Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Quantum Secure Multiparty Computation: Bridging Privacy, Security, and Scalability in the Post-Quantum Era

1 College of Engineering, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, 11533, Saudi Arabia

2 School of Computer Science, National College of Business Administration and Economics, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

3 Department of Computer Science and Information Technology, School Education Department, Government of Punjab, Layyah, 31200, Pakistan

4 Faculty of Engineering, Uni de Moncton, Moncton, NB E1A3E9, Canada

5 School of Electrical Engineering, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2006, South Africa

6 International Institute of Techno. & Management (IITG), Avenue des Grandes Ecoles, Libreville, 1989, Gabon

7 Bridges for Academic Excellence—Spectrum, Tunis, Center-ville, 1001, Tunisia

* Corresponding Authors: Sghaier Guizani. Email: ; Tehseen Mazhar. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Next-Generation Cybersecurity: AI, Post-Quantum Cryptography, and Chaotic Innovations)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 1 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.073883

Received 27 September 2025; Accepted 18 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The advent of quantum computing poses a significant challenge to traditional cryptographic protocols, particularly those used in Secure Multiparty Computation (MPC), a fundamental cryptographic primitive for privacy-preserving computation. Classical MPC relies on cryptographic techniques such as homomorphic encryption, secret sharing, and oblivious transfer, which may become vulnerable in the post-quantum era due to the computational power of quantum adversaries. This study presents a review of 140 peer-reviewed articles published between 2000 and 2025 that used different databases like MDPI, IEEE Explore, Springer, and Elsevier, examining the applications, types, and security issues with the solution of Quantum computing in different fields. This review explores the impact of quantum computing on MPC security, assesses emerging quantum-resistant MPC protocols, and examines hybrid classical-quantum approaches aimed at mitigating quantum threats. We analyze the role of Quantum Key Distribution (QKD), post-quantum cryptography (PQC), and quantum homomorphic encryption in securing multiparty computations. Additionally, we discuss the challenges of scalability, computational efficiency, and practical deployment of quantum-secure MPC frameworks in real-world applications such as privacy-preserving AI, secure blockchain transactions, and confidential data analysis. This review provides insights into the future research directions and open challenges in ensuring secure, scalable, and quantum-resistant multiparty computation.Keywords

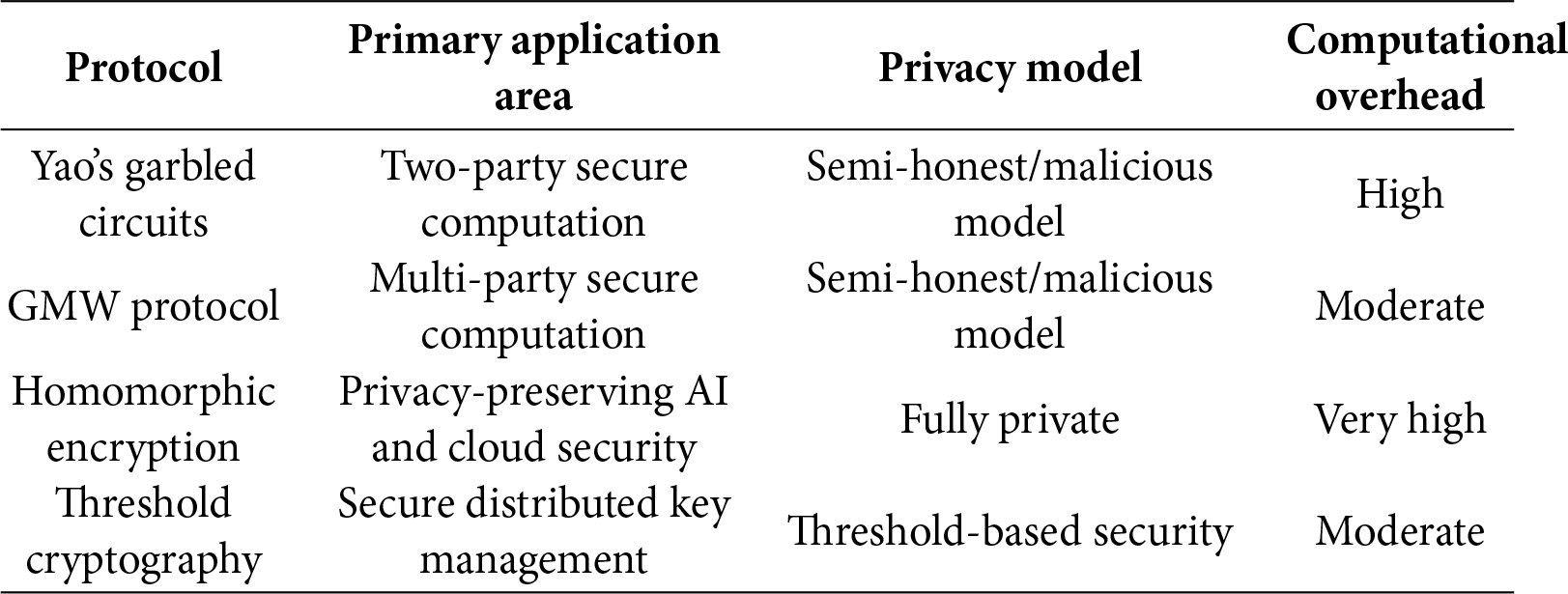

Quantum computing threatens the classical cryptography underpinning secure multiparty computation (MPC) [1]. Shor’s algorithm compromises widely deployed schemes such as RSA and ECC, creating urgent risks across finance, healthcare, AI, and cloud settings. While post-quantum cryptography (PQC) is emerging, its integration with MPC is still early-stage [2] and advances in QKD and quantum-enhanced primitives offer complementary, quantum-resistant avenues [3]. MPC—from Yao’s garbled circuits [4] to GMW, secret sharing, and FHE [5–7] supports privacy-preserving ML, finance, medical analytics, and blockchain [8–11] but faces heavy computation/communication costs and reliance on quantum-vulnerable primitives [12–14]. This review bridges classical MPC and quantum-secure computation, surveying developments, challenges, and gaps, and includes nine Python implementations with outputs to ground key concepts.

Despite progress, key gaps remain:

• Scalability and efficiency constraints, especially in multi-party and real-time settings [12,13].

• Immature, under-validated integration of PQC within MPC frameworks [14].

• Lack of standards and interoperability for hybrid classical–quantum models [3].

• Incomplete resilience against advanced quantum adversaries. Addressing these requires algorithmic advances alongside hardware readiness, protocol standardization, and real-world implementations to keep MPC viable in the post-quantum era.

The major contribution of the study is

• The study examines classical MPC foundations (secret sharing, homomorphic encryption, oblivious transfer); assesses quantum threats from algorithms such as Shor’s and Grover’s to existing MPC.

• The study examines PQC options for MPC—including lattice-, hash-, and code-based approaches.

• The study examines the quantum-oriented techniques relevant to MPC, such as QKD, quantum homomorphic encryption, and quantum-enhanced zero-knowledge proofs.

• The study also examines the scalability of MPC and identifies future directions involving integration with blockchain, federated learning, and secure cloud computing.

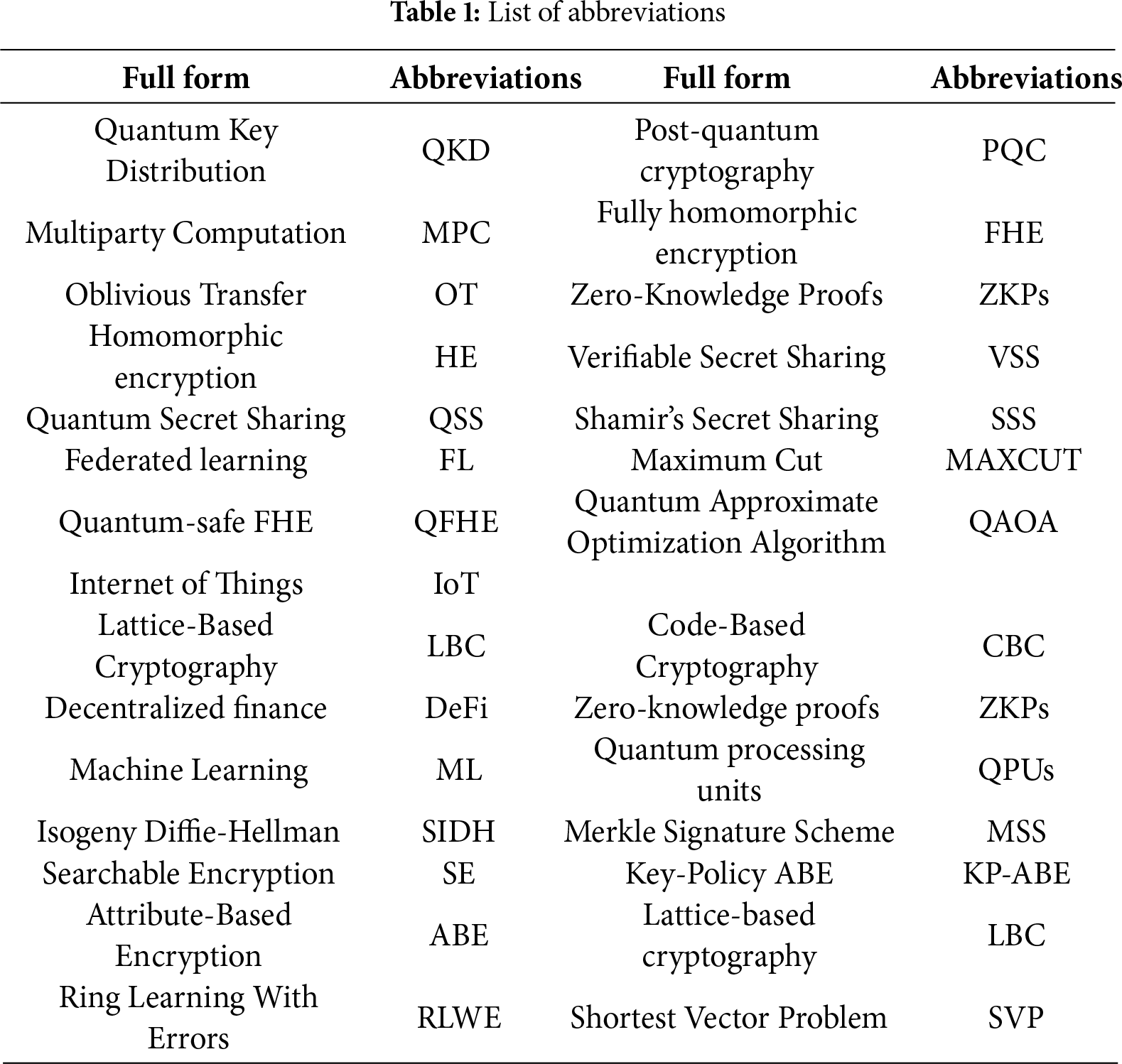

Section 1 introduces motivation, background, and scope; Section 2 covers classical MPC foundations and limitations under quantum threat; Section 3 analyzes quantum computing’s impact on MPC security; Section 4 surveys post-quantum techniques applicable to MPC; Section 5 discusses hybrid classical-quantum transition models; Section 6 addresses scalability and real-world implementations; Section 7 highlights open challenges and future directions; and Section 8 concludes with implications for cybersecurity and data privacy. Table 1 shows the list of abbreviations.

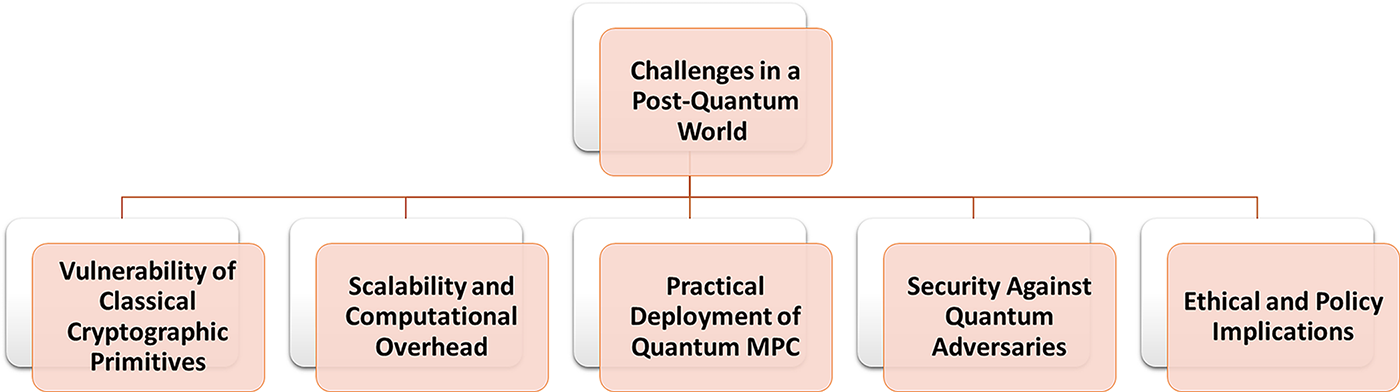

2.1 Challenges in a Post-Quantum World

Quantum computing disrupts MPC’s cryptographic foundations: Shor’s algorithm breaks RSA/ECC/Diffie–Hellman [15] while Grover’s algorithm weakens symmetric primitives [1,4], threatening core MPC assumptions [16]. PQC and quantum cryptography provide countermeasures [17], but adapting MPC requires advances in security, scalability, deployment, and governance [18].

Classical dependencies heighten risk: many MPC constructions rely on number-theoretic public-key systems vulnerable to Shor [19,20], and symmetric schemes face quadratic search speedups, demanding larger keys [21]. Secret-sharing and oblivious-transfer variants that inherit number-theoretic assumptions also face quantum-era exposure [22].

Scalability pressures intensify: quantum-resistant schemes often use larger keys and heavier algebra, increasing memory, bandwidth, and compute costs for MPC [23] lattice-based approaches exemplify these overheads [24]. Given MPC’s multi-round communication, layering PQC further strains bandwidth and hinders practicality [25].

Deployment remains challenging: limited quantum infrastructure (e.g., QKD links) constrains real-world rollouts [26,27]. Migration will require hybrid designs that preserve classical compatibility while introducing quantum-resistant components [28] amid evolving standardization—NIST’s PQC process is progressing, but a unified MPC integration path is not yet finalized [29]. Fig. 1 summarizes these challenges.

Figure 1: Challenges in the post-quantum world

Security against quantum adversaries expands in scope: quantum side-channels stress traditional assumptions [30], quantum-accelerated threats target privacy-preserving AI built atop MPC [31], and “harvest-now, decrypt-later” endangers long-term confidentiality [32].

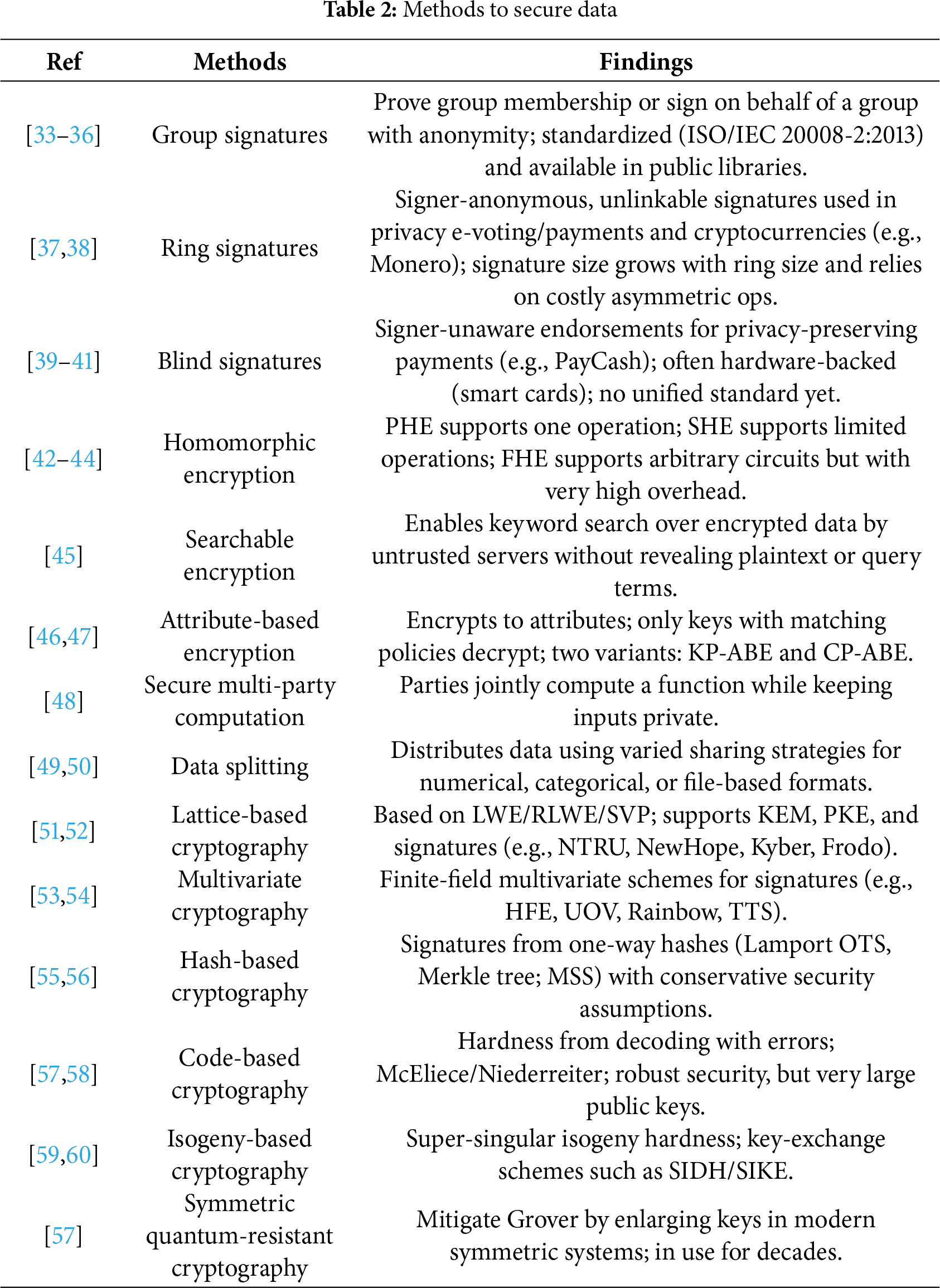

In response, emerging directions include integrating AI and blockchain, leveraging quantum techniques, and developing self-healing cybersecurity to improve resilience alongside quantum-resistant measures such as PQC and QKD, and hybrid (classical–quantum) transition strategies for IoT and blockchain systems. Table 2 summarizes methods to secure data.

Quantum capability exacerbates data-sovereignty asymmetries and pressures encryption policy and global cybersecurity governance [61]. Quantum-enabled conflict heightens national-security risks, calling for international accords on quantum-safe communications and standards [62]. Adoption hinges on usability and cost—quantum-secure protocols must be deployable without prohibitive complexity [63]. A coherent response combines PQC, quantum-safe communications, and hybrid classical–quantum frameworks.

The rapid advancement of quantum computing poses unparalleled challenges to traditional cryptography techniques, endangering the security of digital infrastructures worldwide. This review study [64] examines the influence of quantum computing on cybersecurity. It highlights issues with algorithms such as Shor’s and Grover’s that may compromise conventional encryption techniques like RSA, ECC, and AES. The study [65] looks at AI’s increased accuracy and speed in spotting phishing attempts, zero-day vulnerabilities, and complex persistent threats. Recent developments like quantum computing, the combination of AI and blockchain, and the growing importance of self-healing systems in bolstering cybersecurity framework resilience are also covered. The study [65] provides a critical analysis of a number of topics, such as data privacy, ethical considerations, and adversarial attacks.

2.2 Comparative Overview with Existing Surveys

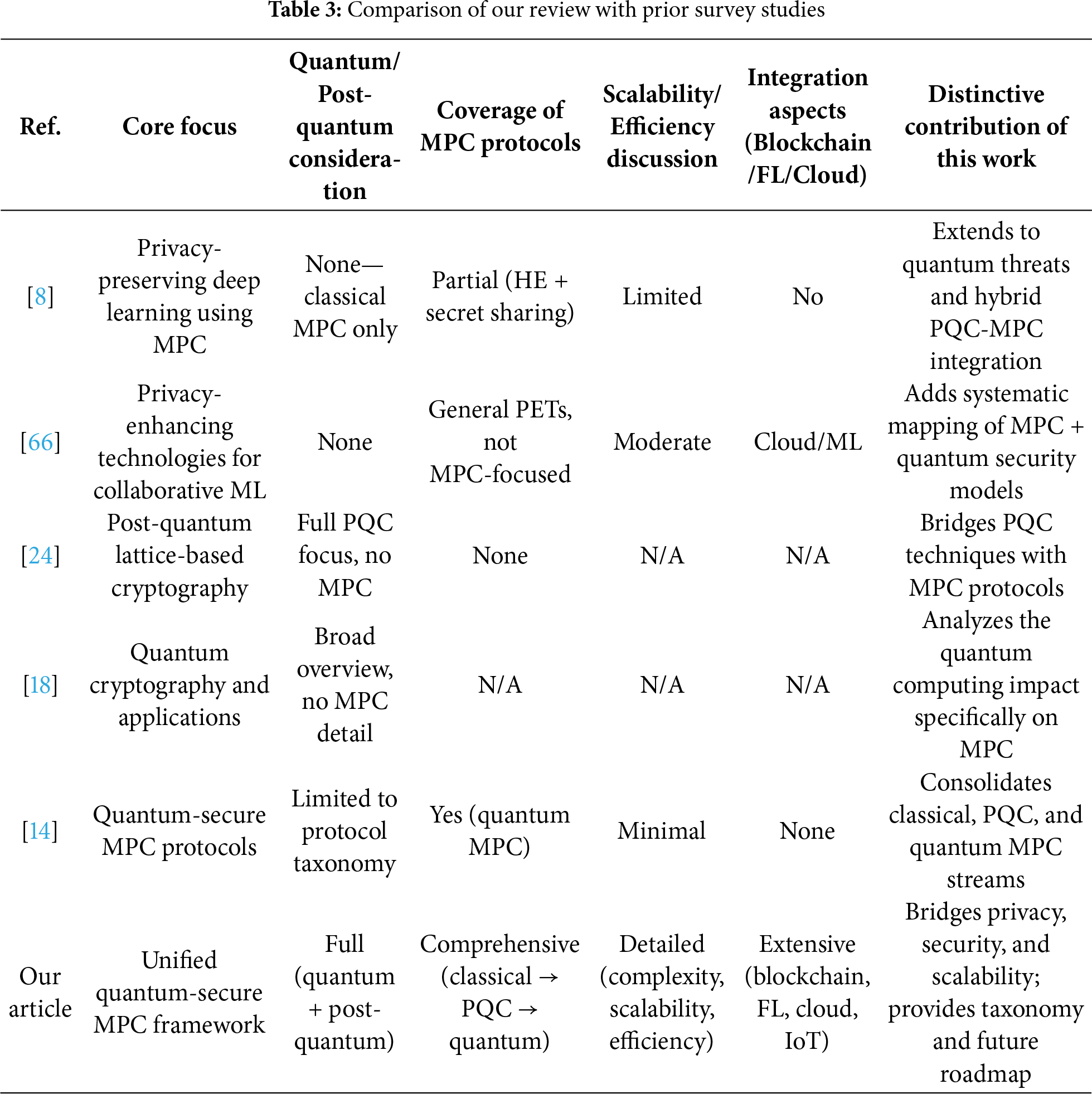

Table 3 contrasts representative surveys—typically focused on classical MPC or PQC in isolation—with this work’s integrated review that bridges MPC, post-quantum, and quantum-enabled paradigms, emphasizing privacy, scalability, and hybrid transition architectures.

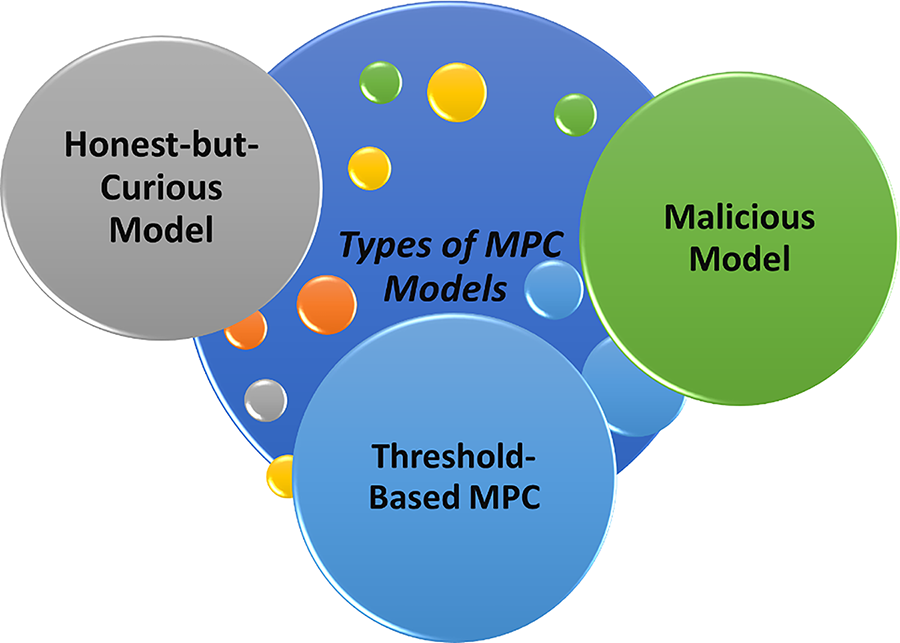

3 MPC: Foundations and Classical Approaches

Secure multiparty computation (MPC) allows multiple parties to jointly compute a function over private inputs while revealing only the final output, enabling privacy-critical collaboration in finance, healthcare, and distributed AI [1,2]. Originating with Yao’s garbled circuits for two-party computation [4], MPC has evolved to multi-party frameworks with fault tolerance, leveraging primitives such as homomorphic encryption, oblivious transfer, and zero-knowledge proofs [7,10]. Adversarial models include honest-but-curious, where participants follow the protocol but attempt inference [67] and malicious, where deviations or data exfiltration occur [68]. Threshold (t-of-n) schemes maintain security if a minimum number of participants remain honest [69]. Core security mechanisms include secret sharing [2,6,22], homomorphic encryption for computation over ciphertexts [7,10,70], oblivious transfer for selective data exchange [22,71], and zero-knowledge proofs for correctness verification without revealing private data [72]. Fig. 2 depicts common MPC models.

Figure 2: Types of MPC models

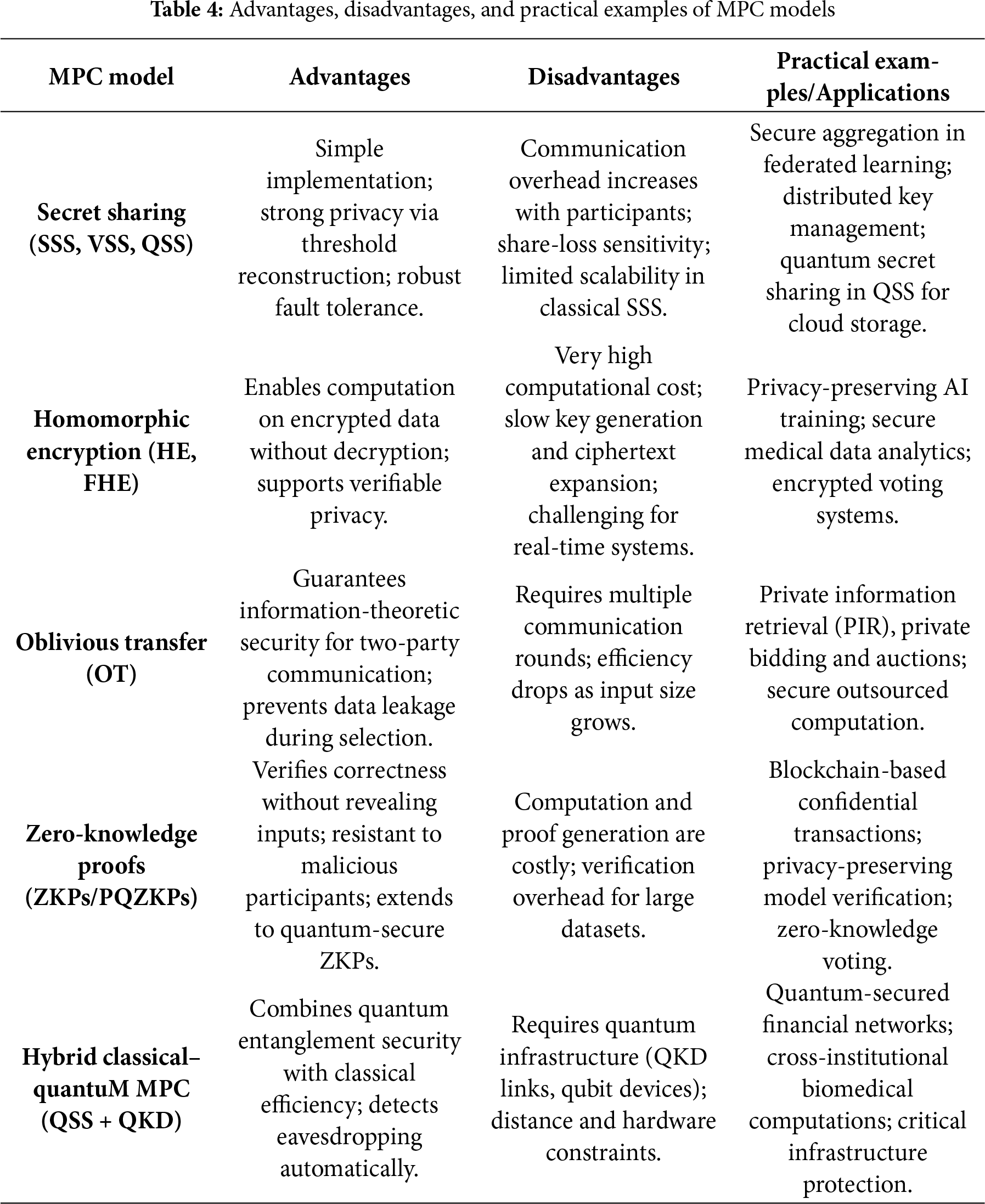

Table 4 illustrates the advantages, disadvantages, and practical examples of major MPC models, including Secret Sharing, Homomorphic Encryption, Oblivious Transfer, Zero-Knowledge Proofs, and hybrid Classical–Quantum frameworks, highlighting their respective trade-offs in privacy, scalability, and computational efficiency.

MPC supports privacy-preserving collaborative ML across siloed datasets [66], privacy-critical finance (e.g., auctions, fraud detection, secure voting) [73], regulated healthcare/genomics analytics [74], and privacy in blockchain smart contracts and transactions [75]. Despite these gains, classical MPC remains resource-intensive and faces scalability limits in a post-quantum context where underlying assumptions may fail.

3.3 Classical Cryptographic Techniques for MPC

MPC combines complementary primitives to ensure confidentiality, correctness, and robustness.

Shamir’s scheme uses a degree-(t−1) polynomial; any t shares reconstruct via Lagrange interpolation, providing perfect secrecy for coalitions < t [76,77]. Additive sharing splits a secret into random summands (lightweight but unrecoverable if a share is lost) [78]. Verifiable secret sharing lets recipients check share validity against a dishonest dealer at added cost [79].

3.3.2 Shamir’s Secret Sharing (SSS) vs. Quantum Secret Sharing (QSSS)

Secret sharing enables authorized-subset reconstruction with fault-tolerant, distributed trust for key management, storage, and private computation. Classical SSS achieves t-of-n recovery via polynomial interpolation [76,77], whereas QSS distributes secrets using quantum states/entanglement to attain information-theoretic (quantum-mechanics-based) security suitable for quantum-capable infrastructures.

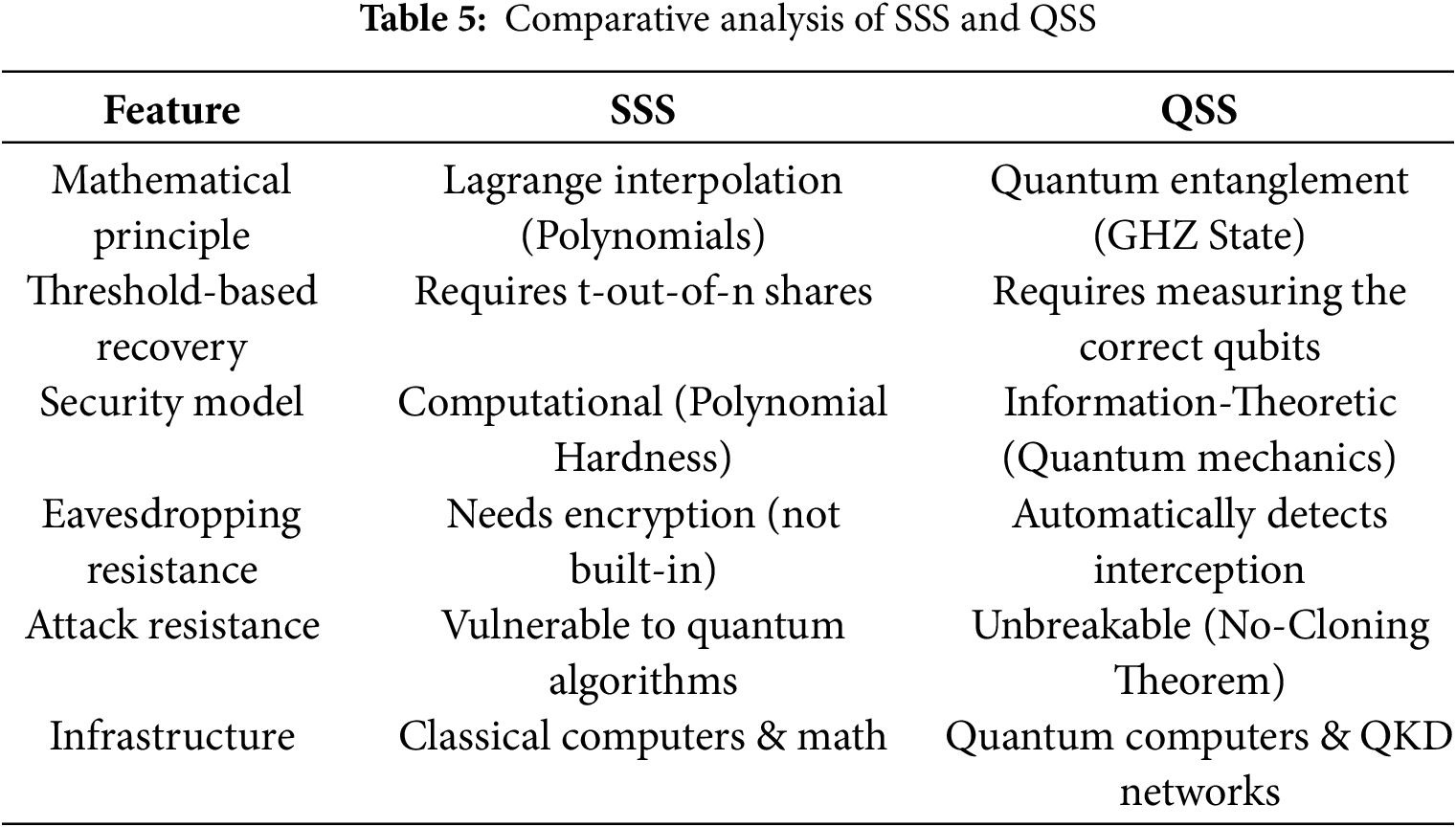

Table 5 highlights SSS vs. QSS: SSS uses polynomial interpolation for threshold recovery and offers computational security on classical infrastructure, but remains exposed to future quantum attacks. QSS employs entanglement and QKD to provide eavesdropping detection and information-theoretic security, yet currently requires specialized quantum networks, limiting near-term scale. Both achieve secure sharing; QSS is cryptographically stronger but constrained by hardware maturity.

3.3.3 Homomorphic Encryption (HE)

HE enables computation on ciphertexts for cloud, MPC, and privacy-preserving ML [80]. PHE supports a single operation (e.g., RSA× [80] Paillier+ [81]); SHE permits limited ops with bootstrapping overhead [82]. FHE supports arbitrary encrypted computation but is costly [83]. Modern schemes (BGV/BFV [83] CKKS [84]) and bootstrapping advances (e.g., RLWE-based, ~1–2 levels with maintained CKKS precision) improve practicality [85]. In PPML, HE supports encrypted training/inference and can be coupled with FL to protect updates (e.g., PFMLP) [86]; large-scale deployments combine DP and HE to reduce privacy risk [87,88]. Costs remain high, but optimizations (Paillier acceleration, batching) and adaptive parameterization reduce overhead [87,89].

3.3.4 Comparison between Secret Sharing and Homomorphic Encryption

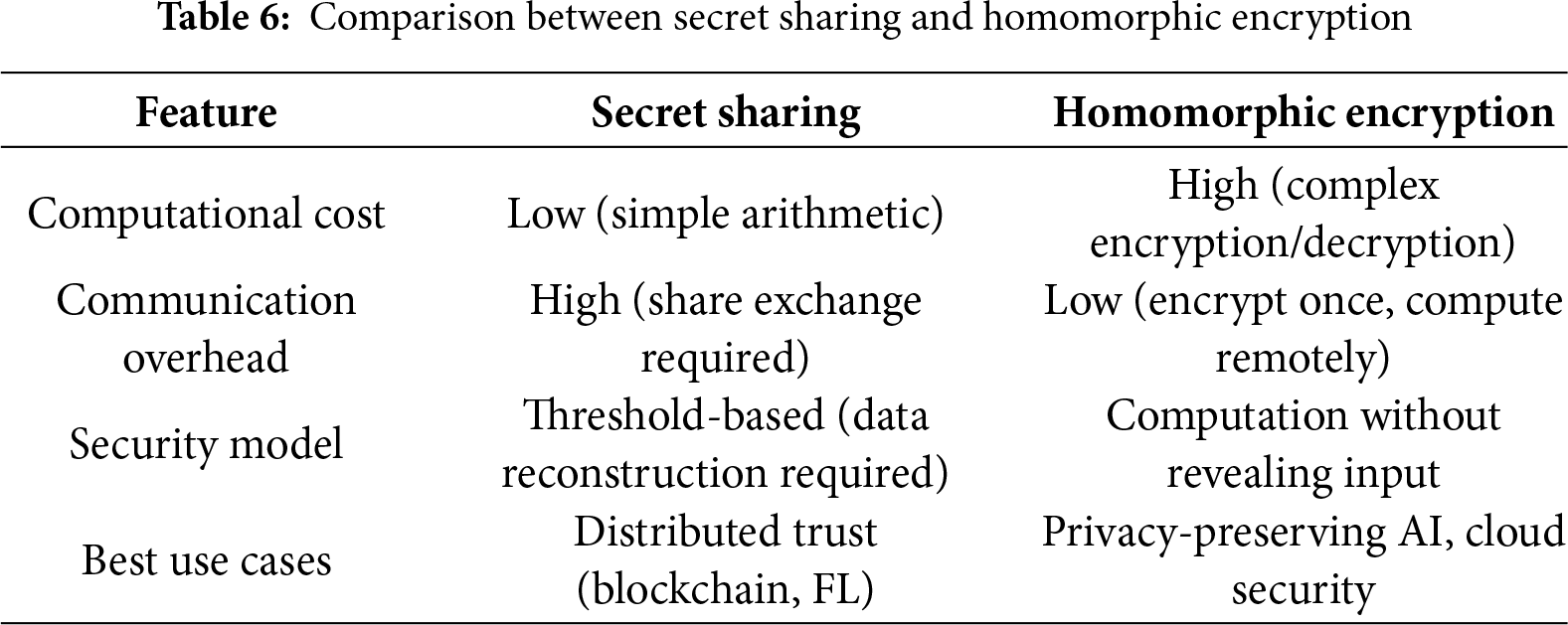

Secret sharing distributes trust and enables threshold access—well-suited to blockchain key management and secure FL—but increases communication and reconstruction overhead. HE minimizes interaction and enables third-party processing without plaintext exposure—ideal for cloud—but shifts cost to encrypted computation (notably FHE). In MPC, the two are complementary: sharing saves compute at bandwidth/interaction cost, while HE reduces interaction at higher compute cost. Table 6 summarizes the comparison.

Both secret sharing and homomorphic encryption (HE) are core to MPC: secret sharing excels when distributed trust and threshold recovery are essential, while HE enables computation on untrusted platforms without exposing plaintext. The choice depends on scalability, efficiency, and security trade-offs. Building on these foundations, the next section reviews MPC protocols that leverage them—Yao’s Garbled Circuits, the GMW protocol, and HE-based frameworks.

GC realizes secure two-party computation: a “garbler” encrypts a Boolean circuit and an “evaluator” computes on garbled tables without learning intermediates [4]. Inputs are obtained via OT [88]. GC reveals only the final output but entails notable precomputation/communication overhead [90]. Optimizations (free-XOR, half-gates, compact encodings) cut costs and enable private set intersection, auctions, and private inference [91].

OT lets a receiver obtain one of many messages without revealing the choice, while the sender learns nothing—supporting MPC, PIR, and GC input delivery (1-out-of-2, k-out-of-n) [92]. It underpins private database queries and secure biometrics [93]. Though interaction-heavy, OT extension amortizes costs for large batches, making protocols practical at scale [94].

3.3.7 Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKP)

ZKPs prove knowledge without revealing the witness, strengthening privacy in blockchain, authentication, and MPC workflows [95]. Forms include iZKP [96], NIZK [97], and succinct NIZK (ZK-SNARKs) for compact, fast verification [98]. While proof generation can be costly, advances in recursive/efficient proofs and hardware acceleration are reducing overheads [95,99].

Threshold schemes distribute decryption/signing/key-gen so only a quorum acts, removing single points of compromise [100]. TSS enables collaborative signing (e.g., threshold ECDSA) for authentication, multisig, and consensus without exposing private keys [96,101]. Threshold encryption splits decryption for distributed key management and secure cloud access. Costs grow with threshold size, but modern designs using ECC, secret sharing, and MPC optimizations improve efficiency [97].

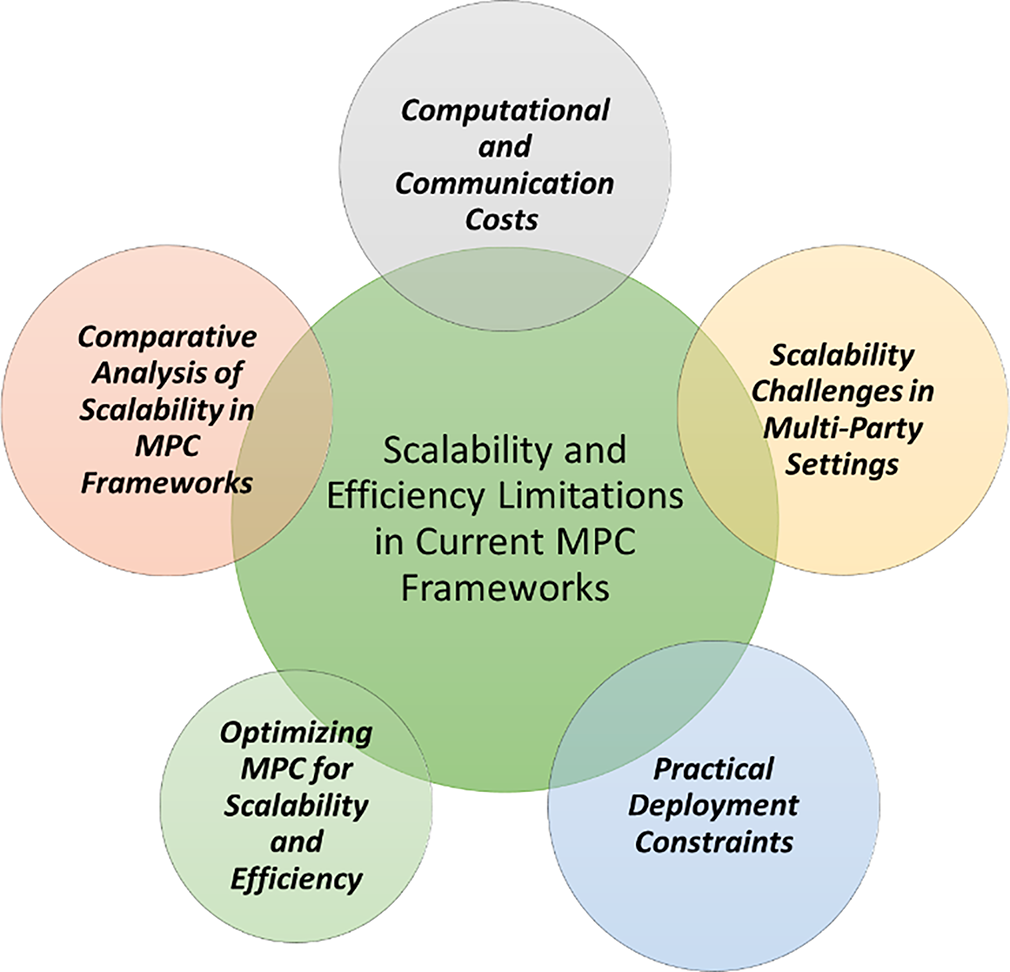

3.4 Scalability and Efficiency Limitations in Current MPC Frameworks

MPC offers strong privacy but encounters real-world friction from heavy computation, substantial communication, and inefficiencies that worsen with more parties and larger data. Fig. 3 summarizes these scalability and efficiency limits.

Figure 3: Scalability and efficiency limitations in current MPC frameworks

3.4.1 Computational and Communication Costs

Per-gate cryptography dominates runtime and bandwidth: garbled circuits encrypt full circuits, yielding large ciphertexts [98]. HE preserves confidentiality but incurs slow arithmetic and ciphertext expansion [102]. GMW is fast on XOR yet slows on AND due to interactive multiplications [103]. Interactive designs increase rounds and latency, especially across distributed/cloud settings.

3.4.2 Scalability Challenges in Multi-Party Settings

Beyond 2PC, threshold schemes add verification steps with (often) linear/superlinear growth; malicious security requires extra proofs, inflating computation and messaging; communication-heavy protocols struggle under network asynchrony, limiting real-time, large-scale use.

3.4.3 Practical Deployment Constraints

CPU/memory/power demands hinder IoT/mobile deployment; limited standardization (vs. AES/RSA) fragments implementations; adding ZKP or blockchain hardens security but compounds computational load and latency.

3.4.4 Optimizing MPC for Scalability and Efficiency

Leaner Boolean/arithmetic circuits, GPU/FPGA parallelization, and lower-round/non-interactive MPC reduce runtime and synchronization. In FL, HE enables encrypted gradient exchange but needs optimizations (e.g., Paillier acceleration, batching) to curb compute [86,102]. Network-aware FL balances privacy with compute/link limits [104]; adaptive encryption tunes cryptographic load to system budgets [105]. Hybrid designs combining HE, differential privacy, and lightweight MPC aim to sustain scalability without relaxing security.

4 Comparative Analysis of Scalability in MPC Frameworks

We conducted Python-based simulations to compare execution times for classical and quantum MPC, highlighting performance trade-offs and scalability limits.

4.1 Classical MPC Simulation (Symmetric Encryption & Secret Sharing)

The classical setup uses symmetric encryption (Fernet) with secret sharing to distribute computation: a secret is encrypted once, shared among

4.2 Quantum MPC Simulation (Quantum Secret Sharing—QSS)

The quantum setup employs QSS via GHZ-state entanglement across

A comparative plot shows classical MPC times rising steeply with

5 Quantum Computing and Its Impact on MPC Security

Quantum superposition and entanglement enable speedups that both open new capabilities and undermine cryptographic assumptions underlying MPC [106,107]. Core algorithms—especially Shor’s and Grover’s—have direct implications for MPC security and motivate quantum-resistant countermeasures [108,109].

5.1 Shor’s Algorithm and Its Impact on Cryptographic Primitives

Shor’s algorithm factors integers and computes discrete logarithms in polynomial time, breaking RSA and ECC and, by extension, MPC systems relying on these for key exchange and authentication [104,110,111]. PQC (lattice-, hash-, and code-based) is therefore prioritized, and quantum-resistant MPC integrates such primitives to preserve security post-quantum [112,113].

5.2 Grover’s Algorithm and Its Impact on Symmetric Cryptography

Grover’s algorithm yields a quadratic speedup for exhaustive search, weakening symmetric ciphers and hashes used within MPC channels and commitments [113–115]. Maintaining equivalent security typically requires longer keys, increasing computational cost, and stressing resource-constrained deployments [116].

6 Threats to Cryptographic Primitives Used in MPC

Quantum capabilities erode bounded-adversary assumptions in classical MPC [94]. Diffie–Hellman becomes insecure under Shor [117], while FHE is lattice-based and currently viewed as quantum-resistant, future advances could affect practicality at scale [113,118]. Commitments and ZKPs tied to factoring/discrete-log are at risk [119], and Grover-style acceleration tightens brute-force bounds affecting proofs and verification [95]. In privacy-preserving AI, DP and HE help protect models/data, yet quantum-enhanced model-inversion may pressure DP guarantees, requiring stronger defenses [120].

6.1 Potential Attack Scenarios in a Quantum World

“Harvest-now, decrypt-later” threatens long-term confidentiality as ciphertexts are stockpiled for future decryption [110,121]. Quantum-aided side channels may better extract keys from noisy computations [87,108]. Threshold mechanisms (e.g., SSS) could face accelerated reconstruction attacks [114,122]. In federated learning, quantum algorithms may amplify model inversion against encrypted gradients [106]. Even lattice schemes could be stressed by improved quantum-assisted lattice reduction, motivating PQC+QKD hybrids [116,122]. Mitigations include PQC families and hybrids that integrate QKD, as well as work on quantum-safe FHE (QFHE), noise-robust DP (QDP), and quantum-resistant commitments with explicit quantum adversary models [123–126].

6.2 Limitations of Current Classical MPC against Quantum Adversaries

Classical MPC must raise key sizes and add protections to counter quantum threats, increasing computational overhead [112]. Multi-round interaction already induces latency; incorporating PQC compounds delays, reducing real-time viability [106]. Lattice-based alternatives often require substantial resources, challenging large-scale integration without notable performance trade-offs [111].

6.3 The Need for Quantum-Resistant MPC

Research is advancing quantum-resistant MPC via hybrid classical–quantum models that combine conventional cryptography with QKD for secure channels [107], exploration of quantum homomorphic encryption [116], and QZKPs designed to remain secure against quantum adversaries [115]. Overall, quantum computing necessitates a paradigm shift in MPC security: PQC is promising but introduces computational and implementation burdens; future work must balance security, efficiency, and scalability to keep privacy-preserving computation viable post-quantum [113].

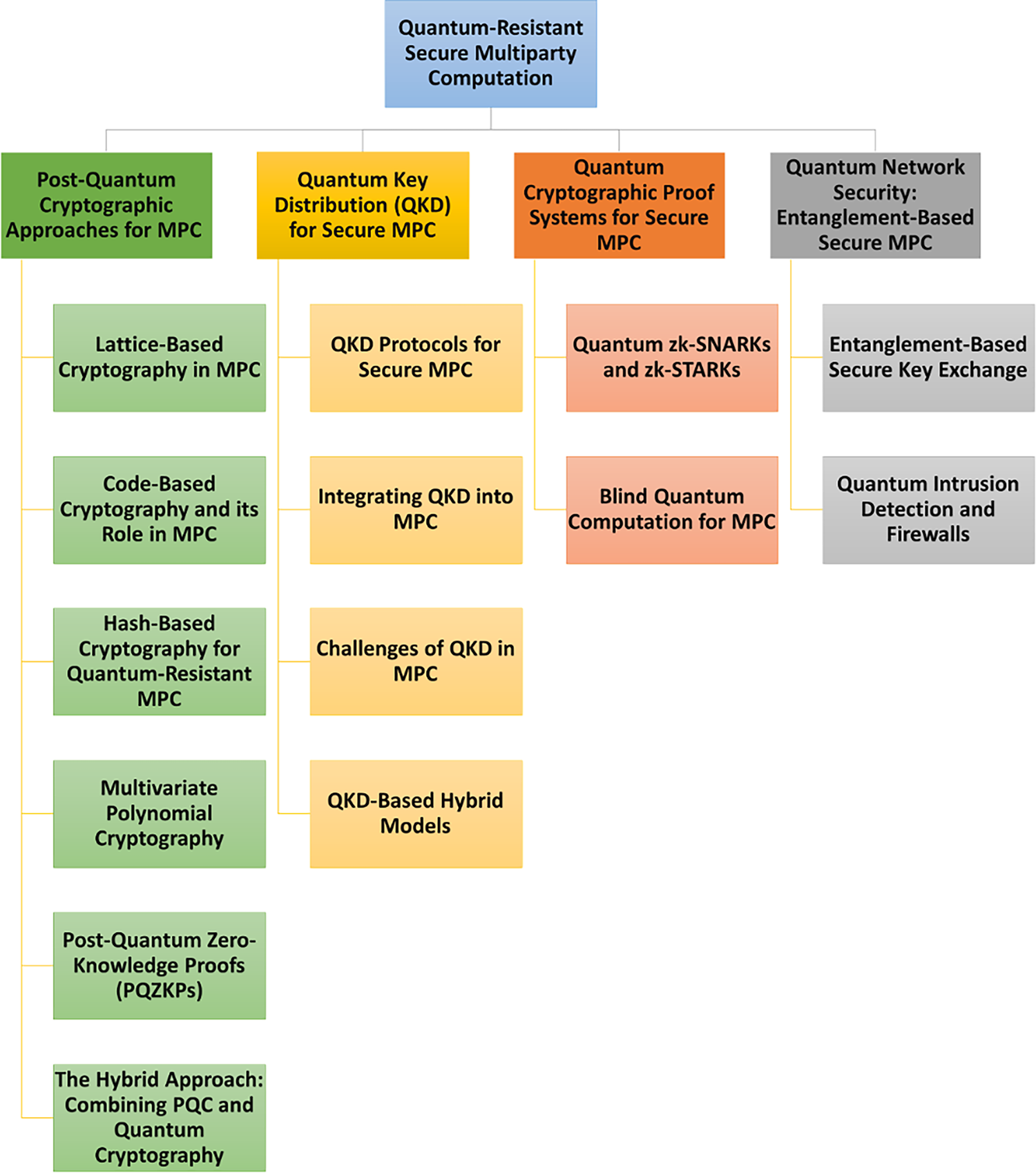

7 Quantum-Resistant Secure Multiparty Computation

PQC comprises cryptographic designs intended to remain secure against quantum-capable adversaries; because RSA, ECC, and Diffie–Hellman are vulnerable to Shor’s algorithm and symmetric schemes lose effective strength under Grover’s algorithm, MPC’s reliance on these primitives necessitates post-quantum replacements [97,98]. Within PQC, lattice-based methods (e.g., LWE/Ring-LWE) provide leading candidates for quantum-resistant MPC; lattice-based FHE enables computation over ciphertexts for privacy-preserving distributed learning, and lattice-based threshold cryptography supports t-out-of-n protocols [103,127,128]. Their principal advantage is strong security with homomorphic properties suitable for MPC, while a key drawback is larger key sizes that increase storage and computation costs [105–107]. Code-based approaches (e.g., McEliece) contribute threshold decryption and commitment constructions for MPC that remain hard even with quantum advances [108–110,112]. Hash-based signatures (e.g., SPHINCS+, LMS) avoid number-theoretic assumptions and are attractive for constrained settings where lightweight authentication for MPC is required [104,111,112]. Multivariate public-key cryptosystems enable quantum-resistant threshold signatures and authenticated key exchange, though large key sizes and implementation complexity currently limit scale [112–114]. Post-quantum ZKPs leverage lattice and hash-based assumptions to preserve verifiability without input disclosure and are being optimized for more efficient zk-SNARKs in verifiable MPC [115,116]. Fig. 4 summarizes the overall quantum-resistant MPC landscape and, given the limits of any single family, motivates hybridization with quantum cryptography (Section 8) [117].

Figure 4: Quantum-resistant secure multiparty computation

8 Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) for Secure MPC

QKD offers information-theoretically secure key exchange, ensuring that even a quantum-equipped adversary cannot undetectably intercept keys [118]. For MPC contexts, widely used protocols include BB84 (basis-randomization with eavesdropping detection), E91 (entanglement-based distribution), and MDI-QKD (which removes trust in measurement devices) [118–121]. Integrating QKD into MPC enables quantum-safe key establishment among participants, strengthens secret-sharing by distributing quantum-secured keys for classical shares, and supports threshold cryptography without classical public-key assumptions. Practical deployment faces infrastructure needs (fiber/satellite links), distance constraints in optical channels, and susceptibility to implementation-level quantum side-channel attacks demonstrated in real systems [118,122,124]. To mitigate these issues, QKD–PQC hybrid models combine QKD for link/key establishment with lattice- or hash-based schemes for computation and authentication, enabling end-to-end quantum-resistant MPC; an example is a federated learning system that uses QKD for inter-node key exchanges while employing lattice-based encryption during computation, with ongoing work on quantum repeaters and error correction to extend distance and robustness [112,124].

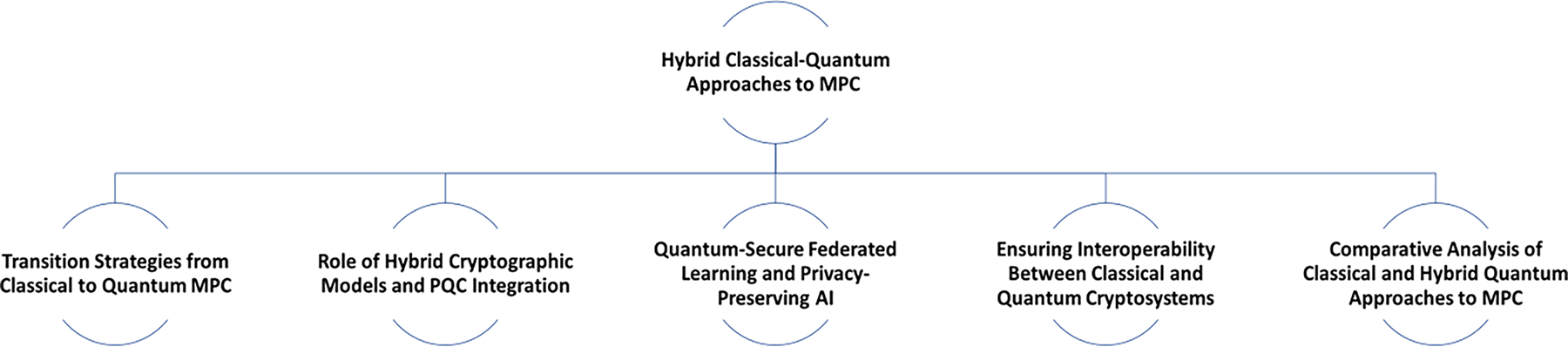

9 Hybrid Classical–Quantum Approaches to MPC

Transitioning MPC to quantum-resistant operation strengthens security, but it must balance immature hardware with interoperability. This section outlines phased migration, hybrid cryptography with PQC, quantum-secure FL, and interoperability needs.

9.1 Transition Strategies from Classical to Quantum MPC

A pragmatic path augments established MPC (homomorphic encryption, secret sharing) with PQC defences [129]. Hybrid key-exchange can run classical and quantum-safe components in parallel, while lattice-based HE and multi-key FHE serve as transitional blocks [130]. Quantum-inspired classical methods (e.g., tensor networks) are explored for secure computation [131], and VQAs/QAOA help stabilize workloads under noisy hardware [132].

9.2 Role of Hybrid Cryptographic Models and PQC Integration

Hybrid models combine classical primitives with PQC (lattice, multivariate, code-based) to secure MPC during migration [133]. A representative design keeps classical ZKPs, uses QKD for channels, and pairs AES-256 for bulk data with PQC KEMs for session setup [134]. High-assurance sectors are piloting such hybrids in line with national migration initiatives [129]. Fig. 5 illustrates these approaches.

Figure 5: Hybrid classical-quantum approaches to MPC

9.3 Quantum-Secure Federated Learning and Privacy-Preserving AI

FL benefits from quantum-aware protections—quantum HE and DP with quantum noise—to counter inference/poisoning risks [123,130]; practical systems often combine classical MPC for training with QKD-secured aggregation, and investigate variational quantum classifiers to reinforce privacy [132]. Scalability remains challenging [24]. QKD improves security but stresses key management and channels, motivating hybrid designs that preserve performance [123].

9.4 Ensuring Interoperability between Classical and Quantum Cryptosystems

Interoperability is critical as RSA/ECC erode under Shor [110]; hybrid key-exchange supports coexistence with legacy systems [111], while quantum-safe KEMs (e.g., NTRUEncrypt-based) replace classical agreements [112]. With quantum communication standards still maturing, hybrid protocols that span classical and quantum security keep cloud/IoT viable during transition [135], and hardware modules must integrate with enterprise stacks as SMQC explores hybrid key-management paths [136].

10 Comparative Analysis of Classical and Hybrid Quantum Approaches to MPC

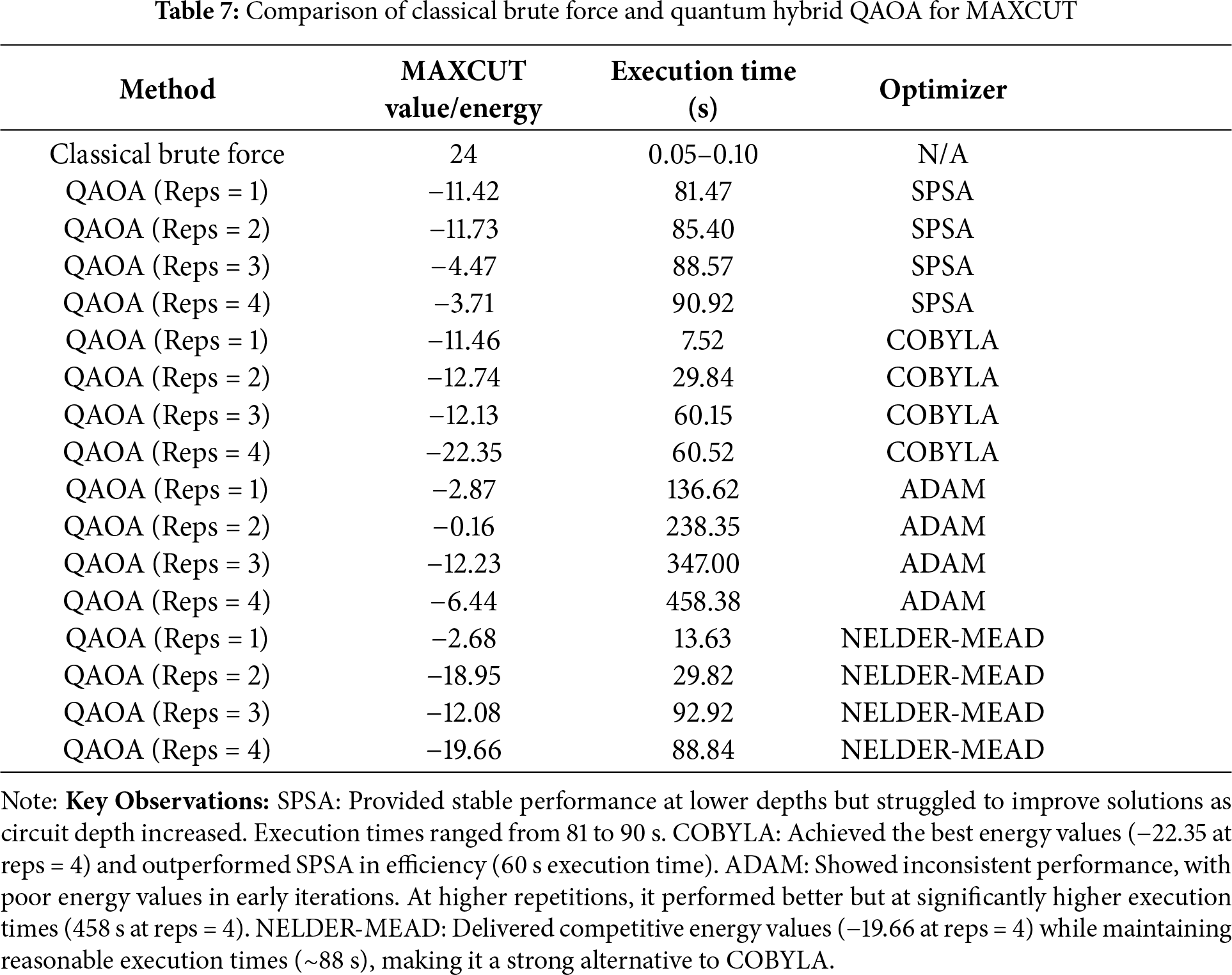

We benchmarked MAXCUT with a classical brute-force solver and a hybrid QAOA pipeline to compare efficiency, scalability, and trade-offs.

10.1 Classical MAXCUT Performance

Brute-force guarantees the optimum but scales as

Table 7 contrasts brute-force with hybrid QAOA under different classical optimizers (SPSA, COBYLA, ADAM, Nelder–Mead), showing distinct time–accuracy trade-offs within the QAOA framework.

Increasing the number of repetitions (reps) improved solution quality in most cases, but execution time scaled accordingly.

10.3 Implications for MPC and Cryptographic Applications

Findings indicate that classical methods remain preferable for small–mid scale instances, while hybrid approaches (e.g., QAOA-assisted key distribution and secure multiparty transactions) open paths to scalable, quantum-aware security. Priority next steps include adaptive hybrid optimization across classical optimizers, higher-depth QAOA with error mitigation on QPUs, and hardware evaluations to assess the deployability of hybrid quantum MPC in real infrastructures.

11 Future Directions and Open Research Challenges

Securing MPC amid advancing quantum capability requires progress in post-quantum design, cross-technology integration, and governance.

11.1 Advancing Post-Quantum MPC Protocols

Robustness hinges on quantum-safe primitives (lattice, code, multivariate) and protocols that balance security, performance, and scale; key thrusts include quantum-resistant key exchange, MPC-efficient homomorphic encryption, quantum-secure threshold systems, and quantum-aided verifiable computation, while minimizing added computational overhead.

11.2 Integration with Emerging Technologies (Blockchain, AI, Cloud Security)

MPC with blockchain and ZKPs enables confidential smart contracts and DeFi without trusted third parties; in AI, federated learning with quantum-aware MPC and quantum-assisted anonymization strengthens privacy at scale [137]. For cloud, post-quantum–secure storage and MPC-protected data-in-transit are essential and quantum-enabled, AI-driven detection can enhance real-time defence—together delivering confidentiality, integrity, and resilience.

11.3 Policy and Ethical Implications of Quantum MPC

Standards bodies must finalize and enforce post-quantum baselines to preempt RSA/ECC obsolescence and guide migration across regulated sectors [138]. Growing geopolitical competition underscores the need for international agreements to deter quantum-powered cyber conflict [139]. Ethical risks span bias/opacity in quantum-AI systems and potential mass decryption enabling surveillance at scale [140], demanding coordinated action by technologists, policymakers, legal experts, and ethicists.

This work surveyed quantum-secured MPC and its integration with hybrid cryptographic models, post-quantum mechanisms, and emerging quantum technologies. We highlighted opportunities for stronger security against quantum adversaries alongside practical hurdles in performance, interoperability, and deployment.

Hybrid classical–quantum approaches strengthen MPC by combining PQC with established tools such as lattice-based cryptography, zero-knowledge proofs, and homomorphic encryption, enabling a gradual transition from classical to quantum-resilient systems. Empirical evidence on MAXCUT shows QAOA yields competitive solutions; optimizer choice is pivotal, with COBYLA offering the best balance of quality and efficiency. Classical methods remain superior on small instances, but scalability constraints intensify with problem size; hybrid quantum methods offer a promising path for larger-scale settings. Increasing QAOA depth improves approximation quality, and evaluations on real quantum hardware (beyond simulators) are likely to provide more accurate benchmarks. Practical adoption hinges on seamless interoperability between classical MPC and quantum-enhanced protocols, where protocol compatibility, computational overhead, and regulatory compliance remain open challenges.

Progress depends on advances in quantum hardware (reduced noise, longer coherence, higher gate fidelity) and movement toward fault-tolerant devices to support robust quantum-enhanced cryptography. Standardized hybrid cryptographic frameworks will be essential for staged migration, with adaptive schemes designed to operate efficiently across mixed classical–quantum infrastructures. Real-world deployment in finance, healthcare, and secure AI training will require demonstrable scalability, cost-effectiveness, and compliance with emerging quantum-safe standards. Although full-scale quantum computing is still developing, adopting hybrid, quantum-resilient cryptography now is a prudent step to ensure long-term security.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Sghaier Guizani and Tehseen Mazhar perform the Original Writing Part, Software, and Methodology; Sghaier Guizani, Habib Hamam, and Tehseen Mazhar perform Rewriting, investigation, design Methodology, and Conceptualization; Habib Hamam and Tehseen Mazhar perform related work part and manage results and discussions; Habib Hamam and Tehseen Mazhar perform related work part and manage results and discussion; Sghaier Guizani, Habib Hamam, and Tehseen Mazhar perform Rewriting, design Methodology, and Visualization; Tehseen Mazhar and Habib Hamam perform Rewriting, design Methodology, and Visualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lindell Y. Secure multiparty computation. Commun ACM. 2020;64(1):86–96. doi:10.1145/3387108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Garg S, Srinivasan A. Two-round multiparty secure computation from minimal assumptions. J ACM. 2022;69(5):1–30. doi:10.1145/3566048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Monyk C. Quantum cryptography. In: Handbook of information and communication security. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2010. p. 159–74. [Google Scholar]

4. Yao AC-C, editor. How to generate and exchange secrets. In: Proceedings of the 27th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (SFCS 1986); 1986 Oct 27–29; Toronto, ON, Canada. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 1986. [Google Scholar]

5. Hazay C, Venkitasubramaniam M, Weiss M, editors. The price of active security in cryptographic protocols. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2020 May 10–14; Zagreb, Croatia. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

6. Cramer R, Daza V, Gracia I, Urroz JJ, Leander G, Martí-Farré J, et al. On codes, matroids, and secure multiparty computation from linear secret-sharing schemes. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 2008;54(6):2644–57. doi:10.1109/tit.2008.921692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cramer R, Damgård I, Nielsen JB, editors. Multiparty computation from threshold homomorphic encryption. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2001 May 6–10; Innsbruck, Austria. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

8. Zhang Q, Xin C, Wu H. Privacy-preserving deep learning based on multiparty secure computation: a survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(13):10412–29. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3058638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou J, Feng Y, Wang Z, Guo D. Using secure multi-party computation to protect privacy on a permissioned blockchain. Sensors. 2021;21(4):1540. doi:10.3390/s21041540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kumar AV, Sujith MS, Sai KT, Rajesh G, Yashwanth DJS, editors. Secure multiparty computation enabled e-healthcare system with homomorphic encryption. In: IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

11. Mazhar T, khan S, Shahzad T, khan MA, Saeed MM, Awotunde JB, et al. Generative AI, IoT, and blockchain in healthcare: application, issues, and solutions. Discov Internet Things. 2025;5(1):5. doi:10.1007/s43926-025-00095-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Lipinska V, Ribeiro J, Wehner S. Secure multiparty quantum computation with few qubits. Phys Rev A. 2020;102(2):022405. [Google Scholar]

13. Damgård I, Nielsen JB, editors. Scalable and unconditionally secure multiparty computation. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference; 2007 Aug 19–23; Santa Barbara, CA, USA. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

14. Mohanty T, Srivastava V, Debnath SK, Stănică P. Quantum secure protocols for multiparty computations. J Inf Secur Appl. 2025;90(2):104033. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2025.104033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhu H. Survey of computational assumptions used in cryptography broken or not by Shor’s algorithm [dissertation]. Montreal, QC, Canada: McGill University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

16. Montanaro A. Quantum algorithms: an overview. npj Quantum Inf. 2016;2(1):1–8. doi:10.1038/npjqi.2015.23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ktari J, frikha T, Hamdi M, Affes N, Hamam H. Enhancing blockchain security and efficiency through FPGA-based consensus mechanisms and post-quantum cryptography. Recent Adv Electr Electron Eng. 2025;18(7):946–58. doi:10.2174/0123520965288815240424054237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sahu SK, Mazumdar K. State-of-the-art analysis of quantum cryptography: applications and future prospects. Front Phys. 2024;12:1456491. doi:10.3389/fphy.2024.1456491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang Y, Zhang H, Wang H. Quantum polynomial-time fixed-point attack for RSA. China Commun. 2018;15(2):25–32. doi:10.1109/cc.2018.8300269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Jing Z, Gu C, Ge C, Shi P. Cryptanalysis of a public key cryptosystem based on data complexity under quantum environment. Mob Netw Appl. 2021;26(4):1609–15. doi:10.1007/s11036-019-01498-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Bonnetain X, Naya-Plasencia M, Schrottenloher A. Quantum security analysis of AES. IACR Trans Symmetric Cryptol. 2019;2019:55–93. doi:10.46586/tosc.v2019.i2.55-93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yang Z, He D, Qu L, Xu J. On the security of a lattice-based multi-stage secret sharing scheme. IEEE Trans Dependable Secur Comput. 2022;20(5):4441–2. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2022.3209011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Borges F, Reis PR, Pereira D. A comparison of security and its performance for key agreements in post-quantum cryptography. IEEE Access. 2020;8:142413–22. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3013250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nejatollahi H, Dutt N, Ray S, Regazzoni F, Banerjee I, Cammarota R. Post-quantum lattice-based cryptography implementations: a survey. ACM Comput Surv (CSUR). 2019;51(6):1–41. doi:10.1145/3292548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lu Y, Ding G. Quantum secure multi-party summation with graph state. Entropy. 2024;26(1):80. doi:10.3390/e26010080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zapatero V, van Leent T, Arnon-Friedman R, Liu W-Z, Zhang Q, Weinfurter H, et al. Advances in device-independent quantum key distribution. npj Quantum Inf. 2023;9(1):10. doi:10.1038/s41534-023-00684-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mao Y, Zeng P, Chen TY. Recent advances on quantum key distribution overcoming the linear secret key capacity bound. Adv Quantum Technol. 2021;4(1):2000084. doi:10.1002/qute.202000084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ricci S, Dobias P, Malina L, Hajny J, Jedlicka P. Hybrid keys in practice: combining classical, quantum and post-quantum cryptography. IEEE Access. 2024;12:23206–19. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3364520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Schneier B. Nist’s post-quantum cryptography standards competition. IEEE Secur Priv. 2022;20(5):107–8. doi:10.1109/msec.2022.3184235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Lu C, Telang E, Aysu A, Basu K, editors. Quantum leak: timing side-channel attacks on cloud-based quantum services. In: Proceedings of the Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI 2025; 2025 Jun 30–Jul 2; New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

31. Yamany W, Moustafa N, Turnbull B. OQFL: an optimized quantum-based federated learning framework for defending against adversarial attacks in intelligent transportation systems. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2021;24(1):893–903. doi:10.1109/tits.2021.3130906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fiedler R, Günther F, editors. Security analysis of signal’s PQXDH handshake. In: Proceedings of the IACR International Conference on Public-Key Cryptography; 2025 May 12–15; Røros, Norway. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. [Google Scholar]

33. Boneh D, Boyen X, Shacham H, editors. Short group signatures. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference; 2004 Aug 15–19; Santa Barbara, CA, USA. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

34. Delerablée C, Pointcheval D, editors. Dynamic fully anonymous short group signatures. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Cryptology in Vietnam; 2006 Sep 25–28; Hanoi, Vietnam. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

35. Camenisch J, Groth J, editors. Group signatures: better efficiency and new theoretical aspects. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Security in Communication Networks; 2004 Sep 8–10; Amalfi, Italy. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

36. Pointcheval D, Stern J. Security arguments for digital signatures and blind signatures. J Cryptol. 2000;13(3):361–96. doi:10.1007/s001450010003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Liu JK, Wei VK, Wong DS, editors. Linkable spontaneous anonymous group signature for ad hoc groups. In: Proceedings of the Australasian Conference on Information Security and Privacy; 2004 Jul 13–15; Sydney, Australia. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

38. Dodis Y, Kiayias A, Nicolosi A, Shoup V, editors. Anonymous identification in ad hoc groups. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2004 May 2–6; Interlaken, Switzerland. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2004. [Google Scholar]

39. Camenisch JL, Piveteau J-M, Stadler MA, editors. Blind signatures based on the discrete logarithm problem. In: Workshop on the Theory and Application of of Cryptographic Techniques; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

40. Stadler M, Piveteau J-M, Camenisch J, editors. Fair blind signatures. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 1995 May 21–25; Saint-Malo, France. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1995. [Google Scholar]

41. Abe M, Fujisaki E, editors. How to date blind signatures. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security; 1996 Nov 3–7; Kyongju, Republic of Korea. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1996. [Google Scholar]

42. Paillier P, editor. Public-key cryptosystems based on composite degree residuosity classes. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 1999 May 2–6; Prague, Czech Republic. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

43. ElGamal T. A public key cryptosystem and a signature scheme based on discrete logarithms. IEEE Trans Inf Theory. 1985;31(4):469–72. doi:10.1109/tit.1985.1057074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Rivest RL, Adleman L, Dertouzos ML. On data banks and privacy homomorphisms. Found Secur Comput. 1978;4(11):169–80. [Google Scholar]

45. Han F, Qin J, Hu J. Secure searches in the cloud: a survey. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2016;62:66–75. [Google Scholar]

46. Goyal V, Pandey O, Sahai A, Waters B, editors. Attribute-based encryption for fine-grained access control of encrypted data. In: Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2006 Oct 30–Nov 3; Alexandria, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

47. Bethencourt J, Sahai A, Waters B, editors. Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption. In: Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP’07); 2007 May 20–23; Oakland, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2007. [Google Scholar]

48. Du W, Atallah MJ, editors. Secure multi-party computation problems and their applications: a review and open problems. In: Proceedings of the 2001 Workshop on New Security Paradigms; 2001 Sep 10–13; Cloudcroft, NM, USA. [Google Scholar]

49. Li L, Lu R, Choo K-KR, Datta A, Shao J. Privacy-preserving-outsourced association rule mining on vertically partitioned databases. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2016;11(8):1847–61. doi:10.1109/tifs.2016.2561241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Domingo-Ferrer J, Ricci S, Domingo-Enrich C. Outsourcing scalar products and matrix products on privacy-protected unencrypted data stored in untrusted clouds. Inf Sci. 2018;436(4):320–42. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2018.01.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Bos J, Costello C, Ducas L, Mironov I, Naehrig M, Nikolaenko V, et al., editors. Frodo: take off the ring! practical, quantum-secure key exchange from LWE. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2016 Oct 24–28; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

52. Hoffstein J, Pipher J, Silverman JH, editors. NTRU: a ring-based public key cryptosystem. In: Proceedings of the International Algorithmic Number Theory Symposiumv. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

53. Kipnis A, Patarin J, Goubin L, editors. Unbalanced oil and vinegar signature schemes. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 1999 May 2–6; Prague, Czech Republic. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

54. Ding J, Schmidt D, editors. Rainbow, a new multivariable polynomial signature scheme. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Cryptography and Network Security; 2005 Jun 7–10; New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

55. Lamport L. Constructing digital signatures from a one way function. Menlo Park, CA, USA: SRI International; 1979. [Google Scholar]

56. Merkle RC, editor. A certified digital signature. In: Proceedings of the Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology; 1989 Apr 10–13; Houthalen, Belgium. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1989. [Google Scholar]

57. McEliece RJ. A public-key cryptosystem based on algebraic. Coding Thv. 1978;4244(1978):114–6. [Google Scholar]

58. Niederreiter H. Knapsack-type cryptosystems and algebraic coding theory. Prob Contr Inf Theory. 1986;15(2):157–66. [Google Scholar]

59. Jao D, De Feo L, editors. Towards quantum-resistant cryptosystems from supersingular elliptic curve isogenies. In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Post-Quantum Cryptography; 2011 Nov 29–Dec 2; Taipei, Taiwan. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

60. Campagna M, Costello C, Hess B, Hutchinson A, Jalali A, Karabina K, et al. Supersingular isogeny key encapsulation. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: NIST Computer Security Resource Center; 2022. [Google Scholar]

61. Abdikhakimov I. Preparing for a quantum future: strategies for strengthening international data privacy in the face of evolving technologies. Int J Law Policy. 2024;2(5):42–6. doi:10.59022/ijlp.189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Gulyamov S, Abdikhakimov I. The quantum threat: examining the impact of quantum computing on international cybersecurity and the urgent need for new legal frameworks. Jurisprud. 2024;4(2):102–12. [Google Scholar]

63. Thanalakshmi P, Rishikhesh A, Marion Marceline J, Joshi GP, Cho W. A quantum-resistant blockchain system: a comparative analysis. Mathematics. 2023;11(18):3947. doi:10.3390/math11183947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Ali S, Wadho SA, Talpur KR, Talpur BA, Alshudukhi KS, Humayun M, et al. Next-generation quantum security: the impact of quantum computing on cybersecurity—threats, mitigations, and solutions. Comput Electr Eng. 2025;128(3):110649. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2025.110649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Ali S, Wang J, Leung VCM. AI-driven fusion with cybersecurity: exploring current trends, advanced techniques, future directions, and policy implications for evolving paradigms—a comprehensive review. Inf Fusion. 2025;118(3):102922. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Soykan EU, Karaçay L, Karakoç F, Tomur E. A survey and guideline on privacy enhancing technologies for collaborative machine learning. IEEE Access. 2022;10:97495–519. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3204037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Chida K, Hamada K, Ikarashi D, Kikuchi R, Genkin D, Lindell Y, et al. Fast large-scale honest-majority MPC for malicious adversaries. J Cryptol. 2023;36(3):15. doi:10.1007/s00145-023-09453-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Ananth P, Choudhuri AR, Goel A, Jain A, editors. Two round information-theoretic MPC with malicious security. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2019 May 19–23; Darmstadt, Germany. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

69. Braun L, Damgård I, Orlandi C, editors. Secure multiparty computation from threshold encryption based on class groups. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference; 2023 Aug 20–24; Santa Barbara, CA, USA. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2023. [Google Scholar]

70. Cohen R, Haitner I, Omri E, Rotem L. From fairness to full security in multiparty computation. J Cryptol. 2022;35(1):4. doi:10.1007/s00145-021-09415-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Burra SS, Larraia E, Nielsen JB, Nordholt PS, Orlandi C, Orsini E, et al. High-performance multi-party computation for binary circuits based on oblivious transfer. J Cryptol. 2021;34(3):34. doi:10.1007/s00145-021-09403-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Ishai Y, Kushilevitz E, Ostrovsky R, Sahai A. Zero-knowledge proofs from secure multiparty computation. SIAM J Comput. 2009;39(3):1121–52. doi:10.1137/080725398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Sangers A, van Heesch M, Attema T, Veugen T, Wiggerman M, Veldsink J, et al., editors. Secure multiparty PageRank algorithm for collaborative fraud detection. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security; 2019 Feb 18–22; Frigate Bay, St. Kitts and Nevis. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

74. Froelicher D, Troncoso-Pastoriza JR, Raisaro JL, Cuendet MA, Sousa JS, Cho H, et al. Truly privacy-preserving federated analytics for precision medicine with multiparty homomorphic encryption. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5910. doi:10.1101/2021.02.24.432489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Gao H, Ma Z, Luo S, Wang Z. BFR-MPC: a blockchain-based fair and robust multi-party computation scheme. IEEE Access. 2019;7:110439–50. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2934147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Dawson E, Donovan D. The breadth of Shamir’s secret-sharing scheme. Comput Secur. 1994;13(1):69–78. doi:10.1016/0167-4048(94)90097-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Lai C-P, Ding C. Several generalizations of Shamir’s secret sharing scheme. Int J Found Comput Sci. 2004;15(2):445–58. doi:10.1142/s0129054104002510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Holmgren J, Lombardi A, Rothblum RD, editors. Fiat-shamir via list-recoverable codes (or: parallel repetition of gmw is not zero-knowledge). In: Proceedings of the 53rd Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing; 2021 Jun 21–25; Online. [Google Scholar]

79. Kandar S, Dhara BC. A verifiable secret sharing scheme with combiner verification and cheater identification. J Inf Secur Appl. 2020;51(11):102430. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2019.102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Rivest RL, Shamir A, Adleman L. A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems. Commun ACM. 1978;21(2):120–6. doi:10.1145/359340.359342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Ryu J, Kim K, Won D, editors. A study on partially homomorphic encryption. In: Proceedings of the 2023 17th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (IMCOM); 2023 Jan 3–5; Seoul, Republic of Korea. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2023. [Google Scholar]

82. Acar A, Aksu H, Uluagac AS, Conti M. A survey on homomorphic encryption schemes: theory and implementation. ACM Comput Surv. 2018;51(4):1–35. doi:10.1145/3214303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Mert AC, Öztürk E, Savaş E. Design and implementation of encryption/decryption architectures for BFV homomorphic encryption scheme. IEEE Trans Very Large Scale Integr (VLSI) Syst. 2019;28(2):353–62. doi:10.1109/tvlsi.2019.2943127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Agrawal R, Chandrakasan A, Joshi A, editors. Heap: a fully homomorphic encryption accelerator with parallelized bootstrapping. In: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE 51st Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA); 2024 Jun 29–Jul 3; Buenos Aires, Argentina. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2024. [Google Scholar]

85. Kim A, Deryabin M, Eom J, Choi R, Lee Y, Ghang W, et al. General bootstrapping approach for RLWE-based homomorphic encryption. IEEE Trans Comput. 2023;73(1):86–96. doi:10.1109/tc.2023.3318405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Fang H, Qian Q. Privacy preserving machine learning with homomorphic encryption and federated learning. Future Internet. 2021;13(4):94. doi:10.3390/fi13040094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Xing EP, Ho Q, Dai W, Kim J-K, Wei J, Lee S, et al., editors. Petuum: a new platform for distributed machine learning on big data. In: Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2015 Aug 10–13; Sydney, NSW, Australia. [Google Scholar]

88. Naor M, Pinkas B, editors. Efficient oblivious transfer protocols. London, UK: SODA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

89. Konečný J, McMahan HB, Yu FX, Richtárik P, Suresh AT, Bacon D. Federated learning: strategies for improving communication efficiency. arXiv:161005492. 2016. [Google Scholar]

90. Yadav VK, Andola N, Verma S, Venkatesan S. A survey of oblivious transfer protocol. ACM Comput Surv (CSUR). 2022;54(10s):1–37. doi:10.1145/3503045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Heath D, Kolesnikov V, editors. Stacked garbling: garbled circuit proportional to longest execution path. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference; 2020 Aug 17–21; Santa Barbara, CA, USA. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

92. Ben-Efraim A, Cong K, Omri E, Orsini E, Smart NP, Soria-Vazquez E, editors. Large scale, actively secure computation from LPN and free-XOR garbled circuits. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2021 Oct 17–21; Zagreb, Croatia. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

93. Bringer J, Chabanne H, Patey A. Privacy-preserving biometric identification using secure multiparty computation: an overview and recent trends. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2013;30(2):42–52. doi:10.1109/msp.2012.2230218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Asharov G, Lindell Y, Schneider T, Zohner M. More efficient oblivious transfer extensions. J Cryptol. 2017;30(3):805–58. doi:10.1007/s00145-016-9236-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Sun X, Yu FR, Zhang P, Sun Z, Xie W, Peng X. A survey on zero-knowledge proof in blockchain. IEEE Netw. 2021;35(4):198–205. doi:10.1109/mnet.011.2000473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Canetti R, Gennaro R, Goldfeder S, Makriyannis N, Peled U, editors. UC non-interactive, proactive, threshold ECDSA with identifiable aborts. In: Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2020 Nov 9–13; Virtual Event. [Google Scholar]

97. Challarapu N, Chivukula S. Elliptic curve cryptography applied for (k, n) threshold secret sharing scheme. ECS Trans. 2022;107(1):1021. doi:10.1149/10701.1021ecst. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Wang Y, Malluhi QM, editors. Reducing garbled circuit size while preserving circuit gate privacy. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Cryptology in Africa; 2024 Jul 10–12; Douala, Cameroon. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. [Google Scholar]

99. Guan Z, Wan Z, Yang Y, Zhou Y, Huang B. BlockMaze: an efficient privacy-preserving account-model blockchain based on zk-SNARKs. IEEE Trans Dependable Secur Comput. 2020;19(3):1446–63. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2020.3025129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Yu K, Tan L, Yang C, Choo K-KR, Bashir AK, Rodrigues JJ, et al. A blockchain-based shamir’s threshold cryptography scheme for data protection in industrial internet of things settings. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(11):8154–67. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3125190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Zhang Y, Liu F, Zuo H. Improved quantum (t, n) threshold group signature. Chin Phys B. 2023;32(9):090308. doi:10.1088/1674-1056/acac0a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Chillotti I, Gama N, Georgieva M, Izabachène M. TFHE: fast fully homomorphic encryption over the torus. J Cryptol. 2020;33(1):34–91. doi:10.1007/s00145-019-09319-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Heath D, Kolesnikov V, Peceny S editors. Masked triples: amortizing multiplication triples across conditionals. In: Proceedings of the IACR International Conference on Public-Key Cryptography; 2021 May 5–13; Edinburgh, UK. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

104. Baritompa WP, Bulger DW, Wood GR. Grover’s quantum algorithm applied to global optimization. SIAM J Optim. 2005;15(4):1170–84. doi:10.1137/040605072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Yin X, Zhu Y, Hu J. A comprehensive survey of privacy-preserving federated learning: a taxonomy, review, and future directions. ACM Comput Surv (CSUR). 2021;54(6):1–36. doi:10.1145/3460427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

106. Chauhan V, Negi S, Jain D, Singh P, Sagar AK, Sharma AK, editors. Quantum computers: a review on how quantum computing can boom AI. In: Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE); 2022 Apr 28–29; Greater Noida, India. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2022. [Google Scholar]

107. Dyakonov MI. Will we ever have a quantum computer?. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

108. Banchi L, Pereira JL, Jose ST, Simeone O. Statistical complexity of quantum learning. Adv Quantum Technol. 2024:2300311. [Google Scholar]

109. Lohia A. Quantum artificial intelligence: enhancing machine learning with quantum computing. J Quantum Sci Technol. 2024;1(2):6–11. doi:10.36676/jqst.v1.i2.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

110. Melnikov A, Kordzanganeh M, Alodjants A, Lee R-K. Quantum machine learning: from physics to software engineering. Adv Phys X. 2023;8(1):2165452. doi:10.1080/23746149.2023.2165452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

111. Khan TM, Robles-Kelly A. Machine learning: quantum vs classical. IEEE Access. 2020;8:219275–94. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3041719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Shuford J. Quantum computing and artificial intelligence: synergies and challenges. J Artif Intell Gen Sci (JAIGS). 2024;1(1). [Google Scholar]

113. Tian J, Sun X, Du Y, Zhao S, Liu Q, Zhang K, et al. Recent advances for quantum neural networks in generative learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2023;45(10):12321–40. doi:10.1109/tpami.2023.3272029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Kumar S, Simran S, Singh M, editors. Quantum intelligence: merging AI and quantum computing for unprecedented power. In: Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Trends in Quantum Computing and Emerging Business Technologies; 2024 Mar 21–22; Lavasa, India. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2024. [Google Scholar]

115. Mangini S, Tacchino F, Gerace D, Bajoni D, Macchiavello C. Quantum computing models for artificial neural networks. Europhys Lett. 2021;134(1):10002. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/134/10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

116. Zhang C, Lu Y. Study on artificial intelligence: the state of the art and future prospects. J Ind Inf Integr. 2021;23:100224. [Google Scholar]

117. Yang Q, Liu Y, Chen T, Tong Y. Federated machine learning: concept and applications. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol (TIST). 2019;10(2):1–19. doi:10.1145/3298981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

118. Somani U, Lakhani K, Mundra M, editors. Implementing digital signature with RSA encryption algorithm to enhance the Data Security of cloud in Cloud Computing. In: Proceedings of the 2010 First International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Grid Computing (PDGC 2010); 2010 Oct 28–30; Solan, India. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2010. [Google Scholar]

119. Kim JK, Ho Q, Lee S, Zheng X, Dai W, Gibson GA, et al., editors. Strads: a distributed framework for scheduled model parallel machine learning. In: Proceedings of the Eleventh European Conference on Computer Systems; 2016 Apr 18–21; London, UK. [Google Scholar]

120. Shokri R, Stronati M, Song C, Shmatikov V, editors. Membership inference attacks against machine learning models. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2017 May 22–26; San Jose, CA, USA. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2017. [Google Scholar]

121. Hall R, Fienberg SE, Nardi Y. Secure multiple linear regression based on homomorphic encryption. J off Stat. 2011;27(4):669–91. [Google Scholar]

122. Coates A, Huval B, Wang T, Wu D, Catanzaro B, Andrew N, editors. Deep learning with COTS HPC systems. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2013 Jun 16–21; Atlanta, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

123. Gilad-Bachrach R, Dowlin N, Laine K, Lauter K, Naehrig M, Wernsing J, editors. Cryptonets: applying neural networks to encrypted data with high throughput and accuracy. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2016 Jun 20–22; New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

124. Pise S, Agarkar AA, Jain S, editors. Unleashing the power of generative AI and quantum computing for mutual advancements. In: Proceedings of the 2023 3rd Asian Conference on Innovation in Technology (ASIANCON); 2023 Aug 25–27; Pune, India. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2023. [Google Scholar]

125. Liu Y, Kang Y, Xing C, Chen T, Yang Q. Secure federated transfer learning. arXiv:1812.03337. 2018. [Google Scholar]

126. Jerbi S, Fiderer LJ, Poulsen Nautrup H, Kübler JM, Briegel HJ, Dunjko V. Quantum machine learning beyond kernel methods. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):517. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36159-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Seide F, Fu H, Droppo J, Li G, Yu D, editors. On parallelizability of stochastic gradient descent for speech DNNs. In: Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2014 May 4–9; Florence, Italy. New York, NY, USA: IEEE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

128. Abadi M, Chu A, Goodfellow I, McMahan HB, Mironov I, Talwar K, et al., editors. Deep learning with differential privacy. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2016 Oct 24–28; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

129. Yin B, Yin H, Wu Y, Jiang Z. FDC: a secure federated deep learning mechanism for data collaborations in the Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(7):6348–59. doi:10.1109/jiot.2020.2966778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

130. Pöppelmann T. Efficient implementation of ideal lattice-based cryptography. It-Inf Technol. 2017;59(6):305–9. doi:10.1515/itit-2017-0030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

131. Luchnikov IA, Tiunov ES, Haug T, Aolita L. Large-scale quantum annealing simulation with tensor networks and belief propagation. arXiv:2409.12240. 2024. [Google Scholar]

132. Li Q, Quan J, Shi J, Zhang S, Li X. Secure delegated variational quantum algorithms. IEEE Trans Comput-Aided Des Integr Circuits Syst. 2024;43(10):3129–42. doi:10.1109/tcad.2024.3391690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

133. Micciancio D. Lattice-based cryptography. In: Encyclopedia of cryptography and security. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. p. 713–5. [Google Scholar]

134. Nosouhi MR, Shah SW, Pan L, Zolotavkin Y, Nanda A, Gauravaram P, et al. Weak-key analysis for BIKE post-quantum key encapsulation mechanism. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2023;18(3):2160–74. doi:10.1109/tifs.2023.3264153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

135. Shafiq M, Gu Z, Cheikhrouhou O, Alhakami W, Hamam H. The rise of “internet of things”: review and open research issues related to detection and prevention of iot-based security attacks. Wirel Commun Mob Comput. 2022;2022(1):8669348. doi:10.1155/2022/8669348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

136. Garms L, Paraïso TK, Hanley N, Khalid A, Rafferty C, Grant J, et al. Experimental integration of quantum key distribution and post-quantum cryptography in a hybrid quantum-safe cryptosystem. Adv Quantum Technol. 2024;7(4):2300304. doi:10.1002/qute.202300304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

137. Ben-Efraim A, Nissenbaum O, Omri E, Paskin-Cherniavsky A, editors. Psimple: practical multiparty maliciously-secure private set intersection. In: Proceedings of the 2022 ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security; 2022 May 30–Jun 3; Nagasaki, Japan. [Google Scholar]

138. Cramer R, Damgård IB, Dziembowski S, Hirt M, Rabin T. Efficient multiparty computations with dishonest minority. BRICS Rep Ser. 1998;5(36):19441. doi:10.7146/brics.v5i36.19441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

139. Inbar R, Omri E, Pinkas B, editors. Efficient scalable multiparty private set-intersection via garbled bloom filters. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Security and Cryptography for Networks; 2018 Sep 5–7; Amalfi, Italy. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

140. Cleve R, Gottesman D, Lo H-K. How to share a quantum secret. Phys Rev Lett. 1999;83(3):648. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.83.648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools