Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Lexical-Prior-Free Planning: A Symbol-Agnostic Pipeline that Enables LLMs and LRMs to Plan under Obfuscated Interfaces

Graduate School of Information, Production and Systems, Waseda University, Kitakyushu, 808-0135, Japan

* Corresponding Author: Zhendong Du. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 12 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074520

Received 13 October 2025; Accepted 16 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Planning in lexical-prior-free environments presents a fundamental challenge for evaluating whether large language models (LLMs) possess genuine structural reasoning capabilities beyond lexical memorization. When predicates and action names are replaced with semantically irrelevant random symbols while preserving logical structures, existing direct generation approaches exhibit severe performance degradation. This paper proposes a symbol-agnostic closed-loop planning pipeline that enables models to construct executable plans through systematic validation and iterative refinement. The system implements a complete generate-verify-repair cycle through six core processing components: semantic comprehension extracts structural constraints, language planner generates text plans, symbol translator performs structure-preserving mapping, consistency checker conducts static screening, Stanford Research Institute Problem Solver (STRIPS) simulator executes step-by-step validation, and VAL (Validator) provides semantic verification. A repair controller orchestrates four targeted strategies addressing typical failure patterns including first-step precondition errors and mid-segment state maintenance issues. Comprehensive evaluation on PlanBench Mystery Blocksworld demonstrates substantial improvements over baseline approaches across both language models and reasoning models. Ablation studies confirm that each architectural component contributes non-redundantly to overall effectiveness, with targeted repair providing the largest impact, followed by deep constraint extraction and step-wise validation, demonstrating that superior performance emerges from synergistic integration of these mechanisms rather than any single dominant factor. Analysis reveals distinct failure patterns between model types—language models struggle with local precondition satisfaction while reasoning models face global goal achievement challenges—yet the validation-driven mechanism successfully addresses these diverse weaknesses. A particularly noteworthy finding is the convergence of final success rates across models with varying intrinsic capabilities, suggesting that systematic validation and repair mechanisms play a more decisive role than raw model capacity in lexical-prior-free scenarios. This work establishes a rigorous evaluation framework incorporating statistical significance testing and mechanistic failure analysis, providing methodological contributions for fair assessment and practical insights into building reliable planning systems under extreme constraint conditions.Keywords

Planning serves as a crucial capability that bridges high-level intentions with low-level execution. Traditional symbolic planning systems rely on explicitly defined predicates and action models, employing heuristic search, hierarchical task networks (HTN), or satisfiability solving (SAT/SMT) to identify action sequences in state spaces that satisfy goal constraints. STRIPS/ADL established standard semantics, Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL) provided unified representations for domains and problems, Graphplan and the FF/FD series laid solid foundations for heuristic construction and holistic solving frameworks, while SAT/SMT-based approaches demonstrated excellence in complex constraint and optimization scenarios. Validators such as VAL provide formal guarantees for plan correctness. This classical paradigm of “explicit models + systematic search” emphasizes structural interpretability and verifiability.

In recent years, LLMs have demonstrated the potential of “language as model”: through prompt engineering, chain-of-thought (CoT), tool usage, or program sketch generation, models can directly generate plans or intermediate subgoals within natural language space. Text-to-PDDL efforts attempt to translate natural language into formalized descriptions usable by classical planners. However, recent investigations have exposed fundamental limitations: when symbolic interfaces (predicate/action names) are decoupled from natural semantics through obfuscation—retaining only their structural roles—existing LLMs or Large Reasoning Models (LRMs) exhibit severe performance degradation [1,2]. This phenomenon reveals a critical research gap: models’ apparent planning success largely depends on lexical priors and script-like co-occurrences in training data rather than genuine structural reasoning about preconditions, effects, and state transitions.

Research Gap and Motivation. While prior work has extensively documented this lexical dependency problem, three fundamental questions remain unaddressed: First, can models achieve reliable planning performance when lexical priors are completely removed? Existing baseline approaches show near-zero success rates in Mystery domains, but it remains unclear whether systematic methods can overcome this barrier. Second, what mechanisms enable structural reasoning without semantic cues? The field lacks concrete solutions that operate purely on logical consistency rather than lexical matching. Third, how do validation-driven approaches compare to raw model capabilities in such extreme conditions? Understanding whether systematic verification matters more than intrinsic model capacity has important implications for building reliable AI systems.

Addressing these gaps is critical for several reasons:

• Theoretical necessity: Genuine planning capabilities must be independent of surface lexical forms—a system that only works with familiar vocabulary cannot claim true structural reasoning.

• Practical robustness: Real-world applications often encounter novel domains where training-time vocabulary associations are unavailable or misleading.

• Evaluation rigor: Without lexical-prior-free testing, we cannot distinguish memorization from reasoning, leading to overestimated capabilities.

• System reliability: As AI systems assume critical decision-making roles, verification mechanisms become essential safety infrastructure.

Our Approach and Contributions. This paper addresses the question: under lexical-prior-free symbolic interfaces, how can models construct executable plans that achieve specified goals? We propose a symbol-agnostic closed-loop planning pipeline that enables structured reasoning through systematic validation and iterative refinement. Our approach implements a complete generate-verify-repair cycle comprising six processing components (semantic comprehension, language planner, symbol translator, consistency checker, STRIPS simulator, VAL validator) and two control components (repair controller, signal aggregator). The system operates entirely on structural relationships—preconditions, effects, state dependencies—without any name-based semantic inference.

Comprehensive evaluation on PlanBench Mystery Blocksworld demonstrates that our method achieves 46.2%–48.0% success rates across GPT-4 (Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4) [3], GPT-4o (Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 Omni) [3], and o1-mini [4], representing more than 10-fold improvements over baseline direct generation (0%–19.1%). A particularly noteworthy finding is the convergence of final success rates across models with vastly different intrinsic capabilities, suggesting that systematic validation and repair mechanisms play a more decisive role than raw model capacity in lexical-prior-free scenarios. We adhere to fair evaluation standards consistent with existing benchmarks (LLMs: GPT-4/4o; LRMs: o1-mini; index boundary filtering), providing systematic evidence from holistic to mechanistic levels through rigorous statistical protocols (Wilson CI, two-proportion z-tests, effect size

Novelty and Contributions. This work makes four distinct contributions to the field:

• Methodological novelty: We propose the first complete symbol-agnostic closed-loop planning pipeline specifically designed for lexical-prior-free environments, introducing targeted repair strategies (First-Step Constraint, Precondition Probing, Parameter Swap & Landmarks, Budget-Adaptive Retry) that address empirically identified failure patterns.

• Evaluation rigor: We establish comprehensive evaluation protocols incorporating Wilson confidence intervals, two-proportion z-tests, effect size measures, temporal robustness analysis, retry benefit curves, hazard risk profiles, and NPMI association analysis—providing reproducible evidence that withstands statistical scrutiny beyond existing benchmarks.

• Mechanistic insights: We reveal distinct failure patterns between model types (LLMs struggle with local precondition satisfaction; reasoning models face global goal achievement challenges) and demonstrate how validation-driven mechanisms enable performance convergence across heterogeneous models, advancing understanding of when and why systematic verification matters.

• Practical contribution: We provide fairness-aware data specifications (index boundary filtering), chart-to-script mappings for reproducibility, and empirical evidence that

These contributions establish that structural reasoning without lexical priors is achievable through systematic validation-driven approaches, with implications extending to program synthesis, theorem proving, and other multi-step reasoning tasks requiring verifiable correctness guarantees. To facilitate comprehension of specialized terminology for readers less familiar with planning formalisms and statistical methodologies, Fig. 1 provides visual explanations and plain-language descriptions of key technical concepts used throughout this work.

Figure 1: Comprehensive glossary of technical terminology used in this paper. Left column: Planning and formal methods concepts. Right column: Statistical and evaluation metrics

This chapter systematically reviews research progress related to lexical-prior-free planning. We first review the development of symbolic planning, analyzing the capabilities and limitations of existing planning systems. We then survey research on LLMs applications in planning tasks, focusing on their performance and dependency patterns. Next, we examine verification-driven and repair-based approaches, highlighting critical distinctions from our symbol-agnostic pipeline. We then analyze related work on symbol obfuscation and lexical-prior-free evaluation. Finally, we review research progress in planning evaluation methodologies.

2.1 PDDL Planning Language and Symbolic Planning Research

2.1.1 PDDL’s Formalization Framework

The PDDL was proposed by [5] and has become the standard language for symbolic planning. Understanding the structural nature of PDDL is crucial for analyzing the feasibility of lexical-prior-free approaches, as the core assumption of obfuscation techniques is that the logical dependencies of planning reasoning are independent of specific lexical choices.

PDDL employs a modular design where domain definitions

• Type system

• Predicate signatures

• Action schemas

PDDL supports multiple semantic models, with STRIPS semantics [6] being the most fundamental and widely used. In the STRIPS model, states are represented as sets of atomic predicates, and action effects are divided into add effects add

Given initial state

1. For all

2.

The key insight of this formalization framework is that plan executability and correctness are entirely determined by structural relationships (precondition satisfaction, state transition logic) rather than the specific meanings of symbols.

2.1.2 Development of Classical Planning Algorithms

Based on the PDDL framework, the development of symbolic planning algorithms provides important insights for understanding structured reasoning. The FF planner proposed by [7] demonstrated how to utilize structural information for efficient reasoning through heuristic search and the concept of helpful actions. FF’s success indicates that effective planning reasoning depends on accurate modeling of precondition and effect relationships, providing an important reference framework for analyzing LLM planning capabilities.

The Fast Downward system developed by [8] further demonstrated the importance of structured representation. The system achieved performance breakthroughs through multi-level abstraction and precise state transition modeling. More importantly, Fast Downward provided a standardized experimental platform for planning research, and its rigorous correctness verification mechanisms laid the technical foundation for subsequent LLM planning evaluation.

2.1.3 Theoretical Analysis of Computational Complexity and Reasoning Capabilities

Theoretical analysis proposed by [9] provides important insights for understanding the nature of planning reasoning. They proved the PSPACE-completeness of STRIPS planning, indicating that even under the most simplified STRIPS framework, planning remains a computationally hard problem requiring structured reasoning rather than simple pattern matching. This theoretical result has important implications for analyzing LLM planning capabilities: if models truly master planning reasoning abilities, they should be able to handle such computational complexity rather than relying solely on lexical patterns.

HTN planning proposed by [10] reduces search complexity by introducing domain knowledge, but the success of this approach precisely illustrates the important impact of domain knowledge on planning performance. Recent work has explored alternative complexity management strategies through collaborative approaches where multiple language model instances coordinate to solve planning problems, demonstrating effectiveness in related reasoning tasks such as machine translation, sentiment analysis, and text summarization [11]. However, these multi-model approaches typically rely on semantic information exchange and domain-specific coordination mechanisms. This observation provides theoretical support for lexical-prior-free evaluation: by removing domain-specific lexical cues, the pure reasoning capabilities of models can be assessed more accurately, independent of coordination strategies or semantic priors.

2.2 Research on LLMs Applications in Planning Tasks

2.2.1 Exploration of Early Direct Generation Methods

The application of LLMs in planning tasks began with attempts at direct sequence generation. Reference [12] first systematically studied the potential of language models in planning tasks by fine-tuning GPT-2 [13] models to generate simple action sequences. The important finding of this research was that models performed well in controlled environments but had significant limitations when handling complex causal relationships, particularly in tasks requiring precise state tracking.

The introduction of chain-of-thought techniques brought new possibilities to planning tasks. Reference [14] proposed chain-of-thought reasoning that significantly improved performance on complex reasoning tasks by guiding models through structured reasoning (state analysis

2.2.2 Research on Structured Approaches and Tool Enhancement

Recognizing the limitations of direct generation methods, researchers began exploring more structured approaches. Reference [15] proposed template-based planning methods that significantly reduced the proportion of invalid plans by constraining the generation process through predefined action templates. The key insight of this work is that structured constraints can improve plan executability, but template design still relies on domain-specific knowledge.

Reference [16] systematically analyzed the possibilities of combining LLMs with symbolic planners. Their research showed that LLMs have advantages in understanding natural language descriptions but still need to rely on traditional planners’ verification mechanisms to ensure logical consistency. This finding directly supports the necessity of adopting validation-driven methods in this paper.

2.2.3 Discovery and Analysis of Performance Limitations

The groundbreaking research by [1] first systematically exposed the fundamental limitations of LLMs in planning tasks. Through comprehensive evaluation on standard planning benchmarks, they found that even the most advanced models performed poorly on tasks requiring precise logical reasoning. More importantly, they identified models’ strong dependence on domain knowledge in training data.

Reference [17] further analyzed the nature of LLM planning capabilities. Through controlled experiments, they found that model success largely depends on memory of common scenarios rather than genuine causal reasoning abilities. This finding has important implications for understanding the cognitive capability boundaries of LLMs.

Reference [18] specifically studied GPT-4’s performance on classical planning tasks, finding that even the latest models still have significant defects in tasks requiring multi-step reasoning. Their analysis showed that models tend to generate plans that “look reasonable” but are logically incorrect. Reference [19] extended this evaluation to reasoning-enhanced models, specifically assessing OpenAI’s o1-mini on PlanBench, and confirmed that even with enhanced reasoning capabilities, models still cannot reliably plan without systematic validation when lexical priors are removed.

2.3 Verification-Driven and Repair-Based Approaches

Recent advances in LLM reasoning have increasingly emphasized iterative refinement through external feedback mechanisms. Representative approaches include ReAct [20], which interleaves reasoning traces with environment actions, and Reflexion [21], which employs verbal self-reflection to learn from task failures. While these verification-driven paradigms demonstrate substantial improvements on complex reasoning tasks, they operate under fundamentally different constraints than our symbol-agnostic pipeline.

Critical Distinctions from Our Approach

ReAct generates reasoning traces (“thoughts”) alongside actions, leveraging environmental observations to guide dynamic replanning in tasks like question answering and web navigation. Reflexion extends this through episodic memory and verbal self-reflection, where models generate natural language summaries of failures to improve subsequent attempts. Both approaches achieve strong performance in semantically rich environments but rely fundamentally on interpretable symbolic interfaces.

Our approach differs across four critical dimensions:

Lexical Prior Dependency. ReAct and Reflexion operate where action names and feedback maintain natural semantics, enabling models to leverage training-time associations. Our pipeline addresses complete lexical obfuscation where symbols like “overcome” or “province” bear no relationship to planning concepts. This qualitative distinction renders language-based reflection ineffective (baseline: 0%–19.1% success), while our formal verification mechanisms achieve 46.2%–48.0% success rates.

Verification Mechanisms. Existing approaches use language-based feedback—environmental observations in ReAct, verbal critiques in Reflexion—requiring semantic understanding. We employ formal verification through STRIPS simulation and VAL validation, operating purely on structural logic (precondition satisfaction, state transitions) without symbol semantics, providing rigorous correctness guarantees.

Repair Strategy Specificity. ReAct and Reflexion adopt general-purpose refinement strategies: regenerating reasoning traces or adjusting high-level plans based on verbal feedback. Our repair controller implements four specialized strategies (First-Step Constraint, Precondition Probing, Parameter Swap & Landmarks, Budget-Adaptive Retry) targeting distinct structural failure modes identified through empirical analysis—interventions impossible without formal state tracking.

Evaluation Scope. ReAct and Reflexion are evaluated on tasks where semantic priors aid reasoning (web navigation, household tasks with meaningful action names). Our evaluation protocols target the lexical-prior-free regime with rigorous statistical testing (Wilson CI, effect sizes, hazard profiles), assessing genuine structural reasoning independent of lexical memorization.

These distinctions align with cognitive science perspectives on abstraction [22,23]: while ReAct and Reflexion advance iterative refinement in semantically grounded environments, they do not address reasoning when semantic scaffolding is removed. Our work demonstrates that systematic validation and repair, when designed for symbol-agnostic operation through formal verification, can achieve reliable performance where lexical priors are completely absent—establishing a complementary paradigm for systems facing novel domains or adversarial settings where training-time associations are unavailable.

Recent work has further emphasized the necessity of external verification for reliable planning. Reference [24] provided a systematic analysis categorizing LLM contributions to planning into three roles: solver, verifier, and heuristic provider, demonstrating that verification-driven workflows significantly outperform direct generation across multiple benchmarks. These developments reinforce our core thesis that validation-driven closed-loop mechanisms are not merely beneficial but essential for achieving reliable planning under symbol-agnostic conditions.

2.4 Symbol Obfuscation and Lexical Prior Removal Research

2.4.1 Identification of the Lexical Prior Problem

The impact of lexical priors on AI system performance was first identified in the knowledge representation field. Reference [25] pointed out that many seemingly intelligent behaviors are actually memory of patterns in training data rather than genuine reasoning capabilities. This observation provided a theoretical foundation for subsequent lexical-prior-free research.

In the planning field, reference [2] first explicitly proposed the concept of lexical priors. Through comparative experiments, they found that when using familiar domain vocabulary (such as “pick-up,” “put-down”), LLMs performed well, but this performance mainly came from memory of common patterns in training corpora.

Reference [26] further deepened this understanding by proposing the “System 1” vs. “System 2” analytical framework. They argued that LLMs primarily rely on fast pattern recognition (System 1) while lacking deep logical reasoning capabilities (System 2). This analysis provides important insights for understanding the nature of LLM planning capabilities.

2.4.2 Design and Implementation of PlanBench Mystery Domains

The core contribution of PlanBench [27] is the systematic construction of “Mystery” domains, which provides a standardized technical framework for lexical-prior-free evaluation. Mystery domains use symbol obfuscation techniques to replace all predicate and action names in classical planning domains with semantically neutral random vocabulary, thereby cutting off lexical cues that models might depend on.

Formal Definition of Obfuscation Mapping

The construction of Mystery domains is based on bijective mapping

• Arity preservation:

• Type consistency: Type hierarchy structure

• Structural isomorphism: Logical structure of preconditions and effects is completely preserved

Concrete Example: Blocks World Obfuscation

Taking the classical Blocks World domain as an example, the original domain (Listing 1) includes the following core elements:

Listing 1: Original Blocks World Domain

(:predicates

(clear ?x - block)

(holding ?x - block)

(on ?x ?y - block)

(ontable ?x - block)

(handempty))

(:action pick-up

:parameters (?x - block)

:precondition (and (clear ?x) (ontable ?x) (handempty))

:effect (and (not (ontable ?x)) (not (clear ?x))

(not (handempty)) (holding ?x)))

After obfuscation, the Mystery domain (Listing 2) might become:

Listing 2: Obfuscated Mystery Domain

(:predicates

(province ?x - block) ; originally clear

(pain ?x - block) ; originally holding

(planet ?x ?y - block) ; originally on

(harmony ?x - block) ; originally ontable

(craves)) ; originally handempty

(:action overcome

:parameters (?x - block)

:precondition (and (province ?x) (harmony ?x) (craves))

:effect (and (not (harmony ?x)) (not (province ?x))

(not (craves)) (pain ?x)))

Mapping Consistency and Verification

The obfuscation process ensures consistency: within a single evaluation, the mapping remains fixed to avoid “same word, different meaning” interference. The obfuscated domain is verified through the VAL validator to confirm logical equivalence with the original domain. For example, whether it’s ‘(clear a)’ or ‘(province a)’, their roles in state transitions are identical.

Semantically Neutral Random Replacement

The construction of Mystery domains employs a strict random replacement strategy, randomly selecting replacement vocabulary from a predefined semantically neutral vocabulary. Key characteristics include:

• Complete semantic irrelevance: Replacement vocabulary (such as planet, province, pain, harmony, craves, etc.) is completely unrelated to original planning concepts, avoiding any semantic cues.

• Randomness guarantee: The vocabulary selection process is random, not based on semantic similarity or any meaningful associations. For example, the ‘clear’ predicate representing the “clear” concept might be replaced by ‘province’, having no connection to spatial or political concepts.

• Consistency constraints: Although selection is random, mappings remain fixed within a single evaluation, ensuring ‘clear’ always corresponds to ‘province’, avoiding “same word, different meaning” confusion.

2.4.3 Development of Symbol Obfuscation Techniques

The proposal of PlanBench marks the formal establishment of lexical-prior-free evaluation methods. Reference [27] designed a systematic symbol obfuscation framework that cuts off lexical cues models might depend on by replacing predicate and action names with semantically neutral random vocabulary.

Building on these foundations, recent work has continued to explore LLM robustness under obfuscation. Reference [28] evaluated frontier models (GPT-5, Gemini 2.5 Pro) on both standard and obfuscated PDDL tasks, finding that while performance on standard tasks now competes with classical planners like LAMA, obfuscation still causes significant degradation—confirming persistent reliance on token semantics despite architectural improvements. Notably, their work identifies Gemini 2.5 Pro as exhibiting reduced sensitivity to obfuscation compared to earlier models, suggesting incremental progress in symbolic reasoning capabilities. Reference [29] introduced PLANET, a comprehensive benchmark collection specifically designed to evaluate LLM planning capabilities across diverse obfuscation strategies, providing standardized evaluation protocols that complement PlanBench’s Mystery domains.

Reference [30] built upon this by studying the effectiveness of different obfuscation strategies. They compared the effects of random obfuscation, adversarial obfuscation, and structured obfuscation, finding that adversarial obfuscation (using semantically opposite vocabulary) was most effective at exposing models’ lexical dependencies.

Reference [31] proposed more refined obfuscation techniques by maintaining consistency in certain semantic categories to study the role of different levels of lexical knowledge. Their research showed that even abstract semantic category information affects model performance.

These recent advancements validate the continued relevance of symbol-agnostic evaluation while highlighting that raw model improvements alone remain insufficient without systematic validation mechanisms.

2.4.4 Theoretical Analysis of Lexical-Prior-Free Evaluation

Reference [23] analyzed the theoretical foundation of symbol obfuscation from a cognitive science perspective. They argued that genuine intelligence should be able to handle arbitrary symbol systems without depending on specific lexical conventions. This viewpoint provides cognitive science support for lexical-prior-free evaluation.

Reference [22] further discussed the relationship between abstraction capabilities and lexical independence. She pointed out that an important characteristic of higher-level cognitive abilities is the capacity to abstract and transfer between different symbol systems, an area where current AI systems still show significant deficiencies.

Reference [32] proposed similar views in ARC (Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus) research, emphasizing the importance of evaluating systems’ genuine reasoning capabilities rather than memory abilities. Although ARC focuses on visual reasoning, its design philosophy is highly consistent with lexical-prior-free evaluation.

2.5 Research Development in Planning Evaluation Methods

2.5.1 Development of Planning Evaluation Frameworks

The development of planning evaluation methods is closely related to understanding the nature of planning capabilities. Reference [33] emphasized the importance of standardized evaluation at the AIPS-2000 conference, particularly noting that the lack of unified correctness standards was an important factor hindering progress in planning research. This viewpoint provided important impetus for subsequently establishing rigorous verification mechanisms.

The establishment of the International Planning Competition (IPC) [34] confirmed a multi-dimensional evaluation framework whose core principle is that planning algorithm evaluation must be based on rigorous correctness verification, not merely surface performance metrics. This principle has important guiding significance for understanding LLM planning capabilities as it emphasizes the importance of structured verification relative to heuristic evaluation.

2.5.2 Development of Validation Tools

The development of VAL represents an important advance in planning evaluation technology. Reference [35] designed a complete PDDL validation framework, providing authoritative correctness checking tools for the entire planning community. VAL’s importance lies not only in its technical implementation but also in establishing unified validation standards.

Reference [36] further extended validation technology in their PDDL+ research, addressing validation problems for continuous time and hybrid systems. Their work showed that as planning language expressiveness increases, validation technology must develop accordingly.

Reference [37] developed comparative frameworks for various validation tools, systematically analyzing the advantages and disadvantages of different validation methods. Their research provided guidance for selecting appropriate validation tools.

Recent developments have further advanced planning evaluation methodologies. Reference [38] conducted comprehensive studies on error detection and correction in PDDL domain models, revealing that LLMs demonstrate stronger capabilities in translation tasks than in direct planning, supporting our design decision to separate semantic comprehension from plan generation. This finding emphasizes the importance of rigorous validation mechanisms when employing LLMs in planning workflows—a principle we adopt throughout our evaluation protocol by using VAL for sound plan verification.

We can see that: the symbolic planning field has developed mature theoretical foundations and technical frameworks; applications of LLMs in planning tasks have made progress but still face fundamental limitations; verification-driven approaches like ReAct and Reflexion have advanced iterative refinement in semantically rich environments through language-based feedback, yet the lexical-prior-free regime remains unaddressed; symbol obfuscation techniques provide effective means for rigorous evaluation of structural reasoning capabilities; and the continuous development of evaluation methods provides important support for research progress. These research achievements collectively lay a solid foundation for the work in this paper.

This chapter proposes a Symbol-Agnostic Planning Pipeline that aims to construct a verifiable and repairable end-to-end planning system under lexical-prior-free constraints. Through modular design, this method achieves structured reasoning that relies entirely on the logical consistency of preconditions, effect relationships, and state dependencies, rather than lexical semantic cues.

3.1 Problem Formulation and Design Objectives

3.1.1 Core Challenges and Problem Setting

Based on the analysis of related work in Section 2, existing LLMs exhibit significant deficiencies in planning capabilities under lexical-prior-free conditions. Specifically:

• Insufficient structural reasoning capabilities: As demonstrated by [1], model failures in Mystery domains are primarily dominated by unsatisfied preconditions and state transition errors, reflecting a lack of understanding of PDDL structural semantics.

• Over-reliance on lexical dependencies: Related work shows that traditional methods based on lexical matching or templates completely fail in symbol obfuscation environments, exposing excessive dependence on surface semantic cues.

• Lack of systematic repair strategies: Existing methods lack structured repair mechanisms based on validation feedback, failing to effectively utilize failure information provided by validation tools like VAL for iterative improvement.

3.1.2 Design Principles and Symbol-Agnostic Mechanisms

Based on the above challenge analysis, this paper’s method follows the following core design principles:

• Structure-first principle: Rely solely on the logical consistency of preconditions, effect relationships, and state dependencies, completely avoiding dictionary matching or semantic inference based on names.

• Validation-driven principle: Establish a “generate

• Budget-aware principle: Maximize success rate within limited attempt budgets, with particular focus on marginal gains in small budget scenarios.

What Makes the System Symbol-Agnostic

Beyond merely processing obfuscated symbols, our system achieves genuine symbol-agnosticism through architectural design where every component operates on structural relationships rather than semantic interpretations. This distinguishes our approach from systems that tolerate random symbols but still rely on semantic reasoning internally:

• Structural constraint extraction: The SC module extracts constraints not through lexical matching (e.g., recognizing “pick-up” patterns) but by parsing PDDL structural relationships directly from domain specifications: which predicates appear in which action preconditions (

• Formal set-theoretic verification: STRIPS simulation operates through set membership checking (

• Structure-preserving translation: The ST module performs bijective mapping based solely on structural signatures extracted from domain specification

• Failure-pattern-driven repair: RC’s four strategies target structural failure modes identified through position-based analysis (step

• Constraint propagation without semantics: When RC updates constraint set C or modifies text plan

This architectural symbol-agnosticism is verifiable: the same pipeline, without modification or recalibration, achieves consistent performance across different obfuscation mappings

Let the set of feasible plans in the obfuscated symbol space be:

where

Given attempt budget

The optimization objective of this method is:

where

3.2 System Overview and Processing Workflow

To provide readers with an intuitive understanding of our approach, we first present the complete end-to-end processing workflow through a concrete example, then detail each component and mechanism in subsequent sections.

Our system adopts a modular pipeline architecture with six core processing components and two auxiliary control components. The system receives natural language task description

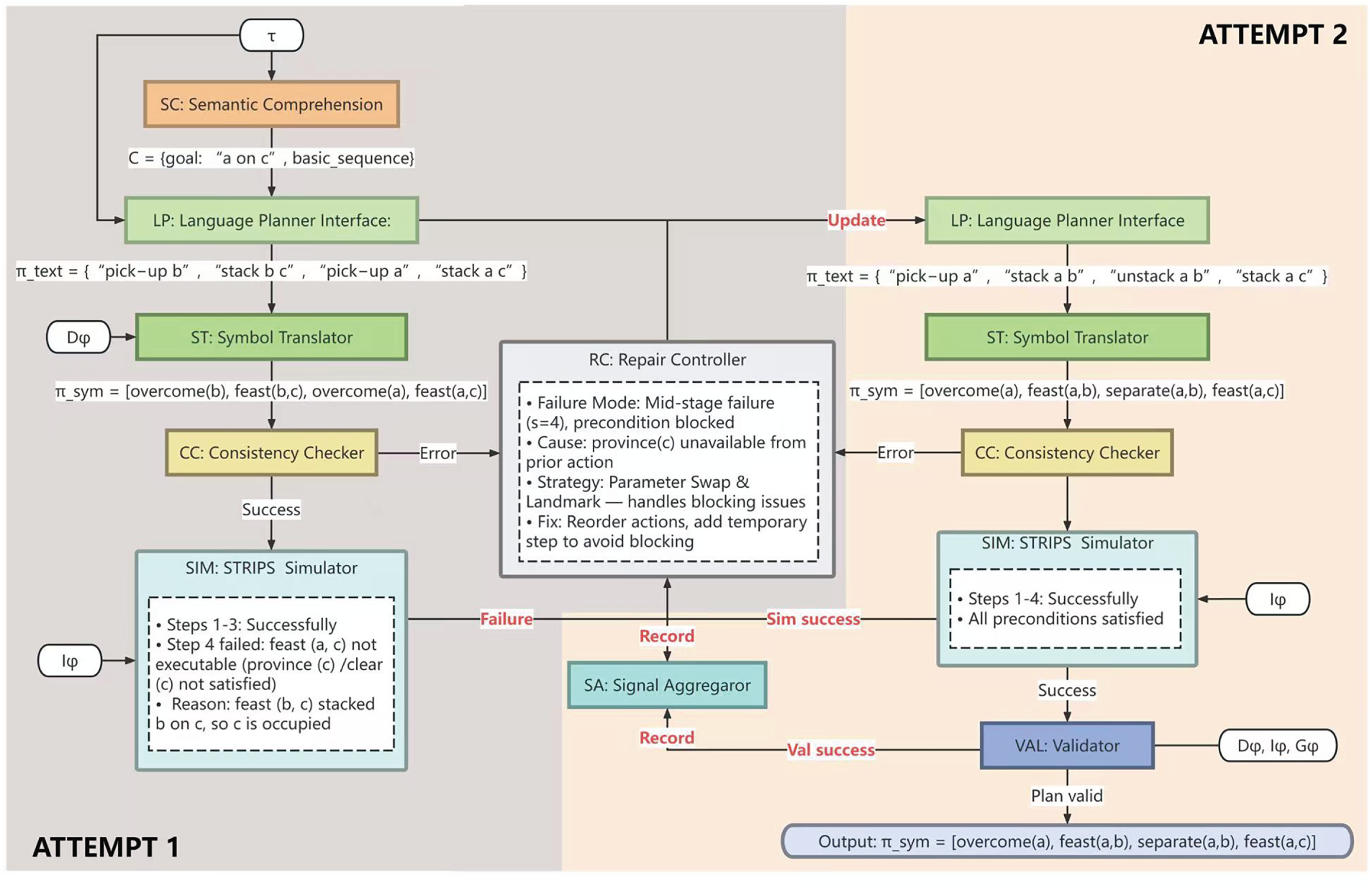

Fig. 2 illustrates the complete workflow through a concrete example with goal “stack a on c” in a Mystery domain. The figure demonstrates:

Figure 2: System architecture and processing workflow of the symbol-agnostic closed-loop planning pipeline illustrated with a two-attempt example

• Data flow progression: How external inputs (

• Mystery domain mappings: The complete symbol obfuscation (pick-up

• Validation checkpoints: Three-tier validation mechanism (CC static checking, SIM step-by-step simulation, VAL semantic validation) with explicit branch points for Pass/Reject decisions.

• Failure-repair cycles: Two complete attempts showing initial failure at step 4 due to blocked preconditions, RC’s strategy selection (Parameter Swap & Landmarks), and successful convergence after repair.

• Signal aggregation: Continuous monitoring by SA component collecting validation signals from all checkpoints throughout the process.

3.2.2 Walkthrough of the Example

The workflow demonstrates two complete processing cycles:

Attempt 1: Initial Generation and Failure Detection

The process begins with SC extracting constraints from task description

The plan passes CC’s static consistency check and enters SIM for execution with initial state

Repair Cycle: Strategic Intervention

RC analyzes the failure pattern—a blocked precondition at mid-segment step—and selects the Parameter Swap & Landmarks strategy from its four available strategies. RC updates constraint set C to include landmark injection and parameter reordering instructions, then feeds this enhanced constraint back to LP for regeneration.

Attempt 2: Repaired Generation and Successful Validation

LP regenerates with updated constraints, producing text plan [“pick-up a”, “stack a b”, “unstack a b”, “stack a c”]. ST translates to: [overcome(a), feast(a,b), separate(a,b), feast(a,c)], where separate is the Mystery symbol for unstack. This enhanced plan includes temporary intermediate actions to avoid blocking.

The repaired plan passes CC’s check, successfully executes all steps in SIM (with SA collecting success signals), and passes VAL’s final semantic validation confirming goal planet(a,c) is achieved. The system outputs the validated symbol plan, demonstrating successful convergence within budget

This example illustrates the core mechanism: validation-driven feedback enables intelligent repair through structured failure analysis, achieving effective planning under lexical-prior-free constraints.

3.3 Core Processing Components

Having seen the overall workflow, we now detail each component’s design and functionality.

3.3.1 Sequential Processing Pipeline

The six core components form the main processing pipeline:

Semantic Comprehension Module (SC)

SC extracts structured constraints from natural language task description

Interface definition:

Language Planner (LP)

LP receives both constraint set C (from SC) and task description

Interface definition:

Symbol Translator (ST)

ST maps text plan

Interface definition:

Consistency Checker (CC)

CC performs static screening before expensive simulation, implementing a binary decision mechanism. Plans with obvious errors (unsatisfied preconditions, parameter type mismatches) are rejected with diagnostic information and sent directly to RC. Valid plans proceed to simulation, reducing computational overhead.

Interface definition:

STRIPS Simulator (SIM)

Plans passing CC enter SIM for step-by-step execution simulation using initial state

Interface definition:

VAL Validator Interface (VAL)

Plans successfully passing SIM proceed to VAL for rigorous semantic validation. Using domain

Interface definition:

3.3.2 Auxiliary Control Components

Two components provide system-wide control and monitoring:

Repair Controller (RC)

RC is the core control component responsible for parsing validation failure signals and executing repair strategies. RC does not directly modify symbol plan

RC implements four core repair strategies:

• First-Step Constraint: When failure occurs at

• Precondition Probing: Perform completion or action replacement based on missing predicate information.

• Parameter Swap & Landmarks: Execute parameter swapping for highly coupled action-predicate pairs, or insert intermediate predicate landmarks (as demonstrated in the workflow example).

• Budget-Adaptive Retry: Dynamically decide continuation strategies based on marginal gains.

Signal Aggregator (SA)

SA operates as a parallel monitoring component, continuously archiving validation signals from CC, SIM, and VAL throughout the entire pipeline. This aggregation supports statistical analysis and interpretability profile generation.

3.4 Data Contracts and System Invariants

Core data artifacts flow through the system:

• Constraint set C: Contains action parameter constraints, required predicate sets, mutual exclusion hints, and type constraints. Flows from SC to LP, and can be updated by RC during repair.

• Text plan

• Symbol plan

• Validation reports: Contains failure steps, missing preconditions, violated constraints, etc. Generated by CC, SIM, and VAL; collected by SA; analyzed by RC.

The system ensures structural consistency through invariants:

• Structure preservation invariant: All translation and repair operations preserve PDDL structural semantics, disallowing name-based semantic inference.

• Validation consistency invariant: All validation operations are strictly executed within the obfuscated symbol space, avoiding semantic leakage.

• Repair locality invariant: Repair operations only affect C and

3.5 Repair Strategies and Budget Management

Based on Mystery domain failure patterns identified by [1], the system implements targeted repair strategies:

• First-step failure (

• Mid-segment failure (

• False cue interference: High-coupling action-predicate pairs discovered through NPMI analysis (e.g., overcome<–>pain) mislead reasoning. Repair prevents false cues through enhanced consistency checking.

The system evaluates marginal gains after each attempt:

When

This chapter’s proposed Symbol-Agnostic Planning Pipeline systematically addresses planning challenges in lexical-prior-free environments through modular design and validation-driven repair mechanisms. The method strictly adheres to structural consistency principles, completely avoiding dependence on lexical semantics, providing an effective approach for evaluating the genuine planning capabilities of LLMs. The next chapter will verify this method’s performance on PlanBench Mystery domains through detailed experiments.

This chapter provides detailed specifications of all aspects of the experimental design, including dataset selection, model configuration, and evaluation metrics, ensuring the reproducibility of experimental results and comparability with existing benchmarks.

4.1.1 PlanBench Mystery Blocksworld

This study adopts Mystery Blocksworld from the PlanBench benchmark proposed by [27] as the primary evaluation domain. Mystery Blocksworld uses symbol obfuscation techniques to replace all predicate and action names in the original Blocksworld domain with semantically irrelevant random vocabulary. As described in Section 2, this obfuscation preserves the integrity of PDDL structural semantics while completely removing lexical priors, providing an ideal testing environment for evaluating models’ pure structural reasoning capabilities. Where necessary, we conducted consistency checks on the logistics and sokoban domains to confirm the structure-preserving properties of obfuscation mappings across different task families.

4.1.2 Instance Selection and Evaluation Standards

To ensure consistency and reproducibility of evaluation standards, this study strictly follows the “index boundary filtering” method from PlanBench’s original scripts to determine the evaluation instance set. This filtering criterion, established by [27] in their original research, effectively controls the distribution of instance scale and complexity. To avoid scale ambiguities arising from data selection terminology, we uniformly adopt the “all data” standard for reporting throughout the main text. All models and configurations are compared on the same instance set, ensuring fairness and comparability of results.

4.1.3 Symbol Obfuscation Consistency Guarantee

In each evaluation run, the obfuscation mapping

4.2 Model and Inference Configuration

To ensure comparability with the research results of [27], this study selects models that overlap with those in their research for evaluation. Specifically, we use GPT-4 and GPT-4o as LLM representatives, and o1-mini as a large reasoning model (LRM) representative. It should be noted that although Reference [2]’s research also included the o1-preview model, this study does not include comparative results for that model due to its discontinued API access. This model selection strategy ensures comparability with existing research while covering the current mainstream range of language model capabilities.

To ensure comparability of cross-model results, all models adopt unified inference parameter configurations. Temperature parameter T, top-p sampling, maximum token count, stop sequences, and system prompts are kept consistent across models. In particular, this study employs a default single-sample generation (

4.3 Prompt Engineering and Component Configuration

The SC and LP modules employ templated prompt strategies with structured slots. The prompt design explicitly includes action parameter placeholders, required predicate set declarations, and mutual exclusion and rejection constraint hints, providing clear structured guidance to models. Particularly emphasized is that the prompt design strictly prohibits any form of name-based semantic analogy or dictionary matching. These constraints ensure that models must rely on structural logic rather than lexical memory for plan generation, complying with lexical-prior-free evaluation requirements.

The ST configuration similarly follows strict structural principles. The translation process only performs structural mapping and type/parameter consistency checking, maintaining strict consistency with the preconditions (pre), add effects (add), and delete effects (del) of domain definition

The CC in this study’s main experiments employs complete static screening mechanisms, covering type consistency checking, invariant verification, and basic reachability analysis. This strict static checking can filter obvious errors before entering expensive simulation validation, improving overall system efficiency. It should be clarified that the main experiments in this paper do not perform strict-off downgrading, always maintaining the strictest static screening settings.

4.4 Budget and Retry Strategies

This study employs the budget set

The system evaluates marginal gain

The feedback routing mechanism routes feedback information to corresponding strategies in the RC (Repair Controller) based on the first failure step

The main experiments in this study employ the complete Symbol-Agnostic Closed-Loop Pipeline (SC

For external comparisons, we compare the results of this method with the aligned standard results publicly reported by [27] under obfuscated/mystery settings. This comparison can intuitively demonstrate the degree of improvement of this method relative to existing techniques.

4.6 Evaluation Metrics and Statistical Methods

Success rate is defined as

Time analysis employs multiple robust statistics to address the skewed distribution of execution times and the impact of outliers. We report median, 90th percentile (p90), and trimmed mean (with trimming parameter

Retry benefit analysis characterizes the relationship between success rate and budget through the

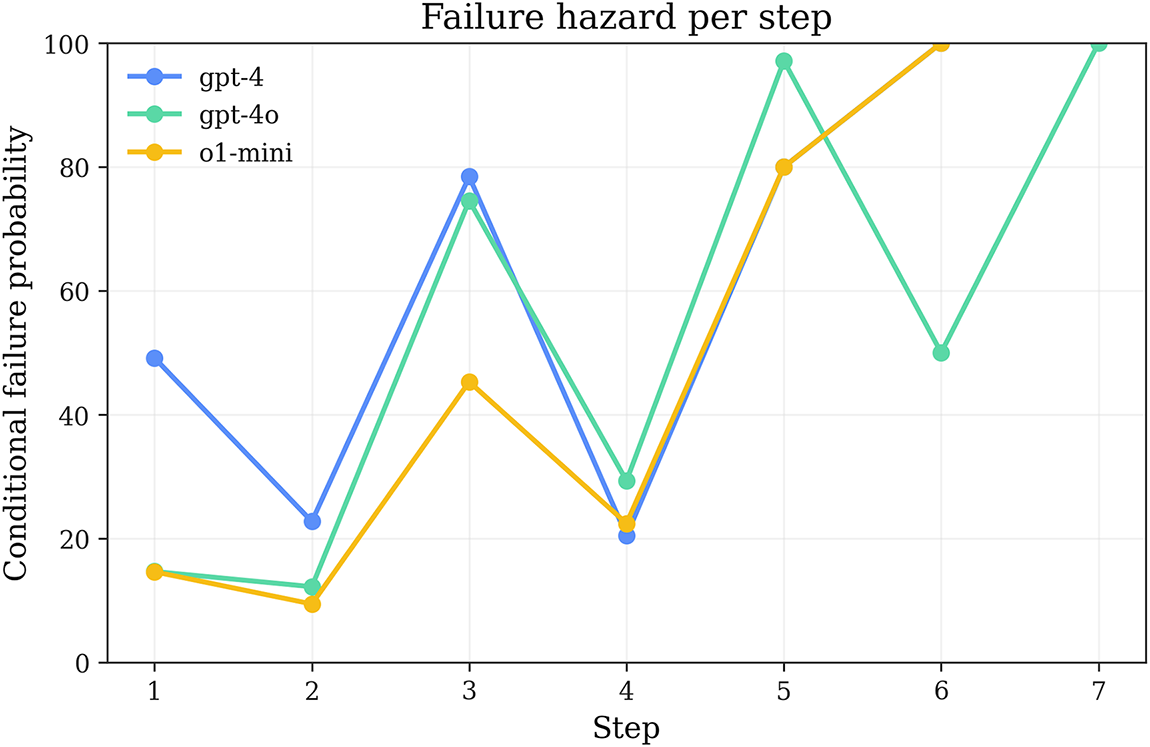

Risk profiling employs the hazard function

Failure component analysis decomposes failure sources into translation errors (translate), simulation errors (sim), and validation errors (val), analyzing the proportions and overlap patterns of each component. Particular attention to high-overlap regions between sim and val can reveal systematic defects—when both validation methods consistently report errors, this often points to deep reasoning problems rather than surface errors. This component decomposition helps understand the root nature and propagation paths of errors.

Semantic association strength analysis employs NPMI to measure association strength between actions and predicates. NPMI is defined as

The complete evaluation framework established in this chapter ensures reproducibility of experimental results, statistical rigor, and comparability with existing research. Through systematic comparison with the benchmark results of [2], we can objectively evaluate the effectiveness of the Symbol-Agnostic Closed-Loop Pipeline proposed in this paper. The next chapter will report detailed experimental results and analysis based on this framework.

This chapter systematically reports and analyzes experimental results. It should be noted that since the baseline study by [2] only publicly reported success rate metrics without releasing complete experimental data including runtime, retry patterns, failure distributions, etc., this chapter conducts method comparison only in the success rate dimension, with all other analyses focusing on the detailed behavioral characteristics of the Symbol-Agnostic Closed-Loop Pipeline proposed in this paper. This analytical strategy ensures comparability with existing research while enabling deep revelation of the working principles of the closed-loop repair mechanism.

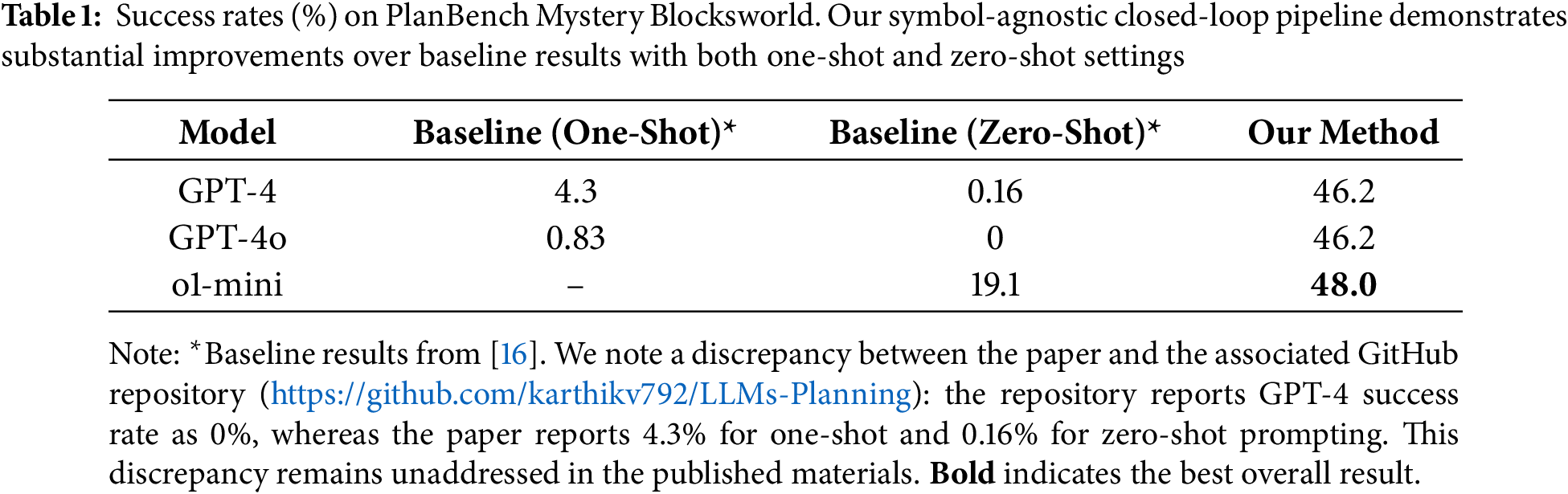

Table 1 presents the overall success rate comparison between our method and baseline methods on PlanBench Mystery Blocksworld. The baseline methods adopt direct generation strategies, where models receive task descriptions and directly output complete plans without verification or repair, evaluated under both one-shot and zero-shot prompting settings.

Results show that our method achieves significant performance improvements across all evaluated models. For GPT-4, the success rate increases from baseline direct generation’s 4.3% (one-shot) and 0.16% (zero-shot) to 46.2%, achieving more than 10-fold absolute improvement. This magnitude of improvement clearly demonstrates the value of the validation-driven closed-loop mechanism—in Mystery domains without lexical priors, relying solely on models’ one-shot generation capabilities makes task completion nearly impossible, while through systematic “generate

The improvement for GPT-4o is even more pronounced, rising from baseline’s 0.83% (one-shot) and 0% (zero-shot) to 46.2%. Notably, GPT-4o’s zero-shot baseline is 0%, meaning not a single direct generation succeeded among 600 evaluation instances, highlighting the extreme challenge posed by Mystery domains’ complete deprivation of lexical prior dependencies. However, equipped with the closed-loop pipeline, GPT-4o achieves the same 46.2% success rate as GPT-4, indicating that when endowed with structured verification and repair capabilities, different LLM architectures tend to converge in final planning quality.

o1-mini, as a representative of large reasoning models, although its zero-shot baseline performance (19.1%) already significantly outperforms GPT-4 and GPT-4o’s direct generation results, still improves to 48.0% through our method’s closed-loop pipeline, achieving the highest success rate among all models. This approximately 29 percentage point absolute improvement has important theoretical significance: it demonstrates that even for models with enhanced reasoning capabilities, systematic validation-driven methods can still bring substantial improvements. o1-mini’s better performance in direct generation scenarios stems from its intrinsic reasoning mechanisms, but this capability does not render the closed-loop repair redundant; rather, it forms a synergistic enhancement effect with the closed-loop mechanism.

It should be emphasized again that the baseline methods employ direct generation strategies, where models have only one generation opportunity without involving verification, repair, or retry processes. Therefore, the comparison between baseline and our method is essentially a comparison between two paradigms: “single-shot generation without feedback” vs. “multi-round validation-driven repair.” Subsequent sections’ detailed analyses of runtime, retry patterns, failure distributions, etc., are specifically focused on the closed-loop pipeline proposed in this paper and do not apply to baseline methods.

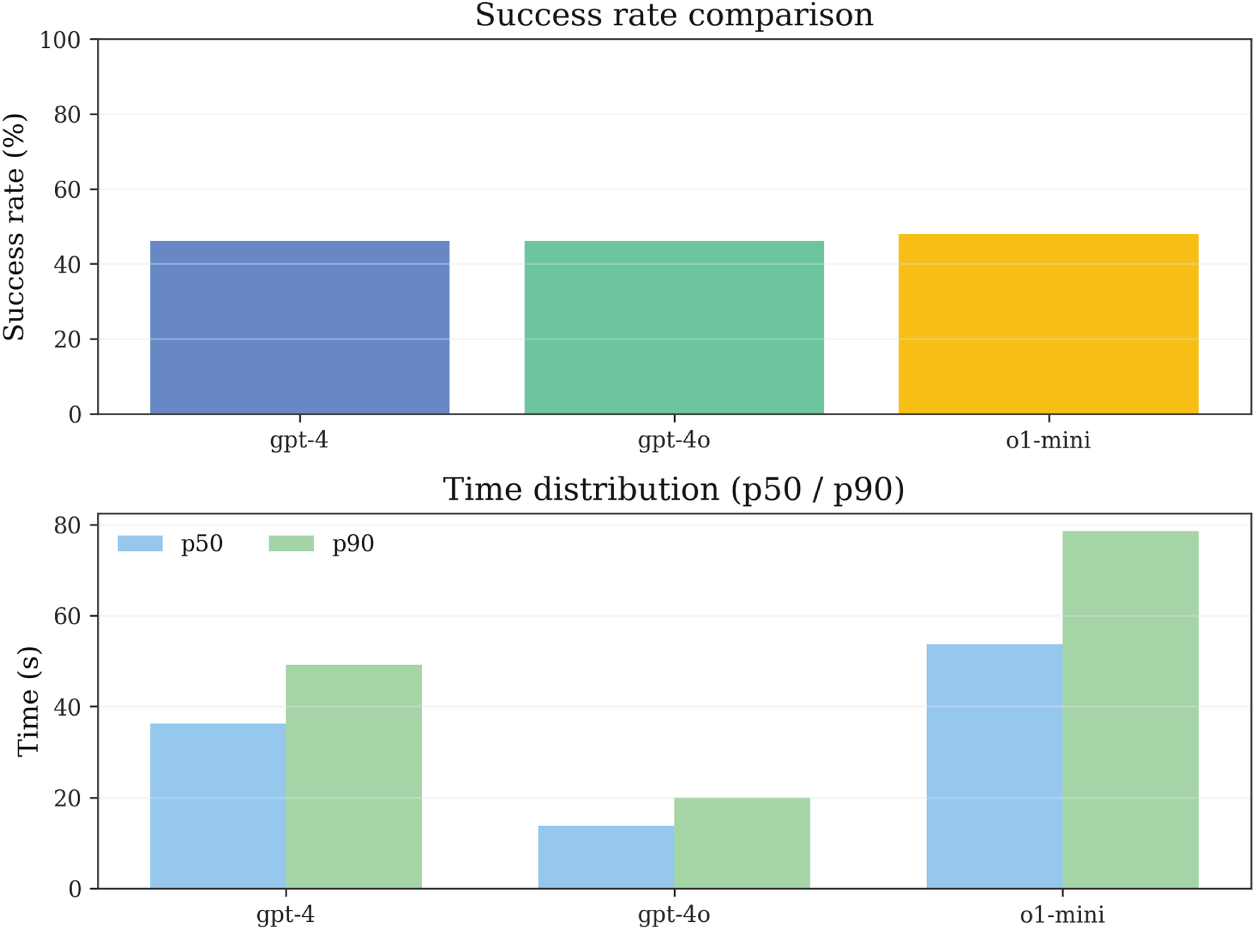

Fig. 3 presents the end-to-end runtime distribution under our method’s closed-loop pipeline for the three models. Time statistics employ three robust statistics—median (p50), 90th percentile (p90), and mean—to address the skewed characteristics of time distributions. It should be clarified that these timing data only reflect the execution efficiency of our method and do not involve comparison with baseline methods, as the baseline study did not publicly release runtime data.

Figure 3: Runtime distribution overview: end-to-end execution time statistics (p50, p90, mean) across models showing efficiency stratification in the closed-loop pipeline

Across the evaluation instance set, the three models exhibit clear performance stratification. GPT-4o demonstrates the shortest execution latency, with p50, p90, and mean of 13.79, 19.93, and 14.64 s, respectively. GPT-4’s corresponding statistics are 36.25, 49.21, and 36.05 s, approximately 2.63 times that of GPT-4o (based on p50 comparison). o1-mini has the longest execution window, with p50, p90, and mean of 53.74, 78.54, and 49.45 s, respectively, approximately 3.90 times that of GPT-4o.

This stratification pattern remains consistent across instance subsets of different difficulty levels. On the relatively difficult gb500 subset, the p50 values for the three models are 37.49, 14.16, and 57.95 s, respectively; on the relatively simple gb3_100 subset, the corresponding values are 26.84, 11.25, and 11.69 s. Simpler instances overall exhibit shorter and more concentrated time distributions, but the relative ordering of “GPT-4o fastest, GPT-4 middle, o1-mini longest” remains stable. It should be noted that on the gb3_100 subset, o1-mini’s latency approaches that of GPT-4o (11.69 vs. 11.25 s), indicating that in simple task scenarios, the additional computational overhead of reasoning models can be effectively amortized.

From a system design perspective, these latency differences reflect different working modes of models in the closed-loop pipeline. GPT-4o possesses significant efficiency advantages while achieving similar success rates (46.2%), making it suitable for application scenarios with higher real-time requirements. Although o1-mini requires a longer execution window to support its deep reasoning process, it achieves the highest final success rate (48.0%), forming a complementary relationship with GPT-4o in the trade-off between “low latency vs. robust achievement.” Combined with the failure component analysis in Section 5.5, it can be seen that o1-mini tends to achieve goals through global planning optimization rather than frequent local repairs, a strategy that, while more time-consuming, can handle more complex constraint relationships.

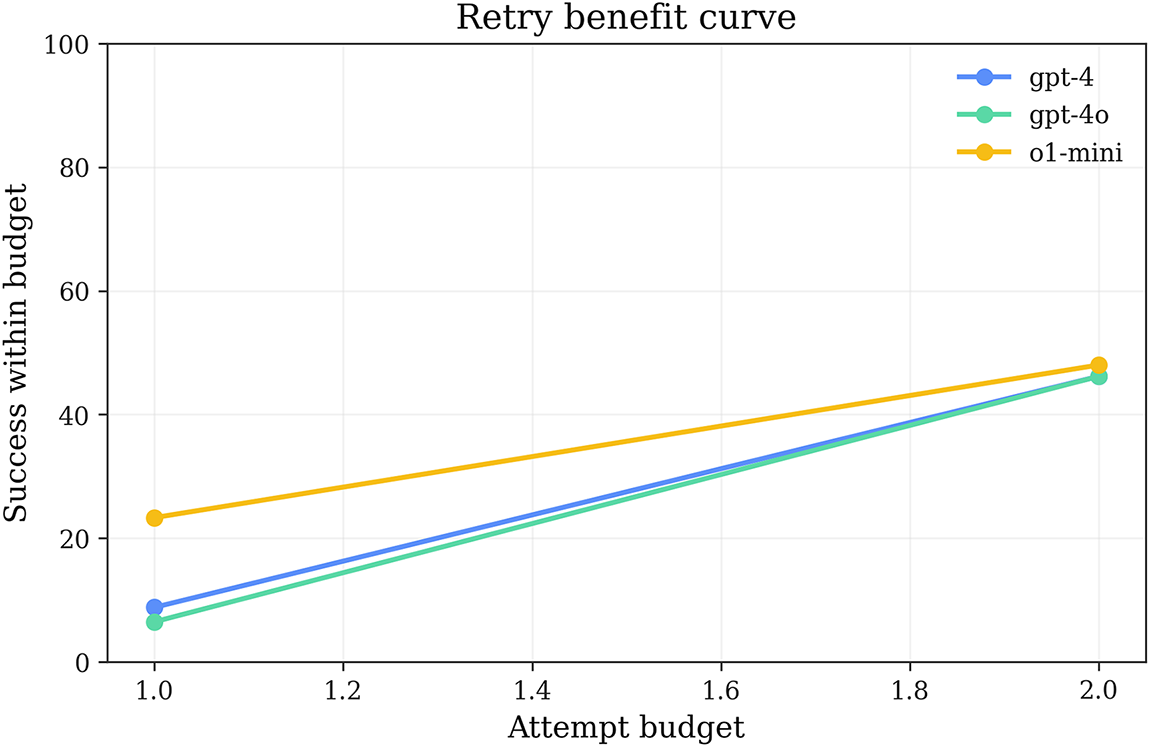

Fig. 4 presents the variation curve of success rate

Figure 4: Retry benefit curves: success rate progression with budget allocation and average attempt counts demonstrating convergence within

Across the evaluation instance set, the average attempt counts for the three models are: GPT-4 1.91, GPT-4o 1.935, o1-mini 1.767. This result indicates that most instances determine success or failure within 1-2 attempts, highly consistent with the assumption about the empirical inflection point

o1-mini’s relatively lower average attempt count (1.767 vs. 1.91/1.935) reveals its unique working mode. Combined with the failure component analysis in Section 5.5, it can be seen that o1-mini’s failures concentrate more on global goal non-satisfaction rather than local precondition deficiencies. This means o1-mini tends to generate plans with good local consistency; when the first attempt’s plan structure is basically reasonable, minor landmark injection or parameter swapping can complete repairs; when structural defects are significant, the model can quickly identify and abandon ineffective paths, avoiding futile repeated attempts.

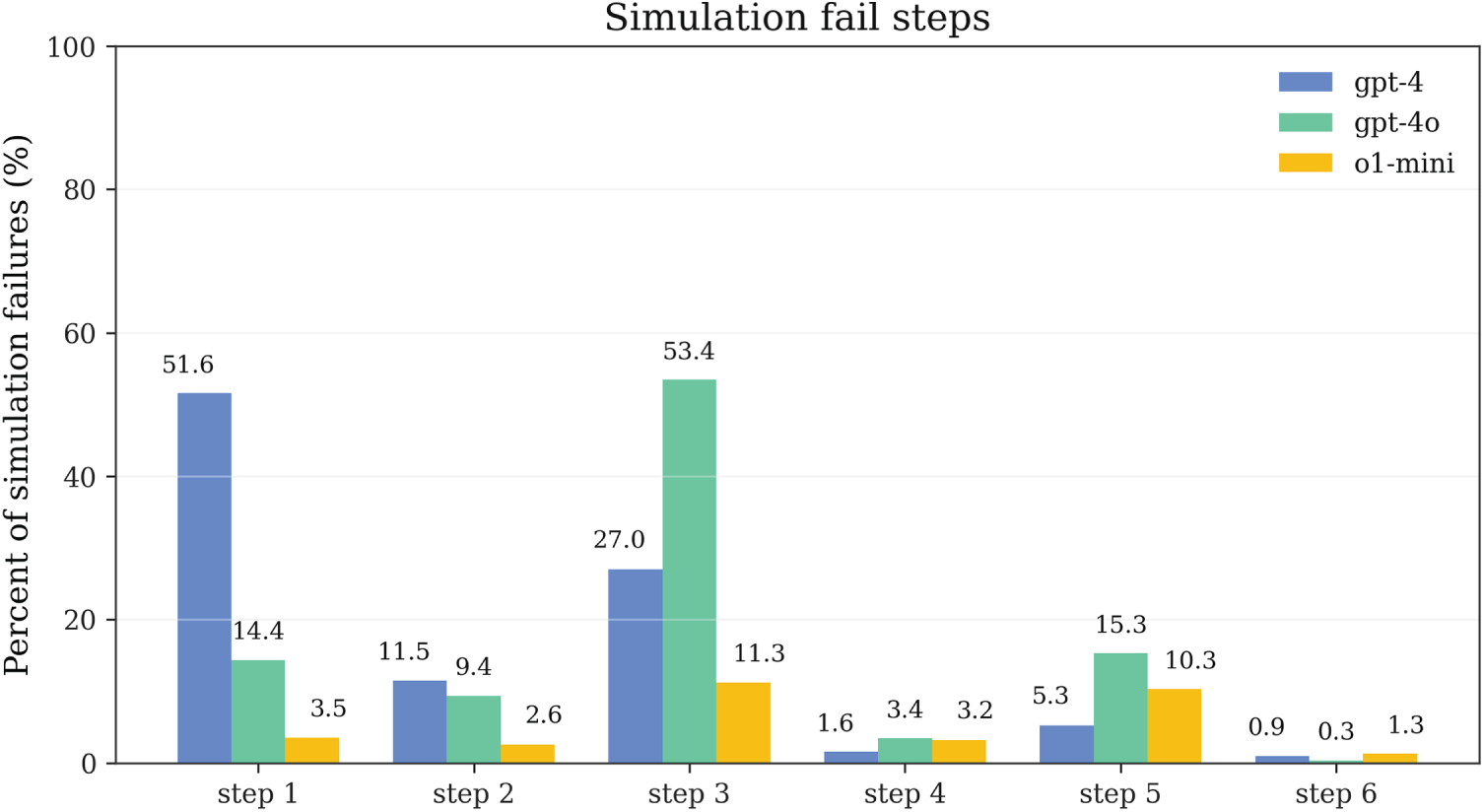

Fig. 5 presents the hazard function distribution

Figure 5: Step-wise hazard distribution: conditional failure probability by execution step revealing dual-peak risk pattern at entry and mid-segment stages

Results show that failure risk exhibits a bimodal clustering pattern at the entry point (

Mid-segment failures relate more to missing necessary landmarks and action sequence design. In Mystery domains, due to complete absence of lexical cues, models struggle to maintain complex state dependencies in action chains like stack/unstack. For example, when needing to move block A from position B to position C, intermediate steps may be required to clear position C or temporarily place A, and managing these intermediate states is extremely challenging without semantic hints.

Cross-model comparison shows that the three models have similar hazard distribution morphologies but differ in peak intensities. o1-mini has relatively lower hazard values at the first step, indicating that its stronger initial planning capability can reduce errors in the entry phase. However, its hazard values in the mid-segment remain significant, indicating that even strong reasoning models still face challenges in maintaining consistency of multi-step state transitions. This finding provides empirical support for the repair strategies designed in Section 3: the First-Step Constraint strategy focuses on completeness checking of basic preconditions, while the Parameter Swap & Landmarks strategy focuses on handling mid-segment state maintenance issues, with the two strategies precisely corresponding to the bimodal risk distribution.

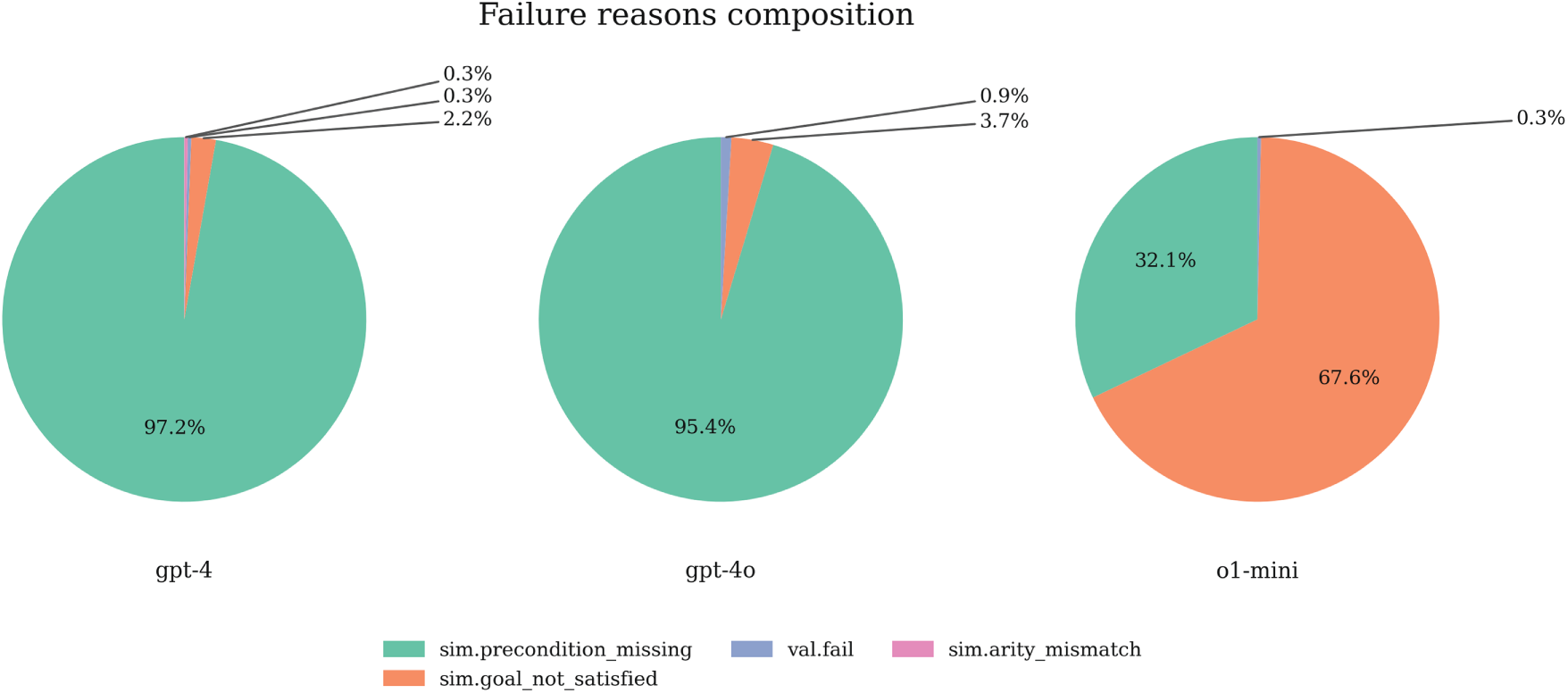

5.5 Failure Composition and Overlap

Fig. 6 presents the failure component distribution for the three models during our method’s execution. It should be noted again that these failure data come from validation steps (CC, SIM, VAL) internal to the closed-loop pipeline, reflecting cases that still fail after multiple rounds of repair, which are qualitatively different from baseline direct generation failures. Total failure counts are: GPT-4 323 cases (600-277), GPT-4o 323 cases (600-277), o1-mini 312 cases (600-288), consistent with the success rate data in Table 1.

Figure 6: Failure composition distribution: breakdown of failure reasons across models highlighting distinct failure modes between precondition errors and goal satisfaction issues

The composition proportions of failure reasons reveal fundamental differences in structural reasoning capabilities between different model types. For LLMs GPT-4 and GPT-4o, failures are highly concentrated on missing preconditions (sim.precondition_missing)—GPT-4 has 314 cases (approximately 97.2%), GPT-4o has 308 cases (approximately 95.4%). The proportion of goal non-satisfaction (goal_not_satisfied) is very small, with 7 cases (approximately 2.2%) and 12 cases (approximately 3.7%), respectively. This pattern indicates that the main difficulty for LLMs in Mystery domains lies in accurately identifying and satisfying local preconditions for each action. Even after multiple rounds of repair, these models still struggle to establish correct action-predicate dependency relationships without any lexical hints. However, once preconditions are satisfied, plans usually can ultimately achieve goals, indicating that these models’ global planning capabilities are not entirely absent.

In contrast, o1-mini exhibits a distinctly different failure pattern. Its failures primarily stem from goal non-satisfaction (211 cases, approximately 67.6%), with missing preconditions accounting for only 100 cases (approximately 32.1%). This reversal indicates that o1-mini possesses stronger local consistency maintenance capabilities, able to generate plans where each step satisfies preconditions, but still has room for improvement in strategic selection and path planning for global goal achievement. In other words, o1-mini’s plans are often syntactically and locally logically correct—each action can be legally executed, but at the global level may have chosen a path that can execute but cannot achieve goals.

This differentiated failure pattern provides an important perspective for understanding the working principles of the closed-loop repair mechanism. For GPT-4/4o, the repair process primarily involves filling missing preconditions and adjusting action parameters, which is precisely the domain of First-Step Constraint and Precondition Probing strategies. For o1-mini, the repair process more involves global path replanning and intermediate state redesign, corresponding to the functionality of Parameter Swap & Landmarks strategies. It should be emphasized that the four repair strategies proposed in this paper fully consider such inter-model differences in design, thus achieving robust improvement effects across different models.

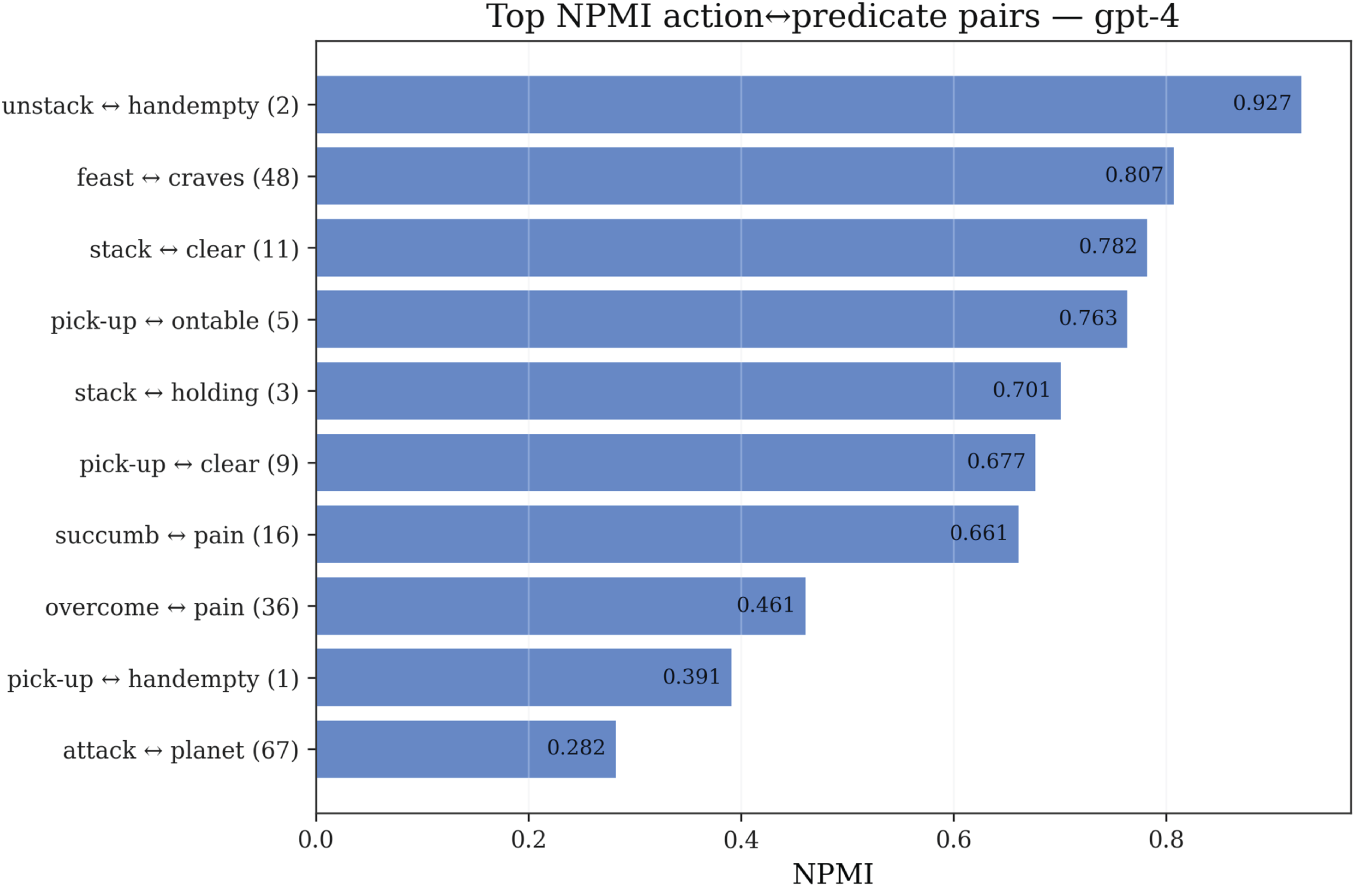

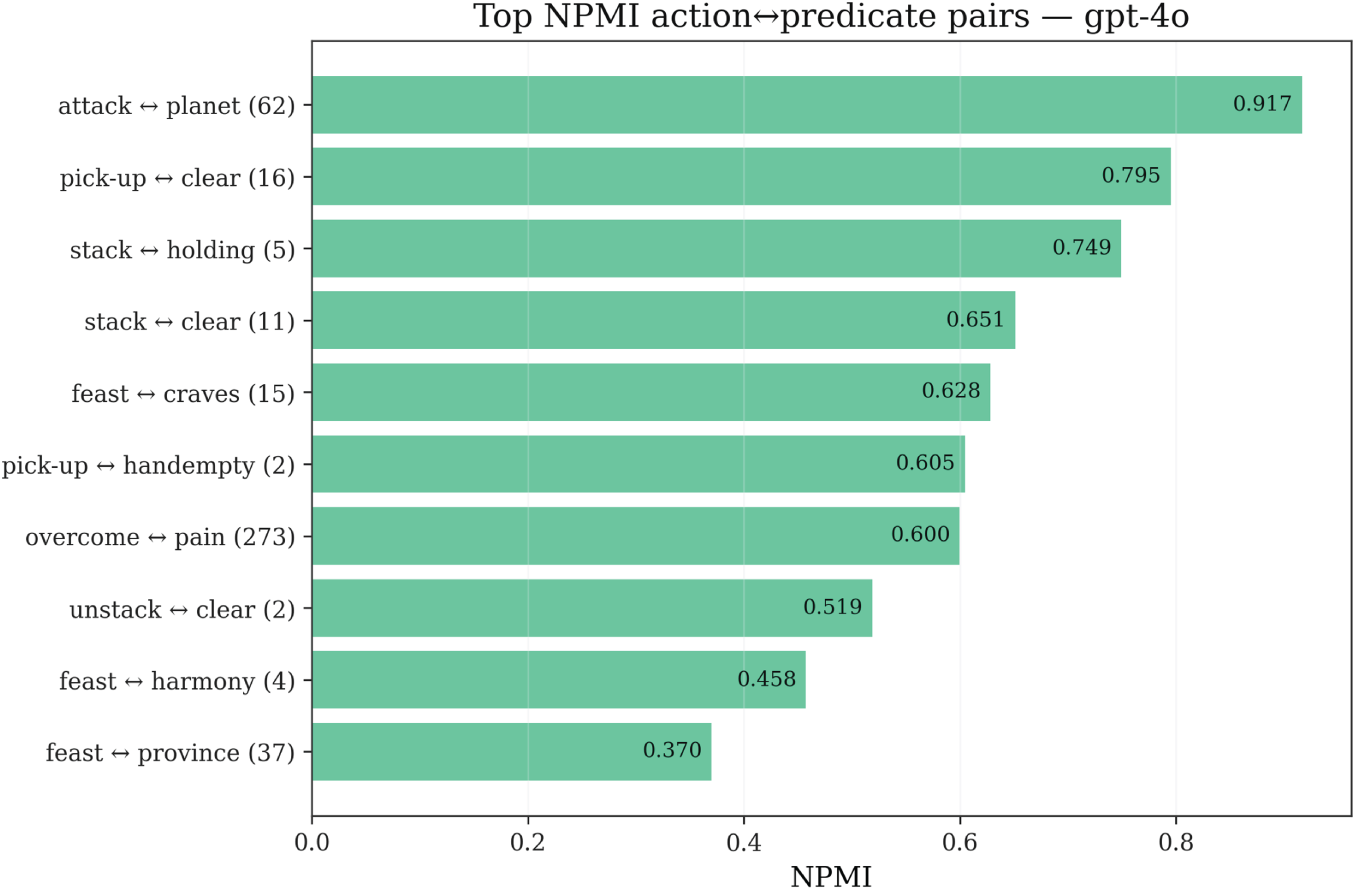

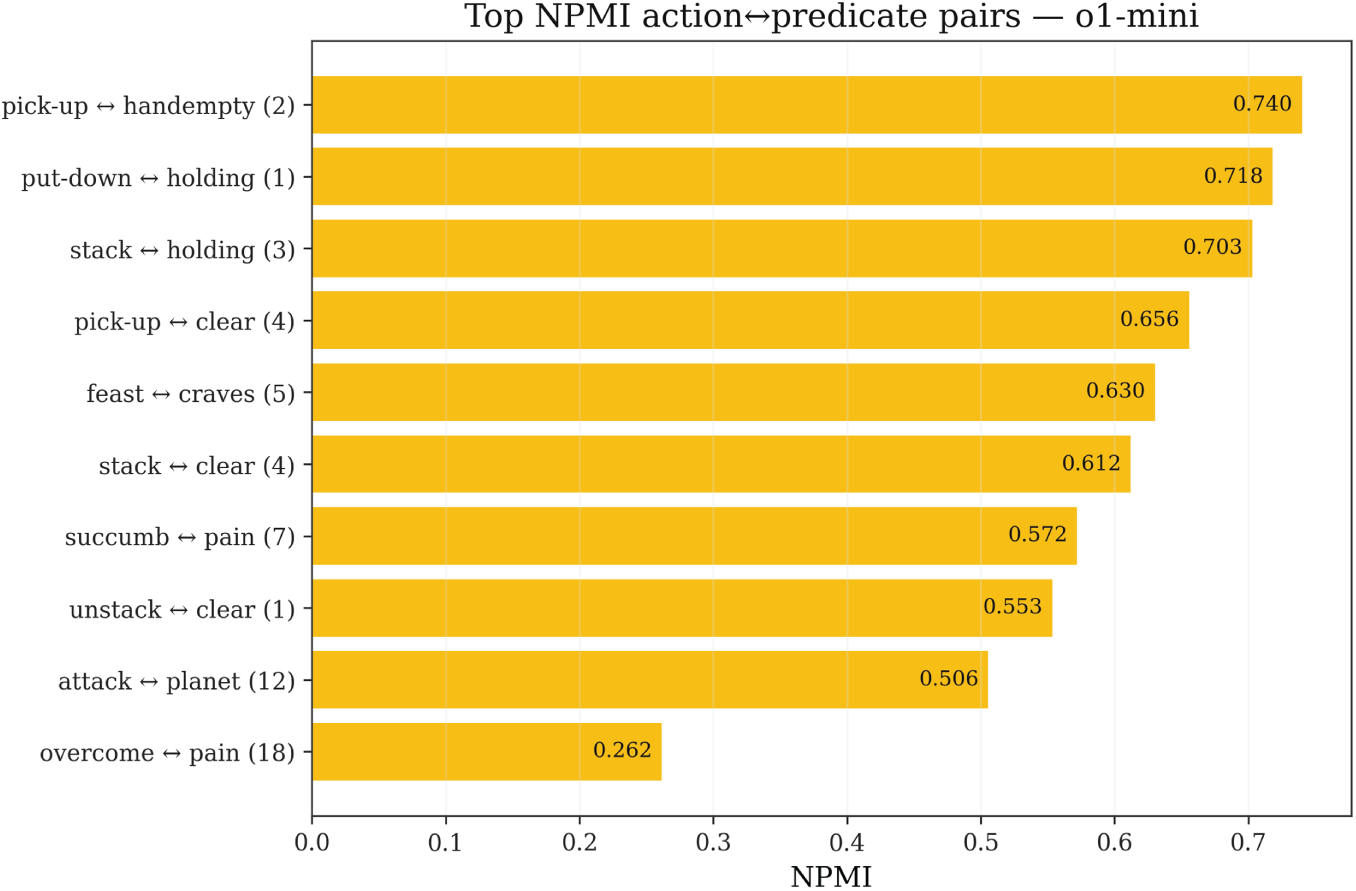

Figs. 7–9 present the Top-K coupling pairs of NPMI between actions and predicates for the three models in Mystery domains. NPMI analysis is specifically focused on generation patterns observed inside the closed-loop pipeline of our method, revealing association structures among obfuscated symbols. Since symbols in Mystery domains themselves are randomly selected, semantically irrelevant vocabulary, any high coupling reflects reasoning preferences or misleading patterns formed by models without semantic cues.

Figure 7: NPMI action-predicate associations for GPT-4: Top-K positive and negative coupling pairs revealing semantic association patterns in obfuscated symbol space

Figure 8: NPMI action-predicate associations for GPT-4o: Top-K positive and negative coupling pairs revealing semantic association patterns in obfuscated symbol space

Figure 9: NPMI action-predicate associations for o1-mini: Top-K positive and negative coupling pairs revealing semantic association patterns in obfuscated symbol space

High positive coupling pairs reflect models’ tendency to frequently associate certain actions with specific predicates. For example, overcome (corresponding to pick-up in the original domain) may exhibit high positive coupling with pain (corresponding to holding). In the original domain this is a correct structural dependency (pick-up action leads to holding state), but in Mystery domains models must establish such associations through pure structural reasoning rather than lexical memory. The emergence of high positive coupling indicates that models to some extent capture such structural dependencies, but may also reflect spurious associations—certain random word pairs are erroneously associated due to accidental co-occurrence in training data.

Negative coupling pairs reflect structural exclusion relationships, such as mutual exclusivity between one action’s preconditions and another action’s delete effects. These negative couplings are equally important in repair strategies, as they indicate which action combinations are naturally incompatible and should be avoided during planning.

Cross-model comparison shows that the three models’ NPMI distribution patterns differ, reflecting different strategies in handling obfuscated symbols. GPT-4 and GPT-4o’s coupling patterns are relatively scattered, indicating these models attempt to establish diverse action-predicate associations but lack consistent structural understanding. o1-mini’s coupling pattern is relatively concentrated, indicating it can more stably identify key structural dependencies. These coupling patterns directly guide the Parameter Swap & Landmarks repair strategy designed in Section 3—by identifying highly coupled action-predicate pairs, RC can adjust parameter order or insert necessary intermediate predicates in a targeted manner, thereby suppressing spurious associations and completing necessary structural dependencies.

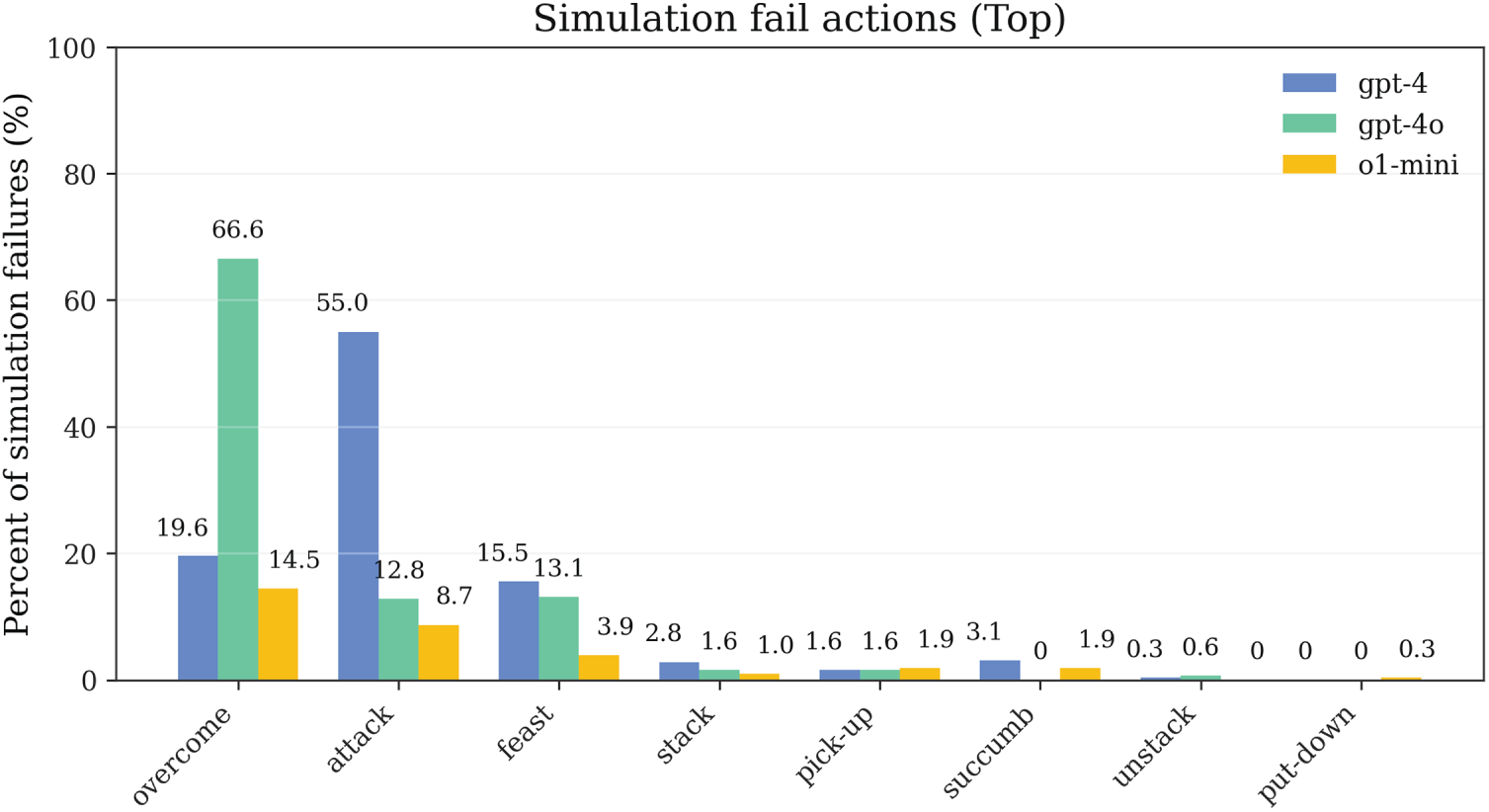

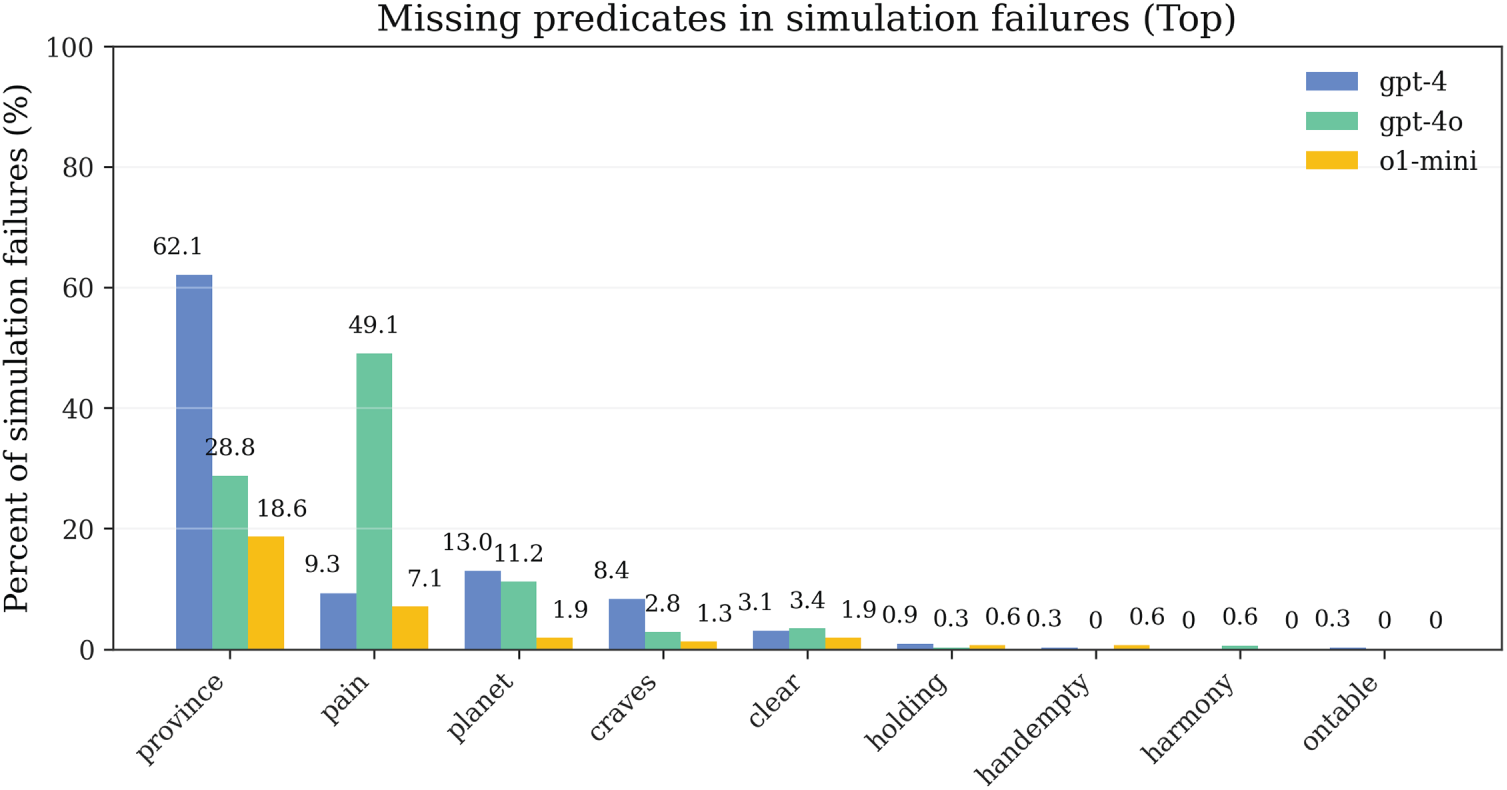

5.7 Simulation Distribution Analysis

Figs. 10–12 present the distribution characteristics of actions, predicates, and step numbers during SIM (STRIPS Simulator) validation, respectively. These three types of distributions characterize the structural characteristics of the planning process inside the closed-loop pipeline of our method from different perspectives, providing fine-grained empirical foundations for understanding failure modes and optimizing repair strategies.

Figure 10: Action distribution in simulation: frequency comparison of action types between successful and failed planning attempts

Figure 11: Predicate distribution in simulation: frequency comparison of predicate occurrences between successful and failed planning attempts

Figure 12: Step number distribution in simulation: failure concentration across execution steps showing consistency with hazard profile

The step number distribution (Fig. 12) exhibits a consistent bimodal pattern with the hazard curve in Fig. 4, further confirming that entry and mid-segment are high-incidence areas for failures. This consistency is not coincidental—the hazard function characterizes risk from a probability perspective, while the step number distribution characterizes actual failure events from a frequency perspective, and the correspondence between the two validates the robustness of statistical analysis. The action distribution (Fig. 10) shows that certain action types (such as obfuscated symbols corresponding to overcome, feast) have significantly higher frequencies in failure cases than their proportions in success cases, indicating these actions involve more complex precondition dependencies or state transition logic. In the predicate distribution (Fig. 11), basic state predicates (such as obfuscated symbols corresponding to province, harmony, craves) have the highest appearance frequencies in failure first steps, confirming the conclusion that first-step failures are primarily caused by unsatisfied basic preconditions.

Cross-analysis of these three types of distributions reveals the priority structure of repair strategies. High-frequency clusters in action distributions vary in the same direction as high-coupling segments in NPMI, indicating that certain action-predicate combinations naturally have higher complexity and should be prioritized during repair. Combined with the failure component proportions, optimization paths for the closed-loop pipeline of our method can be summarized as: First, at the entry stage, impose first-step consistency checking and parameter constraints through CC ’s static screening and First-Step Constraint repair strategy to ensure completeness of basic preconditions; Second, at the mid-segment stage, inject necessary landmarks (such as maintaining sequential relationships of clear, holding, on states) and perform parameter swapping and local reordering through Parameter Swap & Landmarks strategy to maintain complex state dependencies. This phased, targeted repair strategy is the key mechanism enabling the closed-loop pipeline to achieve high success rates within limited budgets.

The experimental results above comprehensively validate the effectiveness of the Symbol-Agnostic Closed-Loop Pipeline proposed in Section 3. From significant improvements in overall success rates to fine-grained internal behavior analysis, all metrics consistently indicate that validation-driven repair mechanisms have substantial value in planning tasks without lexical priors. Compared with baseline direct generation methods, the closed-loop pipeline enables models to still achieve close to 50% success rates under extreme conditions completely lacking semantic cues through systematic “generate

Having demonstrated the overall effectiveness of our approach, we now turn to ablation experiments that systematically examine the individual contributions of key architectural components. While the preceding analyses reveal what the system achieves, the following ablation study clarifies why each component is necessary and how they synergistically integrate to produce the observed performance gains.

To validate the effectiveness of our symbol-agnostic closed-loop architecture, we conduct ablation experiments that systematically degrade key components while preserving system executability. Unlike conventional ablation studies that completely remove modules, our approach recognizes that certain components (e.g., Symbol Translation, Language Planner, VAL validator) represent hard constraints—removing them would cause complete system failure rather than gradual degradation. Instead, we focus on weakening three critical mechanisms that enable the closed-loop refinement process: targeted repair strategies, precise failure diagnosis through step-wise validation, and deep constraint extraction from domain specifications.

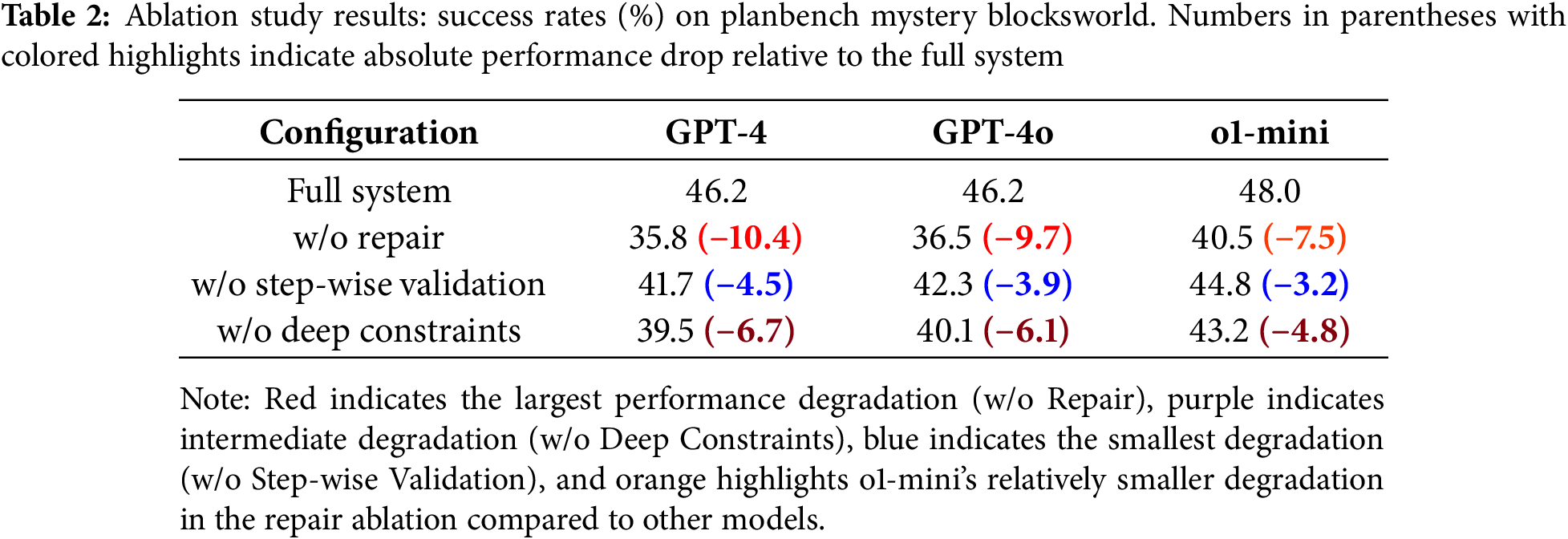

We evaluate three degraded configurations against the full system. In the w/o Repair configuration, the repair controller performs random regeneration when validation fails, discarding all failure information and restarting from scratch. This tests whether our failure-pattern-driven repair strategies (First-Step Constraint, Precondition Probing, Parameter Swap & Landmarks, Budget-Adaptive Retry) provide advantages over naive multi-attempt baselines. The w/o Step-wise Validation configuration removes the STRIPS simulator from the validation pipeline, forcing plans that pass consistency checking to proceed directly to VAL validation. Without intermediate state tracking, the repair controller receives only binary success/failure signals rather than precise diagnostic information about which step failed and which predicates were unsatisfied. Finally, the w/o Deep Constraints configuration weakens the semantic comprehension module to extract only surface-level type and arity information, omitting dependency chains (e.g., holding(?x) requires prior pick-up(?x)), mutex relationships, and landmark orderings. All ablation experiments use the same evaluation protocol as our main results, with attempt budget

Table 2 shows that removing any component leads to statistically significant performance degradation. The targeted repair mechanism provides the largest contribution, with performance drops of 10.4%, 9.7%, and 7.5% for GPT-4, GPT-4o, and o1-mini respectively when replaced with random retry. This validates our core hypothesis that systematic failure analysis and targeted interventions significantly outperform naive regeneration. Interestingly, o1-mini shows smaller degradation (7.5% vs. 10.4% for GPT-4), suggesting that models with stronger intrinsic reasoning capabilities benefit less from external repair guidance—yet even o1-mini experiences substantial improvement from our failure-driven approach, indicating that validation-based refinement remains valuable across the capability spectrum.

Weakening constraint extraction causes intermediate degradation of 4.8–6.7% across models. This demonstrates that sophisticated structural analysis—capturing not just primitive type constraints but also action dependencies, mutual exclusions, and necessary orderings—substantially improves initial plan quality. Without these deep constraints, language models generate structurally valid but logically inconsistent plans more frequently (e.g., attempting stack before satisfying holding preconditions), increasing reliance on downstream repair mechanisms. The repair controller can partially compensate for degraded constraint extraction, as evidenced by performance remaining well above randomized baselines (39.5% vs. 0%–4.3%), but the limited attempt budget prevents full recovery.

Removing step-wise validation causes the smallest but still significant degradation of 3.2%–4.5%. While VAL’s binary feedback alone can support basic repair functionality, precise failure localization enables more efficient convergence. When the system knows that step 3 failed due to missing predicate on(?x,?y), the repair controller can apply targeted precondition probing. Without this information, repair strategies must operate on coarser signals, leading to less effective interventions. The modest impact suggests that binary validation provides substantial value, but incremental improvements from diagnostic precision accumulate meaningfully across multiple repair attempts.

We conduct two-proportion z-tests comparing each ablation against the full system. All degradations achieve significance at

The convergence of ablated configurations toward a relatively narrow performance range (35.8%–44.8%) further supports this interpretation. When degraded through different mechanisms (weakening repair, diagnosis, or constraint extraction), heterogeneous models with substantially different baseline capabilities arrive at similar performance levels. This implies that the full system’s superior performance (46.2%–48.0%) emerges from synergistic integration of multiple components rather than any single dominant factor. Each mechanism addresses a distinct failure mode in the symbol-agnostic planning process, and their coordinated operation enables reliable performance under extreme lexical-prior-free constraints where semantic intuitions provide no guidance.

These ablation results confirm that our symbol-agnostic closed-loop pipeline represents a cohesive architectural design where multiple components contribute non-redundantly to overall effectiveness. The substantial gap between even the best single-component degradation and the full system underscores the necessity of complete integration across constraint extraction, failure diagnosis, and targeted repair mechanisms. Combined with the behavioral analyses in preceding sections, this chapter establishes both what our method achieves and why each architectural decision is essential. The next chapter will summarize the main contributions of this research and discuss future directions.

6 Limitations and Future Directions

While our symbol-agnostic pipeline demonstrates substantial improvements over baseline approaches in lexical-prior-free planning, several limitations warrant acknowledgment.

A fundamental limitation lies in the difficulty of precisely quantifying computational cost-performance tradeoffs. Unlike classical planners where complexity can be characterized through formal bounds (e.g., PSPACE-completeness), our pipeline involves iterative LLM invocations whose costs are heterogeneous and context-dependent. Different repair strategies incur vastly different computational expenses: First-Step Constraint requires minimal overhead, while Precondition Probing may trigger multiple LLM calls, and Budget-Adaptive Retry performs complete plan regeneration. The relative frequency of these failure modes varies unpredictably across problem instances and model architectures. Moreover, LLM inference costs exhibit non-uniform scaling—GPT-4 and GPT-4o employ different pricing tiers per token, while o1-mini incorporates internal chain-of-thought reasoning that inflates token consumption without transparent cost attribution. Our budget parameter

Additionally, our approach fundamentally relies on the availability of sound validators (VAL, STRIPS simulators), limiting applicability to domains where executable semantics are well-defined. Future work could explore learned verifiers as scalable alternatives and adaptive budget allocation strategies that balance success probability against computational expense through reinforcement learning or Bayesian optimization. Despite these limitations, our work establishes that systematic validation and targeted repair can enable reliable symbol-agnostic planning—a capability previously unattainable through direct LLM generation or general-purpose reflection mechanisms.