledge that NISQ computers are vulnerable to external influences, such as temperature fluctuations and magnetic field interference, which could potentially introduce distortions and errors in the qubits. It is therefore essential to implement a periodic calibration process to ensure the reliability and accuracy of quantum computers. This process allows for the correction and adjustment of the qubits’ state, thereby guaranteeing the precision of the resulting calculations. When quantum resources are accessible to the Quantum Resource Manager, the manager sends requests to each quantum resource at regular intervals. This ensures the availability and accuracy of the current quantum computing resources.

Once the pertinent attributes of the backend quantum resources have been obtained, the Quantum Resource Manager will encapsulate them. Subsequently, all quantum computers will be encapsulated into a unified form, and the requisite interfaces will be provided for utilization by the upper layers. The unified interface encapsulation has the potential to streamline the development process for developers, enhance cross-platform compatibility, and facilitate maintenance. Over time, it could contribute to the establishment of industry standards and interoperability, stimulate the advancement and implementation of quantum computing technology, facilitate integration and sharing of quantum computing resources from diverse vendors and organizations, and accelerate the development and growth of the quantum computing ecosystem.

The principal objective of the Quantum Resource Mapper is to virtualize the underlying quantum resources. At this juncture, the quantum cloud remains the principal avenue for accessing quantum computers. The quantum cloud offers a range of backend resources with varying attributes, necessitating a meticulous selection process on the part of the user to identify the optimal resources for their intended task. Nevertheless, at present, users are unable to readily ascertain the attributes of quantum resources and their respective queuing information, which consequently imposes an additional burden on users when utilizing them. In order to address this issue, we propose the Quantum Resource Mapper. The Quantum Resource Mapper virtualizes all available computing resources accessed via the Quantum Resource Manager, creating a unified resource pool. Each resource retains its original topology and qubit attributes, enabling unified management and intuitive display of all quantum resources. This addresses the shortcomings of the existing quantum cloud. As a consequence of the unification of interfaces across all quantum resources, it is now straightforward to obtain a range of information pertaining to the underlying quantum resources.

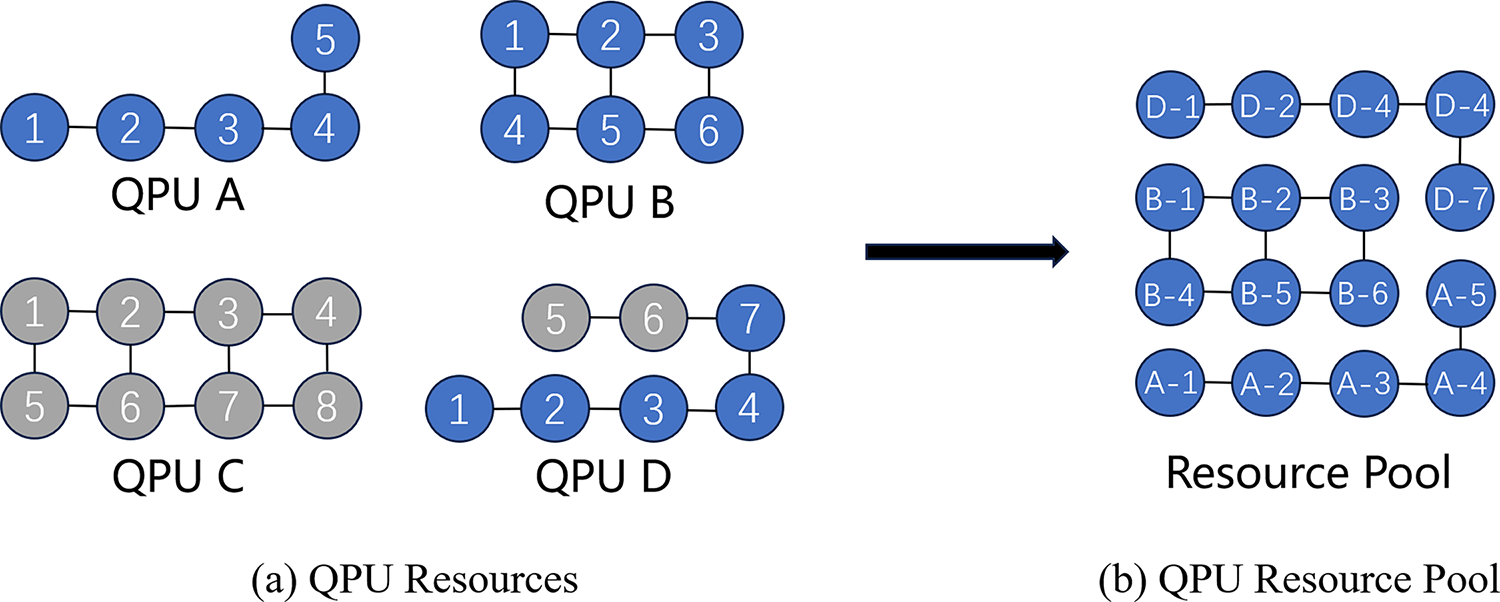

Specifically, at the topology level, all available quantum computing and qubit resources are integrated, as shown in Fig. 2a. Four quantum backends, labelled A, B, C, and D, are connected to the Quantum Resource Manager. Backends A and B are quantum computers, respectively, containing a 5-qubit QPU and a 6-qubit QPU, and both function normally. Backend C is a quantum computer containing 8-8-qubit QPU, which is currently unavailable for various reasons, including device maintenance and calibration. Quantum computer D contains a 7-qubit QPU, but some of its qubits are unusable. The integration situation is illustrated in Fig. 2b. Quantum computing resources that are operational are incorporated directly into the resource pool. Conversely, those that are not available are also excluded. In the case of quantum computing resources with some unavailable qubits, a threshold is applied. If the number of available qubits exceeds half of the total number of qubits in the QPU, the available qubits are included in the resource pool. Conversely, if the number of available qubits is less than half of the total number of qubits in the QPU, the QPU is excluded from the resource pool. The configuration in question offers three advantages.

Figure 2: QPU mapping

1. Improved resource utilization: if a quantum computer has a substantial number of unavailable qubits, its effective computing power will be significantly constrained. By excluding them from the resource pool, it is possible to ensure that only those quantum computers with a high number of effective qubits are used for computational tasks, thus improving resource utilization.

2. Optimizing task scheduling: Insufficient usable qubits can lead to inefficiency or failure in performing certain specific tasks. The process of task scheduling can be simplified by excluding these quantum computers, thus ensuring that tasks are assigned to the most suitable quantum computers for execution and improving overall task execution efficiency.

3. Enhancing the reliability of task execution: Unavailable qubits may usually be caused by hardware failures, ambient noise, calibration errors, and so on. The positional relationship between these unavailable qubits and other elements in the topology will have a significant impact on the compilation effect, which in turn will affect the execution of the quantum algorithm and the accuracy of the results. The exclusion of quantum computers with more than half of their available qubits unavailable reduces the incidence of compilation failures and errors due to hardware problems, thereby enhancing the reliability of task execution.

The Quantum Resource Mapper integrates the quantum devices of quantum cloud service providers into a unified pool of resources, thereby creating an architectural framework that optimizes resource allocation and scheduling on a global scale. This ensures that each quantum task is allocated the requisite resources and that the overall utilization of resources is maximized. Furthermore, this architectural approach enhances the compatibility and scalability of the quantum cloud as a whole, while simplifying the process for users, who can easily submit tasks, view results, and analyze data without having to delve into the underlying details of the quantum computer.

4.3 Quantum Resource Allocator

The Quantum Resource Allocator decides how to use the quantum resources in the pool for each circuit. The current quantum resource allocation schemes are essentially based on the user’s experience when selecting the backend. However, it is important to recognize that the chosen quantum backend may not necessarily represent the optimal solution. The first issue is the queuing problem, whereby users are unable to directly access the backend quantum resource queuing situation. This results in significant discrepancies in the demand for each quantum chip and the queuing time for different quantum resources. IBM, for instance, has a median queuing time of 60 min for its quantum cloud, which is relatively lengthy [30]. Furthermore, the discrepancy in demand between different quantum chips can reach 100 times, resulting in a significant proportion of computing resources being underutilized. Secondly, there is the issue of optimizing the selection of qubits. The existing quantum cloud does not perform global quantum resource management. Consequently, the existing resource allocation is based on the specified backend, which is not an optimal solution for the whole quantum cloud resource.

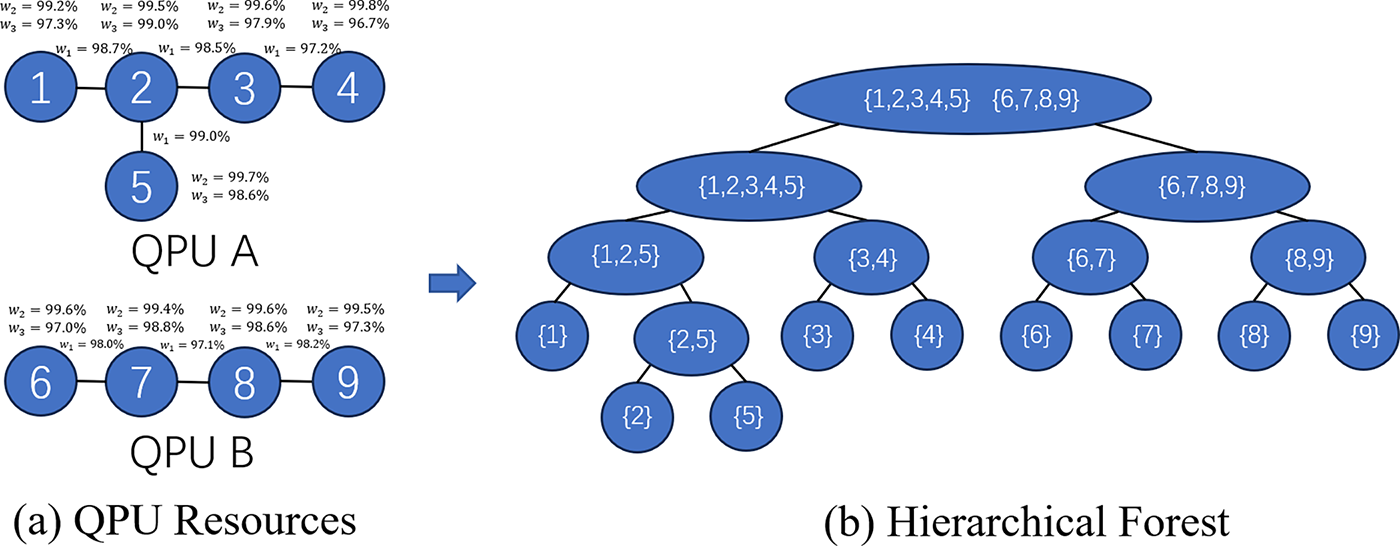

To solve these problems, the Quantum Resource Manager’s resource pool is employed to optimize the global resource allocation in accordance with the quantum cloud resources. First, the resource pool topology and qubit attributes of the entire quantum cloud are obtained from the Quantum Resource Mapper. Thereafter, the improved community detection algorithm is employed to create the hierarchical forest, wherein each tree represents a backend quantum resource, the leaf nodes on each tree represent specific physical qubits, and the internal nodes represent the set of nodes, i.e., the community, that is discovered each time. Subsequently, the initial allocation of available areas is determined based on the aforementioned hierarchical tree creation process.

The community detection algorithm is a method for identifying densely connected subgroups within a network or graph. Its objective is to partition the nodes in a network into subsets, such that nodes within the same subset exhibit a high connection density and a low connection density between different subsets. This partitioning can facilitate an understanding of the network’s structure and function, the identification of potential key nodes, and the discovery of potential community structures.

A number of community discovery algorithms have been developed, but there is still scope for improvement in terms of efficiency. Therefore, this paper, proposes a new scheme for constructing hierarchical forests based on the FN greedy community detection algorithm. This algorithm is a greedy clustering algorithm that clusters the modularity degree

It is important to note that, at the commencement of the algorithm, the qubit nodes are initialized. Each node, or qubit, is regarded as an autonomous community, comprising all the leaf nodes in the hierarchical forest. For each node, the modularity is calculated both with and without the node being moved to a neighbouring community,

An elevated value signifies a more appropriate partition. The origin denotes the modularity of the newly formed partition after the merging of the two communities and the original partition, respectively.

The computation of modularity gains and merging between communities must be performed repeatedly, with iterations until no further modularity gains can be identified. The process will yield n hierarchical trees. It is important to note that each internal node, or community, in the hierarchical tree is connected in the quantum resource topology. This is in accordance with the connectivity of the qubits required for the operation of the quantum circuit.

Following the acquisition of the hierarchical forest, the necessary quantum resource can be ascertained by means of the qubit number of the circuit and the order in which the forest was created. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, Fig. 3a, the quantum resources contained within the quantum backend are illustrated, while Fig. 3b depicts the created hierarchical forest. In the present case, the circuit under consideration necessitates the allocation of resources, comprising three qubits. The identification of the requisite quantum resource layer is conducted sequentially, in accordance with the creation order. It is concluded that the optimal quantum resources are 1, 2, and 5 qubits in quantum resource A. This method facilitates the reasonable allocation of all available resources within the quantum cloud.

Figure 3: Hierarchical forest establishment

After the pre-allocation of qubit regions for the present circuit by the Quantum Resource Allocator, the sub-topology constituted by these qubits and the associated qubit attributes is transmitted to the Quantum Mapping Optimizer. The latter then completes the mapping of the circuit on the sub-topology. The objective of this study is to construct a circuit comprising multiple qubit gates between physically connected qubits. In this paper, the SABRE heuristic scheme is utilized. A partitioned fidelity scoring metric has been constructed, taking single-qubit gate fidelity, two-qubit gate fidelity, and measurement fidelity as the key characteristics of qubit operations in the quantum backend. The metric is demonstrated in Eq. (2):

Whilst the optimization of circuits is not the primary objective of this paper, the Quantum Mapping Optimizer is an essential component of the computational framework that is proposed. In contradistinction to prior optimizations that were compiled, the present requirement is to perform optimization with quantum resources that are allocated by the Quantum Resource Allocator.

Once the circuit mapping has been completed, the quantum resources occupied by the mapped circuits are used as the resources required for the creation of the virtual QPU. This is then sent to the backend to complete the execution of the circuit after creation. Concurrently, the Quantum Resource Mapper is informed of the occupied resources, and the mapper sets the occupied qubits to the occupied state. Furthermore, a physical buffer scheme is employed with the objective of enhancing the fidelity. It is observed that crosstalk is significantly more pronounced between neighboring qubits than between qubits with multi-hop spacing. Consequently, the n-hop qubits situated in the vicinity of the occupied qubit that has been returned to the mapper are simultaneously placed in the occupied state. While this results in a slight reduction in throughput, it also enhances fidelity. Upon completion of the circuit execution by the quantum backend and the subsequent return of the result, the Quantum Resource Mapper releases the occupied quantum resources to the resource pool, thereby enabling their utilization for the next circuit resource allocation.

This section presents an evaluation of the proposed virtualization strategy, based on throughput, fidelity, task duration time, and under different loads. Throughput and fidelity are evaluated using a simulated quantum cloud environment constructed by IBM, which represents a snapshot of the actual machine. Additionally, the system load is modelled by an internal queuing model that interacts with the aforementioned virtual QPU strategy.

In order to provide a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of the proposed framework, three distinct evaluation metrics are adopted, each of which targets a key performance dimension. Firstly, the Trial Reduction Factor (TRF) [34] is a metric that quantifies the ratio between the number of trials required for standalone quantum circuit execution and those needed for concurrent execution. Specifically, this metric is utilized to gauge the throughput of individual quantum backends, while the average TRF across all backends facilitates the evaluation of the overall quantum cloud throughput. Secondly, the Probability of a Successful Trial (PST) [35] is defined as the proportion of trials that yield expected results relative to the total number of trials. This metric is employed to assess the fidelity of quantum backends within the quantum cloud environment. Thirdly, the User Waiting Time Improvement Percentage (TIP) is a dedicated metric designed to determine the reduction ratio of the optimised or accelerated time compared to the baseline time. In this formula,

The dataset has been meticulously curated from existing works (RevLib [36], QASM-Bench [37], Quiper [37]), encompassing quantum algorithms across optimization, simulation, and general quantum computing—with varied qubit counts and gate depths. A total of 1000 diverse circuits model user inputs for paradigm assessment, and 50 are selected for fidelity evaluation. These benchmarks, which have a broad application, feature a wide distribution of qubits: 130 circuits (1–5 qubits), 180 circuits (6–10 qubits), 180 circuits (11–15 qubits), 180 circuits (16–20 qubits), 180 circuits (21–25 qubits), 100 circuits (26–30 qubits), 50 circuits (>30 qubits). The average number of qubits required is 16.23.

The VQPU’s overall performance metrics is evaluated through comparative analysis with two baseline schemes, each designed with distinct core objectives. The initial approach is a “Load-Balancing” strategy, in which tasks are allocated exclusively to suitable quantum backends with main target of optimizing the level of fidelity of user-submitted quantum circuit designs. It is important to note that this scheme lacks sufficient consideration for quantum cloud throughput and overlooks the parallelization techniques required during backend selection and task mapping processes. Conversely, the second baseline employs parallel execution techniques with a core focus on minimizing user waiting time. This is pursued without regard for other critical performance metrics, such as circuit fidelity. This methodology is formally designated as the “Multi-Programming” approach.

5.1.4 Quantum Cloud Simulation Infrastructure

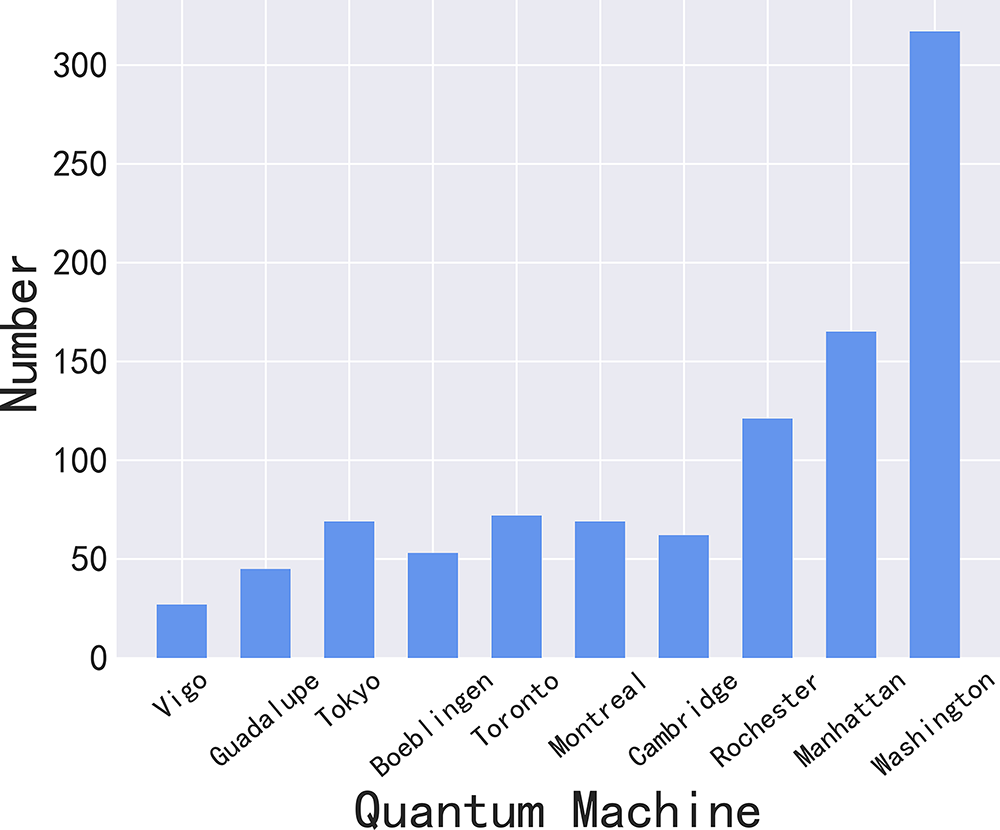

In order to validate the proposed quantum resource virtualisation strategy, a simulated quantum cloud environment was constructed for the purpose of simulating the provision of quantum computing cloud services. Specifically, the IBM Qiskit [38] Simulator and the IBM Quantum Backend Device Model were utilised to simulate quantum computing resources, with 10 backends selected: “Vigo” (5 qubits), “Guadalupe” (16 qubits), “Tokyo” (20 qubits), “Boeblingen” (20 qubits), “Toronto” (27 qubits), “Montreal” (27 qubits), “Cambridge” (28 qubits), “Rochester” (53 qubits), “Manhattan” (65 qubits), and “Washington” (127 qubits). Further information about these backends can be found on the IBM Quantum Systems website [13]. It is important to note that, in the physical system, the circuit runtime is primarily determined by the number of times the circuit is executed. In order to ensure an accurate replication of the aforementioned scenario, the circuit was modelled in the scheduling experiments based on its actual runtime. This is imperative for the successful completion of experiments investigating the waiting time and qubit time occupancy of the QPU.

5.1.5 Experimental Hyperparameter Setting

In this section, we introduce hyperparameter tuning. First, the weighting factor

The majority of extant quantum backends in quantum cloud environments are experiencing overloaded queuing circuits. Consequently, the efficacy of the proposed architectural design is initially verified under conditions of high load. In order to validate the proposed framework, 1000 quantum circuits are arbitrarily inputted, and a total of 50 independent experiments are carried out. Fig. 4 illustrates the mean scheduling of each backend. It has been observed that the number of tasks executed by different backends varies. It is evident that the number of qubits in the backend directly correlates with the number of quantum tasks assigned for execution. The lowest number of tasks executed on the “Vigo” system can be attributed to the fact that it has a limited number of qubits, with an average of 16.23 qubits per dataset. The “Washington” backend is responsible for the management of the highest volume of tasks, a consequence of its 127 qubits capacity which facilitates the support of most circuits within the dataset.

Figure 4: Distribution of quantum circuits in each backend

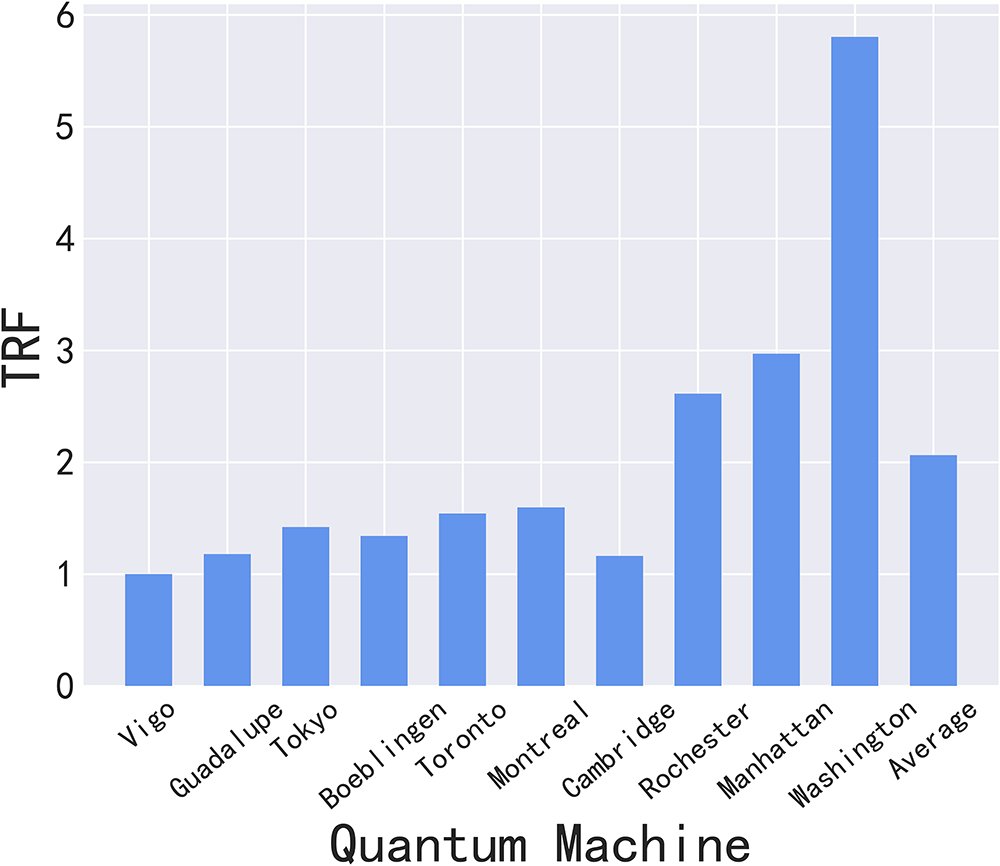

Fig. 5 presents the average TRF of the 10 quantum backends post-scheduling via the proposed framework, derived from 50 experimental trials. Notably, the framework demonstrates the capability to more than double the throughput of the quantum cloud.

Figure 5: Throughput for each quantum backend and quantum cloud

The variation trend of the TRF is consistent with that of the number of running tasks, with both metrics increasing as the qubit count of the backend grows. It is noteworthy that the “Vigo” and “Guadalupe” backends exhibit qubit counts that are below the average qubit number of circuits in the experimental dataset. This limitation restricts their capacity to execute circuits concurrently, resulting in a TRF of approximately 1. In contrast, backends with a higher qubit count (e.g., “Washington”) demonstrate a TRF enhancement of over fivefold. This is due to the fact that an increased number of qubits enables a greater number of quantum circuits to be run in parallel, thereby boosting overall throughput. Furthermore, minor discrepancies in TRF are observed between backends with the same qubit count, specifically “Toronto” and “Montreal.” This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that TRF is influenced both by task queue order and by the backend’s qubit topology and individual qubit quality.

5.2.2 Task Implementation Evaluation

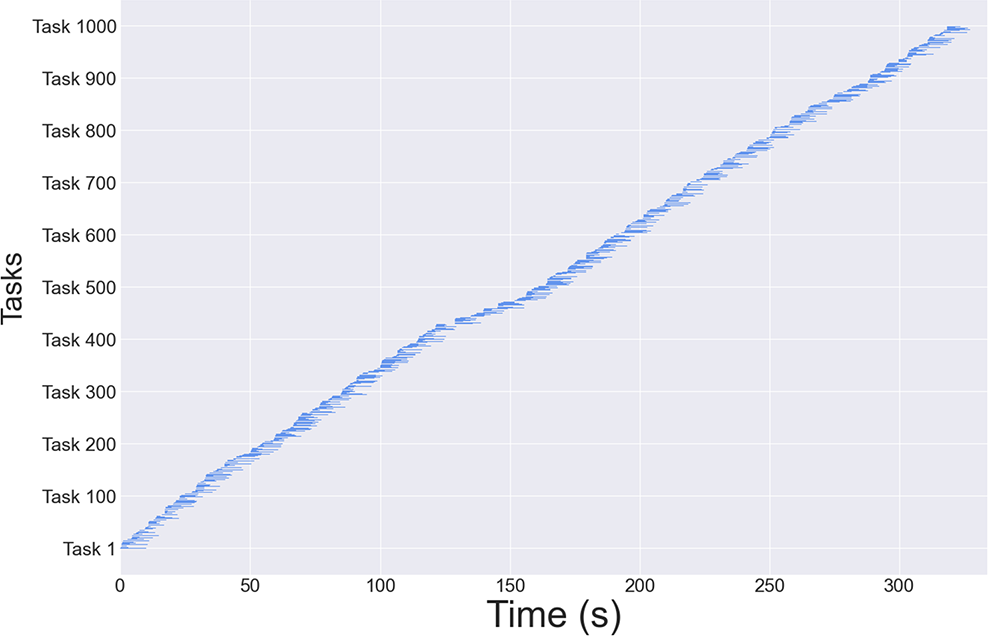

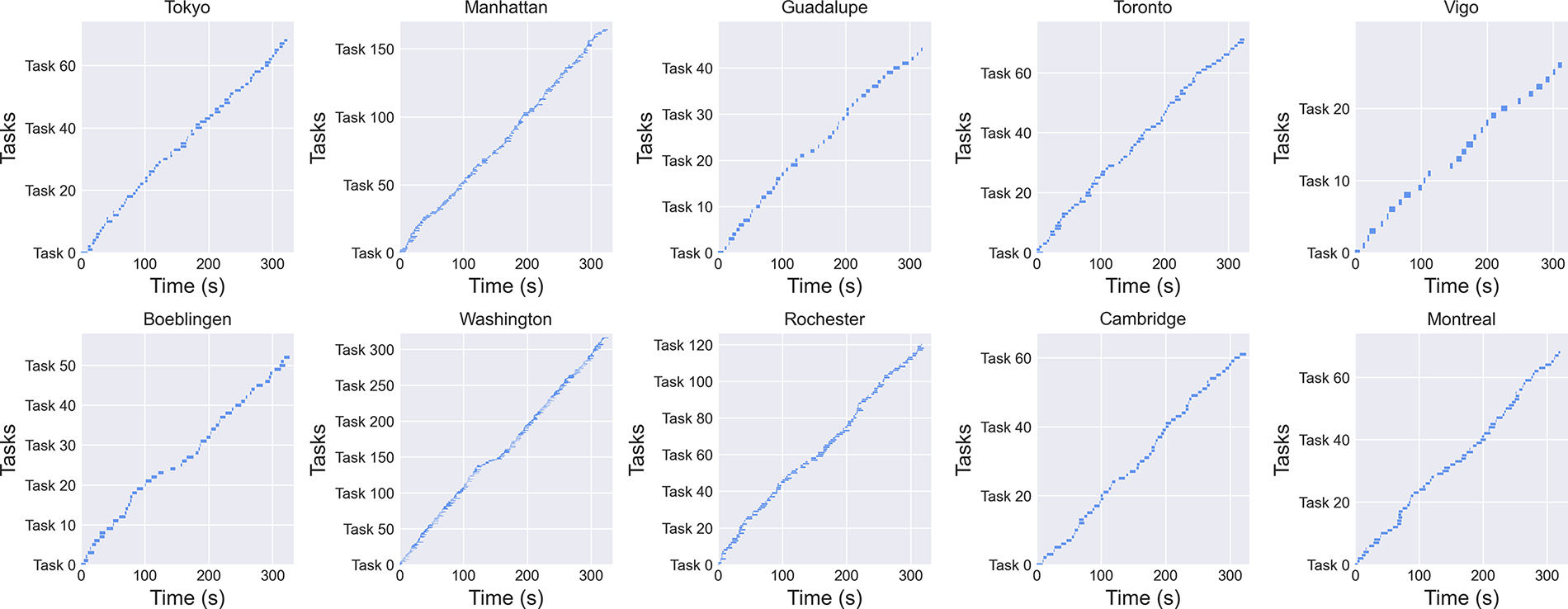

In order to verify the continuity of task implementation, we plot the task execution time of one of the experiments as a Gantt chart. The results of the experiment are presented in Figs. 6 and 7. Fig. 6 illustrates the Gantt chart of the overall task execution of the quantum cloud platform, whereas Fig. 7 depicts the Gantt chart of the task execution assigned to each backend.

Figure 6: Gantt chart of the execution time

Figure 7: Gantt chart of circuit execution time of each backend

As illustrated in Fig. 6, throughout the execution of one thousand quantum tasks, there is no interruption in the overall process, with all tasks queued for execution in an orderly manner. During the queuing process, the current task will filter out the appropriate qubits from the available set and, if no suitable qubits are identified, the task will await the completion of the executing quantum task, which will then release the required qubit resources. And as can be seen in Fig. 7, the majority of quantum backend tasks demonstrate satisfactory continuity of execution. Nevertheless, there are occasions when the “Vigo” and “Guadalupe” processes are subject to disruption. This is attributed to the limited qubit resources available to them. When a substantial number of tasks with extensive qubit requirements are queued, they are unable to generate virtual QPUs in the backends. As a result, they are only capable of remaining idle and awaiting the entry of executable circuits into the queue.

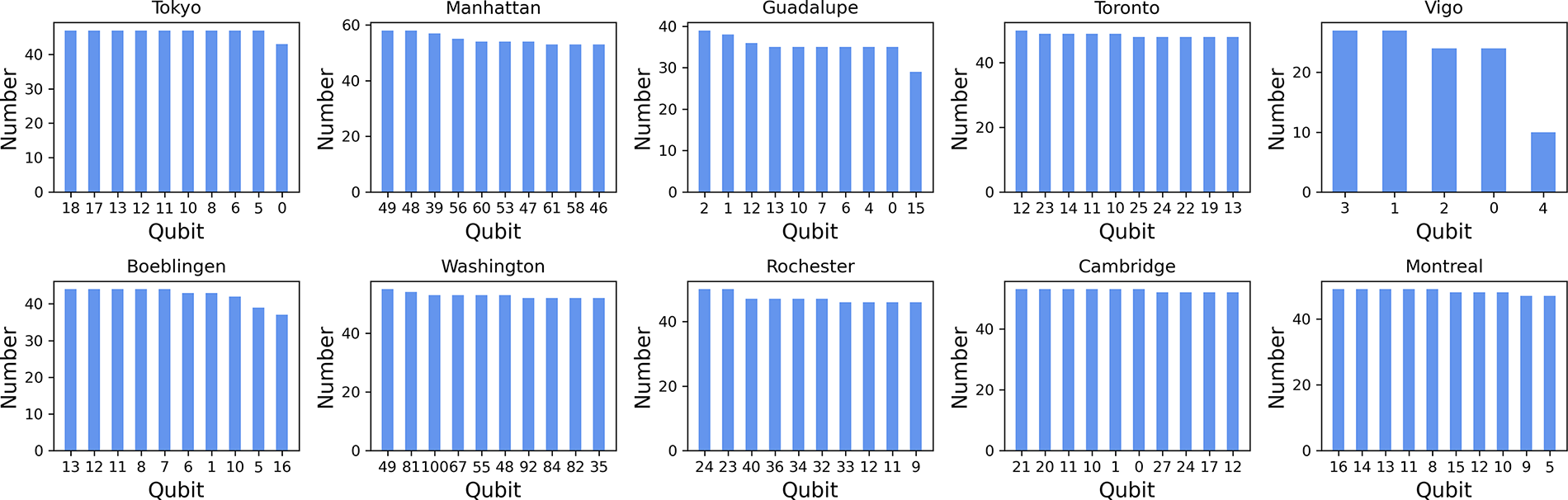

In order to verify the quantum resource occupancy when the virtual QPU is created, a count is made of the number of times each quantum backend is occupied during the execution of one thousand quantum tasks. The resulting data is presented in Fig. 8, which shows the top ten qubits occupied by each backend. It can be seen that, except for “Vigo” and “Guadalupe”, which have a number of qubits much less than the average value, there is not a significant difference in the number of times the rest of the quantum backends are occupied in the top ten positions. This also serves to demonstrate that the VQPU scheme is capable of distributing disparate tasks to varying quantum resources in a manner that is more balanced and equitable, exhibiting the desired load-balancing capability. Furthermore, the occupancy of qubits on different quantum backends varies, which is attributable to the topology and quality of the qubits on the quantum chip.

Figure 8: Qubit occupancy

5.2.3 Comparative Analysis with Baselines

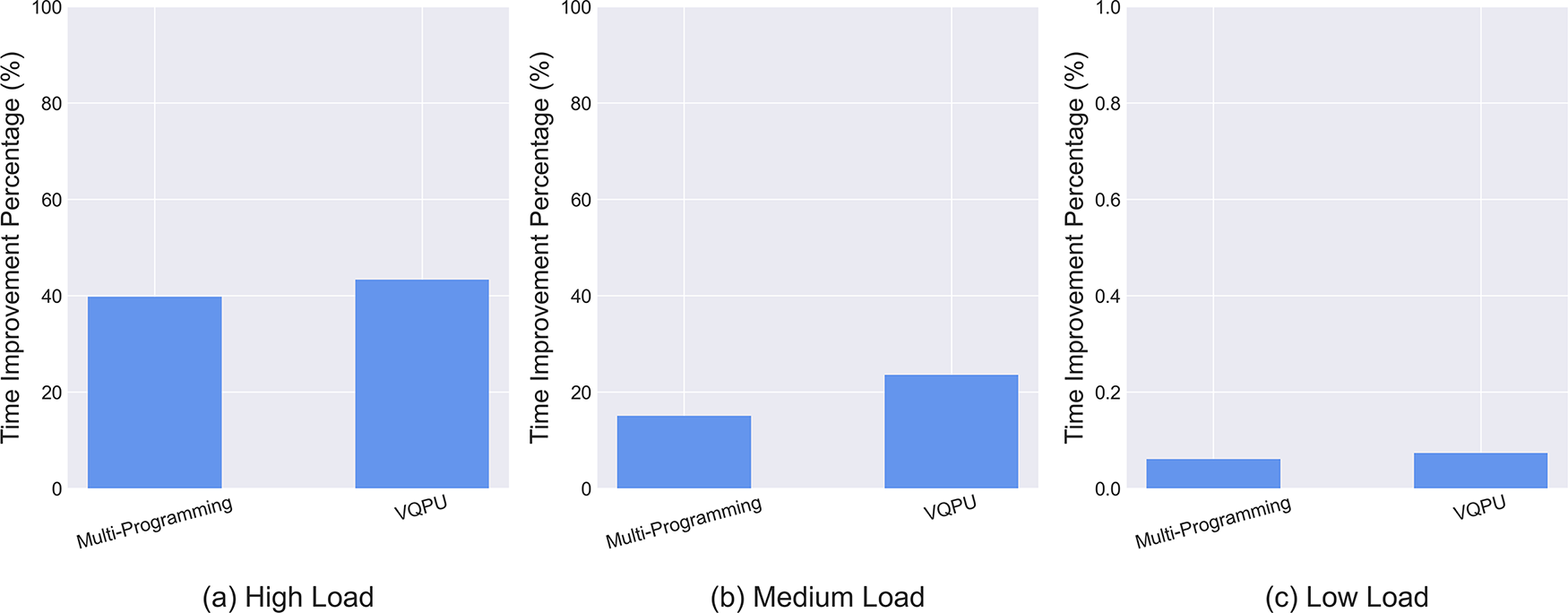

To verify the effectiveness of the presented paradigm, a comparative analysis is conducted against two distinct scheduling schemes under different load conditions. As illustrated in Fig. 9, the TIP of the VQPU scheme and the Multi-programming scheme are compared to the baseline Load-Balancing scheme for 1000 quantum tasks under different loads. It is evident that under high loads, both schemes demonstrate a significant improvement; however, the VQPU scheme exhibits a greater enhancement. This is attributable to the asynchronous execution of VQPU, a feature that obviates the necessity for the user to wait for the completion of the preceding task when there are idle qubits on the quantum computing device. Under medium load, both optimization schemes also improve, but it can be seen that the VQPU scheme improves more significantly compared to the Multi-programming scheme, which is because the asynchronous execution of VQPU is more effective under medium load. As the load diminishes, the parallel execution capability of Multi-programming and VQPU also declines, thereby facilitating an escalating number of tasks to be executed individually.

Figure 9: Time improvement percentage for different optimization frameworks

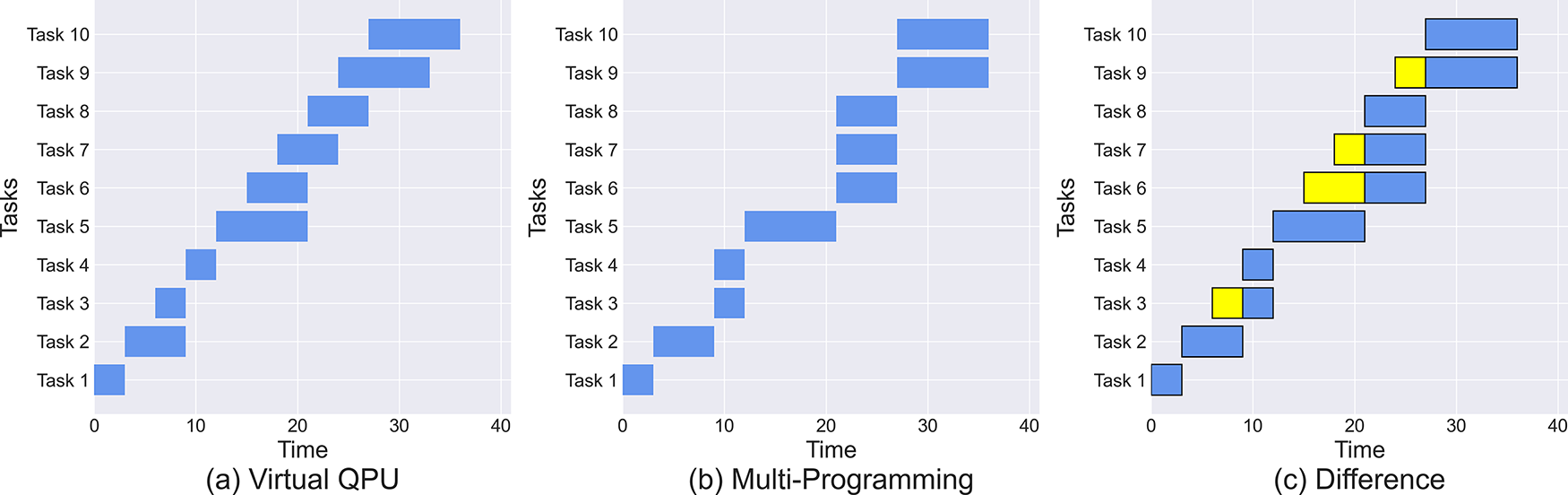

It is imperative to emphasize that, despite the improvement of the TIP in the Multi-programming scheme, the characteristic of sharing the quantum backend temporally results in an increase in user waiting time. As illustrated in Fig. 10, which presents the Gantt charts of ten specific task executions, our proposed scheme Fig. 10a is capable of compilation and execution as soon as there are resources in the resource pool to satisfy the execution of the currently waiting circuit. In contrast, the Multi-programming scheme, Fig. 10b, necessitates a wait for the completion of the previous circuit, which evidently increases the user’s waiting time. The difference is shown in yellow in Fig. 10c.

Figure 10: Difference between the two frameworks in terms of user waiting time

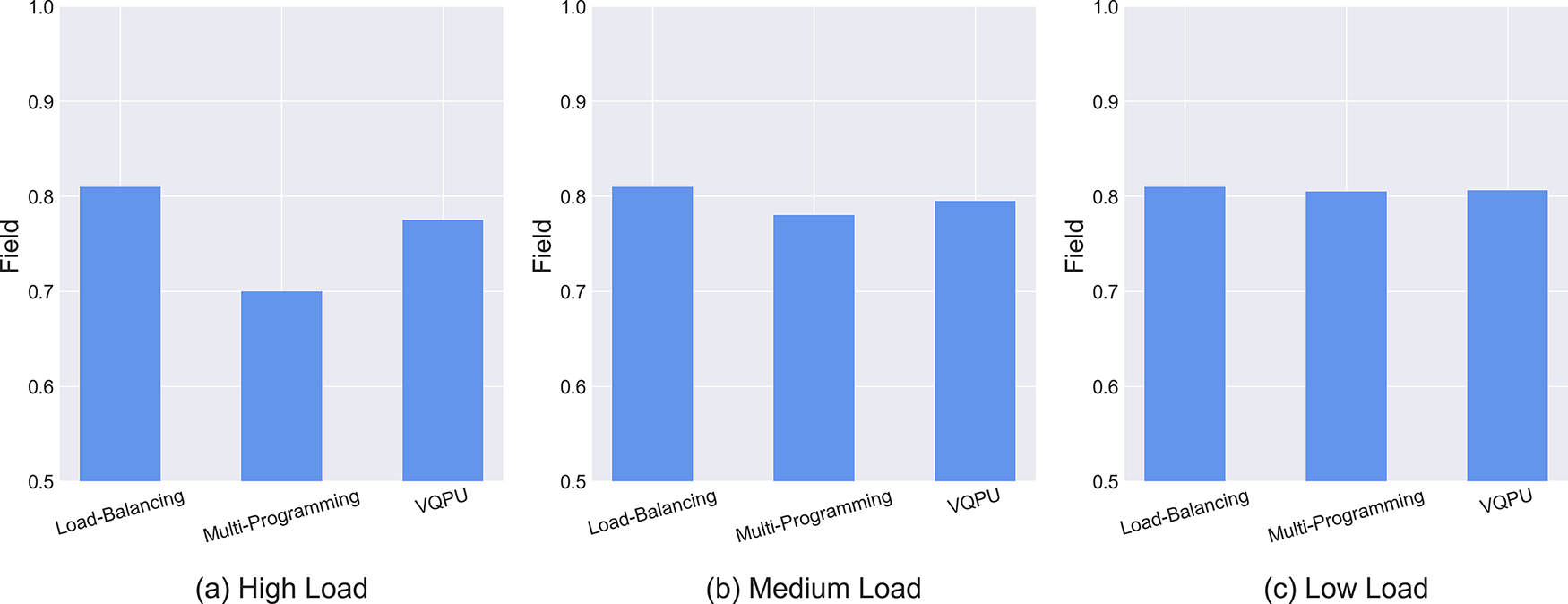

For the fidelity evaluation, we further compare our proposed VQPU using 2 disparate baseline scheduling schemes across different load conditions. To enhance the efficiency of the simulations, we have selected 50 circuits from the initial 1000 for the fidelity experiments.

Fig. 11a illustrates the average fidelity of each scheme after a sequence of circuits is executed on the simulated quantum cloud system under high-load circumstances. As can be observed, the load-balanced scheme demonstrates superior performance under high load conditions, attributable to its reduced inter-qubit crosstalk in comparison to the remaining two schemes with concurrent execution. In contrast, the Multi-programming scheme exhibits slightly reduced fidelity compared to the proposed scheme, primarily due to the discrepancy in the number of gates across different circuits when executing multiple circuits in parallel. In the case of Multi-programming parallel execution, the circuit with the smaller number of gates must await the completion of the circuit with the greater number of gates, which results in increased interference to the circuit with the fewer gates and a subsequent reduction in fidelity.

Figure 11: Comparison of task fidelity for different frameworks

The results of the fidelity experiments conducted under medium load are presented in Fig. 11b. In general, the discrepancy in fidelity between the three schemes is diminished, which is attributable to the reduction in the number of circuits executing in parallel and the concomitant increase in the probability of executing them individually under medium load. This results in a decrease in inter-qubit crosstalk. As the load is further reduced, both parallel execution schemes gradually degrade to separate execution, resulting in a fidelity that is identical to that illustrated in Fig. 11c. Notwithstanding the reduction in fidelity of the VQPU scheme in comparison to a single execution under high loads, the advantages in terms of enhanced execution efficiency and quantum cloud throughput are considerable.

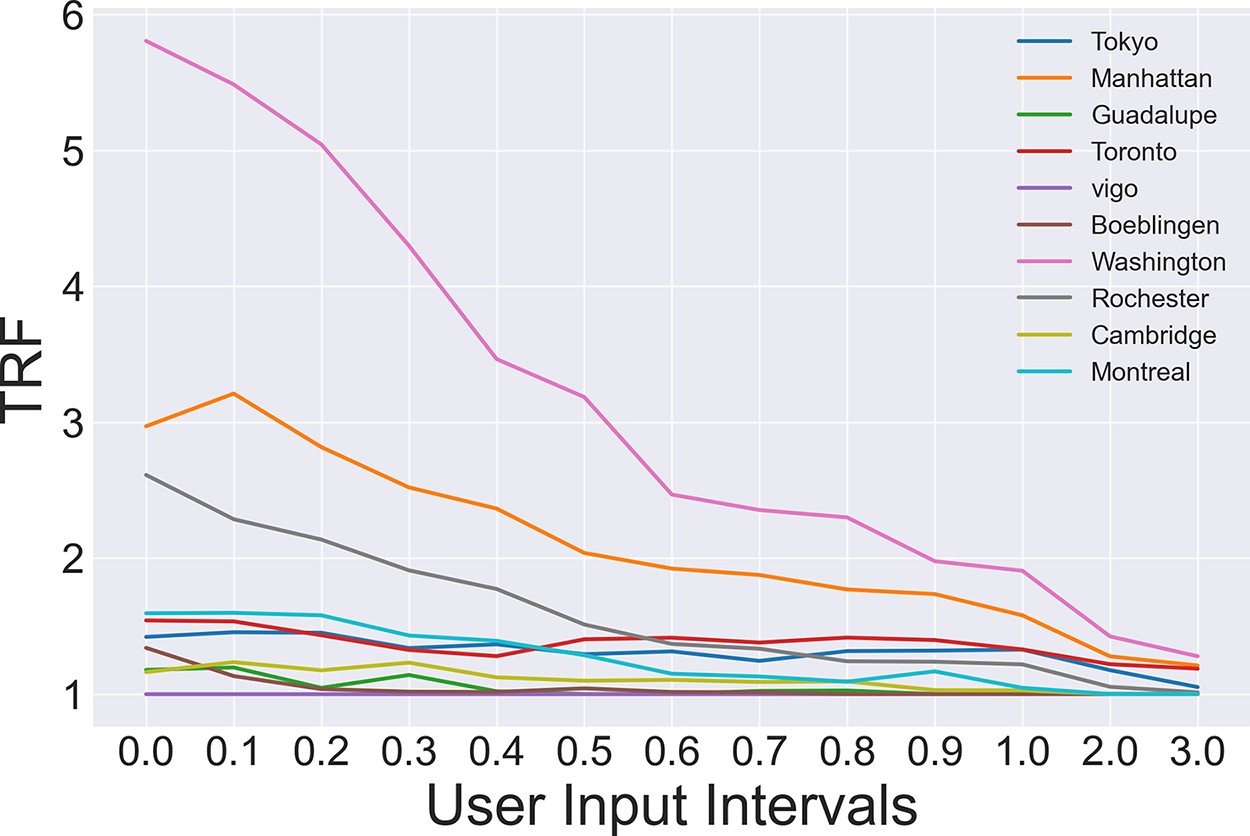

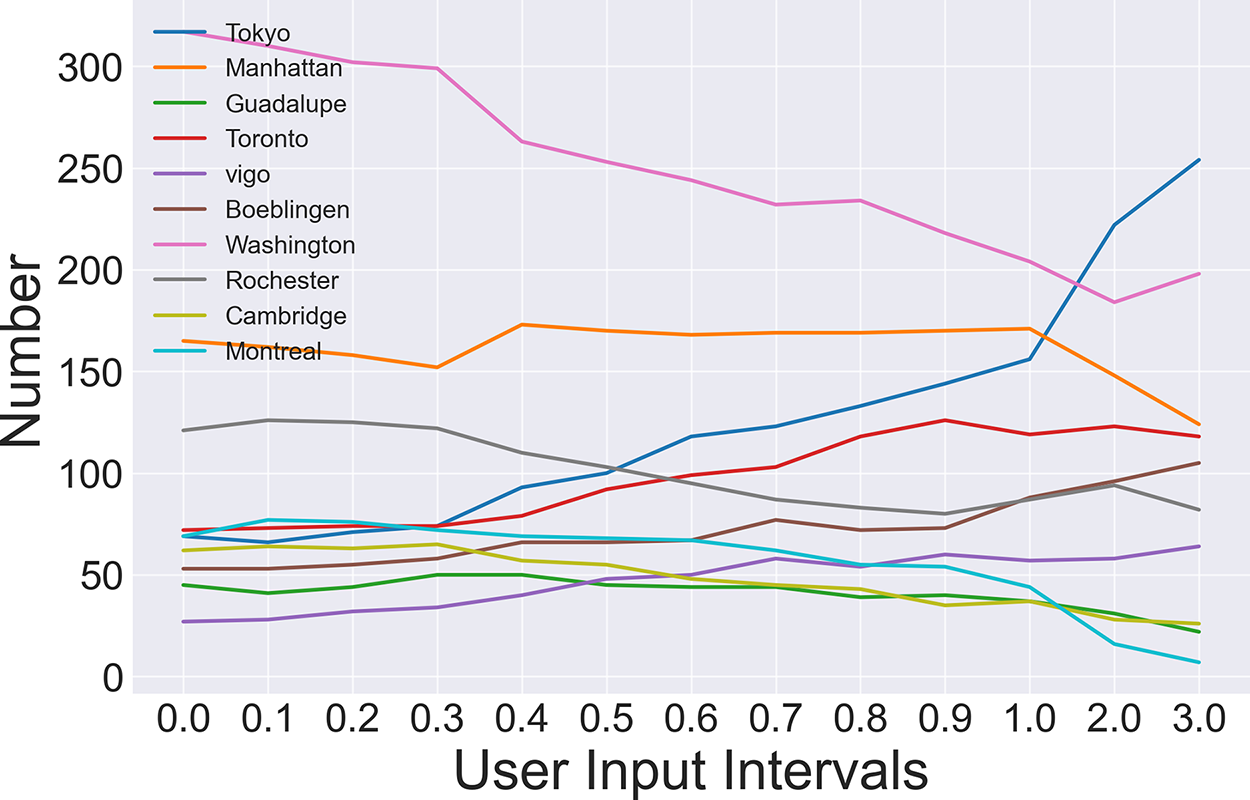

To explore the influence of the proposed VQPU scheme on the quantum cloud throughput under varying loads, we have conducted a series of analytical experiments. Specifically, we conducted simulations in which users submitted tasks by inputting 1000 quantum tasks into the user waiting queue at varying frequencies. Fig. 12 illustrates the evolution of the quantum cloud and its time-dependent response functions (TRFs) for each backend with varying input time intervals under different loads. Overall, the TRF of the quantum cloud demonstrates a diminution with an increase in the input time interval. The “Washington” backend displays the most pronounced decline in slope, which can be attributed to its larger qubit count. As a result, the reduction in parallel policy implementation is more pronounced as the interval increases. Conversely, Vigo’s throughput remains constant, as its smaller number of qubits precludes the possibility of parallel execution of multiple circuits.

Figure 12: Throughput vs. user input intervals

Furthermore, an investigation was conducted to ascertain the relationship between load and the number of tasks executed by the quantum backend. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 13, which illustrates that the trend of the number of tasks exhibits significant variation among different quantum backends. In particular, the number of tasks performed by certain quantum backends is observed to decrease as the load decreases. This is exemplified by the “Washington” quantum backend, which includes some qubits of inferior quality. These are selected for use with the intention of increasing the system throughput when the load is high. However, as the load decreases, the probability of these qubits being selected decreases significantly, resulting in a corresponding decrease in the number of tasks. Conversely, if the qubits are of high quality, such as “Tokyo”, their probability of selection rises as the load declines.

Figure 13: Load vs. the number of tasks

At high loads, the system is unable to accommodate additional tasks. Nevertheless, at low loads, an increase in the time interval between tasks, as specified by the user, allows for the execution of a greater number of tasks.

5.2.5 Superparameter Influence

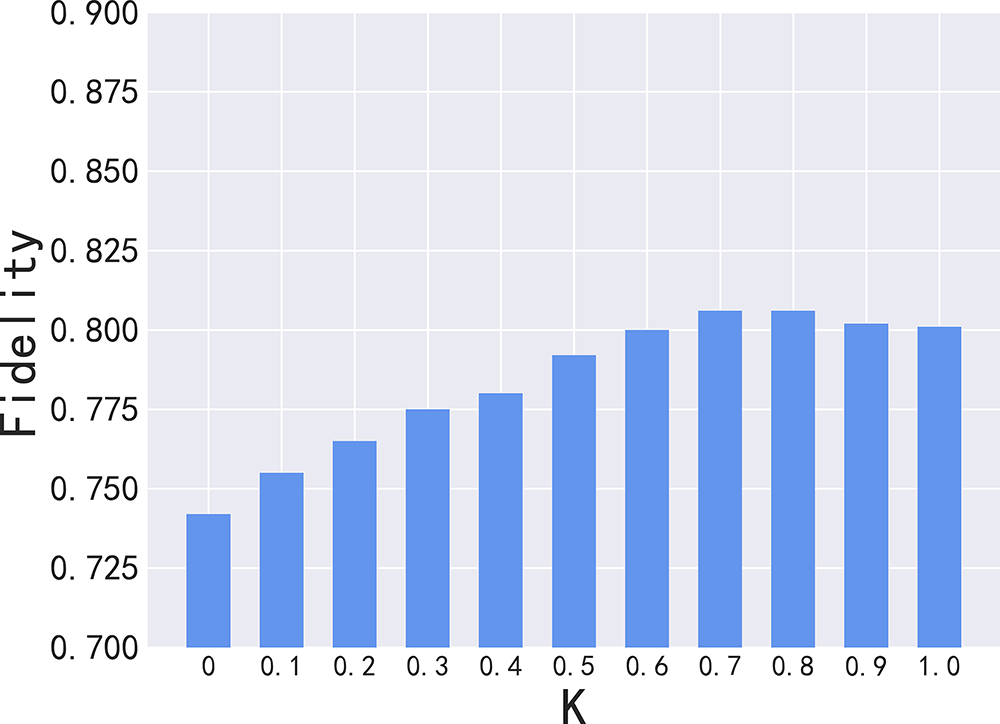

In order to verify the effect of K value and circuit fidelity, the K value was set to different values between 0 and 1, and then fidelity experiments were conducted for 100 circuits under low load. The rationale behind choosing a low load is to have sufficient qubits for selection in order to reflect the difference in different K values. The results are displayed in Fig. 14. It is evident that the circuits exhibit optimal fidelity when K is set to 0.7/0.8. When k = 0, qubit selection considers only topology, while bit properties gradually dominate as K increases.

Figure 14: Relationship between K and fidelity

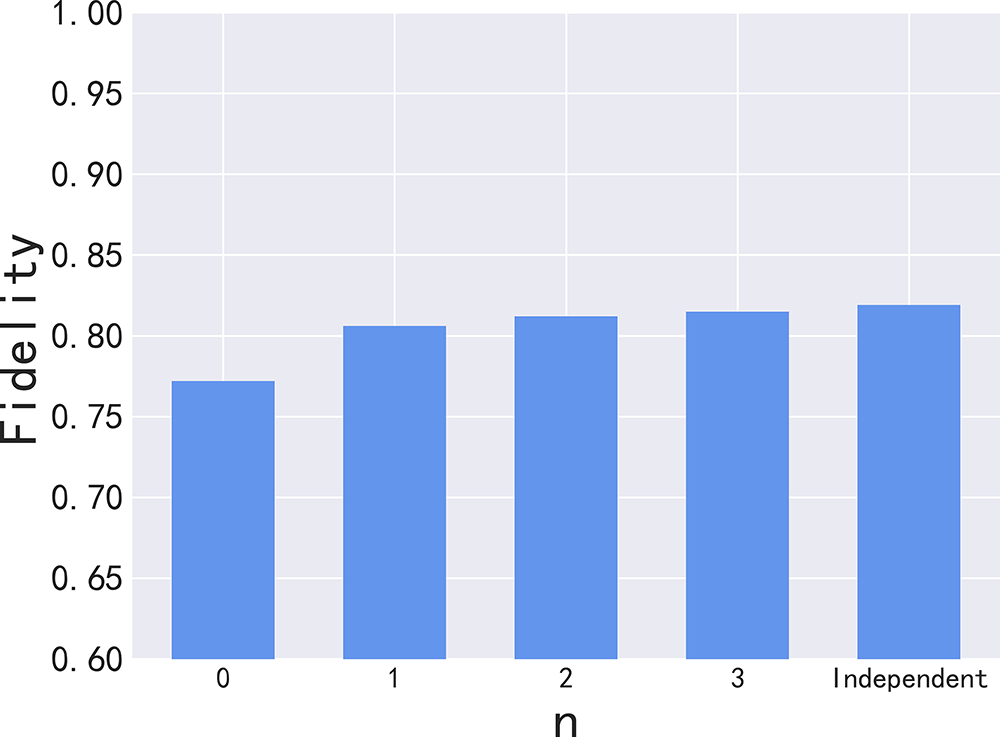

Furthermore, supplementary experiments were performed to validate the impact of physical buffers on fidelity. These tests involved parallel-implemented circuits configured with varying numbers of physical isolation hops, and their results were contrasted with those of circuits executed in a standalone manner. The outcomes of these experiments are presented in Fig. 15. In the absence of physical buffers (i.e., n = 0), the fidelity is at its lowest. However, when n is 1 or 2, a substantial enhancement in fidelity is observed, with no substantial discrepancy observed when compared to execution alone. Consequently, it is typically configured to 1 during the scheduling process, to optimize system throughput without compromising fidelity.

Figure 15: Physical buffer size n and fidelity

The present paper puts forward a fresh quantum computing paradigm, Virtual QPU (VQPU), for quantum cloud environments. The objective is twofold: firstly, to facilitate the efficient management of quantum resources and secondly, to enhance the user experience. VQPU automates the entire process, thereby allowing users to submit quantum tasks without having to consider the availability and load of the backend hardware. The proposed framework is predicated on the user’s input to create a virtual QPU that is tailored to the specific task in use. The compilation of circuits is then completed and submitted for execution on the aforementioned virtual QPU. Moreover, the architecture in question decouples qubits, thus allowing for the asynchronous execution of user-submitted circuits. This, in turn, enhances the flexibility of the quantum cloud. The VQPU oversees a unified backend, thereby alleviating the burden on users and improving the performance of the quantum cloud. The effectiveness of VQPU in managing quantum tasks and backend resources is validated through experimentation, thereby providing a foundation for more complex quantum cloud scheduling efforts. In the future, optimizations will be carried out for the VQPU, specifically including the following: firstly, upgrading the scheduling algorithm, such as introducing AI to predict load to achieve dynamic resource allocation; secondly, improving the mapping algorithm to enhance qubit utilization and reduce gate error rates; simultaneously, strengthening the security protection system to ensure user data security; in addition, perfecting the fair scheduling mechanism and designing a multi-user task priority allocation strategy. It is anticipated that these optimizations will enhance the performance, security, and reliability of the VQPU in the quantum cloud environment.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Danyang Zheng, Zheng Shan, Jinchen Xv, Xin Zhou; data collection: Danyang Zheng; analysis and interpretation of results: Danyang Zheng, Xin Zhou; manuscript drafting: Danyang Zheng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Danyang Zheng, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study did not involve human or animal subjects, and thus, no ethical approval was required. The study protocol adhered to the guidelines established by the journal.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Herman D, Googin C, Liu X, Sun Y, Galda A, Safro I, et al. Quantum computing for finance. Nat Rev Phys. 2023;5(8):450–65. doi:10.1038/s42254-023-00603-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Orús R, Mugel S, Lizaso E. Quantum computing for finance: overview and prospects. Rev Phys. 2019;4(3–4):100028. doi:10.1016/j.revip.2019.100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Grover LK. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing—STOC’ 96; 1996 May 22–24; Philadelphia, PA, USA. p. 212–9. doi:10.1145/237814.237866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gong C, Dong Z, Gani A, Qi H. Quantum k-means algorithm based on trusted server in quantum cloud computing. Quantum Inf Process. 2021;20(4):130. doi:10.1007/s11128-021-03071-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Magann AB, Grace MD, Rabitz HA, Sarovar M. Digital quantum simulation of molecular dynamics and control. Phys Rev Res. 2021;3(2):023165. doi:10.1103/physrevresearch.3.023165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Fadli S, Rawal BS, Mentges A. Hybrid quantum machine learning using quantum integrated cloud architecture (QICA). In: 2023 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC); 2023 Feb 20–22; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 419–25. doi:10.1109/ICNC57223.2023.10074394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Berganza Gómez R, O.’Meara C, Cortiana G, Mendl CB, Bernabé-Moreno J. Towards AutoQML: a cloud-based automated circuit architecture search framework. In: 2022 IEEE 19th International Conference on Software Architecture Companion (ICSA-C); 2022 Mar 12–15; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 129–36. doi:10.1109/ICSA-C54293.2022.00033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hibat-Allah M, Mauri M, Carrasquilla J, Perdomo-Ortiz A. A framework for demonstrating practical quantum advantage: comparing quantum against classical generative models. Commun Phys. 2024;7(1):68. doi:10.1038/s42005-024-01552-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Preskill J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum. 2018;2:79. doi:10.22331/q-2018-08-06-79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. El Euch H, Zidan MAA, Abdelaty AMA, AbdelAty MMA, Khalil A. Quantum random access memory system. United States patent US 11,651,266. 2023. [Google Scholar]

11. Hsu J. Intels 49qubit chip shoots for quantum supremacy. Ces. 2018 [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://spectrum.ieee.org/intels-49qubit-chip-aims-for-quantum-supremacy. [Google Scholar]

12. Google. Quantum computing playground [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://www.quantumplayground.net/. [Google Scholar]

13. IBM. Ibm quantum systems [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 1]. Available from: https://quantum.cloud.ibm.com/. [Google Scholar]

14. Das P, Tannu SS, Nair PJ, Qureshi M. A case for multi-programming quantum computers. In: Proceedings of the 52nd Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture; 2019 Oct 12–16; Columbus, OH, USA. p. 291–303. doi:10.1145/3352460.3358287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Niu S, Todri-Sanial A. Enabling multi-programming mechanism for quantum computing in the NISQ era. Quantum. 2023;7:925. doi:10.22331/q-2023-02-16-925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Dou X, Liu L. A new qubits mapping mechanism for multi-programming quantum computing. In: Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Parallel Architectures and Compilation Techniques; 2020 Oct 3–7; Virtual. p. 349–50. doi:10.1145/3410463.3414659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Resch S, Gutierrez A, Huh JS, Bharadwaj S, Eckert Y, Loh G, et al. Accelerating varia-tional quantum algorithms using circuit concurrency. arXiv:2109.01714. 2021. [Google Scholar]

18. Liu L, Dou X. QuCloud: a new qubit mapping mechanism for multi-programming quantum computing in cloud environment. In: 2021 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA); 2021 Feb 27–Mar 3; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 167–78. doi:10.1109/HPCA51647.2021.00024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ravi GS, Smith KN, Murali P, Chong FT. Adaptive job and resource management for the growing quantum cloud. In: IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE); 2021 Oct 17–22; Broomfield, CO, USA. p. 301–12. doi:10.1109/qce52317.2021.00047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Van Meter R, Horsman D. A blueprint for building a quantum computer. Commun ACM. 2013;56(10):84–93. doi:10.1145/2494568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chong FT, Franklin D, Martonosi M. Programming languages and compiler design for realistic quantum hardware. Nature. 2017;549(7671):180–7. doi:10.1038/nature23459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Fu X, Rol MA, Bultink CC, van Someren J, Khammassi N, Ashraf I, et al. An experimental microarchitecture for a superconducting quantum processor. In: Proceedings of the 50th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture; 2017 Oct 14–18; Boston, MA, USA. p. 813–25. doi:10.1145/3123939.3123952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Barenco A, Bennett CH, Cleve R, DiVincenzo DP, Margolus N, Shor P, et al. Elementary gates for quantum computation. Phys Rev A. 1995;52(5):3457–67. doi:10.1103/physreva.52.3457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Debnath S, Linke NM, Figgatt C, Landsman KA, Wright K, Monroe C. Demonstration of a small programmable quantum computer with atomic qubits. Nature. 2016;536(7614):63–6. doi:10.1038/nature18648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Koch J, Yu TM, Gambetta J, Houck AA, Schuster DI, Majer J, et al. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the Cooper pair box. Phys Rev A. 2007;76(4):042319. doi:10.1103/physreva.76.042319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhong HS, Wang H, Deng YH, Chen MC, Peng LC, Luo YH, et al. Quantum computational advantage using photons. Science. 2020;370(6523):1460–3. doi:10.1126/science.abe8770. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Bechtold M. Bringing the concepts of virtualization to gate-based quantum computing [master’s thesis]. Stuttgart, Germany: University of Stuttgart; 2021. [Google Scholar]

28. Wu W, Wang Y, Yan G, Zhao Y, Zhang B, Yan J. On reducing the execution latency of superconducting quantum processors via quantum job scheduling. In: Proceedings of the 43rd IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design. New York, NY, USA: Newark Liberty International Airport Marriott; 2024. p. 1–9. doi:10.1145/3676536.3676678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Mineh L, Montanaro A. Accelerating the variational quantum eigensolver using parallelism. Quantum Sci Technol. 2023;8(3):035012. doi:10.1088/2058-9565/acd0d2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Park G, Zhang K, Yu K, Korepin V. Quantum multi-programming for grover’s search. Quantum Inf Process. 2023;22(1):54. doi:10.1007/s11128-022-03793-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Suchara M, Kubiatowicz J, Faruque A, Chong FT, Lai CY, Paz G. QuRE: the quantum resource estimator toolbox. In: 2013 IEEE 31st International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD); 2013 Oct 6–9; Asheville, NC, USA. p. 419–26. doi:10.1109/ICCD.2013.6657074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Salm M, Barzen J, Leymann F, Weder B. Prioritization of compiled quantum circuits for different quantum computers. In: 2022 IEEE International Conference on Software Analysis, Evolution and Reengineering (SANER); 2022 Mar 15–18; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 1258–65. doi:10.1109/SANER53432.2022.00150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang M, Das P, Nair PJ. Qoncord: a multi-device job scheduling framework for variational quantum algorithms. In: 2024 57th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO); 2024 Nov 2–6; Austin, TX, USA. p. 735–49. doi:10.1109/MICRO61859.2024.00060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Tannu SS, Qureshi MK. Not all qubits are created equal: a case for variability-aware policies for NISQ-era quantum computers. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems; 2019 Apr 13–17; Providence, RI, USA. p. 987–99. doi:10.1145/3297858.3304007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Last T, Samkharadze N, Eendebak P, Versluis R, Xue X, Sammak A, et al. Quantum Inspire: qutech’s platform for co-development and collaboration in quantum computing. In: Novel Patterning Technologies for Semiconductors, MEMS/NEMS and MOEMS 2020; 2020 Feb 23–27; San Jose, CA, USA. doi:10.1117/12.2551853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Green AS, Lumsdaine PL, Ross NJ, Selinger P, Valiron B. Quipper: a scalable quantum programming language. In: Proceedings of the 34th ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation; 2013 Jun 16–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 333–42. doi:10.1145/2491956.2462177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Cross AW, Bishop LS, Smolin JA, Gambetta JM. Open quantum assembly language. arXiv:1707.03429. 2017. [Google Scholar]

38. JavadiAbhari A, Treinish M, Krsulich K, Wood CJ, Lishman J, Gacon J, et al. Quantum computing with Qiskit. arXiv:2405.08810. 2024. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools