Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Big Data-Driven Federated Learning Model for Scalable and Privacy-Preserving Cyber Threat Detection in IoT-Enabled Healthcare Systems

1 Department of Computer Science, University of Sharjah, University City Sharjah, Sharjah, P.O. Box 27272, United Arab Emirates

2 Department of Software Engineering, Faculty of Information Technology, Al-Ahliyya Amman University, Amman, 19328, Jordan

3 Department of Computer Science, College of Computer Science and Information Technology, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, P.O. Box 1982, Dammam, 31441, Saudi Arabia

4 School of Computing, Horizon University College, Ajman, P.O. Box 5700, United Arab Emirates

5 Riphah School of Computing & Innovation, Faculty of Computing, Riphah International University, Lahore Campus, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

6 Applied Science Research Center, Applied Science Private University, Amman, 11118, Jordan

7 Department of Software, Faculty of Artificial Intelligence and Software, Gachon University, Seongnam-si, 13120, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Khan M. Adnan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Intrusion Detection Systems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 29 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074041

Received 30 September 2025; Accepted 14 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The increasing number of interconnected devices and the incorporation of smart technology into contemporary healthcare systems have significantly raised the attack surface of cyber threats. The early detection of threats is both necessary and complex, yet these interconnected healthcare settings generate enormous amounts of heterogeneous data. Traditional Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), which are generally centralized and machine learning-based, often fail to address the rapidly changing nature of cyberattacks and are challenged by ethical concerns related to patient data privacy. Moreover, traditional AI-driven IDS usually face challenges in handling large-scale, heterogeneous healthcare data while ensuring data privacy and operational efficiency. To address these issues, emerging technologies such as Big Data Analytics (BDA) and Federated Learning (FL) provide a hybrid framework for scalable, adaptive intrusion detection in IoT-driven healthcare systems. Big data techniques enable processing large-scale, high-dimensional healthcare data, and FL can be used to train a model in a decentralized manner without transferring raw data, thereby maintaining privacy between institutions. This research proposes a privacy-preserving Federated Learning–based model that efficiently detects cyber threats in connected healthcare systems while ensuring distributed big data processing, privacy, and compliance with ethical regulations. To strengthen the reliability of the reported findings, the results were validated using cross-dataset testing and 95% confidence intervals derived from bootstrap analysis, confirming consistent performance across heterogeneous healthcare data distributions. This solution takes a significant step toward securing next-generation healthcare infrastructure by combining scalability, privacy, adaptability, and early-detection capabilities. The proposed global model achieves a test accuracy of 99.93% ± 0.03 (95% CI) and a miss-rate of only 0.07% ± 0.02, representing state-of-the-art performance in privacy-preserving intrusion detection. The proposed FL-driven IDS framework offers an efficient, privacy-preserving, and scalable solution for securing next-generation healthcare infrastructures by combining adaptability, early detection, and ethical data management.Keywords

Cybersecurity is the act of protecting systems, networks, and sensitive data against unauthorized access, interruption, and emerging cyber threats in the digital era [1,2]. With the increased interconnection and dependency of individuals, organizations, and governments on digital infrastructures, data availability, confidentiality, and integrity have become a crucial area of concern [3,4]. To mitigate risks and secure critical resources, it is essential to implement a comprehensive set of active, multilayered defense strategies tailored to the evolving complexity of cyber threats.

IDS is a fundamental cybersecurity technology in such a scenario and is essential for detecting unauthorized or malicious network traffic [5,6]. IDS systems typically use traffic analysis, behavior profiling, and pattern recognition to identify anomalies and known attack signatures. Traditional IDS infrastructures, however, are usually built on centralized machine-learning models, where sensitive information from multiple sources is collected at a single site for training [7,8]. This centralized dependency not only limits adaptability to emerging cyber threats but also raises ethical and regulatory concerns by increasing the risk of data exposure and patient privacy violations in healthcare environments. This leads to major issues regarding data privacy, exposure, and adherence to regulatory guidelines, particularly in highly sensitive fields like healthcare [9]. Moreover, centralized IDS often struggles with the increasing scale, velocity, and heterogeneity of network traffic, leading to performance degradation, data imbalance, and limited adaptability to novel or evolving attack patterns. These challenges highlight the critical gap between existing centralized architectures and the dynamic, distributed nature of modern IoT ecosystems.

The advent of interconnected healthcare systems enabled by smart medical devices, Electronic Health Records (EHRs), wearable sensors, and telemedicine platforms has also increased the complexity of cybersecurity [10,11]. Such systems generate high-dimensional, heterogeneous, and high-velocity data in large volumes across geographically distributed regions, a common feature of Big Data. Real-time analysis of this type of data is important for detecting emerging threats and reducing response time. However, conventional IDS and centralized analytics pipelines cannot scale with such data-intensive environments. Hence, there is an urgent need for innovative, adaptive solutions that ensure privacy, scalability, and real-time detection across decentralized, data-sensitive networks, such as healthcare IoT systems.

This challenge underscores the need to integrate Big Data analytics into cybersecurity frameworks, leveraging parallel processing, feature engineering, and intelligent data summarization to manage massive and complex healthcare data streams [12]. Yet, applying Big Data techniques alone is insufficient unless combined with a privacy-aware learning strategy that avoids data centralization [13].

Traditional machine learning techniques typically rely on centralized data collection, where all training data must be aggregated on a single server. This approach poses significant privacy, security, and scalability challenges, especially in domains like healthcare and IoT, where sensitive or distributed data cannot be easily shared [14–17]. To address these critical needs, this research adopts FL—a decentralized machine learning paradigm [14–16] that enables multiple clients (such as hospitals, edge devices, or healthcare units) to collaboratively train a global intrusion detection model without sharing raw data [17–20]. Instead of transmitting sensitive data, only model updates (such as gradients or weights) are communicated to a central coordinator. This not only preserves data privacy and minimizes communication costs but also aligns with healthcare-specific regulations like HIPAA and GDPR.

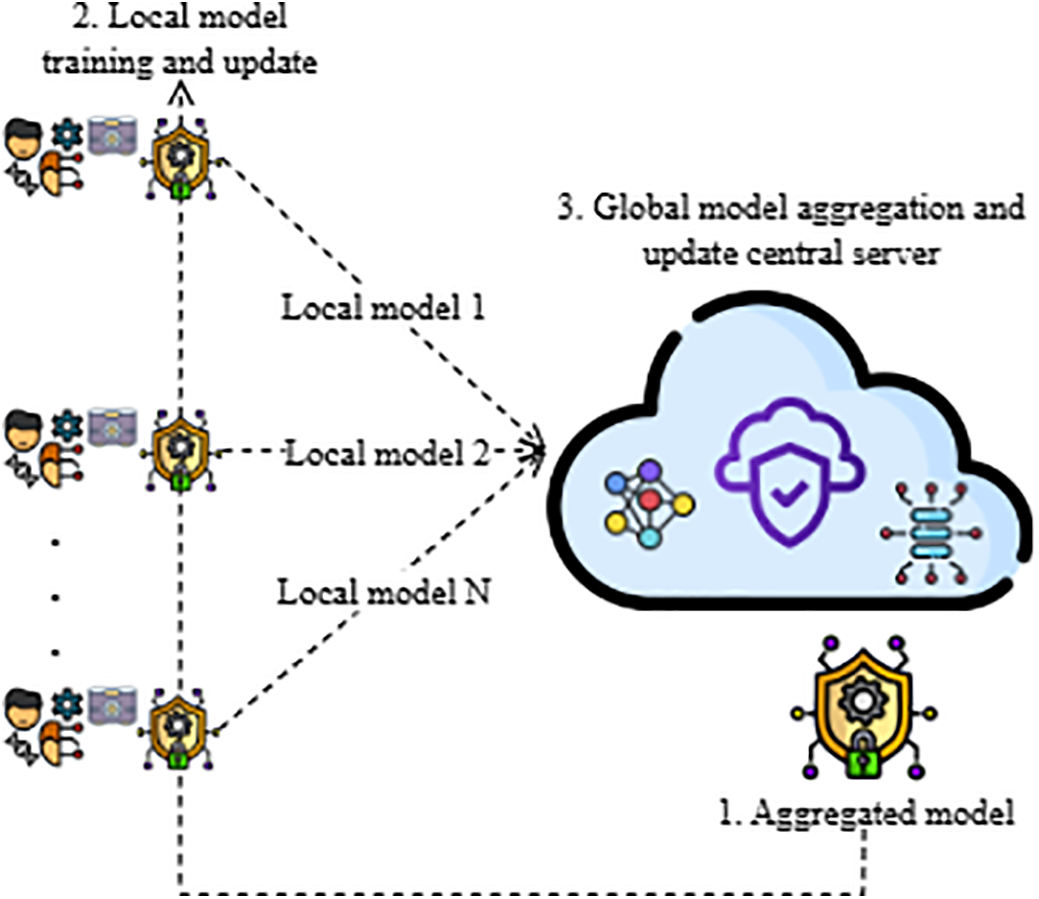

FL [21,22] empowers IDS to perform real-time, privacy-preserving, and interpretable threat detection across distributed and data-sensitive environments such as smart cities. In this paradigm, individual client nodes—including edge devices, sensors, and institutional systems—carry out local training on their respective data without transmitting raw records. As illustrated in Fig. 1, these locally trained models are securely sent to a central server, where a global model is aggregated. This decentralized approach ensures collaborative learning while preserving data locality and reducing exposure risks. FL is particularly well-suited to smart city infrastructure, where data is highly heterogeneous and spans critical domains such as healthcare, transportation, energy, and public safety. Without centralized data pooling, FL reduces privacy concerns while providing scalability and responsiveness, both of which are necessary in current cyber threat detection systems.

Figure 1: FL architecture for privacy-preserving intrusion detection in healthcare IoT systems

While FL provides notable benefits in terms of privacy preservation and distributed model training, it still faces specific operational challenges [23,24]. The primary objectives of a modern cybersecurity system are to gain stakeholders’ trust, coordinate actions to inform decisions, and respond promptly in critical scenarios. Other areas, like public safety and critical infrastructure, require more than merely detecting a cyber threat; they also require the ability to act swiftly and confidently. A cybersecurity framework based on FL should therefore prioritize secure data exchange, distributed joint detection, and effective implementation responsiveness to enable timely countermeasures and successful deployment in distributed environments [25–27].

The combination of Big Data analytics and FL yields a system well-adapted to contemporary connected healthcare conditions. The former provides strong parallel processing capabilities for large, complex datasets, whereas the latter is privacy-preserving, system-scalable, and data-local during the learning process. When combined, they can provide an encouraging path toward designing new IDS that can promptly and safely detect a broad range of cyber threats.

This study introduces a privacy-preserving FL–based IDS that maintains sensitive healthcare data in a decentralized manner, thereby ensuring confidentiality and regulatory compliance. By integrating Big Data analytics with advanced preprocessing, the model efficiently handles large-scale, diverse traffic for improved detection accuracy and adaptability. Overall, it provides a scalable and intelligent solution for real-time intrusion detection in distributed healthcare systems.

Several research studies have explored advanced techniques to enhance intrusion detection performance while addressing challenges such as data privacy, decentralization, and scalability. Classical centralized IDS designs tend to have excessive communication overhead and privacy risks due to the exposure of consolidated information. To eliminate these constraints, this study has increasingly considered FL coupled with Big Data analytics, which enables training models across multiple sources without revealing sensitive central data. This incorporation provides scalable, privacy-preserving IDS solutions that can efficiently operate in complex, heterogeneous environments.

In this research [28], a Ciphertext-Policy Attribute-Based Keyword Search and Data Sharing (CPAB-KSDS) scheme is introduced to enhance data security in cloud environments. The model alleviates the shortcomings of the previous approaches by supporting attribute-based keyword search and data sharing on encrypted data. The primary strength of CPAB-KSDS is that it eliminates the need for multiple interactions with the Public Key Generator (PKG) when updating keywords. The proposed scheme is also known to be secure against chosen-ciphertext and keyword attacks and has been tested to be efficient in practical performance tests.

In this research [29], a novel mechanism, Public Key Encryption with Authentication Search (PKE-AS), is proposed to address critical challenges in secure data sharing and access control in cloud environments. The research identifies the shortcomings of current Searchable Encryption (SE) schemes, especially their susceptibility to internal threats and keyword-guessing attacks. PKE-AS will therefore introduce an authentication-based search protocol that uses the Shared Secret Key (SSK) to encrypt keywords and generate the trapdoor, thereby improving the system’s resilience against more intrusive attacks. The outcomes of experiments illustrate the method’s low execution time and practical applicability, demonstrating better performance than classical SE approaches while providing high-level security guarantees for encrypted cloud data.

According to recent research [30], hybrid IDS that integrate deep learning with traditional machine learning methods have shown promising results in enhancing network security. One such study proposes a novel algorithm that combines Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks with K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) for both binary and multi-class classification tasks on the NSL-KDD dataset. The LSTM model captures temporal dependencies in network traffic, while KNN adds complementary classification strength. Experimental findings reveal improved accuracy, precision, and recall compared to standalone traditional models, highlighting the effectiveness of hybrid strategies in detecting evolving cyber threats.

In [31], the authors presented a deep learning-driven Network IDS (NIDS) optimized explicitly for Internet of Things (IoT) environments, addressing critical challenges such as high-dimensional data, class imbalance, and real-time detection needs. Recognizing the explosive growth of IoT devices and their susceptibility to cyber threats, the proposed framework leverages edge computing to efficiently classify network traffic at the network periphery, thereby reducing latency and conserving bandwidth. The methods used to preprocess data in the study were more complex (i.e., random under-sampling, feature scaling, class weighting) as these approaches were intended to reduce data skewness and enhance generalization. Moreover, the authors considered various feature selection methods to improve model efficiency without reducing its detection accuracy. This system was carefully tested on the CICIoT2023 benchmark dataset, which showed impressive results: the proposed 1D-Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) achieved a high F1-score of 93.8%. The results highlight the model as a potentially effective method for classifying benign traffic and the seven most common IoT-specific attacks, as well as a highly effective method for intrusion detection in resource-limited IoT environments.

In [32], the authors introduce FS-DL, a memory-friendly and fast NIDS that uses feature selection and deep learning to improve accuracy and runtime. Techniques such as standard deviation filtering and association rule mining are employed to eliminate attribute redundancy, improve data quality, and minimize computational expense in FS-DL. The model utilizes an extremely minimalist three-layer neural network with a small number of neurons, achieving good detection performance despite using a limited number of input features. FS-DL was designed to operate in Software-Defined Networking (SDN) environments, enabling the detection of anomalies in real-time with minimal impact on other resources. Hard experimental evidence demonstrates its efficiency in detecting threats within the network, with fast and scalable performance.

In [33], the authors present a comprehensive taxonomy of machine learning approaches for constructing NIDS, highlighting their potential to overcome key limitations of traditional systems. The study emphasizes how ML techniques enhance detection rates, reduce false alarm occurrences, and support the identification of previously unseen intrusions. It also provides a critical review of benchmark datasets and recent innovations in ML-driven NIDS frameworks, outlining the strengths and weaknesses of various algorithms. The findings suggest that ML-based IDS can offer adaptive, accurate, and robust network protection, paving the way for more intelligent and resilient cybersecurity solutions.

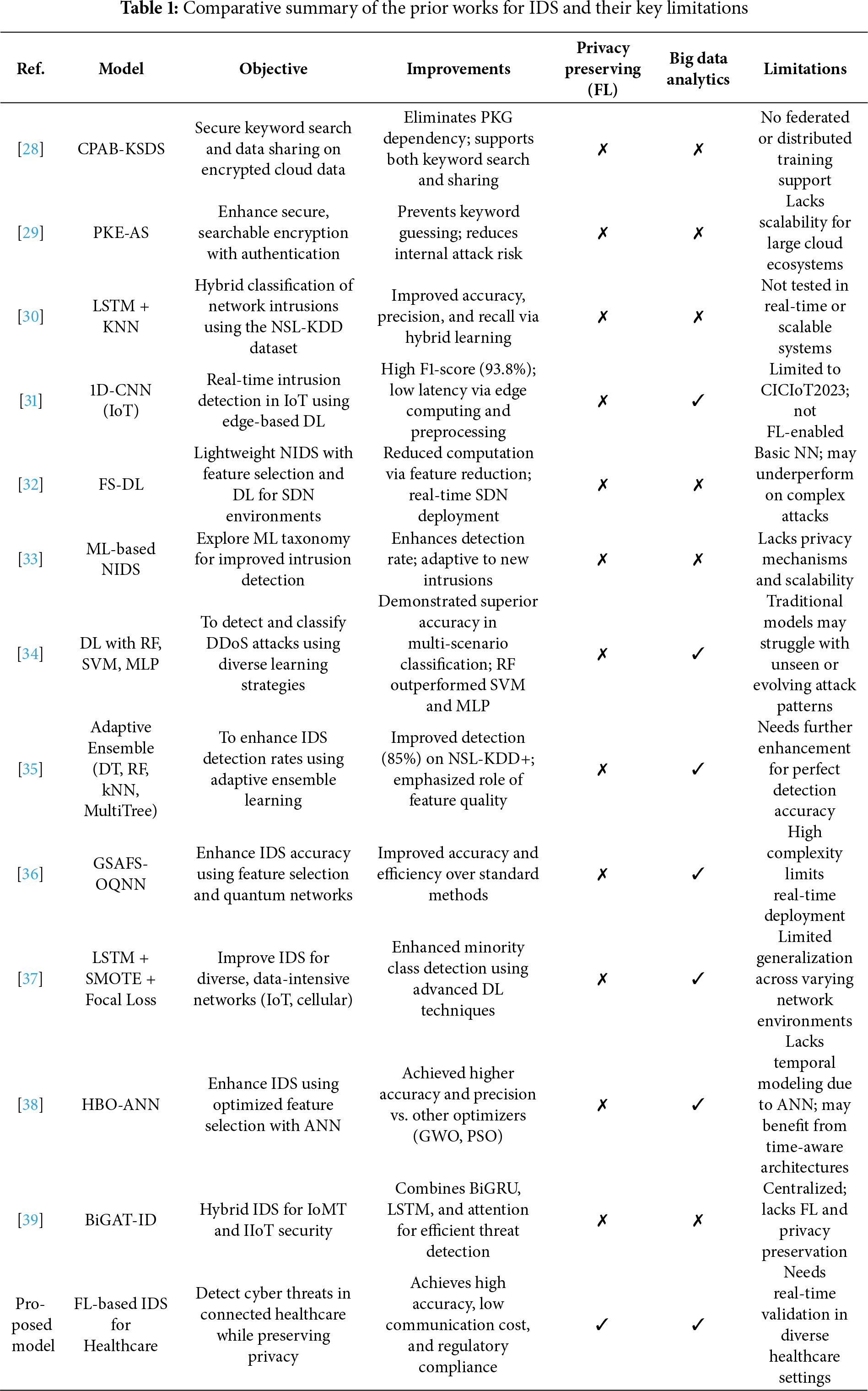

Table 1 shows that recent advancements in IDS span a wide range of models, from traditional encryption-based methods like CPAB-KSDS and PKE-AS to more sophisticated deep learning and hybrid machine learning approaches. While most models significantly improve detection accuracy, precision, or computational efficiency, only a few address critical aspects such as privacy preservation and Big Data analytics. Notably, the proposed FL-based IDS for healthcare stands out by integrating privacy, scalability, regulatory compliance, and Big Data processing, marking a substantial step forward in securing next-generation connected environments.

3 Limitations of Prior Published Works

Despite significant progress in intrusion detection and data security, several limitations persist across the reviewed models:

3.1 Lack of Privacy-Preserving Mechanisms

Many reviewed models ([28] CPAB-KSDS, [29] PKE-AS, [30] LSTM + KNN, [31] 1D-CNN, [32] FS-DL, [33–35]) do not incorporate privacy-preserving techniques such as FL. As a result, they risk exposing sensitive data during centralized model training, making them unsuitable for privacy-sensitive domains like healthcare or finance.

3.2 No Big Data Handling in Critical Models

Several security-focused models ([28–32]) lack integrated Big Data analytics capabilities, making them less suitable for environments with massive, heterogeneous data streams (e.g., smart cities, IoT networks). This limits their ability to extract meaningful insights from high-volume traffic in real time.

4 Contribution of the Proposed Model

The reviewed literature demonstrates diverse contributions that address core aspects of modern cyber threat detection:

4.1 Privacy-Preserving and Decentralized Learning

The Proposed FL-based IDS addresses this gap by integrating FL to ensure that sensitive healthcare data remains decentralized. This enhances privacy compliance (e.g., HIPAA) while maintaining strong detection capabilities.

4.2 Big Data-Enabled Intelligence

The Proposed Model demonstrates the integration of Big Data techniques and preprocessing strategies to process large-scale network traffic efficiently. This enables better detection accuracy and greater adaptability in data-intensive environments.

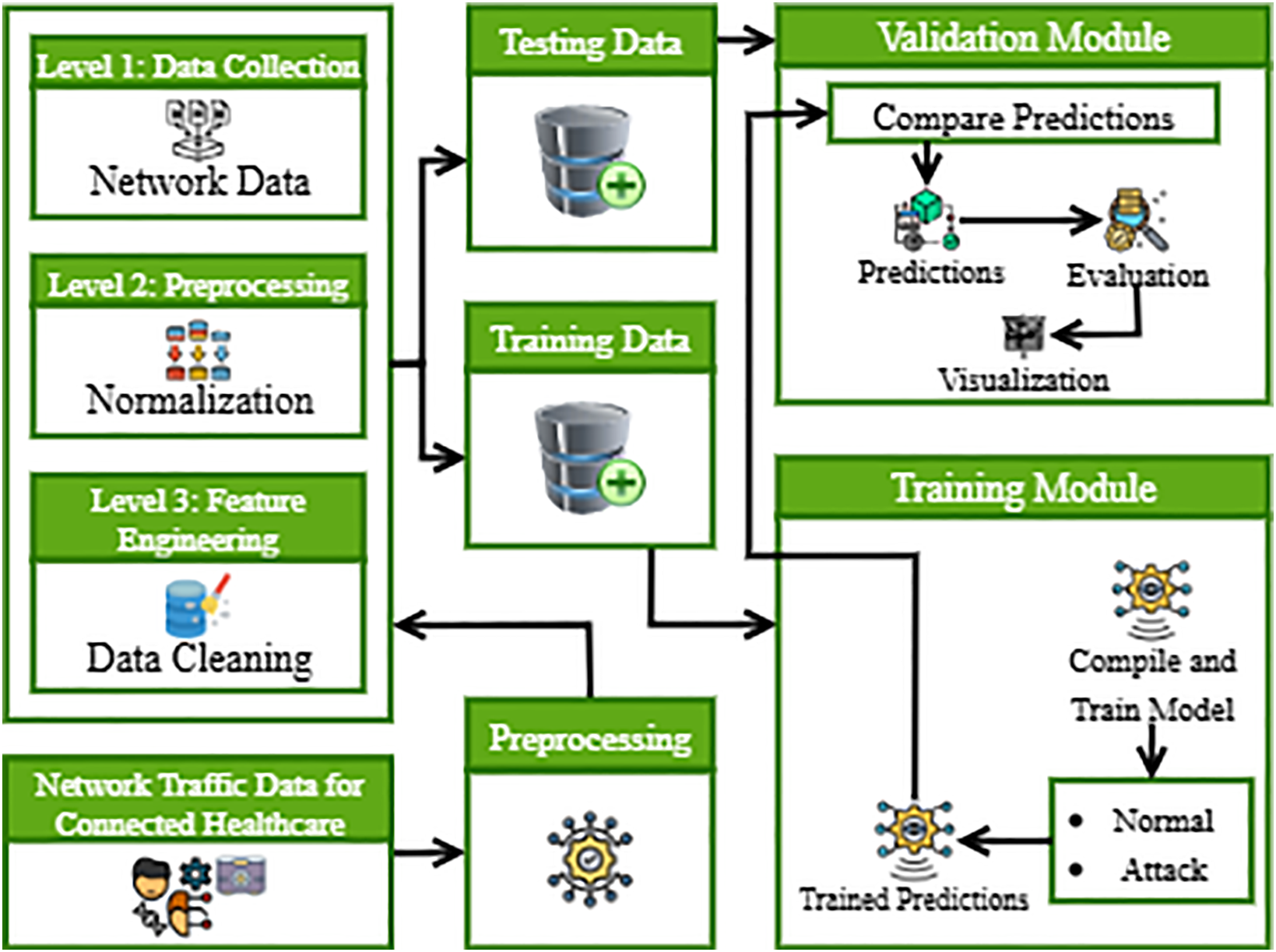

Modern connected healthcare systems produce massive volumes of heterogeneous data, significantly increasing exposure to cyber threats. Traditional IDS, often centralized, faces critical limitations in handling such data due to privacy concerns, poor scalability, and an inability to process real-time, distributed data effectively. To overcome these challenges, the proposed model introduces a novel Federated Learning (FL)-based cyber threat detection framework, integrated with Big Data Analytics to enable robust, privacy-preserving, and scalable IDS deployment in connected healthcare environments. Unlike prior FL-based IDS studies that rely on static averaging and fixed retraining cycles, this framework introduces reliability-weighted aggregation and adaptive retraining to dynamically optimize global model convergence and robustness. FL ensures that local hospital data remains decentralized, maintaining patient confidentiality while allowing collaborative model training. Big Data techniques enable efficient handling of high-dimensional, large-scale traffic patterns. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the proposed model offers enhanced threat detection accuracy, reduced communication overhead, and compliance with regulatory standards (e.g., HIPAA), making it highly suitable for real-world, distributed healthcare settings.

Figure 2: Overview of the proposed model (local client)

Fig. 2 illustrates that the process is initiated using a network traffic dataset collected from connected healthcare environments. The data is then passed through a preprocessing stage that comprises three levels (Level 1: Data Collection, Level 2: Normalization, and Level 3: Feature Engineering and Data Cleaning). After preprocessing, the dataset is split into training and testing sets. The training data is used to train machine learning models and generate predictions. These predictions are then validated using the validation module, which evaluates them against the test data to assess the model’s performance and accuracy.

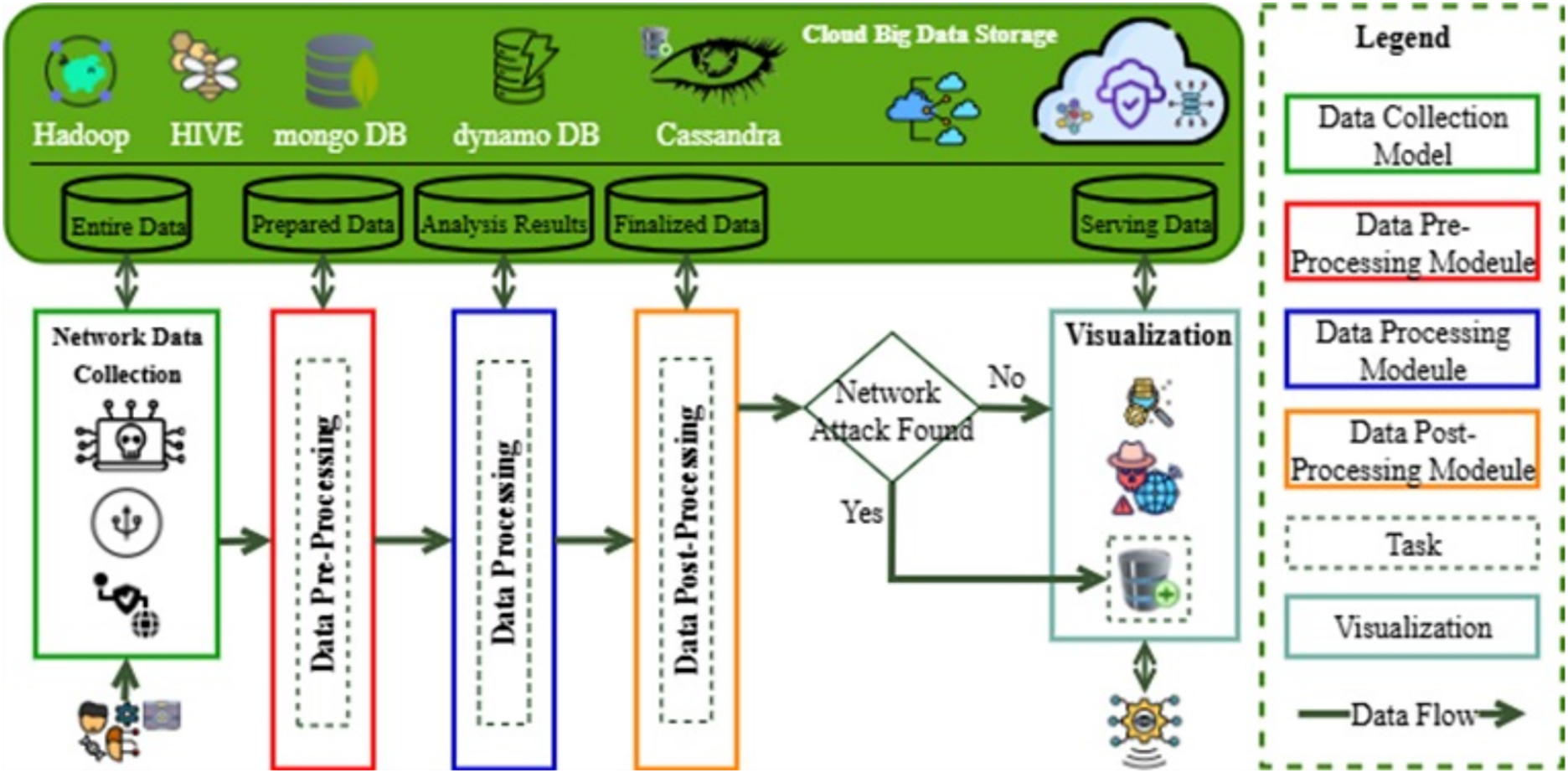

Fig. 3 depicts an integrated, big-data-driven cybersecurity architecture tailored for connected healthcare networks. The process begins with the collection of diverse network data, including traffic logs and device-level communication, which is then passed through three systematic stages: data pre-processing, processing, and post-processing. These stages refine the data by cleaning, selecting features, and performing analytical transformations to enhance quality and relevance for intrusion detection. At each step, intermediate outputs are stored across robust cloud-based big data platforms, including Hadoop, Hive, MongoDB, DynamoDB, and Cassandra. These storage systems enable scalable handling of high-volume, heterogeneous healthcare traffic, supporting real-time accessibility and secure archival. After processing, the system evaluates the refined data to detect potential network attacks; if an intrusion is detected, it triggers alerts and provides insights for further action. Otherwise, the data is forwarded to a visualization module that helps interpret security trends and system behavior. Architecture ensures a seamless flow between data refinement and intelligent storage, providing a transparent, scalable foundation for robust cyber threat detection in healthcare environments.

Figure 3: Abstracted workflow of the proposed model (local client)

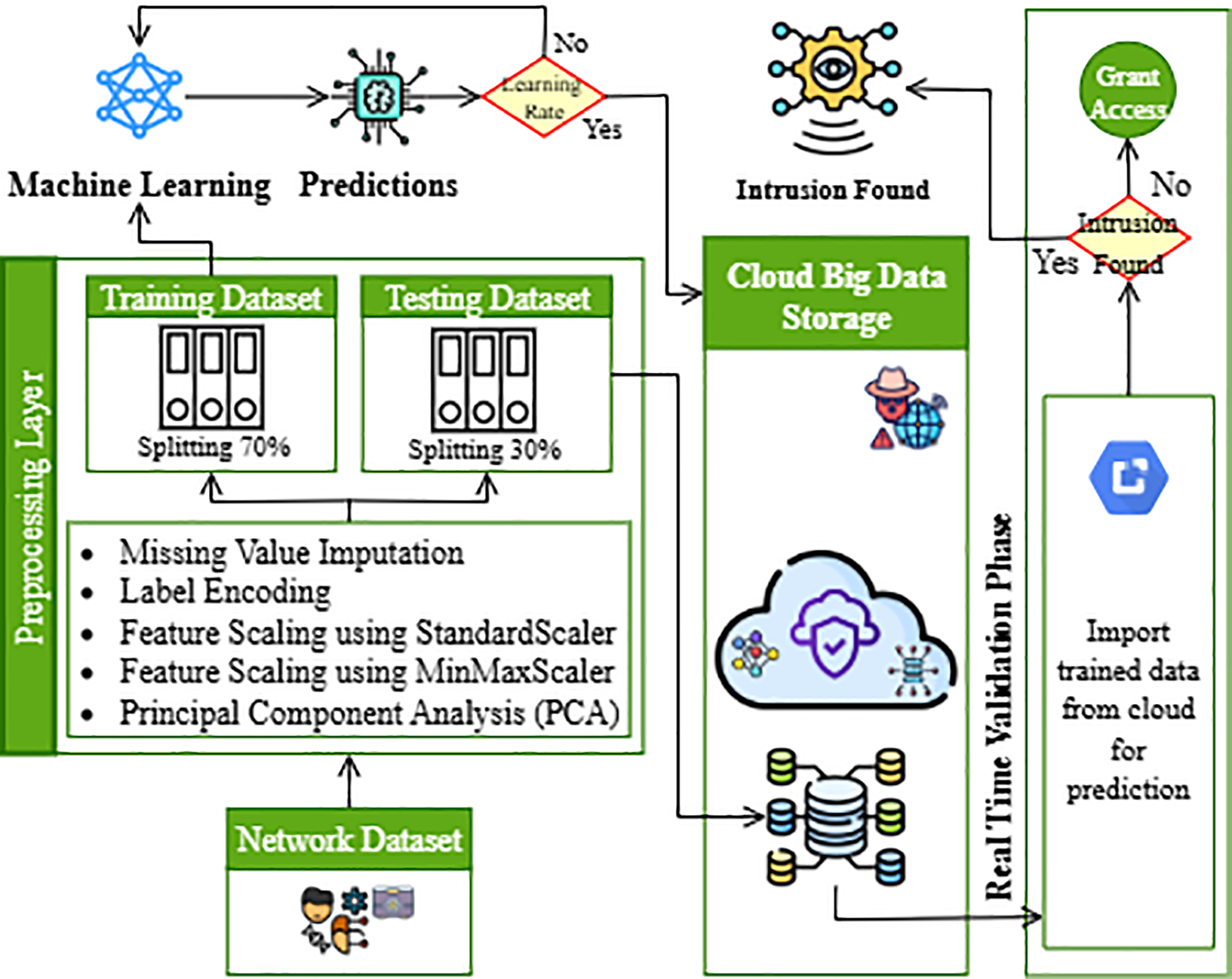

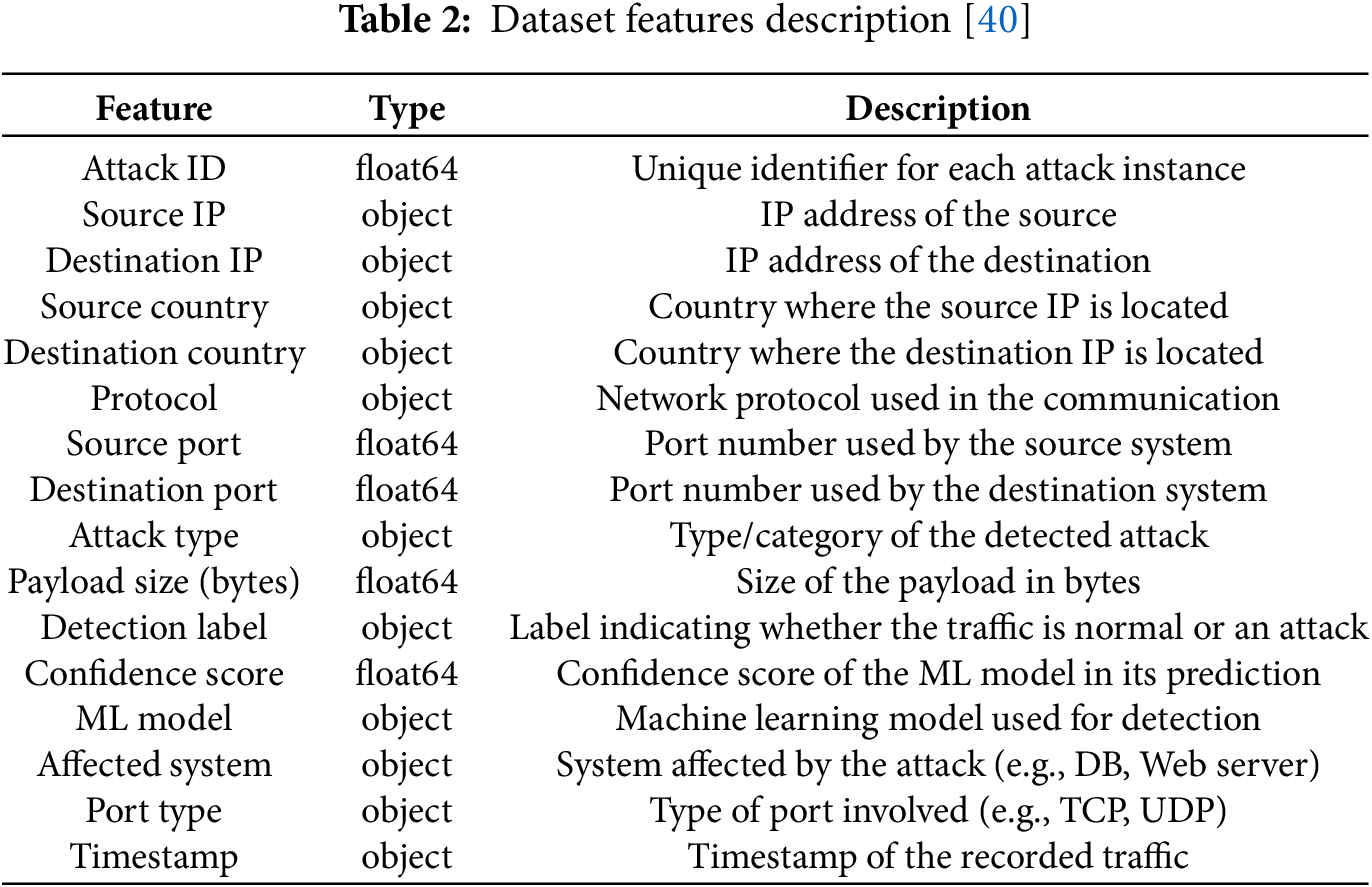

Fig. 4 illustrates a cloud-assisted machine learning framework for intrusion detection in network environments. The process begins with the collection of raw network traffic data through a structured dataset, as detailed in Table 2 [40].

Figure 4: Detailed structure of Proposed Model (Local Client) for intrusion detection

This data then undergoes a comprehensive preprocessing phase involving missing value imputation, label encoding, and multi-method feature scaling (StandardScaler, MinMaxScaler), along with dimensionality reduction using Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

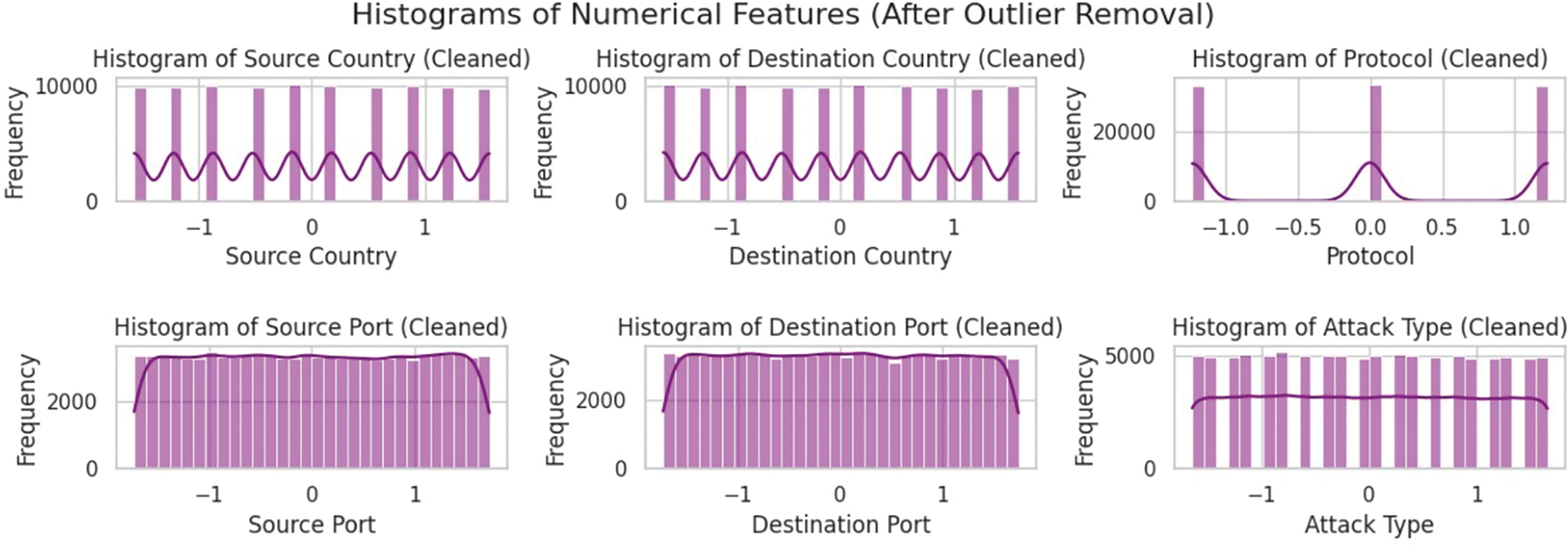

Fig. 5 presents histograms of numerical features after applying Z-score outlier detection and removal. Initially, features such as port numbers, payload size, detection label, and confidence score exhibited skewed or irregular distributions due to the presence of extreme values. By applying a Z-score threshold of 3, rows with significant deviations from the mean were identified and eliminated. The cleaned dataset, visualized in this figure, now demonstrates more balanced and uniform distributions across features, improving the reliability of downstream machine learning tasks. This step is crucial in enhancing model performance by reducing noise and variance caused by outliers.

Figure 5: Histograms of numerical features after outlier removal using the Z-score method

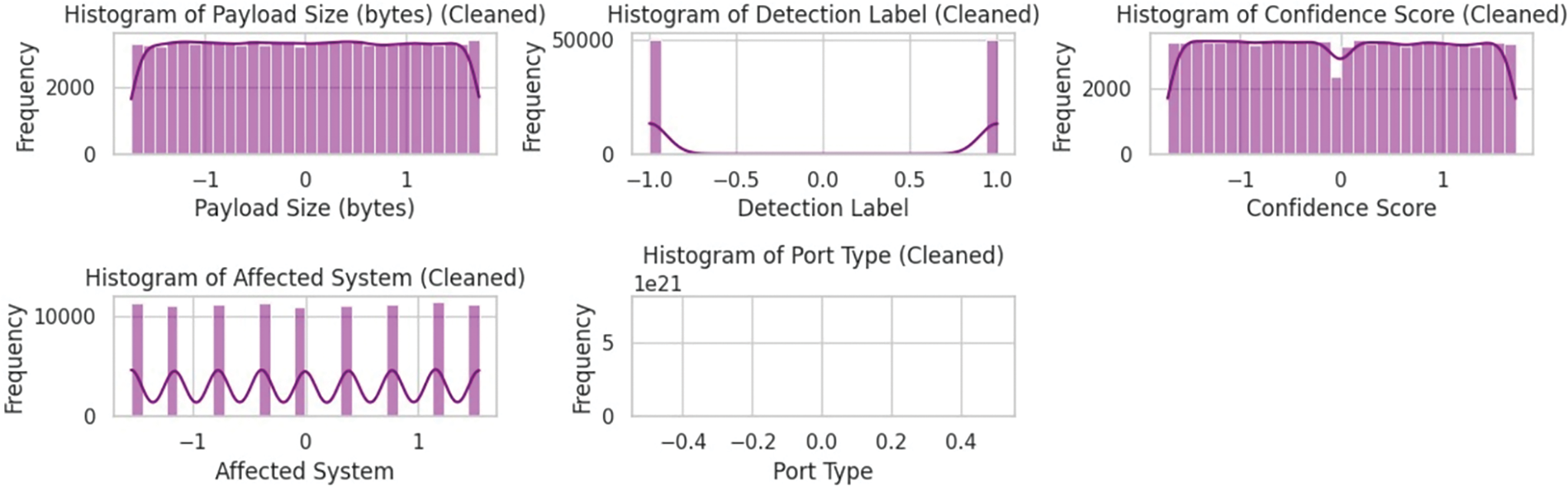

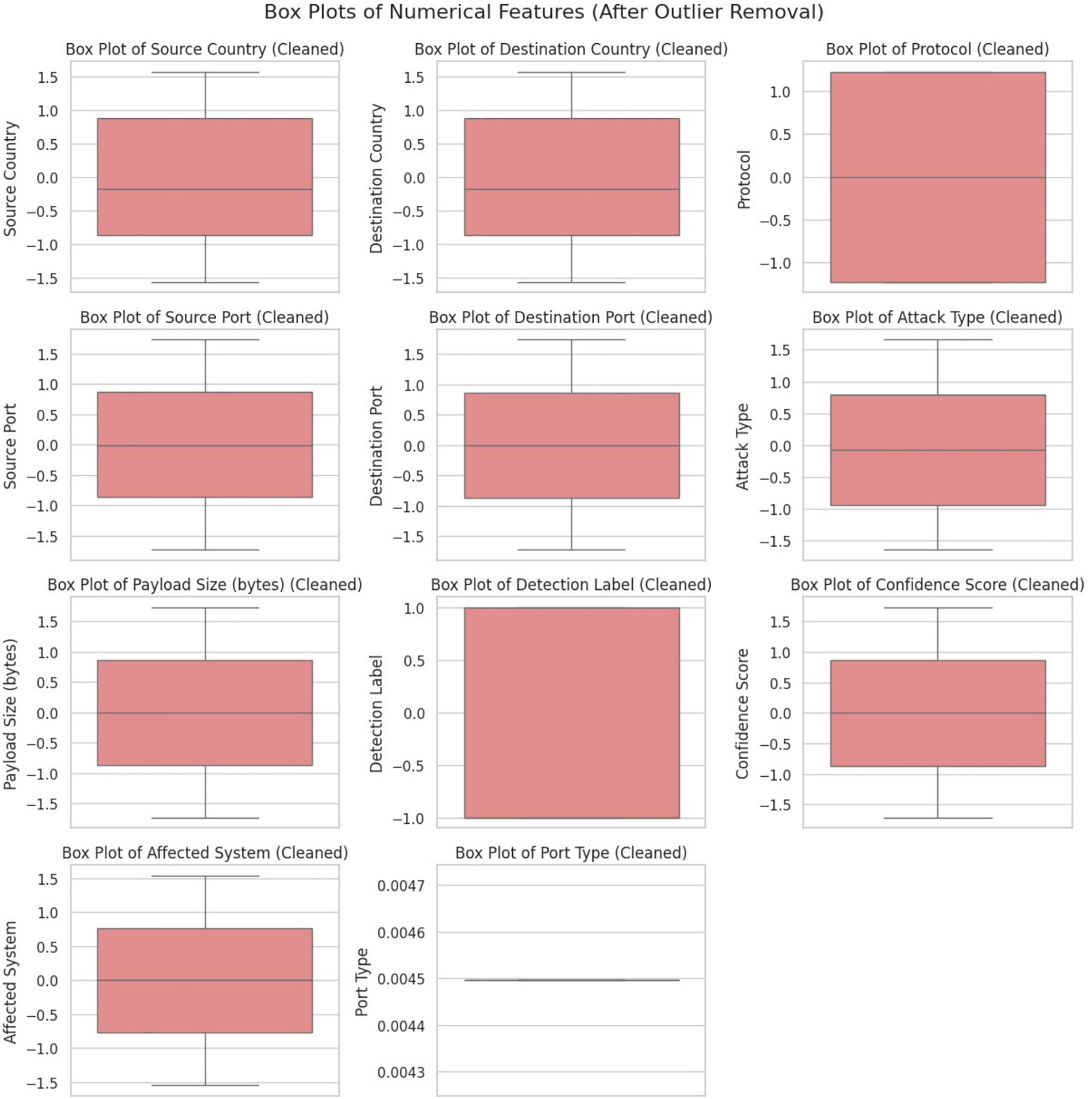

Fig. 6 illustrates the distribution of numerical features after applying outlier removal techniques. The box plots show that extreme values have been effectively reduced, resulting in more compact and symmetric distributions. This cleaning process improves data quality, stabilizes feature ranges, and supports more robust and consistent training across distributed nodes in the FL model.

Figure 6: Box plots of numerical features (after outlier removal)

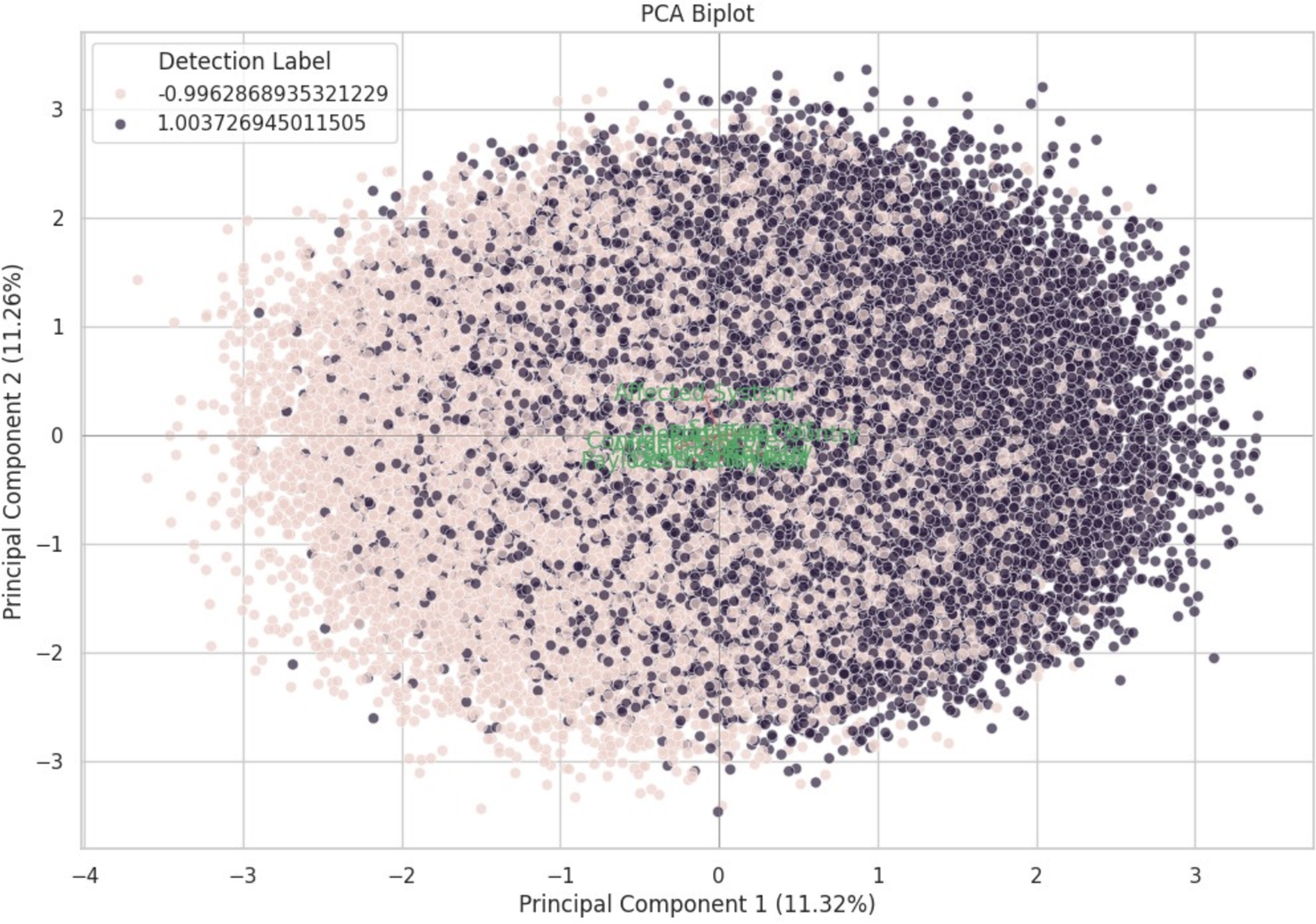

Fig. 7 presents a PCA biplot illustrating the separation between detection labels in the reduced 2D feature space. Principal Component 1 (PC1) and Principal Component 2 (PC2) explain 11.32% and 11.26% of the total variance, respectively. Data points are colour-coded based on their detection label, providing insight into class separability. Additionally, green feature vectors (loadings) highlight the influence of original features on each principal component, aiding in the interpretability of the dimensional reduction and helping visualize key contributing attributes in the classification task.

Figure 7: PCA biplot for feature space visualization

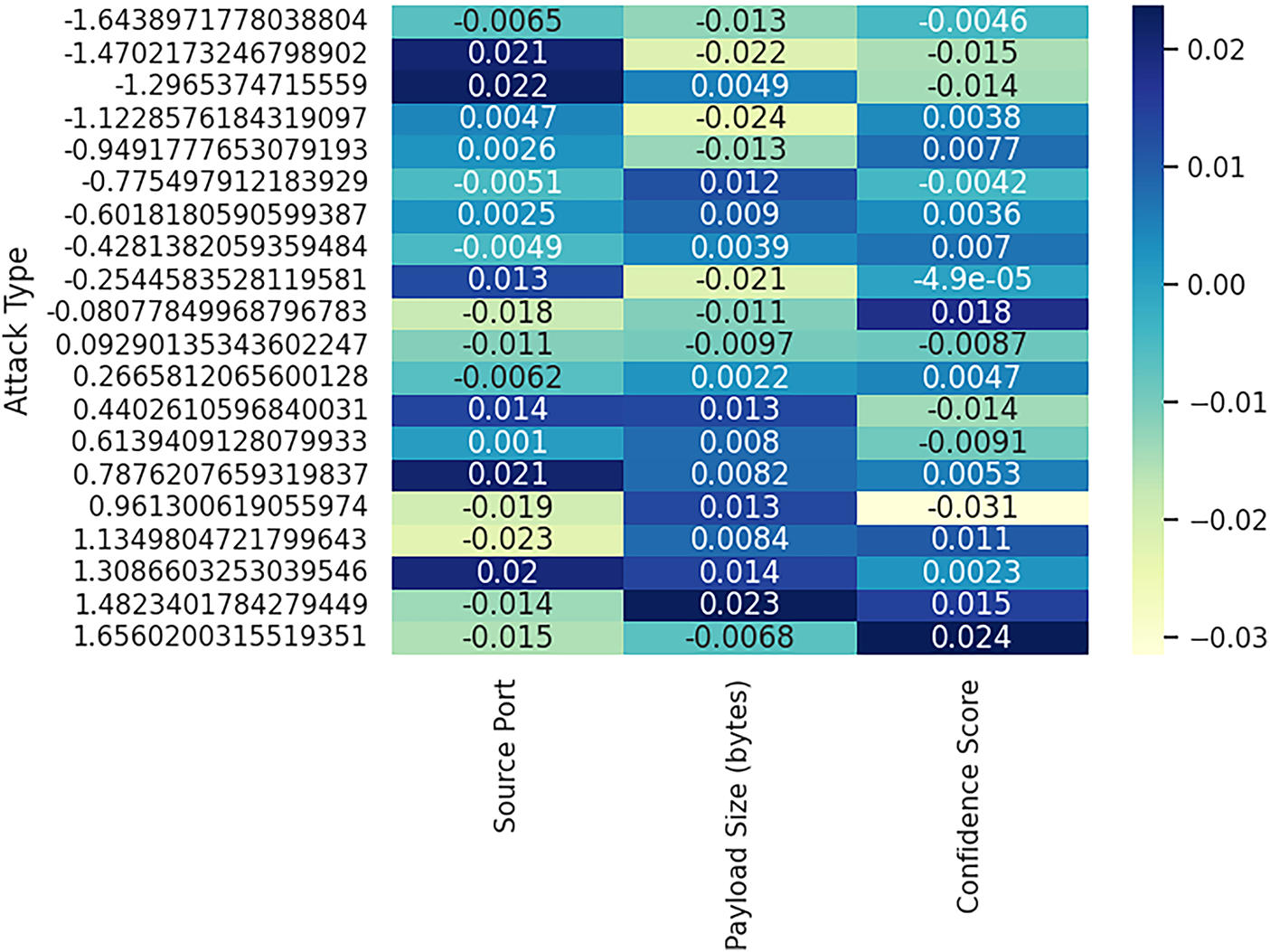

Fig. 8 illustrates that the heatmap visualizes the average values of key numerical features—Source Port, Payload Size (in bytes), and Confidence Score—grouped by each distinct Attack Type. Each cell’s color intensity reflects the magnitude and direction of the feature’s average, enabling quick comparative analysis across different attack behaviors. For instance, certain attack types exhibit higher confidence scores or larger payload sizes, which can be crucial in identifying and differentiating threats. This representation facilitates pattern discovery and can aid in feature prioritization for intrusion detection models.

Figure 8: Heatmap of average feature values across different attack types

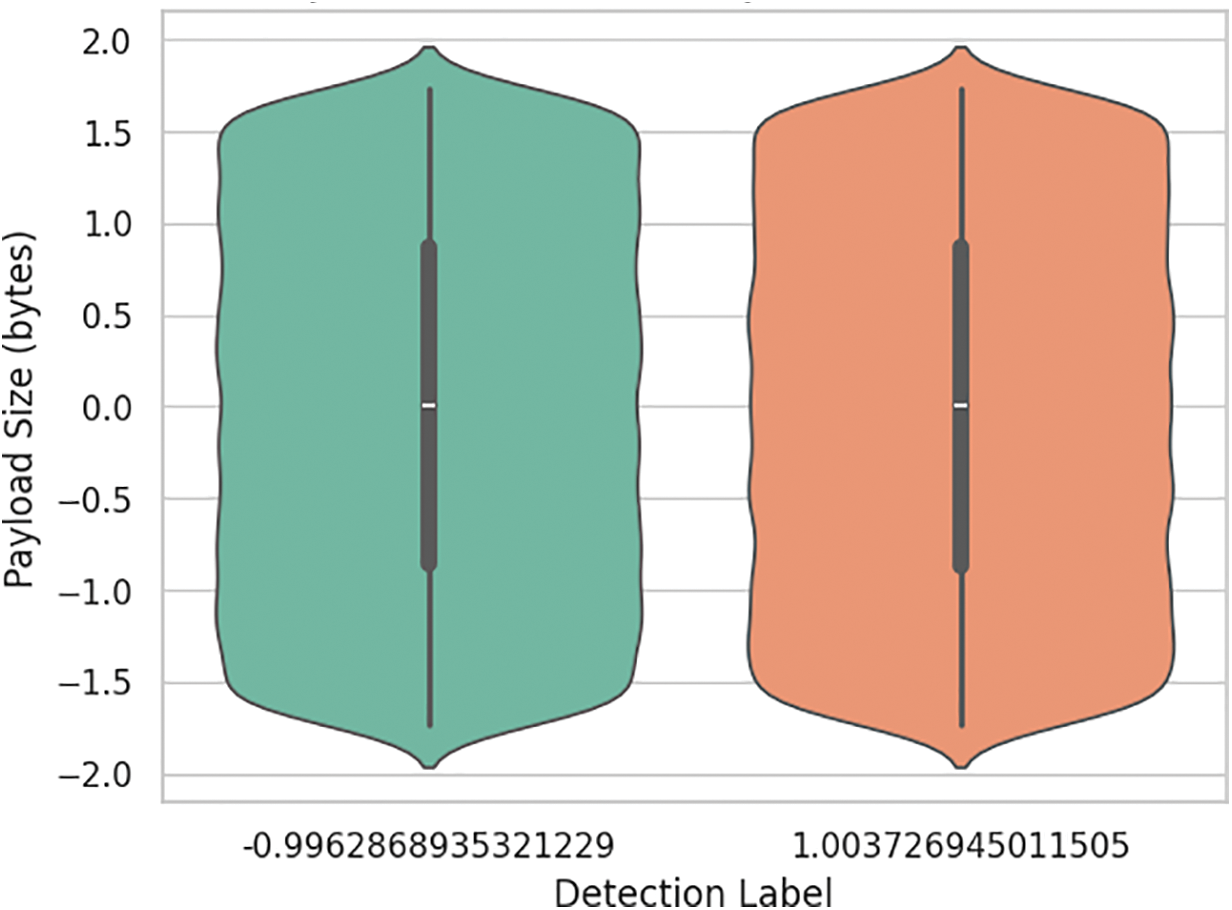

The violin plot in Fig. 9 displays the distribution of Payload Size (in bytes) across two detection outcomes, labeled by Detection Label. The shape and width of each violin represent the density and spread of payload sizes within each class. Both classes show a relatively symmetric and comparable distribution, indicating that payload size alone may not be a strong discriminator between detection outcomes. However, this visualization provides insights into central tendencies and the presence of outliers, supporting feature evaluation for classification tasks.

Figure 9: Violin plot of payload size distribution by detection outcome

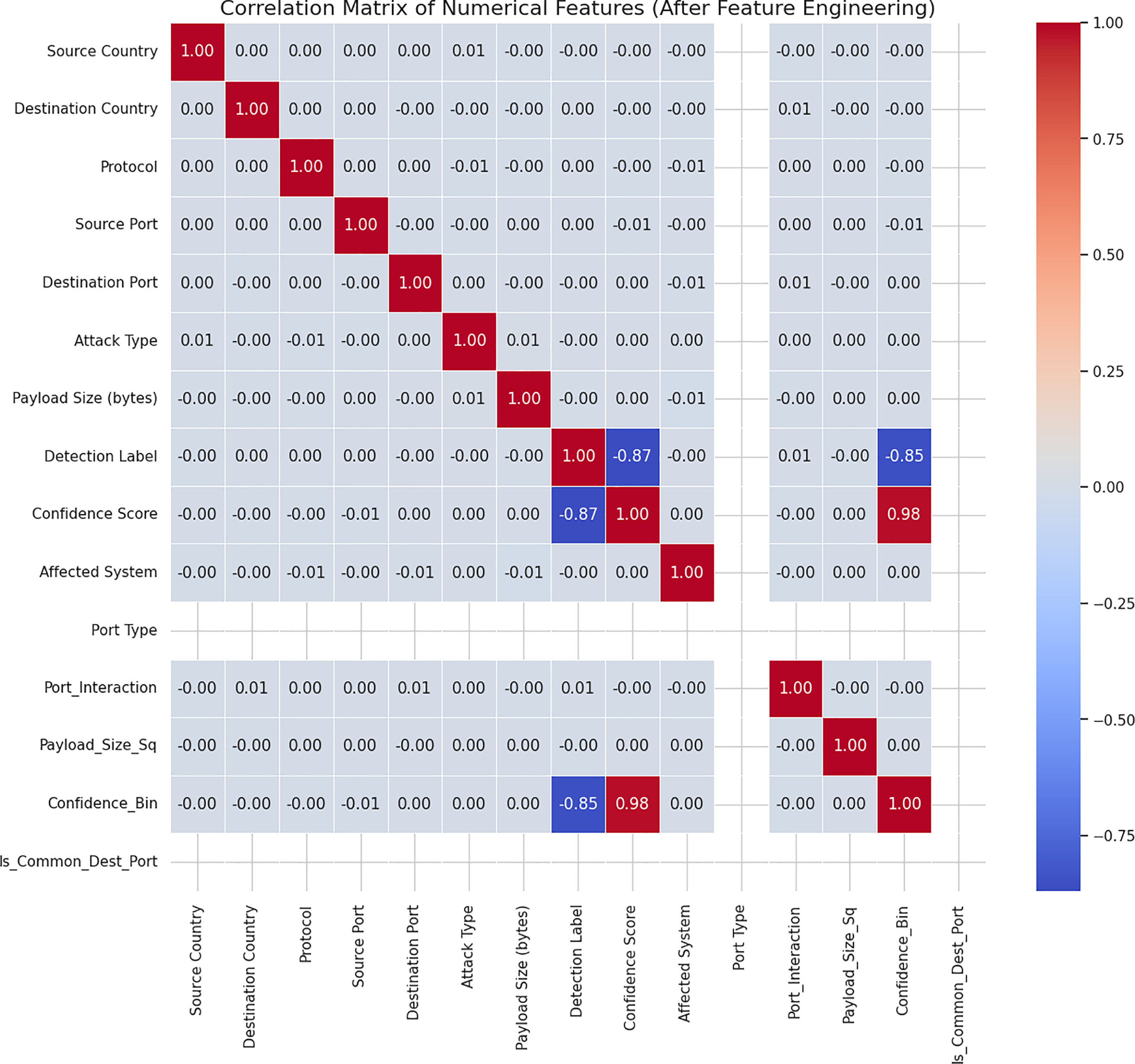

Fig. 10 shows the correlation matrix of numerical features after applying feature engineering techniques. This matrix highlights relationships between original and newly derived features such as Port_Interaction, Payload_Size_Sq, Confidence_Bin, and Is_Common_Dest_Port. Strong correlations can be observed—for example, Detection Label shows a high negative correlation with Confidence Score (−0.87), and a high positive correlation with its binned version Confidence_Bin (0.98), indicating its predictive relevance. Similarly, engineered features like Payload_Size_Sq and Port_Interaction exhibit low correlations with other variables, supporting their inclusion as independent predictors. This analysis validates the effectiveness of feature engineering in enriching the dataset with minimally redundant and potentially informative attributes.

Figure 10: Correlation matrix of numerical features after applying feature engineering

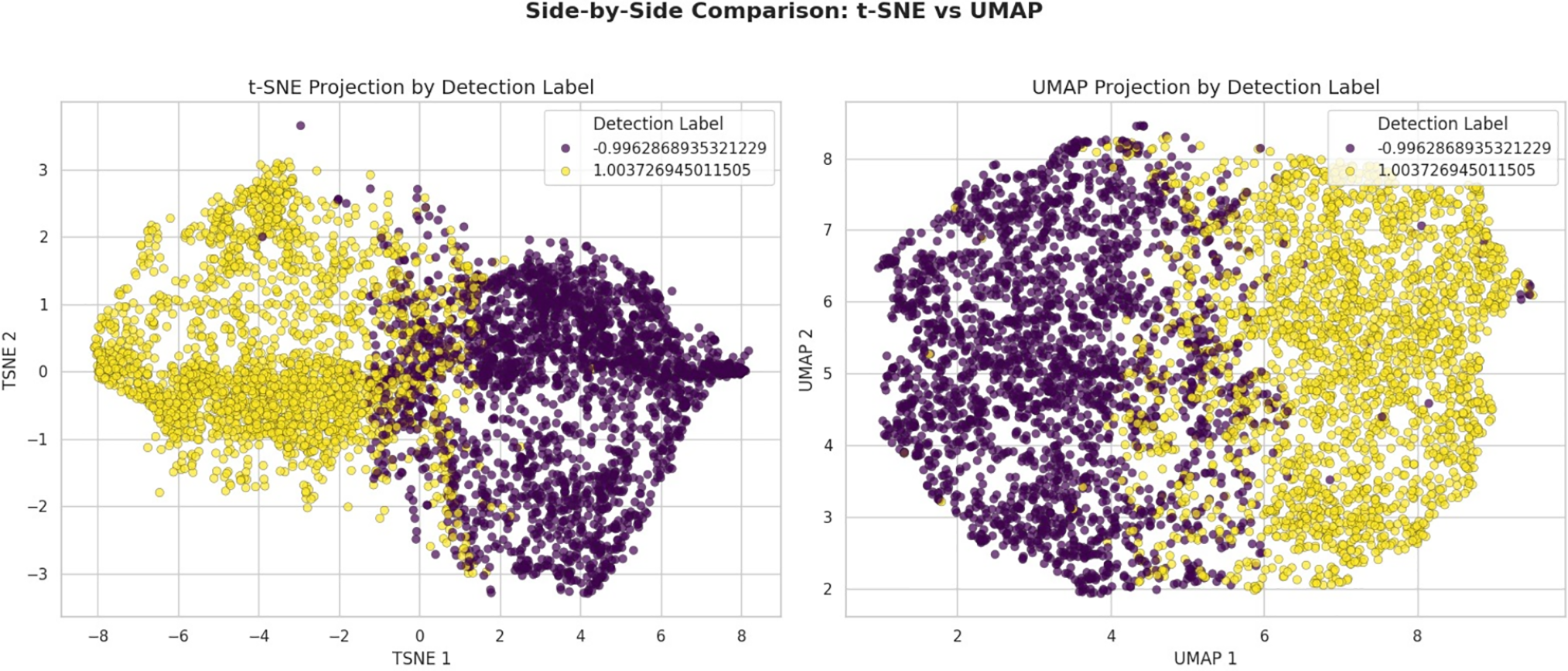

Fig. 11 compares two powerful dimensionality reduction techniques—t-SNE and UMAP—applied to the intrusion detection dataset. Both visualizations project high-dimensional feature representations into two dimensions based on the Detection Label, revealing distinguishable clusters of attack and normal instances. The t-SNE plot (left) displays well-separated groupings with some overlapping regions, highlighting the preservation of local neighborhoods. Meanwhile, the UMAP projection (right) maintains a more transparent global structure and more compact separation, making it better suited for downstream analysis, such as anomaly detection. This comparative view highlights the effectiveness of both methods in capturing the intrinsic structure of network behavior patterns.

Figure 11: Visual comparison of t-SNE and UMAP projections colored by detection label

The preprocessed data is split into 70% for training and 30% for testing. The machine learning model uses the training data to learn predictive patterns, and its output is validated against the testing data. Once a model with an optimal learning rate is achieved, predictions are stored and managed in a scalable cloud big data storage system. In the real-time validation phase, trained models are imported from the cloud to classify new inputs. If no intrusion is detected, access is granted; otherwise, alerts are raised. This architecture ensures efficient data processing, robust storage, and real-time threat mitigation while leveraging the flexibility and scalability of cloud infrastructure.

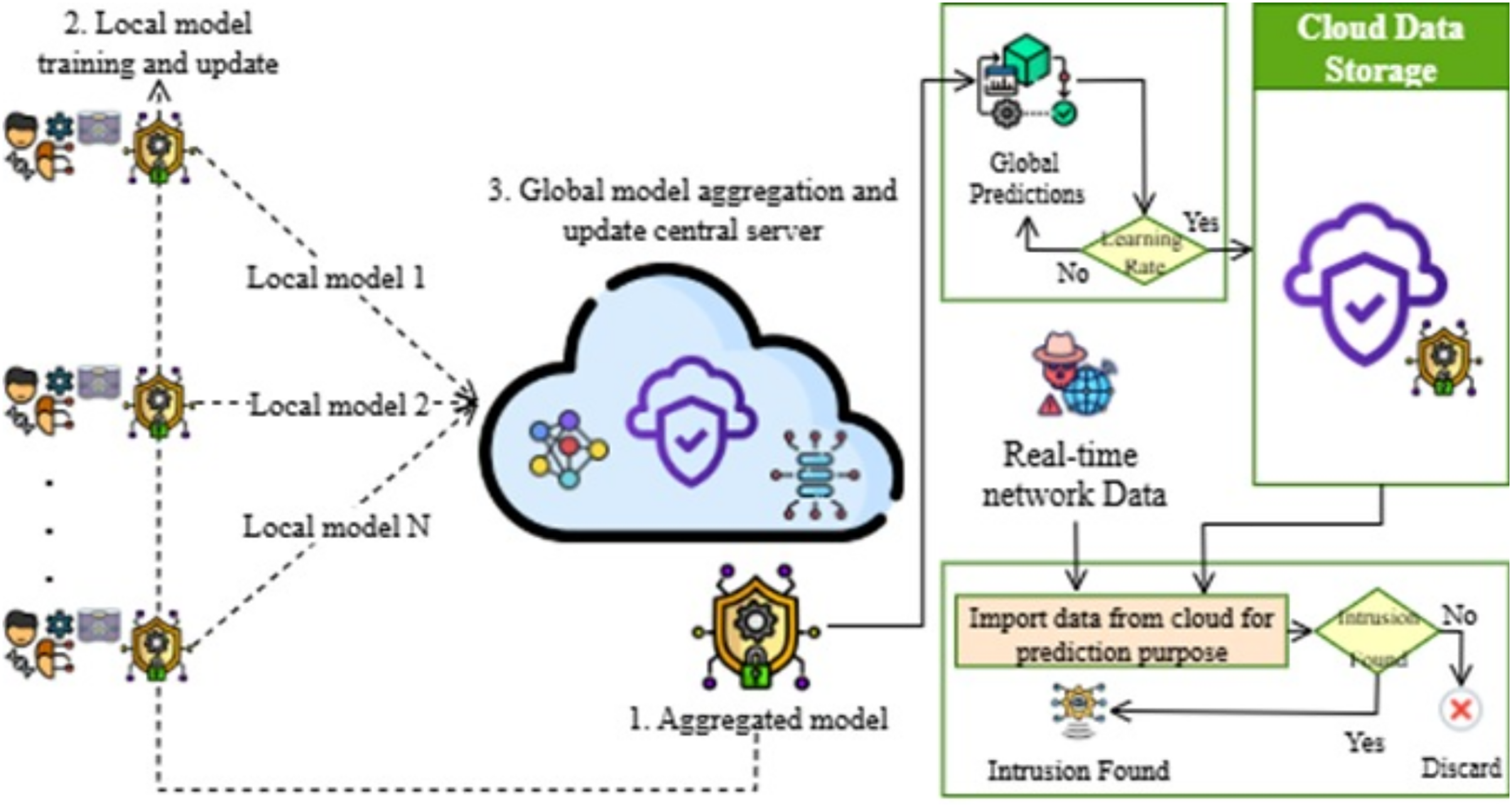

Fig. 12 illustrates the architecture of a cloud-assisted FL model designed for real-time intrusion detection in distributed network environments. The process begins with decentralized edge clients (e.g., organizations, IoT gateways, or enterprise nodes), each possessing its own local traffic data batch

Figure 12: Proposed model (Global client)

5.1 Local Model Training and Update

Each node

where

Gradient-Based Update at Client-Side

Clients perform local updates using stochastic gradient descent:

where

5.2 Reliability Scoring for Aggregation

To avoid propagating weak updates, each client is evaluated using a reliability score

where

5.3 Weighted Global Aggregation and Model Refinement

The central cloud server aggregates all received local models via reliability-weighted averaging:

The updated model

5.4 Convergence Monitoring and Adaptive Re-Training

To detect convergence, a loss threshold

If the convergence condition fails, underperforming clients

5.5 Real-Time Prediction and Cloud Storage Integration

Once validated, the global model is deployed in the cloud for real-time prediction on streaming network traffic

Decisions are made based on a probability threshold

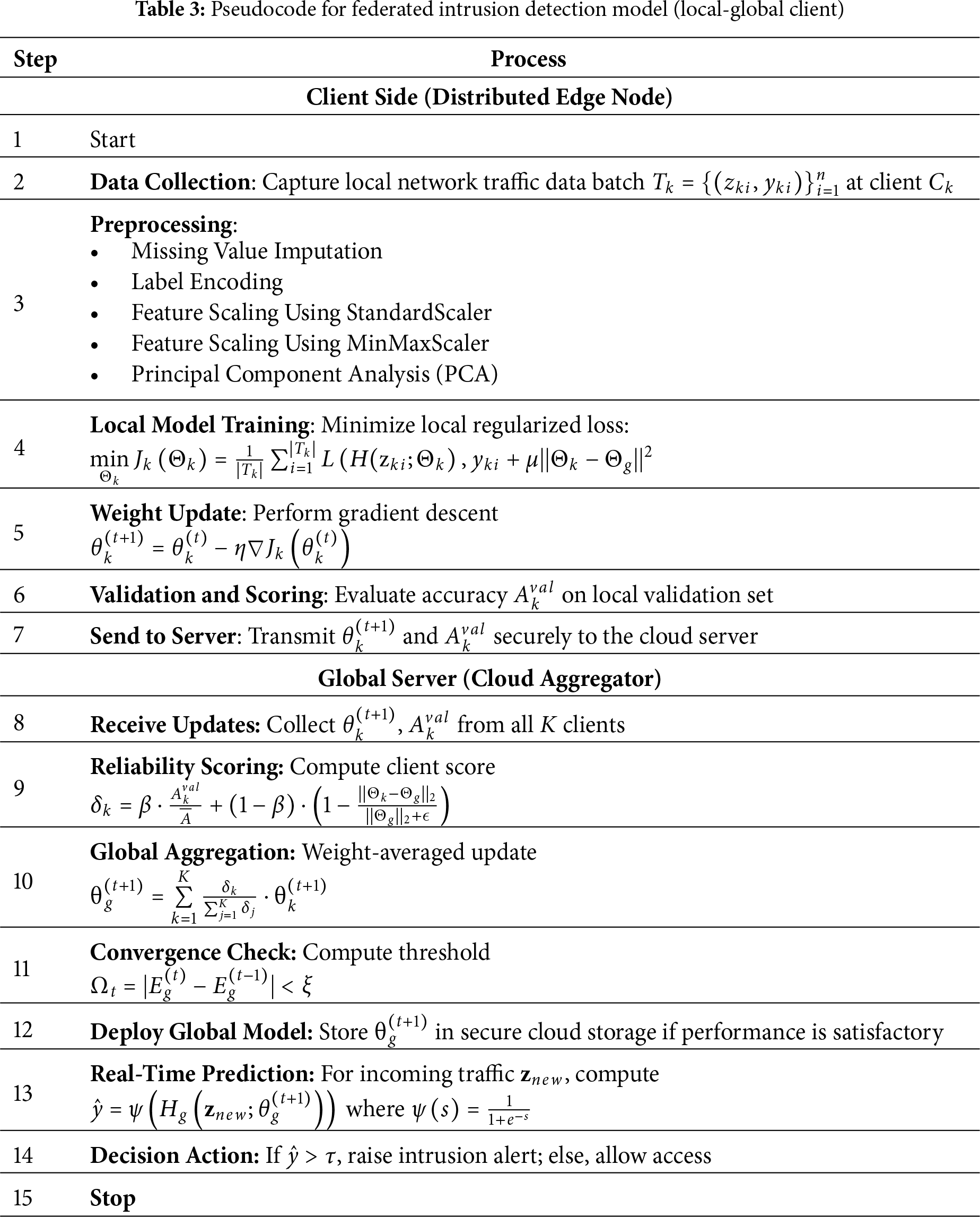

This hierarchical FL-based intrusion detection model enables secure, scalable, and collaborative threat monitoring without requiring the sharing of raw network data. Figs. 2–12 outline the full workflow—from local model training to global aggregation in the cloud and real-time intrusion prediction. The optimized global model is centrally stored and used to detect attacks in live network traffic, ensuring both privacy and timely responses. Table 3 presents the core pseudocode behind this federated detection process.

Traditional IDS face critical challenges related to data privacy, centralized bottlenecks, and limited scalability in distributed environments. To address these limitations, the proposed FL-based framework leverages decentralized training to preserve sensitive information while enabling collaborative model development. A real-world cyberattack dataset comprising both numerical and categorical network features is used to validate the approach. After preprocessing steps, including missing value handling, encoding, and feature scaling, the data is split into 80% training and 20% test sets. A fully custom-built FL simulation is implemented in Google Colab using Python, without external FL libraries, to emulate client-server interactions. Clients independently train local models on partitioned data and transmit only the learned weights to a central server, where reliability-weighted aggregation is performed to update the global model. Model performance is then evaluated using comprehensive diagnostic metrics, as outlined in Eqs. (7)–(14), confirming the model’s effectiveness in privacy-preserving, scalable, and accurate cyber threat detection.

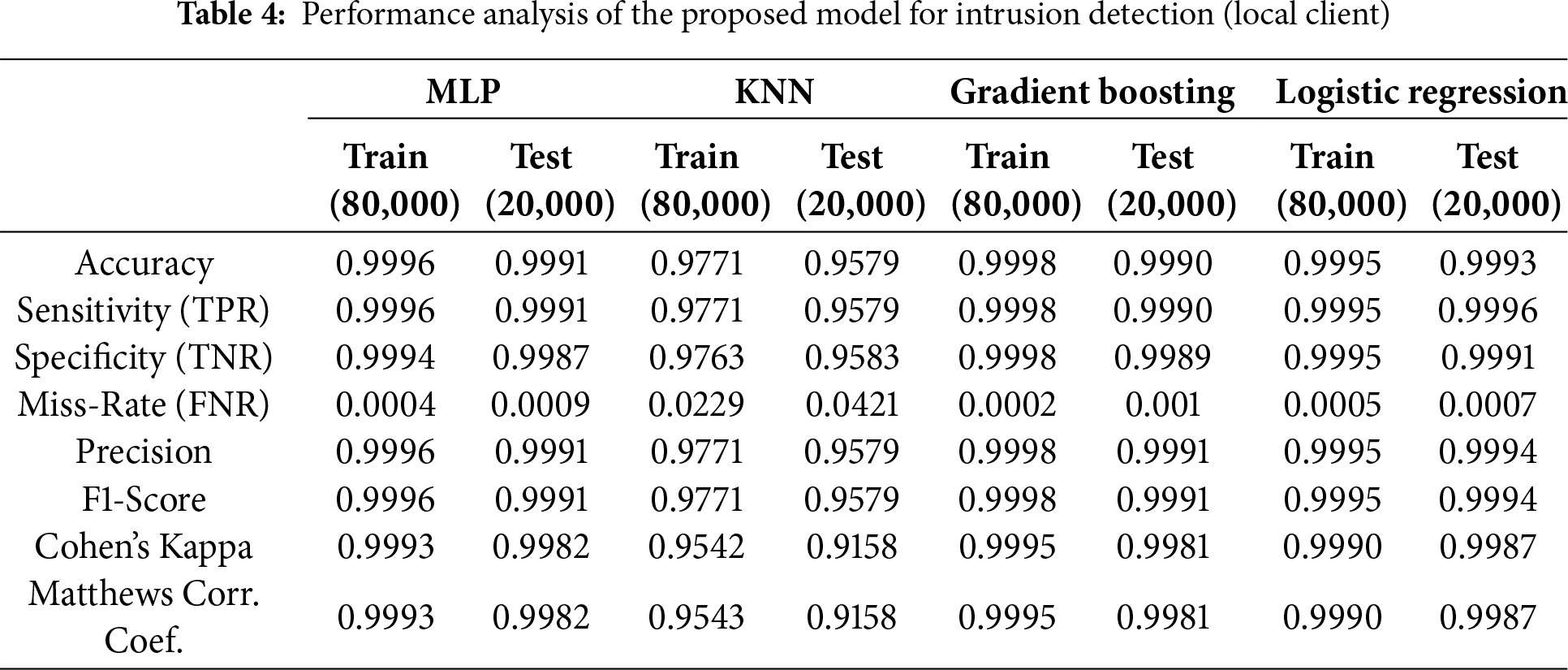

Table 4 provides a comparative evaluation of four machine learning models—Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), KNN, Gradient Boosting, and Logistic Regression—based on their local client-side performance for intrusion detection. The evaluation is conducted on an 80,000:20,000 train-test split.

During training, all models except KNN show excellent results with accuracy values exceeding 0.999. MLP, Gradient Boosting, and Logistic Regression demonstrate strong learning capabilities with minimal loss and high agreement with the ground truth, as indicated by their high Cohen’s Kappa (≥0.9990) and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) scores. However, testing performance is the more critical indicator of generalization. On unseen data, MLP achieves the highest test accuracy of 0.9991, followed closely by Logistic Regression (0.9993) and Gradient Boosting (0.9990). All three maintain near-perfect sensitivity, precision, and F1-scores, confirming their strong ability to detect threats while minimizing false positives and false negatives. In contrast, KNN lags, with a notably lower test accuracy of 0.9579, reflecting weaker generalization and higher error margins under real-world conditions.

While training performances are close across models, Logistic Regression shows the highest test accuracy (0.9993), making it the most reliable model for intrusion detection in a federated local setup. Its superior balance between accuracy, reliability (Kappa/MCC), and precision makes it a top candidate for secure and scalable deployment.

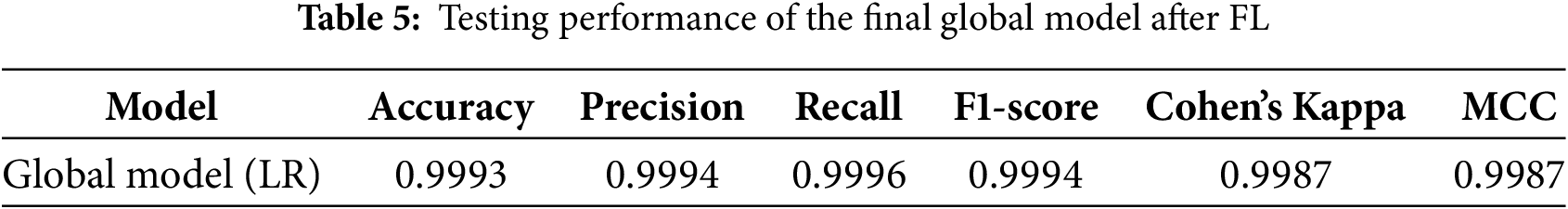

After applying the FL, the global Logistic Regression model—trained using collaboratively selected features from distributed clients—demonstrates exceptional generalization performance on the test dataset. As shown in Table 5, the model achieves a near-perfect accuracy of 99.93%, effectively identifying intrusion patterns with minimal errors. Its precision (0.9994) and recall (0.9996) confirm a strong balance between detecting true positives and minimizing false negatives, while the high F1-score (0.9994) reflects its overall predictive stability. Additionally, reliability metrics such as Cohen’s Kappa (0.9987) and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (0.9987) indicate near-complete agreement with actual labels, even in the presence of class imbalance. This performance highlights the robustness, scalability, and privacy-preserving nature of the FL-driven model, making it highly suitable for real-time intrusion detection in decentralized and sensitive network environments.

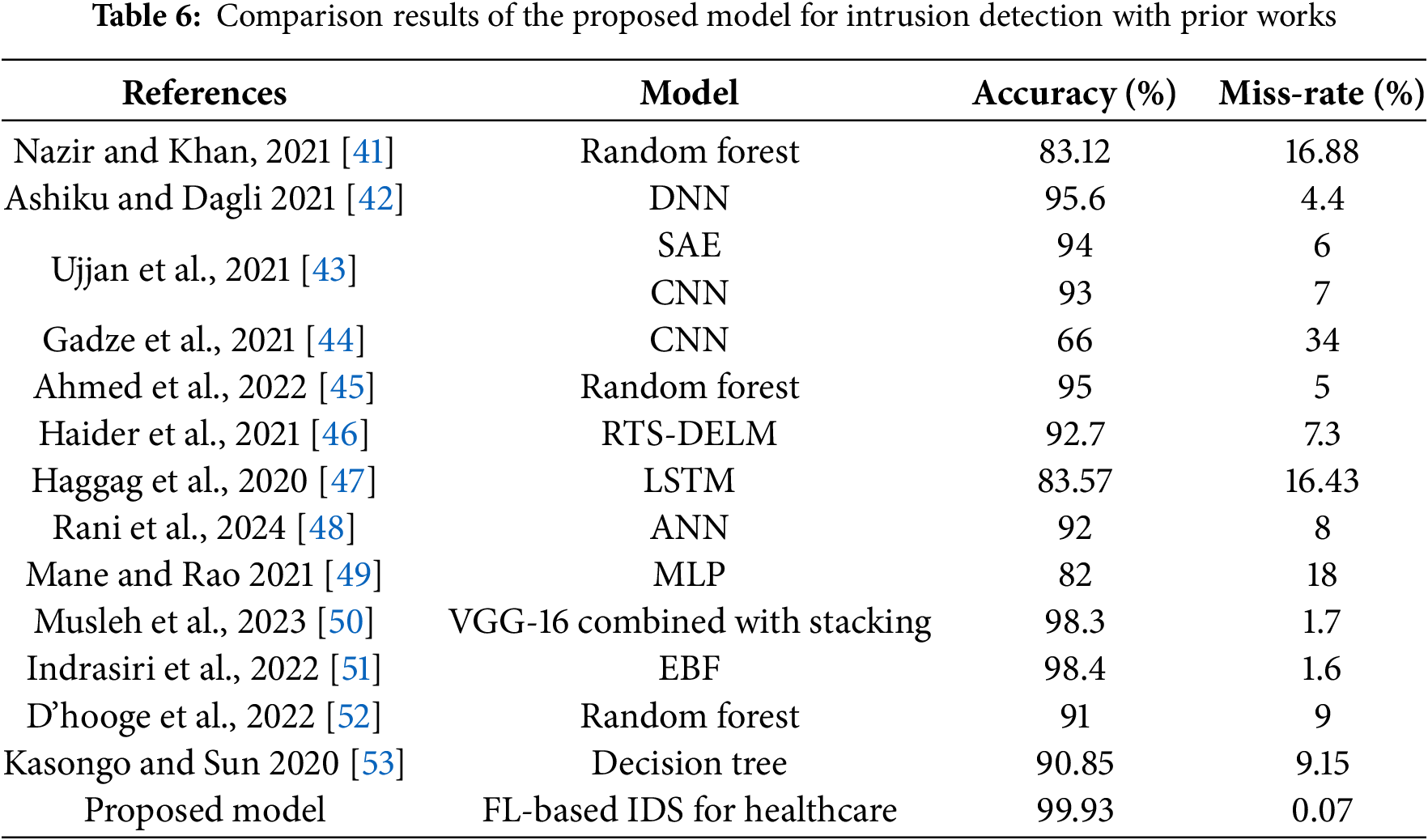

Table 6 shows that the proposed FL-based IDS significantly outperforms existing methods by achieving an exceptional accuracy of 99.93% and a remarkably low miss-rate of just 0.07%. This highlights the model’s ability to detect intrusions with near-perfect precision while minimizing false negatives. Such performance is especially critical in sensitive environments, such as healthcare, where real-time, privacy-preserving, and reliable threat detection is essential.

In modern cybersecurity landscapes, several pressing challenges hinder the effectiveness of traditional IDS. These include centralized data dependencies, privacy violations, scalability issues, and limited adaptability to distributed environments such as IoT, edge devices, and smart networks. Moreover, sharing raw network traffic data raises severe compliance concerns, especially under stringent data protection regulations. To address these issues, this research proposes a Big Data–driven Federated Learning (FL) model for real-time intrusion detection, enabling decentralized clients to collaboratively train models without sharing raw data, thereby preserving confidentiality and data locality. The framework efficiently handles distributed data processing and reduces computational burden by limiting communication to model parameters rather than raw datasets. Its design inherently minimizes latency and supports horizontal scalability, making it suitable for large-scale and resource-constrained healthcare IoT environments. The final global model achieved 99.93% accuracy, 0.9994 F1-score, and 0.9987 MCC, confirming strong generalization and threat-detection capabilities. Overall, the proposed approach demonstrates that FL can deliver privacy-preserving, scalable, and computationally efficient intrusion detection for next-generation connected infrastructures. As part of future work, runtime comparisons will be conducted with centralized and lightweight FL baselines to validate the framework’s efficiency and scalability further. Additionally, multi-dataset validation using benchmark datasets such as UNSW-NB15, BoT-IoT, and CIC-IDS2017, along with k-fold cross-validation and multiple independent trials, will be explored to comprehensively evaluate model generalization, statistical consistency, and robustness across diverse network environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Noura Mohammed Alaskar, Saif Jasim Almheiri, Muzammil Hussain and Adnan Khan: collected data from different resources, performed formal analysis and simulation, and contributed to writing—original draft preparation. Muzammil Hussain, Atta-ur-Rahman and Khan M. Adnan: writing—review & editing, and performed supervision. Noura Mohammed Alaskar, Saif Jasim Almheiri, Atta-ur-Rahman and Adnan Khan: drafted pictures and tables. Khan M. Adnan: performed revisions and improved the quality of the draft. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: In our study data takes the form famous repository, Kaggle, and it is publicly available on the following link. Ayinde B. Cyberattacks Detection Kaggle, 2024. https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/lastman0800/cyberattacks-detection (accessed on 01 September 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zaman U, Imran, Mehmood F, Iqbal N, Kim J, Ibrahim M. Towards secure and intelligent Internet of Health Things: a survey of enabling technologies and applications. Electronics. 2022;11(12):1893. doi:10.3390/electronics11121893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Safitra MF, Lubis M, Fakhrurroja H. Counterattacking cyber threats: a framework for the future of cybersecurity. Sustainability. 2023;15(18):13369. doi:10.3390/su151813369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hassani H, MacFeely S. Driving excellence in official statistics: unleashing the potential of comprehensive digital data governance. Big Data Cogn Comput. 2023;7(3):134. doi:10.3390/bdcc7030134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Lehto M. Cyber-attacks against critical infrastructure. In: Cyber security. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 3–42. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-91293-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Le Jeune L, Goedemé T, Mentens N. Machine learning for misuse-based network intrusion detection: overview, unified evaluation and feature choice comparison framework. IEEE Access. 2021;9:63995–4015. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3075066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kocher G, Kumar G. Machine learning and deep learning methods for intrusion detection systems: recent developments and challenges. Soft Comput. 2021;25(15):9731–63. doi:10.1007/s00500-021-05893-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Khraisat A, Alazab A. A critical review of intrusion detection systems in the Internet of Things: techniques, deployment strategy, validation strategy, attacks, public datasets and challenges. Cybersecurity. 2021;4(1):18. doi:10.1186/s42400-021-00077-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Heidari A, Ali Jabraeil Jamali M. Internet of Things intrusion detection systems: a comprehensive review and future directions. Clust Comput. 2023;26(6):3753–80. doi:10.1007/s10586-022-03776-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jin H, Luo Y, Li P, Mathew J. A review of secure and privacy-preserving medical data sharing. IEEE Access. 2019;7:61656–69. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2916503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Osama M, Ateya AA, Sayed MS, Hammad M, Pławiak P, Abd El-Latif AA, et al. Internet of Medical Things and healthcare 4.0: trends, requirements, challenges, and research directions. Sensors. 2023;23(17):7435. doi:10.3390/s23177435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Imran M, Zaman U, Imran, Imtiaz J, Fayaz M, Gwak J. Comprehensive survey of IoT, machine learning, and blockchain for health care applications: a topical assessment for pandemic preparedness, challenges, and solutions. Electronics. 2021;10(20):2501. doi:10.3390/electronics10202501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ameedeen MA, Hamid RA, Aldhyani THH, Al-Nassr LAKM, Olatunji SO, Subramanian P. A framework for automated big data analytics in cybersecurity threat detection. Mesopotamian J Big Data. 2024;2024:175–84. doi:10.58496/mjbd/2024/012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Deebak BD, Hwang SO. Privacy preserving based on seamless authentication with provable key verification using mIoMT for B5G-enabled healthcare systems. IEEE Trans Serv Comput. 2024;17(3):1097–113. doi:10.1109/TSC.2024.3382950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Harshni V, Singh S, Indhumathi R, Kumar NS, Chowdhury S, Patra SS. DLIoMT: deep learning approaches for IoMT-overview, challenges and the future. In: Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Computer, Electrical & Communication Engineering (ICCECE); 2025 Feb 7–8; Kolkata, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICCECE61355.2025.10940162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Saheed YK, Chukwuere JE. CPS-IIoT-P2Attention: explainable privacy-preserving with scaled dot-product attention in cyber-physical system-industrial IoT network. IEEE Access. 2025;13(3):81118–42. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3566980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Anjum M, Kraiem N, Min H, Dutta AK, Daradkeh YI, Shahab S. Opportunistic access control scheme for enhancing IoT-enabled healthcare security using blockchain and machine learning. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):7589. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-90908-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Khan HU, Ali Y, Khan F. A features-based privacy preserving assessment model for authentication of Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) devices in healthcare. Mathematics. 2023;11(5):1197. doi:10.3390/math11051197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ali Y, Han KH, Majeed A, Lim JS, Hwang SO. An optimal two-step approach for defense against poisoning attacks in federated learning. IEEE Access. 2025;13:60108–21. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3556906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Majeed A, Hwang SO. A multifaceted survey on federated learning: fundamentals, paradigm shifts, practical issues, recent developments, partnerships, trade-offs, trustworthiness, and ways forward. IEEE Access. 2024;12(2):84643–79. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3413069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Patni S, Lee J. EdgeGuard: decentralized medical resource orchestration via blockchain-secured federated learning in IoMT networks. Future Internet. 2025;17(1):2. doi:10.3390/fi17010002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hwang SO, Majeed A. Analysis of federated learning paradigm in medical domain: taking COVID-19 as an application use case. Appl Sci. 2024;14(10):4100. doi:10.3390/app14104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Deebak BD, Hwang SO. Federated learning-based lightweight two-factor authentication framework with privacy preservation for mobile sink in the social IoMT. Electronics. 2023;12(5):1250. doi:10.3390/electronics12051250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ghazal TM, Islam S, Hasan MK, Abu-Shareha AA, Mokhtar UA, Khan MA, et al. Generative federated learning with small and large models in consumer electronics for privacy-preserving data fusion in healthcare Internet of Things. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(2):3413–30. doi:10.1109/TCE.2025.3572629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ghazal TM, Hasan MK, Hussein AH, Pandey BK, Ahmad M, Safie N, et al. Federated learning with small and large models with privacy-preserving data space for holographic Internet of Things in consumer electronics. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(2):5259–74. doi:10.1109/TCE.2025.3573033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Blika A, Palmos S, Doukas G, Lamprou V, Pelekis S, Kontoulis M, et al. Federated learning for enhanced cybersecurity and trustworthiness in 5G and 6G networks: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Open J Commun Soc. 2025;6(2):3094–130. doi:10.1109/OJCOMS.2024.3449563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Moussaoui JE, Kmiti M, El Gholami K, Maleh Y. A systematic review on hybrid AI models integrating machine learning and federated learning. J Cybersecur Priv. 2025;5(3):41. doi:10.3390/jcp5030041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bukhari SM, Zafar MH, Abou Houran M, Qadir Z, Kumayl Raza Moosavi S, Sanfilippo F. Enhancing cybersecurity in Edge IIoT networks: an asynchronous federated learning approach with a deep hybrid detection model. Internet Things. 2024;27(4):101252. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2024.101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ge C, Susilo W, Liu Z, Xia J, Szalachowski P, Fang L. Secure keyword search and data sharing mechanism for cloud computing. IEEE Trans Dependable Secur Comput. 2021;18(6):2787–800. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2020.2963978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Subbalakshmi S, Madhavi K. An efficient cloud data sharing and accessing control based on public-key encryption with authentication search. Int J Intell Eng Syst. 2023;16(5):339–49. [Google Scholar]

30. Takale V, Patil A, Lonikar A, Shinde A, Rupnar PV. SecureNet: network intrusion detection using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol. 2024;12(3):439–43. doi:10.22214/ijraset.2024.59791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Hinojosa A, Majd NE. Edge computing network intrusion detection system in IoT using deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 2024 33rd International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN); 2024 Jul 29–31; Kailua-Kona, HI, USA. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICCCN61486.2024.10637611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang L, Liu K, Xie X, Bai W, Wu B, Dong P. A data-driven network intrusion detection system using feature selection and deep learning. J Inf Secur Appl. 2023;78:103606. doi:10.1016/j.jisa.2023.103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Jamadar RA. Network intrusion detection system using machine learning. Indian J Sci Technol. 2018;11(48):1–6. doi:10.17485/ijst/2018/v11i48/139802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Pei J, Chen Y, Ji W. A DDoS attack detection method based on machine learning. J Phys Conf Ser. 2019;1237(3):32040. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1237/3/032040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Gao X, Shan C, Hu C, Niu Z, Liu Z. An adaptive ensemble machine learning model for intrusion detection. IEEE Access. 2019;7:82512–21. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2923640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Aljehane NO, Mengash HA, Hassine SBH, Alotaibi FA, Salama AS, Abdelbagi S. Optimizing intrusion detection using intelligent feature selection with machine learning model. Alex Eng J. 2024;91(4):39–49. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.01.073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Nawaz MW, Munawar R, Mehmood A, Rahman MMU, Abbasi QH. Multi-class network intrusion detection with class imbalance via LSTM & SMOTE. arXiv: 2310.01850. 2023. [Google Scholar]

38. Chinnasamy R, Subramanian M, Sengupta N. Empowering intrusion detection systems: a synergistic hybrid approach with optimization and deep learning techniques for network security. Int Arab J Inf Technol. 2025;22(1):60–76. doi:10.34028/iajit/22/1/6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Gueriani A, Kheddar H, Mazari AC, Ghanem MC. A robust cross-domain IDS using BiGRU-LSTM-attention for medical and industrial IoT security. ICT Express. 2025. 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2025.08.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Cyberattacks detection [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/lastman0800/cyberattacks-detection. [Google Scholar]

41. Nazir A, Khan RA. A novel combinatorial optimization based feature selection method for network intrusion detection. Comput Secur. 2021;102(1):102164. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2020.102164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ashiku L, Dagli C. Network intrusion detection system using deep learning. Procedia Comput Sci. 2021;185(1):239–47. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2021.05.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ujjan RM, Pervez Z, Dahal K, Khan WA, Khattak AM, Hayat B. Entropy based features distribution for anti-DDoS model in SDN. Sustainability. 2021;13(3):1522. doi:10.3390/su13031522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Gadze JD, Bamfo-Asante AA, Agyemang JO, Nunoo-Mensah H, Opare KA. An investigation into the application of deep learning in the detection and mitigation of DDOS attack on SDN controllers. Technologies. 2021;9(1):14. doi:10.3390/technologies9010014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ahmed HA, Hameed A, Bawany NZ. Network intrusion detection using oversampling technique and machine learning algorithms. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2022;8(1):e820. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Haider A, Adnan Khan M, Rehman A, Rahman M, Seok Kim H. A real-time sequential deep extreme learning machine cybersecurity intrusion detection system. Comput Mater Contin. 2021;66(2):1785–98. doi:10.32604/cmc.2020.013910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Haggag M, Tantawy MM, El-Soudani MMS. Implementing a deep learning model for intrusion detection on apache spark platform. IEEE Access. 2020;8:163660–72. doi:10.21227/425a-3e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Rani S, Kumar S, Kataria A, Min H. SmartHealth: an intelligent framework to secure IoMT service applications using machine learning. ICT Express. 2024;10(2):425–30. doi:10.1016/j.icte.2023.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Mane S, Rao D. Explaining network intrusion detection system using explainable AI framework. arXiv: 2103.07110. 2021. [Google Scholar]

50. Musleh D, Alotaibi M, Alhaidari F, Rahman A, Mohammad RM. Intrusion detection system using feature extraction with machine learning algorithms in IoT. J Sens Actuator Netw. 2023;12(2):29. doi:10.3390/jsan12020029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Indrasiri PL, Lee E, Rupapara V, Rustam F, Ashraf I. Malicious traffic detection in IoT and local networks using stacked ensemble classifier. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;71(1):489–515. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.019636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. D’hooge L, Verkerken M, Wauters T, Volckaert B, De Turck F. Discovering non-metadata contaminant features in intrusion detection datasets. In: Proceedings of the 2022 19th Annual International Conference on Privacy, Security & Trust (PST); 2022 Aug 22–24; Fredericton, NB, Canada. p. 1–11. doi:10.1109/PST55820.2022.9851974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Kasongo SM, Sun Y. Performance analysis of intrusion detection systems using a feature selection method on the UNSW-NB15 dataset. J Big Data. 2020;7(1):105. doi:10.1186/s40537-020-00379-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools