Open Access

Open Access

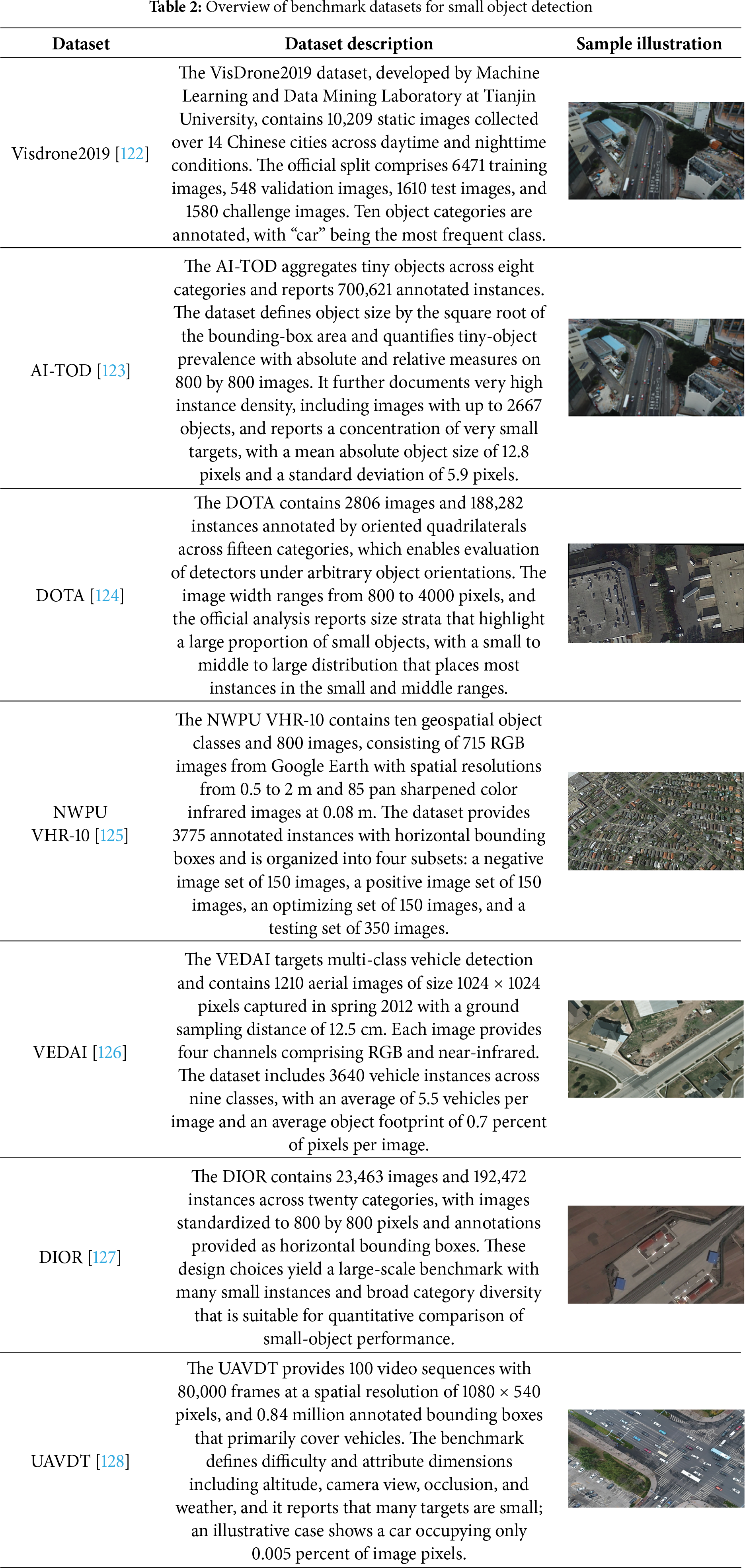

REVIEW

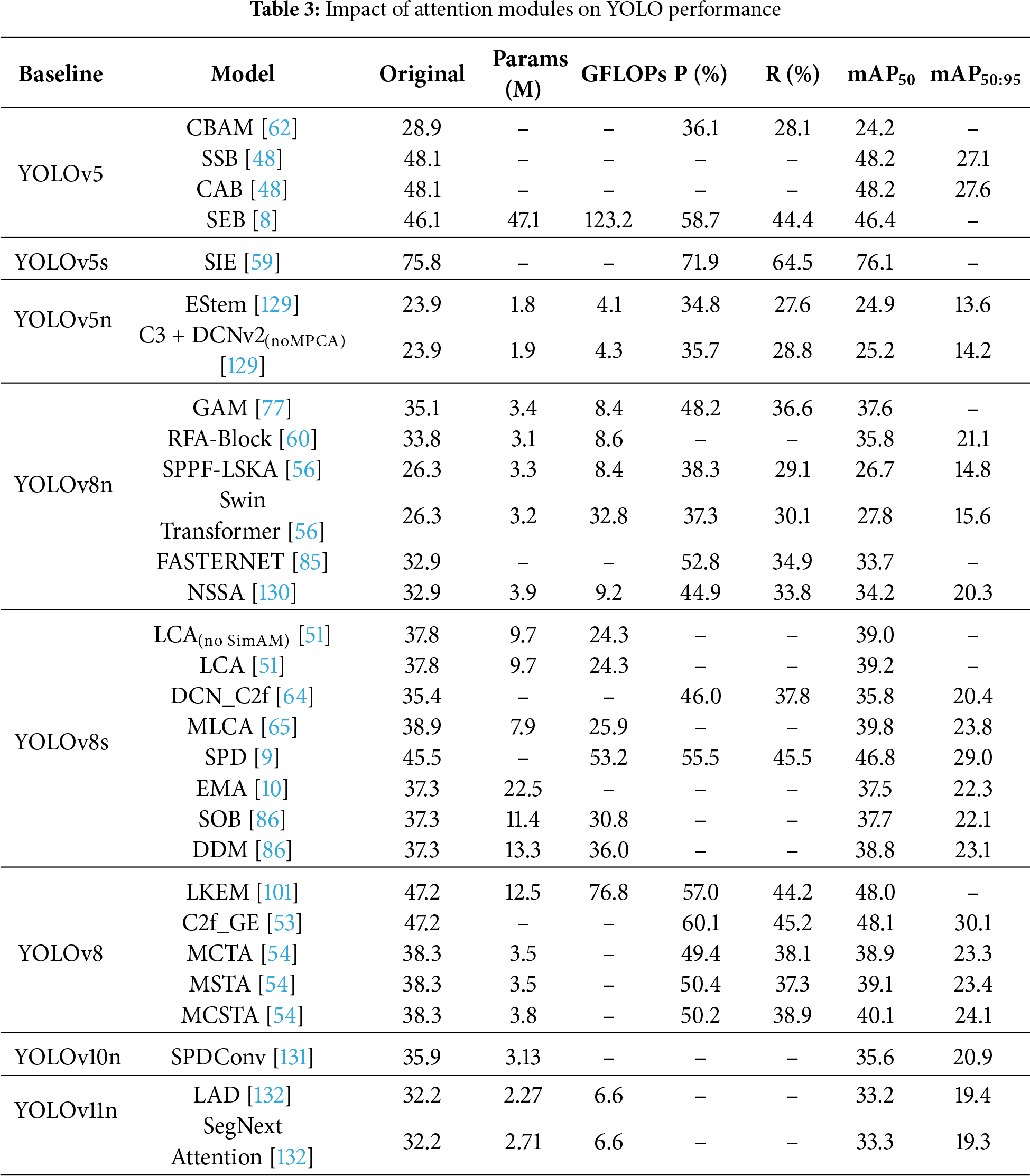

A Comprehensive Literature Review on YOLO-Based Small Object Detection: Methods, Challenges, and Future Trends

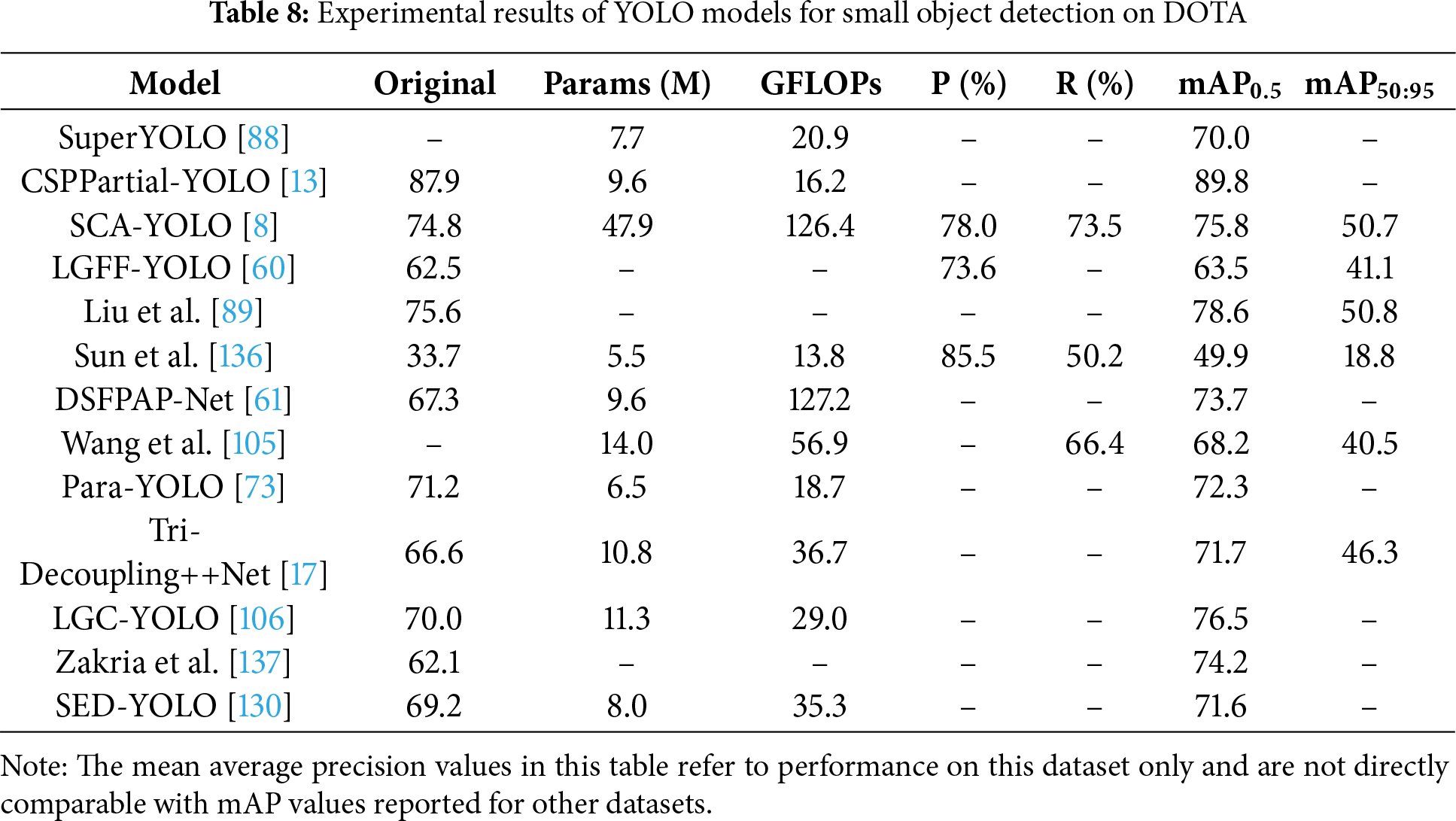

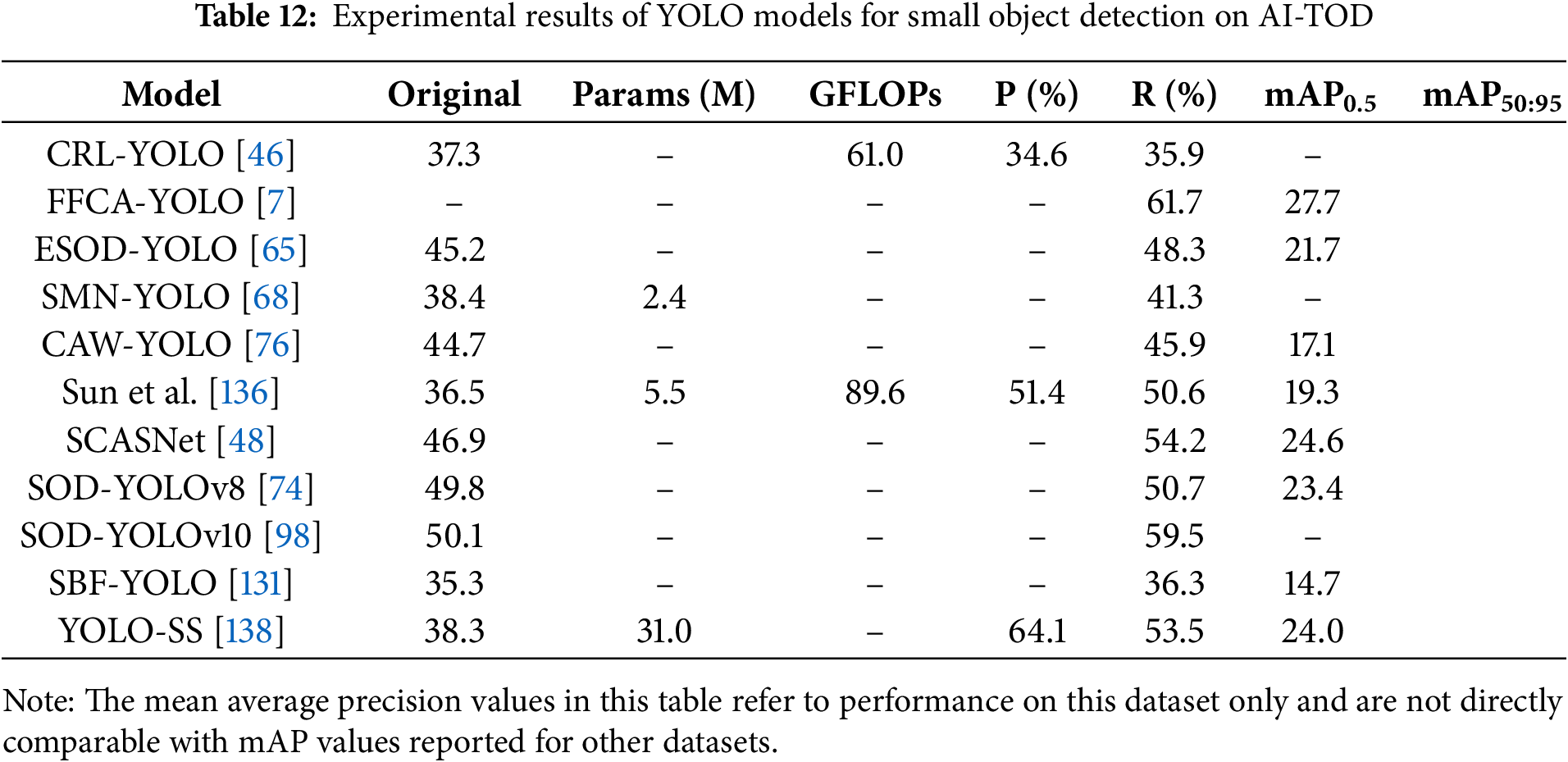

1 School of Computer Science and Technology, Chongqing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Chongqing, 400065, China

2 College of Computer and Cyber Security, Fujian Normal University, Fuzhou, 350117, China

* Corresponding Authors: Jun Liu. Email: ; Mingwei Lin. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 7 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074191

Received 05 October 2025; Accepted 12 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Small object detection has been a focus of attention since the emergence of deep learning-based object detection. Although classical object detection frameworks have made significant contributions to the development of object detection, there are still many issues to be resolved in detecting small objects due to the inherent complexity and diversity of real-world visual scenes. In particular, the YOLO (You Only Look Once) series of detection models, renowned for their real-time performance, have undergone numerous adaptations aimed at improving the detection of small targets. In this survey, we summarize the state-of-the-art YOLO-based small object detection methods. This review presents a systematic categorization of YOLO-based approaches for small-object detection, organized into four methodological avenues, namely attention-based feature enhancement, detection-head optimization, loss function, and multi-scale feature fusion strategies. We then examine the principal challenges addressed by each category. Finally, we analyze the performance of these methods on public benchmarks and, by comparing current approaches, identify limitations and outline directions for future research.Keywords

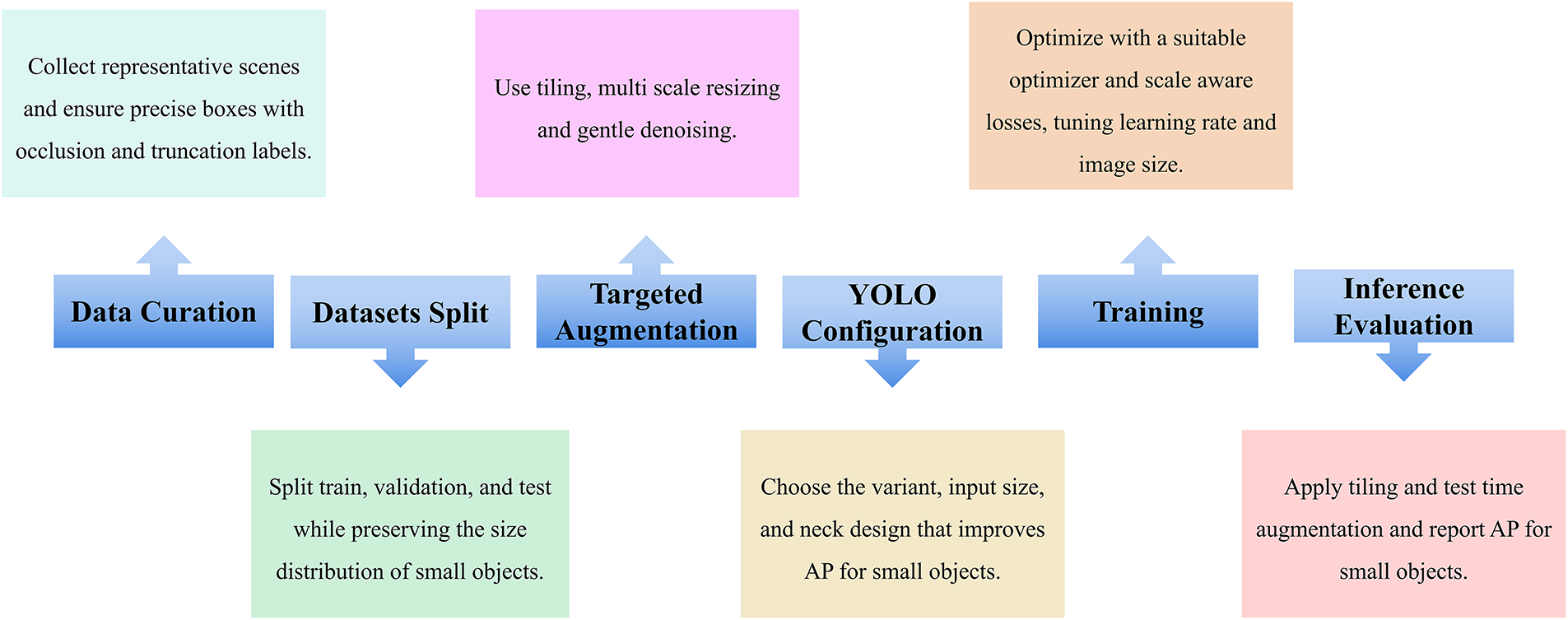

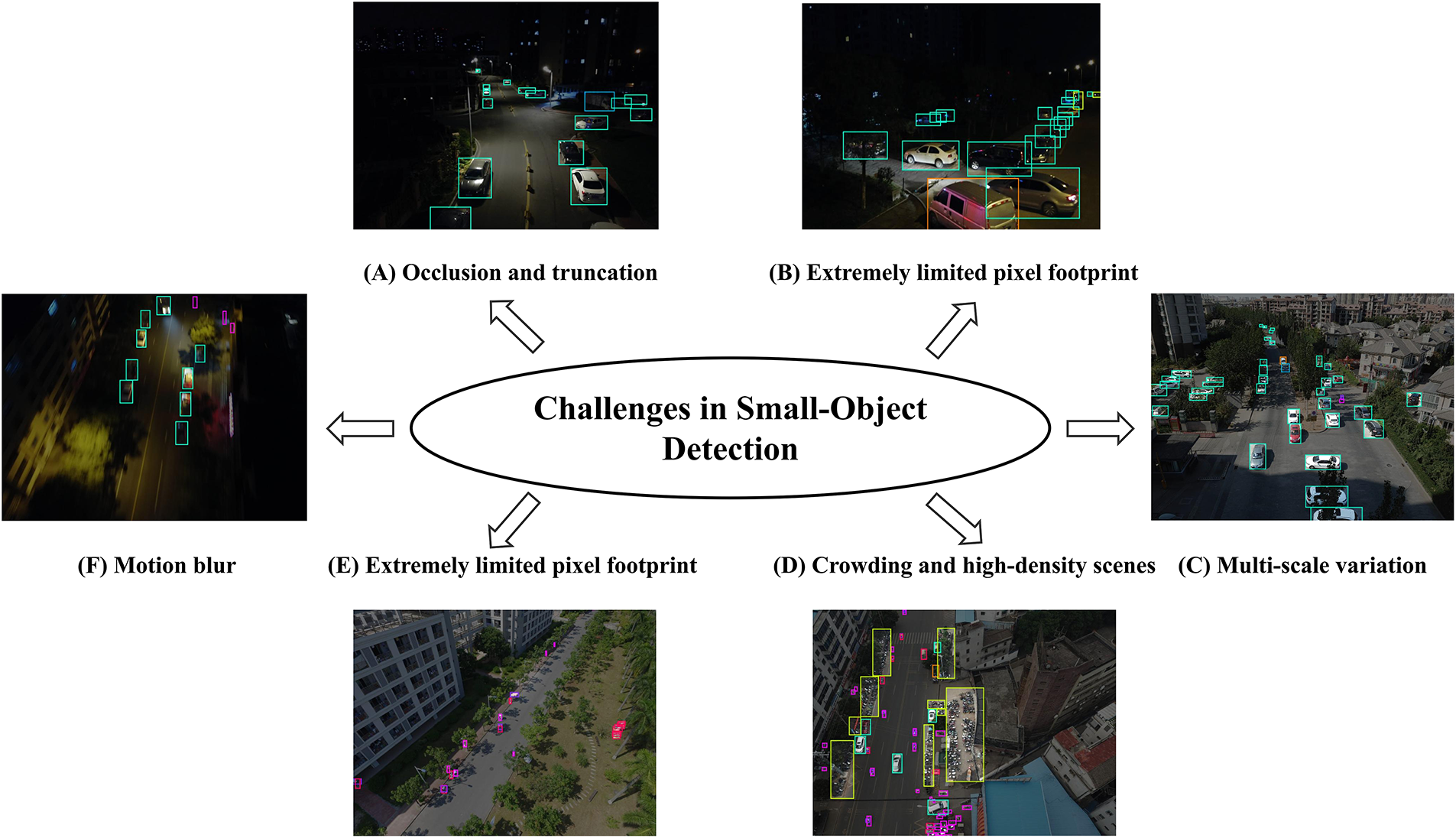

Small object detection is a specialized domain of computer vision that focuses on identifying and localizing objects which occupy only a few pixels within an image. This task has gained increasing prominence since the advent of deep learning-based object detectors, given its importance in diverse application areas such as autonomous driving [1], surveillance [2], aerial imaging [3], and remote sensing [4,5]. However, the severely limited pixel footprint of small objects means that convolutional downsampling can obliterate critical visual details, and small objects are easily confounded by clutter and sensor noise. Consequently, simply applying conventional detection frameworks without modification is insufficient for reliably detecting small objects. Despite continuous advances in general object detection, designing approaches that are simultaneously robust and efficient for small objects remains a central challenge. In 2016, Redmon et al. proposed YOLO [6], the first widely adopted one-stage detector to demonstrate real-time performance by performing detection in a single forward pass. YOLO eliminates the explicit region proposal stage used in earlier two-stage detectors, instead dividing the image into an S × S grid and directly predicting bounding box coordinates and class probabilities for each cell in a single forward pass. This pioneering design demonstrated that high-speed object detection is feasible within a unified end-to-end network, laying the foundation for a new generation of real-time detectors. Fig. 1 outlines a typical workflow for YOLO-based small-object detection.

Figure 1: YOLO workflow for small objects

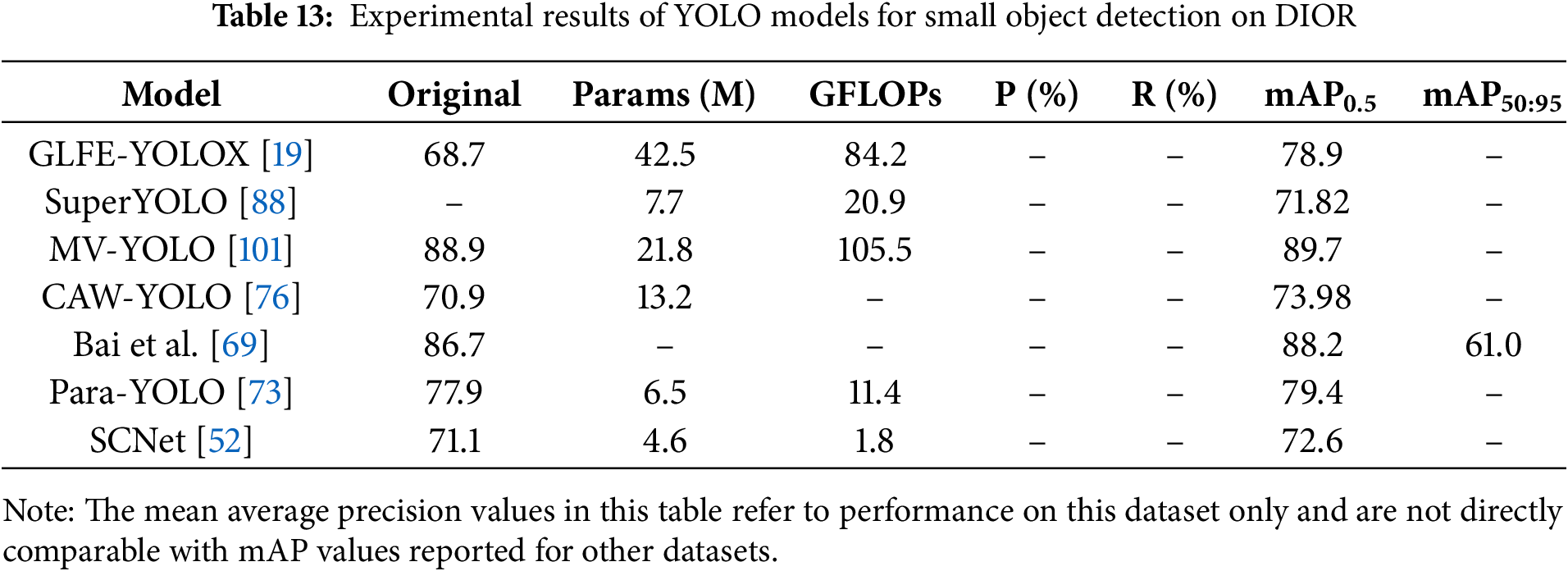

As YOLO has been widely adopted, numerous variants and related methods have emerged to tackle the challenges of small object detection. Some methods [7–11] strengthen feature expressiveness for small objects, improving the recovery of fine-grained cues and the salience of small instances in feature maps. Some methods [12–15] aim to deliver real-time performance under resource constraints, reducing computational and memory overhead while preserving accuracy. Other strategies [16–18] focus on training robustness, introducing scale-aware objectives, data augmentation, and adaptive label assignment to mitigate bias toward larger objects and stabilize optimization.

There are four main directions in which YOLO-based approaches have been extended to improve small object detection. The first category [19,20] focuses on attention mechanisms and feature enhancement. These approaches insert lightweight modules to amplify fine-grained features and incorporate contextual cues around small-object regions. The second category [21,22] involves detection-head redesign. These methods revise prediction heads or output layers in the YOLO architecture to improve localization and classification for small objects. The third category [23,24] comprises loss-function engineering and regression-precision optimization, including new loss terms and training strategies that account for scale imbalance in small-object detection. These methods seek to increase localization precision for small bounding boxes and prevent gradients from being dominated by errors from large objects. The final category [25,26] involves multi-scale feature-fusion techniques, which merge feature maps across layers or scales to retain high-resolution information and recover details lost in deeper stages. Notably, many state-of-the-art YOLO-based detectors combine these directions in hybrid designs that exploit their complementary strengths for small object detection. In this review we treat attention mechanism enhancements and multi scale feature fusion as separate improvement dimensions and we interpret hybrid modules according to the dimension that reflects their primary role.

In recent years, numerous studies have addressed the enhancement of YOLO models to meet this challenge. However, most existing reviews treat YOLO broadly by emphasizing the overall evolution of the YOLO family and cataloguing architectural and training modifications across successive variants [27] and do not systematically examine the adaptations and evaluation protocols unique to tiny targets. Therefore, a systematic review of recent advancements, applications, and future directions in YOLO-based small-object detection is both timely and essential as the field moves toward the next generation of real-time visual intelligence. The main contributions of this review can be summarized as follows:

(1) We identify and select research articles published between 2020 and 2025, with a focus on advancements in YOLO models for small object detection.

(2) We develop a unified theoretical framework that categorizes YOLO-based small-object detection improvements into four enhancement dimensions: attention mechanism enhancements, detection-head and branch redesign, loss-function engineering, and multi-scale feature fusion. Within this framework, we also situate emerging work on dynamic network design and heterogeneous fusion for small-object detection. For each category, we describe representative approaches and provide a critical analysis of their strengths and limitations.

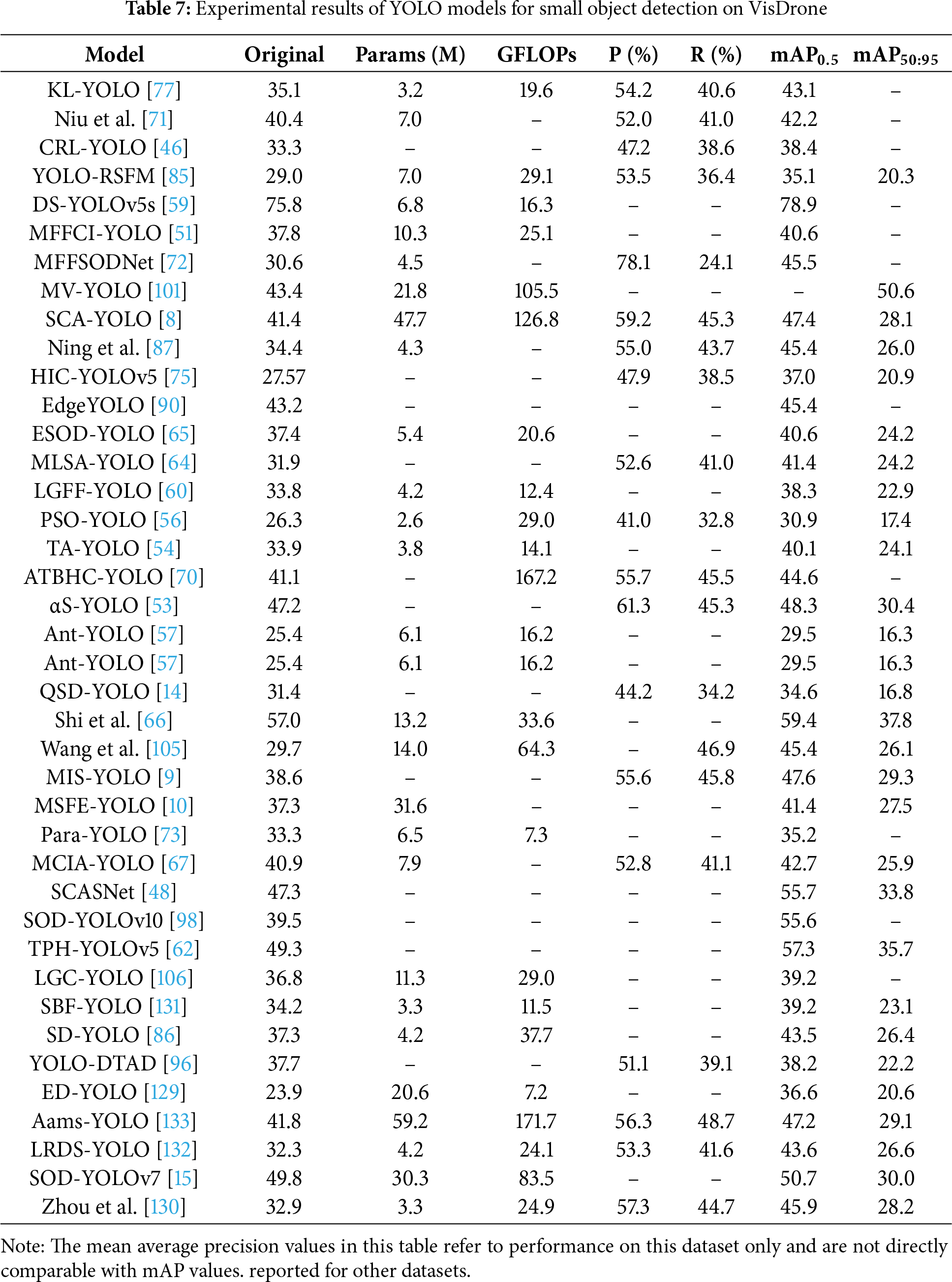

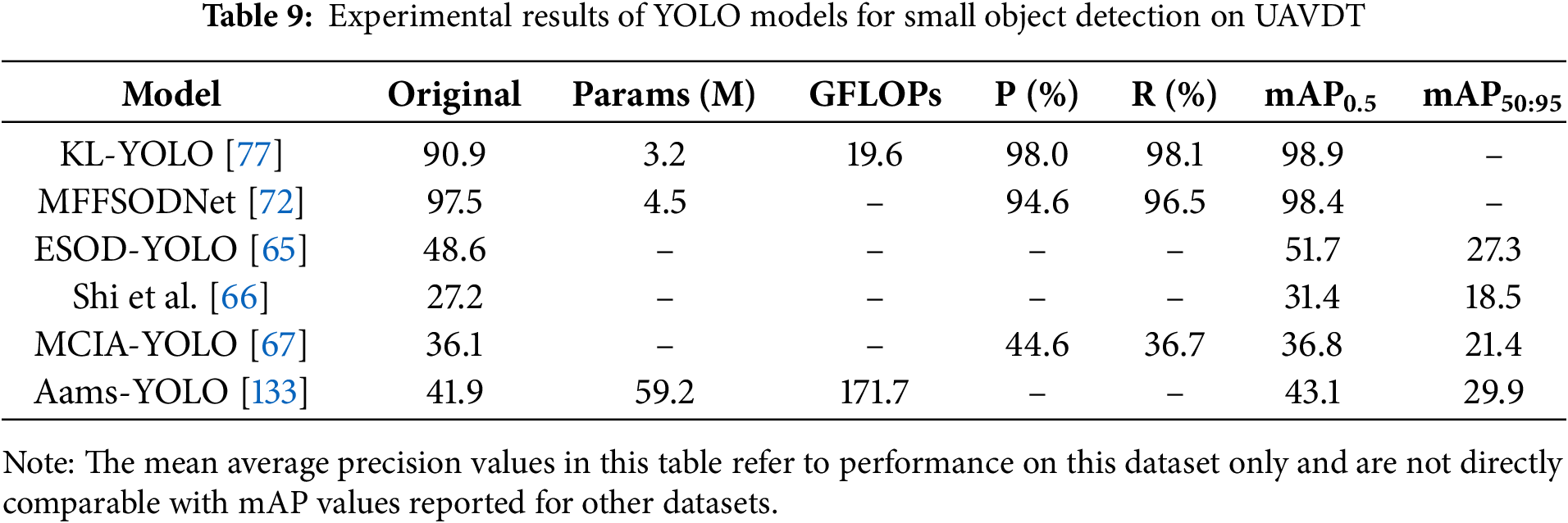

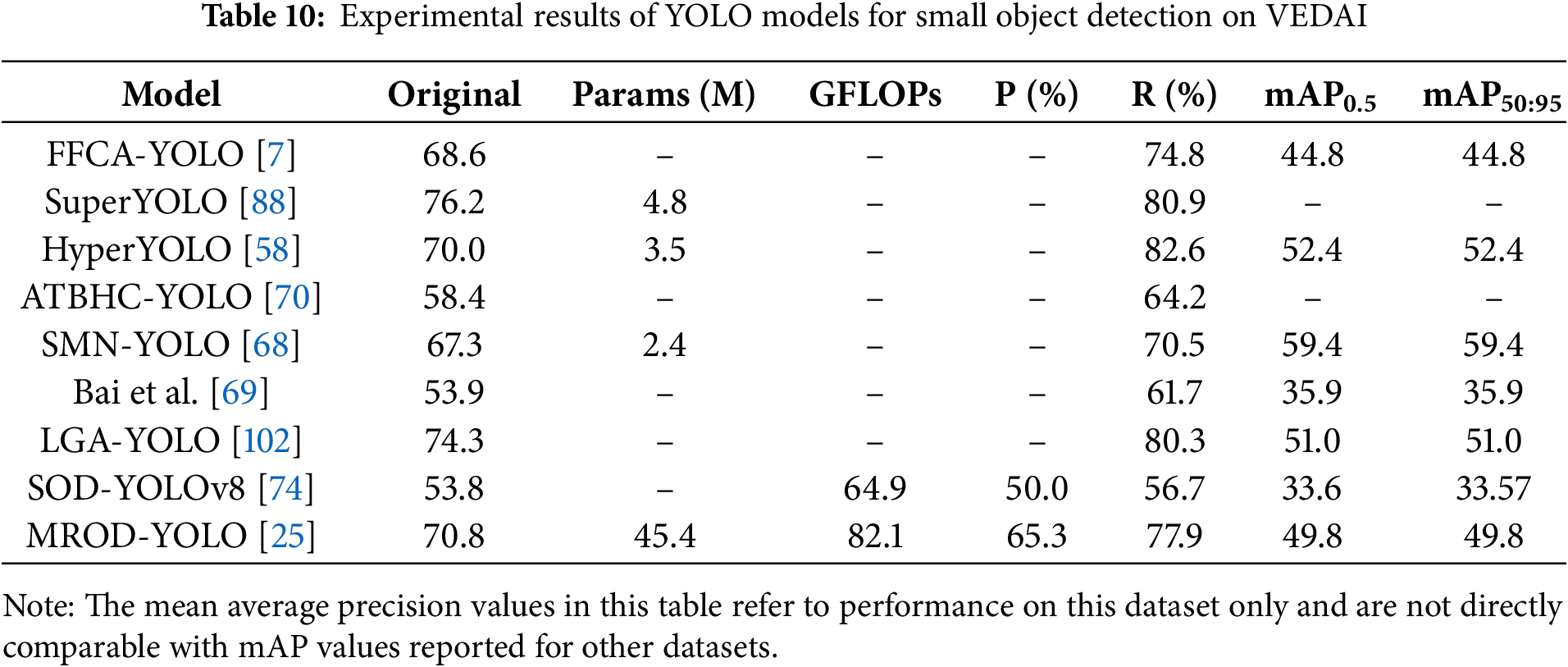

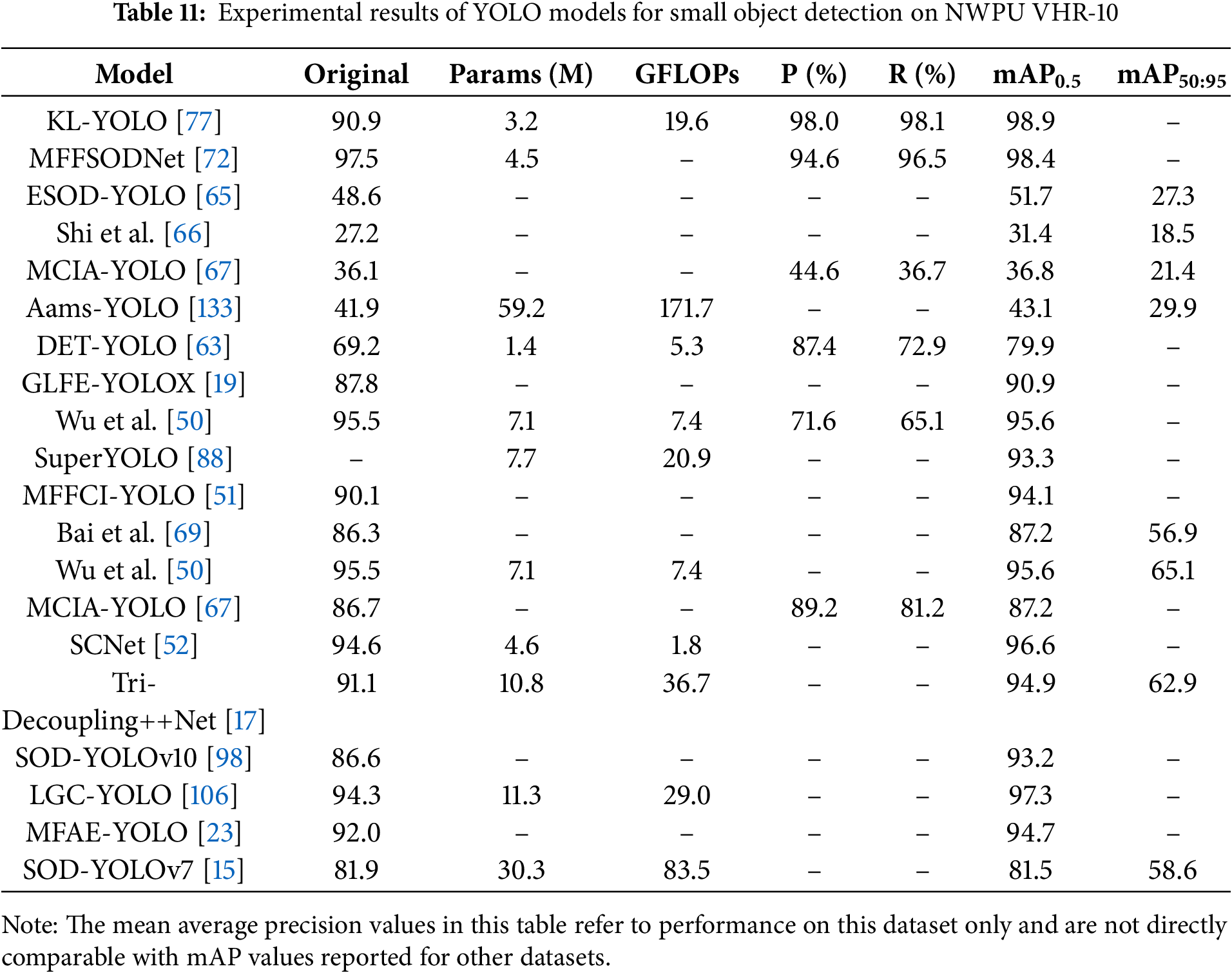

(3) We synthesize and compare experimental results on standard small-object detection benchmarks using metrics such as precision, recall, and mean average precision, thereby offering a detailed evaluation of the performance of YOLO-based detectors.

(4) We present insights and recommendations for future research directions and potential application scenarios for YOLO models in small object detection.

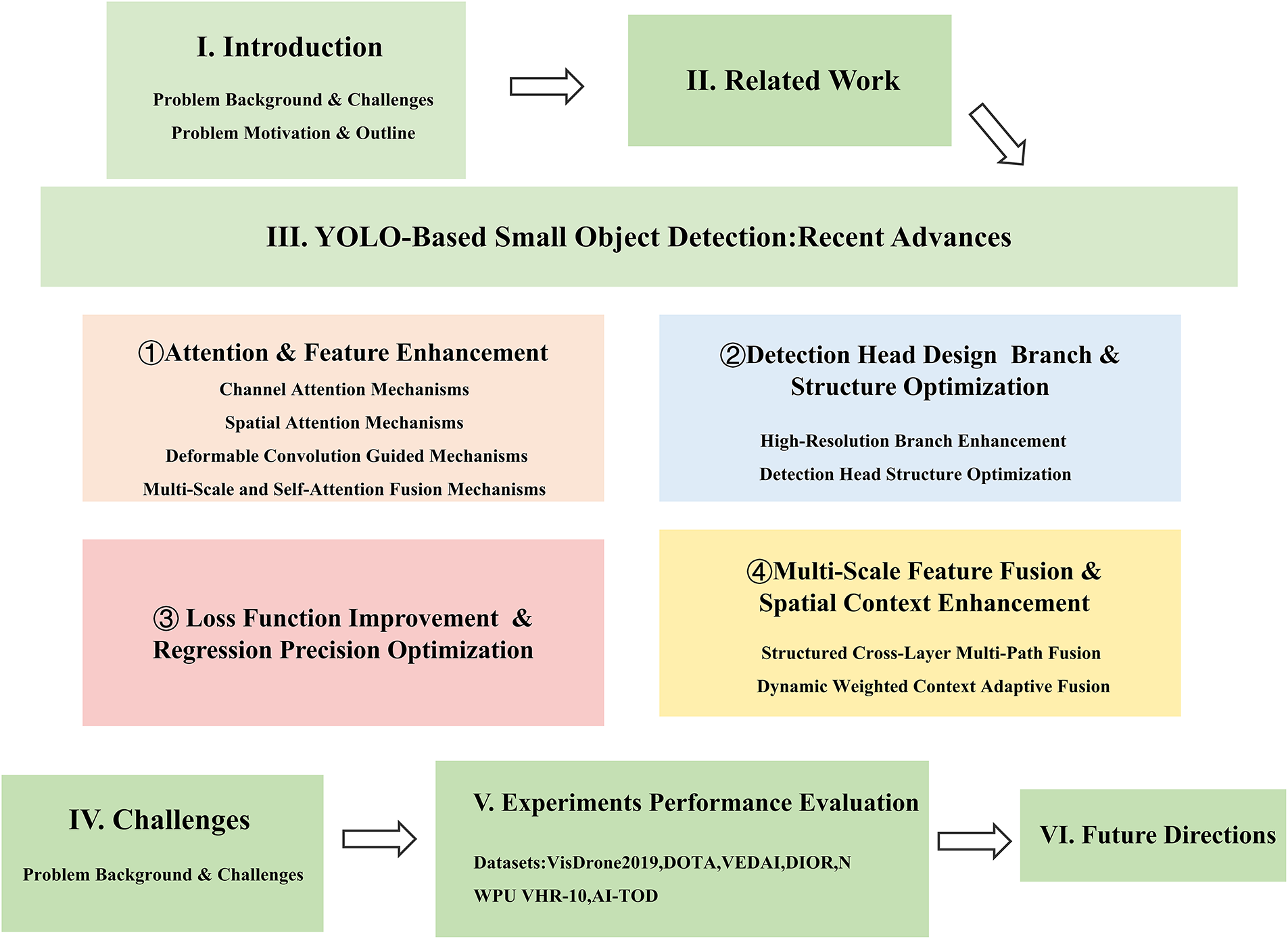

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews fundamental object detection algorithms and related work on YOLO-based small-object detection, develops a unified theoretical framework of four enhancement dimensions, and contrasts this review with existing surveys on the YOLO family. Section 3 provides a detailed survey of architectural improvements specifically designed to enhance small object detection and examines the current challenges associated with these methods. Section 4 presents a comparative analysis of experimental results for various YOLO-based improvements on major benchmark datasets. Section 5 discusses current challenges, identifies open research questions, and highlights promising directions for future work. Section 6 concludes the paper.

Recent advances in object detection have produced a rich body of work on small object detection and on the evolution of the YOLO family of detectors. Small objects exhibit limited spatial support, low signal to noise ratio, and a strong dependence on contextual cues, which jointly expose structural limitations of standard single stage architectures. These limitations have motivated a series of targeted modifications that redistribute representational capacity, reshape prediction heads, adjust optimization objectives, and strengthen multi scale interactions. To position the present study within the broader literature, this section develops a unified theoretical framework that abstracts recent YOLO-based designs into four enhancement dimensions and then contrasts this framework with existing surveys on YOLO and on small-object detection.

From a theoretical perspective, the four enhancement dimensions considered in this review form a coherent framework that restructures how detectors in the YOLO family allocate representational capacity to weak and spatially constrained signals associated with small objects. Attention mechanisms and feature enhancement modules act primarily on internal feature representations. They introduce learnable weighting functions over channels and spatial locations so that the network can amplify informative responses while suppressing background activations that arise from cluttered surroundings. In the case of small objects, the raw convolutional processing pipeline often produces features in which responses from tiny targets are easily submerged by context, which leads to low discriminability in the latent space. Attention modules counter this tendency by implementing a data driven reweighting of signal and noise. Features that correlate with reliable evidence of small objects receive increased importance, whereas channels and positions dominated by background receive reduced influence. This process enlarges the margin between foreground instances and background in the representation space and establishes a more discriminative basis for subsequent prediction layers. Detection head design and branch structure optimization operate at the interface between representation and prediction. The detection head defines how the continuous feature field is sampled into discrete hypotheses over scale, aspect ratio, and spatial position. For small objects, conventional heads with a limited set of strides and anchors can under sample the image plane or assign tiny targets to receptive fields that do not match their spatial extent. Refined heads adjust sampling density, receptive field allocation, and branch specialization so that at least one prediction branch maintains a receptive field that is commensurate with the physical scale of small instances and receives gradients concentrated on that regime. In conceptual terms, the head reparametrizes the mapping from feature space to bounding box hypotheses so that signals associated with small objects are not systematically projected into under resolved or low confidence predictions. Loss function improvement and regression precision optimization shape the learning dynamics that act on these hypotheses. Classical loss formulations balance classification and localization in a manner that is often dominated by medium and large objects, since these objects contribute most of the mass under the loss surface. Small objects, which are more sensitive to localization jitter and annotation noise, may therefore receive weak or unstable gradients. Redesigned loss functions modify the geometry of the optimization problem by increasing sensitivity to localization errors at small scales, by refining the penalty near object boundaries, and by adjusting the relative influence of easy and hard examples. This can be interpreted as a redistribution of gradient energy toward those regions of parameter space that govern the behaviour of small objects, which in turn yields detectors whose decision surfaces are more closely aligned with the fine scale structure of the data. Multi scale feature fusion and spatial context enhancement act at the level of information flow across resolutions. In standard hierarchical networks, shallow layers preserve spatial detail but convey limited semantic abstraction, whereas deeper layers encode strong semantics but lose spatial precision. Effective small object detection requires both properties simultaneously. Multi scale fusion constructs explicit pathways that transmit high level semantic information back to higher resolution feature maps and aggregates contextual information across different scales. Context enhancement further refines this process by enabling the network to integrate cues from surrounding regions that extend beyond the object yet remain informative about its presence and category. At an abstract level, these modules define a graph of interactions among feature maps at different depths and resolutions and learn context dependent mixing coefficients along this graph. For small objects, this leads to representations in which each detection location is supported by both localized detail and coherent context. Taken together, attention driven feature enhancement, redesigned detection heads and branches, loss formulations tailored to precise regression, and multi scale fusion with spatial context constitute four complementary axes of modification. They determine how the network assigns weights to features, how it samples predictions, how gradients propagate through the model, and how information flows across scales. Through a systematic analysis along these four axes, the present review moves beyond a catalogue of modules and instead offers a methodological perspective on how design choices at the architectural and optimization levels jointly determine the detectability of small objects.

Most existing reviews of the YOLO family place their emphasis on the chronological development of the algorithm or on its broad application spectrum. Several representative studies [28,29] carefully enumerate the architectural changes introduced in successive YOLO versions from v1 to v8 and survey a wide range of use cases, they tend to treat the evolution of the detector in an aggregate manner and do not examine in depth the specific difficulties associated with small object detection. These works provide valuable overviews of the architecture and performance trends of the YOLO family, but the level of analysis generally remains at a coarse architectural scale. Other articles extend YOLO reviews into particular application domains or operational contexts. For example, some surveys analyze the deployment of YOLO style detectors in areas such as autonomous driving and medical imaging and highlight their practical impact, while mentioning small objects only as one challenge among many that arise in these settings. Such reviews with a specific domain focus [30–34] concentrate mainly on implementation case studies and on summary level performance indicators, with limited attention to the detailed design choices that contribute specifically to the detection of small objects. In parallel, there exist surveys that consider small object detection as a general task without tying the discussion to a particular detector family. These studies examine generic strategies for handling diminutive targets [35,36] but do not analyze adaptations that are tailored to the YOLO framework.

Taken together, most of the current literature either traces the overall evolution and applications of the YOLO family or discusses small object detection at a detector agnostic level, and the intersection of these two lines of work remains insufficiently explored. Focused reviews that address YOLO based small object detection in a systematic manner are therefore still relatively scarce. The present review builds on the broad insights provided by these YOLO and small object detection surveys and seeks to fill this gap. It adopts an analytical perspective that is explicitly driven by the characteristics of the small object detection problem, in which each architectural or algorithmic modification is interpreted through its capacity to mitigate core obstacles in this setting. Whereas previous surveys primarily recorded what changes occurred in YOLO or where the detector has been applied, the framework developed here investigates how and why particular enhancement strategies address the challenges posed by small objects. The discussion is organized according to four technical dimensions, namely attention mechanism and feature enhancement, detection head design and branch structure optimization, loss function improvement and regression precision optimization, and multi scale feature fusion and spatial context enhancement. This organization supports a more detailed comparative analysis of designs that target small objects than is available in earlier work, and by extending the time span to include methods proposed between 2020 and 2025 and consistently interpreting them through the lens of small object detection, the review refines and enriches the broader overviews offered in the existing literature.

Section 3 examines each of these four categories in depth and analyzes representative approaches and their contributions to advancing small-object detection within the YOLO framework. Fig. 2 shows the organization of the paper.

Figure 2: The organization of the paper

3 YOLO-Based Small Object Detection: Recent Advances

Recent research on YOLO based small object detection can be interpreted through the four enhancement dimensions outlined in Section 2, and this perspective provides a consistent structure for organizing a diverse set of architectural proposals. A first line of work strengthens internal representations through attention mechanisms and feature enhancement modules inserted into the backbone or at the interface between the backbone and the neck, which have been shown to refine fine grained cues that are crucial for very small targets [37,38]. A second line of work redesigns the detection head and the branch structure so that prediction layers are better aligned with the scale and aspect ratio distributions of small objects and so that at least one branch maintains an appropriate receptive field for these instances [39]. A third line of work modifies the loss function and related optimization components in order to adjust the balance between classification and localization, to emphasize accuracy for small objects, and to alleviate class imbalance effects [40]. A fourth line of work focuses on multi scale feature fusion and spatial context enhancement and aggregates information across different resolutions through feature pyramids, dilated receptive fields, and context aggregation modules so that even the smallest objects are represented with sufficient semantic richness and spatial detail [41,42]. In parallel with these four directions, very recent studies from 2024 and 2025 have begun to explore dynamic network design and heterogeneous architectural fusion as emerging hotspots for YOLO based small object detection, and these developments are summarized in Section 3.6. In the remainder of this section, we examine representative methods in each of these four categories, explain how they modify the original YOLO architecture, and summarize their reported performance on public benchmarks, thereby translating the theoretical framework of Section 2 into a concrete comparative analysis of recent advances.

In the analysis that follows the attention dimension and the multi scale fusion dimension play complementary but non overlapping roles. The attention dimension describes how a detector redistributes salience within a single feature level. The discussion therefore concentrates on mechanisms that adjust channel weighting or spatial weighting while the topology across scales in the network remains fixed. The multi scale fusion dimension describes how a detector constructs the paths that couple feature maps at different resolutions. The discussion in that dimension focuses on the design of feature pyramids, bidirectional paths and context aggregation blocks that govern information flow between layers. Many recent models apply both types of modification. In such cases we assign the method to the dimension that drives the main architectural change and we treat the other component as supportive.

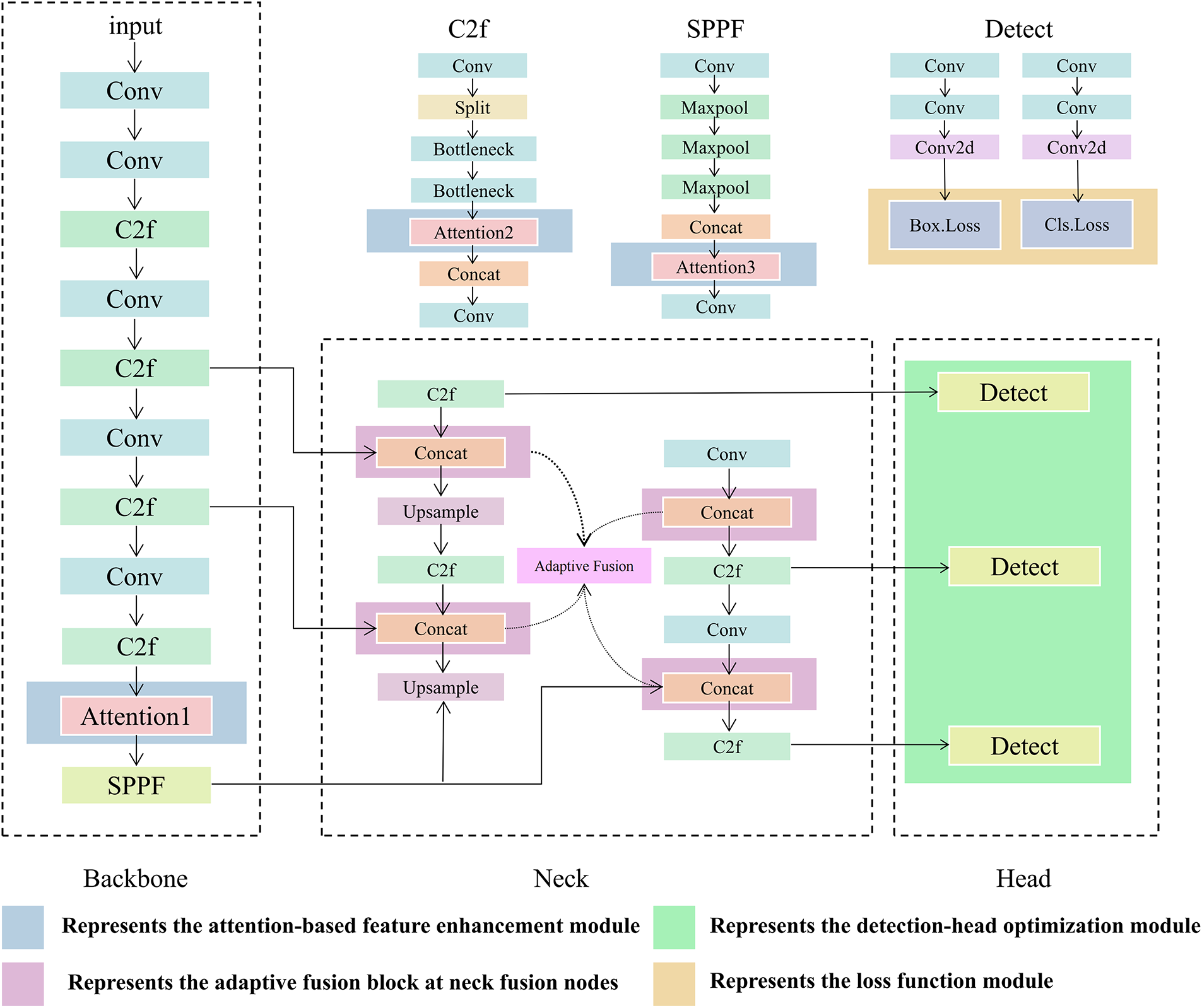

Fig. 3 presents an illustrative schematic based on the YOLOv8 architecture that indicates the typical locations of these four categories of improvements. The color-coded regions mark common loci of modification. Blue denotes attention and feature-enhancement modules that are primarily inserted in the backbone or at the transition into the neck. Green denotes detection-head and branch-structure adjustments at the P3, P4, and P5 heads and at the convolutional layers that immediately precede them. Yellow denotes loss-function and regression-precision components along the training pathway that links head outputs to loss computation and label assignment. Purple denotes multi-scale fusion and spatial-context modules located in the neck, including upsampling and downsampling operators, fusion nodes and adaptive weighting blocks. The color coding reflects typical practice across recent YOLO variants, and YOLOv8 serves only as an example to anchor the discussion. Actual models often mix multiple categories at the same site. For instance, they may combine attention with neck-level fusion or pair a revised head with a tailored loss. The schematic is intended to help readers map each improvement to its architectural location and to understand how changes in one part of the pipeline interact with the others.

Figure 3: Schematic of YOLOv8 highlighting typical loci of four improvement categories

3.1 Attention Mechanism and Feature Enhancement

This subsection introduces attention mechanisms and their role in feature enhancement for small-object detection. Attention modules dynamically highlight informative features or spatial regions, effectively guiding the network to focus on the parts of the image most relevant to small objects. Broadly, attention in YOLO-based small object detectors can be categorized into four groups: (a) channel attention, which reweights feature maps across the channel dimension; (b) spatial attention, which emphasizes particular locations in feature maps; (c) combined or deformable attention mechanisms that capture complex feature dependencies; and (d) hybrid feature enhancement modules that integrate attention with other operations. Each type addresses different aspects of feature representation, and collectively they improve the network’s ability to represent and discriminate small objects under challenging conditions. Although attention and multi-scale fusion are discussed in separate subsections for clarity, the two approaches frequently co-occur within the same module, particularly in the neck, where attention gates or reweights cross-scale information flows. Throughout this subsection we interpret hybrid modules through the lens of attention. The narrative highlights how learned weighting functions reshape feature salience for small objects. The contribution of any embedded multi scale fusion operators is summarized only when it is necessary to understand how attention acts on aggregated features. A detailed comparison of the fusion operators themselves is presented in Section 3.4.

3.1.1 Channel Attention Mechanisms

Channel attention mechanisms selectively recalibrate channel-wise feature responses. These modules function by highlighting informative channels and suppressing redundant or noisy activations, which enables the network to focus on features relevant to small objects and mitigates the dilution of subtle details during the forward pass. Typical channel attention mechanisms include coordinate attention (CA) [43], efficient channel attention (ECA) [44], and squeeze-and-excitation (SE) [45], which enhance or suppress different channels by learning the importance of each feature channel. For instance, SE blocks adaptively reweight channel features based on the global context. Liu et al. introduced the Channel Weighting Module (CWM), which combined an SE block with a 1 × 1 convolution and improved mAP50 by 2.3% on VEDAI. Further refinements focused on making channel recalibration more efficient and lightweight.

In several representative designs, channel attention is not applied in isolation but is coupled with multi scale fusion so that reweighting acts on aggregated cross scale information. Wu et al. [46] fused multi scale features through parallel depthwise and pointwise convolutions followed by SE attention and obtained a 0.6% improvement in mAP. He et al. [47] extended this idea in FOS YOLO with two lightweight modules. ADEM separates features into depthwise and standard convolutional paths before SE based recalibration. LERM applies grouped depthwise convolutions with channel shuffle and a simplified SE structure. Together these modules increase mAP50 by 1.8 percentage points and reduce the parameter count by more than twenty percent. Wang et al. [48] proposed the CPMAEM module in SCAS Net, which uses multi branch depthwise convolutions and sequential channel spatial attention to strengthen multi scale cues. These designs show attention operating within cross scale pipelines. Their core operators perform explicit aggregation across scales, so their fusion behaviour belongs to the multi scale fusion dimension, while this subsection focuses on the attention effect. Readers can find the operator-level analysis in Section 3.4.

Coordinate Attention (CA) mechanisms were also adopted in YOLO-based detectors to embed spatial context into channel attention. By performing separate global pooling along the horizontal and vertical directions, CA encodes positional information into the channel-wise weights, which enables the network to localize small and elongated objects more accurately. This approach was incorporated into various architectures, such as GhostNet and CSP modules. Xie et al. [13] inserted a CA module at the output of each CSP stage to embed long range dependencies along both width and height and reweight channels accordingly, which allowed the model to focus on precise target locations, achieving an mAP of 88.74% on DOTA. Likewise, coordinate attention was used in cross-scale feature connections to adaptively highlight fine-grained targets, such as tiny ships in aerial imagery, and it markedly improved the detection of densely distributed objects [49].

RCA introduced a residual reweighting structure and employed mixed pooling, which strengthened the representation of small and dense objects [50]. Xu et al. [51] developed the Lightweight CSP Attention (LCA) block in MFFCI-YOLOv8, combining depthwise separable convolutions with a SimAM module that introduces no additional parameters for channel reweighting, which resulted in a 1.4% increase in mAP on VisDrone2019. Beyond explicit attention, alternative approaches use channel selection to achieve similar effects. Zhu and Miao [52] proposed the Selective Feature Enhancement Block in SCNet, which ranked channels by their globally pooled L1 norms, processed high- and low-contribution channels differently, and then fused them, attaining an mAP of 96.1% on NWPU VHR-10 and 71.9% on DIOR.

Beyond these mainstream channel-attention schemes, recent studies extended the mechanism to broader and more complex contexts. Hou et al. [53] introduced the C2f-GE module, which combined local feature extraction with global-context heatmaps to enhance channel attention. Transformer-inspired approaches also emerged. For instance, Li et al. [54] presented the Multi-Channel Trans-Attention (MCTA) module, which employed multi-head self-attention to learn inter-channel dependencies and to refine subtle features. Ding and Du [55] further validated this trend in an industrial logo inspection system. They replaced the early C2f blocks in the YOLOv8 backbone with contextual Transformer layers and equipped the detection head with a coordinate-aware CoordSaEBlock that fuses positional encoding with channel attention. This hybrid design produced more discriminative features for fine-grained cigarette-package logos and improved classification accuracy while maintaining real-time throughput on a large-scale production inspection line.

3.1.2 Spatial Attention Mechanisms

Spatial attention mechanisms in YOLO-based detectors focus on where the network should concentrate its attention, emphasizing important regions and contextual cues in the feature maps. For small-object detection, spatial attention is vital for isolating tiny targets from cluttered backgrounds and capturing the surrounding context that might indicate an object’s presence. A key direction in recent research on YOLO-based small-object detection involves leveraging transformer-based spatial attention to explicitly model long-range dependencies. For instance, Zhang et al. [7] introduced a Deformable Attention Transformer after the SPPF layer. The module used learnable reference points to direct sparse self-attention toward salient regions. They further proposed a Spatial Channel Attention Module that modulated spatial and channel information jointly. This combination improved spatial relationship modeling and yielded a 1.7% increase in mAP on the USOD dataset. Similarly, Zhao et al. [56] embedded a Swin Transformer block within the C2f module of the YOLOv8n backbone and increased mAP50 by 1.5%.

Building on these advances, some designs parallelized convolutional and transformer-based paths to capture local details and global dependencies more effectively. YOLO Ant exemplifies this hybrid approach. Its backbone uses depthwise separable convolutions with large kernels to obtain multi scale local representations. Its neck adds an attention module inspired by MobileViT that runs in parallel to the main convolutional stream. This design preserves fine details and global spatial dependencies with high computational efficiency, which makes the model suitable for small object recognition in resource constrained settings [57].

A common theme underlying these spatial-attention designs is the preservation of fine-grained location information for small objects while simultaneously leveraging broader contextual cues. To this end, several methods encoded explicit coordinate information or employed multi-scale pooling operations. Nan et al. [58] introduced coordinate attention by applying one-dimensional global pooling along the height and width axes, generating spatially aware attention maps that guided the network to focus on critical regions while retaining positional details. Similarly, Li et al. [59] proposed the Spatial Information Enhancement (SIE) module, which incorporated coordinate-convolution layers into both the backbone and neck. By pooling along spatial axes and concatenating these features, SIE augmented feature maps with explicit location cues and resulted in a 0.3% increase in mAP for UAV detection tasks.

Beyond coordinate based methods, other models adapt the receptive field in the spatial domain to capture context at multiple scales. Peng et al. [60] developed the Receptive Field Attention module, which modifies dilation rates or kernel sizes according to input features and highlights spatial patterns of small objects. Integrating RFA Conv led to a 2% improvement in mAP on VisDrone2019. Jiang et al. [61] proposed the RA3-DWA module for DSFPAP-Net. It applies a sequence of depthwise convolutions with different dilation rates to accumulate context across scales. A subsequent SimAM driven spatial channel attention mechanism recalibrates features at all detection heads and strengthens the representation of small objects. Zhu et al. [62] developed the Spatial Depthwise Atrous block for YOLOv5 on drone imagery. It fuses depthwise separable convolutions with multi branch dilated paths and then applies channel and spatial attention. This design recalibrates features and significantly boosts small object detection even without explicit positional encodings.

3.1.3 Deformable Convolution Guided Mechanisms

Deformable convolution essentially acts as an attention mechanism by using adaptive sampling and learning offset vectors to shift sampling locations toward more informative regions. In the context of YOLO detectors, this flexibility allows the network to focus on the exact shapes and positions of small objects, improving feature alignment and reducing background confusion.

Several studies successfully integrated deformable convolutional layers into the YOLO backbone or neck to harness these advantages. Chen et al. [63] systematically replaced all standard C2f convolutional units in both the backbone and neck of YOLOv8n with DCNv2 deformable convolutions, granting the network the flexibility to capture local geometric deformations. This modification led to a 2.6% improvement in mAP50, reflecting an enhanced ability to track object contours and keypoints in challenging scenarios. Peng et al. [64], in their MLSA-YOLO framework, introduced the DCN_C2f module by substituting a single 3 × 3 convolution in the C2f bottleneck with a DCNv3 layer. This adjustment allowed the receptive field to deform adaptively in response to object distribution, retaining more fine-grained information for small targets at low resolutions and leading to a 0.4% increase in mAP.

Beyond straightforward replacement strategies, other works coupled deformable convolutions with explicit attention mechanisms for further gains. Xu et al. [65] proposed ESOD-YOLO, featuring the SPPELAN module in the neck, which combined parallel DCNv3 convolutions with a Mixed Local Channel Attention (MLCA) mechanism. In this design, the deformable convolution provided adaptive sampling for geometric and multi-scale information, while MLCA assigned attention weights by jointly considering local feature patterns and global channel context. The addition of SPPELAN to SCCFF resulted in a 0.2% mAP improvement.

Furthermore, some studies integrated deformable convolution into feature fusion modules to better preserve small-object details. Shi et al. [66] designed the Deformable Convolution Guided Feature Learning (DCGFL) module for the backbone, utilizing a DCNv2 layer to dynamically adjust the sampling grid for multi-scale and shape-adaptive representations. This was followed by a channel-attention block to recalibrate feature responses, facilitating robust multi-scale information integration. In the neck, deformable convolution-guided fusion blocks (DCGFF) were employed to align and merge high-resolution shallow features with deep semantic information, ensuring that fine details were retained during fusion. Incorporation of the DCGFL module elevated mAP50 on the VisDrone2021 dataset to 57.6%.

3.1.4 Multi-Scale and Self-Attention Fusion Mechanisms

In YOLO-based small object detection, multi-scale feature fusion enriches representations by innovatively combining multi-scale convolutional processing with various attention mechanisms. This approach preserves fine-grained details while incorporating higher-level context, expanding the receptive field and integrating contextual cues without compromising the discriminability of small-object features.

Within the attention family, several representative designs deploy attention at fusion sites, where it gates or reweights cross scale features. Wang et al. [67] advanced the CSA module by using parallel convolutions and global pooling for multi context aggregation, followed by self-attention and residual fusion, and obtained a 0.6% improvement in performance. Zeng et al. [8] introduced the SCA block, which combined global pooling with SimAM based selection to guide spatial attention during feature fusion and achieved a 0.9% improvement on VisDrone2020. Zheng et al. [68] proposed the MSFAM module, which aggregated multi scale pyramid features and projected them into a joint space for channel and spatial reweighting, resulting in an mAP of 69.3% on VEDAI. Bai et al. [69] d designed a weight adaptive spatial attention mechanism that generated separate spatial maps for semantic and detailed features and balanced their contributions, reaching mAP50 of 87.2% on NWPU VHR-10 and 88.2% on DIOR. Wang et al. [14] proposed DyHead for improved YOLOv8, which unified scale, spatial and task attention within a dynamic head and produced a 1.5% increase in mAP. Liao et al. [70] further advanced this direction with the MS CET block, which coupled parallel dilated convolutions for multi scale context with multi head self-attention and boosted mAP by 1.7%. Collectively, these techniques show a fusion driven strategy in which attention is interwoven with multi scale aggregation and strengthens the granularity and contextual richness of small object representations.

One set of approaches focused on multi branch convolutional modules that gather multi scale information and can be fused or simplified for efficiency. Niu and Yan [71] integrated a Diversified Basic Block into the YOLOv8 backbone. During training, it uses parallel convolutional branches with varied kernel sizes to learn richer features. At inference, these branches are folded into a single convolution to retain multi path expressiveness. In another work, Jiang et al. [72] proposed MSFEM, a multi scale feature extraction module composed of four parallel branches with different kernel sizes, including 1 × 1 and 5 × 5 convolutions, pointwise convolutions and a residual connection. Other designs drew on mixture-of-experts ideas. Chen et al. [73] proposed MPMS for Para-YOLO, where three parallel dynamic-convolution branches of varying sizes operated on different channel proportions and were adaptively fused by a lightweight router, yielding a 1.6% gain in mAP. Liu et al. [74] diversified context extraction in SOD-YOLOv8n with the MFFM module, which divided feature channels into four groups processed by distinct branches and shuffling, achieving mAP50 of 54.62% on VEDAI.

Another prominent direction is the development of hybrid attention mechanisms that combine channel and spatial attention within a unified framework. The Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [64] exemplifies this approach, simultaneously applying both channel and spatial attention to refine feature maps. Tang et al. [75] enhanced YOLOv5 by appending a CBAM block at the end of the backbone, significantly boosting both channel and spatial representations. Building upon this, MSCA-CBAM [76] replaced global pooling in CBAM with a two-dimensional discrete cosine transform, enriching the frequency components during channel excitation and achieving mAP50 of 73.98% on DIOR and 97.50% on RSOD. Beyond CBAM, advanced hybrid attention mechanisms such as the Global Attention Module (GAM) proposed by Xie et al. [77] sequentially applied channel and spatial attention while preserving cross-dimensional dependencies, yielding an mAP50 of 37.6% on VisDrone2019.

A clear trend is the integration of transformer-based or self-attention modules, which are incorporated either alongside CNN backbones or as standalone pipelines, in order to further strengthen local and global context modeling. In TA-YOLO, Li et al. [54] implemented the MCSTA module, using multi-head channel self-attention to globally reweight channels before applying multi-head spatial self-attention to model positional dependencies, with their coordinated output merged via residuals for a substantial 6.2% increase in mAP50. Bai and Li [78] addressed similar challenges in industrial instrumentation by integrating a Swin-Transformer backbone with Focus and depthwise-separable convolutions and by adopting an SPPCSPC block followed by a C3STR neck to strengthen multi-scale feature interaction. This architecture substantially improved the detectability of small pointers and scale markings under complex backgrounds, while still delivering real-time inference on an industrial pointer meter dataset. Ge et al. [79] investigated lightweight UAV-based infrared detection by constructing an S2GM backbone from ShuffleNetV2 blocks with stride 2 and C2f Ghost modules. The design coupled this backbone with an AGFC attention block and a SENet-style multi-feature fusion neck. Together, these components reduced parameters and floating-point operations relative to the YOLOv8n baseline and improved detection accuracy for small infrared targets on the HIT-UAV dataset. The model still satisfied real-time requirements on embedded UAV platforms.

Altogether, these advances reflect a clear shift toward increasingly unified and adaptive multi-scale fusion frameworks in YOLO-based small object detectors. By systematically integrating convolutional, attention-based, and transformer-driven mechanisms, these models achieve a more balanced capture of fine-grained local features and global semantic context. This synergy not only enhances detection accuracy for small objects across challenging datasets but also sets a promising direction for future architectural innovation in the field.

3.1.5 Challenges and Limitations of Attention Mechanisms

Attention mechanisms and feature enhancement modules face intrinsic theoretical limitations when they are applied to small object detection because the underlying feature statistics differ fundamentally from those of medium or large targets. In convolutional backbones the activations corresponding to a very small object are distributed over only a few receptive fields and exhibit low energy relative to the global feature map, which leads to an extremely low signal to noise ratio in both channel and spatial dimensions. Standard attention modules estimate importance weights from these activations through global aggregation or similarity measures and implicitly assume that salient structures dominate the feature distribution. For tiny objects this assumption is violated, since the informative response of the object is often statistically indistinguishable from background fluctuations, and the attention module therefore tends to assign high weights to textured clutter, shadows, or neighboring large instances rather than to the true small target. From the perspective of optimization this misallocation of attention degrades gradient propagation, because the network repeatedly reinforces background dominated channels while the weak gradients associated with small objects are suppressed, which in turn further reduces the separability of their features in the latent space and can ultimately drive the model toward a solution in which small objects are systematically ignored. Moreover, many attention designs are scale agnostic and operate on a single feature map without explicit constraints on spatial extent, so they lack a mechanism to distinguish between a genuine tiny object and a fragment of a larger structure that occupies a similar image region. These theoretical issues indicate that direct insertion of generic attention modules is insufficient for small object detection and must be complemented by designs that are explicitly sensitive to scale and context. Shahapurkar et al. [80] evaluated fine tuned YOLO detectors on the SIRST-UAVB infrared benchmark. Even after extensive tuning, performance remained strong for UAV targets but weak for small birds in cluttered low contrast scenes. This gap illustrates the persistent difficulty of infrared small target detection and the limited suitability of generic YOLO backbones in such regimes. One promising direction is to couple attention with multi scale feature fusion so that the weighting functions are conditioned jointly on local features with fine spatial granularity and on more stable coarse semantic context, which can provide a prior about the plausible location and extent of small objects. This interaction between attention and multi scale feature aggregation is examined in detail in Section 3.4 of this review. Another possible avenue is to introduce additional supervision or regularization for attention maps, for example by aligning them with spatially subsampled ground truth masks or by penalizing overly diffuse responses, so that the learned weighting patterns concentrate more reliably around true target regions. It is also beneficial to design attention modules whose parameterization is constrained by geometric priors such as expected object size ranges or aspect ratios, which can prevent the mechanism from focusing almost exclusively on dominant large scale structures. In summary, the principal challenge for attention driven feature enhancement in small object detection arises from the mismatch between the statistical assumptions of standard attention formulations and the weak, sparse, and easily confounded signals produced by tiny targets, and effective solutions require mechanisms that are explicitly scale sensitive, guided by contextual information, and supported by stronger supervisory signals.

3.2 Detection Head Design and Branch Structure Optimization

For small-object detection, many studies have shown that modifying the YOLO head or adding extra prediction branches can markedly improve the capture of fine details. Broadly, improvements in this category fall into two groups: (1) High-Resolution Branch Enhancement, which adds or preserves finer-scale feature maps for prediction, and (2) Detection Head Structure Optimization, which redesigns the head to better localize small objects. The former mainly addresses the resolution of features used to detect small objects, while the latter involves changes like anchor-free heads, decoupled heads, or specialized layers to handle small-object geometry. By dividing improvements into these two categories, we can see a progression from simply increasing feature resolution for predictions to more fundamental redesigns of the head for small-object accuracy.

3.2.1 High-Resolution Branch Enhancement

A common enhancement in YOLO-based small object detection is adding an extra high-resolution prediction head at an earlier backbone stage to capture fine-grained features. Many studies introduced additional prediction heads at finer spatial scales. By tapping into shallow backbone outputs, these branches effectively preserve subtle textures and edges essential for accurate localization and classification of micro-scale targets, while incurring minimal computational cost. This approach was broadly validated across UAV surveillance, logistics, airport sensing, and underwater detection tasks. It consistently reduced missed detections and improved accuracy [81–84].

Tang et al. [85] implemented this strategy in YOLO-RSFM by appending a shallow P2 head directly to the earliest backbone feature map, without deep feature fusion, thereby concentrating on high-resolution texture and boundary cues. This modification led to a 1.3% increase in mAP. In a similar vein, Qi et al. [86] proposed SD-YOLO, which introduced a Low-Level Detection Head (LLDH) operating on early-stage feature maps, enabling the detection of minute aerial targets that are otherwise lost in deeper layers, with an mAP of 41.2 on VisDrone2019.

Recent studies have further strengthened high-resolution branches through adaptive fusion strategies. Representative examples include MIS-YOLOv8 and the approach of Ning et al. [9,87], which integrate high-resolution predictions with context-aware fusion mechanisms. These approaches are analyzed in more detail in Section 3.6 on dynamic context adaptive fusion.

In parallel with additional high-resolution branches, several works enhance feature fidelity through input or intermediate super resolution techniques. Zhang et al. [88] improved YOLOv5 by removing the Focus module and adding a lightweight encoder decoder super resolution branch during training to reconstruct high resolution features from low resolution inputs. This SuperYOLO design achieved an mAP of 64.4 on the VEDAI validation set. Liu et al. [89] extended this idea with a super resolution perceptual branch between the backbone and the neck. The branch uses residual blocks and up convolutions with a perceptual loss that aligns features to high resolution image patches during training. This scheme yields a 7.4 percentage point gain in mAP.

3.2.2 Detection Head Structure Optimization

Effective small object detection with YOLO architectures increasingly relies on specialized detection head redesigns that address the unique challenges posed by tiny, dense, or variably oriented targets. Recent research has converged on three primary directions: lightweight design and anchor strategy optimization, attention-driven adaptive heads, and architectures focused on task decoupling, spatial alignment, and rotation awareness. These improvements collectively enhance the detection head’s ability to extract, represent, and localize small objects in diverse scenarios.

Reducing the computational footprint of detection heads while maintaining robust representation is crucial for real-time and edge applications. Wu et al. [46,50] tackled the challenge of anchor generation by replacing traditional k-means clustering with a Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm. This approach iteratively refined anchor box dimensions to better match the scale distribution of small objects, yielding a substantial improvement in detection for remote sensing imagery and achieving 63.7% mAP on NWPU VHR-10. Parallel efforts in head design sought to unify and streamline head architecture. Wu et al. [46] introduced CRL-YOLO, which employed a single set of convolutional layers shared between classification and regression, regulated by Group Normalization and a learnable scale factor. This configuration achieved efficient parameter usage and facilitated deployment in resource-constrained environments. Liu et al. [90] developed EdgeYOLO, in which the Lite Decoupled Head eliminated redundant 3 × 3 convolutions and employed structural reparameterization to merge implicit feature learning layers, significantly compressing the head while sustaining effective feature extraction. EdgeYOLO also adopted an anchor-free detection paradigm inspired by FCOS, shifting to per-pixel prediction and discarding anchor-based post-processing, which simplified inference and proved advantageous in scenes with densely clustered small objects. On the MS COCO 2017 dataset, the Lite Decoupled Head enabled EdgeYOLO to achieve 50.6% mAP50. For industrial settings, Yuan et al. [91] presented YOLO-HMC, which pruned unnecessary layers from the YOLOv5 head and adaptively tuned the channel configuration for PCB defect detection, leading to a 3.5% increase in mAP.

To address the limited visibility and ambiguous features of small or densely packed objects, several models injected advanced attention mechanisms directly into the detection head. Peng et al. [60] proposed LGFF-YOLO, in which the Lightweight Detection Head (LDyHead) integrated sequential scale-sensitive, spatial-adaptive, and task-specific attention modules, dynamically modulating feature importance at each stage. The use of a computationally efficient FasterConv module further accelerated inference, and the replacement of the standard head with LDyHead resulted in a 2.1% improvement in mAP50.

This trend toward fine-grained attention is also evident in domain-specific applications. Hu et al. [92] introduced MOA-YOLO, enhancing each detection head with a Multi-head Latent Attention (MLA) module, which enabled the network to better distinguish small fish from background noise, leading to a 6.4% increase in mAP. For X-ray imagery, Cheng et al. [93] developed X-YOLO with an improved Dynamic Head that is aware of task, scale, and spatial information. The architecture adaptively reweighted features for classification and localization across different scales, supporting more accurate detection of small and cluttered targets. Liu et al. [94] investigated conveyor belt safety monitoring and proposed the YOLO-EV2 detector. The model coupled an EfficientNetV2 backbone with a scale-sensitive detection head. The head explicitly enhanced responses to small longitudinal tearing patterns along belt edges under heavy interference. On a coal mine conveyor belt tear dataset, YOLO-EV2 achieved higher mean average precision and frame rate than recent YOLO baselines. These attention-driven modifications enable detection heads to more effectively capture subtle and localized information required for challenging small object scenarios.

A third strand of head optimization targets the decoupling of tasks, explicit spatial alignment, and handling of oriented objects, thereby refining the head’s specialization for small target localization. Mo et al. [95] presented SGT-YOLO, which removed the higher-level (P4/P5) heads to simplify the architecture and introduced a Task-Specific Context Decoupling head. This decoupling enabled more focused feature learning for tiny defects, achieving a 0.4% improvement in mAP50. Building on the theme of task specialization, Jiao et al. [96] developed YOLO-DTAD, embedding a dedicated feature extractor within a decoupled head and employing dynamic loss weighting to strengthen the synergy between classification and localization streams. This architecture led to a 4.1% accuracy improvement. Addressing the alignment of spatial predictions, Zhuang et al. [97] introduced YOLO-KED, which utilized a Dynamic Alignment and Rotated Head (DARH) to coordinate the confidence and localization for each object and to support rotation-aware bounding boxes, achieving a 1.3% improvement in mAP0.5:0.95. For scenes involving arbitrary object orientation, Xie et al. [13] developed CSPPartial-YOLO, which featured a rotational prediction head comprising three parallel branches to estimate location, category, and rotation angle. The training strategy combined Varifocal Loss, ProbIoU Loss, and Distributed Focal Loss to address class imbalance, regression accuracy, and angle prediction stability, respectively. Their approach achieved 89.75% mAP on DOTA.

Collectively, these structural innovations significantly improve the adaptability and robustness of YOLO detection heads for small object scenarios. By integrating lightweight designs, advanced attention mechanisms, and specialized modules for challenging spatial contexts, recent methods have enabled YOLO-based detectors to more effectively localize and recognize small targets across diverse and complex applications.

3.2.3 Challenges of Detection Head and Branch Structure Optimization

Challenges in detection head design and branch structure optimization for small object detection arise from the central role that these components play in mapping continuous feature fields to discrete prediction hypotheses. In single stage detectors such as the YOLO family, each detection head defines a particular sampling of the multi scale feature hierarchy into bounding box and class predictions, and the introduction of additional heads or branches for small objects fundamentally alters this sampling geometry. When an extra prediction head is attached to a feature map with finer spatial stride, the number of candidate boxes increases sharply and many of these candidates occupy highly overlapping receptive fields. From a statistical viewpoint this causes a substantial rise in correlated outputs whose underlying features are almost identical, which increases the probability of false positives unless the allocation of responsibilities across heads is carefully constrained. In principle a head that is intended for small objects should respond only to targets within a particular range of scales, yet in practice the receptive fields of different heads overlap across scale and aspect ratio. As a result, the same object may be explainable by multiple heads, which creates ambiguity in label assignment during training and in confidence allocation during inference. This ambiguity has a direct impact on the optimization landscape. The multi head loss is a sum of coupled terms whose gradients compete for shared backbone parameters. If training targets are not assigned in a scale consistent manner, gradients from different heads may point in conflicting directions in parameter space, which slows convergence and can lead to solutions in which one head dominates while another remains under trained. Small object branches are particularly vulnerable to this phenomenon because they often operate on shallower features with weaker semantics and thus receive noisy supervision. At the same time, each additional head introduces new parameters and increases the dimensionality of the hypothesis space. This enlarges the search space that the optimizer must explore and can cause the model to overfit to spurious correlations in the small object regime. Computationally, extra heads and branches also increase the cost of dense prediction, which runs counter to the real time constraints that originally motivated the YOLO framework and may make some small object oriented designs impractical for deployment on resource limited platforms. These challenges suggest that effective detection head optimization requires more than simply adding fine scale branches. Promising directions include scale aware assignment strategies that enforce a clear partition of object sizes across heads, regularization schemes or knowledge distillation that stabilize gradients in multi head training, and dynamic gating mechanisms that activate only the branches that are informative for a given input distribution. In theoretical terms the goal is to design a prediction layer that increases the sensitivity of the network to small objects while maintaining a well conditioned optimization problem and preserving the global balance between recall, precision, and efficiency that defines high quality single stage detection.

3.3 Loss Function Improvement and Regression Precision Optimization

3.3.1 Recent Advances in Loss Functions for Small Object Detection

Recent studies in YOLO-based small object detection have focused on designing loss functions that incorporate scale-aware weighting, geometry-aware metrics, and adaptive task balancing to address the disproportionate influence of large objects and improve localization precision for small targets. Small objects occupy few pixels, so localization errors can be relatively large and heavily penalized by standard loss functions. Moreover, traditional loss functions like CIoU or DIoU assign equal importance to errors in both large and small bounding boxes, often causing the optimization to be influenced primarily by large-object samples. To address this, researchers have proposed a variety of improved loss functions and bounding-box regression strategies aimed at improving small-object accuracy.

A common theme in recent research is to make the localization loss more sensitive to small errors and to the presence of small targets. One direct approach is to reweight IoU-based losses so that small objects contribute more to the overall loss. For example, Xie et al. [77] proposed the WIoUv3 loss in KL-YOLO, which introduced a dynamic, non-monotonic weighting mechanism to adaptively adjust gradient gains for targets of different sizes. The core formula of WIoUv3 is as follows:

where

Similarly, to balance scale differences, Niu and Yan [71] integrated the Wise-IoU loss into their YOLOv8-based model, which increased the loss for bounding boxes on small objects and decreased it for large ones. Building on this, Wu et al. [50] proposed the Adaptive Weighted IoU, which further adjusted the regression focus to regular-sized anchors, preventing the loss from being dominated by extremely large or small instances. Replacing CIoU with AW-IoU in YOLOv5s achieved 64% mAP on NWPU VHR-10. In a related development, Sun et al. [98] introduced the Adaptive Focal Powerful IoU loss in SOD-YOLOv10. The Adaptive Focal Powerful IoU (FP-IoU) employed adaptive penalty and gradient modulation to assign higher costs to small errors, particularly for small bounding boxes, which in turn discouraged unnecessary enlargement of anchor boxes and accelerated convergence. It achieved 92.81% mAP on RSOD. These reweighting schemes share the goal of ensuring that the regression loss does not treat all errors equally and instead places greater emphasis on small-object bounding boxes that would otherwise be underrepresented.

Beyond weighting schemes, other loss function improvements incorporate additional geometric factors or alternative distance measures to further benefit small-object detection. Several studies proposed modified IoU or distance-based losses that capture object alignment and spatial relationships more effectively. Jiang et al. [16] introduced the Complete IoU with Normalized Wasserstein Distance for small manufacturing defect detection. The method augmented standard IoU with a normalized Wasserstein distance term that measured the displacement between box centers relative to their sizes, which provided a richer gradient signal for optimizing alignment. With CI-NWD, mAP50 increased by 0.4%.

In scenarios with oriented or elongated small objects, incorporating angle and shape information can further enhance localization. Hou et al. [53] proposed the α-SIoU loss in αS-YOLO, which extended the classic SIoU by introducing an adaptive angular control coefficient. This enabled the loss function to dynamically adjust convergence speeds in different directions according to the angular difference between the predicted and ground-truth boxes, facilitating precise localization for small and rotated objects. The α-SIoU loss is formulated as:

where

For general object detection, other approaches refined IoU formulations to improve bounding box regression for small targets. Gu et al. [26] replaced standard CIoU with Efficient IoU in an infrared small target detector. EIoU provided a more balanced treatment of width, height, and center distance, achieving an mAP of 87.5% on the FLIR dataset. Additionally, Mahaveerakannan et al. [99] proposed Shape_IOU, adding a shape-aware component to the IoU computation and enabling more accurate localization of objects with nonstandard measurements or irregular forms, especially small targets that occupy only a few pixels. By emphasizing geometric overlap and shape conformity between predicted and ground-truth boxes, Shape IOU improved detection robustness in challenging small-object scenarios. Du et al. [100] addressed industrial surface defect inspection with the MGF-YOLO detector. The method employed a multi-scale gated fusion neck and adopted a Focaler intersection over union regression loss. The loss suppressed gradients from well localized boxes and amplified gradients from poorly localized predictions. This formulation increased localization sensitivity around tiny steel surface defects and yielded higher mean average precision and recall than a vanilla YOLOv5s baseline.

Some loss functions incorporate scale-adaptive terms to enhance the localization sensitivity for small objects, thereby reducing the dominance of large-object errors in YOLO-based training. Li et al. [18] proposed the Adaptive Scale-Enhanced CIoU loss as part of YOLO-DFA, which modulated the penalty on aspect ratio and scale according to the size of each target, effectively amplifying errors on small objects relative to larger ones. This approach led to a 1.7% improvement in mAP50. Ni et al. [17] adopted a related strategy by introducing an adaptive Focal-EIoU loss in their Tri-Decoupling++ detector. This loss applied focal-like scaling to the components of the EIoU formulation, guiding regression gradients toward more challenging examples, especially small or irregularly shaped targets. With this design, the method achieved 94.4% mAP50 on NWPU VHR-10. In parallel, Wu et al. [50] improved the post-processing of densely packed small objects by integrating SCYLLA-IoU into a soft-NMS scheme. S-IoU used an IoU-based continuous suppression mechanism that retained multiple nearby detections more effectively. The incorporation of S-IoU resulted in a 0.9% improvement in mAP50. Although S-IoU primarily impacts NMS rather than the training loss, it reflects the broader trend of IoU-based innovations designed to better handle crowded small-object scenarios.

There are also hybrid loss strategies that integrate classification and localization terms to further benefit small-object training. For instance, some methods dynamically increase the weight of the classification loss for small objects, ensuring that the network learns to distinguish their subtle features. Jiao et al. [96] adopted dynamic task weighting in YOLO-DTAD, a scheme that prevented the classification of numerous large objects from overwhelming the localization of smaller targets. This loss optimization approach led to a 1.5% mAP improvement. In addition to loss function modifications, enhancements in label assignment and sample selection also contribute to improved small-object detection. Zhou et al. [12] in AD-YOLO introduced a dual-label assignment strategy, where small objects were assigned to multiple prediction scales during training. This multi-scale supervision allowed the loss to be computed from various levels, providing the network with additional opportunities to capture small object features. When combined with ECSA attention and a dedicated small-object detection layer, this strategy achieved a 4.4% mAP improvement.

In summary, ongoing advances in loss function design for small object detection have produced a diverse set of strategies that include reweighting schemes, geometry-aware and scale-aware formulations, as well as dynamic task balancing. These approaches aim to more precisely address the challenges posed by targets that are small, densely distributed, or irregularly shaped. By explicitly amplifying localization and classification signals associated with small objects, and by refining both regression and sample assignment processes, these methods collectively provide a more balanced and effective optimization landscape. As a result, modern YOLO-based detectors are increasingly able to achieve robust performance on small object benchmarks, even in complex and crowded environments.

3.3.2 Challenges and Limitations of Loss Function Improvements

Loss function improvement and regression precision optimization for small object detection face fundamental challenges that stem from the way gradients are distributed over highly imbalanced and heterogeneous data. Standard formulations of classification and localization loss tend to be dominated by medium and large objects, which contribute strong and relatively stable signals, while the weak and noisy responses of small objects induce gradients of much smaller magnitude. The gradient field becomes highly sensitive to hyperparameters that control how much emphasis is placed on rare small objects relative to abundant easy negatives and larger targets. If the weighting is too aggressive, the loss can overfocus on a small subset of difficult instances, which leads to underfitting of more common object sizes and makes training unstable. If the weighting is too conservative, the contribution of small objects remains negligible and the modification fails to change the effective learning dynamics. Even when hyperparameters are tuned carefully, there remains a structural limitation: loss reweighting operates on the outputs of the network and cannot create information that is not present in the underlying features, so it cannot fully overcome the intrinsic scarcity and low signal to noise ratio of small object representations. A further difficulty arises from the design of refined localization losses. Precise overlap based objectives and fine grained boundary terms provide more informative supervision for small boxes whose location error must be measured in a few pixels, yet they often require expensive geometric computations and numerical stabilization, which increases training time and may hinder deployment in large scale or real time regimes. These considerations suggest that loss function improvements for small object detection should be coupled with complementary mechanisms that enhance feature quality and sampling, and that the design of new objectives should emphasize robustness to hyperparameter variation, computational parsimony, and a balanced treatment of different object scales. Practical strategies include adaptive weighting schemes that are learned from data rather than fixed by hand, curriculum style training that gradually increases the influence of small objects as the backbone stabilizes, and multi task formulations in which auxiliary signals such as centerness or boundary uncertainty help to regularize the optimization of fine scale regression.

3.4 Multi-Scale Feature Fusion and Spatial Context Enhancement

Multi-scale feature fusion has improved through redesigned cross-layer connections and adaptive mechanisms, thereby better integrating fine-grained details with high-level semantics for spatial context modeling. Advances in this area generally fall into two complementary strategies: Structured Cross-Layer Multi-Path Fusion and Dynamic Weighted Context-Adaptive Fusion. The former approach introduces architectural modules that explicitly connect and combine feature maps across scales, ensuring the effective utilization of fine-grained details from shallow layers alongside the rich semantics from deeper layers. The latter employs adaptive mechanisms to adjust the fusion process based on contextual cues, enabling the network to dynamically focus on features most relevant to small objects. Together, these architectural and adaptive advances have significantly enriched the multi-scale representations that are vital for precise small object detection. Although many multi-scale fusion methods incorporate attention modules to adaptively refine feature aggregation, we treat fusion and spatial context enhancement as a distinct category in this section for clarity. In this survey, the multi-scale fusion dimension refers to the architectural design that specifies which feature maps interact and at which spatial resolutions. The analysis below focuses on the layout of cross-layer links, the choice of upsampling and downsampling operators, and the rules used to combine features across different depths. Complementary attention-centric perspectives are discussed in Section 3.1.

3.4.1 Structured Cross-Layer Multi-Path Fusion

Enhancing the feature pyramid has long been a foundational approach for small-object improvement. In this context, a variety of multi-branch modules have emerged to extract and merge features at diverse receptive fields, thereby providing a richer representational basis for small object detection. Niu and Yan [71] integrated a Diversified Basic Block into the YOLOv8 backbone. DBB leveraged parallel convolutional branches of different kernel sizes during training and fused them into a single equivalent convolution for inference, enabling the model to learn multi-path representations. Building on this concept, Jiang et al. [72] designed the MSFEM module, in which parallel convolutions were followed by concatenation and compression, capturing both fine and coarse features.

Efforts to enhance channel diversity and context adaptation have led to more sophisticated multi-branch fusions. Chen et al. [73] proposed the MPMS module for Para-YOLO, which grouped convolution branches by channel and employed a learnable router for expert-like multi-scale aggregation, leading to a 1.6% improvement in mAP50. This trend toward parallel, context-aware processing is mirrored by the CSA module of Wang et al. [67], which combined convolution and pooling pathways and then applied self-attention to refine context aggregation, increasing mAP50 on VisDrone2019 by 0.6%. In a complementary fashion, Liu et al. [74] exploited group convolution and channel shuffling in MFFM, which enhanced representational flexibility and achieved 54.62% mAP on VEDAI.

Several structured fusion modules integrate attention or adaptive sampling directly into the merging process. Wu et al. [101] adopted a decomposition strategy in BHFM, splitting large kernels into cascades of smaller convolutions integrated with attention mechanisms, thereby enabling broader contextual capture while constraining parameter growth. This design achieved a 3.4% mAP improvement. The utility of multi-scale kernel integration is particularly notable in vehicle detection. Methods for aligning and fusing features at different resolutions have also advanced, as illustrated by Shi et al. [66], who used deformable-convolution fusion blocks that adaptively sampled and integrated multi-resolution features and improved mAP50 by 0.6% on UAV. By embedding either explicit attention or deformable sampling within the fusion pathway, these approaches enhance the ability of the model to integrate broad context while preserving the fine detail required for reliable small-object detection.

To address the need for capturing wider spatial context without excessive computation, the use of large or dilated kernels within fusion branches has also been explored. Zhang et al. [102] employed a Multiscale Large-Kernel Module to target vehicles of varying sizes, achieving 90.3% mAP on USOD. The architectural philosophy behind these advances was further reflected in the Multiscale Dilated Separable Fusion block of Gu et al. [26], where depthwise kernels and multi-scale decomposition replaced standard convolutions, achieving 81.4% mAP on FLIR.

Beyond within-layer diversification, the effective propagation of information across different network depths has emerged as a critical concern. A variety of redesigned necks and cross-layer fusion mechanisms have sought to strengthen both semantic abstraction and the preservation of low-level detail, especially for objects at the limits of resolution. Wang et al. [14] provided an instructive example by employing a BiFPN-based neck in YOLOv8-QSD, leveraging iterative top-down and bottom-up blending with learnable weights. This configuration achieved a 1.5% mAP50 improvement for challenging distant traffic sign detection.

The principles underpinning bidirectional fusion are further demonstrated in the BPNet architecture proposed by Zan et al. [103], which enhanced the traditional FPN by augmenting cross-scale connections. This approach proved especially effective for fine-grained object detection in real-world surveillance, as reflected in state-of-the-art empirical results. Meanwhile, the benefit of dense connectivity is evident in the Layer-by-Layer Dense Residual Module designed by Ni et al. [17]. Through the establishment of direct semantic pathways between deep and shallow layers, Tri-Decoupling++Net achieved 68.3% mAP on DOTA and 93.6% mAP on NWPU VHR-10.

The exploration of optimal fusion strategies continued in the work of Wang et al. [25], who demonstrated that replacing the PANet module with a conventional FPN could enhance feature resolution, with mAP50 rising from 73.2% to 77.9% in multimodal small-object scenarios. The fusion of enhanced low-level textures with high-level abstractions, as achieved by the FF module in MSFE-YOLO from Qi et al. [10], further exemplified the integration of spatial detail and semantic richness, leading to a 2% improvement in mAP50. At the backbone level, the integration of shallow, detail-rich features with higher-level abstractions has also proven effective for maintaining small-object cues throughout the network. In the work of Zeng et al. [8], such a fusion strategy achieved 47.4% mAP on the VisDrone2020 test set. Tang et al. [104] addressed infrared small target detection by augmenting a YOLO-style backbone with an edge feature enhancement module that strengthened local gradient responses around tiny targets. An infrared relational enhancement module further aggregated multi-scale contextual information within a long-range receptive field. This multi-level fusion increased the detection probability of extremely small and low-contrast targets in infrared scenes and maintained a practical false-alarm rate.

3.4.2 Dynamic Weighted Context Adaptive Fusion

Dynamic Weighted Context-Adaptive Fusion can be understood as a coupling between multi-scale aggregation and attention-based selection. In modern YOLO pipelines, the fusion stage learns spatially and channel-wise varying weights that gate cross-scale flows, often via explicit attention or implicit attention proxies. Readers seeking attention mechanisms per se can refer to Section 3.1. This subsection examines how multi-scale aggregation is coupled with attention-based selection to preserve fine detail, inject global semantics, and suppress background clutter for small-object detection. A representative example is the Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion module proposed by Sun et al. [9] in MIS-YOLOv8, where spatially varying weights are learned for each location in the feature map. This enabled the model to dynamically determine the optimal contributions of high-resolution (P2) and deeper semantic (P3, P4) features at every spatial point, leading to a 6.2% improvement in mAP50. This context-sensitive fusion ensures that the details essential for small object detection are preserved without being overwhelmed by irrelevant information.

Extending this paradigm, Ning et al. [87] developed a parallel P2–P3–P4 detection head architecture in which each head operates on relatively shallow feature maps. The P2 branch incorporates a spatial self-attention mechanism that helps capture long range dependencies and spatial relationships that are critical for distinguishing tiny targets in complex backgrounds. Removing redundant downsampling further preserves discriminative cues and leads to a 2.4% improvement in mAP50. Wang et al. [105] introduced an Adaptive Feature Fusion module within a super resolution aided YOLO framework. The network learns to integrate multi scale features from different layers according to the contextual demands of aerial scenes and surpasses rigid concatenation. The use of AFF yields an 11.11% improvement in mAP and shows the benefit of adaptive fusion in small object scenarios. Together these methods reveal a trend in which dynamic context aware fusion mechanisms improve the extraction of fine-grained information and enhance the reliability of small object detection.