Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Unified Feature Selection Framework Combining Mutual Information and Regression Optimization for Multi-Label Learning

Division of AI Computer Science and Engineering, Kyonggi University, Gwanggyosan-Ro, Yeongtong-Gu, Suwon-Si, 16227, Gyeonggi-Do, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Hyunki Lim. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 51 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074138

Received 03 October 2025; Accepted 27 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

High-dimensional data causes difficulties in machine learning due to high time consumption and large memory requirements. In particular, in a multi-label environment, higher complexity is required as much as the number of labels. Moreover, an optimization problem that fully considers all dependencies between features and labels is difficult to solve. In this study, we propose a novel regression-based multi-label feature selection method that integrates mutual information to better exploit the underlying data structure. By incorporating mutual information into the regression formulation, the model captures not only linear relationships but also complex non-linear dependencies. The proposed objective function simultaneously considers three types of relationships: (1) feature redundancy, (2) feature-label relevance, and (3) inter-label dependency. These three quantities are computed using mutual information, allowing the proposed formulation to capture nonlinear dependencies among variables. These three types of relationships are key factors in multi-label feature selection, and our method expresses them within a unified formulation, enabling efficient optimization while simultaneously accounting for all of them. To efficiently solve the proposed optimization problem under non-negativity constraints, we develop a gradient-based optimization algorithm with fast convergence. The experimental results on seven multi-label datasets show that the proposed method outperforms existing multi-label feature selection techniques.Keywords

Multi-label learning has attracted significant attention in recent years due to its ability to handle scenarios where each instance may be associated with multiple semantic labels simultaneously. It has been successfully applied across a wide range of domains and applications, including image classification [1], text classification [2], emotion recognition [3], fault diagnosis [4], and privacy protection [5]. These diverse applications demonstrate the growing importance of multi-label learning in addressing real-world problems where data exhibit complex and overlapping label structures.

In the fields of machine learning and pattern recognition, it is often necessary to handle high-dimensional data. Such data may contain redundant or irrelevant information that can interfere with learning. Moreover, high-dimensional datasets typically require excessive processing time and a large amount of memory consumption, making them challenging to work with [6]. These issues can degrade the performance of learning algorithms and hinder practical applications. In particular, when the data involves multiple labels per instance-commonly referred to as multi-label data-the complexity of learning grows substantially. In contrast to single-label scenarios, where each sample is associated with a single target, multi-label learning must consider multiple, potentially interdependent targets simultaneously. This increased dimensionality, coupled with inter-label dependency, leads to a combinatorial explosion in both the space and the associated computational complexity [7]. To address these challenges, many studies have introduced feature selection techniques in multi-label settings. Multi-label feature selection algorithms aim to identify and retain the most relevant features while removing unnecessary ones, based on certain evaluation criteria. The resulting feature subset can improve the accuracy of machine learning models, reduce training time, and enhance the interpretability of the data. Moreover, it helps mitigate risks such as the curse of dimensionality and overfitting [8].

Conventional feature selection approaches based on criteria that evaluate features independently of any specific learning model can be broadly categorized into two main streams: information-theoretic filter methods and regression-based embedded methods. The first stream, exemplified by methods such as mRMR [9], evaluates the redundancy between features and relevance to the target using mutual information to tackle the computational intractability of exhaustive subset search. These approaches can effectively capture nonlinear dependencies and pairwise relationships. However, they typically rely on greedy selection strategies, which may fail to consider global feature interactions and often lead to suboptimal solutions. The second stream formulates feature selection as a regression optimization problem, typically minimizing an objective of the form ||XW − ϒ || where X and ϒ are input data and label set, W represents importance of each feature [10]. This framework allows feature selection to be incorporated into a global optimization procedure, thereby enhancing computational efficiency. However, such approaches inherently rely on the assumption of linear dependencies between features and labels, which constrains their capacity to model more complex relationships.

In this paper, we propose a unified feature selection framework that integrates information-theoretic redundancy measures into a regression-based formulation. By unifying these two complementary approaches, the proposed framework mitigates their respective limitations while leveraging their individual strengths. Specifically, we encode the mutual information relationships between features, and between features and labels into a matrix representation, which is then incorporated into the regression objective. This enables the model to retain the nonlinear dependency awareness of mutual information-based methods while benefiting from the efficient optimization capability of regression-based approaches.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

• Novel Objective Function: To overcome the limitations of traditional approaches in multi-label feature selection, we introduce a new objective function that merges efficient regression-based approach and mutual information-based criteria. The proposed function is designed to be simple yet capable of capturing essential information for effective feature selection. Its formulation is described in detail in Sections 3.1 and 3.2.

• Efficient Optimization Algorithm: We develop an efficient algorithm based on gradient descent to optimize the proposed objective function. This algorithm emphasizes fast convergence and reduced computational complexity compared to existing methods. The optimization algorithm is presented in Section 3.3, the complexity analysis is provided in Section 3.4, and the convergence behavior of the algorithm is illustrated in Section 4.3.

• Improved Classification Performance: Through experiments on seven multi-label datasets, we confirm that the proposed method achieves superior classification performance compared to conventional feature selection techniques. Comprehensive comparison experiments and statistical analyses are reported in Section 4.2, accompanied by extensive figures and tables.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews background knowledge on multi-label classification and feature selection methods. Section 3 provides a detailed description of the proposed methodology, including the integration of mutual information and regression objectives. Section 4 presents experimental results using seven benchmark multi-label datasets and compares the performance of the proposed approach with existing methods. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study and discusses potential future research directions.

Feature selection has been widely investigated in single-label learning scenarios, where each instance is associated with only one target. In contrast, multi-label learning, which involves multiple potentially interdependent targets, introduces additional challenges due to increased dimensionality and complex label dependencies. Approaches to handling multi-label data can be broadly classified into two categories: those that transform the problem into a single-label format, and those that directly operate on the multi-label structure [11]. Converting multi-label data into single-label format allows for the direct application of traditional single-label feature selection techniques. However, this transformation often leads to information loss. One common method for this transformation is the Label Powerset (LP) approach, which treats all possible label combinations and treats each as a distinct class label [12]. While straightforward, LP suffers from severe class imbalance, as the number of resulting classes can grow exponentially with the number of labels. To address this, the Pruned Problem Transformation (PPT) method was introduced, which discards infrequent label combinations to mitigate imbalance [13]. However, this pruning also results in the loss of valuable label relationship information.

In contrast, two main feature selection approaches have been proposed to avoid the need for label transformation. The first approach is information-theoretic feature filter. The pairwise multi-label utility (PMU) method is one such approach, which evaluates label correlations using mutual information without transformating labels [14]. However, PMU is easy to finding only locally optimal solutions, since its greedy selection approach inherently constrains the search process and prevents the discovery of globally optimal feature subsets. Lee and Kim conducted a theoretical analysis of feature selection based on interaction information, demonstrating that lower-degree interaction information terms notably influence mutual information under an incremental selection scheme [15]. They further derived the upper and lower bounds of these terms to explain why score functions that consider lower-degree interactions can produce more effective feature subsets. The max-dependency and min-redundancy (MDMR) criterion has been proposed for multi-label feature selection, where a candidate feature is considered beneficial if it exhibits strong relevance to all class labels while remaining non-redundant with respect to other selected features across all labels [16]. However, MDMR is also easy to finding local optimal solution. The quadratic programming feature selection (QPFS) method reformulates mutual information-based evaluation as a numerical optimization problem to escape local optima [7]. However, QPFS requires the computation of a large number of mutual information terms, which can be computationally intensive. Zhang et al. proposed an approach that allows a feature to account for multiple labels by calculating mutual information across pairs of labels [17].

In another research direction, regression-based embedded methods integrate feature selection into the model training process itself. For example, decision tree classifiers naturally perform feature selection during their construction [18]. In multi-label scenarios, several embedded feature selection methods based on regression analysis have been proposed. Fan et al. utilizes ridge regression to construct a selection matrix and employs the

Another category is the wrapper approach, which identifies an optimal feature subset through iterative evaluation guided by a learning algorithm. Wrapper methods utilize classification performance as a direct evaluation metric to select the optimal feature subset. Optimization techniques such as boosting and genetic algorithms have been employed to improve selection quality [28]. The genetic algorithm for feature selection can be used for various applications [29,30]. Despite their effectiveness, wrapper methods are computationally expensive due to repeated classifier evaluations. However, wrapper methods are beyond the scope of this work and are therefore not considered here.

Recent studies have explored logic mining as an interpretable approach to feature selection and rule extraction, primarily implemented through Discrete Hopfield Neural Networks (DHNNs). A hybrid DHNN framework with Random 2-Satisfiability rules was introduced [31], where hybrid differential evolution and swarm mutation operators were incorporated to enhance the optimization of synaptic weights and diversify neuron states during retrieval, leading to improved transparency in decision-making. Similarly, Romli et al. proposed an optimized logic mining model using higher-order Random 3-Satisfiability representations in DHNNs, designed to prevent overfitting and flexibly induce logical structures that capture the behavioral characteristics of real-world datasets [32]. Beyond logic-mining-oriented formulations, recent work has also advanced the theoretical foundations of discrete Hopfield architectures. In particular, a simplified two-neuron discrete DHNN model was introduced, where bifurcation analysis, hyperchaotic attractor characterization, and field-programmable gate array(FPGA)-based hardware implementation demonstrated that even minimal DHNN structures can exhibit rich dynamical behaviors and robust randomness properties [33]. These findings highlight the broader modeling flexibility and dynamic expressiveness of DHNNs, complementing logic-mining-based approaches by reinforcing the underlying stability and dynamical mechanisms upon which interpretable feature-selection frameworks can be built.

Feature selection methods can be broadly categorized into two major streams: mutual information (MI)-based filter approaches and regression-based approaches.

The first stream is represented by classical methods such as mRMR (minimum redundancy maximum relevance) [9], which aim to maximize the relevance between features and labels while minimizing redundancy among selected features. These approaches rely on information-theoretic criteria, particularly mutual information, to measure pairwise dependencies between variables. They are straightforward and model-agnostic, and they can capture nonlinear relationships that linear methods may overlook. Given the full feature set F and the subset of features S that have already been selected, the next feature

where

The second stream is exemplified by regression-based methods such as efficient and robust feature selection via joint

where X is data matrix, ϒ is label matrix. These approaches aim to minimize reconstruction error, while imposing structural regularization to induce sparsity across features. Such methods benefit from global optimization and can naturally incorporate feature-label dependencies into a unified objective. However, because they fundamentally rely on a linear regression model, they are often limited in capturing complex or nonlinear relationships that are essential in many real-world datasets.

Given a dataset

where W is a weight matrix that is subject to a non-negativity constraint. The non-negativity constraint ensures that feature selection is represented by positive values, while unselected features are represented by zeros. The larger the absolute value in W, the more reliable the corresponding feature is considered. After solving this optimization problem, features corresponding to rows with larger norms in W are selected.

The objective function is designed to find features that minimize the difference between the data projected by W and the multi-label targets. To construct this objective function, the Frobenius norm is used. The function is convex with respect to W, allowing the optimization problem to be solved efficiently. The top

Although Eq. (3) offers an efficient convex formulation, its modeling capacity is limited because it only captures linear relationships between features and labels. In multi-label learning, however, three important aspects are often overlooked in such regression-based approaches:

1. Feature redundancy: selecting highly correlated features reduces the generalization power [9].

2. Label dependencies: multi-label data often contains significant inter-label correlations that should be preserved [34].

3. Non-linear dependencies: labels may exhibit complex, non-linear relationships with features.

To address these limitations, we incorporate mutual information into the objective function. Mutual information captures the degree of statistical dependency between random variables and can reflect both linear and non-linear relationships [9,19,24,27,35]. The mutual information between two arbitrary random variables A and B is defined as follows:

where

When the

By calculating these associations, three matrices

where

By combining these values with the regression Eq. (3), an objective function can be designed as follows:

where

• Regression loss

• Redundancy penalty

• Label dependency penalty

• Relevance reward

Optimizing the proposed objective function thus corresponds to selecting features that not only minimize redundancy and maximize relevance and label association, but also contribute to accurately reconstructing the label space through a linear regression model. In this formulation, the regression-based loss captures the predictive structure in a supervised setting, while the mutual information-based terms guide the selection toward features that exhibit strong statistical dependency with the labels and minimal overlap with other features. This hybrid design enables the model to balance predictive accuracy with information-theoretic feature quality. In the next subsection, we present an efficient optimization framework to solve the proposed objective function under the non-negativity constraint.

The convexity of the proposed objective function is primarily determined by the terms

To ensure the positive definiteness of the matrices Q and R, we adjust each matrix by adding the absolute value of its minimum eigenvalue to its diagonal entries. This yields modified matrices

where

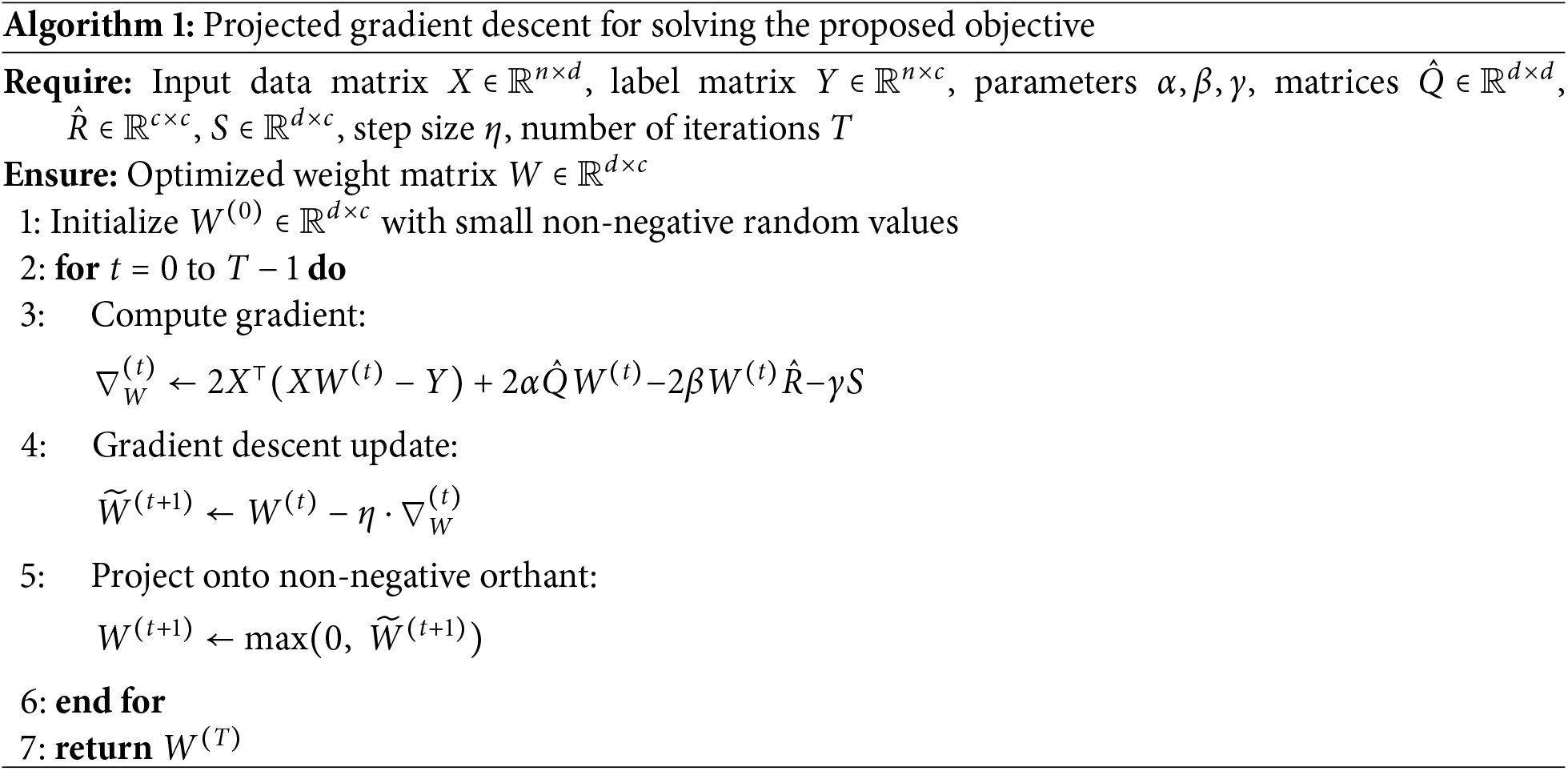

To solve the modified convex objective function with a non-negativity constraint, we employ the projected gradient descent (PGD) algorithm. This algorithm performs optimization based on the gradient with respect to W, and any negative entries in W are projected to zero to enforce the non-negativity constraint. The gradient of the objective function with respect to W is given by:

Algorithm 1 presents the complete procedure of the proposed method. In Algorithm 1, the step size

3.4 Computational Complexity Analysis

The overall computational complexity of the proposed algorithm consists of three main components: (1) the computation of the mutual information-based matrices Q, R, and S; (2) the eigenvalue correction required to ensure positive definiteness of Q and R; and (3) the iterative optimization procedure via projected gradient descent (PGD).

To ensure the convexity of the objective function, we modify Q and R by adding the absolute value of their minimum eigenvalue to their diagonals: Computing the minimum eigenvalue of a symmetric matrix (e.g., via power iteration or Lanczos methods) typically requires

In each iteration of PGD, the gradient with respect to

Combining all components, the overall computational complexity is

The proposed method involves three hyperparameters,

This section presents the experimental results to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method in improving classification performance. We compared classification performance using the Multi-label

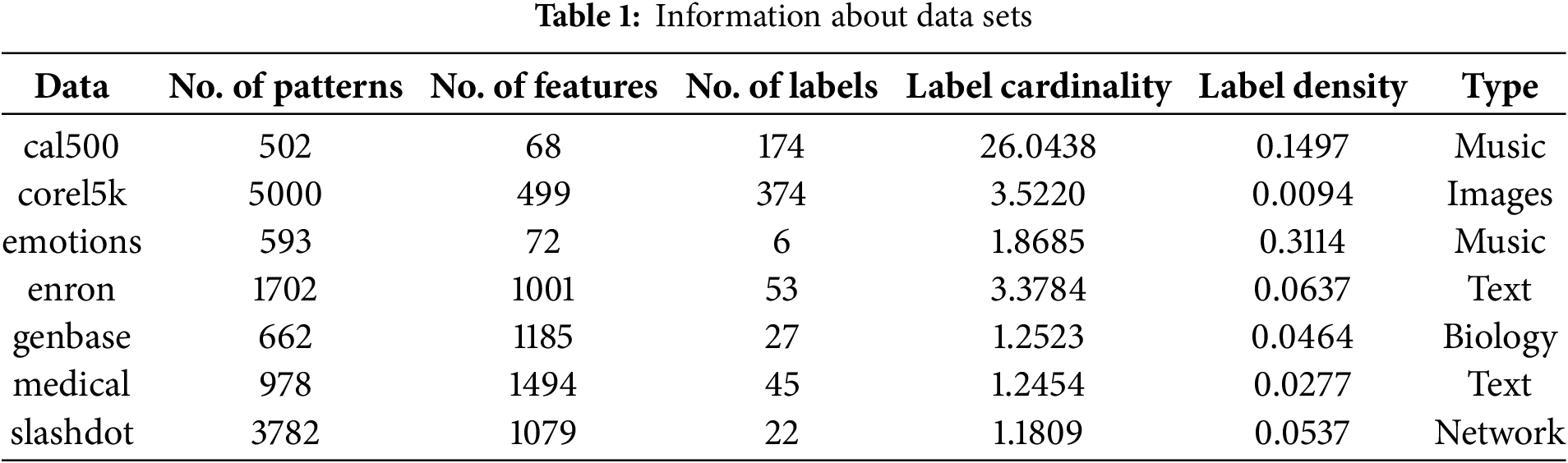

Seven datasets were used in the experiments. The cal500 dataset is a multi-label music annotation dataset consisting of 500 Western popular songs, each annotated with multiple tags describing acoustic, emotional, and semantic content [37]. The corel5k dataset is an image annotation dataset comprising 5000 images, each associated with one or more textual labels from a controlled vocabulary of 260 words. The emotions dataset contains 593 music tracks with 72 audio features, each labeled with one or more of six primary emotional categories [38]. The enron dataset is a text corpus derived from company emails [13]. The genbase dataset is a biological dataset for protein function classification, where each instance represents a protein and each label corresponds to a specific function. The medical dataset consists of 978 clinical free-text reports, each labeled with up to 45 disease codes [39]. The slashdot dataset is a relational graph dataset representing a social network of users from the technology news site Slashdot. It includes directional friend/foe relationships among users, making it suitable for multi-label classification and link prediction tasks in networked data [40]. Detailed characteristics of each dataset are summarized in Table 1.

For evaluation, we used three metrics: Hamming Loss (hloss), Ranking Loss (rloss), and Multi-label Accuracy (mlacc) [8]. Lower values of Hamming Loss and Ranking Loss indicate better classification performance, while higher values of Multi-label Accuracy reflect better performance. The number of selected features was determined based on a proportion

To compare against the proposed method, we selected five existing approaches: AMI [42], MDMR [16], FIMF [8], QPFS [7], and MFSJMI [17]. AMI selects features based on the first-order mutual information between features and labels. MDMR introduces a new feature evaluation function that considers mutual information between features and labels as well as among features. FIMF limits the number of labels considered during evaluation to enable fast mutual information-based feature selection. QPFS reformulates the mutual information problem into a quadratic programming framework to balance feature relevance and redundancy. MFSJMI selects features by considering label distribution and evaluating the relevance using joint mutual information. For all compared methods, including the proposed one, the hyperparameters

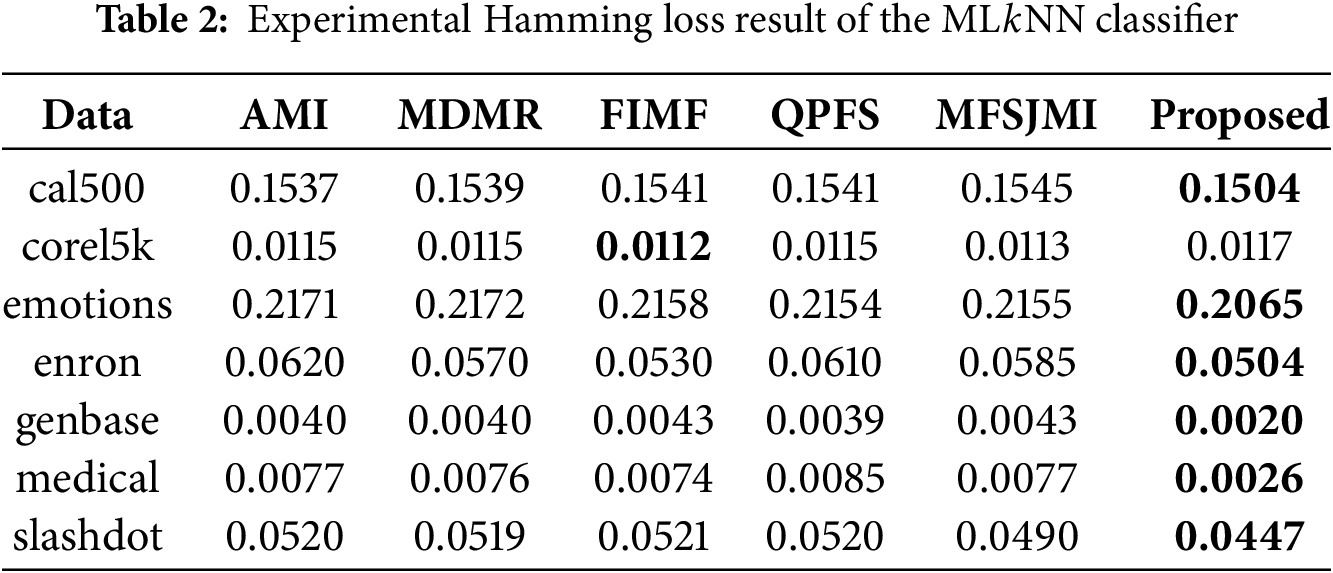

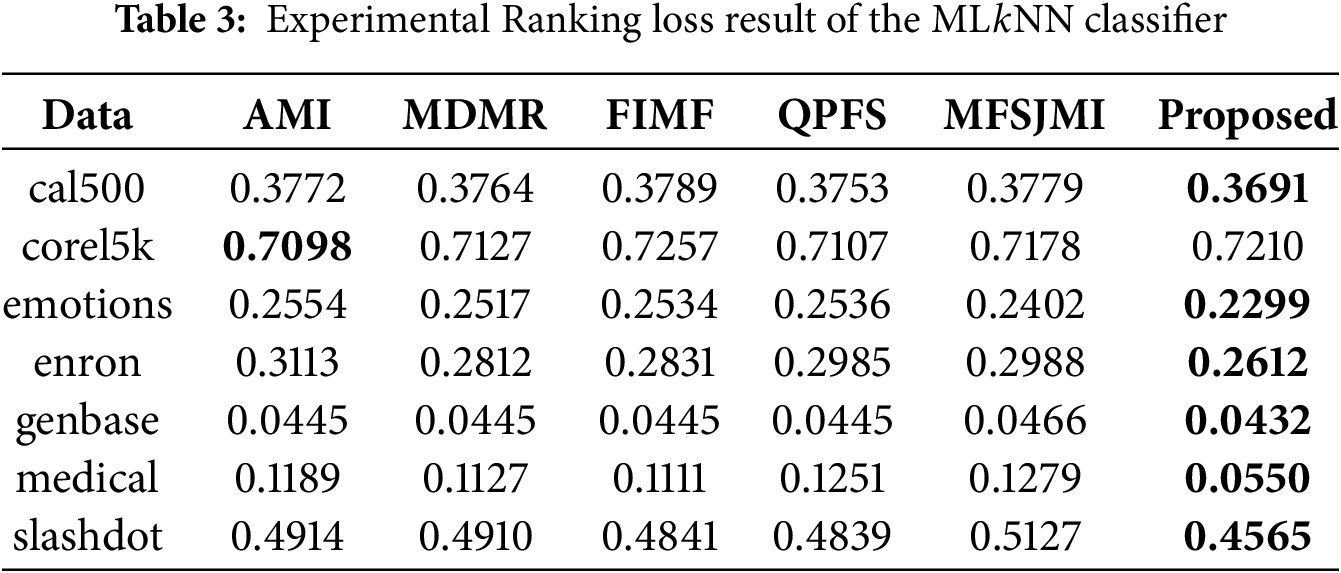

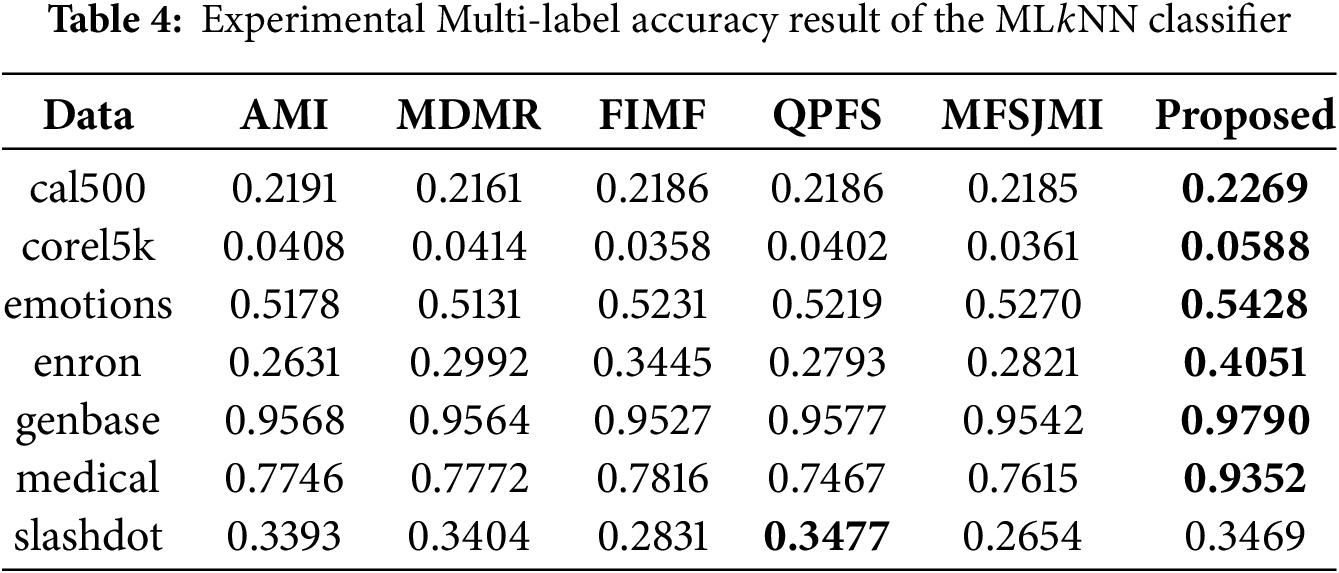

Tables 2–4 summarize the classification performance of different multi-label feature selection methods evaluated with the ML

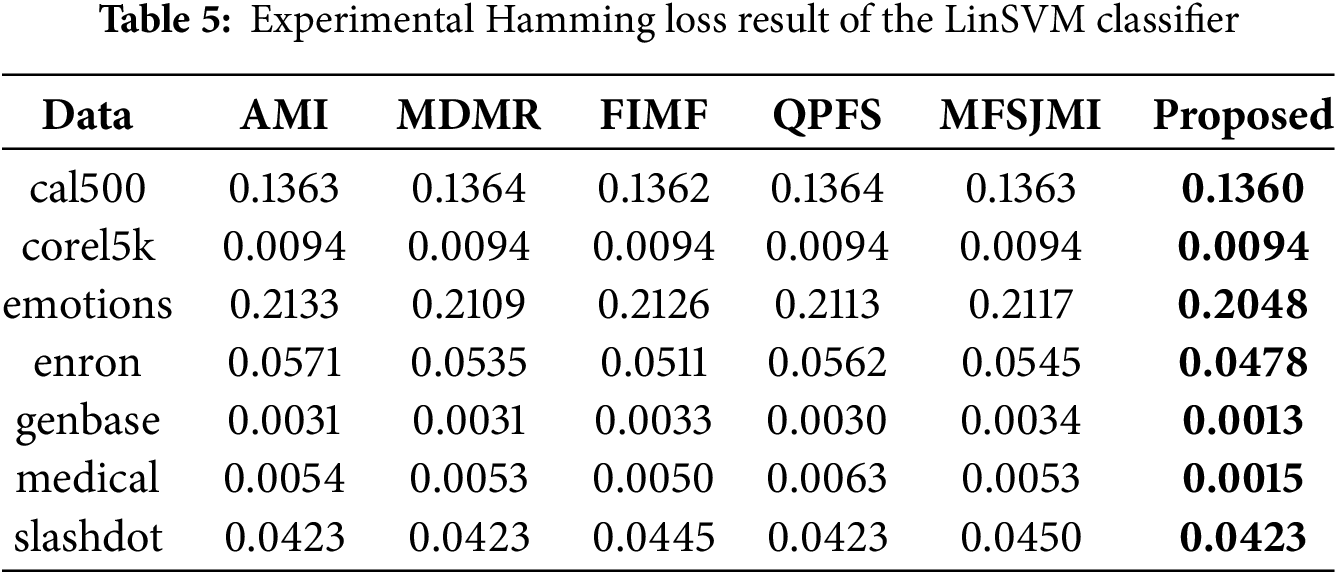

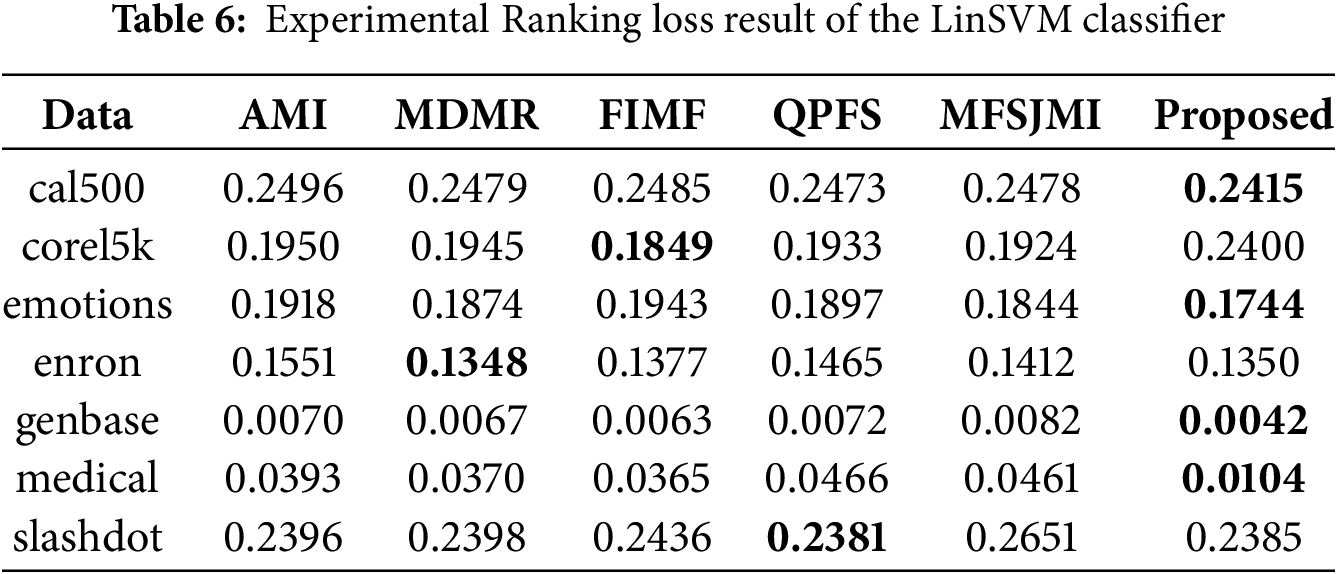

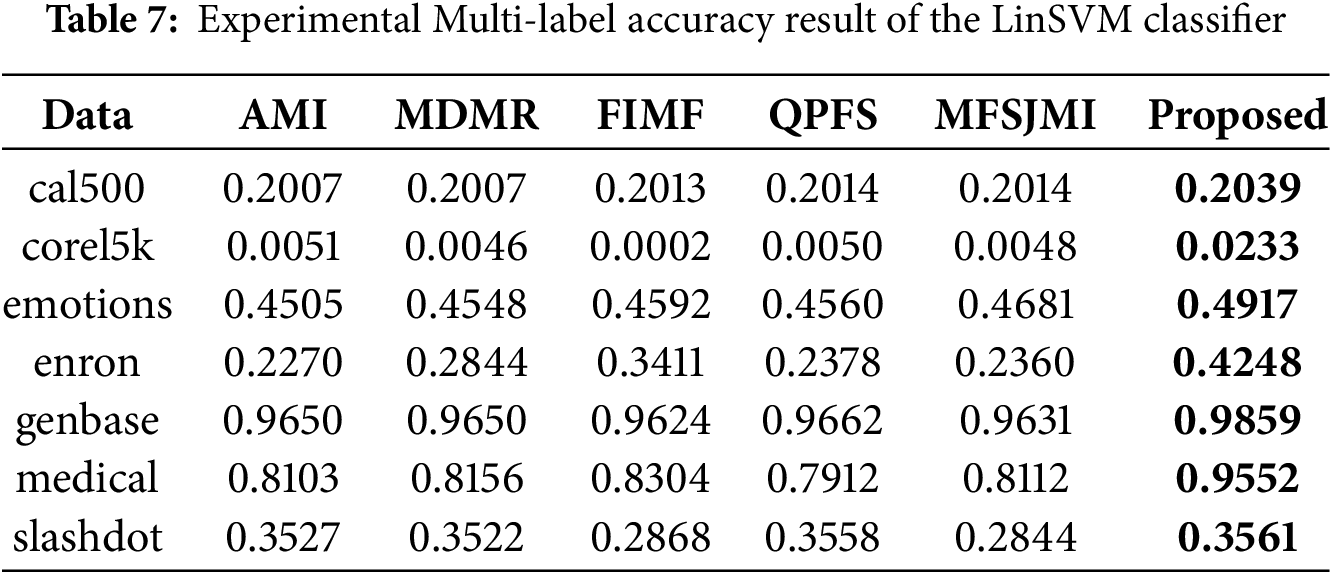

Tables 5–7 present the classification results obtained using the LinSVM classifier. Table 5 summarizes the Hamming loss results. The proposed method achieves the lowest loss on all datasets. These results show that the selected features effectively reduce instance-level prediction errors even when evaluated with a linear classifier. Table 6 presents the Ranking loss results. The proposed method achieves the best results on four datasets-cal500, emotions, genbase, and medical-showing its ability to preserve the label ranking order with minimal degradation. While FIMF slightly outperforms others on corel5k and MDMR performs best on enron, the proposed approach remains highly competitive across datasets. The performance gain on emotions and medical demonstrates that the proposed feature selection method can effectively model label dependencies even under a linear decision boundary. Table 7 reports the Multi-label accuracy results. The proposed method achieves the highest accuracy on six datasets, with particularly large gains on corel5k, enron, and medical. This demonstrates the strong discriminative capability of the selected features and their ability to generalize across datasets with varying label sparsity. FIMF predicted all-zero label vectors in 9 out of 10 runs on Corel5k, leading to nearly zero multi-label accuracy.

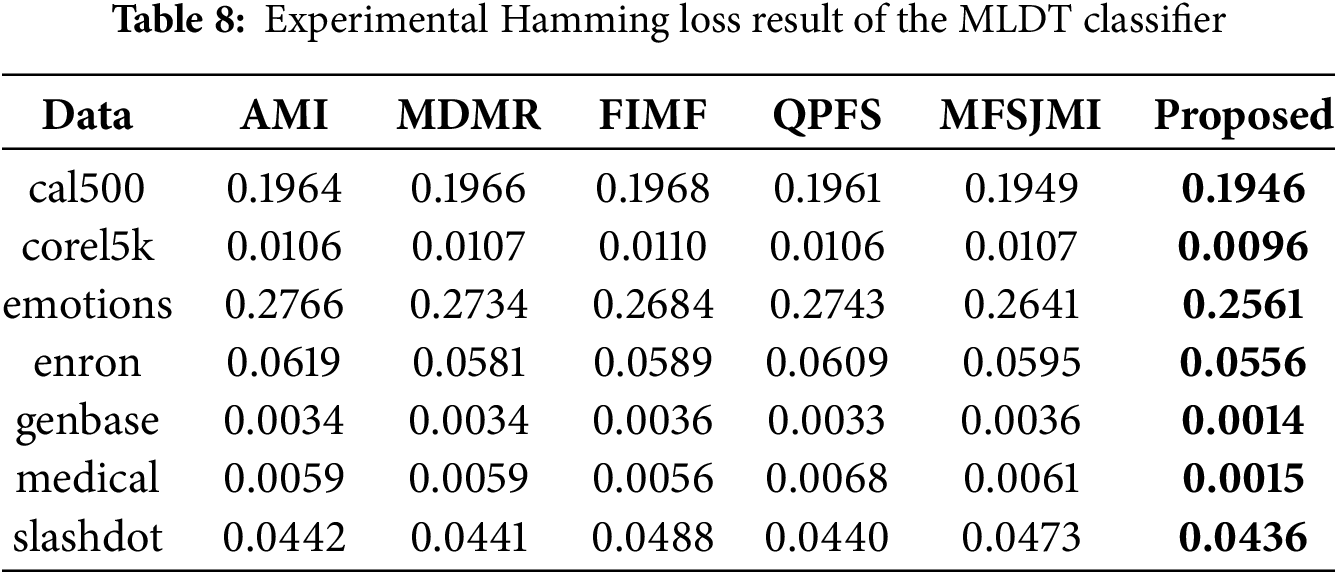

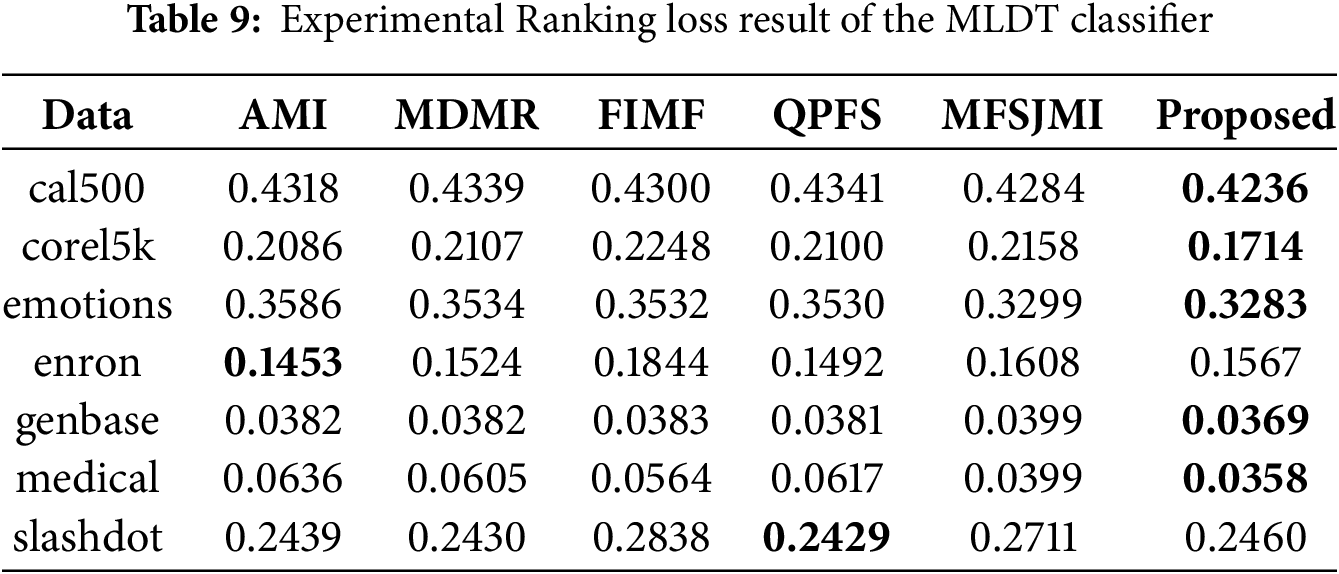

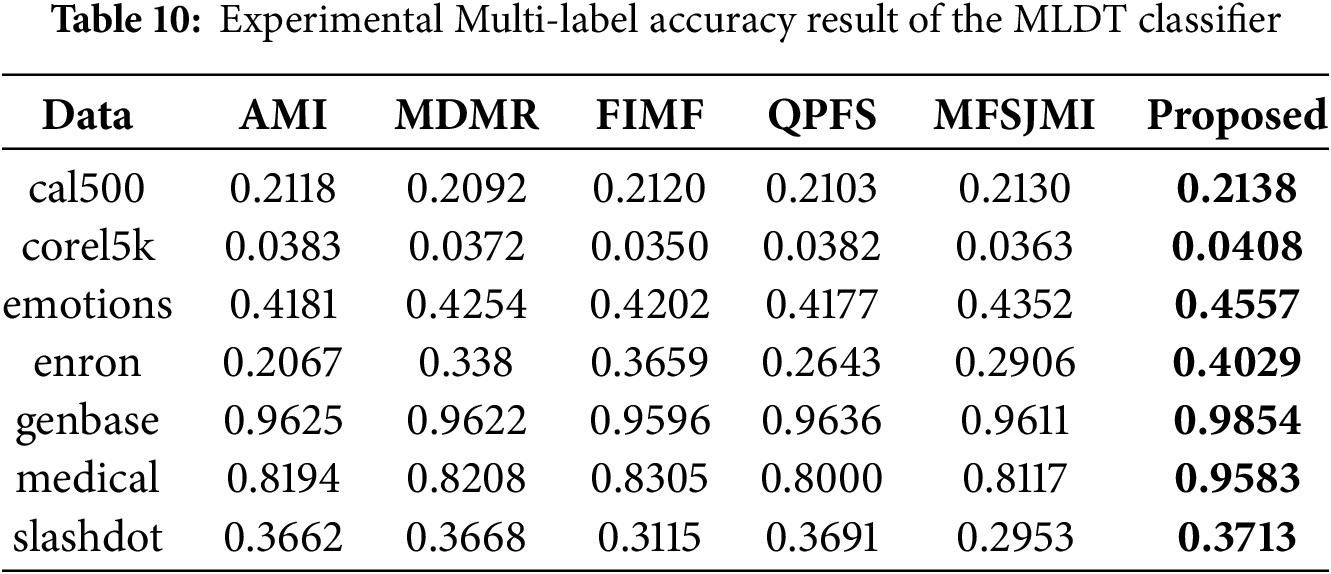

Tables 8–10 summarize the experimental results obtained using the MLDT classifier. Table 8 reports the Hamming loss results. The proposed method achieves the lowest loss on all seven datasets, showing remarkable consistency and robustness. In particular, the performance improvements on emotions, enron, genbase, and medical are significant, indicating that the proposed feature selection strategy effectively reduces label-wise prediction errors even for complex label spaces. Table 9 presents the Ranking loss results. The proposed approach achieves the best performance on five datasets while remaining highly competitive on the others. These results suggest that the proposed method allows the MLDT classifier to better preserve the relative ranking between relevant and irrelevant labels. Notably, the performance gain on corel5k and medical is substantial, confirming that the proposed MI-guided optimization enhances feature selection for both high-dimensional and label-dependent data. Table 10 shows the Multi-label accuracy results. The proposed method achieves the highest accuracy on all seven datasets, highlighting its superiority in overall predictive capability. The large gains on emotions, enron, and medical datasets illustrate that the proposed formulation captures label correlations more effectively than existing feature selection methods.

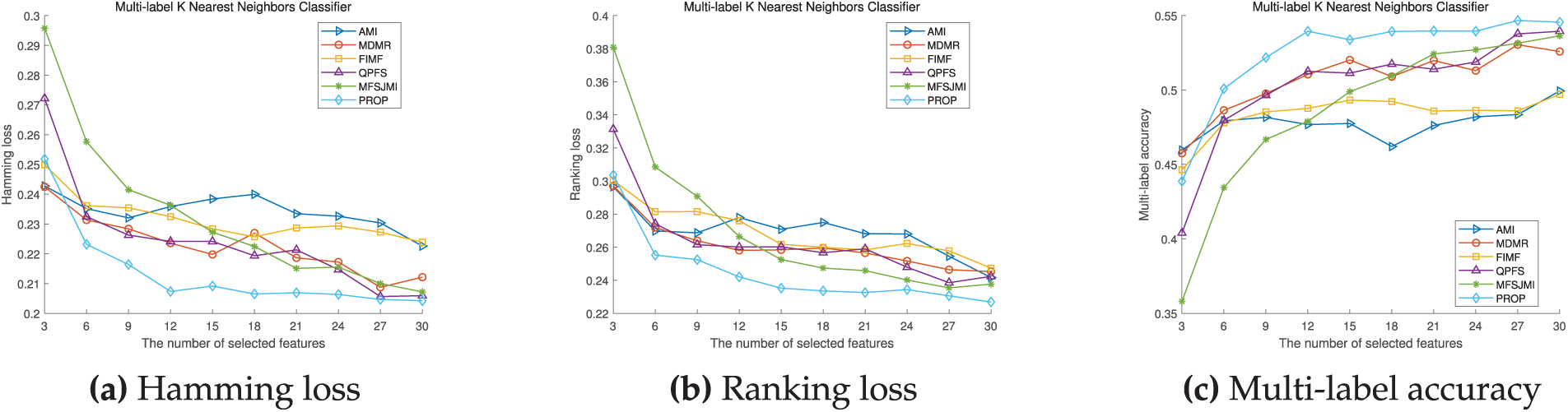

Fig. 1 illustrates the ML

Figure 1: ML

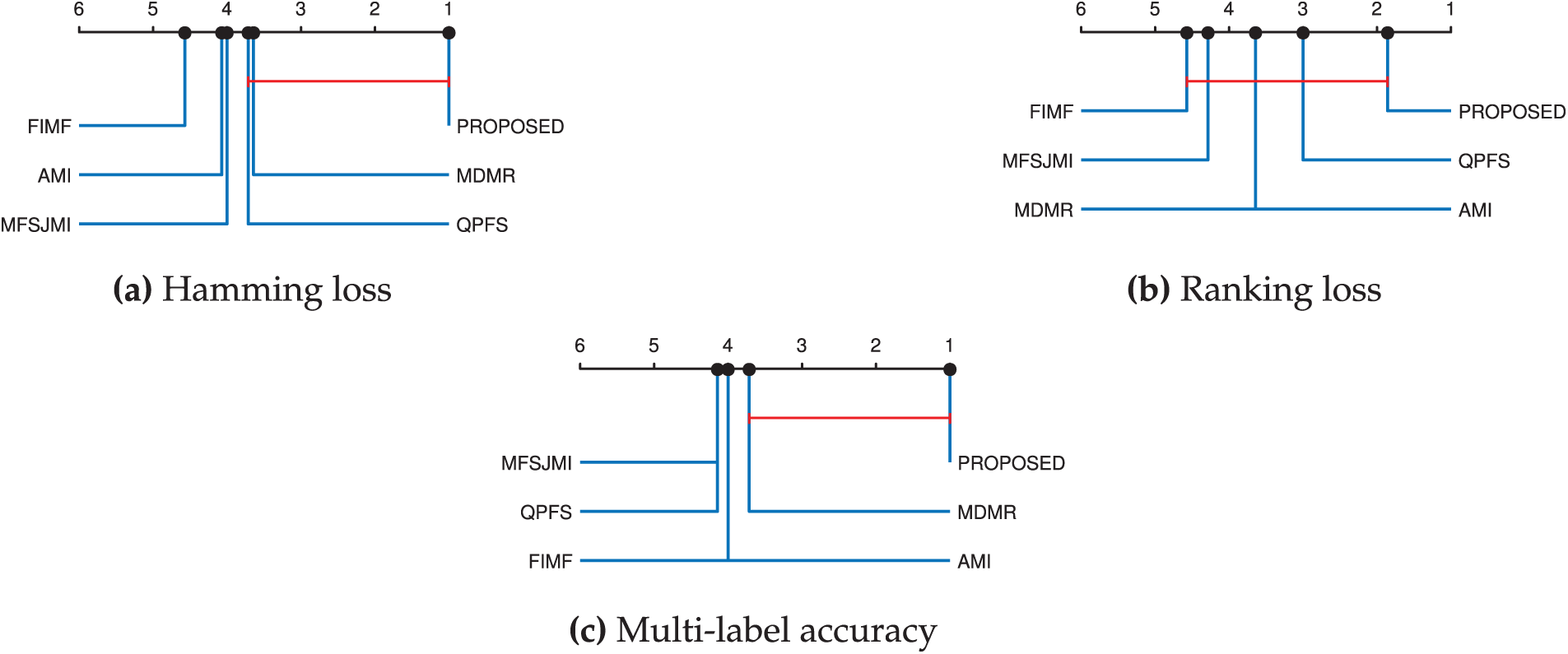

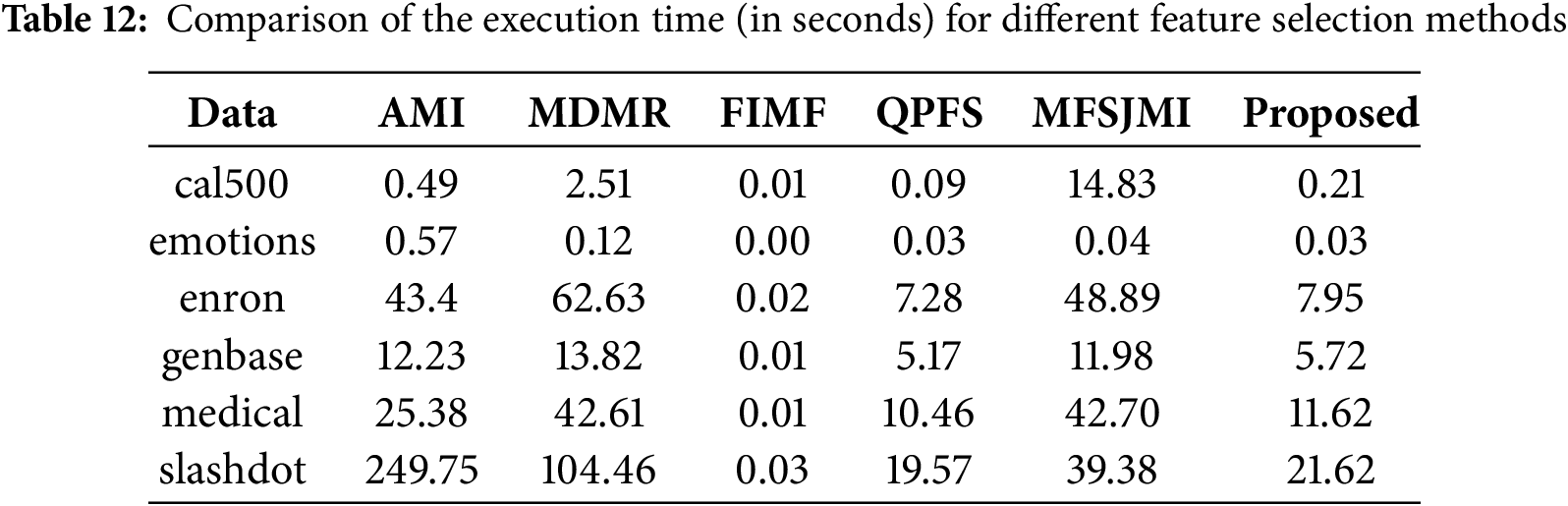

To assess whether the observed MLDT performance differences among the compared feature selection methods are statistically significant across the seven datasets, we performed the Friedman–Nemenyi non-parametric statistical test at a significance level of

Figure 2: Critical Distance diagrams for six compared methods across seven datasets based on (a) Hamming loss, (b) Ranking loss, and (c) Multi-label accuracy. The diagrams are obtained from the Friedman–Nemenyi statistical test with

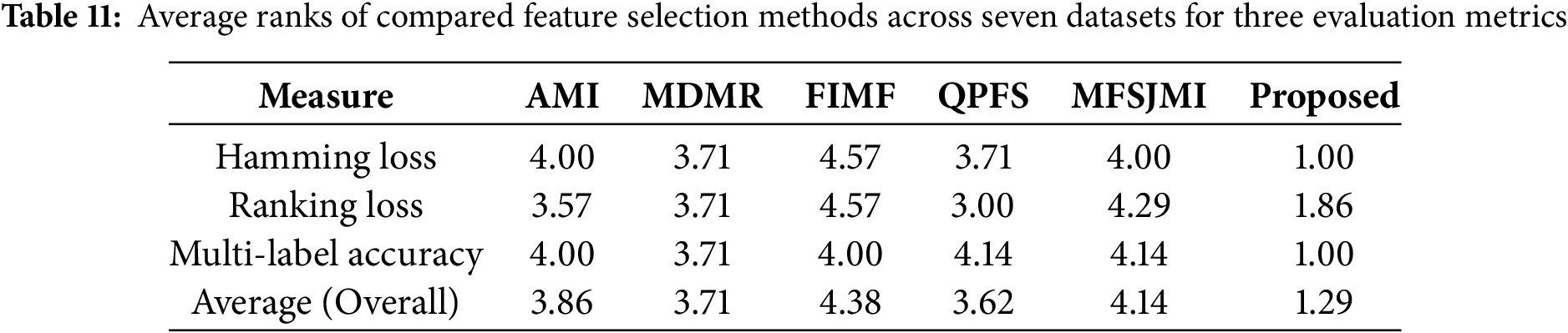

The computational efficiency of each feature selection method was evaluated in terms of total execution time, as summarized in Table 12. All experiments were conducted using MATLAB R2021b on a desktop equipped with an Intel Core i7-11700 CPU (2.5 GHz) and 32 GB of RAM. The maximum number of iterations for the proposed method was set to 100. The proposed method demonstrates competitive or superior computational efficiency compared to most baselines. In particular, it consistently outperforms AMI, MDMR, and MFSJMI, which incur substantial computational overhead due to repeated mutual information estimation or graph construction processes. While the proposed approach is slightly slower than FIMF-whose operations are relatively lightweight-it achieves significantly faster convergence than other information-theoretic methods such as QPFS and MFSJMI, especially on large-scale datasets like enron, genbase, and medical. These results indicate that the proposed optimization framework maintains high scalability without sacrificing selection quality, balancing effectiveness and computational cost efficiently across diverse multi-label datasets.

4.3 Analysis of the Proposed Method

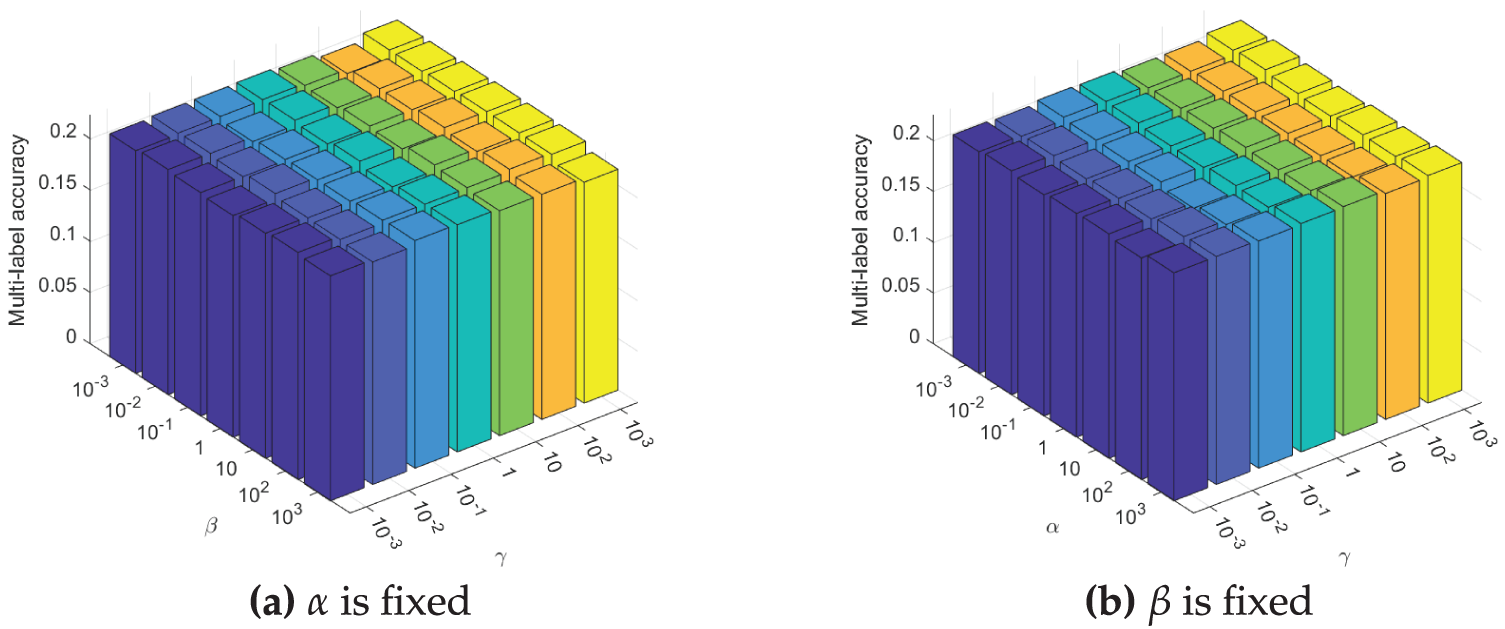

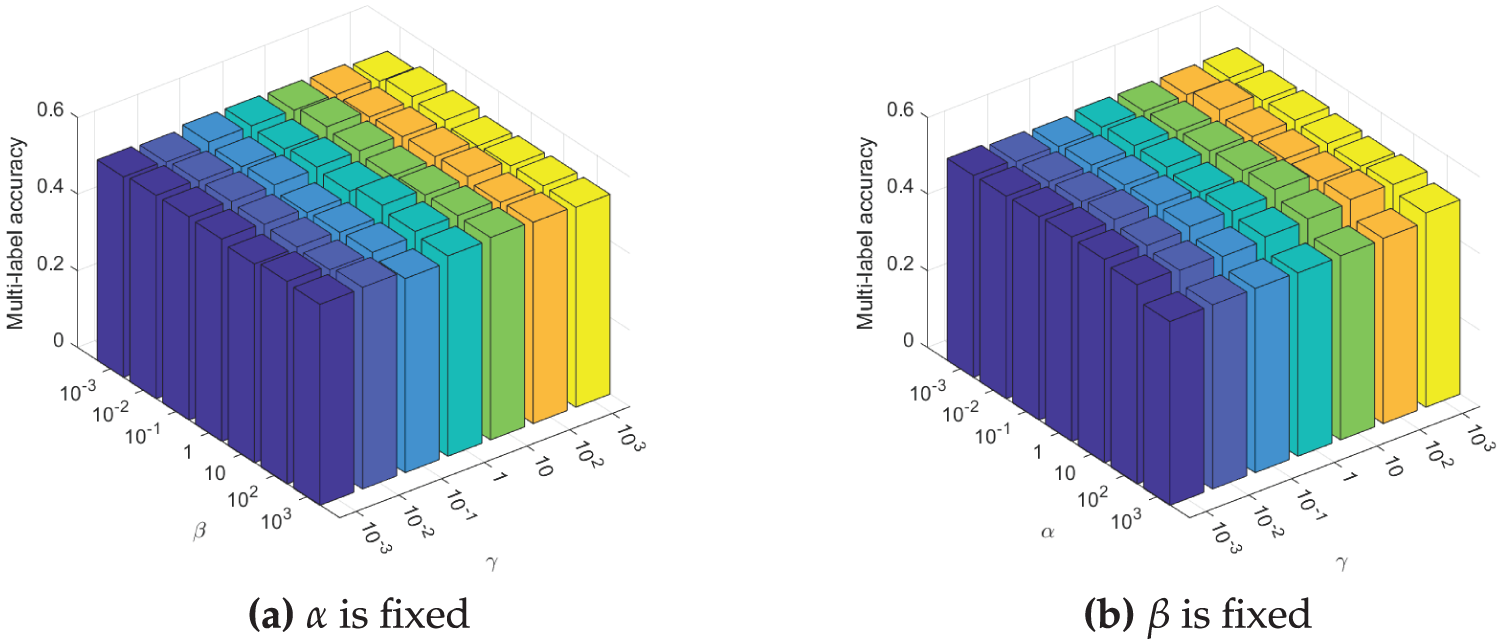

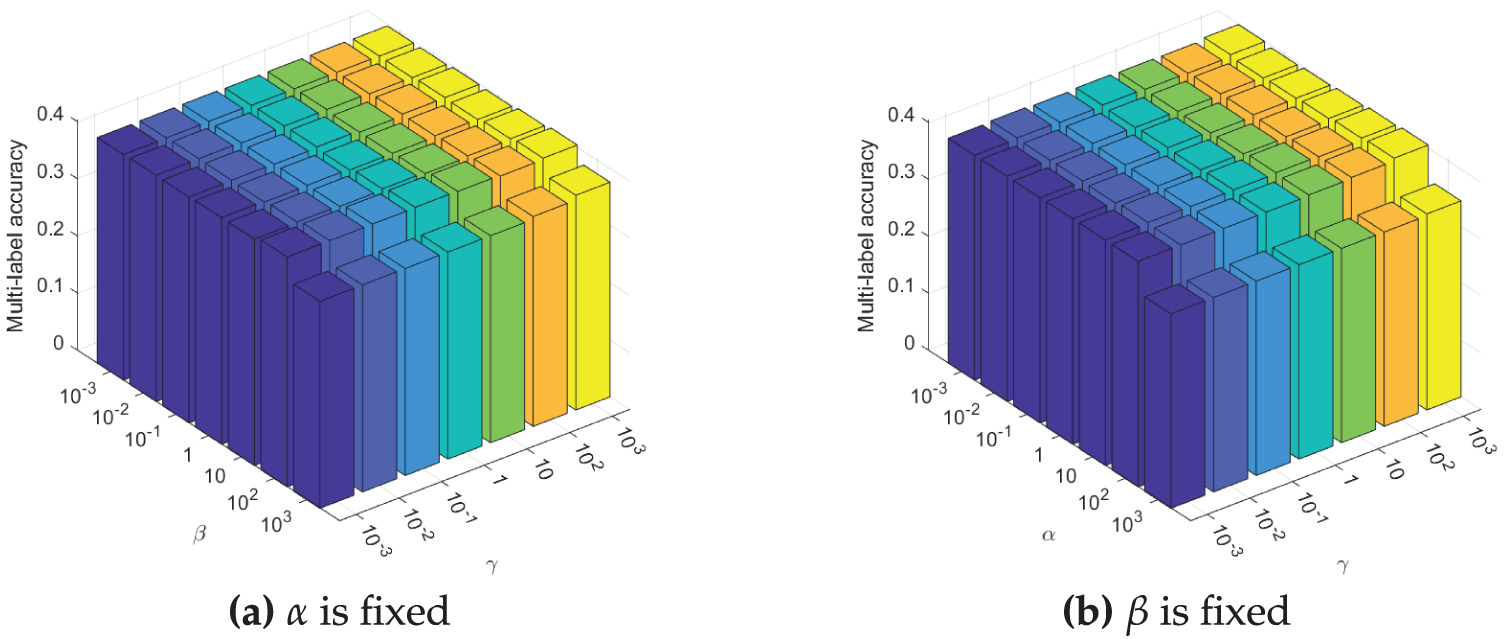

Figs. 3–5 illustrate the sensitivity of the proposed method to its three hyperparameters,

Figure 3: Comparison Multi-label accuracy of ML

Figure 4: Comparison Multi-label accuracy of ML

Figure 5: Comparison Multi-label accuracy of ML

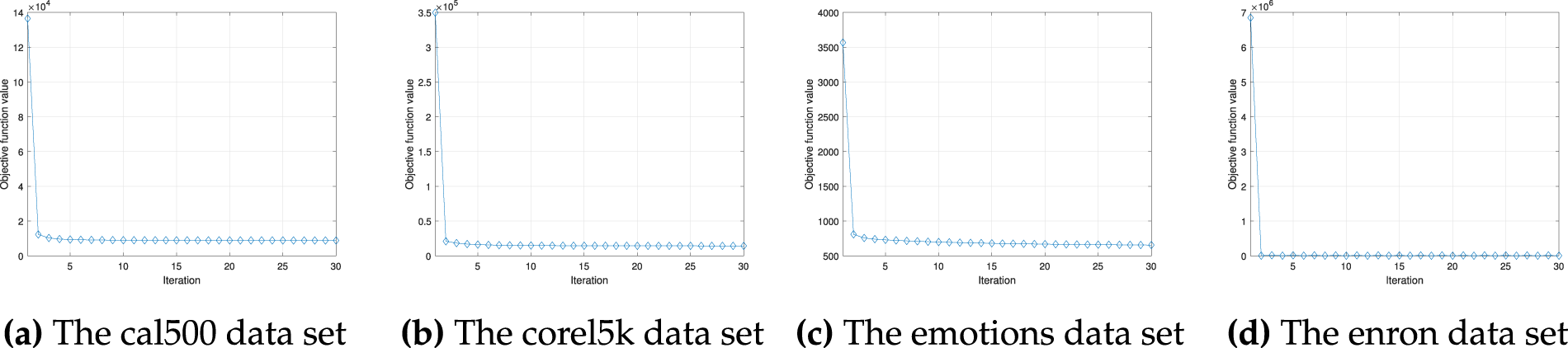

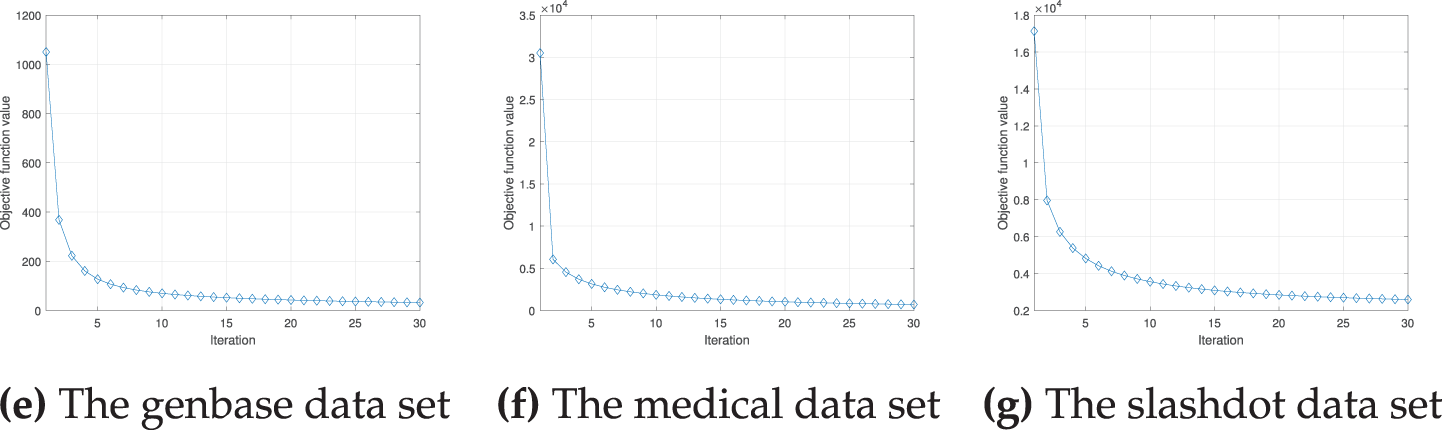

Fig. 6 displays the convergence behavior of the proposed method for all used datasets. The horizontal axis represents the number of iterations of the proposed algorithm, and the vertical axis shows the value of the objective function. The objective function value drops sharply within the first three iterations and appears to converge before the tenth iteration. This indicates that the proposed algorithm operates efficiently.

Figure 6: Convergence rate of the proposed method

In this study, we proposed a novel regression-based objective function for multi-label feature selection that explicitly incorporates mutual information between features and labels. By integrating a mutual information-aware structure into a convex regression formulation, the proposed method enables efficient optimization via projected gradient descent while preserving important statistical dependencies in the data. Empirical evaluations across multiple benchmark datasets and classifiers demonstrate that our approach consistently achieves superior or competitive performance compared to existing methods, confirming its effectiveness and robustness in various multi-label learning scenarios.

Despite its strong performance, the proposed method has several limitations. First, computing mutual information for all feature—feature and label—label pairs can be computationally expensive, especially for high-dimensional datasets. Exploring approximation techniques or sparse estimation strategies may significantly reduce this overhead. Second, the method involves several hyperparameters whose tuning can impact performance and requires careful consideration. Future work will focus on developing adaptive or data-driven hyperparameter selection mechanisms to further enhance usability and generalization.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2020-NR049579).

Availability of Data and Materials: Details of the dataset used in this study are provided in the main text. The dataset is accessible at https://mulan.sourceforge.net/datasets-mlc.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang J, Zhang Y, Wang T, Tang H, Li B. Establishing two-dimensional dependencies for multi-label image classification. Appl Sci. 2025;15(5):2845. doi:10.3390/app15052845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hu W, Fan Q, Yan H, Xu X, Huang S, Zhang K. A survey of multi-label text classification under few-shot scenarios. Appl Sci. 2025;15(16):8872. doi:10.3390/app15168872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Feng Y, Wei R. Method of multi-label visual emotion recognition fusing fore-background features. Appl Sci. 2024;14(18):8564. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4752870/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Han Q, Zhang W, Ma C, He J, Gao W. Robust multilabel feature selection with label enhancement for fault diagnosis. IEEE Transact Syst Man, Cybernet: Syst. 2025;55(11):7841–50. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2025.3598796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Huang F, Yang N, Chen H, Bao W, Yuan D. Distributed online multi-label learning with privacy protection in internet of things. Appl Sci. 2023;13(4):2713. doi:10.3390/app13042713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Elhamifar E, Vidal R. Sparse subspace clustering: algorithm, theory, and applications. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intelle. 2013;35(11):2765–81. doi:10.1109/tpami.2013.57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Lim H, Lee J, Kim DW. Optimization approach for feature selection in multi-label classification. Pattern Recognition Letters. 2017;89:25–30. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2017.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lee J, Kim DW. Fast multi-label feature selection based on information-theoretic feature ranking. Pattern Recognit. 2015;48:2761–71. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2015.04.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Peng H, Long F, Ding C. Feature selection based on mutual information criteria of max-dependency, max-relevance, and min-redundancy. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2005;27:1226–38. doi:10.1109/tpami.2005.159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Nie F, Huang H, Cai X, Ding C. Efficient and robust feature selection via joint l2,1-norms minimization. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 23 (NIPS 2010). Red Hook, NY, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

11. Pereira RB, Plastino A, Zadrozny B, Merschmann LH. Categorizing feature selection methods for multi-label classification. Artificial Intell Rev. 2018;49(1):57–78. doi:10.1007/s10462-016-9516-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tsoumakas G, Vlahavas I. Random k-labelsets: an ensemble method for multilabel classification. In: Machine learning: ECML 2007 (ECML 2007). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2007. p. 406–17 doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-74958-5_38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Read J. A pruned problem transformation method for multi-label classification. In: Proceedings of the New Zealand Computer Science Research Student Conference; 2008 Apr 14–18; Christchurch, New Zealand. p. 143–50. [Google Scholar]

14. Lee J, Kim DW. Feature selection for multi-label classification using multivariate mutual information. Pattern Recognit Letters. 2013;34:349–57. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2012.10.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lee J, Kim DW. Mutual information-based multi-label feature selection using interaction information. Expert Syst Applicat. 2015;42:2013–25. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2014.09.063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lin Y, Hu Q, Liu J, Duan J. Multi-label feature selection based on max-dependency and min-redundancy. Neurocomputing. 2015;168:92–103. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2015.06.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang P, Liu G, Song J. MFSJMI: multi-label feature selection considering join mutual information and interaction weight. Pattern Recognit. 2023;138:109378. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Clare A, King RD. Knowledge discovery in multi-label phenotype data. In: Principles of data mining and knowledge discovery (PKDD 2001). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2001. p. 42–53 doi: 10.1007/3-540-44794-6_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Fan Y, Chen B, Huang W, Liu J, Weng W, Lan W. Multi-label feature selection based on label correlations and feature redundancy. Knowl Based Syst. 2022;241:108256. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2022.108256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li Y, Hu L, Gao W. Multi-label feature selection via robust flexible sparse regularization. Pattern Recognit. 2023;134:109074. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2022.109074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Fan Y, Liu J, Tang J, Liu P, Lin Y, Du Y. Learning correlation information for multi-label feature selection. Pattern Recognit. 2024;145:109899. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li Y, Hu L, Gao W. Label correlations variation for robust multi-label feature selection. Informat Sci. 2022;609:1075–97. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.07.154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hu L, Gao L, Li Y, Zhang P, Gao W. Feature-specific mutual information variation for multi-label feature selection. Informat Sci. 2022;593:449–71. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2022.02.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Dai J, Huang W, Zhang C, Liu J. Multi-label feature selection by strongly relevant label gain and label mutual aid. Pattern Recognit. 2024;145:109945. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Faraji M, Seyedi SA, Tab FA, Mahmoodi R. Multi-label feature selection with global and local label correlation. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;246:123198. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. He Z, Lin Y, Wang C, Guo L, Ding W. Multi-label feature selection based on correlation label enhancement. Inf Sci. 2023;647:119526. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yang Y, Chen H, Mi Y, Luo C, Horng SJ, Li T. Multi-label feature selection based on stable label relevance and label-specific features. Inf Sci. 2023;648:119525. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2023.119525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang ML, Peña JM, Robles V. Feature selection for multi-label naive Bayes classification. Informat Sci. 2009;179:3218–29. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2009.06.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Cho DH, Moon SH, Kim YH. Genetic feature selection applied to KOSPI and cryptocurrency price prediction. Mathematics. 2021;9(20):2574. doi:10.3390/math9202574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Das H, Prajapati S, Gourisaria MK, Pattanayak RM, Alameen A, Kolhar M. Feature selection using golden jackal optimization for software fault prediction. Mathematics. 2023;11(11):2438. doi:10.3390/math11112438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Guo Y, Kasihmuddin MSM, Zamri NE, Li J, Romli NA, Mansor MA, et al. Logic mining method via hybrid discrete hopfield neural network. Comput Indust Eng. 2025;206:111200. doi:10.1016/j.cie.2025.111200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Romli NA, Zulkepli NFS, Kasihmuddin MSM, Karim SA, Jamaludin SZM, Rusdi N, et al. An optimized logic mining method for data processing through higher-order satisfiability representation in discrete hopfield neural network. Appl Soft Comput. 2025;184(B):113759. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bao B, Tang H, Bao H, Hua Z, Xu Q, Chen M. Simplified discrete two-neuron hopfield neural network and FPGA implementation. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2025;72(4):4105–15. doi:10.1109/tie.2024.3451052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Huang S, Hu W, Lu B, Fan Q, Xu X, Zhou X, et al. Application of label correlation in multi-label classification: a survey. Appl Sci. 2024;14(19):9034. doi:10.3390/app14199034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Klonecki T, Teisseyre P, Lee J. Cost-constrained feature selection in multilabel classification using an information-theoretic approach. Pattern Recognition. 2023;141(1):1–18. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2023.109605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang ML, Zhou ZH. ML-KNN: a lazy learning approach to multi-label learning. Pattern Recognit. 2007;40:2038–48. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2006.12.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Turnbull D, Barrington L, Torres D, Lanckriet G. Semantic annotation and retrieval of music and sound effects. IEEE Transact Audio, Speech, Lang Process. 2008;16(2):467–76. doi:10.1109/tasl.2007.913750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Trohidis K, Tsoumakas G, Kalliris G, Vlahavas IP. Multilabel classification of music into emotions. In: International Conference on Music Information Retrieval. Philadelphia, PA, USA: ISMIRSociety; 2008. p. 325–30. [Google Scholar]

39. Pestian J, Brew C, Matykiewicz P, Hovermale DJ, Johnson N, Cohen KB, et al. A shared task involving multi-label classification of clinical free text. In: BioNLP ′07:Proceedings of the Workshop on BioNLP 2007: Biological, Translational, and Clinical Language Processing. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2007. p. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

40. Leskovec J, Huttenlocher D, Kleinberg J. Signed networks in social media. In: CHI ′10:Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2010. p. 1361–70. [Google Scholar]

41. Lee J, Kim DW. SCLS: multi-label feature selection based on scalable criterion for large label set. Pattern Recognit. 2017;66:342–52. doi:10.1016/j.patcog.2017.01.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lee J, Lim H, Kim DW. Approximating mutual information for multi-label feature selection. Elect Letters. 2012;48(15):929–30. doi:10.1049/el.2012.1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Cano A, Luna JM, Gibaja EL, Ventura S. LAIM discretization for multi-label data. Informat Sci. 2016;330:370–84. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2015.10.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Demšar J. Statistical comparisons of classifiers over multiple data sets. J Mach Learn Res. 2006;7:1–30. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools