Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Overall Optimization Model Using Metaheuristic Algorithms for the CNN-Based IoT Attack Detection Problem

1 Faculty of Information Technology, Academy of Cryptography Techniques, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

2 Deputy Director, Academy of Cryptography Techniques, Hanoi, 100000, Vietnam

* Corresponding Author: Le Thi Hong Van. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence for Intrusion Detection Systems)

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 87(1), 81 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.075027

Received 23 October 2025; Accepted 03 December 2025; Issue published 10 February 2026

Abstract

Optimizing convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for IoT attack detection remains a critical yet challenging task due to the need to balance multiple performance metrics beyond mere accuracy. This study proposes a unified and flexible optimization framework that leverages metaheuristic algorithms to automatically optimize CNN configurations for IoT attack detection. Unlike conventional single-objective approaches, the proposed method formulates a global multi-objective fitness function that integrates accuracy, precision, recall, and model size (speed/model complexity penalty) with adjustable weights. This design enables both single-objective and weighted-sum multi-objective optimization, allowing adaptive selection of optimal CNN configurations for diverse deployment requirements. Two representative metaheuristic algorithms, Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), are employed to optimize CNN hyperparameters and structure. At each generation/iteration, the best configuration is selected as the most balanced solution across optimization objectives, i.e., the one achieving the maximum value of the global objective function. Experimental validation on two benchmark datasets, Edge-IIoT and CIC-IoT2023, demonstrates that the proposed GA- and PSO-based models significantly enhance detection accuracy (94.8%–98.3%) and generalization compared with manually tuned CNN configurations, while maintaining compact architectures. The results confirm that the multi-objective framework effectively balances predictive performance and computational efficiency. This work establishes a generalizable and adaptive optimization strategy for deep learning-based IoT attack detection and provides a foundation for future hybrid metaheuristic extensions in broader IoT security applications.Keywords

The Internet of Things (IoT) has emerged as a prominent technological trend with the capability to interconnect billions of physical devices, ranging from sensors and wearables to automated control systems, thereby delivering intelligence and convenience across diverse domains such as healthcare, industry, smart cities, and digital homes [1–4]. However, the explosive growth in the number of devices and the heterogeneity of the IoT ecosystem have significantly increased security vulnerabilities, making IoT systems attractive targets for cyberattacks, particularly distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, flooding attacks, and IoT malware [1,5,6].

Ensuring the security of IoT systems has thus become more critical than ever [2,7,8]. In this context, intrusion detection systems (IDS) play a vital role in monitoring, detecting, and mitigating cyberattacks [7–9].

Artificial intelligence (AI)-based methods, including machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), have been widely employed to address IoT security challenges [2,7,10,11]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have demonstrated superior capability in feature extraction and classification, making them a popular choice for applications involving time-series signals, including intrusion detection [12–14]. Nevertheless, determining the optimal architecture and hyperparameters for CNNs remains a considerable challenge, often requiring computationally expensive manual experimentation and heavily relying on the expertise of researchers [15–17].

To address the problem of CNN configuration optimization, metaheuristic algorithms have emerged as powerful tools owing to their flexibility and effectiveness in solving complex optimization problems [10,15,18–21]. These algorithms are problem-independent and do not rely on gradient information, enabling a comprehensive exploration of the solution space and the ability to address both single-objective and multi-objective optimization. This paper proposes a comprehensive optimization approach that leverages metaheuristic algorithms to configure CNNs for IoT intrusion detection. The proposed method is applicable to both single-objective and multi-objective optimization, thereby allowing the selection of suitable optimization goals for different problem classes. To achieve this, a global objective function is constructed by integrating performance components such as accuracy, precision, recall, and model computational complexity, with corresponding weights. By adjusting these weights, the optimization process can be tailored to specific objectives. Several metaheuristic algorithms, including Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), are proposed and evaluated for CNN configuration optimization. The global objective function is employed as the fitness function in evolutionary algorithms. At each generation, the best configuration is selected as the most balanced one across optimization objectives, i.e., the configuration with the highest value of the global objective function.

This work differs from existing GA-CNN, PSO-CNN, NSGA-II CNN, and hybrid metaheuristic-based intrusion detection models in several aspects:

(1) We introduce a unified multi-objective CNN optimization framework that simultaneously considers accuracy, precision, recall, and model complexity through a normalized weighted formulation.

(2) Unlike prior works that optimize only a subset of hyperparameters, our approach jointly tunes both architectural (number of convolutional layers, kernel size, filters, dense size) and training-level hyperparameters (learning rate, batch size, dropout, patience).

(3) We integrate both GA and PSO as independent optimizers under a common evaluation and search policy, enabling a comparative analysis of their exploration–exploitation balance on IoT attack detection datasets.

(4) We optimize a significantly larger 11-dimensional hybrid hyperparameter space, which is rarely addressed in previous metaheuristic CNN optimization research.

These differences will be described and clarified in the following sections.

2.1 Optimizing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) Using Metaheuristic Algorithms for IoT Attack Detection

The combination of metaheuristic algorithms and CNNs has been extensively studied to enhance attack detection performance in IoT environments [15,22–24]. Metaheuristic algorithms have proven to be effective, robust, and high performing in addressing real-world optimization problems, including classification and optimization tasks [10]. They can optimize deep neural network (DNN) models by tuning hyperparameters and architecture. For instance, one study explored seven metaheuristic algorithms, both genetic and non-genetic, to derive optimal solutions for balancing CNN hardware parameters and accuracy [12].

More specifically, in the context of IoT attack detection, a model called MHADMA-BCIDL was developed, leveraging blockchain technology for enhanced security and integrating a convolutional neural network with bidirectional long short-term memory and attention mechanism (CNN-BiLSTM-Attention) to detect and classify DDoS attacks [25]. This model further employed the Arctic Tern Optimization (ATO) technique for dimensionality reduction during feature selection and the Walrus Optimization (WO) algorithm to fine-tune the hyperparameters of the CNN-BiLSTM-Attention approach [25]. A novel IoT network intrusion detection approach based on Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization Convolutional Neural Network (APSO-CNN) [26] and an adaptive hybrid method combining Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization and Whale Optimization Algorithm (APSO-WOA) [27] were also proposed to optimize CNN hyperparameters, where the fitness value was defined as the cross-entropy loss of the validation set during CNN training.

Another study adopted the Salp Swarm Algorithm (SSA), inspired by the cooperative foraging and navigation behaviors of salps, to select optimal features, followed by employing deep learning classifiers such as CNN, RNN, and DNN for attack classification [28]. For DDoS detection, the Hunger Games Search (HGS) algorithm was applied to optimize data and select the most effective parameters for deep learning models, achieving 100% accuracy on one dataset and 99.99% on another [29]. In the NB-IoT environment, where low-rate DoS attacks are prevalent, the Simulated Annealing (SA) method was employed to adjust CNN weights, providing better global search capabilities and mitigating overfitting issues [30]. Other studies have also utilized GA to search for optimal CNN architectures [31,32].

2.2 Single-Objective and Multi-Objective Optimization

Metaheuristic algorithms exhibit high flexibility and can be applied to various optimization problems, including both single-objective and multi-objective formulations. In single-objective optimization, algorithms such as GA, PSO, and Differential Evolution (DE) have been widely adopted to obtain optimal solutions [12,33,34]. GA operates on a population of candidate solutions and employs genetic operators such as crossover and mutation, along with sophisticated selection mechanisms. PSO, inspired by the collective behaviors observed in nature (e.g., bird flocking), updates particle positions based on both personal best solutions and global best solutions. These algorithms are characterized by their fast convergence rates and ease of implementation in complex parameter spaces [15,35].

In multi-objective optimization, algorithms such as NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm-II), RNSGA-II (Reference point-based NSGA-II), AGE-MOEA (Adaptive Geometry Estimation-based Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm), AGE-MOEA-II, and MOPSO (Multi-objective PSO) have been employed to search for Pareto-optimal solution sets that balance performance and cost [12,23,36]. Multi-objective optimization is particularly important in scenarios where multiple conflicting goals must be addressed, such as maximizing accuracy while minimizing the computational complexity of CNN models [12]. A novel multi-objective swarm optimization approach based on Fuzzy-Pareto-Dominance has also been introduced, extending traditional single-objective algorithms into the multi-objective domain [37].

Common performance factors used in objective functions for CNN-based attack detection models include Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score [10,38,39]. For instance, a CNN–metaheuristic hybrid model achieved 98% accuracy, 96% precision, and 94% recall [10]. Incorporating these performance indicators with computational complexity (often tied to hardware constraints) represents a typical multi-objective approach to optimizing CNN configurations [12,32,36]. In evolutionary optimization of CNNs, the fitness function can be defined as a weighted aggregation of individual objectives [40]. This enables the algorithm to make informed decisions at each iteration, continuously refining solutions to achieve global optimality. Nevertheless, determining optimal parameter settings for metaheuristic algorithms remains challenging and time-consuming, requiring a careful balance between exploration (searching broadly across the parameter space) and exploitation (intensively refining promising regions). Properly defining the objective function is therefore critical, as it directly influences the quality of the resulting solutions.

2.3 IoT Attack Detection Datasets

To evaluate intrusion detection models in IoT environments, the use of reliable datasets is crucial [25,41]. These datasets must reflect realistic IoT network traffic and contain various attack types to train and test detection models [6,38,42–44]. Some commonly used IoT attack detection datasets include:

• BoT-IoT Dataset: Created in 2018 and published in 2019 by the University of New South Wales (UNSW), this dataset is a modern and realistic resource for training botnet attack detection models in IoT networks [9,25,38,45,46]. It contains millions of botnet traffic samples classified into scenarios such as DDoS, DoS, reconnaissance, and information theft [38].

• ToN-IoT Dataset: This dataset was generated from a large-scale, heterogeneous IoT network, reflecting data from all layers of the IoT system, including cloud, fog, and edge [7,9,43]. It plays a critical role in enabling effective intrusion detection in IoT [43].

• CIC-IoT-2022 Dataset: This dataset includes IoT network traffic data representing both normal behavior and multiple attack types, and it is widely used for IoT attack detection and classification tasks employing ML techniques [9].

Compared with older datasets such as KDD99 or NSL-KDD [7,47], newer datasets provide higher fidelity, incorporating modern attack types such as DDoS, information theft, and IoT malware [5,6,9,43].

Studies [9,43] emphasize the importance of representative datasets that are class-balanced and feature-standardized for effectively training AI models. The correct dataset selection is a prerequisite for ensuring fair evaluation of the performance of metaheuristic methods and CNNs.

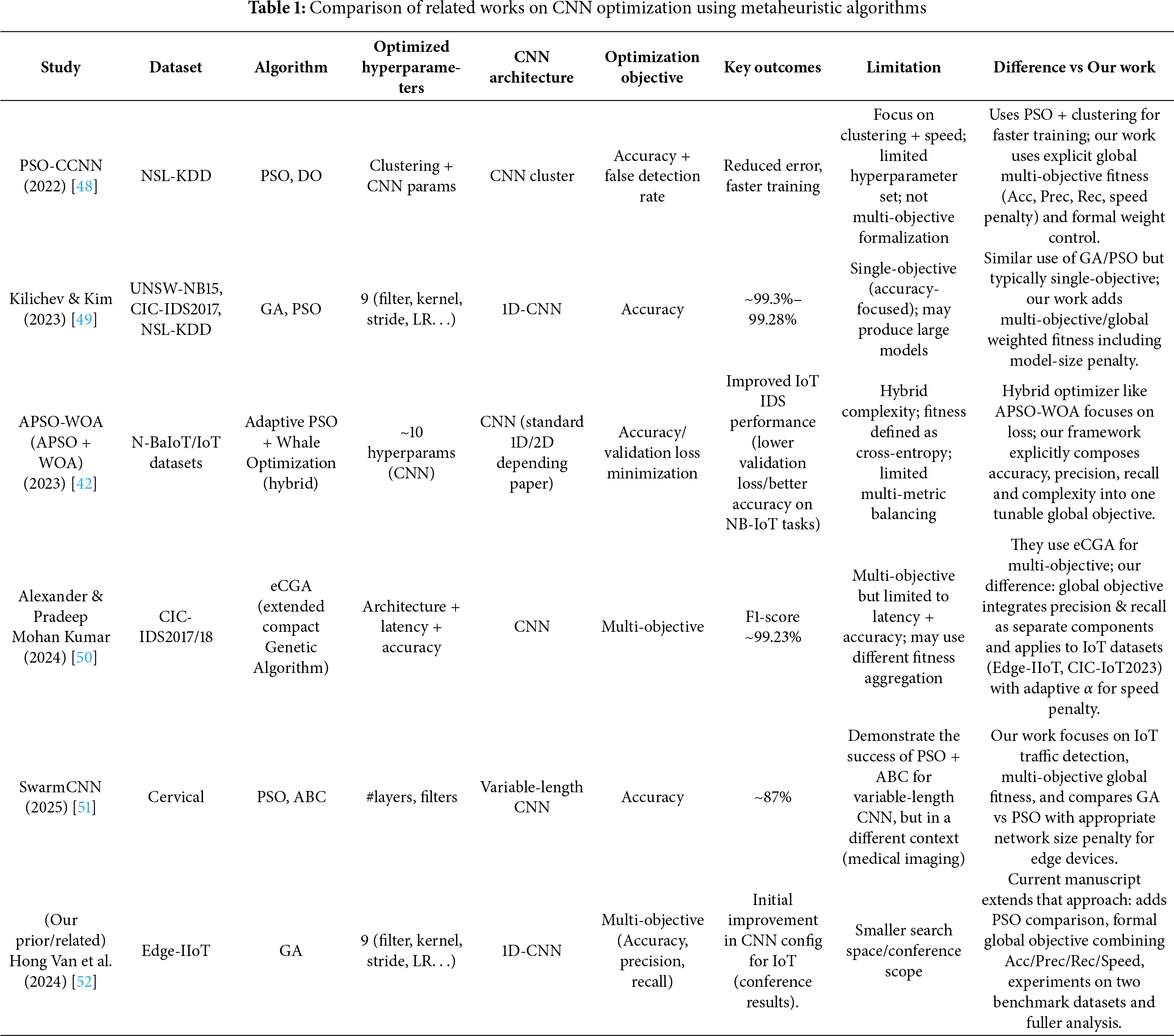

Table 1 compares related works applying metaheuristic algorithms for single-multi-objective CNN configuration optimization, and highlights the focus and distinct improvements in our method. It can be observed that GA and PSO are the most employed algorithms for CNN architecture optimization, particularly when the objective is to enhance accuracy, as in the studies by Kilichev & Kim and APSO-WOA. When the objectives target minimizing latency, computational cost, or training speed, hybrid approaches such as eCGA (Alexander & Kumar) and PSO + clustering (PSO-CCNN) demonstrate effectiveness in balancing model performance with practical deployability. Cases employing PSO + ABC (SwarmCNN) or PSO + WOA (APSO-WOA) further illustrate the flexibility of hybrid metaheuristic approaches, extending the applicability of CNNs across diverse IoT data domains.

The studies reviewed in Table 1 reveal a growing trend in applying metaheuristic algorithms to optimize deep learning models, particularly CNNs, for IoT network intrusion detection. Most work primarily focuses on improving accuracy or specific evaluation metrics such as precision and recall. However, most of these studies still lack a comprehensive approach to balancing detection performance with computational cost—an aspect of critical importance for real-time monitoring systems and resource-constrained IoT environments.

Motivated by this gap, the approach proposed in this paper is to construct a global objective function that integrates performance evaluation components such as accuracy, precision, recall, and the computational complexity of the CNN model, each weighted adaptively. This global objective function enables flexible adjustments according to specific requirements: prioritizing absolute accuracy, maximizing detection coverage, or minimizing computational cost, thereby supporting various real-world deployment scenarios.

To address this multi-objective optimization problem, the paper proposes employing well-established metaheuristic algorithms such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithm (GA) to search for the optimal CNN configuration. In this framework, the global objective function acts as the fitness function during the evolutionary process. Across generations, candidate CNN configurations are evaluated based on their global objective values, and the highest-scoring configuration is selected as the most balanced solution among the objectives. This approach is not only feasible but also provides a flexible and extensible framework for deep learning–based intrusion detection systems in complex IoT environments.

3.1 Configuration Vector Construction

3.1.1 CNN Architecture for IoT Attack Detection Problem

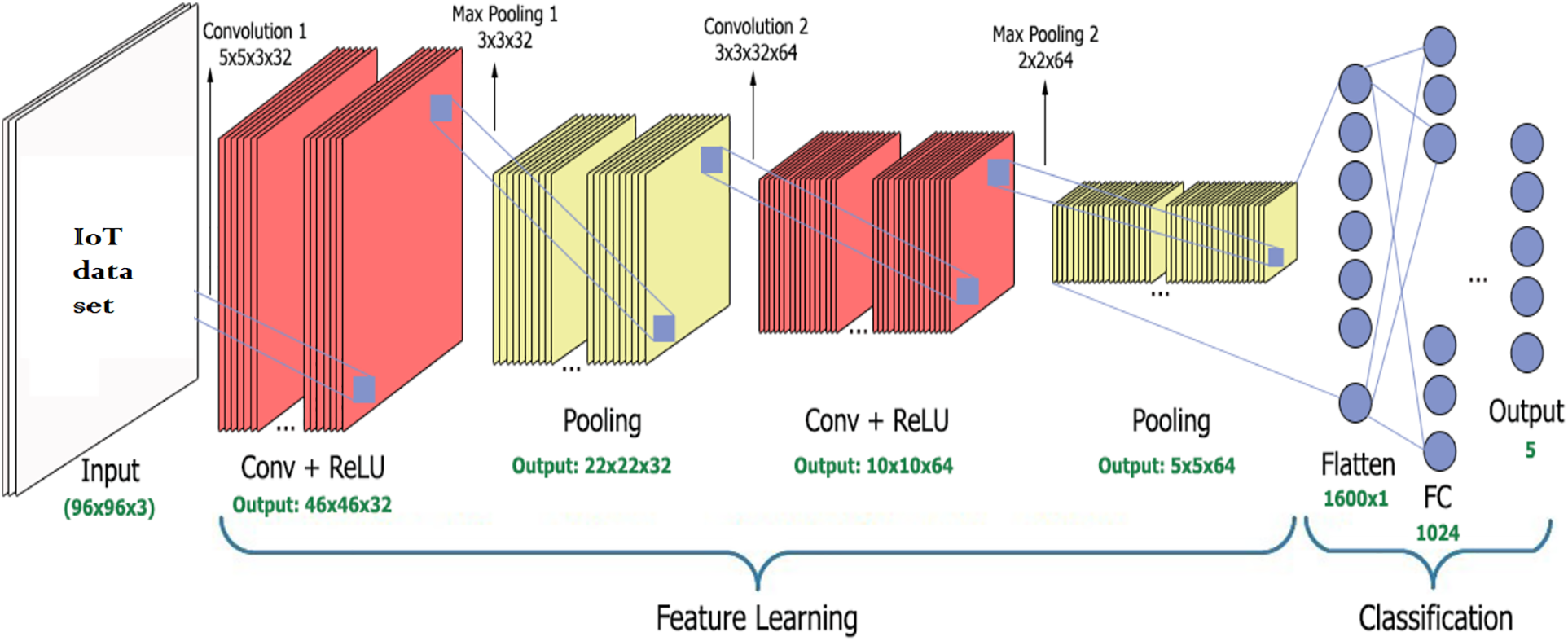

The CNN architecture in the IoT attack detection problem is described in Fig. 1. The CNN model has two types of parameters: training parameters (or parameters) and structural parameters (hyperparameters). Training parameters include the weight array (both the layer weights in the fully connected layer and the shared weight array—the sub-matrices for calculating convolution, also known as the sliding window) and the bias obtained after training the model. Hyperparameters describe the structure of the CNN set up before training. A CNN model has a specific structure determined by the parameters: window size, number of convolution layers, activation function, number of neurons/layers, parameters (filter size, stride, padding, dropout), etc.

Figure 1: Example of a specific CNN structure

Definition 1: CNN Configuration Vector

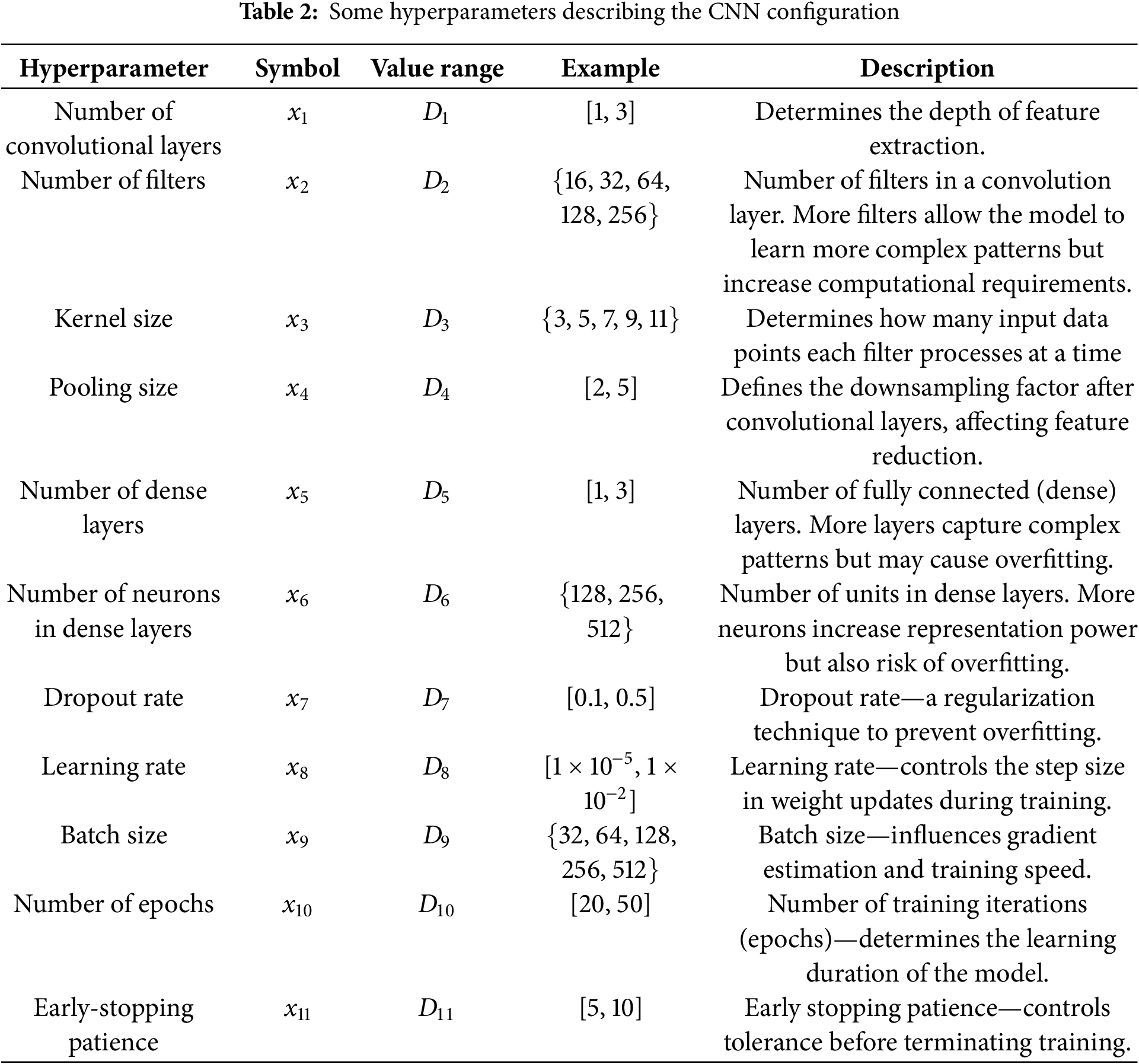

The CNN configuration vector is a set of values corresponding to the hyperparameters used by CNN during the training process. It is denoted as x and defined by Eq. (1), where each component corresponds to one hyperparameter described in Table 2.

3.2 Constructing an Overall Optimization Model to Find the Optimal CNN Configuration Vector for IoT System Attack Detection IoT

The IoT attack detection task that employs the CNN architecture described in Section 3.1 consists of two stages: training and detection. The training stage is performed to obtain a suitable CNN model. Training is executed for each candidate CNN configuration. Current studies on IoT attack detection typically train a CNN with a specific, fixed configuration and do not apply optimization methods to select the best configuration. The objective of the optimization task is to find the optimal configuration vector x* for which the objective function f attains its maximum value. This paper proposes and formulates a comprehensive optimization model applicable to both single-objective and multi-objective optimization. Single-objective optimization is performed with respect to each of the following objectives: accuracy, precision, recall, and performance (e.g., speed). These component objective functions are denoted as follows: f1—accuracy, f2—precision, f3—recall, and f4—speed.

Multi-objective optimization is carried out according to the weighted-sum method—aiming to achieve a balanced trade-off among the conflicting objectives. The optimization model of the comprehensive problem can be expressed as Eq. (2):

where:

– x = { x1, x2, …, x11} denotes a configuration vector

– X represents the configuration space

– f is the optimization function, which also serves as the global objective function in the problem

– fi denotes the individual objective functions,

– wi represents the weight associated with each individual objective function.

3.2.1 Single-Objective Optimization

From Eq. (2) of the general optimization problem, different single-objective formulations can be derived by adjusting the weights accordingly. Specifically:

– Accuracy optimization: f(x) = f1(x); w1 = 1 và w2 = w3 = w4 = 0

– Precision optimization: f(x) = f2(x); w2 = 1 và w1 = w3 = w4 = 0

– Recall optimization: f(x) = f3(x); w3 = 1 và w2 = w1 = w4 = 0

– Speed optimization: f(x) = f4(x); w4 = 1 và w2 = w3 = w1 = 0.

3.2.2 Multi-Objective Optimization

The scalarized multi-objective optimization problem aims to achieve a balance among the competing objectives, where the optimal solution is identified when the global objective function reaches its maximum. In the context of IoT intrusion detection, the complete multi-objective optimization problem is described in Eq. (2), where the global objective function is computed as a weighted aggregation of the individual objective functions. The weights wi represent the relative importance of each objective fi compared to the others. However, the weighted sum only approximates the Pareto front when the weights change.

Accordingly, from the full multi-objective optimization problem, the weights can be adjusted to derive alternative formulations that fit different contextual requirements. Specifically, several representative cases include:

– Balancing Accuracy and speed: when w2 = w3 = 0

– Balancing Accuracy, Precision and Recall: when w4 = 0

– Balancing Accuracy, Precision, Recall and Speed: when all of wi ≠ 0.

3.3 Construction of the Objective Functions

Definition 2: Accuracy Objective Function f1

Definition and formulation of the evaluation function:

Accuracy (Acc) represents the overall correctness of the model. While this metric provides a general evaluation, it may not always reflect the true effectiveness of a model.

For instance, consider two models:

– Model A achieves 99% accuracy but misclassifies a critical case—predicting that a patient does not have cancer when in fact they do (false negative). This results in the patient not receiving treatment, potentially leading to severe consequences. Similarly, in IoT intrusion detection, a dangerous cyberattack could be misclassified as normal traffic, which poses a significant threat.

– Model B, in contrast, achieves only 96% accuracy. However, it does not miss any true positive cancer cases. The lower accuracy is due to some false positives, where healthy patients are incorrectly flagged as having cancer. These cases are later confirmed through further testing and dismissed without critical harm.

This example illustrates that a model with higher accuracy may not necessarily be the safer or more effective choice.

Definition 3: Precision Objective Function f2

To address the limitations of accuracy, precision is introduced as an objective function. Precision measures the proportion of true positives among all predicted positives, and higher precision indicates fewer false positives.

Precision becomes particularly important in scenarios where false positives have severe implications. For example, in spam email detection, a false positive occurs when a legitimate email is mistakenly classified as spam. Misclassifying an important business email—such as one containing a multi-million-dollar contract—can result in significant negative consequences. Therefore, in such contexts, precision should be prioritized when selecting the optimal model.

Definition 4: Recall Objective Function f3

The higher the Recall value, the lower the rate of False Negatives (FN). Recall should be assigned a higher weight when selecting the most appropriate model in scenarios where misclassifying actual Positive instances as Negative leads to severe consequences. For example, in the case of cancer diagnosis, misclassifying a cancer patient as healthy and sending them home without early treatment may result in catastrophic outcomes.

In this study, we do not use the F1-score in the optimization. Instead, we optimize directly for Precision and Recall, as F1-score equally weights both metrics (0.5 each), which may not align with the specific priorities of IoT intrusion detection. Our multi-objective optimization relies solely on accuracy, precision, recall, and model size. F1-score is still reported after training as an external metric, given its widespread use in IDS evaluation.

Definition 5: Speed Objective Function f4

The evaluation of speed is simplified by relating it to the total number of model parameters. Speed is inversely proportional to model complexity, and model complexity is directly proportional to the number of parameters. Therefore, speed is inversely proportional to the parameter count of the CNN model. For each configuration xi, let p (xi) denote the number of parameters; the speed evaluation function is then defined as following Eq. (6):

The use of log10 (p (xi)) serves to normalize the scale, as CNN models often involve a large number of parameters, ranging from tens of thousands to hundreds of millions. The function

For lightweight CNN architectures suitable for IoT environments (e.g., Tiny CNN) to standard deep models such as ResNet-50, AlexNet (2012), and VGG16, the parameter size p (x) typically falls within the range [104, 108]. We exclude extremely large-scale models (e.g., ViT, ResNet-152, etc.), which often exceed p (x) > 108 parameters and are unsuitable for IoT edge devices. To normalize f4 into a value range comparable to the other objective functions fi, we select scaling factors α = 0.005, 0.01, or 0.02.

The scaling factor α in the speed objective function f4 is introduced to normalize the variation in model parameter size and to control the sensitivity of the function to model complexity. Since CNN architectures differ significantly in terms of parameter count—from lightweight IoT-oriented networks (e.g., TinyCNN, MobileNet) to large-scale models (e.g., ResNet-152, ViT)—the same value of α may not ensure a consistent evaluation range across datasets. Therefore, α is selected adaptively according to the dataset characteristics and the expected computational constraints of the deployment environment. Specifically, IoT and edge datasets typically correspond to limited-resource environments, where model speed is more critical; hence, a larger scaling factor (α ∈ [0.01, 0.02]) is employed to amplify the impact of parameter growth on the objective function. Conversely, for cloud-based or high-performance datasets where computational resources are sufficient, a smaller scaling factor (α ∈ [0.001, 0.005]) is preferable to maintain smoother sensitivity and avoid over-penalizing complex models.

The selection of the scaling factor

Definition 6: Global Objective Function f

Among the above-defined evaluation measures, each metric corresponds to specific goals and datasets. To enable flexible application across various IoT intrusion detection scenarios, we construct a global objective function, computed as described in Eq. (2).

We adopt a weighted-sum scalarization as our default multi-objective strategy: the global fitness is computed as f(x). This formulation allows us to incorporate accuracy, precision, recall, and model complexity into a single tunable objective while maintaining compatibility with GA/PSO operators. The weights {w1, w2, w3, w4} were selected based on (1) practical IDS priorities, (2) empirical tuning, and (3) normalization to ensure scale fairness between performance metrics and model complexity. We follow a domain-driven approach: IoT intrusion detection requires high recall to avoid missing malicious events, therefore w3 is slightly higher. The complexity penalty w4 is tuned to reflect the constraints of IoT/Edge hardware.

3.4 Applying Metaheuristic Algorithms to Optimize CNN Configuration in IoT Intrusion Detection

Essentially, solving the optimization problem described in Eq. (2) involves searching within the solution space for an extreme value of the objective function. As shown in Eq. (2) and Table 1, the search space is defined as the Cartesian product of the value domains D1, D2, … D11:

As illustrated in Table 1, the domains D7 and D8 are continuous and contain infinitely many elements, while the remaining domains are discrete. Consequently, from Eq. (7), the search space X is infinite; each vector in the space has 11 dimensions, comprising both discrete and continuous components, without a unified closed-form representation. Therefore, the optimization problem Eq. (2) cannot be solved using conventional mathematical methods that rely on differentiation and extremum-finding. Similarly, brute-force enumeration is infeasible due to the infinite size of the search space. As a result, solving this problem requires the adoption of metaheuristic algorithms to approximate near-optimal solutions.

Depending on the specific task, an appropriate algorithm can be selected. As analyzed and summarized in Section 2, for CNN optimization in IoT intrusion detection, we employ both GA and PSO for experimentation and subsequently analyze the outcomes to evaluate their suitability for different datasets and task scenarios.

In optimization algorithms, the objective function acts as a compass, guiding the search process toward better solutions. By quantifying the fitness of a candidate solution with respect to the desired objectives, it provides a systematic way to rank and compare alternatives. When a well-designed fitness function is adopted, the optimization process is transformed into a tractable optimization problem [10].

3.4.1 Applying the PSO Algorithm

In the PSO framework, each particle represents a set of hyperparameters x, and the swarm X constitutes the collection of all feasible hyperparameter configurations generated during the optimization process. The goal of the proposed method is to identify the optimal hyperparameter set x* ∈ X such that the CNN model achieves maximum performance.

To apply the PSO framework in this study, it is necessary to define the position, velocity, fitness function, local best position (pbest) of each particle, and the global best position (gbest) of the swarm. Building upon the original work in [49], this study extends the approach by focusing on the optimization of 11 hyperparameters in CNN configuration for IoT intrusion detection, with the following key contributions:

• Improvement of the baseline PSO algorithm in [49] by incorporating an automatic stopping criterion for the optimization loop, introducing an early-stopping mechanism, and thereby extending the search space to include hyperparameters such as early-stopping patience and the number of convolutional layers. This expands the set of optimized hyperparameters from 9 to 11, covering both architectural and training parameters.

• Proposal of a multi-objective optimization function that integrates four component objectives, ensuring that the model not only achieves high detection accuracy but also operates at a speed compatible with the limited resources of IoT edge devices. This multi-objective function is employed as the fitness function to evaluate each particle.

• Data preprocessing for efficiency: Duplicate removal and feature reduction are performed on the dataset to reduce dimensionality, accelerate training, and conserve system resources, thereby enhancing model efficiency in resource-constrained IoT environments.

The process begins with the initialization of a particle swarm, where each particle encodes a candidate hyperparameter configuration X. These configurations are used to train and evaluate the 1D-CNN model on the training and validation datasets.

After training, the model performance is assessed through the fitness value of each hyperparameter configuration (1D-CNN particle). The fitness function corresponds to the global objective function f. PSO then updates each particle’s personal best position (pbest) and the global best position (gbest) based on the evaluation results. If the current fitness of a particle exceeds its previous personal best, the algorithm updates its pbest. Similarly, if the fitness of a particle surpasses the current gbest, the global best is updated. Consequently, particle velocities and positions are adjusted to guide the swarm toward more optimal solutions, as defined by the following equations:

• Velocity update: The new velocity for each particle is computed according to Eq. (8):

where:

Eq. (8) represents three main components that influence the particle’s movement: the inertia component, the personal cognitive component, and the social cognitive component.

• Position update: The new position of each particle in the swarm is updated based on the new velocity according to Eq. (9)

The above processes are repeated until the termination condition is satisfied. If the stopping criterion has not been met, the procedure continues with the training and updating of new parameters. Otherwise, an optimal 1D-CNN model along with the corresponding set of hyperparameters x* is obtained.

Finally, this model is evaluated on the test dataset to validate its effectiveness and generalization capability.

To constrain the search space, a function clip() ensures that the new position of each particle remains within the valid search bounds. The proposed method employs a mapping mechanism from particle positions to model hyperparameters, to handle two main categories of hyperparameters:

1. Continuous hyperparameters: Directly mapped from the particle position values in the search space without additional processing.

2. Discrete hyperparameters: Mapped through two steps—quantization of the continuous value, followed by mapping into a predefined set of values (if applicable).

Each dimension in the PSO particle position vector corresponds to a specific hyperparameter of the 1D-CNN model. The mapping mechanism is constructed based on three principles: (1) Direct mapping of particle dimensions to parameters (for continuous real-valued hyperparameters); (2) Quantization of continuous values—for hyperparameters requiring integer values, the continuous values are quantized by rounding to the nearest integer. (3) Constraint mapping into predefined sets—for hyperparameters with finite domains, the quantized values are mapped into a predefined set using a clipping index technique.

3.4.2 Applying the GA Algorithm

Building upon our previous work in [52], in this study we extend the 1D-CNN-GA algorithm to better fit the new context by introducing two additional hyperparameters (x1—Number of convolutional layers and x11—Early-stopping patience). Moreover, different fitness functions are applied corresponding to different definitions of the global objective function f.

We adopt Tournament Selection to choose parent individuals. In this mechanism, a pair of individuals is selected randomly, forming a dynamic selection process that is not entirely dependent on fitness. This approach helps preserve population diversity and provides opportunities for “weaker” individuals to participate in reproduction.

After selecting two parent individuals, offspring are generated through the crossover process. The architecture of the offspring is constructed by combining convolutional neural network blocks (block_list) from both parents. Specifically, a random cut point is determined in the block list of the first parent; blocks before the cut point are inherited from the first parent, while blocks after the cut point are taken from the second parent. This process allows the offspring to inherit favorable characteristics from both parents, while simultaneously introducing diversity into the population through the recombination of different blocks.

To ensure that the search space is thoroughly explored, the offspring undergoes a mutation process, where some of its components are randomly altered. For each hyperparameter (gene) in the offspring, if mutation occurs (based on the mutation rate), its value is updated by generating a new parameter value using the random parameter generation function.

This study proposes an adaptive early-stopping mechanism, designed to reflect the actual dynamics of the optimization process. Unlike previous studies that rely on a fixed number of iterations, this mechanism is based on the continuous evaluation of improvements in the global best solution (gbest) across consecutive iterations.

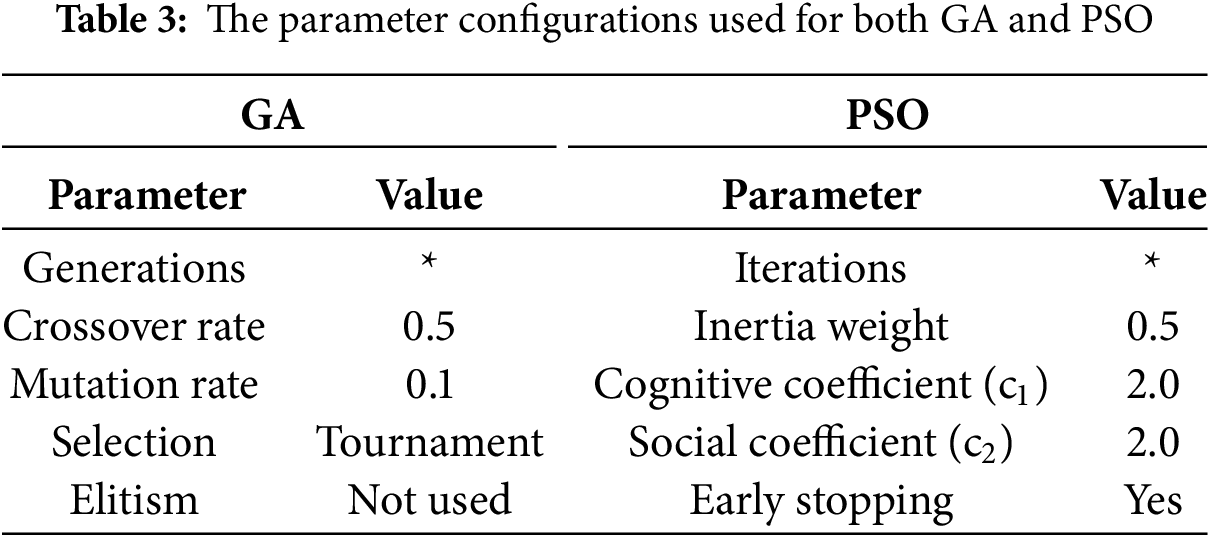

3.4.3 Parameter Settings and Justification

To ensure reproducibility and methodological transparency, the parameter configurations used for both GA and PSO are summarized in Table 3. These settings were selected based on a combination of literature guidelines, empirical pilot testing, and grid search over representative subsets of the search space.

The GA optimizer is using a crossover rate of 0.5 and a mutation rate of 0.1. Tournament selection is applied to maintain population diversity, while elitism is intentionally omitted to allow broader exploration of the search space. The GA employs a crossover probability of 0.5, meaning that only half of the selected parent pairs undergo recombination, which helps maintain stable inheritance of promising CNN configurations while still enabling exploration. A mutation rate of 0.1 perturbs 10% of the hyperparameter genes in each chromosome, preventing premature convergence and ensuring diversity.

For PSO, with an inertia weight fixed at 0.5 to balance the influence of previous velocities. The cognitive and social coefficients are set to c1 = c2 = 2.0, consistent with standard PSO recommendations. An early-stopping mechanism is included to terminate the search when no further improvement is observed.

To maximize the search space, the number of PSO iterations and the number of GA generations are not pre-set (denoted by *). This is different from previous studies. Both optimizers were executed under the same evaluation protocol to ensure consistency in the multi-objective fitness assessment, enabling a rigorous comparative analysis of their optimization behavior.

Our goal was to ensure that the comparison between GA-based and PSO-based CNN optimization remains fair and focuses strictly on the effect of configuration optimization rather than optimizer tuning. Therefore, both GA and PSO models were trained under the same fixed optimizer configuration: Optimizer Adam with default parameters (β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999, ε = 1 × 10−7) and no learning rate scheduler was applied.

4 Experiment Results and Evaluation

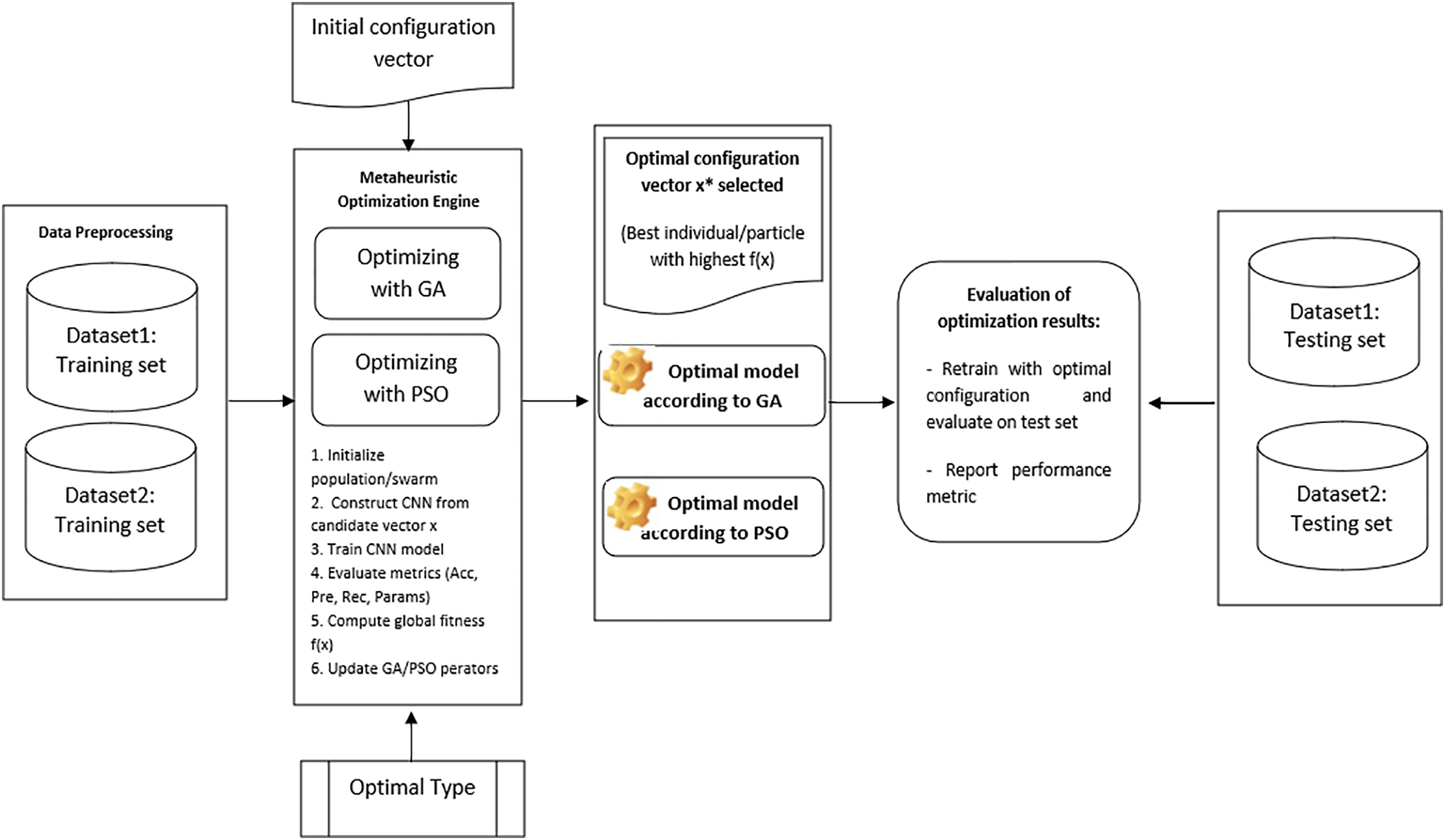

To evaluate the proposed method, we conducted experiments on two different datasets: the full Edge-IIoT dataset [53] and a balanced subset extracted from the CIC-IoT2023 dataset [16]. CIC-IoT2023 contains over 60 million network flows, making it computationally infeasible to perform metaheuristic optimization on the full dataset. To ensure that the subset remains representative, we performed stratified sampling by selecting 10% of the data for each class (label), thereby preserving the original class distribution. The evaluation employed the K-Fold cross-validation method. The experimental model and the proposed multi-objective optimization pipeline are illustrated in Fig. 2. From the two input datasets, the optimization type is selected. For each optimization algorithm, an optimal configuration and its corresponding trained model are obtained. The corresponding test sets of each dataset are then executed on the optimized models to compare and evaluate the optimization results.

Figure 2: Experimental model and the proposed multi-objective optimization pipeline

To evaluate the effectiveness of metaheuristic algorithms on CNN models for the IoT malware classification problem, we conducted experiments on two datasets, Edge-IIoT and CIC-IoT2023, under the following scenarios:

Scenario 1: Using the PSO algorithm combined with the 1D-CNN model (referred to as the 1D-CNN-PSO model). We employed the Edge-IIoT and CIC-IoT2023 datasets with the 1D-CNN-PSO model to optimize the global objective function f(x) with different weight parameters wi

Scenario 2: Using the GA algorithm combined with the 1D-CNN model (referred to as the 1D-CNN-GA model). We employed the Edge-IIoT and CIC-IoT2023 datasets with the 1D-CNN-GA model to optimize the global objective function f(x) with different weight parameters wi.

Each scenario was conducted with four experiments corresponding to different sets of weight parameters wi, as follows:

• Experiment 1: Single-objective optimization with Accuracy (Acc) as the target (w1 = 1; w2 = w3 = w4 = 0)

• Experiment 2: Multi-objective optimization, balancing Accuracy and Inference Speed (w1 = w4 = 0.5; w2 = w3 = 0)

• Experiment 3: Multi-objective optimization, balancing Accuracy, Precision, and Recall (w1 = w2 = w3 = 1/3; w4 = 0;)

• Experiment 4: Multi-objective optimization with all four objectives equally weighted (w1 = w2 = w3 = w4 = 0.25).

All experiments were conducted on Kaggle’s computational environment equipped with a 4-core CPU, 29 GB of RAM, 57.6 GB of disk storage, and an NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU (15 GB).

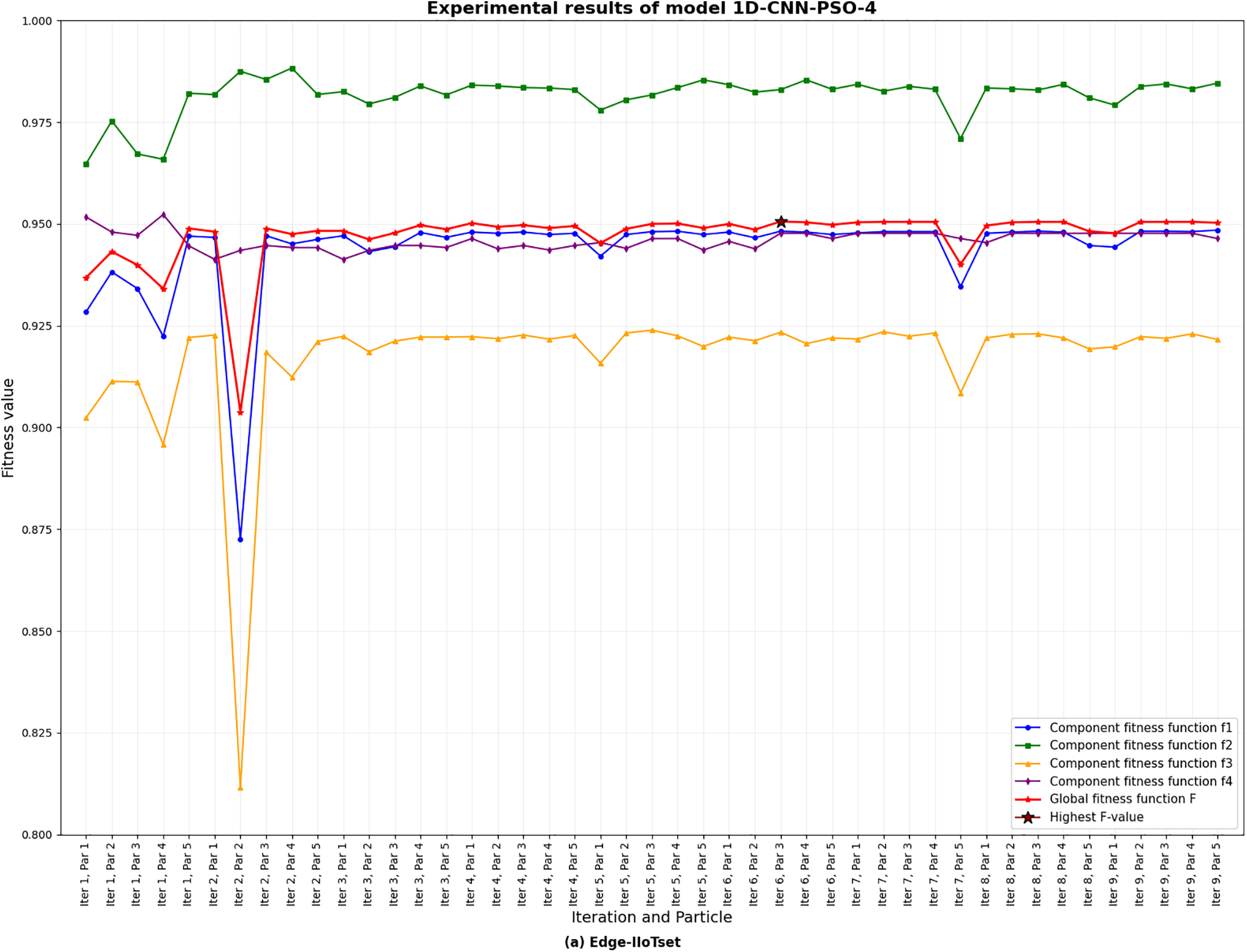

4.2.1 Scenario 1: Experimental Results with 1D-CNN-PSO

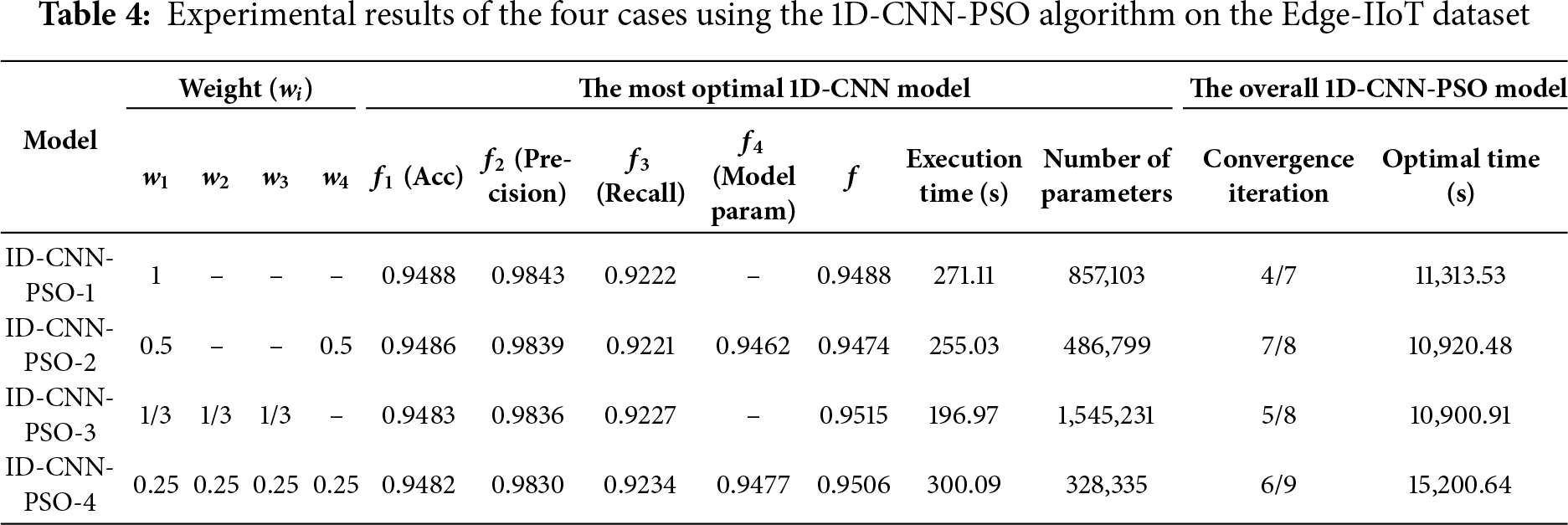

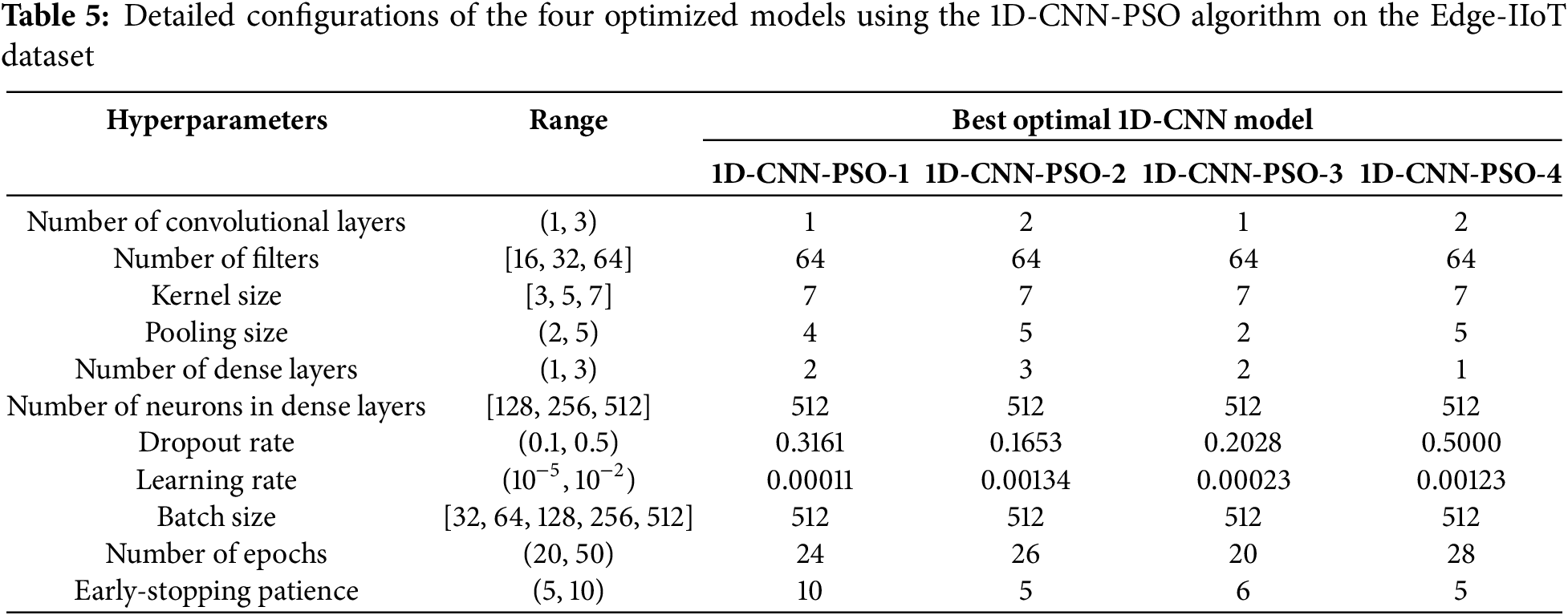

• With Edge-IIoT dataset: The experimental results of the 1D-CNN-PSO algorithm across four different configurations are summarized in Table 4. The detailed configurations of the optimized models for each case are presented in Table 5.

The results indicate a consistent trend across the four models. 1D-CNN-PSO-1 achieved the highest validation accuracy of 94.93% with f = 0.9488. 1D-CNN-PSO-2 slightly decreased to 94.86% with f = 0.9474, showing a trade-off between performance and model complexity. 1D-CNN-PSO-3, consisting of three components, obtained an accuracy of 94.83% but the highest f (0.9515), demonstrating a better balance across metrics. 1D-CNN-PSO-4 achieved 94.82% accuracy, 98.30% precision, 92.34% recall, and an f of 0.9506. Although the accuracy was slightly lower than 1D-CNN-PSO-1, this model provided a better trade-off between performance and model complexity, requiring only 328,335 parameters compared to 857,103 in 1D-CNN-PSO-1.

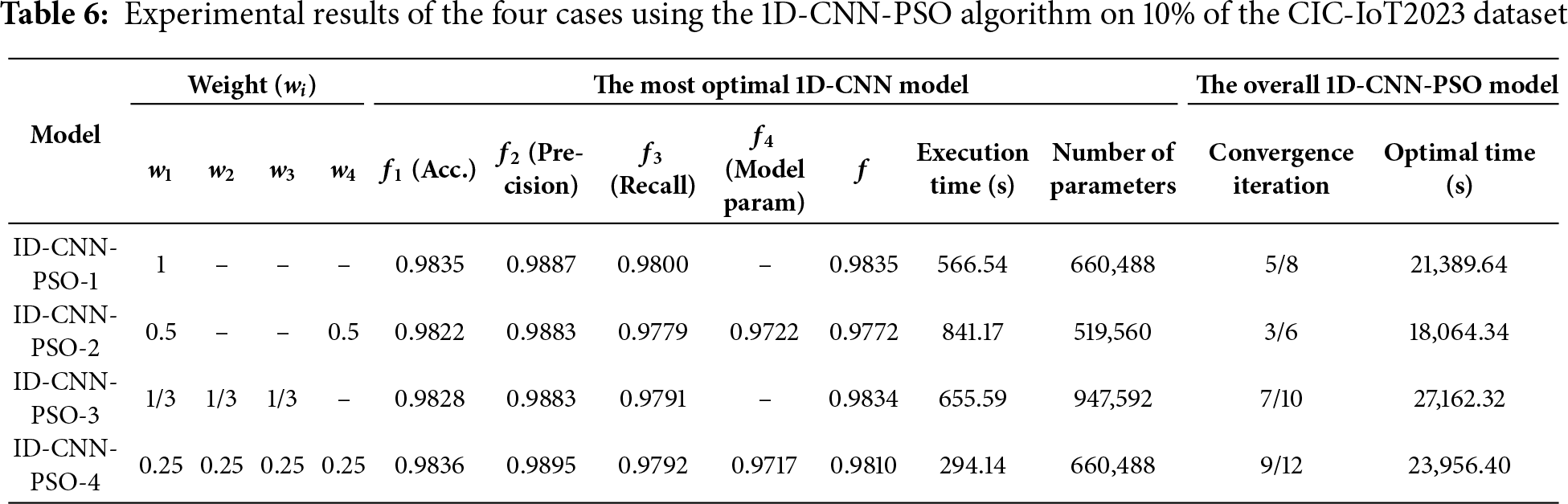

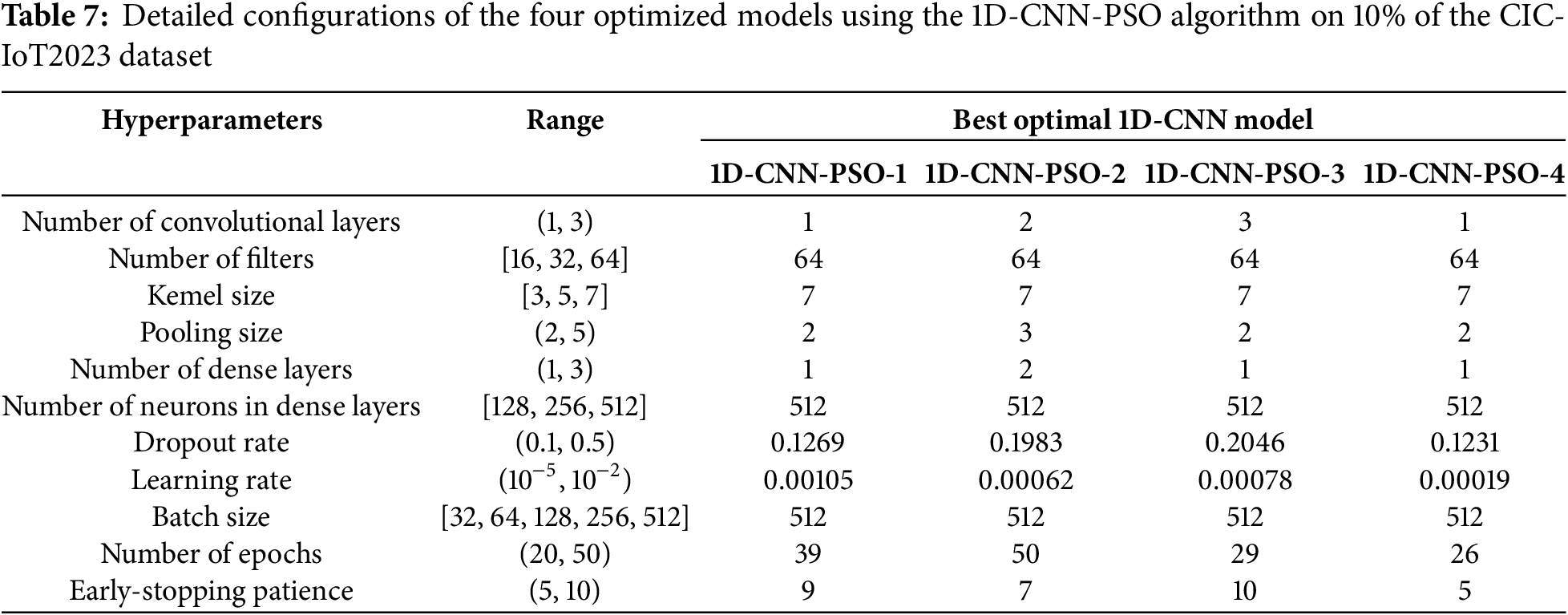

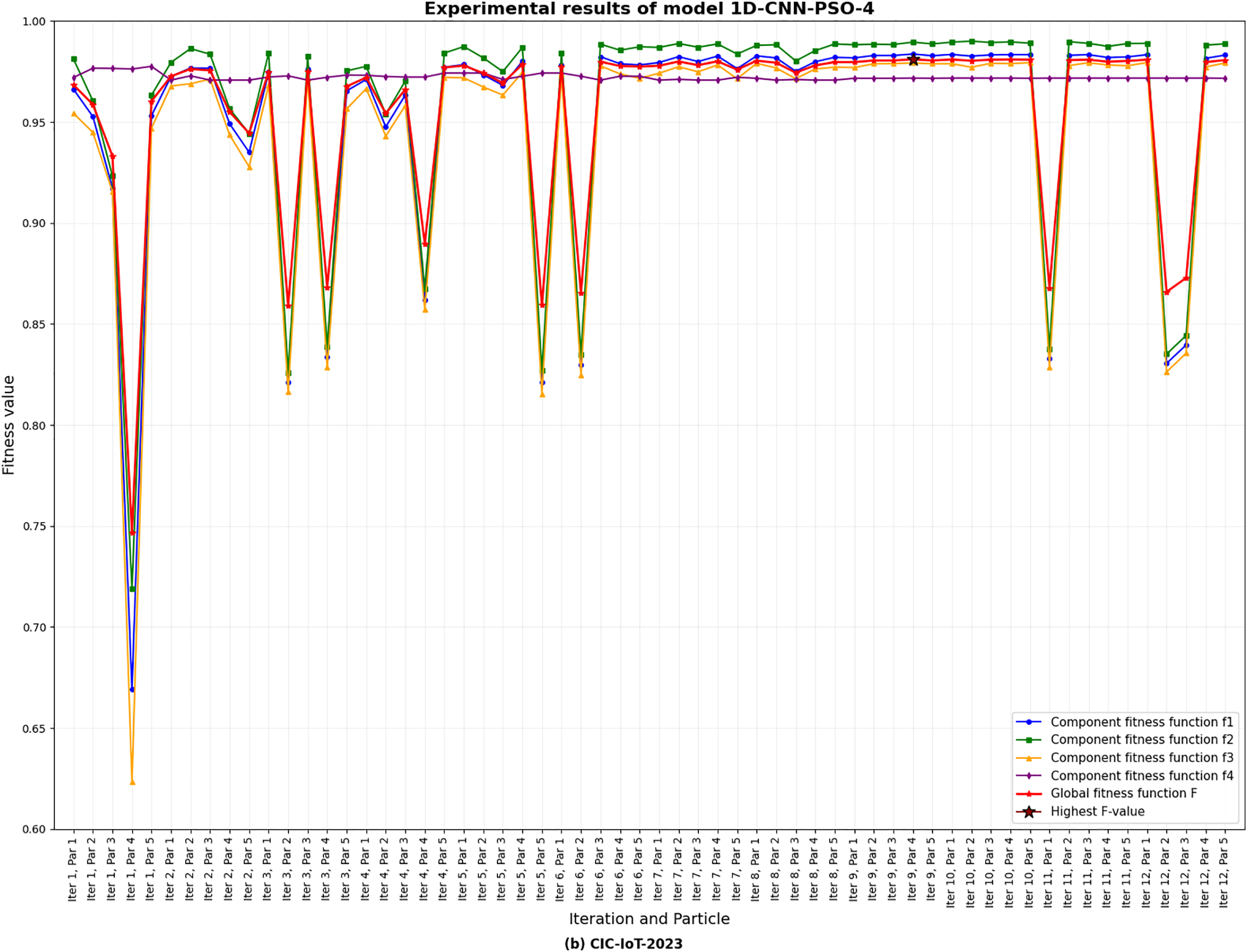

• With CIC-IoT2023 dataset (10% sampled): The corresponding experimental results with 1D-CNN-PSO are presented in Tables 6 and 7, which show the outcomes of the four cases and the detailed model configurations:

On the CIC-IoT2023 dataset, PSO also demonstrates high performance, with 1D-CNN-PSO-1 achieving a validation accuracy of 98.35% (f = 0.9835). PSO-2 slightly decreases to 98.22% (f = 0.9772), while 1D-CNN-PSO-3 reaches 98.28% (f = 0.9834). The 1D-CNN-PSO-4 model achieves a validation accuracy of 98.36%, precision of 98.95%, recall of 97.92%, and F = 0.9810. Although it records the highest accuracy among the PSO models, its f-value is lower than PSO-1 and PSO-3 due to the impact of the model complexity penalty.

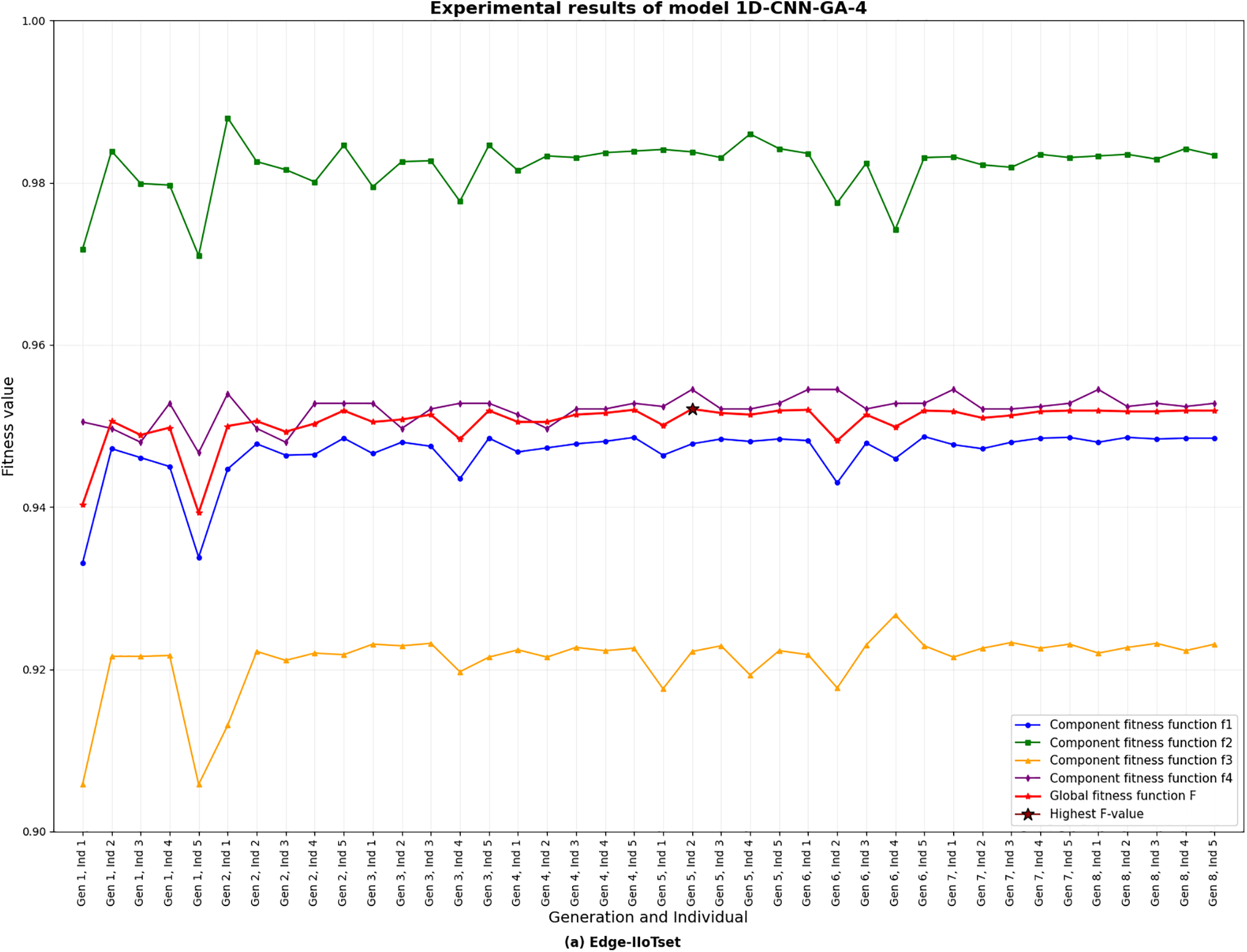

4.2.2 Scenario 2: Experimental Results with 1D-CNN-GA

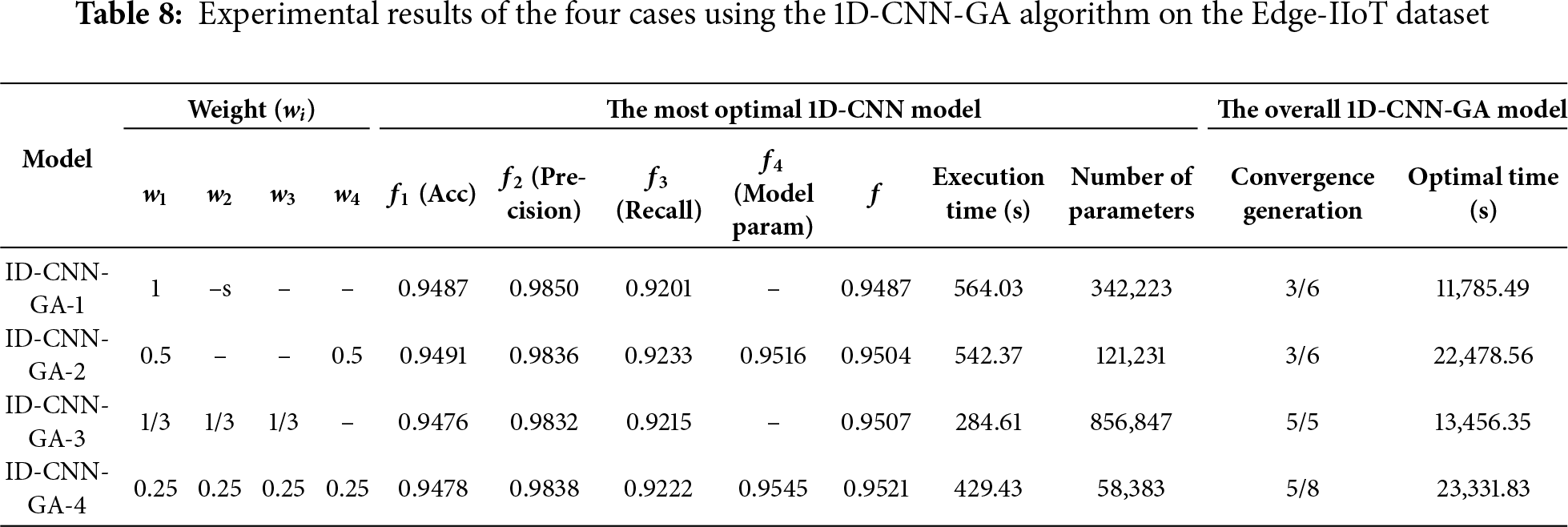

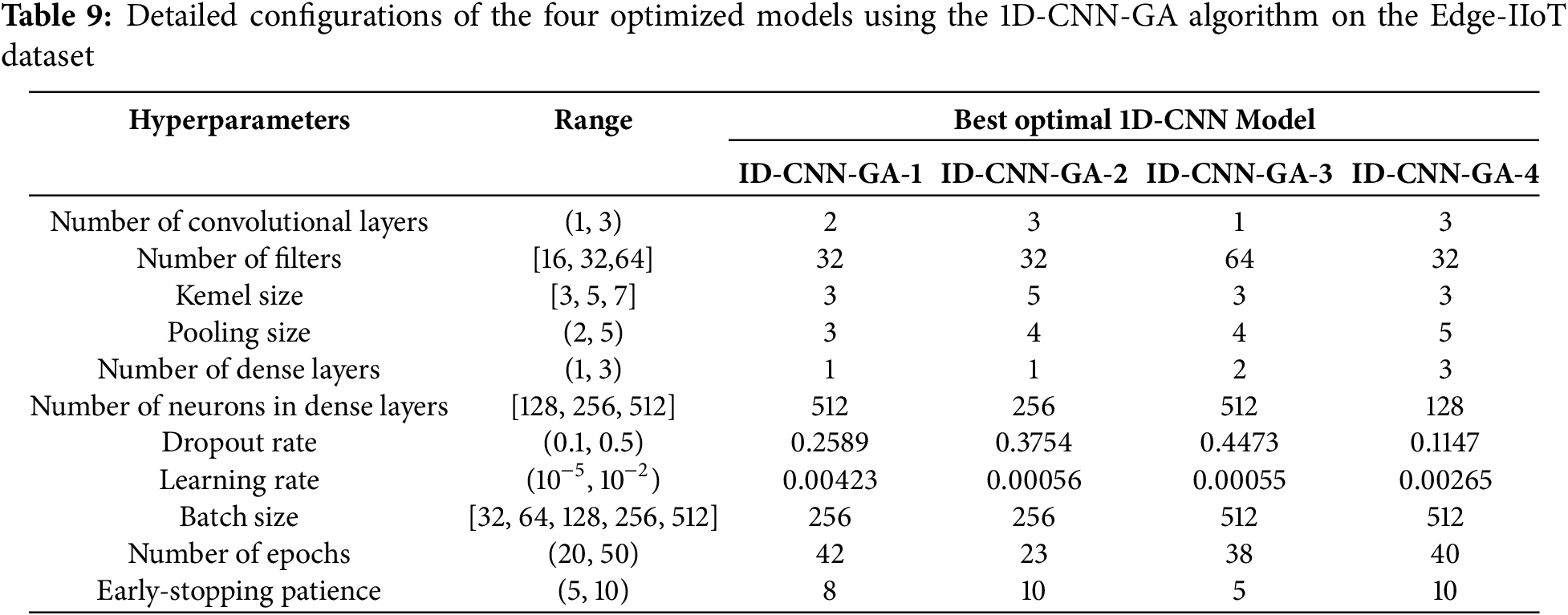

• On the Edge-IIoT dataset: With α = 0.01, the experimental results using the 1D-CNN-GA algorithm across the four cases are presented in Table 8. The detailed configurations of the optimized models for each experimental case with the 1D-CNN-GA algorithm on the Edge-IIoT dataset are shown in Table 9.

On the Edge-IIoT dataset, the 1D-CNN-GA models demonstrate gradual improvements as the optimization function becomes more complex. The 1D-CNN-GA-1 model, which employs a single-objective function, achieves a validation accuracy of 94.87% and a fitness score of f = 0.9487. When the model complexity component is incorporated (1D-CNN-GA-2), the performance slightly improves to 94.91% with f = 0.9504, indicating a positive effect of considering model complexity. The 1D-CNN-GA-3 model, which integrates accuracy, precision, and recall, reaches a validation accuracy of 94.76% with f = 0.9507—higher than 1D-CNN-GA-1 but slightly lower than 1D-CNN-GA-2. Most notably, the proposed improved 1D-CNN-GA-4 model, which optimizes all four components, achieves a validation accuracy of 94.78%, precision of 98.38%, recall of 92.22%, and f = 0.9521—the highest among all GA models. Importantly, 1D-CNN-GA-4 produces an extremely efficient model with only 58,383 parameters, significantly fewer than 1D-CNN-GA-1 (342,223 parameters) and 1D-CNN-GA-3 (856,847 parameters), while maintaining comparable performance. This demonstrates its capability to optimize both accuracy and model complexity simultaneously.

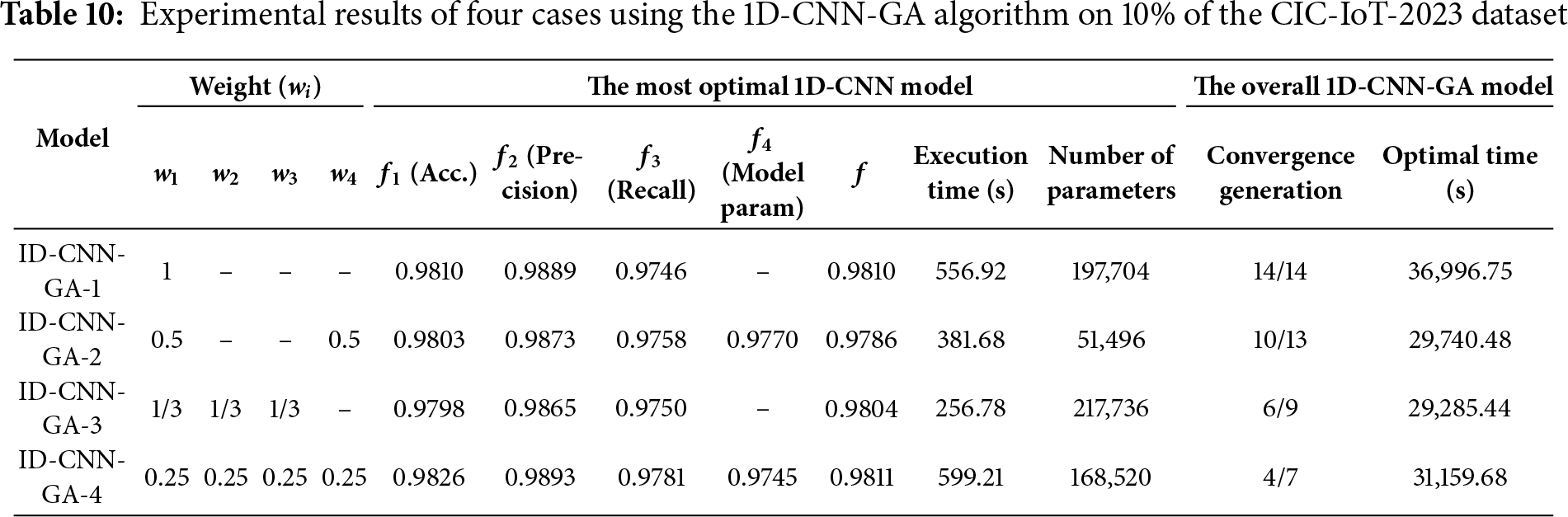

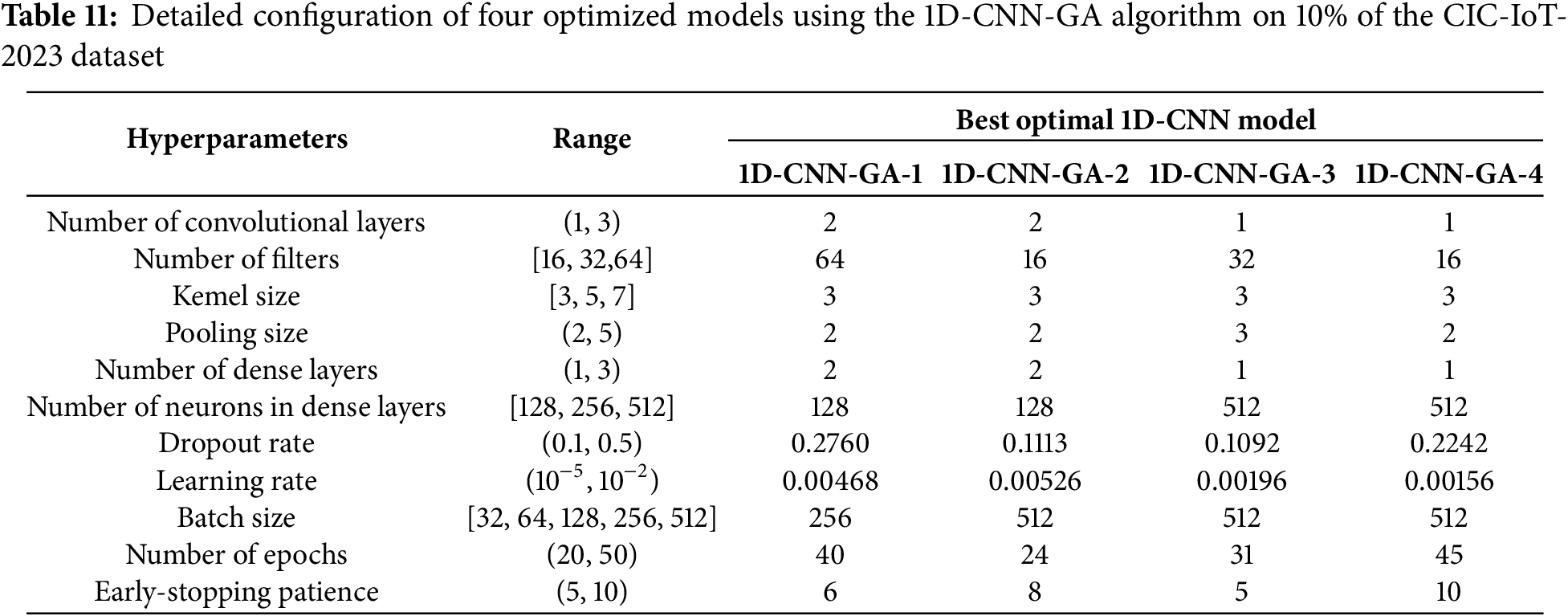

• On the CIC-IoT2023 dataset: The experimental results using the 1D-CNN-GA algorithm across the four cases are presented in Tables 10 and 11. On the CIC-IoT2023 dataset, the GA-based models exhibit substantially higher overall performance. 1D-CNN-GA-1 achieves a validation accuracy of 98.10% with f = 0.9810, while 1D-CNN-GA-2 slightly decreases to 98.03% (f = 0.9786) due to the impact of the model complexity penalty. 1D-CNN-GA-3 records 97.98% accuracy with f = 0.9804, showing a good balance across metrics. The improved 1D-CNN-GA-4 model outperforms the others, achieving a validation accuracy of 98.26%, precision of 98.93%, recall of 97.81%, and f = 0.9811—the highest among all GA models. 1D-CNN-GA-4 produces a model with 168,520 parameters, which is considered reasonable given the complexity of this dataset.

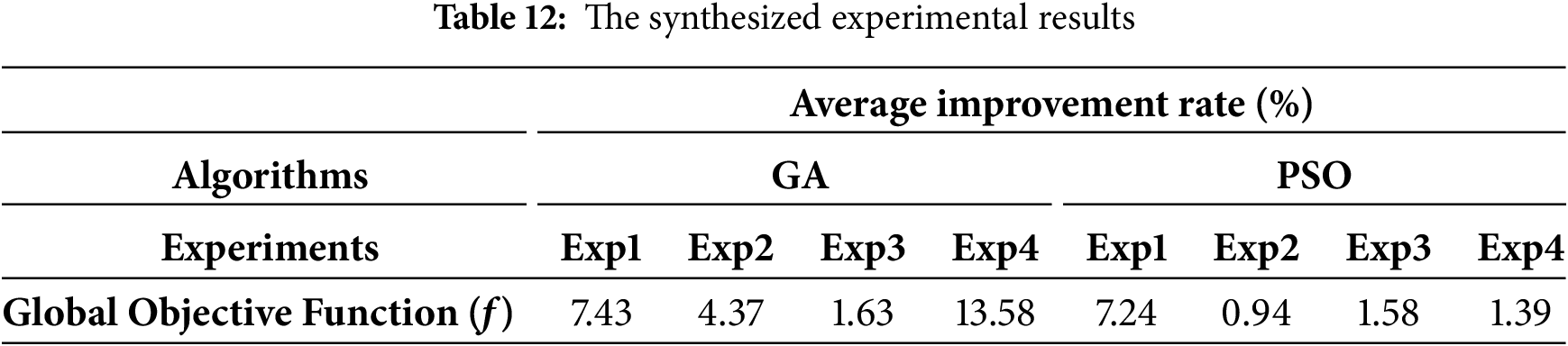

The synthesized experimental results are shown in Table 12. With the GA algorithm: the single-objective optimization achieved the average accuracy improvement rate of 7.43%; the 2-objective optimization achieved the average global function improvement rate of 4.37%; the 3-objective optimization achieved the average global function improvement rate of 1.63%; the 4-objective optimization achieved the average global function improvement rate of 13.58%. With the PSO algorithm: the single-objective optimization achieved the average accuracy improvement rate of 7.24%; the 2-objective optimization achieved the average global function improvement rate of 0.94%; the 3-objective optimization achieved the average global function improvement rate of 1.58%; the 4-objective optimization achieved the average global function improvement rate of 1.39%.

Overall Evaluation

When comparing the two algorithms, 1D-CNN-GA-4 outperforms 1D-CNN-PSO-4 during the optimization process on the Edge-IIoT dataset. Specifically, 1D-CNN-GA-4 achieves a higher global f value (0.9521 vs. 0.9506), better precision (98.38% vs. 98.30%), and, notably, generates a much more compact model (58,383 vs. 328,335 parameters). However, when evaluated on the test set, 1D-CNN-GA-4 exhibits slightly lower performance, achieving an accuracy of 94.88%, precision of 98.43%, recall of 92.27%, and F1-score of 79.76%, whereas 1D-CNN-PSO-4 achieves 94.91% accuracy, 98.35% precision, 92.41% recall, and 80.24% F1-score.

On the CIC-IoT2023-derived dataset, both 1D-CNN-GA-4 and 1D-CNN-PSO-4 demonstrate strong and nearly equivalent performance. 1D-CNN-PSO-4 slightly surpasses GA-4 in validation accuracy (98.36% vs. 98.26%), while 1D-CNN-GA-4 achieves a marginally higher f value (0.9811 vs. 0.9810) due to better balance among components. On the test set, 1D-CNN-PSO-4 maintains a slight advantage with accuracy of 98.32%, precision of 98.90%, recall of 97.91%, and F1-score of 72.11%, compared to 1D-CNN-GA-4 (98.26% accuracy, 98.79% precision, 97.90% recall, and 71.47% F1-score).

The study performed optimization under four different weighting strategies, ranging from single-objective optimization (accuracy only) to multi-objective optimization balancing four components: validation accuracy (f1), validation precision (f2), validation recall (f3), and model complexity/speed penalty (f4). The experimental results provide important insights into the optimization capabilities of both algorithms. Under the single-objective setting (w1 = 1), both GA and PSO achieved high accuracy but produced models with a large number of parameters. This indicates that optimizing solely for accuracy can lead to overfitting and unnecessary model complexity. The multi-objective optimization strategy with balanced weighting (w1 = w2 = w3 = w4 = 0.25) combined with hyperparameter optimization, demonstrated effective performance—particularly for GA—achieving the highest f values on both datasets.

The global fitness values (f) of 1D-CNN-GA-4 (0.9521 on Edge-IIoTset and 0.9811 on CIC-IoT-2023) and 1D-CNN-PSO-4 (0.9506 on Edge-IIoTset and 0.9810 on CIC-IoT-2023) highlight the effectiveness of multi-objective optimization in balancing predictive performance and model complexity. Results also indicate that GA is more suitable for complex multi-objective optimization, whereas PSO effectively balances the primary performance metrics.

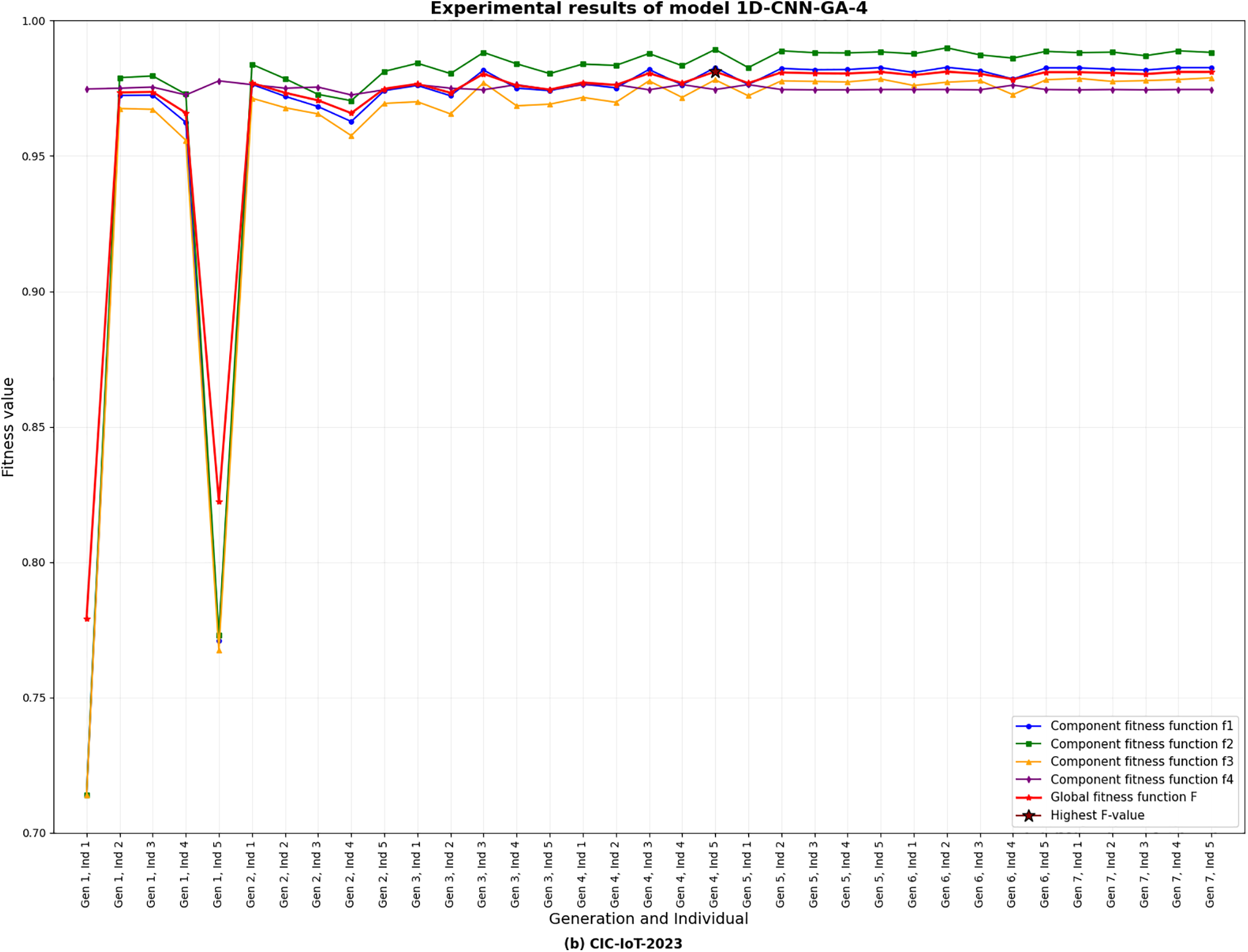

Charts illustrating the global objective function values and the four component objectives for each individual in each iteration/generation on both datasets using PSO/GA are presented in Charts 1–4. These four charts depict the optimization behavior of 1D-CNN models with GA and PSO under balanced multi-objective weighting. They empirically illustrate Pareto-like trade-offs: higher accuracy solutions tend to have more parameters, while complexity-penalized solutions produce lightweight CNNs with slightly lower accuracy. Both algorithms show smooth trade-off frontiers, with the global objective

Chart 1: Results of the 1D-CNN-PSO algorithm on the Edge-IIoT dataset under the balanced weighting scenario of the four component objectives

Chart 2: Results of the 1D-CNN-GA algorithm on the Edge-IIoT dataset under the balanced weighting scenario of the four component objectives

Chart 3: Results of the 1D-CNN-PSO algorithm on 10% of the CIC-IoT2023 dataset under the balanced weighting scenario of the four component objectives

Chart 4: Results of the 1D-CNN-GA algorithm on 10% of the CIC-IoT2023 dataset under the balanced weighting scenario of the four component objectives

For instance, 1D-CNN-GA-4 contains only 58,383 parameters compared to 342,223 parameters in 1D-CNN-GA-1 while maintaining nearly equivalent performance, demonstrating an effective trade-off between predictive performance and computational complexity. Notably, GA exhibits superior balance between performance and complexity when this penalty term is applied.

Execution Time and Convergence Analysis

Another important aspect is the difference in execution time and overall optimization time between the two algorithms. PSO demonstrates a clear advantage with significantly shorter execution times compared to GA on both datasets. On the Edge-IIoTset, 1D-CNN-GA-4 requires 429.43 s, which is considerably longer than the 300.09 s for 1D-CNN-PSO-4. On the CIC-IoT-2023 dataset, 1D-CNN-GA-4 executes in 599.21 s, whereas 1D-CNN-PSO-4 requires only 294.14 s. This indicates that PSO tends to produce models with structures optimized for computational efficiency.

Regarding the number of generations/iterations to reach convergence and total optimization time: on the Edge-IIoTset, PSO converges faster, with 1D-CNN-PSO-4 reaching convergence at iteration 6/9 within 15,200.64 s, whereas 1D-CNN-GA-4 converges at generation 5/8 but requires 23,331.83 s. This demonstrates that PSO exhibits a more efficient search mechanism on this dataset. On the CIC-IoT-2023 dataset, 1D-CNN-GA-4 converges at generation 4/7 in 31,159.68 s, compared to 1D-CNN-PSO-4, which converges at iteration 9/12 in 23,956.40 s. Overall, although PSO achieves shorter optimization times, GA requires fewer generations to converge. This can be attributed to the different convergence behaviors of the two algorithms: PSO tends to converge more rapidly toward promising local solutions, while GA maintains population diversity longer to explore the global search space.

Analysis of the optimal hyperparameter configurations reveals clear differences in the search strategies of the two algorithms. GA tends to favor models with more diverse structures, with the number of convolutional layers varying from 1 to 3 and kernel sizes ranging from 3 to 5. In contrast, PSO shows higher consistency in selecting kernel size (favoring size 7) and batch size (favoring 512), indicating convergence toward empirically effective solutions. This reflects the differing exploration strategies: PSO excels at exploiting promising search regions, whereas GA achieves broader exploration through the stochastic nature of genetic operations.

Regarding model complexity, GA-optimized models often exhibit a wider range of parameter counts (from 58,383 to 856,847 on Edge-IIoTset), reflecting its capacity to explore a more diverse search space. Conversely, PSO tends to produce models with relatively stable sizes, highlighting the algorithm’s fast convergence characteristics. Notably, PSO tends to generate models with more complex structures, as evidenced by higher average number of parameters compared to GA.

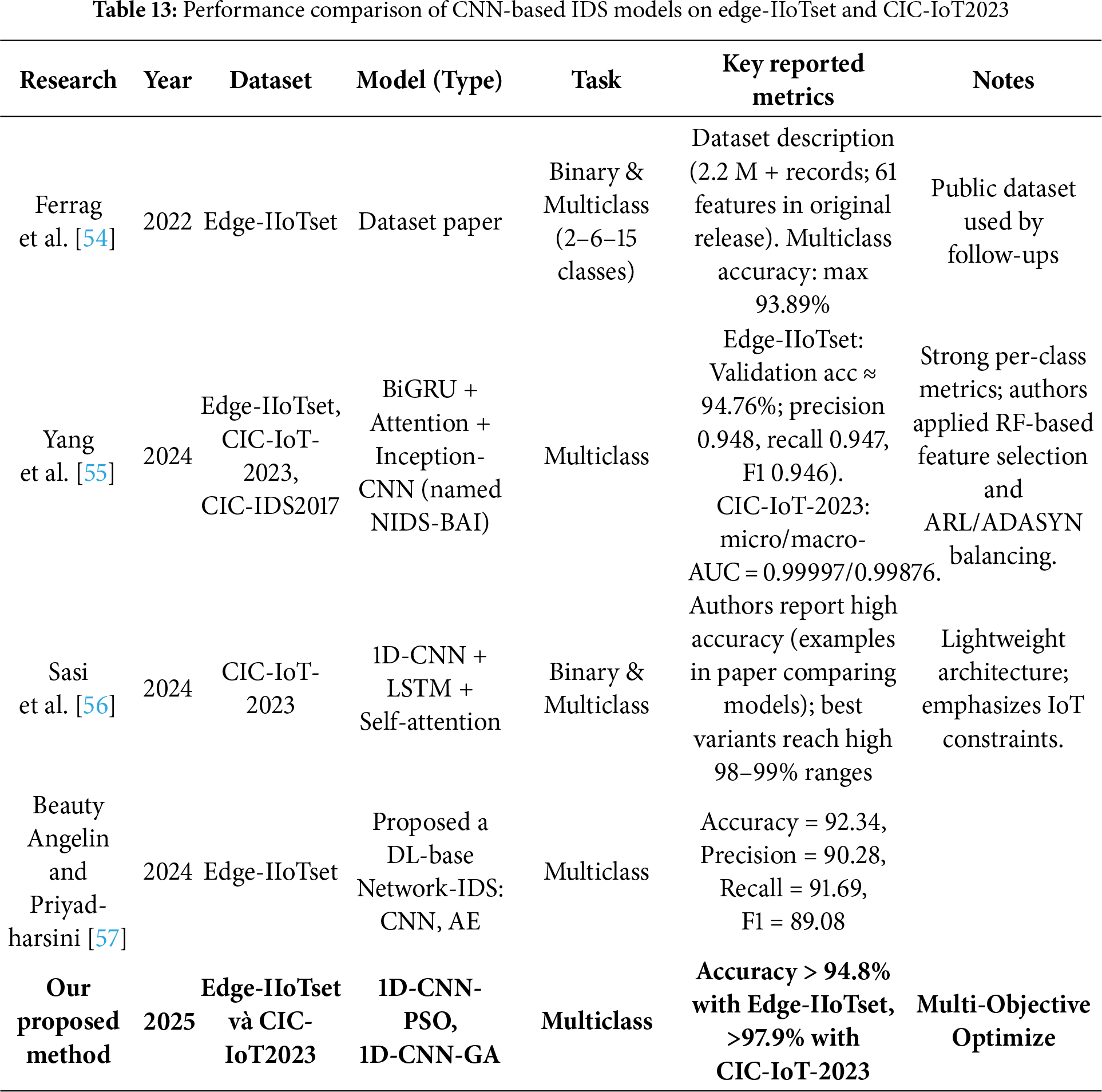

Direct comparison under identical computational budgets was not feasible due to resource constraints and our study’s scope. Following standard practice in NAS and evolutionary deep learning studies, we therefore benchmark our optimized 1D-CNN-PSO and 1D-CNN-GA models against state-of-the-art CNN-based IDS on the same datasets (Edge-IIoTset and CIC-IoT2023). The proposed models were chosen for their demonstrated optimization capabilities, achieving maximum fitness while balancing computational efficiency. Detailed comparative results are presented in the following table (Table 13).

The analysis results indicate that the proposed 1D-CNN models achieve accuracies ranging from 94.88% to 98.32%, placing them among the highest-performing models on the Edge-IIoTset and CIC-IoT2023 datasets. More importantly, the 1D-CNN-PSO and 1D-CNN-GA models demonstrate clear advantages in terms of model size and inference speed—critical factors for real-world applications with limited computational resources.

Compared to other models, the proposed approach not only achieves higher accuracy but also excels in configuration optimization, owing to the integration of PSO in adjusting network architectures and hyperparameters. This enables the 1D-CNN to effectively exploit the data features without requiring complex architectures such as deep convolutional networks (e.g., VGG-16) or specialized time-series models (e.g., InceptionTime).

Optimizing CNN architectures for IoT intrusion detection is a problem of significant scientific and practical relevance. Current studies typically focus on optimizing a single objective—accuracy—which limits generalizability, as other optimization objectives are often neglected. Moreover, existing approaches seldom provide a method for selecting the best CNN configuration for the task. This paper proposes a comprehensive computational framework for optimizing CNN architectures for IoT intrusion detection, applicable to both single-objective and scalarized multi-objective optimization. Additionally, the study develops and implements optimization methods using representative metaheuristic algorithms, namely GA and PSO. The proposed approach is evaluated on two different datasets and compared in detail with relevant prior studies.

The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed optimization approach: both algorithms significantly improve the performance of 1D-CNN models compared to manual tuning, achieving accuracies above 94.8% on Edge-IIoTset and over 97.9% on CIC-IoT-2023. A key contribution of this research is the multi-objective fitness function, which incorporates four components: validation accuracy, precision, recall, and inference speed (based on a model complexity penalty). The 1D-CNN-GA-4 and 1D-CNN-PSO-4 models effectively balance predictive performance and model complexity, achieving high accuracy (94.88%–98.32%) while maintaining optimized network structures.

The study further analyzes specific CNN configuration layers optimized for IoT intrusion detection, highlighting configurations suited to each optimization algorithm and dataset based on the comprehensive optimization framework.

Despite achieving promising detection performance, this study has several limitations. The configuration search space was relatively small, not all hyperparameters were explored, and offline optimization may not capture streaming traffic dynamics. GA performance depends on parameter tuning (crossover, mutation, selection), which may lead to premature convergence, while PSO is sensitive to inertia weight and acceleration coefficients. Practical deployment requires trade-offs: lightweight models suit memory- and latency-constrained edge devices, whereas larger models achieve marginally higher accuracy for cloud-based analysis.

Future work will address these limitations by: (i) extending experiments to larger configuration spaces with additional hyperparameters, (ii) investigating incremental or online optimization for streaming traffic, (iii) exploring hybrid GA–PSO strategies where PSO rapidly searches continuous hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, dropout) and GA explores discrete/structural choices (e.g., number of convolutional blocks), or GA maintains structural diversity while PSO refines promising individuals, (iv) leveraging elitist archives and Pareto filtering to produce compact, high-performing models, (v) applying other metaheuristic algorithms such as Differential Evolution or Artificial Bee Colony, and (vi) incorporating statistical significance testing (Wilcoxon, Friedman, ANOVA) and computational profiling (memory usage, inference latency) across diverse datasets. Moreover, future work may integrate metaheuristic-based feature selection methods (e.g., GMSMFO [58], TVPS–Salp [59], Salp–GWO [60]) with CNN architectural optimization to jointly improve both feature representation and model design. These extensions aim to provide a comprehensive and practical framework for IoT intrusion detection.

Acknowledgement: The article was completed with support from the Academy of Cryptography Techniques.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Le Thi Hong Van, Pham Van Huong and Nguyen Hieu Minh; data collection: Le Duc Thuan; develop the experimental program: Le Thi Hong Van and Le Duc Thuan; analysis and interpretation of results: Le Thi Hong Van, Le Duc Thuan and Pham Van Huong; draft manuscript preparation: Le Thi Hong Van, Pham Van Huong and Nguyen Hieu Minh. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Le Thi Hong Van, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bala B, Behal S. AI techniques for IoT-based DDoS attack detection: taxonomies, comprehensive review and research challenges. Comput Sci Rev. 2024;52(10):100631. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2024.100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tikhe D, Deshpande P, Wani P, Mante J, Kolhe K. Leveraging metaheuristic algorithms for optimal feature selection in IoT cybersecurity: a study on enhancing DDoS attack detection. In: Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Computing, Communication, Control and Automation (ICCUBEA); 2024 Aug 23–24; Pune, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICCUBEA61740.2024.10774813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kostas K. CNN based IoT device identification. arXiv:2304.13894. 2023. [Google Scholar]

4. Choudhary A. Internet of Things: a comprehensive overview, architectures, applications, simulation tools, challenges and future directions. Discov Internet Things. 2024;4(1):31. doi:10.1007/s43926-024-00084-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Akay B, Karaboga D, Akay R. A comprehensive survey on optimizing deep learning models by metaheuristics. Artif Intell Rev. 2022;55(2):829–94. doi:10.1007/s10462-021-09992-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Alatram A, Sikos LF, Johnstone M, Szewczyk P, Kang JJ. DoS/DDoS-MQTT-IoT: a dataset for evaluating intrusions in IoT networks using the MQTT protocol. Comput Netw. 2023;231(1):109809. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2023.109809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Meziane H, Ouerdi N. A survey on performance evaluation of artificial intelligence algorithms for improving IoT security systems. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):21255. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-46640-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Almuqren L, Alqahtani H, Aljameel SS, Salama AS, Yaseen I, Alneil AA. Hybrid metaheuristics with machine learning based botnet detection in cloud assisted Internet of Things environment. IEEE Access. 2023;11(8):115668–76. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3322369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Abreu D, Abelém A. OMINACS: online ML-based IoT network attack detection and classification system. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Latin-American Conference on Communications (LATINCOM); 2022 Nov 30–Dec 2; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/LATINCOM56090.2022.10000544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dey AK, Gupta GP, Sahu SP. Hybrid meta-heuristic based feature selection mechanism for cyber-attack detection in IoT-enabled networks. Procedia Comput Sci. 2023;218(1):318–27. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2023.01.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Adnyana IG, Sugiartawan P, Hartawan INB. Hyperparameter optimization techniques for CNN based cyber security attack classification. Indones J Comput Cybern Syst. 2024;18(3):98427. doi:10.22146/ijccs.98427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Morales-Hernández A, Van Nieuwenhuyse I, Rojas Gonzalez S. A survey on multi-objective hyperparameter optimization algorithms for machine learning. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(8):8043–93. doi:10.1007/s10462-022-10359-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Pereira AL, Kohler M, Pacheco M. Evolutionary convolutional neural network: a case study. Assoc Bras De Intel Comput. 2021;1–6. doi:10.21528/CBIC2021-129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ananthu Suresh SL, Philip AS. Multiple botnet and keylogger attack detection using CNN in IoT networks. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Futuristic Technologies (INCOFT); 2022 Nov 25–27; Belgaum, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/INCOFT55651.2022.10094491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cui H. A review of metaheuristic optimization methods. Appl Comput Eng. 2024;33(1):280–7. [Google Scholar]

16. Abdulkareem SA, Heng Foh C, Shojafar M, Carrez F, Moessner K. Network intrusion detection: an IoT and non IoT-related survey. IEEE Access. 2024;12(1):147167–91. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3473289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Booij TM, Chiscop I, Meeuwissen E. ToN IoT: the role of heterogeneity and the need for standardization of features and attack types in IoT network intrusion datasets. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;9(1):485–96. doi:10.1109/EuroSPW.2021.9444348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sharma A, Kumar D. Hyperparameter optimization in CNN: a review. In: Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computing, Communication, and Intelligent Systems (ICCCIS); 2022 Nov 25–27; Greater Noida, India. p. 237–42. doi:10.1109/ICCCIS60361.2023.10425571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lu Z, Whalen I, Dhebar Y, Deb K. Multiobjective evolutionary design of deep convolutional neural networks for image classification. IEEE Congr Evol Comput. 2020;25(2):277–91. doi:10.1109/tevc.2020.3024708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kaveh M, Mesgari MS. Application of meta-heuristic algorithms for training neural networks and deep learning architectures: a comprehensive review. Neural Process Lett. 2023;55(4):4519–622. doi:10.1007/s11063-022-11055-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Raiaan MAK, Sakib S, Fahad NM, Al Mamun A, Rahman MA, Shatabda S, et al. A systematic review of hyperparameter optimization techniques in convolutional neural networks. Decis Anal J. 2024;11(1):100470. doi:10.1016/j.dajour.2024.100470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gad AR, Haggag M, Nashat AA, Barakat TM. A distributed intrusion detection system using machine learning for IoT based on ToN-IoT dataset. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2022;13(6):1–16. doi:10.14569/ijacsa.2022.0130667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wang B, Sun Y, Xue B, Zhang M. Evolving deep neural networks by multi-objective particle swarm optimization for image classification. In: Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference; 2019 Jul 13–17; Prague, Czech Republic. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2019. p. 490–8. doi:10.1145/3321707.3321735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Jothi KR, Vaithiyanathan B. Developing a hybrid approach with whale optimization and deep convolutional neural networks for enhancing security in smart home environments’ sustainability through IoT devices. Sustainability. 2024;16(24):11040. doi:10.3390/su162411040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Alkhammash M. A metaheuristic approach to detecting and mitigating DDoS attacks in blockchain-integrated deep learning models for IoT applications. IEEE Access. 2024;12:193184–94. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3519132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kan X, Fan Y, Fang Z, Cao L, Xiong NN, Yang D, et al. A novel IoT network intrusion detection approach based on adaptive particle swarm optimization convolutional neural network. Inf Sci. 2021;568(5):147–62. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2021.03.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bahaa A, Sayed A, Elfangary L, Fahmy H. A novel hybrid optimization enabled robust CNN algorithm for an IoT network intrusion detection approach. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):e0278493. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0278493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Alzubi OA, Alzubi JA, Qiqieh I, Al-Zoubi AM. An IoT intrusion detection approach based on salp swarm and artificial neural network. Int J Netw Manag. 2025;35(1):e2296. doi:10.1002/nem.2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Toğaçar M. Detecting attacks on IoT devices with probabilistic Bayesian neural networks and hunger games search optimization approaches. Trans Emerg Telecommun Technol. 2022;33(1):e4418. doi:10.1002/ett.4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Peterson JM, Leevy JL. A review and analysis of the Bot-IoT dataset. IEEE Access. 2021;9:1–12. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.9564345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Mohd Yusof NN, Sulaiman NS. Cyber attack detection dataset: a review. J Phys Conf Ser. 2022;2319(1):012029. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2319/1/012029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Al-Hadhrami Y, Hussain FK. Real time dataset generation framework for intrusion detection systems in IoT. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2020;108(1):414–23. doi:10.1016/j.future.2020.02.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang B, Xue B, Zhang M. Particle swarm optimization for evolving deep convolutional neural networks for image classification: single- and multi-objective approaches. In: Deep neural evolution. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 155–84. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-3685-4_6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Siwakoti YR, Rawat DB. Detect-IoT: a comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms for detecting compromised IoT devices. In: Proceedings of the 24th International Symposium on Theory, Algorithmic Foundations, and Protocol Design for Mobile Networks and Mobile Computing. Washington, DC, USA. New York, NY, USA: The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 2023. p. 370–5. doi:10.1145/3565287.3616529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Mishra V, Kane L. A survey of designing convolutional neural network using evolutionary algorithms. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(6):5095–132. doi:10.1007/s10462-022-10303-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Vidnerová P, Procházka Š., Neruda R. Multiobjective evolution for convolutional neural network architecture search. In: Artificial intelligence and soft computing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 261–70. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-61401-0_25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Nagaraju R, Pentang JT, Abdufattokhov S, CosioBorda RF, Mageswari N, Uganya G. Attack prevention in IoT through hybrid optimization mechanism and deep learning framework. Meas Sens. 2022;24(6):100431. doi:10.1016/j.measen.2022.100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Abd Elaziz M, Dahou A, Abualigah L, Yu L, Alshinwan M, Khasawneh AM, et al. Advanced metaheuristic optimization techniques in applications of deep neural networks: a review. Neural Comput Appl. 2021;33(21):14079–99. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-05960-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hasan M, Islam MM, Zarif MII, Hashem MMA. Attack and anomaly detection in IoT sensors in IoT sites using machine learning approaches. Internet Things. 2019;7(20):100059. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2019.100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ram N, Kumar D. Effective cyber attack detection in an IoMT-smart system using deep convolutional neural networks and machine learning algorithms. In: Proceedings of the 2022 Second International Conference on Advanced Technologies in Intelligent Control, Environment, Computing & Communication Engineering (ICATIECE); 2022 Dec 16–17; Bangalore, India. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/ICATIECE56365.2022.10046735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Hamad QS, Samma H, Suandi SA. Optimization of convolutional neural network hyperparameter for medical image diagnosis using metaheuristic algorithms: a short recent review (20192022). arXiv:2412.17956. 2024. [Google Scholar]

42. Benaissa B, Djebbar M, El-Latif AAA, Belarouci A, Belarouci R. Metaheuristic optimization algorithms: an overview. HCMCOU J Sci Adv Comput Struct. 2024;14(1):34–62. [Google Scholar]

43. Alex C, Creado G, Almobaideen W, Abu Alghanam O, Saadeh M. A comprehensive survey for IoT security datasets taxonomy, classification and machine learning mechanisms. Comput Secur. 2023;132(11):103283. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2023.103283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Gyamfi E, Jurcut A. Intrusion detection in Internet of Things systems: a review on design approaches leveraging multi-access edge computing, machine learning, and datasets. Sensors. 2022;22(10):3744. doi:10.3390/s22103744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Bochinski E, Senst T, Sikora T. Hyper-parameter optimization for convolutional neural network committees based on evolutionary algorithms. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); 2017 Sep 17–20; Beijing, China. p. 3924–8. doi:10.1109/ICIP.2017.8297018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Gurjar S, Aamod BK, Bharadiya V, Gowda BG, Rao M. Meta-heuristic optimization of CNNs with approximate error distributed multipliers. In: Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI); 2024 Jul 1–3; Knoxville, TN, USA. p. 675–9. doi:10.1109/ISVLSI61997.2024.00129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Lee HC, Yu DP, Kim YH. On the hardness of parameter optimization of convolution neural networks using genetic algorithm and machine learning. In: Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference Companion; 2018 Jul 15–19; Kyoto, Japan. New York, NY, USA: The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM); 2018. p. 51–2. doi:10.1145/3205651.3208772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Bhuvaneshwari KS, Venkatachalam K, Hubálovský S, Trojovský P, Prabu P. Improved dragonfly optimizer for intrusion detection using deep clustering CNN-PSO classifier. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;70(3):5949–65. doi:10.32604/cmc.2022.020769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Kilichev A, Kim J. Hyperparameter optimization for CNN-based IoT intrusion detection using GA and PSO. Mathematics. 2023;11(17):1–17. doi:10.3390/math11173724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Alexander R, Pradeep Mohan Kumar K. Genetic algorithm based hyperparameter tuned CNN for identifying IoT intrusions. KSII Trans Internet Inf Syst. 2024;18(3):755–78. doi:10.3837/tiis.2024.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Inik Ö. SwarmCNN: an efficient method for CNN hyperparameter optimization using PSO and ABC metaheuristic algorithms. J Supercomput. 2025;81(8):874. doi:10.1007/s11227-025-07347-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Hong Van LT, Thuan LD, Van Huong P, Minh NH. A new method to improve the CNN configuration for IoT attack detection problem based on the genetic algorithm and multi-objective approach. In: Proceedings of the 2024 1st International Conference on Cryptography and Information Security (VCRIS); 2024 Dec 3–4; Hanoi, Vietnam. p. 1–9. doi:10.1109/VCRIS63677.2024.10813441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Choudhary V, Tanwar S, Choudhury T, Kotecha K. Towards secure IoT networks: a comprehensive study of metaheuristic algorithms in conjunction with CNN using a self-generated dataset. MethodsX. 2024;12(1):102747. doi:10.1016/j.mex.2024.102747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Ferrag MA, Friha O, Hamouda D, Maglaras L, Janicke H. Edge-IIoTset: a new comprehensive realistic cyber security dataset of IoT and IIoT applications. IEEE Access. 2022;10:40281–306. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3165809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Yang K, Wang J, Li M. An improved intrusion detection method for IIoT using attention mechanisms, BiGRU, and Inception-CNN. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):19339. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-70094-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Sasi T, Lashkari AH, Lu R, Xiong P, Iqbal S. An efficient self attention-based 1D-CNN-LSTM network for IoT intrusion detection. Neural Comput Appl. 2025;3(5):375–400. doi:10.1016/j.jiixd.2024.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Beauty Angelin JA, Priyadharsini C. Deep learning based network based intrusion detection system in industrial Internet of Things. In: Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT); 2024 Jan 4–6; Bengaluru, India. p. 426–32. doi:10.1109/idciot59759.2024.10467510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Hussein NK, Qaraad M, Amjad S, Farag MA, Hassan S, Mirjalili S, et al. Enhancing feature selection with GMSMFO: a global optimization algorithm for machine learning with application to intrusion detection. J Comput Des Eng. 2023;10(4):1363–89. doi:10.1093/jcde/qwad053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Qaraad M, Amjad S, Hussein NK, Mirjalili S, Elhosseini MA. An innovative time-varying particle swarm-based Salp algorithm for intrusion detection system and large-scale global optimization problems. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;56(8):8325–92. doi:10.1007/s10462-022-10322-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Qaraad M, Amjad S, Hussein NK, Elhosseini MA. Large scale salp-based grey wolf optimization for feature selection and global optimization. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(11):8989–9014. doi:10.1007/s00521-022-06921-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools