Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Use of Art Therapy in Alleviating Mental Health Symptoms in Refugees: A Literature Review

Department of Psychology, College of Natural and Health Sciences, Zayed University, Dubai, 19282, United Arab Emirates

* Corresponding Author: Jigar Jogia. Email:

# Independent scholar

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2023, 25(3), 309-326. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2023.022491

Received 13 March 2022; Accepted 08 October 2022; Issue published 21 February 2023

Abstract

There are over thirty million refugees globally with severe experiences of trauma. Art therapy intervention allows for nonverbal expression and could alleviate mental health symptomatology among refugees. The present review’s aim was to integrate and summarize the previous research which examined the effects of visual arts on alleviating psychological conditions of refugees. However, due to the paucity of studies which solely used visual arts, we included studies that used visual arts alongside other modalities as part of an expressive arts therapy intervention. The present review synthesizes studies that examined the effect of art therapy on mental health issues of refugees from January 2000 to March 2021. Seven studies (child and adolescent sample, N = 5 and adult sample, N = 2) with a total of 298 refugee participants (n = 298) met our inclusion criteria. The participants were from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Southeast Asia, and Europe. We found three commonly reported mental health disorders, namely Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and Major Depression Disorder. The research highlights how art therapy interventions could be a great starting point to alleviate symptomatology among refugees. Four additional benefits of art therapy which were commonly reported across the seven studies emerged from this review: working with traumatic experience/loss, rebuilding social connection and trust, nonverbal communication and self-expression of loss and trauma, and retelling stories. Art therapy interventions could be used as a starting point in the healing process of traumatized refugees to encourage verbal articulation of their feelings and reduce mental health symptoms. Despite these promising findings, due to a dearth of robust methodologies, further research is required to assess the long-term effectiveness of art therapy.Keywords

According to The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) by the end of 2020, there were 82.4 million people who were forcibly displaced globally, among whom 37% were refugees (26.4 million) and asylum seekers (4.1 million) [1]. The majority of refugees emigrated from the Syrian Arab Republic followed by Venezuela, Afghanistan, South Sudan, and Myanmar [1]. Approximately 40% of the refugees settled in Turkey, Columbia, Pakistan, Uganda, and Germany with 86% settling in developing countries [1]. Unfortunately, there is still a significant population of 6.6 million, or 22% of overall refugee populations, residing in camps with limited access to medical and mental health resources [2].

UNHCR distinguishes refugees from asylum seekers, as asylum seekers are individuals who inquire for sanctuary and their request for shelter has not been met yet [3]. However, within this research we refer to asylum seekers as refugees with a presumption that the asylum seekers are prospective refugees with similar experiences until they are granted permanent asylum.

The overall experience of refugees from pre-immigration to resettlement is concomitant with fear and uncertainty which makes refugees susceptible to serious mental health conditions [4–6]. Significant epidemiological evidence indicates that the most prevalent psychological symptoms among refugees are Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depressive symptoms, although estimates of the level of severity vary greatly [4,7]. The prevailing traumatic events that refugees experience include war, forced immigration, torture, loss of loved ones, and family separation [8,9]. During resettlement stages, the difficulty of learning a new language, assimilating into a new culture, securing financial income, and completing asylum applications with the risk of repatriation could provoke new psychological issues and worsen refugees’ PTSD [10], anxiety disorders, and depressive symptoms [5,11,12].

The American Psychological Association defines anxiety disorders as “a feeling of tension, worried thoughts, and physical changes such as increased blood pressure” [13]. There are a number of anxiety disorders that range from Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD) to panic disorder. Formerly Post PTSD was classed as an anxiety disorder in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–4) but in the most current version (DSM–5) it is categorized under Trauma and Stress Related Disorders and describes symptoms of anxiety, stress, and fear-based symptoms as a consequence of traumatic experiences or stressful events [14]. In addition, individuals with PTSD could show a range of symptoms such as “anhedonic and dysphoric symptoms, externalizing angry and aggressive symptoms, or dissociative symptoms” [14]. PTSD symptomology can often exist for months and sometimes years [15].

Another common psychological issue among refugees is Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), which is hallmarked by low mood and loss of interest or pleasure in people or activities and can be associated with sleep problems, weight loss/gain, decreased concentration, self-harm or suicidal ideation [16]. Kaltenbach and colleagues’ [10] one-year longitudinal study showed that without seeking appropriate mental health support and intervention, post-migration stressors and the number of traumatic experiences could exacerbate refugees’ PTSD. Hence the use of psychological interventions is deemed necessary to help alleviate symptomatology and avoid chronicity of the psychological conditions [17], enhance the quality of life for refugees, and reduce the long-term financial health care costs in the society post immigration [8].

Numerous mental health interventions have been used within refugee populations to reduce their psychological problems. For instance, Turrini and colleagues’ [18] meta-analysis and systematic review of 26 studies with 1,959 refugee participants revealed that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) with a trauma-focused component was the most effective psychosocial intervention to decrease PTSD and anxiety whilst Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) was the most effective intervention to alleviate depressive symptoms. According to Nosè and colleagues, a psychosocial intervention “is interventions with a focus on the interrelation between social circumstances and peoples’ thoughts, emotions and behaviours” (Nosè et al., 2017, as cited in [18]). Whilst these are some of the most well-known psychotherapeutic interventions with a large evidence base, psychotherapeutic research is not clear cut and further research is needed to validate the efficacy of these therapies when used with refugee populations. However, RCT research is widely known in the scientific community to be the gold standard for evidence based psychotherapeutic intervention. For example, CBT research has extensive RCT data. Other traditional therapeutic approaches have proven to be less effective, lengthier and accessible only to a limited number of refugees due to their associated costs [19]. Considering the significant adverse effects of post-migration stressors and the important role daily stressors play in the duration of the mental illness of the refugees, Li and colleagues [5] proposed developing an integrative psychosocial approach, rather than a solely trauma-focused approach to enable refugees to cope with post-migration stressors and reduce mental health symptomology. To date the most effective types of mental health interventions that can be used with refugees remain unclear and require further research [20].

The American Art Therapy Association (AATA) [21] defined art therapy as a multidisciplinary field rooted in the theories of psychology and art conducted by an art therapist. As AATA advises, the main purpose of art therapy is “to improve cognitive and sensorimotor functions, foster self-esteem and self-awareness, cultivate emotional resilience, promote insight, enhance social skills, reduce and resolve conflicts and distress, and advance societal and ecological change” [21].

One of the main theories of art therapy, which focuses on the healing effect of the creative process and its potency in alleviating trauma symptoms, originates from Edith Kramer [22]. Kramer was a painter who conducted art therapy sessions with Friedl Dicker in Terezin concentration camp during World War II to help the children and adults deal with their trauma and despair [22,23]. A previously published stream of research established that PTSD and trauma adversely affect both the physiology and the psychology of the individuals [24]. As Gantt et al. [25] postulated, trauma is a nonverbal problem and after trauma, traumatic memories and emotions remain as “memories without narrative organizations or verbal coding”. Trauma impairs the connection between the rational brain and the emotional mid brain and ultimately causes the individual to re-experience previous trauma [25]. Moreover, considering the flashbacks [25] and “wordless and visual nature” of trauma [26] art therapy is an appropriate intervention method that can abate the ordeal of trauma. It can also reduce anxiety, promote communication of the laden emotional experiences [24,27], and surpass language and cultural barriers greatly experienced by refugees [19]. The positive effect of art therapy on alleviating the symptoms of PTSD with veterans was also established by Schnitzer et al. [28] and Smith [29]. Considering that severe exposure to trauma can adversely affect the verbal memory [26], which may impair daily functioning, it is worth, investigating whether art therapy could be used as an alternative treatment approach rather than merely a palliative intervention with refugees [25]. Furthermore, previous research posits that group art therapy interventions could be more cost-effective [30] and thus cover a greater number of refugees arriving in a new host country [31]. Hence, this review aims to integrate and to summarize the previous research that examined the effect of art therapy interventions on the psychological issues of refugees and to delineate the methodologies used in these studies.

There are various approaches in the field of art therapy with Expressive Arts Therapy (EAT) with Multimodal or Intermodal approaches being the most widely practiced methods [24]. Multimodal approach refers to the view that art therapy should strictly include more than one medium and should use various modalities in order to provide the client with numerous creative opportunities (such as music, movement, visual art, etc.) [24]. EAT capitalizes on the use of art, music, dance/movement, drama, and poetry/writing in a therapeutic setting and uses one or more of these modalities during the therapeutic process.

Visual art encapsulates a variety of mediums [32] and activities such as drawing (with different instruments such as charcoal, paint, pen, and pencil), photography, looking at a well-known piece of art, clay work, sculpting, craft, mask, and collage making [33]. In addition, visual art is one of the most common modalities in expressive art therapy interventions designed for individuals with experience of trauma, depression, and anxiety, as it has been shown to effectively reduce the symptoms of these mental health conditions [33,34]. Avrahami [32] elaborated on the positive effects of visual arts on individuals with different experiences of trauma and reports how different types of mediums, within visual arts, facilitate the healing process of PTSD symptoms. In this review we examine art therapy as an intervention for mental health issues in refuges and concentrate primarily on visual art.

Considering that creative art therapy demands the use of various modalities and mediums to provide options to clients and in order to conduct a review across the studies that use a common art activity, we focused on the research articles that primarily used visual arts in addition to other modalities (e.g., music and dance therapy) during their process of intervention. Unfortunately the number of studies which used one modality (visual arts) in isolation, was scarce. Hence, it was necessary to include the studies that used visual arts in conjunction with other modalities as part of their art therapy interventions.

Visual arts are cost effective, culturally friendly to many ethnicities and nationalities as well as being applicable to a broad age range. Since most individuals have easier access to basic drawing materials such as a pen and paper from early ages, this medium is simple to work with and it does not require experts training (i.e., a professional painter or a musician).

A comprehensive literature search was conducted from three databases: Google Scholar, PubMed, and Cochrane Library of Systematic Review from January 2000 to March 2021. The Boolean operator was used in order to retrieve all the published articles across three databases. Keywords: “refugees” OR “asylum seekers” AND “art therapy”, “refugees” OR “asylum seekers” AND “art therapy intervention”, were used across all databases.

The following inclusion criteria were used to determine which research studies to include in the review. Only peer reviewed articles in English which involved art therapy intervention with refugees or asylum seekers were reviewed. The research studies were included if they examined the mental health symptoms in refugee or asylum seeker populations and used a common method to study them. Therefore, use of visual arts as a primary part of the expressive art therapy intervention process was essential. In addition, a clear indication of the participants’ age, the number of art therapy sessions and mention of the duration of intervention were also among the inclusion criteria.

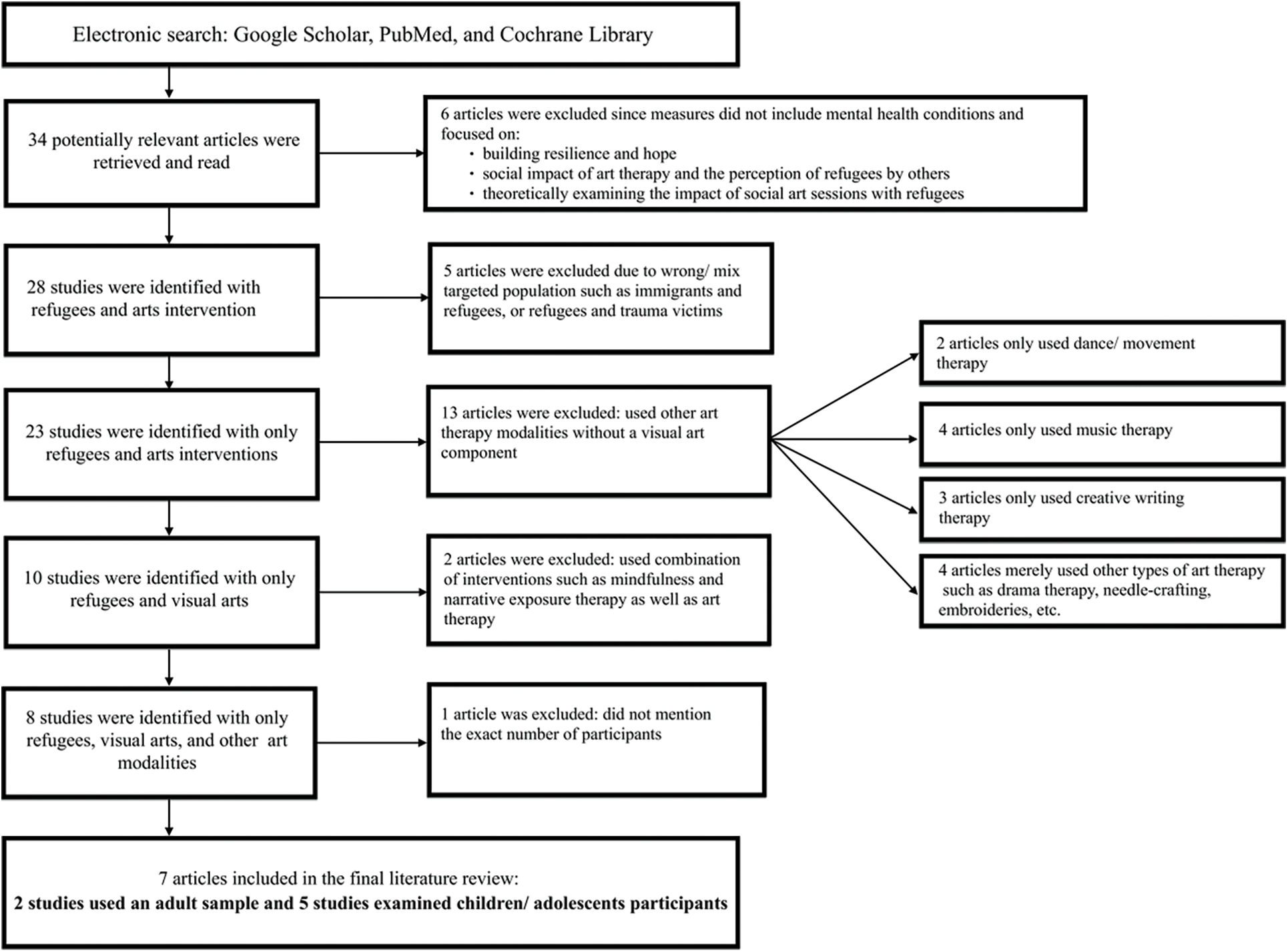

Initially 4,151 articles were retrieved. After using the above inclusion criteria, a review of 450 article abstracts led to full text review of 34 articles, out of which only seven met the inclusion criteria. Fig. 1 provides detailed information on the number of full text article reviews and the screening and exclusion process.

Figure 1: Flow diagram representing the study selection and rationale for article exclusions

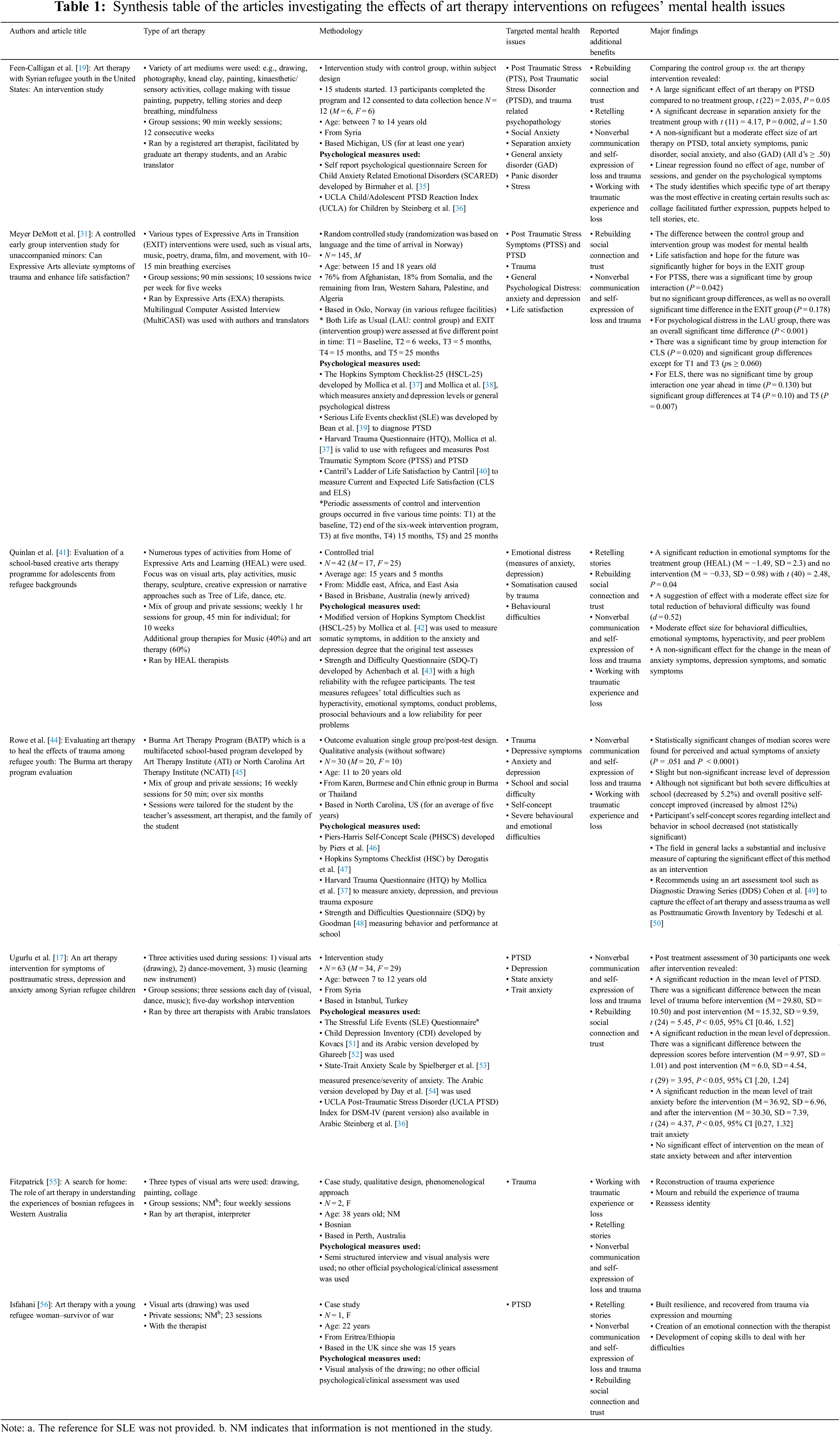

Seven studies were included in our literature review which are shown in Table 1. Table 1 further elaborates on the details of the included journal articles.

From the seven studies reviewed, five examined the mental health symptoms of children/adolescents (below 20 years) and only two focused on adult refugees.

The participants were primarily from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Southeast Asia (Burma), and Europe (Bosnia). The prominent mental health issues among refugees who received art therapy interventions were PTSD and depression, symptoms of anxiety disorders and symptoms of trauma. There is a great level of heterogeneity in the assessment of mental health issues of the participants and a lack of consensus in the effectiveness of art therapy intervention in reducing mental health issues among the refugee participants.

Quinlan et al. [41] concluded that art therapy interventions did not significantly change the depression symptoms of the participants in the treatment group. Rowe et al. [44] reported a non-significant increase in the symptoms of depression. Meyer DeMott et al. [31] did not report changes in depression. Only Ugurlu et al. [17] reported significant reduction in depression by comparing the mean depression scores before and after art therapy. Feen-Calligan et al. [19], Isfahani [56] and Fitzpatrick [55] did not measure depression in their studies.

Quinlan et al. [41] concluded that art therapy interventions did not significantly change the anxiety symptoms of the participants in the treatment group. Meyer DeMott et al. [31] measured psychological distress in their study through using an extended version of HSCL-25, which measures depression and anxiety. They reported a close to significant time by group interaction effect on psychological distress but reported no significant group differences at any point of time. Ugurlu and colleagues [17] measured trait anxiety and state anxiety reported no significant changes in the mean score of their participants’ state anxiety scores before and after art therapy intervention. However, they found a significant reduction in trait anxiety as per participants’ average mean scores post treatment. Feen-Calligan and colleagues [19] reported a significant effect of art therapy on reducing the symptoms of separation anxiety and a moderate effect of art therapy on the participants symptoms of anxiety, panic disorder, and GAD. Feen-Calligan et al. [19] also reported changes in the behavior of the participants in the control group such as building problem-solving and coping skills, as a result of the reduction in the stress levels. Rowe et al. [42] reported a statistically significant changes of median scores for perceived and actual symptoms of anxiety. Fitzpatrick [55] and Isfahani [56] did not measure the mental health issues of their participants (anxiety) with a standardized psychometric tool.

Meyer DeMott et al. [31] reported a significant effect of time by group interaction effect on PTSS of the participants (there was no significant effect of time or group on PTSS). Ugurlu et al. [17] reported that the mean average of participants PTSD scores were statistically reduced post art therapy intervention. Feen-Calligan and colleagues [19] reported a significant effect of art therapy on Post Traumatic Stress (PTS) and a non-significant effect of art therapy on PTSD. Rowe et al. [44], Isfahani [56], Fitzpatrick [55], and Quinlan et al. [41] did not measure PTSD in their studies.

Overall, we found a significant lack of consensus across the seven studies, on the effectiveness of art therapy interventions in alleviating mental health issues among refugee participants.

3.1 Additional Benefits of Art Therapy Commonly Reported across the Seven Studies

We have grouped the additional benefits of art therapy commonly reported across studies: 1) working with traumatic experience or loss, 2) rebuilding social connection and trust, 3) nonverbal communication and self-expression of loss and trauma, and 4) retelling stories.

These additional benefits of art therapy on the refugee populations are consonant with the general benefits of art therapy interventions across populations with different psychological needs [26].

3.1.1 Working with Traumatic Experience or Loss

Art therapy creates a safe, creative space and process for individuals to explore their inner suppressed negative emotions, contemplate on them, or use symbols to draw them [56]. Across the seven studies, four reported that art therapy interventions helped their participants work with their traumatic experience or loss and as a result face some of their painful experiences through drawing, collage making or using other mediums [19,41,44,55]. In a sense, art therapy creates a setting for the refugees to acknowledge and become aware of their emotions. The memory of individuals with the experience of trauma is disturbed with distraught imagery [55] and art therapy through its nonverbal and visual nature allows a symbolic expression that helps to abate the memory of anguish. Working with traumatic experience or loss can occur in the form of acknowledging a sad memory through art, drawing loss with symbols, or listening to someone else’s life event and re-assessing one’s own previous traumatic experience.

3.1.2 Rebuilding Social Connection and Trust

Approximately 70% of the studies in this review conducted group art interventions where participants were either working in groups or were collaborating to complete a shared project. Mostly, the process of creation with the art therapist(s) and other participants who share similar experiences of trauma and forcible displacement, formed a safe environment for the refugees. Which led to positive and social bond formation [17,19,31,41,55,56]. This experience can potentially initiate positive peer relationships outside the art therapy intervention sessions and create a sense of belonging and safety among the group members which are necessary for a “therapeutic outcome” [19]. In addition, the studies in Table 1 imply that receiving attention and being engaged in pleasurable creative activities, with the presence of translators and art therapists, facilitates a sense of trust between the refugee participants and with the therapist(s).

3.1.3 Nonverbal Communication and Self-Expression of Loss and Trauma

All seven studies reported that art therapy helped their participants non-verbally communicate and express their loss and trauma through art therapy interventions. Experiencing trauma is common before refugees arrive in a new country and subsequently struggle to assimilate to the culture and the language of the new environment. The nonverbal nature of art therapy circumvents cultural and language barriers which ultimately allows the participants to feel more in control. As Fitzpatrick [55] explained, the experience of “toxic or disturbing imagery” which occurs as a result of trauma, could be communicated better through art and visual expressions.

In most of the studies, refugees manifested signs of grief and their tribulations via making collages and drawing without verbal articulation. Feen-Calligan and colleagues [19] reported that the use of certain art mediums such as collage making, facilitated self-expression.

Art therapy and being immersed in the creative process allows participants to take a new perspective in exploring and reflecting on what they witnessed or experienced. As Fitzpatrick [55] explained, once the trauma has been expressed symbolically or visually, it allows the individual to change their narratives or the disturbed imagery through art. This outcome was also reported in other studies in Table 1 [19,41,55,56]. In a sense, being engaged in an art activity allows the individual to be present with their current and past feelings and approach painful and suppressed experiences from different perspectives. Moreover, some mediums which were used in the art therapy workshops such as storytelling via collage making also facilitated this process of self-distancing and articulating stories more effectively (e.g., [19]).

This literature review shows that most refugees experience some level of poor mental health, with conditions such as PTSD, anxiety, and MDD most prominent. We identify four fundamental additional benefits of art therapy commonly reported across the seven studies showing positive effects of art therapy intervention mainly with refugee children/adolescents: 1) working with traumatic experience or loss, 2) rebuilding social connection and trust, 3) nonverbal communication and self-expression of loss and trauma, and 4) retelling stories. Conversely, we found a significant a lack of consensus on the effectiveness of art therapy interventions in alleviating mental health issues among refugees. This was in part a consequence of inadequately robust methodologies used across the studies.

This review uncovers the most prominent mental health conditions which have been examined within refugee populations, who received art therapy interventions (mostly children and adolescents, primarily in the MENA region followed by Southeast Asia, and Europe), were PTSD, anxiety, and MDD. Our finding is consistent with the results of Blackmore et al. [57], Turrini et al. [7] and Turrini et al. [18], who also found these three psychological issues to be common among refugees across various ethnicities; these studies also found that the mental illness of refugees remains or could deteriorate further after displacement, due to post-immigration stressors. In a similar vein, Javanbakht et al. [58], Peconga et al. [59], and Ugurlu et al. [17] found that these three psychological conditions were prevalent with Syrian refugees specifically. However, whilst the findings are directionally consistent, there is significant variability in the estimated prevalence of mental health issues across studies due to the significant heterogeneity in methodology and a vast reliance on self-report measures [6] used in evaluating the psychological conditions of refugees where language and cultural barriers existed [4,41].

In our view, the emerging additional benefits of art therapy which were commonly reported across the seven studies are inter-connected, particularly working with traumatic experience or loss and nonverbal communication and self-expression of loss and trauma. The symbolic imagery that comes up in the art work of refugees is a nonverbal reflection of internal experiences of trauma [55]. We believe that in line with the findings of Quinlan et al. [41], Fitzpatrick [55], and Schnitzer et al. [28] creative approaches could be a great starting point to promote the verbal articulation of trauma. The positive effects of visual arts on PTSD, were also reported in the systematic review conducted by Schnitzer et al. [60] on adult trauma survivors. The four additional benefits of art therapy reported in our review are also consistent with the findings of Avrahami [32] who reported the positive effect of visual art therapy on the treatment of PTSD symptoms via helping with “working on traumatic memories, the process of symbolization-integration, and containment, transference, and countertransference”. Avrahami [32] explained that the positive effect of art therapy is seen across various age groups and with different types of trauma experiences.

Another emerging, commonly reported additional benefits of art therapy that we found is rebuilding social connection and trust. This is formed during art therapy sessions as a result of the positive rapport developed between the participants themselves and with the therapist. As Herman-Lewis [61] described, the core experiences of psychological trauma are disempowerment and disconnection from others. Hence, it is vital for any intervention to intend to achieve establishing safety and re-connecting with life and others. Thus, the facilitation role of art therapists is critical given the creation of a safe environment could guide the clients towards a deeper engagement with the art materials [33,62]. In keeping with Li et al. [5], we believe it is vital for refugees to gain certain skills, through the appropriate interventions, to be able to manage psychosocial obstacles post-settlement. As Ugurlu et al. [17] explained, skills such as building resilience and problem solving could be gained through the benefits of art therapy interventions since this intervention allows the individual to acknowledge their unprocessed emotions via the process of art making and communicating in the group. This finding is in consonant with the findings of Bolwerk et al. [63] who reported positive effects of art therapy and particularly building resilience, in their fMRI study with post-retirement adult participants. Feen-Calligan et al. [19] also found participants developed coping skills such as problem-solving skills or calming skills. In addition to rebuilding social connections, the telling of stories is another important commonly reported additional benefit of art therapy that we find in our review. Stories emerge in artwork through a mixture of marks, images, and colours [56]. Refugees may choose to tell a story through the art making process. Despite re-experiencing intense emotional events, refugees permit their story to be told and shared through artwork giving rise to awareness of their experience.

Refugees with severe experience of trauma, confuse the timing of the painful events that happened in the past, as a negative event occurring now or in the future. The presence of “involuntary flashbacks” as well as the severe consistent experience of trauma after the traumatic event, is best explained through the dual representation theory of PTSD by Brewin et al. [64]. In a sense, “dissociation at the time of trauma” leads the refugees to constantly feel that the painful events are happening now (van der Kolk, 1987, as cited in [25]). In our opinion and in line with the findings of Avrahami [32] focusing on retelling stories through art, could help refugees get a real perspective of the chronological order of the events and thus make the painful events of their trauma a past experience.

Overall, there is value in using art therapy interventions with refugee populations to improve their mental health. However, the significant heterogeneity in methodology results in inconsistency in findings across studies. We believe that the absence of consistent and valid psychological and clinical measures used both in assessing the mental health conditions of refugees and lack of quantifiable measures to gauge the effect of art therapy post-treatment is the main reason behind the inconsistent findings of the studies in this review.

Table 1 shows that out of seven reviewed studies only five used psychometric tools to assess the psychological issues of refugees, out of which two used the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) [31,44] and three used two versions of the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL and HSCL-25) [31,41,44] to measure PTSD, MDD, and anxiety symptoms of the participants. Considering findings on the validity of HTQ and HSCL in assessing the prevalence of PTSD, anxiety, and MDD with refugees of various ethnicities [65,66], it is important to develop more accurate psychometric tools. These should account for the cultural context of refugees in order to increase accuracy in measuring the prevalence rate of mental health issues among refugees.

Our findings are in line with Feen-Calligan et al. [19], Meyer DeMott et al. [31], Quilan et al. [41], Rowe et al. [44] who also reported a scarcity of research that uses consistent, standardised, and quantifiable assessment tools to measure the effects of art therapy interventions and how enduring they are with refugee populations. Our review reveals additional methodological limitations across the studies in the field of art therapy including limited sample sizes, lack of Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) studies, and finally a lack of periodic and longitudinal follow up assessment to evaluate the effectiveness of art therapy interventions with refugee populations. In the same vein, a need to improve the scientific quality of the research trials in the creative arts field with general populations (not refugees), has also been reported by Baker et al. [67] and Schnitzer et al. [60].

Our review does have several key limitations. Firstly, we focused on research that used visual art therapy as part of the intervention process in combination with other modalities such as dance, movement, or music therapy. Our rationale for this decision was to be able to conduct a systematic review of studies that used visual arts which is a common modality encapsulating a range of various art activities (e.g., collage-making, drawing). Hence, further systematic research is needed to tease out the various types of expressive art therapy modalities from each other in order to distinguish and compare how each profession of art therapy and different expressive art therapy modalities can affect the mental health conditions of the refugees. Furthermore, studies that had an exploratory nature in conducting group sessions with refugees or did not aim to measure the effect of art therapy intervention on the psychological issues of refugee’s post-treatment were not included in our review. Our decision to focus on the psychological issues of refugees is driven by the critical need for mental health research and care in this population. Finally, given that most of the existing studies in the field examined children and adolescents refugee participants, our findings may not be generalisable to adult populations (only two of the studies we reviewed included adult samples).

We believe in the future there is a need for a well-designed art therapy intervention with a clear therapeutic agenda which could accelerate the process of healing. A great example is how Feen-Calligan et al. [19] selected specific media and tailored art activities according to the mental health conditions of the refugee children in their study and their therapeutic objectives.

We found that there is a dearth of research on adult refugee populations and how art therapy could help them, despite the high rate of mental health issues among them [57]. Hence, it is important for future research to conduct targeted, well controlled research such as RCTs on the effectiveness of art therapy interventions on adult refugees. Cultural sensitivity when measuring the mental health issues among refugees, is a concern, as Blackmore et al. [4] elaborates, “although many of the diagnostic measures had been widely used in different cultural contexts, none had been specifically developed for refugee populations or cross-cultural use”. One of the short-term solutions to address this issue would be to use an established psychological assessment tools translated to the language of the refugee groups that are proven to be effective with that particular ethnicity. For instance, the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSC and HSCL-25) which was used by some of the studies included in Table 1 [31,41,44] and is validated for refugee populations. They aim to measure both depression and anxiety which was referred to as psychological [31] or emotional distress [41] in the studies. We should take into consideration that developing new or validating existing psychometric instruments in order to more accurately assess the level of mental health issues across refugee populations requires a substantial level of resources, as well as familiarity with the language or dialect, and the culture of the refugees [68]. Moreover, it is essential to update the mental health assessment cut-off scores for the refugee population, considering that most of the assessments and their cut-off scores were created a long time ago and do not take into account world events that may contribute to refugee mental health or wellbeing (e.g., the Syrian war in 2011).

It is also vital to develop robust assessments that have high validity, reliability, and standardization in order to use art therapy interventions with wider refugee populations who are still residing in camps or have been internally displaced with limited access to mental health resources. In addition, it is necessary to examine the enduring effect of art therapy interventions with systematic longitudinal research through various assessment points post-treatment.

Unfortunately, there is a dearth of literature comparing the effectiveness of traditional psychotherapeutic interventions with art therapy. Although researchers such as Campbell and colleagues [69] reported a positive effect of art therapy in conjunction with Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) in alleviating trauma symptoms. In one study Sarid et al. [70] compared the effect of art therapy to Cognitive Behavioral Intervention (CBI) on Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) and portrayed that there are some structural similarities in how both intervention methods utilize sensory stimulants via different means. Art therapy uses art materials or different mediums, and CBI uses the “imagery exposures” to decrease physiological reaction to traumatic memories [70]. According to Sarid et al. [70], one difference between art therapy and CBI is reflected in how changes in processing the traumatic experience or processing the explicit traumatic memories takes place. Art therapy is more systematic and “sequential” since it involves a step-by-step process of sensory engagements with art materials, creation of an art piece, and lastly articulation of a personal interpretation of the final product or process (via a relevant narrative to the traumatic experience) [70]. In contrast, during a CBI session, the therapist asks the individual to recall and remember the traumatic events and simultaneously guides the person to adjust the content of their traumatic image in their mind [70].

We suggest a comparative study of similar modalities or a limited number of expressive modalities (e.g., visual arts and music therapy) as well as comparing art therapy with other evidence based therapeutic intervention methods. In line with the findings of Beauregard [71], we also believe that each art modality because of its inherent attributes could affect the intervention outcomes. Finally, it is imperative to implement and choose a culturally sensitive art therapist and an art medium. Both should be culturally relevant to the refugees’ traditions, gender, and age since the participants’ perception of art and the dominant cultural associations of art making could hinder the intervention process and its effectiveness. Hocoy [72] described the cross-cultural issues in art therapy and points out the importance of the familiarity of the art therapist with their own culture and of their clients’ culture. In a sense, it is crucial for the art therapist to be a culturally sensitive, in order to achieve that, they need to have a clear understanding of the language, the social context of their clients, as well as the historic relationship between the client and the culture they are currently living in (the dominant culture) [72]. Hanania [73] also emphasized on the role of the art therapist and how speaking the language of the client “deepens the therapeutic bond”. The authors further recommend using a culturally informed art therapy medium such as embroideries, a form of narrative art through textile, which has been used with Syrian women refugees [73]. Another example of a culturally pertinent medium used as part of an art intervention with Bosnian refugees is the making of a story quilt or needling, in separate groups of men and women [74]. A well-designed art therapy practice which is tailored according to the refugees’ cultural norms and rituals can accelerate the process of healing and recovering from the anxiety of abandonment and loss.

The implication of our research encapsulates using creative art therapies, if not as an alternative approach to replace the traditional therapeutic methods, but as a starting point in the healing process of traumatized refugees to encourage verbal articulation of the feelings and reduction of mental health symptoms.

Our review which includes seven studies with 298 participants revealed the prominent mental health conditions among refugees namely PTSD, anxiety, and MDD. Unfortunately, these psychological issues could last or deteriorate if the appropriate psychological interventions are not designed to serve the mental health needs of this population. Art therapy interventions could be a great starting point to alleviate symptomatology among refugees. The four additional benefits of art therapy commonly reported across the seven studies on the positive effect of art therapy still need further research to be quantifiably assessed in order to validate their generalizability. However, to our knowledge, so far there has not been a literature review that synthesised the art therapy research with refugees. Hence, this review sheds light on where the research stands in working with this population and pinpoints the opportunities for future investigation. Due to the dearth of research, we believe it is timely for policy makers to invest in conducting systematic research with robust methodologies to help refugee mental health.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2021). Refugee data finder. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/. [Google Scholar]

2. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2021). Refugee camps. https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/camps/. [Google Scholar]

3. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2021). Asylum-seekers. www.unhcr.org/asylum-seekers.html. [Google Scholar]

4. Blackmore, R., Boyle, J. A., Fazel, M., Ranasinha, S., Gray. et al. (2020). The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review and metaanalysis. PLoS Medicine, 17(9). DOI 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li, S. S., Liddell, B. J., Nickerson, A. (2016). The relationship between post-migration stress and psychological disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(9), 1–9. DOI 10.1007/s11920-016-0723-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Posselt, M., McIntyre, H., Ngcanga, M., Lines, T., Procter, N. (2020). The mental health status of asylum seekers in middle- to high-income countries: A synthesis of current global evidence. British Medical Bulletin, 134(1), 4–20. DOI 10.1093/bmb/ldaa010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Turrini, G., Purgato, M., Ballette, F., Nosè, M., Ostuzzi. et al. (2017). Common mental disorders in asylum seekers and refugees: Umbrella review of prevalence and intervention studies. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11(1), 1–14. DOI 10.1186/s13033-017-0156-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bogic, M., Njoku, A., Priebe, S. (2015). Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15(1), 1–41. DOI 10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hynie, M. (2018). The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: A critical review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(5), 297–303. DOI 10.1177/0706743717746666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kaltenbach, E., Schauer, M., Hermenau, K., Elbert, T., Schalinski, I. (2018). Course of mental health in refugees—A one year panel survey. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 352. DOI 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Giacco, D., Laxhman, N., Priebe, S. (2018). Prevalence of and risk factors for mental disorders in refugees. In Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 77, 144–152. DOI 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.11.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Heptinstall, E., Sethna, V., Taylor, E. (2004). PTSD and depression in refugee children. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 13(6), 373–380. DOI 10.1007/s00787-004-0422-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. American Psychological Association (2021). Anxiety. https://www.apa.org/topics/anxiety. [Google Scholar]

14. American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th editionWashington DC: American Psychiatric Association. DOI 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Torres, F. (2020). What is posttraumatic stress disorder? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd. [Google Scholar]

16. Frangou, S., Dima, D., Jogia, J. (2017). Towards person-centered neuroimaging markers for resilience and vulnerability in bipolar disorder. Neuroimage, 145, 230–237. DOI 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ugurlu, N., Akca, L., Acarturk, C. (2016). An art therapy intervention for symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety among Syrian refugee children. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 11(2), 89–102. DOI 10.1080/17450128.2016.1181288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Turrini, G., Purgato, M., Acarturk, C., Anttila, M., Au. et al. (2019). Efficacy and acceptability of psychosocial interventions in asylum seekers and refugees: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 28(4), 376–388. DOI 10.1017/s2045796019000207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Feen-Calligan, H., Grasser, L. R., Debryn, J., Nasser, S., Jackson. et al. (2020). Art therapy with Syrian refugee youth in the United States: An intervention study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 69, 101665. DOI 10.1016/j.aip.2020.101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Tribe, R. H., Sendt, K. V., Tracy, D. K. (2019). A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adult refugees and asylum seekers. Journal of Mental Health, 12, 1–15. DOI 10.1080/09638237.2017.1322182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. American Art Therapy Association (2017). About art therapy. https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy/. [Google Scholar]

22. Junge, M. B. (2016). History of art therapy. In: Gussak, D. E., Rosal, M. L. (Eds.The wiley handbook of art therapy, pp. 7–17. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI 10.1002/9781118306543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wix, L. (2009). Aesthetic empathy in teaching art to children: The work of Friedl Dicker-brandeis in Terezin. Art Therapy, 26(4), 152–158. DOI 10.1080/07421656.2009.10129612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Malchiodi, C. A. (2003). Handbook of art therapy. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

25. Gantt, L., Tinnin, L. W. (2009). Support for a neurobiological view of trauma with implications for art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36(3), 148–153. DOI 10.1016/j.aip.2008.12.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Schouten, K. A., van Hooren, S., Knipscheer, J. W., Kleber, R. J., Hutschemaekers, G. J. (2019). Trauma-focused art therapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 20(1), 114–130. DOI 10.1080/15299732.2018.1502712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Schouten, K. A., de Niet, G. J., Knipscheer, J. W., Kleber, R. J., Hutschemaekers, G. J. (2015). The effectiveness of art therapy in the treatment of traumatized adults: A systematic review on art therapy and trauma. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 16(2), 220–228. DOI 10.1177/1524838014555032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Schnitzer, G., Holttum, S., Huet, V. (2022). “My heart on this bit of paper”: A grounded theory of the mechanisms of change in art therapy for military veterans. Journal of Affective Disorders, 297, 327–337. DOI 10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Smith, A. (2016). A literature review of the therapeutic mechanisms of art therapy for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. International Journal of Art Therapy, 21(2), 66–74. DOI 10.1080/17454832.2016.1170055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Uttley, L., Scope, A., Stevenson, M., Rawdin, A., Buck. et al. (2015). Systematic review and economic modelling of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of art therapy among people with non-psychotic mental health disorders. Health Technology Assessment, 19(18), 1–120. DOI 10.3310/hta19180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Meyer DeMott, M. A., Jakobsen, M., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Heir, T. (2017). A controlled early group intervention study for unaccompanied minors: Can expressive arts alleviate symptoms of trauma and enhance life satisfaction? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 58(6), 510–518. DOI 10.1111/sjop.12395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Avrahami, D. (2006). Visual art therapy’s unique contribution in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorders. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6(4), 5–38. DOI 10.1300/J229v06n04_02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chiang, M., Reid-Varley, W. B., Fan, X. (2019). Creative art therapy for mental illness. Psychiatry Research, 275, 129–136. DOI 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Nan, J. K., Ho, R. T. (2017). Effects of clay art therapy on adults outpatients with major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 217, 237–245. DOI 10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Birmaher, B., Brent, D. A., Chiappetta, L., Bridge, J., Monga, S. et al. (1999). Psychometric properties of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCAREDA replication study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(10), 1230–1236. DOI 10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Steinberg, A. M., Brymer, M. J., Decker, K. B., Pynoos, R. S. (2004). The university of california at Los Angeles post-traumatic stress disorder reaction index. Current Psychiatry Reports, 6(2), 96–100. DOI 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Mollica, R. F., Caspi-Yavin, Y., Bollini, P., Truong, T., Tor, S. et al. (1992). The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire: Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 180(2), 111–116. DOI 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Mollica, R. F., Wyshak, G., de Marnette, D., Tu, B., Yang, T. et al. (1996). Hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL-25Manual for Cambodian, Laotian and Vietnamese versions. Torture, 6(Suppl 1), 35–42. [Google Scholar]

39. Bean, T., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E., Derluyn, I., Spinhoven, P. (2004). Stressful life events (SLEUser’s manual. Oegstgeest: Centrum’45. [Google Scholar]

40. Cantril, H. (1965). The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

41. Quinlan, R., Schweitzer, R. D., Khawaja, N., Griffin, J. (2016). Evaluation of a school-based creative arts therapy program for adolescents from refugee backgrounds. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 47, 72–78. 10.1016/j.aip.2015.09.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Mollica, R. F., Wyshak, G., de Marneffe, D., Khuon, F., Lavelle, J. (1987). Indochinese versions of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25: A screening instrument for the psychiatric care of refugees. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(4), 497–500. DOI 10.1176/ajp.144.4.497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Achenbach, T. M., Becker, A., Döpfner, M., Heiervang, E., Roessner, V. et al. (2008). Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: Research findings, applications, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(3), 251–275. DOI 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01867.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Rowe, C., Watson-Ormond, R., English, L., Rubesin, H., Marshall, A. et al. (2017). Evaluating art therapy to heal the effects of trauma among refugee youth: The Burma art therapy program evaluation. Health Promotion Practice, 18(1), 26–33. DOI 10.1177/1524839915626413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Art Therapy Institute. The newcomer art therapy project. http://www.ncati.org/the-newcomer-art-therapy-project. [Google Scholar]

46. Piers, E. V., Herzberg, D. S. (2009). Piers-harris children’s self-concept scale, 2nd editionTorrance, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

47. Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H., Covi, L. (1974). The hopkins symptom checklist (HSCLA self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19(1), 1–15. DOI 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1337–1345. DOI 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Cohen, B. M., Hammer, J. S., Singer, S. (1988). The diagnostic drawing series: A systematic approach to art therapy evaluation and research. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 15(1), 11–21. DOI 10.1016/0197-4556(88)90048-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Tedeschi, R. G., Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. DOI 10.1007/BF02103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kovacs, M. (1981). Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatrica: International Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(5–6), 305–315. [Google Scholar]

52. Ghareeb, G. A. (1995). Arabic version of the children’s depression inventory: The manual. Cairo, Egypt: Al-Nahda Al-Arabia. [Google Scholar]

53. Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushere, R. E. (1970). Manual for the state trait anxiety inventory (selfevaluation questionnaire). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

54. Day, R. C., Knight, C. W., El-Nakadi, L., Spielberger, C. D., Diaz-Guerrero, R. (1986). Development of an arabic adaptation of the state-trait anxiety inventory for children. In: Spielberger, C. D., Diaz-Guerrero, R. (Eds.Cross-cultural anxiety, vol. 3, pp. 113–123. [Google Scholar]

55. Fitzpatrick, F. (2002). A search for home: The role of art therapy in understanding the experiences of bosnian refugees in Western Australia. Art Therapy, 19(4), 151–158. DOI 10.1080/07421656.2002.10129680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Isfahani, S. N. (2008). Art therapy with a young refugee woman–survivor of war. International Journal of Art Therapy, 13(2), 79–87. DOI 10.1080/17454830802503453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Blackmore, R., Gray, K. M., Boyle, J. A., Fazel, M., Ranasinha, S. et al. (2020). Systematic review and meta-analysis: The prevalence of mental illness in child and adolescent refugees and asylum seekers. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(6), 705–714. DOI 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.11.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Javanbakht, A., Amirsadri, A., Suhaiban, H. A., Alsaud, M. I., Alobaidi, Z. et al. (2019). Prevalence of possible mental disorders in Syrian refugees resettling in the United States screened at primary care. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 21(3), 664–667. DOI 10.1007/s10903-018-0797-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Peconga, E. K., Thøgersen, M. H. (2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety in adult Syrian refugees: What do we know? Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 48(7), 677–687. DOI 10.1177/1403494819882137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Schnitzer, G., Holttum, S., Huet, V. (2021). A systematic literature review of the impact of art therapy upon post-traumatic stress disorder. International Journal of Art Therapy, 26(4), 147–160. DOI 10.1080/17454832.2021.1910719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Herman-Lewis, J. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence-from domestic abuse to political terror. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

62. van Lith, T., Fenner, P., Schofield, M. J. (2009). Toward an understanding of how art making can facilitate mental health recovery. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 8(2), 183–193. DOI 10.5172/jamh.8.2.183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Bolwerk, A., Mack-Andrick, J., Lang, F. R., Dörfler, A., Maihöfner, C. (2014). How art changes your brain: Differential effects of visual art production and cognitive art evaluation on functional brain connectivity. PLoS One, 9(7), e101035. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Brewin, C. R., Dalgleish, T., Joseph, S. (1996). A dual representation theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Review, 103(4), 670–686. DOI 10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.07.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Kleijn, W. C., Hovens, J. E., Rodenburg, J. J. (2001). Posttraumatic stress symptoms in refugees: Assessments with the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 in different languages. Psychological Reports, 88(2), 527–532. DOI 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.2.527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Ventevogel, P., de Vries, G., Scholte, W. F., Shinwari, N. R., Faiz, H. et al. (2007). Properties of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) and the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20) as screening instruments used in primary care in Afghanistan. Social Ssychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(4), 328–335. DOI 10.1007/s00127-007-0161-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Baker, F. A., Metcalf, O., Varker, T., O’Donnell, M. (2018). A systematic review of the efficacy of creative arts therapies in the treatment of adults with PTSD. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10(6), 643–651. DOI 10.1037/tra0000353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Ibrahim, H., Ertl, V., Catani, C., Ismail, A. A., Neuner, F. (2018). The validity of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) as screening instrument with Kurdish and Arab displaced populations living in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–8. DOI 10.1186/s12888-018-1839-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Campbell, M., Decker, K. P., Kruk, K., Deaver, S. P. (2016). Art therapy and cognitive processing therapy for combat-related PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. Art Therapy, 33(4), 169–177. DOI 10.1080/07421656.2016.1226643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Sarid, O., Huss, E. (2010). Trauma and acute stress disorder: A comparison between cognitive behavioral intervention and art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37(1), 8–12. DOI 10.1016/j.aip.2009.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Beauregard, C. (2014). Effects of classroom-based creative expression programmes on children’s well-being. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(3), 269–277. DOI 10.1016/j.aip.2014.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Hocoy, D. (2002). Cross-cultural issues in art therapy. Art Therapy, 19(4), 141–145. DOI 10.1080/07421656.2002.10129683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Hanania, A. (2018). A proposal for culturally informed art therapy with Syrian refugee women: The potential for trauma expression through embroidery (Une proposition d’art-thérapie adaptée à la culture de femmes réfugiées syriennes : Le potentiel de la broderie pour l’expression du traumatisme). Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 31(1), 33–42. DOI 10.1080/08322473.2017.1378516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Baker, B. A. (2006). Art speaks in healing survivors of war. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 12(1–2), 183–198. DOI 10.1300/J146v12n01_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools