Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A CNN-Transformer Hybrid Model for Real-Time Recognition of Affective Tactile Biosignals

1 School of Design and Art, Shanghai Dianji University, Shanghai, China

2 Innovation Academy for Microsatellites, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China

* Corresponding Author: Chang Xu. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 99 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2026.074417

Received 10 October 2025; Accepted 13 January 2026; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

This study presents a hybrid CNN-Transformer model for real-time recognition of affective tactile biosignals. The proposed framework combines convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to extract spatial and local temporal features with the Transformer encoder that captures long-range dependencies in time-series data through multi-head attention. Model performance was evaluated on two widely used tactile biosignal datasets, HAART and CoST, which contain diverse affective touch gestures recorded from pressure sensor arrays. The CNN-Transformer model achieved recognition rates of 93.33% on HAART and 80.89% on CoST, outperforming existing methods on both benchmarks. By incorporating temporal windowing, the model enables instantaneous prediction, improving generalization across gestures of varying duration. These results highlight the effectiveness of deep learning for tactile biosignal processing and demonstrate the potential of the CNN-Transformer approach for future applications in wearable sensors, affective computing, and biomedical monitoring.Keywords

Tactile interaction has been widely applied in various fields, including medical surgery [1], real-time health monitoring [2], rehabilitation training [3], and remote control [4,5]. As an essential aspect of human-machine interaction, tactile engagement allows machines to respond more effectively to human needs and contributes to overall well-being [6]. In particular, affective touch gestures provide an important channel for conveying emotions and intentions [7,8], and increasing attention has been given to their monitoring and interpretation in recent years [9].

Early research on affective touch gesture recognition primarily relied on traditional machine learning techniques applied to handcrafted features extracted from tactile biosignals. Typically, features were derived from raw tactile data and then used to train models that learned input-output mappings for gesture prediction. Cooney et al. [10] developed a skin sensor with a photo-interrupter to record tactile interaction data between humans and humanoid robots, and used support vector machines and support vector regression to recognize affective touch gestures. To provide more generalizable benchmarks, the Human-Animal Affective Robot Touch (HAART) dataset [11] and the Corpus of Social Touch (CoST) dataset [12] were introduced in the 2015 Social Touch Challenge. Building on these datasets, subsequent work explored pressure-surface and kinematic features [13], as well as a range of statistical and temporal descriptors. Using these features with a Random Forest classifier, accuracies of 70.9% on the HAART and 61.3% on the CoST dataset were obtained, representing the strongest affective touch gesture recognition performance of that period [14,15]. Although these approaches improved interpretability and achieved moderate recognition performance, they remained dependent on manual feature design and offered limited capacity to capture complex spatiotemporal patterns.

With the rapid development of deep learning, the performance of affective touch gesture recognition has been substantially improved. Deep architectures originally developed for text [16], audio [17,18], and vision [19,20] have been adapted to tactile biosignal classification, including deep neural networks (DNNs) [21], CNNs [22], and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [22]. For example, DNNs combined with hidden Markov models and geometric moments have been applied to tactile robotic skin, but their accuracies on the HAART and CoST datasets were relatively low at 67.73% and 47.17%, respectively [21]. CNN-based models, including both 2D and 3D variants, have shown promising results [23] on the HAART dataset, with the 3D CNNs achieving 76.1% accuracy, surpassing the top-ranked outcome of the 2015 Social Touch Challenge. Similarly, Albawi et al. [24] improved performance on the CoST dataset using a CNN-based model and the leave-one-subject-out cross-validation method, achieving 63.7% accuracy, which exceeded earlier results. Considering the temporal nature of tactile biosignals, RNNs [22] and LSTM [23] models were also explored, and hybrid CNN–LSTM models have demonstrated better performance by jointly modeling spatial structure and temporal dynamics, achieving state-of-the-art accuracy on HAART and CoST in some studies [25]. Recent studies have further demonstrated the effectiveness of CNN–LSTM architectures in sequential biosignal analysis, such as emotion recognition from photoplethysmographic data [26], where the hybrid design significantly improved temporal modeling. Although RNNs and LSTM are commonly used for sequential data, their ability to capture long-term temporal dependencies is fundamentally limited by their step-by-step processing and the gradual decay of information over time. As the sequence length increases, these models often struggle to retain global contextual information due to vanishing gradients and restricted memory capacity. The Transformer architecture [27] overcomes these limitations through its multi-head self-attention mechanism, which computes relationships between all time steps in parallel. This enables direct modeling of long-range temporal dependencies without iterative state propagation, making Transformer particularly suitable for tactile biosignal sequences where meaningful temporal patterns may span extended or non-local time intervals.

In previous studies on tactile biosignal classification using the HAART and CoST datasets, most approaches relied on extracting features from complete sequences collected in each experiment. Such methods require acquiring the full gesture from start to end before making a prediction, which limits applicability in real-time scenarios. However, a touch biosignal recognition model should be capable of making instantaneous predictions of real-time touch gestures in practical human-machine interaction scenarios, rather than waiting until the entire gesture has been completed.

In response to these limitations, this paper proposes a hybrid approach that combines CNNs and Transformer architecture. The CNN component is responsible for extracting local spatial features from tactile biosignals, while the Transformer captures long-range temporal dependencies in sequential data, allowing the two modules to complement one another. Recent developments have further extended this paradigm to sequential text generation, audio processing [28] and physiological signal analysis [29,30], where Transformer-based temporal modeling has demonstrated strong capabilities in capturing complex temporal dynamics. Hybrid structures have also shown promising results in visual perception and biomedical segmentation tasks, illustrating the broader applicability of combining local and global feature modeling. These advances collectively indicate that hybrid CNN-Transformer architectures are well suited for affective biosignal recognition, providing a solid foundation for extending such approaches to tactile biosignal analysis. The main objective of this study is not merely to adopt existing CNN-Transformer architectures, but to adapt and re-purpose them for real-time affective tactile biosignal recognition under sliding-window constraints. Specifically, this work investigates how Transformer-based temporal attention can be effectively integrated into a CNN-dominated framework to refine short-term temporal dynamics in tactile signals, rather than modeling long-range sequence dependencies. The contributions of this work include the design and implementation of a lightweight CNN-Transformer model tailored to affective tactile biosignals. This architectural design explicitly accounts for the characteristics of tactile array data and the low-latency requirements of real-time gesture-based affect recognition. Experiments using the HAART and CoST datasets were conducted to validate the framework, which was designed to output instantaneous gesture predictions based on real-time tactile inputs.

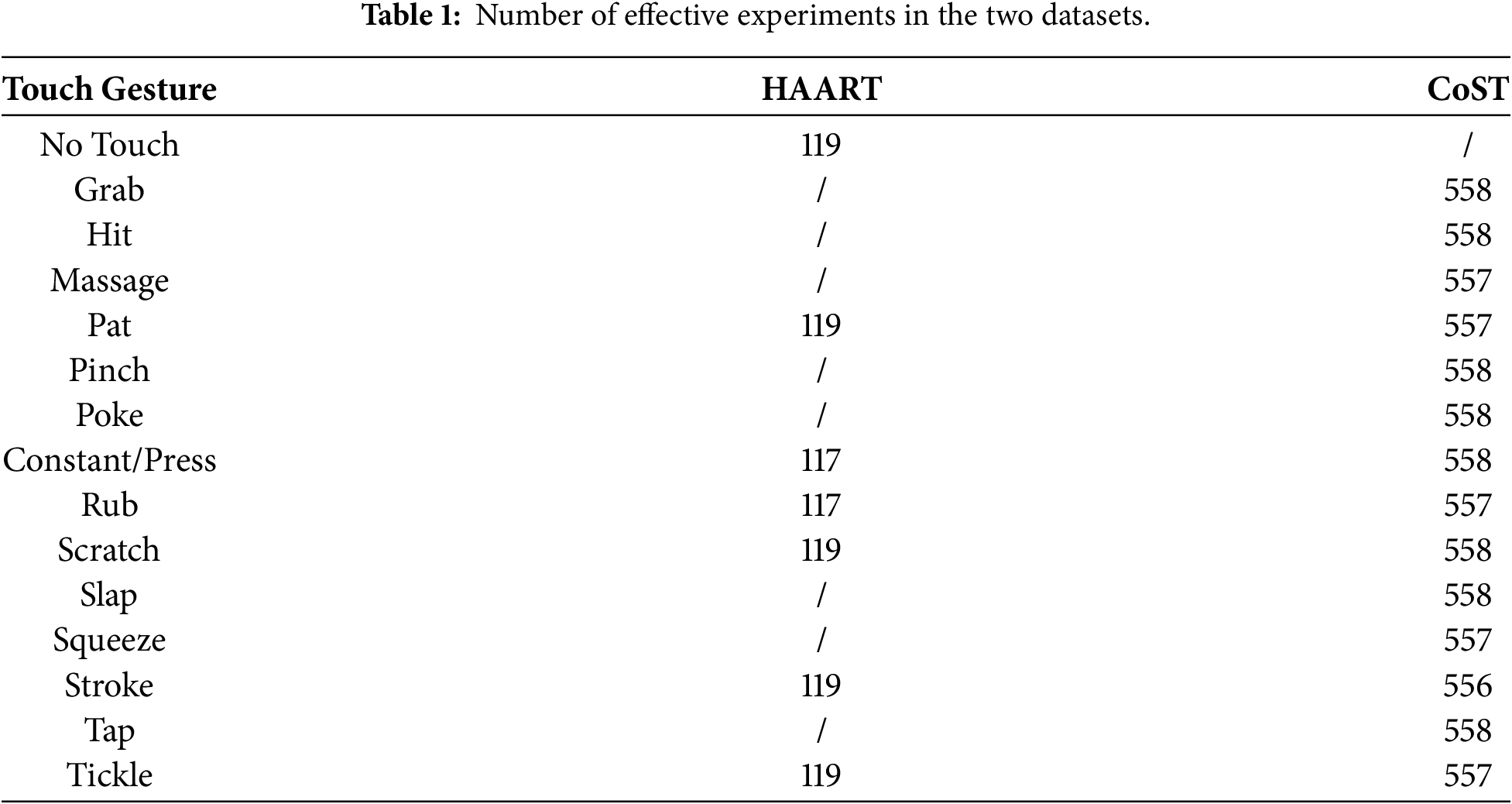

The performance of the proposed model was evaluated using two publicly available datasets, HAART [11] and CoST [12]. These datasets were selected because of their reliability and their widespread use in the affective touch gesture recognition field, which makes them suitable benchmarks for validating and comparing models. By employing these well-established datasets, the performance of the proposed approach can be directly compared with previous studies. An overview of the datasets used in this study is provided in Table 1.

HAART [11] is a publicly available dataset consisting of a grid of 10 × 10 pressure sensors, each of which captures and reports pressure variations in response to contact. Data were gathered from 10 participants, each performing 7 different touch postures, including no touch, constant, pat, rub, scratch, stroke, and tickle. Data collection was conducted on three types of substrates and four different covers applied to the pressure sensors. The substrates included None, Foam and Curve. The covers consisted of Fur, None, Long, and Short. The various substrates and covers create 12 distinct data acquisition scenarios. Each gesture is captured at a frequency of 54 Hz and executed continuously for 10 s, obtaining uninterrupted test results for 8 s after trimming the first and last seconds. Each frame is a snapshot of the entire grid at a specific moment. This creates a dataset consisting of 432 frames per sequence.

The second dataset used in this study was the CoST dataset [12], which contains 7805 tactile biosignal samples collected from human touch gestures performed on a grid of pressure sensors positioned around a human hand. The dataset includes 14 distinct interaction types, namely grab, hit, massage, pat, pinch, poke, press, rub, scratch, slap, squeeze, stroke, tap, and tickle, each recorded at three different intensity levels. These gestures were carried out by 31 participants, with each subject repeating every gesture six times to ensure consistency and variability across individuals. The CoST dataset records tactile signals across 64 sensor channels at a sampling frequency of 135 Hz. Unlike the HAART dataset, where gestures were standardized with uniform durations, the CoST dataset provides gesture sequences of variable lengths, ranging from as many as 1747 frames to as few as 10 frames, which adds additional complexity to classification tasks.

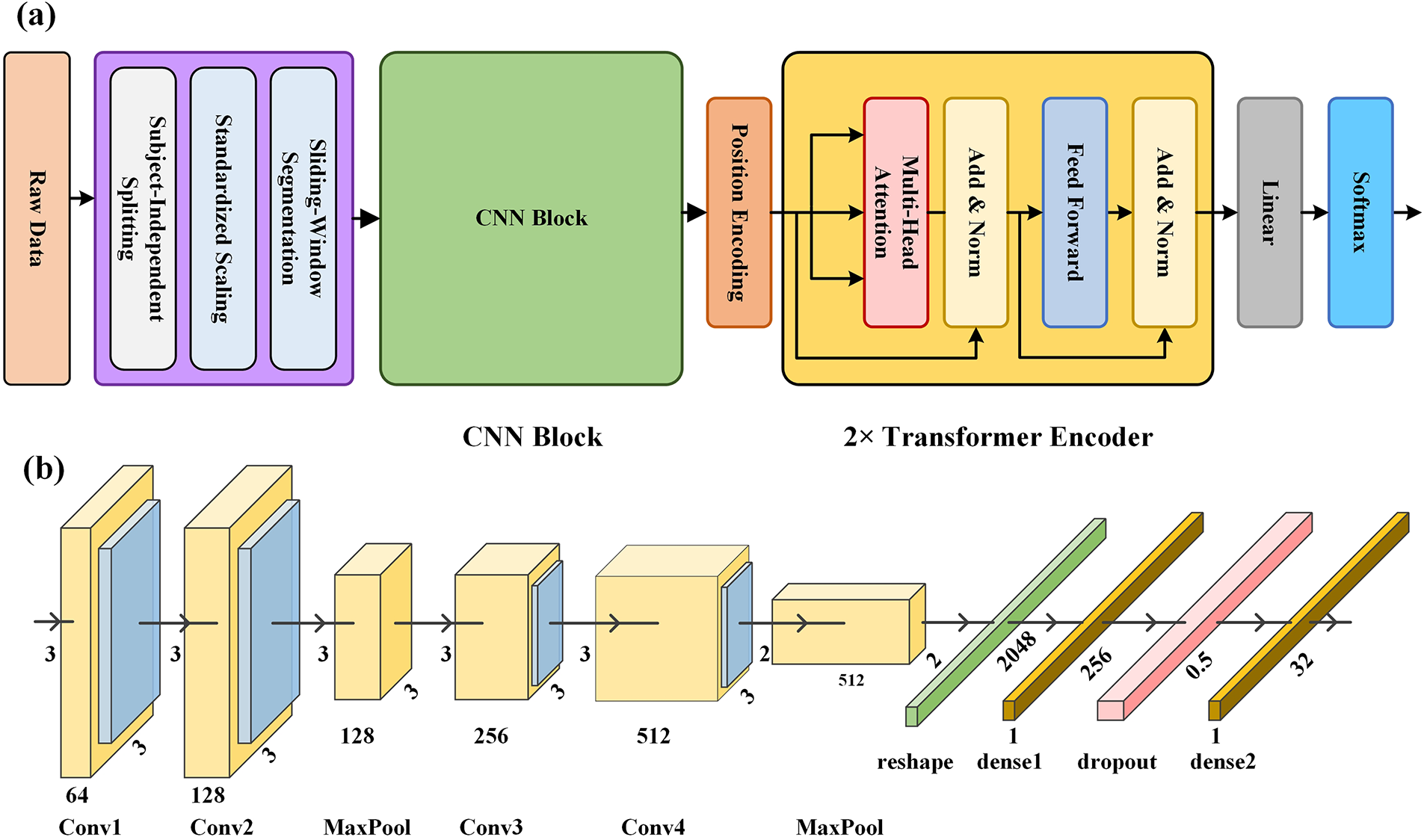

This paper presents a CNN-Transformer classifier developed for the recognition of tactile biosignals using the HAART and CoST datasets. An overview of the proposed architecture is shown in Fig. 1a. The touch gestures data were first preprocessed and then passed through the CNN block to extract local spatial features from the tactile frames.

Figure 1: (a) Overview of the proposed CNN-Transformer architecture, (b) the CNN block in CNN-Transformer architecture.

The CNN block and Transformer layers were integrated to capture long-range dependencies in tactile biosignals for affective touch gesture recognition. Tactile sensor arrays in the HAART and CoST datasets produce spatially organized pressure measurements arranged in grid-like formats, specifically 10 × 10 for HAART and 8 × 8 for CoST. These structured pressure maps are analogous to low-resolution images, where adjacent taxels exhibit spatial correlations similar to neighboring pixels in vision tasks. As a result, CNNs are well suited for processing this type of data, since convolutional kernels can effectively capture local spatial patterns and pressure distributions across the tactile surface. In the CNN-Transformer architecture, the CNN component consists of four 2D convolutional (Conv2D) layers. Each convolutional layer in the diagram corresponds to a Conv2D operation followed by batch normalization and a ReLU activation, forming the complete convolutional block illustrated in Fig. 1b. All Conv2D layers used a kernel size of 3 × 3, stride 1, and padding 1. This standardized configuration facilitated stable convergence of the network and reduced the risk of vanishing gradients. To enhance feature extraction, the outputs after normalization in Conv2 and Conv4 were further processed through a two-dimensional max-pooling layer. Following the final convolutional and pooling operations, the resulting tensor had a spatial dimension of 2 × 2 with 512 channels and was then flattened. Afterward, the flattened representation was routed through a dense layer with 256 units and a dropout layer with a rate of 0.5, providing regularization by randomly ignoring half of the units to prevent overfitting. Fig. 1b presents the complete architecture of the CNN block, in which the processed tensor is subsequently routed through a dense layer with 256 units before being passed to a positional encoding layer with 32 units.

To improve the model’s ability to capture complex dependencies, the Transformer encoder was integrated with a multi-head attention mechanism. The Transformer consisted of two encoder layers, each with four attention heads, a model dimension of 32, and a feedforward hidden dimension of 128. This mechanism allowed the model to simultaneously attend to features extracted from different positions within the temporal sequence, thereby enhancing representational capacity. Within each encoder layer, dropout (rate = 0.5) was applied to both the multi-head attention output and the feedforward sublayer, followed by layer normalization and ReLU activation in the feedforward network. These configurations further stabilized training and improved feature refinement. The Transformer’s ability to parallelize computations significantly accelerates the learning of long-term dependencies in tactile biosignals. By combining CNNs and Transformer components, the hybrid framework achieved a more comprehensive understanding of the temporal dynamics inherent in these tactile signals. For final classification, the output was passed through fully connected and Softmax layers, and a dropout rate of 0.5 was applied within the Transformer encoder to mitigate overfitting and improve generalization performance. In addition to its structural simplicity, the proposed CNN–Transformer model remains relatively lightweight. The CNN front end contains roughly two million trainable parameters, and the overall architecture requires only a modest amount of computation to process each sliding window.

2.2.2 Preprocessing of Datasets

To guarantee fair evaluation and eliminate any possibility of data leakage, subject-independent data splitting was applied to both datasets. All subsequent operations were then performed individually within each subject partition.

Before being processed by the CNN block, the tactile biosignal data underwent a series of preprocessing steps. To improve both computational efficiency and the convergence stability of the model, the data from the two datasets were normalized through standardized scaling [25], as expressed in Formula (1).

here, m and s denote the mean and standard deviation of the pressure data set x, respectively.

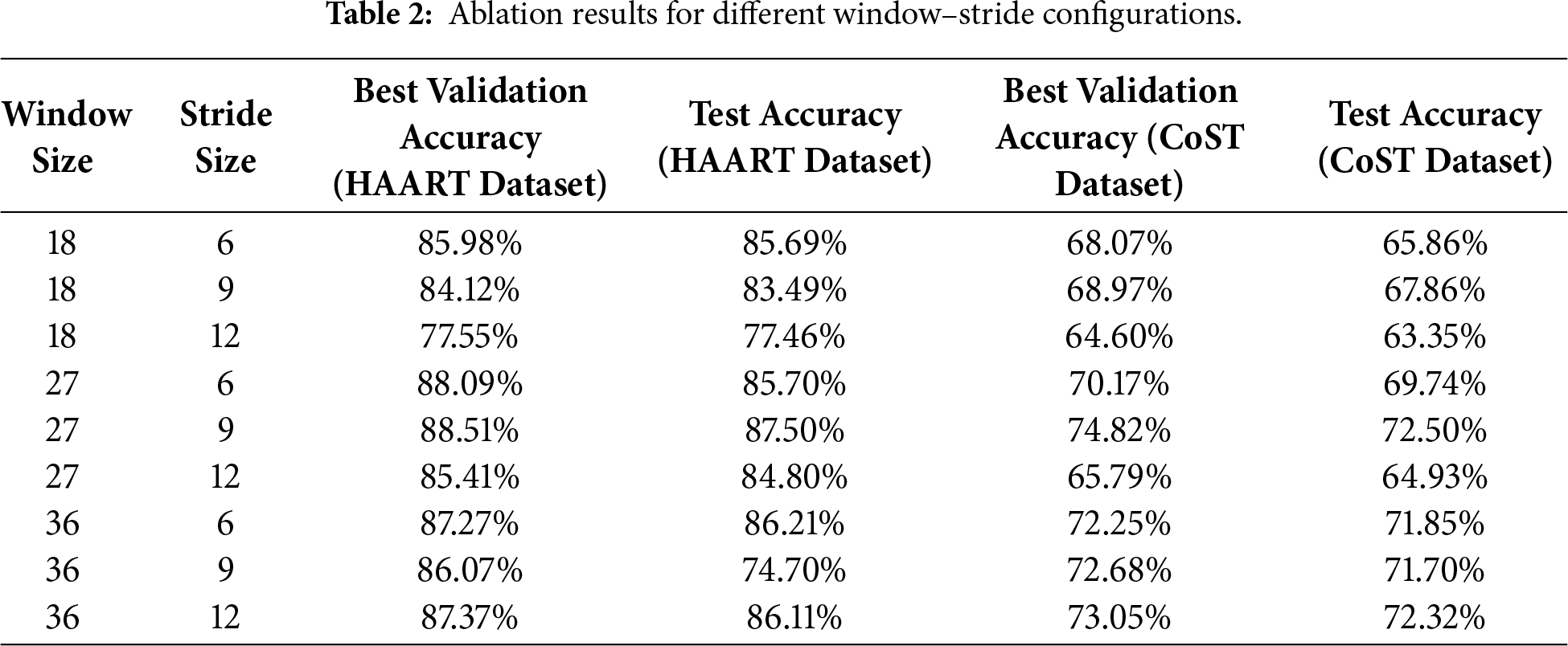

To enable instantaneous touch gesture prediction, a sliding-window segmentation strategy was adopted during data preprocessing. This approach not only provides the temporal context needed for instantaneous prediction but also increases the number of training samples, thereby improving the model’s generalization ability. Consistent with recent real-time gesture recognition systems that typically employ short temporal windows of around 200–500 ms to balance latency and accuracy [31], a similar temporal scale was adopted. To investigate how the temporal window and stride affect our model, a systematic ablation study was conducted across a 3 × 3 set of window-stride configurations. Specifically, the window lengths of 18, 27, and 36 frames (200–500 ms for the two datasets) were evaluated together with strides of 6, 9, and 12 frames. These window lengths are consistent with the temporal intervals commonly used in recent real-time tactile and wearable sensing literature [31], ensuring comparability with prior work. Within this range, the 3 × 3 design allows us to systematically compare short windows, which increase sample count, against longer windows that capture more stable temporal dynamics but reduce sample density. Importantly, to ensure fair and controlled comparison without inflating computational cost, all model components (including architecture, optimizer, learning rate, batch size, and data augmentation) were held constant across all experimental conditions. Only the sliding-window hyperparameters were varied. To constrain the computational cost, the training schedule was reduced from 750 epochs to 450. An early-stopping mechanism with a patience of 30 epochs was further introduced, enabling training to halt automatically once the validation accuracy plateaued. Unlike the main experiments, which relied on 10-fold cross-validation, the ablation employed only the first fold.

As summarized in Table 2, the configuration with a 27-frame window and 9-frame stride yielded the highest validation accuracy and test accuracy for both datasets. Therefore, this setting was adopted as the default configuration throughout this paper.

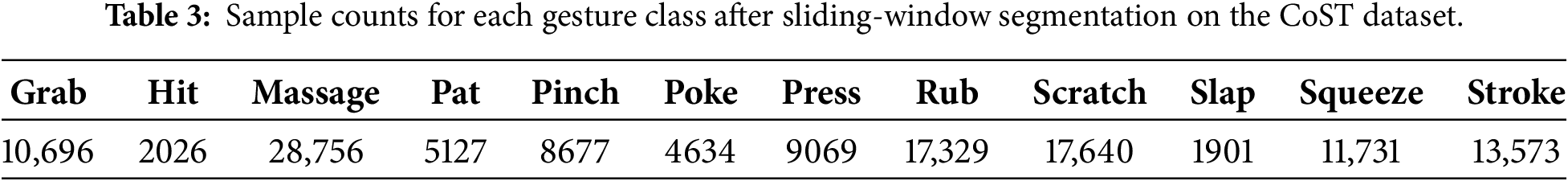

Considering the characteristics of the CoST dataset, where gesture durations vary widely, sliding-window segmentation increases the number of samples in a gesture-dependent manner and therefore affects the class distribution. Table 3 reports the number of data samples generated for each gesture class under the selected window–stride configuration. Although this segmentation strategy substantially enlarges the dataset and supports real-time modeling, differences in gesture duration naturally lead to unequal sample counts across classes.

The experiments were performed on a system that includes a 13th Gen Intel® i9-13900KF CPU @ 5.40 GHz, 32 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4070Ti GPU. The proposed model was implemented using the Python programming framework.

The batch size was set to 128, as it yielded optimal performance, and training was conducted using the SGD optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001. The model was trained for 750 epochs. Model performance was evaluated using a combination of subject-independent 10-fold cross-validation on the training set and a separate subject-level hold-out test set, which is a standard and rigorous evaluation protocol for biosignal recognition tasks. To support real-time applicability, inference efficiency was also assessed. When executed on an NVIDIA RTX 4070Ti GPU, the model demonstrated an average inference latency of approximately 1.3 ms per tactile window, indicating sufficient computational margin for real-time deployment.

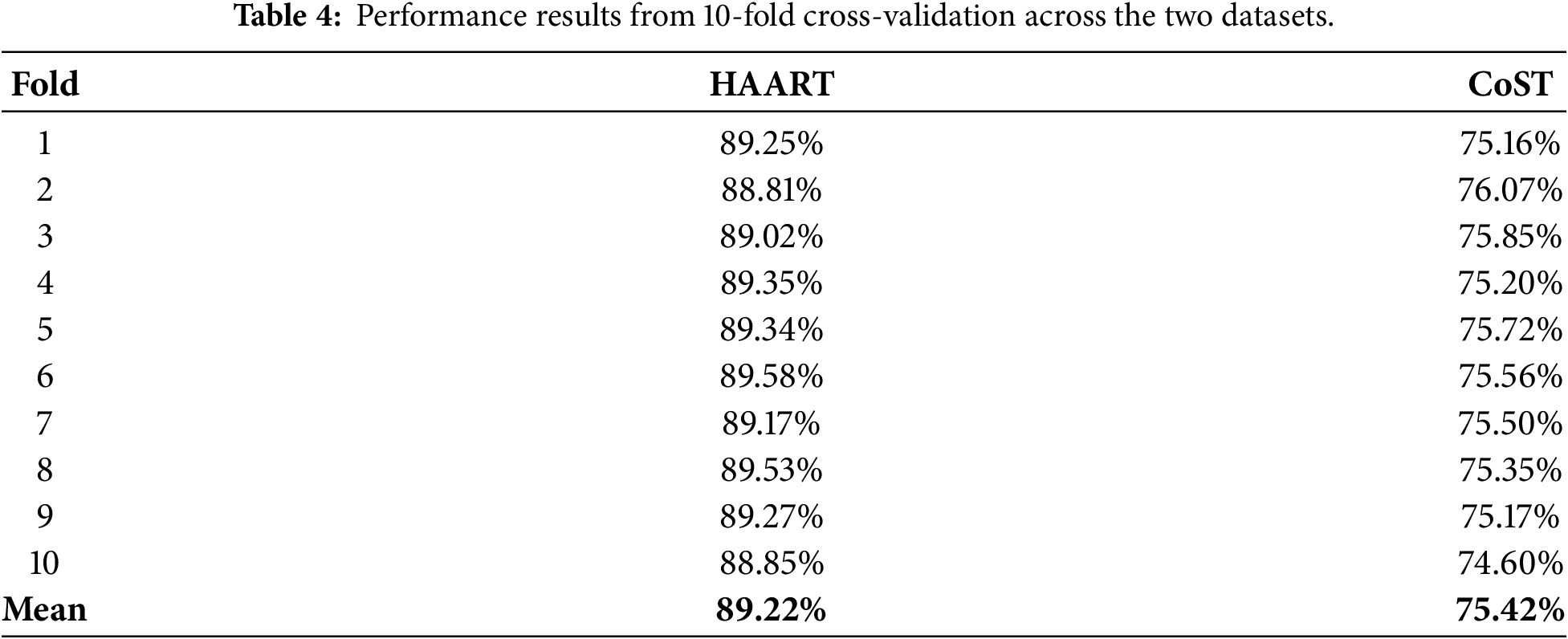

In the experiments, a subject-independent 10-fold cross-validation procedure was applied to the training portion of each dataset. After subject-level splitting, approximately 10% of the subjects in each dataset were reserved as a hold-out test set and were not involved in any training or validation steps. The remaining subjects were used for cross-validation, where the training data were shuffled and divided into 10 nearly equal subsets. In each fold, one subset was used for validation and the remaining nine subsets were used for training. This process was repeated ten times, and the mean classification accuracy across all folds was reported as the primary performance metric. The cross-validation results obtained from the validation sets are summarized in Table 4.

The model trained on the HAART dataset achieved the highest recognition performance, with an average cross-validation accuracy of 89.22%, as reported in Table 4. In comparison, the model obtained an average recognition accuracy of 75.42% on the CoST dataset. To further assess performance, the most effective configuration identified for each dataset was subsequently employed to generate learning curves of accuracy and loss, providing additional insight into training dynamics.

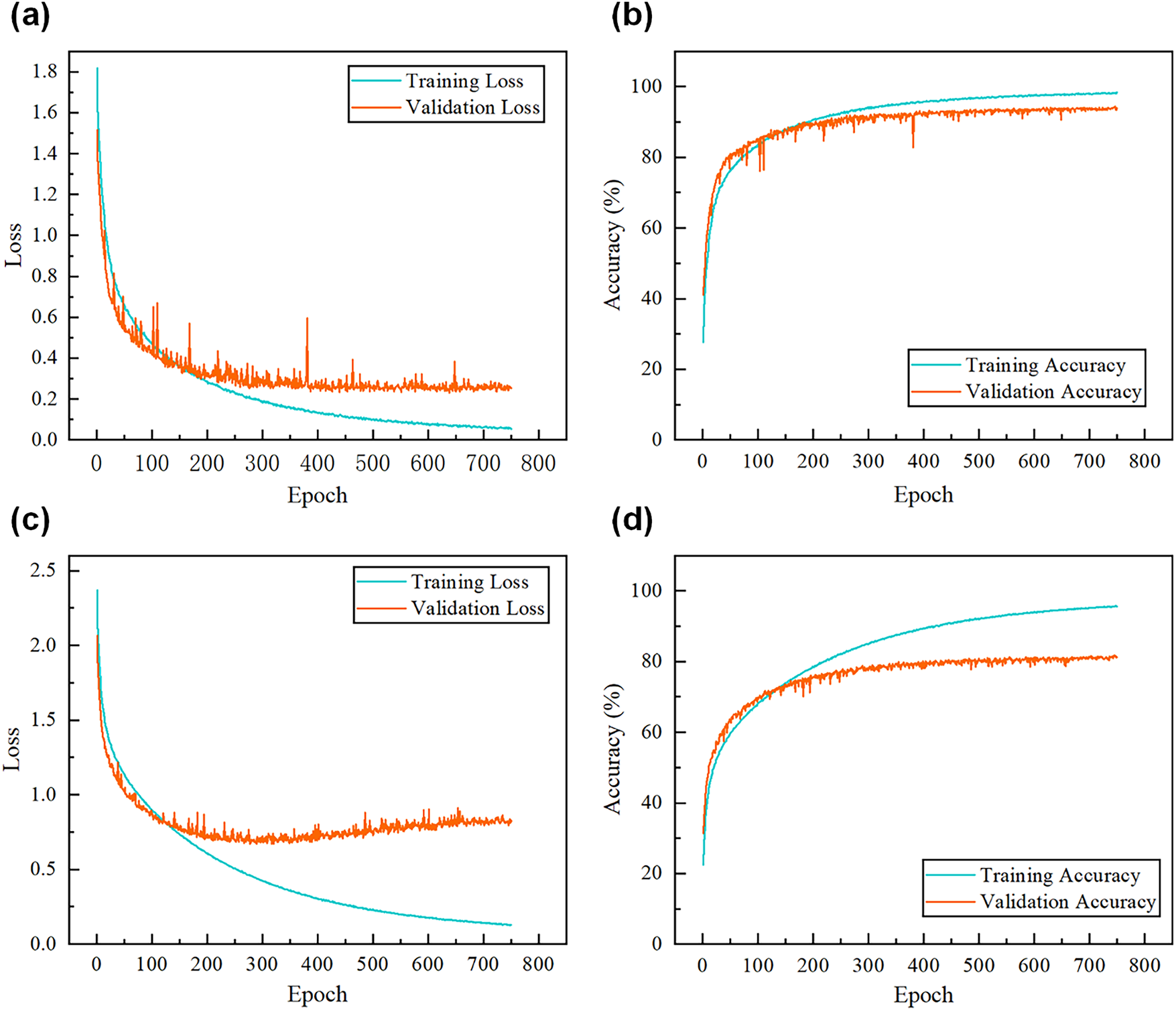

Fig. 2 presents the learning curves obtained for the HAART and CoST datasets. The curves indicate that as the number of training iterations increased, the validation loss decreased while the validation accuracy improved. However, both metrics tended to stabilize after approximately 400 epochs. Training the model for 750 epochs, rather than stopping at 400, produced better overall performance, suggesting that extended training contributes to improved accuracy and stability. This finding is consistent with previous work [32], in which extending training to 750 epochs also resulted in superior outcomes compared with 300 epochs.

Figure 2: (a) Loss curves for the HAART dataset from fold 6, (b) accuracy curves for the HAART dataset from fold 6, (c) loss curves for CoST dataset curve from fold 2, (d) accuracy curves for CoST dataset curve from fold 2.

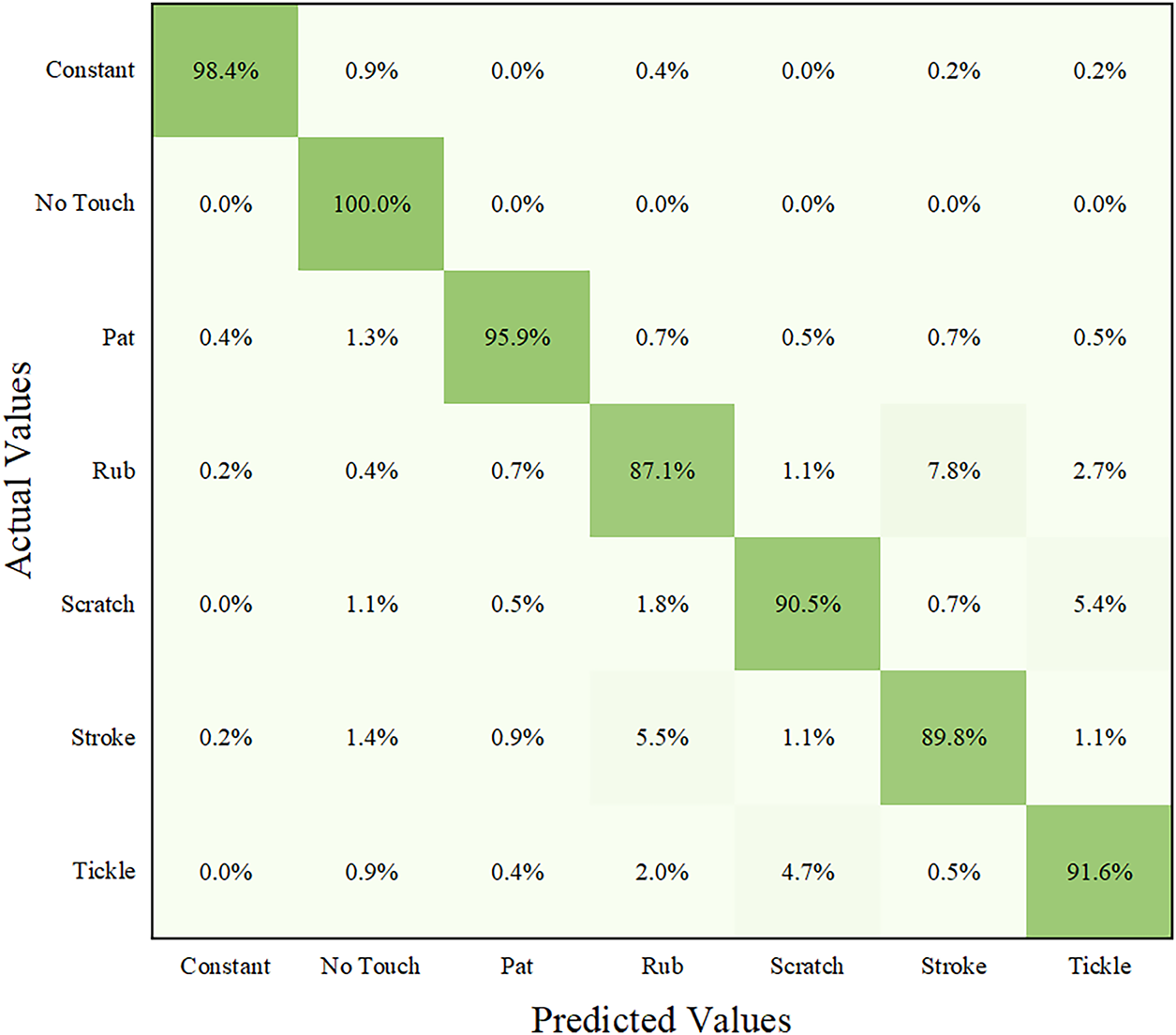

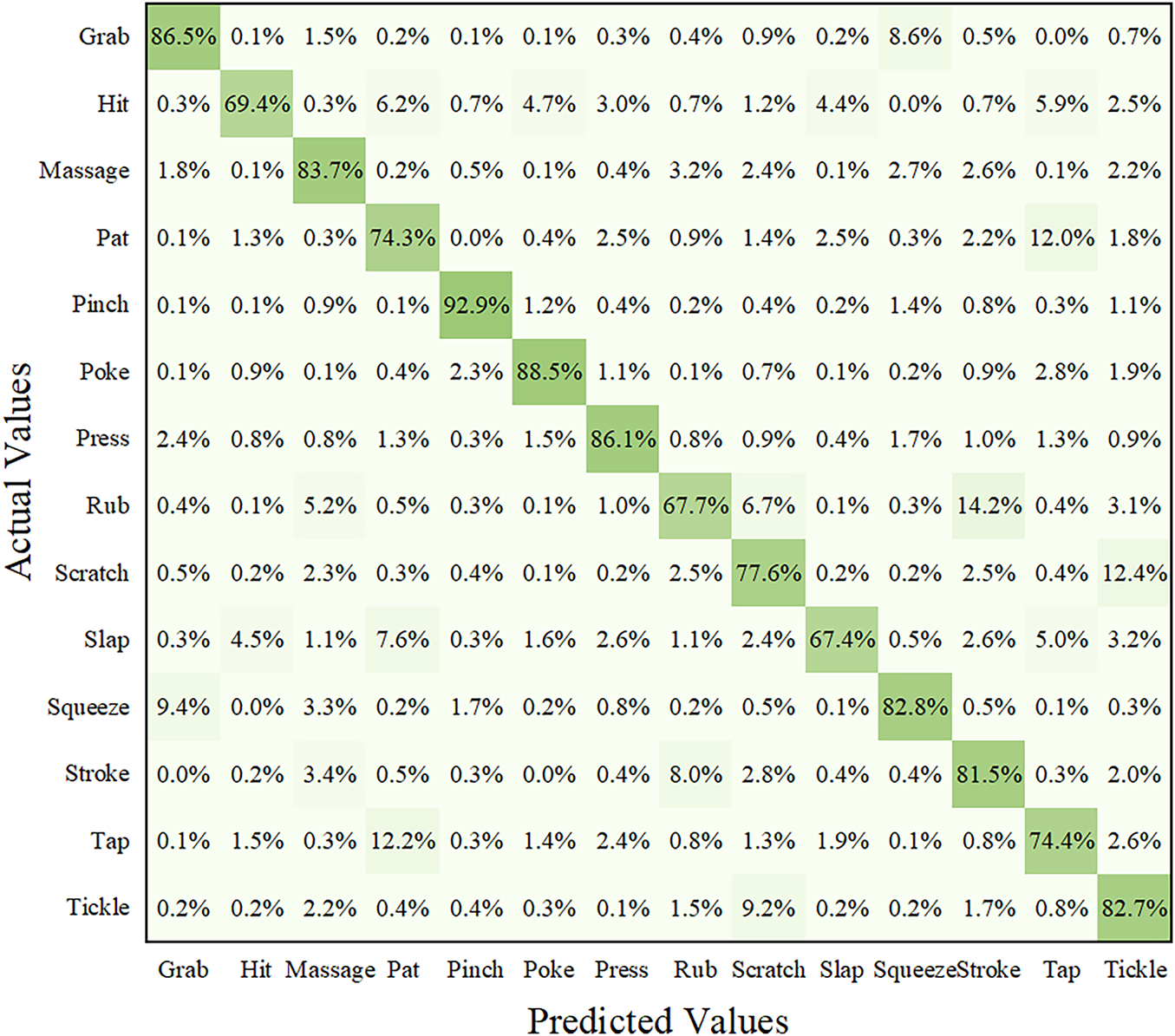

Moreover, the model achieved higher accuracy on the hold-out test set compared with the average accuracy obtained during 10-fold cross-validation. This result indicates that the proposed framework performs effectively in affective tactile gesture recognition and exhibits robustness against overfitting. To provide a more detailed evaluation, confusion matrices were constructed to display the classification performance for each dataset. In these matrices, rows correspond to the actual touch gestures and columns correspond to the predicted gestures, with the diagonal elements representing the proportion of correctly classified samples for each gesture.

The confusion matrices for the HAART and CoST test sets are reported in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. Fig. 3 shows that the highest recognition rate in the HAART dataset was obtained for the “No Touch” gesture, achieving 100% accuracy. Raw signal examination shows that “No Touch” segments produce consistently low-intensity readings across all 100 channels, typically below a value of 10, resulting in a highly compact region in the feature space. This behavior makes “No Touch” data substantially easier to distinguish from active-gesture patterns, which display higher amplitude and greater spatiotemporal variation. As a result, the signals are highly consistent and clearly separable from other active gestures, making this class relatively straightforward for the model to learn and identify. When compared with models proposed in previous studies, the present approach demonstrates superior recognition accuracy across all gestures in the HAART dataset. Furthermore, the model most frequently misclassified “Rub” as “Stroke”, with a misclassification rate of 7.8%. This confusion is expected because both gestures involve continuous sliding contact across the surface, producing highly similar pressure distributions on the 100-channel tactile array. Their frequency content is dominated by low-frequency components with minimal high-frequency transitions, leading to similar temporal-spectral patterns. Fig. 4 indicates that the highest recognition performance was achieved for the “Pinch” gesture in the CoST dataset, reaching 92.9% accuracy. In contrast, the “Slap” gesture achieved a relatively low recognition rate of 67.4%. This discrepancy can be attributed to the intrinsic temporal-spectral characteristics of the “Slap” gesture. Unlike gestures such as “Pinch”, which produce stable, low-frequency pressure patterns, “Slap” generates a brief, high-intensity impulse with rapid spectral transitions and limited temporal consistency. Such transient, broadband events are inherently harder for the model to capture. In addition, the CoST dataset contains the fewest “Slap” samples compared with other categories, further reducing the model’s ability to generalize. Consequently, both the gesture’s impulsive spectral profile and its limited sample availability contribute to its lower recognition accuracy.

Figure 3: Confusion matrix on the HAART dataset.

Figure 4: Confusion matrix on the CoST dataset.

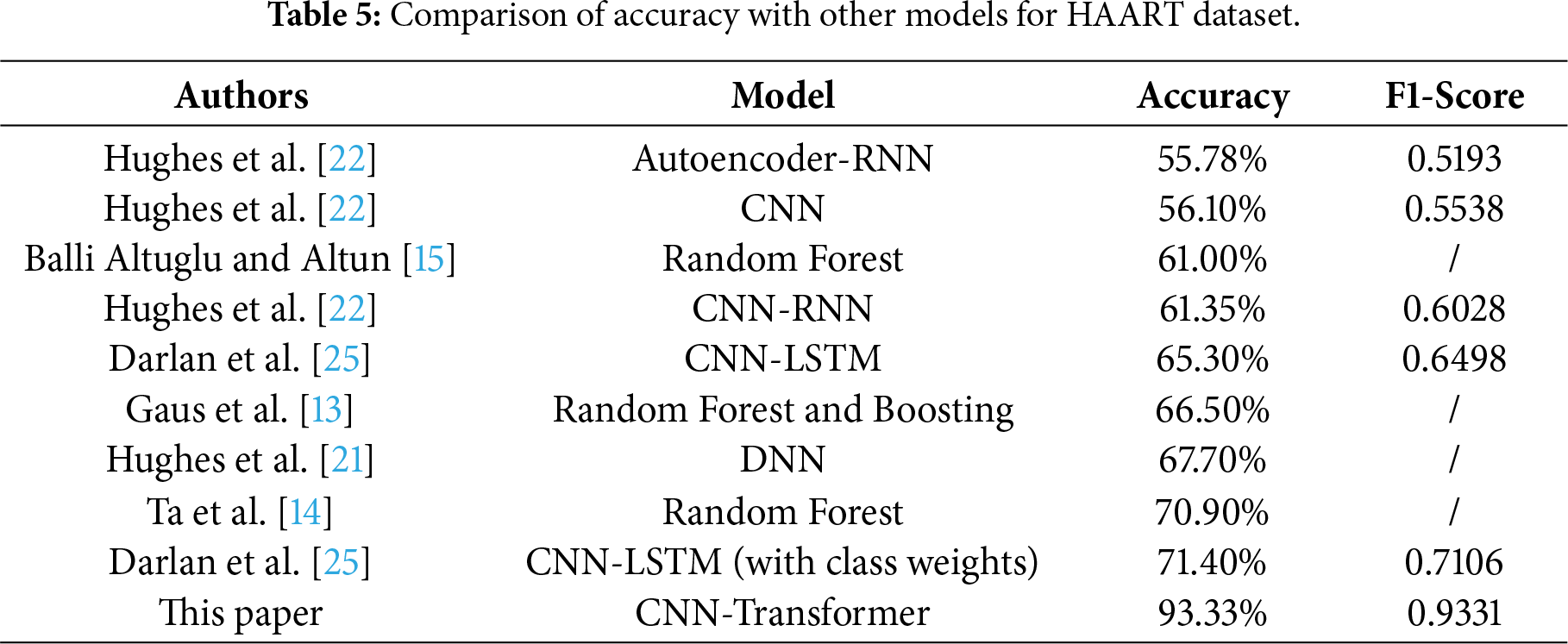

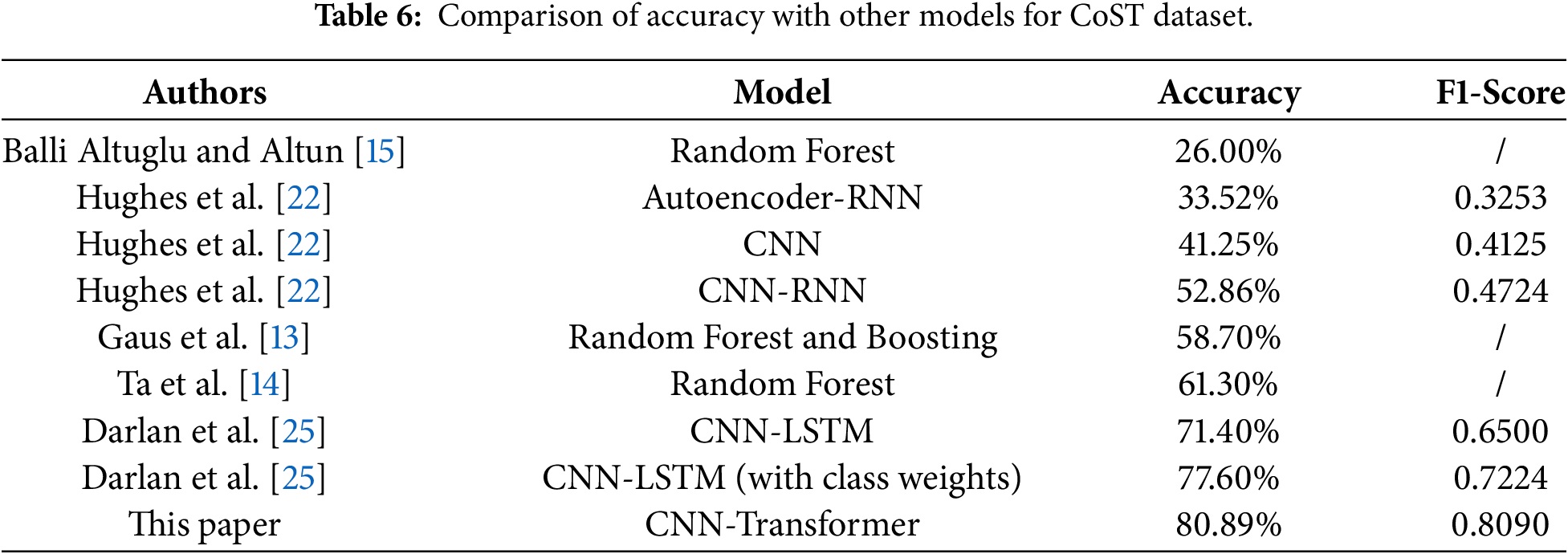

The experimental results were further compared with previously reported touch recognition models using the same datasets to provide a comparative evaluation. It should be emphasized that these comparisons are intended as indicative benchmarks rather than absolute performance rankings, since different studies may rely on distinct methodologies, experimental protocols, feature representations, and classification strategies. In particular, our use of sliding-window segmentation increases the number of training samples and reduces temporal variability within each segment, which may offer an inherent advantage over earlier approaches that operate on full sequences or hand-crafted features. As summarized in Tables 5 and 6, the referenced literature includes commonly used sequence-modeling baselines such as CNN- and LSTM-based architectures.

Across both datasets, the proposed hybrid model achieved substantially higher accuracy than the CNN- and LSTM-based baselines. On the HAART dataset, our method attained an accuracy of 93.33% with an F1-score of 0.9331, outperforming the models developed by Darlan et al. [25], Ta et al. [14], and Hughes et al. [21]. On the CoST dataset, the proposed model achieved an accuracy of 80.89% with an F1-score of 0.8090, yielding clear improvements over the approaches of Darlan et al. [25], Ta et al. [14], and Gaus et al. [13]. These results highlight the effectiveness of integrating convolutional feature extraction with Transformer attention for long-sequence tactile biosignal recognition. In addition, the performance gap between the HAART and CoST datasets can be partly attributed to differences in sensor resolution and dataset characteristics. The higher spatial resolution and more structured contact patterns in HAART provide richer spatial information for convolutional feature extraction, whereas CoST involves lower-resolution inputs and more variable touch interactions, which likely increase intra-class variability and class overlap. Moreover, CoST exhibits a more imbalanced class distribution than HAART, which may further contribute to the lower F1-score despite reasonably high overall accuracy. Taken together, these factors suggest that CoST constitutes a more challenging recognition scenario, even though the proposed architecture remains effective on both datasets.

This study introduces a hybrid framework for affective tactile biosignal classification that integrates CNNs and Transformer architecture. The CNN component effectively extracts spatial information from high-dimensional data, while the multi-head attention mechanism in the Transformer encoder captures global temporal dependencies. The proposed model achieves robust performance in identifying affective tactile biosignals and is capable of handling datasets containing both consistent and variable gesture durations. In contrast to existing hybrid models that were primarily designed for static spatial data, the present approach is specifically tailored to sequential biosignals through the incorporation of temporal windowing, thereby enabling real-time gesture prediction. Experimental evaluations confirm the effectiveness of the hybrid model, with assessments on the HAART and CoST datasets demonstrating notable improvements over previously reported methods. In the HAART dataset, the model achieved 100% accuracy for the “No Touch” gesture, a result consistent with the minimal and stable sensor activation associated with this class. For the CoST dataset, the recognition rate increased by 3.29% compared with previous research [25]. Overall, the CNN–Transformer framework achieved substantial improvements in recognizing affective tactile biosignals across both benchmark datasets.

Future research may incorporate additional factors that influence affective tactile biosignal recognition. For example, the impact of different covering materials in wearable devices should be further examined, as material properties can strongly affect signal transmission quality and the robustness of tactile sensing. In the design of interaction mechanisms for wearable systems, it is therefore essential to carefully consider material selection to ensure reliable and consistent biosignal acquisition. Multimodal expansion also represents a promising direction. Integrating pressure-based tactile signals with additional physiological inputs such as electromyography (EMG) may provide richer complementary information by combining surface contact patterns with underlying muscle activity. This type of fusion has the potential to improve robustness, reduce gesture ambiguity, and enhance generalization in real-world interaction scenarios. Overall, the proposed CNN–Transformer hybrid model provides a strong foundation for advancing tactile biosignal recognition and offers multiple avenues for further development in future work.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Chang Xu and Xianbo Yin; methodology, Chang Xu and Xianbo Yin; software, Chang Xu and Zhiyong Zhou; validation, Chang Xu, Xianbo Yin and Bomin Liu; formal analysis, Chang Xu; investigation, Chang Xu; resources, Chang Xu and Zhiyong Zhou; data curation, Chang Xu; writing—original draft preparation, Chang Xu; writing—review and editing, Chang Xu, Zhiyong Zhou, Xianbo Yin and Bomin Liu; visualization, Chang Xu; supervision, Chang Xu, Bomin Liu and Zhiyong Zhou; project administration, Chang Xu and Zhiyong Zhou; funding acquisition, Chang Xu. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the HAART dataset repository at [https://www.cs.ubc.ca/labs/spin/data], and in the CoST dataset repository at [https://data.4tu.nl/articles/_/12696869/1]. The implementation code will be made publicly available at [https://github.com/Chang-X1994/haptic-recognition—CNN-transformer] upon publication to support reproducibility and further research.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Sitaramgupta VSNV, Sakorikar T, Pandya HJ. An MEMS-based force sensor: packaging and proprioceptive force recognition through vibro-haptic feedback for catheters. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2022;71(5):4001911. doi:10.1109/TIM.2022.3141168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Núñez CG, Navaraj WT, Polat EO, Dahiya R. Energy-autonomous, flexible, and transparent tactile skin. Adv Funct Mater. 2017;27(18):1606287. doi:10.1002/adfm.201606287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang F, Qian Z, Lin Y, Zhang W. Design and rapid construction of a cost-effective virtual haptic device. IEEE/ASME Trans Mechatron. 2021;26(1):66–77. doi:10.1109/TMECH.2020.3001205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Guo ZH, Wang HL, Shao J, Shao Y, Jia L, Li L, et al. Bioinspired soft electroreceptors for artificial precontact somatosensation. Sci Adv. 2022;8(21):eabo5201. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abo5201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Xu C, Zhang H, Zhou Z, Jiang Y. AI-based affective interaction system in emotion-aware social robots. Int J Patt Recogn Artif Intell. 2025;39(14):2559016. doi:10.1142/s0218001425590165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yuan C, Tony A, Yin R, Wang K, Zhang W. Tactile and thermal sensors built from carbon-polymer nanocomposites—a critical review. Sensors. 2021;21(4):1234. doi:10.3390/s21041234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Joolee JB, Uddin MA, Jeon S. Deep multi-model fusion network based real object tactile understanding from haptic data. Appl Intell. 2022;52(14):16605–20. doi:10.1007/s10489-022-03181-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lin Y. A natural contact sensor paradigm for nonintrusive and real-time sensing of biosignals in human-machine interactions. IEEE Sens J. 2011;11(3):522–9. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2010.2041773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Khattak AS, Bin Mohd Zain A, Hassan RB, Nazar F, Haris M, Ahmed BA. Hand gesture recognition with deep residual network using Semg signal. Biomed Tech. 2024;69(3):275–91. doi:10.1515/bmt-2023-0208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Cooney MD, Nishio S, Ishiguro H. Recognizing affection for a touch-based interaction with a humanoid robot. In: Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems; 2012 Oct 7–12; Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal. doi:10.1109/IROS.2012.6385956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jung MM, Cang XL, Poel M, MacLean KE. Touch challenge ′15: recognizing social touch gestures. In: Proceedings of the 2015 ACM on International Conference on Multimodal Interaction; 2015 Nov 9–13; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1145/2818346.2829993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Jung MM, Poppe R, Poel M, Heylen DKJ. Touching the void—introducing CoST: corpus of social touch. In: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction; 2014 Nov 12–16; Istanbul, Turkey. doi:10.1145/2663204.2663242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gaus YFA, Olugbade T, Jan A, Qin R, Liu J, Zhang F, et al. Social touch gesture recognition using random forest and boosting on distinct feature sets. In: Proceedings of the 2015 ACM on International Conference on Multimodal Interaction; 2015 Nov 9–13; Seattle, WA: USA. doi:10.1145/2818346.2830599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ta VC, Johal W, Portaz M, Castelli E, Vaufreydaz D. The Grenoble system for the social touch challenge at ICMI 2015. In: Proceedings of the 2015 ACM on International Conference on Multimodal Interaction; 2015 Nov 9–13; Seattle, WA, USA. doi:10.1145/2818346.2830598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Balli Altuglu T, Altun K. Recognizing touch gestures for social human-robot interaction. In: Proceedings of the 2015 ACM on International Conference on Multimodal Interaction; 2015 Nov 9–13; Seattle, Washington, USA. doi:10.1145/2818346.2830600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Raffel C, Shazeer N, Roberts A, Lee K, Narang S, Matena M, et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J Mach Learn Res. 2019;21:1–67. [Google Scholar]

17. Sun S, Zhang B, Xie L, Zhang Y. An unsupervised deep domain adaptation approach for robust speech recognition. Neurocomputing. 2017;257(6):79–87. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2016.11.063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kucherenko T, Hasegawa D, Kaneko N, Henter GE, Kjellström H. Moving fast and slow: analysis of representations and post-processing in speech-driven automatic gesture generation. Int J Hum. 2021;37(14):1300–16. doi:10.1080/10447318.2021.1883883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chen Y, Liu L, Phonevilay V, Gu K, Xia R, Xie J, et al. Image super-resolution reconstruction based on feature map attention mechanism. Appl Intell. 2021;51(7):4367–80. doi:10.1007/s10489-020-02116-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Fu M, Wu FX. QLABGrad: a hyperparameter-free and convergence-guaranteed scheme for deep learning. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2024;38(11):12072–81. doi:10.1609/aaai.v38i11.29095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hughes D, Farrow N, Profita H, Correll N. Detecting and identifying tactile gestures using deep autoencoders, geometric moments and gesture level features. In: Proceedings of the 2015 ACM on International Conference on Multimodal Interaction; 2015 Nov 9–13; Seattle, Washington, USA. doi:10.1145/2818346.2830601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hughes D, Krauthammer A, Correll N. Recognizing social touch gestures using recurrent and convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); 2017 May 29–Jun 3; Singapore. doi:10.1109/ICRA.2017.7989267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhou N, Du J. Recognition of social touch gestures using 3D convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 7th Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition (CCPR 2016); 2016 Nov 5–7; Chengdu, China. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-3002-4_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Albawi S, Bayat O, Al-Azawi S, Ucan ON. Social touch gesture recognition using convolutional neural network. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2018;2018:6973103. doi:10.1155/2018/6973103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Darlan D, Ajani OS, Parque V, Mallipeddi R. Recognizing social touch gestures using optimized class-weighted CNN-LSTM networks. In: Proceedings of the 2023 32nd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN); 2023 Aug 28–31; Busan, Republic of Korea. doi:10.1109/RO-MAN57019.2023.10309595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mellouk W, Handouzi W. CNN-LSTM for automatic emotion recognition using contactless photoplythesmographic signals. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2023;85(28):104907. doi:10.1016/j.bspc.2023.104907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS); 2017 Dec 4–9; Long Beach, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

28. Tang X, Huang J, Lin Y, Dang T, Cheng J. Speech Emotion Recognition via CNN-Transformer and multidimensional attention mechanism. Speech Commun. 2025;171(4):103242. doi:10.1016/j.specom.2025.103242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Karatay B, Beştepe D, Sailunaz K, Özyer T, Alhajj R. CNN-Transformer based emotion classification from facial expressions and body gestures. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83(8):23129–71. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-16342-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Li F, Zhang D. Transformer-driven affective state recognition from wearable physiological data in everyday contexts. Sensors. 2025;25(3):761. doi:10.3390/s25030761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Qiu H, Chen Z, Chen Y, Yang C, Wu S, Li F, et al. A real-time hand gesture recognition system for low-latency HMI via transient HD-SEMG and in-sensor computing. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2024;28(9):5156–67. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2024.3417236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Andayani F, Theng LB, Tsun MT, Chua C. Hybrid LSTM-transformer model for emotion recognition from speech audio files. IEEE Access. 2022;10:36018–27. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3163856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools