Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Developing a brief measure of mental flexibility for South Africa

1 Learning & Talent Development, Public Institution, Pretoria, 0002, South Africa

2 Industrial Psychology and People Management, College of Business and Economics, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2006, South Africa

3 Research, Peter Berry Consultancy, Sydney, NSW 2060, Australia

4 Centre for Effective Living, Gordon, NSW 2072, Australia

* Corresponding Author: Chris T. G. Jacobs. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(4), 441-450. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.067167

Received 01 August 2024; Accepted 14 April 2025; Issue published 17 August 2025

Abstract

This study aimed to confirm the hierarchical factor structure and the criterion validity of the Brief Mental Flexibility Questionnaire (BMFQ) in the South African context. Three hundred and eighty-five employees from a public institution in South Africa participated in the study. Confirmatory factor analysis affirmed the structural validity of the measure, comprising a general factor of mental flexibility and six distinct processes consistent with acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): cognitive, affective, perceptual, attentional, motivational, and behavioral flexibility. Multiple regression analysis revealed differential predictive weights of these dimensions for general mental health, with cognitive flexibility as the primary predictor. Motivational flexibility emerged as the strongest predictor of adaptive performance. The BMFQ offers practitioners the ability to measure an individual’s overall mental flexibility score alongside specific flexibility dimensions, enabling targeted interventions, employee comparisons, and organisational trend analysis.Keywords

People reporting to work bring a context that shapes their lives and spills into the workplace. Extensive research indicates that improvements in employee well-being increase productivity, profitability, and customer loyalty and reduce staff turnover (Krekel et al., 2019). Psychological flexibility can buffer the effects of stress on psychological and physical health by promoting adaptive cognitive and emotional processes, such as acceptance of setbacks and valued living, thus positively impacting individuals’ well-being and effectiveness in the workplace (Ramaci et al., 2019; Gloster et al., 2020). To optimise performance, organisations must prioritise understanding and supporting workforce mental well-being by employing measures that provide valid and reliable insights for this purpose. Concise, reliable, and valid measures of mental flexibility suitable for emerging country contexts, such as South Africa, have been lacking.

Psychological flexibility in the workplace

Psychological flexibility, the objective of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), offers a way to respond to distress associated with disruptive work-related situations, such as changes in how work is performed (Bond & Bunce, 2003; Bond & Flaxman, 2006; Bond et al., 2008; Hayes et al., 2006). In the ACT framework, the emphasis is not on eradicating the symptoms associated with distress, but rather on finding alternatives to current rigid responses while pursuing valued actions (Hayes et al., 2012). Psychological flexibility is comprised of six therapeutic processes with the following descriptions (Hayes et al., 2012):

• Defusion: Creating distance from thoughts and perceptions, viewing them as separate from oneself, and reducing their impact on behaviour.

• Acceptance: Embracing thoughts and feelings without trying to change them, allowing oneself to experience emotions fully without resistance.

• Self as context: Understanding that one’s identity is more than just thoughts and feelings, recognising the self as a stable perspective from which experiences are viewed.

• Attention to the present moment: Maintaining a mindful awareness of the current moment, focusing on the here and now rather than being preoccupied with past or future events.

• Values: Clarifying what is truly important and meaningful, and using these values as a guide for decisions.

• Committed action: Taking concrete steps toward goals that align with one’s values, even in the face of obstacles or discomfort.

Monnapula-Mazabane and Petersen (2023) elucidate the detrimental influence of widespread stigmas surrounding psychological health in South Africa, resulting in individuals and families addressing such issues in secrecy or not at all. Referring to ‘psychological flexibility’ may thus evoke scepticism and defensiveness in the South African workplace, which is why we use the term ‘mental flexibility’ for our instrument. Instead of employing the traditional six processes of ACT, the terms cognitive (defusion), affective (acceptance), perceptual (self as context), attentional (attention to the present moment), motivational (values), and behavioural flexibility (committed action) were adapted from Hayes et al.’s (2020) conceptualisation.

Existing measures of psychological flexibility

Several measures exist for evaluating psychological flexibility, with the revised Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) and its original version being the most widely used in studies assessing the effectiveness of ACT interventions (Rogge et al., 2019). However, the AAQ and AAQ-II have faced criticism for low discriminative validity, as psychological flexibility demonstrates a high correlation with psychological distress, suggesting the scale may primarily measure broader functional impairment (Tyndall et al., 2019). Consequently, a one-dimensional representation of the construct may fail to capture the complexity of psychological flexibility.

Multi-dimensional measures may provide a more comprehensive understanding of psychological flexibility. The Comprehensive Assessment of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Processes (CompACT) (Francis et al., 2016) enhances nuance by clustering the six ACT processes into three overarching dimensions: openness to experience, behavioural awareness, and valued action. However, some items in the CompACT require reverse scoring, which can undermine the methodological rigour of the measure by introducing unintended loadings on unrelated factors, thereby increasing measurement error (Dalal & Carter, 2015). A psychometric comparison by Ong et al. (2020) indicated that the CompACT displayed poor structural validity. Furthermore, measurement precision at the lower level of the construct is lost by clustering the dimensions into three rather than six processes (Rogge et al., 2019).

Rogge et al. (2019) argue that multidimensional measures of psychological flexibility offer a more discriminative assessment and greater predictive utility, as exemplified by their Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory (MPFI). Rolffs et al. (2018) conducted an in-depth review of existing measures to develop the MPFI, which evaluates the six ACT processes alongside their opposites to assess psychological inflexibility, resulting in 12 distinct scales. However, the MPFI’s reliance on double-barrelled questions and metaphorical or abstract wording may pose interpretive challenges for non-native English speakers, particularly in South Africa. Additionally, a study by Thomas et al. (2021) found that the six ACT processes account for limited variance in the MPFI items and offer minimal predictive utility beyond the general factor of psychological flexibility in relation to health anxiety and depression. Consequently, Thomas et al. (2021) recommended either shortening the measure to focus solely on the general psychological flexibility factor or refining its subscales to enhance incremental validity.

Hayes et al. (2020) underscore the necessity of advancing research in psychological flexibility by enhancing existing measures rather than relying exclusively on a limited set of tools. In line with this, the BMFQ was developed for the South African context to provide a concise, efficient, and psychometrically robust measure of psychological flexibility, supporting the use and applicability of such measures in the region (see Van Lill & Van Lill, 2020). The BMFQ measures both a general dimension of mental flexibility and six distinct flexibility processes, namely cognitive, affective, perceptual, attentional, motivational, and behavioural flexibility.

General mental health as an outcome of psychological flexibility

While psychological flexibility has been linked to various psychological constructs, further investigation is required to understand the specific mechanisms driving these associations (Hochard et al., 2021). For instance, Villatte et al. (2016) demonstrated in an experimental study that interventions targeting acceptance and defusion processes effectively reduced symptom severity, whereas those focused on values-based activation and behavioural commitment significantly enhanced quality of life. These findings highlight the need for measures that can capture the nuance of each ACT process underlying psychological flexibility to better inform interventions. Building on this, the investigation focuses on how different flexibility processes impact general mental health (symptoms related to depression, anxiety, social dysfunction, and loss of confidence), aiming to clarify their distinct contributions to overall well-being.

Adaptive performance as an outcome of psychological flexibility

Adaptive performance involves employees demonstrating the capability to cope with and respond effectively to crises or uncertainty (Carpini et al., 2017; Pulakos et al., 2000). It also encompasses employees’ flexibility in handling novelty and collaborating with colleagues who hold diverse viewpoints (Pulakos et al., 2000). Adaptive performance reflects behaviours associated with effectively adjusting to changing work circumstances and is an opportune terrain for investigating the impact of six ACT processes. However, existing literature concerning the link between psychological flexibility and adaptive performance is sparse. Therefore, there is merit in investigating the individual impact of each distinct ACT process on work-related outcomes, such as adaptive performance.

The current study aimed to develop a concise, efficient, and psychometrically robust measure of psychological flexibility for the South African context and determine its relation to well-being and adaptive performance. To achieve this, we formulated the following hypotheses to examine the BMFQ’s factor structure and predictive utility.

Hypothesis 1: A general factor of mental flexibility can be extracted from the BMFQ items, independent of the covariance that the six processes explain in the same items.

Hypothesis 2: The six mental flexibility domains positively affect general mental health but differ in relative predictive weights for general mental health.

Hypothesis 3: The six psychological flexibility processes positively affect adaptive performance but differ in relative predictive weights for adaptive performance.

A census sampling strategy was used to obtain 385 employees from a South African public service institution. The average age of employees was 43.95 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 9.31 years. The participants self-identified their race as follows: 51% black African (n = 198), 32% white (n = 122), 11% coloured (individuals of mixed ancestry; n = 41), and 6% Indian/Asian (n = 24). The sample consisted of more participants who self-identified as women (n = 284; 71%), with 114 (29%) self-identifying as men. In terms of job roles, most of the sample comprised team members (n = 218; 56%), followed by managers (n = 93; 24%), specialists (n = 66; 17%), and executives (n = 9; 2%)

Research design and item development of BMFQ

A cross-sectional survey design facilitated the development and validation of the newly created BMFQ. This quantitative study made use of three instruments, the BMFQ, the General Health Questionnaire, and the Individual Work Performance Review, which are detailed below.

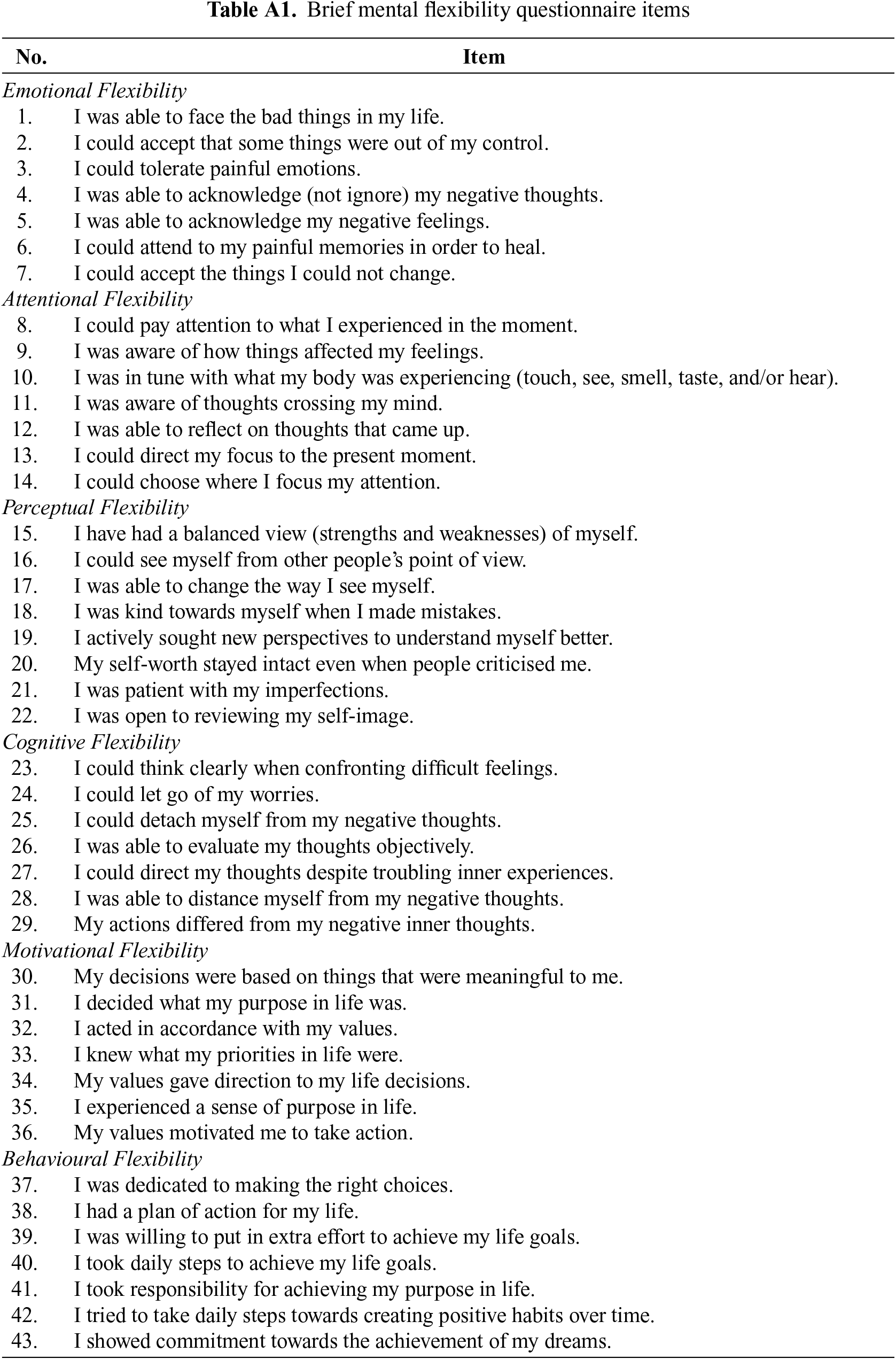

The items for the BMFQ were developed through a collaborative process involving four senior researchers, who worked together to ensure clarity and precision in item formulation. Eight registered psychologists specialising in psychometrics in the South African work context performed an item-sort exercise to evaluate the items, and the outcomes were employed to calculate substantive validity coefficients. The item-sort exercises adhered to the guidelines of Anderson and Gerbing (1991). Following the recommendations of Howard and Melloy (2016), thresholds were applied to modify or, in severe cases, eliminate items displaying low substantive validity. The final iteration of the BMFQ comprised 43 items distributed across six subscales (see Appendix A for items): Emotional Flexibility (7 items), Attentional Flexibility (7 items), Perceptual Flexibility (8 items), Cognitive Flexibility (7 items), Motivational Flexibility (7 items), and Behavioural Flexibility (7 items). Items in the BMFQ are freely available if scientists and/or practitioners share the anonymous data they gather with the instrument’s developers.

The BMFQ directs participants to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with each item as it relates to the past four weeks, presented as statements, utilising a five-point Likert-type scale spanning “Disagree” (1) to “Very much agree” (5). To facilitate a nuanced interpretation of numeric values between the extreme points, the approach proposed by Casper et al. (2020) was employed, with the ratings being “Somewhat disagree” (2), “Neither agree nor disagree” (3), and “Moderately agree” (4). The internal consistency reliability of all dimensions within the BMFQ was satisfactory (α and ω ≥ 0.87).

The 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) (Goldberg, 1978) is commonly employed in occupational health research to assess general mental well-being (Hardy et al., 2003). Ratings are on a five-point scale ranging from “Never” to “Always”. Elevated scores on the GHQ indicate heightened levels of psychological distress.

The Adaptive Performance Scale of the Individual Work Performance Review (IWPR) (Van Lill & Taylor, 2022) was utilised to determine employees’ self-perceived behaviour in coping with workplace stressors. Its five-point behaviour frequency scale ranges from “Never demonstrated” to “Always demonstrated”.

The Department of Industrial Psychology and People Management’s Research Ethics Committee members at the University of Johannesburg (reference number: IPPM-2022-608) approved the study, and consent was obtained from the participating employer organisations. Individual participants also provided informed consent after being briefed on the nature of the research, its voluntary nature, and the exclusive use of their data for research purposes. Data collection was conducted via Qualtrics, a licensed online survey platform, enabling participants to complete the questionnaires securely.

The study’s first objective was to inspect the hierarchical structure of the constructs measured by each BMFQ subscale and the presence of a general Mental flexibility factor. The data analysis employed Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using Version 0.6–8 of the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012; Rosseel & Jorgensen, 2021) in R (R Core Team, 2016). First, the inter-factor correlations among the six subscales were examined, followed by the hierarchical factor structure of the overall Mental flexibility factor. Adhering to the guidelines proposed by Credé and Harms (2015), the plausibility of alternative models, including hierarchical factor models, was explored. The bifactor model underwent analysis of bifactor statistical indices to assess whether unidimensional models more accurately represented the structure of the six factors (Reise et al., 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2016), namely cognitive, affective, perceptual, attentional, motivational, and behavioural flexibility.

Mardia’s multivariate skewness and kurtosis coefficients were 247,545.10 (p < 0.001) and 101.60 (p < 0.001), signalling a non-normal multivariate distribution of the data. CFA employing robust maximum likelihood (MLM) estimation was used due to the moderate sample size (n = 398), the utilisation of rating scales with five numerical categories (see Rhemtulla et al., 2012), and the breach of multivariate normality assumptions (see Bandalos, 2014; Satorra & Bentler, 1994; Yuan & Bentler, 1998). Model–data fit of the CFA models underwent evaluation using the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Brown, 2015; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Adequate fit was defined by RMSEA and SRMR values ≤ 0.08 (see Brown, 2015; Browne & Cudeck, 1992) and CFI and TLI values ≥ 0.90 (see Brown, 2015; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Notably, even when CFIs indicate a marginally good fit (CFI and TLI in the range of 0.90 to 0.95), models could be considered to have an acceptable fit if other indices (SRMR and RMSEA) also fall within the acceptable range (Brown, 2015).

The second objective of this study was to assess the relative predictive weight of each of the six flexibility factors on both General mental health and Adaptive performance. The interpretation of the relative weight of multiple regression coefficients might be incorrect when multi-collinearity exists between the predictive variables (Nimon & Oswald, 2013). Given that the six ACT processes share a psychological flexibility dimension in the MFPI (Thomas et al., 2021) and are likely to display theoretical overlap, dominance analysis was conducted using Version 2.0-3 of the yhat-package in R (Nimon et al., 2021; Nimon & Oswald, 2013). Dominance analysis (DA) is a method used to assess the relative importance of predictors in multiple regression (Azen & Budescu, 2003). It evaluates importance iteratively by comparing each predictor against every other predictor in the model. A predictor is considered more important or dominant when it consistently contributes more to the prediction of the criterion across all possible pairwise comparisons. This analysis provided insights into the relative weight of each flexibility factor as a predictor of General mental health and Adaptive performance.

Descriptive and Reliability Statistics

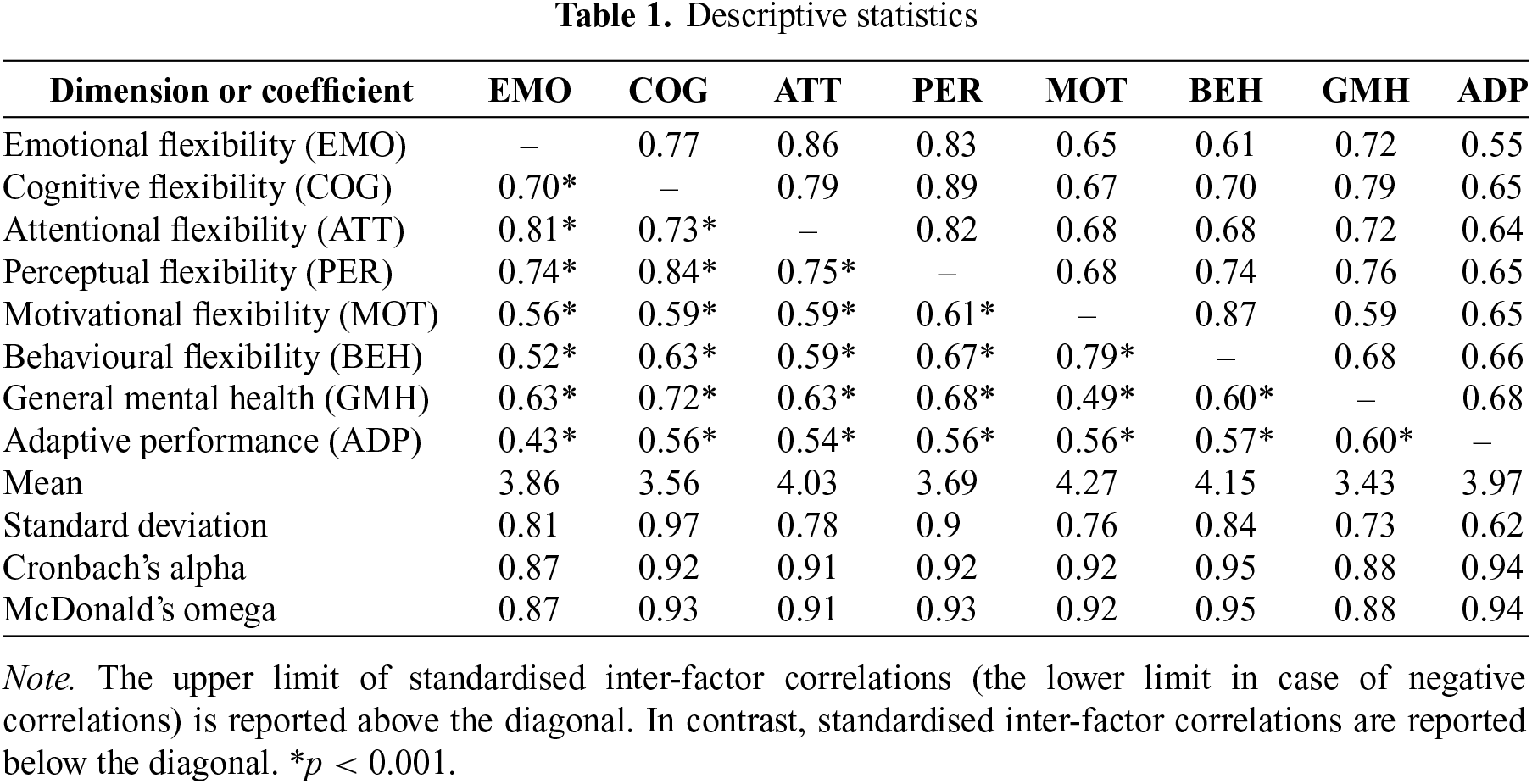

Table 1 presents the mean item score, SD, and reliability estimates of alpha and omega and standardised inter-factor correlations between the latent variables. The inter-factor correlations were derived from an oblique lower-order confirmatory factor model. The model’s absolute and parsimony-corrected fit statistics were deemed satisfactory: χ2 [df] = 4831.84 [2317]; CFI = 0.84; TLI = 0.83; SRMR = 0.07; and RMSEA = 0.06 [0.06; 0.06] (see Brown, 2015; Hu & Bentler, 1999). However, the comparative fit appeared less desirable, which could be attributable to model complexity stemming from the specified number of parameters. Interpreting the inter-factor correlations, shown in Table 1, was deemed appropriate.

The lower-diagonal inter-factor correlations revealed the anticipated correlations among the six Mental flexibility factors. Additionally, the factors exhibited the expected positive correlations with General mental health and Adaptive performance. The magnitude of the inter-factor correlations between the Mental flexibility factors implied the existence of a general Mental flexibility factor.

77% of the inter-factor correlations among the six Mental flexibility factors had an upper limit below the 0.80 cut-off value, as recommended by Rönkkö and Cho (2022), indicating that the majority demonstrated adequate discriminant validity (refer to Table 1). Rönkkö and Cho (2022) categorise inter-factor correlations of 0.80 ≤ UL < 0.90 as marginally problematic. According to this criterion, 33% of the upper limit correlations of the Mental flexibility factors were marginally problematic regarding discriminant validity, but did not present a grave concern.

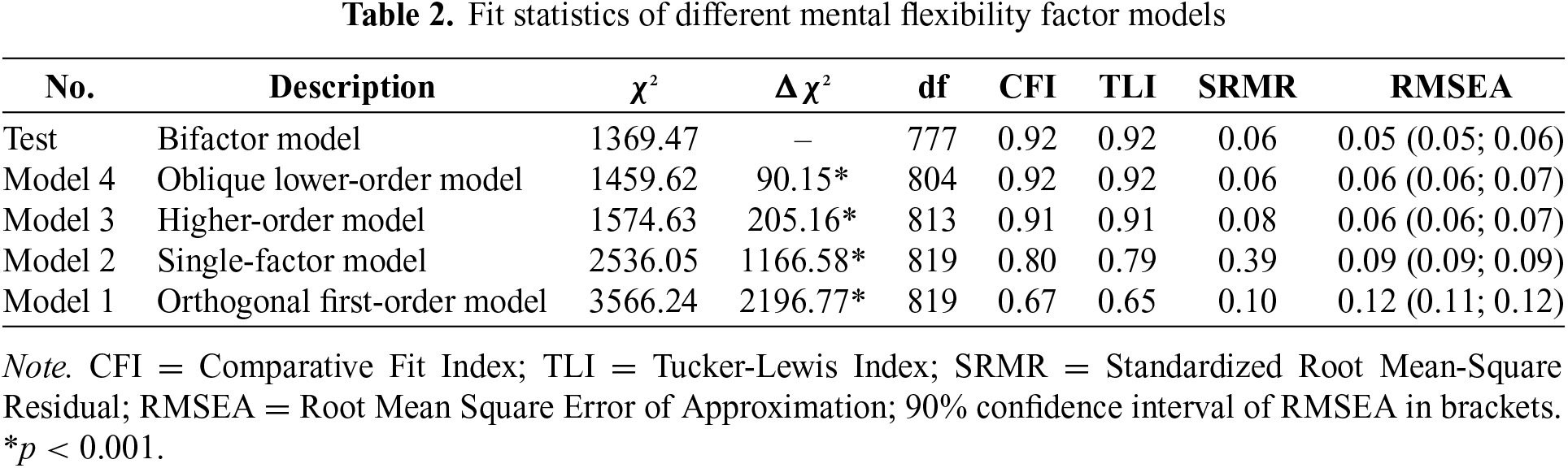

The inter-factor correlations between the six factors suggested the presence of a general factor and, consequently, a hierarchical structure in the data. Therefore, we examined different models to confirm a bi-factor model of mental flexibility. The model–data fit of the various factor models specified is outlined in Table 2.

Structural validity of the BMFQ

The CFI, TLI, SRMR, and RMSEA values indicated poor model–data fit for the first-order and single-factor models. However, an acceptable model-data fit was obtained for an oblique lower-order factor, higher-order factor, and bifactor model, implying the existence of a hierarchical structure in the data. The bifactor models seemed to best fit the data, thereby providing initial support for Hypothesis 1.

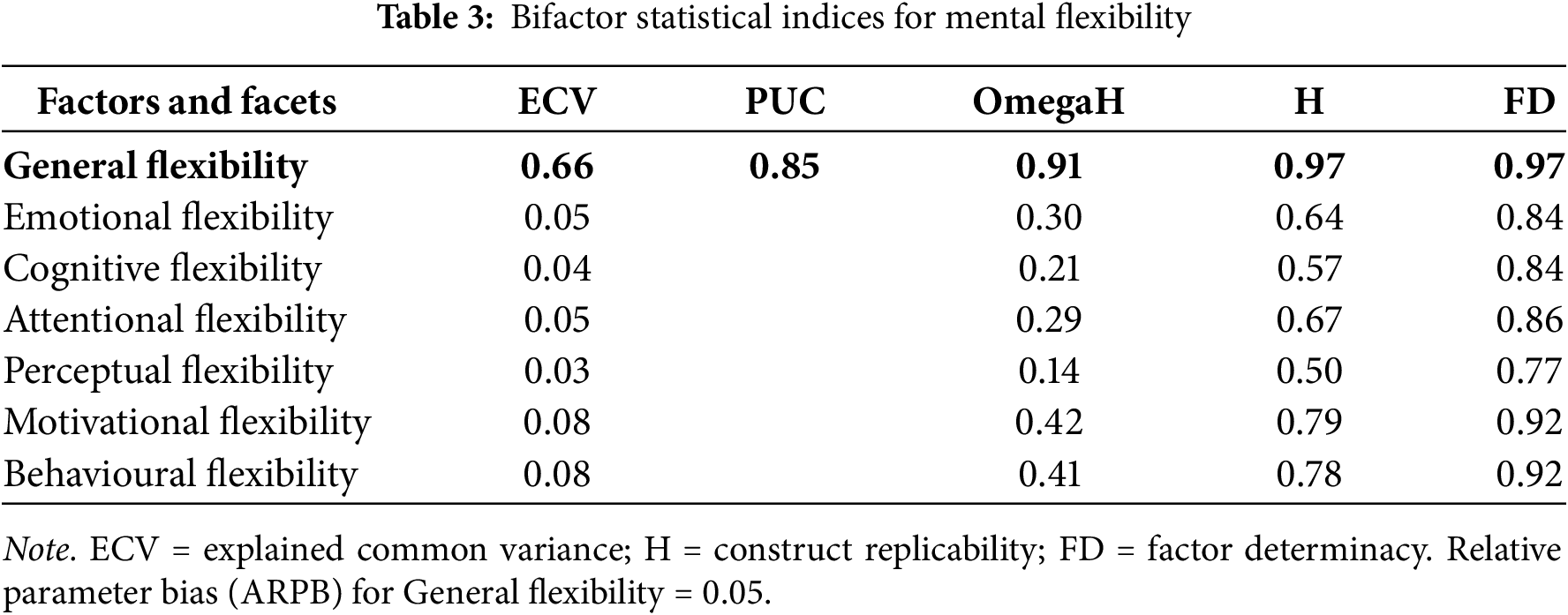

Bonifay et al. (2017) note that the higher fit indices of bifactor models compared to other confirmatory factor models could result from overfitting. Rodriguez et al. (2016) recommend assessing practical meaningfulness through bifactor statistical indices, including explained common variance (ECV), coefficient omega-hierarchical (ωh), construct replicability (H), factor determinacy (FD), percentage of uncontaminated correlations (PUC), and relative percentage bias (ARPB), to assess practical meaningfulness of group factors. Group factors were considered plausible when ωh, H, and FD2 exceeded 0.50, 0.70, and 0.70, respectively (see Dueber, 2017; Reise et al., 2013). An ECV greater than 0.70 and a PUC greater than 0.80 indicated unidimensionality (see Reise et al., 2013). An ARPB between 10% and 15% suggested little difference in factor loadings between a single-factor model and the general factor in a bifactor model (see Rodriguez et al., 2016). Bifactor statistical indices were calculated using Version 0.2.0 of the Bifactor Indices Calculator package (Dueber, 2020) in R (R Core Team, 2016). The results are reported in Table 3.

The data supported the existence of a general factor for Mental flexibility. The results suggested a primarily unidimensional model (ARPB = 0.05; PUC = 0.85; and ECV of g = 0.66). While the bifactor statistical indices suggest a predominantly unidimensional model, the upper limit of inter-factor correlations remains within a range that supports sufficient discriminant validity. This allows for the meaningful interpretation of dimensions independently of the strong general factor, thereby providing additional support for Hypothesis 1.

Criterion validity of the BMFQ

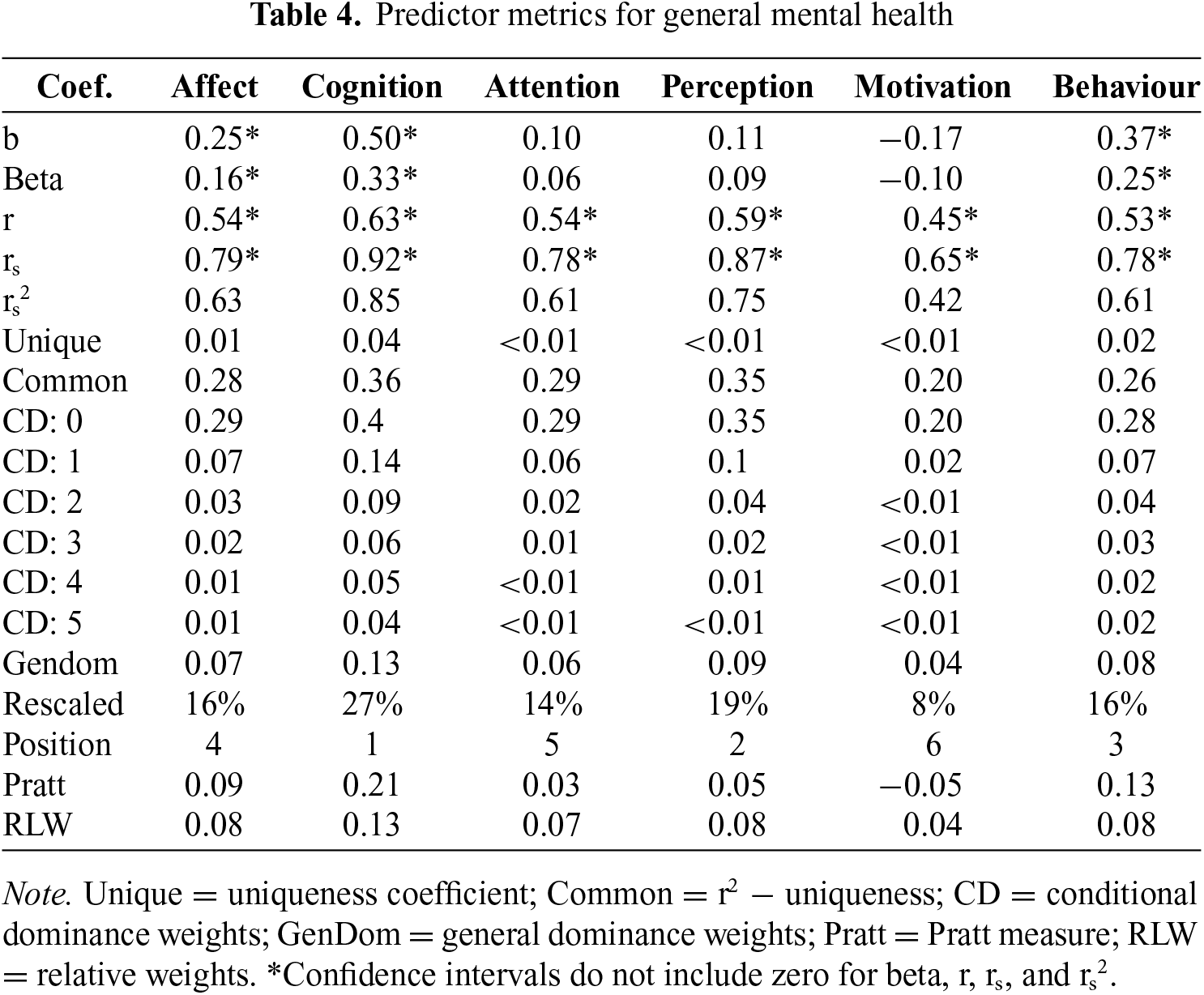

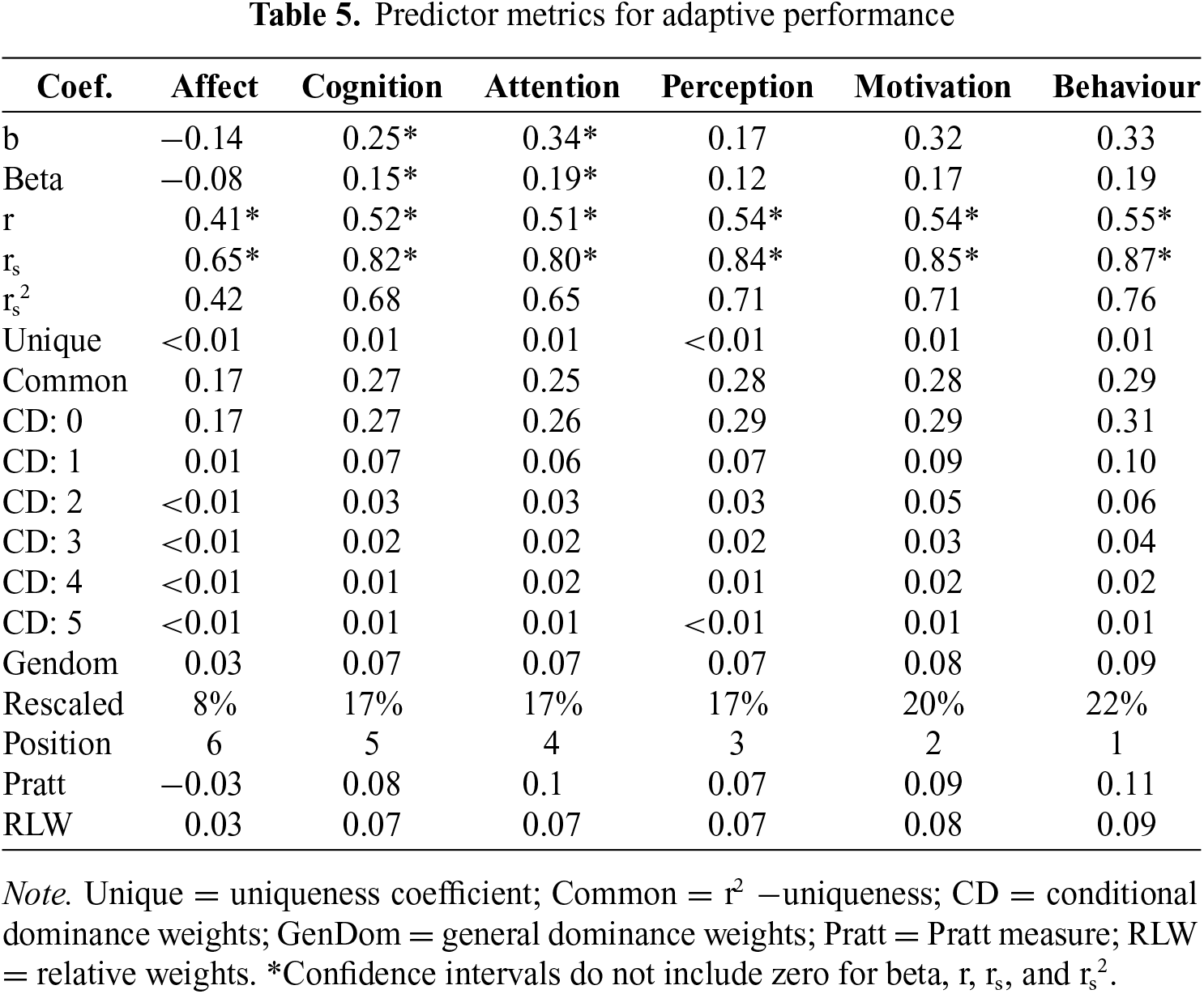

The degree of overlap among the Mental flexibility factors, particularly considering a robust general factor, underscored the importance of conducting a dominance analysis to evaluate the relative predictive weight of each of the six factors impacting General mental health and Adaptive performance. The results of the analysis are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

The results of the dominance analysis indicated that Cognitive flexibility (r = 0.63; GenDom = 27%) was the most important predictor of General mental health, followed by Perceptual flexibility (r = 0.59; GenDom = 19%), Affective flexibility (r = 0.54; GenDom = 16%), Behavioural flexibility (r = 0.53; GenDom = 16%), Attentional flexibility (r = 0.54; GenDom = 14%), and Motivational flexibility (r = 0.45; GenDom = 8%). In support of Hypothesis 2, each of the six factors appeared to be different in relation to General mental health.

According to the general dominance weights, Behavioural flexibility (r = 0.55; GenDom = 22%) appeared to be the most influential predictor of Adaptive performance, followed by Motivational flexibility (r = 0.54; GenDom = 20%). Perceptual flexibility (r = 0.54; GenDom = 17%), Attentional flexibility (r = 0.51; GenDom = 17%), and Cognitive flexibility (r = 0.52; GenDom = 17%) ranked third to fifth, respectively. Affective flexibility (r = 0.41; GenDom = 8%) was the least effective predictor. However, the range of correlations and dominance weights for Adaptive performance are smaller than those reported for General mental health. Hypothesis 3 requires further scrutiny.

The findings suggest that a general factor of mental flexibility can be derived to indicate an overall score on mental flexibility. In addition, each of the six flexibility dimensions demonstrated discriminant validity and meaningful associations with general mental health and adaptive performance, underscoring the relevance of the ACT processes for the South African context.

A general factor of mental flexibility could be extracted from the BMFQ items, distinct from the shared variance explained by the six individual processes. This finding is consistent with Thomas et al.’s (2021) research on the MPFI, with the current South African data validating the existence of a robust general factor of mental flexibility, accounting for 66% of the variance in the BMFQ. However, there was still sufficient discriminant validity to demonstrate that the six processes could be interpreted independently.

The six mental flexibility domains positively influenced general mental health, with varying predictive weights to some extent. When accounting for the intercorrelations between the predictors, cognitive flexibility emerged as the most influential predictor of general mental health, followed by perceptual flexibility, affective flexibility, attentional flexibility, and behavioural flexibility, with motivational flexibility as the weakest predictor. This alludes to the importance of disentangling from uncomfortable inner experiences to improve mental well-being. The findings align with Villatte et al. (2016), who highlighted the central role of cognitive and affective processes in psychological flexibility for effectively reducing symptom severity.

The analysis further indicated that the six psychological flexibility processes positively impact adaptive performance. The relative contributions of each process displayed variations, with behavioural flexibility as the most prominent predictor, followed by motivational flexibility, perceptual flexibility, attentional flexibility, cognitive flexibility, and affective flexibility. While motivational flexibility showed a comparatively modest impact on general mental well-being, its relative importance seems more pronounced in enhancing adaptive performance. Possessing a clear sense of purpose that can guide behaviour implementation appears beneficial for individuals in effectively navigating challenges while maintaining high performance. While the range of correlations and dominance weights for adaptive performance are lower than that for general mental health, the arrangement of the relative weights of the different predictors suggests a meaningful contrast. However, further examination of Hypothesis 3 is necessary to determine the relative importance of each mental flexibility process.

Implications for research and practice

The Brief Mental Flexibility Questionnaire (BMFQ) is a novel measure of psychological flexibility, developed to address workforce mental well-being and productivity within the South African context. The BMFQ offers a unique contribution by enabling the independent interpretation of results for each flexibility subscale. The BMFQ’s value lies in identifying an overall mental flexibility score, offering a concise summary for simple comparison, and differentiation scores on each flexibility dimension, allowing for tailored feedback to individuals and the refinement of developmental strategies. It is feasible to ascertain the extent to which each of the flexibility domains contributes to predicting various psychological outcomes. This approach allows for the evaluation of how each flexibility domain contributes to predicting psychological outcomes, paving the way for targeted interventions that leverage these processes to enhance employee well-being.

Most randomised control trials utilising the ACT framework combine the six processes to create an intervention. However, the BMFQ allows researchers to investigate the impact of interventions aimed at improving the individual processes or possible combinations thereof. Future studies could administer the BMFQ in randomised control trails in South Africa to determine the sensitivity of the assessment to pick up changes in ACT processes given targeted interventions.

Limitations and recommendations

This research was confined to a single parastatal organisation in the South African public service; therefore, the results may not be generalisable to the broader South African population. Additional research in other organisational or contextual settings is necessary to determine whether the findings can be replicated. The present study relied primarily on self-ratings as a single source to explore the relationship between the variables of interest, increasing the risk of method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Future research might benefit from employing supervisor ratings on variables such as performance to establish a more robust model of the criterion validity of the flexibility processes to determine more distal outcomes (Van Lill & Van der Merwe, 2022). Such a study might also demonstrate greater differences in the weight that each process contributes to adaptive performance.

The study’s results indicate that the BMFQ effectively measures the overarching concept of general mental flexibility and constructs derived from the six ACT processes, namely attentional, cognitive, affective, perceptual, motivational, and behavioural flexibility. Given the established link between psychological flexibility and positive mental health outcomes, this measure could serve as a valuable tool for evaluating an individual’s mental flexibility level to identify the specific flexibility domain(s) that may require attention. Each flexibility dimension exhibited substantive associations with general mental health and adaptive performance. Motivational flexibility seems to have a comparatively lesser impact on general mental well-being but takes on greater significance in adaptive performance. Conversely, cognitive flexibility emerged as an important dimension in general mental well-being.

The findings of this study carry important workplace implications regarding the advantages of assessing and improving mental flexibility. The BMFQ demonstrated efficacy in identifying and comparing specific flexibility dimensions associated with the six ACT processes. Thus, it is feasible to ascertain the extent to which each of the flexibility domains contributes to predicting various psychological outcomes. This ability to identify relevant processes paves the way for interventions to proactively harness these processes to improve employee well-being. The study illustrates the importance of mental flexibility and the distinct contributions of its various dimensions to enhancing general mental health and adaptive performance in workplace settings.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the subject matter experts who provided valuable initial feedback on the content validity of the item development process for the BMFQ.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for the research reported in this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Chris T. G. Jacobs, Rinet van Lill, Xander van Lill, Cobus Gerber. Data collection: Chris T. G. Jacobs, Cobus Gerber. Analysis and interpretation of results: Xander van Lill. Draft manuscript preparation: Chris T. G. Jacobs, Rinet van Lill, Xander van Lill, Cobus Gerber. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the participating institutions restrictions.

Ethics Approval: The University of Johannesburg granted ethical clearance for the study (Reference No. IPPM-2020-455).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1991). Predicting the performance of measures in a confirmatory factor analysis with a pretest assessment of their substantive validities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(5), 732–740. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.5.732 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Azen, R., & Budescu, D. V. (2003). The dominance analysis approach for comparing predictors in multiple regression. Psychological Methods, 8(2), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.8.2.129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bandalos, D. L. (2014). Relative performance of categorical diagonally weighted least squares and robust maximum likelihood estimation. Structural Equation Modeling, 21(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.859510 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bond, F. W., & Bunce, D. (2003). The role of acceptance and job control in mental health, job satisfaction, and work performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(6), 1057–1067. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bond, F. W., & Flaxman, P. E. (2006). The ability of psychological flexibility and job control to predict learning, job performance, and mental health. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 26(1–2), 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v26n01_05 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bond, F. W., Flaxman, P. E., & Bunce, D. (2008). The influence of psychological flexibility on work redesign: Mediated moderation of a work reorganization intervention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 645–654. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bonifay, W., Lane, S. P., & Reise, S. P. (2017). Three concerns with applying a bifactor model as a structure of psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(1), 184–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702616657069 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Carpini, J. A., Parker, S. K., & Grin, M. A. (2017). A look back and a leap forward: A review and synthesis of the individual work performance literature. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 825–885. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0151 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Casper, W. C., Edwards, B. D., Wallace, J. C., Landis, R. S., & Fife, D. A. (2020). Selecting response anchors with equal intervals for summated rating scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(4), 390–409. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Credé, M., & Harms, P. D. (2015). 25 years of higher-order confirmatory factor analysis in the organizational sciences: A critical review and development of reporting recommendations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(6), 845–872. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2008 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dalal, D. K., & Carter, N. T. (2015). Consequences of ignoring ideal point items for applied decisions and criterion-related validity estimates. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(3), 483–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-014-9377-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dueber, D. M. (2017). Bifactor indices calculator: A Microsoft Excel-based tool to calculate various indices relevant to bifactor CFA models. Lexington, KY, USA: UKnowledge, https://doi.org/10.13023/edp.tool.01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dueber, D. M. (2020). Bifactor indices calculator. Retrieved from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/BifactorIndicesCalculator/BifactorIndicesCalculator.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Francis, A. W., Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2016). The development and validation of the comprehensive assessment of acceptance and commitment therapy processes (CompACT). Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 5(3), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2016.05.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gloster, A. T., Walder, N., Levin, M. E., Twohig, M. P., & Karekla, M. (2020). The empirical status of acceptance and commitment therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18(1), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.09.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Goldberg, D. (1978). Manual of the general health questionnaire. Slough, UK: National Foundation for Educational Research. [Google Scholar]

Hardy, G. E., Woods, D., & Wall, T. D. (2003). The impact of psychological distress on absence from work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 306–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hayes, S. C., Hofmann, S. G., & Stanton, C. E. (2020). Process-based functional analysis can help behavioral science step up to novel challenges: COVID-19 as an example. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18(10), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.08.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hayes, S. F., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The processes and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Hochard, K. D., Hulbert-Williams, L., Ashcroft, S., & McLoughlin, S. (2021). Acceptance and values clarification versus cognitive restructuring and relaxation: A randomized controlled trial of ultra-brief non-expert-delivered coaching interventions for social resilience. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 21(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.05.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Howard, M. C., & Melloy, R. C. (2016). Evaluating item-sort task methods: The presentation of a new statistical significance formula and methodological best practices. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9404-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Krekel, C., Ward, G., & De Neve, J. E. (2019). Employee wellbeing, productivity, and firm performance: Evidence and case studies. CEP Discussion Paper No. 1605. Dubai, Saudi Aribia: Global Council for Happiness and Wellbeing. Retrieved from: https://s3.amazonaws.com/ghwbpr-2019/UAE/GH19_Ch5.pdf/. [Google Scholar]

Monnapula-Mazabane, P., & Petersen, I. (2023). Mental health stigma experiences among caregivers and service users in South Africa: A qualitative investigation. Current Psychology, 42(11), 9427–9439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02236-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Nimon, K. F., & Oswald, F. L. (2013). Understanding the results of multiple linear regression: Beyond standardized regression coefficients. Organizational Research Methods, 16(4), 650–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428113493929 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nimon, K. F., Oswald, F., & Roberts, J. K. (2021). Interpreting regression effects. Package ‘yhat’. Retrieved from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/yhat/yhat.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Ong, C. W., Pierce, B. G., Petersen, J. M., Barney, J. L., Fruge, J. E. et al. (2020). A psychometric comparison of psychological inflexibility measures: Discriminant validity and item performance. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18(6), 34–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.08.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pulakos, E. D., Arad, S., Donovan, M. A., & Plamondon, K. E. (2000). Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(4), 612–624. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.4.612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

R Core Team (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Reference index. Retrieved from: https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/fullrefman.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Ramaci, T., Bellini, D., Presti, G., & Santisi, G. (2019). Psychological flexibility and mindfulness as predictors of individual outcomes in hospital health workers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Reise, S. P., Bonifay, W. E., & Haviland, M. G. (2013). Scoring and modeling psychological measures in the presence of multidimensionality. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95(2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2012.725437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. É., & Savalei, V. (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 354–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rodriguez, A., Reise, S. P., & Haviland, M. G. (2016). Applying bifactor statistical indices in the evaluation of psychological measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(3), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1089249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rogge, R. D., Daks, J. S., Dubler, B. A., & Saint, K. J. (2019). It’s all about the process: Examining the convergent validity, conceptual coverage, unique predictive validity, and clinical utility of ACT process measures. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 14(1), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.10.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rolffs, J. L., Rogge, R. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2018). Disentangling components of flexibility via the Hexaflex Model: Development and validation of the Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory (MPFI). Assessment, 25(4), 458–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116645905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rosseel, Y., & Jorgensen, T. D. (2021). Latent variable analysis. Package ‘lavaan’. Retrieved from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lavaan/lavaan.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Rönkkö, M., & Cho, E. (2022). An updated guideline for assessing discriminant validity. Organizational Research Methods, 25(1), 6–14. [Google Scholar]

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: Von Eye A., Clogg C. C. (Eds.Latent variables analysis: Applications for developmental research (pp. 399–419Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

Thomas, K., Bardeen, J., Witte, T., Rogers, T., Benfer, N., et al. (2021). An examination of the factor structure of the Multidimensional Psychological Flexibility Inventory. Assessment, 29(8), 1714–1729. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911211024353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tyndall, I., Waldeck, D., Pancani, L., Whelan, R., Roche, B., et al. (2019). The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) as a measure of experiential avoidance: Concerns over discriminant validity. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 12, 278–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.09.005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Lill, X., & Taylor, N. (2022). The validity of five broad generic dimensions of performance in South Africa. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v20i0.1844 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Lill, X., & Van der Merwe, G. (2022). Differences in self- and managerial-ratings on generic performance dimensions. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 48(0), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v48i0.2045 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Lill, X., & Van Lill, R. (2022). Developing a brief acceptance and commitment therapy model for industrial psychologists. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 48(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v48i0.1897 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Villatte, J. L., Vilardaga, R., Villatte, M., Vilardaga, J. C. P., Atkins, D. C., et al. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy modules: Differential impact on treatment processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77(2), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Yuan, K. H., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Normal theory based test statistics in structural equation modeling. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 51(2), 289–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1998.tb00682.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools