Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Recent Advances in Deep-Learning Side-Channel Attacks on AES Implementations

1 School of Physics and Electronic Science, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan, 411201, China

2 School of Computer Science and Engineering, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan, 411201, China

* Corresponding Author: Huanyu Wang. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 3 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074473

Received 11 October 2025; Accepted 18 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Internet of Things (IoTs) devices are bringing about a revolutionary change our society by enabling connectivity regardless of time and location. However, The extensive deployment of these devices also makes them attractive victims for the malicious actions of adversaries. Within the spectrum of existing threats, Side-Channel Attacks (SCAs) have established themselves as an effective way to compromise cryptographic implementations. These attacks exploit unintended, unintended physical leakage that occurs during the cryptographic execution of devices, bypassing the theoretical strength of the crypto design. In recent times, the advancement of deep learning has provided SCAs with a powerful ally. Well-trained deep-learning models demonstrate an exceptional capacity to identify correlations between side-channel measurements and sensitive data, thereby significantly enhancing such attacks. To further understand the security threats posed by deep-learning SCAs and to aid in formulating robust countermeasures in the future, this paper undertakes an exhaustive investigation of leading-edge SCAs targeting Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) implementations. The study specifically focuses on attacks that exploit power consumption and electromagnetic (EM) emissions as primary leakage sources, systematically evaluating the extent to which diverse deep learning techniques enhance SCAs across multiple critical dimensions. These dimensions include: (i) the characteristics of publicly available datasets derived from various hardware and software platforms; (ii) the formalization of leakage models tailored to different attack scenarios; (iii) the architectural suitability and performance of state-of-the-art deep learning models. Furthermore, the survey provides a systematic synthesis of current research findings, identifies significant unresolved issues in the existing literature and suggests promising directions for future work, including cross-device attack transferability and the impact of quantum-classical hybrid computing on side-channel security.Keywords

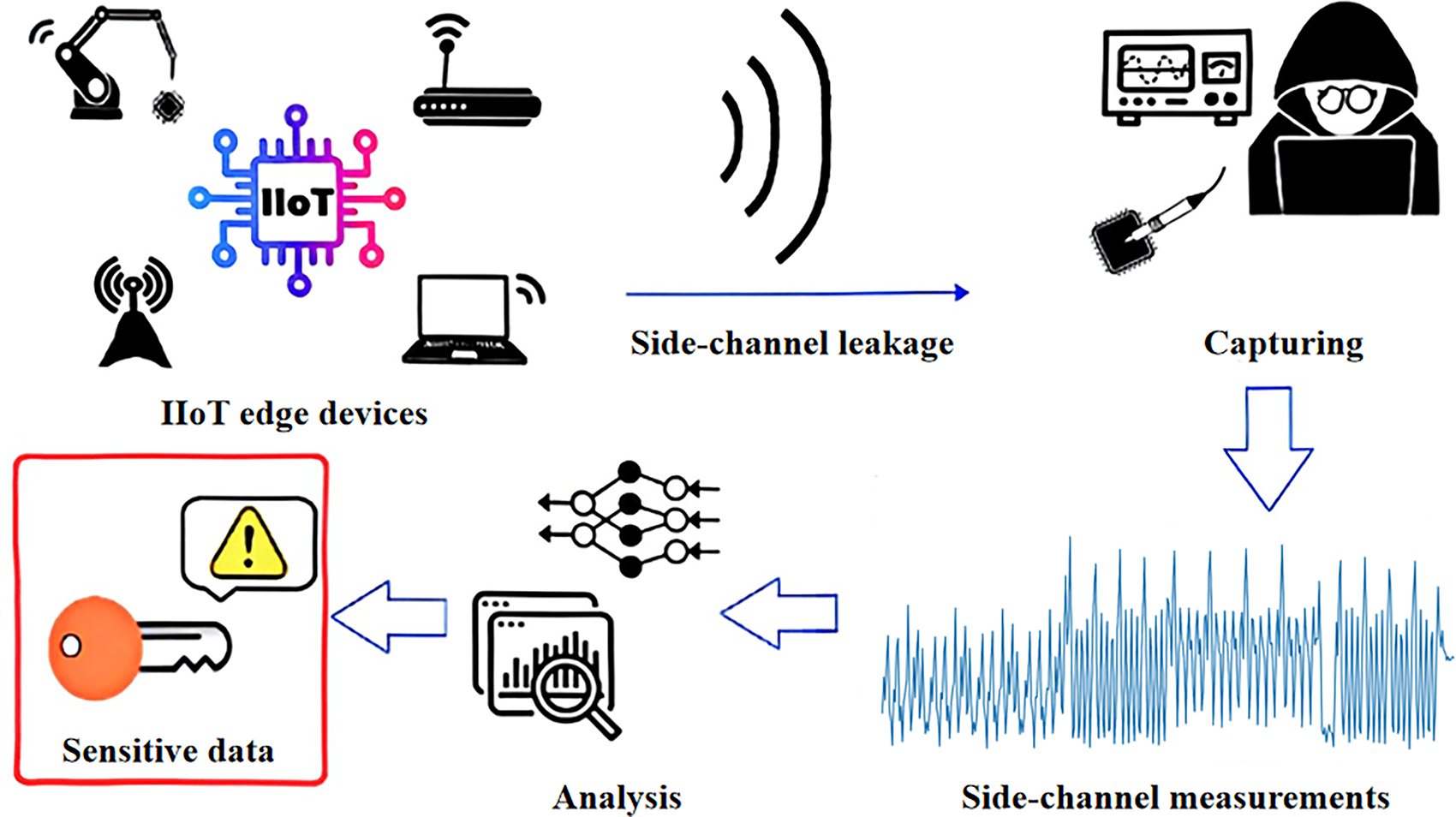

The Internet of Things (IoT) is bringing about a revolution in society with advanced connectivity and real-time analytics, turning sensor data into immediate and actionable insights for better operations. Real-time analytics is key to preventing downtime and managing risks, but integrating it with IoT involves challenges such as securing the system. However, since numerous embedded edge devices commonly execute encryption and decryption operations on-site, significant security concerns are triggered by Side-Channel Attacks(SCAs), as shown in Fig. 1. According to the inherent imperfections of the physical implementations, there might be some physical leakage, such as power consumption and electromagnetic (EM) emissions, and such leakages could disclose sensitive data in IoT embedded devices. Adversaries can exploit these non-intentional physical leakages to analyze and extract the secret. These are called SCAs. The secret key leaking from a cryptographic module could cause information security to be entirely compromised across IoT systems [1].

Figure 1: Illustration of how SCAs extract secrets from physical devices. It depicts the process where attackers capture side-channel leakage from devices, analyze the measurements via techniques like deep learning, and ultimately extract sensitive data

Over the past two decades, diverse side channels have been exploited across various applications. These include compromising cryptographic implementations [2,3], reverse-engineering neural network architectures [4,5], stealing intellectual property [6], monitoring user-browser information [7,8], predicting the output generated by random number generators [9], tracking how code executes [10,11] and intercepting victims’ password from the keystroke [12,13] and fingerprints [14].

Different side channels can be exploited in various practical scenarios. Consider far field EM SCA [15–17] (also called screaming channel attacks), which pose a security threat due to their remote execution capability. These attacks remain effective even when the target device operates in a seemingly secure office environment without direct physical access. Adversaries could position themselves in a neighboring office and capture the EM traces using specialized radio equipment. By analyzing these captured traces, the attacker may achieve various malicious objectives. In another scenario, the adversary might not be interested in the sensitive data itself but rather in the behavior of the victim device. In this case, the attacker could track the execution path of the victim’s code by analyzing the traces of specific blocks or even library functions used by the device [10].

However, the attack scenarios can vary significantly depending on the type of side-channel being exploited. For instance, when power consumption is used as the side channel, the attacker generally requires physical access to the target device to measure power consumption during its operation. A practical example of this could involve an adversary legally acquiring a car, which grants them access to the car’s digital key. Once in possession of the key, the adversary could capture power traces while using the key to communicate with the car. By analyzing these traces, the cryptographic information shared between the car and the key could be extracted. This would enable the adversary to create unauthorized copies of the car key, which could allow them to illegally replicate and sell backup car keys to customers, without the car company’s authorization. This would undoubtedly cause significant damage to the company’s profits and reputation.

Presently, there exist six commonly utilized side channels within both academia and industry, as shown below.

• Power consumption [18], involves exploiting the inherent variations in power consumption exhibited by logic circuits during different operations and with varying data inputs.

• Time consumption [19], exploiting differences that depend on the data in the execution time.

• Optical leakage [20], involves exploiting differences of optical properties of silicon due to changes in voltage or current.

• Acoustic leakage [21], which entails exploiting the piezoelectric characteristics of ceramic capacitors, functions in power supply filtering and the conversion of AC to DC.

• Near field EM emissions [22], resulting from the rapid change of current in the logic components. These emissions exhibit high-frequency components and are typically identified by a close-proximity probe placed in the immediate vicinity of the chip.

• Far field EM emissions (screaming channels) [15], resulting from the coupling that occurs between distinct components on mixed-signal chips. These far-field EM emissions are detectable at a certain distance away from the target device. Thus, attackers do not have to physically approach the victim.

This paper focuses on two side channels: power consumption and EM emissions.

In recent years, Deep Learning (DL) techniques have become extremely prevalent owing to their remarkable ability to find complex patterns and make accurate predictions or classifications from large volumes of data. This popularity is attributed to their success in multiple fields like computer vision [23], natural language processing [24], edge computing [25], and resource management [26]. However, like any great scientific discovery, deep-learning techniques have the potential to be used for malicious purposes. For example, in most Deep-Learning Side-Channel Attacks (DLSCAs), attackers start by building a deep learning model as a leakage profile, aiming to establish a relationship between sensitive data and side-channel traces collected from a copy of the target device—a replica referred to as the profiling device, over which the adversaries have complete control. Afterwards, the profiled model can be utilized to categorize the traces collected from the target device, enabling adversaries to extract sensitive data. Typically, a thoroughly trained deep-learning model is capable of enhancing attack efficiency by several orders of magnitude, which is substantially greater than the performance of traditional signal processing methods [16], such as Correlation Power Analysis (CPA) [27] and Template Attacks (TA) [28]. Furthermore, various deep-learning models have demonstrated their capability in assisting adversaries to bypass diverse countermeasures in side-channel attacks. For example, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have proven to be effective in addressing misaligned traces and overcoming countermeasures based on jitter [29].

As deep-learning based SCAs continue to grow in threat and significance, the foremost concern revolves around effectively mitigating these attacks. It is essential to comprehend the capacities and restrictions of deep-learning based side-channel attacks to develop robust defensive measures in the future. Therefore, comprehensively reviewing literature of DLSCAs is crucial. Although there are certain reviews within the realm of side-channel attacks, their coverage remains inadequate. Reference [30] concludes the conventional SCAs approaches, such as Differential Power Analysis (DPA) [18], template attacks, correlation power analysis, Mutual Information Analysis (MIA) [31], and Test Vector Leakage Assessment (TVLA) [32]. Afterwards, Hettwer et al. review the attacks based on Machine Learning (ML) techniques in [33], for instance the Support Vector Machine (SVM) [34], Decision Trees (DTs) [35] and random forest [36], as presented in the 2020 JCEN journal. In 2023, Picek et al. [37] provided a systematically review of DLSCAs in ACM Computing Surveys, across a broad range of applications and side channels. Reference [38] reviews the current research status of EM-SCA in cryptographic attack scenarios, with a focus on three core dimensions: cryptographic algorithms vulnerable to cryptography, designs and device implementations resistant to attack, and promising emerging EM-SCA attack paradigms. Notably, the review does not place emphasis on the role and application impact of DL techniques in the field of SCA. Reference [39] focuses on attack analysis in SCA based on deep learning techniques, wherein it conducts systematic evaluation and comparative analysis of diverse deep learning-enhanced SCA schemes. Specifically, the performance of these schemes is assessed and compared against the ANSSI SCA database (ASCAD) as the benchmark testbed. Reference [40] provides a comprehensive review of recent advances in attack techniques targeting the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). Specifically, the reviewed attack methods are systematically categorized into four distinct research domains, namely SCAs, fault injection attacks (FIAs), attacks based on machine learning and artificial intelligence (ML/AI), and quantum computing-enabled threats. Reference [41] investigates SCAs targeting implementations of Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) algorithms, and categorizes these attacks from an adversarial perspective to identify the most vulnerable components in the implementations of such algorithms. Building on these foundations, we take a step further by presenting a comprehensive summary of cutting-edge DLSCAs on AES [42] with a particular focus on power analysis and EM analysis across diverse attack scenarios, since AES is the symmetric cryptographic algorithm most widely employed. Our analysis examines these attacks from multiple perspectives, including deep-learning model architectures, hyperparameter optimization, and differences between hardware and software implementations. We need to first stress out that some approaches and works might fit into more than one categories in our survey.

Contributions and Paper Structure

We provide a comprehensive review of how deep-learning techniques can be used in power and EM based analysis to compromise different implementations of AES. AES stands as the most extensively employed symmetric cryptographic algorithm across IoT devices due to its pivotal role in maintaining a specific degree of information security.

For every attack vector, we conduct a systematic review on methodologies presented in the literature and make comparisons across various criteria, including the quantity of measurements needed for the attack, target physical implementations, leakage models, and countermeasures applied. Our primary contribution lies in identifying the DL methods and corresponding parameters that are suitable for specific attack scenarios.

The paper’s structure is outlined below. Section 2 offers a thorough overview of AES, DLSCAs, and various DL approaches. In Section 3, we review research studies on DLSCAs that utilize power consumption as the side channel. In the last, Section 4 exploits open questions related to DLSCAs on AES. Sections 5 and 6 provide a summary of the paper and discuss future works.

This section begins with a review of the AES. Following that, it introduces the concepts of deep learning and explains the role that deep learning plays in enabling side-channel attacks. In addition, it covers various leakage models and commonly utilized evaluation metrics for SCAs.

2.1 Advanced Encryption Standard

AES, a symmetric encryption algorithm, was standardized by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in 2001. It is often the preferred choice for implementing cryptographic modules in IoT embedded devices for applications that requiring secure communications and data encryption. This preference is primarily due to the fact that AES is known for its speed, efficiency, and wide support within the industry. In these cases, AES is implemented with different key sizes with

Using AES-128 as an example, except for the final round, each round consists of four repetitive steps: non-linear substitution (SubBytes), transposition of rows (ShiftRows), mixing of columns (MixColumns), and round key addition (AddRoundKey). The final encryption round is not included the MixColumns instruction. In the AES algorithm, the SubBytes operation involves the replacement of an 8-bit symbol with another symbol, and this substitution relies on a lookup table known as the SBox. AES-128 operations follow matrices in a column-major order of 4

A practical SCA aims to obtain secrets, such as the encryption key used in AES implementations, where the collection of all potential keys is denoted by

Through machine learning techniques, systems can extract features from the provided data, allowing them to acquire their own knowledge. As a subset of machine learning, deep learning makes use of deep neural networks as models. While traditional machine learning models usually work on human-engineered features, deep-learning approaches aim to use the deep neural networks for learning features directly from raw data ahead of the task. DL techniques have become the privileged tool for dealing with the many tasks such as classification and prediction. SCAs leveraging deep learning demonstrate strong potential, with performance varying significantly across architectures

Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) ranks among the fundamental neural network types, comprising three components: one input layer, one or more hidden layer(s), and one final output layer. In each layer, except for the output layer, multiple bias neurons are included, and each neuron maintains a full connection to the subsequen layer. Usually a back-propagation training algorithm is applied to train MLPs, in which two steps are repeated on the training sets: forward pass and backward pass. The model assesses how much the true output differs from the classified one, which is called the network output loss. During the backward pass stage, the weights of neurons are updated by calculating the gradients to reduce the loss.

CNN is a category of neural network that employs shape information by employing convolutional layers [43]. Typically, a CNN model is constructed with a series of convolutional modules, where each module is made up of a convolutional layer with a pooling layer coming after it. Following the final module, there are one or more dense layers. The ultimate dense layer incorporates one neuron per class, employing a softmax activation function for classification. One convolutional layer employs a defined number of convolution filters on the raw data of side-channel traces to extract and learn higher-level features, which the model subsequently utilizes for classification. The output of the convolution operation is often referred to as a feature map. A pooling layer serves to reduce the dimensionality of feature maps extracted by convolutional layers through downsampling. In the context of the side-channel attack, CNN models are usually employed to overcome countermeasures, to break masked AES and, to handle noise in traces [29].

Transformer Network (TN) is a neural network architecture that captures long-range dependencies via self-attention mechanisms, distinguishing it from local-feature-focused models like CNNs [44]. Typically, a Transformer model for side-channel tasks consists of stacked encoder layers, where each encoder layer comprises a multi-head self-attention sublayer and a feedforward neural network (FFN) sublayer. Following the encoder stack, there are one or more dense layers; the final dense layer integrates task-specific outputs, employing a softmax activation function for key-related classification in side-channel attacks. The multi-head self-attention sublayer computes relevance weights between all positions in side-channel trace sequences, enabling the model to focus on leakage-correlated segments across the entire trace length. The FFN sublayer then transforms the attention-augmented features to enhance their discriminative power. In the context of side-channel attacks, Transformer can readily capture dependencies between distant PoIs, making them a choice for countering cryptographic implementations protected by measures like masking [45].

A Graph Neural Network (GNN) [46] is a type of neural network used for graph-related deep learning, comprising three core components: an input layer, one or more message-passing hidden layers, and an output layer. In hidden layers, each node aggregates neighbor features via predefined functions while retaining its own to preserve node characteristics. Typically, GNNs are optimized via gradient-based training with two iterative steps on training data: forward and backward propagation. In backward propagation, parameter gradients are computed to update parameters iteratively, minimizing loss and enhancing GNN’s ability to capture graph correlations. Notably, GNNs are emerging as a promising option for enhancing the accuracy and effectiveness of SCA detection models, a advantage rooted in their demonstrated efficacy in capturing relational information inherent to graph-structured data [47].

An autoencoder (AE) [48] converts the inputs to an efficient internal representation and then generates the output that is very similar to the input. Thus, In an autoencoder, the output layer’s neuron count generally matches the number of inputs. An autoencoder is typically made up of two parts: an encoder and a decoder. The encoder part converts the inputs to an internal representation, and the decoder converts the obtained internal representation to the output. One way to use the autoencoder in SCA scenarios is to denoise the side-channel trace in side-channel measurements [49].

Attention Mechanism and Multi-Scale Convolutional Neural Network (AMCNNet) [50] is a specialized neural network architecture designed for SCA, which enhances feature extraction from multi-dimensional trace data by fusing convolutional layers with attention mechanisms. Typically, an AMCNNet model is composed of a sequence of attention-convolution modules, where each module consists of a multi-channel convolutional layer followed by a channel-wise attention sublayer.The multi-channel convolutional layer applies task-specific filters to raw side-channel traces across multiple data channels, capturing both local temporal features and cross-channel correlations. The channel-wise attention sublayer then assigns adaptive weights to different feature channels, emphasizing leakage-relevant channels while suppressing noise-interfered ones.

2.3 Deep Learning Side-Channel Attack

Side-channel attacks are commonly classified into two categories: non-profiled and profiled.

Non-profiled attacks seek to directly compromise the implementations of cryptography, exemplified by techniques including DPA [18] or CPA [27].

Profiled attacks begin by learning a leakage profile that establishes a connection between the captured side-channel measurements and the cryptographic algorithm’s sensitive intermediate value that is dependent on the key. This learned profile is then utilized to carry out the attack. Profiled attacks generally demonstrate superior efficiency compared to non-profiled attacks when subjected to identical attack conditions. In some specific scenarios, the attack efficiency of profiled attacks can even be several orders of magnitude higher. Nevertheless, it is essential to highlight that setting up profiled attacks generally involves more preparation than non-profiled attacks. In order to understand the leakage profile of the device across all potential values of the sensitive intermediate state, adversaries are required to have full control over one or more copies of the victim device, called profiling device(s), to capture an extensive number of side-channel traces and associated data to construct the leakage profile. Template attacks [28], as an example, utilize traces obtained from the profiling device to generate a set of probability distributions. These distributions are then employed to characterize traces based on the relevant key-dependent intermediate value. This allows the attacker to compare the traces obtained from the targeted device against the templates, facilitating the most probable key used in the cryptographic algorithm [51].

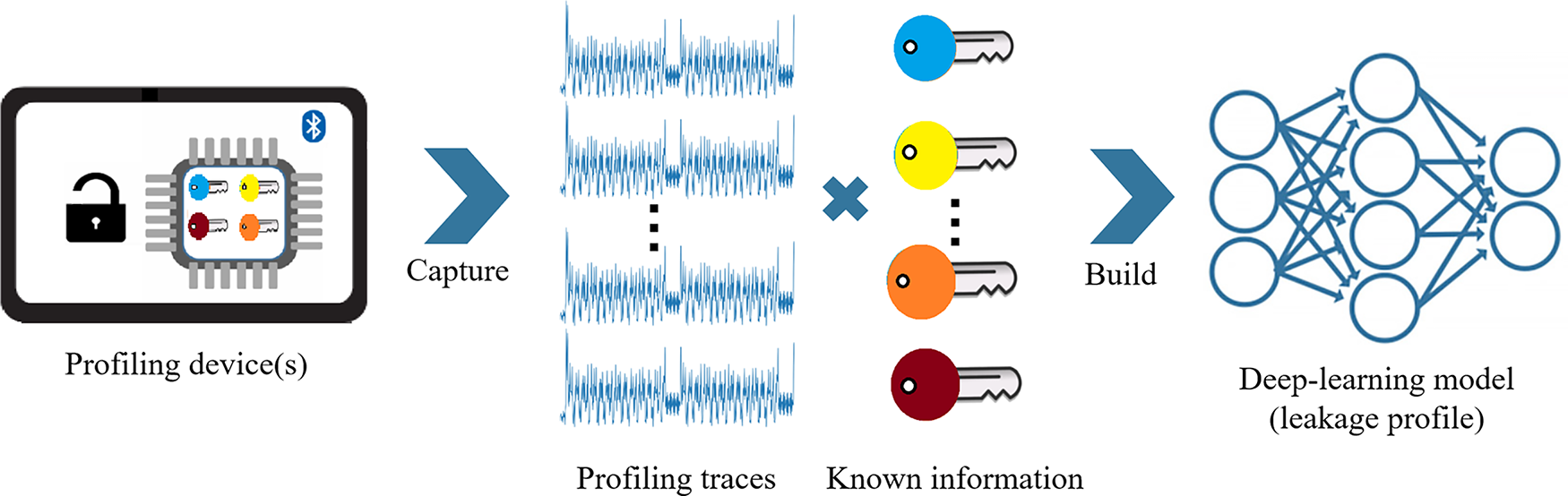

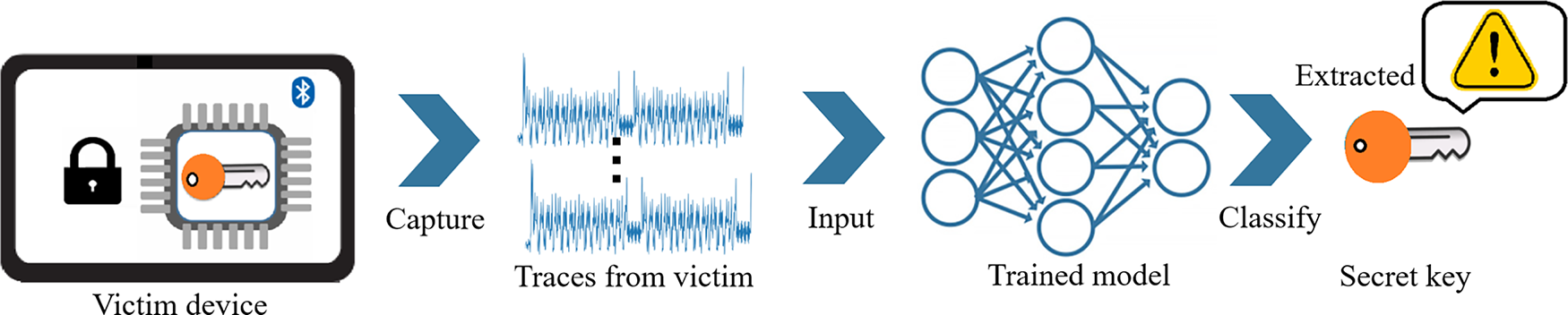

Barring a small number of exceptions, [52], deep learning techniques are frequently employed for side-channel attacks in profiled scenarios in most instances [29,53–56]. Typically, deep-learning side-channel attacks involve the following two steps (as shown in Figs. 2 and 3):

Figure 2: The overview of the profiling stage in DLSCAs on implementations of AES. It illustrates the process: capture side-channel profiling traces from a device with keys, then build a DL model to learn the leakage profile for subsequent attacks

Figure 3: The overview of the profiling stage in DLSCAs on implementations of AES, capture traces from a victim device, input them into a trained deep-learning model, and classify to extract the key

Profiling stage. During this stage, the common assumption is that adversaries possess full control over at least a single profiling device. The device resembles the victim device and programmed with the identical version of the cryptographic algorithm. Therefore, the attacker can capture numerous side-channel traces and gather related information from the profiling device(s) such as known plaintexts and keys.

We use

Attack stage. At this phase, we presume that the adversary can identify a means to capture a restricted set of side-channel traces from the victim device. In addition, the attacker can also record some known information

Notice that a well-optimized deep learning model is able to notably boost how efficient side-channel attacks are, often outperforming traditional signal processing methods by several orders of magnitude. For example, to compromise an AES implementation, the template attack used in [15] requires 52K traces from the target device at 1 m distance. Each trace amounts to an average of 500 measurements conducted under identical encryption conditions. When it comes to the deep-learning based method, reference [16] only requires 350 traces by using the CNN model to compromise the same AES implementation at 15 m distance, which is a five-order improvement in attack efficiency, even with a longer attack distance. However, this increased efficiency comes at a cost: DLSCAs typically demand substantially more preparation resources, such as computational power, training data, and time, compared to conventional techniques. For some cases the adversaries are unable to obtain the copy of the victim device as a profiling device to train the model, the challenge rises. Thus, a big concern for scenarios where deep learning offers clear advantages in SCAs is that adversaries have to obtain one or more profiling devices that resemble the victim device and can be programmed with the identical version of the cryptographic algorithm.

2.3.1 Attack Point and Leakage Model

In a side-channel attack, the attack point refers to a specific point or component in the cryptographic algorithm or its implementation that is targeted by the attacker to exploit side-channel information. This attack point is selected based on its potential to leak information related to the secret key or other sensitive data.

The choice of attack point is determined by various factors, such as the side channel type, the characteristics of the target device or algorithm, and the attacker’s knowledge and resources. In software implementations of AES (microcontrollers, microprocessors), frequently exploited points of attack include both the initial and final rounds’ SBox output. This is because in software implementations, the resulting 8-bit symbol from the SBox procedure is typically transferred from the memory to a data bus, which often leads to a higher power consumption compared to other processes. It is acknowledged that the predominant share of power use in CMOS devices stems from switching activity within a hardware implementation (such as FPGA or ASIC) of AES. As a result, the attack point for hardware implementations of AES is commonly selected as the XORed value derived from the input and output of the last round.

Within a side-channel attack, a leakage model refers to a mathematical or statistical representation that captures how side-channel measurements of a device relate to the underlying operations or data being processed. The leakage model can capture how side-channel measurements correlate with the internal states or computations of the cryptographic algorithm. A leakage model typically describes how the side-channel measurements of a device changes based on the values of specific variables or intermediate data during the algorithm’s execution. Some commonly used leakage models in SCAs include:

1. Identity (ID) model. Under the assumption of the ID model, at the attack point side-channel, measurements are considered to be directly proportional to the processed data’s value. For instance, when the data contains one byte, the ID model generates a set of

2. Hamming weight (HW) model. Within the HW model, the assumption is that side-channel measurements demonstrate proportionality to the number of 1

3. Hamming distance (HD) model. Within the HD model, it is assumed that side-channel measurements exhibit proportionality to how many 0

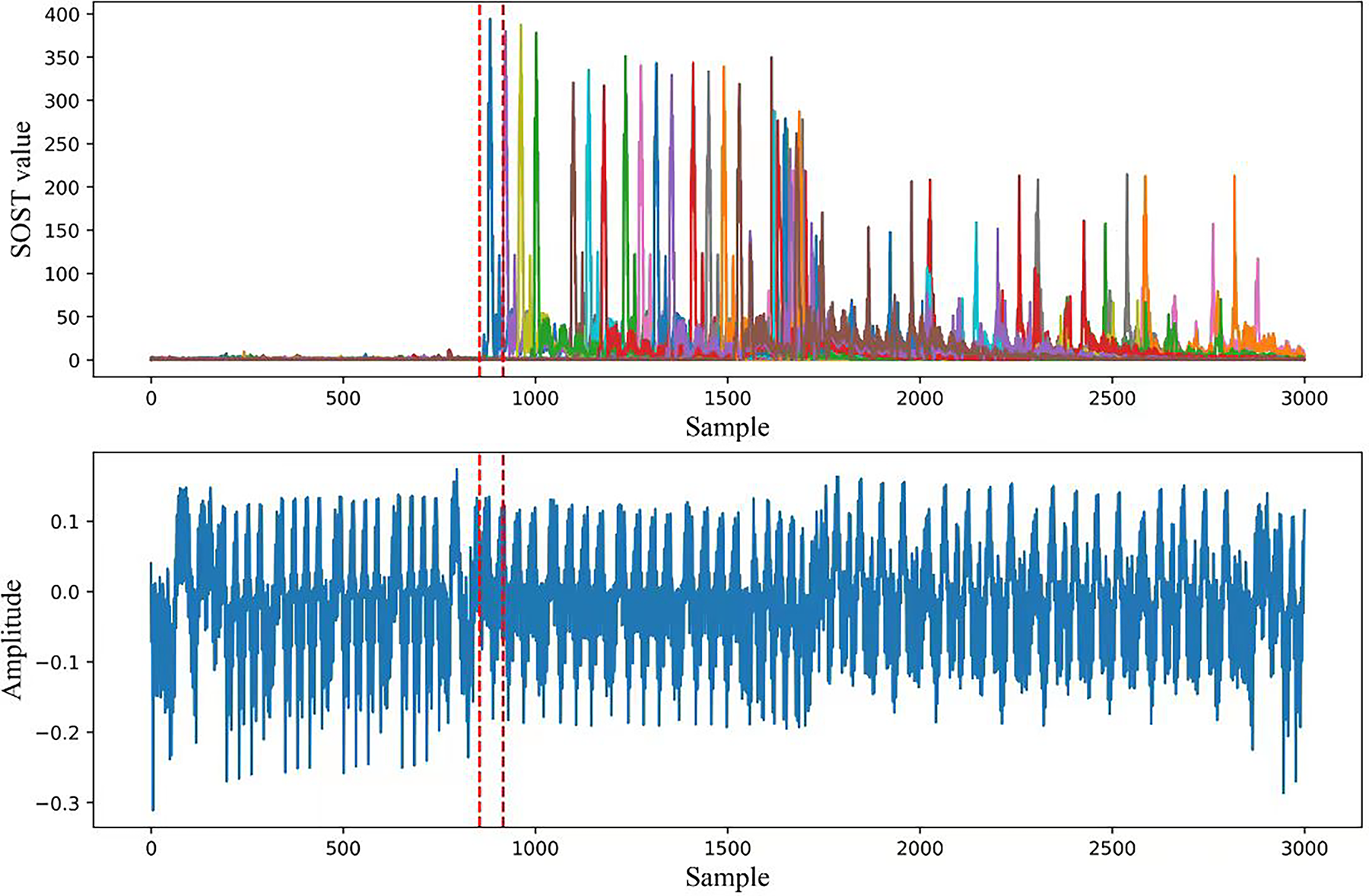

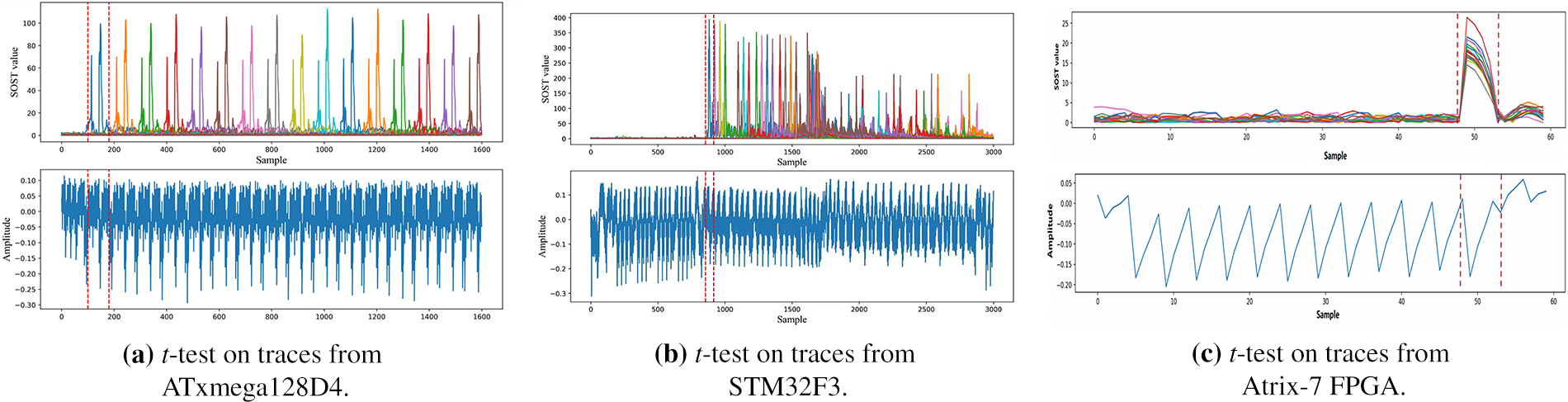

In practical scenarios, the traces obtained to represent the execution of AES can consist of a large number of samples, reaching into the thousands or even millions. Performing an attack in such circumstances can require significant resources and time. To streamline the attack process, adversaries often employ leakage detection methods to identify Points of Interest (PoIs) within the traces [57]. This allows them to concentrate on a smaller subset of points where information leakage is more pronounced. The act of pinpointing the leakage interval in side-channel measurements, aimed at extracting information tied to secrets, is known as leakage detection. The TVLA technique [32], utilizing the widely recognized Welch’s t-test [58], has gained significant prominence as a statistical method for detecting information leakage [59,60]. This approach has become widely used among the available methods to spot information leaks.

To conduct a TVLA, the captured side-channel measurements are initially segregated into two distinct groups based on the associated key-dependent intermediate value, known as the label, processed by the device. This division entails creating a set

In TVLA, the Second-Order Statistical Test (SOST) is employed to evaluate the difference between the two trace groups, which is defined by Formula (1).

where

Fig. 4 shows an example of how leakage detection allocates PoIs for side-channel traces. The upper picture Fig. 4 illustrates the leakage detection results for 16 subkeys in the first round of a STM32F3 MCU implementation of AES-128. The bottom picture Fig. 4 shows an example trace that represents an encryption round. The dashed red line illustrates the PoI allocation for the first SubByte operation in the first round of AES-128. By doing this, adversaries can focus on the specific trace segment and ignore other information to make the profiling stage more efficient.

Figure 4: An example of how leakage detection works for side-channel traces. The top picture shows the leakage detection results for 16 subkeys in the first round of a STM32F3 MCU implementation of AES-128. The bottom picture shows an example trace which representing an encryption round

Within the side-channel community, Success Rate (SR) and Guessing Entropy (GE) [61] stand out as two extensively employed evaluation metrics [62]. These metrics provide a fair and standardized framework for evaluating how effectively an attacker can exploit side-channel leakage to recover cryptographic keys. SR gauges the likelihood of successfully identifying the correct key within a specified number of traces, while GE quantifies the average uncertainty by calculating the expected rank of the correct key within a key-ranking scenario. Together, they offer complementary insights on how efficient and robust side-channel attacks are under different conditions.

The success rate quantifies the likelihood that the correct subkey can be successfully identified using a given set of side-channel traces. It reflects the model’s capacity to reduce uncertainty and precisely pinpoint the subkey within a specified number of traces. A higher success rate indicates that the adversary requires fewer traces to reliably recover the subkey, demonstrating how effective the model is at extracting keys from side-channel leakage. For instance, in the context of single-trace SR, this metric represents the probability that a model can correctly classify the key-dependent value using only one trace. In an experimental setup with 100 testing traces, if the model successfully recovers the key from 90 traces while failing in 10 cases, the single-trace SR for this model in that specific scenario is calculated as 90.0%.

In certain attack scenarios, relying solely on the SR might not be adequate as an evaluation metric, and it is advisable to include guessing entropy as an additional measure. GE offers information about the degree to which the secret key is disclosed given a specific number of traces. Guessing entropy means the degree of uncertainty or randomness associated with predicting the exposure of the secret key via side channels in side-channel attacks. As a common metric for evaluating attack complexity, guessing entropy implies that higher entropy corresponds to a lower likelihood of success for the attacker.

When recovering 8-bit subkeys individually, the guessing entropy is performed independently for every subkey, and the estimation metric used is the Partial Guessing Entropy (PGE), instead of GE [63]. Represented by PGE is the expected rank of the actual subkey. The rank of a subkey serves to measure the position of the correct subkey value

Within DLSCAs, adversaries typically begin by constructing a deep-learning model to serve as a leakage profile, which connects side-channel traces to key-related labels. During the profiling stage, various pre-defined loss functions in the deep-learning community are employed to evaluate the extent to which the trained deep-learning classifier fits the training traces. For example, in most attacks targeting software implementations of AES [16,64,65]. It is common to use categorical cross-entropy loss for quantifying classification errors (see below), as these attacks can often be simplified into multi-class classification tasks.

where

3 Practical Attack Cases of DLSCAs

For identifying capabilities and enabling the comparison of different DLSCAs on AES implementations, power consumption is used as the side channel, we provide a comprehensive review of existing work in this section.

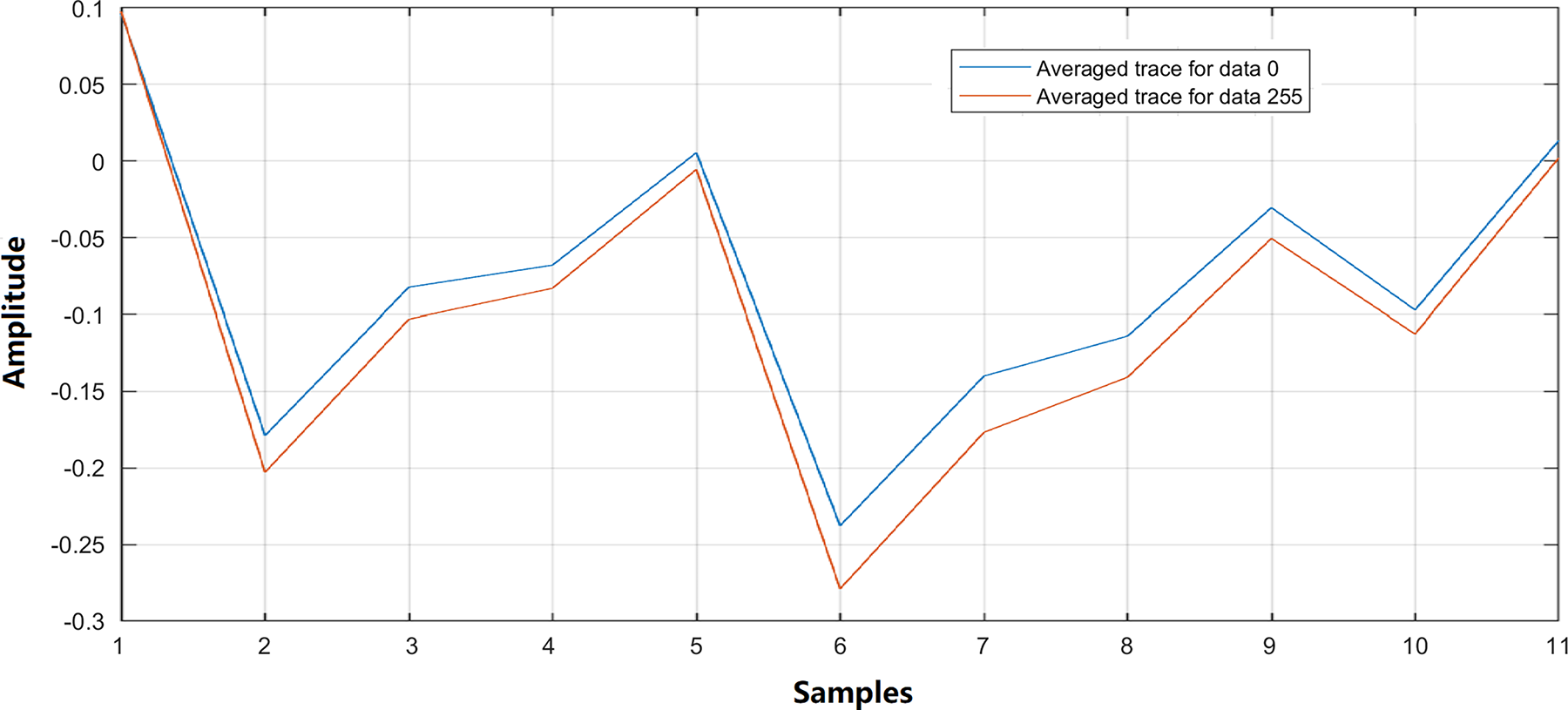

Paul Kocher first introduced power analysis in 1999 [18]. The power consumption of a device can depend on the particular data undergoing processing and the operations being executed. If an operation is correlated with some key-dependent intermediate state, the attacker is able to examine the power consumed by the target device and deduce the key. Power-based side-channel attacks capitalize on fluctuations in power usage during the execution of encryption on the victim device, with such fluctuations potentially differing according to various input data and operations [66]. Fig. 5 shows the comparison of two power traces corresponding to different data calculations within the same instruction, indicating that different data executed by the victim device result in distinct side-channel measurements.

Figure 5: The comparison of two power traces (averaged over 100 times) indicates that different executed data by the victim device results in power consumption (side-channel measurements)

One method to gauge a device’s power consumption is to insert a small resistor in series with the power or ground input, typically referred to as a shunt. Power consumption is determined by dividing the resistor’s voltage drop by its resistance [67]. A series of power measurements obtained by sampling these voltage drops using an oscilloscope over a specific duration is referred to as a trace.

In the following subsections, we start by introducing three publicly available power-based SCA datasets. Afterwards, we show existing works of DLSCAs on both software and hardware AES implementations, employing power consumption as the side channel.

3.1 Publicly Available Datasets for Power Analysis

In power analysis, there are five widely exploited side-channel datasets: ASCAD, DPA_V2, DPA_V4, AES_RD, and AES_HD. These datasets provide traces collected from different cryptographic implementations under various scenarios, enabling the community to evaluate attack techniques and countermeasures.

3.1.1 Datasets of Software Implementations

DPA_V4 (DPA contest V4 Dataset). The DPA_V4 dataset1 is collected from the DPA contest at a later stage. For the DPA_V4 dataset, the target is an Atmel ATMega-163 smart-card implementation of AES with Rotating Sbox Masking (RSM) [68]. Included in it are 16Kb of in-system programmable flash, 512 bytes of EEPROM, 1Kb of internal SRAM and 32 general purpose working registers. A simple reader interface mounted on the SASEBO-W board is used to read the smartcard. The traces are collected with a LeCroy WaveRunner 6100A oscilloscope. The acquisition bandwidth reaches 200 MHz, while the sampling rate is adjusted to 500 MS/s. Containing 80K traces, the dataset has 16 different keys, with each key, there are 5K traces corresponding to the encryption of 5K different plaintexts per key. The dataset requires approximately 64 GB of storage.

ASCAD (ANSSI SCA Dataset). The ASCAD dataset2 includes traces collected from two distinct victim devices: an ATMega8515 implementing a Boolean-masked AES and an STM32F303RCT7 implementing an affine-masked AES. These datasets are commonly denoted as ASCADv1 (for the ATMega8515 implementation) and ASCADv2 (for the STM32F303RCT7 implementation). ASCADv1 comprises 60K synchronized traces captured using a fixed secret key and 300K jitter-based traces obtained with variable keys. The traces’ desynchronization is simulated artificially. To sample measurements in the ASCAD dataset, a digital oscilloscope operates at a sampling rate of 2G samples every second. A temporal acquisition window is set to record the first round of the AES only. Every trace is made up of 1.4K sample points, while the dataset takes up around 77 GB of storage space. ASCADv2 contains 800K traces, each generated with random plaintexts and keys. The traces consist of 1M sample points, covering the entire AES encryption process. The dataset requires approximately 807 GB of storage; however, a smaller extracted dataset is available, which is only 7 GB in size, offering a more convenient option for quick access.

AES_RD. AES_RD3 contains power consumption traces captured from an 8-bit Atmel AVR microcontroller implementation of AES-128, where the algorithm is protected by a random delay countermeasure [69]. The AES_RD dataset contains 50K traces in total and each trace has 3.5K samples, which are captured with the LeCroy WaveRunner 104MXi oscilloscope. These power traces are compressed by selecting 1 sample of each CPU clock cycle. The dataset is compactly organized, occupying less than 1 GB of storage.

3.1.2 Datasets of Hardware Implementations

DPA_V2 (DPA contest V2 Dataset). The DPA_V2 dataset4 is collected as part of the DPA Contest. As an international contest, the DPA Contest permits researchers across the globe to compete on a common basis. Introduced in 2008, this contest has seen four versions completed since that time. In the case of DPA_V2, The target here is an AES-128 hardware implementation, which is set up on the Xilinx Virtex-5 FPGA of a SASEBO GII evaluation board. A high-resolution oscilloscope is used to measure the power consumed by the device when the encryption process takes place. The dataset contains 1M traces in total with 3.2K sample points per trace. The dataset requires approximately 9 GB of storage. For research convenience, the data are well-aligned after the capturing process.

AES_HD. AES_HD5 is a dataset captured from an unprotected AES-128 hardware implementation on a Xilinx Virtex-5 FPGA, integrated into a SASEBO GII evaluation board. Note that the acquisition method is not explicitly mentioned on the AES_HD dataset website. This dataset comprises 100K traces, with each linked to a distinct random plaintext. Each trace contains 1.25K sample points. The dataset is efficiently stored, requiring less than 1 GB of storage space.

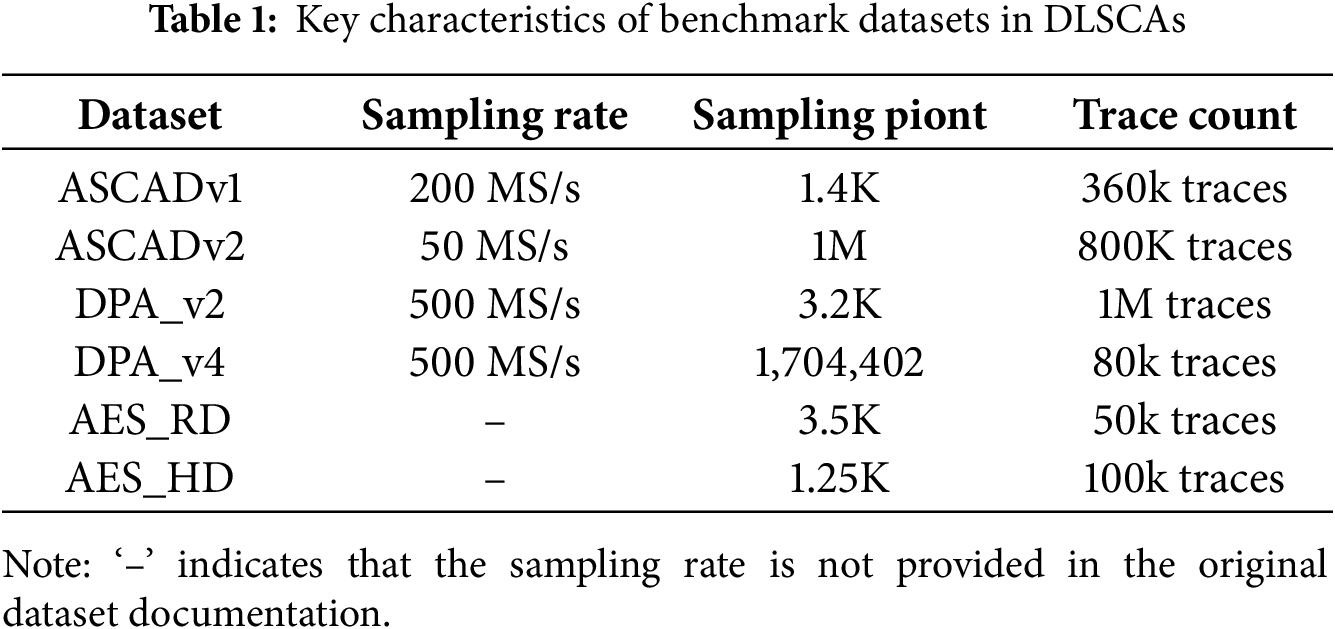

The characteristics of the five datasets are summarized in the subsequent Table 1.

When comparing side-channel analysis datasets such as ASCAD, AES_RD, AES_HD, DPA_V2, and DPA_V4, their relevance to real-world IoT environments can be assessed based on their characteristics and limitations.

ASCAD, AES_RD and DPA_V4, which provide traces from microcontrollers running AES, are highly representative of software-based cryptographic implementations in real-world IoT environment. Software-based AES is widely used in low-cost and resource-constrained IoT devices. A large number of such devices function using low-power chips that lack dedicated cryptographic accelerators, making software implementations the only viable option. Among them, AES_RD and parts of the ASCAD dataset contain traces captured from 8-bit MCU implementation of AES, which can be used to represent low-power, cost-sensitive IoT applications, such as smart sensors, simple automation systems, and basic communication modules, due to their simplicity, low energy consumption, and affordability. However, implementing AES in software on an 8-bit MCU presents significant performance challenges. AES functions as a block cipher, handling data blocks of 128 bits in size, which must be split into multiple 8-bit operations when executed on an 8-bit MCU. This results in a high number of memory accesses, increased computational overhead, and slow encryption speeds.

For the DPA_V4 and another part of the ASCAD dataset, traces are captured from 32-bit MCU implementations of AES. In this case, the data can represent a more scalable approach for software-based AES in IoT, which achieves a more reasonable balance between the security level and the cost. Real-world IoT scenarios that commonly rely on software AES in 32-bit MCUs include industrial automation controllers, connected medical devices, and smart home gateways.

AES_HD, DPA_V2 can be used to represent the IoT applications with hardware cryptographic module, as they both contain traces captured from AES implementations on FPGAs. In contrast, hardware-based AES is preferred for performance-critical applications that demand fast encryption and decryption. IoT devices involved in real-time video streaming, high-throughput communication, or industrial control systems benefit significantly from dedicated cryptographic accelerators, as hardware AES completes encryption operations faster. Security-critical IoT applications, including payment terminals, secure bootloaders, and biometric authentication systems, also rely on hardware AES due to its resistance to attacks.

3.2 Power Analysis of Software Implementations

A software-based AES implementation denotes the execution of the AES algorithm through software or programming code. In this approach, the AES algorithm is executed on a general-purpose computing device, such as a computer or a microcontroller, using software instructions to perform the required cryptographic operations. The software implementation typically involves translating the AES algorithm’s steps, such as key expansion, substitution, permutation, and XOR operations, into programming instructions executable by the device’s Central Processing Unit (CPU). Software implementations of AES are commonly used in various applications, including secure communication protocols, file encryption, and cryptographic libraries.

Advantages of software implementations of AES compared to hardware implementations include:

1. Flexibility: Software implementations offer great flexibility in terms of programmability and adaptability to different platforms and operating systems [70].

2. Cost-effectiveness: Software implementations typically require less upfront investment compared to hardware implementations, as they can utilize existing computing infrastructure without the need for dedicated hardware components [71].

3. Compatibility: Software implementations of AES can be developed to comply with standardized cryptographic libraries and protocols, ensuring compatibility and interoperability with other software systems [72].

In 2011, Hospodar et al. proposed, in the JCEN journal, one of the initial machine learning-based attacks, trains a Least Squares Support Vector Machine (LS-SVM) [73] to classify power traces captured from an AES software implementation based on the first round’s SBox output. Instead of recovering an actual key, Hospodar et al. [74] focus on one single SBox lookup process. The investigation focuses on three significant properties of the SBox output: whether the HW is smaller or larger than 4, whether it is odd or even, together with the value of the fourth least significant bit. This analysis aims to illustrate the impact of LS-SVM hyperparameters on classification accuracy.

Afterwards, in 2013, deep-learning techniques began contributing to power analysis [75]. A three-layer MLP network is applied for training to compromise an AES-128 SmartCard implementation, featuring an 8-bit microcontroller PIC16F84. In [75], the MLP model undergoes training by using the standard sigmoid as the activation function and achieves a 85.2% single-trace attack accuracy to recover the first subkey of the implementation. Since then, the development of neural network-based power analysis targeting various implementations of AES has gradually emerged.

By training a MLP model on the generated patterns, reference [76] is able to improve classification accuracy to 96.5% for the same implementation of AES as in [75]. Afterwards, reference [77] compares the newly introduced MLP based attack in [75,76] with the conventional template attack on the same dataset as in [75,76]. However, in [77], only 2560 traces are captured for training the MLP model, which may lead to the result far away from the optimal. In [77], the PGE result of their MLP model is 1.04 on average, which indicates that the trained model’s capability to extract the subkey from an AES-128 Smart Card implementation which features an 8-bit microcontroller PIC16F84.

In addition to MLPs, reference [56] explores the efficiency of various other deep-learning models in enhancing side-channel attacks using three distinct datasets. In [56], five different deep-learning attack approaches are compared in total: MLP with Principal Component Analysis (PCA), MLP without PCA, CNN, AE and Long and Short Term Memory (LSTM). For the sake of comparison, they also test a machine learning based approach (random forest) and the template attack on the same three datasets. They experimentally show the overwhelming advantage of the deep learning based when it comes to breaking both unprotected and protected AES.

To further examine research on power analysis based on CNNs, Cagli et al. [29] utilize the CNN model alongside a data augmentation method [78], introduced at CHES 2017. This approach aims to overcome the trace misalignment and handle countermeasures based on jitter. Cagli et al. [29] initially highlight the challenges of the traditional template attack strategy, particularly in addressing trace misalignment. This requires the attacker to meticulously realign the captured traces. Subsequently, they conduct experiments demonstrating that the CNN based strategy significantly streamlines the attack process by eliminating the need for trace realignment and precise selection of points that are of interest. In their initial trial, they used CNNs to compromise the implementation of AES on an ATmega328P microprocessor, which featured a uniform Random Delay Interrupt (RDI). By using the HW leakage model to train their CNN network, they achieve to use 7 traces on average to recover a subkey, which confirms that their CNN model is robust to RDI. Additionally, their second experiment introduces clock instability to misaligned traces on the adversary’s side. The findings show that the CNN method is superior to Gaussian templates in performance, regardless of whether trace realignment is performed. Meanwhile, reference [79] also examines the advantages of CNNs in comparison to various ML techniques. Their experiments reveal that methods such as random forest may be a preferable choice over CNN in certain attack scenarios, casting doubt on CNN as the optimal approach for every profiled SCA setting. Another work [80] for CNN based attacks shows that the addition of manually added non-task-specific noise in training sets may prove advantageous to the attack efficiency of the trained network. The addition of such noise may be considered being on par with incorporating a regularization term. a regularization term. CNN models trained on data with additional non-task-specific noise in [80] can successfully recover the key by using 2 traces for the AES_RD dataset. For the case of DPA_V4 dataset, the addition of noise helps the pooled template to break the implementation with 2 traces, which outperforms other CNN-based approaches.

During the profiling stage, the HW leakage model as well as the HD leakage model face a common challenge of dealing with imbalanced data. For instance,if the labels of the data are evenly distributed across the range from 0 to 255, certain classes occur in 1/256 instances (when the HW parameter is set to 0) while one appears in 70/256 instances (When HW parameter is set to 4) by using the HW leakage model. With the aim of reducing the effect of imbalanced profiling data, reference [81] uses a data balancing approach called Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) [82] to ensure a balanced distribution of classes.

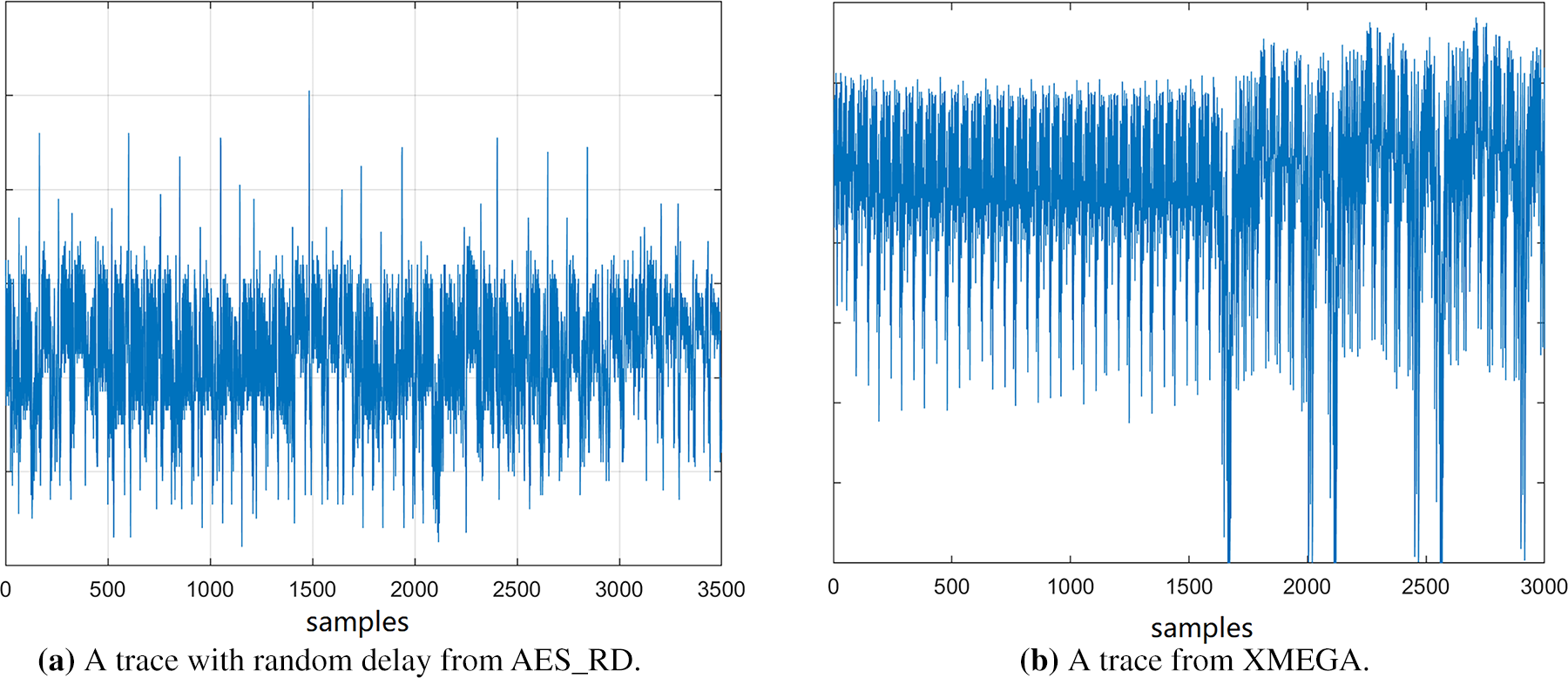

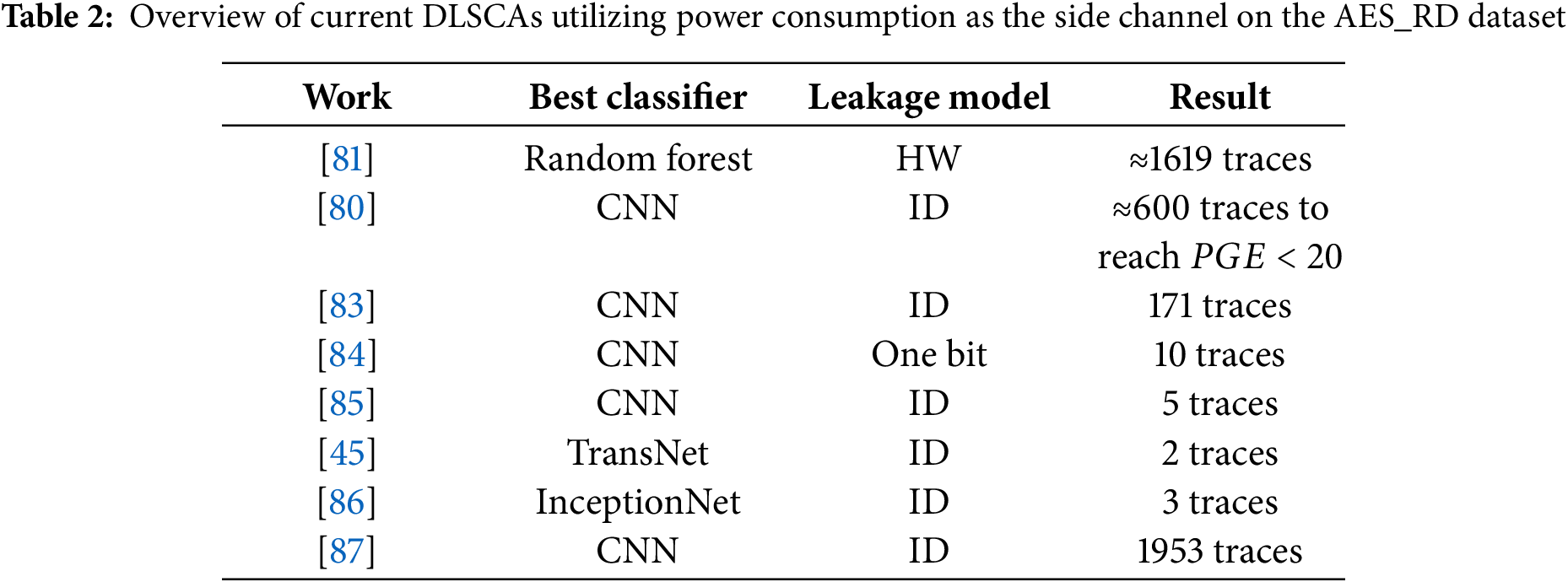

In [88], neural networks are trained using each bit of the intermediate data processed at the attack point as a separate label. Consequently, for a subkey represented as a byte, a total of 8 labels are considered. To address the class imbalance challenge, this method is introduced, unlike the HW leakage model, every bit exhibits almost a uniform distribution. They evaluate the multi-label approach in several datasets. For three publicly available datasets, called ASCAD, AES_RD and AES_HD, the proposed multi-label model requires 202, 10 and 831 traces, respectively, for the subkey recovery. Power traces in AES_RD are captured from an 8-bit Atmel AVR microcontroller implementation of AES-128, where the algorithm is protected via a random delay countermeasure [69]. In all, the dataset consists of 50,000 traces, and each trace is made up of 3500 samples. These power traces are compressed by selecting 1 sample from each CPU clock cycle. Fig. 6a shows an example trace of AES_RD dataset and Table 2 shows the summary of existing DLSCAs on AES_RD dataset.

Figure 6: Plots of traces captured from software implementations of AES. The first figure shows a power trace with random delay captured from an 8-bit AVR microcontroller implementation of AES-128 (AES_RD dataset) and the second plot shows a trace captured from an 8-bit Atmel ATXmega128D4 microcontroller implementation of AES-128

In 2022, the denoising autoencoder is applied in [89] to reduce or remove noise and the countermeasure effect before the training process. The denoising autoencoder is trained by using noisy-clean trace pairs. Regarding the ASCAD dataset, the CNN model in [89] requires 831 traces to retrieve the correct key before the denoising process that uses the trained autoencoder. After degenerating the noise level, the results decrease to 751. Afterwards, Zaid et al. [90] proposed a Conditional Variational AutoEncoder in 2023 TCHES, which bridges DL models and SCA paradigms based on theoretical findings from stochastic attacks. By following the path of [89], Hu et al. [65] further design a multi-loss DAE model which makes the power and near-field EM based SCAs more efficient, presented in 2023 TIFS. Despite their strength, deep-learning techniques face a well-known limitation: reliance on large datasets. This issue has received relatively little focus within the side-channel community. However, within practical scenarios, the quantity of profiling traces available to adversaries is often far smaller than assumed, constrained by factors such as limited preparation time or scheme-specific restrictions. As a result, improving the efficiency of the profiling stage in DLSCAs is also an important area of focus. Reference [91] proposes a Label Correlation (LC) based profiling method, in which transferring the widely used one-hot labels toward their patterns to accelerate the convergence of model profiling. Their experiments demonstrated that both CNN and MLP models could successfully recover subkeys from ASCAD traces with only 10K profiling traces, underscoring the potential of this approach to improve profiling efficiency. Reference [92] proposes a novel CPA method applicable to scenarios where cryptographic algorithms employ parallel implementations of S-boxes, and narrow the performance gap between profiling and non-profiling SCA attacks.

Numerous existing architectures enhance model accuracy through the stacking of multiple network layers, which consequently introduces several challenges: elevated algorithmic and computational complexity, overfitting phenomena, reduced efficiency in the training process, and constrained feature representation capacity. In addition, deep learning methods depend on data correlation, and noise presence often reduces this correlation, thus making attacks more difficult. TN exhibit a strong capability to capture dependency relationships between distant POIs in side-channel traces; leveraging this advantage, Hajra et al. [45] employ TN to launch attacks against cryptographic implementations equipped with protective measures such as masking and desynchronization. Zhang et al. [93] propose a CNN-Transformer architecture, which integrates power analysis techniques to automatically identify and prioritize relevant POIs in side channel power consumption traces. Empirical evaluations on dataset demonstrate that, compared with LSTM and CNN models, this hybrid architecture achieves significantly higher attack efficiency in DL-SCAs. In 2024, reference [50] proposes an AMCNNet for better extraction of the feature and temporal information from traces. Reference [86] suggests applying a network structure based on InceptionNet to side-channel attacks. The proposed network employs a reduced number of training parameters, attains accelerated convergence via parallel processing of input data, and enhances attack efficiency. Additionally, a network architecture based on LU-Net is put forward to denoise side-channel datasets. On the AES_RD and ASCAD datasets, 3 and 30 traces are used to recover the subkeys. Reference [87] designs a lightweight deep learning model by incorporating random convolutional kernels to address the exponentially increasing training time caused by excessive features. Compared with the most advanced methods, the quantity of power traces required as well as the trainable parameters are reduced by over 70% and 94%, respectively. Reference [94] proposes a general side-channel evaluation metric called Leading Degree (LD) for assessing the performance of deep learning models. Through the use of LD as the reward function in the tuning of model hyperparameters based on reinforcement learning, a better model structure is obtained compared with previous state-of-the-art models.

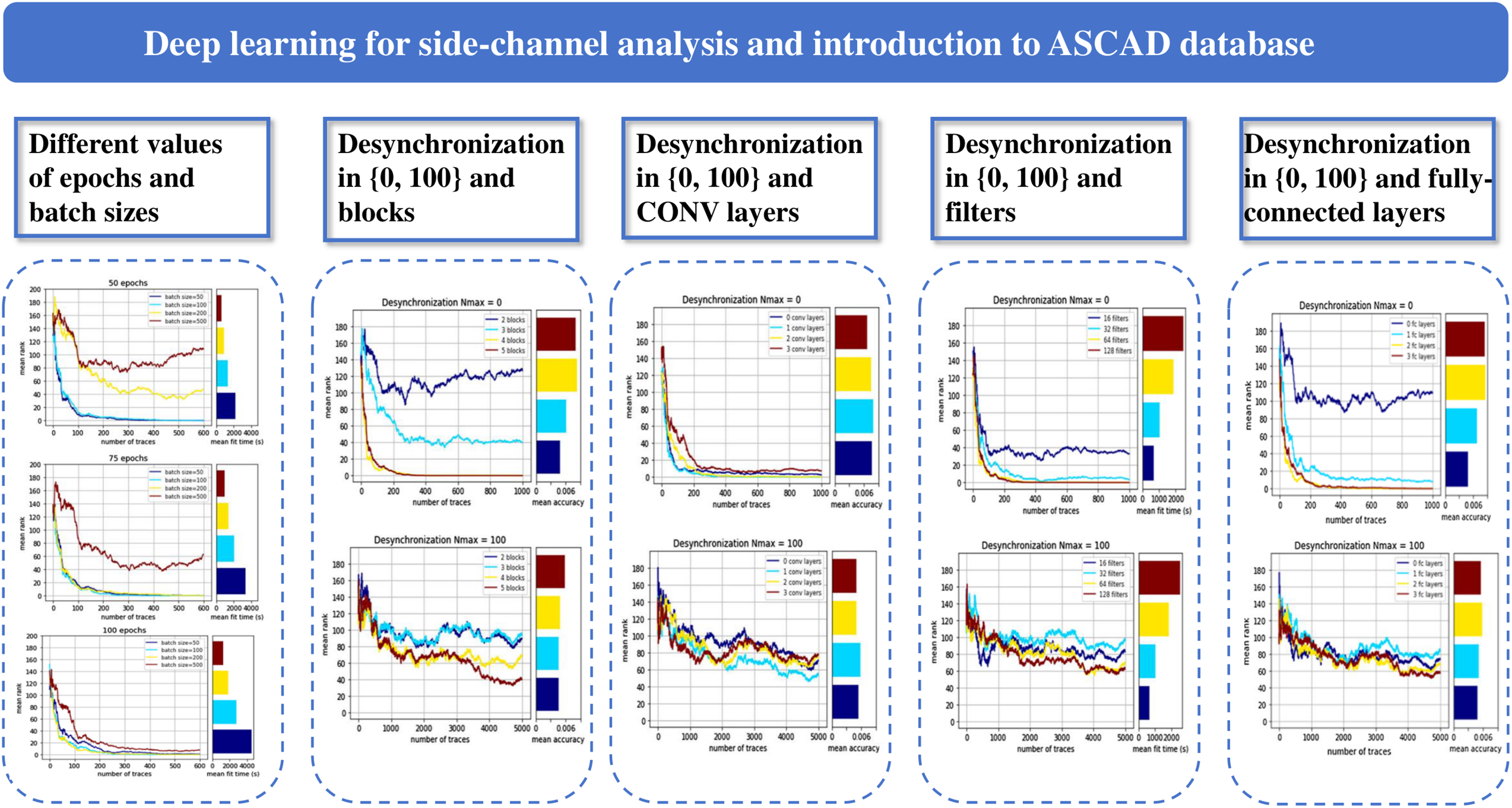

While many existing works focus on the attack efficiency of the designed model, they always keep their hyper-parameterization as a secret. The comprehensive study on the selection of hyperparameters has not been fully explored when developing deep-learning models across various side-channel attacks’ scenarios [95]. In order to address this limitation, reference [96] investigates the impact of modifying hyper-parameters in MLP and CNN models for side-channel attacks. The methodologies for selecting hyper-parameters can serve as a guidance for the following researchers to optimize their own deep-learning models. Specifically, the study not only puts forward a customized hyperparameter selection framework for DL models, encompassing pivotal parameters such as batch size, epochs, filter configurations, and fully-connected layers, but also systematically elucidates how adjustments to these hyperparameters directly modulate critical model attributes, thereby exerting a decisive influence on the reliability of DL-SCA models in practical key recovery tasks. The impact of some hyperparameters on the model is shown in the Fig. 7. In [96], their best CNN model is about to recover a single subkey from a masked AES implementation on an 8-bit ATMega8515 microcontroller utilizing around 200 traces without any desynchronization. For the case of traces with a maximal desynchronization value of 50, they succeeded in achieving a mean rank close to 20 with 5K traces. In the scenario where the maximum desynchronization value is 100, the model requires 5K traces to reach a mean rank near 40. In addition, reference [96] shows that attacks based on MLPs and CNNs exhibit notable superiority over template attacks when traces are desynchronized.

Figure 7: An analysis of deep learning for SCA using the ASCAD database, investigate the impacts of different hyperparameters (epochs, batch sizes, blocks, CONV layers, filters, fully-connected layers) and desynchronization levels on model performance

Hyperparameter optimization plays plays a vital role in enhancing both the performance and robustness of models used in SCAs. Traditional approaches like grid search and random search systematically explore different hyperparameter combinations, though they can be computationally expensive, as shown in many SCA cases [65,97,98]. More sophisticated techniques that include Bayesian optimization offer a more efficient method by modeling the hyperparameter space probabilistically, allowing the search to focus on promising regions of the attack [99,100]. A traditional CNN model is optimized by incorporating an attention mechanism into the convolutional layers, thereby strengthening the model’s capability to capture global information and improving the extraction of leakage information [101]. Another effective strategy is learning rate scheduling, where the learning rate is adjusted dynamically during training, often using techniques like cosine annealing, step decay, or adaptive methods [102]. To elucidate the impact of each hyperparameter of neural networks in side-channel attack scenarios during the feature selection phase, reference [85] employs three visualization techniques to illustrate the internal operations of models: weight visualization [103], gradient visualization [104], and heatmaps [105]. By employing these visualization approaches, reference [85] demonstrates different methodologies to build suitable CNN architectures for different attack scenarios. They show that their optimal model achieves using 3 traces to recover a subkey from DPA_V4 dataset. Comparing this result to [80] and [81], they managed to lower the model’s complexity without degenerating the model accuracy. For the case of ASE_HD, ASCAD and AES_RD datasets, the CNN models in [85] require 1050, 191 and 5 traces to recover the subkey. To address the threats posed by SCAs, one defensive measure involves injecting random noise to enhance security. Reference [106] proposes a novel denoising approachthat combines wavelet coefficient analysis with Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). This integration is tailored to mitigate noise artifacts induced by side-channel countermeasures. Through the preprocessing of noise reduction on traces, only 108 traces are required on the ASCAD dataset compared with [85].

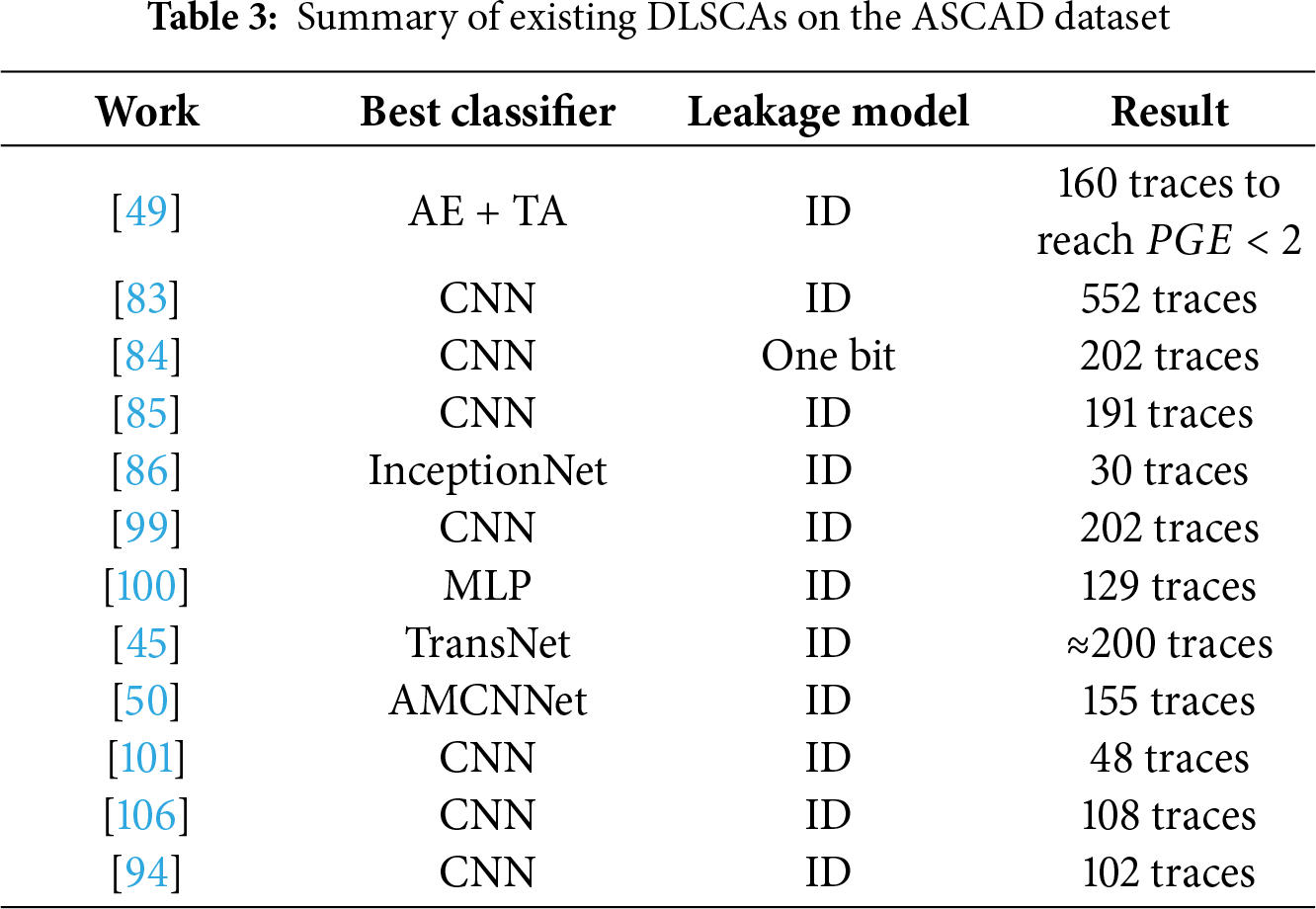

Afterwards, References [99,100] propose two distinct methods for automatically tuning neural networks’ hyperparameters. Reference [100] builds a custom framework denoted as AutoSCA based on Bayesian Optimization, in which the model is selected from 50 iterations of testing various hyperparameter combinations. During every iteration, the Bayesian Optimization function generates a group of hyperparameters for model construction, which is then followed by the training process. They compare different types of neural networks and show that the AutoSCA MLP model reaches the best performance for the ASCAD dataset with the shortest training time, which uses 129 traces to recover a subkey. Another automated hyperparameter tuning approach for SCA is proposed by [99], in which the reinforcement learning framework [107] is used with two reward functions for side-channel metrics to adjust the hyperparameters of convolutional neural network. In [99], 202 traces need to be used for the CNN model to recover a subkey for the ASCAD dataset. Reference [108] formulates SCA problems as graph signal processing (GSP) problems. Leveraging the inherent advantage of GNNs in modeling and analyzing graph-structured data, the study further applies GNNs to SCA tasks to enhance the extraction and utilization of leakage-related features. Table 3 shows the summary of existing DLSCAs on ASCAD dataset.

Most of reported deep-learning based side-channel attacks on AES by 2019 do not account for the influence of board diversity. They conduct training as well as testing of the deep-learning models using the same board’s traces, which is not realistic in a genuine attack scenario.

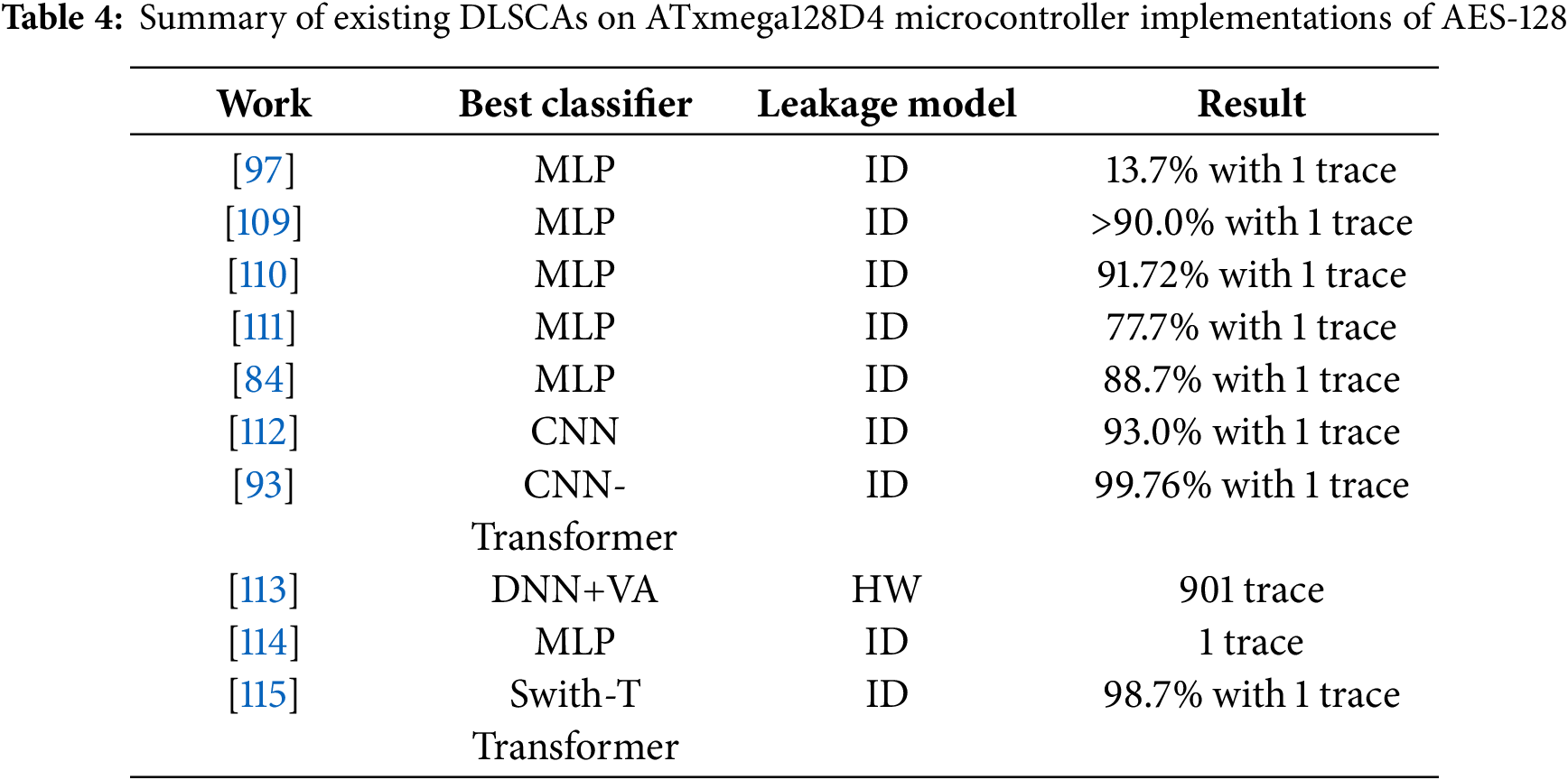

To examine the impact of board diversity on the efficiency of DLSCAs, Das et al. [109] experimentally demonstrate the success rate gap when the trained model is applied to the profiling device vs. the victim device, as presented at the DAC conference. They train deep-learning models using traces obtained from one 8-bit ATxmega128D4 microcontroller implementation of AES and tests this model using traces obtained from another board with the same chip and the same version of AES. Afterwards, Wang et al. [97] investigate to which extent the trained models’ attack efficiency can be mitigated when targeting the victim device with the same implementation but in a different Printed Circuit Board (PCB) as the profiling device. Although the MLP model in [97] demonstrates the ability to recover the key from the training board in 88. 5% of the cases, the success rate drops significantly to 13.7% for the testing board. This demonstrates the potential for overestimating classification accuracy if the training and testing the model on the traces obtained of the same equipment. Notably, the model structure in [97] is relatively simple compared to the complex architectures typically used in computer vision and natural language processing, particularly when the captured traces exhibit a high level of leakage. For instance, the peak leakage value, represented by the SOST value, for the first subkey derived from 5K power traces collected from the ATxmega128D4 microcontroller’s AES implementation, is approximately 70. This value is roughly 15 times higher than the detectable leakage threshold (SOST value

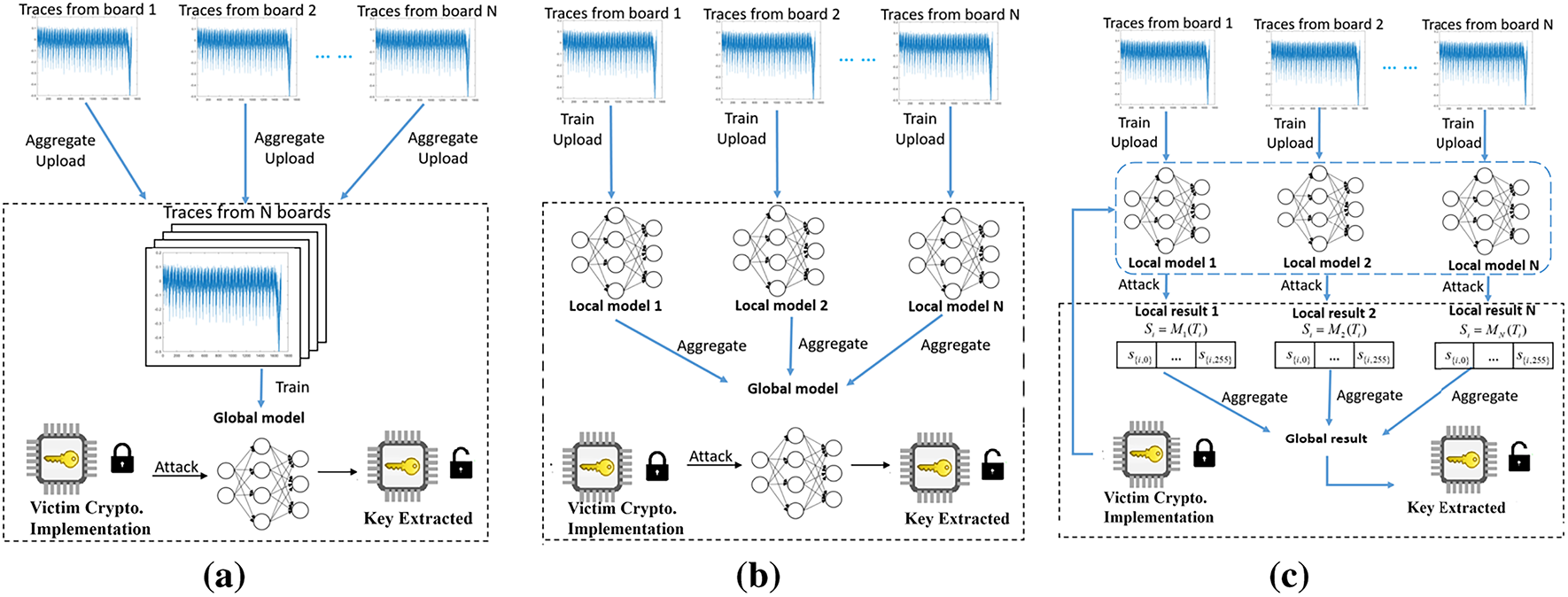

To alleviate the influence of board diversity and improve the efficiency of deep-learning models, a data-level aggregation approach is proposed by [84,109,110]. The fundamental concept of the data-level aggregation approach is to train DL models using traces obtained from multiple boards, rather than one, as shown in Fig. 8a. For example, in [84], 9 profiling devices (the same implementations as in [97]) are used to train a MLP model and increase the probability of key recovery from a single trace, increasing it from 40.0% to 86.1%. To further increase the attack efficiency, reference [110] uses 30 devices for profiling and captured traces are preprocessed by using the PCA technique before the profiling stage. As a result, they successfully achieve a

Figure 8: Illustration of different aggregation methods to mitigate the impact caused by the board diversity in DLSCAs on AES. Fig. 8a presents data-level aggregation, where a model is trained on traces from different devices. Fig. 8b shows model-level aggregation for SCA based on the horizontal federated learning framework, with N participants jointly building a federated deep-learning model. Fig. 8c illustrates output-level aggregation: N classifiers are independently trained on traces from N devices. (a) Data-level aggregation approach [109,110]. (b) Model-level aggregation approach [111]. (c) Output-level aggregation approach [111]

When datasets are dispersed across various sources, the task of matching data while preserving the privacy of the datasets is a widely demanded task. The preservation of the privacy of distributed data, particularly the data stored in individual edge devices, is shown to be consistently crucial [118]. Another technique to combine multiple deep-learning models is the well-known Federated Learning (FL) [119]. FL facilitates allows for training of a global deep-learning model by several participants without the need to share their individual local training data [120]. Like any significant scientific breakthrough, FL has the potential to be employed for malicious purposes. Reference [111] uses the FL framework as a model-level aggregation for the deep-learning based SCA. Fig. 8b illustrates the model-level aggregation of DLSCAs to reduce the impact brought about by board diversity. In their experiments, three 8-bit ATxmega128D4 microcontroller implementations of AES are used to train three MLP models and these models are aggregated into one global MLP. The federated model in [111] achieves a 77.7% average single-trace attack accuracy even though they take board diversity into account. Another aggregation approach proposed in [111] is at the output level, which uses the ensemble learning scheme [121] to integrate the classification outcomes of multiple models trained on various profiling devices as shown in Fig. 8c.

Subsequently, reference [64] achieves in demonstrating the first power analysis using deep learning to a commercial USIM card that implements MILENAGE (based on AES). The researchers successfully trained a CNN model on one USIM and demonstrated its ability to regain the key from a different USIM, using an average of only 20 traces. Afterwards, in 2023, reference [122] introduces a novel method to address the portability issue. This method presents a neural network layer evaluation method based on the ablation paradigm. By evaluating the sensitivity and resilience of each layer, this approach provides useful insights for constructing a Multiple Device Model from Single Device (MDMSD). Physical side-channel analysis generally works under the premise that plaintext or ciphertext is known, but this premise often breaks down in diverse scenarios. Blind SCA tackles this challenge by functioning without awareness of plaintext or ciphertext. Reference [113] proposes the first successful blind SCA on hiding countermeasures, introducing the Multi-point Cluster-based (MC) labeling technique. It is validated on four datasets, including symmetric-key algorithms (AES, ASCON) and the post-quantum cryptography algorithm Kyber. Reference [114] investigates the portability of deep learning-based side-channel attacks on EM traces and perform a comparative analysis of a set of preprocessing and unsupervised domain shift methods. And a large-scale public dataset is provided for benchmarking and reproducing side-channel attacks that handle domain shifts over EM traces.

Although the varied power profiles of IoT devices present a unique challenge for DLSCAs, adversaries still pose a considerable threat. As mentioned earlier, an attacker can prepare a dedicated deep-learning model for a specific target by acquiring an identical device from the market, allowing them to train on highly similar power traces. This approach enables precise modeling of the device’s power consumption characteristics, significantly improving the attack’s effectiveness. Since many consumer IoT devices are mass-produced with identical components and firmware, attackers can exploit this uniformity to extract sensitive information like cryptographic keys or executed operations with high precision.

However, when the target is a dedicated or custom-built device, and the adversary has no opportunity to obtain an identical copy, the challenge becomes more significant. Variations in architecture, firmware optimizations, and even the version of the cryptographic algorithm introduce discrepancies in power consumption, thereby increasing the difficulty for attackers to generalize a pre-trained model.

3.3 Power Analysis of Hardware Implementations

Time can affect leakage in software implementations of AES, and the leakage tends to be less noisy due to the sequential execution of instructions. In contrast to the challenges posed by hardware implementations of AES, this characteristic facilitates deep-learning models in exploring features linked to each subkey through a divide-and-conquer strategy. Traces obtained from hardware implementations often exhibit overlapping features arising from multiple concurrent operations as a result of parallel instruction execution. Consequently, side-channel attacks become intrinsically more difficult, especially within advanced process technology. Here are some advantages of hardware implementations of AES compared to software implementations:

1. Speed and efficiency. Hardware implementations of AES can provide significantly faster encryption and decryption speeds compared to software implementations [123].

2. Lower power consumption. Hardware implementations of AES can be more power-efficient compared to software implementations, especially in resource-constrained devices [124].

3. Physical security. Encryption and decryption operations are performed within dedicated hardware components, rendering it more difficult for attackers to retrieve sensitive data via side-channel attacks or software vulnerabilities [95].

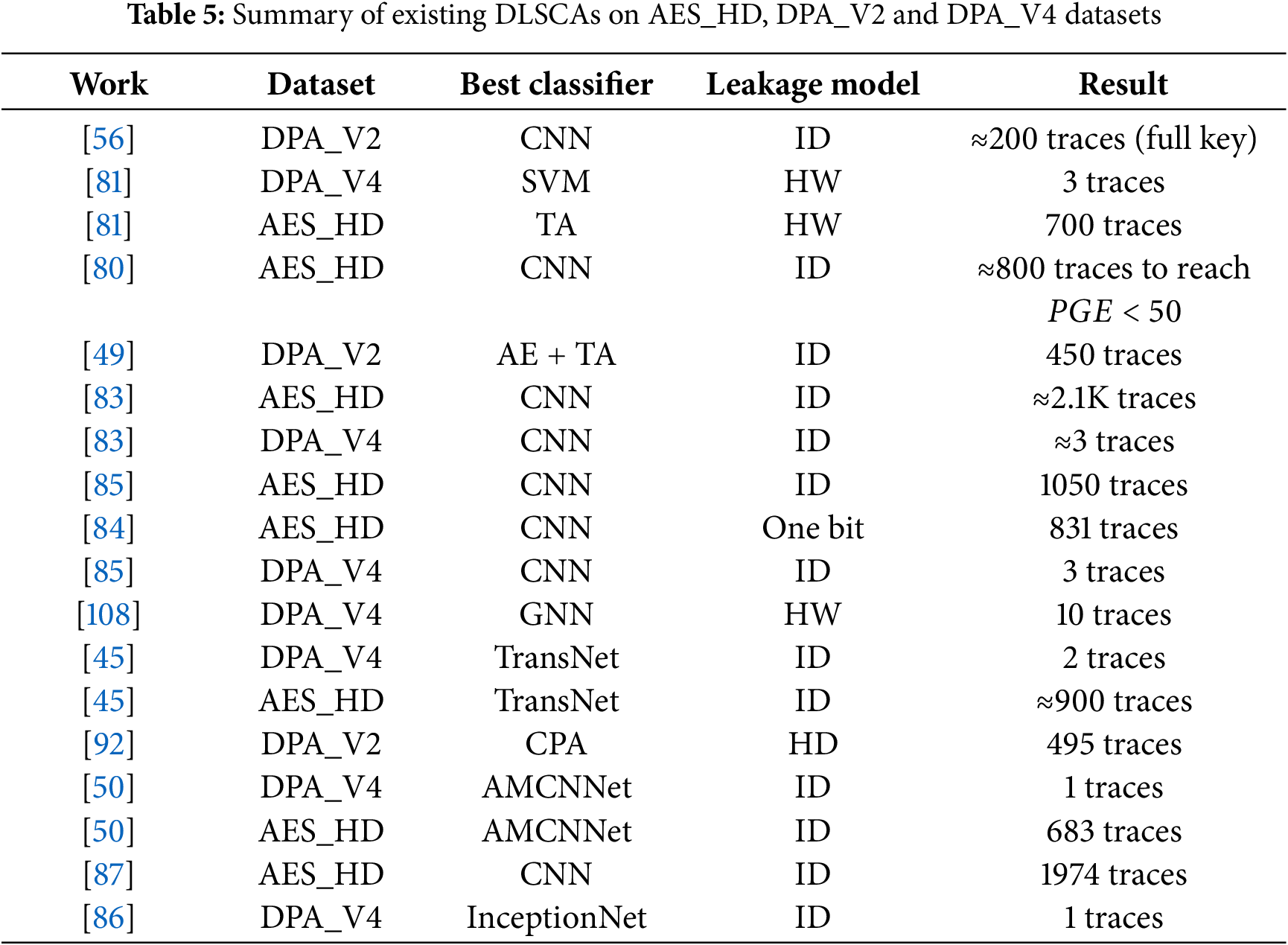

Many existing attacks targeting hardware implementations of AES are founded on two widely recognized datasets: DPA contest V2 [125] and AES_HD [81]. These datasets’ traces are obtained from AES implementations on Xilinx Virtex-5 FPGA series. Table 5 summarizes some existing attack results on these two well-known datasets.

In [81], the random forest approach requires in excess of 5000 traces to retrieve a subkey from the Virtex-5 implementation of AES. Reference [126] investigates the theoretical soundness of CNN in the context of SCAs on hardware implementations of AES. References [56,79,80] showcased effective assaults on Virtex-5 FPGAs through the application of CNNs. In [80], the CNN models trained on data with additional non-task-specific noise in [80] are able to recover a subkey with 25,000 traces for the AES_HD dataset.

Apart from Xilinx Virtex-5 FPGA, a non-profiled attack [127] employs roughly 3.7K traces to compromise a lightweight Artix-7 FPGA implementation of AES. Additionally, reference [128] demonstrates the efficacy of CNN-based side-channel attacks on ASICs. Afterwards, reference [102] introduces a multi-point attack framework named tandem scheme to attack hardware implementations of AES. This approach combines the classification outcomes of CNN models trained at various attack points. In [102], the proposed tandem scheme successfully recovered a subkey from a Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA implementation of AES using 219 traces.

When targeting advanced embedded system implementations of AES with parallel computing and countermeasures, the preprocessing step gains significant importance, especially for degenerating the noise level in the captured traces. Initially, electronic noise inherently exists in cryptographic devices, particularly in hardware implementations. Moreover, noise serves as a fundamental component in many countermeasures designed to mitigate SCA [49]. These noise sources play a crucial role in significantly diminishing the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) of side-channel leakages, thus increasing the level of complexity in side-channel attacks. For the purpose of reducing the noise level in captured power or EM traces, the SCA community begins to use deep learning techniques, especially autoencoders, to mitigate the effects caused by environmental noise or countermeasures. In [49], the training of the Convolutional Denoising Autoencoder (CDAE) involves learning a unique non-linear mapping that converts noisy traces into clean ones throughout the profiling phase. In the attack stage, reference [49] first uses the trained CDAE autoencoder to obtain the ‘clean’ traces. Afterwards, these traces are applied to a trained classifier to extract the secret key. They test their model on two publicly available datasets. For the DPA_V2 dataset, they use the ID of the register value written in the final round as the power model to train the classifier. By utilizing the trained CDAE model for the denoising process, they achieve using 450 traces to recover the key. As for the ASCAD dataset, they achieve to use 160 traces to reach GE less than 2.

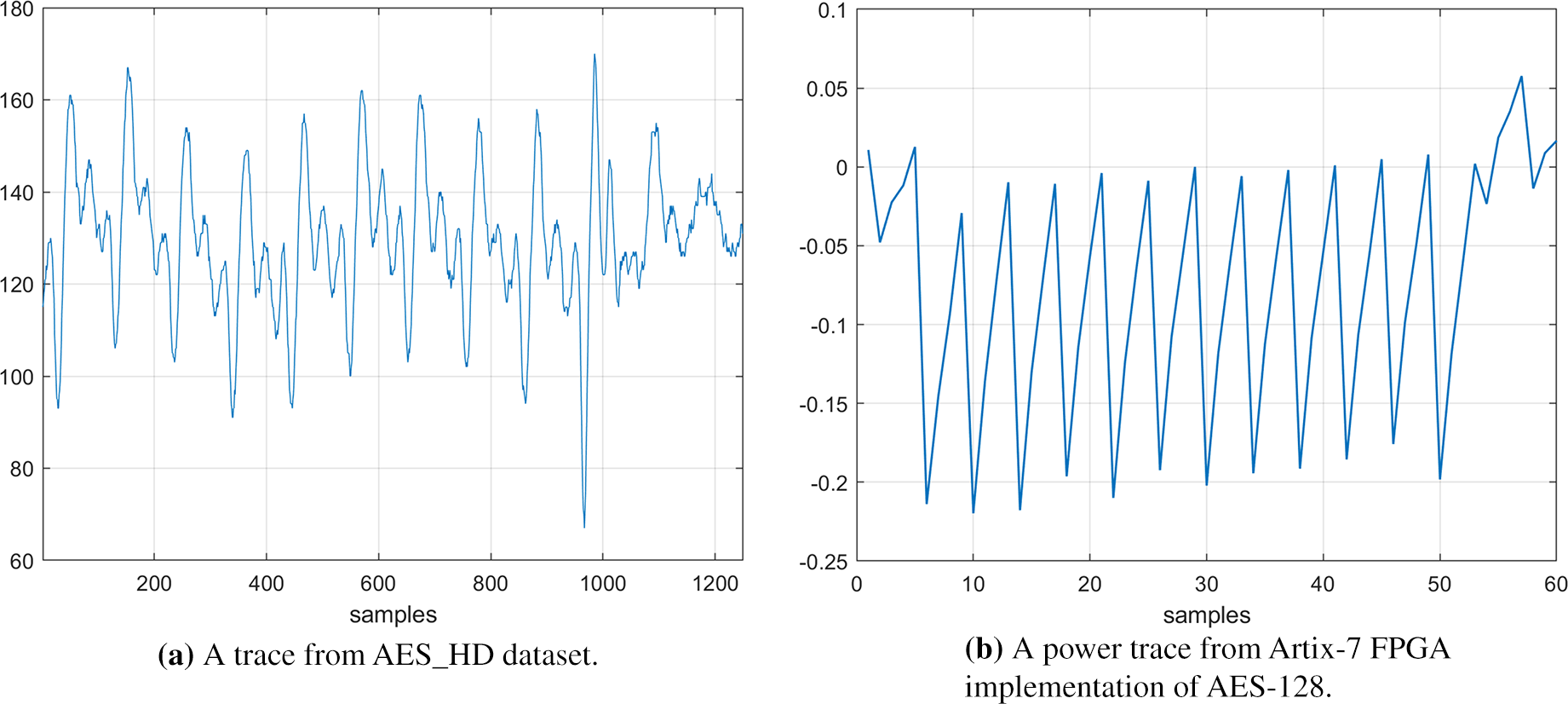

Fig. 9 shows plots of example traces obtained from hardware implementations of AES. Fig. 9a shows a power trace obtained from a Xilinx Virtex-5 FPGA of AES-128 (AES_HD dataset) and Fig. 9b is a trace obtained from a Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA implementation of AES-128. From Fig. 6b in the section of software implementation, distinct operations and executions associated with different subkeys are clearly observable. However, when it comes to the Fig. 9b, we can observe that the trace segment representing 10-round operation of AES-128 obtained from an Artix-7 FPGA implementation execute the entire encryption process within several clock cycles. Intuitively, the task of training deep-learning models becomes more challenging for adversaries due to the requirement of dealing with overlapping features. Besides, by comparing the existing DLSCAs results between software and hardware implementations of AES (as shown in the tables above), it becomes evident that hardware implementations of AES consistently exhibit higher resistance against side-channel attacks compared to software implementations. Considering this, our recommendation for designing a cryptographic module with a focus on DLSCA resistance is to employ hardware implementations accompanied by suitable countermeasures. However, it is unfortunate that many cryptographic modules, particularly those utilized in lightweight IoT edge computing devices, continue to rely on unprotected software implementations due to resource limitations [17]. This leaves a significant number of systems vulnerable to the potential compromise of information security through practical, non-invasive, and highly effective attacks. It is imperative to recognize the existing threat landscape and take proactive measures to address these vulnerabilities.

Figure 9: Graphs of traces collected from hardware implementations of AES. The initial figure depicts a power trace collected from a Xilinx Virtex-5 FPGA of AES-128 (AES_HD dataset) and the second plot shows a power trace obtained from a Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA implementation of AES-128

This section begins with a discussion of the performance of deep learning models used in SCAs. Afterwards, we expand the discussion a bit on the unresolved issues in DLSCAs on AES, followed by an exploration of potential mitigation strategies.

The characteristics of the dataset exert a direct influence on the selection of DL models. For sequential side-channel trace datasets (e.g., ASCAD, AES_RD), where traces exhibit temporal or local feature correlations, CNNs are well-suited for extracting local sequential features through their convolutional layers [96], while Transformers demonstrate superior performance in capturing long-range dependencies via self-attention mechanisms [115]. For datasets with high noise levels and low feature dimensions (e.g., early traces in DPA_V2), MLPs are applicable for basic feature fitting; their performance can be further improved through integration with CNNs or Transformers to achieve enhanced robustness. For graph-structured datasets (e.g., datasets where side-channel trace dependencies are modeled as graphs), GNNs are the only models capable of effectively learning the inter-node relationships within the graph [47].

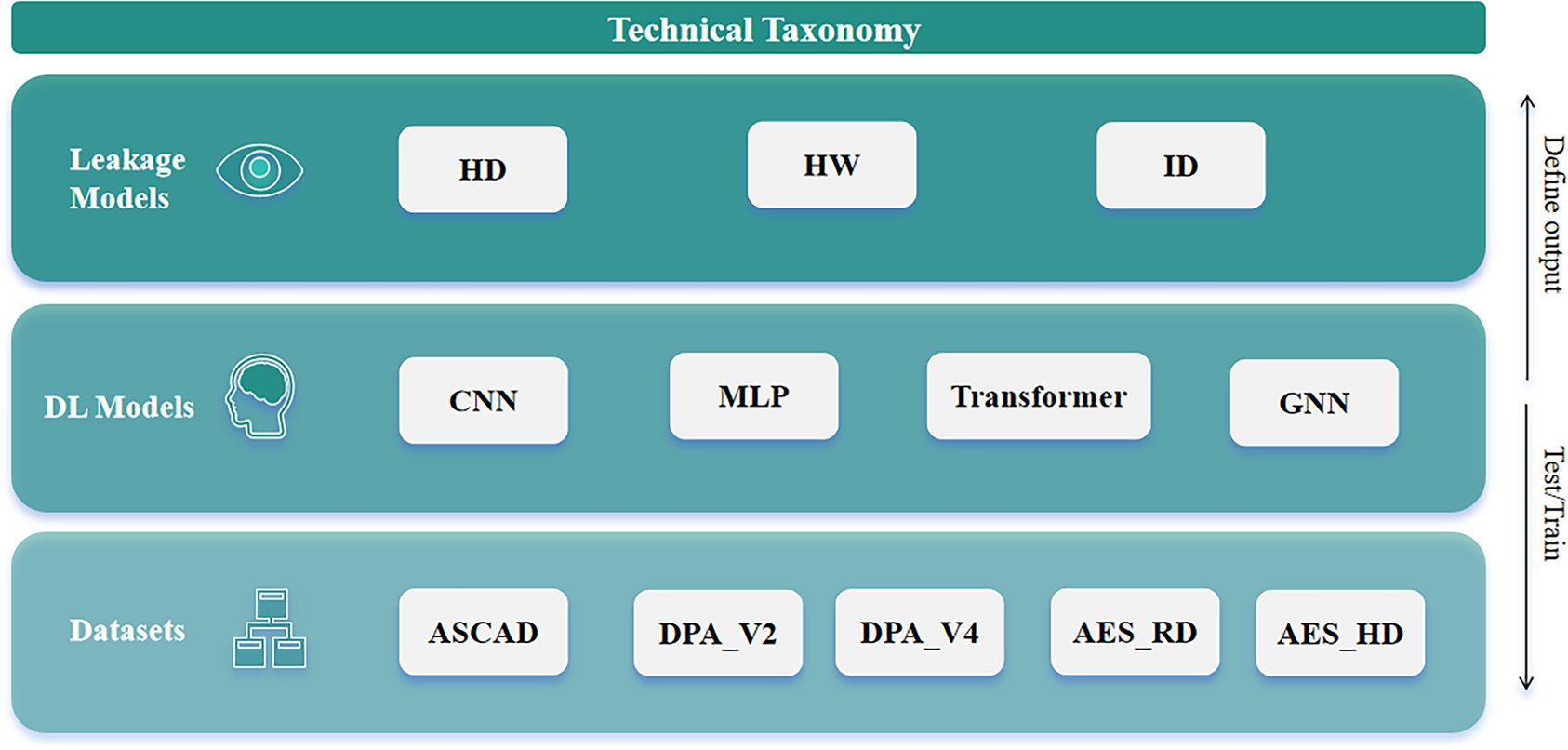

The complexity of leakage patterns dictates the level of “expressiveness” demanded of a DL model. For the ID leakage model, in which leakage exhibits a direct mapping to sensitive data and follows a simplistic pattern, the multilayer perceptron structure of MLPs can adequately fit such linear or weakly nonlinear relationships [88]. For the HD and HW leakage models, in which leakage involves fine-grained patterns related to bit differences or bit weights, the local feature extraction capability of CNNs and the global pattern capture ability of Transformers prove crucial, these models enable the excavation of subtle bit-level patterns corresponding to HD/HW from side-channel traces. In summary, the “complexity level” of the leakage model requires that the DL models possess commensurate feature learning capabilities, ranging from basic fitting to advanced pattern recognition. A technical taxonomy for DL-based side-channel analyses is shown in the Fig. 10.

Figure 10: A technical taxonomy for DL-based side-channel analyses, comprising leakage models, DL models, and datasets

4.2 Analysis on Deep Learning Models

Deep learning methods have grown progressively prominent within the domain of SCAs due to their capacity to deal with complex patterns from side-channel measurements. As highlighted in this work, well-trained deep learning models have proven to be significantly more efficient at extracting secret keys from side-channel traces compared to traditional signal processing methods, especially when the leakage in the captured traces is relatively low. In this subsection, we expand on how different deep learning models discussed in this paper are suited for various attack scenarios.

MLPs are among the simplest deep learning models used in SCAs, typically applied when the side-channel traces are already pre-processed or feature-engineered. For example, as described in Section 3, it is feasible to achieve a high single-trace success rate by using a straightforward MLP model when targeting ATXmega128D4 implementations of AES-128. This is because the traces leaked from the target are typically well-synchronized and noise-filtered.

CNNs, by contrast, are highly effective in capturing spatial hierarchies within data, making them well-suited for side-channel traces, especially when dealing with noisy, desynchronized traces or devices implementing countermeasures. CNNs apply convolutional layers to extract local features in the data, making them especially efficient in identifying subtle leakage patterns without the need for manual feature engineering. In side-channel analysis, CNNs can learn to identify both spatial (across multiple samples) and temporal (across successive clock cycles) correlations, which is critical for capturing key-dependent information from traces. For instance, CNNs have been shown to outperform MLPs in cases where traces contain low leakage levels or are noisy, as they are better at identifying the underlying features that correspond to the secret key. A major benefit of CNNs is their capacity to work with raw side-channel data, reducing the reliance on prior data processing steps and improving attack efficiency, especially in large-scale datasets.