Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Unlocking Edge Fine-Tuning: A Sample-Efficient Language-Empowered Split Fine-Tuning Framework

1 School of Computer Science and Engineering, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, 510006, China

2 School of Computer Science and Technology, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, 430074, China

3 Pazhou Laboratory, Guangzhou, 510640, China

4 New Emerging Technologies and 5G Network and Beyond Research Chair, Department of Computer Engineering, College of Computer and Information Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11574, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Min Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advancing Network Intelligence: Communication, Sensing and Computation)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 66 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074034

Received 30 September 2025; Accepted 05 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The personalized fine-tuning of large language models (LLMs) on edge devices is severely constrained by limited computation resources. Although split federated learning alleviates on-device burdens, its effectiveness diminishes in few-shot reasoning scenarios due to the low data efficiency of conventional supervised fine-tuning, which leads to excessive communication overhead. To address this, we propose Language-Empowered Split Fine-Tuning (LESFT), a framework that integrates split architectures with a contrastive-inspired fine-tuning paradigm. LESFT simultaneously learns from multiple logically equivalent but linguistically diverse reasoning chains, providing richer supervisory signals and improving data efficiency. This process-oriented training allows more effective reasoning adaptation with fewer samples. Extensive experiments demonstrate that LESFT consistently outperforms strong baselines such as SplitLoRA in task accuracy. LESFT consistently outperforms strong baselines on GSM8K, CommonsenseQA, and AQUA_RAT, with the largest gains observed on Qwen2.5-3B. These results indicate that LESFT can effectively adapt large language models for reasoning tasks under the computational and communication constraints of edge environments.Keywords

Recent breakthroughs in large language models (LLMs) are converging with the rapid advancement of edge computing. This convergence gives rise to a critical challenge: how to achieve personalized deployment and efficient fine-tuning of models on edge devices. These devices are severely constrained by computational power, storage, and energy consumption [1–3]. Compared to traditional cloud-based inference, edge-side applications can significantly reduce communication overhead and service latency caused by remote calls, while demonstrating unique advantages in user privacy protection and continuously available intelligent services [4–6]. Edge large models are especially valuable in complex reasoning scenarios, including autonomous driving, industrial inspection, and medical diagnosis [7–10]. However, existing models often scale to billions or even trillions of parameters (e.g., GPT-3 [11], LLaMA [12]), far exceeding the computational and storage capacities of edge devices. This gap between model scale and available resources makes the effective migration and adaptation of large model inference capabilities to the edge a long-standing critical challenge for both academia and industry.

To address this challenge, researchers have explored multiple technical directions. Among them, Split Learning and its federated extension, Split Federated Learning (SFL), have been widely recognized as representative paradigms for overcoming the bottlenecks of edge deployment [13,14]. More recently, approaches that combine the idea of model splitting with parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) have emerged. For example, SplitLoRA has been proposed to enable lightweight adaptation within split architectures [15]. These methods split the model into front and back segments. The edge device processes the front part, while the server handles the remaining layers. This design reduces the client-side computation and memory burden, making split architectures highly suitable for edge intelligence. However, in few-shot and complex reasoning tasks, the effectiveness of split architectures is limited because they still rely on conventional supervised fine-tuning (SFT). Prior studies have shown that SFT and instruction tuning often exhibit low data efficiency in acquiring complex logical induction and reasoning capabilities, typically depending on large-scale annotations or human feedback data [16–18]. In split or federated settings, such low sample efficiency implies the need for more training samples and more frequent communication rounds to accomplish fine-tuning, thereby directly increasing the overall communication cost and undermining the advantages of split architectures for edge deployment. Consequently, the root cause of this limitation does not lie in the architecture itself, but rather in its incompatibility with the supervised fine-tuning paradigm under few-shot reasoning scenarios. Therefore, achieving efficient few-shot fine-tuning in edge environments remains a core open problem that requires novel methodological advances.

By effectively coordinating efficient split federated architectures with an advanced learning paradigm, LESFT provides a practical solution for personalized fine-tuning of LLMs on edge devices under dual constraints of limited resources and scarce data. The proposed framework not only inherits the advantages of split federated architectures in alleviating computational burdens but also introduces paradigm-level innovations that significantly enhance overall resource efficiency by improving data utilization in complex and few-shot reasoning scenarios.

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

• Problem Identification. We systematically analyze existing SFL frameworks and point out a previously overlooked limitation: their reliance on standard supervised fine-tuning leads to poor data efficiency in few-shot reasoning tasks. This limitation inherently increases communication overhead and restricts the applicability of SFL in resource-constrained edge environments.

• Framework Design. We propose LESFT, a new split federated fine-tuning framework that integrates a dual-path contrastive learning paradigm with the split architecture. LESFT leverages logically consistent but linguistically diverse reasoning chains to guide the model toward learning generalizable reasoning patterns, rather than memorizing specific linguistic forms, thus significantly improving few-shot learning effectiveness.

• Comprehensive Empirical Validation. We conduct a thorough empirical study across multiple reasoning domains rather than relying solely on mathematical reasoning tasks. LESFT is evaluated on three representative benchmarks: GSM8K [19] for arithmetic reasoning, CommonsenseQA [20] for commonsense multiple-choice reasoning, and AQUA_RAT [21] for algebraic word-problem reasoning. Experiments on multiple LLM scales consistently show that LESFT achieves substantial improvements over advanced baselines such as SplitLoRA. Notably, on the Qwen2.5-3B model [22], LESFT reaches 76.04% accuracy on GSM8K and yields consistent gains on CommonsenseQA and AQUA-RAT, demonstrating strong generalization across heterogeneous reasoning tasks in edge deployment scenarios.

2.1 Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning of Large Language Models

PEFT has emerged as a mainstream paradigm for adapting pre-trained LLMs to new tasks with minimal cost, preserving their strong generalization capabilities [23,24]. The core idea is to freeze the vast majority of the LLM’s parameters and update only a small, manageable subset.

Prominent PEFT techniques achieve this in various ways. For instance, Adapter Tuning inserts small, trainable modules between existing Transformer layers [25,26], while Prefix-Tuning prepends trainable vectors to the input to steer the model’s attention [27]. Other methods, like BitFit, fine-tune an extremely small fraction of existing parameters, such as the bias terms alone, yet achieve competitive performance [28]. Among the most widely adopted methods is Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [29], which utilizes a low-rank approximation for weight updates to ensure high parameter efficiency.

While these methods effectively reduce the number of trainable parameters, they fail to resolve the critical memory bottleneck during on-device training. This is because backpropagation still requires loading the entire model and storing intermediate activations, resulting in a memory footprint as high as 70% of full fine-tuning [30,31]. This memory requirement is prohibitive for most edge devices, revealing a critical gap: parameter efficiency does not equate to training efficiency. This fundamental limitation motivates architectural-level solutions. Therefore, our proposed LESFT framework leverages model splitting to overcome the memory barrier that traditional PEFT cannot, enabling efficient learning at the edge.

2.2 Federated and Split Learning for LLMs

To fine-tune LLMs on distributed edge data while preserving privacy, research has centered on two main approaches: Federated Learning (FL) and Split Learning (SL).

FL is a key paradigm for edge AI [32–34], but applying it to LLMs faces prohibitive communication and computation costs. A solution is Federated PEFT [35], where clients train and aggregate only lightweight modules. For example, FedLoRA requires exchanging only the LoRA adapters [36]. While this reduces communication, it fails to solve the local training bottleneck, as clients must still load the entire LLM. In contrast, SL directly tackles the local resource issue by partitioning the model. This property makes SL an attractive option for deploying LLMs on resource-constrained devices [37]. A natural extension is to combine SL with PEFT in methods like SplitLoRA, which mitigates the local bottleneck while keeping communication low.

The evolution from FL to SplitLoRA has progressively solved system-level bottlenecks related to communication, memory, and computation. However, these methods share a deeper limitation: their universal reliance on the conventional SFT paradigm. SFT is notoriously inefficient for complex reasoning tasks, often requiring extensive training samples and communication rounds for convergence. With system-level hurdles now largely addressed, this paradigm-level inefficiency emerges as the next critical barrier. Our work, the LESFT framework, is motivated by the need to overcome this very challenge by introducing a more data-efficient learning paradigm for LLMs at the edge.

Conventional response-level fine-tuning, or outcome-supervised learning, provides only sparse feedback from the final output, creating severe credit assignment challenges in complex reasoning tasks [38]. The model often fails to identify which reasoning steps are correct, and may even reach the right answer through flawed reasoning, a weakness reinforced by outcome-level supervision. In contrast, process supervision offers feedback to intermediate steps, yielding more reliable reasoning capabilities [39].

Building on this idea, token-level fine-tuning further refines supervision granularity by directly optimizing generated tokens. This enables more precise and stable learning and has been widely applied in SFT. However, studies show that even in high-quality datasets, many tokens are redundant or detrimental [40], diluting gradients and hindering performance. To address this, selective token optimization strategies estimate token contributions or use perplexity-based weighting to mask or down-weight non-informative tokens, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio and robustness [40,41].

Token-level techniques have also been extended to preference alignment. While Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) simplifies training, it ignores token-level variation in preference signals [42,43]. Token-Level DPO (TDPO) addresses this by modeling alignment as a token-wise Markov Decision Process, improving credit assignment and better matching the autoregressive nature of LLMs [44]. Further, Reinforced Token Optimization (RTO) integrates DPO with PPO, using dense token-level rewards from preference data to enhance policy learning and performance [45]. These advances highlight the effectiveness of token-level methods in improving accuracy and consistency for complex reasoning tasks.

Complementary to weighting and alignment approaches, Natural Language Fine-Tuning (NLFT) [41] strengthens reasoning by contrastively training on correct and incorrect reasoning chains. In this work, we adopt and extend this paradigm for few-shot reasoning in edge environments, simplifying the process to rely only on correct reasoning chains. This positive-sample strategy allows more efficient modeling of high-quality reasoning paths under limited data, improving both robustness and adaptability of LLMs.

3 The Proposed LESFT Framework

To address the computational and data constraints of fine-tuning LLMs on edge devices, we propose the LESFT framework. By integrating model structure splitting with PEFT methods, the framework reduces the computational burden on the edge side while enhancing training efficiency in few-shot scenarios. This section will detail the overall architecture, key designs, and training algorithm of LESFT.

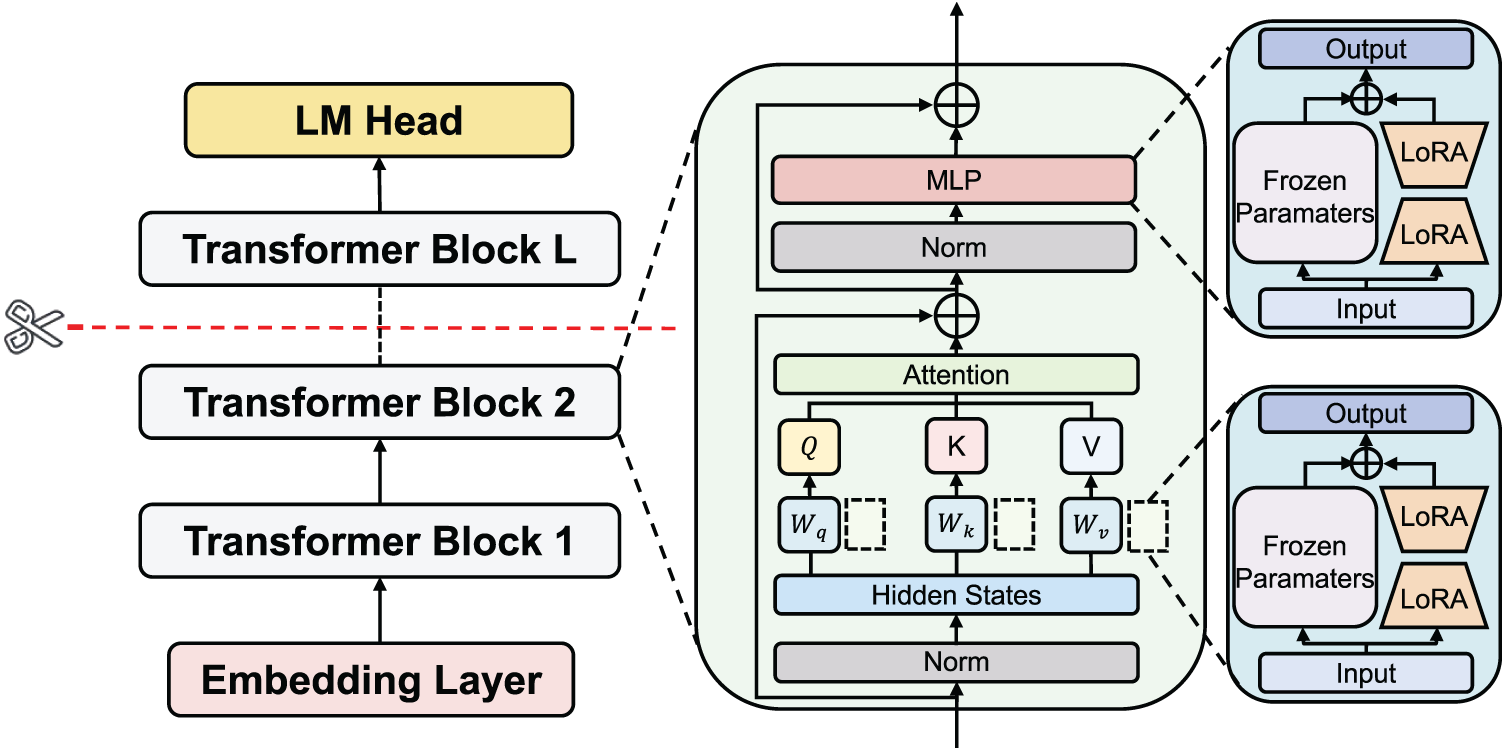

As shown in Fig. 1, LESFT splits a traditional LLM architecture into three parts: an embedding layer, Transformer blocks, and a language modeling head. During inference, the input text is converted into a sequence of token IDs by the client-side tokenizer, and the embedding layer maps these IDs to continuous representations. The intermediate Transformer layers are deployed on the server to perform feature transformation, and finally, the language modeling head outputs a sequence of tokens in an auto-regressive manner.

Figure 1: Schematic of the LLM split architecture

To alleviate the memory bottleneck on edge devices, LESFT deploys the majority of its parameters in the cloud. The client retains only the embedding layer and some lightweight components. Specifically, after the input text is tokenized and embedded locally, it is sent to the server as a high-dimensional tensor. The server then performs the forward pass to output tokens. Since the server does not have a tokenizer, it cannot access the raw data. This mechanism structurally prevents raw data from leaving the local device, thereby ensuring user privacy while achieving computational offloading.

To further reduce the training overhead on the client, our framework introduces the LoRA technique. We partition the overall parameters into pre-trained base parameters,

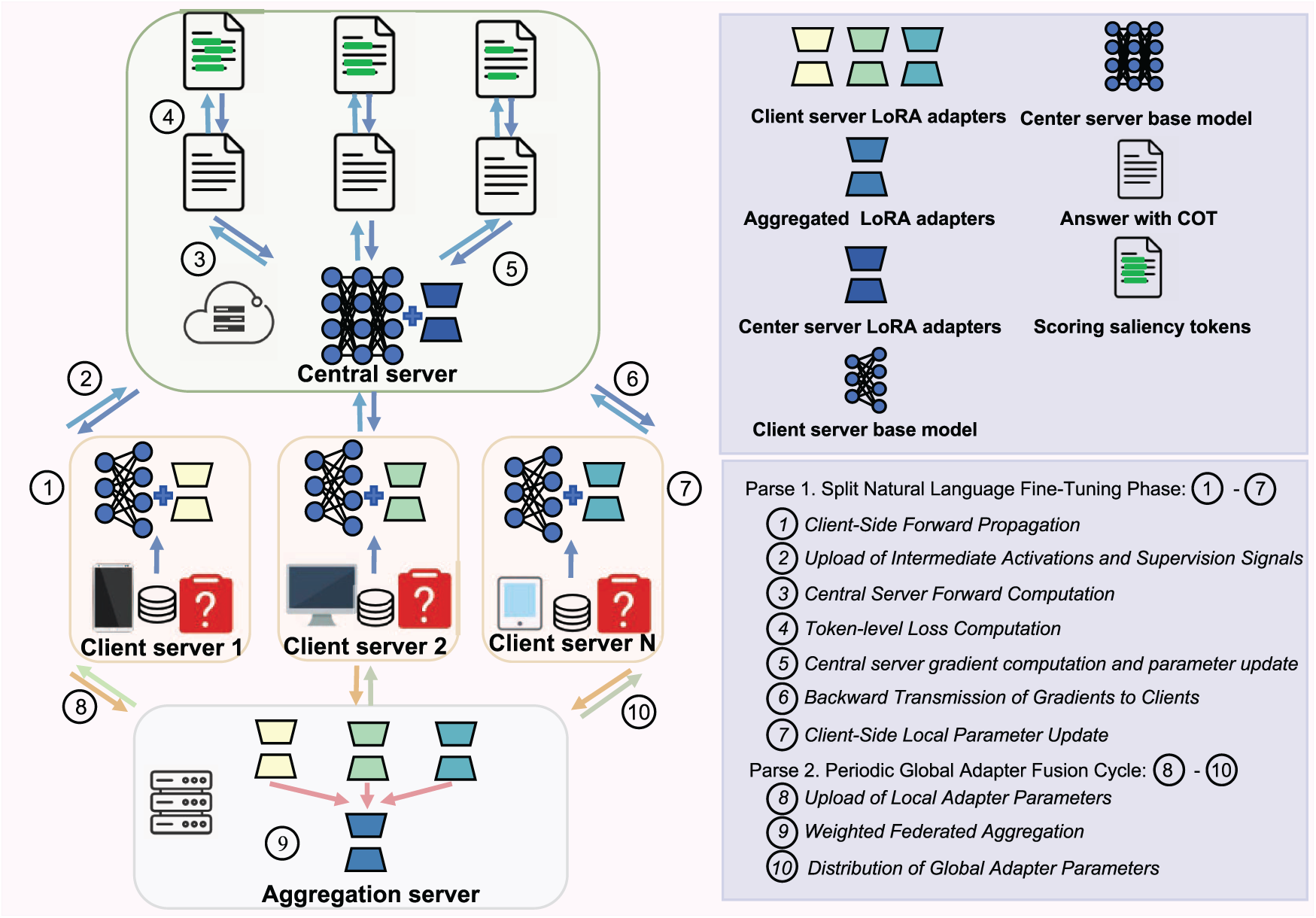

In this section, we define the problem and introduce the LESFT framework, which will be detailed in Section 3.3. The aim is to describe the system model of LESFT, laying a theoretical foundation for the subsequent sections. As illustrated in Fig. 2, we construct a typical scenario where edge users with limited computational resources fine-tune a model for complex reasoning tasks. This system comprises three core components:

Figure 2: The training workflow of LESFT

• Client Server: In this framework, a client is abstracted as an edge node with independent computing capabilities. We denote the set of all participating clients as

• Central Server: The central server is typically a more powerful computing node responsible for managing and updating the parameters of the server-side sub-model. We represent the base model weights on the server as

• Aggregation Server: During the training process, an aggregation entity is required to coordinate updates from all clients. This aggregation server periodically collects and aggregates the set of adapter parameters

We represent the overall model parameters as

where

3.3 Training Workflow of LESFT

This section details the overall workflow of the proposed LESFT framework. LESFT’s core innovation, which sets it apart from existing methods, is a fine-grained, token-level fine-tuning mechanism. We integrate this mechanism into a hierarchical split collaborative fine-tuning architecture. This approach not only enhances the model’s expressive power but also effectively reduces resource overhead. Simultaneously, LESFT incorporates the PEFT technique, LoRA, to further enhance the adaptability and efficiency of the training process.

During the training initialization phase, the central server first processes the base weights of the large model to be fine-tuned and partitions them into a server-side sub-model and a client-side sub-model to accommodate the distributed computational resources. Subsequently, LESFT performs distributed fine-tuning over I consecutive local training rounds. In each round, the clients update only their local adapter parameters, while the server updates its assigned model parameters. After completing I iterations, the aggregation server integrates the sets of LoRA adapter parameters,

Overall, the training process of LESFT consists of two main phase: (i) the split natural language fine-tuning stage, which is executed in every training round; and (ii) the client adapter aggregation stage, which is triggered every I rounds. Fig. 2 illustrates the overall workflow of LESFT, where the training round index is

Phase 1. Split Natural Language Fine-Tuning Phase: The split natural language fine-tuning phase involves client-side and server-side fine-tuning performed by the participating clients and the central server in each training round. This phase consists of the following seven steps.

1. Client-Side forward Propagation: In this step, all participating clients

The client sub-model consists of fixed pre-trained weights

here,

2. Upload of Intermediate Activations and Supervision Signals: After the client completes its local forward propagation, each client

3. Central Server Forward Computation: Upon receiving the activations and labels from all participating clients, the central server feeds these activations into its server-side model to perform the server-side forward pass. The concatenated activation matrices,

where

4. Token-Level Loss Computation: After the server-side model computes the reasoning results, the model base predictions

5. Central Server Gradient Computation and Parameter Update: After computing the token-level loss

where

6. Backward Transmission of Gradients to Clients: After the server completes its backward propagation and updates its LoRA adapter parameters, it computes the gradients of the loss function

7. Client-Side Local Parameter Update: In this step, each client, based on the received activation gradients, continues the backward propagation process on its local sub-model to update the client-side LoRA adapter parameters. For a client

where

Phase 2. Periodic Global Adapter Fusion Cycle: The client adapter aggregation phase is primarily executed by the aggregation server. Its core objective is to integrate and fuse the local LoRA adapter parameters uploaded by each client to achieve global knowledge sharing and model performance improvement. This phase is executed once every I training rounds and consists of the following three steps:

8. Upload of Local Adapter Parameters: In this step, all participating clients

9. Weighted Federated Aggregation: Upon receiving the adapter parameters from all clients, the aggregation server performs a weighted average of their LoRA parameters based on the size of each client’s local dataset to generate a globally unified client LoRA adapter,

This weighted aggregation strategy accounts for the differences in data distribution among clients, which helps to improve the generalization ability and convergence stability of the global model.

10. Distribution of Global Adapter Parameters: After the aggregation is complete, the aggregation server distributes the global adapter parameters

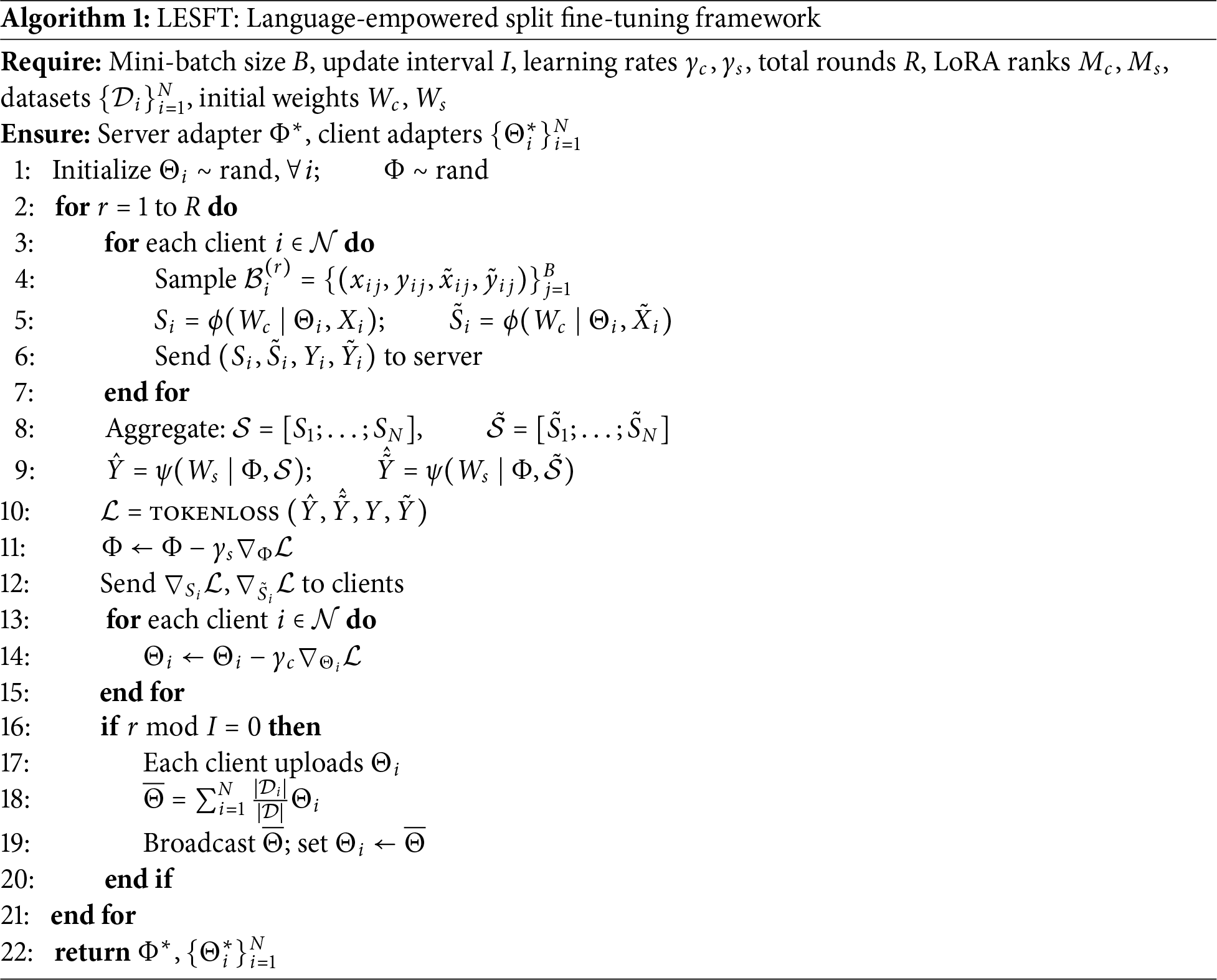

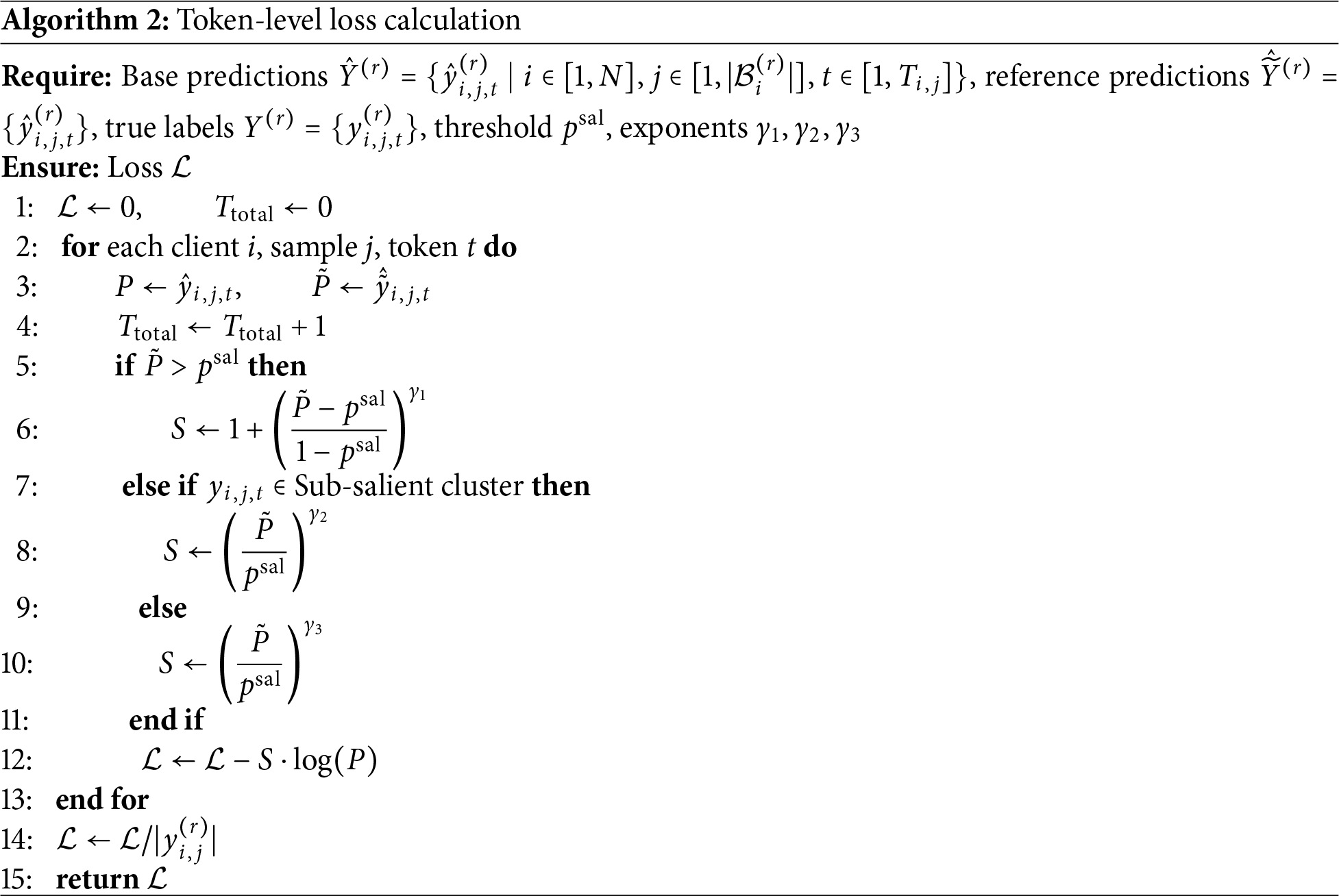

The overall training process of LESFT is summarized in Algorithm 1.

Through the algorithmic process outlined above, the LESFT framework effectively coordinates the computational resources of edge devices and cloud servers while preserving data privacy, providing a systematic solution for the efficient fine-tuning of LLMs in edge environments. The framework not only reduces the computational burden on the edge side but also significantly enhances training efficiency in few-shot scenarios through its natural language fine-tuning mechanism.

Traditional SFT optimizes by minimizing the cross-entropy loss between predictions and ground-truth labels. It treats all tokens in a reasoning chain equally, which can easily lead the model to rely on pattern memorization while neglecting logical deduction. Natural Language Fine-Tuning (NLFT) builds upon this by introducing dynamic weighting and language feedback. On one hand, it identifies salient tokens from positive and negative samples’ reasoning chains to enhance the model’s sensitivity to reasoning. On the other hand, it uses natural language feedback to locate critical steps and penalize erroneous ones, shifting the optimization objective from simple answer fitting to capability-guided learning.

NLFT assumes that answers generated by a large model can be categorized as either correct or incorrect, and it identifies salient tokens by comparing different prompts. However, in practical edge fine-tuning, model outputs are often partially correct and difficult to classify as entirely wrong. In a translation task, for example, multiple results may be semantically correct but differ in fluency and style, making it hard to determine a clear winner. Furthermore, NLFT’s approach, which involves constructing positive and two distinct negative reasoning paths, effectively triples the processing load per sample and significantly increasing computational power requirements and latency.

To address this, we propose an improved scheme that constructs only two paths: a base input and a reference input. This design reduces redundant computation. The base input provides minimal context, while the reference input serves as a quality comparator to guide the model’s learning. This introduces soft prior knowledge and forms a directional constraint on the original task, maintaining the effectiveness of contrastive learning while significantly reducing latency and computational overhead.

For a mini-batch of samples

Let the target output sequence be

When analyzing the reasoning chain generated by the model, we first identify Salient Tokens based on the conditional probability of the reference path,

For these three categories of tokens, we define a scaling weight

where

After obtaining the scaling weight for each token, we use a weighted cross-entropy on the predicted probabilities

This weighted design preserves the emphasis on logically critical tokens from NLFT while using only two input paths, thereby significantly reducing the additional computational and communication overhead in edge scenarios.

The loss calculation process of LESFT is summarized in Algorithm 2.

This section has detailed the overall architecture, training process, and core token-level loss calculation mechanism of the LESFT framework. By introducing natural language fine-tuning into a split federated fine-tuning architecture, the framework provides a systematic solution for the efficient fine-tuning of large models in edge environments. To validate the practical performance and effectiveness of our proposed framework, the next chapter will present a series of comprehensive comparative experiments and analyses conducted on public benchmark datasets.

4.1 Datasets and Data Preparation

To evaluate the generalizability and performance of the proposed framework, this study utilizes three distinct reasoning benchmarks. To simulate data-constrained edge scenarios and test few-shot learning efficiency, we uniformly and randomly sampled 800 instances from the official training set of each dataset.

GSM8K dataset. This dataset contains high quality elementary school level math word problems. The official training split comprises 7473 instances and the official test split comprises 1319 instances.

CommonsenseQA dataset. This dataset is designed for commonsense question answering and consists of multiple choice questions. The official training split comprises 9741 instances and the official test split comprises 1140 instances.

AQUA_RAT dataset. This dataset targets algebraic question answering with rationale annotations and consists of programmatic and textual solutions. The official training split comprises 97467 instances and the official test split comprises 254 instances.

Considering that the base models used in our experiments, such as Qwen2.5-3B, do not possess robust mathematical reasoning capabilities before fine-tuning, it is not feasible to have them directly generate the reasoning chains required for training. Therefore, we adopt a data distillation strategy, using a more powerful teacher model to generate high-quality fine-tuning data. Specifically, we utilize the Llama-3-8B-Instruct model, which achieves an accuracy of 77% on GSM8K, 79% on CommonsenseQA, and 81% on AQUA_RAT, to ensure the reliability of the generated supervision signals. For each dataset, we randomly select 800 samples correctly answered by the teacher model to construct the fine-tuning subset. The selected responses, combined with Chain-of-Thought prompting, provide detailed reasoning chains that serve as the ideal user outputs the student model needs to learn. Concurrently, the original solution steps from each dataset are used as the reference input to provide the constraint signal, thereby satisfying the dual-path input requirement of the LESFT framework.

To comprehensively evaluate our framework, we compare it against four representative fine-tuning methods, spanning centralized to distributed paradigms.

Centralized Supervised Fine-Tuning (Centralized SFT). This baseline reflects the upper-bound performance in a non-privacy-preserving setting, where a central server directly fine-tunes the LLM with LoRA on the entire training set, comprising 800 GSM8K samples in our study.

Federated Averaging (FedAvg). The canonical algorithm in federated learning, adapted here for LoRA-based fine-tuning. In each round, clients train local adapters on their data and upload updates to the server, which aggregates them via weighted averaging. Raw data remain local, ensuring privacy.

Split Learning (SL). A vertical partitioning strategy in which clients hold the front layers and the server holds the remaining ones. Clients send intermediate activations to the server, which completes the forward pass, computes the loss, and returns gradients. No aggregation across clients is performed, making SL suitable for evaluating performance without horizontal knowledge sharing.

SplitLoRA. An advanced variant combining split learning with federated aggregation. Adapter parameters are decomposed into shared and private parts: shared layers are collaboratively trained across clients, while private layers are updated locally to preserve personalization. This design balances knowledge sharing and data heterogeneity.

SplitFrozen [47]. This method is a split learning framework where the initial model layers deployed on client devices are frozen. Clients execute only a forward pass and transmit the resulting activations to a central server. The server holds the remaining layers and manages all training updates, applying parameter-efficient fine-tuning via LoRA exclusively to its portion of the model. This configuration avoids client-side backward propagation and can be combined with pipeline parallelism to reduce device idle time.

We conducted experiments on three models from the Qwen2.5 series with different parameter scales: Qwen2.5-0.5B, Qwen2.5-1.5B, and Qwen2.5-3B. These cover lightweight to medium-size configurations and enable validation under different resource constraints. All experiments used the original pre-trained versions to avoid potential bias introduced by instruction tuning.

A vertical splitting strategy was adopted to simulate edge devices with limited resources. The client was assigned the tokenizer, the embedding layer, and the first quarter of the Transformer layers, while the server processed the remaining layers and the language model head. This allocation reduced the computational burden on the client and enhanced data privacy. The same splitting strategy was applied to all baselines to ensure fairness in comparison.

All experiments were performed on a unified high-performance computing platform equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, PyTorch 2.3.0, and CUDA 12.1. To guarantee consistency, we used AdamW as the optimizer with a learning rate of 5e−5. The batch size per client was set to 1 with gradient accumulation of 4, resulting in an effective batch size of 4. Local training was conducted for 10 epochs on a dataset of 800 samples. Four clients were simulated, and evaluation was performed using identical prompts and validation protocols.

The LoRA configuration was kept uniform across all experiments. The rank was set to 8, lora_alpha to 16, and the dropout rate to 0.2. LoRA was applied to the gate_proj, down_proj, and up_proj linear layers. The salient token threshold was fixed at 0.95, with hyperparameters

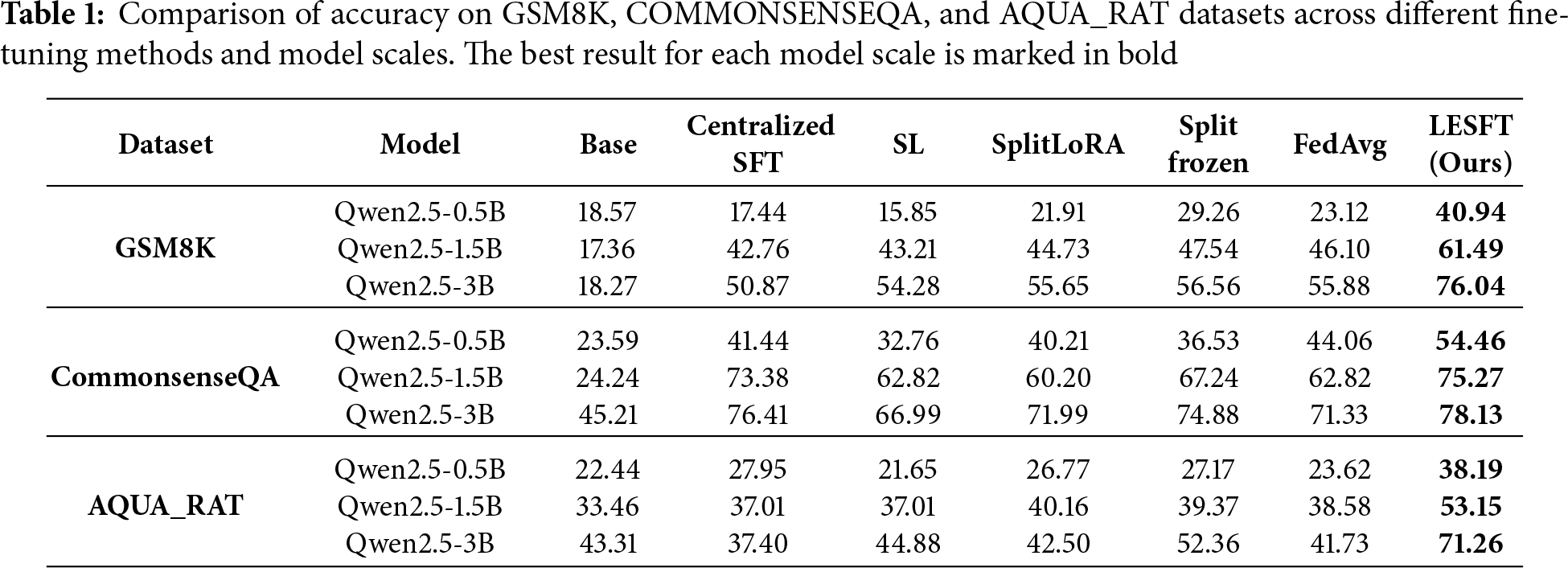

4.3.1 Comparative Analysis of Accuracy and System Overhead

The empirical results are summarized in Table 1. These results demonstrate that the proposed LESFT framework consistently outperforms all baseline methods. This holds true across all three reasoning benchmarks and model scales. This outcome validates the generalizability of our approach. On the Qwen2.5-3B model, LESFT achieves 76.04% accuracy on GSM8K, 78.13% on CommonsenseQA, and 71.26% on AQUA_RAT. These results represent significant relative improvements over the strongest baselines. For example, on GSM8K, LESFT shows a 34.4% relative gain over SplitFrozen, which scored 56.56%. LESFT also achieves a 36.1% relative gain over FedAvg, which scored 55.88%.

The unfine-tuned Base models perform poorly on all tasks. This highlights the necessity of fine-tuning. However, conventional Centralized SFT and SL show inconsistent results. They even cause performance degradation on the 0.5B model for GSM8K. This suggests that standard SFT struggles with catastrophic forgetting in low-resource, low-capacity settings.

The adoption of more advanced methods yields more stable and consistent gains. These methods include FedAvg, SplitLoRA, and SplitFrozen. SplitFrozen, in particular, shows strong performance on GSM8K, reaching 56.56% on the 3B model. This demonstrates the effectiveness of its client-side frozen approach. Nevertheless, these methods still show limited absolute performance. This indicates that architectural optimizations alone are insufficient to solve the core data-efficiency problem in few-shot reasoning.

LESFT’s superior performance stems from its unique learning mechanism. Baselines rely solely on architectural optimization. In contrast, LESFT introduces a token-level weighting strategy. This mechanism is powered by a dual-path contrastive signal. It guides the model to focus on critical logical tokens rather than optimizing all tokens equally. This semantic-level supervision effectively mitigates gradient noise in few-shot scenarios. This process enables the model to stably activate and calibrate its pre-trained reasoning capabilities using limited data.

Furthermore, the experimental results reveal the excellent scalability of LESFT. As the model scale increases from 0.5B to 3B, the performance gap between LESFT and all baseline methods tends to widen. This trend is visible across all three datasets. This indicates that on larger models, LESFT can more fully leverage the advantages of its token selection and weighting mechanism. It thereby more efficiently utilizes the parameter capacity and pre-trained knowledge of large models to achieve significant performance enhancements.

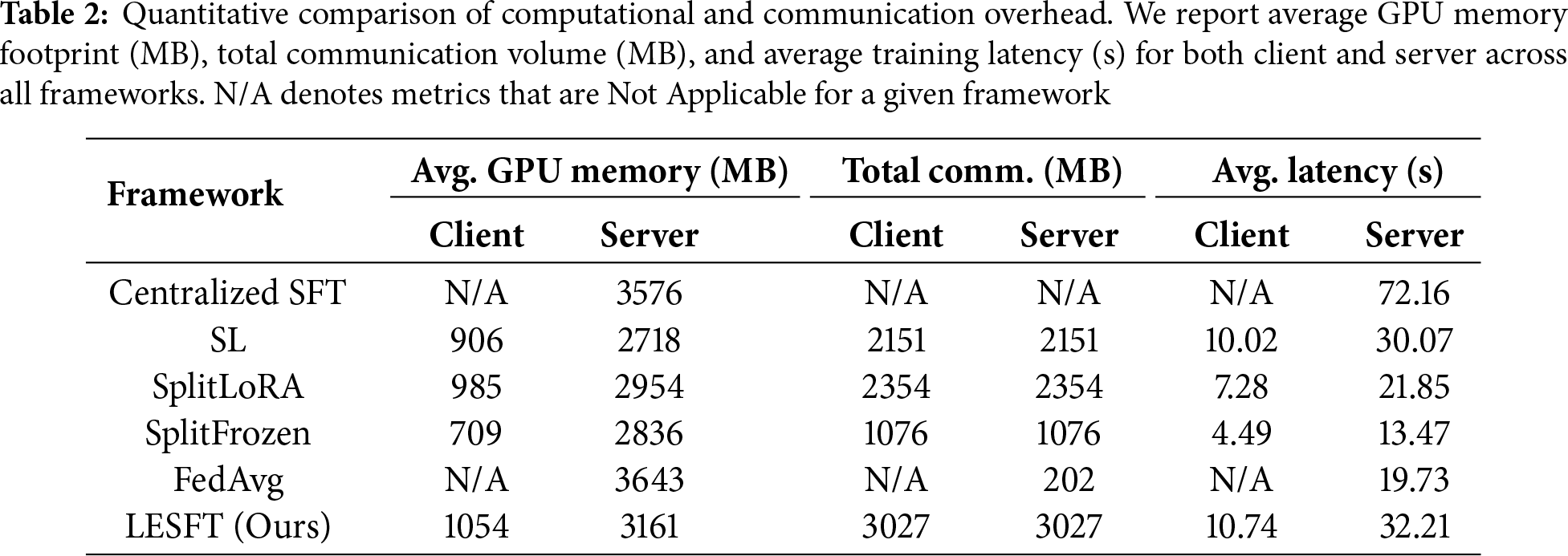

Table 2 quantifies the system overhead. The reported metrics represent the average latency and total communication volume per epoch. The N/A values for Centralized SFT and FedAvg confirm their infeasibility for client-side training. All split-based methods operate within a manageable GPU footprint. Our LESFT framework, however, incurs notably higher client latency and communication volume compared to other baselines like SplitFrozen. This increased cost is an inherent consequence of our dual-path mechanism. This mechanism is essential for generating the contrastive signal. This design represents a deliberate trade-off. We exchange a moderate, acceptable system overhead for the significant task accuracy improvements demonstrated in Table 1.

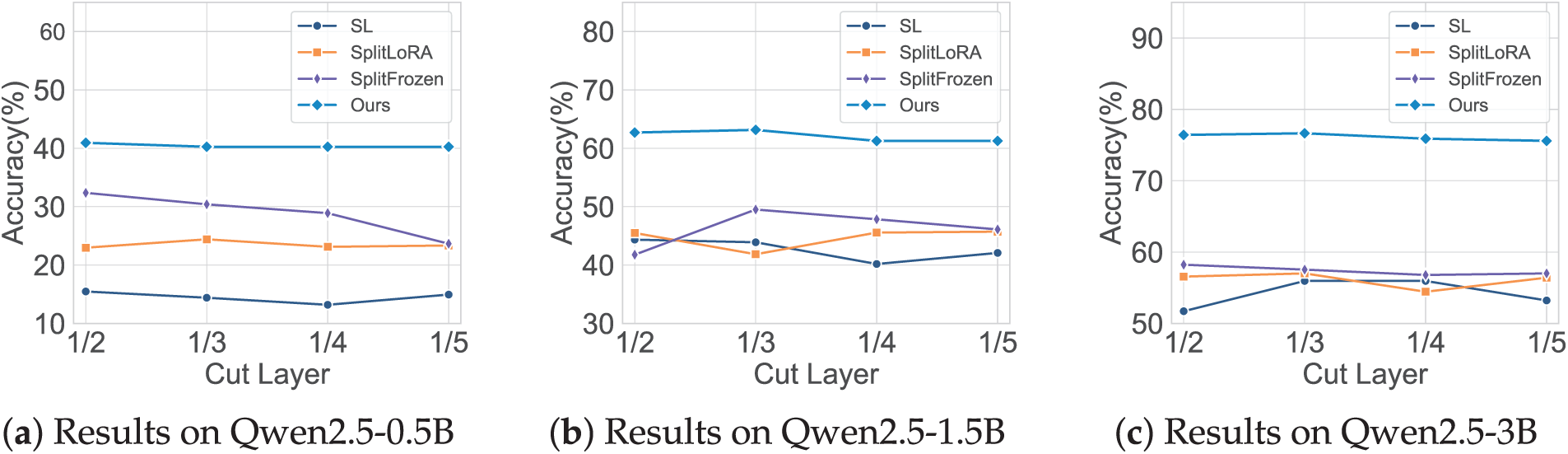

4.3.2 Analysis of the Impact of Varying the Model Split Point

To investigate the robustness of our framework, we conducted an ablation study to evaluate the sensitivity of model performance to the network split point, which is a key hyperparameter. In a distributed learning setting, the choice of the split point directly impacts the client’s computational load and the final performance; therefore, verifying the model’s stability with respect to this choice is of significant importance. We established four different split ratios, deploying the first 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, and 1/5 of the network layers on the client, and recorded the accuracy changes of our method, as well as SL and SplitLoRA, at these different split points.

The experimental results are shown in Fig. 3. Our method exhibits high stability across all tested model scales and split configurations. Its performance curve is considerably flatter compared to the baseline methods, and its accuracy consistently surpasses that of SL, SplitLoRA, and SplitFrozen. Specifically, on the largest Qwen2.5-3B model, the results shown in Fig. 3c indicate that as the split point is adjusted from 1/2 to 1/5, our method’s accuracy remains stable within the range of 75.59% to 76.65%, showing minimal fluctuation. In contrast, the baseline methods demonstrate greater sensitivity to the choice of the split point. The performance of SL and SplitLoRA shows significant fluctuations as the split point changes; for example, on the Qwen2.5-1.5B model, the accuracy of the SL method fluctuates by more than 10%. SplitFrozen shows relatively better stability than SL and SplitLoRA, but its accuracy remains consistently lower than ours across all split configurations. This indicates that while SplitFrozen partially alleviates the sensitivity issue, it does not match the overall robustness and performance of our framework.

Figure 3: Impact of different model split layers on the accuracy of fine-tuning methods on the GSM8K dataset

The results of this ablation study demonstrate that our proposed framework possesses good robustness, as its performance is not sensitive to the choice of the network split point. This offers significant convenience for its fine-tuning application in real-world scenarios.

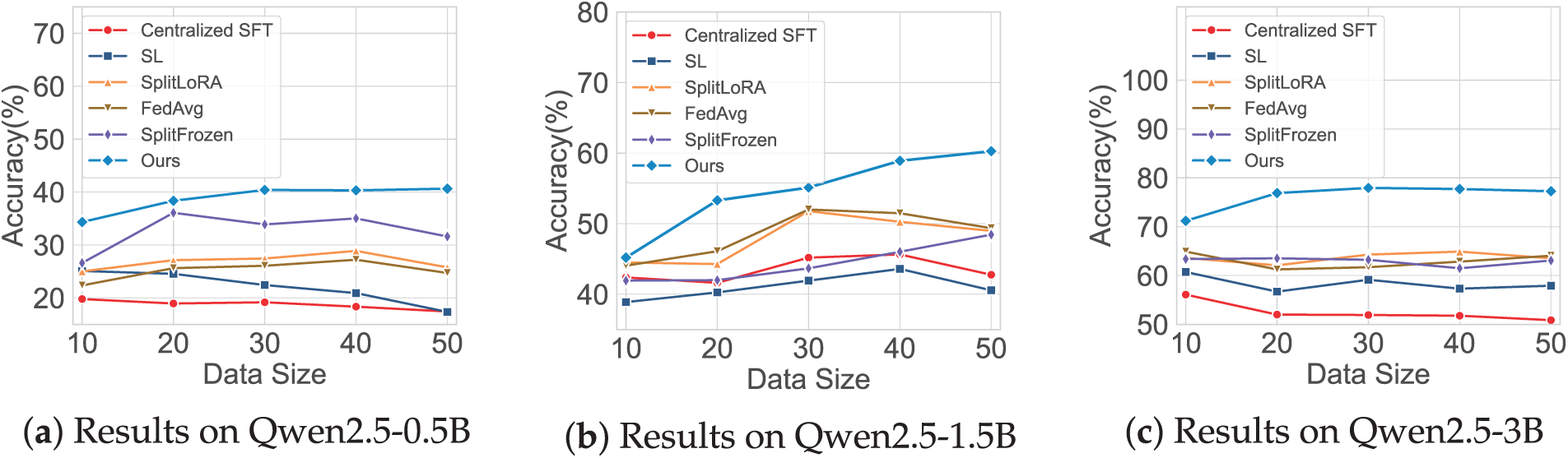

4.3.3 Analysis of the Impact of Varying the Number of Samples

To evaluate the data efficiency of our framework under few-shot conditions, we conducted an experiment where we systematically varied the number of samples used for fine-tuning. In this experimental setup, we simulated a distributed fine-tuning environment with 4 clients and adjusted the size of each client’s local dataset to 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 samples, respectively. For comparison, the Centralized SFT baseline was trained on the corresponding aggregated sample sets, ranging from 40 to 200 total samples.

The experimental results are shown in Fig. 4. As can be seen, the performance of our proposed method is consistently higher than that of all baseline methods across all tested model scales and sample size configurations. This advantage is particularly pronounced in scenarios where data is extremely limited. For instance, on the Qwen2.5-3B model with only 10 samples per client, our method achieves 71.19% accuracy, while SplitLoRA and FedAvg reach 63.61% and 64.90%, respectively. SplitFrozen, despite its improved stability, achieves 63.88%, and Centralized SFT trained on 40 samples yields only 56.10%. As the number of samples increases, the performance of all methods shows an upward trend, but the gap between our method and the baselines remains clear. This indicates that our framework achieves higher data utilization efficiency. This advantage stems from the natural language fine-tuning paradigm, which uses high-level instructions to guide the model in leveraging pre-trained knowledge for task understanding, reducing reliance on large-scale labeled data. These results demonstrate that the proposed framework is well-suited for edge scenarios with constrained data resources.

Figure 4: Impact of different numbers of training samples on the accuracy of fine-tuning methods on the GSM8K dataset

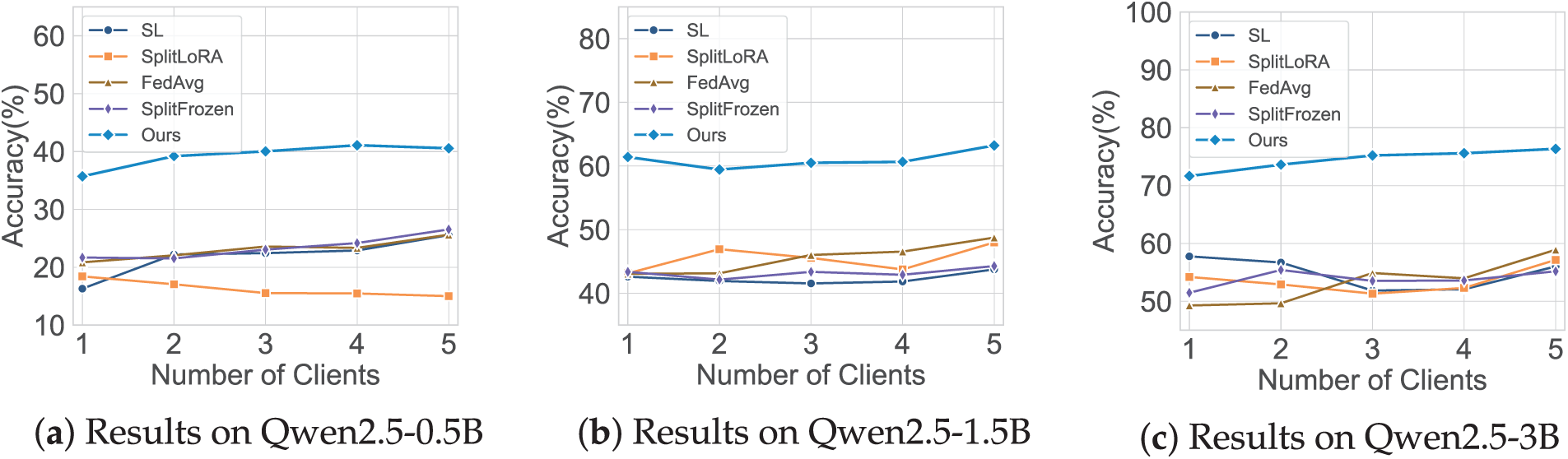

4.3.4 Analysis of the Impact of Varying the Number of Clients

To evaluate the scalability and robustness of our framework under different distributed configurations, we conducted an experiment by varying the number of clients from 1 to 5 while keeping the total training data constant. This simulates realistic federated learning scenarios where data becomes increasingly decentralized.

The results in Fig. 5 show that our method consistently outperforms all baselines across model scales and client counts. On the Qwen2.5-3B model, our accuracy remains above 71% across all settings, reaching up to 76.36% with 5 clients. In contrast, methods such as SplitLoRA and SL exhibit noticeable performance drops as the number of clients increases. SplitFrozen shows better stability but still trails behind our method in overall accuracy.

Figure 5: Impact of different numbers of clients on the accuracy of fine-tuning methods on the GSM8K dataset

This robustness can be attributed to our framework’s dual-path supervision and periodic adapter aggregation. By learning from both base and reference reasoning chains, the model captures core reasoning patterns and reduces reliance on any single client’s data distribution. The aggregation mechanism further enables mutual learning among clients, enhancing generalization in decentralized environments.

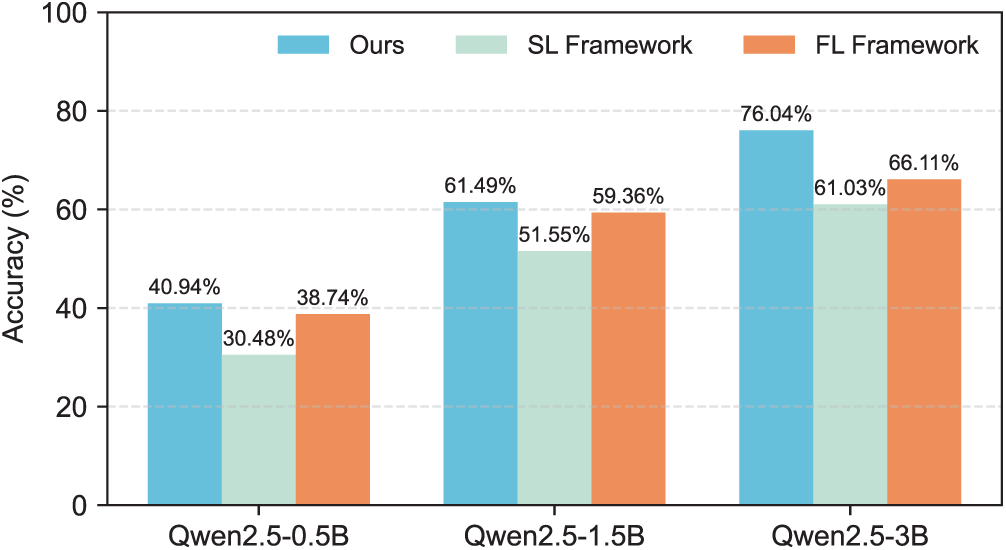

An ablation study was first conducted to validate the architectural components of LESFT. Three configurations were compared, as shown in Fig. 6. The Ours configuration is the complete LESFT SFL framework. The SL Framework applies the paradigm within a pure Split Learning architecture without aggregation. The FL Framework uses a conventional, non-split Federated Learning architecture. The results show the full SFL framework consistently outperforms both architectural variants across all model scales. The performance gap over the FL Framework highlights the benefit of the split-based design. The gap over the SL Framework confirms the critical importance of federated aggregation. These results validate that the synergy of combining split learning and federation is a key factor in LESFT’s effectiveness.

Figure 6: Ablation study on the architectural framework. LESFT (SFL) consistently outperforms both SL framework and FL framework variants across different model scales

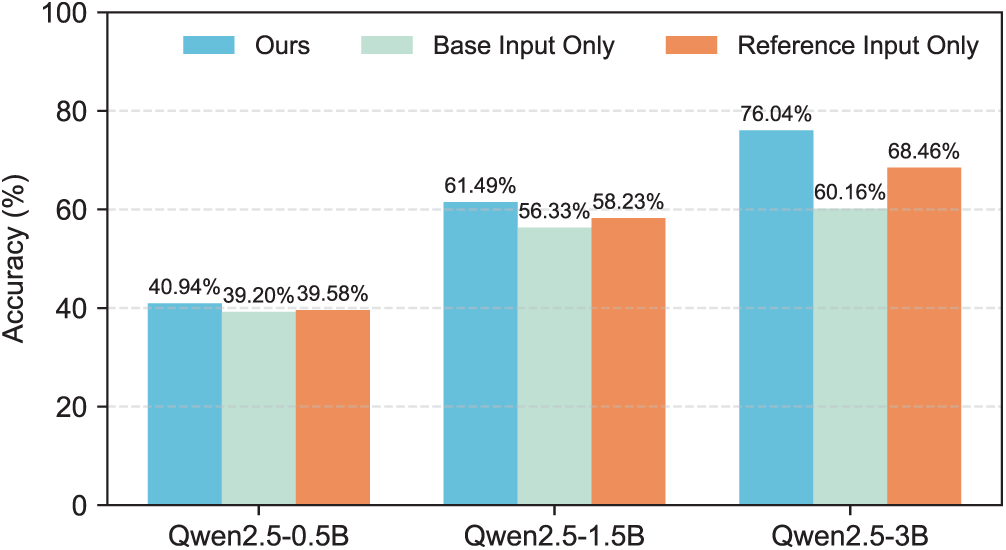

The analysis next isolates the contribution of the core dual-path mechanism. As shown in Fig. 7, the full LESFT model Ours is compared against two single-path variants. These are Base Input Only, which uses only the standard input, and Reference Input Only, which uses only the high-quality reference input for training. The results on the Qwen2.5-3B model are particularly illustrative. The Base Input Only variant achieves 60.16% accuracy. Using the high-quality Reference Input Only improves this to 68.46%. Crucially, the full dual-path model Ours significantly outperforms both, achieving 76.04%. This finding is critical. It demonstrates that the performance gain does not come from merely using a higher-quality input. Instead, the contrastive signal generated by the interaction between the two logically-equivalent paths is essential. This signal guides the model to learn generalizable reasoning patterns and achieve superior data efficiency.

Figure 7: Ablation study on the dual-path mechanism. LESFT consistently outperforms both single-path variants using only the base input or the reference input across different model scales

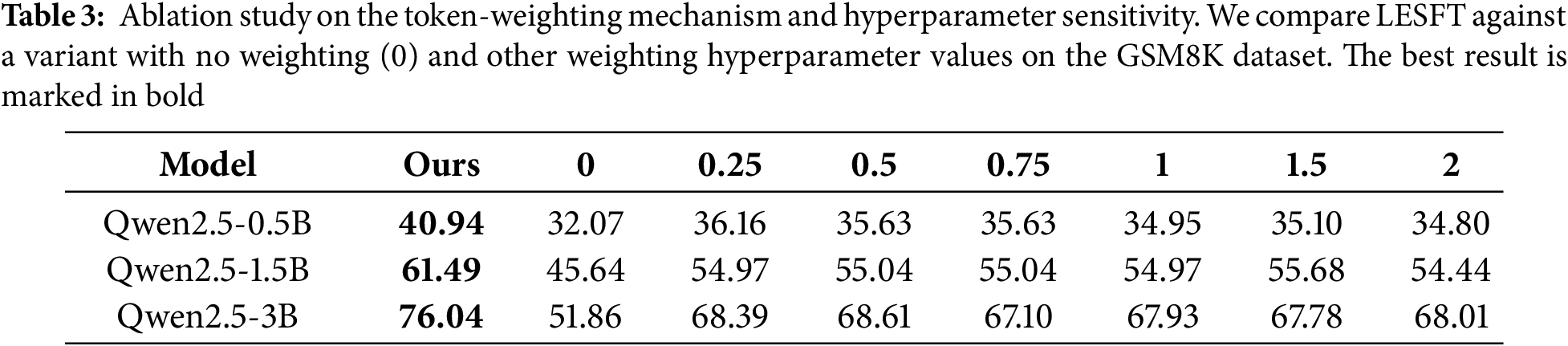

The analysis next examines the effect of the token-weighting mechanism. As shown in Table 3, the proposed adaptive weighting strategy Ours consistently achieves the highest accuracy across all model scales. In contrast, assigning uniform values such as 0 leads to a clear performance drop. For Qwen2.5-0.5B, accuracy decreases from 40.94% to 32.07%. For Qwen2.5-1.5B, accuracy falls from 61.49% to 45.64%. For Qwen2.5-3B, accuracy declines from 76.04% to 51.86%. These results indicate that removing token-level differentiation severely limits reasoning adaptation. The sensitivity analysis further shows that moderate weighting values between 0.25 and 0.75 yield more stable results than extreme values equal to or greater than 1.5. However, none of these settings surpass the adaptive mechanism. This confirms that the proposed token-weighting design is essential for maximizing data efficiency and reasoning accuracy in LESFT.

LESFT emphasizes the token as the fundamental unit of large language models and leverages the dual-path mechanism to highlight differences between base and reference reasoning chains. By contrasting these two paths, the framework guides the model to identify and learn the most informative tokens, thereby improving credit assignment and enabling generalizable reasoning patterns under few-shot conditions. This fine-grained supervision directly addresses the data inefficiency of conventional approaches and explains the consistent gains observed across diverse tasks and model scales.

In addition, the split federated design adapts naturally to edge environments. The model is partitioned so that computation and storage burdens are minimized on clients, while privacy is preserved by keeping raw data local. Periodic aggregation of lightweight adapters allows edge models to exchange knowledge without exposing sensitive information. This mechanism enables each client to benefit from the progress of others, achieving collective improvement across heterogeneous and potentially non-IID data distributions.

The proposed framework is particularly well-suited for reasoning-intensive tasks, where intermediate steps and token-level supervision are critical. Examples include mathematical problem solving, commonsense reasoning, and multi-step question answering. In these domains, the dual-path contrast provides richer signals than outcome-only supervision, allowing the model to capture logical dependencies more effectively. Beyond reasoning tasks, LESFT can also adapt to structured prediction problems such as code generation or symbolic manipulation, where token-level granularity plays a decisive role. Its reliance on modular adapters and federated aggregation further ensures applicability across diverse model scales and heterogeneous client data, making it a general solution for edge deployment in both reasoning-centric and structured learning scenarios.

This paper addresses the incompatibility between efficient SFL architectures and data-inefficient SFT, a key challenge that creates prohibitive communication bottlenecks for LLMs on edge devices. We introduce the LESFT framework, a novel paradigm designed to co-optimize computation, communication, and data efficiency. The core of LESFT is a contrastive-inspired fine-tuning method that uses logically consistent yet diversely expressed reasoning chains to provide a robust supervision signal. This design compels the model to shift from memorization toward generalizable reasoning, which significantly improves data efficiency and directly translates to reduced communication overhead.

Our extensive experiments across three diverse reasoning benchmarks, GSM8K, CommonsenseQA, and AQUA_RAT, validate that LESFT substantially outperforms all state-of-the-art baselines, including SplitLoRA and SplitFrozen. The framework’s superiority stems from its ability to focus on critical logical tokens, allowing it to stably activate and calibrate pre-trained reasoning capabilities with limited data. Our ablation studies further demonstrate the framework’s robustness, showing its performance is stable against variations in network split points and data distribution, highlighting its practical applicability in diverse edge environments.

Future work can extend LESFT in several directions. Enhancing its robustness to non-IID data is critical for complex federated scenarios. Furthermore, developing adaptive split-point mechanisms and integrating lightweight privacy-preserving techniques could enable more intelligent and secure deployments. Combining LESFT with retrieval-augmented generation also offers a path to overcome static knowledge limitations in specialized domains. In conclusion, this work not only provides a validated framework for efficient edge fine-tuning but also demonstrates a promising direction for overcoming resource constraints through the co-design of learning paradigms and system architectures.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant 62276109. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through the Research Group Project number (ORF-2025-585).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Zuyi Huang, Yue Wang; Methodology, Zuyi Huang; Software, Zuyi Huang, Yue Wang; Validation, Zuyi Huang, Jia Liu, Haodong Yi; Formal analysis, Zuyi Huang; Investigation, Zuyi Huang, Haodong Yi, Lejun Ai; Writing—original draft preparation, Zuyi Huang, Yue Wang, Haodong Yi; Data curation, Yue Wang; Visualization, Zuyi Huang; Resources, Jia Liu, Salman A. AlQahtani, Min Chen; Writing—review and editing, Zuyi Huang, Yue Wang, Haodong Yi, Min Chen; Supervision, Min Chen; Project administration, Min Chen; Funding acquisition, Salman A. AlQahtani, Min Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data supporting the results presented in this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zheng Y, Chen Y, Qian B, Shi X, Shu Y, Chen J. A review on edge large language models: design, execution, and applications. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(8):1–35. doi:10.1145/3719664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen Y, Wu C, Sui R, Zhang J. Feasibility study of edge computing empowered by artificial intelligence—a quantitative analysis based on large models. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2024;8(8):94. doi:10.3390/bdcc8080094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yang Z, Ji W, Wang Z. Adaptive joint configuration optimization for collaborative inference in edge-cloud systems. Sci China Inf Sci. 2024;67(4):149103. doi:10.1007/s11432-023-3957-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Xiao W, Ling X, Chen M, Liang J, Alqahtani SA, Chen M. Mvpoa: a learning-based vehicle proposal offloading for cloud-edge-vehicle networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(5):4738–49. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2024.3524469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Shen Y, Shao J, Zhang X, Lin Z, Pan H, Li D, et al. Large language models empowered autonomous edge AI for connected intelligence. IEEE Commun Magaz. 2024;62(10):140–6. doi:10.1109/MCOM.001.2300550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xiao W, Shi C, Chen M, Liu Z, Chen M, Song HH. GraphEdge: dynamic graph partition and task scheduling for GNNs computing in edge network. Inf Fusion. 2025;124(5):103329. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2025.103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chen J, Dai S, Chen F, Lv Z, Tang J, Han L. Edge-cloud collaborative motion planning for autonomous driving with large language models. In: 2024 IEEE 24th International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT); 2024 Oct 18–20; Chengdu, China. p. 185–90. doi:10.1109/ICCT62411.2024.10946488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Nguyen HTT, Nguyen LPT, Cao H. XEdgeAI: a human-centered industrial inspection framework with data-centric Explainable Edge AI approach. Inf Fusion. 2025;116(1):102782. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Shakhadri SAG, Kruthika KR, Aralimatti R. Shakti: a 2.5 billion parameter small language model optimized for edge ai and low-resource environments. In: IFIP International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2025. p. 434–47. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-96231-8_32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li M, Ji W. Lightweight multiattention recursive residual CNN-based in-loop filter driven by neuron diversity. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2023;33(11):6996–7008. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2023.3270729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Brown T, Mann B, Ryder N, Subbiah M, Kaplan JD, Dhariwal P, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv Neur Inform Process Syst. 2020;33:1877–901. [Google Scholar]

12. Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, Martinet X, Lachaux MA, Lacroix T, et al. Llama: open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv:2302.13971. 2023. [Google Scholar]

13. Thapa C, Chamikara MAP, Camtepe SA. Advancements of federated learning towards privacy preservation: from federated learning to split learning. In: Federated learning systems: towards next-generation AI. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 79–109. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-70604-3_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Qu G, Chen Q, Wei W, Lin Z, Chen X, Huang K. Mobile edge intelligence for large language models: a contemporary survey. IEEE Commun Surv Tutorials. 2025;27(6):3820–60. doi:10.1109/COMST.2025.3527641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lin Z, Hu X, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Fang Z, Chen X, et al. Splitlora: a split parameter-efficient fine-tuning framework for large language models. arXiv:2407.00952. 2024. [Google Scholar]

16. Ouyang L, Wu J, Jiang X, Almeida D, Wainwright C, Mishkin P, et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2022;35:27730–44. [Google Scholar]

17. Wei J, Bosma M, Zhao V, Guu K, Yu AW, Lester B, et al. Finetuned language models are zero-shot learners. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022 Apr 25; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

18. Wu XK, Chen M, Li W, Wang R, Lu L, Liu J, et al. Llm fine-tuning: concepts, opportunities, and challenges. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2025;9(4):87. doi:10.3390/bdcc9040087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhong Q, Wang K, Xu Z, Ding L, Liu J, Du B. Achieving >97% on gsm8k: deeply understanding the problems makes llms better solvers for math word problems. Front Comput Sci. 2026;20(1):1–3. doi:10.1007/s11704-025-41102-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Talmor A, Herzig J, Lourie N, Berant J. Commonsenseqa: a question answering challenge targeting commonsense knowledge. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); 2019 Jun 2–7; Minneapolis, MA, USA. p. 4149–58. doi:10.18653/v1/N19-1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ling W, Yogatama D, Dyer C, Blunsom P. Program induction by rationale generation: learning to solve and explain algebraic word problems. In: Proceedings of the 55th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2017 Jul 30–Aug 4; Vancouver, BC, Canada. p. 158–67. doi:10.18653/v1/P17-1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yang A, Yang BS, Hui BY, Zheng B, Yu BW, Zhou C, et al. Qwen2 technical report. arXiv:2407.10671. 2024. [Google Scholar]

23. Han Z, Gao C, Liu J, Zhang J, Zhang SQ. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning for large models: a comprehensive survey. Trans Mach Learn Res. arXiv:2403.14608. 2024. [Google Scholar]

24. Ding N, Qin Y, Yang G, Wei F, Yang Z, Su Y, et al. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning of large-scale pre-trained language models. Nat Mach Intell. 2023;5(3):220–35. doi:10.1038/s42256-023-00626-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hu Z, Wang L, Lan Y, Xu W, Lim EP, Bing L, et al. Llm-adapters: an adapter family for parameter-efficient fine-tuning of large language models. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2023 Dec 6–10; Singapore. p. 5254–76. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.emnlp-main.319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen Z, Xu L, Zheng H, Chen L, Tolba A, Zhao L, et al. Evolution and prospects of foundation models: from large language models to large multimodal models. Comput Mater Contin. 2024;80(2):1753–808. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.052618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li XL, Liang P. Prefix-tuning: optimizing continuous prompts for generation. In: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers); 2021 Aug 1–6; Virtual. p. 4582–97. doi:10.18653/v1/2021.acl-long.353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zaken EB, Goldberg Y, Ravfogel S. Bitfit: simple parameter-efficient fine-tuning for transformer-based masked language-models. In: Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers); 2022 May 22–27; Dublin, Ireland. p. 1–9. doi:10.18653/v1/2022.acl-short.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Hu EJ, Shen Y, Wallis P, Allen-Zhu Z, Li Y, Wang S, et al. Lora: low-rank adaptation of large language models. In: Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2022 Apr 25–29; Virtual. [Google Scholar]

30. Sung YL, Cho J, Bansal M. Lst: ladder side-tuning for parameter and memory efficient transfer learning. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 35. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2022. p. 12991–3005. [Google Scholar]

31. Jin F, Zhang J, Zong C. Parameter-efficient tuning for large language model without calculating its gradients. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; 2023 Dec 6–10; Singapore. p. 321–30. doi:10.18653/v1/2023.emnlp-main.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kuang W, Qian B, Li Z, Chen D, Gao D, Pan X, et al. Federatedscope-llm: a comprehensive package for fine-tuning large language models in federated learning. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2024 Aug 25–29; Barcelona, Spain. p. 5260–71. doi:10.1145/3637528.3671573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang J, Liu Z, Yang X, Li M, Lyu Z. The internet of things under federated learning: a review of the latest advances and applications. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(1):1–39. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.058926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu X, Zhou Y, Wu D, Hu M, Chen M, Guizani M, et al. CPFedAvg: enhancing hierarchical federated learning via optimized local aggregation and parameter mixing. IEEE Trans Netw. 2025;33(3):1160–73. doi:10.1109/TON.2025.3526866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Hu J, Wang D, Wang Z, Pang X, Xu H, Ren J, et al. Federated large language model: solutions, challenges and future directions. IEEE Wirel Commun. 2025;32(4):82–9. doi:10.1109/MWC.009.2400244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yang Y, Long G, Lu Q, Zhu L, Jiang J, Zhang C. Federated low-rank adaptation for foundation models: a survey. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI ’25; 2025 Aug 18–22; Montreal, QC, Canada. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2025/1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Basubeit O, Alenazi A, Radovič B, Milibari A, Canini M, Khayyat Z. LLM optimization without data sharing: a split learning paradigm. In: Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking and Applications (MetaCom); 2025 Aug 27–29; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 75–81. doi:10.1109/MetaCom65502.2025.00019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ghosh S, Evuru CKR, Kumar S, Ramaneswaran S, Aneja D, Jin Z, et al. A closer look at the limitations of instruction tuning. In: Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning; 2024 Jul 21–27; Vienna, Austria. p. 15559–89. [Google Scholar]

39. Lightman H, Kosaraju V, Burda Y, Edwards H, Baker B, Lee T, et al. Let’s verify step by step. In: Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2024 May 7–11; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

40. Pang J, Di N, Zhu Z, Wei J, Cheng H, Qian C, et al. Token cleaning: fine-grained data selection for LLM supervised fine-tuning. In: Proceedings of the Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning; 2025 Jul 13–19; Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

41. Liu J, Wang Y, Lin Z, Chen M, Hao Y, Hu L. Natural language fine-tuning. arXiv:2412.20382. 2024. [Google Scholar]

42. Rafailov R, Sharma A, Mitchell E, Manning CD, Ermon S, Finn C. Direct preference optimization: your language model is secretly a reward model. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2023;36:53728–41. [Google Scholar]

43. Moradi M, Yan K, Colwell D, Samwald M, Asgari R. A critical review of methods and challenges in large language models. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(2):1681–98. doi:10.32604/cmc.2025.061263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Zeng Y, Liu G, Ma W, Yang N, Zhang H, Wang J. Token-level direct preference optimization. In: Proceedings of the Forty-first International Conference on Machine Learning; 2024 Jul 21–27; Vienna, Austria. p. 58348–65. [Google Scholar]

45. Zhong H, Shan Z, Feng G, Xiong W, Cheng X, Zhao L, et al. DPO meets PPO: reinforced token optimization for RLHF. In: Proceedings of the Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning; 2025 Jul 13–19; Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

46. Wei J, Wang X, Schuurmans D, Bosma M, Xia F, Chi E, et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2022;35:24824–37. [Google Scholar]

47. Ma J, Lyu X, Jiang J, Cui Q, Yao H, Tao X. SplitFrozen: split learning with device-side model frozen for fine-tuning LLM on heterogeneous resource-constrained devices. arXiv:2503.18986. 2025. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools