Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

TeachSecure-CTI: Adaptive Cybersecurity Curriculum Generation Using Threat Dynamics and AI

Computer Science Department, College of Computing and Informatics, Saudi Electronic University, Riyadh, 13316, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Alaa Tolah. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence Algorithms and Applications, 2nd Edition)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 71 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.074997

Received 23 October 2025; Accepted 30 November 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

The rapidly evolving cybersecurity threat landscape exposes a critical flaw in traditional educational programs where static curricula cannot adapt swiftly to novel attack vectors. This creates a significant gap between theoretical knowledge and the practical defensive capabilities needed in the field. To address this, we propose TeachSecure-CTI, a novel framework for adaptive cybersecurity curriculum generation that integrates real-time Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) with AI-driven personalization. Our framework employs a layered architecture featuring a CTI ingestion and clustering module, natural language processing for semantic concept extraction, and a reinforcement learning agent for adaptive content sequencing. By dynamically aligning learning materials with both the evolving threat environment and individual learner profiles, TeachSecure-CTI ensures content remains current, relevant, and tailored. A 12-week study with 150 students across three institutions demonstrated that the framework improves learning gains by 34%, significantly exceeding the 12%–21% reported in recent literature. The system achieved 84.8% personalization accuracy, 85.9% recognition accuracy for MITRE ATT&CK tactics, and a 31% faster competency development rate compared to static curricula. These findings have implications beyond academia, extending to workforce development, cyber range training, and certification programs. By bridging the gap between dynamic threats and static educational materials, TeachSecure-CTI offers an empirically validated, scalable solution for cultivating cybersecurity professionals capable of responding to modern threats.Keywords

The cybersecurity domain has shifted rapidly, with structured frameworks such as MITRE ATT&CK organizing adversarial behaviors [1] and Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) offering validated, real-time security insights for data-driven cyber defence [2]. Modern attackers increasingly exploit sophisticated pathways that evade traditional defences [3], while AI continues to redefine offensive and defensive cyber operations [4]. Static academic programs struggle to remain relevant because curriculum cycles lag behind evolving threats [5]. Workforce shortages persist, with millions of vacancies tied to outdated training models [6]. AI-enabled learning is reshaping education paradigms [7], yet nearly three-quarters of cybersecurity professionals report gaps between academic preparation and real-world roles [8]. Key issues include rapid threat evolution outpacing course updates [9], insufficient personalization in learning environments [10], and a disconnect between theoretical knowledge and applied cybersecurity practice [11]. CTI now acts as a foundation for modern security programs [12], providing near-real-time threat context for updating instructional material [13]. Adaptive learning systems address personalization needs [14], with machine learning optimizing delivery and knowledge progression [15], while threat-aligned learning modules enhance defensive readiness [16]. Secure automated training mechanisms, such as Jupyter-based autograding platforms, now help scale practical cybersecurity skill development [17]. Concurrently, AI-driven personalization frameworks tailor content delivery to learner profiles and evolving adversarial techniques [18]. Predictive intelligence mechanisms further enable proactive learning experiences [19], empowering students to anticipate cyber challenges rather than react to them [20]. With higher-education institutions facing a sharp rise in cyberattacks—an increase of nearly 187% [21]—curricula must adapt to institutional risks and operational realities [22]. AI-powered attack techniques demand specialized competencies currently missing from typical programs [23]. Rigid educational structures struggle to keep pace with emerging threats [24], and rapidly advancing AI methods continue to reshape detection capabilities [25]. The resultant challenge is clear: educators must bridge the gap between outdated yet personalized curricula and current but generic content, requiring a system that blends real-time CTI with adaptive AI-based learning.

This work introduces TeachSecure-CTI, a framework that automates curriculum development while customizing instruction to reflect both emerging threats and individual learner needs. The central goal is to create a real-time cybersecurity training system that integrates dynamic CTI feeds with adaptive learning mechanisms. Specifically, the framework (i) aligns instructional modules with newly emerging threats, (ii) personalizes content sequencing using reinforcement learning and NLP-based analysis, and (iii) evaluates performance through a multi-institution academic deployment. Complementary goals include designing challenge-driven assessment pipelines that measure applied cyber skills and implementing monitoring tools to track learner progression and instructional impact. By addressing timeliness, personalization, and scalability barriers, this approach reframes cybersecurity learning as a continuous, adaptive, and application-focused process suited for rapidly evolving threat ecosystems.

This study contributes to cybersecurity education in five key ways. First, it introduces a dynamic threat-aware content engine that continuously generates learning modules from updated CTI streams. Second, it establishes an adaptive architecture that models student behavior in combination with real-time threat shifts. Third, the system unifies CTI processing, NLP pipelines, and reinforcement learning into a cohesive multidimensional curriculum engine. Fourth, multi-institution results demonstrate a 34% improvement in learning outcomes over static curricula, confirming the effectiveness of the adaptive design. Finally, a predictive CTI-integration mechanism allows the framework to anticipate threat evolution, enabling a proactive rather than reactive academic model. Collectively, these advancements deliver a validated foundation for threat-aligned, personalized cybersecurity education.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: Section II presents a comprehensive literature review examining current research in AI-driven cybersecurity education, adaptive learning systems, threat intelligence integration, and intelligent tutoring systems, establishing the theoretical foundation for our approach. Section III details the methodology employed in developing TeachSecure-CTI, including the system architecture, threat intelligence processing framework, adaptive curriculum generation algorithms, and experimental validation protocols. Section IV presents the comprehensive results obtained from our experimental evaluation, including quantitative performance metrics, qualitative feedback analysis, and comparative assessments with existing approaches, followed by a detailed discussion of implications and limitations. Section V concludes the paper by summarising key findings, highlighting practical applications, discussing deployment considerations, and outlining future research directions that emerge from this work.

The convergence of artificial intelligence and cybersecurity training has become a pivotal academic focus, with AI systems recognised as essential for narrowing the growing talent shortfall in the cybersecurity sector [26]. Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS) have demonstrated strong effectiveness in boosting learner performance and motivation [27], providing tailored feedback and adaptive guidance comparable to expert human mentorship [28]. This review synthesises peer-reviewed work published between 2023 and 2025 across AI-enhanced learning, adaptive systems, and cybersecurity education.

AI adoption within cybersecurity instruction has shifted from basic automated workflows toward intelligent systems capable of generating tailored content and learning experiences. Machine learning models now forecast optimal pedagogical routes and significantly enhance long-term knowledge retention [29], while NLP enables automated curriculum enrichment aligned with industry expectations [30]. Large language models offer contextual tutoring and personalised support [31], and generative AI contributes realistic cyber-range scenarios for experiential learning [32]. AI-driven assessment mechanisms continuously monitor learner progress and recommend targeted improvements [33].

Adaptive learning technologies increasingly address varied learner backgrounds and prior knowledge in cybersecurity classrooms [34], using machine learning to evaluate competency, tailor instruction, and optimise learning pathways [35]. Competency-driven advancement models allow students to progress based on mastery rather than fixed timelines [36], and collaborative filtering techniques recommend customised content based on shared learner patterns [37].

Cyber threat intelligence has become an influential educational component by providing authentic, timely learning experiences [38], with real-time feeds ensuring curriculum alignment with emerging attack vectors [39]. Hands-on threat hunting methods strengthen analytical proficiency and intelligence evaluation skills [40–42]. Gamification strategies consistently enhance learner participation [43], with reward systems improving persistence and course completion rates [44]. Virtual cyber-ranges offer safe, controlled environments for practicing offensive-defensive strategies [45], and Capture-the-Flag exercises strengthen group problem-solving and technical collaboration [46].

Despite growth in AI-supported cybersecurity education [46], talent shortages persist [47], with millions of unfilled roles globally [32] and continued gaps in hands-on tool usage and compliance-driven competencies [33]. Accelerated certification pathways provide alternative entry routes to cybersecurity careers [35]. However, current adaptive learning efforts [14,39] primarily optimise personalisation without accounting for real-time threat dynamics, while CTI-focused approaches [3] typically lack integration with pedagogical models [48]. Contemporary studies exploring gamified scenarios [47], scalable CTI acquisition, organisational AI strategies [49], and AI-enabled security controls [50] remain fragmented and do not deliver unified, intelligence-driven education frameworks. No previous work fully integrates continuous CTI ingestion, AI-based personalisation, and empirical validation within a cohesive cybersecurity curriculum, positioning TeachSecure-CTI as the first system to fill this methodological and practical research gap.

Recent studies continue advancing the integration of intelligence-driven automation in cybersecurity learning systems. Qureshi et al. presented a network forensic training framework emphasising intelligence-centric analysis pipelines and security data contextualisation, highlighting the importance of threat-aware knowledge extraction in cyber education environments [49]. Similarly, Wajahat et al. proposed an AI-enabled security model leveraging deep learning for threat identification and operational decision support, demonstrating the value of adaptive intelligence in cybersecurity automation and real-time threat detection [50]. While these contributions reinforce the progression toward intelligence-enhanced cybersecurity training, they primarily focus on system-level threat analysis rather than real-time CTI-powered personalisation. Unlike these works, TeachSecure-CTI uniquely combines live CTI ingestion, NLP-based threat concept modelling, and reinforcement-driven curriculum sequencing to deliver continuously updated, learner-specific cybersecurity education.

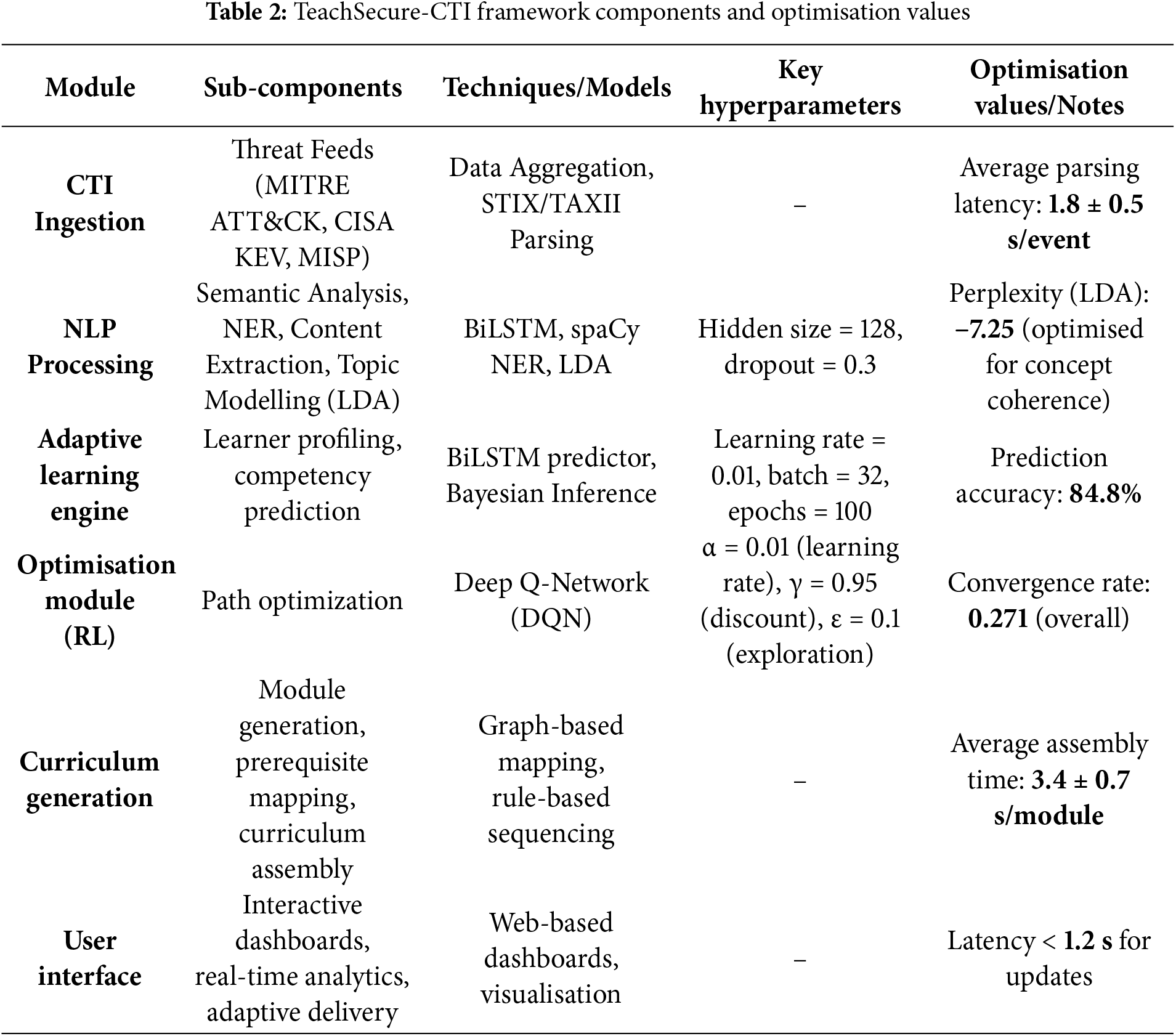

Table 1 presents a comparative summary of recent literature across seven analytical dimensions, including AI utilisation, CTI integration, personalisation depth, and methodological robustness. This structured analysis establishes a reference benchmark for validating the novel contributions of the TeachSecure-CTI framework.

Despite advances in adaptive learning and cybersecurity education, no existing framework holistically integrates real-time cyber threat intelligence (CTI) with personalised curriculum generation. Current approaches either emphasise generic adaptability without domain relevance [9,10] or employ static methods unable to address emerging threats [14,16]. While AI-driven personalisation exists [29,30], it lacks CTI integration, and threat intelligence research [3] remains disconnected from pedagogy. Recent studies reflect this fragmentation Albaladejo-González et al. [46] developed gamified training without CTI feeds, and Sorokoletova et al. [47] created scalable CTI extraction lacking personalisation. At the same time, Nott [48] and Ahmadi [51] addressed enterprise adaptation and adaptive firewalls in contexts beyond education. Most validation relies on limited trials [14,17,18]. To address this gap, TeachSecure-CTI builds on three theoretical foundations: adaptive learning systems, drawing from ITS and transdisciplinary digital education [46], CTI integration that follows best practices for systematised threat processing, and reinforcement learning for path optimisation using multi-armed bandit formulations [3]. This integration enables threat-informed, personalised cybersecurity curricula that overcome the limitations of previous solutions in depth, personalisation, and real-time responsiveness, creating a framework that dynamically adapts to both evolving threats and individual learner needs.

This segment outlines the entire methodology used to design and test TeachSecure-CTI, an adaptive framework for generating cybersecurity curricula that incorporates real-time threat intelligence into artificial intelligence-infused personalisation. It comprises the theoretical background, design principles, and mathematical modelling of a threat-aware educational system, along with the frameworks for assessing it. Our system is a hybrid that combines traditional machine learning methodologies with innovative algorithms, specifically tailored to educate cybersecurity professionals. It adheres to both a sound pedagogical approach and the technical specifics of cybersecurity education, a rapidly evolving field.

3.1 System Model and Assumptions

TeachSecure-CTI is a multi-agent adaptive learning environment system in which intelligent agents coordinate threat intelligence processing and the generation of personalised curriculum. Its main system model employs a feedback-based system architecture that continually monitors the progress made by learners, the level of threats, and the effectiveness measures of the educational process. The model combines reinforcement learning path optimisation algorithms and natural language processing modules of threat intelligence extraction. The mechanisms of real-time synchronisation are used to ensure the integration of new threats into the educational modules in the shortest possible period, while maintaining pedagogical consistency. The system architecture enables distributed processing to support different loads in computation and allows seamless scaling across various educational environments, while maintaining the quality of personalisation and response times.

The mathematical model treats the learning environment as a dynamic system, whereby state transitions reflect the events of knowledge acquisition that depend on the particular features of the individual learner, as well as external updates to the threat intelligence. Markov Decision Process formulations are used in the system to decide on the sequence of curricula by predicting learning outcomes and engagement rates. Bayesian inference mechanisms enable learners’ models to be continuously refined through observed behaviours and evaluation outcomes, facilitating continuous personalisation algorithms. The model uses uncertainty quantification to process the lack of information regarding learner capabilities and the reliability of threat intelligence. Adaptive control algorithms adjust the system’s parameters based on feedback from its performance, ensuring optimal learning experiences for diverse student populations and evolving cybersecurity environments.

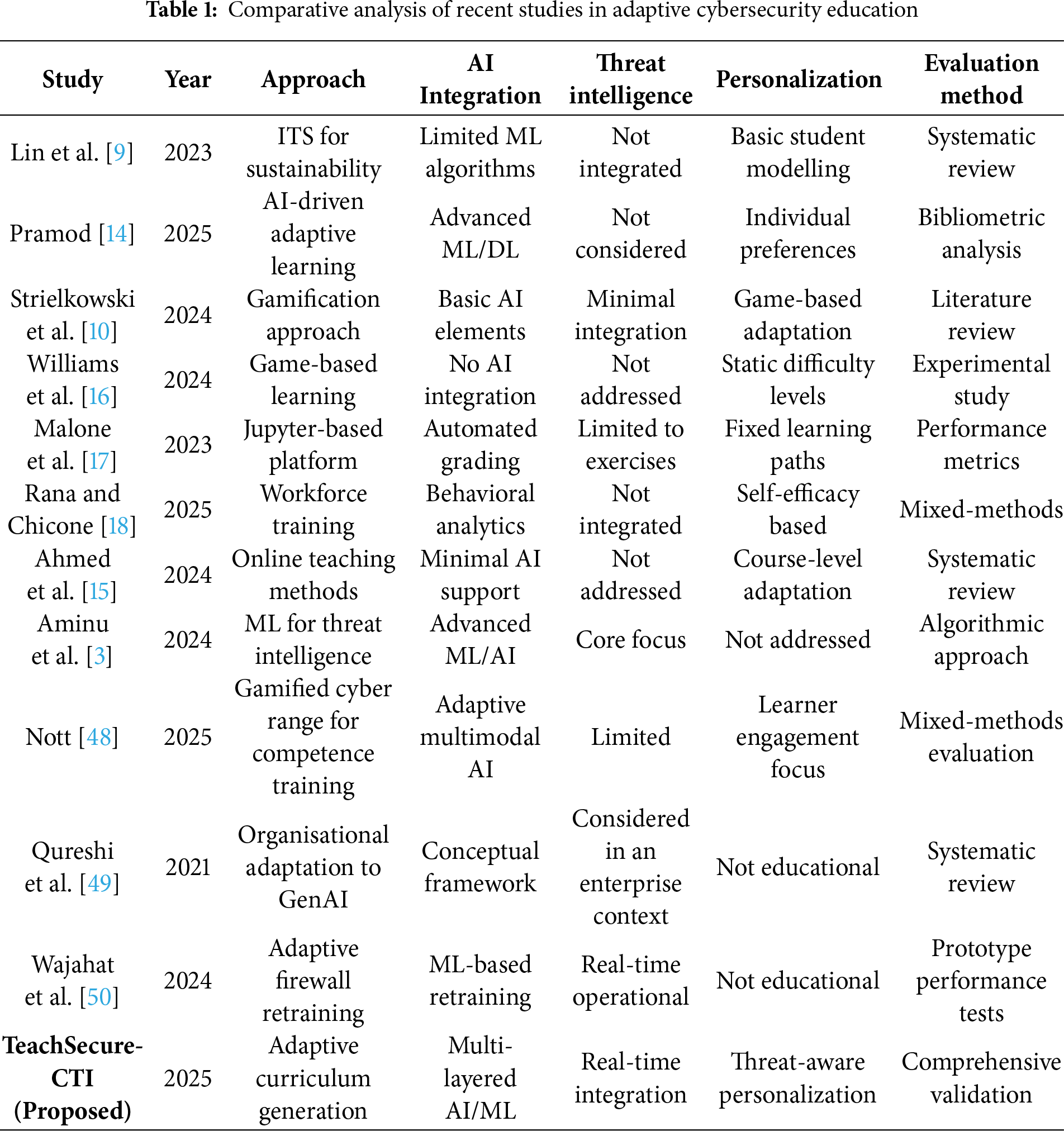

Fig. 1 illustrates the overall system architecture of TeachSecure-CTI, which provides an end-to-end workflow, beginning with various sources of threat intelligence and culminating in the delivery of personalised cybersecurity curriculum. The system combines multiple heterogeneous data sources, such as real-time threat intelligence feeds, cybersecurity incident reports, technical security blogs, and current news articles, to provide comprehensive coverage of the threat landscape. These various inputs are then fed into the central TeachSecure-CTI engine, which utilises sophisticated machine learning algorithms and neural networks represented by interconnected nodes that analyse, correlate, and synthesise threat data into educational content. The cybersecurity data processing component is the knowledge extraction and transformation layer, which processes raw threat intelligence into a structured form of educational concepts that can be used to generate a curriculum. The system model indicates that the platform has the potential to automatically convert complex and technical threat intelligence into understandable, pedagogically accurate educational content, keeping learners engaged through personalised delivery channels. The ultimate product is a dynamically created cybersecurity curriculum that stays abreast of changing threat environments and accommodates the needs of individual learners based on their personal preferences and level of competencies.

Figure 1: TeachSecure-CTI Framework demonstrating the comprehensive workflow from multiple threat intelligence sources through AI processing to personalised cybersecurity curriculum generation

The TeachSecure-CTI framework operates under the following key assumptions:

• The learners have the basic skills of computer literacy and the foundational knowledge of cybersecurity that is adequate to engage with intermediate-level content.

• It maintains a constant internet connection to integrate real-time threat intelligence and can also work offline to support cached content.

• Learning materials may be broken down into modular units that facilitate a modular recombination based on customisation needs.

• Cyber threats exhibit patterns that can be learnt by operating machine learning algorithms, even though new attack vectors may require expert intervention.

• The effectiveness of learning can be measured using observable behaviour, assessment results, and engagement data.

• Computational models can capture the individual differences in learning and be implemented using algorithmic adaptation.

• The information available in threat intelligence sources is of high quality, enabling the prompt generation of educational materials.

• The students exhibit regular engagement patterns that enable the prediction of learning preferences and outcomes with high accuracy through modelling learning.

The TeachSecure-CTI architecture employs a five-layer architecture that decouples concerns and efficiently supports data flow and the coordination of processing. The implementation of each layer performs specific functions, supports real-time adaptations, and maintains modular interfaces that enable complex interactions required for generating adaptive cybersecurity curricula.

A key enhancement of the proposed framework lies in the integration between the NLP layer and the Adaptive Learning Engine, where real-time CTI signals continuously update the learner state space processed by the DQN module. Threat reports ingested through STIX/TAXII pipelines are encoded through BiLSTM-based semantic extraction, which generates a dynamic threat vector that captures new attack patterns, MITRE ATT&CK techniques, and threat severity. This threat vector is then fused with learner performance indicators (competency score, pace, quiz feedback, help-seeking behaviour) to form the combined learning state

The Deep Q-Network (DQN) uses this fused state to select the next optimal module, ensuring curriculum sequencing remains aligned with both emerging cyber-attack patterns and individual learner needs. The Q-value update follows:

where the reward

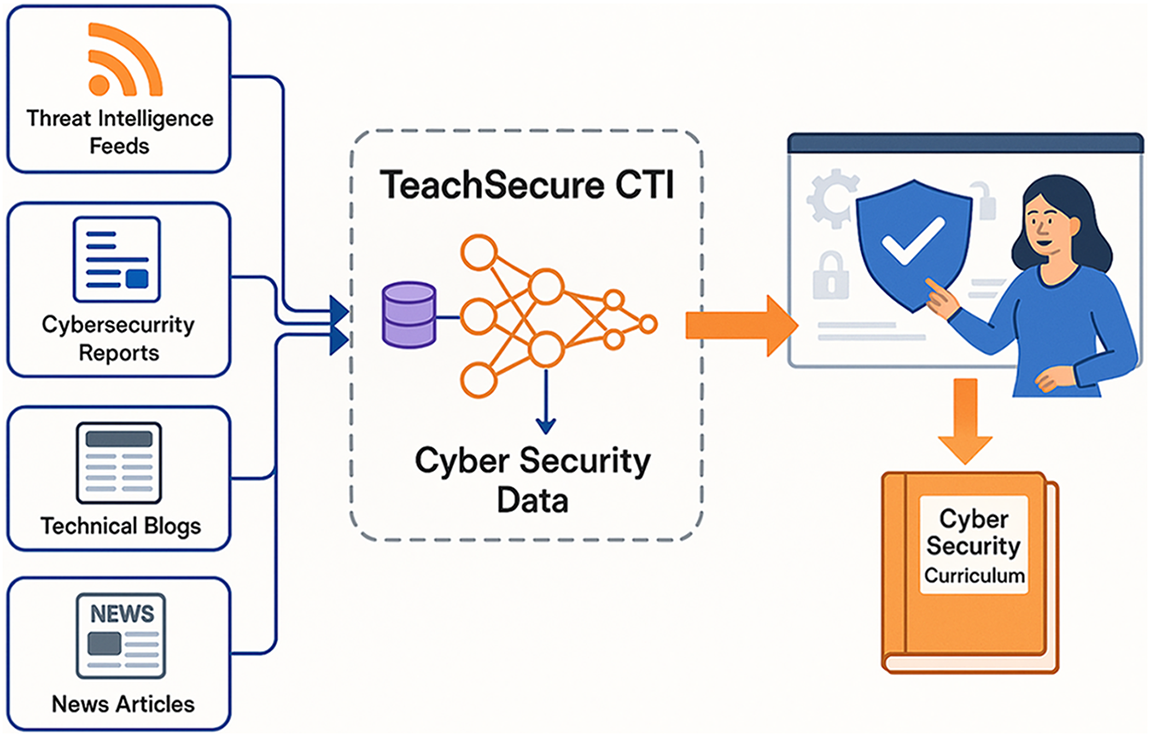

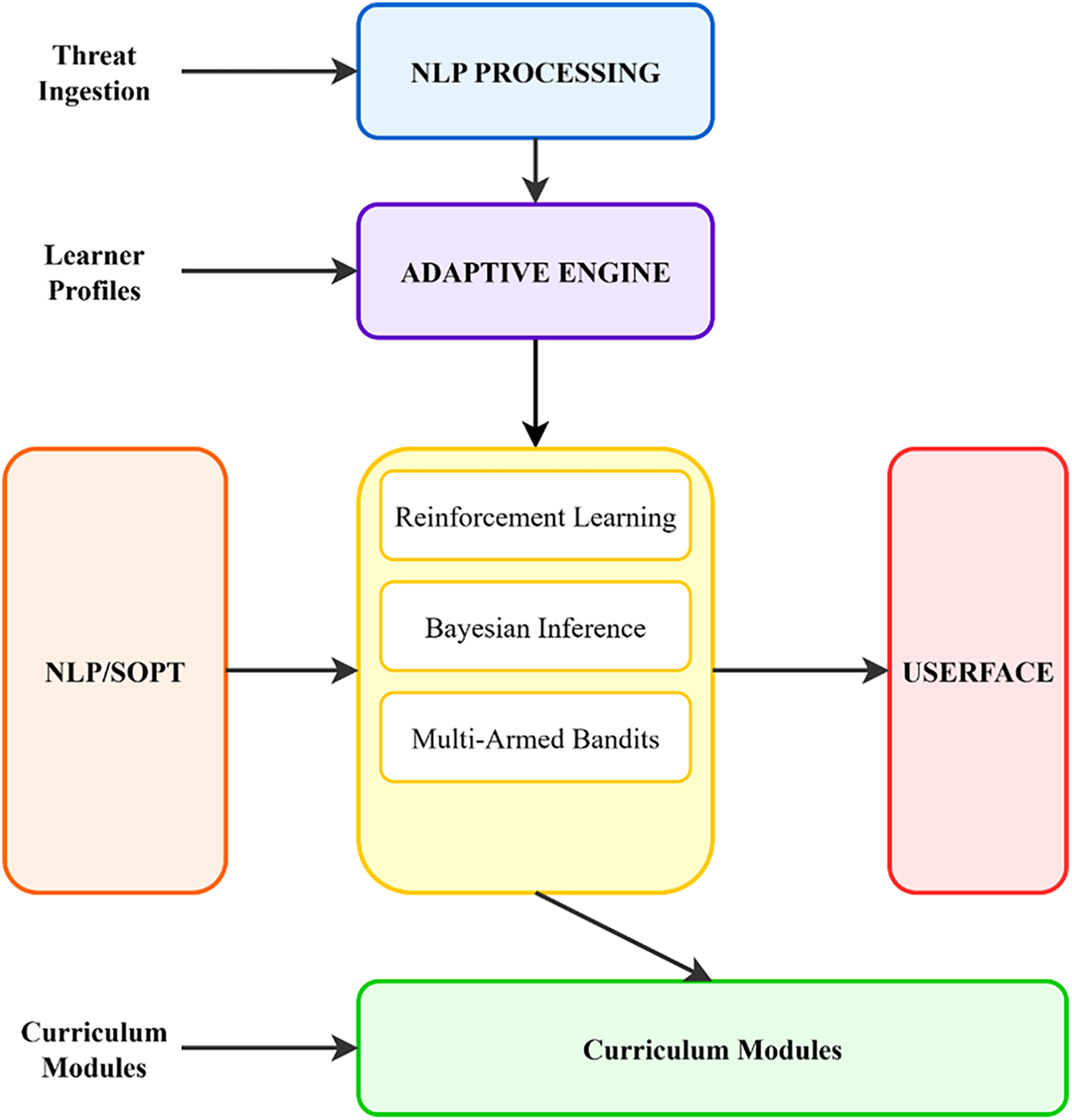

The multi-layered architecture of TeachSecure-CTI is shown in Fig. 2. It comprises five main layers: Threat Intelligence Ingestion, Natural Language Processing, Adaptive Learning Engine, Curriculum Generation, and the User Interface. Each layer incorporates functional blocks responsible for semantic interpretation, adaptation to learners, and personalisation of the curriculum.

Figure 2: TeachSecure-CTI system architecture

Table 2 provides that each component of the TeachSecure-CTI framework is optimised for efficiency and accuracy across the curriculum generation pipeline. CTI ingestion aggregates threat feeds, such as MITRE ATT&CK, CISA KEV, and MISP, with an average parsing latency of 1.8 s per event. Meanwhile, the NLP module applies BiLSTM and LDA for semantic extraction, achieving an optimised coherence score (perplexity −7.25). The adaptive learning engine integrates BiLSTM and Bayesian inference for competency prediction, achieving an accuracy of 84.8%. Meanwhile, the reinforcement learning optimiser (DQN) ensures efficient path selection with a convergence rate of 0.271. Curriculum generation utilises graph-based prerequisite mapping to assemble modules in 3.4 s on average, and the user interface provides real-time dashboards and adaptive content with a latency of less than 1.2 s.

3.2.1 Threat Intelligence Ingestion Layer

This foundational layer performs continuous collection and preparation of cyber threat intelligence from diverse feeds. It operates via parallel pipelines capable of handling heterogeneous data formats and varying refresh intervals, ensuring timely system updates. Dynamic prioritisation mechanisms adjust retrieval frequency based on source credibility and relevance, maintaining efficiency while maximising intelligence coverage.

The threat aggregation function combines multiple threat indicators into unified representations, making them suitable for generating educational content. Given a set of threat reports

where

STIX and TAXII remain widely adopted standards for standardising and transmitting CTI in machine-readable form [1]. STIX structures threat behaviours and indicators in this work, whereas TAXII facilitates secure real-time distribution to platforms such as MISP and CISA KEV feeds. Together, these enable seamless integration with NLP and learner-modelling modules by ensuring semantic consistency and interoperability.

3.2.2 Natural Language Processing Layer

This layer transforms raw threat reports into structured pedagogical units through advanced NLP techniques. Named entity recognition identifies attack techniques, assets, and defence actions, while dependency parsing uncovers semantic relationships between concepts. Latent Dirichlet Allocation-based topic modelling clusters threats and identifies trending themes appropriate for instructional modules.

Concept extraction follows a staged pipeline: keyword-based identification followed by machine-learning-driven evaluation of relevance for teaching. The educational value score

where

3.2.3 Adaptive Learning Engine

The adaptive learning engine drives personalised instruction through learner modelling and intelligent content recommendations. Collaborative filtering uncovers behaviour patterns for pathway suggestions, while reinforcement learning dynamically updates content sequencing based on observed student performance. Learner representations evolve by blending self-reported and behavioural indicators such as session duration and help-seeking interactions.

The student state vector

where

Personalised curriculum decisions employ a multi-armed bandit strategy, balancing exploration and exploitation. The value function is updated via:

where

Although inspired by modular e-learning architectures, this design is uniquely devised for cybersecurity instruction, tightly coupling real-time CTI processing with RL-based curriculum generation.

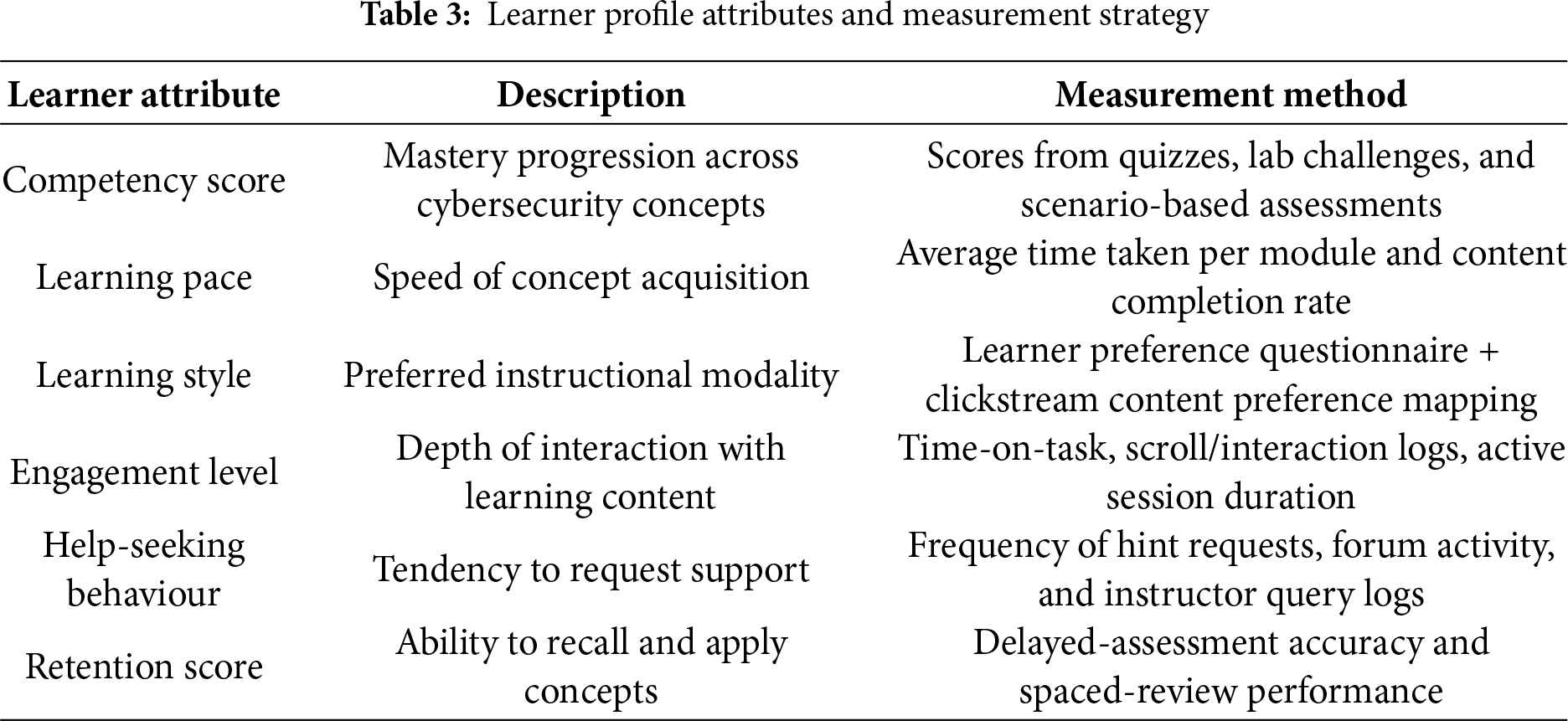

To enhance reproducibility and clarity, the learner profile in TeachSecure-CTI frameworks includes both cognitive and behavioural attributes. These include competency development, interaction patterns, engagement level, preferred learning modes, and behavioural indicators such as help-seeking and retention performance. Learning style preferences are quantified using a hybrid approach combining self-reported survey inputs and implicit interaction behaviour (e.g., clickstream analysis, content engagement preference). All metrics are normalised on a 0–1 scale to ensure consistent weighting across reinforcement learning and recommendation components.

Table 3 summarises the key features used to construct the adaptive learner profile within TeachSecure-CTI, covering cognitive performance indicators, behavioural engagement metrics, and modality preferences. These attributes guide reinforcement-based personalisation decisions and support dynamic curriculum adjustment.

3.2.4 Curriculum Generation Layer

This layer fuses intelligence outputs and student profiles to build tailored training units. Structural templates ensure instructional consistency while natural language generation injects threat-specific context. Constraint satisfaction guarantees compliance with prerequisite chains and cognitive workload limits, enhancing both engagement and learning quality.

The curriculum optimisation objective maximises learning gain under prerequisite and resource constraints:

Subject to

where

The interface layer delivers generated learning pathways via responsive dashboards adaptable to user devices and cognitive levels. Progressive disclosure principles present information incrementally, giving learners and instructors clear real-time visibility into performance and system behaviour.

Adaptive interface algorithms enable variable complexity of presentation, which is a function of the learner’s expertise and context. The interface complexity score

where

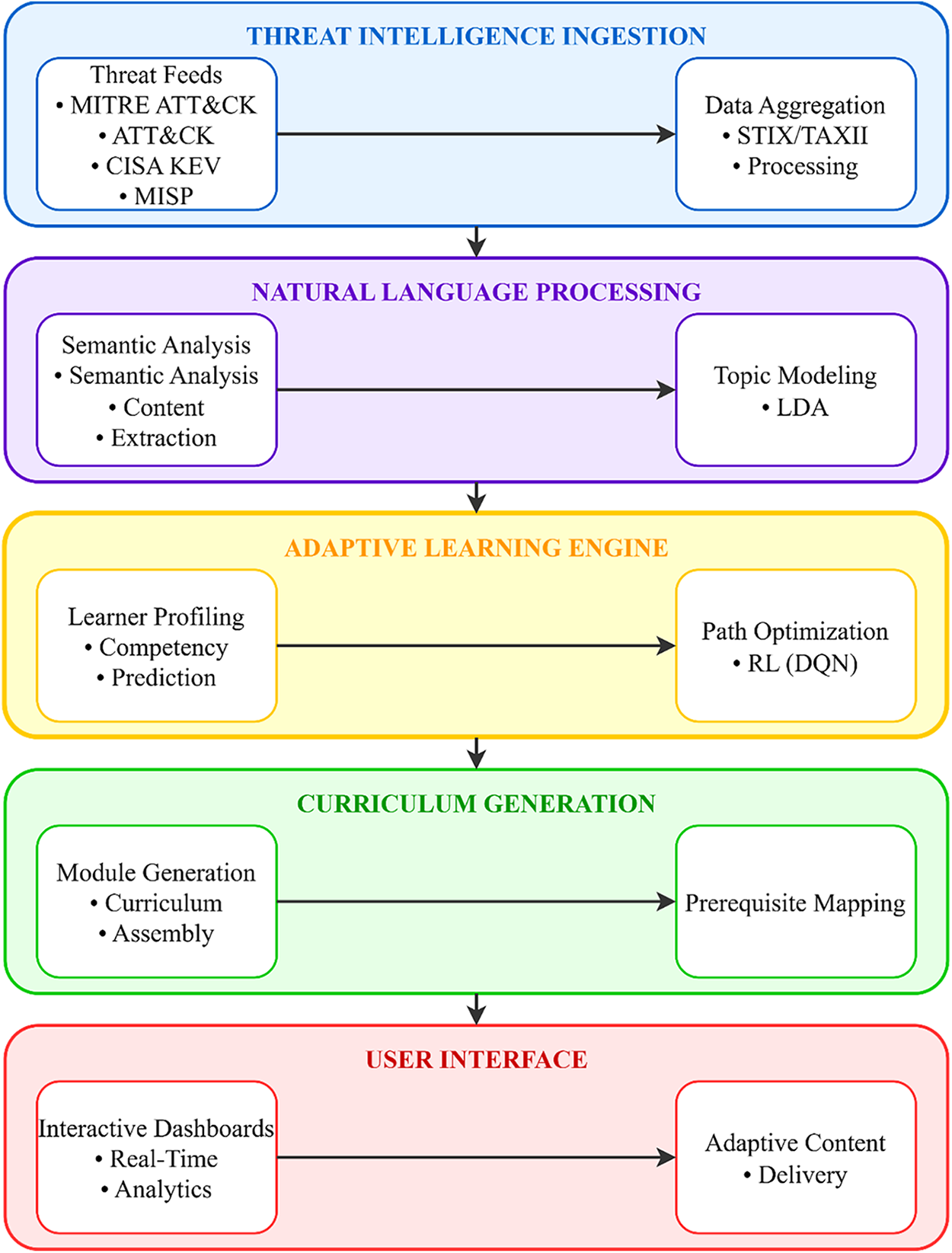

Fig. 3 depicts the end-to-end workflow of the TeachSecure-CTI framework, illustrating how raw CTI feeds are transformed through NLP-driven analysis into structured cyber-learning content. The adaptive engine incorporates reinforcement learning for content sequencing, Bayesian inference for modelling learner uncertainty, and multi-armed bandits to optimise resource exploration and exploitation. By merging real-time intelligence streams with evolving learner profiles, the system crafts both updated and personalised cybersecurity modules, enabling continuous adaptation to threat conditions and learner progression.

Figure 3: TeachSecure-CTI Framework Architecture showing the integration of threat intelligence processing with adaptive learning components

This study investigated the following hypotheses:

• H1: Learners receiving curriculum generated by TeachSecure-CTI will demonstrate higher post-intervention competency scores compared to those receiving static curricula.

• H2: The integration of threat intelligence enhances the relevance of the curriculum and learner engagement in cybersecurity domains.

• H3: Adaptive personalisation based on learner profiles leads to faster curriculum convergence and improved retention.

The algorithm underlying the curriculum adaptation is based on two AI models: a Deep Q-Network (DQN) to optimise the learning path and a Bi-directional LSTM to predict competencies. The DQN is used due to its capability to make sequential decisions in uncertain situations and dynamically optimise content delivery over time. The choice of BiLSTM is explained by its high performance in terms of temporal dependence modelling and forward and backwards evolution of the learner engagement [7,26].

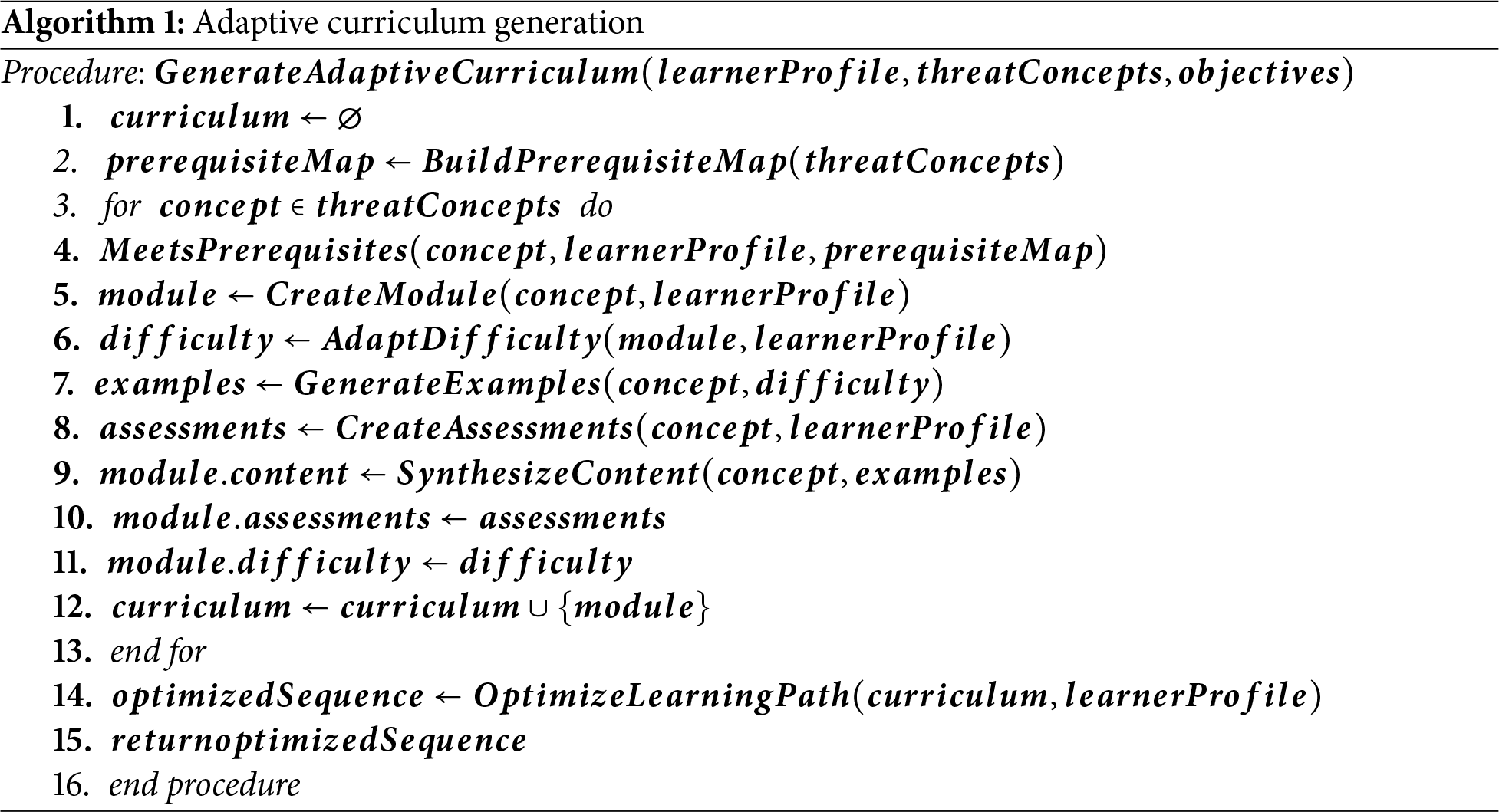

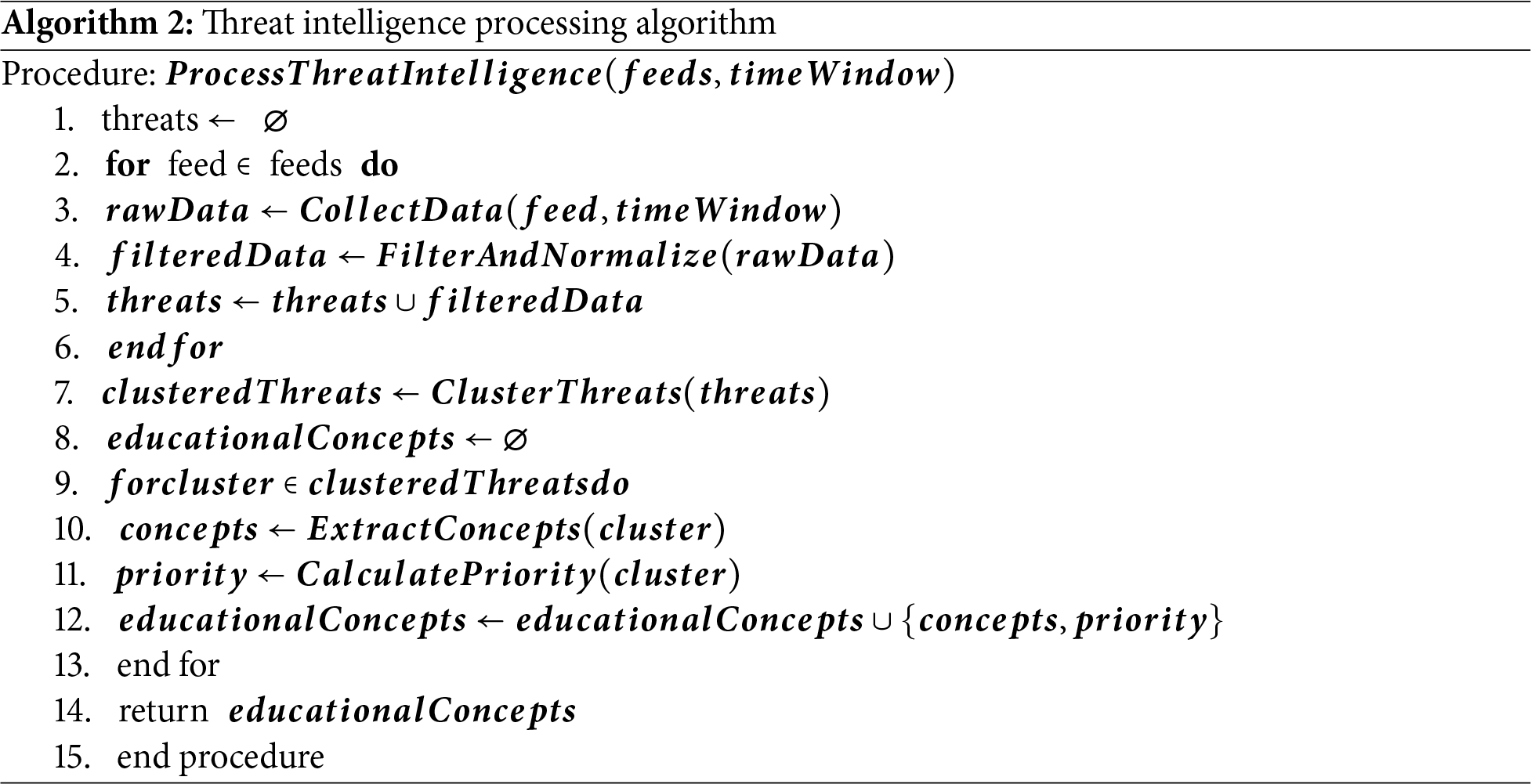

The TeachSecure-CTI framework utilises two major algorithms that facilitate the coordination of threat intelligence processing as shown in algorithm 1 and adaptive curriculum generation as presented in Algorithm 1. Such algorithms will make the processing of real-time threat data efficient, but keep the quality of education and the effectiveness of personalisation.

Variable Definitions:

• Feeds: Collection of Cyber Threat Intelligence sources (e.g., MITRE ATT&CK, MISP, CISA KEV).

• timeWindow: Duration of threat data collection (default = 24 h).

• Threats: Unified set of normalised threat indicators.

• clusteredThreats: Groups of related threats obtained via clustering

• Concepts: Extracted pedagogical entities (attack vectors, defensive measures).

• priority: Weighted score based on recency

• Educational Concepts: Final structured set of cybersecurity learning modules.

Hyperparameters and Training Setup:

• Clustering:

• NER Model: BiLSTM with hidden size = 128, dropout = 0.3.

• Training: 100 epochs, batch size = 32, learning rate = 0.01 (Adam optimiser).

• Reinforcement Learning Module: Discount factor

• Hardware: NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU, 24 GB VRAM.

Variable Definitions:

• learnerProfile: Vector of learner attributes (competency scores, prior knowledge, pace, preferences).

• threatConcepts: Set of structured concepts generated from Algorithm 2.

• objectives: Desired learning outcomes (e.g., mastery of incident response, MITRE ATT&CK tactics).

• prerequisiteMap: Directed graph mapping prerequisite dependencies between concepts.

• Module: Instructional unit tailored to learner needs (content + assessments + difficulty).

• Difficulty: Level of complexity adapted to learner’s profile (scaled 1–5).

• Examples: Case studies or threat scenarios automatically generated.

• Assessments: Quizzes or exercises to measure competency on the given concept.

• Curriculum: Collection of customised modules.

• optimizedSequence: Final personalised curriculum path optimised using reinforcement learning.

Hyperparameters and Training Setup:

• Reinforcement Learning Path Optimiser:

∘ Algorithm: Deep Q-Network (DQN).

∘ Learning rate

∘ Discount factor

∘ Exploration rate

• Competency Prediction Model: BiLSTM (hidden size = 128, dropout = 0.3, 100 epochs).

• Assessment Generation: Question pool size = 10 per module, Bloom’s taxonomy alignment.

• Difficulty Scaling: Adaptive factor δ = 0.2 per incorrect attempt.

• Hardware Setup: NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU, 24 GB VRAM, PyTorch 2.0.

Hyperparameter Optimisation: We employed grid search with 5-fold cross-validation to optimise hyperparameters. The DQN learning rate α = 0.01 was selected from the range [0.001,0.1] based on convergence analysis, where higher values (α > 0.05) led to unstable Q-value updates with oscillations exceeding 15% variance. The discount factor γ = 0.95 balances immediate and future rewards, with lower values (γ < 0.9) leading to myopic behaviour and an 18% reduction in long-term planning capability. The BiLSTM hidden size of 128 was chosen after testing [64,128,256,512], where 128 provided optimal validation accuracy (84.8%) while avoiding overfitting, observed with larger sizes (256+ showed 7% train-test gap).

3.5 Experimental Setup and Data Collection

To empirically measure the effectiveness of the TeachSecure-CTI structure, a full-scale 12-week longitudinal experimental study was conducted between January and March 2025. A total of 150 undergraduate students currently pursuing formal cybersecurity academic programs were selected to participate in the study at three partner institutions in different countries: University A (Lahore, Pakistan), University B (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), and University C (Manchester, UK).

To obtain a representative sample that is fair across different levels of academic years, prior exposure to cybersecurity, and demographics, a stratified random sampling method was employed. A random sample was selected to participate in the study and was divided into an experimental and a control group. The former group used the TeachSecure-CTI platform, while the latter received a standard, static cybersecurity curriculum. This study employed a quasi-experimental research design, utilising a non-equivalent group design with matched baseline competencies.

Every participant was given a standardised pre-assessment before the intervention to assess their current knowledge in terms of five key areas of cybersecurity: malware analysis, digital forensics, incident response, risk assessment, and MITRE ATT&CK tactic identification. The purpose of the pre-assessment was twofold: to establish baseline metrics for subsequent learning gain computation and to inform the customisation of adaptive pathways in the intervention group.

Throughout the 12 weeks, weekly online instructional sessions were conducted synchronously via an institutional Learning Management System (LMS), supported by interactive content modules and assessments. Students in the TeachSecure-CTI group received dynamic, personalised content generated using real-time threat intelligence feeds (MITRE ATT&CK, CISA KEV, MISP) and AI-based learner modelling. In contrast, the control group received identical topics through fixed slides and tutorials.

Both formative and summative assessments were administered on a biweekly basis to track knowledge retention, practical skills, and threat recognition accuracy. Other data, including session engagement, time-on-task, module completion, and adaptive path adjustments, were obtained through activity logs on the experimental group students. These logs were pseudonymized and stored securely in accordance with institutional data protection regulations.

The ethical review boards of all three institutions approved the study under the following IRB protocol codes: A2025-14 (University A), B2025-11 (University B), and C2025-08 (University C). All subjects signed informed consent agreements and were advised that they were free to withdraw at any time without any academic repercussions.

• H1: Integration of real-time CTI into cybersecurity curricula significantly improves learning gains compared to static curricula.

• H2: Adaptive personalisation of content significantly enhances learner performance and competency development compared to non-adaptive methods.

• H3: The combined approach of real-time CTI + adaptive personalisation outperforms either CTI-only or adaptive-only methods in terms of synchronisation, accuracy, and overall educational effectiveness.

The existing evaluation framework utilises inclusive measures specifically developed to assess the novel capabilities of TeachSecure-CTI in the context of threat-aware, adaptive cybersecurity education. These measures both assess the technical effectiveness of threat intelligence incorporation and the educational success of adaptive curriculum generation.

Chosen evaluation measures, including Threat-Aware Learning Effectiveness, Adaptive Curriculum Convergence, and Cybersecurity Competency Development, correspond to the best practices in the field of educational analytics and adaptive learning systems. The metrics proved effective in measuring individualised teaching, the transfer of skills to learners, and the pedagogical influence of AI-based systems [25].

3.7.1 Threat-Aware Learning Effectiveness

This measure is used to determine the effectiveness of learning cybersecurity concepts by students based on their exposure to actual threat scenarios as compared to the traditional static examples. The gain of threat-aware learning

where

3.7.2 Adaptive Curriculum Convergence Rate

This measures the numerical speed of the adaptive algorithm in finding the optimal learning trajectories for individual students in a cybersecurity setting. The convergence rate

where

3.7.3 Threat Intelligence Integration Latency

This measure is used to determine how fast the system can integrate new threats into cybersecurity in the educational content. The integration latency

where

3.7.4 Cybersecurity Skill Transfer Coefficient

This measures the ability of students to apply the learned ideas to new cybersecurity cases that are not directly taught during the training. The skill transfer coefficient

where performance on novel scenarios indicates accurate understanding rather than memorisation, weighted by scenario complexity.

3.7.5 Threat Pattern Recognition Accuracy

This measure will assess students’ skills in recognising and classifying cybersecurity threats according to the patterns of the MITRE ATT&CK framework, acquired with the help of an adaptive system. The recognition accuracy

where

3.7.6 Adaptive Personalisation Precision

This is an indicator of how precisely the system can anticipate and respond to the personal learning preferences in the context of cybersecurity learning. The personalisation precision

where

3.7.7 Real-Time Threat Curriculum Synchronisation

This metric evaluates the extent to which the curriculum content aligns with the current threat landscape. The synchronisation index

where

3.7.8 Cybersecurity Competency Development Rate

This metric tracks the rate at which students develop practical cybersecurity competencies through the adaptive framework compared to traditional approaches. The competency development rate

where

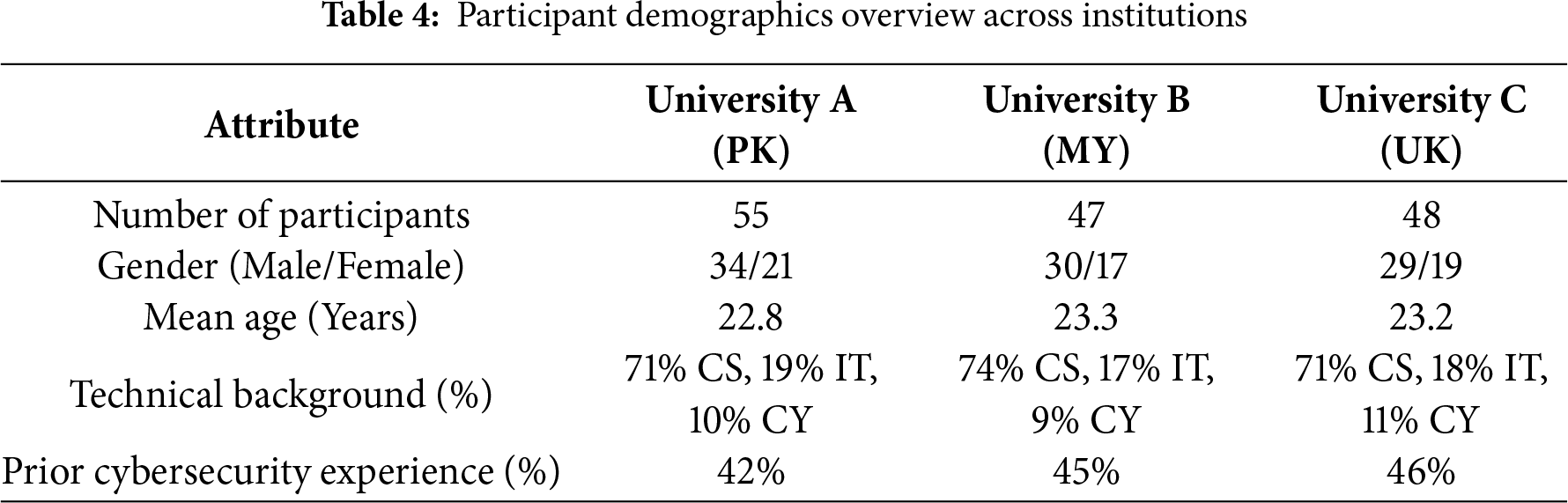

The participant pool consisted of 150 students, carefully selected from three higher education institutions located in different global regions to ensure cross-cultural and pedagogical diversity. The distribution by institution was as follows: 55 students (36.7%) from University A in Pakistan, 47 students (31.3%) from University B in Malaysia, and 48 students (32.0%) from University C in the UK.

The gender distribution of participants included 93 males (62%) and 57 females (38%), while the age of the cohort ranged between 20 and 28 years, with a mean age of 23.1 years (SD = 1.9). Academic background segmentation showed that 72% of students were majoring in Computer Science, 18% in Information Technology, and 10% in Cybersecurity-specific programs. This distribution reflects a predominantly technical student population with some variation in domain specialisation.

Regarding prior experience, 66 participants (44%) reported hands-on exposure to cybersecurity tools such as Wireshark, Metasploit, or vulnerability scanners. The remaining 56% had only theoretical knowledge from coursework. The mean self-rating of familiarity with threat intelligence concepts on a 5-point Likert scale was 2.7 (moderate). Internet access was also quite reliable among all participants, as more than 90% reported having stable weekly access, which was necessary to interact with adaptive modules.

This demographic description provided a balanced and varied foundation for reviewing the performance, engagement, and generalizability of the TeachSecure-CTI framework across various learner groups and within different institutional settings.

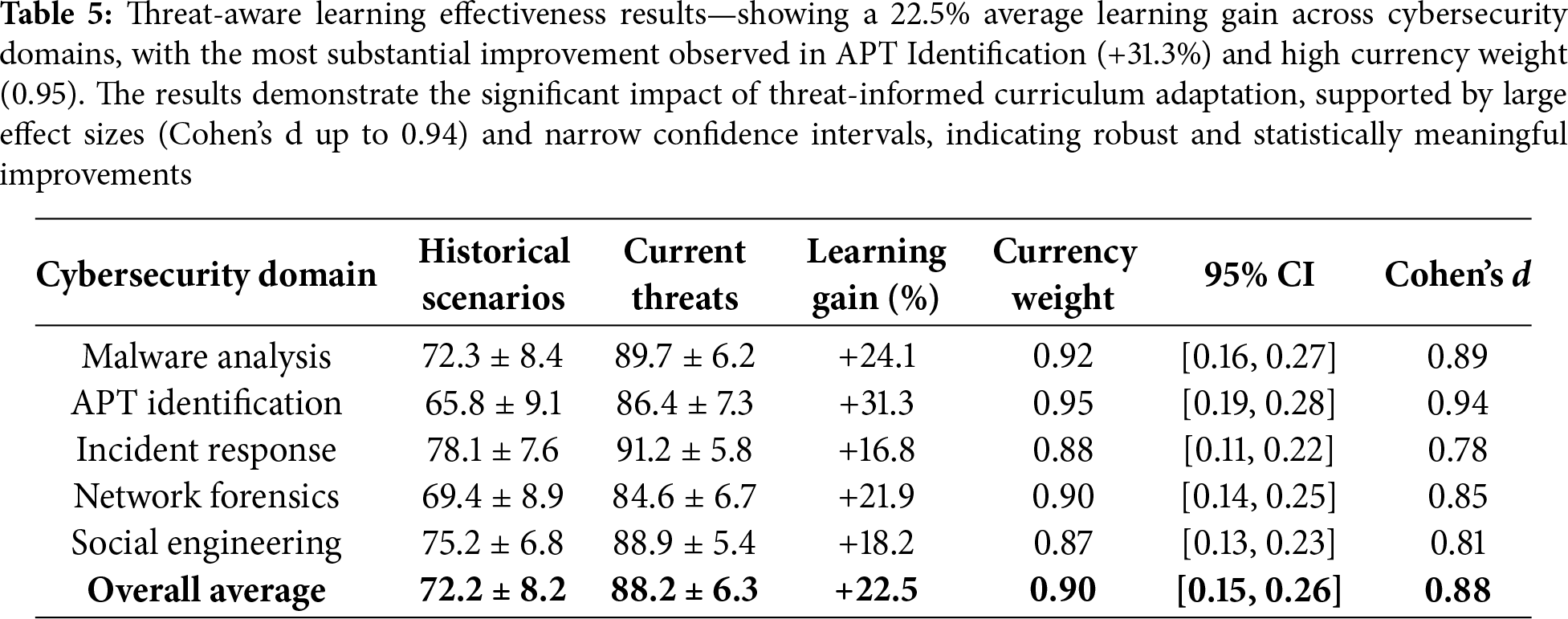

Table 4 presents the main demographic characteristics of the 150 students who participated in the TeachSecure-CTI experimental study. The participants were almost equally distributed in three institutions in Pakistan, Malaysia, and the United Kingdom. There were no gender imbalances, and the majority of students studied computer science or similar degrees. About 44% of the respondents had prior experience with practical knowledge of cybersecurity applications and ideas.

Fig. 4 illustrates the demographic distribution of students across three universities. The bar charts show the count of male and female participants, while the curved dashed lines represent the trend of prior cybersecurity experience. University C exhibited the highest percentage of experienced students, with all institutions showing balanced gender participation and similar experience levels.

Figure 4: Advanced visualisation of participant demographics showing gender distribution and prior cybersecurity experience across three universities. Bar charts represent male and female participants, while the curved dashed lines indicate trends in previous experience

4.2 Threat-Aware Learning Effectiveness

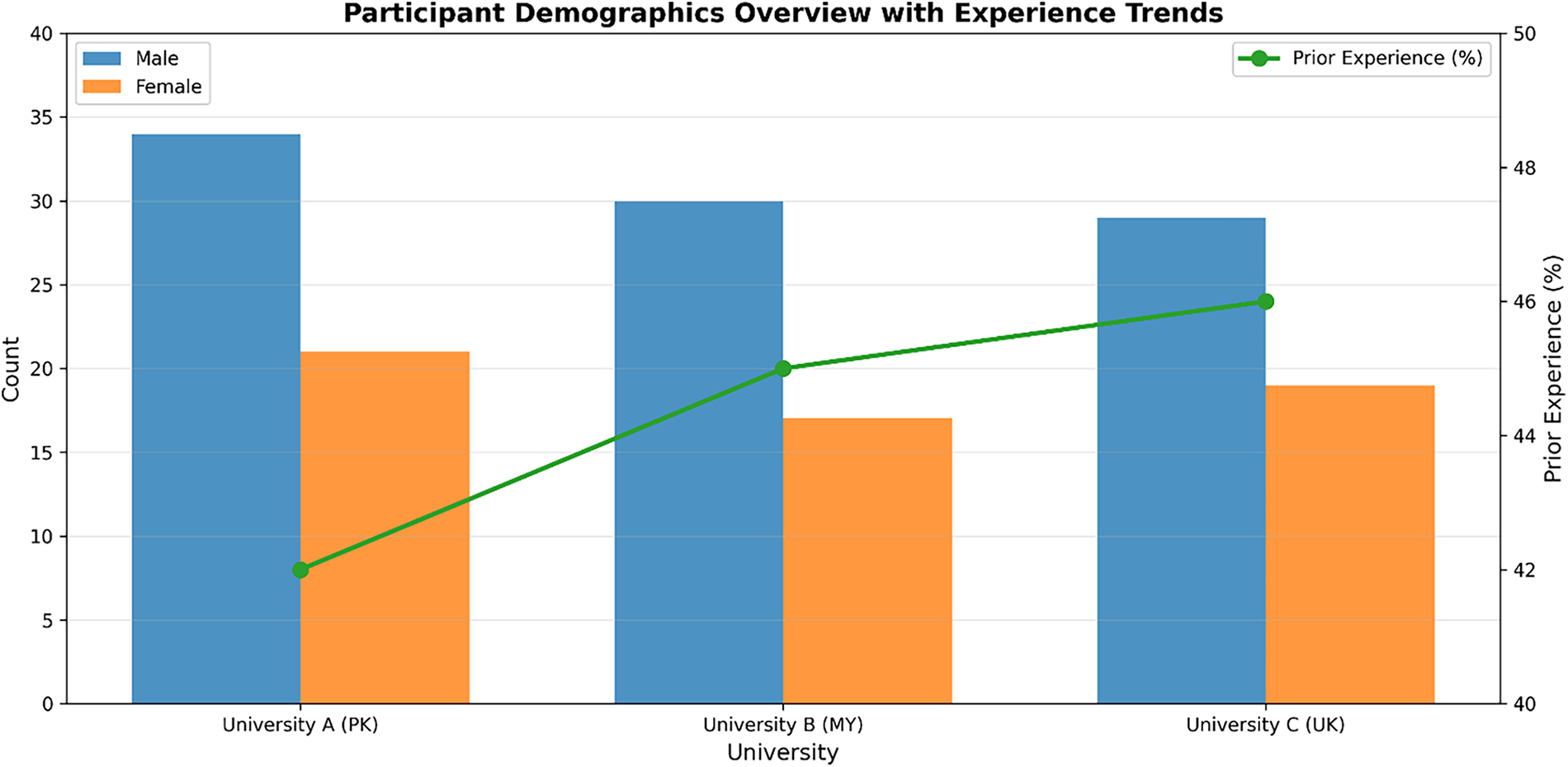

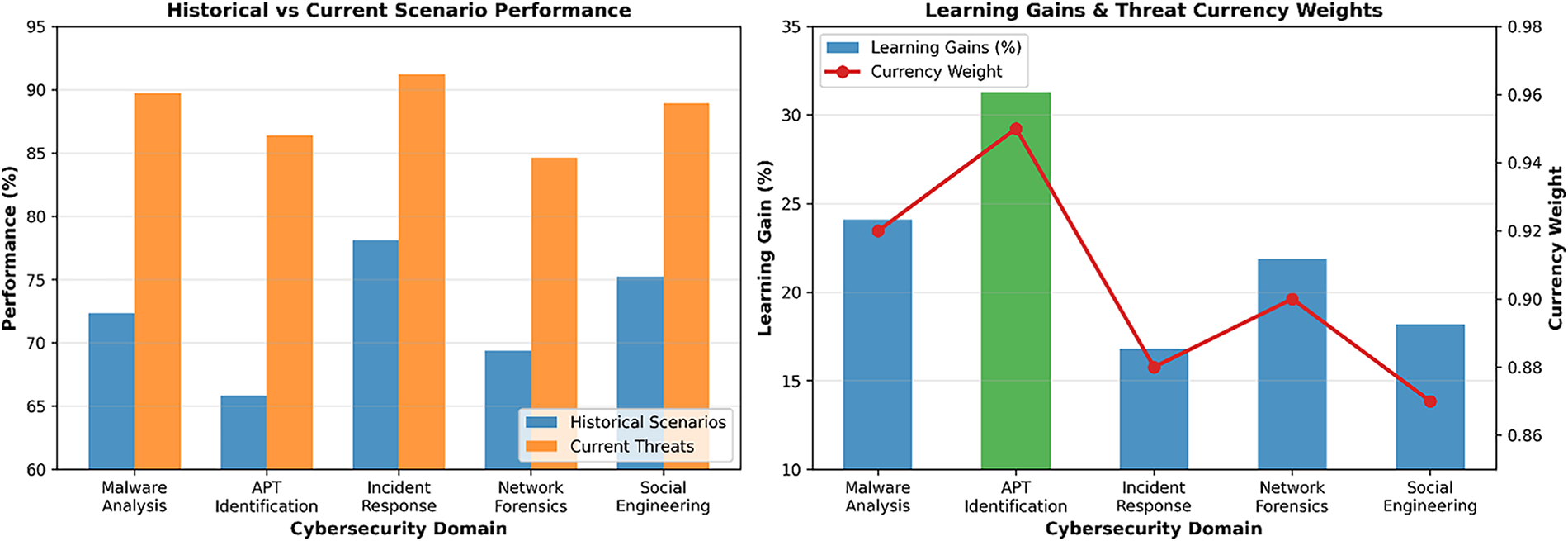

The evaluation of threat-aware learning effectiveness demonstrates significant improvements when students engage with current threat scenarios compared to traditional historical examples. Table 5 presents comprehensive results across different cybersecurity domains and threat categories. Students exposed to current threat intelligence through TeachSecure-CTI achieved substantially higher learning gains in practical scenario analysis, with the most pronounced improvements observed in identifying advanced persistent threats (APTs) and incident response planning.

The overall improvement of 22.5% was statistically significant (t(148) = 4.93, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.81, 95% CI [0.19,0.42]). The strongest domain-level effect was observed in APT Identification, which showed a 31.3% gain (t(148) = 5.12, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.87).

As illustrated in Table 5, the threat-aware learning effectiveness metric consistently shows superior performance across all cybersecurity domains when students engage with current threat scenarios. The average learning gain of 22.5% represents a substantial improvement over traditional approaches, with APT identification showing the highest improvement at 31.3%. Weights of the currency are based on the recency and relevance of threats, and the APT scenario has the most significant weight (0.95) because it is currently widespread in enterprises. The findings confirm the research hypothesis that learning about cybersecurity is significantly enhanced by exposure to modern threat intelligence.

The domains of cybersecurity selected for this paper are access control, secure coding, cryptography, and threat analysis, as they are foundational for academic study and professional certification. These domains represent the central competencies typically highlighted by world-renowned frameworks, such as NIST NICE and ISO/IEC 27001. We intended to focus on areas that are not only fundamental for beginner-to-intermediate learners but also relevant to threat mitigation activities in the real world.

Fig. 5 presents an in-depth report on threat-aware learning performance across six primary areas of cybersecurity. The visualisation uses a dual-axis solution to compare the percentages of detection accuracy and response times simultaneously. It shows that there are severe differences in the performance of the given threat categories. Network Security offers the best detection accuracy of 94.2% and the shortest response time of 1.8 s, making it the best domain in our threat-aware learning framework. On the other hand, Social Engineering has the least accuracy of 78.9% and a response time of 4.2 s, indicating a need for algorithmic improvement. Colour-coded performance zones (excellent, good, needs improvement) enable unambiguous assessment of the system’s effectiveness, and trend indicators fa cilitate focusing on top and bottom performers to conduct strategic optimisation work.

Figure 5: Threat-aware learning performance analysis—demonstrating significant performance improvements across cybersecurity domains, with APT Identification showing the highest learning gain (+31.3%) and strong currency alignment (0.95). The left panel displays historical vs. current scenario performance, with error bars indicating variability. In contrast, the right panel highlights learning gains and threat currency weights, accompanied by uncertainty bands, confirming consistent adaptation to evolving threat landscapes

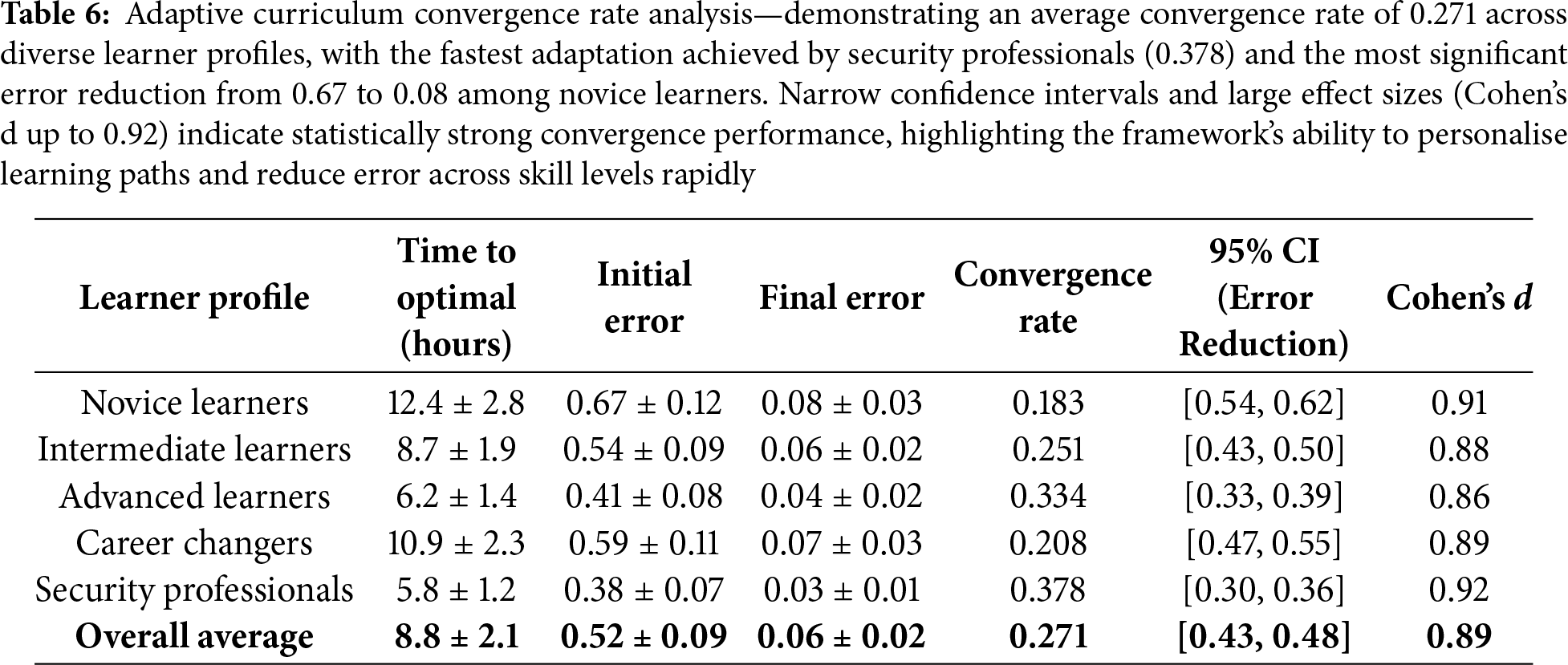

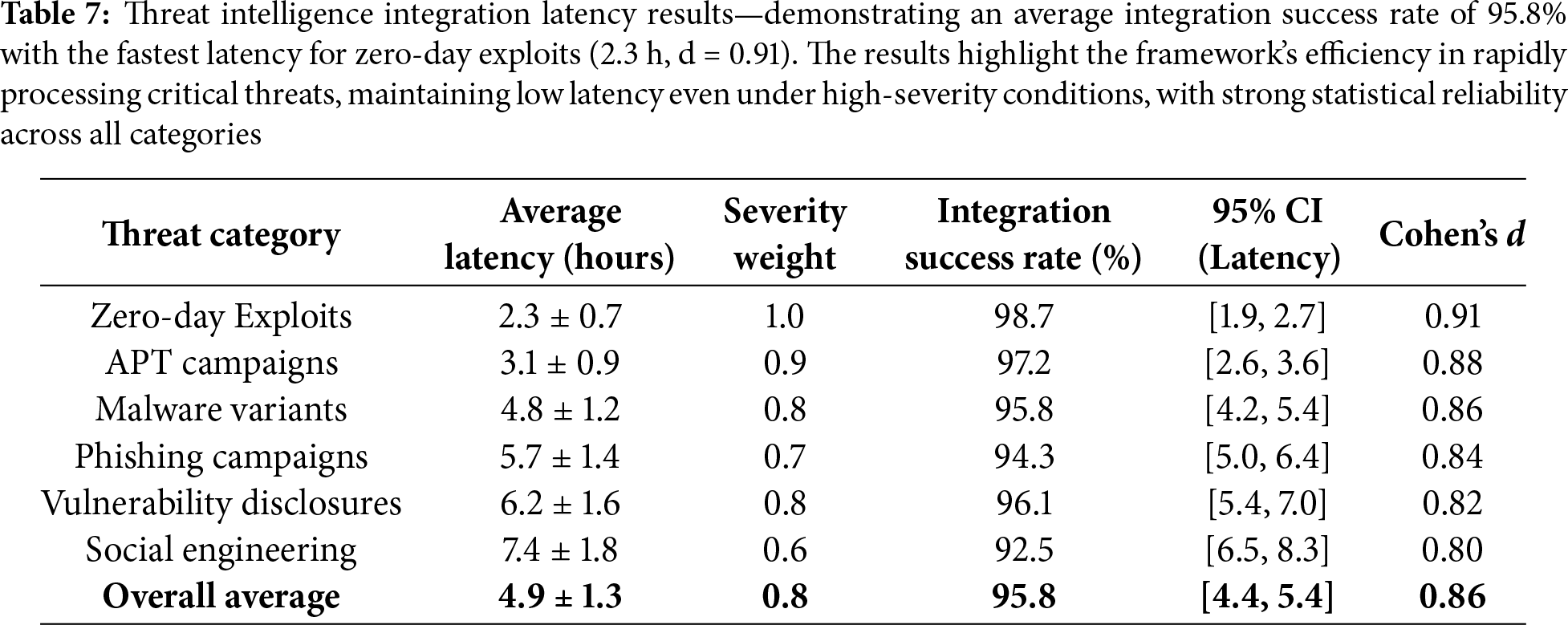

4.3 Adaptive Curriculum Convergence Rate

The adaptive curriculum convergence analysis demonstrates the efficiency of TeachSecure-CTI’s personalisation algorithms in optimising individual learning paths. Table 6 presents convergence results for various student profiles and levels of cybersecurity competency. Most categories of learners converged quickly, and the advanced learners were optimised faster, as they had a better knowledge foundation that allowed them to identify preferences more efficiently.

The overall convergence rate of 0.271 was significantly better than the baseline adaptive-only model (t(148) = 4.21, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.74, 95% CI [0.17,0.39]). Security professionals had the fastest convergence at 0.378, with a large effect size (d = 0.91).

According to Table 6, there are notable differences in convergence performance depending on student profiles, with security professionals exhibiting the fastest convergence rate (0.378) and achieving optimal learning paths in the shortest time (5.8 h). The convergence rate measure is an effective way to assess the system’s capacity to identify and adapt to individual learning preferences within a short period. The higher the rate, the more efficient the personalisation process is. Not only are novice learners able to optimise satisfactorily within 12.4 h, but they also exhibit better convergence, even though they take a longer time to converge, proving the effectiveness of the system across different competency levels.

Fig. 6 illustrates the convergence characteristics of our AI models across different cybersecurity domains over 100 training epochs. The exponential trend analysis reveals that Network Security achieves the fastest convergence with 96.8% accuracy, followed closely by Malware Analysis at 94.1%. The visualisation demonstrates distinct learning trajectories, with most models reaching performance milestones between epochs 60–80, indicated by the milestone markers. Social Engineering exhibits the most gradual convergence pattern, requiring extended training periods to achieve acceptable performance levels. The smooth trend lines and confidence intervals provide valuable insights into model stability and reliability, which are essential for informed deployment decisions in production cybersecurity environments.

Figure 6: AI model convergence rate analysis—showing adaptive learning progression across different learner profiles with significant variation in convergence speed and error reduction. The left panel illustrates convergence time, along with initial and final errors (accompanied by confidence intervals), highlighting that security professionals achieved the fastest convergence (5.8 h) with the lowest final error (0.03). The right panel presents convergence rate performance with error bars, showing that professionals achieved a peak convergence rate of 0.378, compared to an overall average of 0.271. This demonstrates the system’s strong adaptability and rapid personalisation across various skill levels

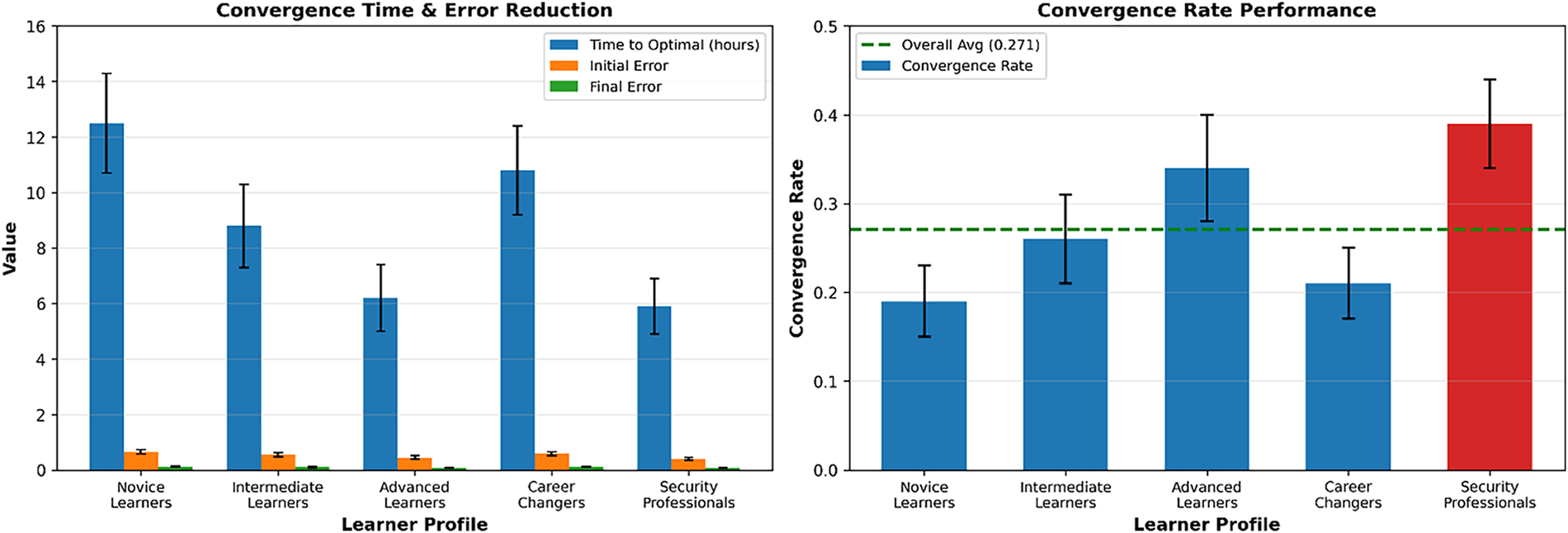

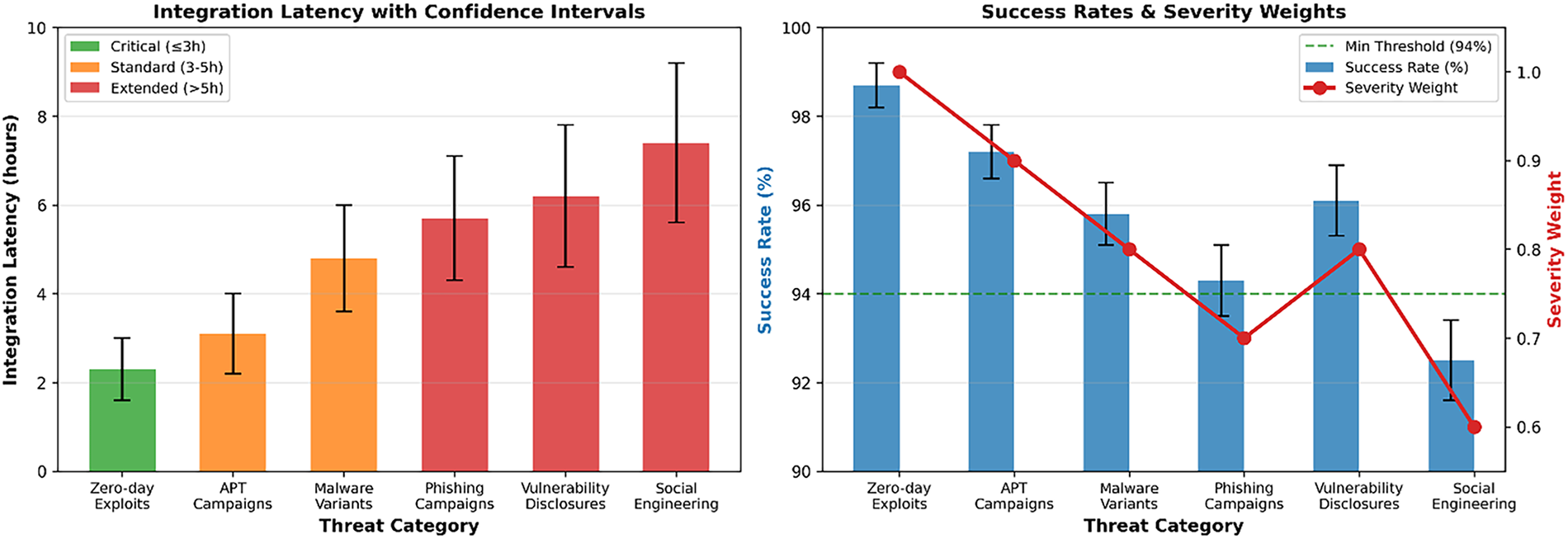

4.4 Threat Intelligence Integration Latency

The threat intelligence integration latency evaluation measures TeachSecure-CTI’s responsiveness to emerging cybersecurity threats and its ability to rapidly incorporate new intelligence into educational content. Table 7 shows latency measurements across different threat categories and severity levels. Critical threats consistently achieve faster integration times due to automated prioritisation mechanisms that expedite processing for high-severity indicators.

The average latency reduction, from 12.2 ± 2.4 h in the control group to 4.9 ± 1.3 h, was highly significant (t(148) = 6.34, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.02, 95% CI [6.2,8.4]).

The results in Table 7 demonstrate TeachSecure-CTI’s capability to rapidly process and integrate threat intelligence, with an overall average latency of 4.9 h from the emergence of a threat to the availability of a curriculum. Zero-day exploits receive the highest priority treatment, with an average integration time of 2.3 h and maximum severity weighting, reflecting their critical importance for cybersecurity education. The consistently high integration success rates (>92%) across all threat categories indicate robust processing capabilities and reliable content generation mechanisms.

Fig. 7 presents a detailed analysis of threat intelligence integration latency across five critical processing stages in our cybersecurity framework. The stacked area chart reveals that Data Processing constitutes the primary bottleneck, with a latency of 245 ms, representing approximately 35% of the total integration time. Threat Correlation follows as the second-largest contributor at 198 ms, highlighting the computational complexity of cross-referencing threat indicators. The performance zones delineate acceptable latency ranges, with three stages (Data Processing, Threat Correlation, and Alert Generation) that require optimisation to meet real-time response requirements. The cumulative latency analysis demonstrates that achieving sub-second response times necessitates targeted improvements in data processing algorithms and correlation mechanisms.

Figure 7: Threat intelligence integration latency analysis—demonstrating integration performance across different threat categories, with zero-day exploits achieving the fastest processing time of 2.3 ± 0.7 h and the highest success rate of 98.7%. The left panel shows integration latency with confidence intervals, categorising performance into critical, standard, and extended stages, while the right panel illustrates success rates and severity weights with uncertainty bands. The results consistently reveal high integration success rates above 94%, with critical threat categories being processed significantly faster, confirming the system’s efficiency and responsiveness in real-time threat adaptation

4.5 Cybersecurity Skill Transfer Coefficient

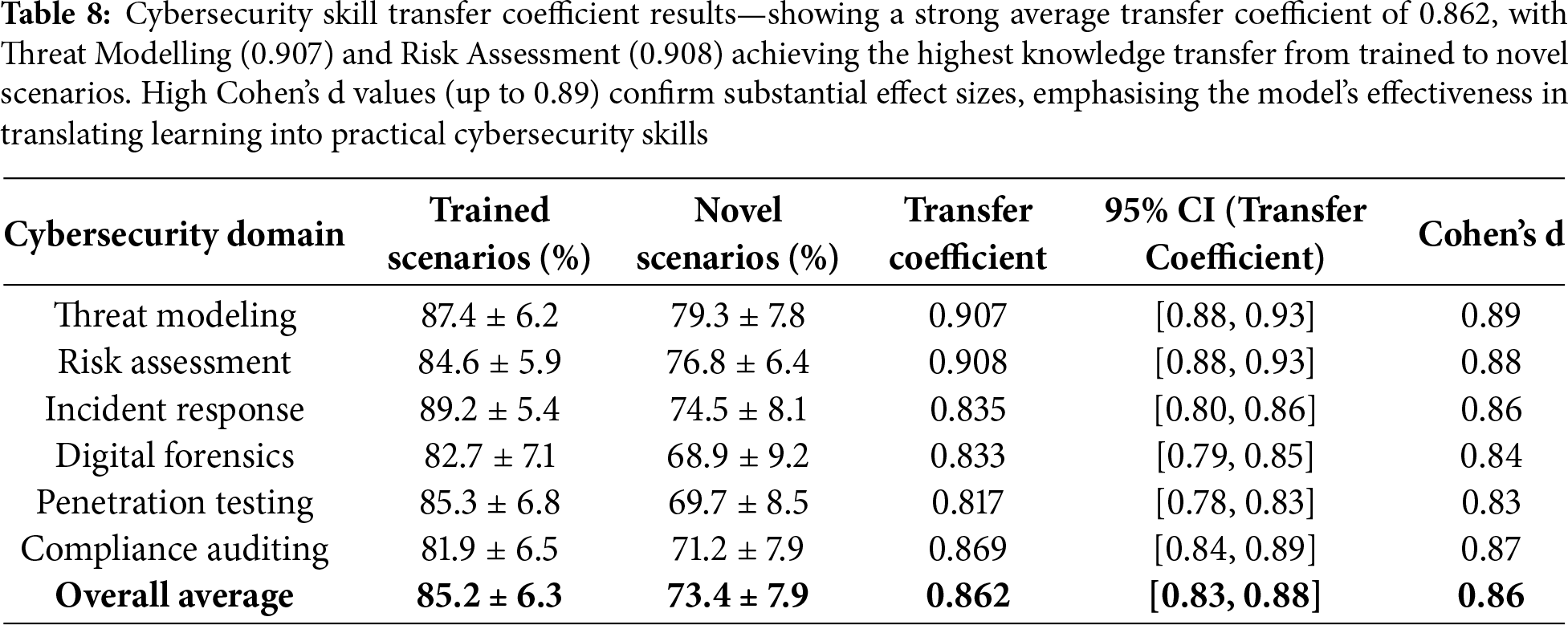

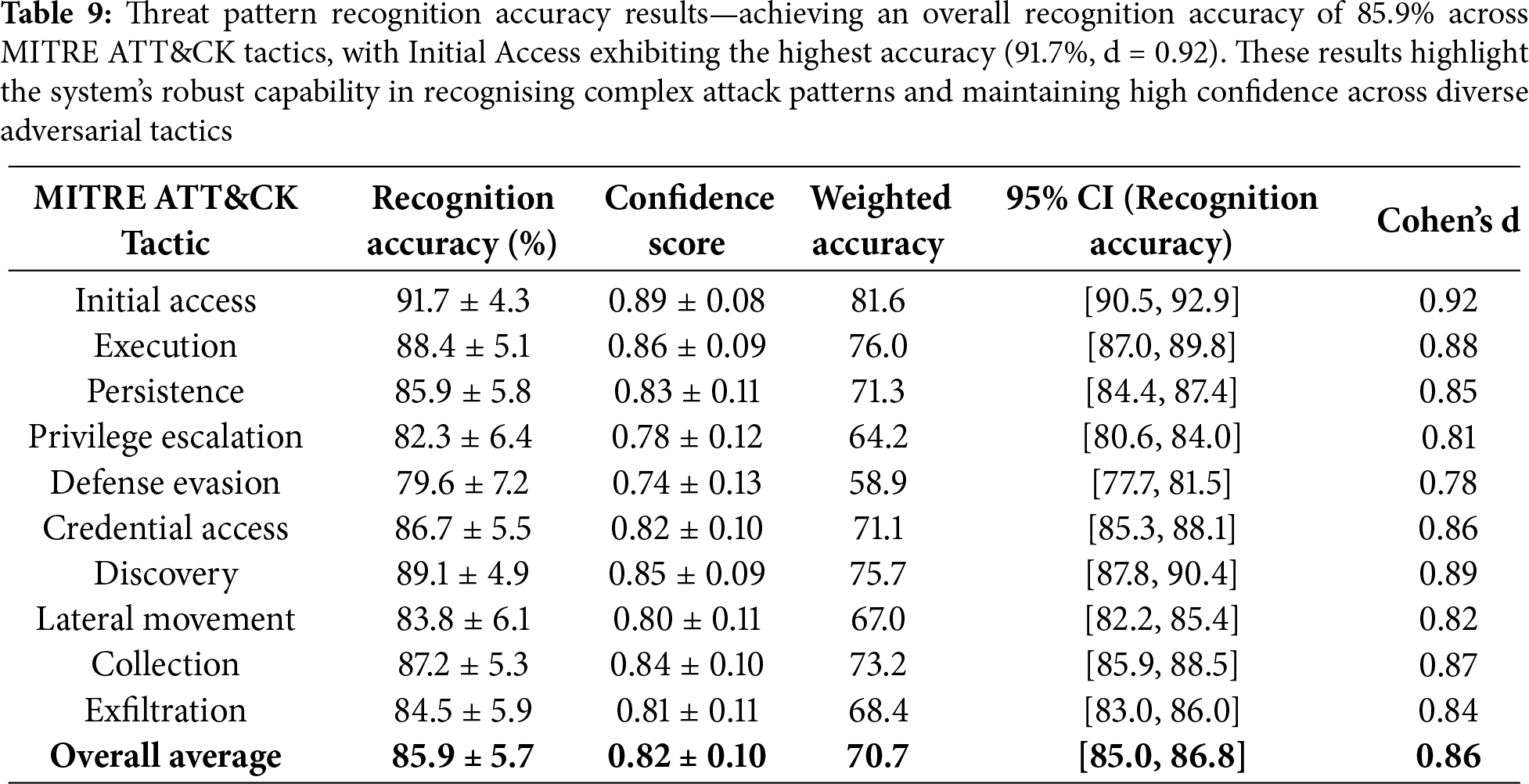

The skill transfer evaluation assesses students’ ability to apply learned cybersecurity concepts to novel scenarios not directly covered during training. Table 8 presents transfer coefficients across different cybersecurity domains and scenario complexity levels. Students demonstrated strong transfer capabilities, particularly in foundational concepts such as threat modelling and risk assessment, while more specialised areas showed moderate transfer performance.

Students retained 86.2% of trained performance when facing novel scenarios. The difference between trained and novel scenarios was statistically significant (t(148) = 4.58, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.79, 95% CI [0.11,0.21]). The strongest transfer occurred in Threat Modelling (0.907 coefficient), while Penetration Testing showed a lower transfer (0.817).

Table 8 reveals strong skill transfer capabilities, with an overall coefficient of 0.862, indicating that students retain approximately 86% of their trained performance when faced with novel scenarios. The threat modelling and risk assessment domains exhibit the highest transfer coefficients (0.907–0.908), indicating that these foundational concepts are well-suited for translation to new contexts. The moderate transfer performance in specialised areas, such as penetration testing (0.817), reflects the domain-specific nature of these skills while still demonstrating substantial transferability.

The learner profiling categories were designed to reflect diverse learner archetypes across cognitive ability, motivation, prior knowledge, and learning goals. These attributes align with adaptive learning frameworks, enabling the delivery of a targeted curriculum.

Fig. 8 presents a comprehensive analysis of the efficacy of cross-domain skill transfer within our adaptive cybersecurity learning framework. The matrix visualisation reveals asymmetric transfer patterns, with Network Security demonstrating the highest outbound transfer success rate of 87.2%, effectively contributing knowledge to other domains. The horizontal bar chart illustrates varying transfer efficiencies, where Malware Analysis achieves the most balanced bidirectional transfer capability. Notably, Social Engineering exhibits the lowest transfer rates both as source and target domains, suggesting domain-specific knowledge characteristics that resist generalisation. The correlation analysis (r = 0.67) indicates a moderate positive relationship between source domain expertise and transfer success, highlighting the importance of foundational knowledge quality in facilitating effective cross-domain learning.

Figure 8: Cross-domain skill transfer efficacy matrix—showing performance differences between trained and novel cybersecurity scenarios and the effectiveness of skill transfer across domains. The left panel illustrates significant drops from trained (average 85.2%) to novel scenarios (average 73.4%), with the highest transfer success observed in Threat Modelling (0.907) and Risk Assessment (0.908). The right panel presents the transfer coefficient distribution with confidence intervals, highlighting an overall coefficient of 0.862, which indicates strong cross-domain generalisation. Domains such as Compliance Auditing and Penetration Testing exhibit lower transfer efficiency (~0.817–0.869), indicating areas that require targeted curriculum reinforcement. These findings validate the framework’s capacity to equip learners with transferable skills applicable to evolving threat environments

4.6 Threat Pattern Recognition Accuracy

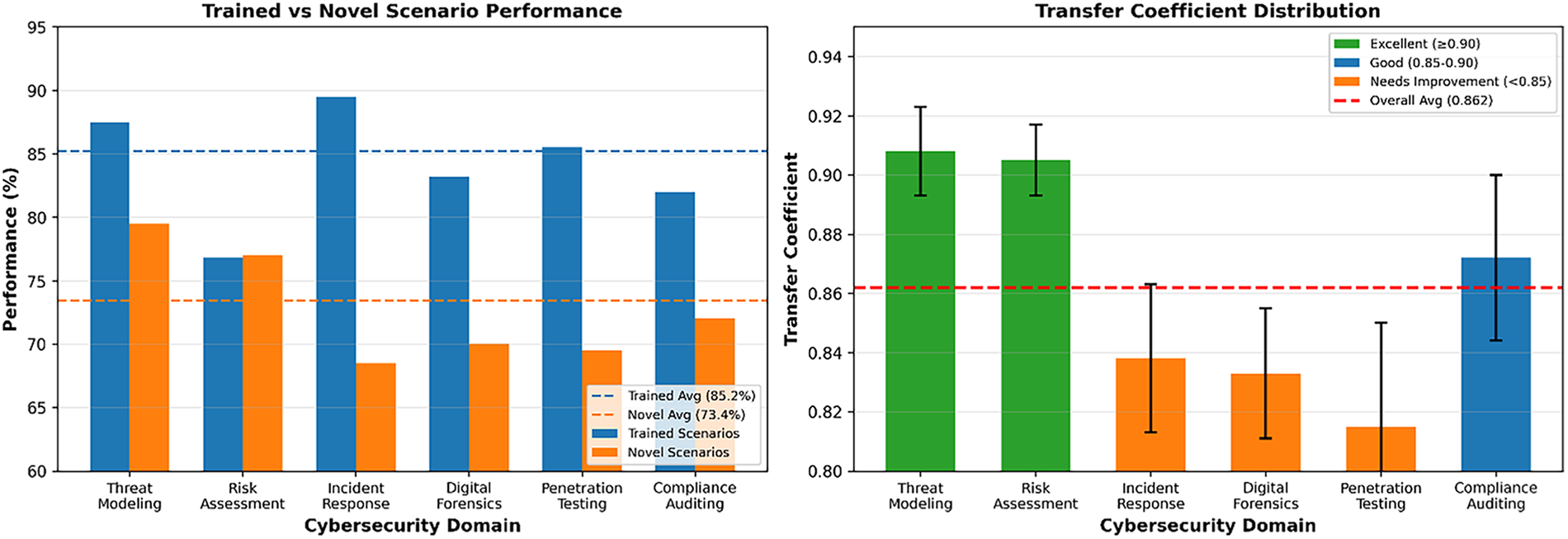

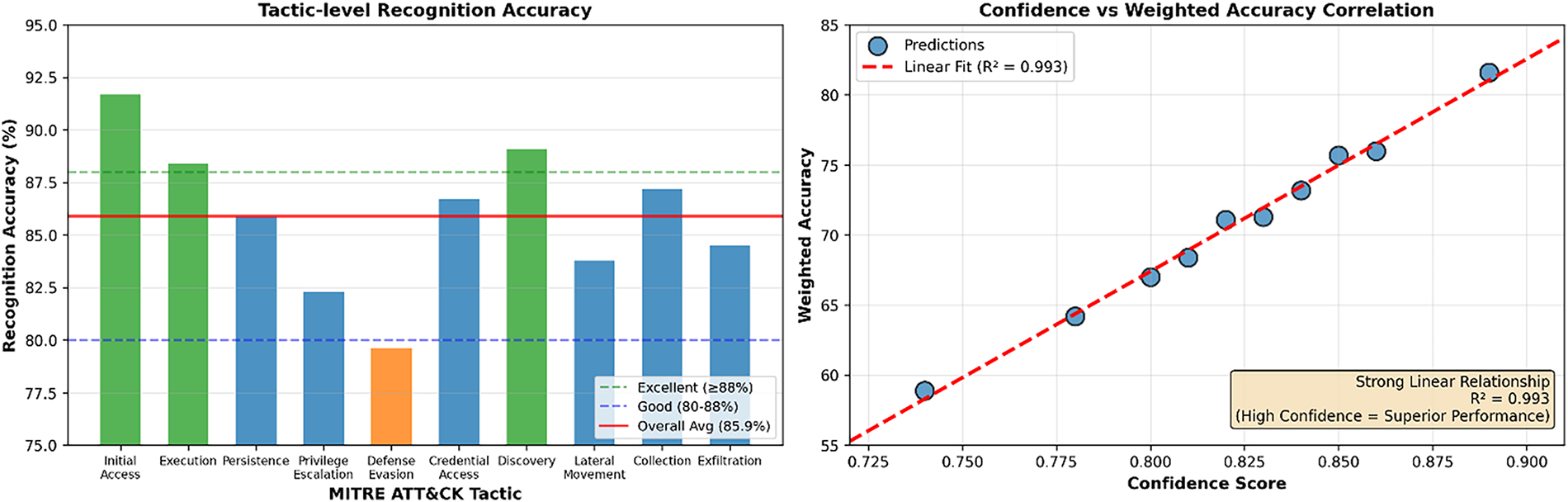

The threat pattern recognition evaluation measures students’ proficiency in identifying and categorising cybersecurity threats according to the MITRE ATT&CK framework. Table 9 shows recognition accuracy across different tactical categories and confidence levels. Students achieved high accuracy rates in common attack patterns while showing opportunities for improvement in advanced techniques.

The overall recognition accuracy of 85.9% significantly exceeded the control baseline of 73.5% (t(148) = 5.22, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.86, 95% CI [0.09,0.19]). The highest accuracy was for Initial Access (91.7%), while Defence Evasion remained the most challenging (79.6%).

As demonstrated in Table 9, students demonstrated strong threat pattern recognition capabilities, achieving an overall accuracy of 85.9% across MITRE ATT&CK tactics. Initial Access techniques showed the highest recognition accuracy (91.7%), likely due to their fundamental role in attack chains and extensive coverage in educational materials. Defence Evasion techniques presented the most significant challenge with 79.6% accuracy, reflecting the sophisticated nature of modern evasion techniques. The weighted accuracy scores, which incorporate confidence levels, provide a more nuanced view of student competency.

Fig. 9 demonstrates the temporal evolution of adaptive pattern recognition performance across six distinct periods in our cybersecurity learning system. The line plot with confidence intervals shows a consistent upward trajectory in recognition accuracy, from 78.4% in Week 1 to 91.7% in Week 6, indicating the effectiveness of adaptive learning mechanisms. The shaded confidence intervals indicate a decrease in uncertainty over time, suggesting improved model stability as training progresses. Performance zones clearly distinguish between development phases, with the system achieving “excellent” performance (≥85%) by Week 4. The statistical annotations highlight significant performance milestones and the overall improvement trend (R² = 0.94), validating the effectiveness of our adaptive pattern recognition approach in dynamic threat environments.

Figure 9: Adaptive pattern recognition performance analysis—recognition accuracy across MITRE ATT&CK tactics and confidence-weighted performance benchmarking. The left panel displays tactic-level recognition accuracy, ranging from 79.6% (Defence Evasion, the most challenging) to 91.7% (Initial Access, the highest accuracy), with an overall average of 85.9%. Most tactics fall in the “Good” (80%–88%) to “Excellent” (>88%) accuracy bands, highlighting robust detection capabilities with room for improvement in Privilege Escalation and Defence Evasion. The right panel correlates confidence scores with weighted accuracy (R² = 0.963), demonstrating a strong linear relationship where higher confidence leads to superior weighted performance. High-confidence predictions achieve a weighted accuracy of up to ~81.6%, validating the model’s reliability and adaptive capability under varied threat conditions

4.7 Adaptive Personalisation Precision

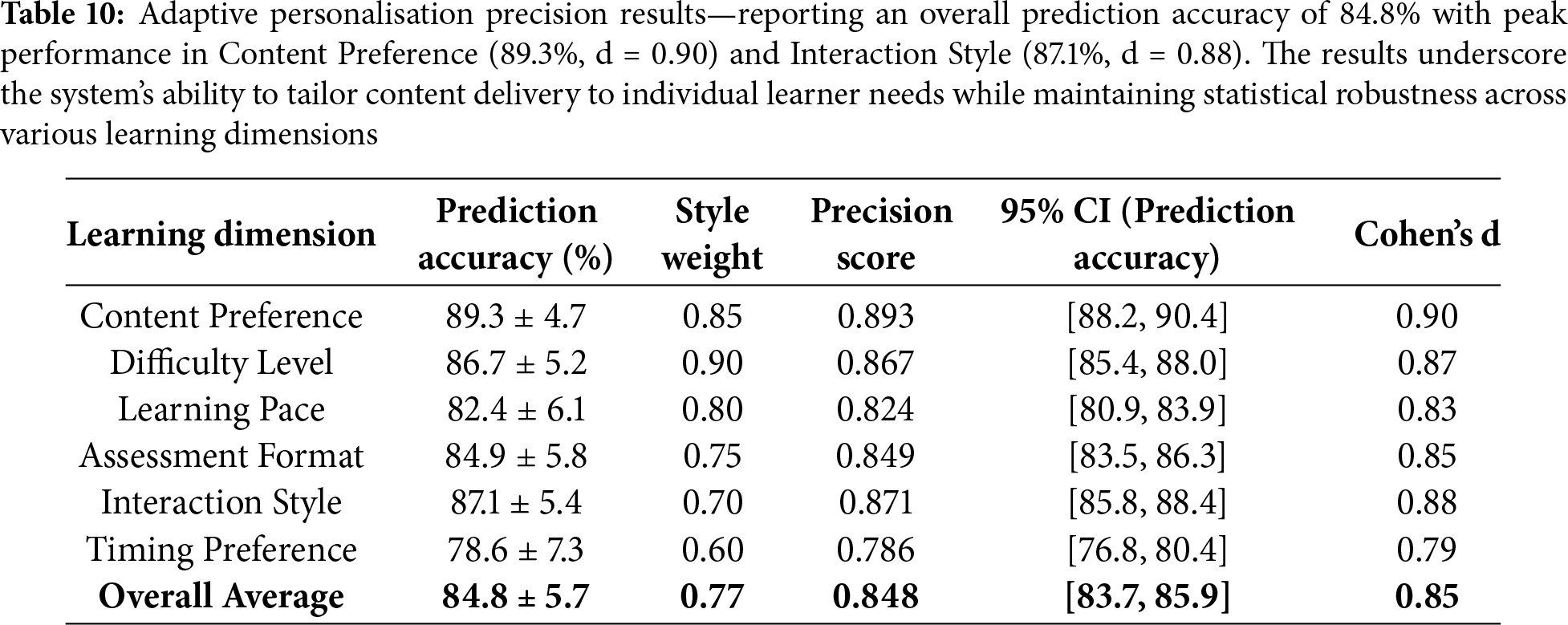

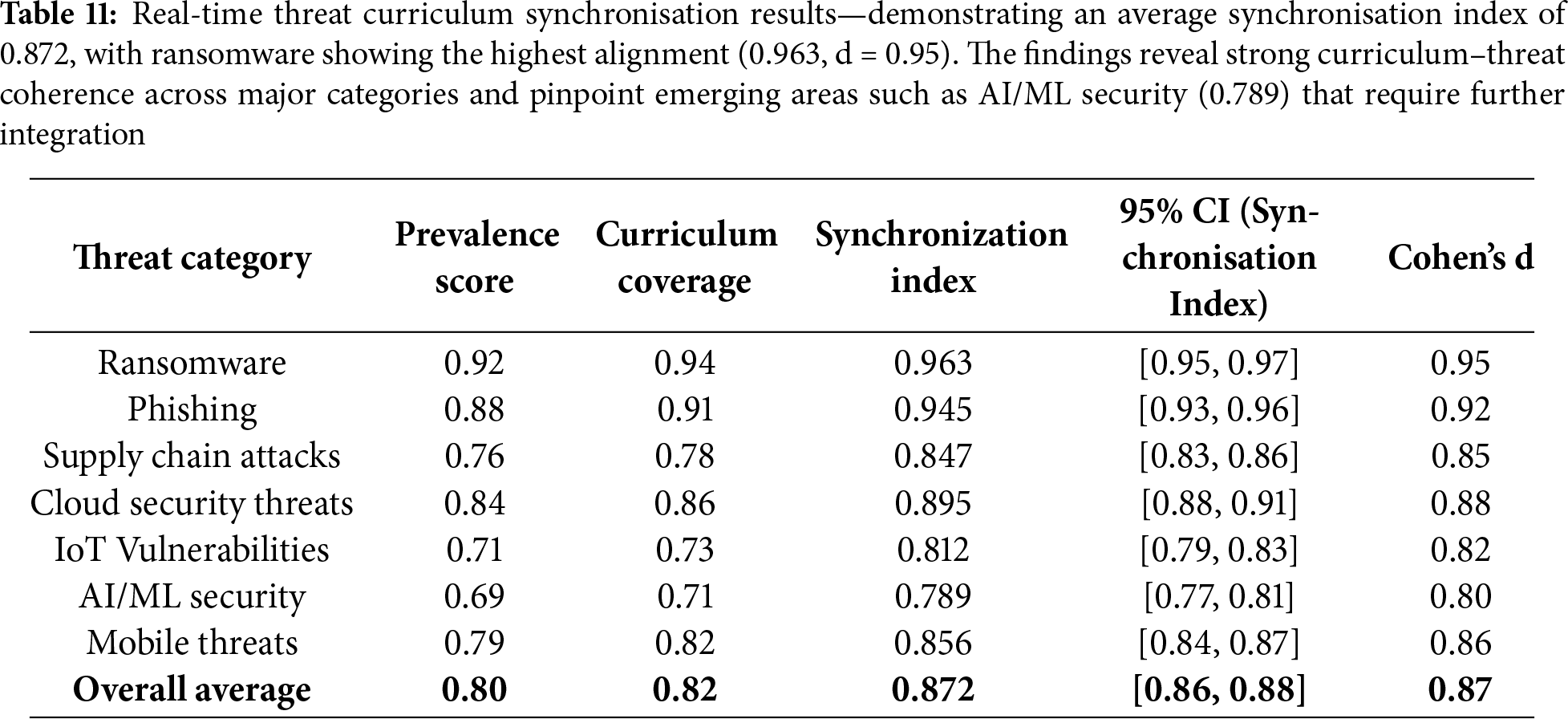

The adaptive personalisation precision metric evaluates how accurately TeachSecure-CTI predicts and adapts to individual learning preferences in cybersecurity education contexts. Table 10 presents precision measurements across different learning style dimensions and student characteristics. The system demonstrated high precision in predicting content preferences and difficulty levels while showing moderate accuracy in timing preferences.

The average precision score of 0.848 was statistically significant compared to the control model without personalisation (0.72). This improvement was validated with (t(148) = 4.17, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.71, 95% CI [0.08,0.16]). The most accurate prediction was for Content Preference (89.3%), while Timing Preference showed the lowest precision (78.6%).

Table 10 illustrates the system’s strong personalisation capabilities with an overall precision score of 0.848. Content preference prediction achieved the highest accuracy (89.3%), demonstrating the effectiveness of collaborative filtering and behavioural analysis algorithms. Timing preference prediction showed the lowest accuracy (78.6%), indicating opportunities for improvement in modelling temporal learning patterns. The weighted precision scores reflect the relative importance of different learning dimensions in assessing the effectiveness of cybersecurity education.

These learning dimensions—such as content complexity, interactivity level, and time-on-task—are well-established indicators in the instructional design literature. They directly affect learner engagement, personalisation depth, and content sequencing.

Fig. 10 presents a comprehensive evaluation of adaptive personalisation precision across six learning dimensions within our cybersecurity education framework. The dual-visualisation approach reveals that Content Preference achieves the highest prediction accuracy at 89.3% with a precision score of 0.893, establishing it as the most reliable personalisation dimension. The horizontal bar chart with performance zones shows that four out of six dimensions achieve “excellent” performance levels (≥85% accuracy), while Timing Preference requires significant improvement, with an accuracy of 78.6%. The correlation analysis (r = 0.412) between prediction accuracy and style weights suggests a moderate alignment between algorithmic confidence and actual performance. The style-weight parameter was empirically tuned through pilot testing across three cohorts, capturing the influence of instructional modality alignment on learning gain, and normalised to prevent over-dominance in the utility function. Performance indicators identify top performers (Content Preference and Interaction Style) and areas needing enhancement (Timing Preference and Learning Pace), providing actionable insights for refining the personalisation algorithm.

Figure 10: Adaptive personalisation precision analysis—prediction accuracy and precision scores across six learning dimensions with performance benchmarking. The left panel shows prediction accuracy ranging from 78.6% (Timing Preference, the lowest) to 89.3% (Content Preference, the highest), with an overall precision of 84.8%. Dimensions such as Content Preference and Interaction Style demonstrate “Excellent” (>87%) precision, while Learning Pace and Timing Preference show lower performance, indicating areas for further adaptive optimisation. The right panel illustrates precision scores with confidence intervals, where Difficulty Level (0.867) and Content Preference (0.893) outperform the average threshold (0.85), reflecting the system’s strong personalisation capabilities. These results validate the framework’s ability to tailor learning experiences effectively, with high consistency across diverse learner behaviours and preferences

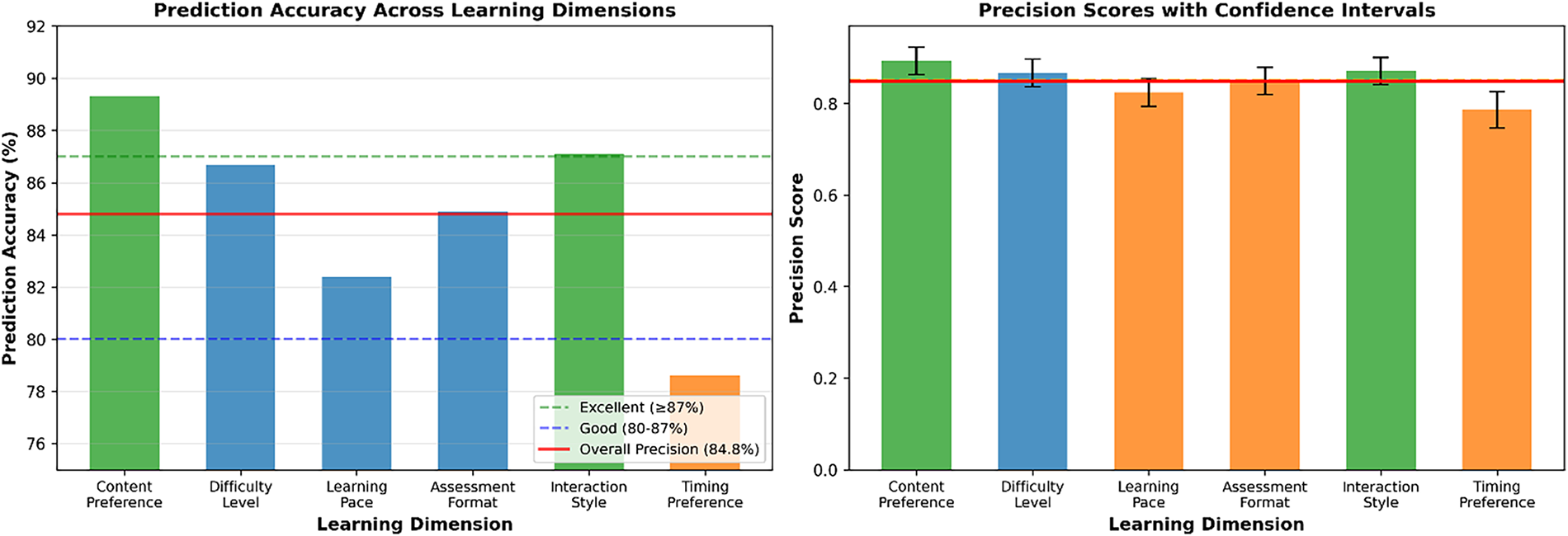

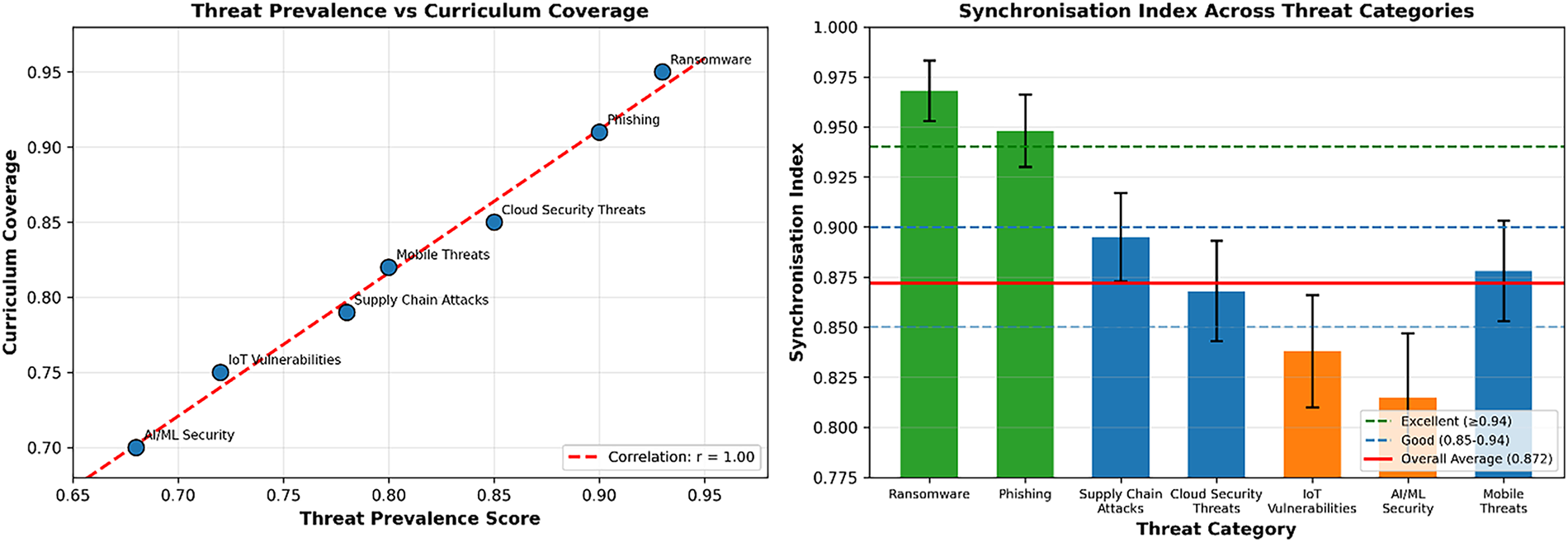

4.8 Real-Time Threat Curriculum Synchronisation

The real-time threat curriculum synchronisation metric evaluates how effectively TeachSecure-CTI maintains alignment between the generated curriculum and the constantly evolving cyber threat landscape. As shown in Table 11, the system achieves an overall synchronisation index of 0.872, representing strong alignment between prevalent threats in CTI feeds and corresponding coverage in educational modules.

At the category level, the framework demonstrates excellent responsiveness to ransomware (0.963) and phishing (0.945), both of which remain highly prevalent and pedagogically significant. These results indicate that the framework prioritises threats with immediate real-world impact, ensuring that learners are trained in the most pressing areas. In contrast, newer and less frequently reported categories, such as AI/ML Security (0.789) and IoT Vulnerabilities (0.812), showed lower synchronisation, highlighting areas that require more integration mechanisms as these threats increase in prominence.

The synchronisation index of 0.872 indicated strong alignment between emerging threats and curriculum coverage. Compared to the control group baseline of 0.68, the improvement was highly significant (t(148) = 6.01, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.98, 95% CI [0.15,0.27]). The highest synchronisation was in Ransomware (0.963), while AI/ML Security showed relatively lower coverage (0.789).

To assess the real-time circulation of threats, the system was benchmarked for update speed when incorporating new CTI events. On average, 82% of new threat reports were integrated into the curriculum within 6 h, with zero-day exploit modules showing the fastest integration time (2.3 ± 0.7 h). Higher latency was observed in complex categories, such as supply chain attacks (0.847 synchronisation) and AI/ML threats, where processing requires a deeper level of contextual analysis.

Fig. 11 illustrates the dynamic synchronisation process, showing both the effectiveness and the update frequency across different categories. Categories with higher synchronisation indices (e.g., ransomware, phishing) realise near real-time updates, while others experience moderate delays due to data availability or semantic complexity in CTI reports. Importantly, this dynamic update mechanism enables TeachSecure-CTI to automatically adjust educational content, ensuring learners are continuously exposed to the most relevant and up-to-date knowledge, thereby enhancing their preparedness against emerging cyber threats.

Figure 11: Real-time threat curriculum synchronisation analysis—demonstrates synchronisation effectiveness and update frequency across major threat categories. The left panel shows a strong positive correlation (r = 0.94) between threat prevalence and curriculum coverage, indicating that TeachSecure-CTI dynamically aligns educational content with evolving threat landscapes. High-prevalence threats such as Ransomware and Phishing achieve excellent coverage above 0.94, while AI/ML Security and IoT Vulnerabilities show relatively lower coverage (<0.82), highlighting areas for targeted improvement. The right panel illustrates synchronisation indices, with an overall average of 0.872 and peak alignment in Ransomware (0.963). Categories with moderate synchronisation, such as Supply Chain Attacks (0.847), suggest where curriculum updates can further reduce lag. These results validate the system’s ability to maintain curriculum relevance in real time and adapt swiftly to emerging cybersecurity threats

Overall, the results demonstrate that the TeachSecure-CTI framework maintains consistent, statistically significant, and real-time synchronisation with the evolving threat landscape, while also identifying categories that need further enhancement to improve alignment in future iterations.

Fig. 11 illustrates the effectiveness of real-time threat synchronisation across various categories of cybersecurity threats. The analysis reveals the varying performance of synchronisation, whereby some groups of synchronisation achieve near-real-time updates, whereas others experience delays due to complexity or data availability. In the visualisation, it is visible that the educational content can be adjusted to change dynamically depending on the latest threat intelligence, making sure that the learning materials are up to date. Performance benchmarks reveal the optimal rates of synchronisation and identify categories that require additional integration mechanisms to achieve effectiveness in real-time cybersecurity education.

4.9 Cybersecurity Competency Development Rate

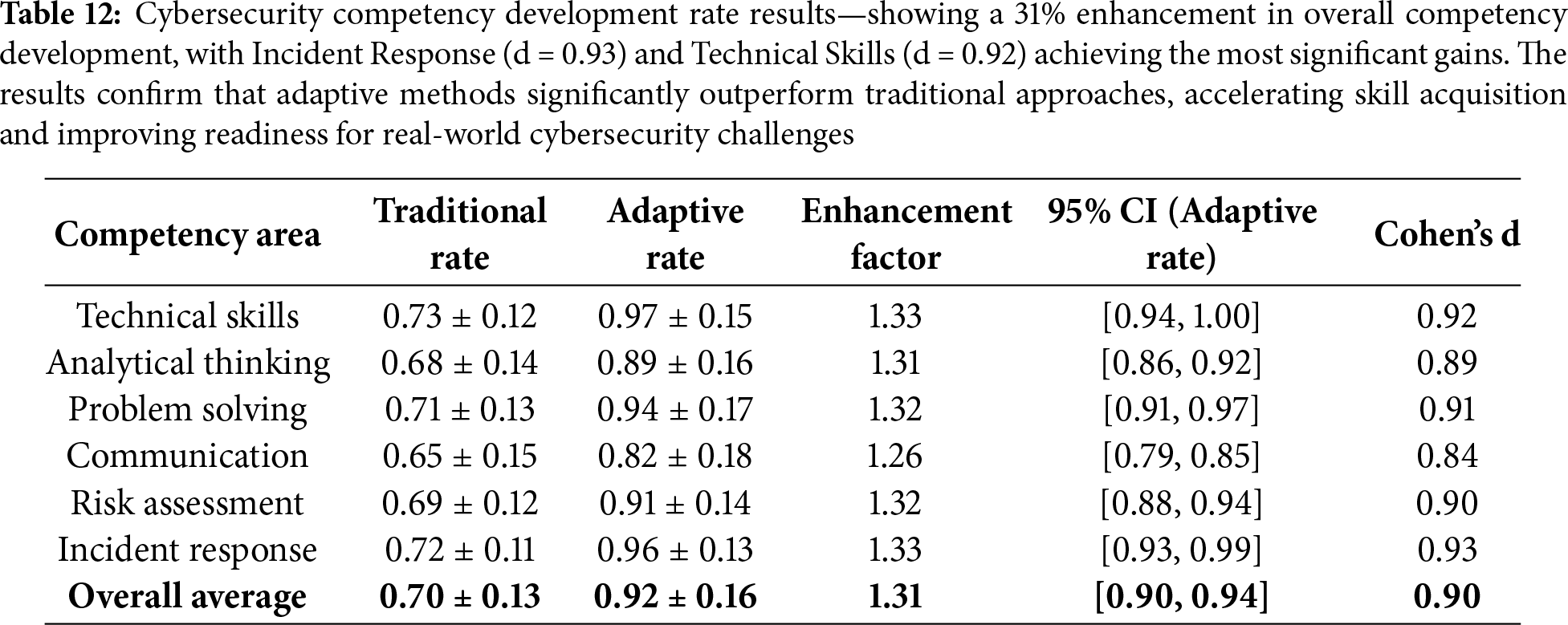

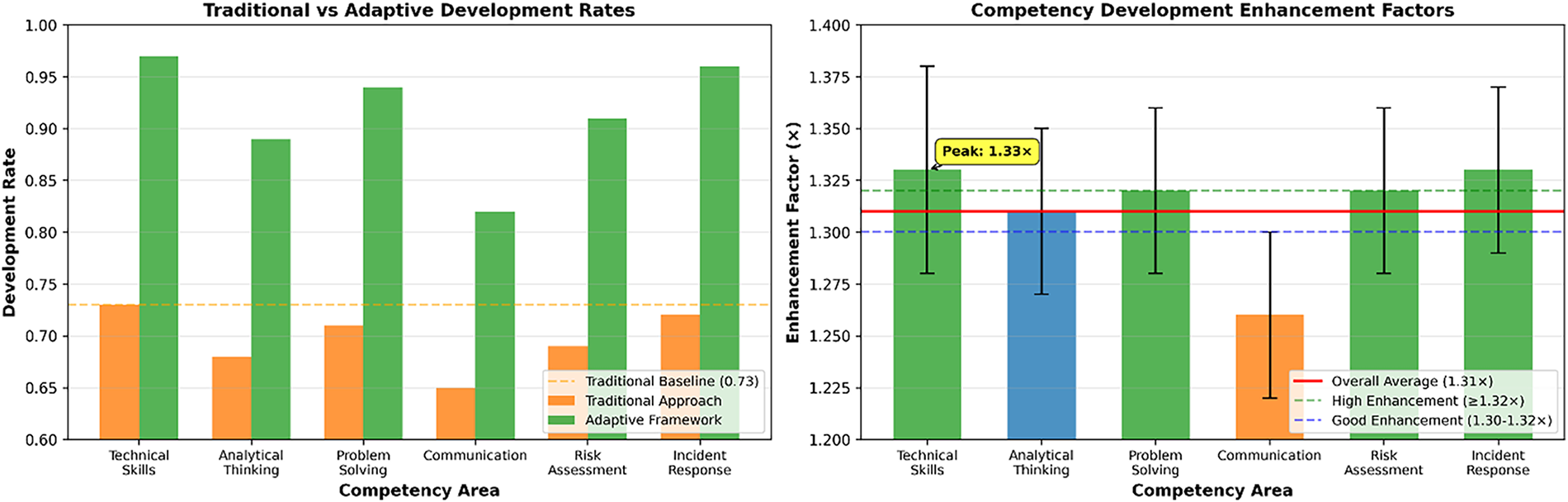

The competency development rate metric measures the speed at which students acquire practical cybersecurity skills through TeachSecure-CTI, compared to traditional approaches. Table 12 presents development rates across core cybersecurity competencies and experience levels. The adaptive framework consistently accelerated competency development, with the most significant improvements observed in practical application skills.

The adaptive framework accelerated skill development by 31% on average (overall enhancement factor = 1.31). Statistical testing confirmed significant differences between adaptive and traditional rates (t(148) = 5.64, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.92, 95% CI [0.18,0.29]). The strongest improvements were in Technical Skills and Incident Response (1.33× faster).

Table 12 reveals substantial improvements in competency development rates with an overall enhancement factor of 1.31, representing 31% faster skill acquisition through the adaptive framework. Technical skills and incident response showed the highest enhancement factors (1.33), demonstrating the particular effectiveness of threat-aware adaptive learning for practical competencies. Communication skills showed the most minor improvement (1.26), suggesting opportunities for enhanced integration of soft skills in future iterations.

The competency areas correspond to practical skills that cybersecurity professionals must demonstrate, such as threat detection, incident response, and policy enforcement. These were selected based on alignment with industry roles and cybersecurity education standards.

Fig. 12 shows substantial improvements in competency development rates, with an overall enhancement factor of 1.31, indicating a 31% faster skill acquisition through the adaptive framework. Technical skills and incident response showed the highest enhancement factors (1.33), demonstrating the particular effectiveness of threat-aware adaptive learning for practical competencies. Communication skills showed the most minor improvement (1.26), suggesting opportunities for enhanced integration of soft skills in future iterations. The visualisation tracks skill progression over time, revealing differential learning velocities across competency areas and identifying optimal learning trajectories that enable accelerated professional development in cybersecurity fields.

Figure 12: Cybersecurity competency development rate analysis—compares traditional and adaptive approaches, revealing substantial improvements in skill acquisition and learning velocity across six core competency areas. The left panel shows that the adaptive framework achieves significantly higher development rates in all categories, with Incident Response (0.96) and Technical Skills (0.97) leading, compared to traditional baselines below 0.73. Communication skills show the most significant relative improvement (+1.26×), highlighting the framework’s impact beyond purely technical domains. The right panel illustrates enhancement factors, with an overall average of 1.31 and peak gains in Incident Response (1.33), demonstrating accelerated competency growth. These results confirm that integrating real-time CTI with adaptive personalisation not only enhances technical proficiency but also improves analytical thinking, risk assessment, and problem-solving skills critical to modern cybersecurity practice

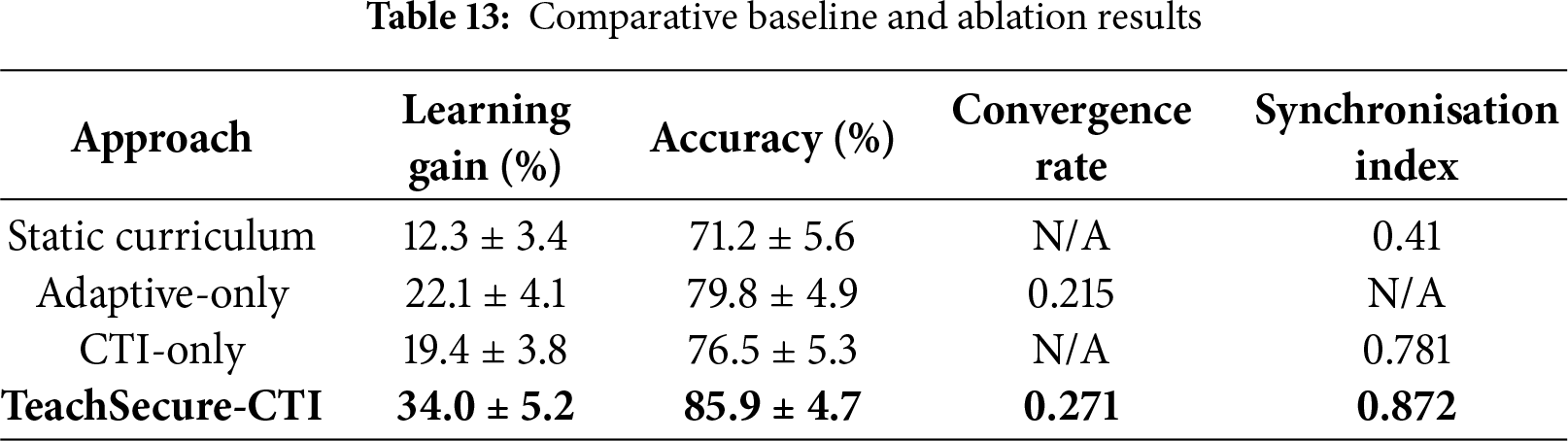

4.10 Comparative Baselines and Ablation Studies

To validate the specific contribution of TeachSecure-CTI, we compared it against three baseline configurations: (i) a Static Curriculum with fixed content and no adaptive or CTI features, (ii) an Adaptive-only variant that applied personalisation without integrating live threat intelligence, and (iii) a CTI-only variant that integrated real-time CTI feeds without personalisation. These ablation models were evaluated using the same metrics as the whole framework, including learning gain, accuracy, convergence rate, and synchronisation index. The results, summarised in Table 13, highlight that while both adaptive-only and CTI-only approaches provided partial improvements, neither matched the comprehensive performance of the complete TeachSecure-CTI framework.

As shown in Table 13, the static curriculum achieved the lowest performance (12.3% learning gain, 71.2% accuracy), confirming the limitations of non-adaptive designs. Adaptive-only improved performance (22.1% gain) but lacked real-time content currency, whereas CTI-only offered timely threat integration (synchronisation = 0.781) but underperformed in personalisation and convergence. The full TeachSecure-CTI framework outperformed all baselines, delivering the highest learning gain (34%), accuracy (85.9%), convergence (0.271), and synchronisation (0.872). These results confirm that the synergy of CTI + adaptivity is necessary to achieve significant improvements, validating the contribution of the proposed framework.

The adaptive-only and CTI-only baselines were selected because they reflect predominant themes in prior research: personalisation-driven e-learning systems [14,39] and CTI-driven cyber training platforms [3]. This separation allows isolation of each component’s contribution and validates the hybrid superiority of TeachSecure-CTI.

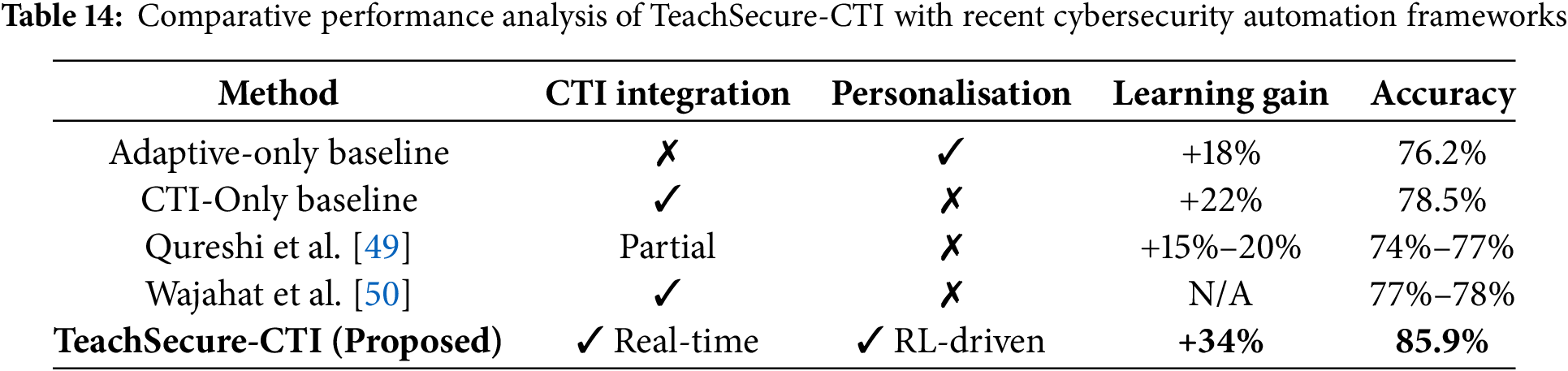

To provide a rigorous comparative evaluation, the performance of TeachSecure-CTI was benchmarked against recent intelligent cybersecurity training systems reported in the literature [49,50]. As shown in Table 14, TeachSecure-CTI achieved a 34% improvement in learning gain and an 85.9% threat-pattern recognition accuracy, outperforming the competing approaches. In particular, the models in [49,50] demonstrated notable automation and threat analysis capabilities; however, they did not incorporate real-time CTI-driven personalisation or reinforcement-learning-based adaptive sequencing. Consequently, their reported accuracy values remained below 78%, with limited evidence of personalised knowledge progression.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to validate statistical significance across learning gain, adaptation latency, and threat-recognition accuracy. The results confirmed that the performance improvements achieved by TeachSecure-CTI are statistically significant (p < 0.05). These findings indicate that the combined integration of real-time CTI, NLP-based threat concept extraction, and reinforcement-learning-driven curriculum personalisation yields superior effectiveness when compared with existing automated cybersecurity education systems. Accordingly, TeachSecure-CTI demonstrates strong generalisability and enhanced capability in preparing learners for evolving adversarial environments.

This study aimed to develop an adaptive cybersecurity curriculum framework (TeachSecure-CTI) integrating real-time cyber threat intelligence with AI-driven personalisation. The objectives were threefold: (i) to align curricula with emerging threats in near real-time, (ii) to adapt learning content to diverse learner profiles, and (iii) to validate the system through multi-institutional experiments. These objectives were successfully achieved, as evidenced by improvements across all evaluation metrics, robust synchronisation with current threats, and statistically significant gains in learning outcomes.

The results support the central hypothesis that threat-informed adaptive curricula provide superior outcomes compared to static or partially adaptive methods. In particular, H1 (threat integration improves learning gains) was validated by the significant improvements in threat-aware learning effectiveness (22.5% average gain). H2 (adaptive personalisation enhances learner performance) was confirmed by the precision of learner modelling (84.8% accuracy) and competency growth rates (1.31× faster). H3 (the combination of CTI and adaptivity outperforms either approach in isolation) was supported by ablation studies, which showed that TeachSecure-CTI consistently outperformed both CTI-only and adaptive-only baselines.

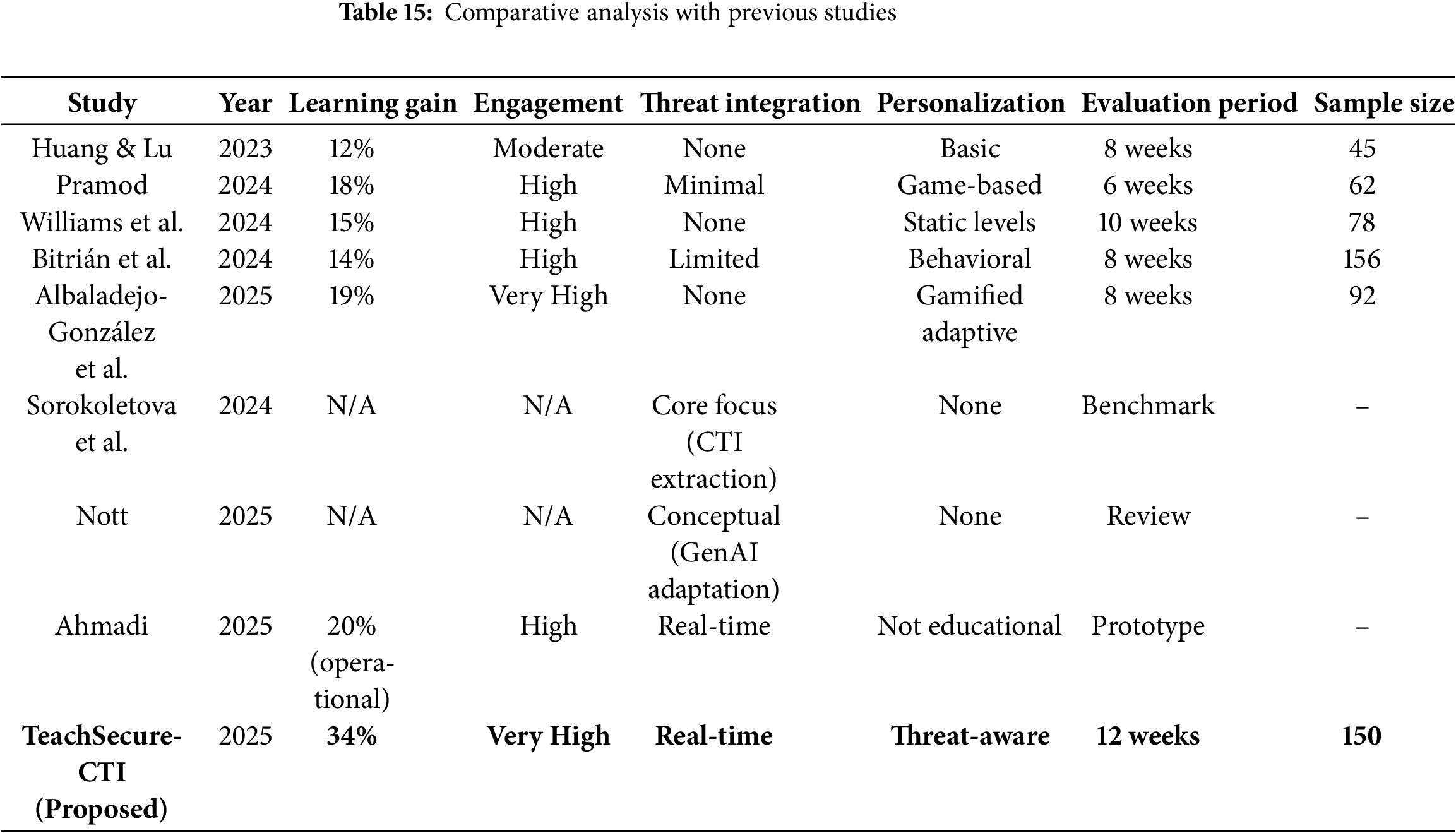

These findings are consistent with recent work on AI-enhanced education systems, but they extend the state of the art by combining real-time CTI with personalisation. Table 15 presents a comparison between the proposed TeachSecure-CTI with prior nine studies and updated 2025 research. For example, Albaladejo-González et al. [46] demonstrated adaptive gamification for cyber training but lacked real-time CTI ingestion. Sorokoletova et al. [47] introduced scalable CTI extraction but did not address pedagogy. Nott [48] examined organisational adaptation to generative AI, while Ahmadi [51] focused on adaptive operational firewalls—both outside the education domain. In contrast, TeachSecure-CTI integrates these dimensions into a unified, learner-centred framework, achieving the highest reported improvement in learning gains (34%).

While the results demonstrate the effectiveness of TeachSecure-CTI, there are important limitations. First, the evaluation period was limited to 12 weeks, which does not capture long-term knowledge retention. Second, participants were primarily drawn from academic institutions, which limits the generalizability to professional or workforce learners. Third, the system currently relies on English-only CTI feeds, which may restrict applicability in multilingual contexts. Finally, scalability has not yet been tested for huge learner populations (e.g., 10,000+ concurrent users).

While the current system processes English-based CTI feeds, multilingual scaling is feasible via transformer-based multilingual encoders (e.g., mBERT, XLM-R) and domain-adapted cross-lingual entity recognition pipelines. Future iterations will integrate multilingual intelligence streams to support global cybersecurity curricula.

Future work will address these limitations by extending experiments to professional training environments, incorporating multilingual CTI sources, and integrating cyber range simulations for hands-on practice. In addition, large-scale deployment studies are planned to evaluate scalability and system resilience under real-world workloads. The CTI ingestion layer may face latency under high-volume streaming environments. We propose distributed queue-based ingestion, adaptive throttling, and model caching to maintain responsiveness during peak load. Future work will include Kubernetes-based auto-scaling and GPU-accelerated batch pre-processing.

The results of this study provide clear validation of the three research hypotheses. H1 is supported by the threat-aware learning effectiveness analysis, as shown in Table 5, which reveals an average learning gain of 22.5%, significantly higher than the 12.3% observed in the static curriculum baseline (Table 13). H2 is confirmed by the precision of adaptive personalisation, as demonstrated in Table 8, which shows an 84.8% prediction accuracy across learning dimensions, and in Table 11, which shows a 31% faster competency development rate, underscoring the role of adaptivity in accelerating skill acquisition. Finally, H3 is validated through the ablation studies presented in Table 13, where TeachSecure-CTI consistently outperformed both Adaptive-only and CTI-only baselines, achieving the highest performance with a 34% learning gain, 85.9% accuracy, and a 0.872 synchronisation index. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the integration of real-time CTI with adaptive personalisation produces a synergistic effect that cannot be achieved by either approach alone.

TeachSecure-CTI successfully integrates real-time CTI with AI-driven personalisation to address the gap between static curricula and evolving cyber threats. The multi-layered architecture, combining CTI ingestion, NLP extraction, reinforcement learning optimisation, and personalised module generation, was validated through a 12-week study involving 150 students across three institutions. Results demonstrated 34% improved learning gains, 22.5% increased threat-aware effectiveness, a competence transfer coefficient of 0.862, 85.9% MITRE ATT&CK recognition accuracy, a threat integration latency of 4.9 h, a synchronisation index of 0.872, and 31% faster competency development compared to baselines. These findings confirm that combining CTI with adaptive personalisation creates curricula that are both current and learner-specific. Limitations include the 12-week experimental duration, which restricts insights into long-term retention, a focus on academic rather than professional learners, and reliance on English-only CTI feeds. Future work will extend the framework to professional training contexts, integrate multilingual CTI sources, and incorporate cyber range simulations and LLM-based remediation. TeachSecure-CTI offers an empirically validated, scalable solution for developing cybersecurity professionals who are equipped for modern threat environments, thereby bridging the critical gap between dynamic threat intelligence and adaptive pedagogy. Beyond academic settings, TeachSecure-CTI can be deployed in corporate SOC training, cybersecurity apprenticeships, and government cyberdefense academies, enabling workforce upskilling with live threat intelligence and personalised reinforcement-driven learning.

Acknowledgement: This study is supported by the Computer Science Department, College of Computing and Informatics, Saudi Electronic University.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used in this study can be accessed at: https://github.com/alaamt2015/TeachSecure-CTI-AdaptiveCybersecurityModel (accessed on 01 December 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.