Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Knowledge-Distilled CharacterBERT-BiLSTM-ATT Framework for Lightweight DGA Detection in IoT Devices

1 Network and Information Center, Nanchang University, No. 999 of Xuefu Road, Nanchang, 330031, China

2 School of Mathematics and Computer Sciences, Nanchang University, No. 999 of Xuefu Road, Nanchang, 330031, China

3 School of Artificial Intelligence, Wenzhou Polytechnic, Chashan Higher Education Park, Ouhai District, Wenzhou, 325035, China

4 School of Software, Nanchang University, Nanchang, 330031, China

5 School of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 639798, Singapore

* Corresponding Authors: Weiping Zou. Email: ; Deyu Lin. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 85 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074975

Received 22 October 2025; Accepted 16 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

With the large-scale deployment of the Internet of Things (IoT) devices, their weak security mechanisms make them prime targets for malware attacks. Attackers often use Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) to generate random domain names, hiding the real IP of Command and Control (C&C) servers to build botnets. Due to the randomness and dynamics of DGA, traditional methods struggle to detect them accurately, increasing the difficulty of network defense. This paper proposes a lightweight DGA detection model based on knowledge distillation for resource-constrained IoT environments. Specifically, a teacher model combining CharacterBERT, a bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) network, and attention mechanism (ATT) is constructed: it extracts character-level semantic features via CharacterBERT, captures sequence dependencies with the BiLSTM, and integrates the ATT for key feature weighting, forming multi-granularity feature fusion. An improved knowledge distillation approach transfers the teacher model’s learned knowledge to the simplified DistilBERT student model. Experimental results show the teacher model achieves 98.68% detection accuracy. The student model maintains slightly improved accuracy while significantly compressing parameters to approximately 38.4% of the teacher model’s scale, greatly reducing computational overhead for IoT deployment.Keywords

With the rapid development of the Internet of Things (IoT) technology, billions of intelligent devices have achieved widespread interconnection and deeply penetrated key fields such as smart homes, industrial control, and intelligent transportation. However, IoT devices are generally designed with a focus on performance over security, resulting in weak security mechanisms and making them highly vulnerable to malware infections. Among various attack methods, the Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) is employed by malware to dynamically create malicious domains for launching attacks. In botnets, the DGA serves as a key bridge to the zombie Command and Control (C&C) server, allowing attackers to remotely control a large number of infected devices [1]. For example, the notorious Zeus Botnet, Conficker Worm and other malware use DGA domains to communicate with control servers, then steal user data and launch Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. This DGA-based attack mode significantly extends the lifecycle of malicious activities and poses a severe security threat to IoT infrastructure. DGA detection is more challenging to lightweight compared to other security tasks due to three unique characteristics: (1) DGA domains are dynamically generated with numerous variants, requiring the model to retain strong feature representation capabilities, and lightweighting is prone to reducing generalization; (2) DGA detection in IoT scenarios needs to process DNS traffic in real-time, with stricter constraints on memory usage (usually <500 MB) and latency (required <100 ms) [2], while other security tasks such as static malware detection can be processed offline; (3) DGA domain features are sparse, and key distinguishing information is easily lost during lightweighting, making it harder to balance performance and resource consumption compared to structured malware features. To address these challenges, recent studies have made improvements in the following aspects: (1) Developing high-precision new DGA detection models using advanced deep learning technologies; (2) Optimizing the deployment efficiency of trained models through lightweight technical means such as Knowledge Distillation, Embedding Dimensionality Reduction, and Quantization Compression. Thus, the research proposed in this paper focuses on the design of lightweight deep learning DGA detection models for IoT scenarios, striving to achieve efficient DGA detection on IoT devices with limited resource constraints and providing a technically feasible solution for building a secure IoT ecosystem.

Current research on DGA detection algorithms can be primarily categorized into two types: methods based on traditional machine learning and methods based on deep learning. In the research on DGA malicious domain detection using traditional machine learning, researchers manually extract DGA features and input them into classifiers. Yang et al. [3] adopt a strategy combining semantic analysis and an ensemble classifier to improve the detection performance of phrase-based DGA domains; Selvi et al. [4] and Cucchiarelli et al. [5] respectively extracted features from the perspectives of masked N-gram features and Jaccard similarity, and combined classification models such as Random Forest and Support Vector Machine (SVM) to achieve efficient and robust DGA domain detection. To tackle the challenges of real-time performance and computational complexity, Ma et al. [6] designed an Rf-C5 model based on an improved Relief algorithm and C5.0 decision tree, while Mao et al. [7] proposed a DNS defense model integrating multi-features and multi-classification algorithms, both of which effectively improved detection performance. Additionally, researchers have explored the classification of DGA domain families and the extraction of information entropy features, further expanding the detection paradigm. However, these methods still suffer from issues such as weak generalization performance for unknown domains, over-reliance on manual feature engineering, and data privacy protection concerns.

Current research indicates that deep learning methods exhibit superior generalization capabilities when dealing with new DGA variants [8]. In the research on DGA malicious domain detection using deep learning, a variety of neural network-based models have been applied to enhance detection performance. Yang et al. [9] proposed an improved Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) algorithm, which combines a multi-branch convolution module and a focal loss function to strengthen the ability to identify DGA domains; Woodbridge et al. [10] and Qiao et al. [11] respectively used long short-term memory (LSTM) networks and attention mechanisms (ATT) to achieve real-time and efficient DGA domain detection, which is particularly suitable for large-scale network environments without the need for additional information support; Duc Tran et al. [12] developed the LSTM.MI algorithm, which effectively mitigates the class imbalance problem in DGA multi-classification, while the framework proposed by Morbidoni et al. [13], which integrates n-gram embedding and LSTM.MI, improves the classification accuracy and stability of the model in data-scarce scenarios. Furthermore, to address challenges such as low-randomness DGA domains and dictionary-generated DGA, research teams have explored innovative methods including the ATT-GRU model, composite models, and the eXpose neural network structure. These deep learning models have achieved remarkable results in improving detection accuracy and reducing false positive rates, but they still face problems such as data privacy protection and cross-institutional data sharing.

This study focuses on constructing a lightweight DGA detection framework suitable for IoT environments. Its main contributions include: (1) Proposing a CharacterBERT-BiLSTM-ATT hybrid model tailored for DGA detection. The integration innovation lies in the cascaded architecture of “character-level encoding-sequence modeling-dynamic weighting”: the character embedding output of CharacterBERT is used as the input of BiLSTM to capture sequential dependencies of domain names, and the ATT layer performs cross-layer weighted fusion of BiLSTM hidden states and CharacterBERT embeddings to emphasize discriminative features. (2) Achieving an efficient model lightweight through an optimized feature-level knowledge distillation strategy. We take the well-performing CharacterBERT-BiLSTM-ATT as the teacher model and the lightweight DistilBERT as the student model. The distillation innovation lies in the “dual-modal input fusion” design: the student model (DistilBERT) simultaneously receives two types of inputs—CharacterBERT-style character-level indices and DistilBERT’s standard token-level inputs. A weighted fusion of hard labels and the teacher model’s feature outputs is adopted for distillation loss, which is more adaptive to DGA detection than distillation schemes tailored for general natural language processing (NLP) tasks. This strategy reduces the model parameter size from 650 MB to 250 MB while maintaining comparable detection accuracy.

2.1 Domain Generation Algorithm

As the core technology for malware to generate random domains to maintain C&C communication, the Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) dynamically generates a large number of domains through methods such as pseudo-random number generation, vocabulary combination, or time seeds to evade static blacklist-based detection mechanisms [14]. In the Internet of Things (IoT) environment, DGA attacks exhibit the following characteristics: First, IoT devices are resource-constrained and cannot deploy complex detection algorithms; Second, the wide distribution of devices leads to high data fragmentation; Third, botnets often use IoT devices as springboards to launch large-scale DDoS attacks using DGA domains [15]. With the continuous evolution of DGA technology, the difficulties in detecting such domains are concentrated in two aspects: the random nature renders traditional rule-based matching methods ineffective, and the dynamic generation feature requires detection models to achieve real-time updates [16].

CharacterBERT [17] is an innovative natural language processing model that integrates the dynamic contextual representation mechanism of ELMo (Embeddings from Language Models) into the classic BERT architecture. Through character-level modeling, it significantly enhances the contextual representation ability of words. Unlike the traditional BERT model that relies on a fixed subword vocabulary, CharacterBERT uses a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based character encoder as its core component, which can dynamically generate semantic representations based on the character sequence of any input word. This architecture effectively avoids the limitations of predefined vocabularies and demonstrates excellent robustness when dealing with professional terms, domain-specific new words, and spelling errors, making it particularly suitable for professional text analysis in fields such as medicine and law [18].

The technical innovations of this model include the following dual mechanisms: Architecture Level: It extracts the morphological features of words through character-level convolution operations and integrates the ATT to generate context-related word vectors, systematically alleviating the vocabulary fragmentation problem caused by traditional word segmentation methods. Application Level: Its character-driven design endows the model with strong cross-domain transfer capabilities—it can quickly adapt to new domain data without reconstructing the vocabulary, and only requires a small amount of fine-tuning to improve the performance of downstream tasks such as text classification and sequence labeling.

2.3 Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Networks

A BiLSTM network [19,20] is an extended form of the standard LSTM network architecture. It improves sequence modeling capabilities by introducing a bidirectional information flow mechanism. The traditional LSTM model can only capture the historical information of the input sequence (i.e., past context), while BiLSTM integrates two independent LSTM branches—a forward LSTM and a backward LSTM. At each time step, it synchronously integrates the forward sequence information and backward sequence information of the current morpheme, thereby significantly enhancing the model’s ability to represent the context of the entire sequence.

Through the fusion of information in both forward and negative directions, BiLSTM can use the left and right contexts when modeling language sequences, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to express complex syntactic structures and long-distance dependencies, especially suitable for natural language processing tasks that require fine semantic understanding, such as named entity recognition, sentiment classification, and medical text analysis. The BiLSTM structure enables the model to obtain complete contextual information for each position in the sequence simultaneously, a feature that is crucial in many tasks that require precise contextual understanding. The bidirectional processing mechanism of BiLSTM provides an effective way to solve this kind of problem. The advantage of BiLSTM over standard LSTM is the ability to perform more accurate feature extraction with full contextual information, but at the cost of increased computational complexity (nearly twice as much) and the inability to be used for real-time sequence prediction (because the complete sequence is required as input).

Knowledge Distillation [21] is a model compression and knowledge transfer technology. Its core is to transfer the knowledge learned by a high-performance but complex teacher model to a student model with a simpler structure and higher computational efficiency, enabling the student model to significantly reduce the number of parameters and computational overhead while maintaining performance close to that of the teacher model.

The essence of Knowledge Distillation is imitation learning, which enables the student model to learn the representation characteristics of the teacher model rather than just its final predictions. The specific implementation process includes: first, training a high-precision but complex teacher model to achieve high performance on the target task; then, designing a structurally simplified student model and training the student model using the output of the teacher model as a supervision signal.

The student model has significantly fewer parameters and lower computational requirements, so it can be deployed in resource-constrained environments such as mobile terminals and embedded devices. By transferring the teacher’s knowledge, the performance of the student model often surpasses that of a directly trained model of the same scale. Soft labels provide rich supervision information, promoting the student model to learn the potential patterns of data and reducing the risk of overfitting. Knowledge from multiple teacher models can be distilled into a single student model to achieve the effect of ensemble learning.

3.1.1 Overall Teacher Model Architecture

The malicious domain detection algorithm based on CharacterBERT-BiLSTM-ATT is a comprehensive detection method that integrates the advantages of multiple deep neural network structures. In this structure, the CharacterBERT module is first used to perform character-level encoding and semantic representation on the input domain name string, converting the original domain name text into a character-level vector matrix rich in contextual semantics. Next, the BiLSTM-ATT module is used to further capture the semantic relationships and feature dependencies before and after the domain name sequence and highlight important features through the ATT to obtain more accurate feature expressions.

The combined structure of CharacterBERT-BiLSTM-ATT shows significant advantages in the Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) detection task. Malicious domains generated by DGA often have irregular structures and strong randomness, making them difficult to effectively identify by traditional methods. The CharacterBERT module can handle unknown characters and spelling variations, so that the model is no longer limited to a predefined vocabulary and can efficiently process random, variant, or abnormal domain name character combinations. Through the BiLSTM and the ATT of the BiLSTM-ATT module, the model’s ability to perceive the context of characters before and after, and the global feature dependence can be further improved. This enables the algorithm to effectively focus on the key abnormal signals in the malicious domain name string and improve the recognition accuracy and robustness of new, unknown, and variant DGA domains. This comprehensive architecture organically integrates the refined feature capture at the character level, the pattern recognition ability of the convolutional neural network, and the dynamic weight assignment of the ATT, thereby significantly improving the overall performance of malicious domain detection.

The integration innovation of the model lies in the cascaded architecture of “character encoding-sequence modeling-dynamic weighting”: the output of CharacterBERT is used as the input of BiLSTM, and the ATT layer performs cross-layer weighted fusion of BiLSTM output and CharacterBERT embedding instead of simple concatenation. In the training strategy, DGA domain-specific corpus is introduced for fine-tuning during CharacterBERT pre-training, and a “warm-up learning rate + early stopping” strategy is adopted to avoid gradient vanishing. This integration method and training optimization make the model more adaptive to DGA detection tasks.

3.1.2 CharacterBERT Encoding Module

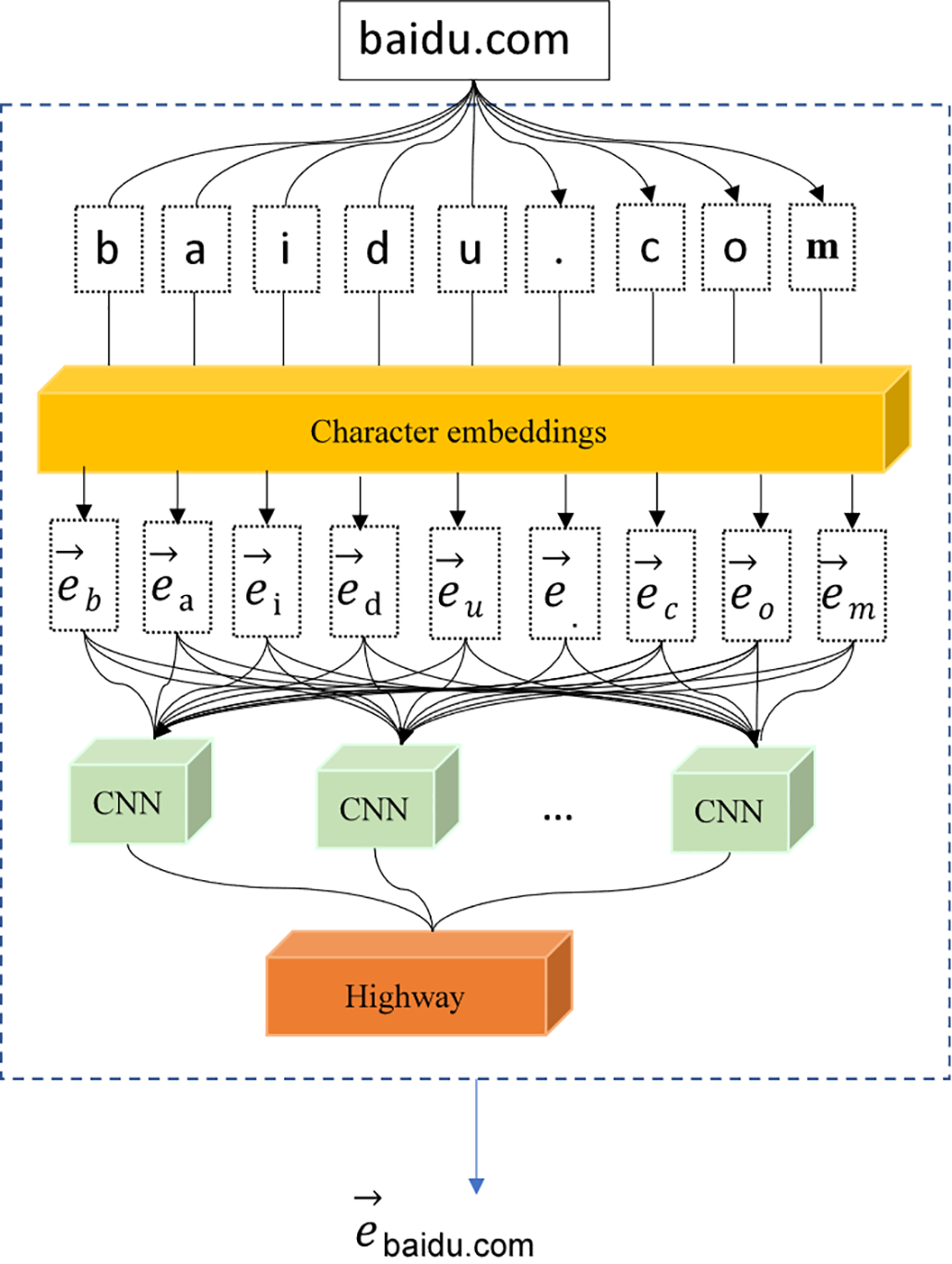

In terms of architecture and training strategy, CharacterBERT is consistent with the traditional BERT model—both use a Transformer structure to capture contextual semantics and adopt methods such as masked language modeling and next-sentence prediction for pre-training. In addition, CharacterBERT avoids reliance on a fixed vocabulary; when adapting to a new domain, it does not need to create a new vocabulary or conduct additional training, thereby improving the flexibility and efficiency of cross-domain transfer. The CharacterBERT component adopts the core module of the full architecture, including 12 layers of Transformer encoders. Compared with token-level models such as BERT-base, CharacterBERT does not rely on a predefined vocabulary and directly processes individual characters. In the test set, the detection accuracy for variant DGA domains (such as domains containing typos and special symbols) reaches 98.9%, which is higher than the 96.3% of token-level models. Taking the malicious domain “xqz92mdkf.net” as an example, the token-level model splits it into meaningless subwords, while CharacterBERT can extract the sequence features of random characters, providing effective support for subsequent detection. In domain name processing tasks, CharacterBERT shows significant advantages compared with the traditional BERT model. Since domain names often contain special characters, random combinations, and complex variations, the fixed vocabulary mechanism of the traditional BERT model usually cannot fully characterize these features and may lead to semantic fragmentation. As shown in Fig. 1, the CharacterBERT model achieves effective feature extraction of domain name sequences through character-level embedding (Character embedding) and finally converts the original character-level input into a numerical matrix that can be used for downstream feature extraction. The following takes the domain name text “baidu.com” as an example to elaborate on the entire data processing process in detail.

Figure 1: CharacterBERT architecture diagram

At the beginning of the process, the domain name string “baidu.com” to be analyzed is regarded as the minimum unit of the model input. According to the character-level embedding mechanism of the model, the input string is split into a character sequence character by character, i.e., “b”, “a”, “i”, “d”, “u”, “.”, “c”, “o”, “m”. The steps in the diagram show the splitting process using the word “baidu.com” as an example, while in the preprocessing stage of this study, the domain name characters are split accordingly. The CharacterBERT model performs character embedding on each split character. Specifically, each character is mapped to the corresponding character embedding vector through a learnable embedding matrix. This step is marked as “Character embeddings” in the diagram, and the generated character-level embedding vector is denoted as

Subsequently, these character embedding vectors are used as the input of the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to capture local features and contextual information between characters. The main function of the CNN layer is to extract feature combinations of different character subsequences in the domain name string, such as local patterns or specific combination rules that may exist between characters. Assuming that the i-th convolution kernel acts on the continuous character embedding subsequence

In the formula,

After the convolution operation, the local features generated by each convolution kernel undergo feature selection through the Max Pooling layer to retain the most significant feature representations. The feature vectors extracted by the CNN layer are input into the Highway Network layer. The Highway Network is used to smooth the feature expression output by the CNN, enhance the representativeness of features, and at the same time alleviate the problems of gradient disappearance or gradient explosion that may occur during the training of deep networks. The output features of the Highway Network can be calculated by the following formula:

where,

After the steps of character embedding, convolution feature extraction, and feature fusion of the deep network, the domain name “baidu.com” is converted into a fixed-dimensional vector representation

3.1.3 Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory-Attention Feature Extraction Module

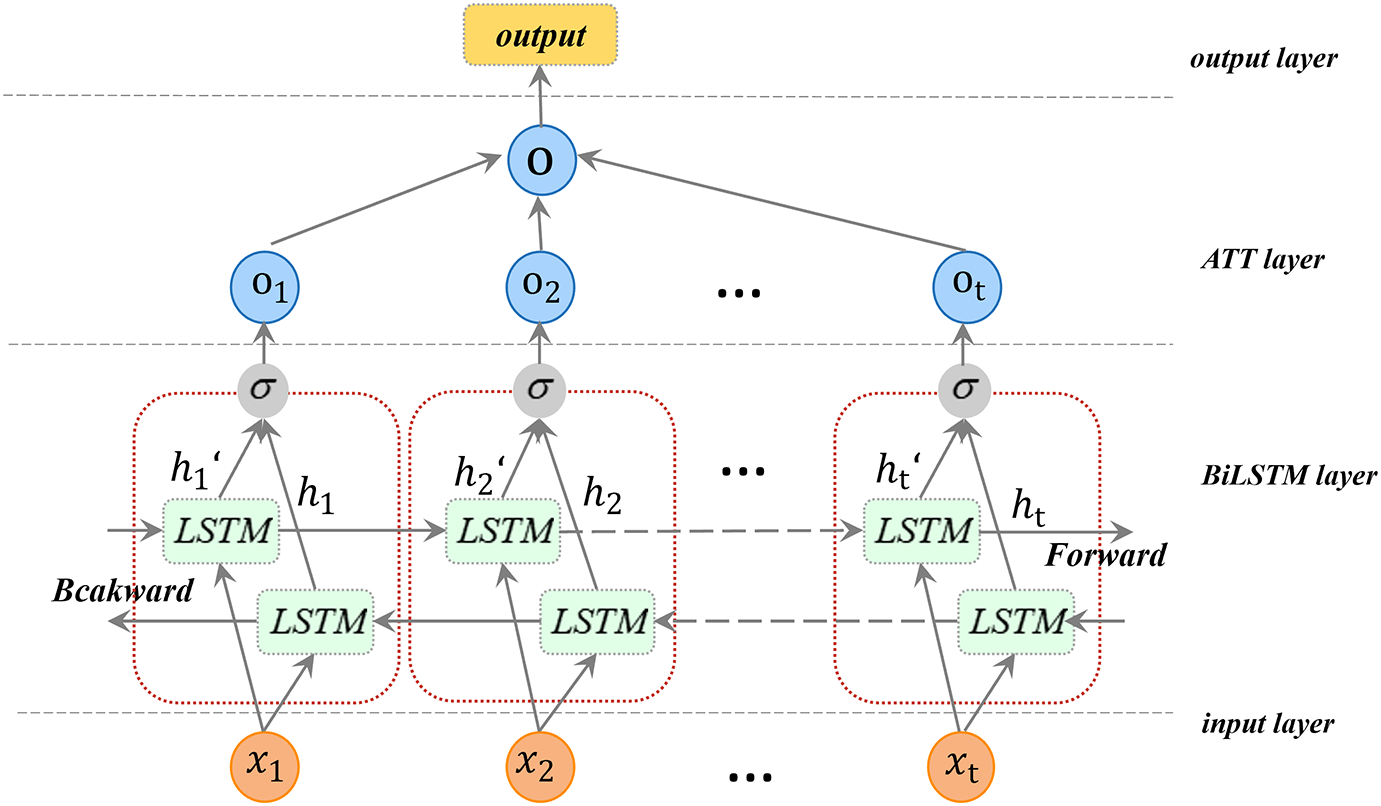

The BiLSTM-ATT [22,23] module proposed in this paper introduces an ATT based on BiLSTM. By assigning different weights to different parts of the text sequence, it enhances the model’s ability to focus on key features. In sequence feature extraction, the traditional LSTM or BiLSTM usually adopts a fixed feature summarization method, which is difficult to dynamically highlight important information according to the task. In contrast, the ATT allows the model to automatically and selectively focus on key features or segments in the sequence by calculating the attention weight of each time step, thereby improving the pertinence of feature extraction. The character-level semantic embeddings output by CharacterBERT (dimension: 768) are fused with the sequence-dependent features generated by the BiLSTM layer through splicing. Specifically, the output dimension of the BiLSTM layer (hidden size: 128, bidirectional) is 256, and the stitching operation merges the two types of features along the feature dimension to generate a fusion feature vector with dimension 1024. This fusion strategy preserves the integrity of character semantic features and sequence-dependent features, providing sufficient information for subsequent the ATT to focus on key patterns of DGA domain names. As shown in Fig. 2, this module includes an input layer, the BiLSTM layer, the ATT layer, and the output layer.

Figure 2: BiLSTM-ATT structure diagram

In BiLSTM, the input sequence is fed into two LSTM networks (forward and backward), respectively. The forward LSTM processes the sequence from front to back and generates the forward hidden state

Meanwhile, the backward LSTM processes the same sequence from back to front and generates the backward hidden state

Finally, the hidden states of the two directions are concatenated to form the output representation at this time step:

where

In order to further improve the model’s ability to express the features of text sequences, this study introduces an ATT to dynamically pay attention to the key information in the sequence. The ATT adopted in this paper is the Additive Attention (also known as Bahdanau Attention). The importance score

Then, the attention weight

where,

To prevent the model from overfitting, use Dropout regularization after the feature representation:

BiLSTM-ATT better senses the semantic association of preceding and subsequent characters in the domain name string with the help of a two-way structure, and further highlights the features of abnormal characters or key character sequences through the ATT.

DistilBERT [24] is obtained using knowledge distillation technology on the basis of CharacterBERT, and the basic structure of the CharacterBERT model is the same as BERT, but the number of Transformer layers has been adjusted, and the token-type embedding and pooler are removed. The model size of DistilBERT is only 40% of the size of the original BERT model, and the model inference time is shortened to 60% of the BERT model, with performance on downstream tasks similar to that of BERT. The selection of DistilBERT as the student model in this study is based on three key considerations tailored to IoT DGA detection requirements:

• Its structural compatibility with the teacher model ensures efficient knowledge transfer. Both DistilBERT and CharacterBERT are derived from the BERT architecture and rely on Transformer encoders for contextual feature extraction, avoiding structural mismatches that could hinder the distillation of character-level semantic knowledge and sequence-dependent features learned by the teacher model. This compatibility is critical for retaining the teacher model’s strong performance in detecting variant DGA domains with random characters or spelling variations.

• Its lightweight design aligns with IoT resource constraints. DistilBERT reduces computational overhead by pruning redundant Transformer layers and removing non-essential components, resulting in a parameter size and memory footprint that meet the strict requirements of IoT edge devices. Compared with other lightweight models such as TinyBERT, DistilBERT maintains a higher hidden layer dimension, which is conducive to preserving the fine-grained feature representation capability required for DGA detection.

• Its proven effectiveness in text classification tasks provides a reliable foundation. DistilBERT has demonstrated robust performance in natural language processing tasks involving short text and irregular sequences—scenarios highly consistent with DGA domain detection. Unlike specialized lightweight models that require task-specific fine-tuning, DistilBERT’s pre-trained generalizability reduces the risk of overfitting to limited DGA datasets, ensuring better generalization to unseen malicious domain variants.

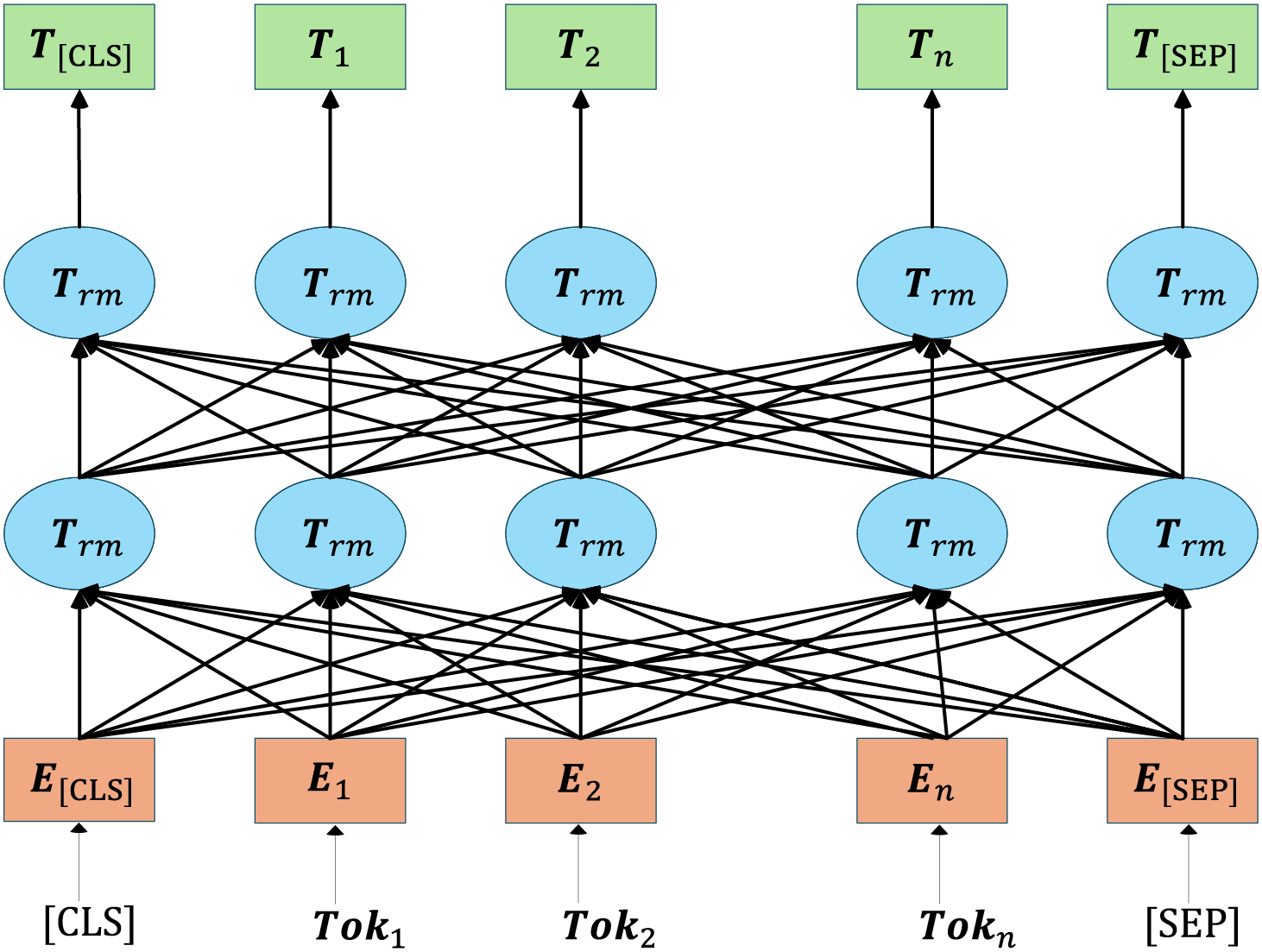

The basic structure of the DistilBERT model is shown in Fig. 3. After inputting a text sequence into the DistilBERT model, DistilBERT processes the input sequence to generate a text serialization vector. DistilBERT segments sentences using “[CLS]” and “[SEP]”, and the segmented sentences are represented in the model as E, denoting a serialized vector representation of each token in the input text for subsequent model training. Each word is transformed into a feature vector Tn rich in text semantic information after a multi-layer Transformers Encoder structure, which serves as the final output of DistilBERT. DistilBERT can dynamically represent word vectors at the sentence level based on the vocabulary itself and sentence context information; when polysemy appears in the input text, the model combines the contextual language environment of the word to obtain different word vector outputs. After pre-training, the DistilBERT model can obtain the eigenvector T[CLS] containing the semantic information of the text context. In addition, the DistilBERT model converts the word sequence E = [E1, E2, …, En] into the corresponding word vector T = [T1, T2, …, Tn], enabling the model to further capture local features of the text.

Figure 3: DistilBERT structure diagram

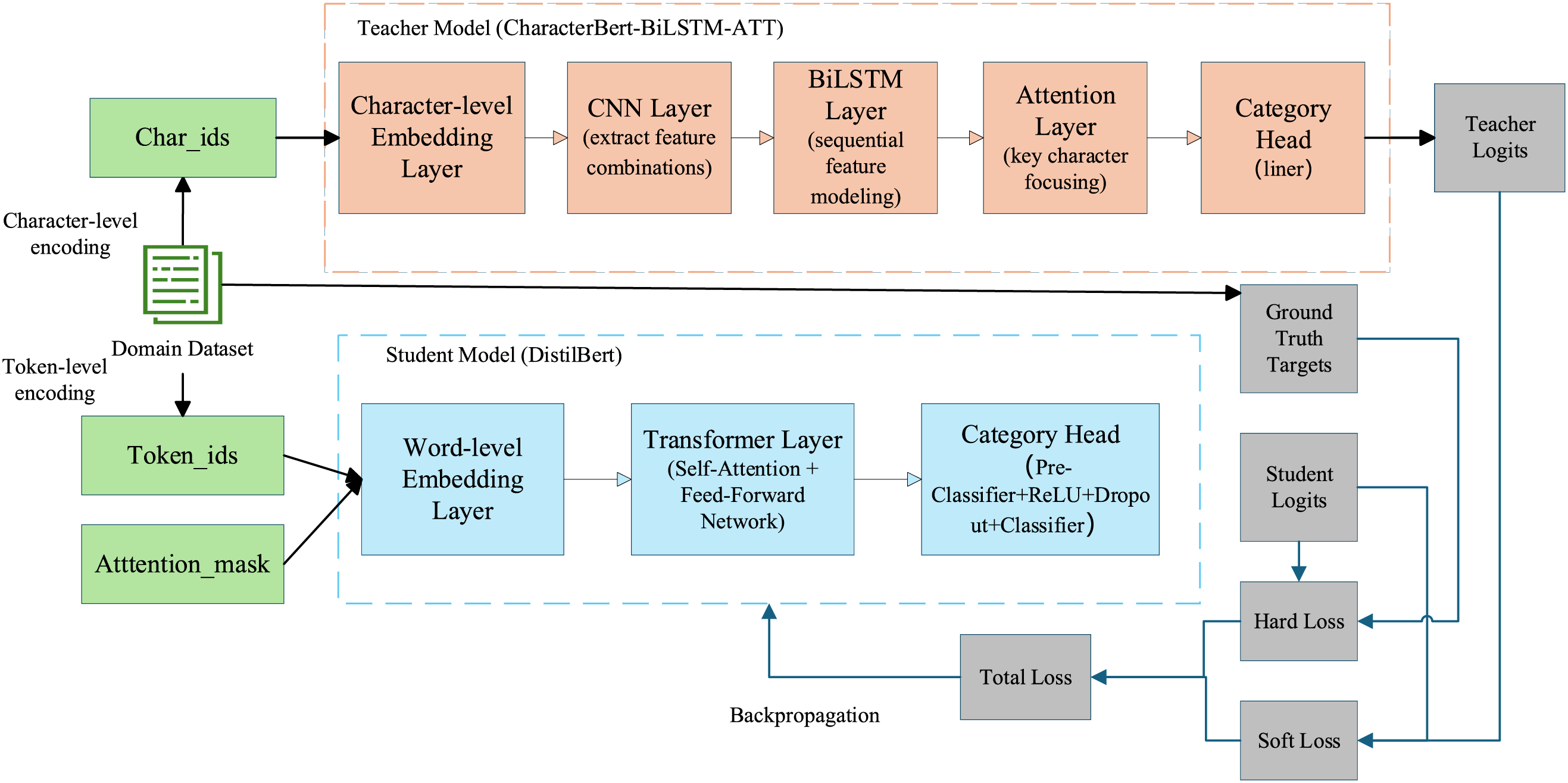

3.3 Knowledge Distillation Module

The teacher model shows significant accuracy advantages over traditional methods in DGA detection. However, due to the deployment target of the model is IoT devices, its memory and computing power resources are limited, coupled with the need for real-time recognition, which puts forward high requirements for the design of algorithm models. Therefore, this paper adopts the method of knowledge distillation to transfer the knowledge learned in the high-precision teacher model to lightweight students through the training process of offline distillation by reconstructing the combinatorial loss function model, as shown in Fig. 4. This allows the student network to output as close as possible to the distribution of the teacher network at a small network scale, thereby improving its convergence speed and performance, which is more suitable for deployment on IoT devices.

Figure 4: Knowledge distillation process diagram

In the training process of knowledge distillation, the loss function of the student network contains two parts: hard loss

where

The soft loss and hard loss are specifically defined as follows:

Soft loss (

where

Hard loss (

where y is the one-hot encoded real label, and

To achieve the efficient deployment of the DGA malicious domain detection model in IoT devices, this study applies Knowledge Distillation technology to lightweight the original CharacterBERT-BiLSTM-ATT model. The original hybrid model is used as the teacher model, and DistilBERT and TinyBERT are introduced as the student model architectures. Knowledge transfer is used to compress the model parameters, significantly reducing the computational resource overhead while maintaining the same detection accuracy, thereby adapting to the hardware limitations of IoT edge devices. To prove the reliability of our experimental results, we have released the source code to https://github.com/CHEAMli/DGA_detect_ditilBERT.

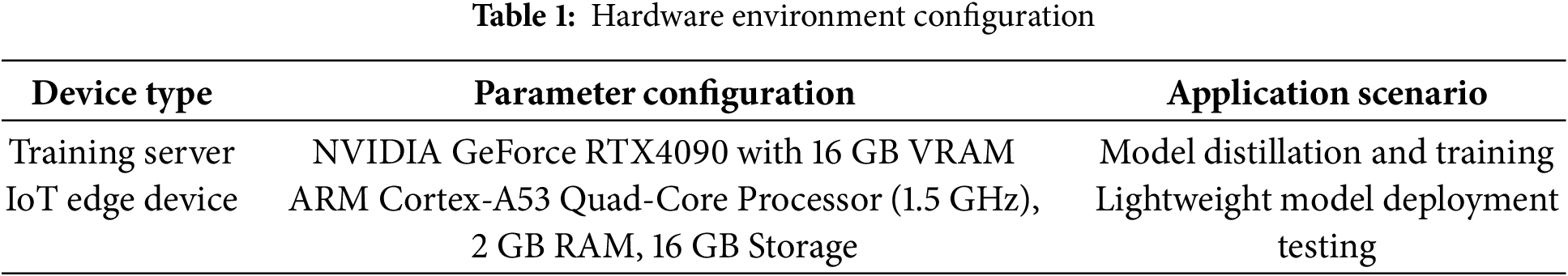

The hardware environments used for model training and deployment testing are shown in Table 1, including the configuration parameters of the training server and IoT edge device, which ensure the feasibility of model training efficiency and edge deployment verification.

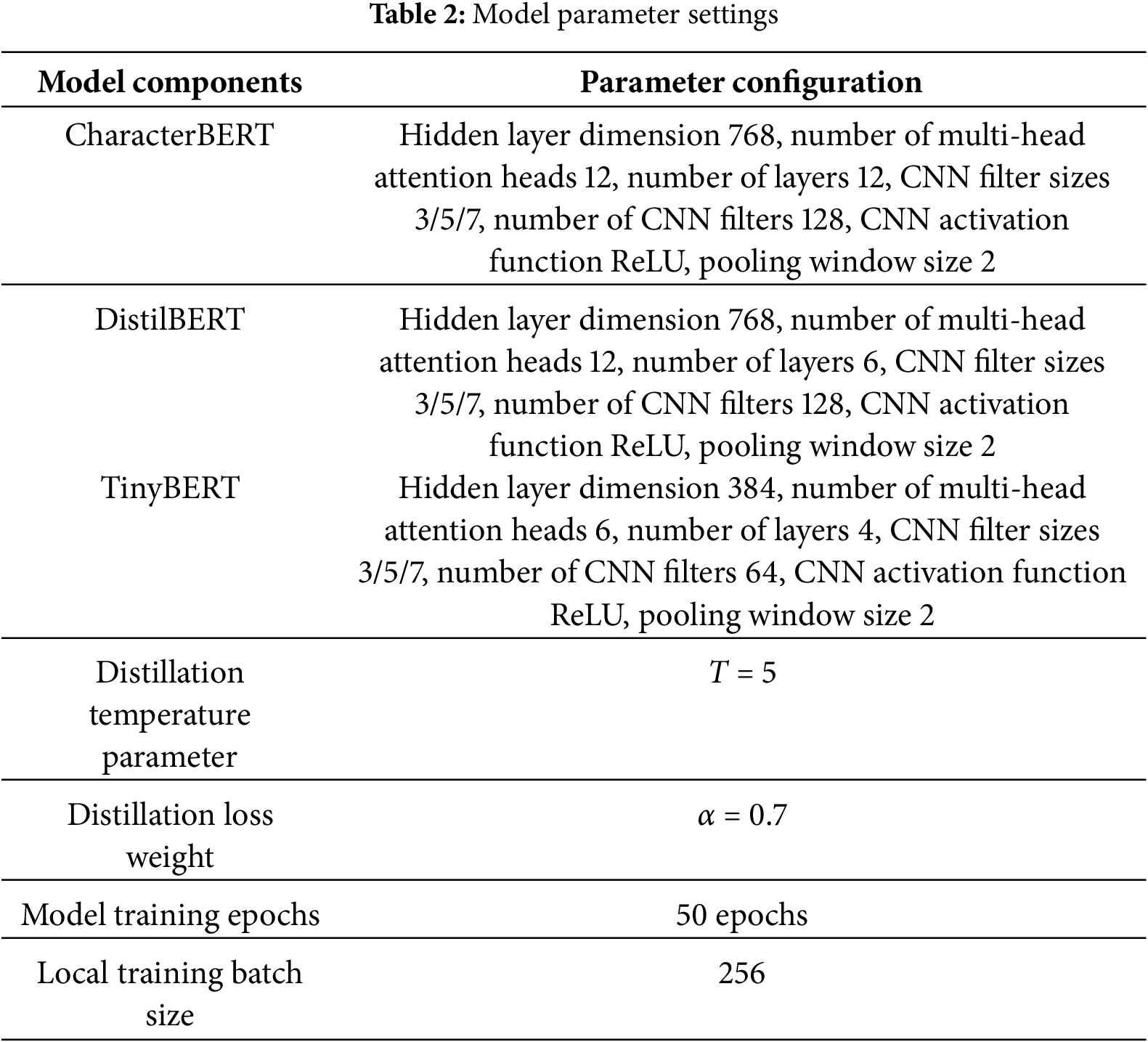

Key parameter settings of each model component and training process are detailed in Table 2. These parameters are determined through multiple pre-experiments to balance model performance and computational efficiency, such as the hidden layer dimension of CharacterBERT and DistilBERT, the number of Transformer layers, and hyperparameters related to knowledge distillation (temperature T and loss weight α).

In the field of DGA malicious domain detection, classic datasets such as the DGArchive Dataset, 360 DGA Dataset, Alexa Top 1 million, Tranco Dataset, and related private datasets are mainly used. These datasets collect a large number of DGA malicious domains and are established to provide researchers with diverse, authentic, and challenging samples, so as to promote the effective evaluation and improvement of DGA malicious domain detection algorithms. The dataset categories used in this paper are as follows:

• DGArchive Dataset [15]: Maintained by Daniel Plohmann and supported by Fraunhofer FKIE, it is a public dataset dedicated to DGA (Domain Generation Algorithm) research. The dataset contains approximately 45.7 million malicious domains from 62 different DGA families and approximately 15.3 million benign Non-Existent Domain (NXDomain) domains, which can be used for comparative analysis and model training. This data is widely used in security scenarios such as malicious domain identification, botnet research, and DGA detection.

• 360 DGA Dataset [25]: Provided by the Qihoo 360 Netlab Open Data Platform, it covers DGA domains generated by more than 50 types of malware, Exploit Kit domains, C2 control end addresses, etc., and is suitable for model training, rule formulation, and threat intelligence research.

• Tranco Dataset [26]: Aims to provide a more stable, fair, and less manipulable domain ranking system. It generates ranking results by integrating multiple sources (such as Crux, Umbrella, Majestic, etc.). Compared with traditional website rankings, Tranco is more suitable for long-term trend analysis and security research.

• Real Network Domain Dataset (RND): This dataset is a collection of domain name samples captured at the network exit of a university in a certain province of China within a certain period of time, including the ports and access volumes of the domains. The dataset contains a total of more than 1 million real domain name instances.

For the normal domain dataset, we select a suitable number of normal domains, set the character length of the real network domain dataset to less than 20, and select domains with relatively large access volumes as normal domains.

For the malicious domain dataset, this paper selects an appropriate number of 32 DGA categories from 137 DGA categories in the latest DGArchive dataset and 12 DGA categories from 67 categories in the 360 DGA dataset. When the amount of data exceeds 20,000, we select the first 20,000 data items of the DGA category to finally form the DGA malicious domain dataset. After preprocessing, the DGA malicious domain dataset contains a total of approximately 650,000 pieces of data, and the normal dataset contains approximately 630,000 pieces of data. When training the model, the cross-validation method is used to divide the dataset, and the number of samples in the training set, validation set, and test set is divided in a ratio of 8:1:1.

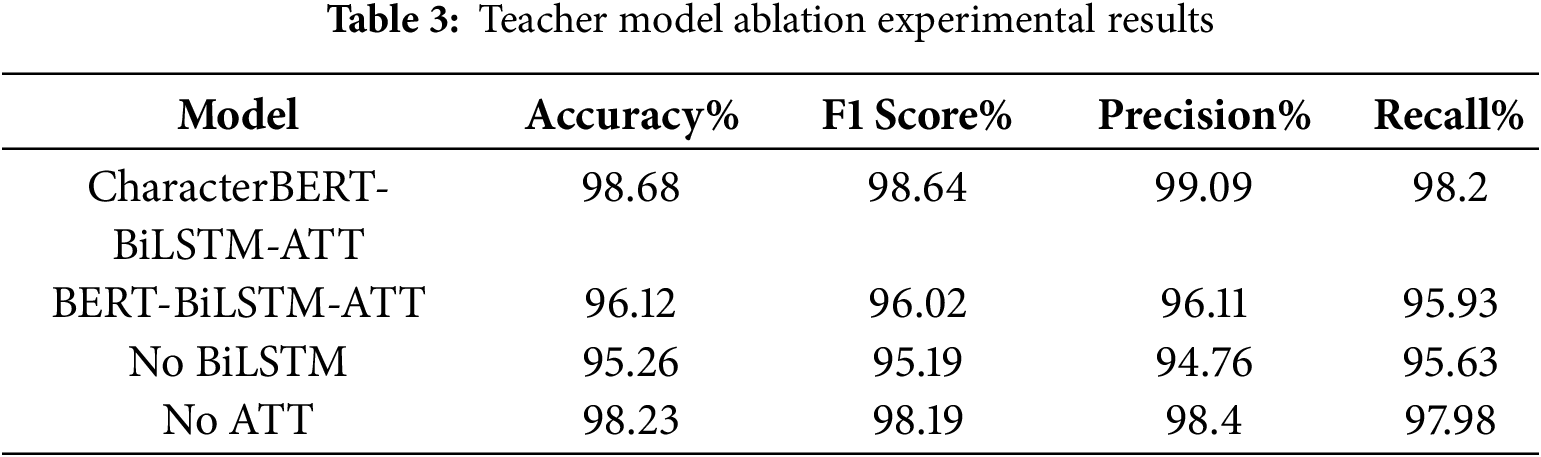

4.3.1 Teacher Model Ablation Experiment

In order to comprehensively verify the effectiveness of each module of the CharacterBERT-BiLSTM-ATT proposed in this paper, an ablation experiment is designed to further clarify the contribution of each module to the overall performance of the model. The results of the ablation experiment are shown in Table 3.

The ablation experiments further confirmed the significant contribution of CharacterBERT, BiLSTM and ATT modules in improving the overall classification performance, among which the performance of CharacterBERT model and BiLSTM was the most significant, while the ATT further optimized the model performance. This fully reflects the rationality and effectiveness of the model structure design in this paper.

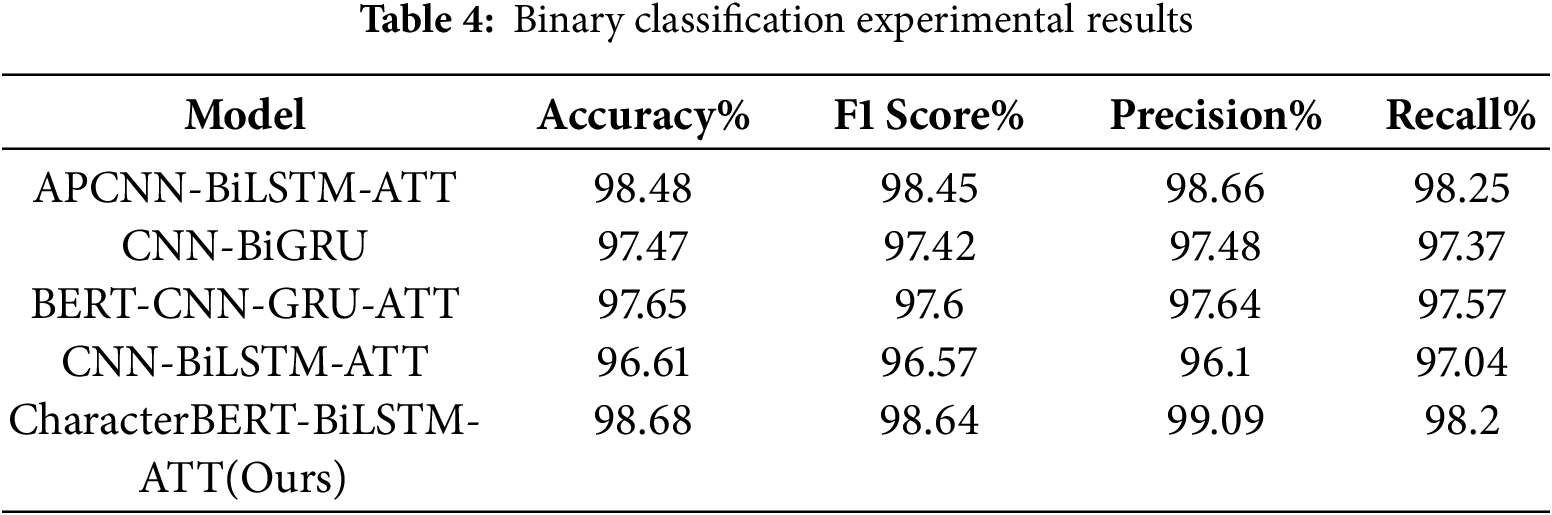

4.3.2 Teacher Model Comparison Experiment

To more comprehensively verify the effectiveness of the teacher model proposed in this paper, several current mainstream and representative models are selected for comparative analysis.

• APCNN-BiLSTM-ATT Model: This model combines APCNN and BiLSTM and uses an ATT to capture multi-scale features of text, which is suitable for text classification tasks with rich semantics.

• CNN-BiGRU Model: This model performs word splitting and one-hot encoding, uses CNN to extract local features, and uses BiGRU to extract rich feature information, which improves the model’s understanding of text context and is suitable for classification tasks sensitive to sequence context.

• BERT-CNN-GRU-ATT Model: Combines BERT to provide contextual semantic representation, and enhances the domain name category recognition ability through the parallel structure of CNN and GRU, effectively extracts the relationships between domain names, and improves the accuracy of text classification.

• CNN-BiLSTM Model: Uses Word2Vec and CNN to extract domain name features, and BiLSTM extracts contextual features in a fine-grained manner, which effectively uses contextual information and improves the delicacy and comprehensiveness of text feature capture.

The comparison experiment results are shown in Table 4. The teacher model proposed in this paper performs best in accuracy, F1 score, and precision. Compared with the second-best APCNN-BiLSTM-ATT model, it has accuracy improvement of 0.20%, F1 score improvement of 0.19%, and a significant 0.43% improvement in precision. In recall rate, the model in this paper reaches 98.2%, slightly lower than the 98.25% of the APCNN-BiLSTM-ATT model, with a 0.05% difference. This shows the model can effectively capture text semantic information and excel in relevant text identification. Although it has a slight recall-rate deficiency, its overall performance advantage is obvious. Compared with other models, its performance advantage is more prominent, verifying the effectiveness of BiLSTM-ATT mechanism in text classification. Through comparison with mainstream models, it shows advantages in text feature extraction, multi-scale information fusion, and classification accuracy, verifying the effectiveness and reliability of the CharacterBERT-BiLSTM-ATT model.

4.4 Knowledge Distillation Experiments

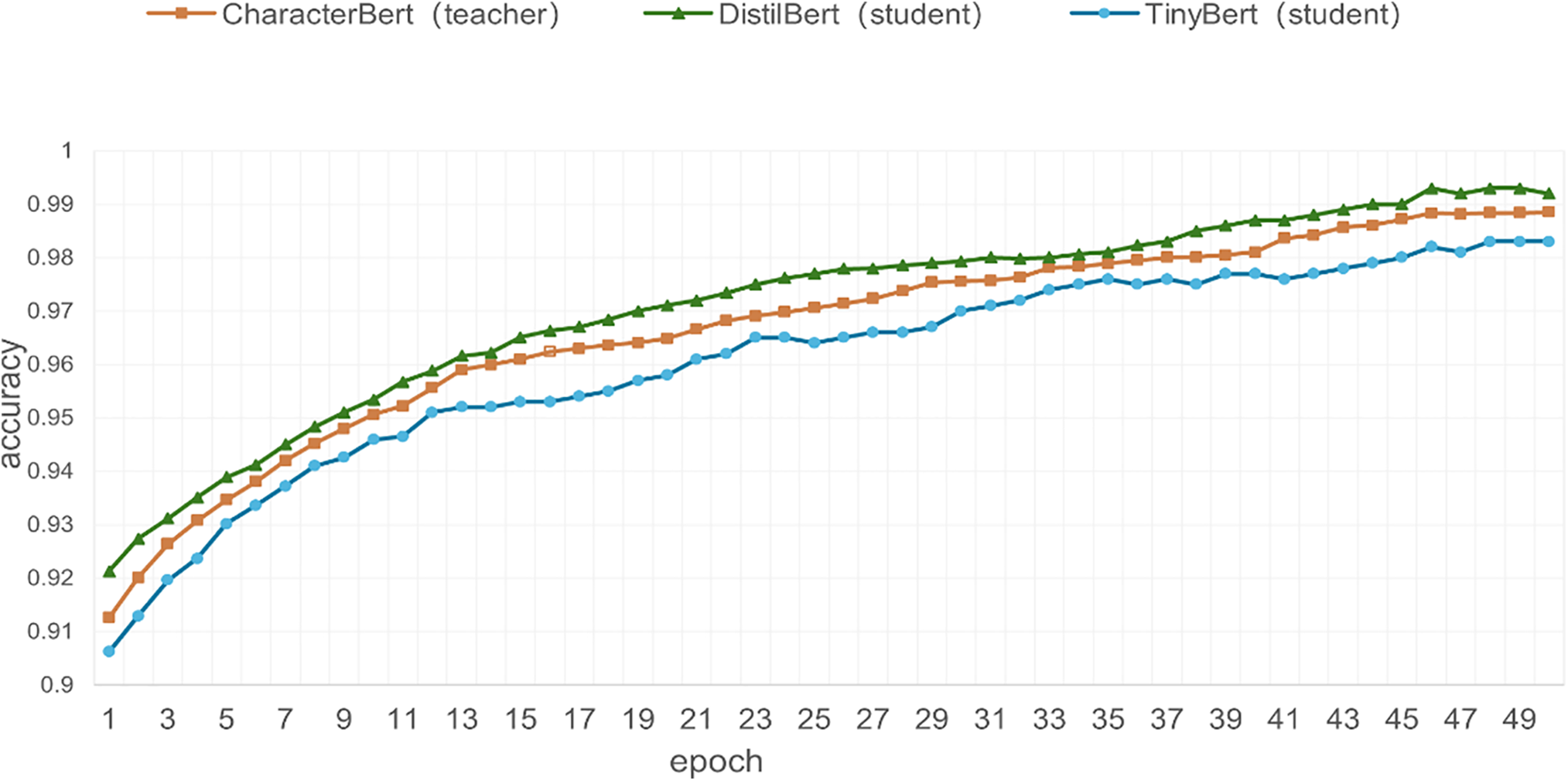

In this paper, DistilBERT and TinyBERT are selected as student models in Knowledge Distillation to learn from the pre-trained teacher model CharacterBERT. A comparative experiment is conducted to analyze which student model is more applicable. The comparison experiment results are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Comparison diagram of experimental results of teacher model and student models

4.4.1 Sensitivity Analysis of Knowledge Distillation Hyperparameter

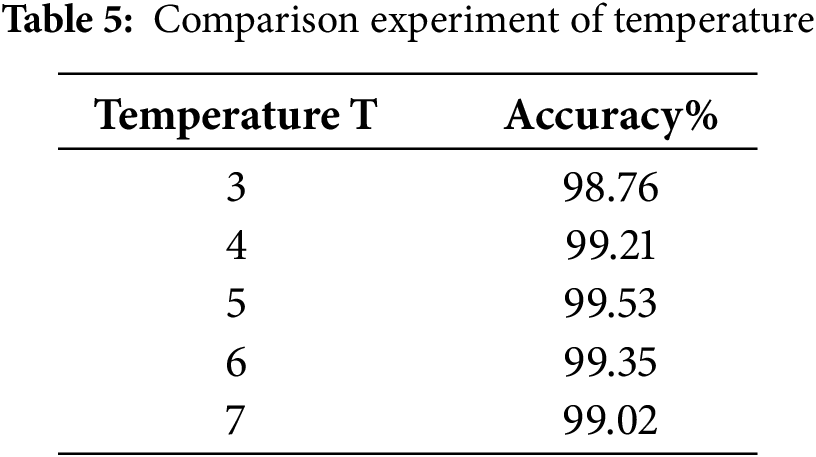

To verify the effectiveness of the selected hyperparameters (distillation temperature T and loss weight α), two groups of control experiments are designed:

Fix α = 0.7, test the model performance when T = 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. The results are shown in Table 5.

When T = 5, the model achieves the best comprehensive performance. When T is too low (T < 5), the soft label distribution is too concentrated, and the student model cannot fully learn the potential knowledge of the teacher model; when T is too high (T > 5), the soft label distribution is too scattered, introducing noise interference.

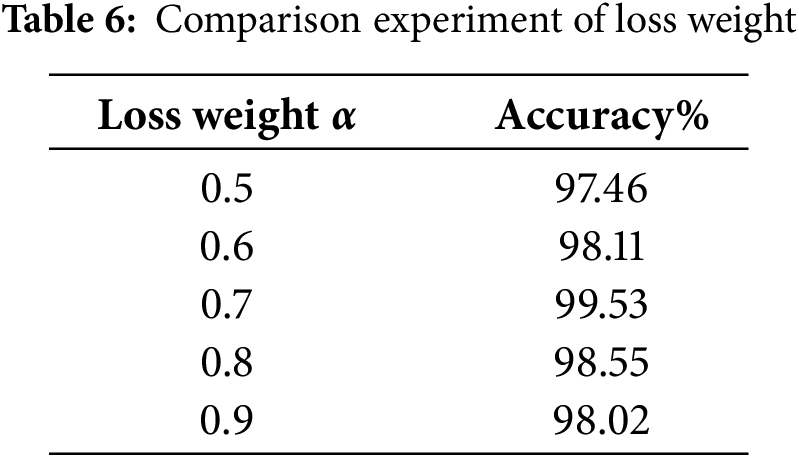

Fix T = 5, test the model performance when α = 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9. The results are shown in Table 6.

The results show that α = 0.7 achieves the optimal balance between soft loss and hard loss: when α < 0.7, the knowledge transfer is insufficient; when α > 0.7, the constraint of hard labels is weakened, leading to a decrease in classification accuracy.

4.4.2 Model Size and Efficiency Metrics

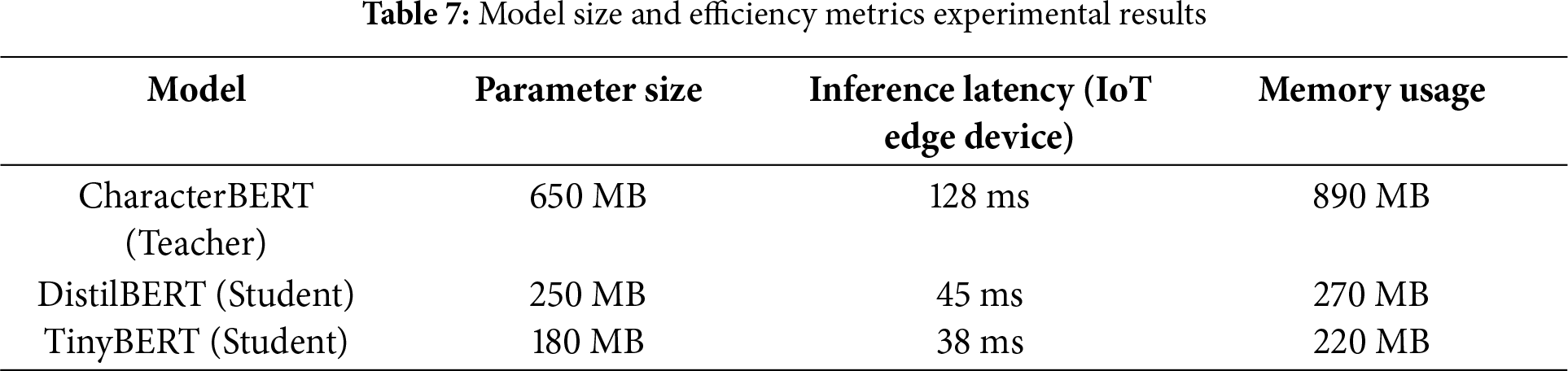

To evaluate the lightweight effect of the student models after knowledge distillation, we tested the parameter size, inference latency on IoT edge devices, and memory usage of the teacher model and student models. The results are shown in Table 7.

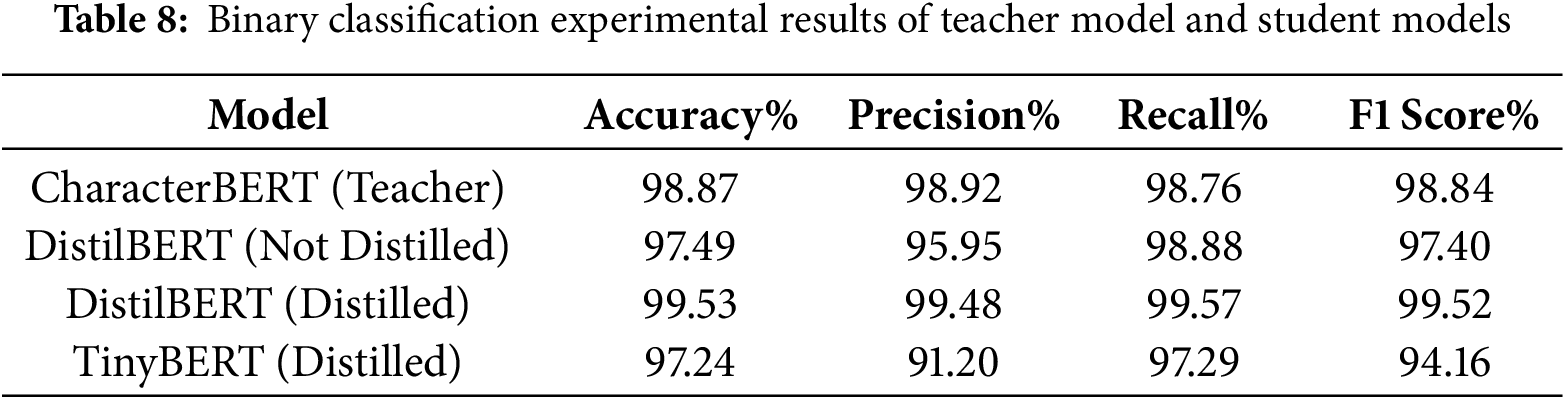

4.4.3 Binary Classification Performance

The binary classification performance of the teacher model and student models is shown in Table 8. Notably, the distilled DistilBERT model achieves an accuracy of 99.53%, which not only exceeds the non-distilled DistilBERT (97.49%) but also outperforms the teacher model (98.87%). This indicates that the knowledge distillation strategy effectively transfers the teacher model’s learning experience to the student model.

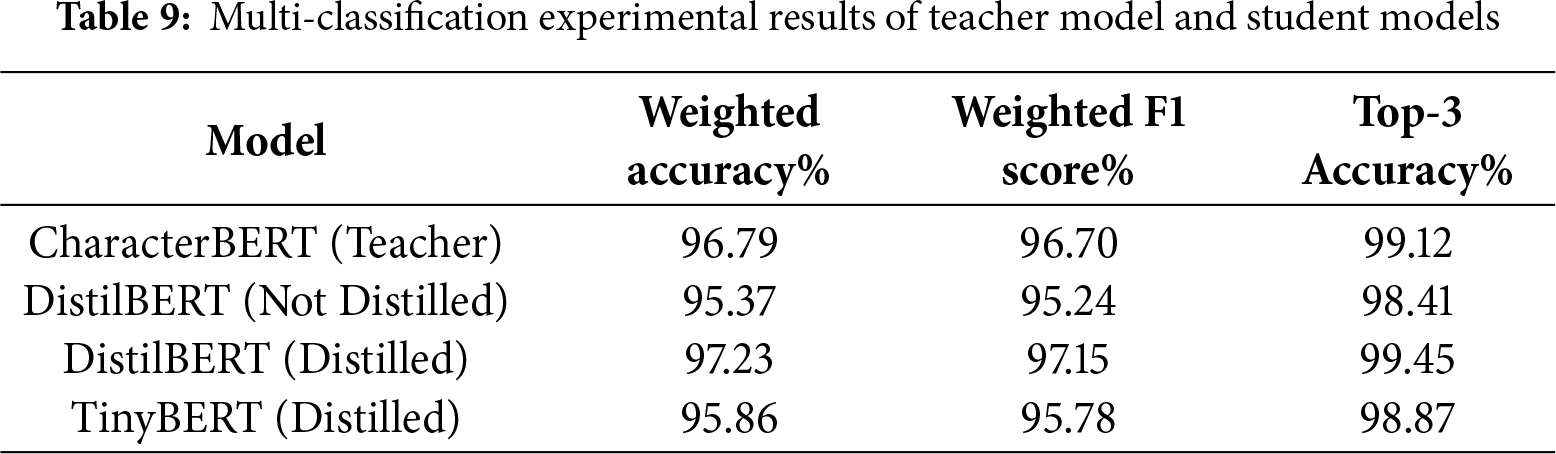

4.4.4 Multi-Class Detection Results

For the multi-classification task of 44 DGA families, the performance metrics of each model are shown in Table 9. The distilled DistilBERT model achieves a weighted accuracy of 97.23% and a Top-3 accuracy of 99.45%, both higher than the teacher model’s 96.79% and 99.12%. This proves that the student model retains strong ability to distinguish between different DGA families, and its robustness in complex classification scenarios is further verified.

4.4.5 Result Analysis and Discussion

In the student model, DistilBERT has a parameter size of 250 MB and an inference latency of 45 ms, and TinyBERT has a parameter size of 180 MB with a latency of 38 ms, both of which meet the requirements for deployment in resource-constrained IoT environments. Among them, DistilBERT outperforms the teacher model in all metrics for the binary classification task. Based on the F1 score of 99.52% and the knowledge distillation process, the potential reasons are inferred as follows: during knowledge distillation, the soft labels transfer the generalization knowledge of the teacher model, reducing the risk of overfitting; meanwhile, the distillation loss function balances the soft label knowledge and hard label constraints, enabling the student model to learn a more robust feature distribution. In the multi-classification task, its weighted accuracy is 97.23%, and the accuracy of the top three is 99.45%, which is better than the teacher model’s 96.79% and 99.12%, proving its robustness in complex family classification. At the same time, DistilBERT is highly viable for edge deployment. Its memory footprint is only 270 MB (890 MB for teacher models), and inference latency is reduced by 65%–78%. It demonstrates its robustness in complex family classification. However, TinyBERT is inferior to the teacher model in all indicators because of the small number of parameters and the overly simplified structure. In the end, DistilBERT achieves the best balance between model compression, inference efficiency, and detection performance, and its performance even surpasses that of teacher models, making it suitable for edge devices to achieve high-precision and low-latency real-time detection.

This study designs a DGA domain detection framework based on deep learning to address the challenge of identifying malicious Domain Generation Algorithms. We propose a CharacterBERT-BiLSTM-ATT hybrid deep learning model, which combines CharacterBERT to achieve character-level semantic representation, uses BiLSTM to capture sequence dependencies, and integrates an ATT to achieve multi-dimensional feature fusion, thereby significantly improving the feature extraction ability. Experimental results show that this model has excellent performance in pattern recognition and robustness, and is suitable for large-scale network security applications.

Considering the resource constraints of IoT devices and the demand for lightweight models, we perform Knowledge Distillation on the hybrid deep model, significantly reducing the computational resource overhead. Specifically, the number of model parameters is reduced to 38.4% of the original scale, and the computational complexity is greatly reduced, making it easier to deploy on edge computing devices and in IoT environments. Experiments show that the student model has performance comparable to that of teacher models, and at the same time achieves efficient and real-time DGA malicious domain detection, providing reliable support for IoT security.

Despite certain achievements, this study has room for optimization. Future research can focus on three directions: First, combine knowledge distillation and model pruning to further compress the model for edge/IoT deployment, enhancing practicality. Second, introduce adversarial training and explore federated learning-based defense strategies to improve resistance against variant DGA domains. Third, integrate multi-modal data (e.g., DNS traffic, WHOIS information) with character features to boost detection accuracy and generalization.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was jointly supported by the following projects: National Natural Science Foundation of China (62461041); Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province China (20242BAB25068).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Chengqi Liu; Data collection: Yongtao Li; Analysis and interpretation of results: Weiping Zou; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Deyu Lin; Draft manuscript preparation: Yongtao Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Weiping Zou, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sadique F, Sengupta S. Analysis of attacker behavior in compromised hosts during command and control. In: Proceedings of the ICC 2021—IEEE International Conference on Communications; 2021 Jun 14–23; Montreal, QC, Canada. p. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

2. MoldStud. Essential performance testing metrics for IoT—key factors you can’t ignore; 2025 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Oct 11]. Available from: https://moldstud.com/articles/p-essential-performance-testing-metrics-for-iot-key-factors-you-cant-ignore. [Google Scholar]

3. Yang L, Zhai J, Liu W, Ji X, Bai H, Liu G, et al. Detecting word-based algorithmically generated domains using semantic analysis. Symmetry. 2019;11(2):176. doi:10.3390/sym11020176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Selvi J, Rodríguez RJ, Soria-Olivas E. Detection of algorithmically generated malicious domain names using masked N-grams. Expert Syst Appl. 2019;124:156–63. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2019.01.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Cucchiarelli A, Morbidoni C, Spalazzi L, Baldi M. Algorithmically generated malicious domain names detection based on n-grams features. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;170:114551. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ma D, Zhang S, Zhao H. Improved malicious domain name detection algorithm of Relief-C5.0. Comput Eng Appl. 2022;58(11):100–6. doi:10.3778/j.issn.1002-8331.2012-0475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Mao J, Zhang J, Tang Z, Gu Z. DNS anti-attack machine learning model for DGA domain name detection. Phys Commun. 2020;40:101069. doi:10.1016/j.phycom.2020.101069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Liu L. Research on DGA detection algorithm for botnets of the Internet of Things [dissertation]. Xi’an, China: Xidian University; 2022. [Google Scholar]

9. Yang LH, Liu GJ, Zhai JT, Liu WW, Bai HW, Dai YW. Improved algorithm for detection of the malicious domain name based on the convolutional neural network. J Xidian Univ. 2020;47(1):37–43. (In Chinese). doi:10.19665/j.issn1001-2400.2020.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Woodbridge J, Anderson HS, Ahuja A, Grant D. Predicting domain generation algorithms with long short-term memory networks. arXiv:1611.00791. 2016. [Google Scholar]

11. Qiao Y, Zhang B, Zhang W, Sangaiah AK, Wu H. DGA domain name classification method based on long short-term memory with attention mechanism. Appl Sci. 2019;9(20):4205. doi:10.3390/app9204205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tran D, Mac H, Tong V, Tran HA, Nguyen LG. A LSTM based framework for handling multiclass imbalance in DGA botnet detection. Neurocomputing. 2018;275:2401–13. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2017.11.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Morbidoni C, Spalazzi L, Teti A, Cucchiarelli A. Leveraging n-gram neural embeddings to improve deep learning DGA detection. In: Proceedings of the 37th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing; 2022 Apr 25–29; Virtual. p. 995–1004. [Google Scholar]

14. Antonakakis M, Perdisci R, Nadji Y, Vasiloglou N, Abu-Nimeh S, Lee W, et al. From throw-away traffic to bots: detecting the rise of DGA-based malware. In: Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Security Symposium; 2012 Aug 8–10; Bellevue, WA, USA. Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2012. p. 491–506. [Google Scholar]

15. Plohmann D, Yakdan K, Klatt M, Bader J, Gerhards-Padilla E. A comprehensive measurement study of domain generating malware. In: Proceedings of the 25th USENIX Security Symposium; 2016 Aug 10–12; Austin, TX, USA. Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2016. p. 263–78. [Google Scholar]

16. National Internet Emergency Response Center of China. 2023 China Internet cybersecurity report. Beijing, China: National Internet Emergency Response Center of China; 2024. [Google Scholar]

17. El Boukkouri H, Ferret O, Lavergne T, Noji H, Zweigenbaum P, Tsujii JI. CharacterBERT: reconciling ELMo and BERT for word-level open-vocabulary representations from characters. In: Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics; 2020 Sep 13–18; Barcelona, Spain. p. 6903–15. [Google Scholar]

18. Zhuang S, Zuccon G. CharacterBERT and self-teaching for improving the robustness of dense retrievers on queries with typos. In: Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval; 2022 Jul 11–15; Madrid, Spain. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 1444–54. [Google Scholar]

19. Greff K, Srivastava RK, Koutnik J, Steunebrink BR, Schmidhuber J. LSTM: a search space odyssey. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2017;28(10):2222–32. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2016.2582924. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Graves A, Schmidhuber J. Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional LSTM and other neural network architectures. Neural Netw. 2005;18(5–6):602–10. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2005.06.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Gou J, Yu B, Maybank SJ, Tao D. Knowledge distillation: a survey. Int J Comput Vis. 2021;129(6):1789–819. doi:10.1007/s11263-021-01453-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Minaee S, Kalchbrenner N, Cambria E, Nikzad N, Chenaghlu M, Gao J. Deep learning-based text classification: a comprehensive review. ACM Comput Surv. 2022;54(3):1–40. doi:10.1145/3439726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhou P, Shi W, Tian J, Qi Z, Li B, Hao H, et al. Attention-based bidirectional long short-term memory networks for relation classification. In: Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers); 2016 Aug 7–12; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2016. p. 207–12. [Google Scholar]

24. Sanh V, Debut L, Chaumond J, Wolf T. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv:1910.01108. 2019. [Google Scholar]

25. 360 Netlab. Suspicious DGA from PDNS and sandbox 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jul 12]. Available from: https://github.com/360netlab/DGA. [Google Scholar]

26. Le Pochat V, Van Goethem T, Tajalizadehkhoob S, Korczynski M, Joosen W. Tranco: a research-oriented top sites ranking hardened against manipulation. In: Proceedings 2019 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; 2019 Feb 24–27; San Diego, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools